Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CamSimXR: eXtended Reality (XR) Based Pre-Visualization and Simulation for Optimal Placement of Heterogeneous Cameras

1 Department of Electrical, Electronic and Computer Engineering, University of Ulsan, Ulsan, 44610, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Mathematical Data Science, Hanyang University ERICA, Ansan, 15588, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Dongsik Jo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Extended Reality (XR) and Human-Computer Interaction)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 83 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072664

Received 01 September 2025; Accepted 29 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In recent years, three-dimensional reconstruction technologies that employ multiple cameras have continued to evolve significantly, enabling remote collaboration among users in extended Reality (XR) environments. In addition, methods for deploying multiple cameras for motion capture of users (e.g., performers) are widely used in computer graphics. As the need to minimize and optimize the number of cameras grows to reduce costs, various technologies and research approaches focused on Optimal Camera Placement (OCP) are continually being proposed. However, as most existing studies assume homogeneous camera setups, there is a growing demand for studies on heterogeneous camera setups. For instance, technical demands keep emerging in scenarios with minimal camera configurations, especially regarding cost factors, the physical placement of cameras given the spatial structure, and image capture strategies for heterogeneous cameras, such as high-resolution RGB cameras and depth cameras. In this study, we propose a pre-visualization and simulation method for the optimal placement of heterogeneous cameras in XR environments, accounting for both the specifications of heterogeneous cameras (e.g., field of view) and the physical configuration (e.g., wall configuration) in real-world spaces. The proposed method performs a visibility analysis of cameras by considering each camera’s field-of-view volume, resolution, and unique characteristics, along with physical-space constraints. This approach enables the optimal position and rotation of each camera to be recommended, along with the minimum number of cameras required. In the results of our study conducted in heterogeneous camera combinations, the proposed method achieved 81.7%~82.7% coverage of the target visual information using only 2~3 cameras. In contrast, single (or homogeneous)-typed cameras were required to use 11 cameras for 81.6% coverage. Accordingly, we found that camera deployment resources can be reduced with the proposed approaches.Keywords

By leveraging eXtended Reality (XR) technologies, remote participants can experience real-time interaction within a shared immersive space [1]. In XR-based remote collaboration scenarios, a main aim is to effectively acquire and transmit information from the physical space, where recent studies increasingly employ point clouds for 3D reconstruction research [2]. For example, a flexible multi-camera system has been proposed to integrate multi-view images into a coherent 3D XR space to support workspace awareness [3]. However, such technologies often require substantial effort in pre-visualization and camera setup, as one must account for real-world spatial constraints and camera specifications (e.g., field of view). In addition, optimization is often required to determine the minimum or optimal number of cameras and the position/rotation ranges for each camera, while avoiding occlusion by obstacles [4,5]. From this perspective, recent research has begun using simulated XR environments, where an iterative trial-and-error process in the virtual space allows researchers or users to validate camera setups in the real world, ultimately maximizing scene coverage with an optimized number of cameras [6]. Despite these advancements, most studies have focused on optimizing the number and positions of homogeneous cameras, whereas an increasing number of studies have recently explored heterogeneous camera-based systems. In such systems, optimization problems should be reformulated to account for the differences in field of view, coverage ranges, and resolution across different cameras [7]. For example, while Microsoft’s Holoportation system provides a shared remote experience via a set of stereo cameras installed around an indoor space, it is quite challenging to configure a heterogeneous setup composed of cameras at different locations [8]. Thus, a significant verification effort is required in advance to ensure the minimum number of heterogeneous cameras is installed, thereby reducing installation costs.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a method to determine optimal camera placement for pre-visualization and simulation methodology in XR environments that considers the specific characteristics of heterogeneous cameras and the physical-space constraints. Based on camera parameters inputs such as field of view, effective range, and resolution, the proposed approach visualizes obstacle information from the physical space and determines the installation positions and rotations of each camera. At the same time, several simulations are run to empirically determine the minimum number of cameras required to maintain maximum visibility within a given space. Furthermore, the proposed optimal placement method of our study extends existing homogeneous camera placement approaches into heterogeneous sensor scenarios. The results of the proposed study demonstrate that optimal placement using heterogeneous cameras can use fewer cameras than existing homogeneous-camera methods. The proposed method also effectively identifies unnecessary redundant image captures and blind spots, effectively reducing the number of cameras in use. In summary, the camera-optimal placement method proposed in this study for XR environments facilitates relatively cost-effective, high-precision spatial capture, enabling installations under limited-resource conditions.

The contributions of this paper can be outlined as below:

• Pre-visualization and simulation for optimal placement of heterogeneous cameras: Achieves optimal camera placements by considering effective image capture (without occlusion) for individual camera performance with optimal positions and rotations.

• Optimizing for the minimal number of cameras: Introducing an algorithm for the deployment of a minimal number of cameras within the constraints of real physical space. The method optimizes visual coverage by considering feasible camera placements and the cameras’ actual field-of-view constraints.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related studies on scene capture and remote XR environments using multiple cameras. Section 3 elaborates on the proposed methodology for optimal heterogeneous camera placement. Section 4 details the experimental setup and evaluation findings, while Section 5 discusses the implications and limitations of the proposed methodology.

In XR-based remote collaboration and real-time spatial information-sharing systems, multi-camera systems and optimized sensor arrangements are commonly employed to effectively capture and transmit data about physical space [1,6]. In particular, an increasing number of studies focus on providing users with both immersion and accurate visual perspectives within XR environments, which, in turn, has sparked significant research attention on optimal camera placement [2]. Earlier works have examined which fields of view should be provided from different viewpoints using multiple cameras, as well as which types of cameras should be deployed at which points to achieve the most effective outcomes. More recently, researchers have become interested in heterogeneous camera configurations that combine different camera types (e.g., RGB, depth, PTZ) with varying performance levels and installation constraints [3]. Moreover, the challenge of camera placement has long been studied in domains such as environmental surveillance systems and motion capture [4]. Building on this background, this section reviews prior studies in the following order: (1) capture systems employing multiple cameras, (2) multi-camera-based reconstruction systems for remote XR environments, (3) studies on the use of heterogeneous cameras, and (4) Optimal Camera Placement (OCP) algorithms leveraging mathematical optimization techniques. The section then summarizes the contribution of this study in relation to these works.

2.1 Capture Systems Employing Multiple Cameras

While traditional multi-camera capture systems typically rely on manual installation to deploy cameras at optimal positions and orientations to achieve wider coverage, recent implementations are increasingly adopting partially automated approaches [9]. A classic example is the Art Gallery Problem (AGP), which addresses how many guards are needed to cover a polygonal three-dimensional space. The result states that at least n/3 number of guards are required to cover an arbitrary polygon of n vertices [9]. The camera placement problem may resemble AGP, but with a higher level of complexity due to limited fields of view and resolutions of individual cameras. Because real cameras do not support infinite-range visibility or full 360-degree coverage, the problem remains NP-hard. Nonetheless, concepts derived from the AGP research, such as the Visibility Graph Theory, have been adapted into camera placement algorithms [9]. Moreover, the Motion Capture research domain continues to explore optimal configurations of multi-cameras [10] and three-dimensional arrangements of objects for 3D tracking [11]. These studies led to the introduction of sensor planning methods that account for resolution, focal range, and camera view overlap [11]. In short, research continues to address the problem of optimal camera placement to maximize visibility, as camera placement in complex environments directly affects the accuracy of 3D scene reconstruction and user tracking performance.

2.2 Multi-Camera-Based Reconstruction Systems for Remote XR Environments

In recent years, there have been significant advances in XR-based remote collaboration research leveraging multi-camera systems [5]. One representative example is a collaboration system that integrates multiple RGB camera inputs to capture workspaces and transmit operator actions to remote experts [12]. Earlier research in such a multi-camera-based collaboration system proposed the Multiple Target Video (MTV) system, which shared a remote workspace through multiple fixed cameras [13,14]. Microsoft’s latest Holoportation system reconstructs a real-time environment with remote users in three-dimensional virtual space using arrays of stereo cameras, which are then transmitted to other participants’ Augmented Reality (AR) Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs), creating an immersive co-presence experience [8]. Such multi-camera scene-sharing techniques have generated significant demand in various industrial and service sectors [6,12]. For instance, in remote industrial operations, onsite workers can be monitored from multiple viewpoints via a multi-camera system and receive real-time guidance from online experts [12]. Also, in the medical field, immersive telepresence systems are being developed by reconstructing complex spaces such as operating rooms with multiple RGB-D cameras that ultimately allow remote medical professionals to virtually participate in surgical procedures [15]. Such approaches have been shown to enhance situational awareness and team communication by providing a holistic view of the surgical field to remotely located medical professionals [15]. Building on prior work, this study proposes a method for optimally placing heterogeneous cameras.

2.3 Studies on the Use of Heterogeneous Cameras

In the domain of computer vision, which aims to obtain visual information from real-world spaces, a new wave of research has emerged, emphasizing the integration of heterogeneous cameras with diverse specifications and characteristics to effectively acquire information [15]. A critical question is determining optimal placements that integrate different camera types—such as RGB, depth, and PTZ cameras [15]. That is, research on the setup of a heterogeneous camera network primarily focuses on strategies for camera placement and control that maximize the collection of imaging information with limited resources [15]. Previous studies proposed Binary Integer Programming (BIP) models for heterogeneous camera setups, along with comparative analyses of various approximate optimization methods [16]. These studies have proposed mathematical formulas that incorporate various sensor characteristics, such as field of view (FOV), resolution, depth, and visibility constraints in complex environments, to derive optimal placements that consider sensor capabilities [16]. Key research examples include the use of optimization algorithms to continuously cover regions of interest with video cameras, minimizing installation costs while achieving maximum coverage from multiple angles with minimal heterogeneous camera combinations [17]. These studies further relied on experimental results to further validate mixed installation setups with respect to viewing frustum and angle differences. More recent approaches employ dynamic reconstruction methods based on distributed reinforcement learning for heterogeneous camera networks composed of fixed and PTZ cameras. Here, a new methodology was proposed to ensure high-resolution coverage of regions of interest, in which each camera autonomously adjusts its position and field of view in response to local crowd density [18]. As indicated, ongoing studies on the setup of heterogeneous camera networks need placement strategies that leverage the complementary strengths of heterogeneous camera sensors to enhance performance under resource constraints. Thus, this study proposes an approach that derives optimal heterogeneous camera placements tailored to real-world spatial conditions, aligned with the performance specifications of different camera types.

2.4 OCP Algorithms Leveraging Mathematical Optimization Techniques

A variety of mathematical approaches were developed to formalize the OCP problem. The most straightforward approach is to translate the problem into a binary integer programming model [16]. In this approach, candidate placement positions are discretized, with each position represented by a binary decision variable (‘0’ or ‘1’) indicating whether a camera is installed. Here, field-of-view coverage constraints are applied to ensure that all regions of interest are covered by at least one camera, while the objective functions of an integer programming model aim to maximize coverage or minimize setup cost [16,17]. However, since the problem is NP-complete, exact solutions may become infeasible as the scale increases, prompting the development of approximate algorithms. For instance, greedy algorithms adopt simple heuristics to provide quick solutions by sequentially selecting camera positions with the highest coverage-to-cost ratio, which may, at times, yield solutions that differ from global optimality [16]. Other approaches have used metaheuristic techniques, including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm (ABC), and Genetic Algorithm (GA), to explore optimal solutions in complex spaces [19–21]. For example, PSO has been used to incorporate camera resolution and field of view into 3D placement models, yielding practical solutions when multiple cameras are used [19]. The ABC algorithm was proposed to improve convergence speed while demonstrating comparable coverage performance to GA and PSO, and to offer an optimized multi-camera setup [20]. In addition, multi-objective GA approaches were introduced to simultaneously optimize both camera count and coverage in complex indoor environments, proposing a quantitative evaluation framework that analyzes optimal camera placement solutions and helps identify the balance between resolution requirements and cost-reduction objectives [21]. More researchers are now turning to studies that leverage AI technologies. For instance, in approaches that adopt distributed reinforcement learning, each camera, as an agent, learns to dynamically rotate or reposition itself based on rewards (increments in coverage), thereby optimizing the overall field of vision [22]. Furthermore, the latest approaches employing multi-agent reinforcement learning and distributed optimization are validated through small-scale prototype experiments. For example, collaborative robotic vision systems are proposed that augment overall scene coverage by tracking target objectives by mounting cameras on mobile robots [23]. While conventional research focused on obtaining camera placement solutions within predefined computational time, it is now evolving to incorporate advanced algorithms that identify optimal solutions that account for more complex environmental factors and real-time requirements. Overall, the latest studies extend beyond the traditional coverage optimization problem toward real-time adaptability and intelligent simulation, where the performance of diverse algorithms is actively validated in real XR environment scenarios [23,24]. Against this backdrop, this study proposes methods for the optimized setup of heterogeneous cameras and seeks to evaluate the high-speed computational performance enabling rapid processing within XR environments.

3 System Configuration and Implementation

3.1 System Configuration and Main Ideas

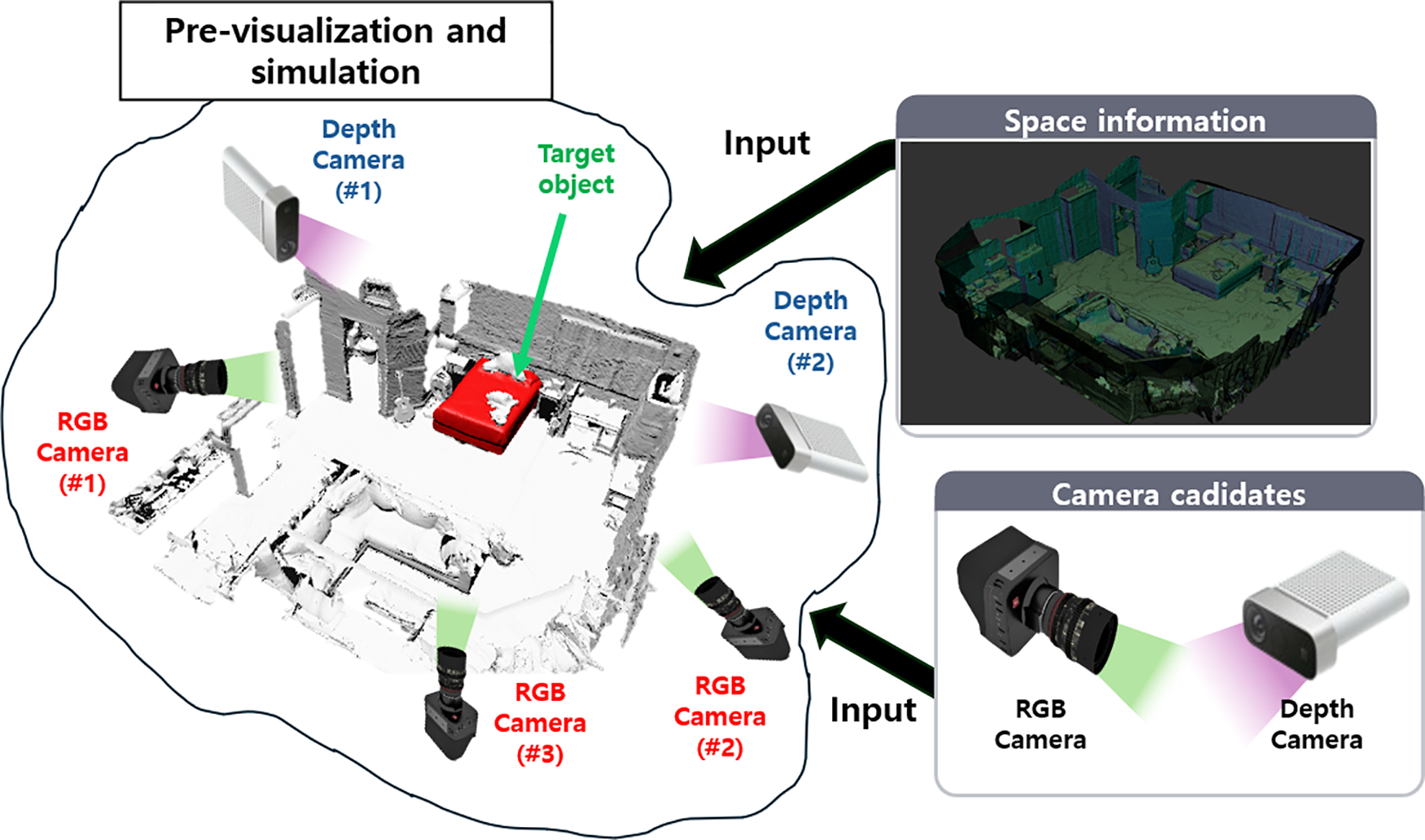

In this study, we constructed a simulation environment for 3D virtual spaces by utilizing 3D scenes derived from datasets of scanned indoor spaces [25]. Specifically, point cloud- or mesh-based indoor models were rendered using ScanNet datasets, enabling realistic measurement of effects such as FOV, obstacles, and occlusion in the simulated environment. For example, as illustrated in Fig. 1, virtual cameras were placed within the simulated space, and their viewing volumes, such as FOV, were visualized to intuitively verify each camera’s coverage range. In this study, we constructed a simulation environment for 3D virtual spaces by utilizing 3D scenes derived from datasets of scanned indoor spaces [25]. Specifically, point cloud- or mesh-based indoor models were rendered using ScanNet datasets, enabling realistic measurement of effects such as FOV, obstacles, and occlusion in the simulated environment. For example, as illustrated in Fig. 1, virtual cameras were placed within the simulated space, and their viewing volumes, such as FOV, were visualized to intuitively verify each camera’s coverage range.

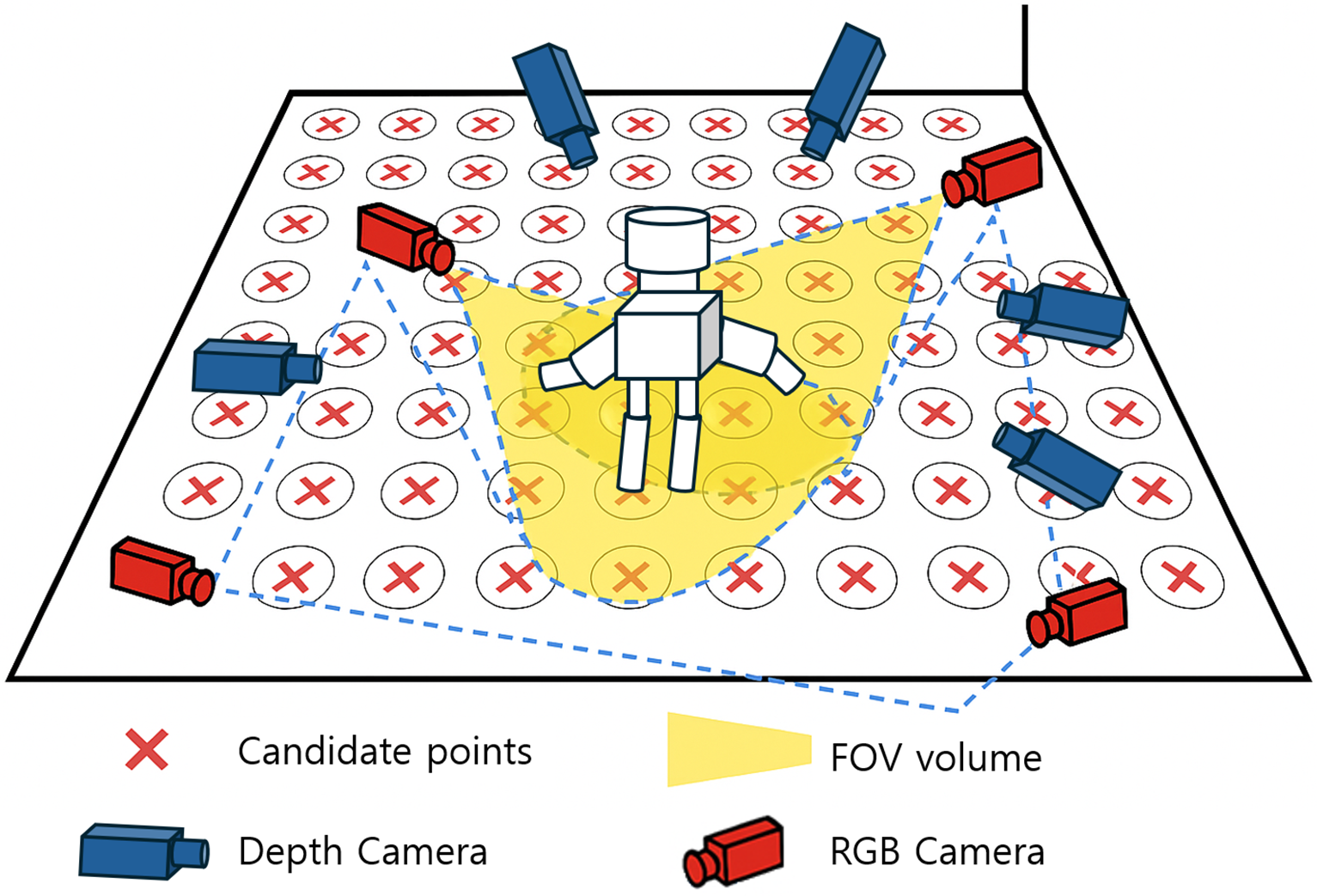

Figure 1: An example illustration of an optimal camera placement algorithm in an XR simulation environment: The red “X” marks on the floor grid denote candidate points for camera installation generated at fixed intervals (e.g., 1 m). Red camera icons indicate virtual RGB cameras placed at selected candidate points. On the other hand, blue camera icons indicate depth cameras. Each camera can have a different FOV and maximum effective range depending on its type (Wide RGB, Narrow RGB, and Depth). The yellow fan-shaped region shows the visible area when the FOV of each camera is projected onto the floor plane or onto specific areas. Blue dotted lines represent the boundaries of the coverage area, while overlapping regions observed by multiple heterogeneous cameras are computed using set union operations to yield the final visible region used to compute the final coverage ratio

Within the XR environment during the pre-visualization process, virtual cameras can be configured with defined parameters, including their FOV and viewing frustum (e.g., maximum range), to emulate the performance of real physical cameras. Here, visibility analysis is performed for a given installation setup by evaluating whether any obstacles lie between each camera and points in the defined space. Candidate installation points can be predefined for each environment, while candidate coordinates are primarily selected as feasible installation locations, such as walls, ceiling corners, and floor edges. For each candidate point, multiple rotation angles are assigned, allowing consideration of alternative view directions from the same positions. This approach represents real-world implications, where wall-mounted cameras may be installed slightly to the left or right when looking into the center of a space. During the initial configuration stage, all candidate virtual cameras are placed at the candidate points for all possible directions from each point. Later, in the simulation process for the visibility analysis and optimization stages, the combinations of these candidates were assessed.

In addition, to accommodate heterogeneous cameras, RGB cameras were initialized with a wide viewing angle and effective ranges of several meters, while depth camera sensors were modeled with a narrower FOV of around 60° and relatively shorter effective ranges (e.g., up to 5 m). Based on such initial configurations, the potential visibility for each candidate camera within the simulated environment was pre-evaluated. Specifically, each candidate camera was assessed to understand the observable ratio of the virtual target object, the degree of occlusion due to obstacles in view, and the extent of the overall spatial coverage. The target object was an arbitrary 3D object placed within the experimental scene, with its shapes represented as a set of sampled points at fixed intervals. This enabled the calculation of the visibility ratio for each candidate camera and target surface point set. The resulting visibility ratios were summarized into a camera-target visibility matrix or in spatial coverage maps, which were subsequently used as inputs in the optimization algorithm (See Fig. 2).

Figure 2: This presents the overall methodology of our optimal camera placement approach for pre-visualization and simulation in the XR environment. Here, we propose an XR simulation method to enhance the overall visibility of target objects by leveraging heterogeneous camera candidates and spatial information, and then using the captured 3D spaces of the real world. The figure illustrates a virtual scene of a typical home interior, with the bed highlighted in red representing the target object

3.2 Mathematical Approaches to Optimization

Our proposed approach formulates the optimization problem as an overall visibility maximization problem by determining the selection of candidate points and the types of cameras when a set of heterogeneous camera data (number of cameras, performance specifications per camera type, FOV, and maximum range) was used in the simulation. The OCP problem is a form of combinatorial optimization problem, which can be generally expressed as a binary integer programming problem [21]. For instance, given a discrete set of candidate positions

1. Set of scene surface points:

2. Set of candidate position and rotation:

3. Set of camera types:

4. User resource constraints related definition: Available number of units

5. Visibility by distance and occlusion test:

For the convenience’s sake, we will omit the statement that

(i) Range condition:

(ii) FOV condition: FOV of a camera shall be expressed as a cone. Visibility criteria are met when the angular deviation from the viewing axis does not exceed half the FOV angle.

(iii) Non-occlusion condition: When obstacle set

For each point

The objective of optimization involving multiple cameras is to maximize the number of points observed by at least one camera out of the overall point set [13]. A camera’s coverage is regarded as valid when the visibility criteria are met and the surface point

The score for point

Furthermore, the proposed approach was calibrated for redundancy to prevent over-coverage of unimportant regions for identifying the camera installation setup that can still maximize coverage of points of interest while meeting the constraints defined by the study. Here, a redundancy penalty was introduced to the objective function, where redundant observation of the points of interest by multiple cameras above a defined threshold was penalized.

This denotes the number of selected cameras capable of observing the target point

here,

Based on the formulation above, the number of excessive observations for each point

In summary, the proposed objective function determines camera parameters by applying per-point clamping

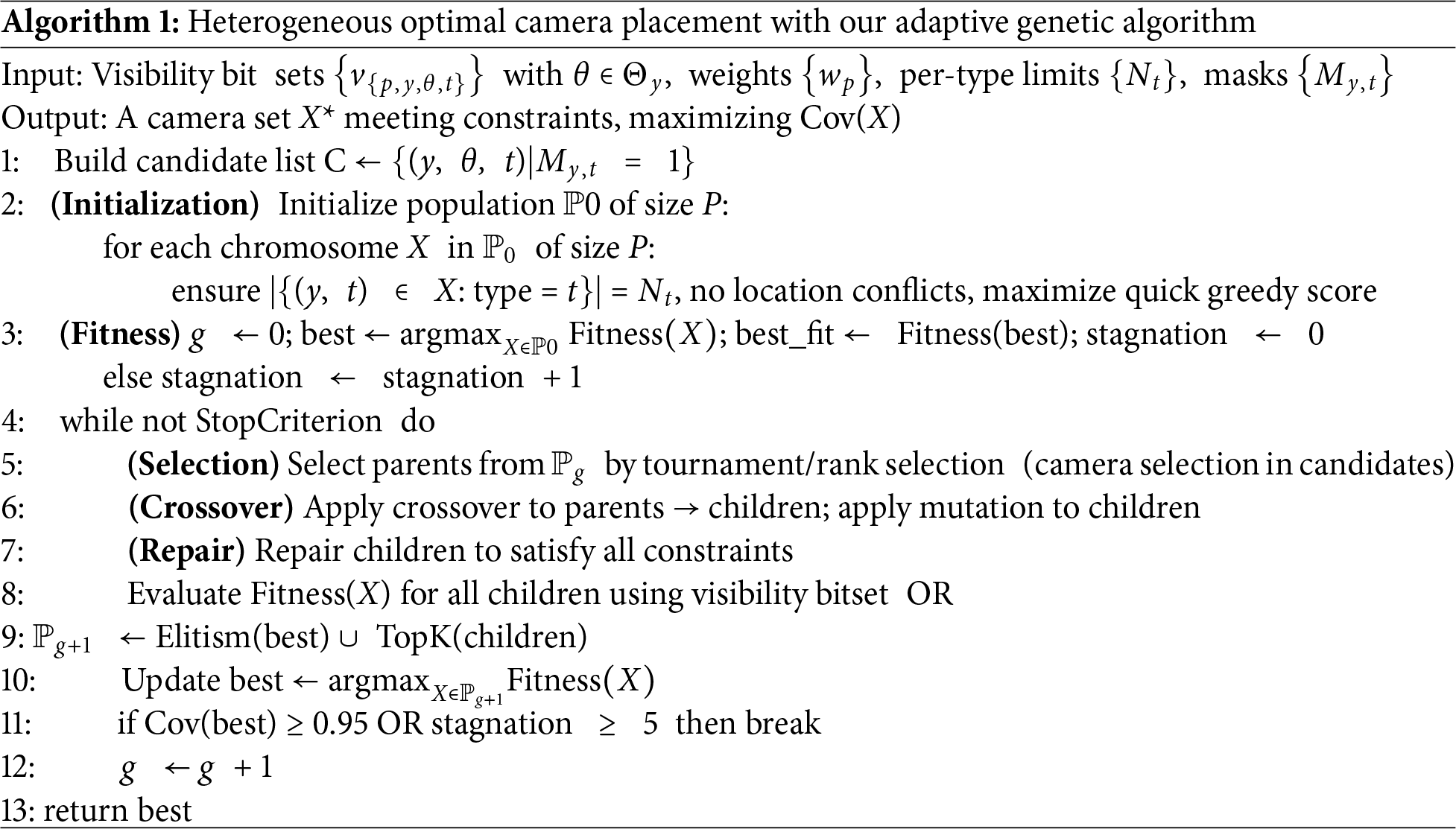

A representative algorithm for finding the optimal camera placement is the metaheuristic Genetic Algorithm (GA) [21]. The genetic algorithm is effective at approximating solutions to complex combinatorial problems, and its performance has been validated in research on camera network optimization [21]. In this study, the genetic algorithm framework was reconfigured to enhance performance. For instance, each generation was configured to maintain a fixed population size, with each individual representing a single camera candidate solution. The setup of all cameras used in a placement was represented as a set of chromosomes, where each gene corresponds to a specific camera. More specifically, a gene was defined as a tuple of a camera ID or type, a candidate location index, and a viewing angle. For example, the chromosome

4.1 Evaluation Metrics of the OCP Algorithm

For the proposed heterogeneous multi-camera placement optimization algorithm, a fitness function can be used to evaluate the performance of each candidate solution. This function returns the total size of visible volume covered by the deployed cameras or the coverage ratio achieved over the target space. For the fitness function to correspond to the objective function

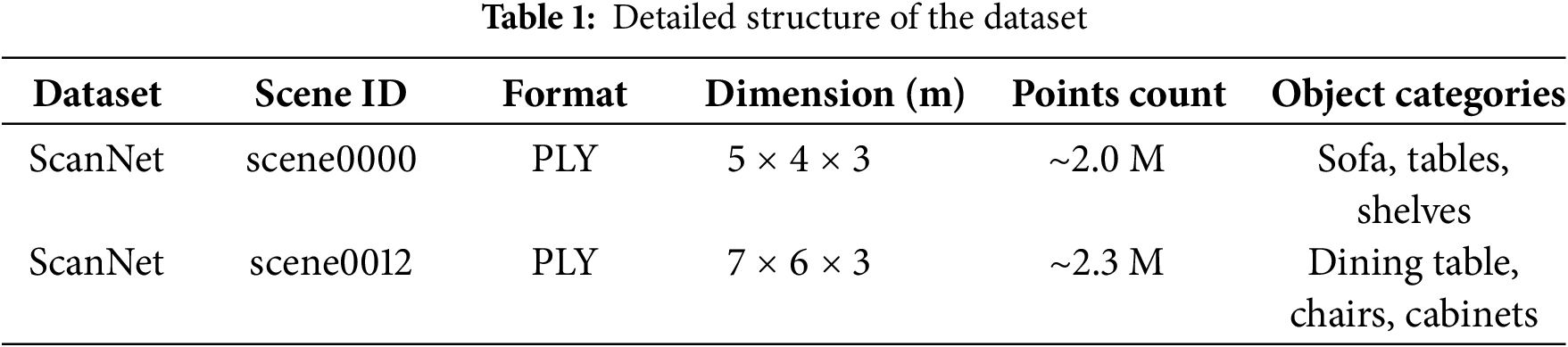

Publicly available datasets for configuring 3D simulation environments were used to evaluate the proposed heterogeneous camera optimal placement algorithm described in the previous section. The datasets were provided in point cloud or mesh formats, reflecting the structure of the actual indoor space and visibility characteristics. Depending on the complexity of the data, partial scenes were selected from two dataset types [25].

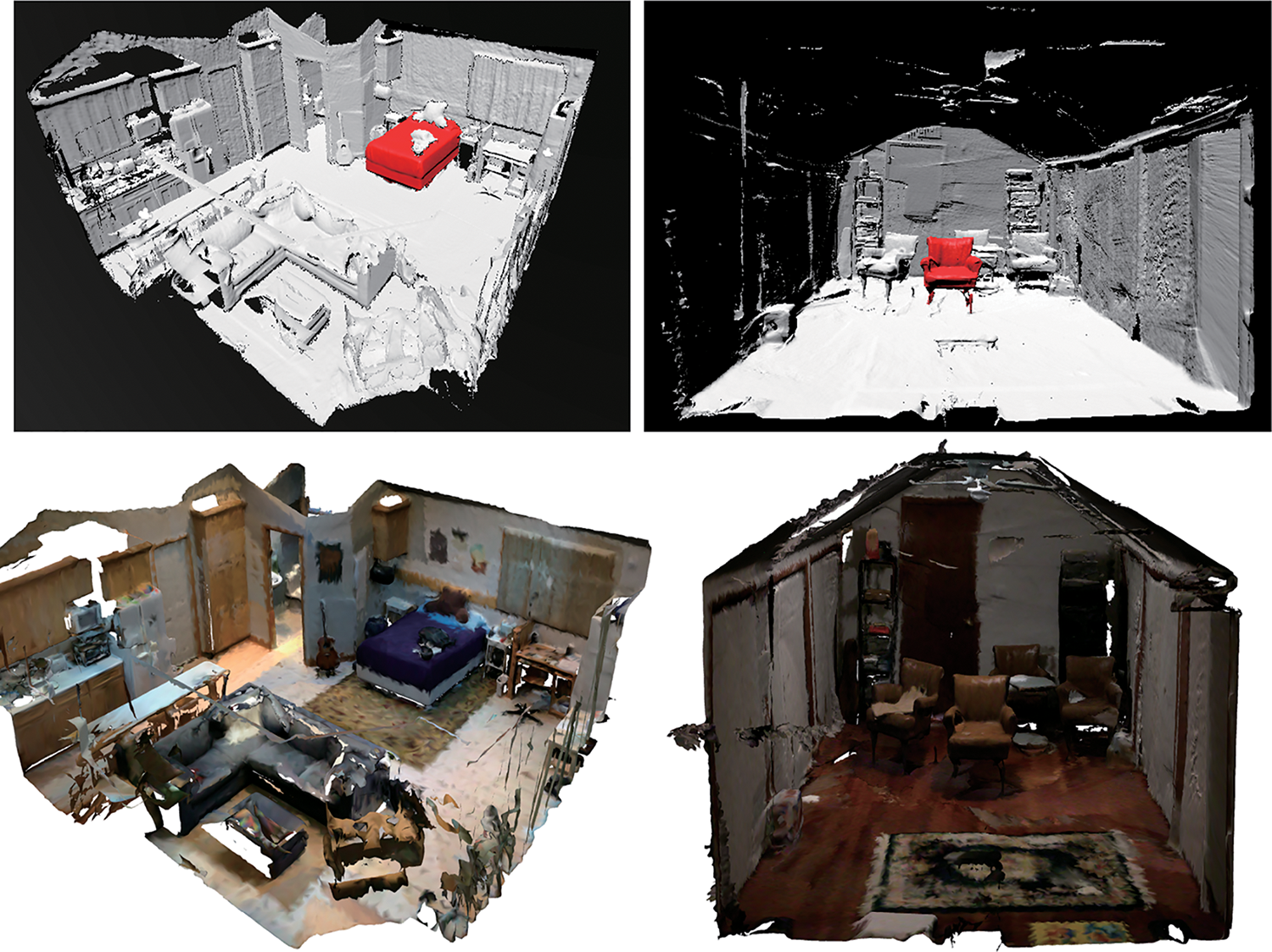

High Complexity Data: The ScanNet provides mesh data captured using RGB-D cameras, offering scenes densely arranged with furniture and structural elements [25]. As the environments contain numerous occlusion factors and complex geometric structures, these datasets are classified as High Complexity environments. In this study, datasets for scene0000(living_room_1) and scene0012(living_room_2) were used. These scenes contain many obstacles, making them suitable for validating occlusion-avoidance strategies in camera placement. Each scene was set to include Mesh files (.ply), RGB images, depth information, and semantic labels (See Fig. 3). Table 1 presents the detailed structure of the datasets used in our simulation experiments.

Figure 3: Examples of experimental dataset scenes used in our study: A mesh view of the ScanNet dataset showing a complex indoor structure with various objects, including a desk, chairs, a bed, shelves, and ceiling elements. Our approaches enable the identification of major objects, such as the bed, which are used to determine object visibility in camera visibility analysis and coverage calculations. In the ScanNet dataset, scene ID “scene0000” (top-left) consists of a total of 152,712 surfaces (polygons), and in contrast, ID “scene0012” (top-right) comprises 211,720 surfaces. In the simulated scenes, pre-determined target objects were positioned, for instance, in the (bottom-left) image, the target is a bed in “scene0000”, and in the (bottom-right) image, it is a sofa highlighted in red in “scene0012”. Then, the visibility of these target objects from the viewing locations is calculated as the basis of quantifying coverage

All datasets were used in Unity3D for experimentation, where ScanNet datasets were used for textures/meshes. By detecting collisions with target object information, the experimental simulation emulated visibility, obstacles, and occlusion.

4.3.1 Selection of POI (Point of Interest) Target Objects in the Simulation Space

To evaluate the optimal placement performance of the proposed algorithm in the simulated environments, fixed target objects were placed within the simulated scenes. The visibility of these target objects from the viewing locations served as the basis for quantifying coverage. For example, in the left image of Fig. 3, the bed was designated as the target object (See Fig. 3).

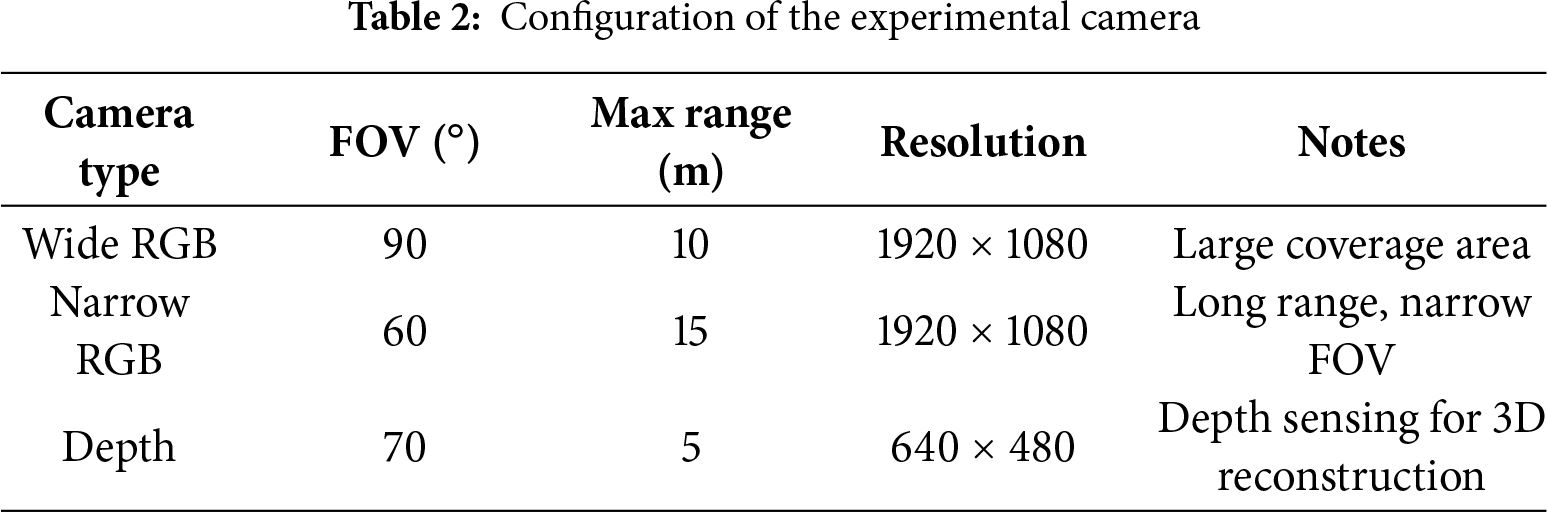

4.3.2 Configuration of Heterogeneous Cameras

First, candidate camera positions and their rotations were predefined in the simulation environment. Candidate positions were set to practical installation locations within 3D spaces, such as walls, ceilings, or floor corners. Multiple possible viewing angles were configured for each of the cameras from the initial position. Moreover, to account for heterogeneous cameras, some cameras were assigned wider field-of-view settings, while others were set to narrow FOV and higher resolution. Updated camera placements were included in the simulations. The configurations used for heterogeneous cameras in the experiment are summarized in Table 2.

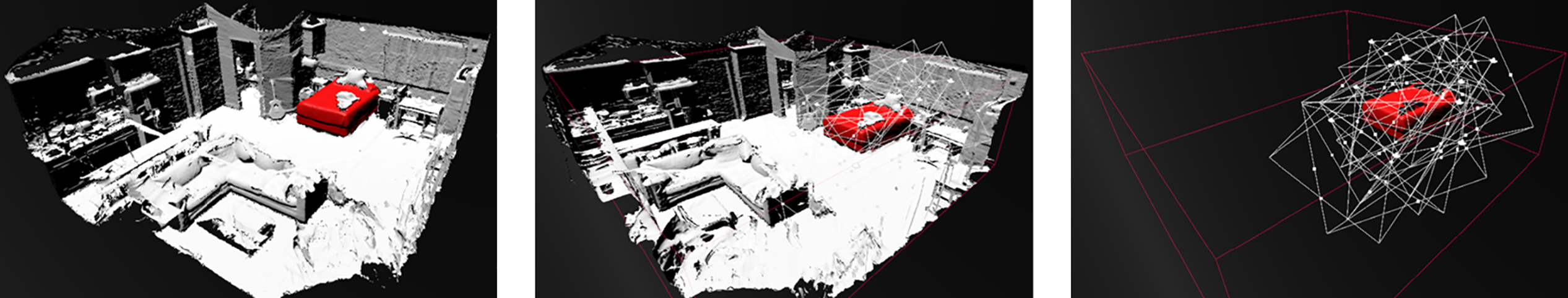

4.3.3 Execution of Simulations

Using the algorithm proposed in Section 3, cameras were placed in the simulation space. The visibility of the cameras was evaluated as follows, to understand which target area points were included in the FOV for each camera candidate.

– What percentage of target surface points can be observed by each camera.

– Whether the FOV is blocked by any obstacles in the environment.

– What percentage of the overall space is covered by the FOV of each camera.

Through these evaluations, with visibility matrices between cameras and target objects, coverage maps of the spaces were generated, which were then used as inputs during the optimization stage. As previously mentioned, the combinatory optimization algorithm, based on simulated visibility information, aimed to achieve maximum coverage with the least number of cameras. In our study, the procedure was configured to confirm the simulation results in terms of coverage of target points upon reaching the specified threshold. In other words, the simulation operation stopped when repeated results showed no further gain in the covered region. Fig. 4 illustrates this simulation process, showing the original scene, the simulation in progress, and the simulation focusing only on the target object.

Figure 4: Original scene (left), simulation process in the scene (center), the simulation process considering only the target object (right)

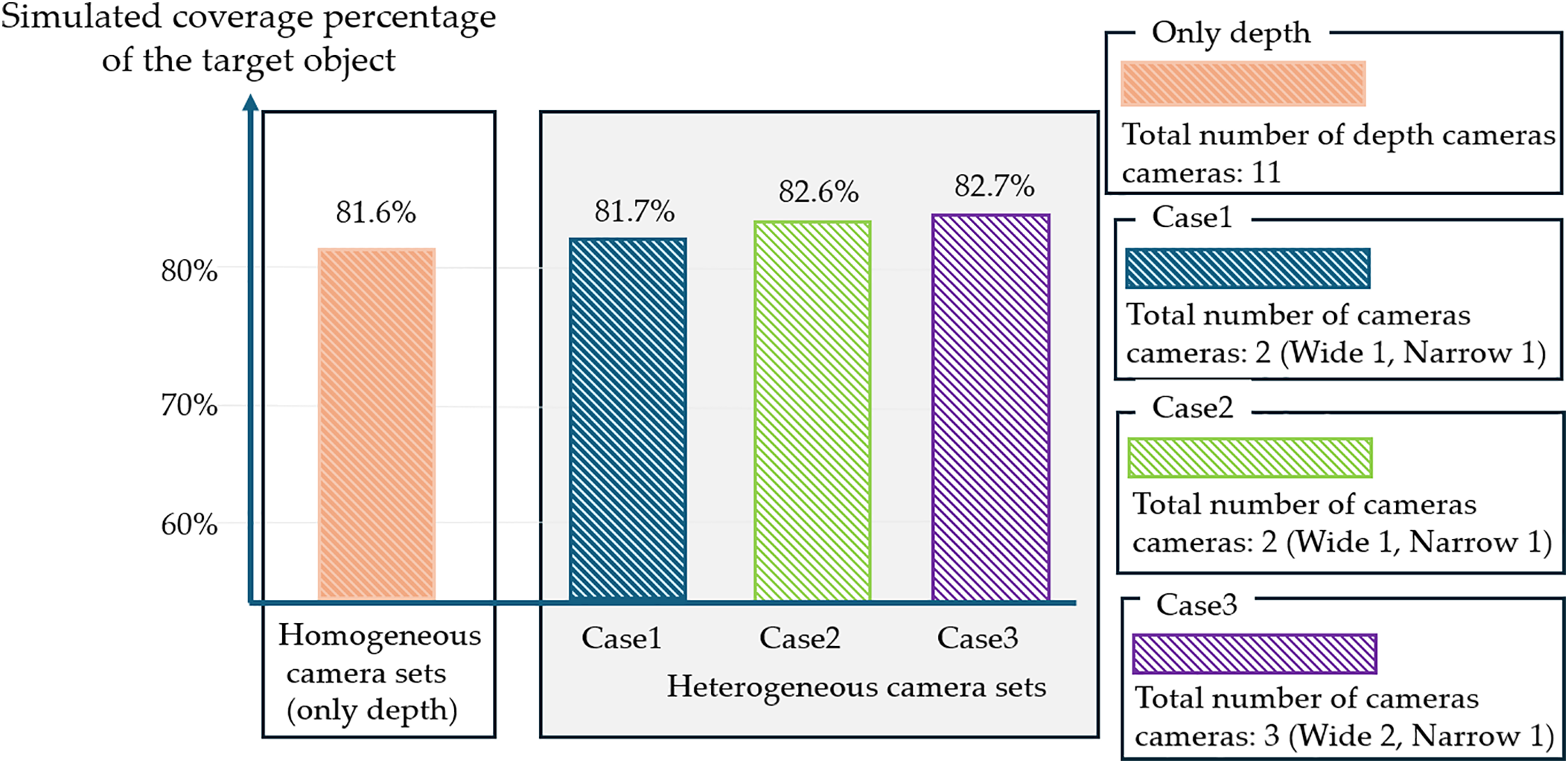

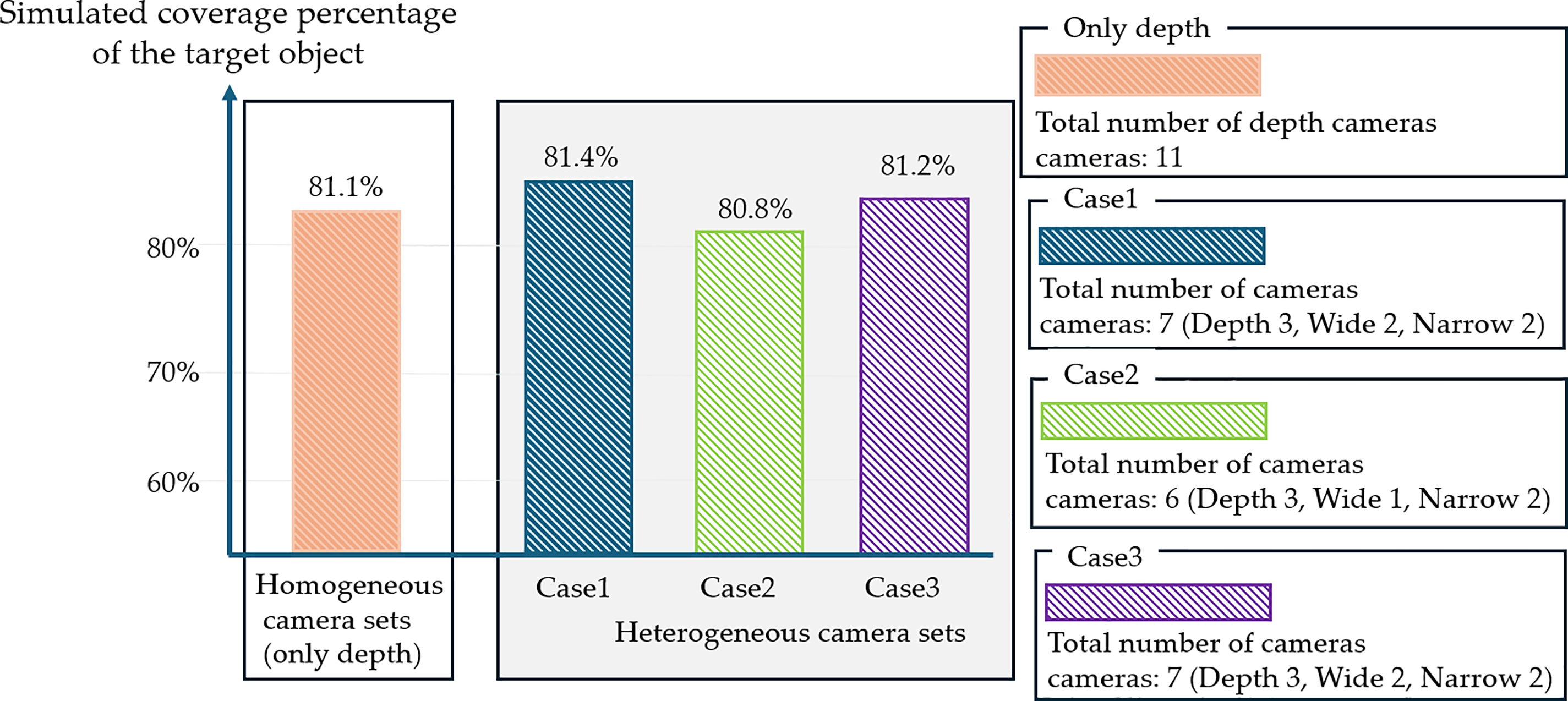

In the experiment, as a preliminary step, in order to make a comparison with homogeneous camera sets, we initially chose a specific camera (e.g., depth camera only) in the simulation environment and manually added and transformed it until the target became clearly observable. This was the same procedure as the simulation process performed by the computing system upon reaching the specified threshold previously mentioned in Section 4.3.3. After that, we compared the results obtained from the simulation using the settings applicable to heterogeneous camera sets. Fig. 5 illustrates the minimum number of cameras required and the corresponding accuracy achieved in Scene0000. As illustrated in the figure, the results demonstrated that only one type of homogeneous cameras was used; the system (e.g., reconstruction or monitoring system) in the experiment configuration usually needed ten or more cameras. The findings indicated that with a heterogeneous approach with mixed camera types, the number of required cameras decreased significantly. Also, the position and orientation of each camera with respect to the transformation were intuitively visualized using three-dimensional information. On average, the simulation required about 30 min to complete. After a certain amount of time, it became possible to easily check the simulation result.

Figure 5: The performance results of simulated coverage percentage of the target object and total number of cameras in “Scene0000” are illustrated. The experimental results indicated that our proposed approach could effectively minimize the number of cameras (e.g., homogeneous depth, only 11 cameras were required vs. heterogeneous cameras 2~3) with similar performance in coverage percentage (e.g., depth only 81.6% vs. heterogeneous cameras 81.7%~82.7%). However, in terms of accuracy, the performance in the case of using heterogeneous camera sets as well as homogeneous camera sets did not appear high because of spatial constraints such as wall and object occlusions. Nevertheless, the results were comparable to those obtained through manual selection of the same type of cameras, but the required number of cameras was greatly reduced. Cases 1~3 reported experiment results from attempts to identify different camera placements within the same scene (Scene0000)

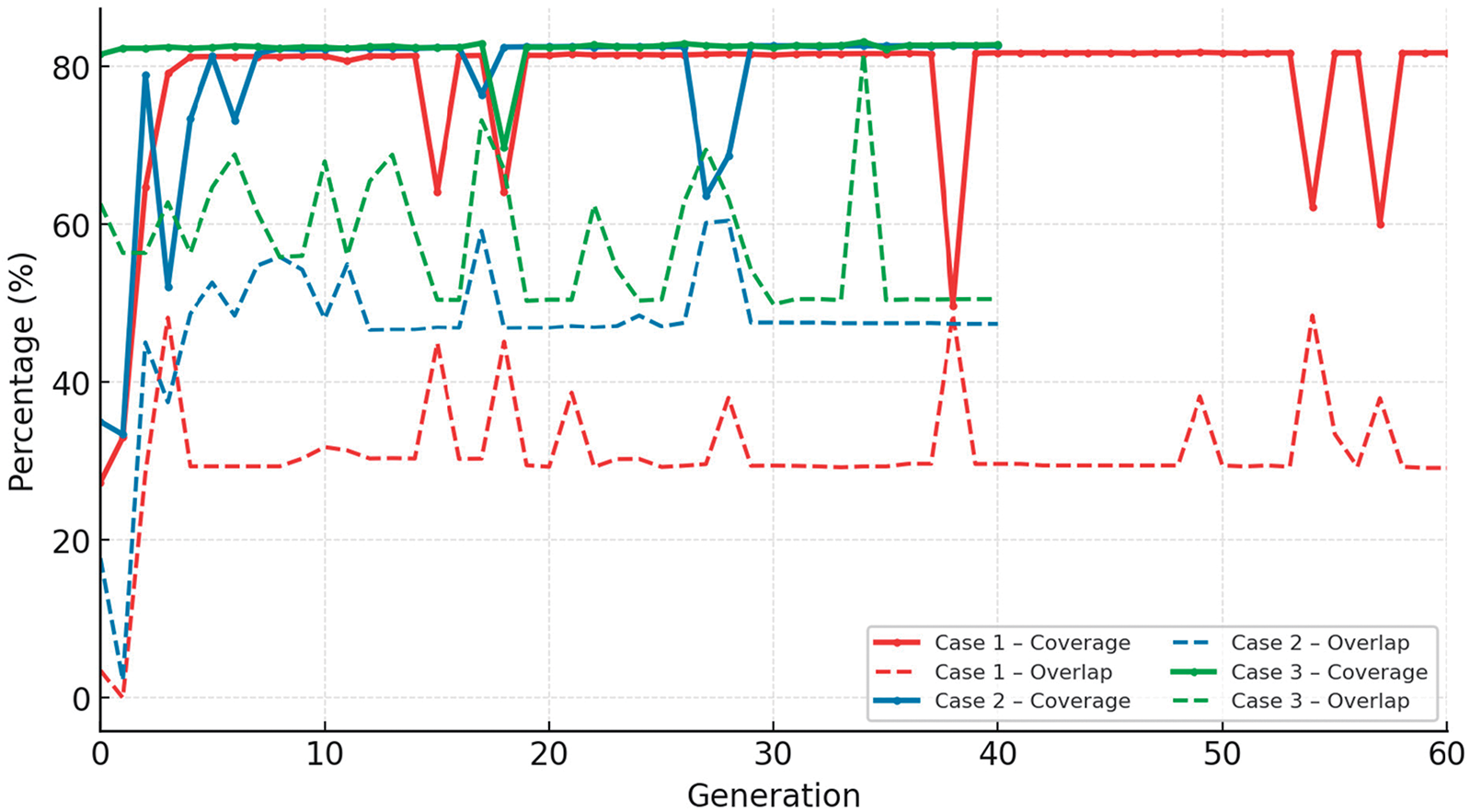

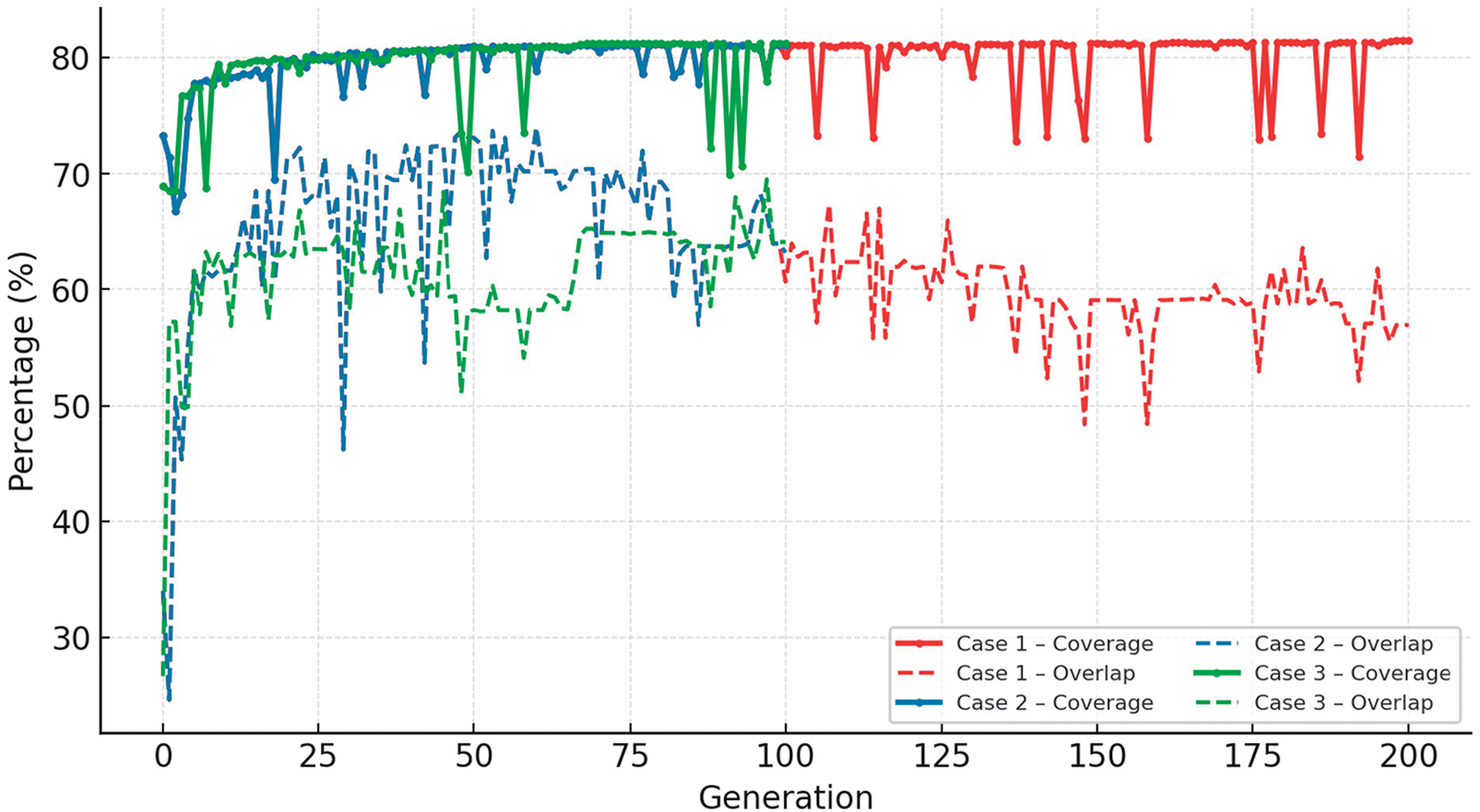

In our experiments, “Scene0000” contained relatively few obstacles, which allowed the genetic algorithm (GA) to approach a near-optimal solution within only a few generations. In contrast, “Scene0012” exhibited a dense spatial structure with numerous obstacles surrounding the target, requiring significantly more iterations for the GA to explore feasible placements. This difference in computational efficiency between the two scenes is clearly illustrated in Fig. 6, which compares the number of required cameras under heterogeneous and homogeneous configurations. These results suggest that key factors such as visibility constraints due to scene geometry, resource-minimizing cost functions, and installation feasibility play critical roles in the convergence behavior of the optimization. Accordingly, heterogeneous camera combinations are shown to contribute to optimal placement by leveraging their complementary capabilities under constrained conditions (e.g., narrow FOVs and occlusions).

Figure 6: Results in “Scene0012”. The heterogeneous configuration maintained mean coverage using 6–7 fewer cameras (a 36%~45% reduction) to the homogeneous depth-only baseline (11 cameras), When obstacle-induced occlusions, the heterogeneous setup enable more efficient optimal camera placement

Fig. 7 in “Scene0000” (See Fig. 7 Top). In the early generations, individuals were quickly propagated, and the best solution was carried out in the next generation, leading to a rapid increase in coverage. Then, crossover operations may significantly change camera combinations, while mutation may shift or remove cameras, which would provide substantial changes in camera pose, resulting in variations due to changing occlusion and overlap to maximize viewing coverage. The fluctuations in Fig. 7, bottom, observed in the graph result from the effects of crossover and mutation, particularly when accompanied by camera removal or viewpoint shifts. This behavior illustrated the mechanism by which the genetic algorithm converged toward an optimal solution under given constraints.

Figure 7: (Top) in “Scene0000”, we found that Case1 stabilized at a low level (30%), Case 2~3 indicated 40%~60% for sufficient target coverage. Due to the relatively low obstacle density in this environment, all cases exhibited a rapid increase in coverage to approximately 80% within 5~10 generations. (Bottom) “Scene0012” results: Solid lines indicated coverage, and dashed lines were plotted for overlap. Camera repositioning during the search may cause temporary drops in coverage, which are generally recovered within a few subsequent generations. Under complex conditions with many occluding objects surrounding the target, there are limited visible regions and frequent conflicts between different viewpoints. The feasible solutions to simultaneously satisfy the occlusion penalty, overlap penalty, and camera count penalty were relatively small. As a result, a larger number of generations were required for the genetic algorithm to explore and converge toward an optimal camera configuration

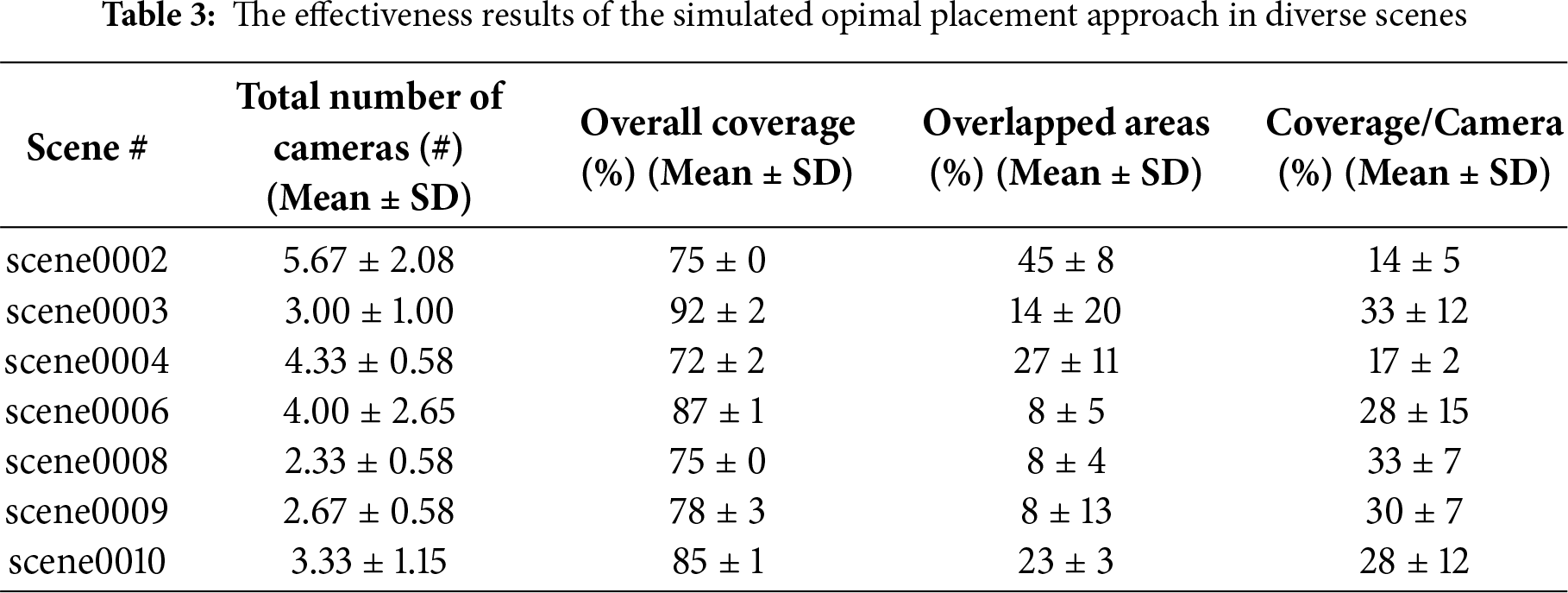

As already mentioned, our method with heterogeneous cameras, which can provide the flexibility to select camera candidates with diverse specifications to achieve more effective coverage, demonstrated improved performance compared to homogeneous configurations (See Figs. 5 and 6). Moreover, we conducted quantitative evaluations related to optimal placement(manual vs. optimal) across a broader range of scenes from the dataset to strengthen the validity, and analyzed statistical significance of the findings. Table 3 presents the results regarding the required number of cameras, overall coverage areas, overlapped areas, and coverage area ratio per camera in several scene conditions. For the experimental evaluation, the optimal placement algorithm was executed five times for each scene, and the average performance was calculated. Here, in most cases, our approach achieved coverage of more than 70%, with some cases reaching beyond 90%. Also, the results in some cases show that the overlapped regions were found to be below 10%. In addition, it was found that the automatically optimal placement strategy allows a single camera to detect a comparatively wide area. For example, one camera was able to cover about 33%. However, some manual adjustment would still be required to detect whole detection coverage, and this optimization process is left for future work.

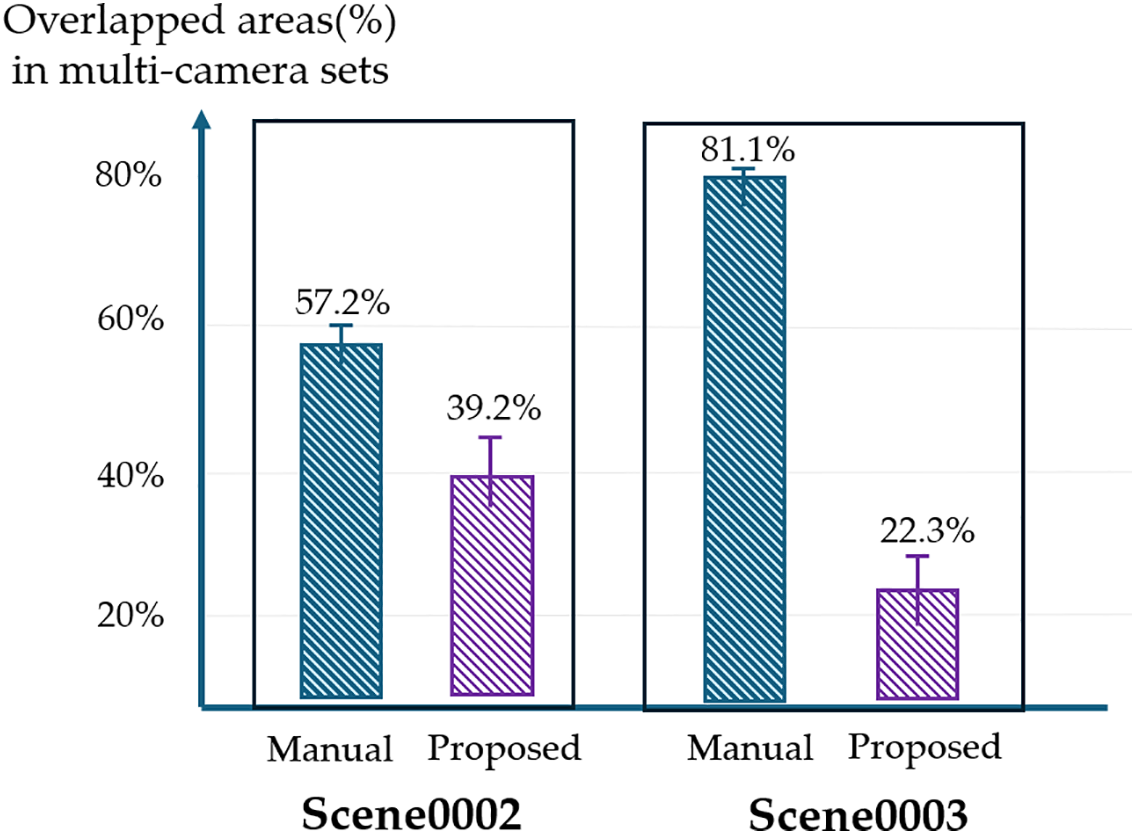

Additionally, to further validate our method, we conducted a comparative analysis between the manual method and the proposed automated algorithm using two selected scenes (scene0002 and scene0003). Ten participants were involved in the study, and each carried out ten trials. In the manual trial, participants were asked to determine the optimal camera positions using the given set of cameras (e.g., the average number of selected cameras presented in Table 3). Participants were master’s and doctoral students in computer science with an average age of 31 years. Fig. 8 shows the results of the comparison between the two methods. Specifically, the results showed a statistically significant difference in overlapped areas (t(9) = −6.44, p < 0.00001 in scene0002, t(9) = −18.3, p < 0.00001 in scene0003). We found that the proposed method can determine effective camera configurations for multiple camera sets to minimize spatial redundancy. Also, the results in the case of scene0003 indicated that our approach was more effective in environments with fewer objects and minimal occlusion. However, no statistically significant difference was found between the two methods in terms of average coverage.

Figure 8: The results of the comparison with respect to overlapped areas between the manual method and the proposed automated algorithm

In our experimental results, we investigated the practical method in terms of optimal camera placement with heterogeneous camera sets. We ran performance experiments (e.g., minimum number of cameras, accuracy, computation time). However, several difficulties and limitations were found when using our method in real-world applications. For example, in the current study, experiments were carried out in a static environment without dynamic objects. Thus, our study did not address the problem of camera placement adapting to moving objects (e.g., human or movable robot). Also, when dealing with high-resolution point clouds, the computational cost can significantly increase. With an excessively large search space, the speed of our algorithm tends to slow down, and may risk settling in a local optimum. Accordingly, for practical deployment in daily life, it is necessary to improve the algorithm (e.g., dynamic point clouds detection). Considering these problems, we have left them for future research.

Recent advances in reconstruction technologies using multi-camera systems will provide more helpful information for real-life awareness, and such an approach is beneficial for implementing immersive XR remote collaboration with the teleported avatar. In the study, we presented the pre-visualization and simulation method for the optimal camera placement of heterogeneous multi-cameras (e.g., RGB and depth cameras) in XR environments. With specifications of each camera, such as FOV and the physical constraints of real-world spaces, the presented method enables visibility analysis that determines not only the optimal positions and rotations for camera setups but also the estimated minimum number. Through our approach, we contributed to cost-effective and efficient camera placement strategies compared to manual-based control and conventional methods, assuming homogeneous camera setups.

There are still several aspects that require improvement to enhance the practical applicability of the optimal placement system. We only applied to indoor scenarios and examined our approach’s benefits, but we may consider more practical outdoor examples (e.g., CCTV, autonomous driving). We will continue to investigate approaches for everyday scenarios and handling moving objects. Thus, we will conduct research to apply various applications in camera configuration of motion capture and tele-conference systems for remote participants. Furthermore, we plan to explore and apply various artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms suitable for an effective solution to our problems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the 2024 Research Fund of University of Ulsan.

Author Contributions: Juhwan Kim implemented OCP algorithms and conducted the experiments; Gwanghyun Jo configured our algorithms and constructed experiment methods; Dongsik Jo organized the overall study and contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets are available on request from the corresponding author in the study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chang E, Lee Y, Billinghurst M, Yoo B. Efficient VR-AR communication method using virtual replicas in XR remote collaboration. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2024;190:103304. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2024.103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Huang X, Yin M, Xia Z, Xiao R. VirtualNexus: enhancing 360-degree video AR/VR collaboration with environment cutouts and virtual replicas. In: Proceedings of the 37th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology; 2024 Oct 13–16; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 1–12. doi:10.1145/3654777.3676377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rasmussen T, Feuchtner T, Huang W, Grønbæk K. Supporting workspace awareness in remote assistance through a flexible multi-camera system and augmented reality awareness cues. J Vis Commun Image Represent. 2022;89:103655. doi:10.1016/j.jvcir.2022.103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Fages A, Fleury C, Tsandilas T. Understanding multi-view collaboration between augmented reality and remote desktop users. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interact. 2022;6(CSCW2):1–27. doi:10.1145/3555607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Fehr D, Fiore L, Papanikolopoulos N. Issues and solutions in surveillance camera placement. In: Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2009 Oct 10–15; St. Louis, MO, USA. p. 3780–5. doi:10.1109/IROS.2009.5354252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kim J, Jo D. Optimal camera placement to generate 3D reconstruction of a mixed-reality human in real environments. Electronics. 2023;12(20):4244. doi:10.3390/electronics12204244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yildiz E, Akkaya K, Sisikoglu E, Sir MY. Optimal camera placement for providing angular coverage in wireless video sensor networks. IEEE Trans Comput. 2014;63(7):1812–25. doi:10.1109/TC.2013.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Orts-Escolano S, Rhemann C, Fanello S, Chang W, Kowdle A, Degtyarev Y, et al. Holoportation: virtual 3D teleportation in real-time. In: Proceedings of the 29th Annual Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology; 2016 Oct 16–19; Tokyo, Japan. p. 741–54. doi:10.1145/2984511.2984517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tarabanis KA, Allen PK, Tsai RY. A survey of sensor planning in computer vision. IEEE Trans Robot Automat. 1995;11(1):86–104. doi:10.1109/70.345940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rahimian P, Kearney JK. Optimal camera placement for motion capture systems in the presence of dynamic occlusion. In: Proceedings of the 21st ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology; 2015 Nov 13–15; Beijing, China. p. 129–38. doi:10.1145/2821592.2821596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Morsly Y, Aouf N, Djouadi MS, Richardson M. Particle swarm optimization inspired probability algorithm for optimal camera network placement. IEEE Sens J. 2012;12(5):1402–12. doi:10.1109/jsen.2011.2170833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rasmussen TA, Huang W. SceneCam: improving multi-camera remote collaboration using augmented reality. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct); 2019 Oct 10–18; Beijing, China. p. 28–33. doi:10.1109/ismar-adjunct.2019.00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gaver WW, Sellen A, Heath C, Luff P. One is not enough: multiple views in a media space. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI ’93; 1993 Apr 24–29; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 335–41. doi:10.1145/169059.169268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fussell SR, Setlock LD, Kraut RE. Effects of head-mounted and scene-oriented video systems on remote collaboration on physical tasks. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2023 Apr 5–10; Ft. Lauderdale, FL, USA. p. 513–20. doi:10.1145/642611.642701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Eck U, Wechner M, Pankratz F, Yu K, Lazarovici M, Navab N. Real-time 3D reconstruction pipeline for room-scale, immersive, medical teleconsultation. Appl Sci. 2023;13(18):10199. doi:10.3390/app131810199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao J, Haws D, Yoshida R, Cheung SS. Approximate techniques in solving optimal camera placement problems. In: Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCV Workshops); 2011 Nov 6–13; Barcelona, Spain. p. 1705–12. doi:10.1109/iccvw.2011.6130455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bisagno N, Xamin A, De Natale F, Conci N, Rinner B. Dynamic camera reconfiguration with reinforcement learning and stochastic methods for crowd surveillance. Sensors. 2020;20(17):4691. doi:10.3390/s20174691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. O’Rourke J. Art gallery theorems and algorithms. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

19. Chrysostomou D, Gasteratos A. Optimum multi-camera arrangement using a bee colony algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques Proceedings; 2012 Jul 16–17; Manchester, UK. p. 387–92. doi:10.1109/IST.2012.6295580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lee JY, Seok JH, Lee JJ. Multiobjective optimization approach for sensor arrangement in a complex indoor environment. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern C. 2012;42(2):174–86. doi:10.1109/tsmcc.2010.2103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Merras M, Saaidi A, El Akkad N, Satori K. Multi-view 3D reconstruction and modeling of the unknown 3D scenes using genetic algorithms. Soft Comput. 2018;22(19):6271–89. doi:10.1007/s00500-017-2966-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rudolph S, Edenhofer S, Tomforde S, Hähner J. Reinforcement learning for coverage optimization through PTZ camera alignment in highly dynamic environments. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Distributed Smart Cameras; 2014 Nov 4–7; Venezia, Italy. p. 1–6. doi:10.1145/2659021.2659052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dai X, Baumgartner G. Optimal camera configuration for large-scale motion capture systems. In: Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC); 2023 Nov 20–24; Aberdeen, UK. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

24. Cao Y, Zhang J, Yu Z, Xu K. Neural observation field guided hybrid optimization of camera placement. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024;9(11):9207–14. doi:10.1109/LRA.2024.3445634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dai A, Chang AX, Savva M, Halber M, Funkhouser T, Nießner M. ScanNet: richly-annotated 3D reconstructions of indoor scenes. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2432–43. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools