Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid Runtime Detection of Malicious Containers Using eBPF

1 Department of Convergence Security Engineering, Sungshin Women’s University, 2, Bomun-Ro 34da-Gil, Seongbuk-Gu, Seoul, 02844, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Future Convergence Technology Engineering, Sungshin Women’s University, 2, Bomun-Ro 34da-Gil, Seongbuk-Gu, Seoul, 02844, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Seongmin Kim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 13 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074871

Received 20 October 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

As containerized environments become increasingly prevalent in cloud-native infrastructures, the need for effective monitoring and detection of malicious behaviors has become critical. Malicious containers pose significant risks by exploiting shared host resources, enabling privilege escalation, or launching large-scale attacks such as cryptomining and botnet activities. Therefore, developing accurate and efficient detection mechanisms is essential for ensuring the security and stability of containerized systems. To this end, we propose a hybrid detection framework that leverages the extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF) to monitor container activities directly within the Linux kernel. The framework simultaneously collects flow-based network metadata and host-based system-call traces, transforms them into machine-learning features, and applies multi-class classification models to distinguish malicious containers from benign ones. Using six malicious and four benign container scenarios, our evaluation shows that runtime detection is feasible with high accuracy: flow-based detection achieved 87.49%, while host-based detection using system-call sequences reached 98.39%. The performance difference is largely due to similar communication patterns exhibited by certain malware families which limit the discriminative power of flow-level features. Host-level monitoring, by contrast, exposes fine-grained behavioral characteristics, such as file-system access patterns, persistence mechanisms, and resource-management calls that do not appear in network metadata. Our results further demonstrate that both monitoring modality and preprocessing strategy directly influence model performance. More importantly, combining flow-based and host-based telemetry in a complementary hybrid approach resolves classification ambiguities that arise when relying on a single data source. These findings underscore the potential of eBPF-based hybrid analysis for achieving accurate, low-overhead, and behavior-aware runtime security in containerized environments, and they establish a practical foundation for developing adaptive and scalable detection mechanisms in modern cloud systems.Keywords

The adoption of microservice architecture (MSA) to ensure stable IT operations in cloud environments enables enterprises to achieve rapid development and adapt to diverse requirements by improving development productivity and operational automation [1]. Unlike the traditional monolithic approach, where applications are developed as a single unified service, MSA divides applications into multiple smaller, manageable services that can be developed, deployed, and scaled independently. Through collaboration among these autonomous services, MSA-based applications form structured and modular systems. Inspired by successful implementations from companies, such as Amazon’s AWS Lambda [2] and Netflix’s open-source services (OSS) [3], many enterprises are increasingly adopting MSA to achieve independent scalability and accelerate service innovation [4].

Containers serve as a fundamental building block that enables the scalable and efficient implementation of MSA [5]. Fundamentally, containers share the host kernel, providing weaker OS-level isolation (e.g., based on namespaces and cgroups) compared to traditional virtual machines relying on hypervisors. However, the deployment of even a single malicious container can compromise the entire host environment, granting attackers opportunities to exfiltrate sensitive data, escape container environments, or intercept internal communications. Moreover, due to the ephemeral nature and short lifespan of containerized applications, precise runtime monitoring and threat detection of a single container remain challenging tasks. Worse yet, the open nature of public container ecosystems (e.g., Docker Hub [6]) substantially lowers the barrier for attackers to distribute malicious containers at scale, thereby exacerbating security risks. Indeed, a recent technical report [7] revealed that container- and Kubernetes-related security incidents affect the entire application life cycle. In particular, runtime incidents were the most prevalent, with 45% of respondents reporting such experiences, while 44% encountered issues during the build and deployment phases. These findings suggest that the overall response to the growing threat of container security remains insufficient.

However, there are several challenges to monitoring and detecting malicious containers at runtime. First, relying solely on existing static analysis tools (e.g., image scanning [8,9]) falls short in accurately detecting malicious actions executed during runtime. Modern adversaries increasingly employ sophisticated techniques to evade traditional detection approaches, with each type of malicious container exhibiting distinct behaviors based on its intended goals. For example, bot containers typically manifest as network-intensive workloads, while cryptominers often display prolonged and intensive CPU usage on the host. Second, anomaly detection in cloud-native environments must account for the transient nature of containers and the rapidly evolving characteristics of workloads. This complexity necessitates comprehensive monitoring not only to identify anomalous traffic patterns or suspicious connections at the network level but also to detect unusual host-level events. Finally, the scarcity of publicly available datasets specifically focused on malicious containers poses additional challenges. Generating meaningful datasets involves complicated procedures—from converting malware samples into container images to executing them within controlled container environments [10]. Consequently, traditional signature-based detection methods, which rely on predefined rules common in legacy intrusion detection systems (IDSs), are limited in detecting novel or sophisticated container-based attacks.

Historically, the decision between host-level and network-level detection approaches mirrors a longstanding cybersecurity debate over the relative merits of host-based intrusion detection systems (HIDS) and network-based intrusion detection systems (NIDS). It is known that neither HIDS nor NIDS has proven universally superior; their effectiveness largely depends on the nature of the threat. Typically, network-level detection excels against external threats such as denial-of-service attacks, whereas host-level detection is more effective at identifying local intrusions, including rootkits and privilege escalation attempts [11].

This long-standing discussion naturally extends to containerized environments and leads to the following core problems addressed in this study:

• Limitation of single-source monitoring: Existing studies typically rely on only one data source (either network flows or system calls) making it difficult to capture the full behavioral characteristics of containers.

• Limited behavioral granularity: Most machine learning–based approaches focus solely on binary classification (benign vs. malicious), without distinguishing between diverse types of malicious behavior.

• Lack of systematic cross-modality comparison: There is no systematic comparative analysis between host-level and network-level monitoring, leaving uncertainty about which modality is more effective under different threat scenarios.

Motivated by this implication, our study addresses the ambiguity surrounding the proper monitoring level (host-level vs. network-level) for detecting various malicious container behaviors. Specifically, we aim to answer the following questions: 1) How can we effectively collect comprehensive runtime information from containers to enable rich feature extraction?, and 2) Which detection approach (host-level or network-level) provides more accurate machine learning (ML)-based identification of malicious behaviors across different container variants?

To achieve these goals, we employ eBPF-based runtime monitoring to simultaneously capture network-level and host-level information at container granularity. By monitoring data directly at the kernel level using eBPF, we can observe container runtime behavior with minimal overhead. The resulting network-flow and system-call data capture both external communication patterns and internal execution activities, providing a rich foundation for feature extraction and behavioral analysis. This enables us to examine whether the context-dependent effectiveness observed in traditional intrusion detection also applies to containerized threats such as bots, cryptominers, and trojans. Specifically, network flows are analyzed to capture communication between containers and external servers, while system-call traces are used to observe internal process behaviors and detect abnormal system states. Using both flow-based and host-based datasets, we perform multi-class classification with ML algorithms to distinguish between malicious and benign containers. Across six malicious and four benign scenarios, host-based detection achieved up to 98.39% accuracy, whereas flow-based detection reached 87.49%. While host-based data offer higher overall accuracy, flow-based analysis provides complementary insights for certain scenario-specific threats. These results highlight that each modality captures distinct behavioral aspects, and integrating both perspectives lays the foundation for a hybrid detection framework capable of more comprehensive and reliable runtime security.

2.1 Container Threat Detection

Containers share the host OS kernel and are characterized by short life cycles that allow them to be created and deleted quickly. They operate in environments where multiple services coexist on a single host, making it challenging for traditional security solutions (e.g., intrusion detection systems) to closely monitor each container’s internal activities. Although containers run independently, they share the same kernel, which remains outside the scope of container-level isolation. As a result, bypassing isolation boundaries poses potential risks, and existing host-level tools struggle to accurately attribute system events or traffic to individual containers [12]. Thus, using a single monitoring point at the host level does not fully capture detailed container information, making real-time observation important. Each container is isolated using namespaces and assigned a virtual Ethernet (veth) interface, which serves as a virtual network interface. The veth interface is created as a pair, enabling communication with the external network. For this reason, the monitoring point should be the interface of each container in order to track the behavior of individual containers at runtime.

Conventional network monitoring tools running in on-premises environments struggle to directly observe intra-container traffic due to container isolation. Previous studies [13,14] used monitoring tools such as perf, strace, and ptrace to monitor system calls. However, these approaches require frequent user-level to kernel-level context transitions whenever a system call is invoked, resulting in performance overhead.

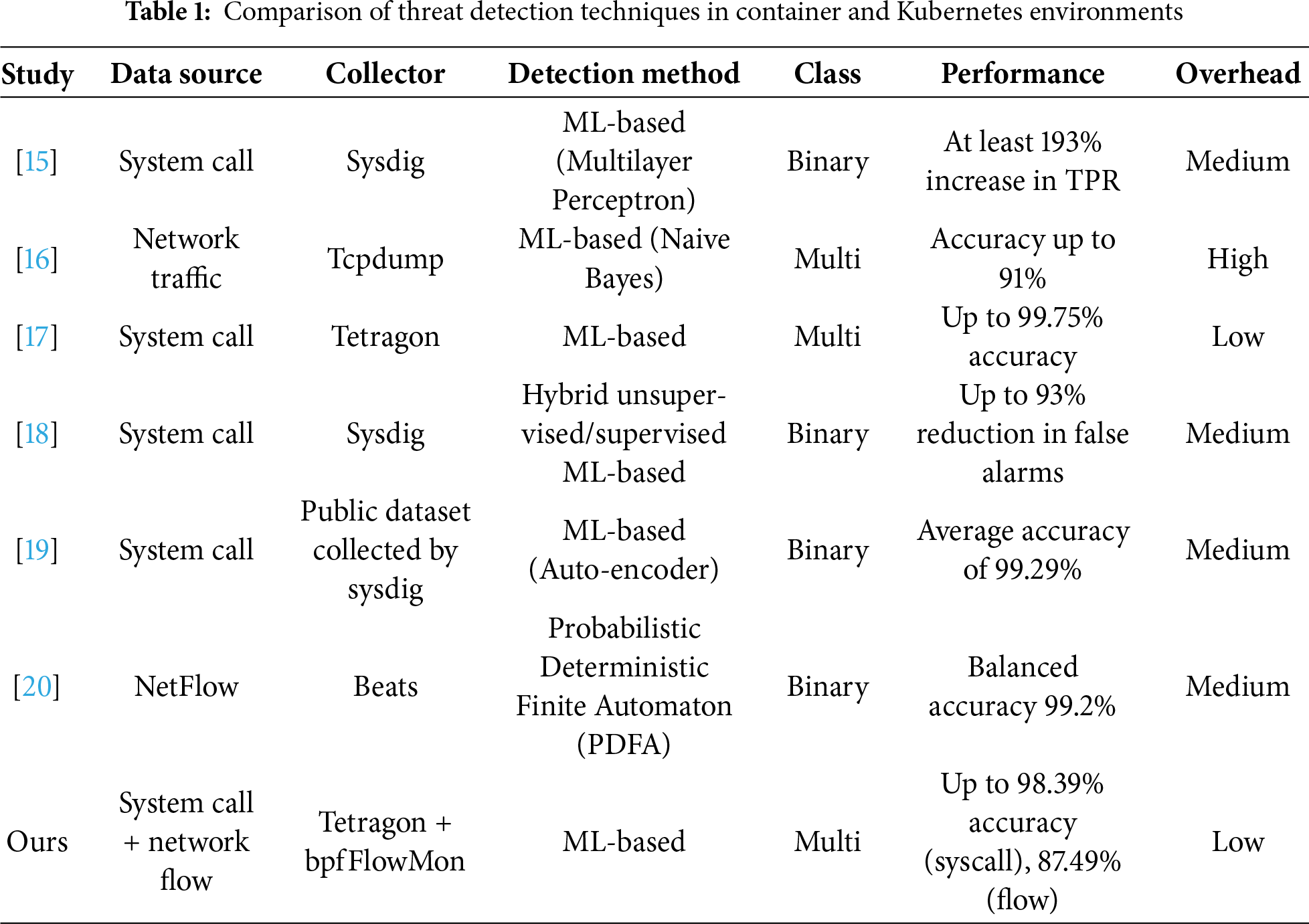

As shown in Table 1, recent studies have applied various detection techniques to container and Kubernetes environments [15–20]. However, most existing approaches rely on a single data modality (e.g., either network flows [16,20] or system calls [15,17–19]) which limits their ability to capture the full behavioral spectrum of container activities. Furthermore, many systems focus on binary anomaly detection [15,18–20], restricting their applicability to diverse and increasingly specialized malicious behaviors. Although several tools demonstrate high performance, they differ significantly in their collection overhead: sysdig requires event transfers to user space despite supporting eBPF, tcpdump incurs high overhead due to packet-level processing, and Elastic’s Beats [21] relies on user-space agents. Only a few studies provide systematic comparisons across different malicious container types [16,17], leaving uncertainty regarding the most effective monitoring strategy. These limitations highlight the need for a kernel-level, low-overhead monitoring mechanism capable of capturing both host and network behaviors.

Extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF) [22] is a technology that enables the execution of sandbox programs in the Linux kernel, allowing for the expansion of existing kernel functionality without modifying the kernel source code or loading kernel modules. As such, it is widely used for packet filtering, performance monitoring, and security enforcement, providing detailed real-time insights into system operations [23]. Notably, the use of eBPF in cloud-native environments provides detailed observability of containerized applications.

Existing studies [17,24,25] demonstrate the potential for efficient data collection and security monitoring by using eBPF for low-overhead runtime tracing of system calls and network traffic, and detection based on security policies. In [17], eBPF is used to efficiently collect data for machine learning–based detection of cryptojacking containers and in [24], the authors build a detection and observation mechanism that mitigates Distributed Denial of Service attacks on Kubernetes through packet filtering using eBPF. Similarly, Her et al. [25] demonstrates that eBPF-based tools can monitor kernel-level process and network activities to enforce security policies and provide comprehensive behavioral analysis. In this study, we used two eBPF-based tools, bpfFlowMon and Tetragon, to monitor network traffic and system calls at runtime, respectively.

2.2 Malware in Cloud-Native Environments

Cloud-native environments are primarily Linux-based, which has led to an increase in attacks that exploit open-source tools by embedding or exploiting Linux malware. According to Sysdig’s research [26], open source malware code is the most frequently used, with Mirai being the most common malware in 2024. XMRig, used for cryptocurrency mining, was also found to be among the most prevalent malware families. Furthermore, Orca Security’s 2024 State of Cloud Security Report found that 87% of cloud malware attacks are carried out by known Trojans [27]. These malware spread in cloud-native environments by exploiting vulnerabilities in cloud infrastructure and applications. Therefore, we focus on their motivations for using containers and their behavioral differences in containerized environments.

Botnet. Basically, a botnet is a group of devices that are infected and controlled to carry out the attacker’s commands, and each device becomes a bot and performs malicious tasks. Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) botnets, in which an attacker uses infected bots to generate massive amounts of traffic to disrupt services, are particularly well-suited to container environments. In cloud environments, malicious containers can easily spread as new instances are added through auto scaling. Thus, when a container is deployed to act as a DDoS agent, it can cause more damage and spread more rapidly than traditional host-based botnets. Moreover, the dynamic nature of the container makes tracking difficult, providing a highly favorable environment for attackers. In addition, because all containers share kernel resources, access to resources can be exploited to disrupt standard processing or operations [28]. By exploiting these characteristics, attackers can add DDoS agents to their botnets and rent them out to others to perform DDoS-as-a-Service operations [29] or monetize them by deploying cryptojacking botnets [30].

Cryptojacking (Mining bot). Cryptojacking, a malicious form of cryptomining, is the unauthorized use of one’s computing resources to mine cryptocurrency stealthily. Attackers use filtering and obfuscation techniques to make detection more difficult, as they need to stay on the system for a long period of time for high returns [31]. Previously, host- and browser-based cryptojacking attacks were the main forms of attack, but in a cloud environment, cryptojacking attacks are much more efficient because they can utilize vast amounts of computing resources. In particular, cryptojacking is the most common form of attack against container-based systems because it is a fast, high-reward attack with minimal effort. Furthermore, since anyone can publicly upload images to Docker Hub, it is easy to deploy container images and create an attack environment, which is why cryptomining accounts for the largest percentage of malicious container images [29].

Trojan. If the container image contains a trojan, malicious code disguised as legitimate software to conceal its true purpose. Also, there is a risk of spreading the infected image due to the portability of the container. Since downloaded images are verified based on the presence of a signed manifest, and Docker does not verify the image checksum downloaded from the manifest, an attacker can send any image with a signed manifest, leaving the verification process vulnerable [28]. In addition, container infections can be spread by injecting malicious payloads to bypass offline scanning. Similarly, we can recognize vulnerabilities through a study [32] that shows that it is possible to inject malicious payloads into the build process of a Docker-based Continuous Integration (CI) system without leaving traces in the source code and continuously update the malware through hidden channels.

In summary, the injection of malicious payloads and the proliferation of malicious containers through public registries can broaden the scope of damage across cloud-based infrastructures. However, container security monitoring tools provided by traditional cloud service providers (CSPs) are typically optimized for their own platforms and have limitations in fully capturing detailed runtime behaviors inside containers. Containers are characterized by volatile lifecycles, automated deployment, and rapid scalability, which make security monitoring more complex even as they enable flexible operations. As a result, detailed process analysis at the container level requires a runtime monitoring approach that is specifically tailored to the container environment.

3 eBPF-Based Hybrid Container Monitoring Framework

This section describes our hybrid monitoring framework that leverages eBPF to collect host-level and network-level behavioral data from containers, enabling comprehensive and efficient runtime detection of malicious activities.

3.1 Motivation and Design Challenges

Modern cloud-native infrastructures demand security solutions that are both lightweight and effective at runtime. Containers, with their rapid instantiation, require observability tools that minimize overhead while maintaining behavioral visibility. Moreover, containers operating within pods in Kubernetes environments share the host’s kernel for executing applications, incurring resource contention [33]. To meet these constraints, we employ eBPF-based telemetry that operates within the kernel, enabling fine-grained tracing of both system-level and network-level activities, without requiring context switches to user space.

Our framework adopts a hybrid approach: one based on system-call traces (host-level), and the other on network flow metadata (flow-level). This design supports the detection of diverse malicious behaviors, ranging from CPU-bound cryptominers to I/O-driven trojans. However, this design also introduces several challenges:

• Feature abstraction gap: eBPF offers rich raw telemetry, but transforming it into ML-usable features requires careful feature engineering and consistent preprocessing [34].

• Scalability and dynamics in Kubernetes environments: Monitoring containers in multi-node clusters requires dynamic interface binding and data aggregation strategies.

• Limitations in utilizing existing tools: eBPF-based security monitoring tools, such as Tetragon [35] and bpfFlowMon [36], require explicit configuration for tracing targets, and provide limited built-in feature abstraction.

This study presents a concrete architecture to address these challenges. We overcome these challenges by adopting monitoring methods tailored to each data type (detailed in Sections 3.2 and 3.3) and implementing a systematic data processing pipeline that transforms raw data into features optimized for machine learning (detailed in Section 4.2). However, scalability across multiple nodes remains a future task, despite being a critical challenge reflecting real operational environments. Our present focus is on establishing a foundation for a hybrid detection methodology through an in-depth analysis of the characteristics of data extracted by both monitoring approaches.

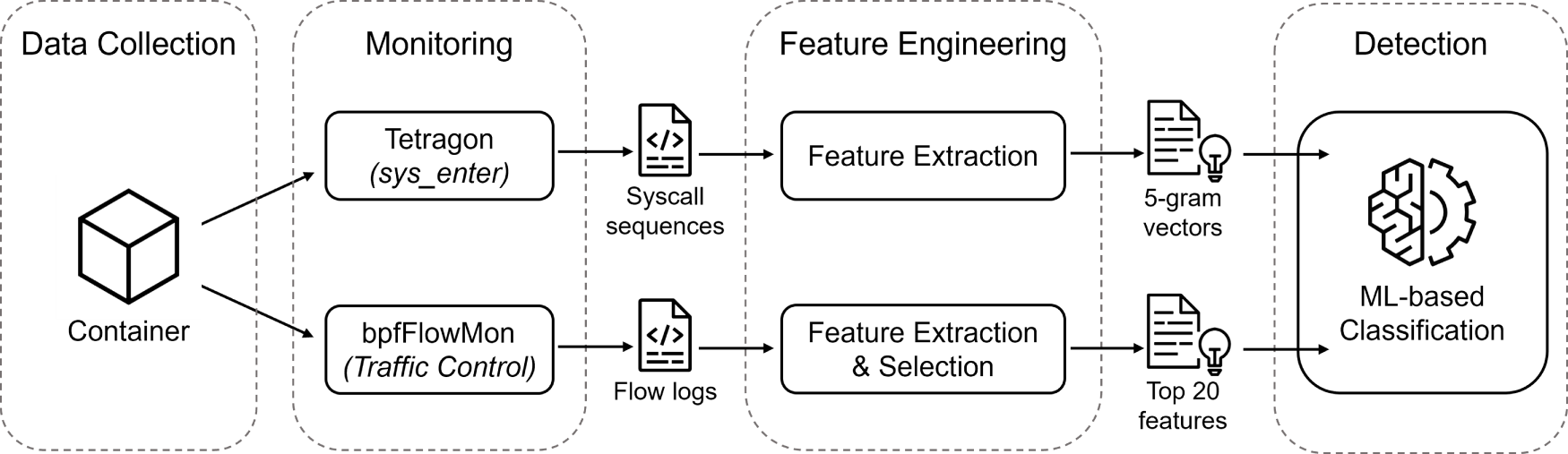

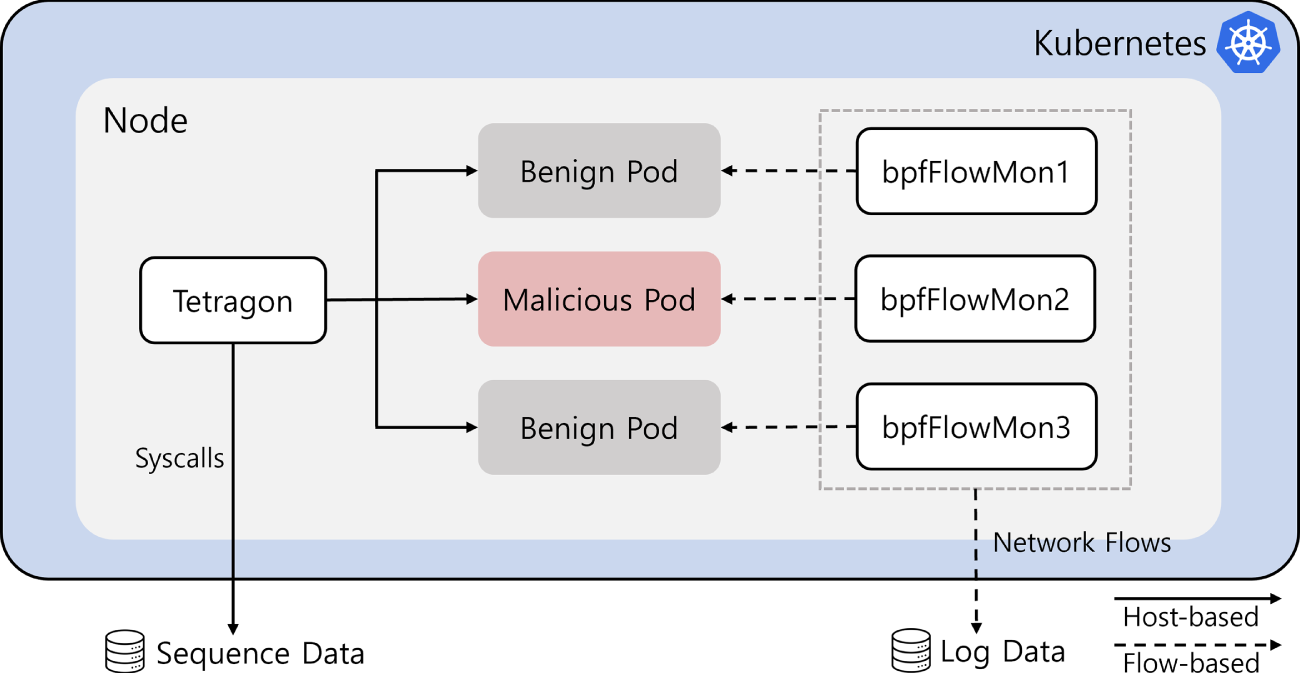

In particular, the challenge of selecting and abstracting relevant features for machine learning remains largely unaddressed despite the growing adoption of eBPF-based monitoring. Existing studies [17,37] have examined host-based and network-based telemetry as separate or complementary data sources. However, these efforts lack a systematic comparison of how features from each context contribute to the detection of diverse container threats. In addition, their analyses are often tailored to specific malware families or focus solely on improving classification performance by aggregating both modalities, rather than evaluating their individual effectiveness in isolation. Our framework is designed to address this gap by providing a controlled, side-by-side comparison of host-level and flow-level monitoring strategies across multiple container attack scenarios. Fig. 1 illustrates the data-processing flow of the proposed architecture, showing how collected system call and network flow data are preprocessed and subsequently passed to a machine learning–based detection module.

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed framework

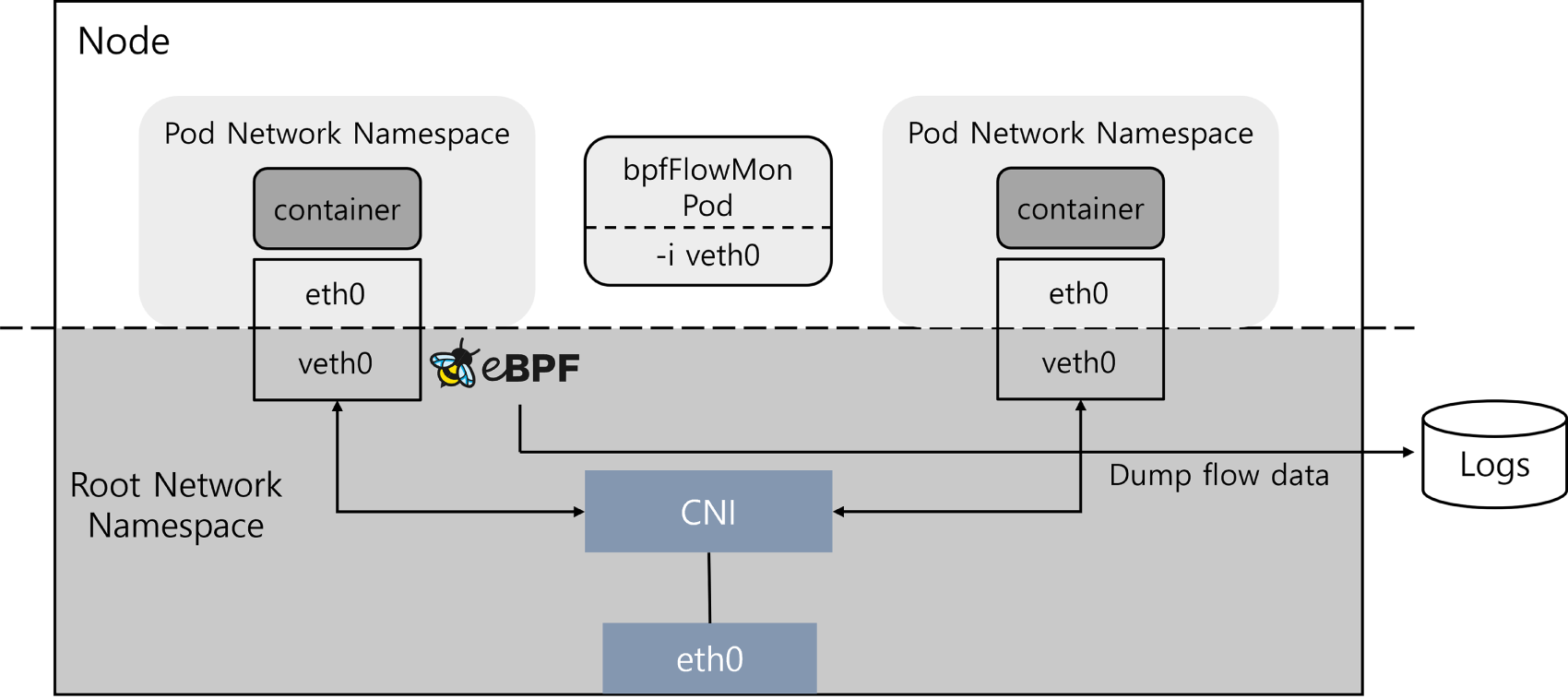

In dynamic cloud-native environments, where IP addresses and routing paths frequently change due to autoscaling and network automation, monitoring network behavior requires adaptive strategies. As the scale and complexity of network traffic increase, traditional packet-level tools (e.g., tcpdump) face challenges in real-time processing, particularly when handling encrypted traffic. This highlights the impracticality of capturing and inspecting every packet in modern containerized environments [38]. To address this, we adopt a flow-based monitoring approach that provides a scalable and lightweight alternative by analyzing traffic metadata rather than full packet contents.

Our implementation leverages bpfFlowMon [36], an eBPF-based monitoring tool that operates entirely within the kernel, enabling efficient metadata collection without incurring userspace overhead. Instead of capturing packets, bpfFlowMon summarizes traffic using flow records based on 5-tuples (source/destination IPs and ports, protocol), which are less affected by encryption and offer a consistent representation of communication patterns.

Fig. 2 illustrates the process of monitoring network traffic from a container veth interface using bpfFlowMon. We deploy bpfFlowMon as a DaemonSet in a Kubernetes cluster to ensure monitoring coverage across nodes. To minimize unnecessary overhead, we explicitly specify each container’s veth interface using the -i argument at runtime, allowing the tool to attach BPF programs only to the relevant interfaces. The monitoring results are exported in JSON format using the tc_flowmon_user binary and stored periodically. These results include byte and packet counts, retransmission statistics, and TCP window properties, which are later processed for ML-based detection. All configurations, including target interfaces, log paths, and execution parameters, are managed through Kubernetes YAML files to ensure reproducibility and scalability. By capturing unidirectional flow data from each container interface before encapsulation, our system enables independent analysis of inbound and outbound behaviors.

Figure 2: eBPF-based network monitoring using bpfFlowMon

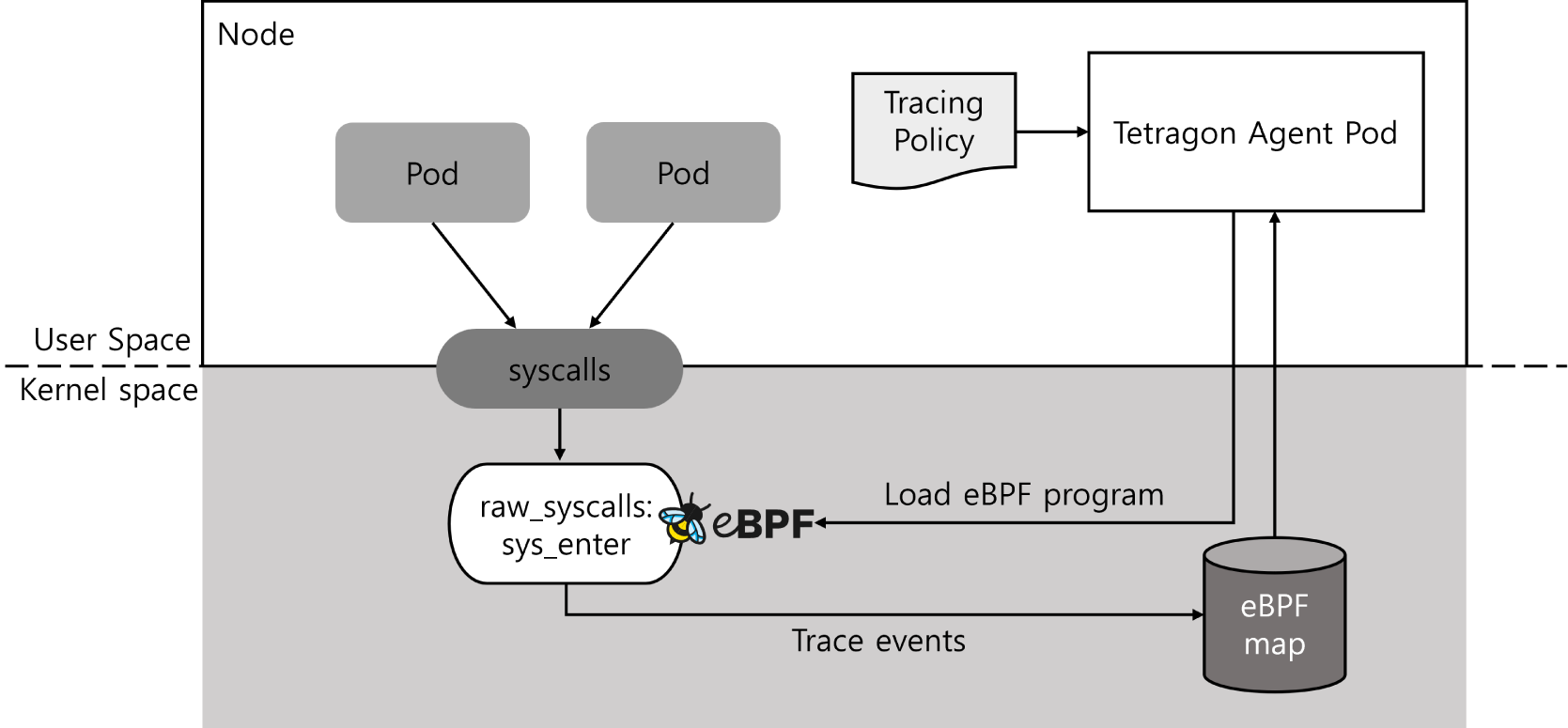

While network telemetry captures communication behaviors, many attacks (e.g., trojans or privilege-escalation attempts) manifest through abnormal system-level activity. For host-level observability, we leverage Tetragon [35], an eBPF-based monitoring framework capable of real-time tracing within the Linux kernel. Host-level monitoring is particularly effective for detecting malicious processes by observing low-level operations, such as file access, process creation, and I/O interactions. Unlike Falco [39], which performs rule-based filtering in user space after collecting events from the kernel, incurring additional context-switch overhead, Tetragon applies its filtering logic directly within the kernel, significantly reducing monitoring overhead. Moreover, Tetragon integrates seamlessly with Kubernetes environments and scales across clusters, making it suitable for large-scale containerized deployments with consistent security policies.

Tetragon’s monitoring logic is governed by a Tracing Policy, a user-defined specification that designates which events, arguments, and hook points should be traced. In our framework, we utilize tracepoints, which are statically defined in the kernel and known for their portability across versions, as the primary hook mechanism. Specifically, we instrument the sys_enter hook to capture system-call invocation events before execution. This enables early detection of suspicious behaviors, such as unauthorized file operations or unusual process activity, which may not be observable through exit-based tracing like sys_exit.

To enhance interpretability and preserve temporal context, we convert raw system-call sequences into n-gram tokens (with n = 5), fixed-length overlapping sequences of five system-call IDs. This n-gram modeling preserves call ordering and highlights recurring behavioral patterns that can be leveraged by machine-learning classifiers. Events are collected through a sidecar container, where Tetragon’s agent pod captures kernel-level traces and emits them to standard output, from which they are aggregated and prepared for downstream analysis. This host-based pipeline complements the flow-based approach by exposing internal behaviors invisible at the network layer, which is especially useful for identifying stealthy or obfuscated malware payloads. Fig. 3 illustrates the process of monitoring system calls using Tetragon.

Figure 3: System call monitoring process based on eBPF using Tetragon

4 Dataset and ML Model Description

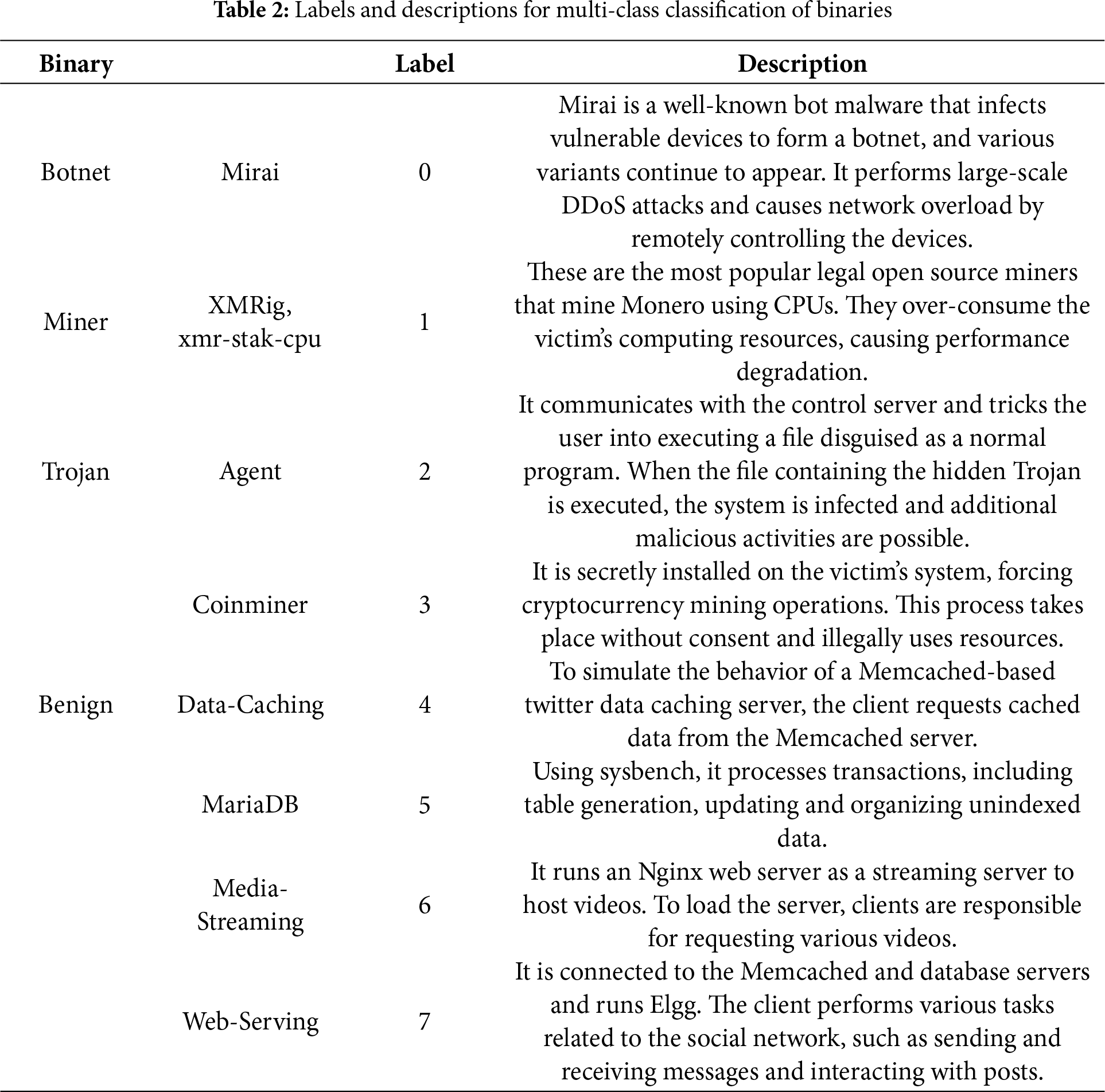

To demonstrate the practical effectiveness of our framework on detecting a diverse range of threat behaviors, we construct a dataset that includes both malicious and benign container scenarios. Table 2 is a description of the label and workload for each data. The malicious containers were run in a container environment based on malware binaries of Mirai, Agent, and Coinminer obtained from public Linux-malware repositories [40] and miner images from Docker Hub [6], and are grouped into three representative categories: Botnet, Trojan, and Miner. First, we use the Mirai malware to emulate bot-like behavior, particularly targeting DDoS functionality. Second, we include Agent and Coinminer samples [40], both of which mimic trojan-like characteristics through deceptive file execution and unauthorized resource use. For mining-based attacks, we use open-source CPU-based miners such as XMRig [41] and xmr-stak-cpu [42], both targeting the privacy coin Monero (XMR), known for its preference in stealth cryptojacking. Note that Trojan is a broad concept that can include a variety of attack behaviors, so we labeled each of them separately.

For benign workloads, we select four representative container types commonly found in cloud service environments: caching, database, media-streaming, and web-serving. We utilize data-caching, media-streaming web-serving from CloudSuite 4.0 [43], which offers containerized benchmarks modeled on real-world service and analytics applications. CloudSuite’s benchmarks are built on real software stacks and is widely used for performance analysis of cloud-native systems. To represent the database workload, we deploy MariaDB [44] using its official Docker image. We simulated realistic usage by applying sysbench [45], a widely used database benchmarking tool, to generate intensive read/write operations on the MariaDB pod running within the Kubernetes cluster.

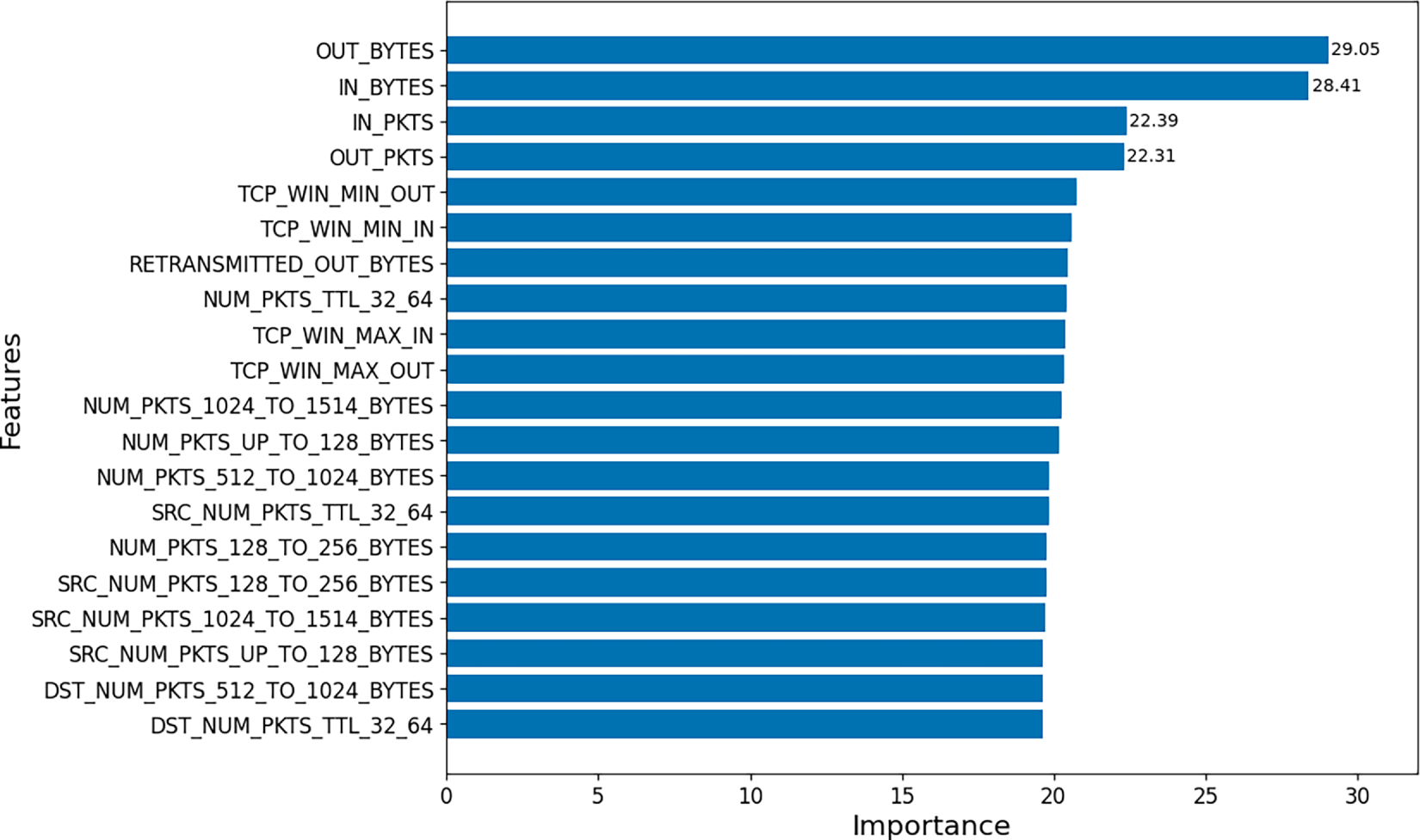

The collected raw data was preprocessed independently for the two monitoring modalities in our framework. For the flow-based dataset, our framework initially collects 99 metadata fields per network connection using bpfFlowMon. To prevent label leakage and ensure generalizability, we derived an 87-dimensional filtered feature set by removing non-informative or identifiable attributes, such as IP addresses and port numbers. TCP_FLAGS-related fields, originally stored as categorical objects, were converted into numerical representations through one-hot encoding, and missing values were replaced with zeros to produce a format suitable for machine learning models. Feature selection was then applied using SelectKBest combined with the chi-squared test to evaluate the statistical relationship between each feature and the target labels and to identify the most discriminative attributes. To determine an appropriate number of features, we compared average classification accuracies across different

Figure 4: Importance of the top 20 features. The x-axis represents the log-transformed chi-square scores obtained from the feature selection process

For system call analysis, we extracted raw traces and converted syscall names to their corresponding x86_64 system call numbers, representing each event as an integer. The sequence of system calls was then tokenized into overlapping 5-g segments, where each instance corresponds to a contiguous window of five system call identifiers. This n-gram modeling technique retains temporal ordering and preserves behavioral context, while producing a fixed-length representation compatible with both traditional and neural network models. The resulting dataset captures subtle behavioral patterns at the system-call level, allowing for the identification of process anomalies and deviations from expected execution sequences.

To evaluate the classification effectiveness of both monitoring modalities, we train a range of machine learning models on the preprocessed datasets. For each modality, the labeled data is randomly partitioned into training and testing sets using a 70:30 split. We explore both conventional and neural classifiers to assess how different algorithms respond to the extracted features. The baseline models include K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), Naive Bayes (NB), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), all implemented using the Scikit-Learn library. In addition, we employ two recurrent models, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, well-suited for processing time-dependent data such as system-call sequences. Both deep learning models are implemented using TensorFlow and Keras, and configured with two recurrent layers, Dropout for regularization, and a final softmax activation layer to support multi-class classification. This training setup allows us to evaluate the learning capacity of each model across both flow-based and host-based contexts, and to identify which combinations of modality and classifier achieve the most accurate detection of malicious container behaviors.

We evaluate our framework in a single-node Kubernetes environment deployed using Minikube [46] on Ubuntu 20.04. Specifically, we use Minikube v1.33.1 with Kubernetes v1.30.2, running within a KVM-based virtual machine. To assess the performance of each classification model, we employ standard evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-Score. The following metrics are defined based on the four indicators of the confusion matrix: true positives (TP), false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), and true negatives (TN). TP denotes the case where the classifier correctly classifies an instance into the class to which it actually belongs.

• Accuracy represents the proportion of accurate predictions among all predictions.

• Precision shows the proportion of positive predictions that are actually correct.

• Recall is the proportion of actual positive observations that are correctly identified as positive.

• F1-Score is defined as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall.

These metrics provide a consistent basis for comparative analysis across both monitoring modalities and all ML models under evaluation. In this context, TP refers to a container correctly identified as belonging to a specific class (e.g., botnet, web-serving) by the classifier.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, both Tetragon and bpfFlowMon are deployed as DaemonSets to ensure continuous monitoring across all active pods within the cluster. Note that Tetragon supports runtime system call tracing by allowing users to explicitly specify the target pod name during execution. In contrast, bpfFlowMon requires monitoring at the interface level, where each YAML configuration file includes a specific veth interface to be traced. Consequently, bpfFlowMon instances are deployed separately to track each container’s network interface independently.

Figure 5: Overview of Tetragon and bpfFlowMon deployment for monitoring pods in Kubernetes

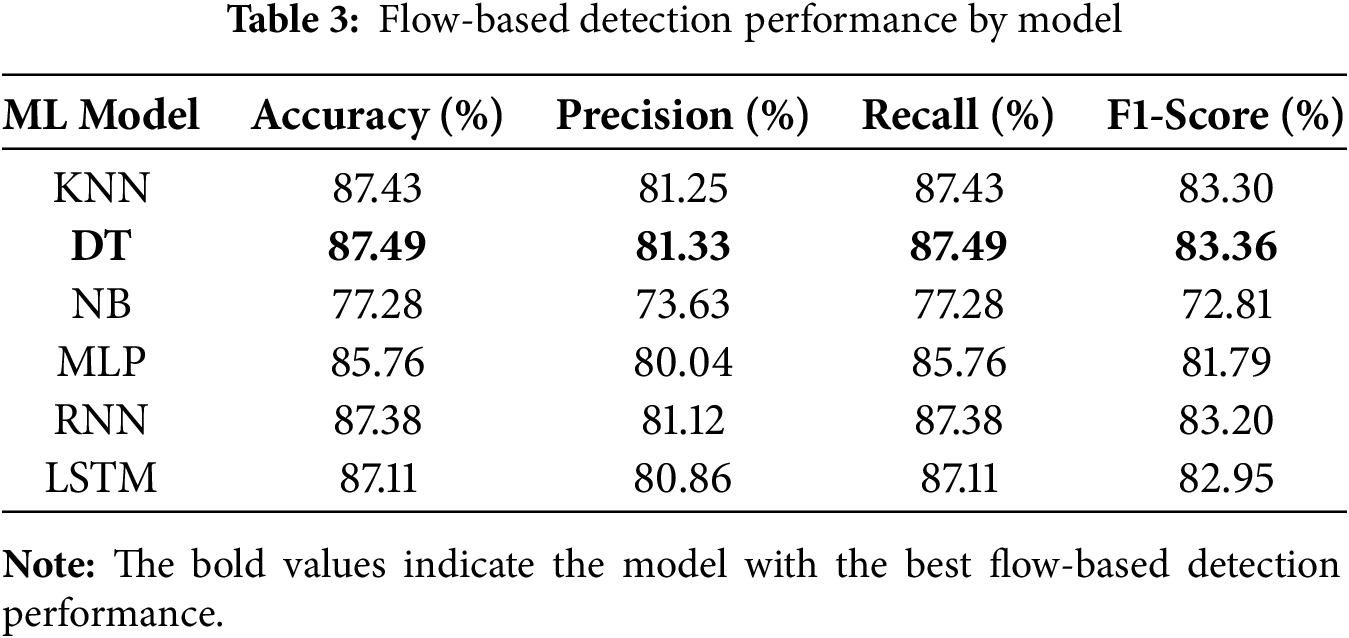

5.2 Flow-Based Detection Performance

Table 3 presents the classification performance of each model on the network flow dataset. Except for NB, all models achieved accuracies above 85%, with DT showing the highest accuracy at 87.49%. Because network flow records were randomly sampled during preprocessing, temporal dependencies between consecutive flows were largely disrupted, limiting the advantage of sequence-aware models such as RNN and LSTM, which therefore exhibited similar performance. In addition, the flow dataset contains highly correlated features, including IN/OUT bytes and IN/OUT packet counts. Since NB assumes conditional independence among features, it cannot effectively capture these correlations, resulting in inferior learning of flow patterns and consequently lower performance. Apart from NB, most models demonstrated comparable results, with DT maintaining the best overall accuracy among the evaluated classifiers.

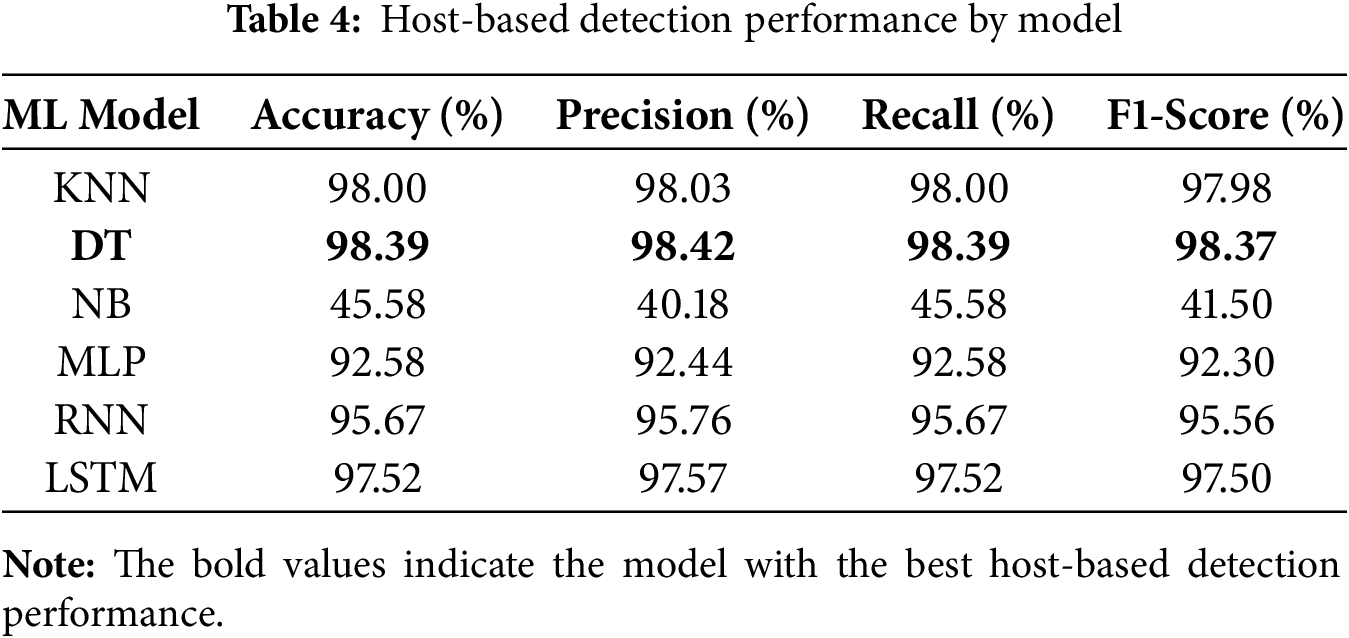

5.3 Host-Based Detection Performance

Table 4 presents the performance of each model on the system-call dataset. All models achieved accuracies above 90%, with KNN and DT exceeding 98%. These results suggest that the behavioral patterns associated with each class are sufficiently regular to be effectively captured by the 5-g representation. Moreover, LSTM, which can learn longer-term dependencies, outperformed RNN by approximately 2%, indicating that sequential dependencies within system-call data are meaningfully reflected in the learning process. In contrast, NB assumes conditional independence among input features and assigns equal importance to them, making it unsuitable for modeling order-dependent information in n-gram-based data. Consequently, NB achieved less than half the accuracy of the other models.

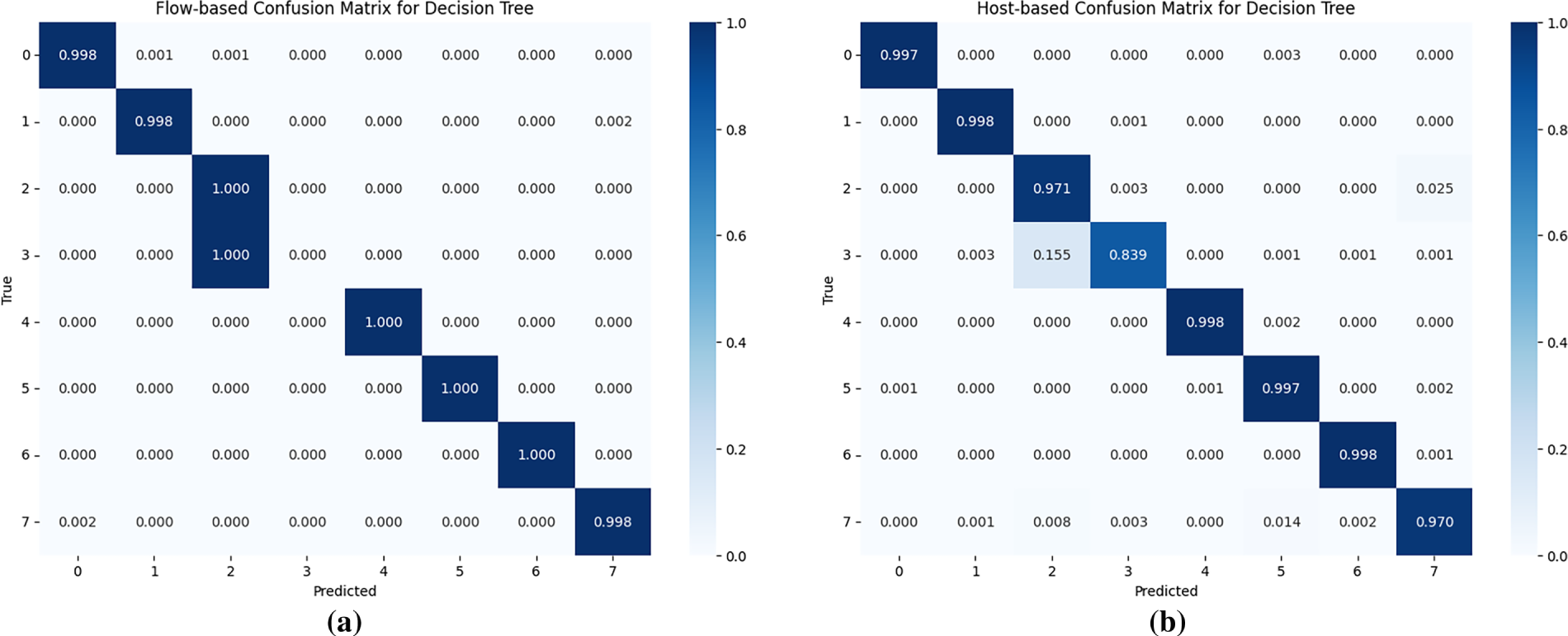

5.4 Confusion Matrix Analysis of the Best Model

Fig. 6 presents the confusion matrices for the DT model, which achieved the highest performance in both system-call and network-flow classifications. The system-call model performed well overall, although some Coinminer samples were misclassified as Agent data. This confusion likely stems from similarities in resource-intensive operations such as file I/O and memory usage that occur during the process of Agent infection through file execution. Additionally, certain Agent samples were misclassified as Web-serving due to overlapping behaviors related to file access. Agents serve static and dynamic files, whereas Web-serving containers also perform frequent file I/O operations as processes access required libraries and configuration files.

Figure 6: Confusion matrices for best performing models by monitoring method: (a) Confusion matrix for the decision tree in flow-based monitoring; (b) Confusion matrix for the decision tree in host-based monitoring. Note that the numeric labels correspond to the following classes: 0 (Botnet), 1 (Miner), 2 (Trojan-Agent), 3 (Trojan-Coinminer), 4 (Data-Caching), 5 (MariaDB), 6 (Media-Streaming), and 7 (Web-Serving)

The DT model based on network flows also demonstrated strong per-class classification performance but occasionally misclassified Coinminer as Agent. This is likely due to similarities in communication patterns with the attacker’s command-and-control (C&C) server, suggesting the need for additional discriminative network features. In contrast, the host-based system-call approach avoided this confusion and maintained a stable per-class accuracy of approximately 84% in correctly identifying Coinminer. This robustness can be attributed to differences in system-call sequence characteristics: Agents exhibit a wide variety of calls focused on signal processing and file access, whereas Coinminers display continuous communication, task logging, and memory-mapping–related operations.

This section discusses the qualitative characteristics of the data that underlie the model’s detection rationale, building upon the quantitative performance results presented in Section 5. By analyzing the distinct behavioral patterns exhibited by each malware type at both the host and network levels, we highlight the significance of these characteristics and emphasize the necessity of the proposed hybrid detection approach.

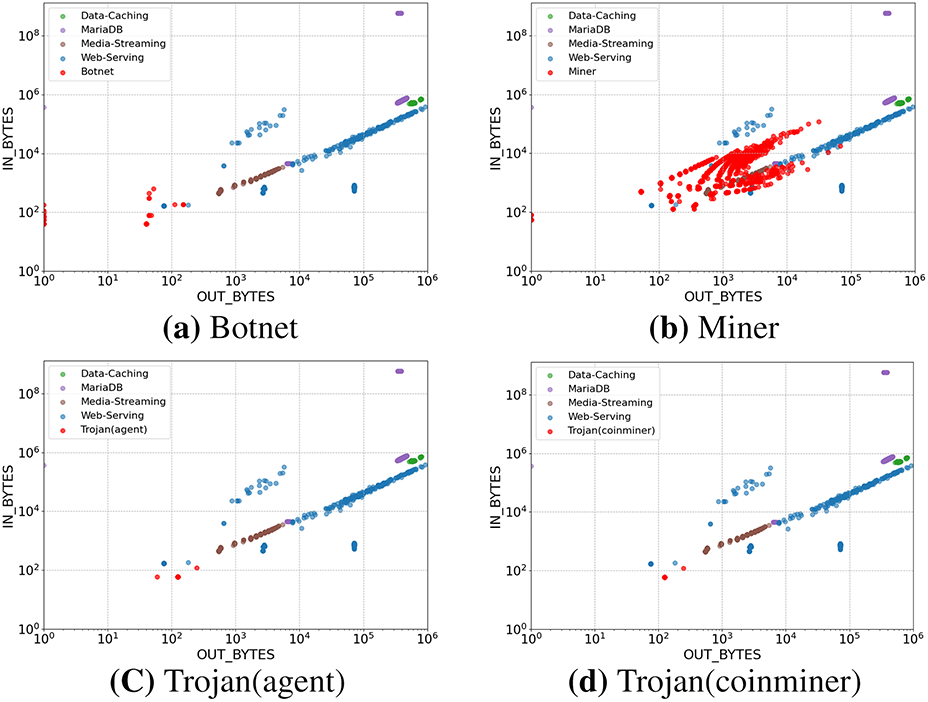

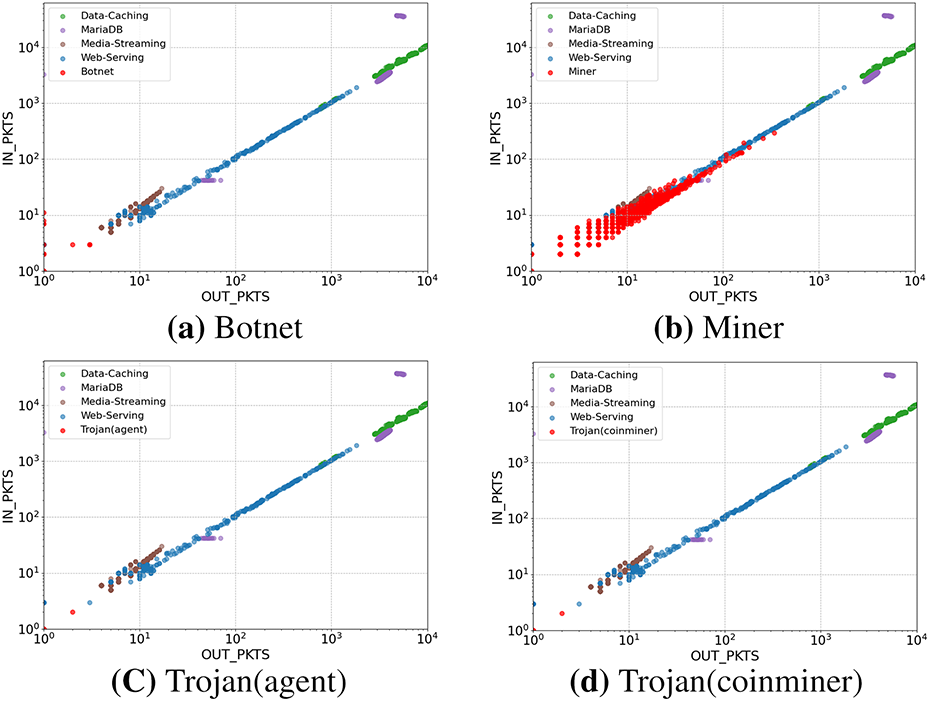

Figs. 7 and 8 visualize the distributional differences in IN/OUT bytes and packets (PKTS) between malicious and benign traffic types. Because the magnitudes of traffic values vary substantially—from very small C&C communications with low byte and packet counts to the much larger volumes observed in Miner and benign traffic—a log scale was applied to better reveal overall distribution patterns. To further minimize visual distortion caused by extreme outliers, the OUT_BYTES and OUT_PKTS values were capped at

Figure 7: Comparison of In/Out Bytes distributions between malicious and benign traffic (log scale)

Figure 8: Comparison of In/Out Packets distributions between malicious and benign traffic (log scale)

Miner traffic, on the other hand, involves continuous and dynamic exchanges, where containers receive tasks from mining pools and report computed results. As a result, incoming traffic exceeds outgoing traffic and exhibits a broader distribution, reflecting the process of continuously receiving new jobs or data such as block headers from mining pool servers. Trojan (Agent) and Trojan (Coinminer) traffic typically originates from small-scale communications during the initial infection stage, when connections with control servers and command channels are established. Both bytes and packet counts are concentrated in the lower range, producing very similar distribution patterns between the two. Therefore, distinguishing between Agent and Coinminer traffic based solely on network-level features remains challenging.

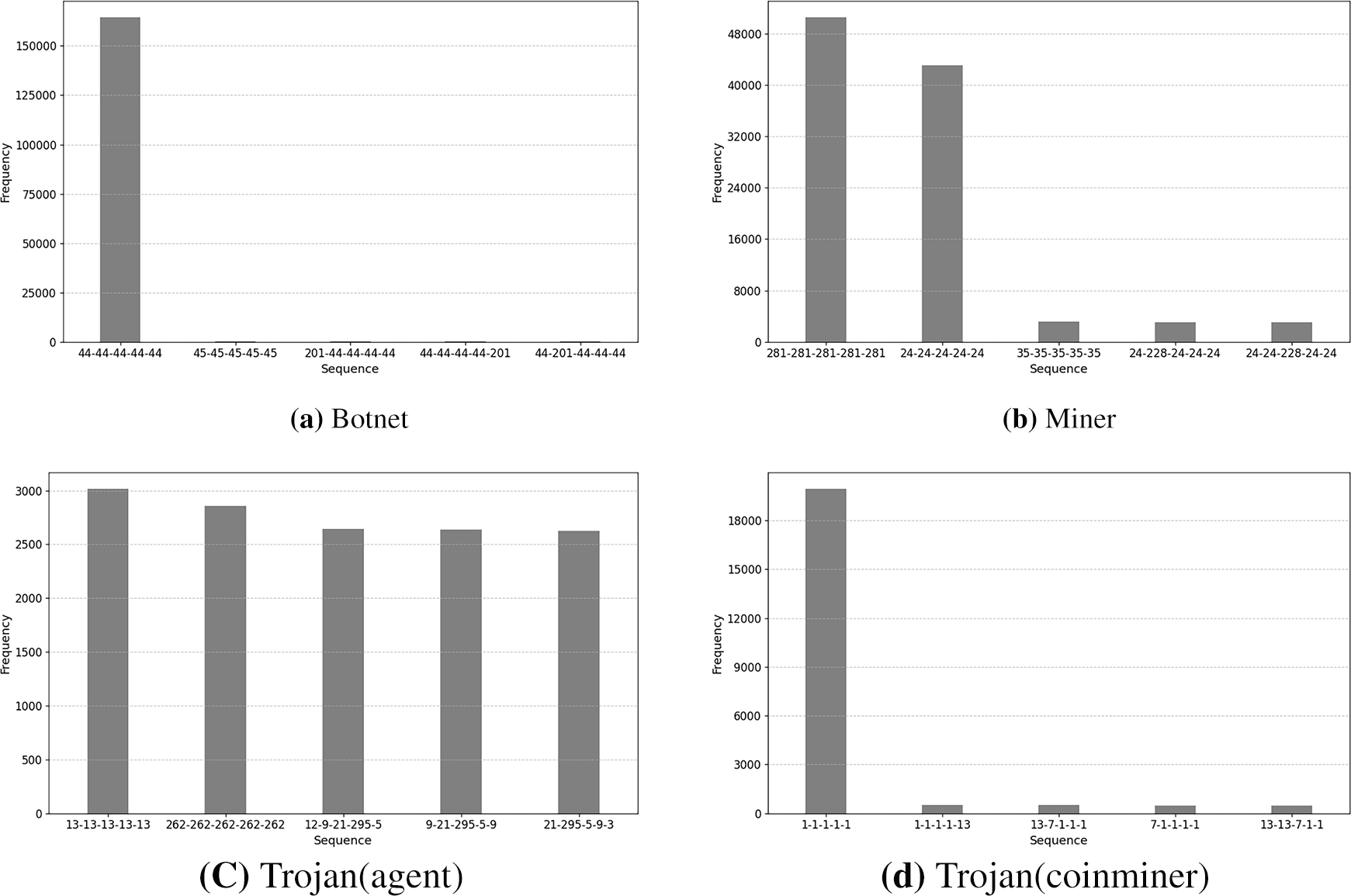

The system-call sequences of malware reveal each threat’s core operational methods and objectives. Fig. 9 reports the top-five sequence statistics for the collected system calls. First, Botnet sequences are dominated by sendto (44), which clearly reflects the botnet’s representative behavior of continuous communication with C&C servers. By contrast, the samples labeled as Trojan (Coinminer) show frequent write calls (1), indicating a focus on recording mining progress and results; this pattern is consistent with a simple, single-task mining operation.

Figure 9: Frequency distributions of dominant system-call sequences by malware type. Here, the x-axis represents 5-gram sequences, each consisting of five consecutive system call numbers

The Miner class exhibits a more sophisticated runtime strategy. Its main execution flow contains repeated calls, such as epoll_pwait (281), sched_yield (24), and nanosleep (35). The use of epoll_pwait supports efficient I/O with the mining pool, while sched_yield and nanosleep reduce CPU monopolization, thereby minimizing anomalous system behavior and facilitating evasion of detection. Finally, the Agent-type trojans display a more diverse distribution of system-call sequences, consistent with advanced agent behavior. These samples show frequent file-system operations, such as newfstatat (262) and access (21), memory mapping via mmap (9), and process-persistence related calls, such as rt_sigaction (13). Such patterns indicate that agents perform preliminary infiltration, maintain persistence, and prepare for subsequent malicious activities beyond mere resource theft.

Each type of malicious activity exhibits distinct characteristics at both the network-flow and system-call levels, indicating that detection methods relying solely on a single data source have inherent limitations. Analyzing these perspectives together enables a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of container behaviors. At the network-flow level, botnets may appear as simple periodic communications with C&C servers, whereas at the system-call level they reveal continuous, repetitive sendto calls characteristic of DDoS activity. Miner traffic may resemble Web-serving behavior, appearing as high-volume data transfers, yet the prominent epoll_pwait and sched_yield call patterns indicate mining processes optimized to minimize performance degradation through efficient resource utilization.

Trojan (Agent) and Trojan (Coinminer) most clearly demonstrate the necessity of comprehensive analysis. Both show short and small-scale traffic flows at the network level. This is largely attributable to the short, periodic packet exchanges and similar session durations that occur during the initial infection phase when both variants establish a communication channel with the control server. Because such interactions produce nearly indistinguishable statistical flow patterns, the aggregated features were insufficient to capture their behavioral differences. To improve discrimination, flow-based analysis would benefit from incorporating richer temporal and structural information, such as session-to-session relationships, sequence-level trends, or multidimensional communication profiles.

Conversely, system-call analysis exposes divergent internal behaviors: Trojan (Agent) performs file-system reconnaissance and persistence operations, whereas Trojan (Coinminer) repeatedly invokes the write call to record ongoing mining activity. These distinctions clarify the different behavioral objectives of the two trojan variants. However, occasional misclassifications still arise due to behaviors that involve common file-access patterns or CPU-related operations, which are shared by both variants. These similarities reduce the discriminative power of short n-gram sequences. Refining system-call features with additional contextual information, such as inter-call timing or duration of activity bursts, may help further differentiate the two classes.

These analyses are derived from a limited dataset, making it difficult to assume universal applicability to real-world environments. To mitigate this limitation, this dataset comprises multiple execution types exhibiting distinct behavioral characteristics, aiming to reflect diverse scenarios that may occur in real-world environments centered around network I/O-intensive, CPU-intensive, and file I/O-intensive activities. Despite the constraint that the dataset used in this study is based solely on specific types of malicious samples and benign workloads, it has demonstrated that behavior-based detection of malicious containers using two modalities operates meaningfully. In real-world environments, the behavior of normal workloads is more diverse, potentially leading to some false positives. However, by leveraging the diverse features extracted from behavioral analysis, this approach is expected to be superior to traditional signature-based detection methods in reducing false negatives (FN), where unknown malicious behavior is missed. Ultimately, these findings underscore the value of a hybrid detection approach that integrates network- and host-level telemetry, enabling robust and precise detection of diverse malicious container behaviors.

In this study, our goal was to examine how different malicious behaviors appear across host- and network-level perspectives, rather than to maximize performance through naive and immediate hybrid integration. Because network-flow data and system-call data differ fundamentally in modality—statistical traffic summaries vs. sequential event traces—constructing a unified feature representation is non-trivial. For this reason, we evaluated each modality independently to clarify their respective strengths and limitations for various threat types. Based on these findings, decision-level fusion (e.g., ensemble or voting) represents a practical direction for future work, as it can combine the outputs of both modalities to resolve ambiguities inherent in single-source detection and improve the overall robustness of runtime container analysis.

In this study, we monitored both system calls and network flows using eBPF-based tools to observe container behavior at runtime. The collected data were subjected to ML-based multi-class classification, demonstrating that detailed and behavior-specific detection of containers is feasible. Experimental results showed that host-based monitoring achieved a maximum accuracy of 98.39%, while network flow-based monitoring reached 87.49%. A comparison of confusion matrices for the best-performing DT model further revealed that, although Coinminer samples were misclassified under flow-based analysis whereas system-call analysis distinguished them correctly, overall per-class classification patterns remained consistent across both modalities. However, when different malware families communicate with attacker servers in highly similar ways, flow-based information alone was insufficient to discriminate between agent-type trojans and Coinminer behavior. In such cases, incorporating host-level information can enhance detection precision.

Flow-based detection relies on packet metadata and therefore cannot identify attacks embedded within packet payloads. While this limits its ability to detect post-intrusion activities, it can still reveal anomalies through inter-container communication patterns or interactions with external endpoints. Conversely, host-based detection effectively identifies malware activities by monitoring internal container operations in real time, but it provides limited insight into network-specific behaviors. Furthermore, detailed analysis of real-world network flows remains constrained because packet payloads are not captured. Hence, flow-based and host-based information should be used complementarily: depending on container behavior, the data source that offers the most discriminative features may differ, and discrepancies between the two can serve as additional cues for verification.

Accurate runtime detection of malicious containers can reduce Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) and enable proactive responses before malicious behaviors escalate, contributing to the stability of containerized environments. The eBPF-based monitoring approach proposed in this work can be extended to detect various types of malware containers. Furthermore, because the framework deploys eBPF-based monitoring tools (bpfFlowMon and Tetragon) as DaemonSets, it is naturally applicable to multi-node Kubernetes clusters. However, in such distributed environments, pods may be dynamically rescheduled across nodes, requiring continuous tracking to maintain temporal consistency of container behavior. This necessitates a monitoring pipeline capable of aggregating and correlating large volumes of flow and system-call data across nodes without introducing latency. Future work will focus on expanding the spectrum of threats detectable at runtime and developing efficient, multi-source monitoring mechanisms suitable for large-scale, complex containerized infrastructures.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is partly supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00351898 and No. RS-2025-02263915), the MOTIE under Training Industrial Security Specialist for High-Tech Industry (RS-2024-00415520) supervised by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT), and the MSIT under the ICAN (ICT Challenge and Advanced Network of HRD) program (No. IITP-2022-RS-2022-00156310) supervised by the Institute of Information & Communication Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jeongeun Ryu, Riyeong Kim, Hyunwoo Choi, and Seongmin Kim; methodology, Jeongeun Ryu, Riyeong Kim, and Seongmin Kim; software, Jeongeun Ryu, Riyeong Kim, and Soomin Lee; validation, Jeongeun Ryu, Hyunwoo Choi, and Seongmin Kim; investigation, Soomin Lee and Sumin Kim; data curation, Jeongeun Ryu and Soomin Lee; writing—original draft preparation, Jeongeun Ryu and Seongmin Kim; writing—review and editing, Jeongeun Ryu, Hyunwoo Choi, and Seongmin Kim; project administration, Seongmin Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Haugeland SG, Nguyen PH, Song H, Chauvel F. Migrating monoliths to microservices-based customizable multi-tenant cloud-native apps. In: 2021 47th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 170–7. doi:10.1109/SEAA53835.2021.00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Amazon Web Services. AWS Lambda Documentation [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/lambda/. [Google Scholar]

3. Netflix. Netflix OSS [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://netflix.github.io/. [Google Scholar]

4. Nadareishvili I, Mitra R, McLarty M, Amundsen M. Microservice architecture: aligning principles, practices, and culture. Sebastopol, CA, USA: O’Reilly Media, Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

5. Bhardwaj A, Krishna CR. Virtualization in cloud computing: moving from hypervisor to containerization—a survey. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46(9):8585–601. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-05553-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Docker. Docker Hub [Internet]. [cited 2025 May]. Available from: https://hub.docker.com/. [Google Scholar]

7. Red Hat. The state of Kubernetes security report: 2024 edition [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://www.redhat.com/en/engage/state-kubernetes-security-report-2024. [Google Scholar]

8. Red Hat. Clair [Internet]. GitHub; 2015 [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://github.com/quay/clair. [Google Scholar]

9. Aqua Security. Trivy [Internet]. GitHub; 2019 [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://github.com/aquasecurity/trivy. [Google Scholar]

10. Nousias A, Katsaros E, Syrmos E, Radoglou-Grammatikis P, Lagkas T, Argyriou V, et al. Malware detection in docker containers: an image is worth a thousand logs. arXiv:250403238. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2504.03238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Debar H, Dacier M, Wespi A. Towards a taxonomy of intrusion-detection systems. Comput Netw. 1999;31(8):805–22. doi:10.1016/s1389-1286(98)00017-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zehra S, Syed HJ, Samad F, Faseeha U, Ahmed H, Khan MK. Securing the shared kernel: exploring kernel isolation and emerging challenges in modern cloud computing. IEEE Access. 2024;12:179281–317. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3507215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Castanhel GR, Heinrich T, Ceschin F, Maziero C. Taking a peek: an evaluation of anomaly detection using system calls for containers. In: Proceedngs of the 2021 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC); 2021 Sep 5–8; Athens, Greece: IEEE. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/iscc53001.2021.9631251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Karn RR, Kudva P, Huang H, Suneja S, Elfadel IM. Cryptomining detection in container clouds using system calls and explainable machine learning. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2020;32(3):674–91. doi:10.1109/tpds.2020.3029088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Araujo I, Vieira M. Enhancing intrusion detection in containerized services: assessing machine learning models and an advanced representation for system call data. Comput Secur. 2025;154:104438. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2025.104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Aly A, Hamad AM, Al-Qutt M, Fayez M. Real-time multi-class threat detection and adaptive deception in Kubernetes environments. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):8924. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-91606-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kim R, Ryu J, Kim S, Lee S, Kim S. Detecting cryptojacking containers using eBPF-based security runtime and machine learning. Electronics. 2025;14(6):1208. doi:10.3390/electronics14061208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tunde-Onadele O, Lin Y, Gu X, He J, Latapie H. Self-supervised machine learning framework for online container security attack detection. ACM Trans Autonom Adapt Syst. 2024;19(3):1–28. doi:10.1145/3665795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. El Khairi A, Caselli M, Knierim C, Peter A, Continella A. Contextualizing system calls in containers for anomaly-based intrusion detection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 on Cloud Computing Security Workshop (CCSW 2022). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 9–21. doi:10.1145/3560810.3564266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Cao C, Blaise A, Verwer S, Rebecchi F. Learning state machines to monitor and detect anomalies on a kubernetes cluster. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 1–9. doi:10.1145/3538969.3543810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Elastic. Beats [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 12]. Available from: https://www.elastic.co/docs/reference/beats. [Google Scholar]

22. eBPF [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 29]. Available from: https://ebpf.io/. [Google Scholar]

23. Pinnapareddy NR. eBPF for high-performance networking and security in cloud-native environments. Int J Sci Res Arch. 2025;15(2):207–25. doi:10.30574/ijsra.2025.15.2.1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sadiq A, Syed HJ, Ansari AA, Ibrahim AO, Alohaly M, Elsadig M. Detection of denial of service attack in cloud based kubernetes using eBPF. Appl Sci. 2023;13(8):4700. doi:10.3390/app13084700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Her J, Kim J, Kim J, Lee S. An in-depth analysis of eBPF-based system security tools in cloud-native environments. IEEE Access. 2025;13:155588–604. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3605432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sysdig. 2025 Cloud-native security and usage report [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://sysdig.com/2025-cloud-native-security-and-usage-report/. [Google Scholar]

27. Orca Security. 2024 State of Cloud Security Report [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://orca.security/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/2024-State-of-Cloud-Security-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

28. Yasrab R. Mitigating docker security issues. arXiv:180405039. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1804.05039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sysdig. 2022 Cloud-Native Security and Usage Report [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: https://sysdig.com/2022-cloud-native-security-and-usage-report/. [Google Scholar]

30. Darktrace. Uncovering the Sysrv-Hello Crypto-Jacking Bonet [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.darktrace.com/blog/worm-like-propagation-of-sysrv-hello-crypto-jacking-botnet. [Google Scholar]

31. Tekiner E, Acar A, Uluagac AS, Kirda E, Selcuk AA. SoK: cryptojacking malware. In: 2021 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 120–39. doi:10.1109/eurosp51992.2021.00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Moriconi F, Neergaard AI, Georget L, Aubertin S, Francillon A. Reflections on trusting docker: invisible malware in continuous integration systems. In: 2023 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 219–27. doi:10.1109/SPW59333.2023.00025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Soldani D, Nahi P, Bour H, Jafarizadeh S, Soliman MF, Di Giovanna L, et al. eBPF: a new approach to cloud-native observability, networking and security for current (5 g) and future mobile networks (6 g and beyond). IEEE Access. 2023;11:57174–202. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3281480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bachl M, Fabini J, Zseby T. A flow-based IDS using Machine Learning in eBPF. arXiv:210209980. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2102.09980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tetragon. eBPF-based Security Observability and Runtime Enforcement [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 11]. Available from: https://tetragon.io/. [Google Scholar]

36. mattereppe. bpfFlowMon [Internet]. GitHub; 2021 [cited 2024 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/mattereppe/bpf_flowmon. [Google Scholar]

37. Liu J, Simsek M, Kantarci B, Bagheri M, Djukic P. Collaborative feature maps of networks and hosts for AI-driven intrusion detection. In: GLOBECOM 2022-2022 IEEE Global Communications Conference. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 2662–7. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM48099.2022.10000985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sharma R, Guleria A, Singla R. An overview of flow-based anomaly detection. Int J Commun Netw Distrib Syst. 2018;21(2):220–40. doi:10.1504/ijcnds.2018.094221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Falco. The Falco Project [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jul 20]. Available from: https://falco.org/docs/. [Google Scholar]

40. Brown T. Linux-malware [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 30]. Available from: https://github.com/timb-machine/linux-malware/tree/main/malware/binaries. [Google Scholar]

41. XMRig [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 15]. Available from: https://hub.docker.com/r/miningcontainers/xmrig. [Google Scholar]

42. xmr-stak-cpu [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 15]. Available from: https://hub.docker.com/r/timonmat/xmr-stak-cpu/. [Google Scholar]

43. CloudSuite [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 15]. Available from: https://github.com/parsa-epfl/cloudsuite. [Google Scholar]

44. MariaDB [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 15]. Available from: https://hub.docker.com/_/mariadb. [Google Scholar]

45. Kopytov A. sysbench [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 6]. Available from: https://github.com/akopytov/sysbench. [Google Scholar]

46. Minikube. Welcome! [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 Aug 15]. Available from: https://minikube.sigs.k8s.io/docs/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools