Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DFT Insights into the Detection of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 Gases with Pristine and Monovacancy Phosphorene Sheets

1 Department of Physics, Chaudhary Charan Singh University (CCS), Meerut, 250004, India

2 Applied Science Cluster, Department of Physics, School of Advanced Engineering, University of Petroleum and Energy Studies (UPES), Dehradun, 248007, India

* Corresponding Authors: Anuj Kumar. Email: ; Abhishek K. Mishra. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 16 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074430

Received 11 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to investigate the adsorption behavior of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 molecules on both pristine and mono-vacancy phosphorene sheets. The pristine phosphorene surface shows weak physisorption with all the gas molecules, inducing only minor changes in its structural and electronic properties. However, the introduction of mono-vacancies significantly enhances the interaction strength with NH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4. These variations are attributed to substantial charge redistribution and orbital hybridization in the presence of defects. The defective phosphorene sheet also exhibits enhanced adsorption energies, along with favorable sensitivity and recovery characteristics, highlighting its potential as a promising gas sensor for NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 at ambient conditions.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileToxic gases possess serious health risks upon inhalation, with effects ranging from mild irritation to life-threatening conditions. Among them, ammonia (NH3), arsine (AsH3), phosphine (PH3), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4) are chemically different, yet they have significance in both environmental and industrial contexts. Ammonia, a colorless gas with a sharp, pungent odor, is naturally released during the decomposition of organic matter and is widely synthesized for use in fertilizers due to its high nitrogen content essential for plant growth. It is highly soluble in water, forming ammonium hydroxide, which is a common component in household cleaners. Although non-flammable under standard conditions, ammonia can form explosive mixtures with air at elevated concentrations. Exposure levels above 20 ppm are considered hazardous, potentially causing irritation to the eyes, skin, and respiratory system. A high concentration of toxic gases leads to severe burns, respiratory failure, or even death [1–4]. Arsine (AsH3) is a colorless, highly toxic, and flammable gas composed of arsenic and hydrogen, primarily used in semiconductor manufacturing and chemical synthesis. Though it may emit a garlic-like odor at high concentrations, arsine is often undetectable at hazardous levels. Even minimal exposure can lead to hemolysis, abdominal pain, respiratory failure, and death, necessitating strict safety protocols [5]. Phosphine (PH3), another highly toxic gas, consists of phosphorus and hydrogen. It is colorless and may have a garlic or fishy odor, though pure phosphine is odorless. It forms naturally in trace amounts through the anaerobic decay of phosphorus-rich matter and is widely used as a fumigant and in electronics manufacturing. Exposure can cause symptoms ranging from nausea and chest tightness to pulmonary edema and fatality, demanding rigorous handling precautions [6].

Carbon dioxide (CO2), while non-toxic at ambient concentrations, plays a central role in Earth’s carbon cycle. Naturally produced through respiration, decomposition, and volcanic activity, CO2 is also heavily emitted by human activities such as fossil fuel combustion and deforestation, contributing significantly to global climate change. In confined spaces, CO2 accumulation can displace oxygen, posing suffocation risks. It is widely used across industries, including food processing, fire suppression, and refrigeration [7,8]. Methane (CH4), the simplest hydrocarbon, is a colourless, odourless, and highly flammable gas formed naturally via anaerobic processes in wetlands and livestock digestion. As the primary component of natural gas, it is a critical fuel source. Although non-toxic, methane can cause oxygen displacement in enclosed environments, creating asphyxiation risks. Additionally, it is a potent greenhouse gas over 80 times more effective than CO2 at trapping heat over a 20-year period, making it a major contributor to global warming. Despite their diverse industrial, agricultural, and energy-related applications, these gases pose significant health, safety, or environmental hazards, underscoring the need for careful monitoring and control strategies [9].

Due to the harmful nature of these gases, it is essential to develop a sensor that can detect these gases in small amounts. In the past decades, the two dimensional materials such as graphene, graphene oxide, boron nitride, MoS2, germanene and silicene have been widely investigated for the applications in the field of energy storage, gas sensors, molecular adsorption, and many other fields due to their high surface area, high carrier mobility, high chemical stability and fast response time [10–15]. Although graphene is the most explored 2D material, it has limited applications in fields such as magnetic field sensors and single-electron detectors. Using density functional theory (DFT), Leenaerts et al. [16] found that the weak interaction between graphene and common gas molecules such as NO, NH3, CO, and H2O, limits its application towards single gas molecule detection. It has been found that MoS2 has weak interaction with gas molecules like O2, H2, H2O, and CH4 etc. as there was no significant change in electronic properties found after adsorption of these gas molecules. Xia et al. [17] studied the adsorption of various gas molecules on germanene using DFT and found that NH3, NO, and NO2 gas molecules strongly interact with germanene, while CO, H2O and CO2 gas molecules interact weakly. Wand et al. studied the adsorption H2, CO, CO2, H2O, NO2, H2S, NH3, and CH4 gas molecules on the SnGe2N4 monolayer surface. Their results showed that all these molecules reveal low adsorption energies and adsorption lengths on the SnGe2N4 surface [18]. Even though these 2D materials have amazing properties, their zero band gap of graphene and low mobilities & heavy electron effective mass of MoS2 limit their applications for high-performance devices. Similarly unstable nature of germanene and silicene in air restricts their applications in electronic devices.

Phosphorene is the quasi-2D knitted sheet of black phosphorus. It has a noticeable direct band gap, which is an advantage over graphene. Its electron mobility is large in comparison to transition metal dichalcogenides (TMD). Its conductance is anisotropic, and it also has optical responses. It has high flexibility, high mechanical strength, and anisotropic elasticity [19]. These properties distinguish the phosphorene from other 2D materials like isotropic graphene and TMDs. This makes the phosphorene a promising material for applications in the fields of nanoelectronics and optoelectronics [20,21]. Phosphorene possesses applications in the field of thin film solar cell [22], field effect transistors [23], and gas sensors [1].

Due to its puckered surface, phosphorene has good absorption properties for several gas molecules. For example, Ghambarian et al. [24] investigated the adsorption of phosgene gas on pristine and defected phosphorene through DFT HSE calculations and found that defective phosphorene is a highly suitable and reusable gas sensor for the detection of phosgene gas. Luo et al. [6] studied the adsorption of hazardous gases NH3, PH3, AsH3 on the graphene and rare earth metal-doped graphene. They found that pristine graphene show weak physisorption towards NH3, PH3, and AsH3 gas molecules. But the rare-earth metal-doped graphene shows enhanced chemisorption toward NH3 and weakened adsorption toward AsH3. They found the sensitivities below 40% for the detection of NH3, PH3, and AsH3. In the present work, we have studied the sensing properties of pristine and mono-vacancy phosphorene towards ammonia, arsine, phosphine, carbon dioxide, and methane by analyzing interaction energy, energy band gap, Bader charge transfer, sensitivity, recovery time, and work function.

Density functional theory (DFT) [25] based calculations were performed using the Quantum ESPRESSO [26] package. We used generalized gradient approximation (GGA) [27] with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional [28] for the exchange-correlation energy of electronic interactions. The Van der Waals (VdW) corrections were included using the Grimme-D3 [29] method to consider the long-range interactions. The Brillouin zone was sampled employing a Monkhorst-Pack grid [30] corresponding to a 5 × 4 × 1 k-point grid for all calculations of geometric optimizations and electronic properties for a 3 × 3 × 1 supercell consisting of 36 atoms. Along the z-direction (perpendicular to 2d sheet), a 20 Å vacuum thickness was added to avoid the neighboring interactions. The interaction energy, Eint, of different gases on the pristine phosphorene sheet (P) and mono-vacancy phosphorene sheet (MVP) was calculated as

where EX-G, EX, and EG are the energies of a gas molecule adsorbed over the P/MVP sheet, P/MVP adsorption substrate, and gas molecules, respectively. A value of Eint < 0 signifies that the interaction process is exothermic, and gas interaction happens concurrently.

The sensing quality of a sensor can be determined in terms of sensitivity (S, %) [6], which is defined as

where

here, σ is the electrical conductivity, A is a material-dependent prefactor containing density-of-states and mobility terms, T is absolute temperature, Eg is the band gap, and kB is Boltzmann’s constant.

The recovery duration was evaluated using the Van’t-Hoff-Arrhenius equation [1] given by

In this equation, ν0 represents the apparent frequency factor (1012 Hz) [31], T signifies the operational temperature, kB stands for the Boltzmann constant, and Ea indicates the energy barrier for desorption. It is commonly assumed that Ea is equivalent to Eint, given that desorption is the opposite of adsorption. This common practice also used by Kumar et al. [1], Kharb et al. [31], Cui et al. [32] and Kalwar et al. [33].

The interaction of gas molecules with P/MVP sheet can lead to alterations in the work function and is determined using Eq. (5) [1].

where Evac represents the vacuum energy level and EF denotes the Fermi energy of the system. The efficiency of the sensor can also be derived from the relative variation in its work function, as described by Eq. (6) [1].

where

The Bader charge [34] analysis was performed to analyze the electron transport dynamics between the gas molecule and the P/MVP sheet. The quantity of charge transfer (Qt) indicates the changes in electronic characteristics on the surface of P/MVP when interacting with the gas molecules, as defined below:

In this context, Qabsorbed(gas) and Qisolated(gas) refer to the charge associated with a gas molecule after it has adsorbed and that of an isolated gas molecule, respectively.

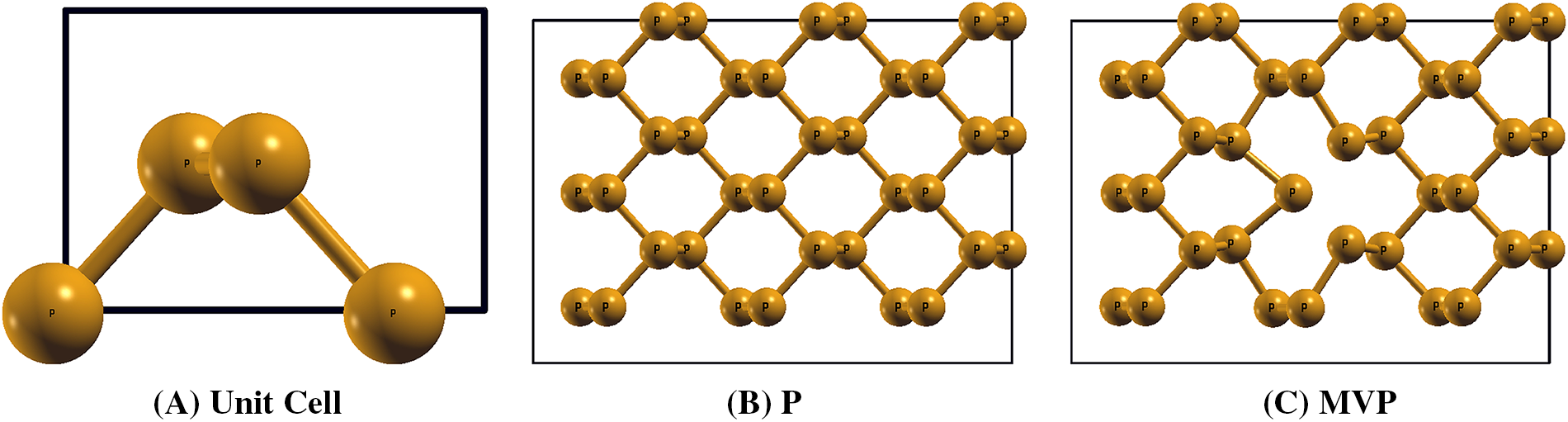

3.1 Geometric Structure of Pristine Phosphorene (P) and Mono-Vacancy Phosphorene (MVP)

The unit cell of phosphorene consists of four phosphorus atoms in an orthorhombic space group, as shown in Fig. 1A, with a lattice parameter of 4.61 and 3.29 Å, which is in good agreement with the previous reports [1]. We used a 3 × 3 supercell consisting of 36 atoms to model the gas molecule interaction studies as shown in Fig. 1B, with lattice dimensions of 13.85 Å

Figure 1: Relaxed structure of (A) Unit cell of phosphorene, and 3 × 3 super cell of (B) Pristine phosphorene sheet and (C) Mono-vacancy phosphorene sheet

In order to investigate the mono-vacancy, we removed one phosphorus atom from the 3 × 3 supercell structure. The structure of the MVP is shown in Fig. 1C. The formation energy

Close to this defect, the armchair bond length of P-P bond measures 2.26 Å, while in zig-zag direction, it was 2.34 Å. In contrast, the bond lengths away from the defect region were 2.26 and 2.22 Å along armchair and zig-zag directions, respectively, which are comparable to those of phosphorene.

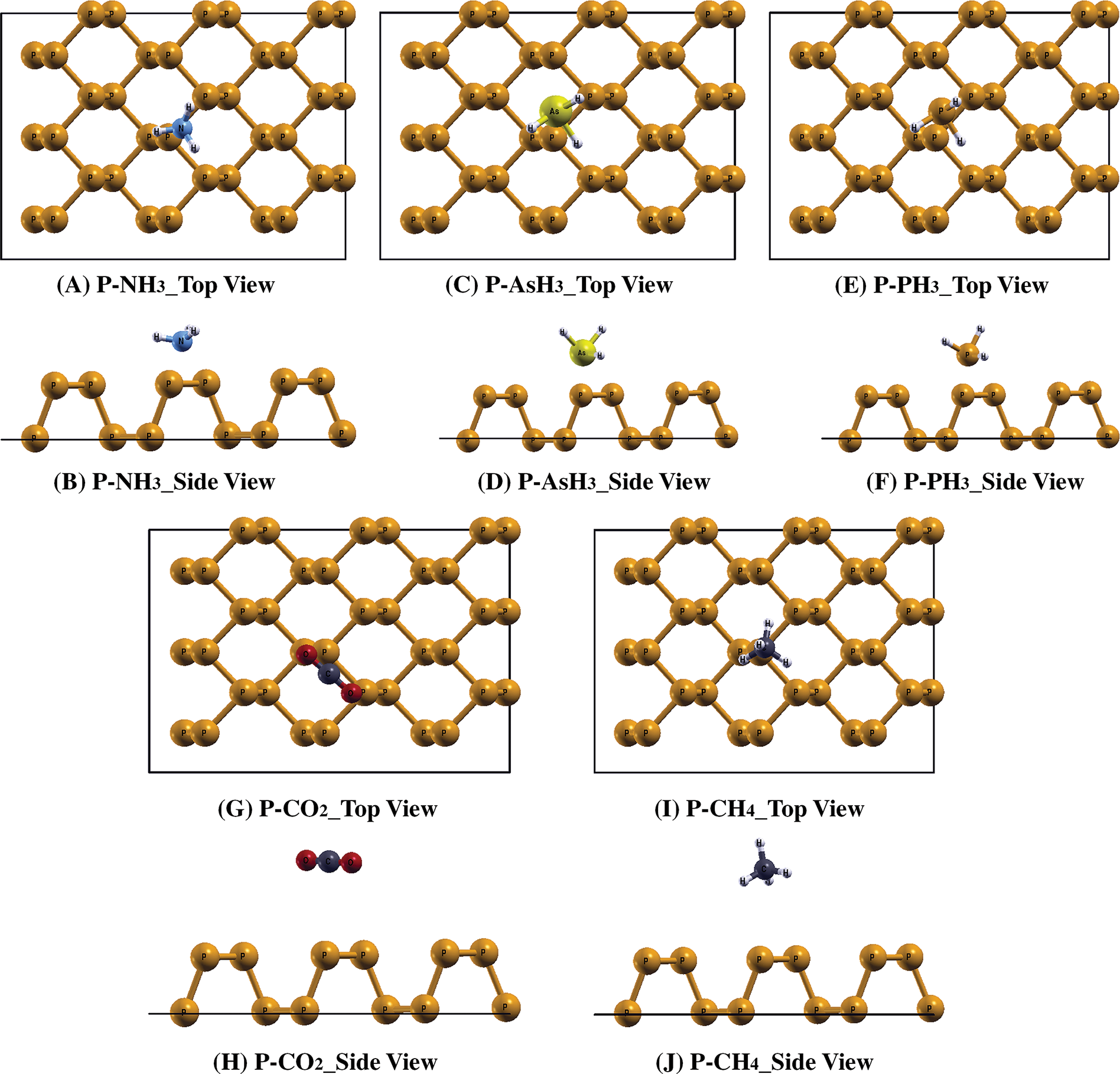

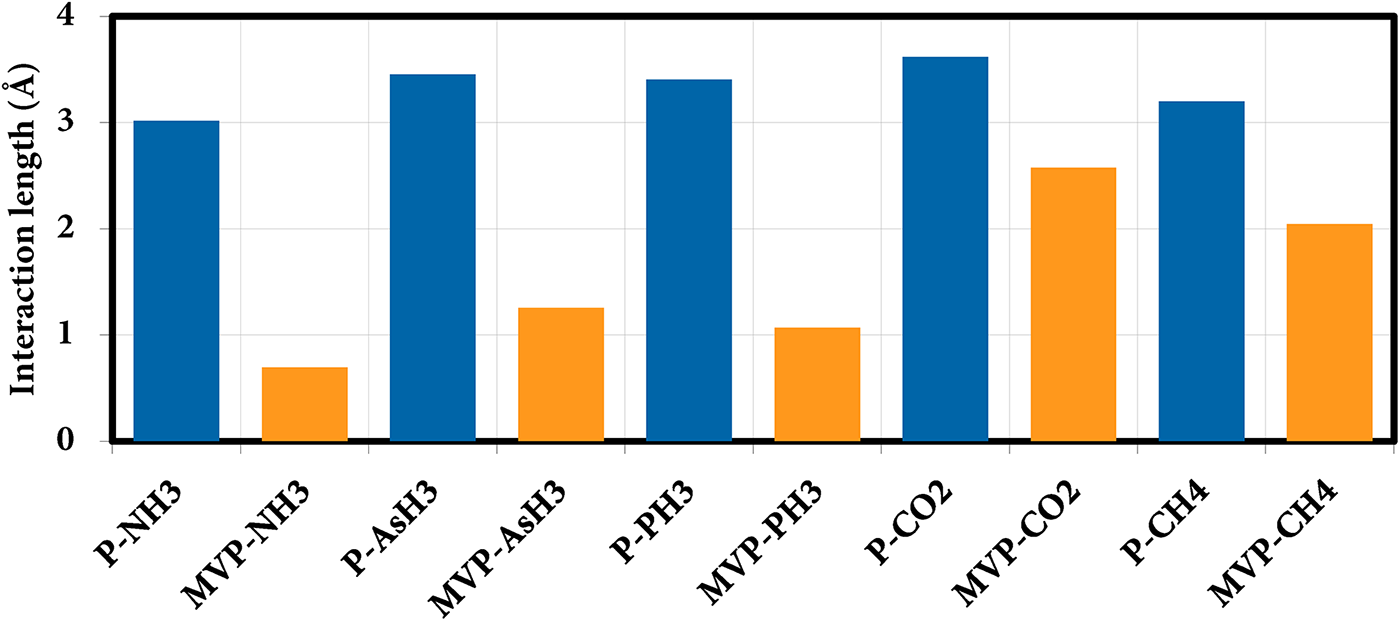

We next investigated the interaction of phosphorene sheets with different molecules by placing molecules close to the sheet in the orientation as shown in the Fig. 2. Interaction lengths between different gas molecules and P & MVP sheets is shown in Fig. 3, while geometry of gas molecules after interaction with sheets is shown in the Figs. 2 and 4, respectively. First, the interaction was investigated on a pristine phosphorene sheet, where we found almost no change in P-P bond length. We found that the interaction length (d) between NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2 and CH4 and the pristine phosphorene sheet was 3.01, 3.45, 3.40, 3.62 and 3.19 Å, respectively with calculated interaction energies to be −0.166, −0.163, −0.157, −0.112 and −0.104 eVs for respective gases showing weak physisorption interactions. The interaction energy data suggest that the interaction ability of these five gas molecules on pristine phosphorene is in the order NH3 > AsH3 > PH3 > CO2 > CH4. In a pristine phosphorene sheet, each phosphorus atom is covalently bonded with three neighboring phosphorus atoms. Each phosphorus atom has five valence electrons (3s23p3). Three of these electrons form three σ bonds with adjacent phosphorus atoms. The remaining two valence electrons create a lone pair that resides in an out-of-plane orbital. This arrangement gives rise to the distinctive puckered honeycomb structure. When a gas molecule interacts with a pristine phosphorene sheet, then Van der Waals interaction between the gas molecules and P sheet leads to higher values of interaction length.

Figure 2: The relaxed structures of (A, B) P-NH3, (C, D) P-AsH3, (E, F), P-PH3, (G, H) P-CO2, (I, J) P-CH4, respectively

Figure 3: Interaction length between different gas molecules and P & MVP sheets

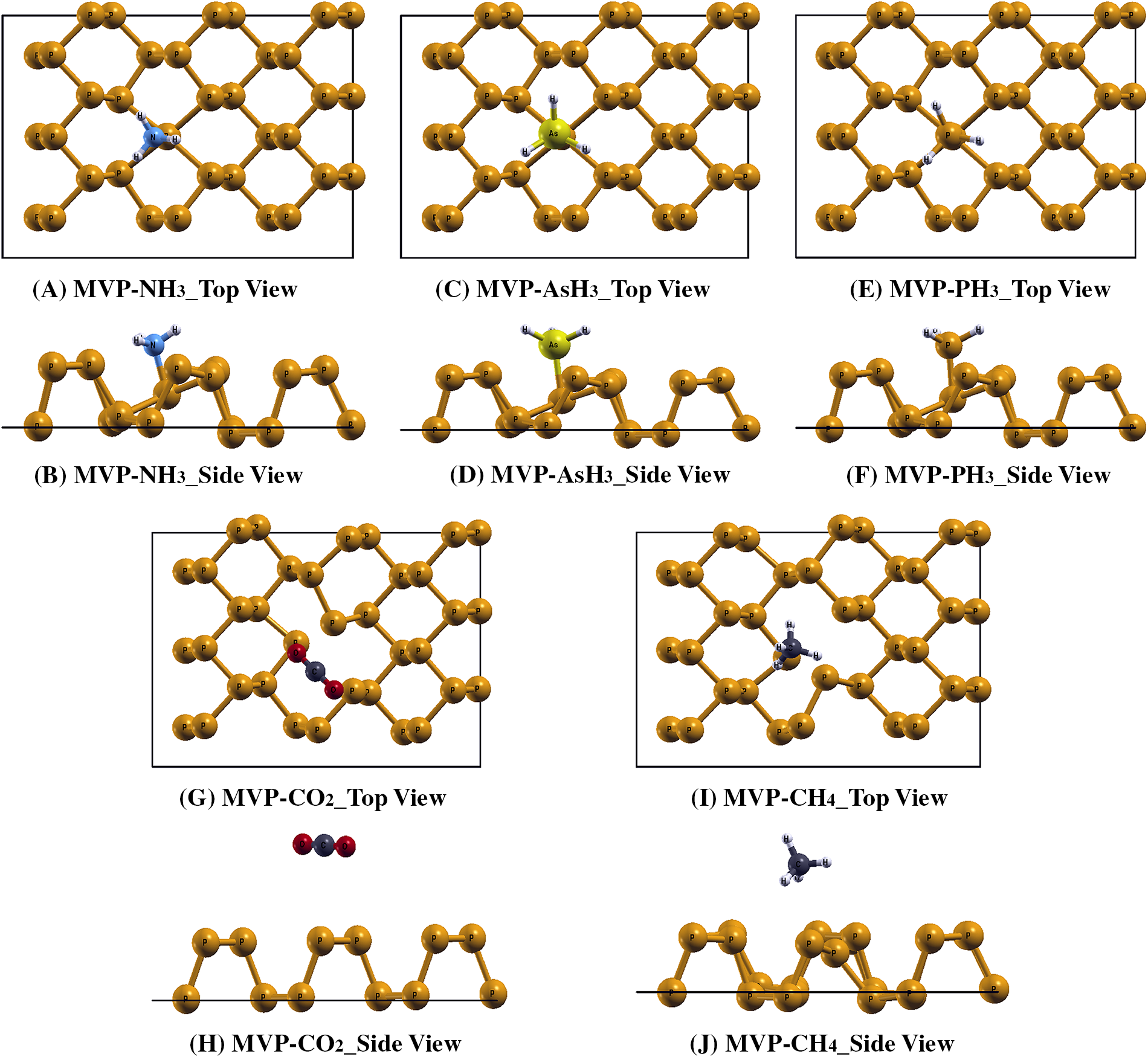

Figure 4: The relaxed structures of (A, B) MVP-NH3, (C, D) MVP-AsH3, (E, F), MVP-PH3, (G, H) MVP-CO2, (I, J) MVP-CH4, respectively

Next, we studied the interaction of various gases on a mono-vacancy phosphorene (MVP) sheet by placing a gas molecule near the vacancy of MVP and allowing the system to relax without any constraints. The interaction lengths between gas molecules and the MVP sheet were 0.69, 1.26, 1.07, 2.58 and 2.04 Å for NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, CH4 gases, respectively. In case of MVP, at the vacancy site each phosphorus atom is bonded with only two adjacent phosphorus atoms compared to three phosphorus atoms in pristine phosphorene sheet. This creates the local deformation and changes in orbital hybridization (Figs. S2 and S3). When NH3, AsH3, or PH3 gas atoms interact with MVP sheet then these gas atoms covalently bind with phosphorus atoms close to the vacancy site. This results in strong interaction and a remarkable reduction in the interaction length. As compared to the pristine phosphorene sheet (P), we observed stronger interactions between vacancy-defected phosphorene sheet and different molecules. The relaxed structures of the MVP sheets after adsorption of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2 and CH4 gas molecules are shown in Fig. 4A–J.

In case of mono-vacancy phosphorene, the interaction energies of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, CH4 gas molecules were −0.343, −0.045, −0.272, −0.522, and −0.519 eV, respectively. The interaction ability of these five gas molecules on MVP is in the order CO2 > CH4 > NH3 > PH3 > AsH3.

On comparing the interaction energies of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 gas molecules on pristine phosphorene and MVP, it was found that vacancy could enhance the bonding strength of all the gas molecules except AsH3. We have given a comparison of the interaction energies of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 gas molecules on pristine phosphorene (P) (blue color) and mono vacancy phosphorene (MVP) in Fig. S1.

This exception in the case of AsH3 arises mainly due to electronic and structural factors. The mono-vacancy introduces unsaturated phosphorus atoms with dangling bonds that generally promote charge transfer and covalent bonding with incoming gas molecules. However, AsH3 possesses a larger atomic radius and weaker electronegativity compared to NH3 and PH3, leading to poor orbital overlap between As–4p and P–3p states at the defect site. As a result, AsH3 fails to form a strong P–As bond and instead exhibits lower interaction energy and a negative Bader charge transfer value (–0.469 e−) (discussed in next section), indicating electron withdrawal rather than bond stabilization. Therefore, unlike other gases, AsH3 interacts less strongly with the defective phosphorene sheet.

In the chemisorbed cases (NH3, PH3, and to a lesser extent AsH3 on MVP), the interaction is predominantly covalent in nature. The mono-vacancy creates unsaturated phosphorus atoms with dangling bonds, which act as active sites for adsorption. The lone-pair electrons on N or P atoms in NH3 and PH3 interact with the P-3p orbitals at the vacancy site, leading to dative (coordinate) covalent bond formation. This is confirmed by the significant reduction in adsorption distance (0.69–1.07 Å), large negative adsorption energies (−0.272 to −0.343 eV), and notable Bader charge transfer (0.256 e− for NH3 and −0.362 e− for PH3) (discussed in next section). In contrast, AsH3 shows a weakly chemisorbed or transition-type interaction due to poor orbital overlap between the larger As–4p orbitals and P–3p defect orbitals, which explains its lower adsorption energy. Meanwhile, CO2 and CH4 exhibit van der Waals-type physisorption, as indicated by larger adsorption distances (>2.0 Å), small charge transfer, and minimal deformation of the MVP lattice.

3.2 Electronic Characteristics of Pristine and Mono-Vacancy Phosphorene Sheets and the Effect of Gas Molecule Interaction

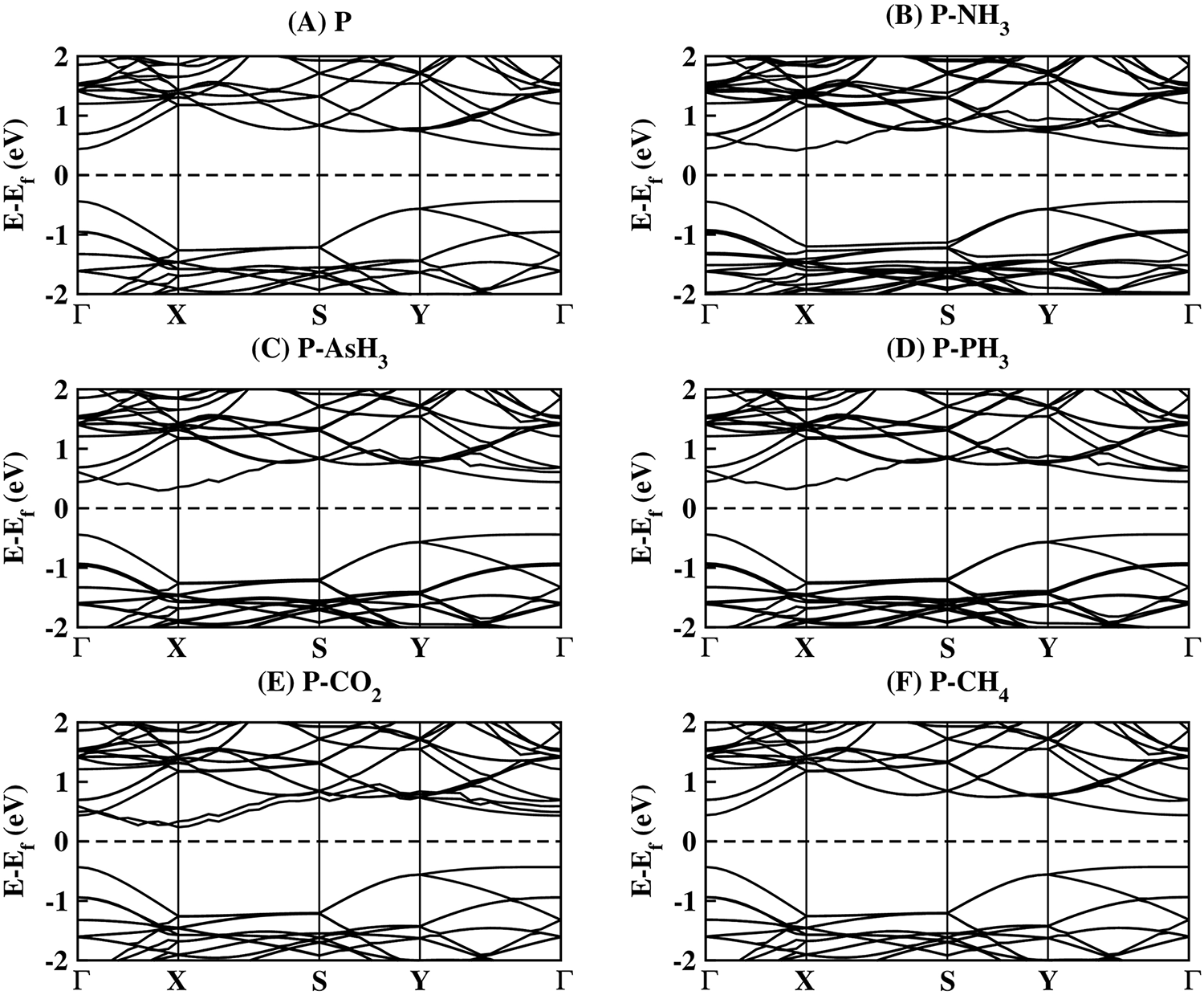

To investigate further the gas molecule interaction and their sensing properties, we studied the electronic properties of systems by analysing their electronic band structures (Fig. 5). Fig. 5A shows the band structure of pristine phosphorene, while Fig. 5B–F shows the band structure of the phosphorene sheets after their interaction with gas molecules NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4, respectively. We observed that due to the weak interaction between different gas molecules and the pristine phosphorene sheet, the electronic bands profile remains almost unaltered.

Figure 5: The band structure of (A) Phosphorene, (B) P-NH3, (C) P-AsH3, (D) P-PH3, (E) P-CO2, and (F) P-CH4 Systems

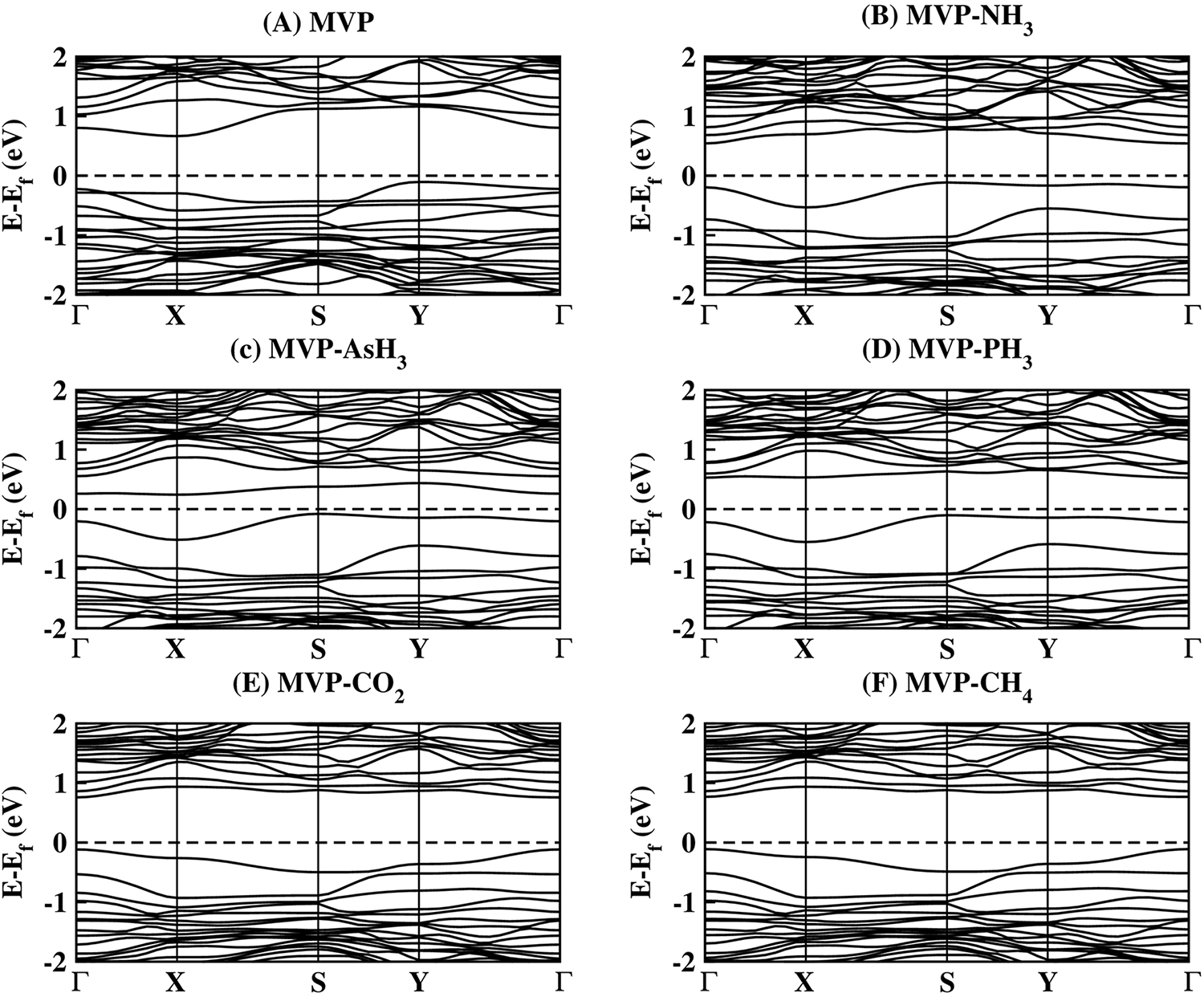

We have given the band structures of MVP sheets before and after gas molecule interaction in Fig. 6. The presence of the defect is shown to induce hole doping within the phosphorene, evidenced by the Fermi level shifting upwards towards the valence band. The band gap identified was indirect, measuring approximately 0.77 eV. Additionally, it was observed that the defect creates localized states in the valence band, indicated by the relatively flat band just below the Fermi level. These localized states act as possible active states for interacting with gas molecules.

Figure 6: The band structure of (A) MVP, (B) MVP-NH3, (C) MVP-AsH3, (D) MVP-PH3, (E) MVP-CO2, and (F) MVP-CH4 systems

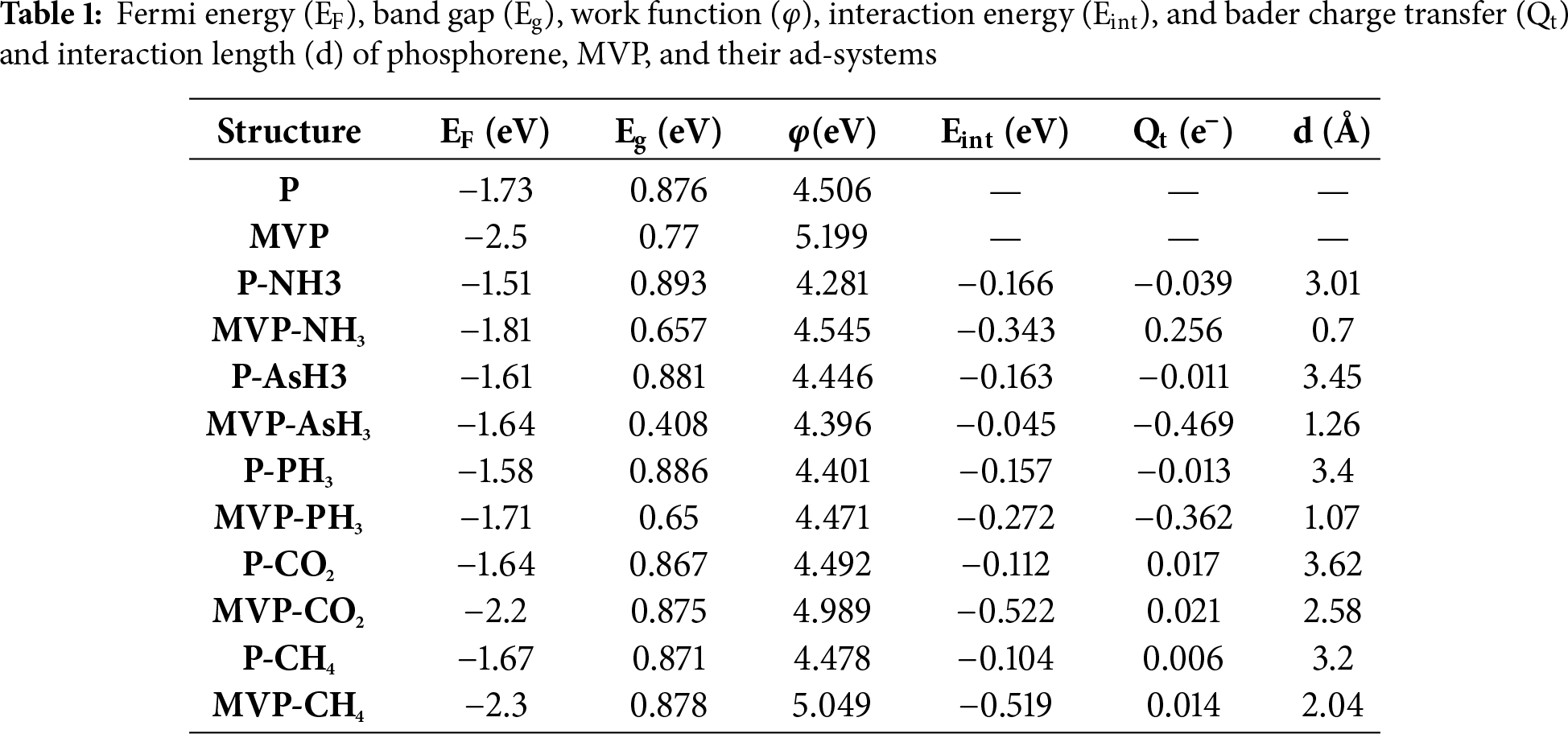

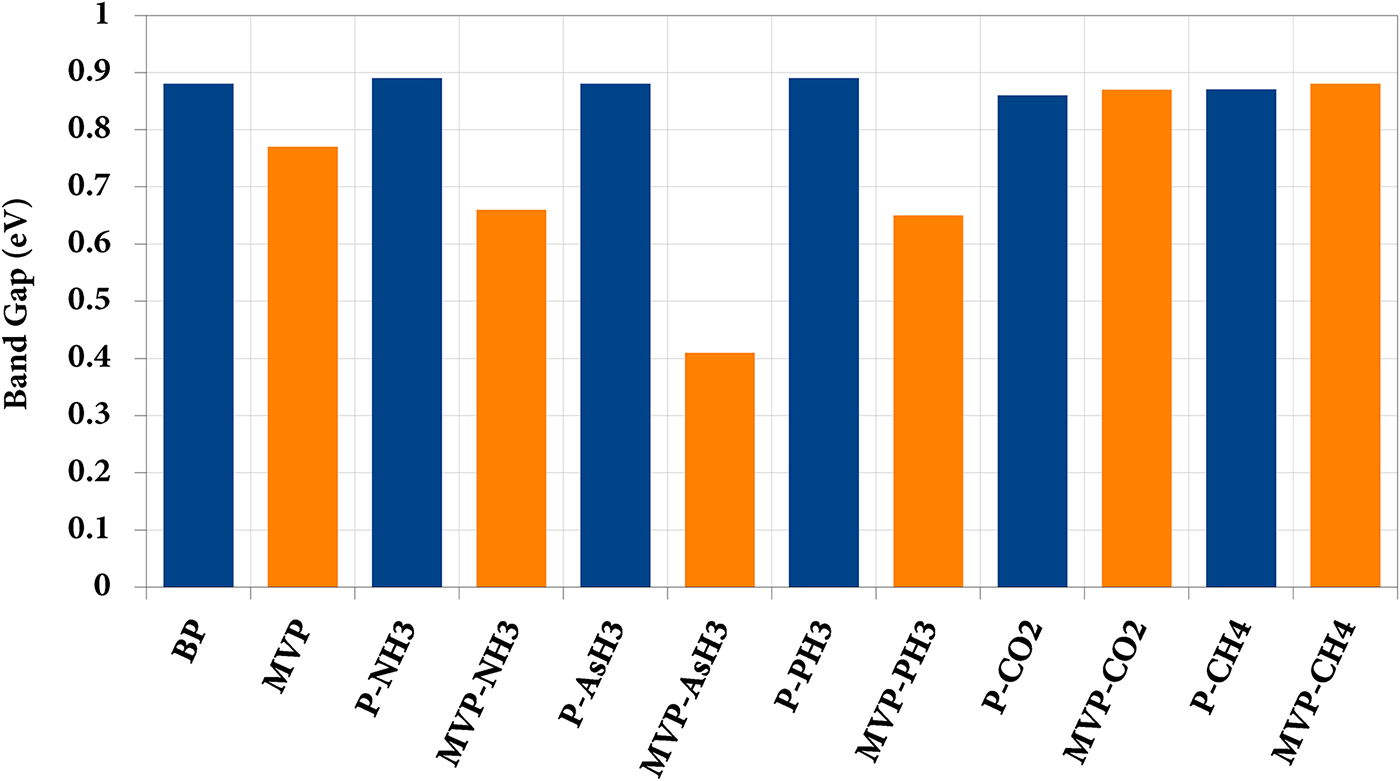

The band gaps of P-sheet, MVP sheet, and the ad-systems are shown in Table 1. The band gap of the pristine phosphorene sheet was found to be 0.87 eV, which reduces to 0.77 eV in the MVP sheet as a result of vacancy. As in the case of pristine phosphorene sheet all gases show weak physisorption interactive nature with no chemical bond formation between molecule and the sheet, a similar interaction is reflected in the electronic band gap analysis, where we observed that band gap remains almost unaltered after different gas molecules interaction (Table 1) indicating very low amount of charge transfer between pristine phosphorene sheet and gas molecules. We have presented a comparative chart of the band gap in Fig. 7. In the case of gas molecules interacting with the MVP sheet, we see significant changes in the band gap values as a result of molecule interaction. The band gap of MVP changes from its original value of 0.77 eV to 0.66, 0.41, 0.65, 0.87, and 0.88 eV after interaction of gas molecules NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4, respectively, which reflects larger charge transfer compared to that in the pristine phosphorene sheet. This was again confirmed through the Bader charge transfer analysis, where a considerable amount of charge transfer is observed between different molecules and the MVP sheet.

Figure 7: The comparative chart of band gap variations in pristine (P) and mono vacancy pristine (MVP) sheets as a result of interaction with different gas molecules

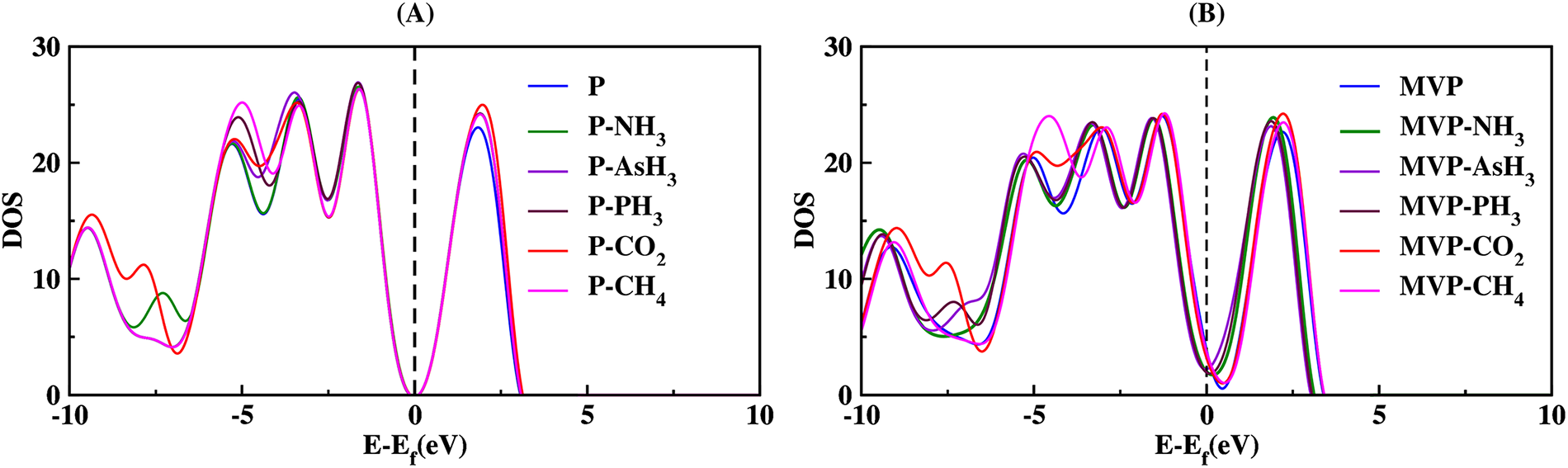

In order to gain a deeper insight into the electronic characteristics, the density of states (DOS) plots for all systems were analyzed (Fig. 8). We found that when NH3, AsH3, PH3 gas molecules interact with pristine phosphorene, there is a slight change in DOS of pristine phosphorene and the Bader charge transfer are −0.039, −0.011, and −0.013 e−, respectively, which shows that there is less transfer of charge from the sheet to gas molecules, behaving NH3, AsH3, PH3 are electron acceptors. While in the case of CO2 and CH4 gas molecules interaction with pristine phosphorene, there are significantly higher values of DOS in the conduction band, and CO2 and CH4 gas molecules interaction show the electron donor characteristics, as the Bader charge transfer are 0.017 and 0.006 e−, respectively.

Figure 8: Comparison graph of DOS of (A) P and (B) MVP with their ad-systems.

The DOS of the MVP sheet underwent significant modifications after the sheet’s interaction with NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 gases. After NH3 interaction, DOS of MVP increases significantly towards the lower energy side near the Fermi level, which further leads to a higher Bader charge transfer of 0.256 e− showing electron donor properties of ammonia gas. AsH3 and PH3 interactions increase the DOS values in the vicinity of the Fermi level and lead to large Bader charge transfer of −0.469 and −0.362 e−, respectively that indicating the electron acceptor behavior of AsH3 and PH3 gas molecules. While CO2 and CH4 interaction slightly changes DOS of MVP towards the higher energy side near the Fermi level, and an increase in peak value of DOS in the conduction band leads to a smaller Bader charge transfer with values 0.021, and 0.014 e−. Hence, CO2 and CH4 molecules show the behavior of an electron donor.

Significant changes of DOS in the vicinity of the Fermi level are anticipated to lead to marked changes in the associated electronic properties. This is highly advantageous for gas sensing purposes. Therefore, the MVP demonstrates greater suitability for sensing NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 compared to pristine phosphorene. We have given projected-density-of-states (pdos) of NH3 and AsH3 molecules interacting with pristine and MVP sheets in Figs. S2 and S3, respectively. We note that a stronger overlap occurs, with noticeable As-sp3 mixing with defect-P (s–p hybrid) orbitals, indicating significant hybridization (Fig. S3).

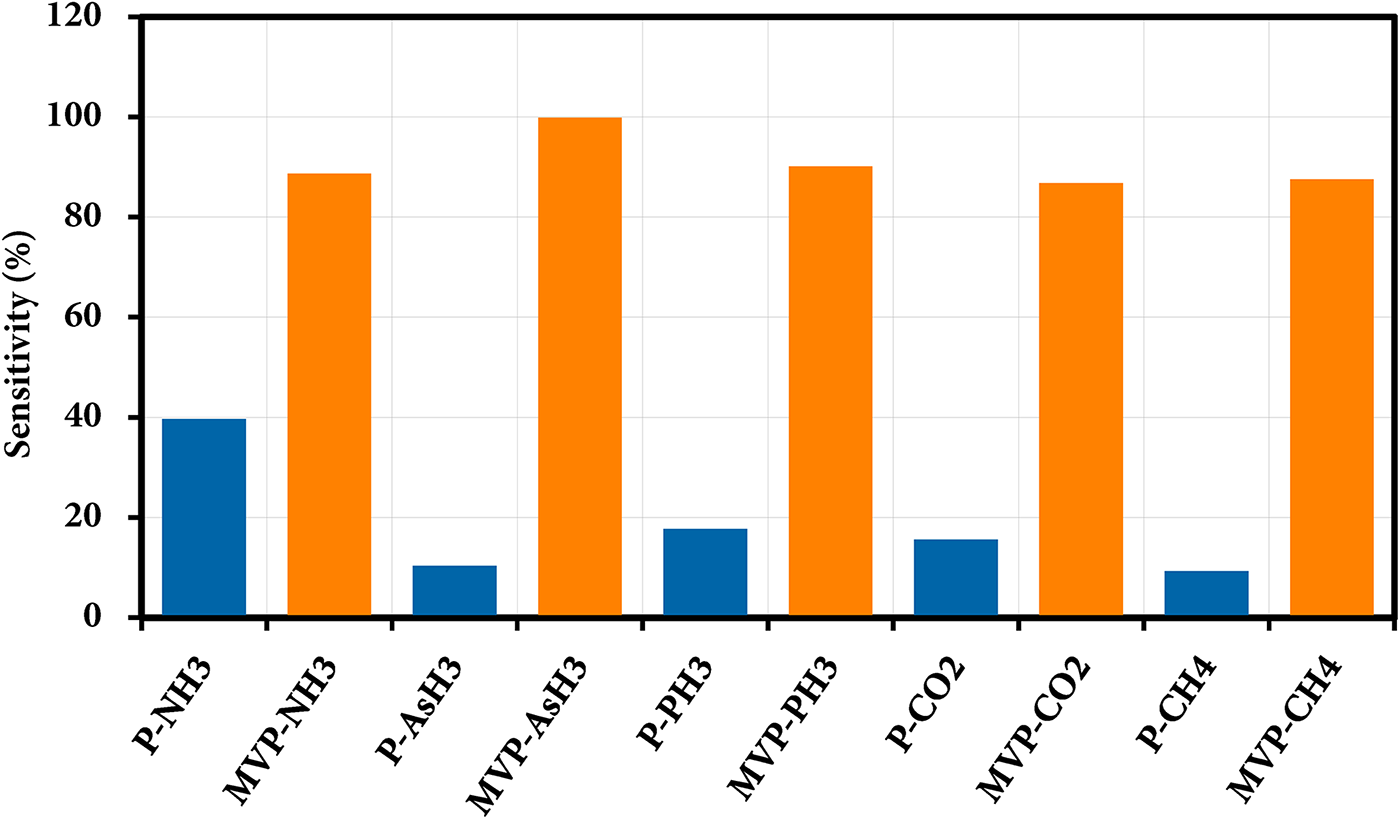

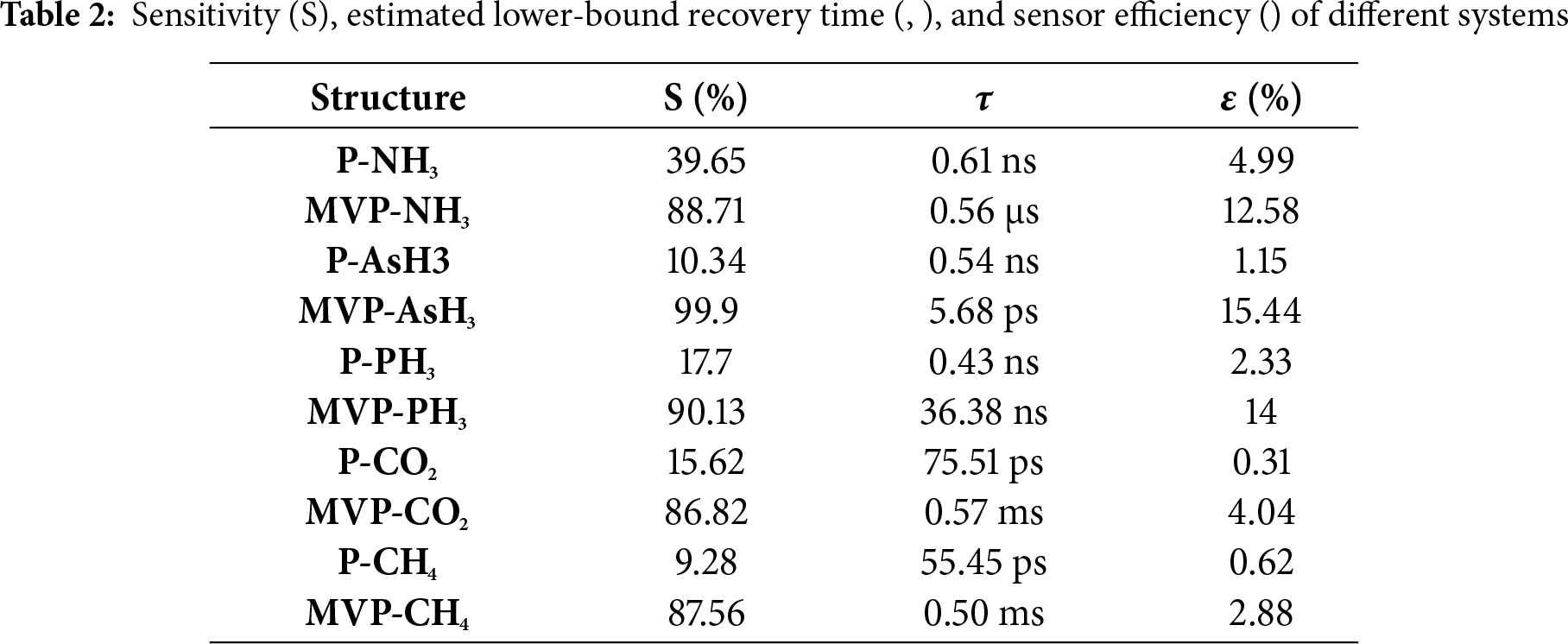

3.3 Sensor Sensitivity, Recovery Time and Efficiency

The sensor responses for all the ad-systems were determined by analyzing the band gap before and after the interactions with the gases. Fig. 9 illustrates the sensitivity (S%), while Table 2 provides the sensitivities measured for NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 to be 39.65%, 10.34%, 17.7%, 15.62%, and 9.28%, respectively. For pristine phosphorene, the band gap shows nearly no changes following the interaction of AsH3 and CH4. However, there is a slight change in band gap noted after the interaction of NH3, PH3 and CO2. Therefore, pristine phosphorene demonstrates a higher sensitivity towards NH3, PH3 and CO2, while it has lower sensitivity towards AsH3 and CH4.

Figure 9: Sensitivity of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 adsystems

In case of MVP, the sensitivity for NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 are 88.71%, 99.9%, 90.13%, 86.82% and 87.56%, respectively. In this case, the increased value of S can be attributed to a significant alteration in the band gap. The changes in the band gap occur due to the interaction of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 gas molecules on the MVP sheet, which leads to enhanced Bader charge transfer between the MVP and the gas molecules with values 0.256, −0.469, −0.362, 0.021, and 0.014 e−, respectively in contrast to −0.039, −0.011, −0.013, 0.017 and 0.006 e− in pristine phosphorene. Upon AsH3 interaction with MVP, although the interaction energy is low, the sensitivity is very high. This indicates that AsH3 is better sensed by MVP. The sensitivity of NO2-doped graphene and Ti3C2 MXene is found to be 25.3% and 6.13%, respectively for NH3 gas [36].

We have also computed the recovery time using Eq. (4). A short recovery time is crucial because it ensures that the sensor is prepared for further measurements, improving the overall efficiency and reliability of gas detection, particularly in applications where gas concentrations fluctuate quickly. The recovery times for various ad-systems are presented in Table 2. The recovery time ranges from milliseconds to picoseconds. At room temperature, physisorbed systems (e.g., CO2, CH4 on P and on MVP) exhibit short lower-bound recovery times in the ps–ms range within the desorption energy,

The interactions between the surface and the adsorbate result in modifications to the work function of the nanomaterial. Therefore, we further determined the work function values and found that the interaction of these gas molecules on both P and MVP sensors caused a reduction in the work function. The work function values are presented in Table 2. The gas molecules NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 tend to exhibit weaker physisorption on pristine phosphorene, leading to only minor changes in the work function, although some modulation occurs due to decreased charge transfer. Consequently, the work function of pristine phosphorene sheet in the presence of these gases is found to be low. In contrast, the covalent adsorption of NH3, AsH3, and PH3 on MVP leads to significant charge transfer, resulting in significant work function changes. Moreover, the physisorption of CO2 and CH4 on MVP causes lower charge transfer and, as a result, lower work function changes as well.

In this work, the adsorption behavior of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 on pristine and mono-vacancy phosphorene sheets was systematically investigated using first-principles DFT calculations. Pristine phosphorene exhibits weak physisorption toward all gas molecules, resulting in negligible structural distortion, minimal charge transfer, and almost unchanged electronic properties. However, the introduction of a mono-vacancy significantly enhances the interaction strength for all gases (except AsH3), due to the presence of unsaturated phosphorus atoms with dangling bonds and localized defect states near the Fermi level. These active defect sites promote stronger charge transfer, shorter adsorption distances, higher sensitivity, and noticeable modifications in band structure and density of states. Among all gases, CO2 and CH4 showed the highest interaction energies on MVP (–0.522 and –0.519 eV, respectively), while NH3 and PH3 induce significant modulation in the electronic properties. The MVP-based systems also exhibit high sensitivity (up to ~99.9%) and ultrafast recovery times ranging from picoseconds to microseconds, making them highly suitable for reusable room-temperature gas sensors.

Overall, the study reveals that mono-vacancy engineering in phosphorene dramatically improves its gas-sensing performance. Therefore, defective phosphorene, particularly MVP, can be considered a promising candidate for sensitive, selective, and reusable detection of NH3, AsH3, PH3, CO2, and CH4 at room temperature.

Acknowledgement: Naresh Kumar is grateful to the Principal, D. N. (P.G.) College Gulaothi, Bulandshahr for allowing him to pursue Ph.D.

Funding Statement: Dr Abhishek K. Mishra (A. K. M.) received the financial support to conduct this research from the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) through a state university research excellence (SURE) grant (SUR/2022/004935).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Naresh Kumar, Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; methodology: Naresh Kumar, Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; software: Naresh Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; validation: Naresh Kumar, Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; formal analysis: Naresh Kumar; investigation Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; resources: Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; data curation: Naresh Kumar; writing—original draft preparation: Naresh Kumar; writing—review and editing: Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; visualization: Naresh Kumar, Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; supervision: Anuj Kumar and Abhishek K. Mishra; project administration: Abhishek K. Mishra; funding acquisition: Abhishek K. Mishra. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are contained within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.074430/s1.

References

1. Kumar N, Mishra S, Gautam YK, Kumar A, Mishra AK. NH3 gas sensing over 2D phosphorene sheet: a first-principles study. Int J Comp Mat Sci Eng. 2024; 2450029. doi:10.1142/s2047684124500295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Behera SN, Sharma M, Aneja VP, Balasubramanian R. Ammonia in the atmosphere: a review on emission sources, atmospheric chemistry and deposition on terrestrial bodies. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2013;20(11):8092–131. doi:10.1007/s11356-013-2051-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Tang X, Debliquy M, Lahem D, Yan Y, Raskin JP. A review on functionalized graphene sensors for detection of ammonia. Sensors. 2021;21(4):1443. doi:10.3390/s21041443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Li R, Jiang K, Chen S, Lou Z, Huang T, Chen D, et al. SnO2/SnS2 nanotubes for flexible room-temperature NH3 gas sensors. RSC Adv. 2017;7(83):52503–9. doi:10.1039/c7ra10537a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Buasaeng P, Rakrai W, Wanno B, Tabtimsai C. DFT investigation of NH3, PH3, and AsH3 adsorptions on Sc-, Ti-, V-, and Cr-doped single-walled carbon nanotubes. Appl Surf Sci. 2017;400(3):506–14. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.12.215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Luo H, Xu K, Gong Z, Li N, Zhang K, Wu W, et al. NH3, PH3, AsH3 adsorption and sensing on rare earth metal doped graphene: DFT insights. Appl Surf Sci. 2021;566:150390. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.150390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kou L, Frauenheim T, Chen C. Phosphorene as a superior gas sensor: selective adsorption and distinct I-V response. J Phys Chem Lett. 2014;5(15):2675–81. doi:10.1021/jz501188k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cai Y, Ke Q, Zhang G, Zhang YW. Energetics, charge transfer, and magnetism of small molecules physisorbed on phosphorene. J Phys Chem C. 2015;119(6):3102–10. doi:10.1021/jp510863p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Aldhafeeri T, Tran MK, Vrolyk R, Pope M, Fowler M. A review of methane gas detection sensors: recent developments and future perspectives. Inventions. 2020;5(3):28. doi:10.3390/inventions5030028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Donarelli M, Ottaviano L. 2D materials for gas sensing applications: a review on graphene oxide, MoS2, WS2 and phosphorene. Sensors. 2018;18(11):3638. doi:10.3390/s18113638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Hidalgo-Jiménez J, Akbay T, Ishihara T, Edalati K. Investigation of a high-entropy oxide photocatalyst for hydrogen generation by first-principles calculations coupled with experiments: significance of electronegativity. Scr Mater. 2024;250:116205. doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2024.116205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Milowska KZ, Majewski JA. Graphene based sensors: theoretical study. arXiv:1404.0052. 2014. [Google Scholar]

13. Kumar R, Goel N, Hojamberdiev M, Kumar M. Transition metal dichalcogenides-based flexible gas sensors. Sens Actuat A Phys. 2020;303:111875. doi:10.1016/j.sna.2020.111875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao S, Xue J, Kang W. Gas adsorption on MoS2 monolayer from first-principles calculations. Chem Phys Lett. 2014;595:35–42. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2014.01.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chen WY, Jiang X, Lai SN, Peroulis D, Stanciu L. Nanohybrids of a MXene and transition metal dichalcogenide for selective detection of volatile organic compounds. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1302. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15092-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Leenaerts O, Partoens B, Peeters FM. Adsorption of H2O, NH3, CO, NO2, and NO on graphene: a first-principles study. Phys Rev B. 2008;77(12):125416. doi:10.1103/physrevb.77.125416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xia W, Hu W, Li Z, Yang J. A first-principles study of gas adsorption on germanene. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16(41):22495–8. doi:10.1039/c4cp03292f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang P, Lin L, Xie K, Ge W, Xue C, Li X, et al. Environmental gas adsorption on SnGe2N4: a theoretical perspective. Langmuir. 2025;41(28):18532–43. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.5c01384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sahoo G, Biswal A. Strain engineered structural, mechanical and electronic properties of monolayer phosphorene: a DFT study. Phys B Condens Matter. 2025;697:416742. doi:10.1016/j.physb.2024.416742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu H, Neal AT, Zhu Z, Luo Z, Xu X, Tománek D, et al. Phosphorene: an unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano. 2014;8(4):4033–41. doi:10.1021/nn501226z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Akhtar M, Anderson G, Zhao R, Alruqi A, Mroczkowska JE, Sumanasekera G, et al. Recent advances in synthesis, properties, and applications of phosphorene. npj 2D Mater Appl. 2017;1(1):5. doi:10.1038/s41699-017-0007-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dai J, Zeng XC. Bilayer phosphorene: effect of stacking order on bandgap and its potential applications in thin-film solar cells. J Phys Chem Lett. 2014;5(7):1289–93. doi:10.1021/jz500409m. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Das S, Demarteau M, Roelofs A. Ambipolar phosphorene field effect transistor. ACS Nano. 2014;8(11):11730–8. doi:10.1021/nn505868h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ghambarian M, Azizi Z, Ghashghaee M. Remarkable improvement in phosgene detection with a defect-engineered phosphorene sensor: first-principles calculations. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2020;22(17):9677–84. doi:10.1039/d0cp00427h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Geerlings P, De Proft F, Langenaeker W. Conceptual density functional theory. Chem Rev. 2003;103(5):1793–874. doi:10.1021/cr990029p. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Giannozzi P, Baroni S, Bonini N, Calandra M, Car R, Cavazzoni C, et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J Phys Condens Matter. 2009;21(39):395502. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J Comput Chem. 2006;27(15):1787–99. doi:10.1002/jcc.20495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(18):3865–8. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Moellmann J, Grimme S. DFT-D3 study of some molecular crystals. J Phys Chem C. 2014;118(14):7615–21. doi:10.1021/jp501237c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Monkhorst HJ, Pack JD. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys Rev B. 1976;13(12):5188–92. doi:10.1103/physrevb.13.5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kharb AS, Kumar K, Chawla AK, Mishra AK. Selective NO gas sensing over TiVCO2 MXene: a realistic computational prediction. Nano Ex. 2025;6(2):025009. doi:10.1088/2632-959x/adda69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Cui H, Gao C, Wang P, Li L, Ye H, Wen Z, et al. DFT study of Zn-modified SnP3: a H2S gas sensor with superior sensitivity, selectivity, and fast recovery time. Nanomater. 2023;13(20):2781. doi:10.3390/nano13202781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Kalwar BA, Wang F, Soomro AM, Naich MR, Saeed MH, Ahmed I. Highly sensitive work function type room temperature gas sensor based on Ti doped hBN monolayer for sensing CO2, CO, H2S, HF and NO. A DFT study. RSC Adv. 2022;12(53):34185–99. doi:10.1039/d2ra06307g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Bader RFW. A quantum theory of molecular structure and its applications. Chem Rev. 1991;91(5):893–928. doi:10.1021/cr00005a013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ramachandran S, Sai Srinivasan KV, Sujith R. Nickel-decorated single vacancy phosphorene-a favourable candidate for hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46(54):27597–611. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.05.206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Joshi M, Ren X, Lin T, Joshi R. Mechanistic insights into gas adsorption on 2D materials. Small. 2025;21(7):2406706. doi:10.1002/smll.202406706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools