Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Research on Deformation Mechanism of Rolled AZ31B Magnesium Alloy during Tension by VPSC Model Computational Simulation

1 School of Applied Science, Taiyuan University of Science and Technology, Taiyuan, 030024, China

2 School of Materials Science and Engineering, Taiyuan University of Science and Technology, Taiyuan, 030024, China

* Corresponding Author: Jinbao Lin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 17 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072495

Received 28 August 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

This work investigates the effects of deformation mechanisms on the mechanical properties and anisotropy of rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy under uniaxial tension, combining experimental characterization with Visco-Plastic Self Consistent (VPSC) modeling. The research focuses particularly on anisotropic mechanical responses along transverse direction (TD) and rolling direction (RD). Experimental measurements and computational simulations consistently demonstrate that prismatic <a> slip activation significantly reduces the strain hardening rate during the initial stage of tensile deformation. By suppressing the activation of specific deformation mechanisms along RD and TD, the tensile mechanical behavior of the magnesium alloy was further investigated. The results show that basal <a> slip has the greatest impact during the initial deformation stage and basal <a> slip activation substantially affects the deformation behavior of AZ31B alloy, causing marked decreases in both yield and tensile strength along RD. Under tensile loading along TD, prismatic <a> slip not only exhibits a synergistic effect on yield strength, but also dominants work hardening during the initial plastic deformation.Keywords

Magnesium alloy, a lightweight material, combines low density with outstanding electrical and thermal conductivity, exceptional stiffness, excellent recyclability, and high specific strength [1–4]. They are widely used in aerospace, electronics and automotive industries. During plastic deformation, hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure of magnesium alloys restricts the number of available slip [5], resulting in poor formability and significant mechanical anisotropy exhibited [6,7]. Moreover, deformation mechanisms are the important determinant of the connection between the crystalline structure of a material and its macroscopic mechanical properties. The main deformation mechanisms of magnesium alloys are basal <a> slip, prismatic <a> slip, pyramidal <a> slip, pyramidal <c+a> slip, contraction twinning (CT), extension twinning (ET). However, the activation of non-basal <a> slip is inhibited at room temperature due to its critical resolved shear stress (CRSS) is much higher than that of the basal <a> slip, which limits the plastic deformation of magnesium alloy [8]. Chapuis et al. [9] and Wang et al. [10] demonstrated tensile deformation of AZ31B magnesium alloy is mainly accommodated through prismatic <a> slip and basal <a> slip. Conversely, Guo et al. [11] showed that tensile deformation of AZ31B magnesium alloys involves both slip systems and extension twinning (ET). Since {10-12} ET is easier to activate, they can coordinate the deformation to some extent when tension along the direction normal to the basal plane, which also makes mechanical behavior in this direction different from the other direction [12,13]. Zhou et al. [14] demonstrated through Schmid factors (SFs) and geometrically necessary dislocations (GND) density analysis that the deformation in the tensile zone of rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy during coiling deformation is primarily caused by the activation of pyramidal <c+a> slip.

With the limited number of slip systems, strong basal textures tend to form throughout plastic deformation in HCP crystal materials [15]. As is well known, the strong basal texture in magnesium alloys is a key factor for their mechanical anisotropy, which substantially impedes their broader engineering application [16–18]. Thus, a deeper understanding of the texture evolution and mechanical behavior of the rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy is crucial.

The activity of twinning and slip systems during plastic deformation significantly affect the microstructural development and macroscopic anisotropy in HCP materials. Through tensile tests along the 0°, 45°, and 90° directions, Bohlen et al. [19] revealed that ZM21 magnesium alloy exhibits a yield anisotropy comparable to that of the conventional AZ31 alloy. And the transverse direction (TD) exhibited the highest yield strength. Although there has been a significant amount of publications showing the correlation between deformation mechanisms and initial orientation [20], this relationship mainly exists in experimental observation. Crystal plasticity modeling elucidates the fundamental mechanisms governing the deformation process. The Visco-Plastic Self-Consistent (VPSC) model serves as a key tool for predicting the mechanical behavior of HCP metals. It effectively captures key behaviors such as mechanical anisotropy, tension-compression asymmetry, texture evolution, and deformation mechanism activity [21–23].

In contemporary mechanics research, the predominant computational frameworks for investigating deformation mechanisms in magnesium alloys comprise Taylor and Quinney [24], crystal plasticity finite element model (CPFEM) [25], Elasto-Visco-plastic Self-Consistent (EVPSC) Model [26], and VPSC Model [27]. The VPSC introduced a rate-dependent ontological relationship [28] and took into account the material anisotropy. Lebensohn et al. [27] employed VPSC to predict the axisymmetric deformation and texture during zirconium alloy rolling, and the results were well consistent with experimental data. Maldar et al. [29] examined how variations in alloy composition affect the tensile properties of Mg alloy and relative activation of specific slip systems using the VPSC model. Zhou et al. [30] employed a combined experimental and VPSC approach, examining twinning and slip mechanisms in extruded Mg alloy across different strain paths. Therefore, the VPSC model has been proven to be a reliable tool for predicting the mechanical behavior of magnesium alloys under various conditions. The current comprehension of texture evolution and deformation anisotropy in strongly basal-textured AZ31B magnesium alloy relies heavily on experimental measurements. However, experiments alone cannot determine the role of a single deformation mechanisms in texture evolution and mechanical behavior. To this end, the VPSC model was employed in this study, where a mechanism is suppressed by setting its CRSS to a critically high value. This method allows for the isolated investigation of a specific deformation mechanism’s effect on texture evolution and other mechanisms, thereby further analyze its impact on mechanical behavior and anisotropy.

The main work of this paper examined how specific deformation mechanisms on the mechanical behavior and anisotropy of AZ31B magnesium alloy. The rolled AZ31B magnesium alloys was used to prepare tensile specimens oriented along RD and TD. The microstructure of AZ31B magnesium alloys was characterized by Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) before and after plastic deformation. Additionally, Schmid factor (SF) analysis was performed on the initial microstructure to guide the Voce hardening parameters. Subsequently, the model simulated the tensile behavior, including stress-strain curves and texture evolution. These simulations allowed for the influence of specific deformation modes on textural development to be elucidated.

2 Experimental and Simulation Procedures

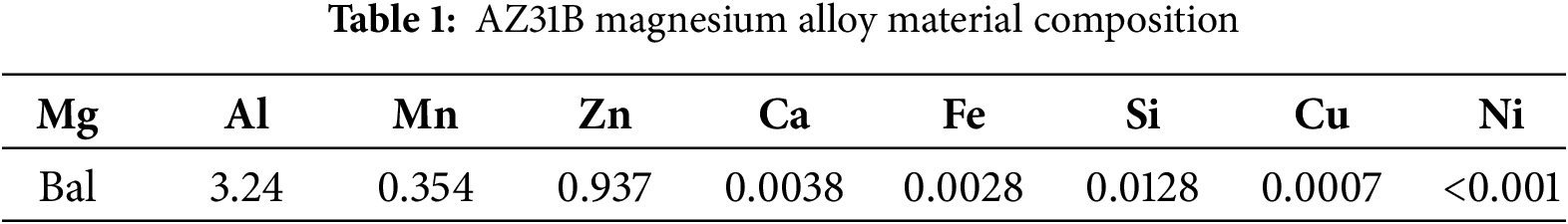

This experiment was conducted out using AZ31B magnesium alloy as the base material, with its specific composition provided in Table 1. As shown in Fig. 1, two tensile specimens with dimensions of 90 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm were prepared by machining along the 0° and 90° directions, respectively. The tensile tests were performed along RD and TD at room temperature using the WDW-E100D electronic universal testing machine, with the strain rate set at

Figure 1: (a) Schematic of the specimen processing, (b) Tensile specimen (mm)

The VPSC modeling framework considers each grain of the polycrystal as an ellipsoid embedded in an infinite homogeneous equivalent medium, and fully considers the interaction between the grains in the polycrystal.

In the VPSC model, the non-linear rate-sensitive constitutive model is used to represent the local viscosity [21,31], as follows:

where

The Voce hardening formulation accurately captures the work hardening characteristics of deformation mechanism in magnesium alloy plasticity simulations. The extended equation [31,32] is:

where

Tomé et al. [33] implemented the predominant twin reorientation scheme within the VPSC framework, enabling quantitative simulation of twin-induced texture evolution and twin volume fraction development. Meanwhile model assumes that the cumulative twin volume fraction for twin system in all grains of polycrystal is expressed as follows:

where

where

Initial texture file and initial pole figures were simulated using the Euler angle data of magnesium alloys tested by EBSD, and grain orientation data for 2000 grains were output to save computational time. Uniaxial tension along RD and TD were simulated by the following velocity gradients represented equation, respectively.

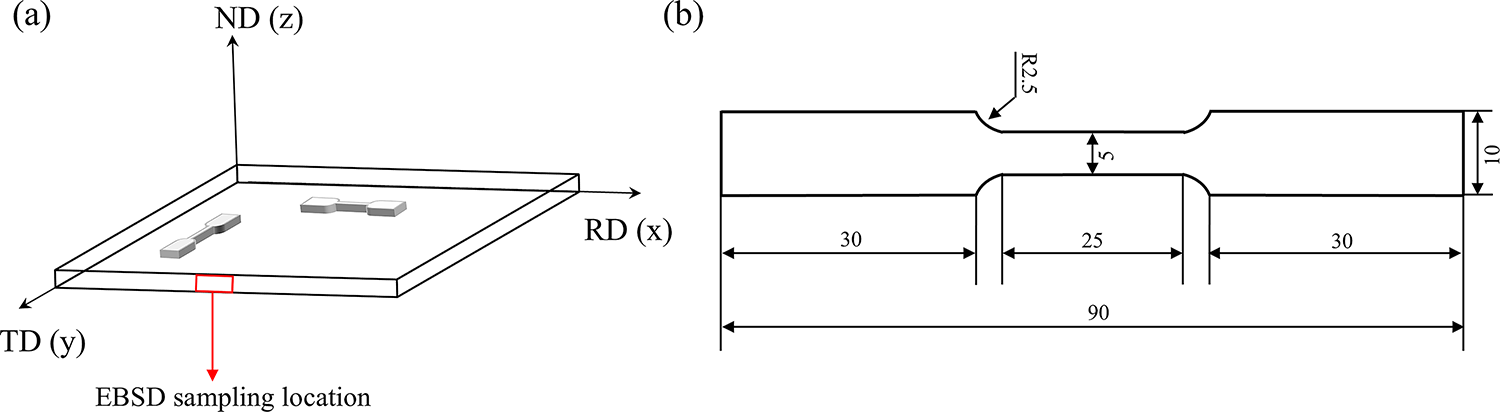

To comprehensively analyze uniaxial tensile deformation behavior of AZ31B magnesium alloy, texture evolution is examined in detail. The EBSD sampling schematic is provided in Fig. 1a. In the corresponding VPSC simulation, the x-axis corresponds to the RD, y-axis to the normal direction (ND), z-axis to the TD. Fig. 2a illustrates the IPF of the AZ31B magnesium alloy. Fig. 2b shows the initial texture and the initial pole figure. A comparison between the experimental and VPSC-calculated pole figures reveals a remarkable similarity, which verifies the feasibility of the VPSC model in the selection of grains. The analysis shows that most grains have their c-axis parallel to ND, demonstrating strong basal texture. Fig. 2c shows the grain size distribution of the AZ31B magnesium alloy, from which the average grain size was determined to be 41.2 μm. Fig. 2d presents Intragranular Misorientation Axis (IGMA) distribution and Grain boundary misorientation angle histograms. Variations in grain orientation can result in differing mechanical characteristics of the material, and these differences are usually expressed in terms of grain boundary orientations. Classification of grain boundaries into low-angle (LAGB, θ < 15°) and high-angle (HAGB, θ > 15°) types are based on the magnitude of the grain boundary orientation difference. Through IGMA analysis, it is observed that the density points are primarily concentrated along <uvt0> axis, suggesting that basal <a> slip or pyramidal <c+a> slip as primary mechanisms during uniaxial tensile deformation of the original AZ31B magnesium alloy [34]. In most cases, basal <a> slip requires lower CRSS than pyramidal <c+a> slip activation [35]. Therefore, basal <a> slip dominates the initial plastic deformation, thus guiding the parameter settings in subsequent research.

Figure 2: Initial state of AZ31B magnesium alloy: (a) Inverse pole figure, (b) Initial pole figure: Measured (left) and simulated (right), (c) Grain size, (d) Misorientation distribution maps and IGMA distribution with misorientation between 0.5°~2°

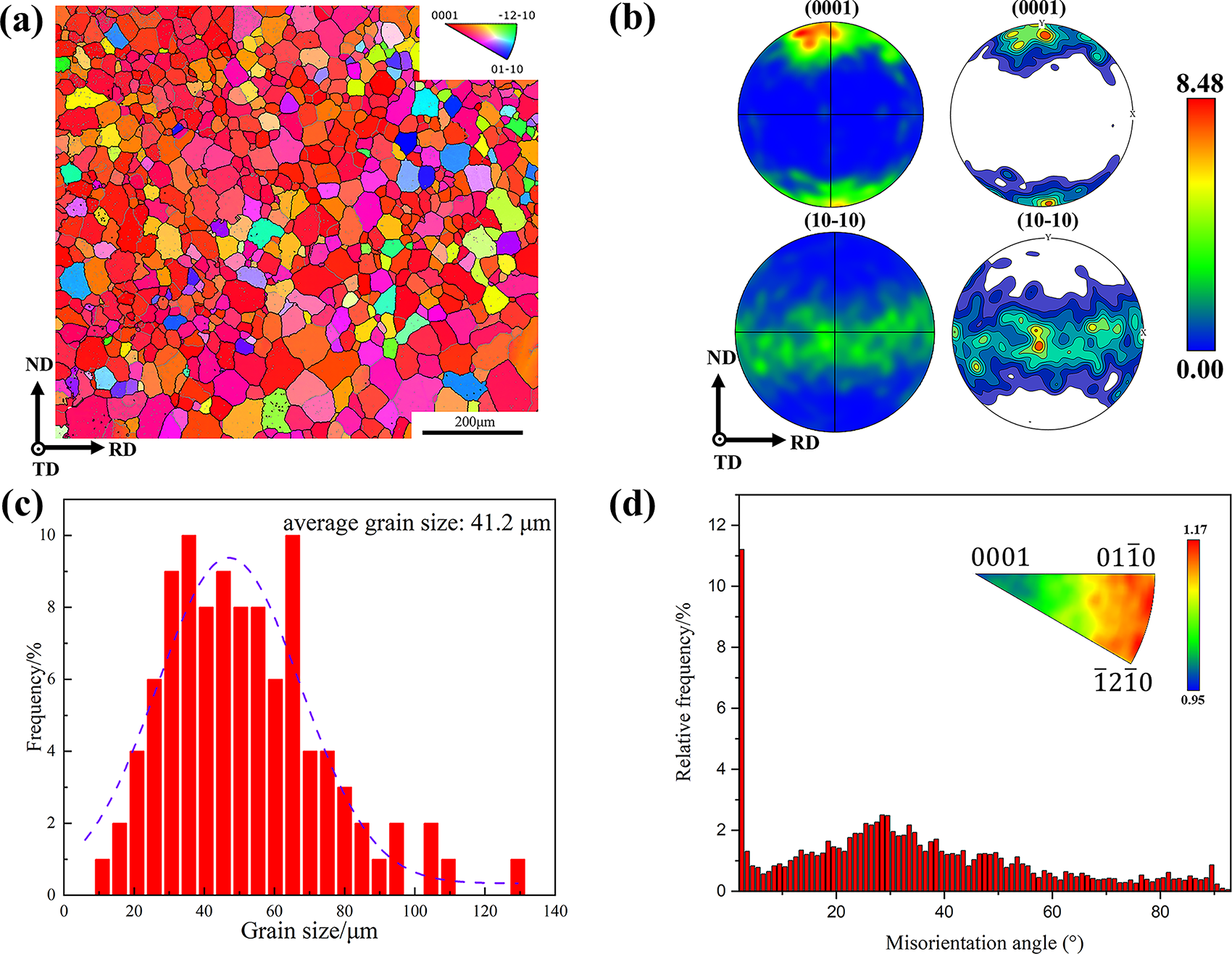

Fig. 3 displays the distributions of the initial SFs along the RD and TD. During the early deformation stages of tensile testing along RD, the average SF were determined to be 0.39, 0.39, 0.45, and 0.42, respectively. Similarly, these values were 0.38, 0.42, 0.43, and 0.43 in the TD, respectively. And the main deformation modes considered were basal <a> slip, prismatic <a> slip, pyramidal <a> slip and pyramidal <c+a> slip, with corresponding CRSS of 41, 99, 200, and 180 MPa, respectively. The critical external stress necessary to activate the specific deformation mechanism in magnesium alloys as follows [36]:

where

Figure 3: SF of the four slip systems: RD loading (a–d), TD loading (a1–d1), SF distribution maps (a2–d2)

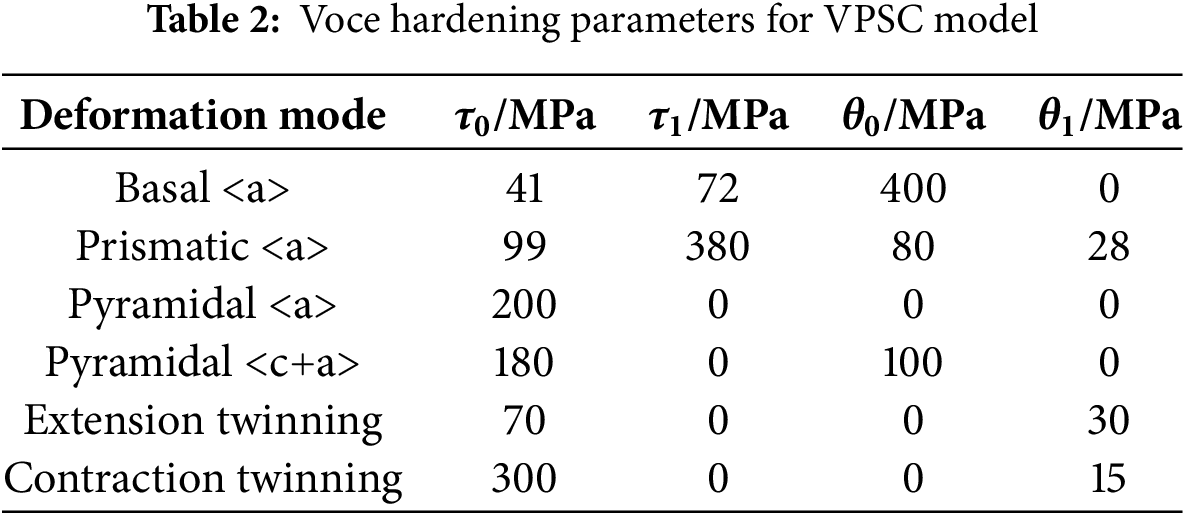

The Voce hardening parameters were optimized within the self-consistent scheme (neff = 10) to accurately replicate the experimental stress-strain response. As shown in Table 2, the VPSC model incorporated six deformation mechanisms to simulate mechanical response. The Voce hardening parameters were optimized through stress-strain curve fitting. The CRSS values determined for deformation mechanisms during tensile plastic deformation were 41, 70, 99, 180, 200, and 300 MPa, respectively. Notably, this order of presentation is consistent with numerous previous studies [37]. Previous studies report the following CRSS values: 0.45–0.81 MPa for basal <a> slip, 2–3 MPa for {10-12} twinning, 39.2 MPa for prismatic <a> slip, 45–81 MPa for pyramidal <c+a> slip and 76–153 MPa for {10-11} twinning [38]. Due to influencing factors such as grain size, morphology, and defects, the simulated values for these deformation mechanisms are relative. Through a methodology combining experimental and polycrystalline theoretical modeling to obtain the CRSS ratio of prismatic <a> slip to basal <a> slip between 2–2.5 [39]. In this study, the ratio was approximately 2.4, the result is the same as previous studies. Agnew et al. [39] identified dislocation activity in both basal and prismatic <a> slip systems, indicating that the applied shear stress was sufficient to activate both deformation mechanisms, as follows:

where σ represents the true stress, λ indicating the angle between the loading direction and the slip direction, and φ denotes the angle subtended by the applied load and slip plane normal. Following Eq. (11), when fixed loading direction, the Schmid factor value determined predominantly on the orientation of grains. In conjunction with the SF, analysis suggests that prismatic and basal <a> slip dominate during the initial deformation.

3.2 Mechanical Behavior Simulation

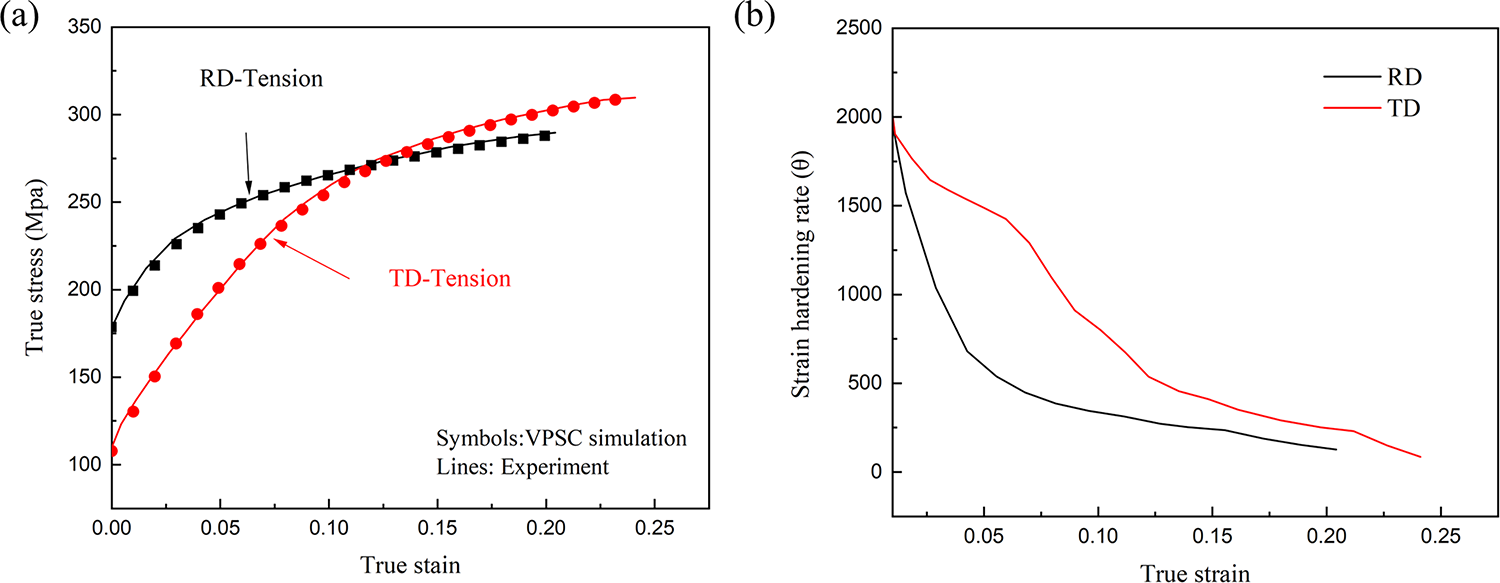

Fig. 4 compares the experimental and simulated true stress-strain curves of rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy under uniaxial tension along the RD and TD. Results reveal the VPSC model accurately captures both the hardening response characteristics and mechanical anisotropy of the alloy. Uniaxial tensile tests demonstrate significant mechanical anisotropy, with the material exhibiting yield strengths of 179 and 109 MPa along RD and TD. And the ultimate tensile strength measurements demonstrate values of 295 and 309 MPa, respectively. The marked difference between the yield strengths along TD and RD, which is due to the inhomogeneity of the initial texture that leads to the activation of different deformation mechanisms when the material during deformation along different loading directions. Furthermore, Fig. 4b further reveals a marked difference in work-hardening rates between the tensile directions, with the TD exhibiting a significantly higher rate than the RD.

Figure 4: (a) Stress-strain curves and (b) work-hardening rates for the AZ31B magnesium alloy tested in RD and TD

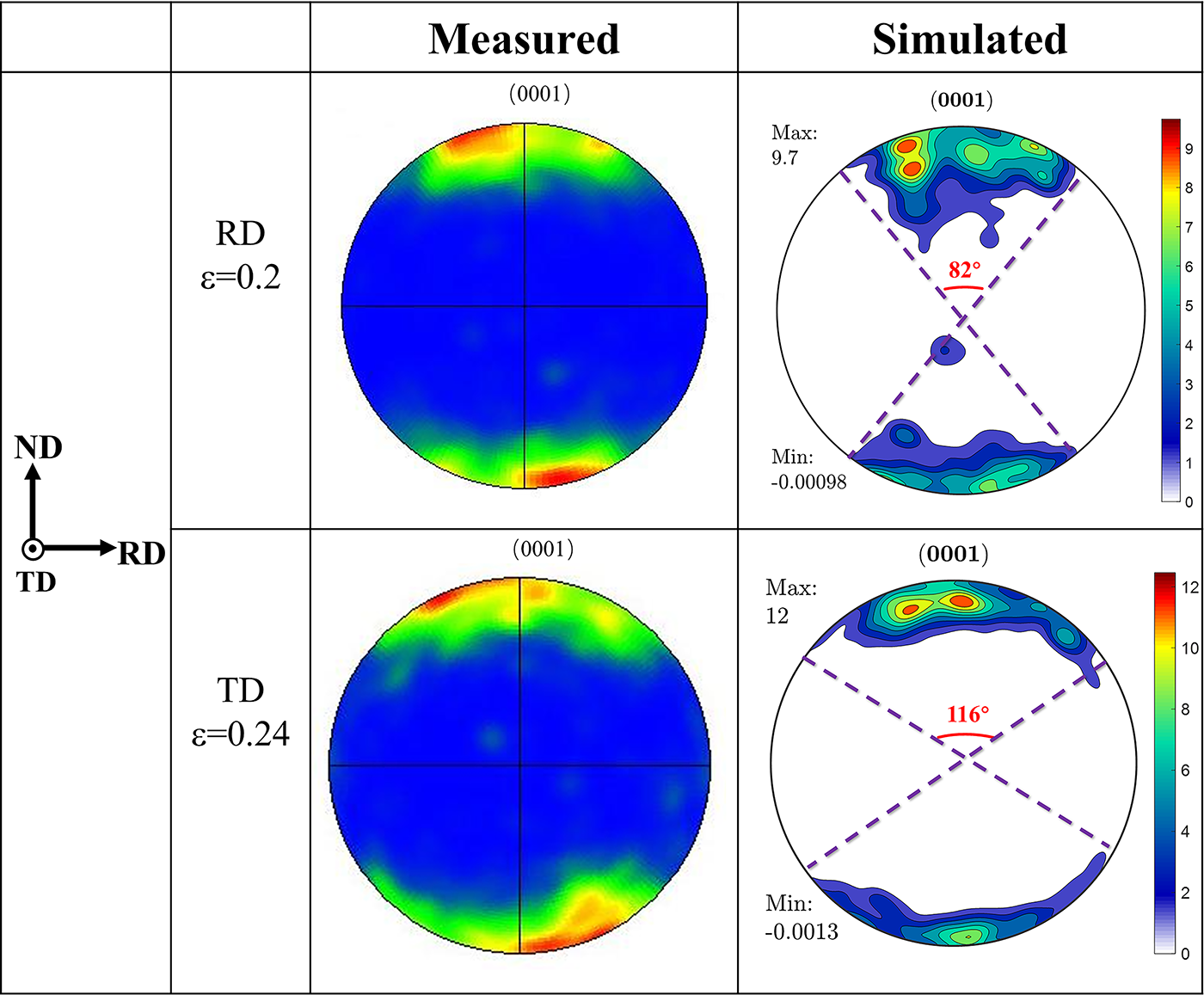

Fig. 5 compares the experimental and simulated (0001) pole figures of rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy under tension along RD and TD. A comparison of the experimental and simulated results verifies the VPSC model’s accuracy in predicting texture evolution. The textures after tensile testing exhibit significant anisotropy between RD and TD. During RD tension, the texture shows a tendency to spread toward the ND and TD with a maximum pole density of 9.7, whereas during TD tension, it exhibits a clear spreading trend toward the RD with a maximum pole density of 12. This anisotropy is preliminarily attributed to differences in deformation mechanisms activation.

Figure 5: Pole figures of AZ31B magnesium alloy from room-temperature uniaxial tension along (a) RD and (b) TD

3.3 Influence of Deformation Mechanism on Mechanical Response and Texture

This study modified the Voce hardening parameters while setting sufficiently high CRSS values to suppress specific slips and twinning. This approach enables facilitates a systematic study of tensile deformation and texture in AZ31B specimens. As the key parameter in crystal plasticity modeling, τ0 in the Voce hardening formulation physically denotes the CRSS value for deformation, with its magnitude determining the onset stress of slip or twinning mechanisms. Controlling the activation of a specific slip mechanism by modifying τ0 (i.e., modifying the CRSS value) to establish the correlation between specific slip system activities and resultant mechanical behavior and texture evolution.

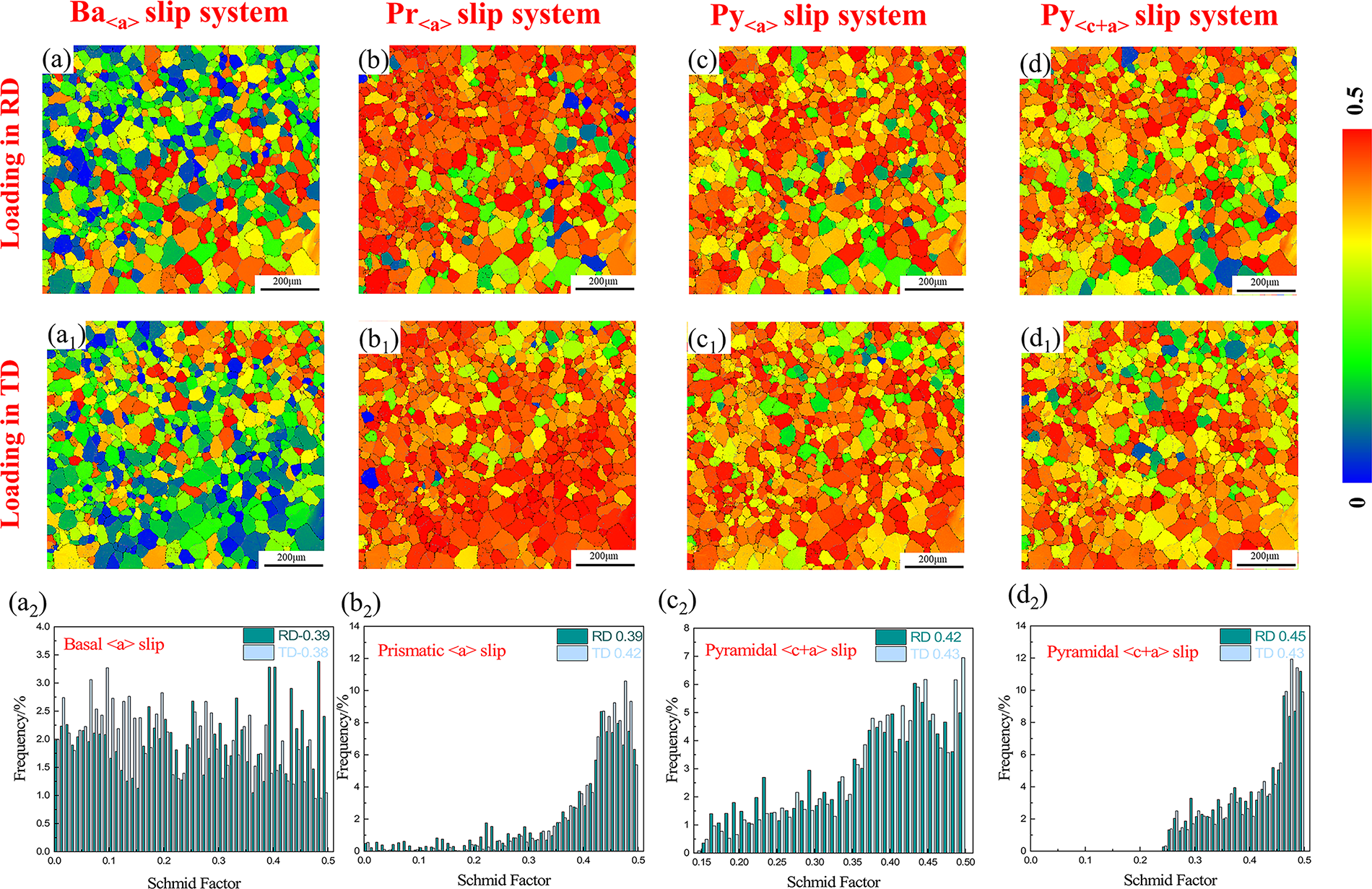

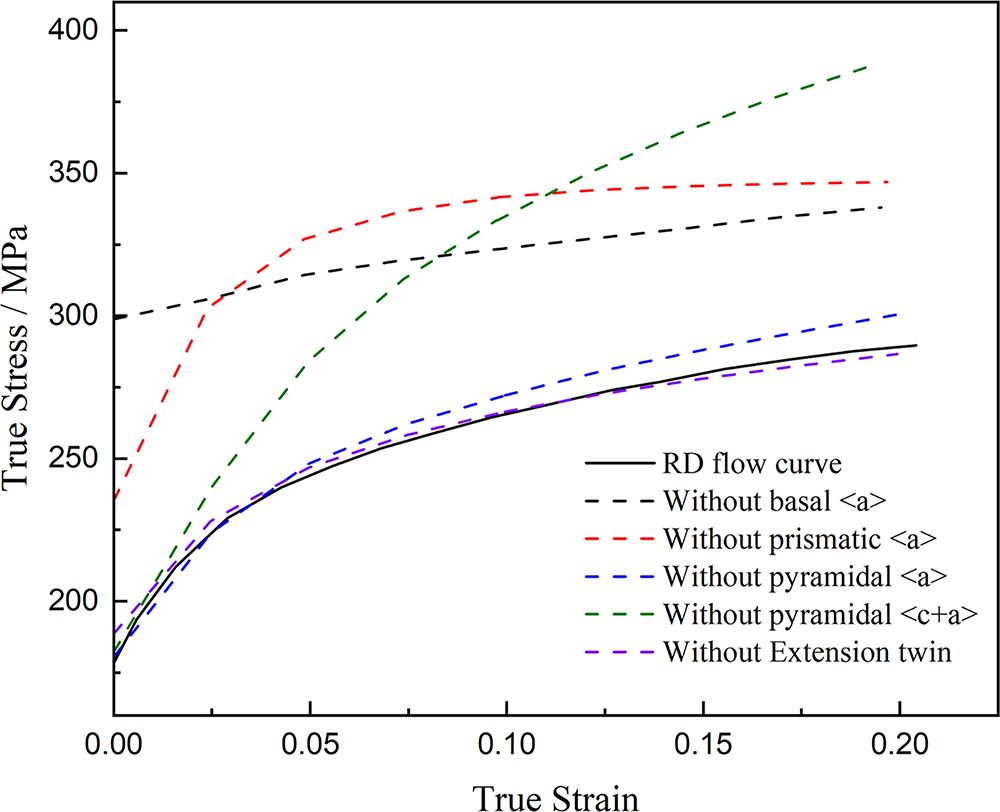

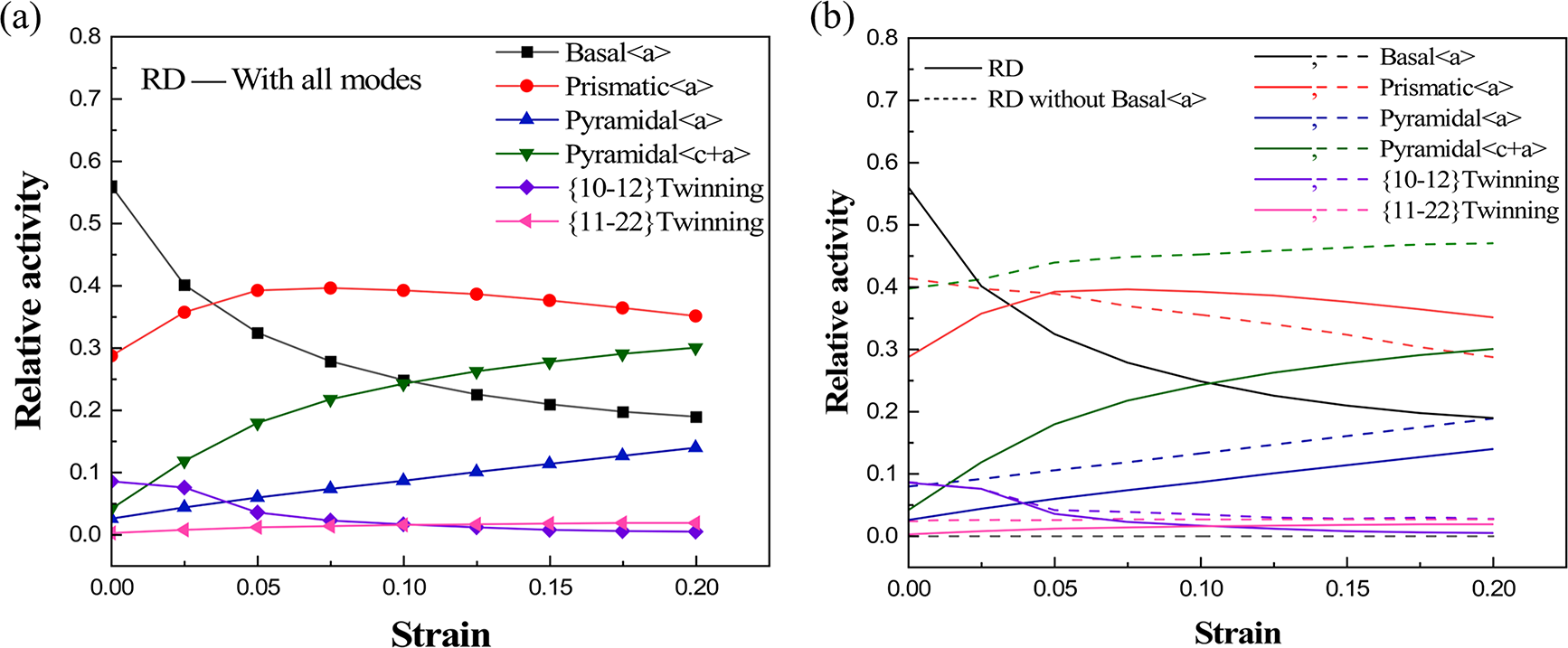

Fig. 6 presents the simulated tensile behavior along RD, while Fig. 7 quantitatively analyzes the activities of other deformation mechanisms by suppressing specific deformation mechanisms. Fig. 6 reveals simulated stress-strain curves following selective suppression of specific deformation mechanisms, thereby systematically validating the impact of individual plastic deformation modes on macroscale mechanical performance. The relative activity levels in Fig. 7a indicate the initial dominance of basal <a> slip during RD tension, owing to its low CRSS, with activation of prismatic <a> slip under favorable SF conditions. Notably, given its lower CRSS relative to other non-basal <a> slip, prismatic <a> slip activates preferentially to coordinate the deformation in <a>-axis of grains during plastic deformation. As strain accumulates, prismatic <a> slip progressively becomes dominant, while the activity of basal <a> slip correspondingly decreases. This phenomenon is caused by grain rotation, more grains are gradually transformed into the basal <a> slip hard orientation, while the CRSS value gradually increases, leading to the activation of prismatic <a> slip. Due to their substantially higher CRSS values compared to basal and prismatic <a> slip, pyramidal <c+a> and pyramidal <a> slip exhibit limited activity initially. With progressing deformation, pyramidal <c+a> slip activate to accommodate strain requirements.

Figure 6: Stress-strain curves for suppressing specific deformation mechanism of AZ31B magnesium alloy under tension along RD

Figure 7: Relative activation of deformation mechanisms for deformation mechanisms of AZ31B magnesium alloy by tension along the RD: (a) All deformation mechanisms are activated, (b) Without basal <a> slip, (c) Without prismatic <a> slip, (d) Without pyramidal <a> slip, (e) Without pyramidal <c+a> slip, (f) Without {10-12} twinning

Fig. 7b illustrates the suppression of basal <a> slip, which leads to a notable increase in pyramidal <c+a> slip, while prismatic <a> slip only rises during initial deformation. Meanwhile, as corroborated by Fig. 6, the predicted curves demonstrate substantial modifications when the basal <a> slip is suppressed. Mechanical characterization demonstrates that basal <a> slip activation substantially affects the deformation behavior of AZ31B alloy, causing marked decreases in both yield and tensile strength along RD. Fig. 7c presents the predictions of deformation mechanism evolution with prismatic <a> slip suppressed. The simulation results reveal a significantly increased activation in both pyramidal <c+a> and pyramidal <a> slip systems. Fig. 7d illustrates the predicted deformation mechanism under suppression of pyramidal <a> slip, revealing that only prismatic <a> slip has most notable change. Fig. 7e depicts predicted deformation mechanisms with pyramidal <c+a> slip suppressed. Analysis indicates that the initial stages of deformation have a minimal impact on the other deformation mechanisms. However, both prismatic <a> and basal <a> slips become more active later in the deformation. Consequently, the suppression of pyramidal <a> slip leads to a marked late-stage hardening response in stress-strain curves in Figs. 6 and 7f illustrate the predicted deformation mechanisms with {10-12} ET twinning suppressed, showing a minimal effect on the overall plastic deformation.

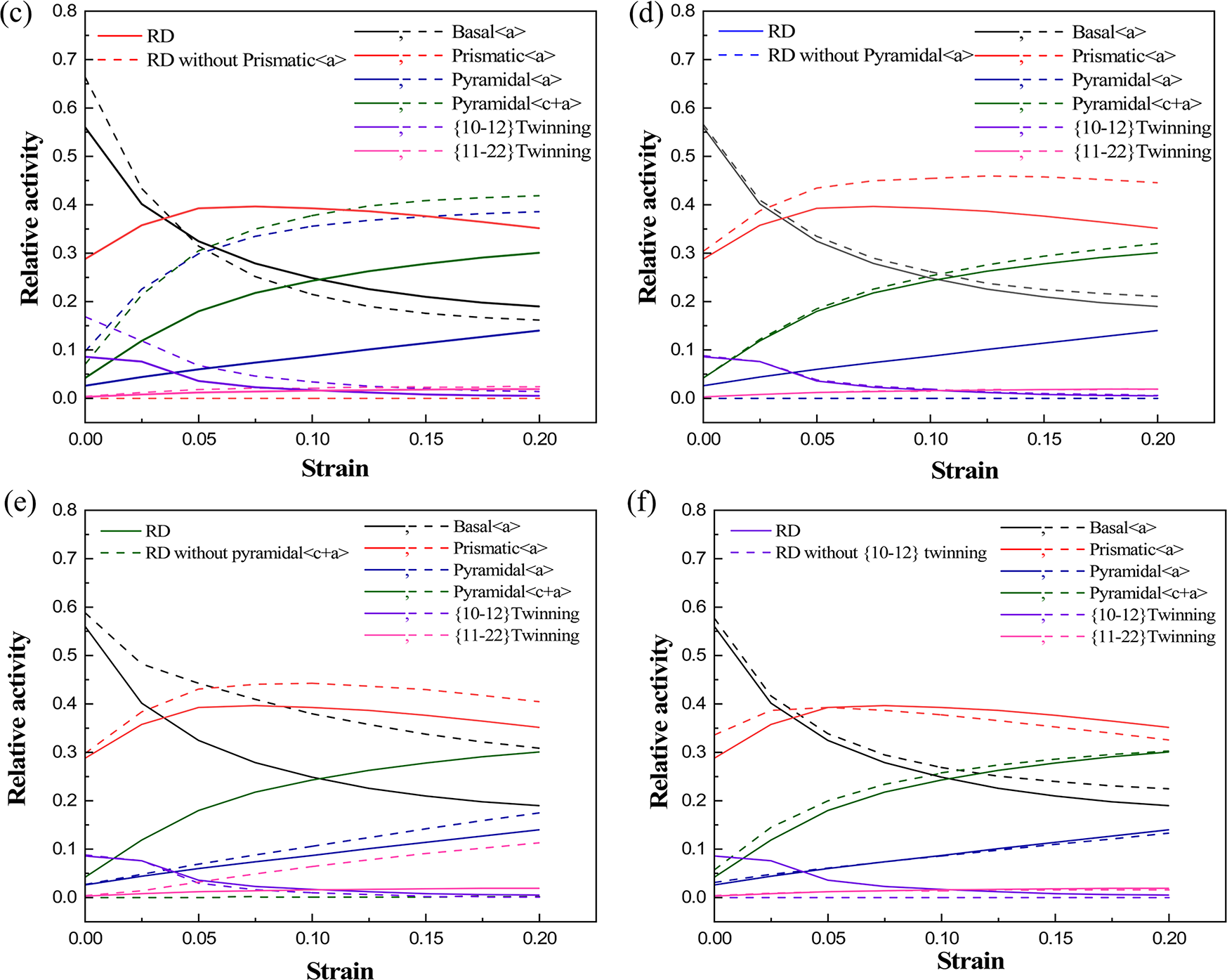

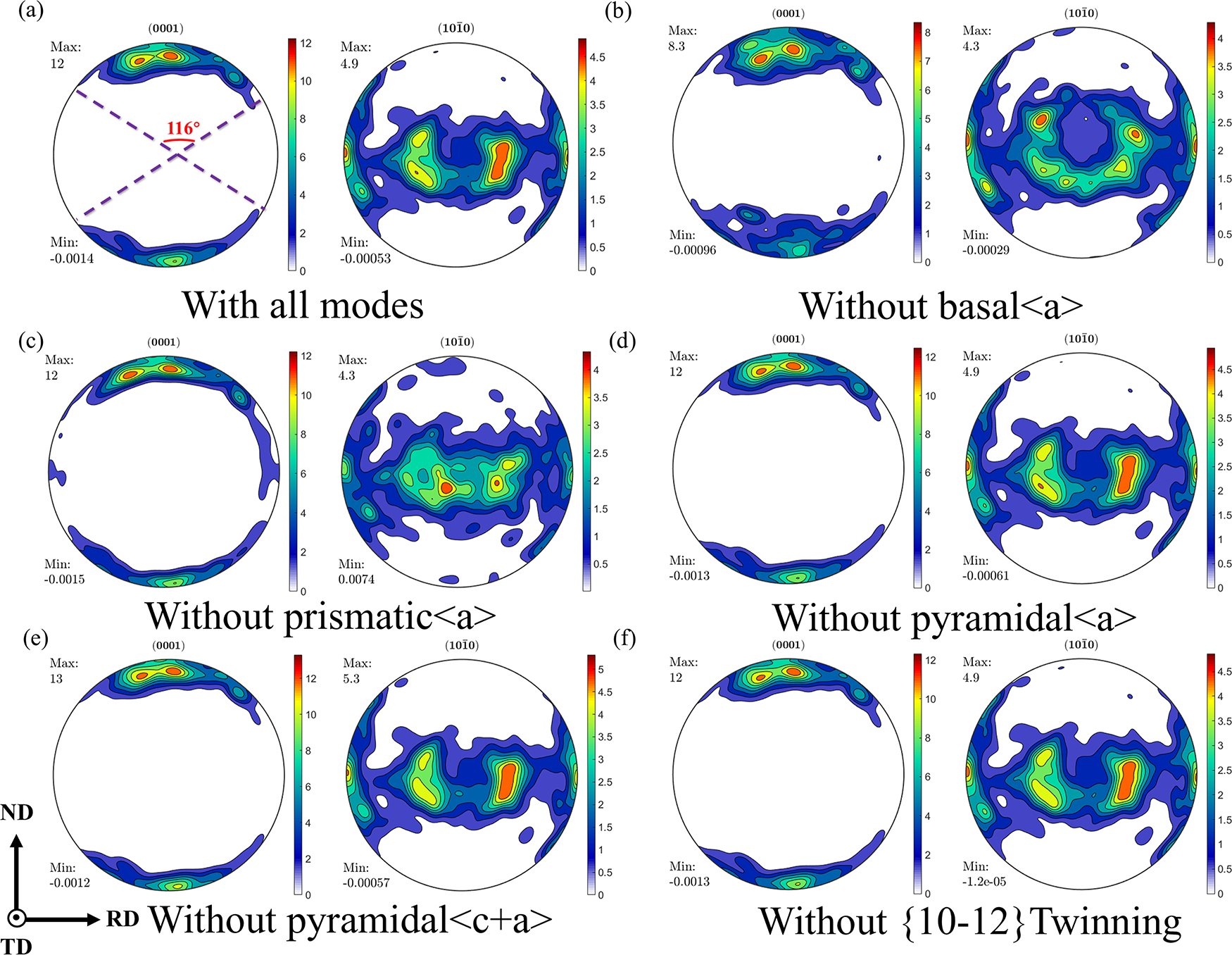

Texture evolution in plastically deformed of AZ31B magnesium alloy is predominantly governed by the activity of slips and twinning deformation mechanisms. Fig. 8 presents the predicted texture under the suppression of specific slip systems and {10-12} extension twinning in rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy during RD tension at a strain of 0.2. Following basal <a> slip suppression, it can be observed that the pole density distribution spreads to 108° from 82° in Fig. 8a. This behavior results from the inability of some grains to deform effectively after basal <a> slip suppression, which restricts dislocation motion and hinders ND grain rotation. Consequently, when basal <a> slip is suppressed, the pole figure distribution is more dispersed and the maximum polar density decreases from 9.7 to 7.8. The results show that the activation of basal <a> slip produces in a more focused grain orientation, thereby increasing the maximum pole figure density. The suppression of prismatic <a> slip promotes increased activity of both pyramidal <c+a> slip and basal <a> slip, resulting in c-axis rotation toward the TD. However, overall trend remains relatively unchanged. Fig. 8d illustrates that suppression of the pyramidal <a> slip does not alter the pole figure significantly. The suppression of pyramidal <c+a> slip intensifies prismatic <a> and basal <a> slip activity, shifting pole density from TD to ND, and raising maximum pole density. Fig. 8f reveals a clear tendency for the texture to be deflected along the ND after suppressing the {10-12} ET, indicating that the activation of the {10-12} ET drives the texture deflection along the TD [40].

Figure 8: Predicted texture during tension along RD: (a) All deformation mechanisms are activated, (b) Without basal <a> slip, (c) Without prismatic <a> slip, (d) Without pyramidal <a> slip, (e) Without pyramidal <c+a> slip, (f) Without {10-12} twinning

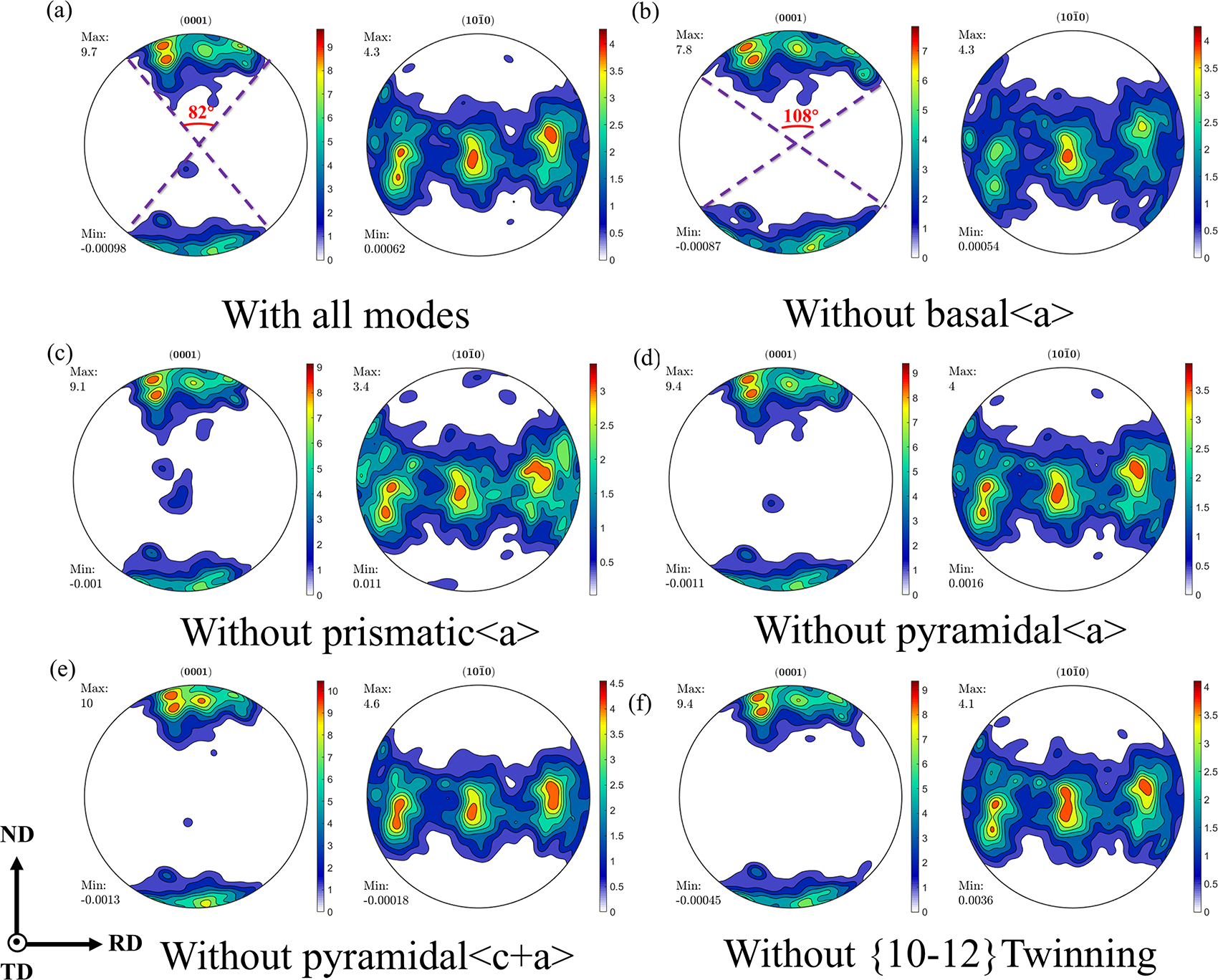

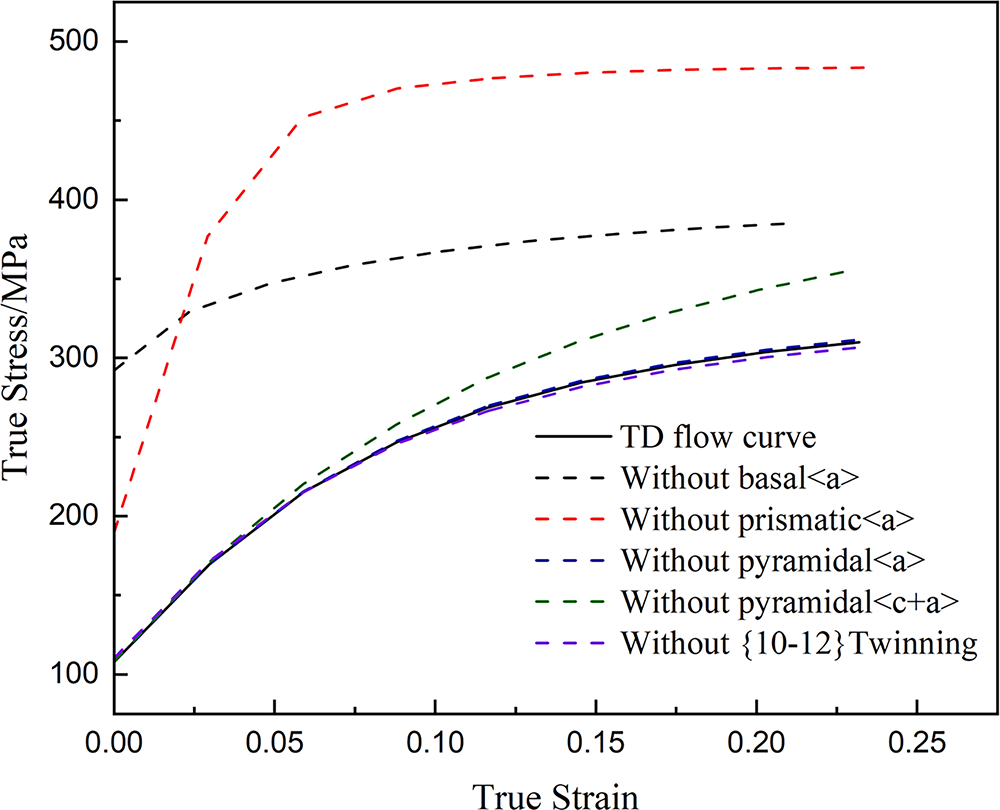

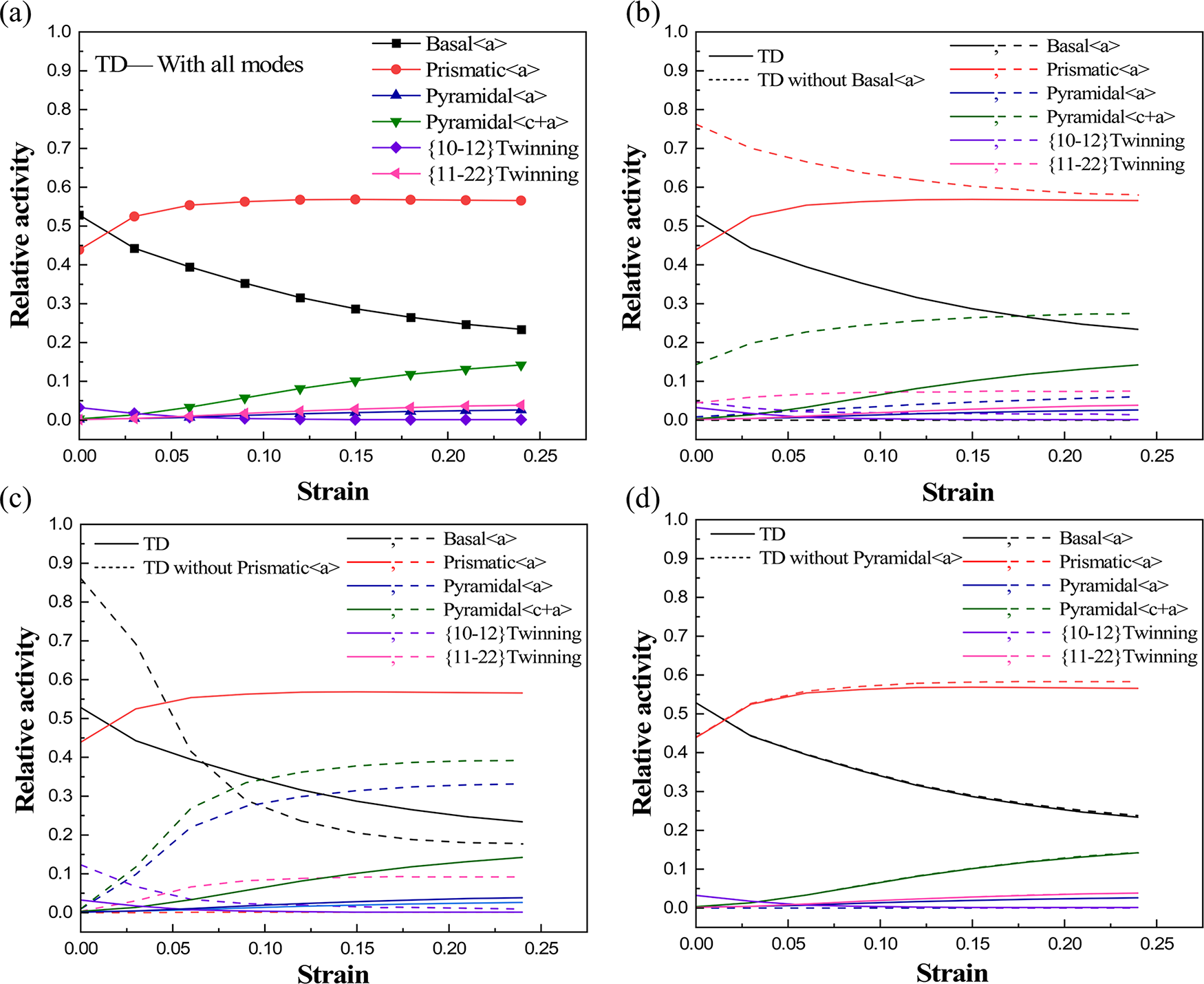

Fig. 9 presents simulated the TD tensile characteristics, while Fig. 10 quantifies the activities of other deformation mechanisms under suppressed specific deformation mechanisms. Fig. 9 reveals that the curve rises notably subsequent to basal <a> slip suppression. The analysis confirms that basal <a> slip activity promotes grain rotation and is the dominant mechanism responsible for the material’s reduced yield strength. Furthermore, prismatic <a> slip not only exhibits a synergistic effect on yield strength, but also dominates the work hardening during the initial plastic deformation. Following pyramidal <c+a> slip suppression, the curve displays only a limited rise in the subsequent stage, suggesting that its activation exerts relatively small influence on mechanical properties. Throughout the tensile deformation along TD, pyramidal <a> slip and {10-12} ET show negligible influence. Given their low CRSS values, prismatic <a> and basal <a> slip are easier activated.

Figure 9: Stress-strain curves for suppressing specific deformation mechanism of AZ31B magnesium alloy under tension along TD

Figure 10: Relative activation of deformation mechanisms for deformation mechanisms of AZ31B magnesium alloy by tension along the TD: (a) All deformation mechanisms are activated, (b) Without basal <a> slip, (c) Without prismatic <a> slip, (d) Without pyramidal <a> slip, (e) Without pyramidal <c+a> slip, (f) Without {10-12} twinning

As shown in Fig. 10a, basal and prismatic <a> slip are the dominant mechanisms throughout the deformation process. Fig. 10b demonstrates the activation of deformation mechanisms when basal <a> slip is suppressed. Analysis confirms increased activity of prismatic <a> and pyramidal <c+a> slip, with the plastic deformation previously accommodated by basal <a> slip now being redistributed through these two activated slip mechanisms. Fig. 10c illustrates the evolution of deformation mechanisms following prismatic <a> slip suppression. Due to the critical role of prismatic <a> slip in deformation coordination, its suppression induces substantial modifications in the deformation mechanisms. The analysis reveals enhanced the activation of basal <a> slip, while both pyramidal <c+a> and pyramidal <a> slip activate increases with accumulated strain. Additionally, {11-22} CT demonstrates only minor activity. As evidenced in Fig. 10d–f, pyramidal <a> slip, pyramidal <c+a> slip, and {10-12} ET have minimal influence on tensile deformation along the TD.

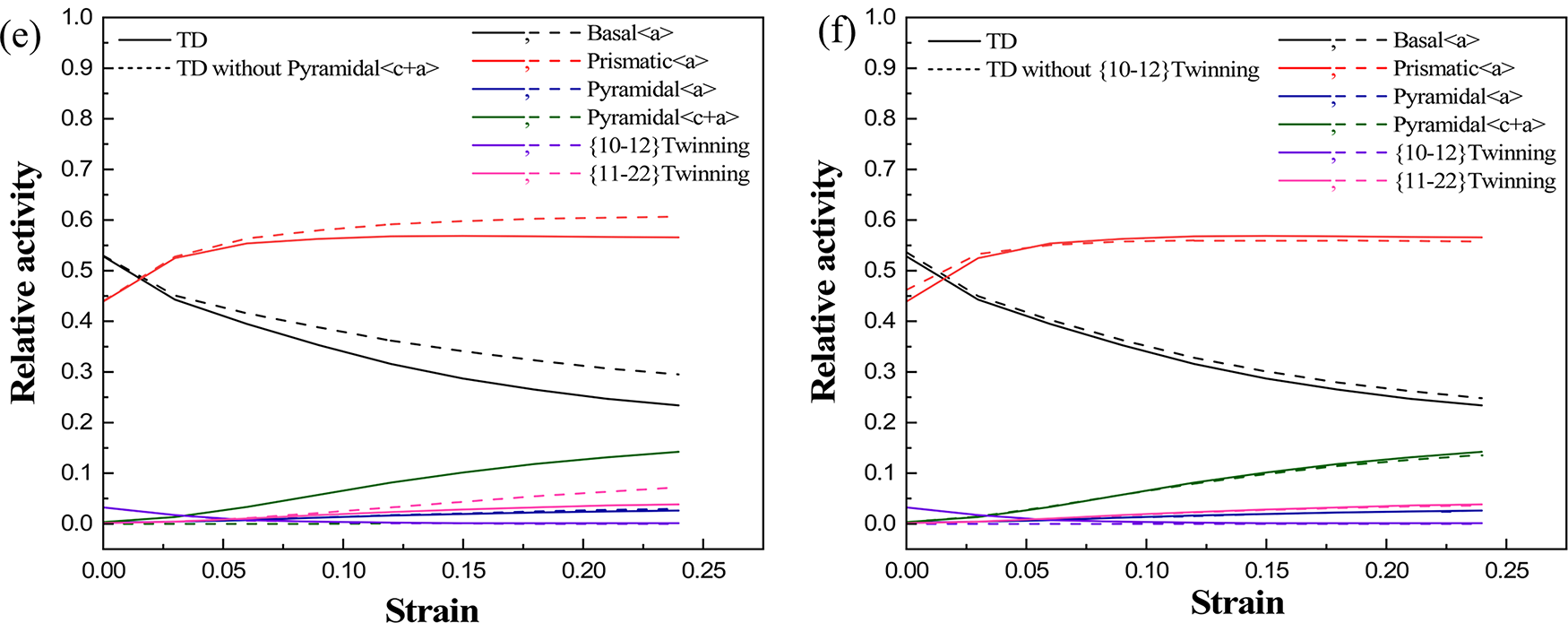

Fig. 11 presents the predicted texture in rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy during TD tension at strain of 0.24 under specific slip systems and {10-12} ET suppression. It is evident that a significant degree of texture spreading occurs toward the RD when prismatic <a> slip is suppressed, with the maximum pole density decreasing from 12 to 8.3. This phenomenon originates from the predominance of prismatic <a> slip during TD deformation. Fig. 11b demonstrates basal <a> slip suppression markedly increases pyramidal <c+a> slip activity, causing a significant redistribution of the pole density toward TD and a reduction in maximum pole density. (10-10) pole figure reveals that after suppression of basal <a> slip, some grains cannot be activated efficiently and the grain rotation is hindered leading to an obvious spreading of the pole figure from the ND toward the center. The results shown in Fig. 11c indicate a distinct redistribution of the pole figure into a toroidal shape following prismatic <a> slip suppression and (10-10) pole figure exhibits pronounced texture modifications. This phenomenon primarily results from the significant activation of pyramidal <a> and pyramidal <c+a> slip following prismatic <a> slip suppression. Furthermore, a small amount of {11-22} compression twinning activity contributes, deflecting the <a>-axis to accommodate strain. Fig. 11d–f reveals that pyramidal <a> slip and {10-12} ET exhibit negligible influence on the pole figure. Pyramidal slip has a relatively minor effect, increasing the maximum pole density from 12 to 13 while leaving the overall distribution trend largely unchanged.

Figure 11: Predicted texture during tension along TD: (a) All deformation mechanisms are activated, (b) Without basal <a> slip, (c) Without prismatic <a> slip, (d) Without pyramidal <a> slip, (e) Without pyramidal <c+a> slip, (f) Without {10-12} twinning

This study employed VPSC model to investigate the mechanical behavior and texture evolution of AZ31B magnesium alloy under different tensile directions.

(1) Activating basal <a> slip facilitates effective grain rotation, thereby reduces the stress required during tensile deformation along the RD and TD, consequently reducing yield and ultimate tensile strength. After suppression of basal <a> slip, some grains cannot be effectively activated, which hinders their rotation toward the ND. Therefore, the activity of basal <a> slip induces significant grain rotation from the RD toward ND, resulting in a more concentrated texture distribution.

(2) When tension along the RD, prismatic <a> slip activation affects the texture to be significantly deflected in ND. Following prismatic <a> slip suppression, the pole figure into a toroidal shape and a significant change of the (10-10) pole figure.

(3) Comparative analysis of tensile results along RD and TD revealed distinct differences in texture evolution and deformation mechanisms. Basal <a> slip predominated during RD tensile deformation, whereas prismatic slip exhibited a higher activity under TD tension. Additionally, {10-12} ET was partially activated during RD deformation but had a negligible influence during TD tension.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (52275356).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xun Chen, Jinbao Lin; data collection: Zai Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Xun Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Xun Chen, Jinbao Lin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Poggiali FSJ, Silva CLP, Pereira PHR, Figueiredo RB, Cetlin PR. Determination of mechanical anisotropy of magnesium processed by ECAP. J Mater Res Technol. 2014;3(4):331–7. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2014.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gu Z, Zhou Y, Dong Q, He G, Cui J, Tan J, et al. Designing lightweight multicomponent magnesium alloys with exceptional strength and high stiffness. Mater Sci Eng A. 2022;855:143901. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2022.143901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zuo J, Hou L, Shi J, Cui H, Zhuang L, Zhang J. Enhanced plasticity and corrosion resistance of high strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy processed by an improved thermomechanical processing. J Alloys Compd. 2017;716:220–30. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.05.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kim SJ, Kim D, Lee K, Cho HH, Han HN. Residual-stress-induced grain growth of twinned grains and its effect on formability of magnesium alloy sheet at room temperature. Mater Charact. 2015;109:88–94. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2015.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhou X, Liu R, Liu Q, Zhou H. Effect of asymmetric rolling on the microstructure, mechanical properties and texture evolution of Mg–8Li–3Al–1Y alloy. Met Mater Int. 2019;25(5):1301–11. doi:10.1007/s12540-019-00263-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yi S, Bohlen J, Heinemann F, Letzig D. Mechanical anisotropy and deep drawing behaviour of AZ31 and ZE10 magnesium alloy sheets. Acta Mater. 2010;58(2):592–605. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2009.09.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yang Y, Zhang Y, Ding C, Liu G, Ma H, Jin L, et al. Enhancing the activity of <c+a> dislocations in Mg alloys via high-energy pulsed current. Acta Mater. 2025;296:121268. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2025.121268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang L, Huang Z, Wang H, Maldar A, Yi S, Park JS, et al. Study of slip activity in a Mg-Y alloy by in situ high energy X-ray diffraction microscopy and elastic viscoplastic self-consistent modeling. Acta Mater. 2018;155:138–52. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2018.05.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chapuis A, Liu P, Liu Q. An experimental and numerical study of texture change and twinning-induced hardening during tensile deformation of an AZ31 magnesium alloy rolled plate. Mater Sci Eng A. 2013;561:167–73. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2012.11.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang B, Deng L, Adrien C, Guo N, Xu Z, Li Q. Relationship between textures and deformation modes in Mg–3Al–1Zn alloy during uniaxial tension. Mater Charact. 2015;108:42–50. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2015.08.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Guo X, Chapuis A, Wu P, Liu Q, Mao X. Experimental and numerical investigation of anisotropic and twinning behavior in Mg alloy under uniaxial tension. Mater Des. 2016;98:333–43. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2016.03.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu X, He D, Zhu B, Liu W, Ye F, Wei F, et al. The ordered orientation gradient “sandwich” texture induced high strength-ductility in AZ31 magnesium alloy. Scr Mater. 2024;253:116296. doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2024.116296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yu M, Cui Y, Wang J, Chen Y, Ding Z, Ying T, et al. Critical resolved shear stresses for slip and twinning in Mg-Y-Ca alloys and their effect on the ductility. Int J Plast. 2023;162:103525. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2023.103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhou C, Le Q, Wang T, Liao Q, Zhu Y, Zhao D, et al. Effect of asymmetry on microstructure and mechanical behavior of as-rolled AZ31 magnesium alloy medium plates during coiling at warm temperatures. Mater Sci Eng A. 2024;894:146174. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2024.146174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou K, Sun X, Wang H, Zhang X, Tang D, Tang W, et al. Texture-dependent bending behaviors of extruded AZ31 magnesium alloy plates. J Magnes Alloys. 2025;13(8):3617–31. doi:10.1016/j.jma.2023.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Linga Murty K, Charit I. Texture development and anisotropic deformation of zircaloys. Prog Nucl Energy. 2006;48(4):325–59. doi:10.1016/j.pnucene.2005.09.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Shi T, Jiang Z, Chen W, Guo M, Zhang J, et al. Relationship among grain size, texture and mechanical properties of aluminums with different particle distributions. Mater Sci Eng A. 2019;753:122–34. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2019.03.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sarkar A, Sanyal S, Bandyopadhyay TK, Mandal S. Implications of microstructure, Taylor factor distribution and texture on tensile properties in a Ti-added Fe-Mn-Al-Si-C steel. Mater Sci Eng A. 2019;767:138402. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2019.138402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bohlen J, Nürnberg MR, Senn JW, Letzig D, Agnew SR. The texture and anisotropy of magnesium–zinc–rare earth alloy sheets. Acta Mater. 2007;55(6):2101–12. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2006.11.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Suwas S, Gottstein G, Kumar R. Evolution of crystallographic texture during equal channel angular extrusion (ECAE) and its effects on secondary processing of magnesium. Mater Sci Eng A. 2007;471(1–2):1–14. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2007.05.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kabirian F, Khan AS, Gnäupel-Herlod T. Visco-plastic modeling of mechanical responses and texture evolution in extruded AZ31 magnesium alloy for various loading conditions. Int J Plast. 2015;68:1–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2014.10.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zecevic M, Knezevic M, McWilliams B, Lebensohn RA. Modeling of the thermo-mechanical response and texture evolution of WE43 Mg alloy in the dynamic recrystallization regime using a viscoplastic self-consistent formulation. Int J Plast. 2020;130:102705. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2020.102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Victoria-Hernández J, Jeong Y, Letzig D. Role of recovery in the microstructure development and mechanical behavior of a ductile Mg-Zn-Nd-Y-Zr alloy: an analysis using EBSD data and crystal plasticity simulations. Int J Plast. 2025;191:104380. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2025.104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Taylor GI, Quinney H. The plastic distortion of metals. Philos Trans R Soc A. 1932;230:323–62. [Google Scholar]

25. Roters F, Eisenlohr P, Hantcherli L, Tjahjanto DD, Bieler TR, Raabe D. Overview of constitutive laws, kinematics, homogenization and multiscale methods in crystal plasticity finite-element modeling: theory, experiments, applications. Acta Mater. 2010;58(4):1152–211. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2009.10.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang H, Wu PD, Tomé CN, Huang Y. A finite strain elastic-viscoplastic self-consistent model for polycrystalline materials. J Mech Phys Solids. 2010;58(4):594–612. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2010.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lebensohn RA, Tomé CN. A self-consistent anisotropic approach for the simulation of plastic deformation and texture development of polycrystals: application to zirconium alloys. Acta Metall Mater. 1993;41(9):2611–24. doi:10.1016/0956-7151(93)90130-K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Asaro RJ, Needleman A. Overview no. 42 Texture development and strain hardening in rate dependent polycrystals. Acta Metall. 1985;33(6):923–53. doi:10.1016/0001-6160(85)90188-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Maldar A, Wang L, Zhu G, Zeng X. Investigation of the alloying effect on deformation behavior in Mg by Visco-Plastic Self-Consistent modeling. J Magnes Alloys. 2020;8(1):210–8. doi:10.1016/j.jma.2019.07.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou C, Hu W, Le Q, Lin Y, Wang T, Jeon H, et al. Revealing the underlying slip/twinning mechanisms of tension-compression asymmetry and anisotropy in Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloys with heterostructure. Int J Plast. 2025;194:104493. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2025.104493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Hutchinson JW. Bounds and self-consistent estimates for creep of polycrystalline materials. Proc R Soc Lond. 1976;348:101–27. doi:10.1098/rspa.1976.0027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen Q, Hu L, Shi L, Zhou T, Yang M, Tu J. Assessment in predictability of visco-plastic self-consistent model with a minimum parameter approach: numerical investigation of plastic deformation behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy for various loading conditions. Mater Sci Eng A. 2020;774:138912. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2020.138912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tomé CN, Lebensohn RA, Kocks UF. A model for texture development dominated by deformation twinning: application to zirconium alloys. Acta Metall Mater. 1991;39(11):2667–80. doi:10.1016/0956-7151(91)90083-D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Inoue SI, Yamasaki M, Ohata M, Kakiuchi S, Kawamura Y, Terasaki H. Texture evolution and fracture behavior of friction-stir-welded non-flammable Mg–Al–Ca alloy extrusions. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;799:140090. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2020.140090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chun YB, Davies CHJ. Investigation of prism <a> slip in warm-rolled AZ31 alloy. Metall Mater Trans A. 2011;42(13):4113–25. doi:10.1007/s11661-011-0800-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Koike J, Ohyama R. Geometrical criterion for the activation of prismatic slip in AZ61 Mg alloy sheets deformed at room temperature. Acta Mater. 2005;53(7):1963–72. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2005.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hu L, Shi L, Zhou T, Li M, Chen Q, Yang M. A visco-plastic self-consistent analysis of tailored texture on plastic deformation behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy sheet. J Mater Sci. 2021;56(34):19199–215. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-06493-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. He JJ, Liu TM, Chen HB, Lu LW, Pan FS. Effects of prior compression on ductility and yielding behaviour in extruded magnesium alloy AZ31. Mater Sci Technol. 2014;30(12):1488–94. doi:10.1179/026708313x13853742547939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Agnew SR, Duygulu Ö. Plastic anisotropy and the role of non-basal slip in magnesium alloy AZ31B. Int J Plast. 2005;21(6):1161–93. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2004.05.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jiang J, Godfrey A, Liu W, Liu Q. Microtexture evolution via deformation twinning and slip during compression of magnesium alloy AZ31. Mater Sci Eng A. 2008;483:576–9. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2006.07.175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools