Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

AdvYOLO: An Improved Cross-Conv-Block Feature Fusion-Based YOLO Network for Transferable Adversarial Attacks on ORSIs Object Detection

1 School of Cryptography Engineering, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Mathematical Engineering and Advanced Computing, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

3 Henan Key Laboratory of Information Security, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Hengwei Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Object Detection: Methods and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 28 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072449

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

In recent years, with the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, object detection algorithms have made significant strides in accuracy and computational efficiency. Notably, research and applications of Anchor-Free models have opened new avenues for real-time target detection in optical remote sensing images (ORSIs). However, in the realm of adversarial attacks, developing adversarial techniques tailored to Anchor-Free models remains challenging. Adversarial examples generated based on Anchor-Based models often exhibit poor transferability to these new model architectures. Furthermore, the growing diversity of Anchor-Free models poses additional hurdles to achieving robust transferability of adversarial attacks. This study presents an improved cross-conv-block feature fusion You Only Look Once (YOLO) architecture, meticulously engineered to facilitate the extraction of more comprehensive semantic features during the backpropagation process. To address the asymmetry between densely distributed objects in ORSIs and the corresponding detector outputs, a novel dense bounding box attack strategy is proposed. This approach leverages dense target bounding boxes loss in the calculation of adversarial loss functions. Furthermore, by integrating translation-invariant (TI) and momentum-iteration (MI) adversarial methodologies, the proposed framework significantly improves the transferability of adversarial attacks. Experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves superior adversarial attack performance, with adversarial transferability rates (ATR) of 67.53% on the NWPU VHR-10 dataset and 90.71% on the HRSC2016 dataset. Compared to ensemble adversarial attack and cascaded adversarial attack approaches, our method generates adversarial examples in an average of 0.64 s, representing an approximately 14.5% improvement in efficiency under equivalent conditions.Keywords

With the rapid proliferation of deep neural networks (DNNs), they have been widely deployed across diverse domains [1–3], including object detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images (ORSIs). Notably, DNN-driven object detection is a cornerstone for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), supporting their critical applications in precision agriculture, military operations, logistics, emergency response, supervision, obstacle detection, and traffic control. This technology not only boosts UAV task performance but also ensures safe and efficient autonomous operations in these key domains [4]. The YOLO [5] series of DNNs can simultaneously accomplish classification and localization tasks via a single forward pass. Specifically, in YOLOv8 [6], the Decouple-Head network employs an Anchor-Free mechanism, which effectively reduces the computational overhead of the head network and addresses critical requirements for real-time inference and model lightweighting in target detection. However, their inherent vulnerabilities remain a critical concern. In recent years, researchers [7–9] have extensively explored adversarial attack techniques against Anchor-Based models. In contrast, there exists a paucity of research on adversarial attacks against Anchor-Free models, and adversarial perturbations trained by the former exhibit limited transferability when applied to the latter. Therefore, investigating transferable adversarial attack techniques for state-of-the-art Anchor-Free models (e.g., YOLOv11 [10] and YOLOv12 [11]) is pivotal for enhancing their adversarial robustness.

Within the domain of target detection, one of the most effective approaches to enhancing the transferability of adversarial attacks involves leveraging multiple models in an ensemble or cascaded architecture [12–14] as adversarial source models for attack algorithms. This strategy employs diversified high-dimensional semantic feature backpropagation to augment both the diversity of adversarial perturbations and the cross-model transferability of attacks. Specifically, by integrating the gradients or decision boundaries of multiple source models, the generated perturbations can encapsulate shared vulnerabilities across diverse network architectures, thereby improving their attack effectiveness against unseen target models. However, in optical remote sensing target detection, the diminutive size and dense spatial distribution of objects necessitate larger input dimensions for detectors to preserve fine-grained details [15,16]. This architectural design leads to substantial model storage footprints and computational complexity. Consequently, the computational overhead required for generating adversarial samples is significantly amplified, particularly when multiple source models are simultaneously employed.

This scalability issue becomes particularly acute in scenarios where real-time adversarial validation is required. While ensemble-based and cascaded-based methods theoretically offer superior transferability, their practical implementation in remote sensing applications is often constrained by the prohibitive computational demands of multi-model optimization. Emerging research has attempted to mitigate this through techniques like gradient checkpointing and mixed-precision training, but these optimizations only partially address the fundamental trade-off between attack diversity and computational efficiency. Thus, developing lightweight adversarial generation frameworks that balance multi-model diversity with resource constraints remains a critical challenge in adversarial remote sensing research.

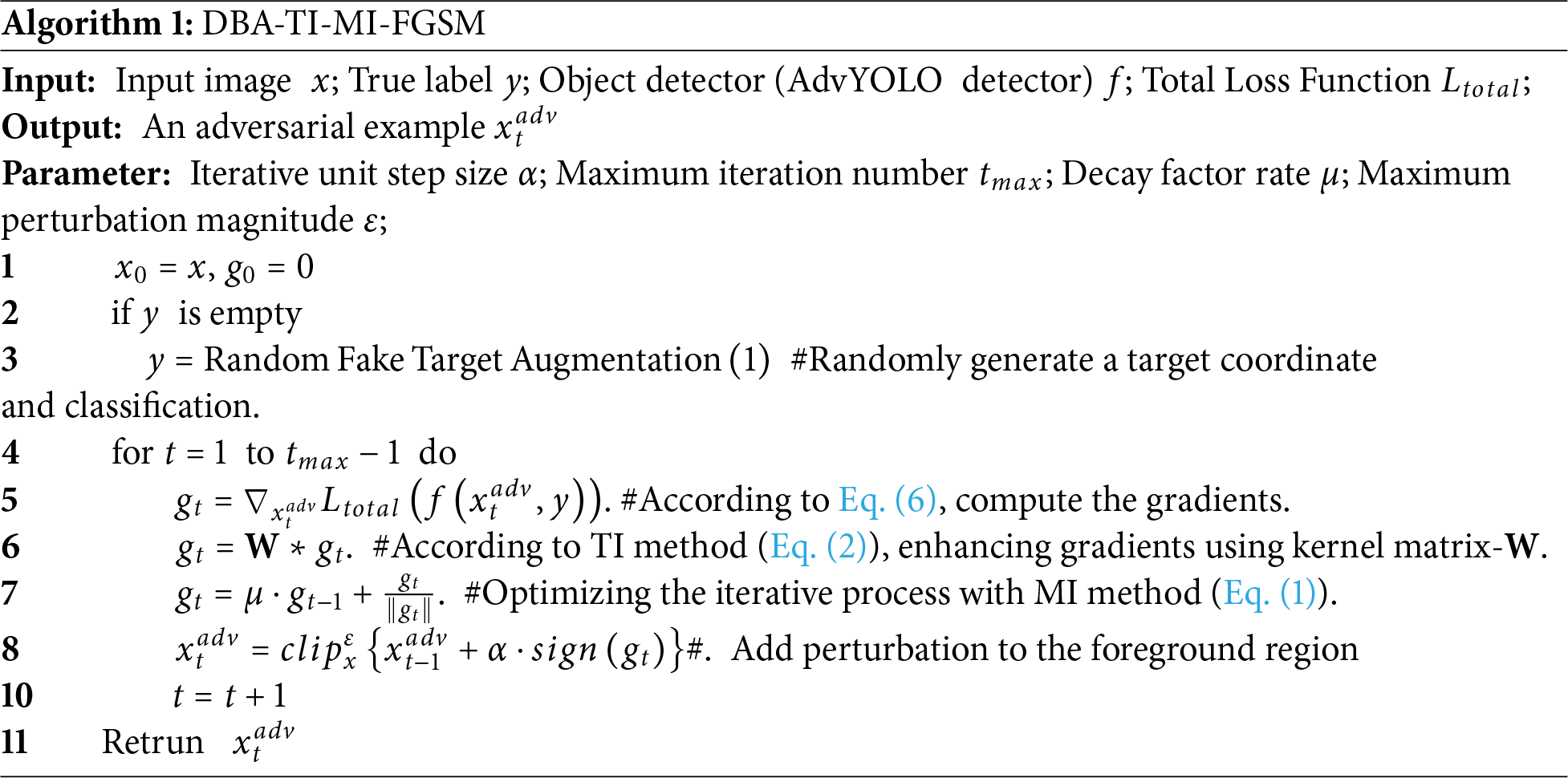

References [17–19] have proposed multi-feature fusion as a strategy to capture high-dimensional semantic associations, which provides novel insights for our research. To address the aforementioned issues, we first analyzed the network architectures of Anchor-Free YOLO-series models, generalized their canonical structural characteristics, and subsequently designed a novel YOLO variant with cross-block feature fusion, termed AdvYOLO. Specifically, we propose a novel convolutional layer integration strategy that embeds three distinct convolutional blocks—C3, C2f, and C3k2—within a unified convolutional layer. This integration is achieved through a synergistic combination of convolutional operations and learnable weighting mechanisms, enabling effective feature fusion across the three block types. To mitigate the prediction-label mismatch inherent to the Anchor-Free mechanism, we developed a dense bounding box loss function. This loss is designed to enhance the adversarial effectiveness of samples in bounding box prediction tasks by explicitly addressing the structural asymmetry between model outputs and ground-truth labels. By integrating transferable adversarial attack techniques, including Translation-invariant (TI) [20] and Momentum Iteration (MI) [21], we further propose the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method, which enables effective adversarial attacks in the domain of optical remote sensing image target detection.

Specifically, the contributions of this work are as follows:

1. We introduce a novel research framework for adversarial transfer attacks. For the first time, we focus on the feature fusion of convolutional blocks within the network architecture of source models, granularizing the scope of network feature fusion analysis to the level of individual convolutional block features. To realize this, we systematically decomposed the network architectures of Anchor-Free YOLO-series models. Through a comparative analysis of their architectural commonalities and discrepancies, we derived a canonical network structure that encapsulates the core design principles of the YOLO family.

2. We integrated three types of convolutional blocks (C3, C2f, and C3k2) and constructed differentiated convolutional layers (DCLayer) through weighting and convolution mechanisms, thereby establishing a convolutional-level integration scheme. This design reduces the parameter count of source models in transferable adversarial attacks while ensuring the extraction of diverse gradient features, which contributes to enhancing the transferability and generalization of adversarial attacks. In the feature fusion of multiple convolutional blocks, we employed weighted fusion, convolutional fusion, and hybrid fusion approaches, and compared the impacts of different fusion methods on the transferability of adversarial attacks.

3. We propose a dense bounding box loss to address the asymmetry issue between predicted bounding boxes and ground-truth bounding boxes under the Anchor-Free mechanism. This method can be seamlessly integrated with techniques such as TI and Momentum Iteration Fast Gradient Sign Method (MI-FGSM), forming the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM algorithm, which enhances the transferability of adversarial examples.

4. Our method was evaluated against four baseline methods on 2 datasets and 7 YOLO-series models. Notably, the latest YOLOv12 object detection network was incorporated into the evaluation to more comprehensively demonstrate the advancement of our work. Results demonstrate that the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method, with the AdvYOLO-cf model (the AdvYOLO with convolutional fusion) as the source model, exhibits superior adversarial attack efficacy and faster adversarial sample generation speed. Notably, compared to the ensemble of YOLOv5su, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv11s, using AdvYOLO-cf as the source model reduces the model size by approximately 12MB and decreases the parameter count by around 3.2M.

To better articulate our research findings, we first review recent research efforts on Anchor-Free YOLO series object detection models and their applications in the optical remote sensing domain. Next, we provide an overview of the research of adversarial attack techniques for object detection, which includes our own prior research work.

Based on the classification of prior knowledge requirements, YOLO object detection models are primarily categorized into Anchor-Based and Anchor-Free frameworks. Anchor-Based detection models utilize precomputed anchor boxes as grid priors to refine the Intersection over Union (IoU) between objects of varying scales and predefined bounding boxes, thereby deriving the confidence scores of true objects across different regions. This category includes well-known architectures such as the original YOLO [4], YOLOv3 [22], YOLOv4 [23] and YOLOv7 [24], all of which adhere to the Anchor-Based paradigm. Since the introduction of YOLOv8 [6], the adoption of a Decouple-Head network as the detection head has enabled anchor-free modeling. By decoupling classification and regression tasks into independent branches, this design simplifies the model architecture while enhancing computational efficiency and detection flexibility. This architectural innovation marked a pivotal advancement for the YOLO series, accelerating its development in real-time object detection scenarios. Following YOLOv8’s release, reducing model size and improving detection accuracy became the primary focus of YOLO’s technical evolution. Within two years, YOLOv9 [25] to YOLOv12 [11] were sequentially proposed and rapidly adopted across diverse domains of object detection. These iterations further optimized the balance between inference speed and precision through lightweight module design and advanced feature fusion techniques. This evolutionary trajectory underscores YOLO’s continuous refinement in architectural efficiency and task adaptability, solidifying its position as a cornerstone in modern computer vision.

In addition to the Decouple-Head network design, several other technical advancements in YOLO research warrant attention. YOLOv8 replaced the Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) module in YOLOv5 with the Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast (SPPF) module, which efficiently extracts multi-scale contextual features through cascaded pooling operations. This component was retained in YOLOv11, demonstrating its enduring utility in multi-scale feature representation. Furthermore, YOLOv8 introduced the CSPLayer_2Conv (C2f) module to replace the CSPLayer (C3) in YOLOv5. YOLOv11 further optimized this lineage by proposing the C3K2 module, which replaces the C2f module with a hybrid architecture combining variable kernel convolutions (3 × 3 and 5 × 5) and channel-separated attention. Additionally, the Cross Stage Partial with Pyramid Squeeze Attention (C2PSA) was integrated to enhance detection performance on small and occluded objects by dynamically weighting spatial regions of interest. YOLOv12 achieved a paradigm shift by fully integrating attention mechanisms into the detection pipeline through Aera Attention (A2) and Flash Attention. The lightweight A2 module partitions feature maps into hierarchical regions to balance global contextual modeling and local detail preservation, while Flash Attention optimizes memory access patterns. These advancements collectively improved model robustness and precision, particularly in cluttered environments with significant occlusion. Notably, Ultralytics incorporated the decoupled head design into YOLOv5u [26], making the model more lightweight. These iterative improvements highlight YOLO’s ongoing evolution toward achieving optimal trade-offs between computational efficiency and detection performance.

With the rapid evolution of Anchor-Free YOLO models, these architectures have been extensively researched and applied in object detection tasks for ORSIs, particularly achieving remarkable detection accuracy in identifying small targets. Xu et al. [15] adapted the enhanced YOLOv8n network for UAV-based object detection, significantly improving detection precision and speed for small and partially occluded objects under complex environmental conditions. Lang et al. [27] further optimized YOLOv8n for optical remote sensing applications, addressing challenges posed by complex backgrounds, limited feature discriminability, varying object densities, and multi-scale targets inherent in this domain. Hou and Zhang [28] incorporated modifications to YOLOv9 into remote sensing object detection workflows, demonstrating enhanced task accuracy through architectural refinements. Sun et al. [29] proposed SOD-YOLOv10 by integrating Transformer-based global context modeling with YOLOv10, effectively augmenting the model’s ability to capture large-scale semantic information in remote sensing scenarios. He et al. [30] evaluated YOLOv11’s performance in high-resolution remote sensing image analysis, systematically investigating its multi-class and multi-object detection capabilities across diverse application scenarios. Zuo et al. [31] provided a comprehensive overview of YOLOv12’s applications in various remote sensing monitoring domains while outlining future technological development trajectories. This body of work collectively highlights the progressive adaptation of YOLO series models to address the unique challenges of remote sensing imagery, including small target detection, complex background interference, and multi-scale feature representation. By leveraging architectural innovations such as decoupled heads, attention mechanisms, and hybrid network designs, these studies have advanced the state-of-the-art in real-time, high-accuracy remote sensing object detection.

It can be seen that in recent years, new Anchor-Free YOLO models have been attracting increasing attention in the field of remote sensing image object detection, which has pointed out new research directions and higher requirements for the development of adversarial attack technologies in this domain. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate whether adversarial examples against early Anchor-Based YOLO models can produce transferable adversarial attack effects on these new models. Alternatively, some early adversarial attack algorithms can be directly applied to these new YOLO models to help improve their adversarial robustness.

2.2 Adversarial Attack on Object Detection

Recent years have witnessed rapid advancements in transferable adversarial attack techniques for object detection, which can be broadly categorized into three classes based on adversarial example generation mechanisms. The first class involves generating adversarial perturbations (typically adversarial patches) through training optimizers [7,8], where the learning rate is set as the unit step size for each iterative training cycle. Under fixed model parameters, adversarial examples are generated by updating the model during training [32,33]. However, due to the inherently small learning rates commonly employed, this approach often demands substantial computational time for adversarial example generation. The second class encompasses gradient-based fast adversarial example generation using sign functions. This method leverages a fixed unit step size as the incremental value for each iteration, with gradients serving as directional indicators to guide the sign function in generating adversarial perturbations. Given that the fixed step size is significantly larger than the learning rate used in training optimizers, this approach enables faster adversarial example generation, thereby becoming the dominant research direction in adversarial example generation. Beyond these two categories, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have been proposed for adversarial example generation [34]. Nevertheless, due to the high complexity of GAN training, their practical implementation and theoretical development remain limited in the current stage. Considering the efficiency requirements for adversarial example generation, this study employs a gradient-based fast adversarial example generation framework using sign functions.

In this research direction, transferable adversarial attack techniques originally developed for image classification have been adapted and applied to object detection tasks. Notably, the Objectness-Aware Adversarial Training algorithm [35] was proposed, which employs YOLOv4 as the source model for adversarial attacks. This approach integrates gradients derived from classification loss, localization loss, and object loss as input variables for sign functions, combined with adversarial example generation methods such as FGSM and PGD-10. Building upon this framework, we propose an adversarial loss function that induces adaptive deformation of predicted bounding boxes, specifically tailored to the IoU calculation characteristics of Anchor-Based models in optical remote sensing object detection. The developed ADM-I-FGSM (Adaptive Deformation Method Iterative Fast Gradient Sign Method) [36] algorithm achieves a white-box adversarial attack success rate (ASR) of 95% in optical remote sensing object detection tasks.

To transfer white-box adversarial attacks to black-box scenarios, the MI-FGSM algorithm [21] was proposed and has achieved favorable transferable adversarial attack performance in the field of image classification. The generation process with momentum can be expressed as follows:

here, gt represents the cumulative gradient value of the previous t iteration, and μ is the delay factor of the momentum term. Previously, we applied the MI-FGSM algorithm to object detection and proposed the FlipColor-MI-FGSM algorithm [32]. This algorithm uses models such as YOLOv3 and YOLOv8 as source models and incorporates data augmentation techniques including image flipping and color transformation, which significantly enhances the transferability of adversarial attacks in object detection. Specifically, the success rate of black-box adversarial attacks reaches 83.7% (on the RetinaNet network). Building on this, to enable adversarial attacks targeting specific objects, we proposed the Random Color and Erasing Noise MI-FGSM (RCEN-MI-FGSM) [33] algorithm. This algorithm, based on our previous work, adds data augmentation mechanisms such as random illumination and random erasing, effectively improving the transferability of targeted adversarial attacks. The maximum success rate of black-box adversarial attacks reaches 82.59% (with RetinaNet as the source model and YOLOv8 as the evaluation model). However, both the FlipColor-MI-FGSM and RCEN-MI-FGSM adversarial attacks require backpropagation operation after multiple data augmentation for gradient computation in each iteration, resulting in considerable time consumption for generating adversarial examples.

To enhance the transferability of adversarial attacks, recent studies have adopted multiple models as ensemble source models, leveraging the diverse decision boundaries reflected in gradients derived from backpropagation through these ensembles. This transferable adversarial attack technique, first developed in image classification, has been adapted for object detection tasks. For instance, Wu et al. [13] integrated YOLOv2, YOLOv3, and R50-FPN for real-time object detection, while Bao [37] combined YOLOv4 and Faster R-CNN to generate adversarial patches for object detectors. Although these methods rely on training optimizer-based strategies for adversarial example generation, they empirically demonstrate that multi-model ensembles significantly improve attack transferability. Building on this foundation, our prior work [38] explored the integration of three Anchor-Based models (YOLOv4, YOLOv5, YOLOv7) to optimize computational efficiency in ensemble adversarial attacks. We proposed the VSM-MI-FGSM algorithm [39], which incorporates an adaptive step-size dynamic adjustment mechanism to balance perturbation magnitude and convergence speed. Additionally, Wang et al. [14] introduced a cascaded adversarial attack framework that sequentially integrates Faster R-CNN-FPN, Faster R-CNN-C4, YOLOv2, and SSD. This cascading architecture differs from the parallel ensemble approach, achieving comparable transferability improvements. Notably, current research gaps exist in applying ensemble adversarial attacks to Anchor-Free models, particularly the state-of-the-art YOLOv11 and YOLOv12 variants. These models’ unique design principles—such as anchor-free bounding box regression and global context modeling—may require specialized perturbation strategies to maintain attack efficacy across diverse decision boundaries. Addressing this limitation would advance the robustness analysis of modern object detection systems under realistic adversarial scenarios.

In addition to the methods discussed, the TI adversarial attack [20] was proposed and applied in adversarial attack research for image classification. This approach simulates the effect of image translation in adversarial attacks using a kernel matrix and generates adversarial perturbations in a single pass. By leveraging kernel-based convolution to approximate translation-invariant transformations, it minimizes the computational overhead associated with repeated perturbation generations caused by data augmentation while significantly enhancing the transferability of adversarial attacks. Specifically, the kernel matrix encodes spatial invariance properties, allowing the perturbation to generalize across different input positions without requiring explicit data augmentation. This innovation reduces reliance on multiple backpropagation optimization steps and enhances the transferability of adversarial examples across different models. The translation-invariant adversarial attack process can be expressed as follows:

where α is the unit step size, ε is the maximum perturbation constraint for each pixel and W is the kernel matrix. In ORSIs object detection, the position of the target is prone to displace, which provides a physical basis for transferable adversarial attacks in TI adversarial attacks. Generating adversarial perturbations in one backpropagation per iteration go improves the efficiency of adversarial attacks and can effectively address the problem of low adversarial efficiency in the FlipColor-MI-FGSM and RCEN-MI-FGSM methods.

In this section, we first introduce the basic motivation behind the proposed method. Based on a detailed analysis of the network structures from YOLOv5 to YOLOv12, we summarize the general network structure of YOLO models. We then provide a detailed introduction to the DCLayer structure and its feature fusion module. Next, we present the design of dense bounding box adversarial loss against the Anchor Free mechanism. Finally, we introduced our adversarial attack algorithm DBA-TI-MI-FGSM.

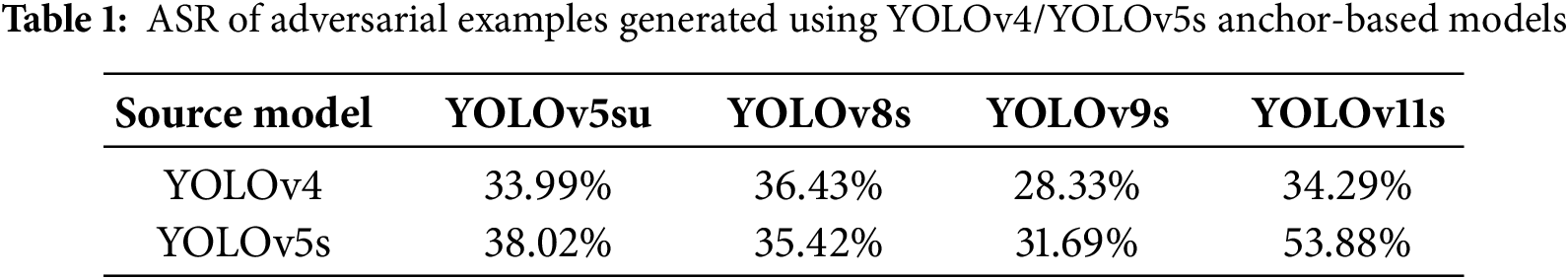

In the adversarial attack experiments for optical remote sensing object detection, adversarial examples were generated using Anchor-Based models (e.g., YOLOv4 and YOLOv5) from previous work on using I-FGSM. Anchor-Free models including YOLOv5s, YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, and YOLOv11s were employed as evaluation models to conduct adversarial attack tests, respectively. For the detailed test parameters, empirically, the maximum perturbation constraint ε was set to 20.0/255.0, the maximum number of iterations to 25, and the fixed step size to 1.0/255.0. The ASR of adversarial attacks are detailed in Table 1.

As is shown in Table 1, it is observed that when Anchor-based models serve as source models for adversarial training, the performance of transferable adversarial attacks against Anchor-Free detectors is poor. The differentiated network structures lead to fundamental differences in the models’ boundary decision mechanisms, thereby forming an insurmountable barrier to the transferability of adversarial attacks between Anchor-Free and Anchor-Based models. Even when YOLOv5s employs different head networks, the correlation of adversarial attacks fails to achieve the effect of transferable adversarial attacks.

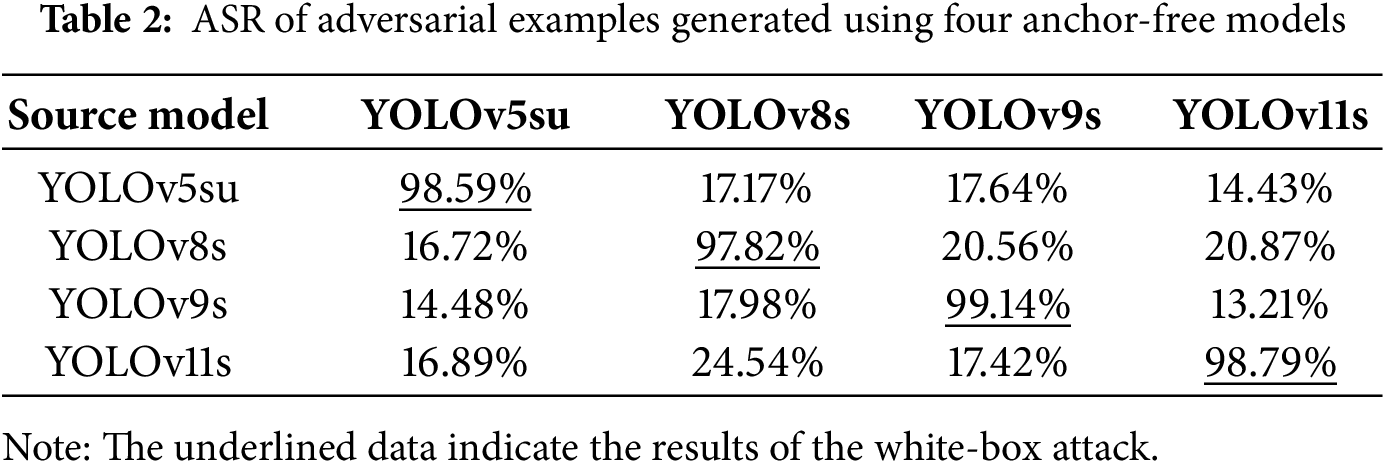

To further investigate the transferability of adversarial attacks for Anchor-Free models, we employed Anchor-Free models such as YOLOv5su, YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, and YOLOv11s as both source models for adversarial attack on using I-FGSM method and evaluation models for adversarial attacks, aiming to further analyze the impact of the selection of adversarial training models on adversarial attacks. The success rates of adversarial attacks are detailed in Table 2. The detailed settings of the hyperparameters are the same as those in the aforementioned experiment.

From Table 2, it is observed that the transferability of adversarial attacks among YOLO models remains poor. Under white-box adversarial attack conditions (underlined results), the ASR approaches 99%, whereas in black-box scenarios, the ASR drops significantly to below 25%. Additionally, although YOLO-series networks have continuously evolved in accuracy and performance, the transferability of adversarial attacks between network generations does not exhibit a strong correlation. This observation indicates that different generations of YOLO models have adopted distinct convolutional modules—tailored to enhance detection accuracy and reduce computational overhead—with considerable differences in structure or parameter configurations. These module-specific design variations lead to significant discrepancies in the models’ feature extraction mechanisms and decision-making boundaries. Consequently, the adversarial attack transferability across these YOLO models remains relatively low. The adversarial attack process inherently constitutes an optimization problem: specifically, it involves searching for optimal points within the sample space that can deceive deep neural networks. Through iterative computations, gradients of samples in the network model space are derived to generate adversarial perturbations. Here, the source model used in adversarial sample generation serves as a “measuring instrument” for quantifying vulnerabilities in the model space, and the diversity of generated adversarial samples depends directly on the diversity of this “instrument”.

It is worth noting that some works have employed ensemble attack methods, which can effectively enhance the transferability of adversarial attacks. However, as the types of object detection are constantly evolving and innovating, a single network structure cannot maintain the diversity of the “measuring instrument”. In ORSIs object detection, factors such as the relatively large default size of images and complex network structures are prone to causing a sharp increase in computational load and data volume. Integrating multiple models often leads to a decrease in the generation rate of adversarial examples and strained GPU computing power. Therefore, we aim to conduct research on the network structure of source models, seeking to propose an object detection network structure with network diversity and high transferability, so as to alleviate the burden of adversarial transfer attacks in optical remote sensing object detection and improve attack efficiency and timeliness.

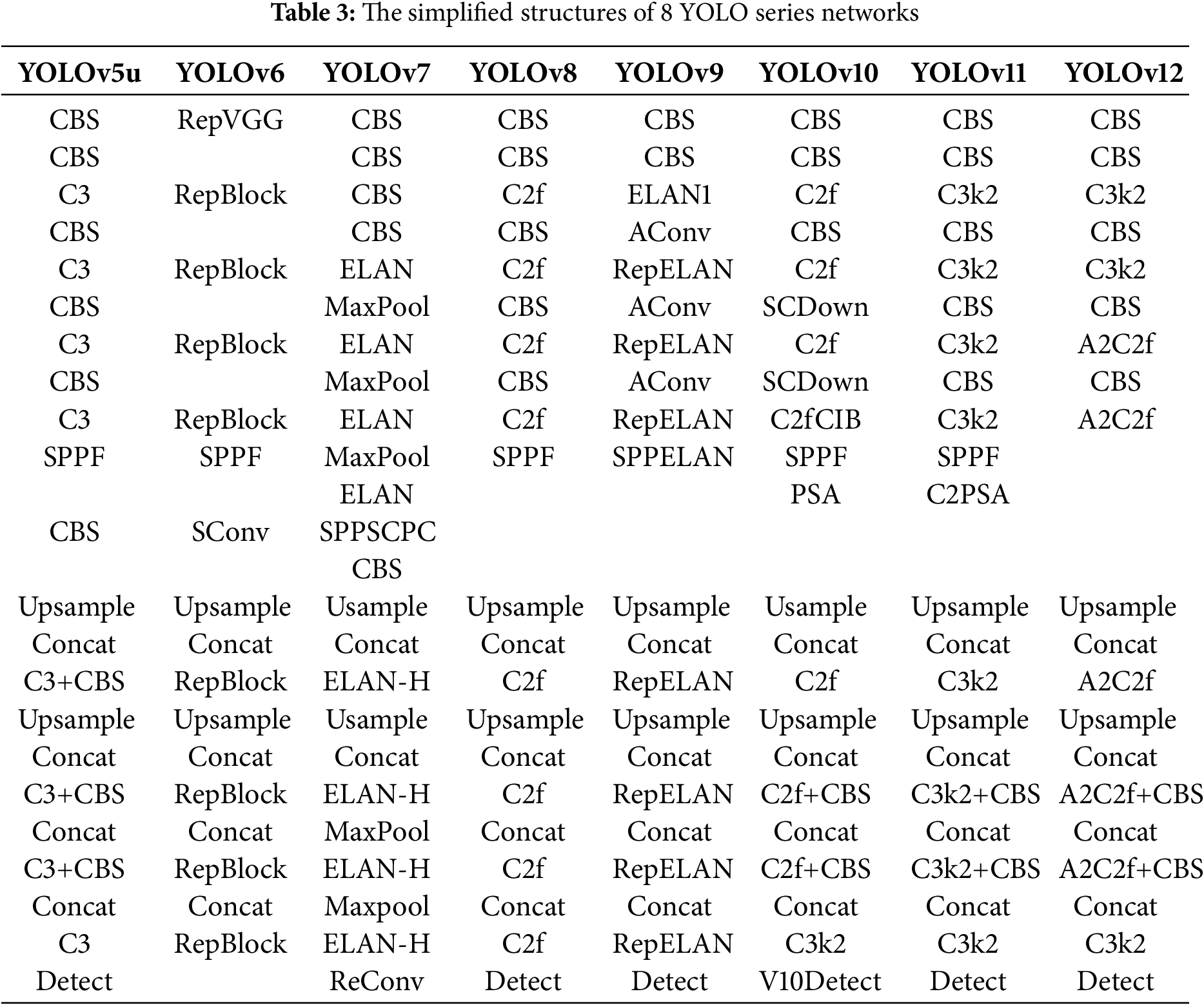

Since the development of YOLO-series networks up to YOLOv12, they have consistently adopted the network structures of Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) and Path Aggregation Network (PAN). Through in-depth analysis of the differences among YOLO-series networks, we find that the primary source of differences in the “measuring instrument” lies in the convolutional units sandwiched between CBS modules, as shown in Table 3.

Through Table 2, it can be observed that YOLO-series networks exhibit structural similarities. The backbone network is constructed using CBS modules (Convolutional layer, Batch normalization, SiLU/LeakReLU activation function) and distinct convolutional blocks, forming a multi-scale feature extraction framework that preserves detailed information. The neck and head networks consist of CBS convolutional blocks, upsampling layers (Upsample), concatenation modules (Concat), detection heads (Detect), and variant convolutional blocks, primarily responsible for multi-scale object prediction and bounding box regression. The connection unit between the backbone and head networks employs modules such as SPPF, C2PSA and A2C2f to fuse global features and extract critical information.

For the purpose of this study, the adversarial transferability of three networks—YOLOv5, YOLOv8 and YOLOv11—was selected as the research focus. Specifically:

• YOLOv5 utilizes the C3 convolutional block, a CSP bottleneck structure with three convolutions that balances computational efficiency and feature representation.

• YOLOv8 adopts the C2f convolutional block, a lightweight variant of the CSP block optimized for faster inference while maintaining multi-scale feature learning capabilities.

• YOLOv11 employs the C3K2 convolutional block, a cross-stage partial bottleneck with kernel size 2, which enhances feature extraction efficiency through compact convolution designs.

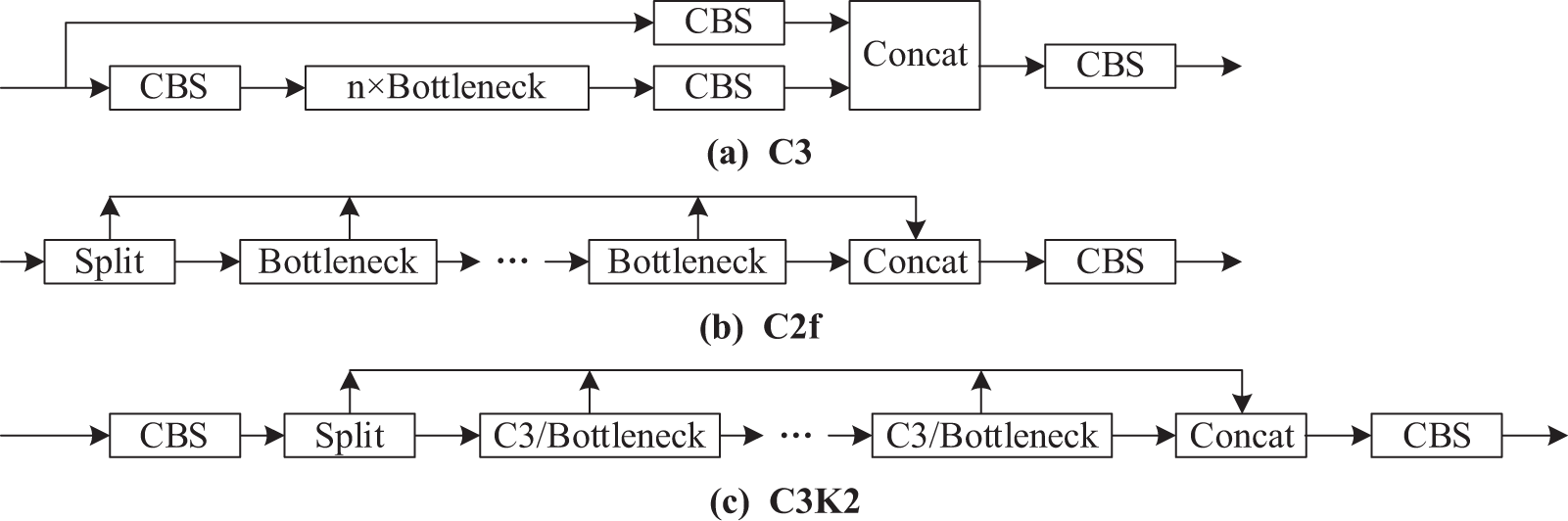

The architectural differences among these networks are visualized in Fig. 1, particularly in the design of convolutional blocks.

Figure 1: Structural diagrams of the C3, C2F, and C3K2 convolutional blocks

Fig. 1 illustrates the distinct computational operations of three convolutional blocks, namely C3, C2f, and C3K2. These divergent operational mechanisms inherently embody differential gradient characteristics within the model. The disparity in “measurement tools” (i.e., the distinct operational configurations) introduces discrepancies in the high-dimensional semantics and decision boundaries across models, which represents a critical challenge to be addressed in transferable adversarial attacks. Consequently, the design philosophy for adversarial network architectures is formulated as follows:

(1) Preserve the differentiated components of each model to the greatest extent possible, thereby enhancing the transferability of adversarial perturbations across diverse model architectures.

(2) Integrate the shared commonalities among the three networks, aiming to reduce computational overhead and data storage requirements.

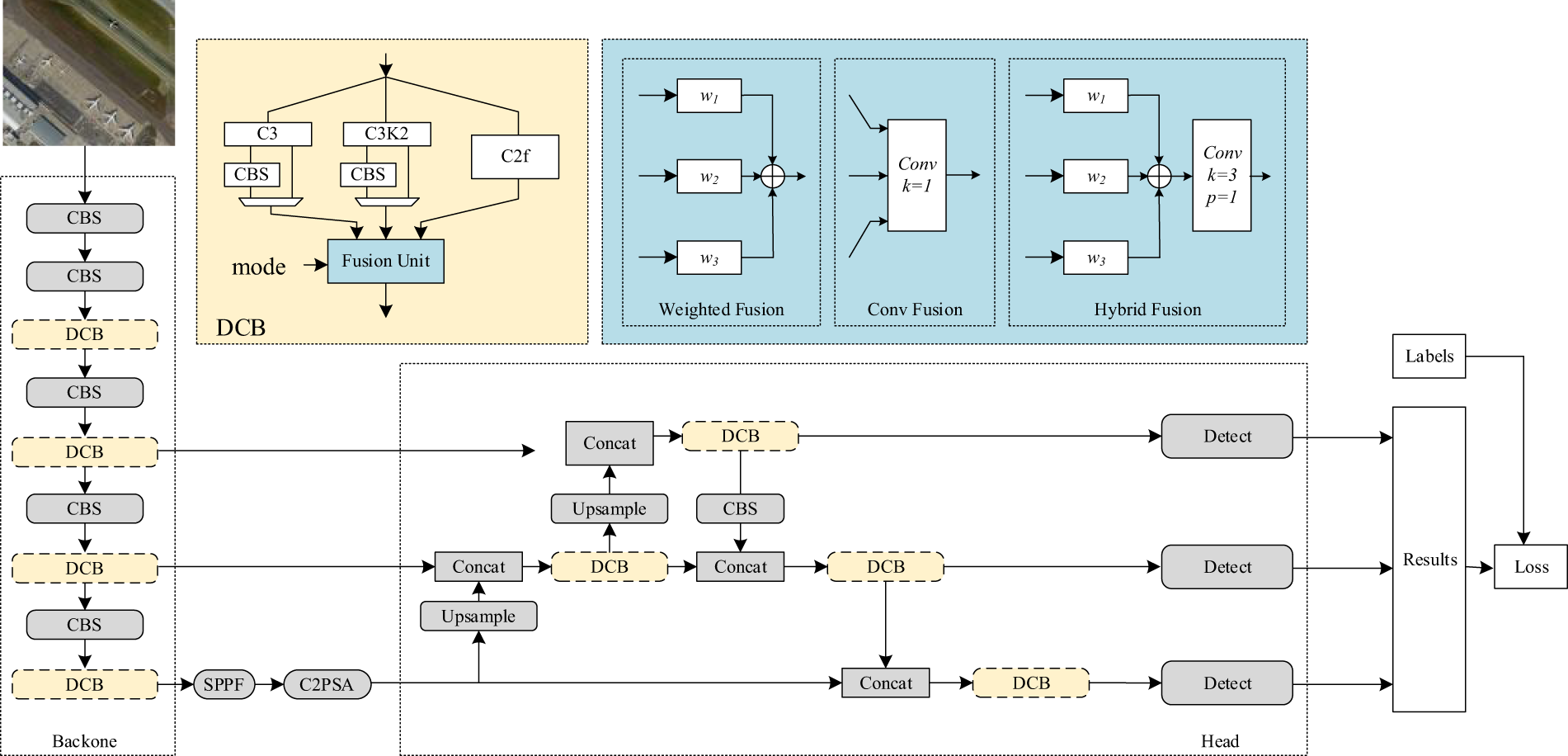

Guided by this design philosophy, we developed the AdvYOLO network, as depicted in Fig. 2. The architecture consists of a universal network and Differentiated Convolutional Blocks (DCB). The universal structure, composed of gray blocks, consists of CBS modules, Upsample modules, Concat modules, and Detect modules. To preserve the diversity of the C3, C2f, and C3K2 convolutional blocks, we integrated these three types of blocks into the DCB. During computation, the three modules operate in parallel to ensure the retention of all features. After the computation of the three convolutional blocks is completed, feature fusion is required to integrate the features extracted by them.

Figure 2: AdvYOLO network architecture

In ensemble adversarial attacks, the gradients obtained from multiple models are aggregated via weighted averaging to generate adversarial perturbations. Similarly, when integrating the outputs of the three convolutional blocks, we employ three common fusion methods: weighted fusion, convolutional fusion, and hybrid fusion. The specific computational operations are detailed in Eq. (3).

here, wi represents the weights of the i-th convolutional block, Conv2d is the convolution operation, and k is the size of the convolution kernel. This approach mirrors the gradient aggregation strategy in ensemble attacks, where differential contributions of individual models are systematically weighted to enhance perturbation transferability. It provides more options for adversarial attacks method. Among them, WeightFusion mode applies learnable weights to linearly combine the outputs of individual convolutional blocks. ConvFusion mode performs 1 × 1 convolutional operations on the outputs of each convolutional block. HybridFusion mode first applies weighted summation to the block outputs using learnable weights, followed by 3 × 3 convolutional operations on the aggregated results.

AdvYOLO can select one of these three modes for cross-block feature fusion. Although all three operations achieve convolutional feature integration, their performance in adversarial transferability may vary and require experimental validation in subsequent stages. For descriptive convenience, the network configurations of AdvYOLO incorporating WeightFusion, ConvFusion, and Hybrid Fusion are abbreviated as AdvYOLO-wf, AdvYOLO-cf, and AdvYOLO-hf, respectively.

In adversarial attacks on anchor-based models, labels are first encoded according to precomputed anchor grids, with confidence scores calculated for each anchor. The labels and model outputs are then decoded into tensors of the same dimension, decomposed into confidence, classification, and location, with corresponding adversarial losses computed separately for each branch. However, the widely adopted decoupled head networks in anchor-free models eliminate the anchor-based paradigm by using fixed grid sizes for bounding box regression. This eliminates the need for anchor-specific label encoding and results in mismatched label-model output dimensions

The Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) function suppresses overlapping bounding boxes by comparing their IoU scores, retaining only the most accurate detections. Widely applied in the prediction stage of object detectors, NMS reduces the number of model outputs to align with the quantity of ground-truth labels by iteratively selecting boxes with the highest confidence scores and suppressing those with IoU exceeding a predefined threshold. However, this filtering process inherently prioritizes optimal detections while discarding suboptimal ones. When these retained boxes are used for adversarial loss calculation and backpropagation, gradient information from suboptimal results is effectively truncated, potentially hindering the generation of targeted adversarial perturbations.

To enable more effective adversarial attacks, we propose decoding model outputs and calculating losses against ground-truth labels. This process inherently results in a mismatch between the number of preselected proposals and ground-truth targets, leading to asymmetric adversarial loss calculation. To address this discrepancy, we introduce a dense bounding box adversarial loss, as formulated in Eq. (4).

where NCbox denotes the total number of candidate bounding boxes generated by the model, NGbox: the total number of the ground-truth targets in labels, BoxAi: the location information of the i-th candidate box, BoxBj the location information of the j-th ground-truth box, and CIoU: the Complete Intersection over Union loss function. While the dense bounding box adversarial loss may increase computational complexity during backpropagation in adversarial attacks, it preserves adversarial features from each candidate box aligned with ground-truth boxes, thereby enhancing adversarial attack effectiveness. Given the flexible classification scenarios enabled by Anchor-Free mechanisms, we adopt Binary Cross-Entropy with Logits Loss (BCEWithLogitsLoss) to improve adversarial attack adaptability. The specific adversarial loss formulation is presented in Eq. (5).

where pc denotes the predicted probability of class C, and yc represents the ground-truth class label. The final adversarial loss is constructed as a weighted combination of the two loss components, as formulated in the following equation.

where

In this section, we elaborate on the dataset, model, baseline methods, experimental setup, and evaluation metrics. We primarily test the adversarial performance of the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method across different datasets and compare it with other baseline methods. Specifically, to further analyze the transferability of adversarial attacks, we propose the adversarial transferability rate (ATR)—a metric designed to quantify the transferability of adversarial attacks. For the effectiveness of transfer-based adversarial attacks, we conduct tests on different source models, and analyze the adversarial transferability degree and adversarial example generation time corresponding to each source model. Finally, we conduct an in-depth investigation into the impact of initialization parameters (e.g., number of iterations, initial step size) on the effectiveness of adversarial attacks.

Dataset. Two datasets, namely NWPU VHR-10 (NWPU) [39,40] and HRSC2016 [41], were utilized in the experiments. Adversarial attack tests were conducted on these datasets to verify the adversarial performance of the adversarial attack method under study across different data scenarios. Both datasets are target detection datasets for optical remote sensing images and are widely adopted in the field of optical remote sensing image target detection, which ensures their persuasiveness for conducting adversarial attack tests.

• The NWPU dataset covers 10 object categories, including aircraft, storage tanks, etc. For adversarial attack testing, we used the officially released validation dataset, which contains 133 images with targets and 27 images without targets as test samples.

• The HRSC2016 dataset is specifically designed for the target detection of ships in optical remote sensing images. Extracted from 6 key ports on Google Earth, this dataset includes 5 object categories: aircraft carriers, naval warships, cargo ships, submarines, and other types of ships. To evaluate adversarial performance, we employed the officially annotated test set of HRSC2016, which comprises 449 images with targets and 4 images without targets.

Models. A total of seven models, including YOLOv5su, YOLOv5mu, YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, YOLOv11s, YOLOv11m, and YOLOv12s, were selected as the targets for adversarial attack testing, and research on transferable adversarial attacks was conducted accordingly. These models were trained independently, and the detection accuracy of each model was maintained at over 87%; for specific accuracy values, refer to Table 4.

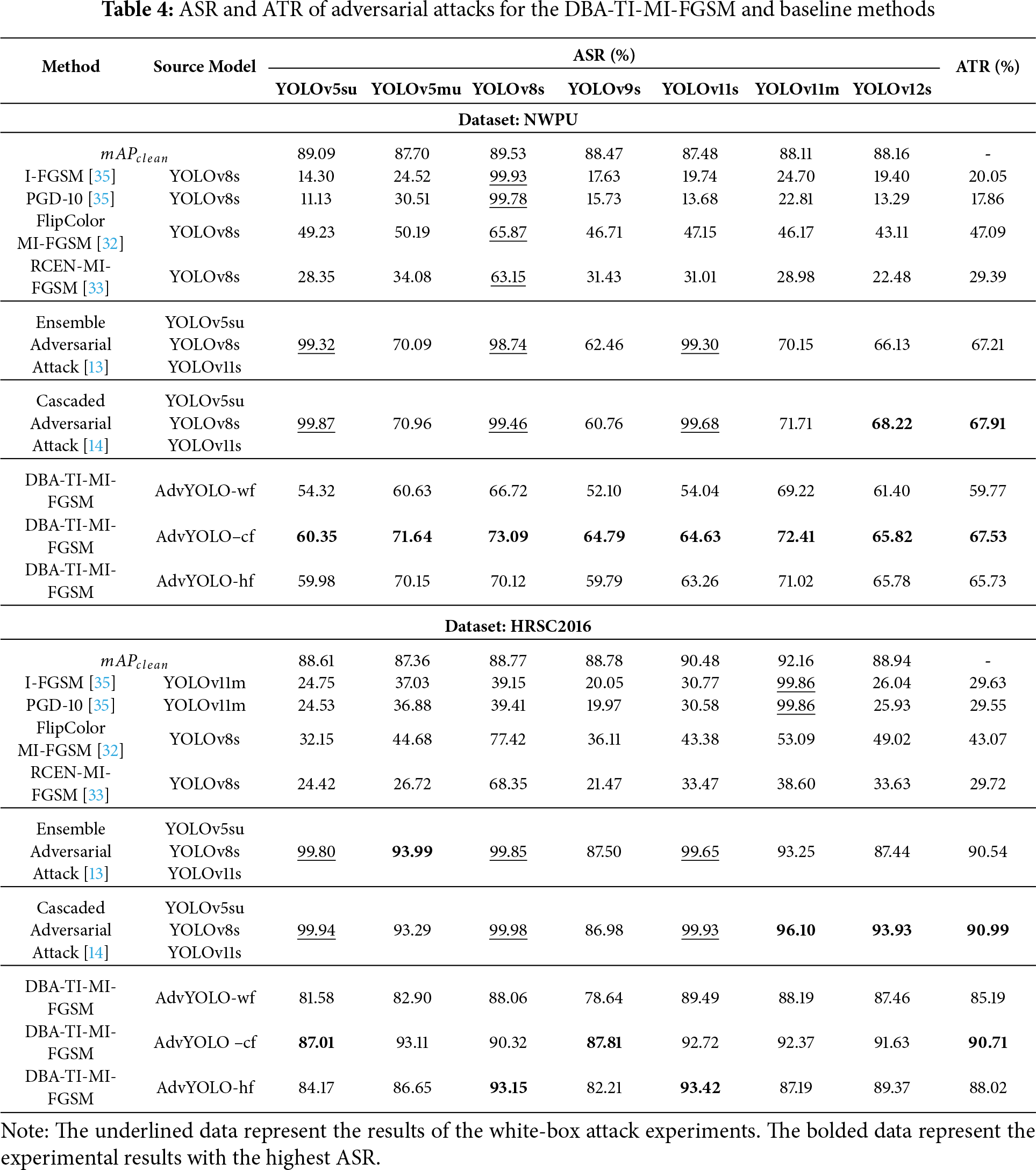

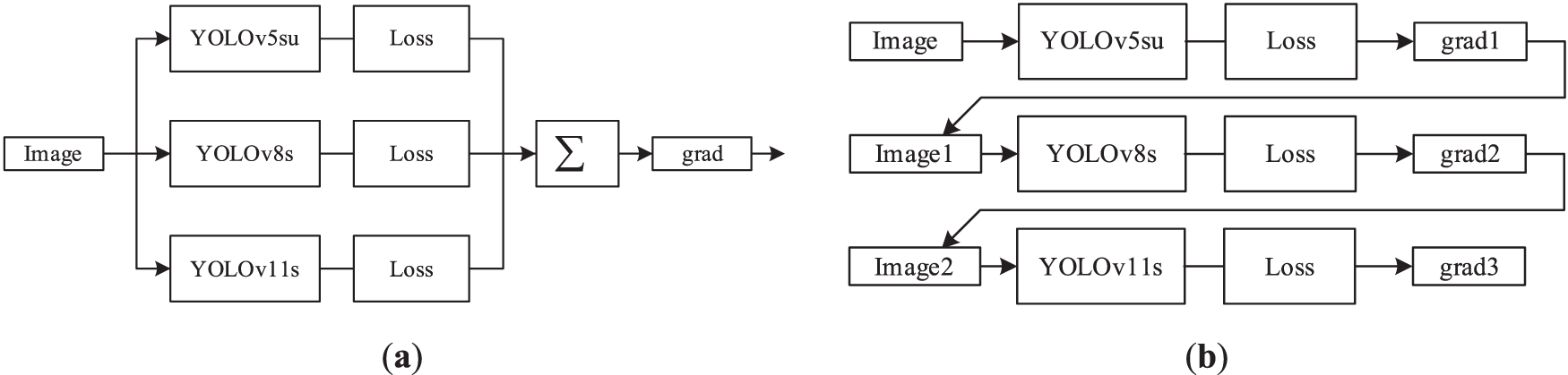

Baseline methods. To evaluate the adversarial performance of the proposed method, six methods—PGD-10 [35], I-FGSM [35], FlipColor-MI-FGSM [32], RCEN-MI-FGSM [33], ensemble-based adversarial attack method [13], cascaded adversarial attack method [14]—were selected as baselines. Among them, the first two baseline methods selected the model with the highest accuracy as the source model for the adversarial attack. The middle two methods chose YOLOv8s as the source model for the adversarial attack as required by the paper. For an in-depth analysis of the transferability of the AdvYOLO model under adversarial attacks, two transferable adversarial attacks were chosen as additional baselines from the perspective of model combination: one is an ensemble-based adversarial attack scheme, and the other is a cascaded adversarial attack scheme, with their adversarial attack structures illustrated in Fig. 3. These two comparative schemes are included to demonstrate the advantages of the AdvYOLO model in terms of adversarial attack effectiveness and adversarial example generation speed.

Figure 3: Architectural diagrams of the ensemble adversarial attack and cascaded adversarial attack. (a) Architectural diagram of the ensemble adversarial attack with YOLOv5su, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv11s as source models. (b) Architectural diagram of the cascaded adversarial attack with YOLOv5su, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv11s as source models

Implementation details. In the adversarial attack experiments, the maximum allowable perturbation constraint was set to 20.0/255.0, which means that each pixel in the generated adversarial examples can deviate from its original value by a maximum of 20 units. The maximum number of iterations was set to 25, indicating that the attack algorithm repeats the perturbation generation process 25 times to iteratively produce more effective adversarial examples. The step size per iteration was fixed at 1.0/255.0, meaning that each pixel in the adversarial example can differ from its value in the previous iteration by a maximum of one unit. The default image input size for the above-mentioned two datasets (NWPU VHR-10 and HRSC2016) is (640, 640).

Metric. ASR, ATR, and average generation time (

The ASR is a critical metric for evaluating the effectiveness of adversarial attacks. Since the object detection task requires predicting both the category of targets and their bounding boxes, the IoU between predicted bounding boxes and ground-truth bounding boxes is introduced as the criterion for accuracy calculation. Specifically, among the numerous prediction results and labels, only when the IoU exceeds a certain threshold (0.50:0.95) will the classification results be counted, recorded, and scored. This allows for the elimination of invalid detections from the prediction results. The calculation formula for the ASR is given in Eq. (7).

where

To evaluate the transferability of different network models during the training process of generating adversarial examples, we propose the Attack Transfer Rate (ATR), which is used to assess the effectiveness of adversarial examples—generated by a model serving as the source model for adversarial training—in attacking other models. The ATR is defined as the average ASR across all models excluding the adversarial attack source model, serving to quantify the effectiveness of transferable adversarial attacks. In accordance with this definition, the calculation formula for the adversarial ATR is presented in Eq. (8).

where

In adversarial attacks, the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method and baseline methods require not only forward propagation on images but also backpropagation to obtain gradients, with adversarial perturbations generated according to their respective algorithms. This results in varying efficiencies of adversarial example generation across different methods and models. Under identical hardware configurations (NVDIA RTX3090) and the same amount of parallel computing data volumes (The batch size is set to 8.), the generation time of adversarial examples can be used to evaluate the complexity of adversarial algorithms and their source models (encompassing both forward and backpropagation processes). Owing to inherent randomness and statistical errors in time measurements for individual samples or single batches of samples, the average generation time of adversarial examples is employed for statistical analysis to more accurately reflect the efficiency of adversarial attack algorithms. The average generation time of adversarial examples is defined as the mean time elapsed to generate adversarial examples, with its calculation formula presented in Eq. (9).

where

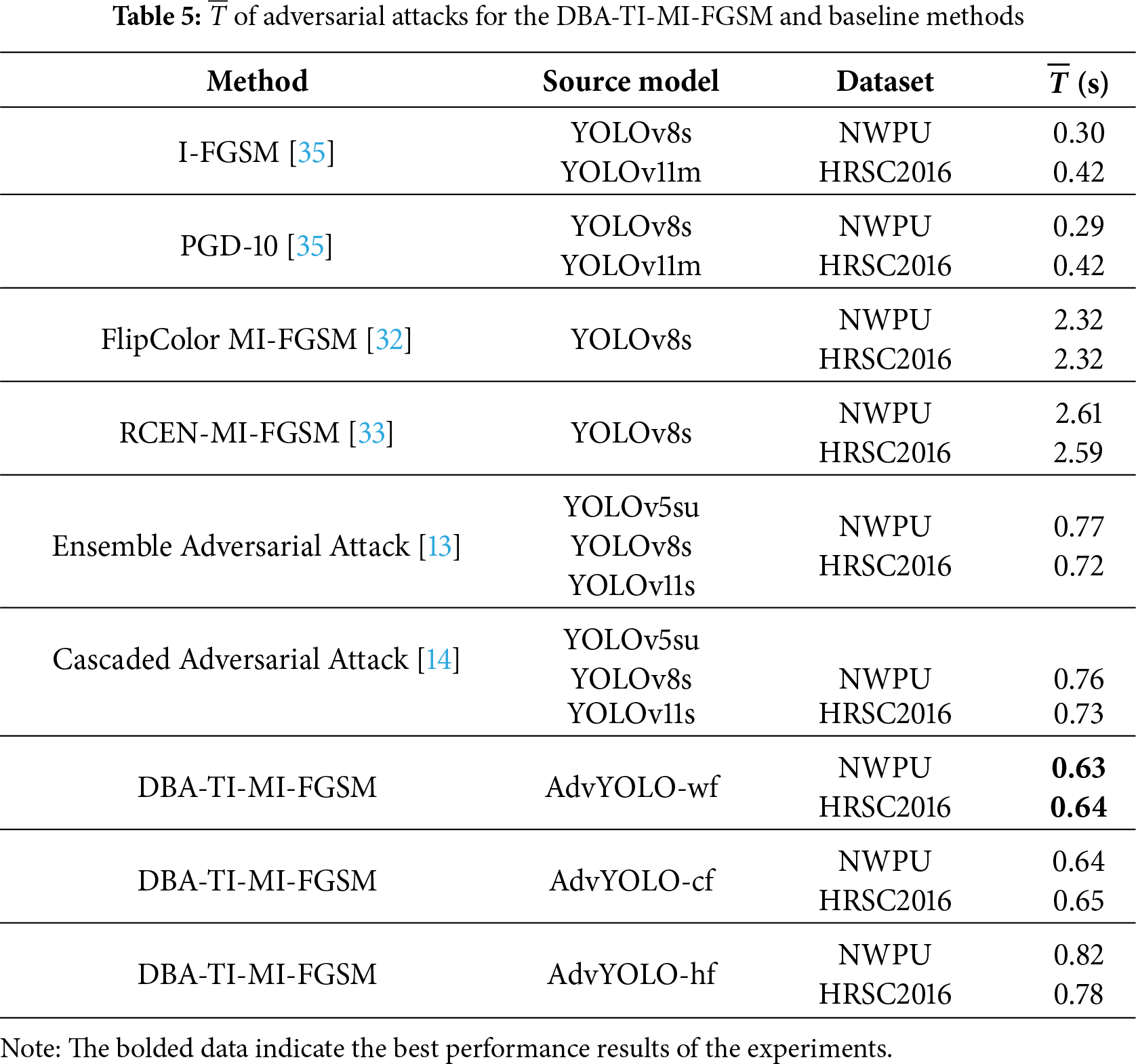

In the attack experiments, DBA-TI-MI-FGSM was subjected to comparative attack testing against the six aforementioned baseline methods across two datasets and six evaluation models. Table 4 presents the experimental results, including metrics of ASR and ATR. Table 5 presents the average generation time (

From Table 4, it can be observed that in the comparison of adversarial attack performance among three variants of the AdvYOLO source model, DBA-TI-MI-FGSM with AdvYOLO-cf exhibits superior ASR and ATR when serving as the source model. On the HRSC2016 dataset, DBA-TI-MI-FGSM with AdvYOLO-hf achieves higher ASR against some models such as YOLOv8s and YOLOv11s, the ATR—calculated as the average of ASRs across evaluation models—was lower than that with AdvYOLO-cf, indicating insufficient stability in the adversarial attack effectiveness of AdvYOLO-hf as a source model.

The DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method with AdvYOLO-cf as the source model was selected as the optimal approach for comparative analysis of adversarial performance against other baseline methods. Compared with other single-model adversarial attack methods, DBA-TI-MI-FGSM demonstrates higher ASR and ATR, outperforming the latest adversarial attack algorithms by a 20% increase in ATR. When compared with multi-source model adversarial attack methods such as cascaded and ensemble adversarial attack schemes, the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM algorithm achieves comparable performance, with an ATR difference of no more than 1%.

Table 5 presents the average generation time of adversarial examples. Under identical hardware configurations and parallel data volume, DBA-TI-MI-FGSM with AdvYOLO-cf achieves faster runtime while maintaining high-level attack transferability compared to other adversarial attack methods. This indicates that the integrated mode across cross-conv-block can reduce sample generation time and enhance the efficacy of adversarial attacks while preserving adversarial attack effectiveness.

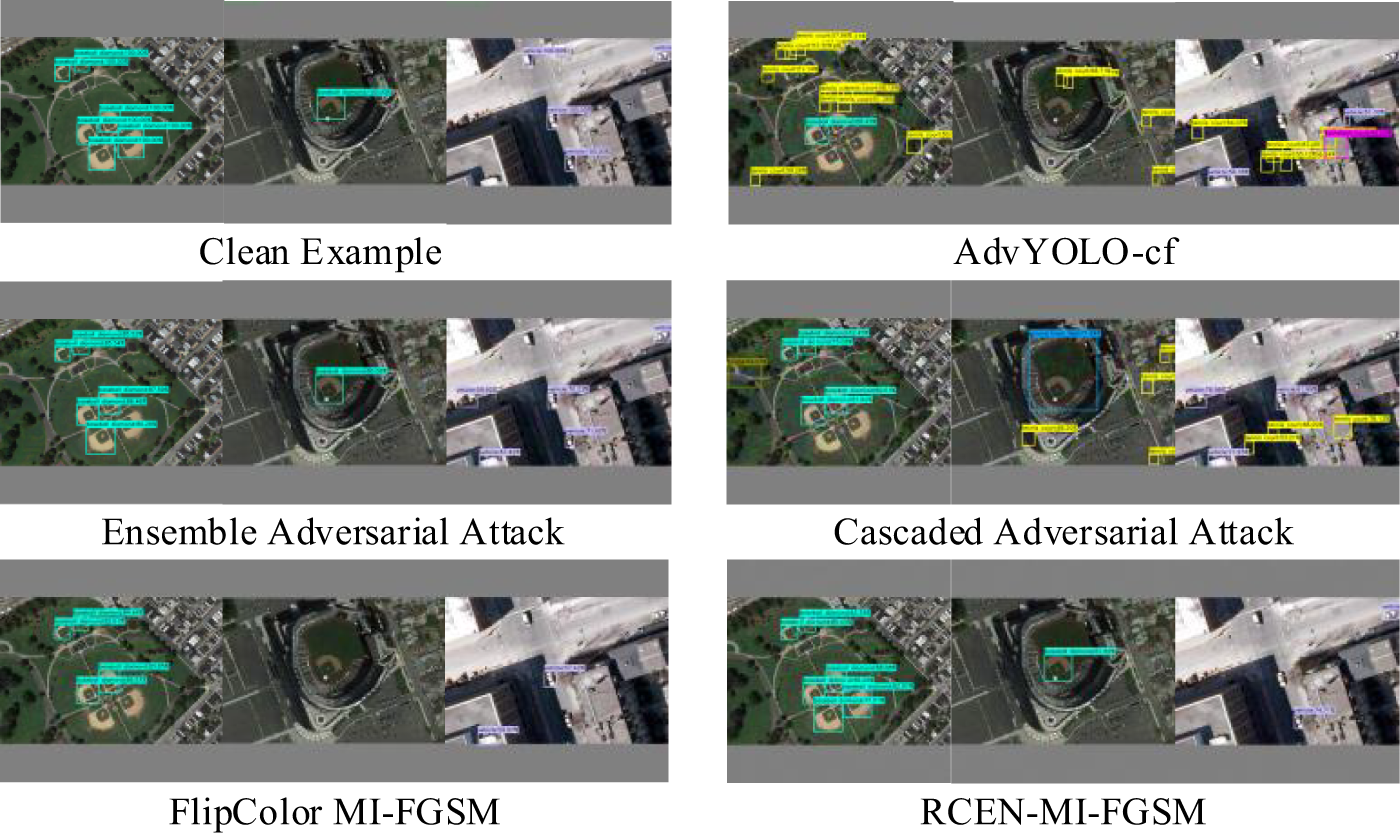

From the data, the ASR under white-box settings is significantly higher than that in black-box adversarial attacks. However, this is not desirable in practice: excessively high ASR targeting a specific model tends to induce overfitting in the optimization of adversarial examples, thereby hindering the achievement of enhanced adaptability of such examples. To further illustrate the effectiveness of adversarial attacks, several generated adversarial examples are presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Demonstration of the attack effects of adversarial samples generated by different baseline methods

4.3 Ablation Analysis of Source Model

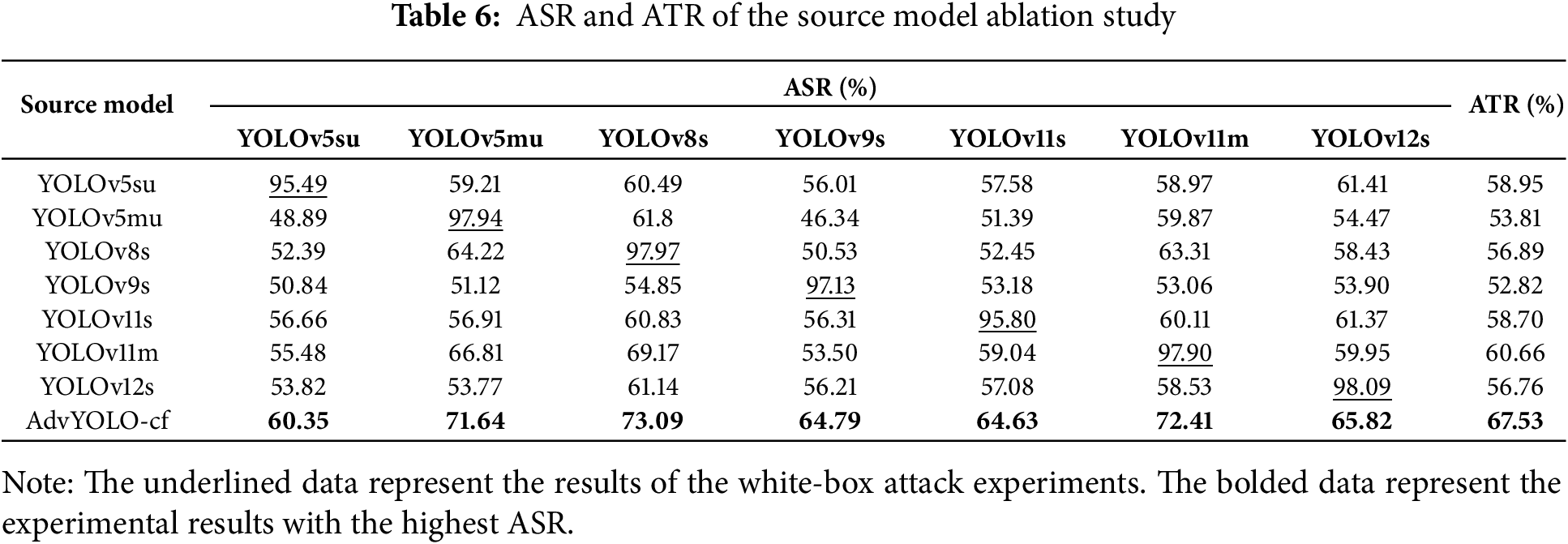

To further validate the impact of source model selection on the ATR, an ablation study on source models was conducted. By fixing the adversarial method as DBA-TI-MI-FGSM with identical hyperparameters, experiments were performed on the NWPU dataset, where seven models were respectively employed as both source models and evaluation models. These results were compared against the source model operating in the AdvYOLO-ConvFusion mode, with detailed experimental findings presented in Table 6.

As shown in Table 6, the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM with AdvYOLO-cf achieves significantly higher ASR and ATR. This partially demonstrates that the ConvFusion mode facilitates the preservation of cross-conv-block features, enabling the generated gradients to exhibit greater diversity and robustness.

In the evaluation of the YOLOv5su model, while our method achieved the lowest performance, it still outperformed other source models when compared comprehensively. This phenomenon is also reflected in Table 4. This phenomenon may be attributed to the inherent robustness and model redundancy of the YOLOv5su model, suggesting that YOLOv5su possesses higher adversarial robustness. The proposed method can effectively assess the latent robustness of object detection models, a property that often cannot be evaluated through accuracy metrics on test set samples.

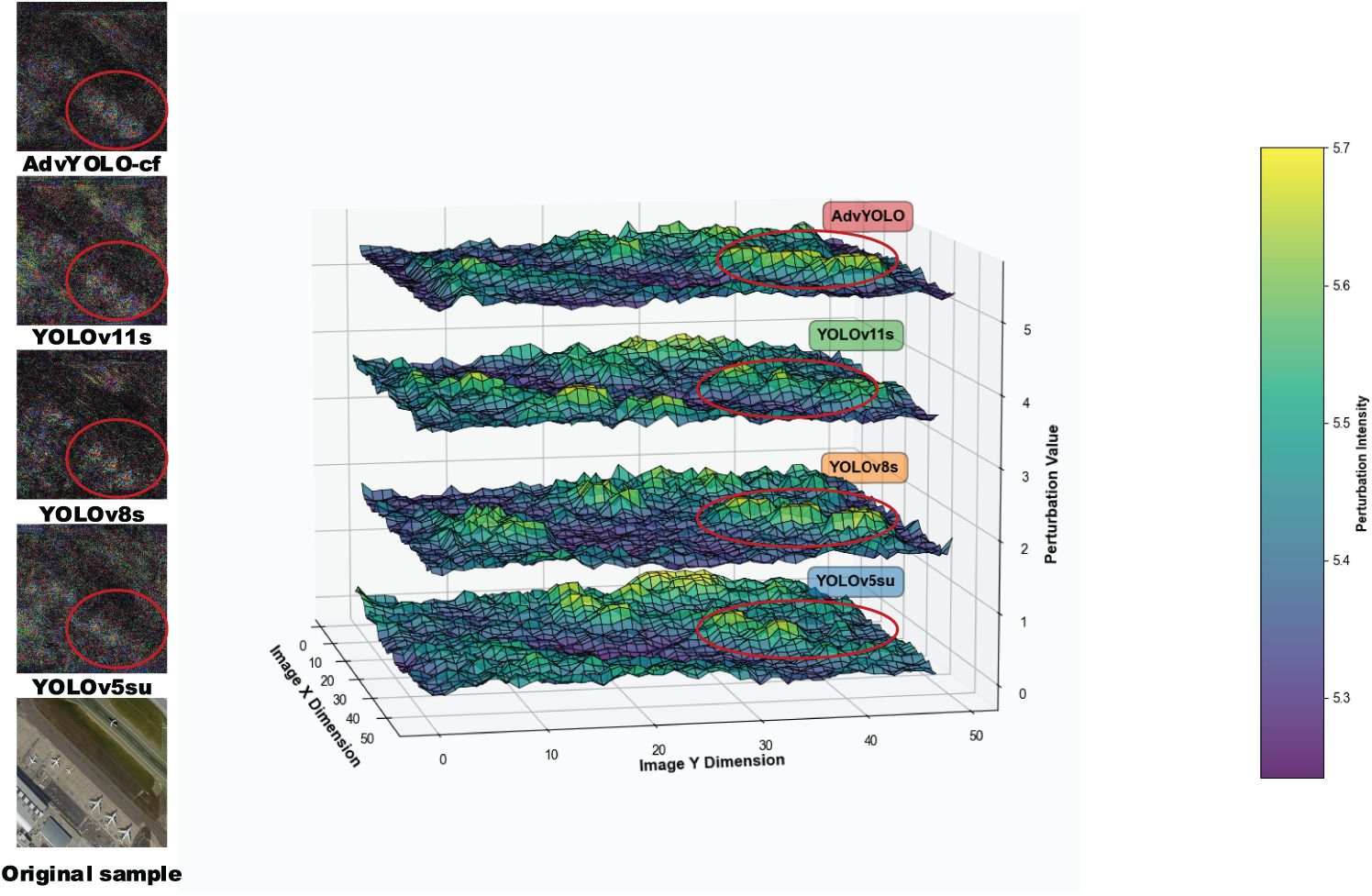

To further investigate the relationships between adversarial perturbations generated by different source models and thereby gain deeper insights into the transferability of adversarial attacks, we first saved the adversarial perturbations produced by four source models. These perturbations were then visualized in a unified 3D coordinate system via superimposition to enhance visualization clarity—note that the original [640 × 640] images were downsampled to [50 × 50] to balance computational efficiency and the preservation of key perturbation features. As illustrated in Fig. 5, under the AdvYOLO-cf network, stronger-magnitude adversarial perturbations are generated in the region marked by the red circle. Importantly, these perturbations largely cover the perturbation magnitudes required to launch effective adversarial attacks against the other three models at the corresponding regional locations of the sample.

Figure 5: The display of adversarial perturbations generated by 4 source models in three-dimensional space

Furthermore, in the ablation study, we observed that large-scale networks tend to be more susceptible to adversarial examples. For instance, under identical adversarial attack conditions with the same source model, a comparative evaluation of YOLOv5s/YOLOv11s vs. YOLOv5m/YOLOv11m revealed that the YOLOv5m and YOLOv11m models are more vulnerable to adversarial examples, despite YOLOv11m achieving higher accuracy than YOLOv11s. This phenomenon may be attributed to excessive redundancy in model scale or insufficient training. However, our hypothesis cannot be validated solely through the aforementioned experimental results on a single dataset. This constitutes an interesting finding that warrants further investigation to enhance the adversarial robustness of models.

We aimed to further investigate how hyperparameters—including the number of iterations, maximum perturbation magnitude, and momentum decay factor—affect adversarial attack transferability and time consumption in the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method. To this end, we conducted experiments on hyperparameter configurations. Experiments were performed using the NWPU dataset as the focused research dataset, with the AdvYOLO-cf model serving as the source model for adversarial attacks. These experiments aimed to separately examine the effects of maximum iteration number, decay factor rate, and maximum perturbation magnitude on adversarial attack transferability, time consumption, and image quality.

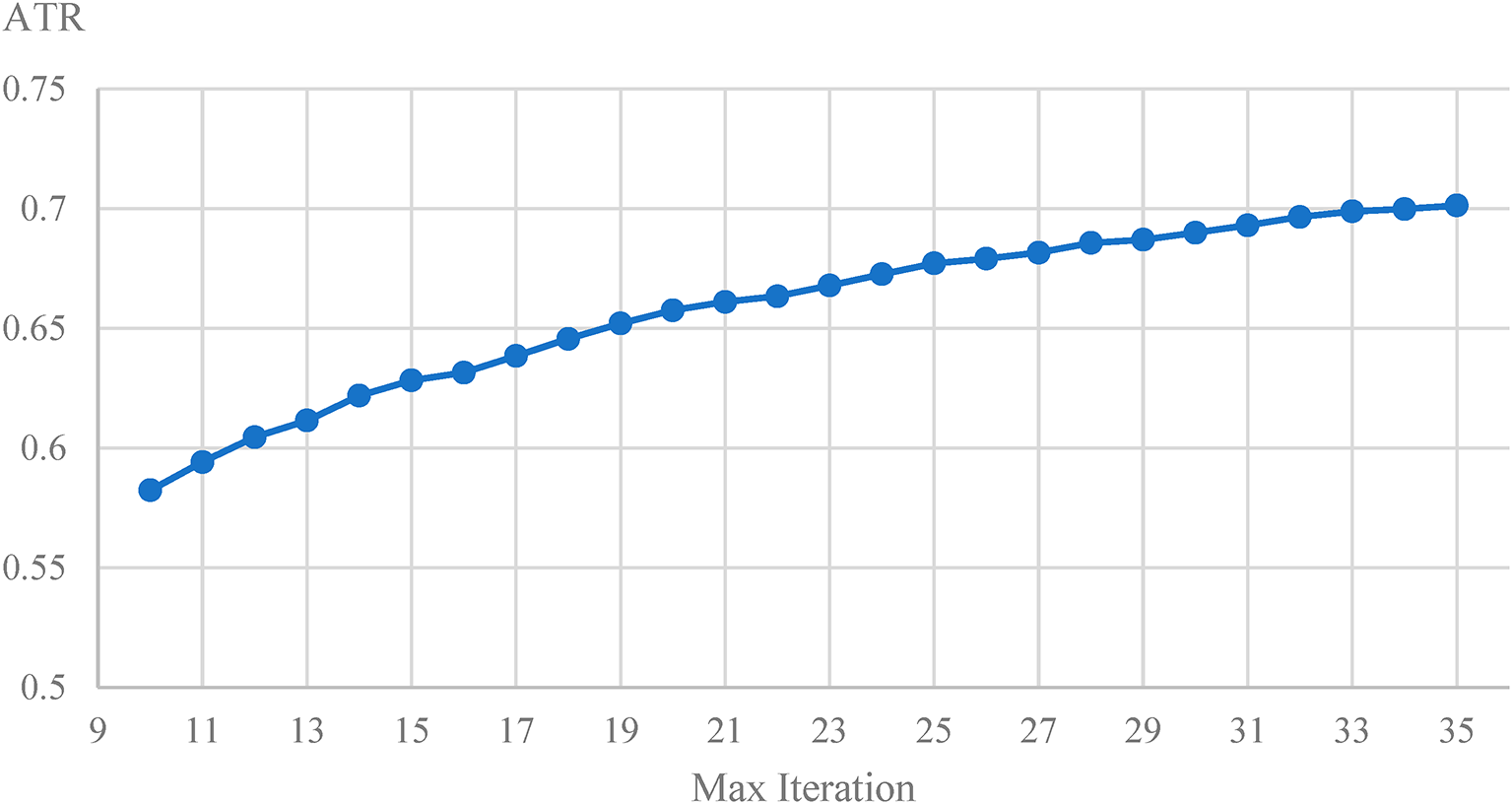

Maximum iteration number. The maximum iteration number

From Fig. 6, it can be observed that the ATR of DBA-TI-MI-FGSM exhibits an upward trend as the number of iterations increases. The hyperparameter of the maximum number of iterations has a rather sensitive impact on the ATR and the time consumption for generating adversarial examples. When the maximum number of iterations is in the range of 10–27, the ATR shows a significant upward trend. On average, for each additional iteration, the ATR increases by approximately 6%. However, when the number of iterations exceeds 27, although the ATR is still rising, the rate of in-crease slows down significantly. According to the data, for each additional iteration, the ATR only increases by about 3%. This shows that the effect of further increasing the number of iterations on improving the attack transferability is gradually weakening.

Figure 6: ATR of the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM algorithm with the change of the maximum iteration number

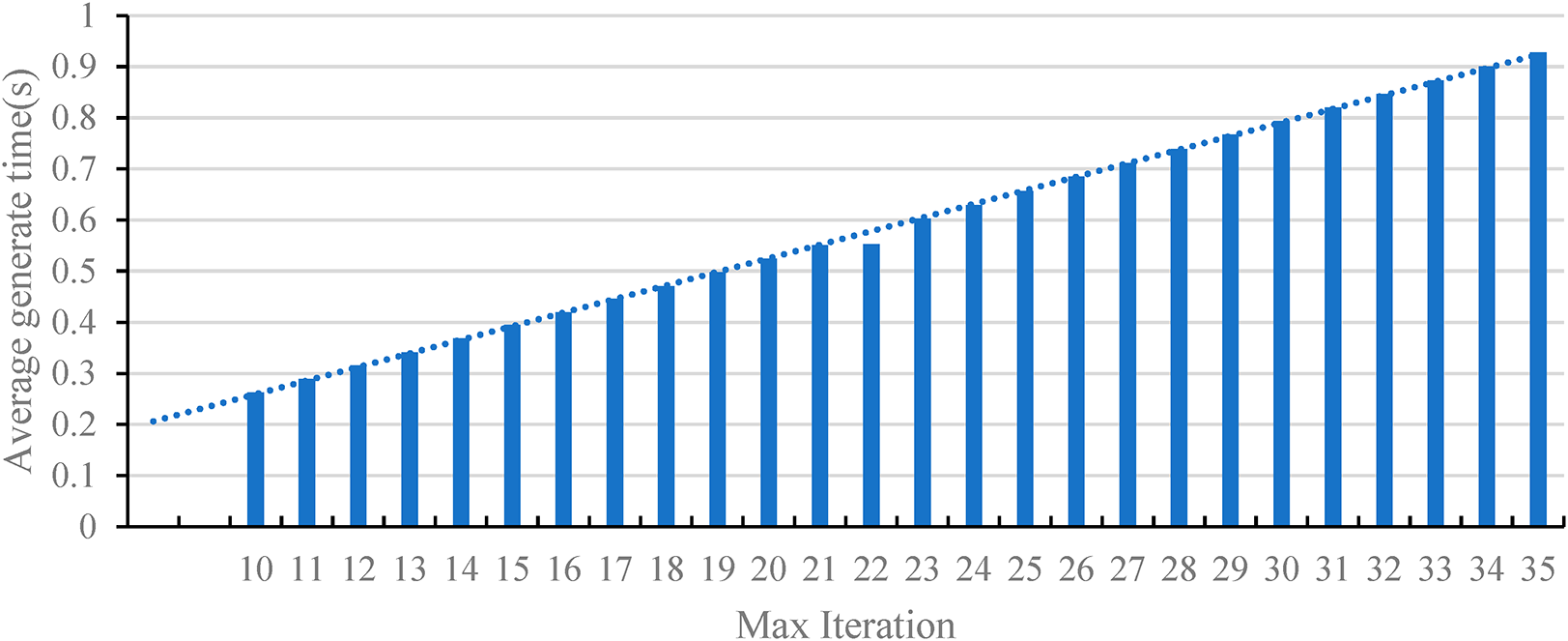

The runtime of the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM algorithm is determined by the model’s forward computation time, backward computation time, perturbation computation time, and the number of iterations. With the model structure and perturbation computation process unchanged, the runtime exhibits a linear relationship with the number of iterations. Through statistical analysis of time consumption across multiple experiments, the variation trend of the average generation time of adversarial examples with increasing iterations is obtained, as shown in Fig. 7. In this figure, the dashed line represents the linear trend line, while the column graphs denote the actual time consumed, which aligns with the aforementioned theoretical analysis. From the perspective of time consumption, as the maximum number of iterations increases, the average time for generating adversarial examples strictly follows a linear growth pattern. Throughout the experiment, for each additional iteration, the average time increases by approximately 0.025 s. This means that when pursuing a higher attack transferability rate, the time cost brought about by the increase in the number of iterations needs to be fully considered. If time resources are limited, a trade-off must be made regarding the maximum number of iterations to balance these two key indicators of ATR and time consumption.

Figure 7:

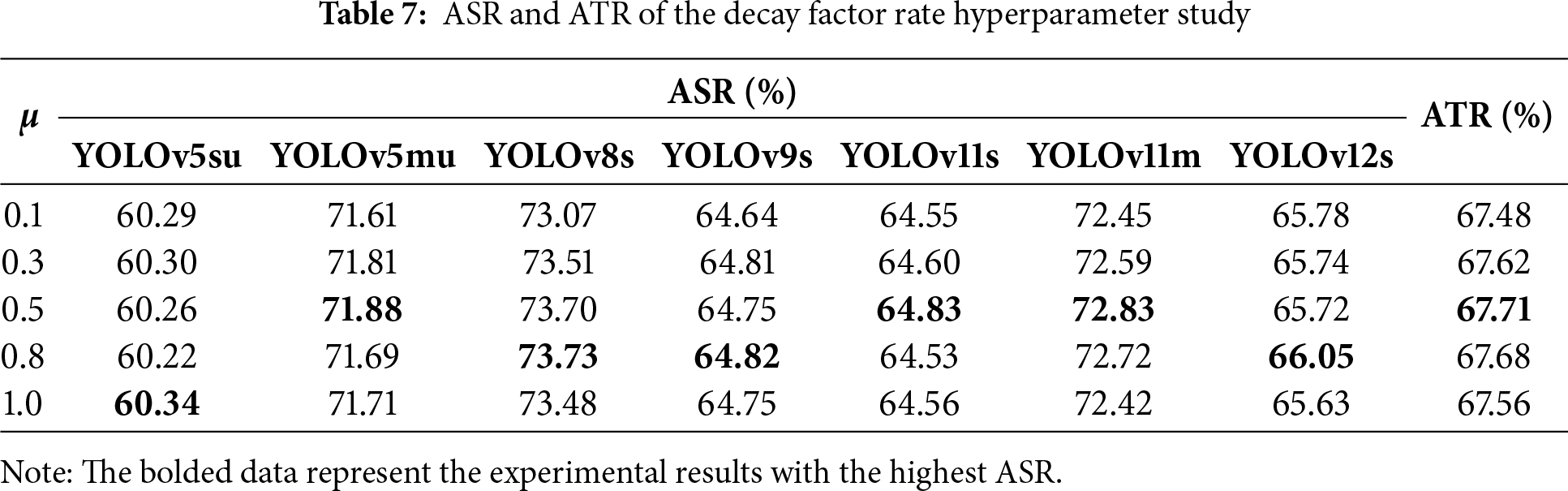

Decay factor rate. In the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM algorithm, the decay factor rate

To simplify the experiment, five values (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, and 1.0) were sampled within the momentum decay factor rate range [0.1, 1.0] for testing. With other experimental settings held constant, adversarial examples were generated on the NWPU dataset and evaluated across the seven models. The experimental results are presented in Table 7.

Our experimental findings reveal that variations in the momentum decay factor exert a minimal influence on the transferability of adversarial attacks. Specifically, changes in the momentum decay factor within the range of 0.1 to 1.0 result in a difference of no more than 1 percentage point in the ASR, and an even smaller impact on the ATR, with the variation not exceeding 0.5 percentage points.

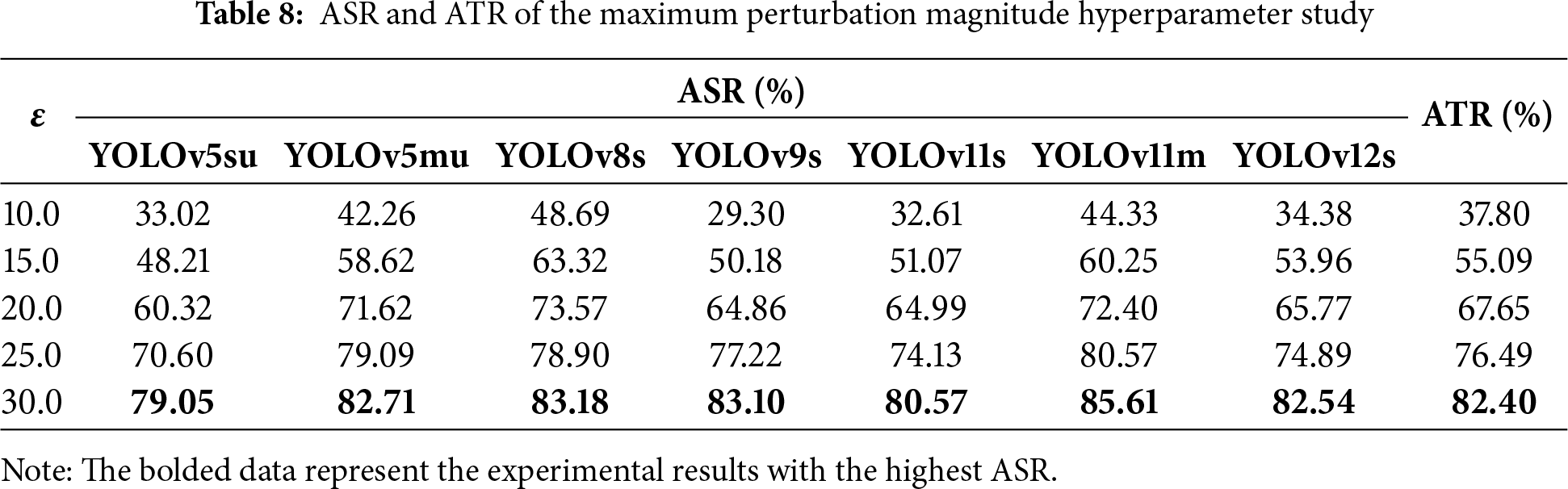

Maximum perturbation magnitude. The maximum perturbation magnitude

Notably, from a sensitivity perspective, the maximum perturbation magnitude’s impact on ASR and ATR is highly interval-dependent. When the value rises from 10 to 20, ASR and ATR improve sharply. For instance, ATR jumps from 37.80% to 67.65%—a 29.85 percentage point increase. For individual models, the growth is also striking: YOLOv5su’s ASR rises by 27.30 percentage points, and YOLOv8s’ ASR increases by 24.88 percentage points. This confirms the low-to-medium range (10–20) is a high-sensitivity interval for the hyperparameter. In this range, small increments effectively boost attack capability.

However, when the maximum perturbation magnitude increases further (from 20 to 30), ASR and ATR become far less sensitive to it. ATR only rises by 14.75 percentage points (from 67.65% to 82.40%). For most models, ASR growth slows to less than 10 percentage points. Take YOLOv5su as an example: its ASR goes from 60.32% to 79.05% (an 18.73 percentage point increase). This is 31.4% slower than the growth in the 10–20 range. This suggests that beyond 20, the hyperparameter enters a diminishing-return interval. Here, increasing perturbations no longer bring proportional gains in attack performance.

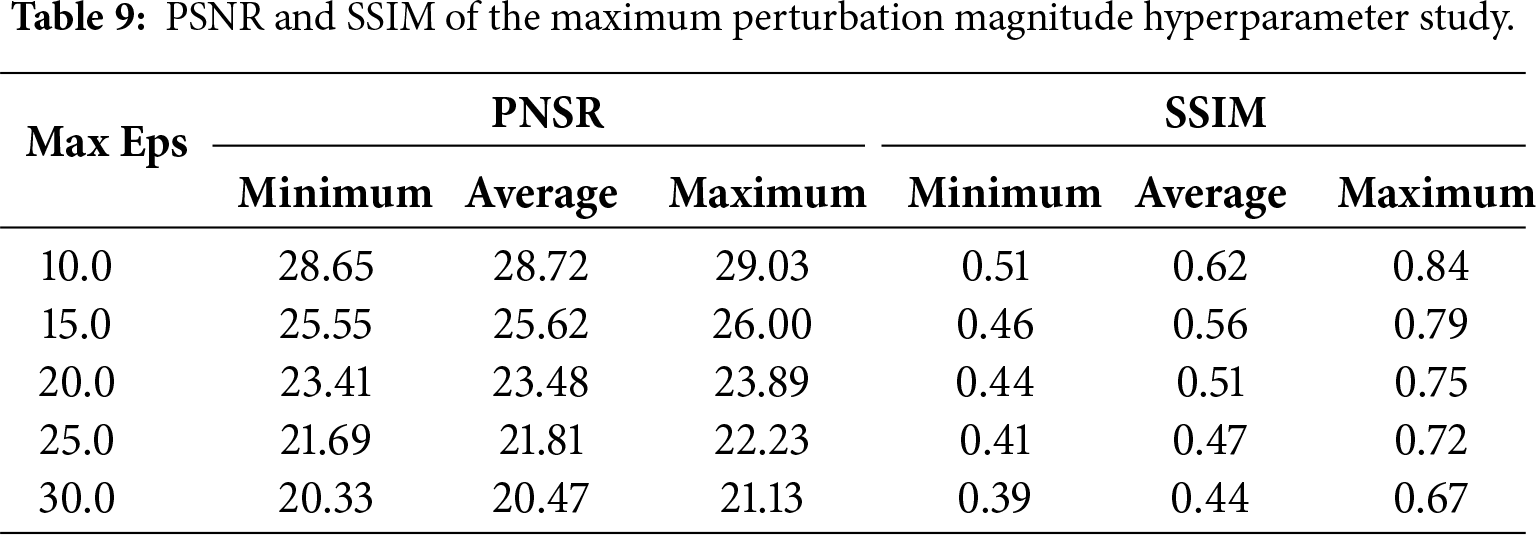

Increasing the maximum perturbation magnitude also harms the image quality of adversarial examples. Importantly, this quality degradation also shows clear sensitivity to the hyperparameter’s value. As shown in Table 9, every 5-unit increase in the hyperparameter leads to a 2.8–3.2 dB drop in average PSNR.

Similarly, average SSIM decreases linearly from 0.62 (at 10) to 0.44 (at 30). The most significant drop (0.11) happens in the 15–20 range—matching the high-sensitivity interval for attack performance. In ORSIs, due to the influence of factors such as the fluctuation of ground height and the different angles of sunlight exposure, the image background is often quite complex. This increases the difficulty of detecting disturbances. In actual adversarial testing, in order to ensure the comprehensiveness of the adversarial robustness test for the target detection model, we hope that the minimum PSNR value of the image should not be lower than 21, and the minimum SSIM value should not be lower than 0.4.

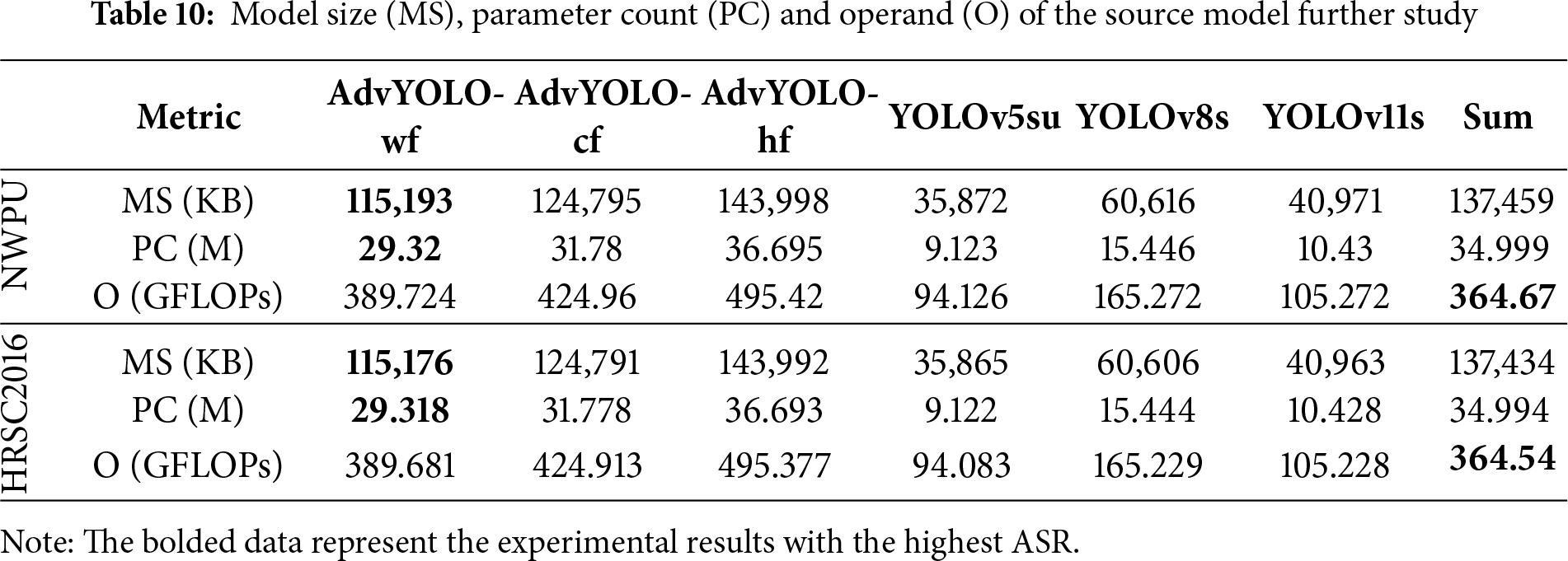

In adversarial attacks, the efficiency of adversarial example generation is significantly influenced by the model size, parameter count, and computational effort of the employed source model. To further analyze the characteristics of the AdvYOLO model, we conducted statistical analyses on the model size, parameter count, and computational effort of three AdvYOLO source model variants across different datasets. For comparative purposes with ensemble adversarial attacks and cascaded adversarial attacks, we also performed statistical analyses on the model size, parameter count, and forward propagation operand t of three source models (YOLOv5s, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv11s) utilized in these attack frameworks. The detailed results are presented in Table 10.

Through comparative analysis, we observe that the model size, parameter count, and forward propagation operand of AdvYOLO-cf fall between those of AdvYOLO-wf and AdvYOLO-hf. When compared to the aggregated metrics of YOLOv5s, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv11s—encompassing their combined model size, parameter count, and operand—AdvYOLO-cf exhibits a smaller model size and fewer parameters, yet requires greater computational effort for forward propagation. This indicates that the reduction in the average generation time of adversarial examples can be attributed to the decreased parameter count of the source model employed in adversarial attacks. Notably, while this efficiency gain is validated, AdvYOLO models (including AdvYOLO-cf) still exhibit relatively high FLOPs and computational demand. To define the threshold of complexity-performance balance, we set it as: a source model meets this balance if its parameter count is under 32M and FLOPs are under 430 GFLOPs—this range ensures efficient adversarial generation while retaining over 65% ATR.

In the field of adversarial attack research on Optical Remote Sensing Images (ORSIs), multi-model ensemble techniques have been proven effective in enhancing adversarial transferability. However, with the increasing diversity and quantity of object detection networks, pure model ensembling is inevitably constrained by GPU computing power and load limitations, failing to adequately meet the requirements for robust adversarial transferability. To address this challenge, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the Anchor-Free YOLO network architecture and propose an improved YOLO network based on a cross-conv-block feature fusion mechanism, called AdvYOLO. Targeting the inherent asymmetry between output results and labels in Anchor-Free mechanism, we introduce a dense bounding box loss function that guides adversarial example generation to produce stronger gradients specifically for bounding box regression. Finally, we present the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method, which integrates translation invariance and momentum iteration techniques to enhance the generalization capability of adversarial perturbations. Experimental results demonstrate that compared with single-model adversarial attacks, under black-box settings, the DBA-TI-MI-FGSM method achieves significantly higher adversarial ASR and ATR with improved stability in attack transferability. When compared with multi-model adversarial attacks, our proposed method delivers comparable performance to multi-model ensemble/cascaded adversarial attacks while exhibiting superior efficiency in adversarial example generation, characterized by reduced computational time and lower model storage overhead.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Leyu Dai, Jindong Wang; data collection: Ming Zhou, Song Guo, Leyu Dai; analysis and interpretation of results: Leyu Dai, Hengwei Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Leyu Dai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang J, Zhu F, Wang Q, Zhao P, Fang Y. An active object-detection algorithm for adaptive attribute adjustment of remote-sensing images. Remote Sens. 2025;17(5):818. doi:10.3390/rs17050818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Meng Q, Yuan Q, Niu W, Wang Y, Lu S, Li G, et al. IIT: accurate decentralized application identification through mining intra- and inter-flow relationships. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2025;22(1):394–408. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2024.3479150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yuan Q, Meng Q, Tao J, Li G, Fei J, Lu B, et al. Multi-agent for network security monitoring and warning: a generative AI solution. IEEE Netw. 2025;39(5):114–21. doi:10.1109/mnet.2025.3579001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kheddar H, Habchi Y, Ghanem MC, Hemis M, Niyato D. Recent advances in transformer and large language models for UAV applications. arXiv:2508.11834. 2025. [Google Scholar]

5. Vijayakumar A, Vairavasundaram S. YOLO-based object detection models: a review and its applications. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(35):83535–74. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-18872-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jocher G, Chaurasis A, Qiu J. Ultralytics YOLOv8 [software]. 2023 [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

7. Zhang Y, Chen J, Peng Z, Dang Y, Shi Z, Zou Z. Physical adversarial attacks against aerial object detection with feature-aligned expandable textures. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–15. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3426272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lian J, Wang X, Su Y, Ma M, Mei S. CBA: contextual background attack against optical aerial detection in the physical world. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:1–16. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2023.3264839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang B, Zhang H, Wang J, Yang Y, Lin C, Shen C, et al. Adversarial example soups: improving transferability and stealthiness for free. IEEE TransInformForensic Secur. 2025;20:1882–94. doi:10.1109/tifs.2025.3536611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jocher G, Qiu J. Ultralytics YOLO11 [software]. 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

11. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. YOLOv12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. [Google Scholar]

12. Zhang Q, Li X, Chen Y, Song J, Gao L, He Y, et al. Beyond ImageNet attack: towards crafting adversarial examples for black-box domains. In: Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2022); 2022 Apr 25–29; Virtual. p. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

13. Wu Z, Lim SN, Davis LS, Goldstein T. Making an invisibility cloak: real world adversarial attacks on object detectors. In: Vedaldi A, Bischof H, Brox T, Frahm JM, editors. Computer Vision—ECCV 2020. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 1–17 doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58548-8_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang X, Chen J, Zhang Z, He K, Wu Z, Du R, et al. Transferable and robust dynamic adversarial attack against object detection models. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(11):16171–80. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3531852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Xu L, Zhao Y, Zhai Y, Huang L, Ruan C. Small object detection in UAV images based on YOLOv8n. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2024;17(1):223. doi:10.1007/s44196-024-00632-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Qiang H, Hao W, Xie M, Tang Q, Shi H, Zhao Y, et al. SCM-YOLO for lightweight small object detection in remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2025;17(2):249. doi:10.3390/rs17020249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Yuan Q, Yu W, Meng Q, Lu S, He W, et al. Entropy-regulated cross-modal generative fusion for multimodal network intrusion detection. Inf Fusion. 2026;126(2):103581. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yasir SM, Kim H. Lightweight deepfake detection based on multi-feature fusion. Appl Sci. 12025;15(4):1954. doi:10.3390/app15041954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang X, Peng Y, Shen C. Efficient feature fusion for UAV object detection. arXiv:2501.17983. 2025. [Google Scholar]

20. Dong Y, Pang T, Su H, Zhu J. Evading defenses to transferable adversarial examples by translation-invariant attacks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 4307–16. [Google Scholar]

21. Dong Y, Liao F, Pang T, Su H, Zhu J, Hu X, et al. Boosting adversarial attacks with momentum. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 9185–93. [Google Scholar]

22. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLOv3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

23. Bochkovskiy A, Wang CY, Liao HM. YOLOv4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934. 2020. [Google Scholar]

24. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. [Google Scholar]

25. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Mark Liao HY. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In: Leonardis A, Ricci E, Roth S, Russakovsky O, Sattler T, Varol G, editors. Proceedings of the 18th European Conference Computer Vision—ECCV 2024; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72751-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jocher G. Ultralytics YOLOv5 [software]. 2020 [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5. [Google Scholar]

27. Lang K, Cui J, Yang M, Wang H, Wang Z, Shen H. A convolution with transformer attention module integrating local and global features for object detection in remote sensing based on YOLOv8n. Remote Sens. 2024;16(5):906. doi:10.3390/rs16050906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hou D, Zhang Y. Object detection model for remote sensing images based on YOLOv9. IAENG Int J Comput Sci. 2025;52(3):1–8. [Google Scholar]

29. Sun H, Yao G, Zhu S, Zhang L, Xu H, Kong J. SOD-YOLOv10: small object detection in remote sensing images based on YOLOv10. IEEE Geosci Remote Sensing Lett. 2025;22:1–5. doi:10.1109/lgrs.2025.3534786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. He LH, Zhou YZ, Liu L, Cao W, Ma JH. Research on object detection and recognition in remote sensing images based on YOLOv11. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):14032. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-96314-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zuo T, Wu B, Gao X, Kou Y, Hou P, Wang Z, et al. Overview of remote sensing monitoring applications based on YOLOv12. In: Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Geology, Mapping and Remote Sensing (ICGMRS); 2025 Apr 25–27; Wuhan, China. p. 603–8. doi:10.1109/ICGMRS66001.2025.11065869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ding Z, Sun L, Mao X, Dai L, Xu B. Adversarial example generation for object detection using a data augmentation framework and momentum. Signal Image Video Process. 2024;18(3):2485–97. doi:10.1007/s11760-023-02924-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ding Z, Sun L, Mao X, Dai L, Ding R. Improving transferable targeted adversarial attack for object detection using RCEN framework and logit loss optimization. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(3):4387–412. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.052196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Jia E, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Zhang F, Feng W, Dong L, et al. An adaptive adversarial patch-generating algorithm for defending against the intelligent low, slow, and small target. Remote Sens. 2023;15(5):1439. doi:10.3390/rs15051439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Choi JI, Tian Q. Adversarial attack and defense of YOLO detectors in autonomous driving scenarios. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); 2022 Jun 4–9; Aachen, Germany. p. 1011–7. doi:10.1109/IV51971.2022.9827222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dai L, Wang J, Yang B, Chen F, Zhang H. An adversarial example attack method based on predicted bounding box adaptive deformation in optical remote sensing images. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10(13):e2053. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.2053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Bao J. Sparse adversarial attack to object detection. arXiv:2012.13692. 2020. [Google Scholar]

38. Dai L, Wang J, Yang B, Wang M, Zhang H. VSM-AP: an adversarial patch generation Method with variable step size mechanism for object detection in aerial images. In: Huang DS, Li B, Chen H, Zhang C, editors. Advanced intelligent computing technology and applications. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 177–88. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-9961-2_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Cheng G, Han J, Zhou P, Guo L. Multi-class geospatial object detection and geographic image classification based on collection of part detectors. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2014;98:119–32. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2014.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cheng G, Zhou P, Han J. Learning rotation-invariant convolutional neural networks for object detection in VHR optical remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sensing. 2016;54(12):7405–15. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2016.2601622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liu Z, Yuan L, Weng L, Yang Y. A high resolution optical satellite image dataset for ship recognition and some new baselines. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods; 2017 Feb 24–26; Porto, Portugal. p. 324–31. doi:10.5220/0006120603240331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chan LC, Whiteman P. Hardware-constrained hybrid coding of video imagery. IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst. 1983;AES-19(1):71–84. doi:10.1109/taes.1983.309421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang Z, Bovik AC, Sheikh HR, Simoncelli EP. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13(4):600–12. doi:10.1109/tip.2003.819861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools