Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Efficient Certificateless Authentication Scheme with Enhanced Security for NDN-IoT Environments

1 Hubei Engineering Research Center for BDS-Cloud High-Precision Deformation Monitoring, School of Artificial Intelligence, Wuchang University of Technology, Wuhan, 430223, China

2 School of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, 430200, China

3 College of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, 210037, China

4 Department of Mathematics, Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut, 250004, Uttar Pradesh, India

* Corresponding Authors: Jianbo Wu. Email: ,

; Qing An. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in IoT Security: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 75 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073441

Received 18 September 2025; Accepted 15 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The large-scale deployment of Internet of Things (IoT) technology across various aspects of daily life has significantly propelled the intelligent development of society. Among them, the integration of IoT and named data networks (NDNs) reduces network complexity and provides practical directions for content-oriented network design. However, ensuring data integrity in NDN-IoT applications remains a challenging issue. Very recently, Wang et al. (Entropy, 27(5), 471(2025)) designed a certificateless aggregate signature (CLAS) scheme for NDN-IoT environments. Wang et al. stated that their construction was provably secure under various types of security attacks. Using theoretical analysis methods, in this work, we reveal that their CLAS design fails to meet unforgeability, a core security requirement for CLAS schemes. In particular, we demonstrate that their scheme is vulnerable to a malicious public-key replacement attack, enabling an adversary to produce authentic signatures for arbitrary fraudulent messages. Therefore, Wang et al.’s design cannot achieve its goal. To address the issue, we systematically examine the root causes behind the vulnerability and propose a security-enhanced CLAS construction for NDN-IoT environments. We prove the security of our improved design under the standard security assumption and also analyze its practical performance by comparing the computational and communication costs with several related works. The comparison results show the practicality of our design.Keywords

The Internet of Things (IoT) has seamlessly integrated into our daily lives, transforming industries and urban infrastructure with its interconnected smart systems. However, the widespread interconnection of IoT devices and the rapid growth of data volume pose significant challenges to the security and efficiency of communication systems. To tackle these problems, named data networking (NDN) has gained recognition as an innovative content-centric communication framework, distinguished by its unique strengths [1,2]. Departing from conventional address-centric network models, NDN adopts a data-centric paradigm enabled by name-driven routing protocols, delivering superior flexibility, scalability, and native security features. In short, NDN shifts the model from host-to-host communication, like the current Internet Protocol (IP), to a data-centric model where users request content by name. However, integrating NDN and IoT contexts introduces multifaceted security complexities. Recall that data is the core resource of NDN-IoT applications, necessitating robust protective measures to safeguard its security. In real-world scenarios, however, data frequently traverses insecure public networks, and faces numerous security threats [3,4]. A key security requirement involves verification mechanisms where data receivers must validate the source’s trustworthiness and confirm the data integrity throughout its transmission path [5]. In addition, an observer in NDN may be able to monitor which content names are being requested, potentially revealing sensitive information. Therefore, user’s privacy should also not be ignored.

Digital signatures is an essential cryptographic mechanism for guaranteeing both data integrity and source authentication. Moreover, in high-throughput applications such as vehicular ad hoc networks and named data networking (NDN) networks, there are a large number of digital signatures that require efficient validation, which puts higher performance requirements on digital signatures. The aggregate signature scheme, initially put forward by Boneh et al. [6], presents an optimal solution by enabling the compression of

Boneh et al.’s framework relies on public key infrastructure (PKI), and its actual deployment faces challenges due to the substantial overhead associated with key management. Alternative aggregate signature schemes using identity-based cryptography have emerged [7] to address PKI’s limitations; however, identity-based setting suffers from the inherent key-escrow issue. The certificateless paradigm [8] elegantly resolves both concerns by employing a hybrid key generation model: the key generation center (KGC) supplies partial secret information while users independently select additional secret components, with public keys derived from the user’s public information [9]. Due to its merits, recent years have witnessed significant academic interest in certificateless aggregate signature (CLAS) schemes for IoT applications [10,11].

To date, a number of CLAS schemes have been designed for IoT applications. Early schemes were designed based on bilinear pairing [12,13], requiring expensive computational costs. Cui et al. [14] designed a pairing-free CLAS scheme for vehicular ad hoc networks. However, their design cannot resist malicious-but-passive KGC attacks (i.e., called as Type 2 attacks) [15]. Xu et al. [16] put forward another CLAS scheme without pairings for VANETs. Zhu et al. [17] pointed out the security vulnerability of [16] in resisting the Type 2 attack and constructed a new scheme with enhanced security. However, their work was further pointed out by Yang et al. [18] to have a security vulnerability of the public-key replacement attack (i.e., called as Type 1 attacks). In [18], Yang et al. then proposed an improved CLAS scheme with new aggregate algorithm, which ensures the validity of all individual signatures participating in the aggregation. But the performance is a weakness of their design. In addition, Zhu and Guan [19] put forward an authentication scheme with conditional privacy protection for vehicular ad-hoc networks based on a CLAS scheme. However, their work cannot achieve Type 1 security [20]. A recent comprehensive survey of CLAS schemes can be found in [21].

More recently, Yue et al. [22] proposed a CLAS scheme for VANETs. However, their design is computationally inefficient and cannot ensure resistance to Type 1 attacks, where an adversary can systematically generate fraudulent signatures for arbitrary messages (refer to Appendix A). This vulnerability fundamentally compromises the unforgeability property, which is a core security requirement for any CLAS schemes. In addition, Wang et al. [23] designed a CLAS scheme for NDN-IoT environments. Wang et al. initially asserted the security of their CLAS construction. Our analysis reveals, however, that their implementation remains vulnerable to public-key replacement attacks. That is, their schemes can not ensure data integrity, thus cannot be deployed in real-world NDN-IoT applications.

Contribution. To solve data security and efficiency problems in NDN-IoT applications, we put forward a new CLAS scheme. The key contributions of this work are outlined below:

1. By presenting a concrete public-key replacement attack, we explored the security vulnerability of a very recent CLAS scheme in [23] proposed for NDN-IoT environments.

2. We systematically examine the root causes behind the vulnerability in [23] and propose an improved CLAS design.

3. We prove the security of our design based on the cryptographic assumption, and analyze its performance. The performance comparison results demonstrate that the improved CLAS scheme not only has better security but also has desirable computational and communication costs. Therefore, our design is suitable for NDN-IoT environments.

4. As an additional contribution, in Appendix A, we analyze the security flaw of a very recent CLAS construction in [22] and propose targeted countermeasures to enhance its security.

Organization. The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as the following: Section 2 introduces the foundational concepts and preliminaries. In Section 3, we review Wang et al.’s scheme in [23] and put forward our security analysis. In Section 4, we introduce our enhanced design with its rigorous security analysis. We evaluate the performance of our proposal in Section 5 and conclude the work in Section 6. In Appendix A, we provide a retrospective analysis of Yue et al.’s construction in [22], including identified security weaknesses and proposed response strategies.

Here, we introduce some required preliminaries, such as notations and elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP).

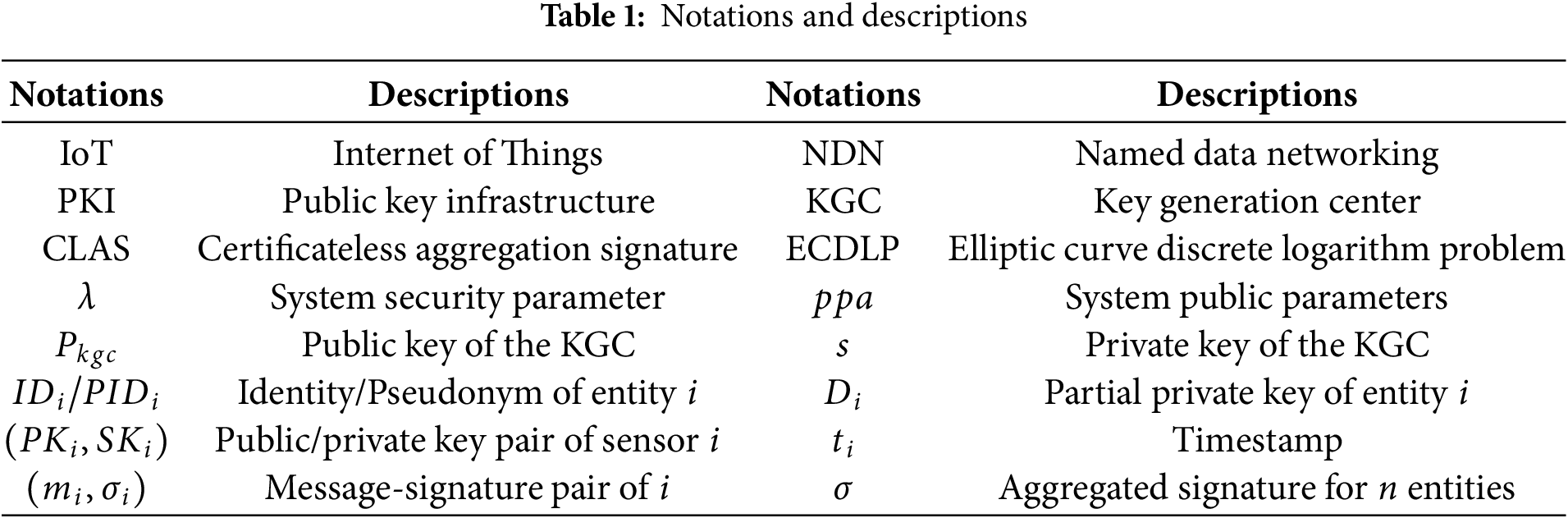

Some notations are listed in Table 1.

Let G be an

3 Security Attack to Wang et al.’s CLAS Scheme in [23]

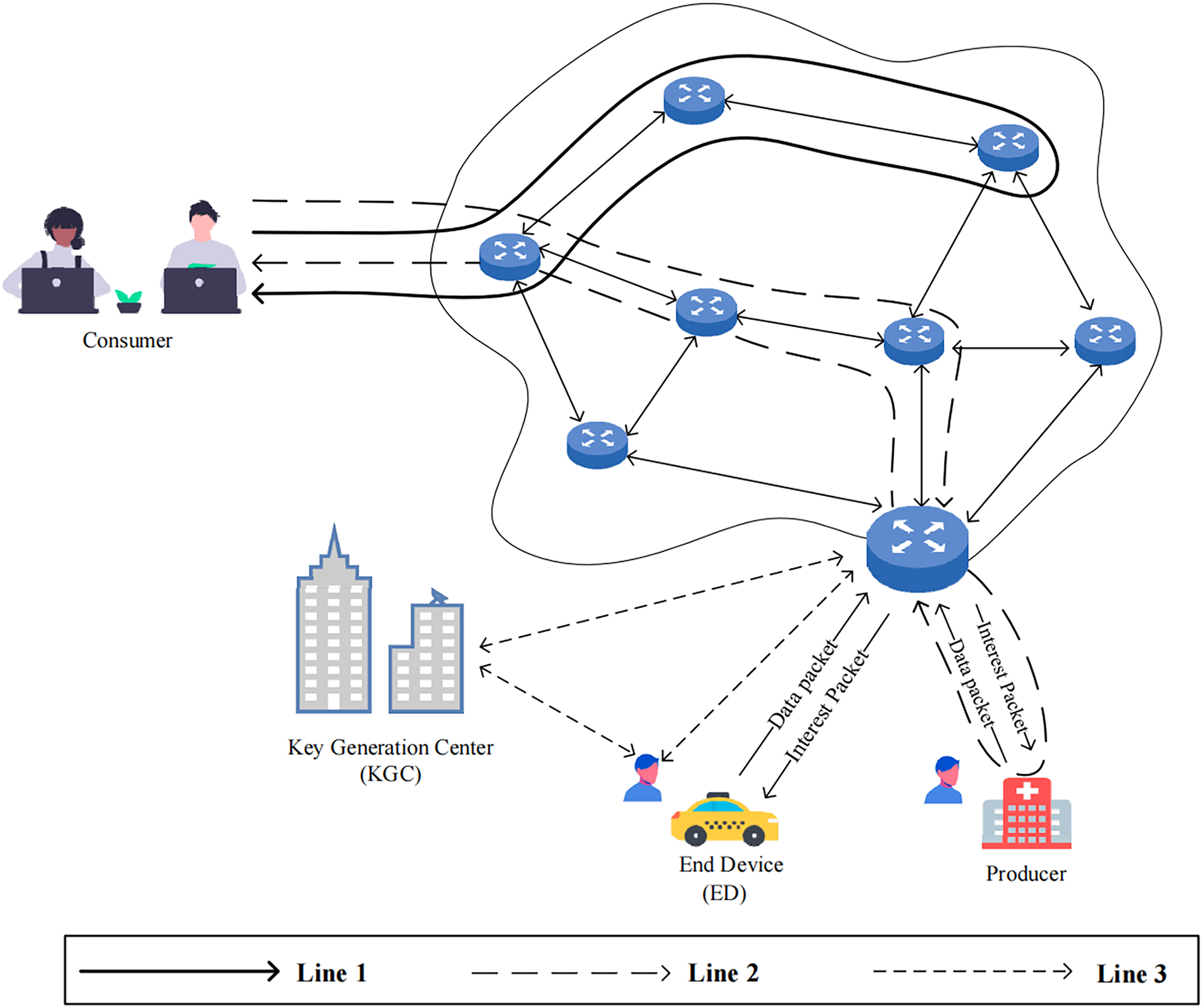

As shown in Fig. 1, there are several entities in [23]. The KGC is responsible for building the system. An end device (ED) can register as a producer or consumer in the network system by interacting with KGC. Acting as a vital element for secure data forwarding, the NDN router checks the integrity of data packets during transmission. It conducts signature verification on the embedded producer details within the data packets. Moreover, it supports batch processing of multiple signatures from multiple end devices. As a data requester, the consumer can send Interest packets to request needed data or services. In addition, the producer, which corresponds to the producer entity in NDN, is in charge of generating data in the NDN-IoT environment. It employs sensor devices to gather information like soil moisture levels, vehicle locations, and indoor temperatures.

Figure 1: Wang et al’s system structure. The figure is adopted from [23]. Line 1 depicts an instance of how a consumer seeks data forwarding from an NDN router. Line 2 showcases the procedure where a consumer requests data packets from multiple producers. Line 3 presents the interaction between terminal devices and the KGC for registration purposes, along with the process of creating an aggregate signature and sending data packets through the NDN router

The CLAS scheme proposed by Wang et al. [23] mainly formed by the following algorithms: System Setup, Device Pseudonym Generation, Device Keys Generation, Signing, Single Signature Verification, and Aggregated Signature Verification. We now briefly review their algorithms to support our analysis.

1. System Setup: Taking a security parameter

(a) Define an

(b) Randomly select a master private key

(c) Choose three hash functions

(d) Store

2. Device Pseudonym Generation: In this algorithm, a terminal device

(a)

(b) KGC recovers

3. Device Keys Generation:

(a)

(b) KGC picks

(c)

4. Signing: To sign a message

(a) Pick

(b) Compute

5. Single Signature Verification: Given

6. Signature Aggregation: For

7. Aggregation Verification: To check the validity of

3.1 Security Analysis to [23]

The first five algorithms in [23] naturally form a CLS scheme and the remaining algorithms are used to perform batch verification of multiple signatures. For ease presentation, our analysis focuses on their CLS scheme. For a CLS scheme, two distinct types of attackers should be considered, i.e., public-key replacement attacker (called as Type 1 attacker) and malicious-but-passive KGC (called as Type 2 attacker). In particular, a Type 1 attacker knows a target user’s secret value. However, the attacker cannot access the user’s partial private key. A Type 2 attacker knows the KGC’s private key but does not allowed to access the target user’s secret value. For more security definitions and security models, please refer to [23].

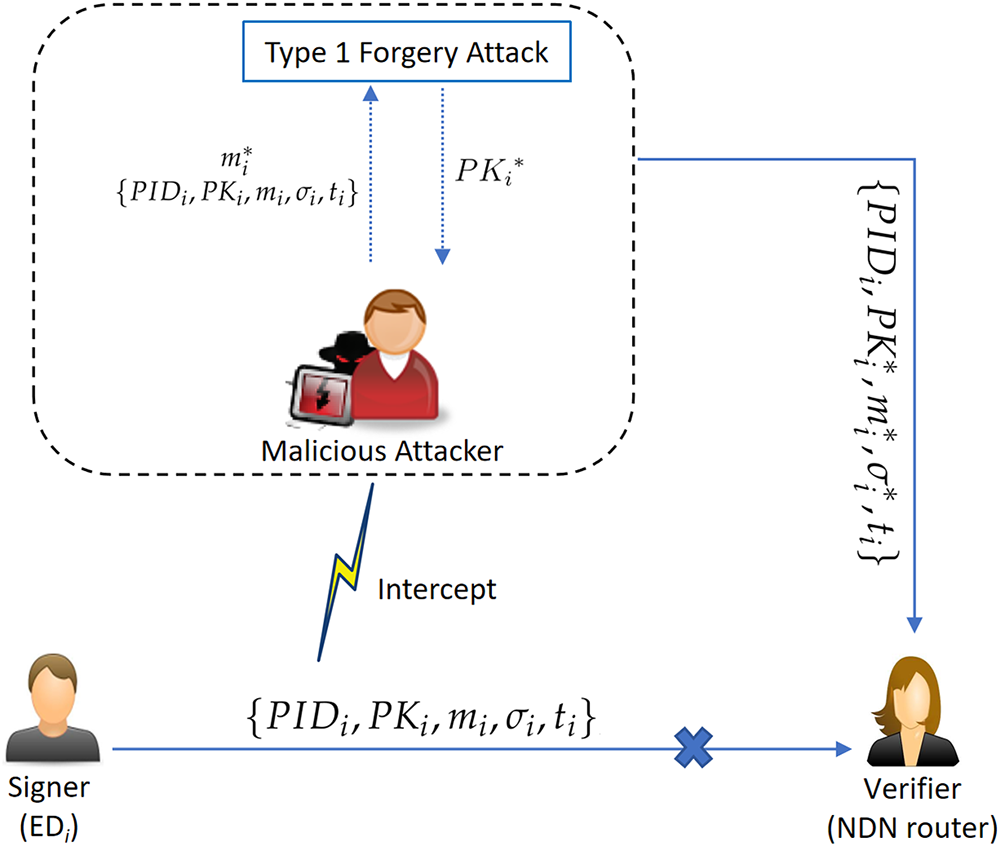

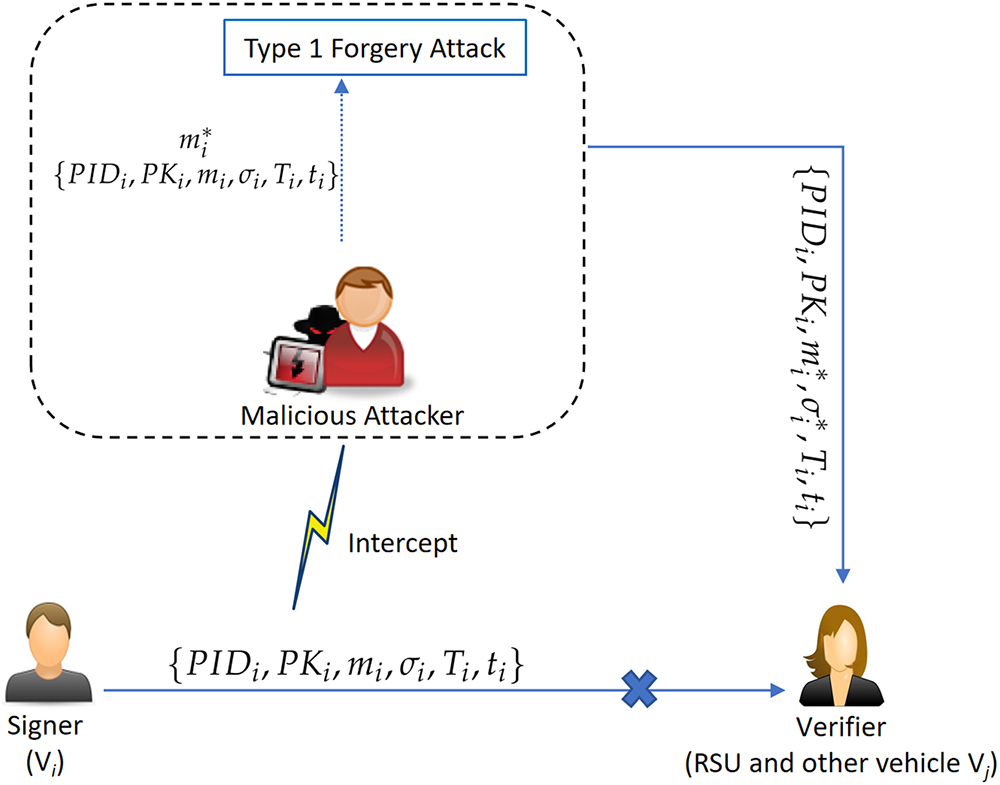

In [23], Wang et al. stated that their design can achieve both Type 1 and Type 2 security. In the following, we show that a Type 1 attacker

Figure 2: An example of the Type 1 attack

(1) Compute

(2) Pick

(3) Set

(4) Select

(5) Set

Now, the correctness of

Since the underlying CLS scheme is insecure, the CLAS construction is therefore cannot achieve unforgeability.

In [23], a verifier checks a received signature through the equation

To patch this vulnerability, our improvement is as follows:

1. The algorithms System Setup and Device Pseudonym Generation are the same as the original scheme.

2. Device Keys Generation:

(a)

(b) KGC picks

(c)

3. Signing: To generate a signature on message

(a) Randomly pick

(b) Compute

4. Single Signature Verification: Given

5. Signature Aggregation: The algorithm is the same as the original scheme.

6. Aggregation Verification: To check the validity of

Following Wang et al.’s proof approach in [23], the modified scheme can be easily proven to be secure. To avoid a lot of repetitive proof work, we omit the proof process here. Compared to the original scheme, the improvement adds one point multiplication, one point addition, and a general hash operation. This is acceptable since the modification achieves greater security.

Here, we proof the security of our improved design. Note that for ease presentation, our proof directly focuses on our underlying CLS scheme. Following the proof idea in [23,24], the improved CLS design is resistant to forgery attacks against Type 1 and Type 2 adversaries.

Theorem 1: The improved CLS scheme is secure against any Type 1 adversary if ECDLP is hard.

Proof: This theorem demonstrates that if a Type 1 adversary

• Stage-1:

• Stage-2: In this stage,

Secret value-Query:

Partial private key-Query:

Public key replacement-Query: Once

Signing-Query: Upon receiving

• Stage-3: Eventually,

If

Theorem 2: The improved CLS scheme is secure against any Type 2 adversary if ECDLP is hard.

Proof: The proof follows a similar approach to that of Theorem 1 and is thus omitted for brevity.

Theorem 3: The improved CLS scheme achieves conditional privacy-preserving.

Proof: In our design, the anonymity of the end device is assured by the pseudonym

In Signing, to generate a signature on a message, three distinct random numbers

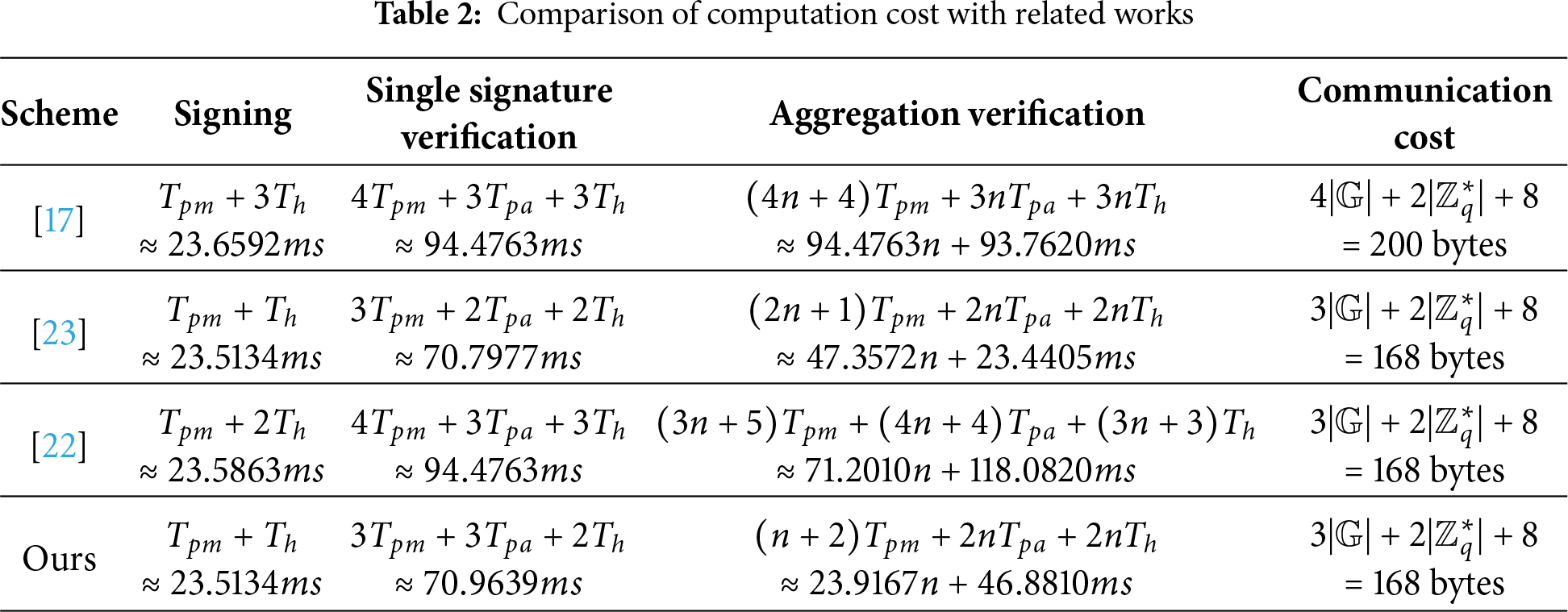

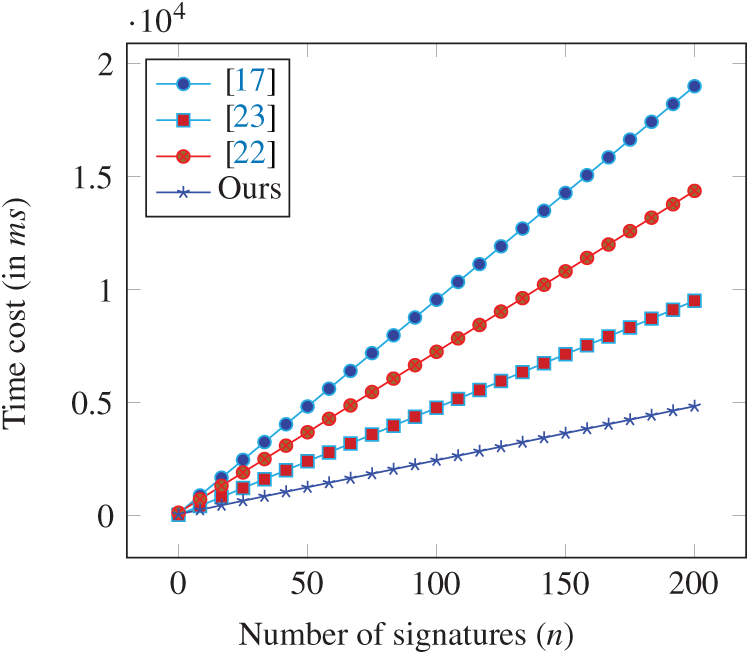

This section analyzes the performance of our design by comparing its computational and communication costs with recent schemes in [17,22,23]. We adopt the experiment parameters provided in [23] for our analysis, which was tested on a Raspberry Pi 3B+ device under the Curve25519 elliptic curve, achieving 128-bit security level. Specifically, the running time for different operations is as follows: general hash

Computational costs. Taking the algorithm Signing in our improved scheme as an example, it executes one point multiplication operation and one general hash operation to generate the signature. Hence, the total computational cost is

In Signing, the cost of our design is the same as that of [23] and lower than that of [17] (i.e., 23.6592 ms) and [22] (i.e., 23.5863 ms). In Verification, the schemes in [17,22] require a relatively high computational cost. Though the cost of our scheme is slightly higher than that of [23], the gap between them is quite small (i.e., 0.1652 ms). In addition, as can be seen from the table and Fig. 3, our scheme achieves the smallest computational cost in Aggregate Verification. Therefore, our scheme has better security and desirable computational cost.

Figure 3: Computational costs comparison between the improved CLAS scheme and [17,22,23] in aggregation verification phase

Communication costs. Based on the above curve parameters, the length of

In summary, our improved scheme not only has better security but also has desirable computational and communication costs.

In Wang et al.’s design in [23], the main reason why their proposal has the security vulnerability under Type 1 attack is that the verification equation

In our improvement, we have made corresponding adjustments to the device private-public key pair generation method, signature generation process, and verification equation, avoiding the problems found in Wang et al.’s design. The above performance analysis shows that compared with existing work, our improvement has reached the optimal state in signature generation, signature batch verification processing, and communication cost. However, our work cannot not achieve optimal performance in terms of single signature verification. This is a cost for our solution in achieving high security. To address this limitation, a feasible approach is to combine certificateless cryptosystems with lightweight hash-based message authentication code [28] to construct new privacy preserving authentication schemes. However, However, this may require a new security model.

In this effort, we explored the security vulnerability of a very recent CLAS scheme in [23] proposed for NDN-IoT environments. By presenting a specific Type 1 attack, our analysis demonstrates how attackers can use their scheme to forge legitimate signatures for fraudulent environmental data. This manipulation allows malicious actors to deceive consumers, thereby guiding them to make wrong decisions. In view of this, we have systematically examined the root causes behind the vulnerability in [23] and proposed an improved CLAS design to secure NDN-IoT applications. We proved its security based on the cryptographic assumption, and analyzed its performance. The performance comparison results showed that our improved scheme not only has better security but also has desirable computational and communication costs. Finally, as an additional contribution, we analysed the security vulnerability of a very recent CLAS scheme in [22] and proposed targeted countermeasures to enhance its security.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Hubei Engineering Research Center for BDS-Cloud High-Precision Deformation Monitoring Open Funding (No. HBBDGJ202507Y), in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62377037).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Feihong Xu, Fei Zhu, Saru Kumari; Methodology, Jianbo Wu, Qing An; Writing—original draft, Feihong Xu and Fei Zhu; Writing—review & editing, Feihong Xu, Jianbo Wu, Qing An, Zhaoyang Han, and Saru Kumari. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Cryptanalysis and Improvement of Yue et al.’s CLAS scheme in [22]

Appendix A.1 Review of the Original Scheme: The CLAS scheme introduced by Yue et al. [22] consists of the following algorithms: System Setup, Pseudonym Identity Generation, Partial Private Key Generation, Vehicle Key Generation, Individual Signature Generation, Single Signature Verification, Aggregated Signature Generation, and Aggregated Signature Verification. For ease of presentation, we only briefly review their first six algorithms to support our analysis, which naturally form a CLS scheme.

1. System Setup: Taking a security parameter

(a) Define an

(b) Choose hash functions

(c) (KGC:) Randomly select a private key

(d) (TA:) Randomly select a private key

(e) KGC and TA store

2. Pseudonym Identity Generation: A vehicle

(a)

(b) TA extracts

3. Partial Private Key Generation: After checking the validity of

4. Vehicle Key Generation:

5. Signing: To sign a message

(a) Select

(b) Calculate

(c) Compute

6. Single Signature Verification: Given

Appendix A.2 Security Analysis to [22]: In [22], Yue et al. stated that their design is secure against both Type 1 and Type 2 attackers. Here, we show that a Type 1 attacker

(1) Compute

(2) Pick

(3) Compute

(4) Set its forgery

Figure A1: An example of the Type 1 attack

Now, the correctness of

Due to the insecurity of the underlying CLS scheme, their CLAS construction cannot achieve unforgeability.

Appendix A.3 Improvement: In [22], a verifier checks a received signature through the equation

To patch this vulnerability, a simple suggestion is to include

References

1. Daniel E, Tschorsch F. IPFS and friends: a qualitative comparison of next generation peer-to-peer data networks. IEEE Commun Surv Tutorials. 2022;24(1):31–52. doi:10.1109/comst.2022.3143147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Benmoussa A, Kerrache CA, Lagraa N, Mastorakis S, Lakas A, Tahari AEK. Interest flooding attacks in named data networking: survey of existing solutions, open issues, requirements, and future directions. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(7):139:1–37. doi:10.1145/3539730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mazhar T, Irfan HM, Haq I, Ullah I, Ashraf M, Shloul TA, et al. Analysis of challenges and solutions of IoT in smart grids using AI and machine learning techniques: a review. Electronics. 2023;12(1):242. doi:10.3390/electronics12010242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mazhar T, Talpur DB, Shloul TA, Ghadi YY, Haq I, Ullah I, et al. Analysis of IoT security challenges and its solutions using artificial intelligence. Brain Sci. 2023;13(4):683. doi:10.3390/brainsci13040683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhu F, Yi X, Abuadbba A, Luo J, Nepal S, Huang X. Efficient hash-based redactable signature for smart grid applications. In: ESORICS 2022. Copenhagen, Denmark; 2022 Sep 26–30. Vol. 13556. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 554–73. [Google Scholar]

6. Boneh D, Gentry C, Lynn B, Shacham H. Aggregate and verifiably encrypted signatures from bilinear maps. In: EUROCRYPT 2003. Warsaw, Poland; 2003 May 4–8. Vol. 2656. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2003. p. 416–32. [Google Scholar]

7. Shen L, Ma J, Liu X, Wei F, Miao M. A secure and efficient ID-based aggregate signature scheme for wireless sensor networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017;4(2):546–54. doi:10.1109/jiot.2016.2557487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Al-Riyami SS, Paterson KG. Certificateless public key cryptography. In: ASIACRYPT 2003. Taipei, Taiwan; 2003 Nov 30–Dec 4. Vol. 2894. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2003. p. 452–73. [Google Scholar]

9. Shim K. A secure certificateless signature scheme for cloud-assisted industrial IoT. IEEE Trans Ind Informatics. 2024;20(4):6834–43. doi:10.1109/tii.2023.3343437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yang W, Wang S, Mu Y. An enhanced certificateless aggregate signature without pairings for E-healthcare system. IEEE Inter Things J. 2021;8(6):5000–8. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.3034307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Aljarwan AZA, Ngadi MA. Review of certificateless authentication scheme for vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Access. 2025;13:100074–94. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3576926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mei Q, Xiong H, Chen J, Yang M, Kumari S, Khan MK. Efficient certificateless aggregate signature with conditional privacy preservation in IoV. IEEE Syst J. 2021;15(1):245–56. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2020.2966526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cahyadi EF, Su T, Yang CC, Hwang M. A certificateless aggregate signature scheme for security and privacy protection in VANET. Int J Distributed Sens Networks. 2022;18(5). doi:10.1177/15501329221080658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cui J, Zhang J, Zhong H, Shi R, Xu Y. An efficient certificateless aggregate signature without pairings for vehicular ad hoc networks. Inf Sci. 2018;451–452:1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2018.03.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kamil IA, Ogundoyin SO. An improved certificateless aggregate signature scheme without bilinear pairings for vehicular ad hoc networks. J Inf Secur Appl. 2019;44(1):184–200. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2018.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xu G, Zhou W, Sangaiah AK, Zhang Y, Zheng X, Tang Q, et al. A security-enhanced certificateless aggregate signature authentication protocol for InVANETs. IEEE Netw. 2020;34(2):22–9. doi:10.1109/mnet.001.1900035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhu F, Yi X, Abuadbba A, Khalil I, Huang X, Xu F. A security-enhanced certificateless conditional privacy-preserving authentication scheme for vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(10):10456–66. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3275077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang W, Fan J, Song K, Zheng Y, Zhang F. An efficient and practical conditional privacy-preserving aggregate authentication for vehicular ad-hoc networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(12):20256–67. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3474210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhu D, Guan Y. Secure and lightweight conditional privacy-preserving identity authentication scheme for VANET. IEEE Sensors J. 2024;24(21):35743–56. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3431557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhu F, Hu Y, Ren Y, Han B, Yang X. Public-Key replacement attacks on lightweight authentication schemes for resource-constrained scenarios. Cyber Secur Applicat. 2025;3:100102. doi:10.1016/j.csa.2025.100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Verma RK, Khan AJ, Kashyap SK, Chande MK. Certificateless aggregate signatures: a comprehensive survey and comparative analysis. J Univers Comput Sci. 2024;30(12):1662–90. doi:10.3897/jucs.116249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yue Q, Jiang W, Lei H. A lightweight certificateless aggregate signature scheme without pairing for VANETs. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):23663. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-08656-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang C, Wu H, Gan Y, Zhang R, Ma M. ECAE: an efficient certificateless aggregate signature scheme based on elliptic curves for NDN-IoT environments. Entropy. 2025;27(5):471. doi:10.3390/e27050471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Xu F, Liu S, Yang X. An efficient privacy-preserving authentication scheme with enhanced security for IoMT applications. Comput Commun. 2023;208:171–8. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2023.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Pointcheval D, Stern J. Security arguments for digital signatures and blind signatures. J Cryptol. 2000;13(3):361–96. doi:10.1007/s001450010003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sasdrich P, Güneysu T. Implementing Curve25519 for side-channel-protected elliptic curve cryptography. ACM Trans Reconfigurable Technol Syst. 2015;9(1):3:1–15. doi:10.1145/2700834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tanksale V. Efficient elliptic curve diffie-hellman key exchange for resource-constrained IoT devices. Electronics. 2024;13(18):3631. doi:10.3390/electronics13183631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Katz J, Lindell Y. Introduction to modern cryptography. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: CRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools