Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Research on UAV–MEC Cooperative Scheduling Algorithms Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning

1 School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China

2 The 54th Research Institute of CETC, Shijiazhuang, 050081, China

3 State Key Laboratory of Networking and Switching Technology, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 100876, China

* Corresponding Author: Ying Liu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 79 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072681

Received 01 September 2025; Accepted 06 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

With the advent of sixth-generation mobile communications (6G), space–air–ground integrated networks have become mainstream. This paper focuses on collaborative scheduling for mobile edge computing (MEC) under a three-tier heterogeneous architecture composed of mobile devices, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and macro base stations (BSs). This scenario typically faces fast channel fading, dynamic computational loads, and energy constraints, whereas classical queuing-theoretic or convex-optimization approaches struggle to yield robust solutions in highly dynamic settings. To address this issue, we formulate a multi-agent Markov decision process (MDP) for an air–ground-fused MEC system, unify link selection, bandwidth/power allocation, and task offloading into a continuous action space and propose a joint scheduling strategy that is based on an improved MATD3 algorithm. The improvements include Alternating Layer Normalization (ALN) in the actor to suppress gradient variance, Residual Orthogonalization (RO) in the critic to reduce the correlation between the twin Q-value estimates, and a dynamic-temperature reward to enable adaptive trade-offs during training. On a multi-user, dual-link simulation platform, we conduct ablation and baseline comparisons. The results reveal that the proposed method has better convergence and stability. Compared with MADDPG, TD3, and DSAC, our algorithm achieves more robust performance across key metrics.Keywords

With the continuous evolution of 5G and 6G, cellular services have expanded from “human–information” to “things and intelligence,” and coverage has transitioned from purely terrestrial to space–air–ground–near-space connectivity [1]. In the IMT-2030 vision [2], future networks demand high computing capacity, ultralow latency, and native intelligence. MEC is regarded as a key enabler for low-latency and customized services. However, traditional terrestrial BS deployments are limited by site acquisition, power, and fibre backhaul, making elastic coverage difficult in emergency response, disasters, event hotspots, or rural areas. Low-altitude UAVs, with agility, high-quality LoS links, and rapid deployment, can carry lightweight edge servers to form mobile computing nodes in the air. With ground MEC nodes and the core cloud, low-altitude UAVs constitute a three-tier air–ground fused computing fabric [3].

Because MEC-equipped UAVs are integrated, coverage, latency, and elasticity are improved. Compared with fixed edge nodes, UAVs provide strong mobility, rapid deployment, and 3D reconfigurability (position and attitude), enabling on-demand temporary coverage for events, emergencies, and rural weak-coverage areas. The elevated LoS links of UAVs yield better channels and lower access latency, which are suitable for ultra-low-latency and highly concurrent services. Offloading some of the computation to nearby UAVs reduces backhaul overhead, decreases end-to-end latency, and decreases terminal energy consumption. When coverage is absent or BSs are impaired, UAVs—as components of non-terrestrial networks—can quickly establish continuous service at a manageable cost. Coordinated multi-UAV and ground MEC systems significantly improve throughput and task success rates [1,3–5]. These benefits, however, result in higher-dimensional states, stronger resource coupling, and stricter multiconstraint management, making online joint optimization central.

In an air–ground fused system, mobile devices, UAVs, and BSs are tightly coupled in wireless channels, computing slack, energy budgets, and task loads, resulting in high nonstationarity. Achieving millisecond-scale joint optimization over link selection, bandwidth shares, transmit power, and UAV trajectories becomes a new challenge in 6G NTN settings [4].

First, states are highly time-varying and noisy: UAV mobility causes frequent LoS/NLoS transitions, with shadowing/multipath inducing sharp channel fluctuations; traffic arrivals are bursty and spatially skewed, creating hotspots; and battery SoC, motor heating, and wind gusts dynamically decrease the available flight time and alter onboard computing power and serviceable users [5,6]. Static, averaged models or preset parameters are thus insufficient; scheduling must adapt online. Second, resources and topology are strongly coupled: per-slot decisions jointly determine link choice, bandwidth shares, power, and local/edge CPU frequencies; UAVs and BSs share spectrum and time, causing cross-layer interference; and UAV queues limit each other, and hard limits on access channels and backhaul create bottlenecks resulting in congestion, rapid energy drain, task backlog, and handover costs [7]. Third, hard constraints coexist with QoS targets: balancing latency, throughput, energy, reliability, and fairness while respecting spectral masks, interference thresholds, queue stability, deadlines, flight safety and no-fly zones, minimum reserve energy and return-to-base constraints; many critical states are only partially observable with delay/noise [8]. These realities set performance ceilings and pose rigid challenges to connecting density and service continuity.

Current practice emphasizes system-level coordination, e.g., building a multilayer edge fabric, via 3D UAV mobility to stand up hot spot cells and compute near data, and easing backhaul and queuing delay [1,3,4,6]. Multi-UAV collaboration and spatial reconfiguration of service pointsvia formation partitioning, dynamic trajectories, and service migration—balance load, and immersive services push rendering forwards to compress end-to-end delay [5,6,9]. When backhaul is limited or shadowing is severe, air-to-air/air-to-ground multihop relays deliver tasks to better nodes; extended to space–air–ground clusters, this yields cross-domain continuity and robust backhaul [10,11]. Robustness can be further improved with RIS-aided interference rejection, security-aware deployment, and network slicing, with transfer learning and partially observable decision-making for cross-scenario adaptation [8,12–14].

Despite progress, practical gaps remain: limited onboard computing and energy tightly couple queues and power on UAVs; under hotspots or backhaul impairments, UAV queues can quickly develop, increasing the return/swap frequency and negatively affecting service continuity [3,9]. Cross-layer coupling persists: under dual connectivity, bandwidth division, interference thresholds, UAV–BS backhaul occupancy, and uplink scheduling interact to form bottlenecks; multi-user concurrency is bounded by hard access/backhaul limits, inducing congestion, rapid energy drain, and backlog [4,5]. Multiple engineering constraints and stringent real-time QoS targets coexist; key states are often partially observed with delay/noise [8,15]. Cross-domain governance and O&M—slicing isolation/SLA compliance, space–air–ground clock alignment, backhaul redundancy and failover—have not been systematized [1,11].

Classical optimization and game-theoretic methods rely on stationarity or relaxations and scale poorly to high-dimensional continuous joint actions under partial observability. Online control provides stability but is short-horizon and sensitive to hand-tuned multipliers; heuristics are brittle across scenarios. Discrete-action MARL requires joint discretization of multiple resources, causing granularity loss or action-space blow-up. Prior MADDPG-style works show feasibility but face instability and seldom offer queue-stability guarantees or deployment guidance. These gaps motivate our centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) based continuous-action design with explicit queue/violation shaping and practical deployability.

Our contribution is an online cooperative scheduling scheme for air–ground-fused UAV–MEC under CTDE hierarchy. During training, the ground side aggregates global information to update policies; during execution, UAVs and devices act independently with lightweight messaging, reducing backhaul and inference latency. Mechanism-wise, we

(i) build a UAV–MEC system model to support DRL training/validation;

(ii) introduce an ALN-Actor to suppress feature distribution drift and gradient jitter while balancing inference latency and representation;

(iii) use an RO-Critic with twin-Q residual orthogonalization to reduce the estimator correlation and tighten the upper bound of the value;

(iv) design a dynamically reward temperature to enforce hard constraints early and enable fine-grained optimization later.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on air–ground-fused MEC, multi-UAV coordination and service placement, classical optimization, and multiagent DRL in wireless/MEC. Section 3 presents the system model and assumptions. Section 4 details the proposed MATD3-all framework. Section 5 describes the experiments (setups, baselines, metrics, results, ablation, and sensitivity). Section 6 concludes and discusses limitations and future directions.

For air–ground-fused UAV–MEC systems, the literature has created a distinct taxonomy across system modelling, resource orchestration, and intelligent control. Azari et al. [1] surveyed the evolution of non-terrestrial networks from 5G to 6G, highlighting three-dimensional heterogeneous coverage with low-altitude platforms, terrestrial macro cells, and the core cloud, and summarized spectrum and backhaul codesign. Xia et al. [3] provide a resource-management perspective on UAV-enabled edge computing, articulating “channel–bandwidth–power–compute” coupling for offloading and coordination and laying out constraints and metrics, which support subsequent learning/optimization formulations.

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) learns policies end-to-end without explicit modelling and has achieved breakthroughs in high-dimensional continuous control (e.g., games [16] and large-scale power grid control [17]). In MEC, DRL addresses latency-constrained problems: Bertoin et al. [15] propose time-constrained robust MDPs to maintain reachability and QoS under uncertainty and observation noise; Chen et al. [18] embed Lyapunov-assisted DRL into joint trajectory/resource allocation for UAV–MEC by converting stochastic arrivals and delay constraints into drift penalties in actor–critic objectives, yielding online schemes that bound average delay and minimize energy. Lyapunov and constrained RL offer generic tools to incorporate average constraints and safety margins [19,20]; Dai et al. [21] present Lyapunov-guided DRL, which transforms queue stability and energy constraints into differentiable penalties with stability guarantees. In practice, this transformation is often defined as “soft constraints + dynamic penalties”: larger penalties early to reach feasibility and smaller penalties later to avoid spiky objective surfaces.

With many concurrent users and coupled links, multiagent RL (MARL) has become the dominant paradigm [22–24]. Zhao et al. [4] model each terminal as an agent to jointly learn link selection and power control in UAV-assisted MEC, resulting in better elasticity/robustness than heuristics under strong coupling. Du et al. [6] use CTDE via MADDPG for joint service placement and offloading in air–ground integrated networks, mitigating nonstationarity during training with centralized critics and enabling low-latency execution. Queue-aware rewards explicitly penalize backlog and violation to reduce tail latency (e.g., Hevesli et al. [25]). Common to CTDE is the use of more information during training (centralized critics) while maintaining lightweight decentralized execution, which is well matched to online control in UAV–MEC [26].

To avoid overestimation and training oscillation in continuous action spaces, MATD3-based variants have proliferated. Cao et al. [27] integrate attention into the centralized critic to focus on influential peers, reducing variance and accelerating convergence. MATD3 inherits twin-Q and delayed policy updates and, combined with CTDE, fits continuous, strongly coupled joint actions (bandwidth, power, and link selection) well; thus, MATD3 is a strong baseline for UAV–MEC resource coordination [28]. For scalability, Ma et al. [29] presented engineering practices (parallel sampling, experience reuse, and structured nets) for large-scale network control. Moreover, architectural advances—value decomposition, attention, and residual decoupling—reduce estimator correlation and increase sample efficiency [30,31]. Layer normalization [32] stabilizes deep policies/values by suppressing activation drift. To reduce online exploration costs and handle strict safety margins, adversarially trained offline actor–critic and transfer learning support cold starts, cross-region reuse, and partial observability [33].

Recent UAV–MEC optimization research spans game-theoretic, online optimization, and heuristic paradigms, each with distinct trade-offs: game-theoretic models seek Nash equilibria but require iterative computation and often assume common knowledge—fragile under partial observability [34]; online optimization (e.g., Lyapunov-drift minimization) offers stability guarantees yet tends to be myopic, lacking long-horizon foresight [35]; and heuristics can degrade under dynamics without careful, scenario-specific tuning [36]. In contrast, DRL learns policies whose value functions capture long-term consequences, enabling anticipatory resource allocation. Prior MARL efforts for UAV–MEC (e.g., MADDPG-based offloading [4,6]) demonstrate feasibility but suffer from gradient instability and value overestimation in high-dimensional continuous spaces. Our CTDE + MATD3 approach natively supports continuous control, mitigates non-stationarity via centralized critics, and keeps on-device execution lightweight; we further introduce Alternating Layer Normalization (ALN) and Residual Orthogonalization (RO) to reduce gradient variance and twin-critic correlation, together with a dynamic reward temperature schedule to curb constraint violations. Collectively, these choices yield faster, smoother convergence and a steadier Pareto across throughput, power, queue, and violations than the above alternatives in highly dynamic MEC–UAV regimes.

In addition, two representative directions deserve mention—ground-to-UAV sub-terahertz channel measurement and modeling, which informs realistic air–ground link assumptions [37], and joint UAV deployment and edge association for energy-efficient federated learning [38], which emphasizes system-level training energy under mobility. We view these as complementary to our focus on unifying continuous, tightly coupled control of association–bandwidth–power–CPU under CTDE, with queue/violation shaping and lightweight deployability.

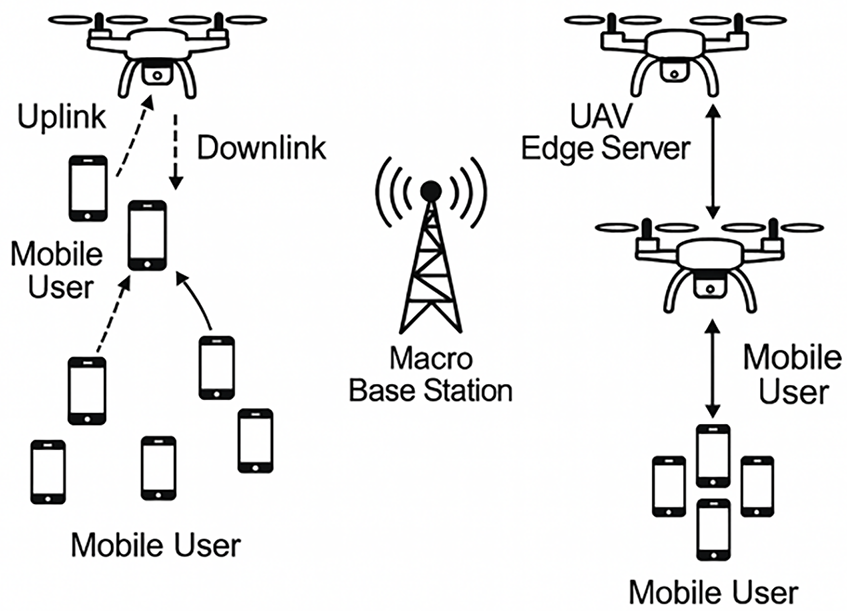

This chapter establishes a discrete-time, slotted system model for the UAV-assisted MEC setting, termed the air–ground integrated collaborative computing model, which provides a unified mathematical foundation for the subsequent algorithm design and performance evaluation. The system model is illustrated in Fig. 1. The air–ground integrated network consists of three layers of entities: a set of N ground mobile terminals

Figure 1: Air–ground integrated collaborative computing model

We adopt centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE). During training, a ground controller aggregates joint observations and actions to update the centralized critics; during execution, each UAV relies only on local observations plus lightweight messages for on-device inference. Policy checkpoints are versioned and periodically pushed to UAVs and terminals over secure links; a watchdog triggers rollback to the last stable version in case of anomalies.

Within each time slot, the pipeline is observation → selection actions → inner resource solve → queue update. Agents proceed in parallel and synchronize at shared constraints (e.g., bandwidth and concurrency caps). This design preserves consistency while keeping runtime overhead low.

First, we model the task queues based on the task arrivals at the mobile terminals. In the air–ground integrated collaborative computing model, let the number of tasks arriving at a mobile terminal in slot be denoted by:

Second, we define three types of task queues in the system model. Let the local task queue at mobile terminal

where

The number of serviceable bits within a single slot t is computed as follows:

where

Under steady-state and light-load assumptions, the average waiting delay of the computation task queue can be approximated by Little’s law as follows:

To guarantee finite delay, we use mean-rate stability: if

To suppress long-term overflow of the physical queues and facilitate online optimization, we explicitly accumulate any excess above the threshold into virtual queues, yielding state variables that can be penalized/controlled. For each mobile-terminal agent, we define two types of virtual queues—local and remote—as follows:

where

By imposing a linear penalty on

We set a backlog threshold

Tasks arriving have finite second moments and the inner resource allocation (bandwidth, concurrency, power and CPU) admits a feasible set. The penalty weight and an annealing floor such that minimizing a one-step Lyapunov drift upper bound yields bounded time-average backlogs for both physical and virtual queues; by Little’s law, the average delay is bounded.

Using a quadratic Lyapunov

In the air–ground integrated collaborative computing model, the task-offloading policy is implemented under a centralized-training, decentralized-execution (CTDE) framework.

Under this policy, the

where

3.2.2 Transmit Power and Bandwidth

When terminal agent

The uplink transmit power of terminal

Within each slot, terminal agent uploads some of its queued tasks over the air to a UAV or the BS. We define the net number of bits that are successfully transmitted within the slot and admitted into the corresponding edge queue as the offloadable task volume (in bits). The calculation proceeds as follows:

First, the channel gain in this model follows a distance-based path-loss model with log-normal shadowing, specifically:

where

Second, the uplink rate of the terminal agent

where

Last, the numbers of bits offloadable to the UAV and to the BS are jointly limited by the access association and the uplink rate, expressed as:

Within each slot t, terminal agent i can transmit bit volumes

The computation latency represents the pure processing time required for the bits assigned to each side at their respective CPU frequencies. Assume that each bit requires \kappa CPU cycles. In slot t, the CPU frequencies allocated to terminal agent

The complete end-to-end latency of the system model can then be approximated as follows:

The uplink transmission energy consumption of the mobile terminal is as follows:

The local computational energy consumption of the mobile terminal is as follows:

The energy consumption of the onboard edge-computing unit of the UAV is calculated as follows:

where

The energy consumption for UAV reception and related communication overhead is as follows:

where

The present energy model excludes UAV propulsion and counts only communication/compute terms (Eqs. (22)–(27)). For short-range hotspot/emergency coverage, this approximation preserves comparative conclusions; for long-range or highly maneuvering missions, a speed-dependent propulsion term should be integrated in future work.

We aim to achieve low latency, low energy consumption, and few constraint violations during long-term operation. Accordingly, in each time slot, we define three core quantities for use in the subsequent objective and constraints.

The throughput in slot t is defined as follows:

Throughput (units: bit/slot or Mb/slot) is the sum of the bits offloaded to the UAV, offloaded to the BS, and executed locally, indicating how much effective work is completed in the current slot.

The total energy of the system includes four communication/compute components, with the specific formulas given as follows:

The task queue serves as a direct proxy for delay; by Little’s law, a smaller average queue length indicates a lower average waiting time. The specific formula is as follows:

To better optimize the system objectives, we define the following constraints:

The bandwidth normalization constraint is as follows:

This constraint ensures that the allocated normalized bandwidth shares at the UAV and BS do not exceed the available resources.

The concurrent access constraint is as follows:

This limits the maximum number of users that can simultaneously access the UAV or BS.

The system energy budget constraint is as follows:

The total communication and computation energy in each slot are limited to ensure that they remain within the allowable system budget.

Dynamic coupling between queues, constraints, and decisions. Spikes in arrivals

3.3.2 Long-Term Constrained Optimization Objective

Under random arrivals and time-varying channels, the policy (which may be stochastic and nonlinear) induces a Markov chain that renders the cost process stable. We minimize the time-averaged composite cost as follows:

Given weights

3.3.3 Drift-Plus-Penalty (DPP) and Reward Shaping

To ensure queue stability and enable online optimization, we use the Lyapunov drift–plus–penalty method. The quadratic Lyapunov function, including physical queues and delay-related virtual queues, is chosen as follows:

Let the one-step conditional drift be:

Then, in each slot, we minimize the following upper bound:

where

For compatibility with policy gradient methods, the problem is equivalently written as maximizing the per-slot reward:

Assume: (A1) exogenous arrivals have finite second moments; (A2) the per-slot inner resource subproblem is feasible and the action set is compact; (A3) a Slater condition holds—there exists a stationary policy that strictly satisfies all long-term constraints with slack

Proposition 1: Under (A1)–(A4), the policy induced by the drift-plus-penalty objective (Eq. (36)) that approximately minimizes the per-slot upper bound ensures there exist constants

4 UAV-MEC Cooperative Scheduling Model Based on MATD3-all

Building on the system modelling in Section 3, we formulate the joint resource allocation problem among mobile terminals, UAVs, and the BS in the air–ground integrated setting as a multiagent MDP under a centralized training, decentralized execution (CTDE) paradigm. We subsequently use MATD3 as the core training framework and incorporate an actor network with alternate layer normalization (ALN), a critic network with Q-value residual orthogonalization (RO), and a dynamic reward temperature mechanism. The result is a cooperative scheduling model that achieves stable long-term convergence and robust decision performance in highly dynamic environments. We refer to this integrated, improved model as MATD3-all, as elaborated below.

4.1 Multi-Agent MDP (CTDE) Modelling

In the air–ground integrated UAV–MEC scenario, ground mobile terminals, low-altitude UAVs, and the BS make parallel decisions over a shared three-dimensional wireless resource pool, forming a multiagent interaction pattern. For a convenient DRL formulation, we abstract the system as a multiagent Markov decision process (MMDP), which can be represented by a tuple

Observation and joint state space

The joint state during training is

Action space

The environment applies a top-K mapping to obtain binary associations:

When dual connectivity is disallowed,

The transition dynamics

MATD3 is a robustness-improved variant of MADDPG for continuous action spaces. During training, each agent is equipped with two centralized critics to curb overestimation via the “twin-Q” mechanism; the actor is updated with delayed policy updates to reduce policy jitter; and target policy smoothing is applied to the target branch to mitigate high-frequency oscillations of target networks. In multiagent RL, two major pain points are nonstationarity and credit assignment. Because the policy of every agent continues to change, the environment appears to drift for any single agent, while the global reward is difficult to decompose. The CTDE paradigm addresses this challenge by letting centralized critics read the joint state–action during training to better reflect true dynamics and provide consistent gradients to all agents, whereas at run time, each terminal acts decentrally from local observations with very low communication and inference overhead.

To further increase sample efficiency and generalizability, we use parameter sharing for actors among homogeneous users and use a shared replay buffer to store joint transitions

For implementation and reproducibility, we detail one gradient-update step: how targets are built, how losses are defined, and how update rhythms are arranged. From the shared replay buffer, a mini-batch (S, A, r, S′) is sampled. The target actor is used to perform policy smoothing and obtain noisy target actions. Both target critics are evaluated, and the minimum is used to suppress overestimation. The current critics are fit to the target with MSE, and the RO regularizer is added. The actor is updated with a delay using Critic-1 as the surrogate objective. Formally:

Targeted actions and twin-Q targets. Given a batch

The target value is then obtained as follows:

The critic loss is as follows:

The actor loss is as follows:

Update the actor once every

Soft updates are:

The training loop follows the CTDE procedure: at each step, each terminal-side actor samples an action from its local observation with Gaussian exploration noise.

The continuous outputs are linearly mapped from

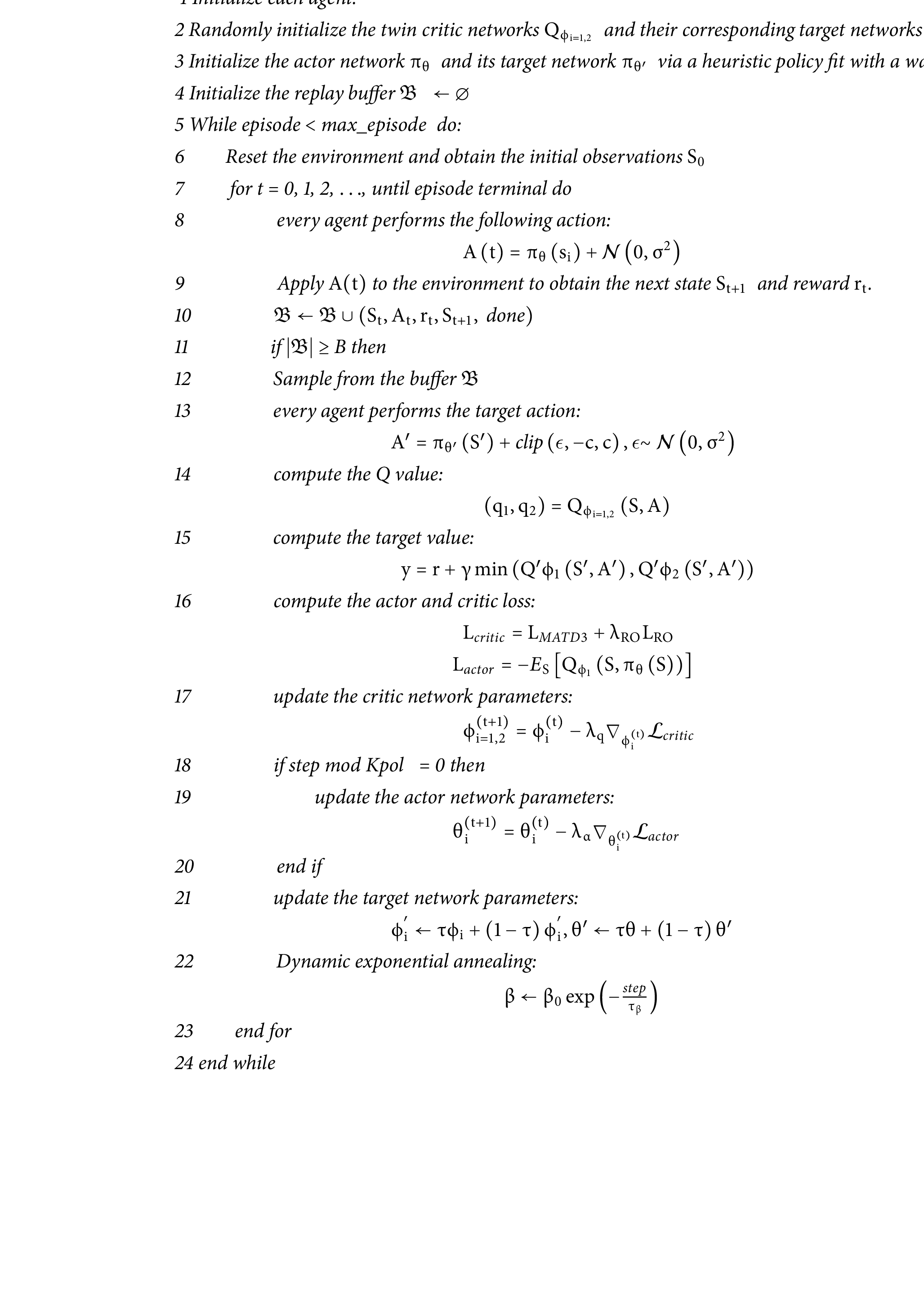

The detailed code is as follows:

4.3 Actor-Critic Network Architecture

Although the twin-Q and delayed policy updates of vanilla MATD3 help suppress overestimation, several issues remain. The gradient variance of the actor increases with depth and dimensionality, making “jitter–recoil” more likely after delayed updates; the TD residuals of the twin critics are highly correlated, so even the min-Q target can oscillate and feed noise back to the actor; and fixed penalty weights cannot simultaneously support the hard penalties needed early to enter the feasible region and the soft surface needed later for fine-grained optimization. To address this issue, we propose a coordinated design of ALN-actor + RO-critic + dynamic reward temperature, which stabilizes learning from three angles: gradient denoising, value decorrelation, and adaptive penalization.

As shown in Fig. 2, the upper part corresponds to decentralized execution: Each user deploys a lightweight actor (ALN-actor) with the alternating normalization backbone Linear–LayerNorm–Linear–LayerNorm–tanh. The input is the local observation S (including link gains, physical and virtual queues); the output is a continuous action A (scores for the two links), which is range-mapped and then fed to the environment to perform Top-K association and address the inner resource allocation. The lower part corresponds to centralized training: two shared critics and their target networks receive the joint state–action pair, compute and target to form the TD target y, and backpropagate policy gradients to all actors. A residual orthogonalization regularizer is imposed between the critics to reduce estimation correlation, while delayed actor updates increase stability. All the interaction data are written to a shared replay buffer. During training, critics can access global information; during execution, each actor relies solely on local observations while adhering to CTDE. With ALN for denoising and twin-Q + RO for stabilizing value estimates, the method achieves smooth, convergent policy learning in high-dimensional continuous control.

Figure 2: Actor–critic network architecture diagram

4.3.1 Alternate Layer Normalization (ALN) Actor Network

With multiple users, the action dimensionality increases linearly with N. In a vanilla fully connected actor, deep stacking tends to cause an activation distribution shift and increase gradient variance; coupled with delayed updates, this manifests as “jitter–recoil.” To alleviate this problem, we propose the ALN-actor (see the upper part of Fig. 2). At execution time, each user deploys a lightweight actor whose architecture repeatedly pulls activations back to a neutral scale layer by layer, markedly reducing gradient variance.

The input of the actor is the local observation

ALN mechanism and numerical stability. The linear output of the

Feature-wise normalization is applied per-sample to it:

When the LayerNorm scale parameter is initialized as

Compatibility with CTDE/delayed updates. MATD3 updates the actor once every

4.3.2 Q-Value Residual Orthogonalization (RO) Critic Network

Owing to strong nonstationarity, the TD residuals of the twin critics tend to shift in sync; their high correlation makes

With strongly time-varying links/loads and sparse penalties, the TD residuals of the two critics are as follows:

Because they often increase and decrease simultaneously, the correlation is high. As a result,

The core idea is to strip from the second residual its component along the first residual, keeping only the orthogonal part:

where the inner product and norms are computed over the batch and

The orthogonalized residual is appended as a regularizer to the critic loss:

Intuitively, the first critic focuses on the principal residual, whereas the second critic is limited to fit only the component orthogonal to the first critic (the complementary residual). This approach explicitly reduces their covariance, yielding a more stable target

4.4 Dynamic-Temperature Reward Function

To jointly optimize throughput, energy, and delay while suppressing violations, we use a decomposed reward structure comprising global cost + constraint penalty + per-agent gain.

(1) Log-compression and smoothing of the global cost

The objective

This compresses extreme values into

(2) Constraint penalty and dynamic reward temperature

The constraint penalty is as follows:

The penalty weight follows a dynamic exponential annealing schedule:

Hard guardrails early on drive the policy quickly into the feasible region, whereas “softer” penalties later facilitate fine-grained tuning.

(3) Per-agent gain and credit assignment

To address credit assignment while steering the policy towards high throughput, low queuing, and low power, we define a per-user term:

where

(4) Instantaneous reward and CTDE alignment

Aggregating the above, the training-time per-slot reward is:

During centralized training, the critics read the global

This chapter validates the proposed UAV–MEC cooperative scheduling strategy. We describe the experimental setup, evaluation metrics, and baselines and then report and analyze the results across multiple figures. Our experiments focus on continuous-control MARL baselines (TD3, DSAC, MADDPG, MATD3) because the decision variables—association, bandwidth shares, transmit power, and CPU frequency—are continuous and tightly coupled. Discrete MARL methods such as MAPPO/QMIX operate on discrete action spaces; applying them here would require discretizing multiple resources jointly, which either yields coarse bins that lose control granularity, or explodes the action space and training cost under the same compute budget. To ensure a fair and tractable comparison, we therefore restrict empirical baselines to continuous-action methods.

We use a self-built air–ground integrated UAV–MEC simulation platform with 10 ground terminal agents, 2 UAVs onboard MEC, and 1 terrestrial BS. The system operates in discrete time slots; terminal agent task arrivals follow a Poisson process. Wireless links include distance-based path loss with log-normal shadowing. Both the UAV onboard computation and the local computation of the terminal agent are limited by the DVFS and energy models. Constraints on bandwidth, transmit power, concurrent access, and dual connectivity are implemented as described in Section 3. Training and evaluation are carried out under the same environmental distribution.

The evaluation metrics include algorithmic indicators during training and system-level KPIs:

Training indicators: reward (per-episode average return), actor loss, and critic loss (sliding-window averages of actor/critic losses).

System KPIs: throughput (per-episode cumulative throughput, Mb), queue (average queue length, Mb/slot; lower is better), power (average power, W/slot; lower is better), and vio (cumulative constraint violations; lower is better).

To facilitate independent verification, we consolidate key environment and training settings in one place: slot length

5.2 KPI Definitions and Explanations

1) Throughput

The effective work completed in a single slot, which includes local execution, offloading to the UAV, and offloading to the BS, is averaged over the entire training/evaluation horizon:

The rate-feasibility constraints are as follows:

Units: Mb/slot. The throughput is higher than better, which represents greater task completion efficiency.

2) Queue

The in-flight workload of the system (by default, the local queue of the terminal agent in addition to the UAV-side remote queue of that terminal agent, including the BS side as well if enabled) is averaged. It is averaged across users and then averaged over time:

Units: Mb (megabits). The queue value is smaller than better, which indicates lower queueing/waiting pressure.

3) Power

The total communication and computation power per slot, which includes the terminal agent’s uplink transmit power, local compute of the terminal agent and onboard the UAV, is averaged over time:

Units: W. The power is lower than better.

4) vio (constraint violation)

Instantaneous soft/hard-constraint overruns, typically including access uniqueness, total-bandwidth caps, and concurrency caps, are made nonnegative (and, if desired, smoothed) and then weight-summed. Some implementations are multiplied by the dynamic reward temperature β(t).

If vio is smaller than better, the ideal value is 0. If the logs record

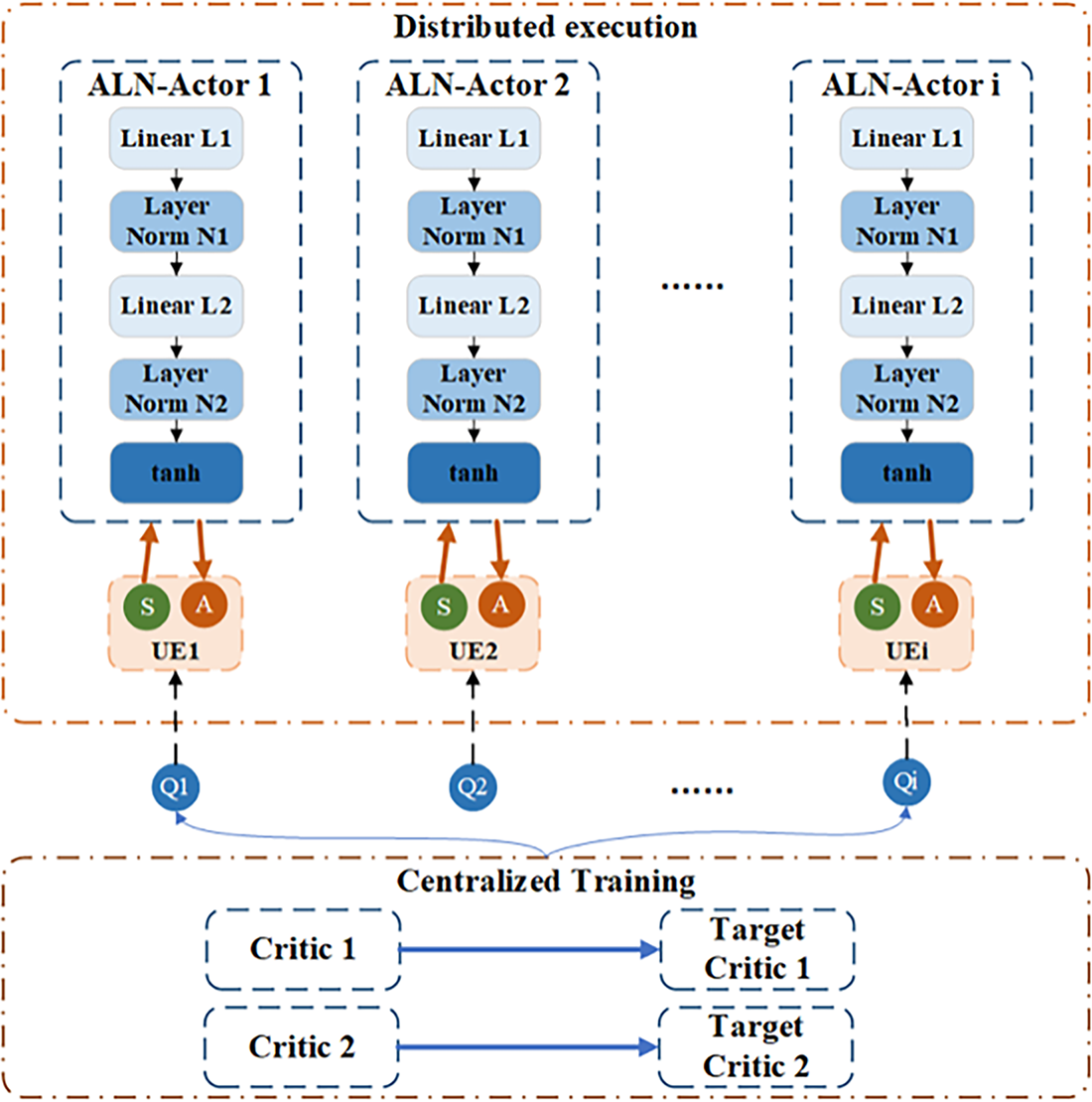

5.3 Convergence and Steady-State Behaviour

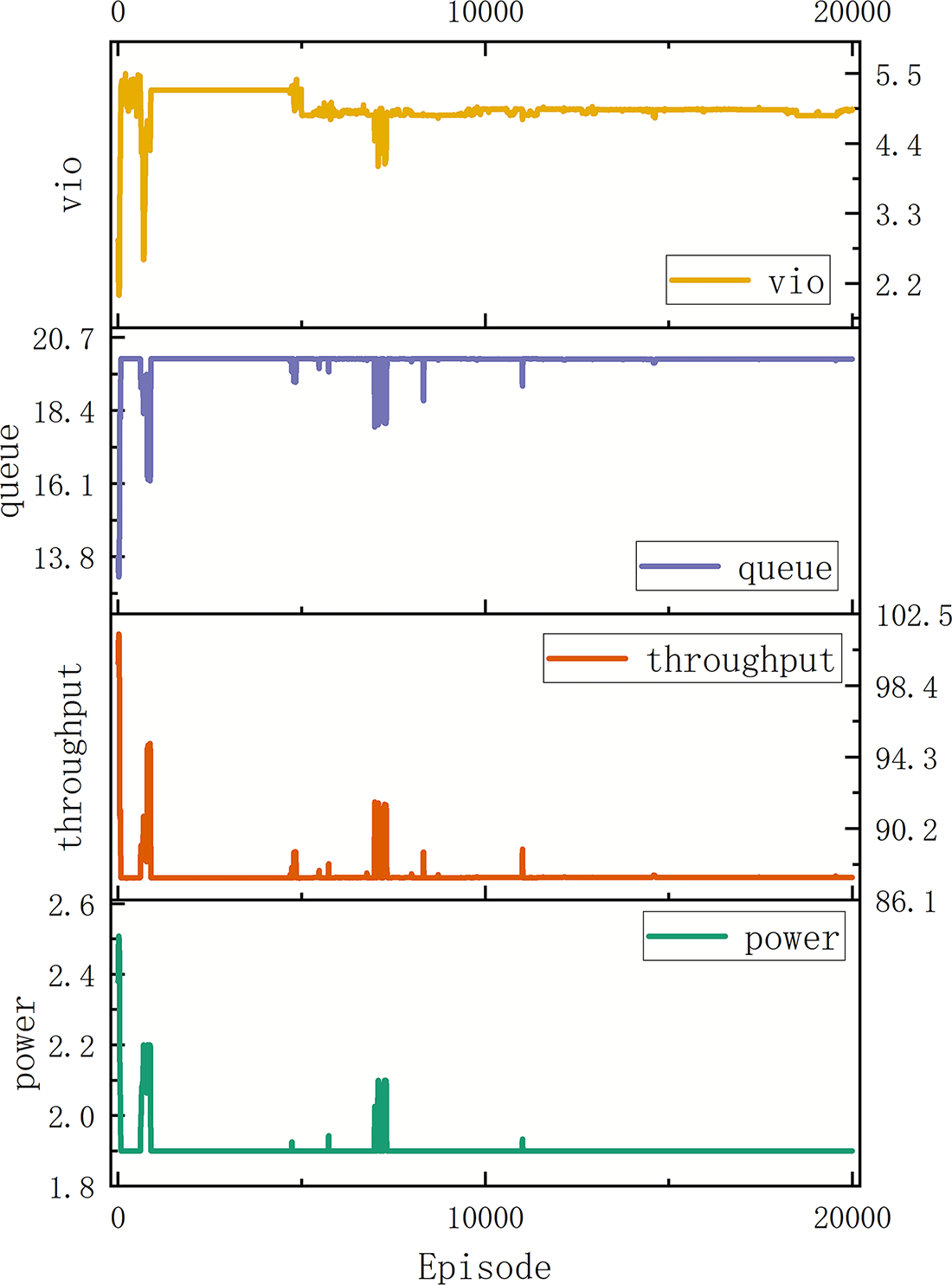

We analyse the convergence of MATD3-all. As shown in Fig. 3, the actor loss decreases monotonically from the start of training and gradually stabilizes; within the first 1000 episodes, it decreases rapidly from approximately 11 to approximately 4.5 and then decreases slowly and converges to a narrow band of 3.6–4.0 by 20,000 episodes. No obvious second blow-up phenomenon is observed during this period. This finding is consistent with the expectation that the ALN-actor reduces policy-gradient variance and stabilizes delayed updates.

Figure 3: Convergence metrics of MATD3-all

Moreover, the critic loss falls from 100 to the 0–5 range within 300–600 episodes, exhibits a few short pulses at approximately episodes 5000, 7000, and 11,000, and thereafter remains with small oscillations. This finding confirms that RO effectively weakens the correlation between the twin-Q residuals, mitigates overestimation and the move-together effect, and reduces noise back-propagated to the actor.

Occasional early/mid-stage spikes are associated mainly with target-action noise, top-K association switches, or shifts in the replay buffer distribution. Owing to the exponential annealing of the dynamic reward temperature, hard penalties early on pull the policy quickly into the feasible region, whereas softer penalties subsequently smooth the gradients and curves. Overall, relative to the initial stage, the actor loss decreases by approximately 65%, and the critic loss decreases by >95% at convergence, indicating good convergence and overall stability.

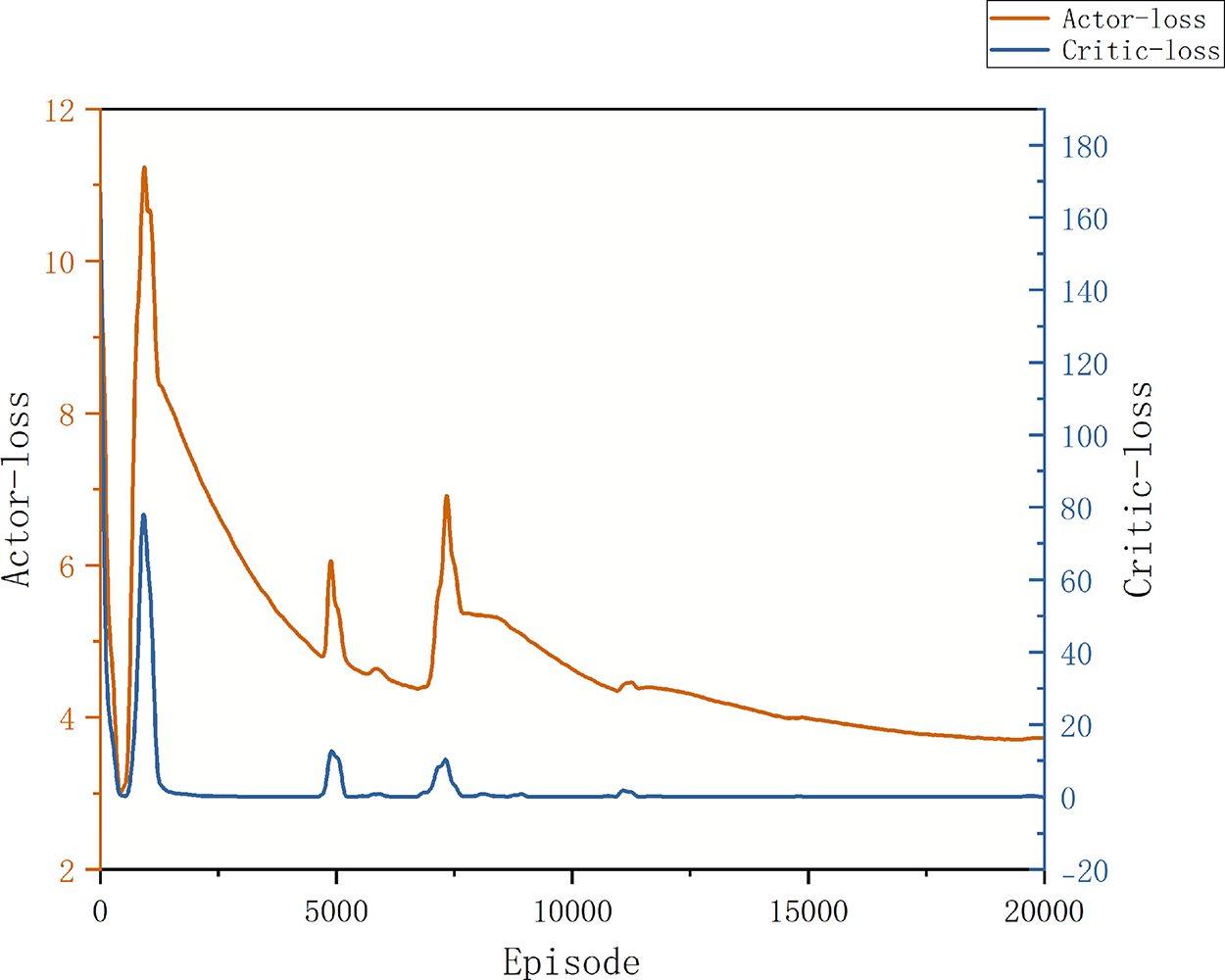

As shown in Fig. 4, considering all four KPIs concurrently, MATD3-all attains the steady-state target of few violations, stable queues, preserved throughput, and controlled power after it reaches steady operation. In early training (the first 2000 episodes), the vio metric exhibits several pronounced spikes, after which it is rapidly suppressed towards a tight stable band; peak values decrease by approximately 60%+ relative to the first spike, and steady-state variance is minimal. The queue remains on a high plateau (approximately 19.8–20.2 Mb), dipping only when throughput surges (“drained” lows) with amplitudes of approximately 10%–15%, which are infrequent. Throughput shows many spikes during early exploration (peaking at approximately 100–103 Mb/slot). After 10,000 episodes, the spikes markedly diminish, the curve becomes smooth, and the steady-state median is 87.4 Mb/slot, with 95% of observations in 86.5–88.0. The power remains close to a low-power baseline (approximately 1.9–2.0 W) and increases briefly to 2.1–2.2 W only when it coincides with throughput peaks; the overall variability is small. These patterns indicate that the dynamic reward temperature achieves a balance between rapid entry into the feasible region and subsequent fine-grained tuning. The occasional throughput peaks with queue dips and slight power upticks are controlled trade-offs, not signs of instability.

Figure 4: KPI metrics of MATD3-all

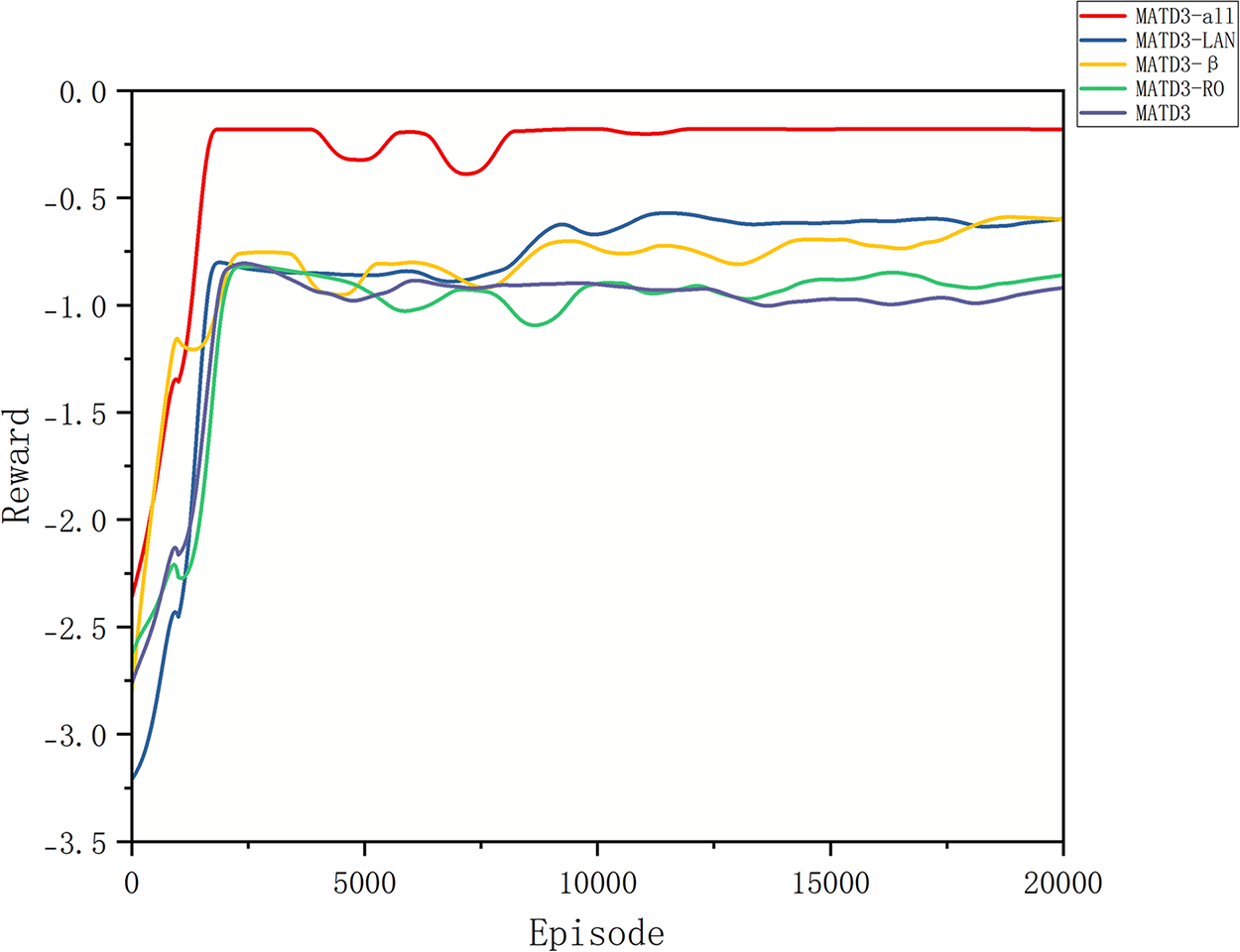

To quantify the independent contributions and synergies of our three improvements (ALN, RO, and dynamic reward temperature), we conduct ablations under identical training budgets and network sizes. With MATD3 as the baseline, we add one module at a time to obtain MATD3+ALN, MATD3+RO, and MATD3+β and compare them with the combined MATD3-Full. All other conditions (seed set, learning rate, target noise, delayed-update frequency, replay size, training episodes, etc.) are held constant for fair comparison.

As shown in Fig. 5, the curve trends indicate that ALN reduces the number of episodes to reach 90% of the steady-state plateau by approximately 30%–50% and decreases the mid/late-stage standard deviation by 20%–35%. The dynamic reward temperature markedly suppresses violations and jitter in the first 1000–2000 episodes, bringing earlier entry into the feasible region by 20%–40% and cutting the rolling variance of the steady-state reward by 15%–25%. Q-residual RO damps correlated noise between the twin Qs, shrinking peak-to-valley swings by 20%–30% in the mid/late stages; when it is used alone, it typically lifts the final steady-state median reward by only 2%–5%. The full combination (all three) benefits simultaneously in terms of faster convergence, lower variance, and fewer violations: relative to vanilla MATD3, episodes to 95% of the peak decrease by 40%, the steady-state median reward increases by 5%–10%, the steady-state variance decreases by 30%–50%, and the peak-to-valley amplitudes narrow by 25%–40%. Overall, the three mechanisms target different phases—entering feasibility vs. late-stage fine optimization—and are complementary.

Figure 5: Rewards in the ablation study

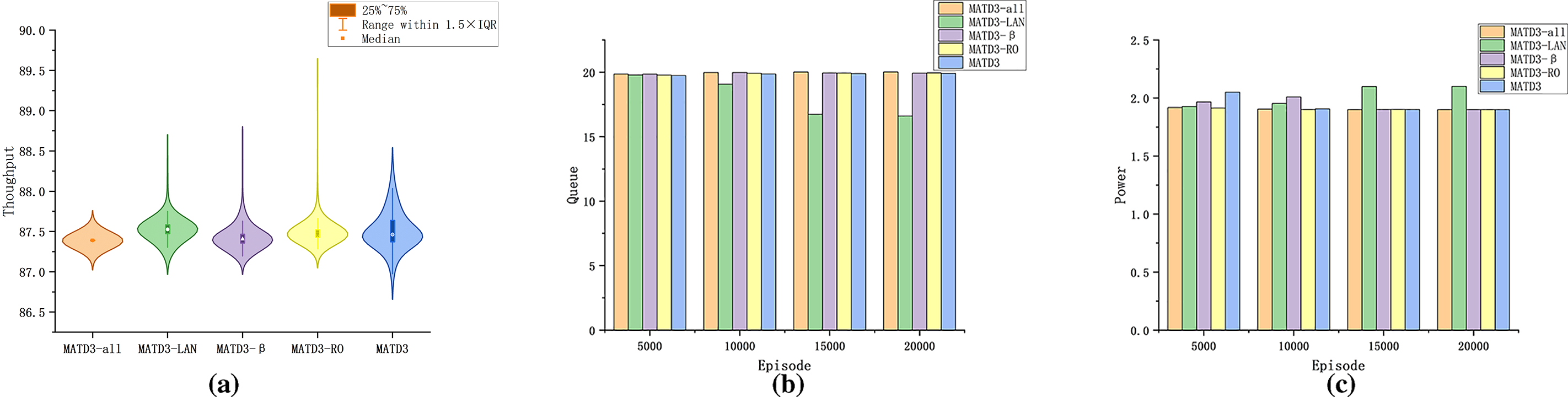

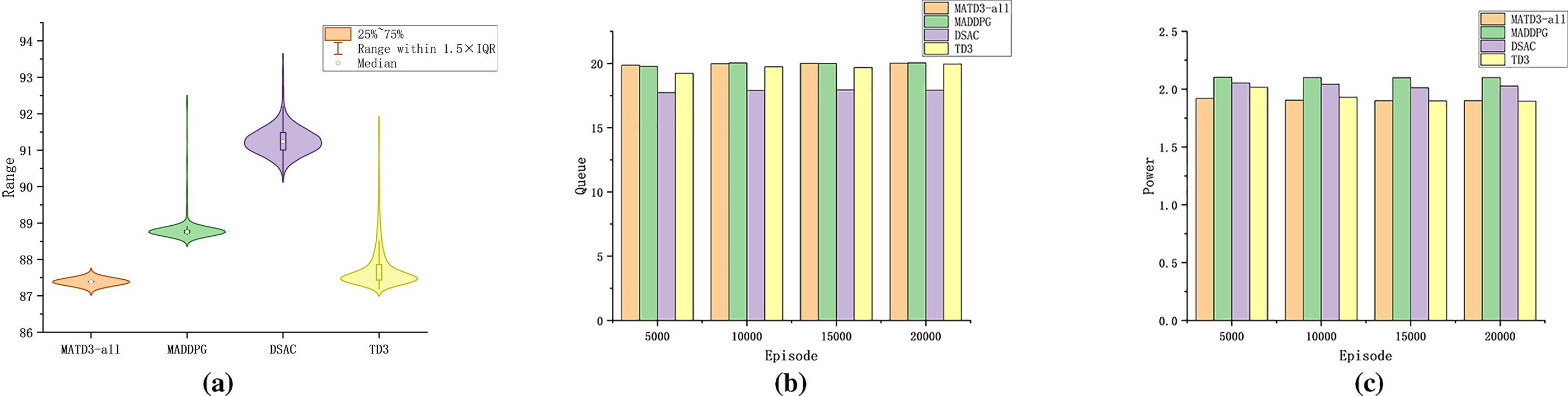

As shown in Fig. 6 Panels (a)–(c), we further analyse the throughput, power, and queue in the ablations:

Figure 6: KPI metrics in the ablation study. (a) Throughput distribution across ablation variants showing interquartile ranges and outliers; (b) Segment-wise mean queue length; (c) Segment-wise mean power consumption

Throughput (a). MATD3-all has an interquartile range (IQR) 25%–45% narrower than that of vanilla MATD3, with whiskers ~30%–50% shorter. The IQRs of ALN and RO are wider than those of MATD3-all by 15%–35% and 10%–25%, respectively, revealing the more aggressive throughput lift of ALN and the more conservative value estimates of RO.

Queue (b). Across four windows (1–5000, 5001–10000, 10001–15000, and 15001–20000), ALN decreases the average queue by 12%–30% vs. vanilla MATD3 (more pronounced early, converging to 10%–15% later). MATD3-all is similar to or slightly below baseline (mainly 0%–8% reductions). β lies between 5%–12% lower than baseline.

Power (c). The ALN consumes the most power—8%–22% above the baseline. RO and MATD3-all are more energy efficient—10%–20% and 12%–18% below baseline, respectively; β again is in the middle (3%–10% lower).

Trade-offs: If low delay/fast queue draining is prioritized, the ALN reduces the queue mean by ≥10% in all windows at a cost of ~10%–20% higher energy. If energy efficiency is prioritized, RO and MATD3-all draw less power, with MATD3-all maintaining lower power (−12%–18%) across all windows while ensuring acceptable queues (baseline level or up to 8% lower) and, per (a), the tightest throughput distribution (narrowest IQR and fewest extremes)—a more balanced Pareto trade-off among throughput, queueing, and energy.

5.5 Comparative Experiments and Analysis

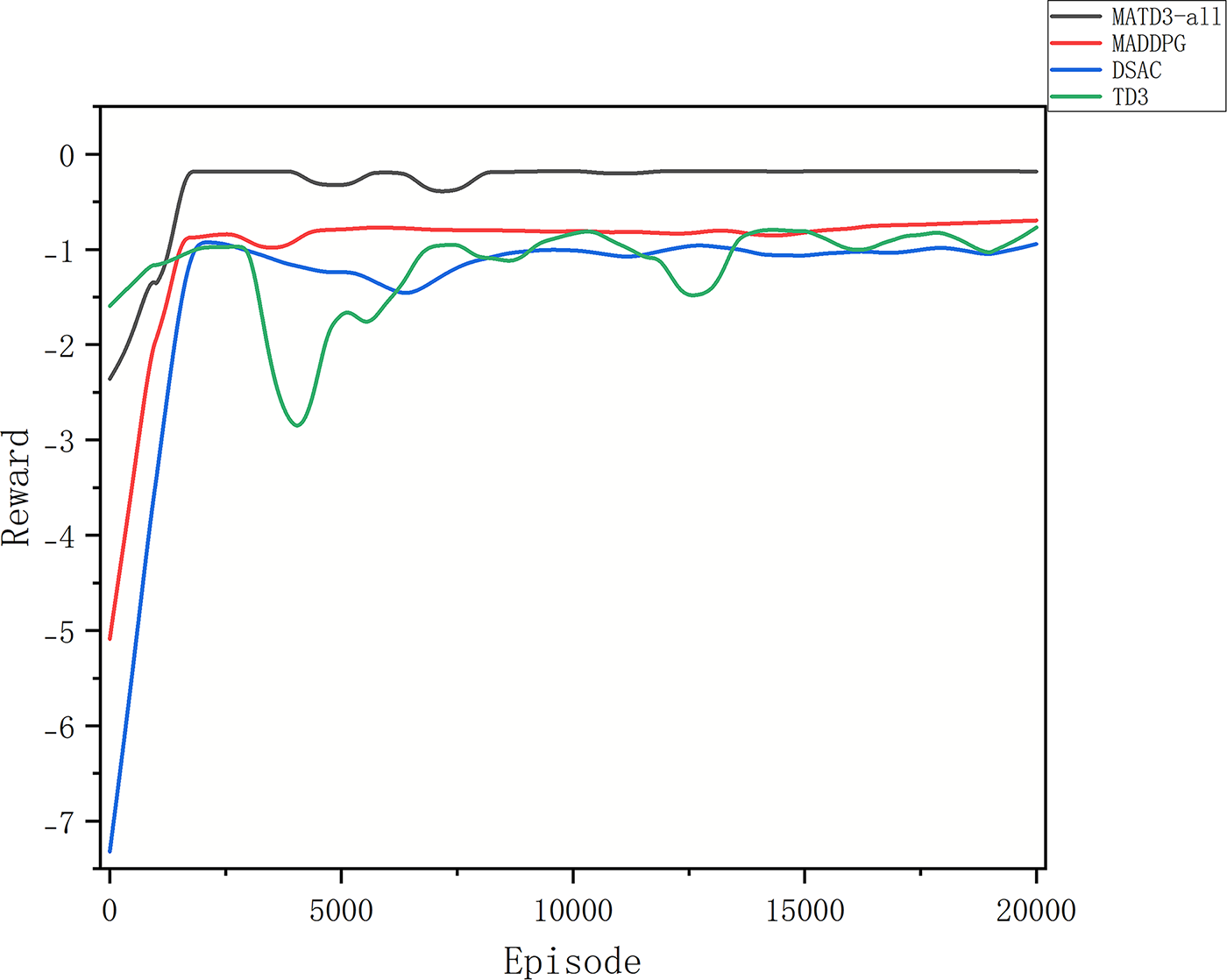

To assess the relative advantages and applicability against mainstream baselines, we compare algorithms representing different paradigms: MADDPG (multiagent deterministic policy gradient), TD3 (strong single-agent, continuous-control baseline), DSAC (distributed soft actor–critic), and our MATD3-all. All are trained in the same environment on the same data trajectories with identical budgets, the same replay size/batch/optimizer, and a fixed seed set while keeping the recommended key hyperparameters of each method for fairness.

As shown in Fig. 7 (Reward), MATD3-all converges fastest to the highest and smoothest plateau—typically reaching ≥90% of its final level within 2000–3000 episodes. The final average return is 10%–20% above MADDPG, 15%–30% above TD3, and 25%–40% above DSAC. The 500-episode sliding variance of MATD3-all is the lowest: approximately 40%–60% of the MADDPG’s and 50%–70% of the TD3’s. MADDPG ranks second—centralized critics help with nonstationarity, but single-critic bias and overestimation cause plateau wobble, and it lags MATD3-all by 2000–3000 episodes. TD3 reaches a reasonable plateau but, as a single-agent method, struggles with multiagent coupling and partial observability, showing phase-wise “dips” and greater variability. DSAC yields the lowest long-term reward here—consistent with its tendency towards higher throughput and lower queues at the expense of higher energy and penalties under our weighting, leaving it disadvantaged vs. TD3 and slower to converge. The ALN (stabilized policy gradient), RO (reduced twin-Q residual correlation), and dynamic reward temperature (hard-early/soft-late shaping) are complementary in MATD3-all, providing simultaneous advantages in terms of speed, final return, and smoothness.

Figure 7: Reward comparison across baselines

As shown in Fig. 8, three subplots jointly reveal the trade-offs among throughput, queue, and power for each method:

Figure 8: KPI comparisons across baselines. (a) Throughput distribution for MATD3-all, MADDPG, TD3, and DSAC; (b) Segment-wise mean queue length; (c) Segment-wise mean power consumption

Throughput (a). The DSAC has the highest median/upper whisker and a “thicker” distribution—it tends to saturate the spectrum and power, followed by MADDPG. MATD3-all and TD3 have similar medians, but MATD3-all has a 20%–40% narrower IQR and shorter tails—it is more robust in the steady state (median on par with TD3 or 3%–8% higher).

Queue (b). DSAC yields the lowest average queue, followed by MADDPG; MATD3-all and TD3 are slightly higher, which is consistent with more conservative offloading/power. The segment means for MATD3-all fluctuate less (the segment std is 25%–35% lower), indicating smoother handling of bursts in the steady state.

Power (c). MATD3-all is the most energy-efficient (or tied), TD3/DSAC is higher, and MADDPG is typically the highest. The segment-mean power of MATD3-all is approximately 10%–20% below the DSAC and 15%–25% below the MADDPG.

Reading the three, the “high-throughput, low-queue” edge of DSAC is offset by higher energy and penalties; thus, its overall reward is not superior. MATD3-all achieves a more robust Pareto balance across throughput–queue–power–constraints, with similar or slightly higher median throughput, tighter steady-state distributions, lower segment-mean power, and lower variability—this matches our design intent (ALN to stabilize gradients, RO to decorrelate twin-Q residuals, and dynamic reward temperature for hard-early/soft-late constraint shaping).

In the multi-terminal, dual-link UAV–MEC setting, MATD3-all exhibits the best convergence speed, steady-state smoothness, and overall return: its reward reaches a higher, smoother plateau, while violations drop rapidly early and remain stably low thereafter. Across KPIs, MATD3-all attains the tightest distributions without sacrificing median throughput, achieves lower average power, and maintains acceptably low queues, yielding a superior throughput–queueing–energy–constraints trade-off.

Taken together, when the objective over-weights ultra-low queue, DSAC can trade energy for more aggressive queue reduction; by contrast, MATD3-all delivers a steadier Pareto with lower power and fewer violations. Under extremely tight energy budgets or very limited training horizons, performance may degrade due to restricted exploration; in such cases, raise the penalty-weight floor, increase the RO weight to further de-correlate critics, and tighten Top-K selection, accepting a modest throughput sacrifice for stability. Consistently, MATD3-all’s traces show narrower KPI distributions and fewer violation spikes at comparable throughput, indicating resilience to workload/channel volatility. Mechanistically, RO reduces twin-critic correlation so actor updates are less sensitive to abrupt channel shifts; ALN stabilizes gradient scale; and the dynamic reward temperature acts as a guardrail that tightens near constraint boundaries.

Focusing on the air–ground integrated UAV–MEC cooperative computing scenario and the operational goals of low latency, low energy, and few violations, this paper builds a discrete-time, slotted system model that encompasses task arrivals and queueing, link access and bandwidth/power allocation, edge-computing service, and energy consumption. On this basis, we propose a robustness-oriented policy learning framework for continuous, high-dimensional, strongly limited environments with MATD3 at its core. Under the CTDE paradigm, we design an ALN-actor (alternate layer normalization) to reduce policy-gradient variance and stabilize delayed updates. We present a Q-value RO critic (residual orthogonalization) to weaken twin-Q residual correlation and suppress overestimation. Additionally, we incorporate a dynamic reward temperature to realize a “rapid entry into the feasible region—smooth fine-tuning thereafter” training schedule. With the Top-K association and an inner-loop resource solver, these three improvements recast the joint scheduling of mobile terminals–UAVs–BS as a learnable and convergent multiagent MDP.

Experiments on a multiuser, dual-link simulation platform validate the effectiveness of both convergence dynamics and steady-state KPIs. Compared with vanilla MATD3 and baselines such as MADDPG, TD3, and DSAC, MATD3-all converges faster, fluctuates less, and yields higher overall returns. Without sacrificing median throughput, MATD3-all achieves tighter queue and power distributions and maintains low levels of constraint violations over time. Ablations further confirm complementarity: the ALN accelerates convergence and markedly reduces queues; RO stabilizes value estimation and lowers energy; and the dynamic reward temperature smooths the transition from exploration to feasibility. Overall, the three yield the most favourable and stable Pareto trade-off. Overall, this work provides a learning-based scheduling solution for highly dynamic, high-dimensional UAV–MEC systems that is convergence controllable, lightweight in execution, and practical for engineering deployment.

Real-world outlook. To move beyond simulation, we envision a hotspot-coverage pilot with 2–4 UAV relays and a BS, where measured traffic arrivals and air–ground link logs drive online fine-tuning, and a hardware-in-the-loop (SDR) rig emulates fast fading and blockage during flight. For production-like operation, an on-prem training/monitoring node orchestrates versioned model delivery to UAVs, health-metric gating (violations/queue/power) with clear thresholds, update windows (e.g., every

Future work. Real-world uncertainties (e.g., wind fields, blockage, and interference) are more complex and call for out-of-distribution robustness and adaptive mechanisms. Scalability to dense networks (50+ users, 10+ UAVs) requires hierarchical clustering, parameter sharing across agent groups, and distributed critic architectures to maintain sub-second inference while avoiding exponential state-action growth.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: First Author: Yonghua Huo—Led the formulation of the research problem and the overall technical roadmap; took the lead in establishing the system model and the optimization objectives/constraints; proposed and implemented the MATD3-all joint scheduling framework, designing and realizing three core improvements—ALN-Actor, RO-Critic, and a dynamic-temperature reward mechanism; built the multi-user, dual-link simulation platform and data pipeline; led all baseline and ablation experiments and completed verification of key figures and results; drafted the main manuscript and integrated/revised the paper. Second Author: Ying Liu—Jointly contributed to problem conceptualization and approach justification; proposed critical revisions to the theoretical setup, system assumptions, and overall paper structure. Third Author: Anni Jiang—Responsible for organizing experimental data; assisted with manuscript revisions, performing experimental verification and error checking. Fourth Author: Yang Yang—Performed full-manuscript language and formatting proofreading, cross-checked references, and organized the supplementary materials. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Azari MM, Solanki S, Chatzinotas S, Kodheli O, Sallouha H, Colpaert A, et al. Evolution of non-terrestrial networks from 5G to 6G: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2022;24(4):2633–72. doi:10.1109/comst.2022.3199901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Singh R, Kaushik A, Shin W, Di Renzo M, Sciancalepore V, Lee D, et al. Towards 6G evolution: three enhancements, three innovations, and three major challenges. IEEE Netw. 2025;39(6):139–47. doi:10.1109/mnet.2025.3574717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xia X, Fattah SMM, Ali Babar M. A survey on UAV-enabled edge computing: resource management perspective. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(3):1–36. doi:10.1145/3626566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao N, Ye Z, Pei Y, Liang YC, Niyato D. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for task offloading in UAV-assisted mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2022;21(9):6949–60. doi:10.1109/TWC.2022.3153316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ren T, Niu J, Dai B, Liu X, Hu Z, Xu M, et al. Enabling efficient scheduling in large-scale UAV-assisted mobile-edge computing via hierarchical reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(10):7095–109. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3071531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Du J, Kong Z, Sun A, Kang J, Niyato D, Chu X, et al. MADDPG-based joint service placement and task offloading in MEC empowered air–ground integrated networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(6):10600–15. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3326820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jing J, Yang Y, Zhou X, Huang J, Qi L, Chen Y. Multi-UAV cooperative task offloading in blockchain-enabled MEC for consumer electronics. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;71(1):2271–84. doi:10.1109/TCE.2024.3485633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen D, Chen K, Li Z, Chu T, Yao R, Qiu F, et al. PowerNet: multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for scalable powergrid control. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2021;37(2):1007–17. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2021.3100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao Y, Liu CH, Yi T, Li G, Wu D. Energy-efficient ground-air-space vehicular crowdsensing by hierarchical multi-agent deep reinforcement learning with diffusion models. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2024;42(12):3566–80. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2024.3459039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wu M, Wu H, Lu W, Guo L, Lee I, Jamalipour A. Security-aware designs of multi-UAV deployment, task offloading and service placement in edge computing networks. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(10):11046–60. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3574061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hu S, Yuan X, Ni W, Wang X, Jamalipour A. RIS-assisted jamming rejection and path planning for UAV-borne IoT platform: a new deep reinforcement learning framework. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(22):20162–73. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3283502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wei Z, Li B, Zhang R, Cheng X, Yang L. Dynamic many-to-many task offloading in vehicular fog computing: a multi-agent DRL approach. In: GLOBECOM 2022—2022 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2022 Dec 4–8; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. p. 6301–6. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM48099.2022.10001342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gao Z, Wang G, Yang L, Dai Y. Transfer learning for joint trajectory control and task offloading in large-scale partially observable UAV-assisted MEC. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(10):11259–76. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3579748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu X, Yu J, Feng Z, Gao Y. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for resource allocation in IoT networks with edge computing. China Commun. 2020;17(9):220–36. doi:10.23919/jcc.2020.09.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bertoin D, Clavier P, Geist M, Rachelson E, Zouitine A. Time-constrained robust MDPs. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37; 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada: Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation, Inc. (NeurIPS); 2024. p. 35574–611. doi:10.52202/079017-1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Arulkumaran K, Deisenroth MP, Brundage M, Bharath AA. Deep reinforcement learning: a brief survey. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2017;34(6):26–38. doi:10.1109/MSP.2017.2743240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang Z, Sun G, Wang Y, Yu F, Niyato D. Cluster-based multi-agent task scheduling for space-air-ground integrated networks. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2025:1. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2025.3553297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen Y, Yang Y, Wu Y, Huang J, Zhao L. Joint trajectory optimization and resource allocation in UAV-MEC systems: a Lyapunov-assisted DRL approach. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2025;18(2):854–67. doi:10.1109/TSC.2025.3544124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xia Y, Wang X, Yin X, Bo W, Wang L, Li S, et al. Federated accelerated deep reinforcement learning for multi-zone HVAC control in commercial buildings. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2025;16(3):2599–610. doi:10.1109/TSG.2024.3524756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu X, Yi Y, Zhang W, Zhang G. Lyapunov-based MADRL policy in wireless powered MEC assisted monitoring systems. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2024—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS); 2024 May 20–20; Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/INFOCOMWKSHPS61880.2024.10620870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dai L, Mei J, Yang Z, Tong Z, Zeng C, Li K. Lyapunov-guided deep reinforcement learning for delay-aware online task offloading in MEC systems. J Syst Archit. 2024;153(2):103194. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2024.103194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pal A, Chauhan A, Baranwal M, Ojha A. Optimizing multi-robot task allocation in dynamic environments via heuristic-guided reinforcement learning. In: ECAI 2024. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: IOS Press; 2024. doi:10.3233/faia240705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu IJ, Jain U, Yeh RA. Cooperative exploration for multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Vienna, Austria. p. 6826–36. [Google Scholar]

24. Li Z, Liang X, Liu J, He X, Xie L, Qu L, et al. Optimizing mobile-edge computing for virtual reality rendering via UAVs: a multiagent deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(17):35756–72. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3580468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hevesli M, Seid AM, Erbad A, Abdallah M. Multi-agent DRL for queue-aware task offloading in hierarchical MEC-enabled air-ground networks. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2025. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2025.3555440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gao Z, Fu J, Jing Z, Dai Y, Yang L. MOIPC-MAAC: communication-assisted multiobjective MARL for trajectory planning and task offloading in multi-UAV-assisted MEC. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(10):18483–502. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3362988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cao Y, Tian Z, Liu Z, Jia N, Liu X. Reducing overestimation with attentional multi-agent twin delayed deep deterministic policy gradient. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;146:110352. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kim GS, Cho Y, Chung J, Park S, Jung S, Han Z, et al. Quantum multi-agent reinforcement learning for cooperative mobile access in space-air-ground integrated networks. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025:1–18. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3599683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ma C, Li A, Du Y, Dong H, Yang Y. Efficient and scalable reinforcement learning for large-scale network control. Nat Mach Intell. 2024;6:1006–20. doi:10.1038/s42256-024-00879-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li T, Liu Y, Ouyang T, Zhang H, Yang K, Zhang X. Multi-hop task offloading and relay selection for IoT devices in mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(1):466–81. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3462731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang Z, Wei Y, Yu FR, Han Z. Utility optimization for resource allocation in multi-access edge network slicing: a twin-actor deep deterministic policy gradient approach. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2022;21(8):5842–56. doi:10.1109/TWC.2022.3143949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ba JL, Kiros JR, Hinton GE. Layer normalization. arXiv:1607.06450. 2016. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Cheng CA, Xie T, Jiang N. Adversarially trained actor critic for offline reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 3852–78. [Google Scholar]

34. Li J, Shi Y, Dai C, Yi C, Yang Y, Zhai X, et al. A learning-based stochastic game for energy efficient optimization of UAV trajectory and task offloading in space/aerial edge computing. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2025;74(6):9717–33. doi:10.1109/TVT.2025.3540964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li G, Cai J. An online incentive mechanism for collaborative task offloading in mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2020;19(1):624–36. doi:10.1109/TWC.2019.2947046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yi C, Cai J, Su Z. A multi-user mobile computation offloading and transmission scheduling mechanism for delay-sensitive applications. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2019;19(1):29–43. doi:10.1109/TMC.2019.2891736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li D, Li P, Zhao J, Liang J, Liu J, Liu G, et al. Ground-to-UAV sub-terahertz channel measurement and modeling. Opt Express. 2024;32(18):32482–94. doi:10.1364/OE.534369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wu T, Li M, Qu Y, Wang H, Wei Z, Cao J. Joint UAV deployment and edge association for energy-efficient federated learning. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2025. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2025.3543365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools