Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

An Overview of Segmentation Techniques in Breast Cancer Detection: From Classical to Hybrid Model

1 Department of Software Convergence, Soonchunhyang University, Asan, 31538, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Medical Electronics Technology, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, 55183, Indonesia

3 Department of Medical IT Engineering, Soonchunhyang University, Asan, 31538, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Se Dong Min. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Vision and Image Processing: Feature Selection, Image Enhancement and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 6 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072609

Received 30 August 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Accurate segmentation of breast cancer in mammogram images plays a critical role in early diagnosis and treatment planning. As research in this domain continues to expand, various segmentation techniques have been proposed across classical image processing, machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and hybrid/ensemble models. This study conducts a systematic literature review using the PRISMA methodology, analyzing 57 selected articles to explore how these methods have evolved and been applied. The review highlights the strengths and limitations of each approach, identifies commonly used public datasets, and observes emerging trends in model integration and clinical relevance. By synthesizing current findings, this work provides a structured overview of segmentation strategies and outlines key considerations for developing more adaptable and explainable tools for breast cancer detection. Overall, our synthesis suggests that classical and ML methods are suitable for limited labels and computing resources, while DL models are preferable when pixel-level annotations and resources are available, and hybrid pipelines are most appropriate when fine-grained clinical precision is required.Keywords

Breast cancer remains a significant global health challenge, affecting millions of women and ranking as one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths [1]. In 2020, approximately 2.3 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer, resulting in 685,000 deaths worldwide. Early detection is essential, as it substantially improves survival rates, with up to 90% of women surviving when the disease is identified at an early stage [2]. The need for timely and accurate diagnostic methods underscores the importance of developing advanced tools and techniques [3,4].

Breast cancer detection can be performed using a range of approaches, including clinical breast examination [5,6], histopathological analysis [7,8], and various imaging modalities such as mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [9]. Among these, mammography remains the most widely used screening tool due to its accessibility and effectiveness in early detection [10–13]. With the growing volume of medical images, image processing techniques, particularly in the context of Computer-Aided Detection (CAD) systems, have become essential for assisting radiologists in analyzing and interpreting mammograms with consistency and efficiency [14,15]. In a typical CAD system, the diagnostic pipeline includes image acquisition, preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, classification, and decision support.

Among these stages, segmentation serves as a crucial step in isolating regions of interest (RoI), such as mass or calcifications, from surrounding breast tissue. The accuracy of segmentation strongly affects the performance of subsequent processes like feature extraction, classification, and diagnosis. Mis-segmentation can lead to poor feature representation and ultimately compromise clinical decisions [16]. However, segmentation can be challenging due to the complex structure of breast tissue and variations in tumor characteristics. These challenges often make accurate boundary delineation difficult, which can impact diagnostic outcomes [17]. Therefore, improving segmentation performance is not only a technical challenge but also a clinical necessity. Its role as the bridge between raw image data and meaningful diagnostic insight makes segmentation both urgent and impactful in breast cancer detection workflows.

To improve segmentation performance in breast cancer detection, a wide range of techniques have emerged over time, evolving from classical image processing methods to increasingly sophisticated ML, DL, and hybrid/ensemble models. Classical approaches, such as thresholding, region growing, and edge detection, laid the foundational groundwork by offering simple, interpretable, and computationally efficient methods [18]. However, their limitations in handling complex tissue textures and subtle tumor boundaries led to the exploration of ML-based techniques like fuzzy clustering and k-means, which introduced learning-based adaptability into segmentation [19]. The recent decade has witnessed a rapid surge in deep learning applications, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with U-Net architectures [20–22], which are capable of capturing high-level features and spatial hierarchies in mammographic images. In practice, U-Net and its variants have been implemented for automated abnormality detection in mammography, enabling end-to-end segmentation of suspicious regions such as masses and microcalcifications without manual localization. By leveraging skip connections and encoder–decoder symmetry, these models achieve precise boundary delineation even in dense breast tissues and have shown superior performance.

Most recently, hybrid and ensemble methods have gained attention for their potential to combine the strengths of previous approaches, balancing accuracy, robustness, and adaptability [23,24]. For example, hybrid CNN frameworks have combined classical clustering techniques with deep architectures, where Fuzzy C-Means assists ROI identification and CNNs refine tumor boundaries [25]. Other designs integrate Transformer modules into U-Net to simultaneously capture local textures and global breast context [26]. More clinically inspired hybrids even incorporate radiologist eye-tracking patterns into CNN attention mechanisms, mimicking expert visual strategies for subtle lesion detection [27]. Rather than replacing earlier approaches, this progression reflects a diversification in segmentation strategies, where classical, ML, DL, and hybrid methods continue to coexist and evolve in parallel. Each approach offers unique advantages depending on the clinical context, computational constraints, and data availability. Recognizing this methodological landscape is important not only for mapping research trends but also for understanding which techniques are best suited to specific diagnostic scenarios in breast cancer imaging.

Several previous review studies have discussed segmentation techniques in breast cancer imaging, each with varying scope and depth. Michael et al. categorized segmentation techniques into classical, ML, and DL approaches, and provided performance metrics across various methods [17]. In contrast, Ranjbarzadeh et al. reviewed segmentation methods by classifying them into supervised, unsupervised, and DL-based approaches, without explicitly discussing performance metrics or future research directions [28]. Rezaei presented a broader review of image-based breast cancer detection, segmentation, and classification across multiple modalities, including mammography, ultrasound, and MRI, but offered only general descriptions of segmentation methods without categorization or comparative performance analysis [29]. In response to these earlier works, the present review broadens the discussion by examining not only classical, ML-based, and DL-based segmentation approaches, but also emerging hybrid strategies, such as Fuzzy C-Means and CNNs combination [25]. Beyond these methodological inclusions, this review also emphasizes structured performance comparisons and systematic analysis of dataset distribution, offering contributions not explicitly addressed in prior works.

To provide a structured and in-depth understanding of segmentation approaches in breast cancer detection, this review adopts a systematic literature review (SLR) using PRISMA method. The study is guided by several research questions designed to explore not only the current state of segmentation methods, but also the datasets commonly used:

RQ1: What segmentation approaches are commonly used in breast cancer detection, and how do they compare in terms of performance and limitations?

RQ2: What are the current trends and performance outcomes of segmentation approaches used in breast cancer detection?

RQ3: What datasets are most frequently utilized in breast cancer segmentation research?

Through this review, we aim to inform researchers and practitioners about the current landscape of segmentation in breast cancer detection and support the development of more accurate and effective diagnostic tools. The rest of this study is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the method, including the PRISMA framework and criteria for study selection for SLR. Section 3 covers results and discussion, where we apply this simple RQ-based taxonomy, including various segmentation approaches, trends, outcomes, and datasets that are frequently used as an answer for all of the Research Questions (RQ1–RQ3). Section 4 discusses challenges and future directions in breast cancer research, and Section 5 concludes the findings of this review.

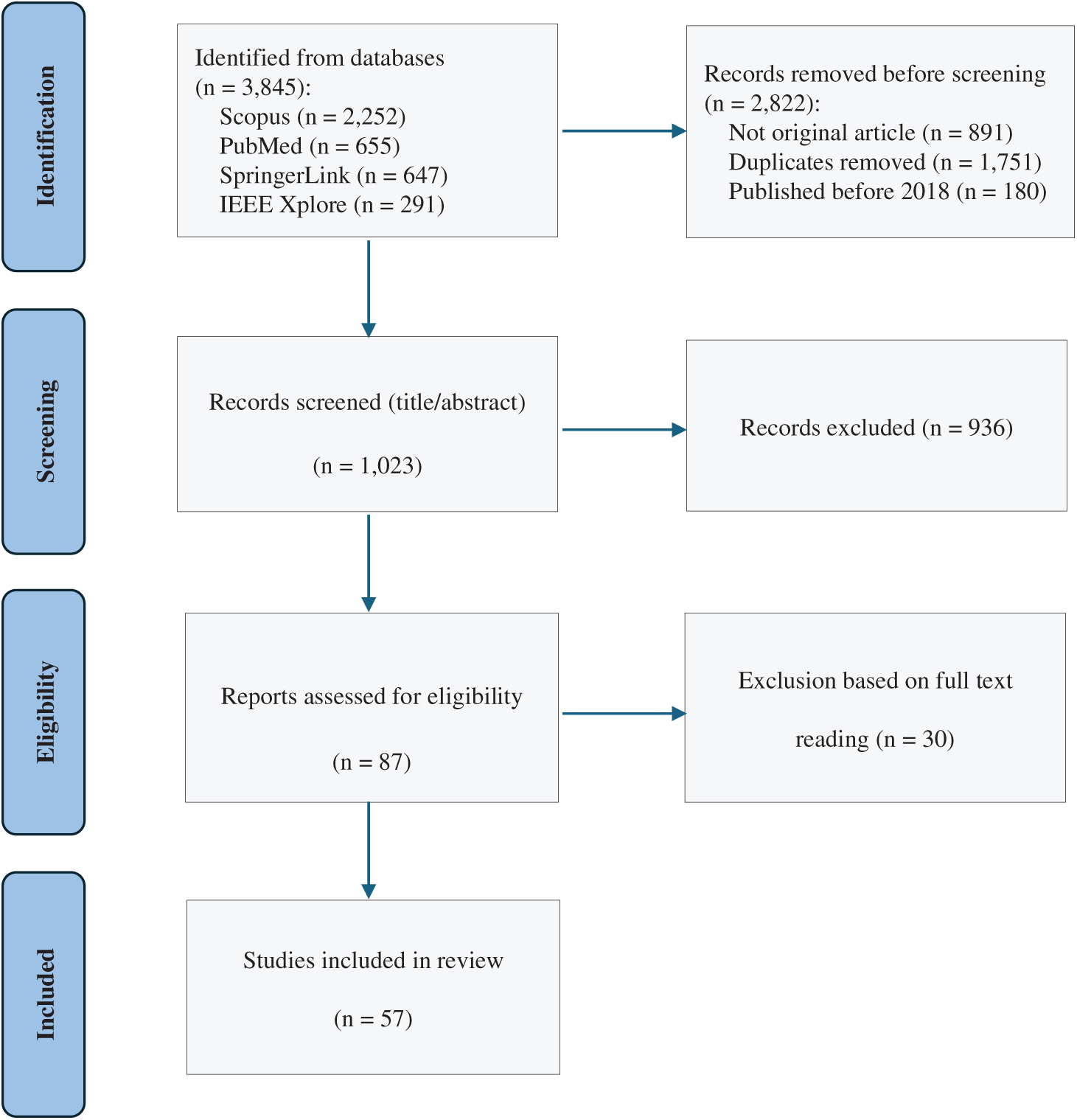

This review employs the PRISMA methodology, which is widely recognized in biomedical research for ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and systematic reporting. Compared with other frameworks, PRISMA is particularly well suited for reviews that involve extensive literature searching, screening, and eligibility assessment, as is the case in breast cancer segmentation studies. Its structured flow diagram and checklist enable clear documentation of inclusion and exclusion processes, thereby strengthening the reliability of the evidence synthesis. The PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1 visually illustrates the overall review process [30]. This systematic and structured approach ensures that the review is based on the highest-quality and most relevant articles, providing a comprehensive overview of the current state of segmentation techniques using mammography.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart illustrating the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies in this review

2.1 Search Strategy and Identification

To locate relevant studies, specific keywords were used in the search across multiple academic databases. Keywords included terms such as “CAD for mammogram”, “mammogram segmentation”, “deep learning mammogram segmentation”, “machine learning mammogram segmentation”, and “hybrid/ensemble mammogram segmentation”. The search was restricted to articles published in English between 2018 and March 2025. The focus on this timeframe ensures that the review covers the most recent advancements in the field, with studies reflecting cutting-edge technologies, including several segmentation and classification methods to process mammograms.

The databases searched included Scopus, IEEE, PubMed, and Springer. These databases were chosen based on their comprehensive coverage of scientific literature in the fields of medical imaging, artificial intelligence, and cancer research. The initial search yielded a total of 3845 records, distributed across the following databases:

– Scopus: 2252

– PubMed: 655

– Springer: 647

– IEEE: 291

This wide-ranging search aimed to capture all potentially relevant studies for CAD techniques in breast cancer detection using mammography, ensuring that both well-established research and newer studies were included. However, not all identified records were suitable for this review. A total of 2822 records were removed before the screening stage for the following reasons:

– 891 records were excluded as they were not original research articles, such as conference proceedings, book chapters, or reviews.

– 1751 duplicate entries were identified and removed to ensure that each study was counted once using Microsoft Excel.

– 180 articles published before 2018 were excluded. A decision was made to remove articles published before 2018 as an additional precaution against outdated techniques and technologies.

At the screening stage, 1023 studies were reviewed by their titles and abstracts. The screening process involved a detailed examination of whether the studies matched the scope of the review, focusing on their relevance to segmentation and classification techniques for breast cancer detection using mammograms. The following exclusion criteria were applied rigorously to ensure only high-quality and relevant studies were considered:

(a) Type of Publication: Only peer-reviewed journal articles were included. Conference papers, book chapters, and other non-journal articles were excluded because they often lack the rigorous review process necessary for ensuring the validity and reliability of the findings. Journal articles are more likely to undergo a thorough peer review, which strengthens the quality of the data and conclusions.

(b) Data Source: The study must use mammogram datasets as the primary data source. Articles focusing on other imaging modalities, such as ultrasound, MRI, or CT scans, were excluded. The exclusive focus on mammogram datasets ensures the review remains consistent with its aim of exploring CAD techniques specific to mammography, which is a key imaging method for breast cancer screening.

(c) Study Focus: The articles needed to center on segmentation tasks in CAD for breast cancer detection. Studies that primarily discussed preprocessing, image enhancement, feature extraction, feature selection, classification, or optimization techniques were excluded.

(d) Access: Articles that required purchase or were not available through institutional subscriptions were excluded from the review. This ensured that all included studies were accessible for further analysis and could be evaluated in full.

After applying these exclusion criteria, 936 studies were excluded, leaving 87 studies for a full-text review. The stringent screening ensured that the remaining studies were closely aligned with the objectives of this review.

In the eligibility phase, the full texts of 87 studies were examined in detail. Each article was thoroughly assessed for its relevance to the review’s focus areas of segmentation and classification in mammogram-based CAD systems. The eligibility assessment was guided by the need to include only studies that contributed substantial findings to these key areas. At this stage, an additional 30 studies were excluded for one or more of the following reasons:

(a) Some studies did not provide sufficient focus on segmentation or classification tasks, instead centering on preprocessing techniques or enhancement methods.

(b) A few studies, while discussing segmentation or classification, lacked adequate performance metrics or methodological detail, making it difficult to assess the techniques’ effectiveness.

(c) Others presented methods that, upon closer inspection, did not align with the goals of the review, such as focusing on imaging modalities other than mammography.

After the thorough identification, screening, and eligibility assessment processes, a total of 57 studies were included in this systematic review. These studies represent the most relevant and high-quality research in the field of breast cancer detection using CAD techniques, specifically focusing on segmentation and classification methodologies applied to mammogram images. The studies included offer insights into a wide range of machine learning and deep learning approaches, and datasets, contributing to the understanding of advancements in this area.

This section presents the findings of the systematic literature review in response to the research questions outlined in the introduction. It is organized into three parts, corresponding to the three main areas of investigation: segmentation approaches, performance trends, and dataset characteristics, which we use as a simple RQ-based taxonomy to interpret and compare the studies.

3.1 RQ1: What Segmentation Approaches Are Commonly Used in Breast Cancer Detection, and How Do They Compare in Terms of Performance and Limitations?

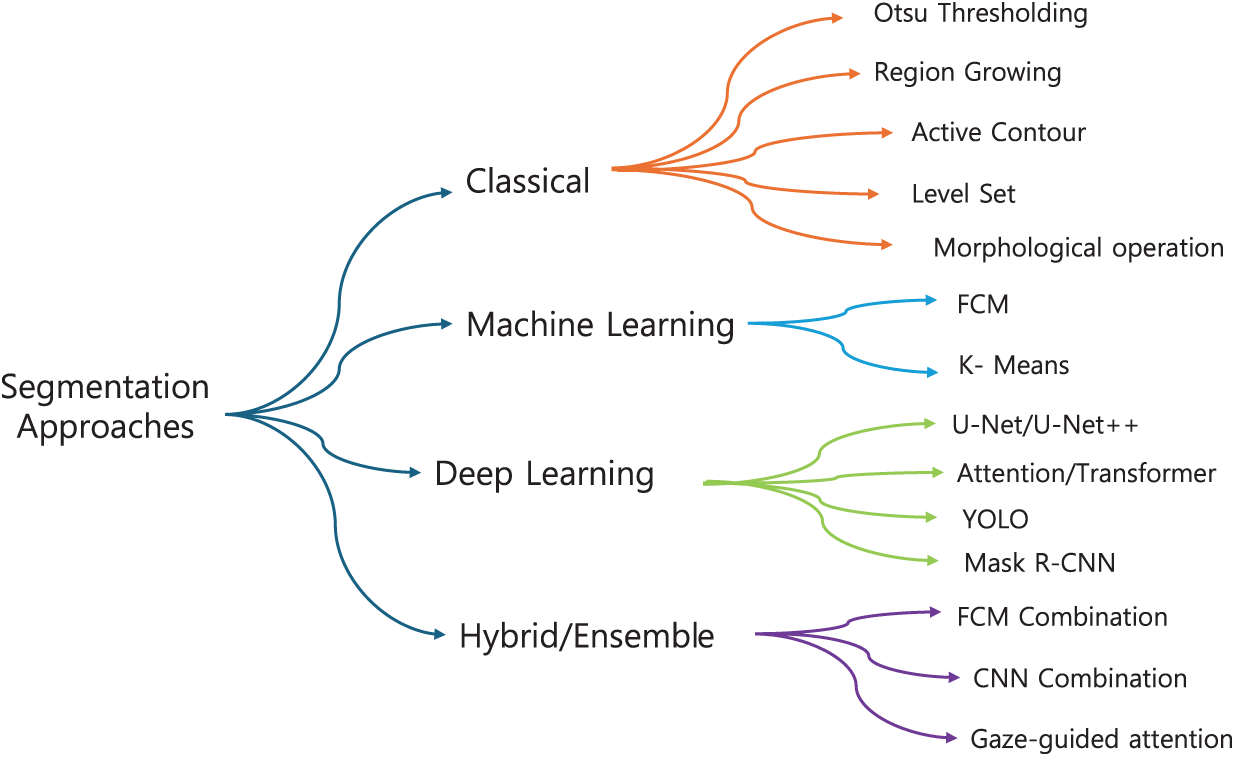

Segmentation is a foundational process in CAD for breast cancer detection, as it isolates regions of interest (ROI) within mammographic images that may indicate abnormal tissue [31]. Effective segmentation is essential for accurately delineating RoI boundaries, enabling further analysis and classification [32]. In this section, we categorize segmentation methods into four main groups: classical, ML-based, DL-based, and hybrid approaches, reflecting both chronological development and increasing algorithmic complexity, and we illustrate this grouping as a hierarchical taxonomy in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Hierarchical taxonomy of mammography segmentation methods. Techniques are grouped into four families: Classical, Shallow ML, Deep Learning, and Hybrid/Ensemble, with representative examples in each branch

3.1.1 Classical Segmentation Approach

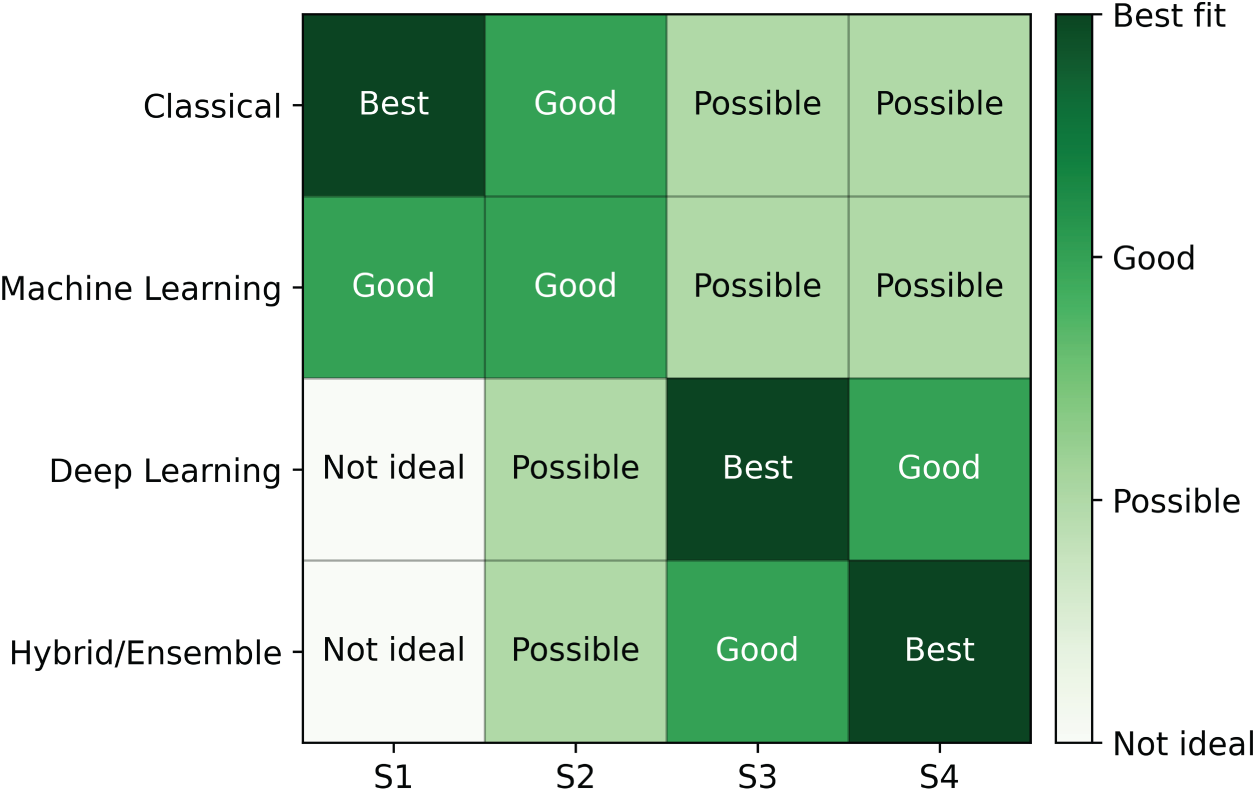

Classical segmentation methods in breast cancer detection usually rely on well-established image processing techniques to extract regions of interest (ROI) from mammograms [33]. These methods typically focus on the separation of suspicious masses or micro-calcifications from normal breast tissue [17]. Several classical approaches, such as threshold-based, region-based, and clustering-based segmentation, can be shown in Table 1.

One of the earliest and most widely used traditional segmentation techniques is Otsu’s method, which determines an optimal threshold by maximizing the variance between the foreground and background intensities. In mammogram segmentation, Otsu serves as the core framework for separating masses from surrounding tissue by identifying intensity cutoffs that best distinguish suspicious regions. Mamindla and Ramadevi [39] extended this principle through a multilevel version of Otsu, where instead of a single binary threshold, multiple thresholds were selected to partition the image into several intensity classes. This refinement allowed the algorithm to capture subtle differences in tissue density, making the segmentation more effective, although image noise still reduced accuracy. Similarly, Santhos et al. [43] reinforced the role of Otsu by combining it with an entropy-based criterion to guide threshold selection in cases of diverse intensity distributions. Here, Otsu’s variance-based separation remained the foundation, while the additional measure helped ensure that thresholds preserved more diagnostic information from the image histogram. Across these studies, Otsu’s method consistently demonstrated its value as a simple, efficient, and interpretable baseline for mammographic image segmentation, even as its direct application was limited by sensitivity to noise and contrast variability.

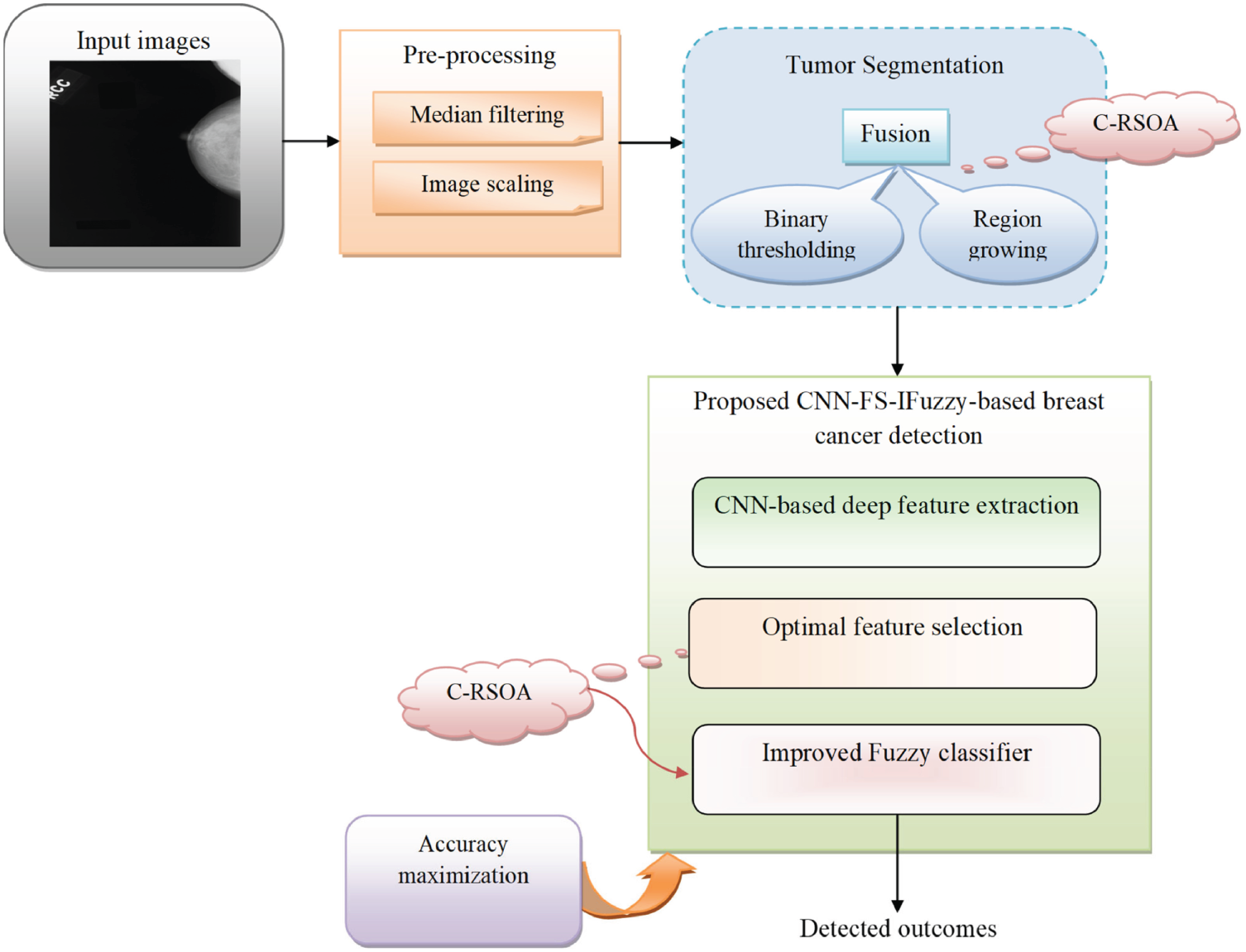

Region and clustering-based techniques have also been widely explored in mammogram segmentation. In 2023, Ref. [35] employed the Ant System-based Contour Clustering (ASCC) algorithm to segment the MIAS mammogram images. This method leveraged the combination of contour-based detection and clustering principles, where marker and walker ants collaboratively identified and refined image contours, enhancing segmentation accuracy by focusing on relevant pixel groups and minimizing processing time. Another recent approach was introduced by [45], who developed an adaptive thresholding with Region Growing Model and applied it to the DDSM dataset (flowchart in Fig. 3). Their workflow began with preprocessing to normalize intensity variations, followed by adaptive thresholding to produce candidate regions. These regions were then refined through an iterative region-growing step, where neighboring pixels were evaluated for similarity to the seed region. This pipeline improved the false discovery rate (FDR) from 24.4% to 19.8%. However, the authors noted that the complexity of mass segmentation remained a challenge, especially in cases involving highly irregular tumor shapes, indicating that while adaptive models enhance accuracy, they do not fully overcome variability in tumor morphology.

Figure 3: Diagram of breast cancer classification using region growing model and binary thresholding (an example of a classical segmentation approach) [45] applied to the DDSM dataset, illustrating preprocessing, candidate region generation, iterative refinement, and post-processing for improved segmentation accuracy (Reprinted with permission from: Umamaheswari et al. (2024) CNN-FS-IFuzzy: A new enhanced learning model enabled by adaptive tumor segmentation for breast cancer diagnosis using 3D mammogram images. Knowledge Based System)

The most recent advancement in traditional segmentation techniques is presented by [36], who developed a method using Gradient-based watershed segmentation applied to a dataset of 760 contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) images. Their pipeline first enhanced the CESM images using preprocessing techniques to improve contrast, after which the gradient magnitude of the image was computed to highlight intensity transitions. Based on these gradients, the watershed algorithm was applied, but with an improved marker-based strategy to avoid over-segmentation. Specifically, morphological operations were used to generate reliable markers, guiding the watershed process to separate tumor boundaries more effectively. Finally, the segmented tumor regions were passed to a DualNet classifier to validate the segmentation and improve diagnostic accuracy. This integrated workflow reduced false positives and preserved boundary precision, resulting in promising performance for breast cancer segmentation (accuracy: 0.938, sensitivity: 0.94, and specificity: 0.96).

The comparative findings in Table 1 and the recent extensions of classical methods [35,36,38,41,43,47] reveal a set of consistent trade-offs. Thresholding-based approaches such as Otsu’s method remain attractive due to their simplicity and low computational burden, but they are inherently sensitive to noise and intensity variations, which limits their generalizability in heterogeneous clinical datasets. Metaheuristic extensions with multilevel thresholding improve stability but introduce additional complexity and parameter tuning, reducing their clinical practicality. Region-based and clustering methods, such as ASCC and adaptive thresholding with region growing, address local intensity variations more effectively, yet they often require carefully chosen seeds and are prone to false positives when tumor boundaries are irregular. Meanwhile, watershed segmentation, especially with marker control, can delineate complex tumor shapes more precisely, but it still depends heavily on preprocessing quality and is vulnerable to over-segmentation. Collectively, these classical methods highlight the trade-off between simplicity and robustness, simpler methods offer transparency and efficiency but struggle with variability, while more adaptive variants achieve higher accuracy at the cost of complexity and reduce ease of integration into clinical workflows. This explains why classical approaches, despite producing competitive performance on controlled datasets, are rarely adopted in practice without hybridization or post-processing support.

3.1.2 Machine Learning (ML)-Based Segmentation Approach

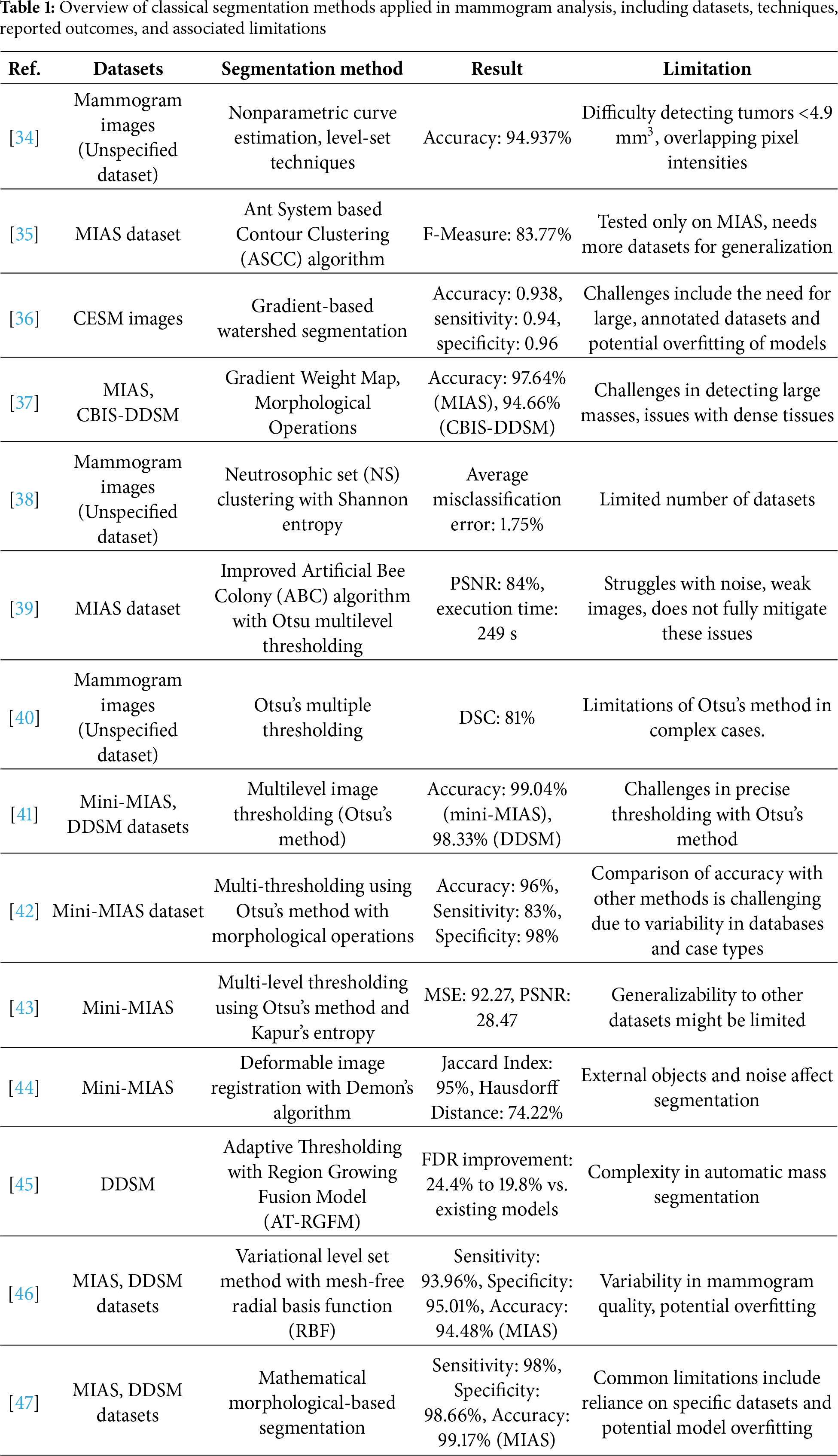

Machine learning (ML)-based segmentation techniques have gained prominence in breast cancer detection due to their ability to learn complex patterns and improve segmentation accuracy [35]; some references and their overviews can be seen in Table 2.

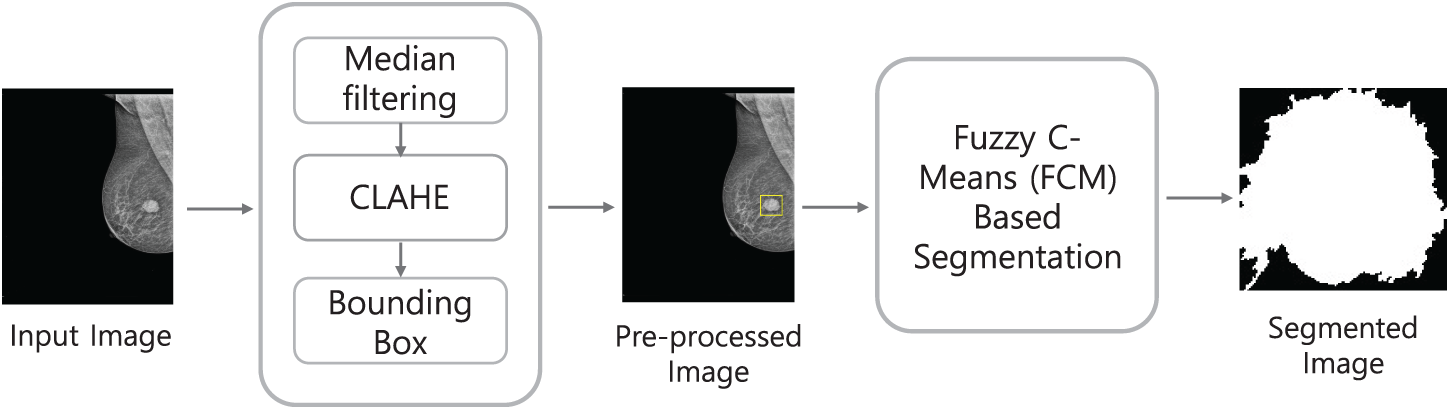

Fuzzy C-means (FCM) has been a widely used method in ML-based segmentation for mammograms; an example of the scheme can be seen in Fig. 4. The process begins with preprocessing steps including median filtering and CLAHE, which reduce noise and enhance local contrast. A bounding box is then applied to isolate the region of interest. The refined image is subsequently segmented using FCM clustering, where pixels are assigned membership values to multiple classes rather than being strictly classified. The final segmented image highlights the suspected tumor region, enabling further diagnostic analysis. Krishnakumar and Kousalya [48] applied FCM to both the DDSM and MIAS datasets. In their model, FCM was advanced with the Distorted Contour (DC) method to improve handling inappropriate borders and intensity variations during segmentation. It starts with FCM clustering to segment mammogram images by assigning membership values to each pixel based on intensity. This is followed by iterative updates of cluster centers until convergence. The addition of the Distorted Contour (DC) method refines the segmentation by correcting irregular borders and compensating for intensity variations, resulting in a more accurate and reliable delineation of tumor boundaries. To improve segmentation efficiency, Ref. [50] proposed a Modified Adaptively Regularized Kernel-based Fuzzy C-Means method tested on the INBreast database. This approach first maps pixel intensities into a higher-dimensional kernel space, enabling better separation of complex tumor boundaries. Adaptive regularization is then applied to stabilize the clustering and reduce sensitivity to noise. In the second stage, statistical texture features are extracted from the segmented regions and classified with a Support Vector Machine (SVM), which further enhances diagnostic reliability. While the method achieved a high ROC AUC of 0.961, its reliance on kernel transformations and additional classification steps increased computational cost, sometimes producing block-like segmentations that required post-processing refinement.

Figure 4: Example of a machine learning-based segmentation workflow using Fuzzy C-Means (FCM), illustrating preprocessing, region-of-interest isolation, and clustering-based segmentation for tumor detection

In the other hand, Ref. [14] applied a modified K-means clustering algorithm to the MIAS and CBIS-DDSM datasets. In this study, K-means worked by partitioning the image pixels into clusters based on similarities in intensity, texture, and shape. This iterative process involved recalculating cluster centers and reassigning pixel memberships to enhance segmentation accuracy. Their method achieved more than 90% of accuracy and sensitivity for each dataset. Despite these successes, the variability in performance across different lesion types raised concerns about the method’s robustness and reliability when dealing with a variety of tumor shapes and sizes. In another study, Rezaee et al. [57] implemented a K-means clustering algorithm as a primary step in segmenting mammogram images before classification. After removing redundant parts and isolating the pectoral region, the remaining breast area was clustered into regions using K-means based on pixel intensity and spatial properties. The authors experimented with cluster counts ranging from 3 to 6, identifying that 4–5 clusters yielded optimal segmentation for delineating mass regions. The K-means algorithm minimized intra-cluster distance using Euclidean distance, iteratively updating cluster centers to better separate regions of interest from surrounding tissues. This segmentation step helped isolate suspected masses, which were then processed further using texture descriptors (e.g., GLCM), Pseudo-Zernike moments, and wavelet features for classification. While effective, the method showed varying accuracy depending on mass type and shape.

Overall, ML-based methods such as FCM and K-means have advanced segmentation by improving flexibility in handling noisy or ambiguous regions and by offering computational simplicity, respectively. FCM provides adaptability through partial membership assignments, which helps preserve boundary details in complex tissues, but its high computational burden, depends on parameter tuning [49], and sensitive to initialization limit scalability for large or heterogeneous datasets [53]. K-means, in contrast, remains efficient and easy to implement, yet its reliance on a predefined number of clusters and limited ability to manage irregular tumor morphologies reduce its robustness across varied lesion types [14]. The trade-off between flexibility and efficiency is therefore evident, which is FCM achieves finer boundary delineation at the cost of computational expense, while K-means offers speed and simplicity but sacrifices accuracy in complex cases.

3.1.3 Deep Learning (DL)-Based Segmentation Approach

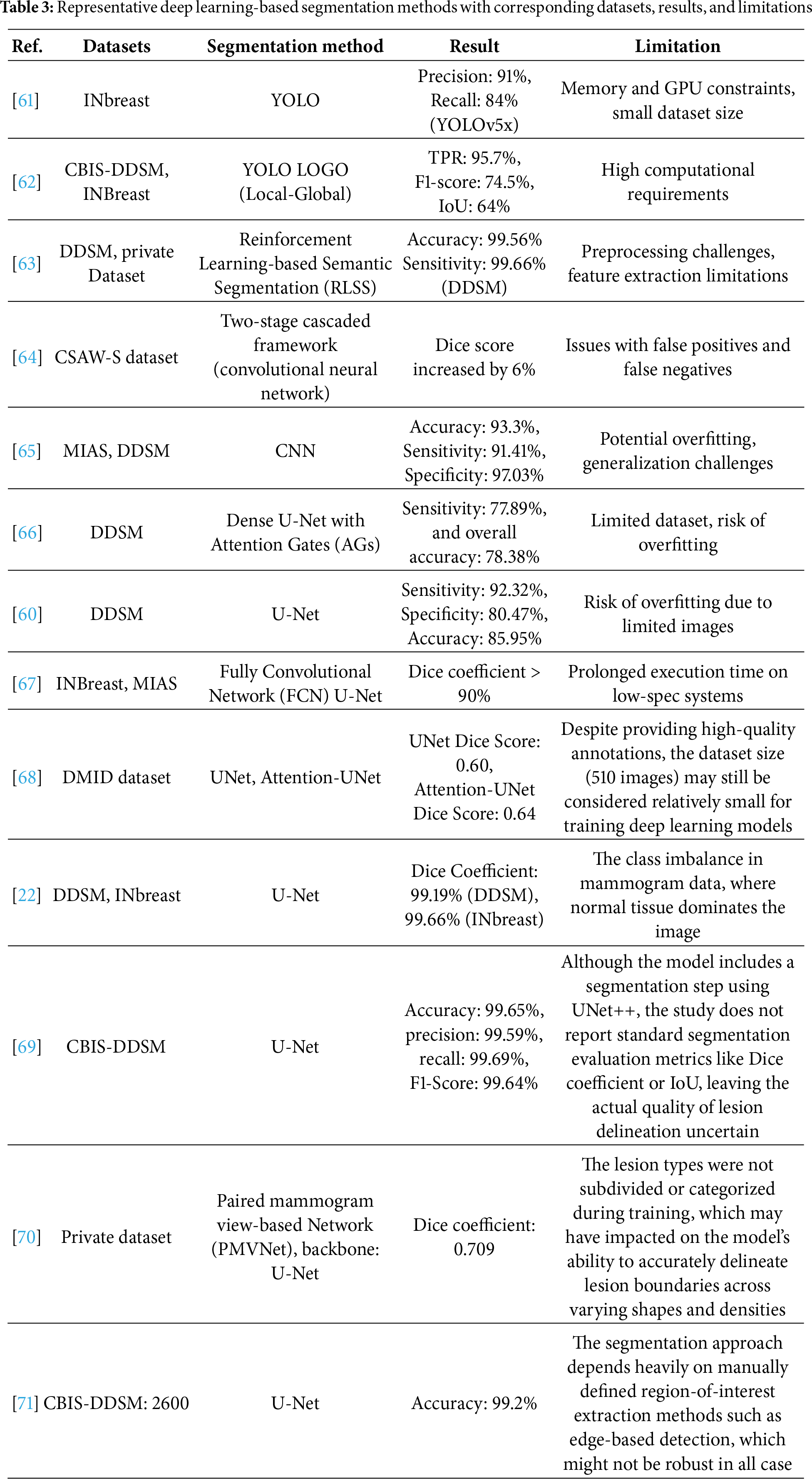

Deep Learning (DL) has revolutionized segmentation tasks in breast cancer detection by leveraging neural networks to automatically learn hierarchical representations from mammogram images [59]. DL-based segmentation methods, like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with variations of U-Net architectures, are widely utilized due to their ability to effectively capture spatial and contextual information, making them well-suited for various segmentation tasks [60], other methods and their performance are presented in Table 3.

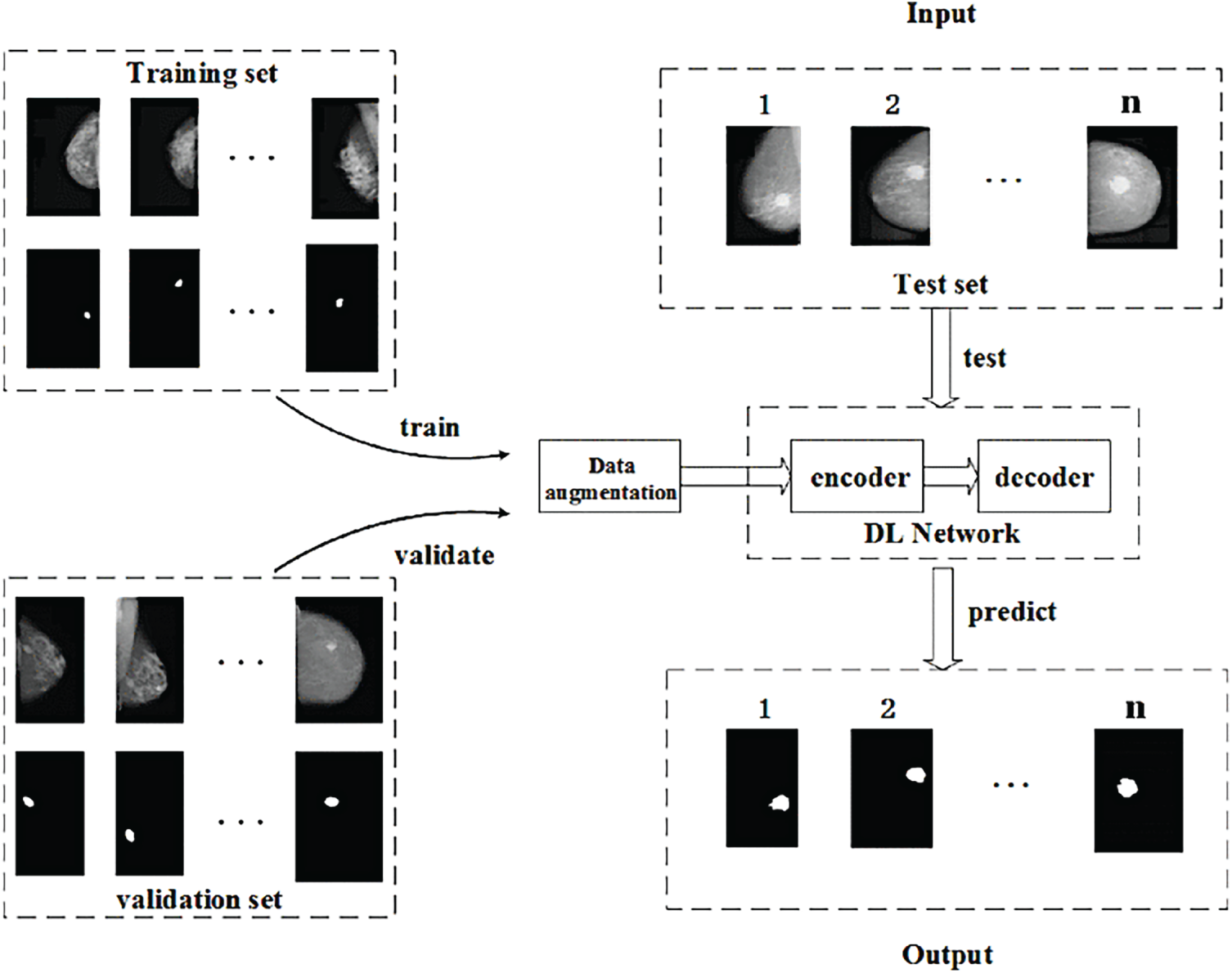

Li et al. [66] developed an attention-dense U-Net for automatic breast mass segmentation using images from the DDSM dataset. The model integrates dense connections within the encoder–decoder framework to enhance feature propagation and capture fine-grained details, while attention gates filter irrelevant information from skip connections, allowing the network to focus on tumor regions more effectively. This combination improves boundary precision and robustness against noise compared to the original U-Net. Fig. 5 illustrates the workflow, where data are augmented and passed through the encoder–decoder network to predict segmentation masks. While the Attention Dense U-Net achieved superior performance over baseline U-Net and state-of-the-art models, the authors acknowledged a risk of overfitting due to the limited dataset size, which could restrict its ability to generalize to broader clinical applications. Moreover, Zeiser et al. [60] applied U-Net for mass segmentation using 2500 cases which the model was enhanced by applying data augmentation techniques, including horizontal mirroring and zooming, to address the limited size of the DDSM dataset and reduce overfitting. The model’s architecture featured down-sampling through convolutional layers with ReLU activation and max pooling to extract features, followed by up-sampling using deconvolution layers to reconstruct the segmented image. The final layer used a 1 × 1 convolution to map outputs to the desired classes, enabling precise mass delineation.

Figure 5: Example of DL-based approach using the attention dense U-Net [66], showing the encoder–decoder structure with attention gates and dense connections for improved breast mass segmentation [Reprinted from: Li, et al. (2019) Attention Dense-U-Net for Automatic Breast Mass Segmentation in Digital Mammogram. IEEE Access 7:59037–59047, doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3036610. Licensed under CC BY 4.0]

Another DL-based method is YOLO, which is commonly used for object detection and has recently been adapted for breast cancer segmentation. Su et al. [62] introduced the YOLO-LOGO segmentation model, which combines the fast ROI detection of YOLO with a Local-Global (LOGO) transformer for precise mass delineation. YOLO first localizes suspicious regions, and the LOGO module then applies dual attention mechanisms: local attention to capture fine tumor boundaries and global attention to preserve contextual breast tissue information. Tested on the CBIS-DDSM and INbreast datasets, the model achieved a high True Positive Rate (95.7%), demonstrating its robustness in complex mammogram backgrounds. However, dual-stage architecture substantially increased computational requirements, limiting scalability for deployment in resource-constrained clinical environments. Similarly, Coskun et al. [61] applied the YOLOv5 model for mass detection using the INbreast dataset. To enhance performance, they integrated a Swin Transformer into the YOLOv5 framework, where YOLOv5 performed fast bounding-box detection of candidate masses while the Swin Transformer enriched feature representations through its window-based self-attention mechanism. This model improved segmentation performance compared to earlier YOLO versions by capturing both local and global contextual information, particularly for irregularly shaped or small tumors. Nevertheless, the added complexity significantly increased GPU memory demands and computational cost, posing challenges for scaling larger datasets.

We can conclude that DL-based segmentation methods have substantially advanced breast cancer analysis by combining hierarchical feature extraction with attention mechanisms. U-Net variants, such as the Attention Dense U-Net [66], and data-augmented U-Net [60], demonstrate strong capabilities in capturing fine structural details and improving boundary definition, yet they remain highly dependent on dataset size and risk overfitting, and may also suffer from prolonged execution times on low-spec systems, which poses practical limitations for clinical deployment. The trade-off here lies between architectural complexity and practical usability: dense connections and attention modules increase accuracy and robustness, but they also heighten computational cost and require large, diverse datasets to generalize effectively. On the other hand, YOLO-based approaches [62], Coskun et al. [61] provide real-time detection, can achieve high sensitivity even in challenging cases with irregular or small tumors. However, these models demand considerable GPU memory and computational resources, making large-scale clinical deployment difficult. Thus, while deep learning approaches currently represent the state of the art in mammogram segmentation, their clinical translation will depend on striking a balance between accuracy, computational efficiency, and robustness across heterogeneous datasets because of overfitting [18,72].

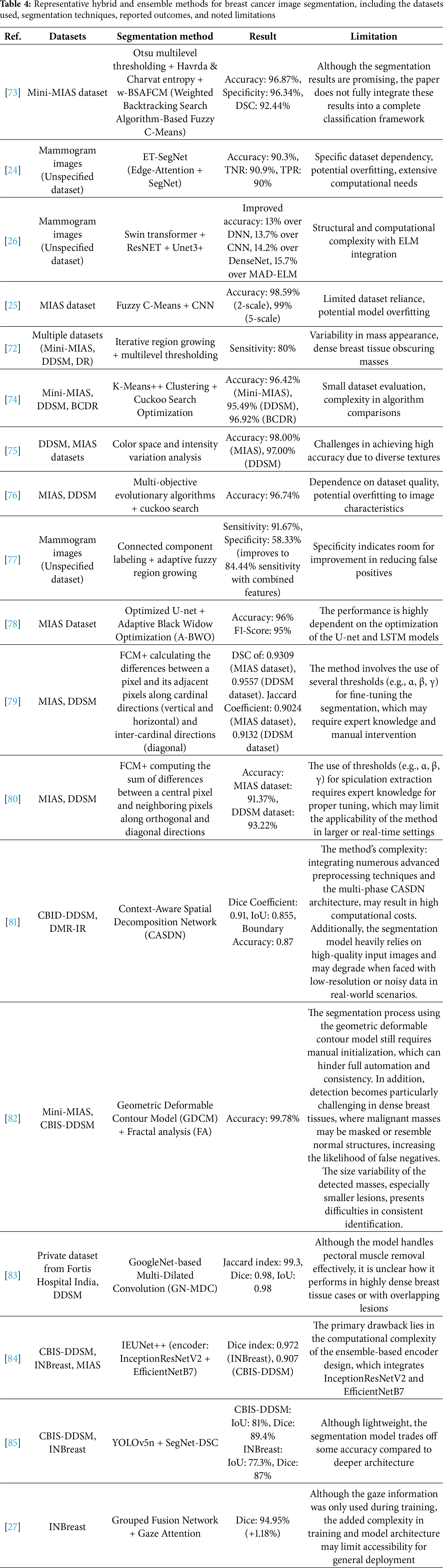

3.1.4 Hybrid/Ensemble Approach

Hybrid/ensemble segmentation methods have emerged as a powerful approach to breast cancer detection, combining the strengths of multiple segmentation techniques to overcome the limitations of individual methods. These hybrid/ensemble models often integrate traditional methods with machine learning (ML) or deep learning (DL) techniques, resulting in enhanced segmentation accuracy and robustness in detecting breast masses and abnormalities, the preview of methods can be seen in Table 4.

Ghuge and Saravanan [26] introduced the SRMADNet, a hybrid method combining the strengths of Swin ResUnet3+ for segmentation and Adaptive Multi-scale Attention-based DenseNet with Extreme Learning Machine (AMAD-ELM) for classification. This hybrid model combines the Swin Transformer with the Unet3+ framework, leveraging the transformer’s capacity for global contextual awareness and Unet3+’s detailed feature mapping through skip connections and multi-scale feature integration. The Swin Transformer acts as an encoder, capturing complex image representations, while Unet3+ refines these features through its advanced decoder structure, ensuring high-resolution segmentation. This combination enhances boundary delineation and segmentation precision, which is crucial for effectively identifying abnormal regions in mammograms. The model was tested on a public dataset and demonstrated a performance improvement of 13.7% over CNN and 14.2% over DenseNet. Furthermore, Jha et al. [25] proposed an ensemble learning-based hybrid segmentation approach utilizing a combination of Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The FCM is used for initial segmentation, which clusters the image data into regions of interest based on pixel intensities, effectively handling the variability in image intensity. The CNN model then refines the segmentation by learning from these clustered outputs, enhancing the accuracy and precision of the segmented regions. This combined method allows for improved delineation of tumor boundaries and better performance in handling complex mammographic features. The model achieved an accuracy of 98.59% (2-scale segmentation), which further improved to 99% (5-scale segmentation).

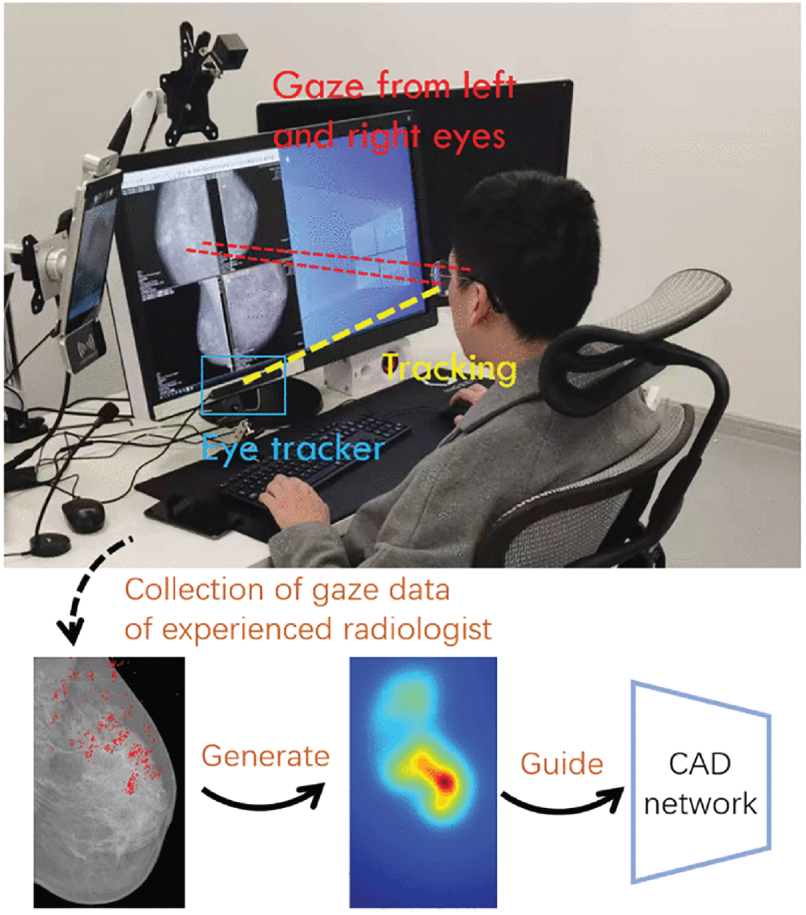

One of the most recent innovations in hybrid segmentation incorporates gaze tracking data to enhance model supervision and mimic radiologist attention. Xie et al. [27] proposed a Grouped Fusion Network that integrates eye-tracking information with deep learning-based segmentation to improve performance, particularly in detecting challenging regions such as small masses and microcalcifications. The architecture consists of two segmentation streams using Attention U-Net variants, each processing different spatial scales of the mammogram. A gaze attention map, derived from radiologist eye-tracking data collected during screening, is used to guide the secondary segmentation stream toward previously under-attended regions. This multi-stream fusion mechanism ensures more comprehensive detection by simulating expert diagnostic behavior, the method development can be seen in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Eye Tracking for Breast Cancer Segmentation (an example of hybrid/ensemble segmentation approach) [27], which integrates radiologist eye-tracking maps with dual Attention U-Net streams at different spatial scales to improve sensitivity in detecting subtle lesions and microcalcifications (Reprinted with permission from: Xie et al. (2025) Integrating Eye Tracking with Grouped Fusion Networks for Semantic Segmentation on Mammogram Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging)

Overall, hybrid segmentation methods represent an important bridge between traditional, machine learning, and deep learning approaches by integrating complementary strengths within a single pipeline. Architectures such as ET-SegNet [24] and SRMADNet [26] highlight how edge-aware modules and transformer-based encoders can enhance boundary precision and contextual understanding, delivering more accurate delineation of tumors compared to single-paradigm models, though they do so at the cost of increased architectural complexity and higher training demands. Ensemble approaches, like the combination of FCM and CNN [25], demonstrate the effectiveness of cascading classical clustering with deep refinement, producing very high accuracy and robustness across heterogeneous data, even if they remain sensitive to intensity variability and require careful parameter tuning. Optimization-based hybrids such as K-Means++ with Cuckoo Search [76] further emphasize stability and adaptability, successfully addressing intensity inhomogeneity and complex tissue structures, yet their reliance on iterative metaheuristics raises concerns about scalability when applied to large clinical datasets. Meanwhile, novel paradigms such as gaze-driven fusion networks [27] provide a unique advantage by explicitly transferring radiologists’ visual attention into the model, improving sensitivity to subtle lesions such as micro-calcifications and reducing false negatives in challenging cases. This strategy shows strong potential for bridging human diagnostic expertise with automated systems. However, the need for eye-tracking data during training requires specialized equipment and expert involvement, which may limit reproducibility, while the multi-stream architecture increases computational overhead. Taking together, these methods illustrate a clear trade-off: hybrids achieve superior segmentation and improved clinical relevance by combining multiple paradigms, but their added complexity, higher computational cost, and reliance on enriched training data still present hurdles for routine deployment.

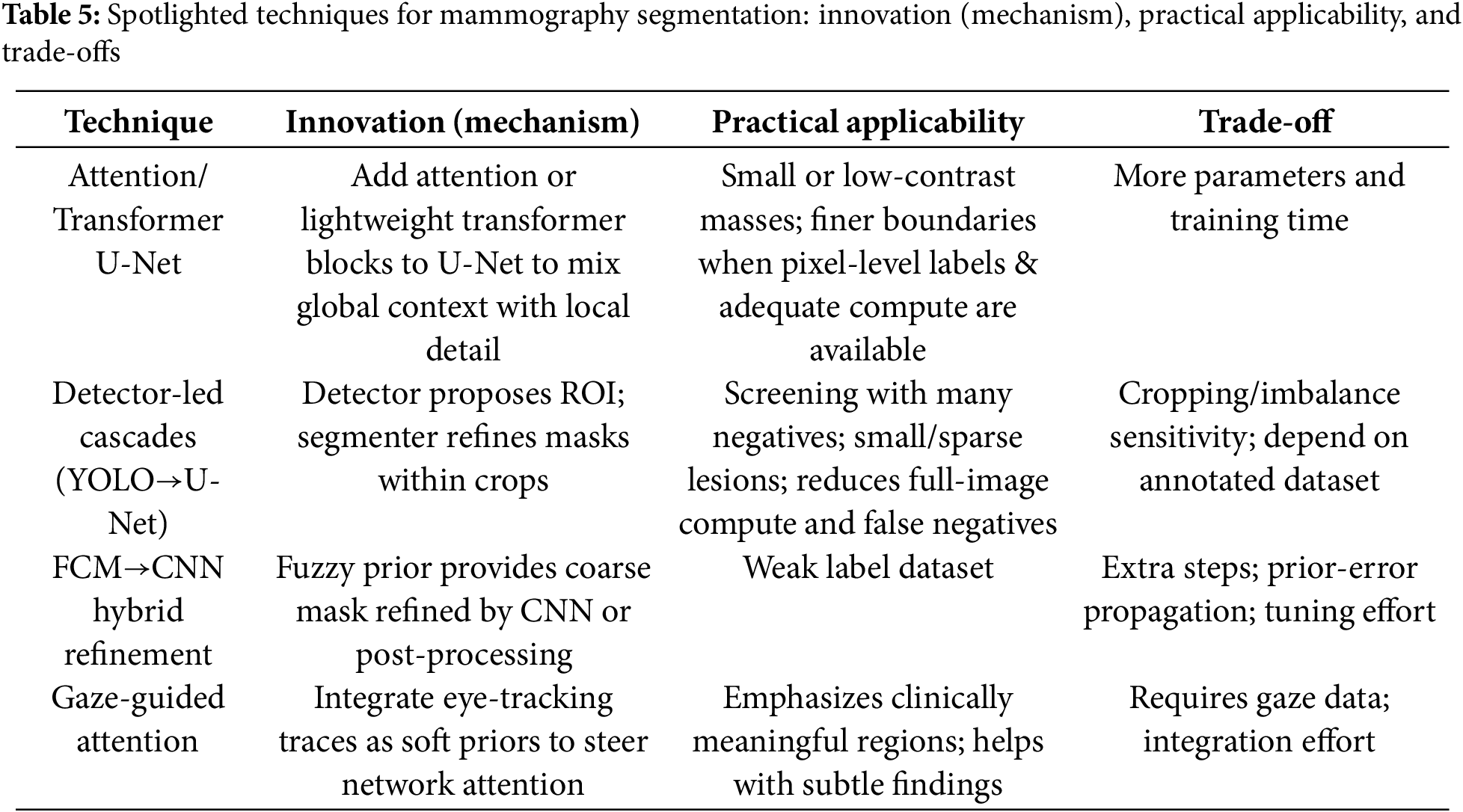

3.1.5 Focused Highlights: Cutting-Edges Techniques within Segmentation Approaches

In this subsection, we highlight several cutting-edge techniques drawn from the four segmentation approaches: Attention/Transformer U-Net, detector-led cascades (YOLO→U-Net), FCM→CNN hybrid refinement, and gaze-guided attention. These techniques were selected for their complementary innovations and clinical relevance under typical data and compute constraints.

1. Attention/Transformer U-Net

U-Net variants enhanced with channel/spatial attention or lightweight transformer blocks strengthen the flow between global context and fine local detail. In mammography, this often tightens boundaries around small or low-contrast masses when pixel-level annotations and sufficient compute are available. For example, Attention U-Net [26,66] has been reported to improve delineation, at the cost of additional parameters and training time.

2. Detector-led segmentation (e.g., YOLO-based pipelines)

In detector-led segmentation, a detector first proposes suspicious regions on the full mammogram, and then a dedicated segmenter (or a detection-to-mask head) refines the lesion outline within each crop. This two-stage pattern reduces full-image compute and can lower false negatives for sparse or small lesions, which is attractive in screening settings with many negatives [61,62]. But their performance depends on annotated datasets and high computational resources.

3. FCM-based hybrid refinement (e.g., FCM + Otsu; FCM + CNN)

A fuzzy clustering step supplies a coarse mask or saliency prior that is then refined, either by classical post-processing or by a CNN. The appeal is combining FCM’s robustness on ambiguous tissue with learned features for sharper edges. For instance, hybrids such as Otsu/entropy with FCM [73], and FCM + CNN ensembles [25] are especially useful on weak label dataset, but they add steps and hyper-parameters to tune.

4. Gaze -guided attention

Radiologists’ eye-tracking traces can be injected as soft priors to steer network attention toward clinically meaningful regions, improving sensitivity to subtle findings without heavy pixel-wise supervision. As noted in our corpus (e.g., gaze-driven fusion [27]), gains depend on the availability and integration quality of gaze data; when present, this cue can complement both DL and hybrid pipelines.

A concise summary of the Section 3.1.5 spotlights is provided in Table 5. For each technique we list the core innovation, practical applicability, and key trade-offs.

3.2 RQ2: What Are the Current Trends and Performance Outcomes of Segmentation Approaches Used in Breast Cancer Detection?

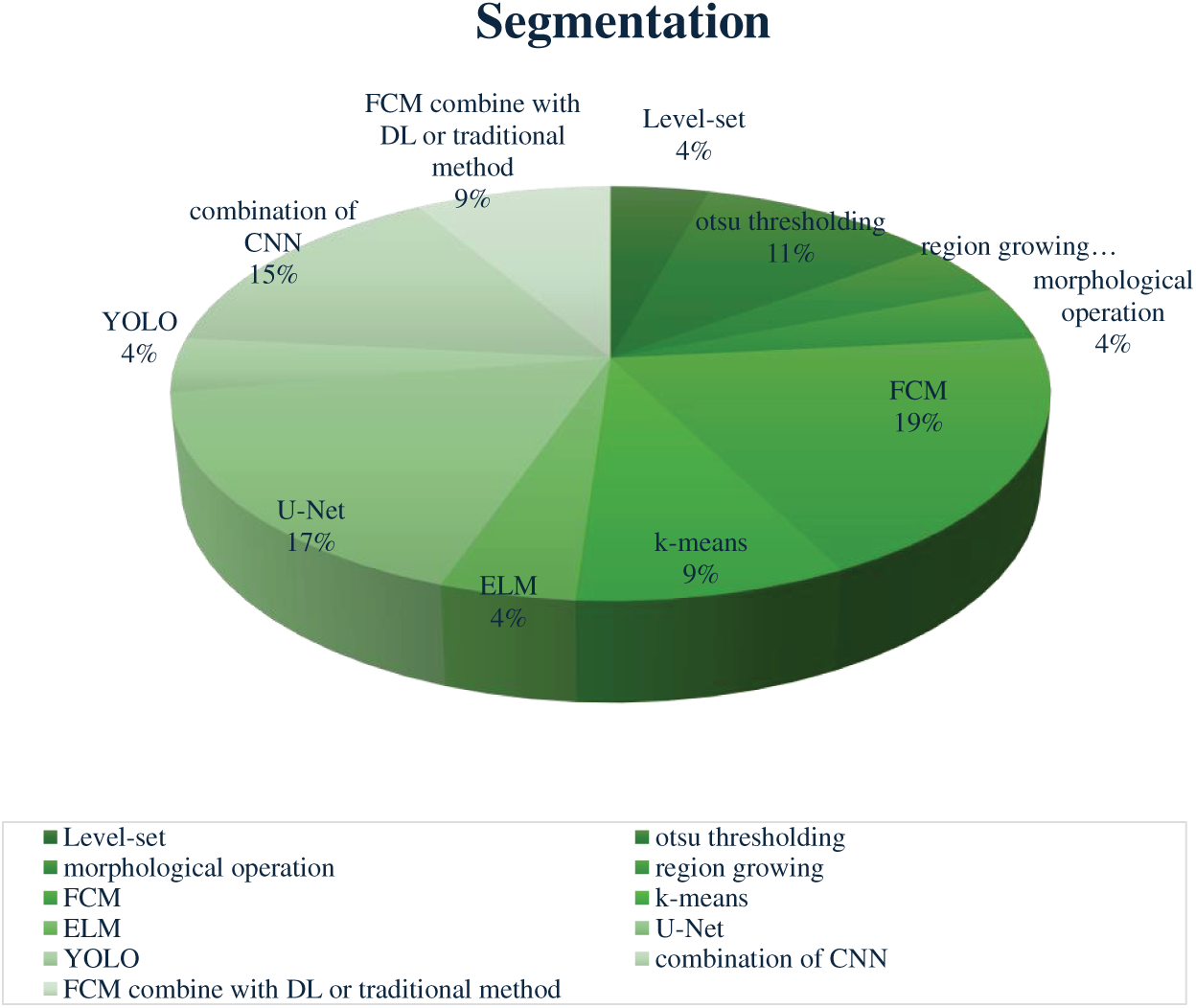

The following chart in Fig. 7 illustrates the distribution of segmentation methods based on references in this article, specifically including only those techniques that are employed by at least two studies. This approach highlights the most recurrent methods, providing insight into the preferred segmentation techniques in breast cancer detection.

Figure 7: Distribution of segmentation methods reported in the reviewed studies. Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) and U-Net variants were the most frequently adopted approaches, followed by combinations of CNN models, Otsu thresholding, and k-means. Less commonly used techniques included YOLO, ELM, level-set methods, and morphological operations

In breast cancer detection, an ML-based approach, Fuzzy C-Means (FCM), is the most widely used segmentation method. FCM’s popularity stems from its ability to manage ambiguous boundaries by assigning each pixel to a degree of membership across clusters rather than a strict binary assignment [86]. This benefit is ideal for mammographic images, where tumor borders are often unclear, allowing FCM to capture nuanced segmentation in complex textures [87]. Krishnakumar and Kousalya [48] applied FCM, achieving high accuracy rates (97.9% on DDSM and 98.76% on MIAS). Similarly, Parvathavarthini et al. [51] used FCM on the Mini MIAS dataset, achieving strong Jaccard and Dice indices (96% and above 98%). Although effective in controlled settings, FCM’s performance can drop due to variations like noise and parameter tuning, showing its sensitivity to specific imaging conditions [59,88]. Followed by the Deep learning U-Net model is favored for its encoder-decoder structure that captures detailed image features. U-Net’s architecture incorporates skip connections, retaining high-resolution spatial information that’s crucial for accurate tumor segmentation [20]. Soulami et al. [22] used U-Net on the DDSM and INbreast datasets, achieving Dice coefficient above 99%. Despite its precision, the study noted class imbalance dataset, where predominant healthy tissue could potentially overshadow smaller malignant areas. Then, Otsu thresholding, this traditional-based method segments images by finding an optimal threshold to separate foreground and background, minimizing intra-class variance [19]. Otsu’s method is beneficial in cases with strong contrast between tumor and healthy tissue, but it can be less effective when dealing with noise or weakly contrasted areas [47].

Another ML-based method (K-means clustering), appearing in 9% of studies, is a segmentation method chosen for its simplicity and computational efficiency. It assigns pixels to a single cluster based on proximity to the nearest centroid, making it suitable for images with clear tumor contrasts [89]. Almalki et al. [58] used K-means on datasets from Qassim Hospital and MIAS, achieving accuracy rates of around 92% and 97%, respectively. Similarly, a hybrid/ensemble approach, such as FCM with other algorithms, enhances its adaptability to different segmentation challenges. For example, Toz and Erdogmus [73] combined Otsu’s thresholding and entropy-based methods with FCM on the Mini MIAS dataset. This approach leverages FCM’s fuzzy clustering with additional algorithmic features to capture detailed tumor structures while minimizing false positives, though further integration into a complete classification framework was suggested for comprehensive diagnostic support [90]. Methods like Level Set, Morphological Operations, Region Growing, YOLO, and ELM each account for 4% of segmentation approaches. These techniques are often applied in specific scenarios where their unique attributes enhance segmentation results. Level Set and Morphological Operations are beneficial for refining boundaries [91], while YOLO has been adapted for rapid segmentation in mammography [92].

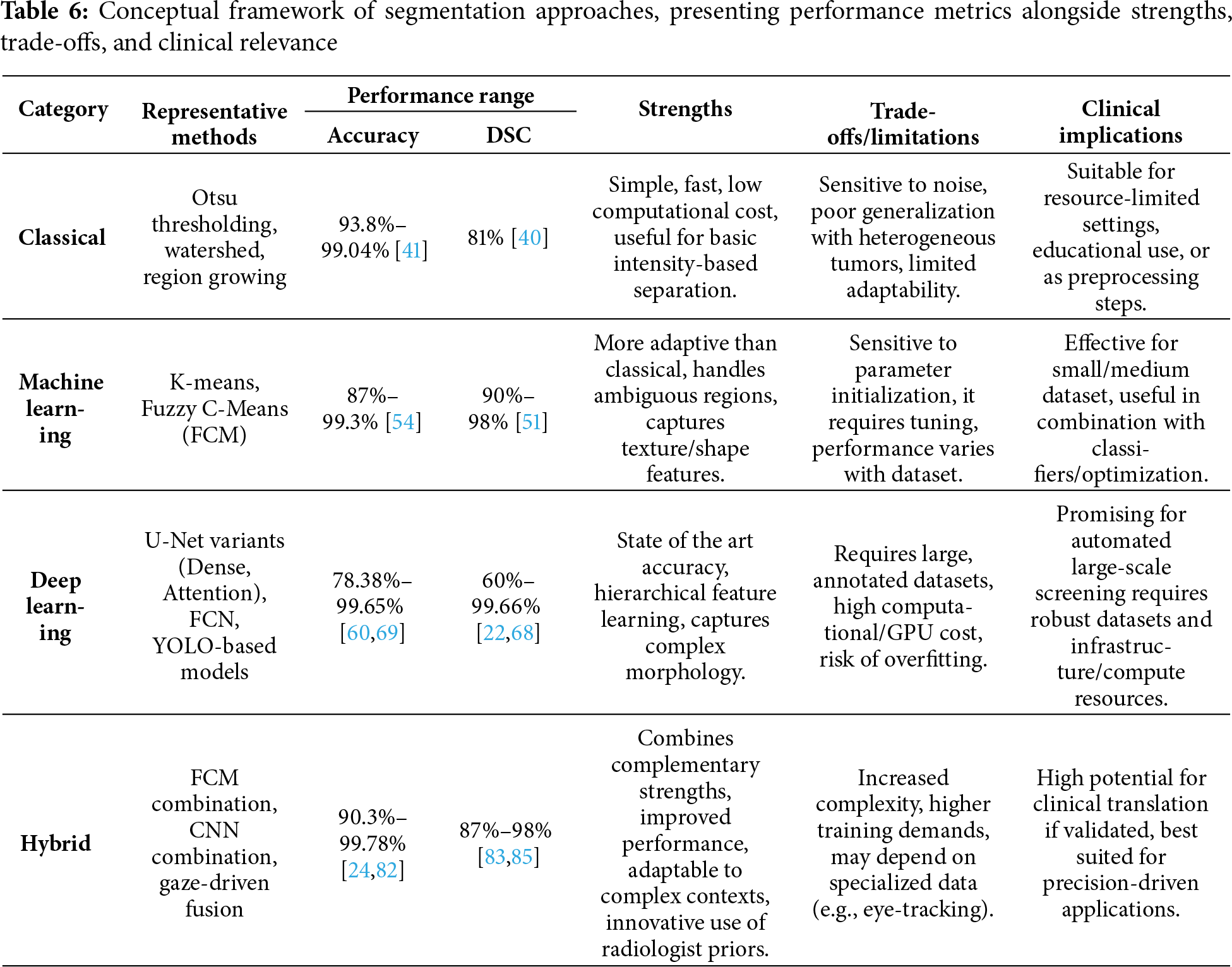

Moreover, Table 6 translates these findings into a conceptual framework that captures the performance range for every representative method, qualitative strengths, trade-offs, and clinical implications of each methodological family. Classical methods, though limited in adaptability, remain valuable in low-resource or educational contexts due to their speed and simplicity. Machine learning approaches, represented by FCM and K-means, extend adaptability to ambiguous regions but require careful parameter tuning and are best applied to small-or medium-scale datasets, or as complementary modules within larger pipelines. For example, a study by Chinnasamy and Shashikumar [52] achieved over 99% accuracy by combining FCM with Grey Code Approximation Preprocessing (GACP) and optimizing with Opposition-based Cat Swarm Optimization (OCSO). In contrast, Rathinam et al. [54] who also used FCM embedded in an intuitionistic fuzzy soft set without any preprocessing or optimization, reported a much lower accuracy of around 87%. This contrast emphasizes how tuning and adaptive strategies significantly influence the performance of the same core algorithm. Deep learning models, such as U-Net variants and YOLO, deliver state-of-the-art accuracy and excel in capturing complex morphologies, but their dependency on large, annotated datasets and high computational resources restricts deployment in under-resourced settings. For instance, Soulami et al. [22] used a standard U-Net trained on full images with preprocessing model and achieved Dice scores exceeding 99% on DDSM and INbreast. On the other hand, Oza et al. [68] modified U-Net into an Attention U-Net and trained it on a more complex, patch-based dataset (DMID). Despite extensive preprocessing, their model achieved a lower Dice of 0.64, largely due to limited input and the absence of optimization techniques. Lastly, Hybrid methods emerge as the most flexible paradigm, combining complementary strengths across categories: ranging from FCM + CNN ensembles to gaze-driven fusion [27], making them highly promising for precision-driven and clinically oriented applications, albeit at the cost of increased complexity and data dependence.

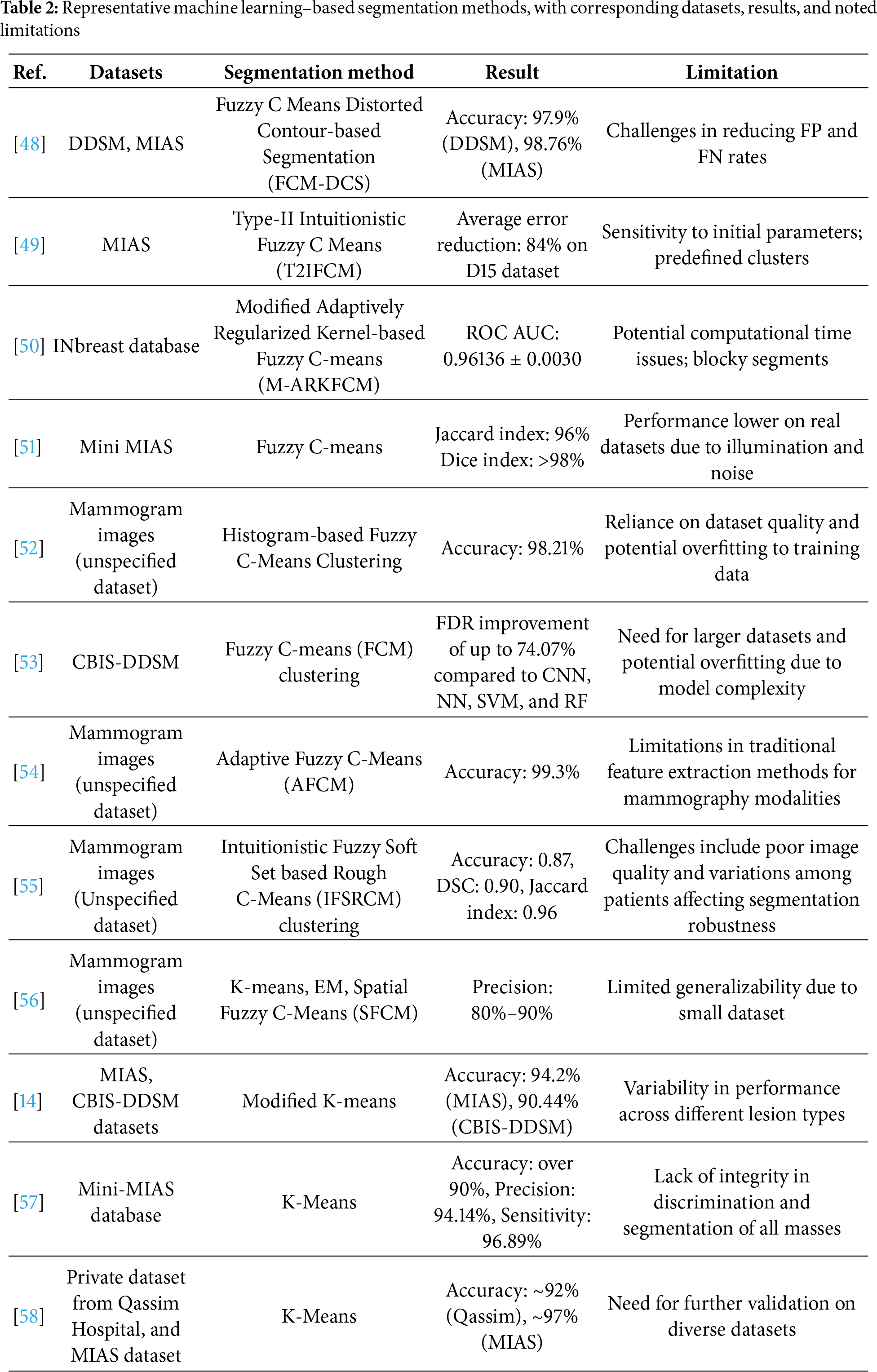

To operationalize the synthesis in Table 6, Fig. 8 maps the four method families to common data/compute scenarios (S1–S4): S1 = small data with weak labels and low compute; S2 = medium data with some labels and moderate compute; S3 = large data with pixel-level labels and high compute; S4 = precision-driven clinical cases requiring fine-grained boundaries.

Figure 8: Method–data–compute decision matrix for mammography segmentation. Rows are method families (Classical, ML, DL, Hybrid/Ensemble); columns denote scenarios S1–S4: S1 small data + weak labels + low compute; S2 medium data + some labels + moderate compute; S3 large data + pixel-level labels + high compute; S4 precision-driven clinical cases. Cell labels indicate Not ideal/Possible/Good/Best fit

As indicated by Fig. 8, classical and Machine Learning methods score well in S1–S2 because they are efficient and robust under limited resources, although their performance degrades on complex textures. Deep learning becomes the best choice in S3, where large, pixel-level annotations and sufficient compute enable state-of-the-art accuracy. Hybrid/ensemble pipelines are most suitable in S4, where combining detectors and segmenters, like fusing FCM with CNNs helps achieve finer boundary delineation at the cost of greater complexity. Practically, classical and ML are preferable for low-resource preprocessing or small cohorts, DL is appropriate for automated screening when annotated data and compute are available, and hybrid designs are recommended when clinical precision is the priority.

Taking together, this structured comparison allows readers to align methodological choices with practical scenarios: for example, prioritizing classical or ML methods in constrained environments, adopting DL for high-performance automated pipelines, and turning to hybrid solutions when the clinical objective requires both robustness and fine-grained accuracy.

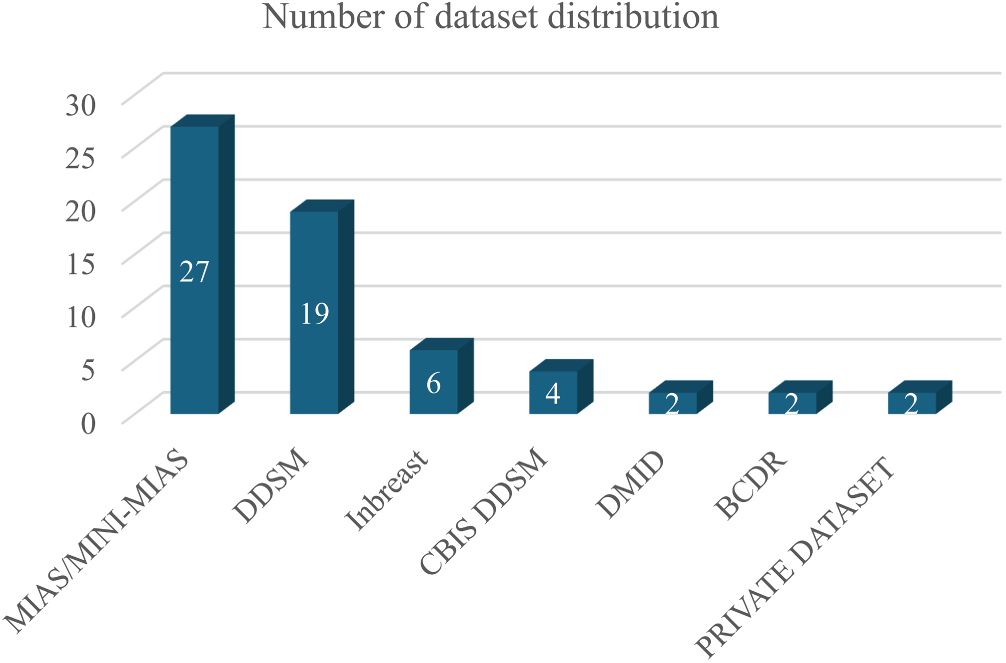

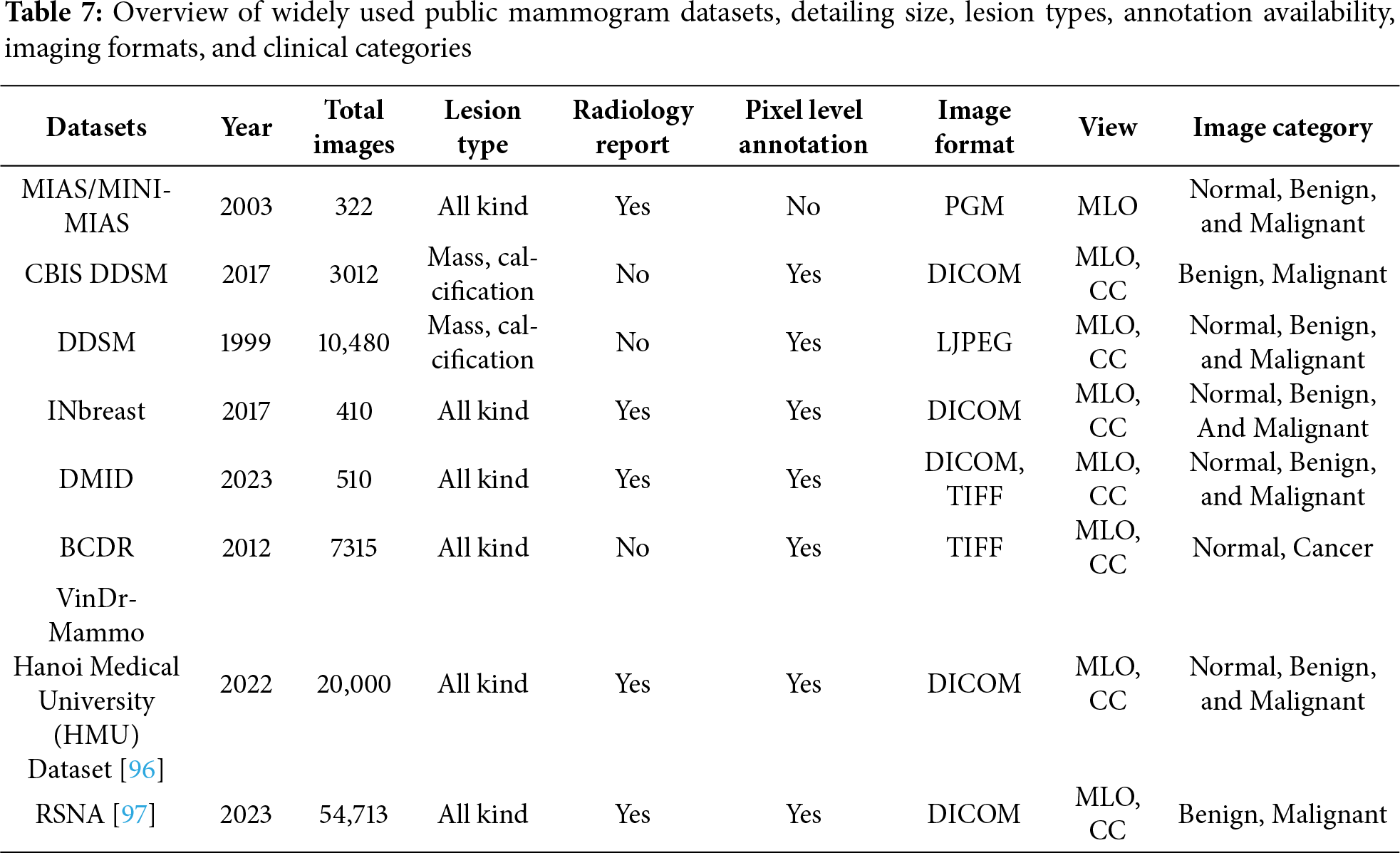

3.3 RQ3: What Datasets Are Most Frequently Utilized in Breast Cancer Segmentation Research?

In this breast cancer detection research, several key datasets are pivotal for training and validating segmentation models. The MIAS/MINI-MIAS dataset [28], established in 2003 with 322 mammogram images, is the most frequently used dataset, appearing in 27 studies. Despite its relatively small size, its historical significance and detailed radiologist reports have made it foundational for traditional and early machine learning models. The DDSM dataset [93], with 10,480 images, is also highly regarded, used in 19 studies, and provides pixel-level annotations for masses and calcifications, making it valuable for deep learning models that require precise training data.

The CBIS-DDSM dataset [94], a more recent addition from 2017 with 3012 images, is used in four studies and stands out due to its pixel-level annotations, supporting advanced segmentation algorithms. The INbreast dataset, with 410 high-resolution DICOM images, appears in six studies and is noted for its detailed pixel-level annotation, enhancing its utility in deep learning applications that demand precise image details.

Other datasets like DMID and BCDR [95], used in each of two studies, provide a range of mammogram views and annotations that cater to both traditional and modern segmentation methods. The DMID dataset, created in 2023 with 510 images, includes comprehensive radiologist reports and supports both MLO and CC views. Similarly, BCDR, with 7315 images, supports a variety of lesion types and mammogram views, contributing to its role in segmentation research. Two studies utilize private datasets, offering customized images that meet specific research needs. However, their limited access can hinder reproducibility and broad applicability. The list of distribution datasets can be found on Fig. 9. In addition, Table 7 shows the common public mammogram datasets widely used for mammogram CAD research.

Figure 9: Distribution of mammogram datasets used in the reviewed studies. MIAS/MINI-MIAS and DDSM were the most frequently employed datasets, while INbreast, CBIS-DDSM, BCDR, DMD, and private datasets appeared less frequently

4 Segmentation Challenges and Future Directions

Breast cancer detection through mammogram analysis has seen rapid advancements with the adoption of machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and hybrid/ensemble methods. However, despite the impressive progress, several opportunities for improvement and challenges remain in the practical deployment of these models.

Segmentation, which involves identifying the regions of interest (ROI) in mammogram images, is a critical step in breast cancer detection. Despite the advancements in segmentation techniques, several persistent challenges remain:

(a) The Complexity of Breast Tissue: Many segmentation methods struggle with the inherent complexity of breast tissue, particularly in dense mammograms [98–100]. Traditional methods, such as Otsu’s thresholding or region-growing, often fail to effectively segment tumours from dense tissues or overlapping structures [39,43]. Machine learning-based techniques like Fuzzy C-Means (FCM), though more adaptive, also face issues with irregularly shaped masses and poorly defined boundaries [48]. Even advanced DL methods like U-Net have difficulty segmenting small or faint lesions in dense tissue, leading to lower sensitivity in such case [33].

(b) Imbalanced Datasets: Many segmentation models are trained on small and homogeneous datasets, such as MIAS and DDSM, which limit their ability to generalize to diverse or complex real-world cases [46,47]. DL models like U-Net require large amounts of annotated data to perform optimally, but overfitting often occurs when trained on limited datasets, reducing performance on unseen images [60,66]. This limitation is further compounded by the lack of large-scale multi-center datasets, meaning that most models are validated only on single-institution cohorts, which restricts their clinical translation and external generalizability.

(c) Spiculated Region Segmentation: Spiculated regions, which represent star-shaped masses with radiating lines, are one of the most challenging aspects of breast cancer segmentation. The sharp, irregular edges of spiculated masses are difficult to capture using traditional segmentation methods. Techniques like Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) and gradient-based approaches have been applied, but even in recent works, achieving precise segmentation of spiculated regions remains a challenge. Pezeshki et al. [79,80] developed a model using FCM combined with texture and shape features. While effective, fine-tuning thresholds in these models require expert knowledge, limiting the method’s broader clinical application.

(d) Computational Complexity: Advanced segmentation techniques, especially DL-based methods like CNN-based U-Nets and YOLO, require substantial computational resources [62]. Hybrid approaches that combine DL models with optimization techniques, are highly accurate but significantly increase computational costs, making real-time clinical deployment challenging [69,74].

(e) Noise and Artifacts: Noise and artifacts in mammogram images, caused by poor image quality or device variability, present challenges for segmentation methods [78]. Misclassified artifacts, often mistaken for regions of interest, contribute to false positives [101]. While advancements in segmentation techniques have improved robustness against noise, challenges persist in maintaining accuracy, particularly in low-quality images [14]. To address these limitations, incorporating a refinement step after segmentation has become increasingly essential [102]. This post-segmentation treatment can help correct errors in delineated boundaries [103], reduce false positives, and ensure that segmented regions align more closely with true anatomical structures [104], enhancing the overall reliability of segmentation outcomes.

Despite significant progress in breast cancer segmentation research, numerous opportunities remain to improve clinical applicability, scalability, and diagnostic robustness. These following directions highlight concrete pathways where segmentation research can move beyond technical improvements to enable adoption in diagnostic practice:

(a) Development of Large, Diverse, and High-Quality Datasets: Existing datasets such as MIAS and DDSM are limited in terms of imaging variability, lesion types, and patient demographics. This limitation restricts model generalizability in real-world clinical practice. Future research should focus on creating or utilizing more comprehensive datasets that include dense breast tissues, spiculated masses, and multi-institutional sources. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can be employed [53,105,106] to synthetically expand existing datasets by generating realistic mammogram images with controlled characteristics (e.g., specific tumor shapes or densities). GAN-based augmentation can improve model robustness, especially in underrepresented lesion categories, and has shown promise in improving generalization for deep learning models trained on limited data. Such approaches also can provide a controlled way to simulate rare clinical scenarios.

(b) Design of Lightweight and Efficient Models for Clinical Deployment: High-performing segmentation models often require substantial computational power/GPUs, which limits their integration into low-resource or real-time clinical settings. There is a growing need for lightweight [85,107] architectures (e.g., MobileNet, EfficientNet, or pruned U-Nets) that maintain high accuracy while reducing latency and memory usage. This makes them suitable for telemedicine, portable mammography devices, where real-time inference on modest hardware is essential in clinical setting.

(c) Post-Segmentation Refinement for Enhanced Precision: Even with accurate initial segmentation, minor boundary inaccuracies and misclassified regions often persist [102], especially in dense or low-contrast mammograms. Future work should explore refinement techniques, such as morphological filtering, boundary smoothing, or region reclassification that are applied after the initial segmentation. These post-processing steps can improve boundary precision, reduce false positives, and align segmented regions more closely with true anatomical structures. Combining automated segmentation with refinement mechanisms can substantially enhance the clinical reliability and trustworthiness of AI-assisted diagnostics, as radiologists depend on precise tumor margins for treatment decisions.

(d) Explainable and Clinically Interpretable Models: The adoption of segmentation tools in clinical workflows depends not only on accuracy but also on transparency. Explainable AI (XAI) frameworks, such as attention visualization, saliency maps [108], or decision heat maps, should be incorporated to allow radiologists to understand and verify model decisions. Future research should prioritize human-centered AI design, enabling AI to act as a support system rather than a black box.

(e) Multistage and Multimodal Integration: Rather than relying solely on pixel-level mammogram data, integrating segmentation with clinical metadata (e.g., patient history, genetic markers) [109], radiomics, or gaze-tracking [27] data (as explored in recent hybrid models) can enhance diagnostic performance. Furthermore, integrating segmentation with downstream tasks (classification, prognosis) will enable comprehensive end-to-end diagnostic systems that support clinical decision-making.

(f) Self-Supervised and Semi-Supervised Learning: Annotating mammograms are resource-intensive and often a bottleneck for training large-scale models. Future research should explore self-supervised, semi-supervised, or weakly-supervised methods to leverage unlabeled data effectively [110]. Techniques such as contrastive learning or pseudo-labeling reduce dependence on expert annotation, improving scalability and enabling continuous model refinement from clinical data streams.

(g) Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Collaboration: Privacy regulations and data-sharing restrictions often limit the creation of large, diverse datasets. Federated learning offers a promising solution by enabling model training across multiple institutions without requiring data centralization. This approach not only preserves patient confidentiality but also improves model robustness by incorporating heterogeneous data sources [111]. In the long term, federated learning could facilitate cross-border collaboration and establish standardized, clinically validated segmentation systems suitable for regulatory approval.

(h) Mobile Screening Application for On-Device Use: Mobile and point-of-care screening require segmentation pipelines that operate under tight data, privacy, and compute constraints. Future work should consolidate recent advances into an edge-friendly workflow that integrates screening, segmentation, and downstream detection or prognosis on portable hardware. Utilize label-faithful generative augmentation, preferably diffusion models conditioned on masks or regions of interest, to synthesize rare or subtle patterns without requiring the acquisition of new patient data.

From a practical perspective, these directions can be translated into actionable recommendations for future tool development. Lightweight models should be prioritized for deployment in low-resource or point-of-care settings, while explainable AI components are critical for clinical adoption where trust and interpretability are required. Multi-center robustness can be addressed through federated learning strategies and the integration of diverse datasets, whereas refinement modules remain essential for high-precision applications such as pre-surgical planning. Semi-supervised and self-supervised methods offer pragmatic solutions for research groups with limited annotation budgets, facilitating wider adoption in real-world practice. At the same time, the most promising directions for clinical translation appear to be those that combine efficiency, transparency, and clinical realism; for example, gaze-tracking–guided attention, which mimics radiologists’ diagnostic behavior, together with lightweight and interpretable architectures, represent concrete pathways toward robust, scalable, and clinically meaningful breast cancer segmentation systems.

This study presents a systematic literature review of 57 selected articles, identified through the PRISMA methodology, to evaluate segmentation techniques in breast cancer detection. The review covers a range of segmentation approaches, including classical, machine learning (ML)-based, deep learning (DL)-based, and hybrid methods, with attention to their advantages, limitations, and contexts of application. Classical and ML-based techniques remain relevant due to their simplicity, interpretability, and lower computational requirements, particularly in resource-constrained settings. DL-based models, especially U-Net and its variants, show superior performance in handling complex tissue structures when sufficient annotated data is available. Meanwhile, hybrid approaches are gaining interest for their potential to combine the strengths of various methods, offering flexibility and improved robustness in segmenting diverse mammographic features. In addition, Segmentation performance across studies varies considerably, influenced by differences in datasets, image quality, preprocessing techniques, and implementation goals. Publicly available datasets such as MIAS, DDSM, CBIS-DDSM, and INBreast serve as essential benchmarks, though challenges remain regarding annotation consistency, limited diversity, and class imbalance. However, recent datasets, such as DMID, RSNA, and VinDR-Mammo, reflect a notable shift toward greater scale and clinical richness, offering larger volumes of images, pixel-level annotations, and accompanying radiology reports. Looking ahead, future work should focus on refining hybrid and lightweight architectures, improving dataset quality and availability, and enhancing post-segmentation refinement. Promoting explainable models and validating them in clinical environments will be essential to bridge the gap between experimental development and real-world diagnostic support. Furthermore, innovations, such as eye-tracking-guided attention, may significantly enhance the applicability of segmentation tools by aligning model predictions more closely with radiologists’ focus patterns, thus supporting more intuitive and collaborative decision-making.

Acknowledgement: The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) and Grammarly solely for English-language editing/refinement under the authors’ supervision. All study design, analysis, and conclusions were produced and verified by the authors. No confidential or personal data was provided to AI tools.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by BK21 FOUR (Fostering Outstanding Universities for Research) (No.: 5199990914048).

Author Contributions: Hanifah Rahmi Fajrin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation and Data curation. Se Dong Min: Supervision and Validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| CAD | Computer Aided-Detection |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| FCM | Fuzzy c-Means |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RoI | Region of Interest |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| PSNR | Peak signal to Noise Ratio |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GLCM | Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| IoU | Intersection over Unit |

| DSC | Dice Similarity Coefficient |

| AUC | Area Under Cover |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| JI | Jaccard Index |

| MSE | Mean Square Error |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ECA | Efficient Channel Attention |

| MLO | Mediolateral-Oblique |

| CC | Cranio-Caudal |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| CS-LBP | Center-Symmetric Local Binary Pattern |

References

1. Zhang M, Mesurolle B, Theriault M, Meterissian S, Morris EA. Imaging of breast cancer-beyond the basics. Curr Probl Cancer. 2023;47(2):100967. doi:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2023.100967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Nagra-Mahmood N, Miller AL, Williams JL, Paltiel HJ. Breast. In: Pediatric ultrasound. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 941–67. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56802-3_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Barba D, León-Sosa A, Lugo P, Suquillo D, Torres F, Surre F, et al. Breast cancer, screening and diagnostic tools: all you need to know. Crit Rev Oncol. 2021;157:103174. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Nugroho HA, Fajrin HR, Soesanti I, Budiani RL. Analysis of texture for classification of breast cancer on mammogram images. Int J Med Eng Inform. 2018;10(4):382. doi:10.1504/ijmei.2018.095088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lohani KR, Srivastava A, Jeyapradha DA, Ranjan P, Dhar A, Kataria K, et al. “Dial of a clock” search pattern for clinical breast examination. J Surg Res. 2021;260:10–9. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.11.043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Albeshan SM, Hossain SZ, MacKey MG, Brennan PC. Can breast self-examination and clinical breast examination along with increasing breast awareness facilitate earlier detection of breast cancer in populations with advanced stages at diagnosis? Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20(3):194–200. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2020.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kaushal C, Bhat S, Koundal D, Singla A. Recent trends in computer assisted diagnosis (CAD) system for breast cancer diagnosis using histopathological images. IRBM. 2019;40(4):211–27. doi:10.1016/j.irbm.2019.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mohapatra S, Muduly S, Mohanty S, Ravindra JVR, Mohanty SN. Evaluation of deep learning models for detecting breast cancer using histopathological mammograms images. Sustain Oper Comput. 2022;3:296–302. doi:10.1016/j.susoc.2022.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ren W, Chen M, Qiao Y, Zhao F. Global guidelines for breast cancer screening: a systematic review. Breast. 2022;64:85–99. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2022.04.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Azour F, Boukerche A. Design guidelines for mammogram-based computer-aided systems using deep learning techniques. IEEE Access. 2022;10:21701–26. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3151830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cao Z, Deng Z, Yang Z, Ma J, Ma L. Supervised contrastive pre-training models for mammography screening. J Big Data. 2025;12(1):24. doi:10.1186/s40537-025-01075-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Giampietro RR, Cabral MVG, Lima SAM, Weber SAT, Dos Santos Nunes-Nogueira V. Accuracy and effectiveness of mammography versus mammography and tomosynthesis for population-based breast cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7991. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-64802-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Eby PR, Ghate S, Hooley R. The benefits of early detection: evidence from modern international mammography service screening programs. J Breast Imaging. 2022;4(4):346–56. doi:10.1093/jbi/wbac041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lbachir IA, Daoudi I, Tallal S. Automatic computer-aided diagnosis system for mass detection and classification in mammography. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(6):9493–525. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-09991-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Loizidou K, Elia R, Pitris C. Computer-aided breast cancer detection and classification in mammography: a comprehensive review. Comput Biol Med. 2023;153:106554. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Mittal H, Pandey AC, Saraswat M, Kumar S, Pal R, Modwel G. A comprehensive survey of image segmentation: clustering methods, performance parameters, and benchmark datasets. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(24):35001–26. doi:10.1007/s11042-021-10594-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Michael E, Ma H, Li H, Kulwa F, Li J. Breast cancer segmentation methods: current status and future potentials. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:9962109. doi:10.1155/2021/9962109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jardim S, António J, Mora C. Image thresholding approaches for medical image segmentation-short literature review. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;219:1485–92. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rahmi Fajrin H, Kim Y, Se DM. A comparative study of image segmentation techniques in mammograms (Otsu thresholding, FCM, and U-Net). In: 2024 International Conference on Information Technology and Computing (ICITCOM); 2024 Aug 7–8; Yogyakarta, Indonesia. p. 334–9. doi:10.1109/ICITCOM62788.2024.10762244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ravitha Rajalakshmi N, Vidhyapriya R, Elango N, Ramesh N. Deeply supervised U-Net for mass segmentation in digital mammograms. Int J Imaging Syst Tech. 2021;31(1):59–71. doi:10.1002/ima.22516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pi J, Qi Y, Lou M, Li X, Wang Y, Xu C, et al. FS-UNet: mass segmentation in mammograms using an encoder-decoder architecture with feature strengthening. Comput Biol Med. 2021;137:104800. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Soulami KB, Kaabouch N, Saidi MN, Tamtaoui A. Breast cancer: one-stage automated detection, segmentation, and classification of digital mammograms using UNet model based-semantic segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;66:102481. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Raaj RS. Breast cancer detection and diagnosis using hybrid deep learning architecture. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;82(2):104558. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sathish Kumar PJ, Shibu S, Mohan M, Kalaichelvi T. Hybrid deep learning enabled breast cancer detection using mammogram images. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;95:106310. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jha S, Ahmad S, Arya A, Alouffi B, Alharbi A, Alharbi M, et al. Ensemble learning-based hybrid segmentation of mammographic images for breast cancer risk prediction using fuzzy C-means and CNN model. J Healthc Eng. 2023;2023(1):1491955. doi:10.1155/2023/1491955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ghuge K, Saravanan DD. SRMADNet: swin ResUnet3+-based mammogram image segmentation and heuristic adopted multi-scale attention based DenseNet for breast cancer detection. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;88:105515. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xie J, Zhang Q, Cui Z, Ma C, Zhou Y, Wang W, et al. Integrating eye tracking with grouped fusion networks for semantic segmentation on mammogram images. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2025;44(2):868–79. doi:10.1109/TMI.2024.3468404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ranjbarzadeh R, Dorosti S, Jafarzadeh Ghoushchi S, Caputo A, Tirkolaee EB, Ali SS, et al. Breast tumor localization and segmentation using machine learning techniques: overview of datasets, findings, and methods. Comput Biol Med. 2023;152:106443. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Rezaei Z. A review on image-based approaches for breast cancer detection, segmentation, and classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;182:115204. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Agrawal S, Oza P, Kakkar R, Tanwar S, Jetani V, Undhad J, et al. Analysis and recommendation system-based on PRISMA checklist to write systematic review. Assess Writ. 2024;61:100866. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2024.100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Baccouche A, Garcia-Zapirain B, Castillo Olea C, Elmaghraby AS. Connected-UNets: a deep learning architecture for breast mass segmentation. npj Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):151. doi:10.1038/s41523-021-00358-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Patil RS, Biradar N, Pawar R. A new automated segmentation and classification of mammogram images. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(6):7783–816. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-11932-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Larroza A, Pérez-Benito FJ, Perez-Cortes JC, Román M, Pollán M, Pérez-Gómez B, et al. Breast dense tissue segmentation with noisy labels: a hybrid threshold-based and mask-based approach. Diagnostics. 2022;12(8):1822. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12081822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Geweid GGN, Abdallah MA. A novel approach for breast cancer investigation and recognition using M-level set-based optimization functions. IEEE Access. 2019;7:136343–57. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2941990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Subramanian S, Rasu G. Segmentation of mammogram abnormalities using ant system based contour clustering algorithm. Int Arab J Inf Technol. 2023;20(3):319–30. doi:10.34028/iajit/20/3/4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kadadevarmath J, Reddy AP. Improved watershed segmentation and DualNet deep learning classifiers for breast cancer classification. SN Comput Sci. 2024;5(5):458. doi:10.1007/s42979-024-02642-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Divyashree BV, Kumar GH. Breast cancer mass detection in mammograms using gray difference weight and MSER detector. SN Comput Sci. 2021;2(2):63. doi:10.1007/s42979-021-00452-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chaira T. Neutrosophic set based clustering approach for segmenting abnormal regions in mammogram images. Soft Comput. 2022;26(19):10423–33. doi:10.1007/s00500-022-06882-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Mamindla A, Ramadevi Y. Improved ABC algorithm based 3D Otsu for breast mass segmentation in mammogram images. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2023;16(2):607–18. [Google Scholar]

40. Soliman NF, Ali NS, Aly MI, Algarni AD, El-Shafai W, Abd El-Samie FE. An efficient breast cancer detection framework for medical diagnosis applications. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;70(1):1315–34. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Laishram R, Rabidas R. WDO optimized detection for mammographic masses and its diagnosis: a unified CAD system. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;110(1):107620. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sheba KU, Gladston Raj S. An approach for automatic lesion detection in mammograms. Cogent Eng. 2018;5(1):1444320. doi:10.1080/23311916.2018.1444320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Santhos KA, Kumar A, Bajaj V, Singh GK. McCulloch’s algorithm inspired cuckoo search optimizer based mammographic image segmentation. Multimed Tools Appl. 2020;79(41):30453–88. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-09310-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sharma MK, Jas M, Karale V, Sadhu A, Mukhopadhyay S. Mammogram segmentation using multi-atlas deformable registration. Comput Biol Med. 2019;110:244–53. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.06.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Umamaheswari T, Murali Mohanbabu Y. CNN-FS-IFuzzy: a new enhanced learning model enabled by adaptive tumor segmentation for breast cancer diagnosis using 3D mammogram images. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;288(1):111443. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Kashyap KL, Bajpai MK, Khanna P, Giakos G. Mesh-free based variational level set evolution for breast region segmentation and abnormality detection using mammograms. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2018;34(1):e2907. doi:10.1002/cnm.2907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]