Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Comprehensive Evaluation of Distributed Learning Frameworks in AI-Driven Network Intrusion Detection

1 Basic Science Research Institution, Kongju National University, Gongju, 32588, Republic of Korea

2 Cyber Security Research Division, Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute, Daejeon, 34129, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Applied Mathematics, Kongju National University, Gongju, 32588, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Convergence Science, Kongju National University, Gongju, 32588, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Dowon Hong. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Driven Intrusion Detection and Threat Analysis in Cybersecurity)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072561

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 20 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

With the growing complexity and decentralization of network systems, the attack surface has expanded, which has led to greater concerns over network threats. In this context, artificial intelligence (AI)-based network intrusion detection systems (NIDS) have been extensively studied, and recent efforts have shifted toward integrating distributed learning to enable intelligent and scalable detection mechanisms. However, most existing works focus on individual distributed learning frameworks, and there is a lack of systematic evaluations that compare different algorithms under consistent conditions. In this paper, we present a comprehensive evaluation of representative distributed learning frameworks—Federated Learning (FL), Split Learning (SL), hybrid collaborative learning (SFL), and fully distributed learning—in the context of AI-driven NIDS. Using recent benchmark intrusion detection datasets, a unified model backbone, and controlled distributed scenarios, we assess these frameworks across multiple criteria, including detection performance, communication cost, computational efficiency, and convergence behavior. Our findings highlight distinct trade-offs among the distributed learning frameworks, demonstrating that the optimal choice depends strongly on system constraints such as bandwidth availability, node resources, and data distribution. This work provides the first holistic analysis of distributed learning approaches for AI-driven NIDS and offers practical guidelines for designing secure and efficient intrusion detection systems in decentralized environments.Keywords

The evolution of communication networks has advanced through successive generations, moving from centralized infrastructures toward highly distributed and heterogeneous ecosystems. In particular, virtualization, edge computing, and the rapid growth of Internet of Things (IoT) devices have reshaped the topology of modern networks, where computation and data exchange are no longer limited to the central backbone but are instead distributed across the network. This structural transformation has improved scalability and service flexibility, but it has also expanded the attack surface, exposing a broader range of vulnerabilities as the number of distributed nodes increases. These vulnerabilities are not only more numerous but also more diverse, since each node may differ in capability, connectivity, and exposure. In such distributed environments, traditional centralized intrusion detection struggles to handle the volume and variability of threats.

Recently, research on AI-based network intrusion detection systems (AI-NIDS) has advanced across diverse directions, and research interest has increasingly moved toward distributed environments. In these settings, data typically remains at the local node, while communication links are often constrained by limited bandwidth and variable delay. To address these conditions, several distributed learning frameworks have been established as key approaches in AI-NIDS research. As representative approaches, Federated Learning (FL) [1] enables collaborative training of a shared model in distributed environments by allowing local nodes to train models independently and aggregate their updates at a server. This design reduces the exposure of raw data and supports privacy preservation in sensitive domains. Building on this concept, Split Learning (SL) [2] adopts a different strategy by partitioning a model into a front-end at the local node and a back-end at the server, where only intermediate activations and gradients are exchanged. This arrangement alleviates computational burden on resource-constrained nodes. Extending these two frameworks, Split-Federated Learning (SFL) [3] integrates the aggregation strategy of FL with the model partitioning of SL. In this hybrid design, local nodes train the front-end components while the server maintains the back-end and aggregates front-end updates, thereby enabling both privacy preservation and reduced local workload. Beyond these server-coordinated frameworks, Gossip Learning (GL) [4] offers a fully decentralized alternative. In this setting, participants exchange model parameters asynchronously with randomly selected peers over a communication graph, without relying on a central server. This decentralized mechanism eliminates single points of failure and provides robustness in dynamic network environments. Collectively, these frameworks can be regarded as fundamental distributed learning approaches for building AI-NIDS in distributed environments, and they have been actively applied in scenarios such as mobile edge computing, radio access networks, and industrial or enterprise IoT systems. Furthermore, prior studies have identified several key challenges for AI-NIDS in such settings, including non-IID data distributions, partial participation of nodes, and resource constraints at local nodes.

Despite recent progress, most prior studies have concentrated on individual frameworks, and their evaluations have generally been restricted to specific settings. Assumptions regarding data partitioning, synchronization, and trust models vary across works, while datasets, attack scenarios, and preprocessing pipelines also differ, making direct comparison difficult. Moreover, system-level factors such as local computational load and communication volume are often treated as secondary considerations or reported with inconsistent definitions. To address these gaps, this paper presents a comparative study of FL, SL, SFL, and gossip learning in the context of AI-NIDS. We define a unified problem setting that incorporates local nodes at the edge, an aggregation server, and realistic network constraints. The evaluation covers multiple dimensions, including detection accuracy, convergence under different data distribution scenarios, computational burden at local nodes, and per-round communication overhead. Finally, experimental results on two representative network intrusion datasets—5G-NIDD and CICIDS2017—under deployment scenarios reflecting realistic 5G and conventional network environments provide comprehensive insights. The outcome is a comparative analysis that offers guidance for designing AI-NIDS in distributed networks, where accuracy, efficiency, robustness, and privacy need to be jointly balanced.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• We provide a systematic comparative study of four major distributed learning frameworks—federated learning (FL), split learning (SL), split-federated learning (SFL), and gossip learning—in the context of AI-NIDS. To enable direct and consistent comparison, we define a unified problem setting that harmonizes assumptions on data partitioning, synchronization, and trust models.

• Our evaluation extends beyond detection accuracy to include system-level aspects such as convergence under non-IID partitions, computational load at local nodes and per-round communication overhead. This multi-dimensional perspective reveals the inherent trade-offs of each approach.

• Through experiments on two representative network intrusion datasets—5G-NIDD and CICIDS2017—under deployment scenarios reflecting realistic 5G and conventional network environments, we provide empirical evidence on the strengths and limitations of each framework. The findings offer practical guidance for selecting and adapting distributed learning approaches when designing AI-NIDS for heterogeneous and resource-constrained environments.

By filling the gap in systematic comparisons, this study contributes to a more consistent understanding of distributed learning algorithms and their roles in network intrusion detection for both researchers and practitioners. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 3 reviews related work on distributed AI-NIDS. Section 2 outlines the four distributed learning frameworks—federated, split, split-federated, and gossip learning. Section 4 introduces our evaluation framework, which defines a unified setting and consistent dimensions, including accuracy, convergence and computational and communication costs. Section 5 presents experimental results with comparative analysis on representative datasets and deployment scenarios. Section 6 concludes with key findings, design implications, and future research directions.

The design of distributed learning frameworks has evolved to meet the challenges of scalability, data privacy, and resource heterogeneity in distributed environments. Several frameworks have been proposed to support collaborative model training without centralizing raw data, each with distinct mechanisms for data handling, model partitioning, and communication. Among them, federated learning (FL), split learning (SL), split-federated learning (SFL), and gossip learning have emerged as representative approaches. These frameworks differ in terms of server involvement, device-side workload, and communication structure, yet all share the goal of enabling scalable and privacy-preserving distributed learning. This section provides an overview of these frameworks, establishing the conceptual foundation for the comparative analysis that follows.

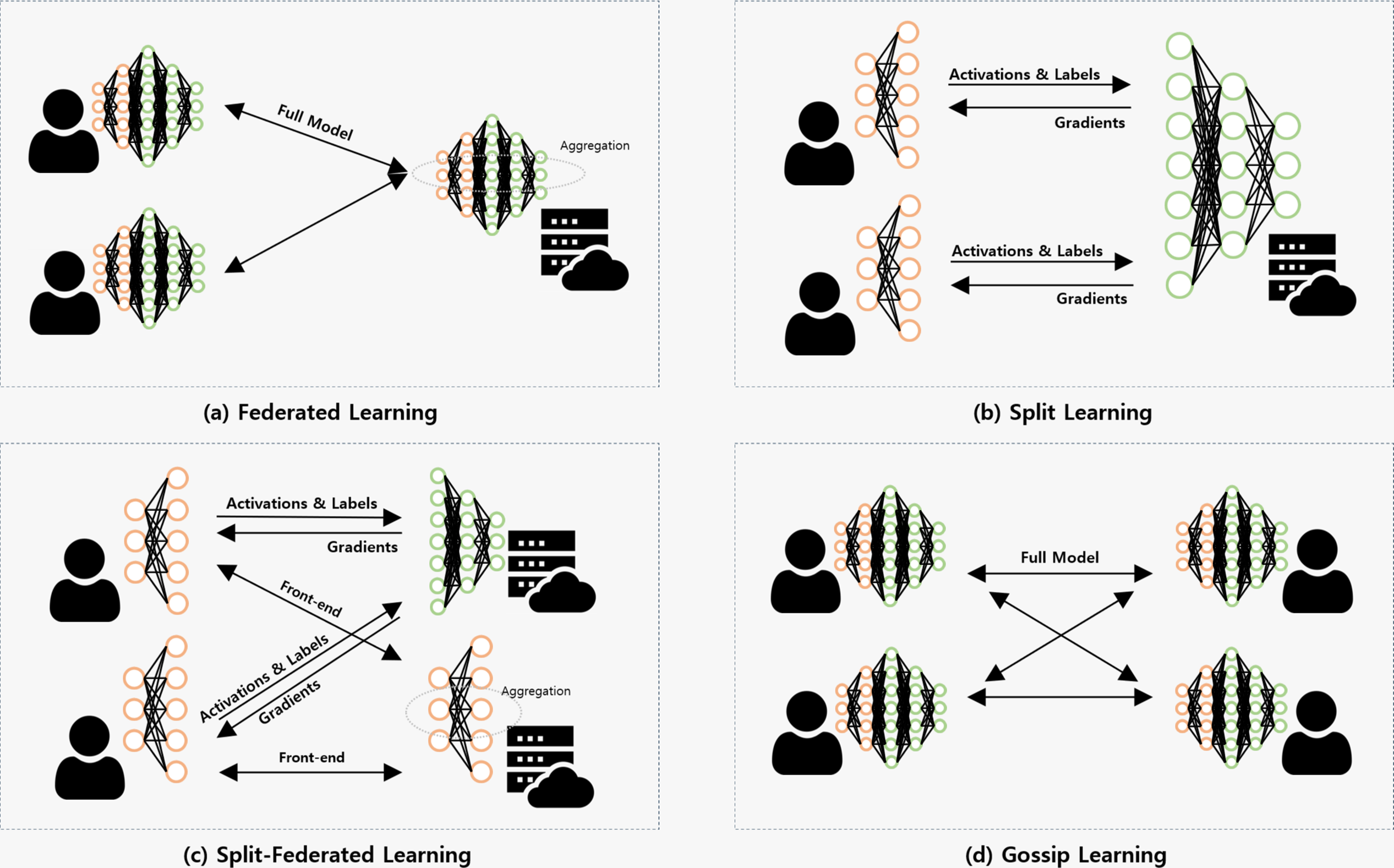

Federated learning (FL) [1] is a collaborative training algorithm in which multiple local nodes train a shared global model without centralizing raw data, as shown in Fig. 1a. Let

where

Figure 1: Workflow comparison of representative distributed learning frameworks

The resulting global model

Split Learning (SL) [2] is a distributed training algorithm designed to alleviate the computational burden on resource-constrained devices while still enabling collaborative model training. In SL, a model is partitioned between the local node and a central server, as shown in Fig. 1b. Typically, the initial layers (front-end) are executed at the local node, while the remaining deeper layers (back-end) are hosted on the server. This design allows local nodes to perform only partial computation, thus reducing their workload and memory requirements.

Formally, let the model be decomposed into two parts:

The activation

After computing the loss, the server performs backpropagation through its back-end layers and sends the gradient with respect to the activation

Split-Federated Learning (SFL) [3] is a hybrid framework that integrates the collaborative aggregation mechanism of FL with the model partitioning principle of SL. The key idea is to offload the heavy computation of deep layers to a central server, while still coordinating distributed training across multiple nodes through federated aggregation (see Fig. 1c). This design enables resource-constrained devices to participate in large-scale collaborative learning without incurring the full computational burden of training entire models.

Formally, the model is decomposed into two components: a front-end

The activation

After computing the loss, the server performs backpropagation through its back-end layers to update

producing the synchronized front-end parameters

Gossip learning (GL) [4] is a fully decentralized training algorithm in which nodes exchange and aggregate model parameters directly with randomly selected peers, without relying on a central coordinator or server. This design eliminates single points of failure and relaxes infrastructural assumptions, while still enabling collaborative learning over horizontally partitioned datasets (see Fig. 1d).

Formally, let the local dataset at node

where

and

To enhance communication efficiency, gossip learning incorporates techniques such as parameter subsampling and token-based flow control, which enable it to operate reliably under bandwidth constraints or bursty communication patterns. Empirical evidence further indicates that GL can match, and in some scenarios even surpass, the performance of federated learning when both are limited to the same communication budget. These findings position gossip learning as a practical decentralized alternative to federated learning.

Federated learning (FL) has been the most widely adopted distributed learning algorithm for network intrusion detection. Early efforts combined standard machine learning or deep models with FL to realize collaborative detection without raw data exchange [5–8]. Later works introduced specialized strategies to cope with communication overhead, imbalance in attack samples, and heterogeneous environments. For instance, Zhang et al. [9] combined hierarchical K-Means aggregation with SMOTE-ENN resampling to address both aggregation efficiency and skewed class distributions. Hamdi [10] applied a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) within an FL framework and evaluated different aggregation rules under imbalanced IoT traffic. Popoola et al. [11] targeted zero-day botnet scenarios, assuming that each device contributed only partial attack knowledge. Beyond basic learning integration, researchers have experimented with diverse FL architectures. Chaabene et al. [12] aggregated decision trees into a random forest ensemble across devices. Wang et al. [13] adopted mutual information–based feature selection to lower dimensionality while preserving accuracy. Yılmaz et al. [14] studied placement strategies of FL-based IDS in lossy IoT networks, highlighting sensitivity to detector location. To enhance security, Ma and Su [15] embedded secure multiparty computation into a semi-supervised FL framework for Software Defined Network (SDN)-based Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT). In healthcare-oriented Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) settings, Itani et al. [16] demonstrated that traditional Machine Learning (ML) models combined with FL could handle device heterogeneity. Otoum et al. [17] and Alharbi [18] introduced federated transfer learning (FTL) with layer freezing and local fine-tuning, enabling adaptation to Non-Independent and Identically Distributed (non-IID) conditions. Fahim-Ul-Islam et al. [19] extended this by incorporating meta-learning and robust aggregation to strengthen interpretability on constrained IoMT devices. Within Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and c, FL has been integrated with different deep models and privacy-enhancing techniques. Khoa et al. [20] leveraged a deep belief network in a collaborative detection design. Li et al. [21] combined FL with Gated Recurrent Unit (GRUs) and fog computing to mitigate Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. Ruzafa-Alcazar et al. [22] introduced differential privacy, whereas Li et al. [23] and Makkar et al. [24] adopted Paillier-based homomorphic encryption. A lightweight approach was further explored by Soomro et al. [25] through symmetric-key encryption and mutual authentication. Mobile networks and next-generation infrastructures have also been addressed. Jayasinghe et al. [26] designed hierarchical FL detection for Beyond 5G, while Maiga et al. [27] used FL in virtualized network functions with hybrid deep models. Singh et al. [28] advanced FL by integrating balanced sampling and feature augmentation, coupled with knowledge distillation. In Open Radio Access Network (RAN), Attanayaka et al. [29] proposed peer-to-peer FL tailored to RIC controllers, whereas Benzaïd et al. [30] introduced continual learning within FL to preserve knowledge over sequential tasks. Alalyan et al. [31] adopted secure peer aggregation, and Pithani and Rout [32] developed clustered FL strategies to counter non-IID data in 6G IoT-edge networks.

While FL has been applied across diverse domains, its reliance on full local training has motivated the exploration of split learning (SL), where only a portion of the model is trained on local devices. Park et al. [33] implemented a model-split intrusion detection framework in the context of 5G networks, where shallow layers are deployed on distributed devices and deeper layers remain at an edge server. Their evaluation on a real 5G testbed showed that this architecture substantially reduced computation and memory requirements at the device side while sustaining detection accuracy close to centralized baselines.

Building upon the complementary strengths of FL and SL, split-federated learning (SFL) has been introduced as a hybrid approach that integrates federated aggregation with model partitioning. In this approach, the front-end model segments are maintained on distributed devices and periodically aggregated in a federated manner, while the back-end remains at a central server. The study in [34] demonstrated that the SFL design alleviates the computational load on individual nodes by confining local updates to front-end models, while maintaining collaborative benefits through federated aggregation and centralized back-end training. Their evaluation confirmed that SFL reduces both training latency and device-side complexity, yet sustains accuracy comparable to conventional FL even under heterogeneous data distributions. Furthermore, the authors emphasized its scalability in large-scale deployments where efficiency in both computation and communication is essential.

In contrast to these server-assisted frameworks, gossip learning eliminates centralized orchestration altogether by propagating model updates through peer-to-peer exchanges across a communication graph. This fully decentralized paradigm inherently removes the risk of single-point failure and provides adaptability in dynamic network settings. Recent work has begun to explore its feasibility for intrusion detection. For example, the study in [35] applied gossip-based collaborative learning to anomaly detection tasks, showing that iterative peer exchanges can converge toward accurate detection performance without requiring a coordinating server. The authors reported robustness against unreliable communication links and scalability across large, heterogeneous topologies.

This section introduces the evaluation methodology used to compare distributed learning algorithms for AI-based intrusion detection. The evaluation framework establishes a unified procedure that balances model performance with system efficiency, ensuring fair comparisons across FL, SL, SFL, and GL.

The purpose of this evaluation framework is to establish a unified methodology for comparing distributed learning algorithms in the context of AI-driven network intrusion detection systems (AI-NIDS). While federated learning (FL), split learning (SL), split-federated learning (SFL), and gossip learning (GL) differ significantly in their training dynamics and communication structures, a consistent evaluation protocol is required to assess their effectiveness under comparable conditions. The evaluation framework defines objectives along two axes. First, it seeks to measure detection capability. The goal is to determine how accurately and reliably each framework identifies malicious traffic under heterogeneous and distributed data conditions. Second, it emphasizes operational efficiency. The focus is on the extent to which each framework can deliver robust performance while respecting practical constraints such as computation, communication bandwidth, and system scalability.

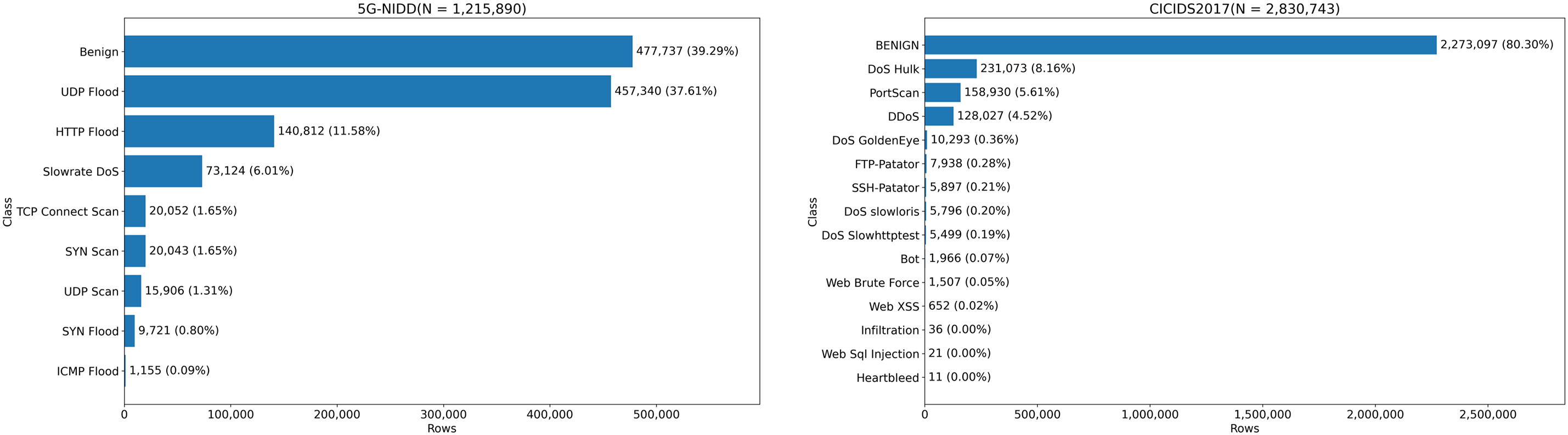

The scope of evaluation extends beyond isolated performance metrics. The methodology incorporates resource usage, communication overhead, and robustness to data imbalance, ensuring that the assessment reflects deployment realities. The unified pseudocode in Algorithm 1 operationalizes this scope by prescribing a common evaluation flow. Each framework is executed under identical conditions of dataset partitioning, training rounds, and hyperparameter settings while logging costs and outcomes in a standardized manner. This abstraction allows results to be compared fairly without introducing structural bias toward any specific framework.

We adopt the unified evaluation procedure in Algorithm 1 to ensure that all learning frameworks are executed under identical conditions. At initialization, each framework instantiates its parameters according to its structure. FL initializes with a single global model

Each training round

Aggregation is performed only in frameworks where coordination across nodes is required. In FL, the server collects the locally updated parameters

Evaluation is conducted at the end of each training round using the validation set

To establish baselines, we incorporate a centralized model that adopts the identical structure of the detection model and is trained with the full dataset. This centralized model serves as an upper-bound reference, while FL, SL, SFL, and GL capture distinct trade-offs in communication, computation, and coordination. The unified evaluation flow ensures that their strengths and weaknesses are revealed under identical budget constraints. Final performance is reported on

The evaluation procedure is structured along four complementary dimensions that collectively capture both the algorithmic accuracy and the system-level feasibility of distributed AI-NIDS frameworks. These dimensions ensure that comparisons extend beyond raw detection capability to include resource usage, communication efficiency, and operational resilience.

Detection Performance. As the most fundamental evaluation dimension, predictive accuracy is quantified using standard classification metrics such as accuracy and F1 score. These indicators reflect the ability of each framework to correctly distinguish benign and malicious traffic under heterogeneous and imbalanced data distributions. Final performance is reported on the held-out test set

where

Training Convergence. Another important dimension is the reliability of convergence during training. This is measured on the validation set

where N denotes the batch size, C the number of classes,

Resource Efficiency. Given that local nodes in distributed environments operate under limited resources, computational footprint is explicitly measured. This includes per-round floating-point operations (FLOPs) and cumulative execution time incurred at local nodes during forward and backward passes. These measurements provide a systematic basis for evaluating whether a framework imposes computational demands that exceed the practical capacity of resource-constrained devices. For quantitative evaluation, the client-side computation cost per global round is defined as

where K denotes the number of local nodes,

Communication Overhead. Communication is often the dominant cost in distributed training, and we explicitly measure it by recording the volume of transmitted and received payloads per round as well as the number of exchanges required. Framework-specific communication patterns are reflected in this metric: FL involves one upload and one download per round, SL and SFL incur batch-level activation–gradient transfers, and GL relies on repeated peer-to-peer parameter mixing. This provides a consistent basis for assessing how framework-specific communication behaviors impact scalability. In addition, the cumulative communication volume is averaged per round across all participating nodes, allowing fair comparison of framework scalability and bandwidth utilization under identical experimental conditions.

By organizing the evaluation along these four dimensions, the methodology ensures that both algorithmic performance and system feasibility are accounted for, thus yielding a balanced and reproducible comparison across distributed learning frameworks.

This section presents the experimental setup and findings for comparing distributed learning frameworks in AI-driven intrusion detection. We evaluate FL, SL, SFL, and GL on a 5G network dataset with a unified backbone and controlled distributed settings, and report results along four dimensions: detection performance (accuracy/F1), convergence behavior, client-side computational footprint, and communication overhead.

To evaluate the distributed learning frameworks under realistic cellular conditions, we adopt 5G-NIDD [36], a contemporary intrusion-detection dataset captured on a fully functional 5G Test Network (5GTN), and the CICIDS2017 dataset, a widely used benchmark that simulates diverse benign and malicious traffic reflecting modern intrusion scenarios.

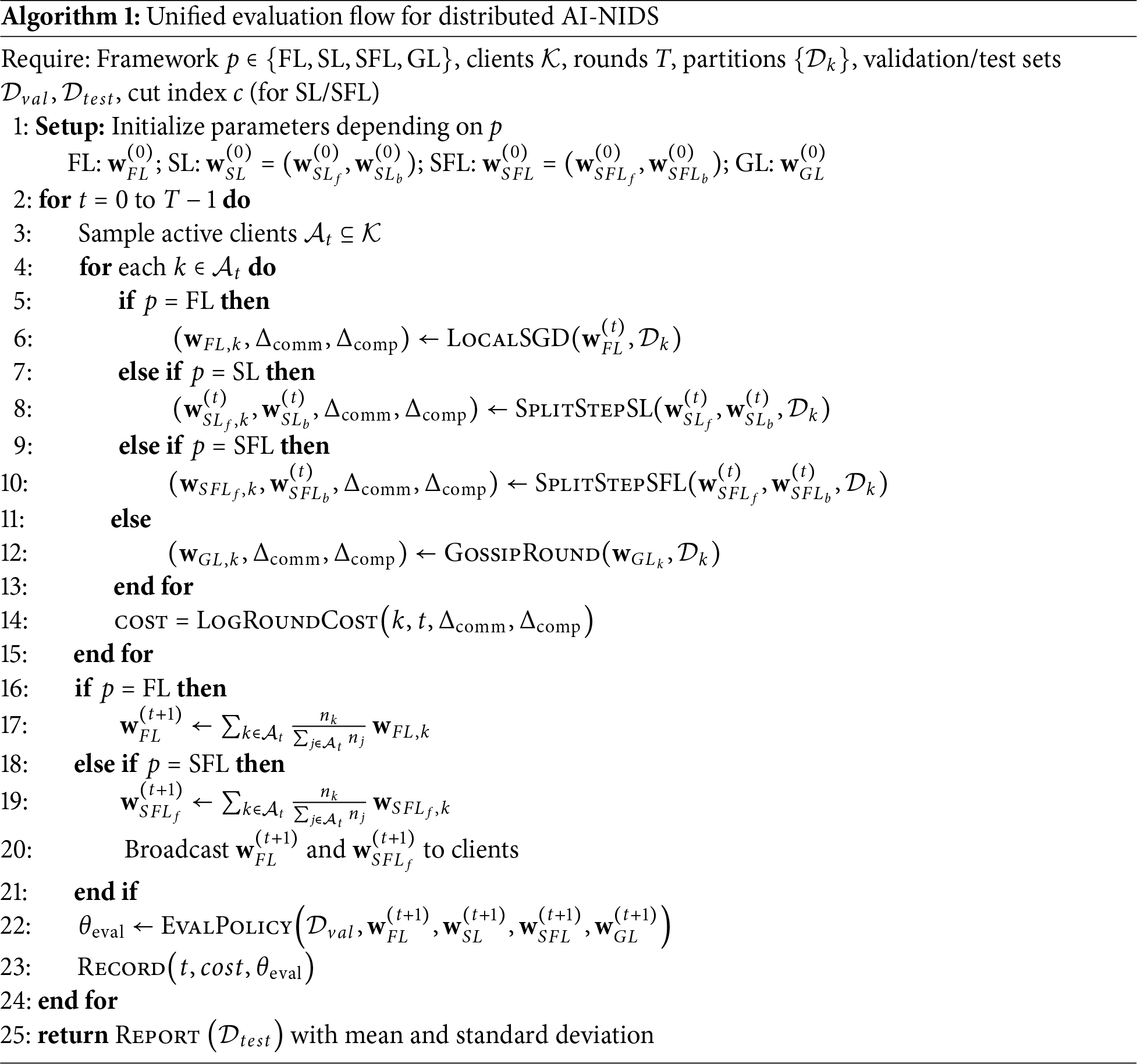

The dataset contains benign and malicious flows that reflect real-world behavior in mobile networks, and was built to address the scarcity of real 5G traffic for AI-NIDS research. Benign traffic was generated by actual handsets attached to 5GTN—covering HTTP/HTTPS browsing and streaming, together with SSH and SFTP sessions via deployed client-server apps on user equipment—so as to preserve natural traffic characteristics. The attack set covers DoS/DDoS and port-scanning families across volume, protocol, and application layers. Specifically, the dataset includes ICMP flood, UDP flood, SYN flood, HTTP flood, slow-rate DoS (e.g., Slowloris and Torshammer), and three types of scans (SYN scan, TCP connect scan, and UDP scan). Captured packets were processed into network flows, yielding 1,215,890 labeled records with both binary (benign vs. malicious) and multiclass tags. The resulting dataset exhibits an imbalanced class distribution, which reflects real network prevalence. Fig. 2 (left) presents a detailed breakdown of the dataset distribution. To transform the raw traffic into an interpretable format for AI models, we applied additional preprocessing steps. Specifically, we converted categorical features using one-hot encoding and normalized numerical features with a min–max scaler. As a result, each data record was represented with 91 transformed features.

Figure 2: Class distributions of the 5G-NIDD (left) and CICIDS2017 (right) datasets

The CICIDS2017 dataset is a widely adopted benchmark for evaluating intrusion detection systems and is designed to reproduce realistic network environments containing both benign and malicious traffic. The dataset includes diverse attack categories, including DoS, DDoS, PortScan, Brute Force, Web-based attacks (SQL Injection and XSS), Infiltration, and Botnet activities, in addition to normal background traffic. Each record corresponds to a bidirectional network flow extracted from packet captures, with 80 numerical and categorical features that characterize statistical, time-based, and content-level properties of network behavior. To maintain consistency with the preprocessing applied to 5G-NIDD, we performed identical feature transformations. Categorical attributes were converted using one-hot encoding, while continuous features were normalized with a min–max scaler. After preprocessing, each sample was represented as a 78-dimensional feature vector. Fig. 2 (right) presents the overall class distribution of the CICIDS2017 dataset. The dataset exhibits strong class imbalance due to the predominance of DoS and PortScan traffic, reflecting real-world intrusion distributions.

For both datasets, we partitioned the samples into training and testing subsets with an 8:2 ratio. The training portion was further distributed across local nodes according to each data distribution scenario (i.e., IID, non-IID, and skewed), ensuring consistency with the evaluation settings described in Section 5.1. This setup allows for a controlled and fair comparison across all distributed learning frameworks.

To ensure fairness across all frameworks, we explicitly describe the implementation setup and assumptions adopted in this study.

Data Distribution Scenarios. To comprehensively evaluate all distributed learning frameworks, we consider three data distribution scenarios: IID, non-IID, and skewed. In the IID scenario, we assume an idealized data environment where each local node holds an equal-sized subset with a class distribution identical to that of the global training set. This setting reflects a balanced and fully homogeneous data partition across nodes, ensuring that all participants contribute equally to the global model aggregation process. To simulate non-IID client datasets, we partition the training set such that both the data volume and class composition differ across local nodes. Specifically, we draw per-node class proportions from a Dirichlet distribution to induce statistical heterogeneity. The concentration parameter is fixed at

Model Configurations and Hyperparameter Settings. For consistent evaluation across all frameworks, we adopt a unified model architecture as the predictive model. The model first projects each input record into a 128-dimensional space through a linear layer, followed by two sequential 1D convolutional layers with 128 and 64 filters, respectively. A max-pooling operation reduces the temporal dimension, after which the output is flattened and processed through two fully connected layers of sizes 128 and 64. The final fully connected layer produces logits over the target classes. Nonlinear transformations use Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activations throughout the network. In SL and SFL configurations, the cut layer is placed immediately after the first convolutional block. This design delegates the projection and first convolutional layer to the local front end, while subsequent convolutional and fully connected layers are processed at the server side. This placement balances the computational burden between local nodes and the server while retaining sufficient feature expressiveness in the smashed activations. All frameworks share a unified set of hyperparameters to ensure consistent training conditions and fair comparison. Each experiment runs for 100 global rounds and a batch size of 256. The learning rate is fixed at

Assumptions. The central aggregator (server) is regarded as benign and trusted, coordinating model aggregation and back-end updates. Local nodes are assumed to behave honestly without adversarial collusion, tampering, or data poisoning. In practical deployment settings, edge nodes are generally provisioned and maintained by a mobile network operator (i.e., service provider), which provides a reasonable degree of operational trust among participating entities. The consideration of malicious or Byzantine behaviors is beyond the scope of this study, as the focus here is on evaluating learning performance and efficiency under cooperative conditions. With respect to network conditions in the distributed learning process, we consider a more practical setting where the network state may occasionally lose stability. Instead of assuming perfectly synchronous participation, we introduce controlled node churn to emulate realistic fluctuations in connectivity. Specifically, in each global training round, 25% of the local nodes are randomly excluded from participation, simulating temporary dropouts or unavailable connections. The remaining 75% of nodes perform local updates and transmit their payloads to the server, after which the aggregation proceeds based on the available contributions. This setup allows the evaluation to account for partial asynchrony and dynamic participation, reflecting conditions that may arise in real distributed network environments.

To evaluate the detection performance of distributed learning frameworks, we conduct experiments on two network intrusion datasets.

5.3.1 Experimental Results on 5G-NIDD Dataset

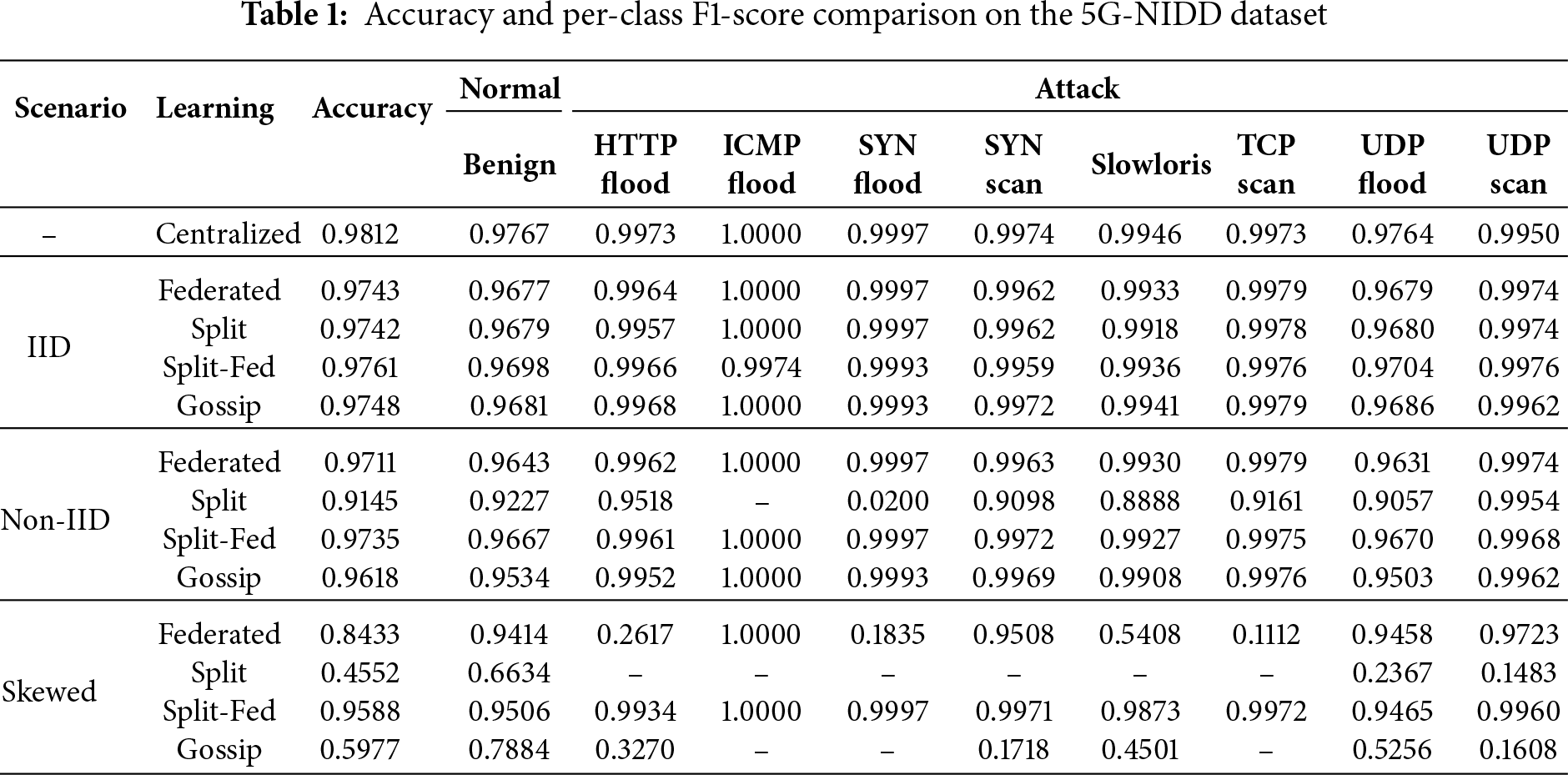

Table 1 summarizes the detection performance of centralized and distributed learning frameworks under three data distribution scenarios: IID, non-IID, and skewed. The comparison highlights how different frameworks respond to variations in data heterogeneity while preserving detection accuracy. Note that we set the number of local nodes equal to the number of attack classes, resulting in eight local nodes in the experimental setup.

Under the IID scenario, all distributed frameworks achieve performance comparable to the centralized baseline. Federated, Split, Split-Fed, and Gossip learning record accuracies above 0.974, with Split-Fed slightly outperforming others at 0.9761. This result indicates that when data is evenly distributed, each framework can effectively approximate the centralized upper bound. In the non-IID scenario, accuracy differences become more pronounced. Federated and Split-Fed maintain high accuracy around 0.9711 and 0.9735, respectively, confirming their resilience to moderate heterogeneity. Gossip also sustains acceptable performance at 0.9618, though slightly lower than federated variants. By contrast, Split learning exhibits significant degradation to 0.9145, reflecting sensitivity to non-IID distribution due to its reliance on per-client front ends without global synchronization. The skewed scenario presents the most challenging case, where client data distributions are severely imbalanced. In this scenario, performance divergence is substantial. Split learning collapses to 0.4552 accuracy, indicating poor adaptability. Gossip partially mitigates this effect but remains limited at 0.5977. Federated learning also struggles, dropping to 0.8433. In contrast, Split-Fed demonstrates strong robustness, achieving 0.9588 accuracy, which is much closer to the centralized reference. This suggests that combining split execution with federated aggregation provides better tolerance against highly skewed data distribution. Overall, the results show that while all frameworks perform well under IID conditions, resilience to non-IID and skewed distributions varies significantly. Split-Fed consistently achieves accuracy closest to the centralized baseline across all scenarios. More detailed per-class performance, including attack-specific detection rates, is provided in Table 1, complementing the aggregated accuracy analysis.

5.3.2 Experimental Results on CICIDS2017 Dataset

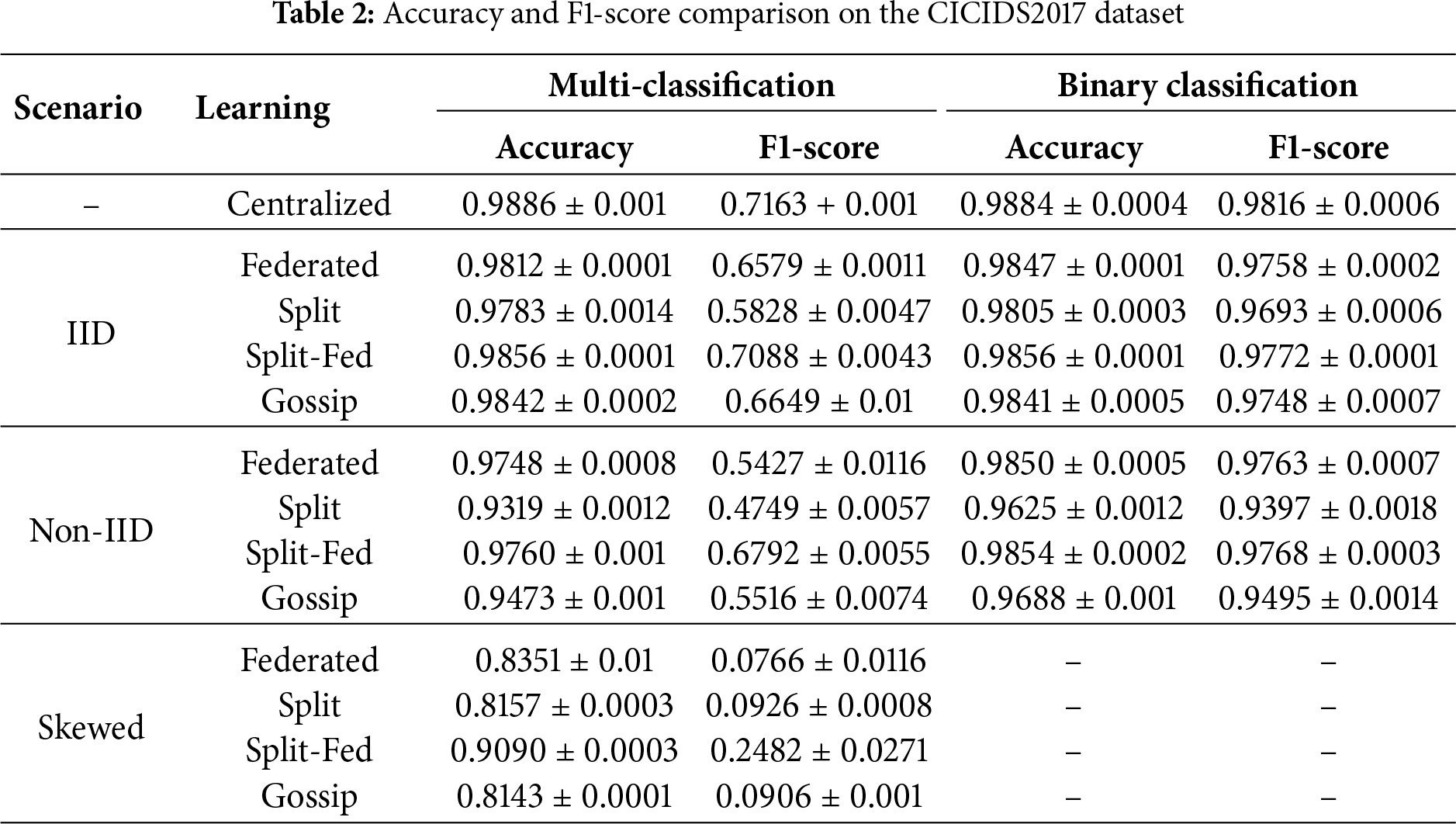

Table 2 presents the evaluation results of distributed learning frameworks on the CICIDS2017 dataset under both multi-class and binary classification settings. The experiments assess how each framework maintains detection accuracy and stability under different data distributions. Three data distribution scenarios—IID, non-IID, and skewed—are considered for the multi-class setting, whereas the skewed configuration is omitted for binary classification, since applying extreme class imbalance to two categories would not represent a realistic detection scenario. All results are averaged over ten independent runs, and the corresponding standard deviations are reported.

Under the IID condition, all distributed frameworks exhibit performance close to the centralized baseline (0.9886

In the non-IID scenario, where class proportions vary across local nodes, the performance gap among frameworks becomes more pronounced. Split-Fed and Federated learning maintain high multi-class accuracies of 0.9760

In the skewed multi-class configuration, where each local node contains samples from only a single dominant class, all methods experience substantial F1-score degradation (e.g., Federated 0.0766, Split 0.0926). Nevertheless, Split-Fed demonstrates notable resilience, maintaining 0.9090

Overall, consistent with the observations from the 5G-NIDD experiments, all frameworks perform comparably to the centralized baseline under IID conditions, while Split-Fed consistently achieves the highest accuracy and F1-score under both non-IID and skewed distributions. These results confirm that Split-Fed provides the best balance between detection performance and robustness in heterogeneous distributed intrusion detection environments.

5.4 Comparison of Convergence Behaviors

To further analyze the optimization dynamics of different distributed learning frameworks, we examine their convergence behaviors on both 5G-NIDD and CICIDS2017 datasets. This analysis provides complementary insights to the accuracy-based evaluations by revealing how each framework progresses during training, stabilizes over time, and responds to varying levels of data heterogeneity. All convergence curves are plotted using the models that achieved the best performance among ten independent runs.

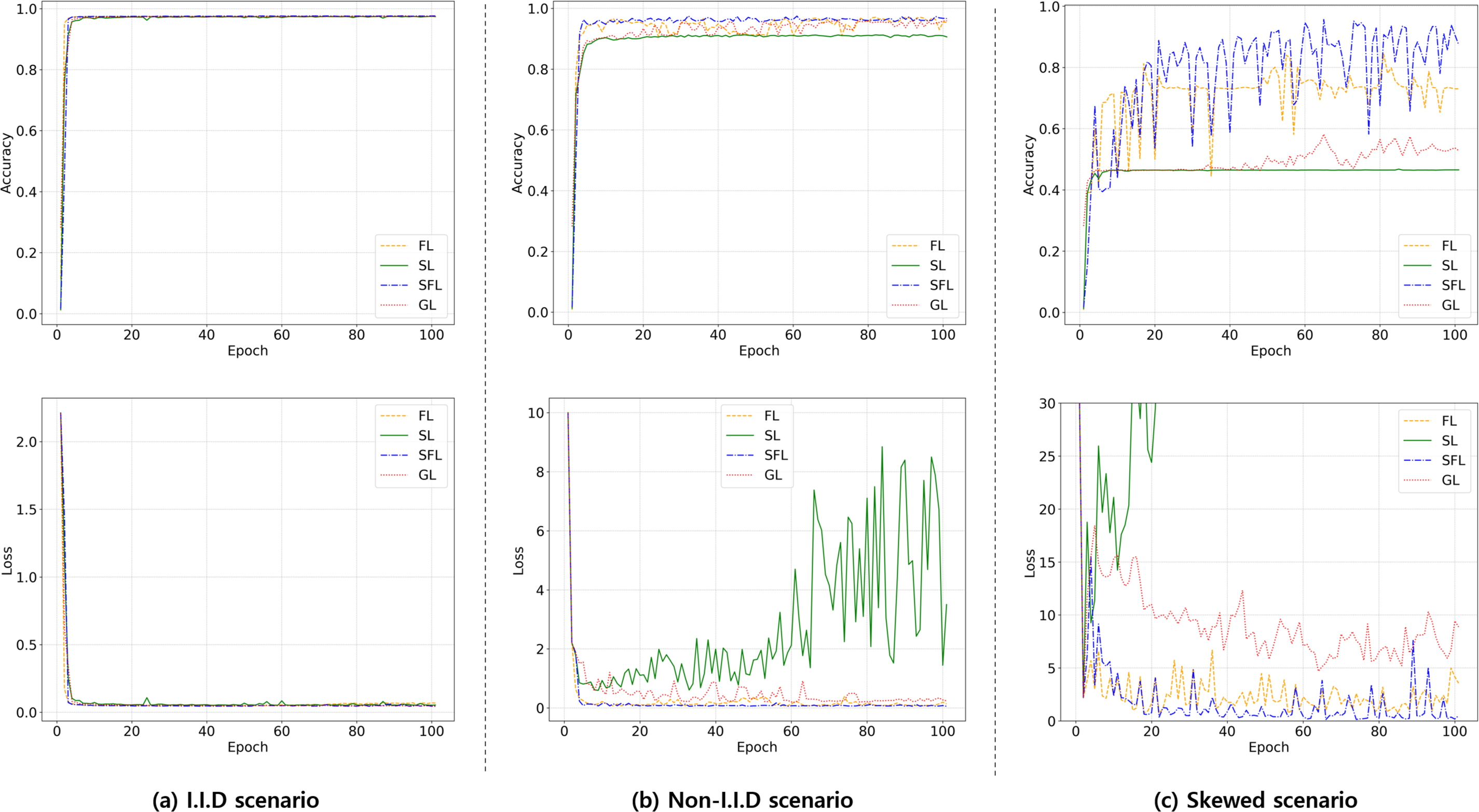

Fig. 3 presents the convergence behaviors of the distributed learning frameworks on the 5G-NIDD dataset across the three data distribution scenarios. These results complement the accuracy outcomes reported in Table 1 by offering a dynamic perspective on optimization stability and training progression. Under the IID scenario, all frameworks achieve rapid convergence during the initial training epochs. Accuracy curves approach the centralized baseline almost immediately, and the loss curves remain low and stable throughout training. This confirms that when client data is evenly distributed, FL, SL, SFL, and GL exhibit comparable optimization dynamics and achieve performance levels close to the centralized reference. In the non-IID scenario, divergence among frameworks becomes apparent. Federated learning and Split-Fed maintain smooth and reliable convergence, consistent with their maximum accuracies observed, 0.9711 and 0.9735, respectively. Gossip learning also converges to a high accuracy level, although its trajectory displays mild oscillations. By contrast, Split learning demonstrates pronounced instability, with highly fluctuating loss values and stagnating accuracy at 0.9145. This instability highlights the structural limitations of split execution without federated synchronization under heterogeneous data distributions. The skewed scenario yields the most pronounced differences. Split-Fed achieves the highest accuracy among distributed frameworks (0.9588), but its accuracy curve reveals stronger oscillations than those observed in the IID and non-IID cases, reflecting the difficulty of training under highly imbalanced client data. Nonetheless, the overall trend indicates consistent progression toward high accuracy. Federated learning shows slower and noisier convergence, stabilizing at a lower level of 0.8433. Gossip learning suffers from persistent instability, with accuracy fluctuating substantially and failing to approach the centralized baseline, converging at 0.5977. Split learning collapses almost entirely, as both loss and accuracy fail to stabilize, resulting in a peak accuracy of only 0.4552. These convergence behaviors demonstrate that while all frameworks are capable of stable learning under IID conditions, their robustness to data heterogeneity varies significantly. Split-Fed consistently provides the most favorable trade-off, delivering both high final accuracy and relatively stable convergence across all scenarios, thereby validating its effectiveness as a hybrid approach that integrates split execution with federated aggregation.

Figure 3: Convergence behaviors of FL, SL, SFL, and GL on the 5G-NIDD dataset across (a) IID, (b) non-IID, and (c) skewed scenarios

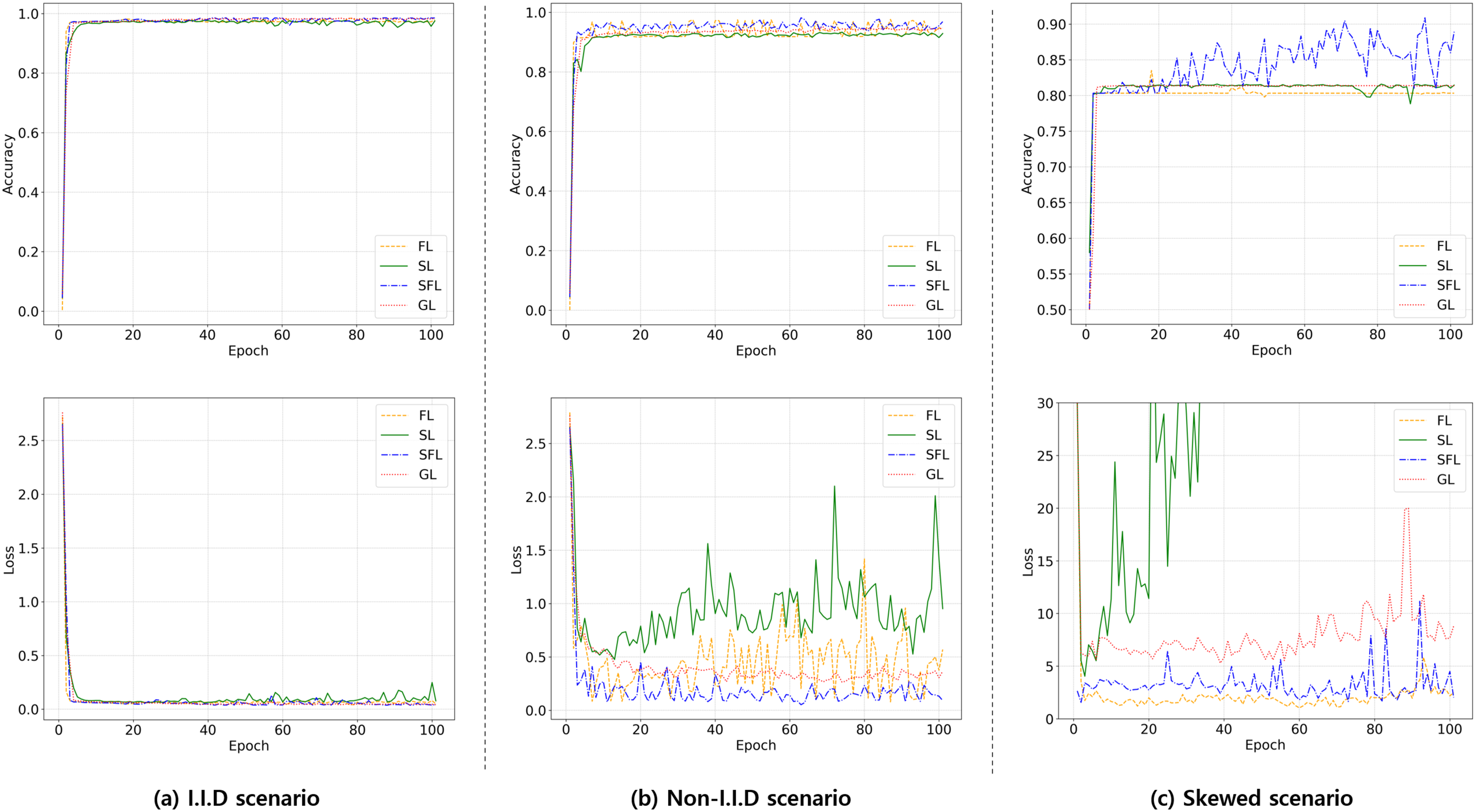

A similar trend is observed in the experiments conducted on the CICIDS2017 dataset. Fig. 4 shows the convergence behaviors of FL, SL, SFL, and GL on the CICIDS2017 dataset across the three data distribution scenarios in the multi-class classification setting. As with 5G-NIDD, these curves complement the accuracy outcomes in Table 2 by revealing optimization stability over training. Under the IID condition, all frameworks converge rapidly within the first few epochs. Accuracy quickly approaches the centralized reference and remains near saturation, while loss stays low and stable throughout training. This indicates that, under balanced data, all methods exhibit nearly identical optimization dynamics. In the non-IID scenario, differences become clearer. Split-Fed and Federated show smooth trajectories with small oscillations and maintain high accuracy, whereas Gossip also converges well but with slightly noisier curves. By contrast, Split displays pronounced instability, where loss oscillates with large spikes and accuracy remains below the other methods, reflecting its sensitivity to heterogeneous local class compositions. In the skewed multi-class configuration, the impact of extreme imbalance becomes apparent. Split-Fed sustains the highest accuracy with moderate oscillations, while federated learning plateaus at a lower yet relatively steady level. Gossip exhibits visible fluctuations in both accuracy and loss, and Split shows the most severe instability, with persistently high and volatile loss that prevents accuracy from improving further. Overall, the CICIDS2017 results align with those observed on 5G-NIDD. All frameworks behave similarly under IID partitions, but their convergence behavior under heterogeneous and skewed distributions varies substantially. Across all scenarios, Split-Fed achieves the most favorable balance between accuracy and convergence stability.

Figure 4: Convergence behaviors of FL, SL, SFL, and GL on the CICIDS2017 dataset across (a) IID, (b) non-IID, and (c) skewed scenarios

5.5 Computation and Communication Costs

A critical dimension of distributed intrusion detection is the computational burden placed on local nodes, which are often resource-constrained compared to centralized servers. To quantify this aspect, we analyze the portion of the detection model that each framework delegates to the local side.

In federated learning (FL) and gossip learning (GL), each local node trains the entire detection model. This entails handling approximately 6.48 MFLOPs per sample and maintaining 128 k parameters, corresponding to the full computational footprint of the model. As such, these frameworks demand significant processing and memory resources from each client, which may challenge deployment in environments with constrained devices. In contrast, split learning (SL) and split-federated learning (SFL) delegate only the front-end of the model to the local side, while the back-end remains centralized. The front-end comprises the projection layer and the first convolutional block, amounting to 0.246 MFLOPs and 12.5 k parameters. This corresponds to roughly 3.8% of the total FLOPs and 9.8% of the parameters relative to the full model. Consequently, the local workload is substantially reduced, allowing lightweight devices to participate in distributed training without incurring prohibitive costs.

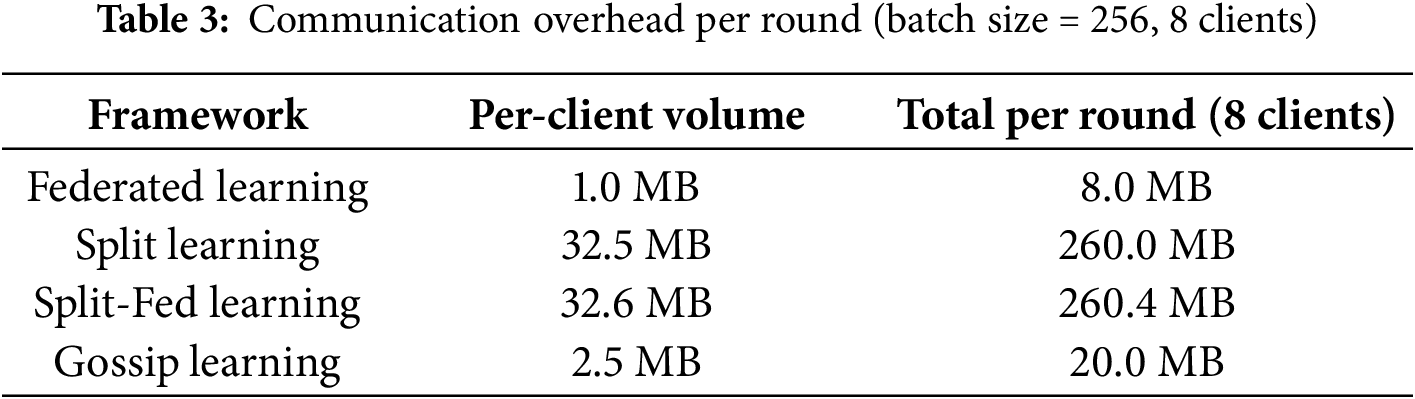

Communication cost is quantified in terms of payloads transmitted between clients and the server (or peers in gossip-based training). To establish a consistent basis, we first present the common assumptions used in the calculation. The input dimension is fixed at 91 (considering the 5G-NIDD dataset), and the total number of parameters in the full detection model is approximately 119,625, corresponding to 0.48 MB assuming 32-bit floating-point representation. The front end, consisting of the projection layer and the first convolutional layer, contains 12,288 parameters (

Based on these assumptions, Table 3 summarizes the per-round communication requirements with eight participating clients. In FL, each client uploads and downloads the entire model per round, which results in

The comparative experiments across 5G-NIDD and CICIDS2017 datasets collectively reveal that the convergence stability and communication–computation trade-offs of distributed frameworks are closely tied to data heterogeneity and structural partitioning. Split-Fed learning (SFL) consistently demonstrated the most favorable balance between model performance and stability, maintaining high accuracy even under skewed data while significantly reducing local computational demands. This result validates the effectiveness of hybrid training that integrates split execution with federated aggregation. In contrast, Split learning (SL) suffered from training instability in heterogeneous settings due to the absence of global synchronization, while Gossip learning (GL) exhibited fluctuating convergence, reflecting its sensitivity to inconsistent peer interactions. Federated learning (FL) achieved stable optimization but incurred higher local computation, making it less suitable for lightweight edge devices.

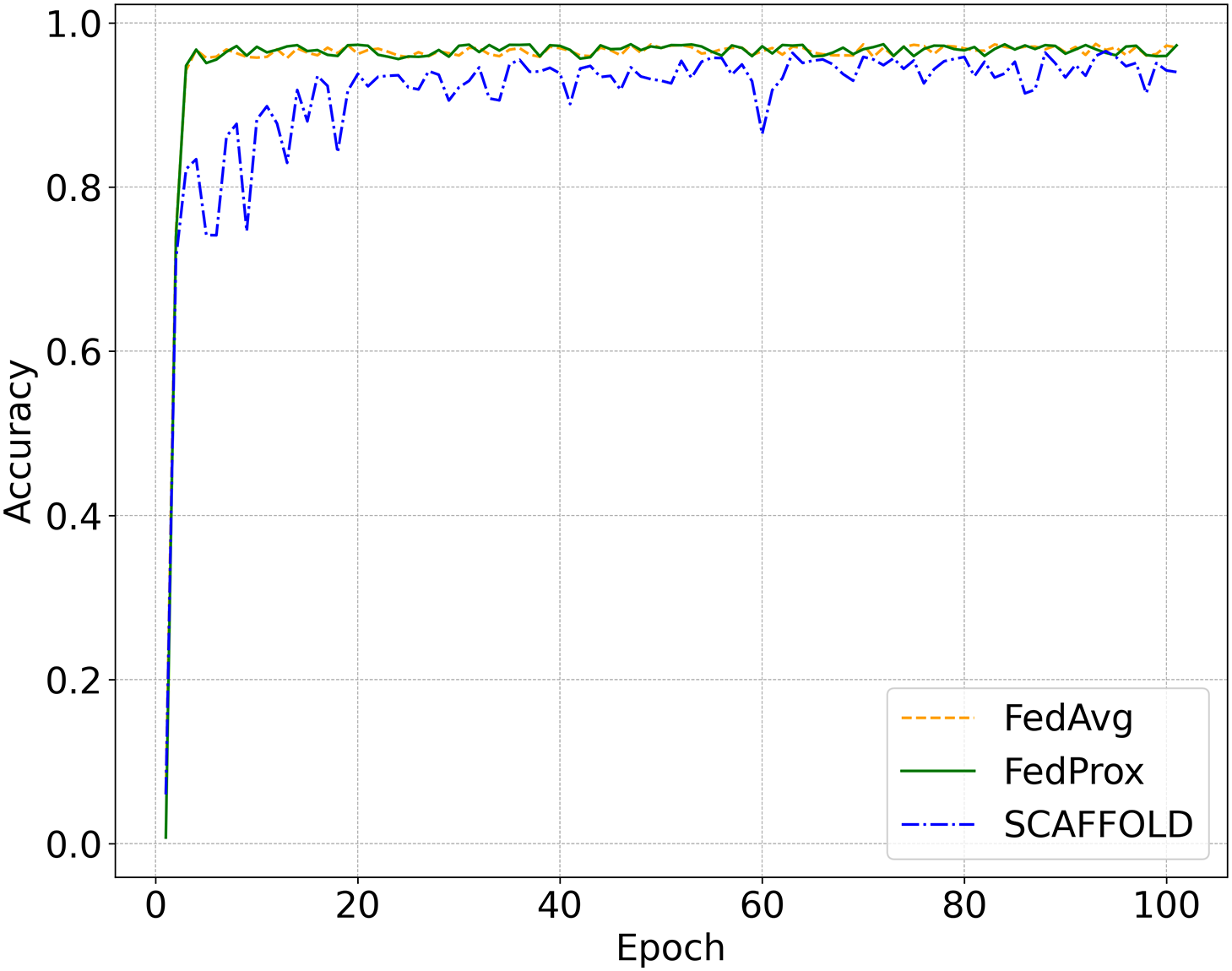

Among federated learning variants, FedAvg was adopted as the representative baseline in this study, as it remains the most widely used aggregation strategy and serves as the canonical reference for evaluating distributed frameworks. To ensure an unbiased comparison, additional validation was conducted using FedProx [37] and SCAFFOLD [38] on the 5G-NIDD dataset under the imbalanced data condition. As illustrated in Fig. 5, all three methods exhibit similar convergence patterns, maintaining accuracies above 0.9 after the early epochs. FedProx exhibits a convergence trend highly similar to that of FedAvg, reflecting stable optimization behavior under heterogeneous data. SCAFFOLD demonstrates slightly higher fluctuations in the early stage, likely due to its control variate adjustment under limited local updates, but ultimately converges to a comparable accuracy level. These results confirm that the learning dynamics of federated optimization remain consistent across different variants and justify the use of FedAvg as a representative benchmark in the comparative evaluation of distributed learning frameworks.

Figure 5: Convergence comparison of federated learning variants (FedAvg, FedProx, and SCAFFOLD) on the 5G-NIDD dataset under the imbalanced data scenario

From a deployment perspective, these findings suggest that framework selection should depend on the operational context. In environments with relatively homogeneous data and adequate device capability, FL or GL can provide efficient solutions with limited communication overhead. However, in scenarios characterized by heterogeneous and resource-constrained nodes—such as Open RAN and large-scale IoT infrastructures—SFL offers a more practical trade-off by offloading the computational burden to the server while preserving distributed learning benefits.

Despite the observed advantages, the evaluation also highlights an inherent limitation of split-based frameworks: their substantial communication payloads caused by transmitting intermediate activations and gradients. Although such costs may be mitigated through compression or asynchronous updates, further research is required to explore scalable communication-efficient variants. Moreover, dynamic network conditions and node intermittency—factors partially modeled in this study through randomized node participation—remain open challenges for real-world deployment.

Limitations and Future Work. This study focuses on evaluating the fundamental learning dynamics and resource trade-offs among distributed training paradigms under benign network and participant assumptions. Although we modeled occasional node dropout to reflect imperfect connectivity, we did not consider malicious or adversarial behaviors. In real-world open network environments, such as Open RAN or federated IoT deployments, adversarial nodes or poisoning attacks may compromise model integrity. Incorporating robust aggregation mechanisms, trust-aware updates, and adversarial-resilient defenses thus represents a crucial extension of this work.

Furthermore, privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy and homomorphic encryption were beyond the current experimental scope. Integrating these mechanisms while maintaining detection accuracy and convergence efficiency poses an important research direction. Future extensions may also explore adaptive split placement and compression-aware communication schemes to improve scalability under bandwidth-constrained or heterogeneous conditions.

This work presented a unified evaluation of four distributed learning frameworks for AI-driven intrusion detection under identical experimental conditions. Results show that all frameworks converge reliably under IID data, but their resilience diverges as heterogeneity increases. Split learning, while reducing device workload, suffers from instability as client-specific front ends diverge under heterogeneous data. Split-federated learning demonstrates the most consistent accuracy across non-IID and skewed scenarios, balancing reduced local computation with federated aggregation. Gossip learning achieves decentralized training without a server but exhibits oscillations under severe skew. Federated learning remains a strong baseline, offering stable performance with moderate coordination costs. System-level analysis highlights the trade-off between computation and communication. Split and split-federated learning shift computation to the server but incur high bandwidth from activation–gradient exchange, while federated and gossip learning impose heavier local computation but require much less communication. Overall, Split-Fed emerges as the most effective compromise, while FL and GL suit bandwidth-limited but capable devices. These findings provide guidance for selecting frameworks in distributed networks and establish a foundation for future work on efficiency, robustness, and privacy in AI-NIDS.

Future work will strengthen the practical value of distributed AI-NIDS. Promising directions include activation compression and quantization for split variants, topology and token control for gossip exchanges, adaptive participation and cut-layer placement under changing bandwidth. Robustness to adversarial behavior and privacy leakage from exchanged signals also warrants deeper study in realistic 5G and Open RAN deployments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was partly supported by the Research year project of the Kongju National University in 2025 and the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00444170, Research and International Collaboration on Trust Model-Based Intelligent Incident Response Technologies in 6G Open Network Environment).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Sooyong Jeong and Cheolhee Park; methodology, Sooyong Jeong; software, Sooyong Jeong; validation, Sooyong Jeong and Cheolhee Park; formal analysis, Sooyong Jeong; investigation, Cheolhee Park; resources, Dowon Hong; data curation, Sooyong Jeong; writing—original draft preparation, Sooyong Jeong; writing—review and editing, Cheolhee Park and Changho Seo; visualization, Sooyong Jeong; supervision, Cheolhee Park and Dowon Hong; project administration, Cheolhee Park; funding acquisition, Dowon Hong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. McMahan HB, Moore E, Ramage D, Arcas BA. Federated learning of deep networks using model averaging. arXiv:1602.05629v1. 2016. [Google Scholar]

2. Gupta O, Raskar R. Distributed learning of deep neural network over multiple agents. J Netw Comput Appl. 2018;116(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2018.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Thapa C, Arachchige PCM, Camtepe S, Sun L. Splitfed: when federated learning meets split learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36(8):8485–93. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i8.20825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hegedus I, Danner G, Jelasity M. Gossip learning as a decentralized alternative to federated learning. In: IFIP International Conference on Distributed Applications and Interoperable Systems; 2019 Jun 17–21; Kongens Lyngby, Denmark. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 74–90. [Google Scholar]

5. Nguyen TD, Marchal S, Miettinen M, Fereidooni H, Asokan N, Sadeghi AR. DïoT: a federated self-learning anomaly detection system for IoT. In: 2019 IEEE 39th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS); 2019 July 7–10; Dallas, TX, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 756–67. [Google Scholar]

6. Rahman SA, Tout H, Talhi C, Mourad A. Internet of Things intrusion detection: centralized, on-device, or federated learning? IEEE Netw. 2020;34(6):310–7. doi:10.1109/mnet.011.2000286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Qin Q, Poularakis K, Leung KK, Tassiulas L. Line-speed and scalable intrusion detection at the network edge via federated learning. In: 2020 IFIP Networking Conference (Networking); 2020 Jun 22–25; Virtual. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 352–60. [Google Scholar]

8. Huong TT, Bac TP, Long DM, Thang BD, Binh NT, Luong TD, et al. Low-complexity cyberattack detection in iot edge computing. IEEE Access. 2021;9:29696–710. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3058528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang J, Yu P, Qi L, Liu S, Zhang H, Zhang J. FLDDoS: DDoS attack detection model based on federated learning. In: 2021 IEEE 20th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom); 2021 Aug 18–20; Shenyang, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 635–42. [Google Scholar]

10. Hamdi N. Federated learning-based intrusion detection system for Internet of Things. Int J Inf Secur. 2023;22(6):1937–48. doi:10.1007/s10207-023-00727-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Popoola SI, Ande R, Adebisi B, Gui G, Hammoudeh M, Jogunola O. Federated deep learning for zero-day botnet attack detection in IoT-edge devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(5):3930–44. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chaabene RB, Ameyed D, Jaafar F, Roger A, Esma A, Cheriet M. A privacy-preserving federated learning for IoT intrusion detection system. In: 2023 9th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT); 2023 Jul 3–6; Rome, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 351–6. [Google Scholar]

13. Wang X, Wang Y, Javaheri Z, Almutairi L, Moghadamnejad N, Younes OS. Federated deep learning for anomaly detection in the Internet of Things. Comput Electr Eng. 2023;108(7):108651. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yılmaz S, Sen S, Aydogan E. Exploring and enhancing placement of IDS in RPL: a federated learning-based approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(13):22945–61. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3553194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ma J, Su W. Collaborative DDoS defense for SDN-based AIoT with autoencoder-enhanced federated learning. Inf Fusion. 2025;117(2):102820. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Itani M, Basheer H, Eddine F. Attack detection in IoT-based healthcare networks using hybrid federated learning. In: 2023 International Conference on Smart Applications, Communications and Networking (SmartNets); 2023 Jul 25–27; Istanbul, Turkey. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

17. Otoum Y, Chamola V, Nayak A. Federated and transfer learning-empowered intrusion detection for IoT applications. IEEE Internet Things Magaz. 2022;5(3):50–4. doi:10.1109/iotm.001.2200048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alharbi AA. Federated transfer learning for attack detection for Internet of Medical Things. Int J Inf Secur. 2024;23(1):81–100. doi:10.1007/s10207-023-00805-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fahim-Ul-Islam M, Chakrabarty A, Alam MGR, Maidin SS. A resource-efficient federated learning framework for intrusion detection in IoMT networks. IEEE Trans Consumer Electron. 2025;71(2):4508–21. doi:10.1109/tce.2025.3544885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Khoa TV, Saputra YM, Hoang DT, Trung NL, Nguyen D, Ha NV, et al. Collaborative learning model for cyberattack detection systems in IoT industry 4.0. In: 2020 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2020 May 25–28; Virtual. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

21. Li J, Lyu L, Liu X, Zhang X, Lyu X. FLEAM: a federated learning empowered architecture to mitigate DDoS in industrial IoT. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2021;18(6):4059–68. doi:10.1109/tii.2021.3088938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ruzafa-Alcázar P, Fernández-Saura P, Mármol-Campos E, González-Vidal A, Hernández-Ramos JL, Bernal-Bernabe J, et al. Intrusion detection based on privacy-preserving federated learning for the industrial IoT. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2021;19(2):1145–54. doi:10.1109/tii.2021.3126728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li B, Wu Y, Song J, Lu R, Li T, Zhao L. DeepFed: federated deep learning for intrusion detection in industrial cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;17(8):5615–24. doi:10.1109/tii.2020.3023430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Makkar A, Kim TW, Singh AK, Kang J, Park JH. Secureiiot environment: federated learning empowered approach for securing iiot from data breach. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(9):6406–14. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3149902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Soomro IA, Hussain SJ, Ashraf Z, Alnfiai MM, Alotaibi NN. Lightweight privacy-preserving federated deep intrusion detection for industrial cyber-physical system. J Commun Netw. 2024;26(6):632–49. doi:10.23919/jcn.2024.000054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jayasinghe S, Siriwardhana Y, Porambage P, Liyanage M, Ylianttila M. Federated learning based anomaly detection as an enabler for securing network and service management automation in beyond 5G networks. In: 2022 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit); 2022 Jun 7–10; Grenoble, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 345–50. [Google Scholar]

27. Maiga AA, Ataro E, Githinji S. XGBoost and deep learning based-federated learning for DDoS attack detection in 5G core network VNFs. In: 2024 6th International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI); 2024 Jun 14–16; Tokyo, Japan. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 128–33. [Google Scholar]

28. Singh G, Sood K, Rajalakshmi P, Nguyen DDN, Xiang Y. Evaluating federated learning-based intrusion detection scheme for next generation networks. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024;21(4):4816–29. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2024.3385385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Attanayaka D, Porambage P, Liyanage M, Ylianttila M. Peer-to-peer federated learning based anomaly detection for open radio access networks. In: ICC 2023—IEEE International Conference on Communications; 2023 May 28–Jun 1; Rome, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 5464–70. [Google Scholar]

30. Benzaïd C, Hossain FM, Taleb T, Gómez PM, Dieudonne M. A federated continual learning framework for sustainable network anomaly detection in o-ran. In: 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2024 Apr 21–24; Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

31. Alalyan F, Bousalem B, Jaafar W, Langar R. Secure peer-to-peer federated learning for efficient cyberattacks detection in 5G and beyond networks. In: ICC 2024—IEEE International Conference on Communications; 2024 Jun 9–13; Denver, CO, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1752–7. [Google Scholar]

32. Pithani A, Rout RR. CFL-ATELM: an approach to detect botnet traffic by analyzing non-IID and imbalanced data in IoT-edge based 6G networks. Cluster Comput. 2025;28(3):198. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04900-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Park C, Park K, Song J, Kim J. Distributed learning-based intrusion detection in 5G and beyond networks. In: 2023 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit); 2023 Jun 6–9; Gothenburg, Sweden. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 490–5. [Google Scholar]

34. Almarshdi R, Fadel E, Alowidi N, Nassef L. Distributed federated split learning based intrusion detection system. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2024;39(5):949–83. [Google Scholar]

35. Ali MN, Imran M, Ullah I, Raza GM, Kim HY, Kim BS. Ensemble and gossip learning-based framework for intrusion detection system in vehicle-to-everything communication environment. Sensors. 2024;24(20):6528. doi:10.3390/s24206528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Samarakoon S, Siriwardhana Y, Porambage P, Liyanage M, Chang SY, Kim J, et al. 5G-NIDD: a comprehensive network intrusion detection dataset generated over 5G wireless network. IEEE Dataport. 2022. doi:10.21227/xtep-hv36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li T, Sahu AK, Zaheer M, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc Mach Learn Syst. 2020;2:429–50. [Google Scholar]

38. Karimireddy SP, Kale S, Mohri M, Reddi S, Stich S, Suresh AT. Scaffold: stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2020 Jul 13–18; Virtual. London, UK: PMLR; 2020. p. 5132–43. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools