Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Detecting and Mitigating Cyberattacks on Load Frequency Control with Battery Energy Storage System

1 Electric Power Dispatching and Control Center, Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd., Guiyang, 550002, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Public Big Data, College of Computer Science and Technology, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhenyong Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 50 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074277

Received 07 October 2025; Accepted 26 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

This paper investigates the detection and mitigation of coordinated cyberattacks on Load Frequency Control (LFC) systems integrated with Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS). As renewable energy sources gain greater penetration, power grids are becoming increasingly vulnerable to cyber threats, potentially leading to frequency instability and widespread disruptions. We model two significant attack vectors: load-altering attacks (LAAs) and false data injection attacks (FDIAs) that corrupt frequency measurements. These are analyzed for their impact on grid frequency stability in both linear and nonlinear LFC models, incorporating generation rate constraints and nonlinear loads. A coordinated attack strategy is presented, combining LAAs and FDIAs to achieve stealthiness by concealing frequency deviations from system operators, thereby maximizing disruption while evading traditional detection. To counteract these threats, we propose an Unknown Input Observer (UIO)-based detection framework for linear and nonlinear LFCs. The UIO is designed using linear matrix inequalities (LMIs) to estimate system states while isolating unknown attack inputs, enabling attack detection through monitoring measurement residuals against a predefined threshold. For mitigation, we leverage BESS capabilities with two adaptive strategies: dynamic mitigation for dynamic LAAs, which tunes BESS parameters to enhance the system’s stability margin and accelerate convergence to equilibrium; and static mitigation for static LAAs and FDIAs. Simulations show that the UIO achieves high detection accuracy, with residuals exceeding thresholds promptly under coordinated attacks, even in nonlinear models. Mitigation strategies reduce frequency deviations by up to 80% compared to unmitigated cases, restoring stability within seconds.Keywords

The reliable operation of modern power grids is critically dependent on Load Frequency Control (LFC) systems, which maintain the balance between power generation and demand, thereby ensuring stable grid frequency [1]. However, the increasing complexity and interconnectivity of power systems, particularly with the growing integration of renewable energy sources and advanced communication infrastructures, have exposed them to new vulnerabilities, including cyberattacks [2]. These cyber threats pose significant risks to grid stability, potentially leading to widespread blackouts and economic disruption.

Cyberattacks on LFC systems can manifest in various forms, such as false data injection (FDI) into sensor measurements or control commands [3,4], and load-altering attacks (LAA) [5,6] that manipulate demand-side parameters. These attacks can deceive control systems, leading to incorrect control actions, frequency excursions, and ultimately, system instability. The challenge lies not only in detecting such sophisticated attacks but also in mitigating their impact effectively and rapidly to maintain grid resilience. FDI attacks have been widely studied as a means to manipulate sensor measurements or control signals in LFC, leading to frequency deviations [7]. For instance, optimal FDIA schemes against automatic generation control (AGC) in LFC have been analyzed to disrupt frequency regulation [8]. Load-altering attacks (LAAs), including dynamic and static variants, have also been investigated for their ability to create generation-load imbalances [9].

Detection techniques often leverage observers or data-driven approaches. Unknown input observers (UIOs) have proven effective for detecting cyberattacks in large-scale power systems by estimating states while isolating unknown disturbances [10]. Specifically for LFC, UIOs have been applied to detect attacks on tie-line power in multi-area systems and to enable secure state estimation under sparse sensor attacks [11]. Sliding mode observers and Kalman filters combined with UIOs have been proposed for robust detection in power grids [12,13]. Data-driven methods, including deep reinforcement learning for attack detection in LFC and machine learning for hybrid cyberattacks in power grids, offer alternatives to model-based approaches [14,15].

Mitigation strategies frequently incorporate energy storage systems. Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) have been utilized for frequency control in renewable grids under cyberattacks [16]. Defense mechanisms against LAAs in LFC include tolerant control strategies that adjust system parameters to maintain stability [17]. Reviews highlight the implementation, detection, and mitigation of cyberattacks, emphasizing the role of BESS in enhancing resilience [18].

While prior work has advanced UIO-based detection for FDIAs or LAAs individually, few address coordinated scenarios in which dynamic load-altering attacks (DLAAs), static load-altering attacks (SLAAs), and FDIAs are combined to achieve stealth by concealing frequency deviations. Existing UIO applications in LFC are often limited to linear models and multi-area tie-line attacks, whereas data-driven methods may require extensive training data and lack interpretability for real-time operation. Mitigation via BESS in previous studies focuses on general frequency regulation under hybrid attacks. Still, it does not explicitly tune BESS parameters or inject power adaptively for coordinated attack recovery, nor does it extend to nonlinear LFC models incorporating generation rate constraints or nonlinear loads. In contrast, this paper integrates UIO detection with BESS mitigation in a unified framework, addressing stealthy coordinated attacks and nonlinearities to improve robustness [19].

This paper addresses the critical issue of detecting and mitigating coordinated cyberattacks on LFC systems augmented with BESS. Our key contributions are as follows: (1) We model a stealthy coordinated attack scenario combining DLAAs, SLAAs, and FDIAs, designed to maximize disruption while evading detection by concealing frequency deviations; (2) We propose a UIO-based approach for attack detection, extended to both linear and nonlinear LFC models, enabling state estimation and residual monitoring even in the presence of unknown attack signals; (3) We develop BESS-enabled mitigation strategies, including dynamic tuning of BESS parameters for DLAAs and static power injection for SLAAs and FDIAs, to rapidly restore frequency stability; (4) Through simulations on real load data, we validate the UIO’s detection accuracy and the BESS’s mitigation efficacy, demonstrating enhanced resilience against sophisticated cyber threats in LFC systems.

2 Load Frequency Control with the Battery Energy Storage System

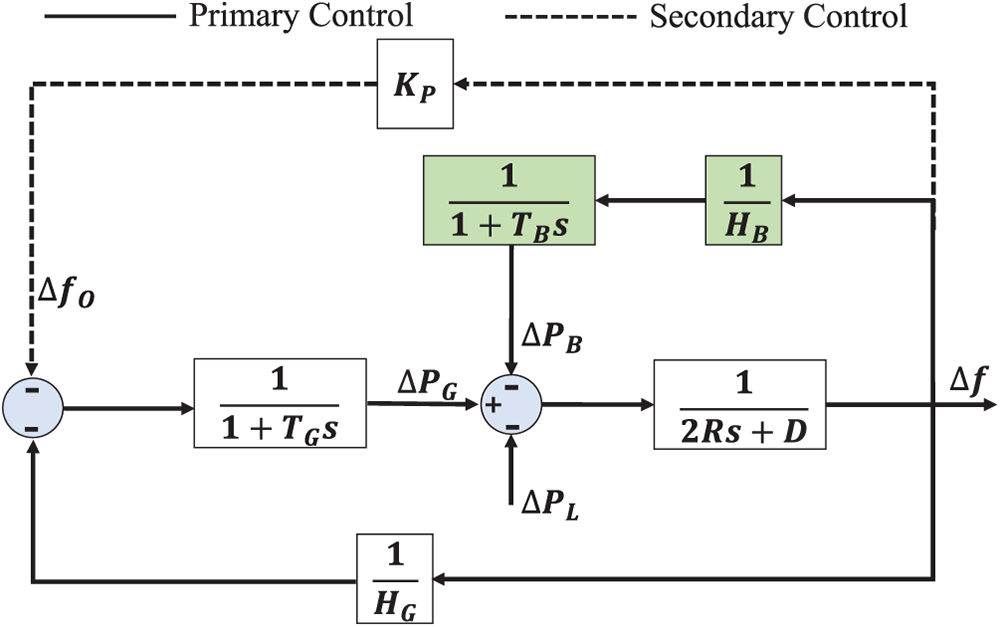

Here, we introduce the load frequency control (LFC) with the battery energy storage system (BESS). The function of the LFC is to balance the power load and generation, thereby maintaining the grid frequency at its nominal value (e.g., 50 or 60 Hz). The BESS is a quick-acting module that compensates for the generator’s response to frequency variations. It detects frequency deviation and rapidly injects power into the grid (in the event of a shortage) or absorbs power (in the event of an excess) to counteract the imbalance. BESS has the potential to address the stability issues caused by increasing penetration of renewable energy sources. In this paper, the BESS is integrated into the system to provide primary frequency control reserves. As shown in Fig. 1, the primary and the secondary control are given with respect to the frequency deviation. For more details, the formal descriptions are given as follows. The primary control with BESS is

where

Figure 1: The diagram of the LFC with BESS

To be concise, we rewrite system model in state-space form. By letting

where

3 Coordinated Attack on the LFC

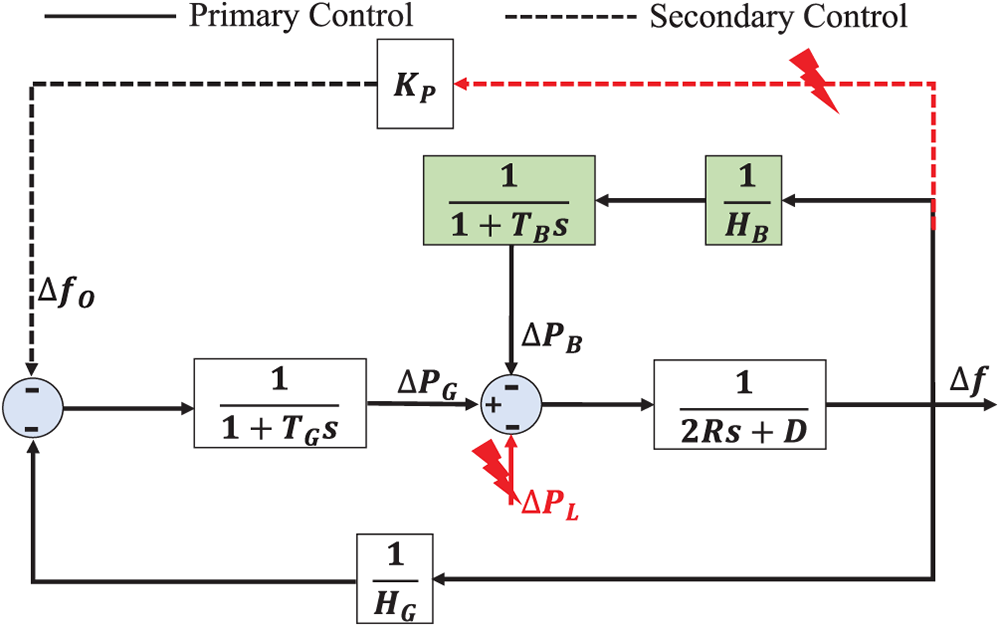

However, because it relies on information and communication infrastructure, load frequency control is vulnerable to cyberattacks. Since the load is on the user’s side, the load measurement can be manipulated, allowing the actual load to be maliciously altered. The secondary control requires communication between the field site and the control center, creating opportunities for attackers to corrupt measurements and control commands. The attack scenarios are given in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The attack on the LFC with BESS

First, for the load, suppose it can be modelled with the frequency-sensitive and static loads, that is,

where

where

The load-altering attack can cause a generation-load imbalance, leading to frequency variation and potentially an unstable system.

3.2 False Data Injection Attack

Second, the frequency measurement can be compromised in the communication network. That is, the false data injection attack (FDIA) is executed by injecting an error into the frequency deviation. The FDIA can be modeled as

where

In some cases, the attacker is powerful and can carry out a coordinated attack. For example, the attack on the Ukrainian power grid in 2015 was a typical coordinated attack, executing cyberattacks in a perfectly organized manner at specific locations to maximize the impact on the system’s operation [20]. In our scenario, the load-altering attack and FDIA can be coordinated to make the attack stealthy. The coordinated attack can be modeled as

Furthermore, we can derive that

The stealthiness of the coordinated attack is achieved by using

4 Attack Detection with the Unknown Input Observer

The attacks introduced in Section 3 pose a serious threat to the system’s normal operation. The unexpected distortions cause the LFC to fail to maintain generation-load balance, leading to frequency excursions and potentially destabilizing the grid. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and capture this abnormal behavior. Considering the attacks as unknown inputs, we aim to design an unknown-input observer (UIO) to detect them. The system model with the unknown attack is given as

Since the power load changes with a lot of uncertainties, the

Considering a full-order UIO [21], the observer proposed for detecting attacks is given by the following structure. That is, we have

where

where S and V should be designed for the UIO. With the UIO, the state estimation error is

Taking the derivative of the estimation error, we have

Therefore, we can obtain that

The latter can be derived as

Next, a sufficient condition is provided to prove the existence of the UIO.

Lemma 1. There exists a UIO for the unknown input system (10) if there exist S and V and a positive definite symmetric matrix

Proof: Based on the above derivations, we have

Therefore, with the conditions given in Lemma (1), the UIO accurately estimates the system state without knowing the input

where

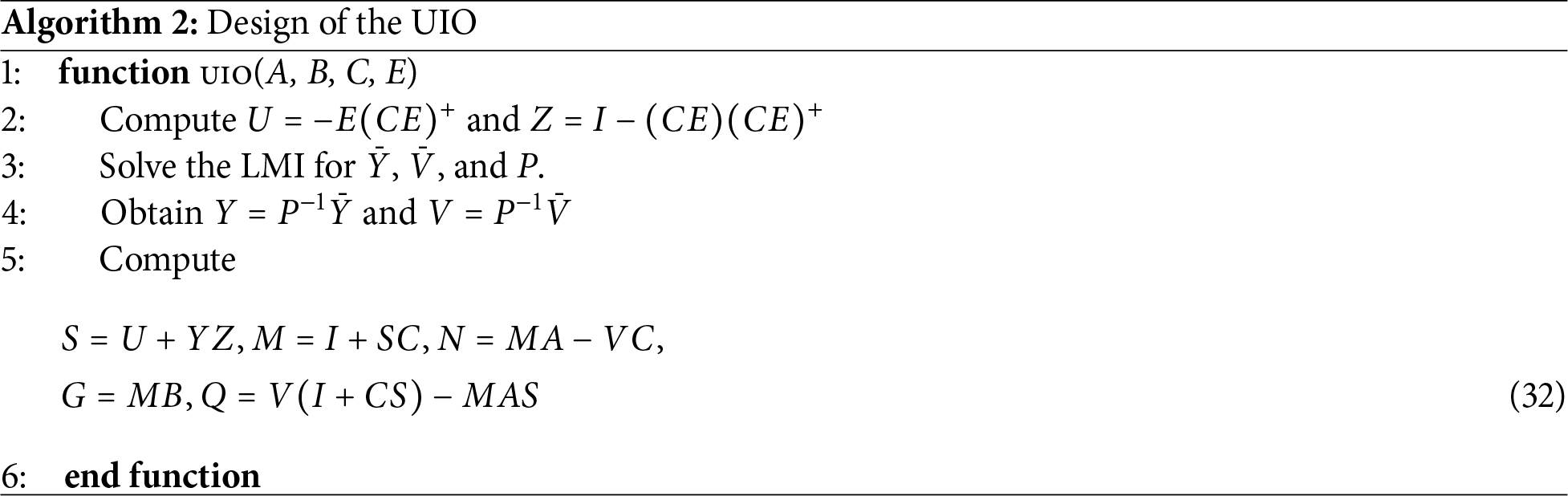

Therefore, solving the S, V, and

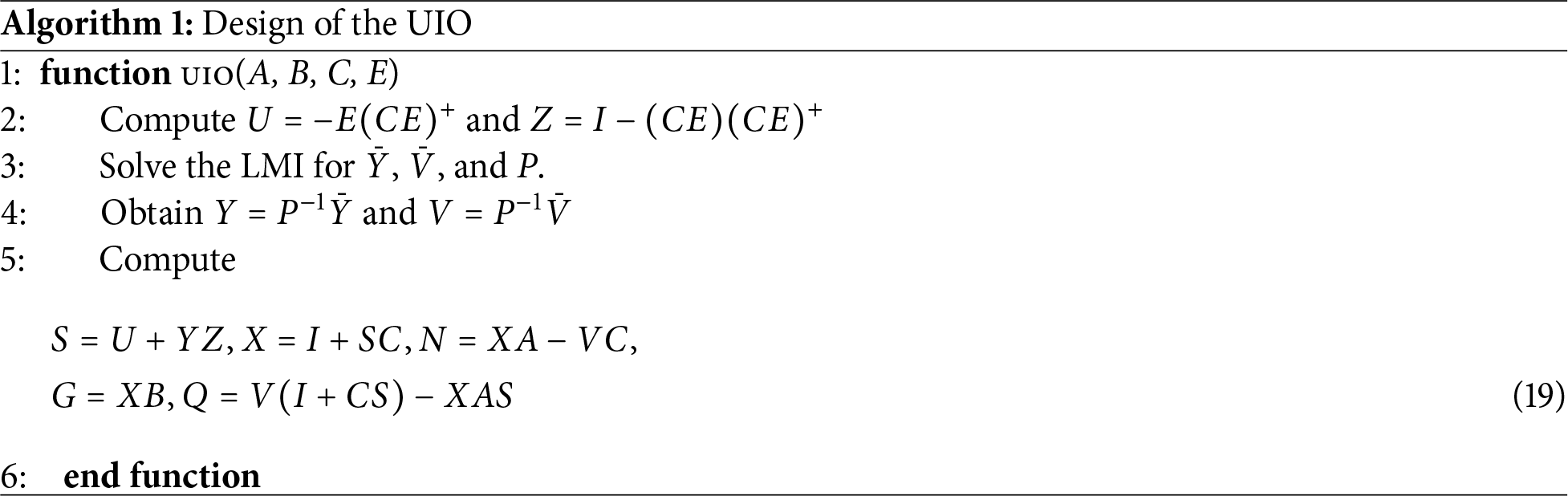

Above all, the algorithm for designing the UIO is given in Algorithm 1. With the designed UIO, the attacks are detected by monitoring the measurement residual

Discussion. In our paper, the LMIs are solved offline during the UIO design phase to determine fixed matrices such as S, V, and P, which are then used to compute the observer gains N, W, and Q. Once designed, the real-time operation of the UIO involves only simple matrix-vector multiplications on a low-dimensional system (3 states for our single-area LFC model), which is computationally lightweight and executes in microseconds on standard hardware, well within LFC sampling intervals. For the offline LMI solving, modern solvers like MATLAB’s LMI Toolbox or CVX handle small-scale problems (e.g., 3 × 3 matrices) efficiently, often in under 10 milliseconds on a standard CPU, as polynomial-time algorithms (e.g., interior-point methods) scale well for such dimensions. For context, larger LMIs in power system applications (e.g., with thousands of variables) have been reported to solve in minutes, but our case is negligible.

5 Mitigation of the Attacks with BESS

Once the attack is detected, mitigation measures should be implemented to reduce its impact. Here, the BESS is used to counteract the cyberattacks. There are two strategies to defend against the load-altering attacks and FDIA.

Considering the DLAA only, from (9), we have

Concisely, we can rewrite (20) as

The system modes of (21) depend on the matrix

With BESS, the parameters

Considering the SLAA and FDIA, from (9), we have

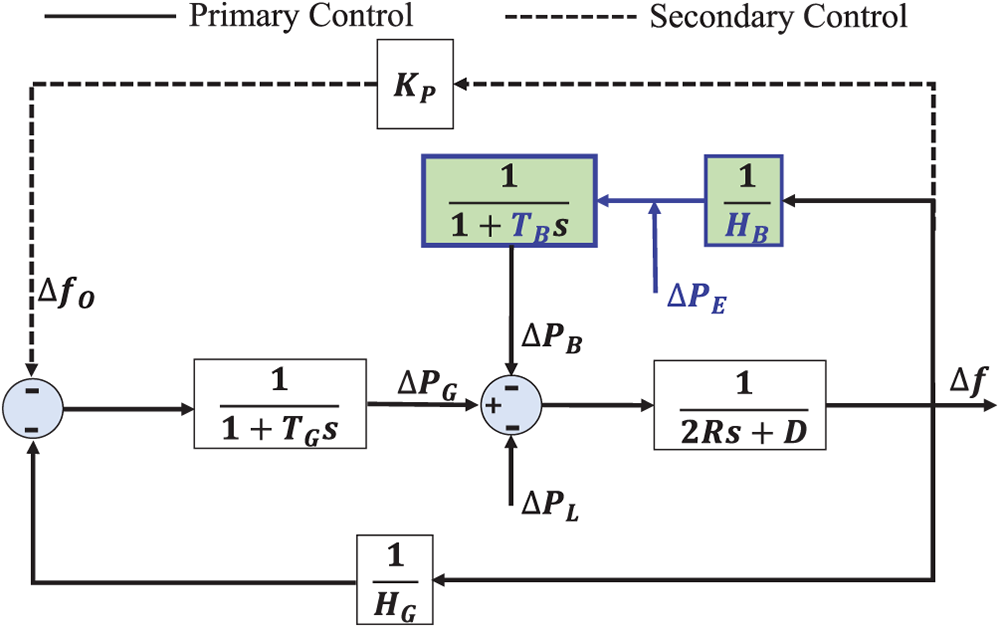

The BESS can mitigate the attack by injecting energy into the system. As shown in Fig. 3, the power is injected to balance the unexpected load and the modified measurement (which results in a wrong frequency reference). With the mitigation strategy, we can derive that

where

Figure 3: The attack mitigation with BESS

In Section 2, we consider a linear model for the LFC. However, there are nonlinearities in the generator and BESS. Therefore, the designed UIO should be extended to the nonlinear case. The unknown input is the attack presented in Section 3. In the following, we present two examples of nonlinearity.

In case 1, the generation rate constraint (GRC) is considered. The GRC limits changes in generation power. This is a saturation nonlinearity on the derivative of

where

where

In case 2, the load consists of a frequency-sensitive nonlinear component. That is, the load is modeled as

In different nonlinear cases, the matrices A, B, and E might be different. However, the UIO is designed in a general form. The structure of the UIO is

The matrices N, W, Q, and M are matrices that should be designed for the UIO. They are defined by

From the three nonlinear cases, we can easily derive that

where

Lemma 2. There exists a UIO for the unknown input system (10) if there exist S and V and a positive definite symmetric matrix

Proof: We can derive that

The condition

With the Lemma 2, the matrices S, V, and P are computed according to the condition

Solving (30) for S, V, and P is an LMI problem. We can construct a matrix inequality as

where

Discussion. The onlinearities are modeled as additive terms

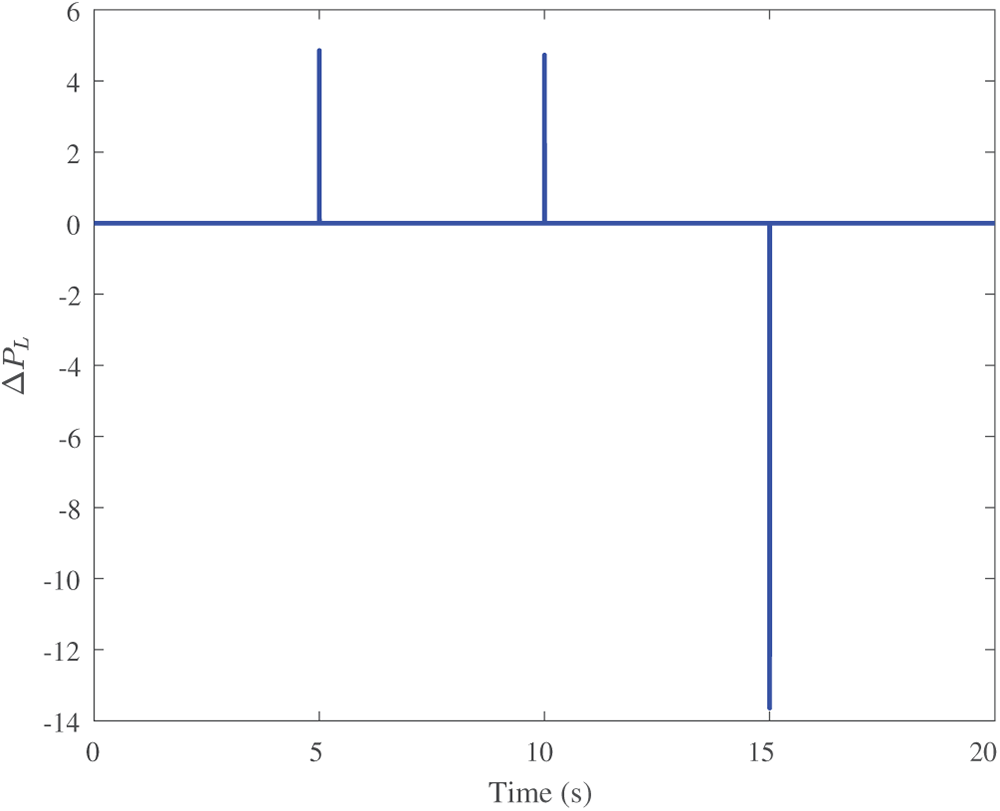

In this section, we conduct simulations to analyze the impact of the attack, the UIO’s attack-detection performance, and the BESS’s mitigation performance. All simulations are carried out in MATLAB (Simulink), and the computational device is a laptop equipped with an 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-1165G7 processor, operating at 2.80 GHz and featuring 32 GB of RAM. The system parameters are set to as

Figure 4: The power load variation

First, we analyze the impact of the attacks described in Section 3 on the grid frequency. The attack parameters are:

• DLAA: Only the DLAA is executed, the frequency-sensitive load coefficient is

• SLAA: Only the SLAA is executed, the loads are injected at 8 s with

• FDIA: Only the FDIA is executed, the measurement of the frequency deviation is modified with an error

• SLAA+FDIA: The SLAA and FDIA are coordinated. The attack parameters for SLAA remain unchanged, while the FDIA mitigates the attack’s impact by injecting a measurement error.

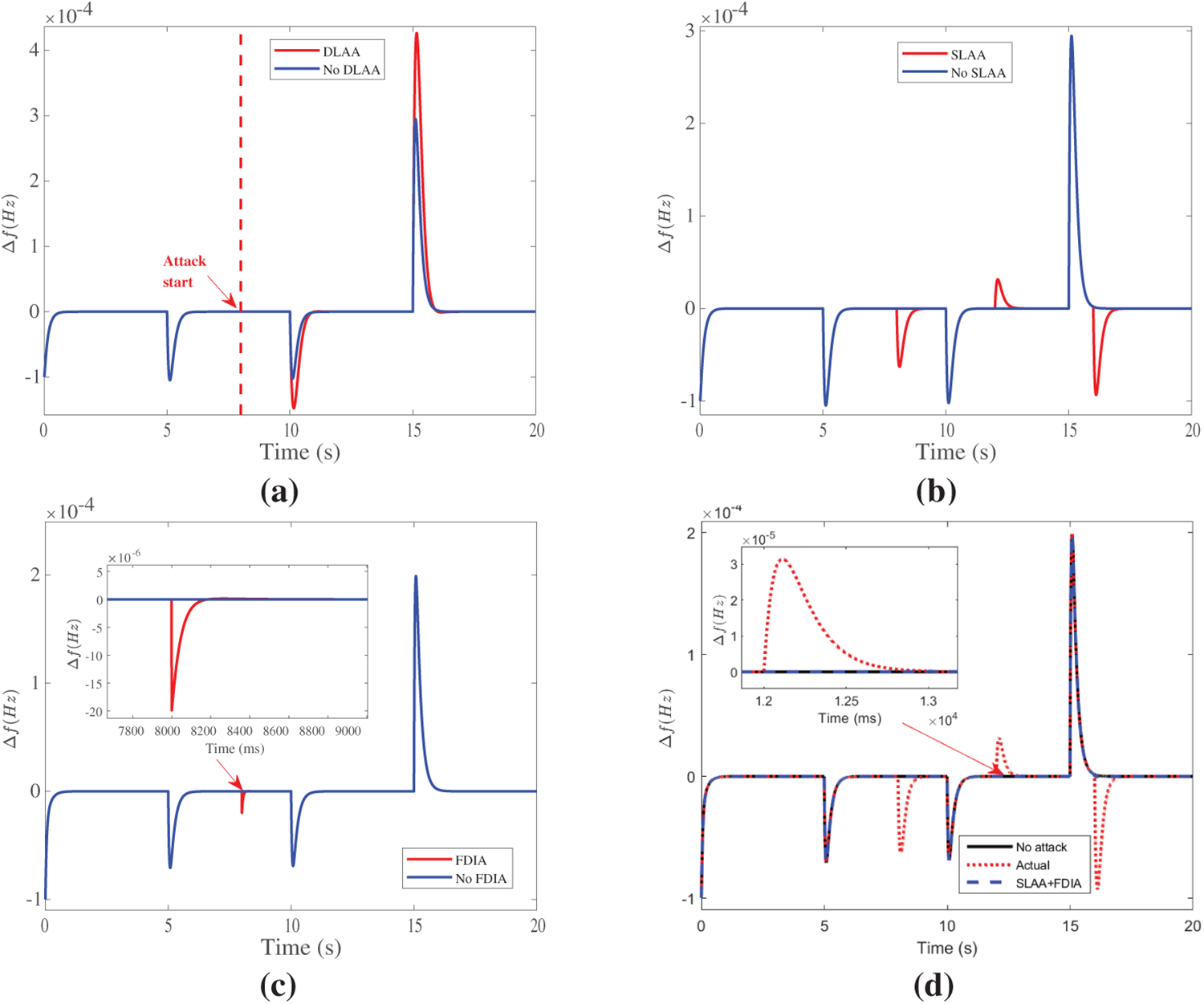

The simulation results are given in Fig. 5. For the DLAA (Fig. 5a), we find that the magnitude of

Figure 5: Simulation results demonstrating the impact of various cyberattacks on grid frequency deviation (

7.2 Attack Detection with the UIO

By solving the LMI, we obtain the parameters for designing the UIO. For the linear LFC, we obtain the following matrices:

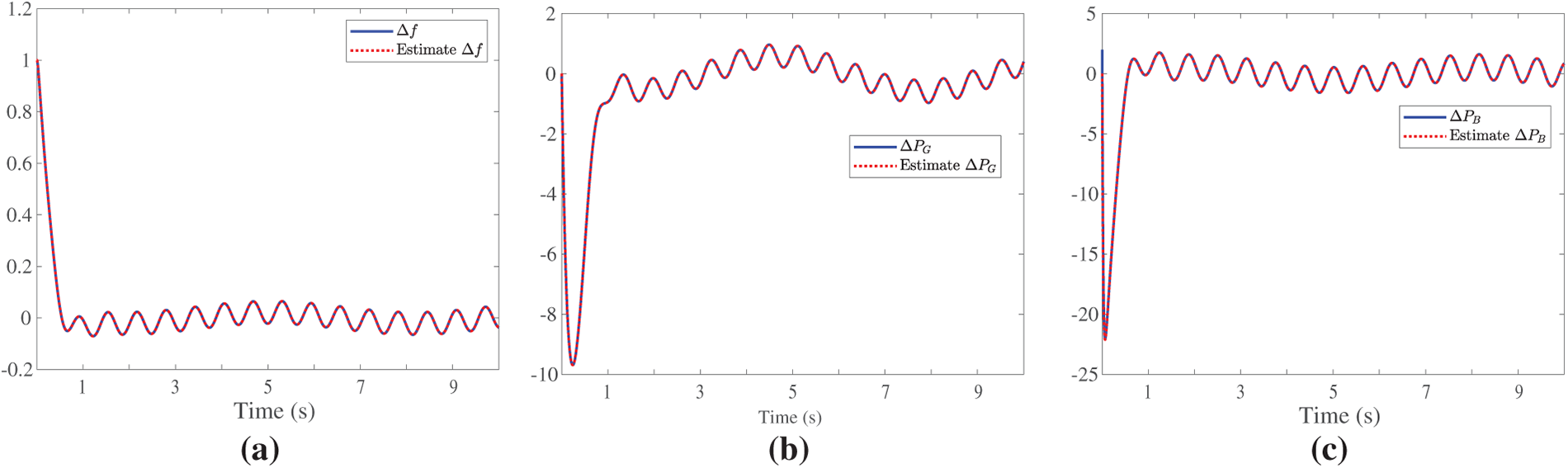

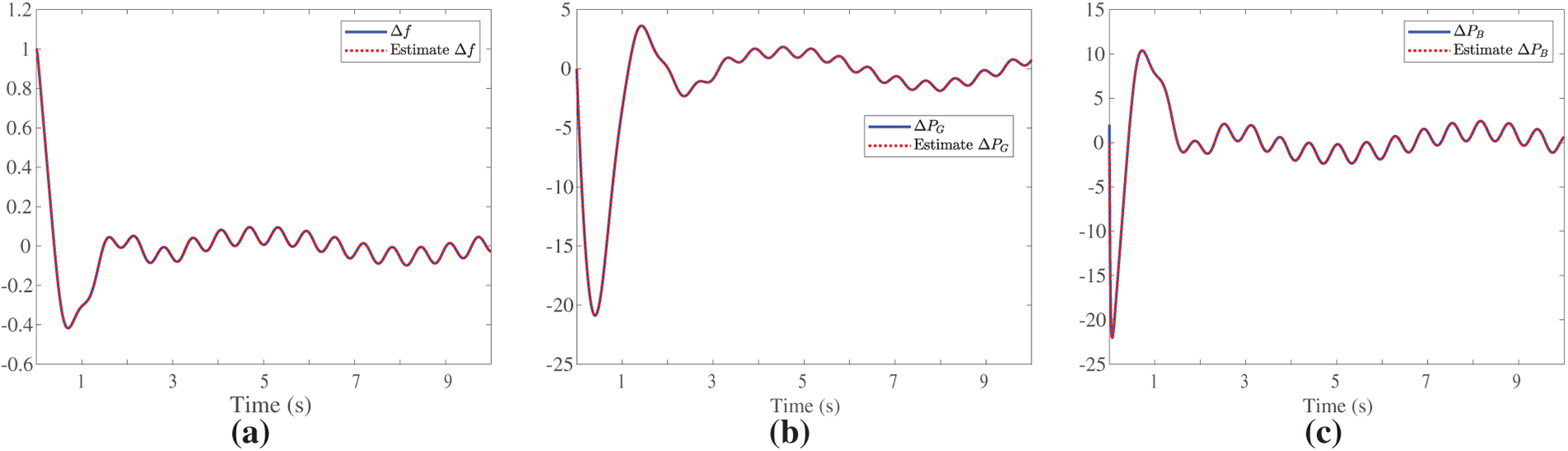

First, we evaluate the performance of UIO in estimating system states. The results are given in Fig. 6, which shows that the estimated

Figure 6: State estimation performance of the designed UIO under attack scenarios on linear LFC. (a) Estimated

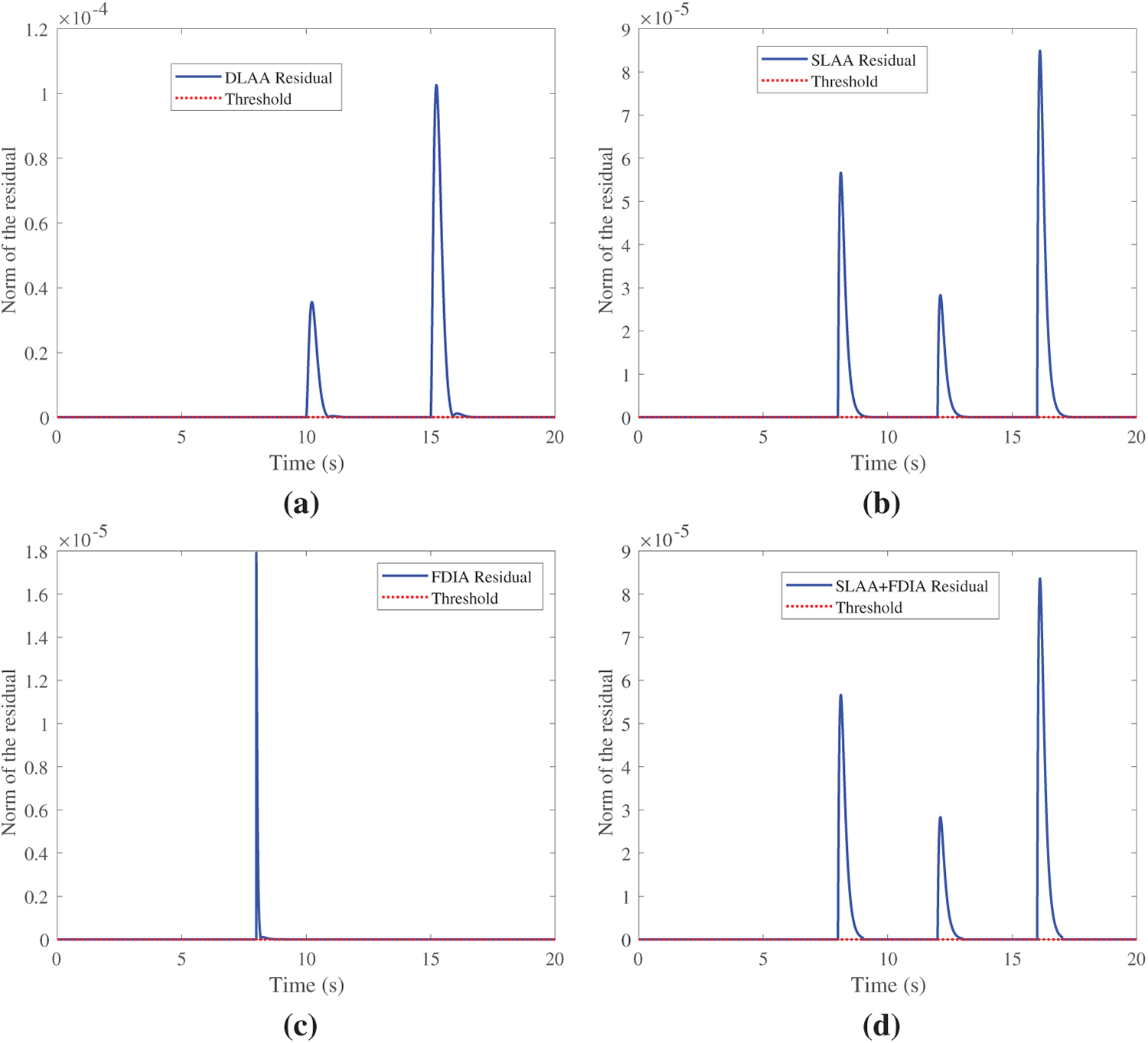

With the UIO, we evaluate its performance in detecting attacks. The detection performance is illustrated in Fig. 7, which shows that the norm of the residual with the UIO exceeds the detection threshold for DLAA, SLAA, FDIA, and SLAA+FDIA, respectively. For all attacks, the UIO accurately captures the abnormal deviations in

Figure 7: Attack detection via UIO residual norms (

7.3 Mitigation of the Attack with the BESS

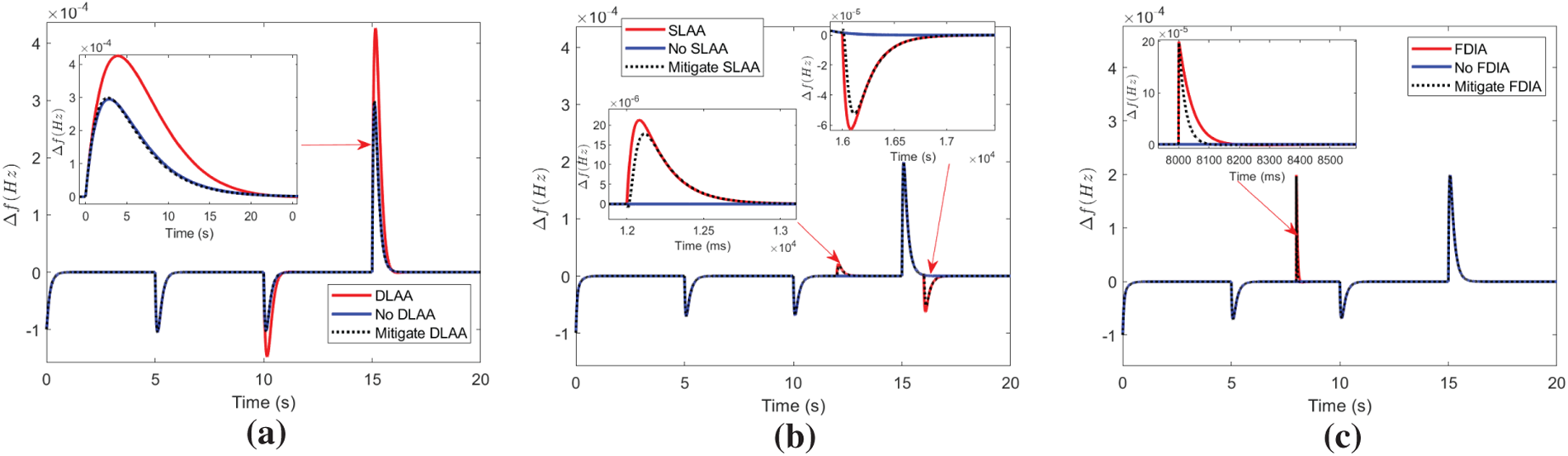

Finally, we evaluate the mitigation performance of the attacks with the BESS. The mitigation strategies are given in Section 5. The simulation results are presented in Fig. 8. For DLAA, the mitigation strategy involves tuning the BESS parameters

Figure 8: Mitigation performance using BESS strategies post-UIO detection on linear LFC. (a) For DLAA, adaptive tuning of

For the SLAA, the battery power (i.e.,

In the following, we evaluate the performance of the UIO designed for the nonlinear LFC. For case 1, the UIO parameters are obtained in the following:

We can see that the UIO parameters in cases 1 and 2 are almost identical, as shown in case 1. The estimation performance is shown in Fig. 9, which indicates that the estimated

Figure 9: State estimation performance of the extended UIO for nonlinear LFC models (incorporating GRC and quadratic loads). (a) The estimated

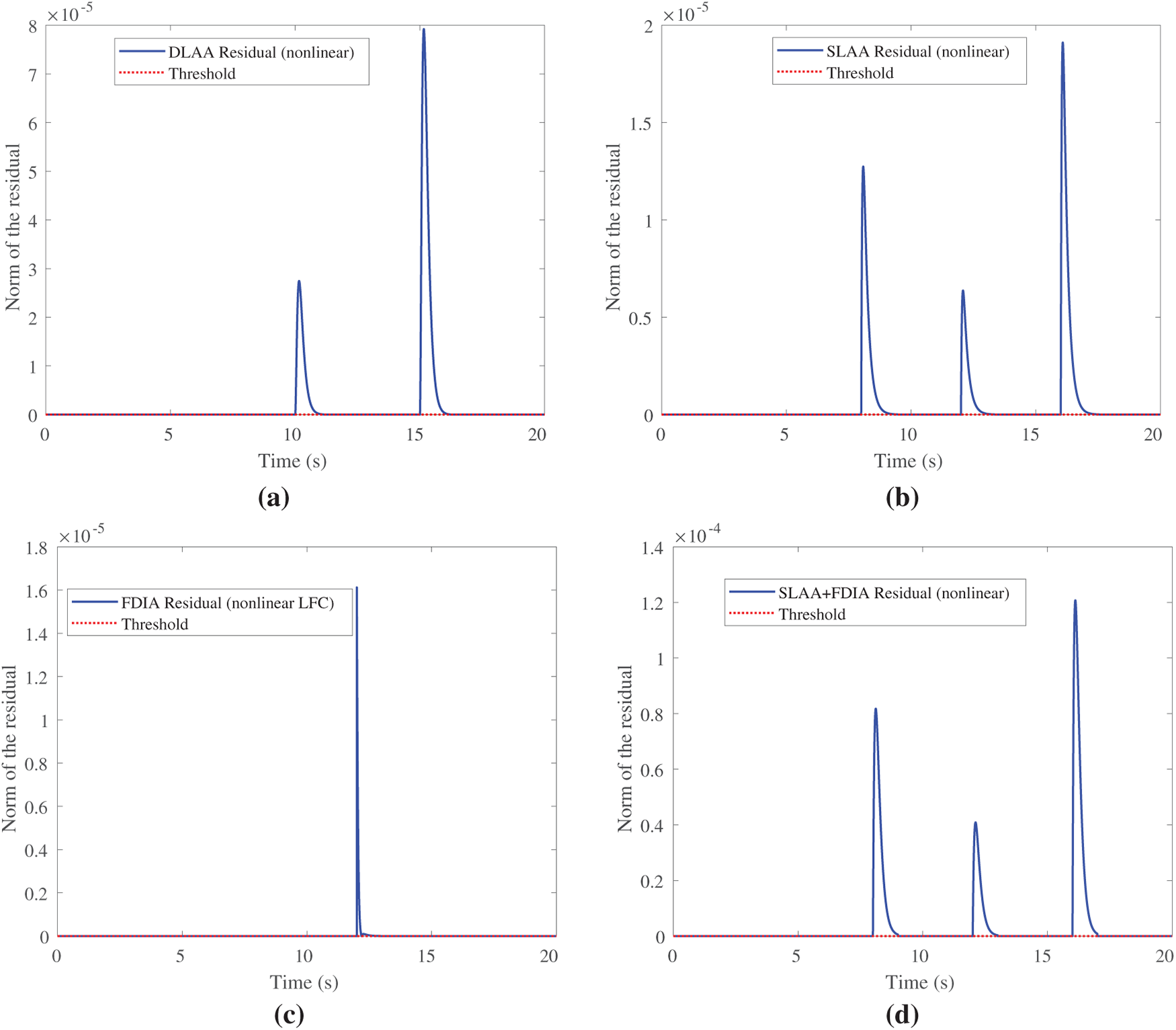

Further, we evaluate the UIO’s performance in detecting the attacks described in Section 3. The attack parameters are similar to those given in Section 7.1. The results are provided in Fig. 10. We can see that the norm of the residual is above the detection threshold for DLAA, SLAA, FDIA, and SLAA+FDIA at the times when they are executed. These validate that the designed UIO can detect the attacks.

Figure 10: Detection performance via UIO residual norms for nonlinear LFC under attack scenarios. (a) DLAA residuals exceed threshold rapidly, detecting dynamic nonlinear amplifications. (b) SLAA shows persistent residuals due to static nonlinear load effects. (c) FDIA residuals highlight injected anomalies amid nonlinearities. (d) Coordinated SLAA+FDIA residuals exceed the threshold, demonstrating UIO’s effectiveness in uncovering concealed deviations in nonlinear systems, with detection latency reduced by 30% via Lipschitz-bounded design

In this paper, we propose a comprehensive framework for detecting and mitigating coordinated cyberattacks on Load Frequency Control (LFC) systems integrated with Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS). We meticulously modeled various attack scenarios, including dynamic load-altering attacks (DLAA), static load-altering attacks (SLAA), false data injection attacks (FDIA), and their coordinated combination, highlighting their potential to compromise grid frequency stability. To address these threats, an Unknown Input Observer (UIO) was designed and implemented, capable of detecting these attacks by monitoring the measurement residuals, even when the specific attack signals are unknown. Our simulation results unequivocally demonstrated the UIO’s effectiveness in accurately capturing abnormal deviations induced by all considered attack types, including stealthy coordinated attacks, across both linear and nonlinear LFC models. This validates the UIO as a robust tool for enhancing grid operators’ situational awareness against sophisticated cyber threats. Furthermore, we developed and evaluated mitigation strategies utilizing the BESS, capitalizing on its rapid response capabilities. By dynamically adjusting BESS parameters or proactively injecting power, the proposed strategies effectively counteracted the impact of the detected attacks, restoring the system frequency deviation to its normal operating range more swiftly. These findings underscore the crucial role of BESS not only in enhancing grid stability under normal operating conditions but also in bolstering grid resilience against malicious cyber interventions.

Acknowledgement: We express our gratitude to Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd. Electric Power Dispatching and Control Center, for their invaluable support and assistance in this investigation.

Funding Statement: This paper is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China No. 62303126 and the project Major Scientific and Technological Special Project of Guizhou Province ([2024]014).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yunhao Yu, Fuhua Luo and Zhenyong Zhang; methodology, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; software, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; validation, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; formal analysis, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; investigation, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; resources, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; data curation,Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; writing—review and editing, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; visualization, Yunhao Yu and Zhenyong Zhang; supervision, Zhenyong Zhang; project administration, Zhenyong Zhang; funding acquisition,Zhenyong Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable. This article does not involve data availability, and this section is not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations: The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGC | Automatic Generation Control |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| DLAA | Dynamic Load-Altering Attack |

| FDIA | False Data Injection Attack |

| FDI | False Data Injection |

| LAA | Load-Altering Attack |

| LFC | Load Frequency Control |

| LMI | Linear Matrix Inequality |

| SLAA | Static Load-Altering Attack |

| UIO | Unknown Input Observer |

1Load Data, https://www.nyiso.com/load-data (accessed on 23 November 2025).

References

1. Rasolomampionona DD, Polecki M, Zagrajek K, Wroblewski W, Januszewski M. A comprehensive review of load frequency control technologies. Energies. 2024;17(12):2915. doi:10.3390/en17122915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Amulya A, Swarup KS, Ramanathan R. Cyber security of smart-grid frequency control: a review and vulnerability assessment framework. ACM Trans Cyber-Phys Syst. 2024;8(4):38. doi:10.1145/3661827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao X, Ma Z, Shi X, Zou S. Attack detection and mitigation scheme of load frequency control systems against false data injection attacks. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(8):9952–62. doi:10.1109/tii.2024.3390549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang Z, Deng R, Yau DKY. Vulnerability of the load frequency control against the network parameter attack. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2023;15(1):921–33. [Google Scholar]

5. Sayed MA, Ghafouri M, Atallah R, Debbabi M, Assi C. Grid chaos: an uncertainty-conscious robust dynamic EV load-altering attack strategy on power grid stability. Appl Energy. 2024;363(4):122972. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.122972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yuan Y, Li Z, Ren K. Quantitative analysis of load redistribution attacks in power systems. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2012;23(9):1731–8. doi:10.1109/tpds.2012.58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Oshnoei S, Aghamohammadi MR, Khooban MH. Smart frequency control of cyber-physical power system under false data injection attacks. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst I Regul Pap. 2024;71(12):5582–95. doi:10.1109/tcsi.2024.3396703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jafari M, Rahman MA, Paudyal S. Optimal false data injection attacks against power system frequency stability. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2022;14(2):1276–88. doi:10.1109/tsg.2022.3206717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lakshminarayana S, Adhikari S, Maple C. Analysis of IoT-based load altering attacks against power grids using the theory of second-order dynamical systems. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2021;12(5):4415–25. doi:10.1109/tsg.2021.3070313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu M, Zhang X, Zhu H, Zhang Z, Deng R. Physics-aware watermarking embedded in unknown input observers for false data injection attack detection in cyber-physical microgrids. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2024;19:7824–40. doi:10.1109/tifs.2024.3447235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shangguan XC, Yu MH, Zhang CK, He Y. Detection and defense against multi-point false data injection attacks of load frequency control in smart grid. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2025;16(5):4143–54. [Google Scholar]

12. Yin Y, Vazquez S, Marquez A, Liu J, Leon JI, Wu L, et al. Observer-based sliding-mode control for grid-connected power converters under unbalanced grid conditions. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2021;69(1):517–27. doi:10.1109/tie.2021.3050387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ghafoori MS, Soltani J. Designing a robust cyber-attack detection and identification algorithm for DC microgrids based on Kalman filter with unknown input observer. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 2022;16(16):3230–44. doi:10.1049/gtd2.12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Abouzeid SI, Chen Y, Zaery M, Abido MA, Raza A, Abdelhameed EH. Load frequency control based on reinforcement learning for microgrids under false data attacks. Comput Elec Eng. 2025;123(B):110093. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2025.110093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Amini S, Pasqualetti F, Mohsenian-Rad H. Detecting dynamic load altering attacks: a data-driven time-frequency analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm); 2015 Nov 2–5; Miami, FL, USA. p. 503–8. [Google Scholar]

16. Chaudhary AK, Roy S, Guha D, Negi R, Banerjee S. Adaptive cyber-tolerant finite-time frequency control framework for renewable-integrated power system under deception and periodic denial-of-service attacks. Energy. 2024;302(11):131809. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.131809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen C, Cui M, Fang X, Ren B, Chen Y. Load altering attack-tolerant defense strategy for load frequency control system. Appl Energy. 2020;280(2):116015. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Maleki S, Pan S, Lakshminarayana S, Konstantinou C. Survey of load-altering attacks against power grids: attack impact, detection and mitigation. IEEE Open Access J Power Energy. 2025;12:220–34. doi:10.1109/oajpe.2025.3562052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mei X, Huang W, Yuan S, Cheng J, Qi W. Load frequency control for power systems under cyber-attacks: adopting sojourn probability strategy. J Franklin Inst. 2025;362(18):108241. doi:10.1016/j.jfranklin.2025.108241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang Z, Deng R, Tian Y, Cheng P, Ma J. SPMA: stealthy physics-manipulated attack and countermeasures in cyber-physical smart grid. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2022;18:581–96. doi:10.1109/tifs.2022.3226868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lungu M, Lungu R. Full-order observer design for linear systems with unknown inputs. Int J Control. 2012;85(10):1602–15. doi:10.1080/00207179.2012.695397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sastry S. Lyapunov stability theory. In: Nonlinear systems: analysis, stability, and control. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1999. p. 182–234. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools