Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Syntactic and Socially Responsible Machine Translation: A POS and DEP Integrated Framework for English–Tamil

Department of Information Technology, School of Computer Science and Engineering, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram Campus, Chennai, India

* Corresponding Author: Rama Sugavanam. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 97 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2026.071469

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 06 January 2026; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

When performing English-to-Tamil Neural Machine Translation (NMT), end users face several challenges due to Tamil’s rich morphology, free word order, and limited annotated corpora. Although available transformer-based models offer strong baselines, they compromise syntactic awareness and the detection and management of offensive content in cluttered, noisy, and informal text. In this paper, we present POSDEP-Offense-Trans, a multi-task NMT framework that combines Part-of-Speech (POS) and Dependency Parsing (DEP) methods with a robust offensive language classification module. Our architecture enriches the Transformer encoder with syntax-aware embeddings and provides syntax-guided attention mechanisms. The architecture incorporates a structure-aware contrastive loss that reinforces syntactic consistency and deploys auxiliary classification heads for POS tagging, dependency parsing, and multi-class offensive detection. The classifier for offensive words operates at both sentence and token levels and obtains guidance from syntactic features and formal finite automata rules that model offensive language structures-hate speech, profanity, sarcasm, and threats. Using this architecture, we construct a syntactically enriched, socially annotated corpus. Experimental results show improvements in translation quality, with a BLEU score of 33.5, UAS/LAS parsing accuracies of 92.4% and 90%, and a 4.5% F1-score gain in offensive content detection compared with baseline POS + DEP + Offense models. Also, the proposed model achieved 92.3% in offensive content neutralization, as confirmed by ablation studies. This comprehensive English–Tamil NMT model that unifies syntactic modelling and ethical filtering—laying the groundwork for applications in social media moderation, hate speech mitigation, and policy-compliant multilingual content generation.Keywords

The emergence of multilingual digital platforms and user-generated content has accelerated the demand for reliable and culturally sensitive machine translation (MT) systems. India is a linguistically diverse nation that encounters several language-related challenges. Although the country’s linguistic landscape is vast, it also encompasses numerous low-resource languages and dialects. Among these languages, Tamil, one of the foremost classical South Indian languages, with complex morphology and rich syntactic structure, presents one of the most difficult cases for precise NMT. English–Tamil translation is challenging due to the contrasting linguistic typology: English follows a subject-verb-object (SVO) word order and exhibits low inflection, whereas Tamil employs a subject-object-verb (SOV) order, high inflection, and agglutinative morphology.

State-of-the-art NMT systems, such as Transformer-based models [1], mBART [2], and mT5 [3], demonstrate remarkable improvements in high-resource language pairs. However, their reliability significantly degrades for English–Tamil translation, particularly when processing social media content that is often code-mixed (e.g., Tanglish), cluttered, noisy, or offensive. Due to differences in syntactic structure, these models find it difficult to translate into divergent language pairs.

Another prominent emerging issue is identifying highly offensive toxic content, and NMT systems trained on large web-scale datasets often translate harmful content without adherence. While some prior work has attempted post hoc filtering or adversarial training, these methods lack linguistic granularity and fail to identify implicit, structure-dependent offensive content. For example, the sentence: “You people are a disease” may be grammatically correct, yet it is contextually toxic. To overcome such challenges, there is a need for a model that integrates offensive language detection and rewrites directly into the translation pipeline—with a syntactically grounded mechanism for ethical filtering.

In this paper, we propose PoSDEP-Offense-Trans, a novel syntax-aware, ethically informed, multi-tasking NMT framework tailored for English–Tamil translation. The architecture enriches the input representation with PoS and dependency parsing features and jointly trains the model on translation, syntactic tagging, and fine-grained offensive-language classification. During translation, it detects offensive content at both the sentence and token levels. Based on the detection, where applicable, it rewrites the sentence using a masked language model to preserve semantic meaning while reducing toxicity. To optimize this multi-objective training paradigm, we employ gradient normalization (GradNorm) to balance task losses dynamically.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses related work; Section 3 describes the proposed model and methodology; Section 4 explains the dataset and annotation strategy; Section 5 presents the experimental results; and Section 6 concludes with future research directions.

NMT for English–Tamil presents challenges due to Tamil’s morphological richness and syntactic divergence. Traditional statistical and phrase-based systems are limited in modeling agglutinative structures. Recent neural models, such as Transformer-based architectures [1] and BPE-enhanced NMT [2], have improved translation quality; AI4Bharat’s IndicTrans [3] advanced translation for Indian languages, including Tamil, through multilingual training. Meta’s NLLB model [4] extended to support multilingual zero-shot translation for more than 200 languages, including Tamil.

Neuro-symbolic methods have been introduced to address semantic fidelity in low-resource settings, particularly in sensitive domains, such as child-oriented content [5]. EnTam v2.0 (Charles University/UFAL) [6], an English–Tamil parallel corpus annotated across multiple domains-Bible, cinema, and news. These methods fail to consider syntactic guidance.

Linguistic features are incorporated into the encoder input [7] to improve translation. Applying Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to dependency trees improves translation in morphologically rich languages [8]. Later, Syntax-aware attention with structural bias was proposed [9] to improve translation quality.

Recent studies have extended syntax integration using tree-based and hierarchical models, employing a tree encoder [10] with attention-head-aware translations. Following tree encoders, hierarchical syntax modules [11] were suggested for morphologically complex languages. Despite these variations, English-Tamil translation remains underexplored. The proposed model addresses this gap by embedding syntactic features in both the encoder and decoder components.

Offensive language detection in culturally sensitive regions is crucial to address the proliferation of toxic discourse on digital platforms. The HASOC 2019 shared task [12] and DravidianCodeMix 2021 [13] have contributed annotated datasets for offensive language classification. YouTube comments are annotated for English, Tamil [14,15], and mixed-code texts [16], and they are classified as containing hate and profanity.

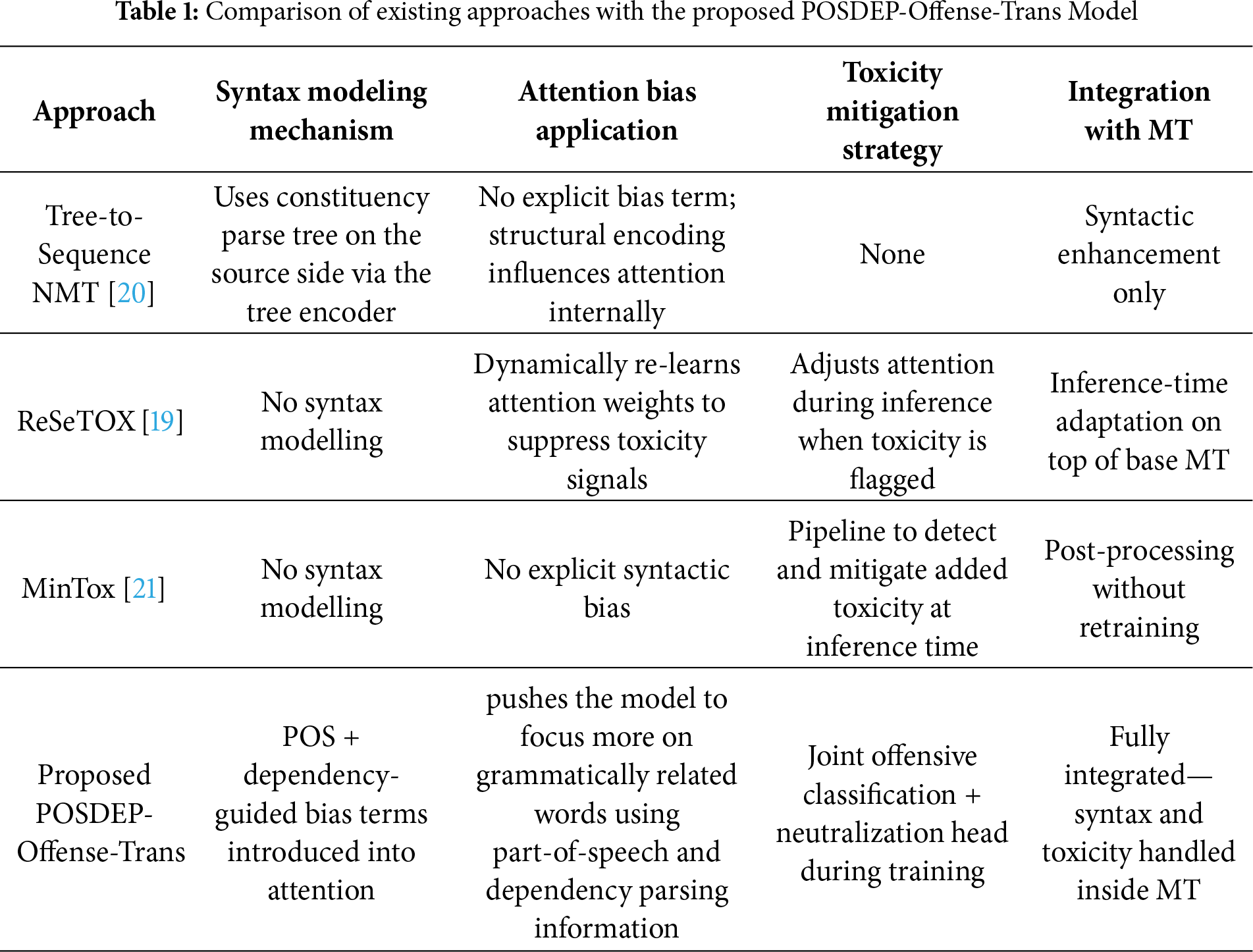

Toxicity based on religion, caste, and gender-based hate abuses is benchmarked by [17] for region-based offense detection. ANSR@DravidianLangTech 2025 [18] achieved macro-F1 scores over 0.73 using cost-sensitive learning. Keyword-level filtering methods [19] and post-editing strategies have been attempted, but lack deep syntactic or semantic integration, and various offenses require attention. The proposed model uniquely performs multi-class offensive classification within the NMT framework. Table 1 highlights existing syntax- and toxicity-aware MT approaches, whereas the proposed POSDEP-Offense-Trans unifies syntactic biasing and offensive-content handling within a single multitask MT framework.

Multi-task learning (MTL) enables shared representations across tasks, such as translation, tagging, and classification [22] showed improvements through joint learning of syntax and translation. Adapter-based multitask training further generalized across benchmarks [23]. Loss-balancing techniques, such as GradNorm [24] and uncertainty weighting [25], stabilized convergence in multi-head architectures.

3 Architecture and Methodology

In this paper, we propose PoSDEP-Offense-Trans, a unified multi-tasking Transformer-based architecture designed to improve English-to-Tamil neural machine translation through syntactic supervision and offensive content understanding. The model jointly performs:

• English-to-Tamil translation

• PoS tagging

• Dependency parsing

• Offensive content classification

This multi-tasking structure improves generalization and robustness, especially in morphologically rich and socially sensitive contexts.

3.1 Overview of the Proposed System

At its core, the architecture is built on the multilingual IndicTrans2 Transformer model, which supports multiple Indian languages, including Tamil. We enhance the base model with syntactic and semantic signals derived from PoS tags and dependency (DEP) relations. Further, we introduce an auxiliary task of multi-class offensive content classification, thereby allowing the model to avoid or appropriately translate ethically sensitive content.

Each input token is a combination of four distinct embeddings:

where:

• Etok [i] is the token embedding obtained via a SentencePiece tokenizer trained with 32 K merge operations.

• Epos [i] is a learned embedding corresponding to the POS tag assigned to the token (from spaCy for English and ThamizhiUD for Tamil).

• Edep [i] corresponds to the dependency relation of the token.

• Eposition [i] is a standard sinusoidal positional encoding used in Transformer architectures.

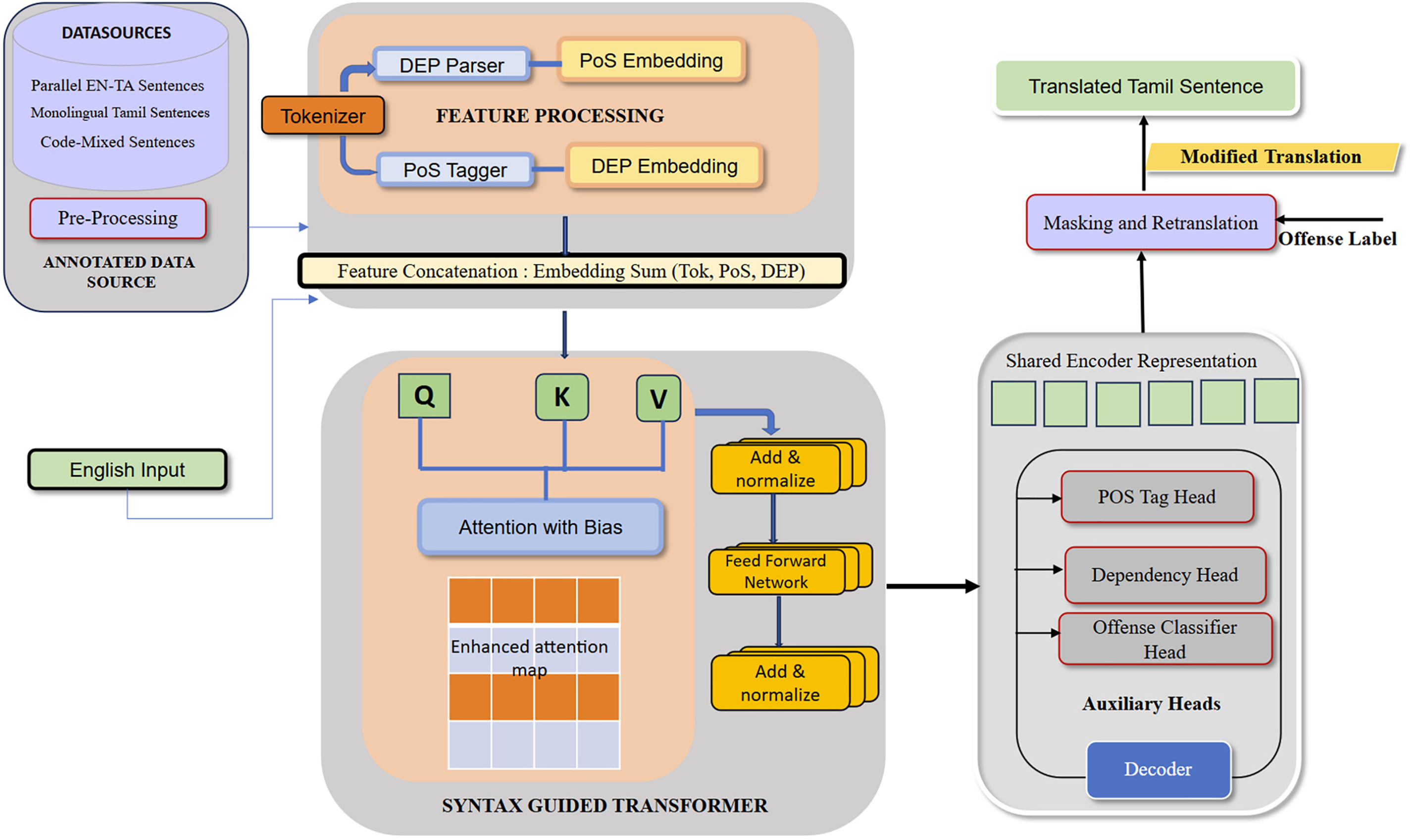

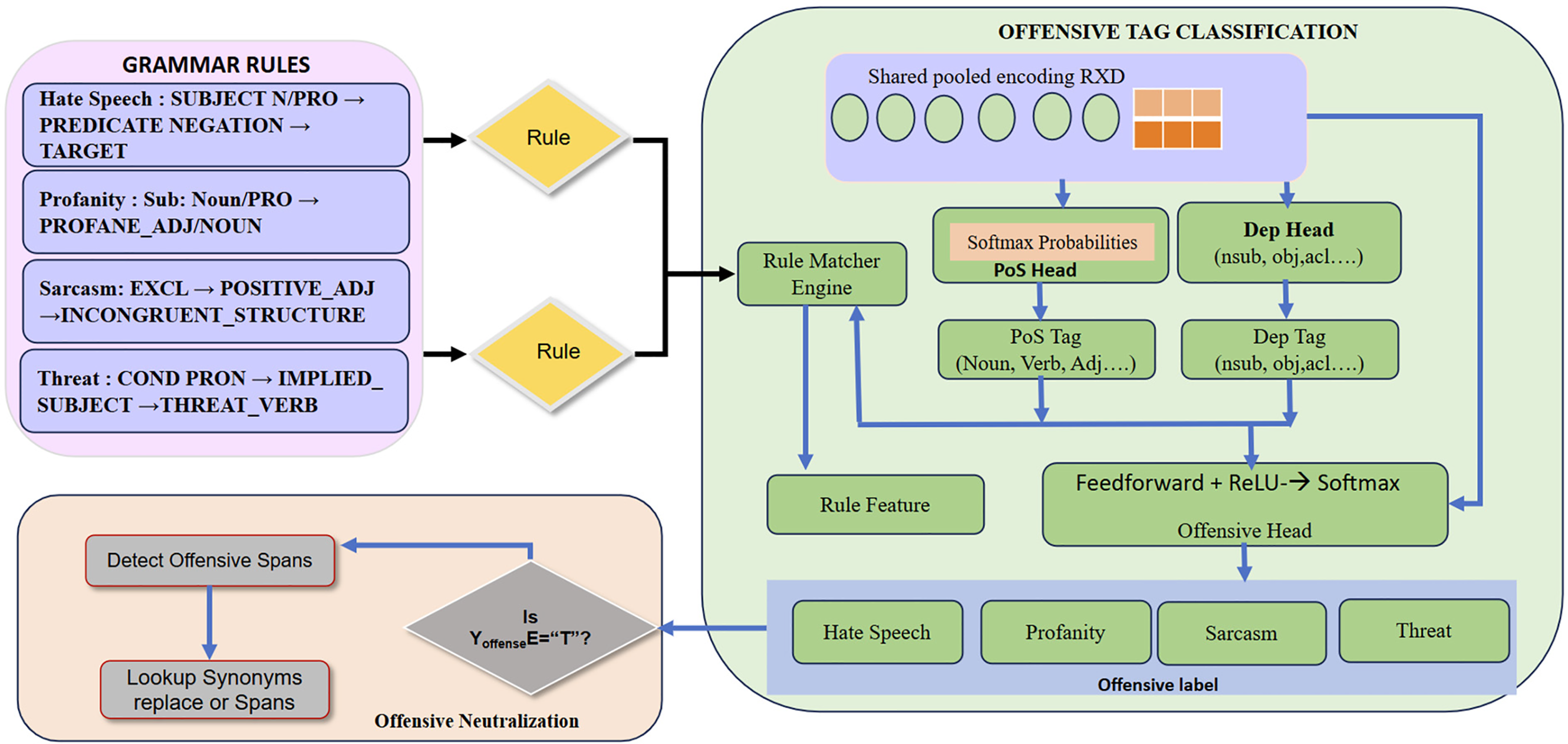

This architecture enables joint optimization of linguistic accuracy and social appropriateness, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overall architecture

This enriched representation enables the encoder to process both the sentence’s surface form and its underlying syntactic structure. The encoder comprises 12 Transformer layers, each containing self-attention and feed-forward sublayers, augmented with syntax-guided bias terms. The decoder structure is similar and includes masked self-attention and cross-attention to the encoder outputs, enabling Tamil translation with teacher forcing during training and the sequential production of translated tokens.

Three additional output heads are introduced:

• A PoS tag predictor trained using cross-entropy loss on PoS annotations.

• A dependency parser using biaffine classifiers to predict head-dependent relations.

• A multi-class classifier for offensive content categories: hate-speech, profanity, sarcasm, and threats.

The scope here has been restricted to four categories based on the high-prevalence corpora and the availability of annotated data. Although offensive language can vary in intensity (e.g., mild vs. strong profanity, implicit vs. explicit hate), these four categories ensure both data quality and balanced coverage, supporting a stable baseline and enabling more fine-grained taxonomies in future work.

This component further empowers the conventional Transformer self-attention mechanism by integrating syntactic knowledge, specifically PoS and dependency relations, guiding attention toward linguistically significant tokens. The Transformer encoder–decoder framework utilizes stacked self-attention and feed-forward layers to model long-range dependencies without recurrence [10]. For an input sequence X = {x1, …, xT}, token embeddings are first augmented with sinusoidal positional encodings to yield the final embeddings. The scaled dot-product self-attention is then computed as:

In Eq. (2), Q, K, and V are linear projections of the hidden states, and dk is the key dimension. When stacking multi-head variants of this operation, the model attends to information from multiple representation sub-spaces.

To ensure the attention is syntax-aware, two bias terms are derived from PoS tag relationships and dependency arcs. Then the attention is modified as:

where:

These biases guide the model to align syntactically related tokens far more strongly by preserving grammatical structure across source and target languages.

3.1.2 Syntax-Aware Contrastive Learning with Offense Classification

For each input, representations from context-aware attention are aligned with their PoS/DEP tags and scored, enabling the model to differentiate between classes. For example, the model can distinguish between an insult as an object and the same word as a part of figurative or general speech.

Given a sentence z and a syntactic variant z′, we require that their embeddings should be closer in representation space than unrelated sentences. This contrastive learning encourages the encoder to generalize across syntactic variations while discriminating against irrelevant content, thereby improving robustness to stylistic shifts and offensive language. The loss function for this contrastive learning is defined in Eq. (4).

z′: Syntactic variant of x, e.g., with clause reordering or passive conversion.

zk: Distractor sentence (negative sample).

τ: Temperature hyperparameter.

This loss improves structural robustness in encoder representations.

The total training loss combines translation and auxiliary objectives that are jointly minimized as follows:

where,

•

•

•

•

•

Dynamic weight tuning is implemented using GradNorm [24]. To maintain equal gradient norms, the weights are adjusted during training. This strategy enables the model to learn context, translate fluently given the syntax, and detect offensiveness without sacrificing accuracy on any individual task.

Our multi-task setup is trained on a mixed dataset combining parallel corpora with syntactic annotations and offensive labels. The learning rate is scheduled using an inverse-square-root decay schedule, and dropout is applied at each sublayer. Training is conducted on 4× A100 GPUs with mixed precision for 20 epochs.

When combined and implemented, these enhancements position the model to outperform traditional NMT systems in low-resource, syntactically flexible, and socially nuanced translation tasks, such as English-to-Tamil with offense mitigation.

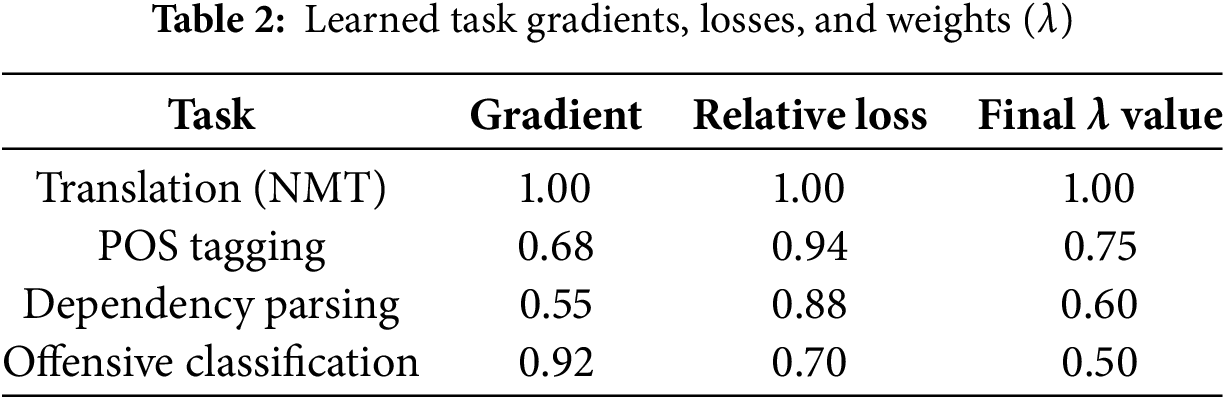

In our setup, we train five tasks: translation, PoS tagging, dependency parsing, offensive classification, and contrastive learning. Each of these tasks differs in scale and difficulty.

When we apply GradNorm:

• The translation task remains the primary task (highest λ1 = 1.0).

• The PoS and dependency tasks are computed and weighted to capture the syntax efficiently without impacting the model.

• The offensive classification head, while important, is down-weighted at an acceptable level to reduce noise and overfitting on sparsely labelled data.

• The contrastive learning head is lightly weighted but still contributes to semantic stability and robustness.

This automatic balancing leads to stable training and better convergence across all tasks, ultimately improving generalization to syntactically varied and socially sensitive English–Tamil inputs. Table 2 presents the relative gradient values for the translation task, the normalized loss, and the final learned weight values.

So, final recommended λ values using GradNorm: λ1 = 1.0, λ2 = 0.75, λ3 = 0.60, λ4 = 0.50, λ5 = 0.45.

3.2 Offensive Language Classification Head

The offensive language classification component of the POSDEP-Offense-Trans model is designed to identify and categorize offensive content during English-to-Tamil translations. In contrast to traditional binary detection approaches that invariably classify content as offensive or non-offensive, our model adopts a multi-class framework, enabling differentiation among categories of offensive language. This framework includes:

• Hate Speech (racist, ethnic, and communal slurs)

• Profanity (vulgar, explicit language)

• Sarcasm (indirect, mocking tone with offensive implications)

• Threats (direct or implied harm, violence)

This multi-class approach is essential in multilingual and multicultural contexts for languages like Tamil. For example, Tamil is a language in which offensive expressions vary widely across categories and require careful handling to maintain the ethical integrity of machine-translated output.

Architecture of the Classification Head

The offensive classification head is attached to the Transformer encoder and operates on the sentence-level representation produced by the final encoder layer. The architecture comprises the following layers:

• Pooled Encoder Representation: A mean-pooling operation is applied across the encoder tokens. Its embeddings are defined as:

where hi is the token embedding for token i in the sentence of length n.

• Feedforward Network: The pooled vector

• Softmax Output Layer: The output is fed into a softmax classifier to predict one of the predefined offensive classes:

• Loss Function

The model is trained using categorical cross-entropy loss:

where by

C: number of offensive categories

yc: one-hot encoded ground truth label

Offensive classification is trained jointly with translation and syntactic tasks using multi-task learning. The corresponding task weight, λ4, in the composite loss function is dynamically tuned via GradNorm. The offensive head learns class-discriminative syntactic and semantic features, allowing the model to distinguish between various racist, ethnic, and communal slurs, hate terms, vulgar language, implicit sarcasm, and explicit threats.

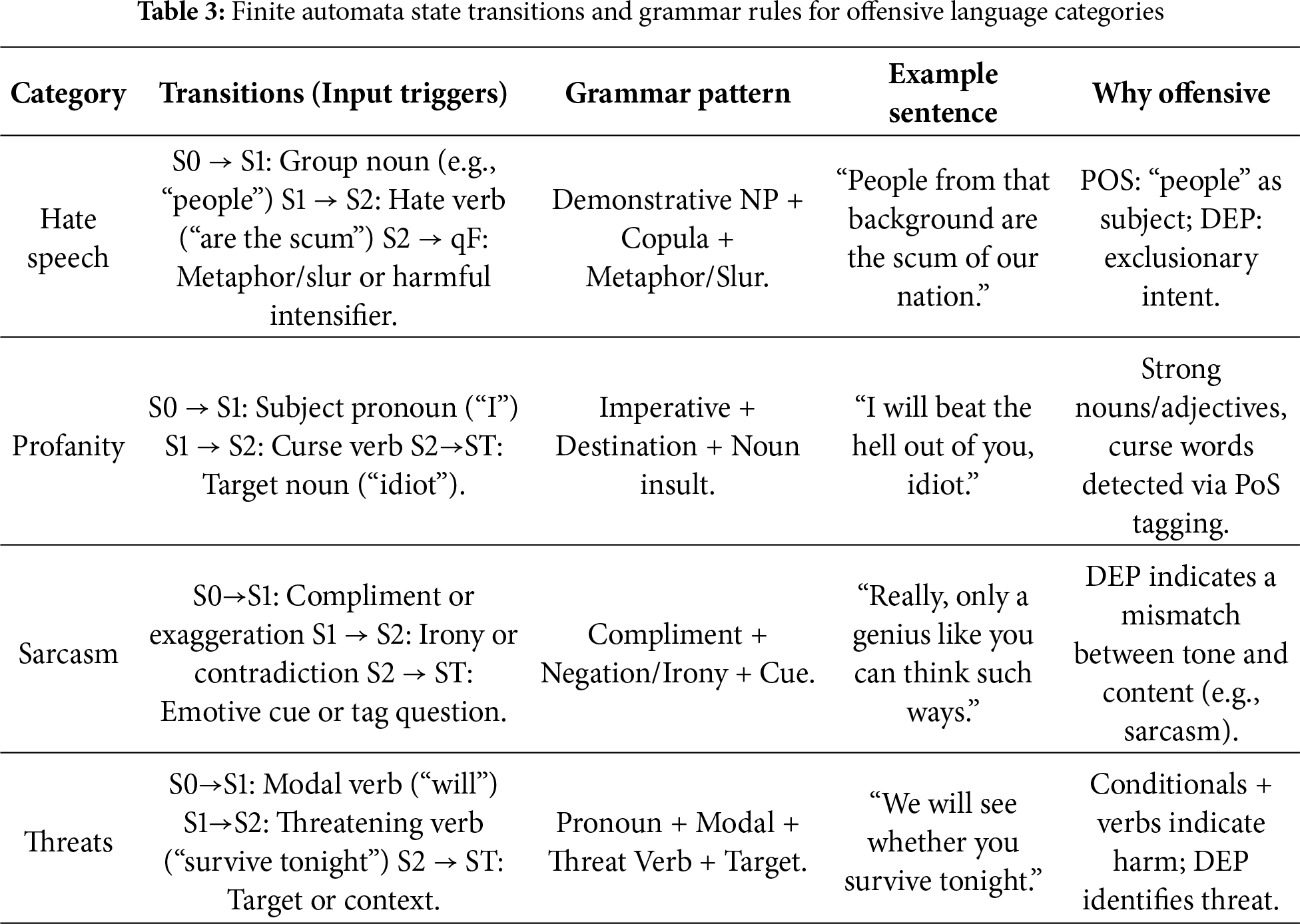

3.3 Finite-State Modelling of Offense Classes

To further enhance interpretability and rule-based validation in offensive content classification, we have defined a grammar-based structure for each offensive language category within our model—namely, Hate Speech, Profanity, Sarcasm, and Threats. These aid in identifying syntactic and semantic structures associated with each type of offensive expression and support training supervision, contrastive loss alignment, and post-inference interpretability. Representation of these grammar rules is defined using automata theory in Table 3.

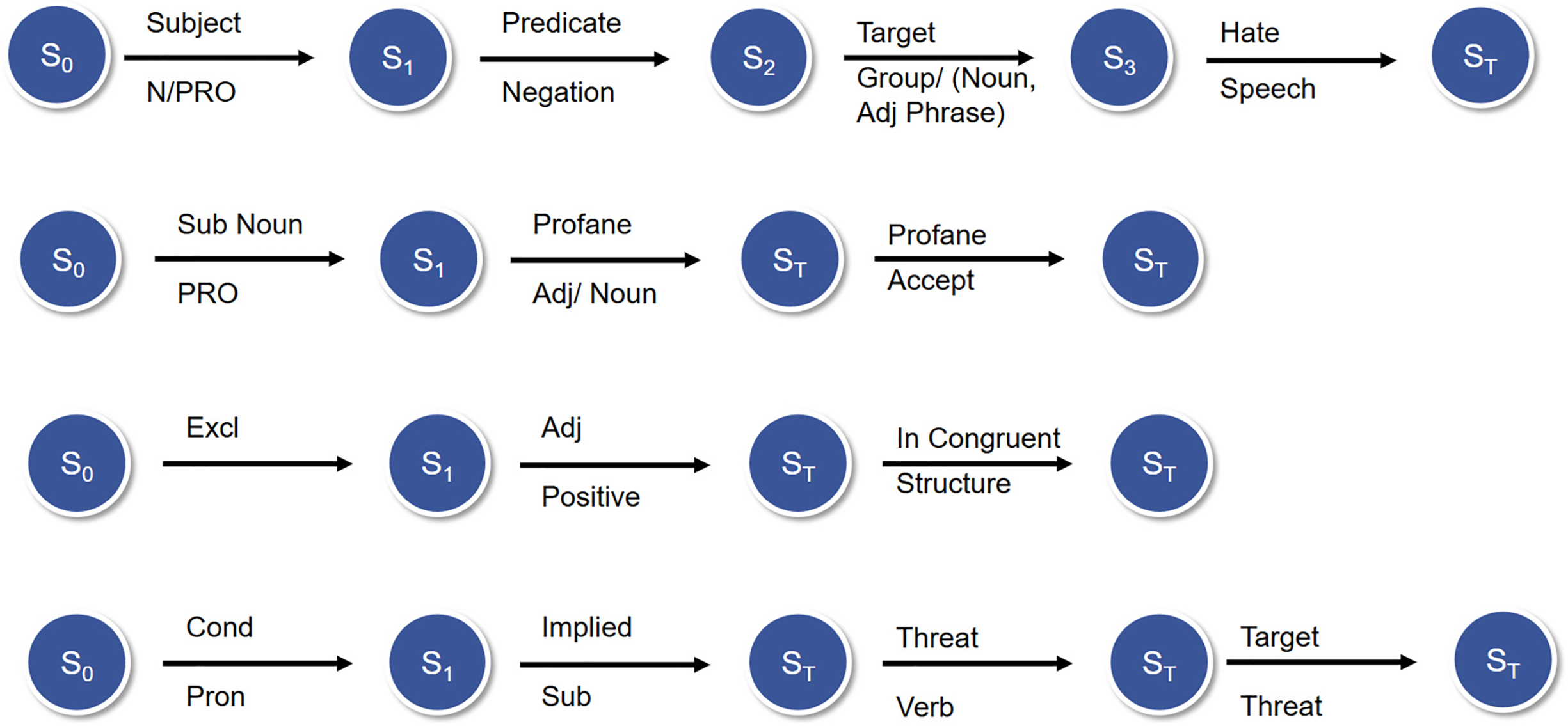

These grammars function as structured representations of syntactic patterns typical of offensive expressions, enabling the neural model to capture nuanced linguistic signals. Based on parts of speech (e.g., nouns, verbs, modals) and dependency relations (e.g., subjects, objects), a rule-based approach is used to identify hate speech, profanity, sarcasm, and threats. During training, these formal structures enhance supervision and guidance for contrastive learning and for aligning offensive classes with specific syntactic templates. These general grammar rules for the classifications are represented as finite automata, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Grammar rules and transitions

The grammar rule for offensive classification is defined as

(i) Hate Speech

S0 → S1 (SUBJECT N/PRO) → S2 (PREDICATE NEGATION) → S3 (TARGET GROUP/ADJ_PHRASE) → ST

S1 state is defined as SUBJ, the speaker is referring to a subject that’s either a noun phrase (NP_SUBJECT) or a pronoun (PRON_SUBJECT). S2 transition is marked as NEGATED_VERB—The predicate (verb phrase) has a negation marker such as don’t, can’t, shouldn’t, or explicitly negative verbs like ban, exclude. S3 is defined as TARGET_GROUP → A social group, ethnicity, gender, religion, or similar group noun, sometimes modified by an adjective phrase.

(ii) Profanity

S0 → S1 (Sub: Noun/PRO) → ST (PROFANE_ADJ/NOUN)

In S1, the PRONOUN directly addresses someone (you, he, she, they), and the identification of PROFANE_TERM, which has an Adjective Insult (stupid, dumb) or a noun insult (idiot, moron), leads to the state target.

(iii) Sarcasm

S0 → S1 (EXCL) → S2 (POSITIVE_ADJ) → ST (INCONGRUENT_STRUCTURE)

This grammar captures tone reversal, in which the state begins with an exclamation that functions as a positive adjective tag for the subsequent state. Then it transitions to NEG_CONTEXT in the next state, thereby contradicting the positive tone.

(iv) Threat

S0 → S1 (COND PRON) → S2 (IMPLIED_SUBJECT) → S3 (THREAT_VERB) → ST (TARGET)

State change in S1 begins with grammar CONDITIONAL_PRON (if you or when you) and then follows IMPLIED_SUBJECT, which is the explicit or implied subject of the threat for the next state, and THREAT_VERB indicating a harm or danger (hurt, kill, ruin, destroy, regret).

The use of a classification head ensures ethical alignment and helps prevent the propagation of toxic content in machine-translated output. It complements the syntactic modules by leveraging grammatical structure to detect nuanced offenses, such as sarcastic intent or implicit threats, particularly challenging in English–Tamil code-mixed and dialect-sensitive contexts. The overall offensive head operation, along with the PoS alignment, is represented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: PoSDEP-offense head operation

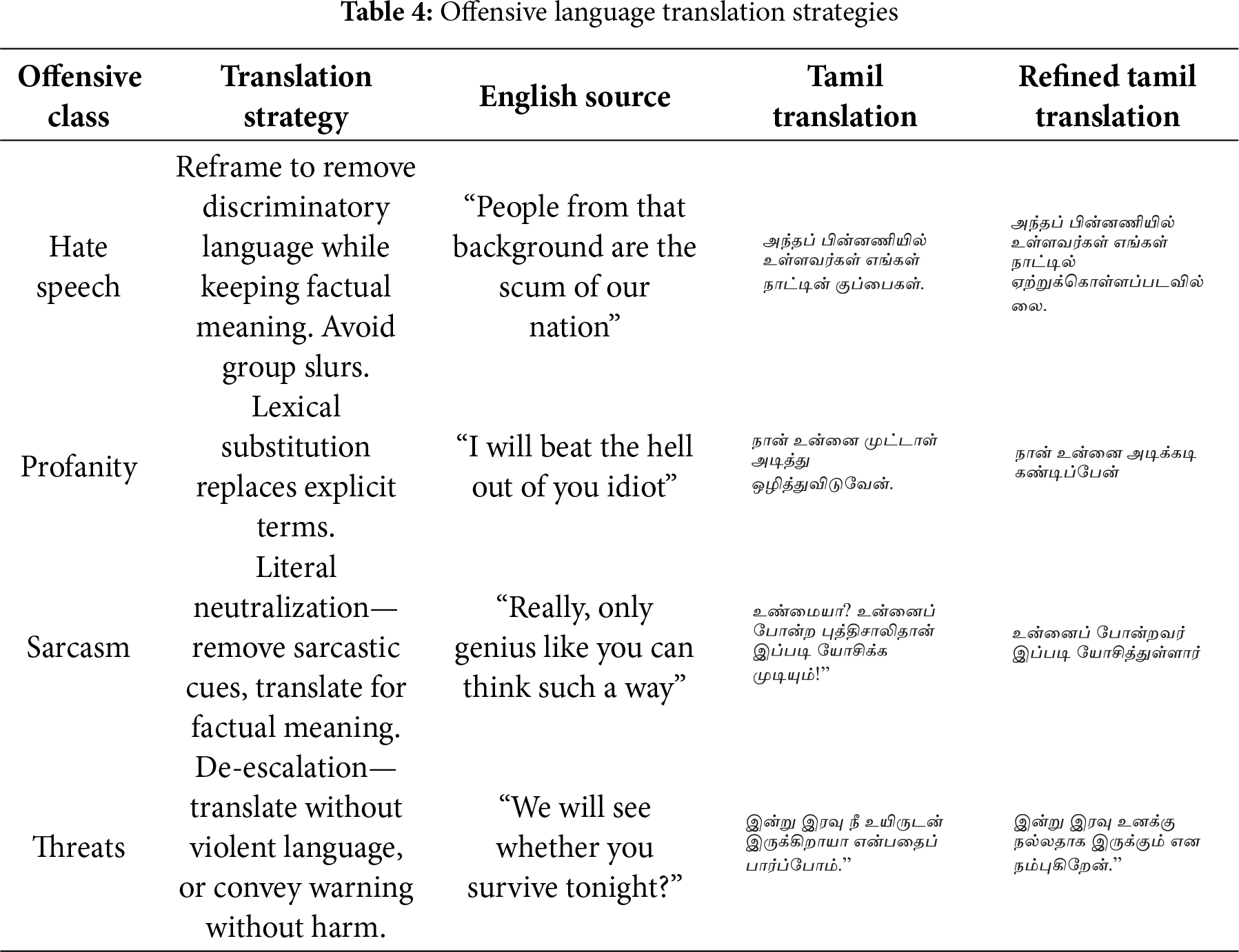

Upon identifying an offensive word, the model searches for the offensive segment in the text and neutralizes it with equivalent Tamil synonyms, producing a clean translation. This is achieved by using a simple equivalent dictionary lookup synonym, which then extracts the equivalents and provides ethically translated text. Table 4 provides the unfiltered offensive Tamil-translated text and the neutralized clean Tamil translation. A simple dictionary lookup achieves these translations. For the identified spans, equivalent replacements are sought and substituted according to the offensive class.

4 Dataset and Annotation Strategy

4.1 Source Data: English–Tamil Parallel Corpora

We have used the publicly available and curated parallel corpora:

• AI4Bharat IndicCorp v2.0 [26] and Samanantar datasets [27]: These datasets provide a high-quality parallel corpus aligned for English–Tamil, extracted from various domains including news, entertainment, government, health, and education.

• OPUS GlobalVoices [28] is a free, open-source project that enhances diversity in sentence structure, style, and lexical variety.

• We supplement all these with manually aligned code-mixed (Tanglish) [14,29] samples obtained from social media comment threads, online forums, and YouTube subtitles.

• Dravidian Codemix dataset [30], which contains Tamil-English code-mixed YouTube comments annotated for offensive language and hate speech. This dataset consists of real, noisy user-generated text in which code-switching and offensive language are frequent.

• The resulting corpus contains:

~1.8 million sentence pairs for parallel English–Tamil translation

~60,000 code-mixed Tanglish sentences

~200,000 Tamil-only monolingual sentences for back-translation

4.2 Offensive Language Annotation

To enable the detection and classification of offensive language, we design a multi-class offensive annotation protocol.

Offensive sentences are tagged into the following mutually exclusive categories:

• Hate Speech—Targeted discrimination based on religion, nationality, language, caste, ethnicity, or gender.

• Profanity—Explicit language or swearing.

• Sarcasm—Polite phrasing used with mockery or ridicule.

• Threats—Statements implying or suggesting harm.

Additionally, non-offensive content is included to maintain class balance.

Annotation Process—Initial sentence filtering using a keyword lexicon and pretrained toxicity detection models. Where about 50K offensive and 100K non-offensive samples were labelled.

Initial filtering employed a keyword lexicon and pretrained toxicity detection models. The corpus is divided into 80%, 10% and 10% for training, validation, and testing, respectively. Final labels were validated by bilingual annotators, with intercoder agreement assessed using Cohen’s κ (κ > 0.82).

4.3 Syntactic Annotation (POS and Dependency Tags)

We have used the Universal POS (e.g., NOUN, VERB, ADJ), dependency relations (e.g., nsubj, root, obj, acl) for English annotation and ThamizhiUD—a Tamil Universal Dependencies-compliant parser, which is Unicode normalized, along with a Universal dependency parser for handling code-mixed languages. These are aligned with the SentencePiece tokenizer using offset mapping.

All textual data underwent automated preprocessing:

• Text Normalization: Automated Unicode normalization and punctuation standardization

• Language Identification: Using langid.py for language filtering

• Transliteration: Rule-based engine for Romanized Tamil to Unicode conversion

• Tokenization: SentencePiece model with 32K merge operations

• Syntactic Annotation: Automated POS and dependency tagging using Universal PoS for English and ThamizhiUD for Tamil, with automatic alignment to subword tokens

The syntactic parsers demonstrated robust performance on their standard test sets:

Labelled Attachment Score (LAS) of 91.5% on Universal Dependencies. Tamil (ThamizhiUD): LAS of 89.0% on its benchmark test set. Additionally, we evaluated transliteration to Romanized Tamil Text, yielding a Character Error Rate (CER) of 3.2% and a Word Error Rate (WER) of 7.8%, indicating high-fidelity conversion suitable for model training. Language identification is performed using langid.py, which achieves 96.5% accuracy and minimizes noise.

Before training, rigorous preprocessing is applied to all textual data to ensure consistency, syntactic alignment, and robustness to noise. First, all English and Tamil texts are normalized—removing extraneous characters, correcting Unicode inconsistencies, and standardizing punctuation. The SentencePiece model is trained with 32K merge operations and then tokenizes sentences. This tokenization ensures subword segmentation suitable for morphologically rich languages like Tamil. For syntactic supervision, PoS and dependency relations are annotated using spaCy (for English) and ThamizhiUD (for Tamil), with mappings aligned to tokenized subword units. Code-mixed (Tanglish) data are transliterated from Romanized Tamil into Unicode Tamil using a rule-based engine, and language identification (via langid.py) filters out non-Tamil sequences. All offensive training samples are labelled and integrated into the corpus, ensuring that offensive content is categorized as hate speech, profanity, sarcasm, or threats. The final output is a fully tagged dataset, suitable for multi-task training involving translation, syntax modelling, and ethical content filtering.

Models are evaluated across all tasks using domain-appropriate metrics. For the English-to-Tamil translation task, we used BLEU, TER (Translation Edit Rate), and chrF++ scores, calculated using the standardized BLEU toolkit to ensure reproducibility. For the PoS tagging task, accuracy is measured at the token level. In contrast, dependency parsing performance is assessed using the Unlabelled Attachment Score (UAS) and the Labelled Attachment Score (LAS), which respectively capture the correctness of syntactic head selection and dependency label assignment. The evaluation of offensive language detection was performed using standard classification metrics—precision, recall, and F1-score—on a balanced held-out test set. To maintain consistency and avoid domain bias, all datasets were split into training, development, and test sets in an 80:10:10 ratio, with stratification by domain (e.g., formal [news and literature] versus informal [social media] text). This evaluation setup ensures a comprehensive assessment of the model’s linguistic competence and real-world adaptability.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed PoSDEP-Offense-Trans model, we conduct extensive experiments across translation quality, syntactic accuracy, and offensive language detection. We compare against several strong baselines and ablation variants to validate the impact of multi-task learning and syntactic supervision.

To thoroughly evaluate the proposed PoSDEP-Offense-Trans model, we designed an extensive experimental framework comprising translation performance, syntactic generalization, and offensive language classification. Our enhancements were integrated into five Transformer-based neural machine translation (NMT) backbones: (i) Transformer-Base—a standard 6-layer encoder-decoder model, (ii) mBART-large—a multilingual sequence-to-sequence model pretrained via denoising objectives, (iii) mT5-base—a multilingual text-to-text Transformer trained on the mC4 corpus, (iv) IndicTrans2—a Transformer optimized for Indian languages, and (v) XLM-RoBERTa (XLM-R)—a pretrained cross-lingual encoder trained on 100 languages using RoBERTa objectives. For encoder-only models like XLM-R, we used a shallow Transformer decoder for generation and added the same syntactic and classification heads. All models were enhanced with our proposed modules: token-level POS and DEP embeddings, syntax-guided attention, syntax-aware contrastive learning, and a multi-class offensive classification head.

The transformer models are trained using 4 × A100 NVIDIA GPUs with 40 GB memory each, utilizing mixed-precision training for efficiency and trained for 20 epochs with a batch size of 1024 tokens, having an Adam optimizer with β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.98, and an inverse square root learning rate schedule with 4K warm-up steps.

We used SentencePiece tokenization with 32K merge operations for both English and Tamil. PoS and DEP annotations were aligned with subword tokens using offset tracking and expansion strategies. The GradNorm method dynamically balances our multi-task loss function, which includes translation, PoS tagging, dependency parsing, offensive language classification, and contrastive objectives, thereby balancing across tasks. Additionally, we evaluate two ablation variants of our model.

To evaluate the proposed PoSDEP-Offense model, we used a set of metrics that are aligned with its multi-task objectives. The evaluation set here has been classified into four broad categories as follows:

• Machine translation quality metrics

• Syntactic evaluation metrics

• Offensive language classification metric

• Offensive language neutralization metric

5.2.1 Machine Translation Quality Metrics

These metrics assess the minimization of the primary translation loss LMT, which is the cross-entropy between the predicted sequence and the ground truth.

(i) BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy)—Measures n-gram overlap between predicted

• pn: Modified n-gram precision,

• wn: Weight for each n-gram order,

• BP: Brevity Penalty.

Interpretation: Higher BLEU indicates improved learning from LMT.

(ii) TER (Translation Edit Rate)

Measures alignment cost not captured by n-gram overlap, reflecting edit distance between output.

Lower TER indicates reduced translation errors via alignment-aware decoding and syntactic reordering.

(iii) chrF++ (Character F-score)

Measures the character-level precision and recall that minimize character loss via:

and

where: P: n-gram precision, R: n-gram recall, β = 2 gives more weight to recall.

This is particularly useful in morphological alignment.

5.2.2 Syntactic Evaluation Metrics

(iv) POS Tagging Accuracy: Percentage of correctly predicted part-of-speech tags at the token-level.

High POS accuracy indicates strong grammatical modeling, supporting more accurate syntax-aware translation.

(v) UAS (Unlabelled Attachment Score) measures the percentage of words that are correctly assigned their syntactic head in the dependency tree, ignoring the label. This score captures the structural correctness of the parse tree.

(vi) LAS (Labelled Attachment Score) measures the percentage of words that are correctly assigned both the syntactic head and the correct dependency label.

(vii) Hallucination Rate (HR) measures the proportion of tokens in the translated output that have no alignment to any token in the source sentence, with a lower HR indicating more faithful translations.

5.2.3 Offensive Language Detection Metrics

These correspond to the classification loss Loffense optimized via cross-entropy on binary labels.

(viii) Macro F1 score.

The Macro F1 Score is the arithmetic mean of the F1 scores computed independently for each class in a multi-class classification task. This score treats all classes equally, regardless of the number of samples per class.

where:

N is the number of classes (e.g., hate, sarcasm, threat, profanity, non-offensive),

F1i is the F1 score for class i, calculated as:

(ix) ROC-AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic—Area Under Curve).

A model’s ability to distinguish between classes is measured by its ROC-AUC. At different threshold levels, the model plots the True Positive Rate (Recall) against the False Positive Rate (1-Specificity). The One-vs-Rest (OvR) technique is commonly used to average across classes in multi-class problems.

5.2.4 Offensive Language Neutralization Metric

It is the ratio of offensive tokens successfully replaced with neutral Tamil synonyms to the total number of detected offensive tokens.

Our model, PoSDEP-Offense-Trans, integrates architectural and training-level variations for Syntax-Guided Attention, PoS and Dependency Parsing Heads, and Offensive Language Detection tasks. The result metrics define feature performance across various tasks.

5.3.1 Translation Results across Architectures

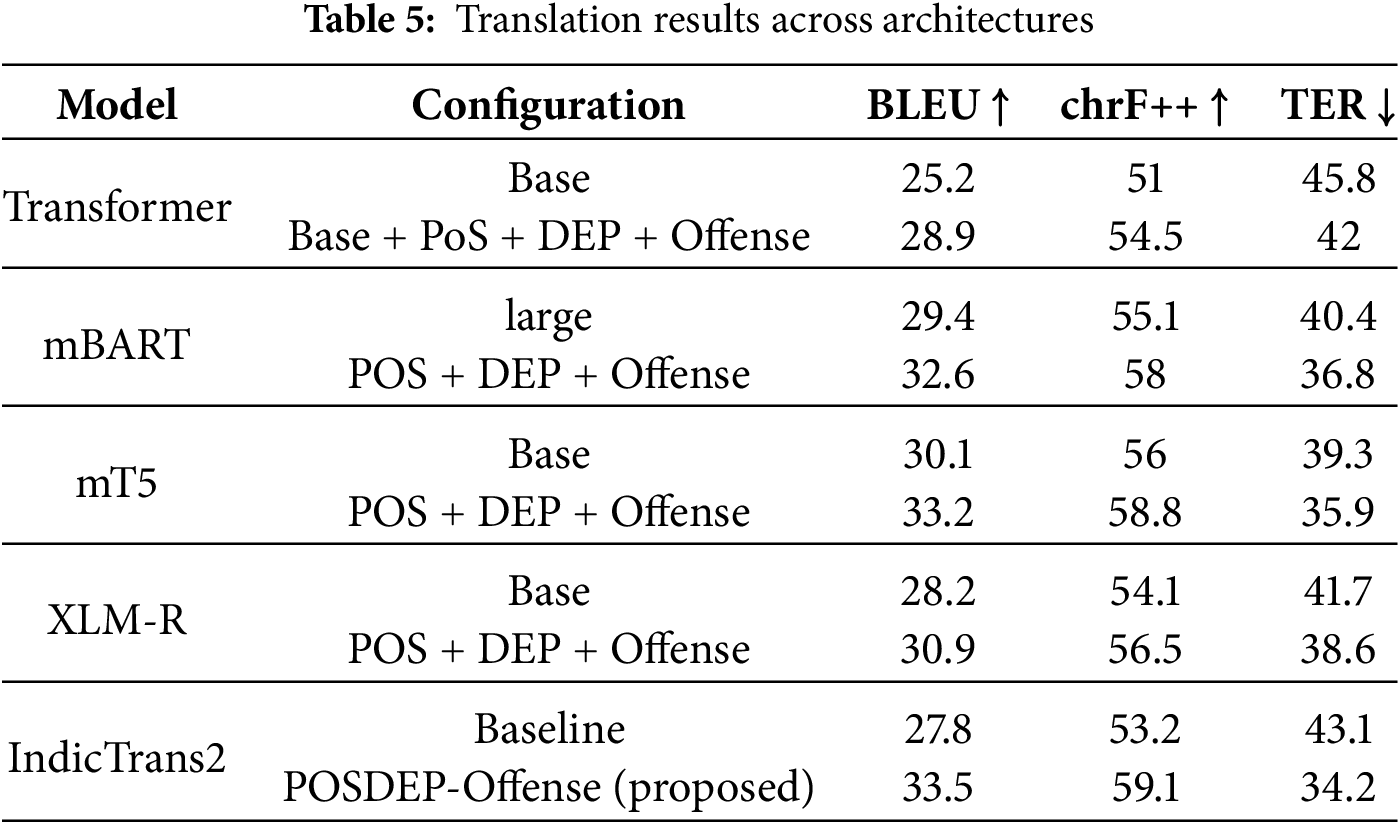

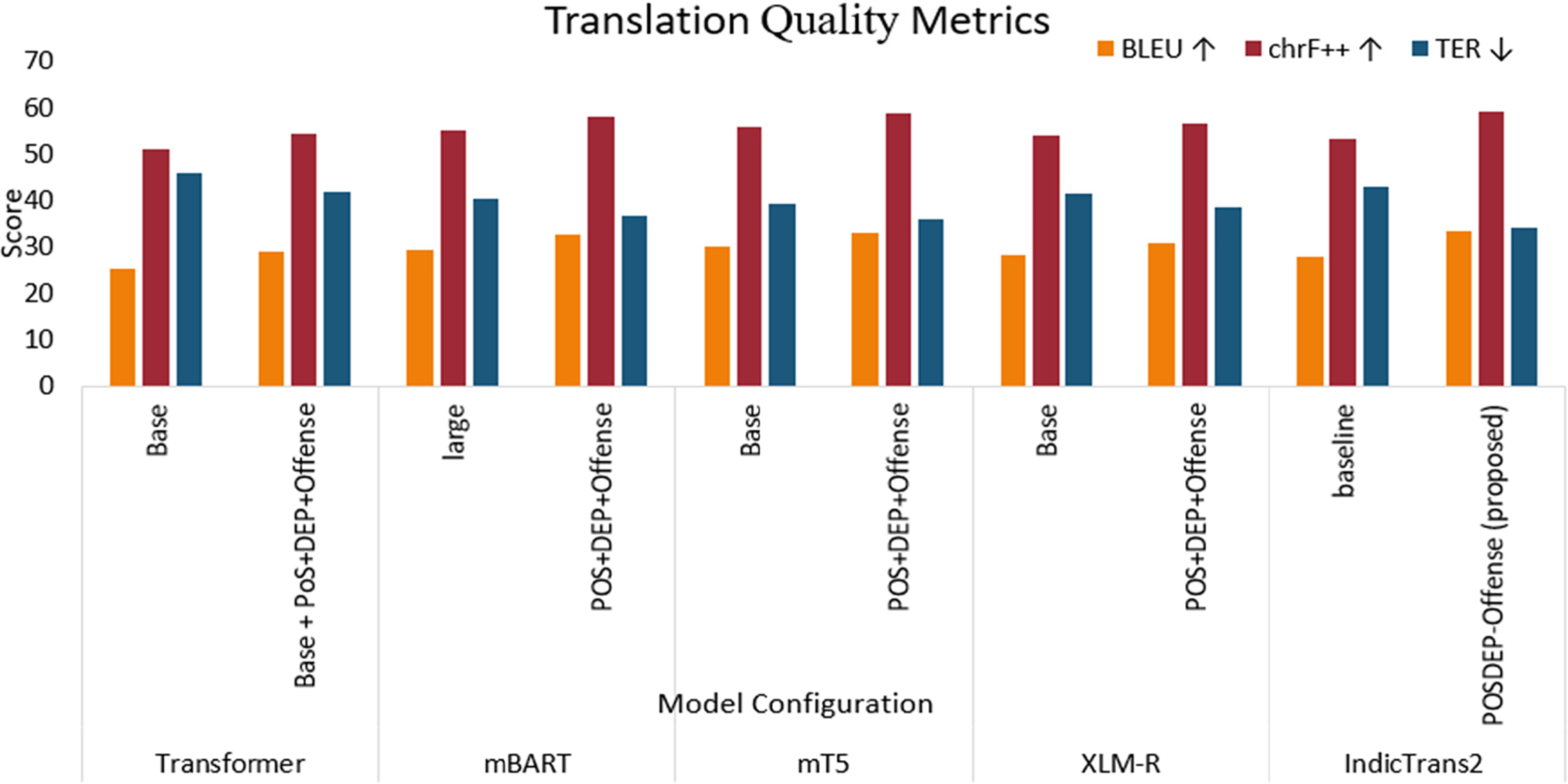

The proposed model, POSDEP-Offense-Trans, is evaluated across five Transformer-based NMT architectures to assess its performance on English-to-Tamil translation. As shown in the table, integrating syntactic supervision (POS and DEP embeddings), syntax-guided attention, contrastive learning, and a multi-class offensive classification head significantly improved translation quality across all architectures. The complete translation evaluation results are summarized in Table 5, and the comparison of these values is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Translation quality metrics for translation across various model variants

For the standard Transformer-Base model, adding our enhancements improved BLEU from 25.2 to 28.9 and reduced TER from 45.8 to 42.0, confirming the value of even shallow syntactic signals in low-resource settings. On pretrained encoder-decoder architectures such as mBART and mT5, our model outperformed their vanilla baselines by +3.2 BLEU and +3.1 BLEU, respectively, while also improving chrF++ and reducing TER. Similarly, the encoder-only XLM-R model, when extended with a Transformer decoder, benefited from our enhancements, achieving 30.9 BLEU and 56.5 chrF++, indicating that syntactic features are beneficial even in pretrained multilingual setups.

Our proposed POSDEP-Offense-Trans model achieves better results, with BLEU 33.5, chrF++ 59.1, and TER 34.2. This indicates that the multitask model helps in increasing performance.

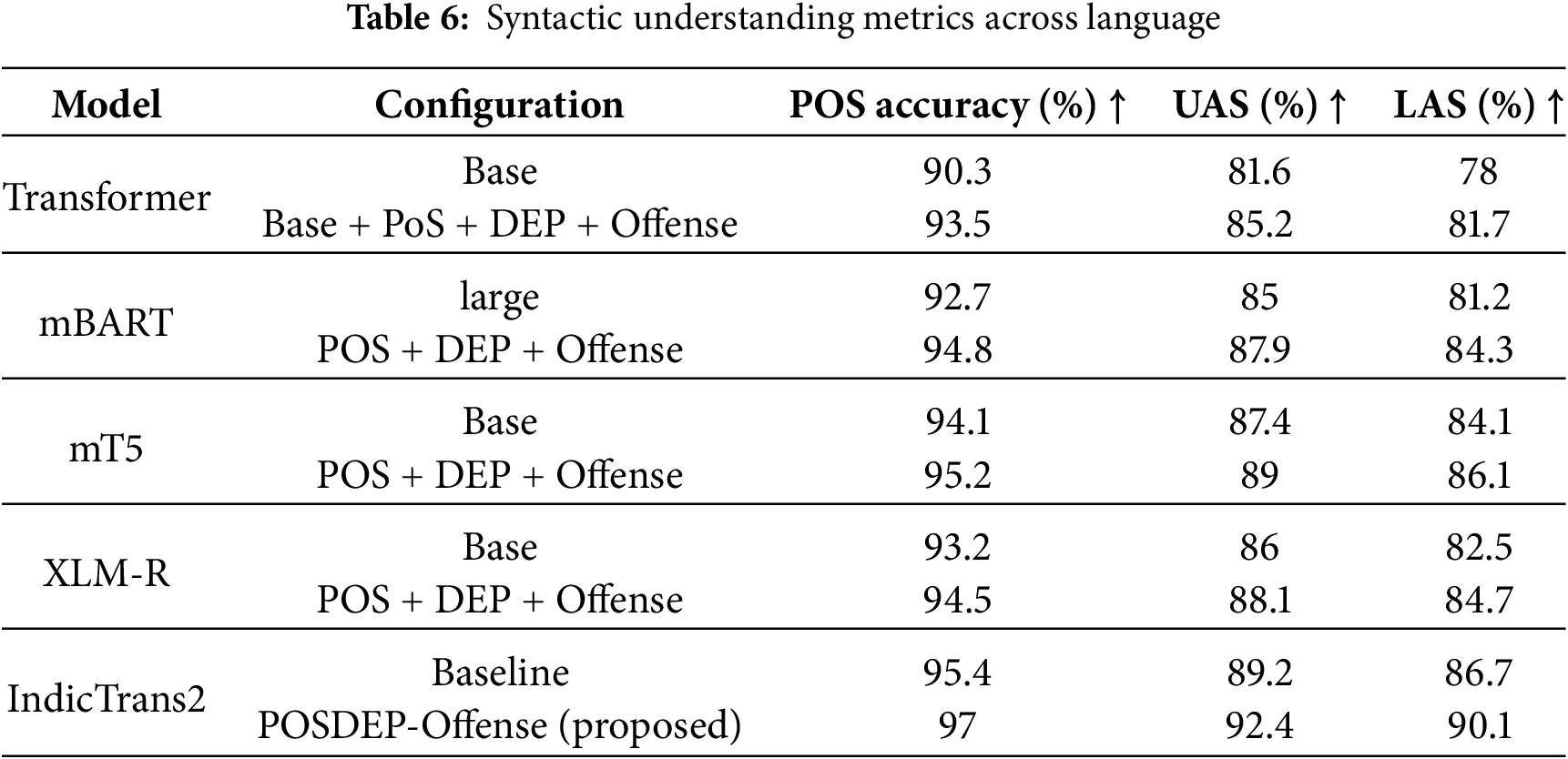

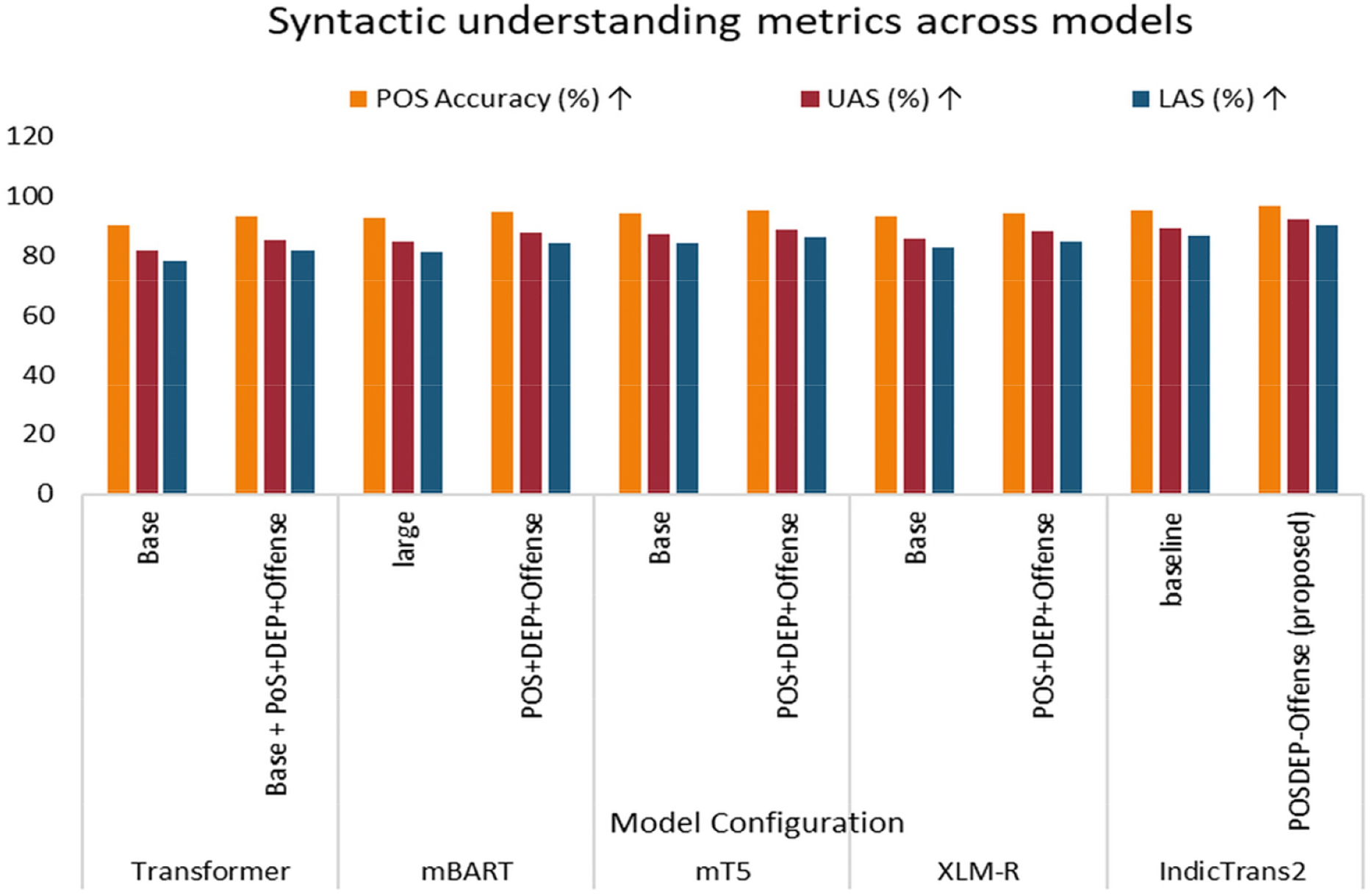

The syntactic understanding performance across various Transformer-based architectures—both in their baseline and enhanced forms—validates the inclusion of Part-of-Speech (PoS) tags and Dependency (DEP) relations. The baseline model achieves 90.3% UAS, 81.6% UAS, and 78% LAS, whereas PosDEP + Offense improves performance to 93.5% POS accuracy, with 85.2% and 81.7% UAS and LAS, respectively. This indicates that syntactic augmentation in the base model has significantly improved performance.

mBART improved from 92.7% POS accuracy and 81.2% LAS to 94.8% and 84.3%, respectively, after enhancement, as it had already been trained multilingually. Similarly, mT5’s PoS tagging accuracy increased from 94.1% to 95.2%, and LAS from 84.1% to 86.1% with the addition of syntax-aware inputs. This clearly indicates that syntax alignment helps even advanced models improve. The scores improved from a baseline LAS of 82.5% to 84.7%, indicating suitability for syntactic tasks when appropriately extended. XLM-R, which helps align offensive classification, showed considerable improvement by leveraging syntactic structures.

Notably, the proposed PoSDEP-Offense-Trans model achieved the highest syntactic performance across all metrics: 97.0% PoS accuracy, 92.4% UAS, and 90.1% LAS. These results were made possible by its architecture that combines syntax-guided attention, multitask learning with PoS and DEP heads, contrastive learning for structural generalization, and balanced optimization with GradNorm. These metric values are presented in Table 6 and Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Syntactic understanding performance evaluation across various models

The significant improvements over baselines indicate that synaptic awareness can be included in models, even multilingual, for reaching contextual awareness that is always difficult in low-resource language pairs like English-Tamil.

While BLEU gains over the baseline are modest, the proposed model demonstrates consistent improvements in hallucination control. Specifically, the baseline system exhibited a Hallucination Rate (HR) of 14.8%, meaning that nearly one in seven output tokens did not correspond to any source token. In contrast, POSDEP-Offense-Trans reduced this to 13.0%, a relative reduction of about 9%.

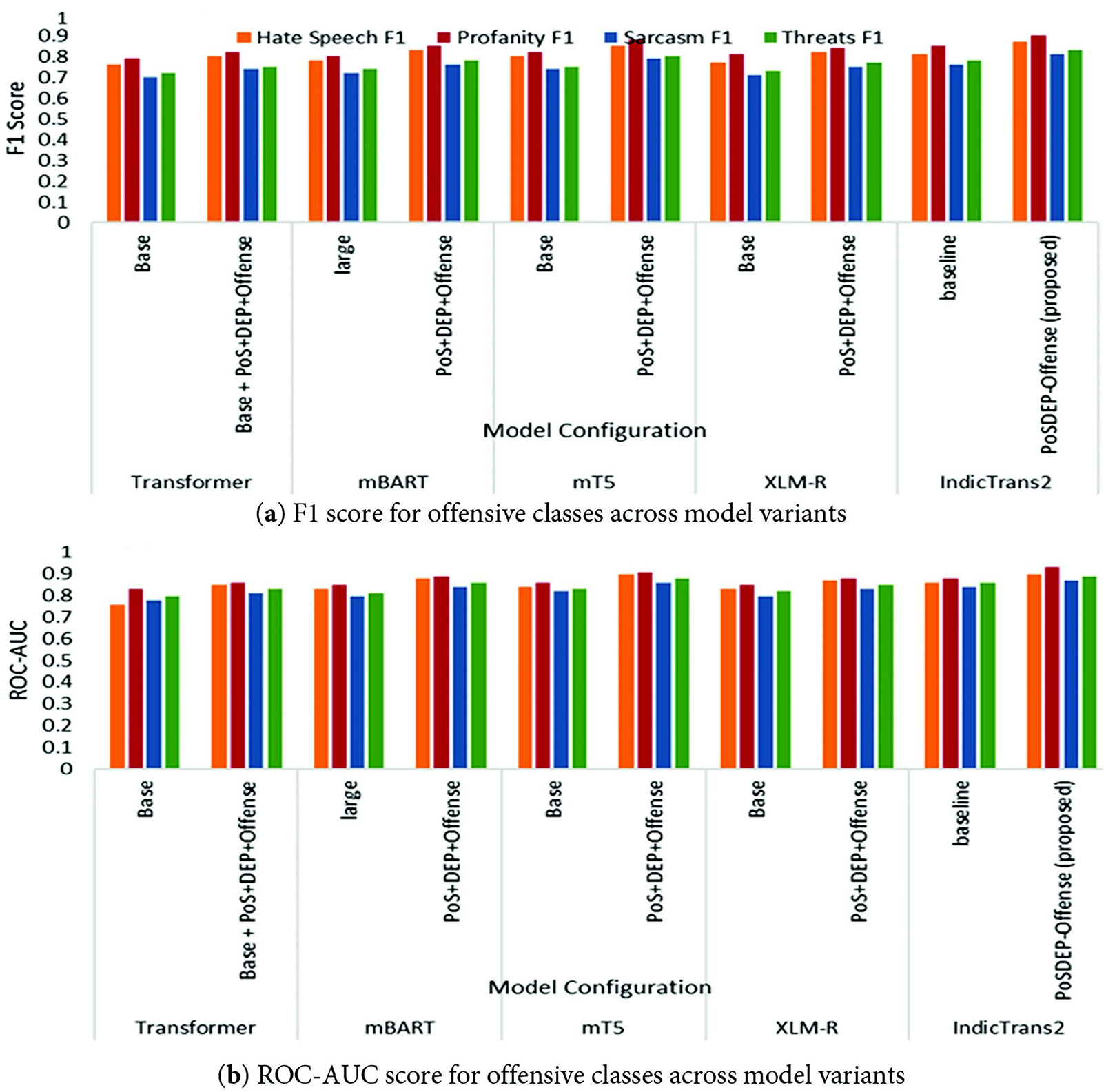

5.3.3 Offensive Language Classification

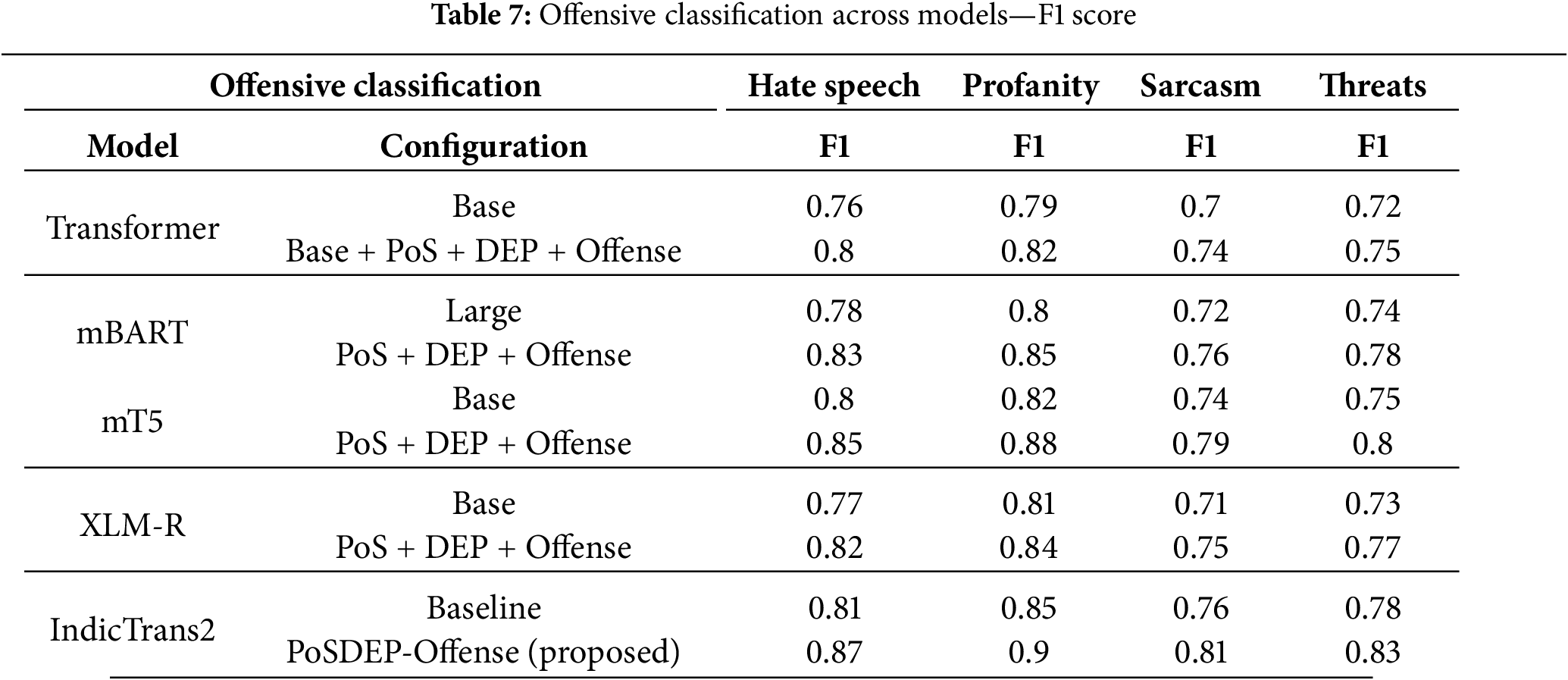

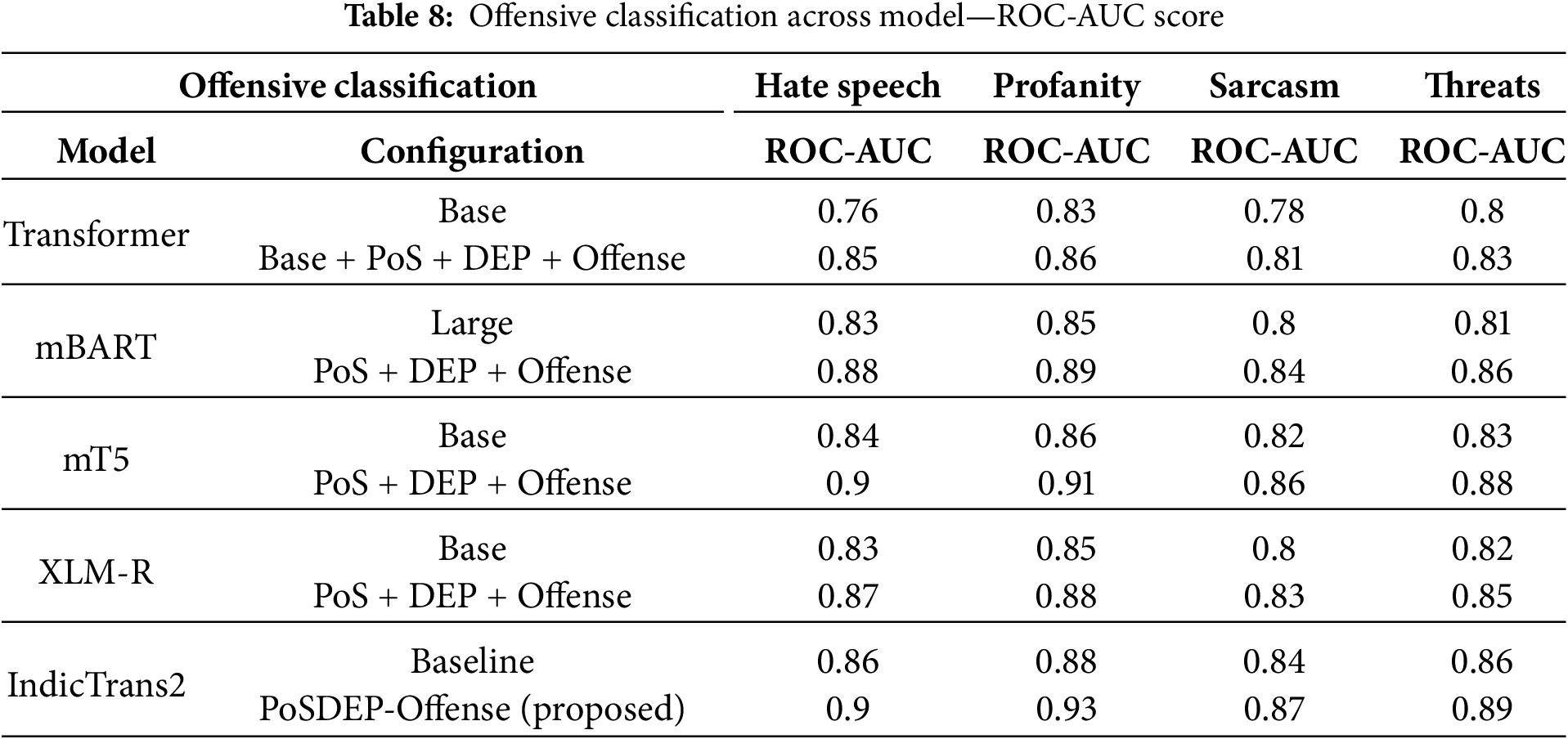

F1 scores for offensive language classification across four categories—Hate Speech, Profanity, Sarcasm, and Threats are evaluated using the models—Base Transformer, mBART, mT5, XLM-R, and the IndicTrans2 included with the proposed PoSDEP-Offense-Trans.

The proposed PoSDEP-Offense-Trans configuration achieves the highest performance across all offensive classes, reaching 0.87 in Hate Speech, 0.90 in Profanity, 0.81 in Sarcasm, and 0.83 in Threats. These results indicate that the proposed model can detect abuse, toxicity, sarcasm, and other threats. Compared with the baseline model, the proposed model delivers consistent improvements across all classes. The mT5 and mBART models are improved by the proposed PosDep-Offense-Trans. However, IndicTrans2 consistently outperforms other models because of its language-specific optimization for Tamil.

Significantly, sarcasm and threats—traditionally the most challenging categories—benefit substantially from the syntax-guided attention mechanism and contrastive learning, which help the model focus on discourse structure rather than surface word cues alone. Additionally, profane content, which is typically easier to detect via lexical patterns, achieves the highest scores across all models; however, IndicTrans2 still achieves a notable 0.90 F1 score, reflecting its superior generalization. Offensive language metrics are summarized in Tables 7 and 8 and graphically shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Offensive classification across models

The enhanced models across all architectures show improved performance when enriched with PoS and Dependency features along with a dedicated offensive classification head. These results confirm the effectiveness of syntactic understanding and task-aware training in improving offensive content detection, particularly for morphologically rich, code-mixed Tamil.

For hate speech detection, performance improves with the addition of syntactic modelling, particularly on IndicTrans2 and mT5. The proposed POSDEP-Offense-Trans model achieves the highest F1 score (0.87) and ROC-AUC (0.90) in this class.

Similarly, for the Profanity class, all models performed well due to strong lexical cues, and the proposed model achieved the best F1 (0.90) and ROC-AUC (0.93). For the Sarcasm class, the proposed model achieves an F1 of 0.81 and an ROC-AUC of 0.87, which appears to be challenging due to the abstract nature. On the threat classification task, the proposed model achieves an F1 score of 0.83 and an ROC-AUC of 0.89, indicating its ability to capture both explicit and subtle forms of threatening language.

In summary, the proposed POSDEP-Offense-Trans model consistently outperforms all offensive categories across both F1 and ROC-AUC metrics, validating the integration of syntax-aware features and multi-class offensive classification within a low-resource English–Tamil NMT pipeline.

The offensive language is evaluated based on two key metrics, the Macro F1 score and ROC-AUC, across various transformer models.

Macro F1 Score reflects the model’s balanced performance across the offensive classes: hate speech, profanity, sarcasm, and threats. The improved models with PoS/DEP and offensive heads consistently outperform their baselines. The proposed POSDEP-Offense-Trans model achieves a Macro F1 Score of 0.91, indicating high generalization across four offensive categories. A high ROC-AUC score suggests the model’s ability to distinguish between offensive and non-offensive content. The proposed configuration outperforms all the models.

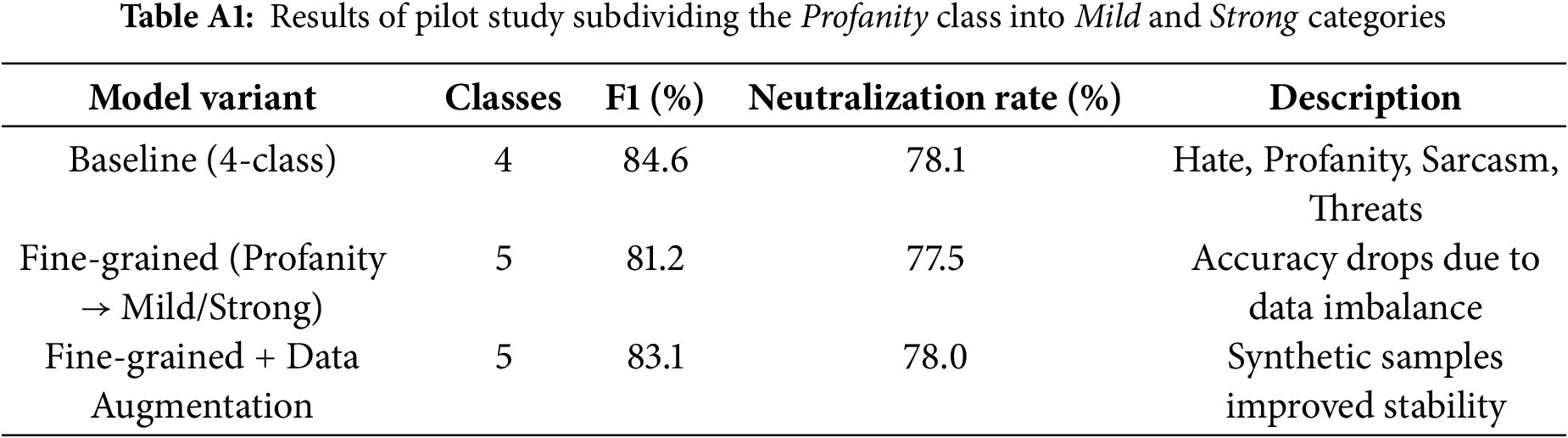

All models show clear improvements with the inclusion of syntactic features and dedicated offense-classification heads. The results support the hypothesis that syntactic structure facilitates semantic disambiguation, particularly when translating offensive or culturally sensitive English content into Tamil. Also, we have conducted a small pilot study by dividing the profanity class into mild and strong, and the results are presented in Appendix A—Table A1.

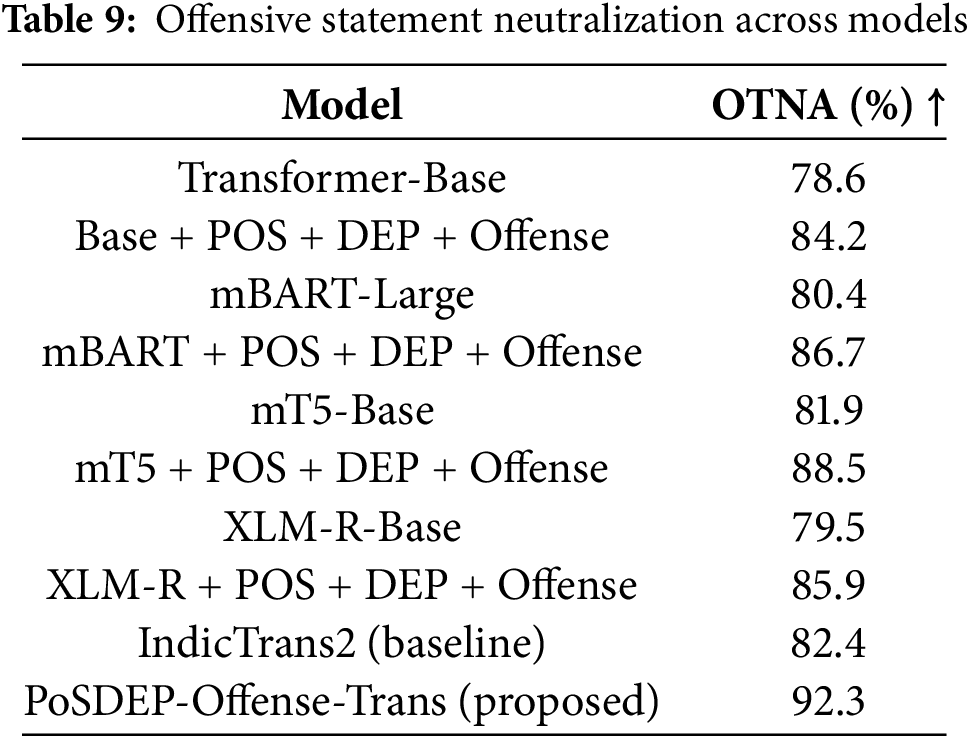

5.3.4 Offensive Neutralization

Table 9 presents the metric used to evaluate offensive neutralization across various models. Again, the proposed model provides better neutralization accuracy.

With the inclusion of any Dravidian Code-Mixed Offensive dataset, offensive neutralization accuracy has improved by around 3 percent.

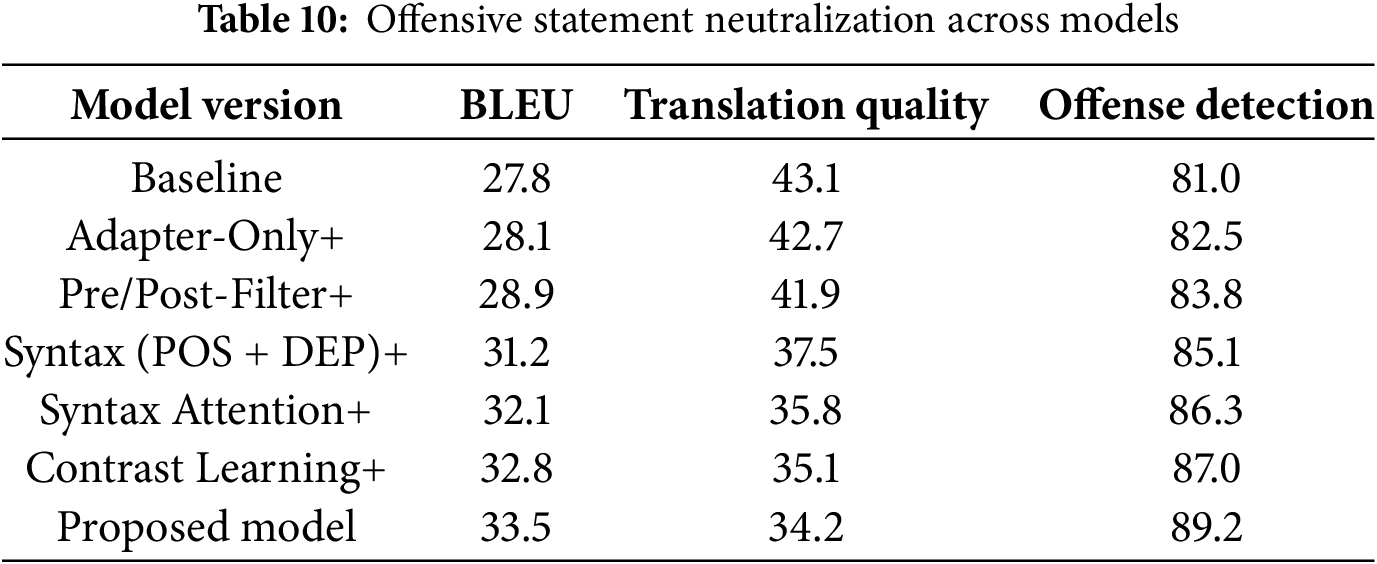

We conducted an extensive ablation study with three seeds, isolating each component. Syntax components show strong statistical significance (p < 0.001); a multitask approach to toxicity control significantly outperforms adapter-only fine-tuning; and post-translation neutralization is more effective than pre-filtering training. All improvements over the baseline are statistically significant (p < 0.001), as defined in Table 10. The synergy between syntactic modelling and ethical filtering demonstrates that these components mutually reinforce one another rather than operate independently.

This result confirms that grammar is more important for accuracy, and integrating all provides reliability.

In this paper, we propose POSDEP-Offense-Trans, a multitask neural machine translation (NMT) model for English-to-Tamil translations; by integrating auxiliary tasks—part-of-speech tagging, dependency parsing, and offensive language classification, our model not only improves translation fluency and accuracy but also ensures grammatical correctness and cultural sensitivity in generated outputs. Experimental results across multiple metrics, including BLEU, TER, chrF++, POS accuracy, UAS, LAS, and F1-score, demonstrate consistent and significant improvements over strong baselines such as mBART50 and vanilla IndicTrans2. Notably, our model achieves a BLEU score of 33.5 and an F1 Score of 89.2 for offensive detection, demonstrating its ability to balance linguistic accuracy with ethical filtering. The model reduces the hallucination rate and generates trustworthy translations.

From an architectural perspective, the inclusion of a syntax-guided attention mechanism and a contrastive loss objective for syntax consistency contributes to stronger encoder representations. Additionally, our multitask learning framework enables more effective feature sharing and generalization across resource-scarce language pairs, particularly benefiting low-resource languages such as Tamil. We further explored context-aware synonym replacement and deeper semantic analysis to improve the context and cultural fluency in neutralized outputs.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Rama Sugavanam contributed to the research idea, designed the methodology, conducted the experimental analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. Mythili Ramu contributed to system development and assisted with manuscript revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data and materials of this paper can be accessed at https://github.com/rama-cs/PoS-DEP-Offense.git.

Ethics Approval: This research does not involve human subjects directly or indirectly. Also, it includes an analysis of text data that may contain offensive or harmful language. No personal or sensitive human information was collected. Therefore, institutional ethical approval was not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A Pilot Study on Fine-Grained Offensive Classes

We performed a preliminary experiment by dividing the profanity category into mild and strong levels. Accuracy has decreased slightly due to data imbalance; however, the model achieved finer distinctions, with an F1 score of 83.1. This validates that our architecture can be directly extended to multi-level offensive taxonomies as richer annotated resources become available.

The initial investigation indicates that sub-categorization may lead to data imbalance, yet the framework performs well for fine-grained distinctions, as shown in Table A1. The minimal drop in accuracy indicates the system requires larger annotated corpora. However, the performance has improved with synthetic augmentation, suggesting that the architecture is capable of handling multi-level offensive taxonomies.

References

1. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:5998–6008. doi:10.65215/ctdc8e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Choudhary H, Pathak AK, Saha RR, Kumaraguru P. Neural machine translation for English-Tamil. In: Proceedings of the Third Conference on Machine Translation: Shared Task Papers; 2018 Oct 31–Nov 1; Belgium, Brussels. [Google Scholar]

3. Ramesh G, Doddapaneni S, Bheemaraj A, Jobanputra M, Raghavan AK, Sharma A, et al. Samanantar: the largest publicly available parallel corpora collection for 11 Indic languages. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2022;10(2):145–62. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Team NLLB. No language left behind: scaling NMT to 200 languages. Nature. 2024;630(8018):841–6. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07335-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Matan P, Velvizhy P. A neuro-symbolic AI approach for translating children’s stories from English to Tamil with emotional paraphrasing. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):20348. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-03290-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ramasamy L, Bojar O, Žabokrtský Z. Morphological processing for English-Tamil statistical machine translation. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Machine Translation and Parsing in Indian Languages (MTPIL-2012); 2012 Dec 15; Mumbai, India. p. 113–22. [Google Scholar]

7. Sennrich R, Haddow B. Linguistic input features improve neural machine translation. arXiv:1606.02892. 2016. [Google Scholar]

8. Bastings J, Titov I, Aziz W, Marcheggiani D, Sima’an K. Graph convolutional encoders for syntax-aware neural machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2017 Sep 9–11; Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhang M, Li Z, Fu G, Zhang M. Syntax-enhanced neural machine translation with syntax-aware word representations. arXiv:1905.02878. 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Gū J, Shavarani HS, Sarkar A. Top-down tree structured decoding with syntactic connections for neural machine translation and parsing. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2018 Oct 31–Nov 4; Brussels, Belgium. p. 401–13. [Google Scholar]

11. Ranathunga S, Ranasinghe A, Shamal J, Dandeniya A, Galappaththi R, Samaraweera M. A multi-way parallel named entity annotated corpus for English, Tamil and Sinhala. Nat Lang Process J. 2025;11(24):100160. doi:10.1016/j.nlp.2025.100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mandl T, Modha S, Majumder P, Patel D, Dave M, Mandlia C, et al. Overview of the HASOC track at FIRE 2019: hate speech and offensive content identification in indo-European languages. In: Proceedings of the 11th Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation; 2019 Dec 12–15; Kolkata, India. doi:10.1145/3368567.3368584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ghanghor N, Krishnamurthy P, Thavareesan S, Priyadharshini R, Chakravarthi BR. IIITK@DravidianLangTech-EACL2021: offensive language identification and meme classification in Tamil, Malayalam and Kannada. In: Proceedings of the First Workshop on Speech and Language Technologies for Dravidian Languages. Kyiv, Ukraine: ACL; p. 222–29. [Google Scholar]

14. Chakravarthi B, Priyadharshini R, McCrae J, Kumar M. Corpus creation for sentiment analysis in code-mixed Tamil-English text. In: Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference; 2020 May 11–16; Marseille, France. p. 2020–7. [Google Scholar]

15. Chakravarthi B, Priyadharshini R, Suryawanshi K, Kumar M, McCrae J, Ponnusamy MR, et al. HopeEDI: a mul-tilingual hope speech detection dataset. In: Proceedings of the FIRE 2021—Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation; 2021 Dec 13–17; Gandhinagar, India. p. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

16. Benhur S, Sivanraju K. Pretrained transformer-based offensive identification in Tanglish. In: Proceedings of the FIRE 2021—Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation; 2021 Dec 13–17; Gandhinagar, India. [Google Scholar]

17. Chakravarthi BR, Priyadharshini R, Muralidaran V, Jose N, Suryawanshi S, Sherly E, et al. DravidianCodeMix: sentiment analysis and offensive language identification dataset for Dravidian languages in code-mixed text. Lang Resour Eval. 2022;56(3):765–806. doi:10.1007/s10579-022-09583-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Nishanth S, Rengarajan S, Ananthasivan S, Rahul B, Sachin Kumar S. ANSR@DravidianLangTech 2025: detection of abusive Tamil and Malayalam text targeting women on social media using RoBERTa and XGBoost. In: Proceedings of the Fifth Workshop on Speech, Vision, and Language Technologies for Dravidian Languages; 2025 May 3; Albuquerque, NM, USA. p. 392–7. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.dravidianlangtech-1.121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. García Gilabert B, Escolano C, Costa-jussà MR. ReSeTOX: re-learning attention weights for toxicity mitigation in machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation; 2024 Jun 24–27; Sheffield, UK. p. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

20. Niehues J, Cho E. Exploiting linguistic resources for neural machine translation using multi-task learning. In: Proceedings of the Second Conference on Machine Translation; 2017 Sep 7–8; Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

21. Eriguchi A, Hashimoto K, Tsuruoka Y. Tree-to-sequence attentional neural machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2015 Aug 7–12; Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

22. Costa-jussà M, Dale D, Elbayad M, Yu B. Added toxicity mitigation at inference time for multimodal and massively multilingual translation. In: Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation; 2024 Jun 24–27; Sheffield, UK. p. 360–72. [Google Scholar]

23. Sanh V, Webson A, Raffel C, Bach SH, Sutawika L, Alyafeai Z, et al. Multitask prompted training enables zero-shot task generalization. arXiv:2110.08207. 2021. [Google Scholar]

24. Chen Z, Badrinarayanan V, Lee CY, Rabinovich A. GradNorm: gradient normalization for adaptive loss balancing in deep multitask networks. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning. London, UK: PMLR; 2018;80:794–803. [Google Scholar]

25. Kendall A, Gal Y, Cipolla R. Multi-task learning using uncertainty to weigh losses for scene geometry and semantics. arXiv:1705.07115. 2017. [Google Scholar]

26. Kunchukuttan A, Kakwani D, Golla S, C. GN, Bhattacharyya A, Khapra MM, et al. AI4Bharat-IndicNLP corpus: monolingual corpora and word embeddings for Indic languages. In: Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference; 2020 May 11–16; Marseille, France. p. 3222–31. [Google Scholar]

27. Ramesh A, Kunchukuttan CK, Jain A, Mittal AG, Kumar P. Samanantar: parallel corpora collection for Indic lan-guages. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021 Aug 1–6; Online. p. 4894–912. [Google Scholar]

28. Tiedemann J. Parallel data, tools and interfaces in OPUS. In: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’12); 2012 May 23–25; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 2214–8. [Google Scholar]

29. Subramanian M, Ponnusamy R, Benhur S, Shanmugavadivel K, Ganesan A, Ravi D, et al. Offensive language detection in Tamil YouTube comments by adapters and cross-domain knowledge transfer. Comput Speech Lang. 2022;76(6):101404. doi:10.1016/j.csl.2022.101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Doddapaneni S, Aralikatte R, Ramesh G, Goyal S, Khapra MM, Kunchukuttan A, et al. Towards leaving no Indic language behind: building Monolingual corpora and models for Indic language. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 12402–26. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools