Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Dual-Stream Framework for Landslide Segmentation with Cross-Attention Enhancement and Gated Multimodal Fusion

1 College of Computer Science, Chongqing University, Chongqing, 400044, China

2 SUGON Industrial Control and Security Center, Chengdu, 610225, China

* Corresponding Author: Yunfei Yin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072550

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Automatic segmentation of landslides from remote sensing imagery is challenging because traditional machine learning and early CNN-based models often fail to generalize across heterogeneous landscapes, where segmentation maps contain sparse and fragmented landslide regions under diverse geographical conditions. To address these issues, we propose a lightweight dual-stream siamese deep learning framework that integrates optical and topographical data fusion with an adaptive decoder, guided multimodal fusion, and deep supervision. The framework is built upon the synergistic combination of cross-attention, gated fusion, and sub-pixel upsampling within a unified dual-stream architecture specifically optimized for landslide segmentation, enabling efficient context modeling and robust feature exchange between modalities. The decoder captures long-range context at deeper levels using lightweight cross-attention and refines spatial details at shallower levels through attention-gated skip fusion, enabling precise boundary delineation and fewer false positives. The gated fusion further enhances multimodal integration of optical and topographical cues, and the deep supervision stabilizes training and improves generalization. Moreover, to mitigate checkerboard artifacts, a learnable sub-pixel upsampling is devised to replace the traditional transposed convolution. Despite its compact design with fewer parameters, the model consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines. Experiments on two benchmark datasets, Landslide4Sense and Bijie, confirm the effectiveness of the framework. On the Bijie dataset, it achieves an F1-score of 0.9110 and an intersection over union (IoU) of 0.8839. These results highlight its potential for accurate large-scale landslide inventory mapping and real-time disaster response. The implementation is publicly available at https://github.com/mishaown/DiGATe-UNet-LandSlide-Segmentation (accessed on 3 November 2025).Keywords

Landslides are among the most destructive geological hazards worldwide, posing a significant threat to human lives, infrastructure, and economic stability. According to the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR), more than 1000 landslide-related disaster events occur annually, causing thousands of fatalities and severe economic losses [1]. Beyond immediate destruction, landslides disrupt transportation networks, damage infrastructure, and contaminate water sources, generating long-term environmental and socio-economic impacts [2]. Historical events such as the 2014 Oso landslide in Washington, which claimed 43 lives, and the 2017 Bijie County landslide in China, which caused 27 fatalities, highlight the urgent need for reliable landslide monitoring and risk assessment systems [3].

Traditional field surveys and manual interpretation methods, though accurate, are time-consuming and labor-intensive, making them unsuitable for large-scale or rapid response applications [1,4]. The emergence of high-resolution remote sensing and increased computing power has enabled more scalable solutions. Machine learning (ML) methods, including Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, and Logistic Regression, have been applied to automate landslide classification, but they often struggle with feature selection, generalization, and scalability [5,6]. Deep learning (DL), particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has advanced the field by learning rich hierarchical representations from complex imagery [2,7]. Multi-source remote sensing data, combining optical, synthetic aperture radar (SAR), and DEM, further supports comprehensive analysis [3,8,9].

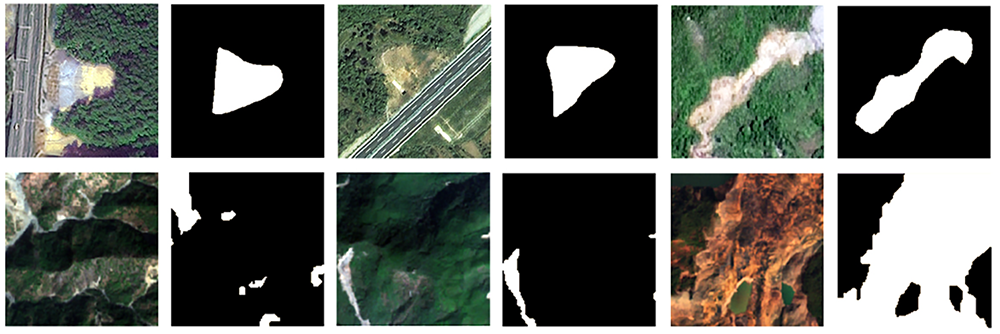

Despite these advances, challenges remain, as illustrated in Fig. 1, since many deep learning studies focus primarily on detection and discrimination between landslide-affected and non-landslide areas, yet often underperform in segmentation, where precise boundary delineation across heterogeneous shapes and scales is required.

Figure 1: Key challenges in landslide segmentation: large variation in shape and scale, confusion with visually similar non-landslide regions (e.g., bare soil, roads, erosion), and the difficulty of detecting small or fragmented landslide areas, sourced from Bijie dataset (top) and LandSlide4Sense dataset (bottom)

Models trained primarily on visually distinct and recent landslides often fail on older, weathered, or vegetation-covered cases [3,4]. Architectures such as Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (Faster R-CNN) utilizing convolutional backbones with pretrained weights also encounter optimization issues such as vanishing gradients, limiting their ability to model complex patterns [5]. Detection frameworks additionally struggle with small-scale and fragmented regions’ landslides, where limited pixel representation leads to missed features [10,11]. In regions with similar spectral signatures (e.g., bare soil, terraced fields, erosion zones), segmentation models frequently produce false positives [12]. Several open-source landslide inventories with reliable annotation techniques have been released in recent years (e.g., [13–15]), providing broader access to annotated data for research and benchmarking. However, many publicly available datasets remain limited in terms of spatial diversity, sensor modality, and annotation consistency, making it challenging to train models that generalize across heterogeneous geomorphological environments.

Landslides occur in various forms; in this study, we focus mainly on shallow slope failures, including rock slides, rock falls, and small debris slides typical of rainfall-triggered mountainous terrains. We focus on advancing landslide segmentation while acknowledging its close relationship with landslide detection. The objective of this work is to design a deep learning framework that not only distinguishes landslide-affected areas but also achieves pixel-level segmentation with accurate boundary delineation, even for small and visually complex regions. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

• We propose an adaptive dual-decoder architecture that processes modality-specific information in parallel streams. A lightweight cross-attention mechanism captures global context in deeper layers, while attention gates refine local spatial details in shallower layers, enabling robust and complementary feature exchange between modalities.

• We introduce a guided multimodal fusion strategy that explicitly combines optical and topographic features at both encoder and decoder stages. The gated fusion module learns adaptive weighting with confidence regularization, ensuring stable and balanced feature integration across modalities.

• We replace conventional transposed convolutions with learnable sub-pixel upsampling, mitigating checkerboard artifacts and improving high-resolution reconstruction quality with reduced computational overhead.

2 Related Studies on Landslide Segmentation

Landslides are highly destructive hazards that require rapid and accurate mapping for effective disaster mitigation. With the advent of deep learning, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and their extensions have become the dominant methodology for landslide segmentation analysis. Recent studies increasingly formulate the task as semantic segmentation, where each pixel in high-resolution optical imagery (typically 0.5–10 m spatial resolution from satellites such as WorldView, PlanetScope, Sentinel-2, or GaoFen) is classified as either landslide or non-landslide.

This section synthesizes prior research on landslide segmentation by organizing representative works according to four key technical challenges identified in recent literature: (1) detecting visually blurred or relic landslides, (2) integrating heterogeneous multi-source data, (3) coping with limited annotated datasets, and (4) improving segmentation accuracy. This organization reflects the main difficulties addressed by our proposed framework and provides context for the design choices discussed in Section 3.

Despite notable progress, landslide segmentation research continues to face these core challenges. The following subsections summarize representative studies corresponding to each aspect.

2.1 Visually Blurred (Relic) Landslides

Inactive or relic landslides are often difficult to identify in optical imagery because their visual characteristics depend on multiple factors such as the time elapsed since failure, vegetation regrowth, surface erosion, and local climatic conditions, which can collectively lead to low-contrast or blurred boundaries in visible-band imagery [3,4]. To address this, multi-stream and attention-based segmentation networks have been proposed. For example, feature-fusion segmentation network (FFS-Net) combines optical texture with DEM-derived topographic cues (i.e., elevation-based terrain attributes such as slope, aspect, and curvature), significantly improving the segmentation of blurred landslides over CNN-based baselines [3]. Similarly, hyper-pixel-wise contrastive learning augmented segmentation network (HPCL-Net) introduces hyper-pixel contrastive learning to enhance feature representation in small or ambiguous landslide patches [16]. Recently, Hu et al. [12] proposed a cross-attention landslide detector (CALandDet) framework that captures global context for improved segmentation of relic landslides, outperforming CNN-based baselines.

2.2 Integrating Multi-Source Data

The fusion of multi-modal inputs such as RGB (Red-Green-Blue), DEM, and slope layers has consistently improved landslide delineation. DEMs contribute elevation gradients and slope breaks that can help clarify landslide boundaries obscured in spectral imagery, although the slope information accurately reflects landslide morphology only when the DEM is acquired after the failure event. Studies using dual-stream networks, such as the gated dual-stream convolutional neural network (GDSNet), demonstrate that gated feature fusion of RGB and DEM inputs achieves higher detection accuracy than single-modality models [3,17]. The Landslide4Sense benchmark further validates this, showing that networks incorporating DEM and slope layers outperform those using only Sentinel-2 optical data across multiple global test sites [8,18]. Other approaches combine mathematical morphology with DEM and orthophoto data to extract reliable landslide polygons [19]. More recently, Wu et al. [9] proposed a hybrid CNN–Transformer fusion network that integrates DEM with optical features, achieving superior accuracy on multi-regional benchmarks.

The scarcity of pixel-wise labeled landslide data presents a critical bottleneck for developing and validating deep learning models. Supervised segmentation networks rely on accurately annotated masks to optimize loss functions, learn discriminative spatial features, and evaluate model performance across heterogeneous terrain conditions. Insufficient labeled data often lead to overfitting and poor generalization, highlighting the need for large, well-annotated datasets to advance reliable and transferable landslide mapping. Manual delineation of landslides is costly and time-consuming, leading to limited training samples. To mitigate this, researchers employ data augmentation, transfer learning, and ensemble methods. For example, Faster R-CNN with aggressive augmentation improved detection recall under limited training data [5]. Transfer learning from large-scale image datasets (e.g., ImageNet) consistently boosts performance; Chandra et al. [4] demonstrated that U-Net with ResNet backbones achieved near-perfect landslide detection accuracy, far surpassing models trained from scratch. Beyond supervised learning, unsupervised and weakly supervised strategies such as multiscale adaptation and contrastive learning are emerging to reduce reliance on extensive ground truth [7].

2.4 Improving Segmentation Accuracy

Recent architectures enhance accuracy through attention mechanisms, multi-scale feature fusion, and advanced decoder designs. FFS-Net integrates multiscale channel attention to balance fine textures with semantic context [3], while the method proposed by Lu et al. [20] applies lightweight multi-scale fusion to boost pixel-level precision. Advanced U-Net variants incorporating multi-sensor inputs and refined loss functions consistently outperform vanilla U-Net baselines [4,19]. Ensemble strategies and hybrid CNN-Transformer models are also being explored for boundary refinement and context modeling [7,10,11,21]. The Landslide4Sense benchmark confirms that specialized fusion-based architectures can yield IoU and F1-score improvements of 5–10% compared to earlier CNNs [8,18]. These developments underscore the importance of multi-branch, attention-augmented, and transformer-based designs for advancing landslide segmentation performance.

This section describes the proposed dual-stream architecture for landslide segmentation from multimodal satellite imagery.

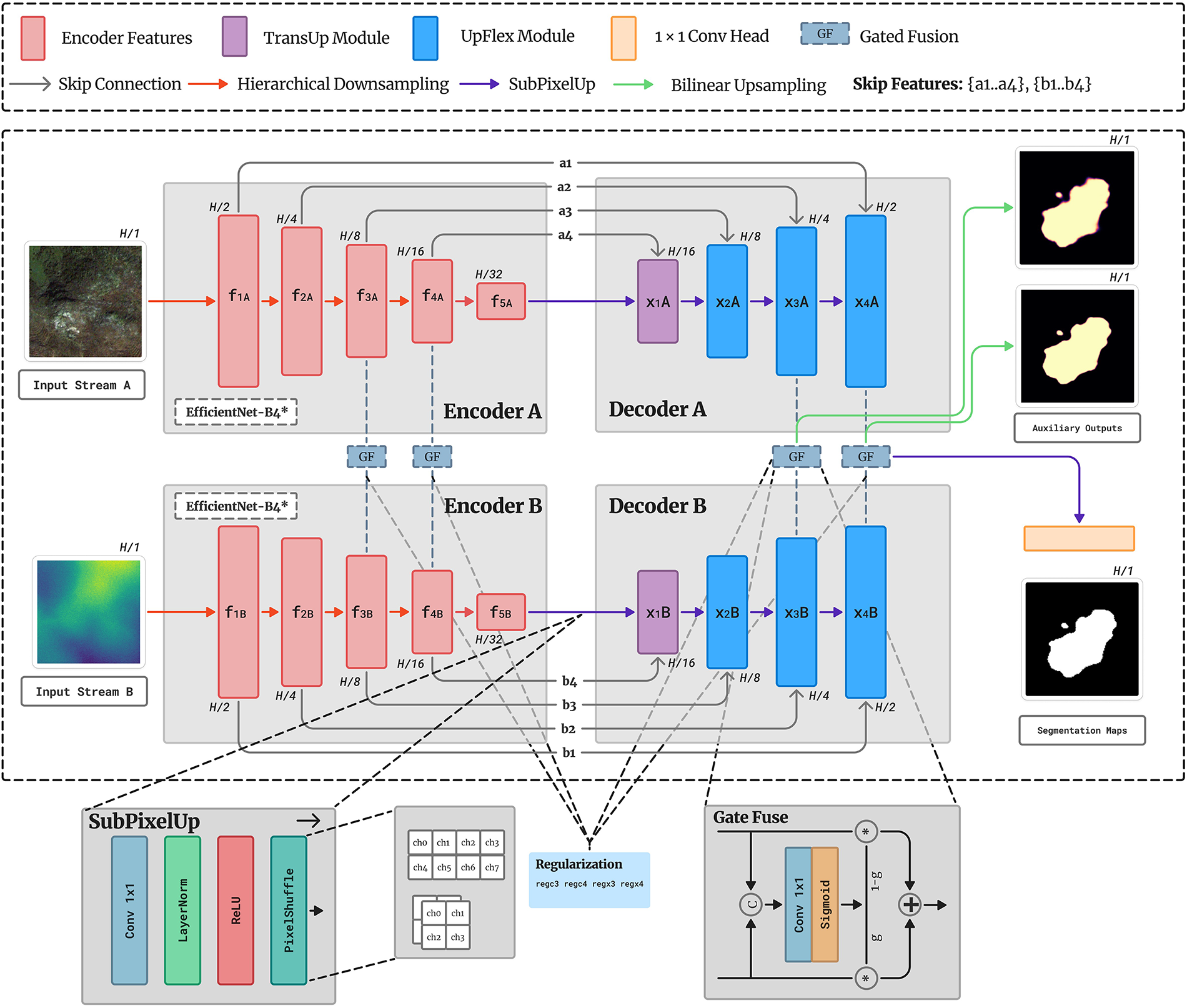

The framework adopts a dual-stream encoder–decoder design to exploit complementary optical and topographic features. As illustrated in Fig. 2, two geographically co-registered inputs Stream A (optical RGB) and Stream B (DEM) are processed by a siamese EfficientNet-B4 backbone [22] with shared weights for consistent feature extraction. Each encoder produces five hierarchical feature maps

Figure 2: Architecture of the proposed dual-stream model for the landslide segmentation

Mid-level features

The fused decoder output is upsampled via SubPixelUp and projected through

3.2 Features Extracted from the Pretrained Network

Both input streams are processed by a similar backbone trained on ImageNet. Each encoder extracts a five-level hierarchy of multi-scale feature maps, capturing fine textures at shallow layers and semantic context at deeper layers. Intermediate features from both streams are retained as skip connections to guide the decoders during reconstruction. Stream A features

The adaptive decoder comprises three complementary modules SubPixelUp, TransUp, and UpFlex that collectively address global alignment, selective fusion, and efficient upsampling. Unlike prior architectures applying upsampling and attention sequentially, this unified design integrates these mechanisms coherently. TransUp performs sub-pixel upsampling with lightweight cross-attention for global context alignment between decoder and skip features. The attention mechanism is applied directly across the skip-feature space rather than through flattened spatial tokens, enabling modality- and depth-aware fusion without excessive computational overhead. UpFlex extends classical U-Net skip connections by integrating sub-pixel upsampling with attention-gated fusion for spatial refinement. Its flexible design operates efficiently across multiple decoder scales without parameter redundancy, adaptively emphasizing salient encoder features while suppressing irrelevant noise. SubPixelUp provides the core upsampling operation, ensuring artifact-free resolution recovery with reduced computational overhead compared to transposed convolutions.

The SubPixelUp module performs learnable upsampling by transforming channel information into spatial resolution through pixel-shuffle [23]. Given input feature

This design enables stable resolution recovery while preserving spatial features, serving as the core upsampling unit in both TransUp and UpFlex.

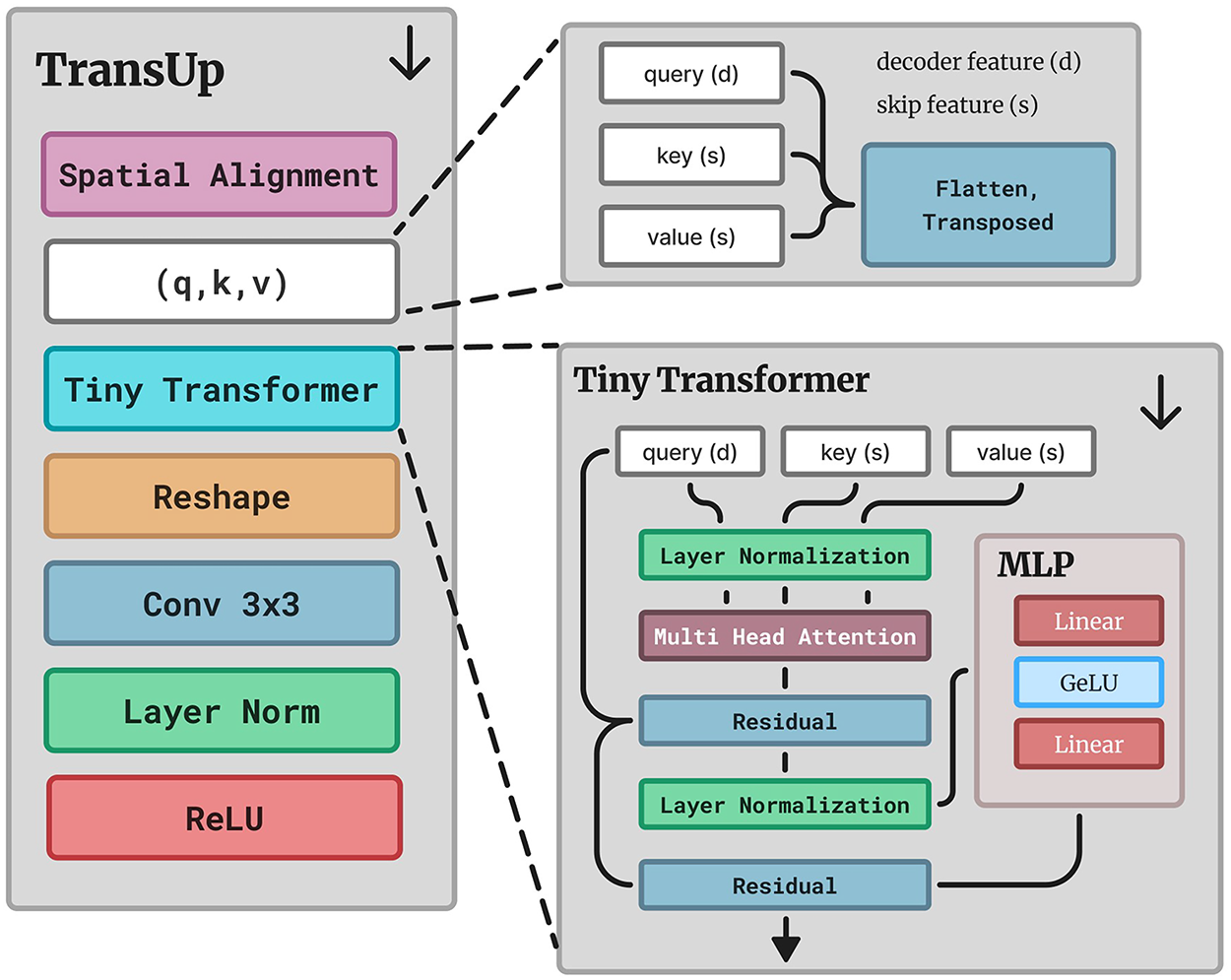

The TransUp module integrates sub-pixel upsampling with lightweight cross-attention for efficient resolution restoration and context alignment. As shown in Fig. 3, decoder feature

Figure 3: The proposed TransUp module

This compact design achieves artifact-free upsampling while enhancing semantic consistency between decoder and skip features without excessive computational overhead.

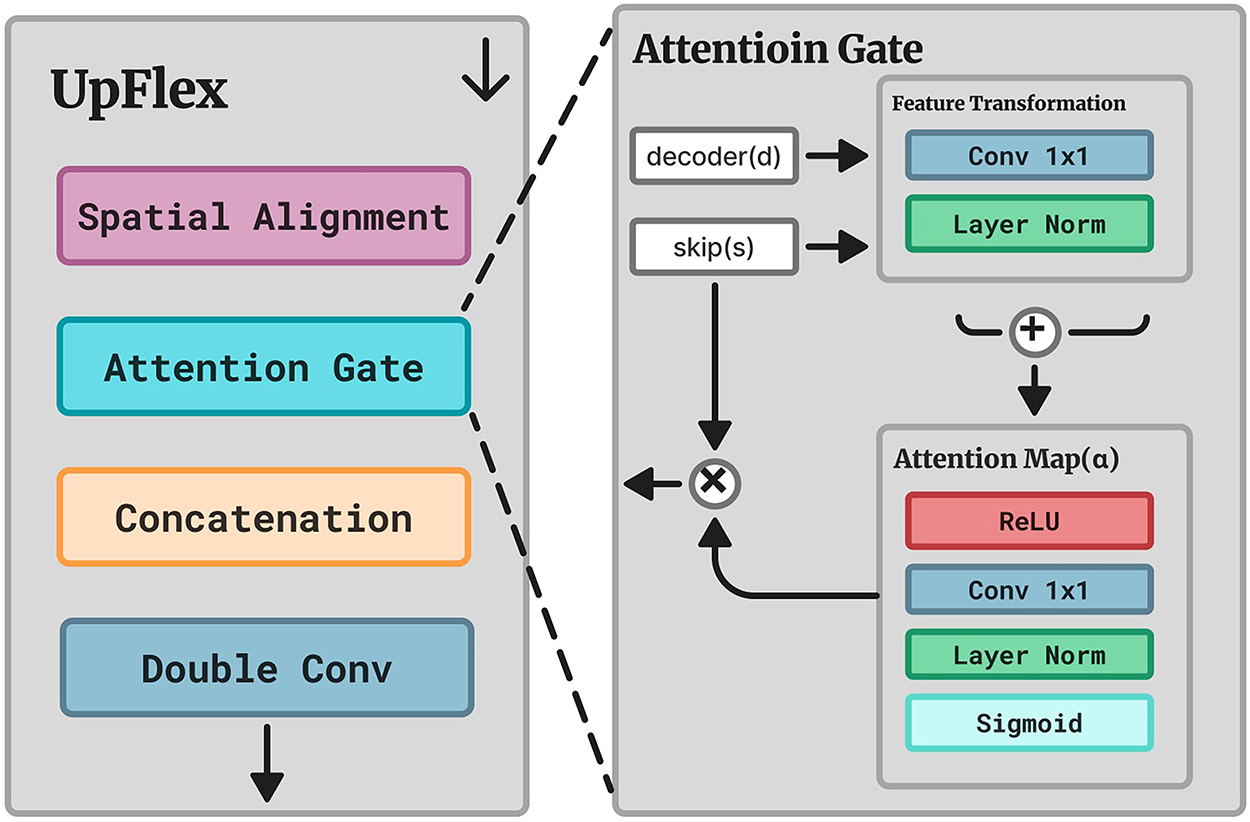

The UpFlex module integrates learnable upsampling, attention-gated skip fusion, and local convolutional refinement. As illustrated in Fig. 4, decoder feature

Figure 4: The proposed UpFlex module

This selective fusion enhances spatial precision and boundary delineation, improving segmentation accuracy.

The proposed fusion design is inspired by the gated multimodal unit introduced in [24] and adapted here for pixel-level feature integration. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the GateFuse module adaptively merges complementary information from the two input streams or their decoder branches. Here,

where

which penalizes uncertain gating (

To address severe class imbalance and guide confident multimodal fusion, the network employs a compound loss combining Tversky segmentation loss [25] with the gating regularization term in Eq. (5). This formulation stabilizes training, improves recall of sparse landslide pixels, and enforces decisive gating across fusion stages. Following the deep supervision strategy in [26], the model generates a main prediction

where

where

In this section, we present the datasets, evaluation metrics, baseline models, and implementation details of our proposed method. We then evaluate performance on two real-world datasets and finally conduct ablation studies.

4.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

While large-scale datasets such as the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Landslide Dataset [27] provide multi-sensor coverage across diverse terrains, co-registered multi-modal datasets remain limited [28]. Optical data suffer from cloud cover and daylight constraints, whereas SAR can penetrate clouds [29], yet few datasets provide co-registered SAR or DEM for effective multi-modal fusion.

The Bijie dataset [30] is an optical benchmark from Bijie City, Guizhou Province, China, covering 26,853

The LandSlide4Sense dataset [8] is a global benchmark comprising Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery (14 bands at 10 m resolution) and DEM-derived features from the Advanced Land Observing Satellite Phased Array type L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (ALOS PALSAR). It provides 3799 training, 245 validation, and 800 test patches (

Landslide segmentation is formulated as binary classification with strong class imbalance. Performance is evaluated using four pixel-level metrics:

where precision and recall measure accuracy and completeness, while F1 and IoU quantify overall segmentation quality. Two image-level metrics assess threshold-independent robustness: AUROC evaluates ranking consistency, and AUPRC summarizes precision–recall trade-offs:

Together, these metrics provide comprehensive evaluation of pixel-wise accuracy and model reliability under class imbalance.

To ensure a comprehensive and fair evaluation, we compared the proposed model with a diverse set of segmentation architectures representing the major evolutionary trends in semantic segmentation for landslides. The selected baselines include both classical convolutional networks and recent attention or transformer-based designs that have been widely adopted in remote sensing and landslide mapping. This diversity allows us to assess the relative contribution of multimodal fusion, attention mechanisms, and adaptive decoding within a unified benchmark.

Among convolutional encoder–decoder networks, U-Net [2], DeepLabv3+ [3] and LinkNet [31] serve as foundational CNN baselines known for their efficiency and strong localization performance. Dual-Stream U-Net [32,33] extends this paradigm to multimodal and multi-temporal settings, providing a reference for assessing the benefit of dual-stream fusion. More recent variants, such as the residual-multihead-attention unet (RMAU-NET) [34] and the dilated convolution and EMA attention with pixel attention-guided unet (DEP-UNet) [35] incorporate residual and dense connections, multi-head attention, and pyramid pooling to enhance multi-scale context and mitigate class imbalance. Together, these architectures establish a strong baseline for evaluating improvements introduced by our adaptive decoder and gated fusion mechanisms.

We further include state-of-the-art attention and transformer-based models to represent the current frontier of landslide segmentation. ShapeFormer [21] leverages vision transformers and shape priors for boundary-aware segmentation, while the enhanced multi-scale residual high-resolution network (EMR-HRNet) [11] fuses multi-resolution features through an efficient refinement module built upon HRNet. The global information extraction and multi-scale feature fusion segmentation network (GMNet) [36] adopts a multi-branch design combining global, local, and morphological features via a gated fusion mechanism. Although these models capture richer context through self-attention and multi-scale fusion, they typically operate on single-modality optical data and lack explicit cross-stream gating or deep supervision. Our framework complements these approaches by unifying attention, multimodal fusion, and adaptive decoding into a lightweight dual-stream architecture specifically tailored for landslide segmentation.

For the Bijie dataset, the landslide and non-landslide samples were merged and split into 70%, 20%, and 10% subsets for training, validation, and testing, yielding 1941, 554, and 278 samples, respectively. For the Landslide4Sense dataset, we adopted the official split of 3799 training, 245 validation, and 800 test images as defined by the dataset authors. All images were resized to

In the Bijie dataset, each patch provides RGB and DEM layers. Stream A receives the RGB composite, while Stream B uses the DEM replicated three times, forming paired six-channel inputs that preserve architectural symmetry. For the Landslide4Sense dataset, Stream A uses RGB channels, and Stream B combines normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), slope, and DEM features. This configuration efficiently combines optical, topographic, and vegetation information, balancing performance and computational cost. The NDVI is computed from the red (R) and near-infrared (NIR) bands as:

This configuration allows both datasets to be processed in a consistent dual-stream manner, while leveraging complementary spectral and topographic information for landslide segmentation.

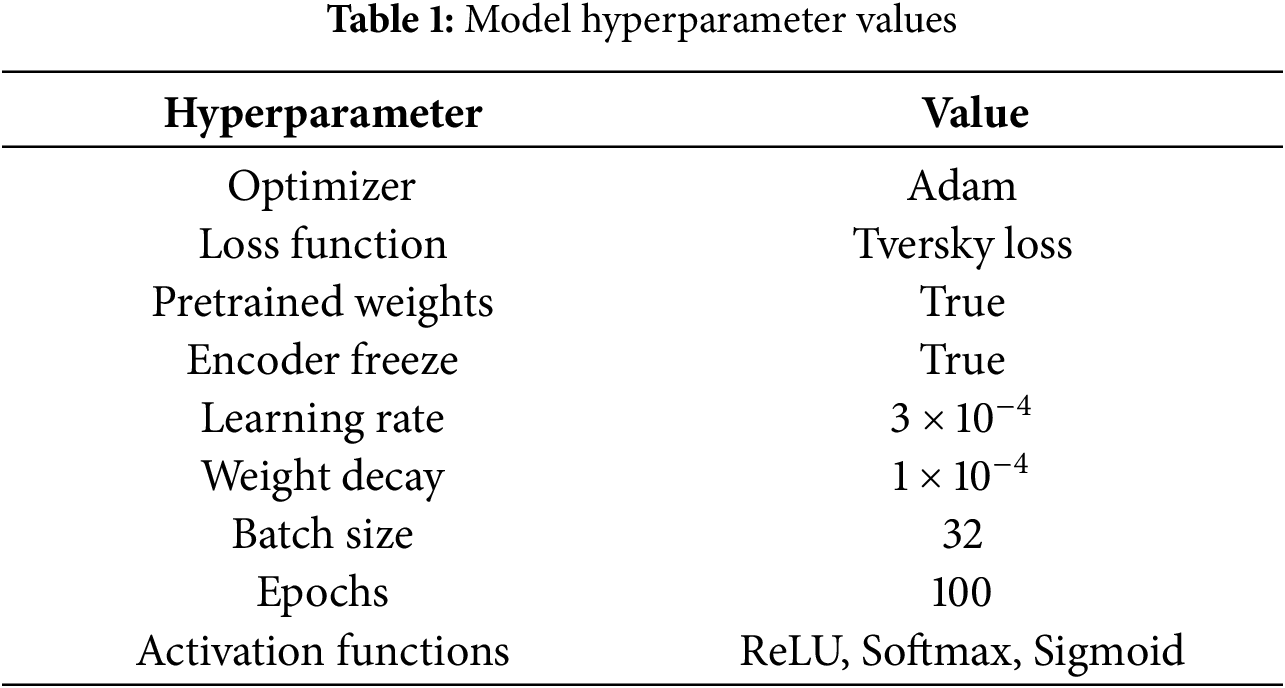

All experiments were conducted in Python 3.10 using PyTorch 2.6.10 on Ubuntu 22.04.4 LTS, with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8350C CPU @ 2.60 GHz, an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) (48 GB). The hyperparameters used are detailed in Table 1.

The Adam optimizer was employed with an initial learning rate of

4.5 Experimental Results and Analysis

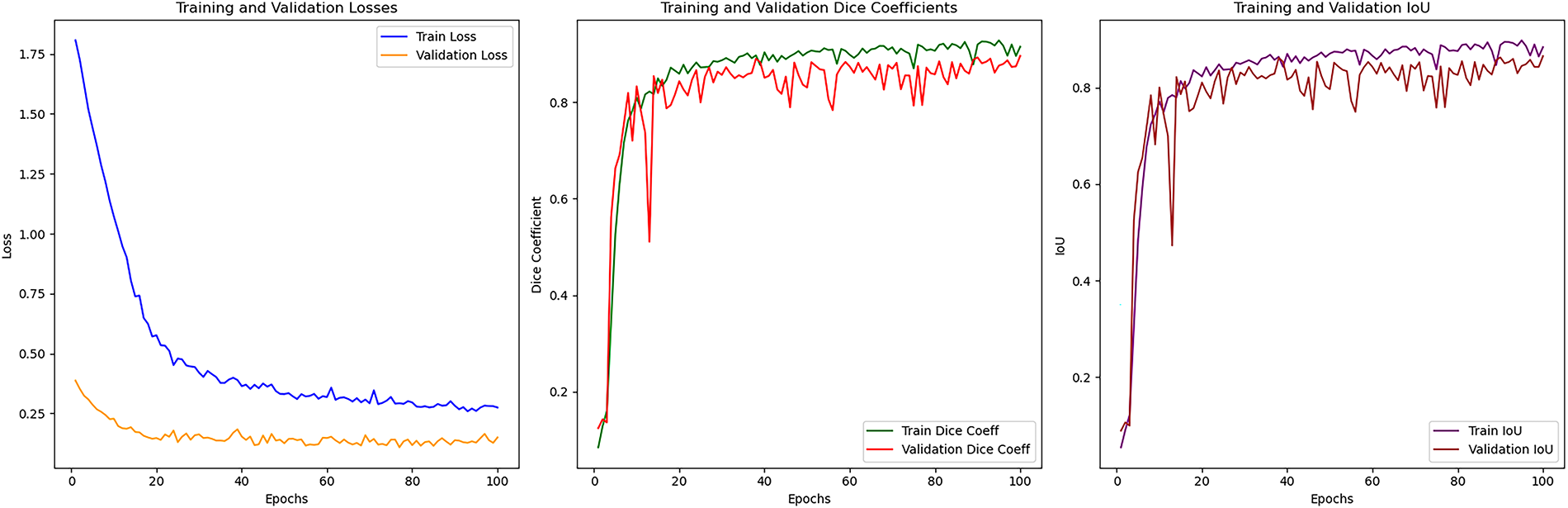

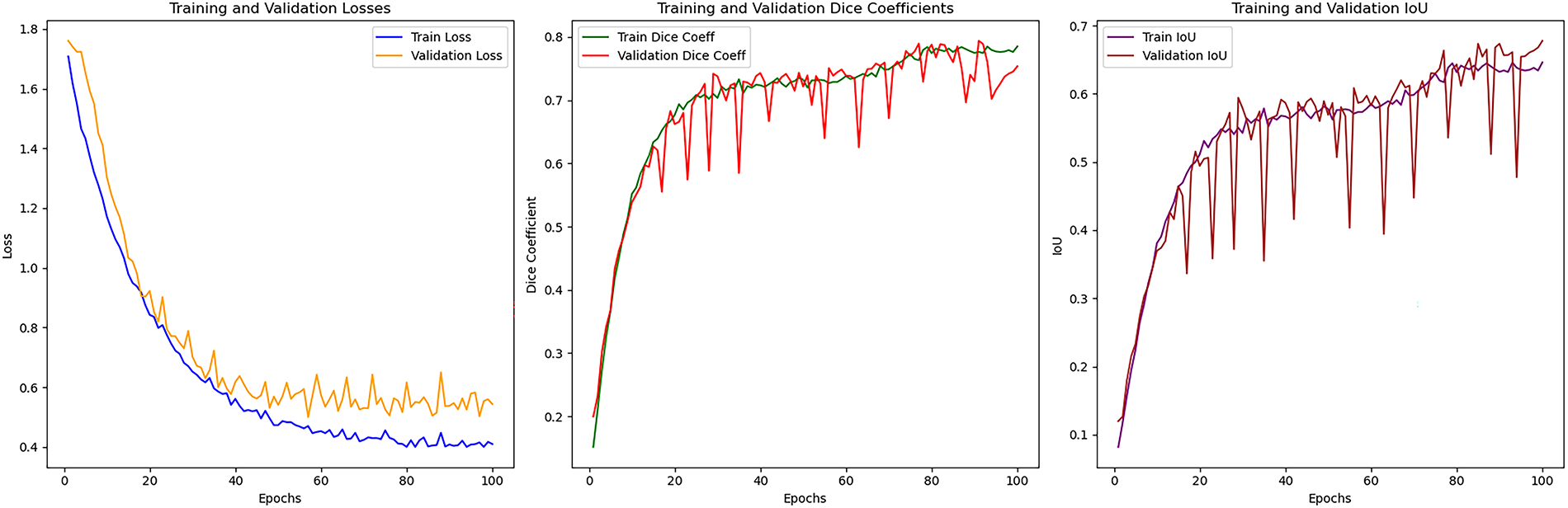

This section presents quantitative and qualitative results on the Bijie and Landslide4Sense datasets. Training and validation curves are provided in Appendix A (Figs. A1 and A2).

4.5.1 Results on the Bijie Dataset

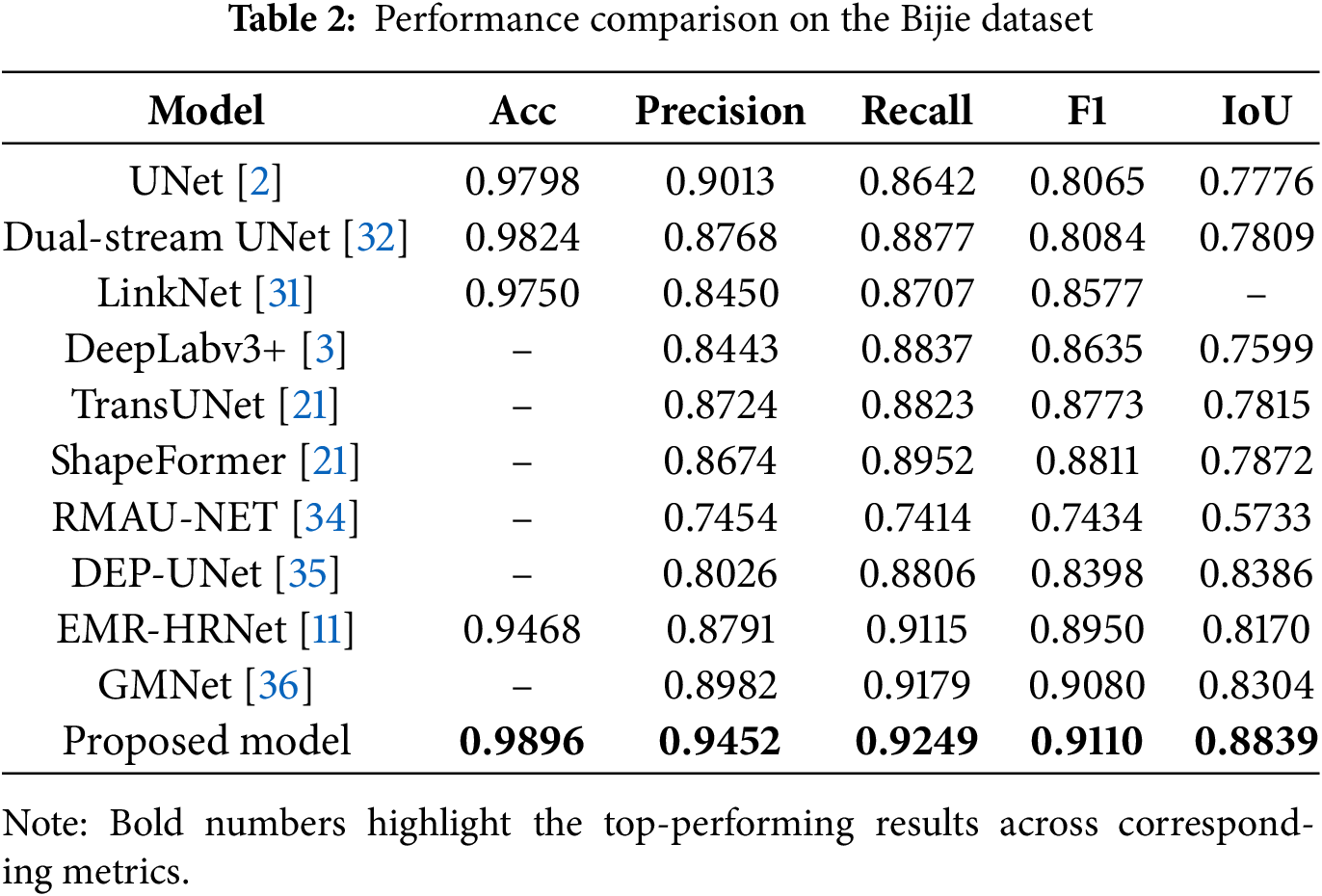

Table 2 compares the proposed model against baseline methods on the Bijie dataset. The proposed framework achieved superior performance across all metrics. Classical CNN models exhibited strong precision but limited spatial overlap (IoU < 0.78), while transformer-based approaches improved recall but showed inconsistent boundary delineation. Recent fusion networks (DEP-UNet, EMR-HRNet, GMNet) enhanced overall quality yet remained inferior to the proposed model.

4.5.2 Results on the Landslide4Sense Dataset

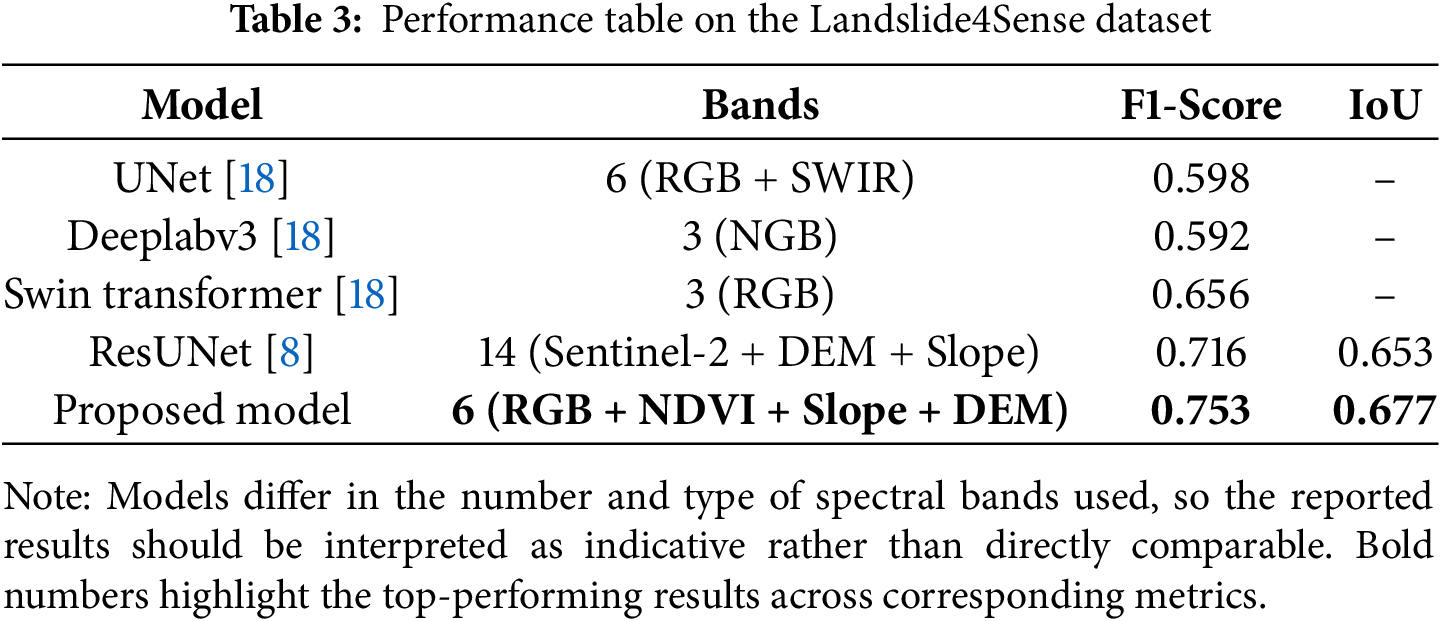

Table 3 summarizes the comparative results on the Landslide4Sense dataset. The proposed model, using six input bands (RGB, NDVI, Slope, and DEM), achieved an F1 score of 0.753 and IoU of 0.677, outperforming the ResUNet baseline [8] trained with all 14 spectral bands. Compared with entries from the Landslide4Sense Competition [18], including U-Net (F1 0.598, RGB + SWIR), Deeplabv3 (F1 0.592, NGB), and Swin Transformer (F1 0.656, RGB), our approach achieved the highest segmentation accuracy with fewer input channels.

We conduct ablation experiments to evaluate the contribution of individual components within the proposed framework, including the choice of backbone network, the effect of fusion strategies, the role of decoder components, and the impact of deep supervision. All experiments were conducted under identical settings for a fair comparison on Bijie dataset.

4.6.1 Effect of Pretrained Backbones

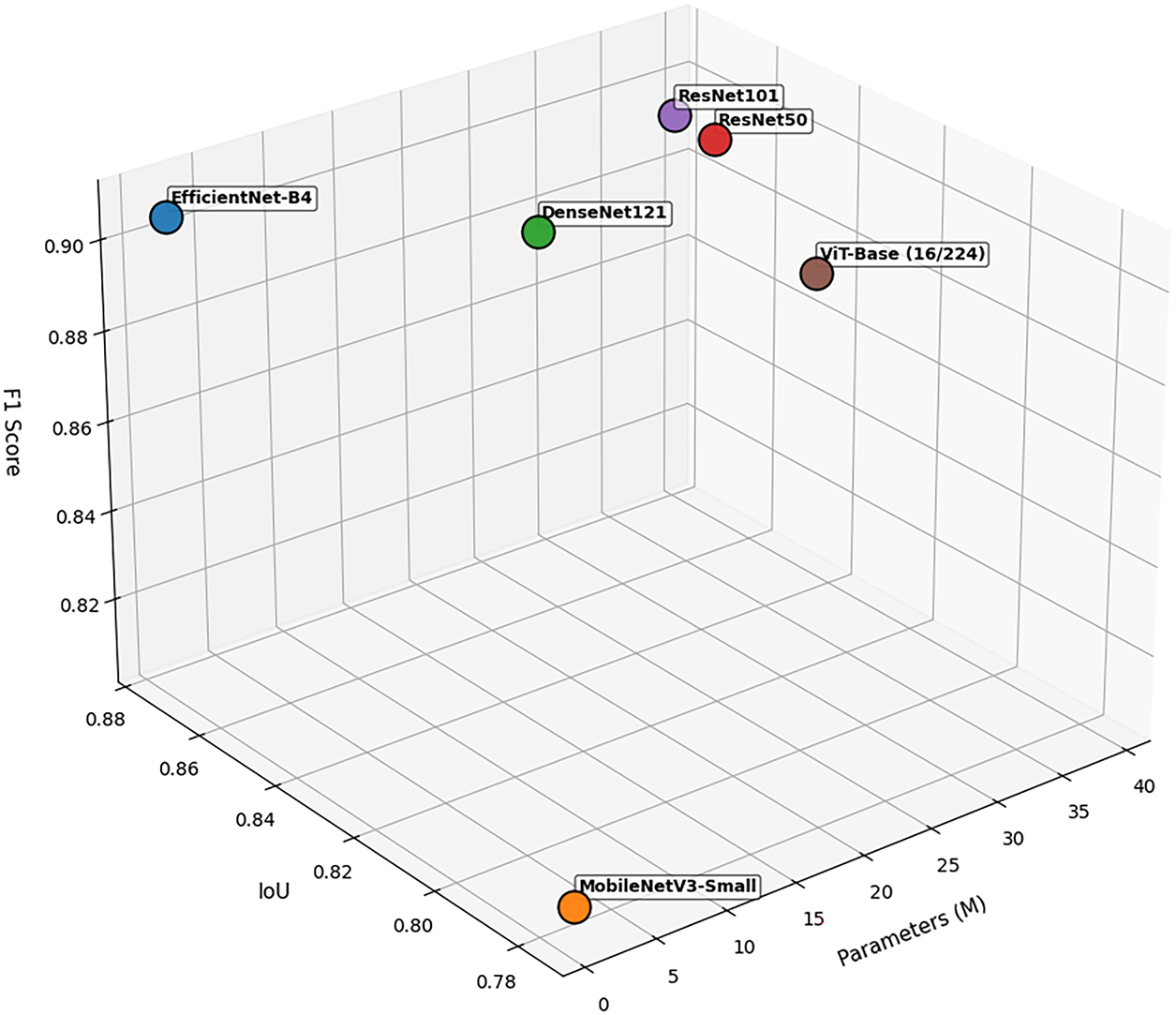

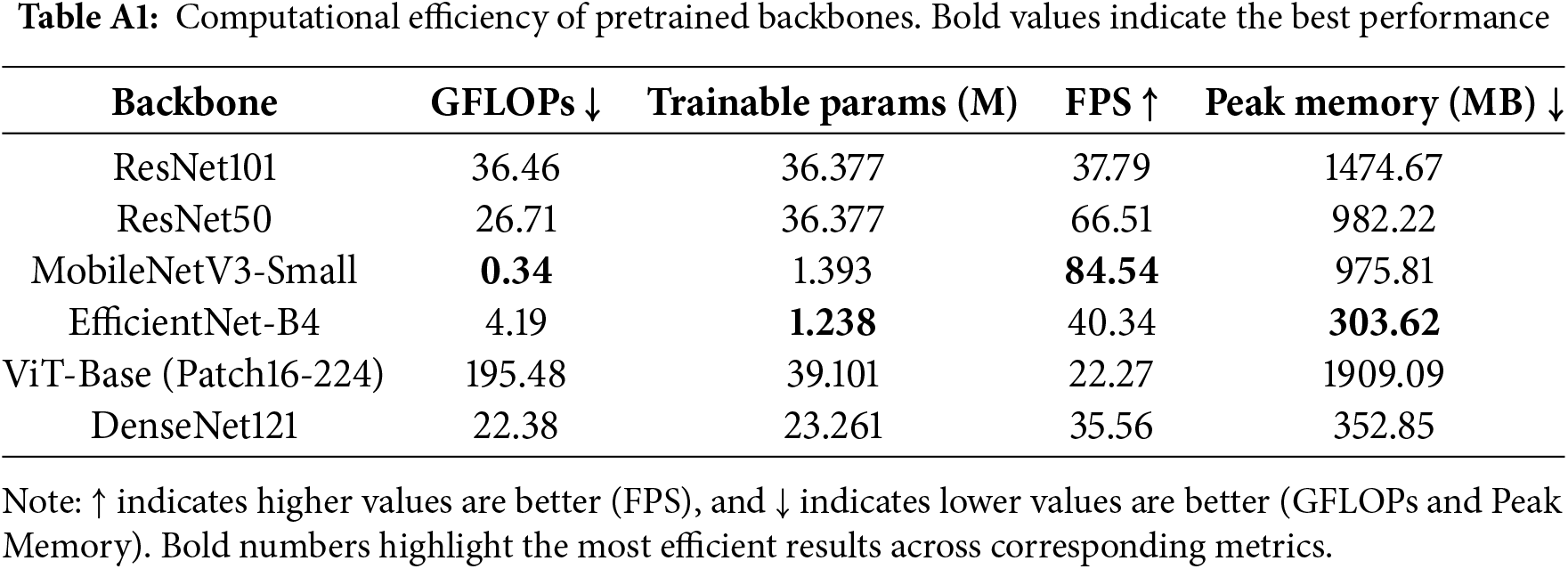

Several pretrained encoders with ImageNet weights were evaluated to assess backbone selection impact on segmentation performance. Fig. 5 illustrates the trade-off between F1 score, IoU, and model parameters.

Figure 5: Influence of different backbones on segmentation performance

Among CNN-based backbones, ResNet50 and ResNet101 achieved comparable performance (F1

Detailed computational efficiency metrics, including GFLOPs, FPS, and memory usage, are provided in Appendix B (Table A1).

4.6.2 Effect of Fusion Strategies

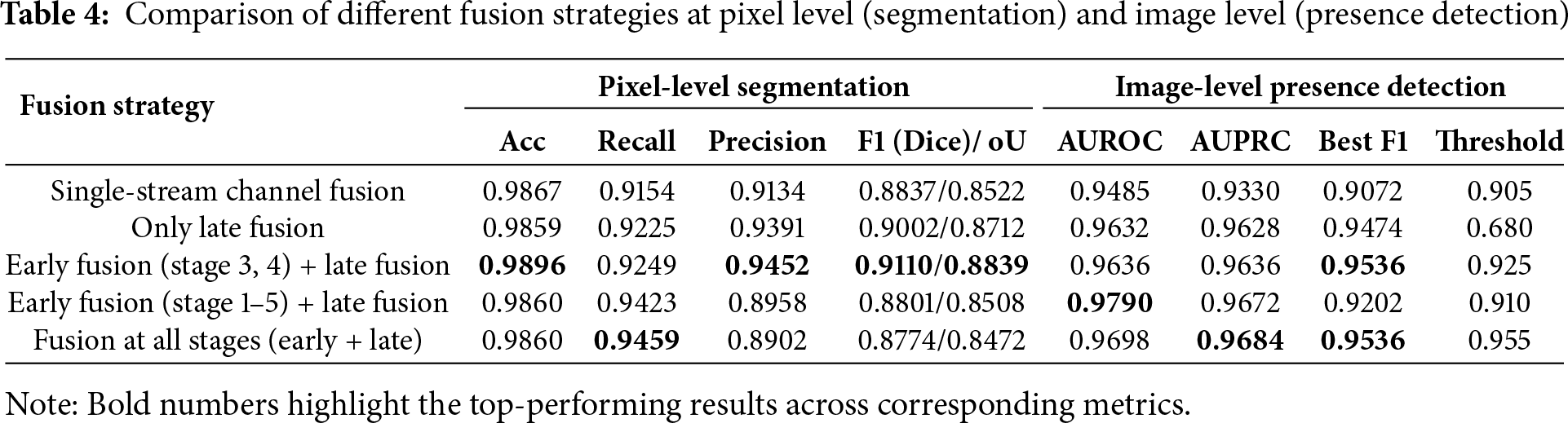

We analyzed the impact of different fusion strategies at both pixel-level (segmentation) and image-level (presence detection) on 278 test images (77 positive, 201 negative). Table 4 compares variants from a single-stream channel fusion baseline to progressively adding late fusion, early fusion at selected stages, and multi-stage fusion.

The single-stream baseline achieved moderate performance but exhibited weaker image-level detection. Late fusion alone improved both segmentation and detection metrics, though the low optimal threshold (0.68) indicates reduced model confidence near decision boundaries. The optimal configuration—early fusion at stages 3 and 4 combined with late fusion—achieved the highest segmentation performance (F1 = 0.9110, IoU = 0.8839) while maintaining robust image-level detection (AUROC = 0.9636, best F1 = 0.9536). Expanding fusion to all encoder stages degraded pixel-level precision despite competitive image-level metrics (AUROC up to 0.9790), suggesting that excessive fusion introduces redundancy and impairs spatial accuracy.

4.6.3 Effect of Decoder Components

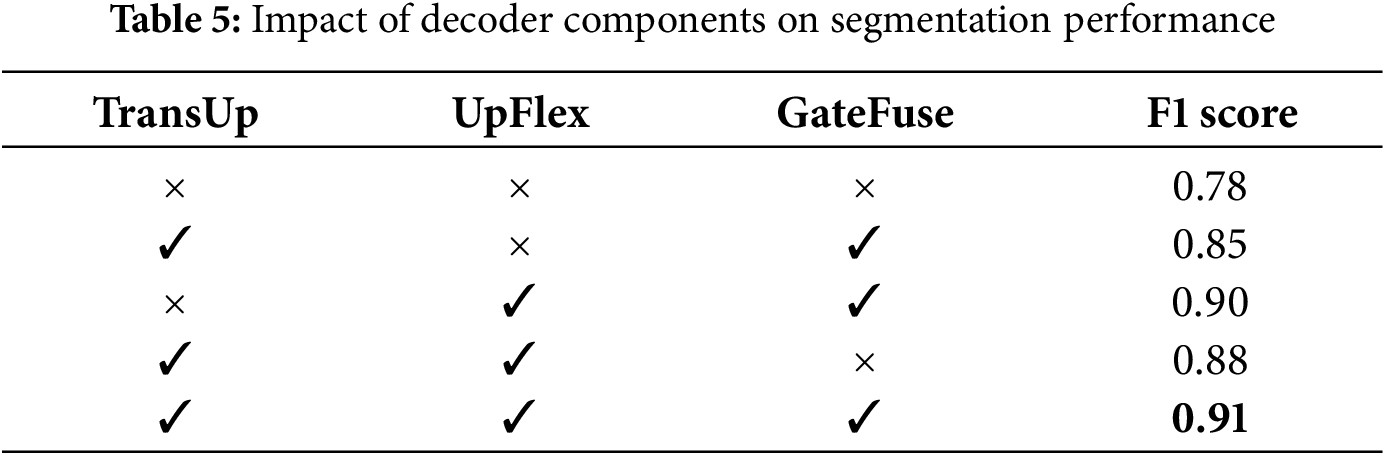

We conducted ablation experiments to assess the contribution of three decoder modules: TransUp, UpFlex, and GateFuse.

Table 5 shows that UpFlex provides the largest individual improvement (F1 = 0.90 vs. baseline 0.78), demonstrating its effectiveness for spatial refinement. TransUp with GateFuse achieves F1 = 0.85, while combining TransUp and UpFlex yields F1 = 0.88. The full configuration with all three modules achieves optimal performance (F1 = 0.91), confirming their complementary contributions to segmentation accuracy.

4.6.4 Effect of Deep Supervision

Deep supervision [26] is a widely adopted technique in segmentation networks, proven to enhance performance by injecting auxiliary losses at intermediate decoder stages to improve gradient flow and regularization. In our study, all experiments incorporated deep supervision (Section 3.5) and regularization (Section 3.4) wherever gated fusion was applied.

Empirically, this design consistently resulted in a performance boost of 1%–2% across metrics compared to training without deep supervision. The improvement was most notable in challenging cases with small or fragmented landslide regions, where auxiliary supervision guided the decoder to produce sharper and more consistent segmentation masks. These findings align with prior evidence that deep supervision strengthens training stability and improves generalization in encoder–decoder networks.

The experimental evaluation highlights key aspects of the proposed framework corresponding to design choices in Sections 3 and 4.

The backbone analysis (Section 4.6.1) confirms that lightweight architectures like EfficientNet-B4 achieve superior segmentation performance with fewer parameters than heavier alternatives (ResNet101, ViT), enabling efficient real-time landslide monitoring without sacrificing accuracy.

Fusion strategy comparisons (Section 4.6.2) show that combining early fusion at mid-level encoder stages with gated late fusion at decoder stages maximizes complementary information while avoiding redundancy. Single-stream fusion achieved baseline performance, but staged gated fusion substantially improved both pixel-level segmentation and image-level detection. Indiscriminate fusion across all levels introduced noise and reduced spatial precision.

Decoder ablations (Section 4.6.3) reveal that UpFlex provides the largest individual improvement through attention-gated skip fusion. The combination of TransUp, UpFlex, and GateFuse achieved optimal performance, validating their complementary roles in semantic alignment, spatial refinement, and adaptive fusion.

Deep supervision (Section 4.6.4) consistently improved training stability and performance by 1%–2%, particularly for small, fragmented landslides where auxiliary losses recovered finer details, aligning with established regularization benefits in encoder–decoder networks.

Baseline comparisons (Section 4.5) demonstrate that integrating staged fusion, adaptive decoders, and deep supervision enables our approach to outperform U-Net variants, ShapeFormer, and GMNet on the Bijie dataset. Results on Landslide4Sense confirm that optimized feature selection (RGB, NDVI, Slope, DEM) outperforms full-band or single-modality inputs, emphasizing strategic data fusion in remote sensing applications.

Limitations and Future Work

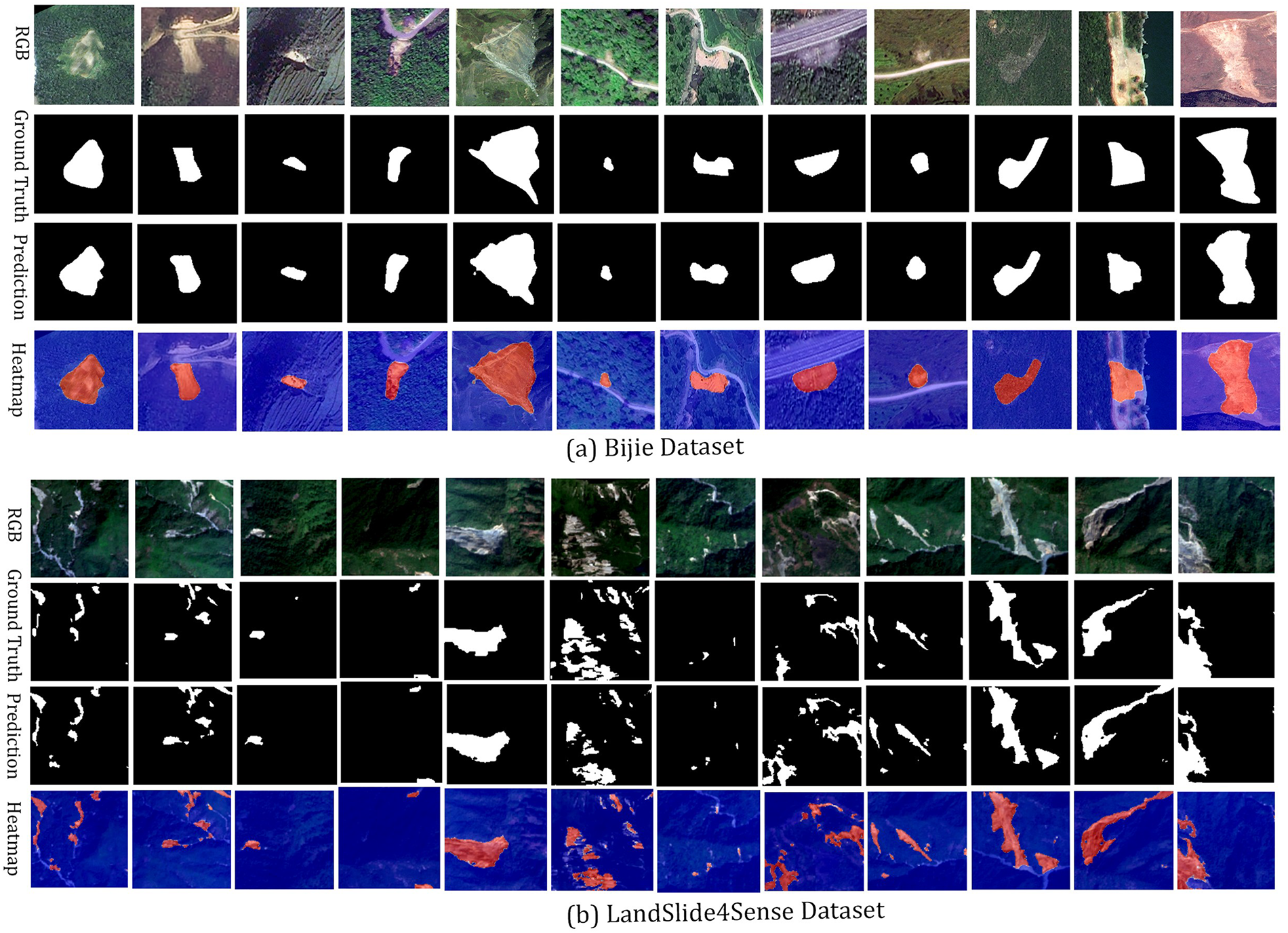

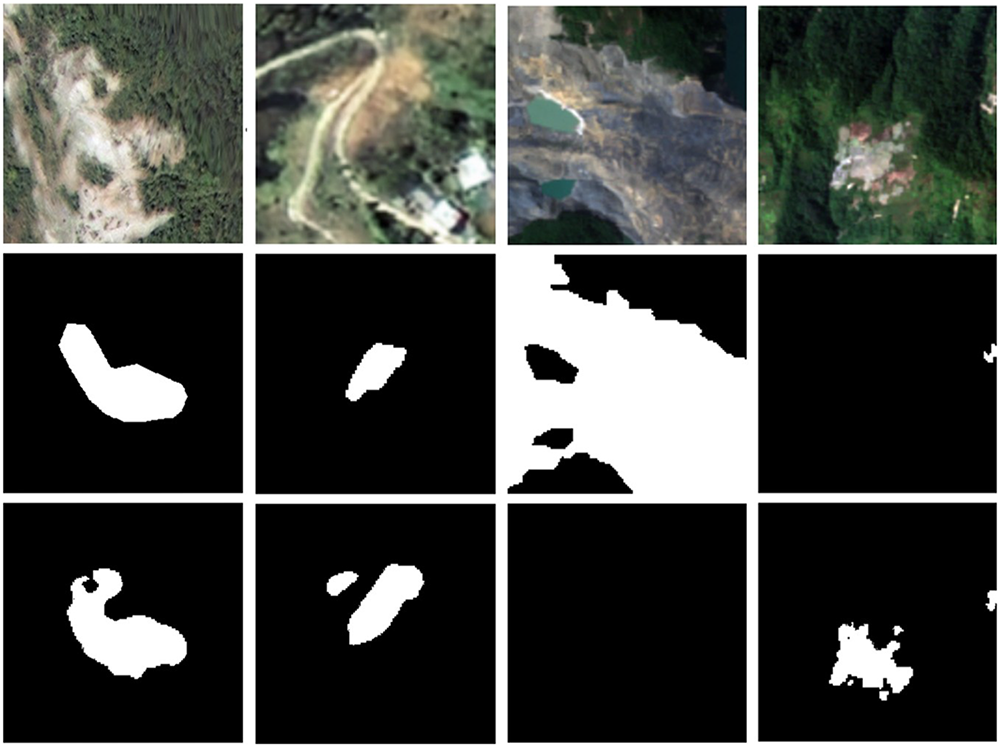

Despite strong results, illustrated in Fig. 6, challenges remain for future work. As shown in Fig. 7, the model still struggles in scenes with complex backgrounds and fine boundaries, occasionally leading to missed or imprecise detections. Performance differences between the Bijie and Landslide4Sense datasets further indicate sensitivity to input data quality, particularly resolution. The Bijie dataset benefits from high-resolution optical and DEMs that capture detailed topographic gradients, whereas coarse DEMs may reduce boundary precision and limit model transferability, a known constraint in large-scale landslide mapping.

Figure 6: Qualitative results of the proposed segmentation framework across two benchmark datasets: (a) Bijie Dataset and (b) LandSlide4Sense Dataset. For each dataset, the sequence displays the RGB image, annotated ground truth, predicted segmentation mask, and heatmap overlaid on the RGB image. The heatmap highlights landslide regions in red (positive) and non-landslide areas in blue (negative)

Figure 7: Examples of challenging cases from the Bijie and Landslide4Sense datasets. Each column shows the RGB image, the annotated ground truth, and the predicted segmentation mask. These samples illustrate failure cases where the model struggles in complex environments, leading to missed detections or inaccurate delineation of landslide boundaries

The current framework is limited to optical and topographic input with single temporal pairs. Future work will focus on integrating synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data for all-weather robustness and employing temporal fusion to capture pre and post-event changes. Incorporating edge-aware refinement, boundary-sensitive loss functions, and domain adaptation will further enhance segmentation accuracy and generalization across varied terrains, making the framework more adaptable for large-scale landslide monitoring.

This study presented a lightweight dual-stream segmentation framework for mapping landslides from remote sensing imagery. The proposed architecture employs a synergistic combination of a dual encoder-decoder design that preserves modality-specific fidelity while enabling cross-stream information exchange through guided gated fusion of optical and topographical features. An adaptive decoder incorporating cross-attention and attention-guided refinement further enhances boundary delineation and reduces false positives. Comprehensive experiments on two benchmark datasets demonstrated the strong performance of the proposed model, achieving an F1-score of 0.9110 and an IoU of 0.8839 on the Bijie dataset, surpassing state-of-the-art baselines.

The proposed model effectively segmented various types of landslides, including shallow slides, rock falls, and debris slides, demonstrating adaptability across datasets with different geomorphological and climatic triggers. Due to its compact design and computational efficiency, the model is well-suited for rapid regional mapping and near real-time disaster response, with potential for integration into operational geohazard monitoring systems. Future work will explore edge-aware refinement modules, multi-temporal and SAR data fusion, and domain adaptation strategies to improve generalization across diverse geographic environments. Through these extensions, the proposed framework is expected to further enhance the reliability, scalability, and practicality of automated landslide inventory mapping in real-world applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the School of Computer Science, Chongqing University, for providing the laboratory facilities and experimental resources that supported this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized ChatGPT (version GPT-5, OpenAI) for assistance in text refinement and LaTeX formatting. The authors have carefully reviewed and revised all AI-assisted content and accept full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 62262045, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 2023CDJYGRH-YB11, and the Open Funding of SUGON Industrial Control and Security Center, grant number CUIT-SICSC-2025-03.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization and methodology, Md Minhazul Islam and Yunfei Yin; experimental setup, Zheng Yuan; programming, Md Minhazul Islam; validation, Md Minhazul Islam, Md Tanvir Islam and Zheng Yuan; formal analysis, Md Minhazul Islam; investigation and data curation, Md Minhazul Islam and Argho Dey; writing—original draft preparation, Md Minhazul Islam; writing—review and editing, Md Tanvir Islam and Yunfei Yin; supervision, Yunfei Yin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code supporting this study is openly available at https://github.com/mishaown/DiGATe-UNet-LandSlide-Segmentation (accessed on 3 November 2025).

The datasets used—Bijie landslide dataset and Landslide4Sense—are both publicly accessible:

• Bijie landslide dataset: Provided by Ji et al. of Wuhan University, this dataset includes 770 landslide images and 2003 non-landslide samples. It can be downloaded from the official site: http://gpcv.whu.edu.cn/data/Bijie_pages.html [30] (accessed on 3 November 2025).

• Landslide4Sense dataset: A multi-sensor landslide benchmark compiled from various global regions (spanning 2015–2021), containing 3799 training images, 245 validation, and 800 test samples, with 14 data bands including Sentinel-2, slope and DEM layers. This is available via the Institute of Advanced Research in Artificial Intelligence (IARAI) Landslide4Sense repository/website: https://www.iarai.ac.at/landslide4sense [8] (accessed on 3 November 2025).

Both datasets are openly available under terms of their original publication and hosting platforms.

Ethics Approval: The data used in this study were publicly available datasets on the Internet. No human participants or animals were involved in this research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that there are no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence the work. There is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service, or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, this manuscript.

Appendix A Training and Validation Curves

This appendix complements the experimental results presented in Section 4.5. Figs. A1 and A2 show the training and validation curves of loss, F1 score, and IoU for the Bijie and Landslide4Sense datasets, respectively. These plots illustrate the convergence behavior and stability of the proposed model during optimization.

Figure A1: Training and validation curves (loss, F1 score, and IoU) for the Bijie dataset

Figure A2: Training and validation curves (loss, F1 score, and IoU) for the Landslide4Sense dataset

Appendix B Computational Efficiency of Pretrained Backbones

This appendix complements the ablation study in Section 4.6 by comparing computational efficiency across different pretrained backbones. Metrics include floating-point operations (GFLOPs), trainable parameters (M), inference speed (frames per second, FPS), and peak GPU memory usage (MB).

References

1. Jiang P, Ma Z, Mei G. Review article: deep learning for potential landslide identification: data, models, applications, challenges, and opportunities. Landsls Debris Flows Hazard. 2025 May. doi:10.5194/egusphere-2025-2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Oak O, Nazre R, Naigaonkar S, Sawant S, Vaidya H. A comparative analysis of CNN-based deep learning models for landslide detection. In: 2024 Asian Conference on Intelligent Technologies (ACOIT); 2024 Sep 6–7; Kolar, India: IEEE. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ACOIT62457.2024.10939989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu X, Peng Y, Lu Z, Li W, Yu J, Ge D, et al. Feature-fusion segmentation network for landslide detection using high-resolution remote sensing images and digital elevation model data. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:1–14. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2022.3233637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chandra N, Sawant S, Vaidya H. An efficient U-Net model for improved landslide detection from satellite images. PFG J Photogramm Remote Sens Geoinf Sci. 2023 Mar;91(1):13–28. doi:10.1007/s41064-023-00232-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Qin H, Wang J, Mao X, Zhao Z, Gao X, Lu W. An improved faster R-CNN method for landslide detection in remote sensing images. J Geovis Spat Anal. 2024 Jun;8(1):2. doi:10.1007/s41651-023-00163-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sreelakshmi S, Vinod Chandra SS, Shaji E. Landslide identification using machine learning techniques: review, motivation, and future prospects. Earth Sci Inform. 2022 Dec;15(4):2063–90. doi:10.1007/s12145-022-00889-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hacıefendioğlu K, Varol N, Toğan V, Bahadır Ü, Kartal ME. Automatic landslide detection and visualization by using deep ensemble learning method. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(18):10761–76. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-09638-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ghorbanzadeh O, Xu Y, Ghamisi P, Kopp M, Kreil D. Landslide4Sense: reference benchmark data and deep learning models for landslide detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–17. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2022.3215209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wu L, Liu R, Ju N, Zhang A, Gou J, He G, et al. Landslide mapping based on a hybrid CNN-transformer network and deep transfer learning using remote sensing images with topographic and spectral features. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2024;126:103612. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2023.103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang H, Liu J, Zeng S, Xiao K, Yang D, Yao G, et al. A novel landslide identification method for multi-scale and complex background region based on multi-model fusion: YOLO + U-Net. Landslides. 2024;21(4):901–17. doi:10.1007/s10346-023-02184-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jin Y, Liu X, Huang X. EMR-HRNet: a multi-scale feature fusion network for landslide segmentation from remote sensing images. Sensors. 2024;24(11):3677. doi:10.3390/s24113677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hu W, Sun G, Zeng X, Tong B, Wang Z, Wu X, et al. Hierarchical cross attention achieves pixel precise landslide segmentation in submeter optical imagery. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):21933. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-08695-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Licata M, Buleo Tebar V, Seitone F, Fubelli G. The Open landslide project (OLPa new inventory of shallow landslides for susceptibility models: the autumn 2019 extreme rainfall event in the langhe-monferrato region (Northwestern Italy). Geosciences. 2023;13(10):289. doi:10.3390/geosciences13100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ferrario MF. Inventory of landslides triggered by heavy rainfall in the Emilia-Romagna region (Italy) in May 2023 [Dataset]. Zenodo; 2024 Aug. doi:10.5281/zenodo.13234762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Rana K, Malik N, Ozturk U. Landsifier v1.0: a python library to estimate likely triggers of mapped landslides. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2022;22(11):3751–64. doi:10.5194/nhess-22-3751-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou Y, Peng Y, Ge D, Yu J, Xiang W. A multi-source data fusion-based semantic segmentation model for relic landslide detection. arXiv:2308.01251. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2308.01251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Wang X, Zheng Y, Liu Z, Xia W, Guo H, et al. GDSNet: a gated dual-stream convolutional neural network for automatic recognition of coseismic landslides. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2024;127:103677. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2024.103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ghorbanzadeh O, Xu Y, Zhao H, Wang J, Zhong Y, Zhao D, et al. The outcome of the 2022 Landslide4Sense competition: advanced landslide detection from multi-source satellite imagery. arXiv:2209.02556. 2022. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2209.02556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Şener A, Ergen B. LandslideSegNet: an effective deep learning network for landslide segmentation using remote sensing imagery. Earth Sci Inform. 2024;17(5):3963–77. doi:10.1007/s12145-024-01434-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lu W, Hu Y, Shao W, Wang H, Zhang Z, Wang M. A multiscale feature fusion enhanced CNN with the multiscale channel attention mechanism for efficient landslide detection (MS2LandsNet) using medium-resolution remote sensing data. Int J Digit Earth. 2024;17(1):2300731. doi:10.1080/17538947.2023.2300731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lv P, Ma L, Li Q, Du F. ShapeFormer: a shape-enhanced vision transformer model for optical remote sensing image landslide detection. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2023;16:2681–9. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3253769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tan M, Le QV. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. arXiv:1905.11946. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1905.11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shi W, Caballero J, Huszár F, Totz J, Aitken AP, Bishop R, et al. Real-time single image and video super-resolution using an efficient sub-pixel convolutional neural network. arXiv:1609.05158. 2016 DOI 10.48550/arXiv.1609.05158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Arevalo J, Solorio T, Montes-y-Gómez M, González FA. Gated multimodal networks. Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32(14):10209–28. doi:10.1007/s00521-019-04559-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Salehi SSM, Erdogmus D, Gholipour A. Tversky loss function for image segmentation using 3D fully convolutional deep networks. arXiv:1706.05721. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1706.05721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li R, Wang X, Huang G, Yang W, Zhang K, Gu X, et al. A comprehensive review on deep supervision: theories and applications. arXiv:2207.02376. 2022 Jul. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2207.02376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xu Y, Ouyang C, Xu Q, Wang D, Zhao B, Luo Y. CAS landslide dataset: a large-scale and multisensor dataset for deep learning-based landslide detection. Sci Data. 2024;11(1):12. doi:10.1038/s41597-023-02847-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fang C, Fan X, Wang X, Nava L, Zhong H, Dong X, et al. A globally distributed dataset of coseismic landslide mapping via multi-source high-resolution remote sensing images. Earth Syst Sci Data. 2024;16(10):4817–42. doi:10.5194/essd-16-4817-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Handwerger AL, Huang MH, Jones SY, Amatya P, Kerner HR, Kirschbaum DB. Generating landslide density heatmaps for rapid detection using open-access satellite radar data in Google Earth Engine. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2022;22:753–73.doi:10.5194/nhess-22-753-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ji S, Yu D, Shen C, Li W, Xu Q. Landslide detection from an open satellite imagery and digital elevation model dataset using attention boosted convolutional neural networks. Landslides. 2020;17(6):1337–52. doi:10.1007/s10346-020-01353-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chaurasia A, Culurciello E. LinkNet: exploiting encoder representations for efficient semantic segmentation. In: 2017 IEEE Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP); 2017 Dec 10–13; St. Petersburg, FL, USA: IEEE. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/VCIP.2017.8305148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Daudt RC, Saux BL, Boulch A. Fully convolutional siamese networks for change detection. arXiv:1810.08462. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1810.08462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yang K, Xia GS, Liu Z, Du B, Yang W, Pelillo M, et al. Asymmetric siamese networks for semantic change detection in aerial images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–18. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3113912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Pham L, Le C, Tang H, Truong K, Nguyen T, Lampert J, et al. RMAU-NET: a residual-multihead-attention U-Net architecture for landslide segmentation and detection from remote sensing images. arXiv:2507.11143. 2025 doi:10.48550/arXiv.2507.11143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li G, Li K, Zhang G, Pan K, Ding Y, Wang Z, et al. A landslide area segmentation method based on an improved UNet. Sci Rep. 2025 Apr;15(1):11852. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-94039-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wang K, He D, Sun Q, Yi L, Yuan X, Wang Y. A novel network for semantic segmentation of landslide areas in remote sensing images with multi-branch and multi-scale fusion. Appl Soft Comput. 2024 Jun;158:111542. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools