Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Advancing Android Ransomware Detection with Hybrid AutoML and Ensemble Learning Approaches

1 Department of Mathematics, Amrita School of Physical Sciences, Coimbatore, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbator, 641112, India

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, College of Applied Studies, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11543, Saudi Arabia

3 School of Computing, Gachon University, Seongnam-si, 13120, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer and Information Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11633, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Ateeq Ur Rehman. Email: " />; Ahmad Almogren. Email:

" />

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 27 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072840

Received 04 September 2025; Accepted 17 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Android smartphones have become an integral part of our daily lives, becoming targets for ransomware attacks. Such attacks encrypt user information and ask for payment to recover it. Conventional detection mechanisms, such as signature-based and heuristic techniques, often fail to detect new and polymorphic ransomware samples. To address this challenge, we employed various ensemble classifiers, such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Bagging, and AutoML models. We aimed to showcase how AutoML can automate processes such as model selection, feature engineering, and hyperparameter optimization, to minimize manual effort while ensuring or enhancing performance compared to traditional approaches. We used this framework to test it with a publicly available dataset from the Kaggle repository, which contains features for Android ransomware network traffic. The dataset comprises 392,024 flow records, divided into eleven groups. There are ten classes for various ransomware types, including SVpeng, PornDroid, Koler, WannaLocker, and Lockerpin. There is also a class for regular traffic. We applied a three-step procedure to select the most relevant features: filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. The Bagging classifier was highly accurate, correctly getting 99.84% of the time. The FLAML AutoML framework was even more accurate, correctly getting 99.85% of the time. This is indicative of how well AutoML performs in improving things with minimal human assistance. Our findings indicate that AutoML is an efficient, scalable, and flexible method to discover Android ransomware, and it will facilitate the development of next-generation intrusion detection systems.Keywords

In the virtual world, Android phones are now an integral part of our daily lives. They are vital to business, medicine, entertainment, finance, and communication. This critical role demonstrates the importance of ensuring adequate security protection. The Internet is linking more and more devices and services, which means that the number and sophistication of cyberattacks with which we must deal are increasing. Malware attacks are among the most significant threats, as they generate billions of dollars in losses worldwide [1,2]. Ransomware is currently among the most destructive forms of attack. There are numerous forms of this, such as crypto-ransomware and lock-screen ransomware. The Lock-screen ransomware blocks you from accessing by displaying imitation warning messages. However, Crypto-ransomware encrypts valuable documents, photos, and videos, making them unrecoverable without a decryption key [3,4]. Simplocker, LockerPin, and WannaLocker are among the popular sets of ransomware that illustrate how attacks are becoming increasingly sophisticated and perilous. There is a need to develop effective methods for detecting cyber threats, as they can cause significant harm and are becoming increasingly difficult to identify.

The primary methods by which traditional identification methods perform well are the use of signatures and heuristics. They are suitable for known threats but not very effective for polymorphic or new ones [5,6]. Static analysis techniques are not effective, as attackers often employ code obfuscation and encryption to bypass security measures [7]. Dynamic analysis is another option, but it requires sandbox testing and substantial computational power, making it difficult to scale in real-time [8,9]. The area of machine learning (ML)-based ransomware detection has grown significantly, as it can identify both traditional and novel attack patterns by examining distinctive behavioral characteristics [10]. However, all the ML models we currently have utilize a single classifier, which is not always effective in terms of generalization and is not particularly efficient against various types of ransomware. Ensemble learning has improved accuracy, but requires manual selection of features and optimization of hyperparameters, making it less flexible and efficient [11]. Additionally, it is challenging to identify threats early on, as most approaches do not detect attacks until significant damage has been caused [12]. In this research, a thorough comparative study is conducted among conventional ensemble-based techniques (such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Bagging) and Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) systems (like TPOT, EvalML, and FLAML) to address these challenges. AutoML, on the other hand, automatically finds the best models, simplifies hyperparameter tuning, and improves generalization. This differs from typical ML processes, which require manual optimization. The goal of this study is to show that AutoML can automate the model-building process and match or beat the performance of traditional ensemble classifiers. This would be an effective and scalable method for discovering Android ransomware. The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

• Automated Detection Pipeline: We introduce a completely automated Android ransomware detection system that combines a three-stage hybrid feature selection approach (filter, wrapper, and embedded methods) with AutoML-based classification, thus minimizing the need for manual configuration and enhancing performance.

• Reorganizing Classes in a Hierarchical Manner: Through the application of hierarchical clustering to consolidate ransomware families into groups that behave similarly, generalization can be enhanced, class imbalance minimized, and training simplified.

• Strict Baseline Comparison: Stratified K-fold cross-validation is used to test rigorous traditional ensemble models to ensure that they are fair and reliable. The results show that AutoML-powered models, particularly FLAML, have better detection accuracy than traditional ensemble baselines, demonstrating their ability to adapt to evolving cyber-attack patterns.

• Evaluation: We offer complete results, including confusion matrices, ROC curves, learning curves, and importance of permutation characteristics that demonstrate the robustness, reproducibility, and scalability of the proposed framework for real-world applications.

2 Related Works and Research Gap

Current advancements in intrusion detection have heavily relied on machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques to identify malicious activity across various topics, including Android ransomware. Intrusion detection systems (IDS) mainly detect threats at the host and network levels. However, their theoretical foundations are highly relevant to the Android environment, where ransomware is a rapidly increasing attack type. Current research on IDS from 2025 [13] suggests that adaptive anomaly detection and multimodal feature utilization are crucial for making systems more resilient against evolving cyber threats. These frameworks were not created solely for the purpose of ransomware. Still, they do illustrate the importance of utilizing detection models that work well in various diverse scenarios and can be automated and scaled. These are also significant concepts in this research. Old-style static analysis techniques, such as feature extraction from app permissions, have been only moderately effective against Android ransomware, especially when the malware is evasive or constantly changing. To address these issues, researchers gradually began to employ dynamic behavioral profiling, i.e., observing API calls, network activity, and system logs during the program’s execution. This approach reduces the likelihood that systems will be targeted by sophisticated ransomware and makes it easier to identify new and established methods by which hackers attack.

Numerous research studies have employed the use of ML and DL models to identify ransomware using these concepts. For example, the authors in [14] proposed an ensemble machine learning approach trained on 203,556 network traffic samples, including benign data and ten ransomware families. Their models achieved precision, recall, and F1-scores that were all above 99%, and feature importance analysis revealed significant behavioral features. They further indicated that certain classes had poorer true positive rates and emphasized the necessity for adaptive methods that can deal with new ransomware types.

Meanwhile, most current research on locating Android malware has increasingly emphasized employing both static and dynamic analysis to avoid problems each technique has independently. Static analysis is effective in identifying bugs, but it may not always be successful against code obfuscation or zero-day threats. Dynamic analysis, on the other hand, costs more in terms of time and processing power, but it gives you a better understanding of behavior. In this area, the DL-AMDet framework is a big step forward. It possesses a static detection module that employs CNN-BiLSTM and an autoencoder-based anomaly detection module. This hybrid approach achieved 99.935% accuracy, which was superior to that of the majority of other state-of-the-art models [15]. These frameworks have served us well, but they still demonstrate that there are trade-offs between their accuracy, scalability, and the difficulty of extracting features. These concerns underscore the need for more research into optimally improved hybrid deep learning solutions, primarily through the combination of ensemble techniques and AutoML systems that can automate feature selection, model optimization, and accommodation of the changing nature of malware.

An Automated Android Malware Detection framework (AAMD-OELAC) was proposed in [16]. It integrates LS-SVM, KELM, and RRVFLN with hyperparameter tuning using a hunter-prey algorithm that significantly enhances detection rates. However, although it performed satisfactorily, the system required frequent updates to remain effective in response to the other side’s alterations. Ahmed et al. [17] compared 392,035 network traffic records and evaluated DT, SVM, KNN, FNN, and TabNet models for binary classification. The work highlighted issues related to computational complexity and poor generalization, despite SVM achieving a 100% recall rate and DT attaining an accuracy rate of 97.24%. It recommended the usage of a combination of various techniques to improve things. There have also been studies on deep learning methods. Khan et al. [18] proposed an LSTM model based on eight feature selection techniques and majority voting to recognize 19 key features from the CI-CAndMal2017 dataset. The optimized LSTM achieved 97.08% accuracy, surpassing previous benchmarks, but larger datasets are required for further verification. Ali et al. [19] presented MALGRA, a dynamic-analysis-driven malware detection system that extracted API-call N-grams and then applied TF-IDF(Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) for selecting the most discriminative behavioral features. The work compared the performance of several classical machine learning models such as Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Decision Tree, and Naive Bayes and found that logistic regression performed best with an accuracy of 98.4% for malware/benign datasets. Interestingly, their results demonstrated that behavioral N-gram features combined with lightweight ML classifiers can outperform many traditional static opcode-based approaches, especially against malware using obfuscation and evasion. AutoML is a game-changing technique in this area only introduced in the recent past. Brown et al. [20] demonstrated the efficacy of AutoML for large-scale malware detection with the SOREL-20M and EMBER-2018 datasets, where AutoML-tuned FFNNs and CNNs outperformed hand-crafted pipelines. Bromberg and Gitzinger [21] developed DroidAutoML, a scalable microservice framework for automatically selecting models and hyperparameters. This was a significant improvement over Drebin and MaMaDroid. All the same, these works pointed out challenges in real-time deployment and the need for adaptive strategies in the face of evolving threat environments. Feature selection has also been a key area of focus. Masum et al. [22] coupled DT, RF, NB, LR, and NN classifiers with feature selection. They proved that Random Forest had higher accuracy, F-beta, and precision measures. Khammas [23] developed a static-analysis technique which operates on raw bytes and employs Gain Ratio to identify the best 1000 n-gram features with an accuracy of 97.74%. Although these results were excellent, it was more challenging to generalize against obfuscated binaries, as it employed only static techniques.

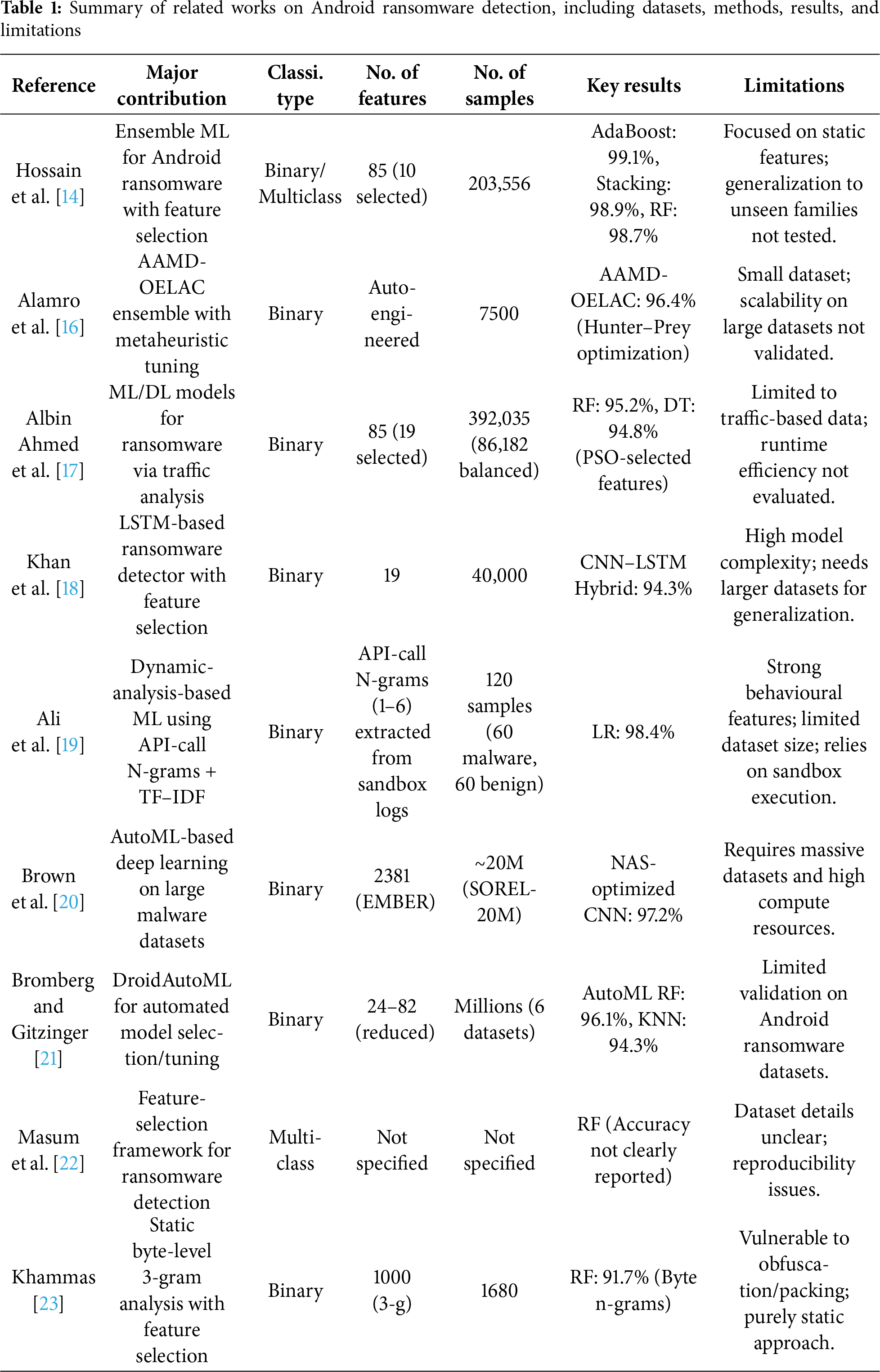

Despite these advances, several issues remain to be solved. Most modern approaches rely on either static or dynamic analysis, which are inefficient against obfuscation techniques or run slowly, making them less effective. Many machine learning models are still based on single classifiers or basic ensembles with hyperparameters that have been manually set. This makes it more difficult to scale and protect against new attacks. Additionally, previous research often utilizes datasets that are too small or outdated, rendering them less applicable in practice. Even ensemble approaches tend not to have automation or explainability, which makes them less effective for operational security. Table 1 provides an overview of significant works, focusing on their datasets, classification strategies, performance measures, and key issues. The table indicates that the majority of recent approaches rely heavily on static analysis or specific traffic datasets, making it challenging for them to handle new types of ransomware. Ensemble and deep learning models have enhanced detection precision but tend to require manual feature engineering and hyperparameter adjustment, rendering them much less scalable as threats constantly evolve. Existing research on AutoML-based techniques holds promise but primarily targets general malware detection. It does not frequently utilize class reorganization or hybrid feature selection to address class imbalance and high-dimensional data issues. To address these issues, this research provides an end-to-end and scalable Android ransomware detection mechanism based on hierarchical class grouping, a three-phase hybrid feature selection process, and ensemble learning powered by AutoML. This mechanism is designed to enhance accuracy, flexibility, and replicability while minimizing human intervention, thereby creating a more effective defense mechanism in practical scenarios.

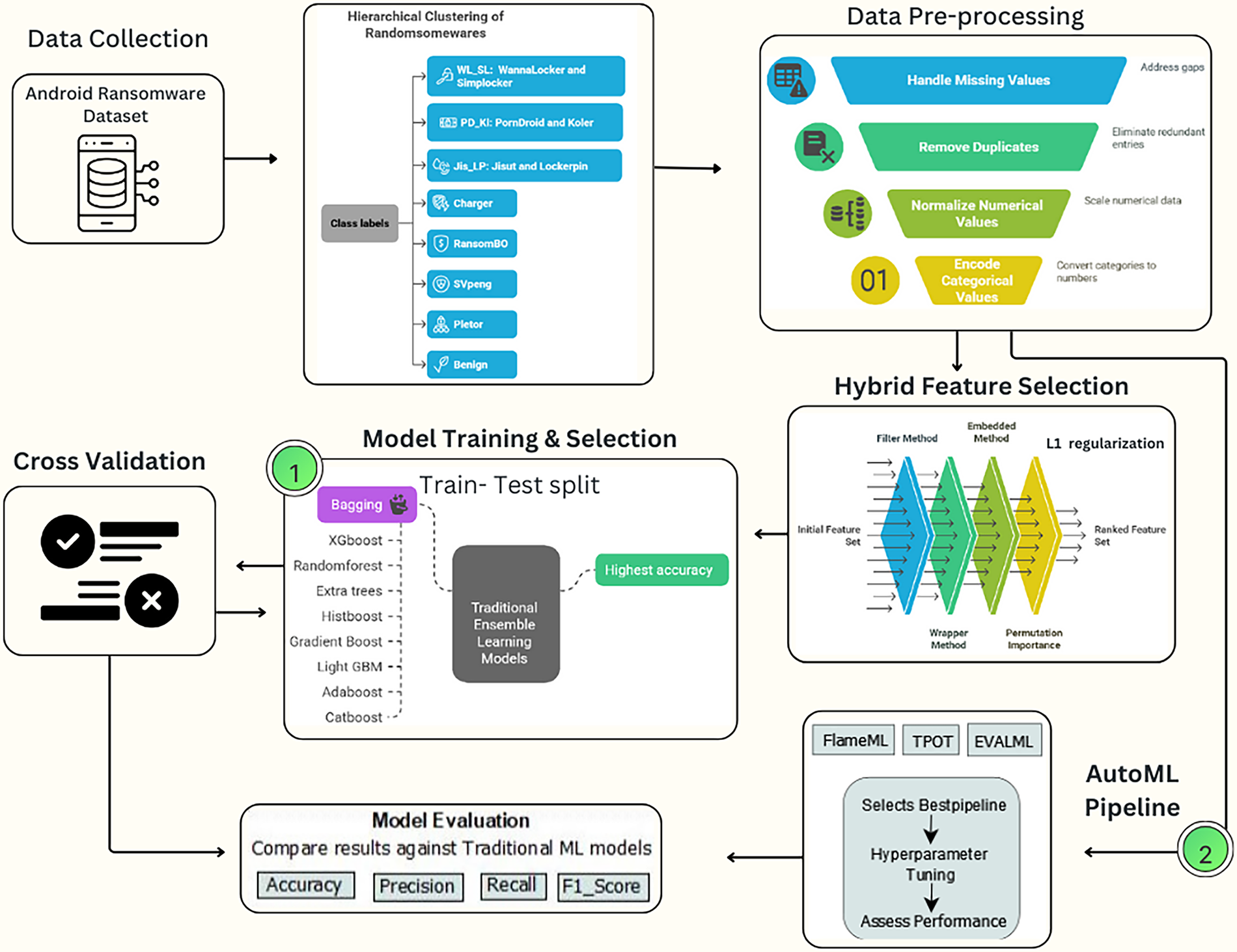

In this research, a fully automated framework overcomes the shortcomings of conventional Android ransomware detection by comparing rigorous ensemble learning algorithms with state-of-the-art AutoML algorithms such as FLAML, TPOT, and EvalML. AutoML streamlines the process by automatically selecting a model, extracting features, and tuning hyperparameters. This contrasts with manually building pipelines and tuning them. This automation reduces the number of personnel required and enables the handling of the ransomware threat’s dynamic nature. The system employs a hierarchical clustering approach to categorize ransomware families into broader groups based on their behavior. This method enhances class balance and facilitates straightforward generalization. Additionally, the entire preprocessing pipeline, along with a hybrid feature selection approach in three stages, including filter, wrapper, and embedded techniques, has been utilized. This method is helpful to minimize dimensionality without losing the ability to differentiate between things. The proposed framework offers a twofold perspective by contrasting legacy ensemble methods and pipelines generated by AutoML, which optimize independently from start to end. Experimental results show that AutoML, specifically FLAML, consistently outperforms the best ensemble baselines in terms of accuracy. It also makes notable improvements in efficiency and scalability. This research lays the groundwork for future advancements in improving next-generation ransomware detection systems. Fig. 1 shows the whole process of the proposed framework for Android ransomware detection.

Figure 1: Proposed framework for Android ransomware detection using AutoML and ensemble baselines

3.1 Materials and Environment Setup

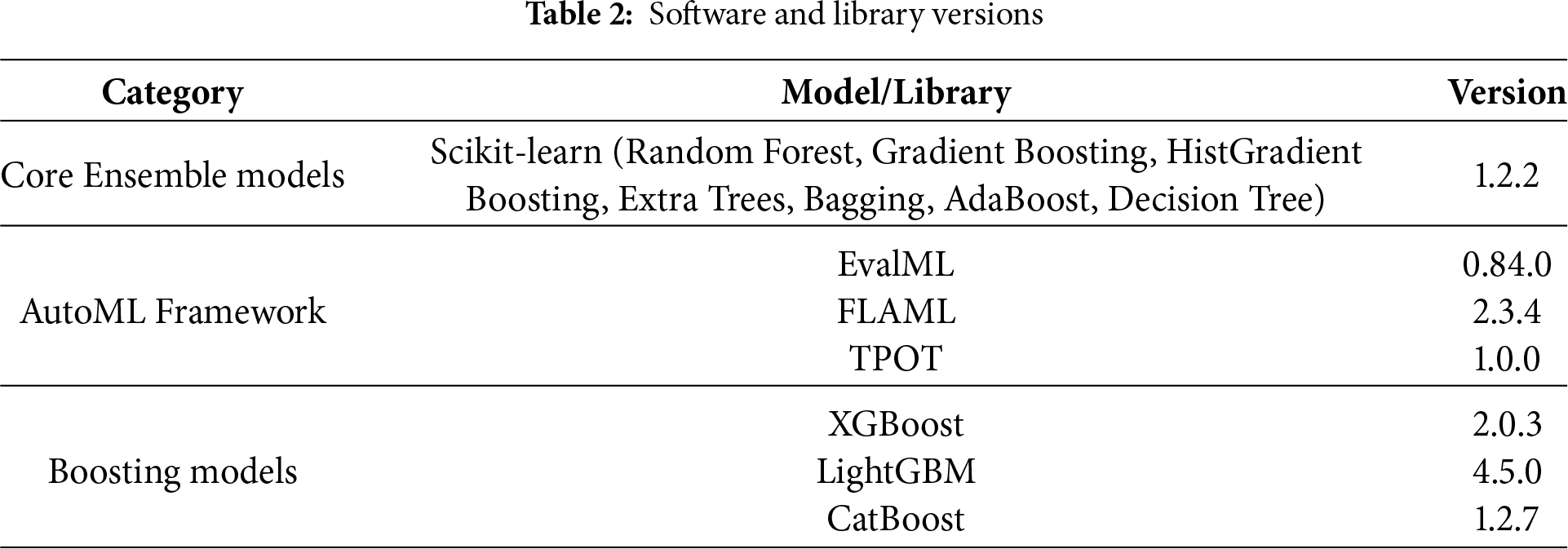

Experiments were conducted partly in a Kaggle notebook environment and partly on a local Windows machine equipped with an Intel Core i7 (14-core) processor and 16 GB of RAM. All experiments were conducted in Python 3.11 using conventional scikit-learn packages, along with state-of-the-art Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) libraries such as FLAML, TPOT, and EvalML, as well as state-of-the-art boosting algorithms including XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost. GPU acceleration was enabled for TPOT with NVIDIA RAPIDS/cuML where possible, and was run in a WSL2 (Windows Subsystem for Linux v2.3) environment. In Kaggle notebooks, GPU acceleration was enabled through the runtime settings of the notebook. The original dataset, after being loaded into memory, consumed approximately 258 MB of RAM. A fixed random seed (42) was used across all experiments to ensure reproducibility of results.

For EvalML, experiments were executed with EvalML 0.84 and Python 3.11. The core dependencies were NumPy (

pip install –upgrade pip; pip install numpy>=1.24 pandas>=1.5 scikit-learn>=1.2 matplotlib>=3.7 evalml==0.84 nlp_primitives

The computer environment and software versions used are listed in Table 2, allowing for precise replication of the reported findings.

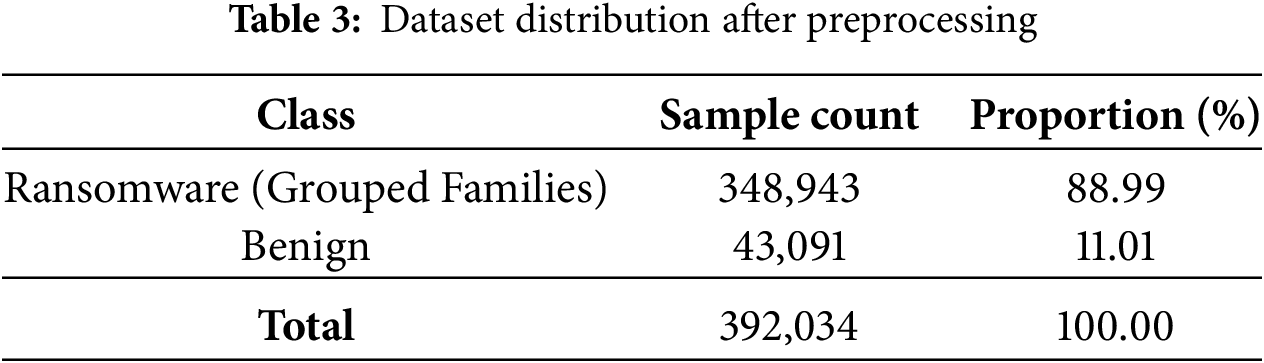

The work in this research utilizes a publicly available Android ransomware dataset from Kaggle [24], which contains both benign and ransomware network traffic samples. The dataset comprises 392,034 network flow records, each described by 86 features, where 81 are numeric and five are categorical. There are 43,091 benign samples and 348,943 ransomware samples representing various Android ransomware families such as Simplocker, LockerPin, and WannaLocker. This allows for an 11-class multi-class classification task where 10 class labels represent different ransomware families and one label represents the benign category. Each sample point refers to a network flow instance and is characterized by flow-based features that encompass connection identifiers, protocol-level features, temporal behaviors, statistical metrics, and TCP flag information. A full preprocessing pipeline was established to ensure data integrity before model development. The dataset was thoroughly checked for duplicates, infinite values, and missing (NaN) values sequentially. Duplicates were not found. Infinite values were substituted with NaN, and after conducting null checks, it was ensured that no rows had to be removed. The final dataset size was therefore not altered, thereby ensuring its completeness and quality. The final dataset held 348,943 ransomware samples (88.99%) and 43,091 benign samples (11.01%), as indicated by Table 3.

The experimental setup utilizes a multi-stage methodology to tackle the inherent problems involved in Android ransomware classification, i.e., class imbalance, feature dimensionality, and the need for automated, scalable model optimization. The solution proposed combines three complementary elements: (i) hierarchical clustering-based class restructuring, (ii) a hybrid feature selection pipeline to counter dimensionality, and (iii) exploration of conventional ensemble learning approaches vs. AutoML-based pipelines. Both of these combine to constitute a comprehensive solution that not only improves classification accuracy but also represents the practical advantages of automation.

Hierarchical Clustering for Class Grouping: The ransomware families usually share the same behavioral patterns, which can cause confusion during the classification phase and lead to noise overfitting in a dataset-specific way. To address this limitation, we performed hierarchical clustering to combine ransomware families at both semantic and behavioral levels, based on class-level centroids. This class reformulation has three valuable advantages:

1. Class Imbalance Mitigation: Consolidating minority classes with behaviorally related families reduces class imbalance, minimizing bias toward the dominant classes while preserving semantic meaning.

2. Computational Efficiency: Reducing the classification problem from 11 to 8 classes decreases training complexity by approximately 27%, resulting in faster training times and reduced computational overhead.

3. Improved Generalization: Grouping into broader behavioral categories makes the model robust, enabling better detection of new ransomware specimens of the same behavioral category.

The preprocessed dataset was transformed into a sparse high-dimensional matrix. Class centroids were computed to represent each ransomware family within the feature space. For a class

where

With these distances, hierarchical agglomerative clustering based on Ward’s linkage was employed in iteratively merging the most similar classes. The gain in within-cluster sum of squares (SSE) when merging two clusters

where

Clustering was used only on ransomware families. The benign category was left distinct to allow models to continue differentiating between malicious and benign traffic. This method minimizes noise by clustering statistically equivalent ransomware families into broader classes, thereby improving robustness and reducing the possibility of overfitting to small variations within families.

The in-depth outcomes of the clustering process, such as dendrogram visualization and the final grouped class distribution, are discussed in Section 4.

Pre-Processing

Preprocessing of data is necessary to ensure the integrity, consistency, and suitability of the dataset for developing machine learning models. The following steps were utilized uniformly to prepare the Android ransomware dataset:

1. Elimination of Duplicate Records: Potential duplicate rows were identified using the duplicated() command and removed to maintain data integrity and prevent redundancy during model training.

2. Handling Missing and Infinite Values: Infinite and large numerical values were substituted with NaN for consistent presentation. Such rows with NaN values were further removed to have a complete and consistent dataset.

3. Feature Segmentation and Normalization: The data was separated into numerical and categorical features to make it easier for correct preprocessing. The numerical features were scaled using the assistance of StandardScaler, as in Eq. (4), to enable the characteristics to be compared:

where

4. Categorical Encoding: The categorical features were encoded into numerical representations using LabelEncoder, preserving category identity without the dimensionality increase that is associated with One-Hot Encoding.

With these preprocessing steps, the dataset was rendered standardized, noise-free, and well-structured, providing a sound foundation for feature selection, class clustering, and subsequent model training.

3.4 Hybrid Feature Selection Strategy

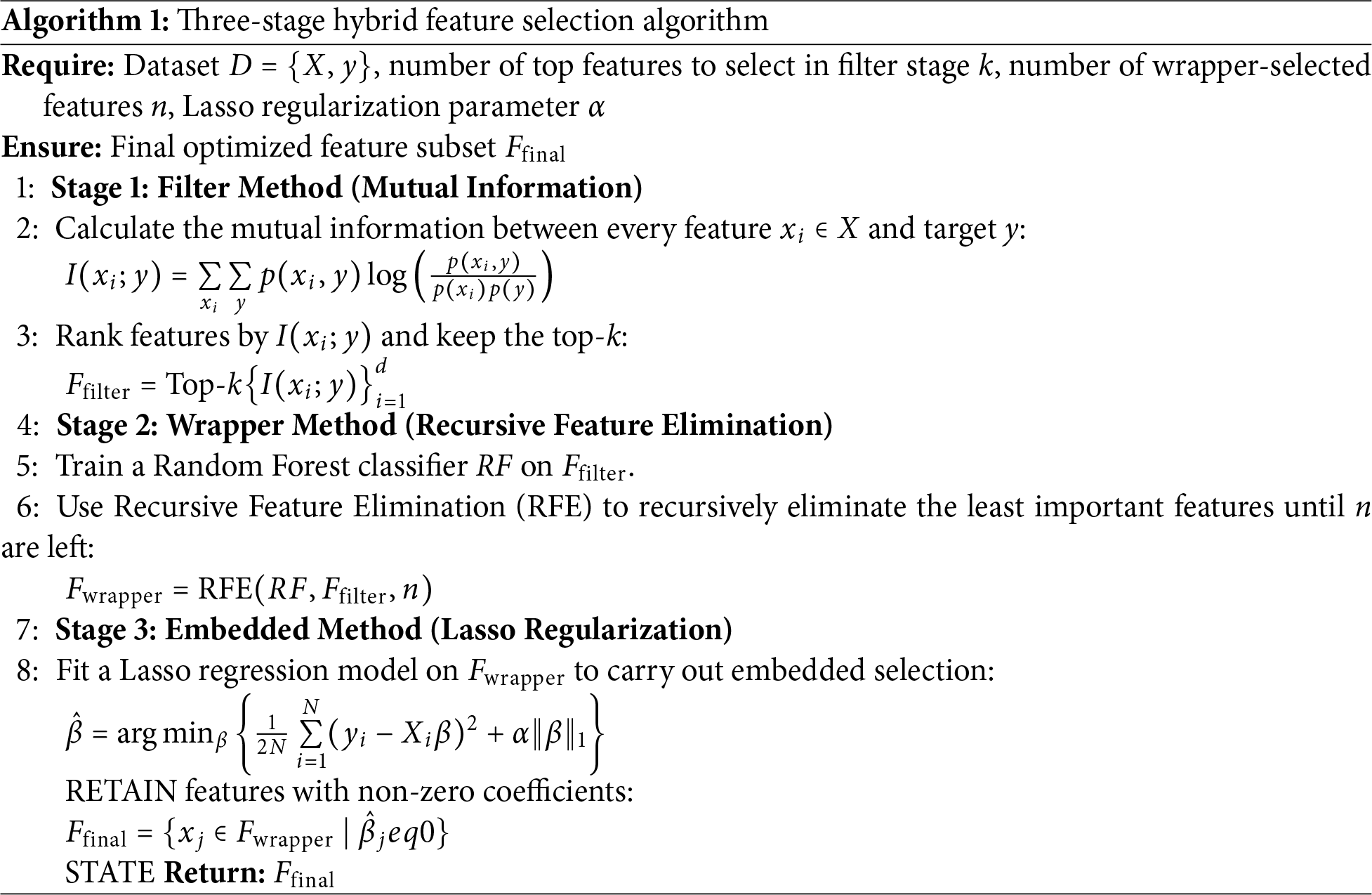

Feature selection is a critical part of machine learning workflows that improves dimensionality reduction, eliminates duplicate or unnecessary features, and improves model performance and computational cost. For these purposes, we employed a three-stage hybrid feature selection strategy that leverages the strengths of filter, wrapper, and embedded methods by capitalizing on their complementary advantages. This approach is mathematically discussed in Algorithm 1.

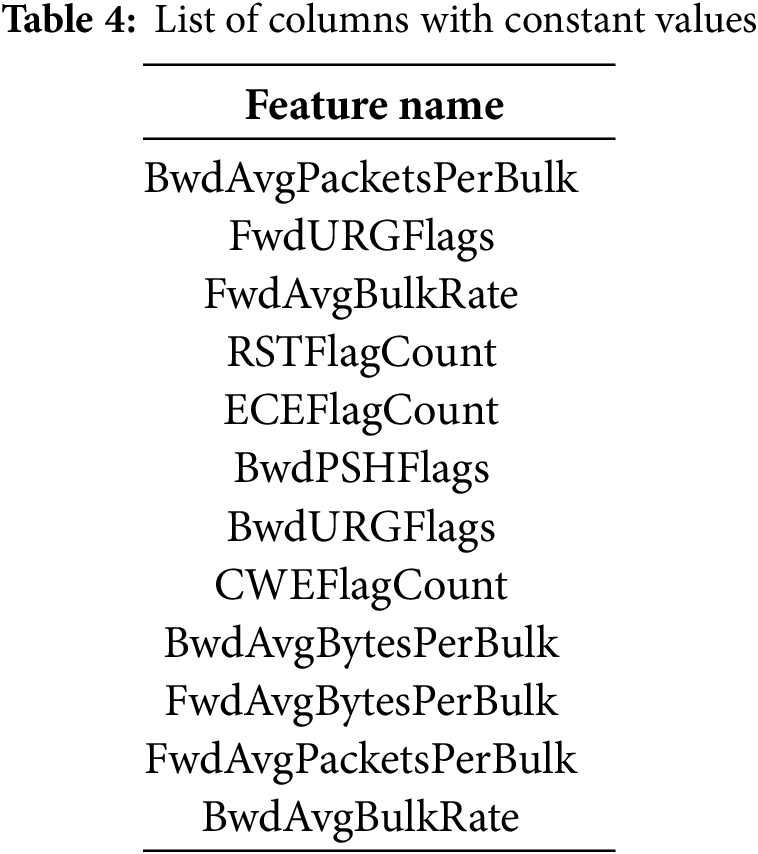

This three-step architecture combines the speed of filter methods and model-agnostic features, the interaction sensitivity of the wrapper method, and the embedded regularization’s sparsity-promoting feature. The outcome is a small highly discriminative feature subset that enhances generalization, minimizes overfitting, and minimizes training time. Constant or near-constant-value columns were eliminated in preprocessing, as seen in Table 4, before executing the feature selection pipeline.

This was done because qualities with fixed values exhibit no sample-to-sample variation and thus bring no discriminatory power to the model. Additionally, they may lead to an unwanted increase in computational complexity without improving performance.

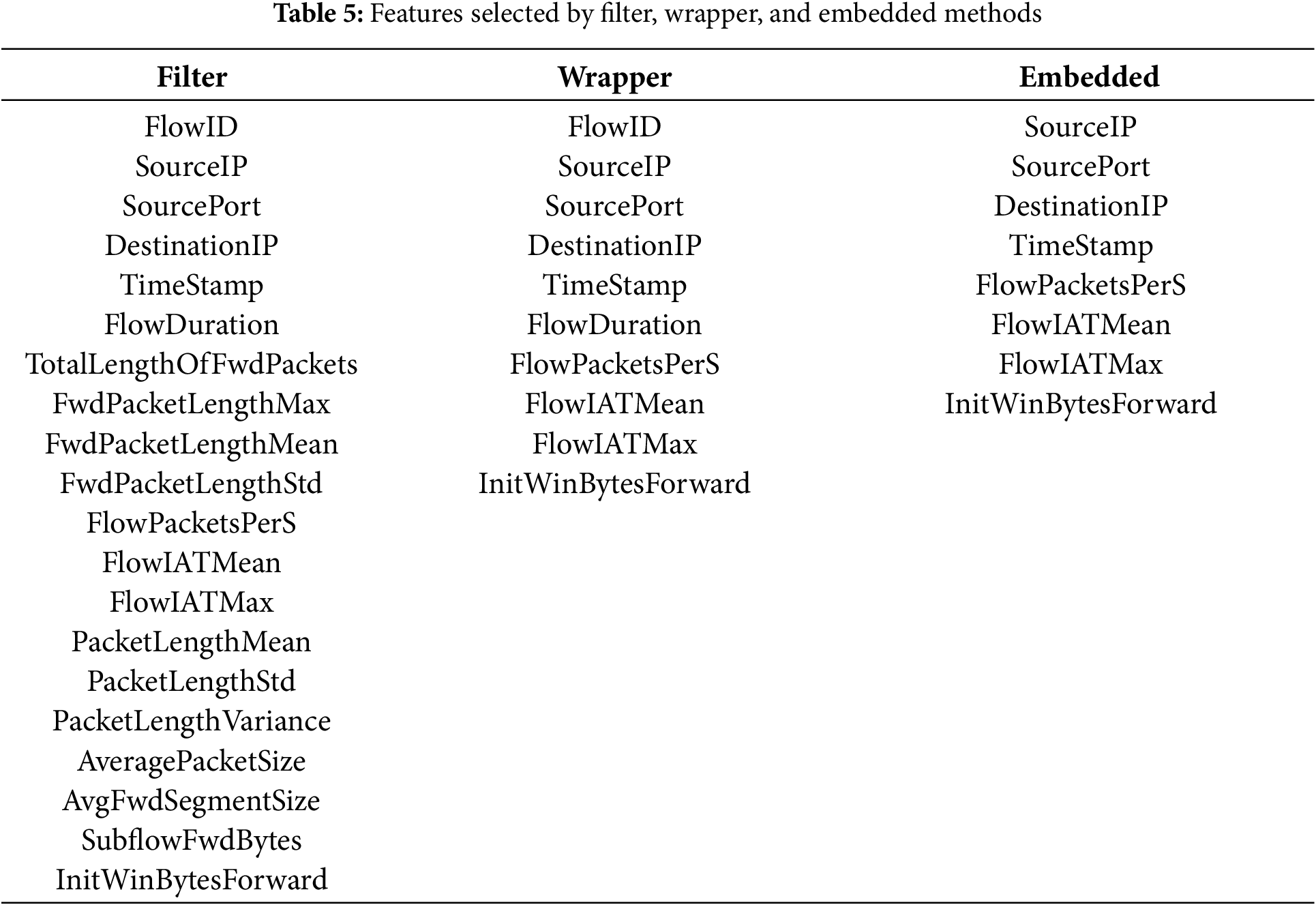

Step 1: Filter Method. We started by applying the SelectKBest method with Mutual Information (mutual_info_classif) as the scoring metric. This approach assesses the relationship between each feature and the target variable, selecting the top 20 features that yield the greatest information gain in classification.

Step 2: Wrapper Method. The learnt features from the filter method were then enhanced by Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest classifier as the base estimator. RFE removes the least important feature recursively based on model performance until we are left with the top 10 most significant features.

Step 3: Embedded Method. We then employed L1-regularized (Lasso) regression with SelectFromModel on the outcome of RFE. L1 regularization was selected because it possesses the ability to impose sparsity by setting the weights of less informative features to a specific value, thereby supporting both feature selection and model learning. This helps curb redundancy in the high-dimensional feature space, enhances generalization by reducing the probabilities of overfitting, and emphasizes the most discriminative features involved in ransomware detection. Table 5 presents the features selected at each step of the feature selection.

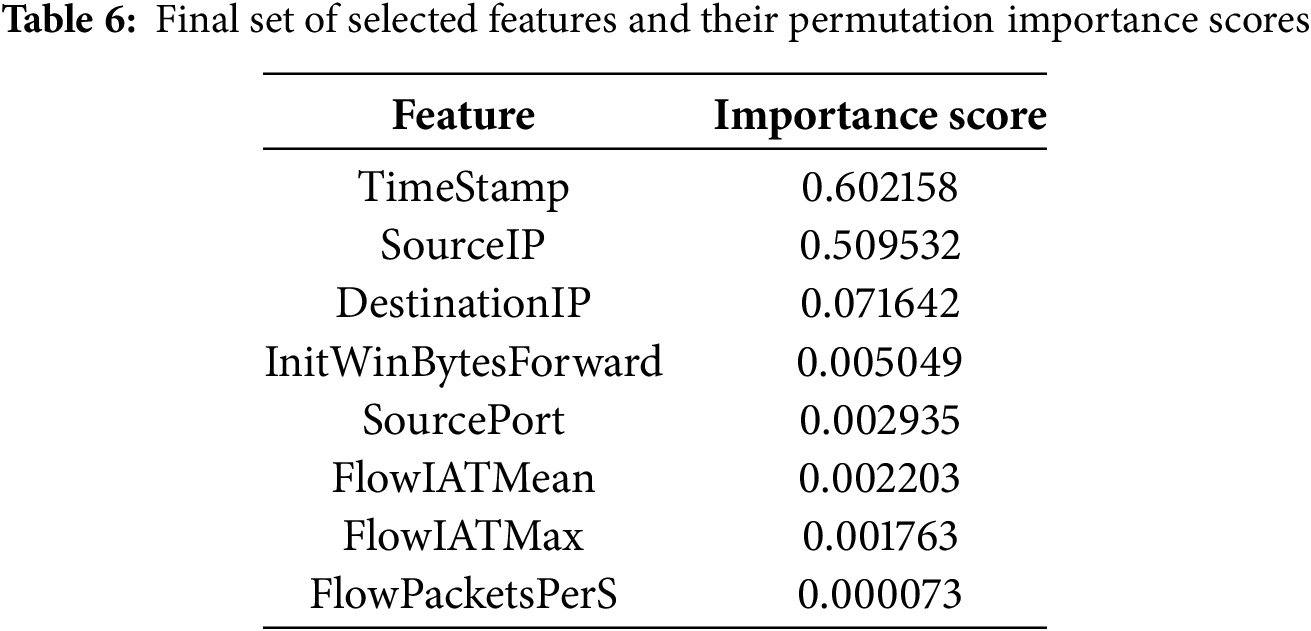

As a measure of the discrimination capability of the chosen set of features, we employed Permutation Importance, a model-agnostic interpretability technique that estimates the importance of each feature by measuring how predictive accuracy decreases when we randomly perturb individual features. This method allows that the importance scores of the features not to be affected by the internal weighting scheme of a given model; hence, we have a fair and unbiased evaluation. After feature selection, the final features and their permutation importance scores are listed in Table 6. It indicates that TimeStamp was identified as the most significant feature (importance score: 0.6022), indicating the vital role played by temporal patterns in identifying malicious activity. This finding aligns with previous studies that highlight the importance of timing anomalies and burst patterns as key features of ransomware activity. Network-layer features such as SourceIP and DestinationIP also scored highly, once more emphasizing the importance of IP-level traffic patterns in discriminating between benign and malicious flows. Additionally, temporal features derived from flows like FlowIATMean, FlowIATMax, and InitWinBytesForward were significant contributors by capturing inter-arrival time aspects and window-based flow behavior. Although the features SourcePort and FlowPacketsPerS had lower individual importance scores, they are still valuable additions whose collective contribution enhances the model’s discriminative ability. In conclusion, the selected feature subset optimizes the trade-off between dimensionality reduction and predictive performance preservation. By selecting the most informative features, the generated models are more effective, less prone to overfitting, and better at generalizing across new ransomware strains. This reduced feature set served as a basis for subsequent ensemble and AutoML-based classification trials.

Ensemble learning is especially useful in the scenario of Android ransomware detection, primarily because it averts overfitting, which is the issue with most high-dimensional and imbalanced datasets. By aggregating several base learners, ensemble approaches make predictions more stable, decrease variance, and prevent one single model from memorizing noise or artifacts from minority classes. This feature is vital in security datasets, where generalization to unknown families of ransomware needs to be made [14,22]. This work compares some of the most popular ensemble methods as baselines. Random Forest-based bagging alleviates variance by bootstrap aggregation and majority voting. Boosting algorithms, such as Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM, iteratively train a sequence of weak learners to reduce residual errors and achieve state-of-the-art classification performance on tabular problems, including traffic analysis and malware classification. Extra Trees, a variant of Random Forest, adds extra randomization in choosing splits and further improves variance reduction with increased computational efficiency. Histogram-based boosting variants enhance scalability by feature binning, thereby accelerating training on extremely large datasets. Recent contributions like PerpetualBooster provide a hyperparameter-free alternative by adjusting boosting iterations and depth through a single budget parameter, effectively solving the tuning problem that exists within conventional ensembles. Combined, these models provide coverage of bagging, boosting, randomization-based, and parameter-free methods, creating a thorough baseline collection for measuring AutoML pipelines. This creates a robust performance benchmark and emphasizes the additional benefits of automation for enhancing scalability.

3.5.1 Justification of Baseline Selection

The nine baseline models capture the key ensemble learning paradigms typically employed in network security:

• Bagging: Bagging and Random Forest reduce variance through averaging predictions across bootstrapped samples.

• Boosting: Gradient Boosting, HistGradientBoosting, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost work to fit sequentially to minimize residuals with high predictive capability.

• Randomization-Based: Extra Trees employ random selection of splits to enhance generalization and efficiency.

• Classical Baseline: AdaBoost is added as a baseline classical boosting reference, even though it is prone to overfitting on highly unbalanced datasets.

3.5.2 Consistency of Experimental Design

To promote fairness, all baseline models were trained from a common stratified 80:20 train/test split and underwent identical preprocessing operations, that is, deletion of duplicates, scaling, label encoding, and class organization in hierarchy. This ensures that if performance differences are observed, they will reflect the model’s ability and not the leakage of data, distribution changes, or different preprocessing.

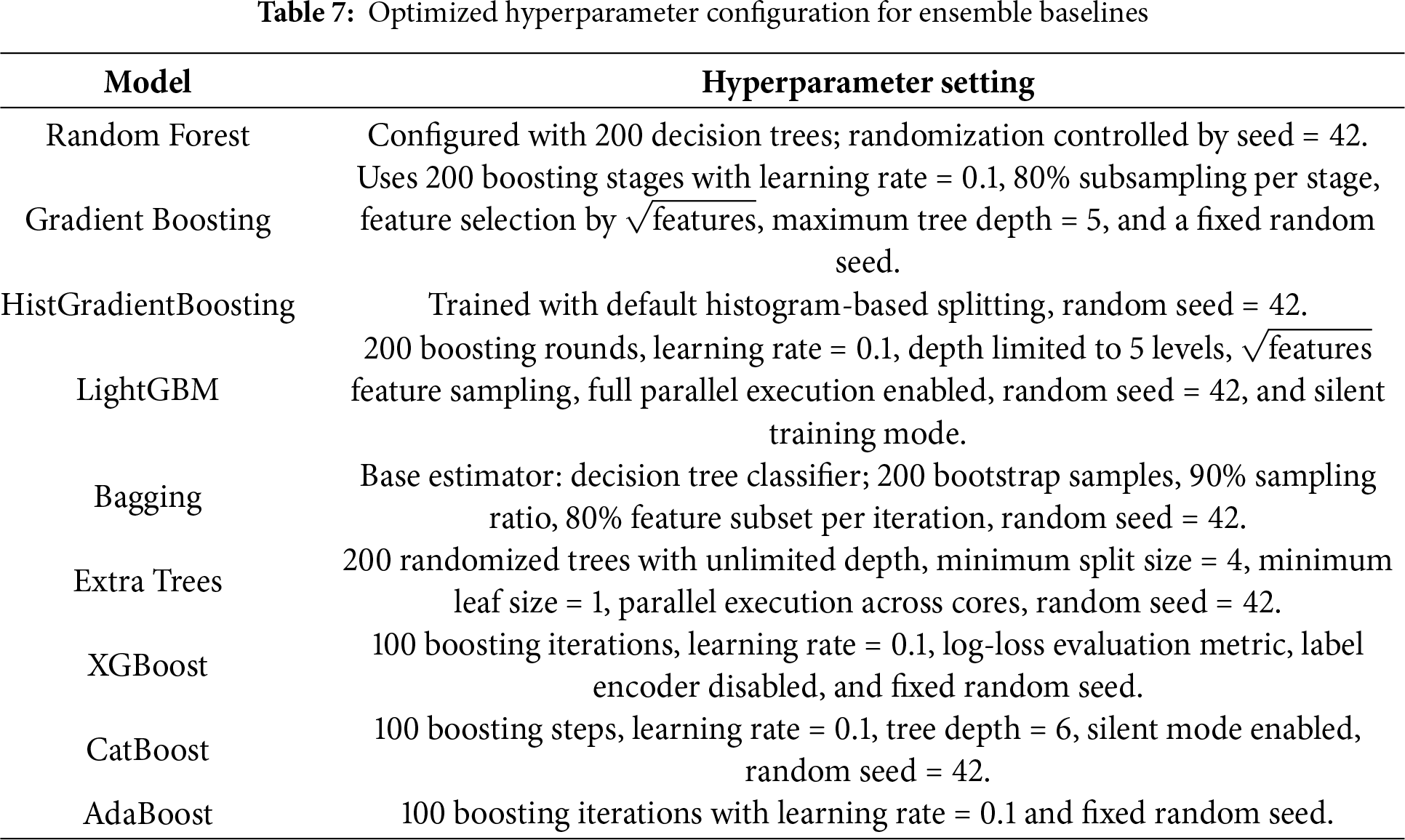

3.5.3 Hyperparameter Optimization

All baseline model hyperparameters were systematically optimized with randomized search and stratified 5-fold cross-validation to maximize macro-averaged F1-score. The best hyperparameters can be found in Table 7. All other unmentioned parameters were left with the default values from the library for reproducibility.

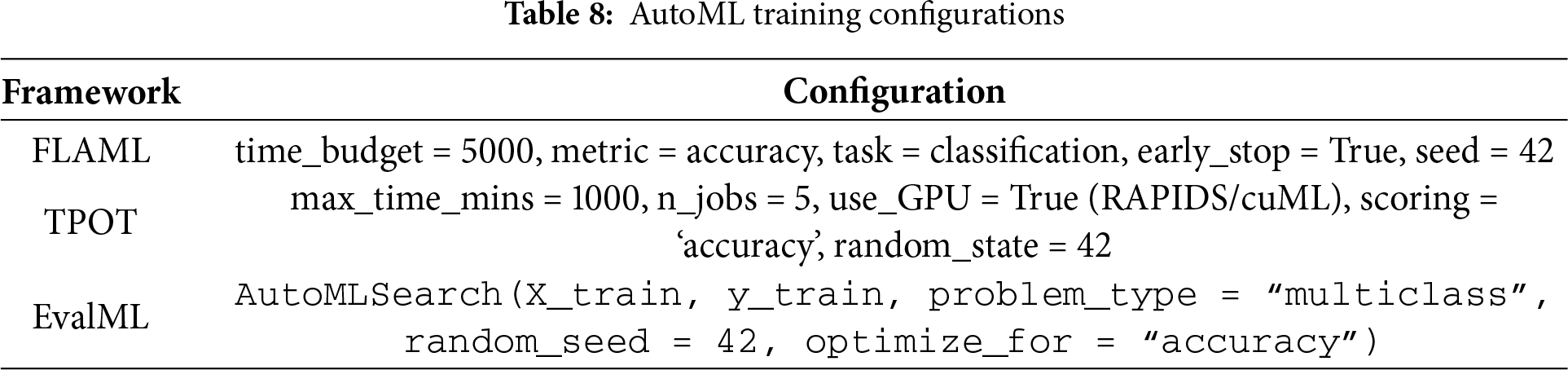

AutoML reduces human effort by automatically preprocessing features, selecting models, and adjusting hyperparameters, thereby enhancing scalability and reproducibility. AutoML is especially important in cybersecurity because the model needs to respond quickly to changing threats. We compared three AutoML frameworks FLAML, TPOT, and EvalML that were chosen for their contrasting design philosophies.

• FLAML: A computationally efficient, lightweight AutoML library that dynamically scales the time and computational resources to find near-optimal learners within constrained time budgets, making it ideal for repeated retraining in security scenarios [21].

• TPOT: Uses genetic programming to develop end-to-end machine learning pipelines such as preprocessing, model selection, and hyperparameter optimization. The use of GPU acceleration with NVIDIA RAPIDS/cuML greatly enhances exploration speed on large ransomware datasets [25].

• EvalML: Offers an interpretable and predictable AutoML process via Bayesian optimization, with built-in categorical data and class imbalance handling, and the ability to create deployment-ready models through automated hyperparameter tuning [26].

All experiments for AutoML were conducted using uniform preprocessing pipelines, stratified train-test splits, and a fixed random seed (random_state = 42) for replicability. A summary of the training settings has been provided in Table 8.

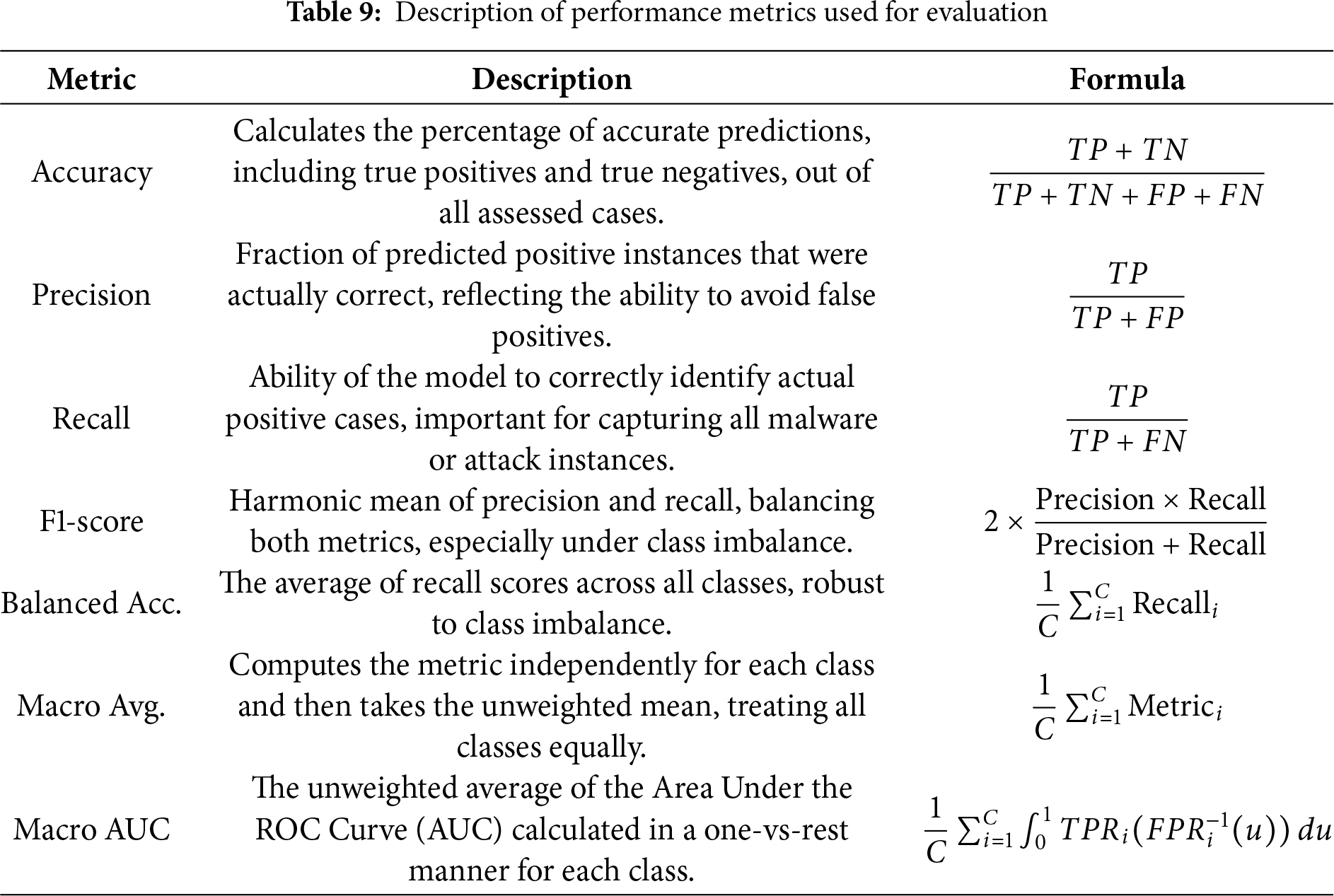

Throughout the evaluation stage, the performance of the trained model was assessed using various standard metrics to confirm its effectiveness in detecting Android ransomware. This check was conducted using the test dataset, which was excluded from the training procedure to provide an unbiased evaluation of the model’s capability to generalize. The performance metrics used in this study are detailed in Table 9.

The performance of the proposed framework was comprehensively evaluated using a stratified 80:20 train-test split, which preserved the original class balance. This ensured that ransomware and benign traffic were represented proportionally in the test and training sets. Additionally, some ransomware families were excluded from the training step to test the model’s ability to generalize against novel threats, a crucial consideration for its real-world effectiveness.

This section demonstrated the experimental outcome of our Android ransomware detection system, comparing classical ensemble learning methods with AutoML-based ones. In addition to the final accuracy values, we include cross-validation results, learning curve analysis, and confusion matrix analysis to ensure that the performance is stable, unbiased, and not simply a result of overfitting or anomaly in datasets. Our findings suggest that although ensemble baselines produce acceptable performance, AutoML systems, especially FLAML, always achieve higher accuracy, scalability, and efficiency, underscoring their pragmatic benefits in automating pipeline optimization.

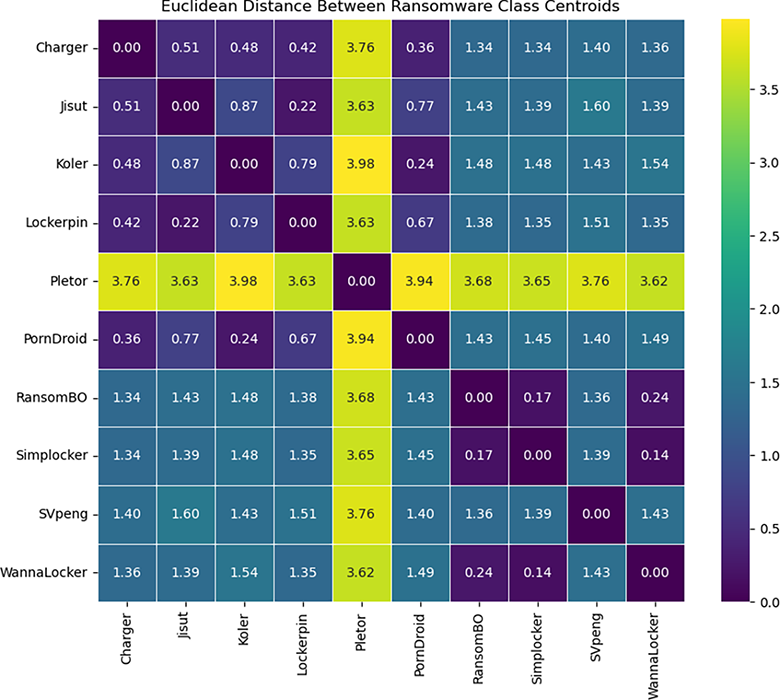

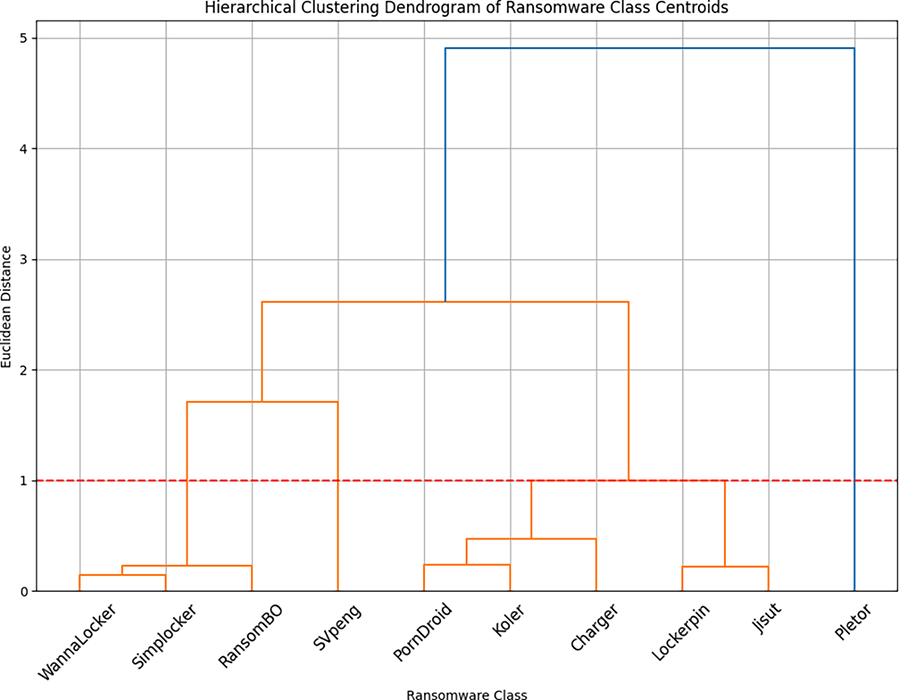

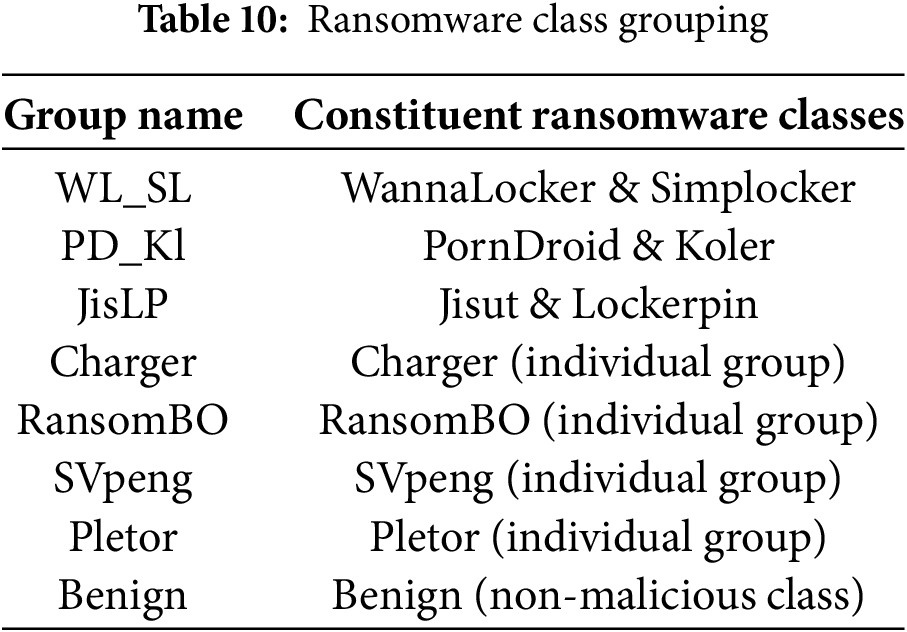

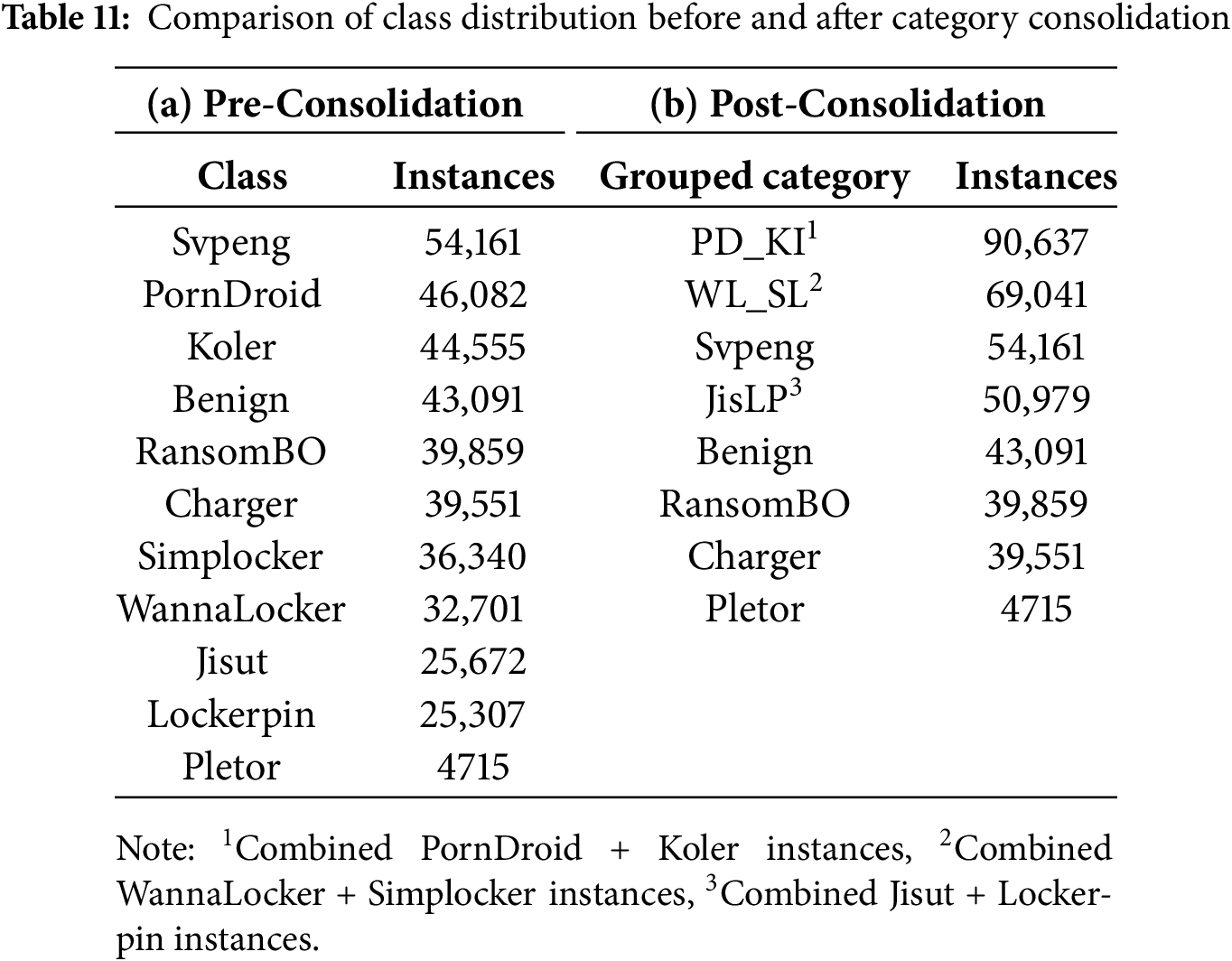

Within our initial exploratory analysis, we employed hierarchical clustering to recluster ransomware families into behaviourally coherent groups. The Euclidean distance matrix, shown in Fig. 2, captures pairwise similarities between centroids of classes, with darker color indicating closer distance. Interestingly, Pletor was seen as an outlier, always having high distances from other families, reflecting its distinctive behavior. The dendrogram in Fig. 3 indicates the hierarchical relationships between the families; classes that combine at lower distances are more similar. For instance, WannaLocker and Simplocker, and Koler and PornDroid, were close relatives, reflecting a high behavioral similarity between them. To identify meaningful clusters, we imposed a horizontal cutoff line at a distance threshold of 1, resulting in eight ransomware groups, as listed in Table 10. In addition, Table 11 compares the initial class distributions with the regrouped distributions and shows a reduction in class complexity that may improve generalization.

Figure 2: Pairwise Euclidean distances between class centroids

Figure 3: Dendrogram of ransomware class centroids

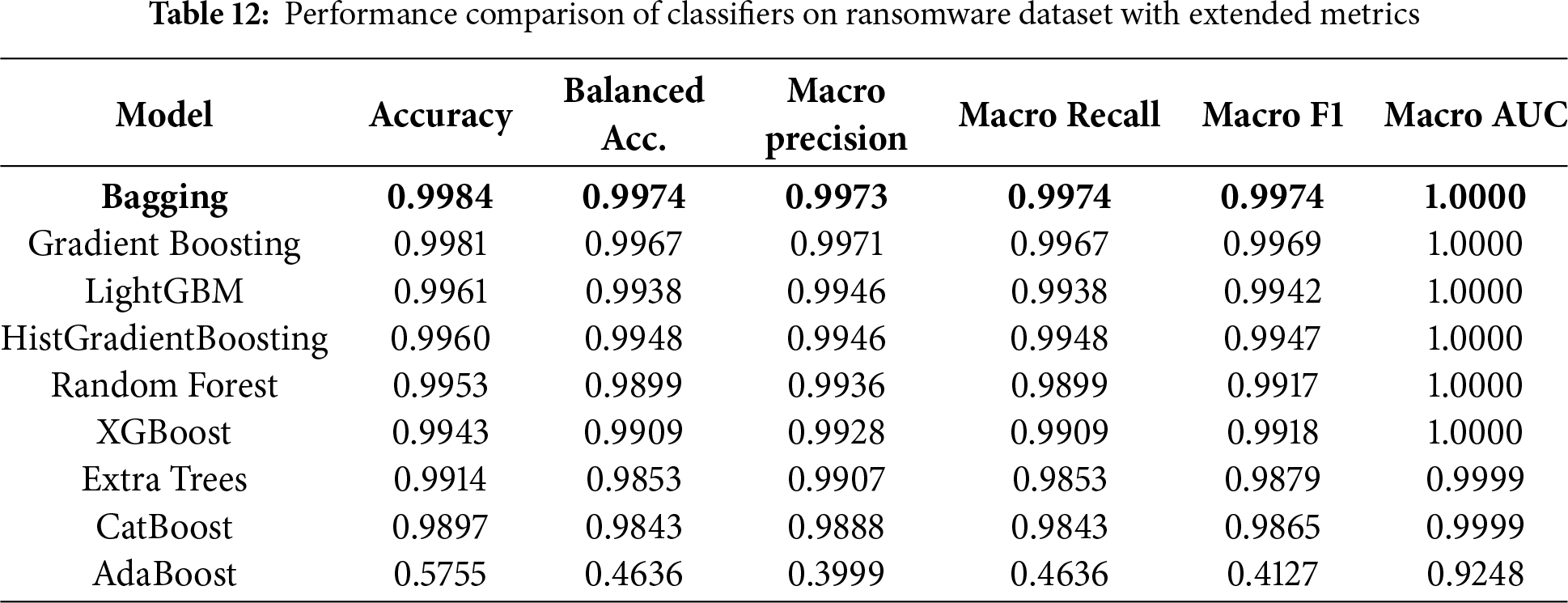

4.1 Ensemble Learning Approach

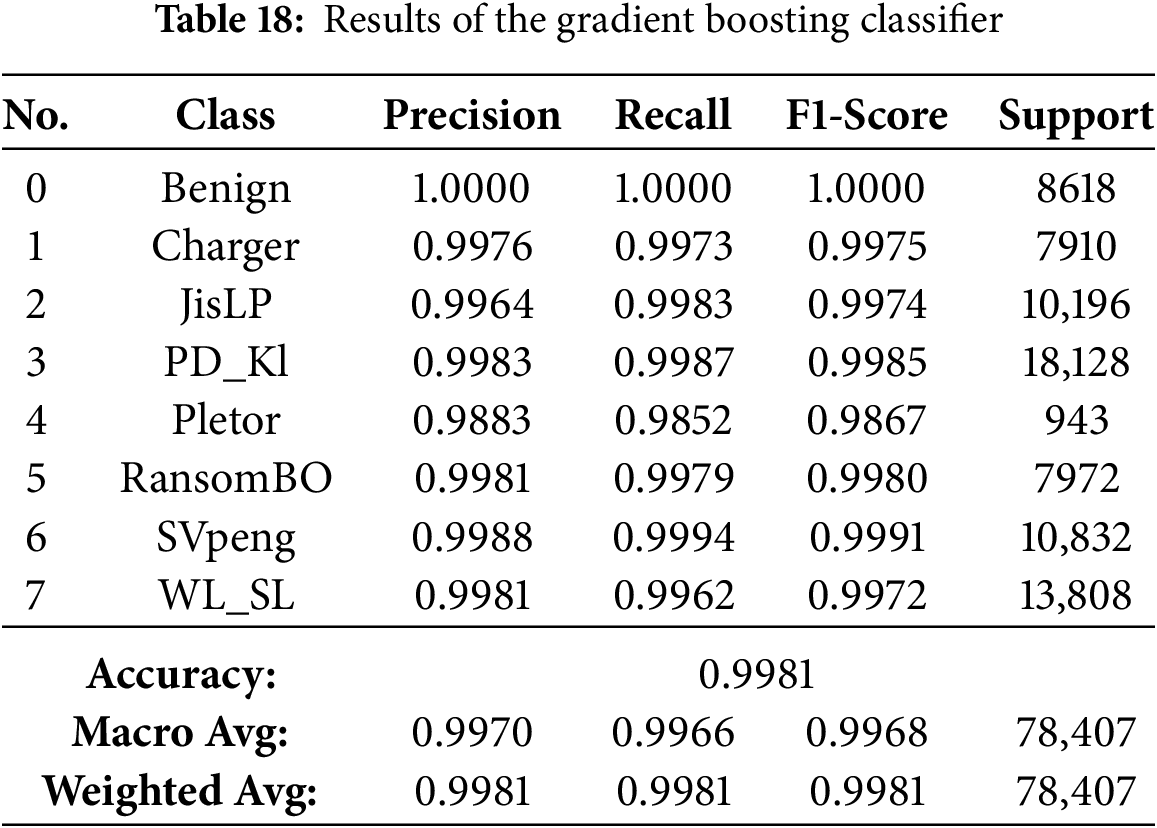

We have utilized and compared nine ensemble methods according to their capability to detect Android ransomware. All models were trained and tested using a stratified data split to create a class-balanced dataset. The metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score) have been used to evaluate them. Comparison results are shown in Table 12. In general, the ensemble algorithms performed better than standard DNNs and CNNs, with eight out of nine models achieving an accuracy of over 99%. More concretely, the best results were achieved with Bagging, Gradient Boosting and Random Forest; their accuracies and F1-scores are nearly 100%. These results highlight the high potential of these models in accurately distinguishing between normal and adversarial traffic.

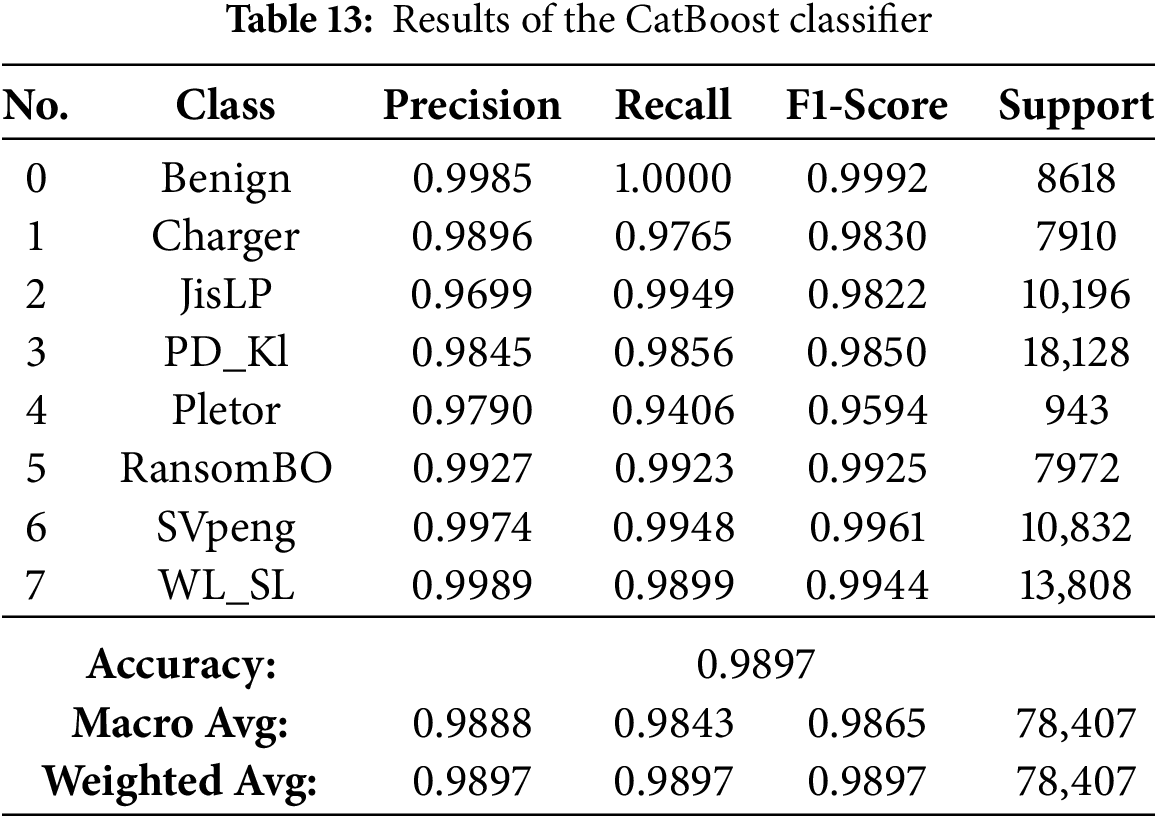

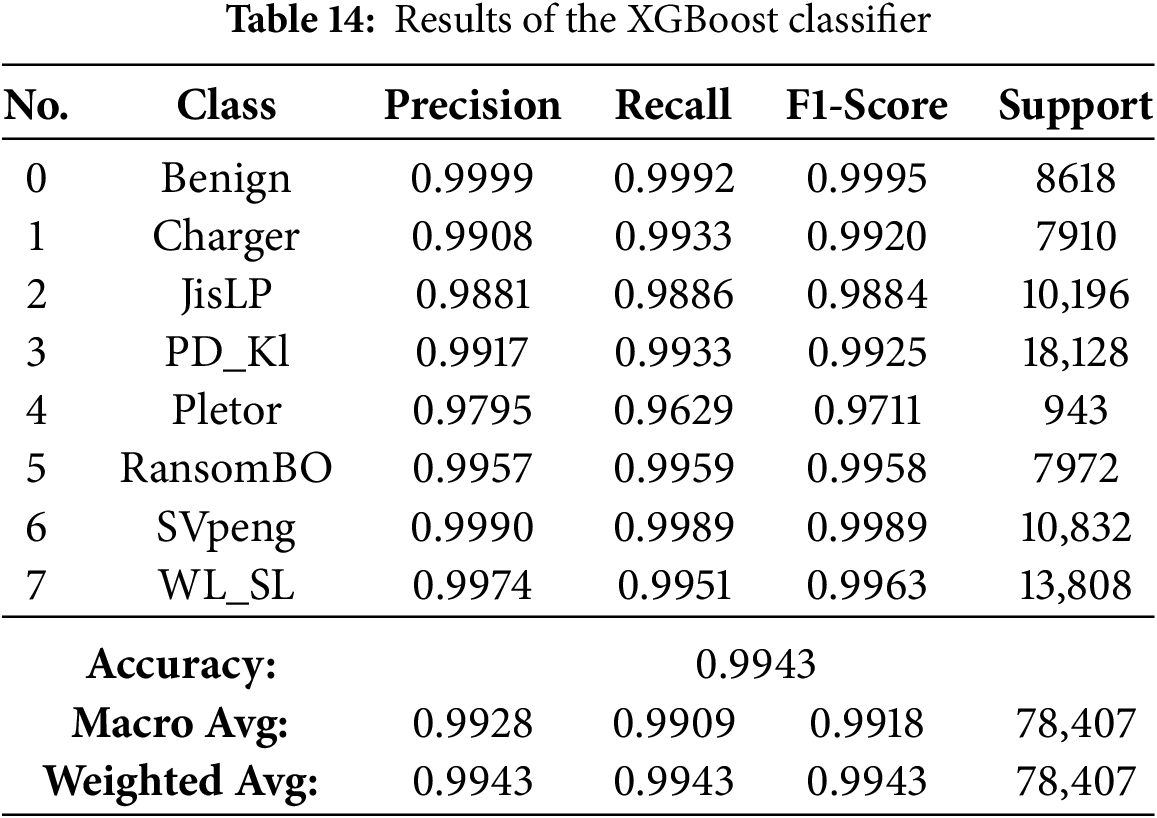

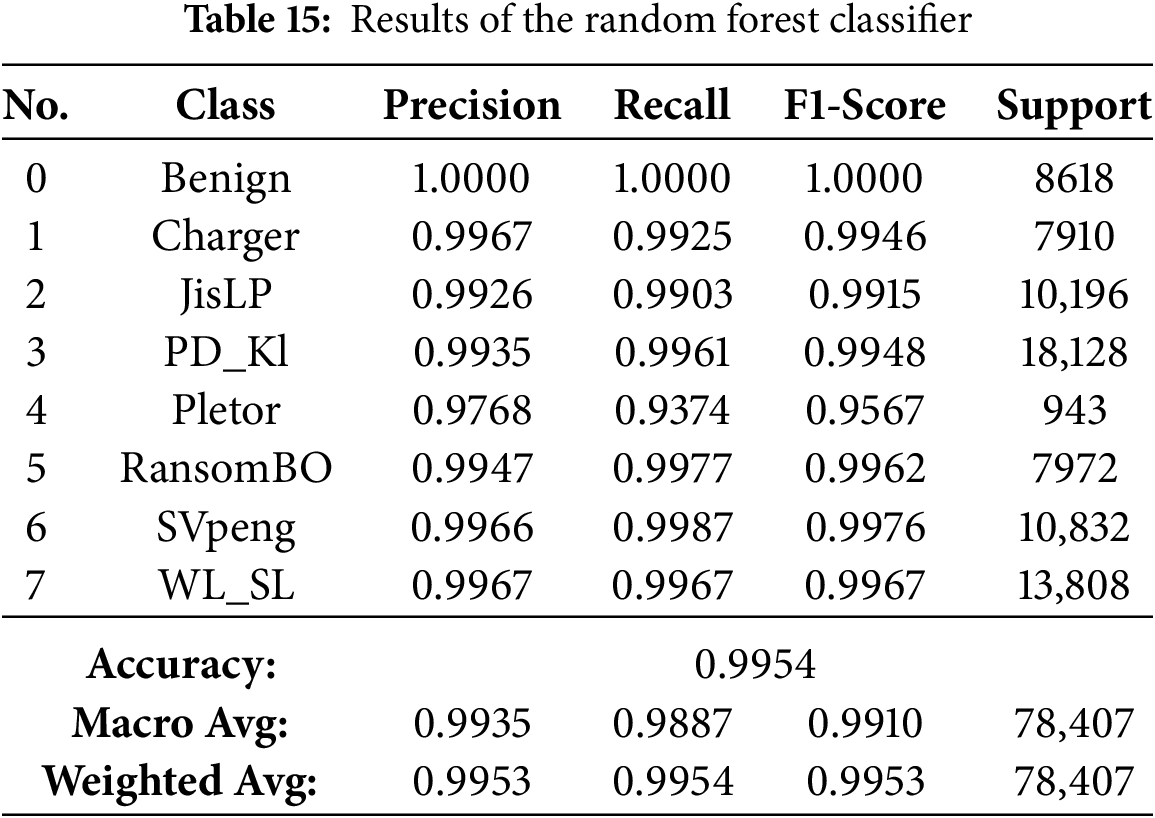

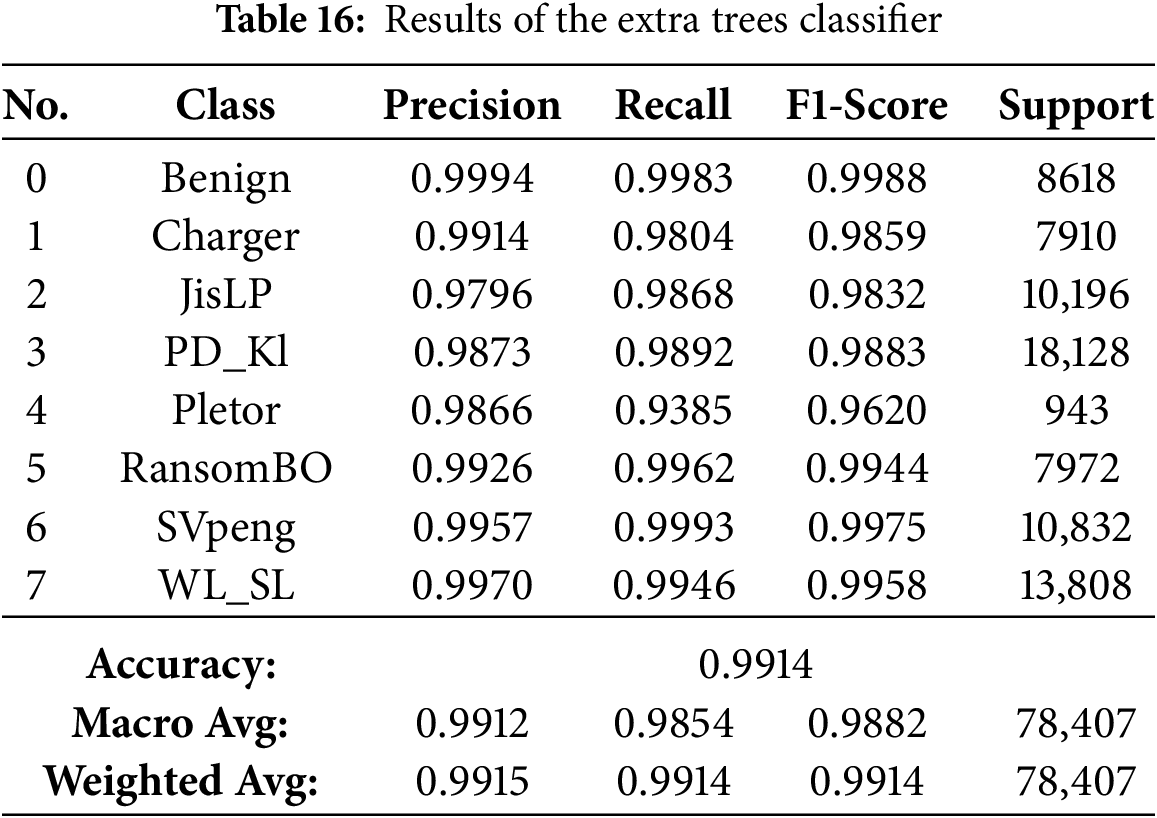

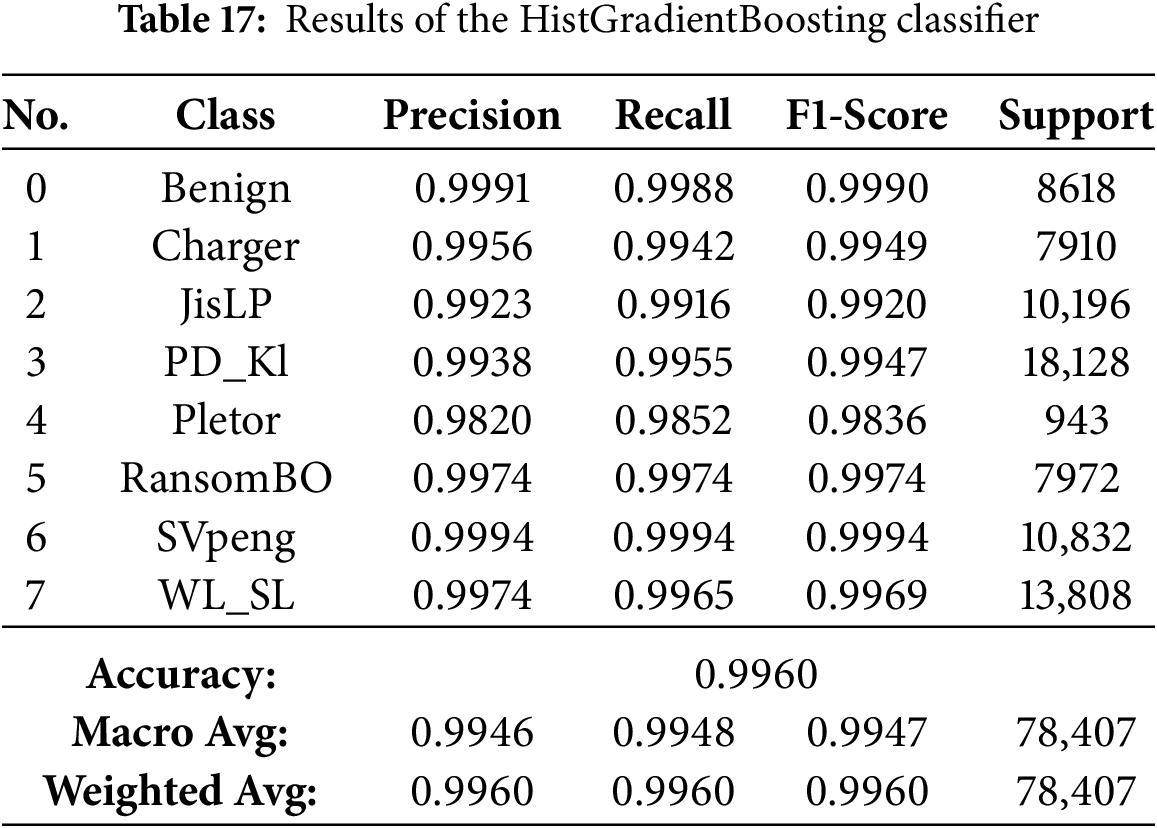

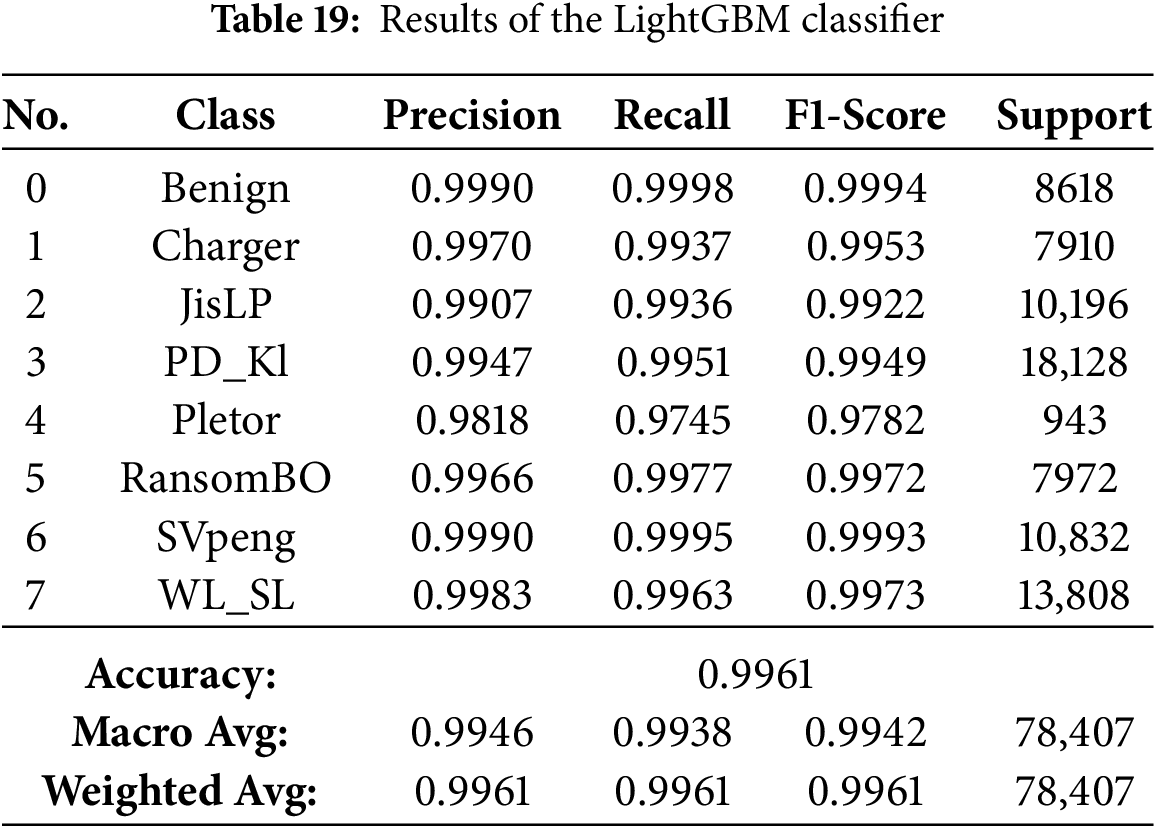

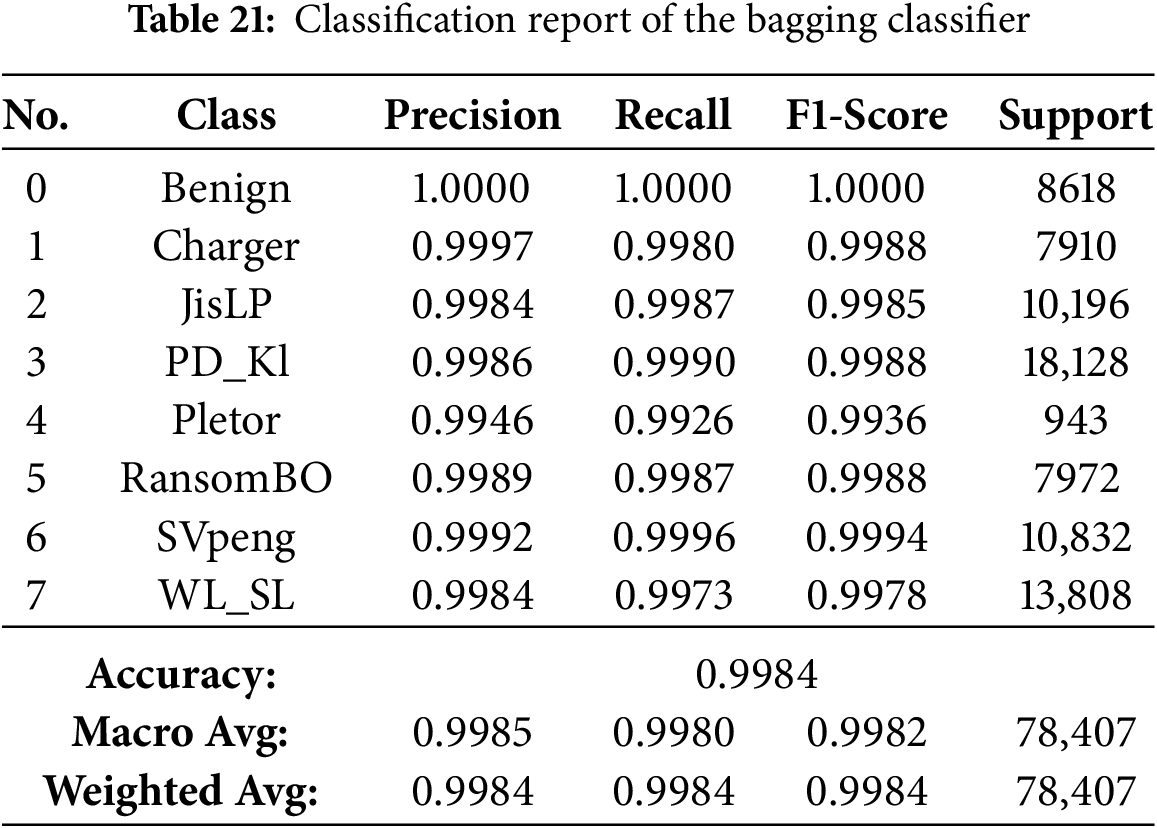

The results presented in Tables 13–21 demonstrate visually that ensemble learning is an effective model for detecting Android ransomware. They maintained an exceptional performance at all times, with a global accuracy >99.4%, and macro/weighted F1-scores above 0.99 for every technique mentioned above (Random Forest, XGBoost, Bagging, Gradient Boosting and HistGradientBoosting). These models not only have good majority class performance, but also surprisingly high precision and recall for minority families such as Pletor and Charger, which further demonstrates their capability in dealing with imbalanced datasets.

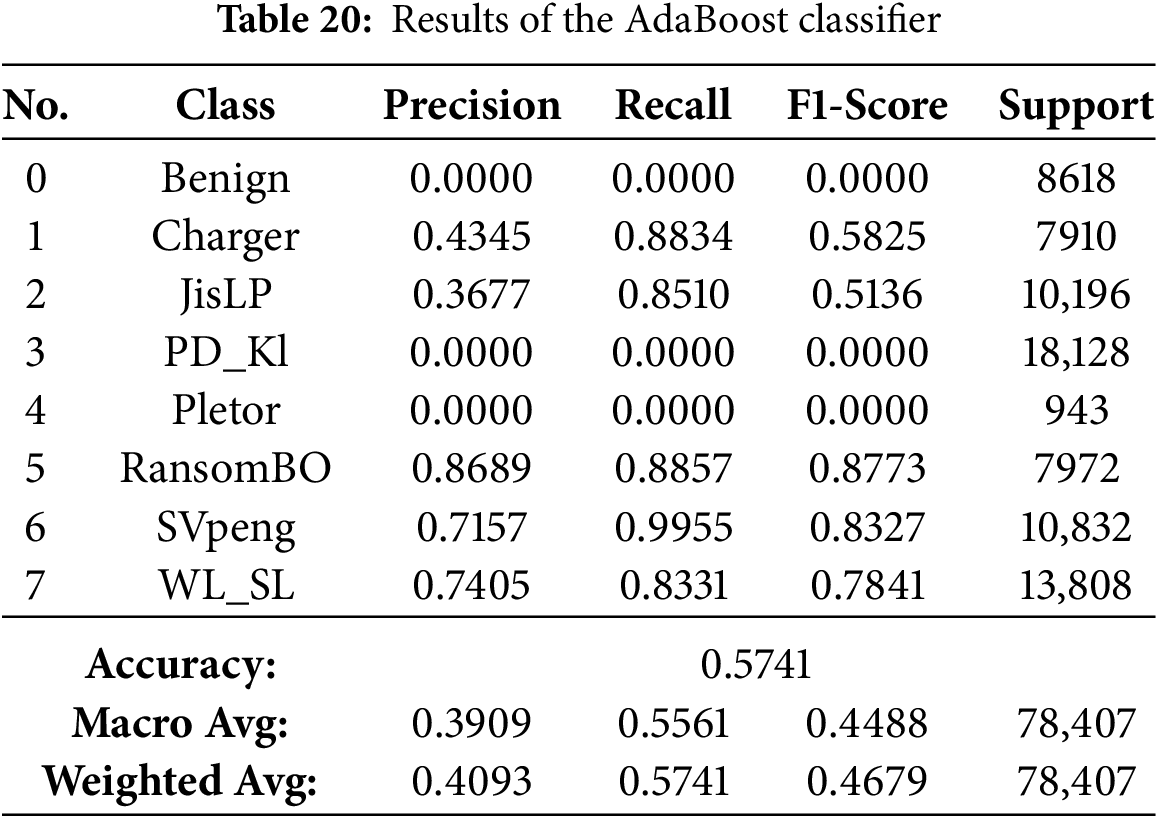

On the other hand, Extra Trees, CatBoost and LightGBM were performing quite well (98.9%–99.6% accuracies), but somewhat less consistently in the multimodal class detection than RF for minority classes. On the other hand, except for performance, which was severely downgraded with overall accuracy falling to 57.4% and poor class-wise F1-scores, indicating it possesses weak generalization ability in multi-class ransomware detection. Finally, the conclusions are that Bagging, Gradient Boosting, HistGradientBoosting, Random Forest and XGBoost as their best recommendable ensemble algorithms; and good baselines for what to compare against more complex AutoML-based or hybrid models.

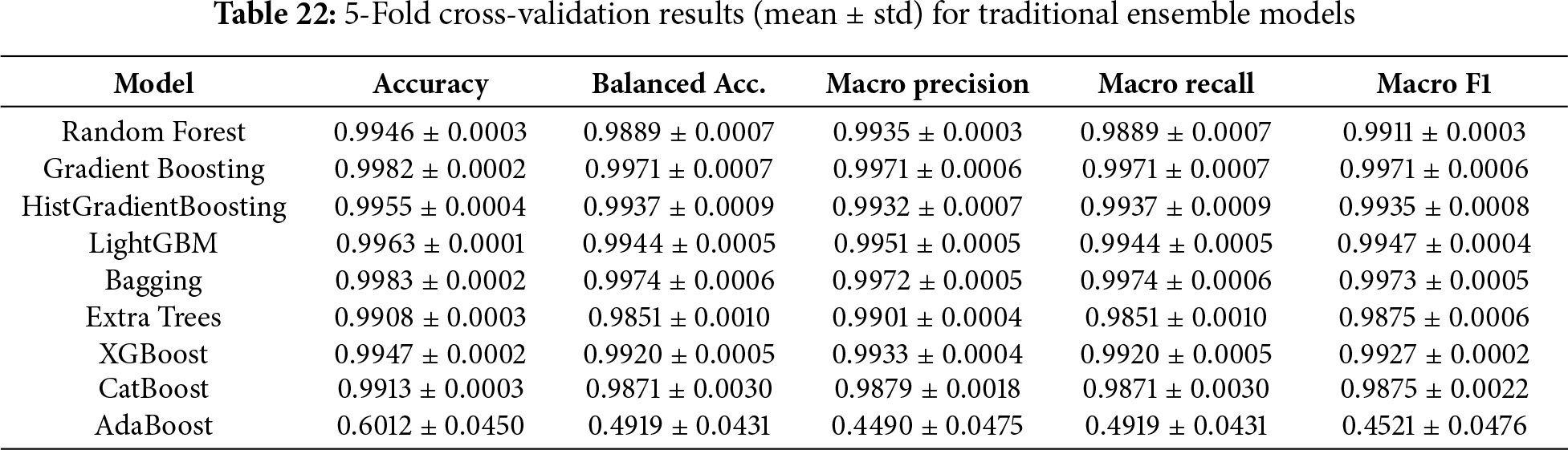

To ensure the reliability of our conclusions as well as to mitigate a potential performance bias introduced by one train-test split, we conducted 5-fold stratified cross-validation. The results in Table 22 indicate that, there are standard deviations under all settings and this justifies the model maintains similar performance on separate folds of the dataset.

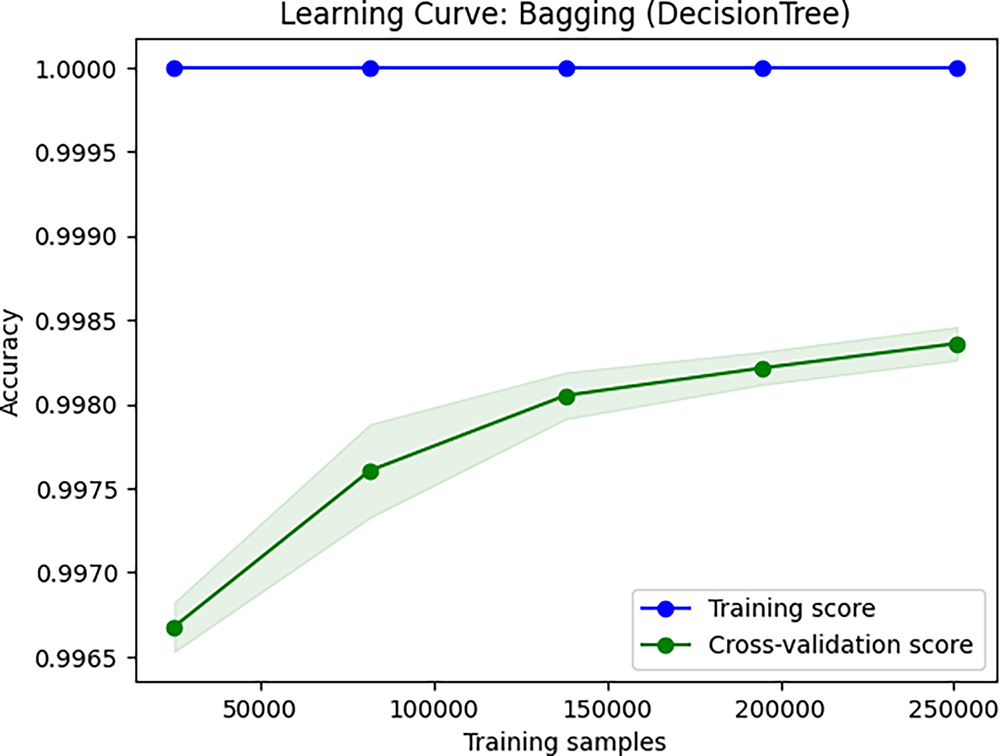

For a deeper understanding of Bagging classifier’s behavior, we also investigated its learning curve as shown in Fig. 4. This curve displays the same metric on the training set and the cross-validation set at varying numbers of training samples. It can be observed that the cross-validation accuracy begins at a lower level and then gradually increases as more training data is presented, indicating that the model’s overfitting is reducing and it is learning more generalizable patterns.

Figure 4: Bagging learning curve plotting training vs. validation accuracy against increasing training sizes. Convergence shows there is no overfitting

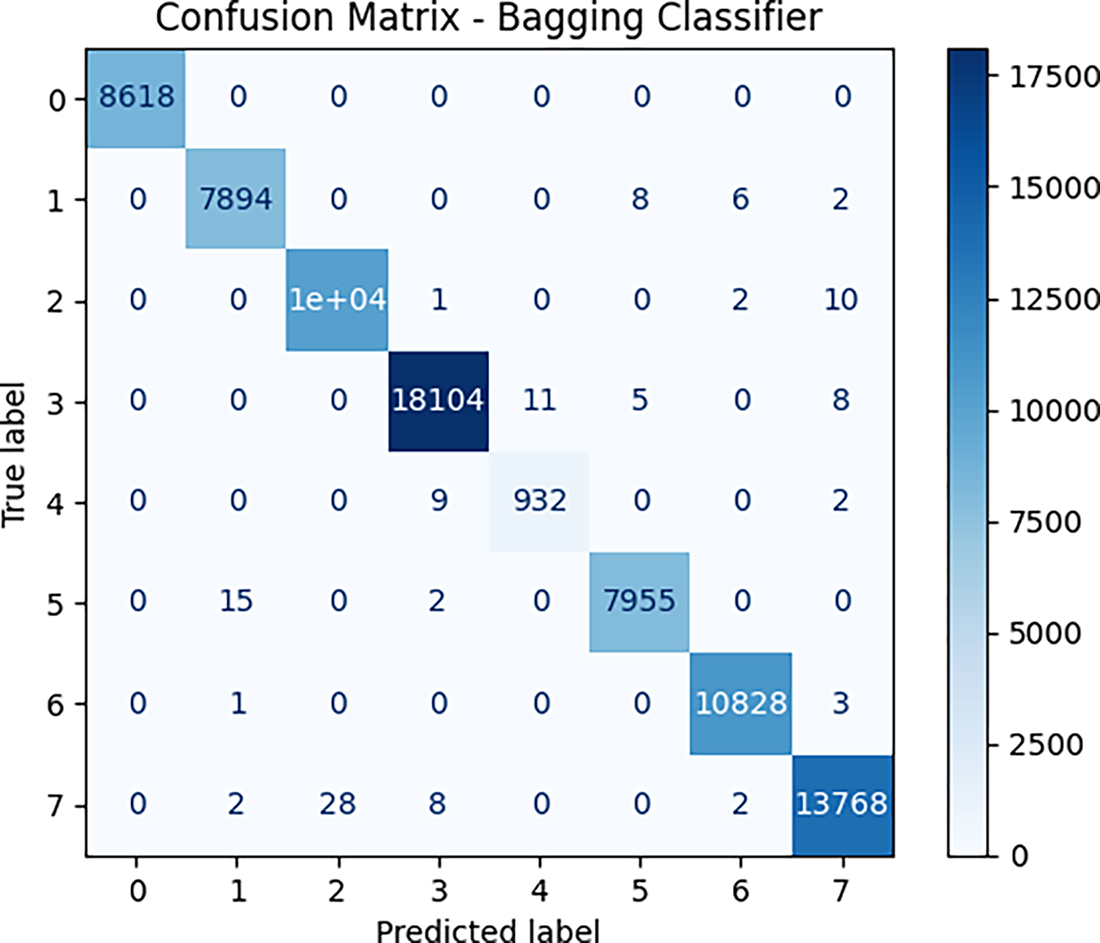

The continued separation of the training and validation curves reflect a certain degree of variance- the model is probably overfitting at this point. However, the validation curve is still increasing, indicating that more data benefits the model, and its generalization performance will improve. Robust cross-validation scores support that the models do generalize well. This robustness stems from the use of L1-regularized feature selection, which discards less relevant features, as well as from ensemble methods, which decrease variance by averaging and thereby overcome overfitting. The Bagging classifier emerged as the best performer among all evaluated models. For further assessing its performance, the confusion matrix in Fig. 5 confirms that for most predictions, there are only a few misclassifications for all classes.

Figure 5: Confusion matrix for bagging classifier

The results further support the argument that the Bagging classifier is the best model for Android ransomware classification. Scoring critically high accuracy of 99.84%, it demonstrates ideal precision and recall for all ransomware families, demonstrating the capacity to filter out false positives or negatives. For the family of gradient boosting models, Gradient Boosting (GB) turned out to be better than today’s options, including LightGBM, HistGradientBoosting, XGBoost, and CatBoost, due to its superior compatibility with multi-class ransomware specifics. The Random Forest classifier did also perform well with an accuracy of 99.54% and is thus a solid choice for this classification problem. While the Extra Trees classifier was great and had an accuracy of 99.14%, it was not as strong as the best performing models. At the other end of the scale, conversely, AdaBoost did much worse than the competition with a small 57.41% accuracy, likely proving that its boosting is not particularly well coordinated for the difficult multi-class task of android ransomware data. Cross-validation and learning curve examination ensure the performance shown is trustworthy and not due to data bias/overfitting. However, the validation accuracy for smaller training sizes is increasing slowly in the learning curve, which means that the convergence speed of the Bagging classifier is limited and can be a bottleneck for large-scale or real-time applications. In contrast to ensembles consisting of manually designed models, AutoML-powered models, such as FLAML, can dynamically optimize hyperparameters and model selection, which often results in faster convergence and efficient learning that overcomes this limitation.

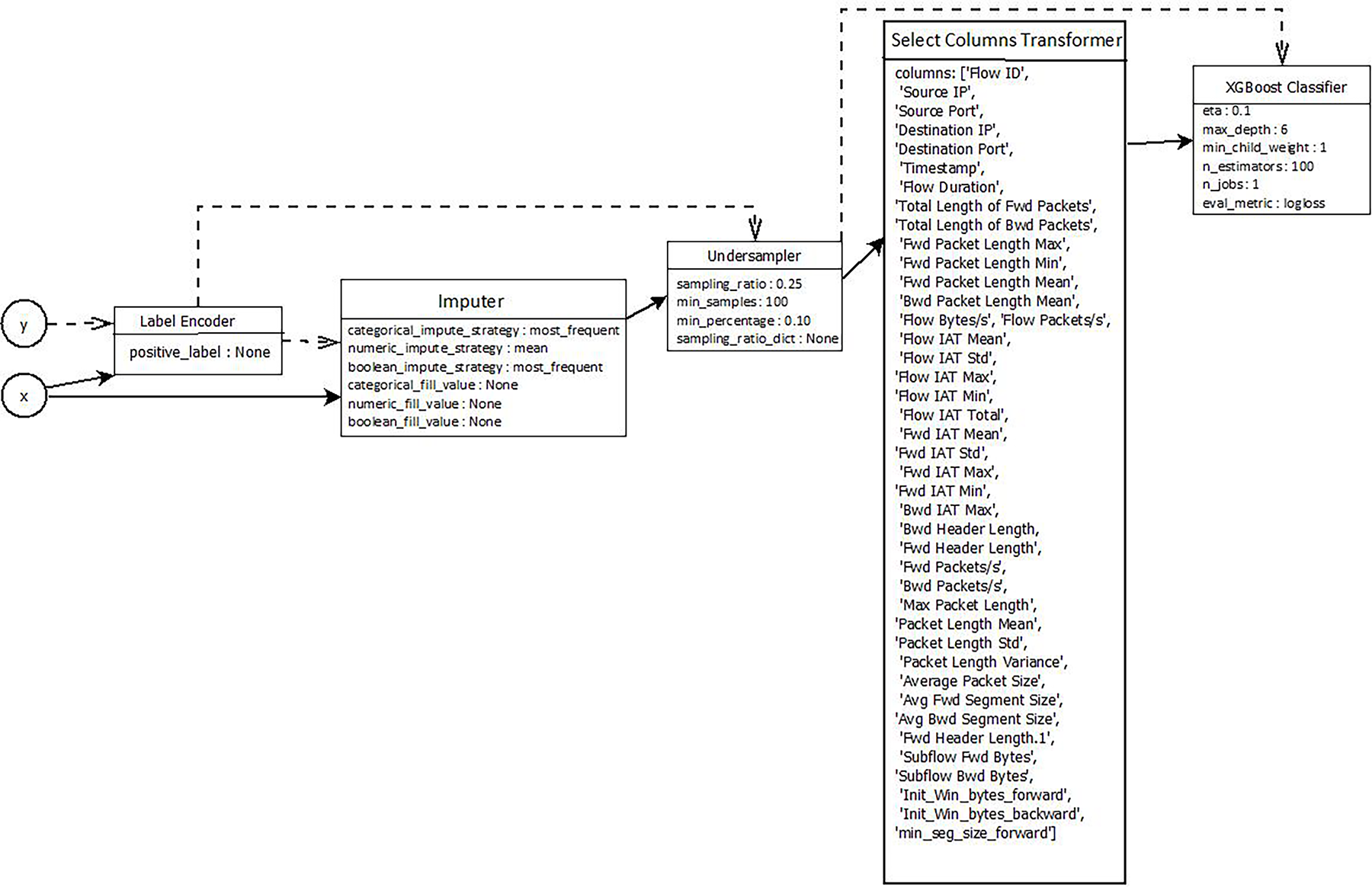

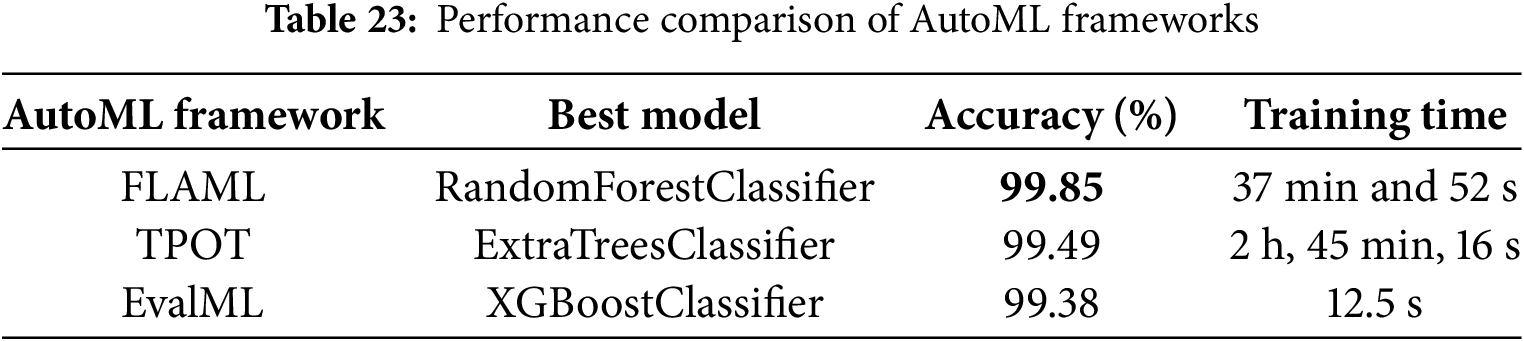

Three highly popular AutoML toolkits were analyzed for automating the choice of models/hyperparameters: EvalML, TPOT and FLAML. They avoid the extensive manual experimentation required to find an optimal pipeline by conducting a targeted search for near-optimal pipelines, making experimental efforts more affordable and competitive with or even better than exhaustive searches. Interpretability and handling of imbalanced data are also a focus of EvalML, in combination with internal preprocessing logic. The best pipeline (label encoding, missing value imputation, under sampling and then a column wise transformation), resulted into an XGBoost model found by EvalML. With both these preprocessing steps in a pipeline, we obtained approximately 99.38% accuracy with just about 12.5 s of training! As shown in Fig. 6, the component-wise structure of EvalML provides an excellent trade-off between interpretability and accuracy.

Figure 6: EvalML best pipeline

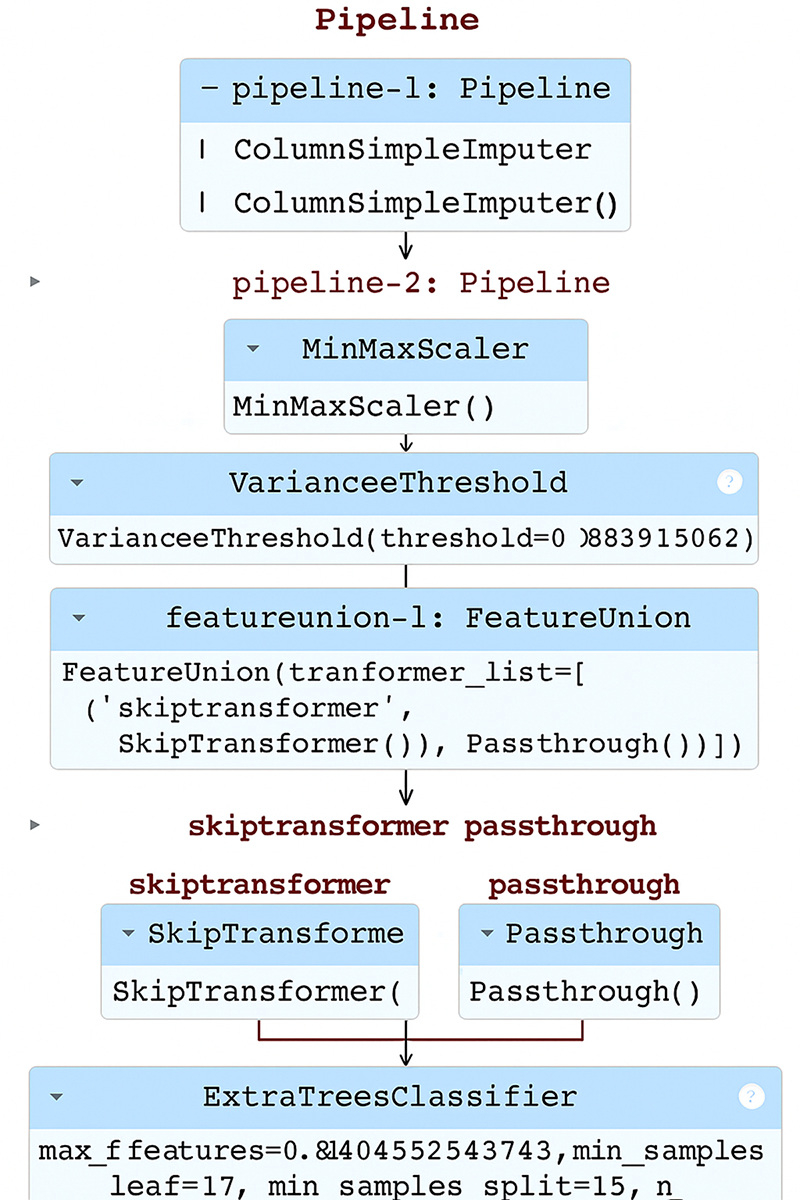

TPOT uses a method called genetic programming to breed, develop and refine pipelines, even with a limited configuration (only 5 generations and 20 individuals), TPOT generated AoB pipeline, which contains pipelines with one or more pre-processing stages such as imputation, scaling, variance filterer, and feature union. The last model, which was built on an ExtraTreesClassifier achieved an outstanding performance of 99.49% with the overall training time being about 2 h and 45 min. The resulting pipeline structure in Fig. 7 illustrates the flexibility of TPOT to build intricate and efficient architectures.

Figure 7: TPOT best pipeline

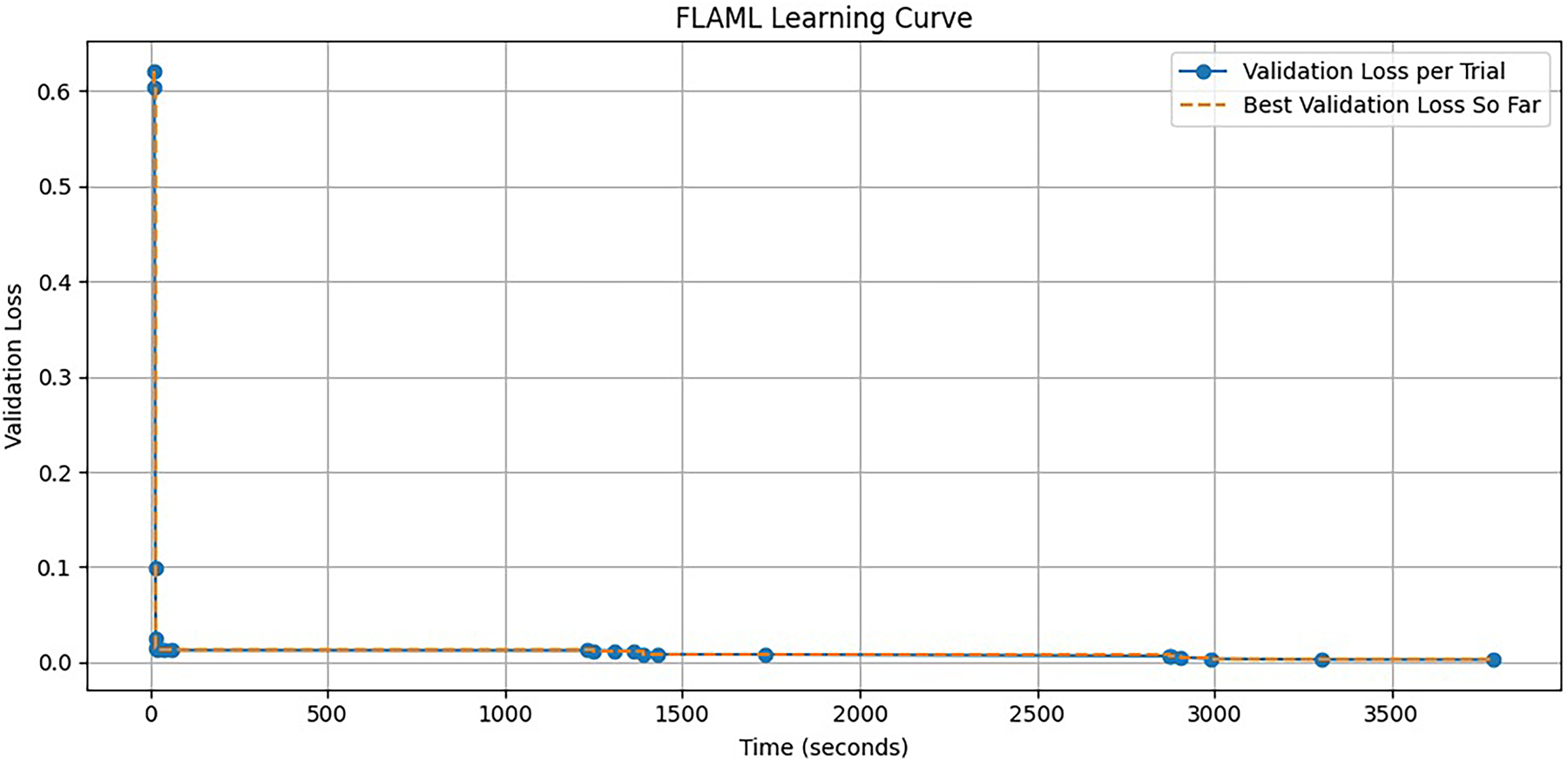

Conversely, FLAML focuses on fast and lightweight AutoML at a low computational cost. With a tight timing of 300-sec (5-min) budget, FLAML efficiently converged to an effective Random Forest Classifier, attaining the best-observed accuracy of 99.85%. The best setting had a final setup with 92 estimators and hyperparameter tuning for maximum features, leaf nodes at entropy splitting. The learning curve in Fig. 8 illustrates the efficiency and scalability of FLAML for quick turnaround experiments.

Figure 8: FLAML learning curve

From the comparative study of the above three AutoML frameworks (Table 23), it is evident that there are clear trade-offs between accuracy and effort during training. FLAML selected the Random Forest classifier as the best model and achieved a top accuracy of 99.85% at around 38 min of training time. TPOT chose an Extra Trees classifier with a lower accuracy (99.49%) and a much more expensive cost of training, almost 3 h took for performing evolutionary search during model selection. Compared to this, EvalML performed extremely well, selecting an XGBoost predictor with 99.38% accuracy and running in just 12.5 s. Despite its lower accuracy, this was by far the fastest result out of any framework.

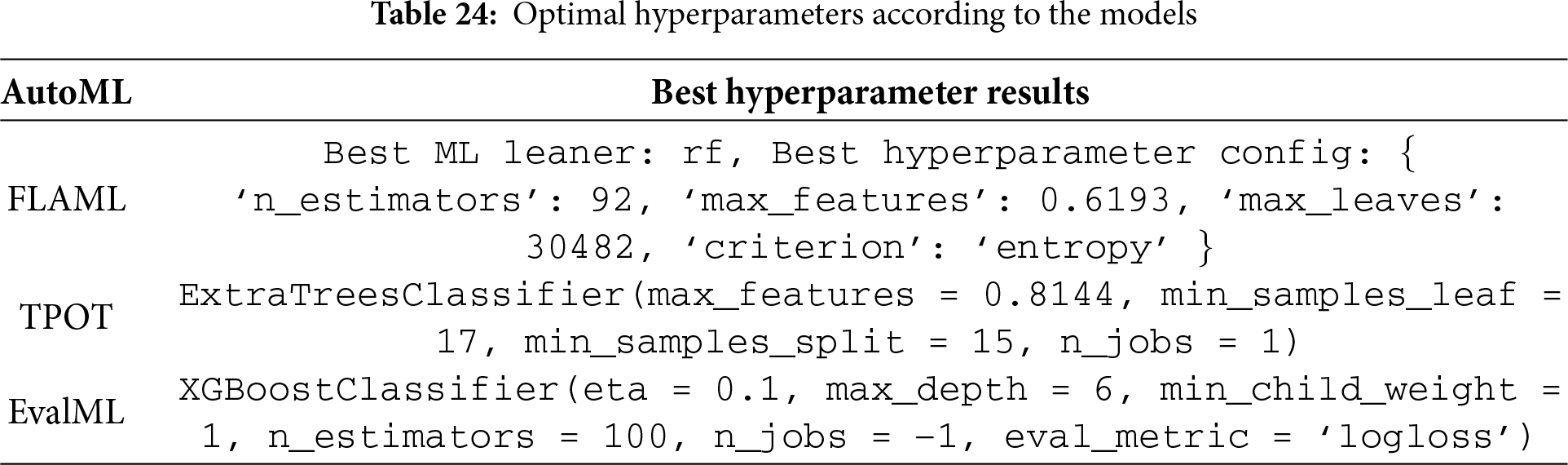

Specific hyperparameter settings, detailed in Table 24, can reveal how each framework fine-tunes the models it uses. FLAML optimized Random Forest with 92 estimators and entropy splitting as well as feature sampling control, while TPOT specialized Extra Trees to have constraints on split and leaf samples. XGBoost configuration for EvalML used a max depth of 6, learning rate (eta) of 0.1 with 100 estimators and was supported by automated preprocessing steps to include label encoding, imputation, undersampling as well column selection. These findings highlight that, even though FLAML returned the accurate model overall but EvalML’s trade-off between accuracy and computation was better than other methods, which is very beneficial in situations for a fast convergence.

The experiments were performed in a laboratory setting with an offline dataset. The AutoML techniques used in the study are demanding as they need storage of previous iterations’ results, to reutilize previous computations for the following iteration. This phenomenon results in a conflict between memory (or CPU) and elapsing time for computation. In certain situations, both resources get heavily taxed as the earlier trial parameter results have to be kept in memory for further operations. While some AutoML tools, including H2O itself (Rob0 machine learning platform among others) offer model explainability features, this was not investigated in this paper. To ensure evaluations are fair and consistent, these explainability tools were intentionally excluded. Another drawback of this study is that several AutoML modules are maintained and updated regularly leading to differences in their performance. Therefore, different results may be obtained due to other implementations in the future, and they may even improve upon what has been presented [27–29].

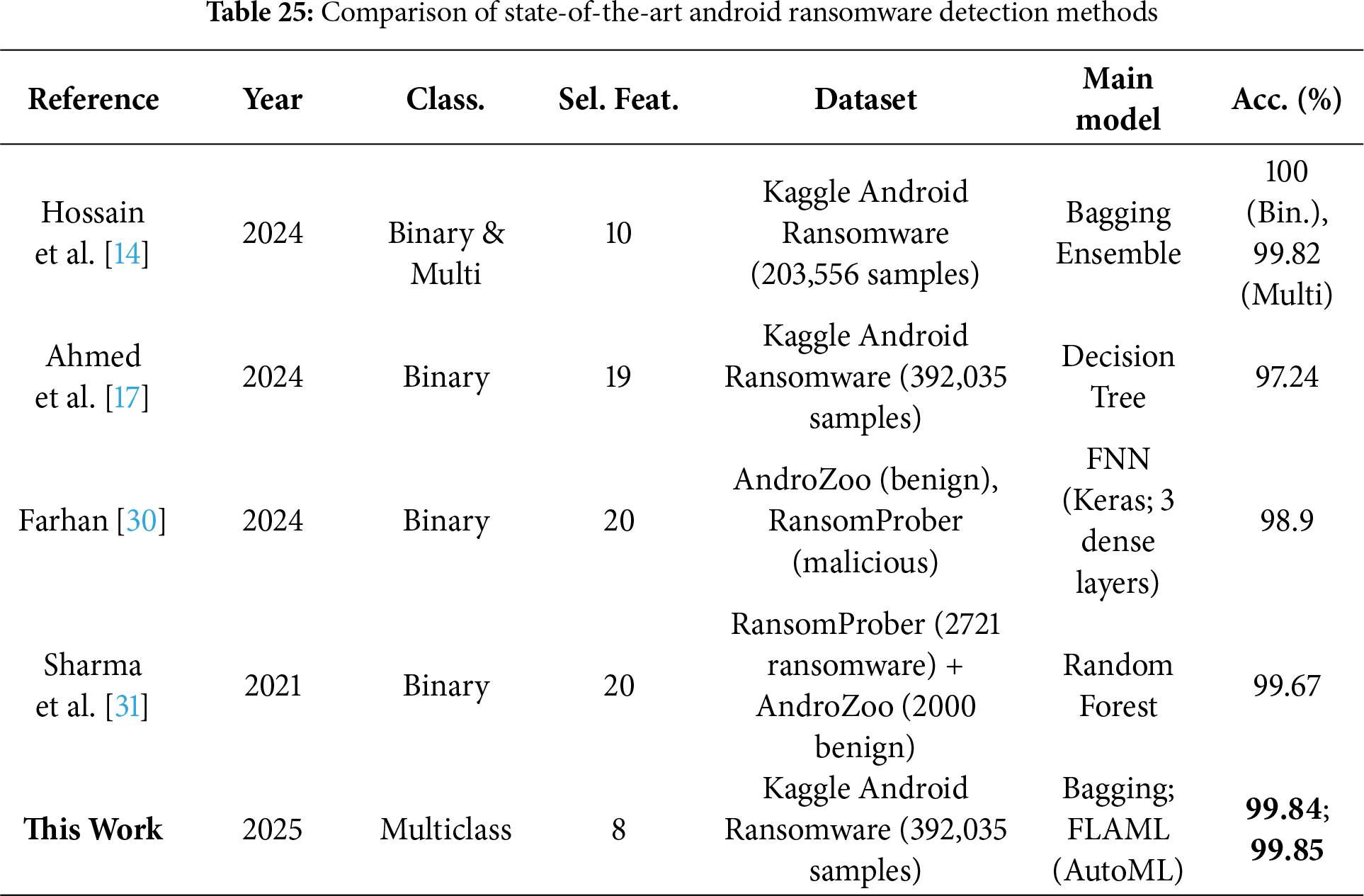

To assess the efficiency of classical and automated approaches to Android ransomware detection, a comparative study was conducted that integrated findings from the current literature with the intended hybrid AutoML ensemble approach, as depicted in Table 25. Classic ensemble methods, including Bagging, Gradient Boosting (GB), and Random Forest, performed remarkably well in terms of detection accuracy, with all models achieving an accuracy of over 99.75%. Interestingly, the Bagging model achieved the best performance at 99.84%, closely followed by GBM at 99.83% and Random Forest at 99.75%. This reflects their ability to perform well under diverse ransomware behaviors. Other methods, such as LightGBM, HistGradientBoosting, XGBoost, and CatBoost, also reported high performances. Nonetheless, AdaBoost performed poorly, with an accuracy of 59.67%, likely due to its vulnerability to imbalanced and multiclass data distributions. Conversely, the emergence of Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) frameworks has transformed model building by reducing the need for extensive manual configuration and still achieving competitive or even better results. Among these, FLAML excelled by achieving a peak precision of 99.85% within a restricted time, proving to be both efficient and accurate. TPOT, which utilizes genetic programming to search for fully optimized pipelines, achieved an accuracy of 99.49%, albeit at the expense of a longer execution time. The EvalML, whose combined preprocessing and model tuning achieved a better 99.38% accuracy through a more efficient process. Alternative research approaches have also proposed architectures, such as DroidAutoML, a microservice-based framework that claims an improvement of up to 11% over more conventional tools like Drebin and MaMaDroid. AutoML-generated deep learning models have been successfully applied to large-scale malware datasets, such as SOREL-20M and EMBER-2018, achieving impressive detection performance in both static and online analysis settings. These observations demonstrate the potential of AutoML as a highly effective and scalable solution for detecting Android ransomware.

This study presents the use of ensemble learning models and AutoML-powered pipelines in the context of Android ransomware detection. Using a three-stage hybrid feature selection method based on hierarchical class grouping, the proposed framework proved to be highly resilient. The Bagging and FLAML were identified as the best-performing classifiers. All the above processes, along with stratified train-test splits, cross-validation, learning curves, confusion matrices, and ROC analysis, were performed to ensure the results’ reliability and reproducibility. The results highlight the power of AutoML to reduce human effort, speed up pipeline building, and obtain competitively or even better accuracy compared to manually tuned ensemble baselines. These findings make AutoML a promising candidate for future intrusion detection systems, particularly in settings where rapid model adaptation is needed to mitigate the latest threats. Although the showcased framework demonstrates excellent performance when modeled in controlled laboratory environments, its industrial scalability and real-world usability have yet to be proven. Subsequent work ought to focus on deployment experiments on big scales in production-like network environments to test inference latency, throughput, resource usage, and integration overhead. Furthermore, longitudinal testing on streaming network traffic is recommended to assess the framework’s robustness against concept drift and the dynamic nature of ransomware variants. Such findings will provide strong proof of concept for the framework’s applicability to security operations centers (SOCs) and establish a compelling argument for its real-world deployment.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported through the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-498), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Kirubavathi Ganapathiyappan conceptualized the study, supervised the overall research framework, and coordinated the methodology and validation strategies. Chahana Ravikumar conducted the experimental implementation, including ensemble model training, AutoML pipeline integration, and performance evaluation. Raghul Alagunachimuthu Ranganayaki was responsible for data preprocessing, designing hybrid feature selection, and developing hierarchical clustering-based class regrouping techniques. Ayman Altameem provided methodological guidance, technical insights on experimental design, and a critical review of the manuscript. Ateeq Ur Rehman contributed to the optimization and analysis of AutoML models, as well as manuscript writing and critical review. Ahmad Almogren contributed to writing, reviewing, and editing, provided comparative benchmarking with state-of-the-art approaches, and administered the project, providing technical guidance throughout the study. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data obtained from Kaggle can be found at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/android-ransomware-detection (accessed on 25 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Almomani I, Qaddoura R, Habib M, Alsoghyer S, Al Khayer A, Aljarah I, et al. Android ransomware detection based on a hybrid evolutionary approach in the context of highly imbalanced data. IEEE Access. 2021;9:57674–91. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3071450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kirubavathi G, Varun Vijay RN. Composition and adaptation of ensemble learning for Android malware detection. In: Roy NR, Singh AP, Kumar P, Kaul A, editors. Cyber security and digital forensics. redcysec 2024. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Singapore: Springer; 2025. p. 445–57. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-3284-8_35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kirubavathi G, Regis Anne W, Sridevi UK. A recent review of ransomware attacks on healthcare industries. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag. 2024;15:5078–96. doi:10.1007/s13198-024-02496-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kirubavathi G, Anne WR. Behavioral based detection of android ransomware using machine learning techniques. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag. 2024;15:4404–25. doi:10.1007/s13198-024-02439-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Alraizza A, Algarni A. Ransomware detection using machine learning: a survey. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2023;7(3):143. doi:10.3390/bdcc7030143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hasan MM, Biswas MSS, Karim MS, Rahman MKH, Ahmed MFU, Shatabda S, et al. Enhancing malware detection with feature selection and scaling techniques using machine learning models. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):93447. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-93447-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Adriansyah R, Sukarno P, Wardana AA. Android malware detection using ensemble learning and feature selection with insights from SHAP explainable AI. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Soft Computing and Machine Intelligence (ISCMI); 2024 Nov 22–23; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 187–92. doi:10.1109/ISCMI63661.2024.10851666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mahindru A, Arora H, Kumar A, Gupta SK, Mahajan S, Kadry S, et al. PermDroid: a framework developed using proposed feature selection approach and machine learning techniques for Android malware detection. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):10724. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-60982-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Alsubaei FS, Almazroi AA, Atwa WS, Almazroi AA, Ayub N, Jhanjhi NZ. BERT ensemble based MBR framework for Android malware detection. Sci Rep. 2025;15:14027. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-14027-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hossain MA, Islam MS. A novel hybrid feature selection and ensemble-based machine learning approach for botnet detection. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21207. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48230-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mohanraj A, Sivasankari K. Android traffic malware analysis and detection using ensemble classifier. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(12):103134. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2024.103134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Alhogail A, Alharbi RA. Effective ML-based Android malware detection and categorization. Electronics. 2025;14(8):1486. doi:10.3390/electronics14081486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pai V, Pai K, Manjunatha S, Hirmeti S, Bhat VV. Adaptive network anomaly detection using machine learning approaches. EURASIP J Inf Secur. 2025;2025(1):29. doi:10.1186/s13635-025-00216-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hossain MA, Hasan T, Ahmed F, Cheragee SH, Kanchan MH, Haque MA. Towards superior Android ransomware detection: an ensemble machine learning perspective. Cybersecur Applicat. 2025;3:100076. doi:10.1016/j.csa.2024.100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Nasser AR, Hasan AM, Humaidi AJ. DL-AMDet: deep learning-based malware detector for android. Intell Syst Appl. 2024;21:200318. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2023.200318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Alamro H, Mtouaa W, Aljameel S, Salama AS, Hamza MA, Othman AY. Automated Android malware detection using optimal ensemble learning approach for cybersecurity. IEEE Access. 2023;11:72509–17. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3294263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ahmed AA, Shaahid A, Alnasser F, Alfaddagh S, Binagag S, Alqahtani D. Android ransomware detection using supervised machine learning techniques based on traffic analysis. Sensors. 2024;24(1):189. doi:10.3390/s24010189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Khan I, Din F, Khan F, Saqib S, Ullah S, Haider Z, et al. Recurrent neural network and multi-factor feature filtering for ransomware detection in Android apps. Int J Innovat Sci Technol. 2024;6:1021–30. [Google Scholar]

19. Ali M, Shiaeles S, Bendiab G, Ghita B. MALGRA: machine learning and N-gram malware feature extraction and detection system. Electronics. 2020;9(11):1777. doi:10.3390/electronics9111777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Brown A, Gupta M, Abdelsalam M. Automated machine learning for deep learning-based malware detection. arXiv:2303.01679. 2023. [Google Scholar]

21. Bromberg YD, Gitzinger L. DroidAutoML: a microservice architecture to automate the evaluation of Android machine learning detection systems. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science. IFIP International Conference on Distributed Applications and Interoperable Systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 148–65. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-50323-9_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Masum M, Hossain Faruk MJ, Shahriar H, Qian K, Lo D, Adnan MI. Ransomware classification and detection with machine learning algorithms. In: Proceedings of the IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); 2022 Jan 26–29; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 316–22. doi:10.1109/CCWC54503.2022.9720869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Khammas BM. Ransomware detection using random forest technique. ICT Express. 2020;6(4):325–31. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2020.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chakraborty S. Android ransomware detection dataset. Kaggle. 2023. doi:10.34740/KAGGLE/DSV/4987535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Gyimah NK, Akinie R, Mwakalonge J, Izison B, Mukwaya A, Ruganuza D, et al. An AutoML-based approach for Network Intrusion Detection. In: SoutheastCon 2025. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1177–83. doi:10.1109/southeastcon56624.2025.10971461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Olson R, Moore J. TPOT: a tree-based pipeline optimization tool for automating machine learning. In: Automated machine learning. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 151–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05318-5_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Neto EC, Iqbal S, Buffett S, Sultana M, Taylor A. Deep learning for intrusion detection in emerging technologies: a comprehensive survey and new perspectives. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(11):340. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11346-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bhukya R, Moeed SA, Medavaka A, Khadidos AO, Khadidos AO, Selvarajan S. SPARK and SAD: leading-edge deep learning frameworks for robust and effective intrusion detection in SCADA systems. Int J Crit Infrastruct Prot. 2025;49:100759. doi:10.1016/j.ijcip.2025.100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Selvarajan S, Manoharan H, Abdelhaq M, Khadidos AO, Khadidos A, Alsaqour R, et al. Diagnostic behavior analysis of profuse data intrusions in cyber physical systems using adversarial learning techniques. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):7287. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-91856-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Farhan RI. An approach to Android ransomware detection using deep learning. Wasit J Pure Sci. 2024;3(1):90–4. doi:10.31185/wjps.325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sharma S, Challa R, Kunmar R. An ensemble-based supervised machine learning framework for Android ransomware detection. Int Arab J Information Technology. 2021;18(3A):422–9. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools