Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Static Analysis for Improving the Efficacy of Security Vulnerability Detection in Source Code

School of Engineering and Technology, International University of La Rioja, Avda.de La Paz, 137, Logroño, 26006, La Rioja, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 11 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074566

Received 14 October 2025; Accepted 21 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

As artificial Intelligence (AI) continues to expand exponentially, particularly with the emergence of generative pre-trained transformers (GPT) based on a transformer’s architecture, which has revolutionized data processing and enabled significant improvements in various applications. This document seeks to investigate the security vulnerabilities detection in the source code using a range of large language models (LLM). Our primary objective is to evaluate the effectiveness of Static Application Security Testing (SAST) by applying various techniques such as prompt persona, structure outputs and zero-shot. To the selection of the LLMs (CodeLlama 7B, DeepSeek coder 7B, Gemini 1.5 Flash, Gemini 2.0 Flash, Mistral 7b Instruct, Phi 3 8b Mini 128K instruct, Qwen 2.5 coder, StartCoder 2 7B) with comparison and combination with Find Security Bugs. The evaluation method will involve using a selected dataset containing vulnerabilities, and the results to provide insights for different scenarios according to the software criticality (Business critical, non-critical, minimum effort, best effort) In detail, the main objectives of this study are to investigate if large language models outperform or exceed the capabilities of traditional static analysis tools, if the combining LLMs with Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools lead to an improvement and the possibility that local machine learning models on a normal computer produce reliable results. Summarizing the most important conclusions of the research, it can be said that while it is true that the results have improved depending on the size of the LLM for business-critical software, the best results have been obtained by SAST analysis. This differs in “Non-Critical,” “Best Effort,” and “Minimum Effort” scenarios, where the combination of LLM (Gemini) + SAST has obtained better results.Keywords

Software security vulnerabilities are rising, with open-source software reporting an 89% annual increase [1]; the most common issues are Cross-site Scripting (XSS), SQL Injection, and Memory Corruption [2,3]. This trend, combined with organizations’ efforts to raise awareness about implementing adequate system defenses [4], contributes to the growing economic impact of breaches, with the average cost reaching USD 4.88 million—a 10% increase over the previous year—and global IT investment expected to grow 9.8% in 2025 [5], reflecting the expanding scope of vulnerabilities affecting all sectors worldwide [6,7].

Artificial intelligence technologies, particularly Generative Pretrained Transformers (GPT), have demonstrated human-like abilities in text generation, comprehension, and recognition [8], and are being exploited in cybercrime through phishing, DeepFakes, and malicious GPT attacks [9,10], while also enabling AI-assisted vulnerability detection [11,12].

The increasing complexity of technologies and methodologies together with the AI revolution, remarks the need for a secure and speed the process of Software Development Life Cycle (S-SDLC) to address the high demand, reducing the overall cost of vulnerability management [13,14] and the number of manual activities without reducing the quantity of controls. Lack of controls can lead to the leakage of sensitive information, privilege escalation, and a detrimental impact on system performance and efficiency, affecting both corporate entities and individual users [15–18].

Implementing a robust SAST solution requires not only cybersecurity expertise but also a deep understanding of the entire technology stack, increasing effort and costs as systems evolve [19,20]. The absence of a proper SSDLC contributes to the growing frequency and impact of cyberattacks, highlighting the need to integrate secure development practices from the earliest stages to mitigate risks and enhance resilience against emerging threats [16,21,22].

Around 68% of the world’s population—about 5.5 billion people—are now online [23]. As AI adoption can lower overall cybersecurity costs [24], this expanding digital landscape underscores the need for secure and scalable technologies. However, research on integrating artificial intelligence into Static Application Security Testing (SAST) remains limited. Existing studies often focus on specific vulnerability categories or small datasets and explore only a narrow range of model architectures. This study aims to evaluate the benefits and limitations of integrating or alone the AI into static code security analysis, examining how it can improve defect detection, vulnerability identification, and overall efficiency compared to traditional tools, considering factors such as accuracy, analysis time, and impact on development workflows.

Specifically:

1. Evaluate different language models (LLM) solutions that are specifically trained for code analysis and can be executed locally.

2. Apply a range of prompt engineering techniques to determine whether these techniques improve the results compared with widely used open-source static analysis tools (SAST).

a. Tools SAST.

b. LLM (minimum adjustments).

c. LLM with prompt engineering.

The experiment will aim to answer the following key research questions or hypotheses:

• Q1. Do the results produced by LLMs outperform those of traditional static analysis tools?

• Q2. Is there an improvement when combining LLMs with SAST tools?

• Q3. Can reliable results be achieved with locally deployed models on a standard desktop computer?

Data privacy remains a central concern in adopting AI-based technologies. Most experiments were conducted on standard laptops or small servers, except for Gemini. This approach can benefit governments and corporations, as running analyses on local machines reduces dependency on large infrastructures and enables early detection of potential vulnerabilities during implementation.

The main contributions of this work are:

1. Compare each local LLM, a cloud based LLM service (Gemini), and the top performing SAST tool (FindSecBugs) to address Question 1.

2. Evaluate the impact of combining local LLMs with cloud services on detection quality, thereby tackling Question 2.

3. Benchmark a broad set of locally deployable LLMs (CodeLlama 7B, DeepSeek Cod-er 7B, Gemini 1.5 Flash, Gemini 2.0 Flash, Mistral 7B Instruct, Phi 3 8B Mini 128K Instruct, Qwen 2.5 Coder, StarCoder 2 7B) to answer Question 3.

4. Restrict the study to a single, widely used programming language (Java), eliminating confounding variables introduced by heterogeneous technology stacks.

5. Use a standardized test set: the OWASP benchmark project, which contains both vulnerable and non-vulnerable Java programs. To improve the OWASP benchmark functionality, it has been developed an adaptation that enables LLMs to participate in the analysis workflow, thereby extending the tool’s functionality and introducing new automated evaluation modes over Benchmark’s test suite.

6. Assess the results across multiple operational contexts—business critical, non-critical, best effort, and minimum effort environments [25].

The rest of the work is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the cybersecurity context, specifically the Secure Software Development Life Cycle (S-SDLC), and the AI landscape, including the large language models (LLMs) used in the experiment and their salient characteristics. Also, it provides the relative work of this experiment. Section 3 details the phases and the activities used to configure, run and collect the experiment results, as well as the preprocessing steps required before the analysis. Section 4 shows the results analysis of the experiment interpreting the data and answering the research questions. Finally, Section 5 offers the conclusions, highlights the main contributions and the further path of proposed research.

2 Background and Relative Work

Static Application Security Testing (SAST) analyzes source code without execution to detect vulnerabilities early in the SDLC [26–28]. Its core, taint analysis, tracks untrusted data through program paths to identify flaws such as SQL injection and XSS [29–31]. While SAST is cost-effective and fast [32], its real-world detection capability is limited, often producing many false positives and highlighting the need to improve recall [19,33,34].

SAST tools, while limited in detecting some vulnerabilities, are crucial for analyzing all code paths [28]. Their main drawback is high false-positive rates [28,34], which can cause developer fatigue and reduce confidence in the tool [19]. Research addresses this by enhancing precision and usability through machine learning, enabling better vulnerability inference, false-positive prediction, and scalable analyzers for industrial applications [19,27,32].

Large Language Models (LLMs) are reshaping Static Application Security Testing (SAST) by addressing traditional limitations such as low recall and lack of repository-level context [35]. Models like GPT-4 achieve higher F1 scores in vulnerability detection due to their ability to reason across broader code contexts and understand complex semantics [36]. Hybrid approaches, such as LSAST, combine conventional data-flow analysis (e.g., CodeQL) with LLM-driven taint inference and contextual reasoning, previously achievable only manually [37]. However, LLMs often produce high false-positive rates, sometimes exceeding 60% [38]. Nevertheless, recent studies challenge this assumption, showing that high false-positive rates stem not from intrinsic LLM limitations but from inadequate or noisy code context. When equipped with precise and complete contextual information—such as through frameworks like LLM4FPM—LLMs can achieve F1 scores above 99% on benchmark datasets (e.g., Juliet) and reduce false positives by over 85% in real-world projects [39]. Research now leverages LLMs for filtering and alert adjudication, with prototypes like FPShield significantly reducing false positives and developer effort [36]. The emerging trend integrates LLMs with traditional SAST, using analyzers for data flow and LLMs for semantic validation, prioritization, and correction suggestions [37].

The Juliet test suite [40] is a widely used NSA-developed benchmark for evaluating static code analysis tools in C/C++ and Java. It consists of thousands of synthetic test cases covering a broad range of CWE-classified vulnerabilities, with both vulnerable and fixed versions to facilitate tool validation [34]. Similarly, the OWASP Benchmark dataset [41], which we employ in this work, contains 2740 synthetic Java test cases focusing on web application vulnerabilities such as SQL Injection, XSS, Command Injection, LDAP Injection, Path Traversal, Weak Encryption/Hashing, Insecure Cookies, Trust Boundary, Weak Randomness, and XPath Injection, with a balanced mix of true and false positives. Both datasets use synthetic code to provide controlled and reproducible benchmarks for evaluating security tools.

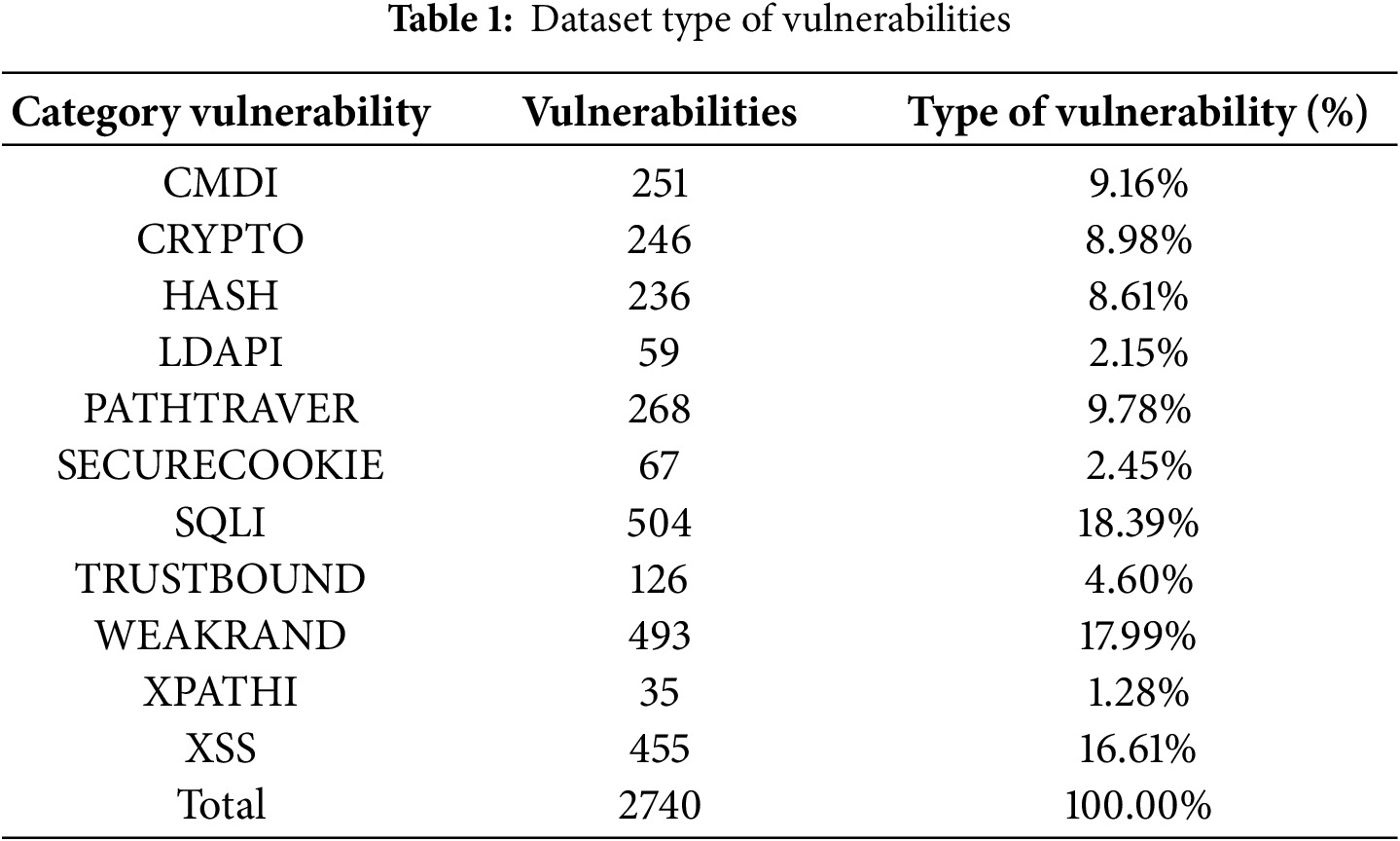

Below, Table 1 shows the categories of vulnerabilities and percentage based on the total.

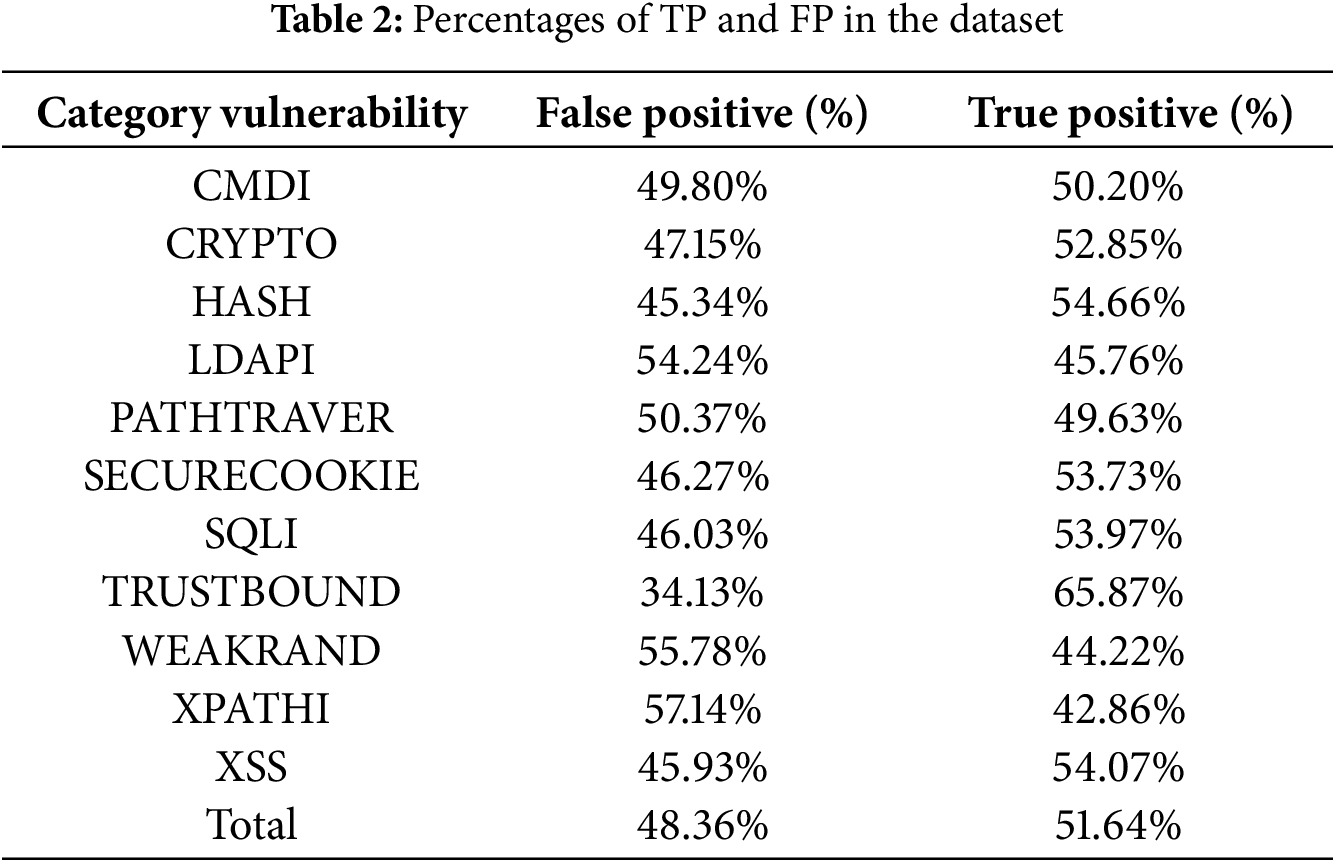

Table 2 shows the percentage of true vulnerabilities and identifies the false positives for each category.

2.3 Large Language Models (LLM)

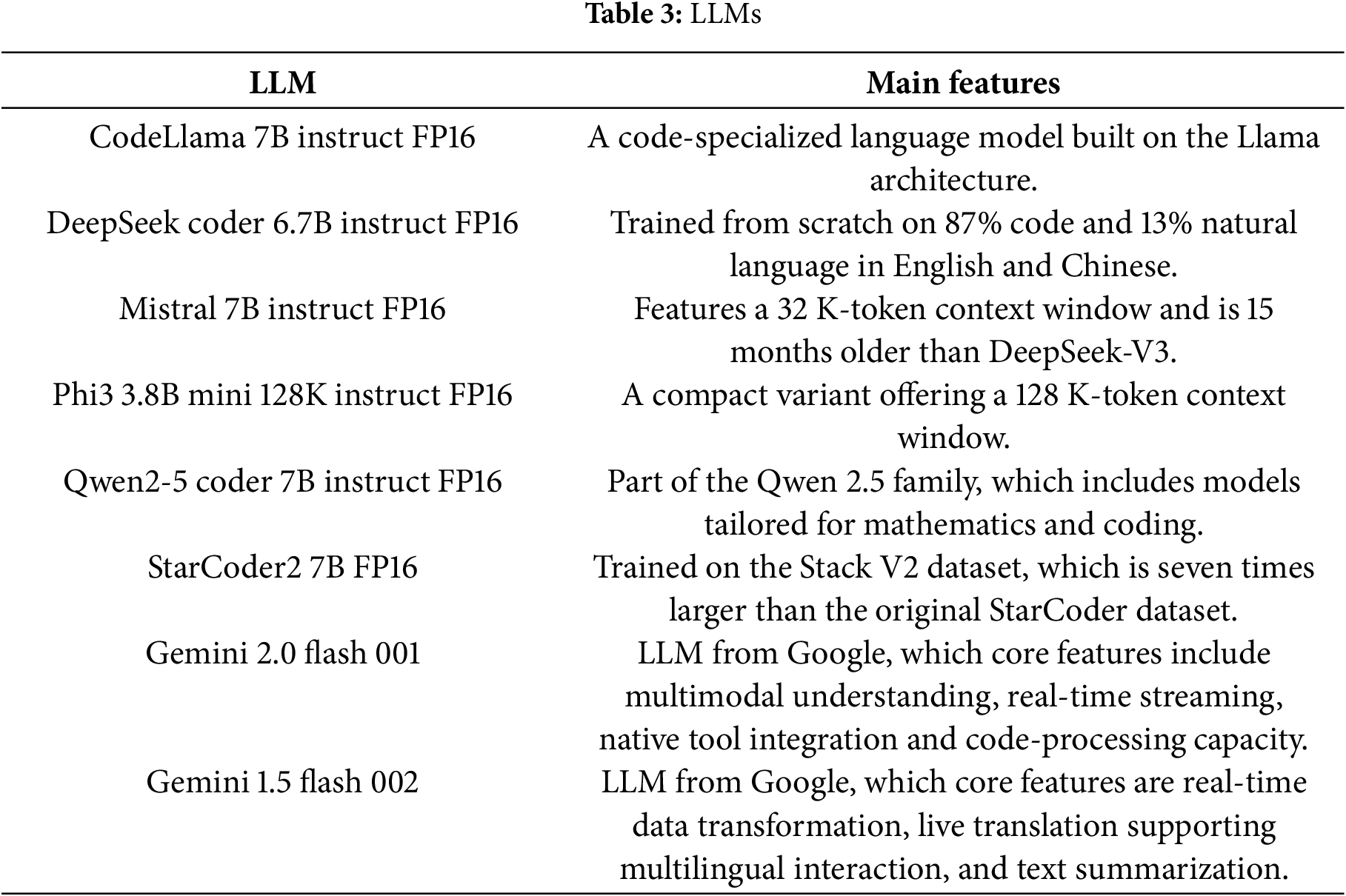

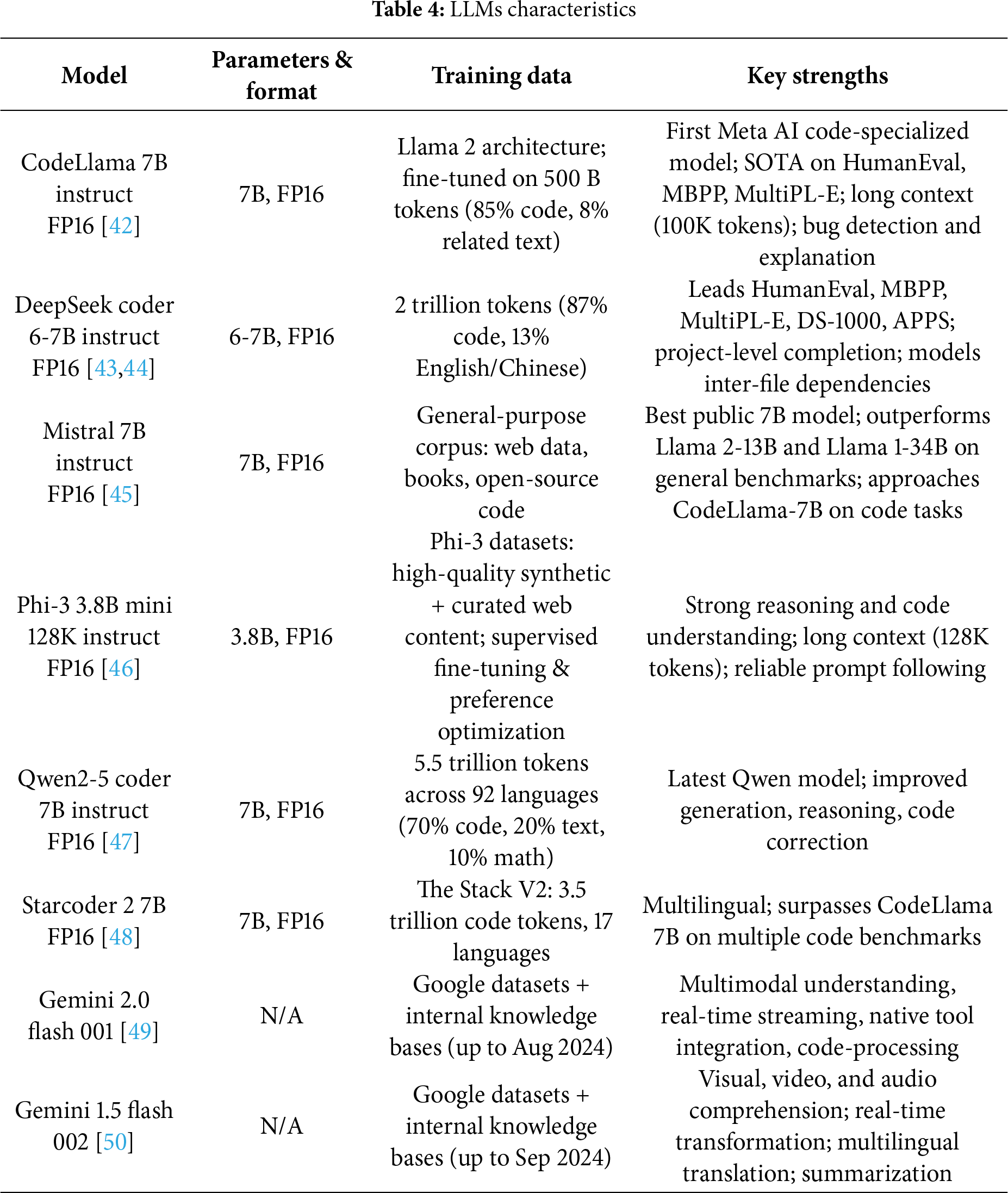

The continual expansion of different LLM variants and sizes yields a wide array of models, with new ones being trained every day using diverse techniques and/or architectural typologies. To compare the corpora of these models and select a reasonably sized subset that can be run in the near term on a variety of laptops, the following models were chosen, as shown in Table 3.

For static code analysis, models that can interpret code are essential. Accordingly, the “Instruct” variant was selected, as it contains largely code-centric training data and the most accurate Floating-Point 16 (FP16) checkpoint. This provides a superior balance between precision and performance compared to the quantization 3 (Q3), quantization 4 (Q4), quantization 6 (Q6), and quantization 8 (Q8) quantized models, which reduce accuracy to shrink the model size. In Table 4, the detailed available specification of each LLM used in the experiment are presented.

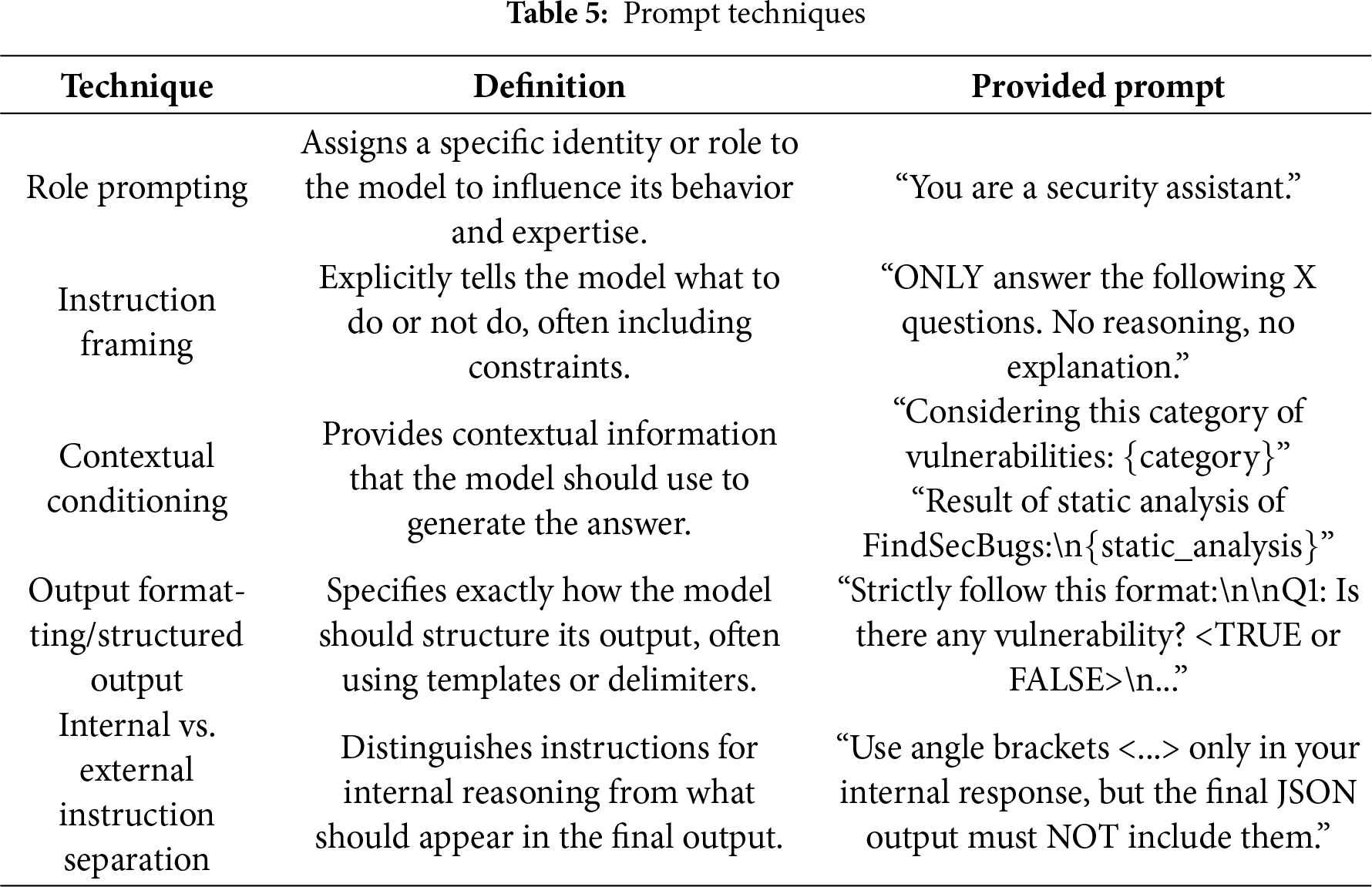

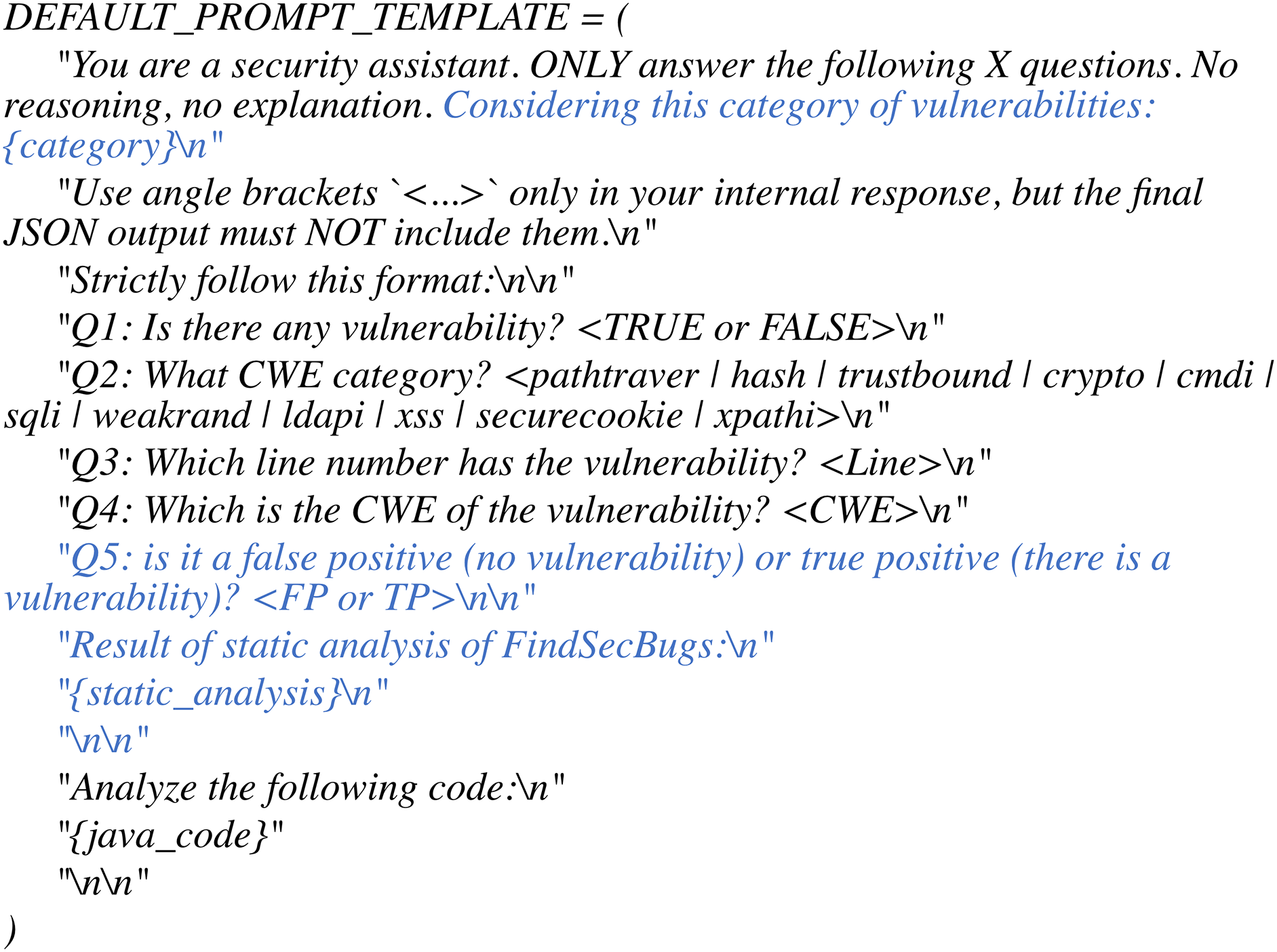

Prompt engineering techniques are structured methods for designing inputs (prompts) to guide a language model’s behavior to produce desired outputs. These techniques aim to improve accuracy, relevance, and format consistency by explicitly instructing the model on how to respond. Common strategies include role prompting, instruction framing, output formatting, and contextual conditioning. Same prompt template was provided to all LLMs using the techniques described in the Table 5 [51,52].

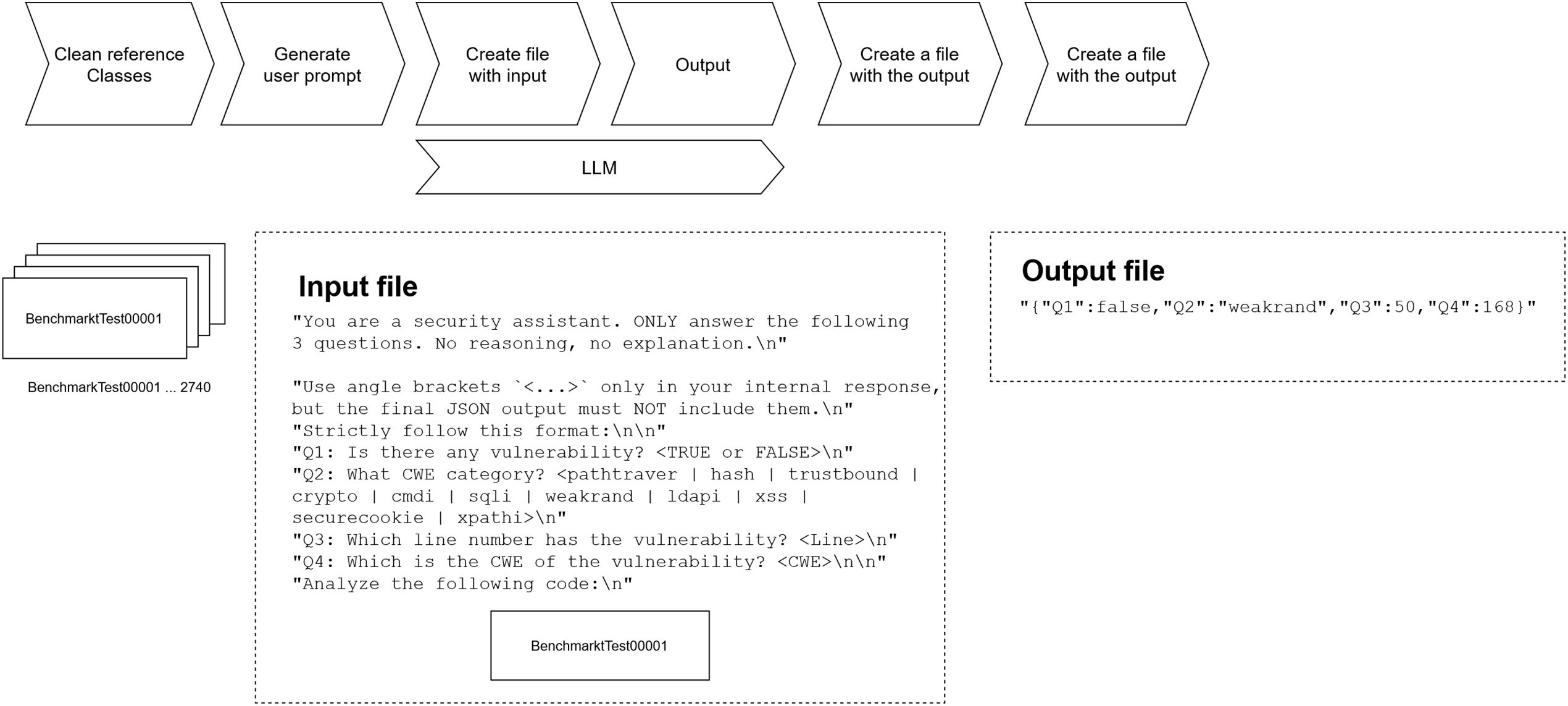

To ensure controlled and consistent outputs during the experiment, the following generation parameters were used. The temperature was set to 0.0, making the model’s responses deterministic and minimizing randomness. Top-p sampling was set to 0.9 and top-k sampling to 20, balancing the diversity of outputs while restricting the model to plausible continuations. A repeat penalty of 1.0 was applied, indicating no explicit discouragement of token repetition. Fig. 1 shows the prompt used in the experiment, while blue shows the difference in the second prompt.

Figure 1: Prompts used in the experiment

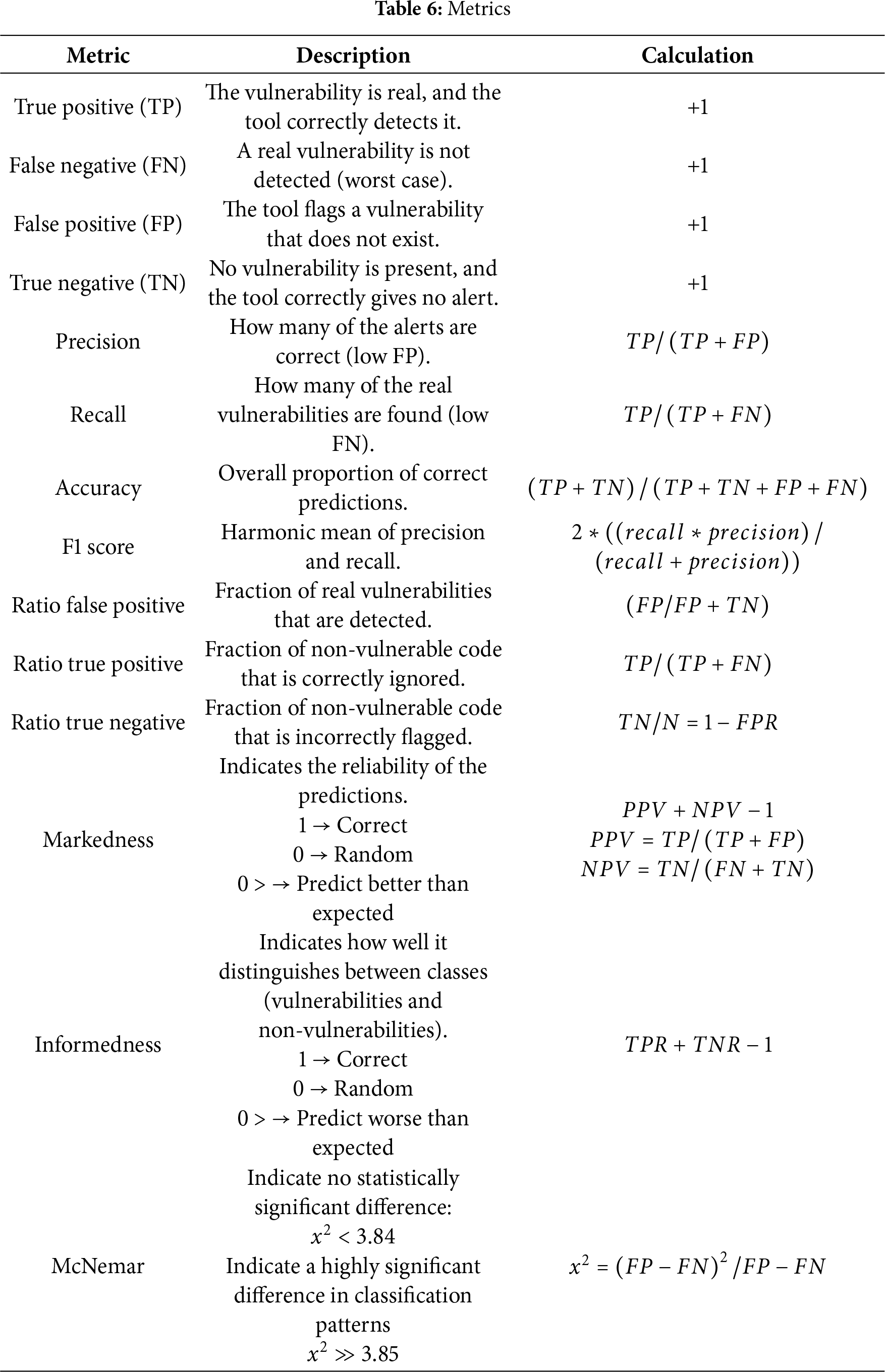

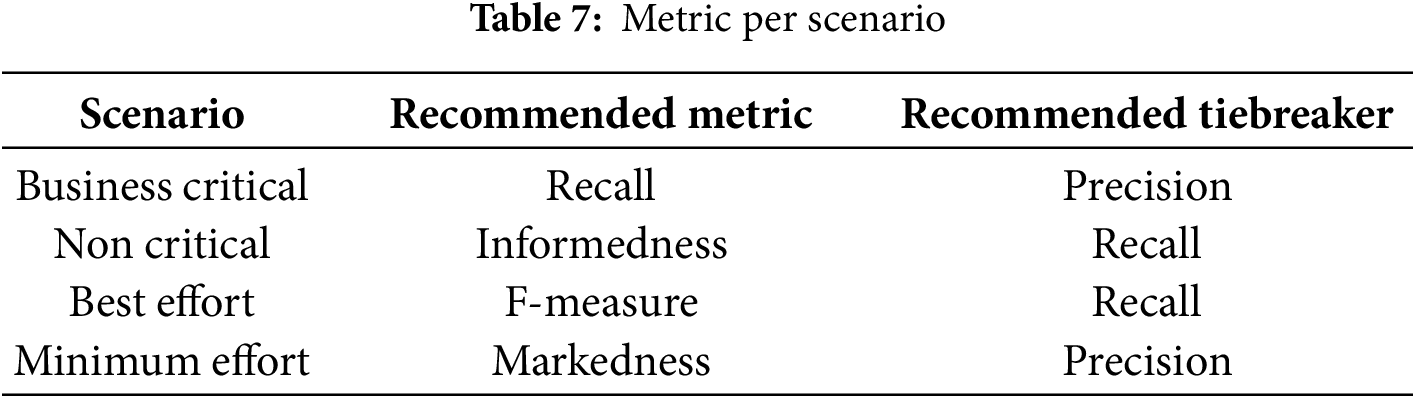

Below are the metrics presented in the Table 6 that will be used to evaluate static vulnerability analysis. All of them have wide acceptance in academia and are commonly employed for static code verification.

On the other hand, the results will be categorized according to different objectives:

• Business-critical applications: Tools that detect the largest number of vulnerabilities or the fewest vulnerabilities per detection. These scenarios have the necessary resources to fix all vulnerabilities and to verify or correct false positives.

• Non-critical applications: Tools that detect a high quantity of vulnerabilities while minimizing false positives. This category includes companies where a leak or vulnerability could cause significant losses.

• Best effort: Tools that detect a large number of vulnerabilities while reporting few false positives.

• Minimum effort: Tools that detect the fewest false positives. Focused on small and medium-sized businesses. [25].

The metrics for the different scenarios will be evaluated as shown in the Table 7.

In the context of SAST tools, the most recent and relevant work related to advances in the use of LLMs for static detection of security vulnerabilities in software without requiring application execution has been researched and analyzed.

Khare et al. [52] evaluated LLMs across languages and datasets, finding moderate accuracy—strong on simple vulnerabilities but weak on complex reasoning tasks. Prompting techniques like step-by-step reasoning improve results. While LLMs sometimes outperform static analysis tools, they are not yet reliable for full-scale vulnerability detection, but it shows great potential as complementary tools. Similarly, Das Purba et al. [53] compared GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Davinci, and CodeGen for SQL injection and buffer overflow detection, observing high recall, but low precision due to false positives. Guo et al. [54], Yin et al. [55], and Shimmi et al. [56] further showed that performance varies widely depending on prompting strategy, dataset quality, and model fine-tuning, while Almeida [57] demonstrated that few-shot and chain-of-thought prompts increase consistency. Nevertheless, two recent, comprehensive surveys by Sheng et al. [35] and Zhou et al. [58] caution that LLMs are currently limited by insufficient contextual awareness for complex, inter-file dependencies, leading research to focus on function-level detection rather than practical repository-level analysis. In contrast, our work addresses these limitations by evaluating a broader set of vulnerability categories, integrating context from a Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tool, and utilizing multiple LLMs with a unified taxonomy and consistent dataset, enabling robust cross-model comparisons under similar conditions.

Some studies focus on the security awareness of LLMs. For example, Sajadi et al. [59] found that GPT-4, Claude 3, and LLaMA 3 rarely issue security warnings unless explicitly prompted. Other studies go further, examining LLM-generated code; Aydın and Bahtiyar [60] revealed that JavaScript produced by LLMs often contains vulnerabilities such as XSS or unsafe use of eval(). In contrast, our study focuses on evaluating LLMs’ ability to detect vulnerabilities in existing source code, rather than generating or self-auditing new code.

Hybrid approaches have shown in combining LLMs with traditional analyzers. Jaoua et al. [61] demonstrated that integrating static analyzer results during training or inference enhances review accuracy, and Munson et al. [62] used Semgrep with LLMs to reduce false positives. This necessity for hybrid models is further supported by Zhou et al. [58], whose survey highlights that blending LLMs with program analysis or other modules is a primary adaptation technique to overcome the contextual limitations of language models. Our work extends this hybrid direction by integrating the FindSecBugs analyzer with multiple LLM architectures and prompt strategies, applied to the OWASP Benchmark dataset.

Beyond detection, LLMs have been used for localization and malicious code analysis. Wu et al. [63] proposed VFFinder to identify vulnerable functions in source code by analyzing natural language CVE descriptions, which in experiments on open-source projects improves vulnerability localization accuracy compared to traditional methods. Hossain et al. [64] trained a Mixtral-based LLM to detect malicious Java snippets, outperforming traditional SAST tools but requiring several iterative refinements. Additionally, Blefari et al. [65] proposed SecFlow, an agentic LLM-based framework for modular post-event cyberattack analysis and explainability from raw logs, utilizing a RAG component for contextualized reasoning. Similarly, Belcastro et al. [66] introduced KLAGE, a methodology that integrates Knowledge Graphs, XAI (LIME) and LLMs to enhance network threat detection, classification, and generation of explainable reports from network traffic logs. He et al. [67] showed that combining LLM-derived features with machine learning improves defect detection, particularly with few-shot prompting. While these works enhance specific tasks such as localization or malware detection, our study targets comprehensive vulnerability identification. The study of Li et al. [36] leverages LLM reasoning to automatically inspect the results of very broad SAST tools. They develop a GPT-based prototype, called FPShield, to automatically identify and eliminate potential false positives from SAST results.

A separate line of research of general LLM used on highly specialized fine-tuned transformers is addressed by some studies. Smaili et al. [68] proposed a transformer-based framework (CodeGATNet) that utilizes a specialized model (CodeBERT) in combination with an Attention-Driven Convolutional Neural Network component, this together with long-range data-flow dependencies through a Convolutional Attention Network (CAN) offers an alternative than relying on complex prompting of LLMs, However, this specialization is a limitation: adapting CodeGATNet to new languages or vulnerability classes typically demands a full, costly model retraining, whereas general LLMs can often integrate new context via simple prompting and inference-time augmentation.

Finally, [25] proposed evaluating detection tools using four effort-based categories—Business Critical, Non-Critical, Best Effort, and Minimum Effort—which we adopt to contextualize our results.

Overall, our work presents an evaluation of vulnerability detection using lightweight LLMs that can be run on standard laptops, as well as LLMs accessed via API-based services. The study integrates one of the most widely used static application security testing (SAST) tools, FindSecBugs, and employs a dataset derived from OWASP’s benchmark test suite. The evaluation focuses on measuring detection precision and categorizing the results into four practical risk categories: Business Critical, Non-Critical, Best Effort, and Minimum Effort from an overall perspective, taking into account all security vulnerabilities, and also from the perspective of each specific vulnerability. While we restrict our analysis to Java programming language and a synthetic dataset, this choice allowed us to validate and compare the performance of multiple LLM architectures under the exact same conditions and scenarios, significantly reducing external interference from variables like differing code bases or language complexities. Furthermore, the OWASP Benchmark provides good ground truth, which is essential for the precise measurement of detection metrics and the robust categorization of results into our four risks.

In the following chapter the experiment is described in the Section 3.1, along with its results at the Section 3.2.

3.1 Research Questions Definition

The experiment aims to investigate the effectiveness of using LLMs for software vulnerability, Specifically, we address the following questions or hypotheses:

• Q1. Do the results produced by LLMs outperform those of traditional static analysis tools?

This question focuses on comparing the accuracy of LLMs with SAST tools in detecting software vulnerabilities, rather than evaluating computational performance or runtime efficiency. The goal is to assess whether LLMs could potentially serve as an accurate alternative or complement to traditional tools.

• Q2. Is there an improvement when combining LLMs with SAST tools?

Hybrid approach to integrate LLMs with SAST tool in order to evaluate the combination also in a bigger LLMs.

• Q3. Can reliable results be achieved with locally deployed models on a standard desktop computer?

These questions focus on comparing local LLMs which could improve the privacy in large companies as well as the anticipation of vulnerabilities.

3.2 Description of the Methodology

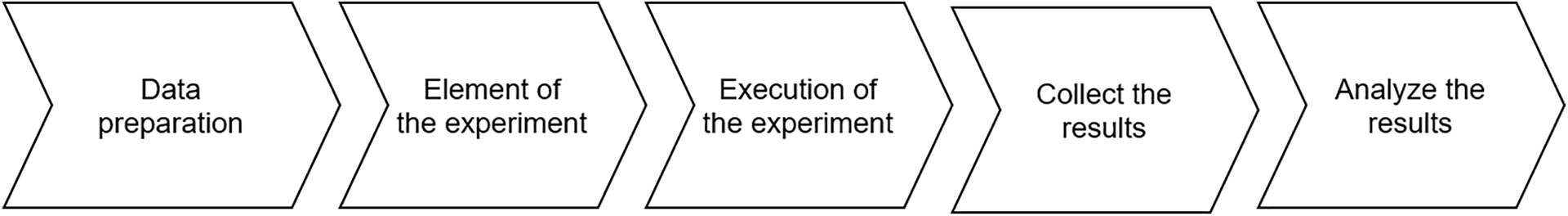

The preparation of the experiment involves several key phases, as outlined in Fig. 2 below:

Figure 2: Phases of the methodology

3.2.1 Selection of LLM, SAST and Dataset

At the time the experiment was conducted, the most relevant model architectures that could feasibly run on a laptop (and were specifically trained for code generation and understanding) were: CodeLlama 7B, DeepSeek Coder 6.7B, Mistral 7B, Phi-3 Mini, Qwen2-5 Coder 7B, and StarCoder2.

To select an appropriate static application security testing (SAST) tool for Java, several open-source solutions were evaluated using the OWASP Benchmark. FindSecBugs, in its latest version, demonstrated the highest detection accuracy among the tools tested. Its widespread adoption and continued community support further reinforce its suitability for integration into secure software development workflows [41].

To ensure focused evaluation and minimize noise from unrelated factors, a synthetic dataset specifically designed for Java was used. This dataset provides a wide range of vulnerability categories relevant to static analysis [41,62].

To reduce bias and prevent direct influence on the models, the dataset will be cleaned by removing all explicit references to specific vulnerabilities, Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) identifiers, and expected outcomes. This de-contamination ensures that the models operate solely on the contextual information available, allowing us to evaluate their reasoning and generalization abilities in environments that lack explicit prior knowledge.

3.2.3 Elements of the Experiment

A script will be developed in Python, taking advantage of its extensive library ecosystem and its seamless integration with large-language-model frameworks such as Ollama. This choice helps reduce errors that can arise from unstable or incompatible libraries.

For the evaluation phase, we will employ Benchmark Java-OWASP [41], an official OWASP project that provides a curated dataset and a standardized framework for running test classes on SAST tools. The benchmark will be extended to include large-language-model (LLM) evaluations, as the original repository does not support comparisons with LLM-based systems. For this reason, we will develop additional components that execute the benchmark scenarios and capture the predictions generated by the LLMs, enabling a comparison between traditional SAST tools and the proposed LLM approach.

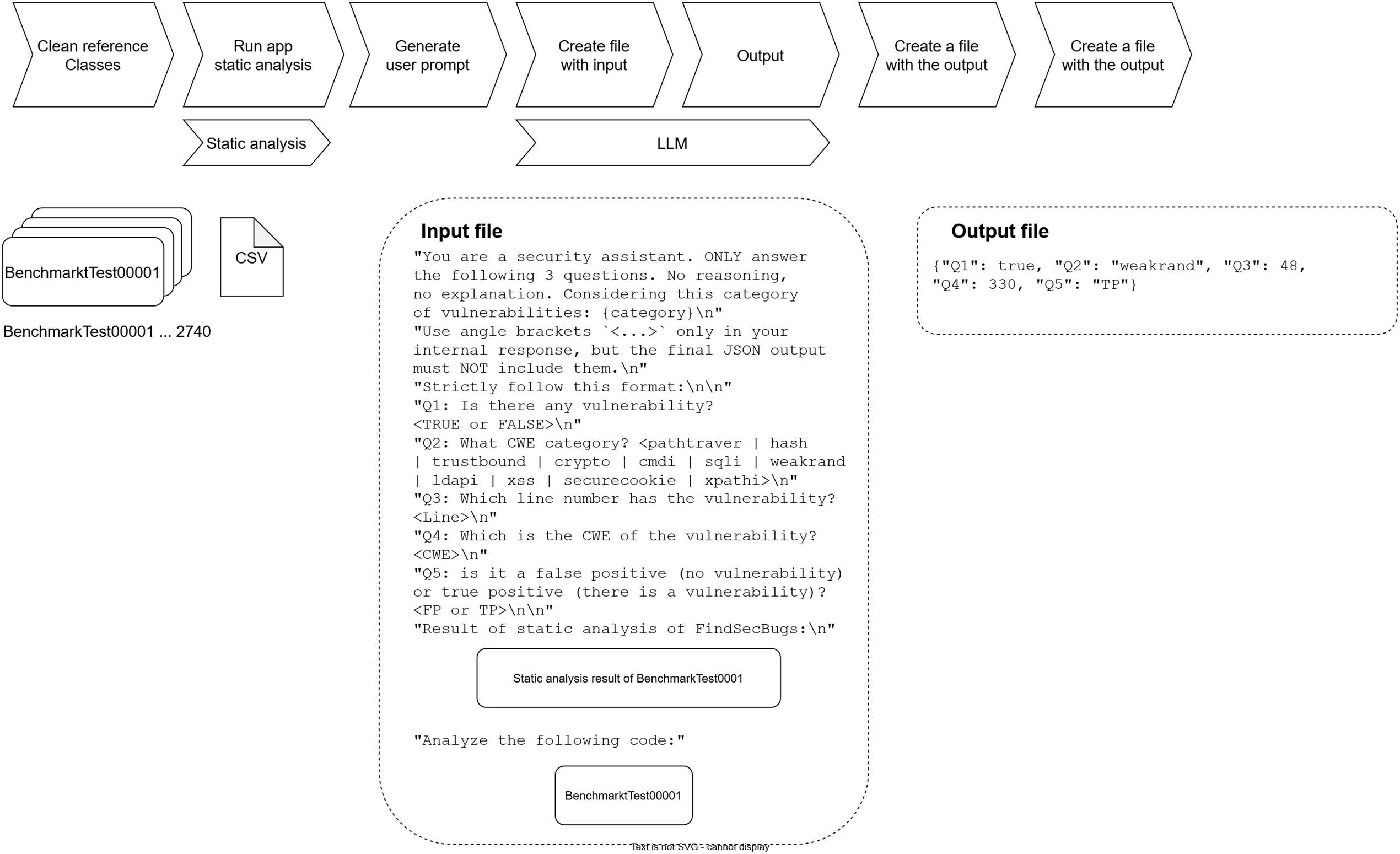

A total of 2740 scenarios will be processed. For every scenario the original input and the LLM’s response will be captured and stored in a structured format, enabling a detailed comparison after the fact. The entire workflow will be automated to guarantee reproducibility, consistency of results, and full traceability of the experiment. Fig. 3 illustrates the process of the first prompt execution, while the Fig. 4 shows the process of the second prompt execution including the SAST analysis.

Figure 3: Execution of first prompt

Figure 4: Execution of the second prompt

Two full test-suite runs will be performed:

1. LLM with detection vulnerability questions illustrated in the Fig. 3.

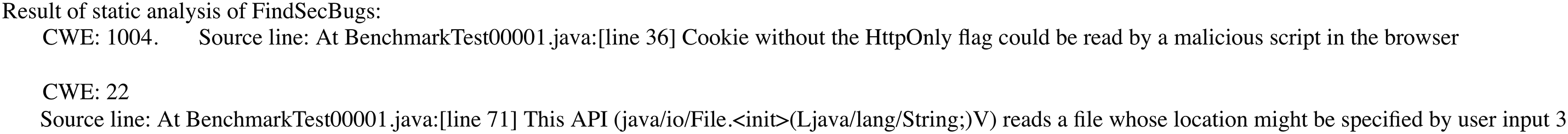

2. Combination of the results in SAST Tool (FindSecBugs) and LLM illustrated in the Fig. 4, while the Fig. 5 shows an example of SAST result into the prompt.

Figure 5: Example of content included as SAST into the prompt

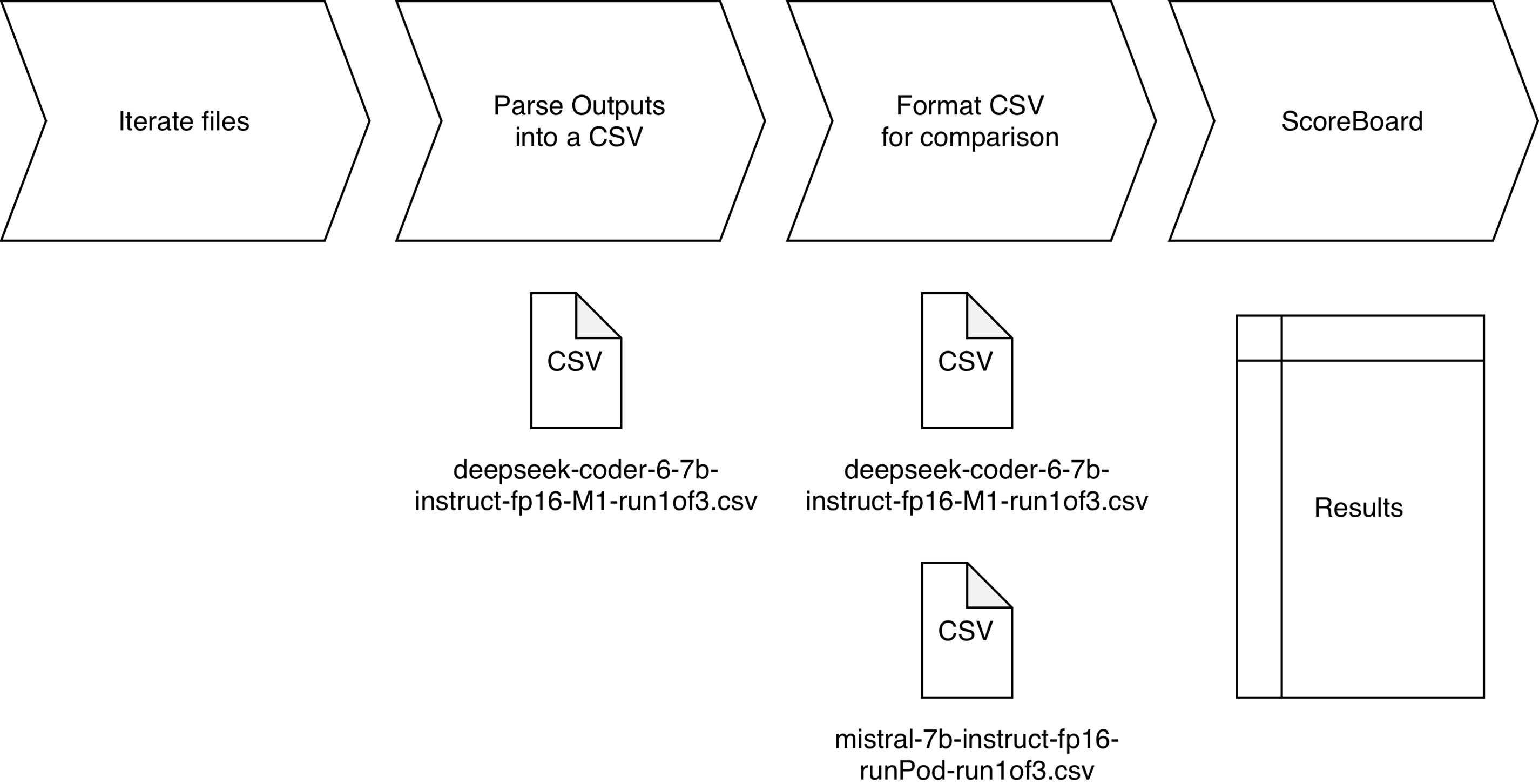

The results produced by the models will be processed to normalize their format and facilitate comparison with other techniques such as OWASP Benchmark. This process will include tasks such as text cleaning, semantic labeling, and extraction of key performance indicators. The resulting data will be stored in a structured database, ready for quantitative and qualitative analysis using selecting metrics.

The evaluation will use standard performance metrics (precision, recall, F1-score, and true-positive ratio) that are widely adopted for vulnerability detection [25]. As shown in Fig. 6, all results will be aggregated and grouped to facilitate a direct comparison with conventional static-analysis tools. In addition, we will conduct a preliminary quality assessment to confirm that the LLM outputs lie within the acceptable range.

Figure 6: Process to compare results

The analyzed results and conclusions will be presented in a clear and structured manner, using comparative charts, summary tables, and qualitative interpretations to facilitate understanding of the findings. The goal is to provide a comprehensive view of the model performance, highlighting strengths, identifying limitations, and pointing out areas for improvement in future work.

3.2.7 Method Limitations and Considerations

While we limit our analysis to the Java programming language and a synthetic dataset, this controlled setting allows for a fair comparison of multiple LLM architectures under identical conditions, minimizing external factors such as varying codebases or language-specific complexities. The dataset covers a representative spectrum of security issues, including command injection, path traversal, weak hash algorithms, cryptographic algorithm misuse, cross-site scripting (XSS), LDAP-related flaws, and trust-boundary violations, thereby providing a comprehensive evaluation of model capabilities. Although our experiments focus on open-source LLMs, the framework could be extended to include newer open-source or commercial LLMs of different sizes, as well as traditional SAST tools, offering broader benchmarking opportunities. Nevertheless, practical considerations—such as dataset size, vulnerability diversity, and computational cost—necessitate imposing limits when selecting models and scenarios to ensure consistency, reproducibility, and meaningful results.

3.3 Implementation of the Methodology

The steps of the implementation are the following:

An exhaustive review of all the classes in the dataset was carried out to remove references that might disclose the type of vulnerability involved. In particular, patterns such as those defined in the @WebServelet annotation were identified, for example:

@WebServlet (value = “/pathtraver-00/BenchmarkTest00001”)

To automate this cleansing step, we developed a dedicated script that performs bulk removal of such references, thereby ensuring the semantic neutrality of the classes with respect to the vulnerability type they represent. The script is available in the repository provided in this paper “CleanReferences.py”.

3.3.2 Elements of the Experiment

The element that has been required to implement or configure are the following:

• Environment preparation

• Script Implementation

• Extension of the application OWASP Benchmark

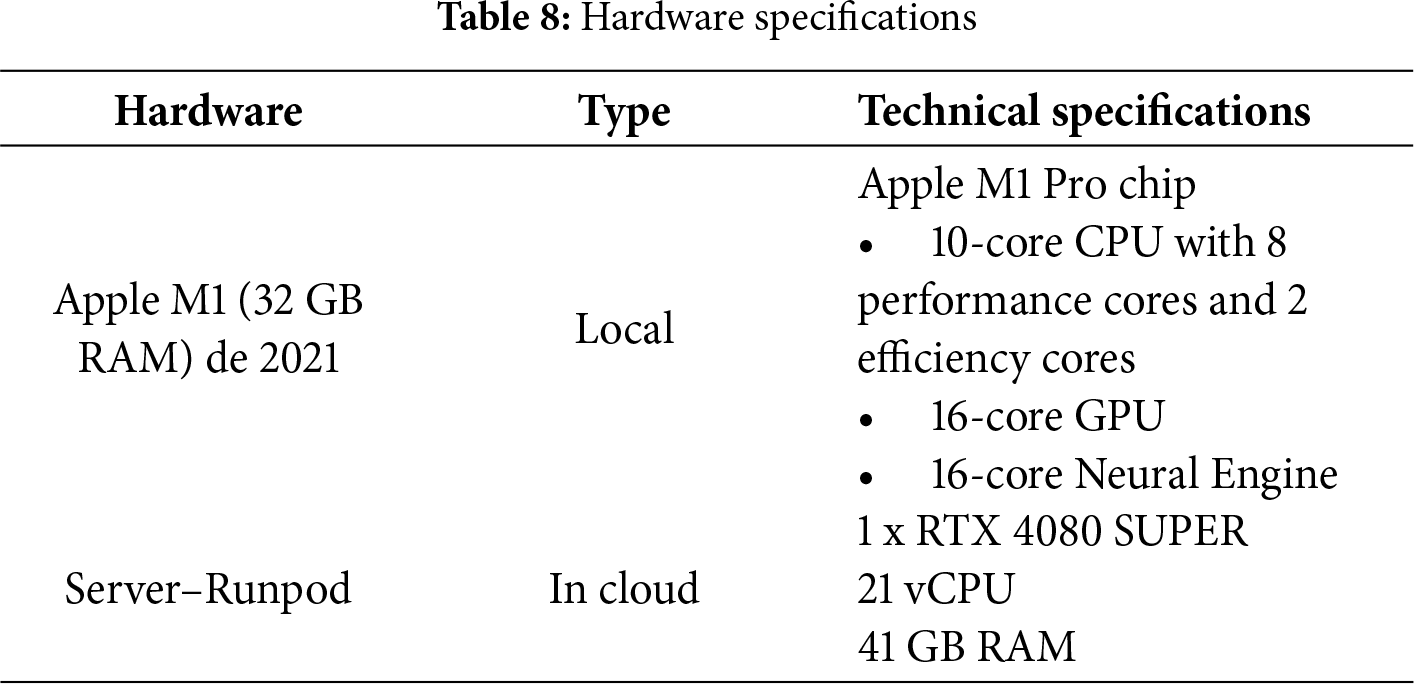

Environment preparation. For the development and execution of the tests, two environments were prepared. The first is a local workstation equipped with Apple Silicon (M1) architecture, primarily used for analysis, development, data processing, and running certain LLMs. The second environment consists of a remote server specifically configured for running the experiment and collecting associated metrics. Further technical details about the experiment hardware are provided in Table 8.

Script implementation. The script is designed to scan multiple Java source files, leveraging large-scale language models (LLMs) to identify potential security vulnerabilities. Analysis is performed via prompt engineering: each file is sent to an LLM (Gemini or Ollama), and both the prompt and the model’s response are stored in structured text files.

Ollama supports executing language models in both local and remote environments and provides a broad catalog of pre-trained models accessible through its libraries. In this work, a variety of strategies were applied to ensure the robustness, reproducibility, and efficiency of the automated analysis:

• Standardization of the output format: The models were forced to return responses in JSON format, thereby facilitating subsequent automated analysis and reducing ambiguity in result interpretation.

• Execution in multiple iterations: For some models, several runs were performed on the same source files to assess the stability and consistency of their responses, as well as to correctly configure the model’s deterministic outputs.

• Integration with Gemini and usage-limit management: The Gemini model was added as an additional backend, with programmed delays between requests to respect API usage restrictions.

• Optimization toward deterministic outputs: Generation parameters were tuned (e.g., temperature = 0.0) to prioritize more deterministic responses over random or probabilistic ones, enabling a more precise and reproducible evaluation

Extension of the application OWASP Benchmark. The OWASP Benchmark [41] is a widely adopted standard reference for comparative evaluation of security-analysis tools, including static, dynamic, and hybrid scanners. However, it does not natively support integration with large-scale language models (LLMs).

In addition, this Benchmark includes a ranking system that allows tools to be compared across distinct vulnerability categories. To leverage these capabilities, we have developed an adaptation that enables LLMs to participate in the analysis workflow, thereby extending the tool’s functionality and introducing new automated evaluation modes over Benchmark’s test suite.

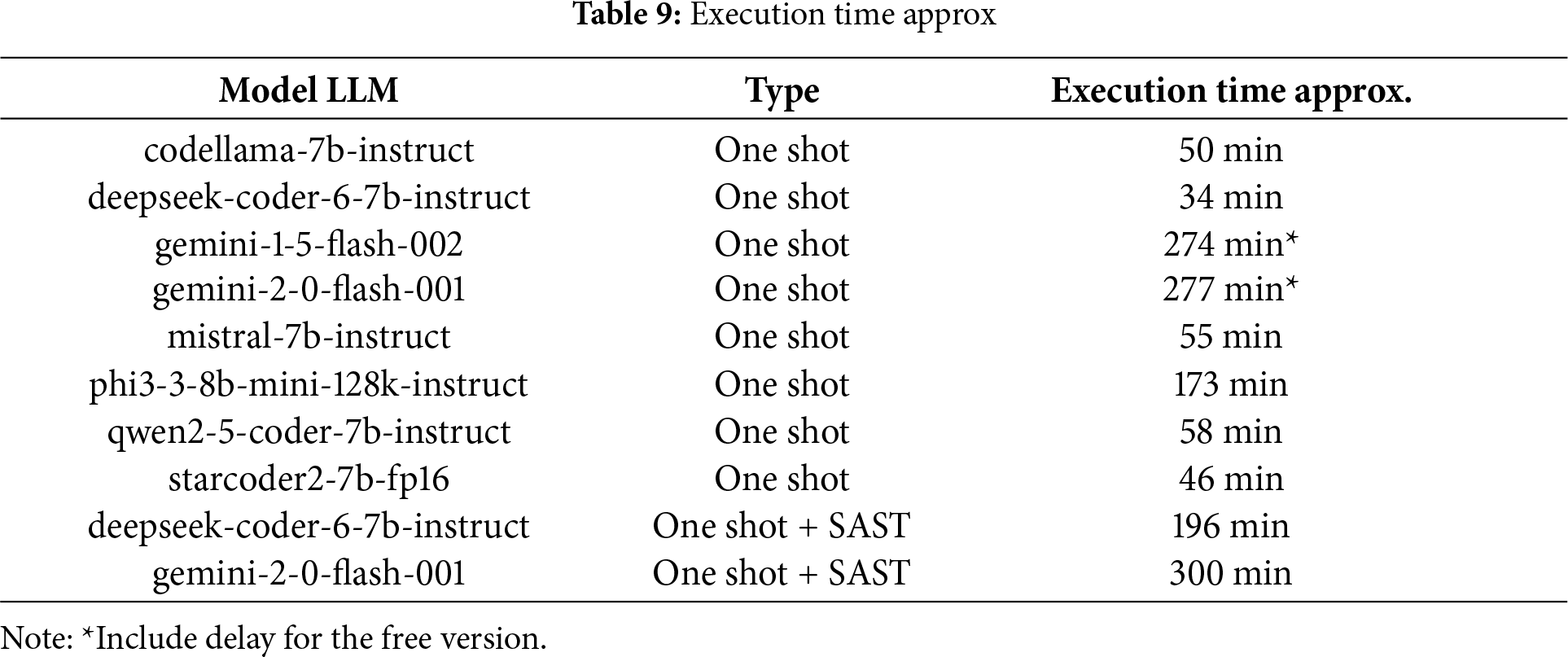

Table 9 shows the execution time of the single LLM and the SAST with the LLM. The One-Shot strategy has demonstrated faster performance compared to using SAST results, even without accounting for the delay introduced by the free-tier limitations of LLM as a Service.

All LLM models were executed, generating 2740 outputs for subsequent analysis. Based on the outputs a script is implemented to convert the results into a CSV file, enabling the OWASP Benchmark application (along with its built-in extensions) to perform the comparative analysis.

The process begins with a consistency check of the outputs, verifying that each LLM has produced a response that falls within the permitted value ranges.

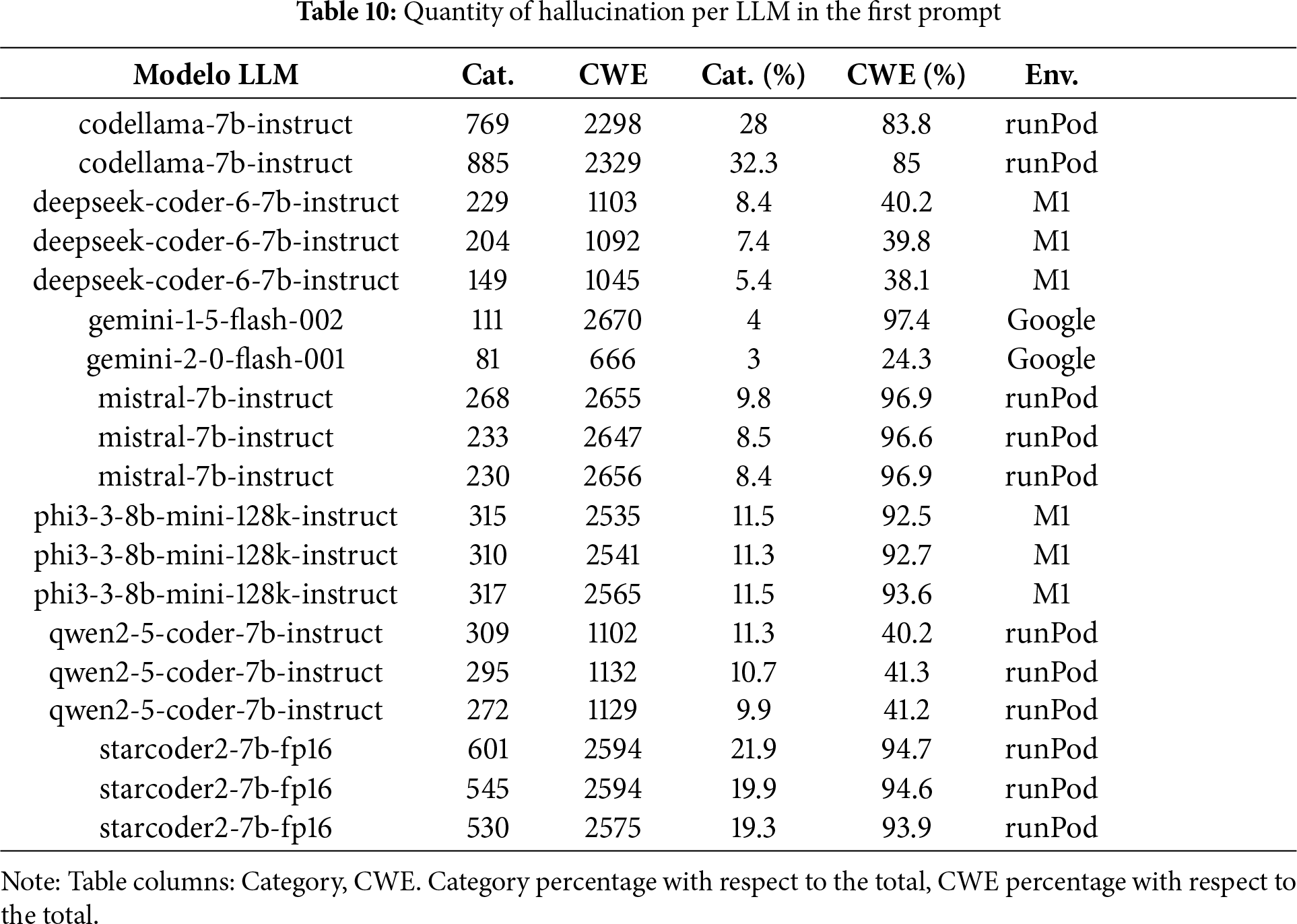

Following this verification, preliminary analyses are presented before the final results. The hallucinations generated by each LLM are flagged, indicating either invented categories or CWEs that lie outside the acceptable range.

Table 10 displays the number of “hallucinations”, when the output was out for the range proposed in the prompt, and their percentage relative to the total. To ensure that the results are more deterministic than probabilistic, since LLMs have a probability factor, there are several instances of model execution to test that the values are very similar and to verify with certainty that the result is not a matter of luck.

For the first prompt, Gemini 2-0 Flash showed the lowest hallucination rate relative to the provided categories and CWEs, while Gemini 1.5 Flash performed worst in returning valid CWEs.

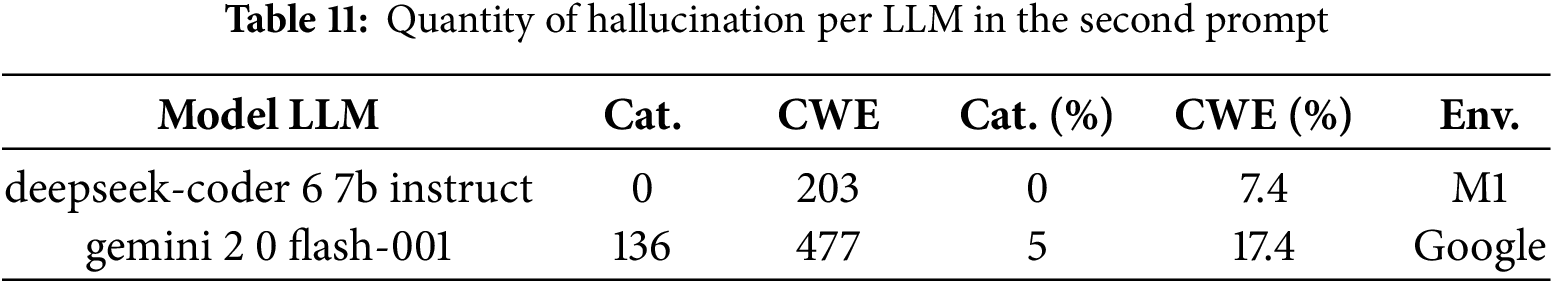

In Table 11, the “hallucinations” from the second prompt are displayed, and they already include a prior analysis performed by a static-analysis tool that lists the CWE, possible category, and description of the potential vulnerability.

The results for DeepSeek Coder 6-7B-Instruct are better than for Gemini 2-0-Flash 001. Based on the hallucination outcomes, this could be seen as a lack of corpus update regarding the CWEs; therefore, the LLMs have been evaluated on the vulnerability category rather than on specific CWEs for the first prompt.

For the second prompt, which includes the results of static code analysis, the category is fed as input, and the model is asked to confirm whether it is indeed a true positive (TP) or a false positive (FP) and whether it preserves the category or changes it in the output.

• Actual Category == Expected Category && Is a Real Vulnerability == Is a Vulnerability

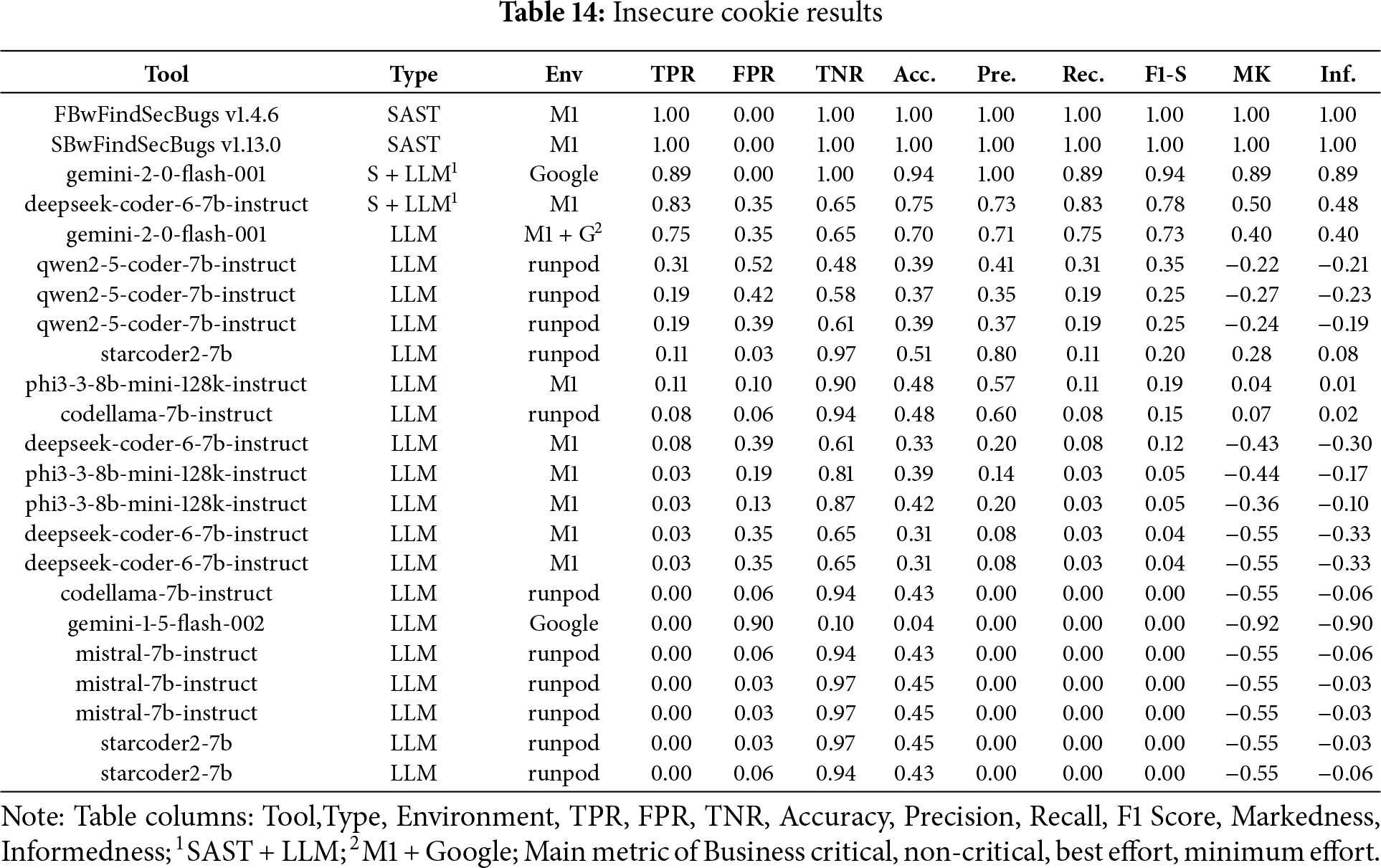

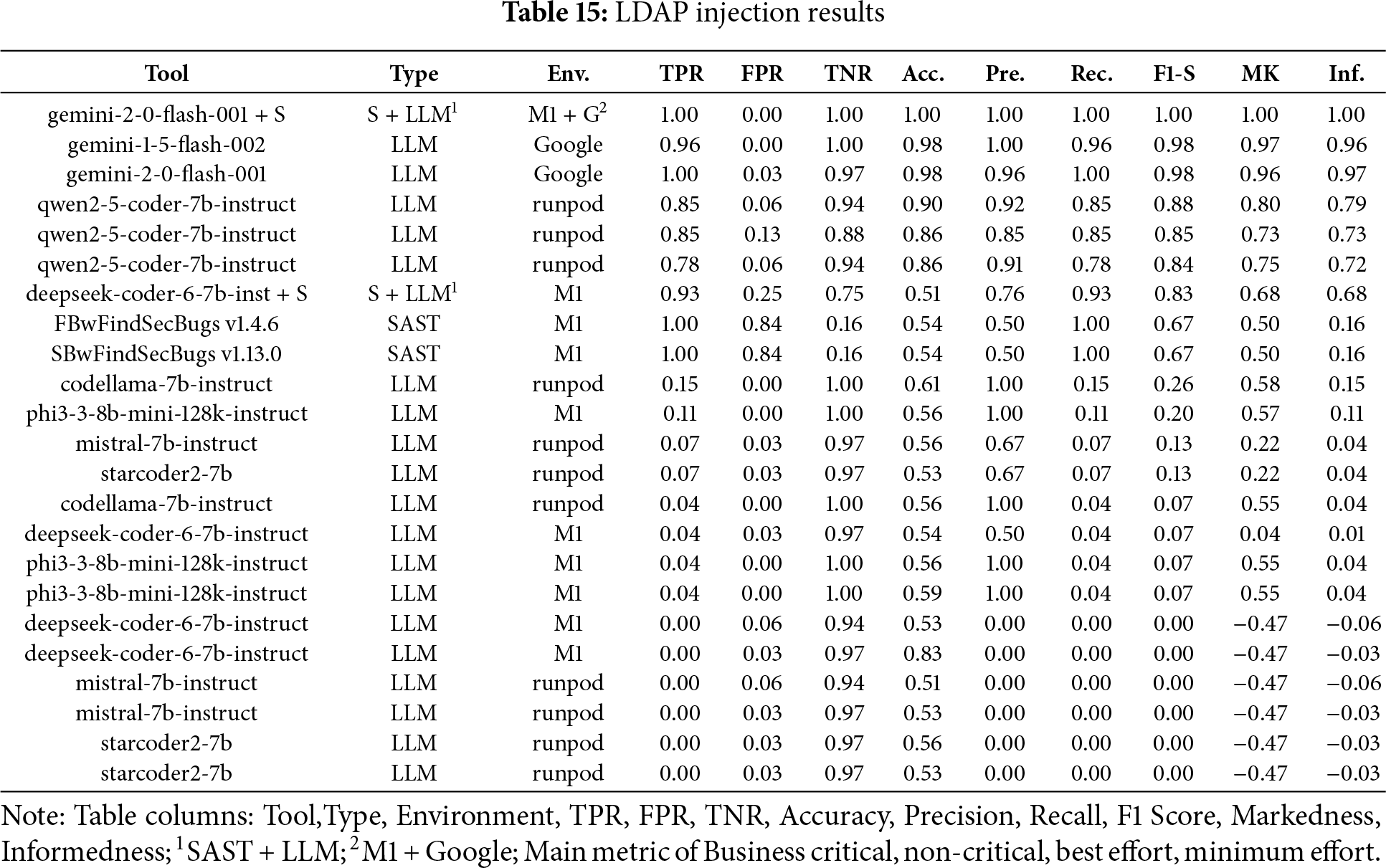

Below are the overall results with all metrics broken down by category: Command injection, insecure cookie, LDAP injection, path traversal, SQL injection, trust boundary, weak encryption algorithm, weak hashing algorithm, weak randomness, XPath injection, and XSS.

Overall Results

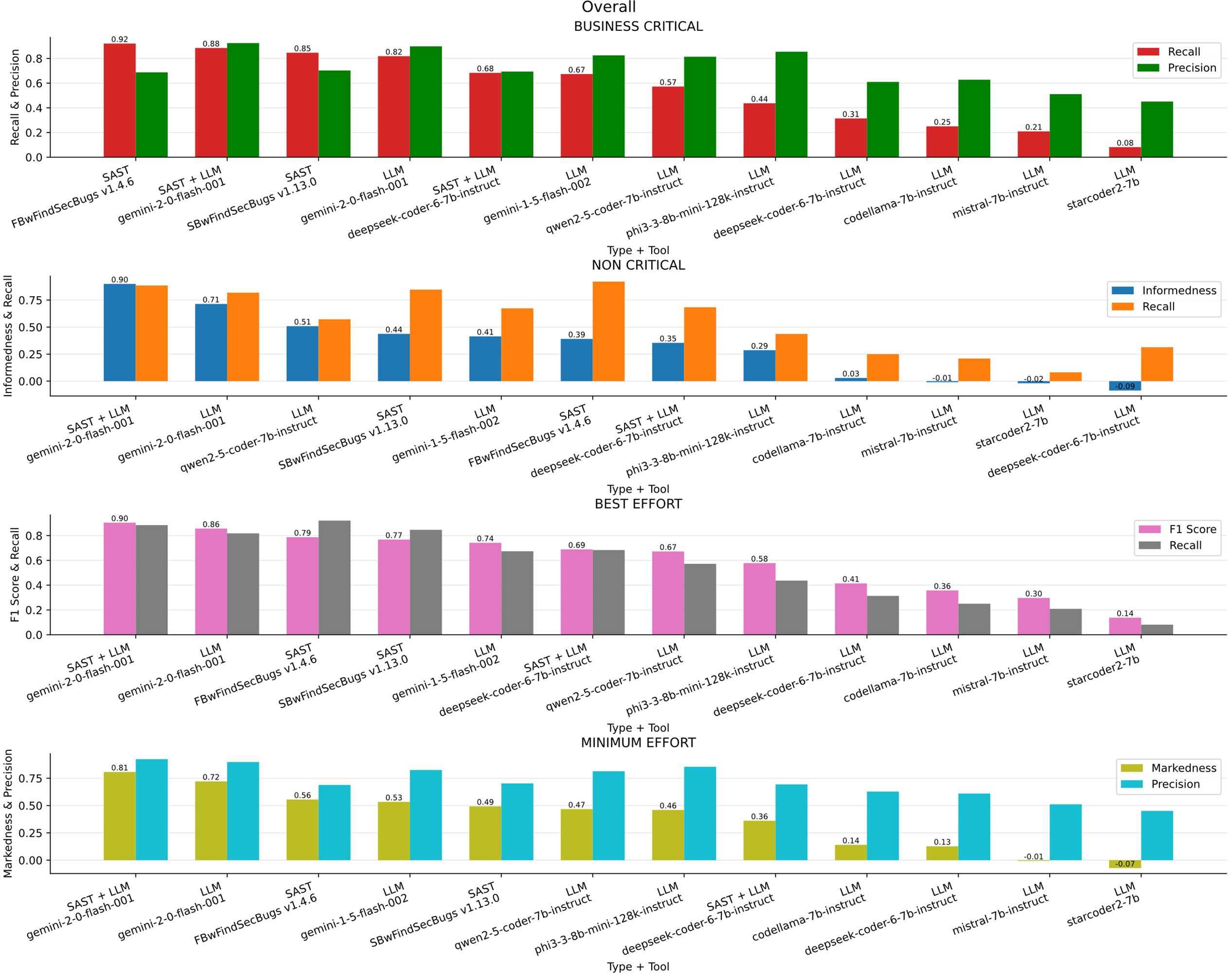

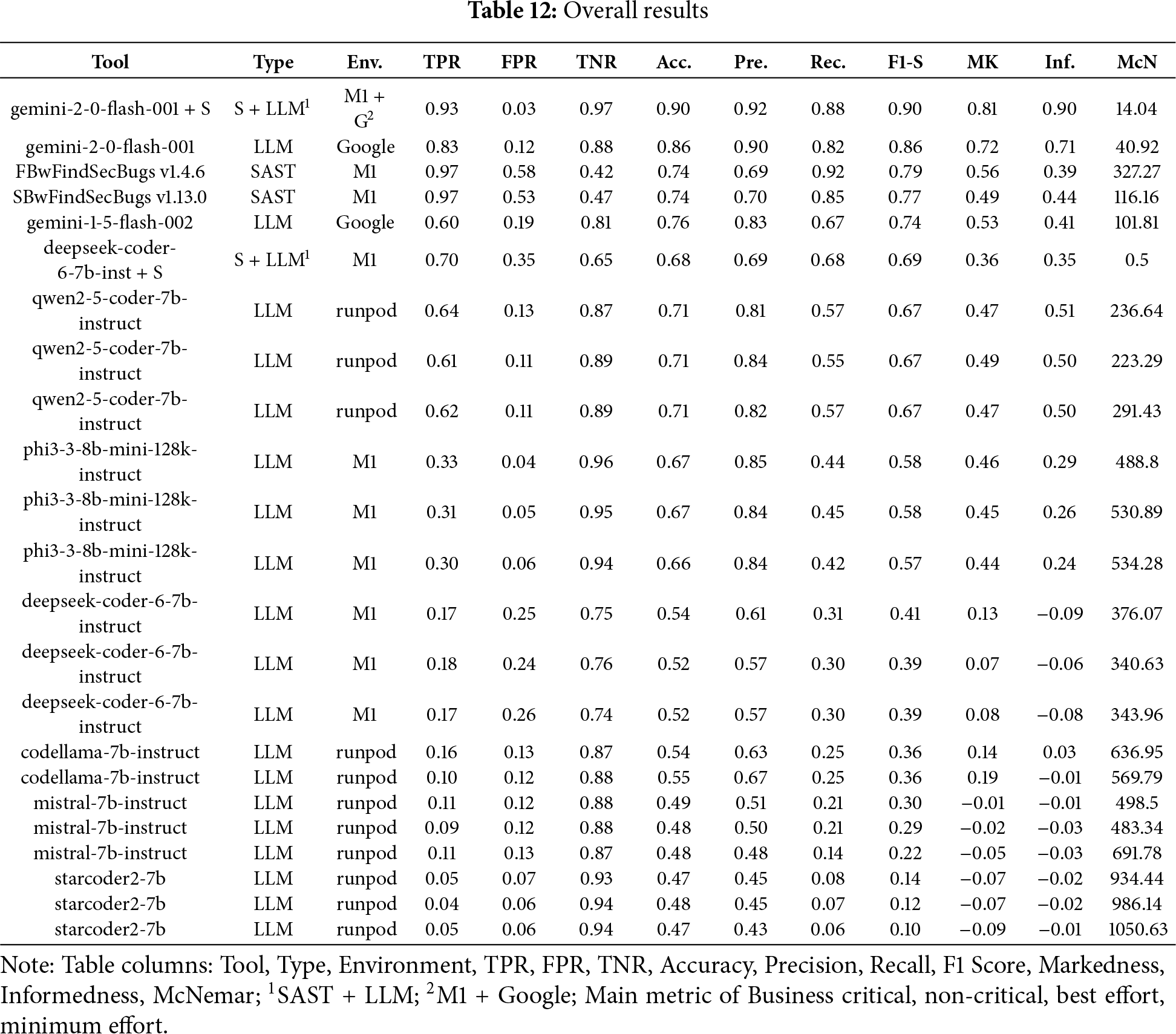

In the Fig. 7a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for all vulnerabilities across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort) in contrast, Table 12 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. In scenarios where detecting the most real vulnerabilities is critical, such as in high-assurance systems where Recall is the primary metric, FindSecBugs v1.4.6 delivered the best results. However, for scenarios that prioritize balanced detection, minimal manual effort, and more accurate findings, the best performance came from Gemini 2 together with FindSecBugs results. The metric McNemar reflects statistical disagreement or difference in predictions between tools.

Figure 7: Overall results

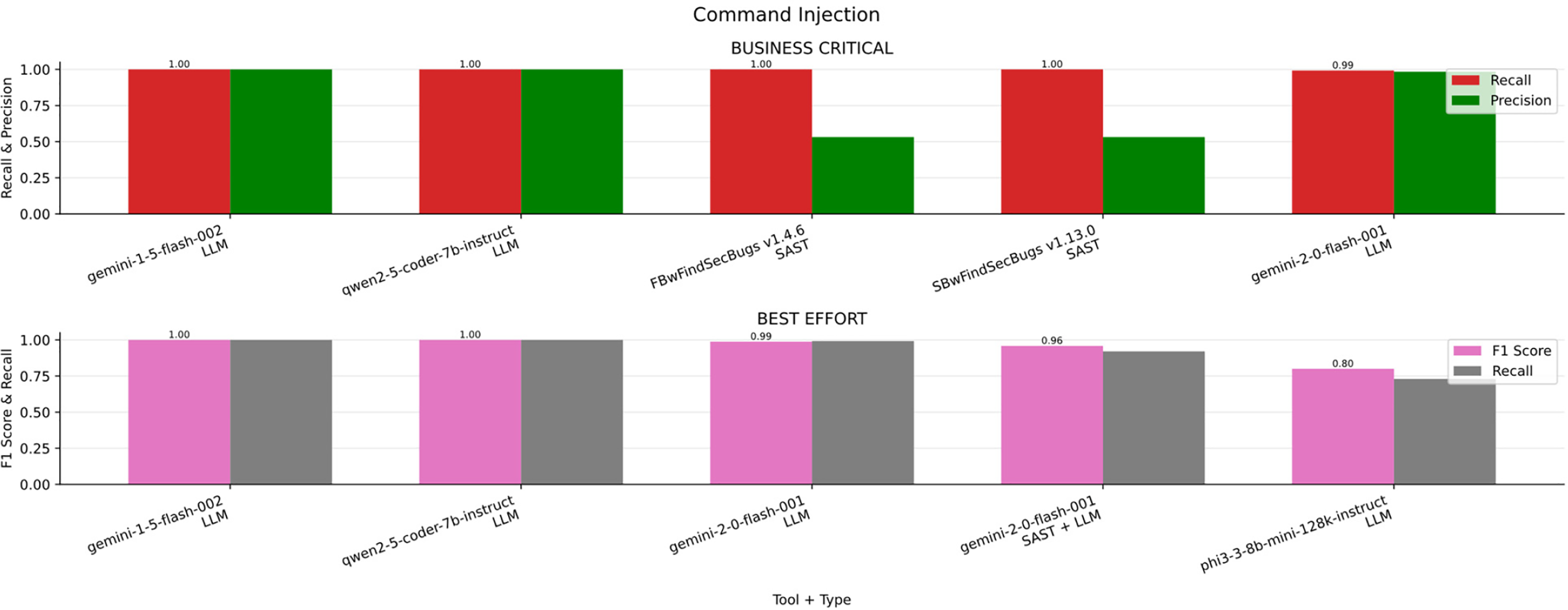

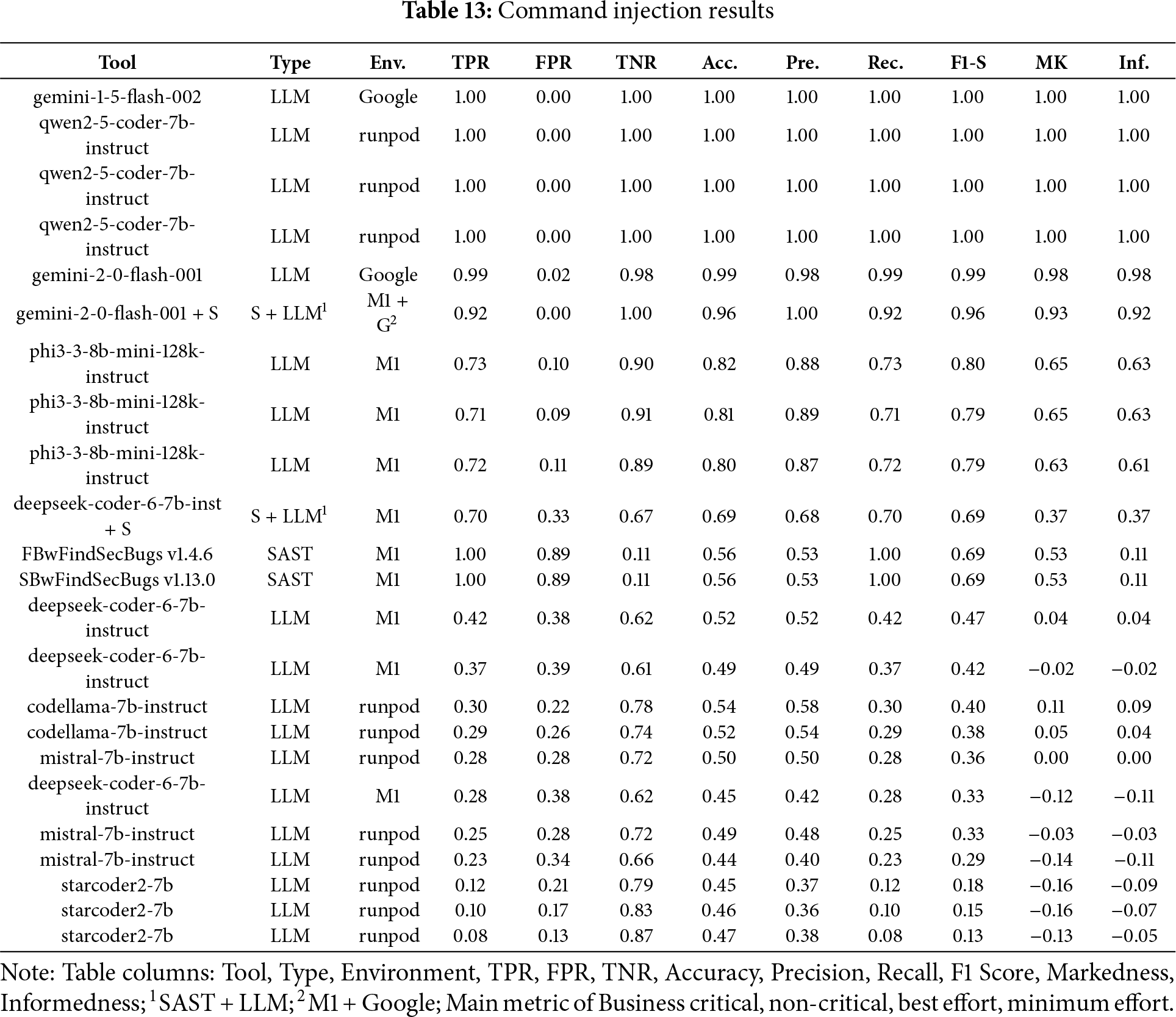

Command Injection

In the Fig. 8a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for Command Injection across the four scenarios (Business critical and Best effort) in contrast, Table 13 ranked by F1-S summarizes the key performance metrics for detecting command injection vulnerabilities. Gemini v1.5 was the top performer in the business-critical scenario, achieving the highest Recall, the most important metric when missing a real vulnerability is unacceptable. Additionally, it maintained strong Precision across other scenarios, making it suitable even when balancing detection quality and effort.

Figure 8: Command injection results

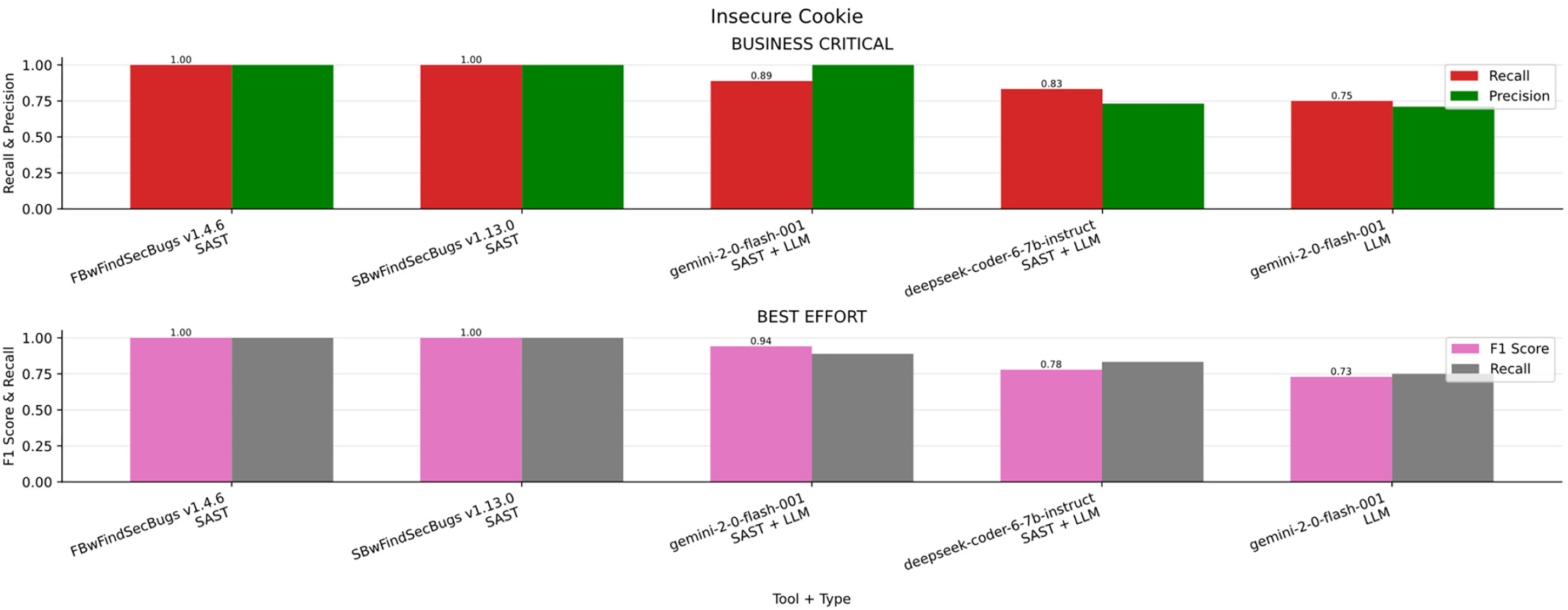

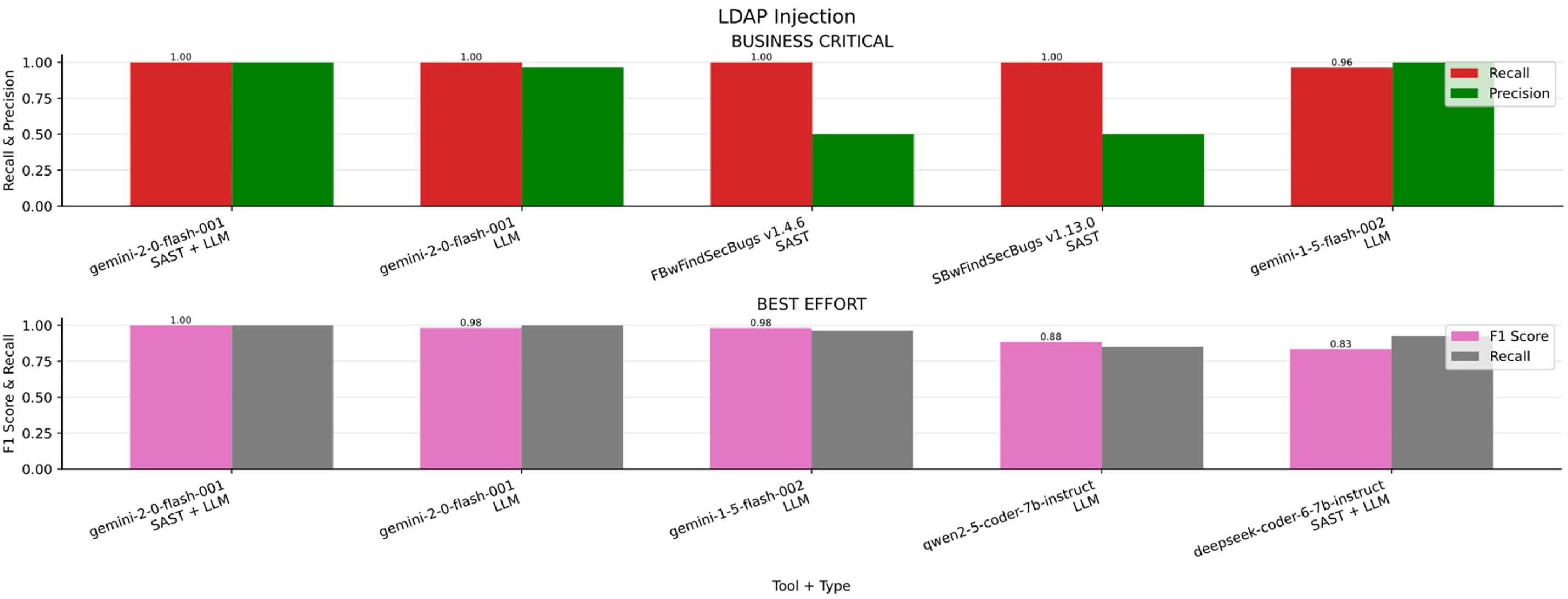

Insecure Cookie

In the Fig. 9a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for Insecure Cookie across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort) in contrast, Table 14 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. FindSecBugs v1.4.5 was the best choice in the business-critical scenario, among all the other scenarios providing strong precision and balance between minimum effort, best effort and non critical systems.

Figure 9: Insecure cookie results

LDAP Injection

In the Fig. 10a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for LDAP Injection across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort) in contrast, Table 15 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. FindSecBugs v1.4.5 was the best performer in the business-critical scenario, where maximizing Recall is essential to avoid missing real vulnerabilities in high-risk systems. In contrast, Gemini 2.0 combined with SAST achieved superior results in the non-critical, best-effort, and minimum-effort scenarios, offering a stronger balance between detection accuracy and reduced manual effort, as aligned with the respective priorities of Informedness, F1-score, and Markedness.

Figure 10: LDAP injection results

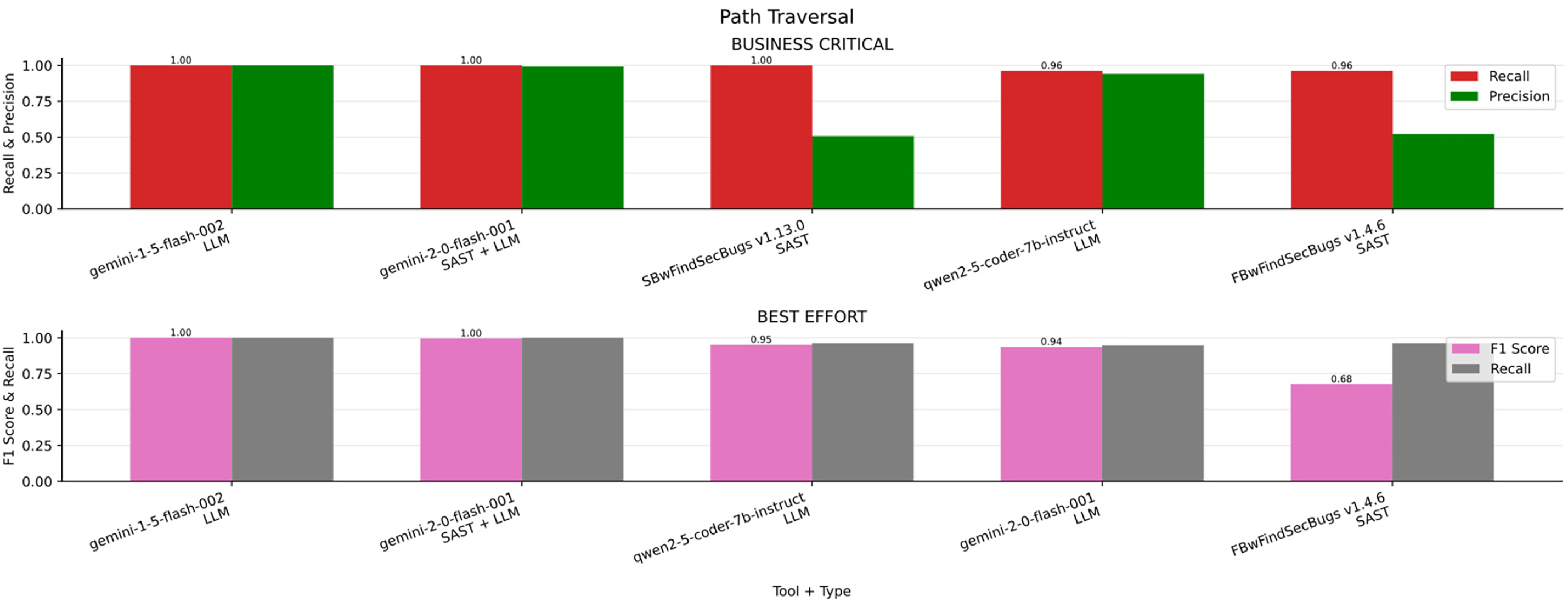

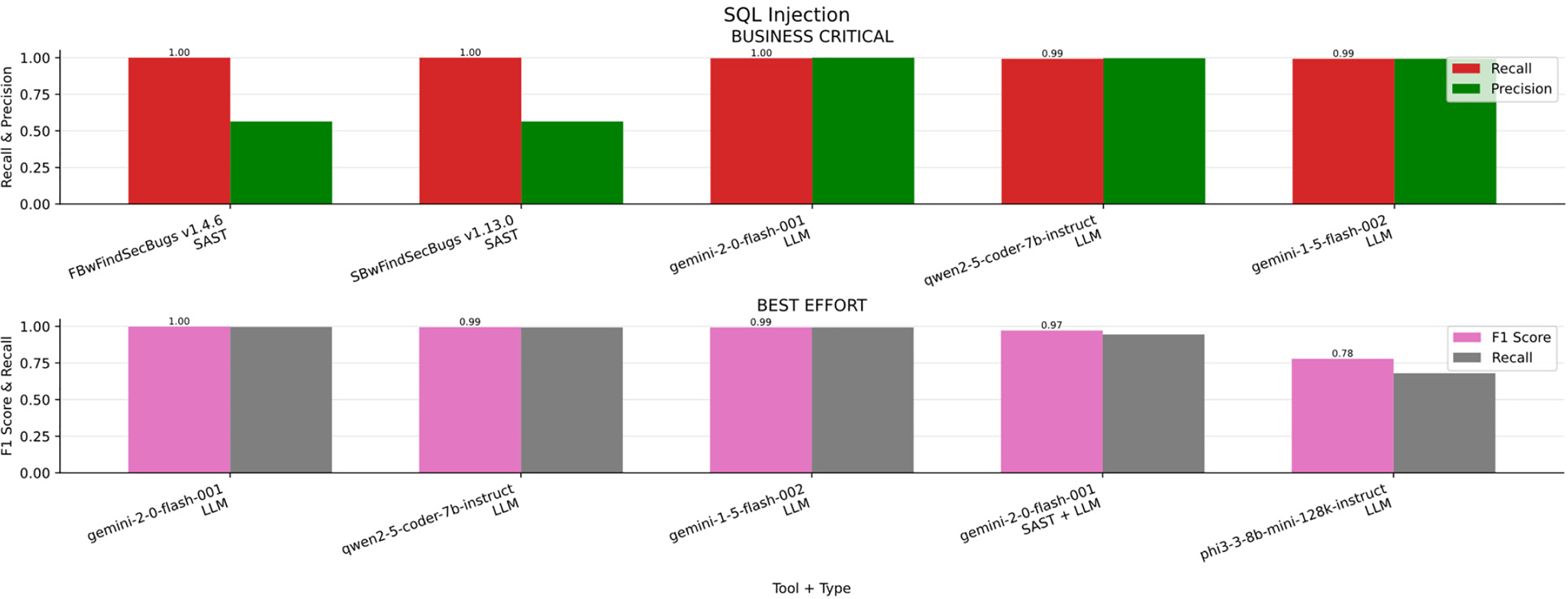

Path Traversal

In the Fig. 11a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for Path Traversal across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort) in contrast, Table 16 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. Across all evaluated scenarios, Gemini v1.5 and Gemini v2.0 combined with SAST achieved superior performance compared to other LLM-based approaches, demonstrating strong adaptability and effectiveness across varying levels of security requirements.

Figure 11: Path traversal results

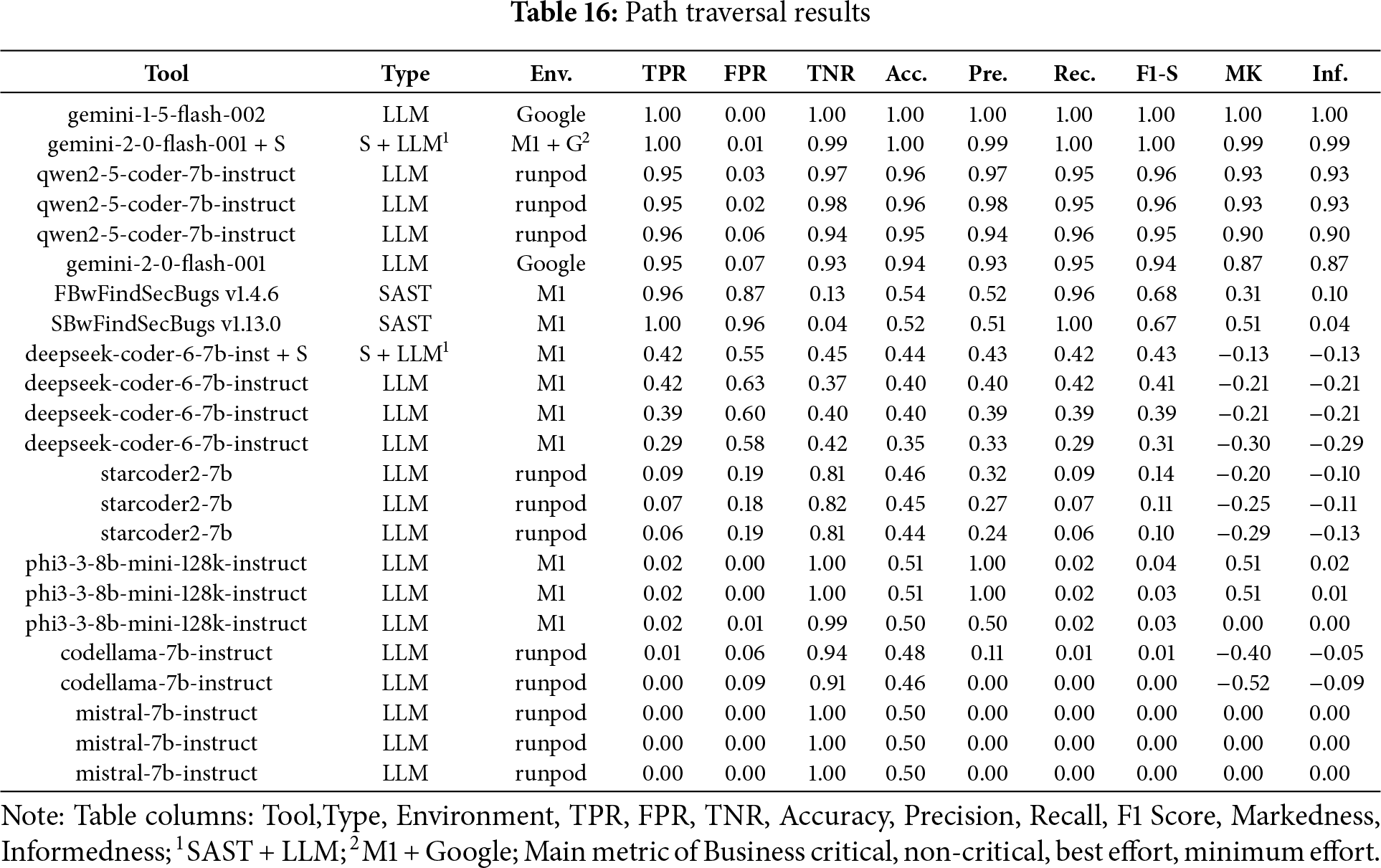

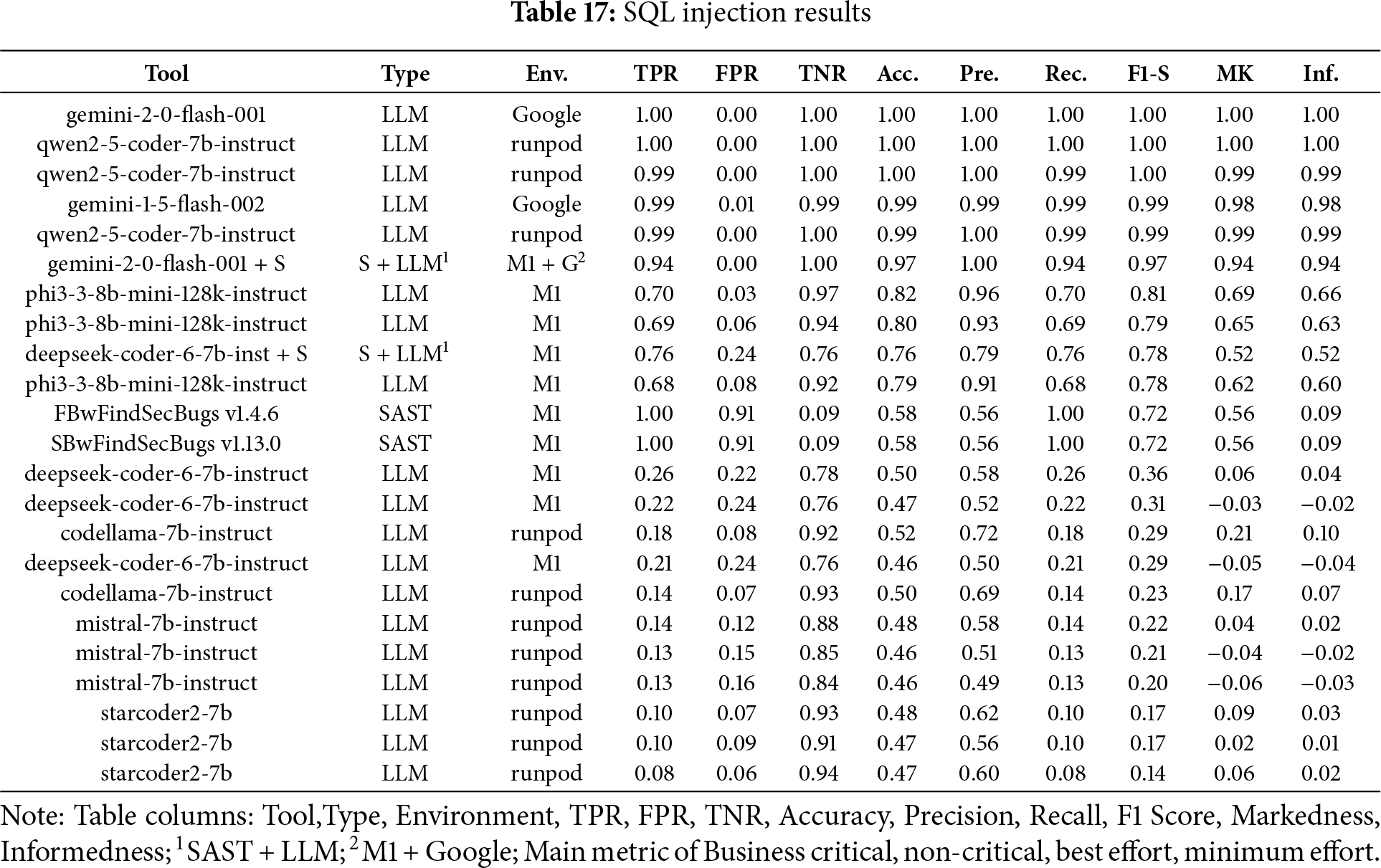

SQL Injection

In the Fig. 12a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for SQL Injection across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort) in contrast, Table 17 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. While Gemini v2.0 outperformed in most scenarios, FindSecBugs was more stable and effective in the business-critical scenario, where high Recall is the top priority.

Figure 12: SQL injection results

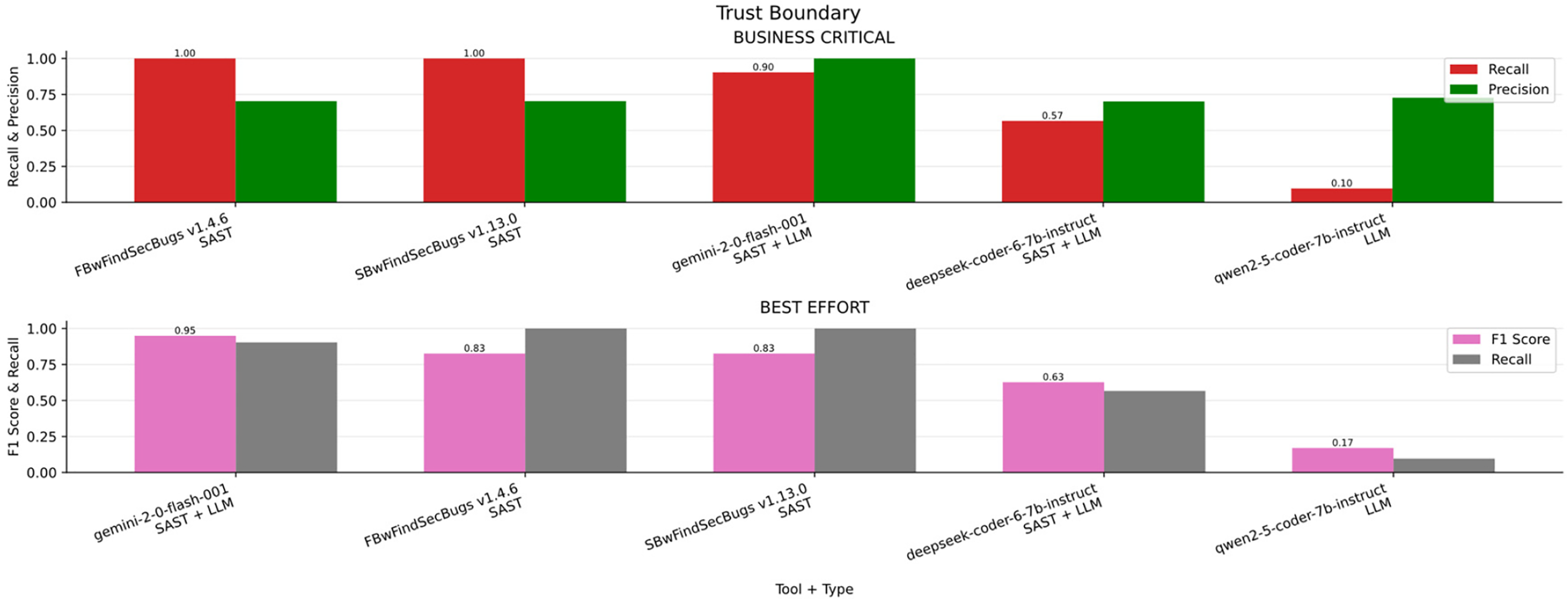

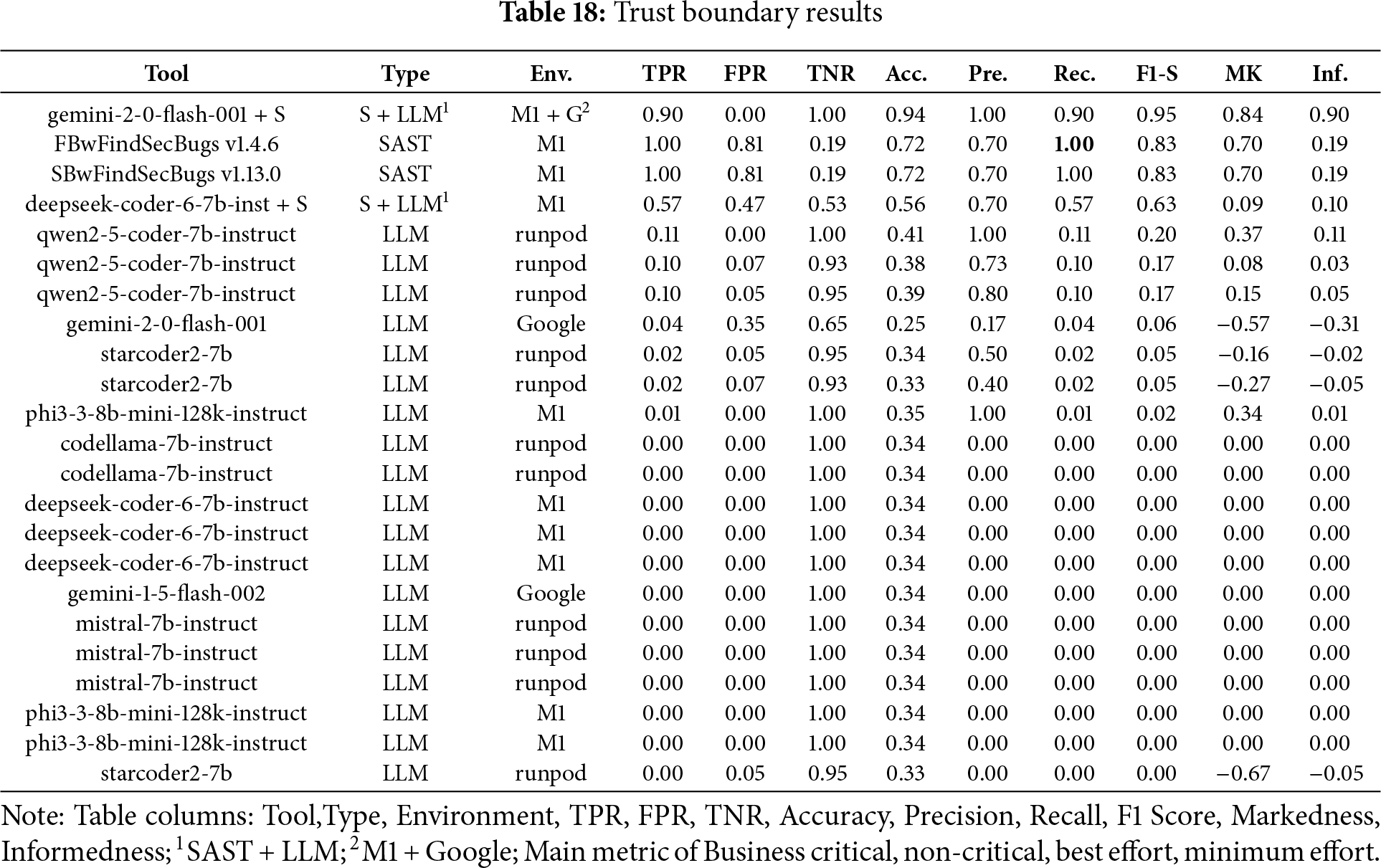

Trust Boundary

In the Fig. 13a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for Trust Boundary across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort), Table 18 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. FindSecBugs achieved the highest Recall overall, making it the most effective tool in scenarios where detecting all real vulnerabilities is critical. However, Gemini v2.0 with SAST integration achieved top Recall in three scenarios while also offering better Precision, making it a strong alternative where a balance between detection and false positives is important.

Figure 13: Trust boundary results

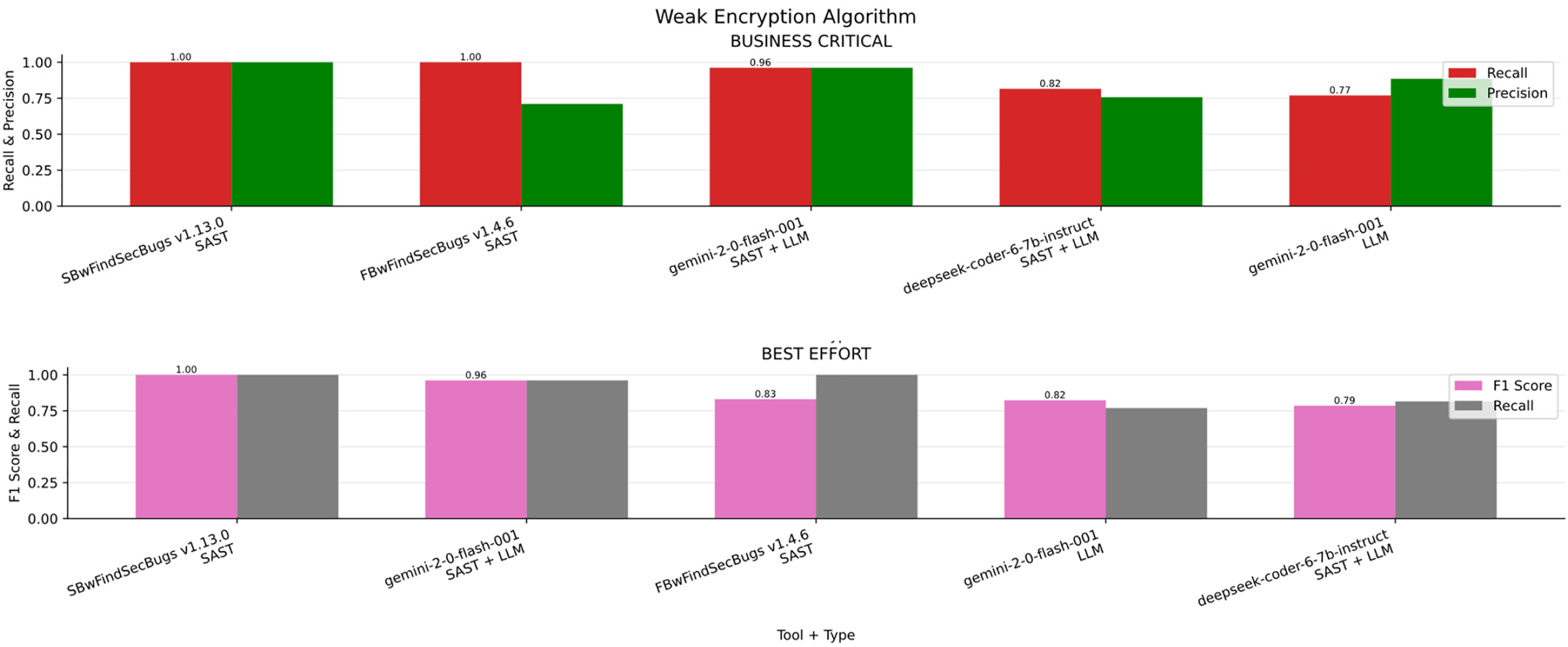

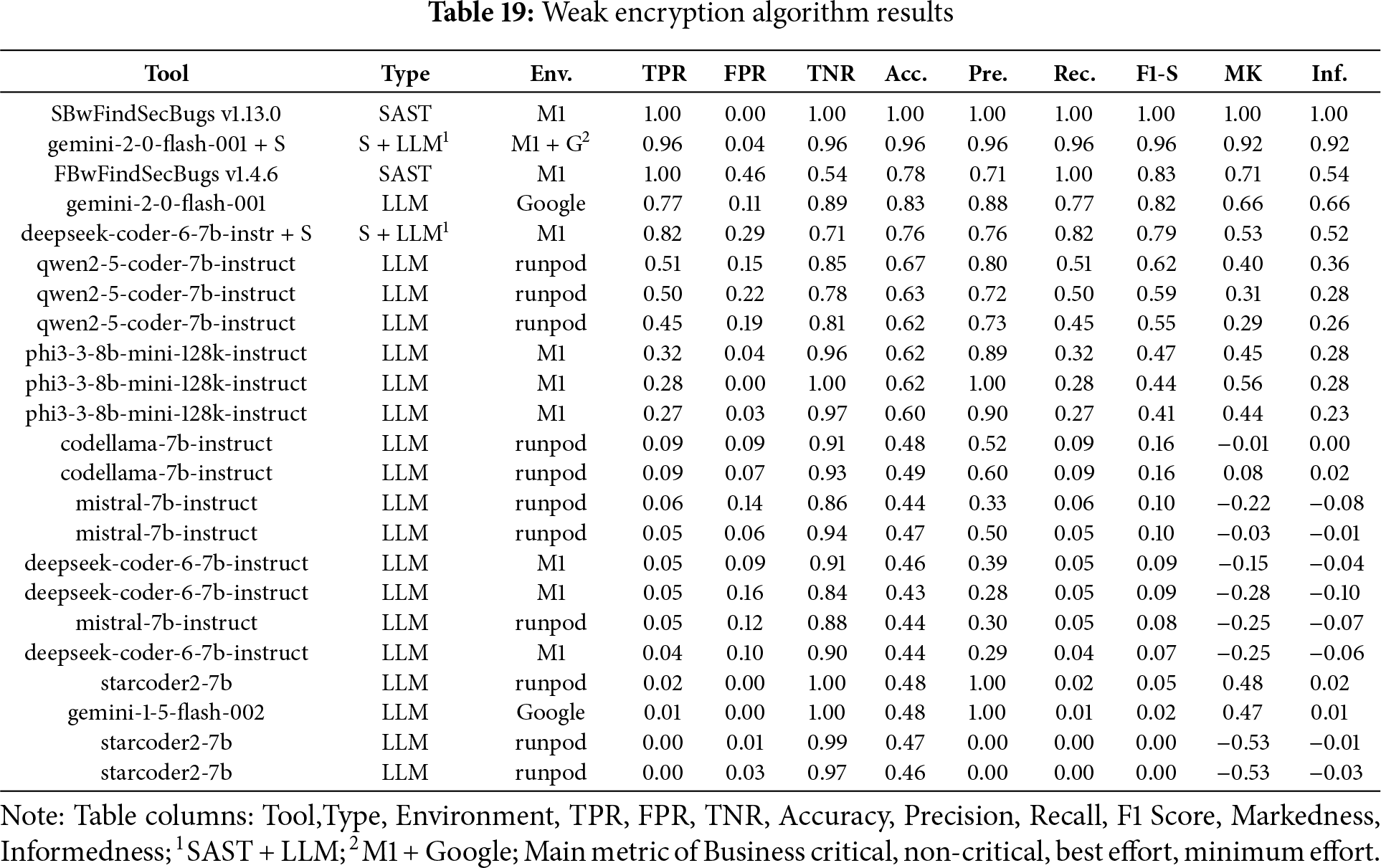

Weak Encryption Algorithm

In the Fig. 14a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for Weak Encryption Algorithm across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort). Table 19 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. FindSecBugs v1.13 delivered the best results, closely followed by Gemini v2.0 combined with FindSecBugs. For the remaining scenarios (including non-critical, best-effort, and minimum-effort) FindSecBugs v1.13.0 achieved the highest overall performance, with Gemini v2.0 + SAST integration consistently ranking second.

Figure 14: Weak encryption algorithm results

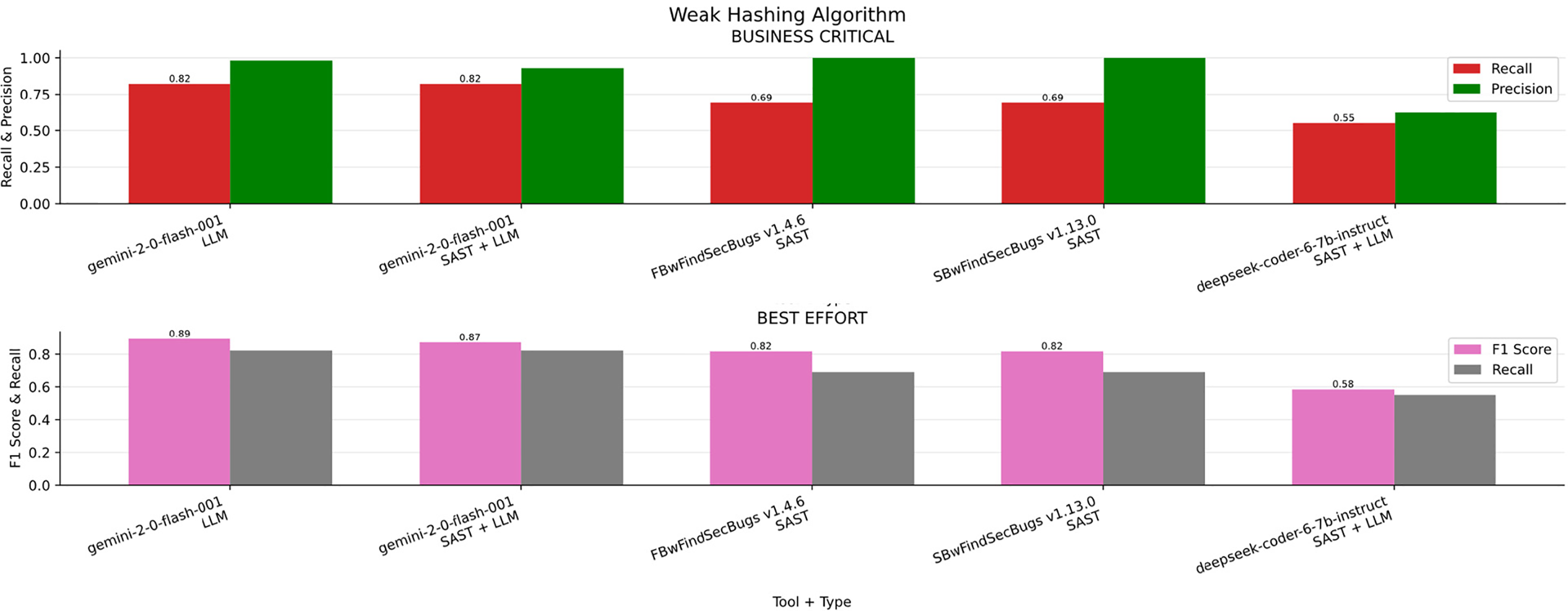

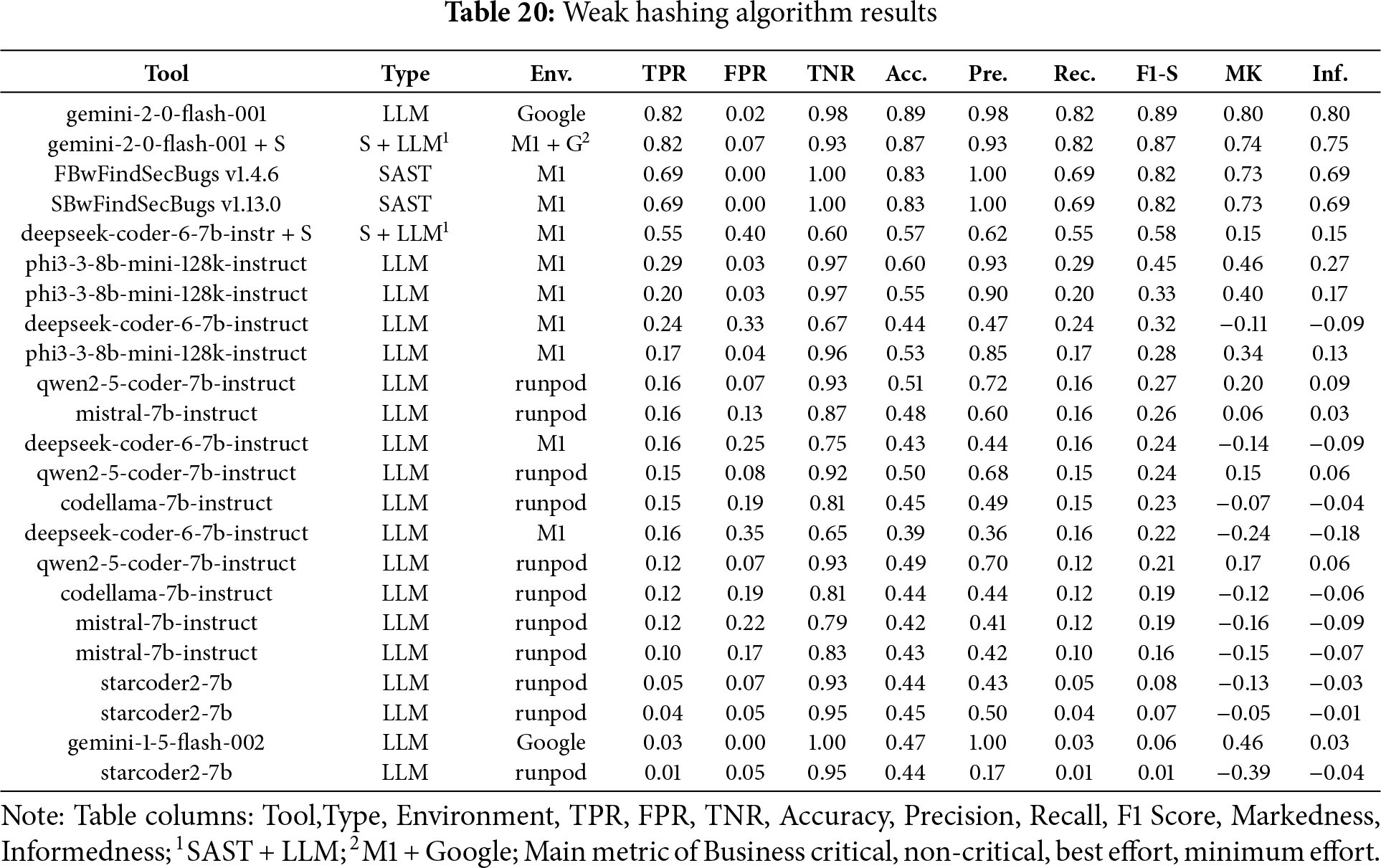

Weak Hashing Algorithm

In the Fig. 15a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for Weak Hash Algorithm across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort). Table 20 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. Gemini v2.0 was the top performer in the business-critical scenario, closely followed by Gemini v2.0 combined with SAST. In all other scenarios, Gemini v2.0 consistently delivered the best results.

Figure 15: Weak hashing algorithm results

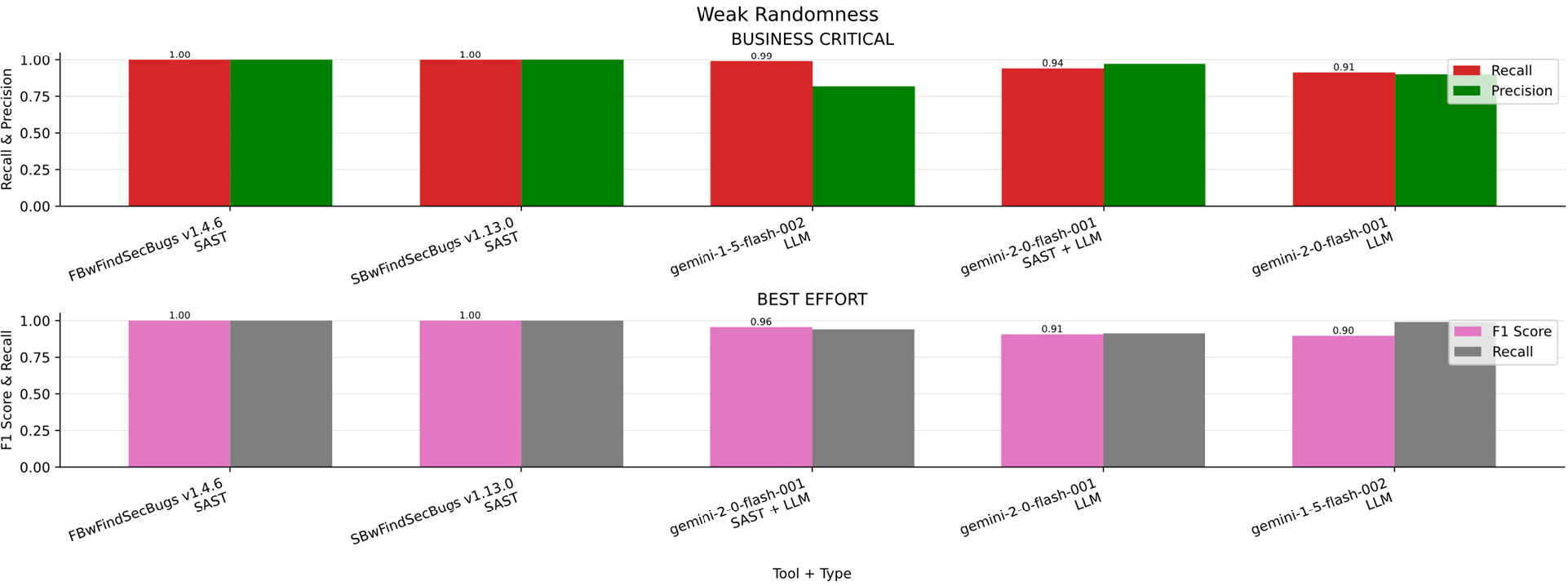

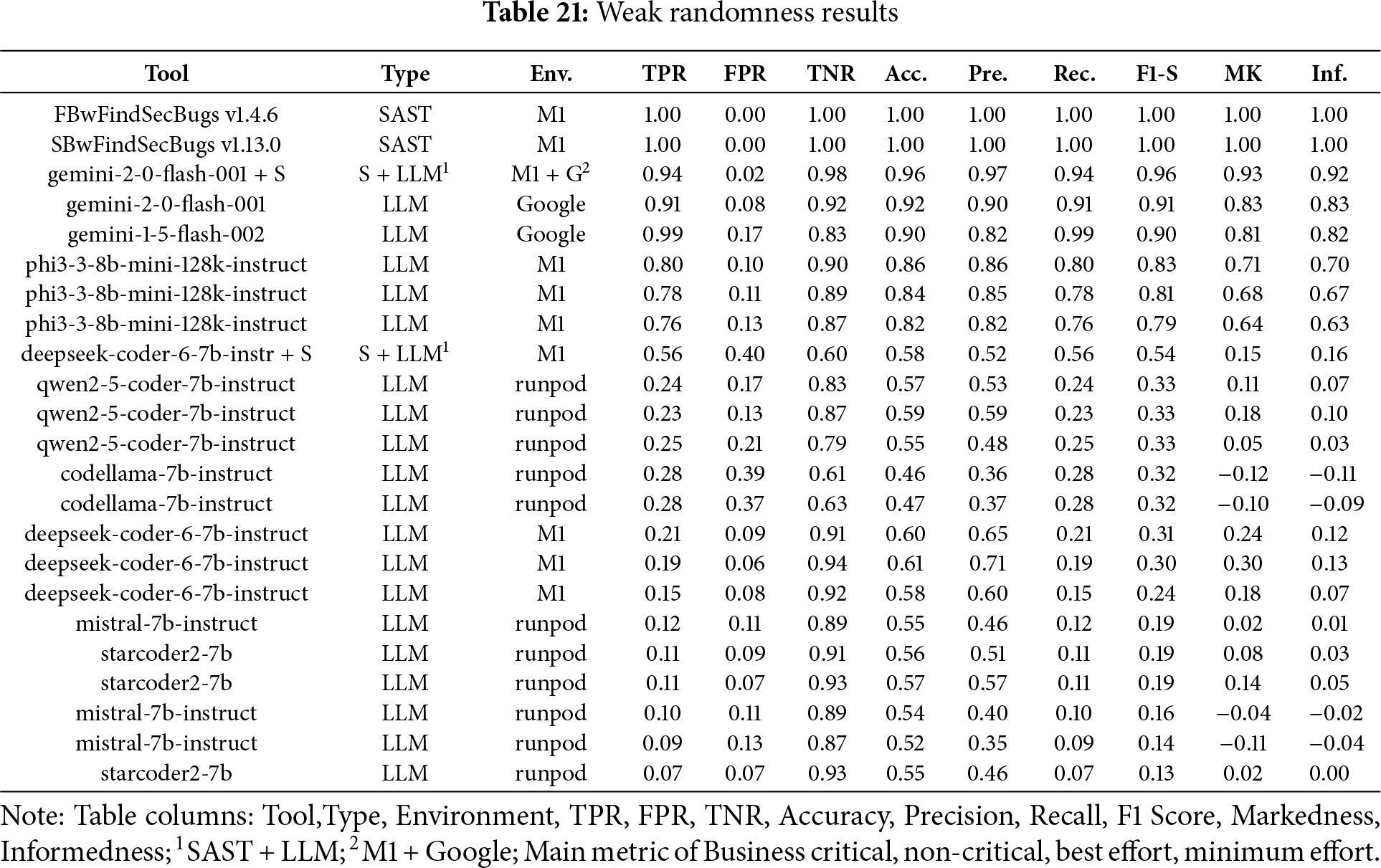

Weak Randomness

In the Fig. 16a bar chart summarizing the results obtained for Weak Randomness across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort). Table 21 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. FindSecBugs (both versions) consistently outperformed all other tools across all scenarios, demonstrating strong and reliable detection regardless of the use case.

Figure 16: Weak randomness results

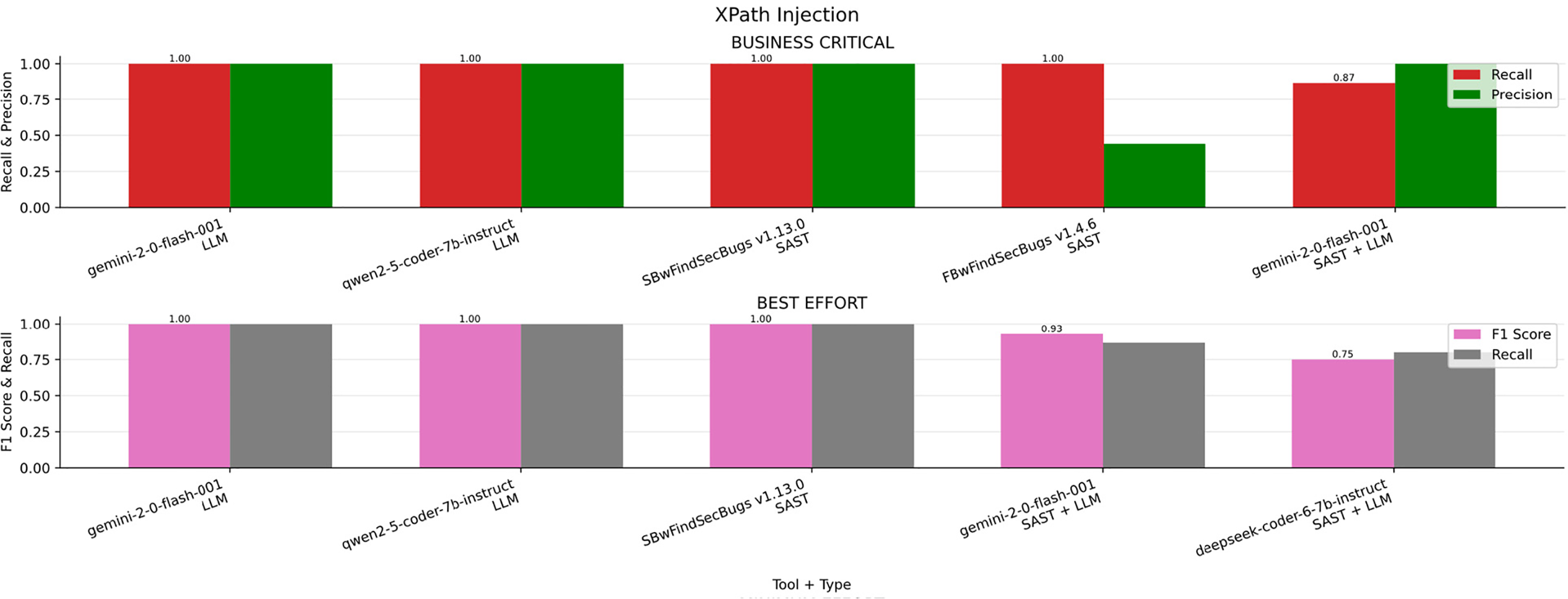

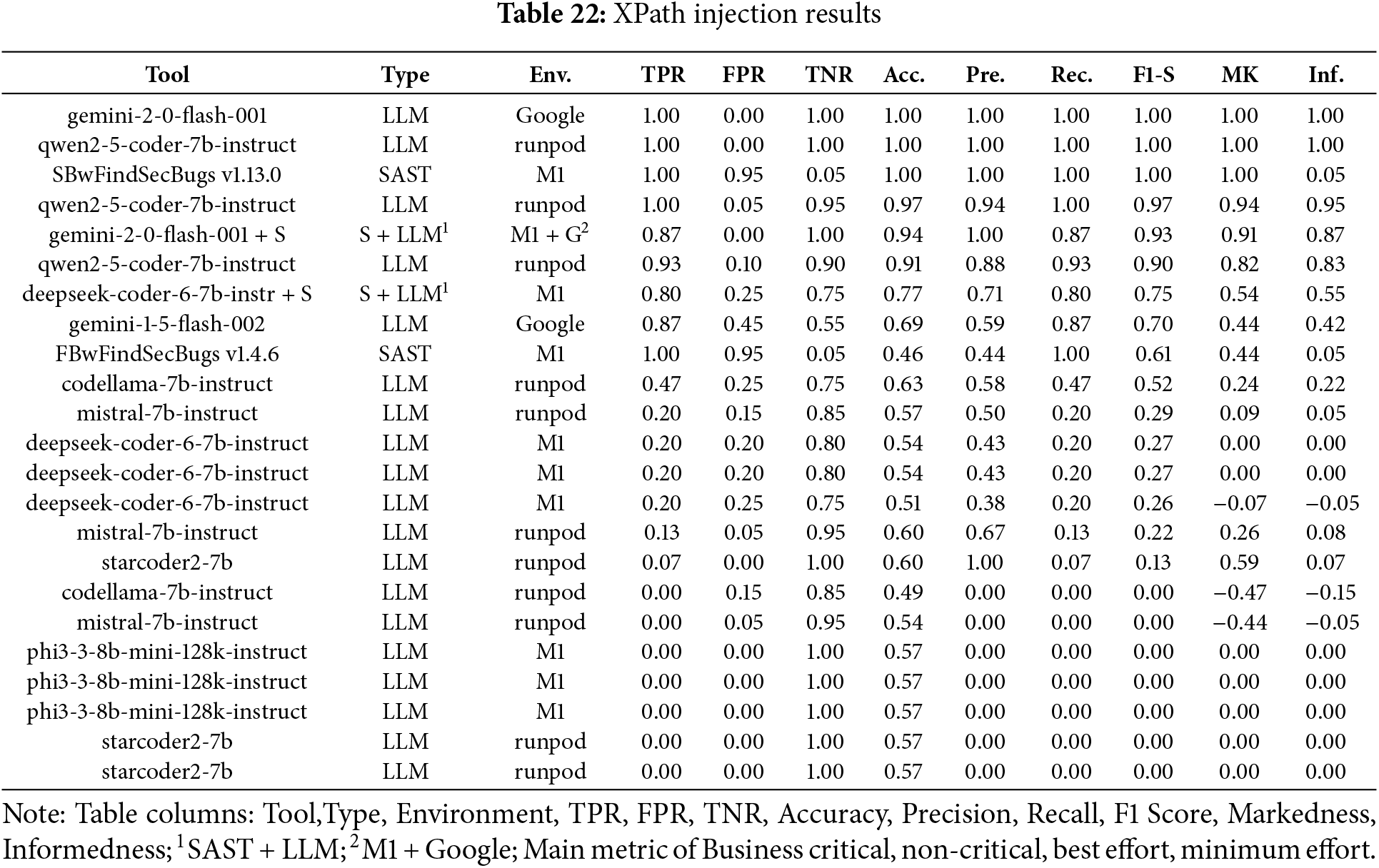

XPath Injection

In the Fig. 17A bar chart summarizing the results obtained for XPath Injection across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort). Table 22 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. Both Gemini v2.0 and Qwen 2.5 demonstrated superior performance across all evaluated scenarios. This consistency suggests that these models possess a strong understanding of XPath-related security patterns, enabling effective detection regardless of the specific use case.

Figure 17: XPath injection results

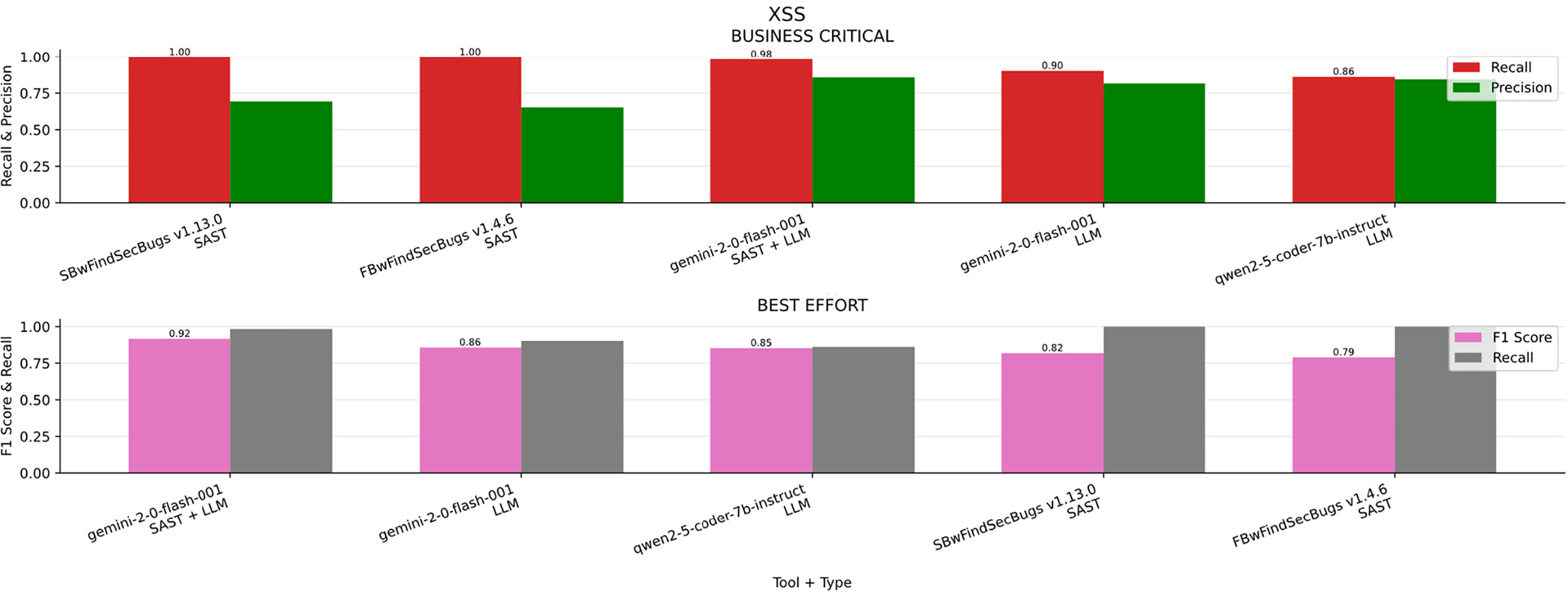

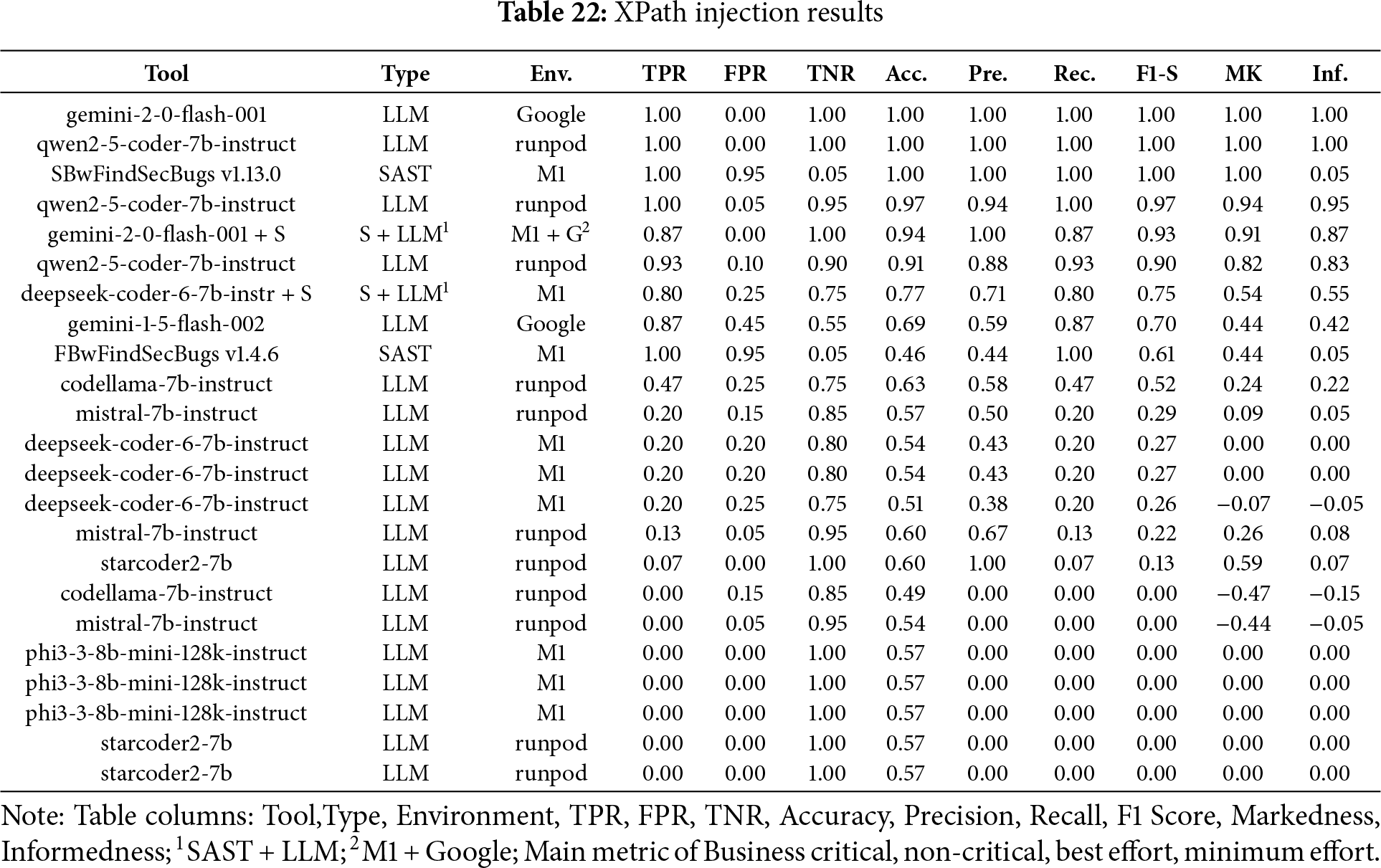

XSS (Cross-Site Scripting)

In the Fig. 18A bar chart summarizing the results obtained for XSS across the four scenarios (Business critical, Non critical, Best effort, minimum effort). Table 23 ranked by F1-S presents the overall metrics. Business-critical scenario, FindSecBugs delivered the highest Recall, making it the most effective at detecting all real issues when missing vulnerabilities is unacceptable. However, it exhibited lower Precision compared to Gemini v2.0 combined with SAST, which produced fewer false positives.

Figure 18: XSS results

Technology is advancing rapidly, giving rise to a multitude of new technologies as well as new vulnerabilities. Cybersecurity must therefore seek an ally to keep pace with this rapid expansion. Is artificial intelligence truly a support for cybersecurity? What advantages and disadvantages does it bring?

In the context of the Secure Software Development Life Cycle (S-SDLC), one of the most critical activities is the review of source-code vulnerabilities, typically performed with Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools. The principal drawback of these tools is the high rate of false positives. Consequently, it is essential to explore the potential of artificial intelligence in SAST. Leveraging AI could provide a substantial advantage by enabling earlier detection of vulnerabilities, thereby dramatically reducing cost and effort.

This study differs from other works mainly in its focus: it aims to evaluate the efficiency of large language models (LLMs), LLMs combined with SAST, or SAST alone on a specific programming language (Java), which is widely used in enterprise environments. The work explicitly addresses the removal of any external inferences, such as code references or comments that might alter the outcome itself. Additionally, it distinguishes itself in its evaluation methodology; it does not merxely concentrate on the best possible result but considers various real-world business contexts: Business-critical, Non-critical, Best-effort, and Minimum-effort [7].

This work will address the following questions:

Do the Results of Large Language Models (LLMs) Exceed Those of Traditional Static Analysis Tools?

In the experiment, models with 7 B and 8 B parameters were used, along with an LLM containing more than 109 B parameters (Gemini). Although the performance of the models improves with increasing size, for “Business-Critical” software the best results were still achieved by the standalone SAST application. In contrast, for “Non-Critical”, “Best-Effort”, and “Minimum-Effort” scenarios, the combination of Gemini + SAST yielded superior outcomes.

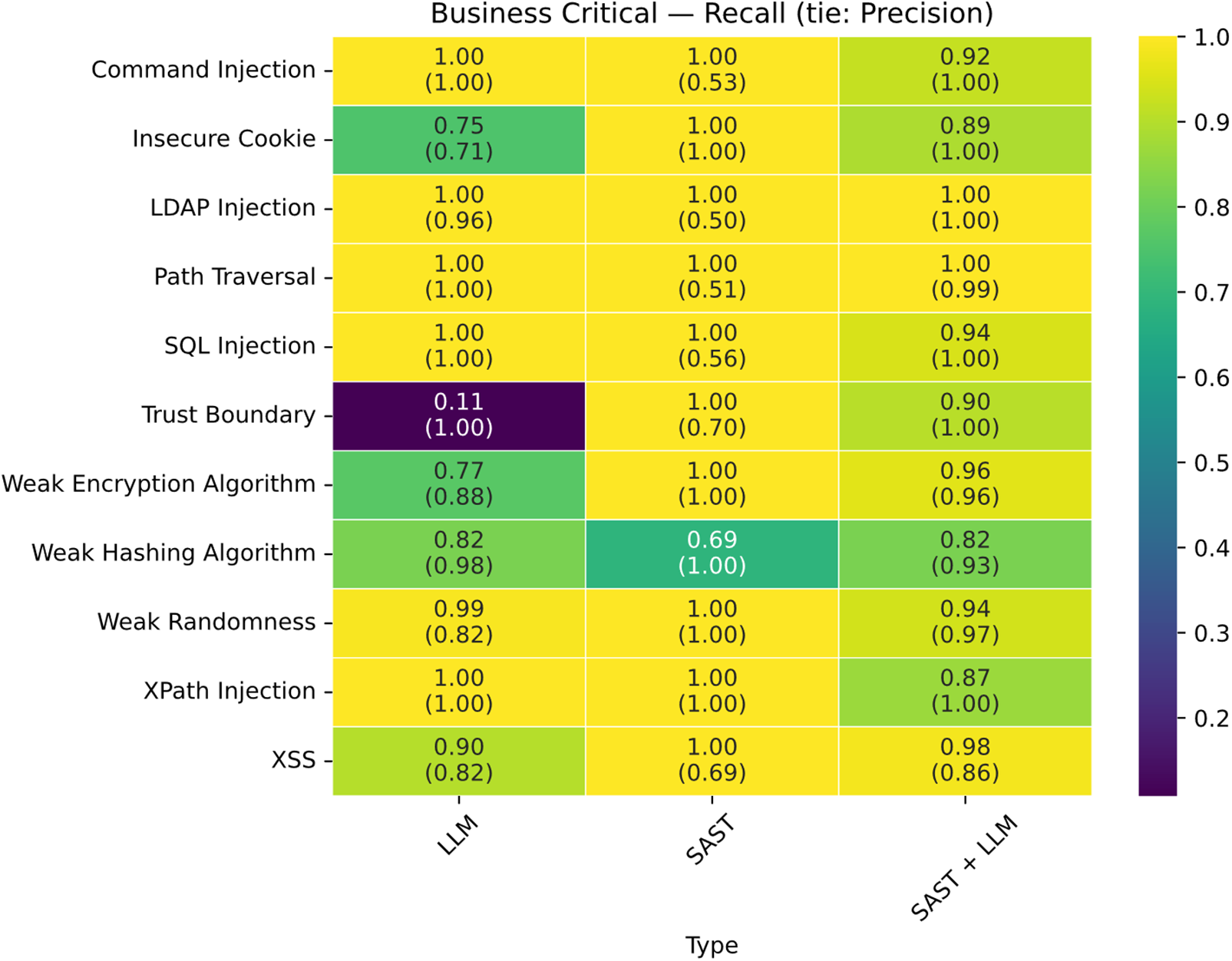

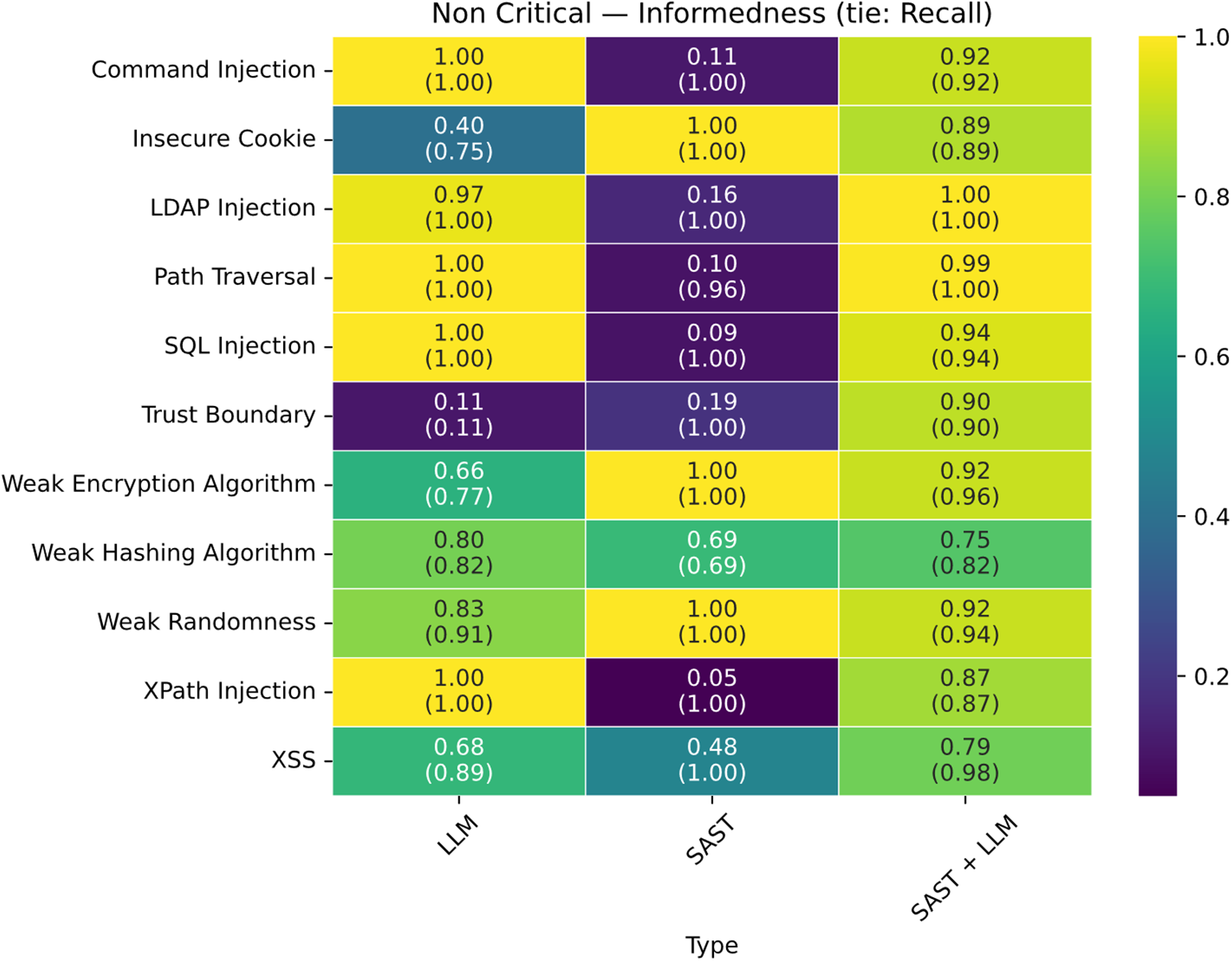

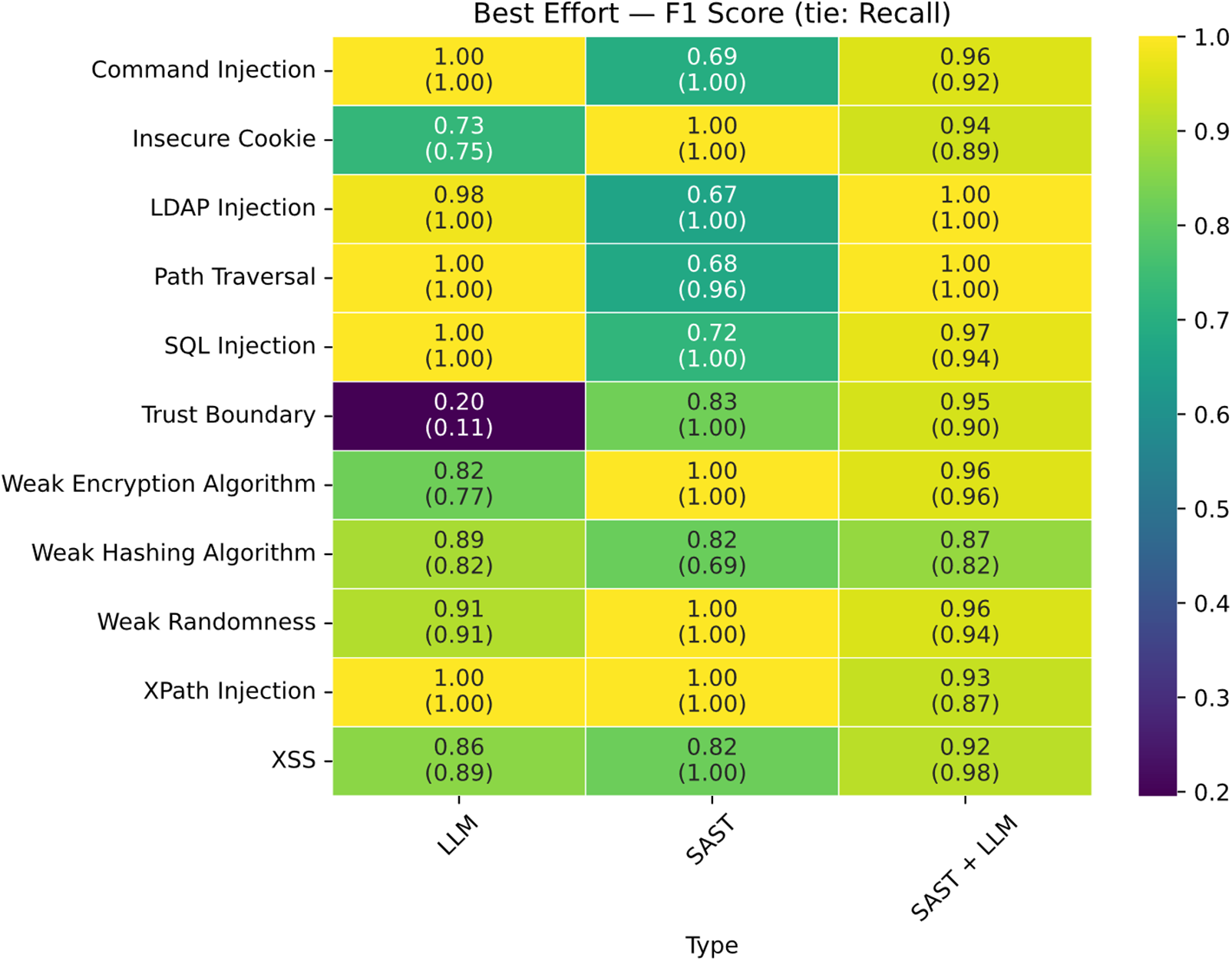

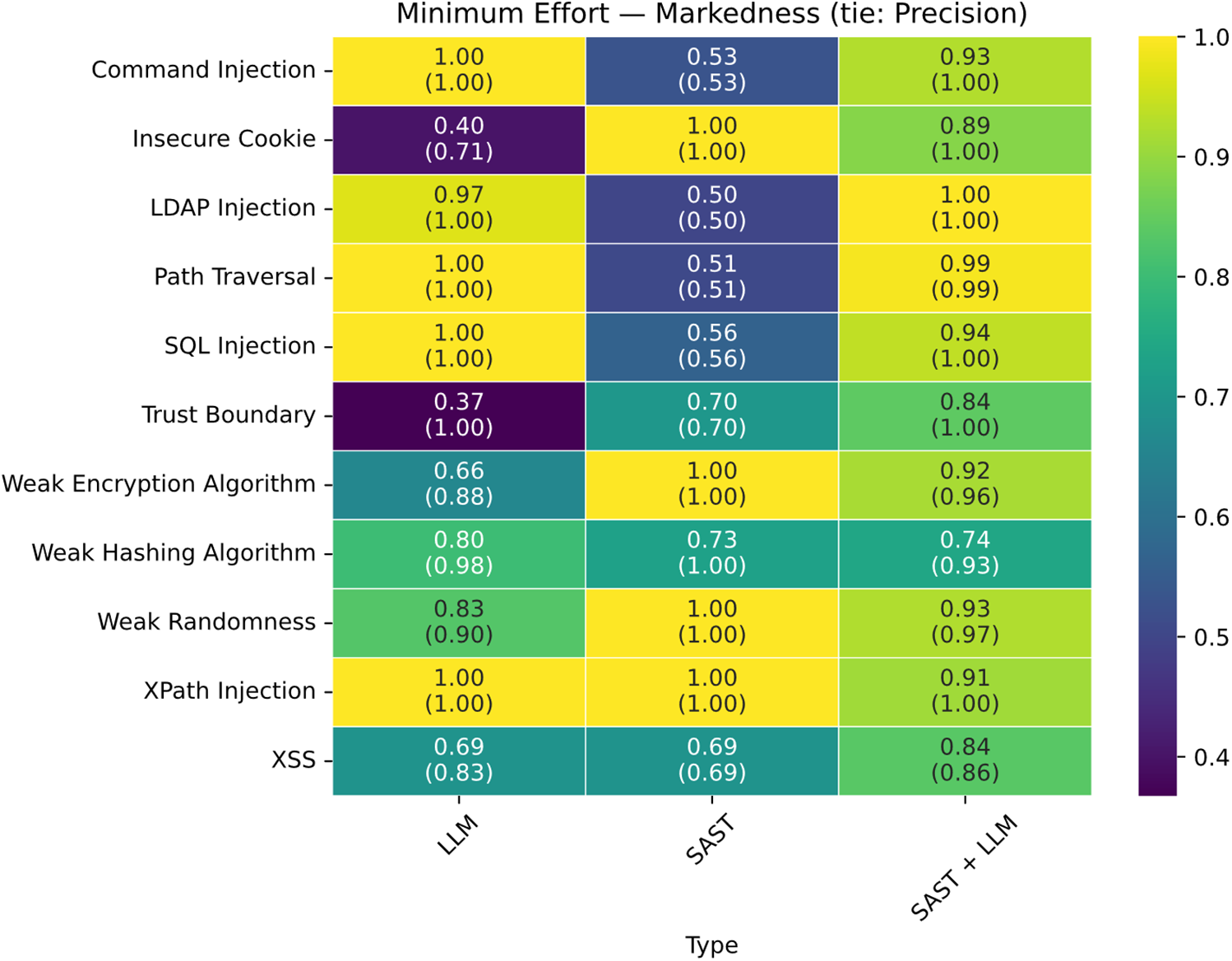

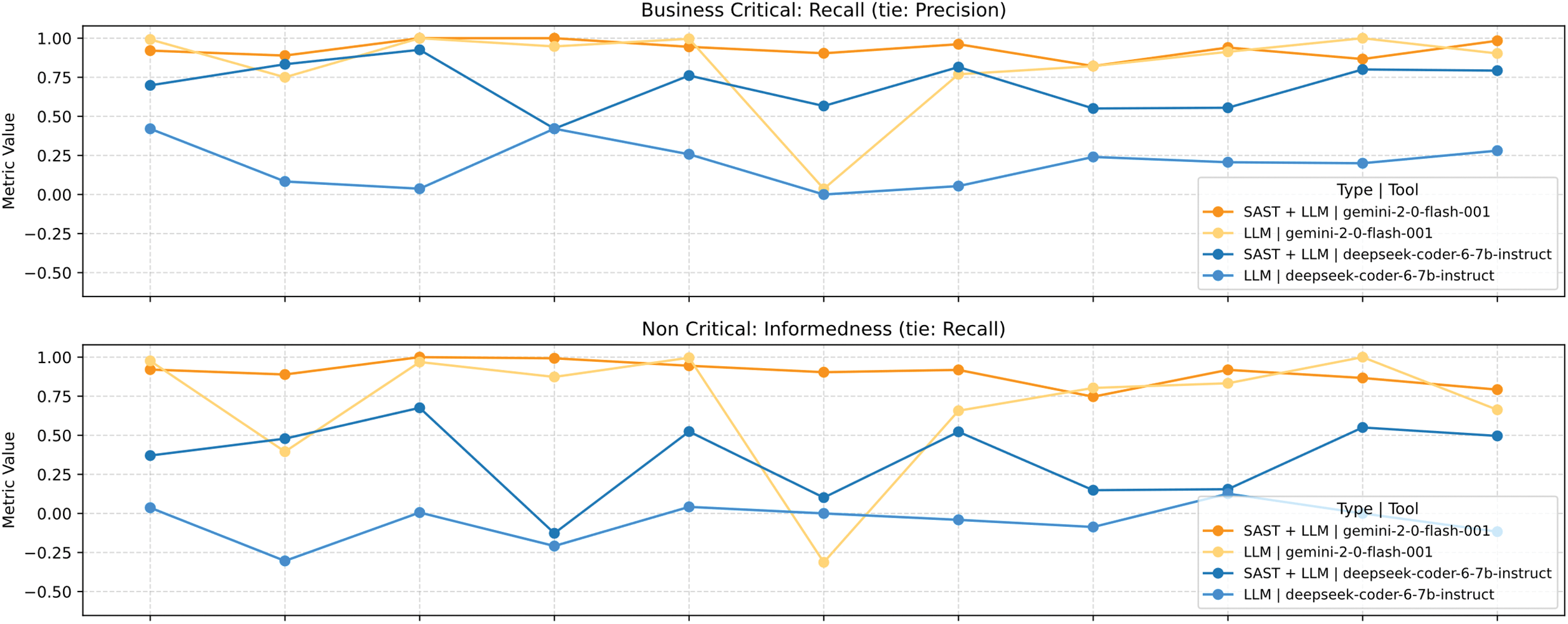

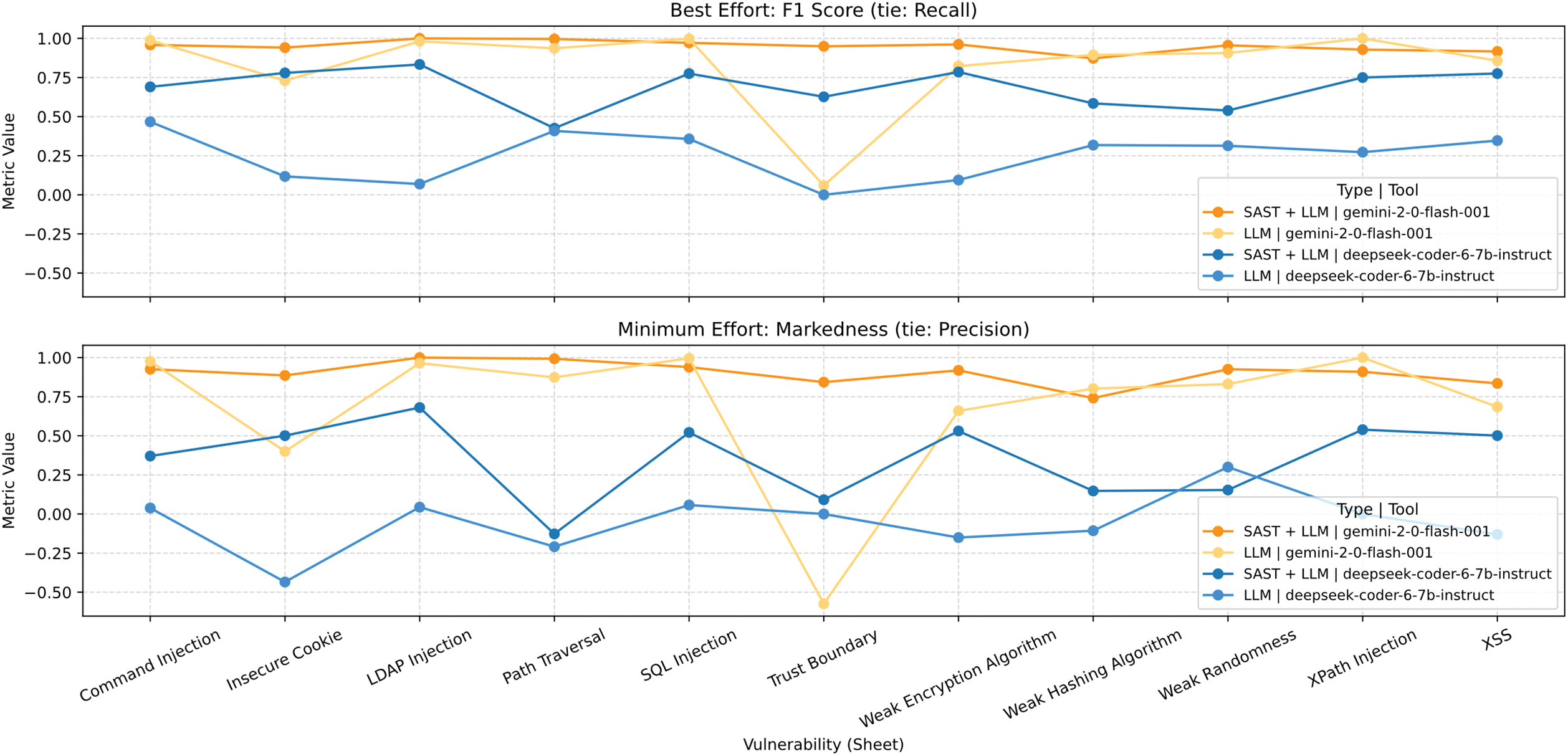

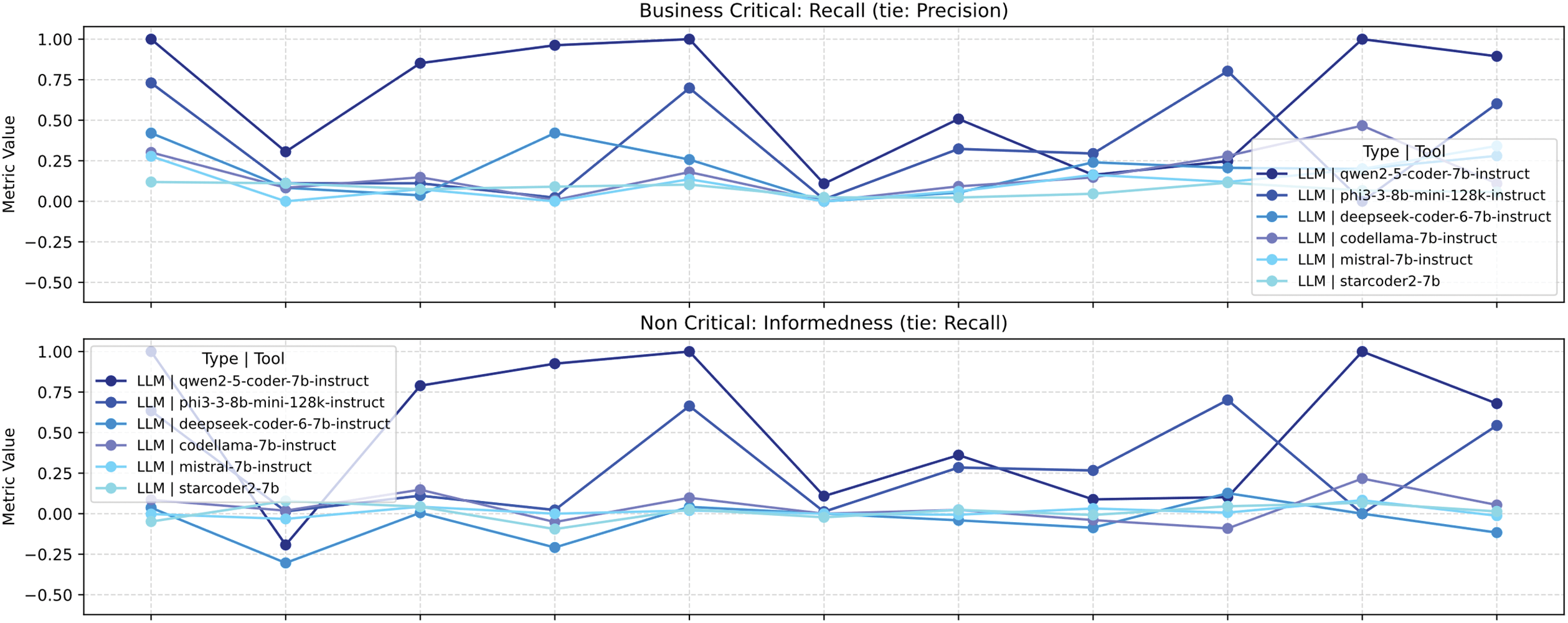

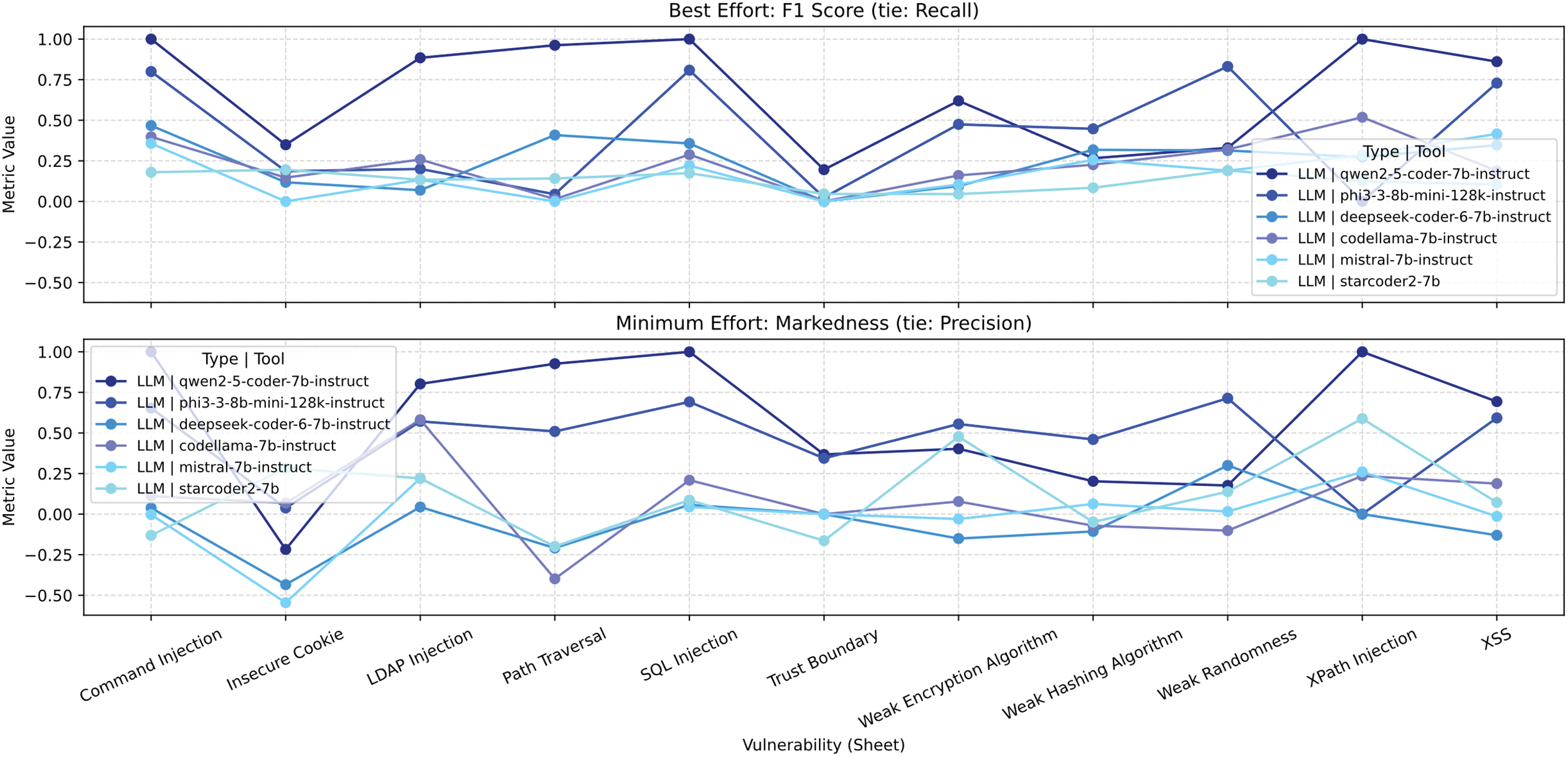

The vulnerabilities for which the traditional tool was outperformed in the “Business-Critical” category (Fig. 19) are those related to Command Injection, Path Traversal, and SQL Injection; Gemini achieved higher precision than SAST in these cases. Conversely, in the “Non-Critical” (Fig. 20), “Best-Effort” (Fig. 21), and “Minimum-Effort” (Fig. 22) scenarios, a significant advantage was observed for the LLM + SAST combination.

Figure 19: Matrix of business critical results

Figure 20: Matrix of non critical results

Figure 21: Matrix of best effort results

Figure 22: Matrix of minimum effort results

Is There an Improvement When Combining LLMs with SAST Tools?

Fig. 23 shows significant improvements are observed for many vulnerabilities, with a marked enhancement in trust-boundary issues. However, in some cases the combined approach worsens the results, such as for XPath Injection.

Figure 23: Comparison of local LLM and LLM as a service with SAST

Thus, it can be concluded that the combination of LLMs and SAST yields a significant improvement, both for 7 B-parameter models and for 109 B-parameter models.

Are Reliable Results Obtained with Locally Hosted Models on a Typical Workstation?

Fig. 24 shows that the 7-B-parameter Qwen 2.5 Coder achieves satisfactory performance (scores > 0.8) on several vulnerability categories (including LDAP Injection, Path Traversal, and XPath Injection) across all tested scenarios (Business-Critical, Non-Critical, Best-Effort, and Minimum-Effort). However, for other types of vulnerability the performance is less encouraging. Consequently, the use of 7-B models is not recommended as a replacement for dedicated SAST tools.

Figure 24: Vulnerability comparison between LLMs

We have worked to demonstrate the potential that language models (LLMs) can bring to cyber-security in the context of static code analysis (SAST), both as standalone solutions and in combination with other tools.

LLMs represent a technology with great promise for vulnerability detection and for reducing false positives. However, their behavior is not entirely predictable, as these models are trained on massive datasets and their output depends on the input context, without guaranteeing deterministic responses.

Despite their probabilistic nature, we have observed that it is possible to steer their outputs toward more deterministic behaviors through careful prompt engineering.

It would be valuable to explore models trained specifically on corpora focused on vulnerability detection. This could reduce model size, improve accuracy, and facilitate integration into resource-constrained enterprise environments. Because this field is rapidly evolving, we recommend in-depth research into LLM-based agents and techniques such as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) using MCP (Modal Context Protocol), which can enhance results without retraining the model, simply by augmenting its knowledge with external contextual information.

Among the main advantages of LLMs is their accuracy, sufficient to consider them a useful complement to traditional SAST. However, the primary limitations include the processing time required to analyze large volumes of code and the limited contextual capacity, which can hinder analysis of large classes or files.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, José Armando Santas Ciavatta; methodology, José Armando Santas Ciavatta, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera, software, José Armando Santas Ciavatta; validation, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera, Javier Bermejo Higuera, Juan Antonio Sicilia Montalvo, Tomás Sureda Riera, Jesús Pérez Melero; formal analysis, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera, Javier Bermejo Higuera, Juan Antonio Sicilia Montalvo, Tomás Sureda Riera, Jesús Pérez Melero; investigation, José Armando Santas Ciavatta, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera; resources, José Armando Santas Ciavatta, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera; data curation, José Armando Santas Ciavatta, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera, Javier Bermejo Higuera, Juan Antonio Sicilia Montalvo, Tomás Sureda Riera, Jesús Pérez Melero; writing—original draft preparation, José Armando Santas Ciavatta; writing—review and editing, José Armando Santas Ciavatta, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera; visualization, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera, Javier Bermejo Higuera, Juan Antonio Sicilia Montalvo; supervision, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera, Javier Bermejo Higuera, Juan Antonio Sicilia Montalvo, Tomás Sureda Riera, Jesús Pérez Melero; project administration, Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera, Javier Bermejo Higuera, Juan Antonio Sicilia Montalvo, Tomás Sureda Riera, Jesús Pérez Melero; funding acquisition, no funding. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [Experiment-SAST-LLM-Tools] at https://github.com/eltitopera/Experiment-SAST-LLM-Tools (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Akhavani SA, Ousat B, Kharraz A. Open source, open threats? Investigating security challenges in open-source software. arXiv:2506.12995. 2025. [Google Scholar]

2. CVEDetails. CVEDetails—2025: the most critical web application security risks [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.cvedetails.com/vulnerabilities-by-types.php. [Google Scholar]

3. Riskhan B, Ullah Sheikh MA, Hossain MS, Hussain K, Zainol Z, Jhanjh NZ. Major vulnerabilities of web application in real world scenarios and their prevention. In: 2025 International Conference on Intelligent and Cloud Computing (ICoICC); 2025 May 2–3; Bhubaneswar, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/icoicc64033.2025.11052016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Guo Y, Bettaieb S, Casino F. A comprehensive analysis on software vulnerability detection datasets: trends, challenges, and road ahead. Int J Inf Secur. 2024;23(5):3311–27. doi:10.1007/s10207-024-00888-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gartner. Worldwide IT spending forecast [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2025-01-21-gartner-forecasts-worldwide-it-spending-to-grow-9-point-8-percent-in-2025. [Google Scholar]

6. Check Point Software. Q1 2025 global cyber attack report [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://blog.checkpoint.com/research/q1-2025-global-cyber-attack-report-from-check-point-software-an-almost-50-surge-in-cyber-threats-worldwide-with-a-rise-of-126-in-ransomware-attacks/. [Google Scholar]

7. Check Point Software. Global cyber attacks surge 21% in Q2 2025: europe experiences the highest increase of all regions [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://blog.checkpoint.com/research/global-cyber-attacks-surge-21-in-q2-2025-europe-experiences-the-highest-increase-of-all-regions/. [Google Scholar]

8. Kiela D. Test scores of AI systems on various capabilities relative to human performance [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/test-scores-ai-capabilities-relative-human-performance?focus=Language+understanding~Predictive+reasoning. [Google Scholar]

9. Singh T. Artificial intelligence-driven cyberattacks. In: Cybersecurity, psychology and people hacking. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan; 2025. p. 167–88. [Google Scholar]

10. Ayodele TO. Impact of AI-generated phishing attacks: a new cybersecurity threat. In: Intelligent computing. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 301–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-92605-1_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Harzevili NS, Belle AB, Wang J, Wang S, Jiang ZMJ, Nagappan N. A systematic literature review on automated software vulnerability detection using machine learning. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(3):1–36. doi:10.1145/3699711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. El Husseini F, Noura H, Salman O, Chehab A. Advanced machine learning approaches for zero-day attack detection: a review. In: 2024 8th Cyber Security in Networking Conference (CSNet); 2024 Dec 4–6; Paris, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/csnet64211.2024.10851751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Madupati B. AI’s impact on traditional software development. arXiv:2502.18476. 2025. [Google Scholar]

14. Santos R, Rizvi S, Cesarone B, Gunn W, McConnell E. Reducing software vulnerabilities using machine learning static application security testing. In: 2021 International Conference on Software Security and Assurance (ICSSA); 2021 Nov 10–12; Altoona, PA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 15–23. doi:10.1109/icssa53632.2021.00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Odera D, Otieno M, Ounza JE. Security risks in the software development lifecycle: a review. World J Adv Eng Technol Sci. 2023;8(2):230–53. doi:10.30574/wjaets.2023.8.2.0101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Valdés-Rodríguez Y, Hochstetter-Diez J, Diéguez-Rebolledo M, Bustamante-Mora A, Cadena-Martínez R. Analysis of strategies for the integration of security practices in agile software development: a sustainable SME approach. IEEE Access. 2024;12(8):35204–30. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3372385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Vidyasagar V. DevSecOps: integrating security into the DevOps lifecycle. Int J Mach Learn Res Cybersecur Artif Intell. 2025;16(1):11–25. doi:10.5281/zenodo.15483597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Adriani ZA, Raharjo T, Trisnawaty NW. Comprehensive examination of risk management practices throughout the software development life cycle (SDLCa systematic literature review. Indones J Comput Sci. 2024;13(3):3844. doi:10.33022/ijcs.v13i3.4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhu J, Li K, Chen S, Fan L, Wang J, Xie X. A comprehensive study on static application security testing (SAST) tools for Android. IEEE Trans Software Eng. 2024;50(12):3385–402. doi:10.1109/tse.2024.3488041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nguyen-Duc A, Do MV, Luong Hong Q, Nguyen Khac K, Nguyen Quang A. On the adoption of static analysis for software security assessment—a case study of an open-source e-government project. Comput Secur. 2021;111(6):102470. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Böhme M, Bodden E, Bultan T, Cadar C, Liu Y, Scanniello G. Software security analysis in 2030 and beyond: a research roadmap. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2025;34(5):1–26. doi:10.1145/3708533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sarkar T, Rakhra M, Sharma V, Singh A, Jairath K, Maan A. Comparing traditional vs agile methods for software development projects: a case study. In: 2024 7th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I); 2024 Sep 18–20; Greater Noida, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 47–55. doi:10.1109/ic3i61595.2024.10829321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. ITU. Using the internet in 2024. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/pages/stat/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

24. IBM. Cost of a data breach report. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/think/x-force/2025-cost-of-a-data-breach-navigating-ai. [Google Scholar]

25. Antunes N, Vieira M. On the metrics for benchmarking vulnerability detection tools. In: 2015 45th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN); 2015 Jun 22–25; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 283–94. doi:10.1109/DSN.2015.30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. de Vicente Mohino J, Bermejo Higuera J, Bermejo Higuera JR, Sicilia Montalvo JA. The application of a new secure software development life cycle (S-SDLC) with agile methodologies. Electronics. 2019;8(11):1218. doi:10.3390/electronics8111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Golovyrin L. Analysis of tools for static security testing of applications [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Leonid-Golovyrin/publication/372134053_Analysis_of_tools_for_static_security_testing_of_applications/links/64a5dce2b9ed6874a5fc718a/Analysis-of-tools-for-static-security-testing-of-applications.pdf. [Google Scholar]

28. Ferrara P, Olivieri L, Spoto F. Static privacy analysis by flow reconstruction of tainted data. Int J Soft Eng Knowl Eng. 2021;31(7):973–1016. doi:10.1142/s0218194021500303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao J, Zhu K, Lu C, Zhao J, Lu Y. Benchmarking static analysis for PHP applications security. Entropy. 2025;27(9):926. doi:10.3390/e27090926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Díaz G, Bermejo JR. Static analysis of source code security: assessment of tools against SAMATE tests. Inf Softw Technol. 2013;55(8):1462–76. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2013.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li Y, Yao P, Yu K, Wang C, Ye Y, Li S, et al. Understanding industry perspectives of static application security testing (SAST) evaluation. Proc ACM Softw Eng. 2025;2(FSE):3033–56. doi:10.1145/3729404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li K, Chen S, Fan L, Feng R, Liu H, Liu C, et al. Comparison and evaluation on static application security testing (SAST) tools for Java. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE 2023); 2023 Dec 3–9; San Francisco, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2023. p. 921–33. doi:10.1145/3611643.3616262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ansgariusson W, Ståhl J. Comparative analysis of static application security testing tools on real-world java vulnerabilities. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/search/publication/9189955. [Google Scholar]

34. Higuera B, Higuera JB, Montalvo S, Villalba JC, Pérez JJN. Benchmarking approach to compare web applications static analysis tools detecting OWASP top ten security vulnerabilities. Comput Mater Contin. 2020;64(3):1555–77. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.010885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sheng Z, Chen Z, Gu S, Huang H, Gu G, Huang J. LLMs in software security: a survey of vulnerability detection techniques and insights. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;58(5):1–35. doi:10.1145/3769082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li K, Liu H, Zhang L, Chen Y. Automatic inspection of static application security testing (SAST) reports via large language model reasoning. In: Zhang S, Barbosa LS, editors. Artificial intelligence logic and applications. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 128–42. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-0354-1_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Keltek M, Hu R, Sani MF, Li Z. LSAST: enhancing cybersecurity through LLM-supported static application security testing. In: ICT systems security and privacy protection. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 166–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-92882-6_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Çetin O, Ekmekcioglu E, Arief B, Hernandez-Castro J. An empirical evaluation of large language models in static code analysis for PHP vulnerability detection. J Univers Comput Sci. 2024;30(9):1163–83. doi:10.3897/jucs.134739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Charoenwet W, Thongtanunam P, Pham VT, Treude C. An empirical study of static analysis tools for secure code review. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis (ISSTA 2024); 2024 Jul 15–19; Vienna, Austria. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2024. p. 691–703. doi:10.1145/3650212.3680313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. NIST. SARD acknowledgments and test suites descriptions. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.nist.gov/itl/ssd/software-quality-group/sard-acknowledgments-and-test-suites-descriptions. [Google Scholar]

41. OWASP. Benchmark project. [cited 2025 Octo 12]. Available from: https://owasp.org/www-project-benchmark/. [Google Scholar]

42. Meta. Introducing code llama. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://github.com/meta-llama/codellama. [Google Scholar]

43. DeepSeek. DeepSeek coder. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://deepseekcoder.github.io/. [Google Scholar]

44. PromptLayer. Implementation details. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.promptlayer.com/models/deepseek-coder-67b-instruct. [Google Scholar]

45. Mistral. Mistral 7b. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://mistral.ai/news/announcing-mistral-7b. [Google Scholar]

46. Ollama. Phi3. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://ollama.com/library/phi3. [Google Scholar]

47. Ollama. Qwen2.5-coder. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://ollama.com/library/qwen2.5-coder. [Google Scholar]

48. Starcoder. StarCoder 2. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://github.com/bigcode-project/starcoder2?tab=readme-ov-file. [Google Scholar]

49. Google. Gemini 2.0. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/models/gemini/2-0-flash. [Google Scholar]

50. Google. Gemini 1.5. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://developers.googleblog.com/en/gemini-15-flash-8b-is-now-generally-available-for-use/. [Google Scholar]

51. Bigcode. Big code models leaderboard. [cited 2025 Oct 12]. Available from: https://huggingface.co/spaces/bigcode/bigcode-models-leaderboard. [Google Scholar]

52. Khare A, Dutta S, Li Z, Solko-Breslin A, Alur R, Naik M. Understanding the effectiveness of large language models in detecting security vulnerabilities. In: 2025 IEEE Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST); 2025 Mar 31–Apr 4; Napoli, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 312–23. [Google Scholar]

53. Das Purba M, Ghosh A, Radford BJ, Chu B. Software vulnerability detection using large language models. In: 2023 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSREW); 2023 Oct 9–12; Florence, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 321–8. doi:10.1109/ISSREW60843.2023.00058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Guo Y, Patsakis C, Hu Q, Tang Q, Casino F. Outside the comfort zone: analysing LLM capabilities in software vulnerability detection. In: Computer security—ESORICS. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. p. 271–89. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-70879-4_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Yin X, Ni C, Wang S. Multitask-based evaluation of open-source LLM on software vulnerability. IIEEE Trans Software Eng. 2024;50(11):3071–87. doi:10.1109/tse.2024.3470333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Shimmi S, Saini Y, Schaefer M, Okhravi H, Rahimi M. Software vulnerability detection using LLM: does additional information help? In: 2024 Annual Computer Security Applications Conference Workshops (ACSAC Workshops); 2024 Dec 9–10; Honolulu, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 189–98. doi:10.1109/acsacw65225.2024.00031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Almeida J. Prompt engineering: a comparative study of prompting techniques in AI language models. In: 2025 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC); 2025 Mar 15; Princeton, NJ, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 87–95. doi:10.1109/ISEC64801.2025.11147384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhou X, Cao S, Sun X, Lo D. Large language model for vulnerability detection and repair: literature review and the road ahead. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2025;34(5):1–31. doi:10.1145/3708522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Sajadi A, Le B, Nguyen A, Damevski K, Chatterjee P. Do LLMs consider security? An empirical study on responses to programming questions. Empir Softw Eng. 2025;30(4):101. doi:10.1007/s10664-025-10658-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Aydın D, Bahtiyar Ş. Security vulnerabilities in AI-generated JavaScript: a comparative study of large language models. In: 2025 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR); 2025 Aug 4–6; Chania, Crete, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 203–12. doi:10.1109/csr64739.2025.11130176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Jaoua I, Ben Sghaier O, Sahraoui H. Combining large language models with static analyzers for code review generation. In: 2025 IEEE/ACM 22nd International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR); 2025 Apr 28–29; Ottawa, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 157–66. doi:10.1109/msr66628.2025.00038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Munson A, Gomez J, Cárdenas ÁA. With a little help from my (LLM) friends: enhancing static analysis with LLMs to detect software vulnerabilities. In: 2025 IEEE/ACM International Workshop on Large Language Models for Code (LLM4Code); 2025 May 3; Ottawa, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 41–9. doi:10.1109/llm4code66737.2025.00008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Wu Y, Wen M, Yu Z, Guo X, Jin H. Effective vulnerable function identification based on CVE description empowered by large language models. In: Proceedings of the 39th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE 2024); 2024 Oct 27; Sacramento, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2024. p. 789–99. doi:10.1145/3691620.3695013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Hossain AA, Mithun Kumar PK, Zhang J, Amsaad F. Malicious code detection using LLM. In: NAECON 2024—IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference; 2024 Jul 15–18; Dayton, OH, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 356–64. doi:10.1109/naecon61878.2024.10670668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Blefari F, Cosentino C, Furfaro A, Marozzo F, Pironti FA. SecFlow: an agentic LLM-based framework for modular cyberattack analysis and explainability. In: Proceedings of the 2025 Generative Code Intelligence Workshop (GeCo IN); 2025 May 23; Bologna, Italy. Aachen, Germany: CEUR Workshop Proceedings; 2025. p. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

66. Belcastro L, Carlucci C, Cosentino C, Liò P, Marozzo F. Enhancing network security using knowledge graphs and large language models for explainable threat detection. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2026;176(7):108160. doi:10.1016/j.future.2025.108160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. He T, Yang M, Hu W, Chen Y. Analysis of the effectiveness of large language model feature in source code defect detection. In: 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Information Technology (AICIT); 2024 Sep 20–22; Yichang, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 276–84. doi:10.1109/aicit62434.2024.10730232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Smaili A, Zhang Y, Mekkaoui DE, Midoun MA, Talhaoui MZ, Hamidaoui M, et al. A transformer-based framework for software vulnerability detection using attention-driven convolutional neural networks. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;160(9):111859. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.111859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools