Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LUAR: Lightweight and Universal Attribute Revocation Mechanism with SGX Assistance towards Applicable ABE Systems

1 The School of Computer Science and Technology, Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Chongqing, 400065, China

2 Chongqing Unicom Industrial Internet Co., Ltd., Chongqing, 401121, China

* Corresponding Author: Fei Tang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Privacy-Enhancing Technologies for Secure Data Cooperation and Circulation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 69 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073423

Received 17 September 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) has emerged as a fundamental access control mechanism in data sharing, enabling data owners to define flexible access policies. A critical aspect of ABE is key revocation, which plays a pivotal role in maintaining security. However, existing key revocation mechanisms face two major challenges: (1) High overhead due to ciphertext and key updates, primarily stemming from the reliance on revocation lists during attribute revocation, which increases computation and communication costs. (2) Limited universality, as many attribute revocation mechanisms are tailored to specific ABE constructions, restricting their broader applicability. To address these challenges, we propose LUAR (Lightweight and Universal Attribute Revocation), a novel revocation mechanism that leverages Intel Software Guard Extensions (SGX) while minimizing its inherent limitations. Given SGX’s constrained memory (Keywords

In the digital era, the rapid advancement of cloud computing has brought data security and privacy protection to the forefront of both academic and industrial discussions. As enterprises and organizations increasingly migrate their data storage and processing to cloud environments, ensuring secure and efficient access control while maintaining data confidentiality has become a pressing challenge [1–3].

Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE), introduced by Sahai and Waters [4], is widely recognized for its fine-grained access control capabilities. Unlike Identity-Based Encryption (IBE) [5], ABE binds ciphertexts and secret keys to sets of attributes rather than unique identities. Decryption is permitted only if the attributes embedded in a user’s key satisfy the predefined access policy. This design makes ABE particularly well-suited for applications including secure cloud computing [6–8], healthcare data sharing [9,10], Internet of Things [11], and social networks [12–14].

Despite its advantages, ABE suffers from a long-standing challenge in attribute revocation—the ability to prevent access for users whose attributes have been revoked. Existing revocation strategies typically fall into two categories: direct [15–17] and indirect [18–20]. In both cases, the revocation mechanism either imposes high computation/storage overhead or sacrifices forward security by allowing revoked users to access previously obtained ciphertexts.

To mitigate these problems, researchers have explored ciphertext update mechanisms [21] as well as hardware-based solutions [15,22] using Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs), particularly Intel SGX [23]. However, traditional TEE-based ABE revocation schemes often rely on storing revocation lists or transformation keys inside the enclave, quickly exceeding SGX’s 90MB memory limit and creating a central point of failure.

To address these challenges, we propose LUAR (Lightweight and Universal Attribute Revocation), a novel revocation framework that integrates Ciphertext-Policy ABE (CP-ABE) with Intel SGX in a lightweight and generalizable manner. LUAR features a timestamp-based key expiration mechanism, lightweight Merkle-proof-based verification, and a ciphertext blinding strategy that protects sensitive information from enclave exposure. These innovations reduce reliance on SGX memory, eliminate the need for key/ciphertext updates, and enable seamless integration with a variety of ABE schemes.

Our key contributions are as follows.

• Lightweight. LUAR introduces an efficient attribute revocation mechanism that avoids re-encrypting all cloud-stored files upon attribute changes or key revocation. Even under Cloud Service Provider (CSP)-user collusion, LUAR ensures secure and low-cost revocation without a heavy computational burden. It minimizes reliance on complex encryption, revocation list maintenance, and conversion key management within the TEE, alleviating the 90 MB SGX memory constraint in a personal computer.

• Universal. LUAR is designed for flexibility and scalability. While implemented with the classic BSW07 scheme [24], it supports seamless integration with other ABE variants. It maintains low computation and communication overhead, making it suitable for large-scale or resource-constrained settings. LUAR also supports horizontal scalability in multi-user cloud environments, offering a practical solution for fine-grained access control.

• LUAR implementation. Experiments show stable SGX processing time (

Direct and Indirect Revocation. ABE systems is often categorized into direct and indirect methods. In direct revocation, such as in Wang et al. [16] and FDR-CP-ABE [17], a revocation list is embedded during encryption, allowing data owners to control access. However, this increases ciphertext size and imposes frequent updates. In indirect revocation, seen in schemes like RABE [19] and RS-CPABE-ASP [20], the trusted authority periodically updates keys for legitimate users. These approaches often require both key and ciphertext renewal, leading to high communication overhead. In summary, while these schemes can prevent unauthorized access, they introduce significant operational complexity and communication costs, particularly in dynamic or large-scale environments.

Blockchain-Based Revocation. Blockchain-assisted ABE revocation has emerged as an approach to provide decentralized and tamper-resistant revocation tracking. For example, some schemes utilize smart contracts to maintain and query revocation status [25–29]. This design enhances transparency and auditability without relying on a single trusted entity. However, practical deployment faces limitations such as high gas costs, transaction latency, and synchronization issues between blockchain and off-chain access control. Moreover, integrating blockchain with real-time ABE operations remains challenging due to the mismatch in performance requirements. In summary, blockchain-based revocation offers strong decentralization and transparency, but its overhead and complexity limit its applicability to time-sensitive or large-scale systems.

TEE-Based Revocation. TEE-assisted revocation leverages secure hardware like Intel SGX to enforce attribute revocation with integrity guarantees. For instance, HR-ABE [15] uses SGX to perform epoch-based checks with Merkle proofs, ensuring that revoked users cannot bypass access control even under adversarial settings. Similarly, Fan et al. [22] generate ephemeral keys inside SGX per access attempt to isolate secrets. However, both rely heavily on SGX for storage and computation, which is constrained by limited enclave memory (e.g., 90 MB EPC in SGX) and is vulnerable to side-channel attacks [30,31]. Furthermore, the need to store revocation state or perform complex computations within SGX leads to scalability bottlenecks. In summary, while TEE-based revocation enhances security through hardware-enforced isolation, many designs suffer from over-reliance on enclave resources and reduced efficiency in high-load or multi-user scenarios.

Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (CP-ABE) is a type of ABE technique that enables DOs to encrypt their data in such a way that only users possessing specific attributes can decrypt it. Instead of defining particular recipients, DOs specify an access structure that dictates the required attribute combinations for decryption. For example, an access structure such as “

The fundamental concept of CP-ABE is embedding the access policy directly into the encryption process. A user can decrypt a ciphertext only if their attribute set satisfies the predefined access policy. The CP-ABE scheme consists of four main steps: Setup, Key Generation, Encryption, and Decryption. The detailed algorithm is presented below. (1)

Intel Software Guard Extensions (SGX) [23] is a hardware-level security technology developed by Intel to enhance data privacy and protection in modern computer systems. SGX enables applications to execute code and process sensitive data within a secure, hardware-isolated region known as an enclave. These enclaves provide a robust defense against interference from malicious software, compromised operating systems, and other external threats.

A key aspect of SGX is the interaction between enclave and non-enclave code, facilitated by two essential mechanisms: Enclave Call (Ecall) and Out Call (Ocall). Ecall allows untrusted external code to invoke functions inside the enclave, while Ocall enables enclave code to call functions outside its secure boundary. These mechanisms are fundamental to ensuring seamless communication between trusted and untrusted components while maintaining the security guarantees of SGX. Besides, SGX supports remote attestation that allows users to verify the authenticity and integrity of an enclave in a remote environment. This process establishes a secure communication channel between interacting parties. Through remote attestation, SGX guarantees that only verified and uncompromised environments are authorized to participate in sensitive operations.

In existing SGX-based schemes, there is excessive reliance on SGX as a black-box execution environment, leading to critical challenges: (1) SGX acts as a superuser, requiring unconditional trust in its security; (2) it must store revocation lists or numerous transformation keys, increasing storage burden; and (3) it handles both decryption and re-encryption internally, causing high computational overhead and potential plaintext leakage via side-channel attacks. To address these issues, we propose an optimized approach that reduces SGX dependency while preserving security and efficiency. The key improvements are as follows.

Minimized trust dependency. SGX no longer performs decryption or re-encryption operations. Instead, it ensures the proper execution of internal programs while preventing plaintext exposure. Even if the CSP gains access to intermediate data during SGX processing, it remains unable to derive the original plaintext, thereby reducing the trust burden placed on SGX.

Optimized storage management. SGX no longer maintains user revocation lists or a large number of transformation keys. Instead, it retains only a single transformation key for removing blind factors in ciphertext. This significantly reduces memory consumption and mitigates system performance bottlenecks.

Lightweight computation. SGX is solely responsible for verifying the legitimacy of user requests, ensuring that keys are valid and not revoked. Once verification is complete, SGX uses the transformation key to remove blind factors from ciphertext without engaging in complex encryption or decryption, significantly improving execution efficiency.

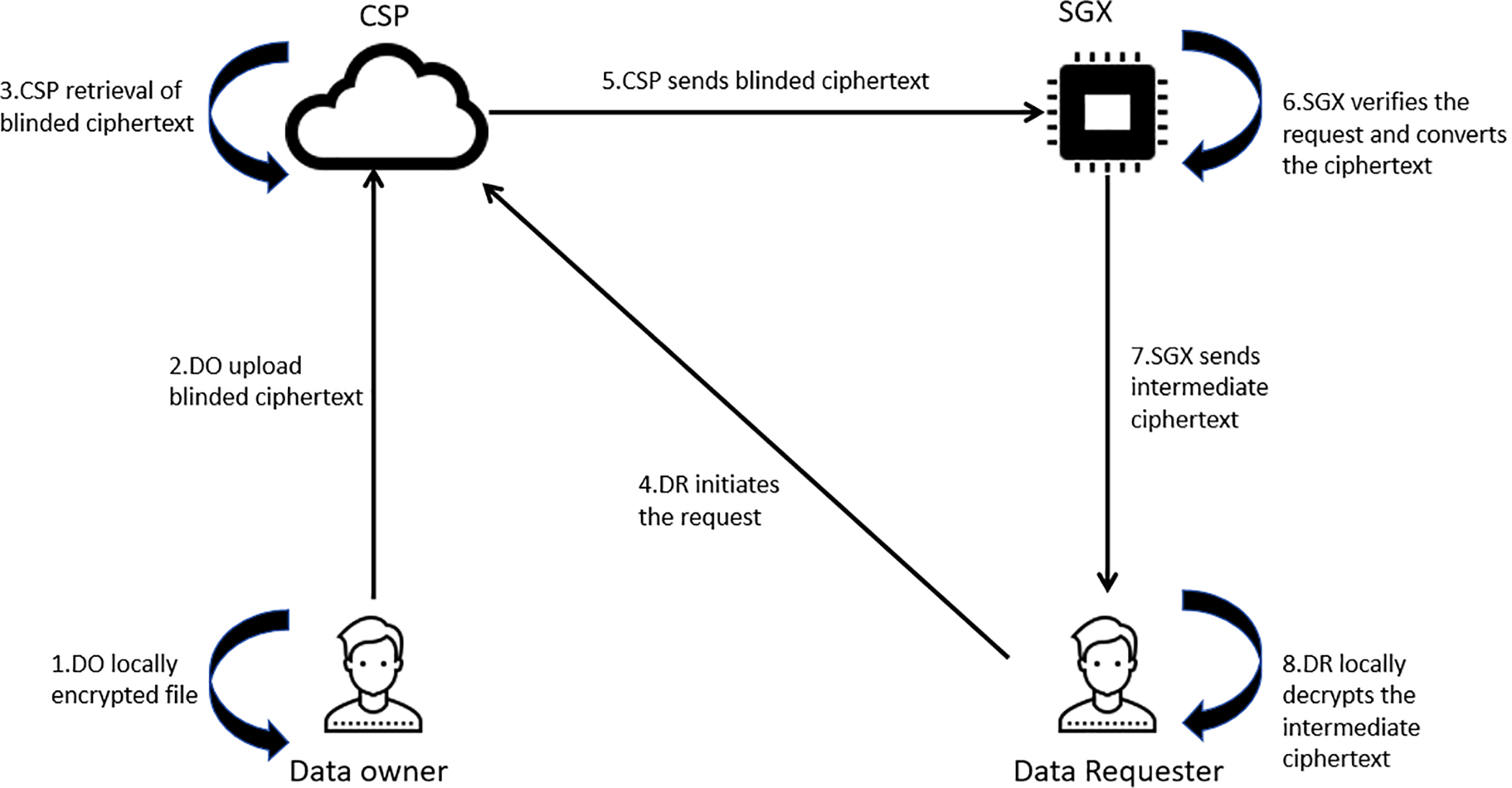

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the system architecture comprises four key entities: Software Guard Extensions (SGX), Cloud Service Provider (CSP), Data Owner (DO), and Data Requestor (DR). (1) SGX: provides a protected execution environment for generating the system’s master key, public key, and user keys. It plays a crucial role in verifying user legitimacy and transforming ciphertext to remove blind factors while ensuring data privacy. Importantly, SGX does not directly expose plaintext data, thus maintaining security even in untrusted environments. (2) CSP: is responsible for storing encrypted files uploaded by users. Beyond storage, the CSP ensures secure file retention and provides encrypted data to SGX when authorized access is granted. (3) DO: is responsible for encrypting and uploading data to the CSP. By defining access policies during encryption, the DO ensures that only authorized users can access the data. Additionally, blind factors can be embedded in the ciphertext to enhance security, obfuscating data to prevent unauthorized decryption. (4) DR: is the entity requesting data from the cloud. To access data, the DR submits a request to the CSP, retrieves the encrypted file, and collaborates with SGX to decrypt it using its local user key. Note that trusted authorities (e.g., government or enterprise identity providers) are responsible for issuing user attributes, but are considered external to the LUAR design and are not involved in the revocation or decryption workflow.

Figure 1: System architecture

The proposed mechanism operates through the following five key phases.

System Initialization. SGX generates the system master key and public key. The master key is securely stored within the SGX as a critical component for subsequent user key generation, while the public key is made available on the CSP for use in data encryption and access control.

User Key Generation. Trusted institutions, such as government agencies, banks, and official organizations, provide valid user attributes to the SGX environment. Upon receiving a request, SGX generates the corresponding user key, embedding an expiration date to facilitate lightweight revocation and request verification. Unlike traditional CP-ABE schemes, this method enhances security by ensuring that expired or revoked keys cannot be used for decryption. Once the key is generated, it is securely transmitted to the user via a remote attestation-based secure channel.

Encryption. Data encryption is carried out in two stages. In Stage 1, the DO generates a symmetric key to encrypt the file and then encrypts the symmetric key based on a selected access policy. In Stage 2, the DO incorporates a blind factor into the ciphertext to generate a blinded ciphertext, which is then uploaded to the CSP for secure storage.

SGX Verification and Transformation. When the DR initiates a data access request, the CSP retrieves the corresponding blinded ciphertext and forwards it, along with the request details, to the SGX. SGX first checks whether the key’s expiration date is earlier than its internal clock time; if expired, the request is rejected. Next, SGX verifies the authenticity of the expiration date using the time-binding factor in the DR’s key and checks whether the key has been revoked. If the request is deemed valid, SGX removes the blind factor from the ciphertext to obtain an intermediate ciphertext, which is then returned to DR. This process preserves data confidentiality and integrity while enforcing strict access control.

User Local Decryption. The DR utilizes their private key to decrypt the intermediate ciphertext and obtain the symmetric key. Finally, the symmetric key is used to decrypt the encrypted file, restoring the plaintext data.

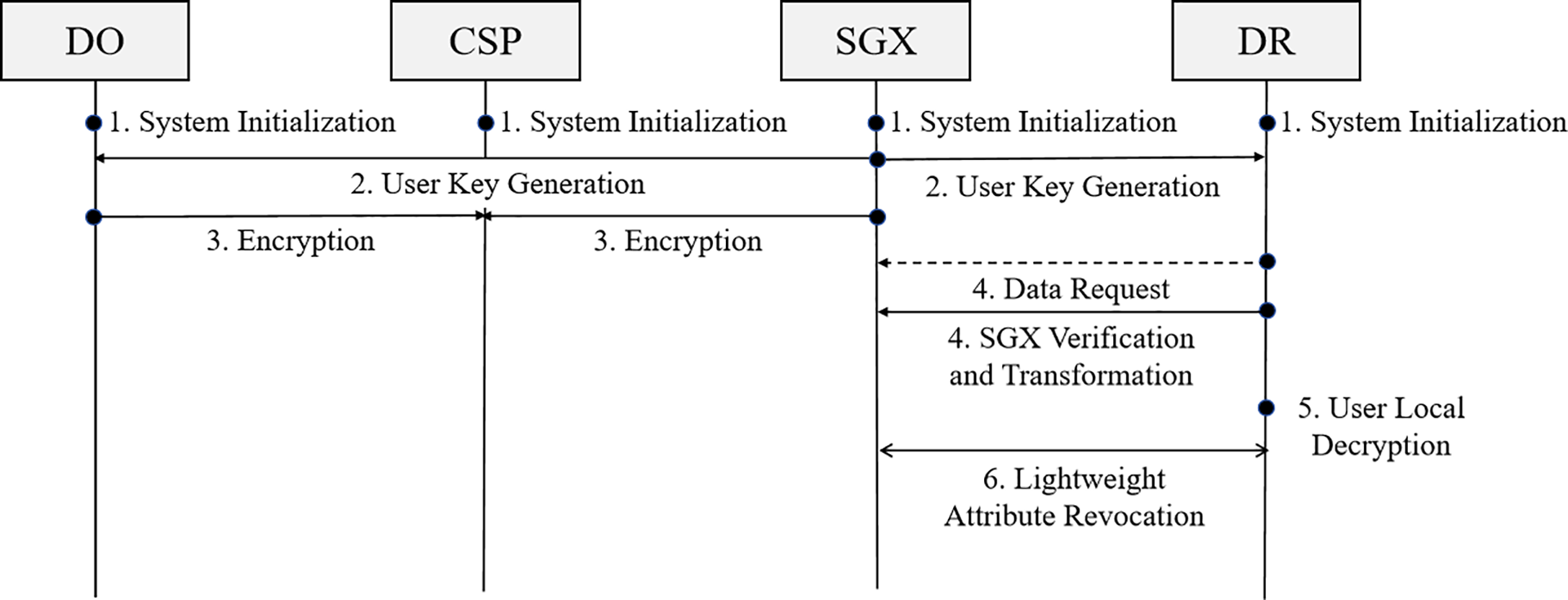

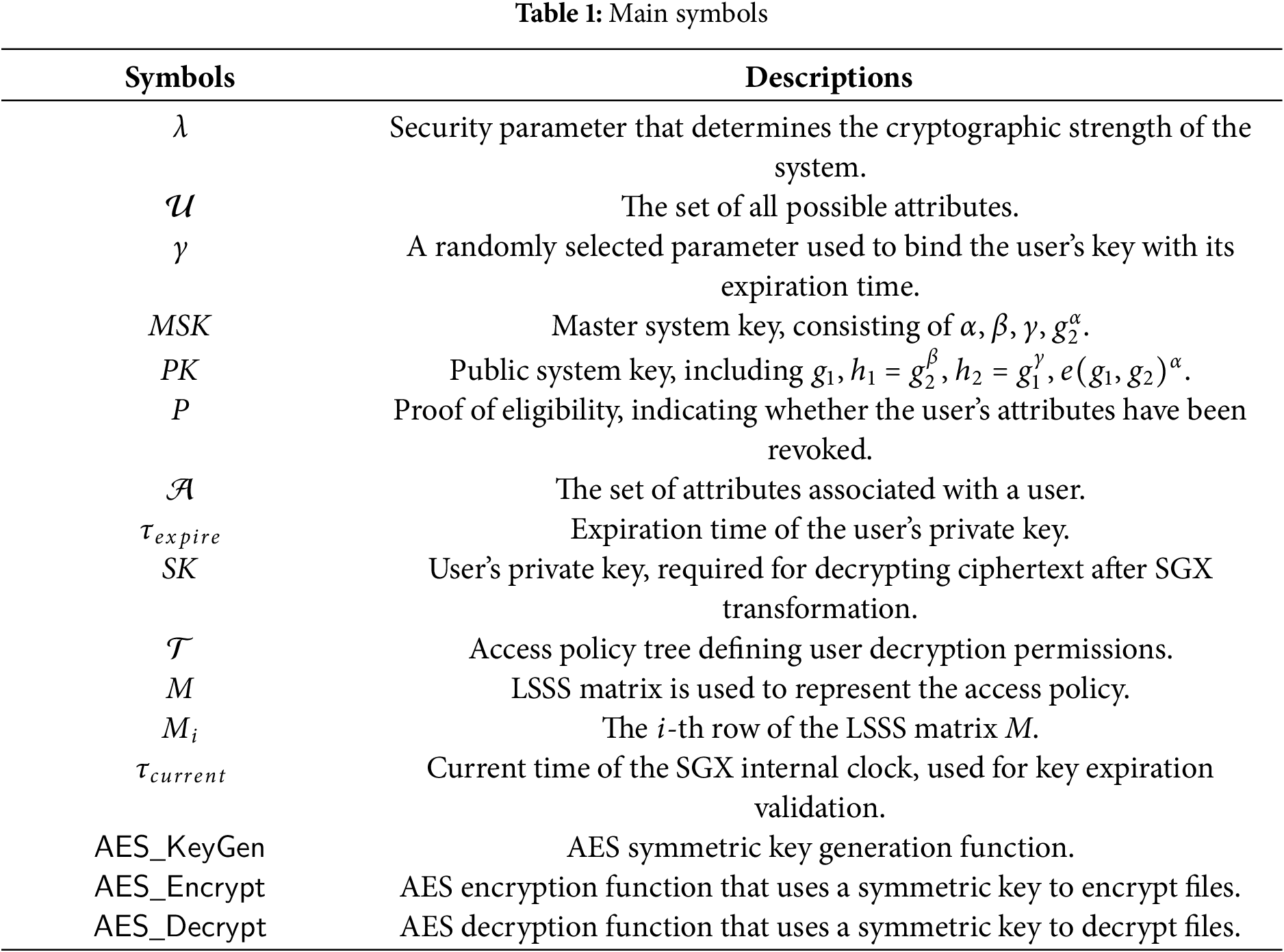

We provide a comprehensive implementation phase of LUAR and the flowchart is as shown in Fig. 2. The relevant symbols and descriptions are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2: The flowchart of the LUAR framework

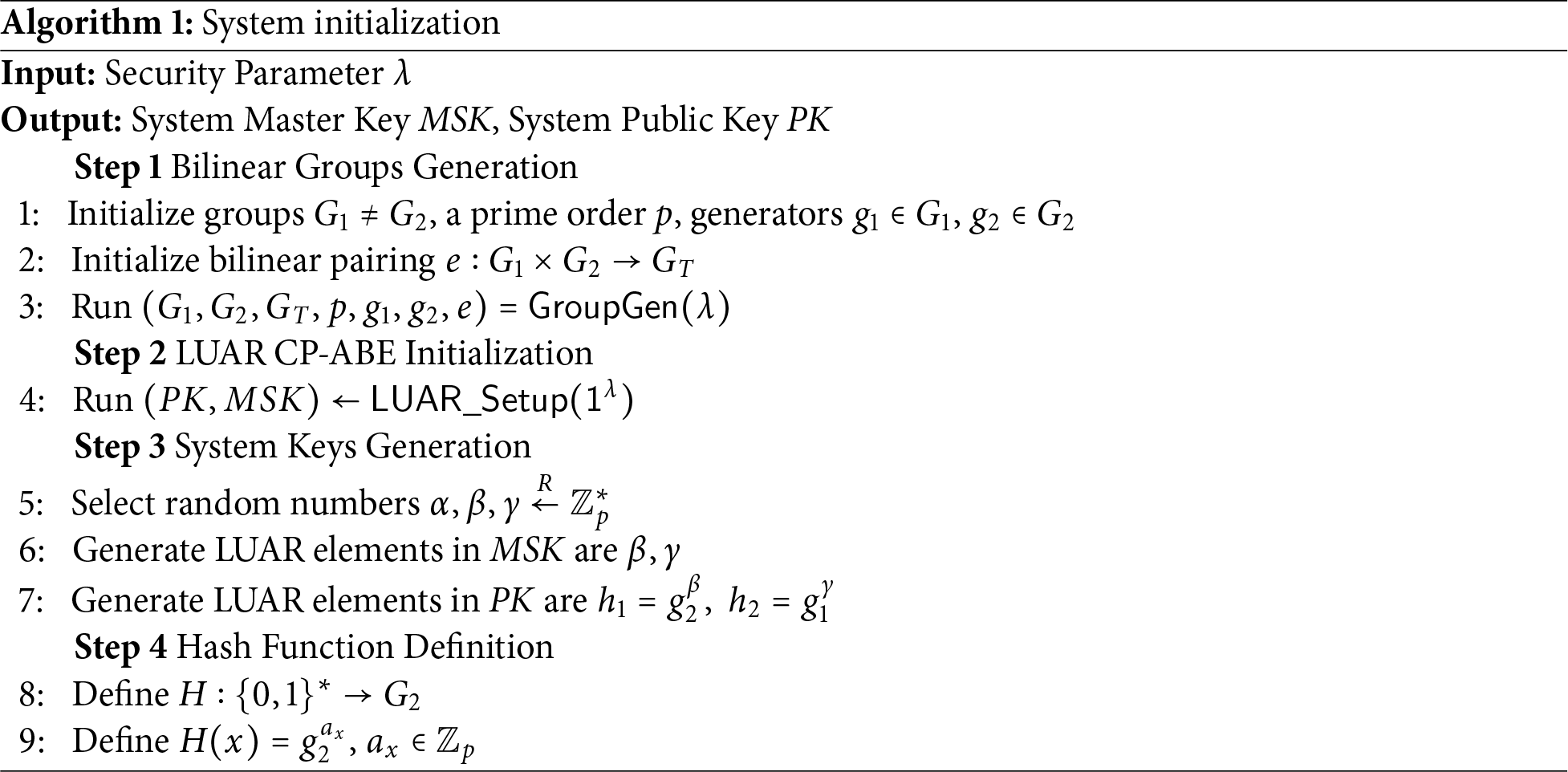

The initialization phase lays the cryptographic foundation for LUAR and ensures the secure deployment of critical components. During this phase, the code responsible for verifying user requests and removing the blinding factor is securely embedded into the SGX enclave. Upon launch, SGX generates a unique identifier to establish its trusted identity. Users can verify the integrity and authenticity of SGX via Intel’s remote attestation mechanism. The complete initialization phase consists of four steps. The details are described below and presented in Algorithm 1.

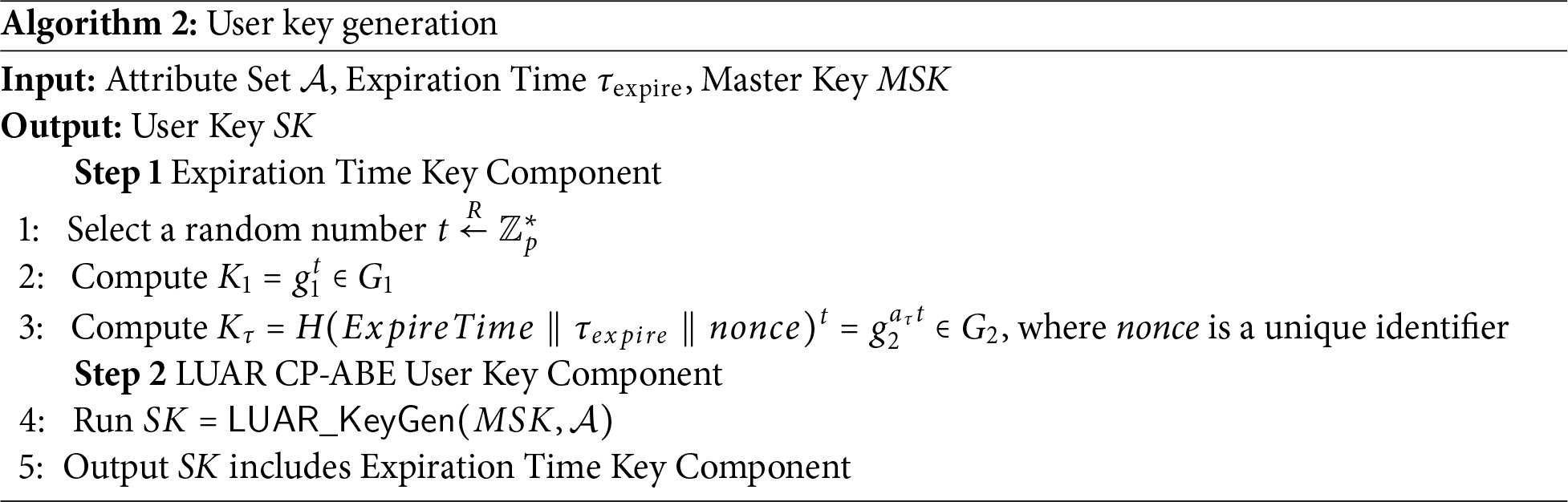

User key generation is performed within the SGX enclave. Unlike traditional CP-ABE schemes, LUAR integrates an expiration timestamp into each user’s key, enabling efficient and lightweight attribute revocation while maintaining system security. The detailed process of user key generation is outlined in Algorithm 2.

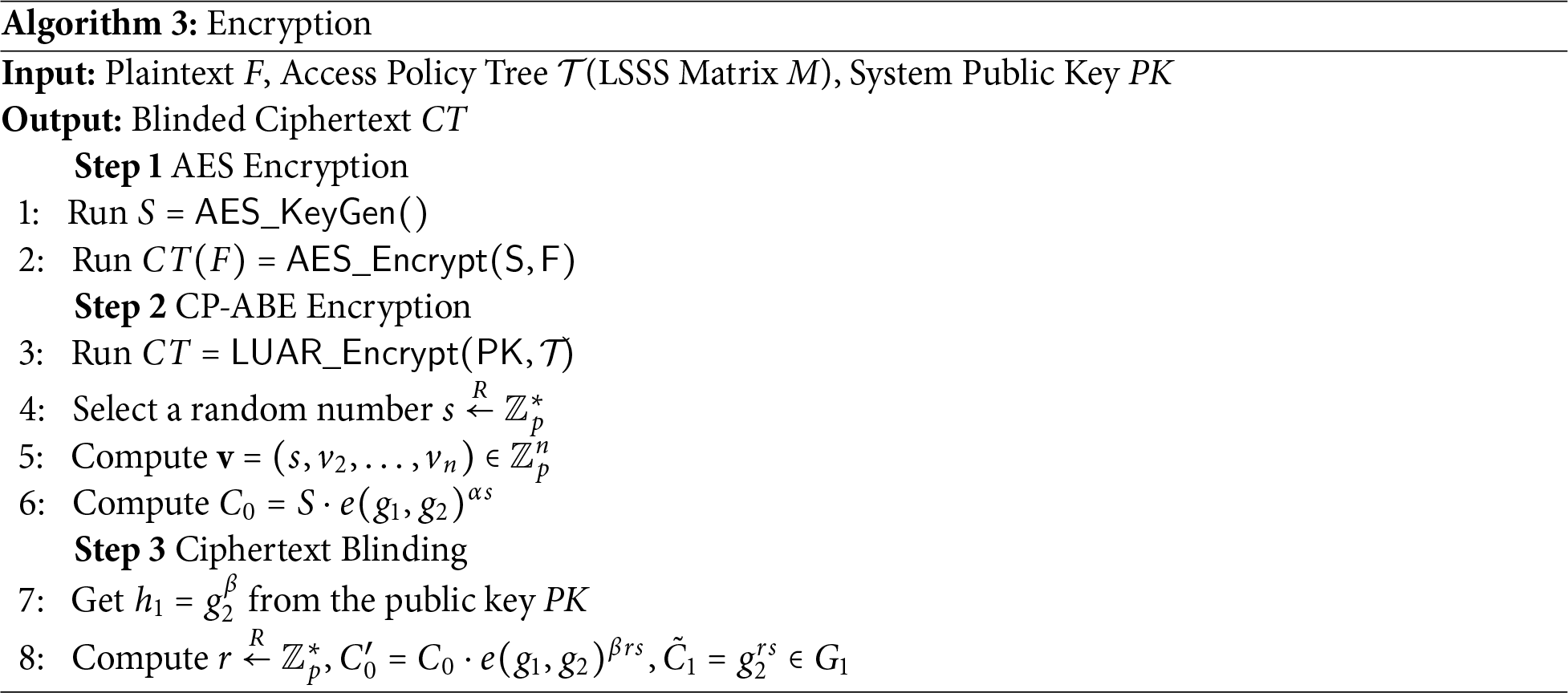

Unlike traditional CP-ABE encryption schemes, LUAR incorporates a ciphertext blinding mechanism to mitigate potential collusion between the CSP and malicious users. To achieve this, the encryption process is divided into three distinct steps: Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Encryption, CP-ABE Encryption, and ciphertext Blinding. This design ensures that even if a malicious user obtains the ciphertext from the CSP, they cannot decrypt it using an expired key. The detailed steps of the data encryption process are described in Algorithm 3.

5.4 SGX Verification and Transformation

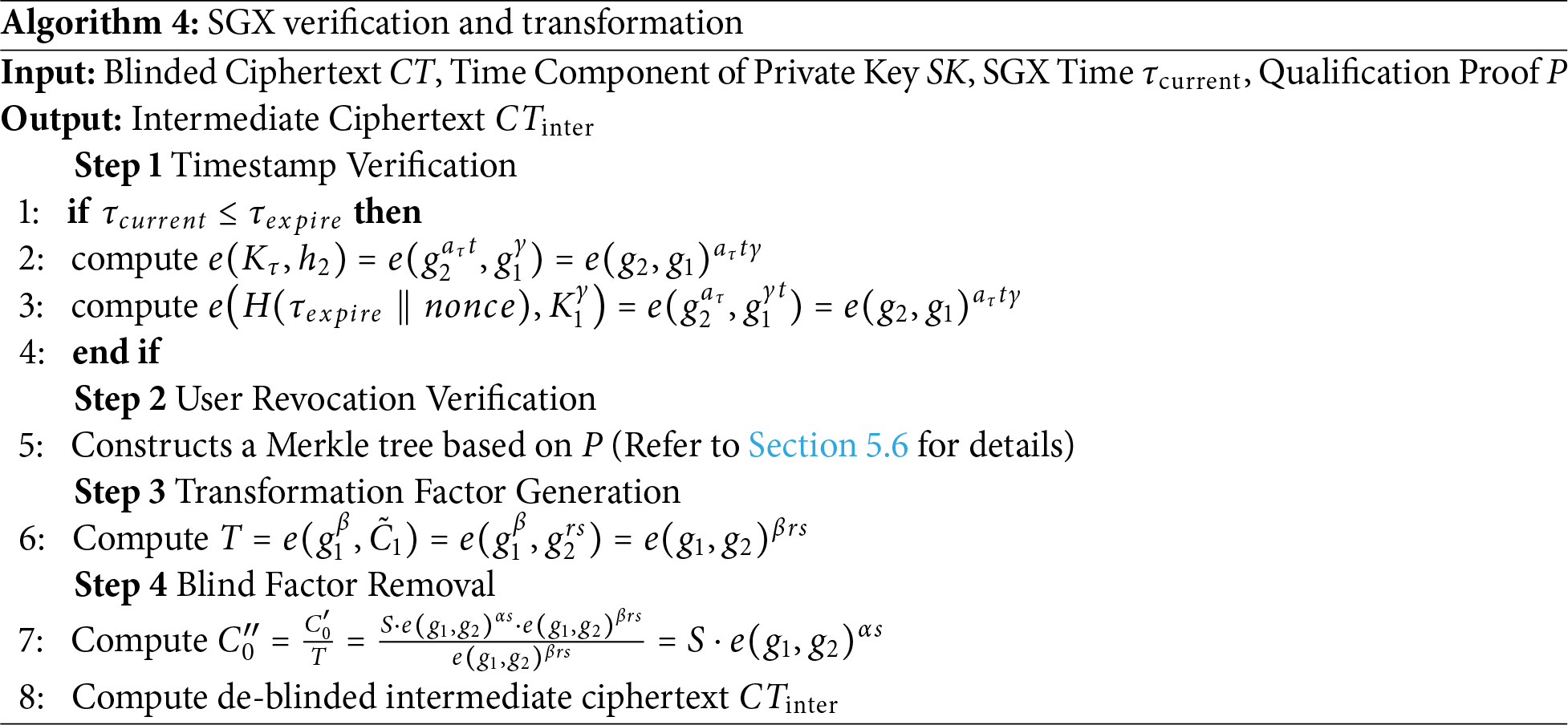

In our scheme, SGX is primarily utilized for permission verification and blind factor removal. The design carefully accounts for SGX’s memory constraints and potential side-channel threats. Unlike traditional black-box models, SGX functions in a quasi-white-box manner, meaning that even if the CSP can monitor the execution inside SGX and manipulate the inputs and outputs, it still cannot compromise the plaintext. The detailed process of the SGX verification and transformation phase is presented in Algorithm 4.

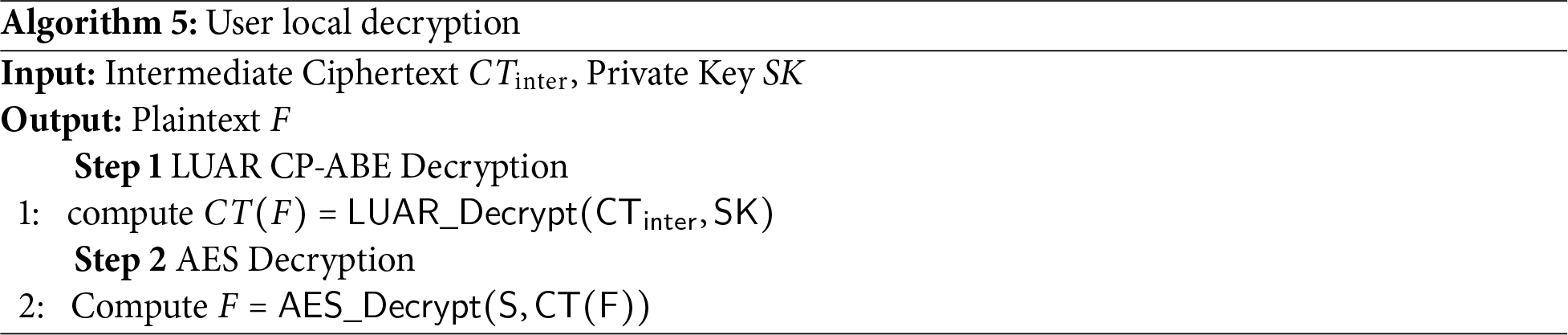

After receiving the intermediate ciphertext returned by SGX, the DR uses their private key SK to decrypt it. If the user’s attributes meet the access policy requirements, they will successfully decrypt the plaintext; otherwise, the decryption will fail. The algorithm flow for the user’s local decryption phase is as described in Algorithm 5.

5.6 Lightweight Attribute Revocation

This mechanism includes two types of revocation: passive revocation and active revocation, each requiring a distinct handling strategy. Passive revocation (User key expiration). Key expiration is the most common form of key invalidation in practical applications. In this passive revocation scenario, since the DO embeds a blinding factor into the ciphertext during encryption, even if the DR colludes with the CSP, they cannot recover the plaintext. Once the DR’s key expires, it will fail the timestamp verification phase performed within SGX. This effectively addresses the issue of key expiration without requiring additional intervention. In other words, even if the CSP can access intermediate data during SGX execution, LUAR prevents both CSP and DR from using expired keys to decrypt data.

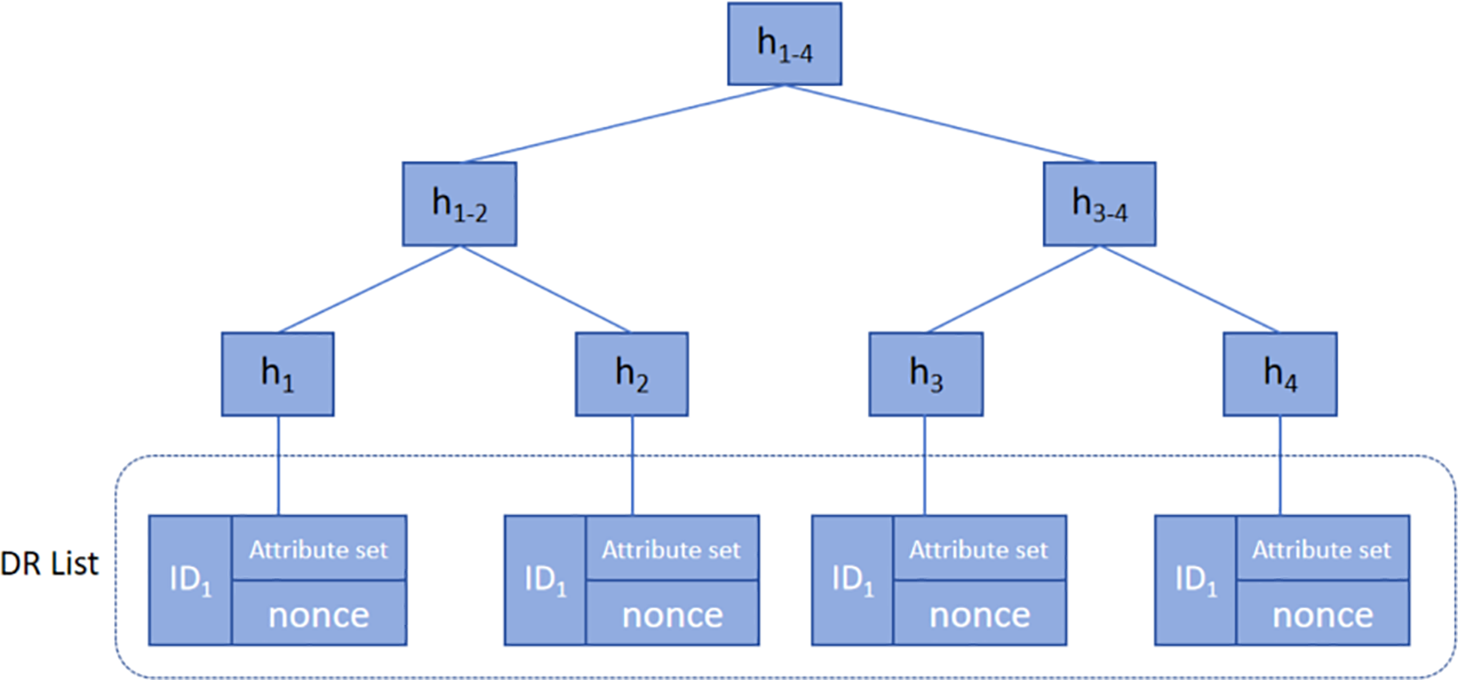

Active revocation (User attribute revocation). Active revocation occurs when a user’s key is still valid, but the associated attributes have been changed or revoked. In such cases, the authorized institution must update the user’s attributes and re-execute the key generation algorithm within SGX. A new user key is issued, and the DR proceeds with the standard decryption process when requesting data. To prevent revoked users from decrypting data with outdated keys, our scheme employs a Merkle tree to support active revocation without transmitting the entire DR list. Instead, only a logarithmic-size (

Figure 3: Merkle tree-based revocation list construction

After constructing the Merkle tree, the root hash

LUAR is designed to be a universal enhancement layer that integrates seamlessly with standard CP-ABE frameworks. In this section, we briefly describe how LUAR is embedded into the widely adopted BSW07 scheme [24], and focus on the added logic of timestamp binding, ciphertext blinding, and SGX-assisted transformation. LUAR consists of four core algorithms:

The primary function of

6.2 Key Generation with Timestamp Binding

The primary function of

The primary function of

The primary function of

Generality and Integration Flexibility. One of LUAR’s core strengths lies in its generality—the ability to integrate seamlessly with a wide range of CP-ABE schemes without modifying their fundamental operations. LUAR achieves this by treating itself as a modular revocation overlay layer that interfaces with standard ABE procedures. It appends lightweight timestamp-related components to user keys and delegates revocation checks to a trusted SGX enclave, without interfering with the encryption or decryption algorithms of the underlying scheme. This design is particularly compatible with bilinear pairing-based ABE schemes that rely on linear secret-sharing structures, such as BSW07. However, integration with non-standard ABE schemes (e.g., lattice-based or those using non-linear access policies) may require slight adaptation. Overall, LUAR’s abstraction of revocation logic enables a plug-and-play mechanism that enhances ABE frameworks with minimal implementation overhead and broad applicability, universality of ABE systems without compromising their original functionality or security assumptions.

The primary objective of this scheme is to provide a secure cloud data sharing solution that addresses high attribute revocation costs and SGX overload through the use of attribute-based cryptography and SGX encoding. We make the following threat assumptions about the system entities: The CSP may engage in malicious activities, attempting to extract sensitive information from cloud data, including potentially accessing intermediate execution states of SGX. Additionally, there may be collusion between the CSP and users, where the CSP sends blinded ciphertexts directly to users with revoked attributes, allowing them to decrypt files using outdated keys. And the DO is assumed to be fully trusted.

The security of LUAR relies on standard cryptographic assumptions and the security properties of trusted execution environments. We formalize the security proof through security game definitions and polynomial-time reductions. Specifically, we define the Indistinguishability under Chosen-Plaintext Attack (IND-CPA) security game between the challenger C and the adversary A.

System Setup: The challenger C runs the initialization algorithm to generate the master public key PK and master secret key

Query Phase 1: During this phase, A can adaptively query the following oracles. (1) Key Generation Oracle

Challenge Phase: In this phase, A submits two equal-length messages

Query Phase 2: A retains access to the oracles but may not query keys satisfying

Guess: A outputs a guess

Theorem 1 (IND-CPA Security). Assuming the Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) problem is hard in groups

Game 0: Standard IND-CPA game.

Game 1: Modify challenge ciphertext by replacing

Game 2: Introduce a blind factor with

Game 3: SGX verifies timestamp through a hash binding equation such that

Theorem 2 (Collusion Resistance). For any polynomial-time adversary A controlling at most

Side-Channel Risk Mitigation. SGX enclaves provide strong memory isolation yet remain vulnerable to side channels (e.g., cache leakage, speculative execution) [30,31]. LUAR reduces the attack surface by keeping sensitive plaintext and heavy cryptography outside SGX. The enclave is limited to timestamp verification, Merkle-path checking, and blind-factor removal over intermediate data. Even if execution patterns are observed, blinded ciphertext prevents disclosure of plaintext or keys. Standard hardening (e.g., access-pattern randomization, noise) can further strengthen LUAR, though full treatment is beyond this paper.

Trusted Time Assumption. LUAR’s passive revocation compares enclave time

In this section, we evaluate the performance and benefits of the proposed scheme. We implemented our solution and two comparison schemes on a physical machine running 64-bit Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, equipped with an Intel Core i7-12700H (12 cores, 20 threads) and 16 GB memory. Experiments were conducted in SGX simulation mode to eliminate network I/O impact, and operation times were recorded. Only one SGX group was deployed in this setup. In real-world scenarios, multiple SGX groups can be horizontally scaled to handle different attribute combinations, operating independently without interference.

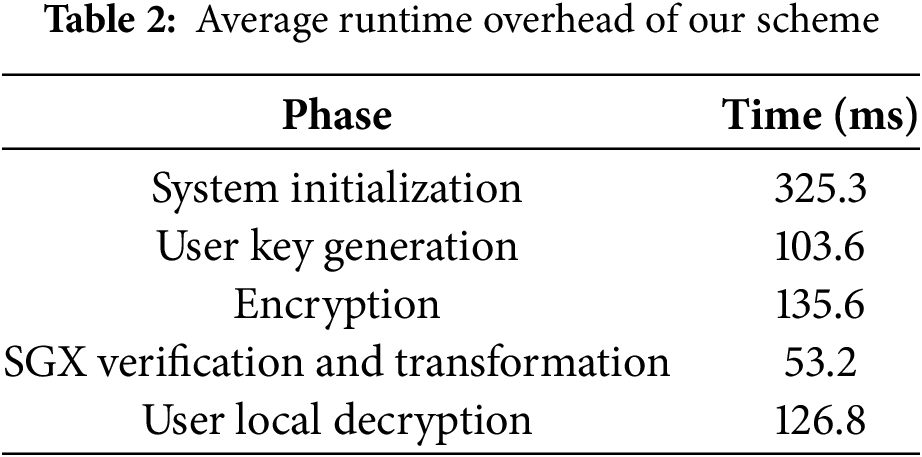

8.1 Fixed Access Policy and Fixed Data Size

This experiment focuses on evaluating the runtime overhead of the proposed scheme. We conducted 30 independent trials and averaged the results. The access policy used for testing is defined as:

To clarify performance characteristics, we analyzed time-critical operations in each stage, excluding network I/O. During initialization, most time (

It is worth noting that the total runtime within the SGX was only

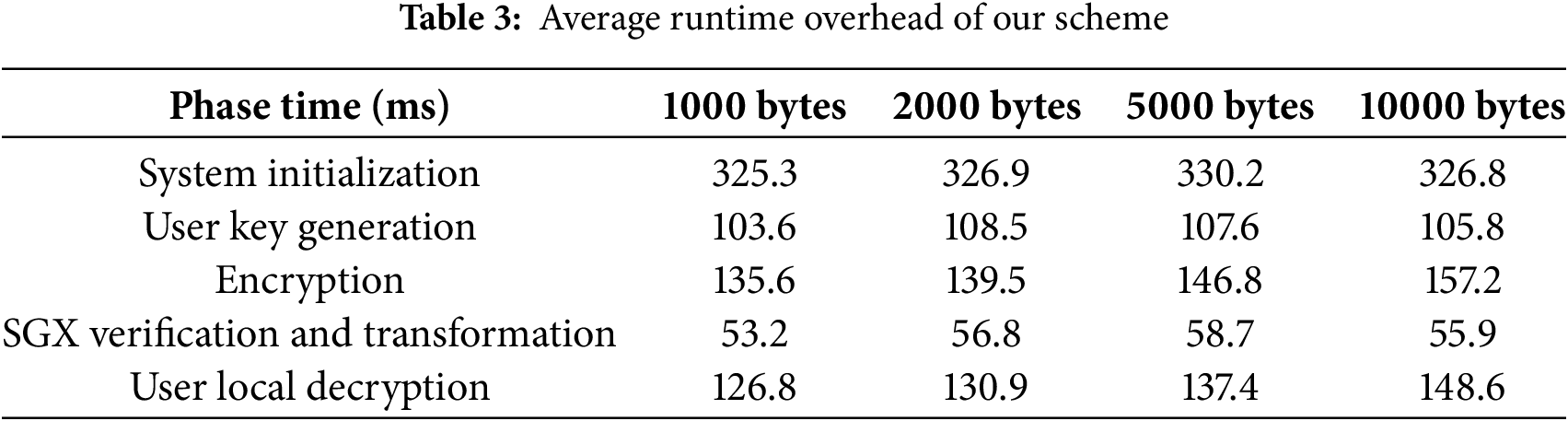

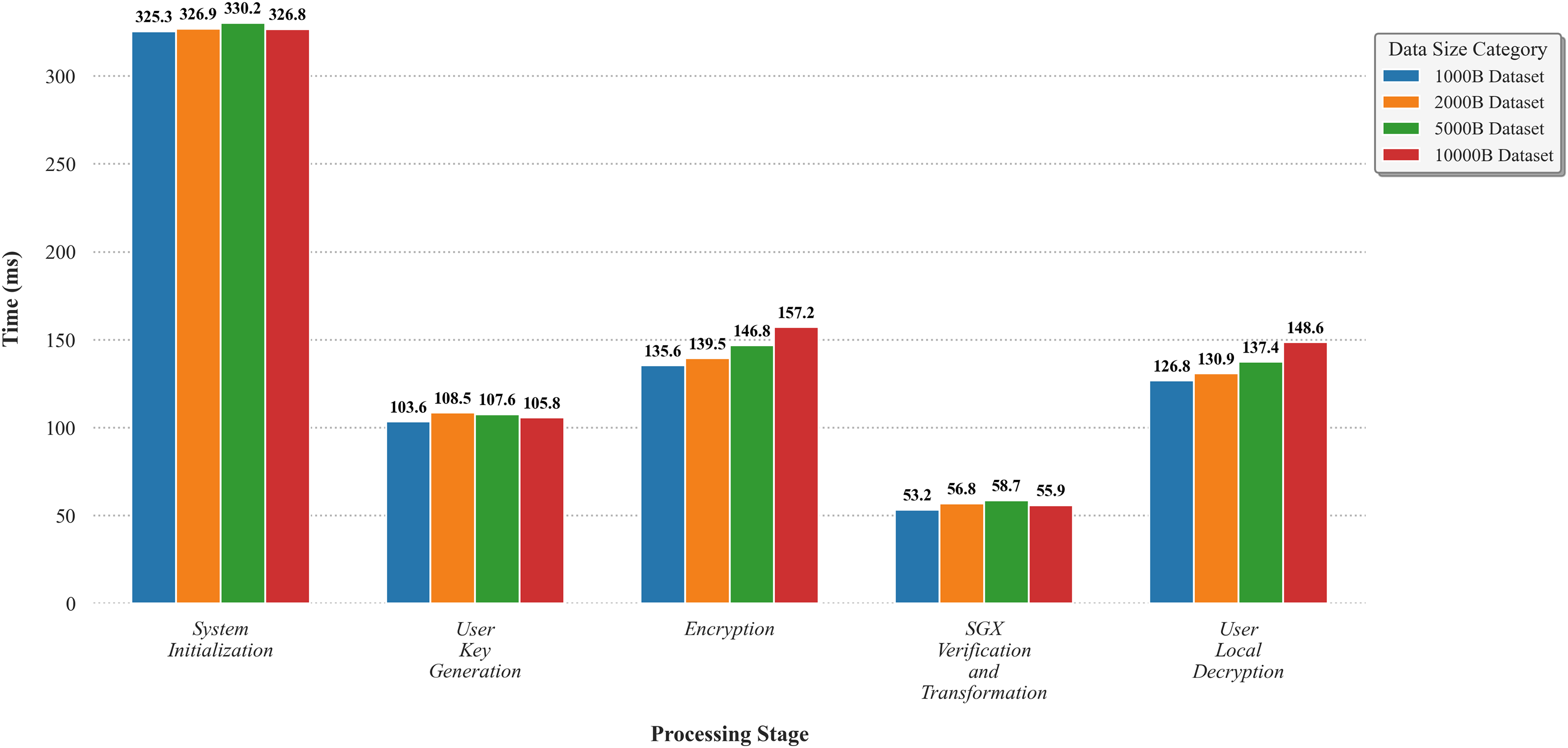

8.2 Fixed Access Policy and Variable Data Size

In this experiment, we continue to use the fixed access policy:

To visualize the performance trends, the data were plotted as a bar chart, as shown in Fig. 4. From the chart, it is evident that the SGX verification and transformation stage, the potential system bottleneck, does not exhibit a strong correlation with ciphertext size. Although larger ciphertext sizes slightly impact the efficiency of local encryption and decryption, the increase in time consumption is marginal. Overall, the scheme’s performance remains unaffected by the size of the encrypted data. In conclusion, the experimental results indicate that the runtime overhead of our scheme scales well with increasing data sizes. The ciphertext size has a minimal impact on overall performance, and no performance bottleneck was observed in the SGX-related operations.

Figure 4: The average runtime overhead of our scheme

8.3 Variable Access Policy and Fixed Data Size

We evaluate variation in response time, from the moment the DR initiates a request to the time the plaintext is obtained, as the complexity of the access policy increases. The access policy is of the form

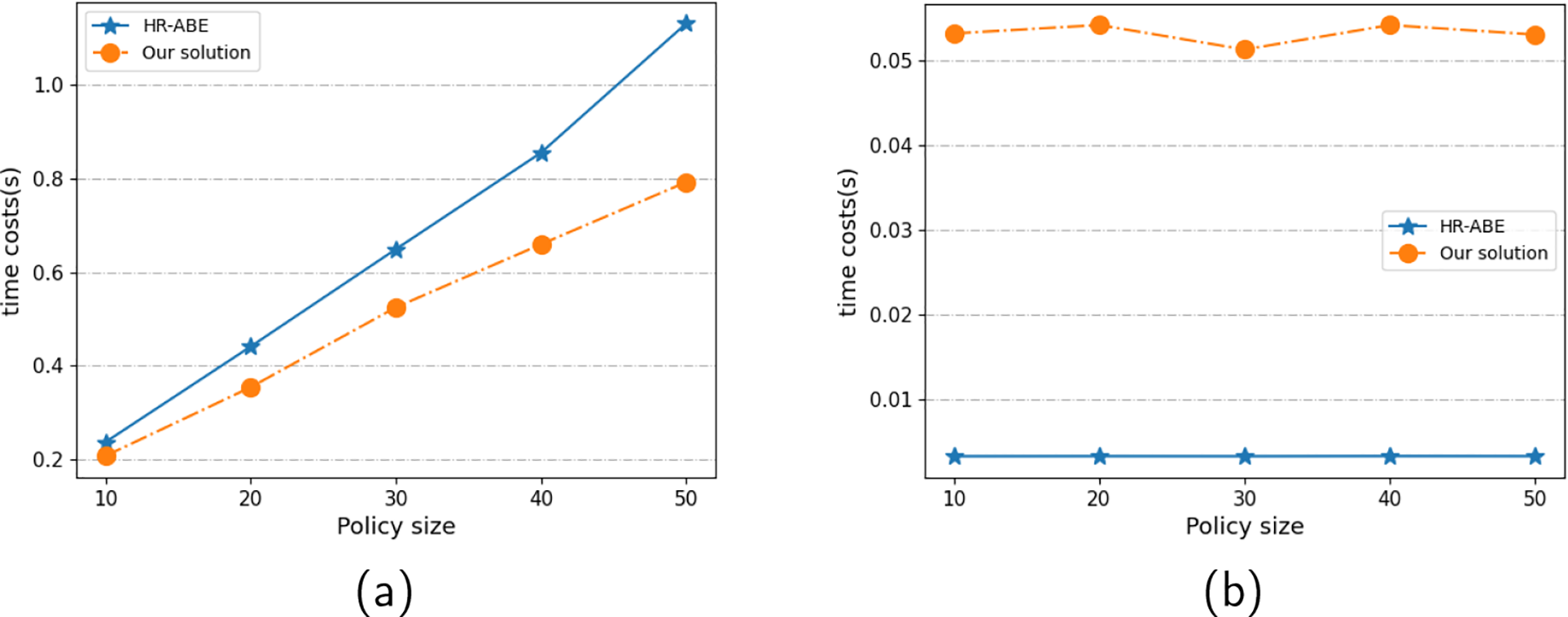

Comparison with the HR-ABE [15] scheme. The HR-ABE scheme implements attribute revocation using a Merkle tree-based revocation list. Similarly, our scheme also utilizes the Merkle tree; however, it introduces a significant optimization: in the common case of key expiration, no additional operations are required to prevent DRs from decrypting data using expired keys. Only in cases of active revocation does our scheme follow the same process as HR-ABE. Additionally, HR-ABE uses a key-splitting mechanism, which requires the CSP to process the access policy twice for a single ciphertext, once per conversion key. This results in higher processing overhead compared to our scheme.

From a broader perspective, HR-ABE adopts a malicious server model, embedding two time-related parameters in each ciphertext to ensure provable security even if the cloud colludes with revoked users. While this enhances security guarantees, it comes at the cost of increased cryptographic complexity and ciphertext size. In contrast, our scheme assumes a semi-honest server model—reasonable in regulated or auditable real-world deployments, allowing LUAR to achieve a simpler and more efficient design.

During decryption, HR-ABE delegates most of the policy-layer processing to the CSP, while SGX merely removes the blinding factor from the ciphertext. In contrast, our scheme uses SGX to verify timestamps and revocation status and to generate conversion factors for removing the blinding factor. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the SGX time in HR-ABE is negligible, whereas in our scheme, it remains consistently around

Figure 5: Compared to HR-ABE, (a) the total processing time and (b) the SGX processing time, vary with the policy length

In summary, LUAR adopts a semi-honest server model instead of HR-ABE’s malicious one, enabling a more lightweight and efficient design. Furthermore, unlike HR-ABE, LUAR considers generalizability as a key design goal, supporting seamless integration with various ABE schemes, thus offering broader applicability beyond specific cryptographic constructions.

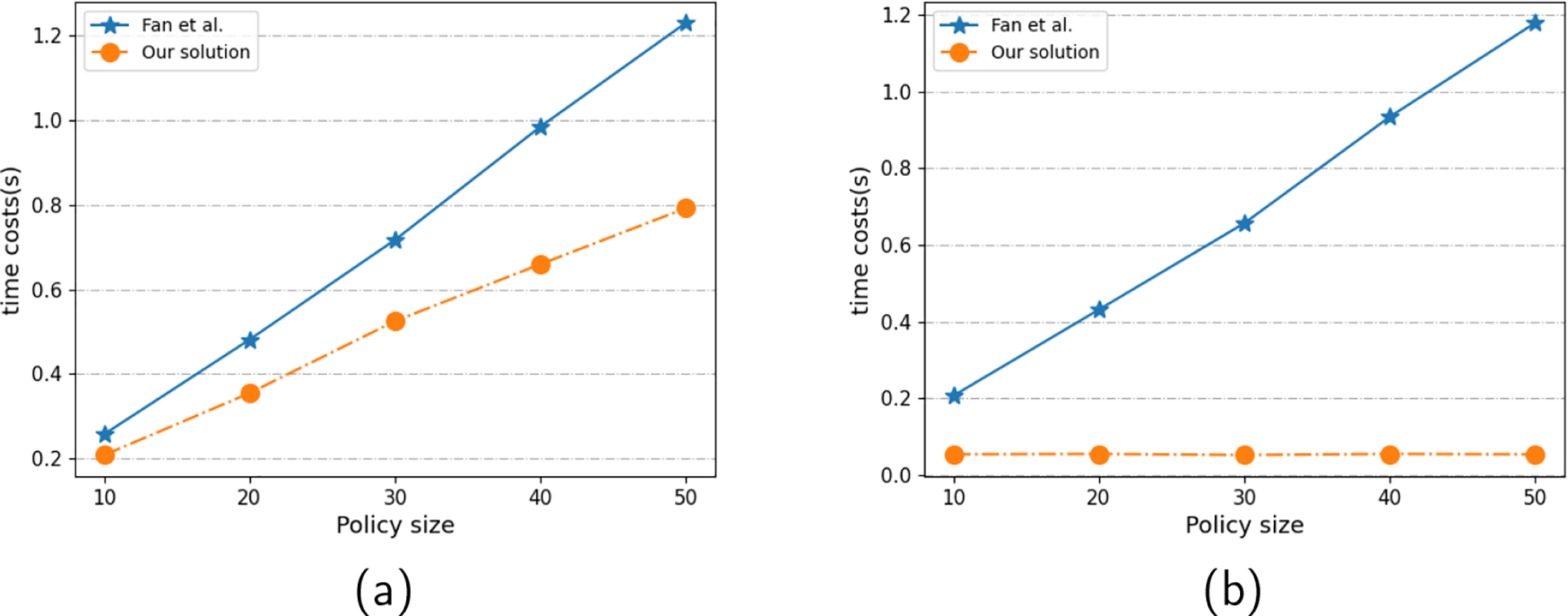

Comparison with the Fan et al. [22] scheme. Fan et al.’s scheme utilizes SGX to generate a one-time CP-ABE key per user request and performs the entire decryption operation within SGX. This design maintains a revocation list inside SGX and generates ephemeral keys on demand, an approach that rapidly consumes enclave memory and results in latency bottlenecks under frequent access scenarios. In contrast, our approach avoids storing revocation state or transformation keys within the enclave. Instead, it uses lightweight Merkle proofs combined with timestamp-based expiration to validate revocation, significantly reducing SGX memory usage and computation overhead.

Our approach offloads most of the cryptographic burden from SGX, limiting its role to lightweight tasks such as verifying the legitimacy of requests and removing ciphertext blinding. As shown in Fig. 6a, the time difference between our scheme and Fan et al.’s scheme increases with the growth of the access policy. Fan et al.’s approach requires SGX to both generate keys and decrypt ciphertexts, which leads to a growing SGX processing burden. As depicted in Fig. 6b, their SGX processing time increases with policy size, whereas our scheme maintains a stable SGX processing time of around

Figure 6: Compared to Fan et al.’s scheme, (a) the total processing time and (b) the SGX processing time, vary with the policy length

To conclude, by leveraging a lightweight verification mechanism and relaxing the collusion-resistance assumption, LUAR minimizes SGX workload while preserving security under the semi-honest model. Moreover, in contrast to Fan et al.’s scheme, which is tightly coupled with a specific ABE configuration, LUAR emphasizes universality, enabling broader adaptability across different CP-ABE frameworks.

In addition to runtime performance, LUAR is specifically designed to minimize both communication overhead and SGX enclave memory consumption—two critical factors for practical deployment in TEE-assisted attribute-based encryption systems.

Communication Overhead. LUAR introduces a lightweight Verification and Transformation phase within the SGX enclave, which verifies the data requester’s legitimacy and removes the timestamp-based blinding factor from the ciphertext. After this transformation, the resulting ciphertext becomes equivalent to a standard CP-ABE ciphertext and can be directly decrypted by the data requester using their private key. The only additional communication introduced by LUAR is between the cloud storage server and the enclave—both managed by the CSP. As a result, from the perspectives of the data owner and data requester, LUAR does not incur any extra communication overhead compared to traditional ABE-based schemes. For example, the transformed ciphertext length remains at 331 bytes, identical to a conventional BSW07 ciphertext. The Merkle proof passed to SGX during revocation checking typically ranges between 600 and 800 bytes, depending on the tree depth, which is negligible relative to the ciphertext or data file size.

SGX Memory Consumption. LUAR is designed with resource efficiency in mind. Each Verification and Transformation operation inside the enclave requires only

8.5 Deployment and Scalability Considerations

Multi-enclave scale-out. LUAR’s enclave logic is stateless and lightweight (timestamp check, Merkle-path verification, blind-factor removal), so requests can be sharded across multiple SGX enclaves without inter-enclave dependency (already noted as feasible in our prototype discussion).

Bounded per-request enclave time. The SGX verification/transformation stage averages

Network considerations. Our evaluation isolates compute by running in simulation mode (excluding network I/O). In deployment, end-to-end latency will add communication overhead, while the enclave’s constant-time transformation remains the fixed core cost.

Revocation at scale. LUAR adopts a Merkle-tree revocation structure; each request carries an

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the School of Computer Science and Technology and the School of Cyber Security and Information Law at Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications for administrative and technical support, as well as the computing resources provided during this study.

Funding Statement: The authors acknowledge support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFF0704102), the Chongqing Education Commission Key Project of Science and Technology Research (Grant No. KJZD-K202400610), and the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation General Project (Grant No. CSTB2025NSCQ-GPX1263).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Fei Tang and Ling Yang; methodology, Fei Tang, Ping Wang, and Jiang Yu; software, Jiang Yu, Huihui Zhu, and Mengxue Qin; validation, Ping Wang, Jiang Yu, and Huihui Zhu; formal analysis, Fei Tang, Ping Wang, and Jiang Yu; investigation, Jiang Yu and Huihui Zhu; resources, Mengxue Qin and Ling Yang; data curation, Ping Wang and Jiang Yu; writing—original draft preparation, Ping Wang and Jiang Yu; writing—review and editing, Fei Tang, Huihui Zhu, and Ling Yang; visualization, Jiang Yu and Ping Wang; supervision, Fei Tang and Ling Yang; project administration, Fei Tang; funding acquisition, Fei Tang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Fei Tang) upon reasonable request. No personally identifiable information is included in the shared materials.

Ethics Approval: This study does not involve human participants or animals and therefore did not require ethics approval. No personally identifiable information was processed.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen Y, Zheng Q, Yan Z, Liu D. QShield: protecting outsourced cloud data queries with multi-user access control based on SGX. IEEE Trans Parallel Distributed Syst. 2021;32(2):485–99. doi:10.1109/tpds.2020.3024880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ghayvat H, Pandya S, Bhattacharya P, Zuhair M, Rashid M, Hakak S, et al. CP-BDHCA: blockchain-based confidentiality-privacy preserving big data scheme for healthcare clouds and applications. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2022;26(5):1937–48. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2021.3097237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shen J, Zhou T, He D, Zhang Y, Sun X, Xiang Y. Block design-based key agreement for group data sharing in cloud computing. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2019;16(6):996–1010. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2017.2725953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sahai A, Waters B. Fuzzy identity-based encryption. In: Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2005. Vol. 3494. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2005. p. 457–73 doi:10.1007/11426639_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Boneh D, Franklin MK. Identity-based encryption from the weil pairing. In: Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2001. Vol. 2139. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2001. p. 213–29. [Google Scholar]

6. Hwang YW, Lee IY. A study on CP-ABE based data sharing system that provides signature-based verifiable outsourcing. In: 2021 International Conference on Advanced Enterprise Information System (AEIS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

7. Wang J, Huang C, Xiong NN, Wang J. Blocked linear secret sharing scheme for scalable attribute based encryption in manageable cloud storage system. Inf Sci. 2018;424(9):1–26. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2017.09.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xie M, Ruan Y, Hong H, Shao J. A CP-ABE scheme based on multi-authority in hybrid clouds for mobile devices. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2021;121(5):114–22. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Quan G, Yao Z, Chen L, Fang Y, Zhu W, Si X, et al. A trusted medical data sharing framework for edge computing leveraging blockchain and outsourced computation. Heliyon. 2023;9(12):e22542. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li F, Liu K, Zhang L, Huang S, Wu Q. EHRChain: a blockchain-based EHR system using attribute-based and homomorphic cryptosystem. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;15(5):2755–65. doi:10.1109/tsc.2021.3078119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li J, Zhang Y, Ning J, Huang X, Poh GS, Wang D. Attribute based encryption with privacy protection and accountability for CloudIoT. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2022;10(2):762–73. doi:10.1109/tcc.2020.2975184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Baden R, Bender A, Spring N, Bhattacharjee B, Starin D. Persona: an online social network with user-defined privacy. ACM SIGCOMM Comput Communicat Rev. 2009;39(4):135–46. [Google Scholar]

13. Dong W, Dave V, Qiu L, Zhang Y. Secure friend discovery in mobile social networks. In: 2011 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM; 2011 Apr 10–15; Shanghai, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2011. p. 1647–55. [Google Scholar]

14. Jahid S, Mittal P, Borisov N. EASiER: encryption-based access control in social networks with efficient revocation. In: ASIACCS ’11: Proceedings of the 6th ACM Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security; 2011 Mar 22–24; Hong Kong, China. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2011. p. 411–5. [Google Scholar]

15. Li X, Yang G, Xiang T, Xu S, Zhao B, Pang H, et al. Make revocation cheaper: hardware-based revocable attribute-based encryption. In: 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 3109–27. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang H, Zheng Z, Wu L, Li P. New directly revocable attribute-based encryption scheme and its application in cloud storage environment. Clust Comput. 2017;20(3):2385–92. doi:10.1007/s10586-016-0701-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Chen X, Li J, Li H, Li F. Attribute-based data sharing with flexible and direct revocation in cloud computing. KSII Trans Internet Inf Syst. 2014;8(11):4028–49. [Google Scholar]

18. Rasori M, Perazzo P, Dini G, Yu S. Indirect revocable KP-ABE with revocation undoing resistance. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;15(5):2854–68. doi:10.1109/tsc.2021.3071859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xu S, Yang G, Mu Y. Revocable attribute-based encryption with decryption key exposure resistance and ciphertext delegation. Inf Sci. 2019;479(8):116–34. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2018.11.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Huang X, Xiong H, Chen J, Yang M. Efficient revocable storage attribute-based encryption with arithmetic span programs in cloud-assisted internet of things. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(2):1273–85. doi:10.1109/tcc.2021.3131686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sahai A, Seyalioglu H, Waters B. Dynamic credentials and ciphertext delegation for attribute-based encryption. In: Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2012. Vol. 7417. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2012. p. 199–217. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32009-5_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Fan Y, Liu S, Tan G, Qiao F. Fine-grained access control based on Trusted Execution Environment. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;109(60):551–61. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.05.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Costan V, Devadas S. Intel SGX explained. Cryptology ePrint Archive; 2016. Paper 2016/086. [Google Scholar]

24. Bethencourt J, Sahai A, Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. In: 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP ’07); 2007 May 20–23; Berkeley, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2007. p. 321–34. [Google Scholar]

25. Yu J, Liu S, Xu M, Guo H, Zhong F, Cheng W. An efficient revocable and searchable MA-ABE scheme with blockchain assistance for C-IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(3):2754–66. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3213829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li J, Li D, Zhang X. A secure blockchain-assisted access control scheme for smart healthcare system in fog computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(18):15980–9. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3268278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhai Y, Yang H, Yao J, Wang T, Zhou Y, Zhu F, et al. CR2-ABE: a blockchain-assisted coercion-resistant and revocable attribute-based encryption for IoMT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(9):13075–96. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3523959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu C, Wang D, Li D, Guo S, Li W, Qiu X. Trusted access control mechanism for data with blockchain-assisted attribute encryption. High-Conf Comput. 2025;5(2):100265. doi:10.1016/j.hcc.2024.100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yang X, Chang Z, Jiang M. Blockchain-assisted revocable hierarchical attribute-based encryption electronic medical record sharing scheme. J Big Data Comput. 2024;2(2):79. doi:10.62517/jbdc.202401211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. van Schaik S, Milburn A, Österlund S, Frigo P, Maisuradze G, Razavi K, et al. RIDL: rogue in-flight data load. In: 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 88–105. [Google Scholar]

31. Kim T, Peinado M, Mainar-Ruiz G. STEALTHMEM: system-level protection against cache-based side channel attacks in the cloud. In: 21st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 12). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2012. p. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools