Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ES-YOLO: Edge and Shape Fusion-Based YOLO for Traffic Sign Detection

1 Beijing Key Laboratory of Information Service Engineering, Beijing Union University, Beijing, 100101, China

2 School of Computer Science and Technology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China

* Corresponding Author: Songjie Du. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 88 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073599

Received 22 September 2025; Accepted 22 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Traffic sign detection is a critical component of driving systems. Single-stage network-based traffic sign detection algorithms, renowned for their fast detection speeds and high accuracy, have become the dominant approach in current practices. However, in complex and dynamic traffic scenes, particularly with smaller traffic sign objects, challenges such as missed and false detections can lead to reduced overall detection accuracy. To address this issue, this paper proposes a detection algorithm that integrates edge and shape information. Recognizing that traffic signs have specific shapes and distinct edge contours, this paper introduces an edge feature extraction branch within the backbone network, enabling adaptive fusion with features of the same hierarchical level. Additionally, a shape prior convolution module is designed to replaces the first two convolutional modules of the backbone network, aimed at enhancing the model’s perception ability for specific shape objects and reducing its sensitivity to background noise. The algorithm was evaluated on the CCTSDB and TT100k datasets, and compared to YOLOv8s, the mAP50 values increased by 3.0% and 10.4%, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method in improving the accuracy of traffic sign detection.Keywords

The rapid advancement of autonomous driving technology is transforming the transportation sector and enhancing both road safety and traffic efficiency. As we progress towards the widespread adoption of autonomous driving, the accurate recognition and response to traffic signs become in-creasingly important. Traffic signs serve as the foundation of road safety regulations, providing vi-tal guidance for navigation, speed control, and hazard warnings, thereby ensuring safe and orderly traffic flow. However, traffic sign detection presents significant challenges. In real-world traffic scenarios, factors such as adverse weather conditions, poor lighting, and and long-distance imaging can result in blurred edges of traffic signs, causing inaccuracies in detection models and leading to missed detections and false positives.

To address the issues of missed detections caused by low contrast, blurred edges, and occlusions of traffic signs, this paper introduces an edge feature extraction branch into the model. This branch focuses on capturing blurred edges and adaptively fuses with the corresponding level features of the backbone network. The two branches interact, further enhancing the model’s capability to represent edge information. Meanwhile, to tackle the problem of false positives caused by background elements resembling traffic sign shapes in complex road environments, this paper designs a convolutional module with shape priors. This module enhances the model’s ability to perceive specific traffic sign shapes, enabling it to focus more on features that match the prior shapes, thereby reducing background noise interference and significantly decreasing the false positive rate. The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

i. Based on YOLOv8, this paper designs and adds an edge branch to the backbone network. Through the adaptive fusion module, the two branches interact, enhancing the model’s ability to perceive edge information.

ii. This paper designs a convolutional module with shape priors, which enhances the model’s ability to recognize specific shapes of traffic signs, reduces interference from complex backgrounds, and thus improves the model’s ability to perceive traffic signs.

iii. This paper adds a P2-level small object detection head to YOLOv8, enhancing the model’s ability to detect small objects. Experiments on the CCTSDB and TT100K datasets confirm that the proposed method achieves improvements in mean Average Precision (mAP50) of 3.0% and 10.4%, respectively, over YOLOv8.

This section primarily introduces the existing related research work on traffic sign detection, edge information guidance, and shape feature perception.

Traffic-sign detection is a prominent research topic in autonomous driving; as deep learning has matured, numerous algorithms have been proposed for classifying and detecting road traffic signs. The mainstream traffic sign detection algorithms are one-stage detection algorithms. Examples include SSD [1] and the YOLO family, with YOLO widely used and continually improved for its detection efficiency.

Recent work has converged on multi-scale representation and attention mechanism. Manzari et al. [2] introduce a hybrid pyramid transformer with attribute convolution to fuse global–local features across scales, improving robustness to sign-size variation. Li et al. [3] propose an illumination-invariant hierarchical feature enhancement network and plugg it into existing object detectors. Gao et al. [4] propose adaptive–spatial attention that weights informative regions during multi-scale fusion, strengthening small-object representation. Reference [5] couples GIoU loss with a refined PANet-style neck on YOLOv4 to optimize multi-scale fusion and box regression. Yao et al. [6] modify the YOLOv4 FPN and add a receptive-field module to the backbone to expand context and extrac-tion capacity. Yu et al. [7] exploit inter-frame dependencies via a VGG–YOLOv3 architecture that links adjacent frames for sequence-aware detection. Feature strengthening with auto-augmentation and tightly-coupled extractors further improves small-sign robustness. Wang et al. [8] add a YOLOv5 feature-enhancement module and an auto-learned augmentation policy to increase robustness. Wang et al. [9] further design a tightly coupled feature structure and a new extractor to improve sensitivity to small signs. Zhang et al. [10] introduce C3Ghost to cut computation for real-time inference while preserving accuracy. Wei et al. [11] propose a fusion module plus a corner-expansion encoder to sharpen corner cues and improve localization. Liang et al. [12] augment sparse R-CNN with coordinate attention on ResNeSt and add adaptive and test-time enhancement to raise accuracy and robustness. Zhang et al. [13] integrate exposure–tone–brightness enhancement with an encoder/aggregator producing multi-receptive-field features and fusing multi-resolution maps. Zhang et al. [14] replace standard blocks with structurally re-parameterized modules and add pyramid weighting to narrow cross-scale semantic gaps. Attention and neck designs evolve toward cross-stage attention, sub-pixel channel integration with inter-layer interaction, and multi-scale attention with spatial aggregation. Shi et al. [15] employ cross-stage attention and a neck that more fully merges detailed and semantic information. Zhao et al. [16] use sub-pixel convolution to fold channel information into spatial resolution and propose MIFNet to strengthen inter-layer interaction. Zhang et al. [17] present a multi-scale attention module and a spatial aggregator that injects low-level spatial cues into high-level features. Xie et al. [18] develop GRF-SPPF and the SPAnet architecture with dual shortcuts and an extra small-object head to en-hance path aggregation. Zhang et al. [19] combine channel–spatial attention with RFB-based fusion to diversify receptive fields at low cost. Luo et al. [20] integrate Ghost modules with efficient multi-scale attention in YOLOv8 to accelerate inference while retaining accuracy. Khan et al. [21] propose a unified two-stage framework that turns each FPN level into a scale-specific proposal generator via multiple RPNs and then classifies the proposals, yielding stronger multi-scale detection on high-resolution satellite images. Du et al. [22] use space-to-depth to fold spatial cues into channels for multi-scale targets, introduce select-kernel attention for adaptive focusing, and adopt a weighted WIoUv3 loss to stabilize regression and training. Cui et al. [23] build cross-layer multi-sequence, multi-scale fusion within a transformer detector, combined with channel–spatial attention and an inverted residual moving block to enhance positional cues while retaining efficiency. Zhang et al. [24] add a small-object detection layer and integrate a bidirectional FPN into a one-stage detector to strengthen multi-scale fusion and improve small sign detection. Shen et al. [25] perform decision-level camera–LiDAR fusion: detect/track images and point clouds separately, associate with Aggregated Euclidean Distance and optimal matching to improve robustness under occlusion. Zhou et al. [26] propose multi-scale enhanced feature fusion—using activation-free attention to emphasize saliency, a fusion pyramid to integrate multi-level semantics, and global–local aggregation to couple long- and short-range context.

Despite steady advances, detecting very small signs remains brittle: down-sampling and stride quantization smear fine contours and suppress weak signals. Edge localization is easily perturbed by clutter, motion blur, and compression noise, yielding inaccurate boundaries and unstable regression. Meanwhile, large intraclass shape variation from scale, viewpoint, and occlusion continues to challenge robustness to shape changes.

Although edges are nominally low-level cues, they remain indispensable for representation learning and, when used as guidance, enhance the perception of edge-salient targets. Sun et al. [27] leverage target-related edge semantics to steer high-level feature extraction, enforcing structure-aware representations. Zhou et al. [28] propose an edge-guided cyclic localization network with parallel decoders—one for edge extraction and one for feature fusion—to produce edge-enhanced features. Luo and Liang [29] model semantic-edge correlation via a semantic-edge interaction network that combines a multi-scale attention interaction module with a semantic-guided fusion module. Together, these approaches demonstrate the value of edge cues in emphasizing target structure, guiding high-level features, and improving localization accuracy. Recent studies also exploit intrinsic shape cues to strengthen target-specific perception. Although edge and shape cues are well established in semantic segmentation, their efficient exploitation in traffic-sign detection remains limited.

In the traffic scenarios of autonomous driving, the detection of traffic signs still faces several challenges, such as small target size, occlusions, low contrast, and complex backgrounds, which can lead to missed detections and false positives. Therefore, detectors must deliver real-time performance and high accuracy so that vehicles have sufficient time to respond to complex traffic situations.

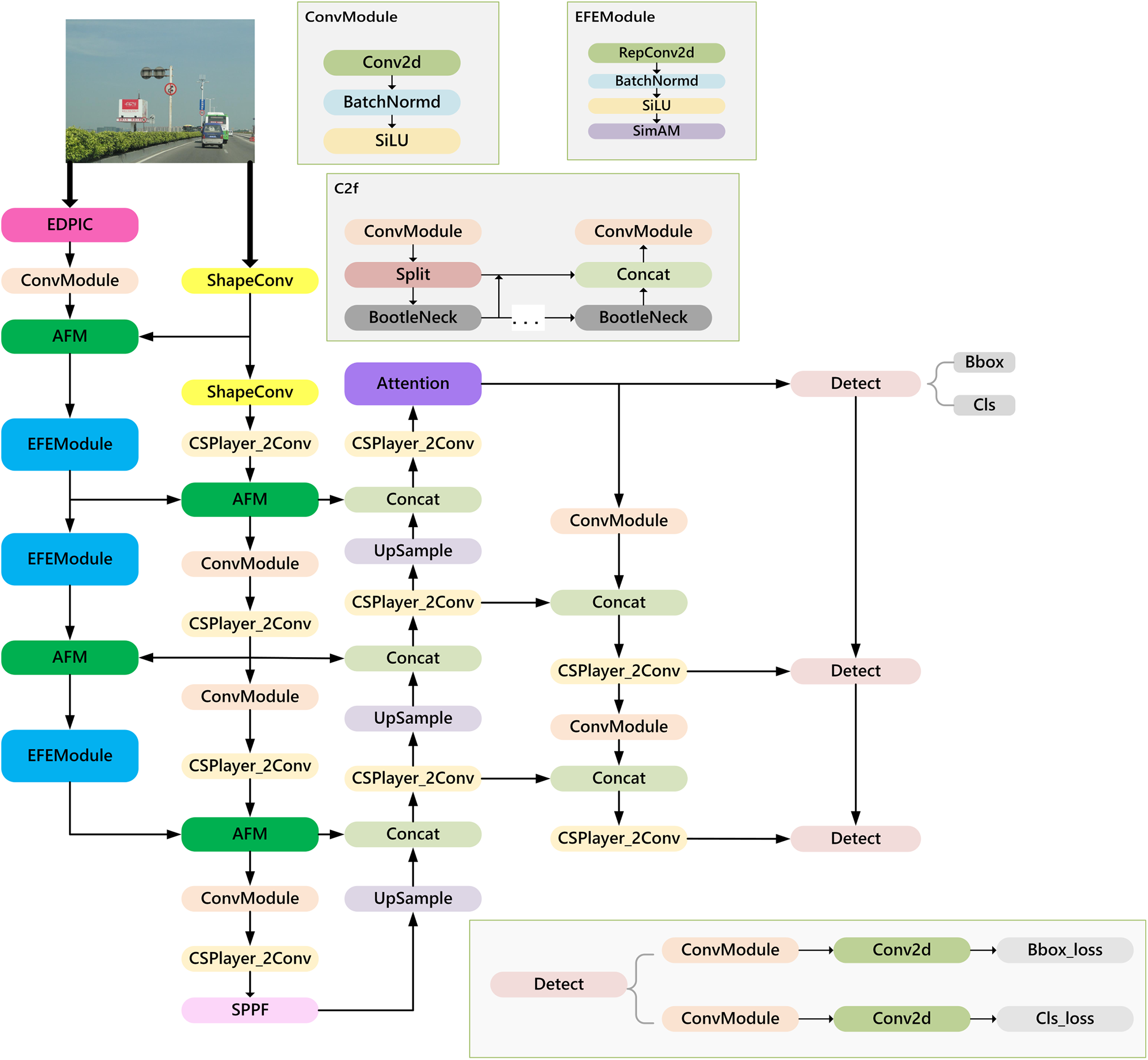

Fig. 1 shows the overall architecture of ES-YOLO. The backbone network includes the original YOLOv8 backbone branch and an edge feature extraction branch. We replace the first two convolutional blocks in the backbone with the proposed shape-prior convolutional modules and add a P2-level small-object detection head. The edge-extraction branch mitigates edge blurring caused by weather and illumination changes. By introducing shape-prior knowledge and a small-object detection head, the method reduces background interference and occlusion-induced false positives, thereby enhancing the detection of small targets.

Figure 1: ES-YOLO

3.1 Edge Feature Extraction Branch

Adding an edge feature extraction branch to the backbone network aims to enhance the network’s ability to perceive and extract edge and contour information. In complex, dynamic scenes, background clutter (e.g., trees, street lights, buildings) and weather-induced edge blurring can cause missed detections. By incorporating the edge extraction branch, the model’s representation capability of edges and contours is strengthened, allowing it to better focus on traffic sign areas with clear edges.

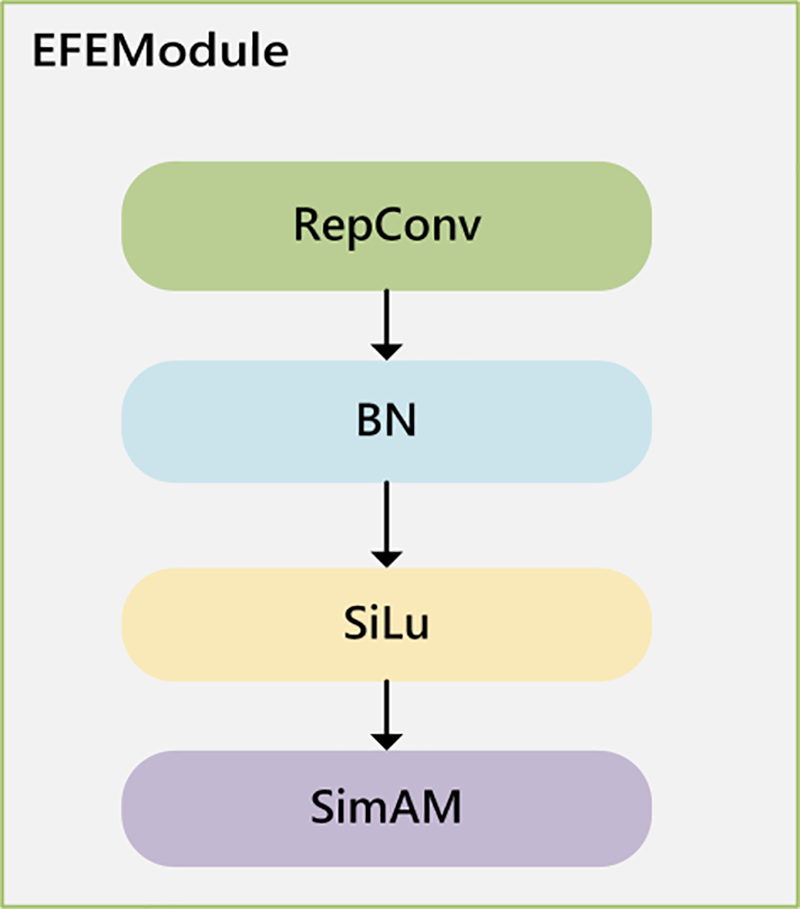

The edge extraction branch consists of an edge map extraction module, convolutional blocks, an edge feature extraction module, and an adaptive feature fusion module. The raw image first passes through the edge-map extractor, which uses a Sobel operator. Next, the edge feature extraction module performs convolutional downsampling, focusing on refining and enhancing edge features to provide the model with richer edge information. The adaptive feature fusion module learns the optimal weights for fusing the same level features of the two branches. At the same hierarchical level, features from the two branches guide each other. This allows the high-level semantic information of the backbone features to guide the edge information extraction process, while using edge features to constrain the extraction range of high-level semantic information. This integration of geometric details from edge information enables the model to better focus on traffic sign areas, enhancing its anti-interference capability and alleviating issues of missed and false detections. The structure of the edge feature extraction module is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Edge feature extraction block

The re-parameterization technique [30] retains the excellent feature extraction capabilities of multi-branch structures, enabling the extraction of rich edge features from the edge map. This is highly effective for the network to capture detailed information such as edges and contours. Additionally, it decouples the planar structure of the inference stage from the multi-branch structure of the training stage, effectively improving computational efficiency and reducing inference time, which is crucial for the quick response required in traffic sign detection.

The final layer of the edge feature extraction module is a parameter-free attention mechanism [31] (SimAM). Unlike conventional channel or spatial attention, SimAM introduces no extra parameters; it minimizes an energy function to estimate the importance of each neuron and produces a 3-D attention map that adaptively enhances edge cues useful for detection. Since the edge map extracted by the Sobel operator contains not only the edge information of traffic signs but also introduces noise interference, the flexibility and lightweight nature of the parameter-free attention mechanism are utilized to reshape the feature map, effectively suppressing irrelevant information. This enables the network to focus more on local details to obtain richer features.

The approach of the parameter-free attention mechanism is as follows: First, calculate the channel statistics

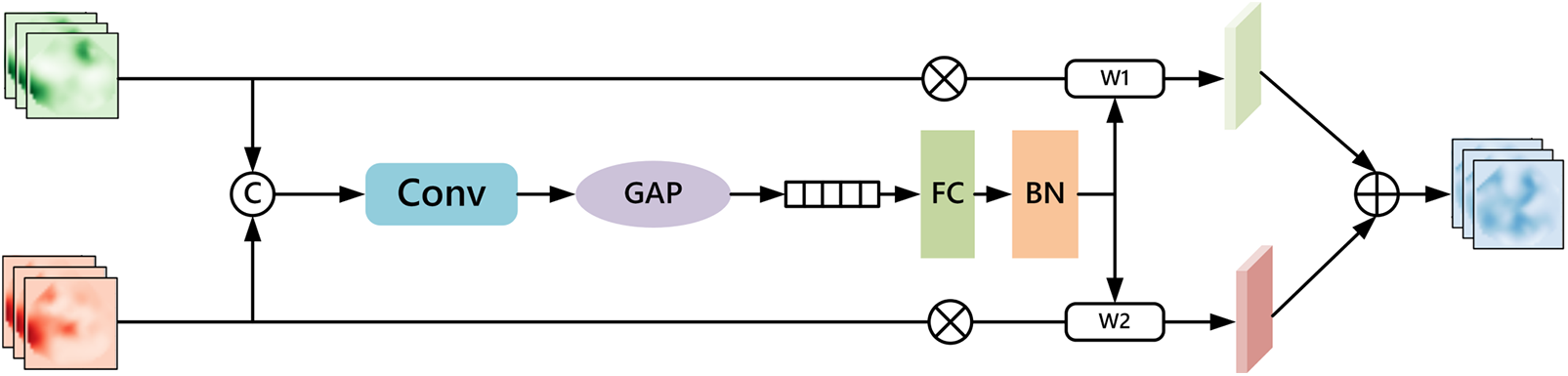

3.2 Adaptive Feature Fusion Module

To better fuse the same-level features of the edge branch and the backbone branch, enhancing the complementarity of the features and enabling the model to not only understand what the target object is but also more accurately locate the target’s boundaries, this paper designs an adaptive feature fusion module. Its structure is shown in Fig. 3. It consists of convolutional layers, pooling layers, and linear layers.

Figure 3: Adaptive feature fusion module

The process can be described as follows: For the input same-level edge branch features

Next, the integrated feature information is input into the global average pooling layer, compressing the feature map of each channel to obtain the global representation features Z. Z is then fed into the fully connected layer, normalized, and activated to obtain the weights

In the traffic sign detection task, the backbone of YOLOv8 can extract some low-level edge contour information and high-level semantic information from the image. However, to improve the model’s sensitivity to and capability to represent edge information of traffic signs, this method adaptively fuses the more refined and complete edge features extracted from the edge map with the features extracted by the backbone. The adaptive feature fusion module is alternately used in the backbone and the edge branch. This fusion enables high-level semantics from the backbone to guide edge extraction (focusing the edge branch on target-related boundary regions) and, conversely, uses edge features to refine high-level semantic extraction in the backbone. This is because the detailed information provided by the edge branch is often overlooked by the backbone branch. In summary, the adaptive feature fusion module learns to balance the contributions of the edge branch and the backbone branch, achieving the guidance of high-level semantic information for edge feature extraction and the optimization of semantic feature extraction by edge information. This inter-action significantly enhances the performance of traffic sign detection, particularly the accuracy and robustness in complex environments.

Compared with other edge-guided fusion processes, our method does not treat the edge map as an auxiliary channel fused with semantic features by static concatenation or a fixed mixing ratio. We first distill high-frequency structure with re-parameterized convolutions and suppress low-SNR responses with a parameter-free attention mechanism to obtain a denoised boundary representation; at multiple neck scales, a joint global summary of the two streams produces a bounded pair of weights that simultaneously modulate the semantic and edge features, and bi-directional fusion is performed before the detection heads. When boundaries are reliable, their weight is increased; when boundaries are unreliable, their influence is reduced, yielding a reliability-weighted, content-adaptive coupling rather than fixed-ratio stacking. This mechanism complements the shape prior and is more robust for small and thin targets and in cluttered backgrounds.

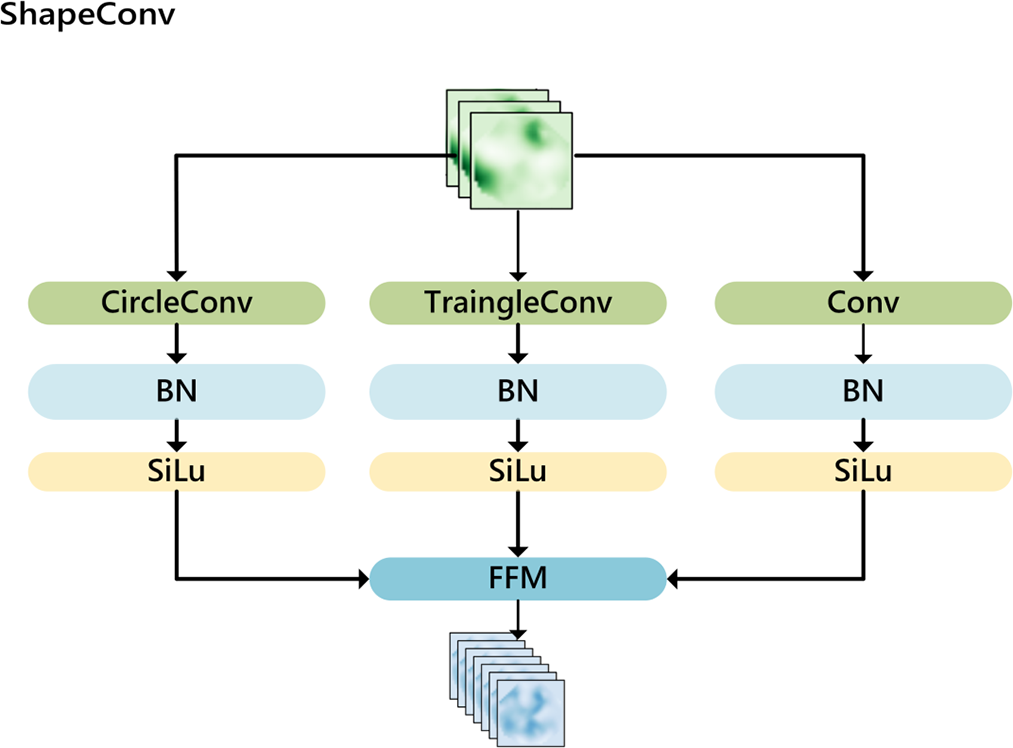

3.3 Shape-Prior Convolutional Block

Traffic signs have fixed shapes, including circles, triangles, and rectangles. Their shape features are very prominent and important for identification. Therefore, this paper considers incorporating the shape prior knowledge of circles and triangles into the feature extraction process. A circular convolutional kernel block and a triangular convolutional kernel block are designed, forming the basis of the shape-prior convolutional block. Its structure is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Shape prior convolution block

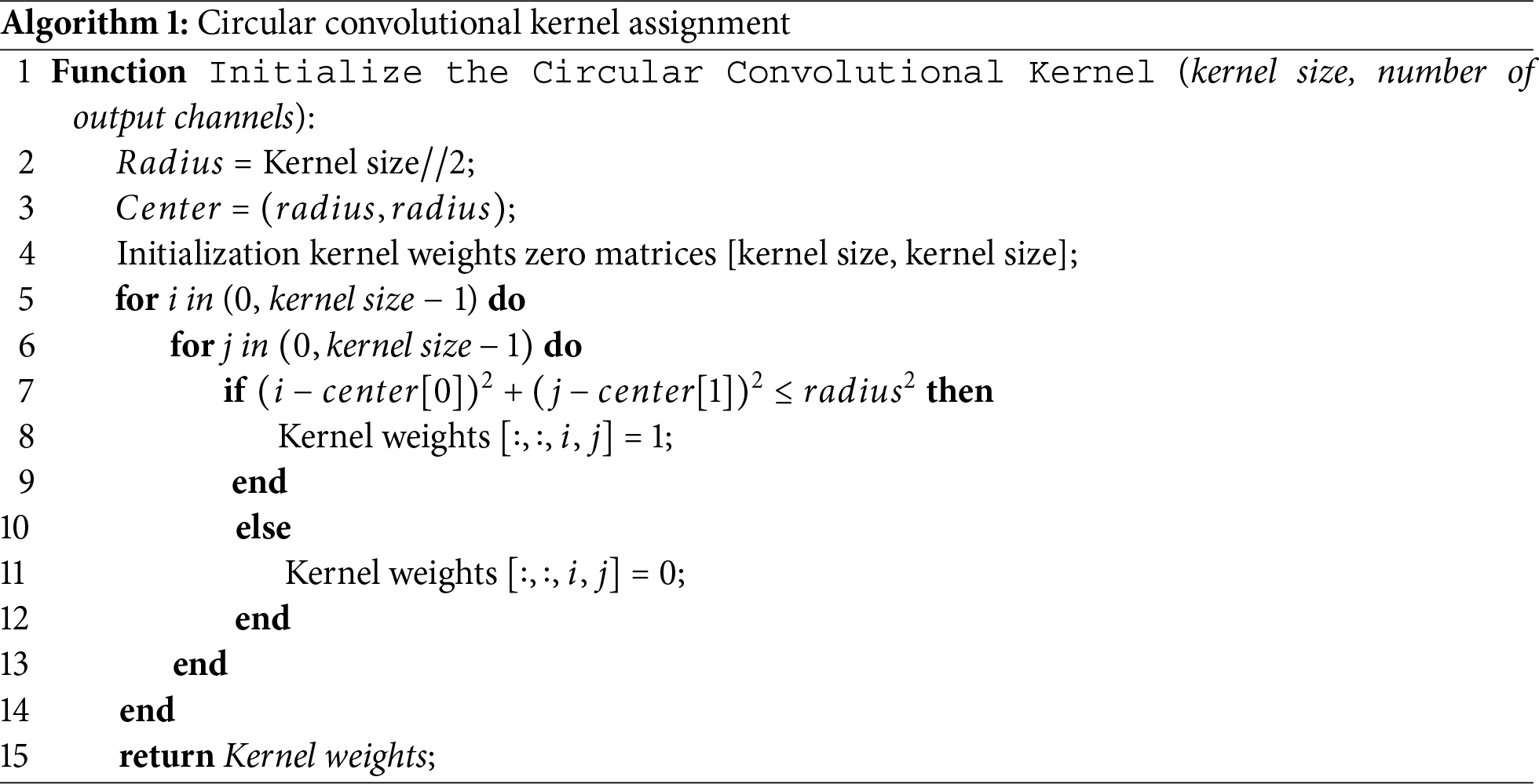

By embedding shape information as priors directly into the convolutional kernels, the method enables the model to perceive and respond more effectively to features that match these shapes. Because cues such as shape, edges, and contours are low-level, they are more easily captured in the shallow layers of the network; accordingly, we replace the first two backbone blocks with the pro-posed shape-prior convolutional blocks to enhance the model’s capability to represent objects with specific shapes. The design of the circular-kernel block is detailed in Algorithm 1.

The following example shows the weights of a circular convolutional kernel with a kernel size of 5:

The initialization process for the weights of the triangular convolutional kernel is similar. For a kernel size of 5, the weights of the triangular convolutional kernel are:

By initializing the convolutional kernel weights with circular and triangular shape priors, we fix the kernel parameters in the first shape-prior layer, enhancing the network’s ability to perceive fixed shapes. In the second layer of the shape-prior block, the kernel parameters are learned dynamically, allowing the model to remain sensitive to shape while fine-tuning the prior. This design provides advantages for traffic-sign detection: in complex, dynamic scenes, signs appear at multiple scales and views; embedding shape priors improves robustness across scales and viewpoints and ensures the network can extract specific shapes. Real-world roads also contain cluttered backgrounds that occlude signs, making it difficult for traditional detectors to recognize partially occluded targets. Introducing shape-prior convolutions leverages local shape cues, enhancing the detector’s ability to recover occluded targets and reducing missed and false detections caused by occlusion.

Prior edge-guided and shape-aware detectors commonly fuse edge maps and semantic features by static concatenation or fixed-ratio addition, often with single-direction guidance at a single scale near the head. ES-YOLO learns input-conditioned gates across multiple neck scales to modulate the semantic and edge streams, and performs bi-directional fusion before the detection heads, so that the fusion weights adapt to image content and scale. The shape-prior convolution block introduces an explicit structural bias toward canonical traffic-sign geometries, complements edge cues, reduces boundary confusion with background textures, and strengthens discrimination for small and thin signs. These choices clarify how ES-YOLO differs from previous designs and provide a mechanistic explanation for the consistent improvements observed on TT100K, CCTSDB, and GTSRB, partic-ularly under illumination change, occlusion, and scale variation.

Experiments were conducted on Ubuntu 20.04 with PyTorch 1.12 using an NVIDIA TITAN V GPU. We trained with SGD (initial learning rate 0.01), batch size 8, for 20 epochs, and enabled au-tomatic mixed precision. The method proposed in this paper is trained and tested on the CCTSDB [32] and TT100K da-tasets. The TT100K dataset is a public dataset collected in China, containing 16,000 images and 27,000 instances of traffic signs. The CCTSDB dataset comprises over 17,000 images, including scenarios with variations in lighting, different scales, and occlusions or damage.

To compare the performance of the method proposed in this study with other methods, the following evaluation metrics were used: precision, recall, mean Average Precision (mAP50), Floating Point Operations (FLOPs), and Frames Per Second (FPS).

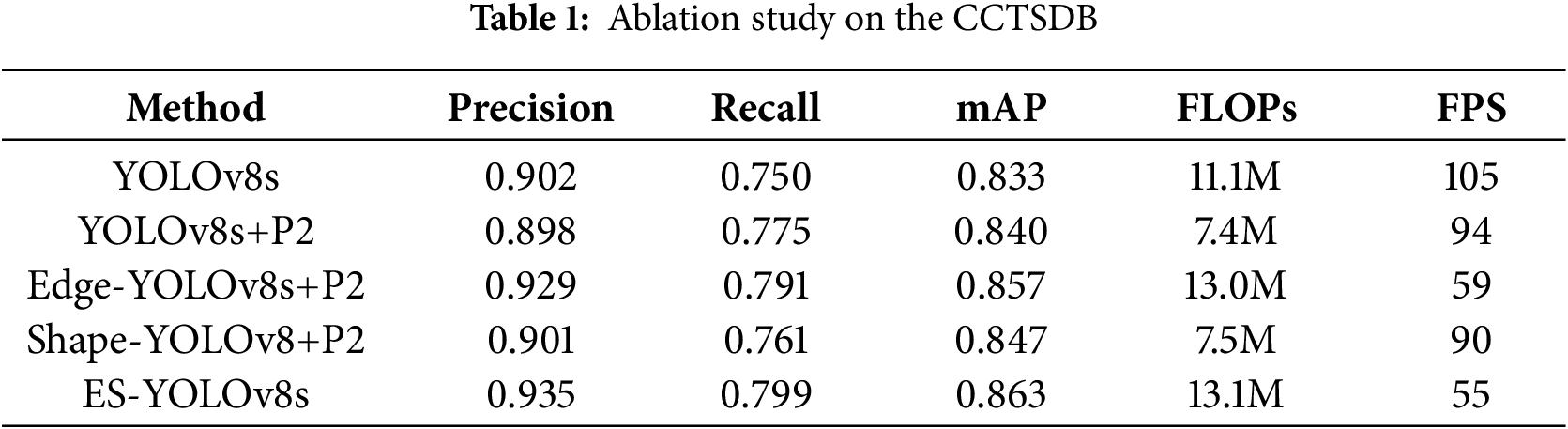

To verify the performance improvement brought by the enhanced methods proposed in this study, ablation experiments were designed to evaluate the performance of each module. The input size for all experiments was set to 640

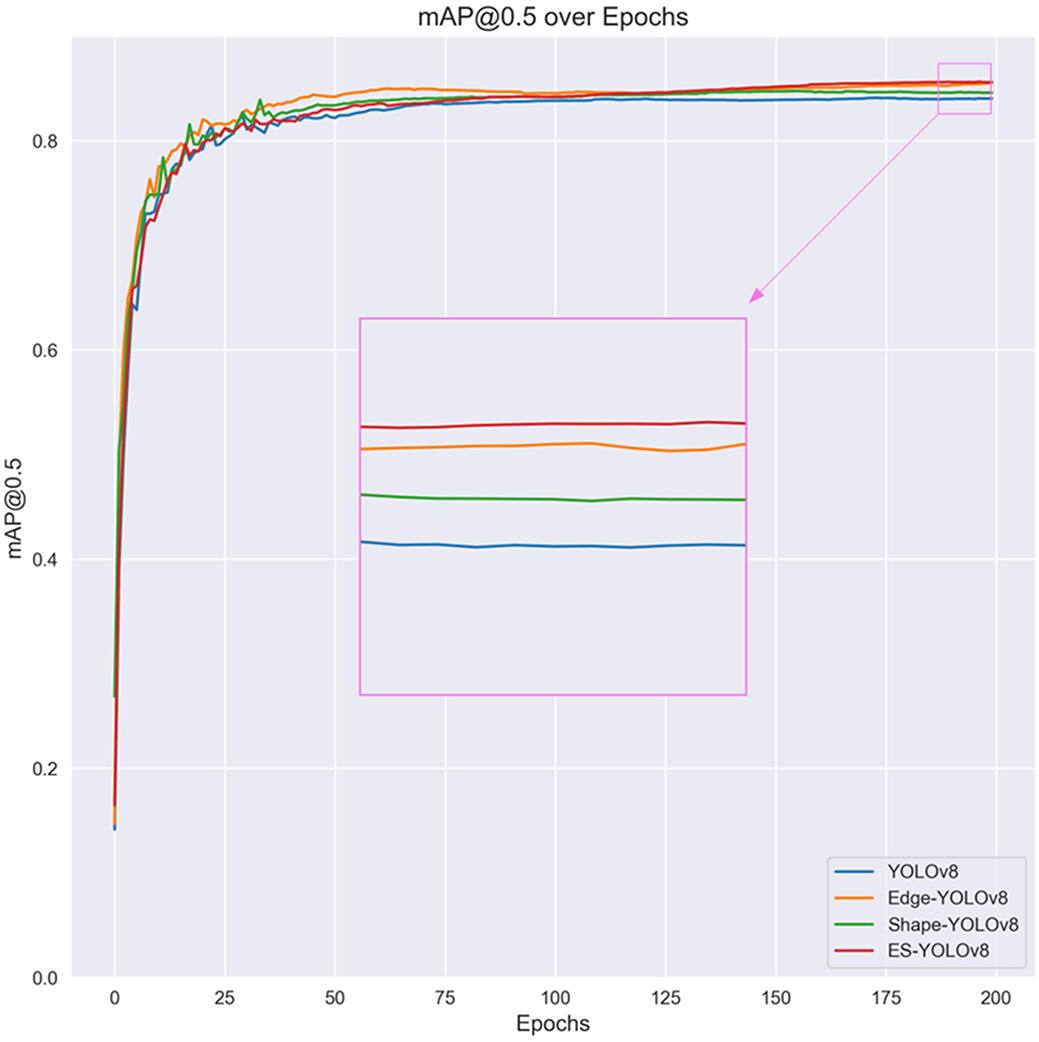

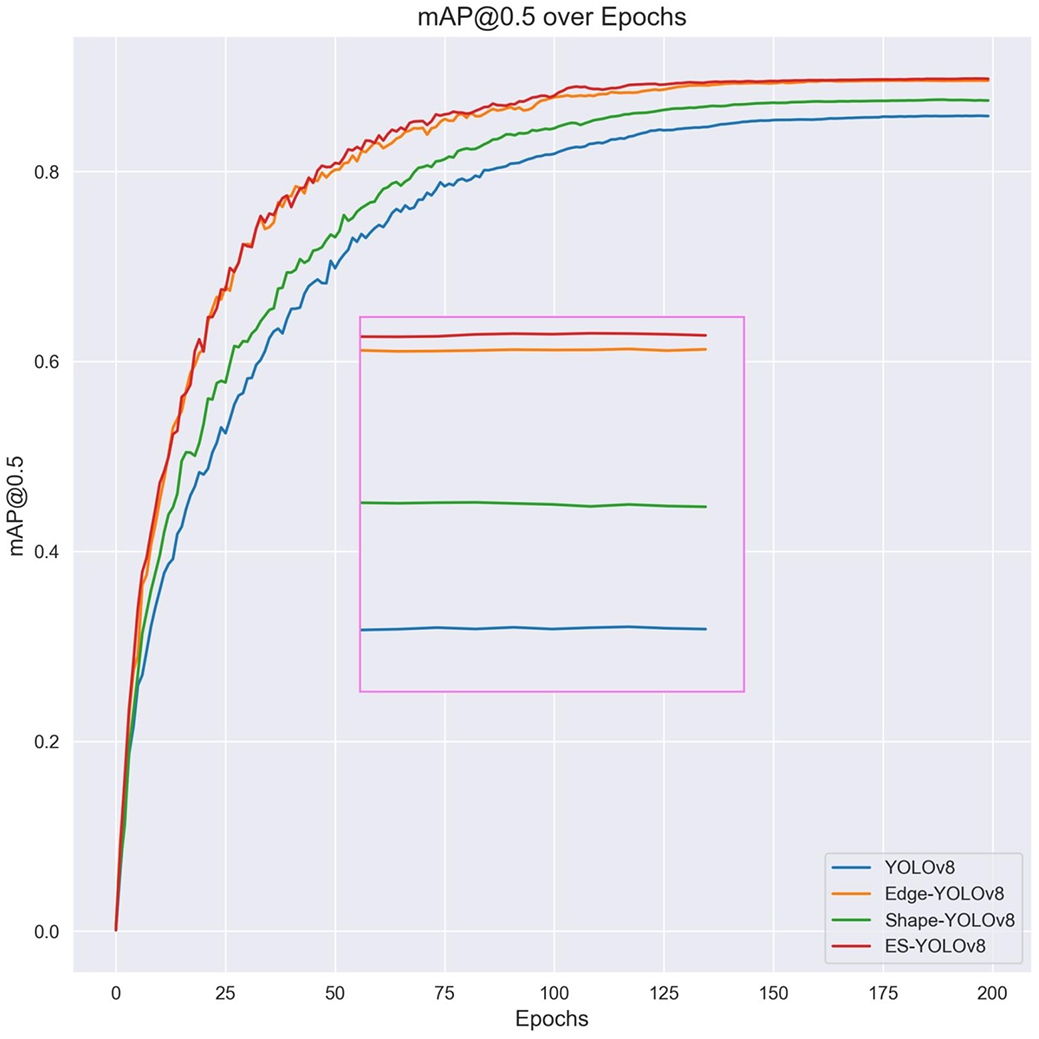

From the data in Table 1, it can be seen that after adding the P2-level detection head and re-moving the large detection head, the mean Average Precision (mAP50) increased by 0.7%. On this basis, adding the edge extraction branch increased the mean Average Precision by 1.3%. Adding the shape-prior convolutional block increased the mean Average Precision by 0.7%. When the edge extraction branch and shape-prior convolutional block were combined, forming the ES-YOLOv8s network structure proposed in this paper, the mean Average Precision improved by 3% compared to the YOLOv8s structure. This fully demonstrates the effectiveness of the edge extraction branch and shape-prior convolutional block proposed in this paper. Additionally, the improvements in pre-cision and recall rates demonstrate a reduction in false positives and an increase in true positives, effectively mitigating the issues of missed and false detections. Fig. 5 shows the change in mean Average Precision during the training process.

Figure 5: mAP curve on CCTSDB

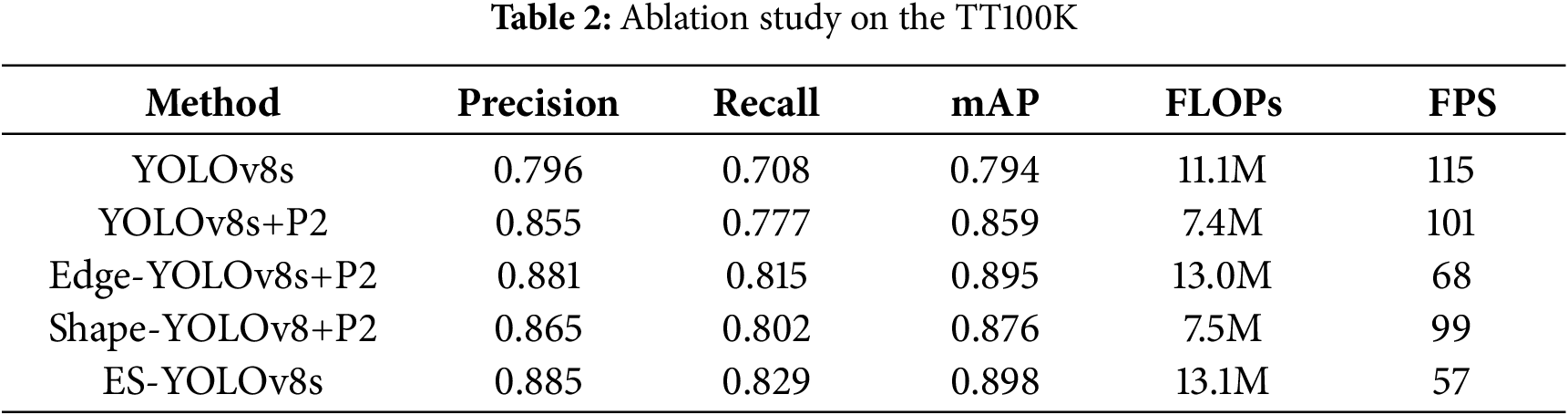

From the data in Table 2, it can be seen that after adding the P2-level detection head and re-moving the large detection head, the mean Average Precision (mAP50) increased by 6.5%. On this basis, adding the edge extraction branch increased the mean Average Precision by 4.0%. Adding the shape-prior convolutional block increased the mean Average Precision by 1.7%. When the edge extraction branch and shape-prior convolutional block were combined, forming the ES-YOLOv8s network structure proposed in this paper, the mean Average Precision (mAP50) improved by 10.4% compared to the YOLOv8s structure. Fig. 6 shows the change in mean Average Precision during the training process.

Figure 6: mAP curve on TT100K

Notably, on CCTSDB the addition of the P2 small-object head yields only a +0.7% mAP gain, whereas on TT100K the same change produces a +6.5% mAP gain. This suggests that TT100K contains a higher proportion of small, thin, and distant traffic signs. The discrepancy aligns with the design rationale of ES-YOLO: edge cues and shape priors impose stronger constraints for small objects and blurred boundaries, leading to larger overall improvements on TT100K. In contrast, targets in CCTSDB are generally more discernible, so the gains are smaller but stable and consistent. Taken together, results on the two datasets indicate that ES-YOLO delivers improvements in a consistent direction across different data distributions, demonstrating robustness and transferability.

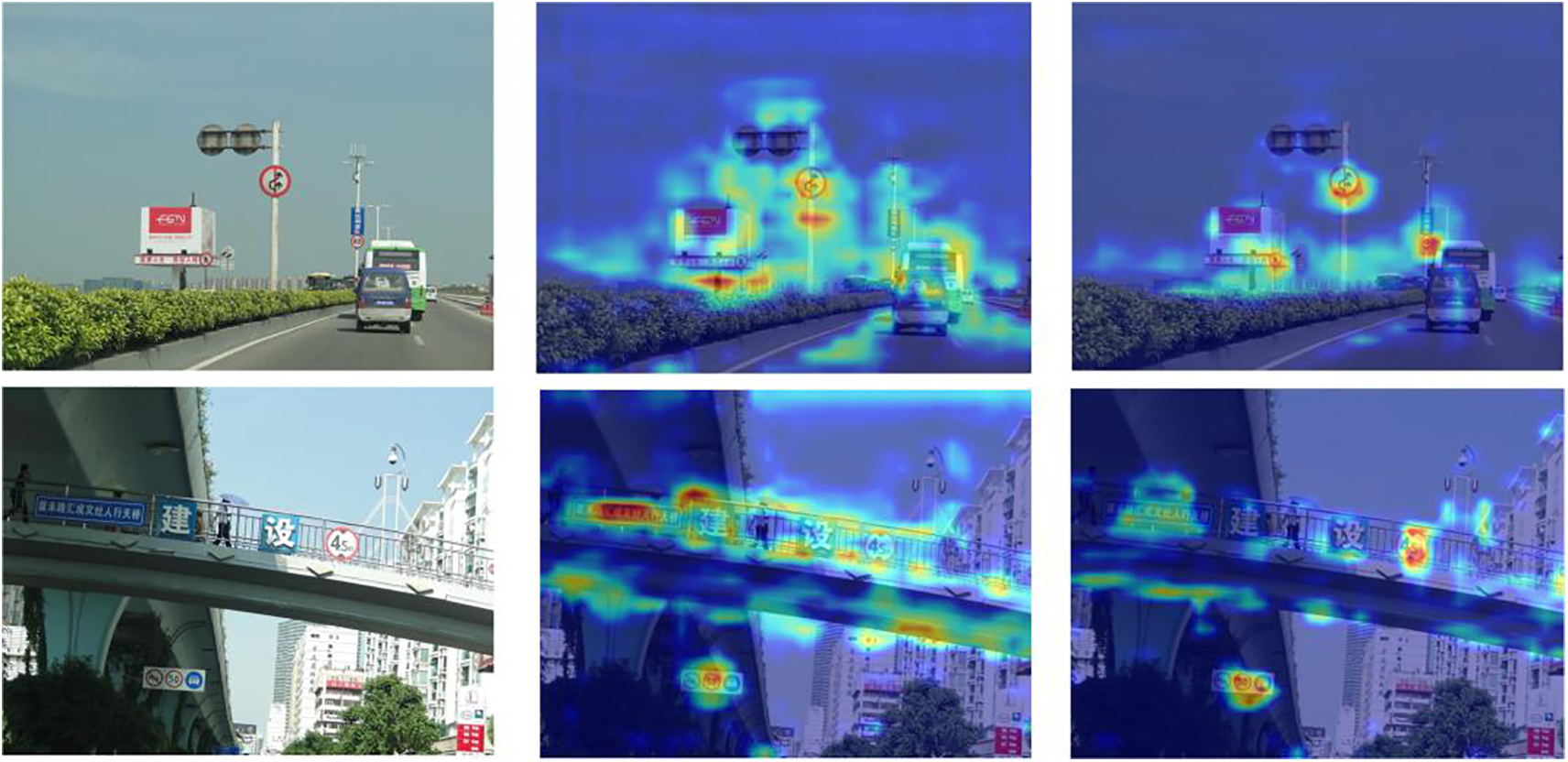

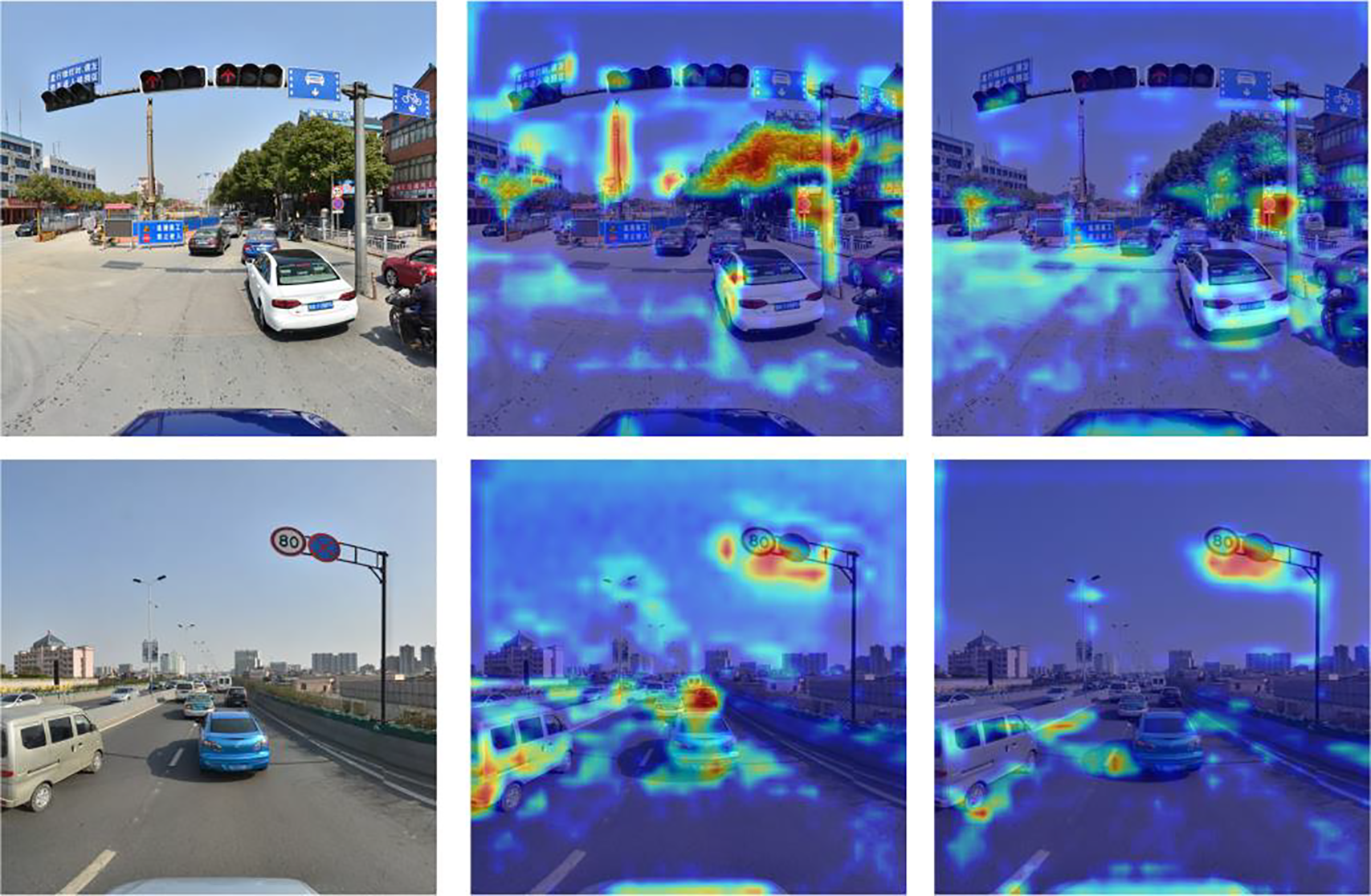

To verify that the edge extraction branch and shape-prior block help the model focus on traffic-sign regions, suppress background interference, and improve sensitivity to and capability to represent specific shapes, we visualize feature maps as heatmaps. We select the last feature map of the backbone for visualization. Heatmap comparisons on CCTSDB and TT100K are shown in Figs. 7 and 8.

Figure 7: Heatmap visualization of the detection results on CCTSDB dataset

Figure 8: Heatmap visualization of the detection results on TT100K dataset

Figs. 7 and 8 respectively present the heatmap comparisons. The left column shows the original images, the middle column shows YOLOv8 heatmaps, and the right column shows heatmaps from our method. In Fig. 7, YOLOv8 exhibits a scattered attention pattern in complex backgrounds; attention often leaks to irrelevant elements such as trees and sky, leading to imprecise edge focus around the signs. By contrast, our method—leveraging the edge-feature extraction module and the shape-prior block—concentrates attention on sign regions and markedly reduces back-ground noise. In the second row, YOLOv8 over-attends to bridge structures and shadows, which dilutes focus on the signs, whereas our method highlights the critical edge areas and improves detection.

In Fig. 8, the first row contains heavy background clutter with many vehicles and buildings. Here YOLOv8 spreads attention to car rooftops and building façades, resulting in insufficient coverage of the signs; our method enhances edge awareness, suppresses interference, and achieves more precise localization. The second row represents a low-contrast scenario: YOLOv8 shows weak edge attention and fails to capture blurry boundaries, while our method strengthens boundary focus and improves recognition. These results demonstrate improved robustness and accuracy in both cluttered backgrounds and low-contrast settings, effectively reducing missed and false detections.

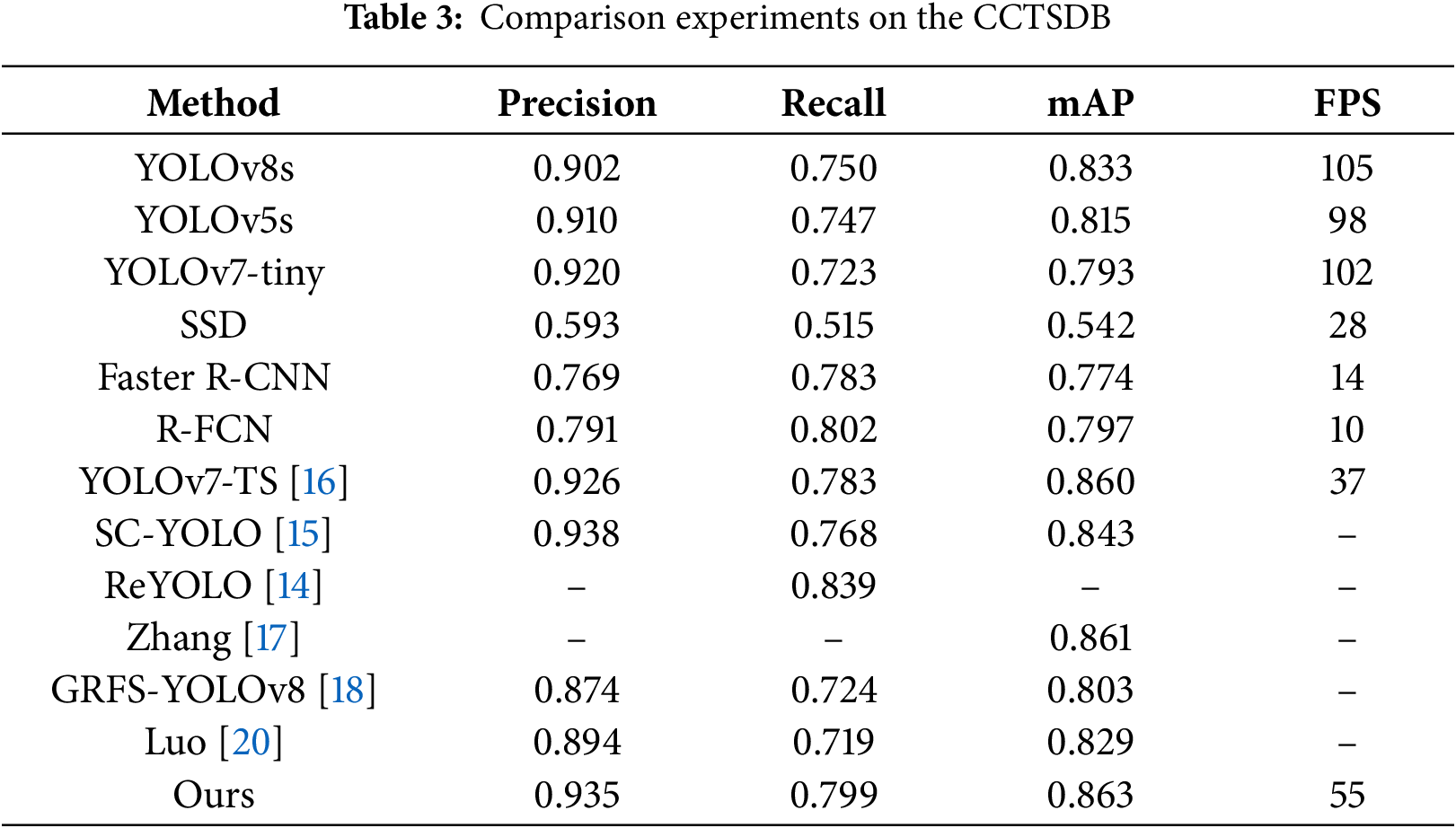

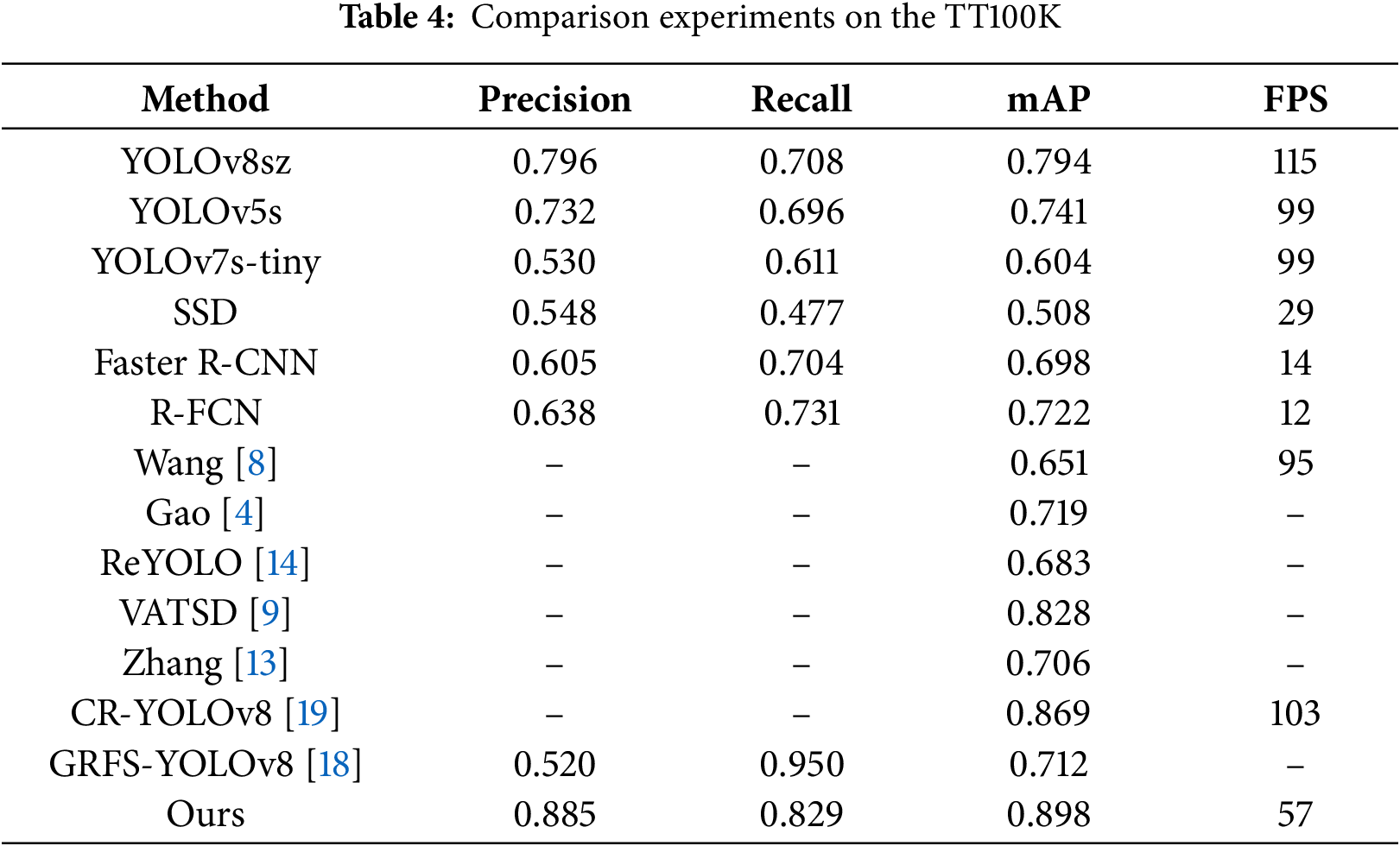

4.3 Comparison Experiments with Mainstream Detection Mode

To verify the performance of the proposed detection algorithm, comparisons were made with mainstream single-stage and two-stage detection models. Considering that the proposed improvements are based on YOLOv8s, this study chose smaller models from the YOLOv5 and YOLOv7 series for comparison. Each model was given an input size of 640

According to the data in Tables 3 and 4, the proposed method shows significant improvement in mean Average Precision (mAP) compared to other mainstream single-stage detection models, while meeting the speed requirements for real-time detection.

Under low contrast, blurred boundaries, and partial occlusions, the mAP gains indicate that ES-YOLO is robust to challenging conditions. At the same time, the edge branch and the shape-prior module introduce only a modest increase in parameters and computation, and the inference speed remains real-time under our setting, which meets the requirements of traffic scenes. Compared with the single-stage baseline, ES-YOLO improves accuracy while keeping latency acceptable; compared with typical two-stage detectors, it avoids the overhead of proposal generation and repeated feature resampling, achieving competitive accuracy with lower latency. Overall, ES-YOLO offers a balanced accuracy–efficiency trade-off and is suitable for real-world applications that require both robustness and real-time performance.

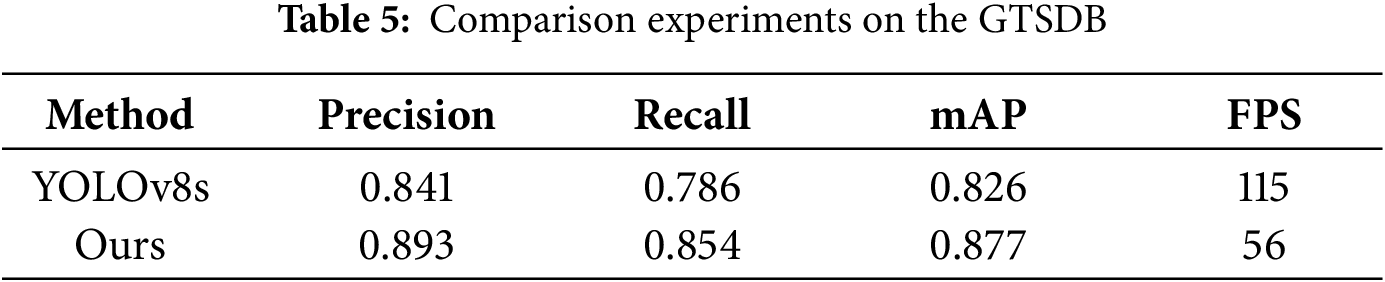

As is shown in Table 5, we conduct an additional evaluation on GTSDB to assess cross-dataset generalization. ES-YOLO attains an mAP of 0.877, surpassing 0.826 of YOLOv8s with a gain of 5.1 percentage points, indicating effectiveness on full-scene images with small signs and cluttered backgrounds. Throughput decreases from 115 FPS to 56 FPS yet remains real-time. The outcome is consistent with the trends on TT100K and CCTSDB, underscoring robustness and deployability.

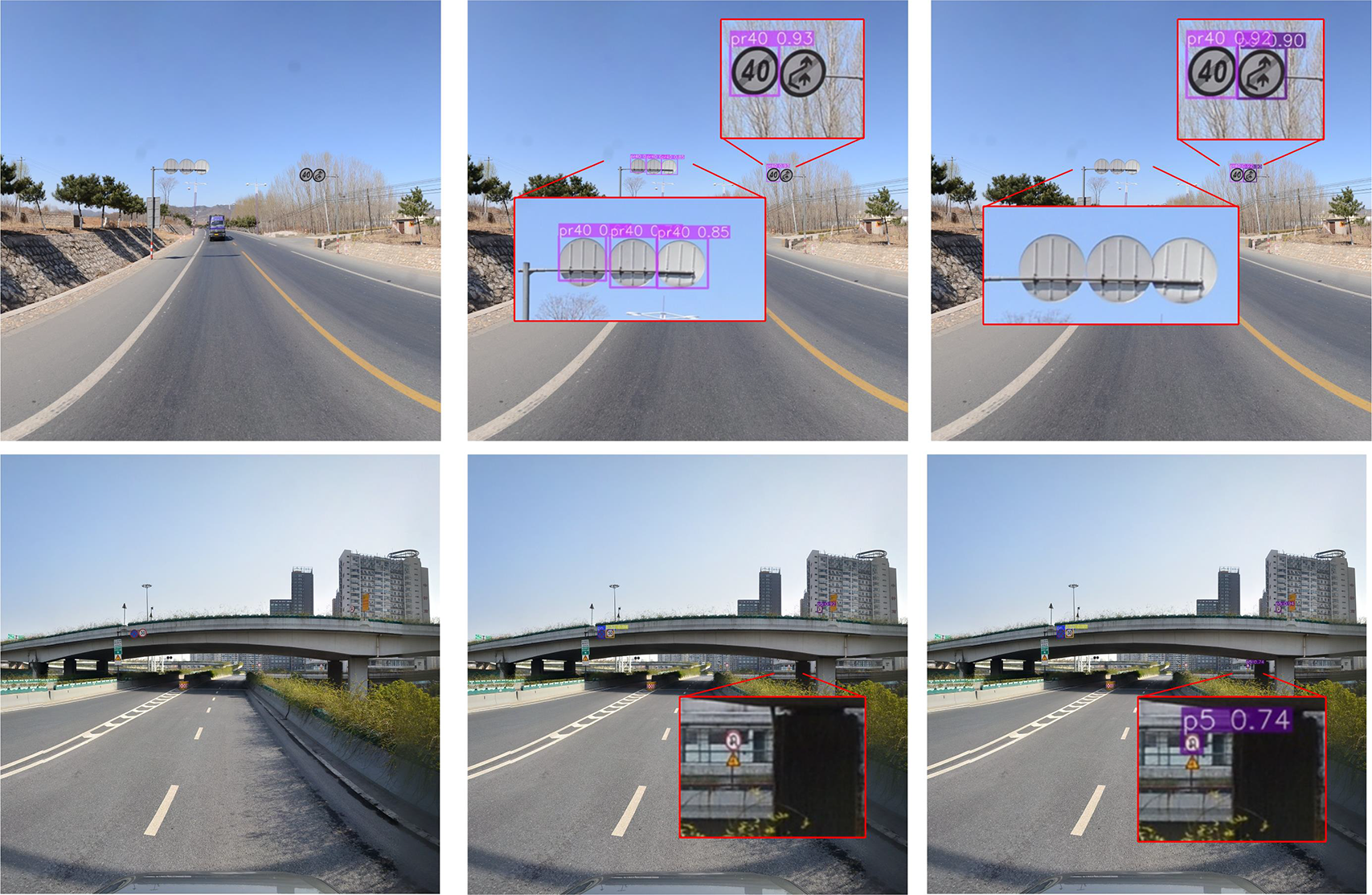

As shown in Figs. 9 and 10, YOLOv8 results are in the middle column and our method in the rightmost column. Fig. 9 illustrates a low-contrast nighttime scene. Under this challenging condition, YOLOv8 struggles to separate signs from the background because poor lighting reduces contrast; its bounding boxes are vague and the confidence scores are 0.33 and 0.48 in the examples from the middle column. This indicates insufficient boundary capture in low-contrast settings. In contrast, the proposed method, which incorporates an edge-extraction module, enhances sensitivity to subtle boundaries: the boxes more accurately cover the traffic-sign regions and the confidence scores rise to 0.73 and 0.85, demonstrating improved robustness in low-contrast scenarios.

Figure 9: Comparison of detection results between YOLOv8 and the proposed method on CCTSDB in low-contrast sce-narios

Figure 10: Comparison of detection results between YOLOv8 and the proposed method on TT100K in complex back-ground and partial occlusion scenarios

Fig. 10 presents the detection performance under complex backgrounds and partial occlusion conditions. In the first row, representing a complex background scenario, YOLOv8 produces false detections on background elements such as signposts and trees, resulting in offset detection boxes and low confidence scores. This is a common issue for traditional models when handling complex scenes. In contrast, the proposed method leverages the shape-prior convolutional module to effectively utilize the shape information of traffic signs, focusing the model’s attention on the actual traffic signs. The results show that the detection boxes are more accurately centered on the traffic signs, with confidence scores consistently above 0.85. Furthermore, in the second row, depicting a partially occluded scenario, YOLOv8 fails to detect the traffic sign occluded by the bridge. However, the proposed method successfully compensates for the missing information through shape priors, accurately detecting the partially occluded sign and precisely marking its location. These results demonstrate that the proposed method has significant advantages in addressing missed and false detections caused by complex backgrounds, low contrast, and partial occlusion.

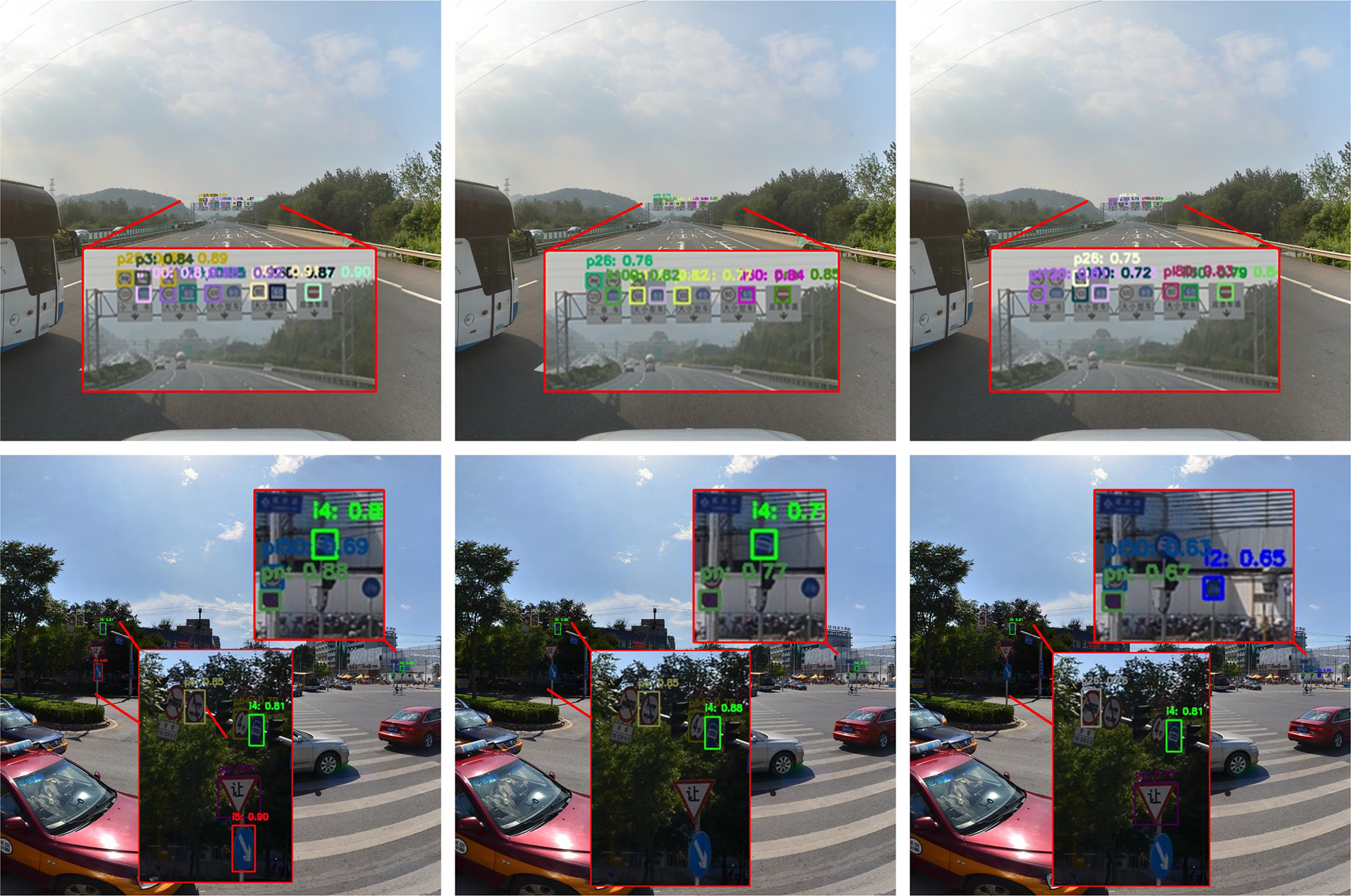

In Figs. 11 and 12, the left column shows our method, the middle column shows RT-DETR, and the right column shows TPH-YOLOv5. As the figures indicate, our method outperforms both baselines in low-contrast night scenes and under complex backgrounds. In Fig. 11, it yields more accurate traffic-sign detections with higher confidence and tighter boxes, demonstrating stronger robustness to low contrast. By comparison, RT-DETR produces misaligned boxes with lower confidence, while TPH-YOLOv5 suffers more missed detections and false positives due to limited adaptation to low-light conditions. In Fig. 12, our approach also performs well in cluttered back-grounds, accurately detecting small and partially occluded signs with high confidence. RT-DETR shows moderate performance but struggles on small/occluded targets; TPH-YOLOv5 misses multiple signs and has a higher false-positive rate. Overall, these results show that the proposed method handles low contrast, background clutter, and partial occlusion more effectively, reducing missed and false detections and exhibiting greater robustness.

Figure 11: Detection results comparison between the proposed method and other models on CCTSDB

Figure 12: Detection results comparison between the proposed method and other models on TT100K

This paper presents ES-YOLO, which introduces an edge feature branch and a shape-prior convolution and performs input-conditioned bi-directional adaptive fusion in the neck, enabling high-level semantics and fine-grained boundary information to complement each other and thereby improve the localization and discrimination of traffic signs. We validate the approach on multiple datasets, and the results show stable gains on small and thin targets, low-contrast scenes, partial occlusions, and cluttered backgrounds, while maintaining real-time inference and demonstrating deployability. Remaining key challenges lie in complex driving conditions and engineering constraints. Rain, fog, strong backlight, and nighttime reduce the signal-to-noise ratio of boundaries and diminish the effectiveness of the fusion weights and the shape prior; domain shifts across devices, lenses, and regions affect model consistency; insufficient coverage of long-tailed classes and extremely small targets can still trigger false negatives and false positives; sustaining high throughput with low latency on embedded platforms is also challenging. Future work will focus on three directions: first, improving robustness under rain, fog, nighttime, and strong backlight; second, expanding evaluation across datasets, devices, and diverse road scenarios to enhance cross-domain generalization; and third, advancing model light weighting and inference acceleration to meet real-time deployment on on-device and embedded platforms.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62572057, 62272049, U24A20331), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 4232026, 4242020), Academic Research Projects of Beijing Union University (Grant No. ZK10202404).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Weiguo Pan and Songjie Du; Methodology, Weiguo Pan and Songjie Du; Software, Bingxin Xu and Bin Zhang; Validation, Songjie Du, Hongzhe Liu and Bin Zhang; Formal analysis, Weiguo Pan, Songjie Du and Hongzhe Liu; Investigation, Bingxin Xu and Bin Zhang; Resources, Weiguo Pan; Data curation, Bingxin Xu; Writing—original draft, Songjie Du; Writing—review & editing, Weiguo Pan and Hongzhe Liu; Visualization, Songjie Du and Bingxin Xu; Supervision, Weiguo Pan; Project administration, Weiguo Pan and Songjie Du; Funding acquisition, Weiguo Pan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: CCTSDB: https://datasetninja.com/gtsdb; TT100K: https://cg.cs.tsinghua.edu.cn/traffic-sign/.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Nomenclature | Description |

| YOLOv8s | You Only Look Once (v8, Small) |

| ES-YOLO | Edge- and Shape-Fusion YOLO |

| AFM | Adaptive Fusion Module |

| SPPF | Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast |

| BN | Batch Normalization |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

| FC | Fully Connected Layer |

| NMS | Non-Maximum Suppression |

| mAP50 | Mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.50 |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

References

1. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

2. Manzari ON, Boudesh A, Shokouhi SB. Pyramid transformer for traffic sign detection. In: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE); 2022 Nov 17–18; Mashhad, Iran. p. 112–6. [Google Scholar]

3. Li N, Pan W, Xu B, Liu H, Dai S, Xu C. Ihenet: an illumination invariant hierarchical feature enhancement network for low-light object detection. Multimed Syst. 2025;31(6):407. doi:10.1007/s00530-025-01994-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gao E, Huang W, Shi J, Wang X, Zheng J, Du G, et al. Long-tailed traffic sign detection using attentive fusion and hierarchical group softmax. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(12):24105–15. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3200737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Saxena S, Dey S, Shah M, Gupta S. Traffic sign detection in unconstrained environment using improved YOLOv4. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(2):121836. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yao Y, Han L, Du C, Xu X, Jiang X. traffic sign detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv4-tiny. Signal Process Image Commun. 2022;107(3):116783. doi:10.1016/j.image.2022.116783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yu J, Ye X, Tu Q. Traffic sign detection and recognition in multiimages using a fusion model with YOLO and VGG network. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(9):16632–42. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3170354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang J, Chen Y, Dong Z, Gao M. Improved YOLOv5 network for real-time multi-scale traffic sign detection. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(10):7853–65. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-08077-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang J, Chen Y, Ji X, Dong Z, Gao M, Lai CS. Vehicle-mounted adaptive traffic sign detector for small-sized signs in multiple working conditions. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;25(1):710–24. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3309644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang S, Che S, Liu Z, Zhang X. A real-time and lightweight traffic sign detection method based on ghost-YOLO. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(17):26063–87. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-14342-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wei H, Zhang Q, Qin Y, Li X, Qian Y. YOLOF-F: you only look one-level feature fusion for traffic sign detection. Vis Comput. 2024;40(2):747–60. doi:10.1007/s00371-023-02813-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liang T, Bao H, Pan W, Pan F. Traffic sign detection via improved sparse R-CNN for autonomous vehicles. J Adv Trans. 2022;2022(1):3825532. doi:10.1155/2022/3825532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang J, Lv Y, Tao J, Huang F, Zhang J. A robust real-time anchor-free traffic sign detector with one-level feature. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput Intell. 2024;8(2):1437–51. doi:10.1109/tetci.2024.3349464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang J, Zheng Z, Xie X, Gui Y, Kim GJ. ReYOLO: a traffic sign detector based on network reparameterization and features adaptive weighting. J Ambient Intell Smart Environ. 2022;14(4):317–34. doi:10.3233/ais-220038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Shi Y, Li X, Chen M. SC-YOLO: a object detection model for small traffic signs. IEEE Access. 2023;11:11500–10. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3241234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao S, Yuan Y, Wu X, Wang Y, Zhang F. YOLOv7-TS: a traffic sign detection model based on sub-pixel convolution and feature fusion. Sensors. 2024;24(3):989. doi:10.3390/s24030989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang J, Ye Z, Jin X, Wang J, Zhang J. Real-time traffic sign detection based on multiscale attention and spatial information aggregator. J Real Time Image Process. 2022;19(6):1155–67. doi:10.1007/s11554-022-01252-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xie G, Xu Z, Lin Z, Liao X, Zhou T. GRFS-YOLOv8: an efficient traffic sign detection algorithm based on multiscale features and enhanced path aggregation. Signal Image Video Process. 2024;18(6):5519–34. doi:10.1007/s11760-024-03252-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang LJ, Fang JJ, Liu YX, Le HF, Rao ZQ, Zhao JX. CR-YOLOv8: multiscale object detection in traffic sign images. IEEE Access. 2023;12:219–28. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3347352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Luo Y, Ci Y, Jiang S, Wei X. A novel lightweight real-time traffic sign detection method based on an embedded device and YOLOv8. J Real Time Image Process. 2024;21(2):24. doi:10.1007/s11554-023-01403-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Khan SD, Alarabi L, Basalamah S. A unified deep learning framework of multi-scale detectors for geo-spatial object detection in high-resolution satellite images. Arab J Sci Eng. 2022;47(8):9489–504. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-06288-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Du S, Pan W, Li N, Dai S, Xu B, Liu H, et al. TSD-YOLO: small traffic sign detection based on improved YOLO v8. IET Image Process. 2024;18(11):2884–98. doi:10.1049/ipr2.13141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cui Y, Han Y, Guo D. TS-DETR: multi-scale DETR for traffic sign detection and recognition. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2025;190(12):147–52. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2025.01.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang H, Liang M, Wang Y. YOLO-BS: a traffic sign detection algorithm based on YOLOv8. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):7558. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88184-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Shen Z, He Y, Du X, Yu J, Wang H, Wang Y. YCANet: target detection for complex traffic scenes based on camera-LiDAR fusion. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(6):8379–89. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3357826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhou G, Zhang Z, Wang F, Zhu Q, Wang Y, Gao E, et al. A multi-scale enhanced feature fusion model for aircraft detection from SAR images. Int J Digit Earth. 2025;18(1):2507842. doi:10.1080/17538947.2025.2507842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sun Y, Wang S, Chen C, Xiang TZ. Boundary-guided camouflaged object detection. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022 Jul 23–29; Vienna, Austria. p. 1335–41. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhou X, Shen K, Weng L, Cong R, Zheng B, Zhang J, et al. Edge-guided recurrent positioning network for salient object detection in optical remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2022;53(1):539–52. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2022.3163152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Luo H, Liang B. Semantic-edge interactive network for salient object detection in optical remote sensing images. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2023;16:6980–94. doi:10.1109/jstars.2023.3298512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ding X, Zhang X, Ma N, Han J, Ding G, Sun J. RepVGG: making VGG-style convnets great again. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 13733–42. [Google Scholar]

31. Yang L, Zhang RY, Li L, Xie X. Simam: a simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. p. 11863–74. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhang J, Zou X, Kuang LD, Wang J, Sherratt RS, Yu X. CCTSDB 2021: a more comprehensive traffic sign detection benchmark. Hum Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2022;12:23. doi:10.1007/13673.2192-1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools