Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evolve and Revoke: A Secure and Efficient Conditional Proxy Re-Encryption Scheme with Ciphertext Evolution

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, 202, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Tung-Tso Tsai. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in IoT Security: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 65 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073553

Received 20 September 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Cloud data sharing is an important issue in modern times. To maintain the privacy and confidentiality of data stored in the cloud, encryption is an inevitable process before uploading the data. However, the centralized management and transmission latency of the cloud makes it difficult to support real-time processing and distributed access structures. As a result, fog computing and the Internet of Things (IoT) have emerged as crucial applications. Fog-assisted proxy re-encryption is a commonly adopted technique for sharing cloud ciphertexts. It allows a semi-trusted proxy to transform a data owner’s ciphertext into another re-encrypted ciphertext intended for a data requester, without compromising any information about the original ciphertext. Yet, the user revocation and cloud ciphertext renewal problems still lack effective and secure mechanisms. Motivated by it, we propose a revocable conditional proxy re-encryption scheme offering ciphertext evolution (R-CPRE-CE). In particular, a periodically updated time key is used to revoke the user’s access privileges while an access condition prevents a malicious proxy from re-encrypting unauthorized ciphertext. We also demonstrate that our scheme is provably secure under the notion of indistinguishability against adaptively chosen identity and chosen ciphertext attacks in the random oracle model. Performance analysis shows that our scheme reduces the computation time for a complete data access cycle from an initial query to the final decryption by approximately 47.05% compared to related schemes.Keywords

The prevalence of cloud computing [1] and the emergence of various fog computing [2] applications have changed our ways in the utilization, sharing, and value-added creation of information. In diversified Internet of Things (IoT) applications such as intelligent transportation systems [3] and healthcare management systems, IoT devices play a crucial role in the circulation and sharing of gathered information. Specifically, in the healthcare applications, the widespread use of wearable devices and various wireless sensors enables healthcare professionals to remotely monitor patients’ physiological data. The personal health data collected through IoT devices can serve as a valuable resource for medical research.

However, data owners might be concerned about data privacy and confidentiality when sharing their data in clouds. Another challenge is how to revoke user’s access privileges, so as to achieve forward security. Proxy Re-Encryption (PRE) schemes [4–10] are commonly adopted techniques for sharing data in cloud environments. A PRE scheme allows an authorized proxy like a fog node to convert a ciphertext intended for some person into another one designated for the other person. The proxy is viewed as a semi-trusted party and should not be able to learn any information about shared ciphertexts.

In 2007, Canetti and Hohenberger [11] presented the first Chosen-Ciphertext Attack (CCA)-secure PRE mechanism with bidirectionality allowing ciphertext conversion between both parties. Green and Ateniese [12] came up with an identity-based proxy re-encryption (IB-PRE) in the same year. Nevertheless, Weng et al. [13] pointed out that although PRE schemes had been widely used for delegated decryption, traditional PRE mechanisms could not provide fine-grained access control. To cope with this problem, they addressed the concept of conditional proxy re-encryption (C-PRE) in which ciphertexts can only be re-encrypted if received re-encryption key satisfies the predefined condition specified by its data owner. In 2009, Chu et al. [14] presented the conditional proxy broadcast re-encryption (CPBRE) to support broadcast decryption. In 2011, Shao et al. [15] proposed an IB-CPRE system suitable for the fine-grained access control over encrypted emails. In 2018, Zeng and Choo [16] introduced a sender-specified PRE (SS-PRE) which could be viewed as a variant of C-PREs. Their SS-PRE scheme restricts that a proxy can only re-encrypt ciphertexts from a specific sender. This approach effectively addresses the over-delegation problem of PRE.

In 2021, Yao et al. [17] presented a revocable proxy re-encryption scheme providing ciphertext evolution. Their scheme allows a data owner to delegate decryption rights to authorized users and periodically evolve ciphertexts to reach the goal of revoking user. In 2023, Yao et al. [18] came up with an IB-PRE system with the property of single-hop conditional delegation and supports multi-hop ciphertext evolution. Yet, both schemes fail to consider the key-escrow issue in identity-based setting. Combined with ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE), Worapaluk and Fugkeaw [19] proposed a blockchain-assisted PRE in 2023. Their scheme supports both user and attribute revocation with auditability. Nevertheless, the blockchain only stores the revoked attribute list, and thus does not achieve genuine ciphertext evolution. Moreover, their scheme lacks both formal security proofs and integrated security analyses of potential information leakage in blockchain-assisted PRE.

In 2025, Singh et al. [20] proposed a lightweight and revocable certificateless public key encryption without bilinear pairings. Although their scheme also offers the characteristic ciphertext evolution, it essentially is not a PRE mechanism and would be not well-suited for flexible data sharing in clouds. Considering the merits of certificateless public systems, Eltayieb et al. [21] proposed a certificateless PRE (CL-PRE) for data sharing in clouds. Nevertheless, their scheme only satisfies the security requirement of chosen plaintext attacks (CPA). Zhou et al. [22] further addressed a certificateless conditional PRE (CL-CPRE) scheme for data sharing in IoT clouds. Although their scheme provides the functionality of ciphertext evolution and dynamic user key-update, it achieves only CPA security and fails to support the user revocation.

In recent years, fog-assisted PRE schemes [23–26] have gained popularity in data sharing. It enables a data owner to encrypt data and then allows a semi-honest fog node (proxy) to re-encrypt it for authorized recipients. However, existing schemes still present several limitations and research gaps:

• Incomplete functionality in C-PRE schemes: Prior C-PRE schemes [13–16] have provided fine-grained access control and hence solved the problem of over-delegation. However, they fail to consider the revocation problem and cannot support the functionality of ciphertext evolution, which is important to cloud ciphertext renewal.

• Unresolved security issues in revocable schemes: Although the scheme introduced by Yao et al. [17] further supports the characteristics of revocability, their identity-based framework still suffers from the key-escrow problem. In a related work, Lin and Chen [23] proposed a revocable IB-PRE scheme for fog computing environments. Nevertheless, we observe that the scheme still has the over-delegation and key-escrow problems and fails to support ciphertext evolution.

To overcome these limitations and address the gaps in existing research, we propose a fog-assisted revocable C-PRE scheme with ciphertext evolution (R-CPRE-CE). Our work is motivated by the need for an integrated and secure mechanism that simultaneously solves the problem of over-delegation, revocability, ciphertext evolution, and key-escrow. The primary contributions of this paper are as follows:

• Conditional re-encryption with user revocation: The proposed R-CPRE-CE scheme not only incorporates a predefined access condition to prevent over-delegation, but also uses a periodically updated time-key to efficiently revoke a user’s access privileges.

• Ciphertext evolution for forward security: With ciphertext evolution, our R-CPRE-CE scheme allows cloud ciphertexts to be shared across time periods and fulfills forward security.

• Elimination of the key-escrow problem: By employing an anonymous key generation technique, our R-CPRE-CE scheme effectively solves the inherent key-escrow problem in identity-based systems.

Although our R-CPRE-CE scheme builds upon similar concepts from previous PRE systems, it offers many advantages over the schemes of Yao et al. [17,18] and the Lin and Chen [23]. Specifically, the identity-based frameworks of Yao et al. [17,18] inherently suffer from the key-escrow problem. In contrast, the proposed R-CPRE-CE scheme eliminates this risk by employing an anonymous key generation technique. Furthermore, compared to the Lin-Chen system [23], our work provides better functionality by incorporating both conditional PRE to prevent over-delegation and a ciphertext evolution mechanism to ensure forward security. Computationally, the proposed system also demonstrates better performance, particularly in terms of the one-time access metric compared to Yao et al. [17], as detailed in Section 5.2.

The remaining parts of this paper are organized below. Section 2 briefly reviews some preliminaries in relation to the proposed scheme. We give the formal security model and definition for the proposed system in Section 3. A concrete R-CPRE-CE scheme is presented in Section 4. We analyze the security and performance of our scheme in Section 5. Finally, a conclusion is made in Section 7.

This section introduces the essential cryptographic backgrounds and computational assumptions.

Let

• Bilinearity: If

• Non-degeneracy: For generators

• Computability: Let

2.2 The Problem of Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH)

Given

2.3 The Assumption of Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH)

The assumption of DBDH holds if any probabilistic polynomial-time adversary

where

This section outlines the system model, core algorithms, and security model of the proposed scheme.

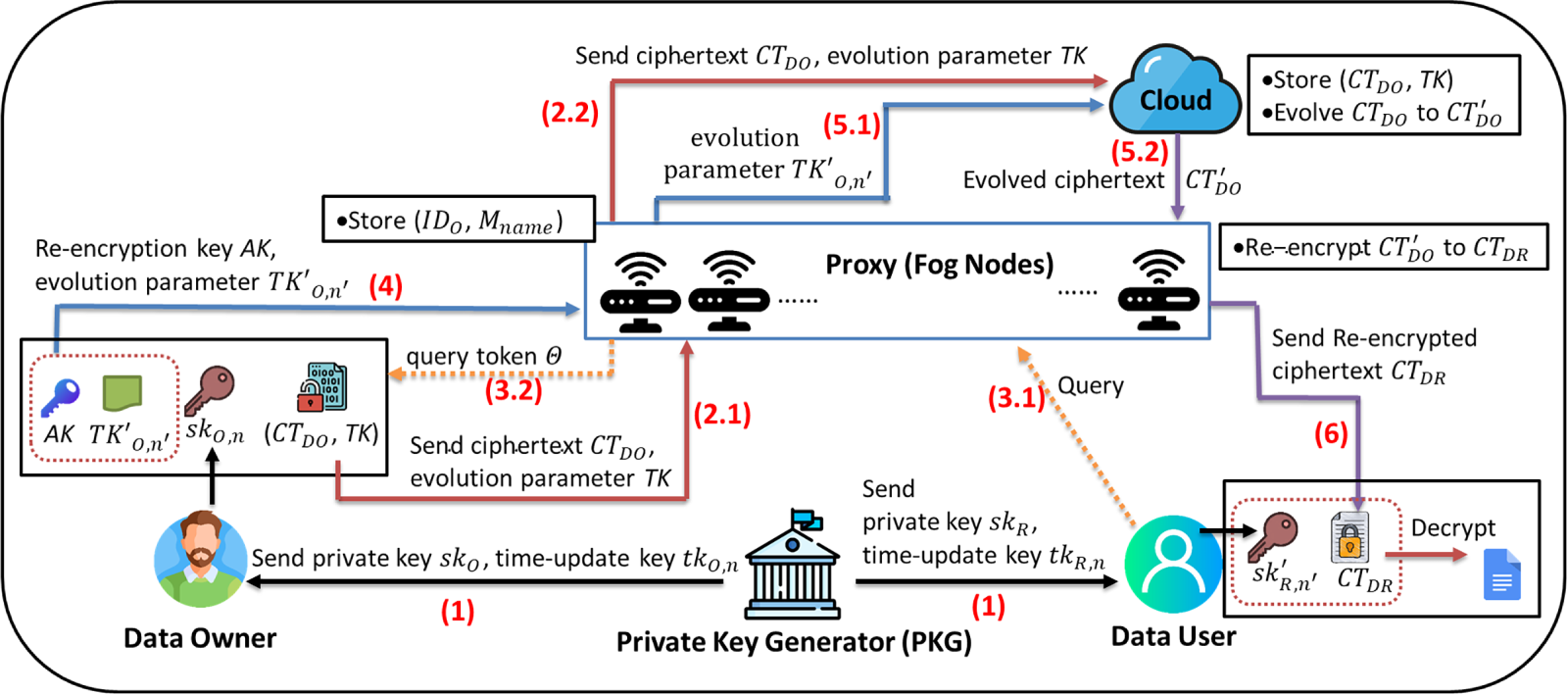

The proposed R-CPRE-CE system includes three layers of participated parties and an additional Private Key Generator (PKG) for key generation. As shown in Fig. 1, the User Layer transmits the demand for ciphertext via the Proxy Layer to the Cloud Layer. Furthermore, the proxy also obtains re-encryption keys from the data owner, transforms cloud evolved ciphertexts, and forwards the result to users. In the fog computing environment, the proxy is usually composed of a group of distributed fog nodes.

Figure 1: The proposed R-CPRE-CE system model

The algorithms utilized in the proposed scheme are defined as follows:

1. Setup

2. InitialKeyGen

3. TimeUpdateKeyGen

4. Encryption

5. Query

6. ReKeyGen

7. Evolve

8. Re-Encryption

9. Decryption

Correctness: The correctness property guarantees that (1) a legitimate user holding the valid private key for the current time period

• Correctness of decryption:

For all users whose identities have not been revoked at time period

– Decryption by the Data Owner

– Decryption by the Data User

• Correctness of revocation:

For all users whose identities have been revoked at time period

This section defines the security game of indistinguishability against adaptively chosen identity and chosen ciphertext attacks (IND-PrID-CCA), where PrID stands for Proxy Identity, between a probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) adversary

Definition 1: (IND-PrID-CCA) If no PPT adversary

Setup. The challenger

Phase 1. The adversary

– Initial Private Key Query:

– Time-Update Key Query:

– Re-Encryption Key Query:

– Decryption Query:

Challenge.

Phase 2. Upon getting

– Initial private key queries for the target identity

– Whenever

– Re-encryption key queries involving

– Decryption queries involving (

– The number of queries is bounded by

Guess. When Phase 2 is finished, the adversary

In the security model, we defined several query restrictions for the adversary capabilities to correctly reflect a realistic attack scenario while maintaining tractability of the security proof. For instance, in phase 2, an initial private key query for the target identity is disallowed. This is a standard assumption in IND-PrID-CCA security games, since the adversary holding the target private key can easily decrypt the ciphertext and trivially break the security. This restriction ensures that the adversary’s success advantage does not rely on possessing the target secret key. Furthermore, a decryption query involving the challenge ciphertext is disallowed. Such a restriction is crucial for modeling chosen-ciphertext attacks (CCA) where an adversary cannot directly submit the challenge ciphertext to decryption oracles. It simulates a circumstance where attackers cannot access the victim’s decryption device, but must rely on other queries to gain information.

Although these restrictions are standard in formal security models, it is important to consider their alignment with real world attack scenarios, particularly in a fog computing environment with multiple semi-trusted proxies. In practice, an adversary might compromise one or more fog nodes and attempt to use them as re-encryption or decryption oracles. Our security model implicitly addresses this by providing the adversary with more query capabilities. For instance, the adversary can request re-encryption keys for any non-challenge identity and decrypt any ciphertext except for the specific challenge ciphertext itself. This simulates a powerful attacker who has significant control over the network but has not yet compromised the specific target’s final decryption device or process. The core security of the challenge ciphertext relies on the cryptographic hardness of the underlying problem, even if the adversary can observe and manipulate other related ciphertexts through compromised proxies. To the best of our knowledge, no model can perfectly capture all real-world nuances. The IND-PrID-CCA model provides a well-accepted abstraction for demonstrating security against adaptive attacks in such distributed environments.

4 Construction of Proposed Scheme

Building upon the previously defined algorithms, we now present a concrete construction.

• Setup

Given a security parameter

(1)

(2) A random value

(3)

(4)

• InitialKeyGen

The initial private key is generated through the interactive steps:

(1) The registering user

(2)

(3) PKG returns

(4) The user

(5) The

• TimeUpdateKeyGen

The time-update key is generated through the interactive steps:

(1)

(2) PKG returns the time-update key

(3) The

(4)

• Encryption

Let

(1) Compute

(2) Compute an evolution parameter as

(3) Set

(4) Output

The data owner

• Query

When a data user

Then

• ReKeyGen

After receiving the token

(1) Select random values

(2) Compute the hash value of the access condition

(3) Compute the re-encryption key

(4) Compute the evolution parameter

Subsequently, the data owner sends

• Evolve

Upon receiving

(1) Compute

where

(2) Set the evolved ciphertext as

• Re-Encryption

When the proxy gains the re-encryption key

(1) Compute

At this stage, the ciphertext and re-encryption key must associate with the same access condition

(2) Compute

(3) Output the ciphertext

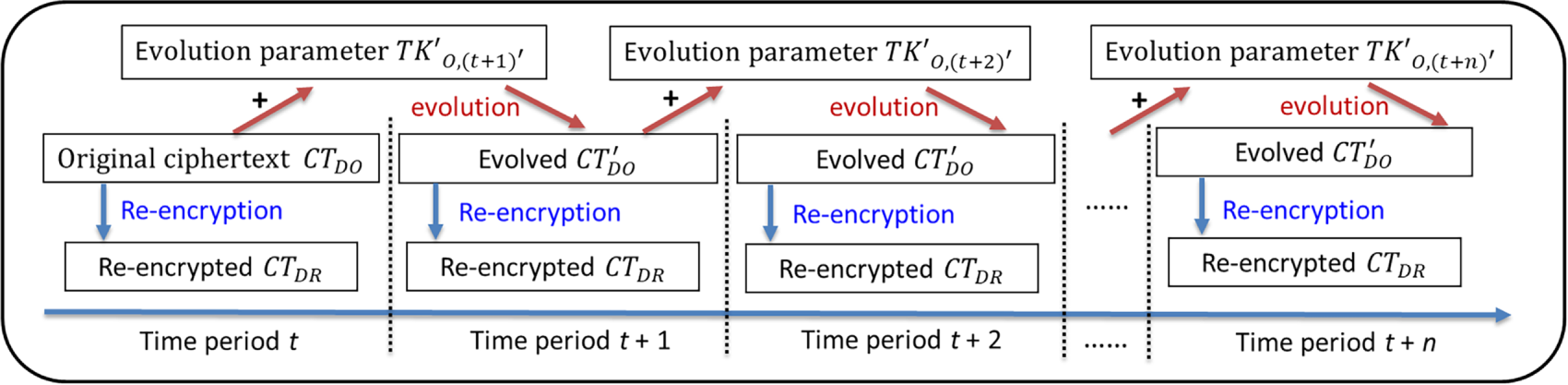

Figure 2: Illustration of ciphertext evolution and re-encryption process across time periods

• Decryption

The decryption process is classified into two cases. The first is performed by a data owner

(1) Computes the decryption key

The correctness of Eq. (28) could be easily confirmed, since

(2) Recover the message

The second is performed by the data user

(1) Compute the parameter

(2) Compute the decryption key

The correctness of Eq. (31) could be easily confirmed, since

(3) Recover the message

5 Security Proof and Comparison

Based on previously defined security model, this section provides the formal security proof for the proposed R-CPRE-CE scheme. Meanwhile, some comparisons with similar systems are also made.

We show that the proposed R-CPRE-CE system is provably secure in the security notion of IND-PrID-CCA as Theorem 1. We prove the security of our scheme using a reductionist argument in the random oracle model (ROM). The core idea is to demonstrate that if a PPT adversary can break the IND-PrID-CCA security of our scheme, then we can construct an algorithm to solve the DBDH problem, which is assumed to be computationally intractable. In the ROM, an adversary must query a random oracle for a result rather than computing it independently. This model is a widely used idealization in cryptography and can simplify the proof of complex cryptographic protocols. When instantiating the random oracles with real world hash functions like Secure Hash Algorithm 3 (SHA-3), we follow common cryptographic practices to mitigate potential attacks. Specifically, the inputs to the hash functions are carefully structured, e.g., concatenating identities with nonces or other distinct values, to prevent collision attacks and other structural vulnerabilities that could arise from a naive implementation. Thus, we believe that such an instantiation will not introduce new weaknesses into our scheme. However, a true random oracle does not exist in the real world. A ROM-proven-secure scheme could also be insecure in the standard model. Extending our current mechanism to fulfill standard model security requires significant modifications and inevitably increases the computation complexity. Consequently, we leave the adaptation to achieve standard model security as our future work.

Theorem 1: (Proof of IND-PrID-CCA)

Let

and

Proof: Let

Setup. The challenger

Phase 1. The adversary

–

–

–

– Initial Private Key Query: For any initial private key queries of an identity

– Time-Update Key Query: For any time-update key queries of

– Re-Encryption Key Query: For any re-encryption key queries of

– Decryption Query: For any decryption queries of

Challenge.

1. It can be assumed, without loss of generality, that

2. Otherwise,

Phase 2. After getting the challenge ciphertext

Guess. At the end of Phase 2,

Analysis: The confidentiality of the proposed scheme is directly guaranteed by the hardness of the DBDH assumption. The core of this proof lies in how the challenger

To better estimate

–

–

–

–

Since

To be precise, in any time-update key query,

By calculation, when

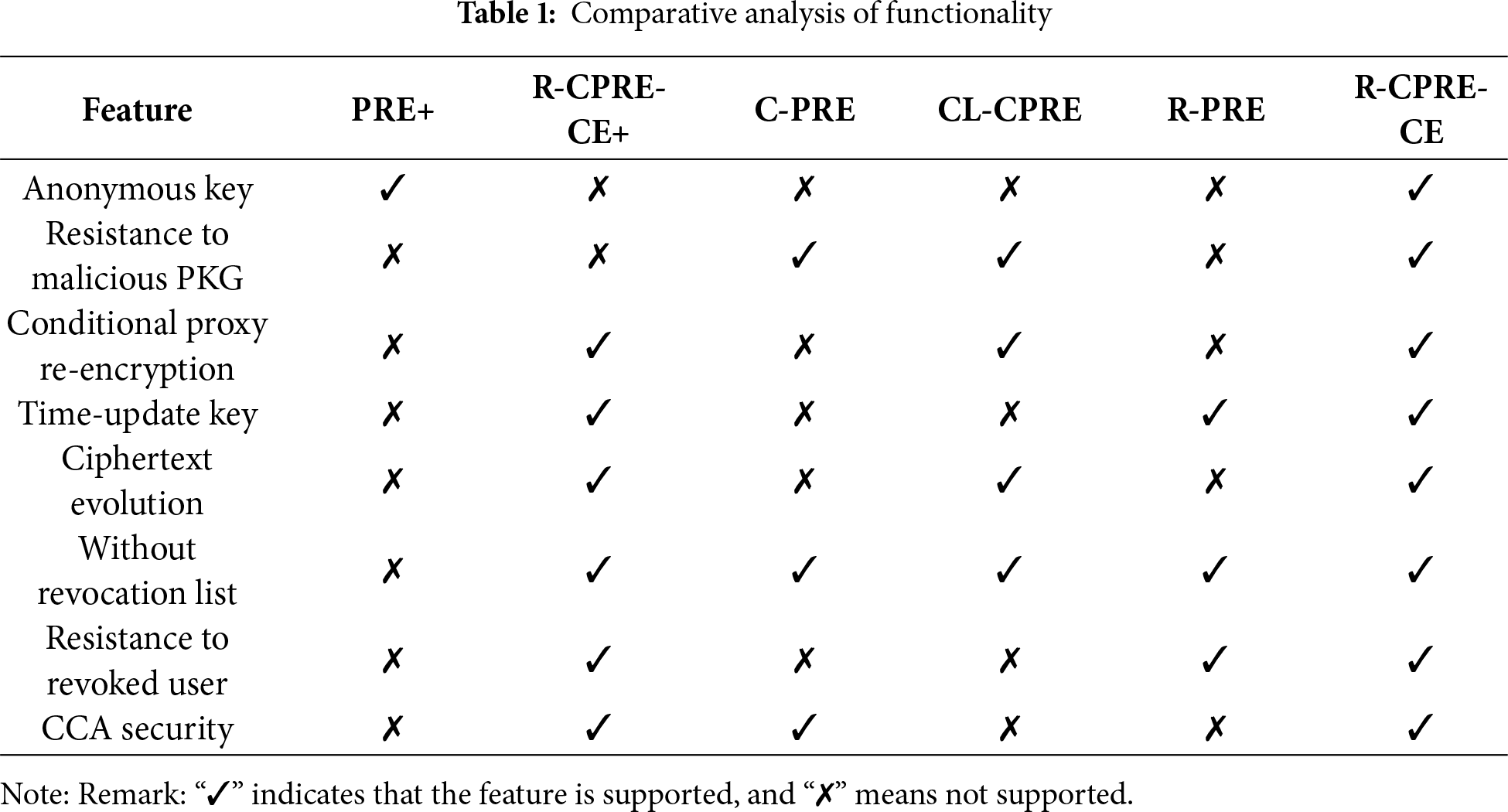

This subsection presents a functional comparison and performance analysis with similar studies, including Zhang et al.’s (PRE+ for short) [26], Yao et al.’s (R-CPRE-CE+ for short) [17], Fang et al.’s (C-PRE for short) [6], Zhou et al.’s (CL-CPRE for short) [22], and the Lin-Chen (R-PRE for short) [23]. Table 1 summarizes the comparison of functionality. It can be observed that the schemes of R-CPRE-CE+ and R-PRE do not support anonymous key generation, and neither of them, including the PRE+, can resist a malicious PKG. Among the schemes of PRE+, C-PRE, CL-CPRE, and R-PRE, only the R-PRE provides the property of time-update key, and most of them could not simultaneously fulfill conditional proxy re-encryption, time-update key, and ciphertext evolution.

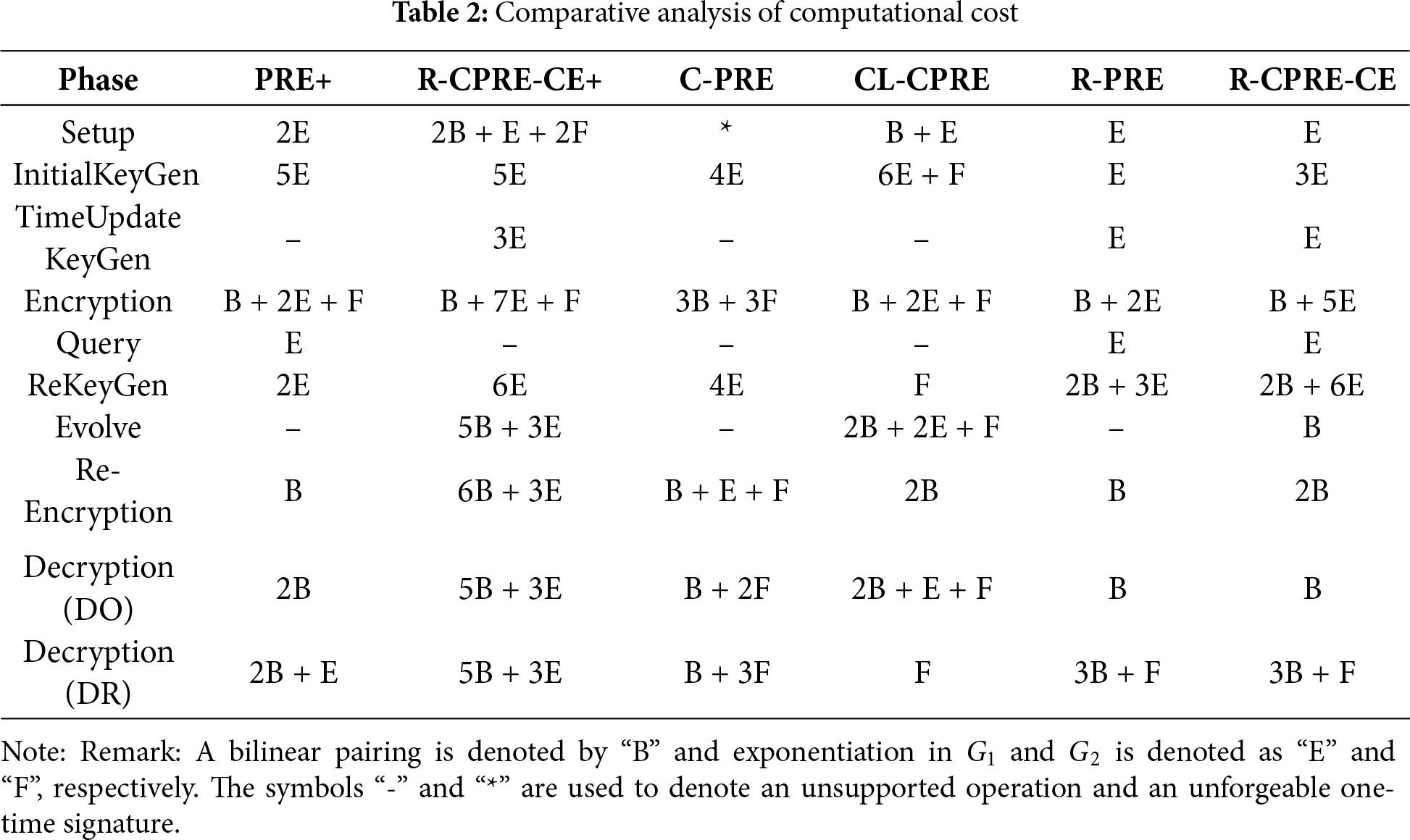

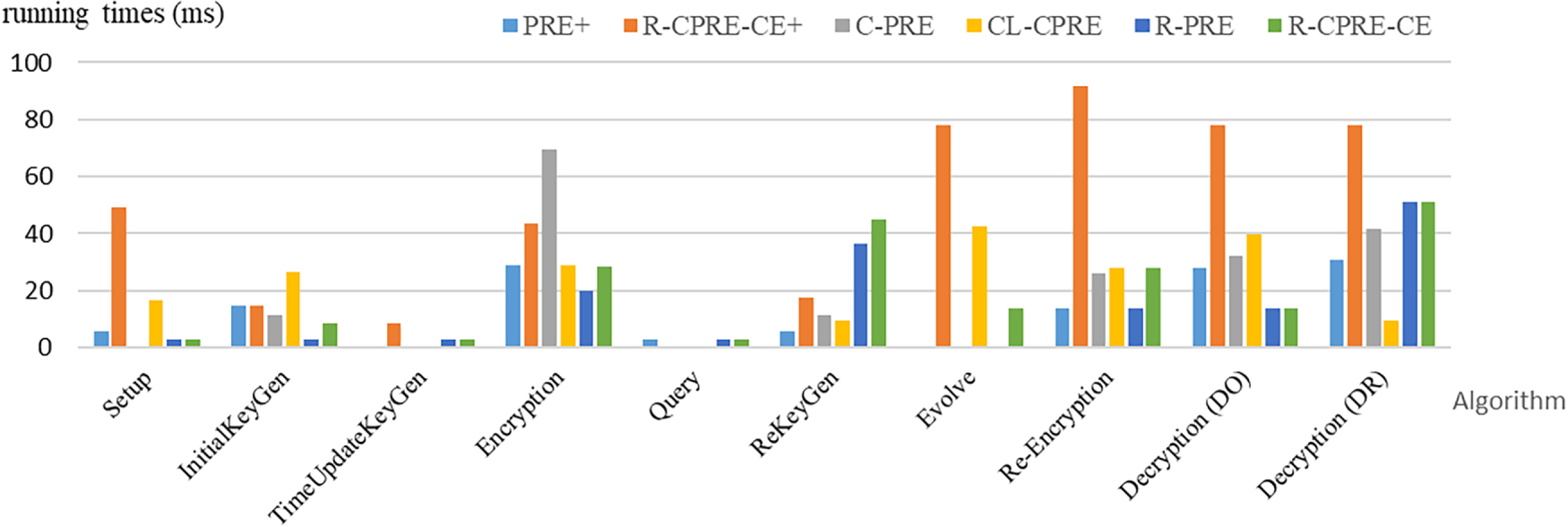

In Table 2, we focus on computational complexity and evaluate time-consuming operations. Among these mechanisms, ours and R-PRE have the same computational advantage in the generation of time-update key algorithm. In particular, our system is efficient in the Setup phase, requiring only one exponentiation (E). The C-PRE scheme has to additionally generate a strongly unforgeable one-time signature. Besides, our system is one of only three schemes to feature the Evolve function, which is crucial for forward-security or state updates. Its cost is a single pairing (B), which is significantly more efficient than the costs of R-CPRE-CE+ and CL-CPRE schemes. The Decryption (DO) cost is just B, on par with R-PRE, the most efficient scheme in this category. Although the computational complexity of ReKeyGen and Re-Encryption in our system is slightly higher than compared works, the proposed system offers a strong balance of performance and advanced features, making it a better choice for practical applications. Fig. 3 illustrates the approximate running time using the test environment of Intel Core i5-8250U CPU @ 1.60 GHz, 2.7 GB RAM, and Ubuntu 18.04.4 LTS with the Pairing-Based Cryptography (PBC) library (version 0.5.14).

Figure 3: Comparison of approximate running times

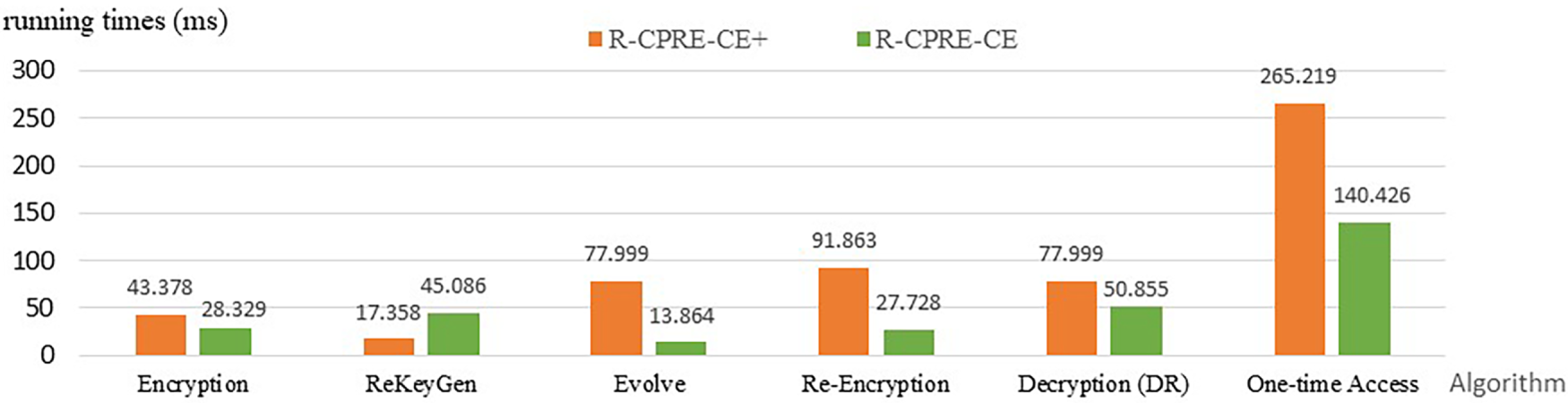

As shown in Fig. 3, R-PRE and ours only need 2.893 ms to run Setup. In the InitialKeyGen phase, our scheme takes 8.679 ms. In the TimeUpdateKeyGen phase, R-PRE and our schemes need a runtime of 2.893 ms which is better than that of 8.679 ms in R-CPRE-CE+ scheme. Our scheme is also efficient in Evolve (13.864 ms) and Decryption by DO (13.864 ms). The PRE+ scheme has the best runtime of 5.786 ms in ReKeyGen. Although the R-PRE scheme has a comparable runtime in TimeUpdateKeyGen, Encryption and Re-Encryption, they fail to provide the functionality of ciphertext evolution and anonymous key generation. Since the R-CPRE-CE+ scheme also supports user revocation and ciphertext evolution, we further make a detailed evaluation with our system in Fig. 4. Note that in the comparison of Fig. 4, we just consider core algorithms including Encryption, ReKeyGen, Evolve, Re-Encryption, and Decryption by DR. Here, we also added a one-time access metric to evaluate the total computation time required for a data user to complete the entire process from sending a query to the final decryption. From the comparison illustrated in Fig. 3, it is evident that the R-CPRE-CE+ scheme is more efficient in the ReKeyGen algorithm, which requires a runtime of only 17.358 ms compared to 45.086 ms for our proposed scheme. Nevertheless, our scheme still outperforms the R-CPRE-CE+ scheme in all other core algorithms. As for the one-time access metric, which simulates the total computation time from an initial query to the final decryption in practice, the result shows that our scheme reduces the runtime by approximately 47.05% when compared to 265.219 ms of the R-CPRE-CE+ scheme.

Figure 4: Comparison between the R-CPRE-CE+ and our R-CPRE-CE schemes

This section discusses the practical applications and academic contributions of our proposed R-CPRE-CE scheme. We aim to highlight how our scheme addresses critical challenges in fog-assisted cloud data sharing and give a potential direction for future research.

As to the assessment of our framework’s effectiveness, it is essential to consider not only runtime performance, but also its accuracy. In the context of cryptographic schemes, the concept of “accuracy” is formally defined as correctness. As shown in Section 3.2, our R-CPRE-CE scheme is well-designed and correct, because any unrevoked user holding a valid private key can decrypt the corresponding ciphertext with the probability of 1. Such a deterministic guarantee is a fundamental prerequisite for any secure encryption system and ensures the reliability of our framework. Thus, the effectiveness of our scheme is demonstrated by its proven correctness and the results of computational evaluation detailed in Section 5.2.

Concretely speaking, the proposed R-CPRE-CE scheme is designed to provide a secure and integrated data sharing mechanism for distributed systems, especially in fog-assisted clouds. In the application of healthcare management, a data owner needs to revoke the access privilege of certain data users due to privacy concerns. Our system employs a periodically updated time key to achieve this without re-encrypting the original data. For the application of intelligent transportation systems, in which data gathered from vehicles and mobile sensors must remain valid for continuous time periods, the ciphertext evolution of our scheme provides crucial benefits. Additionally, the incorporation of a predefined access condition can prevent unauthorized re-encryption by a semi-trusted proxy. This property is important for assuring data confidentiality and integrity in diverse IoT environments where data delegation has to be strictly controlled.

A crucial issue of the ciphertext evolution is its security guarantees across multiple time periods, i.e., forward and backward secrecy. The proposed R-CPRE-CE scheme is designed to ensure forward secrecy, since the compromise of a previous private key does not leak the confidentiality of current and future ciphertexts. This is because each time-update key is derived from a unique hash value. Consequently, an adversary who even obtains an old time-update key cannot derive another valid one for the subsequent period. Similarly, the backward secrecy is also fulfilled in the proposed scheme, because the compromise of a current key will not result in the successful derivation of past keys. Regarding the expressiveness of the access condition, our current construction supports a single, atomic condition c for efficiency. The framework can easily support conjunctive (AND) conditions without increasing overhead. Specifically, we can express the access condition c to be a concatenation of multiple attributes (e.g., c = “role: doctor || department: cardiology”) before it is hashed. However, supporting disjunctive (OR) conditions is non-trivial and would take significant changes in algorithms or increase ciphertext size.

From the perspective of academic contributions, our work addresses the inherent problem of key-escrow in traditional identity-based cryptosystems, such as those by Yao et al. [17,18], by employing an anonymous key generation technique. Although the existing literature has discussed the individual aspects such as revocability (e.g., the Lin-Chen [23]), ciphertext evolution (e.g., Yao et al. [17]), and conditional access control, an integrated mechanism with provable security is still lacking. The proposed R-CPRE-CE scheme successfully fulfills this goal by combining the above functionalities. Despite these contributions, we recognize that the main limitation of our current system is that it does not yet achieve standard model security and requires further efforts to reduce the computational complexity. The computational costs of the ReKeyGen and Re-Encryption algorithms in our scheme are higher than some counterparts, which warrants a deeper analysis of its impact on real-time performance. This higher cost is a trade-off for better functionalities such as conditional access and ciphertext evolution. Crucially, the most computationally intensive operation, ReKeyGen, is performed by a data owner, who typically has the sufficient computing power. The Re-Encryption task, performed by the fog node, has a quantifiable latency (approximately 27 ms in our tests) that is manageable for modern fog devices. Although this design mitigates the direct impact on the real-time responsiveness of fog nodes, a further optimization is still a key future research.

The credibility of the proposed framework would benefit from quantitative ablation studies and parameter sensitivity analyses. An ablation study analyzes the impact of performance by removing individual components such as the conditional access control or the ciphertext evolution. However, these components are integrated as the core security objectives of our scheme. For instance, the removal of conditional access control will bring back the over-delegation problem, while that of ciphertext evolution would break forward security. Therefore, our design represents an integration of essential functionalities rather than a collection of separable modules. Similarly, for parameter sensitivity analysis, the computational cost of the adopted cryptographic primitives (i.e., bilinear pairings and exponentiations) scales with the chosen security parameter. It would be a valuable future direction to make a more granular analysis across various aspects.

In this paper, we proposed a fog-assisted R-CPRE-CE system, i.e., revocable conditional proxy re-encryption scheme offering ciphertext evolution. Our scheme aims at dealing with two challenges of cloud data sharing: user revocation and cloud ciphertext evolution. The former is achieved by using a periodically updated time key while the latter is realized via an evolution parameter generated by the data owner. In addition, to further restrict the unauthorized behaviors of the malicious proxy, an access condition is incorporated with the proposed re-encryption mechanism. Specifically, we utilize anonymous key generation technique, so as to prevent the key-escrow problem of identity-based systems. From the perspective of security, we formally prove that the proposed system satisfies the security model of IND-PrID-CCA under the assumption of DBDH. Compared with previous similar studies, our scheme provides not only competitive performance, but also more comprehensive functionalities. However, there are still some limitations of our current system that would be important directions for future work. First, the underlying security proof is constructed in the random oracle model. It would be better to adapt the current mechanism for a more rigorous security proof in the standard model. Second, to appeal to more resource-constrained IoT mobile applications, the computational complexity of ReKeyGen and Re-Encryption algorithms requires further optimization. Third, to support more complex access policies, such as conjunctive and disjunctive conditions, would increase more practical applicability. Finally, conducting ablation studies and a comprehensive parameter sensitivity analysis would further enhance the robustness and credibility of our framework.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Council of Republic of China under the contract numbers NSTC 114-2221-E-019-055-MY2 and NSTC 114-2221-E-019-069.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Han-Yu Lin and Yi-Jia Ye; methodology, Yi-Jia Ye; validation, Han-Yu Lin, Tung-Tso Tsai and Yi-Jia Ye; formal analysis, Yi-Jia Ye; resources, Tung-Tso Tsai; data curation, Yi-Jia Ye; writing—original draft preparation, Han-Yu Lin; writing—review and editing, Tung-Tso Tsai; supervision, Han-Yu Lin; funding acquisition, Han-Yu Lin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mell P, Grance T. The NIST definition of cloud computing. Nat Inst Stand Technol. 2011;53:1–7. [Google Scholar]

2. de Brito MS, Hoque S, Steinke R, Willner A, Magedanz T. Application of the fog computing paradigm to smart factories and cyber-physical systems. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol. 2018;29(4):e3184. doi:10.1002/ett.3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen Y. The application of IoT-assisted intelligent transportation system. In: Proceedings of 2023 Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers (IPEC); 2023 Apr 14–16; Dalian, China. p. 317–20. doi:10.1109/IPEC57296.2023.00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen Z, Li S, Huang Q, Wang Y, Zhou S. A restricted proxy re-encryption with keyword search for fine-grained data access control in cloud storage. Concurr Comput Pract Exp. 2016;28(10):2858–76. doi:10.1002/cpe.3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Deng RH, Weng J, Liu S, Chen K. Chosen-ciphertext secure proxy re-encryption without pairings. In: Cryptology and network security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008. p. 1–17. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-89641-8_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Fang L, Susilo W, Ge C, Wang J. Chosen-ciphertext secure anonymous conditional proxy re-encryption with keyword search. Theor Comput Sci. 2012;462(2):39–58. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2012.08.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liang K, Liu JK, Wong DS, Susilo W. An efficient cloud-based revocable identity-based proxy re-encryption scheme for public clouds data sharing. In: Computer security—ESORICS 2014. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014. p. 257–72. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11203-9_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mizuno T, Doi H. Hybrid proxy re-encryption scheme for attribute-based encryption. In: Information security and cryptology. Vol. 302. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. p. 288–302. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16342-5_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shao J, Cao Z, Liang X, Lin H. Proxy re-encryption with keyword search. Inf Sci. 2010;180(13):2576–87. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2010.03.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Son J, Kim D, Hussain R, Oh H. Conditional proxy re-encryption for secure big data group sharing in cloud environment. In: 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS); 2014 Apr 27–May 2; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 541–6. doi:10.1109/INFCOMW.2014.6849289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Canetti R, Hohenberger S. Chosen-ciphertext secure proxy re-encryption. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2007 Oct 29–Nov 2; Alexandria, VA, USA. p. 185–94. doi:10.1145/1315245.1315269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Green M, Ateniese G. Identity-based proxy re-encryption. In: Applied cryptography and network security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2007. p. 288–306. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72738-5_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Weng J, Deng RH, Ding X, Chu CK, Lai J. Conditional proxy re-encryption secure against chosen-ciphertext attack. In: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Information, Computer, and Communications Security; 2009 Mar 10–12; Sydney, Australia. p. 322–32. doi:10.1145/1533057.1533100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chu CK, Weng J, Chow SSM, Zhou J, Deng RH. Conditional proxy broadcast re-encryption. In: Information security and privacy. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. p. 327–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02620-1_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Shao J, Wei G, Ling Y, Xie M. Identity-based conditional proxy re-encryption. In: 2011 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2011 Jun 5–9; Kyoto, Japan. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/icc.2011.5962419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zeng P, Choo KR. A new kind of conditional proxy re-encryption for secure cloud storage. IEEE Access. 2018;6:70017–24. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2879479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yao S, Dayot RVJ, Kim HJ, Ra IH. A novel revocable and identity-based conditional proxy re-encryption scheme with ciphertext evolution for secure cloud data sharing. IEEE Access. 2021;9:42801–16. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3064863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yao S, Dayot RVJ, Ra IH, Xu L, Mei Z, Shi J. An identity-based proxy re-encryption scheme with single-hop conditional delegation and multi-hop ciphertext evolution for secure cloud data sharing. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18(2):3833–48. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2023.3282577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Worapaluk K, Fugkeaw S. An efficiently revocable cloud-based access control using proxy re-encryption and blockchain. In: 2023 20th International Joint Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (JCSSE); 2023 Jun 28–Jul 1; Phitsanulok, Thailand. p. 178–83. doi:10.1109/JCSSE58229.2023.10202130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Singh MR, Barik RK, Qurashi SN, Thokchom S, Roy DS. A novel pairing free revocable certificateless encryption with ciphertext evolution for healthcare system. IEEE Access. 2025;13:27940–51. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3533367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Eltayieb N, Elhabob R, Abdelgader AMS, Liao Y, Li F, Zhou S. Certificateless proxy re-encryption with cryptographic reverse firewalls for secure cloud data sharing. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2025;162(12):107478. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhou Y, Li Y, Liu Y. A certificateless and dynamic conditional proxy re-encryption-based data sharing scheme for IoT cloud. J Internet Technol. 2025;26(2):165–72. doi:10.70003/160792642025032602002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lin HY, Chen PR. Revocable and fog-enabled proxy re-encryption scheme for IoT environments. Sensors. 2024;24(19):6290. doi:10.3390/s24196290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lin HY, Tsai TT, Ting PY, Chen CC. An improved ID-based data storage scheme for fog-enabled IoT environments. Sensors. 2022;22(11):4223. doi:10.3390/s22114223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Lin HY, Tsai TT, Ting PY, Fan YR. Identity-based proxy re-encryption scheme using fog computing and anonymous key generation. Sensors. 2023;23(5):2706. doi:10.3390/s23052706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang J, Bai W, Wang X. Identity-based data storage scheme with anonymous key generation in fog computing. Soft Comput. 2020;24(8):5561–71. doi:10.1007/s00500-018-3593-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools