Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Defending against Topological Information Probing for Online Decentralized Web Services

1 Shanghai Key Lab of Intelligent Information Processing, College of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200433, China

2 Research Institute of Intelligent Complex Systems, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200433, China

* Corresponding Author: Yang Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cyberspace Mapping and Anti-Mapping Techniques)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 10 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073155

Received 11 September 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Topological information is very important for understanding different types of online web services, in particular, for online social networks (OSNs). People leverage such information for various applications, such as social relationship modeling, community detection, user profiling, and user behavior prediction. However, the leak of such information will also pose severe challenges for user privacy preserving due to its usefulness in characterizing users. Large-scale web crawling-based information probing is a representative way for obtaining topological information of online web services. In this paper, we explore how to defend against topological information probing for online web services, with a particular focus on online decentralized web services such as Mastodon. Different from traditional centralized web services, the federated nature of decentralized web services makes the identification of distributed crawlers even more difficult. We analyze the behavioral differences between legitimate users and crawlers in decentralized web services and highlight two key behavioral attributes that distinguish crawlers from legitimate users: instance interaction preferences and hop count in profile viewing patterns. Based on these insights: we propose a supervised machine learning-based framework for crawler detection, which is able to learn the federation-aware feature representations for users. To validate the framework’s effectiveness, we construct a labeled dataset that integrates real users with real-trace driven simulated crawlers in Mastodon. We use this dataset to train various supervised classifiers for crawler detection. Experimental results demonstrate that our framework can achieve an excellent classification performance. Moreover, it is observed that federation-aware features are effective in improving detection performance.Keywords

Topological information plays a critical role in understanding online web services, particularly online social networks (OSNs) [1]. Extensive studies are based on OSNs’ topological information, i.e., the social graphs [2–5], as such information underpins a wide range of applications such as information diffusion [6], community detection [7–9], and recommender systems [10]. However, the topological information, characterizing the relationships among the users of online web services, is not only a foundation for functionality but also a target for adversarial exploitation. In particular, large-scale web crawling-based information probing has become a pressing concern. Such probing enables unauthorized data harvesting, cross-community profiling, and manipulation of users’ social relationships, thereby threatening the leakage of topological information.

While the risks of information probing have long been recognized in centralized OSNs such as Facebook and Twitter/X, these platforms retain the advantage of centralized governance. Uniform policies, platform-wide blacklists, and coordinated access control mechanisms allow them to defend against crawler-based attacks [11–14] more conveniently. By contrast, online decentralized web services, exemplified by the decentralized online social networks (DOSNs) [15–18], operate as federations of independently administered servers (instances), each maintaining only a partial view of the global social graph. This architectural openness, while empowering for users, also creates unique vulnerabilities. Open registration and distributed governance reduce the barrier for adversaries to deploy automated accounts across multiple instances, allowing large-scale cross-instance topology probing [19,20]. Moreover, existing defensive approaches, such as per-account or per-IP rate limiting, are coarse-grained [21]. They are insufficient against sophisticated crawlers that can closely mimic legitimate users by posting content, following accounts, and generating realistic interaction histories [22]. In particular, in DOSNs such as Mastodon [23], the lack of centralized oversight impedes instances from sharing crawler detection strategies or coordinating blacklists, leaving decentralized ecosystems exposed to greater probing threats. As decentralized services continue to grow in scale, the need to defend against topological information probing is increasingly urgent.

This paper takes a defense-oriented perspective on topological information probing by investigating the behavioral distinctions between legitimate users and crawlers in decentralized web services. We leverage these distinctions to design a machine learning-based crawler detection framework. Our empirical analysis highlights two key behavioral properties that differentiate legitimate users from crawlers, i.e., instance interaction preference and social distance in profile viewing patterns. Legitimate users tend to interact primarily with proximate neighbors within their home instance, whereas crawlers show no such preference and often access distant or arbitrary positions in the social graph. Building on these insights, we construct a labeled dataset by combining real user data with real-trace-driven simulated crawlers, in which actual Mastodon user behavior traces guided the generation of simulated crawler activity. We then extract both conventional and federation-aware features and use them to train supervised classifiers for crawler detection. The key contributions of this paper are as follows.

• We present a comprehensive user behavioral analysis in DOSNs, identifying distinct cross-instance interaction patterns and profile viewing patterns between legitimate users and crawlers.

• We construct and label a dataset comprising both legitimate user data and crawler activities simulated based on real traces from Mastodon, enabling empirical evaluation.

• We propose a supervised machine learning-based detection framework for identifying crawlers in DOSNs based on ActivityPub and evaluate its effectiveness as a practical defense using a labeled Mastodon dataset.

By addressing the unique challenges of decentralized ecosystems, this work advances the protection of users and platforms against topological information probing, thereby strengthening the long-term security and trustworthiness of decentralized web services.

2 Background and Data Analysis

2.1 Decentralized Online Social Networks and Mastodon

DOSNs have increasingly attracted attention as privacy-preserving alternatives to conventional, corporate-controlled platforms. This trend further accelerated following Twitter’s acquisition and renaming as X in 2022 [24]. In contrast to single-provider platforms, a DOSN platform is a federation of servers (usually called instances) that exchange data through open standardized protocols. The ActivityPub Protocol [25] is currently the dominant standard for DOSNs. It enables users on one instance to follow, mention, and share content with users on any other instance. It can preserve the global social graph while leaving each instance free to design its own moderation policies, data-retention rules, and community norms. People often use the term Fediverse to describe the ensemble of online social networks that consist of different instances. The Fediverse encompasses a diverse range of platforms, including microblogging services like Mastodon [26], image-sharing platforms like Pixelfed [27], and video hosting services like PeerTube [18]. A user enrolls in the network by choosing an instance as its home instance1, creating an account, and subsequently forming social ties both within and across instances. Each account maintains a profile page that aggregates account information, posts, and replies.

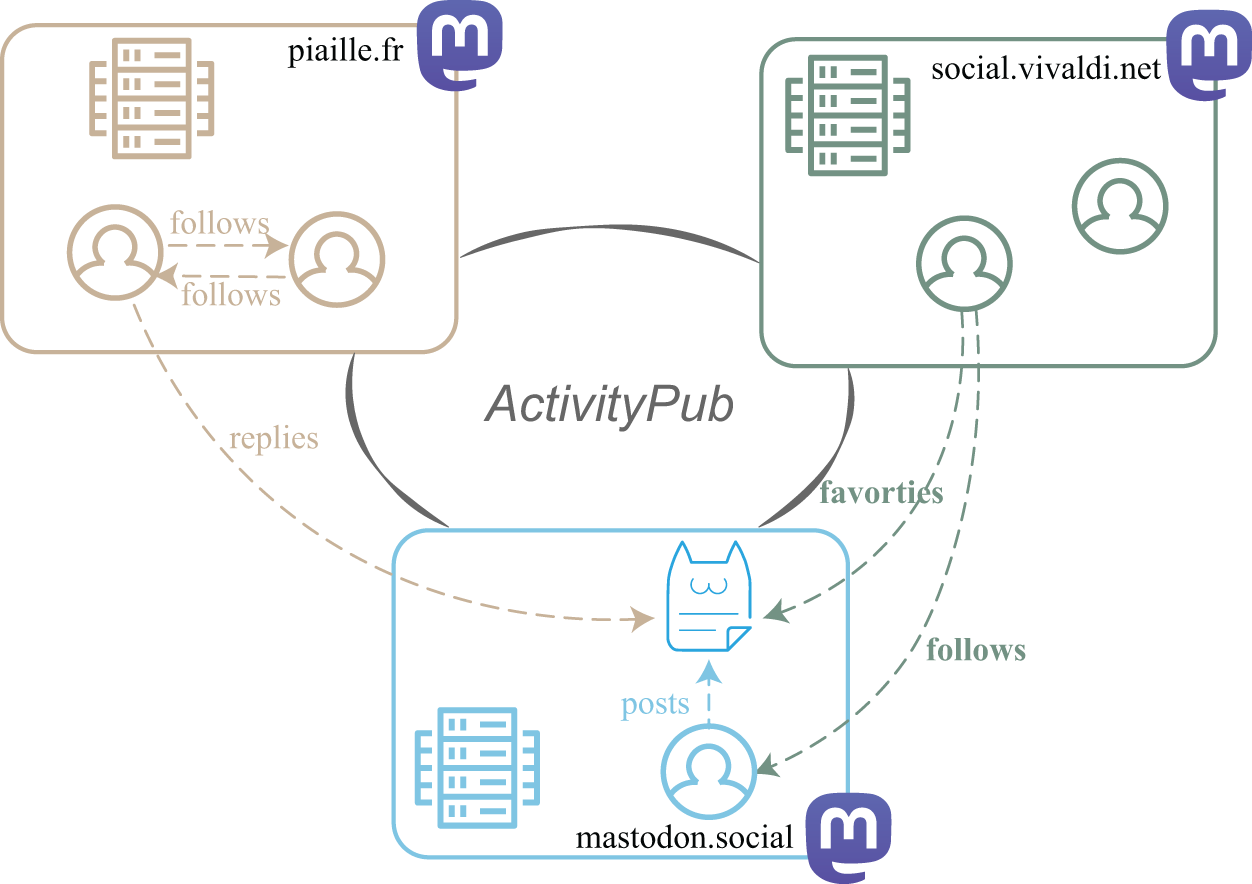

Mastodon is one of the most well-known DOSNs. Like Twitter/X, it functions as a microblogging platform where people can publish original posts and repost other users’ posts. As shown in Fig. 1, Mastodon’s network consists of multiple instances, in which users can interact across the federated network by following, liking, reposting, and replying. To assist newcomers in finding a suitable instance, Mastodon provides a curated list of recommended instances on its official website [28], while also allowing users manually to search for instances. To balance discoverability, self-governance and privacy, Mastodon offers three feeds: home, trending, and live feeds. The home feed is personalized, featuring content from the accounts or hashtags the user follows. The trending feed is sorted according to a “trending score”. The live feeds show the latest posts from the federated instances. Different feeds make it possible that crawlers can adopt different crawling strategies. Additionally, Mastodon allows users to configure the visibility of their profiles in multiple ways:

Figure 1: Interactions in Mastodon via ActivityPub: examples of follow relationships and content actions (posts, favorites, replies) occurring across instances

• Public: In this mode, users’ followers and followees are displayed, the platform recommends their accounts to others, and the accounts are visible in search engines.

• Private: In this mode, users must manually approve follow requests. Their followers and followees are not displayed to other users, their accounts are not recommended to others and are not visible in search engines.

• Custom: In this mode, users can manually configure the above settings according to their preferences.

In our work, we focus only on public accounts, assuming that user profiles, along with their follower and followee lists, can be viewed. Notably, unlike centralized OSNs, Mastodon imposes specific visibility restrictions: when viewing another user’s follower and followee lists, one can only access users who belong to the same instance [21]. This limitation affects users’ browsing and interaction behaviors, which will be further discussed in the following part of this section.

The goal of a crawler is to comprehensively collect user profiles and social relationships, and to construct a relational network among users. The collected data may later be exploited for commercial analytics, social-graph inference, or large-scale model training. Traditionally, crawlers targeting online social platforms adopt the breadth-first search (BFS) strategy, expanding and collecting user data layer by layer [29,30]. In Mastodon-like DOSNs, live feeds timelines continuously push real-time published posts, providing a new entry for crawlers. As a result, a number of collection methods have emerged that directly crawl active posting users by monitoring live feeds [19,20]. These two crawler types are the primary drivers of topological information leakage. Accordingly, we focus on defending against these two crawler types.

BFS Crawlers: The crawlers register accounts across multiple instances to gain access permissions and then recursively traverse the social graph in a BFS manner under the instance’s rate limit. They start from several seed users and expand to followers and followees, with a bias toward densely connected neighborhoods to improve discovery efficiency [29,30]. As a result, BFS crawlers typically produce a higher volume of profile views than legitimate users, while the hop counts from the initial seed users slowly increase over time. To better mimic human activity, the crawler also triggers lightweight interactions such as replies or favorites. Additionally, due to Mastodon’s instance-based architecture, users can only view the users hosted on the same instance when viewing follower or followee lists. Therefore, profile views and interaction behaviors generated by one BFS crawler are almost exclusively confined to users within the same instance.

Live Feeds Crawlers: The crawlers register accounts across multiple instances to gain access permissions. They continuously fetch posts from live feeds timelines and subsequently access the profiles of users who have recently posted [19,20]. They also produce superficial interactions, such as replying to or favoriting posts. The primary goal of live feeds crawlers is to passively and efficiently collect active users’ data. As this strategy is driven by live feeds timeline which aggregates the latest posts from all instances, it usually results in a high volume of cross-instance profile views and interactions. Moreover, the pattern of profile view hops is highly variable, lacking the smooth, incremental growth seen in BFS.

Understanding the behavioral characteristics of users is essential for distinguishing between legitimate users and crawlers in DOSNs. In this subsection, we analyze activity patterns of legitimate users and crawlers across multiple dimensions.

2.3.1 Legitimate User Behavior Analysis

Thoroughly modeling legitimate user behavior in DOSNs presents inherent challenges due to limitations in server-side observability. Although Mastodon offers an open API that allows developers and researchers to access public user information, including follower and followee lists, posts, replies, favorites, it does not expose detailed browsing behavior such as profile views. This omission is particularly significant, as profile viewing behavior serves as a key indicator in identifying crawler-like activity [11]. To compensate for this observability gap, our behavior analysis draws upon (i) established behavioral insights from prior studies on centralized OSNs, e.g., RenRen, Facebook, Orkut, and (ii) empirical analysis of Mastodon-specific user behavior using the dataset collected by FediLive [19] during the period from 22 November to 2 December 2024.

Prior work shows that profile views are heavily skewed: over 90% of users make or receive fewer than 10 views, while only 0.4% view more than 50 profiles [11]. Profile view activity is also topologically localized: more than 80% of profile views occur within a two-hop neighborhood [11]. Additionally, a strong positive correlation exists between the number of social connections and profile view count, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of approximately 0.75 [31]. Therefore, we synthesize the profile view of users according to the Pearson correlation with user degree. Let

where

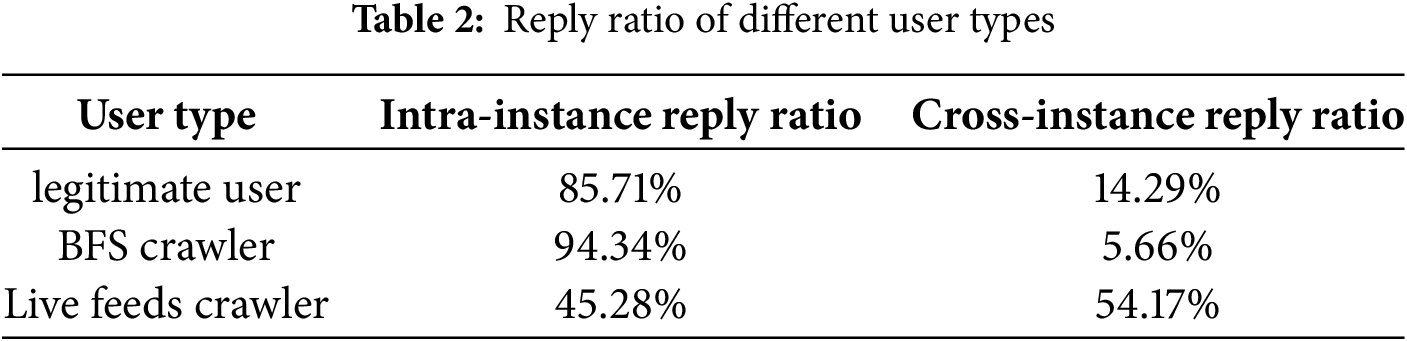

We further analyzed reply2 interactions. The results reveal a pronounced intra-instance communication pattern: 85.71% of all replies occurred within the same instance, while only 14.29% occurred across instances. On a user-level basis, the average intra-instance reply ratio is 93.13%, compared to just 6.87% for cross-instance replies. Furthermore, to quantify users’ reply preferences more precisely, we computed the ratio between intra-instance and cross-instance reply probabilities, excluding trivial cases where an instance only contains a single user. The results show that users in most instances demonstrate a significantly stronger tendency to reply to users within their home instance.

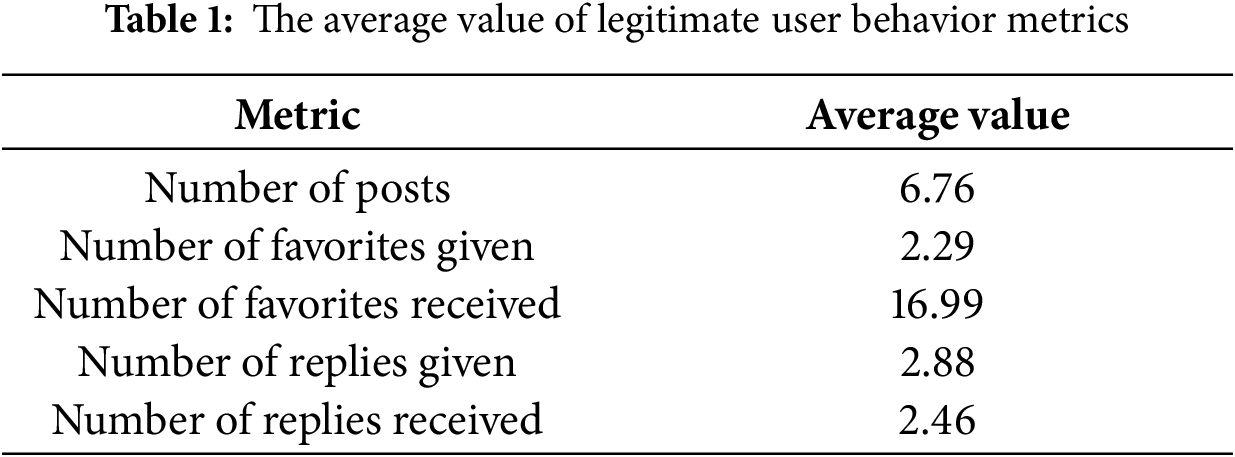

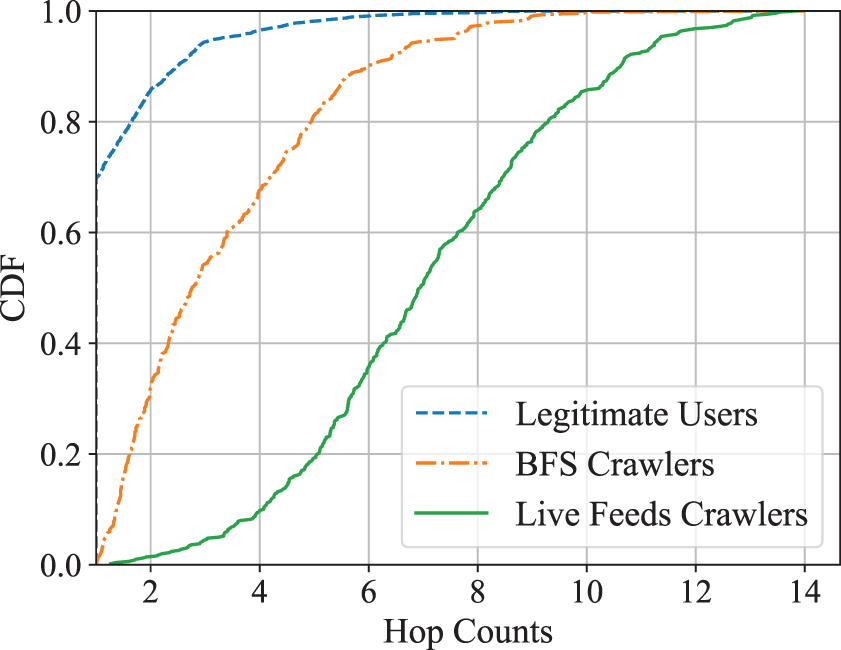

To establish a reliable baseline for typical legitimate user behavior in Mastodon, we calculated the average activity metrics of all users over a two-week observation window. This time frame captures stable patterns of engagement while minimizing the influence of short-term anomalies. Table 1 shows that the average active Mastodon user posted 6.76 posts, gave 2.29 favorites, received 16.99 likes, and exchanged 2.46 replies. These values reflect the modest engagement levels characteristic of the majority of users in Mastodon.

While average values provide a significant summary, they fail to capture the diversity and imbalance inherent in user behavior. To better illustrate this, we used complementary cumulative distribution functions (CCDFs) to visualize user activity features. The distribution of posts (Fig. 2a) per user follows a classic heavy-tailed pattern: the majority of users contribute only a small number of posts, while a small minority are responsible for a disproportionately large share of content production.

Figure 2: (a) CCDF of the posts posted by Mastodon users during a two-week period. (b) CCDF of the favorites given and received by Mastodon users during a two-week period. (c) CCDF of the replies given and received by Mastodon users during a two-week period

Fig. 2b reveals that while most users give or receive relatively few favorites, a small subset accumulates a significantly higher number. Notably, the “Favorites Given” curve lies above the “Favorites Received” curve, indicating that favoriting behavior is slightly more evenly distributed than being favorited.

Fig. 2c reveals that both “Replies Given” and “Replies Received” follow heavy-tailed distributions, indicating that while most users participate in only a limited number of reply interactions, a small subset exhibits significantly higher activity. Notably, the two curves are closely aligned across most of the range, suggesting that replying is almost proportional to being replied to.

2.3.2 Behavior Analysis of Crawlers

To investigate crawling behavior in DOSNs, we simulated crawlers on Mastodon. In contrast to legitimate users, crawlers are designed to resemble legitimate user accounts in both profile and general behavioral patterns, with the goal of extracting user data as extensively and unobtrusively as possible. Although crawlers may attempt to mimic legitimate user behavior, empirical observations of crawling activity on Mastodon reveal behavioral discrepancies in specific dimensions [19,20]. To better reflect crawler-specific operating characteristics, features such as profile view, cross-instance interaction, and hop count3 of profile views are selectively inflated to reflect crawler-specific patterns. It is important to note that Mastodon has a rate limit for accounts. By default, all endpoints and methods can be called 300 times within 5 min [21]. This constraint significantly impacts the crawling speed. In practice, crawlers must operate under this limitation while still attempting to maximize data collection efficiency within allowable requests.

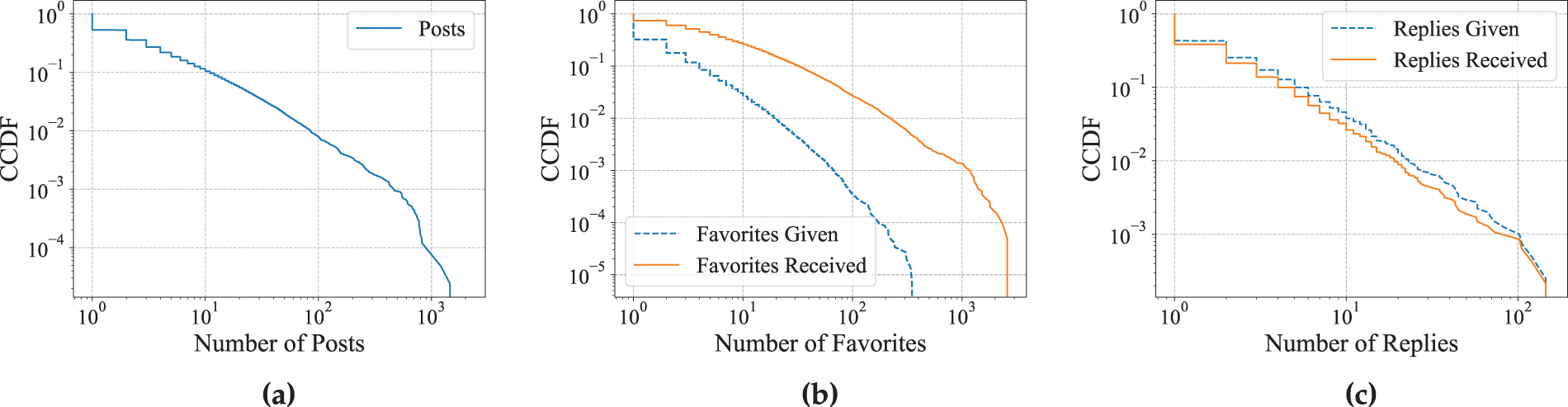

Under the constraints described above, we first synthesized crawler profiles parameterized by empirical user behavior. Then, as detailed in Section 2.2, we simulated two representative crawling strategies—BFS and live feeds—crawlers and generated 1000 synthetic crawlers (500 per type). Subsequently, to validate how well the simulated crawlers reflect real-world strategies, we compared their behavioral patterns with those of legitimate users, revealing two important differences.

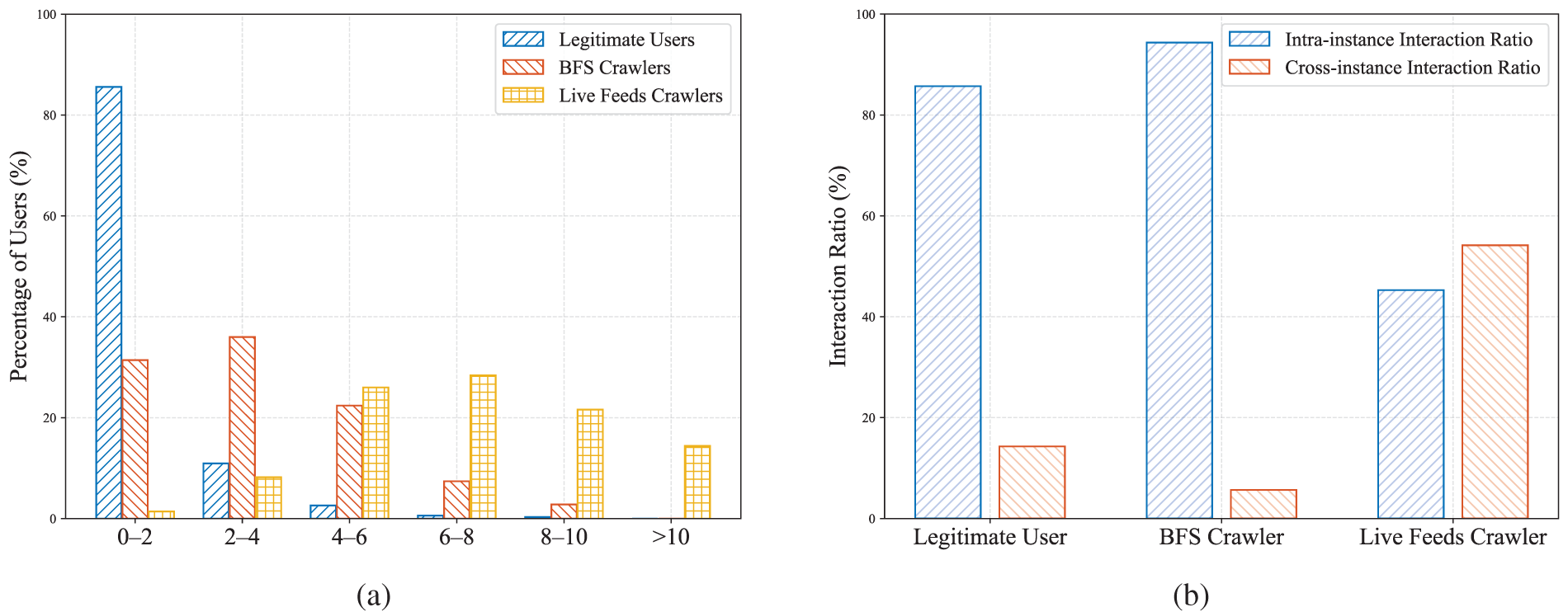

Profile views are highly non-local. Fig. 3 shows the hop count distribution of profile views made by different types of crawlers and legitimate users. Compared to legitimate users, crawlers generally access profiles that are farther away in the social graph. This trend is particularly pronounced for live feeds crawlers, whose hop count distribution is relatively uniform, reflecting the randomness of their browsing behavior. In contrast, BFS crawlers display a long-tail hop distribution, with almost all profile views occurring within 6 hops from the seed users. Overall, legitimate users typically access profiles within a 1-4 hop range, while crawlers are more likely to perform high-hop, non-local visits.

Figure 3: Cumulative distribution of the hop counts of profile views in Mastodon with different types of users

Cross-instance interaction ratio is different from legitimate users. Table 2 compares the intra-instance and cross-instance reply ratios of different user types. Legitimate users predominantly interact within their home instance, with 85.71% of replies directed toward users from the same instance. BFS crawlers exhibit even stronger intra-instance locality, with over 94% of their replies occurring within the same instance. In contrast, live feeds crawlers demonstrate a strikingly different pattern: over half (54.17%) of their replies are directed toward users in other instances. This reflects their timeline-driven browsing strategy, which is less bound by structural locality and more influenced by activity levels across the federated network. These differences in cross-instance behavior offer a valuable signal for distinguishing crawlers from legitimate users.

3 Crawler Detection System Design

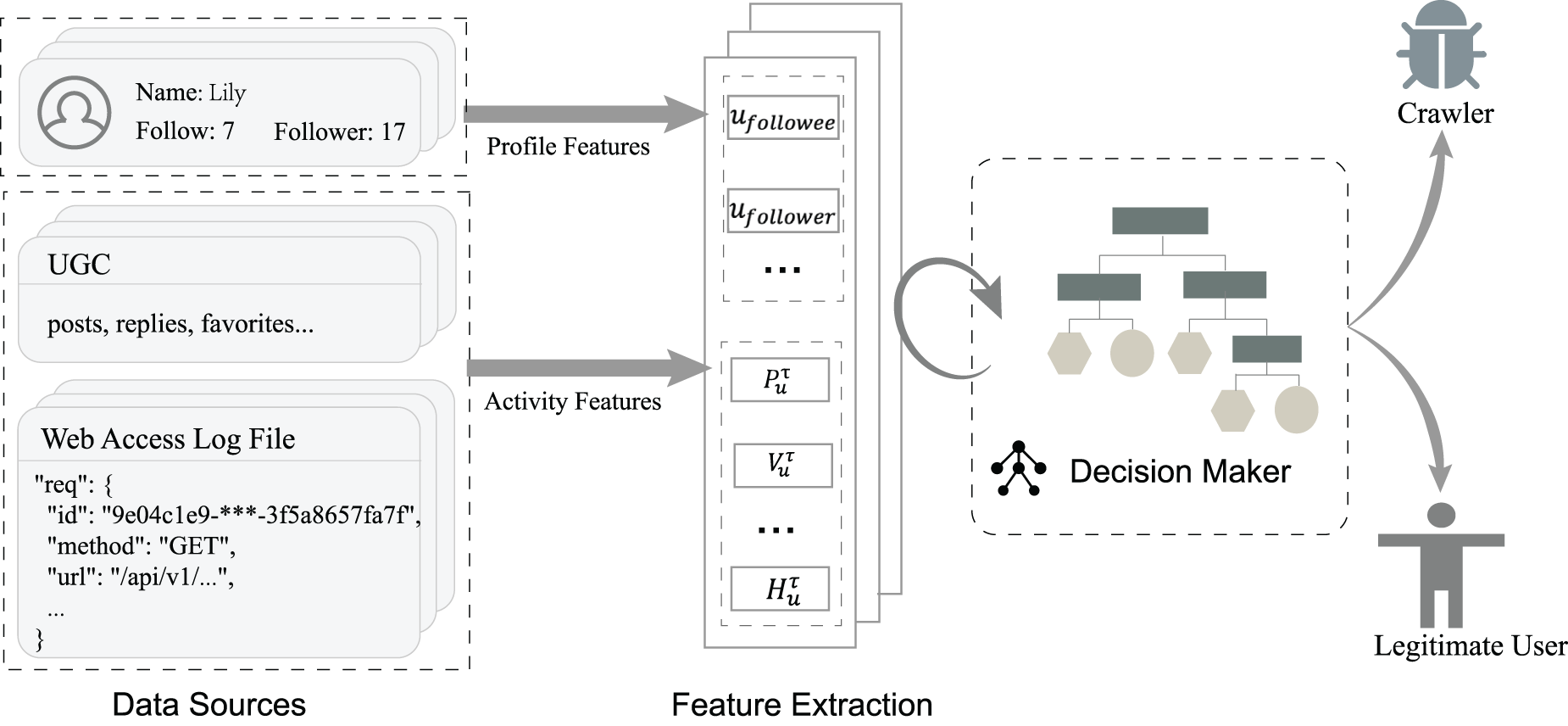

In this paper, we propose a machine learning-based crawler detection framework from the perspective of instance administrators, aiming to differentiate legitimate users and crawlers by comparing the profile and activity characteristics. The framework can be deployed across instances, enabling each administrator to take action against detected crawlers. The illustration of the framework is shown in Fig. 4, which consists of three procedures, namely, Data Sources, Feature Extraction and Decision Maker. The data sources are from each instance’s user profiles, UGC, and web access logs (see Section 3.2). We then extract features from these data. The features are detailed in Section 3.2. Finally, the decision maker applies the trained classifier to detect crawlers. Section 3.4 describes the decision maker module.

Figure 4: Overview of the framework

The data collection phase involved the following sources: (i) web access logs; (ii) user profiles; (iii) user-generated content (UGC). The observation window is set to two weeks, and only user behavior and access records within this period are counted.

From the server logs, timestamped requests for profile views are extracted. For each request, the viewer and viewee identifiers and their respective home instances are extracted, duplicate records are removed, and obvious non-human traffic (such as known bots) is filtered. For each user observed during the window, its user profile can be retrieved via the platform API. From UGC, posts, replies, favorites are collected and their corresponding counts are calculated. Subsequently, the multi-source data is merged, timestamps are unified, and accounts that may interfere with cross-instance metrics (such as suspended, deleted, or single-user instances) are removed. Based on this, user-level aggregate metrics are generated, including the number of followers and followees, as well as the number of posts, replies, favorites, and profile views within the observation window, interactions within and across instances, and the average hop count of profile views based on the social graph.

To extract meaningful features for crawler detection, we combine several conventional features, such as posts volume, with federation-aware activity features, such as cross-instance interaction ratio. This extraction process is performed in a manner that captures both the statistical dynamics and interaction patterns, providing a comprehensive representation of users’ behavior. These features are then used as inputs to the supervised machine learning model, which is trained to differentiate between legitimate users and crawlers.

For the computation of features, we fix an observation window

• follower count: Define

• followee count: Let

• post volume:

• reply volume:

• favorite volume:

• profile view count:

• mean social hop count: For each profile view

with

• cross-instance interaction ratio: Let

Concatenating the hop count, cross-instance ratio and all conventional features together, we introduce a decision maker module to determine whether an account is a crawler. This module is implemented using a supervised machine learning classifier, which takes the extracted features as input. A variety of mainstream supervised learning algorithms can be employed, including Logistic Regression [32], C4.5 [33], Support Vector Machine (SVM) [34], Random Forest [35], and gradient boosted decision trees (GBDT) such as XGBoost [36], LightGBM [37] and CatBoost [38]. Once the classifier is selected, its parameters are optimized using the training and validation datasets. After that, the trained classifier will be able to make a judgment based on a user’s features. Their basic principles and representative formulas are introduced as follows.

Logistic Regression is a linear classifier that estimates the probability of a sample belonging to the positive class using the logistic (sigmoid) function

where

C4.5 constructs a decision tree by recursively selecting features that maximize the information gain ratio. For a dataset S, the information gain of feature A is defined as

with

The gain ratio adjusts for bias toward multi-valued features

SVM aims to find a hyperplane that maximizes the margin between two classes. The optimization problem is formulated as

subject to

where C is the penalty parameter. Kernel functions

Random Forest is an ensemble method that builds multiple decision trees using bootstrap samples and random feature subsets. Each tree

where T is the number of trees. This mechanism enhances robustness and reduces overfitting.

3.4.5 Gradient Boosted Decision Trees

GBDT is an additive model where trees are built sequentially, with each new tree fitting the residuals of the previous ensemble. Its general objective is

where

Specifically:

• XGBoost applies a second-order Taylor expansion of the loss and introduces explicit regularization to improve generalization.

• LightGBM improves training efficiency through Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB), and adopts a leaf-wise tree growth strategy with depth constraints.

• CatBoost employs ordered boosting and specialized encoding for categorical features, reducing overfitting and enhancing performance on categorical data.

In this section, we conducted experiments on a commodity laptop with an Apple M1 Pro CPU and 16GB of RAM, using the dataset we constructed to evaluate the effectiveness of our framework for crawler detection in DOSNs. And we addressed the following research questions (RQs):

• RQ1: How do different algorithms compare in their ability to detect crawlers (Section 4.3)?

• RQ2: To what extent does crawler activity level affect detection performance (Section 4.4)?

• RQ3: Does incorporating hop count and cross-instance interaction features improve classification accuracy (Section 4.5)?

We utilized raw data sourced from FediLive [19], which contains posts, replies, and favorites from Mastodon users between 22 November and 2 December 2024. For each user, we extracted the counts of followers, followees, posts, favorites, and replies, and calculated the cross-instance interaction ratio. Additionally, we computed the hop counts of simulated profile viewing. The simulation details are provided in Section 2.3. We generated two synthetic crawler types—BFS crawlers and live feeds crawlers—based on the target outlined in Section 2.2. We then constructed two labeled evaluation datasets, 3000 legitimate users with 500 BFS crawlers and 500 live feeds crawlers separately. Each dataset was split into train and test partitions (80/20) using stratified sampling with a fixed random seed of 42.

We evaluate the detection performance of models using F1-score [39] and AUC [40]. For comprehensively understanding the calculation of these two metrics, we firstly give the computation of Precision and Recall. Precision quantifies the share of predicted positives that are true positives and is pertinent when the cost of false positives is high. Recall measures the share of true positives that are correctly identified and is critical when the cost of false negatives is high.

where TP is True Positive, TN is True Negative, FP is False Positive, and FN is False Negative.

F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that summarizes their trade-off. F1-score could be calculated by

AUC measures the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, capturing a model’s threshold-independent ability to discriminate between positive and negative classes. The AUC is given by

where TPR is calculated as defined in Eq. (13), FPR is given by

and K is the number of points when the ROC curve is approximated using the trapezoidal method: that is, the number of all points

4.3 Performance of Classification Algorithms (RQ1)

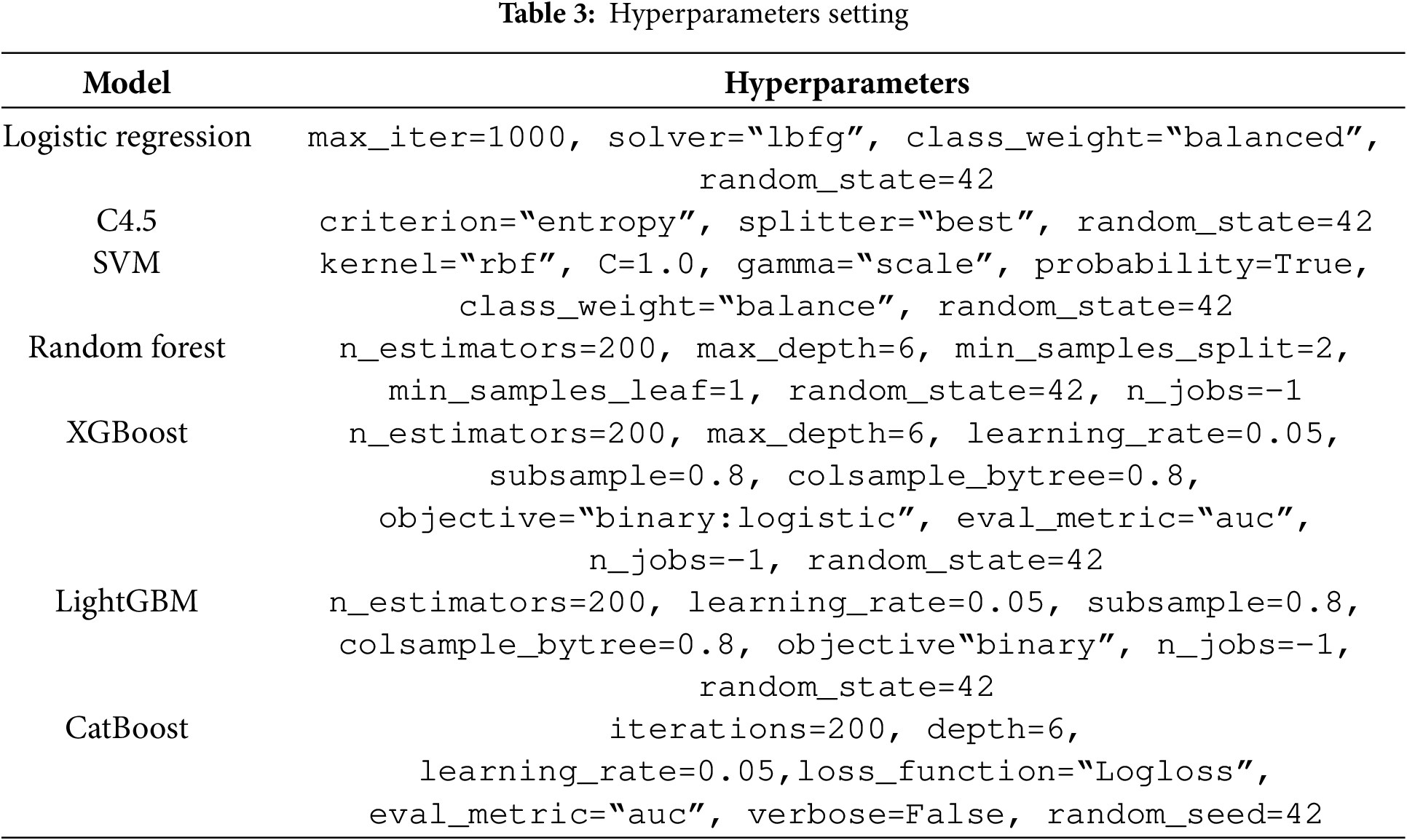

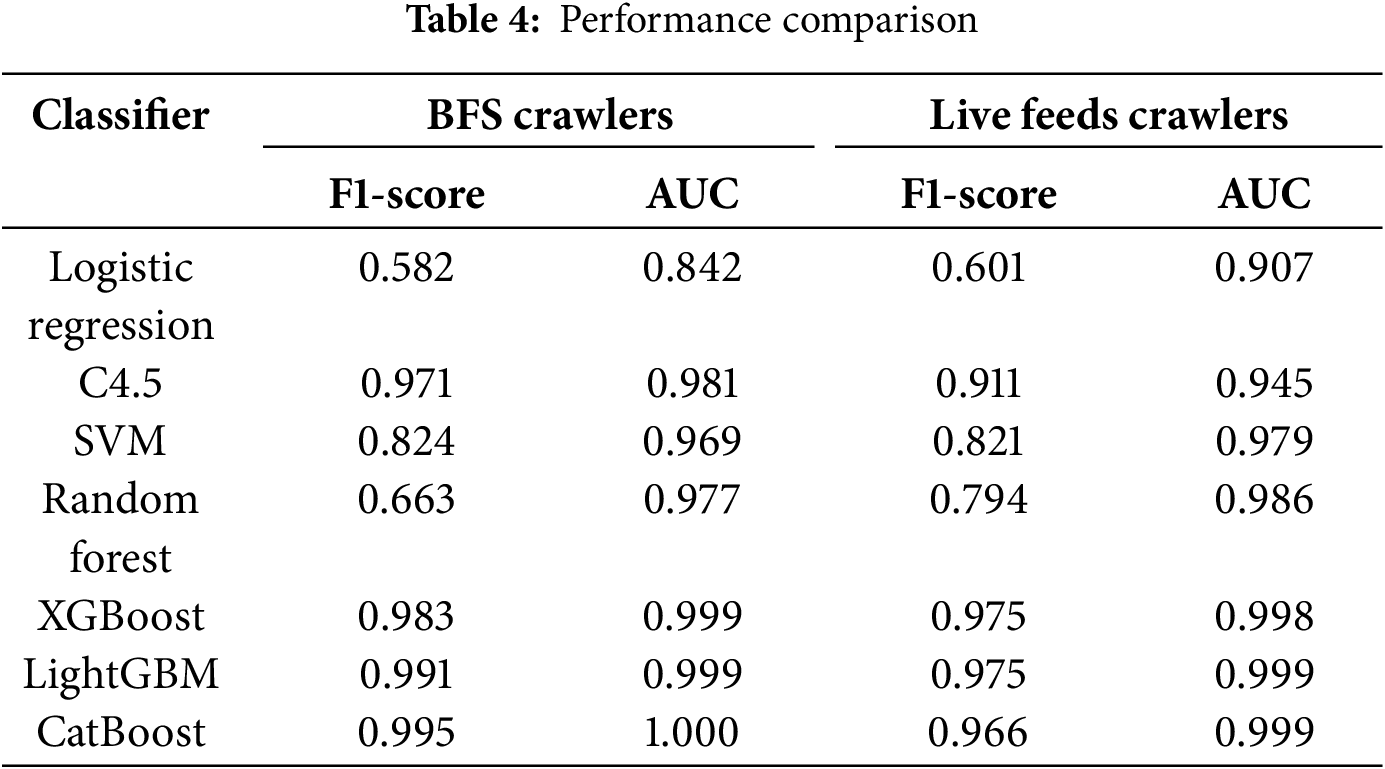

We compared seven supervised machine learning methods on two types of crawlers. The parameter settings for each method are shown in Table 3. The results are shown in Table 4. Overall, GBDT methods outperform other classifiers.

For the BFS crawlers, GBDT dominates: CatBoost attains F1-score = 0.995 and AUC = 1.000, with LightGBM and XGBoost close behind (LightGBM: F1-score = 0.991, AUC = 0.999; XGBoost: F1-score = 0.983, AUC = 0.999). The traditional C4.5 decision tree also performs strongly (F1-score = 0.971, AUC = 0.981). In comparison, SVM yields F1-score = 0.824 (AUC = 0.969), Random Forest F1-score = 0.663 (AUC = 0.977), and Logistic Regression is the weakest (F1-score = 0.582, AUC = 0.842).

For the live feeds crawlers, F1-scores are generally lower than in the BFS setting, yet GBDT retains its advantage. LightGBM and XGBoost both reach F1-score = 0.975 (with AUC = 0.999 and 0.998, respectively), followed by CatBoost (F1-score = 0.966, AUC = 0.999). C4.5 records F1-score = 0.911, AUC = 0.945; SVM and Random Forest achieve F1-score = 0.821, AUC = 0.979 and F1-score = 0.794, AUC = 0.986, respectively; Logistic Regression remains lowest (F1-score = 0.601, AUC = 0.907).

Additionally, we recorded the time cost of training CatBoost and LightGBM. The results show that CatBoost can process millions of samples per second on a resource-constrained device (1,249,926.8 samples/s) and LightGBM can process tens of thousands of samples (203,699.6 samples/s).

4.4 Impact of the Activity Level on Detection (RQ2)

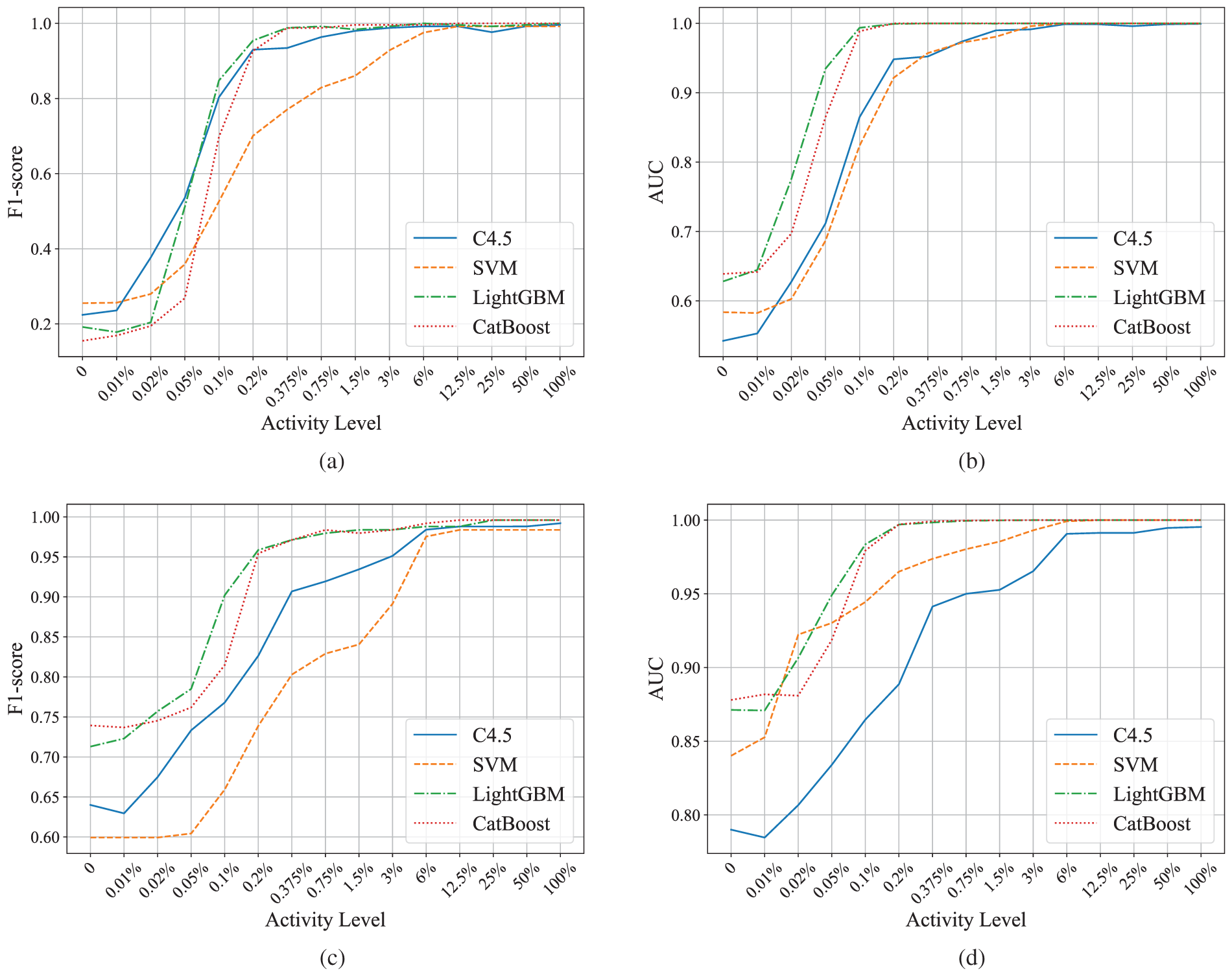

We investigated the impact of crawler activity levels on detection performance. The activity level of each crawler increased from 0% to 100% systematically, representing the intensity of the crawler’s behavior of browsing profiles.

For each activity level, we evaluated the detection performance across various machine learning models, including C4.5, SVM, LightGBM, and CatBoost. LightGBM and CatBoost represent GBDT models; SVM provides a non-tree, margin-based approach; and C4.5 provides interpretable rules and thresholds as a benchmark. These four models cover ensembles, kernel methods, and single-tree rules.

The experimental results (see Fig. 5) indicate a clear trend where increasing the crawler activity level generally improves the detection performance, with the F1-score and AUC reaching their highest values at higher activity levels. Notably, the detection models perform differently depending on the activity level. For both BFS and live feeds crawlers, models such as LightGBM and CatBoost tend to outperform others at moderate to high activity levels, exhibiting significant improvements in both precision and recall as the activity level escalates.

Figure 5: (a) F1-score on the BFS crawlers across different detection models. (b) AUC on the BFS crawlers across different detection models. (c) F1-score on the live feeds crawlers across different detection models. (d) AUC on the live feeds crawlers across different detection models

The experiment’s findings suggest that as the activity level increases, the models become more effective in identifying crawler behavior, although the challenge of false positives remains as activity levels rise. This experiment highlights the importance of tuning the detection models for various activity intensities to optimize both detection accuracy and efficiency. Additionally, when crawlers operate at very low activity levels, they can obtain little data over any given window, making it difficult to reconstruct meaningful portions of the network topology. Consequently, even if our framework under-performs in this regime, slow crawlers cannot accumulate enough observations to obtain large-scale topological information.

4.5 The Effectiveness of Hop Count and Cross-Instance (RQ3)

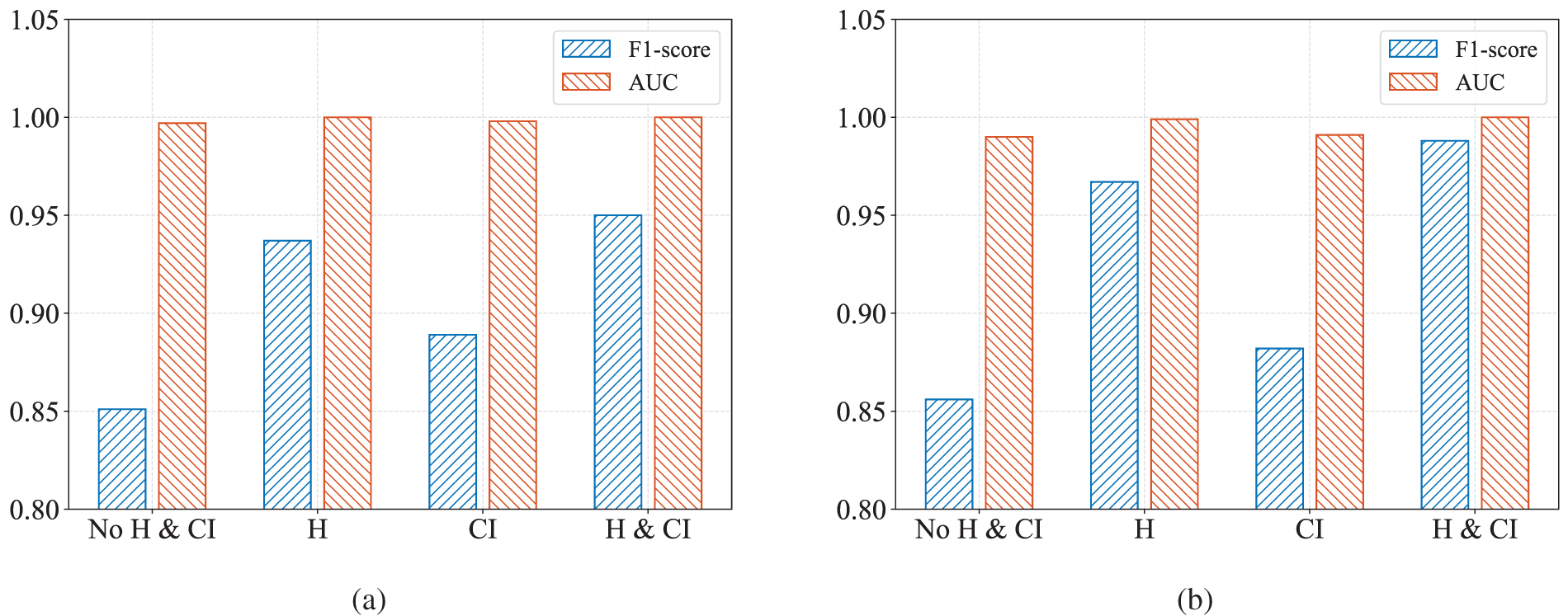

We hypothesized that incorporating hop count and cross-instance interaction features improves classification accuracy. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a comparative experiment with CatBoost algorithm using two configurations: one using conventional features alone, the other augmented with hop count and cross-instance interaction ratio features.

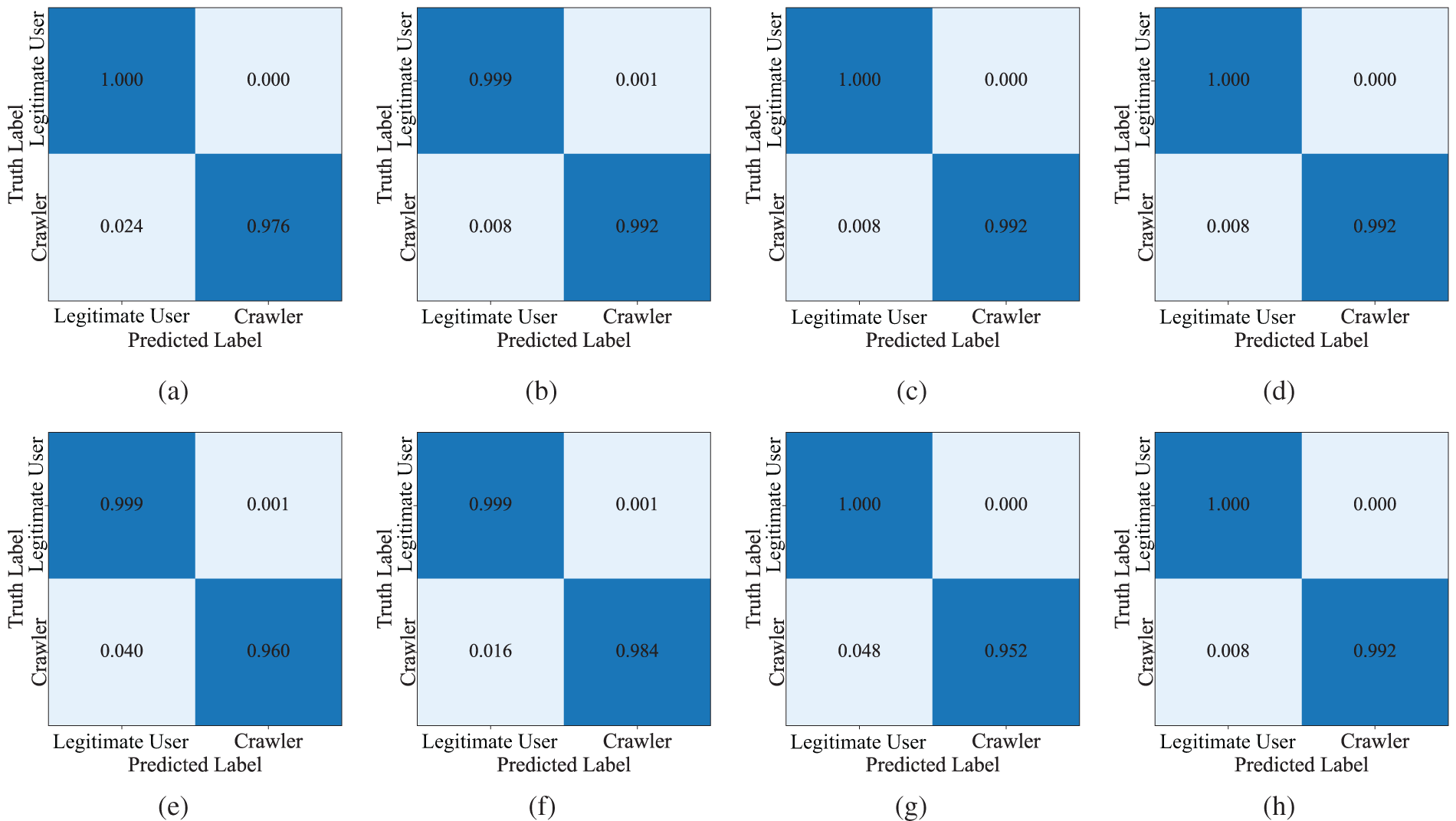

The results of the experiments are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. In both types of crawlers, adding only hop count and cross-instance interaction ratio improves detection performance. This is because these two features help capture the potential behavioral patterns of legitimate users and crawlers, thus improving the model’s detection performance. The Fig. 7 shows how the hop count (H) and cross-instance interaction ratio (CI) affect classification across. For BFS crawlers (top row), the baseline already distinguishes crawlers well with perfect specificity for legitimate users. Adding either H or CI reduces crawler false negatives to 0.008. The combination H & CI preserves these gains, indicating both features contribute complementary but partly overlapping signal for BFS behavior. For live feeds crawlers (bottom row), the baseline is weaker. Adding H substantially improves detection. Using CI alone is less effective here, reflecting that live feeds crawlers’ cross-instance activity can resemble that of active legitimate users. Crucially, combining H & CI yields the best performance.

Figure 6: F1-score and AUC on (a) BFS crawlers and (b) live feeds crawlers across four different scenarios: without hop count and cross-instance (No H & CI), with hop count only (H), with cross-instance only (CI), and with both hop count and cross-instance (H & CI)

Figure 7: Confusion matrices under four feature settings for two types of crawlers. Top row: BFS crawlers; bottom row: Live-feed crawlers. From left to right: (a) and (e): baseline without federation-aware features (No H & CI); (b) and (f): adding Hop count (H) only; (c) and (g): adding cross-instance ratio (CI) only; (d) and (h): adding H & CI together

We analyzed the distribution of hop counts across different user types to evaluate the impact of hop count on detection performance. Fig. 8a shows significant differences in hop count distributions among legitimate users, BFS crawlers, and live feeds crawlers. BFS crawlers and live feeds crawlers tend to have shorter hop counts, while legitimate users exhibit more diverse hop counts with a larger proportion of longer hops. This indicates that hop count can serve as an effective feature for distinguishing between legitimate user behavior and crawler activity. Next, we assessed the impact of cross-instance interaction features. Specifically, we calculated the intra-instance and cross-instance interaction ratios for each user type. The findings from Fig. 8b show that legitimate users have a significantly higher intra-instance interaction ratio than live feeds crawlers but slightly lower than BFS crawlers. Moreover, BFS and live feeds crawlers differ markedly in cross-instance interaction ratios. These discrepancies highlight the potential of cross-instance interaction features to differentiate user behavior.

Figure 8: (a) Hop count distribution of different user types; (b) Comparison of intra-instance and cross-instance interactions among different types of users

5.1 Crawler Detection in Online Web Services

Early studies on crawler detection focused on centralized online web services such as Twitter/X and Facebook, leveraging traffic pattern analysis [12], social graph [11], and analytical learning techniques [13,14]. These approaches evolved from simple rule-based filters to sophisticated multi-dimensional systems. Our crawler detection model based on supervised machine learning belongs to the category of analytical learning, so we focus on the related work of this approach in the following text.

A variety of machine learning algorithms have been applied to crawler detection, including decision trees, SVM, Random Forests, and deep learning architectures [13,14,41,42]. Prior studies have leveraged features such as click sequences, page dwell time, referrer chains, and request intervals to train supervised classifiers. Stevanovic et al. [13] applied data mining classification algorithms to static web server access logs. Their work effectively classified user sessions as belonging to web crawlers or human visitors and identified which of the web crawlers’ sessions exhibit malicious behavior. Wan et al. [14] proposed PathMaker to detect and constrain persistent distributed crawlers. By adding a marker to each Uniform Resource Locator (URL), it can trace the page that leads to the access of this URL and the user identity who accesses this URL. Ro et al. [41] presented a method that can detect distributed crawlers by focusing on the property that web traffic follows the power distribution. Zhao et al. [42] introduced a federated deep learning crawler detection model that analyzed access behaviors while preserving privacy.

However, these methods are designed for centralized web services and they do not take into account the characteristics of online decentralized web services.

5.2 Topological Information Probing in Online Decentralized Web Services

Recent studies about online decentralized web services have focused on various aspects of their topological information [26,43–45].

Cava et al. [43] examined user roles in Mastodon, focusing on information consumption and boundary spanning behaviors. It identifies how users interact within their instance and across others, providing a framework to understand user behavior in a decentralized context. These insights are valuable for topological information probing, as they help in distinguishing between legitimate user interactions and potential crawler activities based on behavioral patterns and network boundaries. Failla et al. [44] focused on Bluesky, a decentralized platform similar to Mastodon, it provides valuable lessons for understanding social interactions and user behavior in decentralized networks. By analyzing user activity and content dissemination patterns, the paper offers insights into how crawlers could exploit network topology and user interactions. This work highlights the importance of understanding content propagation and user interconnection patterns to defend against probing attempts. Zignani et al. [26] investigated how Mastodon’s decentralized architecture impacts the formation of user neighborhoods and networks. The study found that each instance within the Mastodon network has a unique social footprint, influencing users’ interactions both within and across instances. This decentralized structure creates new opportunities for topological information probing, as understanding these neighborhoods and their connectivity patterns can help attackers identify potential targets and paths for crawling. Jeong et al. [45] presented the BlueTempNet dataset, a novel dataset capturing the temporal dynamics of user-driven social interactions on the decentralized social media platform Bluesky. Their findings provide a foundational understanding of the types of data that crawlers might exploit.

These studies highlight the central role of topological information in understanding the structure and evolution of decentralized social platforms and provide a foundation for modeling and measurement in the DOSNs.

6.1 Applicability to Different Platforms

In this paper, we conducted a study on defending against topological information probing in DOSNs, using Mastodon as a case study. The proposed framework is also applicable to other ActivityPub-based platforms, including PeerTube and Pixelfed.

Our framework can be deployed per instance and runs on the instance’s own server. During the training phase, we believe federated learning is an ideal path forward, as it aims to enable each instance in the federated network to independently train its local model and achieve collaborative learning by aggregating the local models of all instances. During the detection phase, it only uses data locally available to that instance, so it does not aggregate cross-instance information and does not require centralized coordination.

6.3 Unsupervised Methods for Crawler Detection

Unsupervised anomaly detection methods, such as autoencoders and clustering-based approaches, are especially effective in scenarios where we do not have explicit features for anomalies, and they can uncover hidden patterns based on the structure of the data itself. Given that the crawlers in DOSNs have fixed characteristic patterns currently, they can be identified by supervised learning methods. If crawler behavior evolves to more sophisticated evasion techniques, unsupervised models might be more suitable for detecting crawlers, as they can discover hidden patterns based on the data’s inherent structure and capture previously unseen anomalies.

6.4 Alternate Strategies for Misclassified Users

During the crawler detection process, legitimate users might occasionally be misclassified as crawlers. To minimize harm and support remediation, we suggest graceful failure and appealability such as a CAPTCHA or a temporary rate limit. Misclassified users can appeal to the instance administrator. Given our framework’s high classification accuracy, such cases are rare and only impose a minimal burden on instance administrators.

Detecting crawlers is a vital and complex task that is necessary for defending against topological information of DOSNs. This study highlights that, in contrast to centralized OSNs, DOSNs exhibit unique characteristics, in which legitimate users typically exhibit preferences for intra-instance or cross-instance interaction, whereas crawlers exhibit behaviors that significantly differ from those of legitimate users. Building on this insight, this paper introduces a supervised machine learning-based crawler detection framework that capitalizes on these behavioral distinctions to detect crawlers, thereby mitigating topological information probing for online decentralized web services. By incorporating features such as hop count and cross-instance interaction ratios, the proposed framework effectively differentiates between legitimate users and crawlers, thereby safeguarding the topological information of DOSNs. Additionally, this study finds that reducing crawler activity levels can negatively impact the classification performance of the framework. When crawler activity is reduced to levels resembling those of legitimate users, distinguishing between the two becomes more challenging. However, low activity levels also limit the crawling speed, so our framework can still mitigate unnecessary crawler traffic, thus reducing the risk of topology information probing on DOSNs.

While our framework with federation-aware features achieves strong performance on Mastodon, we see several promising directions to further enhance effectiveness and generalization. For dataset, we plan to extend the collection beyond the current two-week window to a multi-month window and multiple DOSNs (e.g., PeerTube, Pixelfed). For features, beyond the current ones, we will develop richer features, such as the difference between users’ activity level and their home instances’ average activity level, to further improve crawler detection. For methods, we will explore an ensemble model that combines deep learning models such as GNN and GBDT models to fully utilize all features and improve detection accuracy.

Acknowledgement: We thank Du Liu from the College of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence at Fudan University, for his assistance in proofreading this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant (No. 2022YFB3102901), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62072115, No. 62102094), Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan Project (No. 22510713600).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yang Chen; methodology, Yang Chen and Xinli Hao; evaluation, Xinli Hao; data analysis, Xinli Hao; writing—original draft preparation, Xinli Hao; writing—review and editing, Yang Chen, Qingyuan Gong and Xinli Hao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1A user’s home instance is the server where the user’s account is hosted.

2A reply denotes a direct response from one user to another user’s post within the platform.

3Hop count is the number of edges on the shortest path between the viewer and the viewee in the social graph.

References

1. Jin L, Chen Y, Wang T, Hui P, Vasilakos AV. Understanding user behavior in online social networks: a survey. IEEE Commun Mag. 2013;51(9):144–50. doi:10.1109/mcom.2013.6588663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Leskovec J, Horvitz E. Geospatial structure of a planetary-scale social network. IEEE Trans Comput Socia Syst. 2014;1(3):156–63. doi:10.1109/tcss.2014.2377789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen X, Lui JCS. Mining graphlet counts in online social networks. In: 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Data Mining, ICDM ’16; 2016 Dec 12–15; Barcelona, Spain. p. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

4. Peel L, Delvenne JC, Lambiotte R. Multiscale mixing patterns in networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(16):4057–62. doi:10.1073/pnas.1713019115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Chen Y, Hu J, Xiao Y, Li X, Hui P. Understanding the user behavior of Foursquare: a data-driven study on a global scale. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2020;7(4):1019–32. doi:10.1109/tcss.2020.2992294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li H, Xia C, Wang T, Wen S, Chen C, Xiang Y. Capturing dynamics of information diffusion in SNS: a survey of methodology and techniques. ACM Comput Surv. 2021;55(1):1–51. doi:10.1145/3485273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Newman MEJ. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(23):8577–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Yang J, Leskovec J. Defining and evaluating network communities based on ground-truth. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Mining Data Semantics, MDS ’12; 2012 Aug 12–16; Beijing, China. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

9. Ahajjam S, El Haddad M, Badir H. A new scalable leader-community detection approach for community detection in social networks. Soc Netw. 2018;54:41–9. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2017.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang M, Zhang X, Pedrycz W, Wang S, Wu G. Learning fine-grained user preference for personalized recommendation. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2025;30(6):2544–56. doi:10.26599/tst.2024.9010216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mondal M, Viswanath B, Clement A, Druschel P, Gummadi KP, Mislove A, et al. Defending against large-scale crawls in online social networks. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Emerging Networking Experiments and Technologies, CoNEXT ’12; 2012 Dec 10–13; Nice, France. p. 325–36. [Google Scholar]

12. Jacob G, Kirda E, Kruegel C, Vigna G. PUBCRAWL: protecting users and businesses from CRAWLers. In: Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Conference on Security Symposium, Security ’12; 2012 Aug 8–10; Bellevue, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

13. Stevanovic D, An A, Vlajic N. Feature evaluation for web crawler detection with data mining techniques. Expert Syst Appl. 2012;39(10):8707–17. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2012.01.210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wan S, Li Y, Sun K. Protecting web contents against persistent distributed crawlers. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2017 May 21–25; Paris, France. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

15. Jeong U, Ng LHX, Carley KM, Liu H. Navigating decentralized online social networks: an overview of technical and societal challenges in architectural choices. arXiv:2504.00071. 2025. [Google Scholar]

16. Balduf L, Sokoto S, Ascigil O, Tyson G, Scheuermann B, Korczyński M, et al. Looking at the blue skies of Bluesky. In: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM on Internet Measurement Conference, IMC ’24; 2024 Nov 4–6; Madrid, Spain. p. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

17. Raman A, Joglekar S, Cristofaro ED, Sastry N, Tyson G. Challenges in the decentralised web: the Mastodon case. In: Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference, IMC ’19; 2019 Oct 21–23; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 217–29. [Google Scholar]

18. Polinski M, Jo R, McAfee K, Bustamante FE. The centralization of a decentralized video platform—a first characterization of PeerTube. ACM SIGCOMM Comput Commun Rev. 2025;54(4):25–35. doi:10.1145/3717512.3717516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Min S, Wang S, Luo Y, Gao M, Gong Q, Xiao Y, et al. FediLive: a framework for collecting and preprocessing snapshots of decentralized online social networks. In: Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, WWW ’25; 2025 Apr 28; Sydney, NSW, Australia. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2025. p. 765–8. [Google Scholar]

20. Zia HB, Castro I, Tyson G. Mastodoner: a command-line tool and python library for public data collection from Mastodon. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, CIKM ’24; 2024 Oct 21–25; Boise, ID, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 5314–7. [Google Scholar]

21. Mastodon (social network). Mastodon documentation; [cited 2025 Sep 10]. Available from: https://docs.joinmastodon.org/. [Google Scholar]

22. Yang Z, Wilson C, Wang X, Gao T, Zhao BY, Dai Y. Uncovering social network Sybils in the wild. ACM Trans Knowl Discov Data. 2014;8(1):1–29. doi:10.1145/2556609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mastodon (social network). Mastodon. [cited 2025 Sep 10]. Available from: https://mastodon.social/. [Google Scholar]

24. Jeong U, Sheth P, Tahir A, Alatawi F, Bernard HR, Liu H. Exploring platform migration patterns between Twitter and Mastodon: A user behavior study. In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, ICWSM ’24. Vol. 18; 2024 Jun 3–6; Buffalo, NY, USA. p. 738–50. [Google Scholar]

25. The Social Web Working Group. ActivityPub; [cited 2025 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.w3.org/TR/2018/REC-activitypub-20180123/. [Google Scholar]

26. Zignani M, Gaito S, Rossi GP. Follow the “Mastodon”: structure and evolution of a decentralized online social network. In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, ICWSM ’18. Vol. 12; 2018 Jun 25–28; Palo Alto, CA, USA. p. 541–50. [Google Scholar]

27. PixelFed. PixelFed project: pixelfed (2025). [cited 2025 Sep 10]. Available from: https://pixelfed.org/. [Google Scholar]

28. Mastodon (social network). Mastodon-social networking that’s not for sale. [cited 2025 Sep 10]. Available from: https://joinmastodon.org. [Google Scholar]

29. Catanese SA, De Meo P, Ferrara E, Fiumara G, Provetti A. Crawling Facebook for social network analysis purposes. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Intelligence, Mining and Semantics, WIMS ’11; 2011 May 25–27; Sogndal, Norway. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

30. Bhat SI, Arif T, Malik MB, Sheikh AA. Browser simulation-based crawler for online social network profile extraction. Int J Web Based Commun. 2020;16(4):321–42. doi:10.1504/ijwbc.2020.111377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Strufe T. Profile popularity in a business-oriented online social network. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Social Network Systems, SNS ’10; 2010 Apr 13; Paris, France. New York, NY, USA: ACM. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

32. Hosmer DWJr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

33. Quinlan JR. C4.5: programs for machine learning. San Francisco, CA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

34. Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20(3):273–97. doi:10.1023/a:1022627411411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

36. Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’16; 2016 Aug 13-17; San Francisco, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 785–94. [Google Scholar]

37. Ke G, Meng Q, Finley T, Wang T, Chen W, Ma W, et al. LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. Red Hook, NY, USA: ACM; 2017. p. 3149–57. [Google Scholar]

38. Prokhorenkova L, Gusev G, Vorobev A, Dorogush AV, Gulin A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’18; 2018 Dec 3–8; Montréal, QC, Canada; Red Hook, NY, USA: ACM; 2018. p. 6639–49. [Google Scholar]

39. Manning CD. Introduction to information retrieval. Rockland, MA, USA: Syngress Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

40. Fawcett T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Patt Recogn Lett. 2006;27(8):861–74. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ro I, Han JS, Im EG. Detection method for distributed web-crawlers: a long-tail threshold model. Secur Commun Netw. 2018;2018(1):9065424. doi:10.1155/2018/9065424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhao J, Chen R, Fan P. TS-finder: privacy enhanced web crawler detection model using temporal-spatial access behaviors. J Supercomput. 2024;80(12):17400–22. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06133-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. La Cava L, Greco S, Tagarelli A. Information consumption and boundary spanning in decentralized online social networks: the case of Mastodon users. Online Soc Netw Media. 2022;30(7):100220. doi:10.1016/j.osnem.2022.100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Failla A, Rossetti G. “I’m in the Bluesky Tonight”: insights from a year worth of social data. PLoS One. 2024;19(11):e0310330. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0310330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Jeong U, Jiang B, Tan Z, Bernard HR, Liu H. Descriptor: a temporal multi-network dataset of social interactions in Bluesky social (BlueTempNet). IEEE Data Descr. 2024;1:71–9. doi:10.1109/ieeedata.2024.3474640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools