Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Survey of Federated Learning: Advances in Architecture, Synchronization, and Security Threats

1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, North South University, Bashundhara, Dhaka, 1229, Bangladesh

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Green University of Bangladesh, Purbachal American City, Kanchon, 1460, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Author: Rashedur M. Rahman. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073519

Received 19 September 2025; Accepted 21 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Federated Learning (FL) has become a leading decentralized solution that enables multiple clients to train a model in a collaborative environment without directly sharing raw data, making it suitable for privacy-sensitive applications such as healthcare, finance, and smart systems. As the field continues to evolve, the research field has become more complex and scattered, covering different system designs, training methods, and privacy techniques. This survey is organized around the three core challenges: how the data is distributed, how models are synchronized, and how to defend against attacks. It provides a structured and up-to-date review of FL research from 2023 to 2025, offering a unified taxonomy that categorizes works by data distribution (Horizontal FL, Vertical FL, Federated Transfer Learning, and Personalized FL), training synchronization (synchronous and asynchronous FL), optimization strategies, and threat models (data leakage and poisoning attacks). In particular, we summarize the latest contributions in Vertical FL frameworks for secure multi-party learning, communication-efficient Horizontal FL, and domain-adaptive Federated Transfer Learning. Furthermore, we examine synchronization techniques addressing system heterogeneity, including straggler mitigation in synchronous FL and staleness management in asynchronous FL. The survey covers security threats in FL, such as gradient inversion, membership inference, and poisoning attacks, as well as their defense strategies that include privacy-preserving aggregation and anomaly detection. The paper concludes by outlining unresolved issues and highlighting challenges in handling personalized models, scalability, and real-world adoption.Keywords

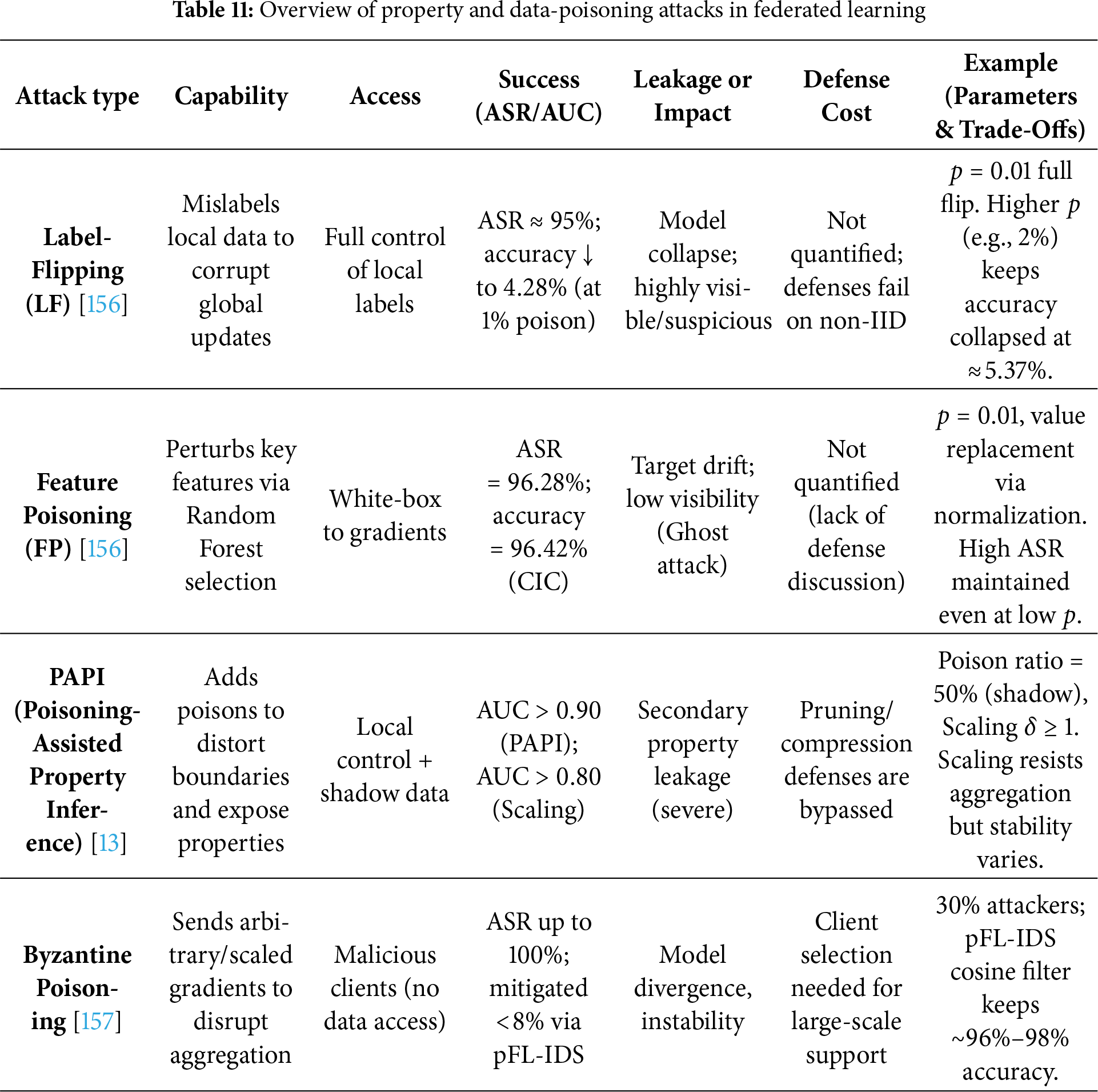

The rise of artificial intelligence and its integration into modern society have created transformative advancements in science, industry, and daily life. The success of machine learning (ML), particularly deep learning models, relies on their ability to learn complex patterns from large and diverse datasets to demonstrate capabilities in pattern recognition, prediction, and decision making [1]. These advances depend on processing of a vast amount of data and large-scale aggregation from domains such as medical diagnostics, financial transactions, and autonomous driving [2,3]. The practice of accumulating and centralizing large amounts of data, often containing deeply personal information such as financial transaction information, location histories, and genomic sequences, has precipitated growing tension between technological progress and the fundamental right to privacy [4,5]. The tension is amplified by the high-profile data breaches and studies showing that even anonymized data can be re-identified with ease through a linkage that correlates de-identified datasets with publicly available information [6,7].

The growing privacy concern and rising public demand for data privacy and data sovereignty have led the government and regulatory bodies worldwide to enact data protection legislation. Landmark legislative frameworks, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in the United States, represent a paradigm shift in data governance with establishment of legal requirements for data handling such as data collection, processing, storage, data minimization (collecting only necessary data), purpose limitation (using data for the specified purpose for which it was collected), and granting individuals rights to access and erase their data [8]. These regulations have created an operational reality for the technology industry to make privacy preservation not merely an ethical consideration but a legal and commercial necessity, and increased the search for the technical dilemma of how to extract value from collective data without compromising the privacy of individuals [9].

Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a promising decentralized machine learning paradigm by leveraging distributed datasets [10,11]. FL enables collaborative model training across multiple clients, such as mobile devices, hospitals, and financial institutions, to train a shared global model without the need for raw data in a central location. Clients train models on their private dataset locally and share parameter updates to the central server, which then aggregates these updates to refine the global model [12]. Data localization provides a built-in layer of privacy protection against server-side data breaches and external attackers. However, a significant amount of research has demonstrated that the shared model updates are information-rich and can be exploited by a malicious server to infer sensitive information about clients’ private training data, whether a specific data point was part of the training set or not, or reconstruction attacks that aim to recover original training data from shared model updates [13,14].

Despite its promise, FL faces a cluster of practical and scientific challenges that slow its translation from controlled experiments to production systems. These challenges include multi-axis heterogeneity (data, model, and system), the unexpected privacy leakage conveyed by intermediate representations and model updates, large communication and computation costs on constrained devices, and vulnerabilities to poisoning and adaptive inference attacks. Synchronization and straggler management remain unresolved in large, volatile networks, and there is a persistent gap between theoretical guarantees and the behavior of realistic, compressed, or asynchronous protocols. Finally, the field suffers from fragmented evaluations and a lack of standardized benchmarks, which complicates reproducibility and the comparison of proposed defenses and optimizations [11,13,15]. These limitations motivate an integrative review that synthesizes recent advances, highlights cross-cutting trade-offs, and proposes a concrete research agenda to guide reliable, privacy-aware deployment of federated learning. This survey, therefore, synthesizes recent work into a coherent taxonomy, highlights the practical trade-offs, and draws attention to under-explored but high-impact issues such as benchmarking, reproducibility, and governance.

Federated learning has matured rapidly, while its research directions have become fragmented. Many surveys focus narrowly on a single problem or on one application domain. Few synthesize recent advances across architectures, synchronization, and security together, especially work published between 2023 and 2025.

This survey fills that gap. It centers on three core dimensions that shape practical FL systems: architectural choices for data and model distribution, synchronization mechanisms for heterogeneous clients, and privacy and security techniques for representation sharing. We give special attention to recent multi-party vertical FL, hybrid VFL-HFL frameworks, transformer-based personalization, and transfer methods that address sparse overlap. We also examine synchronization policies that trade stability for scalability and defenses that balance privacy, utility, and cost.

By keeping these dimensions in view at once, the survey reveals interactions that single-topic reviews miss. For example, personalization choices change privacy risk. Compression and client selection alter synchronization dynamics. Our scope covers methodological advances and their implications for deployment in healthcare, IoT, and edge systems.

1.3 Contributions of This Survey

This review offers a unified taxonomy that links architectures, synchronization strategies, and security mechanisms into a single analytical frame. That taxonomy makes it possible to compare methods along shared axes instead of treating each paper as an isolated solution.

We position this work against existing surveys by emphasizing cross-dimensional effects rather than narrow improvements. Where prior reviews catalog algorithms or applications, we highlight how heterogeneity, timing, and privacy interact and shape design trade-offs. We draw on 98 peer-reviewed papers from 2023 to 2025 to support our analysis. From that corpus, we extract recurring design patterns and note where progress is substantive and where fragmentation persists.

Finally, we deliver a focused research roadmap. Key directions include modular FL kernels that separate representation learning from task heads, adaptive privacy controllers that tune protection by measured leakage risk, standardized benchmarks and threat models, certified and layered defenses against adaptive attackers, and theoretical bounds for realistic protocols that combine compression, asynchrony, and privacy noise. We also call for operational toolkits for monitoring, debugging, and auditing that fit privacy constraints. Together, these contributions aim to guide research toward scalable, auditable, and deployable federated systems.

1.4 Structural Design of the Survey Work

Section 1 introduces the paper. It states the motivation and background in Section 1.1. It defines the scope of this survey in Section 1.2. It summarizes our main contributions in Section 1.3. It explains the structural design and how to navigate the review in Section 1.4.

Section 2 presents a comparative analysis of recent surveys. It highlights what prior reviews cover and what they miss. It explains where this survey adds value.

Section 3 develops our taxonomy of federated learning. The taxonomy links data distribution, training synchronization, and security threats.

Section 4 details the PRISMA-based methodology used for this review. It outlines the systematic search, screening process, and study selection criteria, which yielded the 98 studies included in the qualitative synthesis.

Section 5 presents the fundamentals of federated learning. Section 5.1 defines the core components: clients, the central aggregator, and the standard training workflow including local update, aggregation, and model dissemination. Section 5.2 reviews the primary FL architectures. It explains horizontal FL, vertical FL, federated transfer learning, and personalized FL, and it clarifies the assumptions and use cases that distinguish each paradigm. Section 5.3 contrasts synchronization strategies by comparing synchronous training with its straggler trade-offs and asynchronous alternatives with their staleness and convergence issues. Section 5.4 outlines key privacy and security concerns, focusing on representation and gradient leakage, membership attack, property inference, poisoning, and backdoor attacks, and it frames the defensive primitives commonly applied.

Section 6 contains focused literature reviews organized by architecture. Section 6.1 examines vertical federated learning with three threads: handling heterogeneous participants, communication efficient and privacy enhanced protocols, and generative data augmentation techniques for low overlap scenarios. Section 6.2 examines horizontal FL by covering hybrid and heterogeneous designs, methods for communication optimization and feature selection, and application oriented frameworks that emphasize domain constraints. Section 6.3 surveys federated transfer learning, reviewing architectural proposals, privacy mechanisms, and concrete domain applications. Section 6.4 addresses personalized federated learning, detailing personalization mechanisms, fairness, and community structure, and cross-modal and domain-specific deployments.

Section 7 reviews synchronization strategies in depth. Section 7.1 surveys synchronous FL with straggler mitigation and semi-synchronous scheduling. Section 7.2 covers asynchronous FL with staleness compensation and scalable aggregation.

Section 8 reviews privacy and security research. Section 8.1 focuses on data leakage, including Gradient Attacks and Defenses, and on Privacy-Preserving Encodings. Section 8.2 examines poisoning attacks, backdoors, defense methods, and audit-style detection approaches.

Section 9 distills challenges and future directions. It organizes open problems into twelve items, from heterogeneity to sustainability. It ends with concrete research directions and a roadmap for researchers and practitioners.

Section 10 concludes by summarizing key findings and restating the survey contributions.

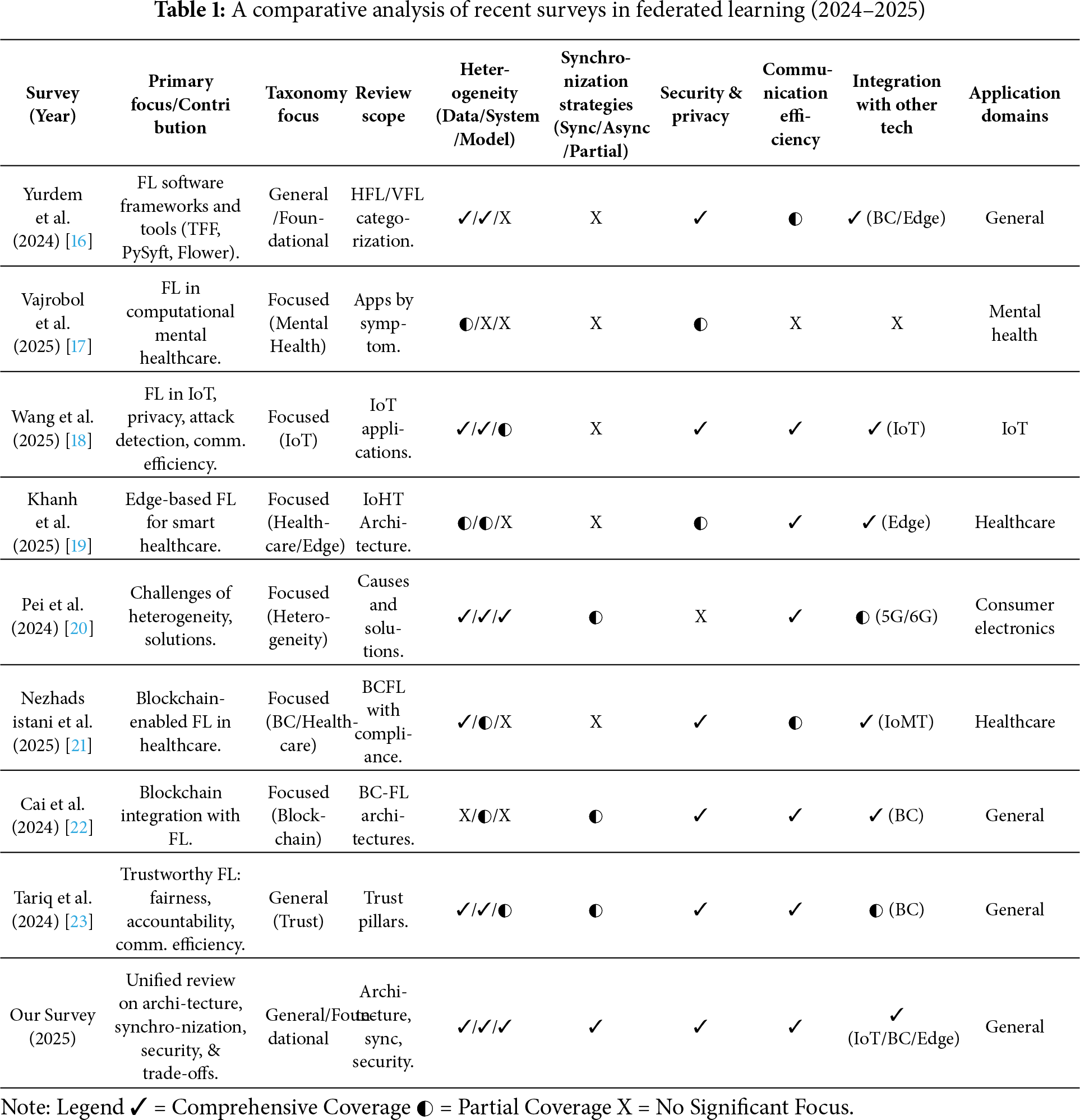

2 Comparative Analysis of Recent Surveys

To underscore this survey’s distinctive contribution, we carry out a structured gap analysis that contrasts its scope, methodology, and findings with recent Federated Learning (FL) surveys from 2024–2025. The results indicate a persistent shift toward specialization in the literature, emphasizing the need for a unified perspective that examines interactions and trade-offs among core FL components.

Yurdem et al. (2024) [16] deliver a survey centered on FL software frameworks and tools, including TensorFlow Federated (TFF), PySyft, and Flower. They examine core principles, strategies, use cases, and available resources, while classifying FL variants (HFL/VFL) and addressing related issues like privacy and security in these tools. Although this provides a useful guide for developers choosing frameworks, the content remains largely catalog-like for current software options. As a result, it omits an in-depth, consolidated evaluation of the balances between key FL design elements (architecture, synchronization, security) that transcend particular framework details.

Vajrobol et al. (2025) [17] narrow their scope to FL applications in computational mental healthcare, surveying pertinent datasets and grouping use cases by mental health indicators such as depression, stress, and sleep patterns. They also cover various ML/DL frameworks in this clinical niche. While this domain-specific lens is noteworthy for healthcare experts, it inherently restricts broader insights into universal FL hurdles (e.g., general data heterogeneity or communication optimization outside healthcare) and omits a cohesive classification linking key FL aspects across varied fields.

In parallel, Wang et al. (2025) [18] examine FL tailored to Internet of Things (IoT) environments. They tackle privacy, threat detection, and communication efficiency in IoT setups with dense sensor networks and devices, detailing FL’s role in such scenarios. Yet, this targeted perspective curtails its reach, omitting a wider dissection of FL fundamentals beyond IoT and failing to integrate discoveries from disparate FL domains into a holistic model that evaluates architectural compromises.

Khanh et al. (2025) [19] hone in on edge-centric FL, especially for smart healthcare (IoHT). They assess AI-supported edge architectures and introduce an FL-driven IoHT framework aimed at minimizing latency and handling edge resource limitations. This confined emphasis on edge computing in healthcare diminishes its general relevance; the survey avoids a thorough breakdown of compromises pertinent to FL at large and skips a broad taxonomy extending past the edge/healthcare domain.

By comparison, Pei et al. (2024) [20] furnish a targeted and methodical assessment of heterogeneity (device, data, model) in FL. They probe the origins of heterogeneity and organize current approaches for these issues, yielding substantial insight into this domain. That said, their primary fixation on heterogeneity precludes a holistic dialogue on how such approaches influence other vital FL facets like security protections, synchronization options, or systemic resilience. The evaluation of key inter-pillar compromises is thus overlooked.

Nezhadsistani et al. (2025) [21] delve into Blockchain-augmented FL (BCFL), but confines itself to health care applications. They scrutinize BCFL elements like consensus mechanisms and encryption techniques, plus metrics for deployment and adherence to standards such as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), GDPR in health care scenarios. This constrained intersection of blockchain and health care sharply limits its breadth, excluding a general FL viewpoint and a cohesive breakdown of architectural, synchronization, and security compromises applicable outside the BCFL health care specialty.

Lastly, Cai et al. (2024) [22] delve into blockchain-FL fusion (BC-FL). They evaluate advantages like enhanced decentralization and security, alongside drawbacks such as efficiency and storage issues, while organizing architectures and countermeasures. This blockchain-specific orientation means the survey forgoes a standalone FL overview and neglects a full examination of architecture-synchronization-security dynamics beyond the BC-FL paradigm.

These surveys show a clear tendency toward specialization. Some works highly concentrate on a single technical challenge, for example, heterogeneity [20], while others limit their scope to a single application domain, such as mental health [17]. Technology-centric reviews examine specific integrations such as blockchain with FL [21,22], or FL for IoT applications [18]. These focused studies provide depth and concrete solutions within their niches, but they also produce a fragmented picture of the field.

Across the literature, three recurring themes stand out. First, privacy and security remain the primary concerns and are treated either broadly [16] or as the central organizing principle in surveys of trustworthy FL [23]. Second, communication efficiency appears as a cross-cutting topic in many reviews, sometimes examined as an engineering constraint and sometimes framed as a component of trustworthiness [23]. Third, heterogeneity in data, system, and model dimensions receives varying levels of attention; Pei et al. provide one of the more systematic treatments of all three heterogeneity types [20].

Specialized surveys supply valuable, deep analyses, but they seldom analyze trade-offs across architectural, timing, and security choices. That omission leaves practitioners without guidance when a single deployment decision affects multiple objectives. Our survey addresses this gap by synthesizing advances from 2023 to 2025 and by explicitly analyzing interactions among architectures, synchronization strategies, and security mechanisms. Table 1 summarizes this comparative landscape and shows how prior surveys differ in focus and coverage.

In short, specialized reviews deliver rigorous treatments of important subproblems. A unified review is still needed to connect those treatments into a practical design space. This article aims to provide that integration and a practical roadmap for researchers and system builders working toward deployable, trustworthy federated learning systems.

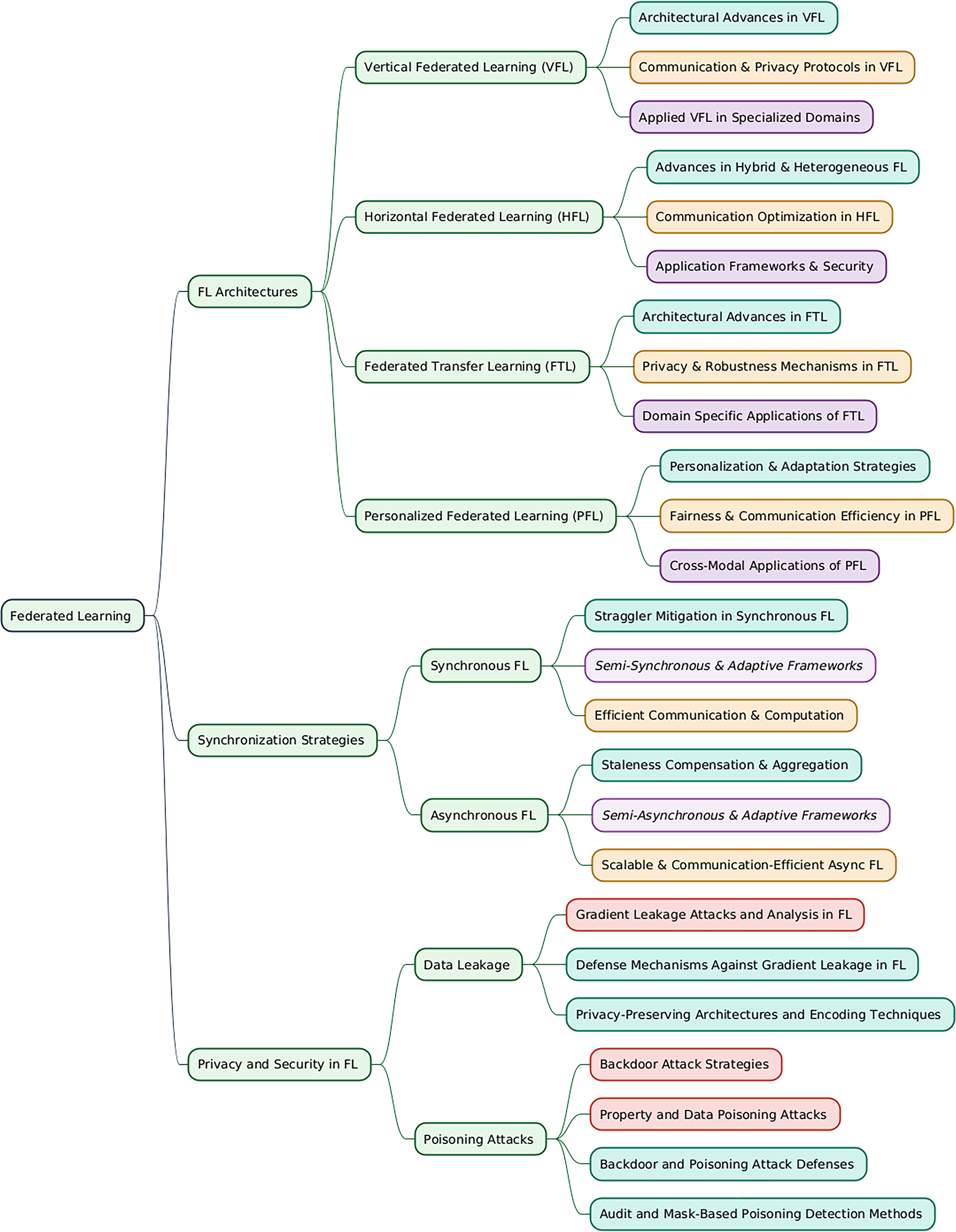

3 Taxonomy of Federated Learning

The architecture, complexity, and applicable use cases of a federated learning system are dictated by the data partition across participating entities or clients. The categorization of reviewed papers is based on three fundamental questions: how the data is split, how models are synchronized, and how to defend against attacks. The FL systems are categorized into four primary architectures based on their distribution of features and samples, which are identified as Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL), Vertical Federated Learning (VFL), Federated Transfer Learning (FTL), and Personalized FL. Based on how model update synchronization is performed, the FL system is categorized into Synchronous and Asynchronous FL, and considering the vulnerabilities, the papers are divided into two categories: Deep leakage-based vulnerabilities and Data Poisoning-based vulnerabilities. This architectural choice mostly shapes the nature of the security and privacy challenges a system will face, along with determining the primary attack surfaces and the corresponding defense strategies required to prevent those attacks.

While classic surveys such as Kairouz et al. [15] organized federated learning around algorithmic families, problem settings, and privacy primitives, our survey departs from that framing in three concrete ways. First, we elevate training synchronization to a primary design axis alongside data distribution and security so that timing and staleness are treated as explicit variables that affect algorithm choice and risk. Second, we analyze cross-dimensional interactions rather than catalog techniques independently, showing how an architectural decision reshapes privacy leakage, communication cost, and robustness. Third, we extend the empirical window to cover 2023 through 2025 and thereby capture recent innovations such as prototype aggregation, hybrid VFL HFL architectures, transformer-based personalization, and adaptive privacy controllers. Together, these elements form a practical design map that links research choices to deployment trade-offs and evaluation criteria.

This taxonomy demonstrates a unified perspective by synthesizing and organizing recent specialized works into a coherent structure. Rather than presenting parallel surveys on FL for Healthcare (Vajrobol et al., 2025 [17] and Khanh et al., 2025 [19]), FL for IoT (Wang et al., 2025 [18]), Trustworthy FL (Tariq et al., 2024 [23]), or FL Heterogeneity (Pei et al., 2024 [20]), the three-axis model provides a common foundation that classifies each along Architecture, Synchronization, and Security. For example, an IoT study (Wang et al., 2025 [18]) is positioned under the Architecture axis as an application domain with synchronization needs that are often asynchronous due to device heterogeneity and with security threats that reflect IoT attack surfaces. A survey on Trustworthy FL (Tariq et al., 2024 [23]) fits as a deep analysis within the Security and Privacy axis. This unified approach encourages practitioners to view these areas as interconnected components of a single design space and to assess the trade-offs that arise across axes.

This unified perspective is essential for practice because earlier taxonomies that emphasize only data partitioning or security often relegate synchronization to an implementation detail or a subproblem. This is evident in the recent literature. Application-specific surveys, such as those on IoT (Wang et al., 2025 [18]) and healthcare (Khanh et al., 2025 and Vajrobol et al., 2025 [17,19]), identify low latency and communication efficiency as critical challenges within their domains. Problem-specific surveys on heterogeneity (Pei et al., 2024 [20]) present device heterogeneity and stragglers as primary problems and list asynchronous interaction as a future research direction. Security-focused surveys on Trustworthy FL (Tariq et al., 2024 [23]) and Blockchain-enabled FL (Cai et al., 2024 and Nezhadsistani et al., 2025 [21,22]) include communication efficiency and consensus within broader pillars of trustworthiness and scalability. General framework overviews such as Yurdem et al. (2024 [16]) describe system and data heterogeneity and communication overloads as distinct challenges rather than as a primary organizing principle. While these perspectives are valuable, they can obscure a fundamental high-level design trade-off. This taxonomy elevates synchronization because the choice between Synchronous FL and Asynchronous FL is an early and consequential decision. It is not only a remedy for heterogeneity. It is a primary architectural choice that governs core system behavior and interacts in a cascading manner with the other two axes.

Our organizing principle directs practitioners to a clear decision between two paradigms with nonnegotiable costs. For example, Synchronous FL is appropriate when the primary goals are model stability and simpler security integration, since secure aggregation protocols are straightforward to implement in lockstep. The corresponding cost is the straggler problem, where overall training speed is limited by the slowest client. Asynchronous FL is appropriate when the priority is higher throughput and scalability, since it removes the straggler bottleneck. The associated cost is model staleness, which arises from the use of outdated gradients and complicates convergence analysis, can degrade model accuracy, and increases the complexity of secure aggregation.

This perspective supports informed and deliberate system-level design. By presenting Architecture, Synchronization, and Security as the primary interacting design choices, the taxonomy provides a complete map for practice. These are not independent problems to be solved one by one. A decision on one axis directly influences the others. For example, selecting an asynchronous synchronization model to improve scalability complicates the security model for secure aggregation and may encourage architectural personalization to manage divergence caused by staleness. The framework, therefore, promotes holistic reasoning about how interdependent design choices shape outcomes, rather than addressing heterogeneity or security in isolation.

Fig. 1 illustrates the proposed taxonomy of Federated Learning (FL) systems, classifying them according to three key aspects. These categories include the method of data distribution (e.g., Horizontal, Vertical, Transfer FL, and Personalized FL), the model synchronization strategy (Synchronous vs. Asynchronous), and major security considerations such as data leakage and data poisoning vulnerabilities.

Figure 1: A taxonomy of federated learning systems

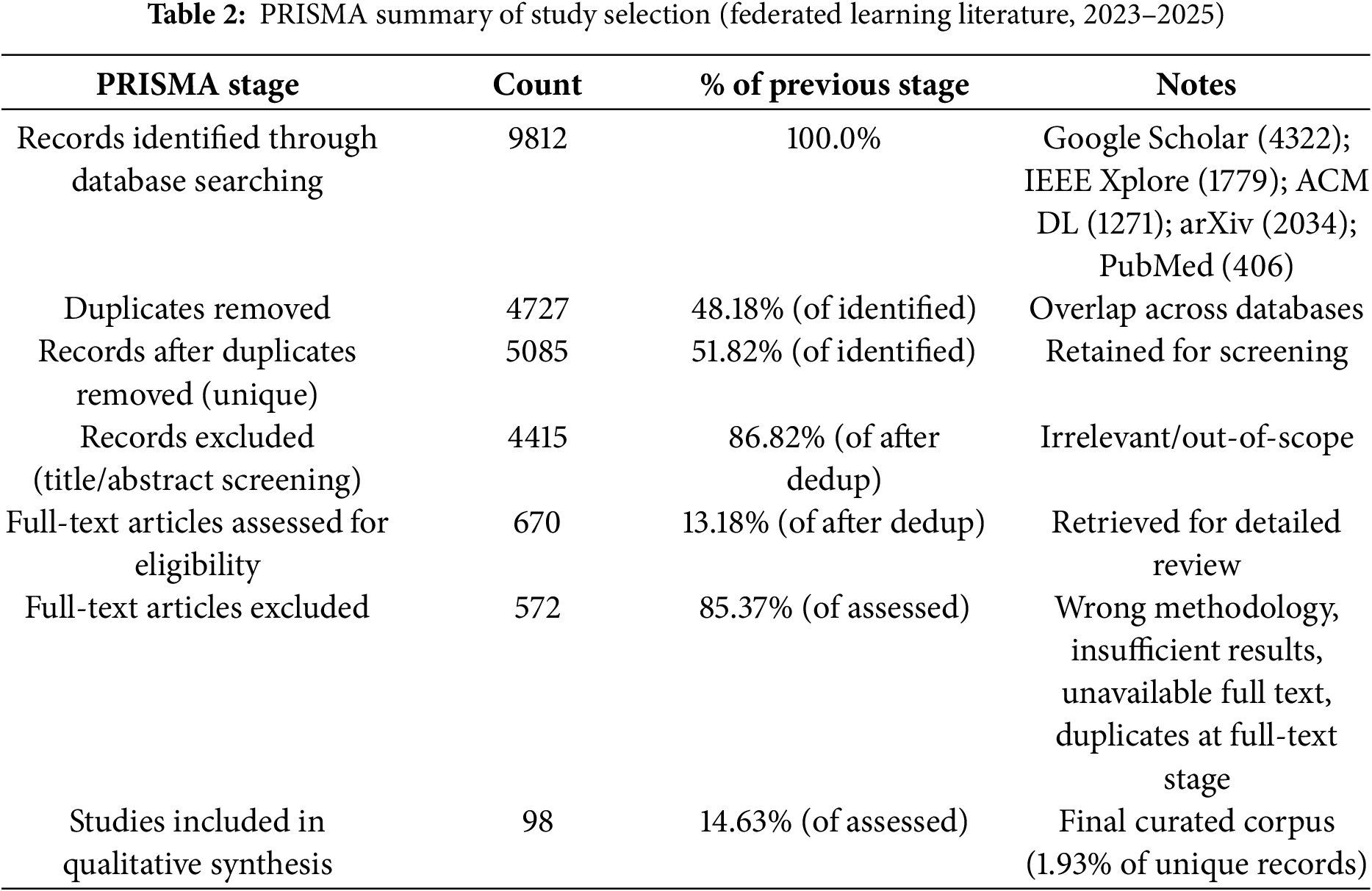

4 Methodology and Literature Selection

We adopted a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020-based methodology to identify and curate recent research on federated learning (FL) for the purposes of validating a unified taxonomy. The PRISMA-adapted approach was refined to prioritize top-tier publications and contributions from leading research institutions. The overall workflow combined systematic retrieval, automated and manual deduplication, dual-reviewer title/abstract screening, and independent full-text eligibility assessment across multiple scholarly repositories. The identification stage is summarized in Table 2. Searches were executed to target records published between January 2023 and October 2025.

4.2 Information Sources and Search Strategy

To balance domain specificity and breadth, we applied a two-tier search approach. Primary indexed sources (IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and Scopus) were queried to capture peer-reviewed computing and engineering literature. Supplementary sources (Google Scholar, arXiv, and PubMed) were searched to ensure coverage of cross-disciplinary studies and applications of FL. The search strategy combined core terms (e.g., “federated learning”, “decentralized learning”) with topic-specific keywords corresponding to the review’s taxonomy. Logical operators, phrase searches, and year filters were applied.

The topic-specific queries were constructed using the following taxonomy topics: Vertical Federated Learning, Poisoning Attacks, Jamming Attacks, Asynchronous FL, Synchronous FL, Heterogeneous FL, Personalized FL, Federated Transfer Learning, Gradient Leakage, Privacy-Preserving FL, Differential Privacy, and Hybrid FL.

4.3 Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

All records retrieved from the five repositories were exported into a centralized screening database and deduplicated using automated matching (title, DOI, author list), followed by manual inspection for near-duplicates. Screening proceeded in two stages:

Title and Abstract Screening.

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for topical relevance and compliance with pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion required original research (methods, experiments, or empirical evaluations) relevant to FL and one or more taxonomy topics. Exclusion criteria included non-research items (editorials, commentaries), works not focused on FL, or papers lacking sufficient methodological detail. Conflicts were resolved through discussion.

Full-Text Eligibility Assessment.

Full texts were retrieved for all records that passed title/abstract screening. Two reviewers independently assessed each full text against the inclusion/exclusion criteria and recorded a primary reason for exclusion where applicable.

4.4 Data Extraction and Synthesis

From the included studies, we extracted bibliographic metadata, research objectives, FL setting (e.g., cross-device vs cross-silo, vertical vs horizontal), threat model or challenge addressed, proposed methods or defenses, datasets, experimental setup, evaluation metrics, and key empirical results. Extracted items were organized to support taxonomy validation and to identify trends, gaps, and open problems. We used narrative synthesis to integrate methods and findings, supplemented by quantitative summaries (counts, timelines, topic prevalence) where appropriate.

4.5 Search Results and Selection

The combined search returned 9812 records (Google Scholar 4322; IEEE Xplore 1779; ACM Digital Library 1271; arXiv 2034; PubMed 406). After automated and manual deduplication, 4727 duplicates were removed, yielding 5085 unique records for title/abstract screening. Title/abstract screening excluded 4415 records (86.82% of screened), leaving 670 full texts for retrieval and eligibility assessment. Following full-text review, 572 articles were excluded for pre-specified reasons (wrong methodology, insufficient results, unavailable full text, or duplicates identified at full-text stage), producing a final qualitative synthesis of 98 studies.

All counts and percentages reported in Table 2 are internally consistent and derived from the stage totals above.

4.6 Meta-Analysis of Relevant Literature

Fig. 2 combines two complementary views of the search results and topic distribution. Fig. 2a shows the initial retrieval across five repositories (n = 9812), with Google Scholar yielding the largest share (4322), and IEEE Xplore (1779), arXiv (2034), and ACM Digital Library (1271) contributing substantial domain-specific coverage. Fig. 2b shows the 5085 unique papers mapped to the review’s taxonomy topics: Privacy-Preserving FL dominates (1050), followed by Personalized FL (725) and Heterogeneous FL (600). Less represented topics include Hybrid FL (210) and Jamming Attacks (170). This two-panel map contextualizes the broader landscape from which the final n = 98 studies were systematically selected.

Figure 2: Figure shows summary of literature sources and topic prevalence. Fig. 2a shows the distribution of 9812 identified records across five databases. Fig. 2b displays the distribution of 5085 unique papers across taxonomy topics

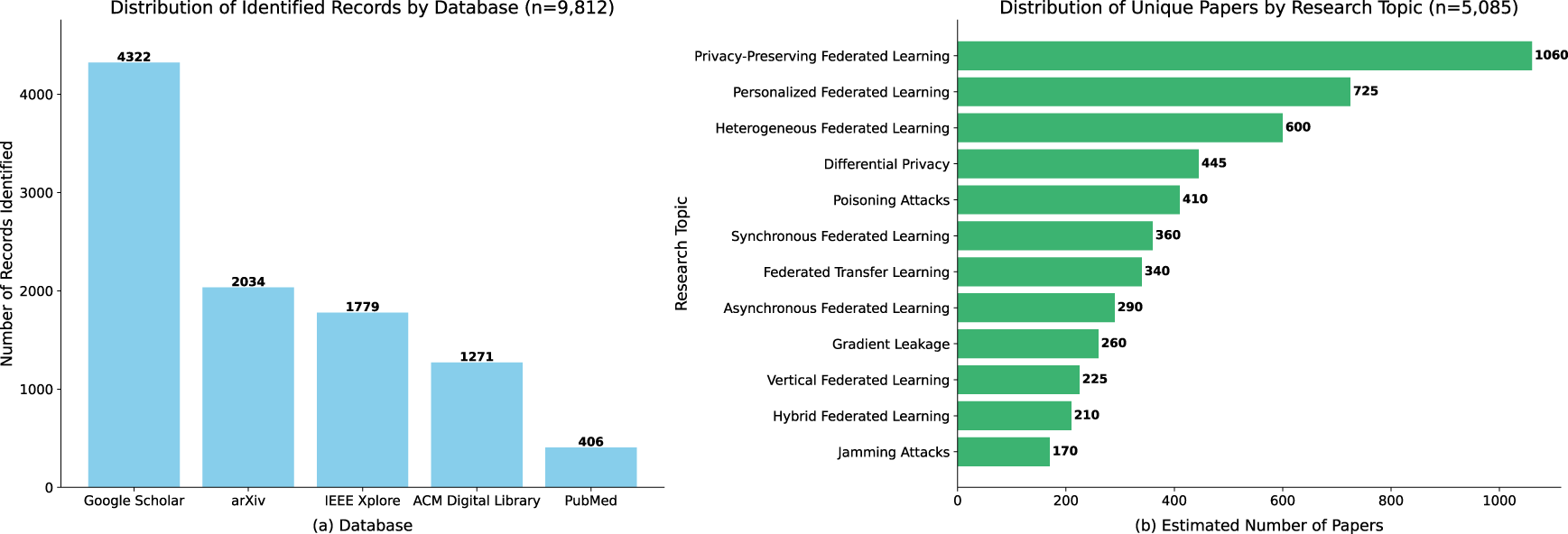

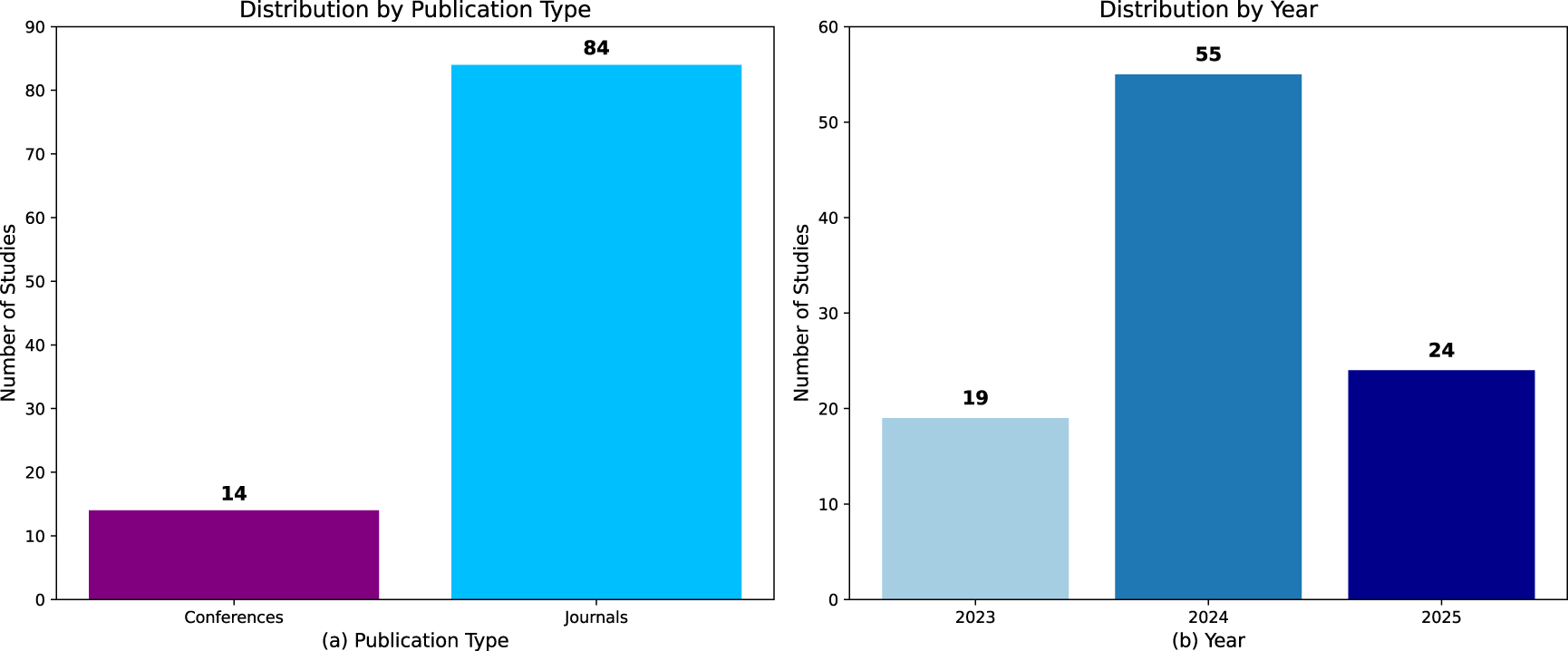

Fig. 3 combines publication-type and temporal-distribution views of the final corpus. Fig. 3a shows the distribution of publication types, with journals comprising roughly 80%–85% of included studies and conferences approximately 15%–20%, reflecting the field’s maturation and emphasis on reproducible, archival work. Fig. 3b shows the temporal distribution across 2023–2025: research activity peaked in 2024 (constituting more than half of the corpus), while 2023 and 2025 each contribute smaller but meaningful shares. Together, these panels illustrate both the venue profile and the recent surge in FL research that motivated the present taxonomy and gap analysis.

Figure 3: Distribution of the 98 included studies by publication type and year. Fig. 3a shows the breakdown by publication venue, where journals account for 84 studies (

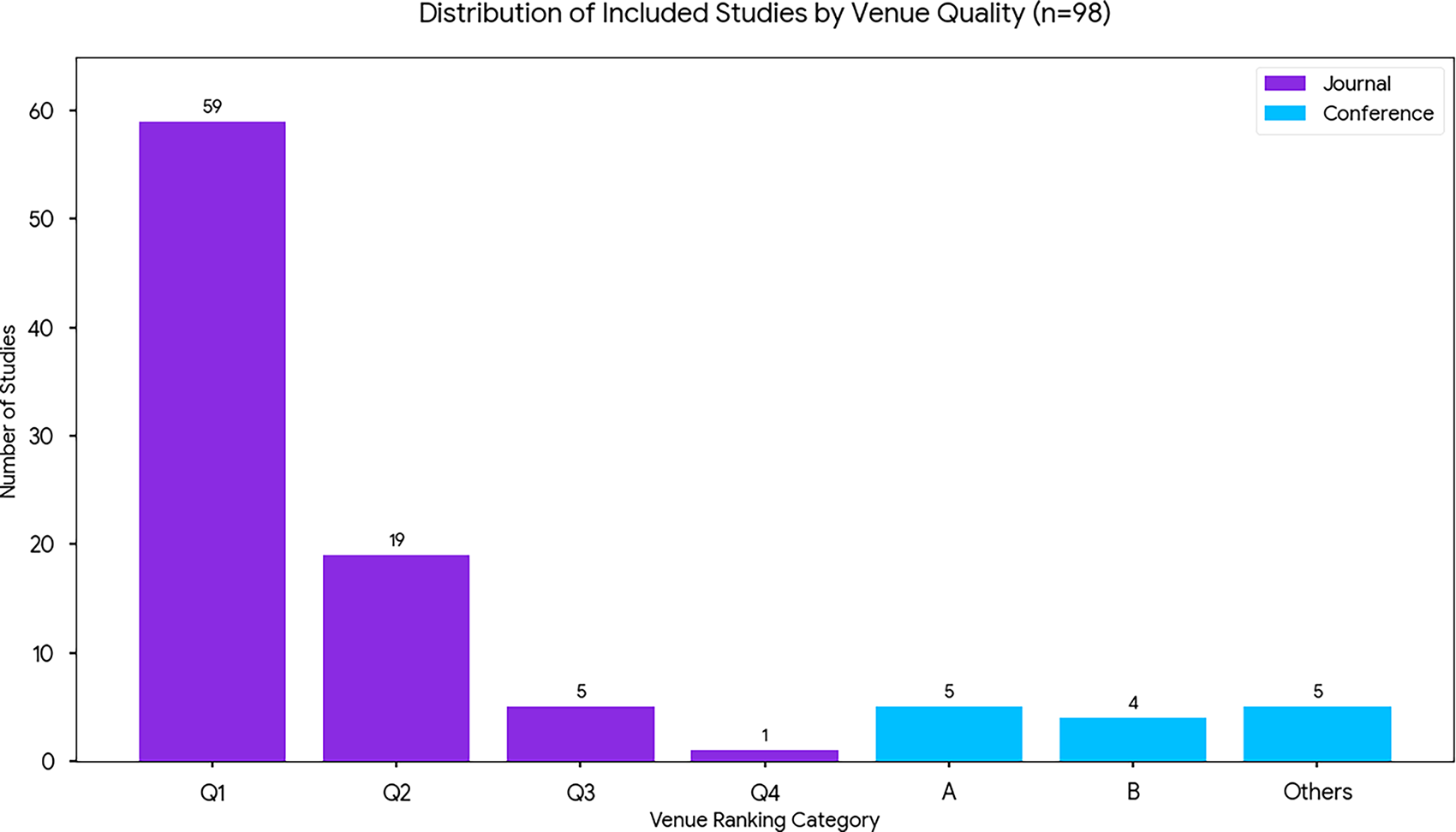

Fig. 4 displays the venue quality distribution of the included works, categorized by journal quartiles (Q1–Q4) and conference rankings (A, Others). A majority of journal publications fall within Q1 and Q2 quartiles, underscoring their concentration in leading outlets such as IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst., Information Fusion, and ACM Computing Surveys. Conference contributions primarily originate from A-ranked venues (e.g., NeurIPS, ICML, AAAI), with a small proportion from unranked or regional events. This pattern confirms the overall quality and credibility of the selected corpus. Taken together, these findings highlight a maturing research ecosystem in federated learning that substantiates the corpus as the basis for taxonomy validation and gap analysis.

Figure 4: Venue quality distribution by journal quartile (Q1–Q4) and conference ranking

5 Fundamentals of Federated Learning (FL)

Federated Learning is a machine learning technique that enables multiple participating clients to collaboratively train a shared global model without exchanging their raw, sensitive local data with the central server [10]. This decentralized training approach is driven by the imperative to maintain data privacy and ownership in scenarios involving highly regulated or proprietary datasets, where data centralization is impractical or undesirable [24]. FL focuses on aggregating computation instead of data aggregation, where individual clients perform local model updates on their private datasets, and only the model updates are shared and aggregated at a central server [10]. This architectural design offers stronger privacy compared to traditional centralized learning methods, where all training data resides in one single location, making it a single point of vulnerability open to various attacks and potential regulatory failures [25]. The collaborative learning process enables the global model to benefit from the collective learning of all participating clients, which allows the global model to generalize from a richer and more diverse dataset than any single client possesses, all while keeping data private and secure in local servers. This is particularly crucial in domains that run under a regulatory framework such as healthcare, where patient data often cannot legally leave the hospital where it was generated to keep patients’ sensitive data protected [26,27]. The core principles of FL revolve around model refinement through an iterative process that involves two key components: Clients and a Central Server, which works as an Aggregator [15,28,29].

In the FL architecture, clients are distributed entities that hold the training data and possess the computational resources to train local models. These are the endpoints that hold the raw, often sensitive, training data and are also equipped with the necessary computational power to perform model training locally. Kairouz et al. (2021) [15] highlight a fundamental and critical distinction within the field, which categorizes FL into two primary standards based on the characteristics of these clients: Cross-Device Federated Learning and Cross-Silo Federated Learning.

Cross-Device Federated Learning: Training at Massive Scale The Cross-Device FL involves a massive number of end-user devices [30]. These clients are devices that consist of smartphones, tablets, Internet of Things (IoT) gadgets, or personal computers, each with a relatively small amount of data. The scale of this setting may reach millions, or even billions, of participating users and devices [31].

Client & Data Characteristics Each client in the Cross-Device FL environment holds a relatively small dataset that reflects the direct interaction of a single user. This data is inherently non-identically and independently distributed (non-IID) across the network and captures unique personal characteristics, behaviors, preferences, and environments [32].

Environmental Constraints Individual devices in Cross-Device FL have limited resources, such as low computational power, memory, and battery life, which limits the complexity of the models that can be trained locally. Clients often connect over unreliable or low-bandwidth networks such as cellular data and public Wi-Fi, which makes frequent and large model updates impractical [33]. The user base of available clients is highly dynamic. Devices may participate opportunistically and can drop out unexpectedly due to network issues, user behavior, or low battery. These issues pose a significant challenge to the synchronization and convergence of the global model [34].

Cross-Silo Federated Learning: Collaborative Institutional Training

The Cross-Silo FL setting involves a smaller, stable, and powerful cohort of clients. These clients are not individual devices but rather institutional entities, data centers, or organizations, often referred to as “silos” that possess their own dataset but are unwilling or unable to share the data directly [35]. The number of participants ranges from two to around one hundred. The purpose of this kind of collaboration is to include hospitals collaborating on medical research, financial institutions developing fraud detection models, or independent research labs combining their findings.

Client & Data Characteristics

Each silo represents an individual organization or institution that holds a large and generally high-quality dataset collected from its own users, systems, or operations. While these datasets are rich enough to train effective local models, they have a tendency to reflect only the specific characteristics of that particular institution, such as a hospital’s patient demographics or a company’s customer base [36]. As a result, models trained in isolation suffer from limited generalizability. Cross-Silo Federated Learning enables multiple silos to collaboratively train and create a shared global model without sharing their raw data. The global model benefits from a broader, more diverse range of data than any single silo could have achieved if it had trained on its own local data only [37].

5.2 Central Server: Aggregator

Most federated learning setups consist of a central server that serves as the coordinator and aggregator of the training process. Its main responsibilities include initialization of the global model, selection of a subset of clients for each training round, collection of model updates from those clients, and aggregation of gradient updates to create and refine the global model, which is then sent back to the clients in an iterative process. In many threat models, the central server is considered honest-but-curious. It follows the protocol correctly but may try to infer sensitive information from the model updates of clients it receives [14]. The level of trust placed in the server influences the strength and type of privacy mechanisms that need to be employed, such as secure aggregation or differential privacy.

5.3 Standard Federated Learning Workflow

The foundational algorithm behind most federated learning (FL) implementations is Federated Averaging (FedAvg), introduced by McMahan et al. in 2017 [10]. The FedAvg algorithm combines local stochastic gradient descent (SGD) on client devices with an iterative averaging of model updates on the central server. This process serves as the foundational framework for training a single global model across decentralized clients without requiring them to share their local data. A standard FL process unfolds in iterative communication rounds, with each round generally consisting of four key stages:

Initialization, Client Selection and Model Distribution: The central server starts a round by selecting a random subset of its available clients to participate in the current round and sends the current state of the global model to each of the selected clients.

Local Training: After receiving the global model, each selected client initializes its local model and performs one or more steps of an optimization algorithm, typically Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), on its local dataset. The number of local training epochs is a crucial hyperparameter. While performing more local epochs can reduce the number of communication rounds required for the global model convergence, this may lead clients to overfit their local data and diverge from the shared global objective, a phenomenon referred to as “client drift” [38]. To solve this issue, algorithms such as SCAFFOLD [39] have been proposed, which use control variates to track and compensate for the difference between the local and global models.

Update Communication: Each client sends its computed model update, which is communicated to the server as the difference between the updated local weights (new) and the initial global weights back to the central server.

Aggregation: The server waits to receive updates from a predetermined number of participating clients. Once updates received from a number of clients reach a specific threshold, the server aggregates these updates to construct the new global model. In the FedAvg algorithm, this aggregation is a weighted average of the client parameters, where each client’s update is weighted by the number of data points in its local dataset.

This weighting method ensures that clients who trained on more local data have a proportionally greater influence on the final global model. Once aggregation is computed, the process repeats with the new global model sent to the client in the next round. This iterative procedure of sharing gradients continues until the model converges on a held-out validation set or reaches a predefined number of rounds.

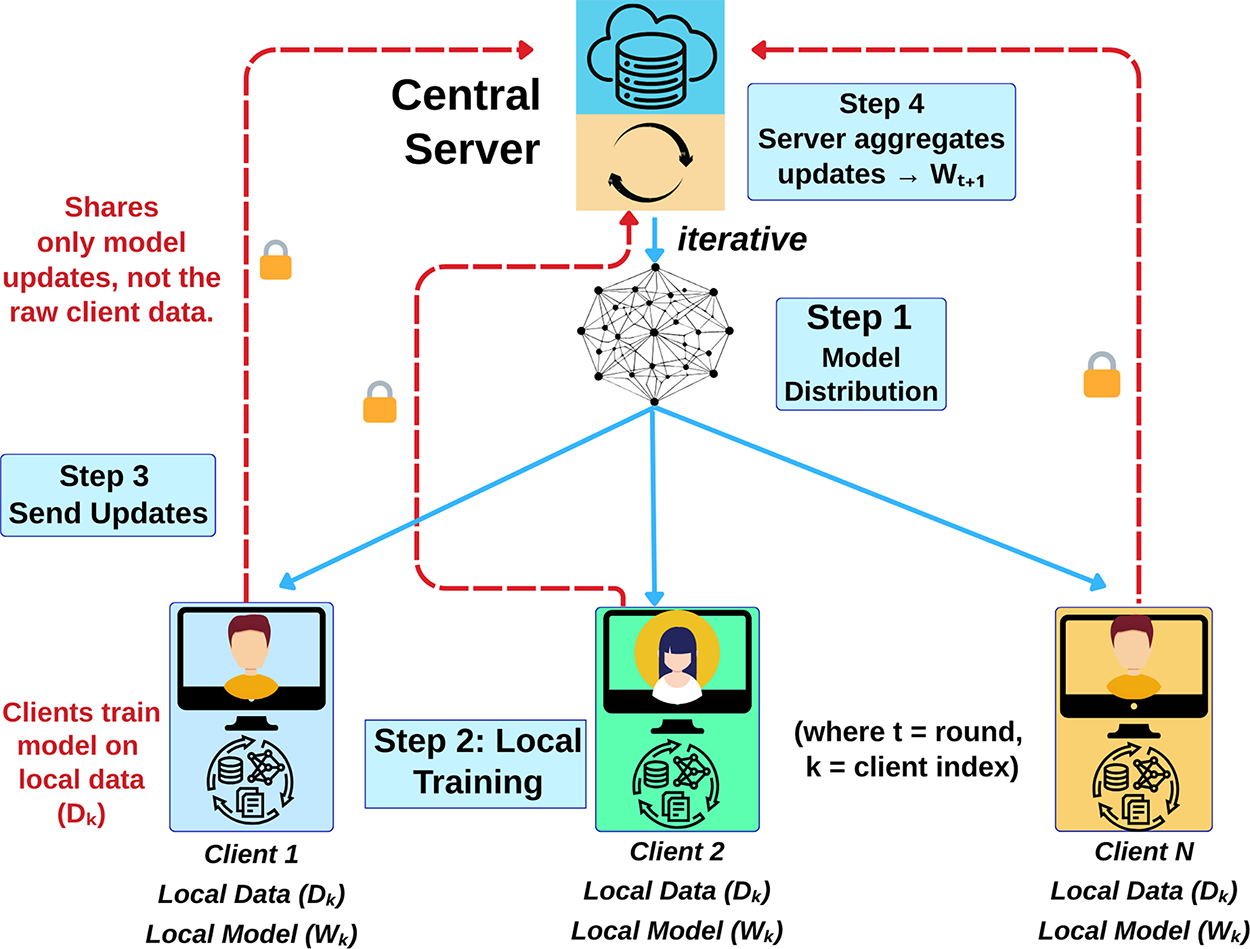

Fig. 5 shows the iterative process of the FedAvg algorithm. The process begins with Step 1, where a central server distributes a global model to multiple clients. In Step 2, each client independently trains this model on its local data, which never leaves the device. Following local training, clients send their model updates back to the server in Step 3. Finally, in Step 4, the server aggregates these individual updates to produce an improved global model for the next iteration. This entire process ensures data privacy by sharing only model updates, not the raw client data.

Figure 5: The Federated Averaging (FedAvg) learning process

5.4 Federated Learning Architectures

The FL architectures can be categorized into four categories, which are Horizontal Federated Learning, Vertical Federated Learning, Federated Transfer Learning, and Personalized Federated Learning.

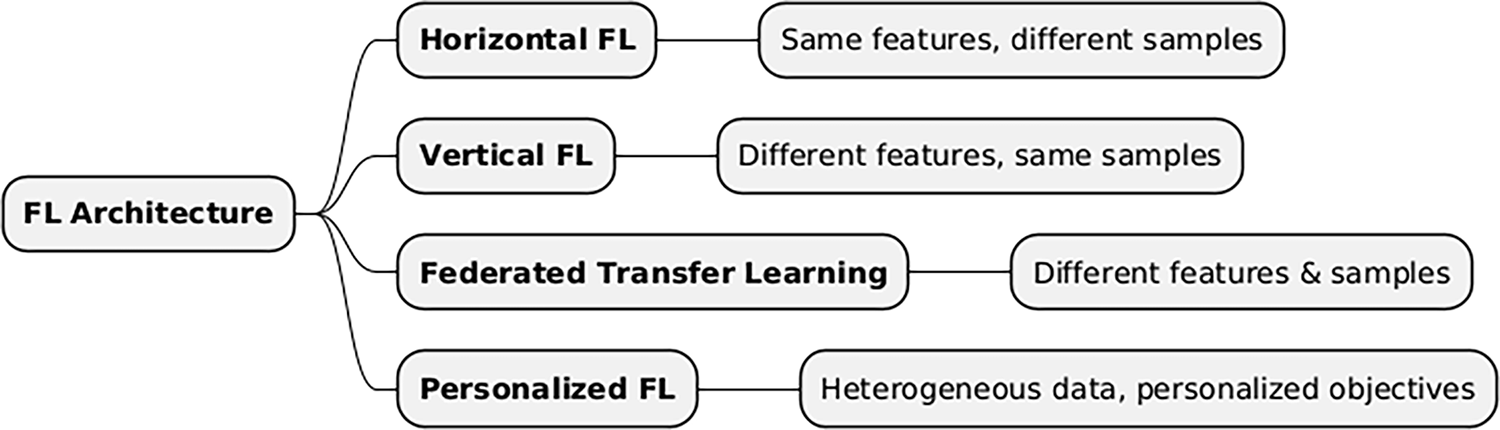

Fig. 6 illustrates a classification of Federated Learning (FL) architectures based on how data is distributed among clients. The categories include Horizontal FL, where clients share the same feature space but have different data samples, Vertical FL, where clients have different features for the same set of samples, Federated Transfer Learning, applied when clients differ in both their features and samples, and Personalized FL, which addresses data heterogeneity by training models personalized to individual client objectives.

Figure 6: Classification of federated learning architectures

5.4.1 Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL)

Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL) is an approach where participants train models on local data that shares the same features but has different data instances (samples), which are often non-identically distributed (non-IID) [40–42]. HFL generally follows an iterative procedure where a central server aggregates model parameters from clients, who train locally on private data [43,44]. While raw data never leaves the client, ensuring inherent privacy [45], security risks like inference and model poisoning attacks remain [46]. Additional mechanisms like secure aggregation are used to mitigate these threats.

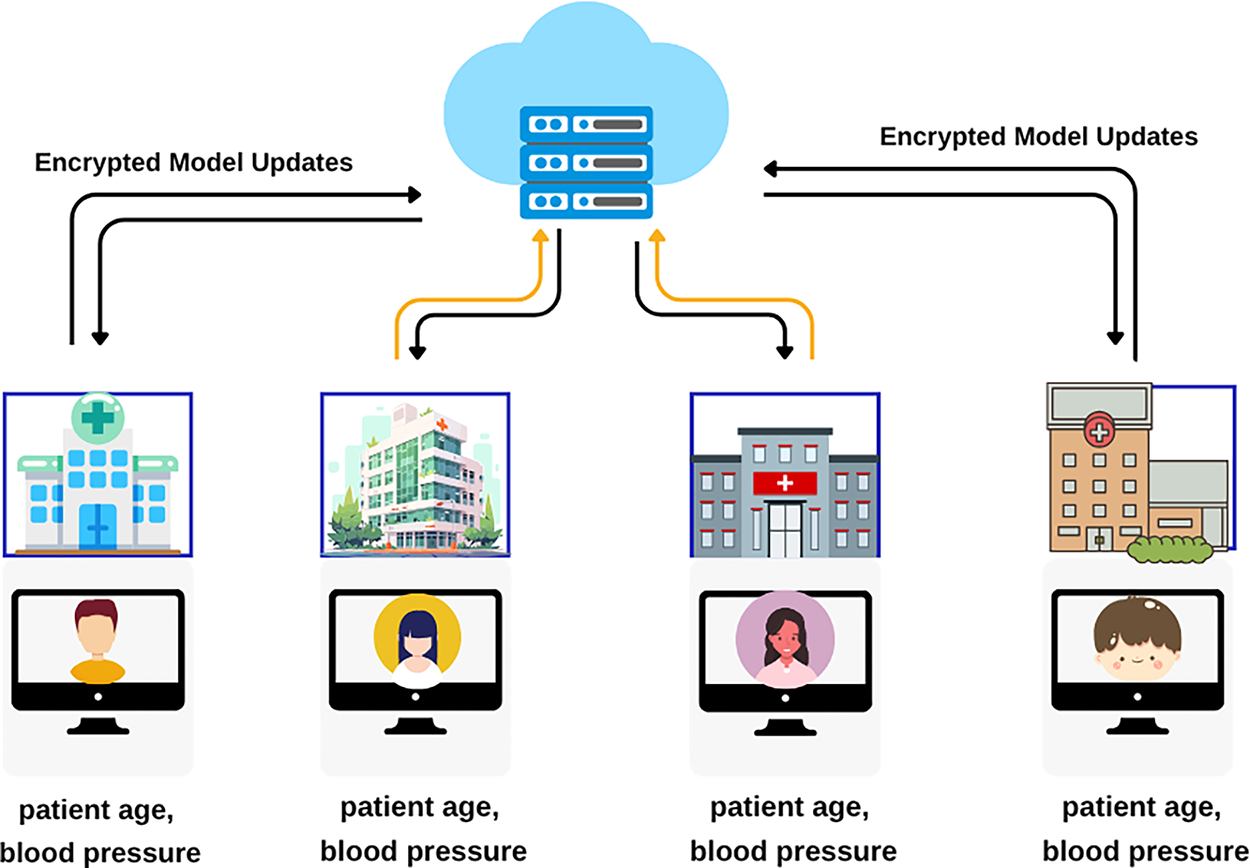

Fig. 7 illustrates Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL), where multiple hospitals hold the same types of data (e.g., patient age, blood pressure) for their respective patients. HFL is widely used in domains like healthcare, finance, and mobile computing.

Figure 7: Horizontal federated learning

5.4.2 Vertical Federated Learning (VFL)

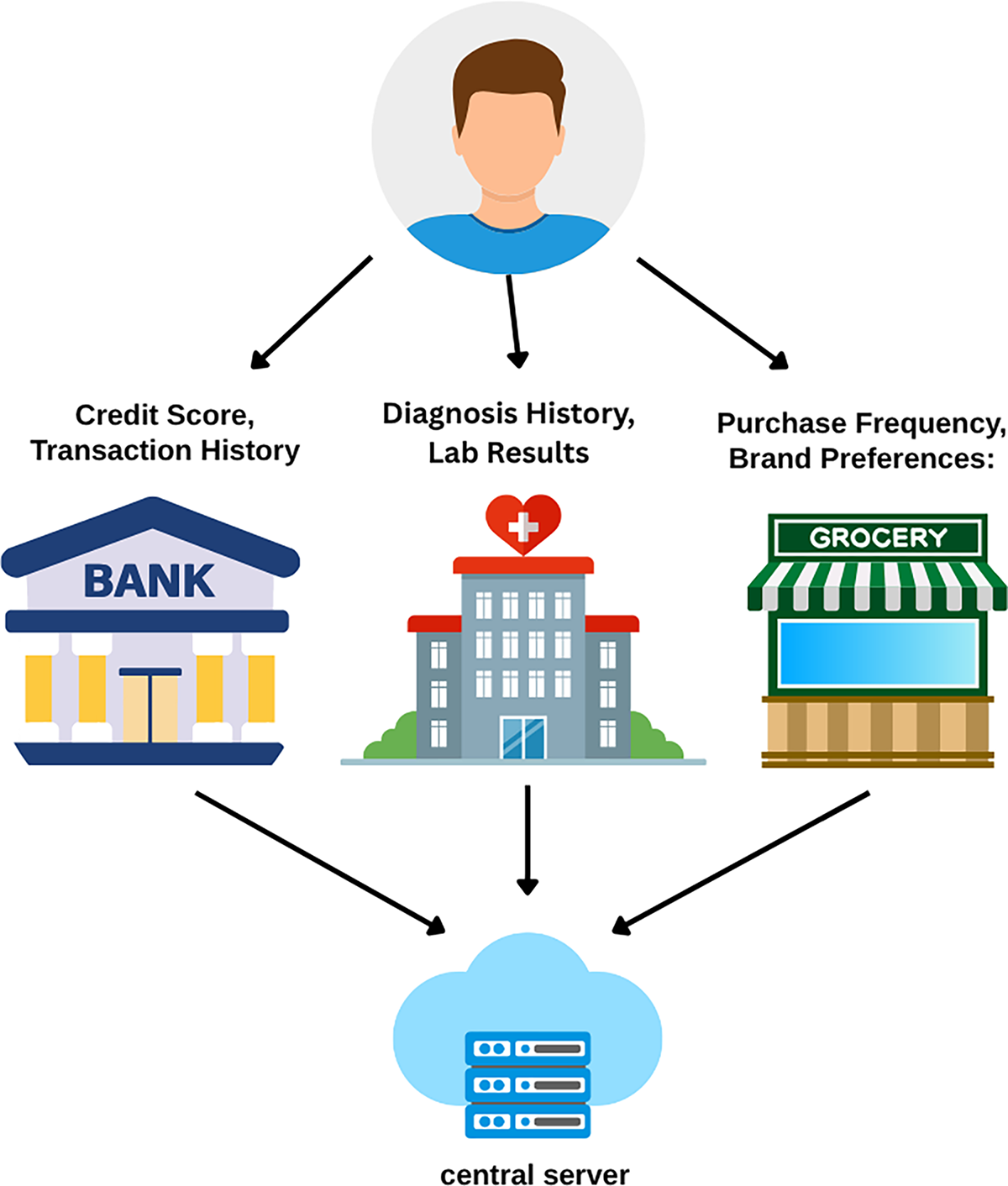

Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) applies when participants have datasets with the same samples (e.g., users) but different features [47]. For instance, a bank holds a user’s financial features while an e-commerce site holds their behavioral features. Parties first securely identify common samples (e.g., via private set intersection [48]) and then collaboratively train a model. Each party trains a portion of the model on its unique features, and a coordinator combines intermediate results to update the global model. This leverages combined features for a more powerful model than any single party could build [49,50].

Fig. 8 illustrates the concept of Vertical Federated Learning (VFL). This paradigm is applied when different organizations hold different features for the same set of users. As shown, a bank may have a user’s financial data (e.g., credit score), a hospital holds their medical records (e.g., diagnosis history), and a grocery store has their purchase history. In VFL, these entities collaborate to train a comprehensive model by jointly computing model updates using their distinct features, coordinated by a central server, without revealing their private data to each other.

Figure 8: Vertical federated learning

VFL is not immune to risks like inferring private features from shared gradients [51–53], so it is often integrated with techniques like homomorphic encryption (HE) or differential privacy (DP). VFL also faces challenges with computational efficiency, communication overhead, and convergence. VFL architectures are well-suited for cross-sector collaboration, such as in financial services, healthcare, and marketing [54,55].

5.4.3 Federated Transfer Learning (FTL)

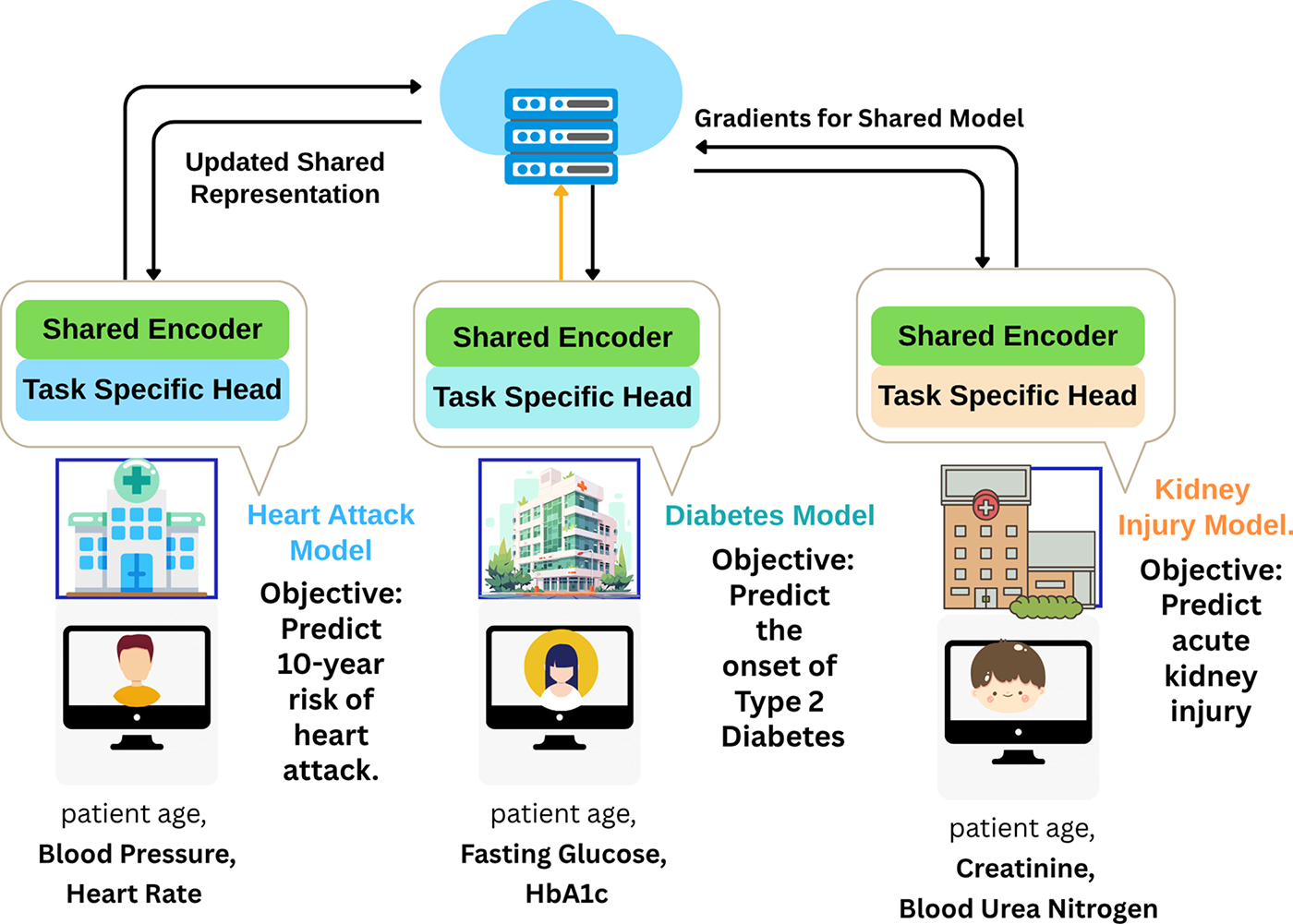

Federated Transfer Learning (FTL) combines federated and transfer learning to train models across data silos with different features and different samples [56]. Unlike HFL or VFL, FTL handles scenarios with little to no overlap in features or samples, making it suitable for cross-domain organizations with high data heterogeneity [57]. In FTL, parties with unique, non-overlapping datasets (e.g., health wearables and banking apps) improve local models by transferring knowledge from other domains [58,59]. This relies on transferring knowledge via a shared representation [60]. A central server aggregates intermediate results (like hidden layer representations) to distill generalizable patterns into a shared model.

Fig. 9 illustrates Federated Transfer Learning (FTL), used when participants have different tasks and feature sets, as with the medical models shown. Each model combines a local “Task Specific Head” with a “Shared Encoder.” Gradients from the shared encoder are sent to a server, which aggregates them to create an updated, shared representation.

Figure 9: Federated transfer learning in healthcare

FTL architectures often incorporate domain adaptation, knowledge distillation, and cross-domain representation learning [57,61,62]. To minimize privacy risk, privacy-preserving mechanisms like secure aggregation, differential privacy, and homomorphic encryption are often integrated [56,63,64].

5.4.4 Personalized Federated Learning (PFL)

Personalized Federated Learning (PFL) addresses statistical heterogeneity, as the standard “one-size-fits-all” global model can be suboptimal for clients with non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data [65]. PFL enables each client to train a personalized model that combines collective insights with client-specific data, useful for tasks like keyboard prediction where user data varies widely [66].

One common PFL method divides parameters into shared global parameters (for general trends) and private local parameters (for unique characteristics) [67,68]. Other PFL techniques include regularization-based methods like FedProx, which penalizes divergence from the global model [69], clustering clients with similar data [70], and meta-learning for rapid adaptation [71].

Implementing PFL is challenging, demanding more computation and communication than standard FL [72], and requires robust privacy-preserving protocols [73].

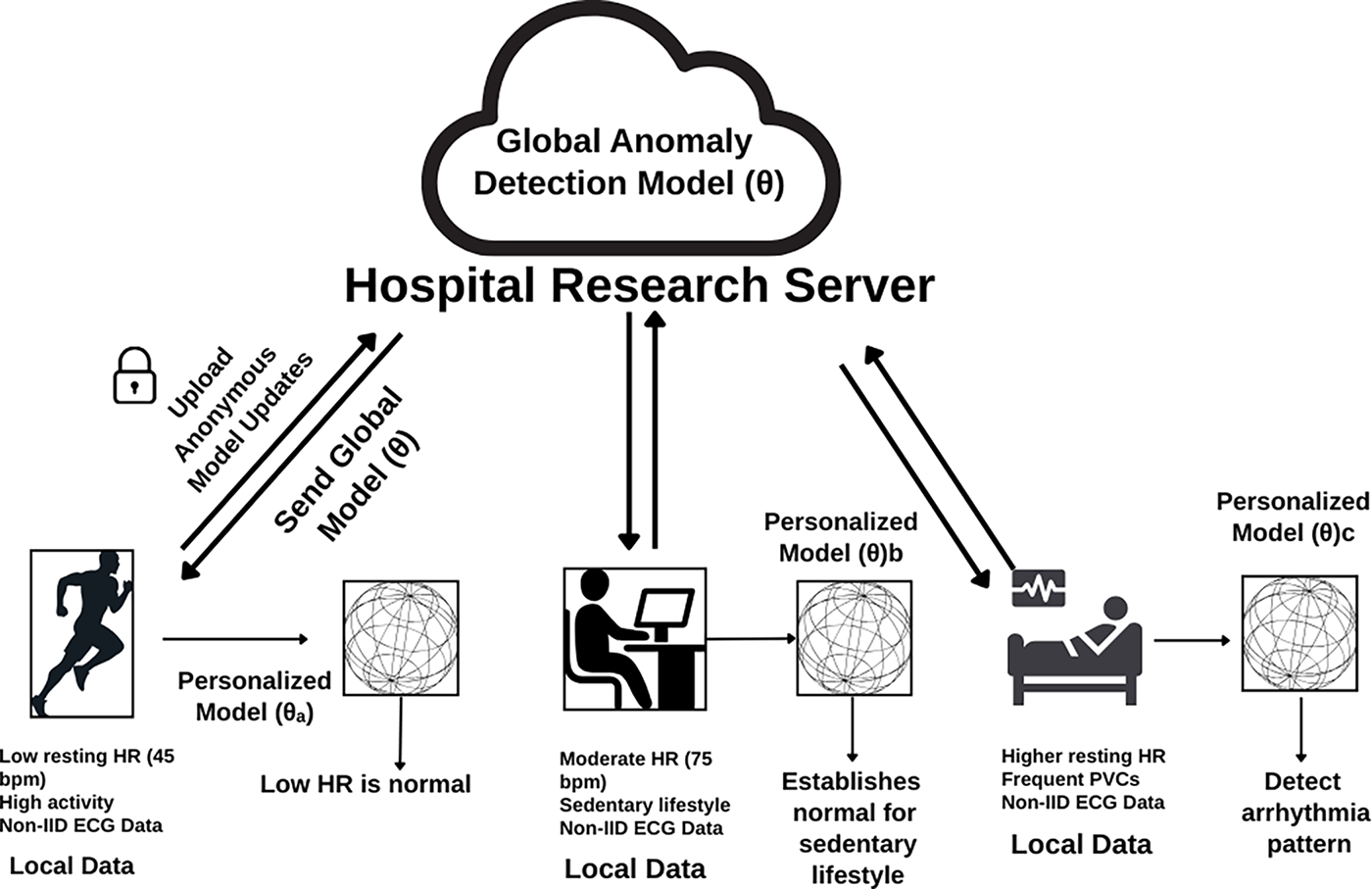

Fig. 10 illustrates Personalized Federated Learning (PFL) applied to healthcare. A global model is trained using data from diverse clients (e.g., an athlete, a sedentary user, and a patient with cardiac anomalies). The model is then personalized on each user’s local, non-IID electrocardiogram (ECG) data to generate specialized models without sharing sensitive health information.

Figure 10: Personalized federated learning in healthcare

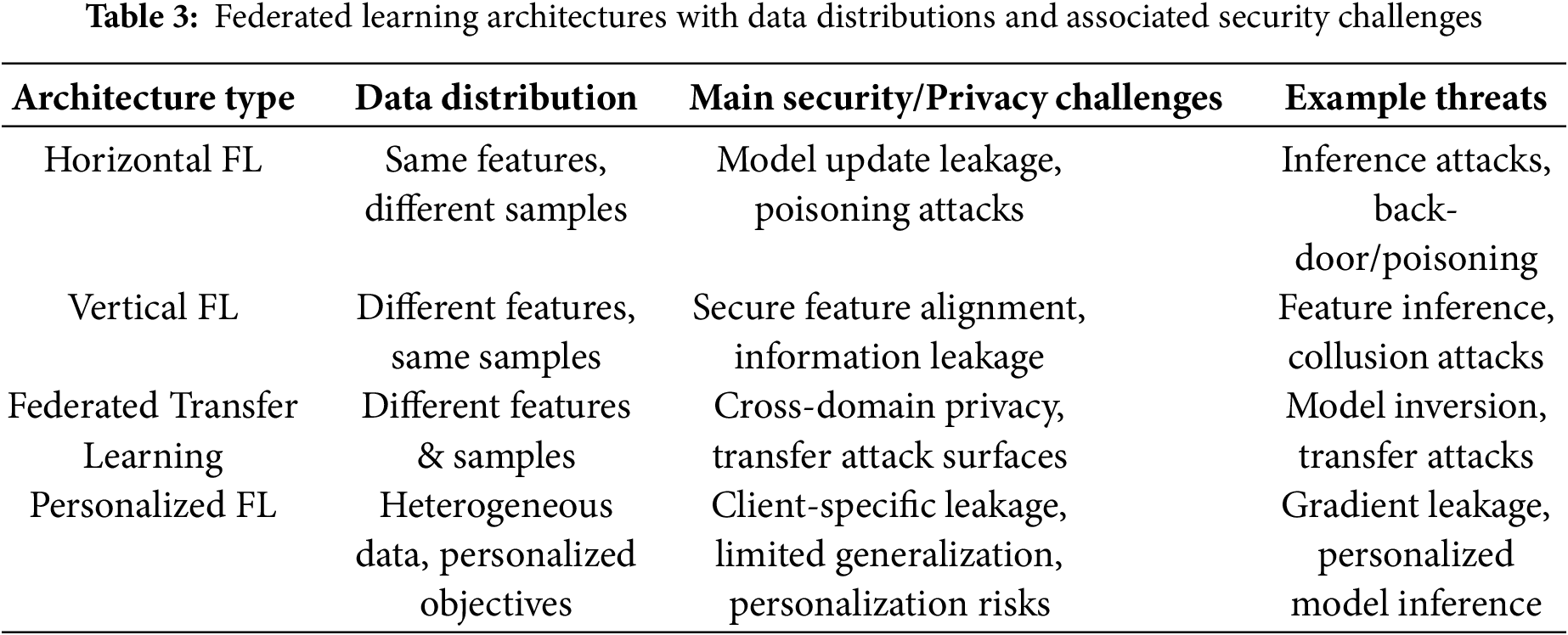

Table 3 summarizes the federated learning architectures along with their data distributions, key security issues, and common threats.

5.5 Synchronization Strategies: Synchronous vs. Asynchronous

5.5.1 Synchronous Federated Learning (SFL)

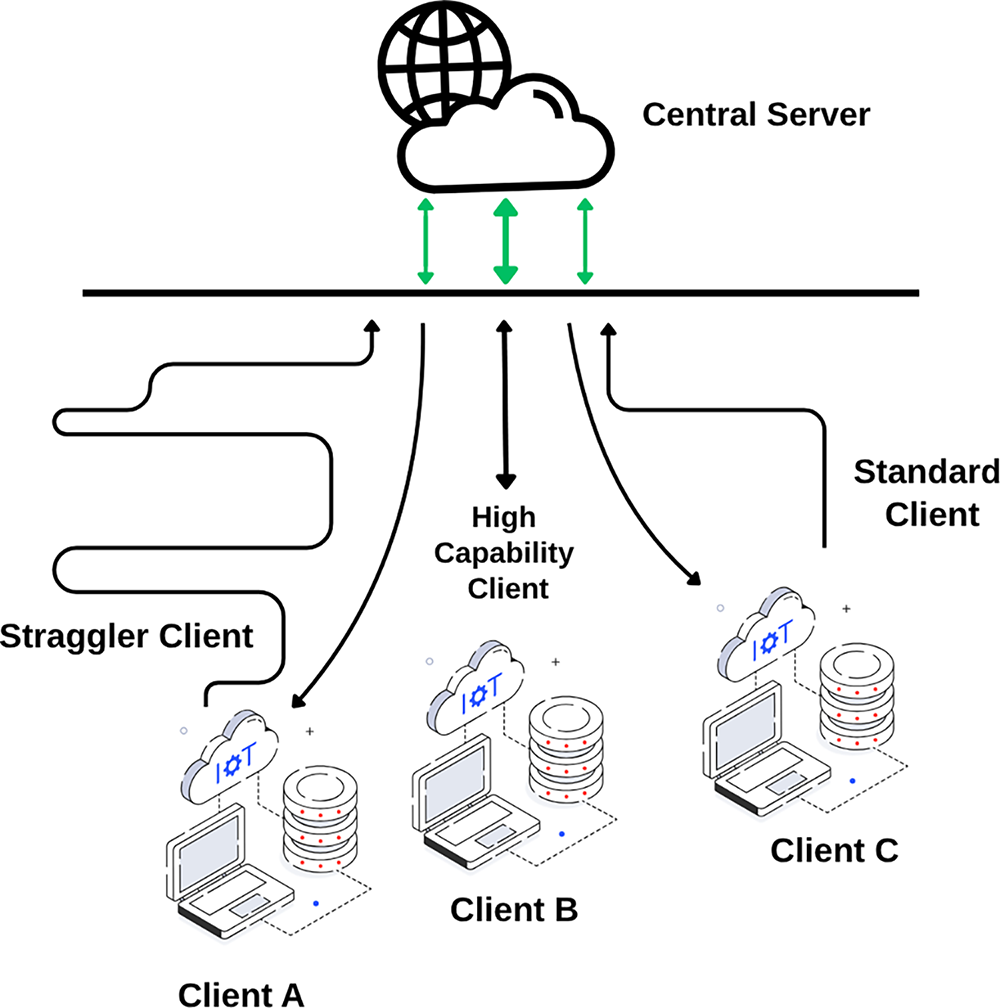

In Synchronous Federated Learning (SFL), clients train and send updates simultaneously. The central server aggregates updates only after receiving contributions from all predefined clients in that round. This ensures all updates are based on the same global model, leading to consistent learning. However, the system must wait for the slowest clients (stragglers), causing delays and wasting resources [31].

Fig. 11 illustrates Synchronous Federated Learning: clients of varying capabilities, including stragglers, upload their model updates simultaneously to a central server, which waits for all participants before proceeding with aggregation. This design ensures model consistency but may introduce delays due to slower clients.

Figure 11: Synchronous federated learning

5.5.2 Asynchronous Federated Learning (AFL)

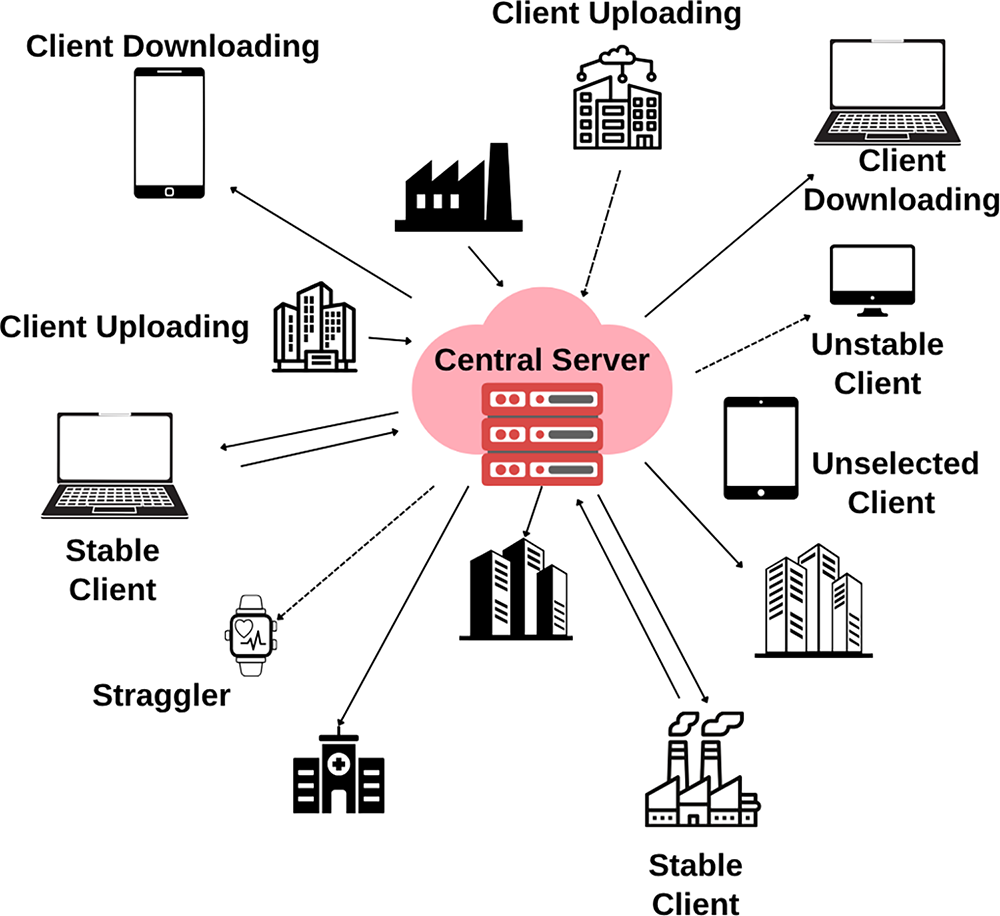

Asynchronous Federated Learning (AFL) allows clients to train independently and send updates when ready. The server updates the global model immediately upon receiving any update, without waiting for others. Clients download the current global model, train locally, and send updates back. The server immediately applies each update, allowing clients to participate freely based on availability.

Fig. 12 illustrates Asynchronous Federated Learning, highlighting the interaction between a central server and a diverse set of clients with varying statuses, including stable clients, unstable clients, and stragglers. The server processes model updates as they arrive, accommodating client heterogeneity and avoiding delays.

Figure 12: Asynchronous federated learning

The core benefit of AFL is scalability, as fast clients do not wait for stragglers [74,75]. However, this introduces “model staleness,” as clients may train on outdated global models, which can harm convergence and stability. AFL is useful in scenarios with unpredictable client availability, such as in large-scale IoT systems or with edge devices.

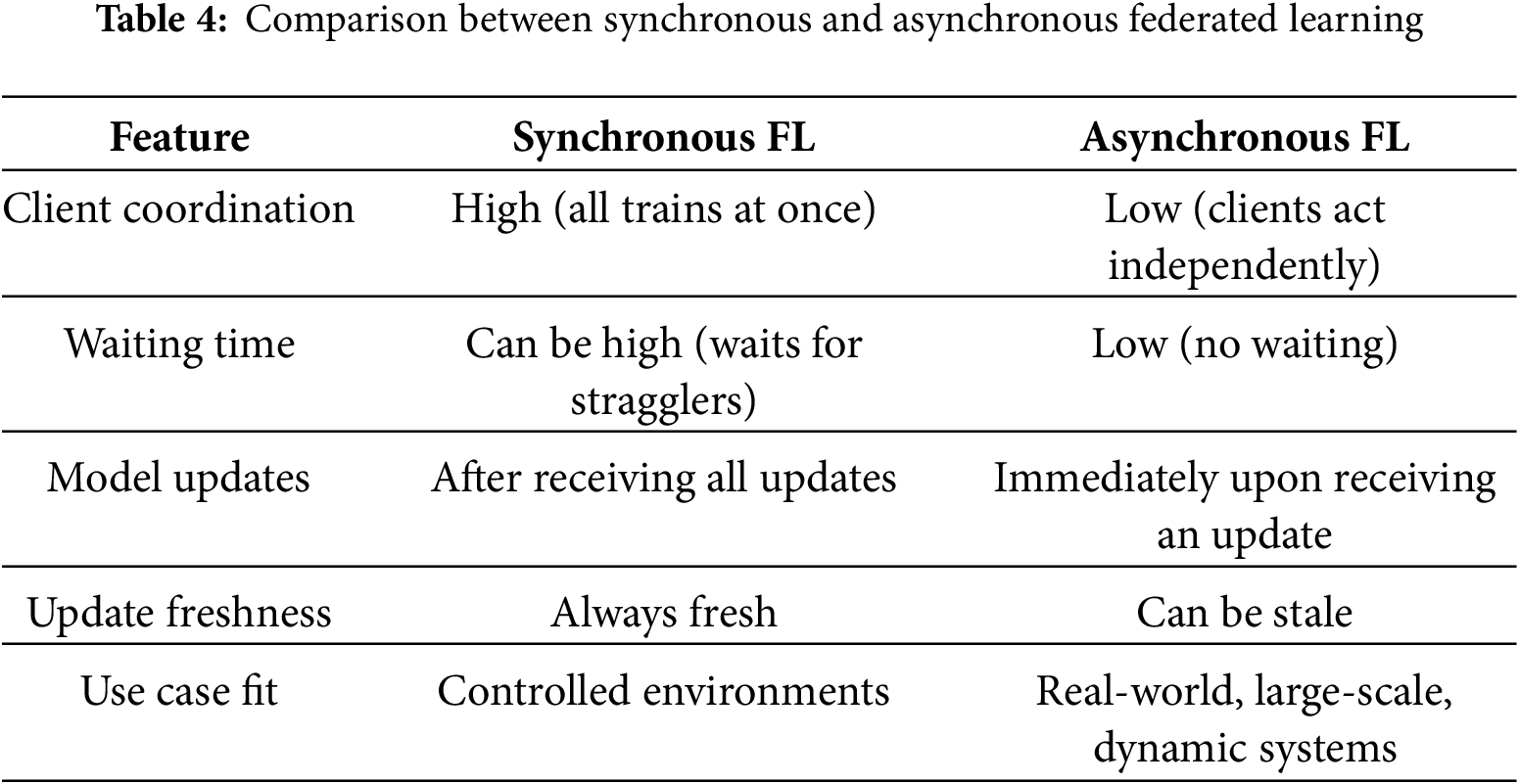

Table 4 presents a simple comparison of synchronous and asynchronous federated learning in terms of coordination needs, waiting time, update behavior, and practical suitability.

5.6 Privacy and Security in Federated Learning

5.6.1 Threat Models in Federated Learning

The security and privacy of FL systems are evaluated against two foundational adversary models, which define the goals of corresponding defenses:

• Honest-but-Curious (or Semi-Honest): This model assumes an adversary, typically the central server, that strictly adheres to the FL protocol’s steps. However, it is “curious” and will leverage the information it legitimately receives (e.g., model updates) to passively infer sensitive information about the clients’ private data, such as attempting to reconstruct training samples. Defenses against this model focus on privacy.

• Byzantine (or Malicious): This adversary actively works to disrupt, corrupt, or control the learning process and does not follow the protocol. This adversary can be a client or the server, and may take arbitrary actions such as sending intentionally malformed data (data poisoning) or carefully crafted model updates (model poisoning) to degrade the global model’s performance or insert a hidden backdoor.

Data Leakage refers to the unintentional leak of sensitive information from model updates, even when raw data is not shared. There are several ways for data leakage to happen:

Membership Inference Attacks (MIA): An adversary attempts to determine if a specific data sample was used in the training set, often by exploiting differences in model behavior on seen vs. unseen data [76].

Gradient Leakage (Model Update Leakage): Shared model updates can be exploited to reconstruct original training data (e.g., images or text) using techniques like Deep Leakage from Gradients (DLG) [77].

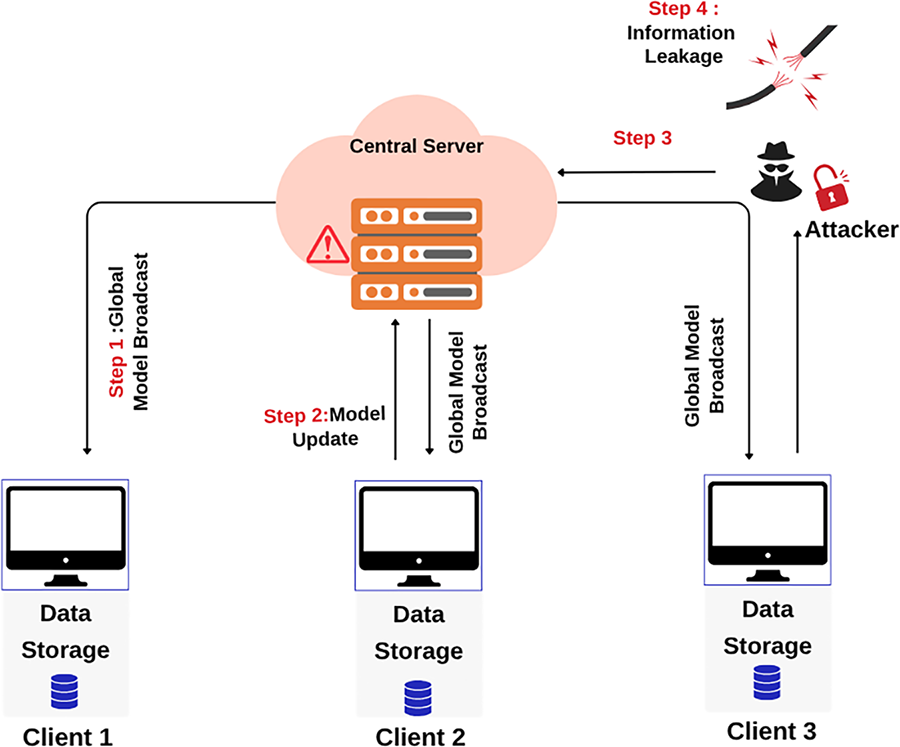

Fig. 13 illustrates an information leakage attack in an FL system. The server broadcasts the model (Step 1), and clients send back updates (Step 2). A malicious attacker intercepts these updates (Step 3) and analyzes them to infer or reconstruct sensitive information from the client’s private data, leading to information leakage (Step 4).

Figure 13: Data Leakage attack in federated learning

Property Inference Attacks: An adversary infers high-level statistical properties of the training data (e.g., demographic attributes) that may not be related to the model’s primary task [13].

Reconstruction Attacks: An attacker attempts to recreate full or partial input samples from information leaked via model updates or predictions [78,79].

A poison attack occurs when malicious clients intentionally manipulate the training process by sending harmful data or updates, aiming to degrade the global model’s performance or introduce specific errors. This threat is significant in FL because the server cannot see the clients’ raw data and must trust their updates.

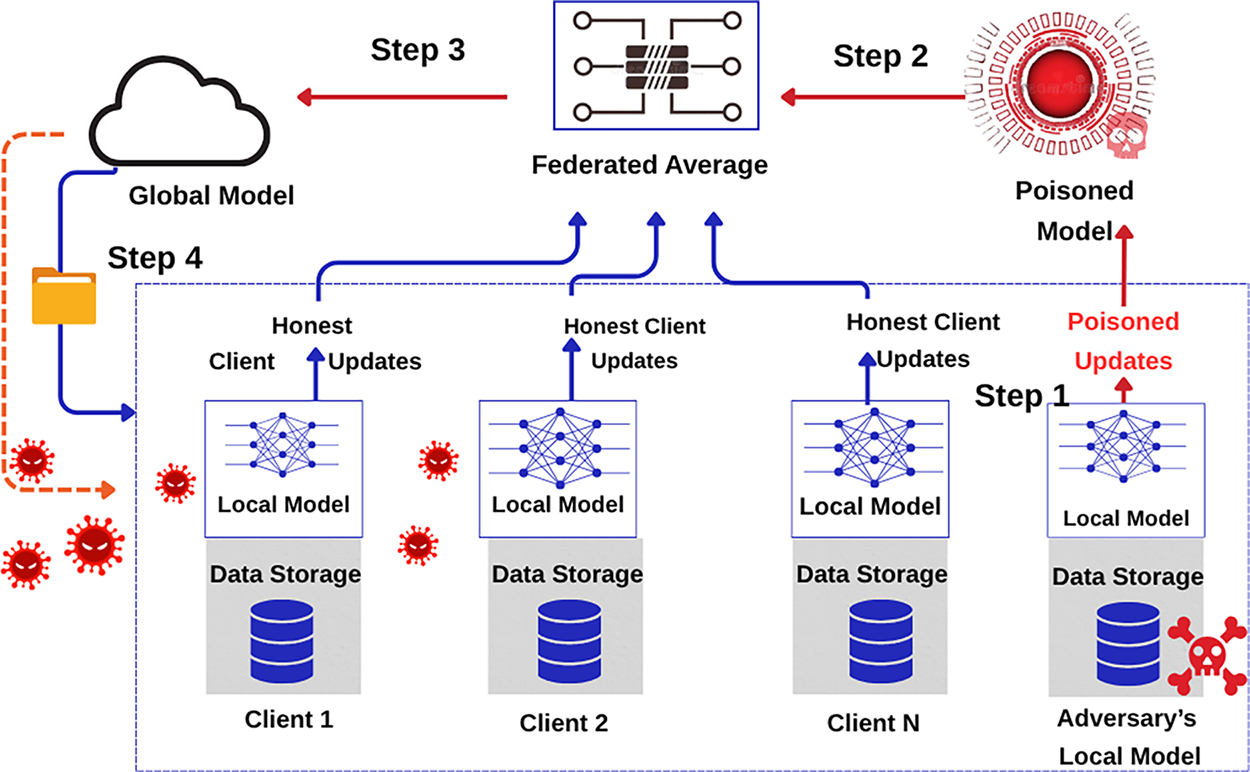

Fig. 14 illustrates a poisoning attack: an adversarial client injects malicious updates (Step 1), which are then aggregated during the federated averaging process (Steps 2–3). These poisoned updates contaminate the global model (Step 4), affecting all honest clients.

Figure 14: Poisoning attack in federated learning

Data Poisoning Attacks: Attackers poison their local training data (e.g., by flipping labels) to make the model learn incorrect patterns [80].

Model Poisoning Attack: The attacker crafts a malicious model update directly, designed to reduce accuracy or introduce a backdoor [81].

Mitigations include robust aggregation methods (e.g., Krum, trimmed mean), anomaly detection to flag suspicious updates [82], client reputation systems, and privacy mechanisms like differential privacy or secure aggregation [83].

6 Literature Reviews on Federated Learning Architectures: VFL, HFL, FTL, PFL

6.1 Vertical Federated Learning (VFL)

6.1.1 Architectural Advances in VFL with Heterogeneous Participants

Feng et al. in 2024 [84] propose MMVFL, a novel vertical federated learning (VFL) framework that supports multiple participants and multi-class classification tasks. This addresses the critical limitation of Traditional VFL methods, which are typically limited to two participants and binary classification, which restricts their applicability in real-world scenarios where data is distributed across many organizations and involves more complex classification problems. MMVFL addresses the challenge of enabling collaborative learning across decentralized data silos where participants share the same sample IDs but have different feature spaces while preserving privacy and extending scalability to multi-class classification tasks and multiple participants. The framework integrates multi-view learning (MVL) principles into the VFL setting, which enables label information to be shared from the label-holding participant to others via a privacy-preserving optimization process that learns pseudo-label matrices and applies sparsity constraints to transformation matrices. MMVFL methodology involves all K participants to train a model locally to generate pseudo-labels (

Wang et al. in 2025 [85] propose PraVFed, a framework for heterogeneous vertical federated learning (VFL) that addresses model heterogeneity and high communication costs. PraVFed allows each passive party to use its own unique, heterogeneous model and train it locally for several rounds. To reduce frequent communication, the active party sends labels protected by differential privacy to the passive parties. After training, each passive party creates an embedding of its local data, which is then masked using a secure cryptographic technique to protect feature privacy. These masked embeddings, along with a weight that reflects how well each local model performs, are sent to the active party, which aggregates them using the provided weights. This aggregated information is then used to train the final global model. The framework achieves a 70.57% reduction in communication cost on the CINIC10 dataset. While it provides formal privacy guarantees for both feature and label information, the approach suffers from memory overhead from handling embedding values from all clients.

Zhang et al. in 2024 [86] introduce HeteroVFL, a VFL framework for two-level distribution in Industry 4.0, extending split learning with prototype aggregation and DP-protected smashed data sharing. Within regions, clients send smashed data; the server forms local class prototypes and aligns them to global prototypes via a joint loss combining classification and prototype consistency, enabling cross-region transfer without raw data or model sharing. On MNIST, Federated MNIST (FEMNIST), and CIFAR-10, HeteroVFL surpasses Split and SplitFed (e.g., 96%–97% vs. 90%–89% at n = 3) with lower communication and faster time-to-accuracy despite more epochs, and degrades less as regions grow. DP noise preserves privacy but reduces accuracy and slows convergence;

The architectural advances in VFL, such as MMVFL, PraVFed, and HeteroVFL, highlight the research trend in VFL, which is moving beyond the theoretical homogeneous two-party environment to the practical heterogeneous realities of multi-institutional collaboration. The reviewed papers approach heterogeneity from different angles. The MMVFL [84] framework expands VFL’s scope to multi-party and multi-class scenarios by sharing pseudo-labels [84], which is a foundational step for wider applicability. PraVFed [85] and HeteroVFL [86] frameworks take this further by respectively addressing model and data distribution heterogeneity. These approaches are complementary rather than competing. For instance, PraVFed’s focus on allowing diverse local model architectures could be combined with MMVFL’s multi-party framework. HeteroVFL introduces a more complex, two-level hierarchical structure for Industry 4.0 that uses prototype-based aggregation for knowledge sharing across differing regions, which contrasts with the representation-learning approach in PraVFed. PraVFed and HeteroVFL integrate differential privacy to increase privacy and security, but the reliance on these abstractions introduces potential information loss, memory overhead, and degradation of model accuracy compared to fine-grained gradient updates.

6.1.2 Communication-Efficient and Privacy-Enhanced Protocols in VFL

Valdeira et al. in 2025 [87] introduces Error-Feedback Vertical Federated Learning (EF-VFL), a communication-efficient vertical federated learning (VFL) algorithm that employs error feedback-based compression to mitigate high communication overhead when training models across distributed, feature-partitioned clients. The method solves the inefficiency of existing VFL approaches, which either require vanishing compression errors for convergence or suffer from suboptimal convergence rates (e.g.,

Fan et al. in 2024 [88] propose FLSG, a defense strategy against passive label inference attacks in vertical federated learning, where existing privacy techniques like differential privacy fail because attacks are conducted entirely locally. FLSG intervenes at the server level by generating multiple random Gaussian gradients, computing cosine distances to the original gradients, and replacing the original with the most similar synthetic gradients when the distance falls below a threshold. Experimentation of the paper on six real-world datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, CINIC-10, Yahoo Answers, Loan Default Prediction, BHI) shows that FLSG can reduce the success rate of passive label inference attacks by more than 40%, which outperformed other methods such as gradient clipping, noise gradients, and multistep gradients. Furthermore, it achieves this while using lower computational resources and having minimal impact on the model’s accuracy. However, the study does not explore more complex situations where multiple malicious parties are involved.

Gong et al. in 2024 [89] propose a universal multi-modal vertical federated learning (VFL) framework based on homomorphic encryption to address the challenges of data silos, multi-modal data distribution, and privacy in collaborative machine learning. The solution couples a two-step transformer (cross-domain and multi-modal encoders) with a bivariate Taylor expansion that rewrites cross-entropy into addition/multiplication compatible with additively homomorphic encryption, enabling fully encrypted training without a third party. All exchanged gradients and losses are encrypted and masked under an honest-but-curious model. Experiments show accuracy gains of 1.33 on TWITTER-15 and 1.11 on TWITTER-17. On IEMOCAP, emotion accuracy rises by nearly 5, especially for unaligned data. While the methodology relies on approximating the cross-entropy function using a Taylor series expansion, the proposed protocol provides strong privacy guarantees, eliminating the need for a third-party coordinator for enhanced safety.

Valdeira et al. in 2025 [87], Gong et al. in 2024 [89], and Fan et al. in 2024 [88] highlight the two primary and technical challenges of communication overhead and privacy that are central to VFL’s practical deployment. EF-VFL [87] mitigates the efficiency problem through a sophisticated error-feedback compression mechanism and achieves a faster theoretical convergence rate

6.1.3 Generative Data Augmentation and Applied VFL in Specialized Domains

Xu et al. in 2024 [90] propose ELXGB, an efficient privacy-preserving XGBoost for VFL that secures alignment, training, and inference via a trusted authority for keys, Cloud Service Provider (Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN))-assisted PSI, and Paillier-plus DP-based node splitting under an honest-but-curious, non-colluding model. ELXGB builds the first tree with homomorphic encryption-based node split (HENS) and subsequent trees with differential privacy-baesd node split (DPNS), uses a gradient cache to keep leaf weights lossless, and applies attribute and direction obfuscation to hide node attributes and model structure during inference. On Credit Card (30,000 samples, 23 features) and Bank Marketing (45,211 instances, 17 features), accuracy nearly matches vanilla XGBoost (

Xiao et al. in 2025 [91] address insufficient overlapping data in VFL by proposing FeCGAN, which combines a central generator with distributed discriminators, FedKL aggregation that weights clients by KL divergence, and VFeDA to synthesize pseudo features for non-overlapping segments, thereby reducing learning divergence without exposing raw data. On Fashion-MNIST and CIFAR-10, FeCGAN raises classification accuracy by about 14.9%–39.2% over centralized/distributed Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) baselines, outperforms Local-GAN and federated learning with zero-shot data augmentation at the clients (Fed-ZDAC) [92] by up to 10.45%, and achieves higher Inception Scores and lower Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), while sparse representations converge faster (

Yan et al. in 2024 [93] propose Fed-CRFD, a cross-modal VFL framework for collaborative Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) reconstruction across hospitals with heterogeneous modalities and limited multimodal overlap, addressing domain shift that standard FL fails to resolve. Fed-CRFD disentangles modality-specific and modality-invariant features via an auxiliary modality classification and enforces cross-client latent consistency on overlapping patients to align invariant representations during aggregation. On fastMRI (T1w/T2w) and a private clinical dataset, it outperforms FL baselines, raising Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) from 33.30 to 35.35 dB over FedAvg on fastMRI and from 29.95 dB to 30.95 dB on the private set (p < 0.05), with Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) gains and robustness when vertical overlap drops from 10% to 2%. With three clients, PSNR improves from 33.77 to 35.65 dB and Structural SSIM from 0.9192 to 0.9389, and downstream tumor segmentation achieves higher Dice and lower Average Symmetric Surface Distance (ASSD). Overheads are modest (

Xu et al. (ELXGB) [90] and Xiao et al. (FeCGAN) [91] show a shift from creating general-purpose frameworks to developing highly specialized solutions for specific algorithmic, data, and domain challenges. ELXGB provides a highly secure and efficient protocol specifically for training XGBoost models, a widely used model type where secure non-linear operations are a major hurdle [90]. FeCGAN tackles the fundamental problem of insufficient sample overlap by using a distributed generative model to augment the client datasets themselves [91]. These two approaches are complementary, and a system could potentially use FeCGAN for data augmentation before applying a secure training protocol like ELXGB. Yan et al.’s Fed-CRFD [93] showcases a complex domain challenge in medical imaging by redesigning the model architecture to include feature disentanglement, creating a shared representation space from cross-modal data [93]. While all three aim to enhance VFL’s practicality, their approaches are fundamentally different: ELXGB customizes the process, FeCGAN enhances the data, and Fed-CRFD re-engineers the model. Together, these papers illustrate a shift towards building VFL frameworks that will likely focus less on foundational protocols and more on their sophisticated integration with specific machine learning paradigms and the unique constraints of high-impact application domains.

6.1.4 Assessing Privacy-Communication-Utility Trade-Offs in VFL Deployment

Assessment of privacy-communication-utility trade-offs in real-world VFL deployments requires practitioners to evaluate three competing metrics simultaneously and their interdependencies. The reviewed VFL protocols illustrate a framework for such assessment: first, quantify computational cost by measuring per-round client-side overhead (seconds or CPU cycles) relative to baseline FedAvg, quantify communication cost as bandwidth consumed per round (kilobytes or reduction percentage), and quantify utility loss as accuracy or convergence degradation. Second, practitioners must recognize that trade-off severity is data- and model-dependent, not universal. For instance, HeteroVFL demonstrates that DP integration with

Practitioners deploying VFL should first define deployment constraints—acceptable accuracy loss threshold (typically 1%–5%), bandwidth budget (megabytes per round), device computational budget (seconds per round), and privacy requirements (threat model and sensitivity level)—then match these to frameworks optimized for those constraints. PraVFed’s 70.57% communication reduction is valuable only when bandwidth is the bottleneck; its memory overhead from embedding aggregation becomes prohibitive in cross-organizational settings with dozens of passive parties [85]. The assessment process should prioritize compression and selective privacy for non-sensitive model components rather than uniform heavyweight protection. Research on adaptive mechanisms Section 8.1.2 shows that risk-aware, dynamic privacy allocation achieves better privacy-utility balance than fixed-budget approaches across all training rounds [94,95]. Finally, evaluation must include realistic non-IID data splits and multi-round aggregation, as trade-offs under synthetic homogeneous splits diverge substantially from production deployments where client data distributions vary by order of magnitude and model degradation compounds across rounds.

6.2 Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL)

6.2.1 Architectural Advances in Hybrid and Heterogeneous Federated Learning

Yu et al. in 2025 [96] propose a communication-efficient hybrid federated learning framework designed for e-health applications where data exhibits a complex three-tier horizontal-vertical-horizontal distribution structure. The issue addressed is that existing Horizontal or Vertical Federated Learning (HFL/VFL) methods are inefficient for horizontal-vertical-horizontal structure, and either demand excessive communication of raw data for accuracy or suffer from poor model performance. The authors solve this by introducing a framework that has two aggregation phases and one intermediate result exchange. The vertically partitioned data between hospitals and patient-owned wearable devices is handled by exchanging intermediate results to train sub-models collaboratively without sharing raw data. A local aggregation phase at an edge node creates a unified device-side model to manage the first layer of horizontal partitioning across wearable devices within a single hospital’s purview to enhance training efficiency. Finally, a global aggregation phase handles the second horizontal partitioning layer across different hospital-patient groups to create a generalized model. This process is operationalized through a newly developed Hybrid Stochastic Gradient Descent (HSGD) algorithm. The paper provides a convergence analysis of the HSGD algorithm and uses the results to come up with three adaptive strategies for tuning crucial hyperparameters (aggregation intervals P and Q, and learning rate) to balance communication cost and model accuracy. However, the theoretical convergence proof is provided for the i.i.d., whereas experiments are run on non-IID data, the theoretical guarantees may not fully extend to these cases.

Peng et al. in 2024 [97] propose a Hybrid Federated Learning algorithm for Multimodal Internet of Things (IoT) Systems Hybrid Federated Learning Model (HFM) to address the challenge of efficiently training models on data that is distributed across both different devices (sample space) and different data types or sensors (feature space) under stringent resource constraints. The core problem is that the trade-off between the high computational demands of processing high-dimensional multimodal data such as images, audio, and sensor signals, and the limited memory and compute capabilities of IoT devices and edge servers along with complex data distribution, where data is partitioned both horizontally (across different locations or silos, such as households or factories) and vertically (across different sensor modalities, like cameras and microphones within a single silo), and made more difficult by the presence of non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data across silos. HFM solves this by creating a two-tiered federated system where it first applies Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) to train models on different data modalities, such as image, audio from different IoT devices without sharing raw data and distributing the computational load across the feature space (different modalities) within each silo such as household or factory, allowing IoT devices to process their own data modalities and share only embeddings. It then employs Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL) to aggregate the learned models from all the different ’silos’ (e.g., multiple households) to build a single global model. VFL partitions computing resources across feature spaces (modalities) among IoT devices within each silo, while HFL distributes learning across sample spaces (silos) via a global server. The paper provides a theoretical analysis, proving that the convergence of HFM depends on the frequency of VFL and HFL communications as well as the number of vertical and horizontal partitions, and it also empirically demonstrates that HFM outperforms baseline methods in terms of convergence rate and error on two public multimodal datasets. However, the current theoretical framework and experiments assume periodic synchronous updates and do not address potential real-world issues arising from heterogeneous IoT devices or modalities.

Yi et al. in 2023 [98] propose FedGH (Federated Global prediction Header), a framework for heterogeneous federated learning (FL) that addresses the challenge that traditional horizontal FL methods often require the server and clients to use the same model structure, which is impractical due to varying device capabilities. To solve this, FedGH allows each client to use a client-specific heterogeneous feature extractor while sharing a homogeneous global prediction header. During training, each client trains its local model and computes a local averaged representation (LAR) for each data class it possesses and uploads these to the server along with corresponding labels. The server aggregates LARs across clients to train a generalized global prediction header via gradient descent. This globally trained header, which encapsulates knowledge from all participating clients, is then distributed back to the clients, where the global header substitutes the local headers. This approach significantly reduces communication and computation cost by avoiding the transfer of large model parameters and instead sending only the small average representations. This method also strengthens privacy by sending only the abstract representation instead of more revealing data or model details, and does not depend on the availability of a public dataset as it trains the global prediction header using class-wise averaged representations from clients’ local data instead of requiring public data. The FedGH approach distinguishes feature extraction from prediction, which enables model heterogeneity and allows knowledge transfer through the shared header. Experimental results of FedGH show higher accuracy over state-of-the-art personalized FL methods, such as Federated Prototype Learning (FedProto), LG-FedAvg, on non-IID datasets, with up to 85.53% reduction in communication overhead. However, the authors acknowledge that creating a local averaged representation for a class with numerous data samples might lead to information distortion.

The advancements in HFL highlight a trend of dismantling rigid architectural assumptions in HFL to accommodate the profound heterogeneity of real-world applications. The works by Yu et al. [96] and Peng et al. [97] move beyond the pure HFL/VFL dichotomy by treating HFL and VFL not as monolithic options, but as modular components to be assembled based on the problem’s structure. Yu et al. design a specific three-tier H-V-H structure for e-health data [96], while Peng et al. propose a two-tiered VFL-within-HFL architecture for multi-modal IoT systems [97]. These frameworks highlight that as FL is applied to more complex scenarios, rigid distinctions between HFL and VFL are dissolving in favor of flexible, multi-layered designs. In contrast, FedGH [98] tackles heterogeneity at the model level by decoupling the model into a client-specific feature extractor and a shared global prediction header, which allows clients with varying resources to participate effectively using a highly communication-efficient knowledge transfer mechanism. These methodologies are potentially complementary; for instance, the HFL aggregation stage in the hybrid frameworks proposed by Yu et al. or Peng et al. could leverage a FedGH-like mechanism to allow participating silos to use different model architectures. Hybrid models offer tailored solutions for complex data distributions but increase architectural complexity, while FedGH elegantly solves model heterogeneity at the risk of information loss via its class-averaging mechanism.

6.2.2 Communication Optimization and Feature Selection in HFL

Banerjee et al. in 2024 [99] propose Fed-FiS and Fed-MOFS, two cost-efficient feature selection (FS) methods for horizontal federated learning (HFL), where clients share a common feature space but possess different data samples to address the challenge of identifying a relevant and non-redundant subset of features that can be commonly used across all clients to enhance global model performance to reduce training time and computational costs. The authors also point out that existing FS methods are designed for centralized systems, which fail to account for data heterogeneity and communication constraints in HFL systems where clients share a common feature space but suffer from statistical divergence and local feature selection bias. Fed-FiS utilizes mutual information (MI) to quantify feature relevance locally, and clustering for local feature selection at each client, which is followed by a global ranking based on aggregated feature importance scores. Fed-MOFS extends this with multi-objective optimization (Pareto optimization) to explicitly maximize feature relevance, minimize redundancy, and client-specific variations during global selection, which results in a globally ranked feature set derived from Pareto fronts. The paper evaluates both models on diverse datasets such as NSL-KDD99, IoT, and credit scoring under IID/non-IID distributions, and demonstrates efficiency by achieving a 50% reduction in feature space and twice the speedup of comparable methods with improved accuracy and convergence. However, the dependency on mutual information measures may introduce computational overhead on client devices.