Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Hybrid Experimental-Numerical Framework for Identifying Viscoelastic Parameters of 3D-Printed Polyurethane Samples: Cyclic Tests, Creep/Relaxation and Inverse Finite Element Analysis

1 National Research Centre “Kurchatov Institute”, Moscow, 123182, Russia

2 Moscow Center for Advanced Studies, Moscow, 101000, Russia

3 Applied Mechanics Department, Bauman Moscow State Technical University, Moscow, 105005, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Arthur Krupnin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Perspective Materials for Science and Industrial: Modeling and Simulation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 18 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073161

Received 11 September 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

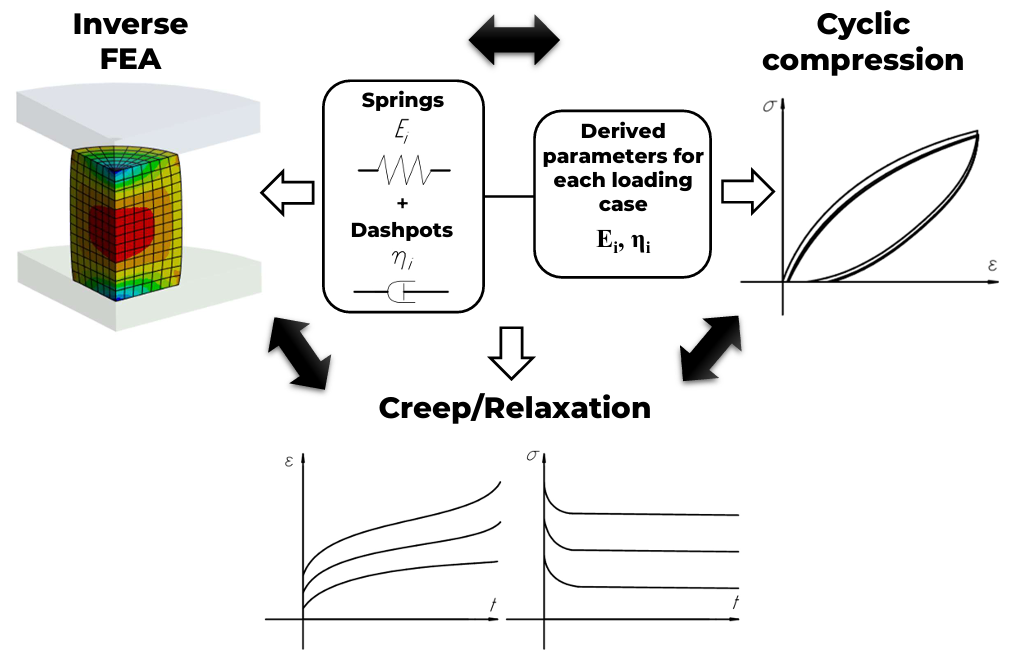

This study presents and verifies a hybrid methodology for reliable determination of parameters in structural rheological models (Zener, Burgers, and Maxwell) describing the viscoelastic behavior of polyurethane specimens manufactured using extrusion-based 3D printing. Through comprehensive testing, including cyclic compression at strain rates ranging from 0.12 to 120 mm/min (0%–15% strain) and creep/relaxation experiments (10%–30% strain), the lumped parameters were independently determined using both analytical and numerical solutions of the models’ differential equations, followed by cross-verification in additional experiments. Numerical solutions for creep and relaxation problems were obtained using finite element analysis, with the three-parameter Mooney-Rivlin model and Prony series employed to simulate elastic and viscous stress components, respectively. Energy dissipation per cycle was quantified during cyclic compression tests. The results demonstrate that all three models adequately describe material behavior within the 0%–15% strain range across various strain rates. Comparative analysis revealed the Burgers model’s superior performance in characterizing creep and stress relaxation at low strain levels. While Zener and Burgers model parameters from uniaxial compression showed limited applicability for energy dissipation calculations, the generalized Maxwell model effectively captured viscoelastic properties across different strain rates. Notably, parameters derived from creep tests provided a more universal assessment of dissipative properties due to optimization based on characteristic curve regions. Both parameter sets described polyurethane’s elastic-hysteretic behavior with approximately 20% error, proving significantly more accurate than the linear strain-time dependence hypothesis. Finite element analysis (FEA) complemented numerical modeling by demonstrating that while the generalized Maxwell model effectively describes initial rapid stress-strain changes, FEA provides superior characterization of steady-state processes. This computational approach yields more physically representative results compared to simplified analytical solutions, despite certain limitations in transient analysis.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileToday, 3D printing has become widespread across numerous medical fields, including maxillofacial surgery (craniofacial implants) [1], prosthetic components [2], dental molds [3], medical equipment manufacturing [4], tissue engineering [5,6], and ophthalmology [7]. Thus, modern medicine widely utilizes various implants that help restore or improve bodily functions. Among the variety of polymers, biocompatible thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPU) are of particular interest for the manufacture of medical devices, owing to their wear resistance, tailored mechanical properties, and viscoelastic behavior inherent in native tissues and organs [8,9]. This combination of attributes underpins their widespread biomedical application [10,11]. In conjunction with 3D printing, this facilitates the fabrication of patient-specific, fatigue-resistant implants engineered to provide the required biomechanical response [12]. During use, implants are continuously subjected to mechanical stresses caused by various factors such as patient movement, pressure from surrounding tissues, etc. To ensure implant reliability and longevity, it is necessary to properly evaluate both the mechanical properties of the implant material and the viscoelastic characteristics of the products, which determine how well the material can withstand loads and deformations without failure or loss of functional properties. Viscoelastic evaluation is particularly important for implants experiencing cyclic loading, which can lead to material fatigue and, consequently, changes in properties or structural failure. To assess elastic-hysteretic characteristics of materials and products, uniaxial cyclic compression tests are used, which characterize material behavior under repeated loading. To evaluate material behavior under prolonged loading throughout the implant’s service life, creep and stress relaxation tests must be conducted. Therefore, proper assessment of material properties and viscoelastic characteristics of implants results from comprehensive research and represents a crucial condition for product reliability and safety, helping ensure implant durability and reduce the risk of failure or damage.

The theory of linear viscoelasticity represents a generalization of classical continuum mechanics approaches—elasticity theory on one hand, and viscous fluid mechanics on the other. In recent years, interest in viscoelasticity research has grown significantly due to the rapid implementation of polymers, which creates the need for developing calculation principles for structural elements made from these materials [13,14]. Rheological coefficients can be obtained through two main types of testing: creep and stress relaxation experiments.

Several approaches exist for mathematically describing material behavior. Currently, the use of integral and differential equations is widespread. Initially, aiming to describe time-dependent deformation of solids, Newton’s viscosity law and Hooke’s elasticity law were combined, resulting in the concept of a Maxwell viscoelastic body. This gave rise to the theory of rheological models, where materials are represented as systems of springs and dashpots. In reality, such models serve as analogies rather than exact descriptions of phenomena. However, by combining elastic and viscous elements, one can create schemes that at least qualitatively reproduce the behavior of real materials under load [15]. While finite element methods are widely used for viscoelastic parameter identification, structural rheological models persist due to their ability to characterize all deformation stages quantitatively and qualitatively, including loading rate effects on parameters. The study [16] introduces a method for characterizing the viscoelastic properties of soft hydrated biomaterials that eliminates the influence of prestress and enables rapid testing of degradable samples. The approach involves performing standard mechanical compression tests at varying strain rates, followed by mathematical analysis of the acquired dataset to extract material parameters based on a generalized Maxwell model. This method was validated using a stable elastomer (polydimethylsiloxane) and a labile hydrogel (gelatin) under a defined strain rate. For comparison, step-relaxation testing was conducted to assess lumped parameter estimation. The results confirmed that both methods yield equivalent elastic parameters, while the proposed technique provides improved accuracy in estimating short-term relaxation constants. This approach offers a promising framework for the mechanical characterization of biological materials with limited temporal stability, facilitating rapid and reliable parameter extraction. In [17], a new analytical function (the apparent elastic modulus strain-rate spectrum) for extracting lumped parameter constants for Generalized Maxwell (GM) linear viscoelastic models from stress-strain data is proposed. The function is derived from the tangent modulus of the GM model’s stress-strain response under constant loading. By fitting experimental data obtained across different strain rates to this function, viscoelastic material parameters can be determined rapidly. This single-curve fitting approach yields viscoelastic constants comparable to those obtained through the original epsilon dot method, which relies on a multi-curve global optimization with shared parameters. Study [18] developed a strategy to modulate viscoelastic relaxation times in gels without affecting their elastic properties. Using agarose and acrylamide hydrogels infused with dextran solutions (0%–5% w/v), alongside polyurethane sponge controls, the authors demonstrated that increased liquid viscosity prolongs relaxation times in sponges but leaves hydrogel elasticity unchanged, as quantified by strain-rate compression tests and modeling based on a standard linear solid model. A micromechanical characterization method for soft hydrated materials using constant strain-rate nanoindentation under stress-free initial conditions is represented in [19]. By introducing a self-consistent definition of indentation stress/strain and a depth-independent strain-rate expression, the bulk compression epsilon-dot method to nanoindentation was adapted. This approach enabled the precise determination of instantaneous/equilibrium moduli and relaxation time constants in displacement-controlled commercial nanoindenters. The stress-free testing conditions make the method based on the GM model particularly suitable for investigating micromechanical properties of hydrogels and biological tissues at cellular length scales. A two-step (chemical and enzymatic) crosslinking strategy was implemented in [20] to modulate the viscoelastic properties of gelatin hydrogels. First, gels with different glutaraldehyde concentrations were developed to mimic a wide range of soft tissue viscoelastic behavior. In this work, the SLS model was chosen to describe the viscoelasticity of gels in nanoindentation tests. The strategy proposed allows controlled investigation of cellular adaptation to dynamic mechanical changes by enabling on-demand enzymatic stiffening of the substrate during culture. Cells can thus be exposed to either abrupt increases in equilibrium modulus and elasticity or progressive enhancement of viscous/liquid-like behavior, mimicking age-related pathophysiological processes. In [21], a viscoelastic constitutive model for automotive tread rubber subjected to uniaxial cyclic compression, building upon the Bergstrom-Boyce rheological framework for inelastic elastomers, is proposed. A complete methodology is developed for parameter identification in two summer tire compounds, utilizing cyclic compression test data and Nelder-Mead optimization to achieve accurate prediction of hysteresis losses, providing valuable tools for polymer engineering applications. A structural viscoelastic model for thermomechanical loading analysis, using polymethylmethacrylate under uniaxial compression to demonstrate its parameter identification via experimental data approximation (hyperbolic tangent for strain-rate dependence, logarithmic for creep) and iterative FEM implementation is presented in [22]. The model effectively captures complex material behavior through interacting simple rheological elements, showing good agreement with tests across varying strain rates and stress holds.

This study aims to develop a hybrid methodology for determining viscoelastic parameters of polyurethane specimens fabricated using extrusion-based 3D printing. Through uniaxial cyclic compression, creep, and stress relaxation testing combined with inverse finite element analysis, we identify lumped parameters for Zener, Burgers, and five-parameter generalized Maxwell models, which are capable of characterizing material behavior during short-term and long-term loading regimes, and attempt to investigate the applicability of a unified parameter set for various loading conditions. The energy dissipation per cycle is quantified, and parameters obtained from different experimental methods are systematically compared.

2.1 Samples Fabrication and Mechanical Testing

For mechanical testing, cylindrical specimens with a diameter and height of 20 mm (GOST 20014-13) were fabricated from commercial REC TPU Easy Flex (Moscow, Russia) polyurethane using a Creality Ender V2 (Shenzhen Creality 3D Technology Co, Ltd., Shenzhen, China) 3D printer. The printing parameters included nozzle temperature of 230°C, build plate temperature of 80°C, layer height of 0.2 mm, printing speed of 80 mm/s, and 100% infill density. Uniaxial compression tests were conducted on an INSTRON 5982 (Illinois Tool Works Inc., Glenview, IL, USA) universal testing machine at 23°C using strain rates of 120, 60, 12, 1.2, and 0.12 mm/min, with three specimens tested for each condition. To evaluate elastic-hysteretic properties, specimens were subjected to triangular zero-to-peak cyclic loading with a strain amplitude of 15%. Due to the sensitivity of polyurethane mechanical properties to temperature and humidity variations, and considering that a single cycle at 0.12 mm/min took 50 min to complete, the number of loading cycles was set to 3 for this strain rate and to 5 for all other rates. The elastic modulus was determined from the initial linear portion of the engineering stress-strain curve. Creep and stress relaxation tests were performed at room temperature on the INSTRON 5982 machine using three stress levels corresponding to 10%, 20%, and 30% of the maximum stress obtained during the first cycle of uniaxial compression testing. Each test duration was set to 100 min, as the optimum between the time which is necessary to capture steady creep and stress relaxation phases, and experiment duration, to ensure the curves reached a plateau region suitable for long-term behavior extrapolation.

2.2 Structural Rheological Models

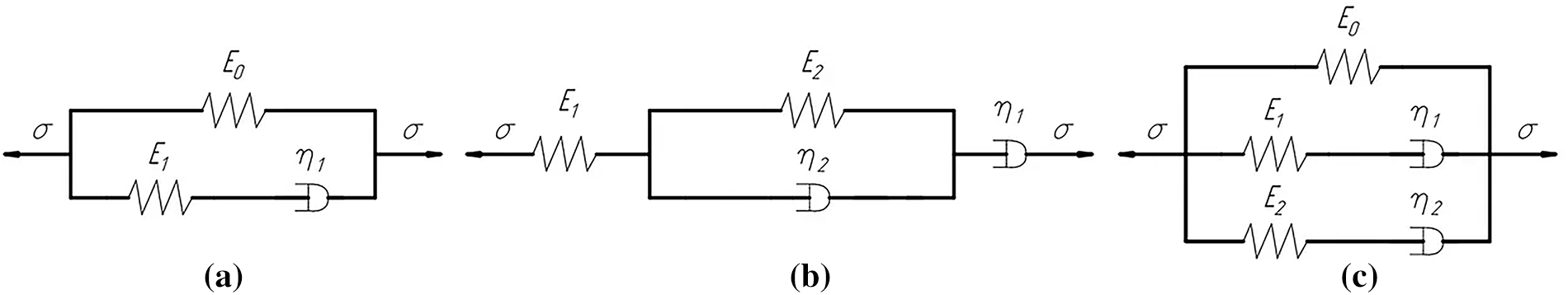

One approach to describing the viscoelastic behavior of materials involves the use of structural rheological models, which represent the material as a system of springs and dashpots with specified stiffnesses and viscosities. The spring stiffnesses and dynamic viscosity coefficients of the damping elements are lumped parameters of the models, determined based on experimental data. This study examines three widely used structural rheological models: the Zener model (SLS—Standard Linear Solid, 3 parameters, Fig. 1a), the Burgers model (BURG—Burgers model, 4 parameters, Fig. 1b), and the Generalized Maxwell model (GM—Generalized Maxwell, 5 parameters, Fig. 1c).

Figure 1: Structural rheological models: SLS (a), BURG (b), GM (c)

The SLS model is the simplest model capable of describing both creep and relaxation behavior of a material [18]. The differential equation of the model is given by:

where σ is the normal stress, ε is the linear strain, E0 and E1 are the elastic moduli of the springs, η1 is the dynamic viscosity of the dashpot, dots denote time derivatives. Here and further, σ and ε refer to engineering stresses and strains. The equivalent spring modulus

Under constant strain rate (

Creep behavior solution (σ (0) = σ0 = const) with the initial condition (

where

Stress relaxation solution (ε(0) = ε0 = const) according to the following initial value problem (

where

Since stress relaxation experiments are less precise due to step-loading artifacts [25], their data were excluded from the parameter fitting process.

The Burgers model consists of two elastic and two viscous elements, representing a series combination of a Maxwell unit and a Kelvin-Voigt unit. The constitutive relation is given by [26]:

where

Under constant strain rate conditions which are expressed by the Cauchy problem (

where parameters a and b are defined in Eq. (S1) (see Section 1.1 in Supplementary materials).

The creep strain solution for the Burgers model (

For stress relaxation under applied constant strain ε0, the Burgers model solution (

where parameters r1,2, a and b are defined according to Eq. (S2) (see Section 1.1 in Supplementary materials)

The Generalized Maxwell Model is a mathematical framework that describes the behavior of viscoelastic materials by accounting for both elastic and viscous properties. This model provides enhanced predictive capability for material response under various loading conditions. The constitutive relation is expressed as [29]:

where

Under a constant strain rate (

The creep process is described by the solution of the constitutive equation at σ = σ0 = const according to the initial condition set (

where C1, C2, l1, l2 are defined in accordance to Eq. (S3) (see Section 1.1 in Supplementary materials).

Stress relaxation is described by the solution of the equation at ε = ε0 = const expressed by the Cauchy problem (

where parameters r1,2, a and b are defined according to Eq. (S4) (see Section 1.1 in Supplementary materials)

All of the aforementioned and further listed mathematical operations were implemented using the Wolfram Mathematica 11.2 (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL, USA) computational software package.

2.3 Procedure for Identification of Viscoelastic Parameters

The lumped parameters of the models were determined by minimizing the objective function F using the conjugate gradient method within the Wolfram Mathematica 11.2 (Wolfram Research, USA) computational software package:

where

The initial approximation in the optimization problem for parameter

For each model, parameter fitting was also performed based on data from creep tests at three loading levels. The parameter fitting was done using the least squares method with a Python program utilizing the Optuna framework (for a more detailed explanation, see Section 1.2 in Supplementary Materials). Minimization of the sum of squared deviations was performed using the standard TPE Sampler method, which works by modeling hyperparameter probabilities using information from previous trials. To verify model applicability, validation was performed using stress relaxation test data with the previously determined parameters. To ensure the robustness and independence of the obtained lumped parameter sets from the initial guess, sensitivity analysis was performed (see Section 1.2 in Supplementary Materials).

2.4 Study of Elastic-Hysteretic Characteristics

To obtain the theoretical loading-unloading law, the differential equations of the models (Eqs. (1), (5), and (9)) were used with the determined parameters and constant strain rate (Eqs. (S7)–(S9)). The solution of the differential equations yielded the time-dependent strain law, and by expressing time through the “stress-time” and “strain-time” dependencies as shown in [21], the loading-unloading law for the first cycle was obtained for the material.

Additionally, considering the simplicity of the loading law, an assumption was made about the linear dependence of strain on time during the first loading cycle, and hysteresis loops were obtained for the triangular strain law. The calculation of specific mechanical energy dissipated per cycle was also performed, quantitatively equal to the area within the curve on the “strain-stress” diagram and determined by Eq. (14), for both theoretical and experimental dependencies. Relative errors in energy determination between models and physical experiments were computed.

where q is the specific mechanical energy dissipated per cycle (J/m³ or MPa),

2.5 Inverse Finite Element Modeling of Creep and Stress Relaxation

There are several models for predicting long-term deformation of polymer materials that account for both viscous and elastic components. This work examines two approaches to describing viscoelastic material behavior. Common finite element (FE) analysis software packages (ANSYS, etc.) use the Prony series linear viscoelastic model based on exponential functions to describe the stress relaxation process (for a more complete formulation, see Section 1.4 in Supplementary Materials). To illustrate the practical application of the implemented material model and identified parameters, finite element modeling of stress relaxation was performed using the ANSYS Workbench (Ansys Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA) software suite. The analysis employed a third-order Mooney-Rivlin material model, which is the minimum-order model capable of capturing the infection points on experimental creep and stress relaxation curves, alongside with incompressibility assumption, which is consistent for modelling polyurethane behavior. The strain energy density function is thus expressed as:

where

The second approach involved numerical determination of Prony series coefficients for the generalized Maxwell model’s mechanical properties [34]:

where

3.1 Samples Fabrication and Mechanical Testing

The uniaxial compression tests yielded stress-strain diagrams for the entire range of strain rates during the first loading cycle (shown in Fig. S6a), as well as hysteresis curves corresponding to the first cycle (presented in Fig. S6b). The dependence of the tangent elastic modulus on strain rate is presented in Table S1. The results demonstrate that the polyurethane’s elastic modulus increases with strain rate, while the hysteresis loop width, which qualitatively characterizes energy dissipation in the system, grows at higher rates. This behavior agrees with test data for conventionally manufactured polyurethanes [8].

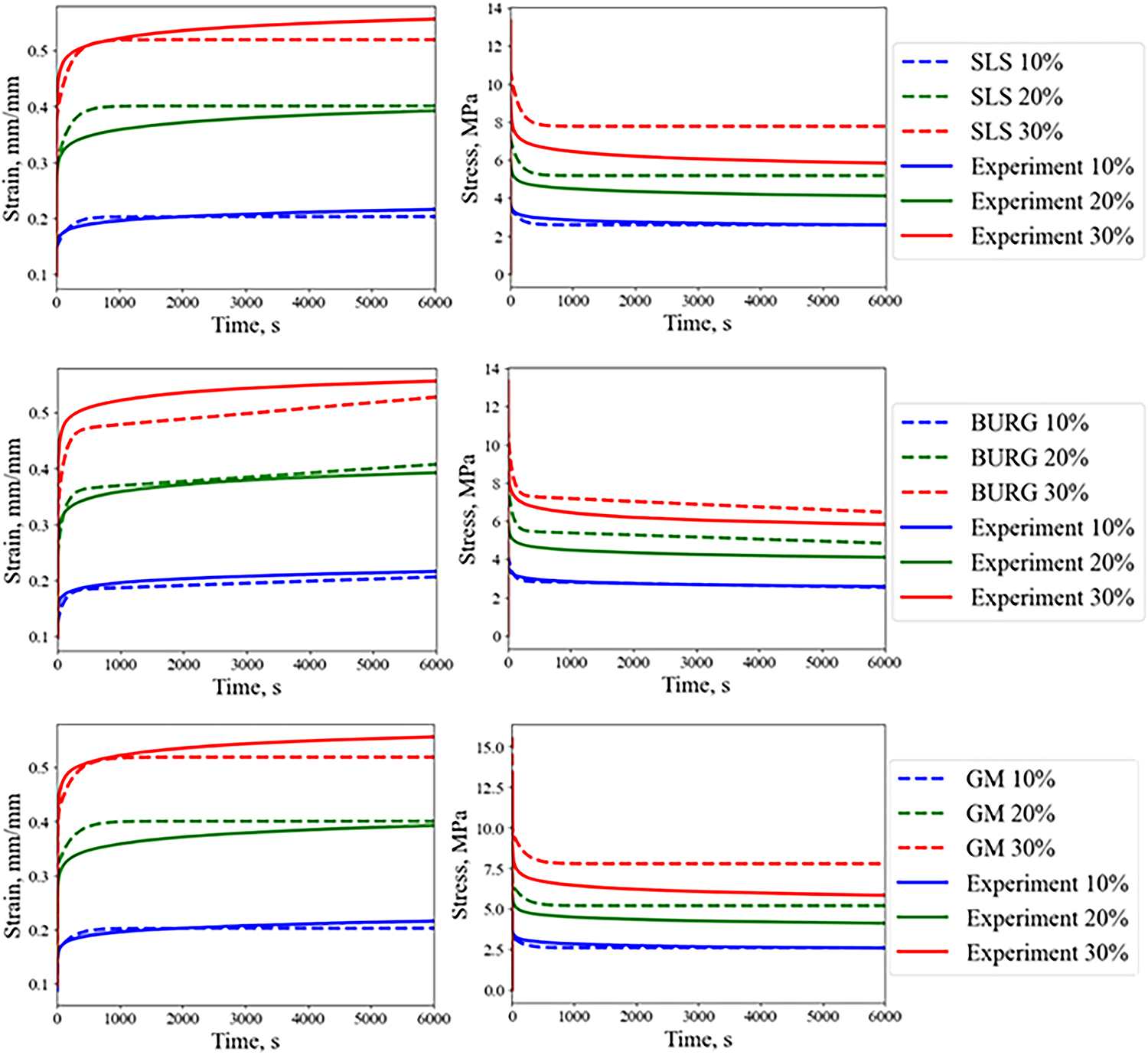

3.2 Procedure for Identification of Viscoelastic Parameters

Following the algorithm described in Section 2.3, the lumped parameters were obtained for the Zener, Burgers, and generalized Maxwell models within the 0–15% strain range corresponding to the first loading cycle. For SLS-model

Figure 2: Experimental and model creep (left) and stress relaxation (right) curves

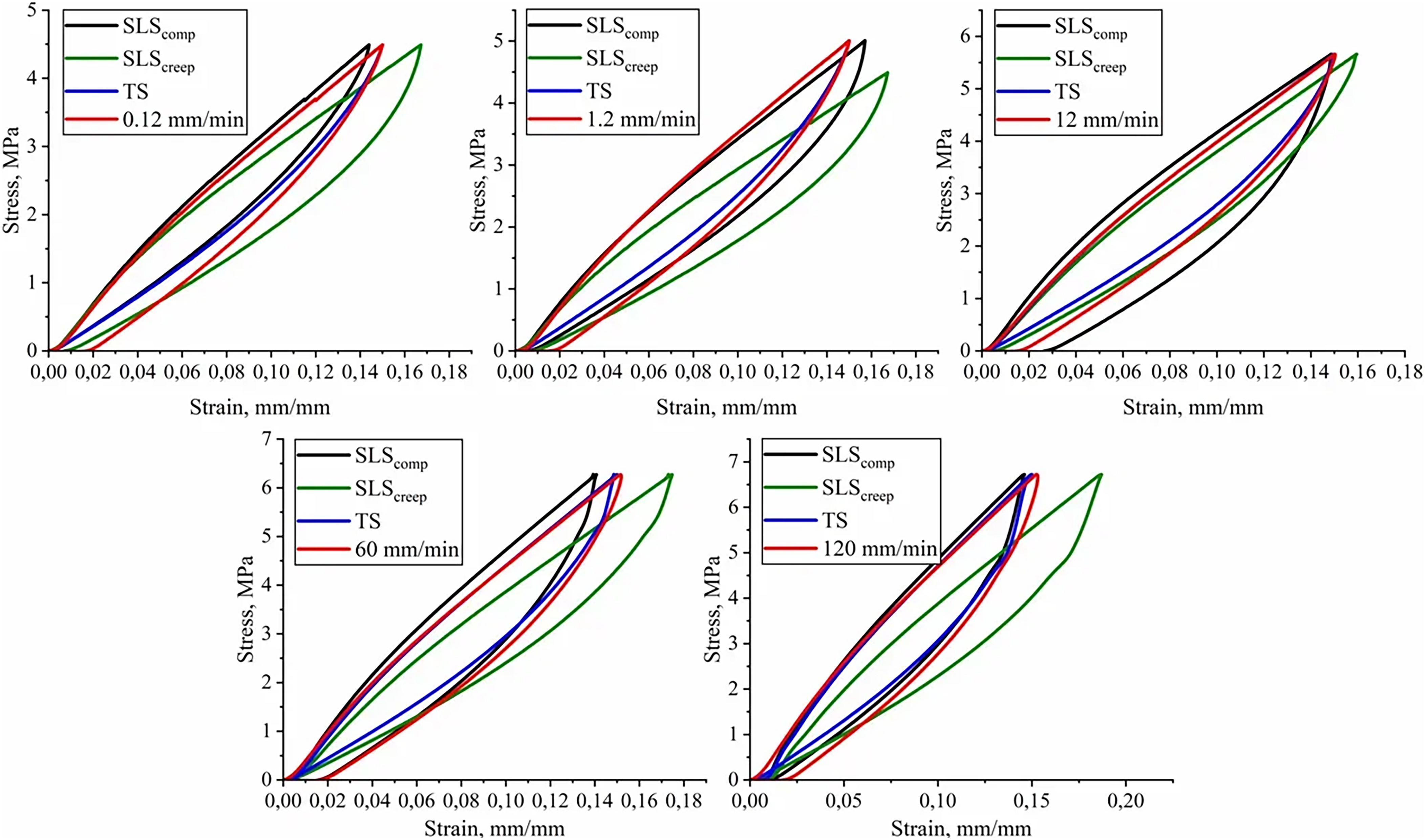

3.3 Study of Elastic-Hysteretic Characteristics

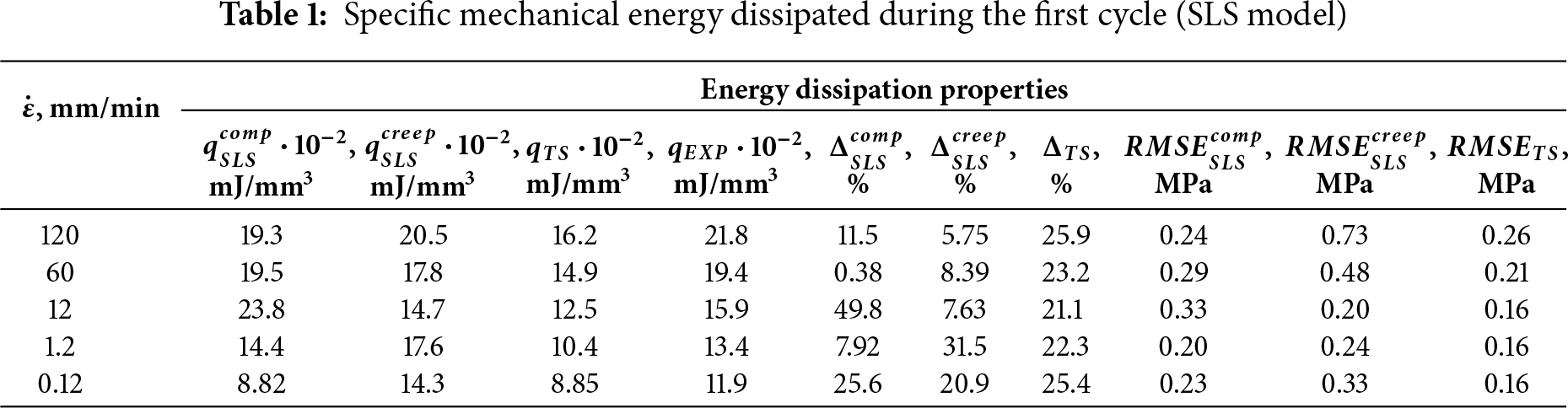

Based on the viscoelastic parameters determined in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, theoretical loading-unloading laws were obtained for all structural rheological models and strain rates using two parameter sets during the first cycle. Additionally, hysteresis dependencies corresponding to the assumption of a linear strain-time relationship in the material are presented. For all derived loading laws, the specific mechanical energy dissipated during the first cycle was calculated. The theoretical and experimental cyclic loading curves for the SLS model are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Experimental and model uniaxial compression curves during the first cycle for the SLS model; SLScomp and SLScreep represent model curves with parameters obtained from uniaxial compression and creep tests, respectively, TS denotes the cyclic loading law under linear strain-time dependence

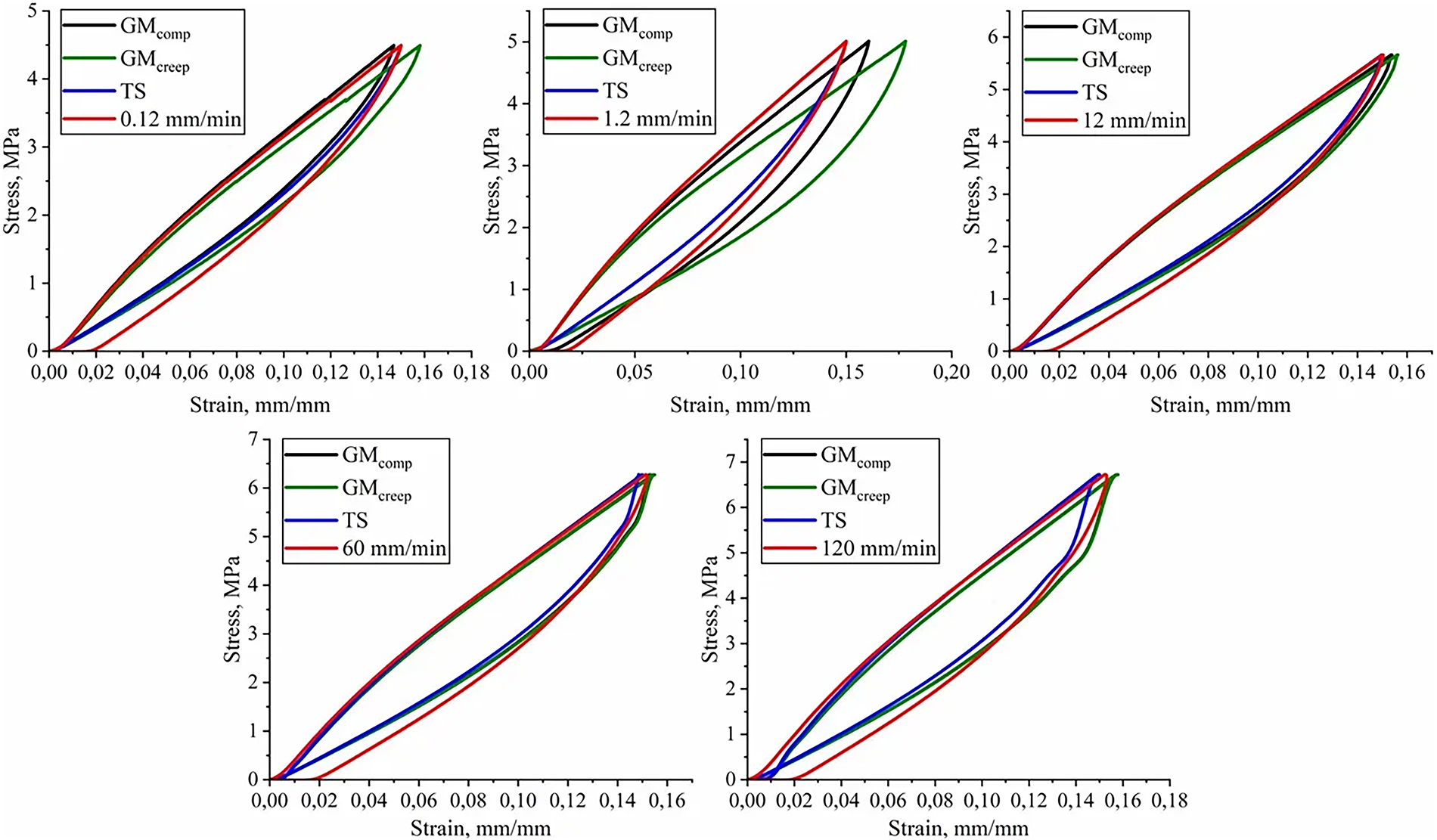

The specific mechanical energy dissipated during the first cycle for the SLS model is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 lists the following energy dissipation quantities for the SLS model:

where

The energy dissipation calculations demonstrate that the SLS model with compression-derived parameters accurately reflects material behavior at strain rates where viscous flow is negligible. This limitation arises from the model’s single dashpot element, which implies only one relaxation time (

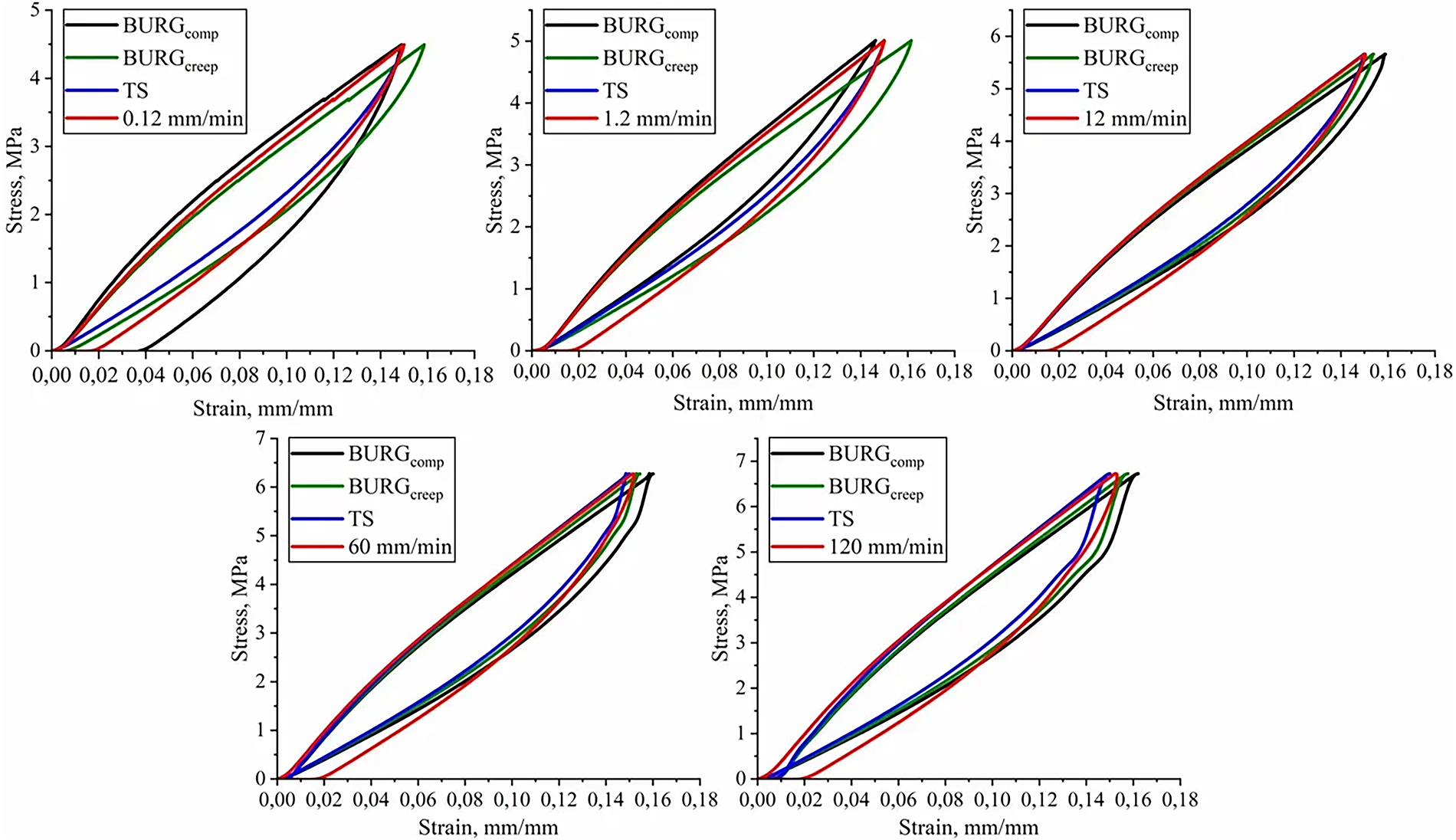

Fig. 4 presents the theoretical and experimental cyclic loading curves for the Burgers model.

Figure 4: Experimental and model uniaxial compression curves during the first cycle for the Burgers model

The specific mechanical energy dissipated during the first cycle for the BURG model is presented in Table 2.

The Burgers model with parameters from cyclic compression tests cannot adequately describe material behavior during unloading at low strain rates, as its viscous elements (with stress proportional to strain rate) show excessive time-delayed deformation upon load removal, failing to properly represent actual material processes. At 12, 60, and 120 mm/min strain rates, the energy dissipation errors remain below 16%, confirming the model’s validity for regimes with viscous flow and near-instantaneous loading. The parameter set from creep tests provides a more accurate material behavior description at low strain rates, which can be explained by characteristic plateau regions in corresponding experimental curves that were used in the minimization procedure.

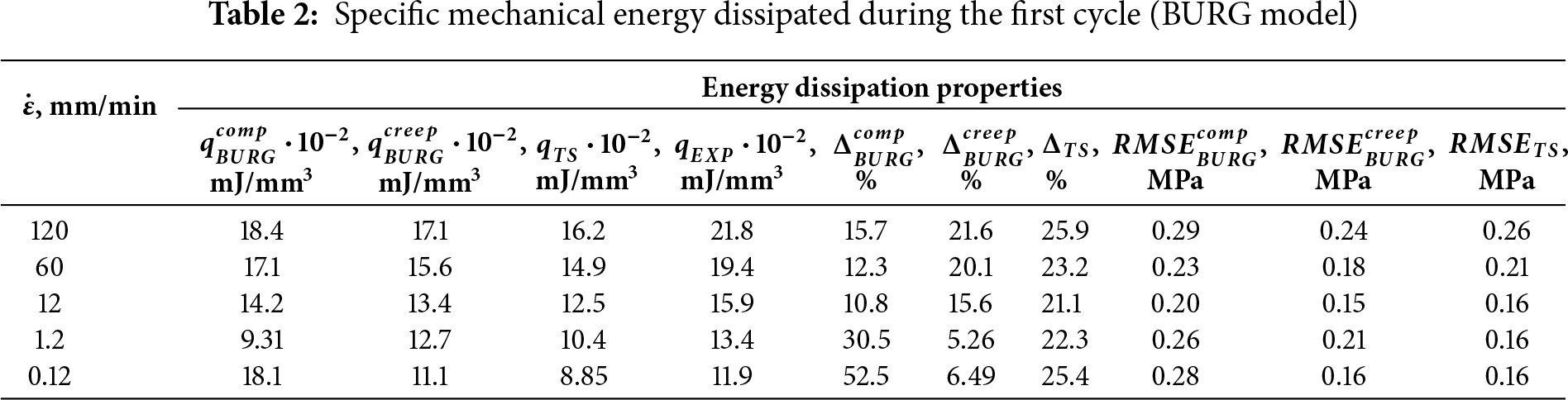

Fig. 5 shows the theoretical and experimental curves for the generalized Maxwell model.

Figure 5: Experimental and model uniaxial compression curves during the first cycle for the Generalized Maxwell model

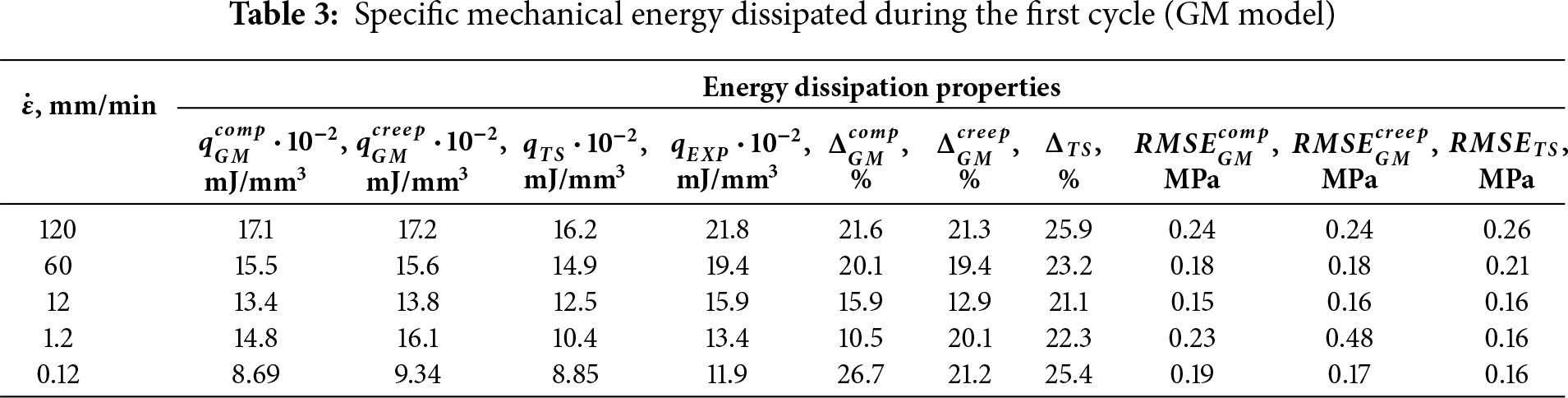

The specific mechanical energy dissipated during the first cycle for the GM model is presented in Table 3.

The parameters obtained from creep testing for the generalized Maxwell model prove more versatile when assessing elastic-hysteretic characteristics. However, at strain rates of 1.2 and 60 mm/min, the parameters derived from cyclic compression demonstrate lower error margins. The Maxwell model describes the dissipative properties of polyurethane with approximately 20% error for both parameter sets across the entire strain rate range. By incorporating additional Maxwell elements into the relaxation spectrum, the model achieves greater accuracy in describing cyclic loading behavior in the material.

3.4 Inverse Finite Element Modeling of Creep and Stress Relaxation

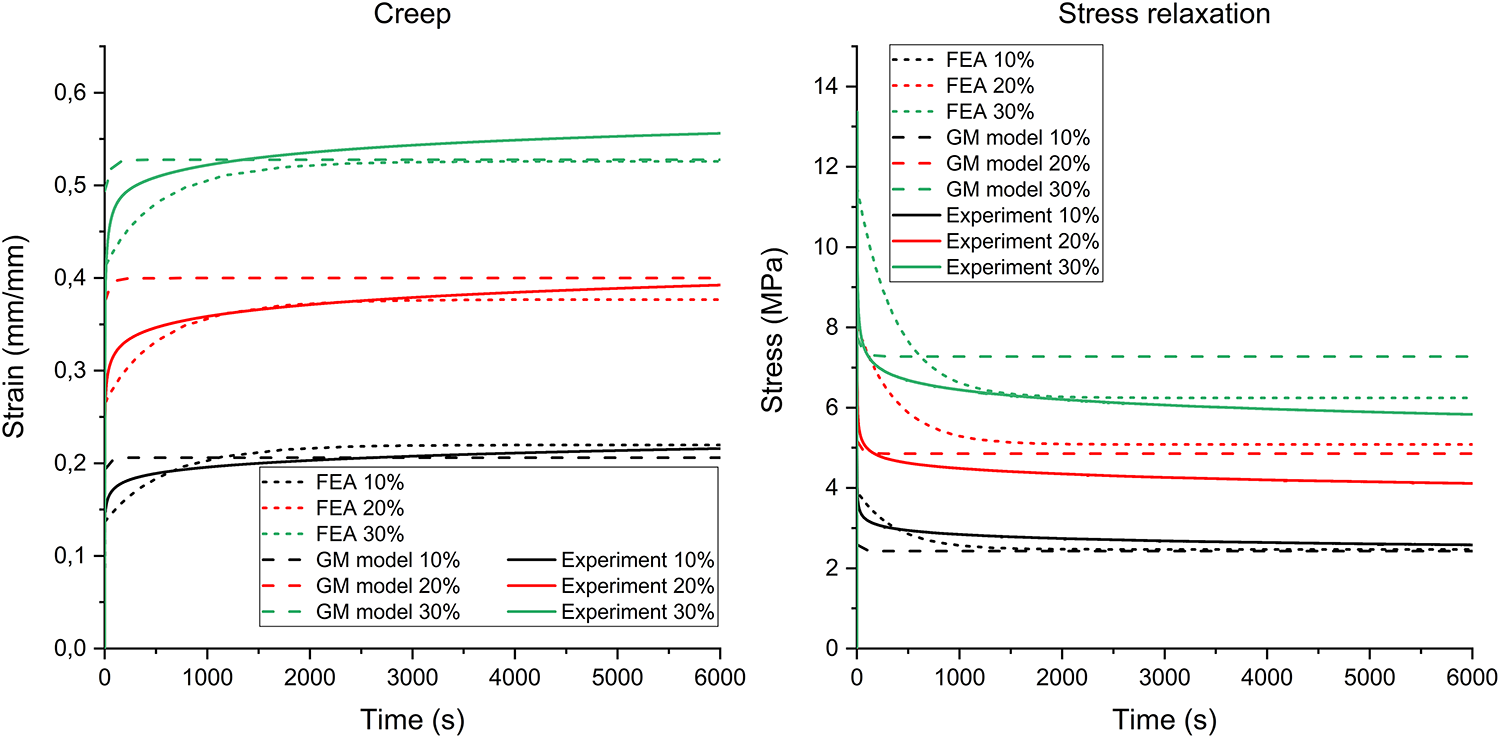

The finite element modeling of creep and stress relaxation processes determined the following parameters: third-order Mooney-Rivlin model coefficients (C10 = 7.256 MPa, C01 = 2.538 MPa, C11 = 3.197 MPa) and first-order Prony series parameters (Relative Modulus = 0.37, Relaxation Time = 380 s). The least squares method was used to determine fourth-order Prony series parameters for the generalized Maxwell model’s mechanical characteristics (τ1 = 43.58 s, e1 = 0.0556, τ2 = 89.21 s, e2 = 0.000386, τ3 = 92.95 s, e3 = 0.00371, τ4 = 99.31 s, e4 = 0.00373). Thus, strain-time and maximum normal stress-time dependencies were constructed (Fig. 6) by solving the inverse problem using two approaches: FEA and numerical optimization methods. The developed models satisfactorily describe the material behavior.

Figure 6: Analytical and FE calculated experimental calculated creep (left) and stress relaxation (right) curves

The generalized Maxwell model accurately describes the initial curve segment featuring rapid stress and strain variations. However, the finite element analysis fails to properly capture these changes, apparently owing to utilizing first-order Prony series constants (relaxation time and relative modulus) to simulate TPUs viscoelastic response, which, as opposed to the GM model formulation with fourth-order Prony series (comprising 4 relaxation times and 4 relative moduli), results in insufficient amount of Prony series components to approximate initial rapid changes in creep and stress relaxation curves, as well as due to inherent discretization limitations when dividing the domain into multiple interacting elements. This approach may produce simulation errors, particularly in regions with sharp stress gradients or large deformations, potentially overlooking key material behaviors during initial loading—including elastic deformation from interatomic adjustments, macromolecular conformational changes, and initial specimen compaction during test setup. This initial transient discrepancy is acknowledged as a limitation of the current FEA implementation. However, for practical applications involving the long-term performance of components, the accurate prediction of the steady-state creep and relaxation phases is of fundamental importance, which the model successfully achieves. When processes stabilize, the FEA demonstrates improved accuracy by incorporating multiple influencing factors (geometry, material properties, loading conditions) that analytical models inherently neglect. Unlike the Maxwell model’s linear assumptions, FEA accommodates nonlinear material responses and finite specimen dimensions, providing superior steady-state behavior characterization despite its transient analysis limitations. The computational approach’s capacity to capture complex interactions offers more physically representative results than simplified analytical solutions.

All of the aforementioned models can accurately characterize TPU samples’ behavior only in a small strain range (0%–15%). At higher strains (20%–30%) linear viscoelastic models provide greater discrepancy with the experimental creep and stress relaxation data which is also marked by the obtained Prony series coefficients distribution, namely, the closely spaced τ2, τ3, τ4 relaxation times with comparatively small corresponding relative moduli suggest, the model’s behavior is predominantly characterized by first order response, providing an insufficient capturing of non-linear effects, which necessitates the application of non-linear viscoelastic theory for a greater accuracy [28].

Mechanical testing was performed on cylindrical specimens fabricated using additive manufacturing from commercial thermoplastic polyurethane REC TPU Easy Flex. The testing produced cyclic loading stress-strain curves, creep curves, and stress relaxation curves, while also characterizing elastic-hysteretic properties. The curves showed consistent similarity across different stress levels and demonstrated good reproducibility in repeated tests, confirming additive manufacturing as a reliable production method for polyurethane components. The study employed a structural approach to characterize the viscoelastic properties of commercial TPU specimens under uniaxial compression and prolonged loading at three strain levels (10%, 20%, and 30%). Experimental compression and creep data yielded parameter sets for Zener, Burgers, and generalized Maxwell models. The derived equilibrium and instantaneous elastic moduli showed strong correlation with experimental data obtained at 0.12 mm/min and 120 mm/min strain rates. The methodology proved effective for describing material behavior under uniaxial compression within a 0%–15% strain range across various strain rates. The investigated viscoelastic models demonstrated the capability to qualitatively describe creep and stress relaxation behavior under specific conditions. While none of the Boltzmann-Volterra-based models captured irreversible microstructural damage accumulation, Burgers model verification against relaxation curves showed its superior performance in describing creep and stress relaxation at low strain levels compared to other models. Accuracy decreased at higher strains, likely due to nonlinear inelastic deformations from atomic rearrangement affecting supramolecular structure dimensions. Cyclic loading simulations were conducted for two parameter sets, including evaluation of the linear strain-time dependence hypothesis for experimentally determined stress laws and calculation of specific mechanical energy dissipation during the first cycle. The models effectively described material behavior under cyclic loading and elastic-hysteretic properties within a 0%–15% strain range. While Zener and Burgers model parameters from uniaxial compression showed limited applicability for energy dissipation calculations, the generalized Maxwell model effectively characterized viscoelastic properties across various strain rates. Creep-derived parameters provided a more universal assessment of dissipative properties due to characteristic curve regions used for optimization. Both parameter sets described polyurethane’s elastic-hysteretic behavior with approximately 20% error, proving more accurate and broadly applicable than the linear strain-time dependence hypothesis. It should be noted that the problem of determining a unique set of viscoelastic lumped parameters is, generally speaking, non-trivial in terms of its applicability to other types of tests. For instance, even accounting for the non-linear dependence of viscosity on stress under creep conditions and achieving a good fit with those experimental results can lead to significant inaccuracies when modeling stress relaxation [28]. Finite element analysis and numerical modeling of creep and stress relaxation processes demonstrated that the generalized Maxwell model effectively describes initial stages with rapid stress-strain changes, while FEA better analyzes steady-state processes, which is in good correlation with similar research [35]. Although finite element modeling serves as a powerful tool for analyzing complex physical processes, it requires careful model construction and results interpretation. The computational approach provides superior steady-state behavior characterization despite its transient analysis limitations, offering more physically representative results than simplified analytical solutions. Nevertheless, the use of models that admit explicit analytical solutions offers the opportunity not only to gain a deeper understanding of the processes influencing the viscoelastic behavior of materials and specimens but also to trace trends and interrelationships between parameters. This is particularly challenging in cases where the model parameters lack a clear physical meaning [36].

This paper introduces a novel hybrid methodology for the precise identification of the lumped parameters in viscoelastic models over a wide range of strain rates. Comprehensive experimental validation demonstrates that the methodology accurately captures the behavior of polyurethanes under cyclic compression, creep, and relaxation loading conditions. Furthermore, model verification via the finite element method confirms its robustness and extends its potential field of application.

Acknowledgement: The studies were carried out using the equipment of the resource centers of the National Research Centre “Kurchatov Institute”. This work was carried out within the state assignment of the National Research Centre “Kurchatov Institute”.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Arthur Krupnin, Nikita Golovkin and Olesya Nikulenkova; methodology, Arthur Krupnin, Nikita Golovkin and Olesya Nikulenkova; software, Nikita Golovkin and Olesya Nikulenkova; validation, Arthur Krupnin, Sergei Chvalun and Fedor Sorokin; formal analysis, Arthur Krupnin, Sergei Chvalun and Fedor Sorokin; investigation, Arthur Krupnin, Nikita Golovkin, Olesya Nikulenkova and Vsevolod Pobezhimov; data curation, Nikita Golovkin, Olesya Nikulenkova and Alexander Nesmelov; writing—original draft preparation, Arthur Krupnin, Nikita Golovkin, Olesya Nikulenkova and Vsevolod Pobezhimov; writing—review and editing, Sergei Chvalun and Fedor Sorokin; visualization, Nikita Golovkin, Olesya Nikulenkova and Vsevolod Pobezhimov; supervision, Sergei Chvalun and Fedor Sorokin; project administration, Sergei Chvalun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Arthur Krupnin, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.073161/s1.

Abbreviations

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FE | Finite Element |

| TPU | Thermoplastic Polyurethane |

| SLS | Standard Linear Solid |

| BURG | Burgers model |

| GM | Generalized Maxwell |

References

1. Yousefiasl S, Sharifi E, Salahinejad E, Makvandi P, Irani S. Bioactive 3D-printed chitosan-based scaffolds for personalized craniofacial bone tissue engineering. Eng Regen. 2023;4(1):1–11. doi:10.1016/j.engreg.2022.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kumar M, Krishnanand, Varshney A, Taufik M. Hand prosthetics fabrication using additive manufacturing. Mater Today Proc. 2023;90(Pt 2):427–33. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.06.396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Akshay Kumar J, Jaya Prakash K, Shivraj Narayan Y, Satyanarayana B. FE-strength evaluation of Ti-6Al-4V alloy dental implant and 3D printing using PLA material. Mater Today Proc. 2023;90(Pt 1):33–8. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.05.732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mace MAM, Reginatto CL, Soares RMD, Fuentefria AM. Three-dimensional printing of medical devices and biomaterials with antimicrobial activity: a systematic review. Bioprinting. 2024;38:e00334. doi:10.1016/j.bprint.2024.e00334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tamo AK, Djouonkep LDW, Selabi NBS. 3D printing of polysaccharide-based hydrogel scaffolds for tissue engineering applications: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;270:132123. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Reddy VS, Ramasubramanian B, Telrandhe VM, Ramakrishna S. Contemporary standpoint and future of 3D bioprinting in tissue/organs printing. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2023;27:100461. doi:10.1016/j.cobme.2023.100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tsui JKS, Bell S, da Cruz L, Dick AD, Sagoo MS. Applications of three-dimensional printing in ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol. 2022;67(5):1287–310. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2022.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. D’Agnol L, Dias FTG, Nicoletti NF, Falavigna A, Bianchi O. Polyurethane as a strategy for annulus fibrosus repair and regeneration: a systematic review. Regen Med. 2018;13(5):611–27. doi:10.2217/rme-2018-0003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Issa A, Rahgozar N, Alam MS. Experimental investigation and seismic analysis of a novel self-centering piston-based bracing archetype with polyurethane cores. Eng Struct. 2023;283(4):115735. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.115735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Navas-Gómez K, Valero MF. Why polyurethanes have been used in the manufacture and design of cardiovascular devices: a systematic review. Materials. 2020;13(15):3250. doi:10.3390/ma13153250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Rusu LC, Ardelean LC, Jitariu AA, Miu CA, Streian CG. An insight into the structural diversity and clinical applicability of polyurethanes in biomedicine. Polymers. 2020;12(5):1197. doi:10.3390/polym12051197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jiang Y, Shi K, Zhou L, He M, Zhu C, Wang J, et al. 3D-printed auxetic-structured intervertebral disc implant for potential treatment of lumbar herniated disc. Bioact Mater. 2023;20(4792):528–38. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Findley WN, Davis FA. Creep and relaxation of nonlinear viscoelastic materials. Mineola, NY, USA: Courier Corporation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

14. Cisneros T, Zaytsev D, Seyedkavoosi S, Panfilov P, Gutkin MY, Sevostianov I. Effect of saturation on the viscoelastic properties of dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;114(10):104143. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.104143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Rabotnov YN. Creep of structural elements. Moscow, Russia: Nauka; 1966. [Google Scholar]

16. Tirella A, Mattei G, Ahluwalia A. Strain rate viscoelastic analysis of soft and highly hydrated biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(10):3352–60. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.34914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mattei G, Ahluwalia A. A new analytical method for estimating lumped parameter constants of linear viscoelastic models from strain rate tests. Mech Time-Depend Mater. 2019;23(3):327–35. doi:10.1007/s11043-018-9385-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Cacopardo L, Guazzelli N, Nossa R, Mattei G, Ahluwalia A. Engineering hydrogel viscoelasticity. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;89:162–7. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.09.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mattei G, Gruca G, Rijnveld N, Ahluwalia A. The nano-epsilon dot method for strain rate viscoelastic characterisation of soft biomaterials by spherical nano-indentation. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2015;50:150–9. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.06.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Mattei G, Cacopardo L, Ahluwalia A. Engineering gels with time-evolving viscoelasticity. Materials. 2020;13(2):438. doi:10.3390/ma13020438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Semenov VK, Belkin AE. Mathematical model of the viscoelastic behavior of rubber under cyclic loading. BMSTU J Mech Eng. 2014;2:46–51. [Google Scholar]

22. Kurkin AS, Kiselev AS, Krasheninnikov SV, Zelenina IA, Gerasin VA, Chalykh AE. Simulation of the deformation diagram of a viscoelastic material based on a structural model. Inorg Mater. 2023;59(15):1546–54. doi:10.1134/s0020168523150062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lin CY. Rethinking and researching the physical meaning of the standard linear solid model in viscoelasticity. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2024;31(11):2370–85. doi:10.1080/15376494.2022.2156638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ahmed HM, Salem NM, Al-Atabany W. Human cornea thermo-viscoelastic behavior modelling using standard linear solid model. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023;23(1):241. doi:10.1186/s12886-023-02985-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Rabotnov YN. Mechanics of deformable solids. Moscow, Russia: Nauka; 1988. [Google Scholar]

26. Martins C, Pinto V, Guedes RM, Marques AT. Creep and stress relaxation behaviour of PLA-PCL fibres—a linear modelling approach. Procedia Eng. 2015;114(1):768–75. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2015.08.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ebert C, Hufenbach W, Langkamp A, Gude M. Modelling of strain rate dependent deformation behaviour of polypropylene. Polym Test. 2011;30(2):183–7. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2010.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Guedes RM, Singh A, Pinto V. Viscoelastic modelling of creep and stress relaxation behaviour in PLA-PCL fibres. Fibers Polym. 2017;18(12):2443–53. doi:10.1007/s12221-017-7479-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mattei G, Ahluwalia A. Sample, testing and analysis variables affecting liver mechanical properties: a review. Acta Biomater. 2016;45:60–71. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2016.08.055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen P. Creep response of a generalized Maxwell model. Int Agrophysics. 1994;8:555–8. [Google Scholar]

31. Wan C, Zhang X, Wang L, He L. Three-dimensional micromechanical finite element analysis on gauge length dependency of the dynamic modulus of asphalt mixtures. Road Mater Pavement Des. 2012;13(4):769–83. doi:10.1080/14680629.2012.732194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Luo R, Lv H, Liu H. Development of Prony series models based on continuous relaxation spectrums for relaxation moduli determined using creep tests. Constr Build Mater. 2018;168(3):758–70. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kohnke P, editor. Theory reference, release 5.7. Canonsburg, PA, USA: ANSYS, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

34. Pelayo F, Blanco D, Fernández P, González J, Beltrán N. Viscoelastic behaviour of flexible thermoplastic polyurethane additively manufactured parts: influence of inner-structure design factors. Polymers. 2021;13(14):2365. doi:10.3390/polym13142365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hedayati R, Shokrnia M, Alavi M, Sadighi M, Aghdam MM. Viscoelastic behavior of cellular biomaterials based on octet-truss and tetrahedron topologies. Materials. 2024;17(23):5865. doi:10.3390/ma17235865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Koruk H, Rajagopal S. A comprehensive review on the viscoelastic parameters used for engineering materials, including soft materials, and the relationships between different damping parameters. Sensors. 2024;24(18):6137. doi:10.3390/s24186137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools