Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhanced BEV Scene Segmentation: De-Noise Channel Attention for Resource-Constrained Environments

1 College of Computer Science, Chongqing University, Chongqing, 400044, China

2 SUGON Industrial Control and Security Center, Chengdu, 610225, China

3 Department of Computer Science, Maharishi University of Management, Fairfield, IA 52557, USA

* Corresponding Author: Yunfei Yin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 90 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074122

Received 02 October 2025; Accepted 25 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Autonomous vehicles rely heavily on accurate and efficient scene segmentation for safe navigation and efficient operations. Traditional Bird’s Eye View (BEV) methods on semantic scene segmentation, which leverage multimodal sensor fusion, often struggle with noisy data and demand high-performance GPUs, leading to sensor misalignment and performance degradation. This paper introduces an Enhanced Channel Attention BEV (ECABEV), a novel approach designed to address the challenges under insufficient GPU memory conditions. ECABEV integrates camera and radar data through a de-noise enhanced channel attention mechanism, which utilizes global average and max pooling to effectively filter out noise while preserving discriminative features. Furthermore, an improved fusion approach is proposed to efficiently merge categorical data across modalities. To reduce computational overhead, a bilinear interpolation layer normalization method is devised to ensure spatial feature fidelity. Moreover, a scalable cross-entropy loss function is further designed to handle the imbalanced classes with less computational efficiency sacrifice. Extensive experiments on the nuScenes dataset demonstrate that ECABEV achieves state-of-the-art performance with an IoU of 39.961, using a lightweight ViT-B/14 backbone and lower resolution (224 × 224). Our approach highlights its cost-effectiveness and practical applicability, even on low-end devices. The code is publicly available at: https://github.com/YYF-CQU/ECABEV.git.Keywords

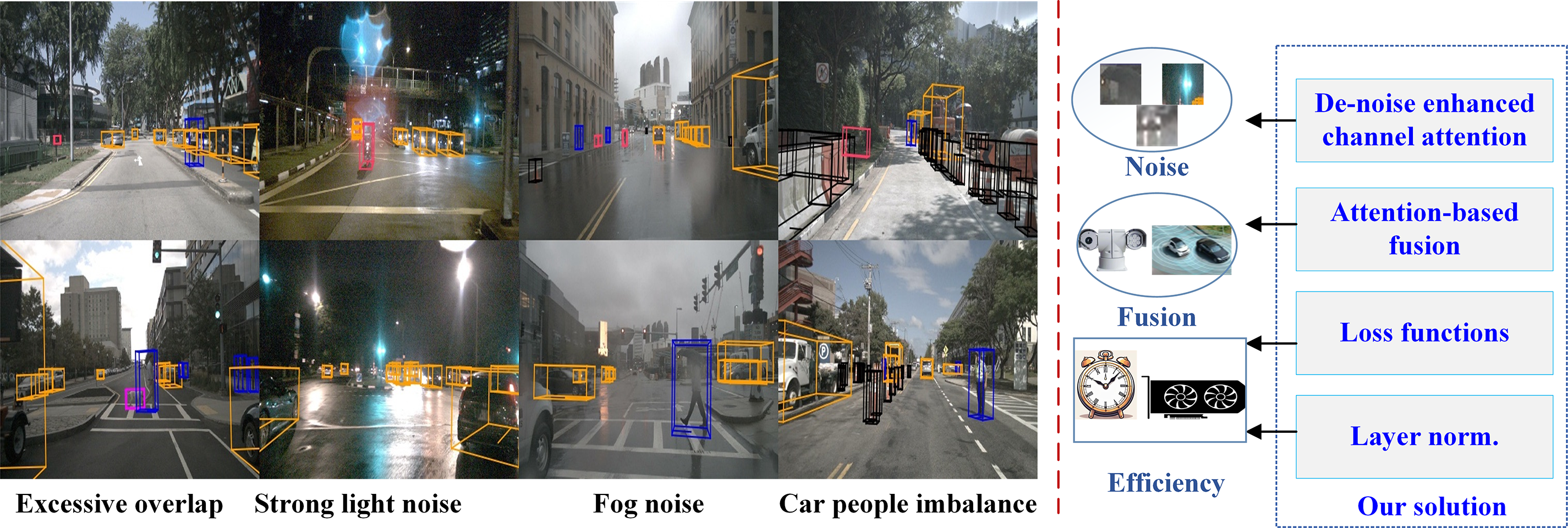

Autonomous vehicles have shown significant advancement in transportation. With accurate and efficient scene segmentation, autonomous vehicles can navigate safely and improve operational efficiency. Commonly, multimodal sensors are employed to assist scene segmentation, such as multiple cameras, LiDAR, and radar. For surround-view perception, cameras offer dense RGB images, LiDAR offers a 3D point cloud, and radar provides the raw cube. Although LiDAR and radar provide more depth measurements, it is a challenge to fuse the related data due to their diverse structures, and LiDAR is also expensive for low-end devices. Bird′s Eye View (BEV) transformation methods using multiple cameras allow for a versatile representation that can be used for various downstream tasks such as map semantic segmentation [1] or 3D bounding box detection [2]. The objective of using BEV is to create a coherent and semantically meaningful top-view representation of the environment by fusing sensor features into a single representation with a shared coordinate system [2]. However, in certain scenarios, BEV transformation methods do not perform well due to the low-end GPU devices. There are three main challenges: (1) out of GPU memory problem because of the complex high-resolution fusion, (2) noise inside the RGB images, and (3) inefficient loss functions struggling to handle the imbalanced classes, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Challenges in BEV scene segmentation vs. our solution. Existing methods struggle to fuse multimodal data that include noise, leading to sensor misalignment and performance degradation, while our solution utilizes de-noise enhanced channel attention to reduce data noise, leverages an improved fusion approach to merge categorical data, and employs specific loss functions and layer normalization to reduce computational overhead and class imbalance

Given the above issues encountered, more attention has been paid to radar-based fusion to make a robust and efficient segmentation of objects and maps with perception. Although LiDAR can provide more accurate inputs, it is more expensive for low-end devices. Therefore, based on the state-of-the-art method BEVCar [3], which makes the fusion of camera and radar data mainstream.

Therefore, to address these challenges, a de-noise enhanced channel attention BEV scene segmentation under insufficient GPU memory, i.e., ECABEV, is proposed in this paper, which consists of two specific sensor encoders, an improved fusion approach that utilizes de-noise enhanced channel attention, a specific layer normalization, and a new designed scalable loss function. With the BEV encoders, it finally generates both map and object segmentation; with the improved fusion approach, the noisy camera data are better refined; with the specific layer normalization and the scalable loss function, the computational efficiency and imbalanced classes are effectively alleviated. The proposed approach is evaluated with the nuScenes datasets [4] that manifests the ECABEV achieves the state-of-the-art performance, and is also robust in challenging situations such as out of memory, noisy data, and time complexity.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows.

(1) A novel de-noise enhanced channel attention-based fusion approach is proposed for the first time, which can refine noisy camera data via the well-designed de-noise enhanced channel attention, and image feature queries based on corresponding radar points, and retrieves relevant information using deformable attention mechanisms. The de-noise enhanced channel attention leverages a dual pooling mechanism combining both global average pooling (GAP) and global max pooling (GMP), enabling the attention module to preserve finer spatial details via GMP and maintain global context via GAP. This effectively filters out irrelevant noise while retaining discriminative features.

(2) A skillful normalization method, i.e., bilinear interpolation layer normalization, is devised, which efficiently downscales intermediate feature maps while maintaining spatial feature fidelity through learned interpolation. This method significantly reduces computational overhead compared with traditional normalization techniques.

(3) A scalable cross-entropy loss function is introduced to dynamically prioritize rare classes based on class frequencies and complexity. The corresponding adaptive weighting mechanism enables balanced learning with less computational efficiency sacrifice.

Recent advancements in BEV segmentation transform multi-view camera inputs into BEV representations for tasks like semantic segmentation and motion forecasting. Projection-based methods, such as SimpleBEV [5] and LSS [6], use voxel-based transformations, with extensions like M2BEV [7] incorporating joint training for 3D object detection. Attention-based approaches, including BEVFormer [8] and CVT [9], leverage transformers for cross-attention, while PETR [10] and its derivatives employ instance queries with positional encoding. Multimodal integration and temporal fusion [7] extend these ideas further. Although attention-based methods excel in modeling, they often rely on implicit geometric encoding, potentially leading to overfitting.

Camera-based perception, Radar-based perception, and LiDAR-based perception are three methods to enhance perception performance. The first method leverages the camera and additional inputs or strategies to enhance performance. BEVStereo [11] combines mono and temporal stereo depth estimation, while BEV-LGKD [12] uses a knowledge distillation framework. Similarly, BEVDepth [13] applies additional ground truth (GT) data. PETRv2 [14] extends PETR [10] with history inputs and varied time horizons during training, making the model robust to different vehicle speeds. BEVFormer [8] employs temporal self-attention and incorporates additional time steps during training. Reference [15] extracts 2D features and lifts them into 3D space using strategies like splatting or sampling. The second method enhances BEV models by leveraging radar’s ability to measure depth, intensities, and relative velocities robustly. ClusterFusion [16] and SparseFusion3D [17] combine radar and camera data in image and BEV spaces. Radar cube methods [18] utilize 2D, 3D, or 4D data for limited object detection tasks. Radar point cloud methods dominate and include grid-based, graph-based [19], and point-based approaches [20]. Despite robustness, challenges like low resolution, noise, and limited semantic capture hinder the performance. The third method utilizes voxelization [19], GNNs [21], range view [18], and BEVCar [3] to extract features from point clouds. Efficient models like PointPillars [20] achieve fast inference but with limited accuracy, while PV-RCNN [19] improves precision using multi-scale features and part-aware stages, but occlusion remains a challenge. GNNs further enhance LiDAR perception by representing point clouds as graphs. For example, GraphRelate3D [22] leverages message passing and dynamic graph updating for classification and segmentation. Recently, to enhance practical applications of BEV perception, resource-constrained perception has attracted much attention. Zhang et al. [23] stated the resource-constrained requirements of autonomous vehicles, and Benrabah et al. discussed the basic research paradigm [24].

2.3 Attention Mechanisms in Vision

Attention mechanisms exhibit significant enhancement capabilities in vision. As mentioned above, the traditional attention mechanisms have propelled the segment and perception in performance improvement, including SENet (Hu et al.) [25], CBAM (Woo et al.) [26], ECA-Net (Wang et al.) [27], and Coordinate Attention (Hou et al.) [28]. Later, Transformer-based methods are widely used in BEV perception that leverage attention mechanisms to project predefined queries onto multi-view image planes. DETR3D [29] introduced a transformer decoder for 3D object detection with a top-down framework and set-to-set loss. CVT [9] applied cross-view transformers for BEV semantic segmentation, while BEVFormer [8] utilized deformable attention to map multi-view image features to dense BEV queries. PETR [10] incorporated explicit positional information from 3D coordinates. Sparse4D [30,31] projected multiple 4D key points per 3D anchor for feature fusion. Recent advancements include StreamPETR [32], which captures temporal information with sparse object queries, SparseBEV [33], which employs scale-adaptive attention and spatio-temporal sampling for dynamic BEV representation, and BEVFusion [34], which introduces an efficient and generic multi-task multi-sensor fusion framework.

In addition, multimodal fusion and segmentation in BEV perception has evolved from radar-only approaches to mixed strategies combining radar and vision [35–38]. FISHING Net [39] introduced a multimodal method to integrate a MLP-based lifting strategy for camera features and the radar data encoded via a UNet-like network using class-based priority pooling. SimpleBEV [5] processed radar data in rasterized BEV format and fused with the bilinearly sampled image features. CRN [40] addressed spatial misalignment with deformable attention [41] to aggregate radar and image features, but required LiDAR supervision for depth modeling. BEVGuide [42] proposed a bottom-up lifting approach, using homography-based projection for image features. All these methods are multimodal fusion and segmentation strategies.

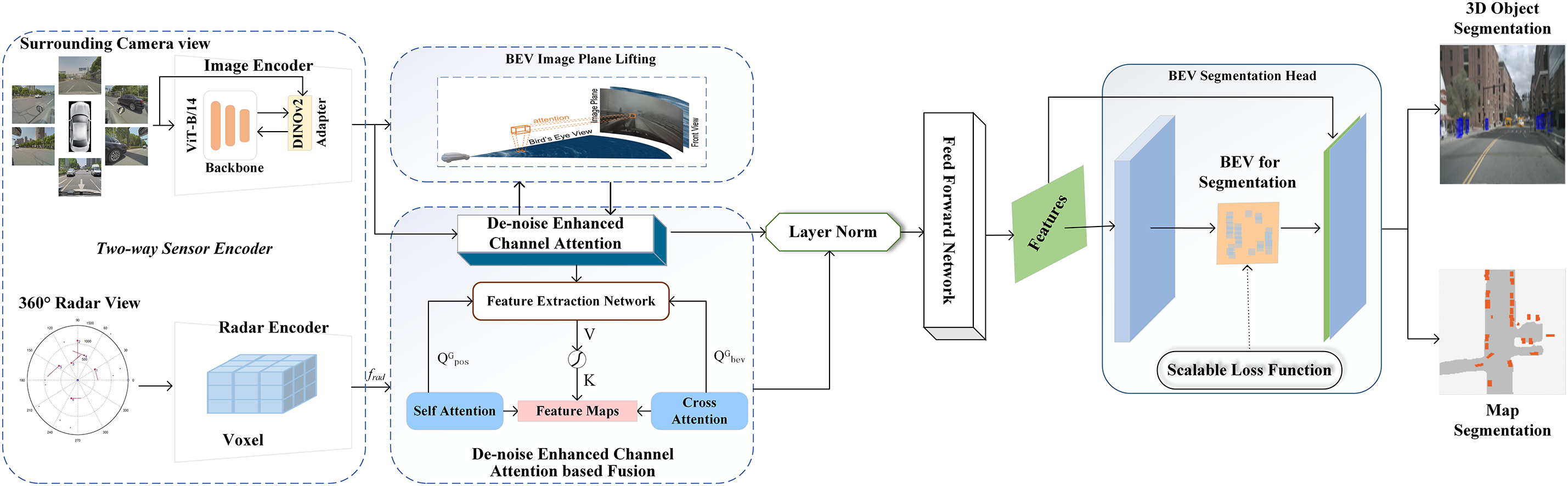

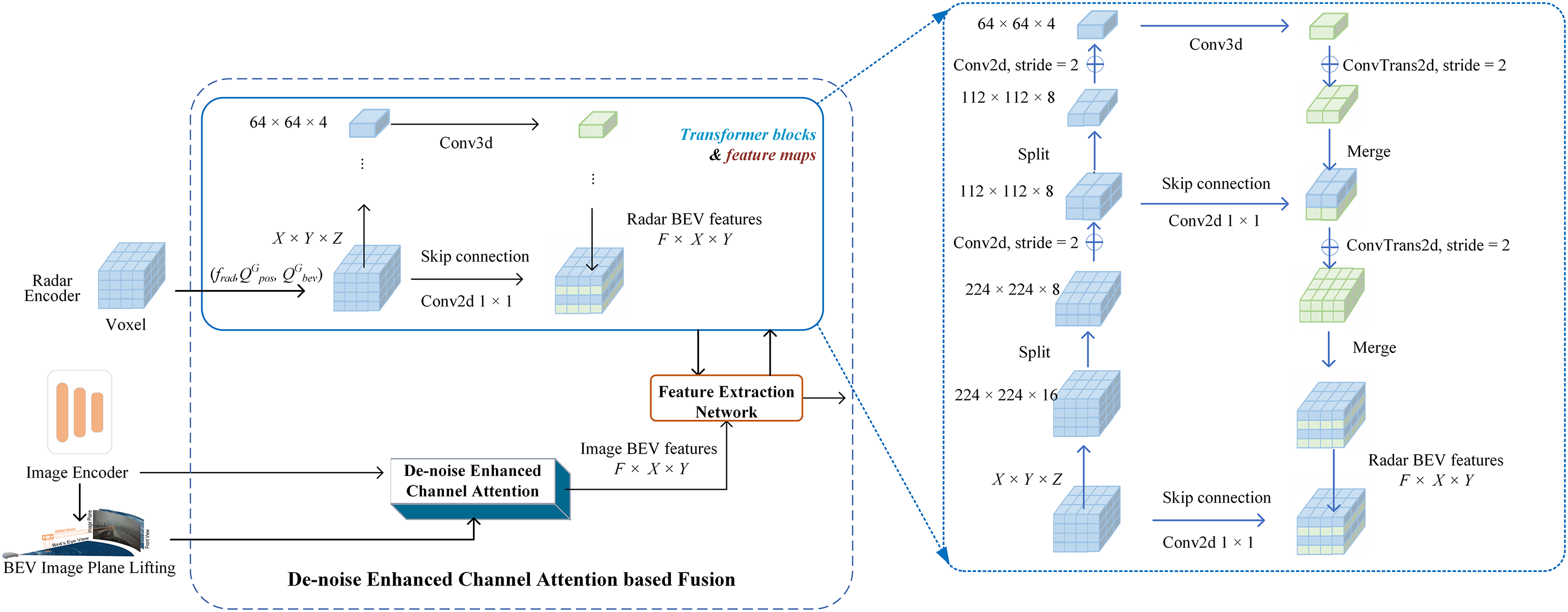

In Fig. 2, we demonstrate the architecture of ECABEV, where ECABEV has two different types of sensor encoders for camera images and radar data, respectively. We pass the image data as an image plane for lifting with the designed de-noise enhanced channel attention, which reduces the noise from the surrounding camera images. Later on, we utilize radar data to initialize the queries. Inside the fusion section, we combine lifted image data with the learnable radar features using cross-attention & self-attention transformer blocks. Traditionally, vanilla self-attention [3] and spatial cross-attention are used for fusion; however, we introduce the de-noise enhanced channel attention based on global average pooling and global max pooling. This is because the surrounding camera captures images containing unnecessary details, causing noise. Finally, we pass the data for the bilinear interpolation layer normalization to feed the feed-forward network and perform BEV segmentation for both the 3D object and the map. We propose the bilinear interpolation layer normalization to effectively address time complexity issues.

Figure 2: The proposed ECABEV architecture. It leverages de-noise enhanced channel attention to increase the de-noising capabilities, employs the improved fusion approach to enhance the unified representation of camera and sensor data, exploits dedicated layer normalization to reduce computational overhead, and uses the well-designed scalable loss function in the segmentation head to dynamically prioritize rare classes (see also Fig. 2). It mainly consists of a two-way sensor encoder, BEV image plane lifting, attention-based fusion, layer norm, and BEV segmentation head, as shown in the following sections

nuScenes [4] is one of the largest datasets in the concept of autonomous vehicles, consisting of different classes of data such as “drivable area”, “carpark area”, “pedestrian crossing”, “walkway”, “stop line”, “road divider”, “lane divider”, etc. However, a critical challenge in leveraging this dataset is its severe class imbalance; frequent classes like “drivable area” dominate the annotations, while rare but safety-critical classes like “pedestrian crossings” are significantly underrepresented. We designed a scalable loss function that can efficiently handle class imbalance in large datasets, nuScenes [4]. Because the nuScenes dataset consists of rare “pedestrian crossing” compared with “drivable area”, which indicates the class imbalance. We describe the main parts of the architecture in the following subsections.

Unlike the traditional methods, a two-way sensor encoder is devised in this paper, which is exploited to process the raw data of both camera and radar in two different encoders. And then, the encodings are collaboratively combined by the well-designed fusion module.

Camera: For encoding camera data, a frozen DINOv2 ViT-B/14 model [43] is employed, as it provides more semantic information than ResNet-based backbones [44]. A ViT adapter with learnable weights [45] is used for processing, and images from N cameras are concatenated at each timestamp, forming an input of dimensions N × H × W. The ViT adapter outputs multi-scale feature maps with F channels at scales of

Radar: Radar data is represented as a point cloud consisting of D key features, i.e., 3D position (x, y, z), uncompensated velocities (vx, vy), and radar cross-section (RCS), which measures surface detectability. To enhance flexibility, the method avoids relying on the built-in post-processing of specific radar models, distinguishing it from earlier approaches [42]. Drawing inspiration from LiDAR point cloud encoding and SparseFusion3D [17], radar points are organized into a voxel grid with dimensions X × Y × Z, corresponding to the resolution of the BEV space and discretization along the height axis.

To efficiently manage memory and reduce bias in densely populated voxels, random sampling is applied to those containing more than P radar points. Each radar point is processed through a point feature encoder with fully connected layers. Max pooling is then applied within each voxel to combine the features into a single vector. These voxel-level features are further processed by a CNN-based encoder to compress the data along the height dimension, resulting in a compact radar BEV encoding called “frad” for subsequent tasks.

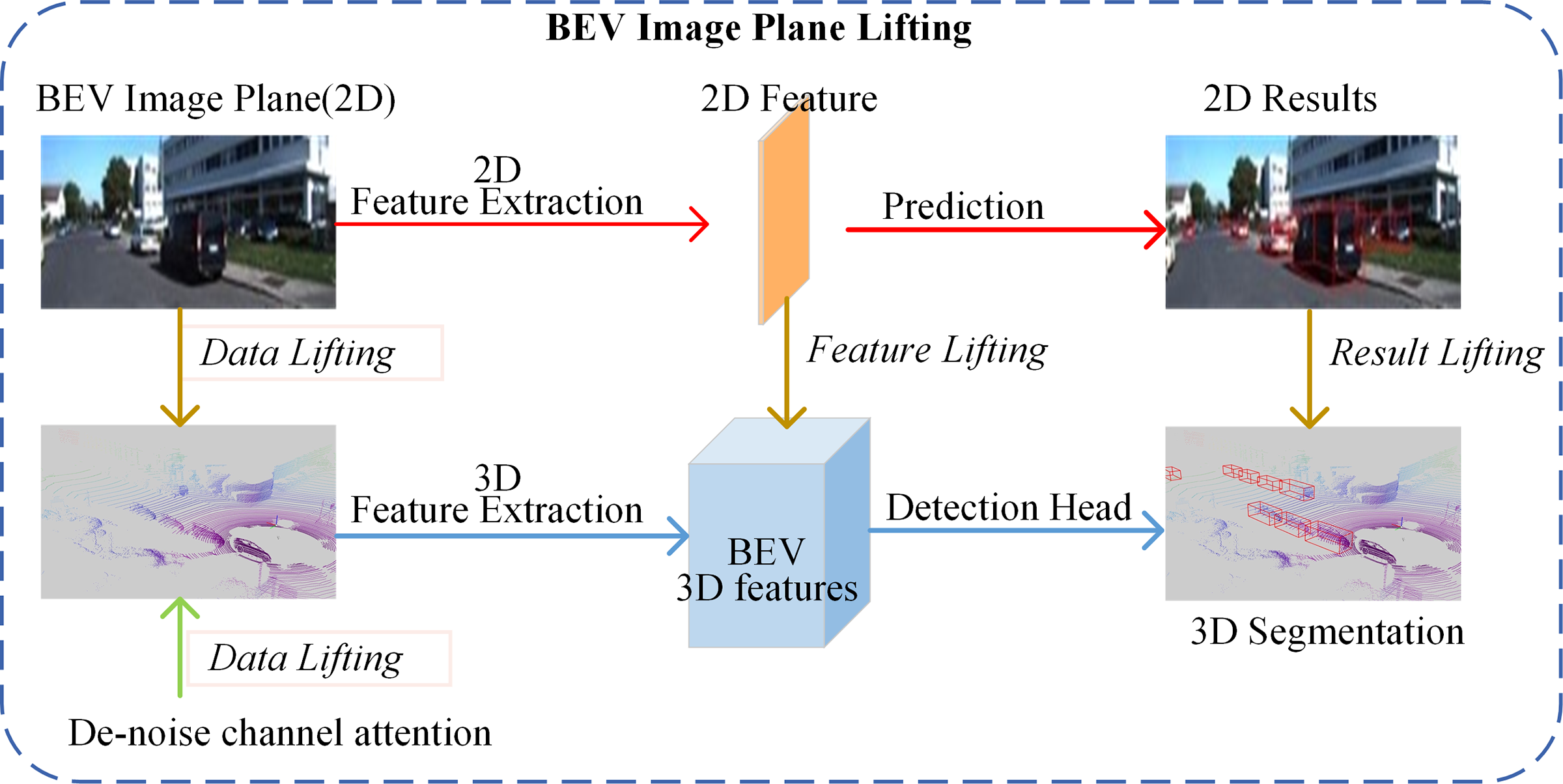

To transform encoded vision features from the 2D image plane into the BEV 3D space, an image plane lifting approach is implemented. Inspired by BEVFormer [8], we also leverage the deformable attention mechanisms [41] to efficiently map features between the 2D features and 3D features, as shown in Fig. 3. Instead of relying solely on traditional query initialization strategies, the approach can incorporate sparse radar points. The deformable attention ensures that the BEV queries are initialized with precise and meaningful spatial priors derived from the radar data. This approach effectively bridges the gap between 2D vision data and 3D spatial understanding, enabling a more accurate and robust feature representation for downstream tasks.

Figure 3: De-noise deformable attention-based BEV image plane lifting

BEV image plane lifting excels at bridging the gap between 2D input features and 3D feature space by offering a strong intermediate representation, which is crucial for detection tasks. By addressing the challenge of dimensional mismatches between 2D inputs and 3D outputs, our approach provides a clearer framework. It also accommodates techniques like pseudo-LiDAR-based approaches. This structured framework offers new insights into how 2D image features are transformed into effective 3D representations for object segmentation.

To integrate lifted image features and encoded radar data, an improved fusion approach is proposed in this paper, which exploits the denoise-enhanced channel attention. Inspired by TransFusion [7,46] that combines camera and LiDAR data for 3D object detection, this kind of fusion is based on the image feature queries around the corresponding radar points, and retrieves relevant information using deformable attention mechanisms [41].

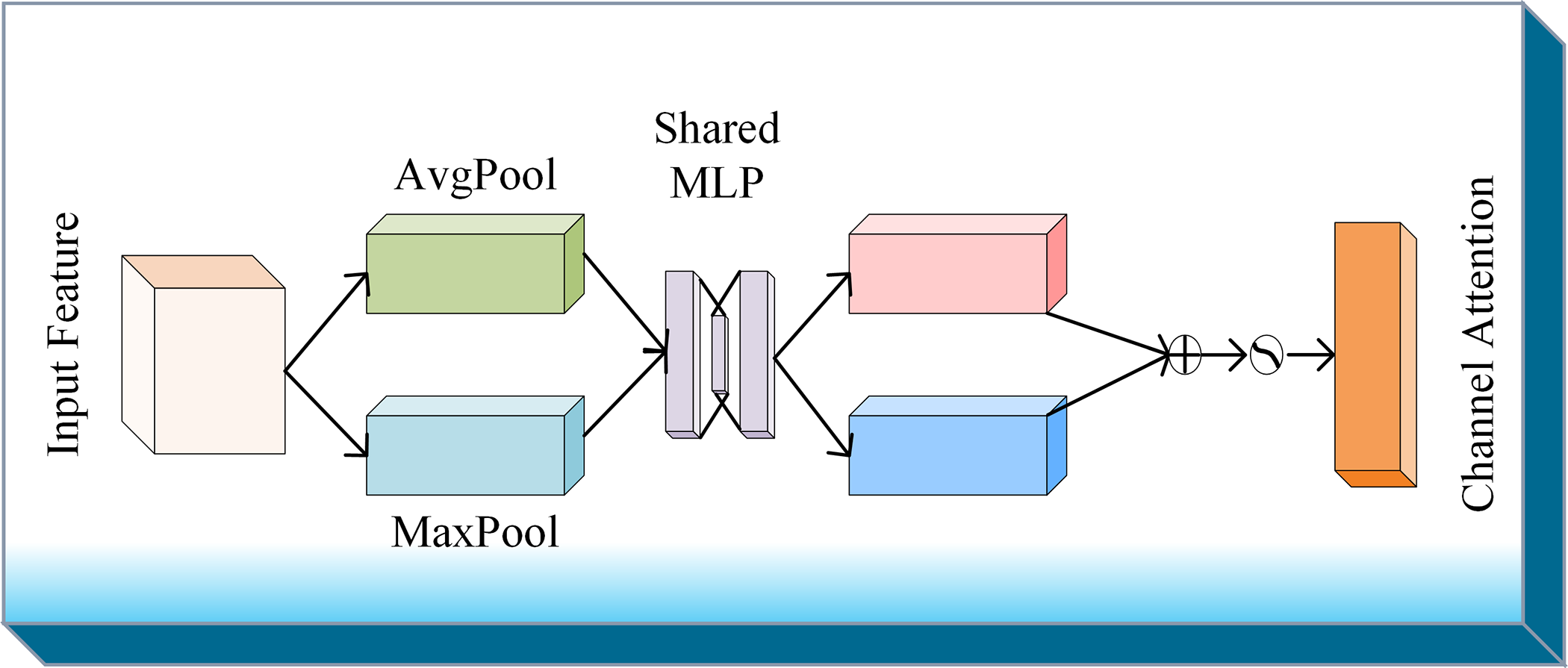

3.4.1 De-Noise Enhanced Channel Attention

As mentioned above, the de-noise enhanced channel attention is devised to increase the de-noising capabilities in noisy conditions, because different channels have different feature focuses on traffic objects, and therefore, channel attention can be used to recalibrate feature maps by emphasizing relevant channels and suppressing the irrelevant ones. To utilize the relevant features, the input feature maps are processed through two parallel pooling operations: max pooling to capture the maximum activation values and average pooling to compute the average activation values across all channels. And then, the pooled features are passed through a shared Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to learn dependencies with the channels, as shown in Fig. 4. The outputs of the two pooling operations are combined and passed through an activation sigmoid function to generate channel-wise attention weights. These weights represent the importance of each channel and are applied to the input feature map to recalibrate it, amplifying significant channels and suppressing less important ones.

Figure 4: De-noise enhanced channel attention

For camera inputs with the guidance of radar data, the above design extracts the corresponding features and projects them into the BEV plane. It applies average and max pooling to capture global patterns and highlight key features. After passing through the shared MLP, the outputs are combined and processed through a sigmoid activation function to generate attention weights. This process refines the feature maps, improving the system’s robustness and denoising capabilities for enhanced performance in noisy conditions.

3.4.2 Design of the Improved Fusion Approach

The improved fusion approach, as shown in the middle-lower part of Fig. 2, focuses on denoising-enhanced channel attention around the related radar points. That is to say, the initial query

As can be seen in Fig. 5, after being processed by De-noise Enhanced Channel Attention, the features from the BEV image plane lifting act as keys and values in the cross-attention mechanism, while the radar data drives the query initialization. A sequence of six transformer blocks (on the right part of Fig. 5) is employed to iteratively refine the fused feature maps, gradually enhancing their joint representation. The final output from the last transformer block is processed through a feature extraction network with a ResNet-18 [44] bottleneck. And then, the fused multimodal features are compressed and organized by the subsequent steps, like layer normalization, segmentation head, and so forth. Because of the role of transformer blocks, the effective fusion of sensor images and radar data is ensured, and the alignment with the BEV space is also maintained.

Figure 5: Design of the improved fusion approach. It leverages the de-noise enhanced channel attention to guide the deep fusion of the lifted image features and radar data.

It is worth noting that BEVFormer [8], BEVDepth [13], CRN [40], and so forth are all attention-enhanced. Unlike these methods, the ECABEV emphasizes global features attentions, and uses it in plane lifting and enhanced camera and radar data fusion. While BEVFormer focuses on local temporal-spatial feature fusion and only involves camera data. BEVDepth designs a lift-splat detector-based deep feature estimator and also only involves camera data. CRN employs deformable cross attention to fuse camera and radar data, but does not use attention to plane lifting. In addition, for resource-constrained environments, channel attention has more efficiency than spatial attention, because there are not enough memories to execute valid space attention extraction [17]. Therefore, all these methods have different characteristics.

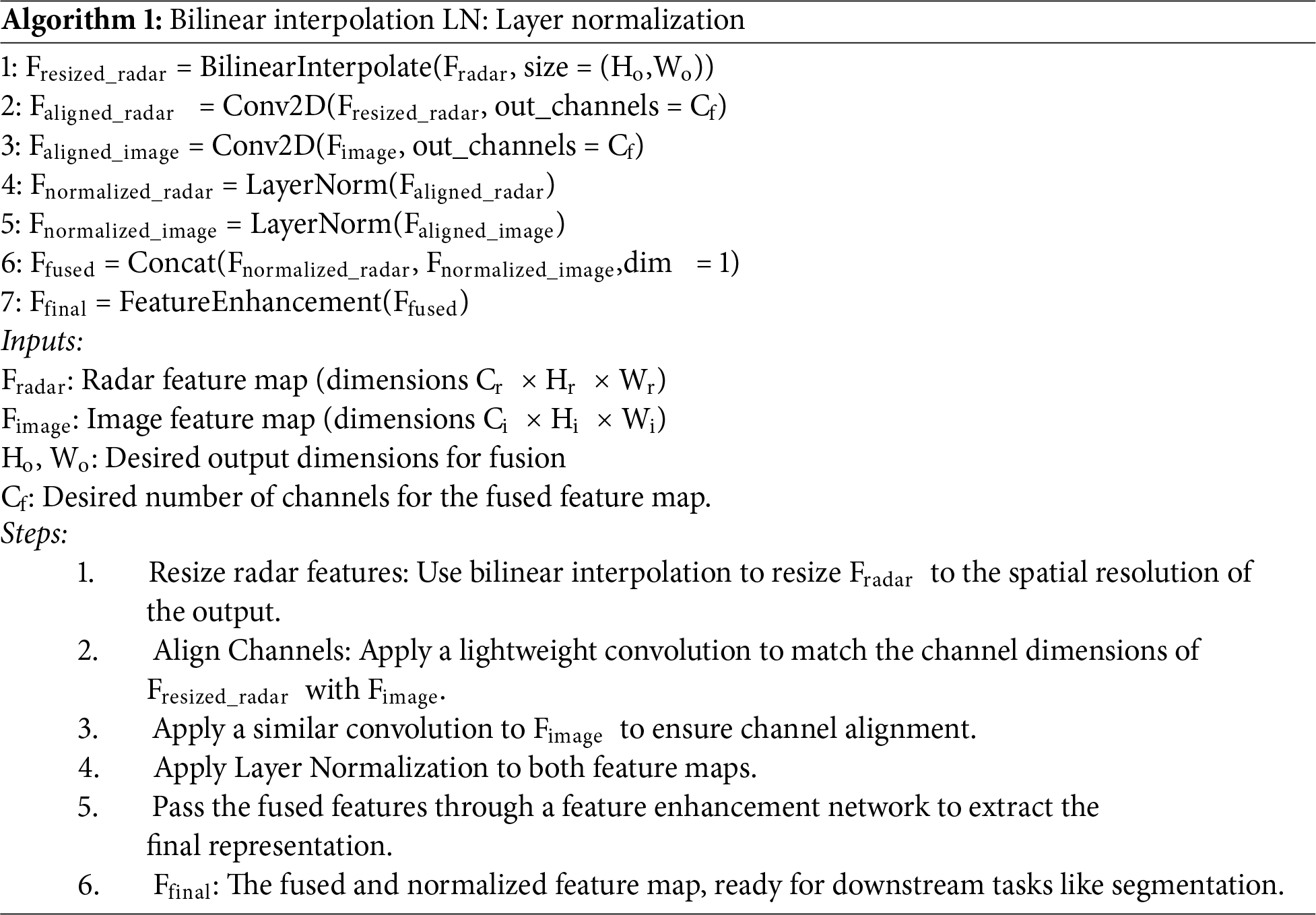

3.5 Bilinear Interpolation Layer Normalization

To ensure spatial feature fidelity, layer normalization with bilinear interpolation is devised, which can improve convergence and keep scale consistency, as shown in the designed Algorithm 1. As can be shown in the designed layer normalization, the normalized features are further refined using lightweight depthwise separable convolutions to enhance their feature representation while adding less computational cost. Finally, the refined chunks are reconstructed into a unified, high-quality feature map through concatenation and a final convolution layer. This method produces enriched, scale-consistent features that are highly effective for complex vision tasks like semantic segmentation, object detection, and robotic manipulation, delivering both computational efficiency and robust feature representation.

For multi-class BEV semantic segmentation, a single segmentation head is employed to handle both object and map predictions. The segmentation head architecture consists of two convolutional layers with ReLU activations, followed by one 1 × 1 convolutional layer that outputs predictions for one object class, such as vehicles and M map classes. The output dimensions are structured as (M + 1) × X × Y, where X and Y represent the spatial resolution of the BEV space. This design allows each pixel in the BEV space to independently predict the presence of an object class, such as a vehicle, while simultaneously associating itself with multiple map categories. Such flexibility is crucial for comprehensive segmentation tasks, as it enables detailed modeling of the environment, capturing both dynamic elements and static features such as road boundaries, lane markings, sidewalks, etc. within the same framework. By allowing a pixel to be assigned to multiple map categories, the model ensures robust and precise predictions.

For BEV object segmentation, we highlight that object-agnostic segmentation [47–49] should avoid relying on instance-specific information during training. Hereby, inspired by [50], we designed the scalable cross-entropy (SCE) BEV loss function, which can effectively improve performance in large-scale settings. Compared with reference [50], they are in different domains and have different focuses, as shown in Eqs. (2) and (3).

where

To address time complexity and GPU memory challenges, SCE BEV loss focuses on critical data subset computations, such as hard negatives, instead of processing all catalog items. nuScenes [4] consists of both the rare subset and the frequent subset. SCE BEV loss employs bucket-based partitioning and approximate maximum inner product search to selectively compute logits for the most impactful elements, significantly reducing computational load while maintaining accuracy.

Bucket-based partition can contribute to long tail categories, for example,

Unlike most previous methods [8,9,42], which primarily focus on predicting roads and occasionally lane dividers, our approach includes additional map classes such as pedestrian crossings and walkways. During training, we supervise the map channels in the segmentation head using a multi-class version of the α-balanced focal loss [51].

where c ∈ [1, C] refers to the semantic classes and

Although individual components such as SCE [50] and focal loss [51] have been used in prior works, their improvement and integration within a lightweight transformer-based architecture alongside channel attention and bilinear interpolation layer normalization constitute a novel, cohesive solution for low-end devices.

To validate the proposed approach, we will compare the ECABEV with the state-of-the-art methods in different scenarios. We found that under limited GPU memory conditions, our accuracy is higher than that of BEVCar [3]. The GPU memory utilization of our approach performs better in all scenarios compared with BEVCar [3].

Dataset and Evaluation Metrics: We conduct experiments exclusively on the nuScenes [4] dataset, a large-scale autonomous driving benchmark comprising 1000 driving scenes collected in Boston and Singapore. nuScenes is one of the few publicly available datasets that provides synchronized multimodal sensor data-specifically six RGB cameras, five radars, and one LiDAR-covering a full 360° field of view. This makes it uniquely suitable for studying BEV semantic segmentation, particularly for multimodal fusion tasks involving camera and radar data. In our research, we use nuScenes for both object and map segmentation, leveraging its rich annotations and diverse urban driving scenarios. The dataset’s extensive use in scientific research in recent years [52] also ensures consistency and comparability with other state-of-the-art methods such as BEVCar [3] and CRN [40]. In contrast, other datasets, Waymo Open Dataset [53], KITTI [54], either lack radar data, provide limited or no semantic map annotations, or focus primarily on LiDAR-based perception, making them less appropriate for evaluating camera-radar BEV fusion frameworks like ECABEV. For BEV semantic segmentation, we use mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) across all segmentation categories as the metric, following the settings of LSS [6].

Metrics: For training and validation, we use the Trainval 1.0 from the nuScenes official website. We use 34,149 samples for training and 6019 samples for testing.

4.2 Architecture and Training Details

The ECABEV framework employs the workflow of BEVDepth [13] with BEVPoolv2 [55] and SparseBEV [33] to handle camera data. Like BEVDepth [11], multi-frame BEV features are accumulated following BEVDet4D [56] and aggregated with an additional BEV encoder. On the other hand, for radar data, multi-sweep radar points are accumulated by using RCS and Doppler speed as features. Similar to GRIFNet [57] and CRN [40], a dual-stream backbone consists of the aforementioned three stages. CenterPoint [58] and SparseBEV [33] are leveraged as the center head and sparse head, respectively. For BEV semantic segmentation, separate segmentation heads are employed for each task, while 3D multi-object tracking uses estimated velocity to track object centers greedily across frames.

Concerning training, a stage way is used to train the model. In the first stage, the feature fusion model for camera and radar data is trained with the channel attention mechanism. As mentioned above, this can mitigate the issue of sensor data being noisy and performance degradation. In the second stage, the proposed Bilinear interpolation layer normalization is employed to reduce time complexity. The resulting 3D tensor is oriented with respect to the forward-facing camera serving as the reference coordinate system. For training and inference, the images of the six cameras are extracted into 224 × 224 feature maps to adapt to the resource-constrained environment and also the ViT adapter. Five radar sweeps are aggregated as input.

During the training, we set the parameters α = 0.25 and γ = 3, shown in Eq. (4). The initial learning rate was set to 3.0e−4, and the maximum iterations were set to 75,000. All experiments were conducted on a Nvidia TESLA P40 GPU, and the AdamW optimizer [59] is utilized. In addition, a pre-trained weight file from the DinoV2 adapter [43] is utilized to encode camera data. To prevent overfitting, image rotation, cropping, resizing, and flipping are applied, as well as radar horizontal flipping, horizontal rotation, and coordinate scaling. We also re-implemented the baseline models to check their performance in a resource-constrained environment.

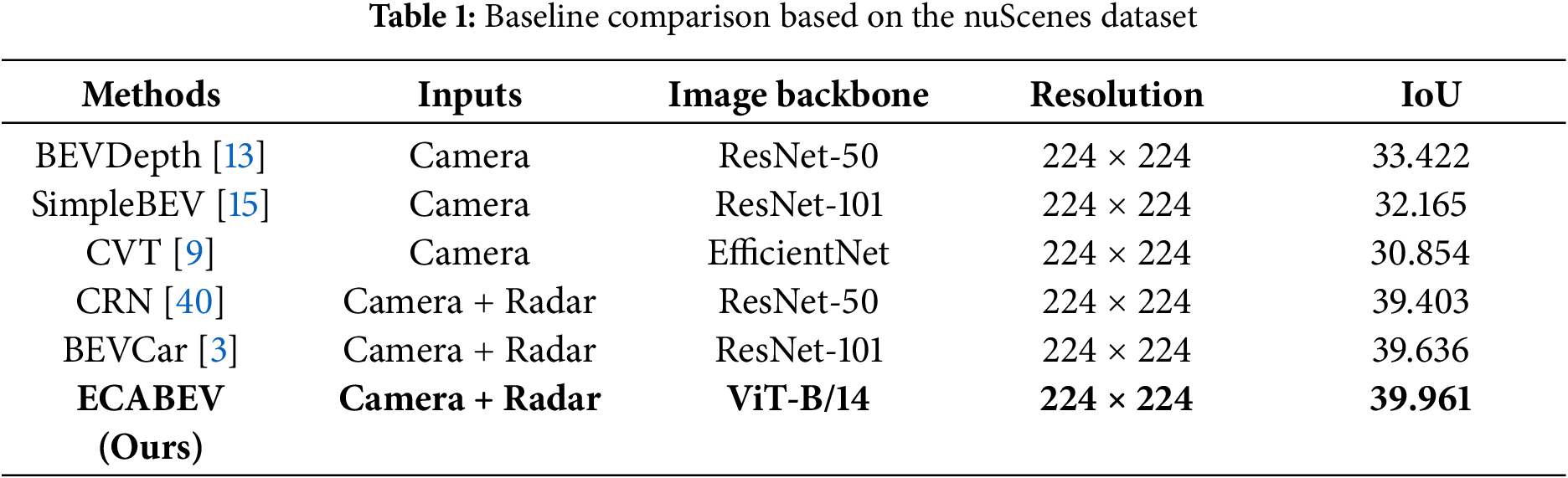

As mentioned above, there are three contributions, i.e., de-noise enhanced channel attention, bilinear interpolation layer normalization, and SCE BEV loss. For the first contribution, it is exploited to refine noisy camera data, for the second contribution, it is designed to downscale intermediate feature maps while maintaining spatial feature fidelity, and for the SCE BEV loss, it is devised to dynamically prioritize rare classes for BEV scene segmentation that need to be object-agnostic. In all designs, resource constraints are given priority consideration. Therefore, in this section, we will compare ECABEV with various baseline works to verify them, as shown in Table 1. The camera-radar fusion methods include BEVDepth [13], SimpleBEV [5], CVT [9], and CRN [40], and the LiDAR-assisted methods include CRN [40] and BEVCar [3] that leverage depth from LiDAR during training. To visualize the robustness from radar data, we compare our model with CRN [40] and BEVCar [3].

Concerning the latter, our model yields a small increase in performance over the BEVCar [3] baseline for the IoU (+0.325). Moreover, our model finds improvement over the BEVDepth [13] (+6.539), SimpleBEV [5] (+7.796), CVT [9] (+9.107), and CRN [40] (+0.558).

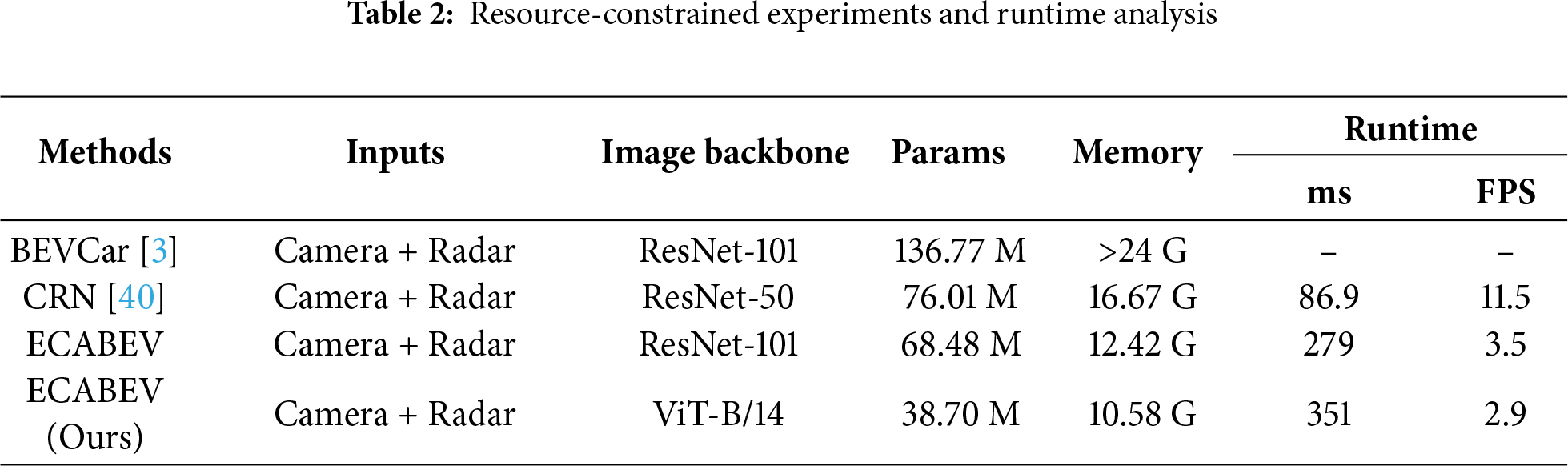

As shown in Table 2, the SOTA BEVCar cannot be utilized in resource-constrained environments, for it arouses an out-of-memory error, while our ECABEV performs so well. Specifically, the parameters of the model, and the memories used by the model far exceed the SOTAs, where ECABEV with a ViT-B/14 backbone achieves the highest accuracy. Overall, it saves about 71.7% in parameters and 55.9% in memories compared with BEVCar. Thus, this confirms that our solution offers a highly compact architecture while remaining deployable on resource-constrained environments.

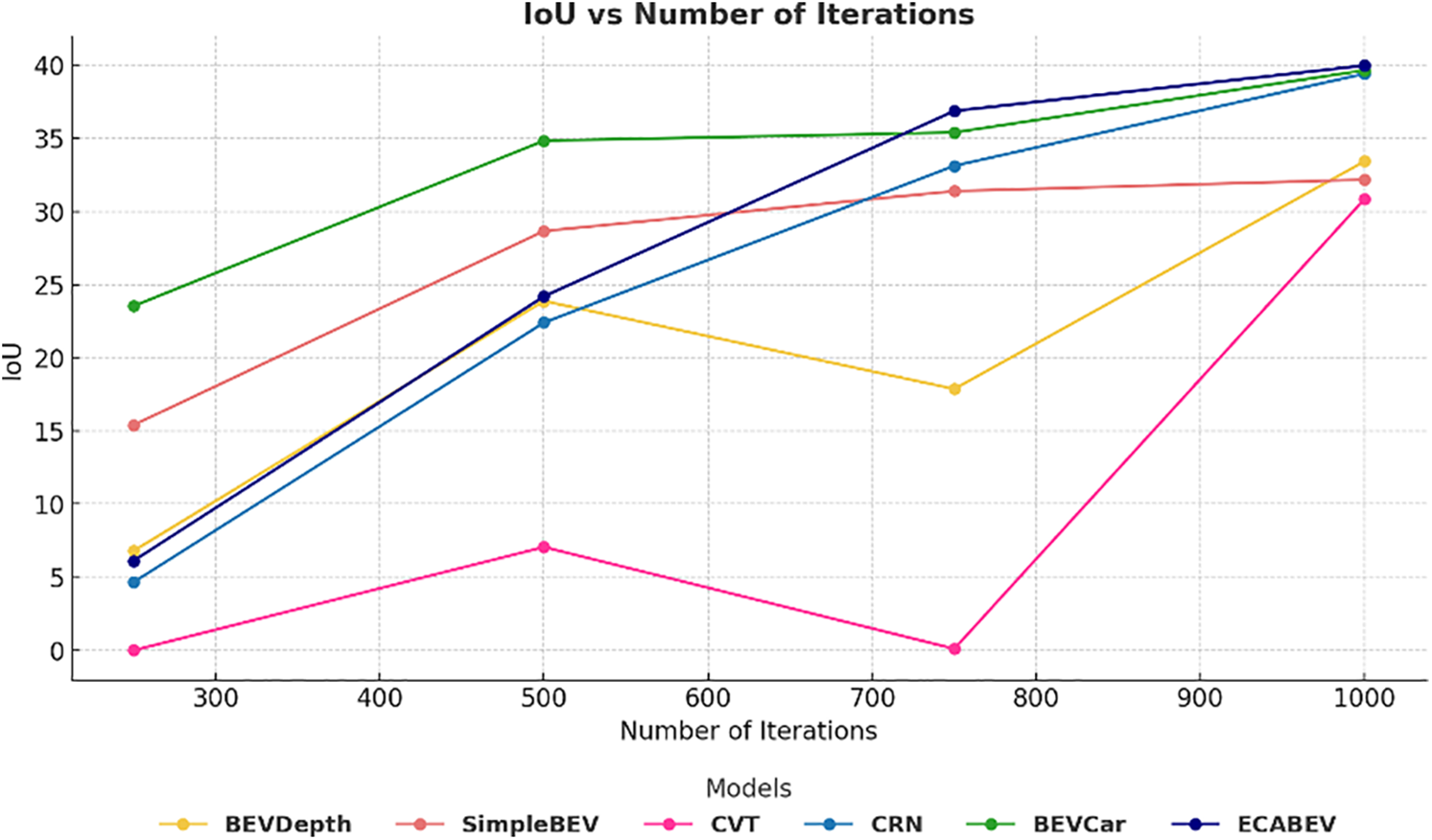

Figs. 6 and 7 show the visualization results of the proposed ECABEV. From Fig. 6, it can be demonstrated that ECABEV performs well during the training of 1000 iterations than other models. It is worth noting that CVT [9] and BEVDepth [13] fall down on the 750th iteration. We speculate that there may be the influence of noisy data, and CVT and BEVDepth cannot adapt well, while ECABEV performs the best adaptation.

Figure 6: Performance based on different numbers of iterations

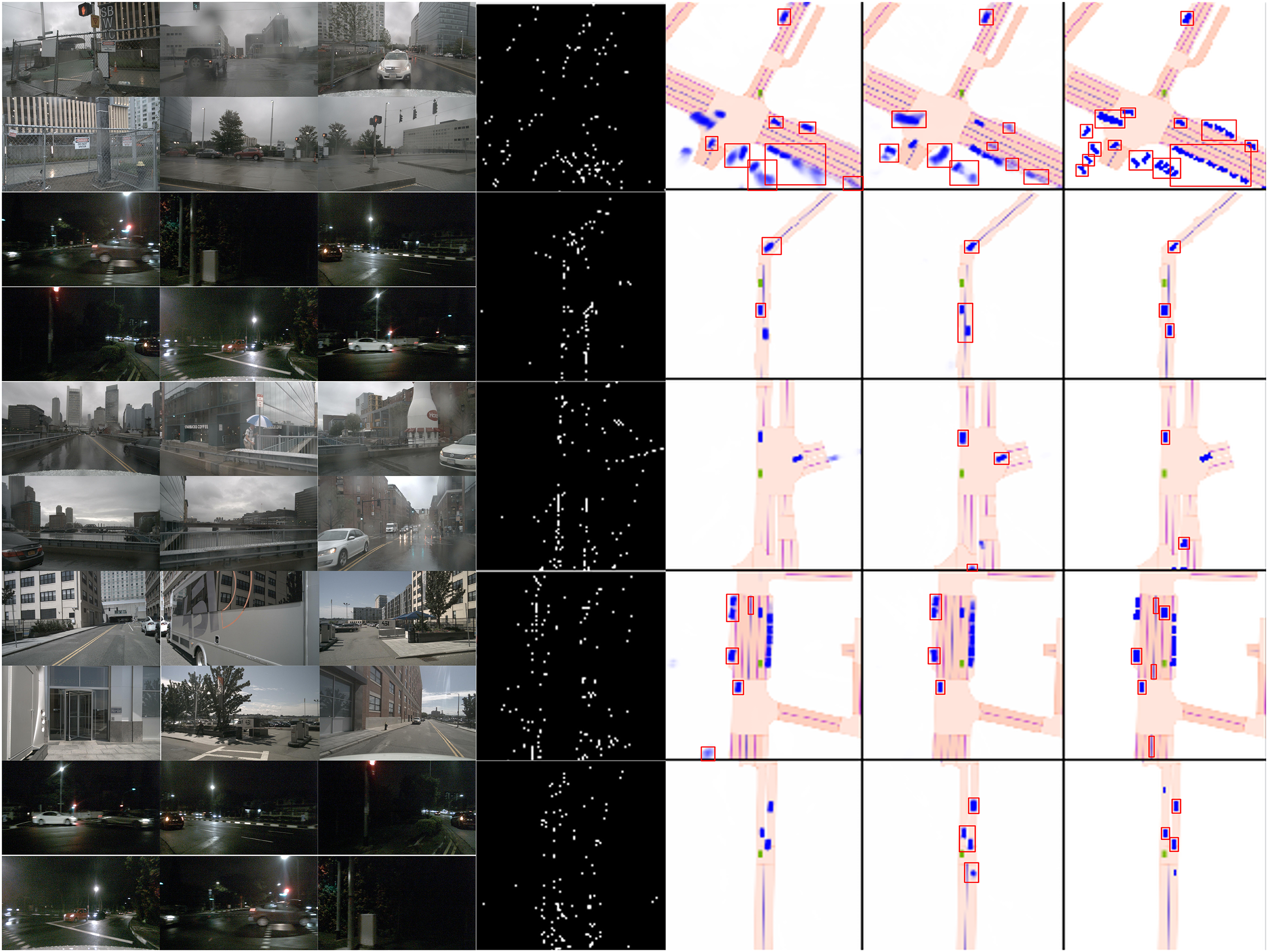

Figure 7: Visual comparisons of BEV segmentation predictions. The left side is the original videos/images, and the right side is the feature maps in different phases. In the final feature maps, red boxes denote predicted objects, and blue boxes indicate ground truth. From left to right, they are CVT [9], BEVCar [3], and ECABEV (ours) in that order

Comparing with other State-of-the-art methods, ECABEV achieves the best result by removing unnecessary noise from the camera input using a de-noise enhanced channel attention and handling imbalanced classes using a scalable cross-entropy BEV loss. Moreover, by incorporating a bilinear interpolation layer normalization, the time complexity issue is also addressed effectively. For traditional vanilla self-attention [3] and spatial cross-attention, they cannot refine the noisy data. The traditional cross-entropy loss function also struggles with large datasets like nuScenes, while our proposed scalable cross-entropy BEV loss function can efficiently handle such large-scale data.

In Fig. 7, we visualize the ego of different baseline models compared with our model. As can be seen, our model has more accurate bounding boxes (red color) compared to ground truth (blue color). We visualized the comparisons of CVT [9], BEVCar [3], and our model. As can be seen in Fig. 7, there are many objects that are blurred, which means they cannot be recognized by CVT and BEVCar, while our model can better recognize them.

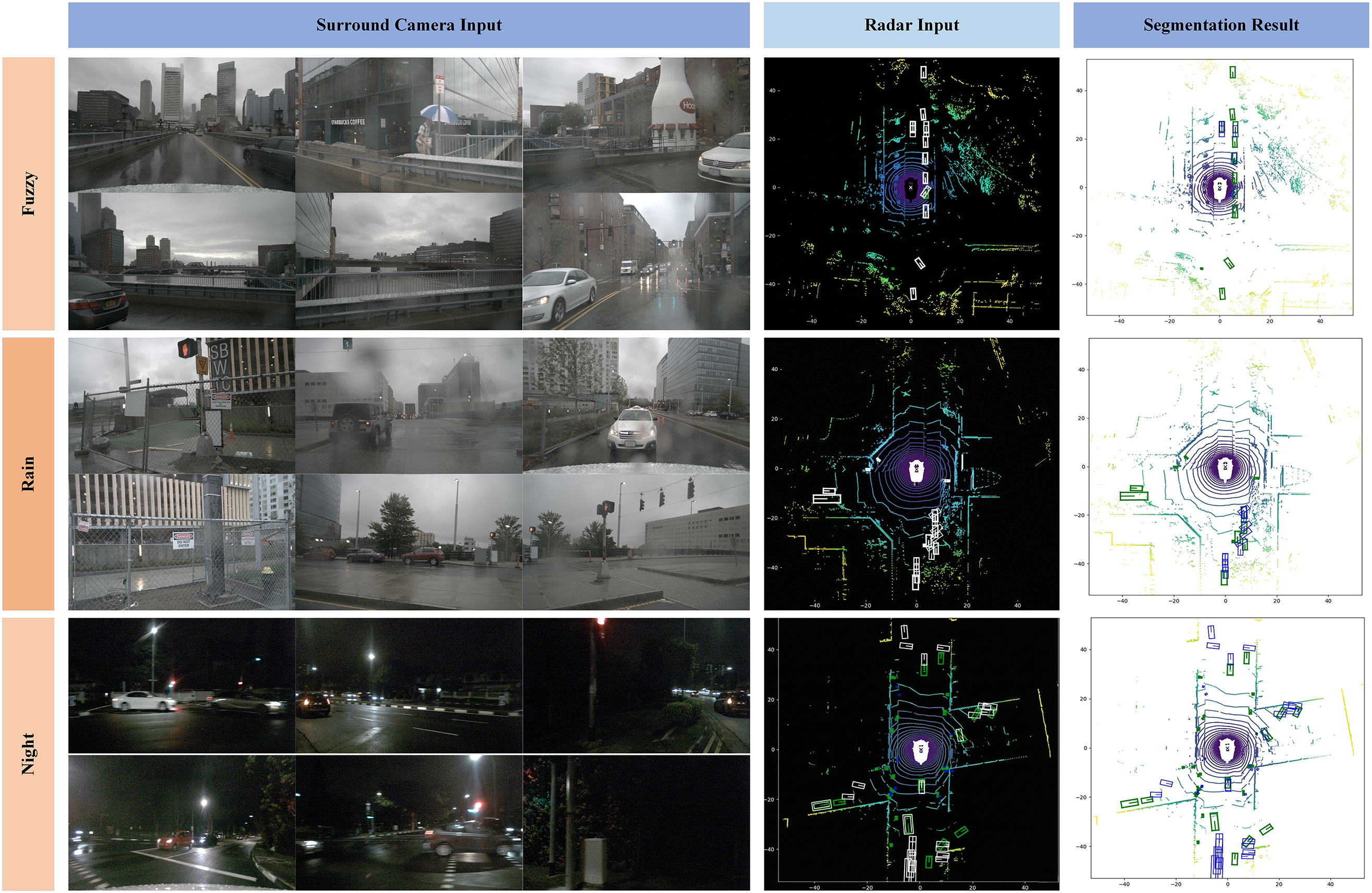

As can be seen in Fig. 8, by using ECABEV, all the objects (segmentation results) are recognized correctly in such adverse weather conditions.

Figure 8: Visualization results for the scene segmentation of fuzzy, rain, and night

4.5 Ablation Study and Analysis

To further analyze the contributions of individual components in ECABEV, we also conducted ablation studies. The experiments were executed and assessed on an Nvidia TESLA P40 GPU with low-end device solutions. Consistent training and validation splits from the nuScenes dataset [4] were exploited, and the utilized metrics include mIoU for semantic segmentation tasks.

The ECABEV framework integrates several critical features that collectively enhance performance while significantly reducing reliance on high-performance hardware. Specifically, the de-noise enhanced channel attention enhances model efficiency by selectively emphasizing significant feature channels and minimizing irrelevant noise in camera data, providing comparable accuracy to traditional high-GPU resource methods. The bilinear layer normalization effectively integrates multi-scale features, optimizing computational efficiency and alleviating computational bottlenecks typically encountered with powerful GPUs. Moreover, the scalable cross-entropy BEV loss manages class imbalance effectively, crucial for robust performance on large-scale datasets such as nuScenes, further highlighting the model’s ability to perform competitively on low-end devices. The corresponding assessments and concerns are as follows.

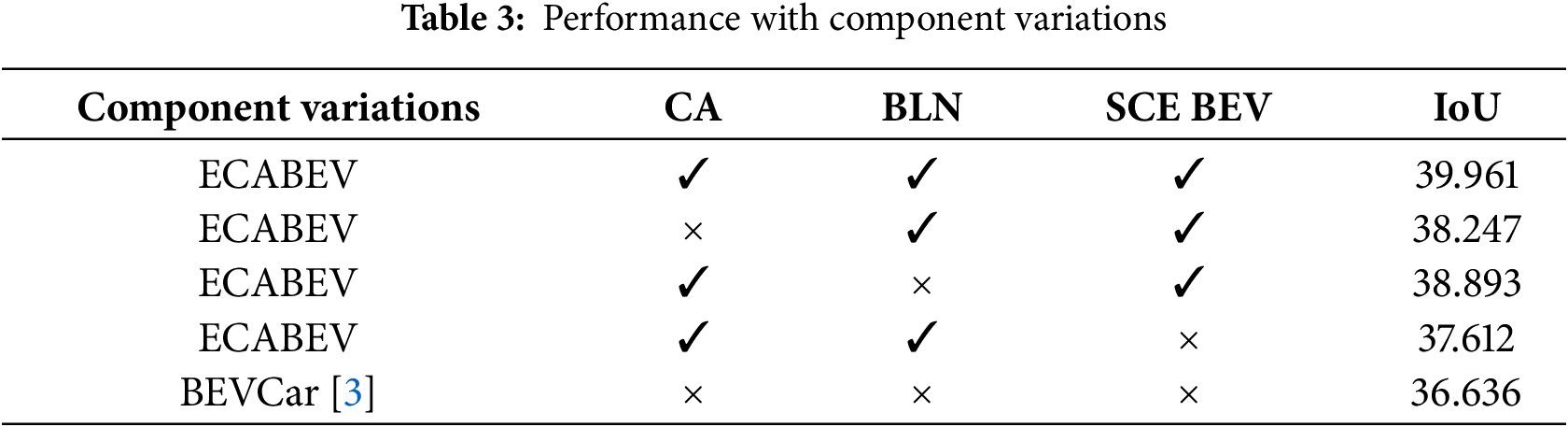

(1) Performance with component variations: Table 3 shows the performance variations with different component configurations. The de-noise enhanced channel attention, denoted as CA, bilinear layer normalization, denoted as BLN, and scalable cross-entropy BEV loss, denoted as SCE BEV, are vital components of the model’s performance. Removing CA leads to a notable IoU reduction (−1.714%) as it minimizes noise in camera inputs by recalibrating feature maps, which is critical for precise segmentation. Excluding BLN results in a moderate performance drop (−1.068%) due to disruption in feature distribution stability and computational efficiency, undermining robust integration. The absence of SCE BEV has the most significant impact (−2.349%) as it tackles class imbalance by prioritizing hard negatives, enhancing the model’s ability to generalize across varied scenarios.

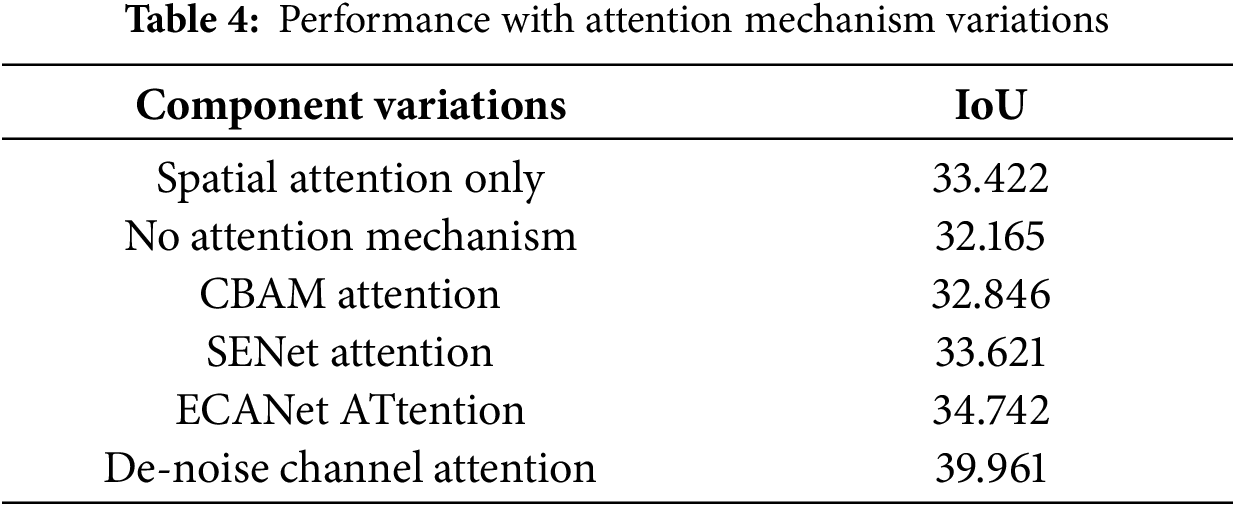

(2) Effectiveness for specific attentions: De-noise enhanced channel attention provides a balance of noise reduction and feature enhancement compared with spatial-only or no-attention setups. To further validate the idea, we replace the proposed de-noise channel attention with ECANet, a widely used lightweight channel-attention baseline. As shown in Table 4, ECANet improves the performance compared with the spatial-only and no-attention variants but still falls short of De-noise channel attention. Although ECANet provides an efficient yet generic channel-attention mechanism, De-noise channel attention is designed to suppress camera noise using radar-guided cues. This task-specific design enables more effective feature refinement and yields superior BEV segmentation accuracy under identical hardware constraints. This confirms that the strategy of de-noise channel attention provides more effective noise suppression and feature refinement in camera radar BEV fusion.

Table 4 shows that the designed de-noise enhanced channel attention surpasses the current representative attention methods.

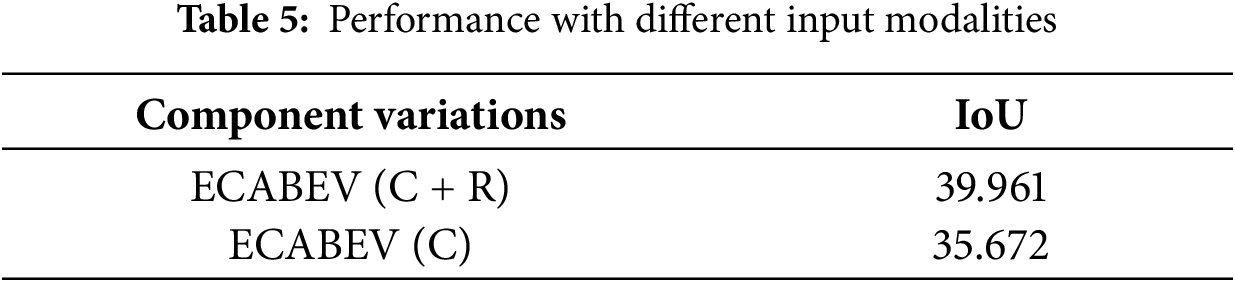

(3) Radar data significantly improves segmentation accuracy by providing robust depth and velocity cues, particularly in radar and camera fusion shown in Table 5.

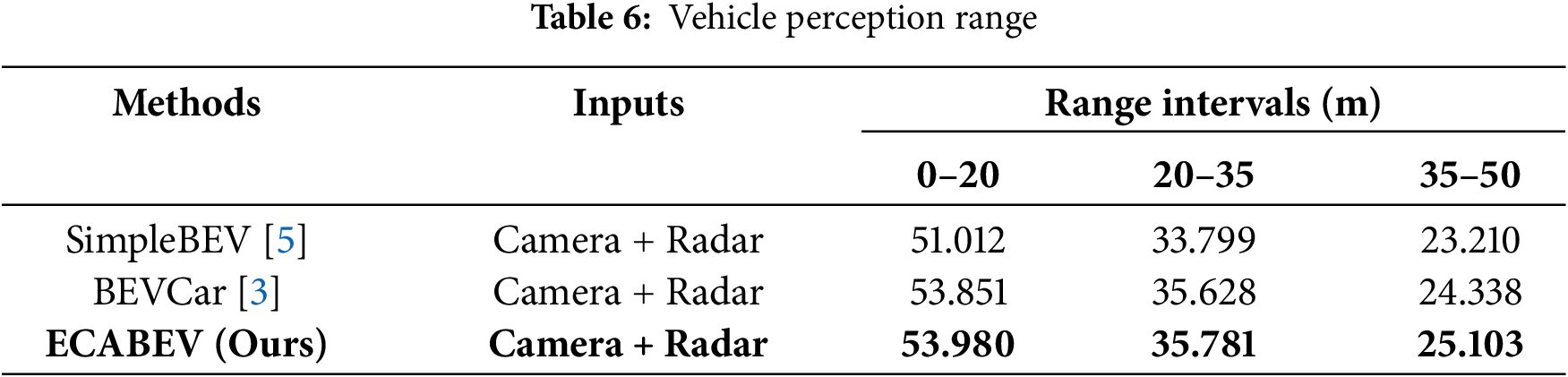

(4) Vehicle segmentation performance across distance ranges: In Table 6, we provide a detailed analysis of vehicle segmentation performance for BEVCar [3], SimpleBEV [5], and our proposed model across three distinct distance intervals: 0–20 m, 20–35 m, and 35–50 m. The results highlight a significant performance disparity between the BEVCar [3] baseline and the ECABEV methods, particularly when considering different distance intervals. For instance, in the 0–20 m range, the camera-only baseline achieves an IoU similar to that of SimpleBEV [5]. However, as the distance increases to the 35–50 m range, the performance of BEVCar [3] deteriorates sharply, dropping to roughly half of its initial IoU. This suggests that the BEVCar [3] approach struggles to maintain segmentation quality at greater distances. While this general performance decline is observed across all camera-radar fusion methods, the severity of the drop is less pronounced in ECABEV compared with the other methods. The segmentation performance of ECABEV remains relatively stable across the distance ranges, demonstrating that the integration of radar measurements significantly improves object segmentation, particularly at longer ranges. This experiment underscores the importance of incorporating radar data, as it helps mitigate the performance degradation typically seen with camera-only methods in more distant regions.

The proposed ECABEV framework effectively addresses critical challenges in BEV scene segmentation for autonomous vehicles, including GPU memory constraints, noisy data, and class imbalance. By incorporating the de-noise enhanced channel attention, the improved fusion approach, and the adaptive BEV loss function, ECABEV outperforms baseline models. Extensive experiments on the nuScenes dataset confirm that ECABEV achieves state-of-the-art accuracy in both object and map segmentation, particularly in resource-constrained environments. The integration of bilinear interpolation and layer normalization enhances computational efficiency without sacrificing accuracy, making the model suitable for deployment on medium-performance GPUs by reducing time complexity. Ablation studies highlight the model’s robustness across varying distance ranges and its inference efficiency, positioning ECABEV as a scalable and efficient solution for multimodal sensor fusion in autonomous driving applications, with promising potential for real-world deployment.

A key direction for future research involves a comprehensive evaluation performance of ECABEV under adverse weather conditions, including heavy occlusion induced by rain, fog, and snow. To establish broader applicability, we plan to benchmark the model against additional large-scale datasets such as Waymo and KITTI. These experiments will critically examine the adaptability of the framework to real-world challenges, ensuring its viability for deployment in safety-sensitive autonomous systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the School of Computer Science, Chongqing University, for providing the laboratory facilities and experimental resources that supported this research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 62262045, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 2023CDJYGRH-YB11, and the Open Funding of SUGON Industrial Control and Security Center, grant number CUIT-SICSC-2025-03.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization and methodology, Argho Dey and Yunfei Yin; experimental setup, Zheng Yuan; programming, Argho Dey; validation, Zhiwen Zeng and Md Minhazul Islam; writing, original draft preparation, Argho Dey; writing, review and editing, Yunfei Yin and Xianjian Bao; supervision, Yunfei Yin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code supporting this study is openly available at https://github.com/YYF-CQU/ECABEV.git. The dataset used—nuScenes is publicly accessible: https://www.nuscenes.org/nuscenes#data-collection.

Ethics Approval: The data used in this study were publicly available datasets on the Internet. No human participants or animals were involved in this research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Peng L, Chen Z, Fu Z, Liang P, Cheng E. BEVSegFormer: bird’s eye view semantic segmentation from arbitrary camera rigs. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2023 Jan 2–7; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 5924–32. doi:10.1109/WACV56688.2023.00588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Huang J, Huang G, Zhu Z, Ye Y, Du D. BEVDet: high‐performance multi‐camera 3D object detection in bird-eye-view. arXiv:2112.11790. 2021. [Google Scholar]

3. Schramm J, Vödisch N, Petek K, Kiran BR, Yogamani S, Burgard W, et al. BEVCar: camera-radar fusion for BEV map and object segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2024 Oct 14–18; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 1435–42. doi:10.1109/IROS58592.2024.10802147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Caesar H, Bankiti V, Lang AH, Vora S, Liong VE, Xu Q, et al. nuScenes: a multimodal dataset for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 11618–28. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Harley AW, Fang Z, Li J, Ambrus R, Fragkiadaki K. Simple-BEV: what really matters for multi-sensor BEV perception? In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2023 May 29–Jun 2; London, UK. p. 2759–65. doi:10.1109/ICRA48891.2023.10160831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Philion J, Fidler S. Lift, splat, shoot: encoding images from arbitrary camera rigs by implicitly unprojecting to 3D. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 13–28; Glasgow, UK. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58568-6_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Witte C, Behley J, Stachniss C, Raaijmakers M. Epipolar attention field transformers for bird’s eye view semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2025 Feb 26–Mar 6; Tucson, AZ, USA. p. 8660–9. doi:10.1109/WACV61041.2025.00839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li Z, Wang W, Li H, Xie E, Sima C, Lu T, et al. BEVFormer: learning bird’s-eye-view representation from multi-camera images via spatiotemporal transformers. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhou B, Krähenbühl P. Cross-view transformers for real-time map-view semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 13750–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu Y, Wang T, Zhang X, Sun J. PETR: position embedding transformation for multi-view 3D object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 8206–14. [Google Scholar]

11. Li Y, Bao H, Ge Z, Yang J, Sun J, Li Z. BEVStereo: enhancing depth estimation in multi-view 3D object detection with temporal stereo. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(2):1486–94. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i2.25234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li J, Lu M, Liu J, Guo Y, Du Y, Du L, et al. BEV-LGKD: a unified LiDAR-guided knowledge distillation framework for multi-view BEV 3D object detection. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2024;9(1):2489–98. doi:10.1109/TIV.2023.3319430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li Y, Ge Z, Yu G, Yang J, Wang Z, Shi Y, et al. Bevdepth: acquisition of reliable depth for multi-view 3D object detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(2):1477–85. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i2.25233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu Y, Yan J, Jia F, Li S, Gao A, Wang T, et al. PETRv2: a unified framework for 3D perception from multi-camera images. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 3239–49. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lin Z, Liu Z, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhu C. RCBEVDet++: toward high-accuracy radar-camera fusion 3D perception network. arXiv:2409.04979. 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Kurniawan IT, Trilaksono BR. ClusterFusion: leveraging radar spatial features for radar-camera 3D object detection in autonomous vehicles. IEEE Access. 2023;11:121511–28. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3328953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yu Z, Wan W, Ren M, Zheng X, Fang Z. SparseFusion3D: sparse sensor fusion for 3D object detection by radar and camera in environmental perception. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2024;9(1):1524–36. doi:10.1109/TIV.2023.3331972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Fent F, Palffy A, Caesar H. DPFT: dual perspective fusion transformer for camera-radar-based object detection. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2025;10(11):4929–41. doi:10.1109/TIV.2024.3507538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shi S, Guo C, Jiang L, Wang Z, Shi J, Wang X, et al. PV-RCNN: point-voxel feature set abstraction for 3D object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 10526–35. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lang AH, Vora S, Caesar H, Zhou L, Yang J, Beijbom O. PointPillars: fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 12689–97. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.01298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shi W, Rajkumar R. Point-GNN: graph neural network for 3D object detection in a point cloud. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1708–16. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu M, Yurtsever E, Brede M, Meng J, Zimmer W, Zhou X, et al. GraphRelate3D: context-dependent 3D object detection with inter-object relationship graphs. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); 2024 Sep 24–27; Edmonton, AB, Canada. p. 3481–8. doi:10.1109/ITSC58415.2024.10919972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang H, Liang H, Wang L, Yao Y, Lin B, Zhao D. Joint resource allocation and security redundancy for autonomous driving based on deep reinforcement learning algorithm. IET Intell Transp Syst. 2024;18(6):1109–20. doi:10.1049/itr2.12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Benrabah M, Mousse CO, Chapuis R, Aufrère R. Efficient and risk-aware framework for autonomous navigation in resource-constrained configurations. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2025;59(3):127–32. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2025.07.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7132–41. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang Q, Wu B, Zhu P, Li P, Zuo W, Hu Q. ECA-Net: efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 11531–9. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hou Q, Zhou D, Feng J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 13708–17. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang Y, Guizilini V, Zhang T, Wang Y, Zhao H, Solomon J. DETR3D: 3D object detection from multi-view images via 3D-to-2D queries. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL); 2021 Nov 8–11; London, UK. [Google Scholar]

30. Lin X, Lin T, Pei Z, Huang L, Su Z. Sparse4D v2: recurrent temporal fusion with sparse model. arXiv:2305.14018. 2023. [Google Scholar]

31. Lin X, Lin T, Pei Z, Huang L, Su Z. Sparse4D: multi-view 3D object detection with sparse spatial-temporal fusion. arXiv:2211.10581. 2022. [Google Scholar]

32. Wang S, Liu Y, Wang T, Li Y, Zhang X. Exploring object-centric temporal modeling for efficient multi-view 3D object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 3621–31. [Google Scholar]

33. Liu H, Teng Y, Lu T, Wang H, Wang L. SparseBEV: high-performance sparse 3D object detection from multi-camera videos. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 18534–44. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.01703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu Z, Tang H, Amini A, Yang X, Mao H, Rus DL, et al. BEVFusion: multi-task multi-sensor fusion with unified bird’s-eye view representation. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2023 May 29–Jun 2; London, UK. p. 2774–81. doi:10.1109/ICRA48891.2023.10160968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang H, Jia D, Ma H. Rainy day image semantic segmentation based on two-stage progressive network. Vis Comput. 2024;40(12):8945–56. doi:10.1007/s00371-024-03287-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Cai Y, Zhou W, Zhang L, Yu L, Luo T. DHFNet: dual-decoding hierarchical fusion network for RGB-thermal semantic segmentation. Vis Comput. 2024;40(1):169–79. doi:10.1007/s00371-023-02773-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lin X, Sun S, Huang W, Sheng B, Li P, Feng DD. EAPT: efficient attention pyramid transformer for image processing. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2023;25:50–61. doi:10.1109/TMM.2021.3120873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Xie Z, Zhang W, Sheng B, Li P, Philip Chen CL. BaGFN: broad attentive graph fusion network for high-order feature interactions. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(8):4499–513. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3116209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Hendy N, Sloan C, Tian F, Duan P, Charchut N, Xie Y, et al. FISHING Net: future inference of semantic heatmaps in grids. arXiv:2006.09917. 2020. [Google Scholar]

40. Kim Y, Shin J, Kim S, Lee IJ, Choi JW, Kum D. CRN: camera radar net for accurate, robust, efficient 3D perception. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 17569–80. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.01615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhu X, Su W, Lu L, Li B, Wang X, Dai J. Deformable DETR: deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021 May 4; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

42. Man Y, Gui LY, Wang YX. BEV-guided multi-modality fusion for driving perception. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 21960–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.02103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Oquab M, Darcet T, Moutakanni T, Vo H, Szafraniec M, Khalidov V, et al. DINOv2: learning robust visual features without supervision. arXiv:2304.07193. 2023. [Google Scholar]

44. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Bhattacharjee D, Süsstrunk S, Salzmann M. Vision transformer adapters for generalizable multitask learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 18969–80. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.01743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bai X, Hu Z, Zhu X, Huang Q, Chen Y, Fu H, et al. TransFusion: robust LiDAR-camera fusion for 3D object detection with transformers. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 1080–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang M, Tian X. Transformer architecture based on mutual attention for image-anomaly detection. Virtual Real Intell Hardw. 2023;5(1):57–67. doi:10.1016/j.vrih.2022.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhu X, Yao X, Zhang J, Zhu M, You L, Yang X, et al. TMSDNet: transformer with multi-scale dense network for single and multi-view 3D reconstruction. Comput Animat Virtual Worlds. 2024;35(1):e2201. doi:10.1002/cav.2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Feng J, He C, Wang G, Wang M. S-LASSIE: structure and smoothness enhanced learning from sparse image ensemble for 3D articulated shape reconstruction. Comput Animat Virtual Worlds. 2024;35(3):e2277. doi:10.1002/cav.2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Mezentsev G, Gusak D, Oseledets I, Frolov E. Scalable cross-entropy loss for sequential recommendations with large item catalogs. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2024 Oct 14–18; Bari, Italy. p. 475–85. doi:10.1145/3640457.3688140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollar P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2999–3007. doi:10.1109/iccv.2017.324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhao T, Chen Y, Wu Y, Liu T, Du B, Xiao P, et al. Improving bird’s eye view semantic segmentation by task decomposition. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 15512–21. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Sun P, Kretzschmar H, Dotiwalla X, Chouard A, Patnaik V, Tsui P, et al. Scalability in perception for autonomous driving: Waymo open dataset. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 2443–51. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Geiger A, Lenz P, Urtasun R. Are we ready for autonomous driving? The KITTI vision benchmark suite. In: Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2012 Jun 16–21; Providence, RI, USA. p. 3354–61. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2012.6248074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Huang J, Huang G. BEVPoolv2: a cutting-edge implementation of BEVDet toward deployment. arXiv:2211.17111. 2022. [Google Scholar]

56. Huang J, Huang G. BEVDet4D: exploit temporal cues in multi-camera 3D object detection. arXiv:2203.17054. 2022. [Google Scholar]

57. Kim Y, Choi JW, Kum D. GRIF net: gated region of interest fusion network for robust 3D object detection from radar point cloud and monocular image. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2020 Oct 24–2021 Jan 24; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 10857–64. doi:10.1109/iros45743.2020.9341177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Yin T, Zhou X, Krahenbuhl P. Center-based 3D object detection and tracking. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 11779–88. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools