Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Heterogeneous User Authentication and Key Establishment Protocol for Client-Server Environment

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Chongqing, 400065, China

2 School of Cyber Security and Information Law, Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Chongqing, 400065, China

3 Faculty of Computer and Software Engineering, Huaiyin Institute of Technology, Huai’an, 233003, China

* Corresponding Author: Fei Tang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Privacy-Enhancing Technologies for Secure Data Cooperation and Circulation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 23 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073550

Received 20 September 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The ubiquitous adoption of mobile devices as essential platforms for sensitive data transmission has heightened the demand for secure client-server communication. Although various authentication and key agreement protocols have been developed, current approaches are constrained by homogeneous cryptosystem frameworks, namely public key infrastructure (PKI), identity-based cryptography (IBC), or certificateless cryptography (CLC), each presenting limitations in client-server architectures. Specifically, PKI incurs certificate management overhead, IBC introduces key escrow risks, and CLC encounters cross-system interoperability challenges. To overcome these shortcomings, this study introduces a heterogeneous signcryption-based authentication and key agreement protocol that synergistically integrates IBC for client operations (eliminating PKI’s certificate dependency) with CLC for server implementation (mitigating IBC’s key escrow issue while preserving efficiency). Rigorous security analysis under the mBR (modified Bellare-Rogaway) model confirms the protocol’s resistance to adaptive chosen-ciphertext attacks. Quantitative comparisons demonstrate that the proposed protocol achieves 10.08%–71.34% lower communication overhead than existing schemes across multiple security levels (80-, 112-, and 128-bit) compared to existing protocols.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of Internet technologies, the client-server architecture has become a cornerstone of modern information systems [1]. It finds extensive application in mission-critical domains such as the Internet of Things (IoT) [2], wireless body area networks (WBANs) [3], and industrial control systems (ICS) [4]. However, the inherent openness and heterogeneity of this architecture introduce significant security challenges to data transmission. These challenges manifest as vulnerabilities to man-in-the-middle attacks, data tampering, and privacy breaches [5], particularly in lightweight IoT communications and critical WBAN medical data transmissions where security failures can have dire consequences [6]. To mitigate these risks and ensure confidentiality, integrity, and non-repudiation, authentication and key establishment (AKE) protocols are widely employed to establish trusted identities and negotiate secure session keys [7].

Current research has yielded numerous AKE protocols based on elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) [8], public key infrastructure (PKI) [9], identity-based cryptography (IBC) [10], and certificateless cryptography (CLC) [11]. However, existing solutions still face critical bottlenecks in adapting to heterogeneous environments, which can be framed as two core conflicts.

Efficiency vs. Resource Constraints. Traditional security protocols, such as those based on Diffie-Hellman (DH) key exchange, often require multiple rounds of interaction, leading to significant communication and computational overhead. In resource-constrained environments like IoT terminals or WBAN devices, this high overhead can degrade real-time performance and drastically shorten device lifespan due to excessive energy consumption. This creates a fundamental conflict between achieving robust security and maintaining the operational viability of lightweight devices.

Architectural Trade-Offs in Heterogeneous Trust Models. A second, more nuanced conflict arises from the architectural trade-offs between different cryptographic systems. On one hand, resource-limited clients are best served by lightweight systems like IBC, which eliminates the prohibitive certificate management overhead of traditional PKI. On the other hand, servers demand robust security without single points of failure. The inherent key escrow vulnerability of IBC, where a key generation center (KGC) knows all client private keys, is an unacceptable risk for a trusted server. While CLC mitigates this key escrow problem, existing protocols predominantly adopt a single, homogeneous system. This approach fails to address the conflicting requirements of clients (who need simplicity) and servers (who need security without escrow), creating a critical need for innovative heterogeneous designs that can harmonize these competing demands.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a signcryption-based heterogeneous user authentication and key establishment protocol (HUAKE). Signcryption, a cryptographic primitive that integrates digital signatures and encryption within a single logical step, provides confidentiality, integrity, non-repudiation, and authentication for sensitive data. By leveraging signcryption, the HUAKE protocol reduces communication rounds while enhancing security. In this protocol, clients adopt IBC, where public keys are directly derived from unique identifiers (e.g., device IDs), eliminating certificate management burdens. Servers adopt CLC, where partial private keys are generated by the KGC and combined with server-specific secret values to form complete private keys. This hybrid approach circumvents IBC’s key escrow risks while avoiding reliance on PKI’s complex certificate chains.

Furthermore, HUAKE integrates identity authentication, key agreement, and data encryption into 1.5 communication rounds through signcryption, significantly reducing interaction complexity and communication overhead. Theoretical analysis and experimental results demonstrate that HUAKE ensures resistance to forgery, replay, key compromise impersonation (KCI) attacks, while achieving superior communication efficiency compared to existing schemes. This makes HUAKE particularly suitable for lightweight secure interactions between resource-constrained devices (e.g., IoT) and servers in client-server environments.

The contributions of this work are fourfold.

• We construct a novel HUAKE protocol based on signcryption, in which IBC-based clients resolve public key certificate management issues, while CLC-based servers simultaneously address certificate management and key escrow risks.

• We formally demonstrate the security of our protocol by mBR model. Security proof revealed that the proposed protocol enables user authentication, key authentication, key establishment, mutual authentication. Moreover, it can also resist forgery, replay, and KCI attacks.

• We demonstrate how HUAKE transitions from a key transport mechanism to a DH-based construction, offering flexibility in AKE protocol design.

• Comparative evaluations against five protocols confirm that HUAKE achieves the lowest communication overhead, making it a practical solution for secure communications in client-server environments.

We characterize the existing literature in Section 2. In the next Section, we focus on the preliminaries. We describe the security model of this protocol in Section 4. In Section 5, we describe our protocol. Then, we illustrate security and performance in sections 6 and 7. Finally, we make a conclusion of the paper.

Public key cryptosystems are broadly categorized into three types based on their authentication mechanisms: PKI, IBC, and CLC [12]. PKI [13] relies on a Certificate Authority (CA) to bind public keys to identities, but the associated certificate management overhead makes it cumbersome for resource-constrained mobile environments. To address this, Shamir introduced IBC [10], which simplifies key management by deriving public keys from identity strings. However, IBC introduces the key escrow problem, as a central private key generator (PKG) knows all users’ private keys. CLC [11] was later proposed to resolve both issues; it eliminates PKI’s complex certificates and mitigates IBC’s key escrow risk by having users contribute a secret value to their full private key, making it well-suited for large-scale networks.

Numerous AKE protocols have been developed for mobile client-server (MCS) environments. However, many early schemes were proven to be vulnerable to security threats like reflection, parallel session, and tracking attacks [14,15]. Other works have explored symmetric encryption techniques [16] or CLC-based multi-server authentication [17], but often lacked a heterogeneous design or incurred significant communication overhead [18].

More recent research has continued to refine AKE protocols. For instance, Qiu et al. [19] proposed a lightweight ECC-based protocol, which was nevertheless found vulnerable during its password update phase. Other schemes have focused on achieving anonymity [20] or provable security against specific threats like KCI attacks [21]. A critical limitation of many of these advanced protocols, including those by Tsobdjou et al. [22] and Rana et al. [23], is their operation within homogeneous environments. While some heterogeneous protocols exist, such as the IBC-to-PKI scheme by Li et al. [24], they do not fully solve the certificate management problem due to their reliance on a PKI-based server. Most recently, Daniel et al. [25] developed a pairing-free ID-AKE protocol with strong security in the enhanced eCK security model, while Ma et al. [26] improved a CL-AKE protocol by Cheng et al. [27] to achieve perfect forward secrecy and reduce computational overhead. While significant, these state-of-the-art solutions do not address the specific challenge of creating a secure, efficient, and truly certificateless heterogeneous link between an IBC-based client and a CLC-based server. Recently, the field of heterogeneous signcryption authentication has seen a surge in research targeting specific application scenarios. For example, Khalafalla et al. [28] designed a cross-domain mutual authentication scheme for Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs) that combines CLC and IBC, leveraging blockchain technology for decentralized trust management. Another work [29] enhances the security of a heterogeneous CLC-PKI scheme by introducing a cryptographic reverse firewall to prevent data leakage.

In this paragraph, we describe the network model, threat model and security goals, bilinear pairings as well as syntax, respectively.

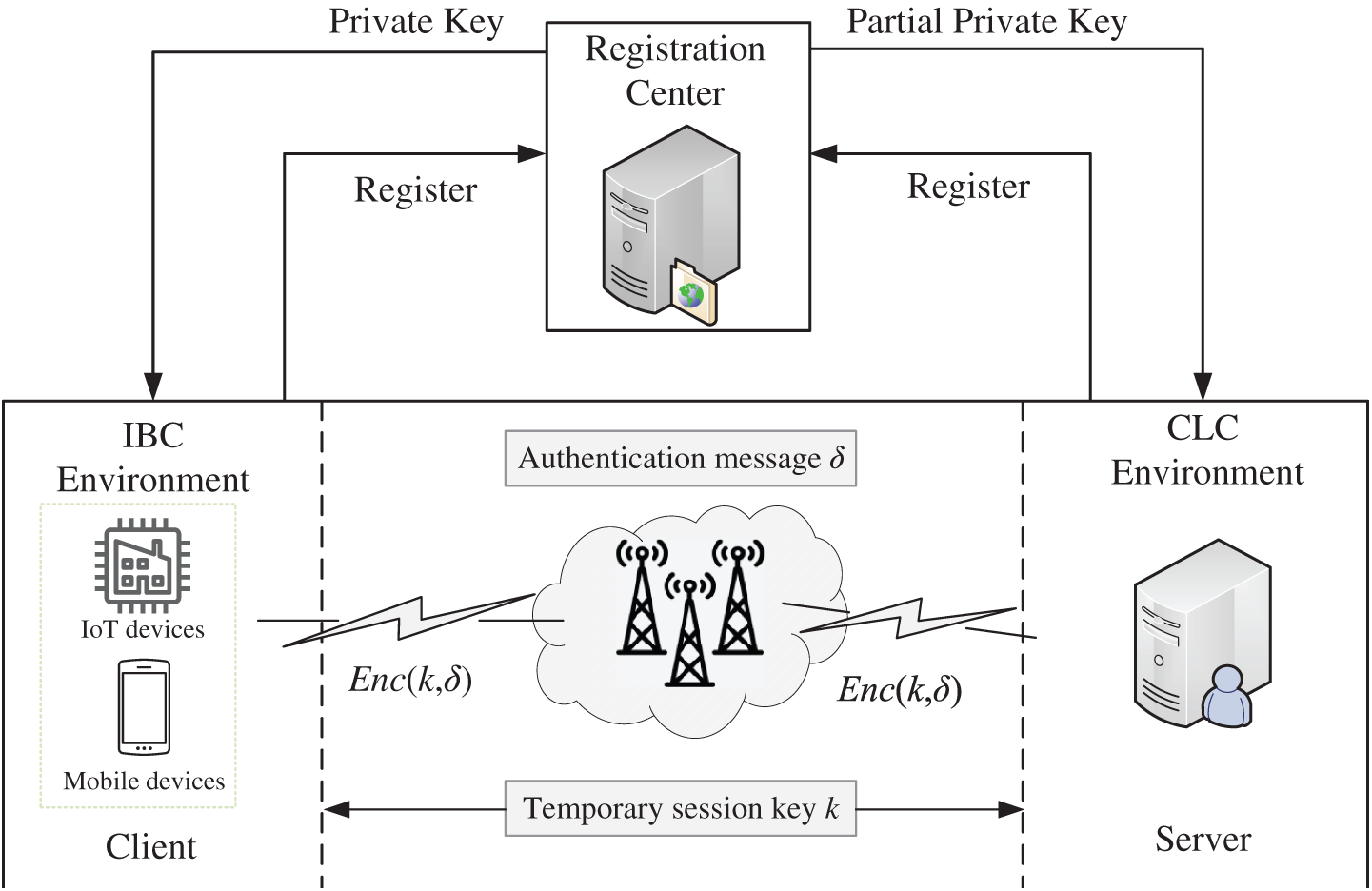

The client-server network architecture supported by our proposed protocol, as depicted in Fig. 1, consists of three core entities: a Registration Center (RC), a server, and multiple clients such as industrial IoT devices. Within this framework, clients and servers interact through wired or wireless communication channels. The RC functions as the central trusted authority, playing a dual role within this heterogeneous framework. For the IBC-based clients, it acts as a PKG, creating their full private keys. For the CLC-based servers, it acts as a KGC, responsible for generating their partial private keys. Beyond key generation, the RC assumes the critical responsibility of managing the credential lifecycle and security. To handle cases where a client’s private key is compromised before its expiration date, the RC maintains and periodically publishes a digitally signed Revocation List (RL). This list contains the unique identifiers of all invalidated credentials, serving as an authoritative source for the server to verify a client’s real-time status. While the RC is inherently trusted due to its custody of client private keys, a distributed RC architecture could optionally be implemented to alleviate key escrow concerns. To initiate communication with a server, the client and server first undergo a registration process with the RC. Subsequently, the client transmits an authenticated message to the target server, which then verifies the client’s legitimacy. Upon successful authentication, both parties engage in ephemeral session key negotiation to establish secure communication.

Figure 1: Network model

Assume the existence of two groups

We now demonstrate security concepts for the HUAKE protocol.

Definition 1: Upon receiving groups

• The computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) problem in

• The gap Diffie-Hellman (GDH) problem in

• The bilinear computational Diffie-Hellman (BDH) problem in

• The decisional bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) problem in

• The gap bilinear Diffie-Hellman (GBDH) problem in

The main security goals achieved in this paper are as follows.

– Forgery Attack: No attacker can establish communication with a client disguised as a legitimate server.

– Replay Attack: This means that adversaries cannot send previous authentication messages to the server for authentication.

– Key Compromise Impersonation Attack: An attacker who has compromised the client

– Session Key Security: In this context, we must ensure that adversaries cannot recover the session key from the information transmitted on public channels.

The syntax of our protocol includes the below seven algorithms.

System Initialization: This phase is executed by RC. It takes a security parameter

Identity-Based-Key-Extraction (IB-KE): This happens in IBC environment. This phase is carried out by RC to create a public/private pair (

Partial-Private-Key-Extract (PPKE): This phase happens in CLC environment. This phase is carried out by RC to generate a partial private key

Set-Secret-Value (SSV): A user with an identity

Set-Private-Key (SPK): This phase is executed by a user with

Public-Key-Extract (PKE): This phase is executed by a user with system parameters and

Key-Establishment: The two communicating parties complete the authentication and key establishment functions according to this protocol. Finally, a common temporary security session key

Our HUAKE protocol is constructed using signcryption technology. The security of a signcryption scheme primarily requires demonstrating the confidentiality of the message and its unforgeability. Therefore, our proof methodology is based on standard signcryption security proofs. However, as our protocol is designed for authenticated key agreement, we have adapted the proof logic by referencing the model in [30] to fit the context of a key agreement protocol. The security proof is modeled as a game between a challenger

The adversary

IB-KE

Create

PKE

PPKE

Corrupt

PKR

Send(

Reveal

Test

Definition 2: Matching conversation: Two oracles

Definition 3: Fresh oracle: We say an oracle

The adversary may repeat all queries besides Test query, but these queries are limited by the three conditions. It cannot make a Reveal query on

Finally,

Definition 4: A user authentication key establishment protocol may be considered secure if it satisfies the tow requirements. 1) In the existence of a passive attacker on

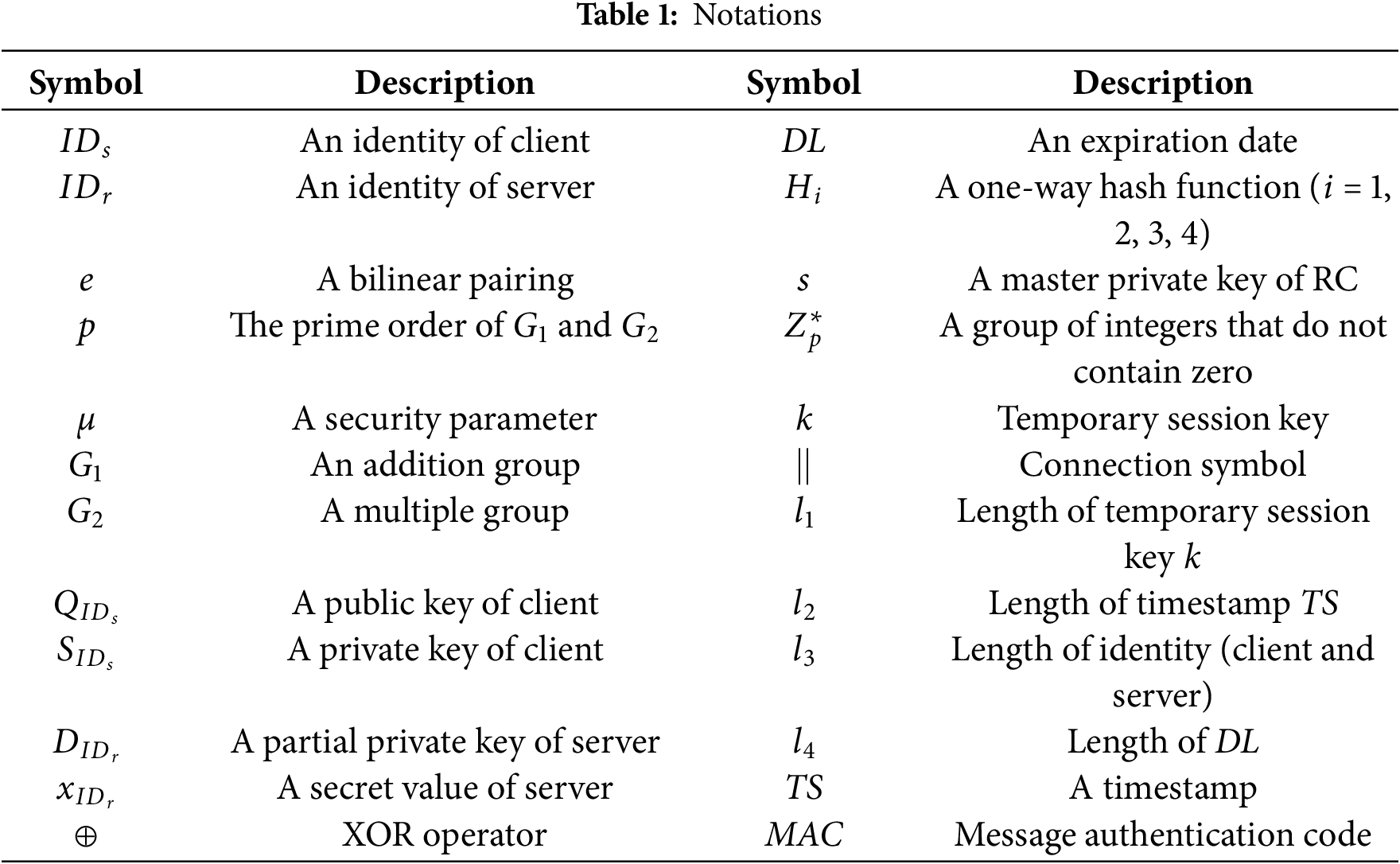

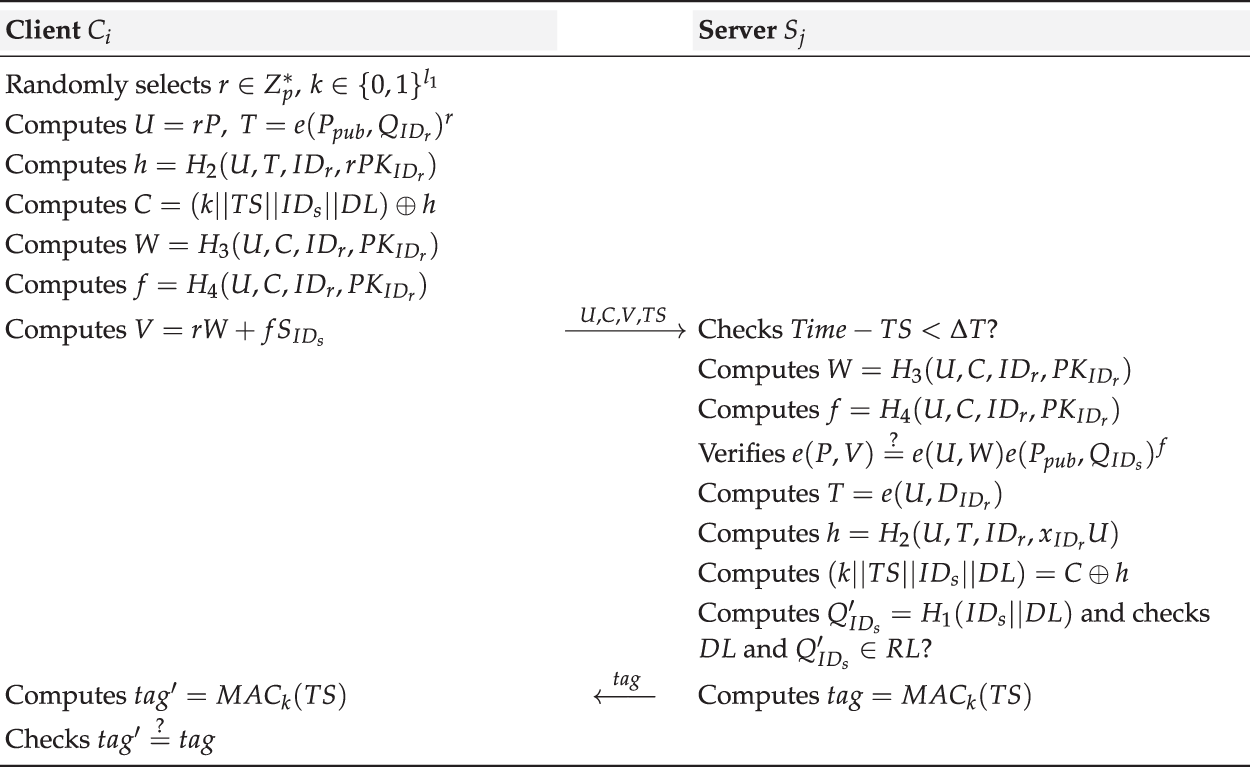

We mainly introduce an efficient HUAKE protocol for a client-server environment in this segment. The following four algorithms show the detailed construction of this protocol. Table 1 explains the main notations.

System Initialization: A security parameter

Both clients and the server need to complete registration on RC before they communicate with each other.

• IB-KE: A client

• PPKE: A server

• SSV: A server

• SPK: Given a secret value

• PKE: Given a secret value

5.3 User Authentication and Key Establishment Phase

In the following steps, both the encryption and signature components share a common random number

1) Randomly selects

2) Computes

3) Computes

4) Computes

5) Computes

6) Computes

7) Computes

When

1) Computes

2) Computes

3) Checks if

4) Computes

5) Computes

6) Recovers the temporary session key

At this point,

Figure 2: User authentication and key establishment process

We commonly use two methods to establish a temporary session key. The first method is Differ-Hellman key exchange protocol where both

Real-time certificate queries, such as the online certificate status protocol (OCSP), add a synchronous network round-trip to each authentication, which degrades the performance of lightweight protocols. To implement a near-real-time key revocation mechanism, the RC maintains a dynamically updated Revocation List (RL), which is digitally signed with its master key. This list records all client credentials that have been confirmed as compromised or are otherwise invalidated.

To avoid imposing a burden on resource-constrained clients, the responsibility for fetching and verifying revocation status is entirely shifted to the more powerful server. The server actively and asynchronously polls the RC at a configurable, fixed interval (e.g., every few minutes, depending on the specific application scenario) to fetch the latest signed RL and caches it locally. When processing a client’s authentication request, the server first validates the client’s signature. Following successful signature validation, the server proceeds to decrypt the authentication message, recovering the session key

While this mechanism introduces additional communication overhead, this cost is primarily borne by the server for its periodic communication with the RC and does not add latency to the client authentication handshake. This trade-off is deemed acceptable, as the server typically possesses a more stable network connection and greater processing power.

We know

The security proof of our HUAKE protocol follows the standard methodology for signcryption schemes, which primarily involves proving confidentiality and unforgeability. However, since our protocol is designed for authenticated key establishment, we have adapted the proof logic from the standard model to fit the context of a key agreement protocol. We use

Lemma 1: There exists a begin adversary on

This Lemma aims ensuring that in the absence of an active adversary, both parties will always agree on the same, uniformly random session key.

Proof of Lemma 1: In this HUAKE protocol, suppose that two participants

Lemma 2: If there exists a PPT adversary

This Lemma establishes the confidentiality of the session key

Proof of Lemma 2: In this proof, we demonstrate how

Initial:

In this game,

IB-KE

Create

PKE

PPKE

Corrupt

PKR

Send

An oracle can be in one of several states: Accepted: Oracle accepts a session key after receiving the appropriate messages. Rejected: In the absence of a session key, an oracle will reject this protocol run and abort it.

(1) When

(2) When

(3) When

Reveal

Test

The success of this simulation is contingent on the challenger

Lemma 3: If there exists a PPT adversary

This lemma establishes the unforgeability of the protocol message against a Type I adversary. It proves that no Type I adversary can forge a valid authentication message without solving the GDH problem, thus ensuring message integrity and authenticity.

Proof of Lemma 3: Initial:

The probability of an adversary guessing correctly by a non-negligible advantage is related to the following events. 1) E1:

Clearly, Pr[

Lemma 4: If there exists a PPT adversary

Proof of Lemma 4: Initial:

This lemma completes the unforgeability proof by addressing the Type II adversary. It demonstrates that even a malicious KGC cannot forge a valid message without solving the CDH problem, thus securing the protocol against insider threats.

In this game,

Create

PKE

Corrupt

The probability of an adversary guessing correctly by a non-negligible advantage is related to the following events. 1) E1:

It is obvious that Pr[

6.3 Informal Security Analysis

The security requirements met by the HUAKE protocol are as follows.

• Forgery Attack: This type of attack means that an adversary can masquerade as a legitimate server. If the adversary is

• Replay Attack: Our protocol can resist replay attacks by taking a timestamp. When

• Key Compromise Impersonation Attack: We consider a scenario where an adversary compromises the client’s long-term private key

• Session Key Security: The attacker wants to recover session keys from the information exchanged on public data and communication channels. In this paper, the session key

It is important to note that the HUAKE protocol, in its current form as a key transport scheme, does not provide forward secrecy. A compromise of the server’s long-term keys would allow an adversary to decrypt previously captured sessions.

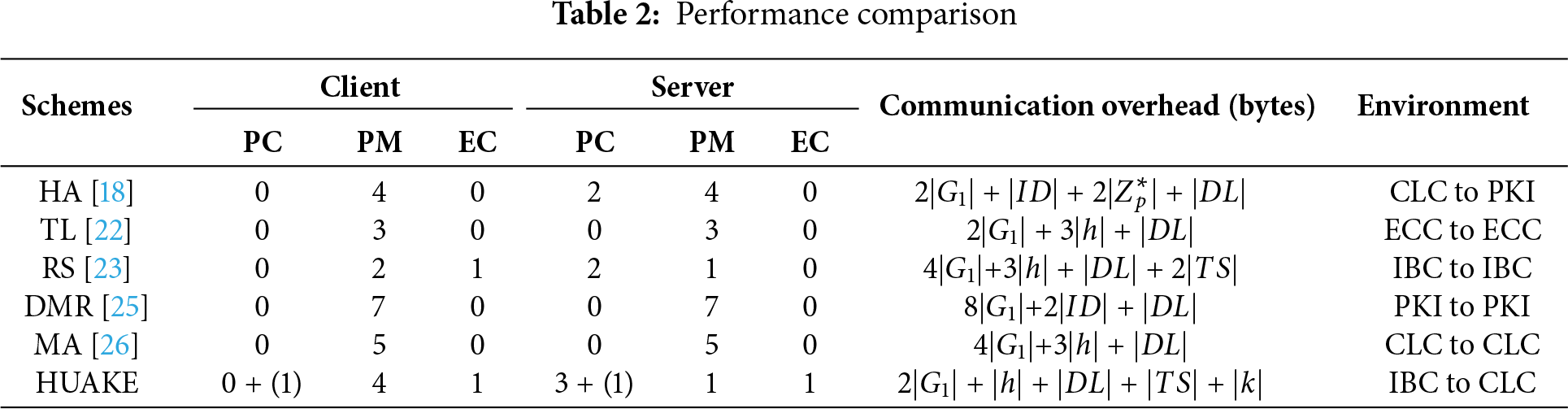

In this section, we evaluate the performance of our proposed HUAKE protocol against five existing protocols: HA [18], TL [22], RS [23], DMR [25], and MA [26]. The evaluation focuses on computational and communication overheads. Table 2 summarizes the theoretical cryptographic operations for each scheme. The notation PC signifies a bilinear pairing operation, PM denotes a point multiplication operation on

To empirically assess the computational overhead, we utilized the JPBC library, which is a widely adopted standard for prototyping and benchmarking pairing-based protocols. We selected Type A pairings for our tests due to their noted computational efficiency, making them a suitable choice for evaluating performance in resource-aware environments. The pairing is built on the elliptic curve

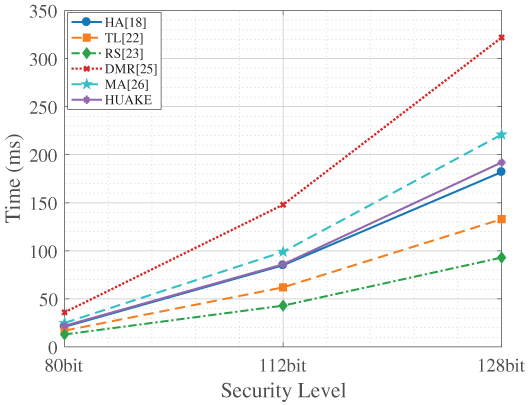

Client-side computational overhead is detailed in Fig. 3. While our protocol’s client-side computation is slightly higher than the lightweight homogeneous schemes TL [22] and RS [23], it remains highly competitive and often superior to other schemes like DMR [25]. More importantly, this moderate computational cost at the client facilitates a crucial advantage: our protocol’s heterogeneous architecture. This allows resource-constrained clients operating in an IBC environment to securely interact with servers in a CLC environment, a flexibility not offered by the purely homogeneous schemes. The slight increase in client-side operations is a well-justified trade-off for this enhanced interoperability and practicality in diverse real-world scenarios.

Figure 3: Computational time of the client for each scheme [18,22, 23,25,26]

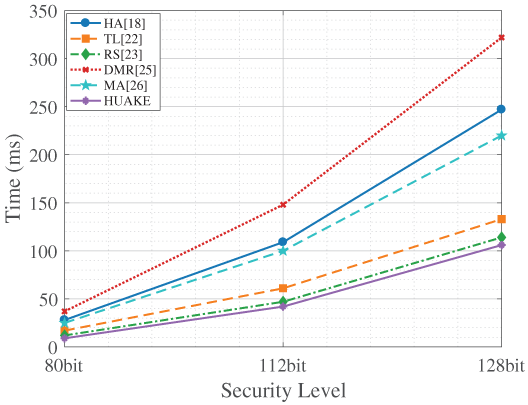

Fig. 4 illustrates the server-side computational overhead. Here, our protocol demonstrates a distinct and significant advantage. Across all tested security levels, Ours consistently exhibits the lowest computational time on the server. This superior server-side efficiency becomes even more pronounced at higher security levels. While server resources are generally more abundant, this notable efficiency contributes to reduced operational costs and better scalability for service providers.

Figure 4: Computational time of the server for each scheme [18,22, 23,25,26]

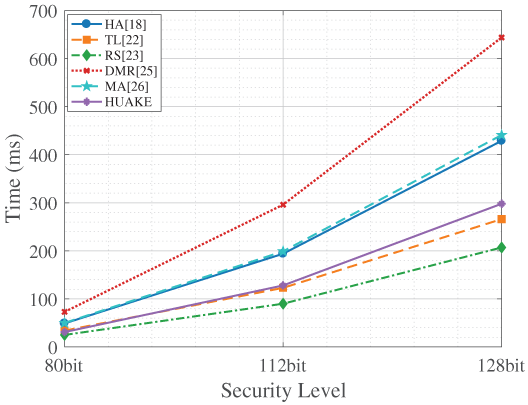

When considering the total computational overhead (client + server), as shown in Fig. 5, our protocol achieves an excellent balance. Ours is demonstrably more efficient in total computation time than HA [18], DMR [25], and MA [26] across all security levels. While the total time for TL [22] and RS [23] can be marginally lower in some instances, these schemes do not offer the heterogeneous environment support that is a core strength of our protocol.

Figure 5: Total computational time for each scheme [18,22,23,25,26]

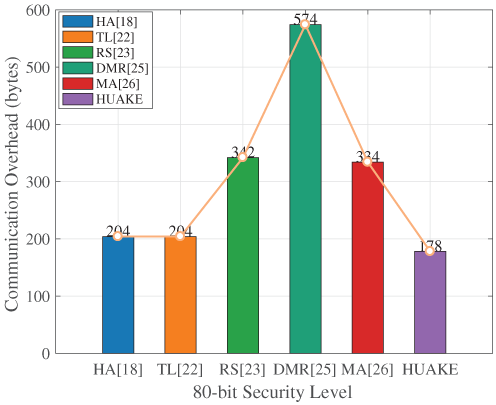

The efficiency of data transmission is paramount, especially for resource-constrained devices. We analyzed the communication overhead of all six protocols, with the following parameters.

Figure 6: Total communication over head with 80-bit security [18,22,23,25,26]

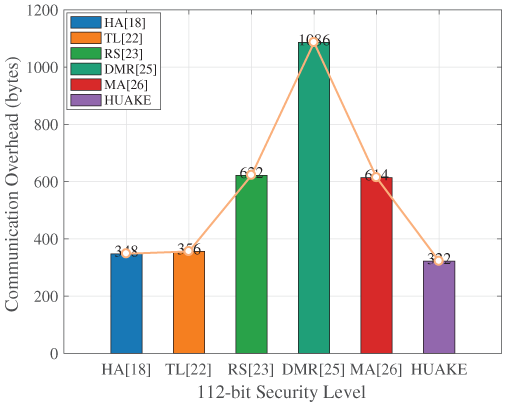

Figure 7: Total communication over head with 112-bit security [18,22,23,25,26]

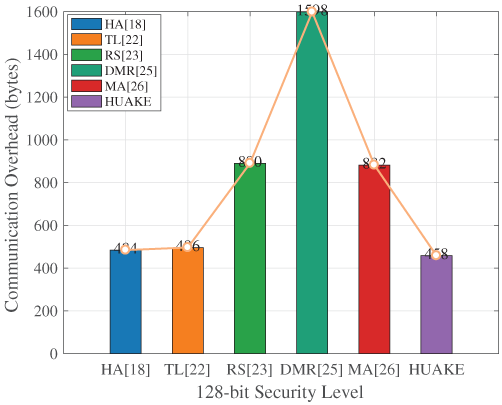

Figure 8: Total communication overhead with 128-bit security [18,22,23,25,26]

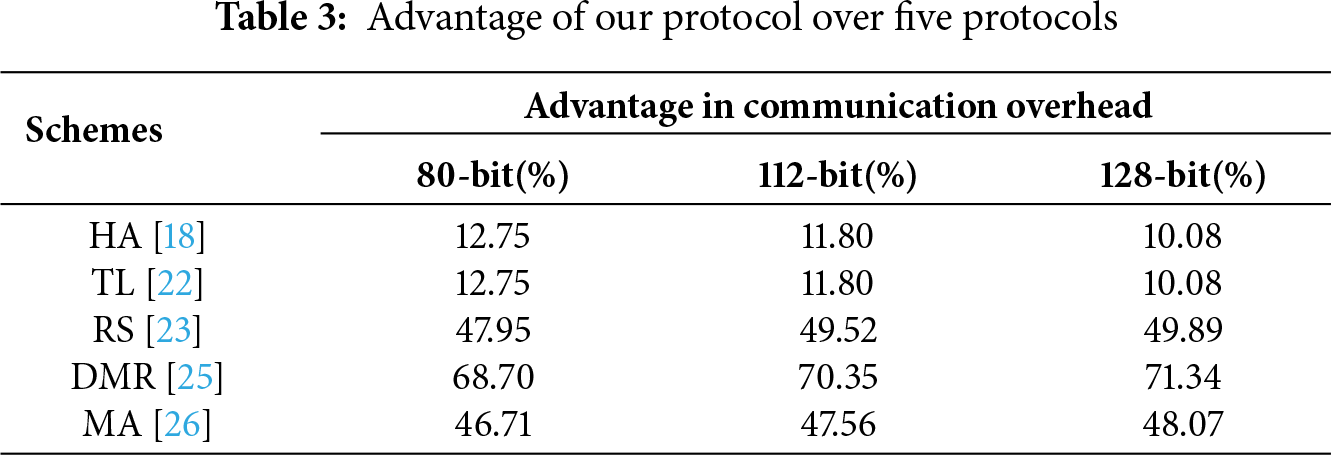

A consistent and striking observation from Figs. 6–8 is that our protocol unequivocally achieves the lowest communication overhead across all evaluated security levels. This superior performance is not marginal but represents a substantial improvement over the compared schemes.

For instance, at the 80-bit security level in Fig. 6, our protocol’s communication cost is significantly lower than all other protocols. Even compared to HA [18] and TL [22], which are relatively efficient, our scheme offers a notable reduction. The advantage becomes even more pronounced when compared to RS [23], MA [26], and particularly DMR [25]. This trend of superior communication efficiency continues and is often amplified at higher security settings. As seen in Figs. 7 and 8, while the absolute communication costs increase for all protocols to ensure stronger security, our protocol maintains its leading position with the smallest data transmission size. The percentage reduction in communication overhead offered by our protocol is substantial, as detailed in Table 3. Our scheme consistently cuts down data transfer by a significant margin compared to HA [18], TL [22], RS [23], MA [26], and especially DMR [25], with advantages often exceeding

This pronounced efficiency in communication overhead is a key advantage of our protocol. By minimizing the amount of data exchanged, Our scheme significantly reduces bandwidth consumption, latency, and energy usage on client devices. This makes our protocol exceptionally well-suited for deployment in bandwidth-sensitive and power-constrained environments, such as mobile networks, IoT ecosystems, and other scenarios where efficient communication is critical. The empirical data strongly supports the theoretical communication cost analysis presented in Table 2, confirming our protocol’s design for optimal communication performance.

7.3 Discussion on Practical Application Scenarios

While its client-side computational overhead is not the lowest, this protocol’s extremely low communication overhead makes it a superior choice in environments where communication is the dominant cost, such as battery-reliant IoT devices on low-power wide-area networks (LPWAN) or implantable wearable medical devices (WBANs). In these scenarios, minimizing data transmission is critical for extending multi-year battery life, rendering the brief, one-time computational cost for authentication a well-justified trade-off for device longevity.

We designed an efficient and secure HUAKE protocol using signcryption for heterogeneous MCS communication. In this protocol, the client belongs to the IBC and the server belongs to the CLC, which is quite applicable to heterogeneous networks. In addition, we proved the security of the proposed HUAKE protocol in the mBR model and described its resilience against other attacks using heuristic analysis. Our performance evaluation indicates that the protocol achieves the least communication overhead compared to the associated protocols. While the protocol excels in communication efficiency, its computational overhead is not optimal, and it does not provide forward secrecy. Future work will focus on achieving forward secrecy by incorporating a key exchange mechanism, while simultaneously optimizing the new construction to reduce computational overhead.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Key Project of Science and Technology Research by Chongqing Education Commission under Grant KJZD-K202400610 and the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation General Project Grant CSTB2025NSCQ-GPX1263.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Huihui Zhu and Fei Tang; methodology, Fei Tang; validation, Ping Wang; formal analysis, Huihui Zhu; investigation, Ping Wang; resources, Fei Tang; writing—original draft preparation, Huihui Zhu; writing—review and editing, Huihui Zhu and Chunhua Jin; funding acquisition, Fei Tang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. For studies not involving humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ali S, Alauldeen R, Ruaa A. What is client-server system: architecture, issues and challenge of client-server system. Recent Trends Cloud Comput Web Eng. 2020;2(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

2. Yousefi S, Karimipour H, Derakhshan F. Data aggregation mechanisms on the internet of things: a systematic literature review. Internet Things. 2021;15:100427. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2021.100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Preethichandra D, Piyathilaka L, Izhar U, Samarasinghe R, De Silva LC. Wireless body area networks and their applications—a review. IEEE Access. 2023;11:9202–20. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3239008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Conti M, Donadel D, Turrin F. A survey on industrial control system testbeds and datasets for security research. IEEE Communicat Surv Tutorials. 2021;23(4):2248–94. doi:10.1109/COMST.2021.3094360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Thankappan M, Rifà-Pous H, Garrigues C. Multi-Channel Man-in-the-Middle attacks against protected Wi-Fi networks: a state of the art review. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;210:118401. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Aski VJ, Dhaka VS, Parashar A, kumar S, Rida I. Internet of Things in healthcare: a survey on protocol standards, enabling technologies, WBAN architectures and open issues. Phys Commun. 2023;60:102103. doi:10.1016/j.phycom.2023.102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Blake-Wilson S, Johnson D, Menezes A. Key agreement protocols and their security analysis. In: IMA international conference on cryptography and coding; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1997. p. 30–45. [Google Scholar]

8. Koblitz N, Menezes A, Vanstone S. The state of elliptic curve cryptography. Des Codes Cryptogr. 2000;19:173–93. doi:10.1023/a:1008354106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Maurer U. Modelling a public-key infrastructure. In: Computer Security—ESORICS 96: 4th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security; Sep 25–27; Rome, Italy. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1996. p. 325–50. [Google Scholar]

10. Shamir A. Identity-based cryptosystems and signature schemes. In: Workshop on the theory and application of cryptographic techniques. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1984. p. 47–53 doi: 10.1007/3-540-39568-7_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Girault M. Self-certified public keys. In: Workshop on the theory and application of of cryptographic techniques. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1991. p. 490–7. [Google Scholar]

12. Braeken A. Public key versus symmetric key cryptography in client-server authentication protocols. Int J Inf Secur. 2022;21(1):103–14. doi:10.1007/s10207-021-00543-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Alrawais A, Alhothaily A, Cheng X, Hu C, Yu J. SecureGuard: a certificate validation system in public key infrastructure. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2018;67(6):5399–408. doi:10.1109/tvt.2018.2805700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang D, Ma Cg. Cryptanalysis of a remote user authentication scheme for mobile client-server environment based on ECC. Inf Fusion. 2013;14(4):498–503. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2012.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hsieh WB, Leu JS. An anonymous mobile user authentication protocol using self-certified public keys based on multi-server architectures. J Supercomput. 2014;70(1):133–48. doi:10.1007/s11227-014-1135-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dey S, Sampalli S, Ye Q. MDA: message digest-based authentication for mobile cloud computing. J Cloud Comput. 2016;5(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/s13677-016-0068-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu B, Zhou Y, Hu F, Li F. User authentication and key agreement protocol for mobile client-multi-server environment. J Cryptol Res. 2018;5(2):111–25. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

18. Hassan A, Eltayieb N, Elhabob R, Li F. An efficient certificateless user authentication and key exchange protocol for client-server environment. J Ambient Intell Human Comput. 2018;9(6):1713–27. doi:10.1007/s12652-017-0622-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Qiu S, Xu G, Ahmad H, Xu G, Qiu X, Xu H. An improved lightweight two-factor authentication and key agreement protocol with dynamic identity based on elliptic curve cryptography. KSII Trans Internet Inf Syst. 2019;13(2):978–1002. [Google Scholar]

20. Jegadeesan S, Azees M, Kumar PM, Manogaran G, Chilamkurti N, Varatharajan R, et al. An efficient anonymous mutual authentication technique for providing secure communication in mobile cloud computing for smart city applications. Sustain Cities Soc. 2019;49:101522. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xu S, Reng X, Chen C, Yuan F, Yang Z. Provably secure certificateless two-party authenticated key agreement Protocol. J Cryptol Res. 2020;7(6):886–98. (In Chinese). doi:10.1109/cis.2009.152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tsobdjou LD, Pierre S, Quintero A. A new mutual authentication and key agreement protocol for mobile client—Server environment. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2021;18(2):1275–86. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2021.3071087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rana S, Obaidat MS, Mishra D, Mishra A, Rao YS. Efficient design of an authenticated key agreement protocol for dew-assisted IoT systems. J Supercomput. 2022;78(3):3696–714. doi:10.1007/s11227-021-04003-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li F, Wang J, Zhou Y, Jin C, Islam S. A heterogeneous user authentication and key establishment for mobile client-server environment. Wireless Netw. 2020;26(2):913–24. doi:10.1007/s11276-018-1839-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Daniel RM, Thomas A, Rajsingh EB, Silas S. A strengthened eCK secure identity based authenticated key agreement protocol based on the standard CDH assumption. Inf Comput. 2023;294:105067. doi:10.1016/j.ic.2023.105067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ma Y, Ma Y, Liu Y, Cheng Q. A secure and efficient certificateless authenticated key agreement protocol for smart healthcare. Comput Stand Interf. 2023;86:103735. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2023.103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cheng Q, Li Y, Shi W, Li X. A certificateless authentication and key agreement scheme for secure cloud-assisted wireless body area network. Mobile Netw Applicat. 2022;27(1):346–56. doi:10.1007/s11036-021-01840-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Khalafalla W, Zhu WX, Elkhalil A, Yan C. An efficient cross-domain mutual authentication scheme for heterogeneous signcryption in VANETs. Cluster Comput. 2025;28(13):838. doi:10.1007/s10586-025-05333-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Khalafalla W, Zhu WX, Elkhalil A, Khokhar S. Efficient authentication scheme for heterogeneous signcryption with cryptographic reverse firewalls for VANETs. Int J Inf Secur. 2025;24(3):1–18. doi:10.1007/s10207-025-01021-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bellare M, Rogaway P. Entity authentication and key distribution. In: Annual International Cryptology Conference. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1993. p. 232–49. [Google Scholar]

31. Wu TY, Tseng YM. An efficient user authentication and key exchange protocol for mobile client-server environment. Comput Netw. 2010;54(9):1520–30. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2009.12.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. De Caro A, Iovino V. jPBC: java pairing based cryptography. In: 2011 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC); 2011 Jun 28–Jul 1; Kerkyra, Greece: IEEE; 2011. p. 850–5. [Google Scholar]

33. Shim KA. An efficient conditional privacy-preserving authentication scheme for vehicular sensor networks. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2012;61(4):1874–83. doi:10.1109/tvt.2012.2186992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools