Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

OPOR-Bench: Evaluating Large Language Models on Online Public Opinion Report Generation

1 State Key Laboratory of Media Convergence and Communication, Communication University of China, Beijing, 100024, China

2 Research Center for Social Computing and Interactive Robotics, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, 150001, China

3 Scientific and Information Technical Research Institute, China Academy of Railway Sciences Corporation Limited, Beijing, 100081, China

* Corresponding Authors: Hao Shen. Email: ; Lei Shi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Big Data and Artificial Intelligence in Control and Information System)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 58 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073771

Received 25 September 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Online Public Opinion Reports consolidate news and social media for timely crisis management by governments and enterprises. While large language models (LLMs) enable automated report generation, this specific domain lacks formal task definitions and corresponding benchmarks. To bridge this gap, we define the Automated Online Public Opinion Report Generation (OPOR-Gen) task and construct OPOR-Bench, an event-centric dataset with 463 crisis events across 108 countries (comprising 8.8 K news articles and 185 K tweets). To evaluate report quality, we propose OPOR-Eval, a novel agent-based framework that simulates human expert evaluation. Validation experiments show OPOR-Eval achieves a high Spearman’s correlation (ρ = 0.70) with human judgments, though challenges in temporal reasoning persist. This work establishes an initial foundation for advancing automated public opinion reporting research.Keywords

Online Public Opinion Reports are critical tools that consolidate news articles and social media posts about crisis events (e.g., earthquakes, floods) into structured reports, enabling governments or enterprises to respond timely to these rapidly spreading incidents [1].

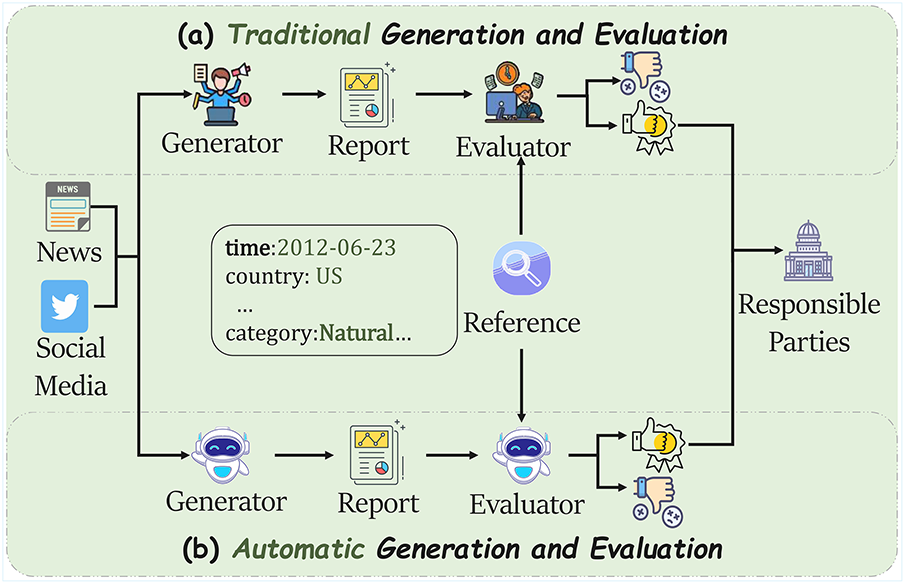

However, the industry’s reliance on manual report generation and evaluation is time-consuming and inefficient, often causing responsible parties to miss optimal response windows and potentially worsen crises. Large language models (LLMs) [2] have made automated report generation technically feasible. However, this specific domain lacks formal task definitions and corresponding benchmarks, hindering systematic research and practical deployment. The absence of systematic research stems from two critical gaps: the lack of a formal task definition for this complex, multi-source generation task, and the absence of a corresponding benchmark dataset.

While the task of OPOR-Gen involves synthesizing multiple documents, it is fundamentally distinct from traditional Multi-Document Summarization (MDS). Traditional MDS primarily focuses on information consolidation, aiming to summarize homogeneous sources (e.g., news-only) into a single unstructured paragraph. In stark contrast, OPOR-Gen demands a full-cycle analytical product. It requires synthesizing highly heterogeneous sources (i.e., formal news and informal social media) into a structured, multi-section report, and critically, moves beyond mere summarization to require the analysis of diverse public viewpoints (Event Focus) and the generation of actionable recommendations (Event Suggestions). Similarly, evaluation frameworks present a critical barrier. Traditional metrics like ROUGE are known to be inadequate for long-form, structured content. While recent LLM-as-a-judge methods show promise [3,4], they typically assess holistic quality and are not tailored to the unique, multi-faceted structural demands of OPOR-Gen, such as simultaneously validating timeline accuracy, opinion diversity, and suggestion feasibility.

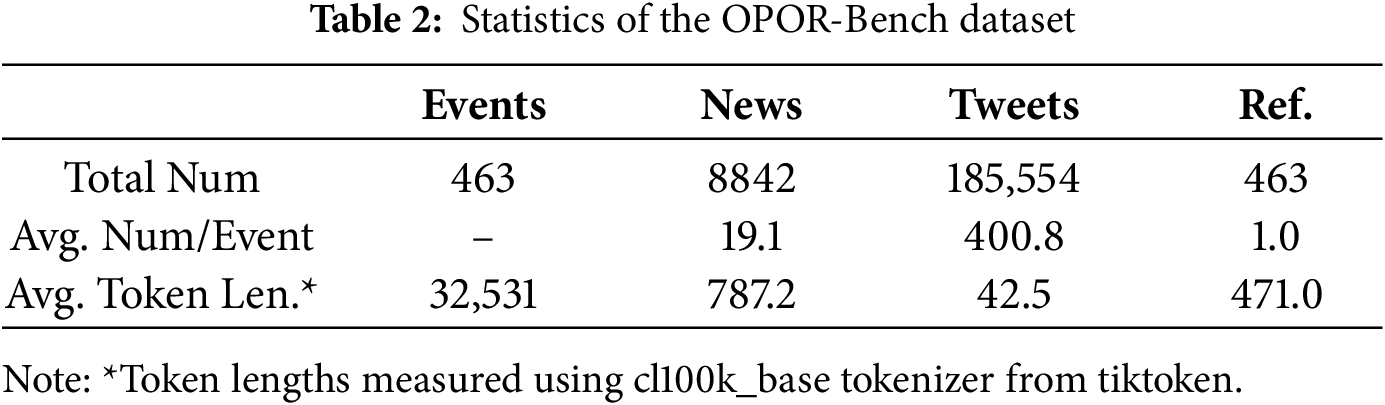

To address these challenges, we define the Automated Online Public Opinion Report Generation (OPOR-Gen) task, which challenges models to synthesize documents from diverse sources (news and social media) about a single crisis event into a structured report (as shown in Fig. 1b). We construct OPOR-Bench, an event-centric dataset with 463 crisis events (2012–2025) across 108 countries, comprising 8842 news articles and 185,554 tweets. Each event includes news articles, social media posts, and a structured reference report.

Figure 1: (a) Traditional methods require manual information consolidation from diverse sources (e.g., news, social media) and labor-intensive report writing and evaluation. In contrast, our (b) Automated approach generates and evaluates reports automatically, significantly accelerating the feedback loop

Furthermore, recognizing that evaluating these complex reports is another major challenge, we develop OPOR-Eval, a novel agent-based framework that simulates human expert judgment through multi-dimensional analysis: factual accuracy (event details verification), opinion mining (sentiment and stance extraction), and solution reasoning (recommendation quality). OPOR-Eval decomposes the evaluation into section-specific assessments, applying tailored criteria for each dimension on a 5-point Likert scale and achieving ρ = 0.70 correlation with human judgments. This automated approach can replace labor-intensive manual evaluation, significantly accelerating the feedback loop for crisis response.

This work makes the following key contributions:

• A New Task and the First Supporting Benchmark. We define a new task, Automated Online Public Opinion Report Generation (OPOR-Gen), and introduce OPOR-Bench, the first event-centric benchmark designed to support it, along with a dedicated annotation tool for quality assurance.

• An Innovative and Reliable Evaluation Framework. We propose OPOR Eval, an agent-based framework for evaluating long-form, structured reports, addressing the limitations of traditional metrics.

• Comprehensive Baselines and In-depth Analysis. We establish strong baselines using frontier models and conduct in-depth analysis of both generation and evaluation. Our findings reveal universal challenges in temporal reasoning and systematic evaluation biases, providing concrete directions for future research.

2 Preliminaries: The Structure of an Online Public Opinion Report

In this section, we break down the structure of an online public opinion report, detailing the five key components that our study aims to automatically generate.

The Event Title serves as a concise identifier that allows readers to immediately grasp the event’s essence. A well-formed title conveys the crisis name, type, and time, facilitating efficient storage and retrieval.

The Event Summary offers a condensed overview of the crisis for rapid comprehension. Inspired by the classic 5W1H framework [5], it covers the Crisis Name (What), Location (Where), Time (When), Cause (Why/How), and Involved Parties (Who). Crucially, we extend this framework with an Impact component, which highlights the event’s consequences to underscore its severity and prompt responsible parties to take actions.

By analyzing the public opinion lifecycle, the Event Timeline provides stage-specific guidance, thereby shifting crisis management from reactive to proactive [6]. While established theories often divide the lifecycle into four phases (Incubation, Outbreak, Diffusion, Decline), the sudden and fast-spreading nature of crises typically merges the Outbreak and Diffusion stages into a single, intense Peak Period, leading us to adopt a three-phase timeline: Incubation, Peak, and Decline.

The Incubation Period features discussion limited to directly affected stakeholders, making detection difficult without specialized monitoring. Despite low activity, these topics possess significant eruption potential—a controversial sub-event can rapidly trigger widespread attention. This period thus serves as a critical early-warning phase for anticipating crisis development.

The Peak Period exhibits exponential growth in attention, participation, volume, and velocity [7]. This expansion broadens scope and deepens complexity through derivative sub-events like official announcements and public controversies. The phase is a critical window for shaping public opinion, as it forges the public’s long-term perception of the event [6].

The Decline Period shows diminishing public interest as focus shifts to newer events [8]. Discussion reverts to directly affected stakeholders, where unresolved issues persist and can reactivate under specific conditions. Thus, rather than a final resolution, this period marks a decline in widespread attention that leaves a lasting reputational impact [9].

During the Peak Period, an event triggers exponential growth in online discussions, leading to topic polarization, rumor surges, and emotional instability [6,8]. Emotional contagion drives this growth, with anger fueling sharing and anxiety driving information-seeking [7]. This volatile mix necessitates multi-perspective analysis beyond event timelines, making group-specific analysis essential for prediction and intervention [10]. The Event Focus deconstructs public opinion by analyzing two participant groups—Netizens and Authoritative Institutions. For each group, the analysis extracts three key insights: (1) Core Topics to reveal their primary concerns; (2) Sentiment Stance to gauge their overall emotional orientation; and (3) Key Viewpoints to highlight their core arguments and stances.

The Event Suggestions section converts complex event data—foundational context (Summary), thematic evolution (Timeline), and divergent viewpoints (Focus)—into actionable recommendations, such as targeted communication strategies or policy adjustments [11]. This translation from analysis to action is critical for accelerating the official response, thereby mitigating the public anxiety and mistrust that stem from delays.

The OPOR-Gen task aims to generate a structured, multi-section report

where

While several crisis-related datasets exist [12–16], they prove inadequate for the OPOR-Gen task due to two critical shortcomings. First, they contain only social media posts, which overlooks the formal perspective provided by news articles. Second, their effective scale is limited; after thorough quality validation, we find only 95 unique events suitable for our purposes, which is insufficient for a reliable benchmark.

3.2.1 Event-Centric Corpus Construction

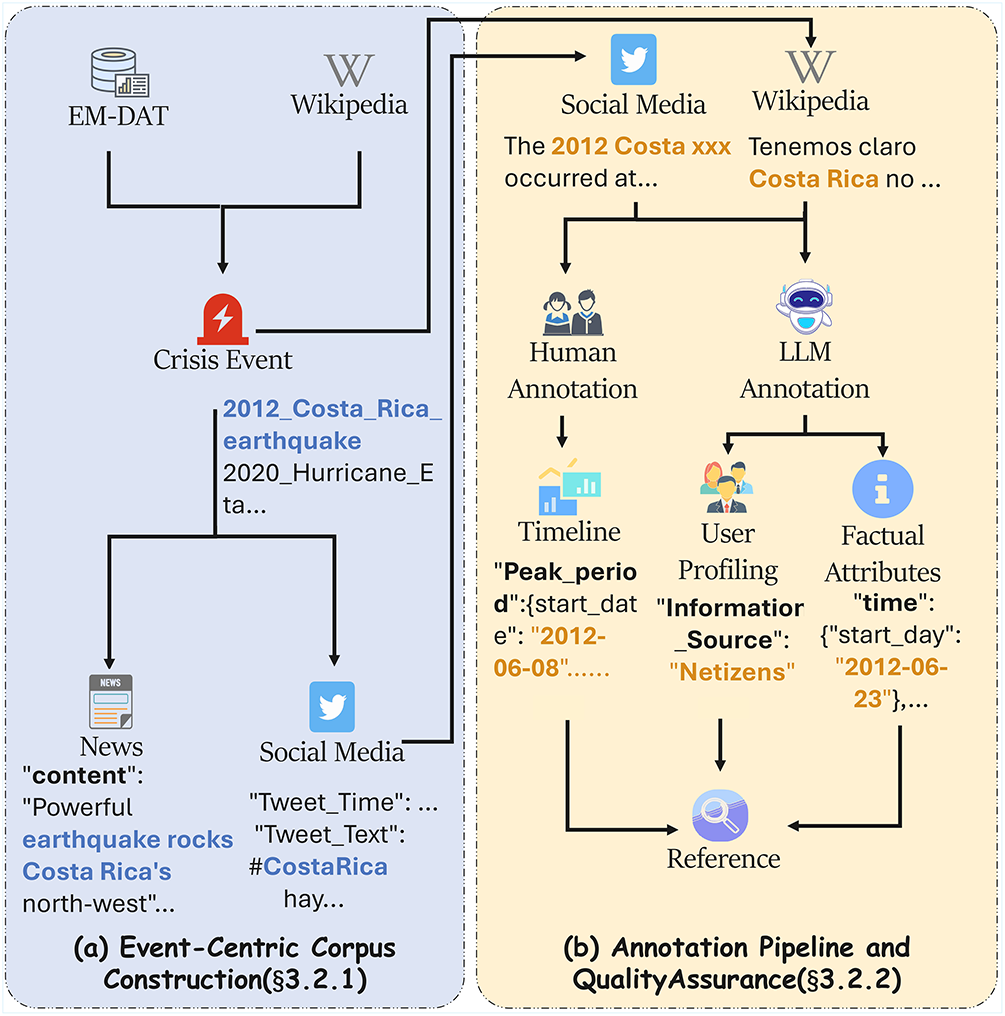

As shown in Fig. 2a, we begin by collecting crisis events from authoritative sources and then gather documents.

Figure 2: Overview of OPOR-Bench construction pipeline. (a) Event-Centric Corpus Construction: Starting from authoritative databases (EM-DAT) and curated lists (Wikipedia), we identify crisis events and collect corresponding multi-source documents—news articles from Wikipedia references and social media posts from X/Twitter API. (b) Dataset Annotation: Three-layered annotation process transforms raw documents into structured data. Human experts annotate timeline phases, while our LLM framework handles factual attribute extraction and social media author classification, ultimately producing a comprehensive reference for each event

Crisis Event Collection

The first stage of corpus construction is to identify a large and diverse set of crisis events that have received sufficient media coverage and generated widespread social media discussion. We gather crisis events (2018–2025) from two sources: the EM-DAT international disaster database [17] for standardized records, and Wikipedia’s curated disaster lists for events with high public interest. After deduplication against 95 seed events from prior datasets, we obtain 368 new events.

• EM-DAT International Disaster Database: Maintained by the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), providing standardized records with verified impact metrics.

• Wikipedia’s Curated Disaster Lists: These lists are community-vetted and often link to well-referenced articles, making them a reliable source. Specific lists we utilize include, but are not limited to earthquakes1, floods2, and wildfires3.

Document Collection

For each event, we collect multi-source documents from two parallel streams.

• News Articles: To ensure both quality and relevance, we employ a two-phase collection strategy. We begin by crawling articles from the vetted “References” section of an event’s official Wikipedia page (e.g., the page for the “2025 Table Mountain fire”4). After this initial crawl, we refine the collection by using a BM25 retriever [18] to rerank articles based on their relevance to event-specific keywords.

• Social Media Posts: Simultaneously, we acquire social media posts via the official X (Twitter) API5, targeting a window from one week before to one month after each event.

3.2.2 Annotation Pipeline and Quality Assurance

To fulfill the multifaceted requirements of the OPOR-Gen task, we perform three distinct annotation tasks (as shown in Fig. 2b): (1) Reference Annotation, to extract key factual attributes about each event; (2) Social Media Annotation, to classify the author type of each post; and (3) Timeline Annotation, to pinpoint the start and end dates of each key phase in the public opinion lifecycle. The first two tasks are automated via our protocol-guided LLM framework, while the third, more complex task is handled by human experts to ensure the highest quality.

LLM-Based Annotation Framework

To address the prohibitive expense and time of manual annotation, we develop a protocol-guided LLM framework with three key components: (1) clear label definitions, (2) detailed annotation criteria, and (3) diverse few-shot examples.

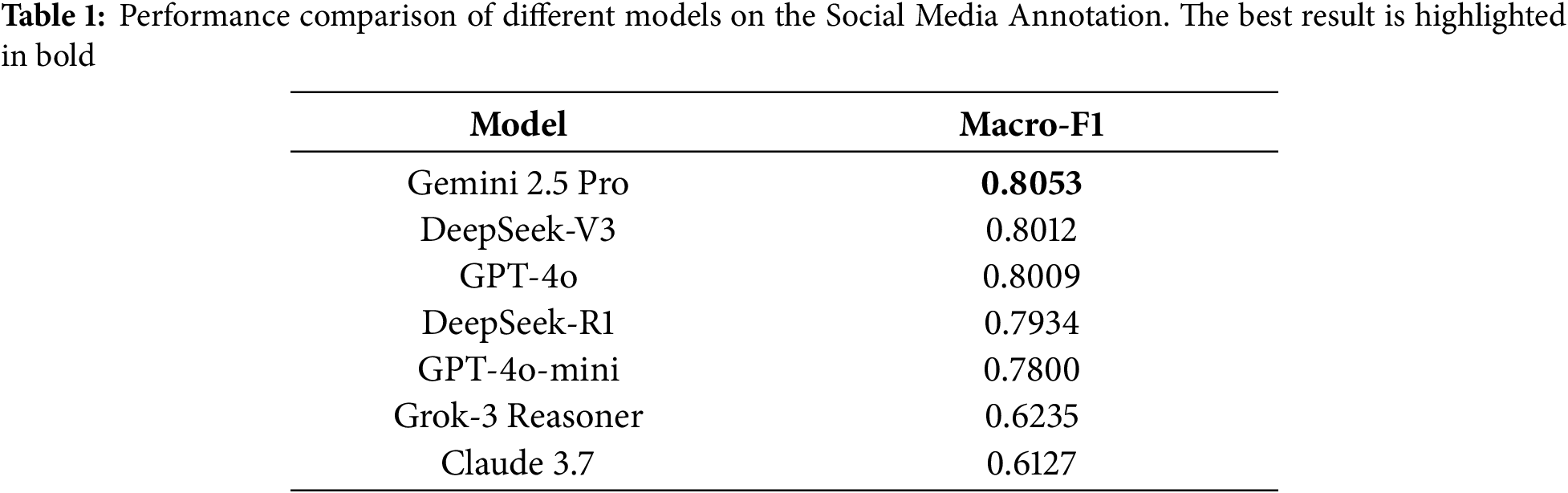

We evaluate a set of frontier LLMs on the Social Media Annotation task. We use the pre-labeled data from the CrisisLexT26 dataset [12] as the ground truth for this evaluation. Each model is prompted to classify the author type of tweets from the dataset. As shown in Table 1, gpt-4o-mini demonstrates the optimal balance between annotation quality and cost, so we select it as the primary model for our protocol-guided annotation tasks.

Reference and Social Media Annotation

In the Reference Annotation task, our framework distills key factual attributes (e.g., location, time, cause) from Wikipedia pages to produce

Human Timeline Annotation

Given the intricate nature of identifying public opinion phases, the timeline annotation is performed entirely by human experts to ensure high quality and reliability. Six in-house experts, all Master’s or PhD students familiar with public opinion lifecycles, conduct the annotation using a dedicated tool6 and following a rigorous, multi-stage protocol. The process proceeds as follows:

• The 463 events are evenly divided among three groups, with two annotators per group.

• Both annotators within each group work independently on the same set of assigned events.

• The two partners then compare and consolidate their results, and are required to discuss every disagreement until a consensus is reached.

• For the rare cases where a consensus cannot be reached, a senior researcher performs a final adjudication. If ambiguity persists, the event is discarded to ensure data integrity.

3.2.3 Dataset Statistics and Analysis

Volume and Length Distribution

As shown in Table 2, the OPOR-Bench provides comprehensive multi-source coverage for each crisis event. The substantial token count per event (averaging 32K+) highlights the significant information distillation challenge inherent in the OPOR-Gen task.

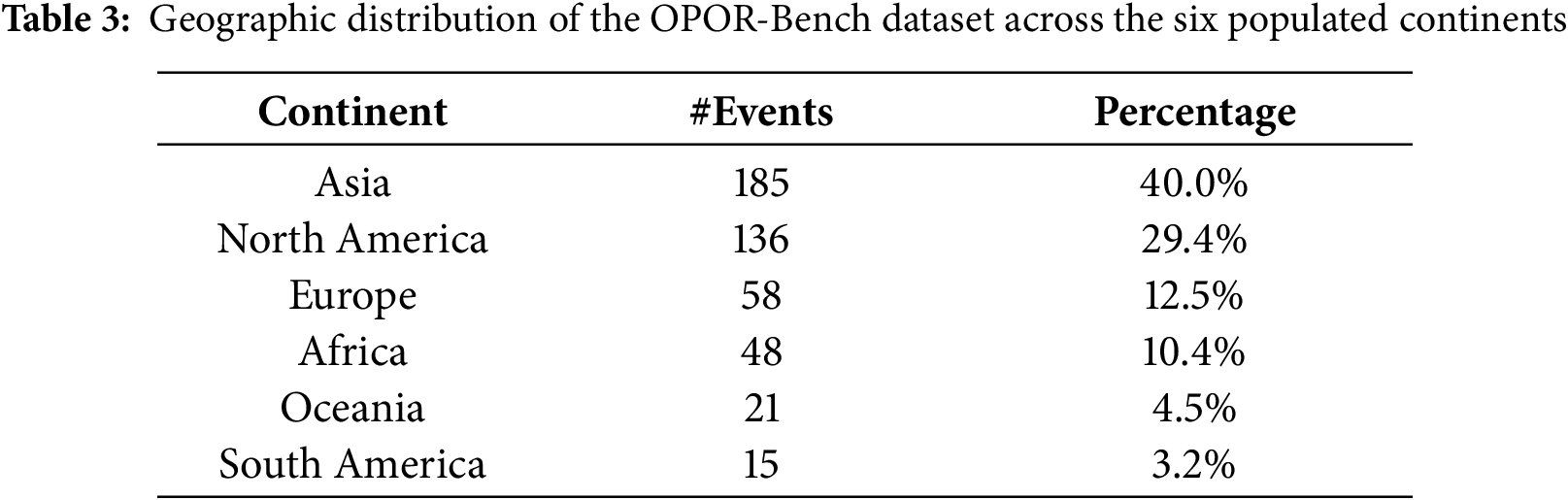

Geographic Distribution

Table 3 shows our dataset spans 108 countries across six continents, ensuring geographic diversity and mitigating potential regional bias.

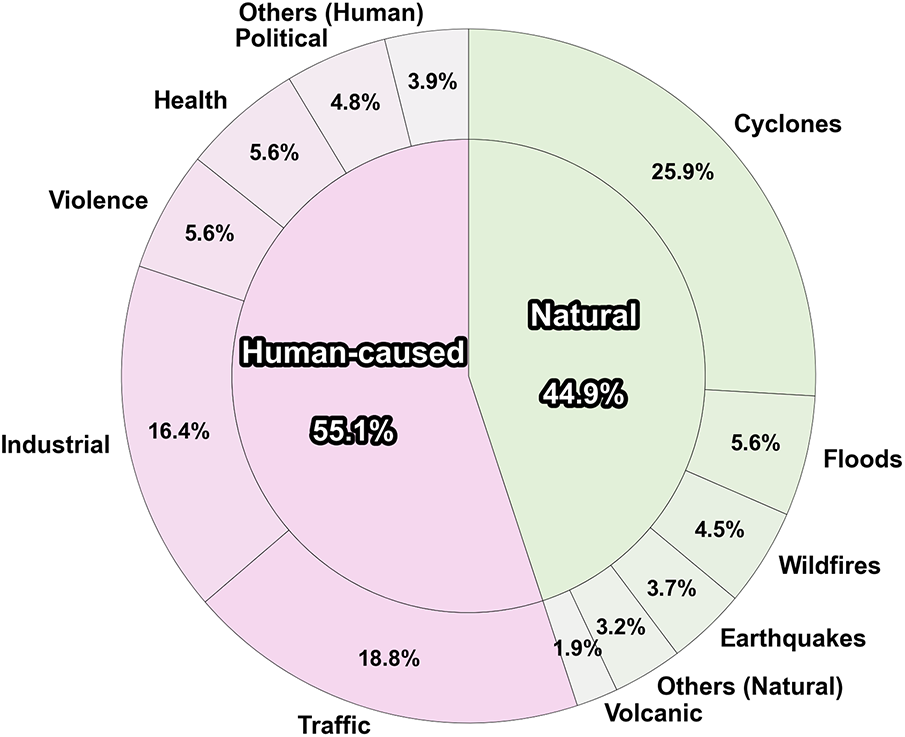

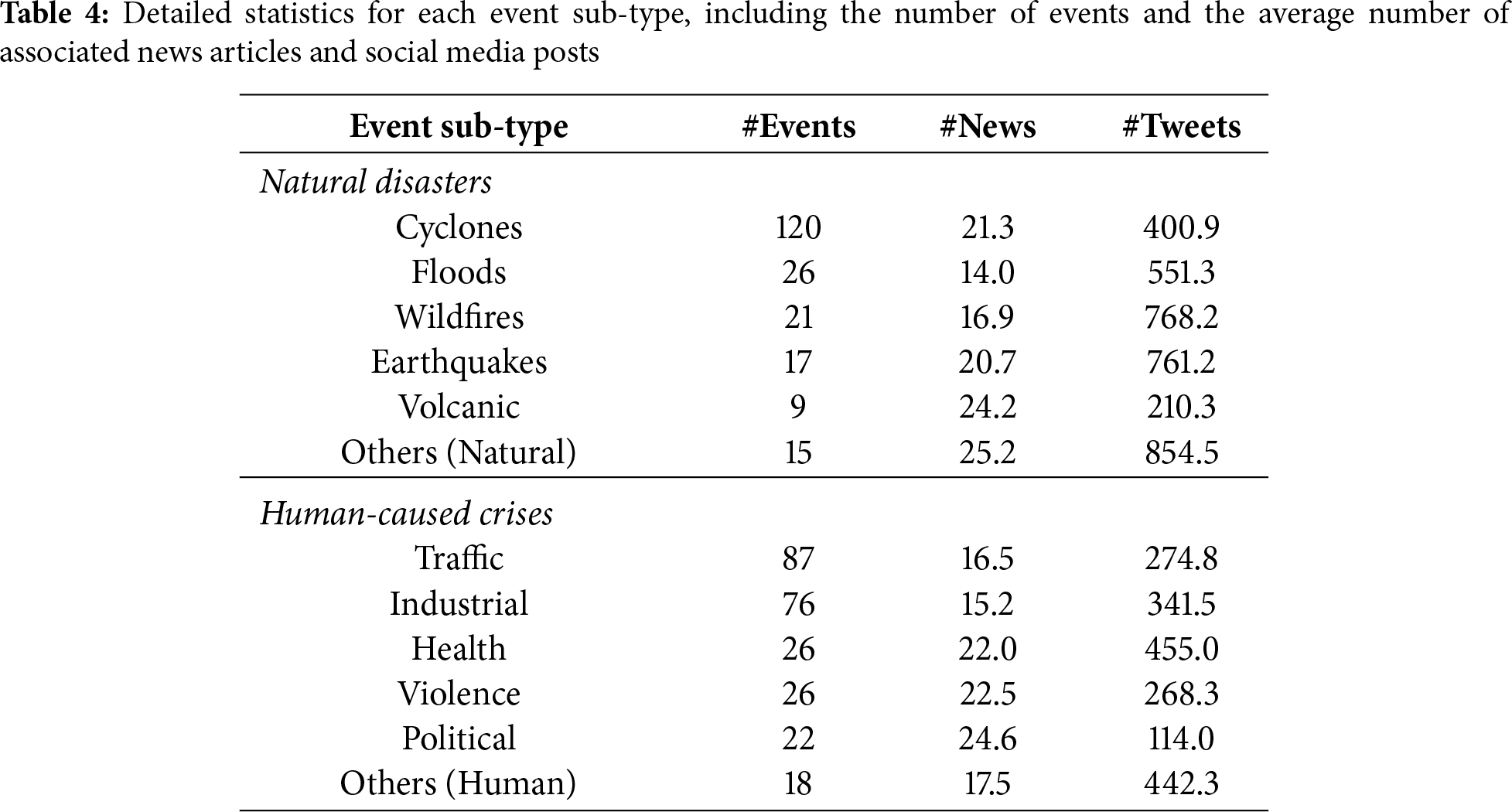

Type and Category Distribution

Fig. 3 shows our dataset’s balanced coverage of natural disasters (44.9%) and human-caused crises (55.1%). Table 4 reveals distinct media coverage patterns across event types—“Political” events generate more news coverage while “Wildfires” trigger higher social media activity—underscoring the necessity of multi-source integration.

Figure 3: The distribution of crisis event types in our dataset. The inner ring shows the top-level classification into Natural Disasters (44.9%) and Human-caused Crises (55.1%). The outer ring displays the breakdown into more specific sub-categories

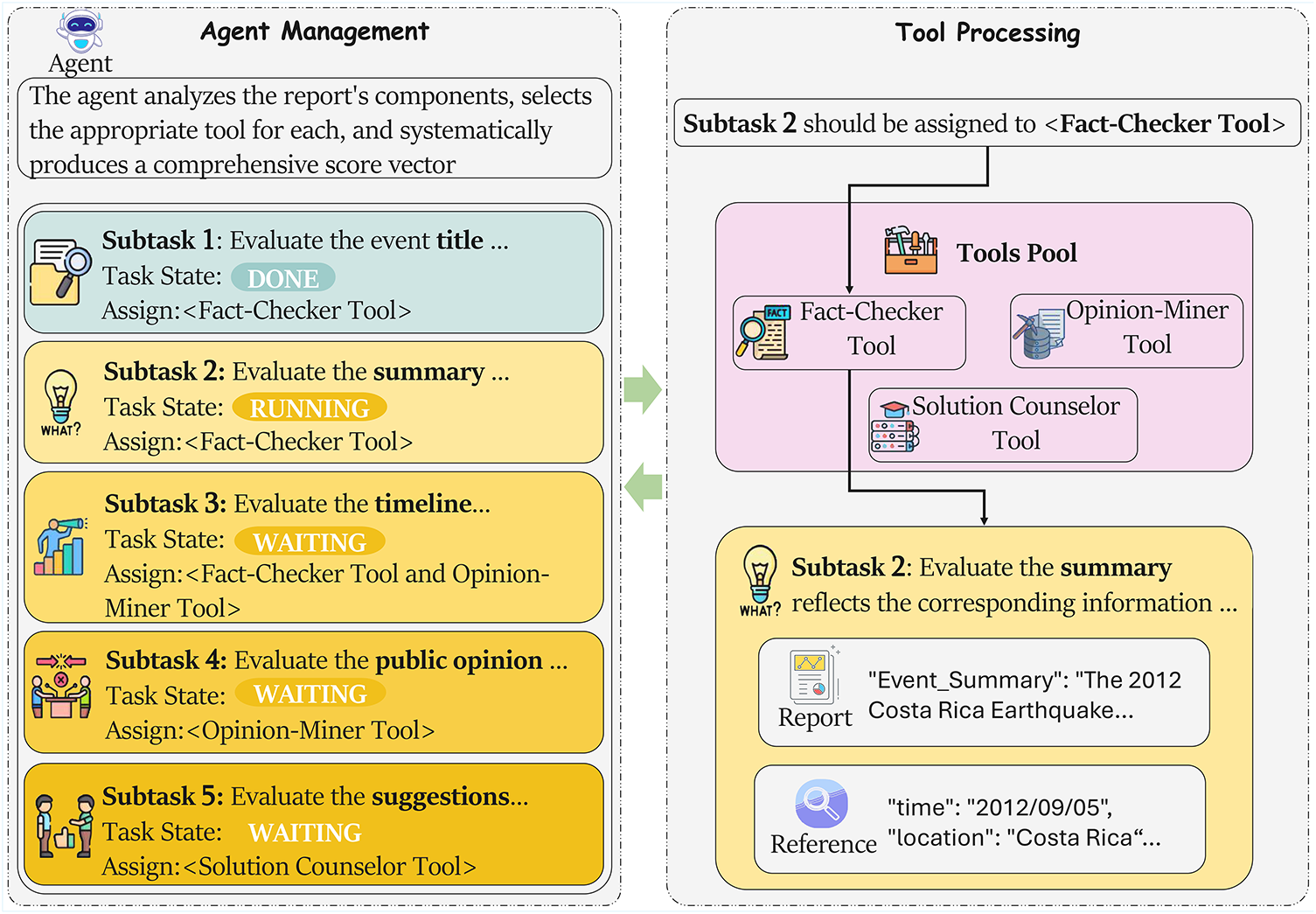

In our framework, the evaluator role (shown in Fig. 1b) is realized through an agent-based architecture that manages three specialized tools. Given a generated report

Our 15 dimensions are established through iterative expert consensus. As shown in Fig. 4, the OPOR-Eval agent (Section 4.2.1) employs three specialized tools: (1) Fact-Checker (Section 4.2.2) for verifying accuracy against references, (2) Opinion-Miner (Section 4.2.3) for evaluating public opinion coverage, and (3) Solution-Counselor (Section 4.2.4) for evaluating recommendations. This transforms evaluation from black-box judgment into a traceable analytical process. See Appendix A for Event Title of scoring guidelines.

Figure 4: The OPOR-Eval architecture: An evaluation agent manages three specialized tools (Fact-Checker, Opinion-Miner, Solution-Counselor) through structured task assignment

The OPOR-Eval Agent manages the evaluation process by analyzing report com ponents, selecting appropriate tools, and producing the comprehensive score vector. Following a reasoning-acting protocol, the agent explicitly externalizes reasoning before each action (see Appendix B for implementation details). This process is formalized as:

where

The Fact-Checker Tool (

The Opinion-Miner Tool (

The Solution Counselor Tool (

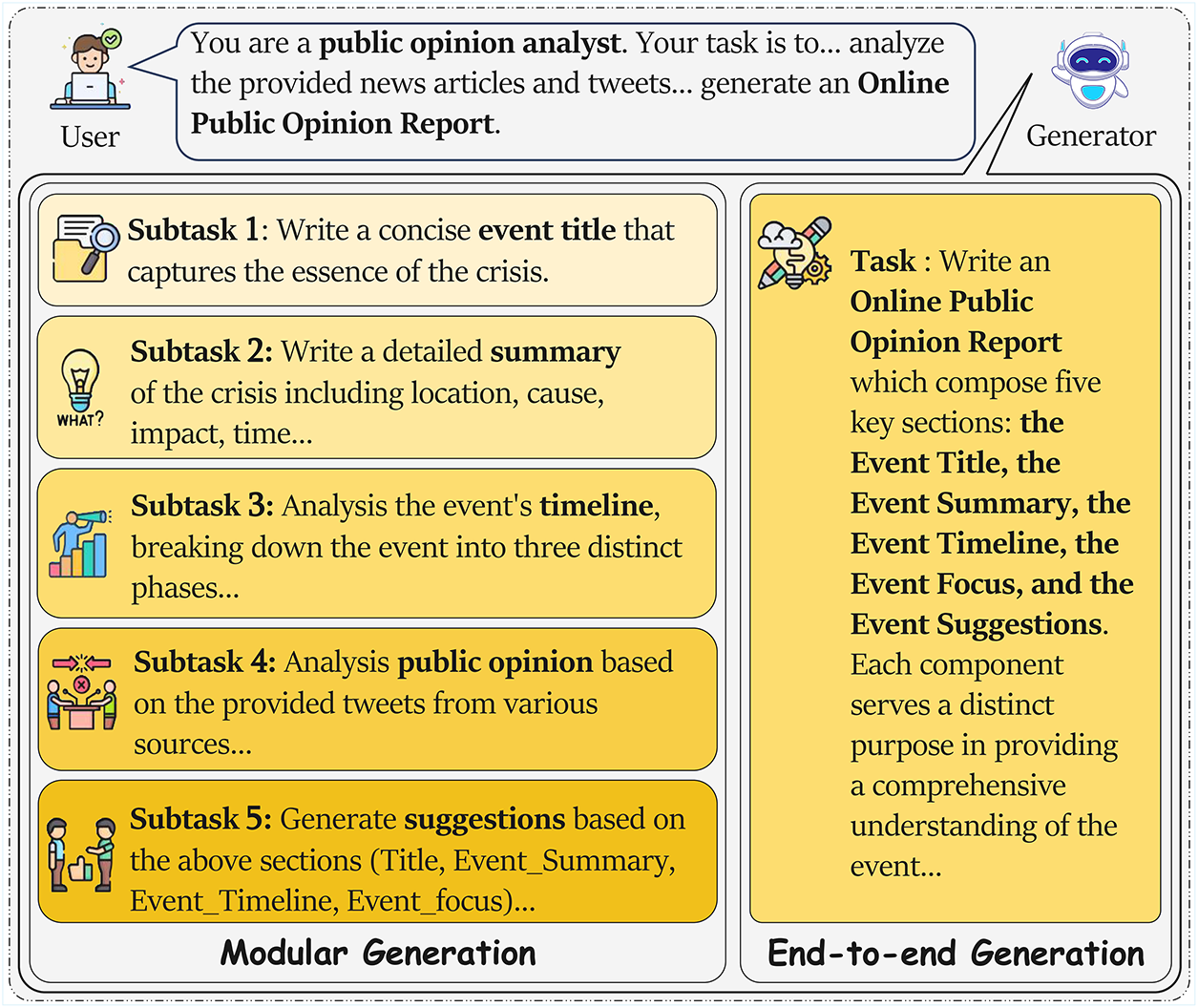

We evaluate five frontier LLMs with 128 K+ context windows: GPT-4o, DeepSeek-R1, DeepSeek-V3, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Llama-3.3-70B. For each model, we employ two distinct generation strategies (Fig. 5): modular generation creating sections independently then assembling them [19], and end-to-end generation producing complete reports in a single pass. See Appendix C for prompt templates.

Figure 5: Comparison of two OPOR-Gen strategies. (Left): Modular generation decomposes the task into five sequential subtasks (title, summary, timeline, focus, and suggestions), with each component generated independently. (Right): End-to-end generation produces all five report components simultaneously in a single pass, maintaining global coherence throughout the document

We use temperature 0.7 for generation and 0.3 for evaluation tasks. All other hyperparameters follow model defaults. Complete configuration details are provided in our dataset repository.

We implement OPOR-Eval with GPT-4o and DeepSeek-V3 to evaluate the generated reports across 15 dimensions following identical protocols. Additionally, we conduct human evaluation on a subset of these reports to validate the overall effectiveness.

5.2 Evaluation Framework Validation

5.2.1 Human Evaluation Protocol

To validate OPOR-Eval, we conduct a two-phase human evaluation with three experts who also design the scoring criteria. Using a dedicated annotation tool ensuring blind evaluation, experts independently score each report. The protocol includes calibration and formal evaluation phases:

• The calibration phase utilizes a preliminary set of 50 reports (5 events by our five baseline models under both generation strategies) to ensure all three experts share a consistent understanding of the criteria. In this phase, the experts independently rate the reports, and their agreement is measured using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC).

• The formal evaluation phase then uses a distinct and larger corpus of 500 reports (from 50 events). The three calibrated experts then independently score this entire corpus, yielding three complete sets of ratings for our human-agent agreement analysis.

5.2.2 Agreement Analysis and Results

In this section, we analyze the results of our human evaluation to answer two key questions: (1) How reliable are our human experts? and (2) How strong is the agreement between our human experts and the OPOR-Eval agents?

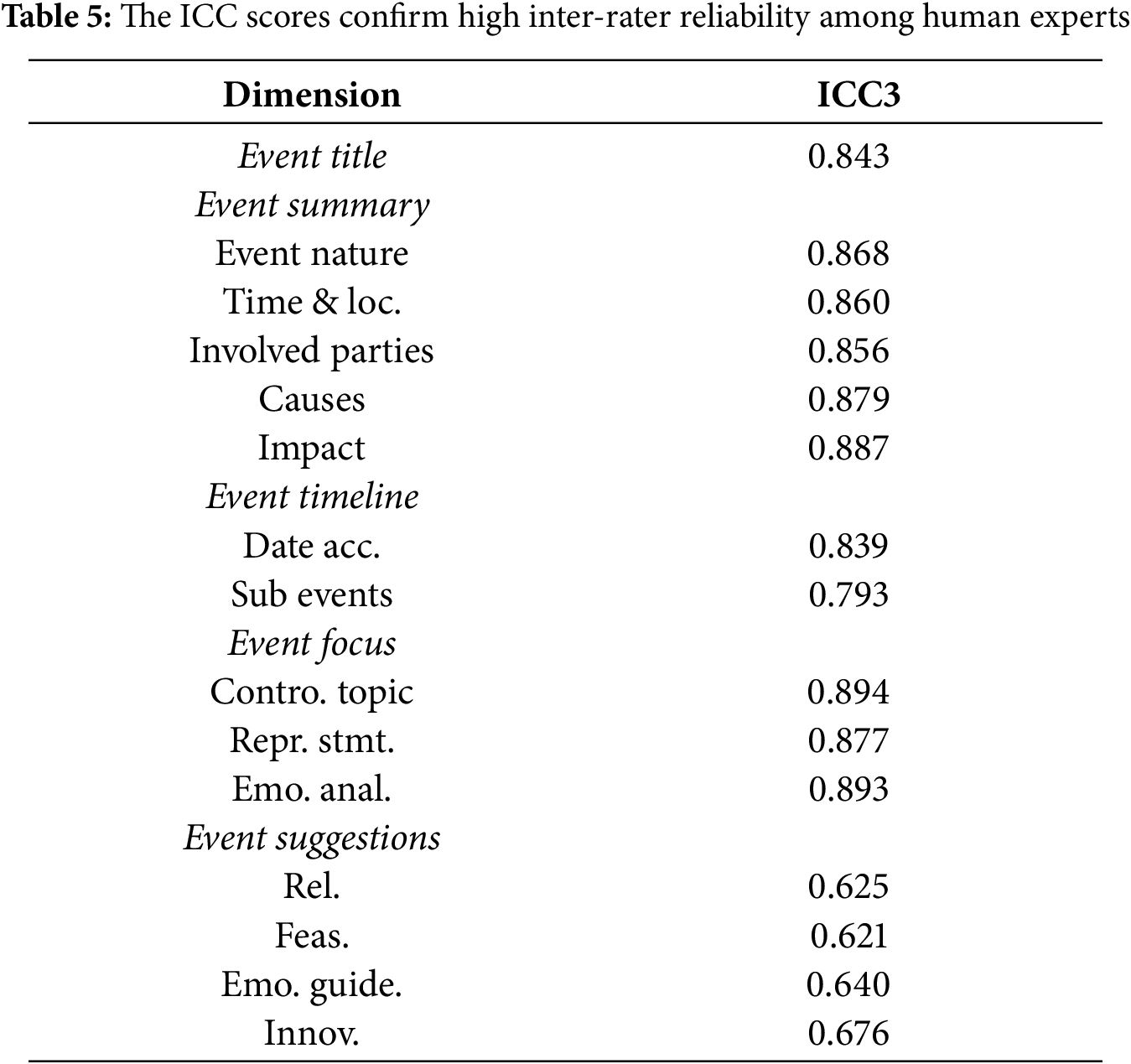

Answer 1: Our human experts demonstrate high inter-rater reliability.

Table 5 shows high inter-rater reliability among human experts. Based on the classification where Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) values are categorized as poor (<0.50), moderate (0.50–0.75), good (0.75–0.90), and excellent (>0.90), most dimensions achieve good to excellent agreement with ICC > 0.75. The relatively lower agreement on Event Suggestions (ICC = 0.64, moderate) reflects the inherent subjectivity in evaluating recommendation quality.

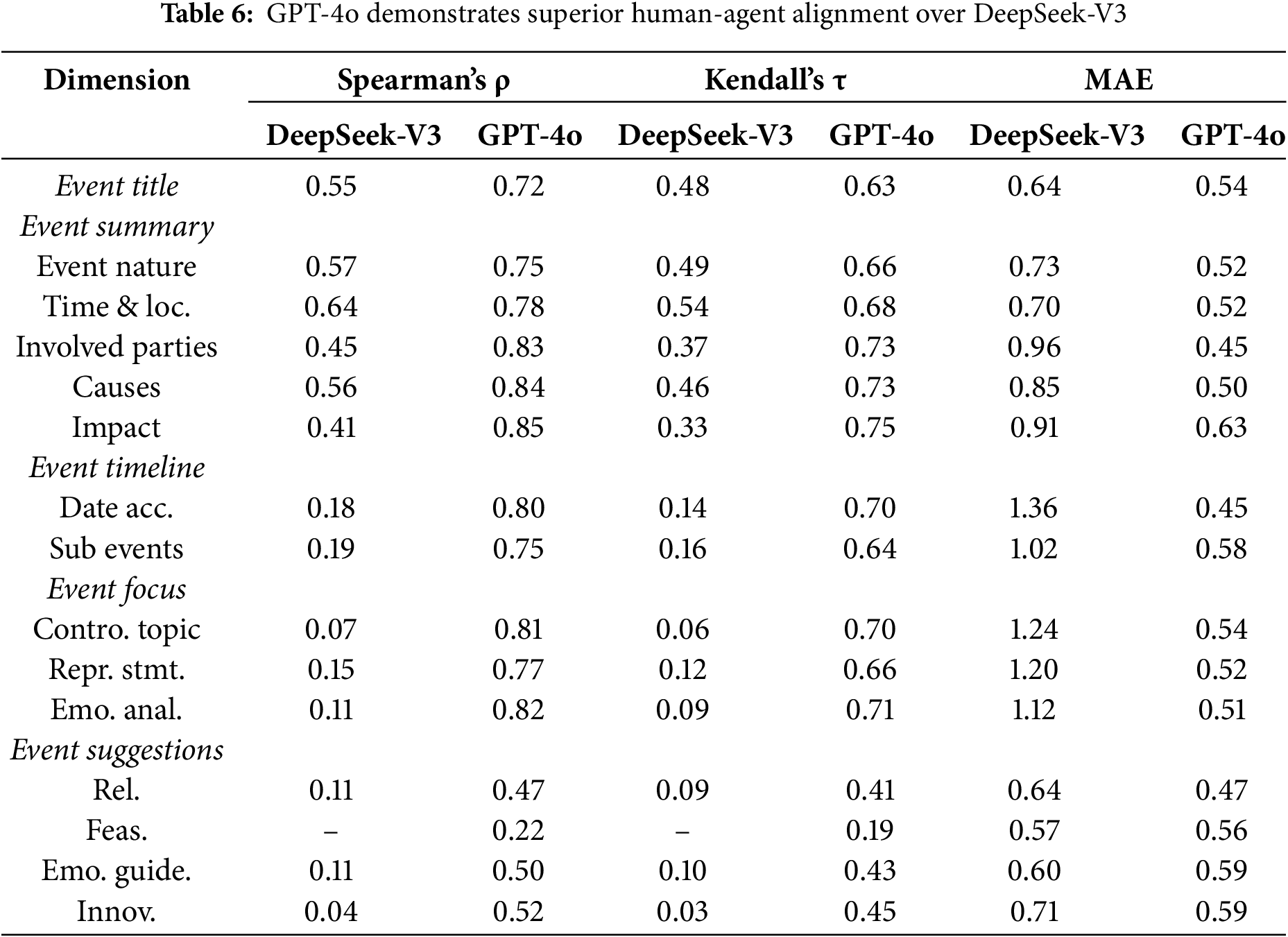

Answer 2: The OPOR-Eval framework achieves strong human-agent alignment with GPT-4o.

Correlation is generally categorized as weak (<0.50), moderate (0.50–0.70), or strong (>0.70). For MAE, lower values indicate better alignment. Our human-agent agreement analysis (Table 6) reveals that the GPT-4o achieves a strong overall alignment (

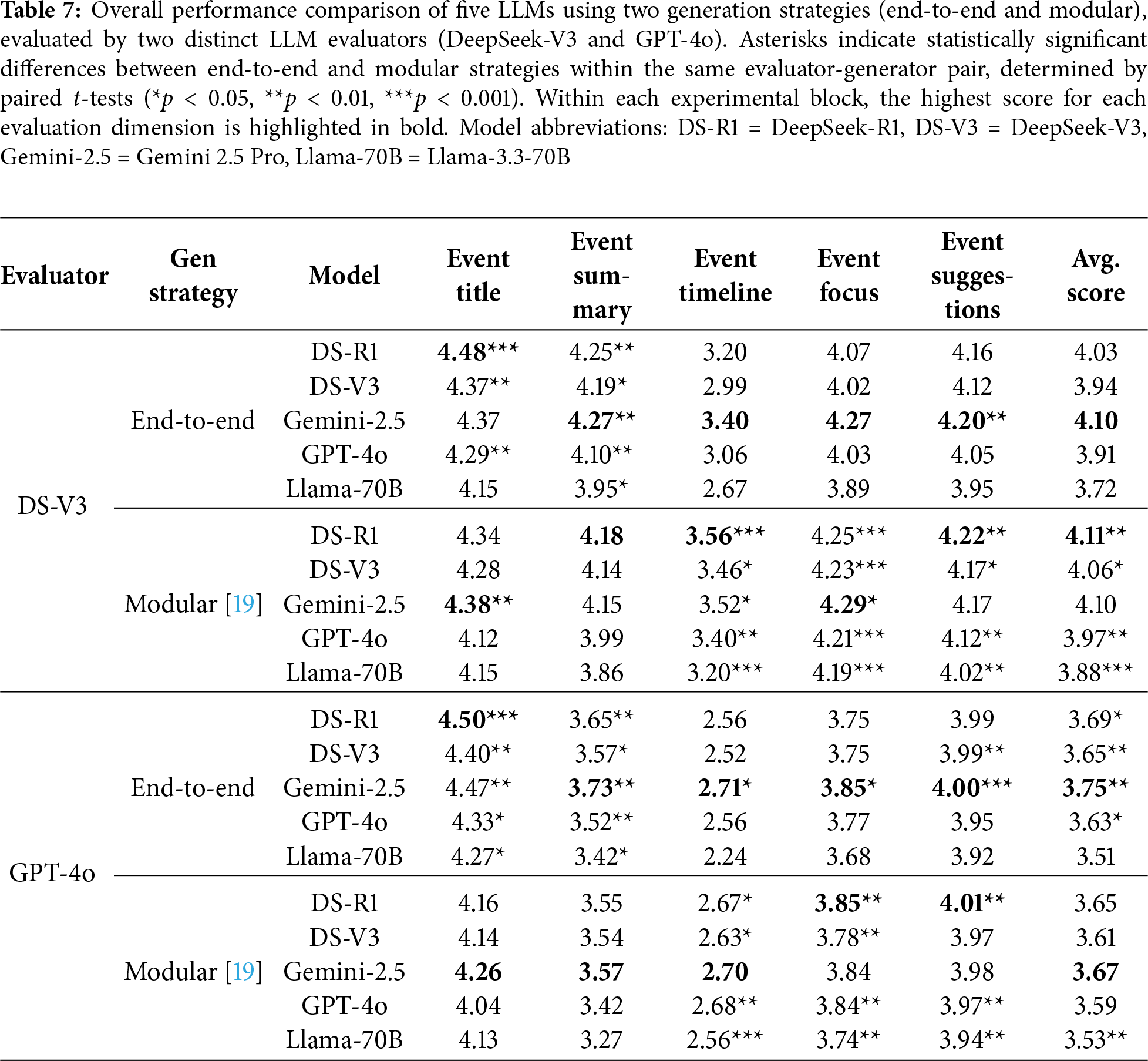

Overall Performance

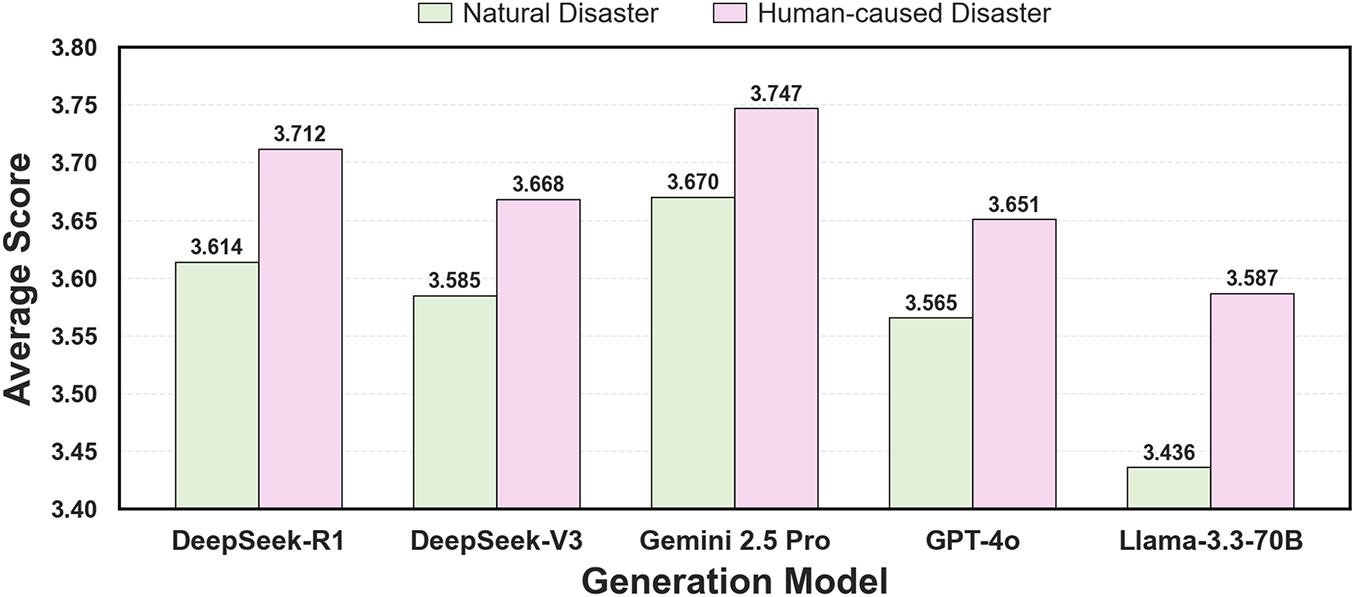

Given GPT-4o’s strong alignment with human judgment, we report the average of its scores across both generation strategies to determine each model’s final performance. As shown in Table 7, Gemini 2.5 Pro leads with an average score of 3.71, followed by DeepSeek-R1 (3.67), DeepSeek-V3 (3.63), GPT-4o (3.61), and Llama-3.3-70B (3.52). The narrow 5.12% gap between the best and worst models indicates they all have a solid baseline capability for the OPOR-Gen task.

Comparison of Generation Strategies

As shown in Table 7, while the end-to-end generation strategy slightly outperforms the modular approach on average (GPT-4o: 3.65 vs. 3.61), our results reveal a clear trade-off: end-to-end excels at high-level synthesis (Title, Summary), while the modular approach is superior for detailed, multi-perspective analysis (Timeline, Focus). This key finding suggests that the optimal strategy is task-dependent, pointing towards hybrid approaches as a promising direction for future research.

6.1.1 Temporal Reasoning Is a Universal Challenge for LLMs

Analysis of GPT-4o evaluation results (Table 7) reveals a notable weakness across all models in the Event Timeline dimension. This weakness is rooted in a dramatic failure on the Date Accuracy sub-dimension (average: 1.25). This failure is consistent even for the top-performing model (Gemini 2.5 Pro: 1.28) and stems from the task’s demand for complex temporal reasoning—identifying inflection points in data trends rather than simply extracting dates from documents.

6.1.2 Difficulty Stems from Information Structure, Not Thematic Contentu

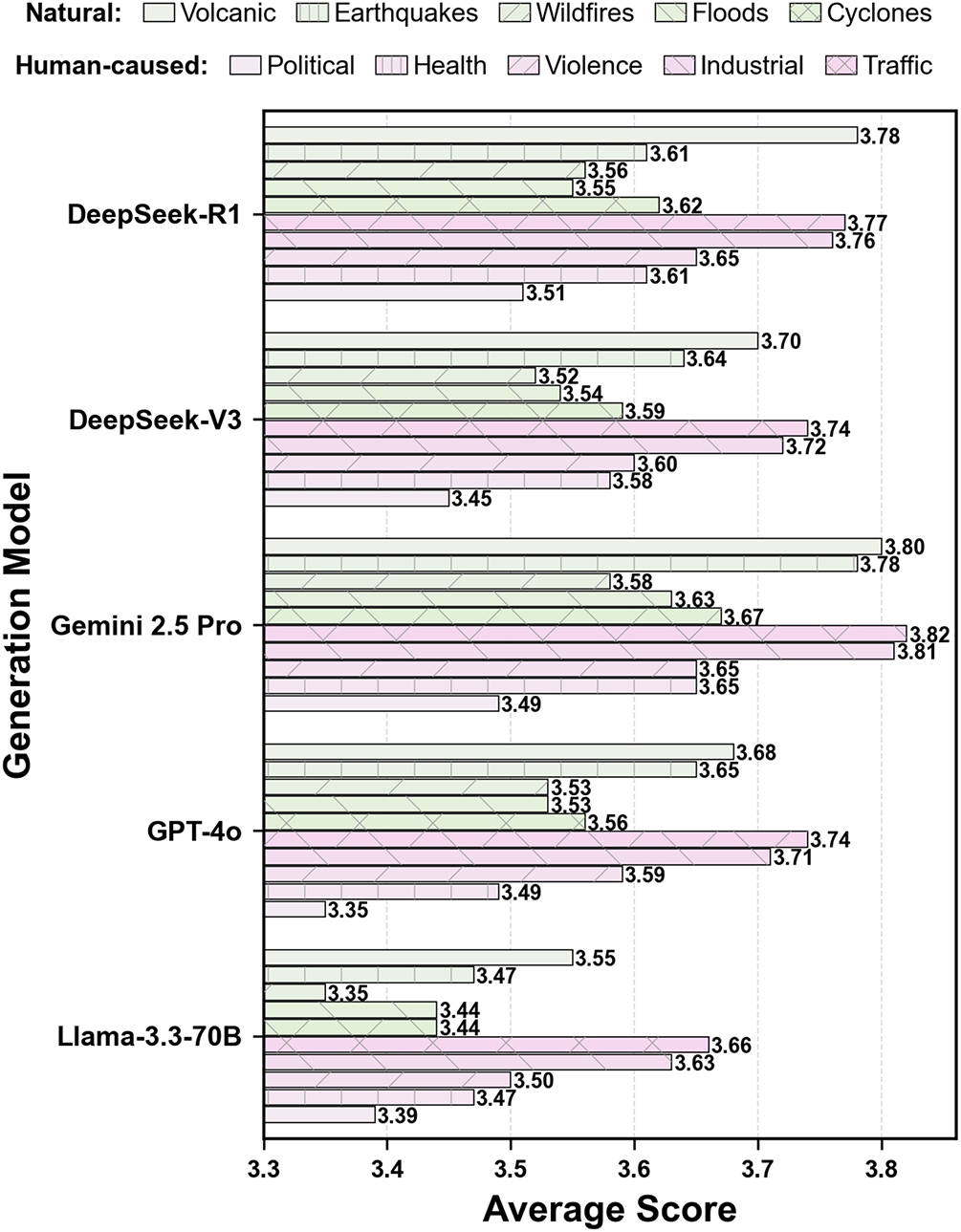

A consistent pattern across all models (Fig. 6) suggests this relationship: performance is significantly higher for Human-caused Disasters than for Natural Disasters. Further examination at the sub-category level (Fig. 7) reveals a clearer distinction: models excel on events with well-defined information structures, like “Industrial” and “Traffic” accidents, but struggle with events characterized by diffuse information, such as “Wildfires” and “Floods”. We hypothesize that this disparity stems from the fact that human-caused disasters typically feature clear causal chains and structured data (e.g., official investigation reports) that are easily processed by LLMs. In contrast, natural disasters generate fragmented information from diverse sources with ambiguous temporal boundaries, posing a fundamental challenge to fact extraction and timeline segmentation.

Figure 6: Consistent performance gap between human-caused (higher) and natural disasters (lower) across all models

Figure 7: Performance correlates with information structure: structured events (Industrial, Traffic) score highest while diffuse events (Wildfires, Floods) score lowest

6.2 Generator Performance Analysis

6.2.1 LLMs Performance Is Remarkably Consistent across All Three Evaluation Categories

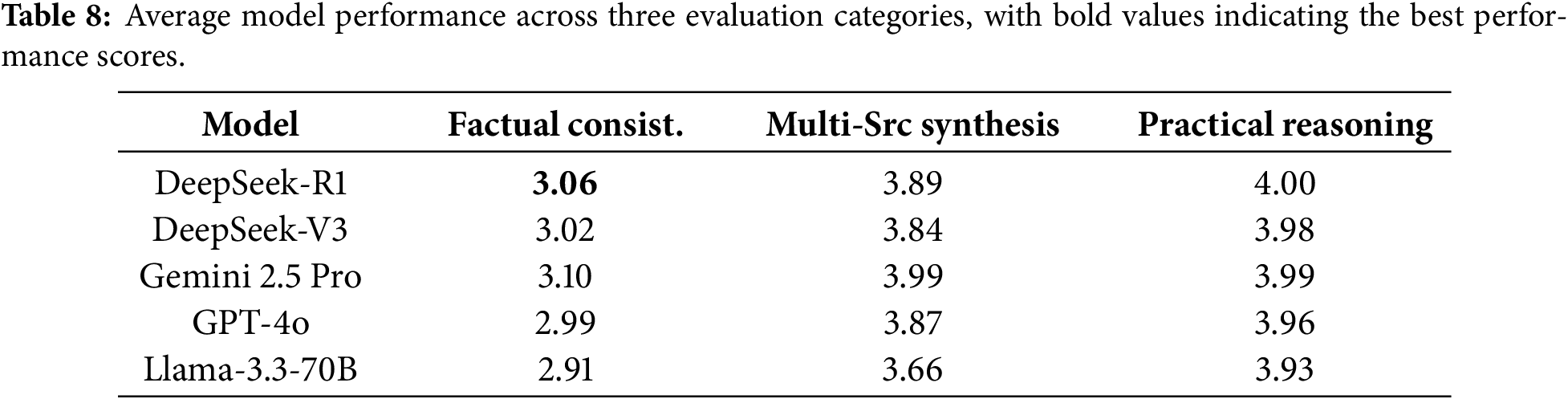

Our evaluation framework evaluates three distinct capabilities: Factual Consistency (via Fact-Checker Tool), Multi-source Synthesis (via Opinion-Miner Tool), and Practical Reasoning (via Solution Counselor Tool). As shown in Table 8, model performance rankings remain remarkably stable across these three capabilities. Pearson correlations between all category pairs exceed 0.84 (p < 0.001), indicating high consistency in model performance across dimensions. This high inter-category correlation provides statistical evidence that current LLMs demonstrate coherent performance across factual verification, information integration, and strategic reasoning, rather than excelling in isolated dimensions.

6.2.2 LLMs Struggle with Information Overload and Multi-Document Synthesis

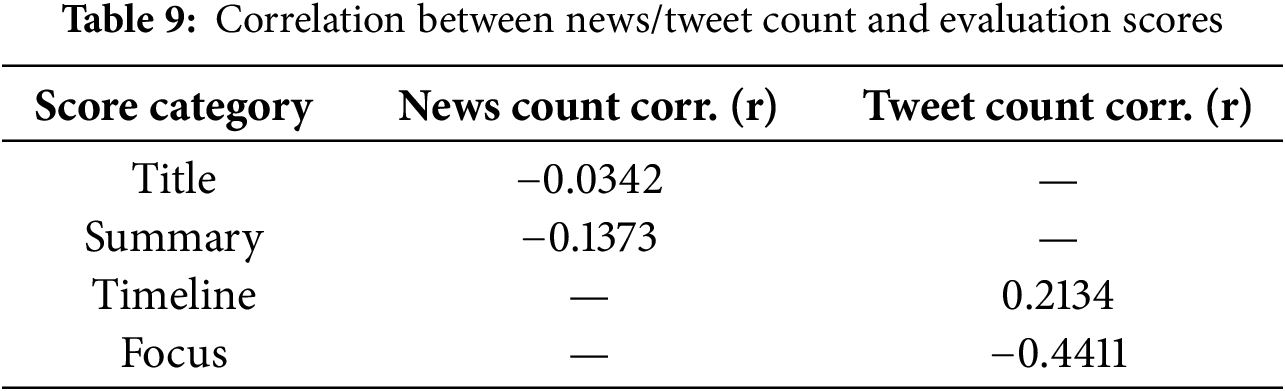

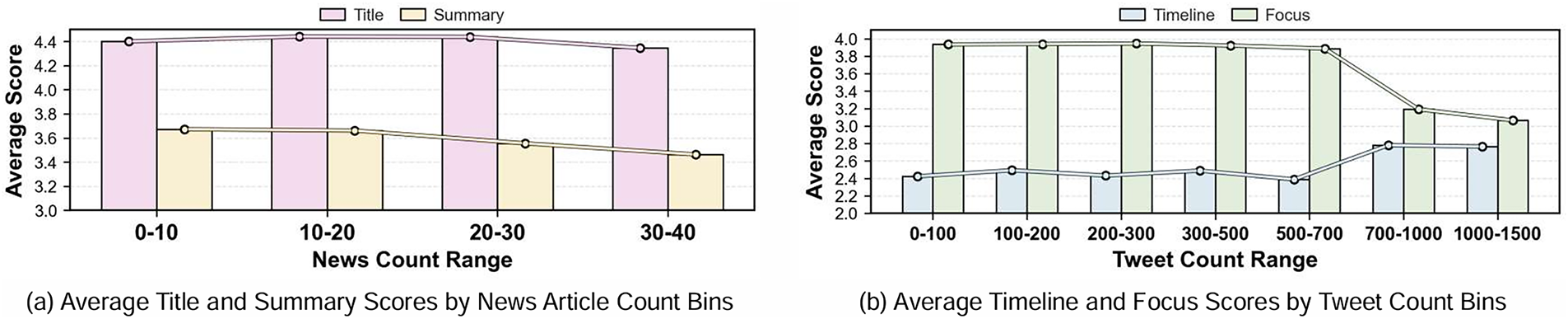

Our analysis reveals that report quality does not simply increase with source document volume, highlighting a critical limitation in the information overload and inefficient multi-document synthesis of current LLMs. Since Title and Summary generation primarily relies on news articles while Timeline and Focus depend on social media data, we analyze their correlations separately.

News Articles: Table 9 shows a negative correlation between article count and the scores for both the Title and Summary, suggesting information overload. Fig. 8a identifies the optimal range: 10–20 articles.

Figure 8: Source document volume exhibits complex relationships with report quality. (a) Title and Summary scores peak with 10–20 news articles, declining with information overload. (b) Tweet volume creates opposing effects: Timeline benefits from more data while Focus degrades, with a critical threshold around 700 tweets

Social Media: Table 9 shows opposing effects: Timeline accuracy benefits from more tweets (r = +0.21, p < 0.001), while Event Focus suffers dramatically (r = −0.44, p < 0.001). Fig. 8b reveals a critical threshold approximately 700 tweets where this trade-off becomes pronounced.

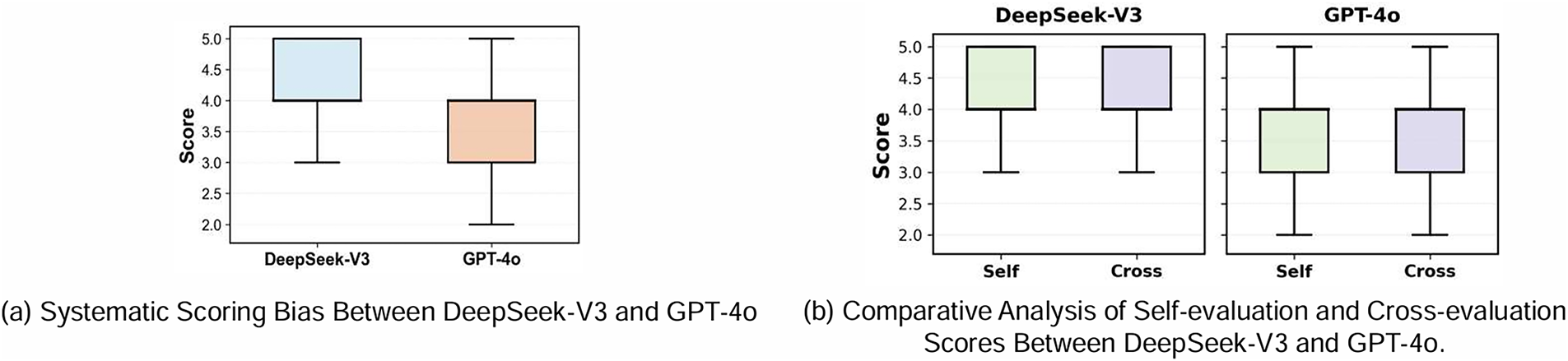

6.3.1 LLM Evaluators Display Inherent Scoring Biases

DeepSeek-V3 consistently assigns higher scores than GPT-4o for identical reports (average: 4.02 vs. 3.62, p < 0.001). Fig. 9a visualizes this bias: GPT-4o shows lower median scores with wider distribution, indicating more stricter criteria and better discrimination, whereas DeepSeek-V3’s scores cluster higher with less variance. This systematic difference proves that absolute scores from different LLM evaluators are not directly comparable, highlighting the need for score normalization or calibration in practical applications.

Figure 9: LLM evaluator characteristics. (a) Systematic scoring bias: DeepSeek-V3 assigns consistently higher scores with less variance compared to GPT-4o’s stricter, more discriminative scoring. (b) Negligible self-evaluation bias: both evaluators maintain objectivity with minimal self-preference (DeepSeek-V3: +0.03) or self-criticism (GPT-4o: −0.02), validating their use in automated evaluation systems

6.3.2 LLM Evaluators Show Strong Objectivity with Negligible Self-Evaluation Bias

To investigate self-evaluation bias, we compare the scores an agent assigns to its own reports (“Self-Evaluation”) vs. those from other models (“Cross-Evaluation”). Our results Fig. 9b show that while self-evaluation biases are statistically significant, their practical impact is negligible: DeepSeek-V3 shows a minor self-preference (+0.03 average score, p < 0.001), while GPT-4o exhibits slight self-criticism (−0.02 average score, p < 0.05). These differences represent less than 1% of the rating scale. This key finding confirms a high degree of objectivity in these LLM evaluators, enhancing the credibility and practical viability of LLM-based evaluation systems.

7.1 Multi-Document Summarization

Multi Document Summarization (MDS) generates comprehensive summaries from document collections on the same topic [20], with applications in news extraction, social media mining, and review analysis [21–24]. Research explores both extractive [25,26] and abstractive approaches [27–30].

However, while the task of OPOR-Gen involves synthesizing multiple documents, it is fundamentally distinct from traditional Multi-Document Summarization (MDS). Traditional MDS primarily focuses on information consolidation, aiming to summarize homogeneous sources (e.g., news-only) into a single unstructured paragraph. In contrast, OPOR-Gen demands a full-cycle analytical product that synthesizes highly heterogeneous sources (i.e., formal news and informal social media) into a structured, multi-section report. Critically, it moves beyond mere summarization to require analysis of diverse public viewpoints through sentiment and stance detection (Event Focus) and generation of actionable recommendations (Event Suggestions).

This structural complexity also means that traditional n-gram metrics (ROUGE, BLEU) [31–34], commonly used for MDS, are inadequate for evaluating long-form, multi-faceted reports [35]. Similar challenges exist in open-ended text generation tasks [36], where gold references are absent and human evaluation suffers from expertise limitations and subjectivity [37,38].

7.2 Text Generation Evaluation

Traditional metrics like ROUGE are inadequate for evaluating long-form, structured content, while recent LLM-as-a-judge methods [3,4] typically assess holistic quality without addressing the multi-faceted structural demands of OPOR-Gen (e.g., timeline accuracy, opinion diversity, suggestion feasibility).

LLM-based evaluation has recently emerged as a promising solution to the limitations of traditional metrics, demonstrating a strong correlation with human judgment while offering superior reproducibility, speed, and cost-effectiveness [4,39–42]. A variety of strategies have been developed. For reference-free evaluation, methods employ techniques like chain-of-thought prompting or proxy question-answering [3,43,44]. Other research focuses on creating benchmarks to evaluate specific attributes, such as instruction following [33,40], factual consistency [45,46], response alignment [47], and even leveraging multi-agent systems for evaluation [48].

Building on these advances, our OPOR-Eval framework employs LLMs as intelligent agents, simulating expert evaluation by using generated reports as contextual background and applying 5-point Likert scale scoring tailored to OPOR-Gen’s unique requirements.

In this paper, we address the critical inefficiency of manual online public opinion reporting. To tackle this, we introduce three core contributions: the OPOR-Gen task for automated report generation; OPOR-Bench, the first multi-source benchmark to support it; and OPOR-Eval, a reliable agent-based evaluation framework achieving strong human correlation that can be generalized to other long-form structured generation tasks. Our experiments establish strong baselines and reveal key challenges, such as complex temporal reasoning and systematic biases inherent in different LLM evaluators. We believe this work not only provides practical guidance for public opinion management but also serves as a valuable resource for related NLP tasks like multi-document summarization and event extraction.

Dataset Scope and Generalizability: The current OPOR-Bench dataset is text-only and predominantly English, which limits generalizability and does not fully reflect the true multimodal and multilingual nature of real-world public opinion.

Reproducibility and Scalability: Reproducibility is constrained by the framework’s reliance on costly, proprietary models (like GPT-4o) and evolving APIs. Furthermore, scalability is challenged by potential dataset biases that may underrepresent marginalized voices.

Ethical Implications: We acknowledge that automated public opinion reporting tools carry a significant risk of misuse (e.g., surveillance or propaganda). Therefore, robust safeguards, bias auditing, and human oversight are necessary for any real-world deployment.

Dataset Expansion: Future work will prioritize expanding OPOR-Bench to be both multilingual and multimodal. This involves incorporating non-English data from diverse cultural contexts and integrating critical visual content (e.g., images, videos) to ensure global applicability.

Hybrid Evaluation: To mitigate circularity and improve robustness, future work should develop hybrid evaluation frameworks. This involves combining LLM evaluators with specialized, verifiable modules (e.g., fact-checking tools, sentiment models) and structured human oversight.

Addressing LLM Evaluation Limitations: Deeper investigation is needed into LLM evaluator reliability, particularly shared capability weaknesses (e.g., blindness to temporal errors) and decision transparency. Future work should explore explainable frameworks to address this opacity.

Shared Capability Weaknesses: Evaluators may be “blind” to errors they are also prone to making, such as the universal temporal reasoning challenge we identified. Future work must integrate hybrid architectures with specialized, verifiable modules (e.g., temporal reasoners, fact-checkers) to address these capability blind spots.

Decision Transparency: Despite our agent-based design, the internal logic for specific score assignments remain opaque. Future work should explore explainable frameworks that incorporate uncertainty quantification and adversarial testing with deliberately flawed reports to improve transparency.

Reproducibility and Real-World Deployment: Future work will focus on improving reproducibility by developing smaller, efficient, open-source agents for generation and evaluation. We will also establish clear ethical guidelines for practical deployment, including robust safeguards for bias auditing and privacy protection.

Bias Mitigation: Systematic research in bias mitigation is needed to address diverse voice representation within the dataset and models. This includes developing new bias detection tools and establishing fairness metrics for public opinion analysis.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. CUC25SG013) and the Foundation of Key Laboratory of Education Informatization for Nationalities (Yunnan Normal University), Ministry of Education (No. EIN2024C006).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Jinzheng Yu, Yang Xu, Haozhen Li; methodology, Jinzheng Yu, Yang Xu, Haozhen Li; software, Jinzheng Yu, Junqi Li; validation, Jinzheng Yu, Yang Xu, Haozhen Li, Junqi Li; formal analysis, Jinzheng Yu, Yang Xu; investigation, Jinzheng Yu, Yang Xu, Haozhen Li; resources, Jinzheng Yu, Junqi Li; data curation, Junqi Li; writing—original draft preparation, Jinzheng Yu; writing—review and editing, Jinzheng Yu, Yang Xu; visualization, Jinzheng Yu, Yang Xu; supervision, Ligu Zhu, Hao Shen, Lei Shi; project administration, Ligu Zhu, Hao Shen, Lei Shi; funding acquisition, Ligu Zhu, Hao Shen, Lei Shi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Lei Shi, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Scoring Guideline for Event Title

The following sections provide the detailed scoring criteria for Event Title. Adopting a methodology similar to that of Kocmi and Federmann [49], each dimension is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where a score of 1 indicates an unacceptable generation and 5 represents an excellent one.

Scoring Guideline for Event Title

The quality of the “Event_Title” is rated on a scale of 1 to 5. Your evaluation should assess to what extent the title incorporates the official “event name” and relevant “keywords” to be clear, specific, and instantly recognizable.

Score 5 (Excellent):

The title perfectly incorporates the official event name (or its recognized alternative) and key keywords in a clear and coherent manner, precisely and unambiguously identifying the crisis event.

Score 4 (Good):

The title clearly references the event name and relevant keywords, allowing readers to readily identify the crisis, though there may be minor room for improvement.

Score 3 (Fair):

The title partially mentions the event name or a few keywords, broadly pointing to the correct crisis but lacking clarity and completeness.

Score 2 (Poor):

The title provides only minimal or vague hints related to the event, leaving the specific crisis unclear to the reader.

Score 1 (Unacceptable):

The title completely fails to mention the event name or any relevant keywords, providing no clear indication of the crisis.

Appendix B Prompts for Evaluation Framework (OPOR-Eval)

Prompt for the Evaluation Agent

Try your best to evaluate the quality of the given public opinion report comprehensively.

<tool introduction>

You have access to three specialized evaluation tools:

Fact-Checker Tool: Verifies factual accuracy by comparing report content against reference data (

Opinion Mining Tool: Analyzes public opinion coverage by examining social media posts (

Solution Counselor Tool: Evaluates recommendation quality using your expert knowledge. Use this for Event Suggestions evaluation.

Use the following format:

Initial Input: the public opinion report to be evaluated. If the report is too long, focus on the section relevant to current evaluation.

Thought: analyze which aspect needs to be evaluated and which tool to use.

Tool to Use: should be one of [Fact-Checker, Opinion-Mining, Solution-Counselor]

Tool Input: the specific content for the selected tool

Observation: the evaluation score (1–5) with reasoning from the tool

… (this Thought/Tool to Use/Tool Input/Observation can repeat N times for each report section)

Thought: I have completed evaluating all sections and can provide final scores

Final Scores: The final output for the i-th report is a 15-dimensional score vector

•

•

•

•

•

•

All prompt templates presented in this appendix were carefully designed with input from domain experts in crisis management and underwent iterative refinement through multiple validation rounds. Due to space constraints, we present representative examples here. We make the complete prompt collection, along with detailed design rationale and optimization process, publicly available with our dataset to ensure full reproducibility.

C.1 Prompt for End-to-End Strategy

Prompt Template for End-to-end Generation Approach

[SYSTEM PROMPT]

1. Role and Goal

You are an expert public opinion analyst. Your primary task is to analyze the provided context (news articles) and input (tweets) to generate a complete, structured public opinion report in a single pass. The output must be a valid JSON object.

2. Field-by-Field Generation Instructions

You must generate content for all five report sections, adhering to the following key guidelines:

• Event_Title: Generate a concise and accurate event title.

• Event_Summary: Generate a detailed summary covering the five core dimensions (Crisis Type, Time/Location, Cause, Impact, etc.).

• Event_Focus: Classify tweets (Netizens/Authoritative Institutions), perform topic clustering and sentiment analysis, and extract 2–3 key viewpoints for each group.

• ... (and so on for Event_Timeline and Event_Suggestions, with their respective constraints).

3. Few-Shot Examples

This section illustrates the expected style and depth for each field.

- - - Content Examples for “Event_Summary” field - - -

{summary_style_examples}

- - - Content Examples for “Event_Focus” field - - -

{focus_style_examples}

... (and so on for other fields)

[TASK DATA]

- - - News Data (Context) Below - - - <input>

- - - Twitter Data (Input) Below - - - <input>

C.2 Prompts for Modular Strategy

Prompt Template for Event Title Generation

1. Role and Goal

You are an expert public opinion analyst. Your task is to generate a concise, neutral, and highly descriptive title based on the news content provided below.

2. Field-by-Field Generation Instructions

• Event_Title: The title should capture the core essence of the event in a single, clear phrase.

3. Few-Shot Examples

• Input: <input_example_1>

• Output Title: <title_example_1>

- - - News Content (Context) Below - - - <input>

1https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_earthquakes (accessed on 01 September 2025).

2https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_floods_in_Europe (accessed on 01 September 2025).

3https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wildfires (accessed on 01 September 2025).

4https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2025_Table_Mountain_fire (accessed on 01 September 2025).

5https://developer.x.com/en/docs/x-api (accessed on 01 September 2025).

6Our dedicated annotation tool significantly streamlines the process by addressing two primary challenges: (1) providing a unified interface where annotators can view all documents and visualizations simultaneously, and (2) automatically enforcing standardized JSON output to ensure data consistency and eliminate manual formatting errors. Internal tests show this tool reduces annotation time per event by over 50%.

References

1. Wang B, Zi Y, Zhao Y, Deng P, Qin B. ESDM: early sensing depression model in social media streams. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024); 2024 May 20–25; Torino, Italia. p. 6288–98. [Google Scholar]

2. Che W, Chen Q, Qin L, Wang J, Zhou J. Unlocking the capabilities of thought: a reasoning boundary framework to quantify and optimize chain-of-thought. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37; 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 54872–904. doi:10.52202/079017-1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu Y, Iter D, Xu Y, Wang S, Xu R, Zhu C. G-eval: NLG evaluation using gpt-4 with better human alignment. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2023 Dec 6–10; Singapore. p. 2511–22. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-main.153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chiang CH, Lee HY. Can large language models be an alternative to human evaluations? In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023 July 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 15607–31. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu W, Huang S, Jiang Y, Xie P, Huang F, Zhao H. Unfolding the headline: iterative self-questioning for news retrieval and timeline summarization. In: Chiruzzo L, Ritter A, Wang L, editors. Findings of the association for computational linguistics: NAACL 2025. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2025. p. 4385–98. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.findings-naacl.248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang Y, Fan C, Gong Y, Yeoh W, Li Y. Forwarding in social media: forecasting popularity of public opinion with deep learning. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2025;12(2):749–63. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2024.3468721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu J, Liu L, Tu Y, Li S, Li Z. Multi-stage Internet public opinion risk grading analysis of public health emergencies: an empirical study on Microblog in COVID-19. Inf Process Manag. 2022;59(1):102796. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Liu Q, Liu Y, Son H. The memory cycle of time-series public opinion data: validation based on deep learning prediction. Inf Process Manag. 2025;62(4):104168. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2025.104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang Y, Liang R, Zhang J, Sun J, Liu Y, Qian Y. Network public opinion detection during the coronavirus pandemic: a short-text relational topic model. ACM Trans Knowl Discov Data. 2022;16(3):1–27. doi:10.1145/3480246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang B, Zhao Y, Lu X, Qin B. Cognitive distortion based explainable depression detection and analysis technologies for the adolescent internet users on social media. Front Public Health. 2023;10:1045777. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1045777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Liu S, Chen S, Wu P, Wu Q, Zhou L, Deveci M, et al. An integrated CRITIC-EDAS approach for assessing enterprise crisis management effectiveness based on Weibo. J Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2024;32(2):e12572. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Olteanu A, Vieweg S, Castillo C. What to expect when the unexpected happens: social media communications across crises. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing; 2015 Mar 14–18; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 994–1009. doi:10.1145/2675133.2675242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Imran M, Mitra P, Castillo C. Twitter as a lifeline: human-annotated Twitter corpora for NLP of crisis-related messages. In: Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’16); 2016 May 23–28; Portorož, Slovenia. p. 1638–43. [Google Scholar]

14. Alam F, Ofli F, Imran M. CrisisMMD: multimodal Twitter datasets from natural disasters. Proc Int AAAI Conf Web Soc Media. 2018;12(1):465–73. doi:10.1609/icwsm.v12i1.14983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Suwaileh R, Elsayed T, Imran M. IDRISI-RE: a generalizable dataset with benchmarks for location mention recognition on disaster tweets. Inf Process Manag. 2023;60(3):103340. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Alam F, Sajjad H, Imran M, Ofli F. CrisisBench: benchmarking crisis-related social media datasets for humanitarian information processing. Proc Int AAAI Conf Web Soc Media. 2021;15:923–32. doi:10.1609/icwsm.v15i1.18115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Delforge D, Wathelet V, Below R, Sofia CL, Tonnelier M, van Loenhout JAF, et al. EM-DAT: the emergency events database. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025;124:105509. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2025.105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lin J, Ma X, Lin SC, Yang JH, Pradeep R, Nogueira R. Pyserini: a Python toolkit for reproducible information retrieval research with sparse and dense representations. In: Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2021 Jul 11–15; Online. p. 2356–62. doi:10.1145/3404835.3463238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bai Y, Zhang J, Lv X, Zheng L, Zhu S, Hou L, et al. LongWriter: unleashing 10,000+ word generation from long context LLMs. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations; 2025 Apr 24–28; Vienna, Austria. p. 36528–46. [Google Scholar]

20. Liu R, Liu M, Yu M, Zhang H, Jiang J, Li G, et al. SumSurvey: an abstractive dataset of scientific survey papers for long document summarization. In: Ku LW, Martins A, Srikumar V, editors. Findings of the association for computational linguistics ACL 2024. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 9632–51. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.findings-acl.574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bilal IM, Wang B, Tsakalidis A, Nguyen D, Procter R, Liakata M. Template-based abstractive microblog opinion summarization. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2022;10(1):1229–48. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Angelidis S, Lapata M. Summarizing opinions: aspect extraction meets sentiment prediction and they are both weakly supervised. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2018 Oct 31–Nov 4; Brussels, Belgium. p. 3675–86. doi:10.18653/v1/d18-1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Nallapati R, Zhou B, dos Santos C, Gulcehre C, Xiang B. Abstractive text summarization using sequence-to-sequence RNNs and beyond. In: Proceedings of the 20th SIGNLL Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning; 2016 Aug 11–12; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany. p. 280–90. doi:10.18653/v1/k16-1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Huang KH, Laban P, Fabbri A, Choubey PK, Joty S, Xiong C, et al. Embrace divergence for richer insights: a multi-document summarization benchmark and a case study on summarizing diverse information from news articles. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2016 Aug 11–12; Mexico City, Mexico. p. 570–93. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.naacl-long.32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mao Y, Qu Y, Xie Y, Ren X, Han J. Multi-document summarization with maximal marginal relevance-guided reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2020 Nov 16–20; Online. p. 1737–51. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-main.136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zheng X, Sun A, Li J, Muthuswamy K. Subtopic-driven multi-document summarization. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); 2019 Nov 3–7; Hong Kong, China. p. 3151–60. doi:10.18653/v1/d19-1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chen Z, Chen Q, Qin L, Guo Q, Lv H, Zou Y, et al. What are the essential factors in crafting effective long context multi-hop instruction datasets? Insights and best practices. In: Che W, Nabende J, Shutova E, Pilehvar MT, editors. Proceedings of the 63rd annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2025. p. 27129–51. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.acl-long.1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ye Y, Feng X, Feng X, Ma W, Qin L, Xu D, et al. GlobeSumm: a challenging benchmark towards unifying multi-lingual, cross-lingual and multi-document news summarization. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2024 Nov 12–16; Miami, FL, USA. p. 10803–21. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.emnlp-main.603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ernst O, Caciularu A, Shapira O, Pasunuru R, Bansal M, Goldberger J, et al. Proposition-level clustering for multi-document summarization. In: Carpuat M, de Marneffe MC, Ruiz Meza IV, editors. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 1765–79. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.naacl-main.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cho S, Song K, Wang X, Liu F, Yu D. Toward unifying text segmentation and long document summarization. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2022 Dec 7–11; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 106–18. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bai Y, Lv X, Zhang J, Lyu H, Tang J, Huang Z, et al. LongBench: a bilingual, multitask benchmark for long context understanding. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguisticss; 2024 Aug 11–16; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 3119–37. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Giorgi J, Soldaini L, Wang B, Bader G, Lo K, Wang L, et al. Open domain multi-document summarization: a comprehensive study of model brittleness under retrieval. In: Bouamor H, Pino J, Bali K, editors. Findings of the association for computational linguistics: EMNLP 2023. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. p. 8177–99. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.findings-emnlp.549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. An C, Gong S, Zhong M, Zhao X, Li M, Zhang J, et al. L-eval: instituting standardized evaluation for long context language models. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024 Aug 11–16; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 14388–411. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fabbri A, Li I, She T, Li S, Radev D. Multi-news: a large-scale multi-document summarization dataset and abstractive hierarchical model. In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Jul 28–Aug 2; Florence, Italy. p. 1074–84. doi:10.18653/v1/p19-1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Krishna K, Roy A, Iyyer M. Hurdles to progress in long-form question answering. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2021 Jun 6–11; Online. p. 4940–57. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.naacl-main.393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ni X, Cai H, Wei X, Wang S, Yin D, Li P. XL2Bench: a benchmark for extremely long context understanding with long-range dependencies. arXiv:2404.05446. 2024. [Google Scholar]

37. Xu F, Song Y, Iyyer M, Choi E. A critical evaluation of evaluations for long-form question answering. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 3225–45. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang D, Yang K, Zhu H, Yang X, Cohen A, Li L, et al. Learning personalized alignment for evaluating open-ended text generation. In: Al-Onaizan Y, Bansal M, Chen YN, editors. Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 13274–92. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.emnlp-main.737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Shen C, Cheng L, Nguyen XP, You Y, Bing L. Large language models are not yet human-level evaluators for abstractive summarization. In: Bouamor H, Pino J, Bali K, editors. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. p. 4215–33. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.findings-emnlp.278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Liu Y, Yu J, Xu Y, Li Z, Zhu Q. A survey on transformer context extension: approaches and evaluation. arXiv:2503.13299. 2025. [Google Scholar]

41. Li J, Wang M, Zheng Z, Zhang M. LooGLE: can long-context language models understand long contexts? In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024 Aug 11–16; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 16304–33. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Calderon N, Reichart R, Dror R. The alternative annotator test for LLM-as-a-judge: how to statistically justify replacing human annotators with LLMs. In: Che W, Nabende J, Shutova E, Pilehvar MT, editors. Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2025. p. 16051–81. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.acl-long.782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Tan H, Guo Z, Shi Z, Xu L, Liu Z, Feng Y, et al. ProxyQA: an alternative framework for evaluating long-form text generation with large language models. In: Ku LW, Martins A, Srikumar V, editors. Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (volume 1: Long Papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 6806–27. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chiang CH, Lee HY, Lukasik M. TRACT: regression-aware fine-tuning meets chain-of-thought reasoning for LLM-as-a-judge. In: Che W, Nabende J, Shutova E, Pilehvar MT, editors. Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2025. p. 2934–52. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.acl-long.147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Luo Z, Xie Q, Ananiadou S. ChatGPT as a factual inconsistency evaluator for text summarization. arXiv:2303.15621. 2023. [Google Scholar]

46. D’Souza J, Babaei Giglou H, Münch Q. YESciEval: robust LLM-as-a-judge for scientific question answering. In: Che W, Nabende J, Shutova E, Pilehvar MT, editors. Proceedings of the 63rd annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (volume 1: long papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2025. p. 13749–83. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.acl-long.675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zheng L, Chiang WL, Sheng Y, Zhuang S, Wu Z, Zhuang Y, et al. Judging LLM-as-a-judge with MT-bench and chatbot arena. arXiv:2306.05685. 2023. [Google Scholar]

48. Wu N, Gong M, Shou L, Liang S, Jiang D. Large language models are diverse role-players for summarization evaluation. In: Natural language processing and Chinese computing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 695–707. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-44693-1_54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Kocmi T, Federmann C. Large language models are state-of-the-art evaluators of translation quality. In: Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation; 2023 Jun 12–15; Tampere, Finland. p. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools