Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Data-Driven Prediction and Optimization of Mechanical Properties and Vibration Damping in Cast Iron–Granite-Epoxy Hybrid Composites

1 Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, 576104, Karnataka, India

2 Department of Mechatronics, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, 576104, Karnataka, India

* Corresponding Author: Subraya Krishna Bhat. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Computational Modeling and Simulations for Engineering Structures and Multifunctional Materials: Bridging Theory and Practice)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 19 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073772

Received 25 September 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

This study presents a framework involving statistical modeling and machine learning to accurately predict and optimize the mechanical and damping properties of hybrid granite–epoxy (G–E) composites reinforced with cast iron (CI) filler particles. Hybrid G–E composite with added cast iron (CI) filler particles enhances stiffness, strength, and vibration damping, offering enhanced performance for vibration-sensitive engineering applications. Unlike conventional approaches, this work simultaneously employs Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) for high-accuracy property prediction and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for in-depth analysis of factor interactions and optimization. A total of 24 experimental test data sets of varying input factors (granite weight%, epoxy weight%, and CI filler weight%) were utilized to train and test the prediction models using an ANN approach and further analyze the interaction effects using RSM. Mechanical properties, including tensile, compressive, and flexural strength, elastic modulus, density and damping properties measured under various testing conditions, were set as output parameters for prediction. This study analyzed and optimized the performance of the ANN model using Bayesian Regularization and Levenberg-Marquardt algorithms to identify the best performing number of neurons in the hidden layer for achieving the highest prediction accuracy. The proposed ANN framework achieved an exceptional average determination coefficient (R2) exceeding 99%, with Bayesian Regularization demonstrating remarkable stability in the 22-neuron range and minimal variation across all properties. RSM and ANN form a powerful framework for predicting and optimizing hybrid G–E composite properties, enabling efficient design for vibration-critical applications with reduced experimental effort and performance optimization.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FilePolymer matrix hybrid composites are advanced materials that consist of various kinds of reinforcements in a polymer matrix to attain improved mechanical or vibrational behaviour that is rarely obtained with the addition of a single reinforcement. Different combinations of reinforcement materials contribute to the unique characteristics of hybrid composites. A polymer matrix made of epoxy, vinyl ester or polymer resin binds the multiple reinforcements and transfers load between them. Hybrid composites allow for tailored mechanical and vibrational properties based on requisite conditions. The capability to engineer specific properties by selecting and proportioning various reinforcements provides polymer matrix hybrid composites with a versatile advantage for tackling diverse engineering challenges [1,2]. Polymer matrix composites (PMCs) reinforced with granite material of various granular sizes and epoxy matrix are potential alternatives to cast iron and other metal alloys as foundations of precision machines. PMCs can offer substantial improvement in damping behaviour, around eight times greater than cast iron and increased thermal stability. Currently, the usage of cast iron material as machine tool bases has significant limitations in reducing the system vibrations which directly affects the product quality [3,4].

Numerous research studies have been carried out on exploring the potential of PMCs by varying the type of reinforcement and filler materials. Subash et al. [5] aimed to develop and characterize eco-friendly epoxy composites reinforced with granite particles in powder form. Granite is naturally dense and brittle, leading to low machinability. This study evaluates the properties of a composite using an epoxy matrix with granite powder as particulate reinforcement, optimizing the ductile nature of pure epoxy by varying the brittle granite filler content. The study mainly focused on assessing its strength, weight, and surface finish by identifying its most effective resin ratio (60% to 70%). Different mechanical and physical tests were conducted to evaluate the composite properties and reject the noncompliant compositions. Studies indicate that the G–E composite of 80:20 weight% (wt%) attained improved compressive strength, while 85:15 wt% resulted in greater flexural strength. These improvements in mechanical properties vary depending on the type of resin matrix used and the treatments applied [6]. Piratelli-Filho et al. [7,8] investigated the vibrational behavior of granite epoxy composite specimens of varying weight fractions and size distribution of granite particulates. Granite rejects with particle sizes smaller than 500 µm were produced through a process of crushing, milling, and segregation. 80:20 G–E ratio was found to be the optimal composition with superior damping behavior, where epoxy resin performed better than polyester resin as matrix material. For wind turbine blade applications, Pawar et al. [9] developed PMCs with jute fiber reinforced epoxy composite blended with granite filler particles. As the fiber loading in the unfilled composites increased, the void content decreased, which corresponded with an increase in tensile and flexural strength. However, in particulate-filled composites, the void content increases with higher filler content, leading to a decrease in mechanical properties.

Studies have explored the use of polymeric resin for hybrid composites, combining marble powder with varying granite powder to evaluate physical and mechanical properties. Research highlights that hybrid composites exhibit a marginal decline in deformability and possess superior density, porosity, and compressive strength compared to pure epoxy composites. Findings also suggest that incorporating waste fillers enhances wear resistance, indicating the composites potential for tribological applications [10,11]. To take account of the damping characteristics, the hybrid G–E composites with Egyptian red granite powder were also experimentally tested by considering particle sizes with 50:25:25 ratio of fine, medium and coarse sizes. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images were utilized to analyze the different failure modes that occurred during experimentation [12]. Arumugam et al. [13] focused on mitigating environmental issues caused by granite dust pollution by converting this waste into high-value electrical insulator products. The matrices and composites underwent comprehensive characterization to assess their structural, thermal, and electrical properties. Composites reinforced with 100 wt% granite dust in a specialized epoxy resin matrix demonstrated superior electrical surface resistivity, higher breakdown voltage, and improved dielectric strength compared to other composites. Hybrid green composites with epoxy base were also prepared with reinforcements of granite particles, jute and cannabis sativa fibers. Composites with 60 wt% granite filler and 4 jute layers showed 5% to 148% increase in mechanical properties and 150% higher thermal conductivity than neat epoxy. Hybrid green composite with cannabis sativa fibers showed improved antibacterial activity against E. coli [14,15].

Hybrid G–E composites made using Cordia Dichotoma fiber were also developed as an alternative material for lightweight applications. Thermogravimetric analysis showed improved thermal stability up to 455°C, with delayed degradation due to inorganic materials [16]. Palm epoxy composites with granite filler particles showed major modifications in their weight, density and tensile strength as a result of alkali treatment [17]. Vibration analysis on G–E composite specimens indicated 80:20 as the optimal G–E ratio with epoxy identified as a better resin matrix than polymeric resin. Integrating epoxy resin with hydroxyl-terminated polyurethane resulted in a significant reduction of void content and enhanced flexural properties [18,19]. Venugopal et al. [20,21] performed structural analysis on a machine column of G–E structure with steel reinforcements using the finite element (FE) method. FE analysis of nine hybrid G–E columns showed 12–20% higher static stiffness and natural frequencies compared to a cast iron column. The effect of drill bit coating materials on the glass fiber and granite powder blended epoxy composites was also tested [22]. Further Taguchi-based optimization and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis was performed to evaluate the drill hole quality in such composites with nanofillers [23]. Studies were also extended to develop similar composite materials by blending red stone particles in epoxy resin matrix for automotive applications [24].

Currently, ANN and other machine learning techniques are widely used to predict the physico-thermo-mechanical properties of hybrid composites, reducing experimental costs and revealing each parameter’s impact on performance. Shishegaran et al. [25] utilized computational models to assess the flexural and compressive properties of epoxy-based artificial stone sludge and powder mixture, with the Taguchi method designing mix proportions based on filler volume, resin strength, and curing temperature. Multiple regression and machine learning (ML) models were compared with statistical parameters and error factors. The experimental design for a hybrid G–E composite with glass fiber reinforcement was developed using a Taguchi L9 symmetric array and ANOVA was applied for the statistical analysis of experimental findings [22]. For identification of optimum configuration, topology optimization and parametric analysis were performed on a vertical machine center column made of G–E composites reinforced with steel [26,27]. Arunramnath et al. [28] utilized the technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) approach to optimize the machining parameters. Based on which, 27 experiments were conducted to analyze the mechanical attributes of G–E composites. Further, the Central Composite Design (CCD) approach was implemented along with a hybrid TOPSIS model to refine the optimal parameters, while also applying RSM techniques to analyze multi-attribute characteristics [29]. RSM-based mathematical models show high consistency and up to 95% accuracy. However, few statistical optimization studies have explored the mechanical properties of hybrid G–E composites. In epoxy-based composites with natural fiber and other reinforcements, ANN models and various statistical approaches have been significantly applied for providing a level of precision that adds to the experimental findings [30,31].

For a hybrid natural composite with nano fillers, Arunachalam et al. [32] utilized RSM and ANOVA approaches to evaluate the relationship between fiber parameters under varying conditions. An ANN model was developed and trained with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, accurately predicting flexural strength and hardness from input parameters like nano-filler percentage, fiber orientation, and fiber sequence. This approach proved effective and reliable for modeling complex material behaviors while minimizing prediction errors [33]. Further studies by Arunachalam et al. applied RSM and ANN to optimize polymer composite formulations, revealing silane treatment as the primary factor affecting flexural strength, with ANN delivering 95% prediction accuracy and surpassing regression analysis. Arunachalam et al. [34] further applied RSM and ANN to optimize polymer composite formulations, revealing silane treatment as the primary factor affecting flexural strength, with ANN delivering 95% prediction accuracy and surpassing regression analysis. In a related study, jute–kenaf–glass fiber hybrids with Al2O3 nanoparticles were assessed to evaluate the effects of fiber orientation, layering sequence, and nanoparticle content on tensile and impact strength. ANN once again outperformed RSM in prediction accuracy, with the best results obtained at 90° fiber orientation, a three-layer sequence, and 5% Al2O3 content [35]. Developed ANN models matching experimental results were able to accurately predict the properties of silane-treated jute/kenaf fiber composites, with the optimized formulation achieving significant improvements in flexural strength and hardness for biomedical applications [36]. Similar ANN and RSM-based prediction models were also utilized for predicting water uptake in biocomposites. Studies highlighted that ANN models had outperformed RSM prediction models with a good fit observed between observed and predicted data [37]. Elumalai et al. [38] utilized ANN to predict the natural frequencies of MWCNT-reinforced GFRP hybrid composite plates, mitigating the computational challenges of finite element modeling. Random Forest Regression achieved the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.995) with 98.5% less error than linear regression, matching Finite Element Method (FEM) coverage with fewer cases and greatly reduced computation time. In bio-based hybrid composites, ANN analysis accurately predicted the wear rate trends, confirming rice stubble fiber content as the most influential factor in enhancing the composite’s wear resistance [39].

A multi-objective optimization of the wear behavior of glass/carbon fiber reinforced epoxy composite showed lower weight loss and friction coefficient for a particular load and speed combination from response surfaces [40]. The experimental values closely match the predicted values from the ANN model, demonstrating that the developed ANN can effectively predict WL and friction coefficient both within and beyond the design space. RSM-ANN technique effectively achieves optimal mechanical property values in minimal time, reducing production costs and conserving resources [41,42]. From the above studies, it was evident that varying granite weight%, epoxy weight% and additional filler materials can significantly influence the vibration and mechanical behavior of polymer matrix composites. Granite particulate variation can enhance stiffness and wear resistance properties and epoxy content can provide structural integrity. Additionally, the cast iron fillers can further enhance the vibration damping and noise reduction properties to their improved energy dissipation characteristics [43,44]. Kumar and Bongale [45] used the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm to train an ANN model that accurately predicted the fatigue strength of hybrid and non-hybrid composites under varying stress levels and frequencies, with predictions closely matching the experimentally obtained S–N curves. Ouladbrahim et al. [46,47] developed a Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA–ANN) hybrid model to predict crack length from strain, stress, and displacement data, achieving superior accuracy over other metaheuristic–ANN methods and validating it through FEM and experiments. Further studies showcase novel ANN-based hybrid optimization frameworks that accurately predict material damage and porosity effects, achieving higher precision than conventional ANN–JAYA and ANN–PSO (Particle Swarm Optimization) methods [48,49]. Studies have in detail focused on enhancing ANN-based damage prediction by integrating advanced optimization techniques and show its superiority over other metaheuristic algorithms [50].

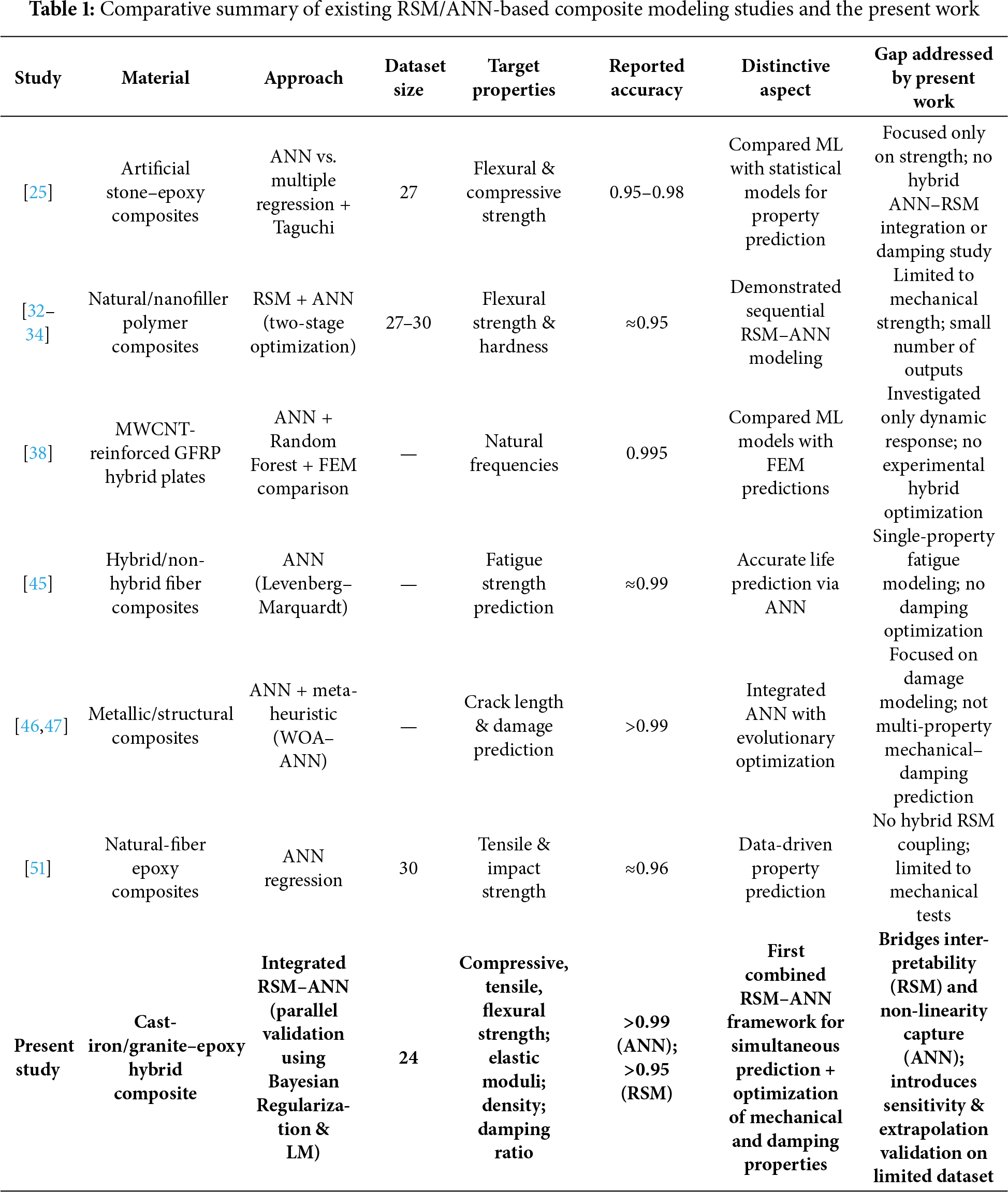

Despite numerous studies employing either RSM or ANN independently for composite material optimization, limited work has explored their combined use for simultaneous prediction and optimization of both mechanical and vibration damping properties. Moreover, existing studies primarily address single-property prediction with smaller variable ranges or different filler systems (e.g., glass, fiber, or nanoparticles). The present study fills this gap by developing an integrated RSM–ANN hybrid modeling framework that (i) accurately predicts multiple mechanical and damping properties from minimal experimental data, (ii) compares performance between Levenberg–Marquardt and Bayesian Regularization algorithms, and (iii) validates predictions via sensitivity analysis and extrapolation. A comparative summary of prior approaches and the proposed framework is given in Table 1.

Most existing studies focus solely on experimental evaluation or use ANN or RSM in isolation, overlooking the benefits of combining these methods. Limited research has addressed the simultaneous prediction of multiple mechanical and damping properties while also analyzing factor interactions and performing optimization, particularly for hybrid granite–epoxy composites reinforced with cast iron (CI) filler particles. The present study focuses on hybrid polymer composites such as Granite Epoxy reinforced with cast iron filler particles designed for applications that require vibration reduction and structural stability. In this study, a comparative analysis of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) is conducted. RSM is employed to explore factor interactions and provide interpretability of the relationships between material composition and performance metrics, while ANN is utilized for high-accuracy prediction of nonlinear behavior. Multiple algorithms such as Bayesian Regularization and Levenberg-Marquardt algorithms were employed to improve the prediction accuracy of ANN models by optimizing the number of neurons in hidden layer. The accuracy of ML models is compared with that of RSM-based polynomial regression models. Finally, the reliability of ML model predictions is verified through a sensitivity analysis with respect to the constituent elements of the hybrid composite.

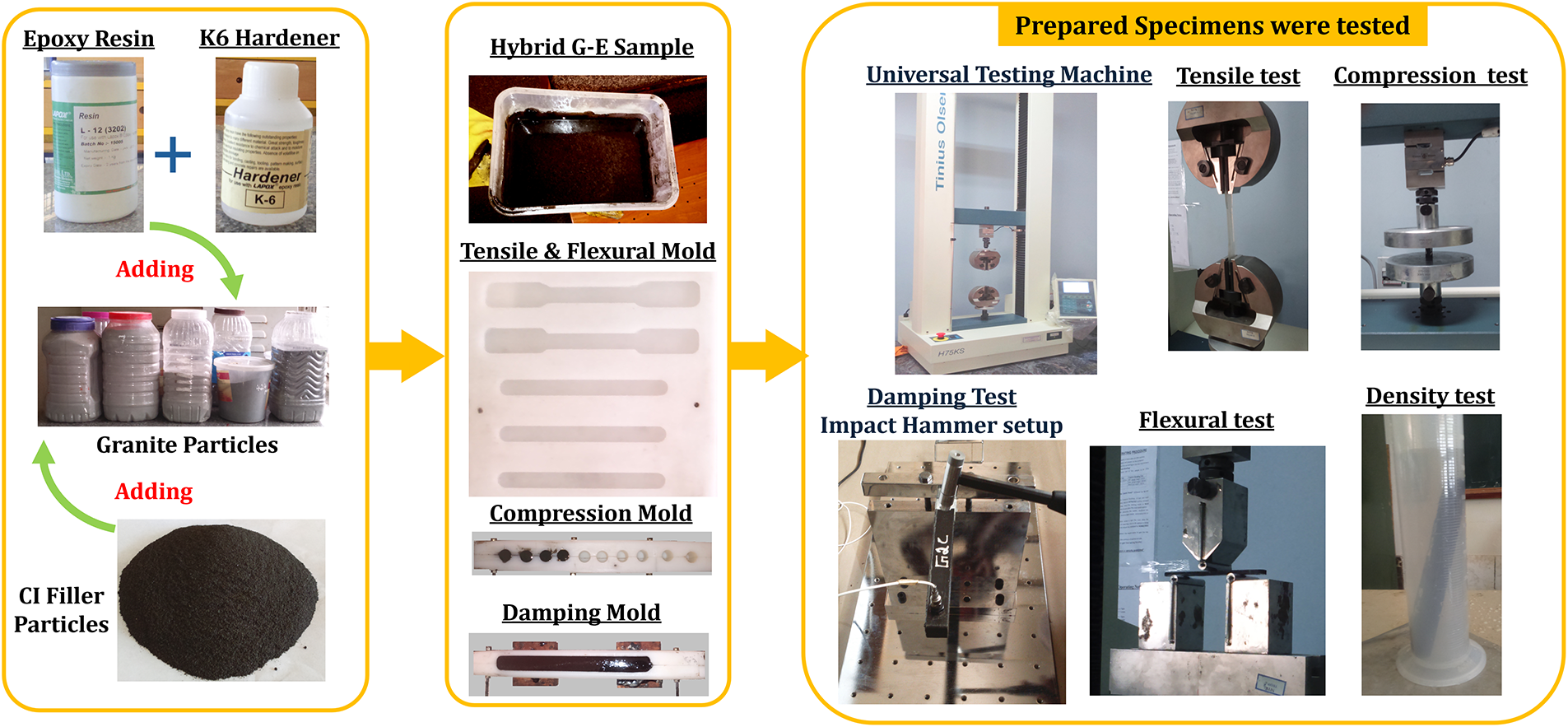

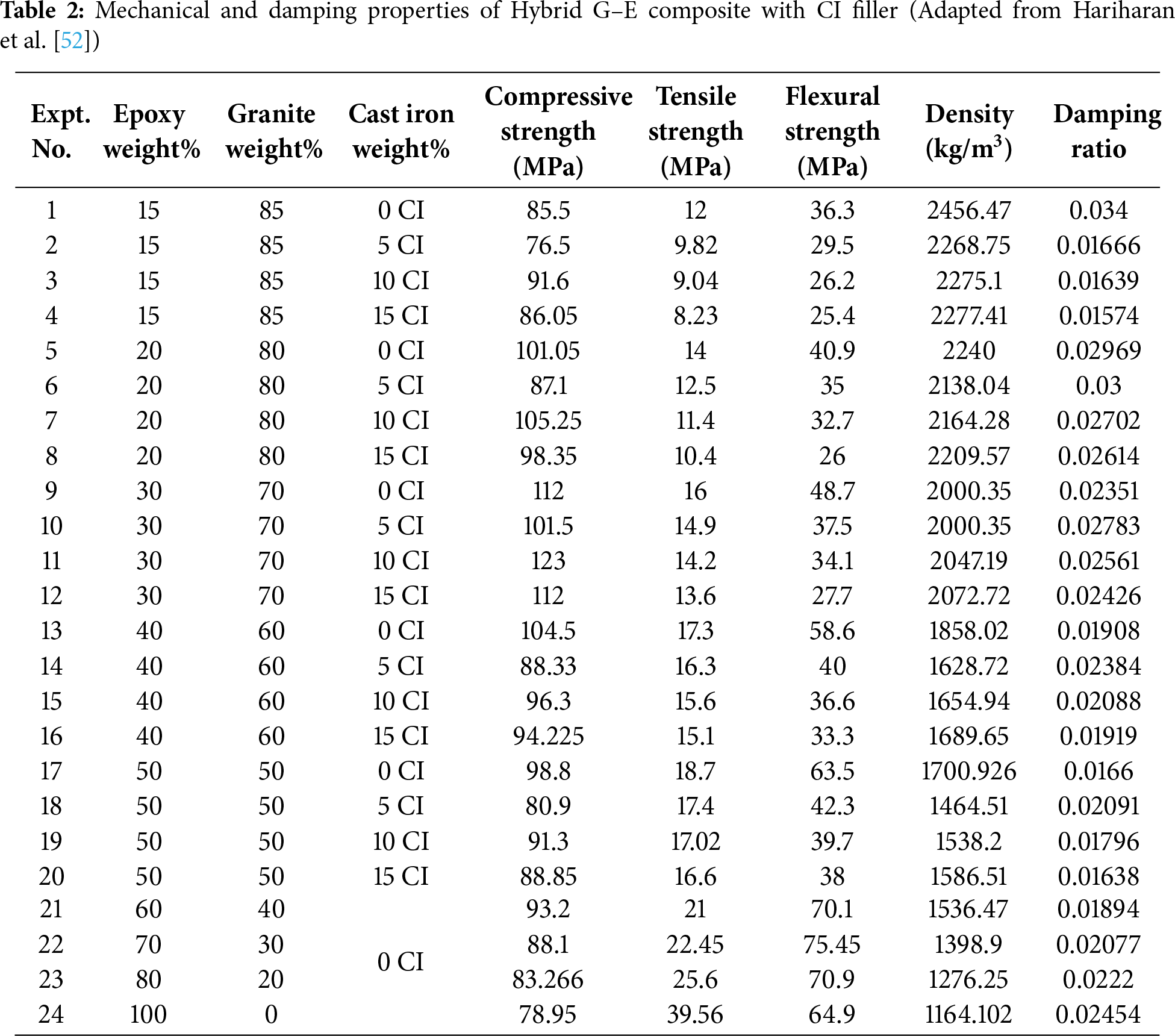

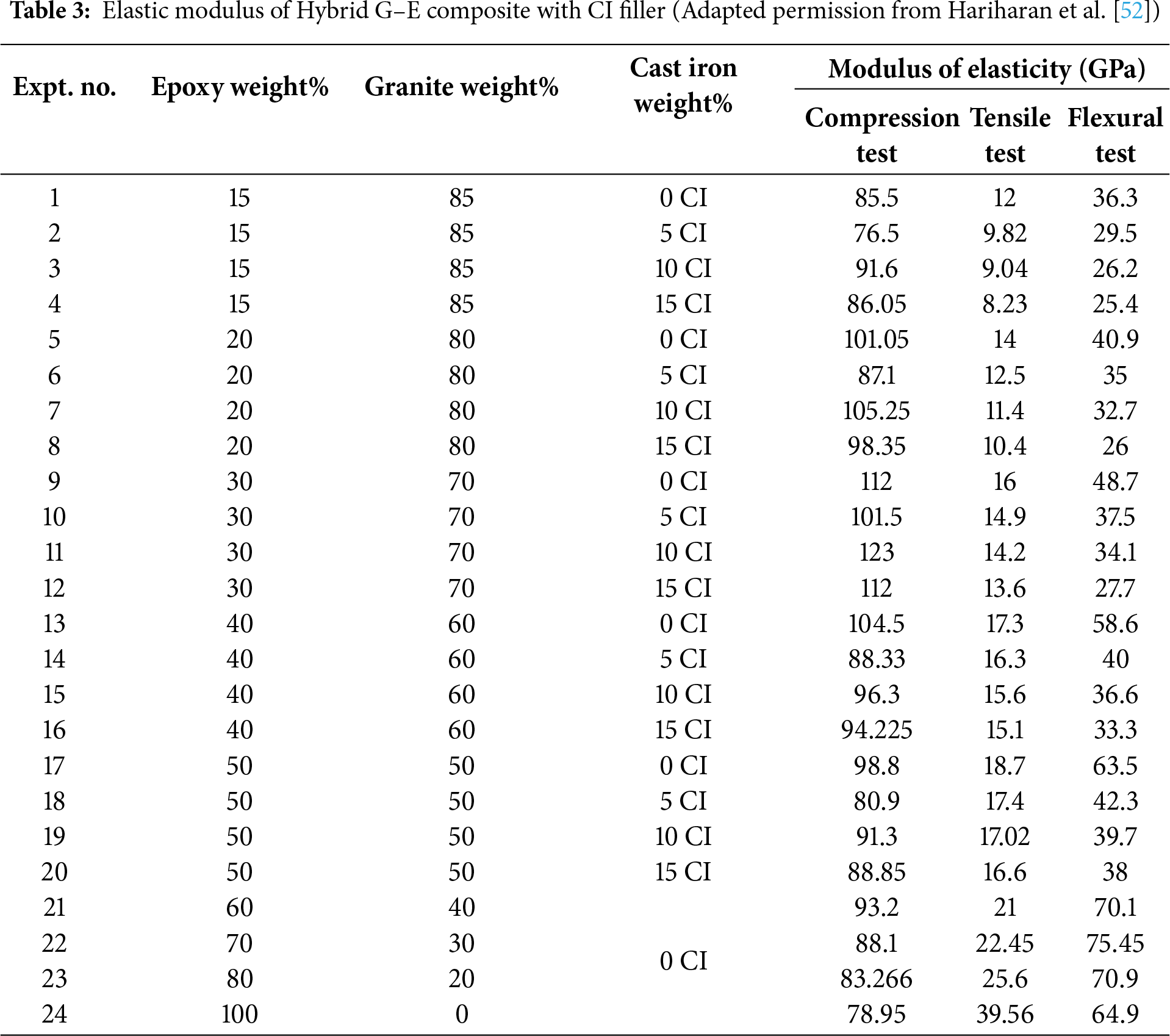

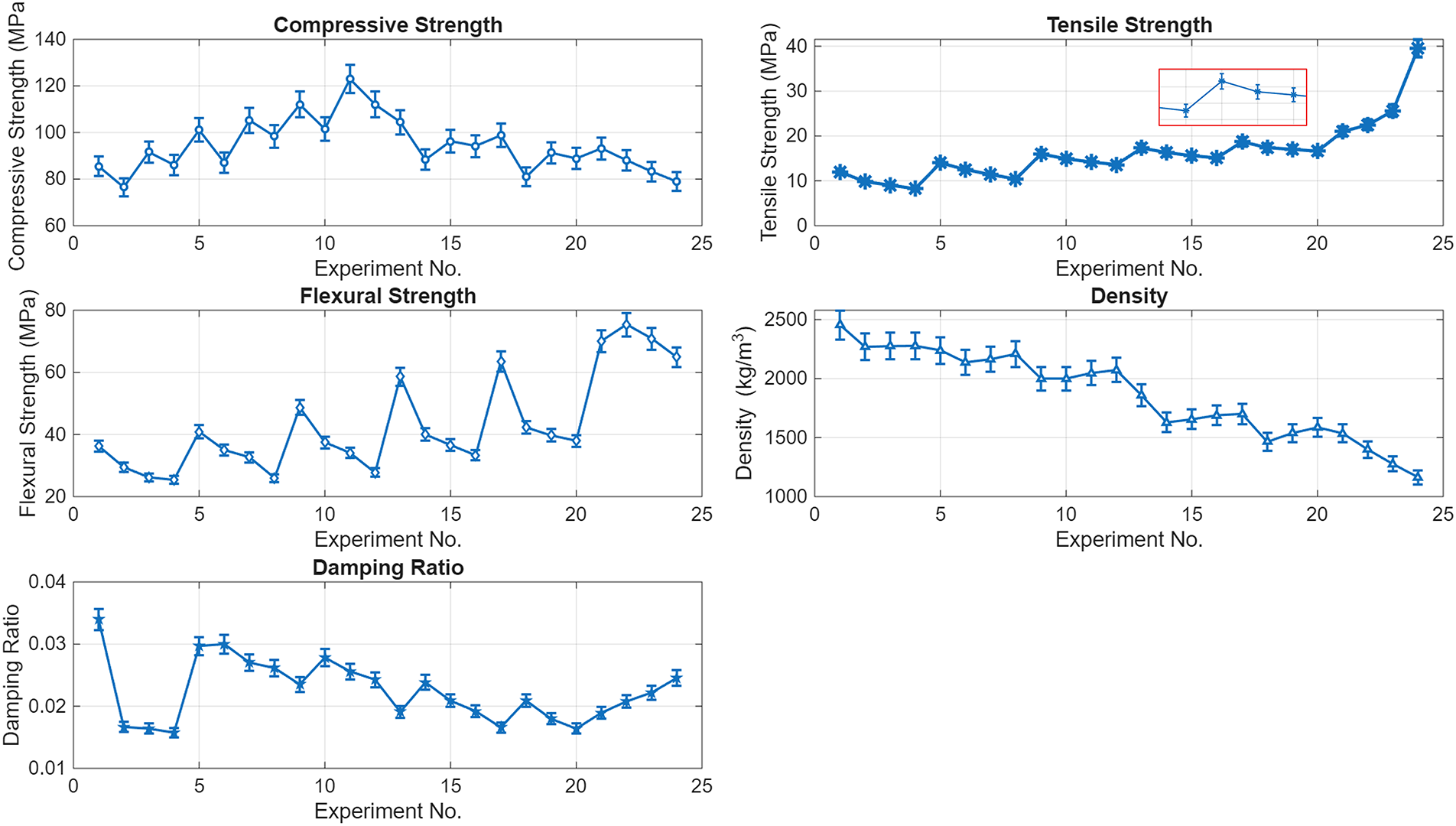

2 Experimental System and Database

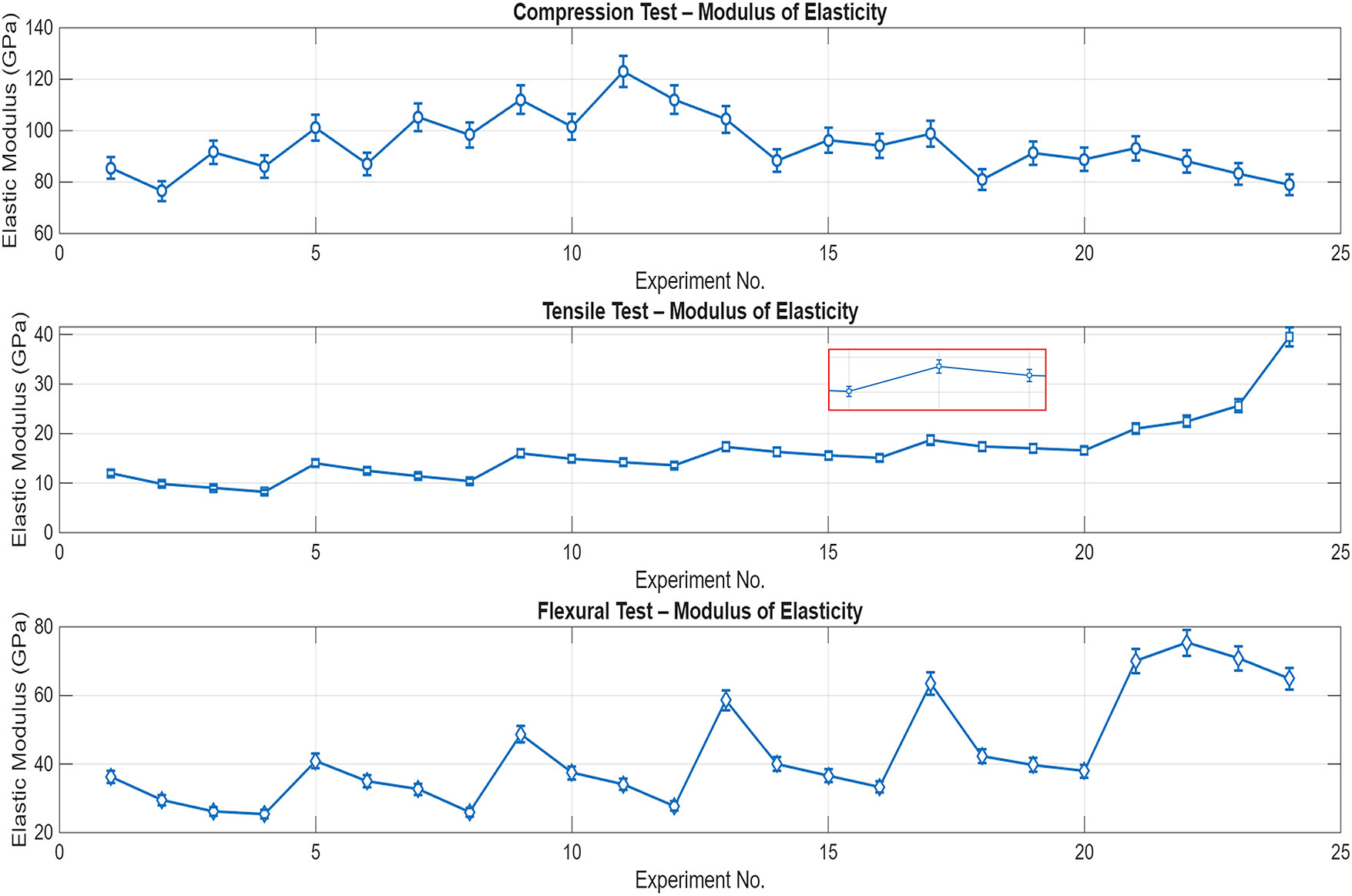

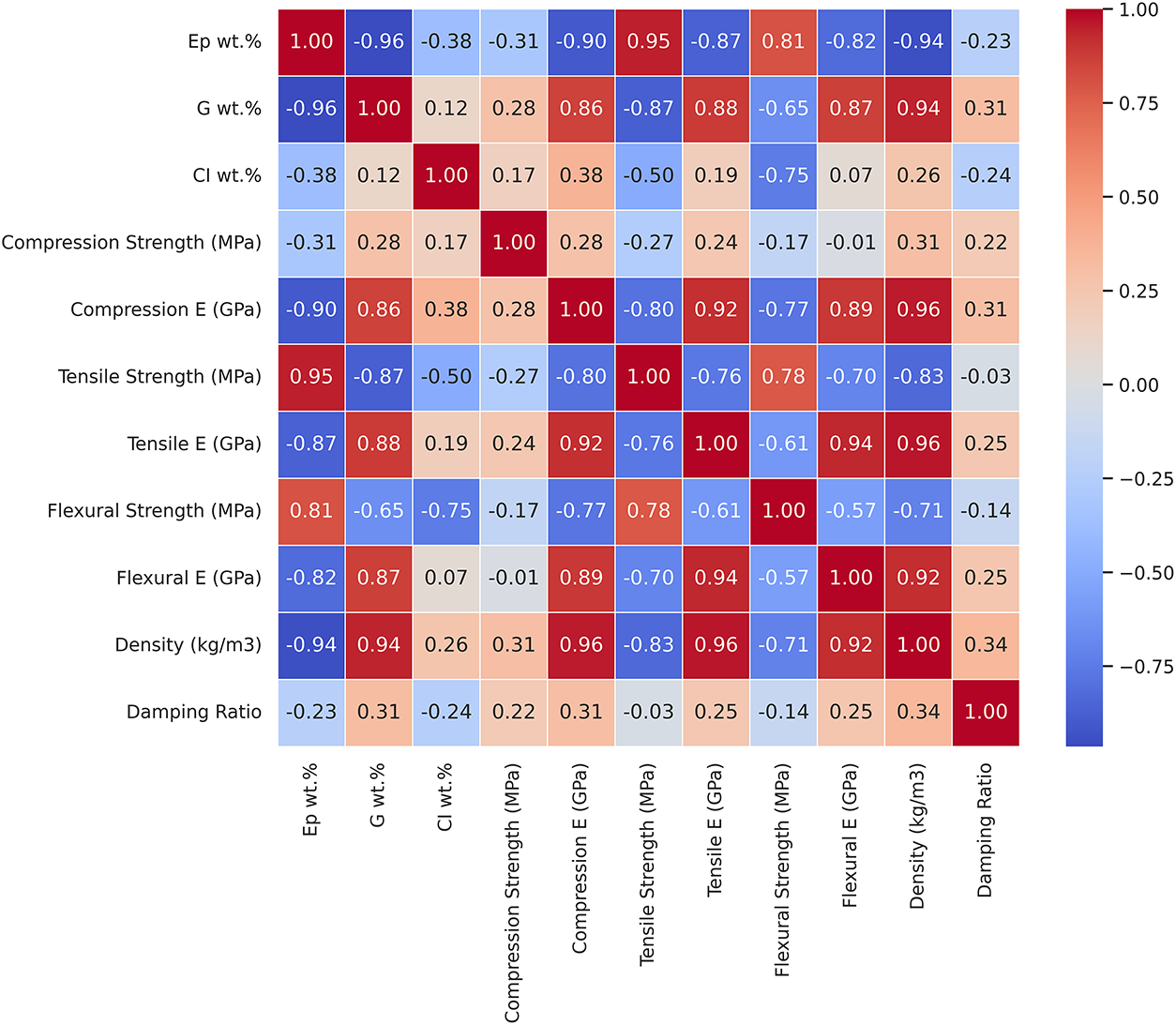

The experimental procedure performed to fabricate and test hybrid G–E composites with CI filler is shown in Fig. 1. Nylon was chosen for mold fabrication due to its non-adhesive nature with epoxy after curing, which facilitates easy specimen removal. The molds were fabricated using shaping, drilling, slitting, and milling processes, comprising ASTM D695 compression molds with 10 cavities for simultaneous specimen production, designed in split bolted halves, as well as dedicated flat-plate molds for tensile and flexural tests and square-section molds for damping specimens. In the experimental study detailed in [52], tensile specimens were fabricated as per ASTM D638, and flexural test specimens using ASTM D790 [52]. In this study, the cast iron (CI) filler is incorporated by partially replacing the granite fraction in the granite–epoxy (G–E) composite. For example, in a 20:80 epoxy–granite base composite, adding 5% CI results in a composition of 20% epoxy, 75% granite, and 5% CI, while 10% CI corresponds to 20% epoxy, 70% granite, and 10% CI. This method ensures that the total percentage of all constituents sums to 100%, with the CI fraction specifically representing the portion of granite replaced. Mechanical test specimens fabricated as per ASTM standards were tested using a 75 kN dual-column Tinius Olsen UTM. Four compression specimens and three tensile and flexural specimens were produced for each weight percentage composition. Compression specimens were cylindrical, measuring 25.4 mm in height and 12.7 mm in diameter, maintaining an L/D ratio of 2. Tests were performed at a constant crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min until specimen fracture at the maximum load. Flexural tests were carried out on specimens with a span length of 72 mm using a three-point bending fixture, while tensile tests were performed at a loading rate of 2 mm/min. The elastic modulus, tensile strength, and flexural strength were recorded for each composition. Specimen density was determined using the water displacement method with a measuring flask. All mechanical properties were evaluated as a function of epoxy content, and the data were recorded using HORIZON software integrated with the UTM system. Four specimens were tested for compression, while three specimens were tested for other tests, and the average values were reported. Damping tests were conducted using a cantilever setup with prismatic granite epoxy specimens. One end was fixed, and an accelerometer on the free end was connected to a DAQ and system. An impact hammer with a metal tip, also linked to the DAQ, provided excitation. The impact hammer test applies a unit force to the specimen’s free end, and the accelerometer measures the resulting vibration, passing the signal to the data acquisition system (DAQ). The DAQ interfaces analog signals with computer software. After signal conditioning, the data is processed in LABVIEW to generate magnitude vs. frequency response curves, allowing determination of the specimen’s natural frequency. The damping factor and logarithmic decrement are calculated using the half-power bandwidth method. This procedure is repeated for all specimens, and response curves are recorded. The mechanical and damping properties data from the experimental tests on the Hybrid G–E composite with CI Filler have been detailed in Tables 2 and 3. The variation of experimental data with error bars as reported in [52] is illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3.

Figure 1: Experimental process carried out to fabricate and test hybrid G–E composites with CI filler

Figure 2: Variation in mechanical and damping properties data of Hybrid G–E composite with CI Filler (Adapted from Hariharan et al. [52])

Figure 3: Variation in elastic modulus of Hybrid G–E composite with CI Filler (Adapted from Hariharan et al. [52])

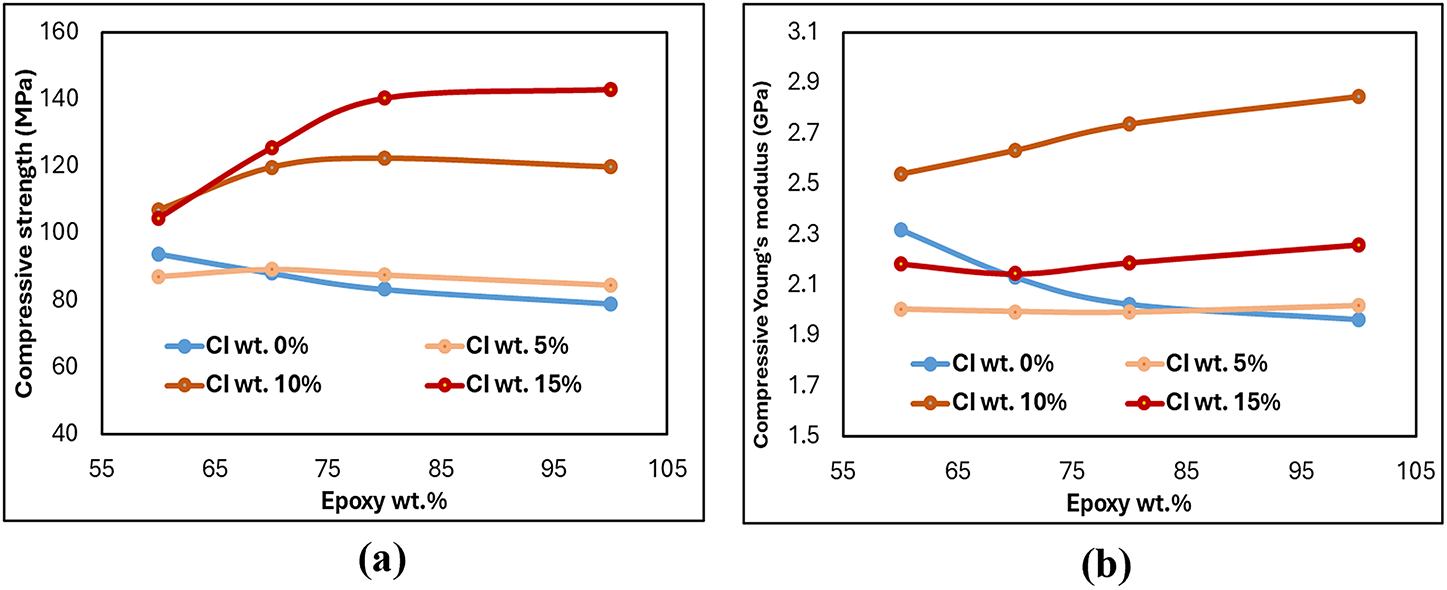

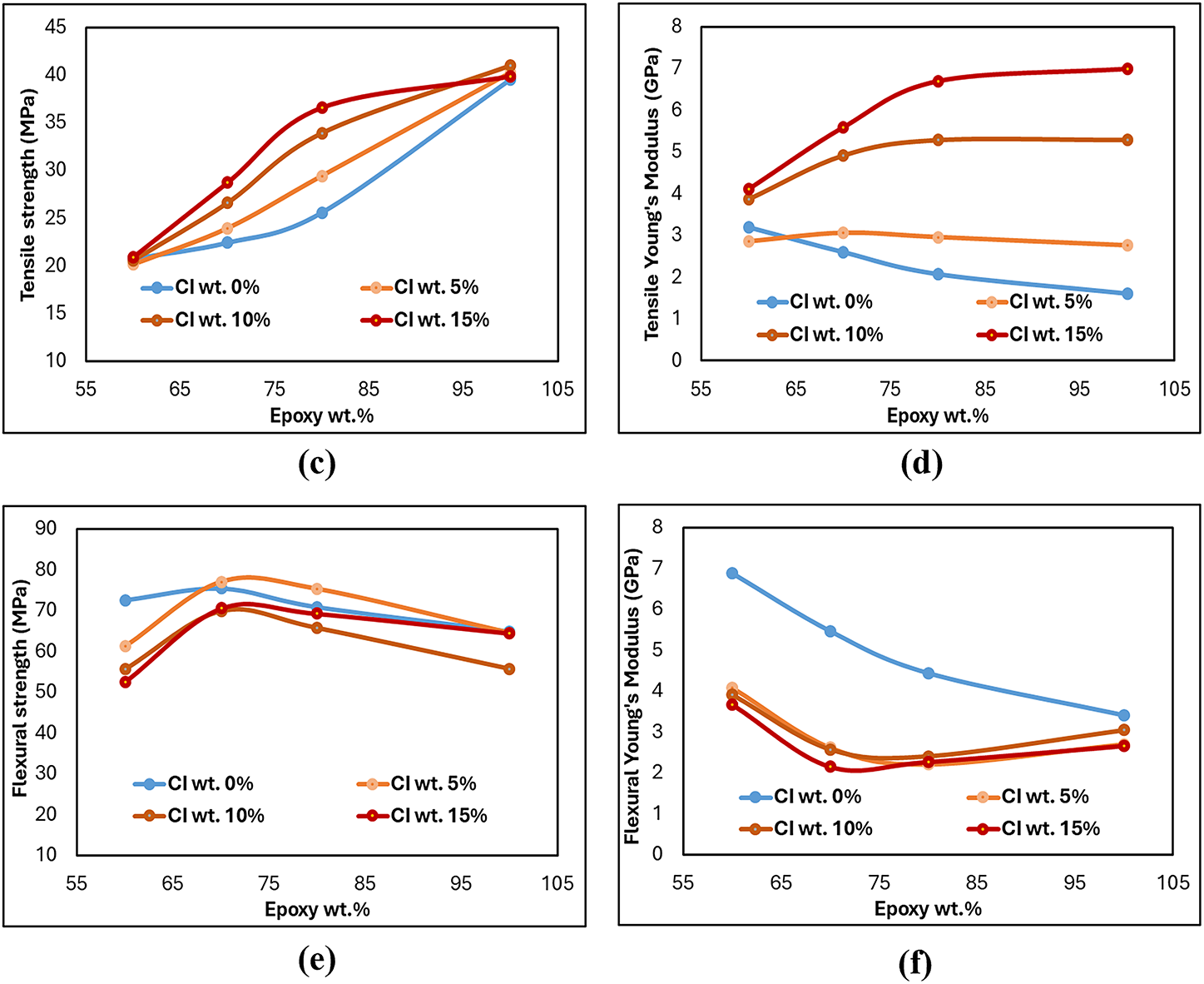

From Table 2, the experimental results showed that the compressive strength of G–E composites without CI filler peaked at 112 MPa for a 70:30 G–E ratio, while excessive granite content (85%) reduced strength due to poor particle–matrix bonding. The addition of 10% CI filler further enhanced compressive strength to 123 MPa at 30% epoxy content, whereas 5% filler had minimal effect. Elastic modulus in compression was highest (4.17 GPa) for an 85:15 G–E ratio and increased to 4.365 GPa with 10% CI filler, indicating greater stiffness with higher granite and optimal CI content. Rigid particles such as granite and CI fillers act as load-bearing inclusions within the epoxy matrix, resisting deformation under compressive loading and thereby enhancing stiffness and compressive modulus. This improvement is primarily attributed to efficient stress transfer between the rigid filler and the surrounding polymer matrix. Similar studies have shown that adding mineral or metallic fillers increases compressive strength and modulus but reduces tensile strength due to interfacial stress concentrations and limited matrix deformability [53,54]. Tensile strength improved with increased epoxy content but declined with higher granite loading; CI filler additions did not significantly enhance tensile performance and, in some cases, reduced it. At higher granite or CI filler loadings, weak interfacial bonding between the granite particles and epoxy matrix can create localized stress zones that act as crack initiation sites under tensile stress. Excessive granite content also promotes particle agglomeration and void formation, interrupting matrix continuity and facilitating premature failure. Similar effects were reported in granite–epoxy composites, where increased granite content reduced tensile strength due to poor filler dispersion and interfacial debonding [55].

Flexural strength increased with epoxy content, reaching 2.07 times that of the 85:15 G–E ratio for the 30:70 mix, with small CI additions providing notable bending resistance improvements. Moderate filler additions improve flexural strength through better load transfer and crack resistance, while excessive granite content causes brittleness and stress concentrations, reducing performance. Similar trends were observed in granite-filled epoxy systems, where flexural strength increased up to an optimal filler ratio and then declined due to particle clustering and poor dispersion [55]. Density measurements revealed maximum values for specimens with 15% epoxy (high granite content) and further increases with higher CI filler percentages, reflecting denser particle packing in the composite structure. Referring to Table 2, the damping factor was highest for the 85:15 G–E ratio and lowest for the 50:50 mix, showing an initial decrease and then a gradual increase as epoxy content rose. This shows a trend likely caused by abundant particle–matrix interfaces and micro-slip at high granite loadings, whereas adding epoxy initially smooths interfaces and reduces interfacial friction, but at higher resin fractions the viscoelastic nature of the matrix itself contributes additional damping. A 5% CI addition produced the largest improvement in damping because a small amount of well-dispersed metal particulates increases interfacial friction, micro-debonding, and internal frictional losses without causing severe agglomeration. Damping in granite–epoxy composites primarily arises from interfacial friction and micro-slip at particle–matrix boundaries, which dissipate vibrational energy. Higher granite content increases the number of such interfaces, promoting micro-debonding and internal friction during cyclic loading. A small addition of metal filler (around 5%) further enhances damping by introducing additional frictional sites without excessive brittleness. Similar trends have been reported in granite-filled epoxy systems, where interfacial slip and particle–matrix interactions were identified as key mechanisms governing damping enhancement [55,56].

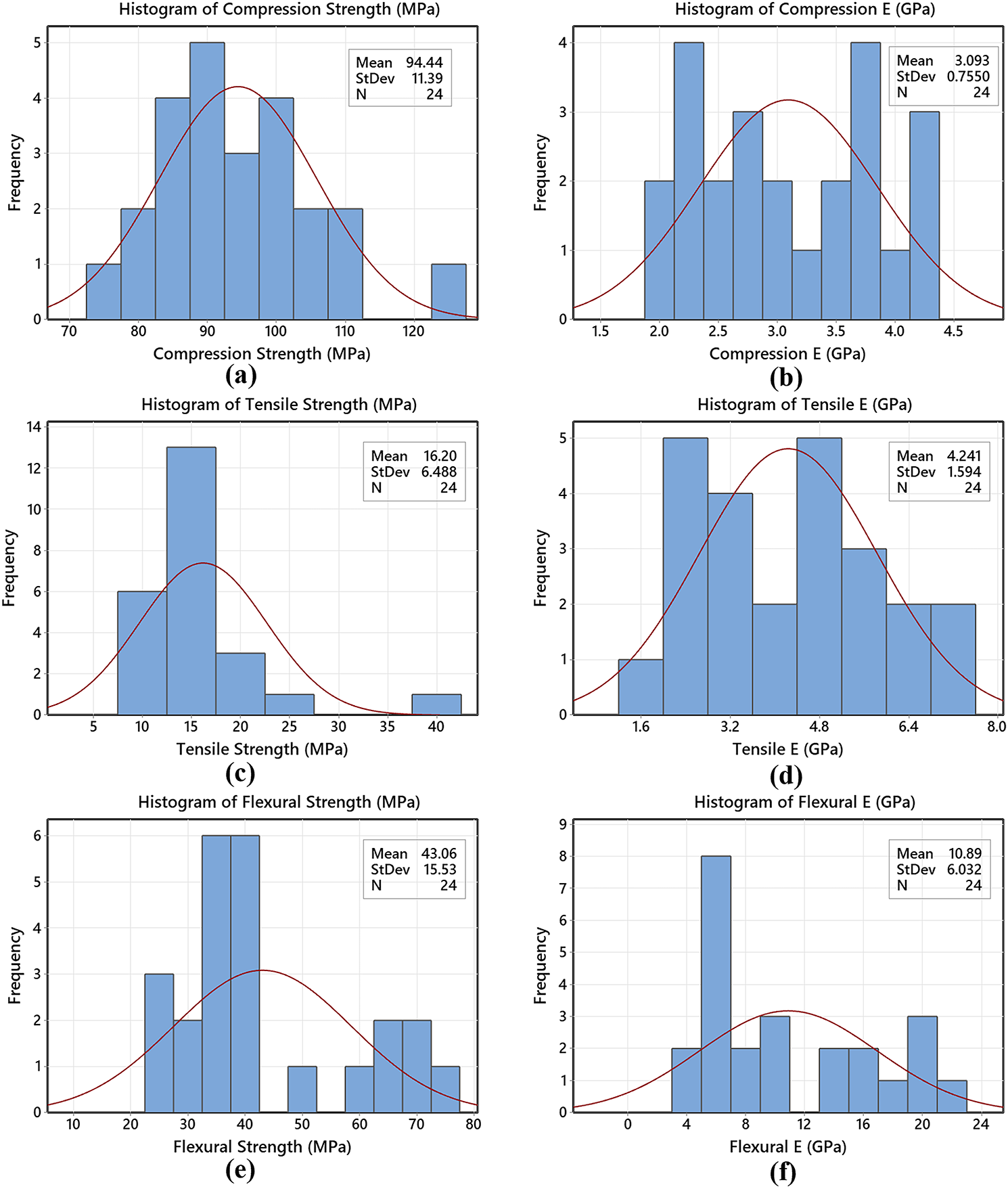

Fig. 4 details the statistical distribution of experimental test data involving the input and output parameters, enabling direct observation of the relationship between parameters. Granite particle weight (%), epoxy content weight (%), and CI filler weight (%) were selected as the input factors. Whereas a wide range of output factors were assessed of the hybrid G–E composite, such as compressive, tensile, and flexural strength, elastic modulus variation under each test, density variation, and damping ratio of the prepared composite specimens. The visualization presented in Fig. 4 helps to identify patterns, such as whether the measured data follows a normal distribution or exhibits skewness, and reveals variations under different experimental conditions. In the compression test, a mean of 94.44 was obtained, indicating the average measurement of compressive strength for varied epoxy weight (%). The standard deviation (St dev) indicates the variability of data around the mean, with a value of St dev = 11.39 indicating that the data points are relatively clustered around the mean. Lower standard deviation values were observed for the elastic modulus measurement under different mechanical tests, which reflects that the spread of data is very close to the mean. In the density test, a relatively high standard deviation value was observed, which indicates the dispersion of values around the mean.

Figure 4: Statistical data distribution of input and output variables of hybrid G–E composites with CI filler

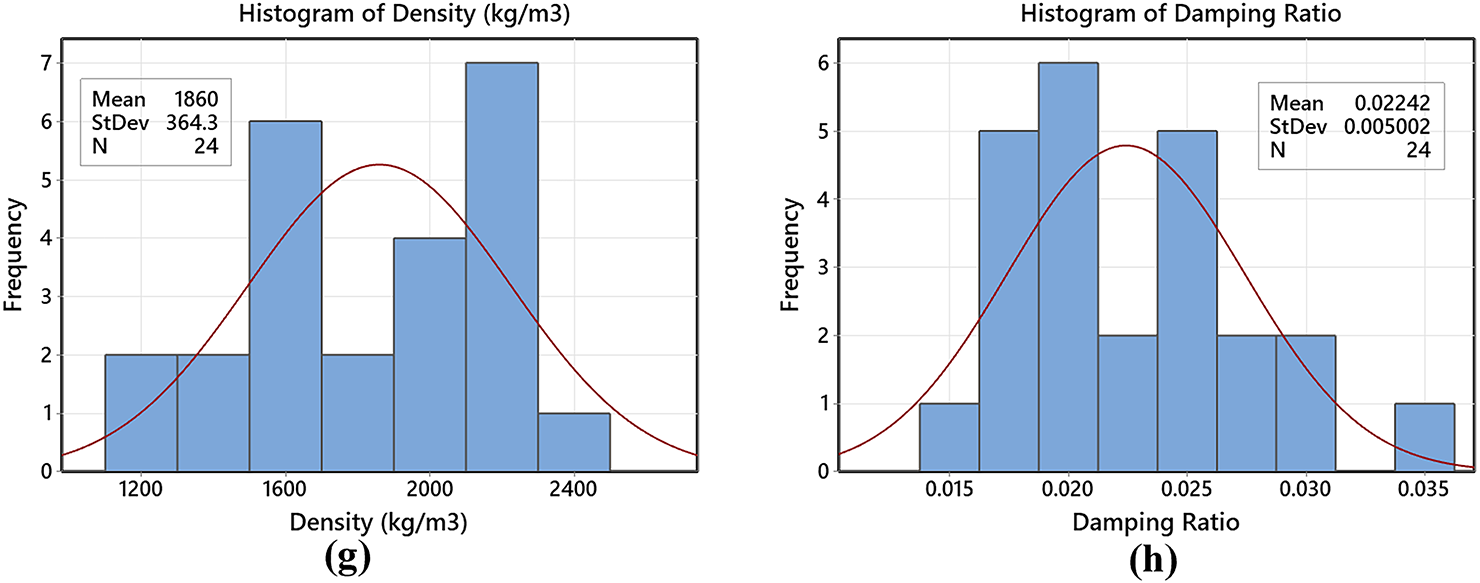

Fig. 5 illustrates the correlation matrix of the input and output variables obtained from different mechanical and damping experimental tests. The matrix was constructed using Pearson’s correlation method to assess the linear relationships between material composition (epoxy weight%, granite weight%, CI filler weight%) and the measured mechanical and damping properties. The correlation coefficients (R), ranging from −1 to +1, were visualized as a color-coded contour plot, where positive values (R > 0) indicate direct correlation, negative values (R < 0) indicate inverse correlation, and values near zero suggest weak or no correlation. To ensure statistical rigor, we performed significance testing for each correlation pair, including p-values and 95% confidence intervals. These results are provided in the supplementary Excel file titled Correlation_Statistics_Full.xlsx.

Figure 5: Correlation matrix of measured mechanical and damping parameters of hybrid G–E composites with CI filler

Out of 28 variable pairs analyzed, 12 were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05). Notably, epoxy weight% showed strong positive correlations with tensile strength, flexural strength, and density, while granite weight% exhibited significant negative correlations with tensile and flexural strength. CI filler weight% showed moderate but statistically significant negative correlations with tensile and flexural strength. Additionally, tensile strength was significantly correlated with both flexural strength and density. These statistically supported relationships reinforce the observed trends in Fig. 5 and validate the influence of composition on composite performance. Other correlations, such as those involving damping ratio, showed weaker associations and were not statistically significant, indicating the need for further investigation with larger datasets.

3 Prediction and Optimization of Mechanical and Damping Properties of Hybrid Composites

The prediction and optimization of mechanical and damping properties of hybrid G–E composites are essential to facilitate the development of composites with customized properties to suit specific application needs. Such models enable precise predictions of material behavior under various conditions, minimizing the reliance on extensive and time-consuming experimental testing. Two effective techniques, RSM and ANN, are utilized in this study. RSM helps to establish relationships between input factors (such as epoxy weight%, granite weight%, and CI weight%) and output properties (like mechanical strength and damping behavior), enabling optimized experimental designs. ANN, with its ability to capture complex non-linear relationships, provides more accurate predictions by learning from composite material datasets. ANN and RSM were chosen for their complementary strengths in modeling and optimization. ANN excels at capturing nonlinear material behavior, while RSM provides insights into interaction effects and parameter optimization. Given the complex dependencies between composition (granite, epoxy, CI filler) and mechanical properties, the combined use of both methods provides a comprehensive modeling framework.

3.1 Response Surface Methodology

The influence of variations in granite, epoxy, and CI filler content on the mechanical and damping properties was examined using RSM. This method is efficient in modeling quadratic surfaces, optimizing process parameters with a reduced number of experiments, and examining interactions between variables. RSM helps develop empirical models, improve processes, and explore interactions among multiple factors [57]. This statistical method uses quantitative experimental data to create regression models and to optimize the responses under the influence of input factors.

In this study, three independent variables were selected for the statistical experimental design: Epoxy Weight (%), Granite Weight (%), and Cast-Iron Filler (%). These factors were varied within specified ranges determined by the experimental design and identified as critical parameters for enhancing the mechanical and damping properties of the hybrid G–E composite.

In this study, Y represents the system’s response, while

In this context, Y represents the predicted response;

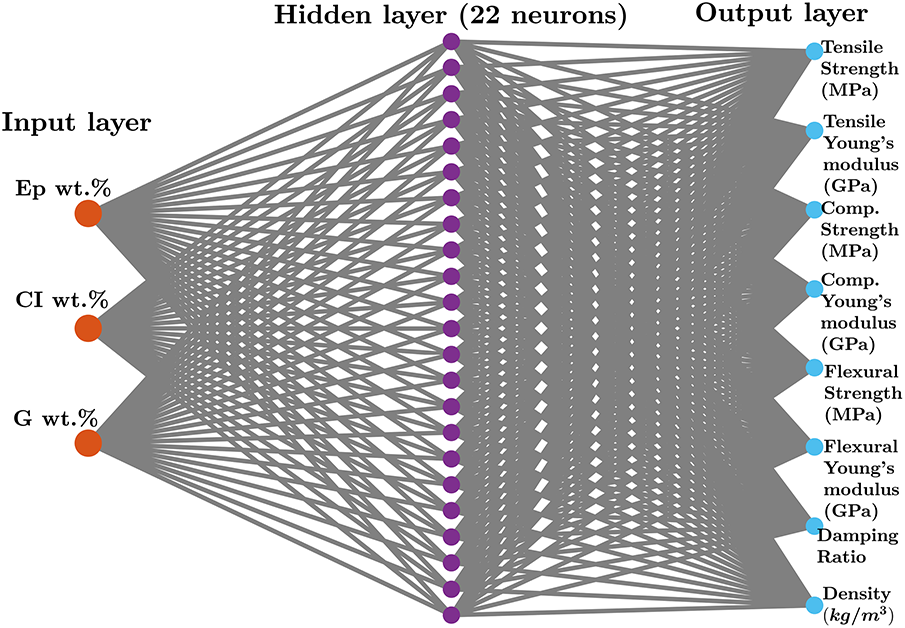

3.2 Artificial Neural Networks

In this study, ANNs are employed as regression models to predict the mechanical and damping properties of the hybrid G–E composite. ANN operates by adjusting input weights, combining them, and processing the result through a transfer function to produce an output. Mathematically, the output of the ANN can be expressed using Eq. (3).

where

Figure 6: ANN architecture

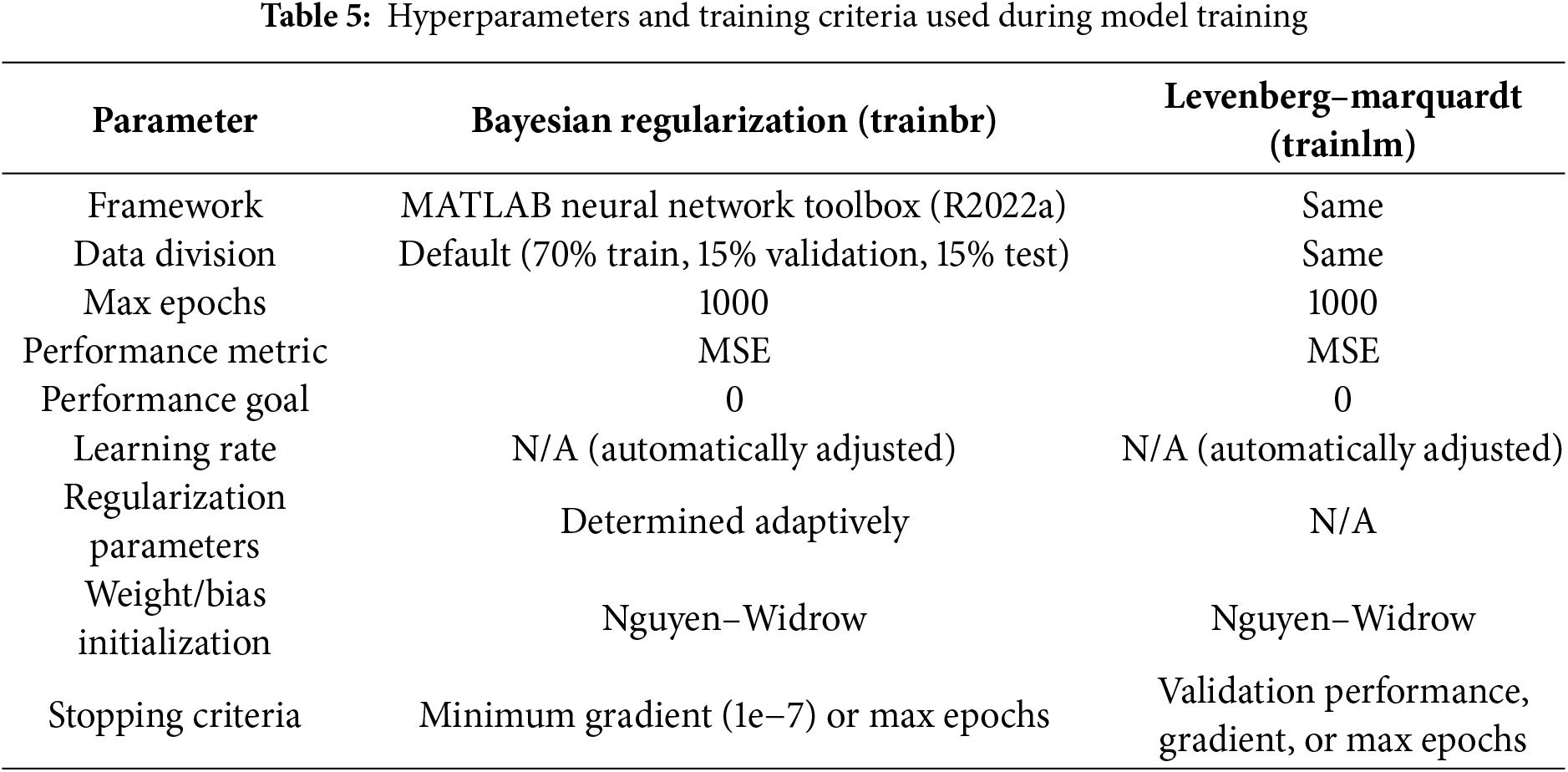

The ANN model employed a single hidden layer with a sigmoid activation function. Hyperparameters such as learning rate and regularization parameters were adaptively tuned by MATLAB’s trainbr and trainlm functions. The training was capped at 1000 epochs, with stopping criteria based on minimum gradient (10−7) or validation performance plateau. Based on the empirical approach proposed by Sheela and Deepa [58], the maximum number of neurons in the hidden layer for a 3-input neuron network is 39. The number of neurons was varied from 1 to 39, and 22 neurons were selected as optimal based on the stabilization of R2 values across all output properties

Although the dataset comprises only 24 experimental samples, this limitation arises from the rigorous and resource-intensive fabrication and ASTM-standard testing procedures required for each hybrid composition [52]. To ensure reliability despite the limited dataset, the Bayesian Regularization algorithm was selected for network training, as it adaptively penalizes overfitting and achieves strong generalization on small data sizes. The dataset was automatically partitioned into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) subsets using MATLAB’s default Neural Network Toolbox protocol. Model reliability was quantitatively evaluated through error metrics—Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) and the coefficient of determination (R2)—and qualitatively verified by comparing predicted and experimental trends. This approach has been shown to provide statistically robust predictions in small-sample composite modeling studies [25,32–34,38].

4.1 RSM Based Regression Modeling

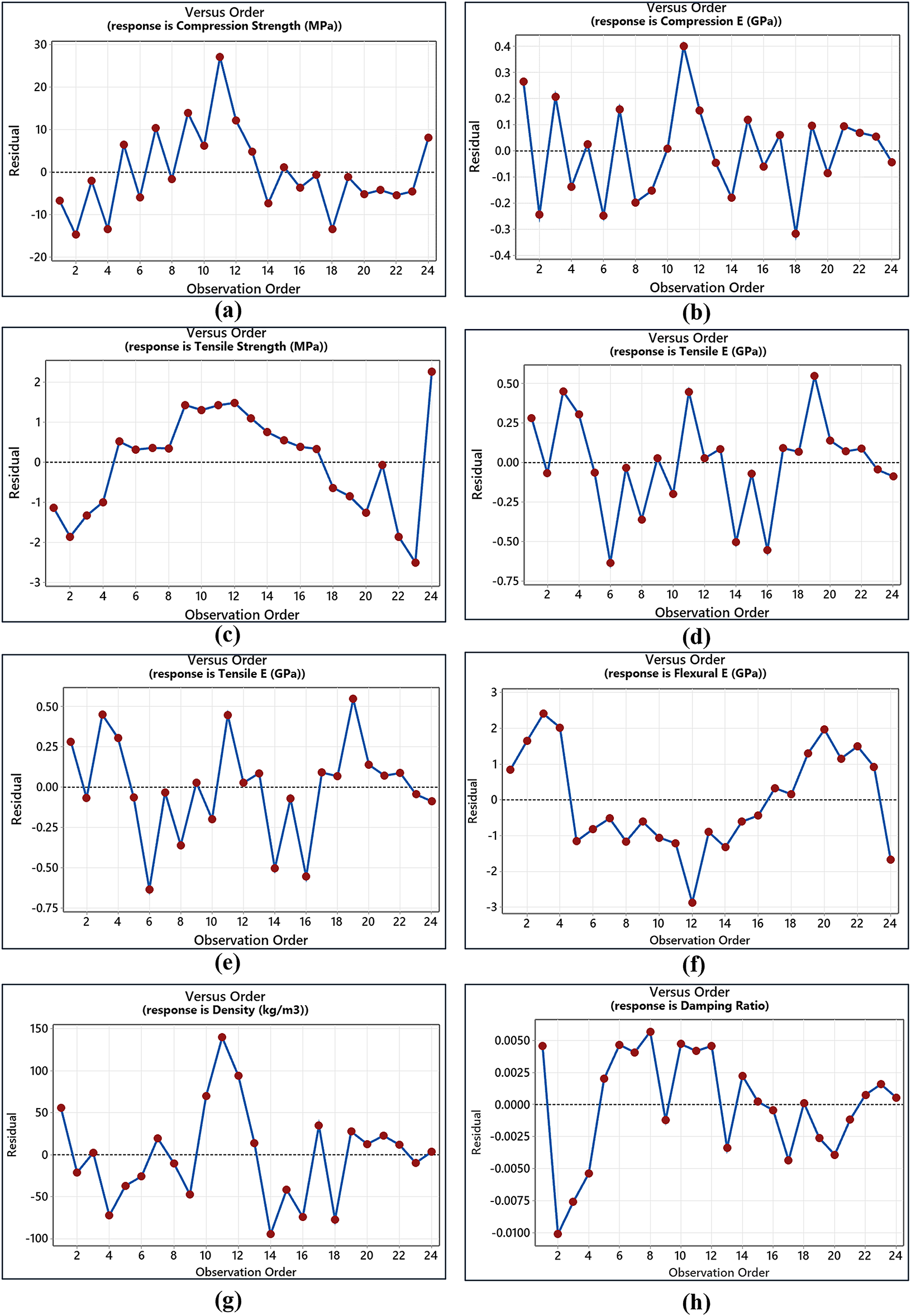

4.1.1 Residual Analysis of Mechanical and Damping Properties of Hybrid G–E Composite

From RSM analysis, the residuals vs. observation order plot representing the differences between observed and predicted mechanical and damping property values as a function of experimental observation order is illustrated in Fig. 7. From the response of compressive strength property in Fig. 7a, a random distribution of residuals was observed, with the majority of points scattered near the zero line. Such variations in residuals indicate that there is no systematic bias in the model predictions. However, the presence of peak residuals in the positive and negative ranges suggests potential inadequacies in capturing certain interactions or nonlinearities in the data. A low R2 value was noted for compressive strength, which suggests that the regression equation details a limited proportion of the variability in the response.

Figure 7: Errors between predicted responses and measured mechanical and damping properties of hybrid composites from RSM based regression model

From the variability noted for tensile strength in Fig. 7c, it can be observed that most residuals are relatively close to the zero-line, particularly at the middle of the dataset, indicating the effectiveness of the model employed. Whereas, for flexural strength, lower magnitude peak residuals were noted, and an increased cluster of data points near the zero line proves that the model predictions for flexural strength are unbiased and accurate for most of the data points. The presence of low-magnitude residuals indicates minor deviations in predictions for specific observations. A high R2 value above 96% was noted for both tensile and flexural strength, affirming that the regression model utilized effectively captured the majority of the relationship between input factors and output responses.

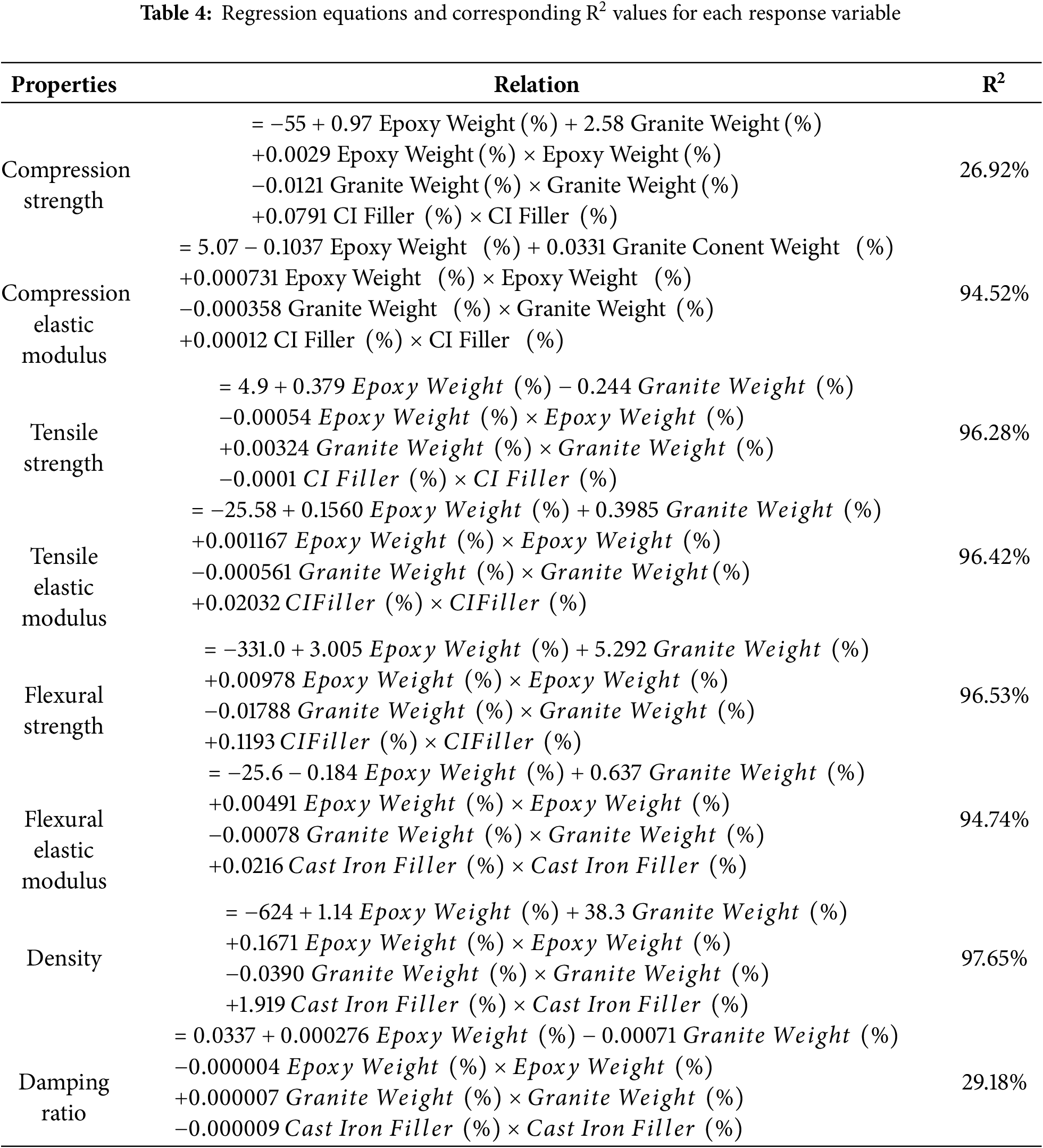

Table 4 details the regression equations developed in the prediction model for each response variable and their corresponding R2 values. From damping ratio responses, the model’s performance, indicated by a low R2 value, suggests that the regression equation details a limited proportion of the variability in the response. The low R2 value may result from insufficient inclusion of interaction terms, higher-order polynomial effects, or unmodeled factors affecting the response. However, the predicted elastic modulus responses from compression, tensile, and flexural tests demonstrate high R2 values and a lack of systematic patterns in the residuals, which underscores the robustness of the model. To improve model accuracy, exploring advanced techniques such as adding higher-order terms, incorporating interaction effects, or utilizing alternative modeling methods like ANN could be beneficial.

It is important to note that the RSM regression models presented here were primarily used for comparative benchmarking against ANN predictions and for visualizing factor interactions. While some models, such as those for compressive strength and damping ratio, exhibit low R2 values, this reflects the inherent limitations of polynomial regression in capturing complex nonlinear behavior. The ANN models, which form the core predictive framework of this study, demonstrated significantly higher accuracy and generalization. Therefore, RSM results are interpreted cautiously and are not used for statistical optimization or conclusive prediction.

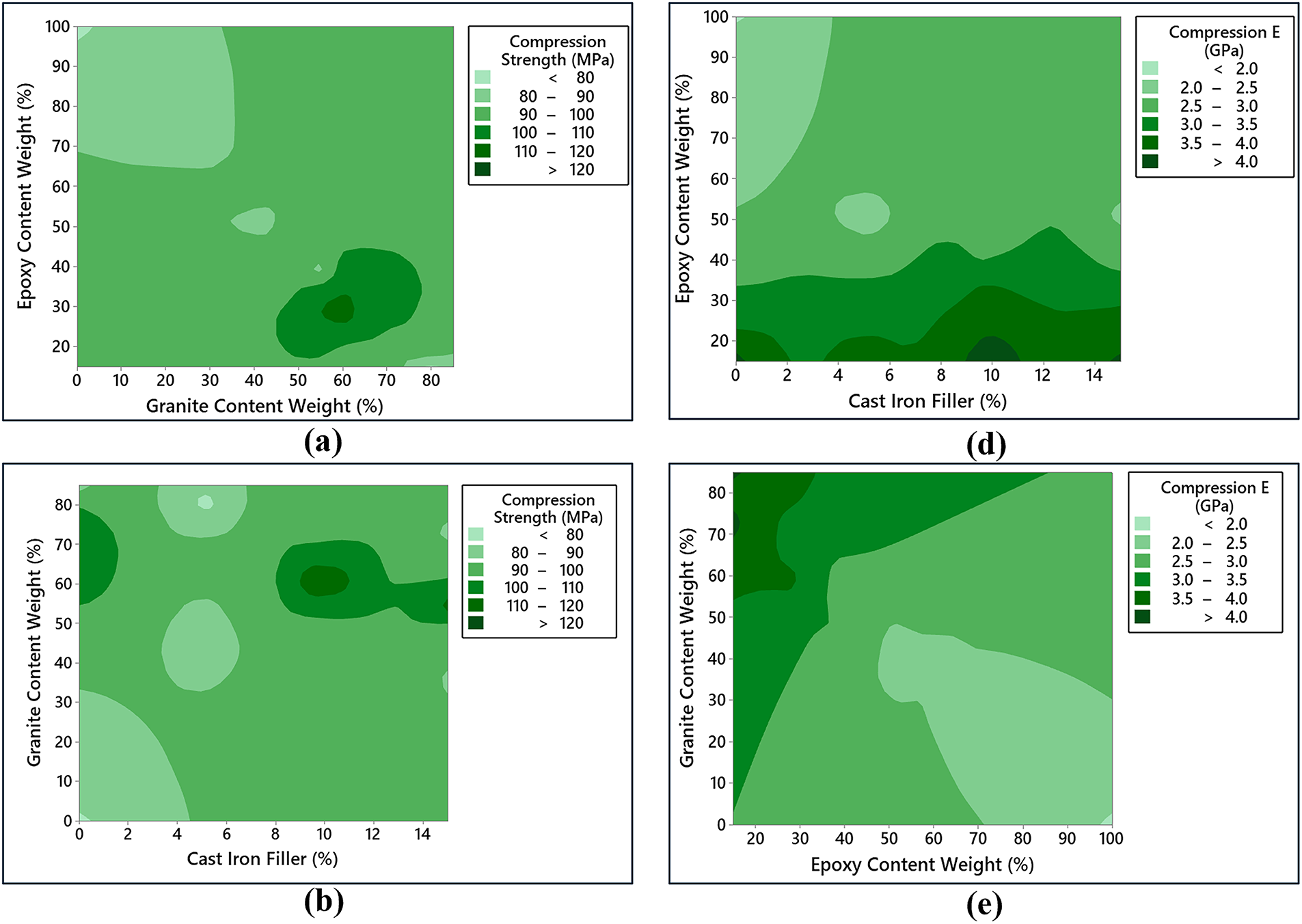

4.1.2 Interaction Effects of Hybrid G–E Composite Constituent Elements

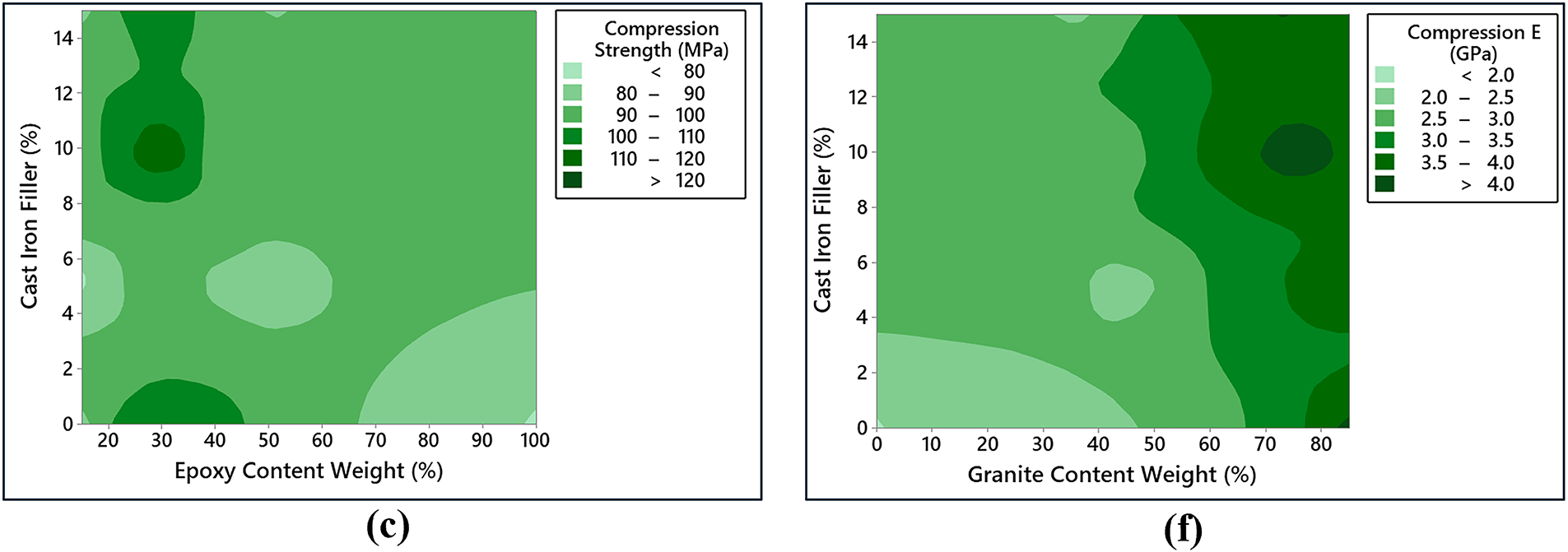

Figs. 8–12 illustrate the response surfaces from regression analysis to evaluate the interaction effects of input and output variables. In Fig. 8a–c, the influence of epoxy wt%, Granite wt% and CI filler wt% on the compressive strength of the hybrid G–E composite was detailed. The analysis reveals that higher compressive strength will be attained for specimens with granite content in a range of 50–75 wt% and epoxy content of 20–40 wt% in the absence of CI filler. Regarding the interaction between CI filler and granite content, it was observed that the presence of 10% CI filler coupled with a higher granite content range significantly enhances the compressive strength. Furthermore, the interaction between CI filler and epoxy content shows that a lower epoxy wt% range combined with an optimal CI filler concentration of 10%, contributes to improved compressive strength in the hybrid G–E composite. The elastic modulus of the hybrid G–E composite measured under compression testing exhibited significant variation based on the composition of CI filler wt%, granite wt%, and epoxy wt% as shown in Fig. 8d–f. Higher CI filler wt% range combined with lower epoxy wt% resulted in an increased elastic modulus, highlighting the reinforcing effect of the CI filler in the composite matrix. Regarding the interaction between granite content and epoxy content, it was observed that an increase in granite content led to a higher elastic modulus, indicating the critical role of granite as a structural reinforcement. These findings suggest that the synergistic effects of material composition play a critical role in optimizing the mechanical performance of the composite.

Figure 8: Interaction effects of input variables on the compressive strength and compressive elastic modulus of hybrid G–E composite. (a) Epoxy wt % vs. Granite wt % on Compression strength (b) Granite wt % vs. CI Filler % on Compression strength (c) CI Filler % vs. Epoxy wt % on Compression strength (d) Epoxy wt % vs. CI Filler % on Compression Elastic Modulus (e) Granite wt % vs. Epoxy wt % on Compression Elastic Modulus (f) CI Filler % vs. Granite wt % on Compression Elastic Modulus

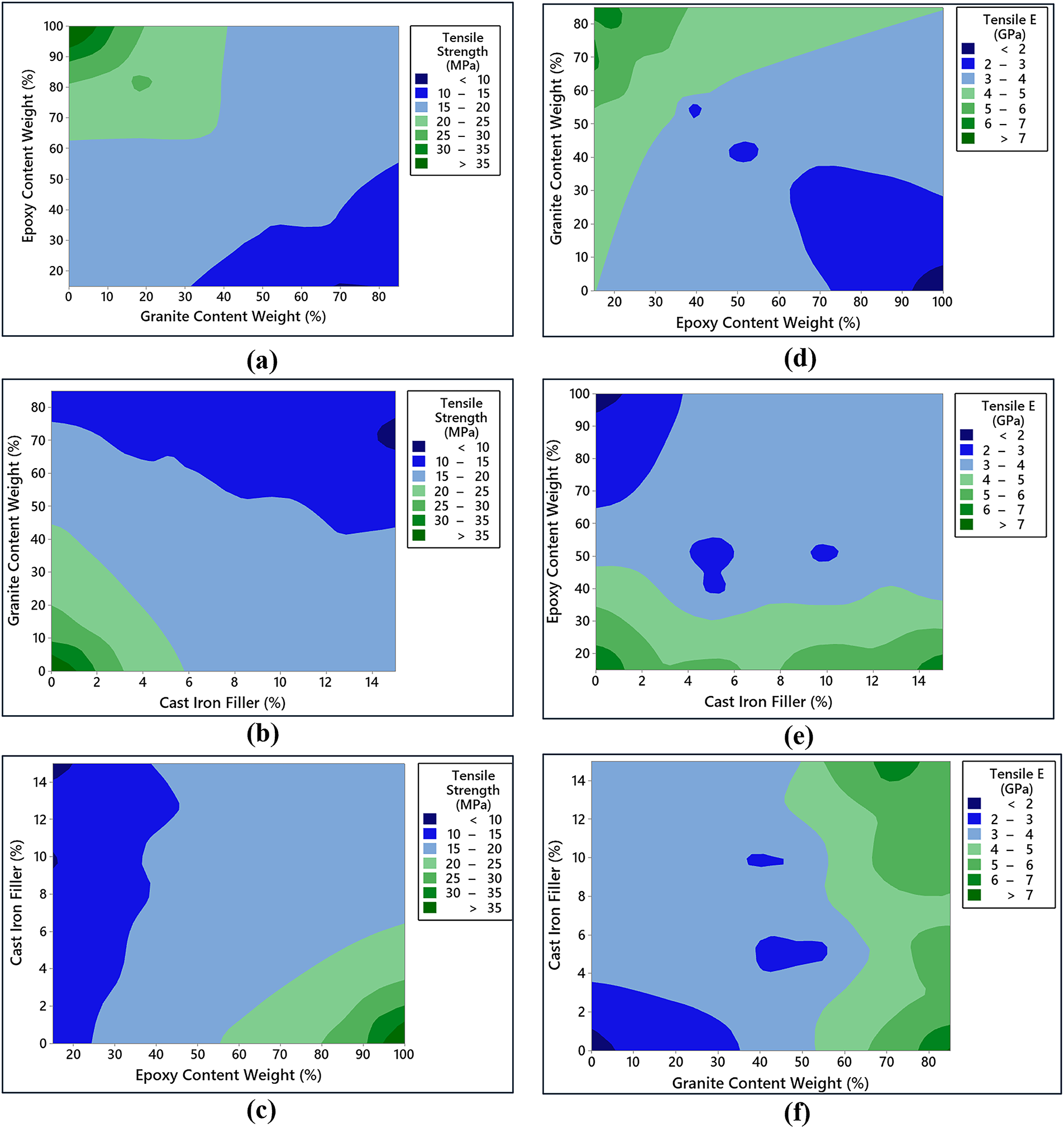

Figure 9: Interaction effects of input variables on the tensile strength and tensile elastic modulus of hybrid G–E composite. (a) Epoxy wt % vs. Granite wt % on Tensile strength (b) Granite wt % vs. CI Filler % on Tensile strength (c) CI Filler % vs. Epoxy wt % on Tensile strength (d) Granite wt % vs. Epoxy wt % on Tensile Elastic Modulus (e) Epoxy wt % vs. CI Filler % on Tensile Elastic Modulus (f) CI Filler % vs. Granite wt % on Tensile Elastic Modulus

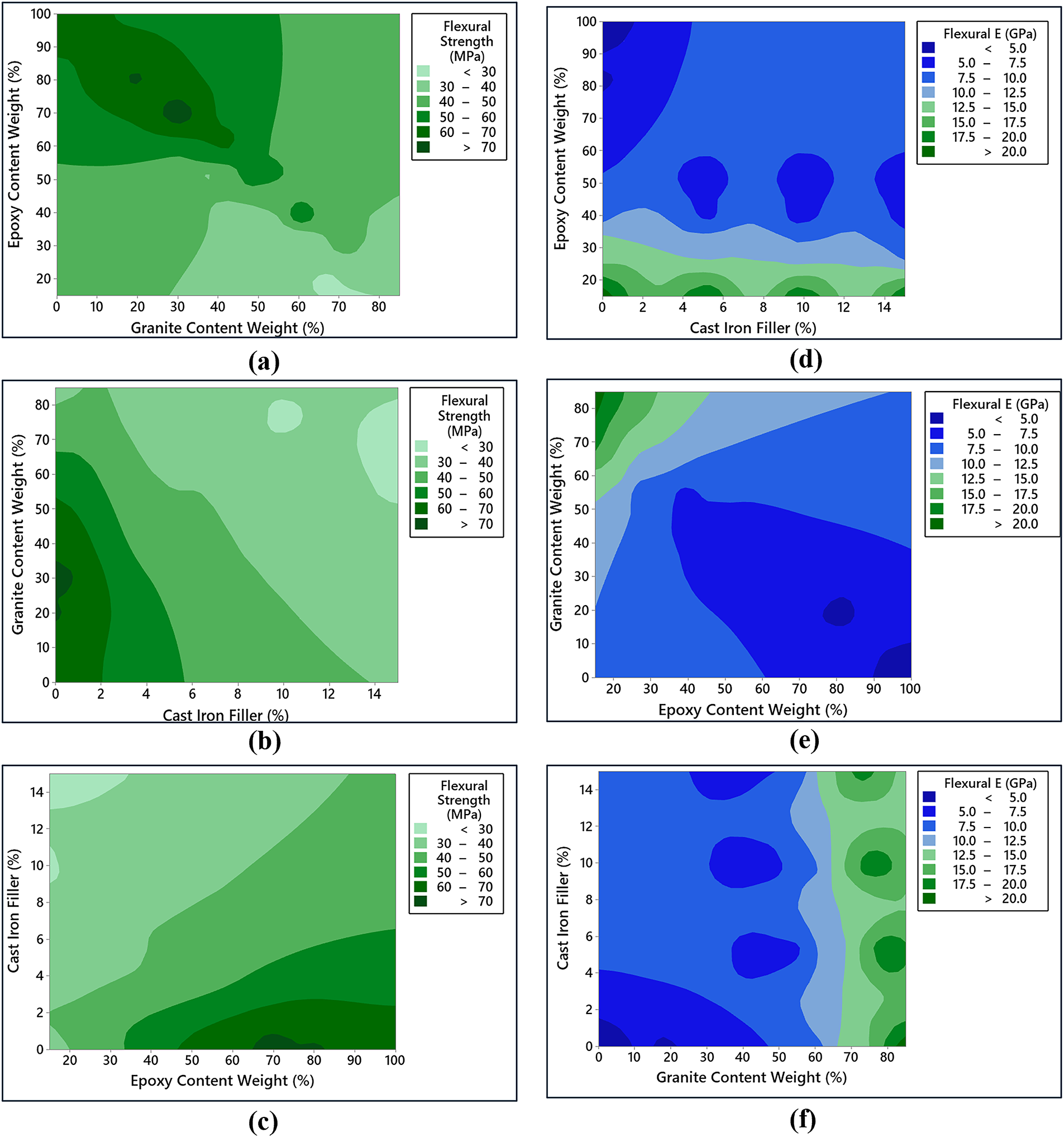

Figure 10: Interaction effects of input variables on the flexural strength and flexural elastic modulus of hybrid G–E composite. (a) Epoxy wt % vs. Granite wt % on Flexural strength (b) Granite wt % vs. CI Filler % on Flexural strength (c) CI Filler % vs. Epoxy wt % on Flexural strength (d) Epoxy wt % vs. CI Filler % on Flexural Elastic Modulus (e) Granite wt % vs. Epoxy wt % on Flexural Elastic Modulus (f) CI Filler % vs. Granite wt % on Flexural Elastic Modulus

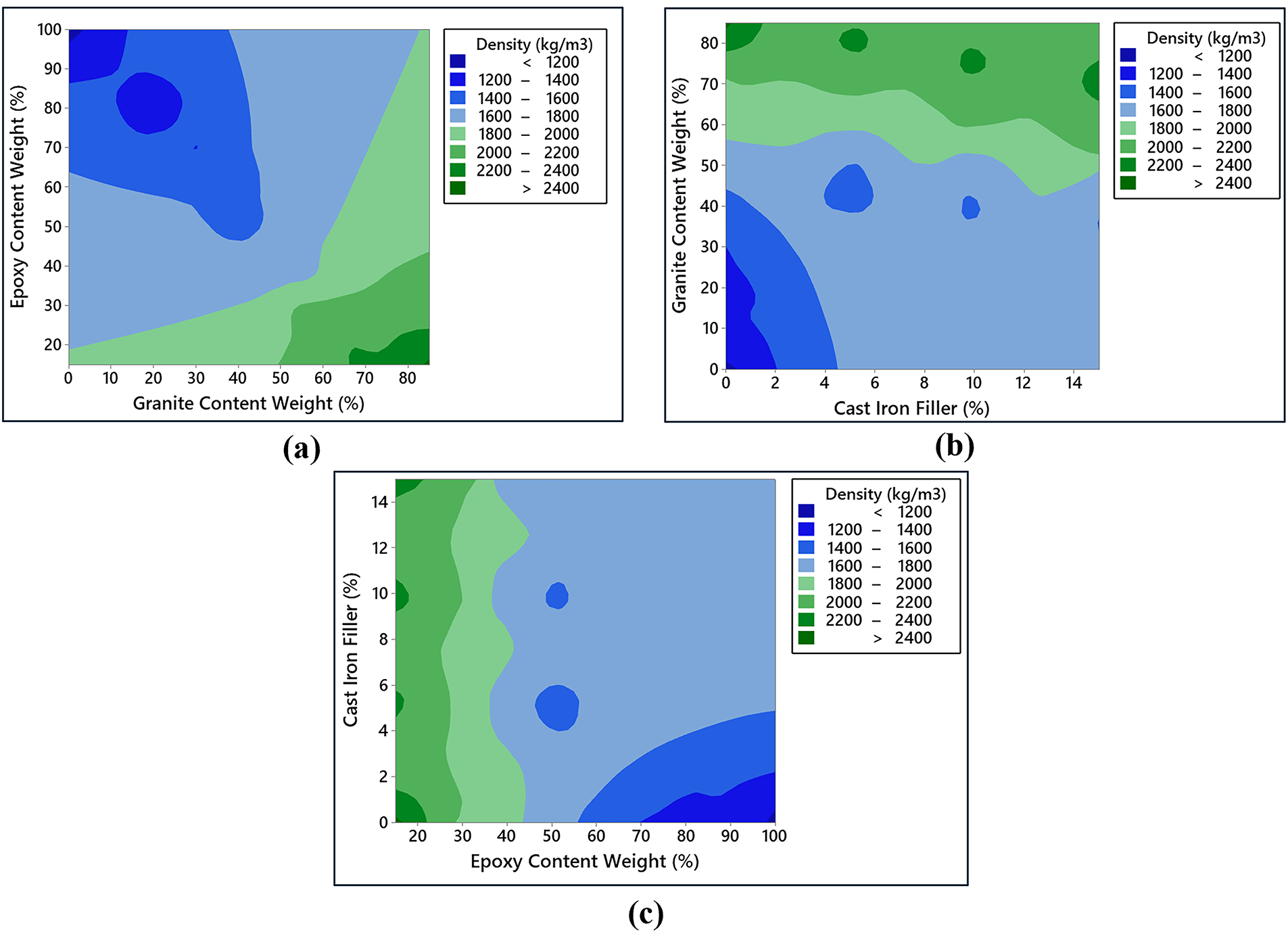

Figure 11: Interaction effects of input variables on the density property of the hybrid G–E composite. (a) Epoxy wt % vs. Granite wt % (b) Granite wt % vs. CI Filler % (c) CI Filler % vs. Epoxy wt %

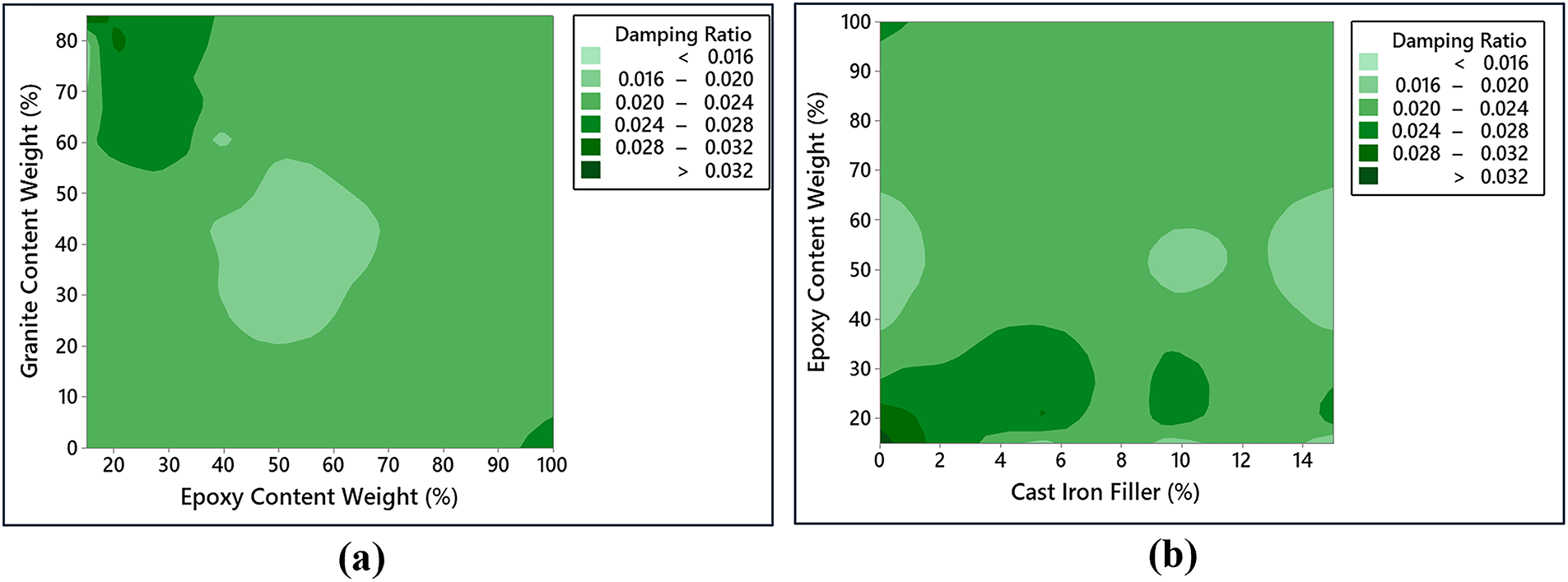

Figure 12: Interaction effects of input variables on the damping ratio of the hybrid G–E composite. (a) Granite wt % vs. Epoxy wt % (b) Epoxy wt % vs. CI Filler % (c) CI Filler % vs. Granite wt %

Fig. 9 details the interaction effects of material composition on the tensile strength and tensile elastic modulus of the hybrid G–E composite. Tensile strength was notably lower as the granite wt% was high and the epoxy wt% was low, likely due to inadequate matrix bonding and inefficient stress transfer. In contrast, higher epoxy wt% range with minimal granite particulates significantly enhanced tensile strength, attributed to improved matrix uniformity and effective load distribution. The interaction between granite particles and CI filler revealed that a low concentration range of both components yielded better tensile strength. Furthermore, increasing epoxy content with lower CI filler concentration ranges also enhanced tensile strength, emphasizing the dominant role of the epoxy matrix in mitigating clustering effects and improving load-bearing capacity. In the case of tensile elastic modulus, higher granite content range consistently increased modulus values regardless of interactions with epoxy or CI filler. This is attributed to the intrinsic stiffness of granite particles, which enhances the rigidity of the composite. Additionally, higher epoxy content improved the tensile elastic modulus across both low and high CI filler concentrations, suggesting that the epoxy matrix effectively reduces micro voids and facilitates better load transfer even in the presence of fillers. Similar influence of input variable ranges on the flexural and density of hybrid G–E composite was illustrated in Figs. 10 and 11. These findings underscore the importance of carefully optimizing the composition of epoxy, granite, and CI filler to tailor the mechanical properties of hybrid G–E composites for specific engineering applications.

The influence of material composition ranges including epoxy, granite particulates and CI filler on damping behavior is illustrated in Fig. 12. Peak damping ratio values were observed at higher granite content ranges combined with minimal epoxy wt% ranges, likely due to the increased energy dissipation from the rigid granite particles in a less rigid matrix. Conversely, a mean damping ratio was noted at intermediate levels of both granite and epoxy, indicating a balanced contribution of the matrix and filler to energy dissipation. Additionally, a high damping ratio was achieved with low CI filler content range and low epoxy levels, as reduced CI filler likely minimizes stiffness, allowing for greater vibration absorption. Similarly, high granite content range paired with low CI filler content also resulted in a high damping ratio, suggesting that granite plays a dominant role in energy dissipation when CI filler levels are minimal.

The observed interaction trends can be physically explained by the combined effects of particle dispersion, interfacial bonding, and stress transfer mechanisms. At moderate granite loadings (50–70 wt%), the granite particles are well dispersed within the epoxy matrix, forming an efficient load-transfer network that enhances compressive and flexural strength. Excessive granite content (≥80 wt%) leads to particle clustering and poor wetting of the filler surface, which weakens matrix continuity and introduces local stress concentrations, thereby reducing tensile and flexural performance. The incorporation of a small fraction of CI filler (≈5–10 wt%) further improves stiffness and damping through the creation of additional interfaces where micro-slip and interfacial friction dissipate vibrational energy. However, at higher CI levels (≥15 wt%), agglomeration and weak particle–matrix adhesion dominate, increasing brittleness and diminishing energy dissipation efficiency. These mechanistic insights are consistent with SEM observations in earlier granite–epoxy studies [12,55,56], confirming that mechanical and damping behavior strongly depend on the microstructural distribution and bonding quality between the epoxy matrix and the embedded mineral and metallic fillers.

Figs. 8–12 illustrate the response surfaces derived from RSM regression models to visualize the interaction effects of input variables on composite properties. These plots are intended to qualitatively assess trends and dependencies. Quantitative comparison of RSM predictions was performed using R2 values (Table 4), which serve as a benchmark against ANN predictions. While RSM provides interpretability, the ANN framework was used for high-accuracy prediction and extrapolation.

4.2 ANN-Based Modeling: Optimization and Prediction of Mechanical and Damping Properties of Hybrid G–E Composite

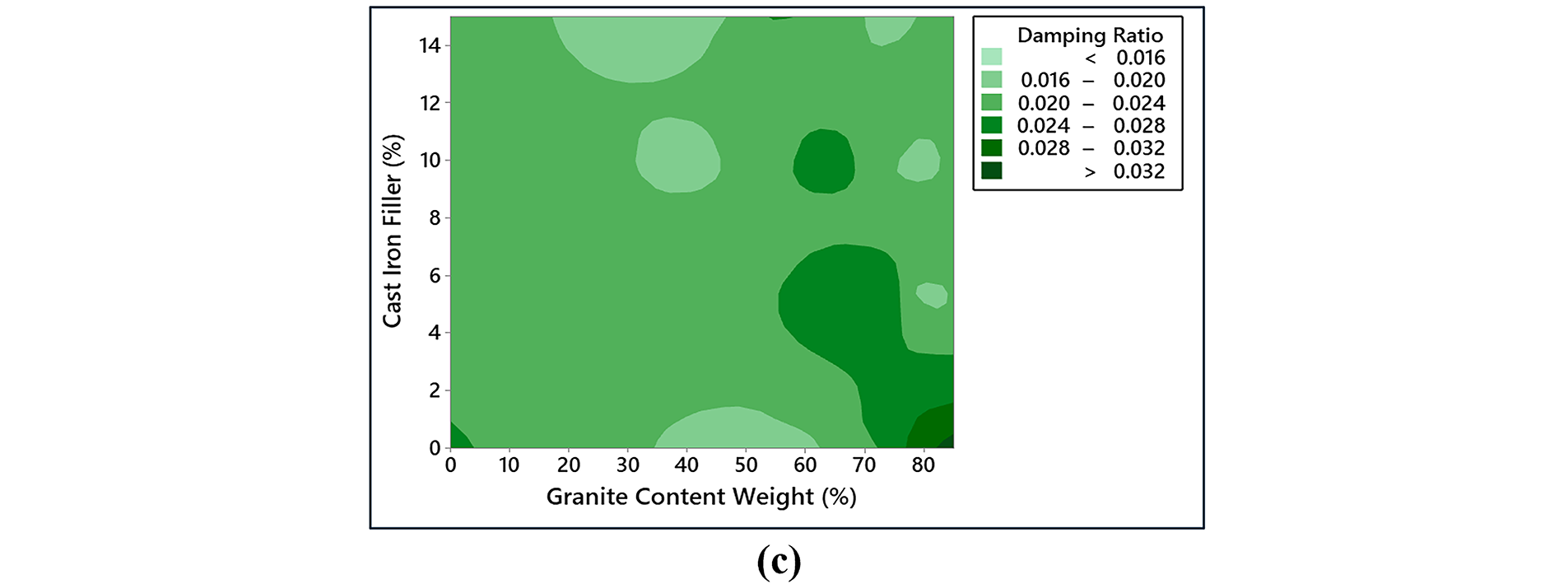

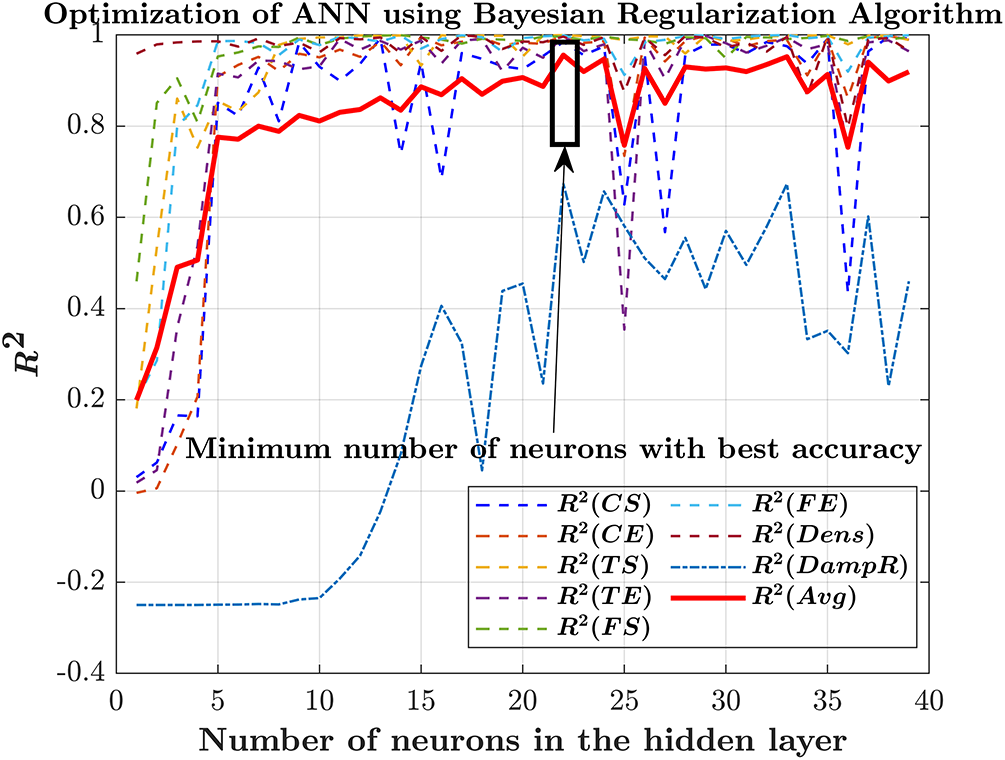

Apart from statistical techniques, ANN based modelling was performed to precisely predict the mechanical and damping behavior of hybrid G–E composites. In this study, the performance of the ANN model was analyzed and optimized using two algorithms: the Bayesian Regularization and Levenberg-Marquardt algorithms. The purpose of testing multiple algorithms was to determine the optimum number of neurons in the hidden layer that would yield the best prediction accuracy, as measured by the coefficient of determination (R2). Figs. 13 and 14 illustrate the optimization of ANN model performance using two different algorithms. The Bayesian Regularization algorithm was employed to enhance generalization by minimizing overfitting, while the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm focused on fast convergence and efficient training. By systematically varying the number of neurons in the hidden layer and evaluating the corresponding R2 values, the study identified the best performing configuration for the ANN model.

Figure 13: Optimization of ANN performance using the Bayesian Regularization algorithm based on the full dataset (CS—Compressive strength, CE—Compression elastic modulus, TS—Tensile Strength, TE—Tensile elastic modulus, FS—Flexural Strength, FE—Flexural elastic modulus, Dens—Density and DampR—Damping Ratio); curve represents the mean R2 variation (±5%) across five independent training trials

Figure 14: Optimization of ANN performance using the Levenberg Marquardt algorithm based on the full dataset (CS—Compressive strength, CE—Compression elastic modulus, TS—Tensile Strength, TE—Tensile elastic modulus, FS—Flexural Strength, FE—Flexural elastic modulus, Dens—Density and DampR—Damping Ratio); curve represents the mean R2 variation (±5%) across five independent training trials

From the ANN optimization plots shown in Figs. 13 and 14, the minimum number of neurons required to attain acceptable prediction accuracy was found to be 22. However, a notable difference in the behavior of the two algorithms was observed for varying number of neurons. In the Bayesian regularization plot, there was a significant increase in the R2 value of mechanical and damping properties with the increase in the number of neurons from 0 to 10. The tensile, compressive and flexural strengths as well as their corresponding elastic modulus properties exhibited lower R2 values while using a lesser number of neurons. As the number of neurons gradually increased, the average R2 values stabilized with minimal variation observed in the 22-neuron range, while greater variation was noted at higher neuron ranges. The average R2 value remained relatively stable even as the number of neurons varied, reflecting the algorithm’s robustness and consistent performance across different mechanical properties. Such variation suggests the stability of the Bayesian Regularization algorithm, making it a reliable choice for maintaining uniform prediction accuracy with reduced sensitivity to model parameters. However, a notable variation in the average R2 value was still observed for the damping ratio with an increase in number of neurons. This could be attributed to the inherently complex and nonlinear nature of damping behavior, which makes it more sensitive to minor changes in network parameters and less predictable compared to other mechanical properties. In contrast, in Fig. 14, significant variation in R2 values was observed in case of the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, regardless of the changes in the number of neurons. Such large variations indicate that the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm is unable to identify the optimum weights and biases of the network for the given dataset due to the inherent complexity and nonlinearities.

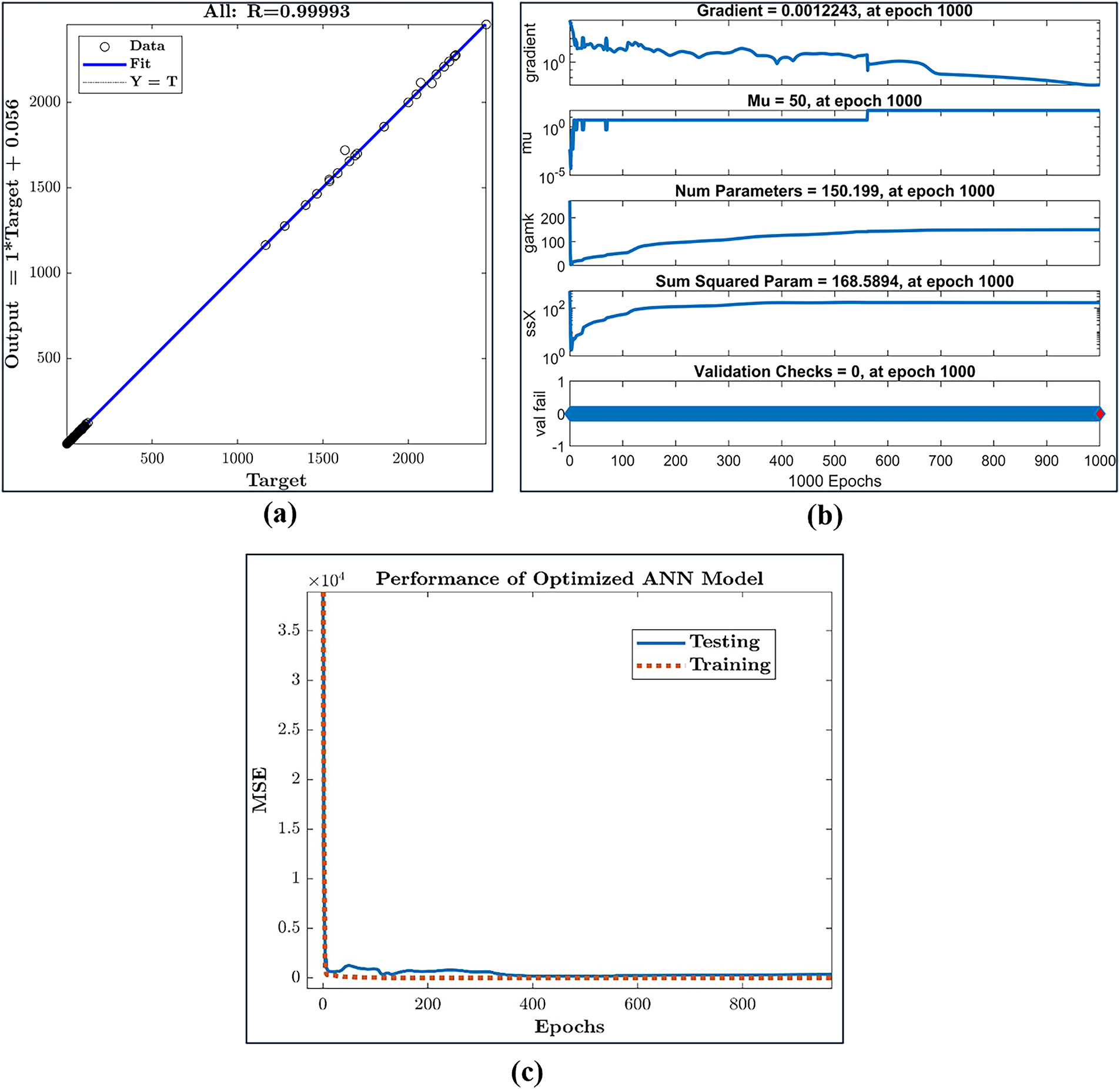

Fig. 15a illustrates the scatter plot of output data vs. actual data using an ANN model with a Bayesian Regularization algorithm for the prediction of mechanical and damping properties of the hybrid G–E composite. As predicted values approach the actual values, points on the scatterplot align closer to the diagonal regression line, indicating satisfactory model performance. A perfect fit occurs when all points lie on the 45-degree line, where outputs equal targets. The training record illustrates the training, validation, and test performance over the training process. Fig. 15b,c demonstrates that the Bayesian Regularization algorithm attained steady convergence with negligible indications of overfitting. The close correspondence between testing and training errors across all iterations indicates that the model effectively generalizes to new, unseen data. This balanced optimization highlights the capability of Bayesian Regularization to manage model complexity while preserving predictive accuracy, ensuring that the extracted patterns accurately represent the underlying data trends.

Figure 15: Scatter plots of (a) output vs. target, (b) training performance summary, and (c) training, testing performance curve of ANN model used for the prediction of the hybrid G–E composite properties

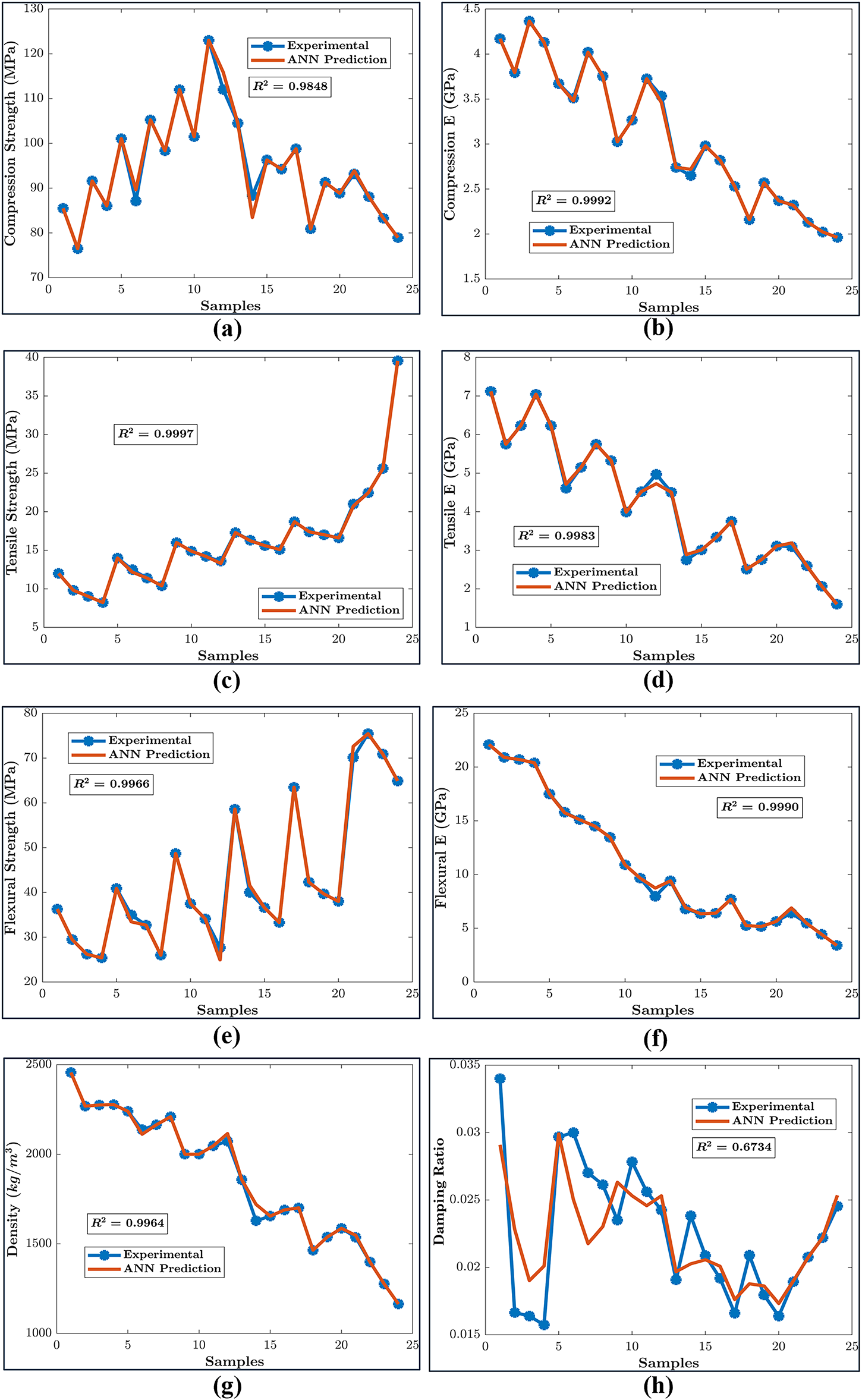

Fig. 16 illustrates the comparison between ANN predicted and experimental values of the mechanical and damping behavior of hybrid G–E composites. A total of 24 data sets of varying granite wt%, epoxy wt% and CI filler wt% were considered to analyze the prediction accuracy of the ANN models developed in this study. Based on experimental data, mechanical properties such as tensile strength, compressive strength, flexural strength, density, damping ratio and corresponding elastic modulus of specimens measured experimentally under different testing conditions were considered as output parameters for prediction. The ANN predicted values for most of the mechanical properties revealed excellent agreement with the experimental results, with an R2 value of above 0.99 except for a minor variation noted for tensile strength. Such a high coefficient of determination indicates that the ANN model can accurately capture the relationships and trends in the dataset for mechanical behavior, reflecting its ability to generalize well for these properties.

Figure 16: Comparison of ANN predictions with the experimental results of the mechanical and damping properties of hybrid G–E composite based on the full dataset. (a) Compression strength (b) Compression Elastic Modulus (c) Tensile Strength (d) Tensile Elastic Modulus (e) Flexural Strength (f) Flexural Elastic Modulus (g) Density (h) Damping Ratio

The high predictive accuracy of the ANN model for strength and modulus can be attributed to the relatively deterministic microstructural mechanisms governing these properties—namely uniform stress transfer across well-bonded epoxy–granite interfaces and the stiffening contribution of the CI filler. In contrast, the lower R2 value for damping ratio reflects the stochastic nature of energy dissipation, which depends on localized friction, interfacial micro-debonding, and internal viscoelastic losses within the epoxy matrix. These mechanisms introduce variability that cannot be fully captured by compositional inputs alone, explaining the model’s slightly reduced precision for damping predictions. Overall, the ANN results are physically meaningful: predicted improvements in compressive and flexural properties with 10 wt% CI filler coincide with the formation of denser microstructures that resist deformation, while the predicted optimum damping at lower epoxy content corresponds to greater interfacial friction and micro-slip between rigid fillers and the viscoelastic matrix.

Higher R2 values generated for tensile properties can be attributed to their predictable stress-strain behavior, characterized by well-defined linear and nonlinear trends. ANN model efficiently captures these patterns benefiting from the consistency and simplicity of tensile data, particularly under uniform testing conditions and material compositions. In the case of compression test data, the compression properties often exhibit stable and predictable behavior under loading, with minimal material irregularities influencing the results. The ANN model benefits from the consistent trends in the dataset, allowing it to achieve high accuracy in predictions. Additionally, the reduced likelihood of localized failures in compression testing enhances data reliability. Flexural properties typically involve bending stress distributions that follow well-defined mathematical relationships. The high R2 value for these properties arises from the ANN model’s ability to effectively capture these bending dynamics, particularly when the material’s response is linear or uniformly nonlinear across samples, reducing prediction error. In contrast, the damping ratio showed a significantly lower correlation, with R2 = 0.6734. Such discrepancy may stem from the inherent variability and complexity of damping behavior, which is often influenced by nonlinear factors and noise in the experimental data, making it more challenging for the model to predict with the same precision. The comparatively lower R2 for damping ratio predictions highlight the inherent complexity of damping behavior in hybrid G–E composites. Unlike mechanical properties such as strength and modulus, which have more direct dependencies on material composition, damping behavior is influenced by multiple microstructural factors, including interfacial bonding, energy dissipation mechanisms, and internal friction between phases. A larger experimental dataset with broader variations in material composition and testing conditions would improve generalizability.

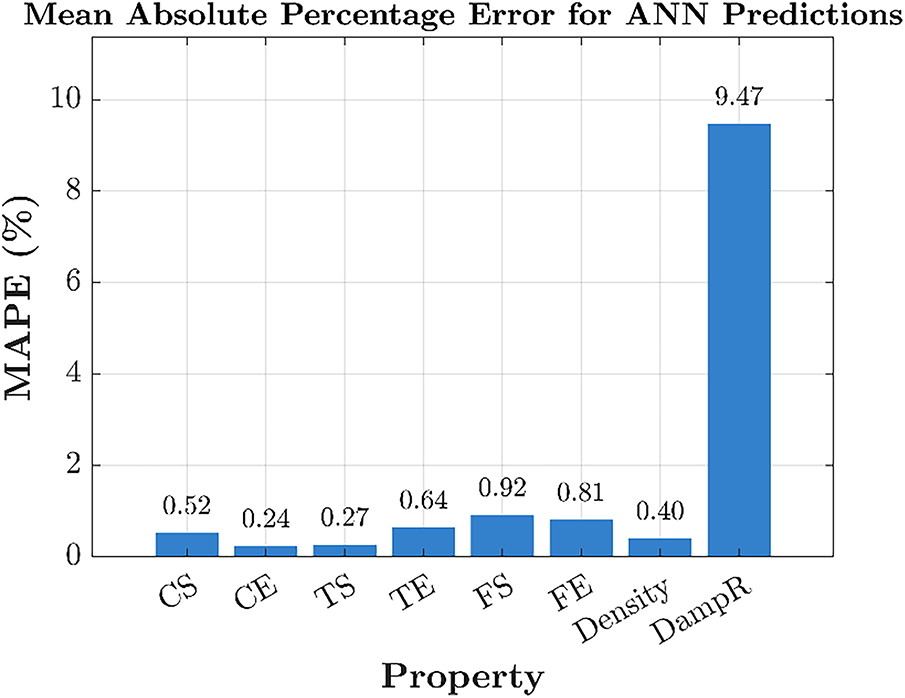

Fig. 17 presents the absolute percentage error (MAPE) for each property in both training and testing datasets. Across all mechanical properties, the average MAPE was below 2%, confirming the model’s predictive reliability. For damping ratio, the MAPE was slightly higher (~10%), consistent with its higher nonlinearity as discussed. This trend indicates that while the model performs exceptionally well for mechanical properties, predicting damping behavior is comparatively more challenging due to its complex response characteristics. The ANN models were implemented using MATLAB Neural Network Toolbox’s standard functions trainbr and trainlm, which include internally optimized settings for weight initialization, learning rate adaptation, and regularization. Default parameters were used unless otherwise specified (Table 5), following MATLAB documentation. These settings are widely used in ANN-based engineering applications, ensuring both reproducibility and comparability with prior studies.

Figure 17: Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of ANN predictions

Fig. 17 presents the absolute percentage error (MAPE) for each property in both training and testing datasets. Across all mechanical properties, the average MAPE was below 2%, confirming the model’s predictive reliability. For damping ratio, the MAPE was slightly higher (~10%), consistent with its higher nonlinearity as discussed. This trend indicates that while the model performs exceptionally well for mechanical properties, predicting damping behavior is comparatively more challenging due to its complex response characteristics. The ANN models were implemented using MATLAB Neural Network Toolbox’s standard functions trainbr and trainlm, which include internally optimized settings for weight initialization, learning rate adaptation, and regularization. Default parameters were used unless otherwise specified (Table 5), following MATLAB documentation. These settings are widely used in ANN-based engineering applications, ensuring both reproducibility and comparability with prior studies.

From the research findings, it was evident that the identified hybrid composite offers a promising alternative for machine tool bases by enhancing structural damping. Granite-based composites, even without additional reinforcements, demonstrate improved dynamic properties, making them a strong substitute for cast iron. Optimizing the granite and CI filler content further improves the stiffness and damping characteristics, making G–E composites well-suited for high-precision machining. In addition to machine tools, these composites also show promise for automotive and construction uses, including vibration-resistant flooring and structural components that enhance overall stability.

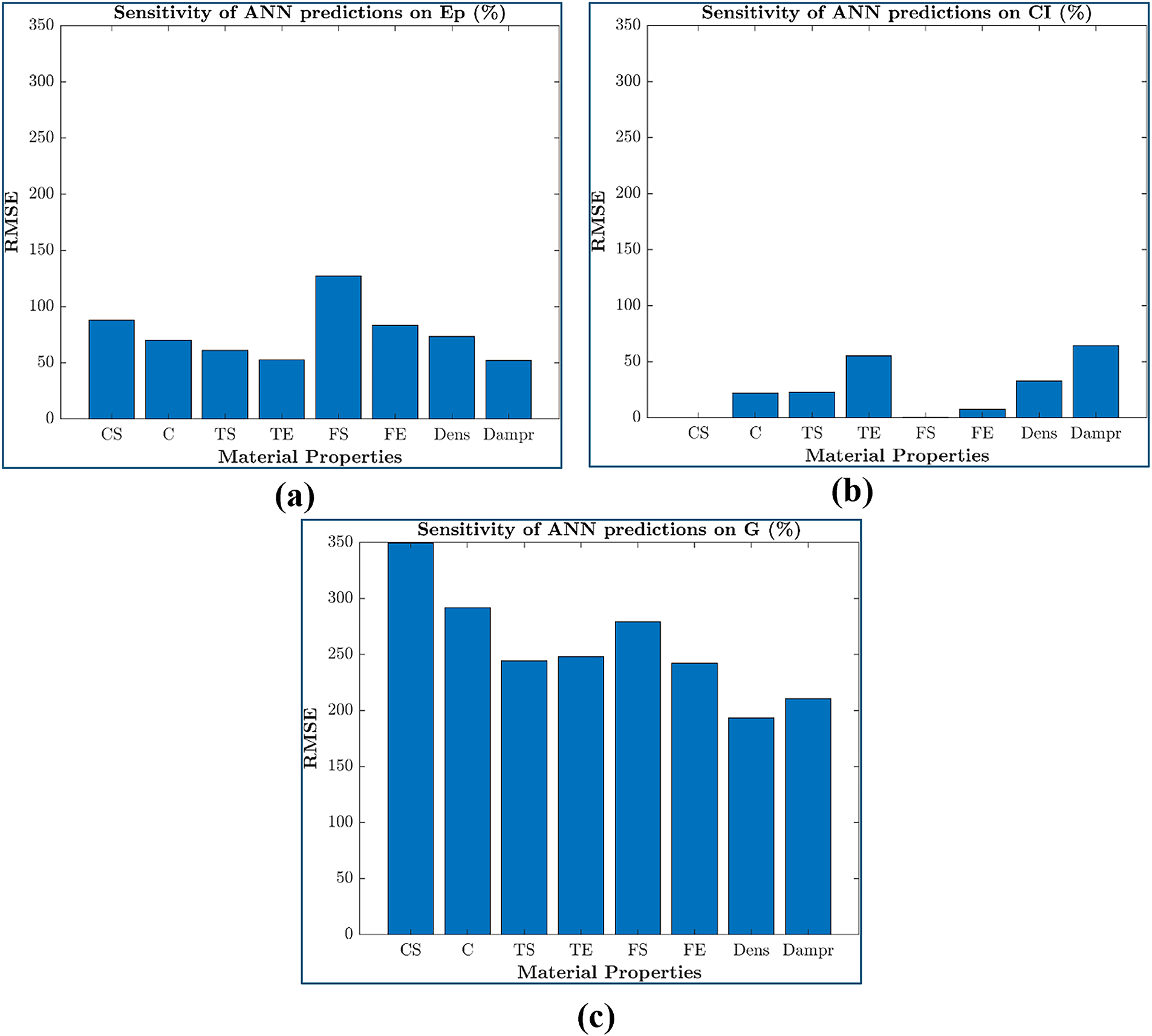

4.3 Sensitivity of ANN Model to the Constituent Elements

In addition to conventional train–validation–test partitioning, a sensitivity analysis was performed to further validate model robustness. Each input factor (epoxy, granite, and CI filler) was sequentially omitted, and the resulting change in prediction error (RMSE and R2) was analyzed. This procedure acts as an internal validation method to confirm that the trained ANN model captures physically meaningful dependencies rather than artifacts of data fitting. The factors can then be ranked according to their absence based on the level of influence they have on the accuracy of ANN predictions. As shown in Fig. 18a, as epoxy wt% was eliminated from the ANN model’s input, the sensitivity of CI filler and granite particulates on both mechanical and damping properties was found to be average. This indicates that while these fillers influence the hybrid composite’s behavior, their impact is moderated by the absence of epoxy material, which acts as the binding matrix. Epoxy typically contributes to the overall structural integrity and load transfer within the composite. Epoxy is essential for distributing stress efficiently among the fillers, improving the composite’s mechanical performance. In its absence, the load transfer mechanism is compromised, causing the fillers to function separately rather than as a unified structure, leading to average sensitivity. Weakened matrix-filler adhesion reduces load-bearing capacity, resistance to flexural deformation and significantly lowers flexural strength. Higher RMSE reflects a significant variation, as flexural strength relies heavily on the synergy between the matrix and fillers. Lower damping caused by the absence of epoxy also increases vibrations, limiting suitability for high-vibration applications.

Figure 18: Sensitivity of input factors on the mechanical and damping properties of hybrid G–E composite

However, in Fig. 18b, as the CI filler was removed, the sensitivity to mechanical and damping properties was very low. Such variation suggests that CI filler has a relatively minor role in influencing the hybrid composite’s behavior. Unlike epoxy, which facilitates stress transfer, or granite particles, which add rigidity, CI filler has weak bonding with the matrix, reducing its influence on mechanical strength. CI fillers often contribute to specific characteristics, such as density or localized strength, but their role in global mechanical and damping performance may be minimal compared to other factors. CI filler has a lesser impact since it enhances density and damping rather than structural integrity. As a rigid particulate, it contributes little to flexural strength due to its limited bonding and stress transfer ability. As a result, its removal has minimal effect on the composite’s overall behavior, supporting the model’s findings. Its primary role is in applications prioritizing vibration damping over mechanical load-bearing performance. In Fig. 18c, as the granite powder was excluded, the sensitivity of the composite’s mechanical and damping properties was very high. This highlights the critical role of granite powder in influencing these properties. Granite powder likely enhances stiffness, strength, and energy dissipation due to its rigid, particulate nature and high surface area, which can improve the load-bearing capacity and energy absorption mechanisms of the composite. Its absence creates a significant void in the material’s reinforcement structure, leading to a sharp decline in performance and high sensitivity in the model predictions. These observations emphasize the hierarchical influence of the input factors, with granite powder being the most critical, epoxy playing a moderating role, and CI filler having a relatively minor impact.

As shown in Fig. 19, the ANN model was further utilized to predict the mechanical behavior of granite epoxy compositions (40:60, 30:70, 20:80, and 0:100) for which experimental data sets were not available in reference [52], providing valuable insights while significantly reducing the need for extensive experimental testing. From Fig. 19a, higher compressive strength was observed for an increased weight percentage addition of CI filler. As the CI filler content increases, the G–E composite gains additional structural strength. This effect becomes more pronounced at higher epoxy wt% since the baseline strength of the epoxy itself is relatively low, allowing the CI filler to make a more significant impact on the overall compressive strength. As the CI wt% is increased, better distribution of CI filler particles within the epoxy matrix can be observed, which in turn, contributes to higher compressive strength. In the case of tensile strength in Fig. 19c, a gradual rise in tensile strength was noted for an increase in epoxy content, with lower strength noted for G–E composite having no additional filler. For 15 wt% CI filler, higher tensile strength was noted for different weight% of epoxy compositions. Such variation indicates that CI filler particles are likely to enhance the overall stiffness and load-bearing capacity of the matrix, leading to improved tensile properties. However, in Fig. 19e, a distinct trend was observed for flexural strength with the addition of CI filler particles. Enhancement in flexural strength was noted for 5 wt% CI filler with 70 wt% epoxy content suggesting an optimal combination of matrix and filler. However, as the epoxy content increases further, flexural strength begins to decline. This reduction may result from diminished filler-matrix interactions or suboptimal dispersion of the filler at higher epoxy levels, ultimately leading to less effective stress transfer. Compressive and tensile modulus peaked at 10 wt% CI filler, indicating enhanced performance with CI filler addition. However, a higher flexural modulus was attained without CI filler, suggesting that the filler may hinder bending resistance due to potential dispersion or compatibility issues. In comparison with experimentally measured values, the predicted values of compressive strength were significantly enhanced by the increased epoxy content and higher CI filler levels.

Figure 19: Prediction of mechanical behavior of hybrid composite with G–E ratios of 40:60, 30:70, 20:80 and 0:100 with varying CI filler weight%. (a) Compression strength (b) Compression Elastic Modulus (c) Tensile Strength (d) Tensile Elastic Modulus (e) Flexural Strength (f) Flexural Elastic Modulus

In this study, the R2 values presented in the optimization plots (Figs. 13–16) were computed using the full dataset of 24 samples. This was intentional, as these figures were designed for architecture tuning and comparative algorithm assessment rather than independent validation. Given the limited dataset size, using the complete set for this stage ensured stable performance trends across varying neuron counts and property types. While such an approach can raise overfitting concerns, several safeguards were incorporated: the Bayesian Regularization algorithm inherently penalized overly complex weight configurations, the optimal neuron counts were moderate, and all variables were normalized to a uniform range. Moreover, the model’s predictions for compositions are not included in the dataset (Figs. 18 and 19) aligned with established material behavior trends, providing indirect evidence of generalization. This combination of regularization, compact architecture, and physical consistency in extrapolated predictions supports the robustness of the ANN model despite the dataset constraints.

4.4 Comparison with Existing Literature

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of ANN models in predicting mechanical properties of polymer matrix composites, though often with slightly lower accuracy or narrower property ranges than achieved here. For example, Kumar and Swamy [59] predicted the fatigue life of glass fiber–reinforced epoxy composites using a dataset of 11 samples, reporting R2 values in the range of 0.99857. Similarly, Sharma et al. [60] applied a feed-forward ANN to predict tribological performance of graphene nano-platelets filled glass fiber reinforced epoxy composites with 9 experimental points, achieving R2 ≈ 0.965–0.986. In the case of natural fiber composites, Nasir and Toubal [51] reported R2 values of 0.96 using 30 samples for ANN-based tensile strength and impact load prediction. Compared to these works, the present study achieves consistently higher R2 values (>0.99 for most properties) while using a similar dataset size, while simultaneously predicting a broader set of output parameters including multiple mechanical strengths, elastic moduli, density, and damping ratio. This improvement is attributed to (i) systematic dataset preprocessing, (ii) optimization of hidden neurons through grid search, and (iii) use of the Bayesian Regularization algorithm, which enhanced model stability and reduced overfitting risk. Furthermore, unlike most earlier studies which focus solely on prediction, the present work integrates ANN with Response Surface Methodology to enable both high-accuracy prediction and factor interaction analysis, providing a more comprehensive framework for composite material design and optimization.

• The present study highlighted the capability of RSM and ANN techniques to effectively predict and optimize the material composition and performance characteristics of hybrid granite–epoxy (G–E) composites.

• The findings reveal key insights into the relationships between input variables and mechanical and damping properties, highlighting the reinforcing role of granite content and the importance of epoxy and CI filler for optimizing strength, stiffness and damping behavior.

• A total of 24 experimental data sets on the mechanical and damping properties of hybrid G–E composites were employed and partitioned into training and testing groups.

∘ The analysis indicated that specimens with 50–75 wt% granite and 20–40 wt% epoxy exhibited higher compressive strength in the absence of filler, whereas incorporating 10 wt% CI filler further enhanced strength at elevated granite contents.

∘ The analysis shows that specimens with 50–75 wt% granite and 20–40 wt% epoxy achieve higher compressive strength without CI filler. Adding 10% CI filler further enhances strength at higher granite content.

∘ The damping ratio increased with higher granite content and lower epoxy proportions, while tensile strength displayed the reverse behavior, improving with greater epoxy content and reduced granite levels.

∘ Flexural strength was found to depend strongly on the epoxy-to-filler ratio, with 5 wt% CI filler and 70 wt% epoxy providing an optimal balance between stiffness and flexibility.

• Optimization plots showed that R2 values for mechanical properties stabilized at around 22 neurons, while the damping ratio varied notably, indicating its complex and sensitive nature to network parameters.

• The Bayesian Regularization algorithm demonstrated superior reliability with stable accuracy and low sensitivity to neuron count, enabling the ANN to predict most mechanical properties with excellent agreement to experimental results (R2 > 0.99), except for minor deviations in tensile strength.

• The ANN model was employed to predict the mechanical behavior of granite-epoxy compositions (40:60, 30:70, 20:80, and 0:100) where experimental data were unavailable, offering valuable insights while significantly minimizing the need for extensive testing.

∘ At higher epoxy wt% of G–E composite, the addition of CI filler significantly enhanced both compressive and tensile strength.

∘ Flexural strength was found to be highly dependent on the epoxy-to-filler ratio, with 5 wt% CI filler and 70 wt% epoxy providing the best balance, emphasizing the importance of matrix-filler interaction in composite performance.

• The current work has certain limitations by considering a relatively small dataset (24 samples), which may limit the generalizability of the models, and the focus on specific composition ranges, which may not capture all potential material behaviors.

• Additionally, damping predictions exhibited higher variability, suggesting the need for further refinement. Future work should utilize larger datasets and investigate hybrid optimization approaches, such as combining ANN with evolutionary algorithms, to further improve accuracy, robustness, and overall applicability in composite design.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education for the valuable support and cooperation during this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Girish Hariharan and Subraya Krishna Bhat; methodology, Girish Hariharan and Subraya Krishna Bhat; software, Girish Hariharan and Subraya Krishna Bhat; validation, Vinyas, Nitesh Kumar and Shiva Kumar; formal analysis, Girish Hariharan and Gowrishankar Mandya Chennegowda; investigation, Girish Hariharan and Subraya Krishna Bhat; resources, Vinyas, Shiva Kumar and Deepak Doreswamy; data curation, Girish Hariharan and Gowrishankar Mandya Chennegowda; writing—original draft preparation, Girish Hariharan and Subraya Krishna Bhat; writing—review and editing, Girish Hariharan and Subraya Krishna Bhat; supervision, Gowrishankar Mandya Chennegowda, Nitesh Kumar and Shiva Kumar; project administration, Gowrishankar Mandya Chennegowda and Deepak Doreswamy; funding acquisition, Vinyas and Shiva Kumar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Subraya Krishna Bhat, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.073772/s1.

References

1. Li S, Cheng P, Ahzi S, Peng Y, Wang K, Chinesta F, et al. Advances in hybrid fibers reinforced polymer-based composites prepared by FDM: a review on mechanical properties and prospects. Compos Commun. 2023;40(2):101592. doi:10.1016/j.coco.2023.101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Seydibeyoğlu MÖ, Dogru A, Wang J, Rencheck M, Han Y, Wang L, et al. Review on hybrid reinforced polymer matrix composites with nanocellulose, nanomaterials, and other fibers. Polymers. 2023;15(4):984. doi:10.3390/polym15040984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Heisel U, Gringel M. Machine tool design requirements for high-speed machining. CIRP Ann. 1996;45(1):389–92. doi:10.1016/S0007-8506(07)63087-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Möhring HC, Brecher C, Abele E, Fleischer J, Bleicher F. Materials in machine tool structures. CIRP Ann. 2015;64(2):725–48. doi:10.1016/j.cirp.2015.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Subhash C, Krishna MR, Raj MS, Sai BH, Rao SR. Development of granite powder reinforced epoxy composites. Mater Today Proc. 2018;5(5):13010–4. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2018.02.286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Omar M, Abdelrhman Y, Hassab IM, Khierldeen WM. Experimental study on compressive strength and flexural rigidity of epoxy granite composite material. JES J Eng Sci. 2021;49(2):198–214. doi:10.21608/jesaun.2021.61303.1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Piratelli-Filho A, Shimabukuro F. Characterization of compression strength of granite-epoxy composites using design of experiments. Mat Res. 2008;11(4):399–404. doi:10.1590/s1516-14392008000400003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Piratelli-Filho A, Levy-Neto F. Behavior of granite-epoxy composite beams subjected to mechanical vibrations. Mat Res. 2010;13(4):497–503. doi:10.1590/s1516-14392010000400012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pawar MJ, Patnaik A, Nagar R. Investigation on mechanical and thermo-mechanical properties of granite powder filled treated jute fiber reinforced epoxy composite. Polym Compos. 2017;38(4):736–48. doi:10.1002/pc.23633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Maluga R, Sunil Kumar M, Ranjan Pati P, Sathees Kumar S. Physical, mechanical and wear characterization of epoxy composites reinforced with granite/marble powder. Mater Today Proc. 2023;13:47. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.02.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mula VR, Ramachandran A, Pudukarai Ramasamy T. A review on epoxy granite reinforced polymer composites in machine tool structures—static, dynamic and thermal characteristics. Polym Compos. 2023;44(4):2022–70. doi:10.1002/pc.27229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Abdelrhman Y, Omar M, Hassab-Allah IM, Shewakh WM, Khierldeen WM, Hedaya M, et al. Mechanical properties and damping characteristics of Egyptian granite-epoxy composite material. Mater Res Express. 2024;11(6):066501. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/ad4f5b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Arumugam H, Iqbal MM, Ahn CH, Rimdusit S, Muthukaruppan A. Development of high performance granite fine fly dust particle reinforced epoxy composites: structure, thermal, mechanical, surface and high voltage breakdown strength properties. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;24:2795–811. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.03.199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chaturvedi R, Pappu A, Tyagi P, Patidar R, Khan A, Mishra A, et al. Next-generation high-performance sustainable hybrid composite materials from silica-rich granite waste particulates and jute textile fibres in epoxy resin. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;177:114527. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.114527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Thandavamoorthy R, Alagarasan JK, Mohanavel V, Velmurugan P, Al-Otibi FO, Hossain I, et al. Fabrication of green composite made by Cannabis sativa fiber reinforced granite filler blended epoxy matrix composite—antimicrobial and structural analysis. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;32(1):2474–81. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.08.105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Reddy BM, Kumar GS, Reddy YVM, Reddy PV, Reddy BCM. Study on the effect of granite powder fillers in surface-treated Cordia Dichotoma fiber-reinforced epoxy composite. J Nat Fibres. 2022;19(6):2002–17. doi:10.1080/15440478.2020.1789022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ojha AR, Biswal SK. Thermo physico-mechanical behavior of palm stalk fiber reinforced epoxy composites filled with granite powder. Compos Commun. 2019;16(5):158–61. doi:10.1016/j.coco.2019.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rama SR, Rai SK. Tensile, flexural, density and void content studies on granite powder filled hydroxyl terminated polyurethane toughened epoxy composite. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2008;27(15):1663–71. doi:10.1177/0731684408088891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bakar M, Duk R, Przybyłek M, Kostrzewa M. Mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy resin modified with polyurethane. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2009;28(17):2107–18. doi:10.1177/0731684408091703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Venugopal PR, Kalayarasan M, Thyla PR, Mohanram PV, Nataraj M, Mohanraj S, et al. Structural investigation of steel-reinforced epoxy granite machine tool column by finite element analysis. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part L J Mater Des Appl. 2019;233(11):2267–79. doi:10.1177/1464420719840592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Venugopal PR, Dhanabal P, Thyla PR, Mohanraj S, Nataraj M, Ramu M, et al. Design and analysis of epoxy granite vertical machining centre base for improved static and dynamic characteristics. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part L J Mater Des Appl. 2020;234(3):481–95. doi:10.1177/1464420719890892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ramesh B, Sathish Kumar S, Elsheikh AH, Mayakannan S, Sivakumar K, Duraithilagar S. Optimization and experimental analysis of drilling process parameters in radial drilling machine for glass fiber/nano granite particle reinforced epoxy composites. Mater Today Proc. 2022;62(3):835–40. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.04.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Somaiah A, Prasad BA, Nath NK. Taguchi-based optimization and ANOVA analysis of drilling parameters for enhanced hole quality in GFRP composites with MgO and TiO2 nanofillers. Mater Circ Econ. 2025;7(1):5. doi:10.1007/s42824-025-00159-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dholi A, Yadav S, Agrawal A, Gupta G. Development of epoxy/red stone dust composites and their characterization for light duty structural and automotive applications. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2025;39(11):1737–56. doi:10.1080/01694243.2025.2464879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Shishegaran A, Saeedi M, Mirvalad S, Korayem AH. Computational predictions for estimating the performance of flexural and compressive strength of epoxy resin-based artificial stones. Eng Comput. 2023;39(1):347–72. doi:10.1007/s00366-021-01560-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Veluswamy A, Venugopal PR, Mani K, Palanisamy D, Marikrishnan T, Arunachalam AT. Topology optimization-based design, development and testing of steel-reinforced epoxy granite vertical machining centre column. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part L J Mater Des Appl. 2024;238(6):1005–20. doi:10.1177/14644207231206453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]