Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Robot Grasp Detection Method Based on Neural Architecture Search and Its Interpretability Analysis

1 South China Sea Marine Survey Center, Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China, Guangzhou, 510300, China

2 School of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Foshan University, Foshan, 528200, China

3 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Industrial Intelligent Inspection Technology, Foshan University, Foshan, 528000, China

4 Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Survey Technology and Application, Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China, Guangzhou, 510300, China

5 Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), Zhuhai, 519000, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenbo Zhu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 52 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073442

Received 18 September 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Deep learning has become integral to robotics, particularly in tasks such as robotic grasping, where objects often exhibit diverse shapes, textures, and physical properties. In robotic grasping tasks, due to the diverse characteristics of the targets, frequent adjustments to the network architecture and parameters are required to avoid a decrease in model accuracy, which presents a significant challenge for non-experts. Neural Architecture Search (NAS) provides a compelling method through the automated generation of network architectures, enabling the discovery of models that achieve high accuracy through efficient search algorithms. Compared to manually designed networks, NAS methods can significantly reduce design costs, time expenditure, and improve model performance. However, such methods often involve complex topological connections, and these redundant structures can severely reduce computational efficiency. To overcome this challenge, this work puts forward a robotic grasp detection framework founded on NAS. The method automatically designs a lightweight network with high accuracy and low topological complexity, effectively adapting to the target object to generate the optimal grasp pose, thereby significantly improving the success rate of robotic grasping. Additionally, we use Class Activation Mapping (CAM) as an interpretability tool, which captures sensitive information during the perception process through visualized results. The searched model achieved competitive, and in some cases superior, performance on the Cornell and Jacquard public datasets, achieving accuracies of 98.3% and 96.8%, respectively, while sustaining a detection speed of 89 frames per second with only 0.41 million parameters. To further validate its effectiveness beyond benchmark evaluations, we conducted real-world grasping experiments on a UR5 robotic arm, where the model demonstrated reliable performance across diverse objects and high grasp success rates, thereby confirming its practical applicability in robotic manipulation tasks.Keywords

In robotic grasping scenarios, manually designed object grasping detection networks are typically tailored for a specific set or category of objects. When faced with objects rapidly passing through a conveyor belt, these objects vary in contours, textures, glossiness, and other physical characteristics. Variations in external object features introduce discrepancies between the data distribution used during training and that encountered in real-world scenarios, a phenomenon commonly termed concept drift. Consequently, the decline in robustness of the model occurs as it encounters difficulties in generalizing and adapting to the external features of unseen objects. When the external features of the objects deviate beyond the scope of the training data of model, it significantly impacts the grasping success rate and challenges the accuracy and stability of the recognition capabilities of the system. While techniques for noise reduction, including Laplacian operators, wavelet thresholding, and Gaussian filtering, can reduce the loss of accuracy, they are often insufficient to ensure system performance when concept drift exceeds the training range of the model. For the concept drift in robotic grasping—stemming from changes in object appearance, lighting, or wear in the gripper—can degrade grasping performance. While deep-learning models can be retrained or fine-tuned to recover accuracy, frequent manual intervention is impractical on the shop floor. Consequently, developing lightweight, autonomous adaptation mechanisms that can detect and mitigate drift without requiring expert intervention or costly retraining has become a critical challenge for reliable long-term deployment.

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) represents a core component of Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) [1] focused on automatically designing deep neural network models with outstanding performance, achieving optimal results for target tasks. NAS has grown rapidly in recent years and is now used in a variety of domains such as computer vision [1–4], speech processing [5–7], and natural language processing (NLP) [8,9]. The research on NAS holds significant theoretical and practical value. First, NAS can rapidly locate the best network architecture through automatic search, enhancing model performance while saving substantial time spent on manual architecture and parameter adjustments. Second, NAS technology does not require specialized knowledge in relevant fields, making it widely accessible to non-experts. However, Neural Architecture Search (NAS) frequently yields networks with numerous parameters and redundant structures, leading to high memory consumption and decreased operational efficiency, particularly in resource-constrained computing environments. In response, researchers have proposed various methods to improve search efficiency and model performance. Hardware-aware NAS methods effectively balance accuracy with hardware constraints. The study in [10] introduces a new hardware-aware NAS framework that considers the suitability of network layer features for hardware mapping, enhancing deployment efficiency. The study in [11] presents a fast hardware-aware NAS method—S3NAS, that can find networks with better delay-accuracy trade-offs than state-of-the-art (SOTA) networks through three steps. The study in [12] introduces a streamlined and scalable hardware-aware NAS framework designed to enhance the precision of optical networks while maintaining the operational efficiency of the target hardware within a two-stage process. Furthermore, NAS methods based on evolutionary algorithms, reinforcement learning, Bayesian optimization, and gradient-based updates likewise confer comparable advantages.

Complex network architectures, characterized by numerous interconnected nodes and edges, not only complicate training by increasing the burden of parameter updates and computations but also demand substantially greater computational resources during deployment. The study in [13] introduced a differentiable neural architecture search (NAS) approach that incorporates computational complexity constraints, resulting in a sparse topology for the discovered architecture. At the same time, the study in [14] employs a binary gating strategy to enable partial channel connections, thereby establishing a sparse connection mode to optimize the efficiency of the search procedure. This method, proposed in reference [15] introduces a technique for directing differentiable channel pruning using an attention mechanism, facilitating the regulation of network depth and width. Therefore, it is clear that when searching for and generating compact networks, network complexity must often be considered.

Deep learning has significantly improved performance across diverse tasks, yielding transformative results across a wide range of domains, including image recognition, natural language processing, and decision-making systems. However, these models typically contain millions of parameters and complex nonlinear structures, making their decision-making process a black box that is difficult for humans to understand and interpret. This opacity not only undermines trust in the models but also raises concerns about the rationale and fairness of their decisions. In recent years, the interpretability of models has been a focal point of attention. The objective of neural network interpretability is to uncover the internal mechanisms of the model and offer an intuitive understanding of its decision-making process. Such research offers insights into how the model extracts features from input data and makes decisions, thereby helping to alleviate the black-box problem. A clear insight into deep learning models plays a key role in optimizing network architectures and enhancing their robustness in real-world applications. To address this need, we investigate the internal mechanisms of visual models using the Class Activation Mapping (CAM) framework [16].

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

(1) The automated design of robot grasp detection networks is achieved by integrating neural architecture search (NAS) with robotics technology, which greatly improves the efficiency of network design.

(2) An improved NAS approach is proposed by introducing an additional attention-based search space optimization method, addressing the issues of complex feature extraction and redundant structures caused by stacking multiple normal cells, thus effectively enhancing the network search efficiency.

(3) We evaluate the comprehensive performance of the searched models by deploying a concise and efficient network on a UR5 robotic arm for physical grasping experiments. Experimental results verify the validity and robustness of our model. Moreover, Class Activation Maps (CAM) are employed to enhance the interpretability and credibility in the outputs of the model.

2.1 Robotic Grasp Detection Technology

2.1.1 Traditional Robot Grasp Detection Methods

Early research on robot grasp detection predominantly utilized analytical and heuristic approaches. Analytical methods rigorously model the physical interaction between the gripper and the object. As reviewed in [17], these methods involve the selection of finger positions and hand configurations guided by kinematic and dynamic equations pertaining to grasp stability and task specifications. Seminal work in this area, such as that of Ferrari and Canny [18], focused on planning optimal grasps based on force closure criteria. However, Analytical approaches typically require comprehensive and precise knowledge of the physical characteristics of object (e.g., geometry, mass, friction), which is often unavailable in real-world scenarios where objects are novel, partially occluded, or have unknown properties.

Heuristic methods, in contrast, often rely on empirical rules and simplified models. As surveyed in [19,20], these approaches are frequently based on the geometric structure of the target object and utilize pre-defined grasping strategies or templates, such as aligning a parallel-jaw gripper with antipodal points on a contour of object. Yet, Heuristic method, while computationally efficient for known objects, are inherently limited by their pre-defined rules and templates. They lack the adaptability to generalize across the vast diversity of object shapes and configurations encountered outside of controlled settings, making them brittle in the face of novelty.

The limitations of these model-based and rule-driven approaches—specifically, their inability to handle perceptual uncertainty and generalize to novel objects—motivated the paradigm shift towards data-driven solutions, particularly those leveraging deep learning, which can learn robust grasping strategies directly from sensory data.

2.1.2 Deep Learning-Based Method for Robot Grasp Detection

With the rapid development of deep learning, more and more people have applied it to robot grasping and detection, making it a prominent research focus [21]. Most deep learning methods learn object feature representations and grasping strategies from a large amount of training data, thereby being able to automatically grasp different types of objects. Early deep learning approaches, such as those presented in [22], demonstrated the feasibility of using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to directly predict grasp configurations from RGB or RGB-D images, achieving significant improvements over traditional methods. However, these models limited their ability to capture complex features, and their performance was constrained by the scale and diversity of the training datasets available at the time.

Subsequent research has explored various architectures and input modalities to enhance performance. For instance, methods based on 3D point clouds [23] aim to leverage richer geometric information, potentially improving grasp accuracy in cluttered environments. Nevertheless, processing 3D point clouds is computationally expensive and often requires non-trivial data pre-processing, posing challenges for real-time deployment on robotic systems with limited computational resources. Similarly, approaches using rendered RGB-D images for pose regression [24] sought to fuse color and depth information. Yet, their performance can be highly sensitive to the quality and calibration of the depth sensors, and the fusion strategy may not fully exploit the complementary nature of the two modalities.

Furthermore, architectural innovations such as the incorporation of multi-scale spatial pyramid modules (MSSPM) [25] and hierarchical feature fusion methods [26] have been employed to enhance the precision and reliability of robotic grasping by capturing features at different scales and resolutions. While effective, these manually designed architectural enhancements often increase the complexity of model, and parameter count. This introduces a significant engineering burden, as designing optimal structures requires extensive domain expertise and iterative trial-and-error, and the resulting models may still suffer from information redundancy or inefficient feature propagation.

Recent studies such as GoalGrasp [27] have proposed that grasping and positioning in occlusion scenarios can be achieved through target semantic reasoning without grasping training, significantly enhancing the zero-shot generalization ability for new objects. However, its control over grasping accuracy and stability is weaker than that of the method proposed in this paper.

The challenges solved in robot grasping and detection, such as the robustness requirements for object diversity and real-time performance, are in line with a wider range of computer vision applications. For instance, in autonomous systems, Emin Güney et al. [28] developed a computer vision-based charging controller for shore-based robots, which shares the same precise visual servo and real-time decision-making requirements as robot grasping. Similarly, the advancements in general object detection directly provide guidance for grasping detection methods. The research of reference [29] on using faster R-CNN to detect traffic signs demonstrated the powerful ability of regional proposal networks in accurately locating objects of interest in the scene. Although our task is to predict the directional grasping of rectangles rather than horizontal bounding boxes, the fundamental principle of using deep neural networks for precise spatial positioning is a common thread. Our approach based on network architecture can be regarded as a development of these concepts. In this approach, the network architecture itself is end-to-end optimized for the specific task of capturing rectangle detection, which may be superior in terms of efficiency and accuracy to those artificially designed backbone networks used in Faster R-CNN.

The framework proposed in this paper also falls within the category of deep learning-based capture and detection methods, however, its uniqueness lies in the adoption of Neural Architecture Search (NAS) technology to achieve an automated design process. Unlike manually designed architectures such as ResNet-based networks [30], or specially designed architectures like SE-ResUNet [31], our method does not presuppose a fixed backbone network or connection pattern. On the contrary, it will automatically discover the optimal network topology from a predefined search space, which includes convolution operations, attention mechanisms, and hybrid CNN-Transformer modules. This NAS-driven approach reduces human bias and engineering workload, while explicitly optimizing for accuracy and efficiency—a key consideration for real-time robotics applications.

Neural network attention mechanisms are motivated by human cognitive processes, enhancing task performance by selectively emphasizing the most relevant input features. These mechanisms improve information processing in terms of flexibility and accuracy through the assignment of varying weights to input elements. In image classification, as network models have expanded and deepened, the expressive power of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) has significantly improved, and numerous studies have focused on exploring deeper and broader trainable structures [32].

The core operation of CNNs is convolution, through which the network can capture rich spatial and channel information. However, some of this information may be irrelevant or interfere with key features, which can negatively impact network performance, increase computational load, and reduce detection accuracy. Therefore, incorporating attention mechanisms to filter redundant information and selectively emphasize critical features can enhance the performance of neural network models.

2.3 Neural Network Architecture Search

Recent developments in deep learning have highlighted Neural Architecture Search (NAS) as an important research direction. It aims to automatically generate high-performance neural networks using limited computational resources, without the need for manual intervention throughout the search process.

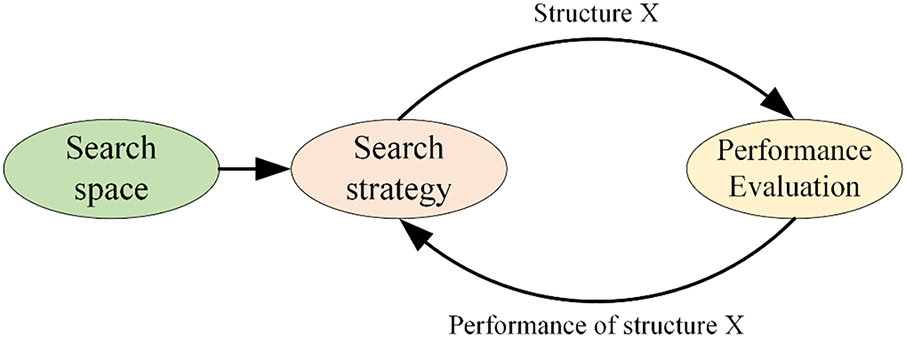

As shown in Fig. 1, Neural Architecture Search (NAS) comprises three primary components: the search space, search strategy, and performance evaluation. NAS employs a search strategy to explore network architectures within a predefined search space and identifies the optimal one based on performance evaluation. The search space characterizes the entirety of feasible network architectures, represented by diverse arrangements of stacked neural units. It encompasses all potential layers, connections, and operations—such as convolution, pooling, and fully connected layers—and their combinations. The design of the search space plays a pivotal role in determining the performance of a NAS algorithm, as it establishes the algorithm’s degrees of freedom and, to some extent, constrains its achievable performance ceiling. Search strategies determine the algorithms employed to efficiently identify optimal network architectures and parameter configurations. The principal approaches currently include Evolutionary Algorithms (EA), Reinforcement Learning (RL), and Gradient-based Update (GU) methods. EA-based neural architecture search [33] simulates the biological evolutionary mechanism and does not rely on gradient information, which allows for faster convergence in the early stages of the search, but requires significant computational resources. RL-based algorithms [3,34] use recurrent networks to construct a model representation of the neural network. These algorithms employ reinforcement learning to optimize the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) towards enhancing the anticipated accuracy of the resultant architecture on the validation dataset. Nevertheless, RL techniques are associated with substantial computational expenses. Conversely, GU-based algorithms offer a more computationally economical alternative. Differentiable Architecture Search (DARTS) [35], is a gradient-update-based NAS algorithm that utilizes gradient descent based on architecture continuous relaxation to perform efficient architecture search. Although GU-based algorithms are computationally efficient, gradient-based optimization methods tend to suffer from high memory usage and inappropriate relaxation when applied. Furthermore, since most existing gradient-based algorithms rely on generational super networks, these algorithms require substantial domain-specific knowledge for effective super network construction. The final component of NAS is performance evaluation, which defines how to assess the performance of candidate architectures to more efficiently identify the best network architecture, such as through network mapping [36].

Figure 1: NAS Search Flowchart

Since it was introduced in [37], Class Activation Mapping (CAM) has attracted widespread attention in computer vision due to its simplicity and insightful nature. CAM is essentially a heatmap that highlights regions in an image that are critical for predicting a specific class, offering a clear visualization of the decision-making process of the neural network. This visualization technique effectively reveals the key areas that the model focuses on, thus offering interpretability of the decision-making process of the neural network. Initially, CAM was generated through a linear combination of feature maps. This approach later led to the development of several related means, covering Grad-CAM, Score-CAM, and Layer-CAM.

For deep convolutional neural networks, after multiple convolution and pooling operations, the final convolutional layer retains both rich spatial features and high-level semantic information. However, the subsequent fully connected and SoftMax layers produce highly abstract features, making them difficult to visualize directly. Therefore, to effectively interpret CNN classification decisions, it is crucial to extract and utilize interpretable features embedded within the last convolutional layer. Inspired by the approach presented in [38], Class Activation Maps (CAM) replaces conventional fully connected layers with Global Average Pooling (GAP). GAP computes the mean of each feature map in the final convolutional layer and generates the network output through a weighted summation. By effectively leveraging spatial information and eliminating the numerous parameters associated with fully connected layers, GAP reduces the risk of overfitting and enhances model robustness.

Class Activation Mapping (CAM) provides a simple and effective method to visualize the regions in the input image that have the greatest impact on the capture prediction of model. By replacing the fully connected layer with a global average pooling layer, CAM generates an intuitive heat map highlighting significant areas, thereby enhancing the transparency of the grab detection process. This is particularly useful for identifying potential failure modes. For instance, when the model wrongly focuses on irrelevant background areas rather than the object itself. This visual feedback provides valuable guidance for debugging and improving the network architecture.

However, CAM also has its inherent limitations. Firstly, CAM usually relies on the final convolutional layer. Due to the previous downsampling operation, this layer has a reduced spatial resolution. As a result, the generated heatmaps are often relatively rough and may lack precise pixel-level positioning, especially for small or slender objects. Secondly, CAM was originally designed for classification tasks and requires careful adjustment to be used for dense prediction tasks like object detection. Although extending the class activation map (CAM) for visualization helps to visualize the regions involved in the object capture decision, it cannot directly explain regression parameters such as capture angle or width. Thirdly, CAM mainly answers the question “where is the model looking”, but cannot answer “why” these areas are considered important. It does not provide causal or semantic insights into the decision-making process of the model. To address these shortcomings, future work will explore more advanced interpretability techniques, providing finer spatial resolution and deeper interpretability capabilities for the classification and regression components of the model.

2.5 Grasping Pose Representation

To generate precise grasping configurations, it is essential to explicitly represent grasping poses. A simple and clear five-dimensional representation method for describing 2D grasps of parallel grippers has been proposed [22], which constructs a gripper rectangle through five parameters. See Eq. (1) for an example:

here,

The variable

The matrices

where

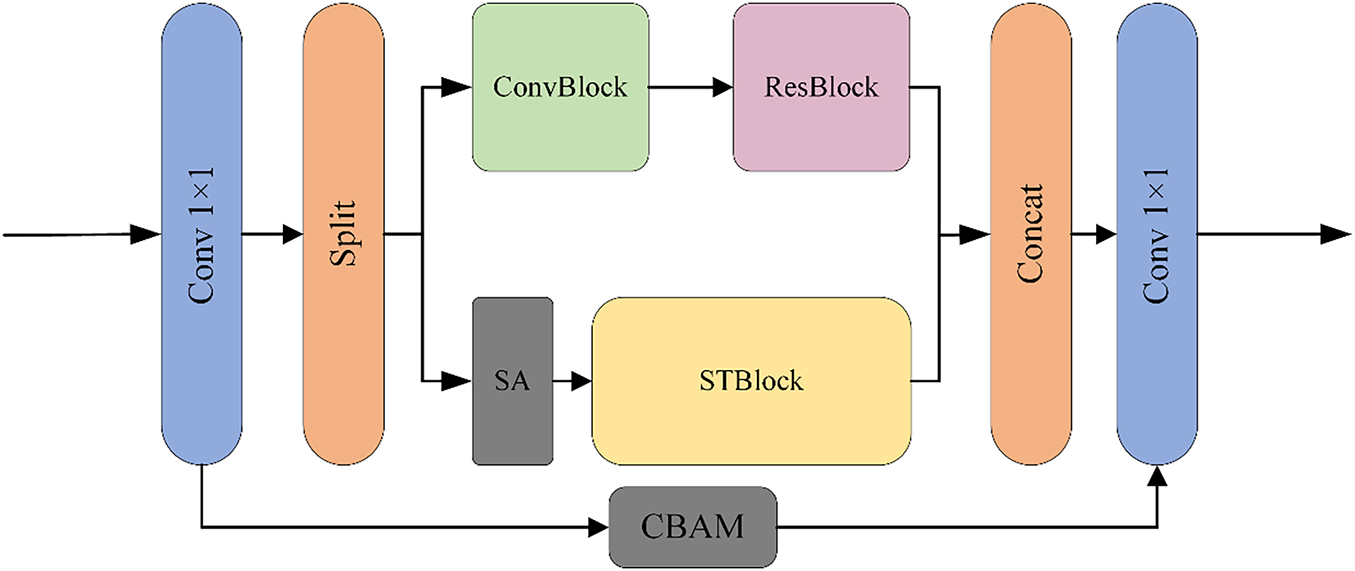

3.1 Res-Swin-CNN Block (RSC Block)

The integration of CNN and Swin Transformer represents a novel approach in deep learning research [37]. As shown in Fig. 2, the module not only integrates the core components of CNN and Swin Transformer but also introduces attention modules and residual structures to enhance local feature extraction and establish long-range dependencies more effectively.

Figure 2: RSC Module Architecture. Input tensor X is split into two branches: Conv-Res path (local detail) and Swin-Transformer path (global context); concatenated features are refined by CBAM and a 1 × 1 conv. Symbols: Conv = convolution, BN = batch normalization, ST = Swin-Transformer, CBAM = convolutional block attention module

The input feature tensor

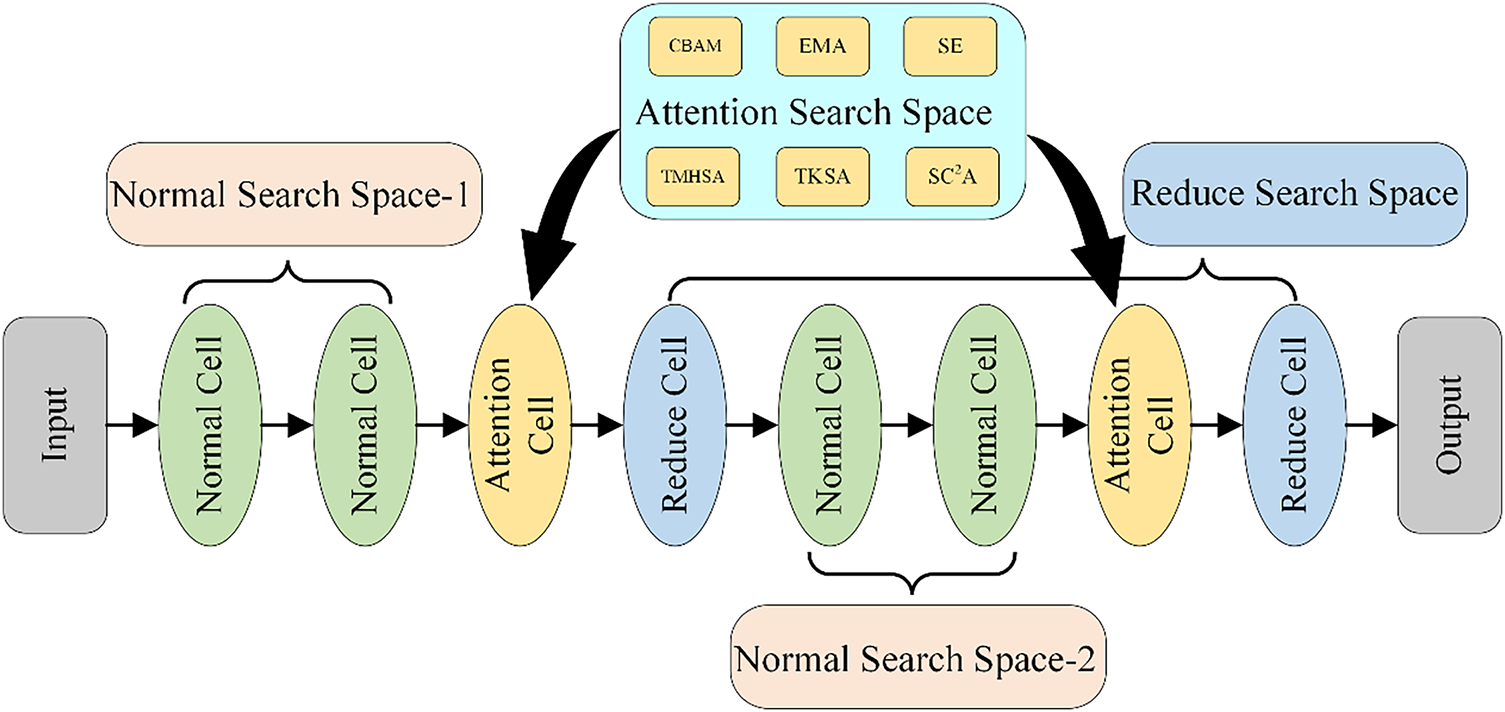

3.2 Search Space Base Attention

Cell-based search methods typically comprise multiple normal cells stacked together, followed by a reduction cell. While this structure can enhance the feature representational capacity of the model, the accumulation of numerous redundant cells within the network results in feature redundancy, which affects the efficiency and performance of the model. To address this issue, we introduce an attention-based cell search space method.

As illustrated in Fig. 3, to enhance the performance of the model, the paper constructs a search space containing six types of attention cells, specifically SE, CBAM, EMA, TMHSA, SC2A, and TKSA. Each module demonstrates different advantages in specific tasks, making them highly adaptable. SE [40] proposed a streamlined attention mechanism that targets channel-level operations, improving the capability of the network to identify and prioritize important channels. In contrast, CBAM [41] combines spatial and channel attention mechanisms to enhance individual channel representations while capturing critical features across diverse spatial locations. While SE and CBAM show significant performance improvements in channel attention, they lack the interrelationship between channels and cannot strengthen feature information representation. In recent years, the Transformer architecture has achieved significant breakthroughs in natural language processing (NLP) and has been progressively adopted for computer vision applications [42]. As the core of Transformer, the self-attention mechanism can establish global dependencies and expands the receptive field, enabling it to capture more contextual information. Reference [43] proposes an effective DeRaining network, which includes the sparse transformer (DRSformer) that solves the redundancy problem in self-attention within Transformer by using the similarity between all query-key pairs for feature aggregation. Specifically, this network designs a learnable top-k selection operator-based attention mechanism (TKSA) that adaptively retains the most important attention scores for each query, thereby achieving better feature aggregation. Although the Transformer excels at global modeling, it still neglects variations in spatial information across channels. To more effectively capture cross-channel dependencies, researchers have proposed several solutions. EMA [44] integrates output features from two parallel sub-networks by learning across space without reducing the channel dimensions, capturing pixel-level pairwise relationships and avoiding the computational overhead of traditional methods.

Figure 3: Attention-based Cell Search Space Embedding Diagram. Six candidate attention cells (SE, CBAM, EMA, TMHSA, SC2A, TKSA) are randomly attached after normal cells during NAS

To efficiently identify the most effective attention cell for our task, we employ a Uniform Random Sampling strategy. Specifically, during the search phase, for each position designated for an attention cell, one module is randomly and independently selected from the pool of six candidates with equal probability. This process is repeated over multiple search iterations to sufficiently explore the search space. The total number of search iterations was set to 500. To accelerate the performance estimation of each sampled architecture, we trained it on a 10% random subset of the training data for 10 epochs and used the resulting validation accuracy as a proxy. Random search is computationally efficient and avoids the overhead associated with more complex search strategies like Reinforcement Learning or Evolutionary Algorithms. At the same time, it provides an unbiased exploration, preventing the search from being prematurely trapped by local optima, which is a potential risk in gradient-based methods. Random search has been shown to be a strong baseline in hyperparameter and architecture optimization [45], often competing favorably with more sophisticated algorithms while being significantly simpler to implement.

We employ a random search method to select an attention cell from this search space and insert it after the stack of normal cells. This method operates by sampling each candidate cell with equal probability during each search iteration. It not only captures more key features but also effectively decreases the impact of redundant characteristics, optimizing the feature extraction process.

3.3 Definition of the Initial Search Space

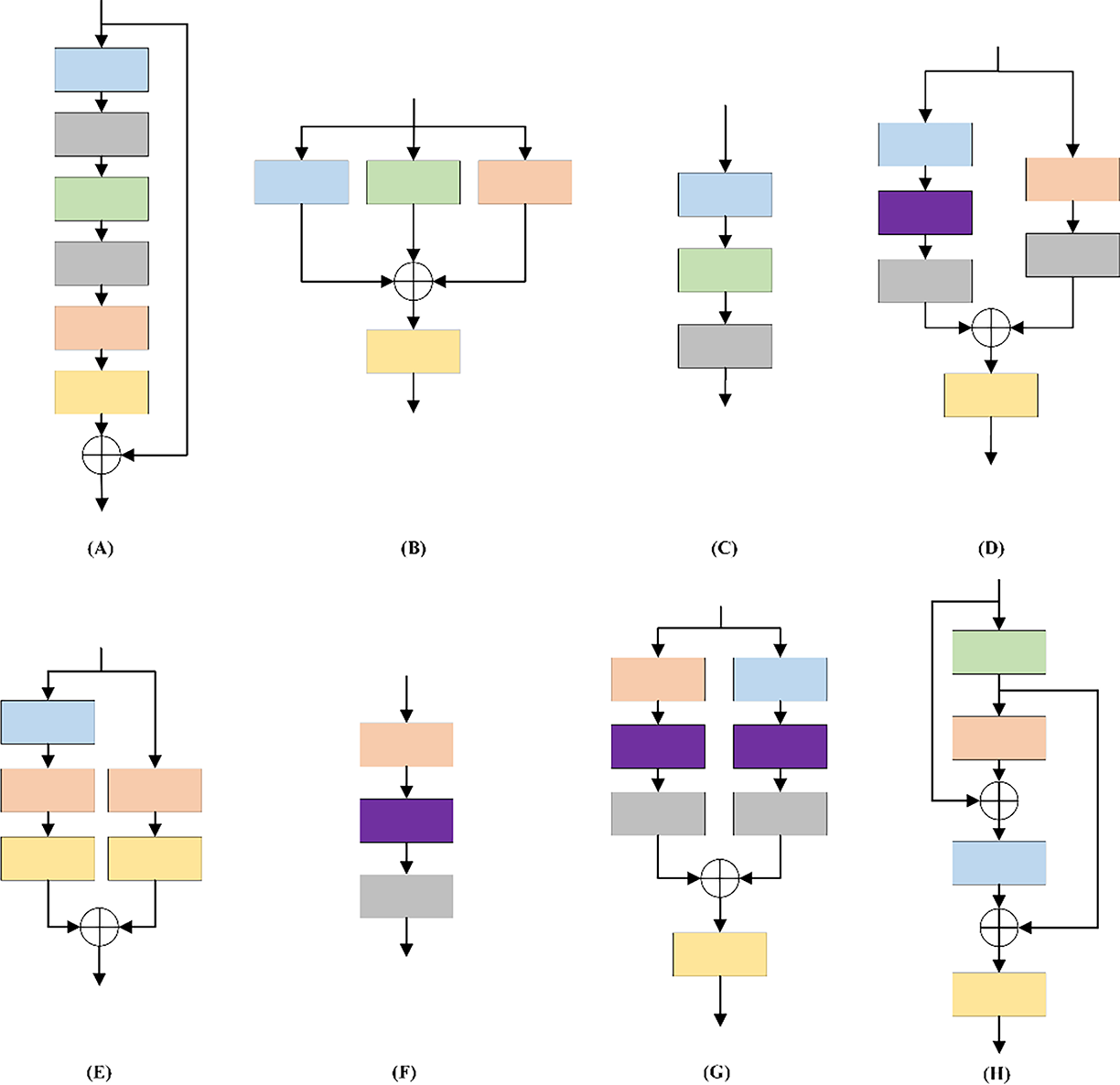

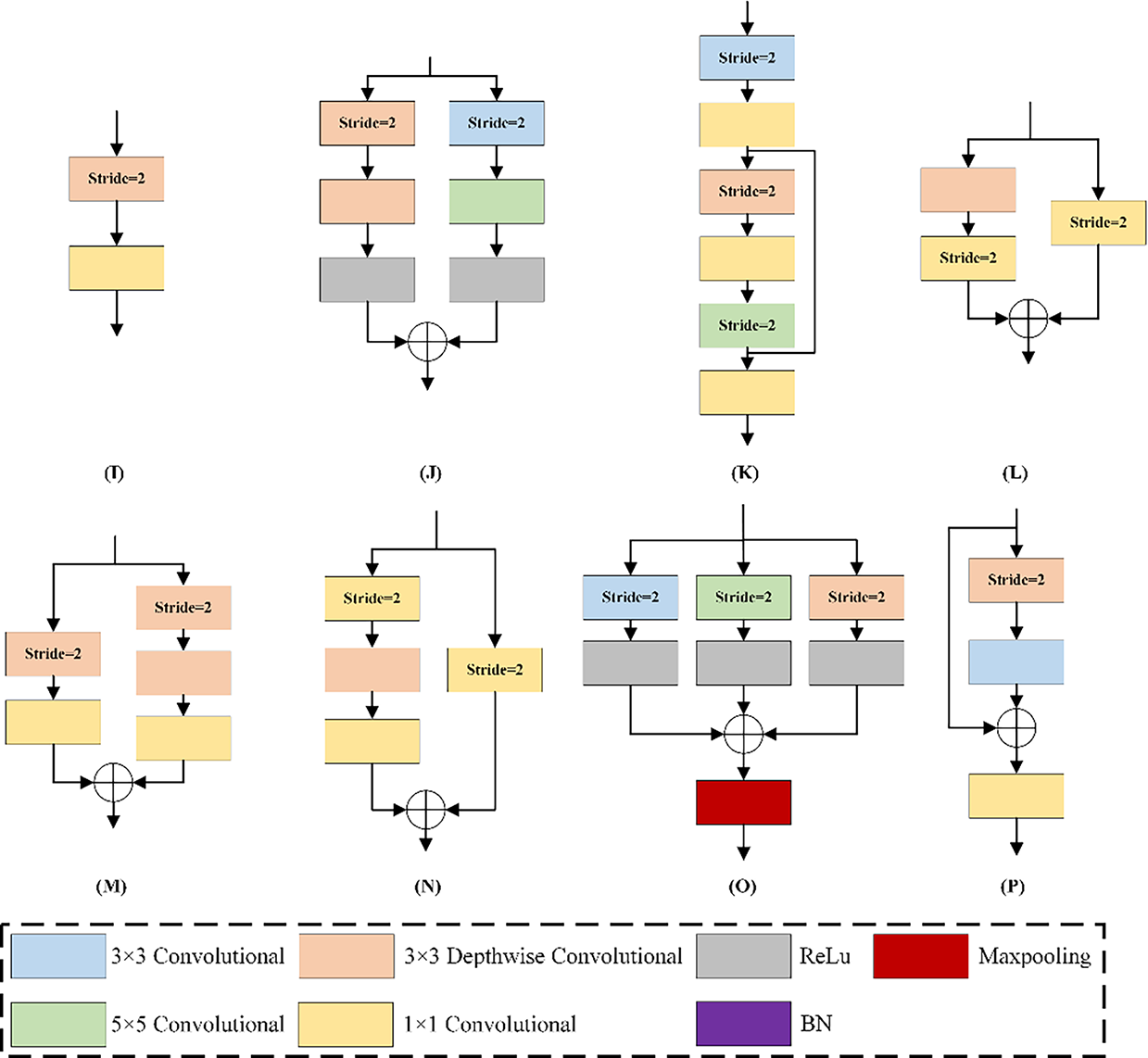

To design an efficient and compact network structure, the paper draws on the design principles of several classic neural network architectures when defining the initial search space. These classic network architectures balance network expressiveness and computational cost through different techniques, providing valuable references. ResNet [39] mitigates the issue of vanishing gradients in deep networks through the incorporation of skip connections, facilitating the development of deeper network structures. Additionally, GoogLeNet [46] improves network performance and efficiency by parallelizing convolution operations of different sizes. The key innovation of this model is its Inception module, which enables the network to adaptively determine the most effective convolution or pooling operation at different scales. MobileNet [47] replaces traditional convolutions with depthwise separable convolution, leading to a significant decrease in both parameters and computational cost. AlexNet [48] not only uses conventional convolution and pooling operations but also introduces the ReLU activation function and Batch Normalization (BN). The ReLU helps prevent the vanishing gradients problem during training, while BN significantly improves the generalization capability of the model. Based on the concepts of these models, the paper designed the search space to include 1 × 1 convolution, 3 × 3 convolution, 5 × 5 convolution, depthwise 3 × 3 convolution, ReLU activation function, BN, and MaxPooling for building the basic cells. The 1 × 1 convolutions enable channel fusion, enhancing the non-linear representational capacity of the network. At the same time, this paper constructed an initial search space comprising eight normal cells, six attention cells, and eight reduction cells, providing the search algorithm with sufficient flexibility and diversity to efficiently explore different network topologies. Normal cells maintain the spatial dimensions of feature maps, attention cells highlight salient information, and reduction cells reduce the feature map size by half. The entire network consists of 4 normal cells, 2 attention cells, and 2 reduction cells. The initial channel number for the network is set to 32. Each Reduction Cell doubles the channel count while halving the spatial dimensions of the feature maps. This configuration balances the network’s depth and width, ensures sufficient representational power, and reduces computational cost. Furthermore, this categorization aids the model in capturing features across various scales, thereby improving its ability to adjust to changes in scale. By establishing a well-balanced initial search space, as depicted in Fig. 4, the paper lay the foundation for network searches aimed at identifying accurate and computationally efficient network structures in subsequent explorations.

Figure 4: Cell structure diagram of the defined initial search space. A-H are Normal cells, and I-P are Reduced cells

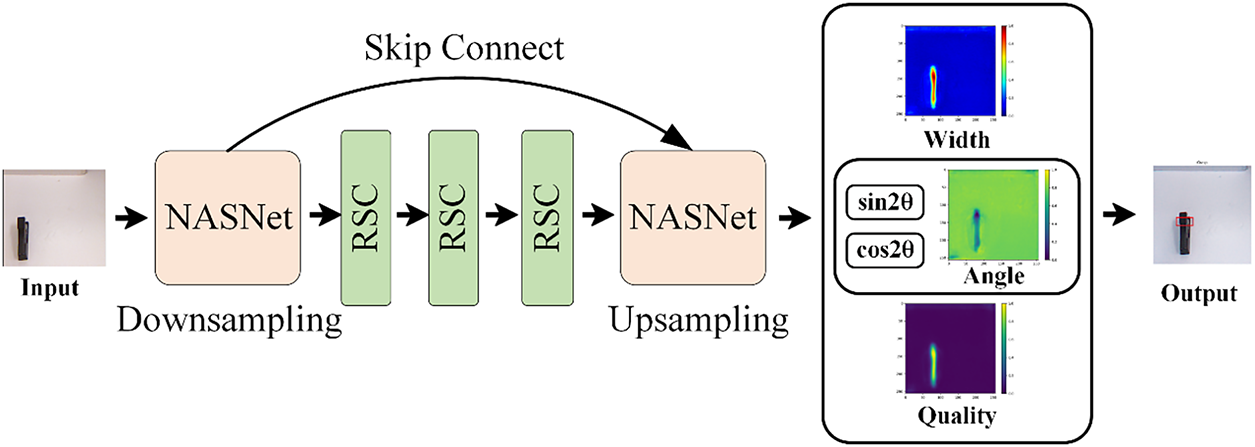

3.4 NAS-based Robot Grasp Detection Network Architecture

As illustrated in Fig. 5, we employ NAS to automatically design the encoder and decoder components of the robotic grasp detection network. Specifically, the proposed network takes the original image as input, extracts image features through the automatically designed network architecture and three RSC modules, and finally outputs three images representing grasp quality, grasp width, and grasp angle. The upsampling operation is implemented using bilinear interpolation. The three output heads are all composed of a single 1 × 1 convolution layer. Specifically, the quality head uses a sigmoid activation function to output values in [0, 1], while the angle and width heads use linear activations. This feature extraction strategy aims to combine the advantages of CNN in capturing detailed features and the Swin Transformer in focusing on global image features. As evidenced by the experimental results, this strategy demonstrates effective performance.

Figure 5: NAS-based Robot Grasp Detection Network Architecture Diagram. Encoder: searched normal/attention/reduction cells + three RSC blocks; decoder: three 1 × 1 heads output Q (quality), Θ (angle), W (width). Up-sampling uses bilinear interpolation. Input: 224 × 224 RGB-D; output: 3 × 224 × 224 maps

Our lightweight network adapts to the target object through two main mechanisms. Firstly, attention-based units (such as SE, CBAM, TKSA) dynamically recalibrate the feature response based on the input, enabling the model to emphasize the channels and spatial regions relevant to the task. For instance, when grasping the deformable sponge, channel attention might amplify features related to texture and flexibility, while for rigid plastic boxes, spatial attention might focus on the edges and corners. Secondly, the multi-scale feature extraction achieved through the combination of Normal, Reduction, and RSC modules enables the network to capture local geometric details and global context information. This is particularly important for dealing with objects of different sizes and shapes.

On this basis, we further emphasize the three adaptability aspects introduced by the NAS framework:

1. Structural adaptability: The NAS algorithm automatically explores the combination of CNN, Swin Transformer, and attention mechanisms, enabling the network to adjust its topological structure based on object features. This enables the model to prioritize local details (such as edges, textures) or global structures (such as shapes, postures) based on the input.

2. Feature adaptability: The RSC module integrates spatial and channel attention mechanisms, enabling dynamic re-weighting of the feature map based on the cues of specific objects. This ensures that the model focuses on the most informative areas (such as the graspable parts), while suppressing irrelevant backgrounds or redundant features.

3. Input modal flexibility: This network supports RGB and RGB-D inputs and can adaptively fuse color and depth information based on object attributes. For instance, for low-texture or reflective objects, depth data might be given more emphasis, while for objects with rich textures or colors, RGB data might be more reliable.

In summary, through the synergistic effect of attention-based dynamic calibration, multi-scale feature extraction, and NAS-driven structure search, the proposed network achieves strong adaptability to various objects and can perform robust and accurate grasping and detection under different shapes, materials, and appearances.

The experiments of the paper are conducted on the Windows 10 operating system, which utilized the PyTorch 1.12 deep learning framework with CUDA 11.6. All experiments were performed on a system equipped with an RTX 4090 GPU and a 13th Gen Intel (R) Core (TM) i9-13900K processor. We trained on the public Cornell and Jacquard datasets, using 90% of the samples for training and 10% for testing. To thoroughly assess model performance, we adopted two data splitting strategies: image-wise (IW) and object-wise (OW) splits. IW strategy involves a random split of the dataset, which allows instances of the same objects to be included in both training and evaluation datasets. On the other hand, the OW strategy partitions the dataset by object instances to prevent any overlap between objects in the training and test sets. These two approaches evaluate the network’s generalization to novel positions of seen objects (IW) and its adaptability to entirely unseen objects (OW). Training was performed using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.01, a batch size of 16, and for 100 epochs. We employed a multi-step learning rate scheduler that reduced the rate by a factor of 0.1 every five epochs to enhance training efficiency and stability.

For the preprocessing of image input, we mainly adjust the RGB image to a size of 224 × 224, normalize the depth map to the range of [0, 1], and use a cross-bilateral filter for restoration. For the model parameters, we set the initial number of channels to 32, the number of cell to 4 normal cell + 2 attention cell + 2 reduction cell, the batch size to 16, and use Adam as the optimizer. Here, the evaluation metrics we use include mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), grasping accuracy, detection speed (fps), and model size (MB). All contrast models (GG-CNN, GR-ConvNet, SE-ResUNet, DSNet, etc.) were retrained under the same data partitioning and input resolution for fair comparison.

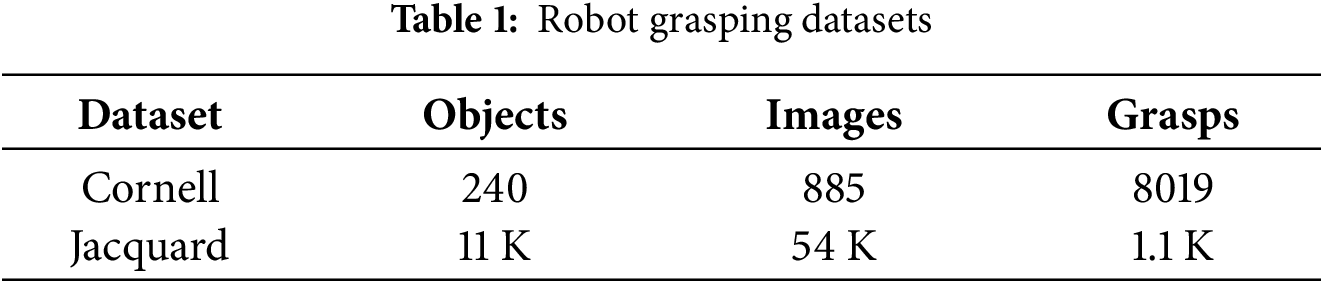

Table 1 presents the two datasets utilized for the training and evaluation of the proposed model. The first dataset is the Cornell Grasping dataset [49], which is renowned for its widespread utilization, comprising 885 RGB-D images and 240 distinct objects. The second is the recently released Jacquard Grasping Dataset [50], which includes 54 K RGB-D images and 11 K objects.

To alleviate overfitting of the smaller Cornell dataset, we applied data augmentation, including random rotation, random shrinkage, and random clipping. For the Jacquard dataset, standard normalization is adopted.

The test model in this paper is evaluated using the following metrics: Intersection over Union (IoU), detection speed, and the number of parameters. The definition of IoU is as follows Eq. (5):

We denote the grasp generated by the network as

(1) The angular difference between the grasp predicted by the network and the ground-truth grasp must be less than 30°;

(2) The IoU between the predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes must exceed 25%.

For loss calculation, this study uses the Smooth L1 Loss, which is also termed Huber loss, to quantify the disparity between the predicted confidence in heat map generation and the confidence in the ground truth. The following expression defines the loss function, where

4.5.1 Results of Neural Architecture Search

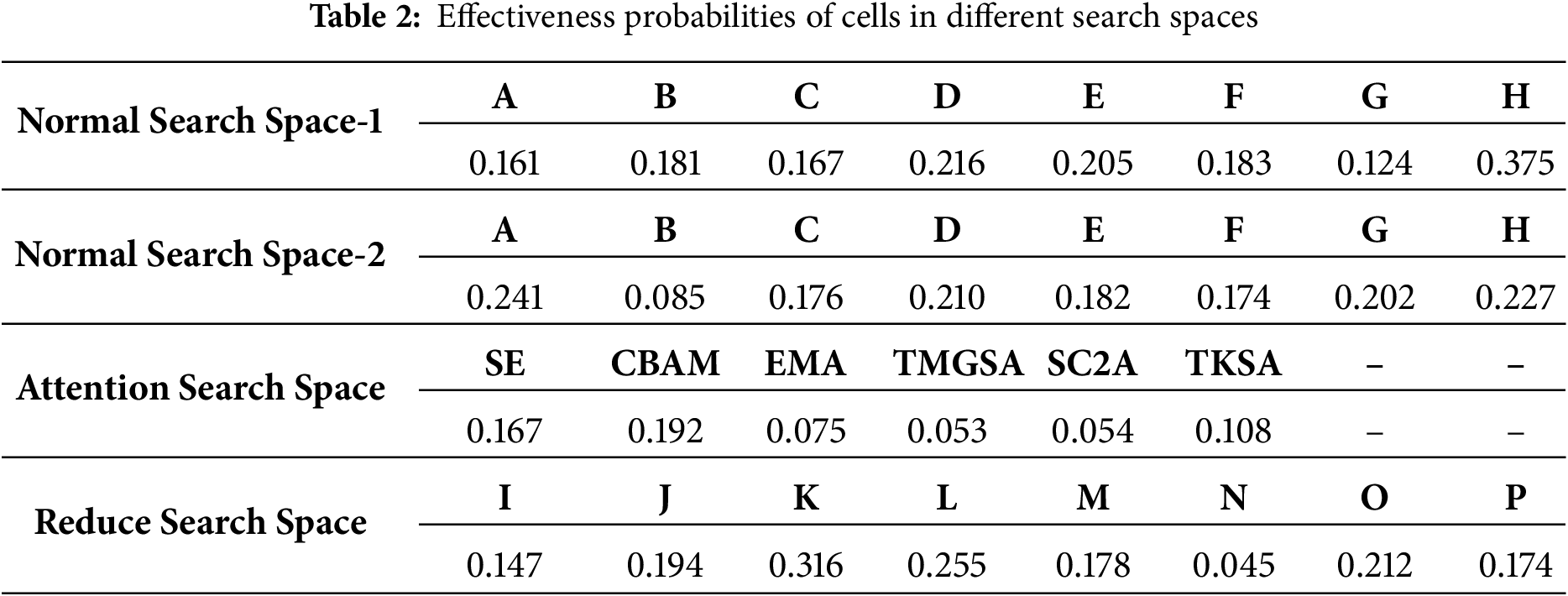

For the search phase, the total number of search iterations was set to 200, and for each search, we selected one Cell from the normal cell space, one from the attention cell space, and one from the reduction cell space, using the cell stacking method shown in Fig. 3. To expedite the search and enhance efficiency, the effectiveness probability for each cell was evaluated. The effectiveness probability refers to the frequency with which a cell appears in the best-performing networks. Here, we calculated the usage frequency of each Cell from the top 50 best-performing networks and used this to determine their relative usage proportions in all generated networks. This approach infers the selection probability of each cell; the resulting probabilities are presented in Table 2.

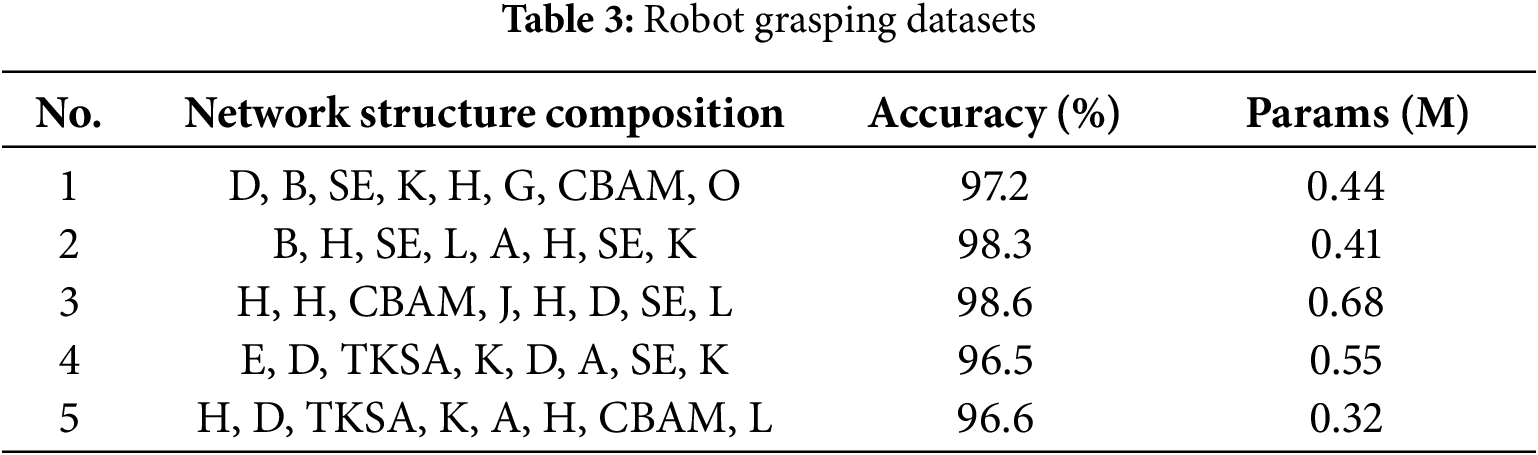

Specifically, the confidence scores for cells H, D, E, and B in the first two layers of Normal cells are 0.375, 0.216, 0.205, and 0.181, respectively. In the last two layers, cells A, H, D, and G demonstrate robust performance, achieving probabilities of 0.241, 0.227, 0.210, and 0.202, respectively. For the Attention cell, CBAM, SE, and TKSA modules exhibited effectiveness probabilities of 0.192, 0.167, and 0.108, highlighting their strong information selection flexibility. For the Reduce cell, cells K, L, O, and J show effectiveness probabilities of 0.316, 0.255, 0.212, and 0.194, demonstrating their importance in the network. Using these data, we selected the top 4 cells with the highest effectiveness probabilities in the Normal and Reduce cell search spaces, and the top 3 in the Attention cell search space, to form the optimized search space. Then, the 5 structures with the best overall performance were selected based on their effectiveness probabilities, and their performance was compared in detail. The comparison of performance is provided in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the 4th structure achieves the highest accuracy of 98.6%; however, it also exhibits the largest parameter count at 0.68 M. Although the 5th structure has the smallest number of parameters, its accuracy does not reach the optimal level. In contrast, the 2nd structure achieves an accuracy close to the best performance while maintaining a relatively small parameter size.

4.5.2 Results on the Cornell and Jacquard Dataset

All experimental results reported in this section are the mean ± standard (Mean ± Std.) deviation of three independent training and testing runs with different random seeds. This provides a measure of the variability and stability of our model’s performance.

Utilizing the sequence (B, H, SE, L, A, H, SE, K), we establish a detection network for capturing poses of the target. The efficacy of this network is assessed using the Cornell and Jacquard datasets. The feasibility of the proposed method was demonstrated by assessing the performance of the network across different object types and input modalities. The input modalities included unimodal inputs, such as depth (D) only and RGB only, as well as multimodal inputs, namely RGB-D. As indicated in Table 1, the Cornell dataset comprises substantially fewer samples than the Jacquard dataset. To mitigate potential overfitting, we applied data augmentation strategies on the Cornell dataset, including random rotation, scaling, and cropping. We used a cross-validation approach to comprehensively assess the model’s validity on the Cornell dataset. This approach divides the dataset into different subsets to enable repeated training and testing across these subsets.

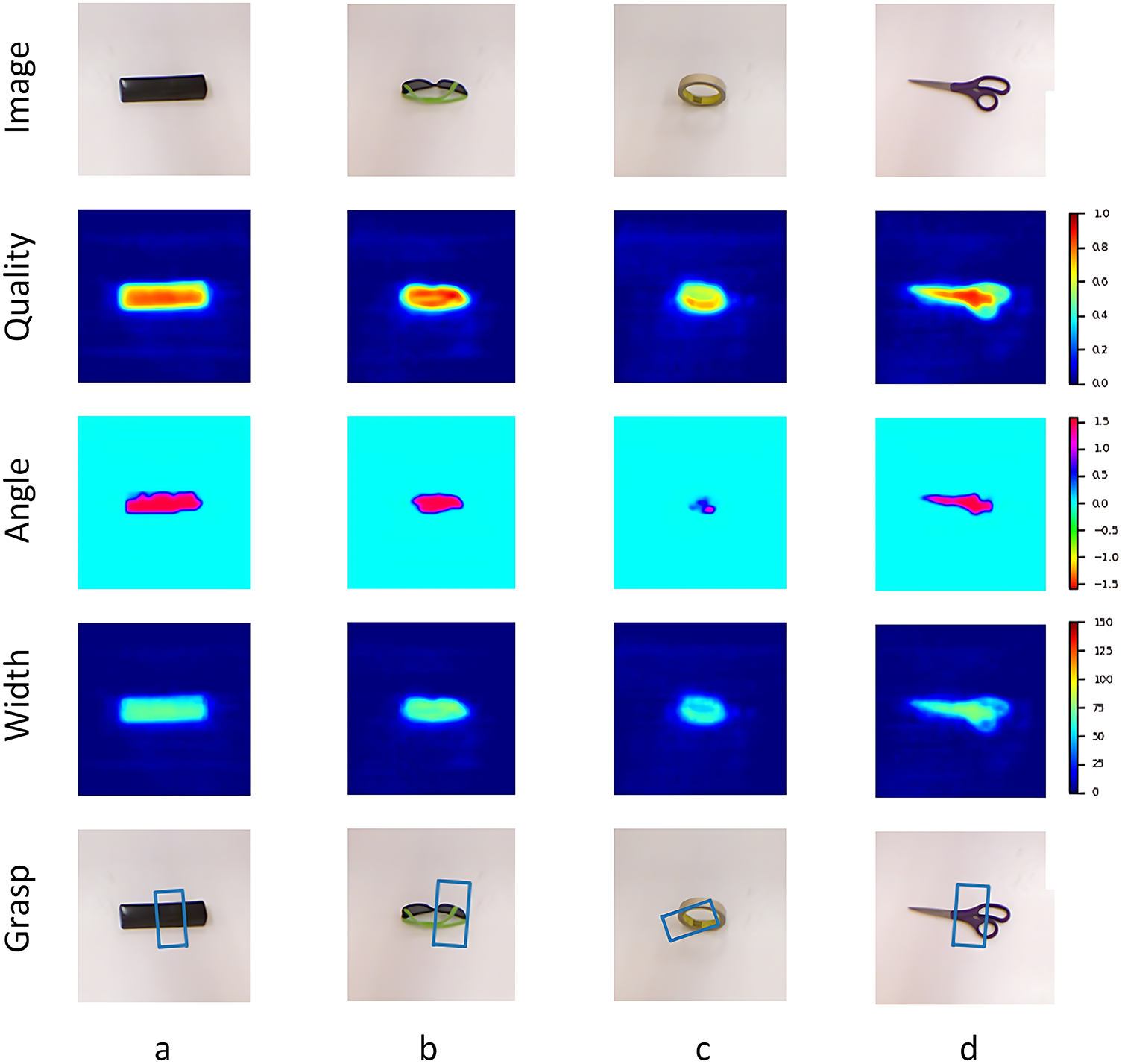

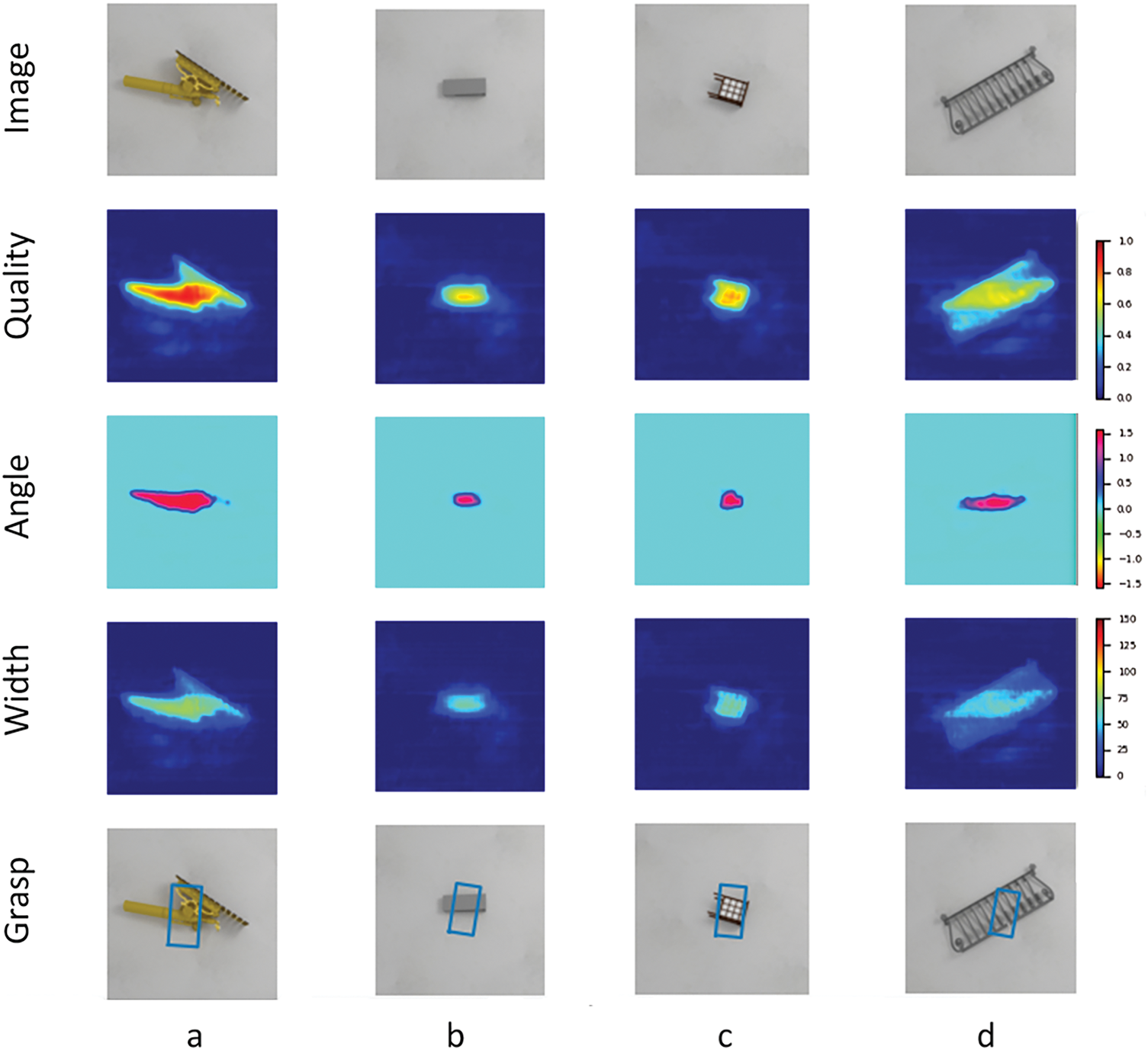

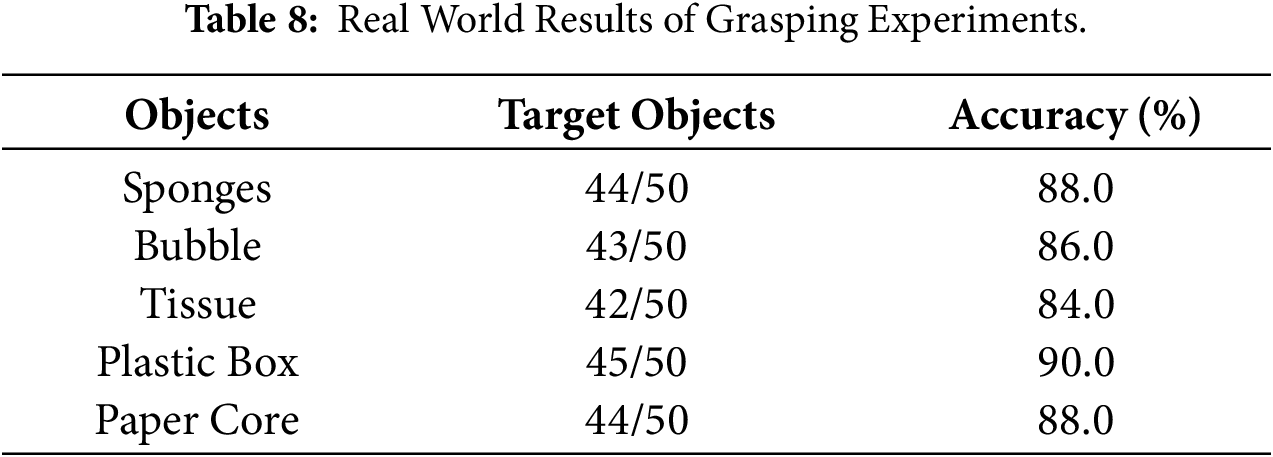

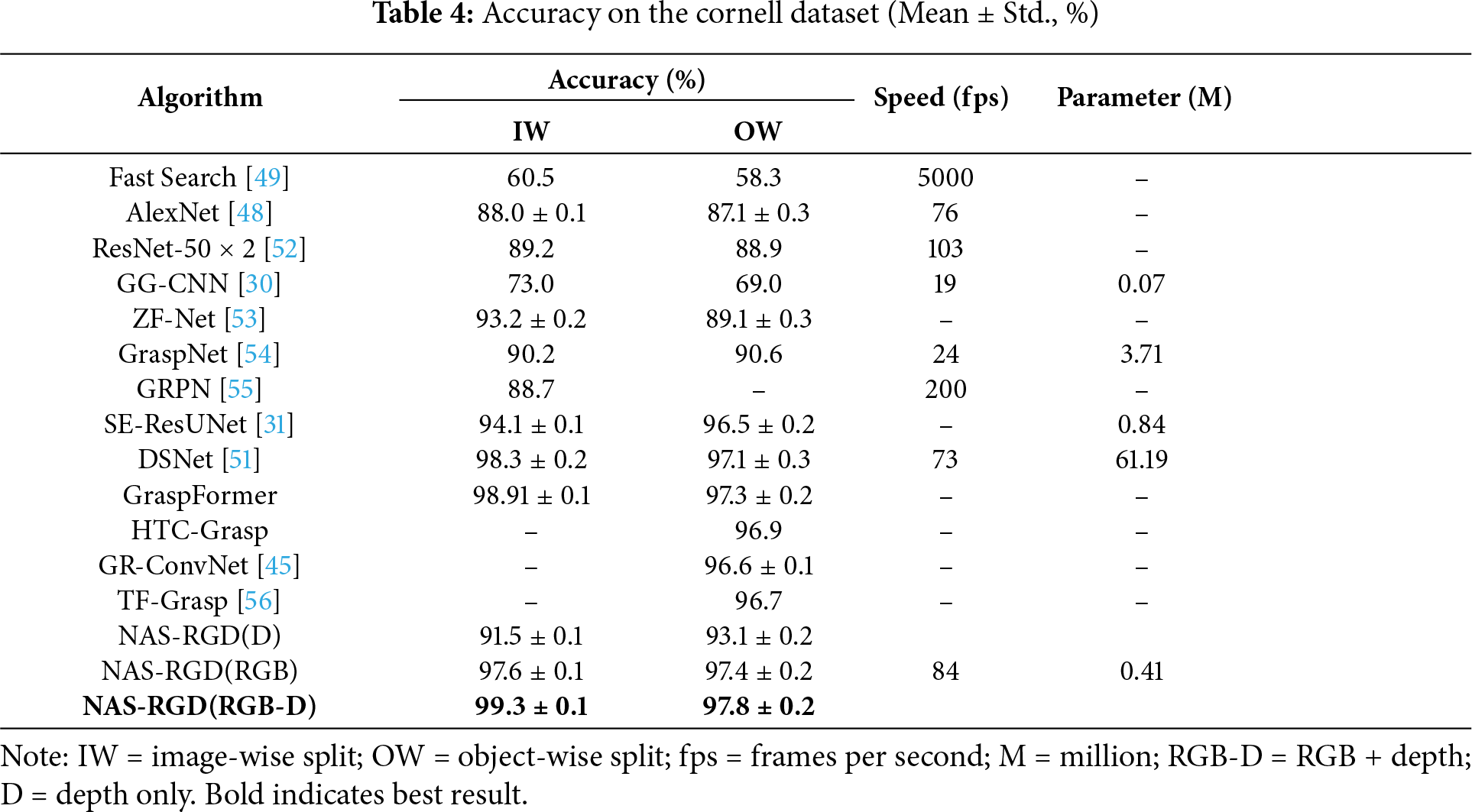

Table 4 presents the performance comparison of our system with other robotic grasp detection methods on the Cornell dataset under various input modalities. When using RGB-D inputs, our system achieved an image-level segmentation accuracy of 98.6% and an object-level segmentation accuracy of 95.8%, outperforming all other grasp detection methods listed in Table 4. Furthermore, it achieved a detection speed of 89 fps with only 0.41 M parameters, surpassing most existing grasp detection approaches. As shown in Tables 4 and 5, our search network demonstrates superior performance with multimodal data compared to unimodal data. Figs. 6 and 7 illustrate the qualitative results on the Cornell and Jacquard datasets, respectively.

Figure 6: Qualitative grasp detection results on Cornell dataset. (a) Input RGB-D. (b) Ground-truth grasp rectangle. (c) Predicted grasp (IoU = 0.92). (d) CAM heatmap overlaid on input. Red regions denote high activation. Best viewed in color and 300 dpi resolution

Figure 7: Figures (a,b) display the results on the Jacquard dataset. Left to right: RGB, depth, predicted grasp, CAM overlay

A paired t-test was conducted between our method and the strongest baseline (DSNet [51]) on the OW split accuracy over three runs. The result (p < 0.05) indicates that the performance improvement of our method is statistically significant.

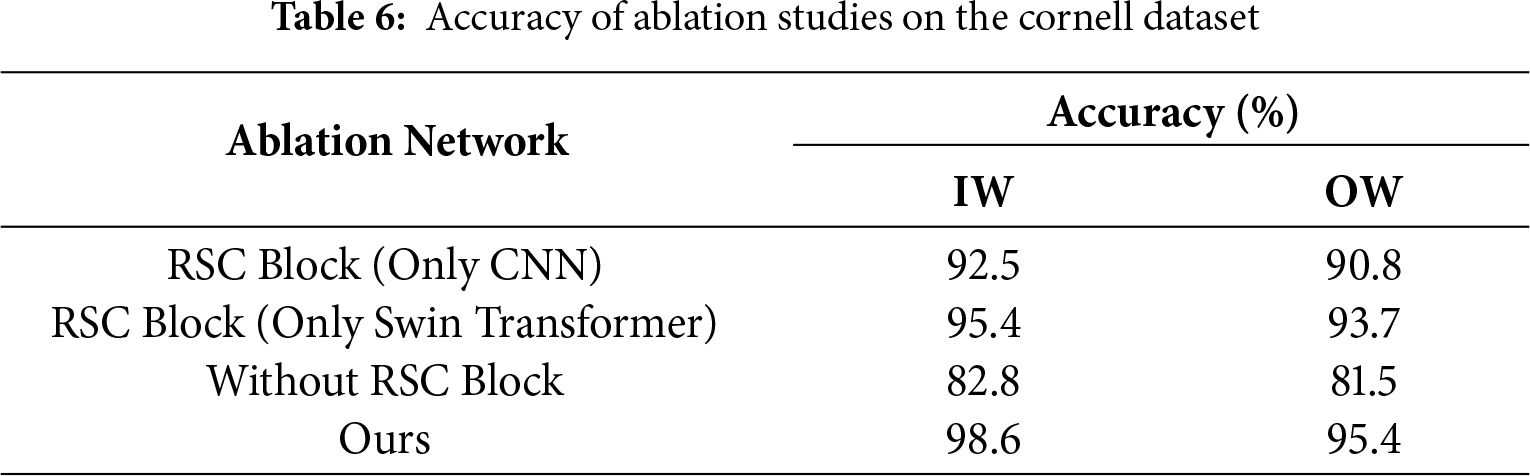

To assess the contributions of the RSC module and the hybrid network architecture, we performed a series of ablation experiments. We evaluated the performance on the Cornell dataset under four different conditions: constructing the RSC module using only CNNs, constructing the RSC module using only the Swin Transformer, removing all RSC modules, and retaining the original structure. All experiments were conducted under consistent conditions, using RGB-D inputs. As shown in Table 5, the model exhibited the worst performance when the RSC module was removed. This is because the RSC module leverages the complementary advantages of CNNs and the Swin Transformer, enabling effective extraction of local features while enhancing global contextual correlations, thus improving the model’s representation capability. Furthermore, when the RSC module was constructed using only CNNs or only the Swin Transformer, the model performance was moderate. However, when both components were combined, the model achieved the best performance.

4.5.4 Real World Grasping Experiments

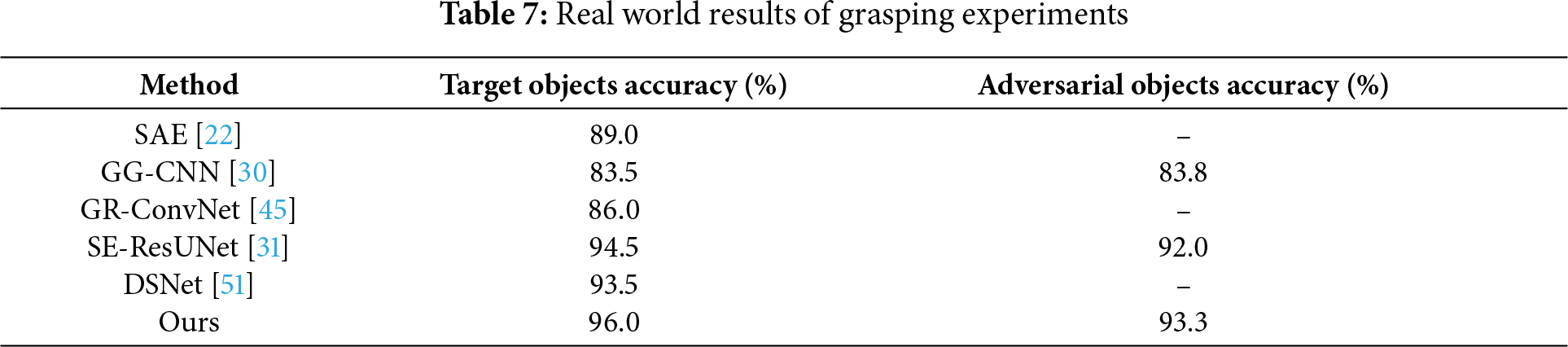

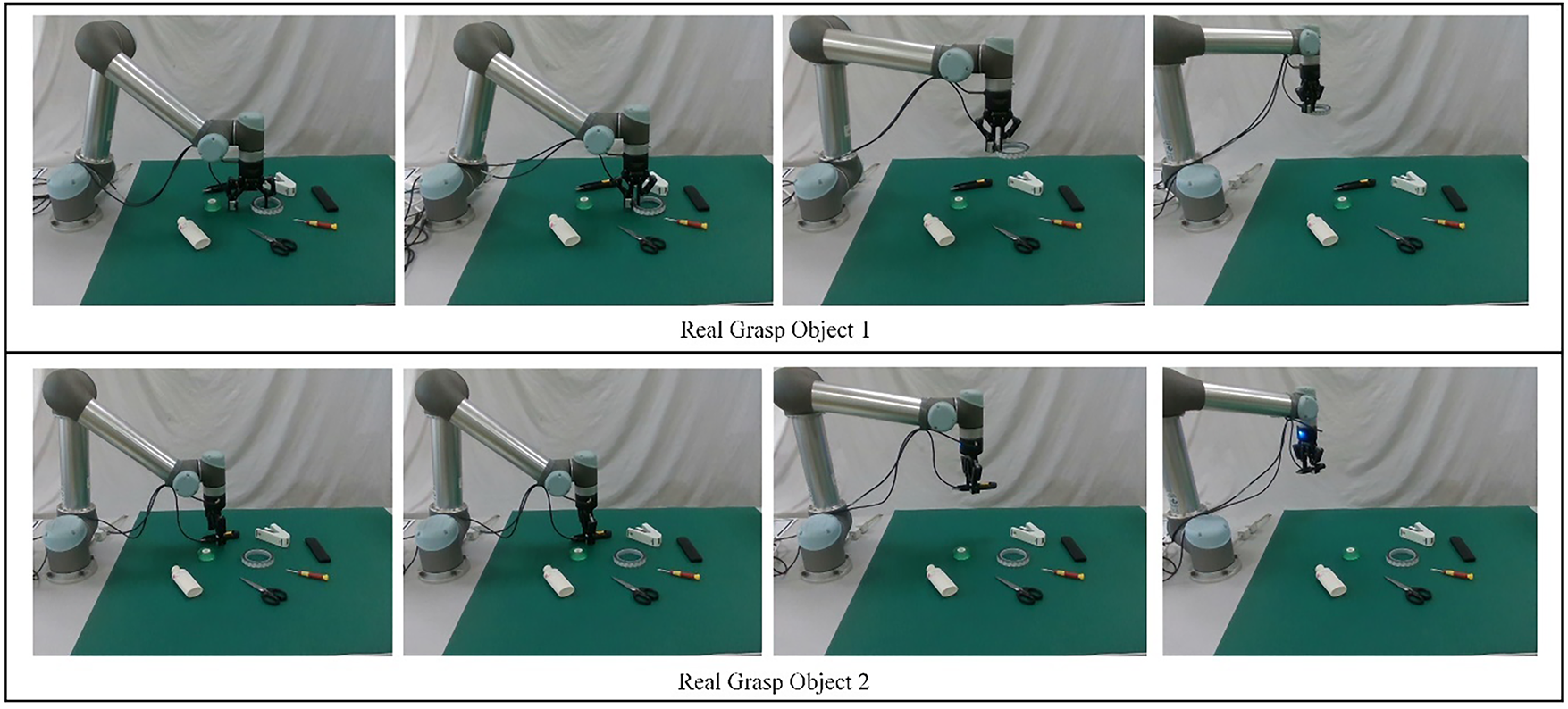

Beyond attaining high performance on two benchmark datasets, we further confirmed the efficacy of our system through real-world robotic grasping experiments. In the experiments, we employed a UR5 robotic arm and adopted an “eye-to-hand” configuration. The estimated grasping poses, including orientation information and grasp width, were transmitted to the robotic control center. Upon receiving the commands, the robotic arm first moved to a position 25 cm above the target object with the two-finger gripper fully open. It then adjusted the gripper’s orientation according to the estimated grasp pose, gradually approached the object, enclosed it within the gripper’s range, and progressively closed the gripper to complete the grasp. We conducted tests using 10 target objects and 3 distractor objects, each placed in 10 different positions and orientations. A total of 100 grasp attempts were made on the target objects, resulting in 96 successful grasps, corresponding to an accuracy of 96.0%. For the distractor objects, 30 grasp attempts were made with 28 successes, achieving an accuracy of 93.3%. Table 6 presents the comparative results between our method and other deep learning-based approaches in robotic grasping.

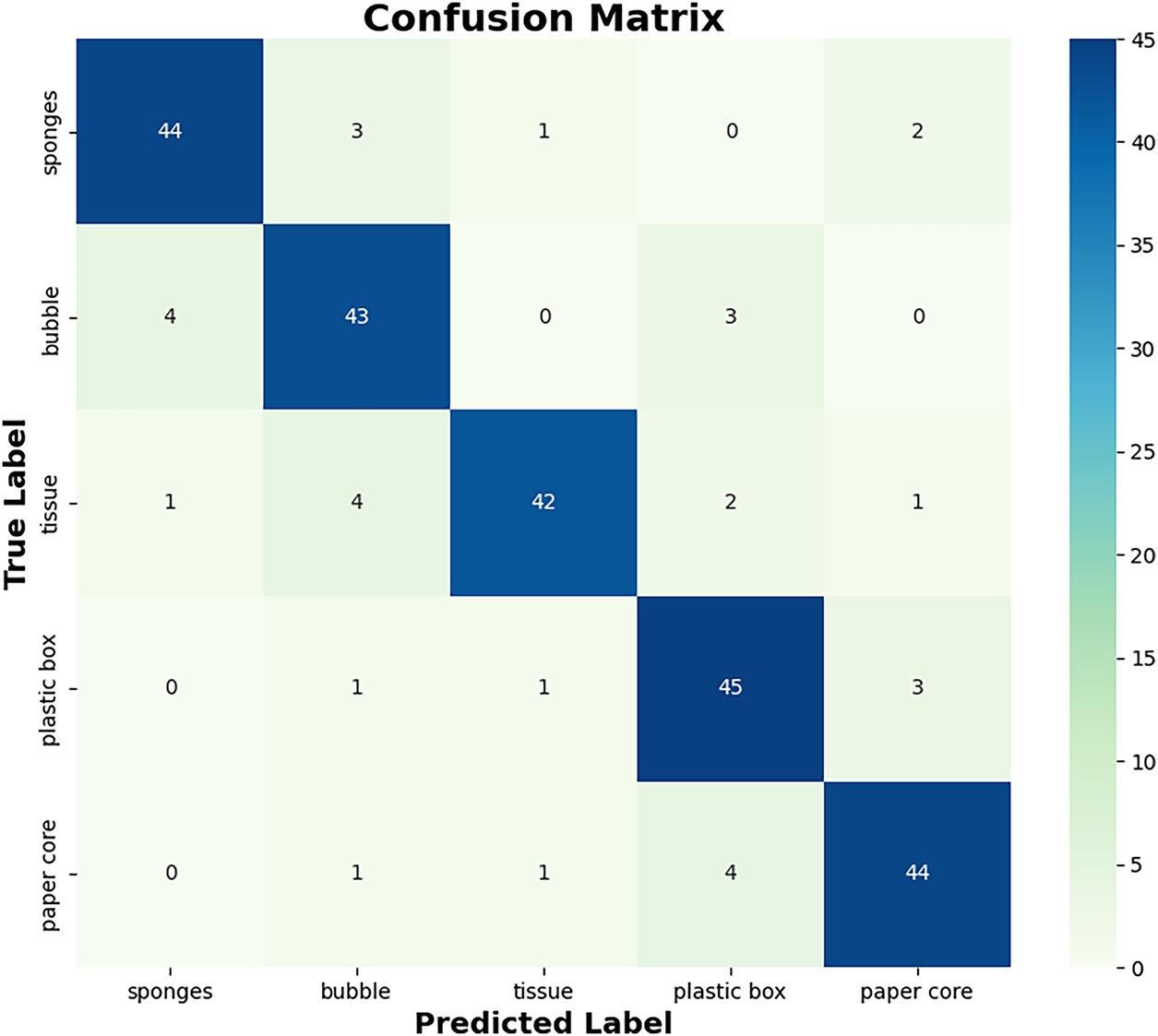

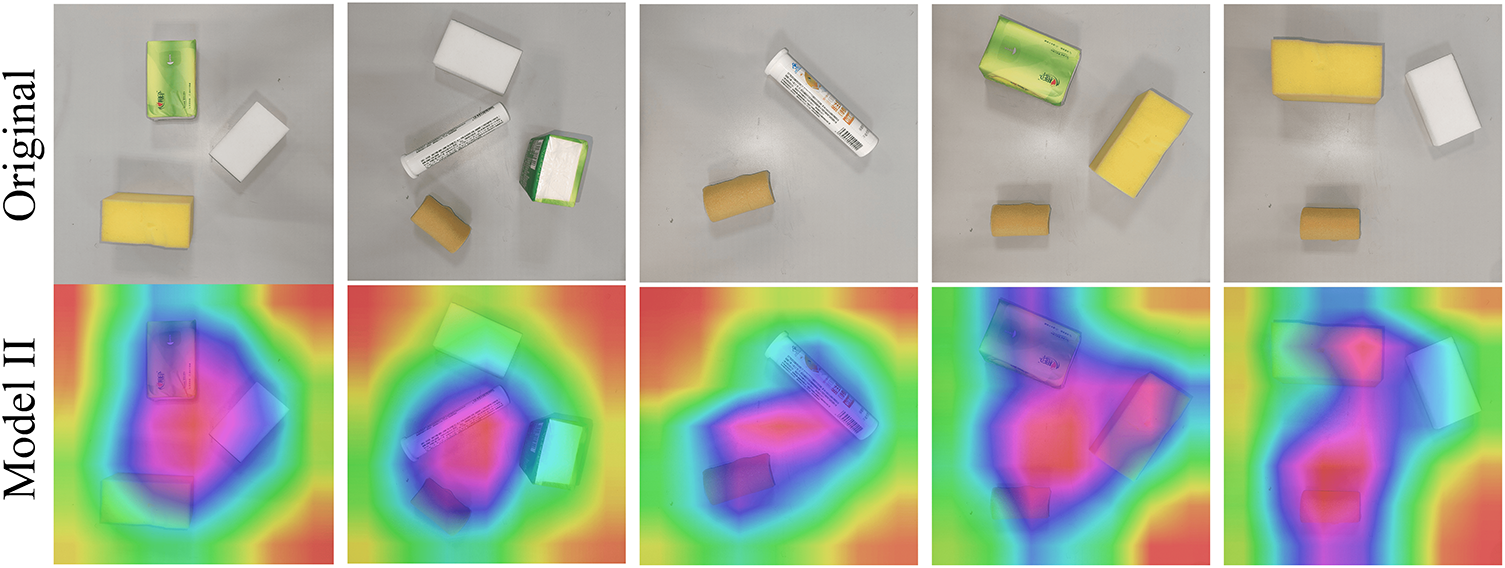

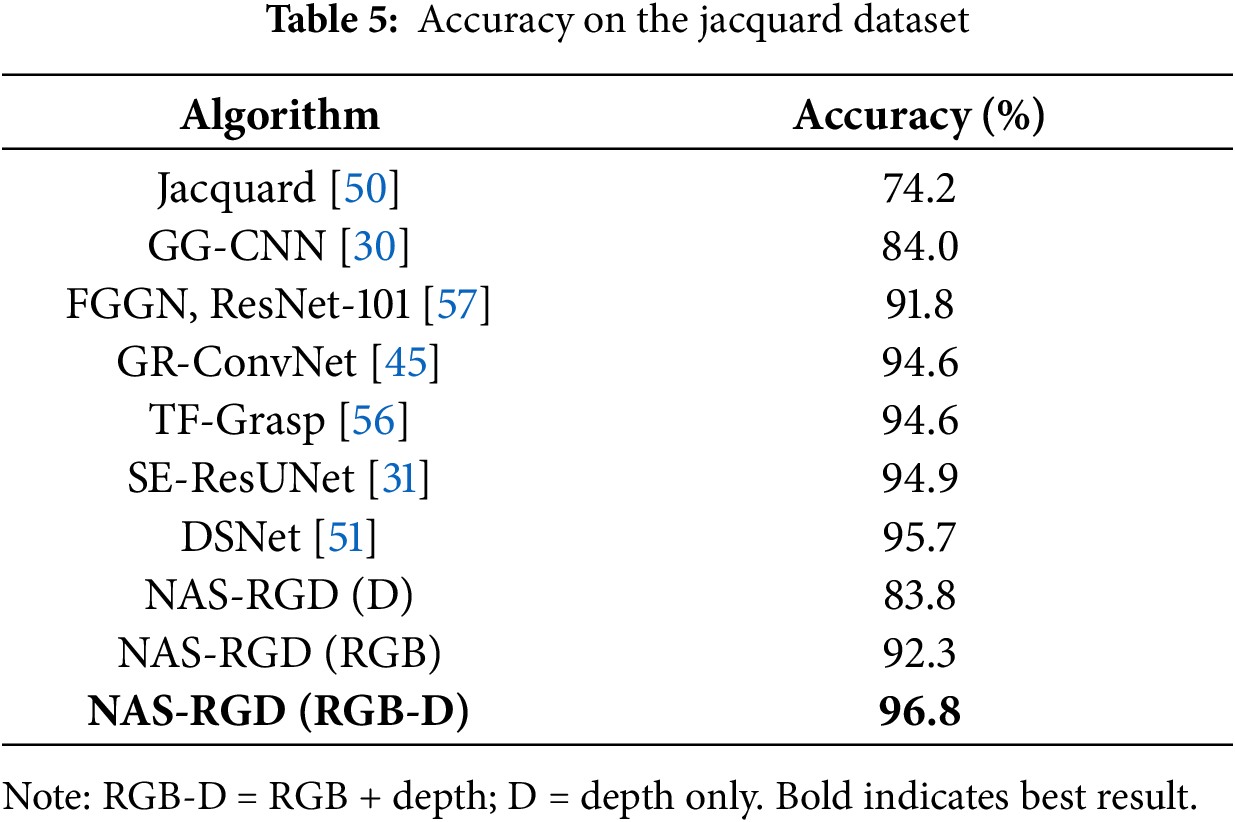

Furthermore, to assess the system’s generalization, we performed grasping tests on previously unseen objects. In this study, five categories of low-stiffness objects were selected, including sponges, bubbles, tissues, plastic boxes, and paper cores. These objects exhibit deformable characteristics, maintaining their shape only within a specific range of gripping force; exceeding a certain threshold results in deformation and eventual damage. Grasping tests were conducted at 10 different positions and orientations. The experimental results are summarized in Table 7. The standardized comparison in Table 7 demonstrates that our method achieves the highest success rate on target objects (96.0%) among all compared methods, while also maintaining a high success rate on adversarial objects (93.3%). This validates the robustness and practical superiority of our searched model in real-world physical grasping scenarios. Fig. 8 illustrates the scenarios of the UR5 robotic arm grasping low-stiffness objects, and Fig. 9 presents the confusion matrix for the five types of low-stiffness objects.

Figure 8: UR5 robotic arm grasping scenarios with low-stiffness objects. Left to right: RGB, depth, predicted grasp, CAM overlay

Figure 9: Confusion Matrix of the Five Types of Low-Stiffness Objects. Cell values = success count/total trials (10 per object). Color bar indicates accuracy (%)

4.5.5 Interpretability Analysis

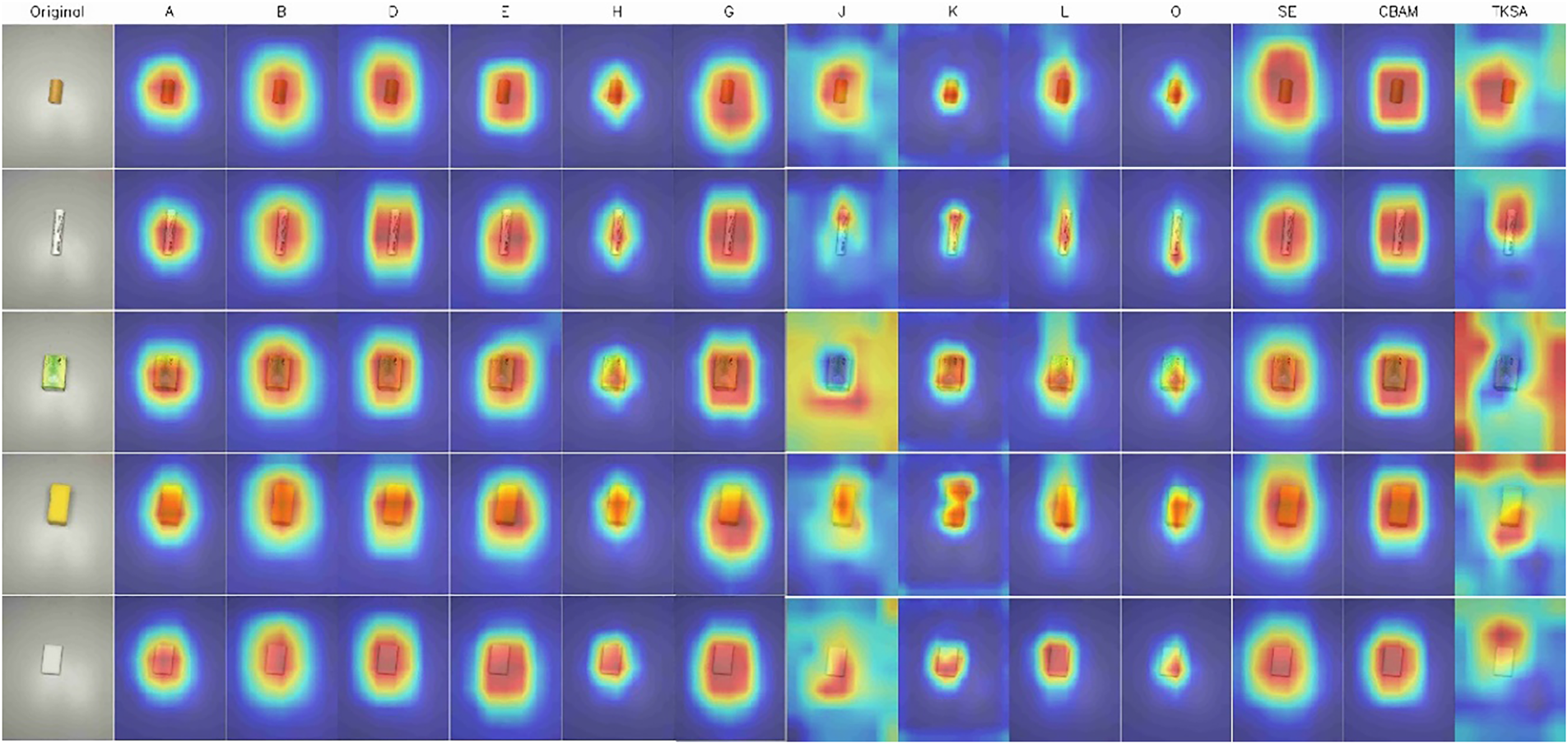

As previously stated, our search model demonstrates cutting-edge performance in accuracy and parametric efficiency, which is substantiated by practical robot grasping trials. However, in the field of computer vision, the internal operation of models often resembles a black box, with obscure behavioral logic. To accurately characterize the model’s feature representations and gain deeper insights into its internal mechanisms, we employed Class Activation Mapping (CAM) for in-depth analysis. This method intuitively highlights the regions where the model focuses during feature representation by generating heatmaps, thereby reflecting the model’s sensitivity to different object classes. Such analysis is crucial for enhancing model credibility, optimizing network architecture, and strengthening the reliability of practical applications. Fig. 10 shows the CAM results corresponding to the highly effective cells for the five types of low-stiffness objects. Darker red regions in the heatmaps indicate higher activation values, implying greater contributions from those regions to the network’s decision-making. It can be observed that the cells H, K, and SE exhibit more precise and concentrated receptive regions, indirectly explaining why these cells have the highest effectiveness probabilities and why the overall model achieves higher accuracy with fewer parameters. In contrast, for one of the low-stiffness objects, the tissue, there is evidence of insufficient feature perception in some cells, which helps explain the relatively lower grasping success rate observed during real-world experiments.

Figure 10: CAMs of Highly Effective Cells Corresponding to the Five Types of Low-Stiffness Objects. Hot color map: dark-red = highest contribution. Dashed circles highlight over- or under-activated regions that correlate with lower success

We designate the capture detection network developed using the architecture (B, H, SE, L, A, H, SE, K) as model II and generate its Class Activation Maps (CAMs) across various target categories. As shown in Fig. 11, Model II continues to focus on the sensitive regions of various objects, further validating the high effectiveness and credibility of our model.

Figure 11: CAMs of Model II on multiple object categories

Although the NAS framework proposed in this paper has achieved excellent performance on the Cornell and Jacquard datasets, it also has certain limitations. For instance, the recently proposed GoalGrasp framework [27] addresses the issue of grasping in partially occluded scenarios by leveraging three-dimensional spatial relationships. However, the method proposed in this paper relies on training data and may fail due to feature loss caused by occlusion.

Furthermore, Although the structure of NAS search performs well within the training distribution, the success rate of grasping decreases when dealing with new categories that differ significantly from the training data, such as flexible objects and transparent objects, for details, please refer to Table 8. Although the final model is lightweight, the NAS search stage still requires hundreds of trainings and evaluations, taking approximately 48 GPU-hours, which is not conducive to rapid deployment to new scenarios.

In future work, we will attempt to introduce unsupervised or self-supervised pre-training to enhance the generalization ability for unknown objects. At the same time, we will also use fine-grained interpretability tools such as (Attention Rollout, Integrated Gradients) to replace CAM and improve the interpretation accuracy.

In this study, we introduce a NAS-based method for adaptive robotic grasp detection. This method automatically designs a high-accuracy and lightweight robotic grasping detection network, effectively improving the success rate of robotic grasping while significantly reducing time costs. Our searched network achieved testing accuracies of 98.3% and 95.8% on the Cornell and Jacquard public datasets, respectively, with a detection rate of 89 fps and only 0.41 M parameters. By maintaining high accuracy (e.g., 98.6% on Cornell IW split) with substantially fewer parameters (0.41 M), our method demonstrates a favorable balance between performance and efficiency compared to existing robotic grasping detection methods. We further evaluated our model through real-world grasping experiments using the UR5 robotic arm, demonstrating its validity and robustness. Additionally, we utilize a CAM-based interpretability analysis to reveal the internal working mechanisms of the neural network, greatly enhancing the credibility of our searched model. In future work, we plan to extend and optimize the proposed NAS approach to facilitate more efficient discovery of high-performance network architectures and to apply it to increasingly complex scenarios.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023B1515120064) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (62273097).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Lu Rong and Manyu Xu; Methodology, Lu Rong, Manyu Xu and Wenbo Zhu; Software, Lu Rong and Zhihao Yang; Validation, Lu Rong, Manyu Xu, and Chao Dong; Formal analysis, Manyu Xu and Yunzhi Zhang; Investigation, Lu Rong and Zhihao Yang; Resources, Wenbo Zhu and Bing Zheng; Data curation, Lu Rong and Zhihao Yang; Writing—original draft preparation, Lu Rong and Manyu Xu; Writing—review and editing, Wenbo Zhu, Kai Wang, and Bing Zheng; Visualization, Zhihao Yang and Yunzhi Zhang; Supervision, Wenbo Zhu and Bing Zheng; Project administration, Wenbo Zhu and Chao Dong; Funding acquisition, Wenbo Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The Cornell Grasping Dataset used in this study is publicly available at https://www.selectdataset.com/dataset/e0a5b83251e7bc6fdf7bdafd538aa2eb (accessed on 28 July 2025). The Jacquard Grasping Dataset is publicly available at https://jacquard.liris.cnrs.fr/ (accessed on 28 July 2025). The specific code and model weights generated during this study are available from the corresponding author, Wenbo Zhu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All real-world robotic experiments were conducted in a controlled laboratory environment using commercially available objects. No human or animal subjects were involved, and thus no ethical approval was required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Elsken T, Metzen JH, Hutter F. Neural architecture search. In: Automated machine learning. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2019. p. 63–77. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05318-5_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jin C, Huang J, Wei T, Chen Y. Neural architecture search based on dual attention mechanism for image classification. Math Biosci Eng. 2023;20(2):2691–715. doi:10.3934/mbe.2023126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zoph B, Le QV. Neural architecture search with reinforcement learning. arXiv:161101578. 2016. [Google Scholar]

4. Wu J, Kuang H, Lu Q, Lin Z, Shi Q, Liu X, et al. M-FasterSeg: an efficient semantic segmentation network based on neural architecture search. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;113(4):104962. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rong X, Wang D, Hu Y, Zhu C, Chen K, Lu J. UL-UNAS: ultra-lightweight U-nets for real-time speech enhancement via network architecture search. arXiv: 2503.00340. 2025. [Google Scholar]

6. Vafeiadis A, van de Waterlaat N, Castel C, Defraene B, Daalderop G, Vogel S, et al. Ultra-low memory speech denoising using quantization-aware neural architecture search. In: 2024 IEEE 34th International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP 2024); 2024 Sep 22–25; London, UK. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/mlsp58920.2024.10734824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lee JH, Chang JH, Yang JM, Moon HG. NAS-TasNet: neural architecture search for time-domain speech separation. IEEE Access. 2022;10:56031–43. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3176003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Klyuchnikov N, Trofimov I, Artemova E, Salnikov M, Fedorov M, Filippov A, et al. NAS-bench-NLP: neural architecture search benchmark for natural language processing. IEEE Access. 2022;10(243):45736–47. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3169897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wan Q, Wu L, Yu Z. Dual-cell differentiable architecture search for language modeling. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2021;41(2):3985–92. doi:10.3233/jifs-210207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li C, Fan X, Zhang S, Yang Z, Wang M, Wang D, et al. DCNN search and accelerator co-design: improve the adaptability between NAS frameworks and embedded platforms. Integration. 2022;87(2):147–57. doi:10.1016/j.vlsi.2022.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lee J, Rhim J, Kang D, Ha S. SNAS: fast hardware-aware neural architecture search methodology. IEEE Trans Comput Aided Des Integr Circuits Syst. 2022;41(11):4826–36. doi:10.1109/TCAD.2021.3134843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Luo X, Liu D, Kong H, Huai S, Chen H, Liu W. LightNAS: on lightweight and scalable neural architecture search for embedded platforms. IEEE Trans Comput Aided Des Integr Circuits Syst. 2023;42(6):1784–97. doi:10.1109/TCAD.2022.3208187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li S, Mao Y, Zhang F, Wang D, Zhong G. DLW-NAS: differentiable light-weight neural architecture search. Cogn Comput. 2023;15(2):429–39. doi:10.1007/s12559-022-10046-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang XX, Chu XX, Fan YD, Zhang ZX, Wei XL, Yan JC, et al. ROME: robustifying memory-efficient NAS via topology disentanglement and gradient accumulation. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2023); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 5916–26. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cheng H, Wang Z, Ma L, Wei Z, Alsaadi FE, Liu X. Differentiable channel pruning guided via attention mechanism: a novel neural network pruning approach. Complex Intell Syst. 2023;9(5):5611–24. doi:10.1007/s40747-023-01022-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou B, Khosla A, Lapedriza A, Oliva A, Torralba A. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bicchi A, Kumar V. Robotic grasping and contact: a review. In: Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2000)—Millennium Conference; 2000 Apr 24–28; San Francisco, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2000. p. 348–53. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.2000.844081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ferrari C, Canny J. Planning optimal grasps. In: Proceedings of the 1992 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 1992); 1992 May 12–14; Nice, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 1992. p. 2290–5. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.1992.219918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sahbani A, El-Khoury S, Bidaud P. An overview of 3D object grasp synthesis algorithms. Robot Auton Syst. 2012;60(3):326–36. doi:10.1016/j.robot.2011.07.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bohg J, Morales A, Asfour T, Kragic D. Data-driven grasp synthesis—A survey. IEEE Trans Robot. 2014;30(2):289–309. doi:10.1109/TRO.2013.2289018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Du G, Wang K, Lian S, Zhao K. Vision-based robotic grasping from object localization, object pose estimation to grasp estimation for parallel grippers: a review. arXiv:1905.06658. 2019. [Google Scholar]

22. Lenz I, Lee H, Saxena A. Deep learning for detecting robotic grasps. Int J Robot Res. 2015;34(4–5):705–24. doi:10.1177/0278364914549607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Caldera S, Rassau A, Chai D. Review of deep learning methods in robotic grasp detection. Multimodal Technol Interact. 2018;2(3):57. doi:10.3390/mti2030057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang C, Xu D, Zhu Y, Martín-Martín R, Lu C, Li FF, et al. DenseFusion: 6D object pose estimation by iterative dense fusion. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019); 2019 Jun 15-20. Long Beach, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 3338–47. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2015;37(9):1904–16. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2015.2389824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chen LC, Papandreou G, Kokkinos I, Murphy K, Yuille AL. DeepLab: semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;40(4):834–48. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2017.2699184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gui S, Gui K, Luximon Y. GoalGrasp: grasping goals in partially occluded scenarios without grasp training. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2025;21(7):5160–70. doi:10.1109/TII.2025.3552653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Güney E, Bayılmış C, Çakar S, Erol E, Atmaca Ö. Autonomous control of shore robotic charging systems based on computer vision. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(6):122116. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Han C, Gao G, Zhang Y. Real-time small traffic sign detection with revised faster-RCNN. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(10):13263–78. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6428-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Morrison D, Corke P, Leitner J. Learning robust, real-time, reactive robotic grasping. Int J Robot Res. 2020;39(2–3):183–201. doi:10.1177/0278364919859066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yu S, Zhai DH, Xia Y, Wu H, Liao J. SE-ResUNet: a novel robotic grasp detection method. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2022;7(2):5238–45. doi:10.1109/LRA.2022.3145064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu X, Deng Z, Yang Y. Recent progress in semantic image segmentation. Artif Intell Rev. 2019;52(2):1089–106. doi:10.1007/s10462-018-9641-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Du Y, Zhou X, Huang T, Yang C. A hierarchical evolution of neural architecture search method based on state transition algorithm. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2023;14(8):2723–38. doi:10.1007/s13042-023-01794-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Dong J, Hou B, Feng L, Tang H, Tan KC, Ong YS. A cell-based fast memetic algorithm for automated convolutional neural architecture design. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(11):9040–53. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3155230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Liu H, Simonyan K, Yang Y. DARTS: differentiable architecture search. arXiv:1806.09055. 2018. [Google Scholar]

36. Jagadheesh S, Bhanu PV, Soumya J. NoC application mapping optimization using reinforcement learning. ACM Trans Des Autom Electron Syst. 2022;27(6):1–16. doi:10.1145/3510381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 9992–10002. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lin M, Chen Q, Yan S. Network in network. arXiv:1312.4400. 2013. [Google Scholar]

39. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2018); 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 7132–41. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Ferrari V, Hebert M, Sminchisescu C, Weiss Y, editors. Computer Vision—ECCV 2018. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2018. p. 3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Han K, Wang Y, Chen H, Chen X, Guo J, Liu Z, et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(1):87–110. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3152247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Chen X, Li H, Li M, Pan J. Learning a sparse transformer network for effective image deraining. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2023); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 5896–905. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ouyang D, He S, Zhang G, Luo M, Guo H, Zhan J, et al. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP 2023); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Rhodes Island; 2023. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10096516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kumra S, Joshi S, Sahin F. Antipodal robotic grasping using generative residual convolutional neural network. In: 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2020); 2020 Oct 24–Nov 24; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 9626–33. doi:10.1109/iros45743.2020.9340777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Szegedy C, Liu W, Jia Y, Sermanet P, Reed S, Anguelov D, et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2015); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

48. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60(6):84–90. doi:10.1145/3065386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Jiang Y, Moseson S, Saxena A. Efficient grasping from RGBD images: learning using a new rectangle representation. In: 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2011); 2011 May 9–13; Shanghai, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2011. p. 3304–11. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2011.5980145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Depierre A, Dellandréa E, Chen L. Jacquard: a large scale dataset for robotic grasp detection. In: 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2018); 2018 Oct 1–5; Madrid, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 3511–6. doi:10.1109/IROS.2018.8593950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang Y, Qin X, Dong T, Li Y, Song H, Liu Y, et al. DSNet: double strand robotic grasp detection network based on cross attention. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024;9(5):4702–9. doi:10.1109/LRA.2024.3381091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kumra S, Kanan C. Robotic grasp detection using deep convolutional neural networks. In: 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2017); 2017 Sep 24–28; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 769–76. doi:10.1109/IROS.2017.8202237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Guo D, Sun F, Liu H, Kong T, Fang B, Xi N. A hybrid deep architecture for robotic grasp detection. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2017); 2017 May 29–Jun 3; Singapore. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 1609–14. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2017.7989191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Asif U, Tang J, Harrer S. GraspNet: an efficient convolutional neural network for real-time grasp detection for low-powered devices. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2018); 2018 Jul 13–19; Stockholm, Sweden. Menlo Park, CA, USA: International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization (IJCAI Org.); 2018. p. 4875–82. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2018/677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Karaoguz H, Jensfelt P. Object detection approach for robot grasp detection. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2019); 2019 May 20–24; Montreal, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 4953–9. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2019.8793751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Wang S, Zhou Z, Kan Z. When transformer meets robotic grasping: exploits context for efficient grasp detection. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2022;7(3):8170–7. doi:10.1109/LRA.2022.3187261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zhou X, Lan X, Zhang H, Tian Z, Zhang Y, Zheng N. Fully convolutional grasp detection network with oriented anchor box. In: 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2018); 2018 Oct 1–5; Madrid, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 7223–30. doi:10.1109/IROS.2018.8594116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools