Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Anomaly Detection with Causal Reasoning and Semantic Guidance

1 China Aerospace Academy of Systems Science and Engineering, Beijing, 100048, China

2 Aerospace Hongka Intelligent Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, 100048, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaochuan Jing. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 84 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073850

Received 27 September 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In the field of intelligent surveillance, weakly supervised video anomaly detection (WSVAD) has garnered widespread attention as a key technology that identifies anomalous events using only video-level labels. Although multiple instance learning (MIL) has dominated the WSVAD for a long time, its reliance solely on video-level labels without semantic grounding hinders a fine-grained understanding of visually similar yet semantically distinct events. In addition, insufficient temporal modeling obscures causal relationships between events, making anomaly decisions reactive rather than reasoning-based. To overcome the limitations above, this paper proposes an adaptive knowledge-based guidance method that integrates external structured knowledge. The approach combines hierarchical category information with learnable prompt vectors. It then constructs continuously updated contextual references within the feature space, enabling fine-grained meaning-based guidance over video content. Building on this, the work introduces an event relation analysis module. This module explicitly models temporal dependencies and causal correlations between video snippets. It constructs an evolving logic chain of anomalous events, revealing the process by which isolated anomalous snippets develop into a complete event. Experiments on multiple benchmark datasets show that the proposed method achieves highly competitive performance, achieving an AUC of 88.19% on UCF-Crime and an AP of 86.49% on XD-Violence. More importantly, the method provides temporal and causal explanations derived from event relationships alongside its detection results. This capability significantly advances WSVAD from a simple binary classification to a new level of interpretable behavior analysis.Keywords

Video anomaly detection (VAD) is a critical technology in domains like public safety and industrial automation, providing a scalable alternative to the inherent limitations of human-led surveillance [1]. Within this field, the weakly supervised video anomaly detection (WSVAD) has become particularly influential. By training on video-level labels, WSVAD alleviates the intensive labor of temporal annotation and promotes better generalization across varied scenarios. However, despite these benefits, WSVAD frameworks struggle with a significant limitation: a lack of semantic specificity and predictive insight regarding anomalous events [2]. Contemporary models can flag the occurrence of an anomaly but often fail to classify its specific nature or offer actionable diagnostic information. In an industrial context, for example, a system might misinterpret harmless steam as smoke from equipment failure, or mistake routine welding sparks for a fire hazard, leading to costly operational disruptions.

This conceptual confusion stems from foundational constraints in WSVAD methodologies. Firstly, coarse, video-level binary labels provide a weak supervisory signal. This signal only confirms an anomaly’s presence and is devoid of information about its specific nature or cause. The resulting lack of meaning-based grounding is the primary source of ambiguity. Secondly, dominant multiple instance learning (MIL) paradigms [3] are effective for leveraging weak labels. However, they typically aggregate snippet-level predictions through oversimplified temporal pooling strategies [4]. These strategies yield weak temporal modeling. They fail to capture the evolving progression and causal logic of events, treating videos as unordered sets of snippets rather than coherent narratives.

To overcome these challenges, research has progressed along two primary avenues. The first seeks to refine the MIL framework with more sophisticated temporal modeling [5–7] or saliency-based feature extraction [8]. While these techniques improve anomaly localization, they remain constrained by the semantically weak video-level labels and do not address the fundamental need for semantic discrimination. The second direction leverages large-scale, pre-trained multimodal models, such as VadCLIP [9], to align visual data with language representations. Although promising, this approach often creates superficial cross-modal links without deep, structured knowledge, and its decision-making process remains opaque. More critically, neither direction adequately addresses the weak temporal modeling inherent in standard MIL at a causal level, leading to a persistent inability to differentiate fine-grained anomalies, a lack of interpretability, and a purely reactive framework with no predictive capability for proactive intervention.

To directly address the intertwined problems of semantic ambiguity and weak temporal modelling, recent state-of-the-art approaches present specific characteristics that leave room for advancement. In the domain of semantic integration, vision-language models such as AnomalyCLIP [10] leverage valuable semantic priors, yet their dependence on static, pre-defined textual prompts can limit the capture of fine-grained, dynamic semantics required to distinguish complex anomaly categories. Concurrently, in temporal modelling, methods like PE-MIL [11] enhance multi-scale feature extraction but typically do not model the causal logic and evolutionary pathways of events, maintaining a focus on post-hoc detection.

This work proposes a novel framework to advance beyond these characteristics. Its strength lies in the synergistic interaction of its core contributions. The framework first introduces an adaptive knowledge-based guidance mechanism. This component constructs hierarchical “concept clouds” from Wikidata [12] and encodes them via BLIP [13]. The goal is to achieve fine-grained conceptual discrimination. This mechanism provides the precise meaning-based concepts necessary for the event relation analysis (ERA) module. The ERA module can then construct meaningful, causal-temporal chains of events. In turn, the ERA module provides predictive capability and causal interpretability. It does so by explicitly modeling temporal dependencies and causal correlations. Critically, the contextual and causal understanding from the ERA guides the conceptual alignment. This focuses attention on the most spatiotemporally relevant visual evidence, creating a closed-loop reasoning system. A temporal context fusion (TCF) module supports this synergy by enriching long-range dependency modeling. Ultimately, this enables a transformative shift from merely detecting anomalies to interpreting and forecasting event evolution.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of related work, analyzing the current state of weakly supervised video anomaly detection and prompt learning. Section 3 introduces the overall architecture of the proposed framework, detailing the temporal context fusion, prompt learning using external knowledge, and the event relation analysis modules. Section 4 presents the extensive experimental results and corresponding analyses to validate the effectiveness of the method. Finally, Section 5 contains the conclusion and discussion, outlining the key findings of this research and discussing potential directions for future studies.

2.1 Weakly Supervised Video Anomaly Detection

VAD research has evolved along several distinct paradigms. A significant body of work focuses on unsupervised learning, which typically operates by learning a model of normal behavior from training data containing only normal events. Anomalies are then identified as deviations from this learned normality. Within this paradigm, one prominent approach is reconstruction-based modeling. For instance, the Inter-fused Autoencoder proposed by Aslam and Kolekar [14] utilizes a combination of CNN and LSTM layers to learn spatio-temporal patterns, flagging anomalies based on high reconstruction errors. An alternative and equally effective direction is prediction-based modeling. TransGANomaly [15] exemplifies this by using a Transformer-based generative adversarial network (GAN) to predict future video frames; a failure to accurately predict a frame indicates an anomalous event. While these methods are powerful, their effectiveness is centered on the assumption that anomalous events are patterns that deviate significantly from a well-defined normality. This assumption can present challenges in complex environments where the variety of normal events is vast and ever-changing.

In contrast, the key challenge of WSVAD is to achieve precise temporal localization of anomalous segments and effective prediction of risk evolution, using only video-level labels. Sultani et al. [16] pioneered a ranking loss–based framework that built the groundwork for later developments. Based on this foundation, Zhong et al. [17] introduced an in-packet consistency loss to enhance training efficiency. However, these early methods typically relied on selecting the highest-scoring segments within a video and treated them as independent instances. Such an approach disregarded the temporal continuity of behavior, resulting in the loss of critical contextual information.

To address this shortcoming, the focus of subsequent research shifted towards recovering temporal dependencies through contextual modeling. For example, Zhu and Newsam [18] applied an attention-based mechanism to capture inter-segment relations. This partially restored temporal structure. However, this approach lacked scene-level structural priors and demonstrated limited performance when handling complex behavioral patterns. To further improve temporal understanding, Cho et al. [3] employed Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to explicitly model hierarchical dependencies within visual representations. These strategies progressively enhanced the modeling of evolving behaviors by optimizing contextual associations. Nevertheless, they all shared a critical and fundamental limitation: they are fundamentally reactive.

This “reactive” nature constitutes a significant gap in current WSVAD methods. Even as temporal modeling becomes increasingly sophisticated, existing frameworks still only detect an event as it occurs or after it has occurred. They cannot anticipate the evolution of a situation. This reactive nature persists even in recent methods with advanced temporal modeling. For instance, PE-MIL [11] employs pyramidal encoding to capture multi-scale temporal contexts; this enhances anomaly localization. However, its temporal reasoning remains implicit and correlational, confined within the MIL framework. The method lacks an explicit mechanism to model the causal logic and evolutionary pathways of events. Such a mechanism is essential for predictive risk assessment. This status quo necessitates a shift in research focus. To transition from passive detection to active risk assessment, the proposed ERA module is designed precisely to fill this gap. By learning these dynamic evolutionary patterns of events, the model transitions from simply identifying anomalies to proactively predicting their potential progression. Furthermore, to provide the rich contextual representation needed for such analysis, the TCF module is designed to capture both short-term and long-range dependencies more effectively than prior temporal modeling approaches.

Beyond the core algorithmic challenges of semantic grounding and causal reasoning, recent research has also explored other practical dimensions of VAD. One critical direction is improving system-level efficiency for real-time deployment. For example, some work proposes an edge-assisted framework. This framework utilizes a lightweight network on edge devices for initial anomaly screening. It transmits only suspicious frames to the cloud for in-depth recognition, saving bandwidth and computational resources [19]. Another important challenge is enabling systems to adapt to new, previously unseen anomaly types without requiring complete retraining. To this end, class-incremental learning networks have been developed, allowing models to learn new anomaly classes on the fly while retaining knowledge of existing ones [20]. While these directions address important system-level and lifelong learning challenges, this work remains focused on the fundamental problem of enhancing the core detection and reasoning capabilities of WSVAD models for known anomaly categories.

2.2 Applications of Prompt Learning in Video Understanding

Prompt learning has gained attention for enhancing conceptual awareness in video understanding. By using knowledge-based references in cross-modal learning, prompts guide model attention toward meaningful regions during inference. This improves alignment and recognition across modalities. In the context of anomaly detection, several studies have begun exploring the integration of prompt learning into WSVAD. Wang et al. [21] proposed using fixed natural language templates to guide action recognition, enabling the model to focus on action-relevant features. However, this manually defined prompting strategy lacked flexibility and struggled to generalize to the diverse and complex anomaly types encountered in WSVAD. To resolve this issue, Ju et al. [22] introduced learnable prompt vectors that can adaptively align with video features. This approach improves the detection of specific anomaly categories. However, these prompt-based methods remained limited to predefined class labels, lacking the capacity to represent visual phenomena.

Most existing prompt-based approaches rely on coarse-grained alignment strategies that are ill-suited for the fine-grained demands of anomaly detection. However, studies that attempt to incorporate external knowledge [5,11] tend to align concepts at the video level. However, they still fail to localize prompts to the relevant anomalous regions accurately. Yang et al. [23] applied implicit graph-based alignment through joint prediction, modestly improving feature-prompt correlation. However, this approach often underperformed in weak anomaly signals, misaligning prompts with irrelevant background regions and leading to a decline in detection accuracy. The limitations of implicit and coarse-grained alignment are also evident in state-of-the-art vision-language models adapted for VAD. Methods like AnomalyCLIP [10] leverage the powerful pre-trained knowledge of models like CLIP. However, they typically rely on static, hand-crafted textual prompts. These prompts are insufficient for capturing the fine-grained, hierarchical meaning of complex anomalous events. As a result, this often leads to superficial cross-modal alignment and limited conceptual discriminability.

To tackle these problems fundamentally, this study introduces a fine-grained visual-text alignment method for noise-sensitive WSVAD. A conceptual prompting module facilitates the precise integration of external knowledge. Specifically, the knowledge-based anchors module moves beyond static prompts. It constructs adaptive “concept clouds” from structured knowledge bases and leverages learnable prompt vectors. This integration achieves fine-grained, context-aware visual-text alignment. It provides the precise conceptual grounding needed to guide model attention. In parallel, an event relation analysis module models the temporal evolution of events. Together, these components significantly enhance the model’s capacity for subtle anomaly detection and proactive risk assessment.

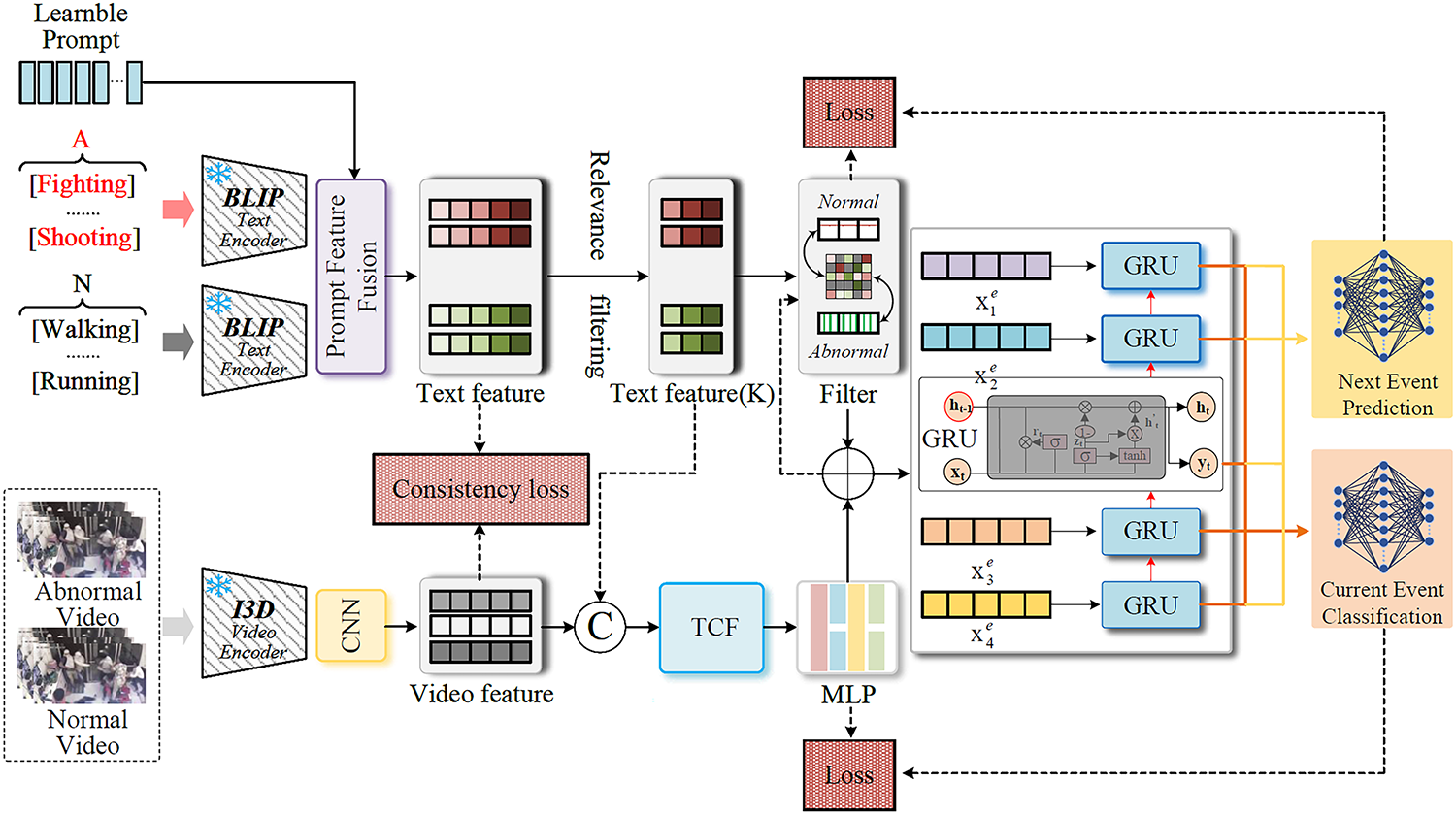

The proposed method restructures the conventional end-to-end anomaly detection process into three distinct yet interconnected stages, each designed to address a specific aspect of weakly supervised video anomaly detection. As illustrated in Fig. 1, these stages operate collaboratively and are jointly optimized through backpropagation, ensuring seamless information flow and unified performance enhancement.

Figure 1: The overall architecture of the proposed framework. The model processes inputs through two parallel streams: a video stream for extracting visual features and a prompt stream for generating semantic anchors. These streams are aligned and fused, with the resulting features fed into the final event relation analysis module to model event evolution for classification and prediction

The first stage, the basic detection module. It determines if an anomaly exists and identifies its temporal location. This stage uses two submodules: the temporal context fusion component (Section 3.2), which captures short- and long-range dependencies, while the causal temporal predictor (Section 3.3), which out-puts segment-level anomaly scores. These scores serve as attention cues for subsequent stages.

The second stage is the semantic enhancement module. It performs a critical transformation of the visual features by integrating them with external conceptual knowledge. It leverages the anomaly scores from the first stage to distinguish between foreground (potentially anomalous) and background regions. Concept-based anchors, derived from knowledge graphs, are aligned with the most relevant foreground segments using an auxiliary alignment loss (Section 3.4). This process refines the raw visual representations into contextually enriched features that are more suitable for downstream tasks.

The third stage, the event relation analysis module, elevates the framework’s capability from passive analysis to active pre-warning. This module models the evolving and logical sequence of events, transcending judgments of isolated moments. Building on the semantically enriched features from the second stage, it utilizes a gated recurrent unit (GRU) network to encode the temporal progression (Section 3.5). Finally, it employs two parallel prediction heads to forecast the current and subsequent event probabilities. This enables the system to anticipate future risks based on learned causal patterns.

The entire method is trained end-to-end with a multi-task objective. The primary MIL-based loss from the first stage drives accurate anomaly detection. In contrast, the conceptual alignment loss from the second stage encourages feature representations to become more interpretable and discriminative. Joint training enables effective gradient sharing across all components. This allows the model to achieve high detection performance and meaningful semantic understanding simultaneously.

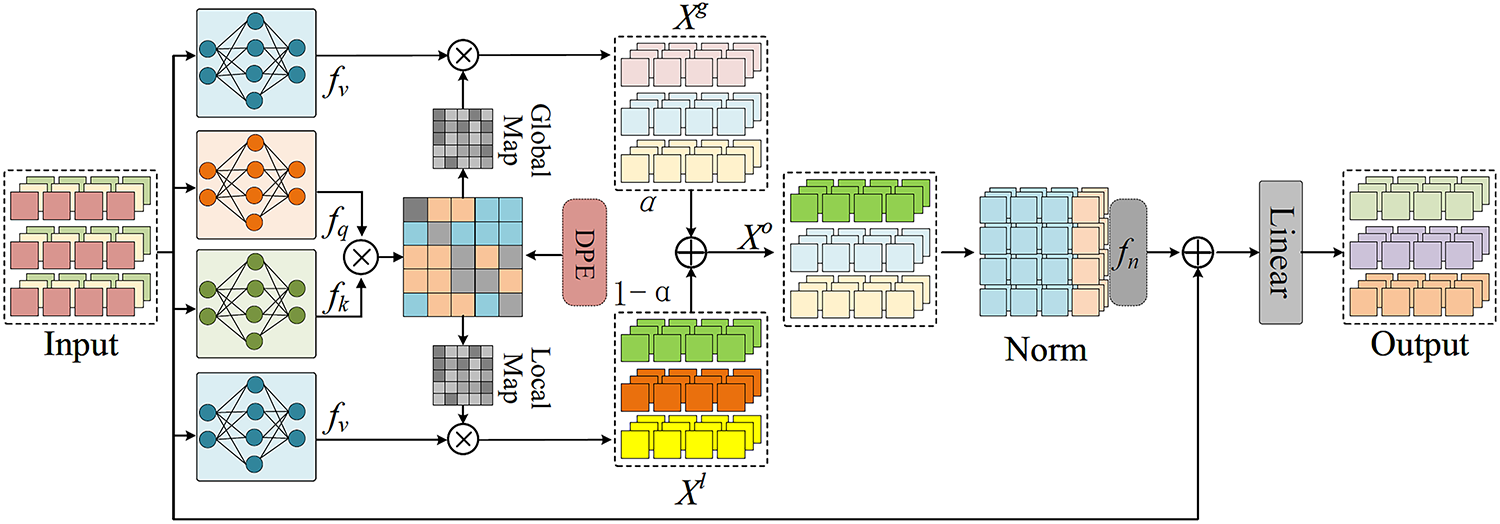

For the fundamental anomaly detection phase, the TCF module is designed to capture intricate temporal connections adeptly. Current methodologies either fail to effectively simulate long-range interdependence by emphasizing local interactions [8] or inadequately represent local correlations by depending on global self-attention [24]. The overall architecture of the TCF module, which addresses these challenges, is illustrated in Fig. 2. The TCF module concurrently gathers information from extensive dependencies and neighbourhood connections, integrating them adaptively via an adaptive gating mechanism. The module focuses on creating an affinity matrix that represents the inherent relationships among pieces. An input feature sequence

Figure 2: Architecture of the temporal context fusion module

The explicit integration of positional information into the similarity computation is achieved through a temporal relationality embedding (TRE),

The temporal relevance embedding is incorporated into the original similarity to create the location-aware affinity matrix,

In this context,

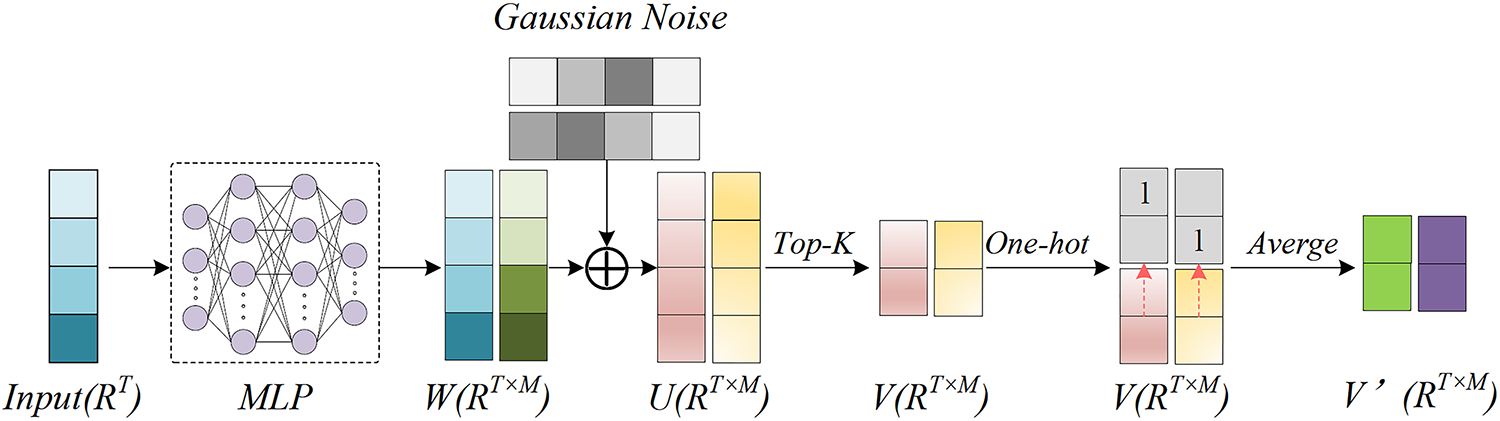

3.3 Causal Temporal Predictor and Classifier

After the enhancement of the TCF module, to further refine the anomaly discrimination-oriented features and make predictions, the causal temporal predictor and classifier is introduced. The module consists of two sequential one-dimensional convolutional layers. Each layer incorporates a GELU activation function and a dropout layer, which enhances the model’s nonlinear representation capability while mitigating overfitting. The procedure is depicted as follows:

Utilizing the finely tuned discriminative features

The MIL paradigm is employed to formulate the principal anomaly detection loss function,

Figure 3: Top-k score selection module

3.4 Knowledge-Guided Semantic Integration

This module is the core of this method. It aims to integrate structured external knowledge into visual features and fundamentally improve the model’s fine-grained conceptual recognition capability. Implementation involves three key steps: constructing semantic anchors, context separation, and visual-semantic alignment.

3.4.1 External Knowledge Prompt Construction

To generate more representative semantic guidance signals than mere category labels, semantic anchors are constructed. Considering the versatility of semantic guidance, this work first selects 12 common relation types from Wikidata [12] as the pre-retrieval semantics, followed by identifying the relation types with the highest occurrence frequency across all anomaly categories as the core retrieval relations

Subsequently, the text encoder

where

3.4.2 Context-Sensitive Separation

To achieve accurate alignment, it is essential to distinguish between the foreground (anomalous) information and the background (normal) information in the video clip. We creatively employ the anomalous saliency score

Utilizing these attention weights, we can derive the weighted video-level foreground feature,

where

3.4.3 Visual and Semantic Alignment

During the alignment step, the objective is to minimize the distance between the foreground visual feature

For a particular video, if it is anomalous, its foreground feature

where

3.5 Event Relation Analysis for Active Risk Assessment

The ERA module elevates the model’s capability from passive detection to active pre-warning. Its primary objective is to model the evolving and logical sequence of event progressions. This enables the prediction of future events, transcending the judgment of isolated moments. The module’s workflow begins by receiving the concept-enriched feature sequence from the TCF and KGSI modules. It then encodes the temporal information using a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). Finally, two parallel prediction heads output probabilities for both current and subsequent events.

Specifically, the input to the ERA module is the semantic-enhanced feature sequence

This hidden state

Based on the encoded event state sequence

3.6 Model Training and Optimization Objective

This paper employs a multi-task learning strategy to jointly optimize all modules of the framework end-to-end. The overall objective function,

The first part is the current event classification loss (

Ultimately, the final joint loss function for the entire framework is a weighted sum of these three objectives:

where

4.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

The XD-Violence dataset [27] is an extensive collection of 4754 unedited videos, covering six categories of violent events sourced from movies, surveillance cameras, and web content. For weakly supervised settings, this dataset is divided into 3954 training videos and 800 testing videos. In contrast, the UCF-Crime dataset [16] comprises 13 categories of abnormal events captured in a wide range of environments, including streets, residential areas, and commercial spaces. This dataset provides 1610 training videos and 290 testing videos.

Following established protocols in previous studies [8,16], the area under the curve (AUC) of the frame-level receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is adopted as the evaluation metric for the UCF-Crime dataset. Meanwhile, for the XD-Violence dataset, the area under the precision-recall curve (AP) at the frame level is used as the evaluation metric [28].

Following established methodologies [5,24], the framework utilises a pre-trained I3D model [29] to extract 1024-dimensional features from RGB video streams based on the Kinetics dataset [30]. The features are extracted from non-overlapping 16-frame segments, which is the standard temporal unit for I3D features and ensures fair comparison with existing methods. For prompt learning with external knowledge, conceptual representations for 13 UCF-Crime anomaly categories and generic XD-Violence categories are expanded using Wikidata. These expanded concepts are encoded into 768-dimensional semantic prototypes using the BLIP ViT-B/16 text encoder. Visual features are aligned with semantic prototypes via a temperature-guided contrastive learning mechanism, where the temperature parameter

Model training is conducted in an end-to-end multi-task learning framework. The Adam optimizer is adopted with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4, weight decay of 5 × 10−4, batch size of 128, and a total of 50 training epochs. A cosine annealing schedule is applied to adjust the learning rate over time.

For generating snippet-level pseudo-labels for the ERA module under weak supervision, the pseudo-label

4.3 Comparison to Current Methods

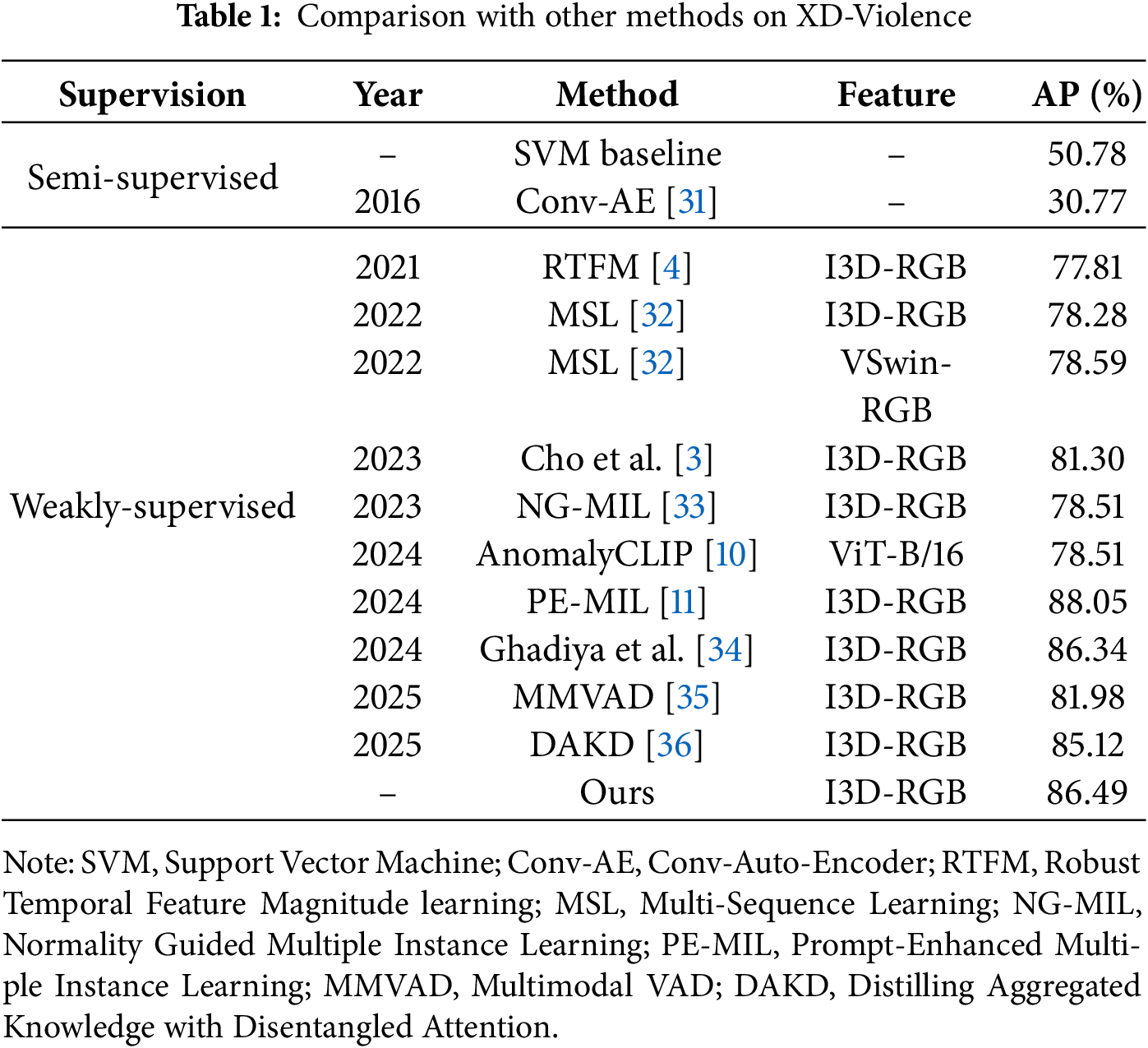

Results on XD-Violence. Table 1 reports the evaluation results on the XD-Violence dataset. Using the exact I3D feature representations as competing methods, the proposed method achieves an AP of 86.49%, outperforming most existing semi-supervised and weakly supervised approaches. This result highlights the effectiveness of the multi-task learning design in detecting anomalies under complex scene conditions.

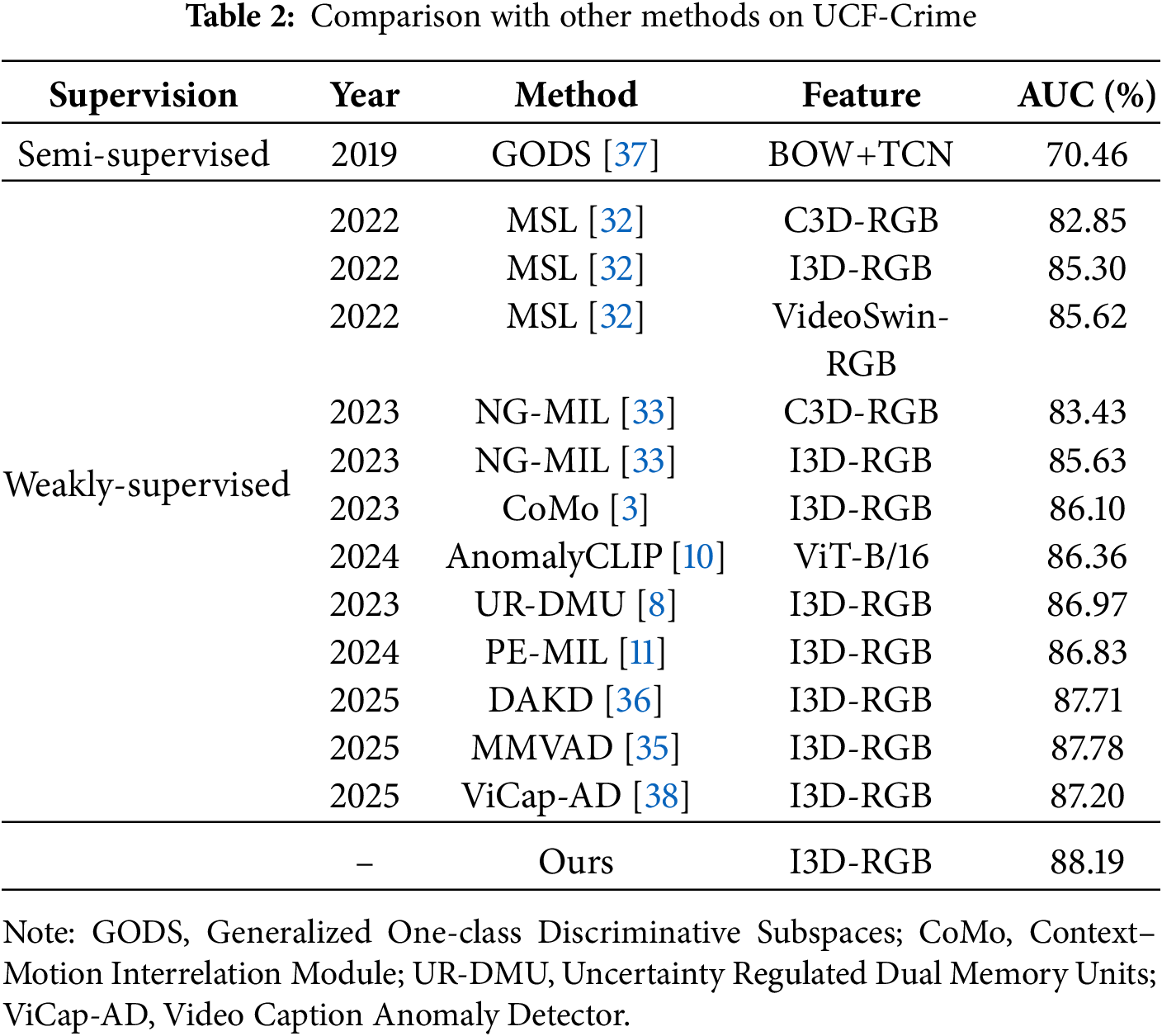

Results on UCF-Crime. Table 2 presents the comparative performance on the UCF-Crime dataset. The proposed framework achieves an AUC of 88.19%, demonstrating competitive results against existing methods. This improvement is primarily attributed to the Knowledge-Guided Semantic Integration module (KGSI). This module integrates structured conceptual information via “semantic anchors.” Unlike traditional approaches, this mechanism enhances the model’s discriminative capacity, particularly on UCF-Crime. This dataset features diverse anomaly categories and high conceptual complexity. These findings indicate the method’s effectiveness in addressing the long-standing challenge of knowledge insufficiency in WSVAD.

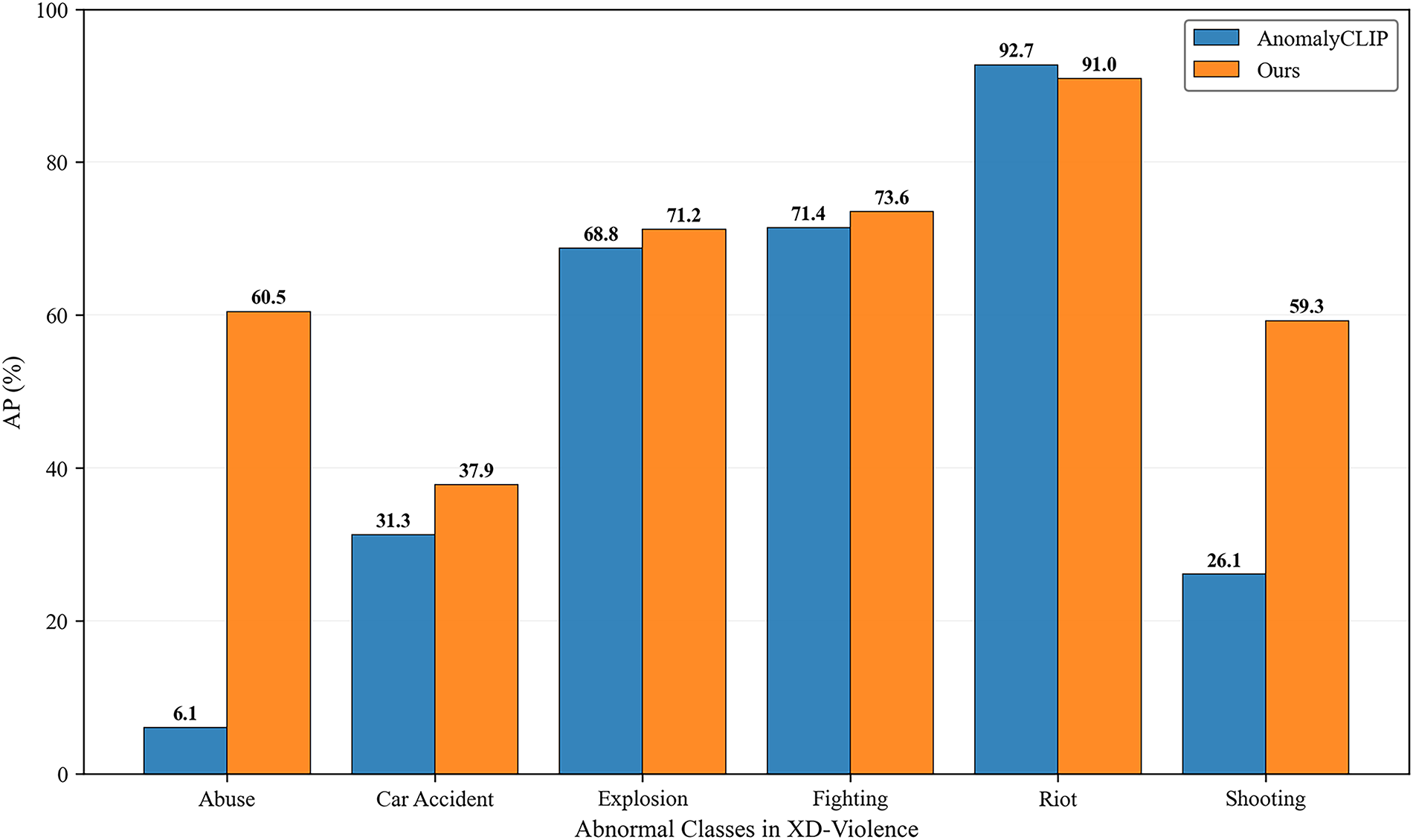

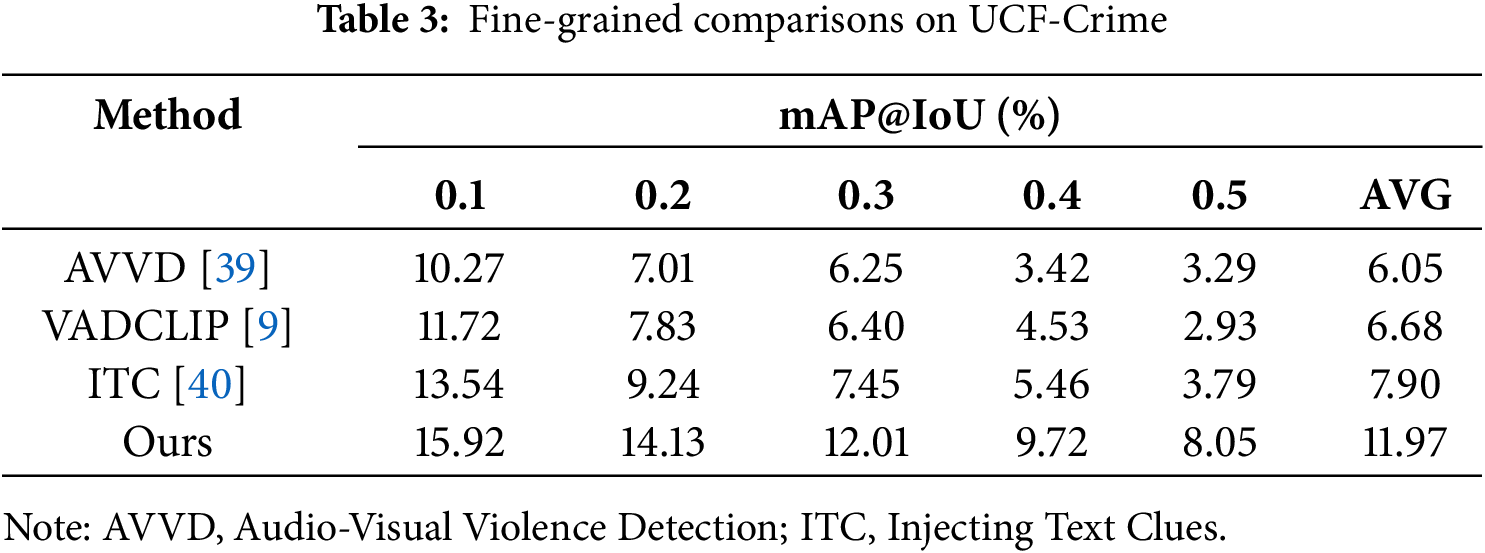

Fine-Grained Recognition Performance. To further validate its efficacy, this study evaluates the proposed approach on the more demanding task of fine-grained anomaly recognition. This capability is demonstrated across both datasets through fine-grained mean Average Precision (mAP) at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds (mAP@IoU) results for UCF-Crime (Table 3) and detailed per-class AP results for XD-Violence (Fig. 4). As outlined in Table 3, the model consistently outperforms contemporary methods, including the fine-grained specialist VADCLIP, across the entire range of IoU thresholds, achieving a state-of-the-art average of mAP (AVG) of 11.97. This result empirically corroborates the central hypothesis: a meticulous alignment between visual evidence and precise semantics is pivotal for enhancing recognition accuracy. The performance margin is particularly accentuated at higher IoU thresholds, underscoring the robustness of the proposed saliency-guided selective alignment strategy.

Figure 4: AP results on individual anomaly classes of XD-Violence

In contrast to prior works that often establish coarse-grained, localized associations between category labels and event proposals, this framework introduces a dual-level granularity refinement. Firstly, it enriches semantic representation by substituting rudimentary category labels with comprehensive semantic anchors derived from external knowledge. Secondly, it institutes a dynamic attention mechanism that leverages anomaly salience scores to selectively focus on the most discriminative frames within a candidate region. This direct and refined correlation between semantically rich concepts and visually salient evidence empowers the model to delineate the full temporal extent of anomalous events with superior precision, especially for those that are subtle or intricate in nature.

To provide a more granular analysis of the model’s fine-grained recognition capabilities, Fig. 4 presents a per-class performance comparison on the XD-Violence dataset against AnomalyCLIP [10]. The results show that this approach demonstrates a significant advantage in most categories. For instance, it achieves a nearly tenfold increase in AP for “Abuse” (60.5% vs. 6.1%) and a clear improvement for “Shooting” (59.3% vs. 26.1%). While AnomalyCLIP [10] holds a slight edge in the well-represented “Riot” category (92.7% vs. 91.0%), this method remains highly competitive and surpasses the baseline in most other tested scenarios. This detailed breakdown highlights the effectiveness of the proposed framework in enhancing the discriminative power for a diverse range of complex events, particularly those that require a deeper semantic understanding.

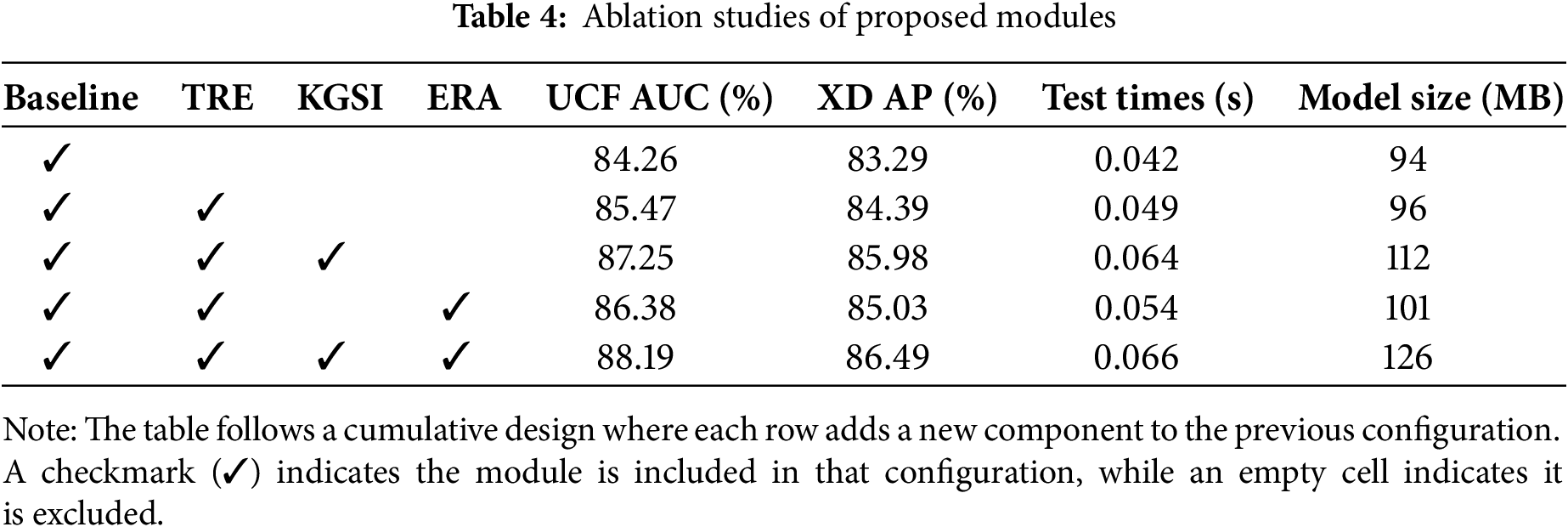

This study conducts a comprehensive ablation study to dissect the contributions of individual components and their synergistic effects within the proposed method. For this analysis, a baseline model is established equipped solely with the temporal context fusion module. This baseline configuration omits the TRE mechanism, utilizing standard self-attention for contextual encoding. Furthermore, the anomaly classification head processes the fused visual features directly to generate an anomaly score. The training of this baseline is supervised exclusively by the anomaly detection loss (

An analysis of the ablation results in Table 4 elucidates the contribution of each key component. Initially, incorporating the TRE mechanism into the baseline (Row 1 vs. Row 2) yields a 1.21% increase in AUC, with a negligible increase in latency (0.007 s) and model size (2 MB), confirming its efficiency in enhancing temporal modeling. Subsequently, the integration of the KGSI module (Row 2 vs. Row 3) delivers a further AUC enhancement of 1.78%. This significant performance gain comes with a moderate computational cost (an additional 0.015 s and 16 MB). This cost is justified by the critical role of conceptual disambiguation. Finally, the entire model configuration, which incorporates the ERA module within a multi-task framework (Row 3 vs. Row 5), achieves peak performance with an AUC of 88.19%. The incorporation of the ERA module for causal reasoning adds only 0.002 s of inference time and 14 MB of parameters, demonstrating that the advanced capability for active risk assessment can be achieved with minimal overhead. This pinnacle result illustrates that a well-formulated auxiliary task, such as fine-grained anomaly categorization, can provide informative gradient signals that regularize the main task, reinforcing the advantages of a co-training paradigm. Crucially, this runtime analysis confirms the model’s practical viability. The complete model’s inference speed of 0.066 s per clip translates to a processing throughput of approximately 15 clips per second. This high throughput rate, representing the average inference latency, comfortably meets the stringent requirements for real-time analysis, underscoring the model’s suitability for deployment in practical surveillance applications.

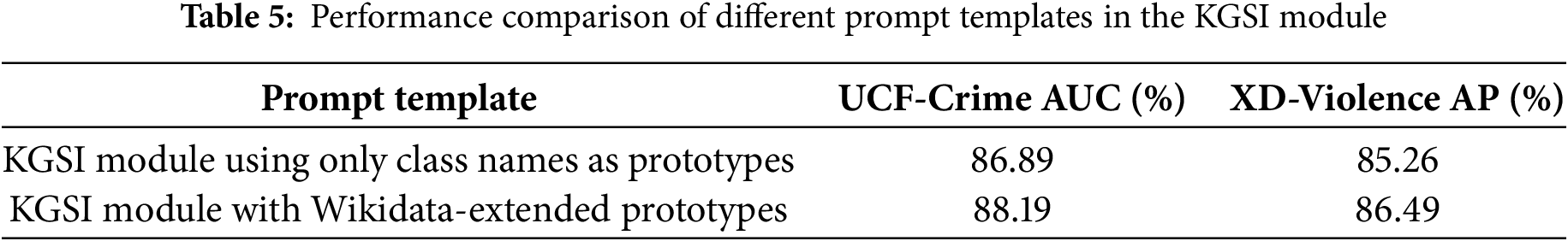

This study further validates the utility of semantic anchors through a comparison of different prompt templates (see Table 5). The results demonstrate that employing Wikidata-augmented semantic prototypes yields notable performance gains over a baseline that uses only class names. Specifically, this approach boosts the AUC on UCF-Crime by 1.30% and the AP on XD-Violence by 1.23%. This outcome suggests a strong link between the semantic richness of prompts and the model’s discriminative power. It confirms that a more descriptive knowledge-based foundation is crucial for enhancing anomaly detection accuracy.

4.5 Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

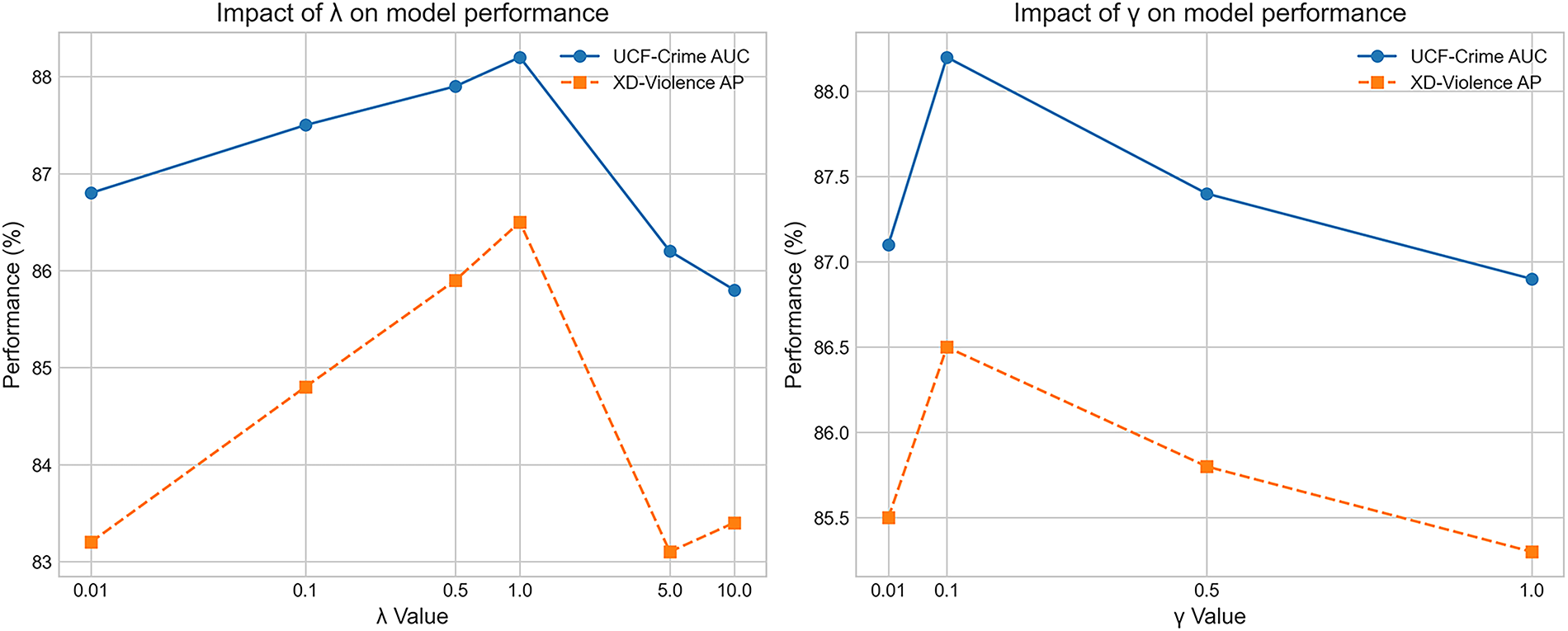

The final performance of the proposed model relies on the effective balancing of its multi-task learning objectives, controlled by hyperparameters

Figure 5: Impact of hyperparameters

The hyperparameter

Similarly, the weight

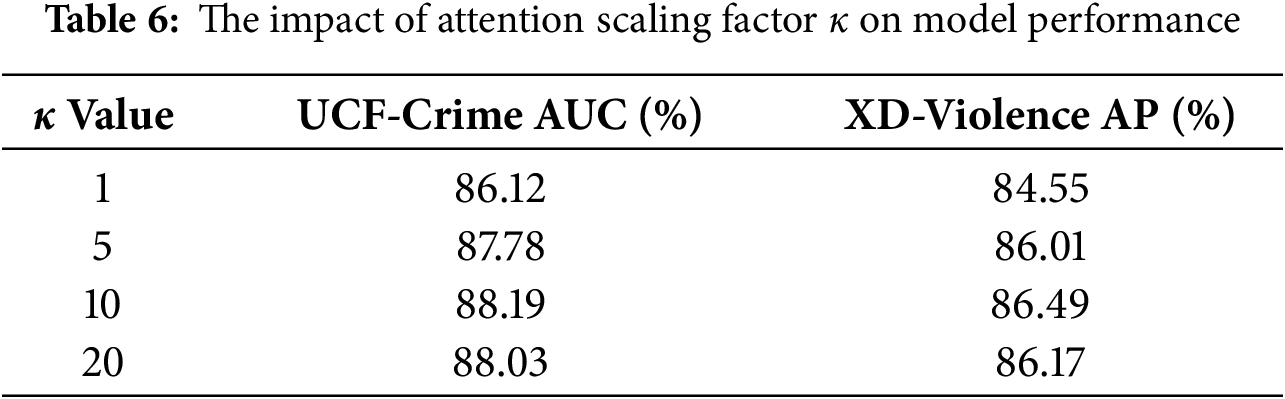

Impact of attention scaling factor

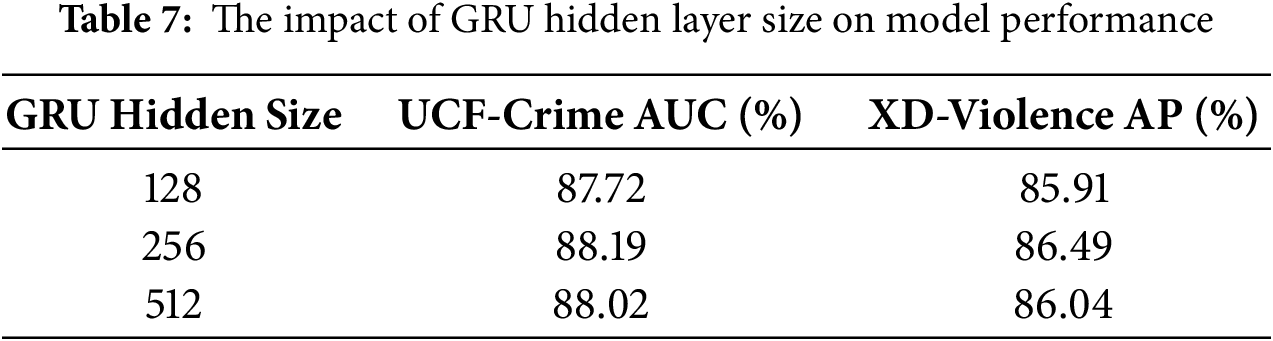

Impact of GRU hidden layer size. The dimensionality of the hidden state in the GRU network directly influences the capacity of the ERA module to encode temporal event evolution. The impact of varying this hidden size is presented in Table 7. A hidden size of 256 yields the best performance, indicating it provides sufficient representational capacity for capturing complex event dynamics without overfitting. A smaller hidden size of 128 appears to limit the model’s temporal modelling capability, while a larger size of 512 may introduce overfitting, as evidenced by the slight degradation in performance metrics.

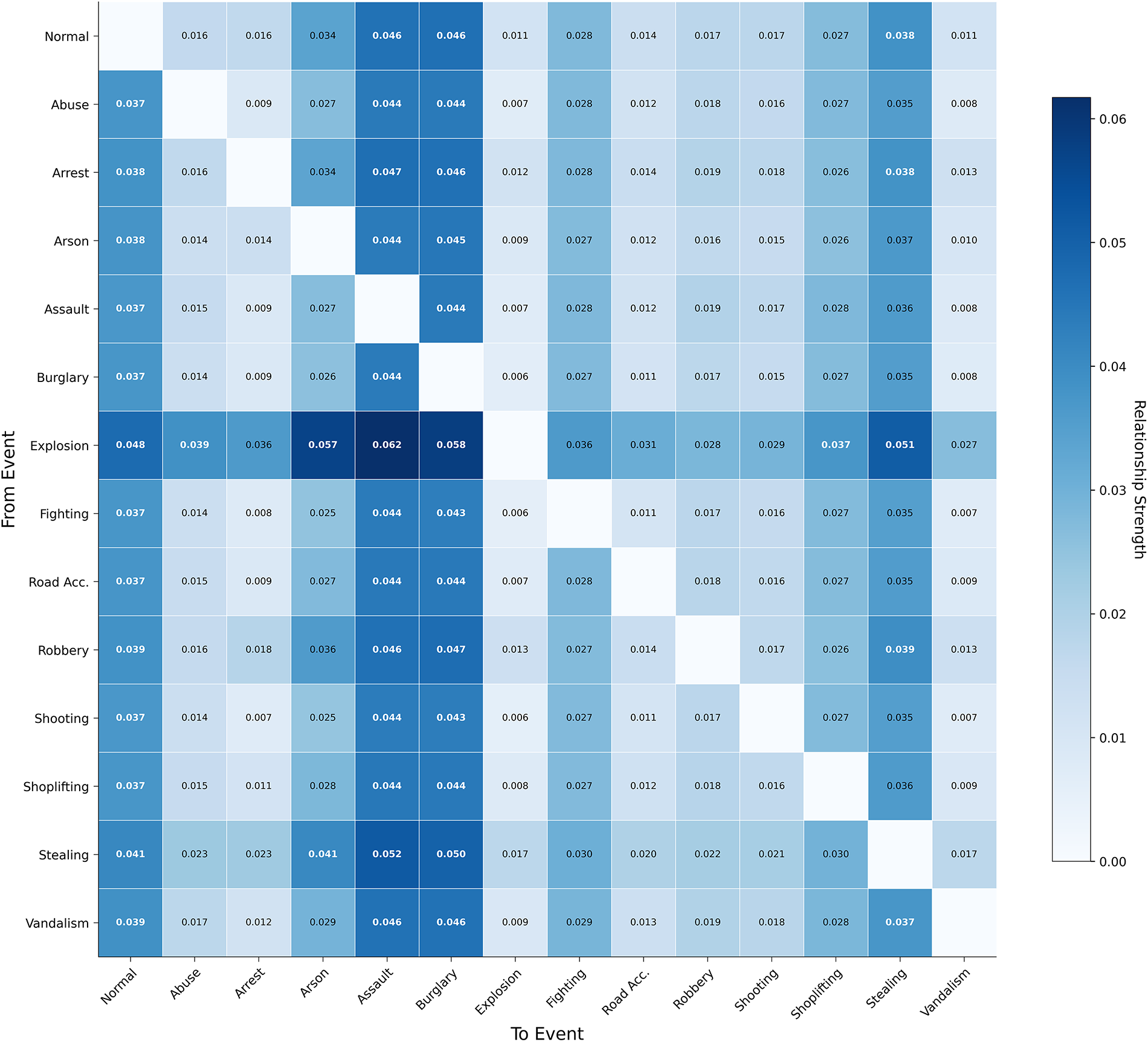

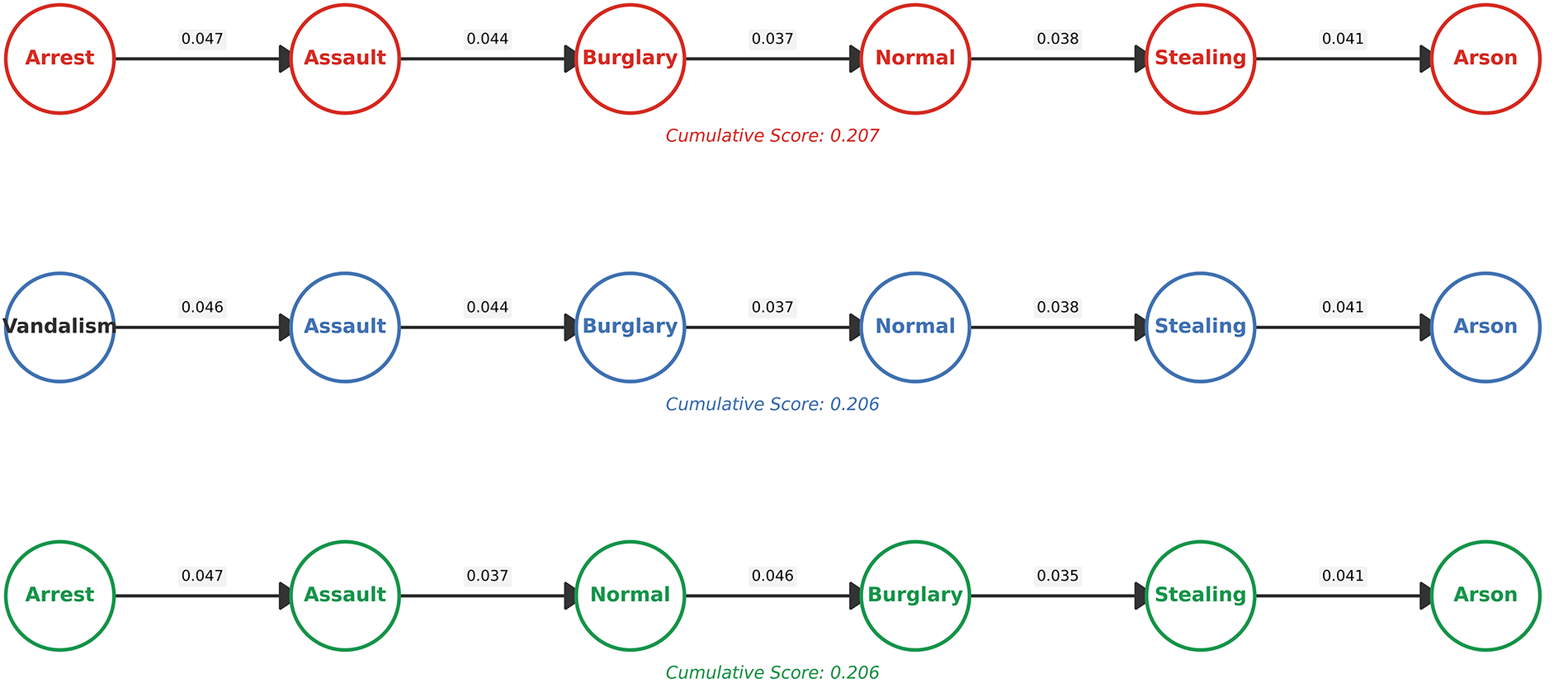

To intuitively demonstrate the effectiveness and interpretive power of the proposed ERA module, the relational knowledge it learned after being trained on the UCF-Crime dataset is visualized. This qualitative analysis offers insight into the model’s capacity to comprehend the logical progression of events. Figs. 6 and 7 present the results.

Figure 6: Heatmap of the learned event transition strengths on the UCF-Crime dataset

Figure 7: Learned evolutionary pathways of high-risk anomalies

Fig. 6 presents a heatmap of the global event transition matrix captured by the ERA module after training on UCF-Crime. In this matrix, each cell (i, j) represents the learned transition strength from a source event i (on the y-axis) to a subsequent event j (on the x-axis), providing a comprehensive map of all pairwise event correlations. This heatmap serves as a visual “map” of the model’s learned common sense, revealing which events are likely to follow others based on the model’s understanding. Brighter cells indicate stronger learned connections.

The heatmap demonstrates that the model has successfully learned logical and high-frequency event progressions that align with real-world intuition. Several strong correlations are observable that would be expected by security professionals: A particularly bright cell at the intersection of the “Explosion” row and “Assault” column, with the highest value of 0.062 in the matrix, indicates the model has robustly learned that explosions often lead to violent confrontations or assaults in the aftermath. Similarly, a strong link is visible from “Stealing” to “Assault” (0.052), capturing a logical escalation from theft to violent confrontation. The model also identifies a notable connection from “Robbery” to “Burglary” (0.046), reflecting a recognized association between different types of property crimes. This visual evidence is crucial as it demonstrates that the ERA module is not a “black box.” The ability to inspect such a matrix provides practitioners with an interpretable tool to understand the model’s reasoning, confirming that its predictions are grounded in logical, learnable event sequences rather than just opaque statistical correlations. This degree of transparency represents a key step toward building trust in automated surveillance systems.

Building upon this global relationship map, Fig. 7 zooms in on the most critical findings by visualizing the top-3 ranked high-risk event trajectories. Each trajectory illustrates a multi-step sequence of events that is highly likely to escalate into a severe anomaly. Crucially, the ability to identify these longer chains showcases the ERA module’s primary strength in modeling long-range temporal dependencies. For instance, the top-ranked trajectory reveals a complex pattern of “Arrest” → “Assault” → “Burglary” → “Normal” → “Stealing” → “Arson”, with a cumulative score of 0.207. The presence of a “Normal” segment within a high-risk chain is particularly insightful, demonstrating that the model can capture subtle, real-world criminal behaviors, such as a perpetrator feigning normalcy between illicit acts.

This result vividly demonstrates the model’s capacity for active risk assessment. By moving beyond the detection of isolated events to understanding their evolutionary patterns, the ERA module provides a deeper, more actionable insight into how dangerous situations develop over time.

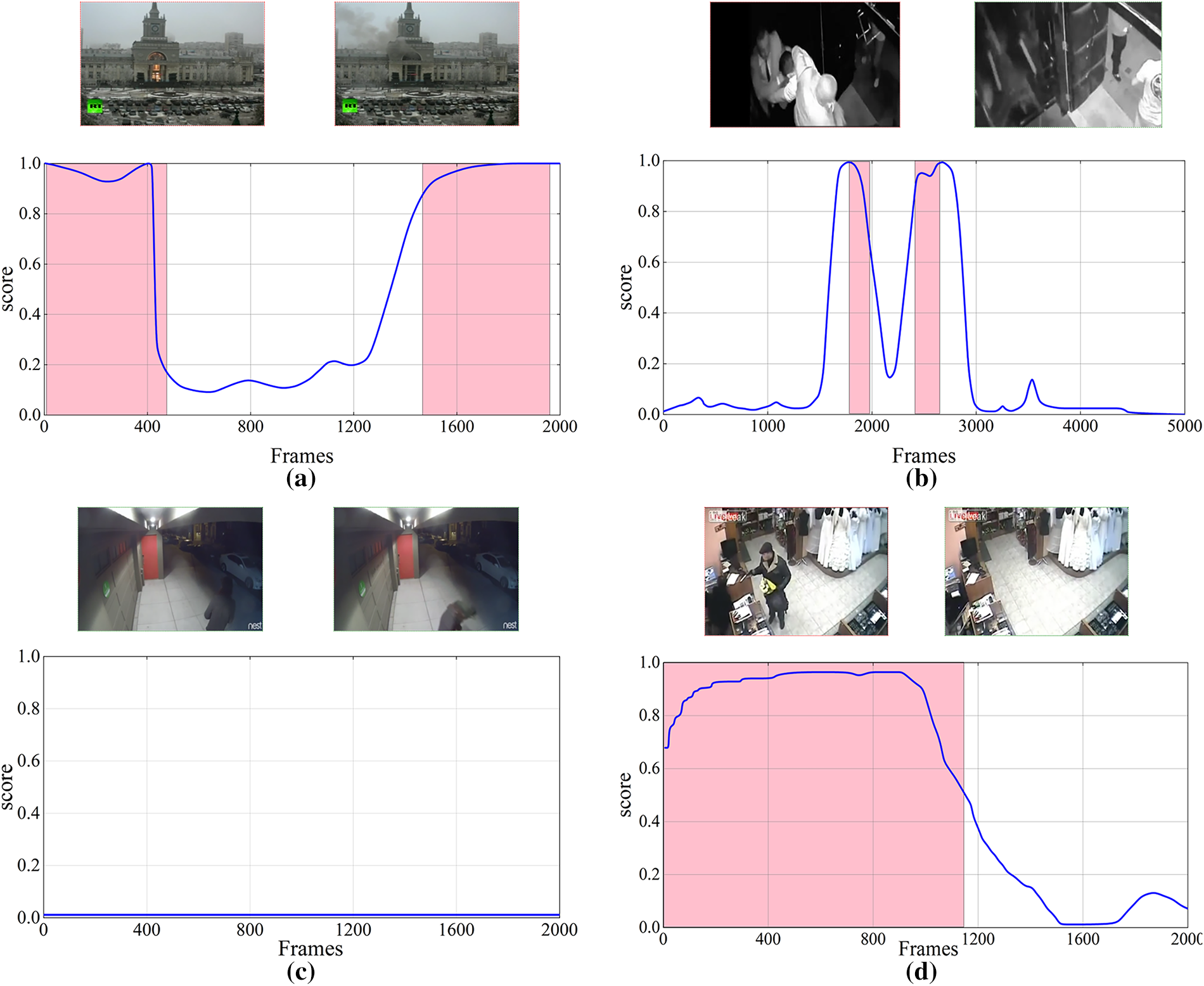

To visually substantiate the quantitative results and demonstrate the method’s practical efficacy, a qualitative analysis of the generated anomaly scores on representative videos from the UCF-Crime and XD-Violence datasets is presented. The anomaly score curves, depicted in Fig. 8, offer a clear visualization of the model’s proficiency in temporal localization. The figure provides compelling evidence of the model’s adaptability in handling anomalies of varying durations and characteristics. For instance, in the ‘Explosion’ example shown in Fig. 8a, the model accurately captures the entire duration of a long, developing event, with the anomaly score gradually increasing as the situation escalates. Conversely, for an abrupt, short-duration event like ‘Fighting’ shown in Fig. 8b, the model responds with a sharp and distinct spike, precisely pinpointing the critical moment. Furthermore, the method performs equally well when handling entirely normal scenarios, as Fig. 8c demonstrates, where the anomaly score consistently remains low, robustly confirming the model’s reliability in distinguishing between normal and abnormal behavior. Similarly, for an anomaly event like ‘Shooting’ shown in Fig. 8d, which occurs in the first half of the video, the model quickly raises the anomaly score close to 1.0 and maintains a high score throughout the event’s duration. This robust capability to handle diverse temporal patterns validates the effectiveness of the TCF module. It confirms that the module, enhanced by the TRE, successfully captures both long-range contextual dependencies and short-term, sudden changes in the video sequence. The strong alignment between the predicted scores and the ground-truth abnormal periods (indicated by the shaded regions) demonstrates that this approach can learn discriminative spatio-temporal representations for accurate anomaly localization, even under the challenging conditions of weak supervision without frame-level annotations.

Figure 8: Visual results of the proposed method on the UCF-Crime and XD-Violence datasets. The blue curve shows the predicted anomaly scores, the light-pink shaded areas mark ground-truth anomalous frames, and red/green boxes highlight representative abnormal and normal events

This study addresses two central limitations in weakly supervised video anomaly detection: the coarse-grained supervision of the MIL framework, which hinders fine-grained recognition, and the absence of temporal-causal reasoning, leading to opacity in the decision-making process. To overcome these challenges, a novel method is introduced that synergistically integrates dynamic semantic guidance with event relation analysis. This approach departs from traditional binary-supervised methods by first incorporating a dynamic semantic guidance module. This component leverages semantic prototypes derived from external knowledge (Wikidata) to provide robust, fine-grained supervision, enabling the model to not only detect anomalies but also distinguish between specific types of anomalies. On the XD-Violence dataset, the model achieves an average AP of 65.6% in fine-grained anomaly classification, demonstrating its capability to perform detailed and accurate semantic discrimination. Furthermore, an ERA module is introduced to model the explicit evolutionary patterns of events. By learning the logical sequences of how situations escalate, the ERA module provides the crucial temporal and causal context for its predictions. By revealing an event’s development over time, the framework demonstrates the logical reasoning behind why a situation is deemed anomalous, thereby addressing a core interpretability limitation of conventional weakly supervised models. The effectiveness of the integrated framework is confirmed by its strong detection performance, achieving a frame-level AUC of 88.19% on the UCF-Crime dataset and an AP of 86.49% on the XD-Violence dataset.

Notably, the presented framework achieves this performance utilizing only RGB inputs. This design choice is motivated by the need to ensure model generality and deployment feasibility. In numerous real-world surveillance scenarios, such as public live streams or legacy security systems, audio data is often unavailable, unreliable, or sensitive to privacy concerns. The establishment of a state-of-the-art baseline with the most universally available visual modality reinforces the framework’s broad applicability. It is acknowledged that audio can provide valuable complementary cues, and its exclusion here constitutes a limitation that points to a clear future direction.

Ablation studies further confirm the complementary effects of the two core contributions: the semantic guidance that enhances what the model sees, and the event relation analysis that provides a logical structure for how events unfold. Together, these facilitate a qualitative transition from simple anomaly detection to a more comprehensive understanding of anomalies. This progression reflects a broader shift from data-driven pattern recognition to knowledge-guided video comprehension, establishing a new paradigm for weakly supervised visual analysis.

Building upon this foundation, future research will focus on advancing the framework’s predictive and reasoning capabilities. A clear path forward involves extending the ERA module’s predictive horizon to multi-step risk forecasting and creating a more holistic system by incorporating complementary data streams. This direction directly addresses the current limitation by integrating critical audio cues available in datasets like XD-Violence. Furthermore, to build upon the introduced causal-temporal reasoning, subsequent work will incorporate more formal causal frameworks, such as structural causal models (SCMs), to achieve a more theoretically grounded understanding of event causality.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, Weishan Gao and Ye Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Weishan Gao and Xiaoyin Wang, writing—review and editing, Xiaoyin Wang and Xiaochuan Jing; data curation, Ye Wang; supervision, Xiaochuan Jing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on the website: https://www.crcv.ucf.edu/projects/real-world/ (accessed on 01 September 2025) and https://roc-ng.github.io/XD-Violence/ (accessed on 01 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Abdalla M, Javed S, Al Radi M, Ulhaq A, Werghi N. Video anomaly detection in 10 years: a survey and outlook. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(32):26321–64. doi:10.1007/s00521-025-11659-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Caetano F, Carvalho P, Mastralexi C, Cardoso JS. Enhancing weakly-supervised video anomaly detection with temporal constraints. IEEE Access. 2025;13:70882–94. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3560767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cho M, Kim M, Hwang S, Park C, Lee K, Lee S. Look around for anomalies: weakly-supervised anomaly detection via context-motion relational learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 12137–46. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tian Y, Pang G, Chen Y, Singh R, Verjans JW, Carneiro G. Weakly-supervised video anomaly detection with robust temporal feature magnitude learning. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 4955–66. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pu Y, Wu X, Yang L, Wang S. Learning prompt-enhanced context features for weakly-supervised video anomaly detection. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2024;33(11):4923–36. doi:10.1109/TIP.2024.3451935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yang Z, Wu P, Liu J, Liu X. Dynamic local aggregation network with adaptive clusterer for anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 404–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19772-7_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li G, Cai G, Zeng X, Zhao R. Scale-aware spatio-temporal relation learning for video anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 333–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19772-7_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhou H, Yu J, Yang W. Dual memory units with uncertainty regulation for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(3):3769–77. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i3.25489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wu P, Zhou X, Pang G, Zhou L, Yan Q, Wang P, et al. VadCLIP: adapting vision-language models for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(6):6074–82. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i6.28423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zanella L, Liberatori B, Menapace W, Poiesi F, Wang Y, Ricci E. Delving into CLIP latent space for video anomaly recognition. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2024;249:104163. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2024.104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen J, Li L, Su L, Zha ZJ, Huang Q. Prompt-enhanced multiple instance learning for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 18319–29. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Vrandečić D, Krötzsch M. Wikidata: a free collaborative knowledgebase. Commun ACM. 2014;57(10):78–85. doi:10.1145/2629489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li J, Li D, Xiong C, Hoi S. BLIP: bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 12888–900. [Google Scholar]

14. Aslam N, Kolekar MH. Unsupervised anomalous event detection in videos using spatio-temporal inter-fused autoencoder. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(29):42457–82. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13496-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Aslam N, Kolekar MH. TransGANomaly: transformer based generative adversarial network for video anomaly detection. J Vis Commun Image Represent. 2024;100(7):104108. doi:10.1016/j.jvcir.2024.104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sultani W, Chen C, Shah M. Real-world anomaly detection in surveillance videos. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 6479–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhong JX, Li N, Kong W, Liu S, Li TH, Li G. Graph convolutional label noise cleaner: train a plug-and-play action classifier for anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 16–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 1237–46. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhu Y, Newsam S. Motion-aware feature for improved video anomaly detection. arXiv:1907.10211. 2019. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1907.10211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hussain A, Khan N, Khan ZA, Yar H, Baik SW. Edge-assisted framework for instant anomaly detection and cloud-based anomaly recognition in smart surveillance. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;160(1):111936. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.111936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hussain A, Ullah W, Khan N, Khan ZA, Yar H, Baik SW. Class-incremental learning network for real-time anomaly recognition in surveillance environments. Pattern Recognit. 2026;170(5):112064. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.112064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang M, Xing J, Mei J, Liu Y, Jiang Y. ActionCLIP: adapting language-image pretrained models for video action recognition. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(1):625–37. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3331841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ju C, Han T, Zheng K, Zhang Y, Xie W. Prompting visual-language models for efficient video understanding. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 105–24. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19833-5_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yang Z, Liu J, Wu P. Text prompt with normality guidance for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 17–21; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 18899–908. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wu P, Liu J. Learning causal temporal relation and feature discrimination for anomaly detection. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2021;30:3513–27. doi:10.1109/TIP.2021.3062192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. arXiv:2103.00020. 2021. [Google Scholar]

26. Manzoor MA, Albarri S, Xian Z, Meng Z, Nakov P, Liang S. Multimodality representation learning: a survey on evolution, pretraining and its applications. ACM Trans Multimed Comput Commun Appl. 2024;20(3):1–34. doi:10.1145/3617833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wu P, Liu J, Shi Y, Sun Y, Shao F, Wu Z, et al. Not only look, but also listen: learning multimodal violence detection under weak supervision. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. p. 322–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58577-8_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gao W, Wang X, Wang Y, Jing X. Dual-stream attention-enhanced memory networks for video anomaly detection. Sensors. 2025;25(17):5496. doi:10.3390/s25175496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kay W, Carreira J, Simonyan K, Zhang B, Hillier C, Vijayanarasimhan S, et al. The kinetics human action video dataset. arXiv:1705.06950. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1705.0695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Carreira J, Zisserman A. Quo vadis, action recognition? A new model and the kinetics dataset. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 4724–33. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Hasan M, Choi J, Neumann J, Roy-Chowdhury AK, Davis LS. Learning temporal regularity in video sequences. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 733–42. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li S, Liu F, Jiao L. Self-training multi-sequence learning with transformer for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36(2):1395–403. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i2.20028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Park S, Kim H, Kim M, Kim D, Sohn K. Normality guided multiple instance learning for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2023 Jan 2–7; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 2664–73. doi:10.1109/WACV56688.2023.00269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ghadiya A, Kar P, Chudasama V, Wasnik P. Cross-modal fusion and attention mechanism for weakly supervised video anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2024 Jun 17–18; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1965–74. doi:10.1109/CVPRW63382.2024.00202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Biswas D, Tesic J. MMVAD: a vision-language model for cross-domain video anomaly detection with contrastive learning and scale-adaptive frame segmentation. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;285(1):127857. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.127857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dalvi J, Dabouei A, Dhanuka G, Xu M. Distilling aggregated knowledge for weakly-supervised video anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2025 Feb 26–Mar 6; Tucson, AZ, USA. p. 5439–48. doi:10.1109/WACV61041.2025.00531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang J, Cherian A. GODS: generalized one-class discriminative subspaces for anomaly detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 8200–10. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lim J, Lee J, Kim H, Park E. ViCap-AD: video caption-based weakly supervised video anomaly detection. Mach Vis Appl. 2025;36(3):61. doi:10.1007/s00138-025-01676-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wu P, Liu X, Liu J. Weakly supervised audio-visual violence detection. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2023;25:1674–85. doi:10.1109/TMM.2022.3147369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Liu T, Lam KM, Bao BK. Injecting text clues for improving anomalous event detection from weakly labeled videos. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2024;33(11):5907–20. doi:10.1109/TIP.2024.3477351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools