Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Real Time YOLO Based Container Grapple Slot Detection and Classification System

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Tatung University, Taipei City, 104, Taiwan

2 Department of Digital Media Design, Tatung University, Taipei City, 104, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Chen-Chiung Hsieh. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Development and Application of Deep Learning based Object Detection)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 9 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072514

Received 28 August 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Container transportation is pivotal in global trade due to its efficiency, safety, and cost-effectiveness. However, structural defects—particularly in grapple slots—can result in cargo damage, financial loss, and elevated safety risks, including container drops during lifting operations. Timely and accurate inspection before and after transit is therefore essential. Traditional inspection methods rely heavily on manual observation of internal and external surfaces, which are time-consuming, resource-intensive, and prone to subjective errors. Container roofs pose additional challenges due to limited visibility, while grapple slots are especially vulnerable to wear from frequent use. This study proposes a two-stage automated detection framework targeting defects in container roof grapple slots. In the first stage, YOLOv7 is employed to localize grapple slot regions with high precision. In the second stage, ResNet50 classifies the extracted slots as either intact or defective. The results from both stages are integrated into a human–machine interface for real-time visualization and user verification. Experimental evaluations demonstrate that YOLOv7 achieves a 99% detection rate at 100 frames per second (FPS), while ResNet50 attains 87% classification accuracy at 34 FPS. Compared to some state of the arts, the proposed system offers significant speed, reliability, and usability improvements, enabling efficient defect identification and visual reconfirmation via the interface.Keywords

If defects in containers are not properly repaired, they can cause significant safety risks and economic losses. Therefore, it is crucial to inspect defects before and after transportation. Currently, container defect detection methods involve observing the interior and exterior of the containers, each with corresponding inspection checklists as shown in Fig. 1. However, these inspections are conducted manually, requiring a substantial amount of time and workforce. Moreover, there is a possibility of subjective judgment errors and missed detections.

Figure 1: Container checking is manually conducted by a human with a checklist. (a) Container and grapple slot; (b) Container inspection checklist (internal and external) [3]

We aim to establish an automated system for detecting container roof defects using the YOLOv7 [1] integrated with the ResNet [2] method. This system seeks to reduce inspection time, minimize workforce utilization, mitigate safety hazards during transportation, and minimize economic losses. Additionally, the detection results can provide recommendations for subsequent actions regarding different types of container defects.

The conventional container inspection comprises several sequential steps to identify structural and functional defects. First, the exterior surfaces are examined for visible signs of damage, including dents, scratches, rust, paint degradation, and other surface irregularities. Next, the container doors are opened to assess the interior walls, ceiling, and floor for cracks, deformations, or other structural anomalies. Subsequently, critical components such as doors, latches, locks, and door tracks are inspected to verify their integrity, operational functionality, and completeness. Finally, the container’s sealing capability is evaluated to maintain adequate enclosure during transport.

In summary, comprehensive defect inspection involves meticulous assessment of the container’s exterior, interior, mechanical accessories, and sealing performance. This process is essential to guarantee safe and reliable operation throughout transportation, minimizing the risk of cargo damage or operational failure.

Section 1 introduces the study’s research background, objectives, and significance. Section 2 comprehensively reviews existing literature on defect detection and image classification techniques. Section 3 details the neural network architectures employed in the proposed methodology, including their design and implementation. Section 4 presents and analyzes the experimental results, highlighting the performance and effectiveness of the system. The last section concludes the study and discusses potential directions for future research.

2.1 Defects Classification by CNN

Wang et al. [4] conducted a comprehensive comparison and analysis of image classification algorithms, encompassing both traditional machine learning and deep learning approaches. The research demonstrates that when utilizing the large-scale MNIST dataset [5], the accuracy of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) [6] reaches 0.88, while the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [7] achieved an accuracy of 0.98. When using the small-scale COREL1000 dataset [8,9], SVM attained an accuracy of 0.86, while CNN achieved an accuracy of 0.83. The experimental findings suggest that conventional machine learning excels in addressing issues associated with small-scale dataset challenges. Conversely, deep learning frameworks attain superior recognition accuracy when dealing with extensive datasets.

Zhang and Zhou [10] introduced an approach known as ML-KNN, a multi-label lazy learning method that draws inspiration from the conventional K-nearest neighbor (KNN) [11] algorithm. In this method, for each test sample, its K nearest neighbors are identified within the training dataset. Subsequently, leveraging statistical information derived from neighboring samples, such as the count of neighbors belonging to the same class, the label set for the test sample is determined using the principle of maximum a posteriori probability (MAP). The authors conducted experiments on three real-world multi-label datasets, demonstrating that their proposed ML-KNN method outperforms alternative multi-label learning algorithms.

Yun et al. [12] proposed a novel approach utilizing Convolutional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) [13,14] and a deep CNN-based defect classification algorithm to address the challenge of the limited occurrence of defects and the difficulty in acquiring sufficient data. The data generation technique based on CVAE generates a significant amount of defect data to train the classification model. Additionally, the authors introduced a conditional CVAE (CCVAE) that produces images for each defect type within a single CVAE model, addressing the issues of data scarcity and class imbalance. The experimental results demonstrated that the model incorporating CCVAE exhibits superior performance.

The Residual Network (ResNet) is a type of deep convolutional neural network designed to address the problem of vanishing gradients in deep neural networks. In deep neural networks, as the network becomes deeper, the gradients may become extremely small, preventing effective learning of the model. We can confirm that this is not caused by overfitting (as overfitting would result in high accuracy on the training set).

To tackle this issue, He et al. [2] proposed a new neural network framework called the Residual Network, which allows the network to be as deep as possible. This Residual block is implemented through a shortcut connection, where the input of the block is directly added to the output layer. This simple addition does not introduce additional parameters or computational complexity to the network. However, it significantly increases the training speed and improves the training effectiveness. Moreover, as the depth of the model increases, this simple structure effectively addresses the performance degradation problem. Shabbir et al. [15] fine-tuned the hyperparameters of ResNet50 to improve the model’s accuracy. After testing on datasets such as RSSCN (remote sensing scene classification image dataset) [16], UC Merced land use dataset (UCM) [17], Corel-1.5K [18], Corel-1K [18], and SIRI-WHU [19], the fine-tuned ResNet50’s hyperparameters gained superior performance when compared to models like POVH [20], VGG [21], Inception-V3 [22], GoogLeNet [23], and AlexNet [24].

de la Rosa et al. [25] addressed the issue of highly imbalanced data in a semiconductor defect image dataset using data augmentation. In other words, the dataset had a small proportion of defective images. They employed geometric transformations through data augmentation to generate seven different datasets, each with twice as many images as the previous one. After training with ResNet50 and using the F1 score as an evaluation metric, the results showed that the data augmentation process yielded positive outcomes, improving the classification results by 3.74%. The conclusion was that generating sufficient synthetic images for minority classes can enhance the model’s performance.

Due to the difficulty in collecting a sufficient quantity of defect samples and the time-consuming manual labeling process, Zhao et al. [26] proposed an innovative defect detection framework exclusively trained on positive samples. They combined Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) [27] and autoencoders for defect image reconstruction, and utilized Local Binary Patterns (LBP) [28] for detecting local contrast of defects in images. Experimental results on fabric images and the DAGM 2007 [29] dataset demonstrated that the proposed GAN+LBP algorithm achieved higher detection accuracy compared to the supervised training algorithm with sufficient training samples.

Bahrami et al. [30] introduced a deep learning-based framework comprising two primary components: The High-Resolution and Temporal Context-based Region Convolutional Neural Network (HRTC R-CNN) [31], designed for detecting corrosion defects, and the Corrosion Defect Characterization (CDC) module tailored for inspecting corrosion defects. The specific methodology involves utilizing HRTC R-CNN to identify the locations of corrosion features, followed by employing CDC to compute the percentage of corrosion across the entire container surface. Experimental results on a corrosion defect dataset demonstrated that the proposed approach surpasses the performance of FMHF [32], Generic Model [33], FPCB [34], VAWT [35], and other competing models. However, their method falls short as it only relies on the proportion of the flawed area to the entire container surface for judgment. For instance, if there is a small hole on an otherwise intact container surface, it might be overlooked due to its small size. Furthermore, in practical applications, most containers in the field have some areas of rust. False alarms may occur frequently if judgment is solely based on the location.

To enhance the detection performance of small objects, Zeng et al. [36] introduced an advanced multiscale feature fusion technique, the atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP) balanced feature pyramid network (ABFPN). They devised a skip ASPP module with various dilation rates to expand the receptive field and incorporated a balanced module to extract underlying features for effective fusion. Experimental results demonstrated this as a dependable and efficient feature fusion approach. Consequently, the ABFPN was integrated as the neck component within the improved PCB defect detection (IPDD) framework for feature fusion, and empirical tests demonstrated that the proposed IPDD framework outperformed seven other state-of-the-art methods in both localization and classification tasks.

2.2 Defects Detection Using YOLO

You only look once version 7 (YOLOv7) was proposed in early July 2022, and it surpassed all known object detectors in speed in the range of 5 FPS to 160 FPS, while maintaining high accuracy. It outperforms various object detectors such as SWIN-L-Cascade-Mask R-CNN [37], ConvNeXt-XL Cascade-Mask R-CNN [38], YOLO series including YOLOv4 [39], Scaled-YOLOv4 [40], YOLOR [41], YOLOv5, YOLOX [42], PPYOLO [43], as well as DETR [44], DINO-5scale-R50 [45], Deformable DETR [46], and ViT-Adapter-B [47].

YOLOv7 reduces approximately 40% of parameters and 50% of computations compared to state-of-the-art real-time object detection models. The optimization of YOLOv7 focuses on model architecture optimization and training process optimization. The authors proposed extended and scaling methods that effectively utilize parameters and computations for model architecture optimization. For training process optimization, YOLOv7 embedded the “bag-of-freebies” concept from YOLOv4, which improves accuracy at the cost of increased training complexity without increasing inference cost. Additionally, re-parameterized techniques replace the original modules, and dynamic label assignment strategies are employed to assign labels more efficiently to different output layers.

Zhao and Zhu [48] have proposed a multi-scale Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) image object detection model based on YOLOv7, known as MS-YOLOv7. This model addresses the challenge of detecting many objects in UAV aerial images, including small objects with high aspect ratios. The authors integrated the CBAM [49] convolutional attention module, introduced a novel pyramid pooling module known as SPPFS, and merged the YOLOv7 network architecture with Swin Transformer units. They also introduced SoftNMS [50] and the Mish [51] activation function. Various experiments were conducted on the open-source VisDrone2019 [52] dataset, and the results showed that compared to the baseline YOLOv7 algorithm, MS-YOLOv7 achieved a 6.0% improvement in mAP0.5 and a 4.9% improvement in mAP0.95.

Zheng et al. [53] proposed an improved YOLOv7 method to detect subtle defects on insulators in complex background images of power transmission lines. The author introduced several modifications to YOLOv7, including using K-means++ for clustering the target boxes in the insulator dataset, adding a HorBlock [54] module and a coordinate attention (CoordAtt) [55] module, and enhancing practical features and weakening ineffective features during feature extraction. The SCYLLA-IoU (SIoU) [56] and focal loss functions were utilized to accelerate model convergence and address the issue of class imbalance. Experimental results demonstrated an average precision of 93.8% for the model, surpassing the YOLOv7 model, YOLOv5s model, and Faster R-CNN model by 3.7%, 4% and 7.6%, respectively.

Xin et al. [57] proposed a PCB defect detection method based on YOLOv4 to achieve automated detection of PCB defects. To enhance accuracy and speed, the authors fine-tuned the YOLOv4 model using the PCB defect dataset released by Peking University’s Intelligent Robot Laboratory. They adjusted the hyperparameters of YOLOv4 and conducted experiments that demonstrated an improvement of 8.152% in mAP with the enhanced YOLOv4 model. They also compared their method with models like Faster R-CNN and feature pyramid network (FPN), showing that their proposed approach yielded the best results.

Le et al. [58] proposed an industrial parts defect detection model based on YOLOv5. They incorporated a coordinate attention mechanism into the feature extraction module to enhance the model’s performance and improve detection accuracy. They optimized the model’s hierarchy through BiFPN, reducing false detection and missed detection rates for small target samples. Finally, they introduced a transformer detector to increase the recognition accuracy of samples. Their experimental results demonstrated that the proposed YOLOv5-based improvement method led to a 5.3% increase in recall rate and achieved a recognition speed of 95 FPS.

Pham et al. [59] proposed a comprehensive deep learning-based workflow for road damage detection, emphasizing inference speed optimization without compromising detection accuracy. To address hardware constraints, their method incorporates image cropping for large-scale inputs and leverages lightweight model architectures. The framework integrates multiple models, including a customized YOLOv7 variant enhanced with Coordinate Attention layers and a Tiny YOLOv7 model, both trained and fused to maximize detection performance. Subsequent developments in the YOLO family have further advanced object detection capabilities. YOLOv8 [60], released in 2023, introduced architectural refinements aimed at improving real-time performance and enhancing accuracy for small object detection. YOLOv9 [61], launched in early 2024, expanded upon these improvements by incorporating novel mechanisms such as programmable gradient information and implicit knowledge learning, achieving state-of-the-art results while maintaining computational efficiency. At the time of this study, YOLOv10 [62] is anticipated to deliver further gains in accuracy, speed, and adaptability, continuing the trajectory of innovation within the YOLO framework. However, from their experimental results, YOLOv8 and YOLOv9 showed slightly higher mAP@0.5 and F1 scores, along with shorter inference times, compared to the default YOLOv7 model. Furthermore, the optimized YOLOv7 model—enhanced with additional Coordinate Attention layers and customized hyperparameters achieved a better F1 score and confidence threshold. Notably, these same optimizations were also applied to YOLOv8, YOLOv9, and YOLOv10, but did not yield improvements; in some cases, they even degraded performance. Therefore, the adoption of the YOLO model is not always the higher version the better. In fact, it depends on the specific application, which may have limited variant conditions, say small size or limited weather conditions, of the detection targets.

With the advancement of container port automation, vision-based systems have become increasingly prevalent in automated terminal operations. Mi et al. [63] introduced a high-speed automated vision framework for recognizing container corner castings. The approach utilizes Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) descriptors to preprocess container images and construct corresponding feature vectors. A trained Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier is then employed to identify the right corner casting. Leveraging geometric symmetry, a flipping mirror algorithm is subsequently applied to efficiently detect the left corner casting. Diao et al. [64] localize container lock holes by isolating the top region of the container from multiple candidate areas, followed by the application of a modified local sliding window technique to detect keyhole regions. HOG features are also extracted and learned through a multi-class SVM classifier. Subsequently, lock holes are precisely located using direct least squares ellipse fitting.

Wang [65] proposed a method based on Local Binary Pattern (LBP) features and a multi-scale sliding window technique to detect individual lock holes. To achieve real-time and accurate recognition, a convolutional neural network (CNN) with an optimized thresholding mechanism is integrated into the framework. Zhang et al. [66] proposed a vision-based measurement system for container lifting operations. The system captures container imagery using a camera and identifies container corners through a hybrid approach that integrates a convolutional neural network with traditional image processing techniques. Specifically, a modified Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) is employed in the initial stage to estimate the coarse positions of container corners. In the subsequent stage, rectangle fitting is applied to refine the detection and accurately localize the corner holes.

Nguyen et al. [67] are among the first to implement YOLO-NAS for container damage detection, targeting the challenging operational environments of seaports and optimizing for both high-speed and high-accuracy performance critical to port logistics. The proposed method demonstrates the superior effectiveness of YOLO-NAS. Comparative evaluations reveal that YOLO-NAS consistently outperforms other state-of-the-art models, including YOLOv8, which yielded lower mAP, precision, and recall under equivalent testing conditions.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to address both the localization and condition classification of container grapple slots (lock holes). We propose a novel two-stage automated detection framework specifically designed to identify defects in container roof grapple slots. In the first stage, YOLOv7 is utilized to accurately localize grapple slot regions in real time. In the second stage, ResNet50 is employed to classify the extracted slots as either intact or defective. The proposed system achieves a detection rate of 99% at 100 frames per second (FPS), while the classification stage attains an accuracy of 87% at 34 FPS, surpassing existing state-of-the-art methods.

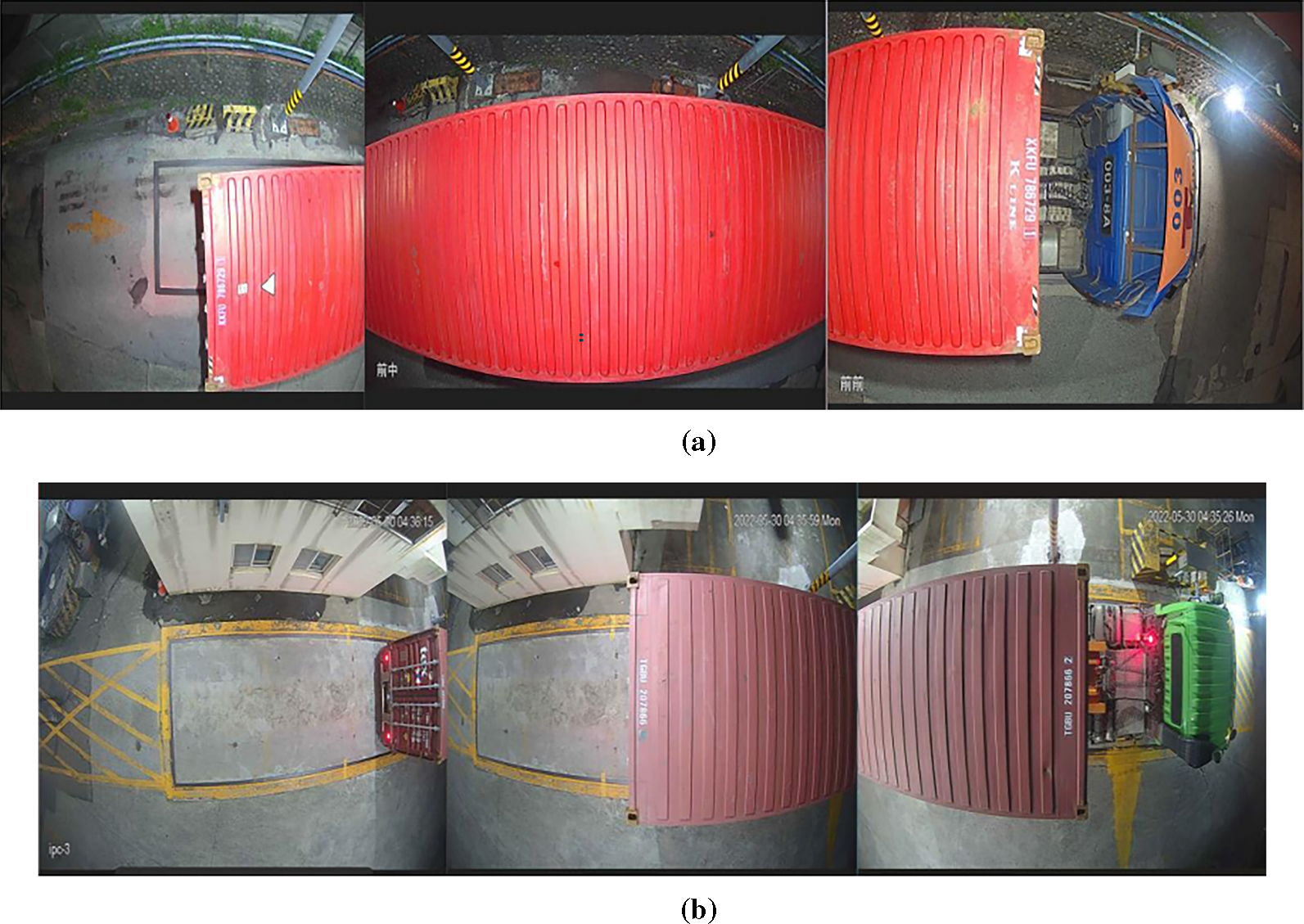

According to the previous chapters and literature review, we have chosen to use YOLOv7 + ResNet50 for grapple slot detection and defect classification in our system. To provide many images required for deep learning, we have installed cameras above the containers at the weighing stations at the entrances and exits of the container yard. Additionally, to accommodate containers of varying lengths, we have set up three cameras to capture images of the containers’ front, middle, and rear sections. Fig. 2 shows the overall architecture of the container defect detection and classification system.

Figure 2: System architecture

Due to the difficulty and danger of manually capturing images of the top of the containers, we have installed cameras above the containers in the front and rear weighing stations of the container yard using poles, as sketched in Fig. 3. Additionally, to accommodate containers of different lengths, we have set up three cameras to capture images of the front, middle, and rear sections of the containers. There are six network cameras in the front and rear stations. The network cameras we used have a resolution of 1920 × 1080 for two cameras and 2592 × 1944 for one camera. They are mounted at a height of 7 m and capture images from a distance of 4 m. Figs. 4 and 5 show the real on-site installation and the captured images from a top view.

Figure 3: Camera setup and installation: (a) top view, and (b) front view

Figure 4: On-site installation for container defect inspection. (a) IP camera. (b) Light

Figure 5: Images captured by the IP camera: (a) Rear field camera. (b) Front field camera

3.3 Grapple Slot Detection and Classification

This section introduces the two models used in the proposed container defect detection and classification system, namely YOLOv7 for detection and ResNet50 for classification.

A dedicated virtual environment was established using Anaconda to facilitate model development. Within this environment, essential Python-based packages required for YOLOv7—including PyTorch, OpenCV, NumPy, and Git—were installed. The complete source code for YOLOv7 was then retrieved from the official GitHub repository (https://github.com/WongKinYiu/yolov7 (accessed on 10 January 2023)) using Git.

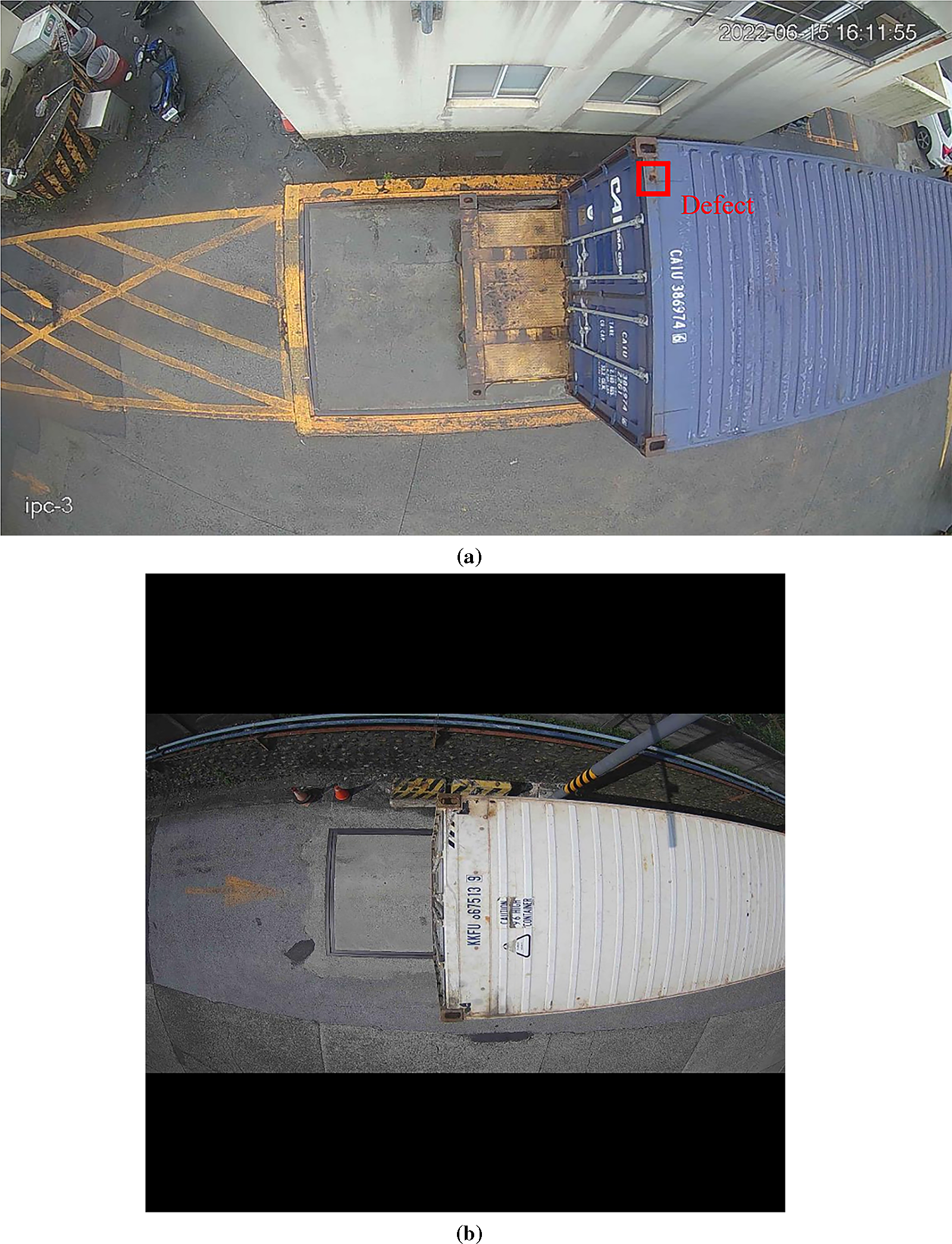

During the initial phase of system development, YOLOv7 was selected as the sole detection model based on its presumed effectiveness in identifying container defects. However, experimental results revealed that defects occupied only a minor portion of the image (see Fig. 6a), and the dataset contained limited defective samples. Consequently, the detection performance was suboptimal. The system architecture was restructured into a two-stage framework to address these limitations.

Figure 6: Some sample images. (a) A defect indicated by a red box. (b) A resized image for normalization

In the first stage of the system, YOLOv7 is employed to detect and localize grapple slot regions, which are subsequently extracted for classification in the second stage. The dataset comprises images at two native resolutions: 1920 × 1080 and 262 × 1944. To standardize input dimensions, OpenCV is used to read each image and reshape it into a square format—1920 × 1920 or 2592 × 2592—by centering the content and padding the shorter dimension with black borders (see Fig. 6b). This preprocessing step mitigates geometric distortion during the subsequent resizing to 640 × 640 for model training.

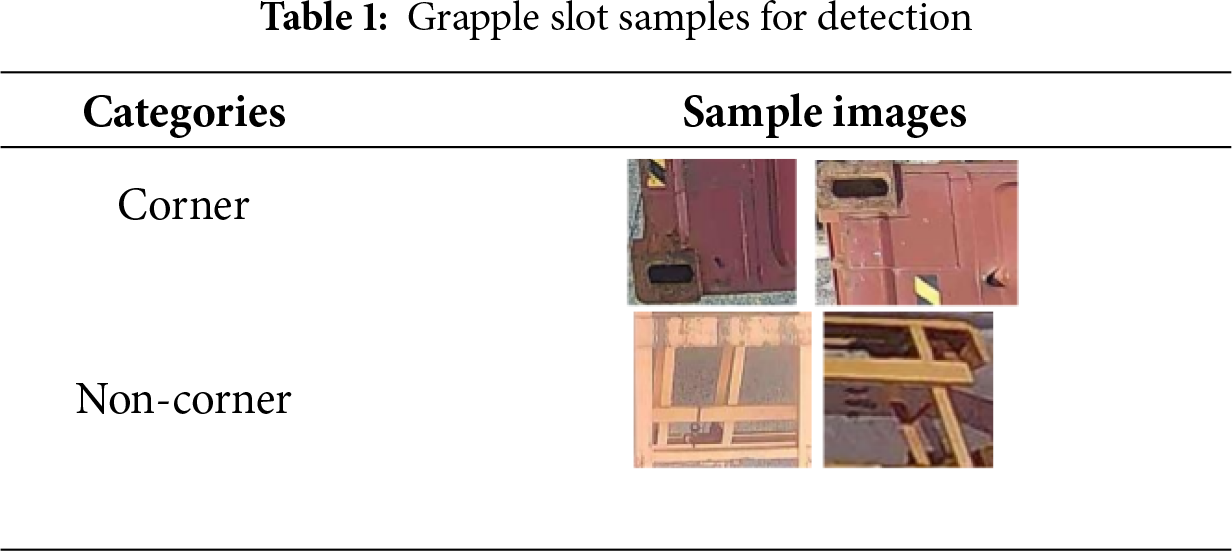

As summarized in Table 1, grapple slot annotation was performed using the tool LabelImg. Images containing grapple slots were labeled with the class “corner,” while those without grapple slots remained unlabeled. Data augmentation was applied using the Python library imgaug to enhance dataset diversity. These steps collectively yielded a dataset tailored for grapple slot detection. We utilized the official YOLOv7 training codebase for model training, modifying the hyperparameters learning rate = 0.001, epoch = 200, and batch size = 16. The built-in data augmentation functionality of YOLOv7 was explicitly disabled, as our dataset had already undergone augmentation. Moreover, YOLOv7 introduces stochastic augmentations at each training iteration, which could lead to inconsistent learning dynamics. We chose not to employ this feature to maintain control over the augmentation process.

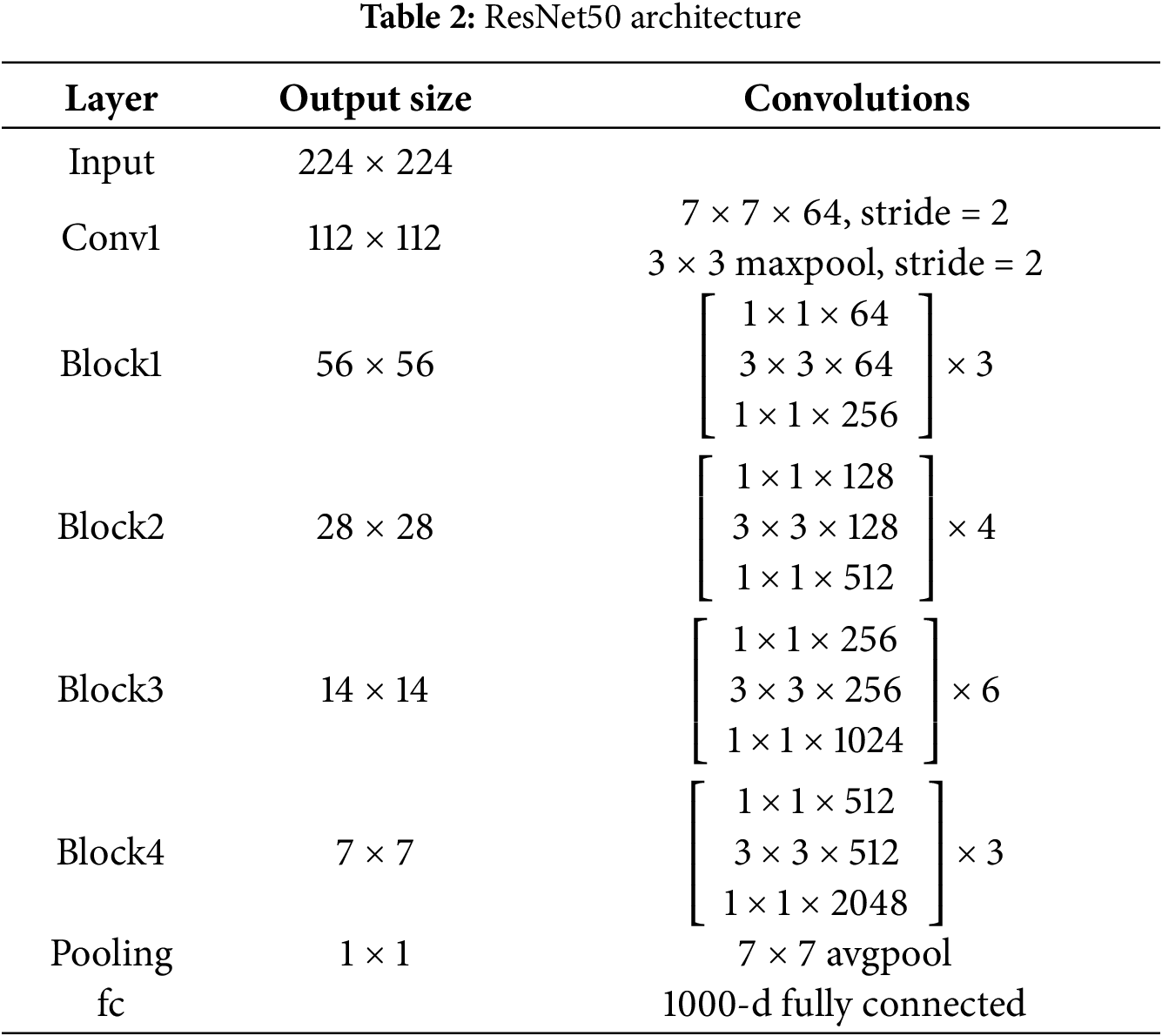

In this stage, a new virtual environment was configured using Anaconda to ensure modularity and reproducibility. Key Python packages—including TensorFlow, Keras, and NumPy—were installed in this environment to support model development. The implementation was done in Python, leveraging the modular functionalities provided by the Keras framework (https://keras.io). Specifically, the class was employed to load image data in batches, facilitating efficient preprocessing and augmentation. As shown in Table 2, the network architecture is constructed using a combination of layers such as ResNet50, Flatten, Dropout, and Dense.

3.3.4 Grapple Slot Classification

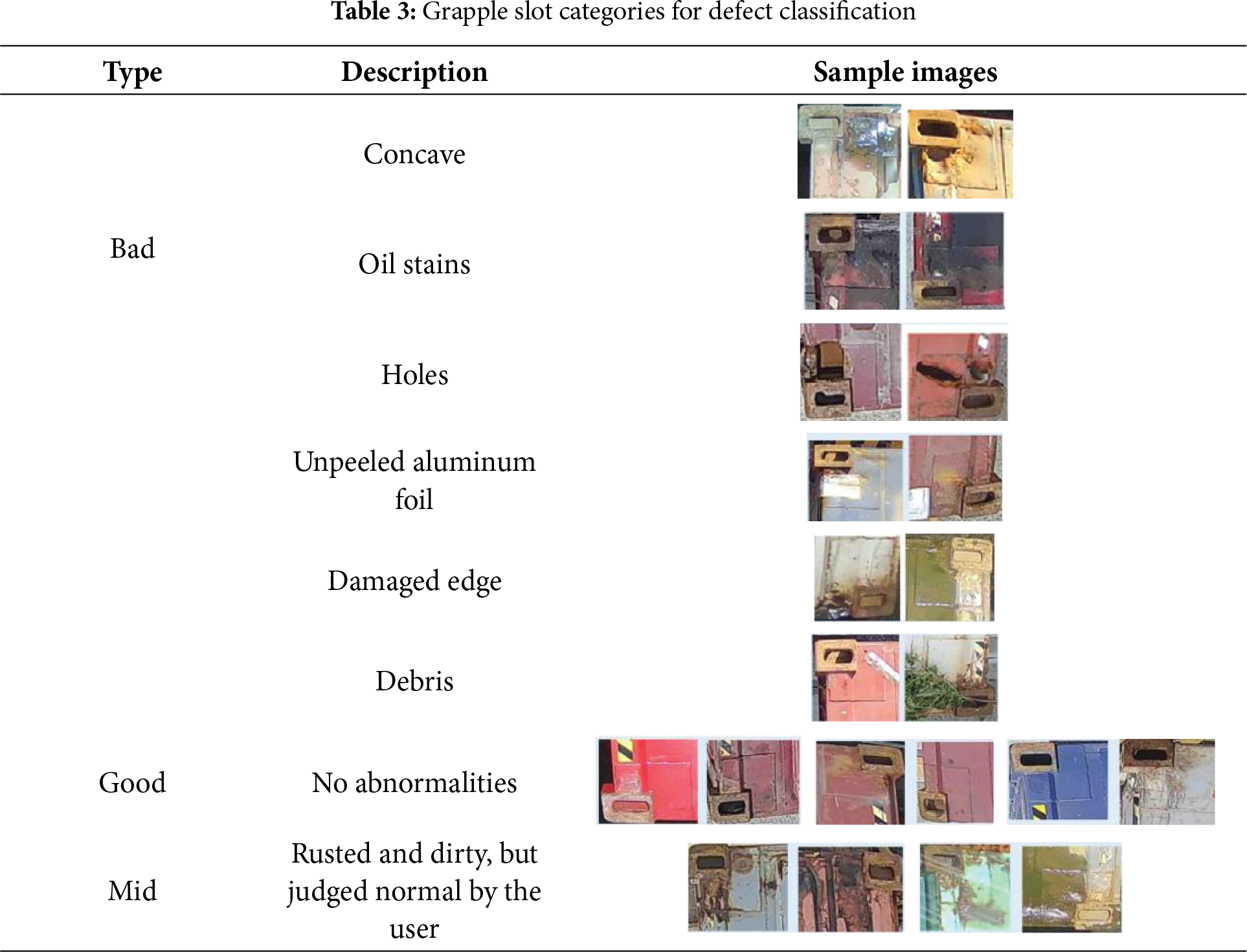

In the initial training phase, grapple slot images extracted from the previous stage were used to classify container conditions into good and bad. These labels were derived from on-site inspections, where personnel manually identified and separated defective containers. However, the binary classification yielded suboptimal results, primarily due to the limited number of defective samples and the inherent subjectivity in human judgment.

To mitigate these issues, an intermediate category—mid—was introduced to represent suspected defects. This class was constructed based on images that were misclassified as bad during the binary training process, reflecting ambiguous or borderline cases. Experimental results demonstrated that the three-class classification (good, mid, and bad) outperformed the binary approach in terms of accuracy and robustness. Consequently, the proposed system adopts this three-class framework. Representative images for each category are illustrated in Table 3. As described previously, the ResNet-50 model was deployed, and the corresponding training hyperparameters are set as follows: learning rate = 0.00001, epoch = 50, batch size = 8, and optimizer = Adam.

3.3.5 Human-Computer Interface Design

This subsection shows the user interface (UI) of the proposed container defect detection and classification system. Upon activation—initiated by the truck driver via a designated control—the system begins evaluating the structural condition of the container. Once the assessment is complete, the classification results are displayed on the UI in real time, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The system user interface displays the classification results of the four corners

4 Experimental Results and Discussion

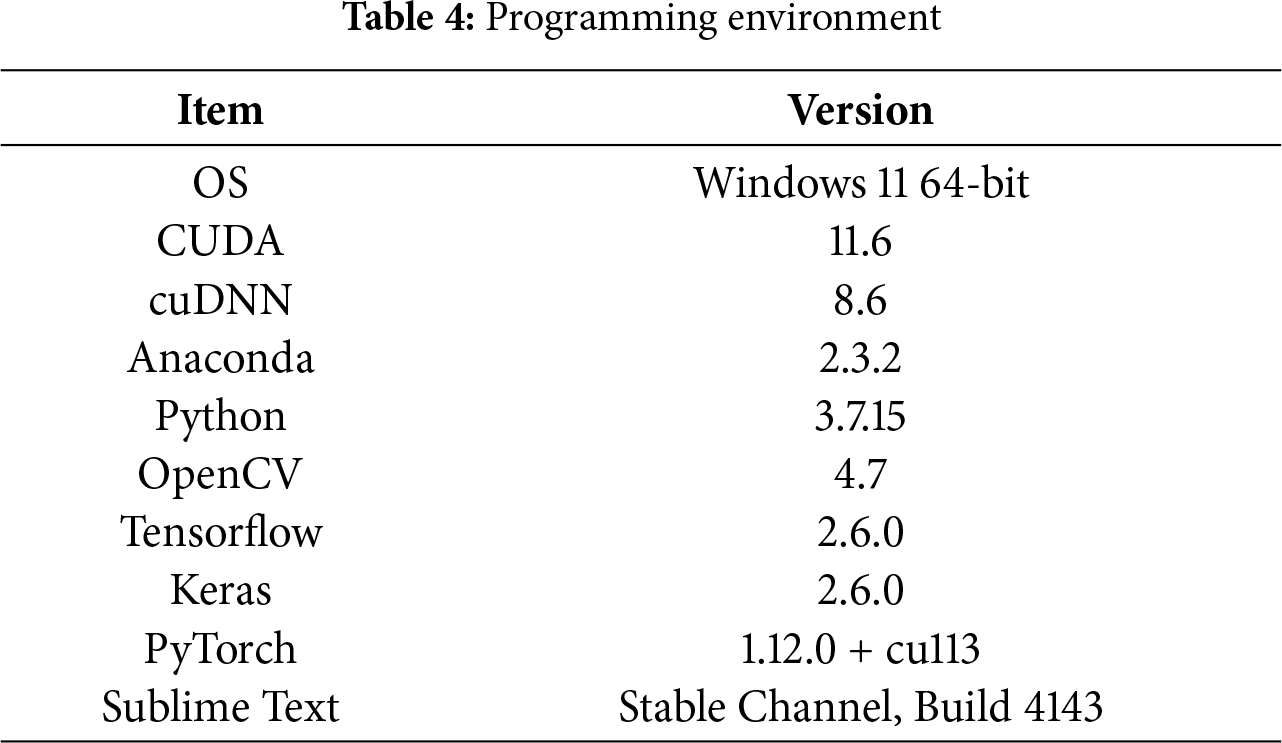

This study’s training and testing procedures were conducted on a personal computer. The system’s hardware specifications include CPU Intel i5-12400F 2.5 GHz, RAM DDR4-3200 32 GB, and GPU Nvidia GeForce RTX3060 12 GB. The corresponding software and programming environment configurations are summarized in Table 4.

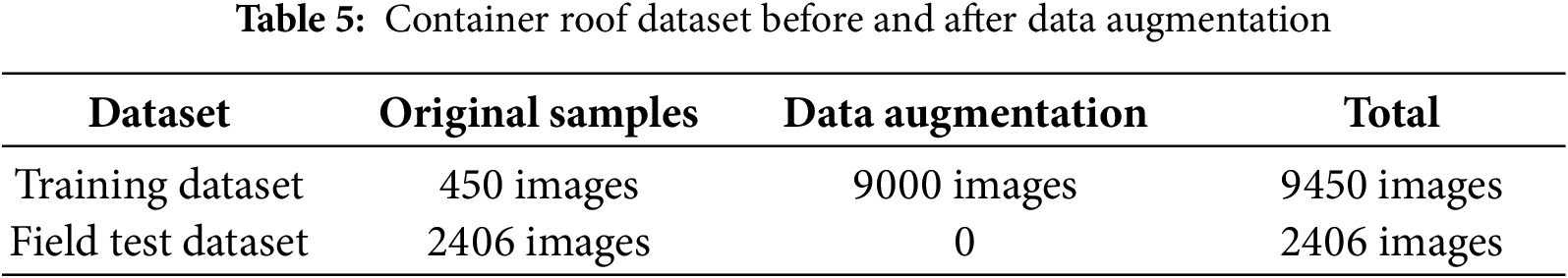

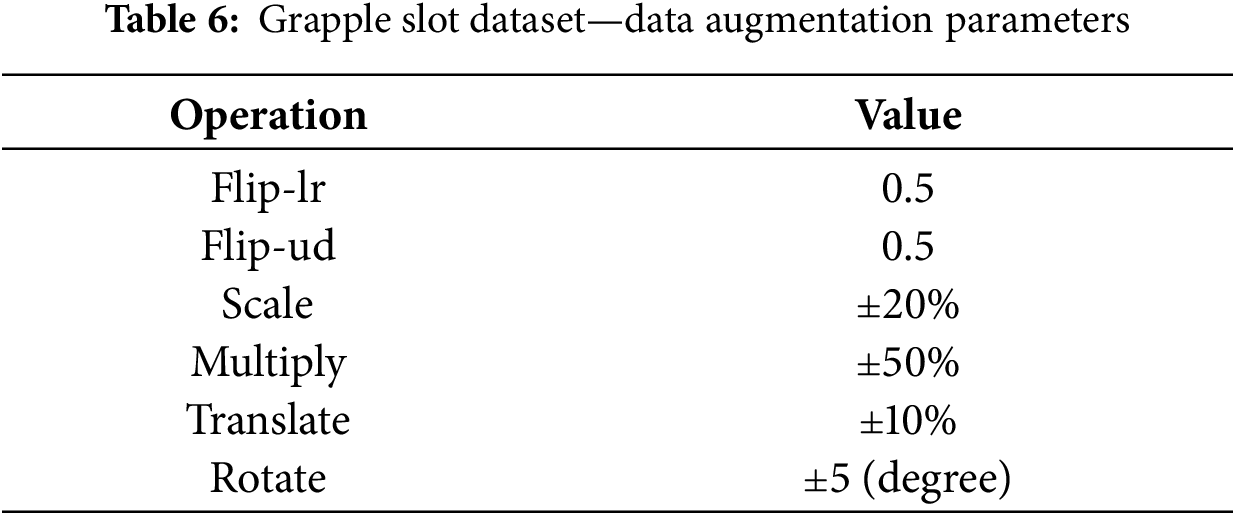

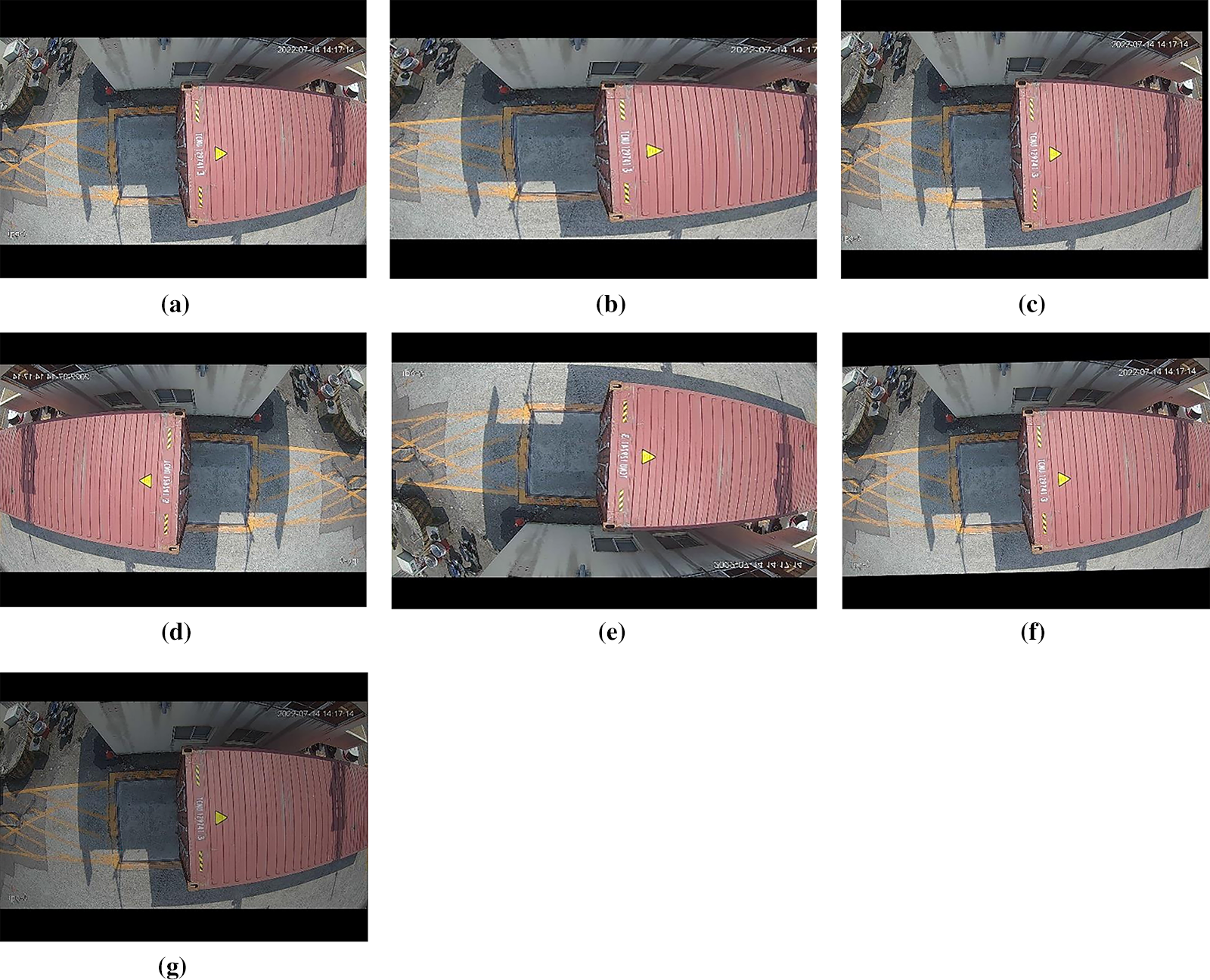

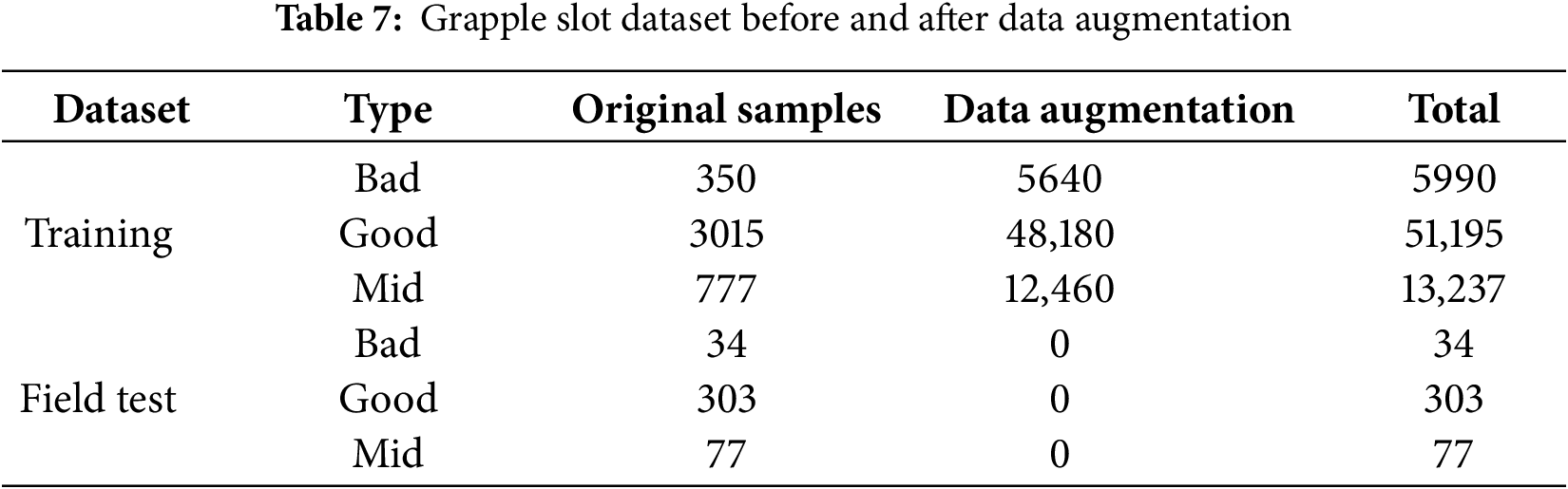

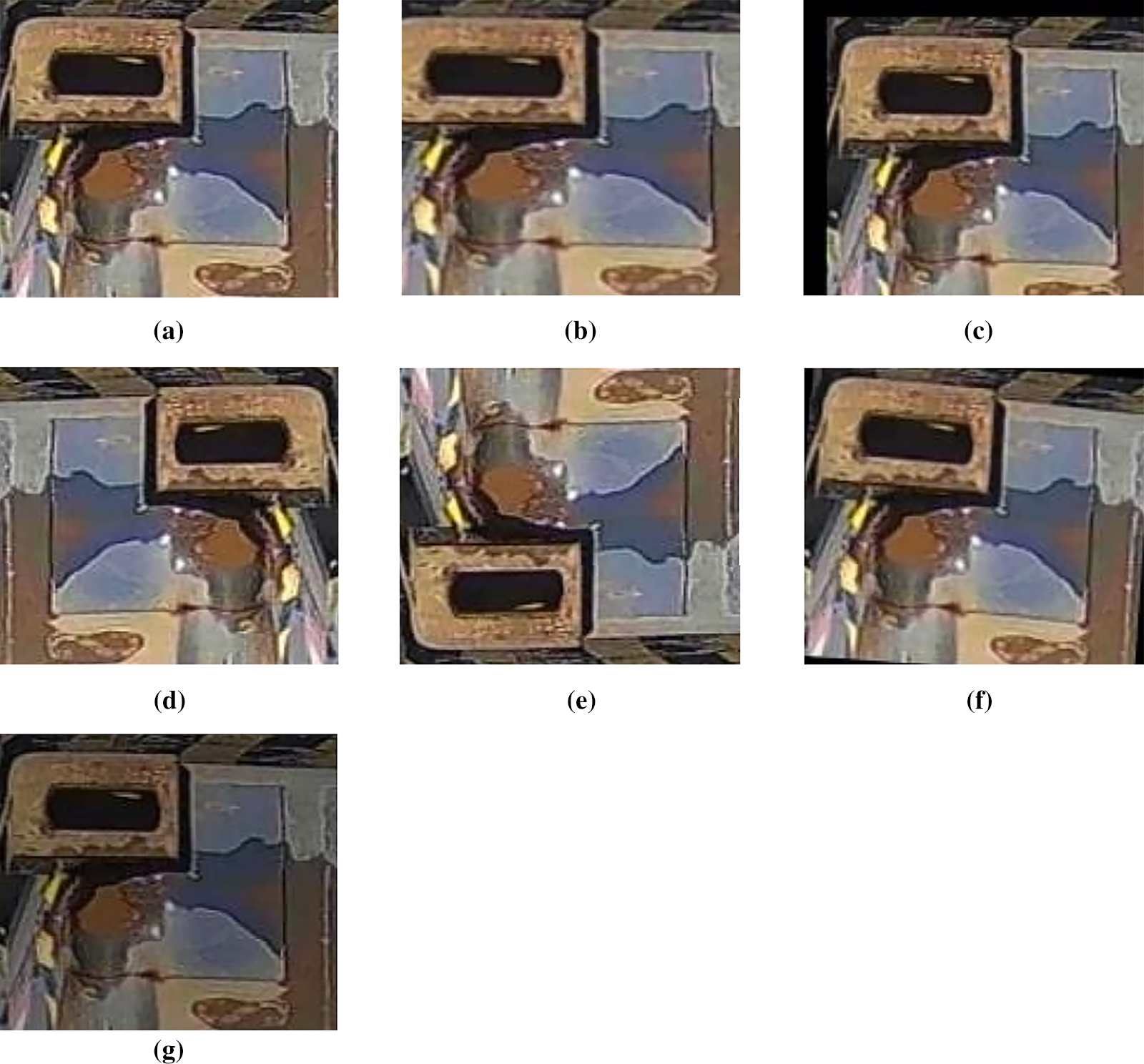

This study utilizes two datasets: one is a container roof for grapple slot detection, and the other is a grapple slot only for classifying grapple slot conditions. Table 5 presents the original sample counts for both datasets and the expanded totals following data augmentation. The augmentation parameters applied to the container roof dataset are detailed in Table 6, and representative augmented samples are illustrated in Fig. 8. Similarly, for the grapple slot dataset, the distribution of samples across categories is summarized in Table 7. The corresponding augmentation parameters are similar to Table 6, with visual examples in Fig. 9.

Figure 8: Operations used for container roof data augmentation: (a) source image, (b) scaling, (c) translation, (d) flip-lr, (e) flip-ud, (f) rotation, and (g) brightness

Figure 9: Operations used for grapple slot image data augmentation: (a) source image, (b) scaling, (c) translation, (d) flip-lr, (e) flip-ud, (f) rotation, and (g) brightness

Two key metrics were employed to evaluate the performance of the proposed container defect detection and classification system: the confusion matrix and mean average precision (mAP). The confusion matrix provides a detailed breakdown of classification outcomes, comprising four components: True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN). These elements form the basis for calculating recall, precision, and overall accuracy, standard indicators in machine learning classification tasks. Meanwhile, mAP was used to assess the effectiveness of the neural network model in object detection.

where APi is the average precision of class i, and N is the number of classes.

This section presents the training outcomes for the grapple slot detection and classification datasets. The training dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets following an 8:1:1 ratio. Data augmentation techniques were applied exclusively to the training set to improve model generalization and robustness.

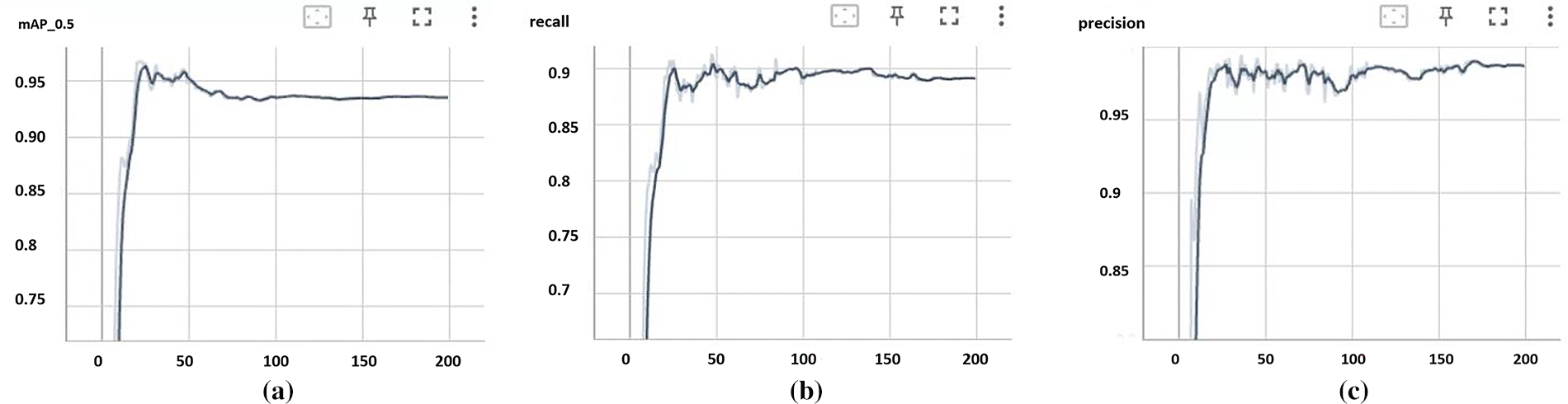

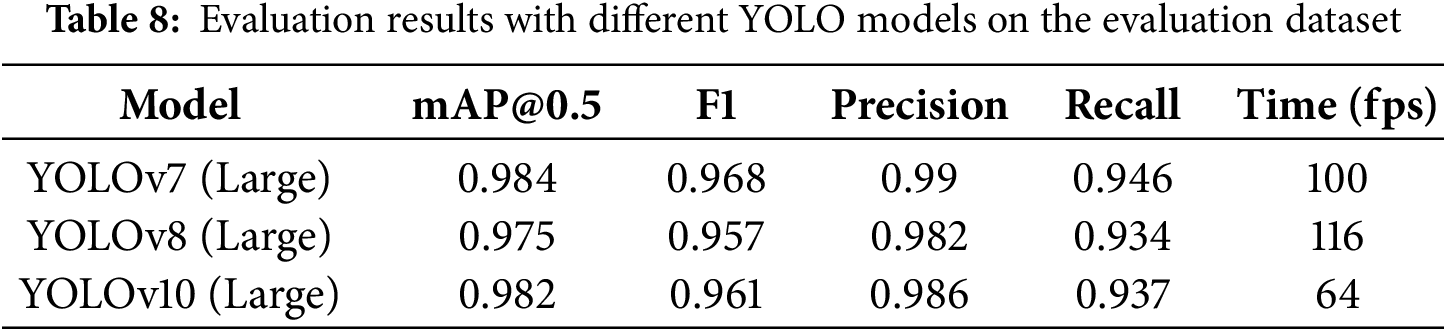

4.4.1 Grapple Slot Detection Training Results

Fig. 10 illustrates the performance metrics—mean Average Precision (mAP), recall, and precision—achieved by the YOLOv7 model after 200 training epochs on the grapple slot detection task. The results are as follows: mAP of 0.984, recall of 0.946, and precision of 0.99. For the more recent YOLO versions (v8, v10), we utilized the ultralytics package [60] for training. After conducting several experiments, we settled large size of the configurations for YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and YOLOv10, as shown in Table 8. To measure inference time, we performed tests on the evaluation dataset using a batch size of 1 to calculate the per-image inference time for the YOLO models. From the training results, YOLOv7 still has a little higher performance metric since we have fine-tuned the hyperparameters and our target is of a small size.

Figure 10: Training results: (a) mAP, (b) Recall, and (c) Precision

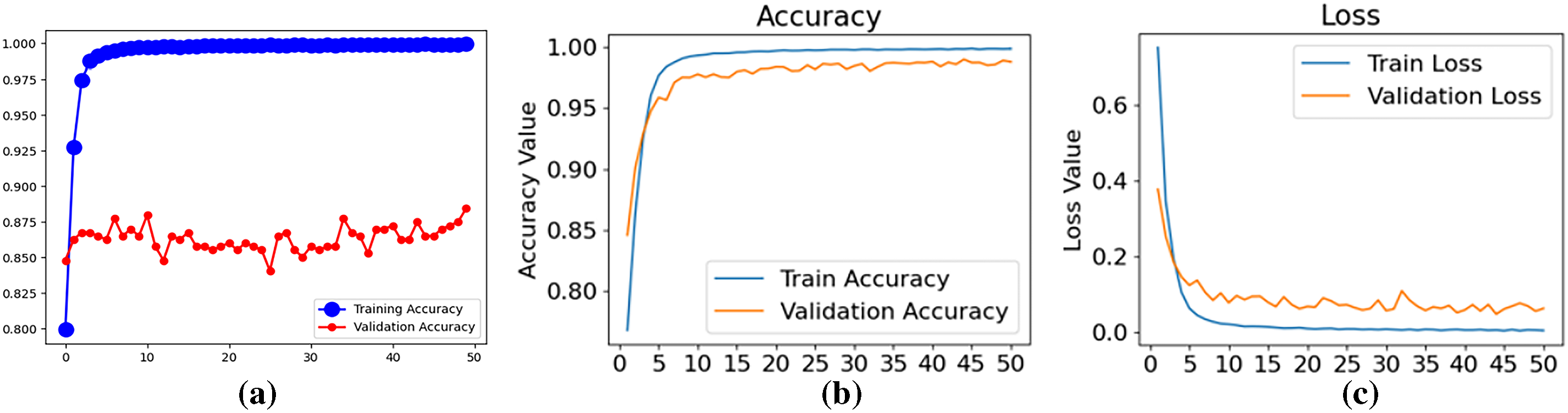

4.4.2 Grapple Slot Classification Training Results

Fig. 11a depicts the training and validation accuracy achieved by the ResNet model over 50 epochs for the hook slot classification task. The model attained a training accuracy of 0.994 and a validation accuracy of 0.884, revealing a notable discrepancy. This gap is attributed to the limited clarity in distinguishing among the three target categories and the scarcity of defective samples, which collectively hinder the model’s generalization capability.

Figure 11: (a) Training and validation accuracy at the initial stage. (b,c) show the accuracy and loss after K-fold training

We employed the K-fold cross-validation technique with K = 5 to mitigate the observed generalization gap and retrained the model over 50 epochs. Fig. 11b,c summarizes the results across five training folds, with the final model achieving a training accuracy of 0.998 and a validation accuracy of 0.987. This approach substantially reduced the discrepancy between training and validation performance. Consequently, all subsequent experimental results are reported under the condition that K-fold cross-validation is applied during evaluation.

This section presents the evaluation results obtained using model weights trained in the preceding phase. Testing was conducted on a separate dataset comprising samples excluded from the training process, ensuring an unbiased assessment of the system’s generalization performance.

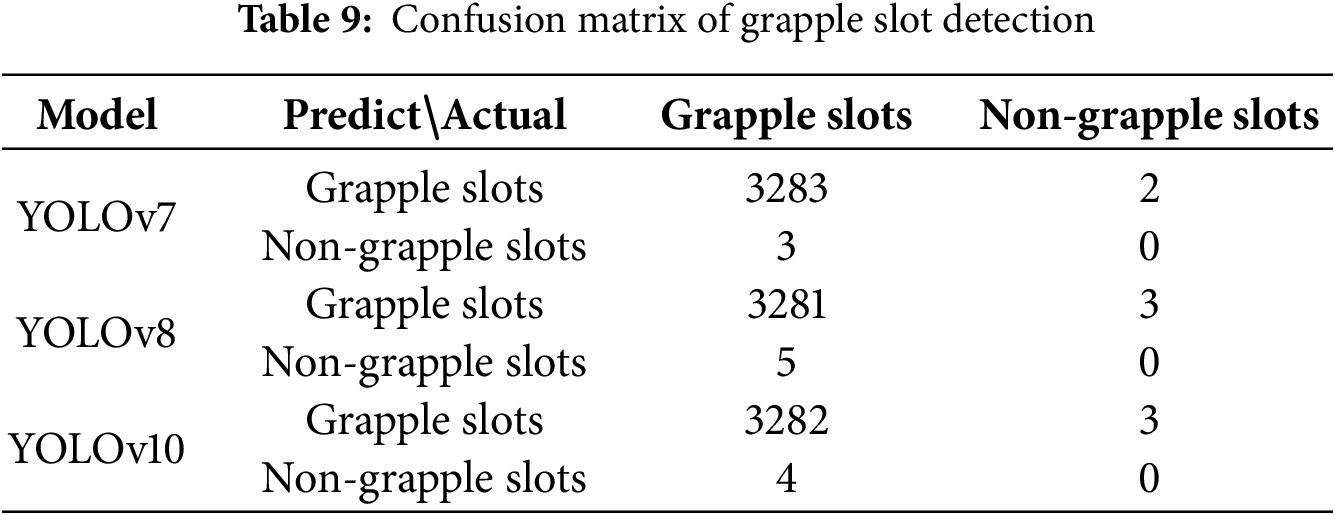

4.5.1 Grapple Slot Detection Field Test Results

Over three days, field testing was performed on 2406 container images collected from field operations. All images were excluded from the training set to ensure unbiased evaluation. Across these containers, a total of 3286 grapple slots were present. The system detected 3285 slots, with only three missed detections and two false positives—either non-grapple regions or duplicate detections—as detailed in Table 9. This yields a detection accuracy of 3283 out of 3286 (0.999), with a processing speed of 100 frames per second (fps).

To increase the detection rate, we conducted the same experiment with the newer versions YOLOv8 and YOLOv10. YOLOv8 introduced an anchor-free design and a more streamlined architecture, thereby enhancing performance. The key innovation of YOLOv10 lies in enabling end-to-end object detection by eliminating the need for Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) during inference. This breakthrough reduces computational overhead and inference latency, thereby enhancing deployment efficiency. As shown in Table 9, the accuracy for YOLOv7 still maintains the highest. This is due to the limited shape and size of the grapple slots in this study, since they are of similar size. However, higher YOLO models may have the opportunity to get higher accuracy since NMS is embedded in YOLOv10, and if the hyperparameters have been fine-tuned.

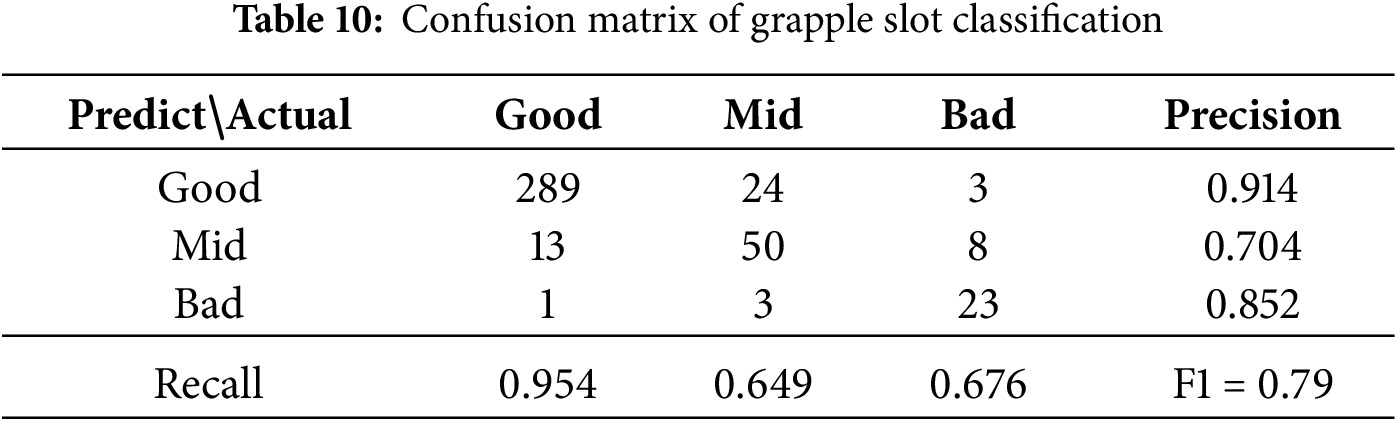

4.5.2 Grapple Slot Classification Field Test Results

The test set comprised 414 grapple slots, all previously unseen during training. Of these, 303 were labeled as “Good,” 34 as “Bad,” and 77 as “Mid.” The evaluation results, summarized in Table 10, focus on the identification performance for “Bad” and “Mid” samples. The system correctly recognized 289 “Good,” 50 “Mid,” and 23 “Bad” slots, yielding an overall recognition accuracy of (289 + 50 + 23)/414 = 0.874. Compared to the conventional manual inspection method, which required reviewing each sheet, the proposed system reduces the workload to approximately 13% of the original. Furthermore, the automatic extraction of grapple slots enables magnified visualization for easier inspection. The detection speed reaches 34 frames per second (fps), supporting real-time deployment.

Though the recall rates are not ideal for the defective grapple slots, due to the differential boundary between the Mid and Bad samples is ambiguous. The precision, recall, and F1 rates for the combined Mid and Bad types are 0.875, 0.757, and 0.812, respectively. Those performances are higher than the separated class types when considering the rigid constraint for the safety issue. Still, human labelling may cause performance drops while a common agreement is not reached to classify some Mid samples to be Good or not. Some examples (false negatives) are given in the next subsection.

4.5.3 Field Test Error Analysis

During grapple slot detection, three images failed to yield valid detections. This was primarily due to image blurs induced by nighttime conditions and fog, as illustrated in Fig. 12. Additional nighttime samples and refinement of data augmentation parameters are recommended to mitigate this issue. Furthermore, two instances of false detection were observed—either misidentification of non-grapple regions or redundant detection of existing grapple slots—as shown in Fig. 13. These errors may be addressed by expanding the set of negative samples and applying stricter confidence thresholds during post-processing.

Figure 12: Different weather detection results: (a) Night and foggy. (b) Sunny day

Figure 13: False detections: (a) Repeated detections. (b) Non-grapple slots

In the grapple slot classification task, three defective slots were incorrectly classified as “Good,” as illustrated in Fig. 14. This misclassification is primarily attributed to the limited availability of defective samples in the training dataset. The absence of similar examples hindered the model’s generalization ability in these cases. We are expanding the dataset by collecting additional samples exhibiting defects to address this limitation. Furthermore, we are investigating the application of generative adversarial networks (GANs) to synthetically generate representative defective samples, thereby enhancing the diversity and robustness of the training data.

Figure 14: Mistakenly classified grapple slots as “Good” though they look like “Bad”

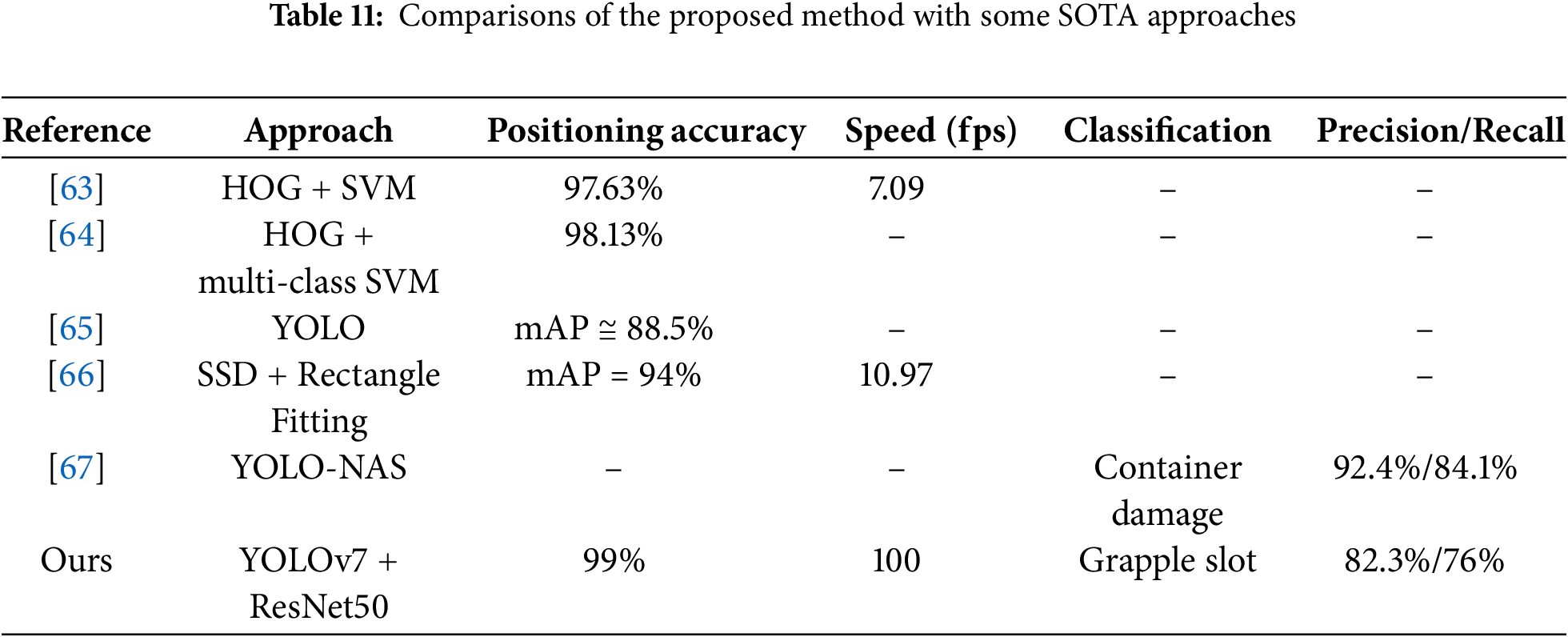

4.6 Comparisons with Some State-of-the-Art

Table 11 presents the comparisons of the surveyed references in Section 2.3 with respect to the deployed approach, the detection target, and the resultant performance. Most previous related works are focused on the grapple slot positioning without status classification. This study is the first to do both container grapple slot localization and status classification concurrently. By applying the YOLOv7 model for real-time object detection, we achieved the highest positioning accuracy at high speed. This study is also the first attempt to do grapple slot classification, which is the critical part of the container checking report.

5 Conclusions and Future Works

This paper presents a method for automated container defect detection that integrates YOLOv7 for object detection to localize grapple slots and ResNet for image classification to categorize them as “Good,” “Mid” (or “Potentially Bad), and “Bad”. The proposed approach aims to streamline inspection by leveraging deep learning techniques to identify and assess grapple slot conditions. An adequate volume of collected grapple slot samples can substantially reduce the likelihood of missed detections. However, the classification task remains challenging due to the limited number of defective samples and the variability of defects arising from diverse operational conditions. These factors contribute to significant heterogeneity among defect types and introduce subjective judgment errors rooted in human perception, resulting in an overall classification accuracy of approximately 87.4%.

Comparing the YOLOv7 inference speed of 100 fps, the bottleneck of the proposed approach is on the RestNet50 with a processing speed of 34 fps. It is still a real-time processing system if required preprocessing, such as input image normalization and user confirmation about the output results, while the container truck is registering.

Future efforts will focus on establishing standardized criteria for defect identification to enhance classification performance and mitigate subjective bias. Additionally, we plan to augment the dataset by generating more diverse defect samples using existing data, potentially through synthetic data generation techniques. The overarching objective of this study is to develop a robust, automated system for analyzing container grapple slots, thereby reducing inspection time, minimizing labor requirements, improving transportation safety, and mitigating associated economic losses.

In future work, we aim to expand the dataset by collecting additional samples through the proposed system and engaging end-users to collaboratively establish standardized criteria for defect identification. This initiative is intended to mitigate subjective judgment errors and enhance the consistency of classification outcomes. Given the limited availability of defective samples, we also plan to investigate using generative models to synthetically produce a broader range of defect scenarios, thereby improving classification accuracy.

Once these efforts yield reliable results, we will leverage the classification outputs to formulate tailored maintenance recommendations based on defect type. This will support users in making informed decisions regarding the necessity and urgency of repair actions. Then, notable EfficientNet is the go-to choice for resource-constrained environments and high efficiency for grapple slot condition classification. ResNet remains a robust and versatile architecture, especially for research and high-resource environments. For practical deployment, EfficientNet often wins in scenarios requiring fast, accurate, and lightweight models. However, ResNet’s simplicity and scalability make it a timeless architecture for experimentation and baseline performance. Advanced models like the Transformer and few-shot learning models are also worth trying in the future.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Orbit Tech, Taipei, Taiwan, for providing the training and field testing dataset.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Chun-An Chen and Chen-Chiung Hsieh; methodology, Chen-Chiung Hsieh; software, Chun-An Chen; validation, Wei-Hsin Huang; formal analysis, Chen-Chiung Hsieh; investigation, Chen-Chiung Hsieh; resources, Wei-Hsin Huang; data curation, Chun-An Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Chun-An Chen; writing—review and editing, Chen-Chiung Hsieh; visualization, Wei-Hsin Huang; supervision, Wei-Hsin Huang; project administration, Chen-Chiung Hsieh; funding acquisition, Wei-Hsin Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data is available upon request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. arXiv:2207.02696. 2022. [Google Scholar]

2. He K, Zhang X, Ran S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 27–30 Jun 2016; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

3. Hoffmann N, Stahlbock R, Voß S. A decision model on the repair and maintenance of shipping containers. J Shipp Trade. 2020;22:5. doi:10.1186/s41072-020-00070-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang P, Fan E, Wang P. Comparative analysis of image classification algorithms based on traditional machine learning and deep learning. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2021;141:61–7. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2020.07.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Deng L. The MNIST database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2012;29(6):141–2. doi:10.1109/msp.2012.2211477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20(3):273–97. doi:10.1007/bf00994018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. LeCun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. 1998;86(11):2278–324. doi:10.1109/5.726791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li J, Wang JZ. Automatic linguistic indexing of pictures by a statistical modeling approach. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2003;25(9):1075–88. doi:10.1109/tpami.2003.1227984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang JZ, Li J, Wiederhold G. SIMPLIcity: semantics-sensitive integrated matching for picture libraries. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intelli. 2001;23(9):947–63. doi:10.1109/34.955109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang ML, Zhou ZH. ML-KNN: a lazy learning approach to multilabel learning. Pattern Recognit. 2007;40(7):2038–48. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2006.12.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Altman NS. An introduction to kernel and nearest-neighbor nonparametric regression. Amer Statist. 1992;46(3):175–85. doi:10.1080/00031305.1992.10475879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yun JP, Shin WC, Koo G, Kim MS, Lee C, Lee SJ. Automated defect inspection system for metal surfaces based on deep learning and data augmentation. J Manuf Syst. 2020;55:317–24. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2020.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Semeniuta S, Severyn A, Barth E. A hybrid convolutional variational autoencoder for text generation. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2017 Sep 9–11; Copenhagen, Denmark. p. 627–37. [Google Scholar]

14. Bowman SR, Vilnis L, Vinyals O, Dai A, Jozefowicz R, Bengio S. Generating sentences from a continuous space. In: Proceedings of the 20th SIGNLL Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning; 2016 Aug 11–12; Berlin, Germany. p. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

15. Shabbir A, Ali N, Ahmed J, Zafar B, Rasheed A, Sajid M, et al. Satellite and scene image classification based on transfer learning and fine-tuning of ResNet50. Math Problems Eng. 2021;2021:1–18. doi:10.1155/2021/5843816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zou Q, Ni L, Zhang T, Wang Q. Deep learning based feature selection for remote sensing scene classification. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2015;12(11):2321–25. doi:10.1109/lgrs.2015.2475299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yang Y, Newsam S. Bag-of-visual-words and spatial extensions for landuse classification. In: Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems; 2010 Nov 2–5; San Jose, CA, USA. p. 270–9. [Google Scholar]

18. Li J, Wang JZ. Real-time computerized annotation of pictures. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2008;30(6):985–1002. doi:10.1109/tpami.2007.70847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zhao B, Zhong Y, Xia GS, Zhang L. Dirichlet-derived multiple topic scene classification model for high spatial resolution remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2015;54(4):2108–23. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2015.2496185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Khan R, Barat C, Muselet D, Ducottet C. Spatial orientation of visual word pairs to improve bag-of-visual-words model. In: Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC) 2012; 2012 Sep 3–7; Surrey, UK. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

21. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations; 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

22. Szegedy C, Vanhoucke V, Ioffe S, Shlens J, Wojna Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 2818–26. [Google Scholar]

23. Szegedy C, Liu W, Jia Y, Sermanet P, Reed S, Anguelov D, et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

24. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2012 Dec 3–6; Lake Tahoe, NV, USA. p. 1097–105. [Google Scholar]

25. de la Rosa FL, Gómez-Sirvent JL, Sánchez-Reolid R, Morales R, Fernández-Caballero A. Geometric transformation-based data augmentation on defect classification of segmented images of semiconductor materials using a ResNet50 convolutional neural network. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;206:117731. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhao Z, Li B, Dong R, Zhao P. A surface defect detection method based on positive samples. In: PRICAI 2018: Trends in Artificial Intelligence. Proceedings of the 15th Pacific Rim International Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Aug 28–31; Nanjing, China. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018; p. 473–81. [Google Scholar]

27. Goodfellow I, Abadie JP, Mirza M, Xu B, Farley DW, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020 Nov 18–22; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 2672–80. [Google Scholar]

28. Ojala T, Pietikäinen M, Harwood D. A comparative study of texture measures with classification based on feature distributions. Pattern Recognit. 1996;29:51–9. doi:10.1016/0031-3203(95)00067-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wieler M, Hahn T, Hamprecht F. Weakly supervised learning for industrial optical inspection. In: Proceedings of the 29th Annual Symposium of the German Association for Pattern Recognition (DAGM 2007). Heidelberg, Germany. 2007 [cited 2023 Apr 10]. Available from: https://hci.iwr.uni-heidelberg.de/node/3616. [Google Scholar]

30. Bahrami Z, Zhang R, Wang T, Liu Z. An end-to-end framework for shipping container corrosion defect inspection. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2022;71:1–14. doi:10.1109/tim.2022.3204091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. p. 580–7. [Google Scholar]

32. He Y, Song K, Meng Q, Yan Y. An end-to-end steel surface defect detection approach via fusing multiple hierarchical features. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2020;69(4):1493–504. doi:10.1109/tim.2019.2915404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ren R, Hung T, Tan KC. A generic deep-learning-based approach for automated surface inspection. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2018;48(3):929–40. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2017.2668395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Luo J, Yang Z, Li S, Wu Y. FPCB surface defect detection: a decoupled two-stage object detection framework. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2021;70:1–11. doi:10.1109/tim.2021.3092510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhou Z, Wang Y, Zhu Q, Mao J, Xiao C, Liu X, et al. A surface defect detection framework for glass bottle bottom using visual attention model and wavelet transform. IEEE Trans Ind Informat. 2020;16(4):2189–201. doi:10.1109/tii.2019.2935153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zeng N, Wu P, Wang Z, Li H, Liu W, Liu X. A small-sized object detection oriented multi-scale feature fusion approach with application to defect detection. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2022;71:1–14. doi:10.1109/tim.2022.3153997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 10012–22. [Google Scholar]

38. Liu Z, Mao H, Wu CY, Feichtenhofer C, Darrell T, Xie S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 11976–86. [Google Scholar]

39. Bochkovskiy A, Wang CY, Liao HYM. YOLOv4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934. 2020. [Google Scholar]

40. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. Scaled-YOLOv4: scaling cross-stage partial network. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 13029–38. [Google Scholar]

41. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Liao HYM. You only learn one representation: unified network for multiple tasks. arXiv:2105.04206. 2021. [Google Scholar]

42. Ge Z, Liu S, Wang F, Li Z, Sun J. YOLOX: exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv:2107.08430. 2021. [Google Scholar]

43. Xu S, Wang X, Lv W, Chang Q, Cui C, Deng K, et al. PP-YOLOE: an evolved version of YOLO. arXiv:2203.16250. 2022. [Google Scholar]

44. Carion N, Massa F, Synnaeve G, Usunier N, Kirillov A, Zagoruyko S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. p. 213–29. [Google Scholar]

45. Zhu X, Su W, Lu L, Li B, Wang X, Dai J, et al. Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2010.04159. 2010. [Google Scholar]

46. Zhang H, Li F, Liu S, Zhang L, Su H, Zhu J, et al. DINO: DETR with improved denoising anchor boxes for end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2203.03605. 2022. [Google Scholar]

47. Chen Z, Duan Y, Wang W, He J, Lu T, Dai J, et al. Vision transformer adapter for dense predictions. arXiv:2205.08534. 2022. [Google Scholar]

48. Zhao L, Zhu M. MS-YOLOv7: YOLOv7 based on multi-scale for object detection on UAV aerial photography. Drones. 2023;7(3):188. doi:10.3390/drones7030188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Ferrari V, Hebert M, Sminchisescu C, Weiss Y, editors. Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14. Munich, Germany. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018; p. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

50. Bodla N, Singh B, Chellappa R, Davis LS. Soft-NMS—improving object detection with one line of code. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 5562–70. [Google Scholar]

51. Misra D. Mish: a self-regularized non-monotonic activation function. arXiv:1908.08681. 2019. [Google Scholar]

52. Zhu P, Wen L, Du D, Bian X, Fan H, Hu Q, et al. Detection and tracking meet drones challenge. GitHub. 2021 [cited 2023 Apr 10]. Available from: https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset. [Google Scholar]

53. Zheng J, Wu H, Zhang H, Wang Z, Xu W. Insulator-defect detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv7. Sensors. 2022;22(22):1–23. doi:10.3390/s22228801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Rao Y, Zhao W, Tang Y, Zhou J, Lim SN, Lu J. HorNet: efficient high-order spatial interactions with recursive gated convolutions. arXiv:2207.14284. 2022. [Google Scholar]

55. Hou Q, Zhou D, Feng J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 13708–17. [Google Scholar]

56. Gevorgyan Z. SIoU loss: more powerful learning for bounding box regression. arXiv:2205.12740. 2022. [Google Scholar]

57. Xin H, Chen Z, Wang B. PCB electronic component defect detection method based on improved YOLOv4 algorithm. J Phys Conf Ser. 2021;1827(1):012167. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1827/1/012167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Le HF, Zhang LJ, Liu YX. Surface defect detection of industrial parts based on YOLOv5. IEEE Access. 2022;10:130784–94. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3228687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Pham V, Thi Ngoc LD, Bui DL. Optimizing YOLO architectures for optimal road damage detection and classification: a comparative study from YOLOv7 to YOLOv10. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData) (2024); 2024 Dec 15–18; Washington, DC, USA. p. 8460–8. [Google Scholar]

60. Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Qiu J. Yolo by Ultralytics. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 10]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

61. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Liao HYM. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv:2402.13616. 2024. [Google Scholar]

62. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. YOLOv10: real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2405.14458. 2024. [Google Scholar]

63. Mi C, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Shen Y. A fast automated vision system for container corner casting recognition. J Mar Sci Technol. 2016;24(1):8. doi:10.6119/JMST-016-0125-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Diao Y, Cheng W, Du R, Wang Y, Zhang J. Vision-based detection of container lock holes using a modified local sliding window method. J Image Video Proc. 2019;2019:69. doi:10.1186/s13640-019-0472-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Wang X. Recognition and positioning of container lock holes for intelligent handling terminal based on convolutional neural network. Int Inf Eng Technol Assoc. 2021;38(2):467–72. doi:10.18280/ts.380226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Zhang Y, Huang Y, Zhang Z, Postolache O, Mi C. A vision-based container position measuring system for ARMG. Meas Control. 2022;56(3–4):596–605. doi:10.1177/00202940221110932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Nguyen TPT, Cho GS, Chatterjee I. Automating container damage detection with the YOLO-NAS deep learning model. Sci Prog. 2025;108(1):368504251314084. doi:10.1177/00368504251314084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools