Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Detection of AI-Generated Text: A Retrieval-Augmented Dual-Driven Defense Mechanism

1 Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100190, China

2 Key Laboratory of Target Cognition and Application Technology (TCAT), Beijing, 100190, China

3 Department of Computer, North China Electric Power University, Baoding, 071003, China

* Corresponding Author: Wen Shi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Large Models and Domain-specific Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 33 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074005

Received 30 September 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) has brought about revolutionary social value. However, concerns have arisen regarding the generation of deceptive content by LLMs and their potential for misuse. Consequently, a crucial research question arises: How can we differentiate between AI-generated and human-authored text? Existing detectors face some challenges, such as operating as black boxes, relying on supervised training, and being vulnerable to manipulation and misinformation. To tackle these challenges, we propose an innovative unsupervised white-box detection method that utilizes a “dual-driven verification mechanism” to achieve high-performance detection, even in the presence of obfuscated attacks in the text content. To be more specific, we initially employ the SpaceInfi strategy to enhance the difficulty of detecting the text content. Subsequently, we randomly select vulnerable spots from the text and perturb them using another pre-trained language model (e.g., T5). Finally, we apply a dual-driven defense mechanism (D3M) that validates text content with perturbations, whether generated by a model or authored by a human, based on the dimensions of Information Transmission Quality and Information Transmission Density. Through experimental validation, our proposed novel method demonstrates state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance when exposed to equivalent levels of perturbation intensity across multiple benchmarks, thereby showcasing the effectiveness of our strategies.Keywords

The rapid advancement of large language models (LLMs) has enabled machines to generate exceptionally fluent and accurate text with unprecedented capability, thereby blurring the distinction between human and machine authorship. The widespread deployment of models such as GPT-3 [1], ChatGPT [2], and DeepSeek [3] has demonstrated significant value across various domains including healthcare and law. However, this technological leap necessitates careful consideration of its broader societal implications [4,5]. The misuse of Large Language Models (LLMs), as well as uses that go beyond their original intentions [6], has raised significant concerns. These issues encompass facilitating academic plagiarism, disseminating AI-generated disinformation, and creating phishing emails. These challenges highlight the urgent need for robust and accurate techniques to detect AI-generated text, which is crucial for harnessing the benefits of natural language generation while mitigating associated risks [7–11].

Existing detection methodologies can be primarily categorized into supervised approaches, adversarial training, and unsupervised methods [12,13]. Although supervised methods and adversarial training have shown promise, they often face limitations such as poor domain adaptability, training instability, and substantial computational requirements [14,15]. In contrast, unsupervised methods, particularly those leveraging statistical features, offer advantages including training-free operation and strong generalization capability [16–18], though their performance heavily depends on the completeness of feature extraction [19].

Concurrently, the emergence of sophisticated evasion techniques has fostered an evolving adversarial landscape. Research on evasion model algorithms has revealed multiple strategies to interfere with detection capabilities, including text editing through external model rewriting, paraphrasing, or insertion of special characters to create semantically equivalent but formally distinct text variants [20]. Additional studies have explored prompt optimization strategies to guide LLMs in evading detection. This establishes a mutually reinforcing relationship: as detection models continuously refine their mining of distinctive features, evasion models develop increasingly sophisticated disruptive elements, driving iterative advancements in both domains [21].

Our statistical observations indicate that when evasion models interfere with text using rewriting and other attack methods, machine-generated and human-written texts exhibit discernible differences in their responses to identical perturbations [22]. Although previous research has theoretically demonstrated that information changes induced by external perturbations can provide valuable evidence for judgment [23], existing approaches primarily rely on single features (such as non-negative curvature), and their performance tends to deteriorate under complex interference like rewriting or sophisticated character manipulation. Further analysis reveals that human-written texts demonstrate significantly greater lexical richness, including a diverse vocabulary of actions, states, and emotions, even when compared to the most advanced AI-generated texts. Crucially, when subjected to perturbations like rewriting, human-written texts exhibit substantial variations in lexical complexity. Machine-generated texts, however, due to their inherently lower baseline complexity, consequently display only minimal changes. This observation raises a fundamental research question: can the differential sensitivity of lexical diversity to perturbations serve as a valuable discriminative feature?

The information-theoretic perspective has gained increasing attention in recent detection research. Drawing from Shannon’s communication theory framework, researchers have explored various quantification methods for information transmission characteristics. Bianchini [24] explores the historical and theoretical connections between information theory and artificial intelligence, tracing their shared notion of “intelligence” and arguing that this conceptual link, despite its imperfections, has spurred significant advancements in AI. And Adams et al. [25] proposed methods for generating high-quality summaries using large models based on information quantity measurement concepts. Inspired by these findings, we investigate the feasibility of designing a systematic quantitative framework to capture the multidimensional variation patterns of textual data under perturbation. To this end, we draw upon information transmission theory to introduce two novel concepts: Information Transmission Quality (ITQ) and Information Transmission Density (ITD). ITQ aims to quantify the generation quality of text sequences by measuring the deviation in probability distributions before and after perturbations to assess information fidelity, while ITD directly measures the richness of entity information in the textual structure by calculating the density of semantic units such as named entities and key terms, thereby reflecting the information-carrying capacity of the content. Logically, the changes in ITQ under perturbation can be explained as follows: tokens in machine-generated texts represent globally or locally optimal solutions selected by greedy optimization algorithms. In contrast, human-written texts are generated randomly based on human thought patterns, aligning more closely with individual cognitive habits and not necessarily corresponding to optimal solutions. Therefore, when perturbations such as rewriting occur, machine-generated texts are more likely to degrade into suboptimal content, leading to a decrease in log probability values. Conversely, the log probability values of human-written texts may fluctuate. Similarly, for ITD, machine-generated texts tend to adopt objective and less specific stances, using fewer words that include explicit entities such as specific names, locations, and times. Even under perturbation, machine models continue to employ generic expressions. In contrast, human-generated content often includes subjective descriptions and provides clear information, especially in news-related contexts. Thus, perturbations cause the information density of machine-generated texts to decline, while the information density of human-generated texts experiences random fluctuations, both increasing and decreasing.

In the context of this task, we treat external perturbations as special “pulse” signals, the perturbed text content as information carriers, and the resulting changes in text information quality and density as signal transmission discrepancies. By observing these discrepancy metrics, we can distinguish the source of the text. From another perspective, leveraging the information bias generated by model interference essentially utilizes the energy of the interference rather than defending against it. To explain further, it mitigates the adverse effects of interference while enhancing the model’s robustness. To validate our statistical conjecture, we propose a verification procedure. First, we employ an Evade strategy model to interfere with both human-generated and machine-generated short texts. Second, drawing on the idea of retrieval augmentation, we select “vulnerable” sentences from the perturbed short texts and extract the features of information transmission bias from these retrieved sentences, ultimately achieving the distinction of short text sources.

In summary, we propose a novel unsupervised interference-resistant text content detection strategy—the Dual-driven Defense Mechanism (D3M)—with core innovations manifested in the following aspects:

1. We employ reverse thinking to proactively utilize the information bias generated by evasion model interference, rather than merely resisting it. This approach represents a paradigm shift in defense strategy, transforming adversarial challenges into discriminative features.

2. Inspired by information transmission theory, we propose a strategy based on “dual-driven defense” metrics to deeply explore the discrepancies in ITQ and ITD caused by perturbations. The algorithm effectively performs identification in zero-shot scenarios and provides interpretable identification basis.

3. Through establishing a comprehensive scientific experimental analysis scheme covering space infiltration interference, retrieval-augmented vulnerable text capture, and dual-driven defense strategy identification, the results demonstrate that our method possesses excellent performance including strong interference resistance and high identification accuracy.

Therefore, the proposed method can serve as an effective auxiliary means for distinguishing between AI-generated content and human-written content, exhibiting significant practical value.

2.1 Deep Learning Detection Methods

Existing deep learning detection methodologies for AI-generated text have evolved through several distinct paradigms, each with characteristic strengths and limitations. Supervised detection methods employ a spectrum of approaches from basic binary classifiers to sophisticated deep learning architectures [26], training end-to-end models to capture discriminative patterns for classification. Notable implementations include the multi-generator, multi-domain framework for black-box detection proposed by Wang et al. [13] and the joint prompt and evidence inference network for multilingual fact checking developed by Li et al. [14]. And Abbas et al. [27] explored detecting AI-generated tweets by analyzing author writing style using graph convolutional networks. To address the need for high-speed scene text detection on resource-constrained devices, Liu et al. [28] introduced YOLOv5ST, a lightweight detector that significantly improves inference speed with only a marginal accuracy loss. However, these supervised approaches typically exhibit limited cross-domain adaptability due to inconsistent parameter fitting across diverse sample distributions. Adversarial training methodologies address generalization challenges through generator-discriminator frameworks [29], where the adversarial dynamics between text generation and origin discrimination drive performance improvements. Teja et al. [30] proposed a framework that quantifies the discrepancy between original and normalized text to improve robustness against semantic adversarial attacks. The RADAR framework by Hu et al. [15] exemplifies this approach through adversarial learning for robust detection. Despite enhanced generalization capabilities, these methods remain susceptible to training instability and mode collapse issues. In contrast, unsupervised techniques have gained prominence by enabling direct judgment based on intrinsic sample characteristics without requiring pre-training. These encompass feature-based recognition analyzing lexical and syntactic patterns [16], watermarking techniques embedding imperceptible markers for subsequent verification [17]. This progression from supervised to unsupervised paradigms reflects the field’s ongoing pursuit of adaptable, efficient, and theoretically-grounded detection mechanisms.

2.2 Statistical Derivative Feature Methods

Statistical derivative feature methods represent a significant advancement in unsupervised detection by leveraging deeper textual characteristics such as semantic patterns, stylistic features, and perturbation responses for discrimination, as comprehensively surveyed by Crothers et al. [18] across various threat models and detection approaches. Within this domain, substantial progress has been achieved through several innovative methodologies: Mitrovic et al. [31] pioneered the use of SHAP metrics for short text source distinction, revealing models’ superior capability in identifying directly generated ChatGPT responses compared to detecting machine-modified human text. West et al. [32] introduced a statistical normalization method based on the Student’s t-distribution to address the heavy-tailed distributions in adversarial texts. Mitchell et al. [23] introduced DetectGPT utilizing probability curvature from perturbations for source identification, which was subsequently optimized by Bao et al. [33] through FAST-DetectGPT to maintain comparable accuracy with enhanced efficiency; the research direction was further extended by Su et al. [34] with DetectLLM incorporating optimized log rank information, while Zeng et al. [35] proposed DALD, a novel framework that aligns the distribution of surrogate models with unknown target LLMs to address the challenge of detecting black-box LLM-generated text without access to model logits.

2.3 Evasion Techniques and Countermeasures

Concurrently, substantial research efforts have been directed toward evasion model algorithms designed to interfere with detection capabilities [36]. These approaches primarily involve text manipulation through external model rewriting, paraphrasing, or insertion of special characters to create semantically equivalent but formally distinct text variants. Some studies have also explored prompt optimization strategies to guide LLMs in evading detection [21]. This has established a mutually reinforcing adversarial relationship between detection and evasion models: detection models continuously refine their feature mining capabilities, while evasion models develop increasingly sophisticated disruptive elements, driving iterative advancements in both domains [22]. Krishna et al. [37] proposed the DIPPER paraphrase model to evade AI-text detectors and a corresponding retrieval-based defense to secure detection against such attacks.

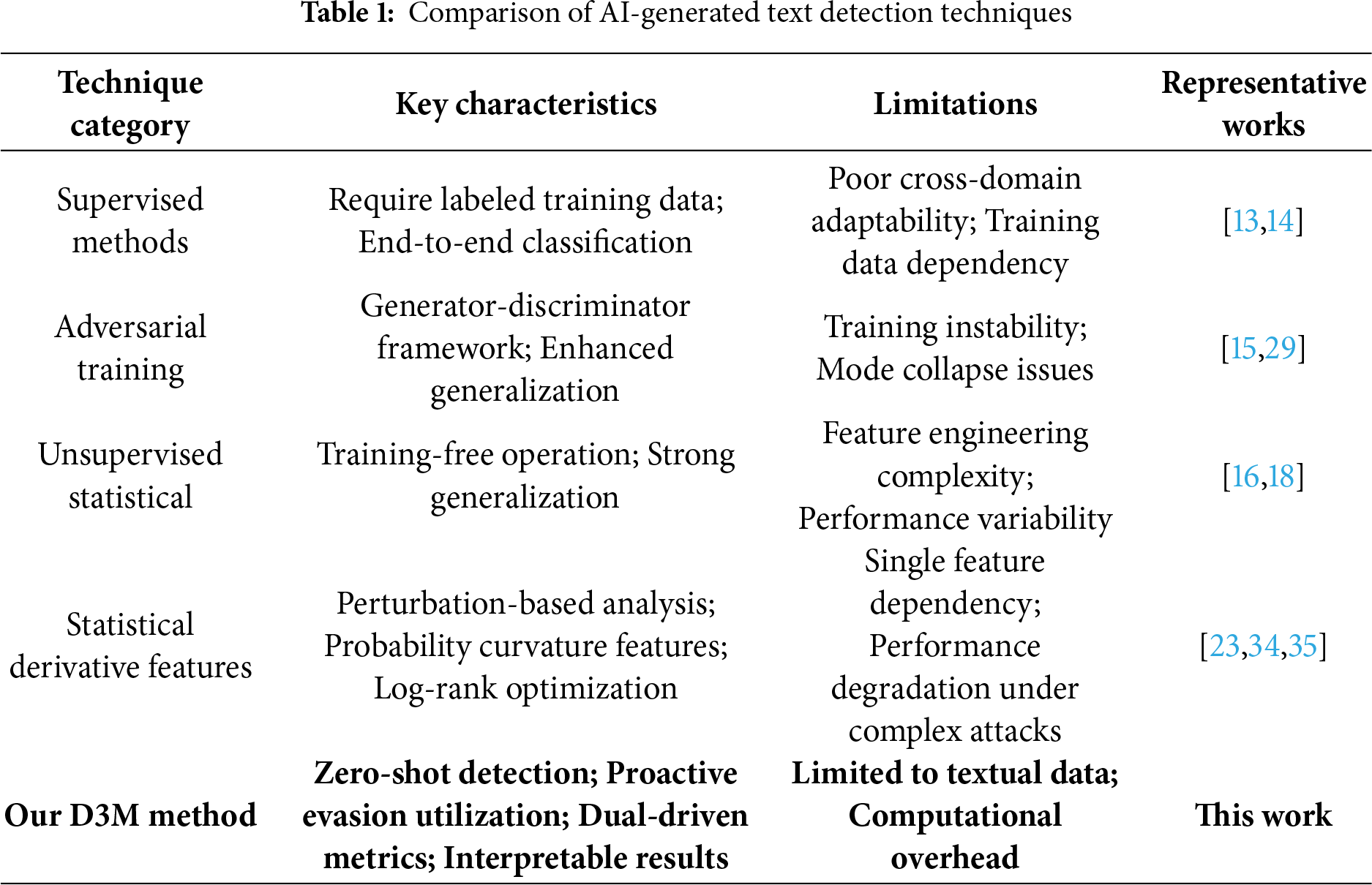

Table 1 provides a systematic comparison of major technical approaches for AI-generated text detection, encompassing the evolution from traditional supervised learning to recent statistical derivative feature methods, clearly illustrating the characteristics and limitations of each category.

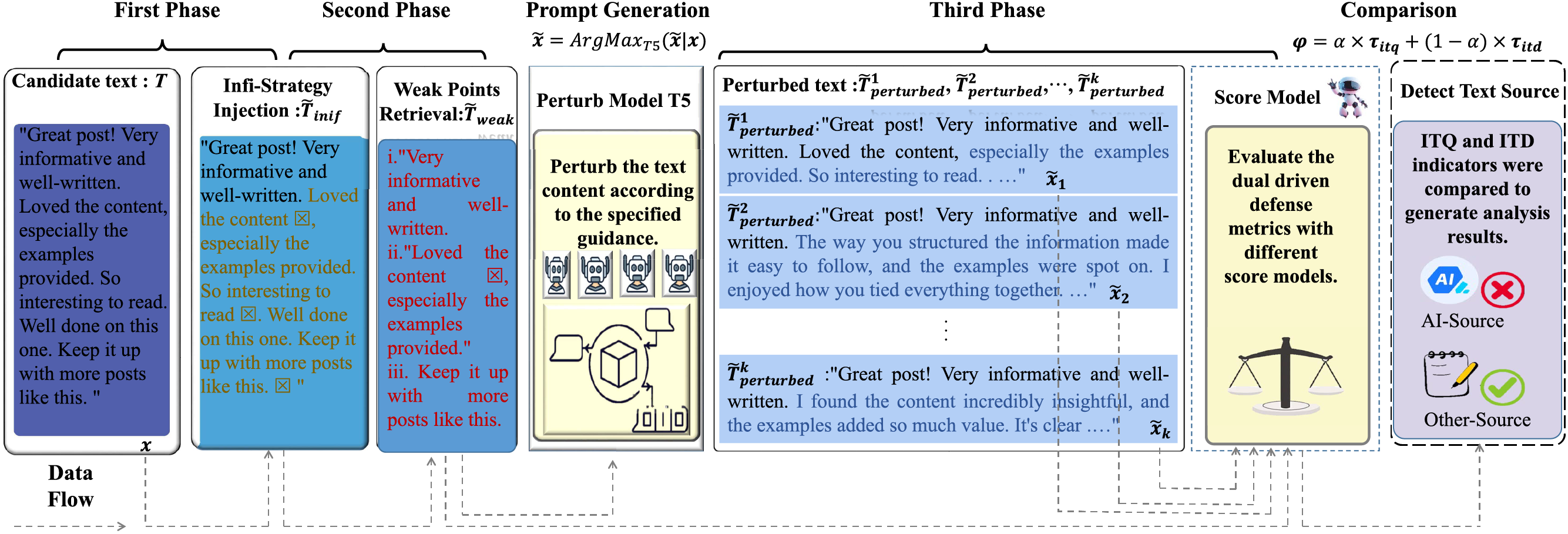

The problem of detecting machine-generated text in zero-shot scenarios can be described as follows: Given a text or candidate paragraphs X, which is a sample to be detected from datasets generated by humans or source models. Next, the text paragraphs are paraphrased using attack strategies by a perturbation model to generate new text passages. Then, an unsupervised-trained scoring model evaluates and scores the text to be detected, acting as the detector for the detection task, based on dual-driven criteria. Finally, the model provides more intuitive explanations to assist in determining the final class label, indicating whether the target text is machine-generated or human-authored. The framework diagram of the algorithm around the data flow is shown in the Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the D3M (Dual-Driven Defense Mechanism) framework data flow. This figure illustrates the complete text processing pipeline from a data flow perspective: raw text input first undergoes space infiltration preprocessing to generate perturbed text; then passes through an entropy-based weak point identification module to screen key text segments; subsequently utilizes a mask-filling model to generate multiple rounds of perturbations on selected segments; and finally computes perturbation discrepancies through the dual-driven metric calculation module for both Information Transmission Quality (ITQ) and Information Transmission Density (ITD), which are fused to produce the final detection score. Arrow directions indicate the sequential data flow between modules

3.1 Space Infiltration Text-Attack

To evaluate the model’s robustness against interference, we implemented a multi-round attack strategy that involves infiltrating random space characters to disrupt the text. In this approach, multiple space characters are randomly inserted before commas in selected text paragraphs, creating complex expression patterns that can effectively evade detection. The core principle of this strategy is to disrupt the coherence of the original text by introducing space characters, which alters the semantic and formatting patterns between machine-generated and human-authored texts. This modification reduces discrepancies in logical coherence, semantic consistency, and overall confusion entropy. Space Infiltration is applied as a uniform pre-processing step to all texts before detection. Its primary purpose is to proactively introduce interference, thereby increasing the inter-class confusion between human-written and machine-generated texts in the dataset and enabling a more effective evaluation of model robustness under adversarial conditions. By leveraging this obfuscation mechanism, the altered text can often evade detection by models reliant on basic statistical features and classifiers. In a specific case, a text paragraph pending to detect

where a new sentence unit

Intuition suggests that identifying weak points or sentences in a paragraph is vital for evaluating the quality of textual paragraphs. Weak points frequently expose the coherence, logical consistency, and information load balance of a textual paragraph, all of which serve as indicators of its quality. Therefore, when faced with text paragraphs that pose challenges in confusion detection, and with the aim of efficiently and accurately distinguishing between human-authored and machine-generated documents, this approach proposes a strategy for identifying weak sentences in text paragraphs based on the aforementioned human cognitive thinking. Subsequently, it analyzes the features of weak sentences to achieve text type discrimination.

From the perspective of information theory, the entropy value of a sentence represents its information content, uncertainty, and predictability. It serves as an important metric for assessing sentence complexity and comprehension difficulty. Specifically, a lower entropy value indicates that the sentence maybe overly simple, repetitive, or lacking in diversity. Additionally, the entropy values of sentences in a text paragraph can be efficiently calculated using pre-trained language models (PTLMs). Thus, we choose to employ sentence entropy as a metric for identifying weak points in text paragraphs.

The strategy for identifying weak points involves utilizing a PTLM to calculate the entropy values of individual sentences in the text paragraph T. Next, the sentences are sorted in ascending order based on their entropy values. If the number of sentences is greater than three, the three sentences with the lowest entropy values are selected as candidate weak sentences. Otherwise, all the sentences are chosen as candidate sentences. The results of indentifying weak points is shown as in Eq. (2),

where

3.3 Dual-Driven Defense Mechanism

Assuming that the weak point sample

where, the mean value

For the above given sample

The function

where, the

Due to the disparity in the scale and range between

where,

Subsequently, the normalized results are generated as in Eq. (10),

Ultimately, the two metrics are combined through weighted summation to derive the final measurement, as in Eq. (11),

where

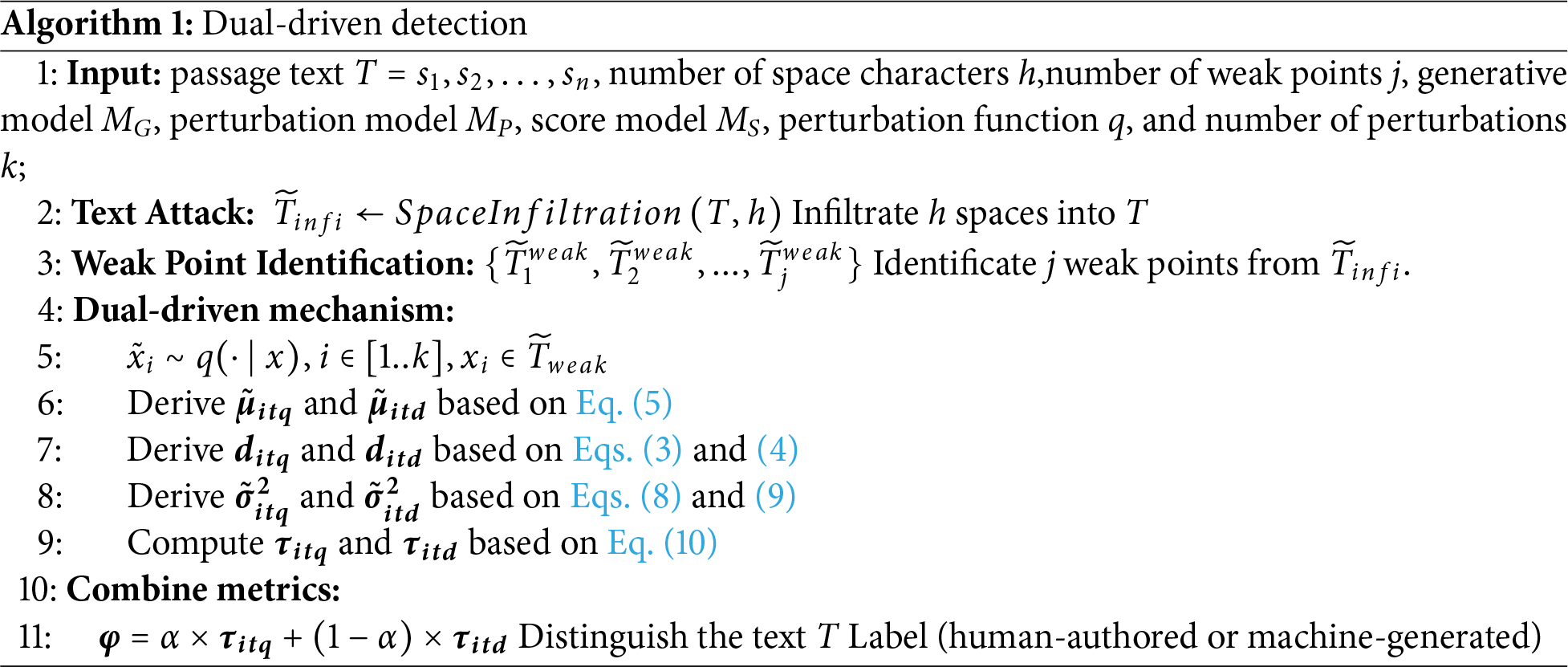

In this section, we present the proposed algorithm in detail, which is designed to address the specific challenges outlined in the problem formulation. The algorithm is structured into four key phases: (1) Space Infiltration, applied uniformly as a pre-processing step to all input texts to increase dataset complexity and evaluate robustness; (2) Weak Points Identification, which retrieves vulnerable sentences based on entropy ranking; (3) Perturbation Generation, where selected weak points are perturbed using a mask-filling model; and (4) Dual-Driven Metric Calculation, where detection scores are derived from discrepancies in Information Transmission Quality (ITQ) and Information Transmission Density (ITD). Algorithm 1 provides a structured overview of the end-to-end workflow, including a concrete example that traces a short text snippet through each processing stage—from space insertion and weak point selection to perturbation and final metric computation. Algorithm 1 serves as a visual guide, allowing readers to quickly grasp the sequence of actions and the logic behind each decision point.

4.1 Experimental Data Preparation

Our research encompasses three datasets: XSum, SQuAD, and Reddit WritingPrompts, which cover diverse everyday domains and provide invaluable insights into the applications of language modeling. The XSum dataset is essential for detecting fabricated news through news articles, the SQuAD dataset represents machine-generated academic essays with Wikipedia paragraphs, and the Reddit WritingPrompts dataset offers a collection of prompted stories, facilitating exploration of the detection of machine-generated creative writing submissions. To ensure the reliability of our findings, we meticulously conduct each experiment using carefully selected samples ranging from 150 to 500 examples, as specified in the text. In each experiment, we use the first 30 tokens of the real text (or only the question tokens for the PubMedQA experiments) as prompts to generate the machine-generated text. Performance assessment is based on the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), a metric that indicates the probability of the classifier correctly ranking a randomly-selected positive (machine-generated) example higher than a randomly-selected negative (human-written) example. It is important to note that all experiments include an equal number of positive and negative examples, ensuring a balanced evaluation framework. By adopting this comprehensive methodology and employing these sophisticated datasets, our research aims to advance the frontiers of knowledge in the field of natural language processing.

Each experiment evaluates a varying number of examples, ranging from 150 to 500. The machine-generated content in these experiments is produced using the GPT-2 model without fine-tuning, with prompts derived from the first 30 tokens of the real text. The text attack chain is defined by two key parameters: the space infiltration number, which is set to 10, and the weak points number, which is set to 3. The core hyperparameters of the perturbation chain include the mask-filling model, the length of the masked spans, and the perturbation rate for the mask-filling model. For most experiments, the T5-3B model is used, except for larger-scale GPT-NeoX experiments, where the T5-11B model is employed. The mask rate is fixed at 15%, and a limited sweep over masked span lengths, particularly 2 tokens, is conducted for the perturbation chain.

We compare our method with various existing zero-shot methods for detecting machine-generated text that also leverage the predicted token-wise conditional distributions of the source model for detection. These methods correspond to statistical tests based on token log probabilities, token ranks, predictive entropy, or probability curvature.

The Log method utilizes the average token-wise log probability of the source model to determine if a candidate passage is machine-generated. Passages with a high average log probability are likely to be generated by the model [22].

The Rank and Log-Rank method uses the average observed rank or log-rank of the tokens in the candidate passage according to the model’s conditional distributions. Passages with a smaller average (log-)rank are likely machine-generated [38].

The Entropy-based method is inspired by the hypothesis that model-generated texts will be more ’in-distribution’ for the model, leading to more over-confident (thus lower entropy) predictive distributions. We find empirically that predictive entropy is often positively correlated with passage fake-ness [39].

DetectGPT utilizes the observation that ChatGPT texts tend to lie in areas where the log probability function has negative curvature to conduct zero-shot detection [23].

Although our main focus is on zero-shot detectors, which do not require retraining for new domains or source models. As a result, we carried out two sets of experiments to evaluate the zero-shot and supervised detection performance of DetectGPT on models with different parameters, and compared them with existing methods.

Considering the inherent differences in the internal logic and external characteristics of samples generated by different models, the machine-generated samples originate from models with varying parameter sizes, ranging from 1.5B to 20B. These models include GPT-2, OPT-2.7, Neo-2.7, GPT-J, and NeoX.

4.3 Experimental Infrastructure

The algorithm was conducted using NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPUs (24 GB memory) with CUDA 11.4, Intel Core i9-11900K processors, and 64 GB system memory. All experiments were implemented in Python 3.8.10 using PyTorch 2.0.1 and Transformers 4.30.2. The average runtime per complete experiment was approximately 2.5 h.

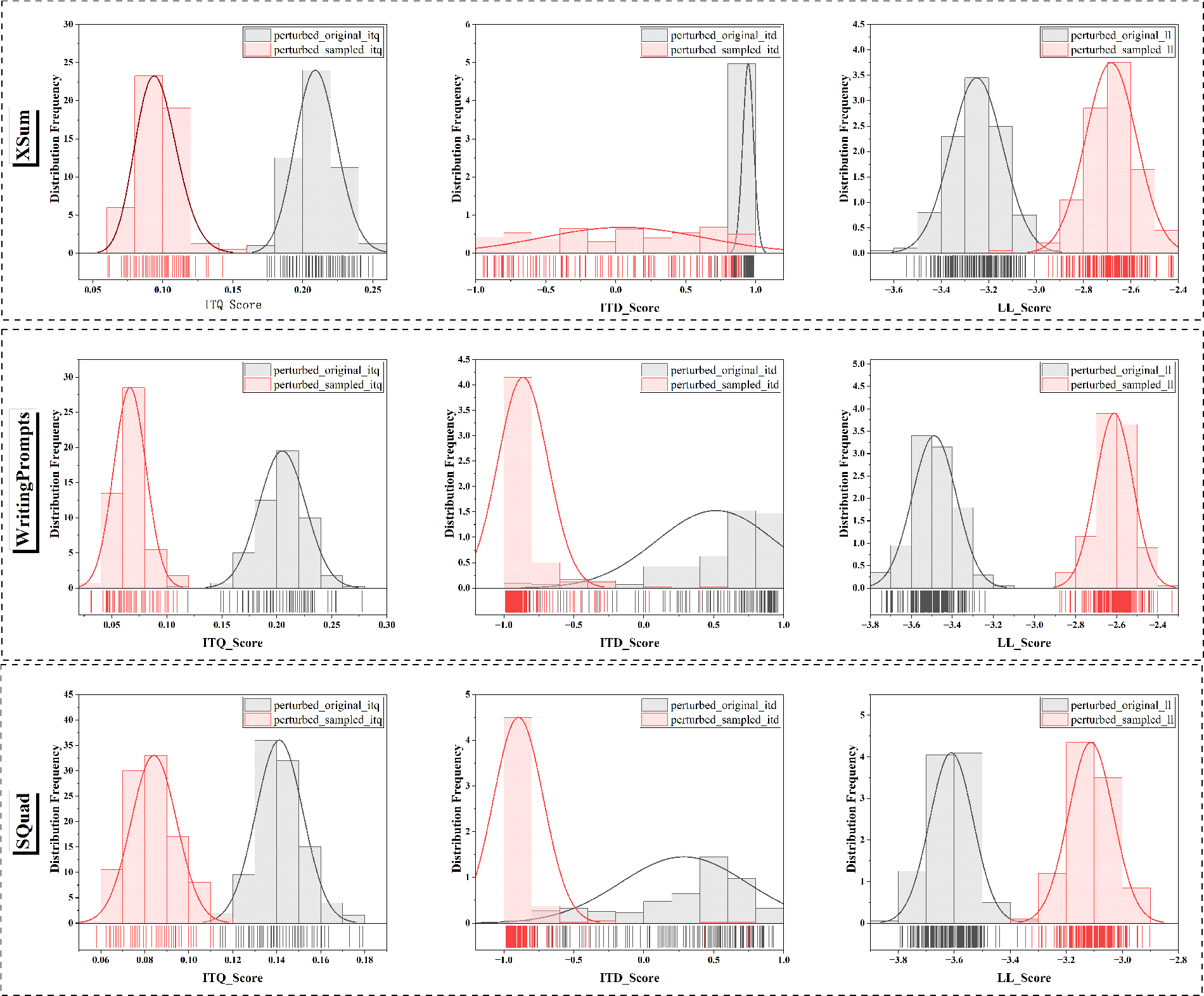

From a statistical perspective, it is essential to first investigate the characteristics of the data samples. To this end, we conduct a statistical analysis of the three-dimensional feature space (including Information Transmission Density, information transmission quality, and information likelihood estimation) for the samples before and after perturbation across three distinct datasets. The experiment involves randomly selecting three sets of sample features from 200 perturbation instances, and the results are presented in Fig. 2. Empirical analysis of the statistical results reveals that the distribution of sample feature values before and after perturbation exhibits significant differences, particularly in the WritingPrompts dataset. However, empirical statistics indicate that a majority of the samples still exhibit overlapping regions in feature values, meaning that the feature values of machine-generated samples post-perturbation are nearly identical to those of human-generated samples. The feature distributions in Fig. 2 reveal a substantial overlap in individual feature values between human and machine-generated samples. This makes direct distinction based on any single metric challenging; however, our dual-driven mechanism successfully overcomes this by disentangling the distributions through a combination of normalized metrics. This synergistic combination of Information Transmission Quality and Information Transmission Density, after proper normalization and weighting, effectively separates the two classes, as conclusively demonstrated by the strong performance results in Table 2.

Figure 2: The statistical distribution results of the randomized data are presented, where the horizontal axis comprises three-dimensional feature metrics (Information Transmission Density, Information Transmission Quality, and information likelihood estimation), and the vertical axis consists of three datasets (SQuad, WritingPrompts, XSum). Each legend within the figure illustrates the distribution of feature values for machine-generated samples(sampled data) and human-authored samples (original data) following perturbation

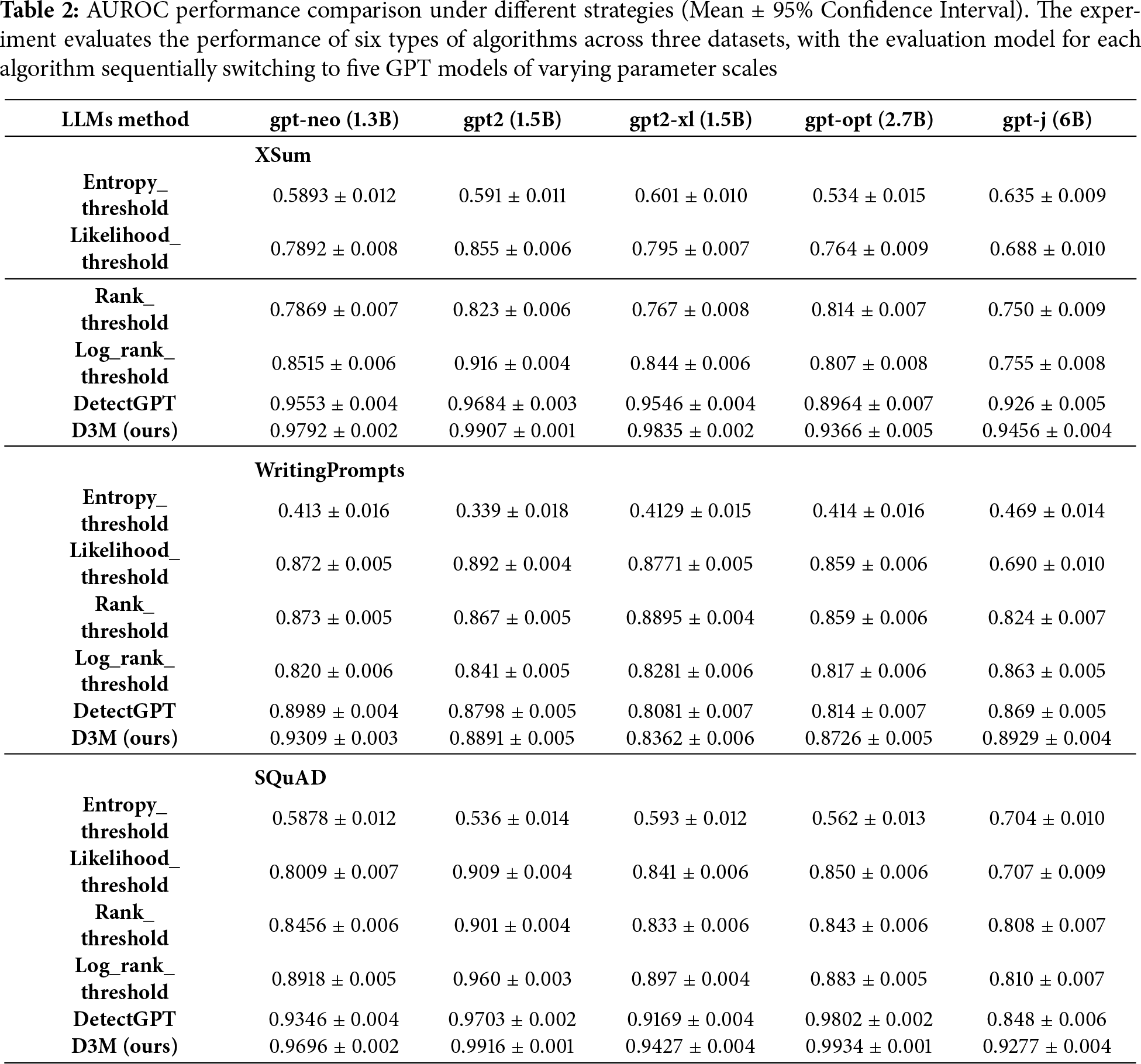

We emphatically compare the performance of typical large language models under different strategies on various datasets under the same experimental conditions. The overall experimental results are presented in Table 2. The performance of our proposed D3M model slightly surpasses that of the detectGPT model and significantly outperforms other benchmark models, highlighting the value of the dual-drive strategy designed within the D3M model. Furthermore, a horizontal comparative analysis of the D3M model’s ability to identify large models with varying parameter scales reveals that the model exhibits higher recognition accuracy for large models with smaller parameter scales. This experimental outcome aligns with foundational theoretical expectations, which posit that the larger the parameter scale of a model, the more closely its generated content resembles human-authored text in style. A vertical comparison of the D3M model’s performance across different datasets shows that it performs best on the XSum dataset, followed by the SQuad dataset, with the WritingPrompts dataset yielding the least favorable results. By examining the characteristics of the different datasets, it is evident that the XSum dataset features the longest average paragraph length among its sample texts, while the WritingPrompts dataset has the shortest. This result is consistent with the phenomenon that variations in ITD and ITQ are more readily captured in longer texts, further underscoring the value of the dual-drive information transmission strategy proposed by the model.

To evaluate the statistical significance of the performance improvements, we conducted paired t-tests. The results demonstrate that our proposed D3M method achieves statistically significant improvements (

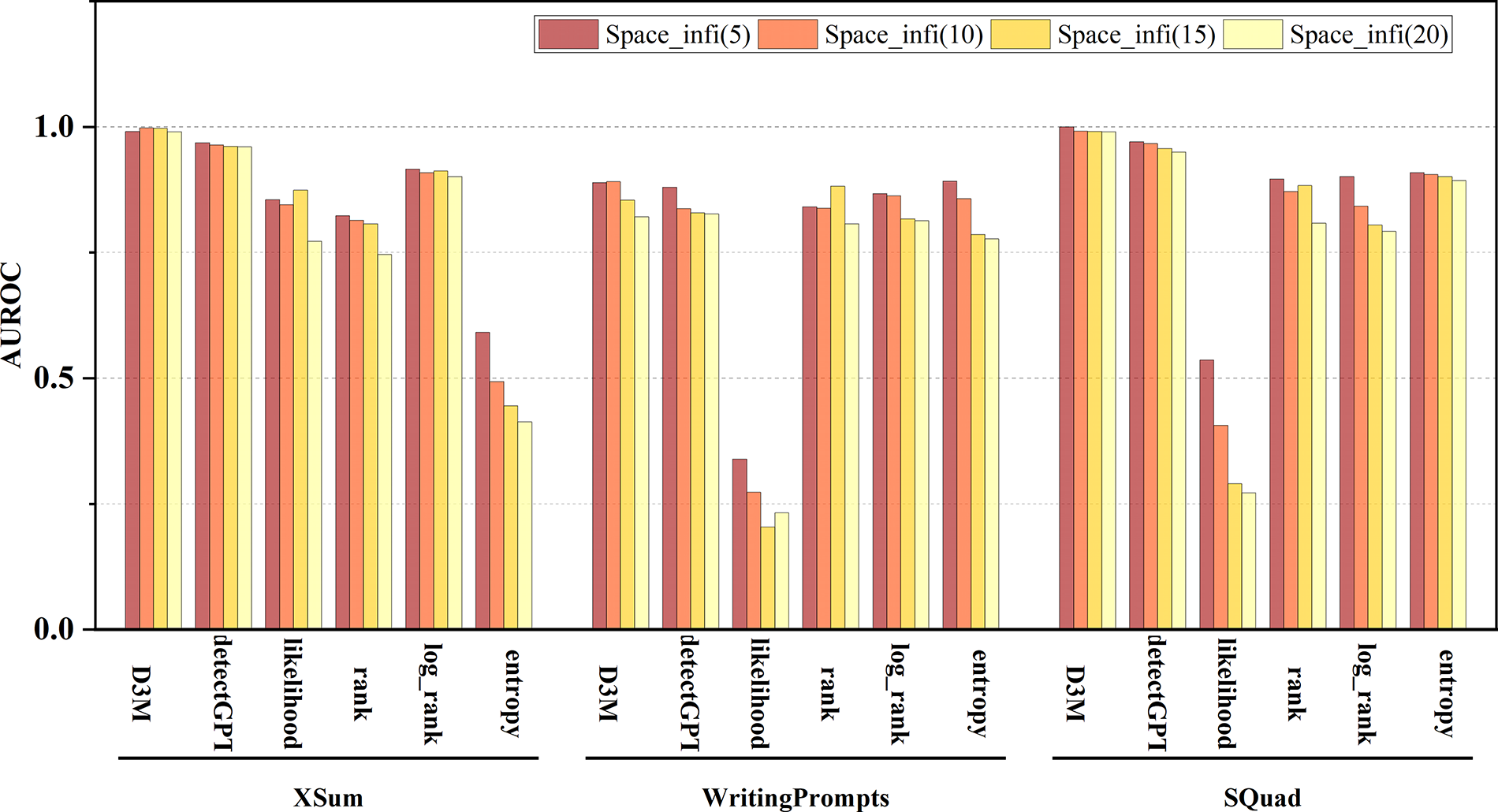

The robustness of an algorithm against interference is of significant importance to its stability. Generally, introducing noise (such as spaces, line breaks, or punctuation) into both machine-generated and human-generated text content can lead to model misjudgments, where human-authored content is mistakenly identified as machine-generated. Therefore, we also designed an evaluation experiment for the interference strategy Space_infi, which involves increasing the intensity of interference by adding spaces within text sentences. We discretely set four levels of interference intensity (ranging from 5 to 20 spaces) to test the performance variations of different algorithmic models. The experimental results, as shown in Fig. 3, indicate that both our proposed D3M algorithm and the detectGPT algorithm exhibit strong resistance to interference. Their performance does not experience a sharp decline as the intensity of interference increases. In contrast, the performance of the likelihood and entropy algorithms declines significantly. Additionally, it is observed that the quality of the dataset has a considerable impact on the test results. The performance of all algorithms on the XSum dataset is superior to that on the WritingPrompts and SQuad datasets, which aligns with intuitive expectations. However, the D3M model maintains stable identification performance even on datasets of lower quality.

Figure 3: Performance results of models under different interference strategy intensities. The performance results are displayed using stacked bar charts, which include three groups of bars representing the performance of six types of algorithms across three datasets. Each algorithm is evaluated using the GPT-2 model as the generative evaluation model

To investigate the impact of key parameters on model performance, this section discusses a series of open questions concerning the number of perturbations, the text masking ratio, and the evaluation model. This analysis aims to dissect the algorithm’s behavior from multiple perspectives.

5.1 Can an Increase in the Number of Perturbations Enhance the Overall Performance of the Algorithm?

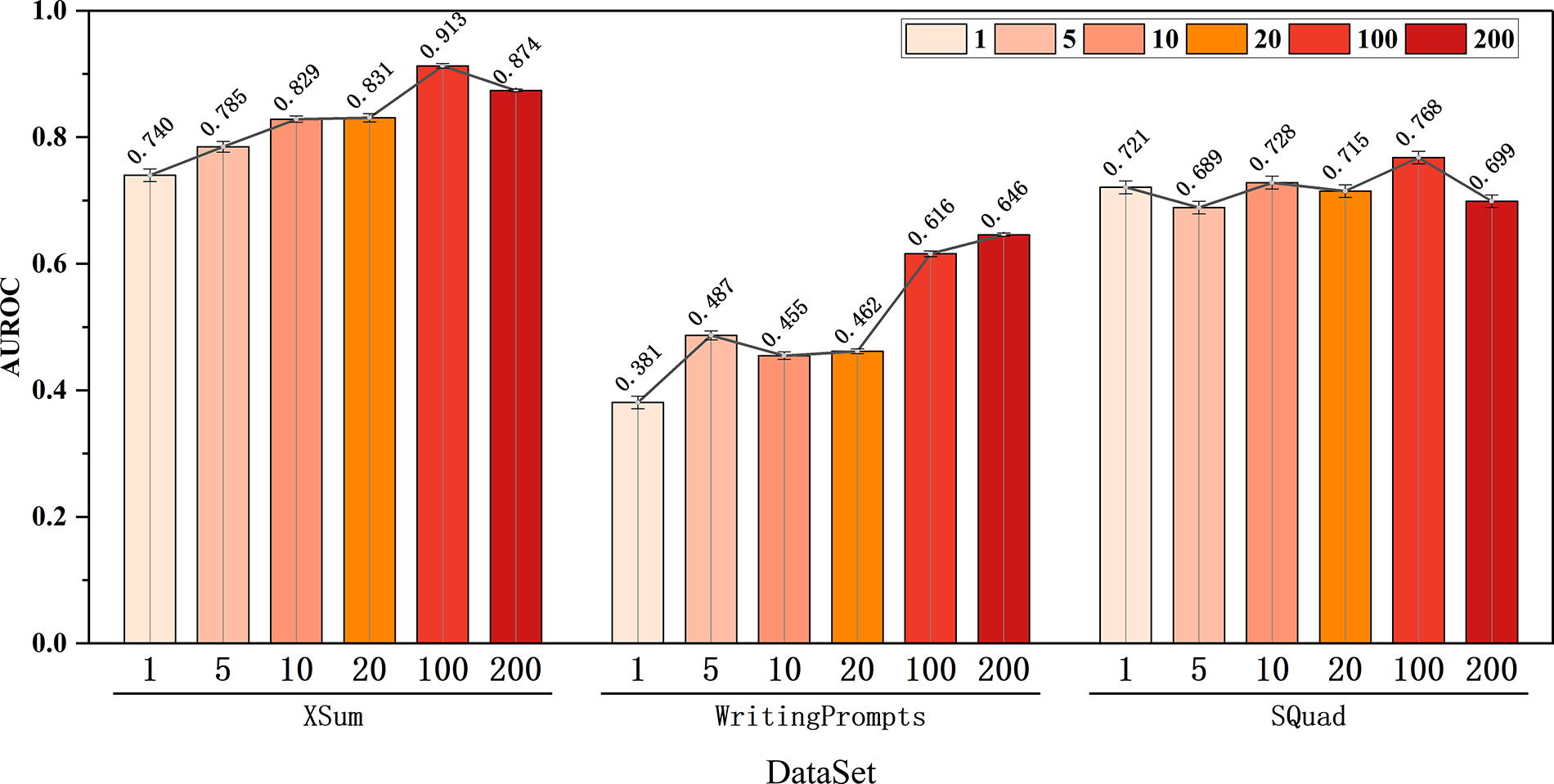

The number of perturbations is a critical factor determining model performance. Theoretically, increasing the number of perturbations can improve the model’s recognition performance, as a higher number of perturbations leads to more pronounced variations in ITD, ITQ, and information likelihood estimation. However, perturbations also introduce errors and, more importantly, increase computational complexity, which results in slower model inference speeds. Therefore, it is necessary to experimentally determine an appropriate number of perturbations to balance model inference performance and computational efficiency. The experimental results, as shown in Fig. 4, involve performance tests of the model under varying numbers of perturbations across three datasets, with the number of perturbations discretely increased from 1 to 200. The performance results indicate that the model’s inference performance significantly improves when the number of perturbations ranges from 1 to 100. However, when the number of perturbations exceeds 100, the model’s inference performance shows no significant improvement and even declines on the SQuad dataset. Consequently, the optimal hyperparameter for the number of perturbations is set to 100, which enhances the model’s inference accuracy while reducing computational complexity.

Figure 4: Model performance under various perturbations in three diverse datasets. The stacked bar chart consists of three groups of bars, each representing the results of six perturbation tests (1, 5, 10, 20, 100, and 200 perturbations). A line graph is overlaid to illustrate the numerical changes and trends in algorithm performance under different numbers of perturbations

5.2 How Does the Proportion of Text Masking Affect the Model’s Performance in the Perturbation Strategy?

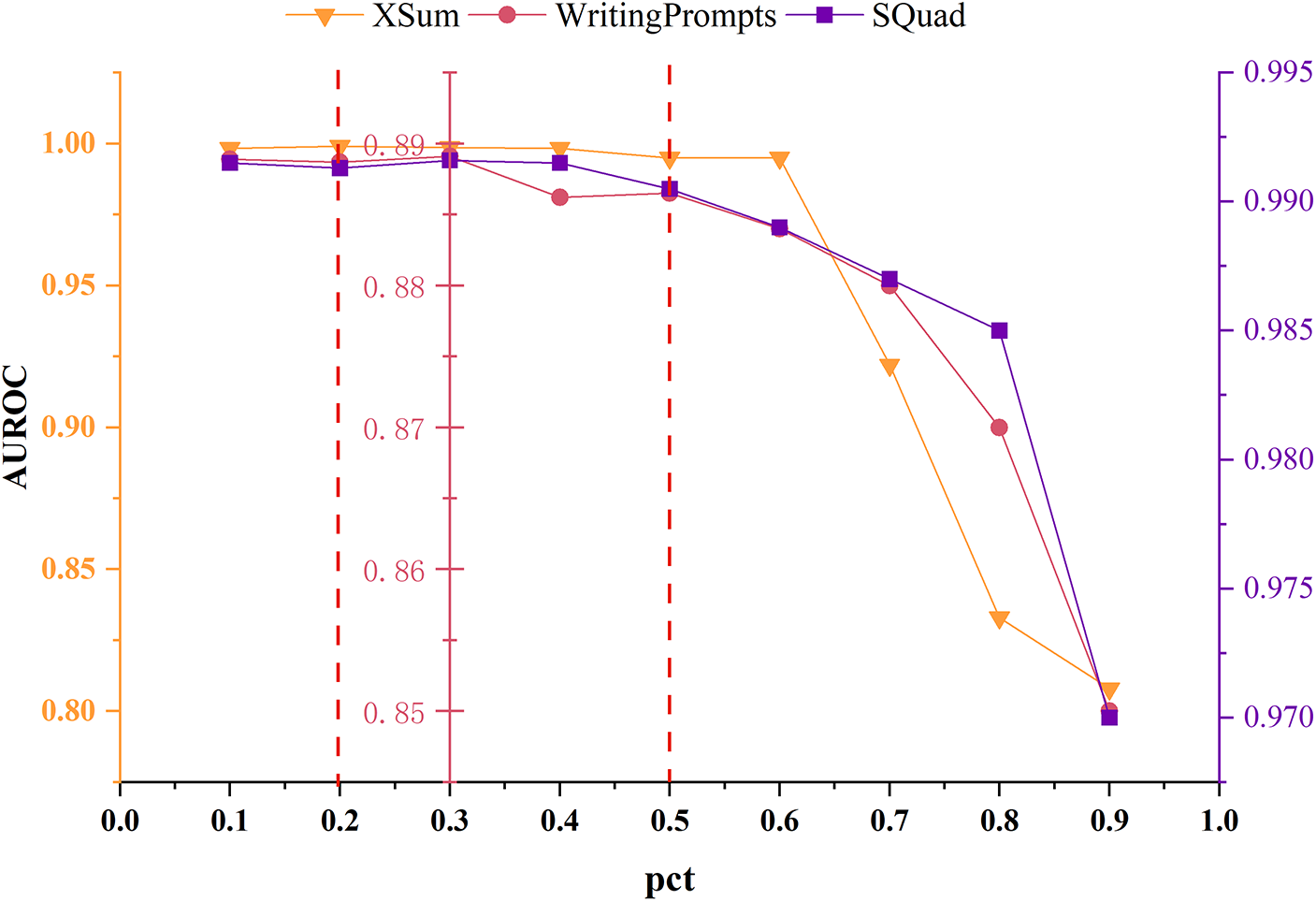

In the algorithmic process, a portion of words or phrases in the text is first randomly sampled and masked, followed by the generation of the masked content using the T53B masking model to complete the text perturbation. A critical aspect of this process is the proportion of text content that is masked, i.e., the ratio of original text words/phrases replaced with special mask identifiers. This proportion is indirectly controlled by the pct (place ceil token) metric. Experiments were conducted by discretely setting pct values from 0.1 to 0.9, and then observing the model’s performance across three types of datasets. As shown in the experimental results in Fig. 5, when the pct value is controlled between 0.2 and 0.3, the model’s accuracy on all three datasets remains high and stable. Therefore, the model’s pct hyperparameter is set to 0.3 to ensure good performance across various datasets.

Figure 5: The performance of the model under different masking proportion strategies across three datasets is tested. The experimental results are displayed in a stacked line graph, which includes three sets of curve results, each representing the performance metrics corresponding to different pct values on different datasets

5.3 How Does Using Likelihood Estimates from an Evaluation Model that Differs from the Source Model Affect the Detection Performance?

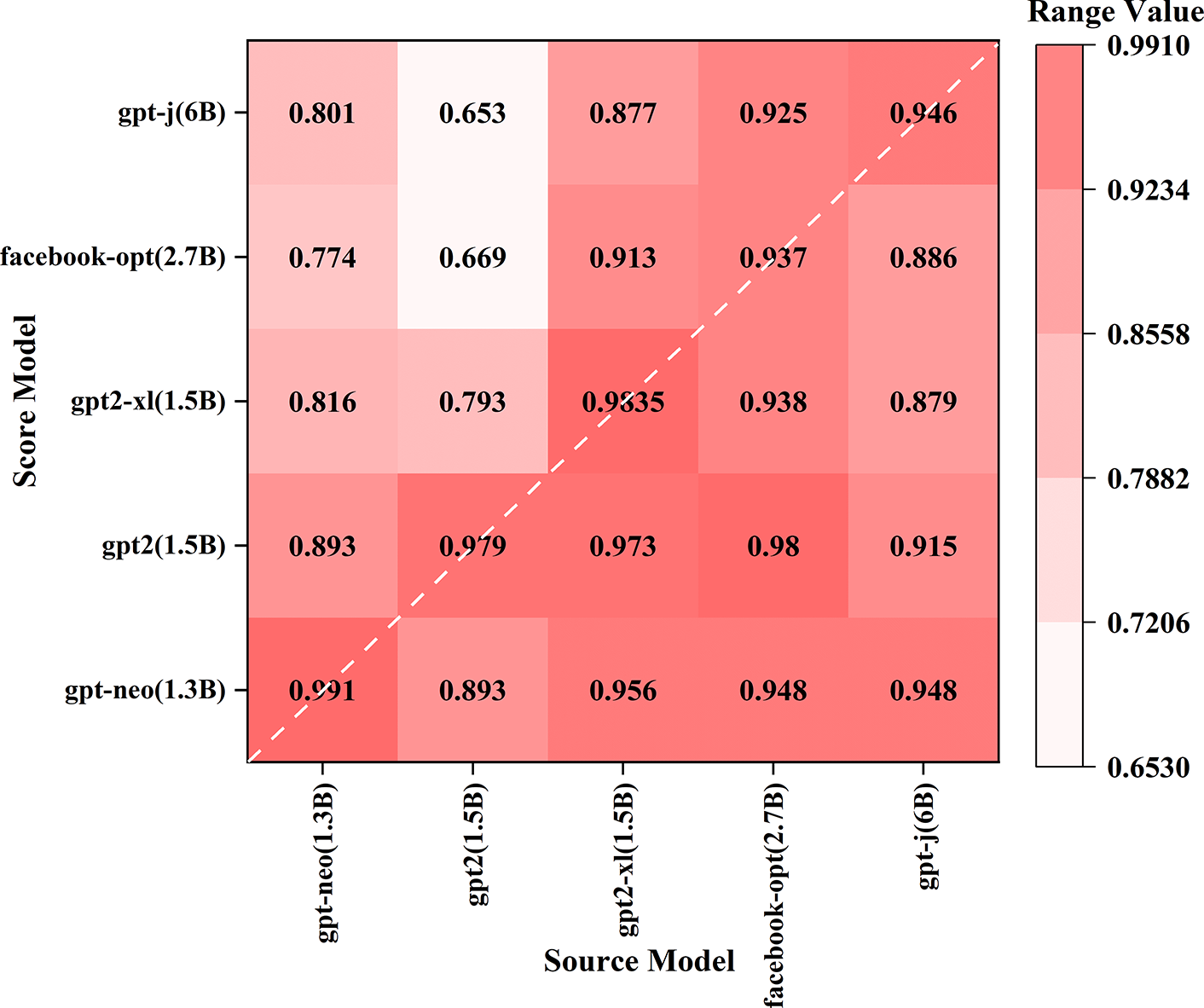

In the overall design, although our experiments primarily target the “white-box” environment for machine-generated text detection, in practical applications, the model used to evaluate text content may differ from the model that generated the text. The evaluation model is designed to determine whether the text is machine-generated or human-authored. However, given the diverse mechanisms and stylistic variations among different large language models, a critical question arises: Does the inconsistency between the evaluation model and the generative model affect the evaluation results? To address this question, we designed an extended experimental test under the following scenario: we aimed to investigate the effect of using a model different from the text-generating model to score candidate passages (as well as perturbed texts). In other words, our goal was to distinguish between human-generated text and text generated by Model A, but without access to Model A for calculating probability parameters. Instead, we used probability parameters calculated by an alternative Model B. Furthermore, we systematically varied the parameter scale of the evaluation model from small to large and conducted a series of comparative experiments. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 6. In this figure, the diagonal values indicate that the source model and the evaluation model are consistent, while the horizontal axis represents the source model, and the vertical axis corresponds to the evaluation model (scoring model). Analysis of the results reveals that the algorithm performs best when the scoring model is consistent with the source model, indicating that the algorithm is most suitable in a white-box setting. Therefore, the algorithm remains inherently a white-box model, and the original conclusion remains unchanged.

Figure 6: Analysis results of the consistency correlation between the generation model and the evaluation model. The experimental results are represented by a correlation coefficient matrix, where one dimension is the text generation model (Source Model), and the other dimension is the text evaluation model (Score Model). Each small square represents the algorithm performance result of a pair of models, with different color depths indicating different numerical values

More interestingly, in cases of model inconsistency, the algorithm performs better when the source model has a larger parameter scale and the scoring model has a smaller parameter scale. This suggests that the algorithm can achieve good performance even with a smaller scoring model. In other words, relatively smaller scoring models can effectively evaluate text generated by much larger source models. This phenomenon has been consistently observed across multiple dataset and model combinations. This finding has significant practical implications for real-world applications, as it enables the development of more efficient detection systems with only a slight reduction in detection accuracy, particularly in resource-constrained environments where computational efficiency is critical.

This study proposes a novel unsupervised text content detection method based on a dual-driven defense mechanism (D3M). Its core contribution lies in establishing two key metrics derived from information transmission theory: ITQ and ITD. These metrics quantify textual perturbation characteristics, thereby enabling reliable discrimination between human-authored and machine-generated content. Furthermore, a comprehensive series of exploratory tests has been conducted to evaluate the extent of influence exerted by key parameters, including specifically the number of perturbations, text masking rate, and selection of discriminative models. Comprehensive experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves outstanding performance across multiple benchmarks, particularly in scenarios involving SpaceInfi interference strategies, exhibiting exceptional detection accuracy, robust resistance against adversarial interference, and strong generalization capability.

Methodologically, this research advances statistical-based detection techniques through its innovative dual-driven verification mechanism and unsupervised learning architecture. The proposed approach not only reduces dependency on annotated data but also provides interpretable detection metrics, effectively addressing limitations of conventional methods in feature selection and generalization. These contributions offer valuable insights for future research in AI-generated content identification and establish a practical foundation for real-world applications requiring trustworthy text source verification.

Looking ahead, this study has several limitations that warrant further investigation. First, the detection scope needs to be expanded to include a wider variety of large-scale models, particularly those with massive parameters and commercially available closed-source models, which may employ different training methodologies and exhibit enhanced camouflage and anti-interference capabilities. Second, the current algorithm is limited to textual content; future work should explore multimodal content detection encompassing text, images, audio, and video. Third, additional interference types such as short-text injection, special character insertion, and sentence position swapping should be incorporated to further validate the model’s robustness. Fourth, it is essential to examine the algorithm’s complexity, particularly in terms of time and space efficiency, as optimization in these aspects is critical for future deployment in practical online business environments.

In summary, given the rapidly advancing capabilities of large language models, accurately identifying machine-generated content to prevent potential security risks arising from undetected AI-disguised human output remains a profoundly important and continuously evolving scientific challenge. This necessitates sustained scholarly attention and iterative research development.

Acknowledgement: We would like to acknowledge the computational resources provided by TCAT Key Laboratory.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Xiaoyu Li and Wen Shi; methodology, Xiaoyu Li and Wen Shi; validation, Xiaoyu Li, Jie Zhang and Wen Shi; formal analysis, Xiaoyu Li; investigation, Jie Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Xiaoyu Li, Jie Zhang and Wen Shi; writing—review and editing, Xiaoyu Li and Jie Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Wen Shi, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Floridi L, Chiriatti M. Gpt-3: its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds Mach. 2020;30(4):681–94. doi:10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Roumeliotis KI, Tselikas ND. Chatgpt and open-ai models: a preliminary review. Future Internet. 2023;15(6):192. doi:10.3390/fi15060192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Deng Z, Ma W, Han Q-L, Zhou W, Zhu X, Wen S, et al. Exploring deepSeek: a survey on advances, applications, challenges and future directions. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2025;12(5):872–93. doi:10.1109/jas.2025.125498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lu N, Liu S, He R, Wang Q, Ong Y-S, Tang K. Large language models can be guided to evade ai-generated text detection. arXiv:2305.10847. 2023. [Google Scholar]

5. Schneider S, Steuber F, Schneider JAG. Detection avoidance techniques for large language models. Data Policy. 2025;7:e29. [Google Scholar]

6. Qu Y, Huang S, Li L, Nie P, Yao Y. Beyond intentions: a critical survey of misalignment in LLMs. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;85(1):249–300. [Google Scholar]

7. Wu J, Yang S, Zhan R, Yuan Y, Chao LS, Wong DF. A survey on llm-generated text detection: necessity, methods, and future directions. Comput Linguist. 2025;51(1):275–338. doi:10.1162/coli_a_00549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tang R, Chuang Y-N, Hu X. The science of detecting llm-generated text. Commun ACM. 2024;67(4):50–9. doi:10.1145/3624725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Popescu-Apreutesei L-E, Iosupescu M-S, Necula SC, Păvăloaia V-D. Upholding academic integrity amidst advanced language models: evaluating BiLSTM networks with GloVe embeddings for detecting AI-generated scientific abstracts. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(2):2605–44. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fariello S, Fenza G, Forte F, Galloro N, Genovese A, Miele G, et al. Distinguishing human from machine: a review of advances and challenges in AI-generated text detection. Int J Interact Multimed Artif Intell. 2025;9(3):6–18. [Google Scholar]

11. He X, Shen X, Chen Z, Backes M, Zhang Y. Mgtbench: benchmarking machine-generated text detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 on ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2024 Oct 14–18; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 2251–65. [Google Scholar]

12. Boutadjine A, Harrag F, Shaalan K. Human vs. machine: a comparative study on the detection of AI-generated content. ACM Trans Asian Low Resour Lang Inf Process. 2025;24(2):1–26. doi:10.1145/3708889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang Y, Mansurov J, Ivanov P, Su J, Shelmanov A, Tsvigun A, et al. M4: multi-generator, multi-domain, and multi-lingual black-box machine-generated text detection. In: Graham Y, Purver, M, editors. Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2024 Mar 17–22; St. Julian’s, Malta. Kerrville, TX, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 1369–407. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.eacl-long.83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li X, Wang W, Fang J, Jin L, Kang H, Liu C. Peinet: joint prompt and evidence inference network via language family policy for zero-shot multilingual fact checking. Appl Sci. 2022;12(19):9688. doi:10.3390/app12199688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hu X, Chen P-Y, Ho T-Y. Radar: radar: robust ai-text detection via adversarial learning. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:15077–95. [Google Scholar]

16. Fröhling L, Zubiaga A. Feature-based detection of automated language models: tackling gpt-2, gpt-3 and grover. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2021;7(1):443. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu A, Pan L, Lu Y, Li J, Hu X, Zhang X, et al. A survey of text watermarking in the era of large language models. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;57(2):1–36. doi:10.1145/3691626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Crothers EN, Japkowicz N, Viktor HL. Machine-generated text: a comprehensive survey of threat models and detection methods. IEEE Access. 2023;11:70977–1002. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3294090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hakak S, Alazab M, Khan S, Gadekallu TR, Maddikunta PKR, Khan WZ. An ensemble machine learning approach through effective feature extraction to classify fake news. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2021;117(6):47–58. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.11.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Muthalagu R, Malik J, Pawar PM. Detection and prevention of evasion attacks on machine learning models. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;266(6):126044. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.126044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Guo B, Zhang X, Wang Z, Jiang M, Nie J, Ding Y, et al. How close is chatgpt to human experts? Comparison corpus, evaluation, and detection. arXiv:2301.07597. 2023. [Google Scholar]

22. Kusuma RD, Nathaniel F, Widjaya A, Gunawan AAS. Veritext: AI-generated text detection based on perplexity and giant language model test room (GLTR). Procedia Comput Sci. 2025;269(7):1702–11. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2025.09.113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mitchell E, Lee Y, Khazatsky A, Manning CD, Finn C. DetectGPT: zero-shot machine-generated text detection using probability curvature. In: ICML’23: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023 Jul 23–29; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 24950–62. [Google Scholar]

24. Bianchini F. Information transmission as artificial intelligence. In: Atti del XLIV Congresso nazionale SISFA: Firenze, 17-20 Settembre 2024. Naples, Italy: Federico II University Press; 2025. p.67–78. [Google Scholar]

25. Adams G, Fabbri A, Ladhak F, Lehman E, Elhadad N. From sparse to dense: GPT-4 summarization with chain of density prompting. In: Dong Y, Xiao W, Wang L, Liu F, Carenini G, editors. Proceedings of the 4th New Frontiers in Summarization Workshop; 2023 Dec 6; Singapore. Kerrville, TX, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 68–74. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.newsum-1.7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Çelikten T, Onan A. HybridGAD: identification of AI-generated radiology abstracts based on a novel hybrid model with attention mechanism. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(2):3351–77. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.051574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Abbas HM. A Novel approach to automated detection of AI-generated text. J Al-Qadisiyah Comput Sci Math. 2025;17(1):1–17. doi:10.29304/jqcsm.2025.17.11958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu Y, Zhao Y, Chen Y, Hu Z, Xia M. YOLOv5ST: a lightweight and fast scene text detector. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;79(1):909–26. [Google Scholar]

29. Lee DH, Jang B. Enhancing machine-generated text detection: adversarial fine-tuning of pre-trained language models. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):65333–40. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3396820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Teja LS, Yadagiri A, Anish SS, Sai SK, Kumar TK. Modeling the attack: detecting AI-generated text by quantifying adversarial perturbations. arXiv:2510.02319. 2025. [Google Scholar]

31. Mitrović S, Andreoletti D, Ayoub O. Chatgpt or human? Detect and explain. Explaining decisions of machine learning model for detecting short chatgpt-generated text. arXiv:2301.13852. 2023. [Google Scholar]

32. West A, Zhang L, Zhang L, Wang Y. T-Detect: tail-aware statistical normalization for robust detection of adversarial machine-generated text. arXiv:2507.23577. 2025. [Google Scholar]

33. Bao G, Zhao Y, Teng Z, Yang L, Zhang Y. Fast-detectgpt: efficient zero-shot detection of machine-generated text via conditional probability curvature. arXiv:2310.05130. 2023. [Google Scholar]

34. Su J, Zhuo TY, Wang D, Nakov P. Detectllm: leveraging log rank information for zero-shot detection of machine-generated text. arXiv:2306.05540. 2023. [Google Scholar]

35. Zeng C, Tang S, Yang X, Chen Y, Sun Y, Xu Z, et al. Dald: improving logits-based detector without logits from black-box llms. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2024;37:54947–73. [Google Scholar]

36. Shen G, Cheng S, Zhang Z, Tao G, Zhang K, Guo H, et al. Bait: large language model backdoor scanning by inverting attack target. In: 2025 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2025 May 12–15; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 1676–94. [Google Scholar]

37. Krishna K, Song Y, Karpinska M, Wieting J, Iyyer M. Paraphrasing evades detectors of ai-generated text, but retrieval is an effective defense. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:27469–500. [Google Scholar]

38. Solaiman I, Brundage M, Clark J, Askell A, Herbert-Voss A, Wu J, et al. Release strategies and the social impacts of language models. arXiv:1908.09203. 2019. [Google Scholar]

39. Ippolito D, Duckworth D, Callison-Burch C, Eck D. Automatic detection of generated text is easiest when humans are fooled. arXiv:1911.00650. 2019. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools