Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mitigating Attribute Inference in Split Learning via Channel Pruning and Adversarial Training

Department of Computer Science, College of Computer and Information Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11362, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Afnan Alhindi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrating Split Learning with Tiny Models for Advanced Edge Computing Applications in the Internet of Vehicles)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 62 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072625

Received 31 August 2025; Accepted 03 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Split Learning (SL) has been promoted as a promising collaborative machine learning technique designed to address data privacy and resource efficiency. Specifically, neural networks are divided into client and server sub-networks in order to mitigate the exposure of sensitive data and reduce the overhead on client devices, thereby making SL particularly suitable for resource-constrained devices. Although SL prevents the direct transmission of raw data, it does not alleviate entirely the risk of privacy breaches. In fact, the data intermediately transmitted to the server sub-model may include patterns or information that could reveal sensitive data. Moreover, achieving a balance between model utility and data privacy has emerged as a challenging problem. In this article, we propose a novel defense approach that combines: (i) Adversarial learning, and (ii) Network channel pruning. In particular, the proposed adversarial learning approach is specifically designed to reduce the risk of private data exposure while maintaining high performance for the utility task. On the other hand, the suggested channel pruning enables the model to adaptively adjust and reactivate pruned channels while conducting adversarial training. The integration of these two techniques reduces the informativeness of the intermediate data transmitted by the client sub-model, thereby enhancing its robustness against attribute inference attacks without adding significant computational overhead, making it well-suited for IoT devices, mobile platforms, and Internet of Vehicles (IoV) scenarios. The proposed defense approach was evaluated using EfficientNet-B0, a widely adopted compact model, along with three benchmark datasets. The obtained results showcased its superior defense capability against attribute inference attacks compared to existing state-of-the-art methods. This research’s findings demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed channel pruning-based adversarial training approach in achieving the intended compromise between utility and privacy within SL frameworks. In fact, the classification accuracy attained by the attackers witnessed a drastic decrease of 70%.Keywords

Distributed Collaborative Machine Learning (DCML) represents a promising approach that allows training machine learning models collaboratively across multiple data sources [1,2]. Specifically, such collaboration reduces significantly computational overhead and the resource demands for training large ML models [3]. Furthermore, DCML outperforms traditional methods by ensuring that the original data remains private and undisclosed [2]. In particular, Split Learning (SL) [4] has emerged as an innovative DCML technique that has attracted considerable attention. SL has been applied in various domains, including autonomous vehicles in 6G networks [5], smart grid load forecasting [6], traffic flow prediction [7], Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) [8], and sequential/satellite data processing [9]. In SL, the machine learning model is divided into client and server sub-models. Specifically, the client side is dedicated to training the initial layers of the model using its local private data. Subsequently, the extracted features are transmitted to the server, which resumes the training process. Such model split reduces the computational load on the client side. This makes SL particularly advantageous for resource-limited devices such as IoT devices, mobile phones, and Internet of Vehicles (IoV) [10–12]. Even though SL prevents the need to transmit raw data, the extracted features can still pose a security risk. In fact, they may be exploited by adversaries to infer sensitive attributes, or reconstruct the original data [13,14].

Various defense methods have been proposed to improve data privacy in the SL framework [15]. Particularly, cryptographic techniques [16–19] were introduced to enable computations on encrypted data. This allows the server to perform forward and backward propagation without accessing the original data. However, such methods involve considerable computational overhead and latency, which exceed the capabilities of tiny devices deployed in IoT or IoV networks [20]. Additionally, Differential Privacy (DP) has been suggested to mitigate potential private information leakage by adding controlled Gaussian or Laplacian noise to the model parameters or the intermediate data [21–23]. Even though DP provides a quantifiable privacy guarantee, it affects the model’s performance [24]. More recently, Adversarial Representation Learning (ARL) [25–27] has been developed to enhance data privacy using two networks. The first one is the primary network used to optimize the model of the utility task while reducing the risk of private data exposure. On the other hand, the second network represents a proxy-adversary model designed to infer sensitive information. Notably, the objective functions in ARL aim at balancing high accuracy for the target task with effective protection of sensitive information.

Notably, most of the existing ARL-based methods for SL framework are not tailored for resource-constrained client devices, such as edge devices within the IoV ecosystem. Conversely, techniques like knowledge distillation, network pruning, and quantization focus on compressing ML models in order to reduce their size without impacting the task accuracy [28,29]. In addition to their primary purpose of optimizing neural networks, network pruning also aims to mitigate the risk of private data leakage during DCML inference phase [26,30].

Considering the existing literature, many privacy-preserving approaches in DCML, particularly in split learning, exhibit a lack of balance between privacy and accuracy on resource-constrained devices. For instance, some methods offer strong resistance to privacy attacks but suffer from significant drops in accuracy. Conversely, other methods maintain acceptable performance but are impractical for deployment on devices with limited computational resources. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a novel defense approach designed to shield against attribute inference attacks. Specifically, adversarial training and network channel pruning are coupled to achieve an improved utility-privacy tradeoff for SL frameworks. More specifically, the proposed Channel Pruning-based Adversarial Training (CPAT) approach consists of two main phases. The first one is held offline for joint adversarial training and channel pruning. The association of these two techniques enables the deep learning model to adaptively adjust and reactivate the channels pruned throughout the training process. This reduces the informativeness of the intermediate data transmitted by the client model, making it more robust against attribute inference attacks. The second CPAT phase consists of the online inference task. In contrast to existing defense methods, like homomorphic encryption, which increase significantly the computational overhead on client devices, this research introduces an efficient and lightweight defense approach against attribute inference attacks on SL frameworks. The primary contributions of this study can be outlined as follows:

• Design and implement a privacy-preserving split learning framework that integrates: (i) adversarial training and (ii) channel pruning. Combining these two techniques during training helps minimize the mutual information between the raw input data and the intermediate features exchanged within the split learning architecture.

• Evaluate the proposed CPAT framework in terms of both utility and privacy by conducting experiments on three benchmark datasets: FairFac [31], CelebA [32], and CIFAR-10 [33].

• Conduct a comparative analysis of CPAT’s performance against state-of-the-art privacy-preserving approaches to demonstrate its effectiveness.

• Couple CPAT with a lightweight model, namely EfficientNet [34] in order to showcase its deployment on resource-constrained platforms, such as Internet of Vehicles (IoV).

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews privacy-preserving approaches in SL framework. The proposed Channel Pruning-based Adversarial Training (CPAT) approach is detailed in Section 3. The experiments conducted to assess the CPAT approach as well as the obtained results are discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study and summarizes the key findings. Moreover, it highlights the potential future directions for this research.

State-of-the-art privacy-preserving techniques in split learning can be broadly classified into three main approaches, namely, Cryptographic techniques, Differential Privacy (DP), and Adversarial Representation Learning (ARL). This section provides a comprehensive overview of these defense approaches and identifies their advantages, limitations, and key research gaps.

In [16,19], the authors introduced a Homomorphic Encryption (HE)-based approach where the client encrypts intermediate data before transmitting them to the server sub-model. Consequently, the server was unable to reconstruct the client’s input data given the intermediate representations or gradients computed during forward and backward propagations. Moreover, Khan et al. [35] integrated Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) with a random masking mechanism to enhance privacy within the SL framework. Specifically, the client applied a random mask to the intermediate representations before transmitting them to two non-colluding servers. These servers employed Function Secret Sharing (FSS), which enabled each to operate on its privately shared function. The primary objective of this approach was to ensure that no single server could reconstruct the client’s data or independently manipulate the feature space. Furthermore, the study in [36] introduced a hybrid method that integrated HE and SMPC to enhance the privacy of data and model parameters in a multi-server hierarchical setting. In particular, the HE ensured the confidentiality of user inputs during both forward and backward propagation, while the SMPC granted robustness by safeguarding the system even when most servers acted dishonestly. Although cryptographic techniques exhibit significant privacy benefits, several drawbacks make them unsuitable for resource-constrained client devices and real-world applications. These challenges include substantial computational and communication overhead, high latency, and complex key management.

The researchers in [23] utilized a DP defense technique to introduce a new activation function called R3eLU. The key idea was to incorporate randomness in the intermediate data in order to prevent reconstructing raw data or inferring private attributes by the attackers. The work in [23] extended the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, which typically assigns zero to negative inputs while keeping positive values unchanged, and introduced R3eLU instead. The latter activation function randomizes the negative inputs using randomized responses and Laplacian noise during the activation computation (instead of zeroing them). Even though DP can provide a verifiable privacy guarantee, its implementation often results in a noticeable degradation in model performance [24].

Alternative defense approaches using noise injections have been explored [21,37]. In particular, the authors in [37] outlined a method to learn additive Laplace noise distributions intended to reduce considerably the informative content of the raw data. Specifically, the method relied on two phases; The first one represents an offline stage where additive noise distributions are calculated as part of a disjoint learning process. In addition, the loss function was designed to balance privacy and accuracy. This was achieved through decreasing the mutual information between the original and intermediate data. On the other hand, during the second online phase (inference phase), the client selects a random distribution from the collection of noise distributions generated in the first phase and applies it to the intermediate activation. Furthermore, the authors in [21] depicted a method that injects dynamically noise into intermediate data based on the input features, leveraging a self-attention mechanism. This enables the model to selectively focus on different feature regions to determine the optimal noise levels. In other words, less noise is added to the sensitive image regions in order to preserve the accuracy of the target task. Conversely, more noise is applied to the less sensitive areas to enhance privacy. One should note that adding noise to the intermediate data during the inference phase may introduce slight computational and latency overheads. This would be inconvenient for real-time applications and/or resource-constrained environments.

In [38,39], the researchers proposed an adversarial training technique by incorporating a proxy adversary model throughout the training phase. In particular, the study [38] demonstrated that defending against data reconstruction attacks does not inherently prevent attribute inference attacks, and vice versa. Therefore, they developed a framework including two distinct proxy adversaries: The adversary classifier and the adversary reconstructor. Besides, the client’s objective function was designed to minimize the cross-entropy loss of the main task, reduce the mutual information between the original and reconstructed data, and maximize the cross-entropy loss of private attributes. Conversely, the server model’s objective function aims at minimizing the cross-entropy loss of the main task. Meanwhile, the adversary classifier relies on the cross-entropy loss between the ground truth labels for the private attribute and the corresponding predictions. Moreover, the authors in [39] highlighted the effectiveness of employing a related, but not identical metric in the optimization function used for adversarial training. Specifically, the client model was trained to enhance the likelihood of the target utility while simultaneously maximizing the entropy of the private attribute. The key benefit of this approach lies in its ability to preserve privacy. Notably, the use of entropy during training eliminates the need for private labels, thereby enhancing data privacy. Moreover, recent studies examined adversarial training defense approaches handling different data modalities [40,41]. Specifically, the research in [40] used a text dataset for a text classification task, while the researchers in [41] employed video datasets in their analytics application. Although both studies reported satisfactory outcomes, further comparisons with other privacy-preserving approaches are necessary to prove their effectiveness. The study in [26] highlighted the susceptibility of adversarial learning methods to data reconstruction and attribute inference attacks. To mitigate these vulnerabilities, DISCO [26] introduced a Filter Generating Network (FGN) on the client side, which generates dynamic filters to selectively prune the channels that are prone to reveal private attributes. These dynamic filters output either Zero or One; Zeros deactivate the channels associated with the private attributes, while Ones activate the channels relevant to the task attribute. FGN was trained to minimize the cross-entropy loss for the target task while maximizing the private attribute’s cross-entropy loss. Although combining channel pruning with adversarial learning improves data privacy by mitigating certain attacks, incorporating FGN increased drastically the overhead on the client side. This limitation is even more significant in resource-constrained environments, such as IoT devices.

Additionally, the authors in [42] combined Class Activation Maps (CAMs) and Autoencoders (AEs) to selectively mask sensitive regions in the input data. Specifically, CAMs were used to identify which parts of the image were important for the primary task and which parts might reveal sensitive attributes. These sensitive regions were then either blurred or blacked out to create a protected version of the input. An autoencoder was trained to learn the mapping from the original feature map to this protected version, enabling it to automatically transform feature maps during inference without modifying the original model. One limitation of this approach is the additional computational overhead, as training and deploying an extra autoencoder increases complexity and may restrict its applicability on resource-constrained devices.

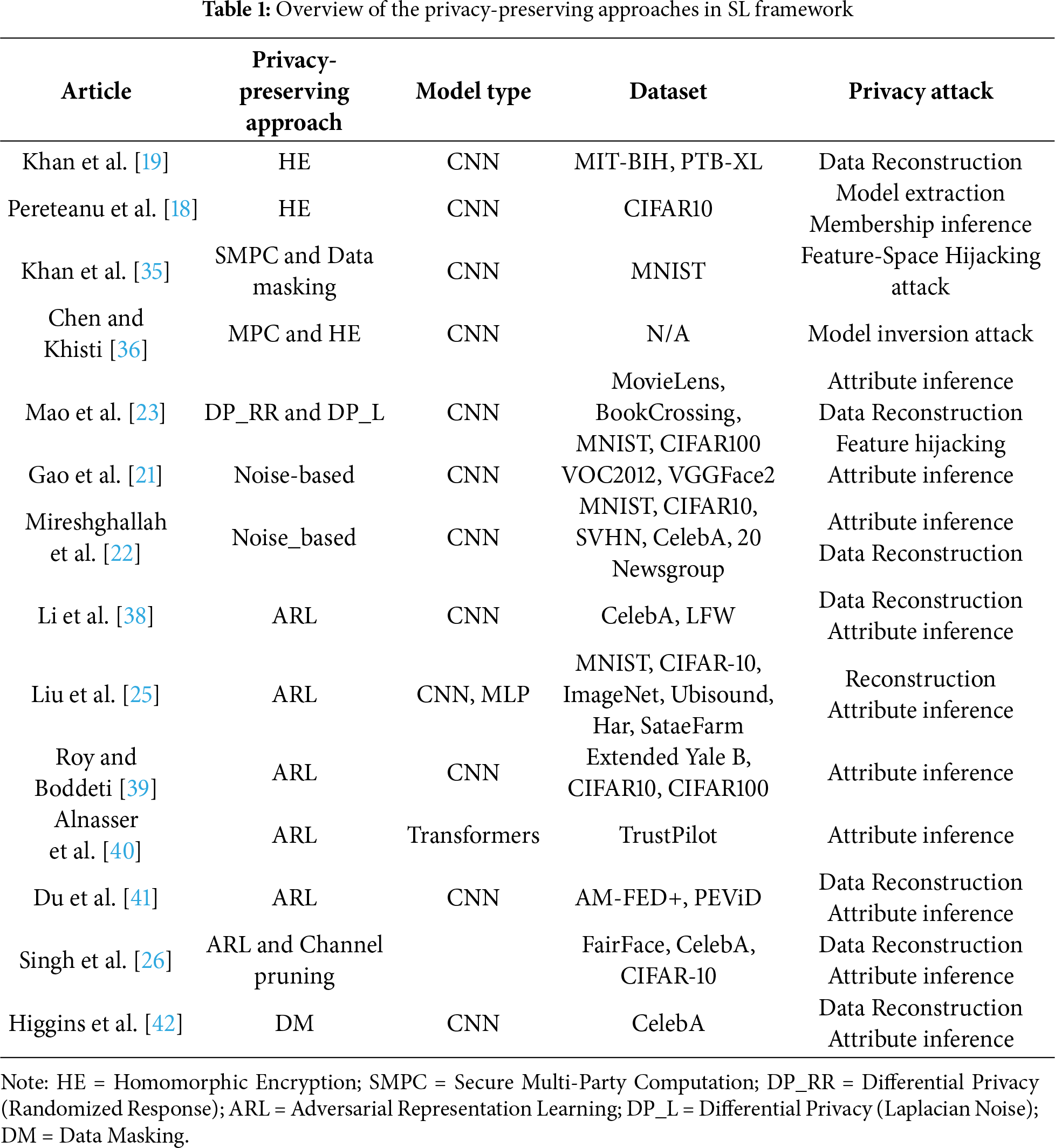

Table 1 summarizes the reviewed defense methods in SL framework, detailing the architecture used, the datasets involved, and the considered targeted privacy attacks. As it can be noticed, the review highlights the promising potential exhibited by the adversarial learning techniques to enhance data privacy within split learning frameworks. However, a significant challenge lies in balancing data privacy, task accuracy, and the computational load on edge devices. To address this challenge, this research depicts a novel defense approach that combines channel pruning with adversarial training to shield against attribute inference attacks.

3 Proposed Channel Pruning Based Adversarial Training

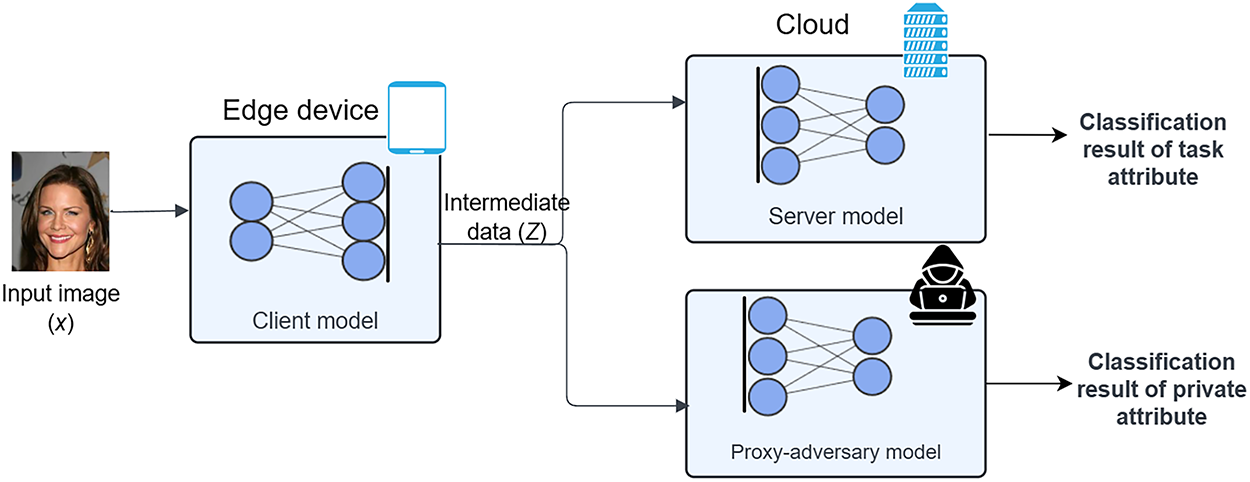

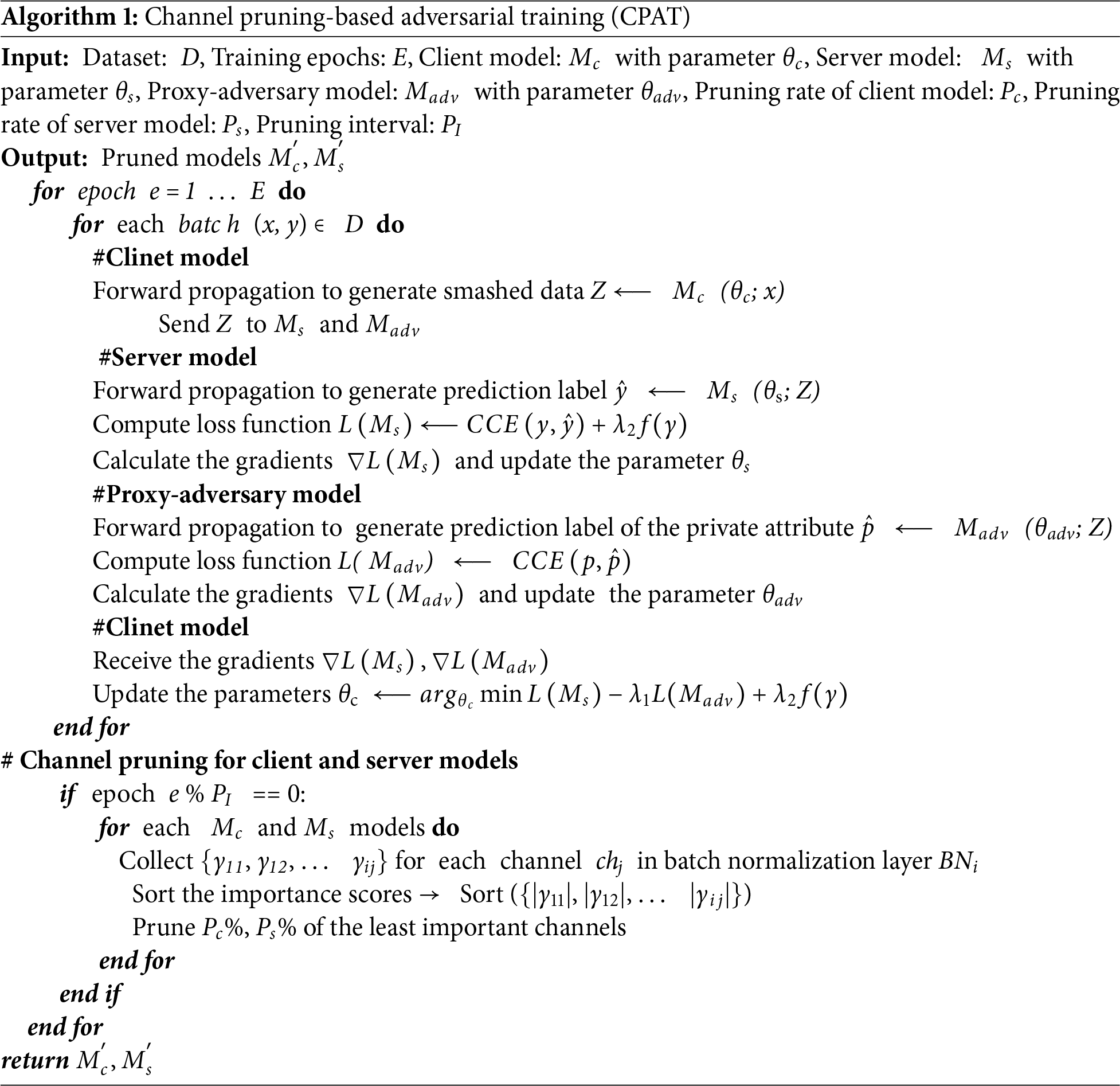

Prior to initiating the training and testing processes, the proposed Channel Pruning-based Adversarial Training (CPAT) approach partitions the machine learning model into client and server sub-models. Consistently, CPAT consists of two main phases; (i) An offline phase which performs simultaneous adversarial training and channel pruning, and (ii) An online phase that consists of the inference stage. Fig. 1 illustrates the adversarial training phase along with the three considered models. Namely, it presents the client model (Mc), the server model (Ms), and the proxy-adversary model (Madv). One should mention that these models are trained jointly using their respective objective functions. This supports the key contribution of this work which applies adversarial training on the client, server, and proxy-adversary models. In particular, the proposed approach aims at maximizing the adversary’s classification error, while minimizing the classification error of the server model. Besides, the scaling factor (γ) associated with the batch normalization layer is jointly optimized during the training phase to identify the least significant network channels without degrading the overall model performance.

Figure 1: Adversarial training in SL framework

Initially, the optimization of the client sub-model parameters is defined as follows:

where θc represents the client model parameters, and λ1 serves as the tradeoff parameter. In addition, L(Ms) refers to the cross-entropy loss function calculated using the ground truth labels of the task attribute and the predictions obtained using the server model. Besides, L(Madv) represents the cross-entropy loss function derived using the ground truth labels of the private attribute and the corresponding predictions generated by the proxy-adversary model. In fact, the client objective function in (1) is formulated to minimize the task attribute loss while maximizing the private attribute loss of the proxy-adversary model.

In order to obfuscate the private attribute transmitted by the client, channel pruning is integrated into the proposed adversarial training process. Specifically, the channels that provide minimal contribution to the model’s target task are pruned. To avoid imposing additional overhead on the client model, the scaling factor, γ, of each channel in the Batch Normalization (BN) layer is utilized as an importance score. In fact, applying L1 regularization to the scaling factor (γ) induces sparsity by penalizing its magnitude during training, enabling the identification of the least significant channels. Consequently, the optimization of the client model’s parameters is represented as follows:

where f(γ) = |γ|, is the L1 regularization term used to achieve sparsity, while λ2 serves as the tradeoff parameter. Additionally, a sub-gradient descent approach [28] is employed as the optimization technique for the non-smooth L1 penalty term.

Moreover, the server model is collaboratively trained alongside the client model in an end-to-end fashion. A cross-entropy loss, quantified using the predicted probability distribution and the ground truth labels, is adopted to assess the performance of the server model. In alignment with the objective function of the client sub-model, an L1 regularization is incorporated into the server’s objective function to achieve sparsity and identify the least significant channels. The server’s objective function is defined as follows:

where CCE represents the categorical cross-entropy which measures the difference between the ground-truth labels

On the other hand, the proxy adversary model obtains the intermediate data, Z, with the intent of inferring the private attribute p. Specifically, the proxy adversary network proceeds as a classifier module optimized through the minimization of the considered CEE loss. In particular, the loss function of the proxy-adversary model is formulated as follows:

where p is the ground-truth label of the private attribute, while

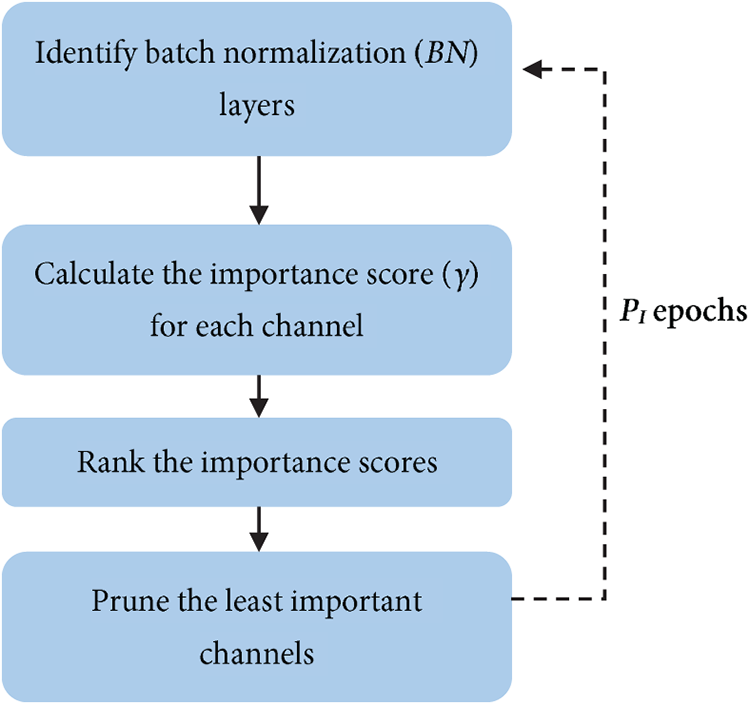

Furthermore, channel pruning is conducted jointly during the training process. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the least significant channels in the BN layers are pruned after PI epochs. This process begins by traversing the client and server sub-models obtained from the previous adversarial training phase to identify all BNi layers. For each sub-model, an importance score is assigned to each channel, chj, based on the absolute value of its corresponding scaling factor, γij. The channels with smaller γ values contribute less to the output and are therefore considered less important. Accordingly, the importance scores are sorted, and the channel pruning is executed according to the predefined pruning ratios.

Figure 2: Pruning the least significant channels according to the scaling factors associated with batch normalization layers

One should note that performing the channel pruning during the training process enables the model to dynamically adjust and reactivate the pruned channels. Consequently, the intermediate data exchanged between the client and the server sub-models becomes less informative and more resistant to attribute inference attacks. In fact, it reduces the mutual information between the intermediate data and the original data within the SL framework. The training process of the proposed CPAT is outlined in Algorithm 1. Moreover, during the online inference phase, the original data X is processed by the client model Mc′ which produces the intermediate activation Z. This intermediate representation is subsequently transmitted to the server model, Ms′, which predicts the class value for the task attribute. Finally, the server handles the resulting outputs and, if needed, forwards them back to the client’s side.

In this research, we adopted the architecture considered in the server side for the threat model. Particularly, the adversary attempts to extract the private attribute using the intermediate data transmitted by the client during the inference process. Additionally, we assume that the attackers have access to the original test set. This enables them to use it for training and testing their own model. Such attacks are practically feasible in case the adversary obtains limited access to the intermediate activations, Z, and the corresponding ground-truth labels of their private attribute (p). Such restricted access might be granted through a malicious or colluding client in SL framework. Furthermore, two scenarios were implemented to examine varying levels of adversarial capabilities. Namely, Attack-1 assumes that the attacker possesses relevant knowledge on the client model’s architecture. On the other hand, Attack-2 presumes that the attacker knows both; the client model’s architecture as well as some hyperparameters such as the learning rate. This additional knowledge of a key hyperparameter presents an elevated threat level.

In the experiments outlined below, three image datasets were considered to validate and analyze the performance of the proposed CPAT approach. In particular, we used the FairFace [31] dataset which includes a collection of 108,501 facial images of resolution of 128 × 128 pixels. It also encloses the race, the gender, and the age group as attributes associated with each image. One should note that in this research, the “gender” was selected as task attribute, while the “race” was considered as the private attribute. Moreover, the CelebA [32] dataset, which encloses 202,599 celebrities’ images of resolution 178 × 218 pixels, was utilized to assess the proposed approach. In fact. CelebA images represent 10,177 unique identities, annotated using 40 attributes. In the subsequent experiments, we chose “smiling” and “male” as task attribute, and private attribute, respectively. Lastly, the CIFAR-10 [33] dataset consists of 60,000 color images, each with a resolution of 32 × 32 pixels, categorized into 10 distinct classes. Each image is manually labelled as either living or non-living. In our experiments, the “class” was used as the task attribute, while the “living/non-living” was considered as the private attribute.

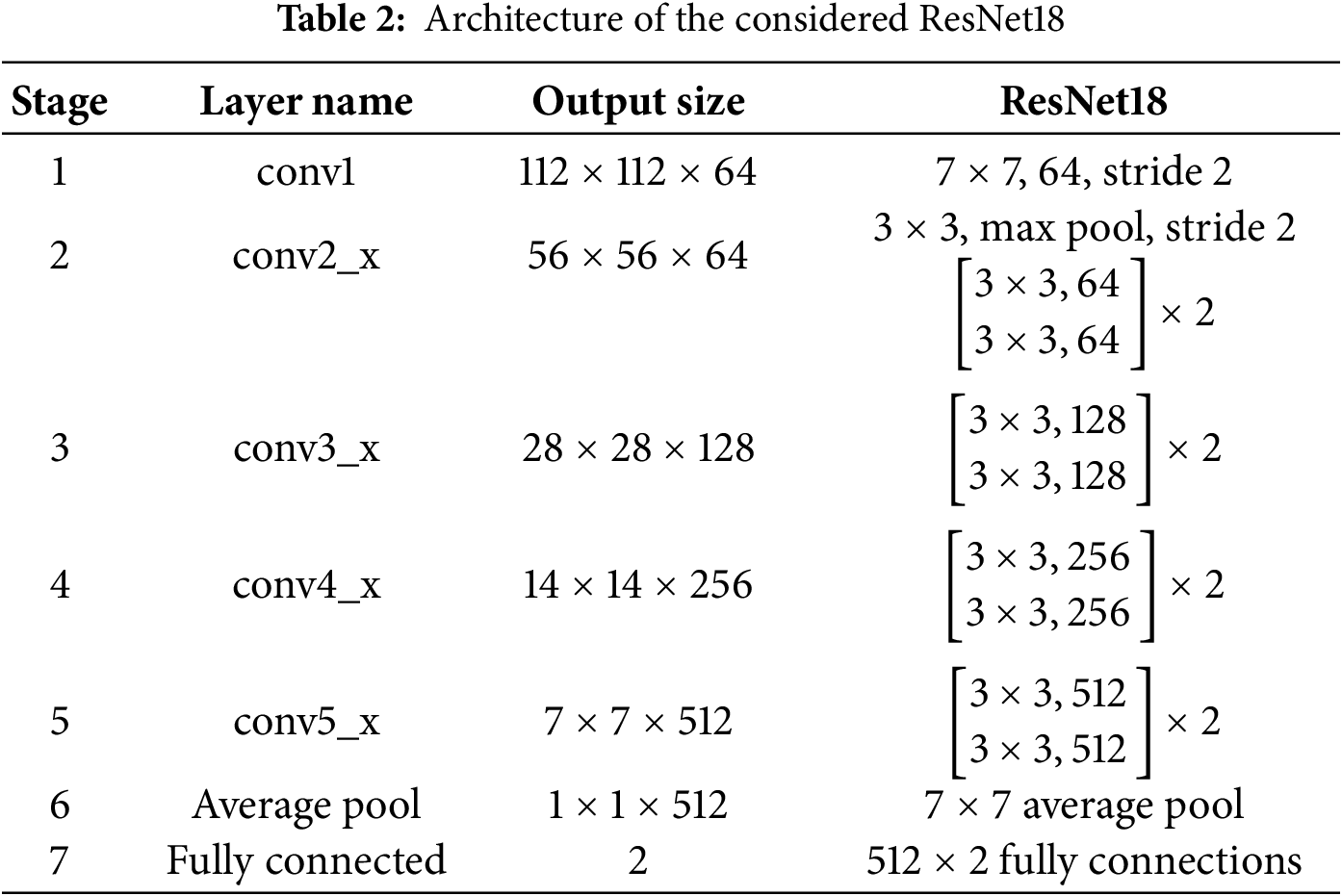

Besides, two Deep Learning (DL) models, namely ResNet18 [43] and EfficientNet-B0 [34] were investigated in this study. In fact, ResNet18 is an 18 layers convolutional neural network structured using eight residual blocks. Each block comprises two convolutional layers, ReLU activation functions, and batch normalization. The key feature of ResNet18 consists in the use of residual, or skip connections, which link earlier layers directly to later ones. This mitigates the vanishing gradient issue during the training process. Table 2 presents the detailed architecture of the considered ResNet18 model.

For the split learning framework setup, we divided ResNet18 network into two halves. The first one includes stages 1 to 3, constituting the client sub-network. The second half enfolds stages 4 to 7, forming the server sub-network. Since the goal of the attribute inference attacks is to classify the private attribute, we adopted the same architecture for both; the server sub-model and the proxy-adversary model.

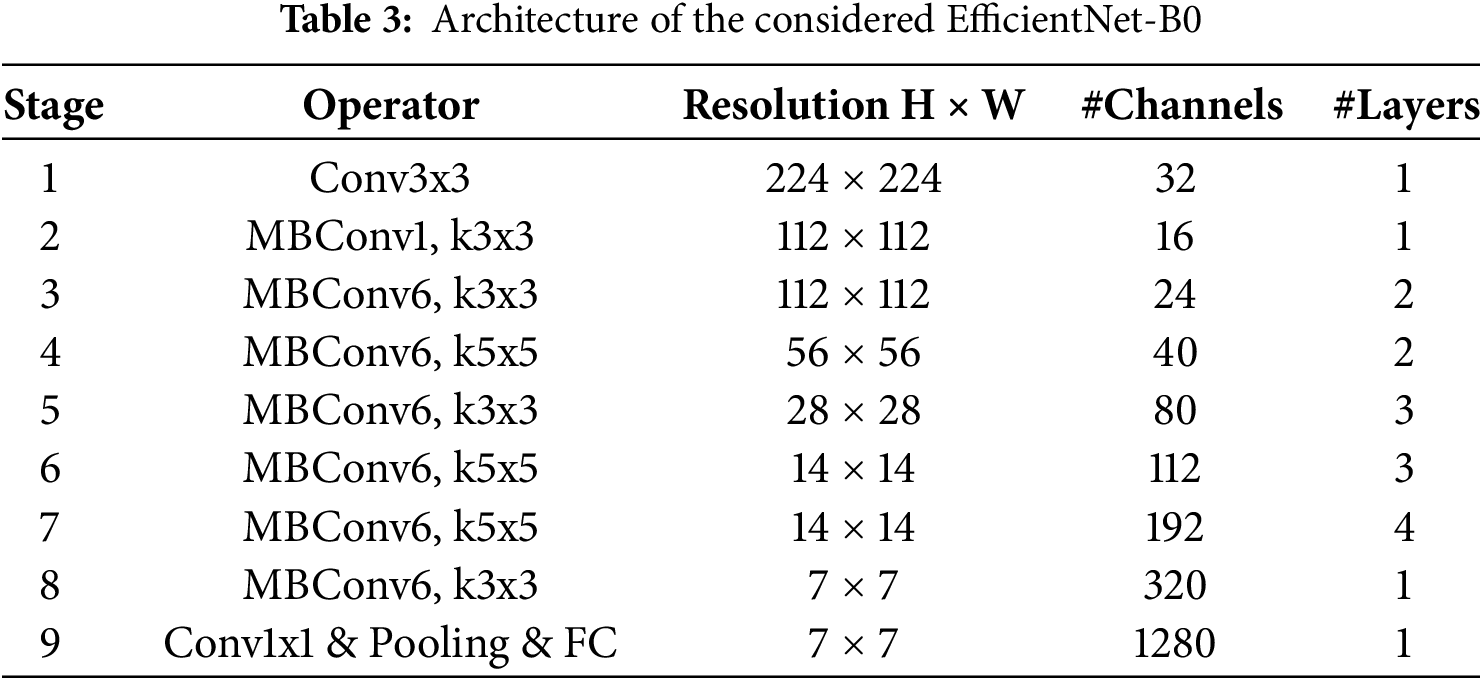

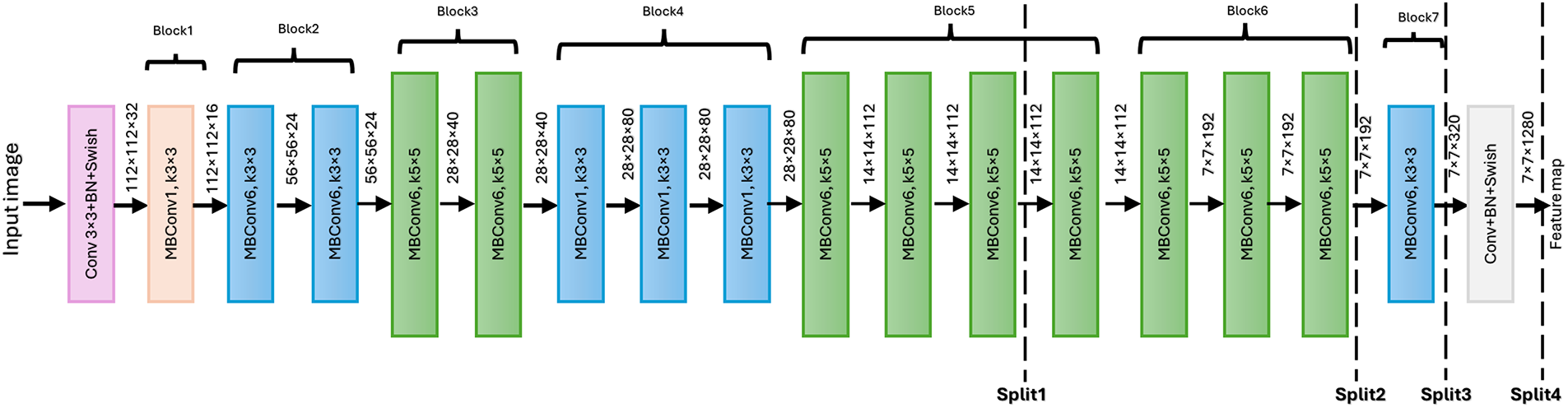

As one of the main objectives of split learning consists in reducing the computational burden on the client side, we also deployed the proposed CPAT approach using the lightweight model EfficientNet which employs Mobile Inverted Bottleneck (MBConv) layers that associate depth-wise separable convolutions with inverted residual blocks. Additionally, it incorporates the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) optimization to further improve performance. One should mention that in this research, we utilized the baseline model EfficientNet-B0 [34]. The lightweight design of EfficientNet-B0 makes it particularly suitable for deployment in environments with constrained resources, including IoT and IoV environments. In the split learning architecture, we divided the EfficientNet-B0 model into two sub-models: the client model includes stages 1 through 8, whereas the server model comprises the final stage. The detailed architecture of the considered EfficientNet-B0 is depicted in Table 3.

Moreover, different statistical metrics were used to assess the classification performance of the proposed CPAT model, and the attribute inference attacks model. Specifically, these performance metrics include the accuracy, the precision, the recall, and the F1-score [44].

This research experiments were conducted using an Intel® Core™ i9-14900F CPU running at 2.00 GHz, 64 GB RAM, and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 SUPER machine. The proposed approach, along with all state-of-the-art methods, were implemented using PyTorch framework [45].

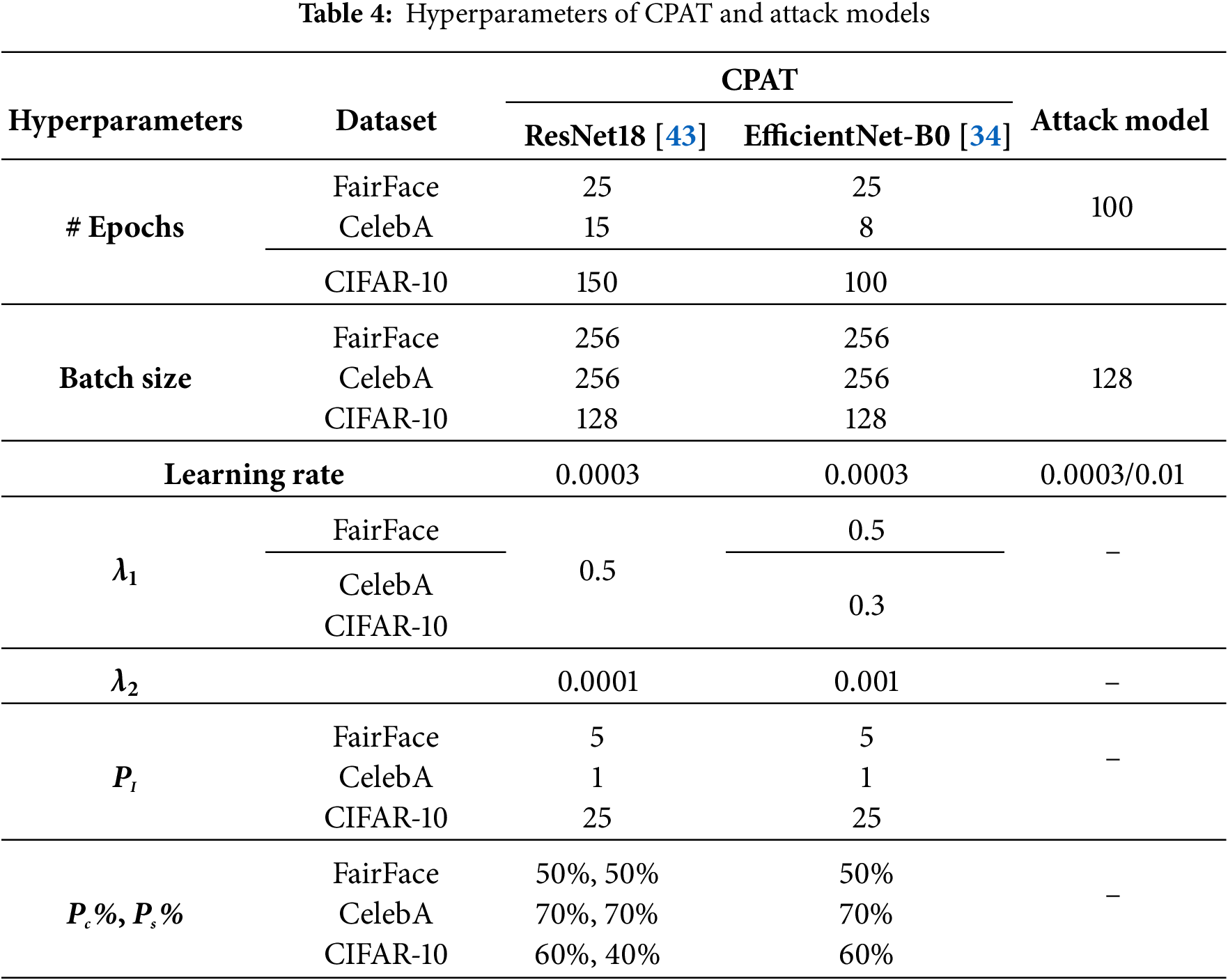

The training of the considered ResNet18 [43] and EfficientNet-B0 [34] models was conducted using a learning rate of 0.0003 and the Adam optimizer across all datasets. The number of epochs was set to 25 for FairFace [31] with both models, while for the CelebA [32] dataset, the number of epochs was set to 15 and 8 for the ResNet18 and EfficientNet-B0 models, respectively. In the case of the CIFAR-10 [33] dataset, the ResNet18 model was trained for 150 epochs, while the EfficientNet-B0 model was trained for 100 epochs. Moreover, the adversarial training tradeoff parameter, λ1, was evaluated using three values: 0.3, 0.5 and 0.7. Based on the experimental results, 0.5 was identified as the optimal value in most cases, achieving an effective balance between accuracy and privacy. Similarly, the channel pruning tradeoff parameter, λ2, was tested with four values: 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001, and 0.00001. Consequently, 0.0001, and 0.001 were chosen for ResNet18 model and EfficientNet-B0 model, respectively, providing the best utility-privacy tradeoff across both datasets.

The attribute inference attack model was trained and tested using the original test subsets of FairFace, CelebA, and CIFAR-10. Specifically, 70% of each dataset was designated for training, while the remaining 30% was utilized for testing. Table 4 provides an outline of the hyperparameter configurations applied to both the proposed CPAT approach and the attack model.

In the following, we present the empirical findings that showcased CPAT effectiveness in obfuscating sensitive data within a typical split learning framework. In particular, we conducted a thorough analysis of the privacy and utility implications of the proposed channel pruning-based adversarial training using benchmark datasets. Moreover, we compared the results obtained using CPAT with those achieved by relevant state-of-the-art techniques. Furthermore, we investigated various factors that affect the model’s performance including the position of the split point, the pruning ratio, the correlation between task and private attributes, and the architecture of the considered attacks. Finally, we evaluated the testing time performance of various defense approaches, as well as the computational cost and model size of the proposed CPAT approach. Further details on all experiments are provided in the following subsections.

4.1 Robustness against Attribute Inference Attacks

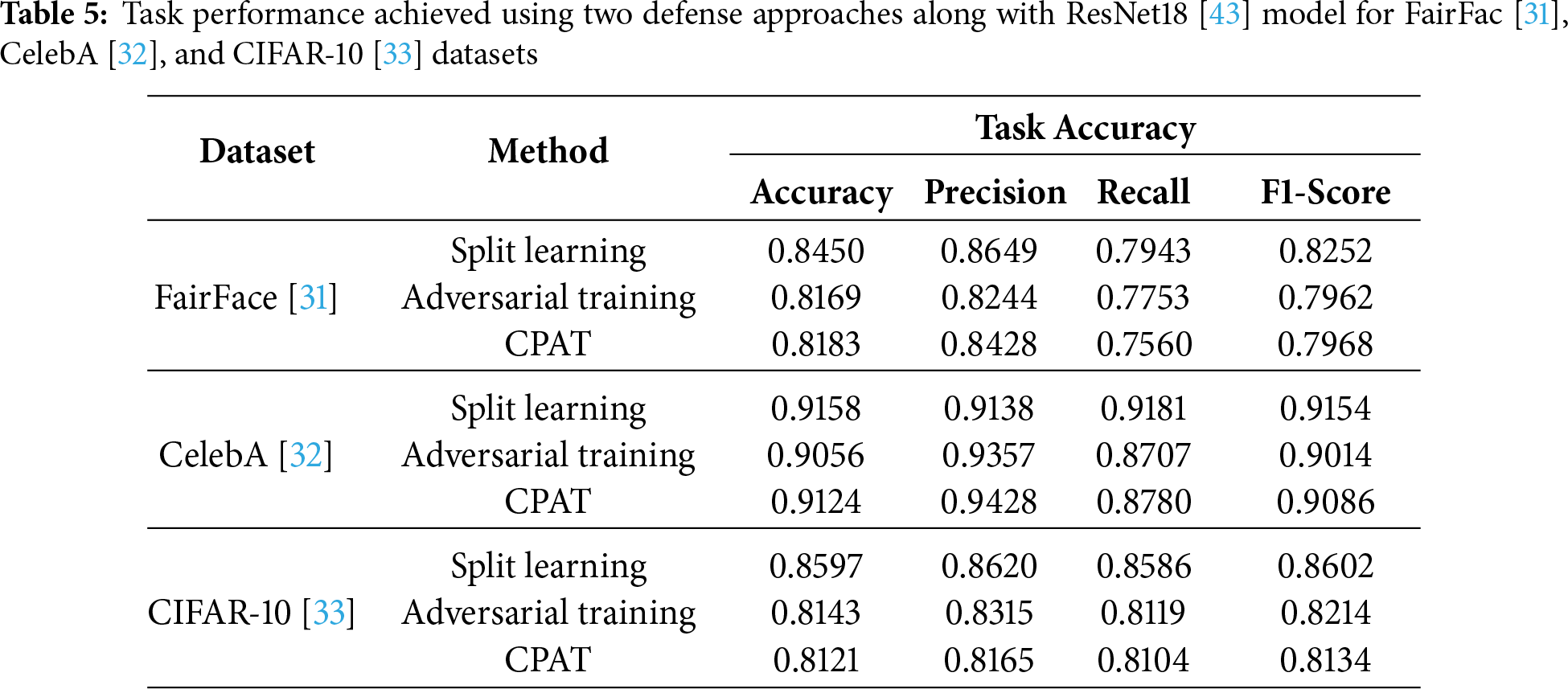

This experiment investigates the model’s performance and the robustness of three different approaches against attribute inference attacks. Namely, these approaches are split learning, adversarial training, and adversarial training with channel pruning. The main objective of these use cases is to demonstrate the effectiveness and privacy implications of integrating two defense techniques within the SL framework. Specifically, a proxy-adversary model was initially employed to perform adversarial training throughout the training process. Then, the channel pruning was incorporated into this adversarial training process. Table 5 shows the task performance achieved by the three approaches using ResNet18 [43] model along with FairFac [31], CelebA [32], and CIFAR-10 [33] datasets.

As it can be seen, the baseline split learning approach yielded high scores across all metrics using FairFace [31]. Precisely, it achieved an accuracy of 84%, a precision of 86%, a recall of 79%, and an F1-score of 82%. On the other hand, the performance of adversarial training and CPAT slightly declined, achieving an accuracy of approximately 81% and an F1-score of around 80%. Similarly, as reported in Table 5, the split learning approach achieved consistently high scores, of approximately 91%, for CelebA [32] dataset with respect to all metrics. Moreover, both adversarial training and CPAT maintained the accuracy level at 91%, with an increase in precision which attained 94%. For the CIFAR-10 [33] dataset, split learning achieved an accuracy of 85%, while adversarial training and CPAT observed a minor decline of about 4%. Overall, the proposed CPAT preserved the task performance at acceptable levels for all datasets.

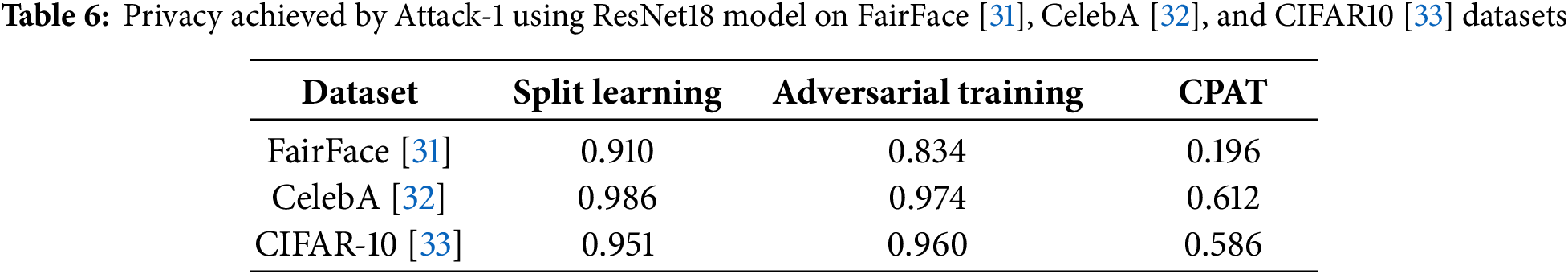

Moreover, Table 6 depicts the accuracy of the attribute inference attacks (Attack-1) in classifying the private attribute given the intermediate data transmitted by the client during the inference process. As one can see, for split learning, the attacker was able to infer the private attribute with remarkably high accuracy, exceeding 90% for all datasets. This result highlights the vulnerability of the transmitted intermediate data to attribute inference attacks, underscoring the critical need for implementing privacy-preservation techniques within split learning frameworks. Besides, the adversarial training enhanced slightly the privacy of intermediate data in such a framework. Specifically, the privacy accuracy decreased by 7% and 1% for FairFace [31] and CelebA [32] datasets, respectively. On the other hand, the proposed CPAT approach yielded significantly better privacy. For FairFace [31] dataset, the privacy accuracy decreased by approximately 70%, while it dropped by around 37% for the CelebA [32] and CIFAR-10 [33] datasets.

This demonstrates that optimizing the scale factor during CPAT training phase leads to an effective identification of the least significant channels. Furthermore, combining adversarial training with channel pruning during the training process reinforces privacy by obfuscating the private attribute in the intermediate data without impacting the model’s overall performance. Accordingly, one can claim that the proposed approach improves resilience to attribute inference attacks and exhibits a better privacy-utility trade-off.

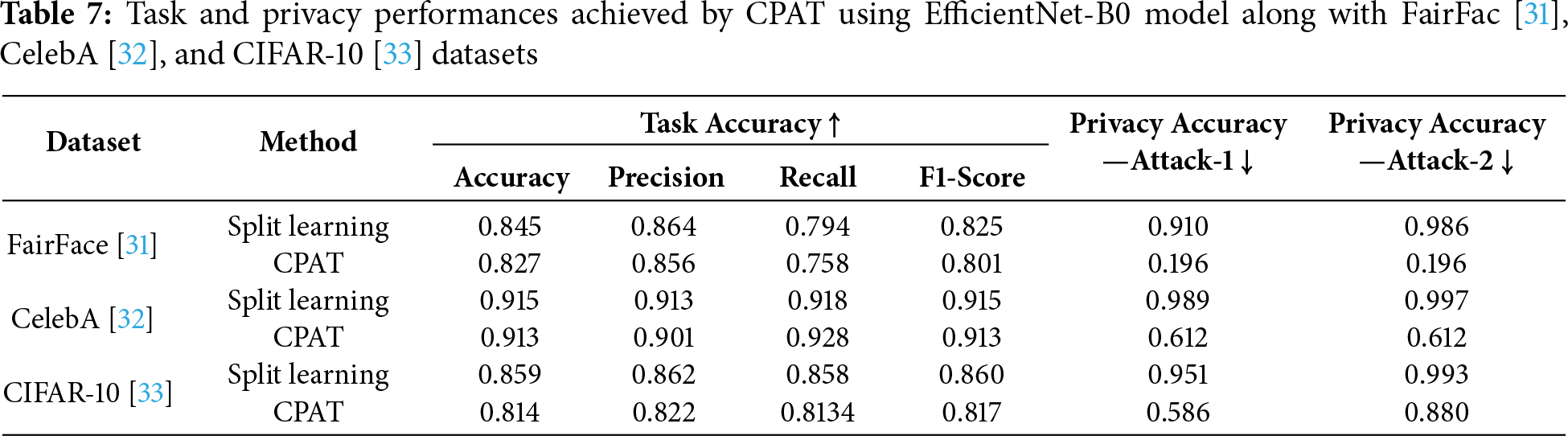

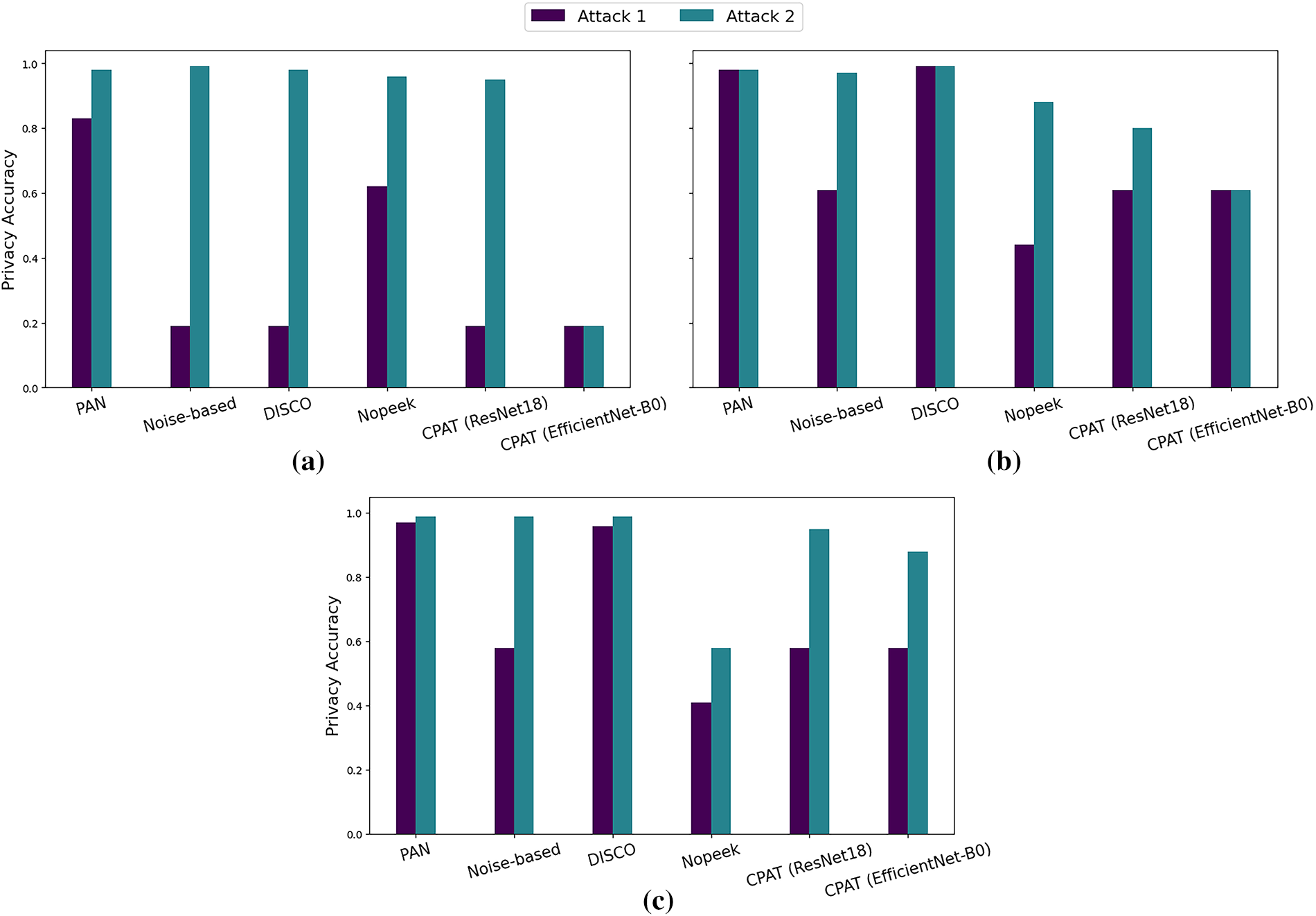

In the next experiment, we investigated the integration of the lightweight EfficientNet-B0 [34] model into CPAT. This experiment was conducted on both attack scenarios using FairFac [31], CelebA [32], and CIFAR-10 [33] datasets. As detailed in Table 7, CPAT task performance decreased slightly, by 2% for FairFace [27] dataset. Despite this minor reduction, CPAT achieved significantly better privacy compared with the baseline approach. Notably, for FairFace [31] dataset, the privacy accuracy decreased by 70% for both Attack-1 and Attack-2 scenarios. One should note that for the Attack-2 scenario, the attacker gains an advantage by leveraging knowledge of the client model’s learning rate, which enhances considerably its ability to infer the private attribute. In fact, the privacy accuracy for Attack-2 reached 98% using the baseline split learning approach. Consistently, the proposed CPAT demonstrated substantial resilience against attribute inference attacks on the CelebA [32] dataset. Specifically, the privacy accuracy dropped by 37% for both attack scenarios without compromising the model’s performance. Similarly, when applying the CPAT approach to the CIFAR-10 [33] dataset, the privacy accuracy decreased by 38% and 11% for Attack-1 and Attack-2, respectively.

These results highlight the effectiveness of the CPAT approach, even when the adversary has access to the client model’s learning rate. The identification and removal of the least significant channels resulted in strong obfuscation of private data. Furthermore, integrating lightweight models with CPAT proved effective, successfully defending against attribute inference attacks while maintaining task accuracy.

4.2 Comparison with Relevant State-of-the-Art Methods

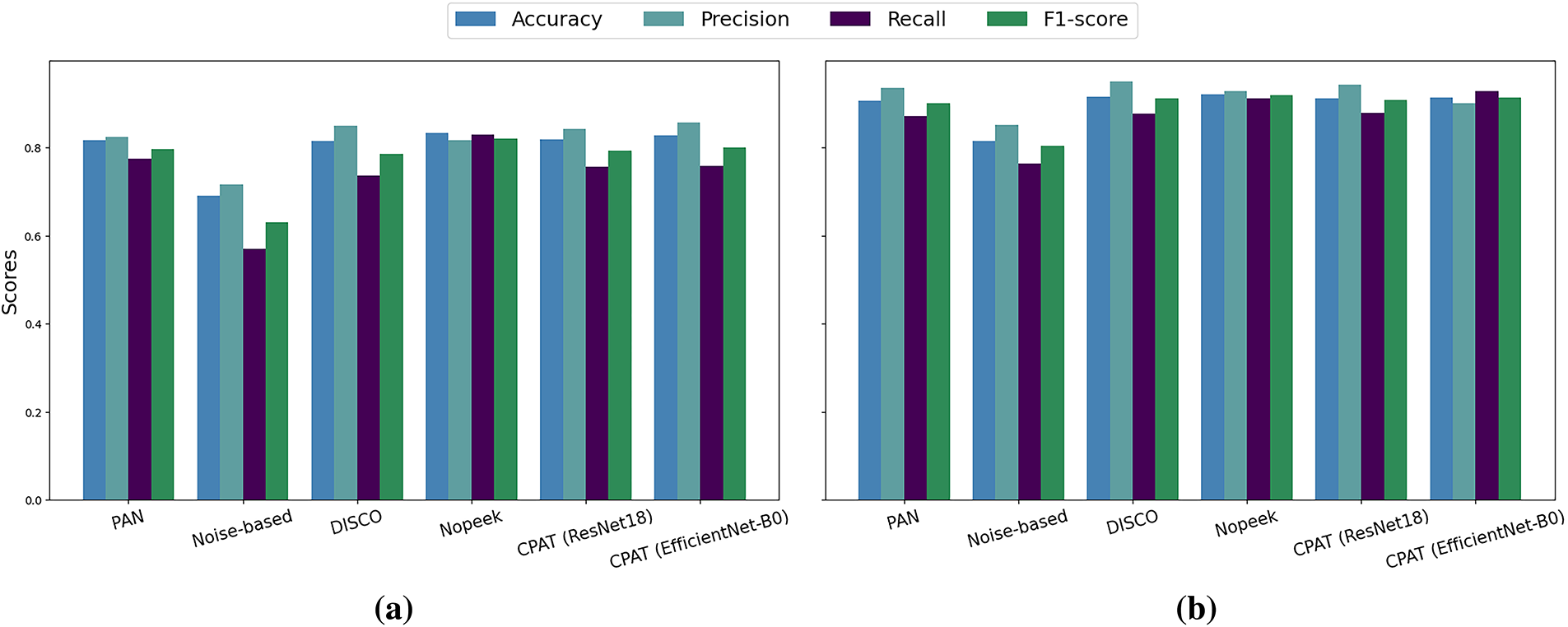

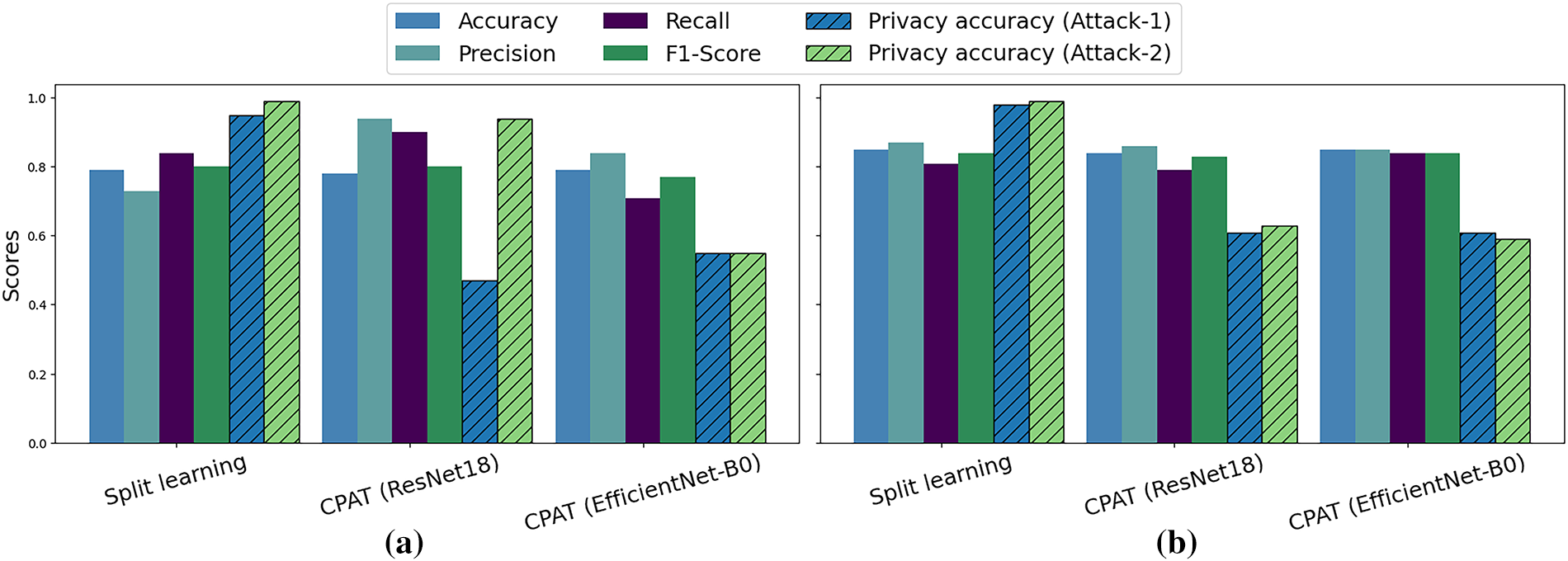

In this section, we compare the performance of the proposed CPAT approach with four relevant defense methods. Namely, PAN [25], Noise-based [46], DISCO [26], and Nopeek [47] were used in this experiment. One should note that these defense methods are also based on ResNet18 [43] model. This ensures a fair and objective comparison of the different approaches. As presented in the previous section, the task accuracy of the baseline-split learning-approach reached 84%, 91%, and 85% for FairFac [31], CelebA [32], and CIFAR-10 [33] datasets, respectively. Fig. 3 demonstrates that PAN [25], DISCO [26], Nopeek [47], and CPAT maintained the task performance at satisfactory levels for all datasets. Specifically, in Fig. 3a, the task accuracy ranged between 81%–83%, while the F1-score was approximately 80% for FairFace [31] dataset. For the CIFAR-10 [33] dataset, the accuracy and F1-score ranged between 81% and 85%. On the other hand, both accuracy and F1-score were maintained at around 90% for CelebA [32] dataset. Conversely, the Noise-based [46] technique yielded a considerable reduction in task performance for all datasets. For instance, the task accuracy decreased to 69% for FairFace [31] dataset, 81% for CelebA [32] dataset, and 46% for CIFAR-10 [29] dataset. Moreover, the F1-score dropped to 62%, 80%, and 48% for FairFac [31], CelebA [32], and CIFAR-10 [33] datasets, respectively.

Figure 3: Task performance achieved by the considered defense approaches using (a) FairFace [31], (b) CelebA [32], and (c) CIFAR-10 [33] datasets

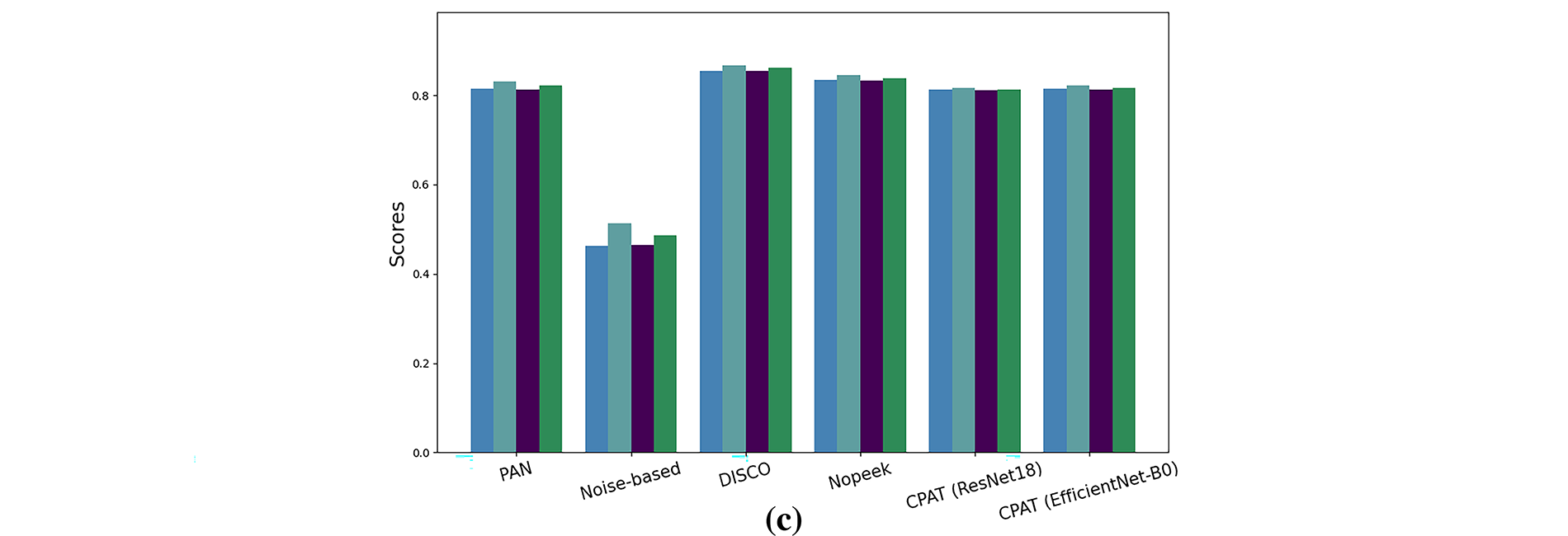

Furthermore, we assessed the effectiveness of all defense approaches in obfuscating the private attribute during the inference phase of the split learning framework. The evaluation was conducted for both attribute inference attack scenarios: Attack-1 and Attack-2. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, PAN [25] and Nopeek [47] moderately improved data privacy against Attack-1 on the FairFace [31] dataset, reducing the privacy accuracy to 83% and 62%, respectively. In contrast, the Noise-based [46] approach, DISCO [26], and the proposed CPAT enhanced significantly data privacy which dropped to approximately 20%. One should note that although the Noise-based [46] approach succeeded in obfuscating the private attribute in the intermediate data, its task accuracy was drastically affected. For Attack-2 scenario, all defense approaches, except CPAT, exhibited high vulnerability to attribute inference attacks, with an accuracy exceeding 90%. In contrast, the proposed approach with EffiecientNet-B0 model demonstrated superior resistance to such attacks. In fact, it maintained the privacy score at approximately 20%, even when attackers had access to the learning rate of the client model.

Figure 4: Privacy accuracy recorded for the attribute inference attacks using five defense approaches on: (a) FairFace [31], (b) CelebA [32], and (c) CIFAR10 [33] datasets

Besides, Fig. 4b depicts the privacy accuracy results obtained by attribute inference attacks on the CelebA [32] dataset. As it can be seen, both attacks were able to infer easily private attributes from intermediate data generated by PAN [25] and DISCO [26] approaches. Additionally, the Noise-based approach [46] and Nopeek [47] considerably perturbed the intermediate data transmitted by the client model in the Attack-1 scenario. However, under more advanced attacks, such as Attack-2, both approaches were unable to obfuscate the private attribute. Particularly, privacy accuracy reached approximately 95% and 88% for Noise-based [46] and Nopeek [47] approaches, respectively. In contrast, the proposed CPAT approach using EffiecientNet-B0 model yielded superior privacy preservation, even when the attacker had access to the client model’s learning rate. Specifically, the classification accuracy for the private attribute in Attack-1 and Attack-2 scenarios dropped to 61%.

For the CIFAR-10 [33] dataset, both the PAN [25] and DISCO [26] defense strategies showed that the attacker could infer the private attribute with high accuracy, reaching 99% for both attack scenarios. On the other hand, the Noise-based [46] defense improved privacy by reducing the privacy accuracy to 58% when defending against Attack-1 as illustrated in Fig. 4c. However, when the attacker knew the learning rate of the client model, the accuracy reached 99%, demonstrating the vulnerability of the Noise-based strategy to Attack-2. In contrast, the Nopeek [47] defense successfully prevented the inference of the private attribute, with privacy accuracy values of 40% and 58% for Attack-1 and Attack-2, respectively. Additionally, the CPAT approach using ResNet18 and EfficientNet-B0 models reduced the privacy accuracy to 58% for Attack-1. However, for Attack-2, the privacy accuracy dropped to 95% and 88% for ResNet18 and EfficientNet-B0, respectively.

These findings indicate that by integrating adversarial training with channel pruning throughout the training process, CPAT reduced the informativeness of intermediate data transmitted between client and server sub-models. This made the model less vulnerable to attribute inference attacks, thereby strengthening privacy within the considered split learning framework.

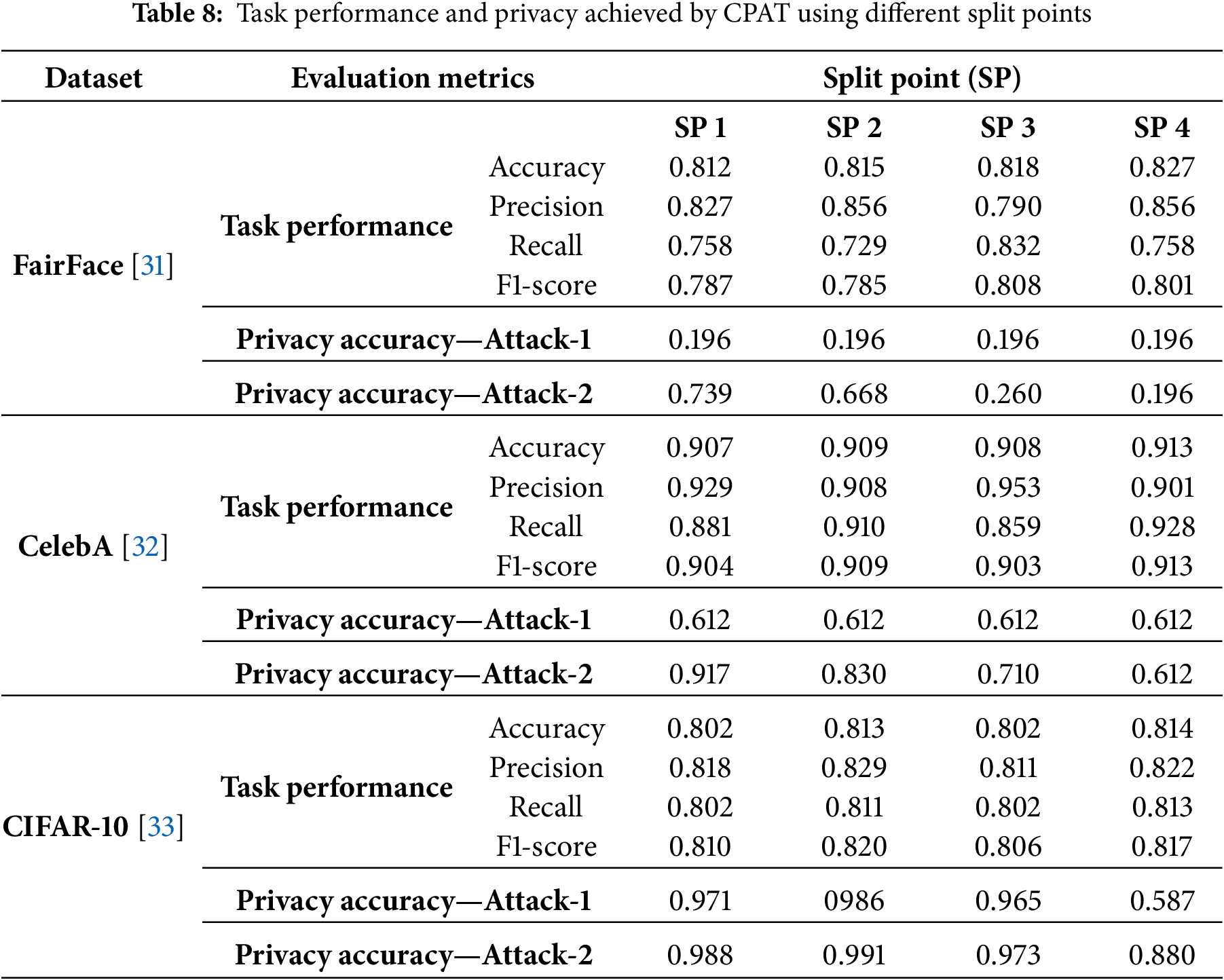

In this experiment, we investigated four different split points for the considered EfficientNet-B0 [34] model. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the network was partitioned at distinct levels to study the impact of each candidate split point. The obtained results are presented in Table 8. As it can be seen, the proposed CPAT approach maintained an acceptable task performance using different split points for FairFac [31], CelebA [32], and CIFAR-10 [33] datasets. The key idea of preserving the task performance lies in selecting appropriate channel pruning ratios for the client and server sub-models. Additionally, for Attack-1 scenario, CPAT yielded superior and consistent resistance to attribute inference attacks. In particular, the attacker accuracy in inferring the private attribute at different split points did not exceed 20% and 60% for FairFace [27] and CelebA [28] datasets, respectively.

Figure 5: Split points associated with EfficientNet-B0 architecture. Adapted from reference [48]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. Licensed under CC BY 4.0

Conversely, defending against a stronger attack where the attacker knows the client’s learning rate, such as Attack-2, proved to be more challenging. The results demonstrate that the privacy accuracy of attribute inference attacks decreased significantly when deeper split points were employed. Specifically, for FairFace [31] dataset, the attacker inferred the private attribute with an accuracy of 73% when Split 1 configuration was adopted. On the other hand, the accuracy dropped to 20% for the Split 4 scenario. Similarly, the privacy accuracy reached 91% when CelebA [32] dataset was associated with Split 1 setting. However, it decreased to 61% for Split 4 with the same dataset. Moreover, for the CIFAR-10 [33] dataset, the attacker achieved 98% accuracy under Split 1, while declined to 88% in the Split 4 setting. This is attributed to the nature of machine learning models; as the layers become deeper, the relationship between input and output becomes increasingly complex.

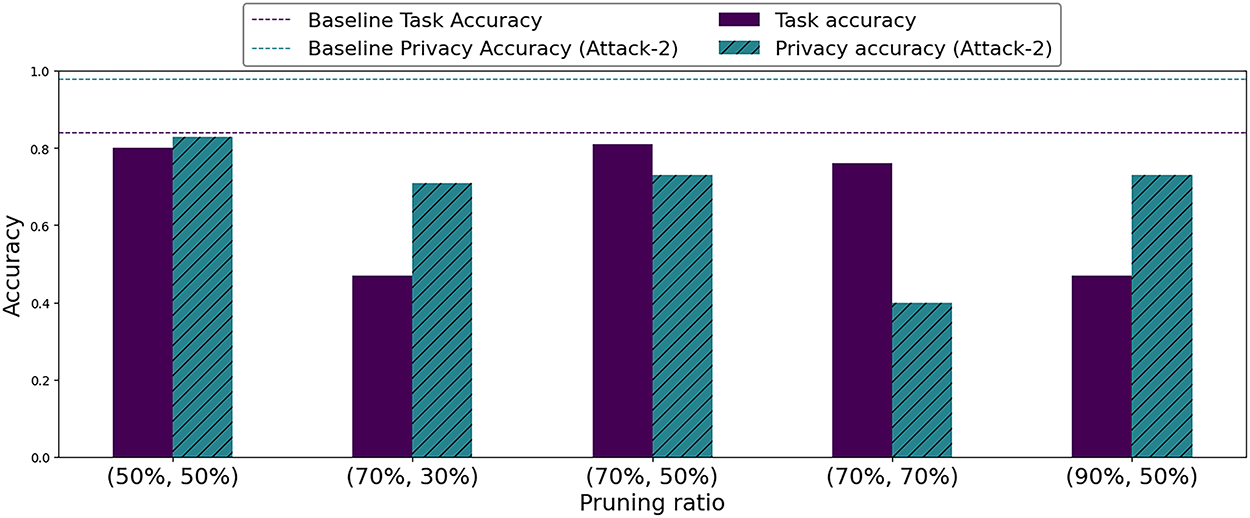

In addition, for Split point Split 1, we first set the pruning ratio to 50% for the server sub-model and evaluated various pruning ratios for the client sub-model. Specifically, we varied the ratio from 50% to 90%. As shown in Fig. 6, the pruning ratio of 50% yielded stable task accuracy. The recorded value remained around 81%. However, the attribute inference attack was able to classify the private attribute with an accuracy of 83%. Furthermore, the aggressive pruning ratio of 90% resulted in a significant decline in terms of task accuracy. It drastically decreased to approximately 50%. In contrast, applying a pruning ratio of 70% yielded the optimal balance between privacy and accuracy. The task accuracy remained at 81%, while the privacy accuracy dropped to 73%.

Figure 6: Task and privacy accuracies achieved by the proposed EfficientNet-B0-based approach using different pruning ratios (Pc%, Ps%) and FairFace [31] dataset

Next, we fixed the pruning ratio of the client sub-model to 70% because it yielded the best results. Moreover, we investigated different pruning ratios for the server sub-model, ranging from 30% to 70%. As it can be seen, using a pruning ratio of 70% to both sub-models, or a high pruning ratio to only one sub-model (70% vs. 30%), affected the model’s performance. Specifically, the task accuracy decreased from 84% to 76%. Consequently, setting the pruning ratios to 70% and 50% for both models mitigate the attribute inference without compromising the task performance.

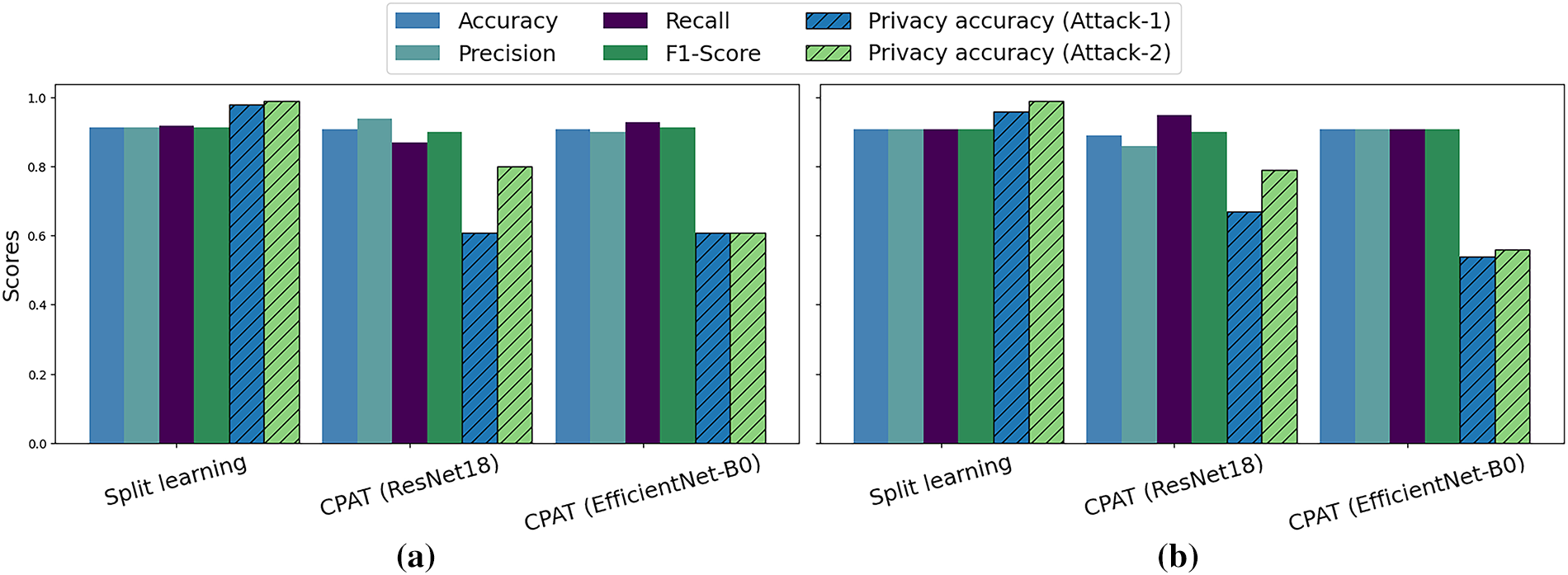

In the following, we consider two attributes spatially correlated when they depend on the same region of interest. For instance, “Smiling” and “Wearing Lipstick” are highly correlated attributes in CelebA [32] dataset. Fig. 7 demonstrates that the task performance achieved by CPAT remains consistently high across all models whether the task and privacy attributes are correlated or not. On the other hand, Split Learning exhibits significant privacy vulnerabilities, with both Attack-1 and Attack-2 with accuracy reaching approximately 100%. In contrast, combining the proposed CPAT with ResNet18 [43] model reduced the privacy accuracy from 99% to less than 80% while maintaining high task accuracy. Furthermore, associating EfficientNet-B0-based CPAT with Split 4 showcased an even better privacy protection, reducing the attack accuracies by 30% to 40%.

Figure 7: Task performance and privacy evaluation of: (a) Uncorrelated attributes; task attribute = Smiling, and private attribute = Male. (b) Correlated attributes; task attribute = Smiling, and private attribute = Wearing lipstick

Consistently, CPAT obfuscated effectively private attributes regardless of the selected task and private attributes. As shown in Fig. 8a, the task and private attributes were “Attractive” and “High cheekbones”, respectively. On the other hand, Fig. 8b sets the task attribute to “High cheekbones”, and the private attribute to “Male”. As it can be seen, the use of ResNet18 [43] model reduced notably the privacy accuracy, particularly in the Attack-1 scenario. Furthermore, deploying EfficientNet-B0 [34] model along with Split 4 configuration reduced the privacy accuracy to less than 60% for both attacks without compromising the model’s performance.

Figure 8: Task performance and privacy achieved when (a) The task attribute is “Attractive”, and the private attribute is “High cheekbones”. (b) The task attribute is “High cheekbones”, and the private attribute is “Male”

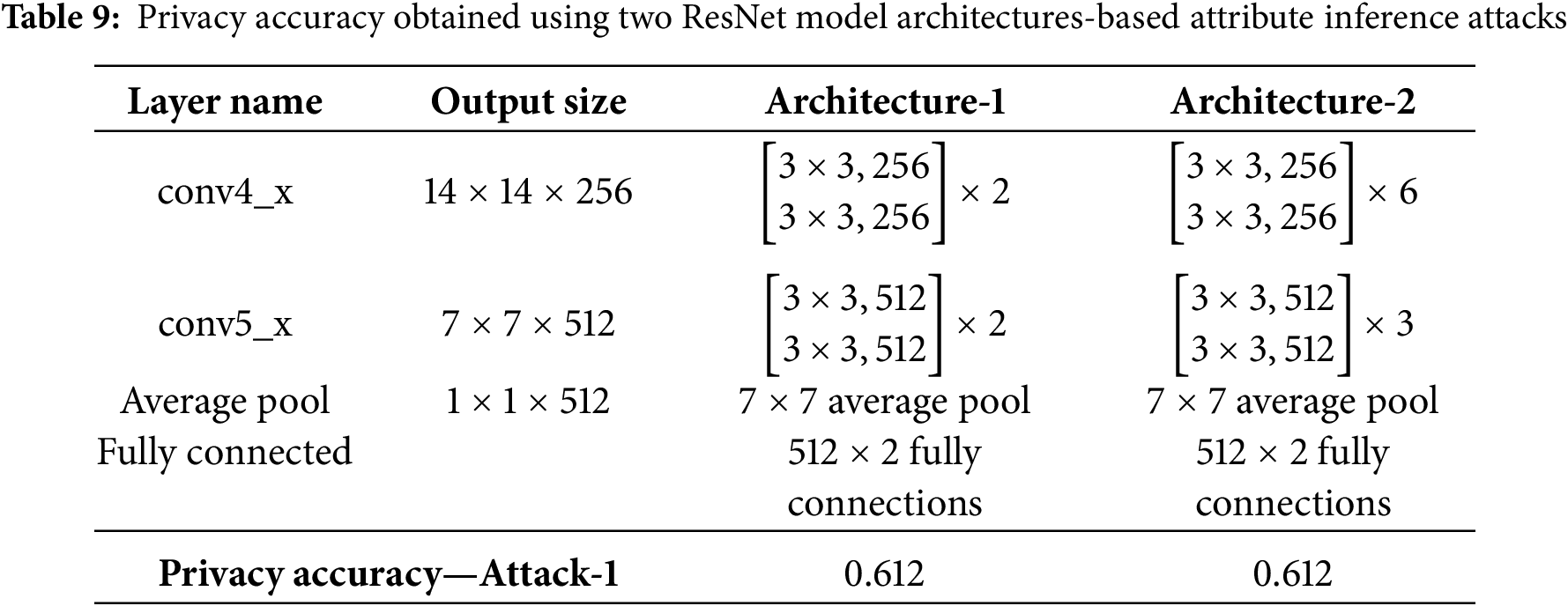

As further investigation, two architectures were selected for the attribute inference attacks. As detailed in Table 9, Architecture-1 corresponds to the second half of ResNet18 [43] model, while Architecture-2 corresponds to the second half of ResNet34 [43] model. One should note that Architecture-1 is the same architecture used as the proxy-adversary model for CPAT training. As one can see, even when the architecture for private inference attacks differs from the one used during training, the intermediate data transmitted by the client effectively obfuscates the private attribute. Specifically, the privacy accuracy of the attribute inference attacks using both architectures remained around 60% using CelebA [32] dataset.

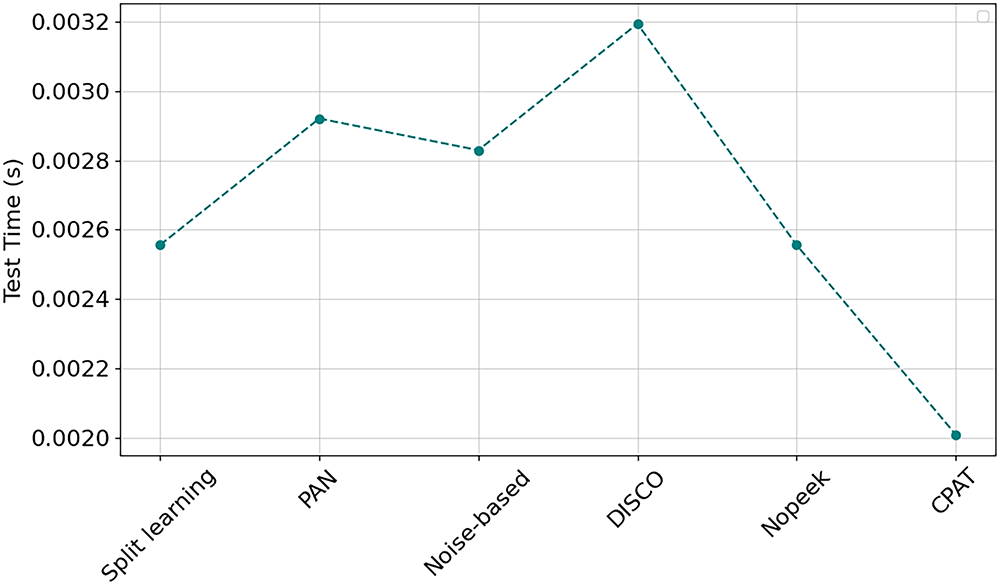

The computational efficiency of the defense approach is crucial for real-time applications and/or resource-constrained environments. Fig. 9 depicts the test time achieved by the baseline approach. Namely, Split Learning achieved a test time of 0.0025 s. Among the four defense approaches, DISCO [26] yielded the highest test time with an increase of 28%. This overhead is attributed to the additional Filter-Generating Network (FGN), which introduces extra forward computations during inference and consequently increases overall latency. Additionally, PAN [25] and Noise-based [46] approaches increased slightly the test time by less than 10%. Nopeek [47] maintained the baseline time of 0.0025 s. In contrast, CPAT significantly reduced the test time, achieving the lowest value at approximately 0.0020 s. This improvement can be attributed to the lightweight model, namely Efficient-Net-B0 [34] adopted in the proposed architecture.

Figure 9: Test time recorded for various defense techniques

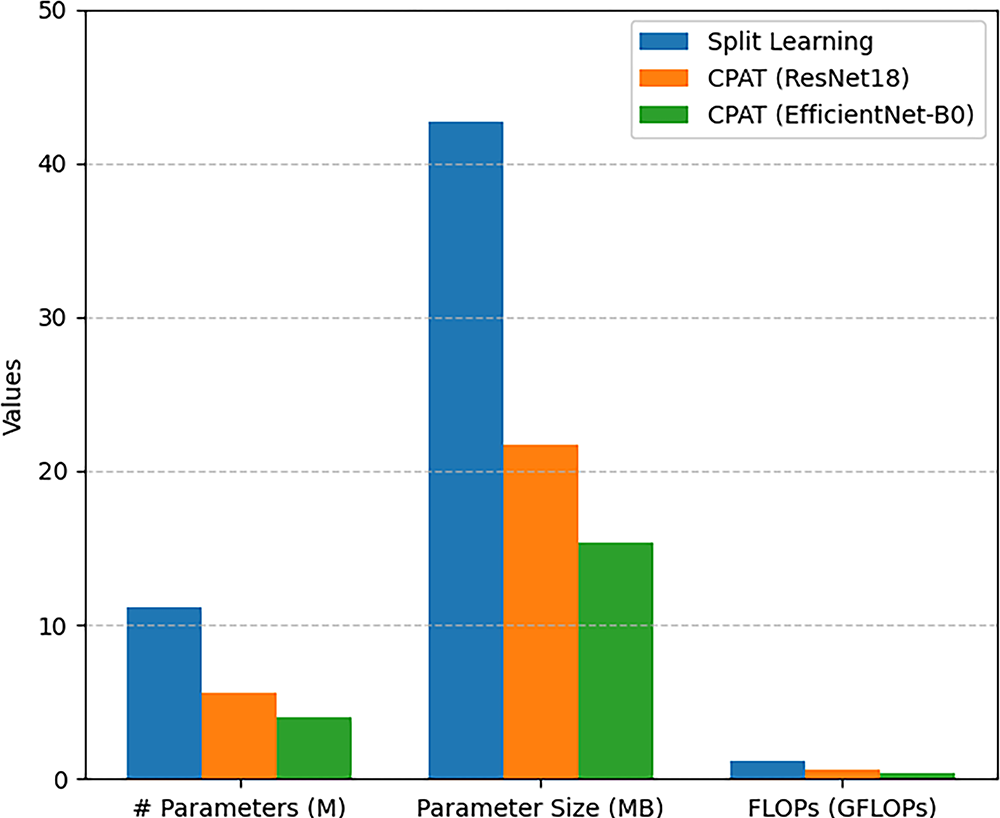

In the following, we compare the computational cost and model size between the baseline Split Learning model and the proposed CPAT approach, using the FairFace [31] dataset with ResNet18 [43], and EfficientNet-B0 [34] models. In particular, three key metrics were considered for this experiment. Namely, we used the total number of parameters measured in Millions (M), the parameter size measured in Megabytes (MB), and the computational cost quantified in Giga Floating Point Operations Per Second (GFLOPs) to assess the computational cost and size of the different models.

ResNet18 [43] contains a high number of parameters and computational operations, which can pose challenges for deployment in resource-constrained devices. Specifically, the Split Learning approach results in 11.17 million parameters and 2.08 GFLOPs, as shown in Fig. 10. In contrast, the CPAT approach achieves a significant reduction in both memory and computational demands. It reduces the number of parameters by approximately 49.8% (from 11.17 to 5.6M), the parameter size by around 49.0% (from 42.64 to 21.74 MB), and the FLOPs by about 48.3% (from 1.18 to 0.61 GFLOPs). Moreover, the CPAT approach was integrated with the lightweight EfficientNet-B0 [34] model, which contains 4M parameters, has a parameter size of 15.29 MB, and requires 0.38 GFLOPs for computation. These results highlight the efficiency of CPAT in terms of computation and memory usage, making it highly suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 10: Number of parameters and FLOPs for Split Learning and CPAT

In summary, choosing an adequate split point and pruning ratio is essential for balancing data privacy, task accuracy, and computational workload on the client side. Additionally, the findings of the experiments showcased CPAT’s generalization capability. In other words, CPAT succeeded in protecting intermediate data, regardless of the selected task and private attributes. In fact, the proposed adversarial learning approach, which relies particularly on channel pruning to eliminate the least significant channels, enhances the obfuscation of the private attributes while maintaining the model’s overall performance. Furthermore, CPAT demonstrated remarkable computational efficiency and suitability for resource-constrained environments.

Data privacy has become a critical concern for state-of-the-art Machine Learning (ML) approaches, as sensitive and private data is often involved in training the intended models. Recently, Split Learning (SL) has emerged as a promising solution by partitioning neural networks into client and server sub-nets. Despite its potential, SL remains vulnerable to various privacy threats, such as attribute inference attacks. In these attacks, adversaries attempt to infer sensitive attributes from the intermediate representations transmitted by the client sub-model. Existing defense approaches that address privacy concerns in SL face significant challenges, such as maintaining an effective tradeoff between utility and privacy, and minimizing computational overhead on resource-constrained edge devices. In order to tackle these challenges, we proposed the CPAT approach, which integrates adversarial training with channel pruning. The primary objective of this association was to reduce the informativeness of the intermediate data transmitted by the client, thereby limiting the adversary’s ability to infer private attributes. Particularly, adversarial learning reduced the risk of private data exposure while maintaining high performance on the utility task. Additionally, the proposed channel pruning conducted alongside the adversarial training, enabled the model to adaptively adjust and reactivate the pruned channels. The results demonstrated that the proposed approach succeeded in balancing privacy and utility for the considered SL framework. Furthermore, the proposed CPAT approach outperformed relevant state-of-the-art techniques by enhancing resilience against attribute inference attacks without compromising the model’s performance.

Future research could focus on developing a comprehensive CPAT framework capable of addressing multiple types of privacy attacks. In particular, extending this work to defend against data reconstruction, attribute inference, and feature hijacking attacks represents a promising direction for further study. This can be achieved by incorporating various proxy-adversary models and designing novel objective functions. Moreover, various architectures can be investigated for the proxy-adversary model to further evaluate the robustness of the CPAT approach across different machine learning models.

Acknowledgement: This research is supported by a grant (No. CRPG-25-2054) under the Cybersecurity Research and Innovation Pioneers Initiative, provided by the National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by a grant (No. CRPG-25-2054) under the Cybersecurity Research and Innovation Pioneers Initiative, provided by the National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: conceptualization: Afnan Alhindi, Saad Al-Ahmadi and Mohamed Maher Ben Ismail; methodology: Afnan Alhindi, Saad Al-Ahmadi and Mohamed Maher Ben Ismail; software: Afnan Alhindi; validation: Afnan Alhindi, Saad Al-Ahmadi and Mohamed Maher Ben Ismail; formal analysis: Afnan Alhindi, Saad Al-Ahmadi and Mohamed Maher Ben Ismail; investigation: Afnan Alhindi, Saad Al-Ahmadi and Mohamed Maher Ben Ismail; resources: Afnan Alhindi; data curation: Afnan Alhindi; writing and editing: Afnan Alhindi, Saad Al-Ahmadi and Mohamed Maher Ben Ismail. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jin D, Kannengießer N, Rank S, Sunyaev A. Collaborative distributed machine learning. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(4):1–36. doi:10.1145/3704807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu B, Ding M, Shaham S, Rahayu W, Farokhi F, Lin Z. When machine learning meets privacy: a survey and outlook. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;54(2):1–36. doi:10.1145/3436755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Madhivanan V, Mathivanan P. An evaluation on the performance of privacy preserving split neural networks using EMNIST dataset. In: Proceedings of the Deep Sciences for Computing and Communications; 2022 Mar 17–18; Chennai, India. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023. p. 332–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-27622-4_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gupta O, Raskar R. Distributed learning of deep neural network over multiple agents. J Netw Comput Appl. 2018;116(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2018.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ali Khowaja S, Khuwaja P, Dev K, Singh K, Nkenyereye L, Kilper D. ZETA: ZEro-trust attack framework with split learning for autonomous vehicles in 6G networks. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2024 Apr 21–24; Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/WCNC57260.2024.10571158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Iqbal A, Gope P, Sikdar B. Privacy-preserving collaborative split learning framework for smart grid load forecasting. arXiv:2403.01438. 2024. [Google Scholar]

7. Tran NP, Dao NN, Do QT, Nguyen TV, Cho S. Privacy-preserving traffic flow prediction: a split learning approach. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN); 2023 Jan 11–14; Bangkok, Thailand. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 248–50. doi:10.1109/ICOIN56518.2023.10048996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang R, Qu Y, Zhu X, Zheng J, Dong C. Mutil-UAV collaborative split learning for frequency-hopping sequence prediction. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Mediterranean Conference on Communications and Networking (MeditCom); 2025 Jul 7–10; Nice, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 53–8. doi:10.1109/MeditCom64437.2025.11104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang W, Han H, Zhang Y, Mu J. Federated split learning for sequential data in satellite–terrestrial integrated networks. Inf Fusion. 2024;103(1):102141. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Luo M, Luo Y, Wan Y, Wang Z. Secure and efficient access control scheme for wireless sensor networks in the cross-domain context of the IoT. Secur Commun Netw. 2018;2018(1):1–10. doi:10.1155/2018/6140978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ayad A, Renner M, Schmeink A. Improving the communication and computation efficiency of split learning for IoT applications. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM); 2021 Dec 7–11; Madrid, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM46510.2021.9685493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yao J. Split learning for image classification in Internet of drones networks. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 24th International Conference on High Performance Switching and Routing (HPSR); 2023 Jun 5–7; Albuquerque, NM, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 52–5. doi:10.1109/HPSR57248.2023.10147979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mireshghallah F, Taram M, Vepakomma P, Singh A, Raskar R, Esmaeilzadeh H. Privacy in deep learning: a survey. arXiv:2004.12254. 2020. [Google Scholar]

14. Pasquini D, Ateniese G, Bernaschi M. Unleashing the tiger: inference attacks on split learning. arXiv:2012.02670. 2020. [Google Scholar]

15. Alhindi A, Al-Ahmadi S, Ben Ismail MM. Advancements and challenges in privacy-preserving split learning: experimental findings and future directions. Int J Inf Secur. 2025;24(3):125. doi:10.1007/s10207-025-01045-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kokaj A, Mollakuqe E. Mathematical proposal for securing split learning using homomorphic encryption and zero-knowledge proofs. Appl Sci. 2025;15(6):2913. doi:10.3390/app15062913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen X, Wang F, Li Y, Yao M, Guo Y. The homomorphic encryption scheme combines split learning to perform privacy protection training on two-dimensional data. Second Int Conf Comput Mach Learn Data Sci. 2025;13730:109–22. doi:10.1117/12.3072380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pereteanu GL, Alansary A, Passerat-Palmbach J. Split HE: fast secure inference combining split learning and homomorphic encryption. arXiv:2202.13351. 2022. [Google Scholar]

19. Khan T, Nguyen K, Michalas A, Bakas A. Love or hate? Share or split? Privacy-preserving training using split learning and homomorphic encryption. In: Proceedings of the 2023 20th Annual International Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST); 2023 Aug 21–23; Copenhagen, Denmark. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/PST58708.2023.10320153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ali Osia S, Taheri A, Shamsabadi AS, Katevas K, Haddadi H, Rabiee HR. Deep private-feature extraction. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2020;32(1):54–66. doi:10.1109/tkde.2018.2878698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gao R, Yang H, Huang S, Dun M, Li M, Luan Z, et al. PriPro: towards effective privacy protection on edge-cloud system running DNN inference. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 21st International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing (CCGrid); 2021 May 10–13; Melbourne, Australia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 334–43. doi:10.1109/ccgrid51090.2021.00043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mireshghallah F, Taram M, Jalali A, Elthakeb ATT, Tullsen D, Esmaeilzadeh H. Not all features are equal: discovering essential features for preserving prediction privacy. In: Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021; 2021 Apr 19–23; Ljubljana, Slovenia. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 669–80. doi:10.1145/3442381.3449965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mao Y, Xin Z, Li Z, Hong J, Yang Q, Zhong S. Secure split learning against property inference, data reconstruction, and feature space hijacking attacks. arXiv:2304.09515. 2023. [Google Scholar]

24. Abuadbba S, Kim K, Kim M, Thapa C, Camtepe SA, Gao Y, et al. Can we use split learning on 1D CNN models for privacy preserving training? arXiv. arXiv:2003.12365. [Google Scholar]

25. Liu S, Du J, Shrivastava A, Zhong L. Privacy adversarial network: representation learning for mobile data privacy. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2019;3(4):1–18. doi:10.1145/3369816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Singh A, Chopra A, Garza E, Zhang E, Vepakomma P, Sharma V, et al. DISCO: dynamic and invariant sensitive channel obfuscation for deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 12120–30. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jeong J, Cho M, Benz P, Hwang J, Kim J, Lee S, et al. Privacy safe representation learning via frequency filtering encoder. arXiv:2208.02482. 2022. [Google Scholar]

28. Liu Z, Li J, Shen Z, Huang G, Yan S, Zhang C. Learning efficient convolutional networks through network slimming. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 2755–63. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. McMahan HB, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BAY. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. arXiv:1602.05629. 2016. [Google Scholar]

30. Alhindi A, Al-Ahmadi S, Maher Ben Ismail M. Balancing privacy and utility in split learning: an adversarial channel pruning-based approach. IEEE Access. 2025;13:10094–110. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3528575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. FairFace dataset 2024 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://github.com/dchen236/FairFace. [Google Scholar]

32. Large-scale celebfaces attributes (CelebA) dataset 2024. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://mmlab.ie.cuhk.edu.hk/projects/CelebA.html. [Google Scholar]

33. The CIFAR dataset 2023 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html. [Google Scholar]

34. Tan M, Le Q. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 36 th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. Long Beach, CA, USA: ICML; 2019. p. 6105–14. [Google Scholar]

35. Khan T, Budzys M, Michalas A. Make split, not hijack: preventing feature-space hijacking attacks in split learning. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM Symposium on Access Control Models and Technologies; 2024 May 15–17; San Antonio, TX, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 19–30. doi:10.1145/3649158.3657039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chen S, Khisti A. SECO: secure inference with model splitting across multi-server hierarchy. arXiv:2404.16232. 2024. [Google Scholar]

37. Mireshghallah F, Taram M, Ramrakhyani P, Jalali A, Tullsen D, Esmaeilzadeh H. Shredder: learning noise distributions to protect inference privacy. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems; 2020 Mar 16–20; Lausanne, Switzerland. Piscataway, NJ, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 3–18. doi:10.1145/3373376.3378522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li A, Guo J, Yang H, Salim FD, Chen Y. DeepObfuscator: obfuscating intermediate representations with privacy-preserving adversarial learning on smartphones. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation; 2021 May 18–21; Charlottesvle, VA, USA. doi:10.1145/3450268.3453519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Roy PC, Boddeti VN. Mitigating information leakage in image representations: a maximum entropy approach. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 2581–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Alnasser W, Beigi G, Mosallanezhad A, Liu H. PPSL: privacy-preserving text classification for split learning. In: Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Data Intelligence and Security (ICDIS); 2022 Aug 24–26; Shenzhen, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 160–7. doi:10.1109/ICDIS55630.2022.00032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Du W, Li A, Zhou P, Niu B, Wu D. PrivacyEye: a privacy-preserving and computationally efficient deep learning-based mobile video analytics system. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2022;21(9):3263–79. doi:10.1109/TMC.2021.3050458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Higgins G, Razavi-Far R, Zhang X, David A, Ghorbani A, Ge T. Towards privacy-preserving split learning: destabilizing adversarial inference and reconstruction attacks in the cloud. Internet Things. 2025;31:101558. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2025.101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Rahmani AM, Yousefpoor E, Yousefpoor MS, Mehmood Z, Haider A, Hosseinzadeh M, et al. Machine learning (ML) in medicine: review, applications, and challenges. Mathematics. 2021;9(22):2970. doi:10.3390/math9222970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Pytorch framework 2024 [Online]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://pytorch.org/. [Google Scholar]

46. Titcombe T, Hall AJ, Papadopoulos P, Romanini D. Practical defences against model inversion attacks for split neural networks. arXiv:2104.05743. 2021. [Google Scholar]

47. Vepakomma P, Singh A, Gupta O, Raskar R. NoPeek: information leakage reduction to share activations in distributed deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW); 2020 Nov 17–20; Sorrento, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 933–42. doi:10.1109/ICDMW51313.2020.00134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhou A, Ma Y, Ji W, Zong M, Yang P, Wu M, et al. Multi-head attention-based two-stream EfficientNet for action recognition. In: Multimedia Systems; Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 487–98. doi:10.1007/s00530-022-00961-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools