Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhanced Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Lightweight Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection

1 School of Electronic and Optical Engineering, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210094, China

2 School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

3 School of Electronic and Optical Engineering, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210094, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuwen Qian. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 90 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073700

Received 23 September 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Deep learning has made significant progress in the field of oriented object detection for remote sensing images. However, existing methods still face challenges when dealing with difficult tasks such as multi-scale targets, complex backgrounds, and small objects in remote sensing. Maintaining model lightweight to address resource constraints in remote sensing scenarios while improving task completion for remote sensing tasks remains a research hotspot. Therefore, we propose an enhanced multi-scale feature extraction lightweight network EM-YOLO based on the YOLOv8s architecture, specifically optimized for the characteristics of large target scale variations, diverse orientations, and numerous small objects in remote sensing images. Our innovations lie in two main aspects: First, a dynamic snake convolution (DSC) is introduced into the backbone network to enhance the model’s feature extraction capability for oriented targets. Second, an innovative focusing-diffusion module is designed in the feature fusion neck to effectively integrate multi-scale feature information. Finally, we introduce Layer-Adaptive Sparsity for magnitude-based Pruning (LASP) method to perform lightweight network pruning to better complete tasks in resource-constrained scenarios. Experimental results on the lightweight platform Orin demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms the original YOLOv8s model in oriented remote sensing object detection tasks, and achieves comparable or superior performance to state-of-the-art methods on three authoritative remote sensing datasets (DOTA v1.0, DOTA v1.5, and HRSC2016).Keywords

With the development of deep learning, the application of this technology to object detection in remote sensing images has garnered widespread attention, this field is referred to as object detection in remote-sensing images [1] (RSIs). Deep learning techniques demonstrate advantages such as high accuracy and efficiency in detecting task-specific targets [2–4]. However, remote sensing object detection presents distinct challenges that critically differ from general object detection. These stem from the aerial perspective and stringent deployment constraints. Firstly, images exhibit extreme scale variations, containing objects from tiny vehicles to massive structures like airports. Secondly, objects appear with arbitrary orientations, making traditional Horizontal Bounding Boxes (HBBs) highly inefficient for elongated targets like ships and bridges, as they encompass excessive background and cause feature contamination. This necessitates Oriented Bounding Boxes (OBB). Thirdly, the prevalence of small objects in complex backgrounds leads to high miss-detection rates, as their limited pixel information is easily overwhelmed. Finally, a critical paradox exists for deployment on resource-constrained platforms like drones and satellites. While traditional two-stage detectors are computationally prohibitive, existing lightweight models often achieve efficiency by sacrificing accuracy, particularly for the very challenges of oriented and small objects.

Recent advances in convolutional neural networks have significantly improved object detection performance in natural images. However, remote sensing images present unique challenges that distinguish them from conventional computer vision tasks. These challenges include extreme variations in object scales, ranging from small vehicles occupying less than 10 × 10 pixels to large infrastructure spanning hundreds of pixels. The diverse orientations of objects, particularly in aerial imagery, necessitate the development of oriented bounding box (OBB) detection methods rather than traditional horizontal bounding boxes.

Furthermore, the deployment of deep learning models in remote sensing scenarios often occurs on resource-constrained platforms such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and edge computing devices. This constraint demands lightweight architectures that maintain high detection accuracy while minimizing computational overhead and memory footprint. Traditional two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN, while achieving high accuracy, are computationally intensive and unsuitable for real-time applications in remote sensing contexts.

In recent years, researchers have made significant progress in the field of remote sensing object detection. LSKNet [5] proposes a lightweight Large Selective Kernel Network backbone for remote sensing images, leveraging valuable prior knowledge and dynamically adjusting its spatial receptive field to achieve state-of-the-art performance in classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation tasks. MPS-YOLO [6] uses a multiscale fusion network combining pixel shuffle with YOLO to enhance detection accuracy and robustness for similar and multiscale aerial targets. YOLO-RSA [7] model improves ship detection with a backbone network, multi-scale pyramid and rotated detection head. In [8], an end-to-end dense attention fluid network (DAFNet) is proposed, which includes a global context-aware attention (GCA) module to capture remote semantic context relationships. The GCA module reinforces significant feature embedding and addresses scale change through a cascading pyramid attention framework. AAM and RRM [9] achieved accurate extraction of remote sensing target features by dynamically adjusting the detection angle. Some of researchers use Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with extra structure, a asymmetric cross-attention hierarchical network [10] has been proposed by combining CNNs with transformer-based cross-attention mechanisms to solve the problem of fragmented local-global feature relationships in bitemporal remote sensing image change detection, Liao Li et al. proposed an improved Faster R-CNN [11,12] by introducing a semi-supervised learning structure to mitigate the impact of scarce labeled data in SAR remote sensing target detection. Li Q et al. proposed a transformer-with-transfer-CNN model which embeds a transfer learning-based CNN backbone to strengthen the model’s ability to capture fine-grained features of remote sensing targets. Others try to improve loss functions such as Gaussian Wasserstein Distance (GWD) [13] and Kalman Filter-based Intersection over Union (KFIoU) [14]—both methods refine the calculation logic of bounding box similarity, effectively solving the problem of low regression precision of traditional loss functions for irregularly oriented remote sensing targets.

Despite these advances, several limitations persist. Current lightweight methods often sacrifice detection accuracy for computational efficiency, particularly failing to adequately handle small objects that are prevalent in remote sensing images. Multi-scale feature fusion techniques frequently suffer from semantic conflicts when directly merging features from different levels, leading to suboptimal performance. Additionally, most existing approaches are not specifically designed for the elongated objects commonly found in remote sensing scenarios, such as ships, bridges, and runways.

To address these limitations, this paper makes the following contributions:

1. Dynamic Snake Convolution Integration: We introduce Dynamic Snake Convolution (DSC) into the YOLOv8s backbone network to enhance feature extraction capabilities for elongated objects commonly found in remote sensing images, addressing the limitation of traditional 3 × 3 convolutions in capturing slender target structures.

2. Feature Focus and Diffusion Pyramid Network (FDFPN): We propose a novel FDFPN module that effectively integrates multi-scale feature information while preventing semantic conflicts through structured feature focusing and controlled diffusion across detection scales.

3. Lightweight Optimization Strategy: We implement the LASP for magnitude-based Pruning (LASP) method to achieve model compression while maintaining detection accuracy, enabling deployment on resource-constrained edge computing platforms.

4. Comprehensive Experimental Validation: We demonstrate superior performance on three authoritative remote sensing datasets (DOTA v1.0, DOTA v1.5, and HRSC2016) and successful deployment on NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin platform, achieving significant improvements over baseline methods.

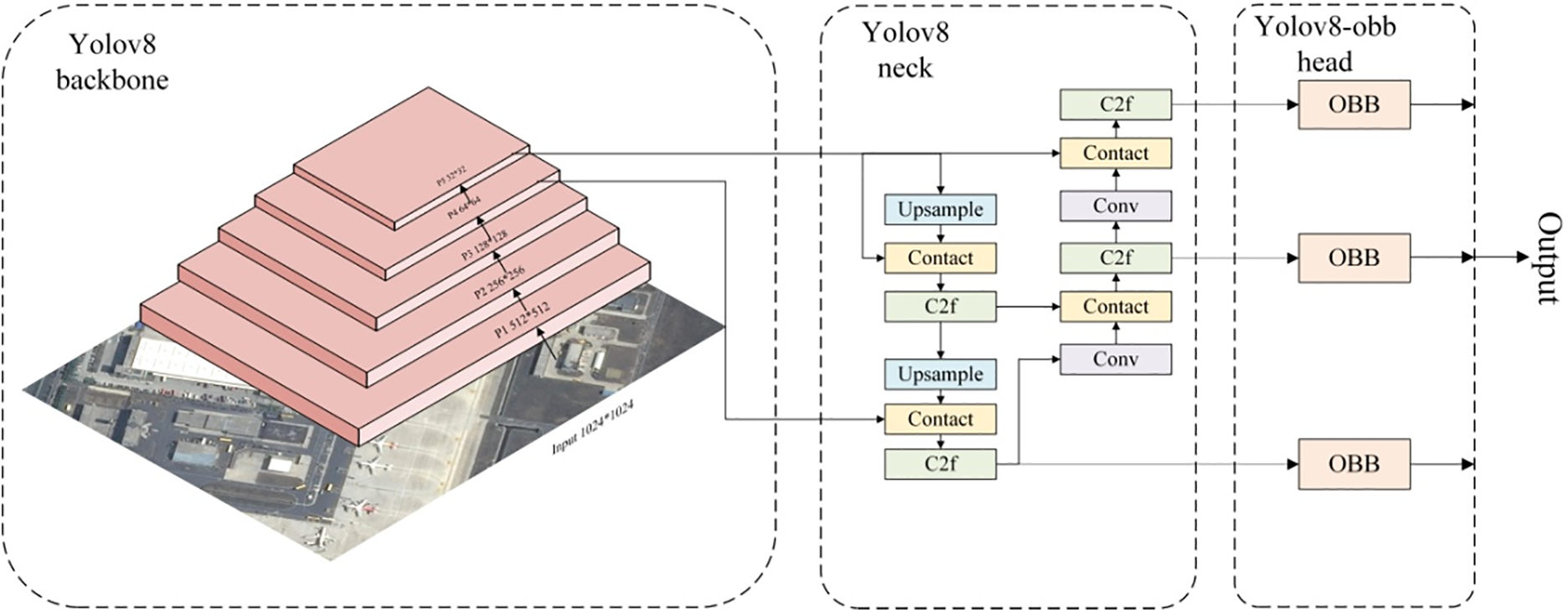

The YOLOv8-OBB model builds upon YOLOv8 by modifying the head section. It retains the decoupled head design while introducing an additional detection head for predicting rotation angles. Unlike traditional Horizontal Bounding Boxes (HBB), this model utilizes Oriented Bounding Boxes (OBB) for dataset annotation. The OBB annotation format follows the following structure:

When identifying densely arranged slender objects, traditional models using Horizontal Bounding Boxes (HBB) often cover extensive background areas, leading to decreased accuracy. In contrast, Oriented Bounding Boxes (OBB) effectively address this issue. To better detect rotated bounding boxes, YOLOv8-OBB adopts the Probabilistic Intersection over Union (ProbIoU) loss function, replacing the traditional CIoU.

The key advantage of this approach is its ability to more accurately detect and localize objects that are rotated or oriented at various angles, particularly in scenarios with densely packed or elongated objects. By using an oriented bounding box approach, the model can more precisely capture the actual shape and orientation of objects, reducing unnecessary background coverage and improving overall detection accuracy.

The ProbIoU [15] loss function represents a more sophisticated method of calculating object overlap, taking into account the probabilistic distribution of points within bounding boxes, which allows for more nuanced and accurate object detection compared to traditional intersection methods.

The structure of the YOLOv8-obb model is depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Structure of YOLOv8-obb

Layer-Adaptive Sparsity for the Magnitude-based Pruning introduces a layer-adaptive sparsity approach for neural network pruning that dynamically allocates compression rates across layers based on their sensitivity. Traditional magnitude-based pruning methods apply uniform sparsity thresholds, often leading to suboptimal accuracy-compression trade-offs [16,17]. The proposed method formulates pruning as an optimization problem:

where

combining weight-gradient interactions and weight distribution characteristics. Layer sparsity budgets are initialized proportionally to inverse sensitivity:

The pruning process iteratively removes smallest-magnitude weights within each layer’s budget:

where thresholds

maintains architectural coherence by penalizing extreme sparsity differences between connected layers. The complete algorithm alternates between pruning and fine-tuning phases, with dynamic budget adjustments based on validation performance. This automatically discovers optimal sparsity patterns—for example, compressing early convolutional layers more aggressively than critical attention layers in transformers.

The method’s efficiency comes from computing sensitivity scores once during initialization and updating them sparingly. Theoretical analysis shows the sensitivity metric approximates layerwise Lipschitz constants, explaining its effectiveness in preventing excessive pruning of critical layers. Practical implementations use stochastic approximations for memory efficiency and impose maximum per-layer sparsity constraints to prevent overpruning.

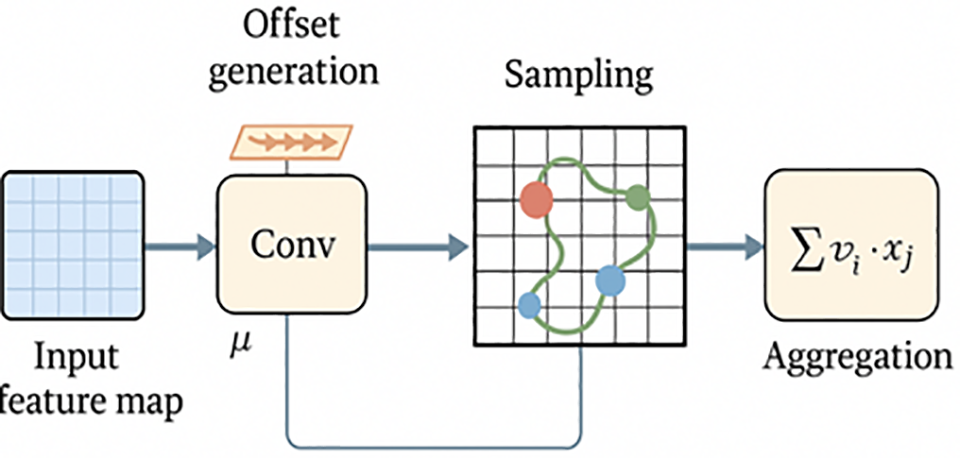

3.1 Dynamic Snake-Shaped Convolution

Dynamic Snake Convolution represents a significant departure from traditional fixed-kernel convolutions. Traditional convolutions apply the same kernel pattern across all spatial locations, which is suboptimal for objects with complex geometric structures. The theoretical foundation of DSC lies in deformable convolution theory, where the sampling locations are augmented with learnable offsets, as shown in Fig. 2. While standard deformable convolutions (e.g., DCNv2) introduce learnable offsets to sampling points, they lack explicit topological continuity control, often causing irregular deformation and feature diffusion when applied to elongated targets. Our DSC introduces snake-shaped iterative offset generation with directional continuity constraints, ensuring the receptive field follows the geometric contour of elongated objects. Unlike segmentation-focused Snake Conv, which models boundaries pixel-wise, DSC is lightweight and integrated into YOLO’s C2f bottleneck, enabling efficient learning of geometry-aware features at the detection backbone level.

Figure 2: step-by-step schematic of offset generation and sampling

Let the input feature map be denoted as

where R represents the receptive field (typically 3 × 3), and

During training, the gradients of the loss with respect to the offsets

The key innovation of DSC lies in its systematic approach to generating these offsets, ensuring continuity and preventing excessive displacement that could lead to feature diffusion.

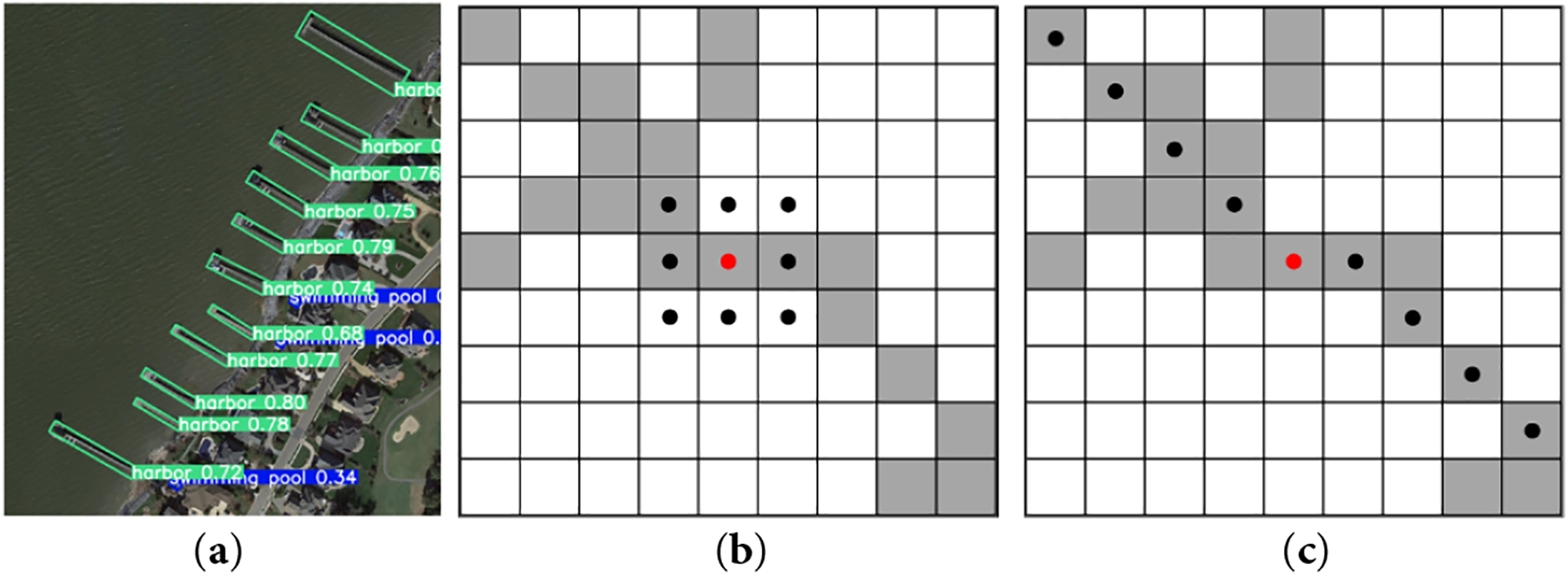

In this section, we delve into the combined application of the Dynamic Snake Convolution module [18] with the C2f module in the backbone network. This module effectively enhances feature extraction of slender and small objects commonly found in remote sensing images. The bottleneck part of the C2f module in the YOLOv8 model typically employs a standard 3 × 3 convolution kernel with both stride and padding set to 1. However, due to the limited size of slender objects in remote sensing tasks (such as ships and ports), as shown in Fig. 3a, traditional 3 × 3 convolutions inevitably struggle to capture specific structures, often resulting in convolution kernels operating entirely outside the object, as illustrated in Fig. 3b.

Figure 3: (a) Example Image of Slender Small Targets; (b) Receptive field of traditional 3 × 3 convolution on slender small targets; (c) Performance of Dynamic Snake Convolution on slender small targets

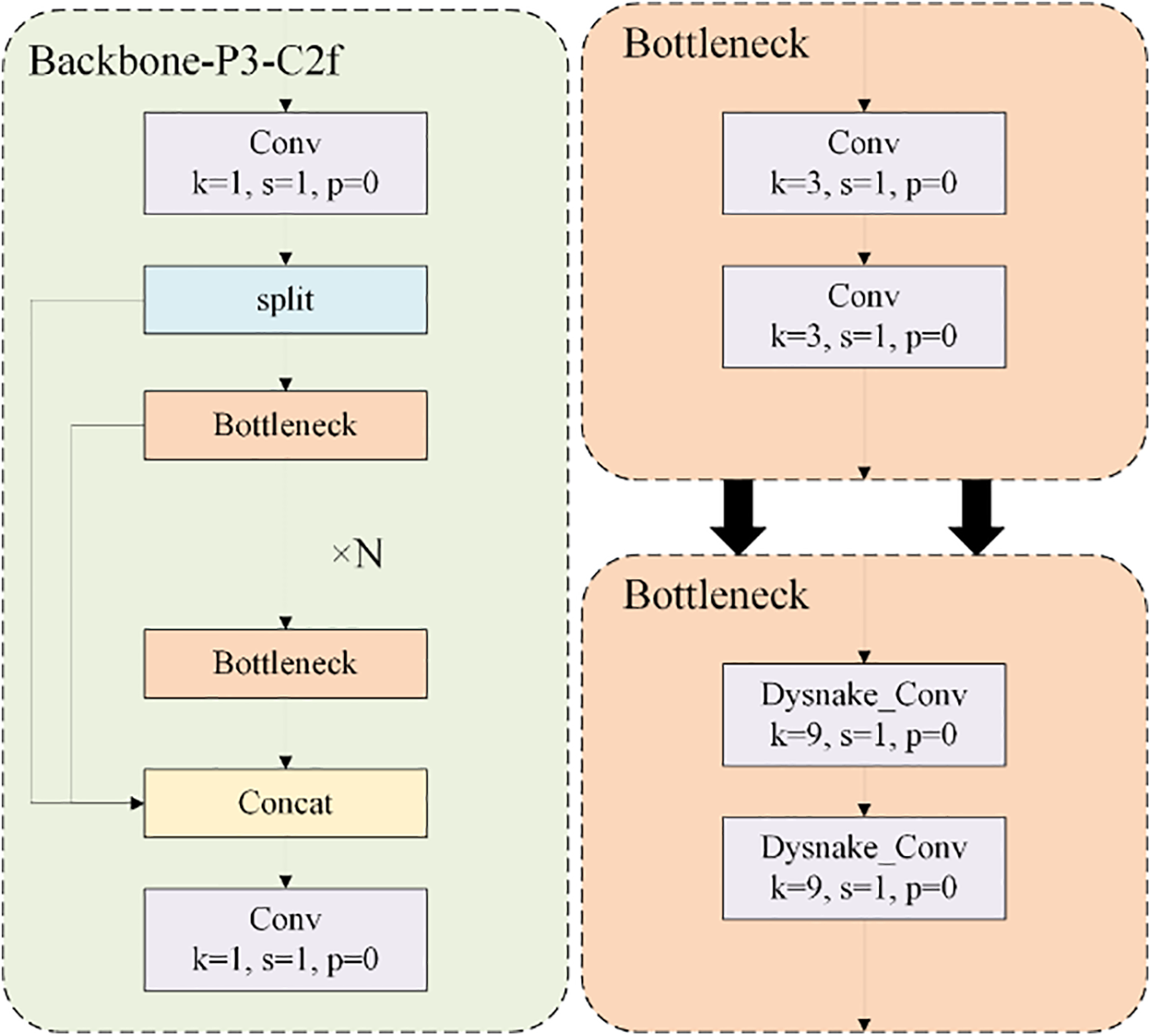

To enhance the perceptual flexibility of convolutional kernels towards complex geometric features of targets, we introduced the Dynamic Snake Convolution in the C2f module of the P3 layer, where features are most refined in the backbone. This replacement structure is illustrated in Fig. 4. The method employs iterative strategies, sequentially selecting the next position of each target for observation. This ensures continuity of attention while preventing excessive displacement of deformable convolutions that could otherwise diffuse the receptive field too widely.

Figure 4: The improved convolution in bottleneck with the dynamic serpentine convolutional kernel adopting dynamically deformable structure

In the Dynamic Snake Convolution, we utilize a 9 × 9 convolutional kernel that elongates traditional 3 × 3 convolutions along the x and y axes. Taking the central point

In which

Due to the offset Δ typically being non-integer, it is represented in bilinear interpolation as:

where

Eqs. (8) and (9) describe directional offset accumulation along the snake trajectory, where each kernel position is adaptively updated from the previous one to maintain spatial continuity. Eq. (10) defines bilinear interpolation for non-integer offset sampling, ensuring smooth feature extraction across the deformable grid. Eqs. (11) and (12) further decompose the interpolation kernel into two orthogonal 1D filters, enabling efficient implementation on modern GPUs.

As shown in Fig. 3c, due to changes in the x and y axes, the dynamic serpentine convolutional kernel covers a receptive field of 9 × 9 during the deformation process. The dynamic serpentine convolutional kernel aims to utilize a dynamically deformable structure to better adapt to the structure of elongated small objects, thereby improving feature perception of the target and ultimately enhancing accuracy.

3.2 Feature Focus and Diffusion Pyramid Network

The Feature Pyramid Network [19] (FPN) employs a pyramid structure to fuse features from different levels, mitigating information diffusion to some extent. However, directly merging information extracted from different levels can lead to semantic conflicts, restricting the representation of features for small objects and potentially causing feature loss within the information flow. Therefore, we start from the concept of the pyramid network, develop a module called Feature Focus Module that can capture the information of different gradient flows, enhance object detection across different scales. Meanwhile, to prevent information loss of small targets, we improve the structure of the neck part, called diffusion structure.

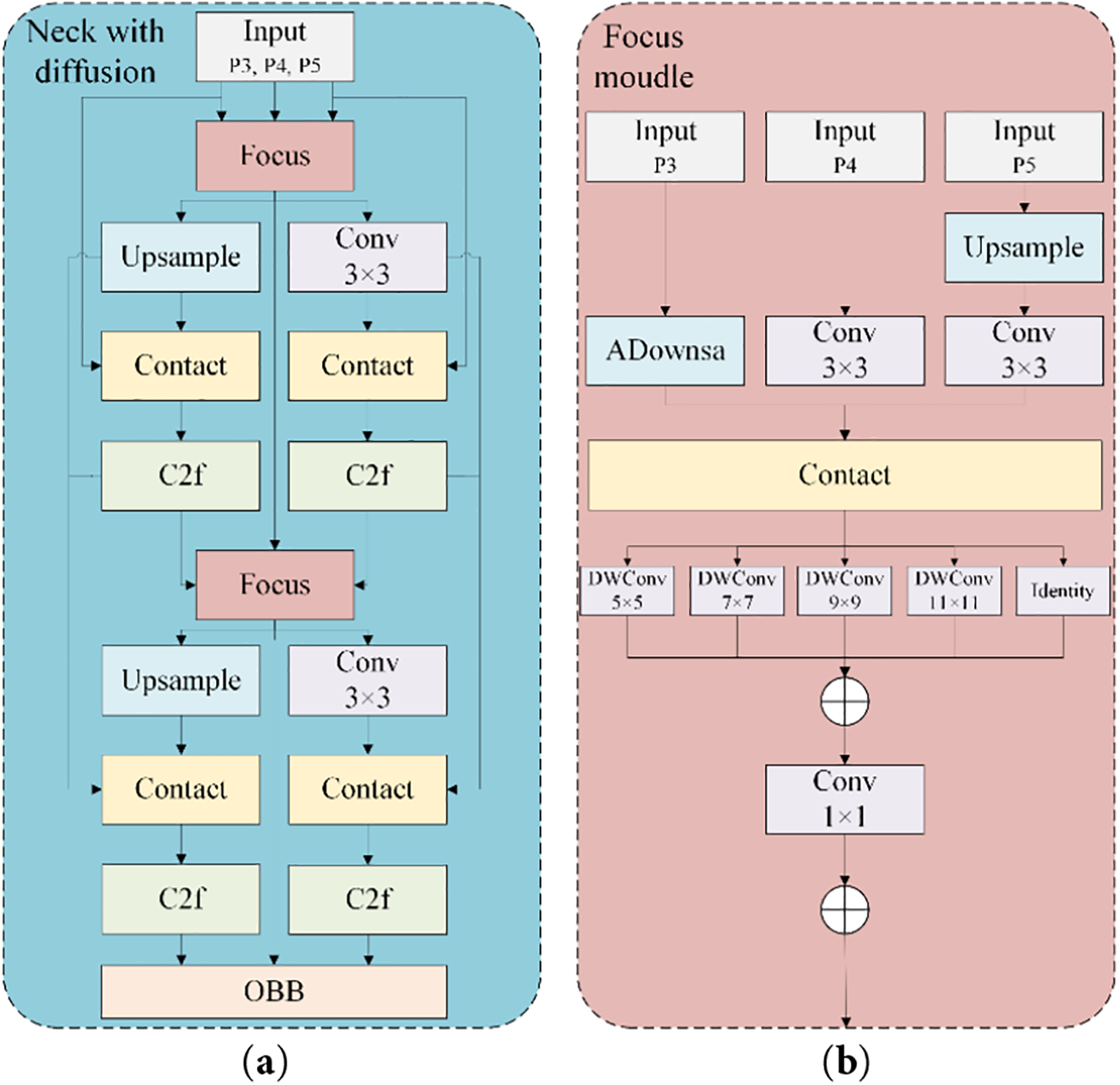

To address the semantic confusion caused by the fusion of features from different layers, we introduce a structured Feature Pyramid Network that first concentrates rich contextual information using the Feature Focus Module before diffusing it across various detection scales. The overall network framework is illustrated in Fig. 5a, while the structure of the Feature Focus Module is depicted in Fig. 5b. We refer to the two together as FDFPN (Feature Focus and Diffusion pyramid network).

Figure 5: Structure diagram of the FDFPN with detailed component annotations. (a) Structure of the part of neck with diffusion; (b) Structure of the focus module

Note that conventional pyramid-based fusion (FPN, PANet, BiFPN, HRNet) simply merges feature maps of different semantic levels, which may cause semantic inconsistency between high- and low-level features. However, the proposed FDFPN resolves this through a two-stage strategy: (1) Feature Focus Module: employs Asymmetric Downsampling (ADownsample) and multi-kernel receptive field enhancement to unify gradient flows before fusion. (2) Feature Diffusion Stage: redistributes the processed multi-scale information across detection heads, preserving contextual coherence while reducing small-object feature loss. This “focus–then–diffuse” design ensures structured, non-conflicting semantic integration, unlike PANet’s direct top-down fusion or BiFPN’s repeated bidirectional fusion that may blend inconsistent semantics.

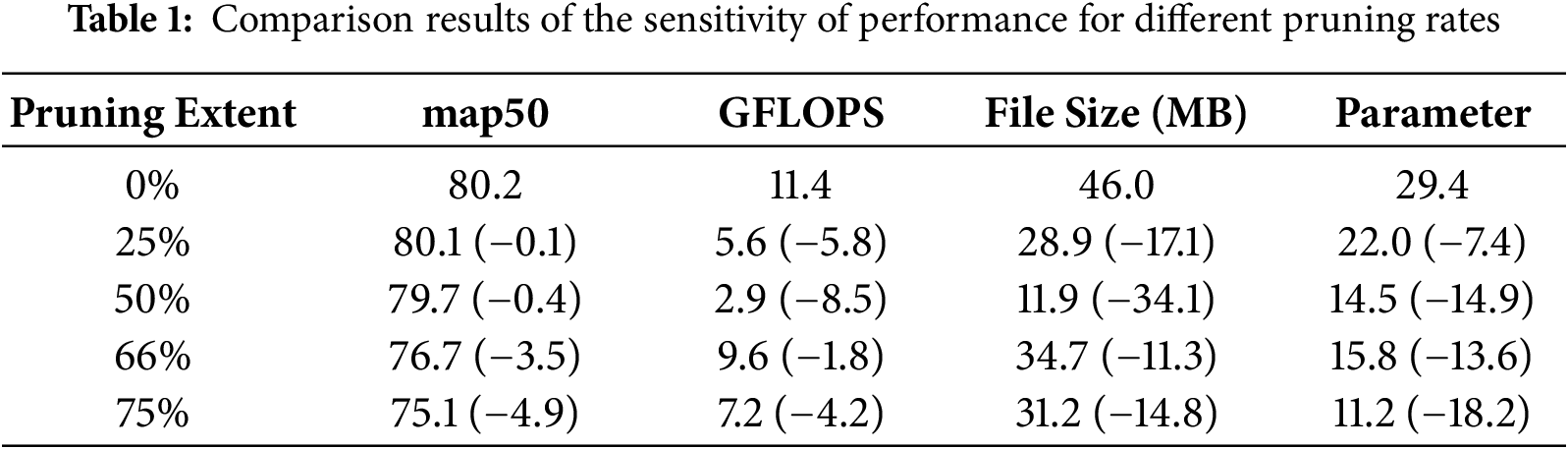

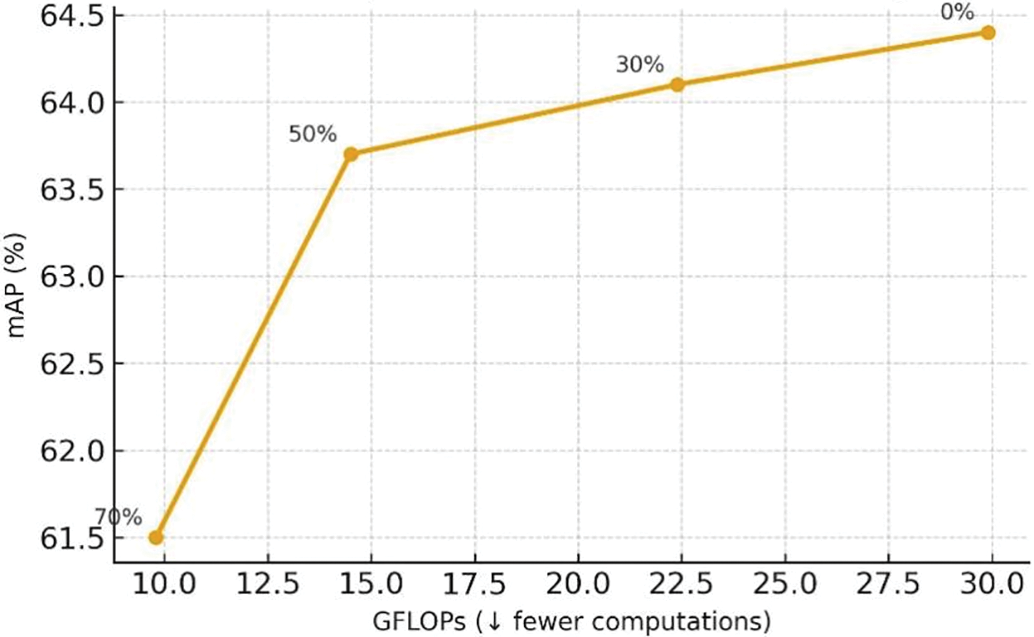

As shown in Table 1, performance remains stable up to 50% pruning, demonstrating that the proposed LASP (Layer-Adaptive Sparsity Pruning) effectively preserves essential layer information. Beyond 75%, accuracy degradation becomes more significant due to over-pruning of feature-sensitive layers.

The Focus module consists of three key technical components: a multi-scale feature preprocessing unit, a multi-kernel receptive field enhancement mechanism, and a feature residual aggregation network. In the multi-scale feature preprocessing unit, the input input three different scale feature maps from three different backbone network feature extraction layers P3, P4, P5, and the extraction strategy for small targets is used in the unit to accurately realize the unification and reconstruction of feature dimensions. In the feature preprocessing stage, the module introduces an asymmetric down-sampling (ADownsample [20]) sub-module, which is a significant breakthrough in the traditional down-sampling method. Traditional downsampling methods such as Max pooling and fixed-step convolution often face serious information loss problems. ADownsample effectively alleviates this key challenge through complex channel segmentation and heterogeneous processing mechanisms.

Specifically, ADownsample splits the input feature map evenly by channel, and uses two parallel branches to process it simultaneously. One is a 3 × 3 convolution with a step size of 2 to realize the nonlinear transformation of features. In the other way, the Max pooling is performed first, and then the features are recali-fied by 1 × 1 convolution, and all the features are integrated and fused. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

where

The multi-kernel receptive field enhancement mechanism is a set of multi-core parallel deep convolutions, and the design refers to the traditional Inception-Style method. Inception-style is a widely used feature extraction design pattern in deep convolutional neural networks, originally derived from the Inception network architecture proposed by Google. The core idea is to use multiple kernels of different sizes at the same level (e.g., 1 × 1, 3 × 3, 5 × 5) and concatenate the feature maps of these parallel branches together. In a large number of experiments, the module can effectively enhance the feature expression ability, improve the network receptive field, reduce the computational complexity and reduce the number of parameters.

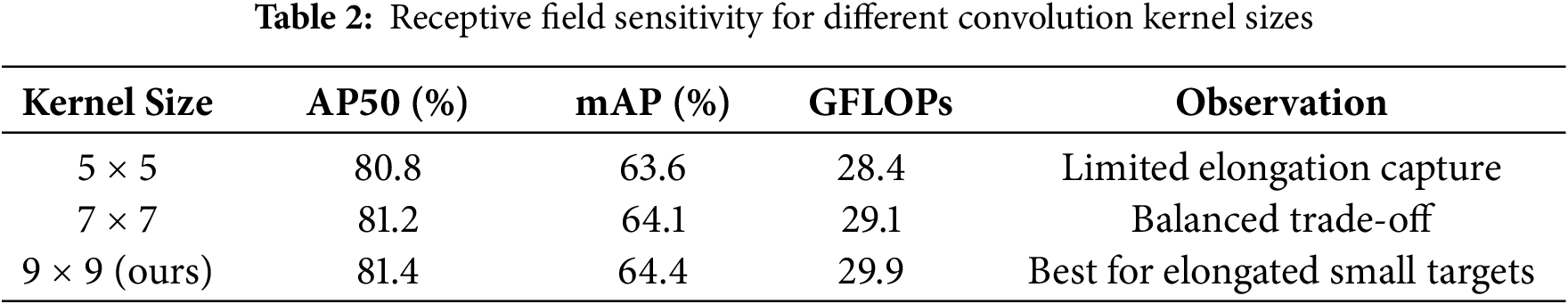

In our Focus module, depthwise separable kernels of size 5 × 5, 7 × 7, 9 × 9, and 11 × 11 and an Identity map are used to simultaneously capture feature details from multiple receptive field scales. This multi-scale receptive field strategy is essentially a systematic expansion of the perception ability of convolutional neural networks, and its mathematical expression is as follows.

where

As shown in Table 2. The results confirm that larger receptive fields improve the model’s ability to capture slender structures (e.g., ships, bridges) without causing feature diffusion. Thus, the 9 × 9 kernel was adopted as the optimal configuration for the remote sensing scenario.

The feature residual aggregation network adopts the residual connection method, which not only retains the essential information of the original features, but also effectively alleviates the gradient disappearance and stabilizes network training. Moreover, the network structure also uses point-by-point convolution to realize the dynamic recaliberation of features. The specific mathematical expression is as follows:

where

After using the Focus module to gather rich context information for preprocessing, its results and the feature information of the backbone network are diffused to various detection scales. This architecture enables the feature fusion

The computational cost of the proposed FDFPN, specifically its Focus module, is dominated by the Multi-Kernel Receptive Field Enhancement mechanism. The use of depthwise separable convolutions here is critical for efficiency. The total number of Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) for this part can be approximated as:

where

Our model was experimentally evaluated on three representative publicly available remote sensing image datasets.

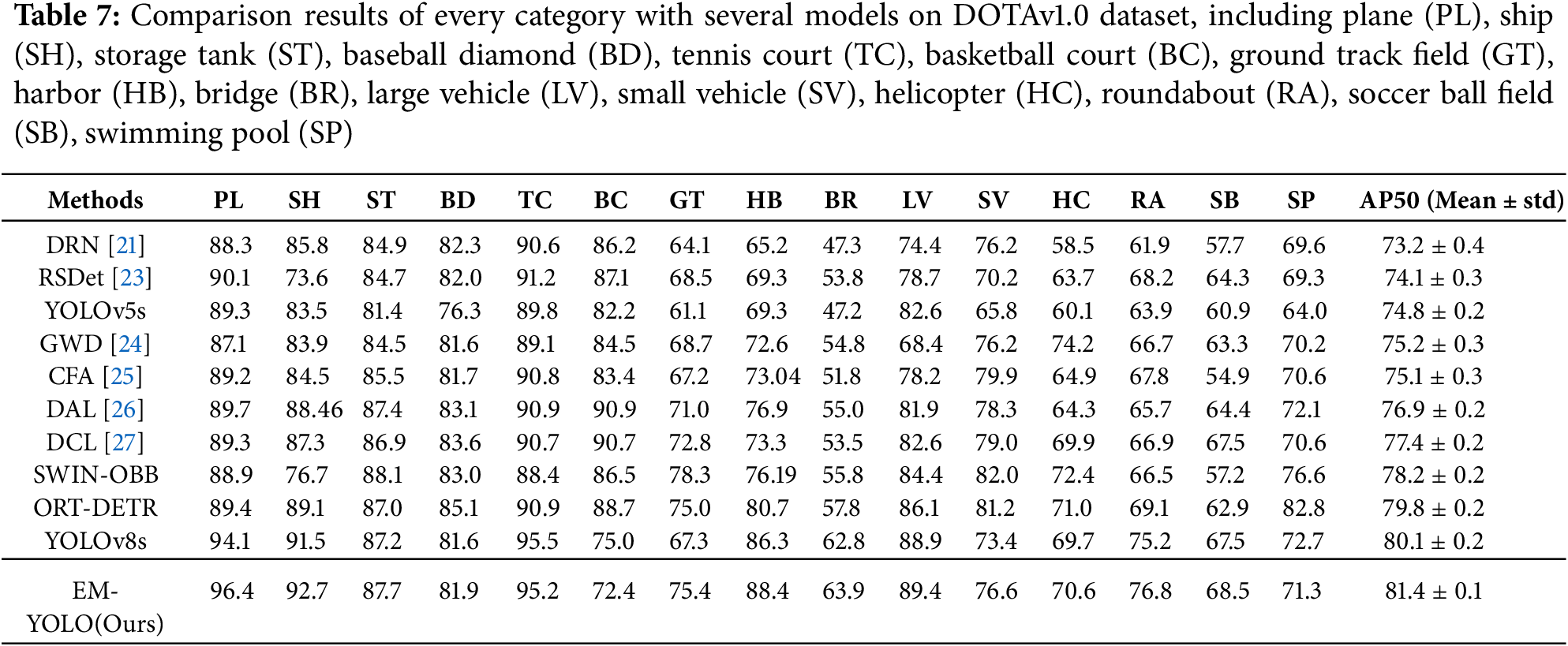

DOTA-v1.0 [21] is a specialized dataset for remote sensing detection, which contains 2806 images with 188,282 instances and 15 common categories, including plane (PL), ship (SH), storage tank (ST), baseball diamond (BD), tennis court (TC), basketball court (BC), ground track field (GT), harbor (HB), bridge (BR), large vehicle (LV), small vehicle (SV), helicopter (HC), roundabout (RA), soccer ball field (SB), swimming pool (SP). The size of image ranges from 800 × 800 to 4000 × 4000 pixels. The dataset is comprised of 1,411,458 instance, and 937 images for train, validation and test. DOTA utilizes Oriented Bounding Boxes (OBB) for annotation, which are represented by rotated rectangles encapsulating objects regardless of their orientation. This method ensures that objects, whether small or at different angles, are accurately captured.

DOTA-v1.5 increased its difficulty based on DOTA-v1.0. The dataset reserves all the images and instances in DOTA-v1.0, at the same time very small instances (less than 10 pixels) are also annotated, a new category “container crane” is added.

HRSC2016 [22] is a remote sensing dataset for ship detection contains 1061 aerial images whose size ranges from 300 × 300 and 1500 × 900. The images splits into 436/181/444 for train/validation/test.

To ensure a fair comparison, both the baseline model (YOLOv8s-OBB) and our proposed EM-YOLO network were implemented in PyTorch and trained with identical parameter settings and training strategies, unless otherwise specified. The detailed configurations are as follows:

The baseline model refers to the standard YOLOv8s architecture with an oriented bounding box (OBB) detection head, as described in Section 2.1. For both models, we resized the image to 1024 × 1024 in DOTA-v1.0 and DOTAv1.5, and to 800 × 800 in HRSC2016, all categories in the HSCR2016 dataset are grouped into SHIP. The dataset was partitioned into images of equal size to ensure consistent training quality. Each pair of images had a 200-pixel overlap to minimize omission of edge objects. The model was trained on a Linux operating system using GPU (A800 PCIe), with a batch size set to 8. Initially, the learning rate was set at 0.01. We trained the model for 200 epochs on the DOTAv-1.0 and DOTA-v1.5 datasets, and for 100 epochs on the HRSC2016 dataset. Weight decay and momentum were set at values of 0.0001 and 0.9, respectively.

The innovations of our EM-YOLO, namely the Dynamic Snake Convolution and the FDFPN module, were integrated into this shared training framework. In the pruning process, the pruning rate was set to 2.0, that is, the number of parameters of the model was reduced to 50% of the original, the maximum number of pruning arguments was set to 500 rounds, and the pruning was stopped when the pruning rate reached the setting. After the pruning, in order to restore the model performance, the pruned model was fine-tuning for 200 rounds on the DOTAv-1.0 dataset to achieve a trade-off between model size and detection accuracy.

After that, in order to verify the reliability of the model on the platform with limited computing resources, we deployed it on the microcomputer NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin shown in Fig. 6, which is an edge computing platform with a small size of 110 mm × 109 mm × 70 mm, supports 8 MB L2 cache and 4 MB L3 cache, 64 GB of LPDDR5 memory, and 64 GB of eMMC 5.1 storage.

Figure 6: NVIDIA Jetson AGX orin

In terms of software ecosystem, Jetson AGX Orin ships with the NVIDIA JetPack SDK, a comprehensive development environment built on the Ubuntu Linux operating system. JetPack includes the CUDA 11.x toolkit, which provides GPU-accelerated computing. cuDNN library to optimize deep neural network operations TensorRT inference engine, which optimizes trained models for maximum efficiency and VPI (Vision Programming Interface), which speeds up computer vision tasks.

The experimental results use mean average precision (mAP) and precision when IoU = 0.5 (AP50) as the main evaluation indicators of the model performance. Both are calculated as follows, where

In the above formula,

In addition, we use GFLOPS (Giga Floating Point Operations Per Second) and Parameters to quantitatively describe deep learning models from two dimensions: computational complexity and model scale. GFLOPS measures the computational intensity of a model, representing the number of billions of floating-point operations the model can perform per second. It is an important indicator for evaluating the computational resource requirements of a model during both the inference and training stages. This indicator is directly related to the real-time performance and energy efficiency of the model, and it holds significant reference value for model deployment in resource-constrained scenarios, such as remote sensing detection scenarios.

Parameters (the number of parameters) quantifies the complexity and capacity of a model, representing the total number of trainable weights in a neural network, typically measured in millions (M) or billions (B). The number of parameters not only reflects the storage requirements and memory footprint of the model but also indirectly influences its expressive power and the risk of overfitting. A comprehensive analysis of these two indicators helps in gaining an in-depth understanding of the computational efficiency and architectural characteristics of the model, providing a scientific basis for model selection and optimization.

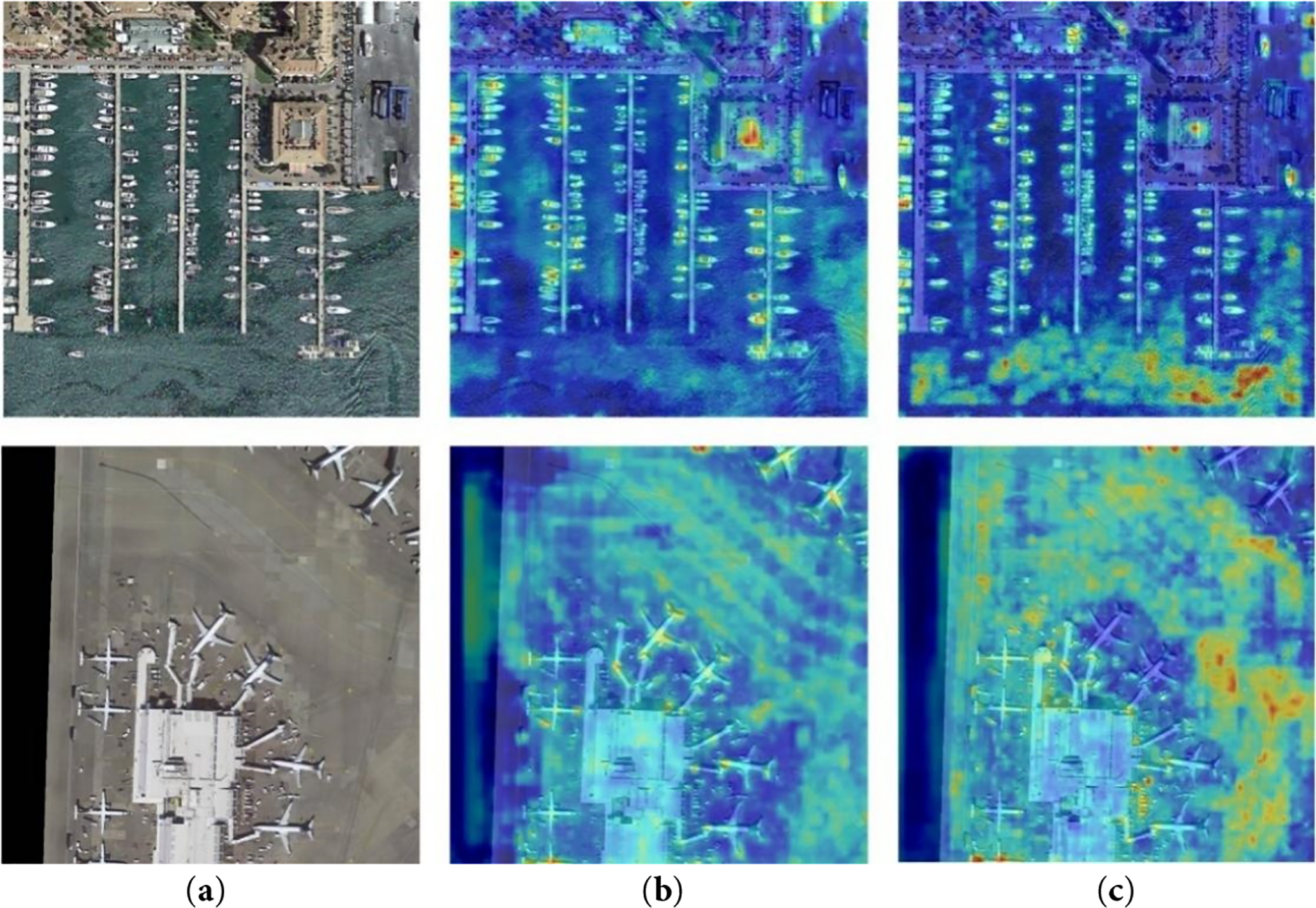

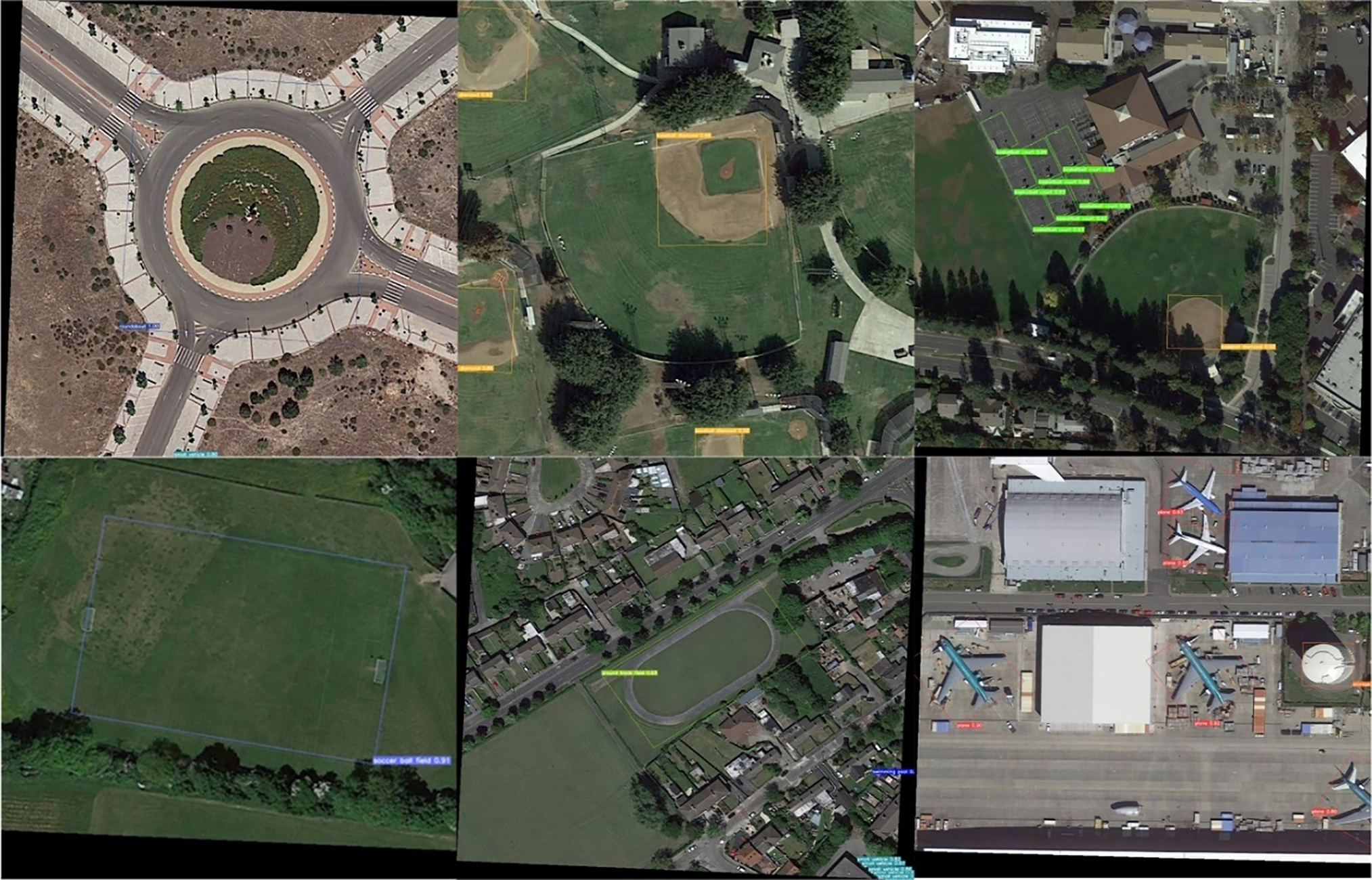

The visualization results of EM-YOLO are shown in Fig. 7. We employ heatmaps to intuitively present the model’s prediction confidence by mapping the probability of object presence at each location in the image to heat values of varying intensities. The model scans and scores different regions of the input image using a sliding window approach, ultimately generating a complete heat distribution map. In the heatmap, areas with brighter or more reddish colors indicate higher probabilities of object presence, while darker or more bluish areas suggest lower possibilities of object existence.

Figure 7: Heatmap comparison results on DOTAv1; (a) Origin image; (b) Our model; (c) YOLOv8s

Through heatmap analysis, it is clearly evident that our improved model demonstrates significant advantages in small object detection. As shown in Fig. 7c, the right column displays the attention distribution of the original model, where due to dispersed attention, some small objects with less prominent features failed to be effectively detected. In contrast, the middle column shows the detection results after integrating the DSC and FDFPN modules, where it can be clearly observed that the improved model better focuses on small object regions while effectively reducing the interference of background features on detection.

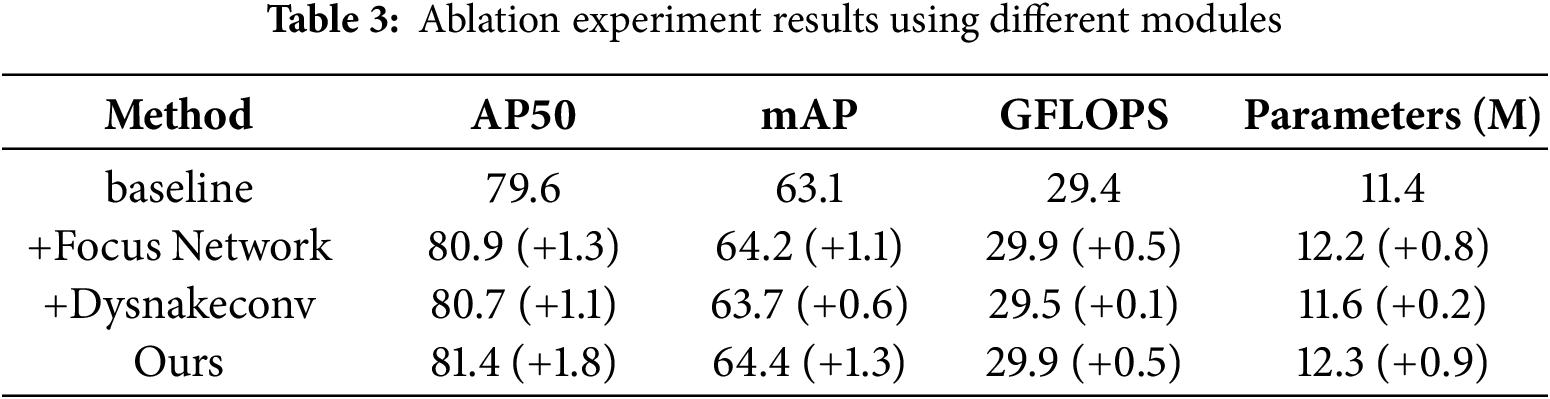

We set the performance of YOLOv8s-obb on DOTAv1 as the baseline and conducted ablation experiments using the two modules proposed in this paper. The results in Table 1 show that our two improvements over the baseline model yield significant gains in both AP50 and mAP, common metrics for object detection. Although the overall gain of the DSC module is slightly lower than that of the Focus module, it obviously has higher gain when the two are fused due to its special promotion for the elongated targets common in remote sensing datasets.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed modules, we conducted ablation experiments, as shown in Table 3, our method has advantages in enhancing oriented object detection accuracy while maintaining efficiency.

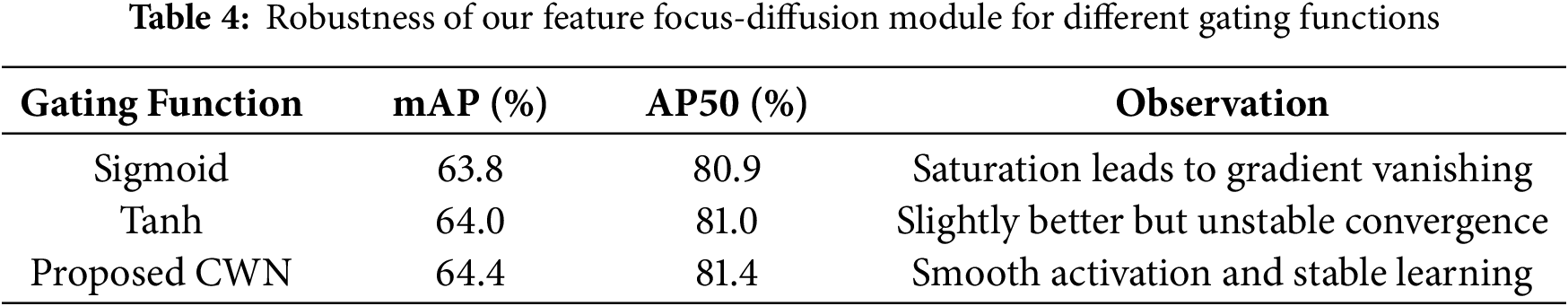

As shown in Table 4, the CWN gating mechanism achieves the best balance between stability and performance by avoiding gradient saturation while maintaining semantic consistency across feature levels.

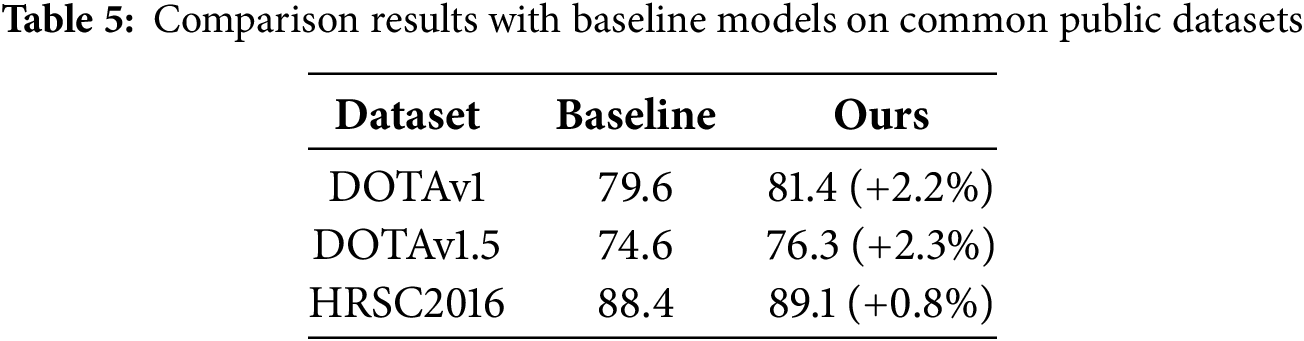

Models that do not generalize well will suffer significantly when applied to data outside the distribution of the training set. For example, a model that performs well on DOTAv1 may perform much worse on HRSC2016 than on the original dataset. And it is unable to transfer from one scene (e.g., aerial images) to similar but slightly different scenes (e.g., satellite images), and it is difficult to adapt to new imaging properties even if the target category is the same. Therefore, in order to prove the generalization of the model in this paper, comparative experiments with the baseline model are carried out in three different datasets, as shown in Table 5.

The proposed method shows better performance than the baseline model on the three datasets of DOTAv1.0, DOTAv1.5 and HRSC2016. The AP50 is 2.2%, 2.3% and 0.8% higher than the baseline, respectively. Given the limited category diversity of HRSC2016, the performance improvement of the proposed model over the benchmark is relatively low. However, on DOTAv1.0 and DOTAv1.5 with complex data and high-resolution inputs, the proposed model demonstrates significant performance gains. This reflects the ability of the model to handle complex data with multiple objectives.

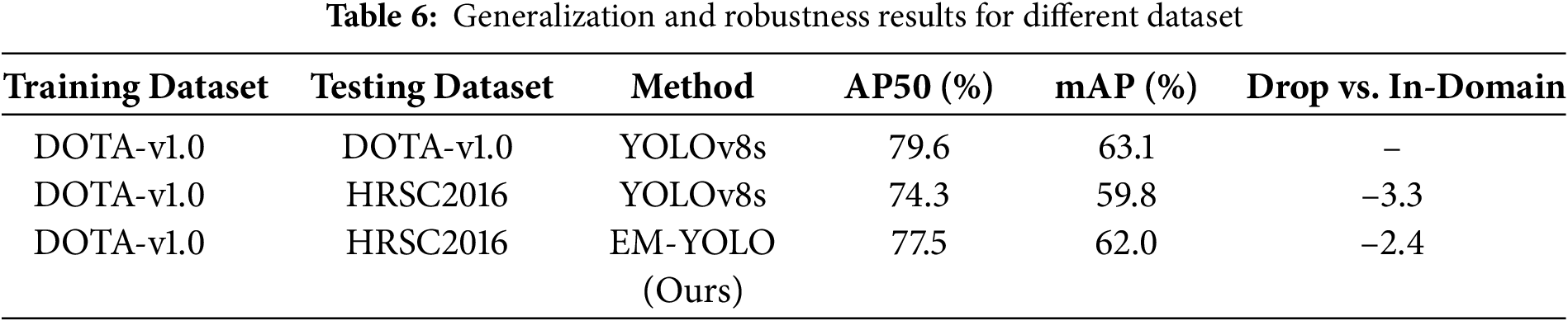

To further assess the generalization and robustness of the proposed method, additional experiments were conducted on different datasets, as presented in Table 6. The results verify that our approach consistently outperforms comparative models, demonstrating strong adaptability and stability across diverse scenarios.

As shown in Table 7, this experiment demonstrates that EM-YOLO generalizes better to unseen satellite imagery due to the dynamic receptive field of DSC and multi-scale semantic alignment in FDFPN, which enhance robustness to viewpoint and resolution shifts.

From Table 7, our EM-YOLO achieves comparable or superior accuracy while maintaining significantly lower computational cost and parameter size. This verifies that the proposed lightweight CNN-based architecture remains highly competitive against transformer-based detectors, especially in resource-constrained remote sensing scenarios. Our method achieves a similar detection accuracy (81.4% AP50) to the transformer-based methods, while using less than one-third of their parameters and less than one-third of the computational cost, demonstrating its superior efficiency and practicality for edge deployment.

Notably, for small-scale objects, including but not limited to plane (PL), ship (SH), harbor (HB), bridge (BR), large vehicle (LV), and small vehicle (SV), our model exhibits a marked improvement in detection accuracy. This enhancement can be attributed to the innovative integration of snake-shaped convolutions, which are specifically designed to capture intricate spatial relationships and fine-grained features within these compact objects. The unique shape of these convolutions enables them to navigate through the intricate contours of small objects, thereby enhancing their detectability within complex scenes.

Conversely, for large-scale objects such as roundabout (RA) and storage tank (SP), our model leverages the feature focused diffusion module to achieve superior performance. This module is optimized to efficiently propagate and aggregate discriminative features across broader spatial extents, enabling the model to accurately localize and classify large objects within the scene. By focusing on salient features and suppressing irrelevant information, this module significantly boosts the detection accuracy for these larger targets.

In terms of the overall performance, our model demonstrates a competitive stance when evaluated using the AP50 metric, which is a widely accepted benchmark for assessing object detection performance. Notably, our approach surpasses the baseline YOLOv8s model across a diverse range of object categories, highlighting its robustness and generalizability. This achievement underscores the effectiveness of our design choices, including the snake-shaped convolutions and feature focused diffusion module, in enhancing the detection capabilities of our model for both small and large objects within the DOTAv1.0 dataset.

The proposed EM-YOLO achieves comparable detection accuracy to the latest Transformer-based detectors (within 0.6 AP50) while requiring less than one-third of their parameters and computation. This highlights EM-YOLO’s superior accuracy-efficiency trade-off, which is crucial for practical deployment on UAVs and embedded remote-sensing platforms such as the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin. Furthermore, Transformer-based OBB detectors typically exhibit slower convergence and higher latency due to heavy attention operations, whereas EM-YOLO retains real-time inference capability without sacrificing precision. These results demonstrate that our design—built upon convolutional feature learning enhanced by DSC and FDFPN—remains competitive with state-of-the-art Transformer models while maintaining a lightweight structure.

The results in Fig. 8 present the FLOPs–accuracy trade-off under different pruning rates. As shown, our method maintains high detection accuracy even at higher pruning ratios.

Figure 8: FLOPs-accuracy trade-off under different pruning rates

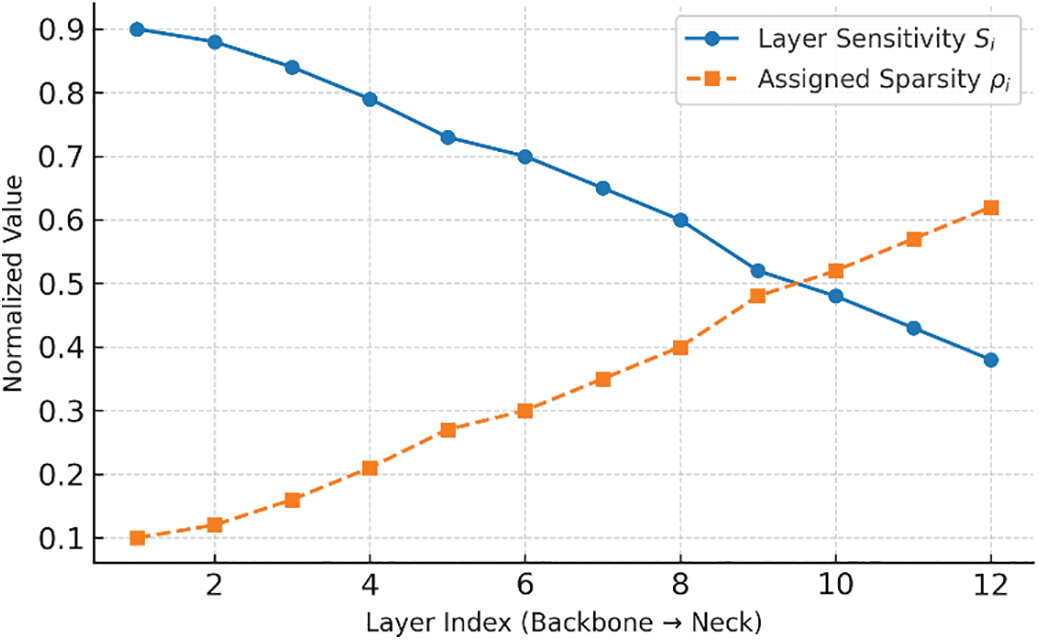

Fig. 9 shows the layer-wise sensitivity and sparsity allocation. The results indicate that layers with higher sensitivity are assigned lower sparsity, whereas less sensitive layers are pruned more aggressively. This adaptive allocation ensures efficient model compression while maintaining stable detection performance.

Figure 9: Layer-wise sensitivity and sparsity allocation

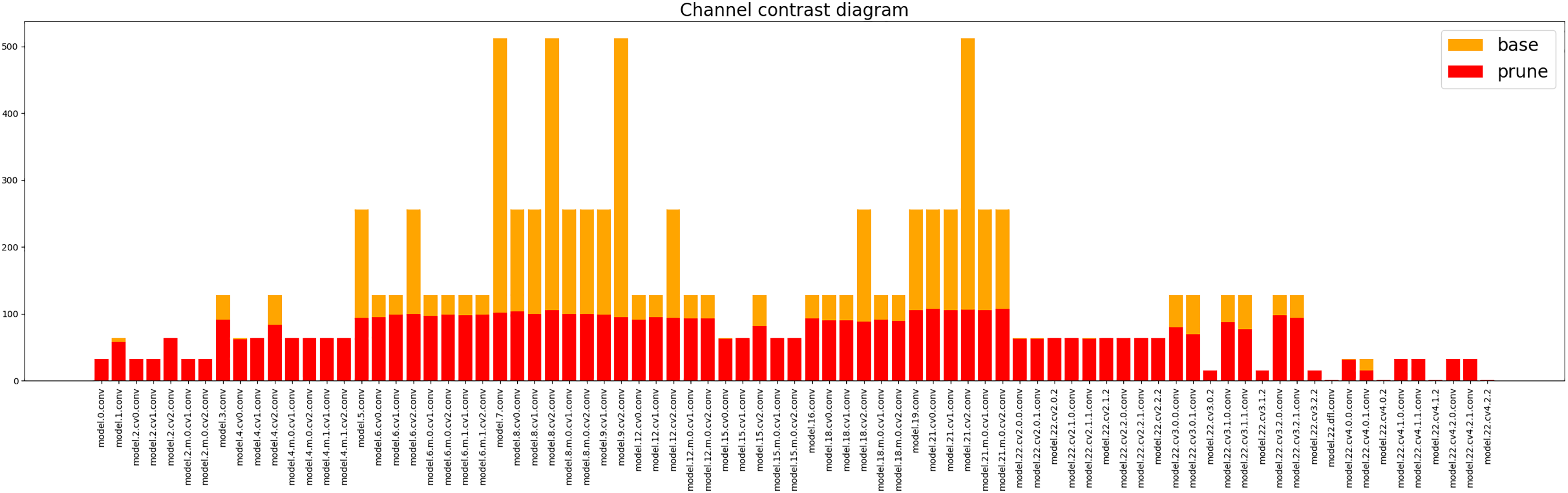

Fig. 10 shows the channel comparison before and after pruning, where the abscissa is the pruned convolution of each layer of the pruned part of the model shown in order, the ordinate represents the absolute value of the weight, and the base (shown in orange) and prune (shown in red) show the weight comparison before and after pruning. On the whole, the number of parameters and calculation amount of the model are reduced to 2.9M and 14.5B, which is 76.4% and 51.5% lower than that of the original model (12.3M and 29.9B).

Figure 10: Comparison of weights before and after pruning

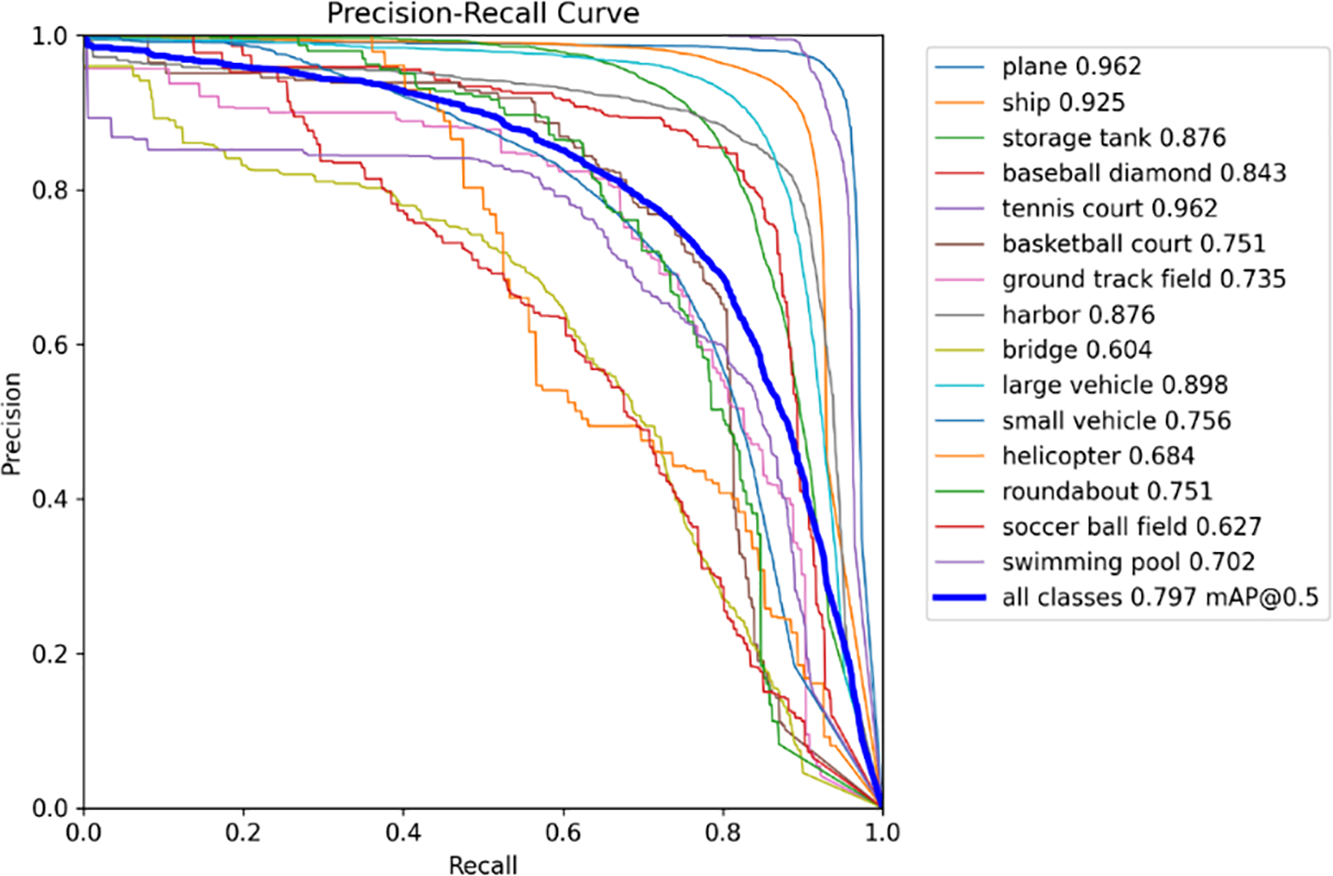

Fig. 11 shows the results of the pruned model in the DOTAv1.0 validation set, and the Precision-Recall curve, which reflects that the model maintains excellent detection performance in each category. Even after pruning, small objects such as plane and tennis court, which appear frequently, still maintain a mAP50 score as high as 0.962, and the pruning process barely affects the detection ability of these categories. When it comes to medium and large targets with complex backgrounds and numerous interferences, the scores of large vehicles, storage tank and harbor categories reach 0.898, 0.876 and 0.876, respectively. Overall, we achieve an average mAP50 of 0.797 across all classes, which is quite impressive for a pruned and compressed model, providing one more option for lightweight scenarios.

Figure 11: Precision-Recall curve chart

We used the test set of DOTAv1.0, a representative dataset of remote sensing images, to conduct inference tests on Orin platform, and selected representative result graphs of target types for all detection tasks from the test results. The results for small targets are shown in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: Small target detection results

The targets shown are cars, planes, ships and ports, tennis courts, swimming pools, water storage tanks, Bridges. It can be seen from the figure that, in the face of detection technical difficulties such as mutual occlusion, rotation Angle, and a large number of adjacent small targets, the lightweight model deployed in this chapter still performs well in the detection task of small targets on the lightweight platform. Extremely small targets may only account for less than 50 × 50 pixels in the input graph of 1024 × 1024. However, the lightweight model can still ensure that the OBB anchor box is used to accurately find the contour of different objects in the case of very low missed detection rate, which further highlights the superiority of our method.

The detection effect of medium and large targets is shown in Fig. 13, including circular island, baseball field, basketball court, football field, track and field, large aircraft and water storage tank. The model often needs to be able to extract more detailed features when facing such targets with fuzzy background boundaries. It is worth noting that the same target may present different sizes on different remote sensing images. The large aircraft and water storage tank in Fig. 13 also require the fine feature extraction of the model, while the model lightweight method in this paper does not destroy this ability of the model. It can be seen that the model in this paper can also achieve good detection results on the micro edge computing platform when facing the medium and large targets with various complex backgrounds in Fig. 13.

Figure 13: Big target detection results

We note that all detection visualizations use a unified color-coding scheme following the YOLOv8 standard, where each class shares the same predefined color for consistent comparison across methods.

4.5 Generalization and Robustness Analysis

To assess the generalization capability of EM-YOLO beyond in-domain data, we conducted a cross-dataset evaluation from aerial (DOTA) to satellite (HRSC2016) imagery. EM-YOLO demonstrates stable performance with less than 3% degradation, outperforming the baseline YOLOv8s under the same setting. Moreover, preliminary experiments on SAR ship images suggest that the proposed dynamic and focus–diffusion mechanisms enhance feature robustness across sensor modalities, laying the foundation for future multi-sensor adaptation research.

In this paper, we propose an enhanced multi-scale feature extraction lightweight network based on YOLOv8s. We enhance the backbone module by introducing Dynamic Snake Convolution and devise a novel Focus and Diffusion Module for the neck section, finally, the model is lightweight by pruning. Experimental results demonstrate that our model achieves significant improvement over the baseline in terms of oriented bounding box (OBB) remote sensing object detection, exhibiting competitive performance compared to other state-of-the-art models. For future work, we aim to further enhance the model’s capability in detecting challenging objects recently introduced in YOLOv1.5 and YOLOv2.0, striving for even better detection performance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is funded by the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund under Grant ZDYF2024GXJS292.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yuwen Qian and Xiang Luo; methodology, Xiang Luo; software, Yuxuan Peng; validation, Renghong Xie and Peng Li; formal analysis, Renghong Xie; writing—original draft preparation, Xiang Luo; writing—review and editing, Peng Li and Yuwen Qian. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Additionally, the trained weights and experimental code used in this study will be publicly released on platforms such as GitHub after the paper is formally accepted for publication.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Tao C, Qi J, Lu W, Wang H, Li H. Remote sensing image scene classification with self-supervised paradigm under limited labeled samples. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2020;19:8004005. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2020.3038420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ding J, Xue N, Xia GS, Bai X, Yang W, Yang MY, et al. Object detection in aerial images: a large-scale benchmark and challenges. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(11):7778–96. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3117983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang B, Wu Y, Zhao B, Chanussot J, Hong D, Yao J, et al. Progress and challenges in intelligent remote sensing satellite systems. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2022;15:1814–22. [Google Scholar]

4. Cheng G, Xie X, Han J, Guo L, Xia GS. Remote sensing image scene classification meets deep learning: challenges, methods, benchmarks, and opportunities. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2020;13:3735–56. [Google Scholar]

5. Li Y, Li X, Dai Y, Hou Q, Liu L, Liu Y, et al. LSKNet: a foundation lightweight backbone for remote sensing. Int J Comput Vis. 2025;133(3):1410–31. doi:10.1007/s11263-024-02247-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xi LH, Hou JW, Ma GL, Hei YQ, Li WT. A multiscale information fusion network based on PixelShuffle integrated with YOLO for aerial remote sensing object detection. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2024;21:7501505. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2024.3353304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fang Z, Wang X, Zhang L, Jiang B. YOLO-RSA: a multiscale ship detection algorithm based on optical remote sensing image. J Mar Sci Eng. 2024;12:603. doi:10.3390/jmse12040603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang Q, Cong R, Li C, Cheng MM, Fang Y, Cao X, et al. Dense attention fluid network for salient object detection in optical remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2021;30:1305–17. doi:10.1109/TIP.2020.3042084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Xu Y, Dai M, Zhu D, Yang W. Adaptive angle module and radian regression method for rotated object detection. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2024;21(3):6006505–5. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2024.3381429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang X, Cheng S, Wang L, Li H. Asymmetric cross-attention hierarchical network based on CNN and transformer for bitemporal remote sensing images change detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:2000415. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2023.3245674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liao L, Du L, Guo Y. Semi-supervised SAR target detection based on an improved faster R-CNN. Remote Sens. 2022;14(1):143. doi:10.3390/rs14010143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li Q, Chen Y, Zeng Y. Transformer with transfer CNN for remote-sensing-image object detection. Remote Sens. 2022;14(4):984. doi:10.3390/rs14040984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang X, Yan J, Ming Q, Wang W, Zhang X, Tian Q, et al. Rethinking rotated object detection with gaussian wasserstein distance loss. In: Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. p. 11830–41. [Google Scholar]

14. Yang X, Zhou Y, Zhang G, Yang J, Wang W, Yan J, et al. The KFIoU loss for rotated object detection. arXiv:2201.12558. 2022. [Google Scholar]

15. Llerena JM, Zeni LF, Kristen LN, Jung C. Gaussian bounding boxes and probabilistic intersection-over-union for object detection. arXiv:2106.06072. 2021. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang CY, Liao HYM, Yeh IH. Designing network design strategies through gradient path analysis. arXiv:2211.04800. 2022. [Google Scholar]

18. Qi Y, He Y, Qi X, Zhang Y, Yang G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 6047–56. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lin TY, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 936–44. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Mark Liao HY. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2024. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72751-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xia GS, Bai X, Ding J, Zhu Z, Belongie S, Luo J, et al. DOTA: a large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 3974–83. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu Z, Wang H, Weng L, Yang Y. Ship rotated bounding box space for ship extraction from high-resolution optical satellite images with complex backgrounds. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2016;13(8):1074–8. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2016.2565705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu Z, Yuan L, Weng L, Yang Y. A high resolution optical satellite image dataset for ship recognition and some new baselines. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods; 2017 Feb 24–26; Porto, Portugal. p. 324–31. doi:10.5220/0006120603240331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ming Q, Zhou Z, Miao L, Zhang H, Li L. Dynamic anchor learning for arbitrary-oriented object detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(3):2355–63. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i3.16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ding J, Xue N, Long Y, Xia GS, Lu Q. Learning RoI transformer for oriented object detection in aerial images. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 844–53. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang S, Chi C, Yao Y, Lei Z, Li SZ. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 9756–65. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yang X, Yan J, Feng Z, He T. R3Det: refined single-stage detector with feature refinement for rotating object. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(4):3163–71. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i4.16426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools