Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Toward Secure and Auditable Data Sharing: A Cross-Chain CP-ABE Framework

1 College of Computer Science and Technology, Taiyuan Normal University, Jinzhong, 030619, China

2 State Grid Shanxi Electric Power Research Institute, Taiyuan, 030001, China

* Corresponding Author: Ye Tian. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 62 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073935

Received 28 September 2025; Accepted 26 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Amid the increasing demand for data sharing, the need for flexible, secure, and auditable access control mechanisms has garnered significant attention in the academic community. However, blockchain-based ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE) schemes still face cumbersome ciphertext re-encryption and insufficient oversight when handling dynamic attribute changes and cross-chain collaboration. To address these issues, we propose a dynamic permission attribute-encryption scheme for multi-chain collaboration. This scheme incorporates a multi-authority architecture for distributed attribute management and integrates an attribute revocation and granting mechanism that eliminates the need for ciphertext re-encryption, effectively reducing both computational and communication overhead. It leverages the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) for off-chain data storage and constructs a cross-chain regulatory framework—comprising a Hyperledger Fabric business chain and a FISCO BCOS regulatory chain—to record changes in decryption privileges and access behaviors in an auditable manner. Security analysis shows selective indistinguishability under chosen-plaintext attack (sIND-CPA) security under the decisional q-Parallel Bilinear Diffie-Hellman Exponent Assumption (q-PBDHE). In the performance and experimental evaluations, we compared the proposed scheme with several advanced schemes. The results show that, while preserving security, the proposed scheme achieves higher encryption/decryption efficiency and lower storage overhead for ciphertexts and keys.Keywords

With the advent of the digital era, data sharing has emerged as a crucial driver of cross-industry collaboration and efficiency enhancement, particularly in sectors such as healthcare, finance, and the Internet of Things, where cross-organizational data exchange has become routine [1]. The frequent circulation of sensitive information necessitates stricter security. In privacy protection, users expect fine-grained control over access rights to prevent unauthorized access and abuse [2]. Traditional centralized storage, although convenient to manage, faces single-point failures, susceptibility to attack, and risks of tampering, making it unsuitable for complex, high-sensitivity sharing scenarios [3].

Against this backdrop, blockchain—a decentralized, immutable, and traceable ledger—is widely recognized as an emerging solution for securing data sharing [4,5]. When combined with distributed storage systems (e.g., InterPlanetary File System IPFS), it improves availability while strengthening integrity and trustworthiness [6,7]. In terms of access control, attribute-based encryption (ABE) has become a key encryption technology for ensuring data privacy because it supports flexible encryption mechanisms based on user attributes [8]. In particular, ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE) allows data owners to embed access policies directly into ciphertext, ensuring that only authorized users can decrypt the data [9]. This mechanism has been widely applied to fine-grained access control and privacy protection. With the rise of blockchain, blockchain-based CP-ABE schemes have attracted increasing attention and become an important research direction for constructing trustworthy data-sharing mechanisms.

Nevertheless, current blockchain-based CP-ABE schemes still have several limitations. First, many schemes rely on centralized Attribute Authorities (AAs), which create single points of failure and abuse of authority. Second, existing solutions lack an effective combination of attribute revocation and granting mechanisms and generally rely on ciphertext re-encryption, resulting in high computational and communication costs that are difficult to meet in blockchain environments with limited resources. Furthermore, most solutions adopt a single-chain architecture [10] and lack on-chain and off-chain coordination, making it difficult to support complex scenarios where data circulation and regulation oversight exist simultaneously.

In response to these shortcomings, we propose a dynamic permission attribute encryption scheme under multi-chain collaboration, which supports multi-institution attribute management and dynamic permission updates. The main contributions include:

• We designed a dynamic attribute revocation and granting mechanism without ciphertext updates, eliminating the computational burden of frequent re-encryption in traditional solutions and enabling more fine-grained and dynamic permission management.

• We constructed a multi-authority collaborative key-generation mechanism that allows multiple AAs to distribute and manage user keys independently, enhancing security and flexibility while mitigating single-authority concentration risk.

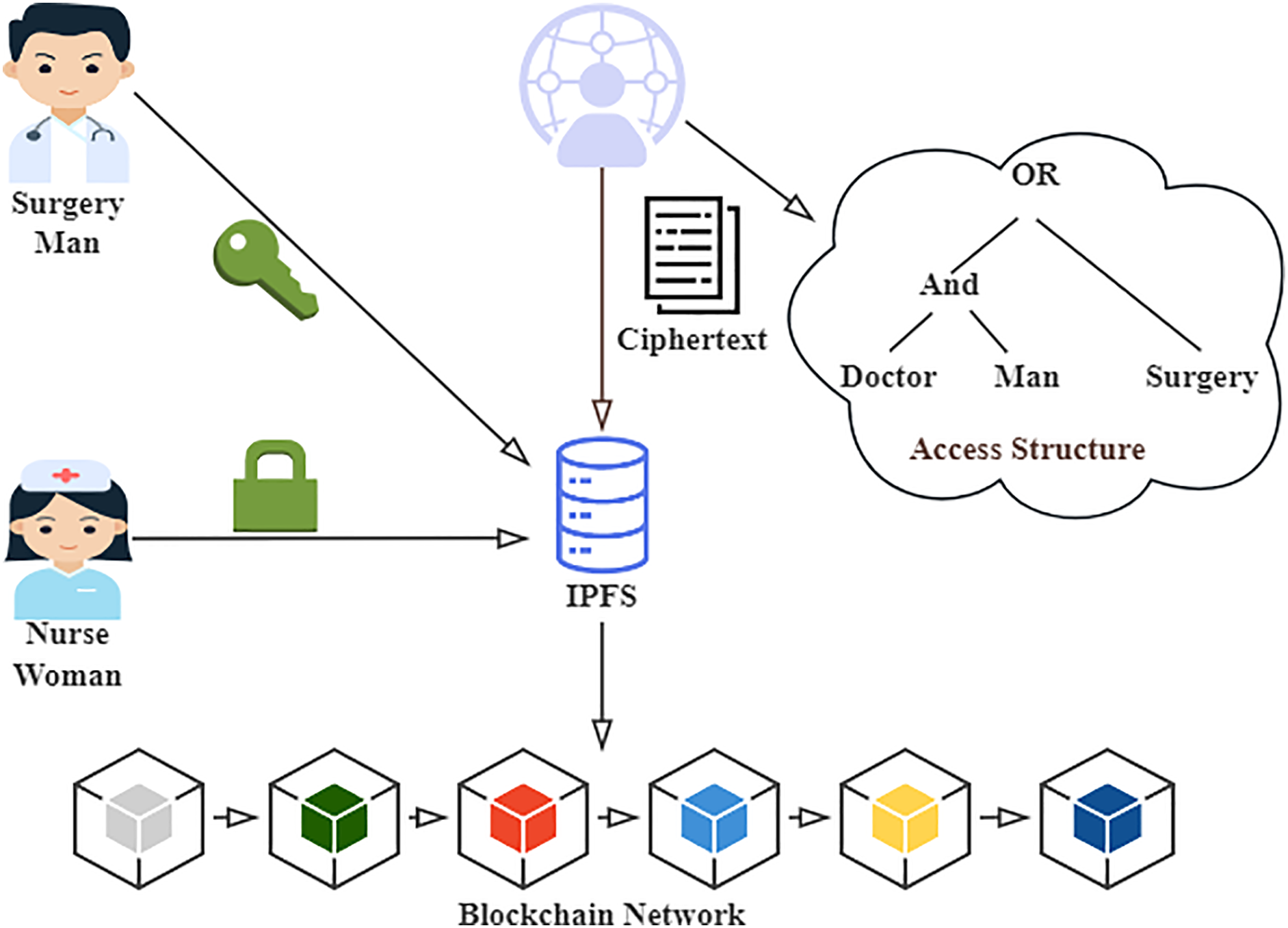

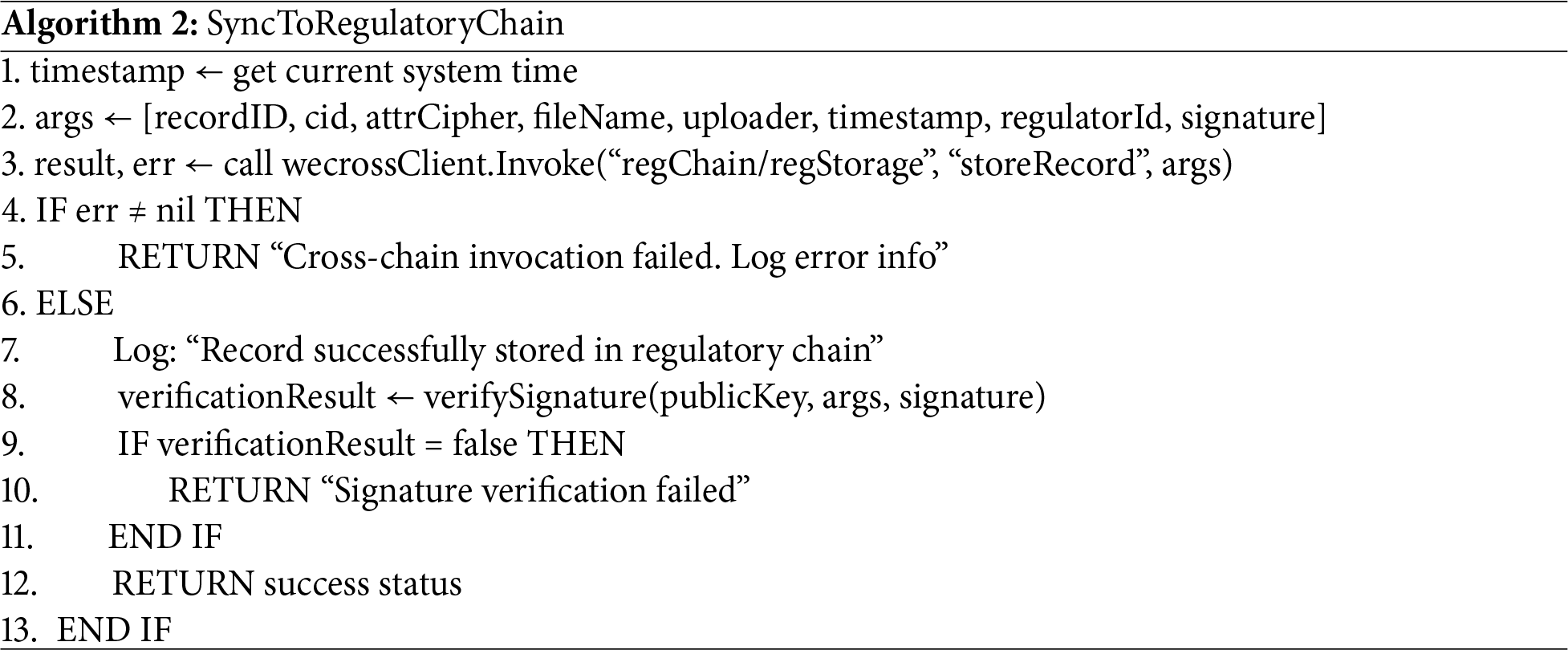

• We designed a multi-chain CP-ABE access-control framework based on Hyperledger Fabric, FISCO BCOS, and IPFS in Fig. 1, supporting structured auditing and traceability of user decryption behavior and dynamic attribute management operations.

Figure 1: Multi-chain collaborative CP-ABE access control scheme

CP-ABE has become a key technology for safeguarding data privacy, owing to its unique advantages in data access control. However, traditional CP-ABE schemes typically rely on centralized authorities, leading to over-centralized privilege management in large-scale systems. To overcome this limitation, researchers have proposed Multi-Authority CP-ABE (MA-CP-ABE) [11–15], which distributes attribute management across multiple Attribute Authorities (AA) to avoid single-point failures. As user privileges evolve, attribute revocation becomes essential for fine-grained access control. Revocation mechanisms can be categorized into user-level and attribute-level revocation. User-level revocation [16] revokes all attribute authorizations once a user loses access rights. Although this approach is simple and direct, it can result in over-restriction of permissions. By contrast, attribute-level revocation [17–19] targets only specific attributes affected by privilege changes. This method improves fine-grained access control but introduces higher computational complexity.

To further enhance security and decentralization, blockchain has been integrated with CP-ABE. Ren et al. [20] developed a blockchain-based distributed key management system combined with Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge (zk-SNARKs), which eliminates single points of failure while protecting access policy privacy, though it does not address attribute revocation. Guo et al. [21] proposed blockchain-aided ABE with escrow-free (BC-ABE-EF) in a consortium chain setting, achieving no key escrow and immediate user revocation. Despite solving key-escrow issues, it still relies on periodic group-key updates and ciphertext re-encryption, incurring significant computation and communication overhead. To reduce update overhead, Li and Qi [22] introduced a pre-decryption mechanism combined with an attribute revocation list, enabling real-time on-chain revocation. However, their approach imposes a fixed upper limit on attribute sets, limiting its scalability in large-scale environments. More recently, Thakur et al. [23] presented the Blockchain-based CP-ABE (BloCPABE) scheme, embedding revocation tags into attribute keys to achieve immediate revocation and anonymous key generation within a blockchain framework.

In addition to security, researchers have sought to improve data-sharing efficiency by reducing blockchain’s high storage costs. One approach integrates IPFS with blockchain [24–26]. In such designs, where blockchain stores only data indexes and audit records, while the actual data are stored on IPFS, reducing on-chain storage demands without compromising immutability. However, as application scenarios expand and requirements grow more complex, single blockchain networks increasingly face challenges in scalability, performance, and cross-organizational collaboration [27]. Consortium blockchains, such as Hyperledger Fabric, have emerged as important solutions owing to their advantages in channel management, chaincode control, and private data collection [28]. Meanwhile, the “Data islands” phenomenon across heterogeneous blockchains has become more pronounced. To address this, cross-chain technologies have emerged: Cosmos [29] and Polkadot [30] enable efficient interoperability via heterogeneous-chain protocols, in parallel, domestic research efforts such as WeCross are drawing growing attention from the academic community.

Despite notable progress in access control and privacy protection, important gaps remain. First, most CP-ABE revocation approaches still rely on key updates and ciphertext re-encryption, imposing heavy computational and storage burdens. Moreover, they do not fully integrate dynamic attribute revocation and granting without ciphertext updates. Second, most blockchain-based CP-ABE schemes use single-chain architectures and provide limited support for multi-chain environments, cross-chain data sharing and coordinated auditing remain unresolved.

In order to tackle these problems, we design a dynamic permission attribute-encryption scheme under multi-chain collaboration, integrating a multi-authority mechanism to improve security, flexibility, and scalability.

3.1 Blockchain Technology and Cross-Chain Communication

Blockchain is a type of distributed ledger technology (DLT) that operates as a decentralized, jointly maintained database where network participants contribute to and manage records. The blockchain system uses digital signatures and encryption algorithms to generate blocks containing data and relies on a consensus mechanism to ensure the majority approval of the participating nodes, making the data secure, safe, and unforgeable. Depending on node access permissions, blockchains are categorized as public, consortium, or private. Constrained by their architectural design, single blockchain systems cannot efficiently exchange data and value with other chains, leading to the so-called “data-island” effect. In order to solve this problem, cross-chain technology has emerged, providing a chain-to-chain communication protocol to enable secure, trustworthy, and efficient data and asset interaction across different chains.

CP-ABE, embeds an access policy directly into the ciphertext, allowing data owners to define flexible access control rules. Unlike traditional identity-based encryption, CP-ABE determines decryption eligibility by matching a user’s attribute set against the embedded policy, plaintext can only be successfully restored when the user attributes meet the policy. This scheme typically comprises four fundamental algorithms:

•

•

•

•

• Define

• Bilinearity:

• Non-degeneracy:

• Computability:

3.4 Linear Secret Sharing Schemes (LSSS)

Assume that an access structure

3.5 Decisional q-Parallel Bilinear Diffie-Hellman Exponent Assumption(q-PBDHE)

Define

If for all probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT)

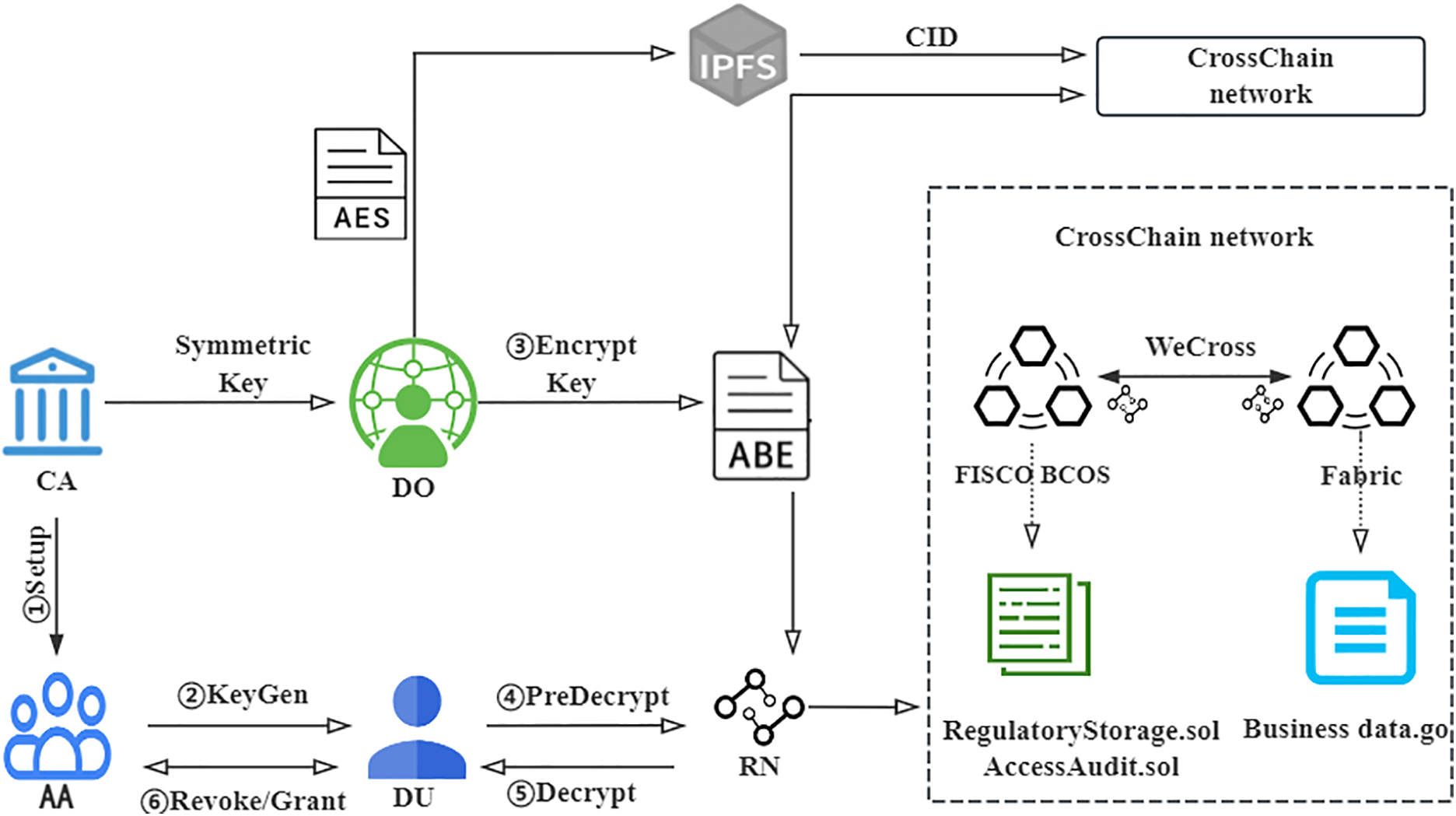

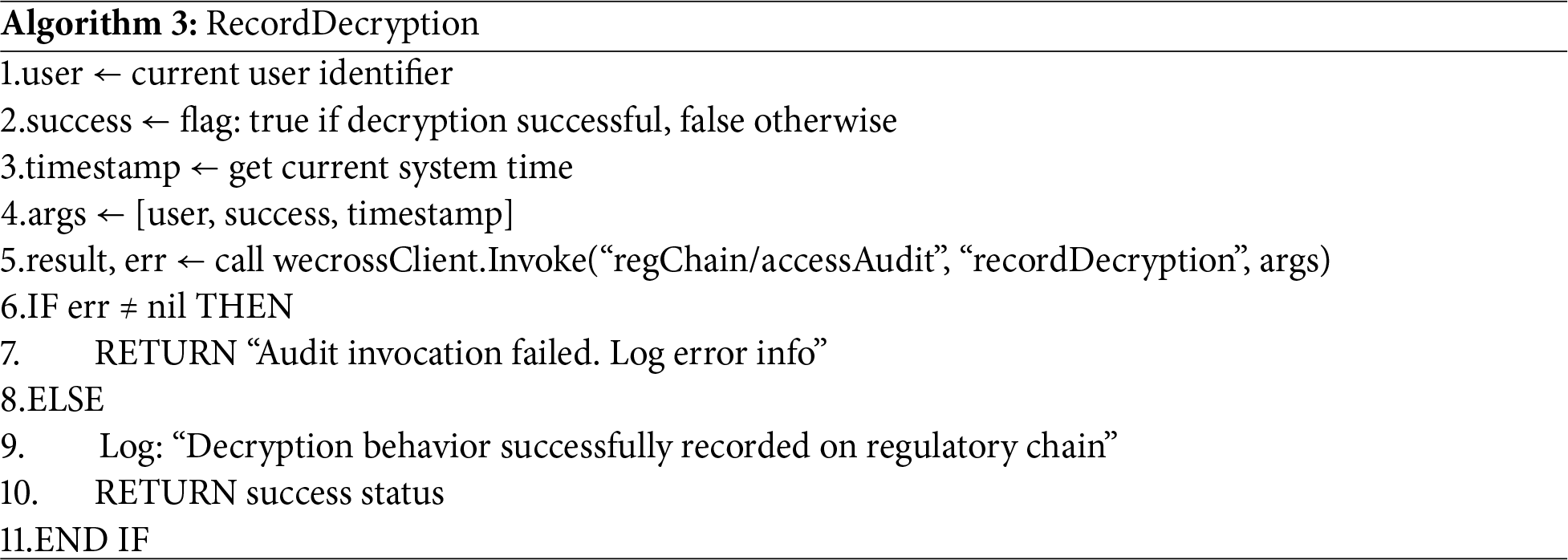

To enable dynamic access control for data sharing and regulatory auditing, we propose an integrated architecture that combines on-chain and off-chain collaboration with dynamic attribute-based encryption, as shown in Fig. 2. The architecture is composed of the Hyperledger Fabric business chain, the FISCO BCOS regulatory chain, IPFS, and an off-chain encryption module. These components provide secure data storage, flexible authorization, auditable record-keeping, and fine-grained access control. The system model involves six core participant categories:

• Central Authority (CA): Initializes the system and generates global public parameters.

• Attribute Authority (AA): Independently manages attributes by category. Each AA issues user attributes with private keys for its managed attributes and supports attribute revocation and granting.

• Data Owner (DO): Responsible for processing raw data, setting access policies, uploading attribute ciphertexts, etc. to the business chain after hybrid encryption.

• Data User (DU): Holds a set of attributes and obtains attribute private keys from the relevant AAs. Using these keys, the DUs decrypt and access data stored on the regulatory chain.

• Regulator Node (RN): Participates in the regulatory chain, receives summaries of regulatory data uploaded from the business chain, and audits user activity records.

• Cross-Chain Network:

• Business Chain: Built on the Hyperledger Fabric Consortium blockchain, it stores IPFS content identifiers (CID), attribute ciphertexts, and other business-related data.

• Regulatory Chain: Implemented on the FISCO BCOS blockchain, it stores structured audit information, including regulatory logs, decryption records, and attribute revocation or granting events.

Figure 2: System architecture

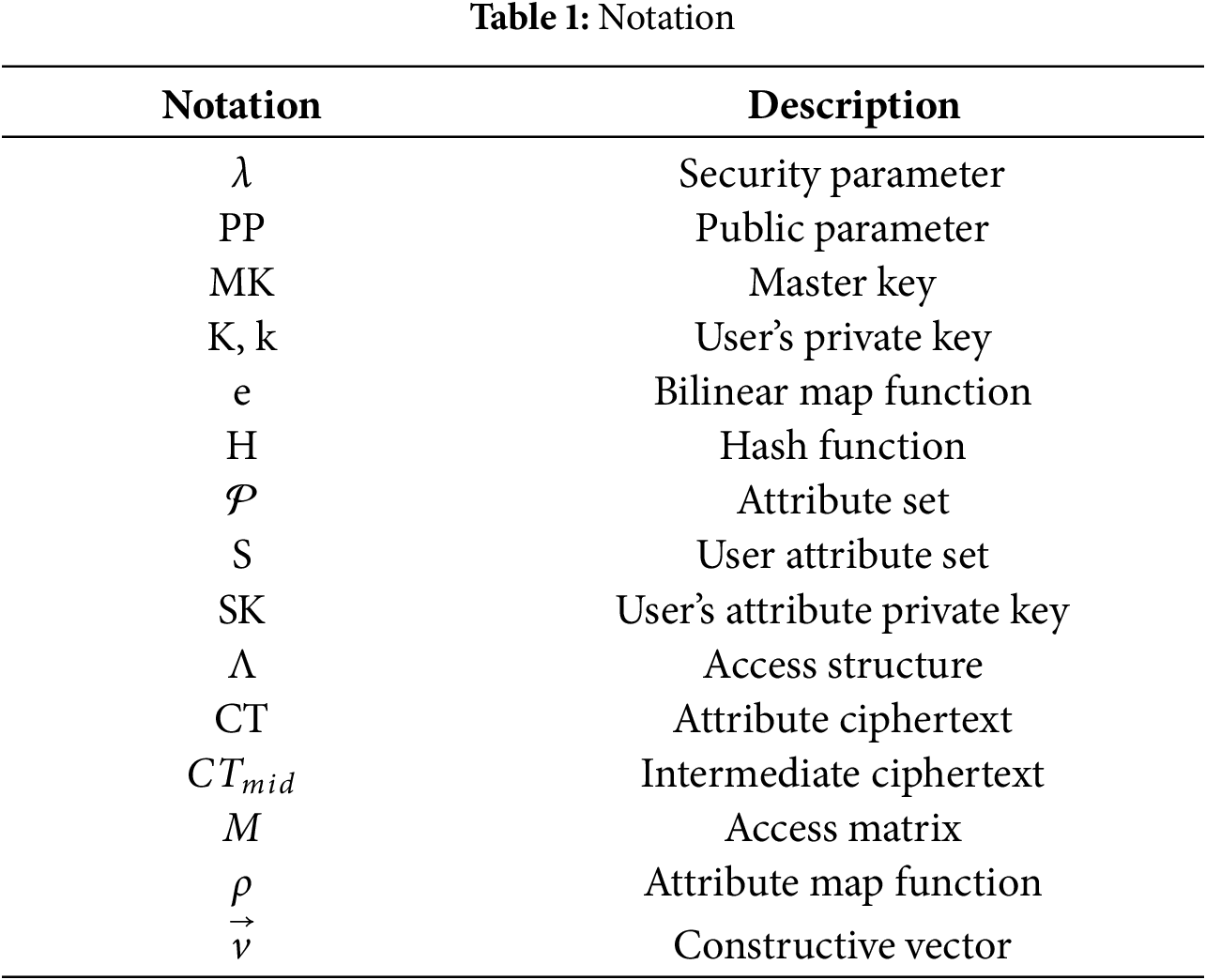

The algorithms of this system operate between different participants and collaborate to achieve key generation, data encryption and decryption, access control and audit operations. The notation used is listed in Table 1. The core algorithms are defined as follows:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• Confidentiality: Unauthorized users, even if they possess partial attributes and key information, cannot recover the original plaintext from the ciphertext, thereby ensuring the confidentiality of the data.

• Pre-Decryption Correctness: Users whose attributes satisfy the access policy can correctly compute the intermediate ciphertext using their private keys and ciphertext. This intermediate ciphertext is then used for subsequent symmetric key recovery and plaintext decryption, thereby ensuring the functionality of the system.

• Forward Security: When a user’s attribute is revoked, the system ensures that even if they previously held a valid key, they are unable to decrypt subsequent ciphertext, thus providing forward security.

• Anti-Collusion: Users who do not satisfy the access policy, even when combining their respective attributes and private key components, cannot bypass the policy to recover the plaintext, effectively preventing illegal collusion attacks.

To formally describe the confidentiality security of this scheme under the off-chain pre-decryption structure, we define a game-based security model to simulate the interaction between an attacker

• Initialization.

• System setup.

• Stage 1: Attribute private key query.

• Challenge.

• Stage 2: Pre-decryption query.

• Guess.

For any probabilistic polynomial time (PPT)

5 Dynamic Permission Attribute-Encryption Scheme under Multi-Chain Coordination

5.1.1 Public Parameter Generation

The system generates public parameters through

5.1.2 Attribute Authority Configuration

5.2 Multi-Authority Secret Key Generation

5.2.1 User’s Private Key Generation

The user DU randomly selects

5.2.2 Attribute Secret Key Generation

Let

Finally, the complete attribute private key is output:

5.3 Design of Encryption Storage and Blockchain Synchronization

5.3.1 Off-Chain Encryption and Storage Design

DO locally generates a symmetric key for encrypting the original plaintext data M, computes the ciphertext C, and uploads it to the IPFS network, retrieving the unique content identifier CID.

5.3.2 Symmetric Encryption and Strategy Packaging

DO executes

• Strategy matrix generation: DO sets

• Linear secret sharing: DO randomly selects a secret value s and constructs a vector

• Attribute ciphertext component

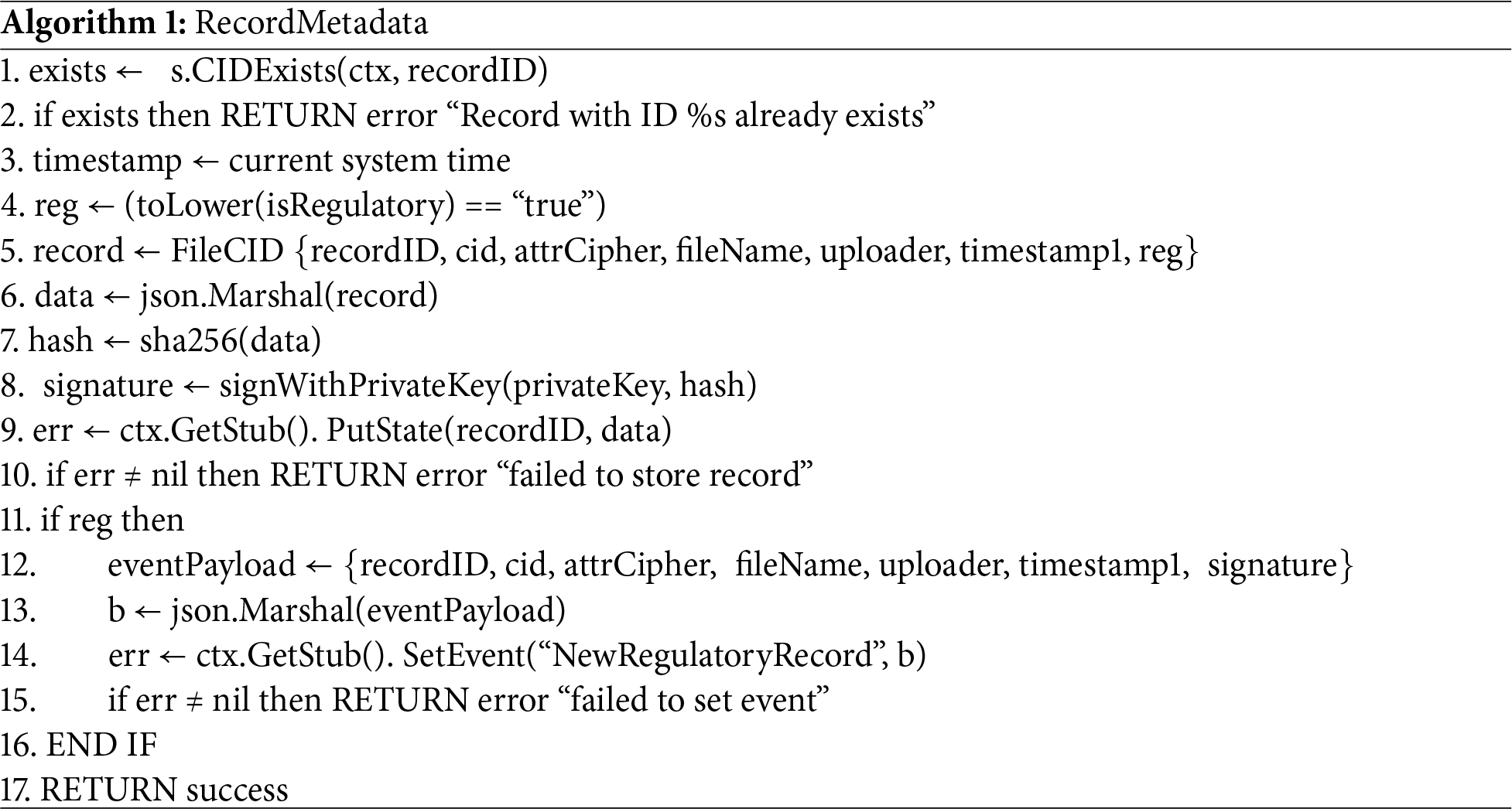

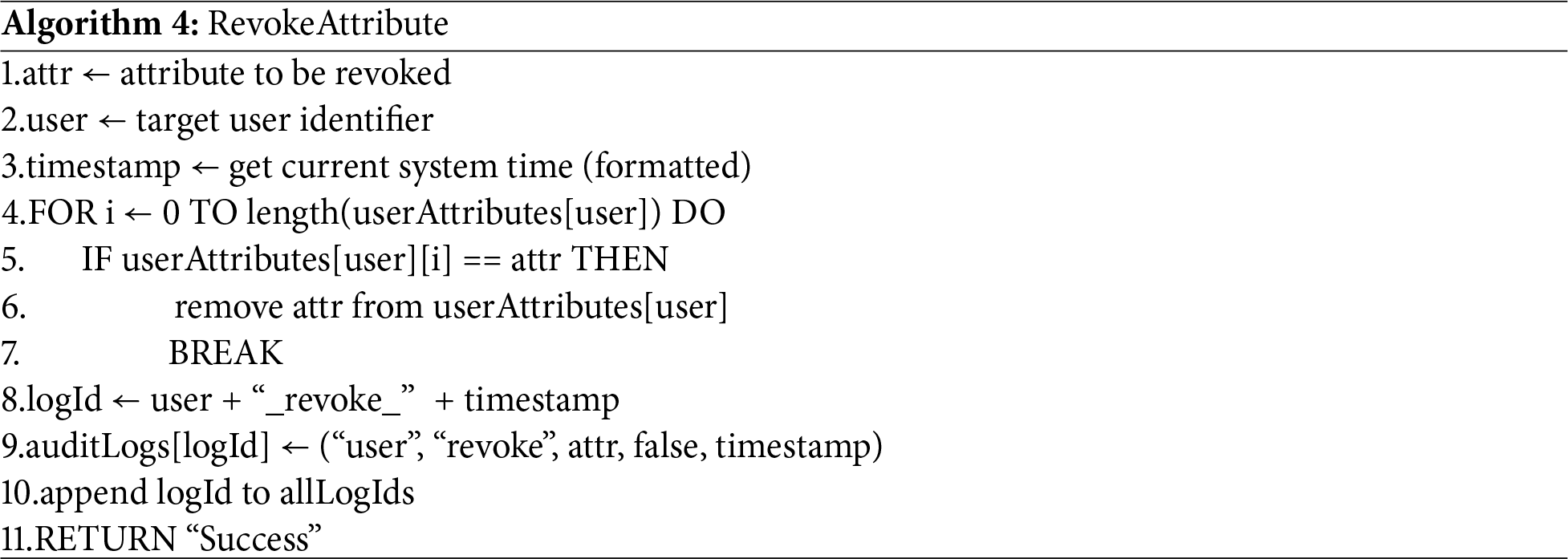

5.3.3 Fabric Blockchain Evidence Storage and FISCO Chain Synchronization

To ensure data storage and regulatory audit capabilities, we deployed the Business Data.go smart contract on the Hyperledger Fabric business chain. This contract stores the CID and attribute ciphertext uploaded by DO. In the implementation, RN on the chain invoke the smart contract’s RecordMetadata function, which first checks whether a record with the same recordID exists. If it does, an error is returned. Next, the current system timestamp is obtained, and the FileCID structure is created, serialized into JSON format and attaches signature. Finally, the function checks if the record is regulatory data and, if so, triggers the NewRegulatoryRecord event. The core algorithm for RecordMetadata is shown in Algorithm 1.

When the NewRegulatoryRecord event is triggered on the Fabric chain, the WeCross routing module extracts data such as recordID, cid, attrCipher, and the current system timestamp. These data are then encapsulated into a cross-chain invocation request and synchronized to the FISCO BCOS regulatory chain via the WeCross routing module. On the regulatory chain, the RN nodes first verify the signature of the cross-chain transmitted data and, if the verification is successful, store the regulatory data on the chain. If the cross-chain invocation fails, the system logs the error and returns the corresponding error message. The core algorithm is shown in Algorithm 2.

5.4 Decrypting Behavior Auditing Mechanism

5.4.1 Attribute Verification and Intermediate Ciphertext Recovery

The off-chain RN executes the algorithm

If the user’s attribute set does not satisfy the policy, return

DU locally executes the final decryption algorithm

5.4.3 On-Chain Decryption Behavior Auditing

After RN completes the pre-decryption of the ciphertext, it triggers the RecordDecryption interface in the AccessAudit smart contract. The system first retrieves the current user identifier, decryption success flag, and timestamp, and packages this information into a request to log the data on the blockchain. Regardless of whether the decryption is successful, this ensures the traceability and regulatory compliance of each decryption operation. The core algorithm is shown in Algorithm 3.

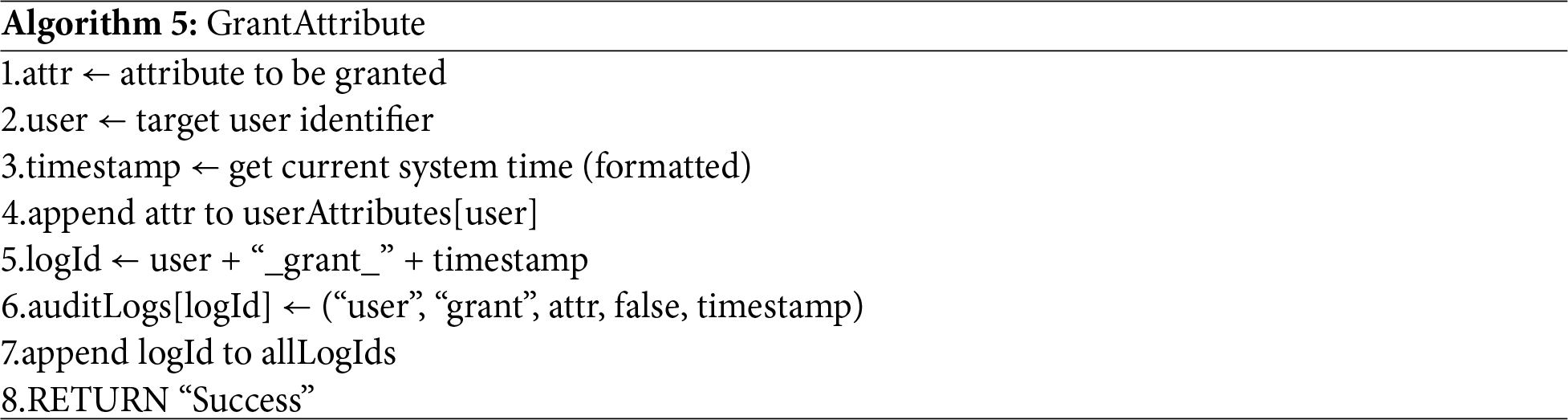

5.5 Dynamic Permission Management

To support fine-grained access control in a blockchain environment, this study designs a set of on-chain operable dynamic attribute management mechanisms that do not require the ciphertext re-encryption. Specifically, it includes three steps: attribute revocation, attribute granting, and on-chain audit records.

When the attribute

When a new attribute is assigned to a user DU, the existing encryption structure does not need to be modified. Only the private key component corresponding to the new attribute needs to be recalculated, and updated the user’s private key:

5.5.3 On-Chain Permission Auditing

After completing the attribute revocation operation, the RN calls the RevokeAttribute interface in the AccessAudit smart contract. The system first retrieves the attribute to be revoked

6.1 Decryption Correctness Analysis

The user finally restores the symmetric key:

This section proves the confidentiality of the proposed scheme under the selective IND-CPA model defined in Section 4.4.

Theorem. If the q-PBDHE assumption in Section 3.5 holds for the group

Proof. We constructed a PPT simulator

Initialization.

Setup.

Step 1: Attribute private key query.

Challenge phase.

Distribution claim. If

Stage 2: Pre-decryption query.

• attribute private key queries, answered as in Phase 1.

• pre-decryption queries on any ciphertext, including

Conclusion. If

In this scheme, each user’s attribute private key is bound to a unified dynamic factor

In this scheme, the user’s attribute private key components,

To enhance the security and robustness of the proposed cross-chain architecture, we expand on the theoretical security model by incorporating practical threat models such as cross-chain replay attacks and man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks.

6.5.1 Cross-Chain Replay Attacks

Replay attacks occur when an attacker intercepts and replays a legitimate request, thereby executing unauthorized actions, such as resubmitting data or operations. As shown in Algorithm 2, to effectively prevent cross-chain replay attacks, our scheme incorporates the current system timestamp when the WeCross routing module extracts regulatory data. This ensures that each cross-chain transaction request contains a unique, time-stamped entry. Moreover, the use of a unique regulatorId further strengthens the integrity of the cross-chain request, ensuring that only requests with the correct regulatorId are accepted. If the system detects a replayed request, it will reject it. This mechanism ensures that even if an attacker intercepts and replays a request, no duplicate actions will be executed, thereby preserving the integrity of the data synchronization process.

6.5.2 Man-in-the-Middle Attacks

MITM attacks occur when an attacker intercepts, alters, or injects malicious data into the communication between two parties, without their knowledge. In the context of cross-chain data exchange, MITM attacks can compromise data integrity, enabling the attacker to manipulate the contents of the request. To effectively prevent MITM attacks, our scheme employs a digital signature mechanism. As shown in Algorithm 1, we first compute the hash of the serialized data and sign it with a private key, ensuring that the data remains tamper-proof. When the data is cross-chain transmitted to the regulatory chain, the RN node on the chain verifies the validity of the request using the corresponding public key. As shown in Algorithm 2, if the signature verification fails, the request will be rejected. By incorporating the signature verification mechanism, we ensure that the data transmitted across chains remains unaltered during the process. Even if an attacker intercepts and modifies the request, the system will reject it due to the signature mismatch. This mechanism effectively prevents MITM attacks and ensures the integrity and authenticity of the cross-chain data.

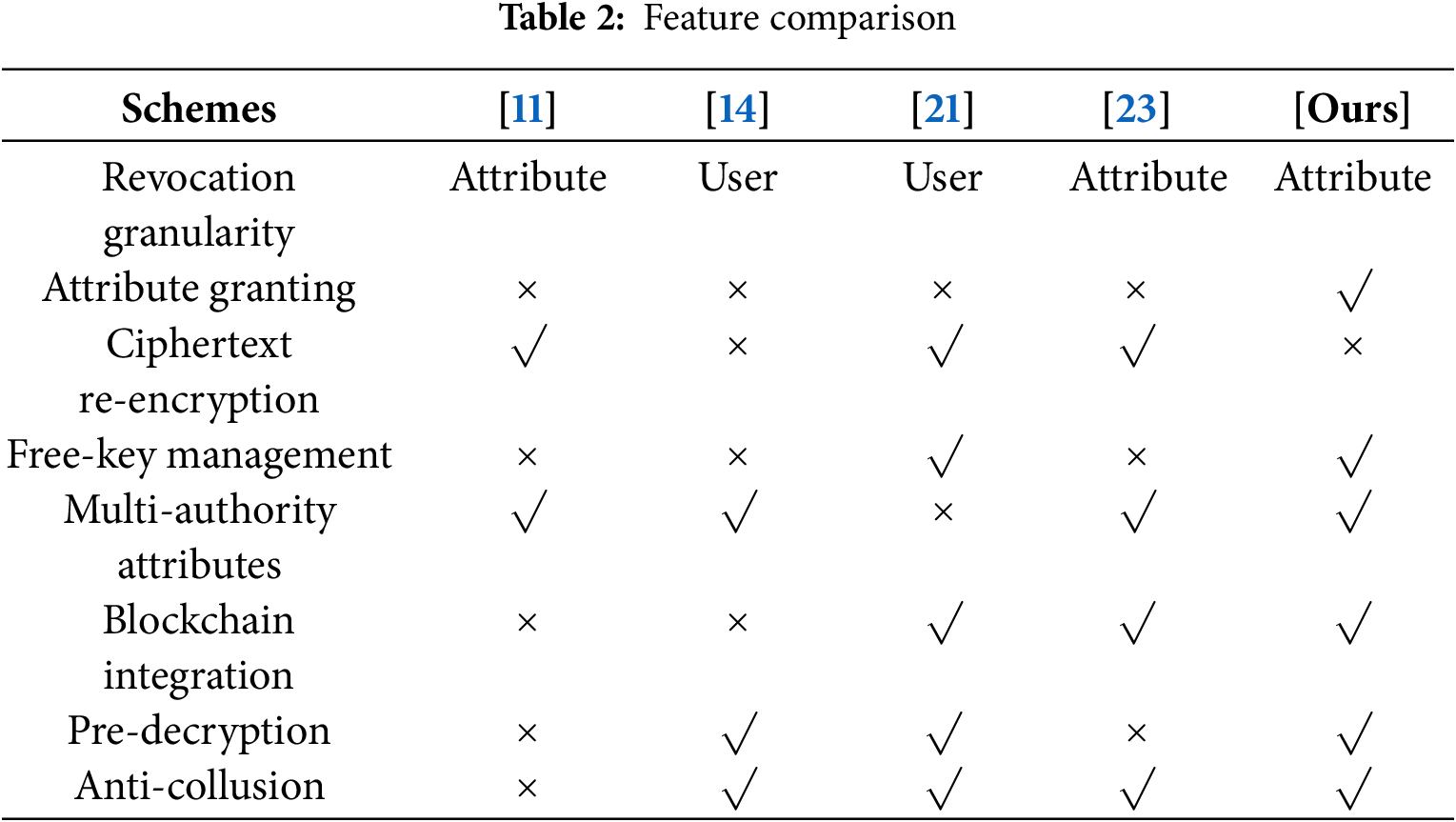

In this chapter, we compare the proposed scheme with other similar schemes and analyze their performance in detail. As shown in Table 2, we evaluate various aspects such as the granularity of encryption, attribute granting, ciphertext re-encryption, free-key management, multi-authority attributes, blockchain structure, encryption for external/public requests, and anti-collusion.

We define

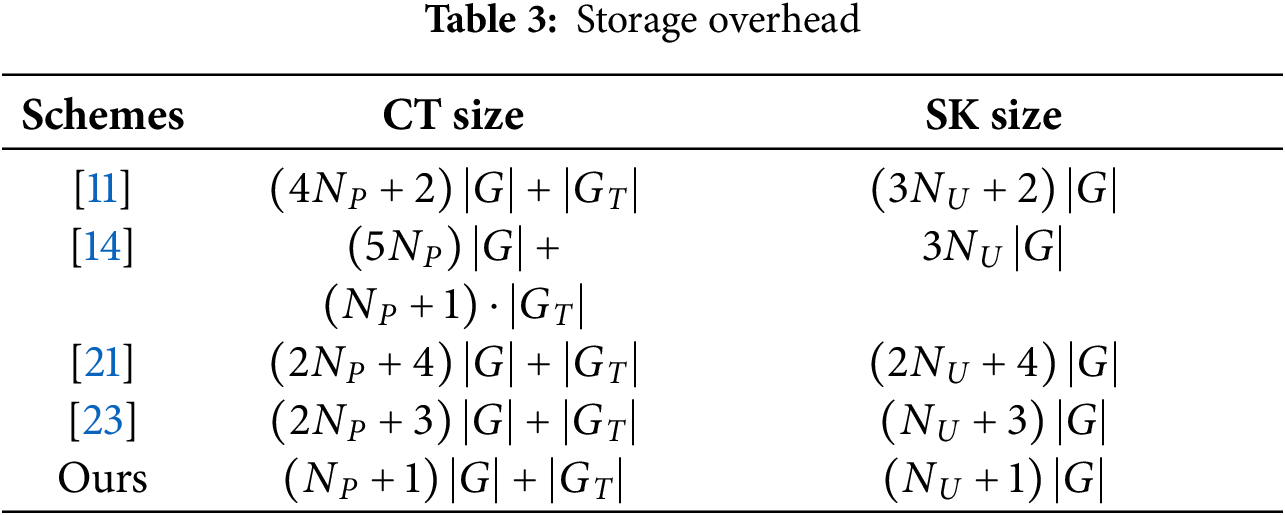

From the storage comparison results shown in Table 3, it can be seen that the proposed scheme reduces the storage overhead effectively, with fewer elements to store. The ciphertext size is only

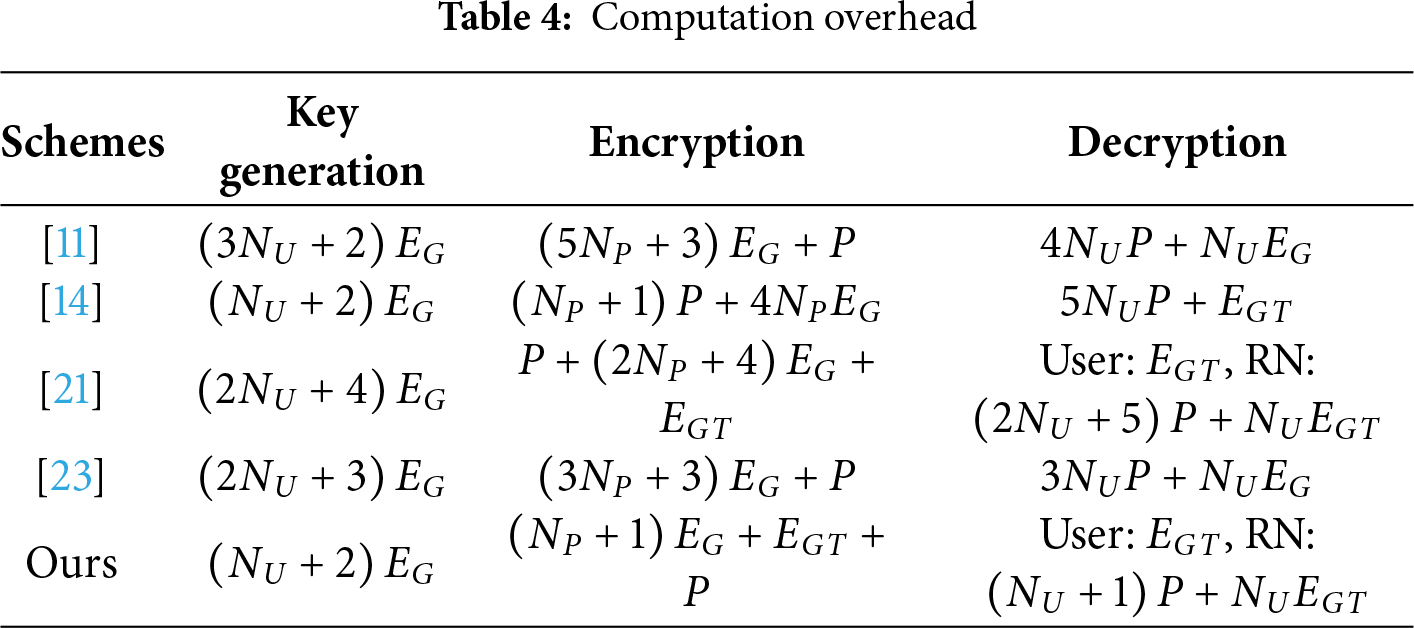

We focus on evaluating the computational overhead of the schemes involved in terms of key generation, encryption, and decryption processes in Table 4. In the key generation phase, the proposed scheme requires only

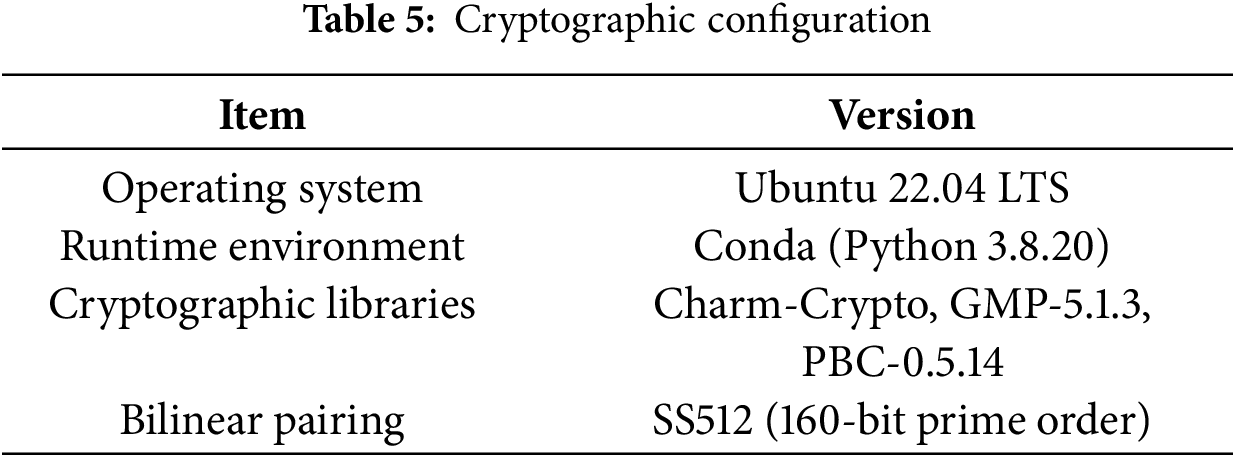

This section presents the experimental environment used to evaluate the proposed scheme. The experimental platform is built on an Intel Core (TM) i9-12900H processor, with 16 GB of RAM and a 512 GB SSD, running on Ubuntu operating system. The cryptographic environment utilizes the Charm-Crypto library, combined with GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic (GMP) and Pairing-Based Cryptography (PBC), running in a Conda environment. Bilinear pairings are implemented using the SS512 elliptic curve over a 160-bit prime order, ensuring the security and efficiency of the cryptographic operations. The detailed configuration is as Table 5:

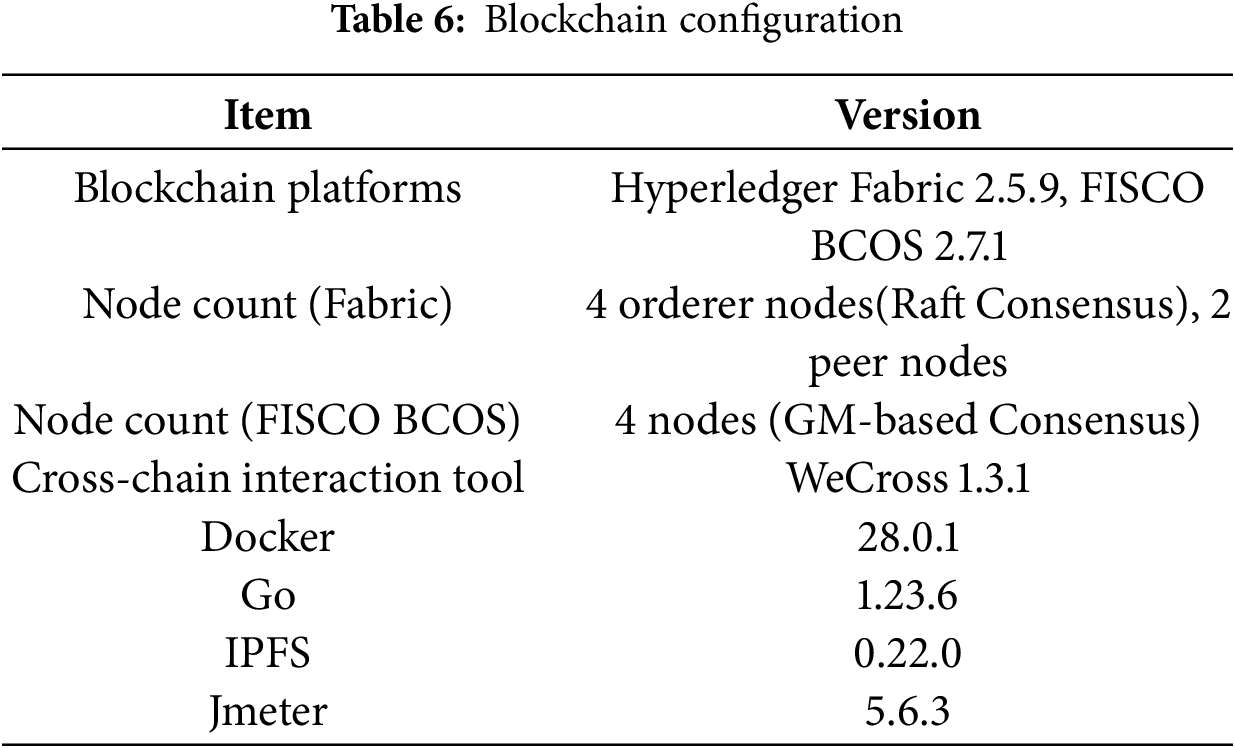

In addition to the cryptographic environment, the experiment also simulates a realistic cross-chain regulatory framework, with Hyperledger Fabric deployed as the business chain and FISCO BCOS as the regulatory chain. Specifically, the Fabric network consists of 4 orderer nodes and 2 peer nodes, while FISCO BCOS is deployed with 4 nodes, ensuring high availability and scalability of the network. The cross-chain routing and communication mechanism established through the WeCross platform guarantees secure and real-time data interaction between the two blockchain networks. The detailed configuration of the blockchain network is shown in the Table 6:

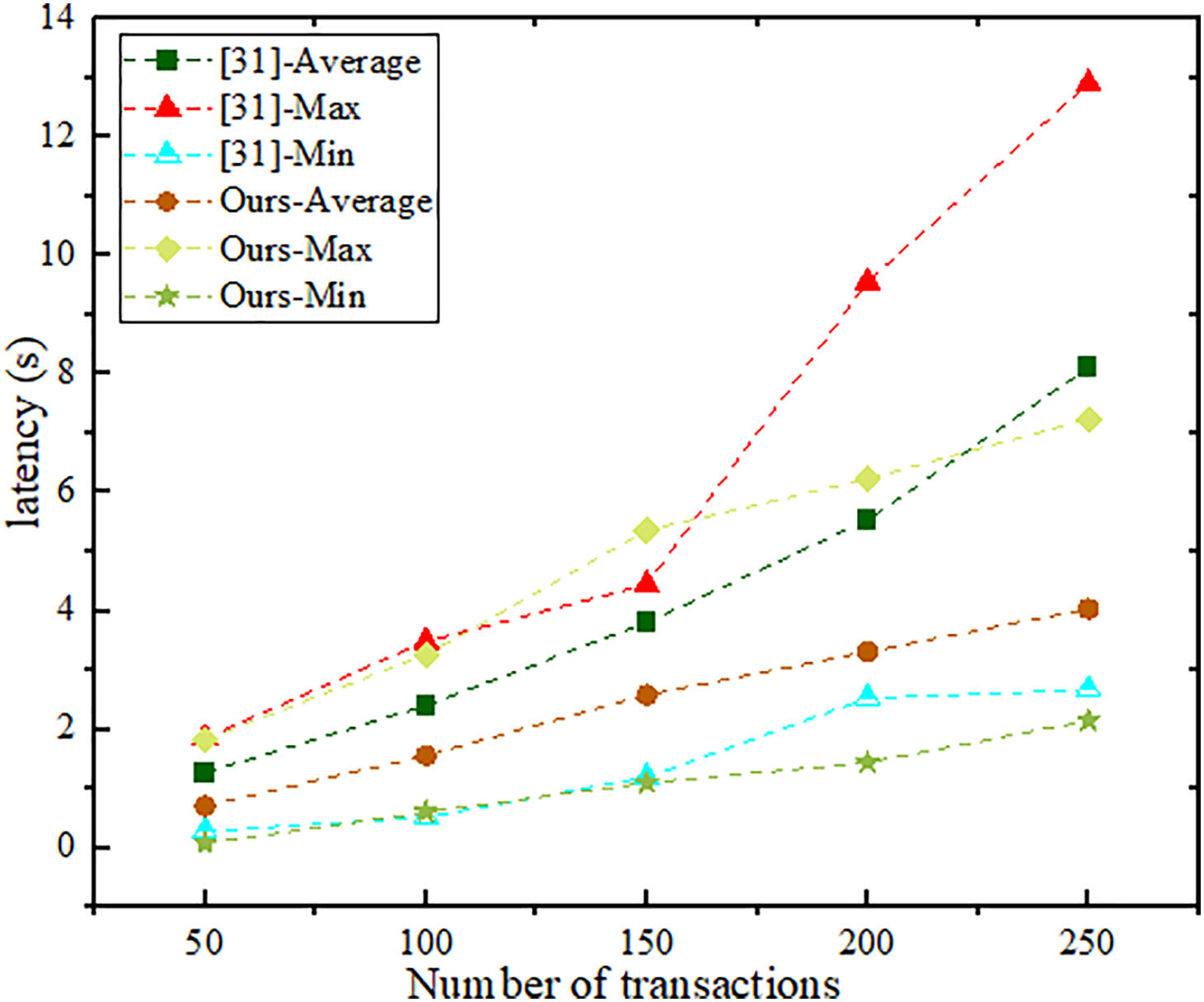

To validate the cross-chain transaction performance of our scheme, we conducted a comparative analysis of the cross-chain transaction latency with Dong et al. [31] their paper proposes a hierarchical attribute-based encryption algorithm (MSC-CP-ABE) based on the main-sidechain architecture, where the sidechain stores the addresses and keys of encrypted data, while the mainchain is responsible for storing the data indices of the sidechain. Cross-chain data transmission is achieved through the P-TL smart contract, ensuring data interaction between the mainchain and sidechain. In our experiment, we used the JMeter performance testing tool to evaluate the maximum latency, minimum latency, and average latency of cross-chain transactions under different transaction volumes (ranging from 50 to 250 transactions), as shown in the Fig. 3. The experimental results demonstrate that under high concurrency, our scheme maintains relatively low latency, showing a performance advantage, especially under higher transaction volumes, where the latency increases at a slower rate, indicating good scalability.

Figure 3: Cross-chain performance comparison

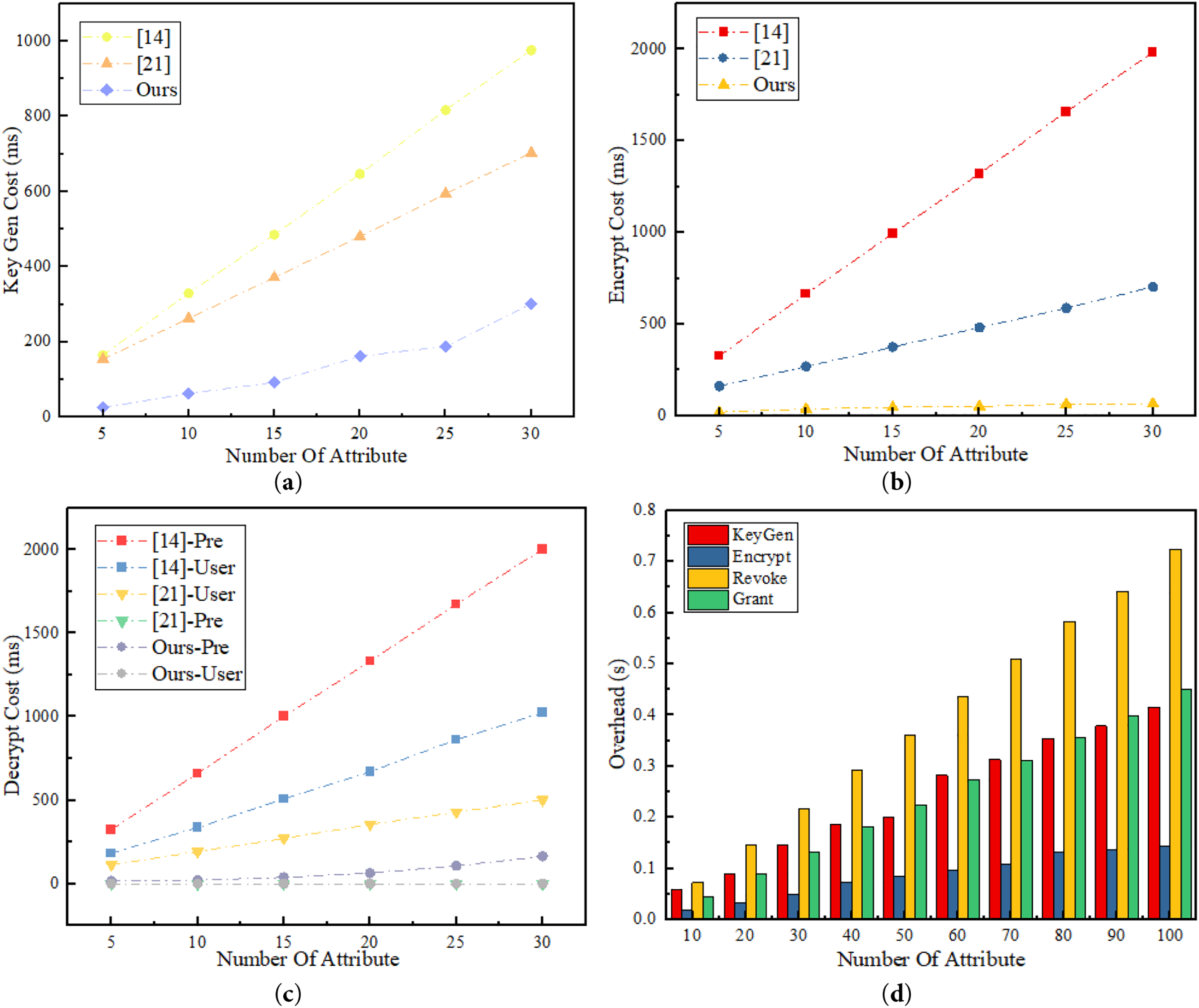

In the cryptographic scheme comparison, to enhance the consistency and reliability of the experiment, all ciphertexts uniformly adopt the ‘AND’ access strategy, and each attribute-scale scenario is repeated 30 times, with the average value calculated. Since other schemes do not involve pre-decryption algorithms, this experiment selects only Scheme [14] and Scheme [21] for comparison. It is important to note that the experimental data for the comparison schemes are based on Java Pairing-Based Cryptography (JPBC) 2.0.0, while this paper uses Charm-Crypto with GMP/PBC. However, both use Type-A and SS512 parameter sets, which are symmetric supersingular pairings (Embedding degree k = 2, subgroup order 160-bit), with consistent security strength (80-bit), making their comparison valid in terms of algorithm complexity and growth trend with attribute size.

Fig. 4a,b shows the comparative results of different schemes in terms of key generation and encryption overheads with respect to the number of attributes. As the number of attributes increases, the overheads of the proposed scheme in both encryption and key generation are significantly lower than those of the compared schemes. Especially in the encryption phase, it remains almost at a very low level, due to the scheme requiring only one bilinear pairing operation. In the comparison of decryption overhead (as shown in Fig. 4c), the scheme [21] transfers a large amount of pre-decryption computation to cloud servers with the help of outsourced decryption technology, which is better than this scheme in terms of pre-decryption. However, it is worth noting that our scheme only requires one exponential operation for final decryption, greatly reducing the computational burden. This makes our scheme especially suitable for devices with constrained computing resources, such as mobile terminals. Additionally, we analyzed the overhead of each phase of our scheme with varying attribute sizes. As shown in Fig. 4d, the costs increased approximately linearly with the number of attributes. Encryption remained consistently low, while key generation and granting increased moderately. Revocation required more time due to the need to generate and disseminate update information to affected attributes, an inherent cost of policy updates. However, even with 100 attributes, all operations remained sub-second, indicating good scalability.

Figure 4: The comparison between several schemes: (a) Key gen cost (b) Encrypt cost (c) Decrypt cost (d) Cost of ours scheme

The dynamic authority attribute encryption scheme under multi-chain collaboration proposed in this research has achieved some success in solving the problems of attribute revocation and granting without ciphertext update, cross-chain supervisory collaboration, and multi-authority key distribution. Through functional analysis, comparative evaluation of storage and computation overheads, and simulation experiments, we demonstrate that the scheme significantly reduces key generation and encryption/decryption delays while maintaining high security, especially suitable for cross-organization and high-frequency authority change application scenarios. In addition, the current design is mainly oriented to the consortium chain, and future work could explore aspects such as authority management strategies in open networks and incentive/reward mechanisms for multi-authority nodes, to enhance the scalability and robustness in a wider range of application scenarios.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to the Shanxi Key Laboratory of Intelligent Optimization Computing and Blockchain Technology for its vibrant intellectual environment and stimulating discussions.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Investigation, study conception and design, methodology, experimental simulation and draft manuscript preparation: Ye Tian, Zhuokun Fan. Data curation, resources, funding acquisition and review and editing: Ye Tian, Yifeng Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chhetri TR, Dehury CK, Varghese B, Fensel A, Srirama SN, DeLong RJ. Enabling privacy-aware interoperable and quality IoT data sharing with context. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;157:164–79. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.03.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li Q, Liu G, Zhang Q, Han L, Chen W, Li R, et al. Efficient and fine-grained access control with fully-hidden policies for cloud-enabled IoT. Digit Commun Netw. 2025;11(2):473–81. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2024.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Islam S, Apu KU. Decentralized vs. centralized database solutions in blockchain: advantages, challenges, and use cases. Glob Mainstream J Innov Eng Emerg Technol. 2024;3(4):58–68. doi:10.62304/jieet.v3i04.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zheng Z, Xie S, Dai HN, Chen X, Wang H. Blockchain challenges and opportunities: a survey. Int J Web Grid Serv. 2018;14(4):352. doi:10.1504/ijwgs.2018.095647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liang B, Yuan F, Deng J, Wu Q, Gao J. Cs-pbft: a comprehensive scoring-based practical Byzantine fault tolerance consensus algorithm. J Supercomput. 2025;81(7):859. doi:10.1007/s11227-025-07342-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen Y, Li H, Li K, Zhang J. An improved P2P file system scheme based on IPFS and blockchain. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2017 Dec 11–14; Boston, MA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 2652–7. doi:10.1109/BigData.2017.8258226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Azbeg K, Ouchetto O, Jai Andaloussi S. BlockMedCare: a healthcare system based on IoT, blockchain and IPFS for data management security. Egypt Inform J. 2022;23(2):329–43. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2022.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sahai A, Waters B. Fuzzy identity-based encryption. In: Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2005 May 22–26; Aarhus, Denmark. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2005. p. 457–73. [Google Scholar]

9. Bethencourt J, Sahai A, Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. In: Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP ’07); 2007 May 20–23; Berkeley, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2007. p. 321–34. doi:10.1109/SP.2007.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mao H, Nie T, Sun H, Shen D, Yu G. A survey on cross-chain technology: challenges, development, and prospect. IEEE Access. 2023;11:45527–46. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3228535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Huang K. Accountable and revocable large universe decentralized multi-authority attribute-based encryption for cloud-aided IoT. IEEE Access. 2021;9:123786–804. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3110824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sandhia GK, Kasmir Raja SV, Jansi KR. Multi-authority-based file hierarchy hidden CP-ABE scheme for cloud security. Serv Oriented Comput Appl. 2018;12(3):295–303. doi:10.1007/s11761-018-0240-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sethi K, Pradhan A, Bera P. PMTER-ABE: a practical multi-authority CP-ABE with traceability, revocation and outsourcing decryption for secure access control in cloud systems. Clust Comput. 2021;24(2):1525–50. doi:10.1007/s10586-020-03202-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yang K, Jia X. Expressive, efficient, and revocable data access control for multi-authority cloud storage. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2014;25(7):1735–44. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2013.253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Xie M, Ruan Y, Hong H, Shao J. A CP-ABE scheme based on multi-authority in hybrid clouds for mobile devices. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2021;121:114–22. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang R, Li J, Lu Y, Han J, Zhang Y. Key escrow-free attribute based encryption with user revocation. Inf Sci. 2022;600:59–72. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.03.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wei J, Chen X, Huang X, Hu X, Susilo W. RS-HABE: revocable-storage and hierarchical attribute-based access scheme for secure sharing of e-health records in public cloud. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2021;18(5):2301–15. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2019.2947920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Deng S, Yang G, Dong W, Xia M. Flexible revocation in ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption with verifiable ciphertext delegation. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(14):22251–74. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13537-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lan C, Liu L, Wang C, Li H. An efficient and revocable attribute-based data sharing scheme with rich expression and escrow freedom. Inf Sci. 2023;624:435–50. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.12.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ren Z, Yan E, Chen T, Yu Y. Blockchain-based CP-ABE data sharing and privacy-preserving scheme using distributed KMS and zero-knowledge proof. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(3):101969. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Guo Y, Lu Z, Ge H, Li J. Revocable blockchain-aided attribute-based encryption with escrow-free in cloud storage. IEEE Trans Comput. 2023;72(7):1901–12. doi:10.1109/TC.2023.3234210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li J, Qi Y. Blockchain data access control method with revocable attribute encryption. Comput Eng Des. 2024;45(2):348–55. (In Chinese). doi:10.16208/j.issn1000-7024.2024.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Thakur A, Ranga V, Agarwal R. Revocable and privacy-preserving CP-ABE scheme for secure mHealth data access in blockchain. Concurr Comput Pract Exp. 2025;37(9–11):e70064. doi:10.1002/cpe.70064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mishra RK, Yadav RK, Nath P. Integration of blockchain and IPFS: healthcare data management & sharing for IoT environment. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(23):27229–50. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-20092-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mahmud M, Sohan MSH, Reno S, Baten Sikder MA, Hossain FS. Advancements in scalability of blockchain infrastructure through IPFS and dual blockchain methodology. J Supercomput. 2024;80(6):8383–405. doi:10.1007/s11227-023-05734-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sun J, Yao X, Wang S, Wu Y. Blockchain-based secure storage and access scheme for electronic medical records in IPFS. IEEE Access. 2020;8:59389–401. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2982964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yuan F, Zuo Z, Jiang Y, Shu W, Tian Z, Ye C, et al. AI-driven optimization of blockchain scalability, security, and privacy protection. Algorithms. 2025;18(5):263. doi:10.3390/a18050263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Cachin C. Architecture of the Hyperledger blockchain fabric. In: Workshop on distributed cryptocurrencies and consensus ledgers. Zurich, Switzerland: IBM Research; 2016. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

29. Kwon J, Buchman E. A network of distributed ledgers. Cosm White Pap. 2018;1–41. [Google Scholar]

30. Wood DG. Polkadot: vision for a heterogeneous multi-chain framework. White Pap. 2016;21(2327):4662. [Google Scholar]

31. Dong J, Jiang R, Zhang Y, Tian S, Wu B. A hierarchical access control and sharing model for healthcare data with on-chain-off-chain collaboration. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2025;48(3):215–31. doi:10.3233/jifs-238935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools