Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

VIF-YOLO: A Visible-Infrared Fusion YOLO Model for Real-Time Human Detection in Dense Smoke Environments

1 School of Computer Engineering, Jiangsu University of Technology, Changzhou, 213001, China

2 College of Information Sciences and Technology, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130117, China

3 School of Teacher Education, Qujing Normal University, Qujing, 655011, China

* Corresponding Authors: Qi Pu. Email: ; Xundiao Ma. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 60 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074682

Received 16 October 2025; Accepted 03 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

In fire rescue scenarios, traditional manual operations are highly dangerous, as dense smoke, low visibility, extreme heat, and toxic gases not only hinder rescue efficiency but also endanger firefighters’ safety. Although intelligent rescue robots can enter hazardous environments in place of humans, smoke poses major challenges for human detection algorithms. These challenges include the attenuation of visible and infrared signals, complex thermal fields, and interference from background objects, all of which make it difficult to accurately identify trapped individuals. To address this problem, we propose VIF-YOLO, a visible–infrared fusion model for real-time human detection in dense smoke environments. The framework introduces a lightweight multimodal fusion (LMF) module based on learnable low-rank representation blocks to end-to-end integrate visible and infrared images, preserving fine details while enhancing salient features. In addition, an efficient multiscale attention (EMA) mechanism is incorporated into the YOLOv10n backbone to improve feature representation under low-light conditions. Extensive experiments on our newly constructed multimodal smoke human detection (MSHD) dataset demonstrate that VIF-YOLO achieves mAP50 of 99.5%, precision of 99.2%, and recall of 99.3%, outperforming YOLOv10n by a clear margin. Furthermore, when deployed on the NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX, VIF-YOLO attains 40.6 FPS with an average inference latency of 24.6 ms, validating its real-time capability on edge-computing platforms. These results confirm that VIF-YOLO provides accurate, robust, and fast detection across complex backgrounds and diverse smoke conditions, ensuring reliable and rapid localization of individuals in need of rescue.Keywords

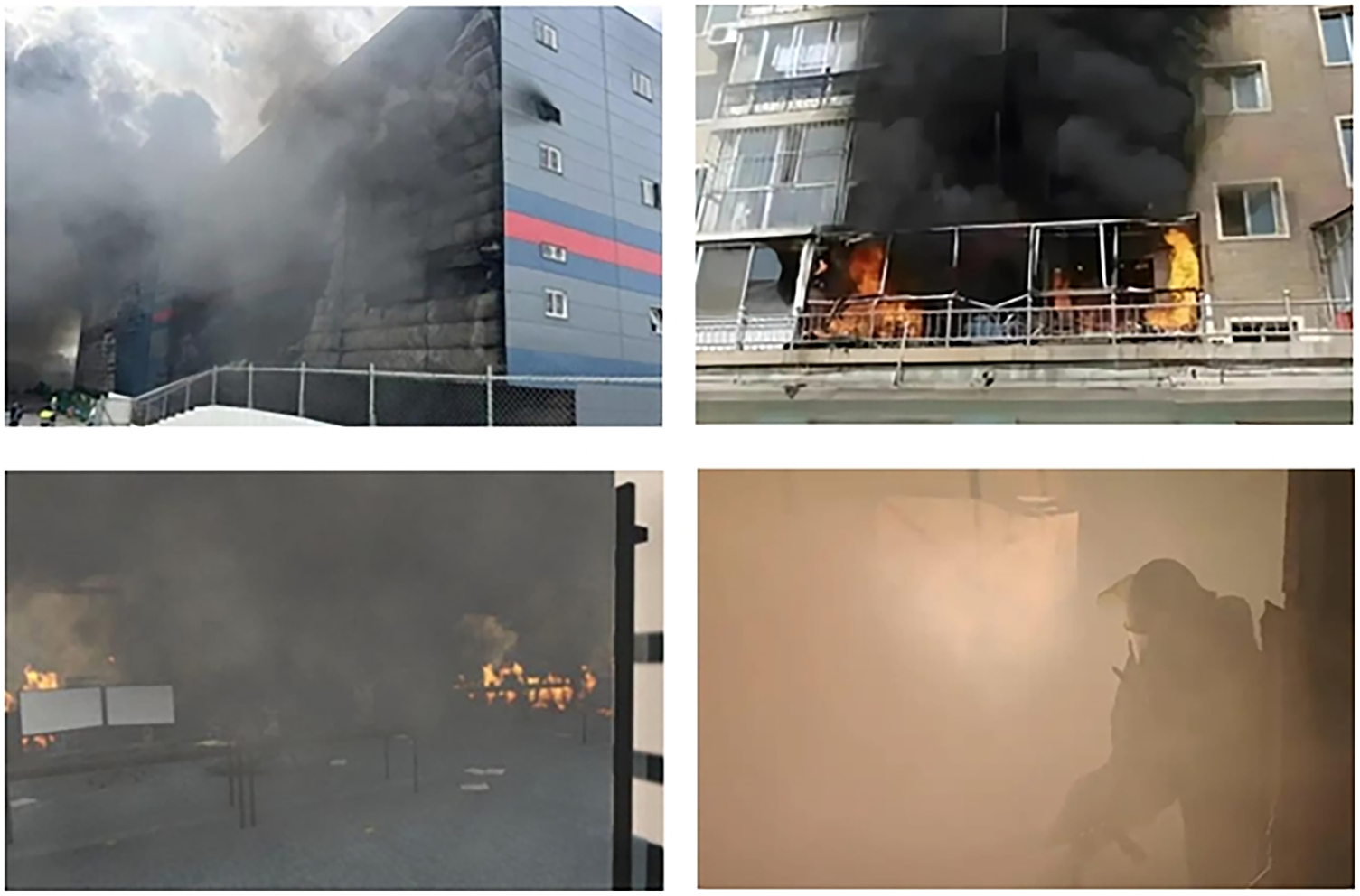

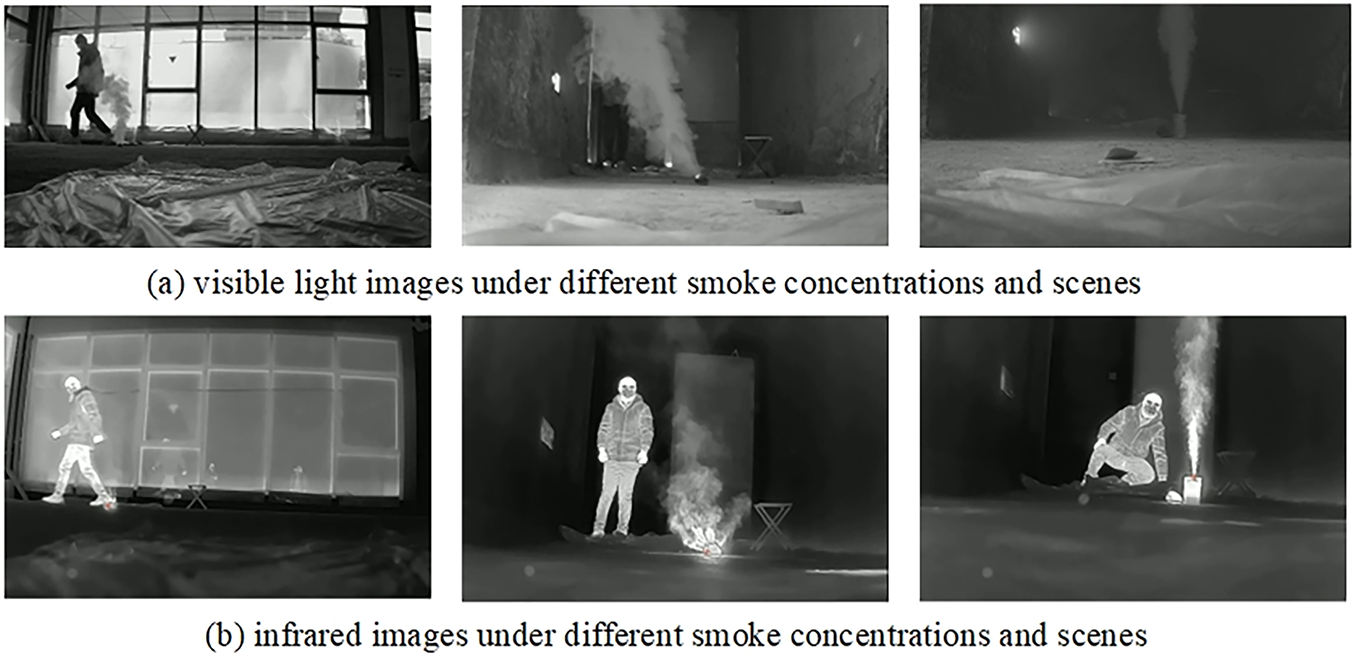

In fire rescue scenarios, dense smoke severely hinders human vision, leading to high risks and delays in locating trapped individuals. Although intelligent rescue robots equipped with cameras and thermal sensors have been introduced into fire-fighting systems, accurately detecting humans under dense smoke remains a challenging task. Smoke causes strong attenuation of visible and infrared light, introduces complex thermal fields, and generates noisy background interference, as shown in Fig. 1. These factors significantly degrade the discriminative features of targets and limit the robustness of traditional object detection algorithms. Therefore, designing a real-time and reliable human detection framework for smoke-filled environments is of great significance for practical fire rescue missions.

Figure 1: Examples of different fire smoke scenarios

In recent years, although deep learning-based object detection models (e.g., SSD [1], Faster R-CNN [2] etc.) have achieved better results in general scenarios, their model parameters are large and computationally intensive, making it difficult to satisfy real-time performance requirements, and they are especially constrained in edge-computing or unmanned platform deployments. In addition, the performance of traditional object detection in low-visibility conditions decreases dramatically, making it difficult to effectively recognize targets that are partially occluded or in the middle of a long distance [3]. In order to cope with the recognition requirements in dense smoke environments, researchers have proposed a series of lightweight pedestrian detection models, such as YOLOv4-tiny, MobileNet-SSD etc., which are able to achieve fast reasoning with low hardware resources, and strike a balance between detection accuracy and efficiency [4,5]. In addition, some researches have introduced techniques such as thermal infrared imagery, modal fusion, and attention mechanism, which further enhance the robustness of the model against factors such as complex smoke occlusion and smoke interference [6]. However, in extreme dense smoke environments, the target features are severely degraded, and detection algorithms based on a single visible light data source have encountered performance bottlenecks, which need to be further optimized by combining multimodal data with the pedestrian detection model synergistically to achieve human object reliable detection against complex backgrounds and environmental changes [7]. Although multimodal perception techniques have been increasingly adopted in low-visibility environments, existing visible–infrared detection frameworks still face inherent limitations when applied to dense smoke rescue scenarios. First, dense smoke causes simultaneous attenuation of visible and infrared signals and introduces complex thermal turbulence, making many current fusion methods (such as U2Fusion [8]) unable to preserve fine-grained structures or maintain stable cross-modal consistency. Second, Transformer-based fusion frameworks such as SwinFusion [9] achieve strong global modeling capability but incur heavy computational overhead, limiting their real-time applicability on edge-computing rescue robots. Third, most multimodal pedestrian detection approaches are not explicitly optimized for severe smoke occlusion; they often exhibit degraded performance when the human body is partially obscured, when smoke density varies drastically, or when background thermal interference is strong. These limitations reveal a critical gap: existing multimodal detection algorithms cannot simultaneously ensure feature integrity, robustness, and real-time efficiency under extreme smoke conditions.

To address these challenges, we propose VIF-YOLO, a visible–infrared fusion YOLO framework for real-time human detection in dense smoke conditions. We adopt YOLOv10n as the backbone because it offers a superior balance of structural efficiency, inference speed, and parameter size compared with earlier YOLO versions, making it highly suitable for real-time deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. In contrast, although Transformer-based detectors provide strong feature modeling capability, their high computational cost and slow inference render them impractical for dense-smoke rescue scenarios that demand strict real-time performance. Specifically, we design a lightweight multimodal fusion (LMF) mechanism based on learnable low-rank representation blocks, which suppresses redundant noise while enhancing salient features of both modalities, enabling stable feature extraction under degraded visibility. In addition, an efficient multiscale attention (EMA) module is incorporated into the YOLOv10n backbone to refine semantic representation across scales while maintaining computational efficiency, making the model suitable for edge deployment. Furthermore, we construct a new dataset, MSHD (multimodal smoke human detection), containing paired visible–infrared images under various smoke concentrations, lighting conditions, and indoor scenarios, to benchmark human detection performance in realistic smoke environments. Compared with existing multimodal methods, VIF-YOLO achieves a better balance between accuracy, fusion quality, and inference speed, making it more suitable for deployment on real rescue platforms.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

1. We propose VIF-YOLO, a novel lightweight detection framework that integrates visible–infrared fusion and multiscale attention to achieve robust human detection in dense smoke environments.

2. We introduce an LMF module that leverages low-rank representation to efficiently fuse multimodal features, balancing detection accuracy and computational cost.

3. We integrate an EMA module into YOLOv10n to enhance multiscale feature perception under low-light and noisy conditions.

4. We construct and release the MSHD dataset, which provides a valuable benchmark for evaluating multimodal detection methods in smoke-filled rescue scenarios.

Extensive experiments on MSHD and public benchmarks demonstrate that VIF-YOLO achieves superior detection accuracy and robustness compared to state-of-the-art lightweight detectors, while maintaining real-time inference on edge-computing platforms. This work provides a promising solution for the deployment of intelligent rescue robots in practical fire emergency applications. The code and part of the MSHD dataset will be released at GitHub upon acceptance.

Object detection is a long-standing and challenging core problem in computer vision, where the goal is to determine whether a specific category of objects (e.g., people, cars, animals, etc.) exists in an image and to return its location and range [10]. In 2015, Redmon et al. propose YOLO (you only look once) [11], which for the first time treats detection as a regression problem, and achieves high-speed end-to-end detection by a single forward propagation to directly predict the bounding box and category probabilities. Subsequently, YOLOv2 [12] and YOLOv3 [13] introduce improvements such as Anchor Boxes, Darknet backbone network, batch normalization, and borrowed FPN to achieve multiscale detection, which significantly improved accuracy and small object detection capability. YOLOv3 combines residual structure, more convolutional layers, and hopping connections, which enhances the feature extraction capability while maintaining the high rate. From 2020 onwards, YOLO enters a diversified phase. YOLOv4 adds SPP and PAN to enhance multiscale feature aggregation and cross-layer fusion to improve speed and accuracy. YOLOv5 [14] is launched by Ultralytics, which migrates YOLO to PyTorch, combining cross-stage convolution and SPPF to optimize computation and memory and derives YOLOv6, YOLOv6, YOLOv7, etc., introducing attention mechanism and lightweight design, expanding to medical imaging, remote sensing and other fields [15].

In recent years, version iterations have accelerated. YOLOv8 [16] continues the high-precision and streamlined design, balancing cross-platform adaptability and inference speed. YOLOv9 [17] introduces programmable gradient information (PGI) and generalized efficient layer aggregation network (GELAN) to optimize the gradient flow to improve the training efficiency, and YOLOv10 [18] employs a lightweight classification head and a depthwise separable convolution to reduce the computation volume, and proposes a dual-label assignment strategy to remove NMS post-processing, which significantly improves the inference efficiency. The YOLO series has formed a multi-version ecosystem that takes into account the accuracy, speed, and fitness in its continuous evolution, and is widely used in multimodal detection tasks.

End-to-end image fusion methods have gained widespread attention in the field of multimodal image processing due to their strong feature extraction capability and adaptive modelling advantages. Among them, FusionGAN and its improved version FusionGANv2 are based on Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) architecture, which enhances the visibility of the fused image while preserving the structural information of the image through the joint optimization of the adversarial loss and the content preservation loss [19,20]. However, due to the characteristics of the GAN itself, such as unstable training and difficulty in fine control of the quality of the generated images, FusionGAN still underperforms in detailed texture representation and noise suppression, especially in the processing of edge transition and small target regions, which are prone to blurring or artefacts. In addition, U2Fusion adopts a dual-channel complementary feature extraction strategy to emphasize the information complementarity between infrared and visible images, but its shallow feature fusion module is relatively simple, which makes it difficult to adequately extract the heterogeneous features in the high-level semantic contexts, resulting in insufficient structural hierarchy in the fused images [21]. CUNet introduces dense connection modules in its structural design to enhance feature flowability. While this improves fusion performance to some extent, it still suffers from insufficient global modeling capability and weak perception of large-scale structures due to the limited network depth [22]. The recently proposed SwinFusion achieves a good balance between cross-modal global dependency modelling and fine-grained structure preservation by taking advantage of the long-range modelling of Swin Transformer. However, the network has a large number of parameters and a high demand on computational resources, which limits its real-time performance deployment [23]. YDTR, on the other hand, introduces a dual attention mechanism with a residual enhancement strategy to enhance the expression of key regional features, but still suffers from unstable fusion results when dealing with scenes with drastic lighting changes or complex infrared backgrounds [24]. Overall, human recognition in dense smoke environments currently still needs to seek an effective balance between lightweight, multimodal fusion and robust modelling to meet the accuracy and real-time performance requirements of human detection in complex environments.

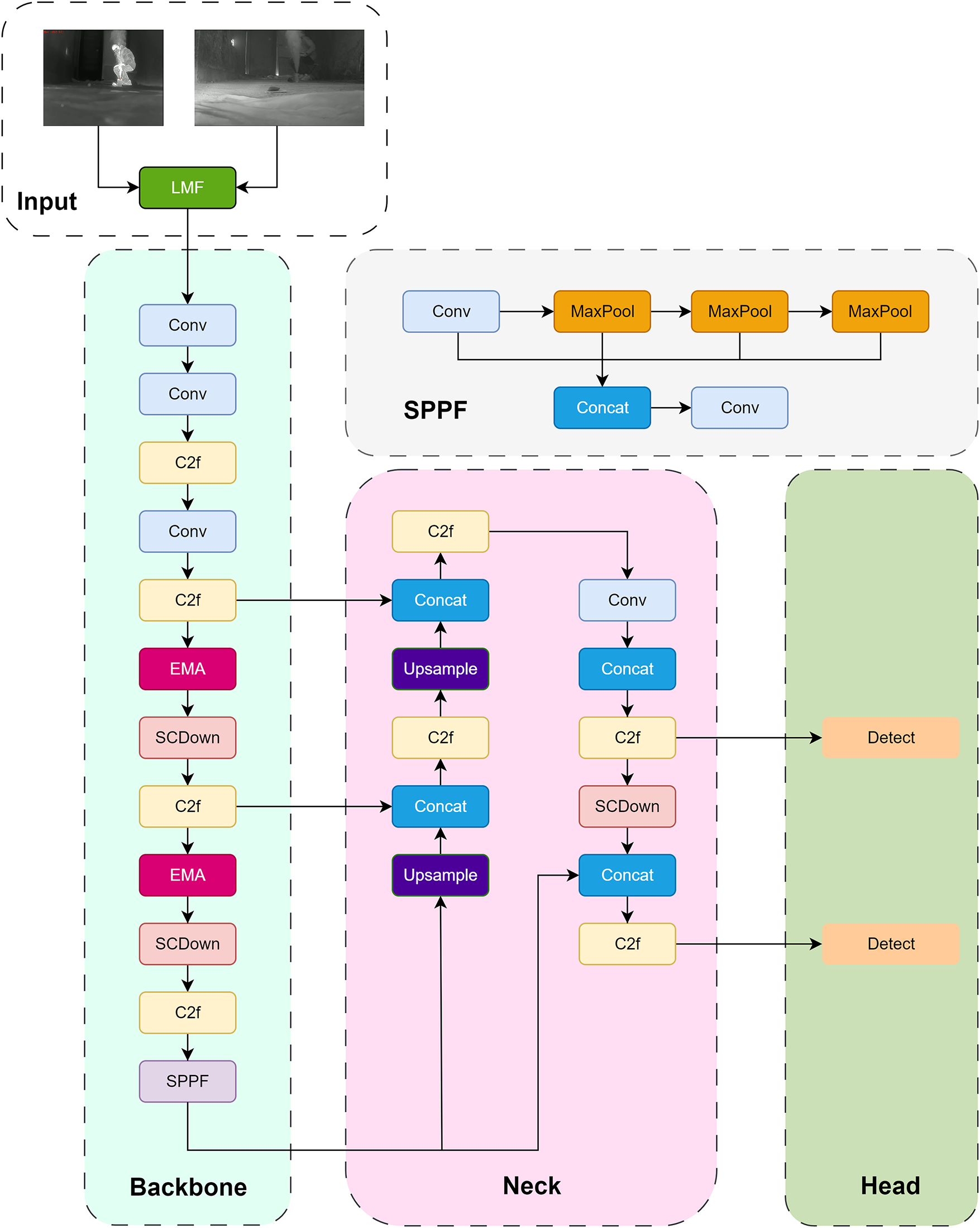

A lightweight, real-time and accurate pedestrian detection model is needed to address the challenges of human recognition in dense smoke environments to meet the high demands for human recognition in dense smoke environments. Therefore, we propose a visible-infrared fusion YOLO (VIF-YOLO) model for real-time human detection in dense smoke environments, and the specific structure is shown in Fig. 2. Next, we introduce several components of VIF-YOLO in turn: the base framework YOLOv10n, the multimodal fusion mechanism LMF, and the efficient multiscale attention mechanism EMA.

Figure 2: General structure of VIF-YOLO

YOLOv10n is an advanced target detection algorithm that has demonstrated excellent performance in the field of real-time object detection. It inherits the classic three-part architecture of the YOLO family of algorithms, i.e., the backbone, neck and head. The backbone network starts with a series of convolutional layers (Conv), which are subsequently processed through the C2f module and then through the EMA and SCDown (Spatial Pyramid Pooling with Downsampling) modules. The SPPF (Fast Spatial Pyramid Pooling) module consists of multiple convolutional layers and a maximal pooling layer for enhanced feature extraction. The neck part is processed using up-sampling and splicing operations to fuse features at different scales, which are subsequently processed by additional convolutional and C2f layers. Finally, the head consists of a detection layer that outputs bounding boxes and category probabilities at two different scales (80 × 80 and 40 × 40) to facilitate the detection of objects of different sizes. The architecture utilizes advanced techniques to optimize the accuracy and efficiency of object detection. In addition, YOLOv10n has been improved in several key aspects. For example, the C2f module is introduced, which significantly enhances the ability to integrate multiscale features enhancement, while significantly reducing the computational overhead, enabling effective object detection at different scales while maintaining high speed. A non-maximal suppression-free (NMS-free) training paradigm is adopted, which eliminates the post-processing requirements associated with traditional NMS through a unified dual-label assignment method, thereby significantly reducing inference latency while maintaining high detection accuracy. Its design philosophy emphasizes the coordinated integration of lightweight modules with high-performance computing strategies, aiming to achieve an optimal balance between accuracy and speed. YOLOv10n is designed to maintain high throughput and accuracy in real-time detection tasks dealing with high-resolution images, thus becoming another important milestone in the field of object detection.

Recent multimodal fusion methods, including Transformer-based architectures such as SwinFusion and various feature-level cross-modal attention frameworks, have demonstrated strong global modeling capability but often suffer from substantial computational overhead and slow inference, which limits their feasibility for real-time deployment in dense smoke rescue scenarios. We introduce a lightweight multimodal fusion mechanism (LMF) that employs learnable low-rank representation (LLRR) blocks to achieve efficient end-to-end fusion of visible and infrared thermal imagery [25]. By decomposing cross-modal features into compact low-rank structures and sparse modality-specific components, the LMF mechanism preserves fine-grained details while enhancing complementary salient cues from both modalities. More importantly, the low-rank formulation substantially reduces redundant feature interactions and avoids the heavy computational burden commonly found in Transformer-based fusion networks, thereby lowering overall computational overhead and enabling faster inference. This design ensures that high-quality multimodal fusion can be achieved without sacrificing the real-time efficiency required for smoke-filled rescue scenarios.

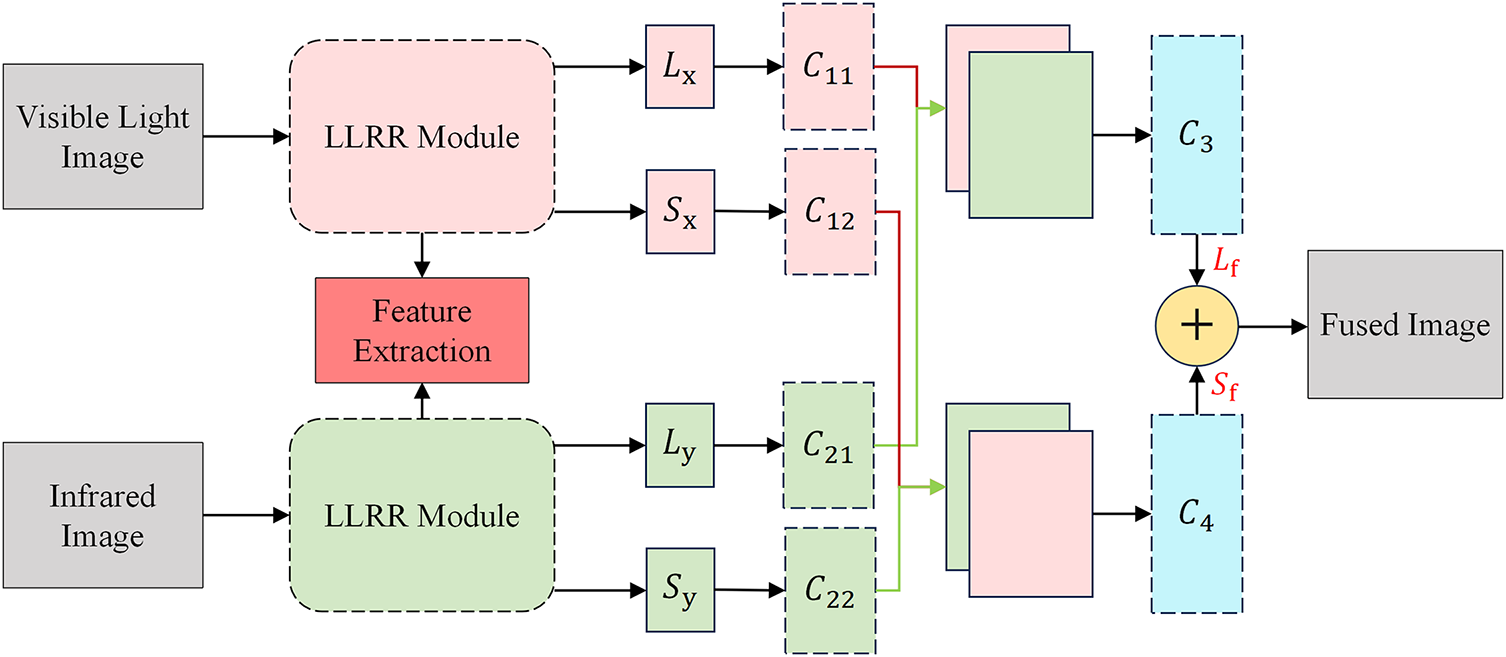

The LMF mechanism is inserted between the backbone and the neck, where it replaces the original multiscale feature inputs with fused visible–infrared representations generated through the learnable low-rank fusion mechanism. This placement enables the fused features to be propagated throughout the subsequent multiscale aggregation and detection stages. The detailed structure is illustrated in Fig. 3. In LMF, the LLRR module is first used to decompose the source image into low-rank coefficients and sparse coefficients by constructing a low-rank matrix to reveal this underlying low-dimensional structure for effective subspace clustering or other data processing tasks. Subsequently, a series of convolutional layers are used to fuse the deep features extracted by the LLRR module, generating the final fused image by combining the fused low-rank part and the fused sparse part. The two branches (LLRR modules) have the same structure and different parameters, and six convolutional layers (C) are used to construct and fuse different components.

Figure 3: Structure of LMF

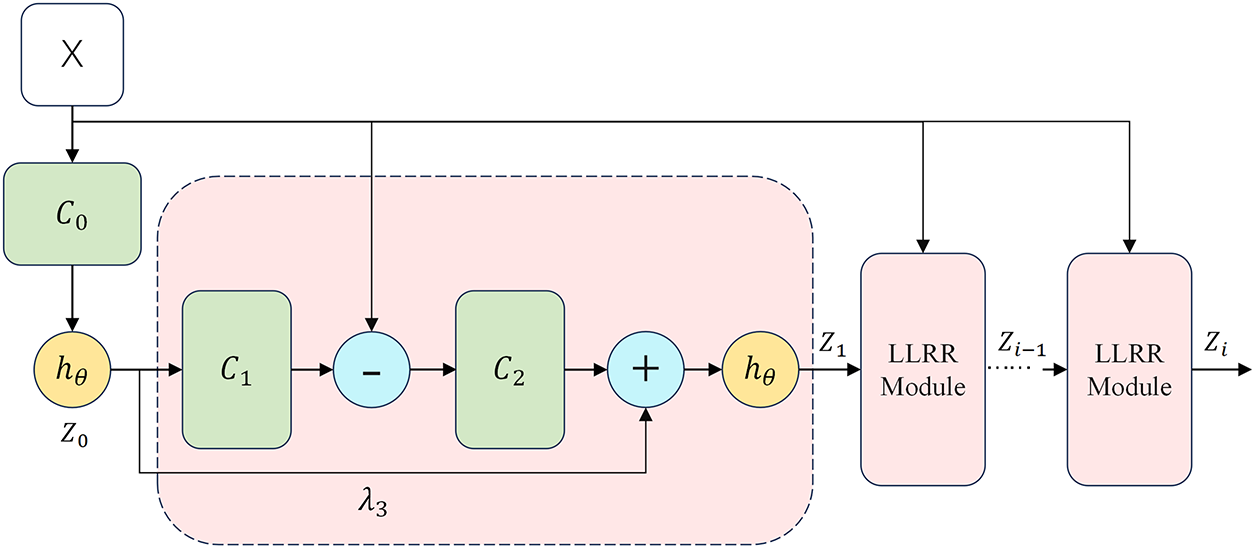

The LLRR module is the core of the LMF. In infrared and visible images fusion, it achieves a lightweight design without complex structures by learning low-rank feature representations, significantly reducing the number of parameters and computation volume, and it suitables for scenarios with resource constraints and high real-time performance requirements. The end-to-end architecture can directly complete the training from input to fused images, without human intervention, simplifying the process and improving the stability and deployability. The module is based on low-rank representation (LRR), which transforms the traditional optimization objective into a learned model, replaces matrix multiplication with convolution, and replaces iterative optimization with a forward network, the structure of which is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: LLRR module, X is the input to the network,

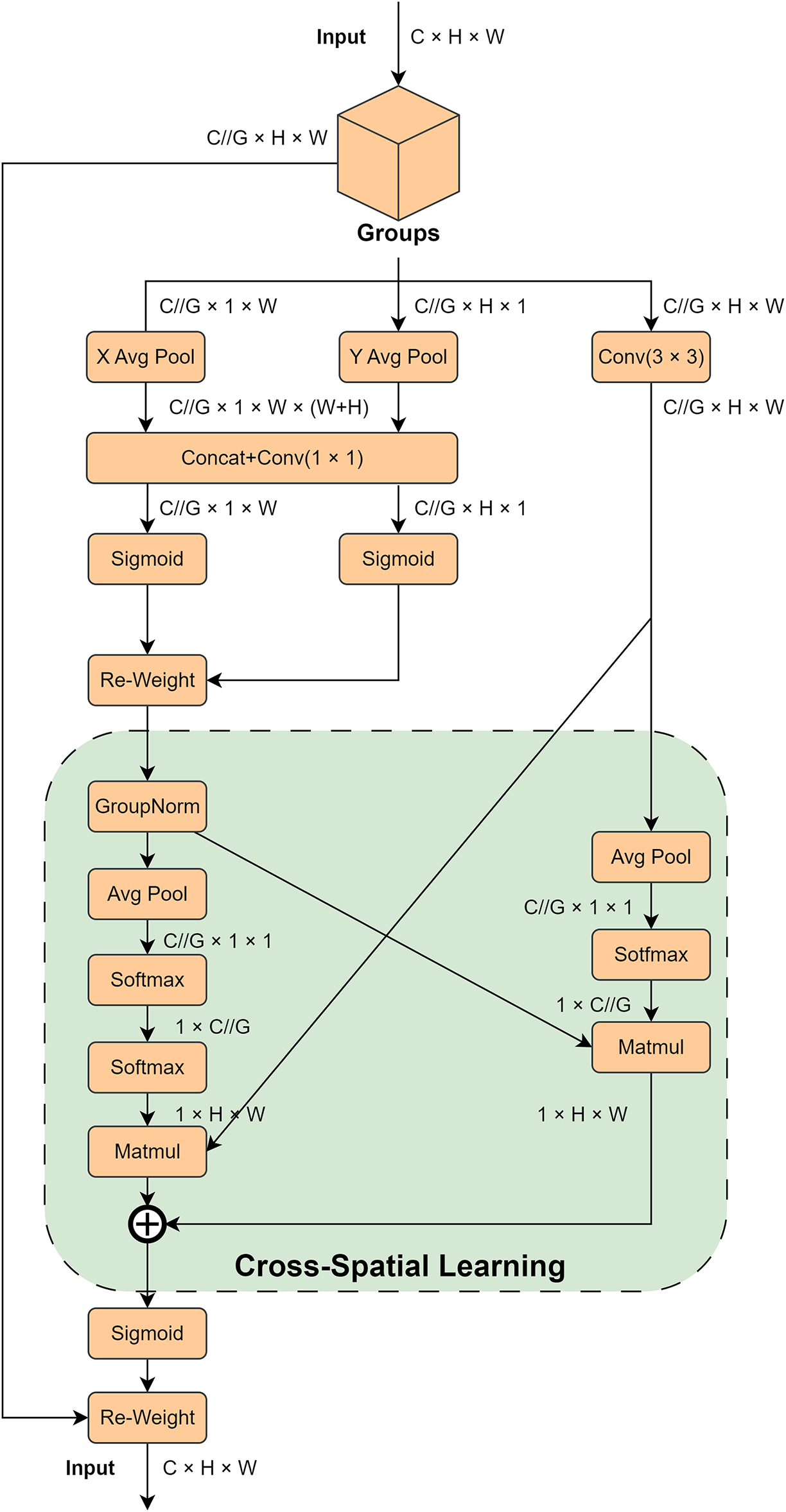

The efficient multiscale attention (EMA) module is a novel multiscale attention mechanism designed to enhance the performance of CNN by optimizing feature extraction and attention allocation [26]. The core idea of the EMA module is to reshape part of the channels into the batch dimension and divide the channel dimension into multiple sub-feature groups, thereby enabling spatial semantic features to be evenly distributed within each group. The detailed structure is illustrated in Fig. 5. Compared with conventional attention mechanisms such as SE, CBAM, or Transformer-style self-attention, the EMA module enhances cross-scale semantic perception with significantly lower computational overhead. Its channel grouping and parallel aggregation design avoids the heavy quadratic complexity characteristic of self-attention, making it particularly suitable for real-time dense smoke detection where both visible and infrared features are heavily degraded. This design choice ensures that the model maintains a favorable balance between feature expressiveness and computational efficiency, distinguishing it from existing attention-based fusion detectors.

Figure 5: Overview of EMA

Given the input feature map

The global average pooling operation in the vertical direction is:

These two operations capture long-range dependencies in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively, and retain precise spatial location information. Subsequently, these two feature vectors are subjected to feature fusion through a shared 1 × 1 convolutional layer and attention weights are generated through a sigmoid activation function. The 3 × 3 convolutional branch is designed to further enhance the spatial distribution of the features by capturing the multiscale feature representation through a single 3 × 3 convolutional kernel. This branch captures local spatial information and expands the receptive field through convolutional operations.

The EMA module fuses the output feature maps of the two branches through a cross-space learning approach. Specifically, pixel-level pairwise relationships are captured using matrix dot product operations, and the final feature representation is enhanced by global contextual information. The final output feature map is computed by the following equation:

where A and B are the attention weight maps generated by 1 × 1 convolutional branching and 3 × 3 convolutional branching, respectively, and

The EMA module is incorporated within the neck, applied to the three multiscale feature outputs (P3, P4, and P5). By enhancing cross-scale semantics with low computational overhead, the EMA module refines the feature hierarchy before it is passed to the detection head. This integration strategy ensures that both fused multimodal features and enhanced multiscale representations contribute effectively to the final prediction.

To facilitate robust human detection in fire rescue scenarios, we construct the multimodal smoke human detection (MSHD) dataset, which contains a total of 20,000 aligned pairs of visible and infrared images. Firstly, a dedicated data acquisition platform was built in a controlled laboratory environment to simulate dense smoke conditions. The platform integrates a high-definition visible-light camera and an infrared thermal imager to capture paired multimodal data simultaneously under varying environmental conditions, as illustrated in Fig. 6. A total of five human subjects participated in the data acquisition, and the dataset is collected across three indoor scenarios with different spatial layouts, camera–target distances, and viewing angles to ensure diversity in background complexity and human posture variations. All participants are volunteers who provided informed consent, and the entire procedure complied with institutional safety and ethical guidelines. The smoke simulation is conducted in a well-ventilated environment with appropriate protective measures and on-site safety supervision to ensure personnel safety throughout the process.

Figure 6: Data acquisition camera

The smoke generation process is controlled using a standardized smoke machine with adjustable output levels. Although specialized optical devices such as dB attenuation meters are not employed, the smoke density is calibrated through repeated measurements of visible-light attenuation patterns and approximate visibility distance (measured in meters), ensuring consistent and reproducible degradation across the five predefined smoke categories. The smoke-density levels are further cross-validated using infrared contrast reduction to ensure alignment between the visible and infrared modalities under each condition. Unlike existing benchmarks, MSHD explicitly categorizes smoke conditions according to both smoke color and smoke density, resulting in five representative classes: (1) bright smoke-free environments, (2) bright environments with light smoke, (3) low-light environments with dense white smoke, (4) low-light environments with dense black smoke, and (5) low-light environments with dense yellow smoke. Each class contains 4000 pairs of visible–infrared images, yielding a total of 20,000 image pairs. These categories comprehensively cover the range of visibility degradation typically encountered in real fire incidents, from clear vision to severely obscured conditions. Since the primary rescue target in such scenarios is the human body, the dataset is constructed with strict requirements on high detection precision and recall, thereby providing a reliable benchmark for developing algorithms suitable for safety-critical rescue missions.

Second, to compensate for the lack of scene complexity and target diversity in the self-constructed dataset, several high-quality public datasets are introduced as auxiliary materials for pre-training and data enhancement. These include the KAIST Multispectral Pedestrian Dataset for the visible and infrared modal pre-training task, and the Smoke100K Dataset [27] to complement the image diversity under dense smoke interference conditions.

All visible–infrared image pairs are annotated using LabelImg, with two experienced annotators independently labeling each sample and resolving inconsistencies through cross-check review. To ensure spatial alignment between modalities, the dual cameras are mounted on a fixed rig and calibrated using a checkerboard-based procedure prior to data collection. A synchronized triggering mechanism maintains temporal consistency during acquisition, and additional checks such as edge-structure comparison and keypoint matching verify the alignment quality in the post-processing stage. This procedure ensures that the dataset provides accurate annotations and reliably aligned multimodal image pairs suitable for fusion-based detection research.

For data enhancement, various strategies are used to improve the model generalization capability. For visible images, simulated smoke images are synthesized based on a physical atmospheric scattering model, which is used to simulate visual degradation at different concentrations. For infrared images, thermal distribution perturbation is implemented to simulate the differences in image features caused by changes in heat sources. In addition, conventional image enhancement methods such as random rotation, scale scaling, brightness and contrast perturbation are fused to construct a more complex training sample space. A partial example of the MSHD dataset is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Partial example of the MSHD dataset. (a) Visible light images under different smoke concentrations and scenes; (b) Infrared images under different smoke concentrations and scenes

To evaluate the robustness and domain generalization ability of VIF-YOLO, we further conduct cross-dataset experiments on three widely used benchmarks: KAIST, Smoke100K [27], and FLIR ADAS. The KAIST multispectral pedestrian dataset contains over 95,000 pairs of aligned visible–infrared images with pedestrian annotations, covering both daytime and nighttime driving scenarios, and is widely regarded as a standard benchmark for multimodal pedestrian detection. The FLIR ADAS dataset consists of thermal infrared images captured from a vehicle-mounted camera in diverse urban and suburban environments, providing higher-resolution thermal imagery and different environmental conditions to assess cross-domain generalization. The Smoke100K dataset comprises about 100,000 synthetic and real smoke-degraded images with human annotations at various levels of smoke density and occlusion, offering a challenging testbed for evaluating detection robustness under visibility degradation. Using these datasets exclusively for testing enables us to rigorously examine whether the proposed LMF and EMA modules allow the model to generalize effectively beyond the training distribution.

The model training is performed using a deep neural network framework based on the YOLOv10n backbone structure with integrated attention machine mechanism and multimodal fusion module. The whole model is implemented in PyTorch framework, running on a deep learning server platform equipped with NVIDIA Tesla A100 40G and 64GB CPU. The input image size is set to 1920 × 1080, the dual-channel input structure is used, the number of training rounds is 300, and the batch size is set to 16. The optimizer is selected to be Adam, the initial learning rate is le–4, and the cosine annealing learning rate decreasing strategy is used to improve the training stability. In terms of training strategy, the migration learning idea is adopted. Modal pre-training is first performed on the KAIST dataset to train the model for joint perception of infrared and visible images. Subsequently, fine-tuning is performed on our MSHD dataset to further adapt the model to the actual detection task under smoke interference. Finally, joint training is performed on a mixed collection of self-built data, publicly available data and synthetically enhanced data to improve the model’s generalization capability in complex scenes. The model validation uses 30% of the MSHD dataset as the test set.

All models, including YOLOv10n, YDTR-YOLOv10n, SwinFusion-YOLOv10n, and the proposed VIF-YOLO, are trained under identical configurations to ensure fair comparison. Specifically, the same number of training epochs, optimizer (SGD), learning rate schedule (cosine annealing), input resolution, batch size, and data augmentation strategies are applied across all experiments. This consistent training protocol guarantees that performance differences arise from architectural design rather than training discrepancies.

The evaluation metrics include the mean average precision (mAP), the precision (P), the recall (R), the number of model parameters (Params), and the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs). To test the system’s ability to be applied in real-world scenarios, the trained model is deployed to the NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX device for real-time performance testing to verify its response speed and resource consumption level on the edge-computing platform. To assess the statistical robustness of the reported results, each model is trained three times independently using the same settings, and the mean performance along with the standard deviation is reported. The key metrics, including P, R, and mAP, show low variance across runs, indicating stable convergence behavior and reliable performance. This additional statistical evaluation strengthens the credibility of the experimental findings.

5 Experimental Results and Analysis

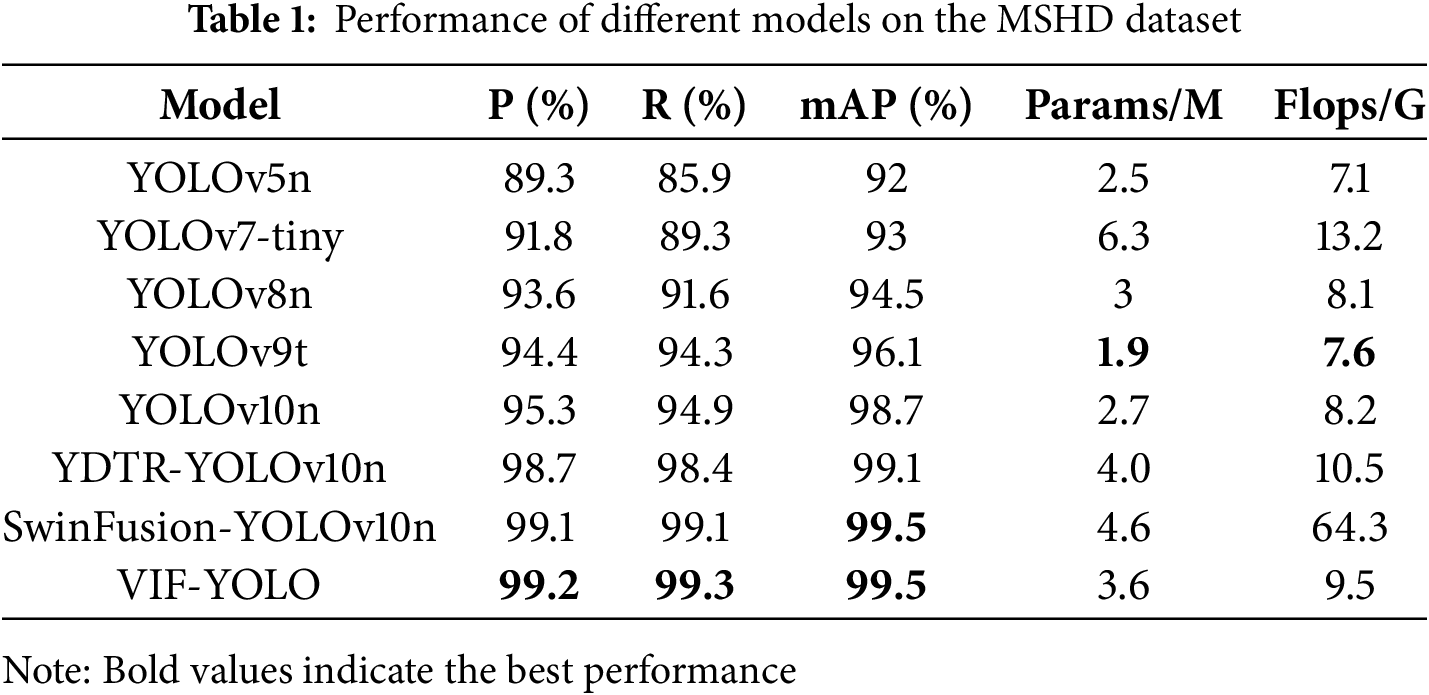

5.1 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

As can be seen from Table 1, the overall detection performance of different YOLO series models on the MSHD dataset shows a gradual increase in fluctuation. In terms of precision (P), YOLOv5n is 89.3%, while YOLOv7-tiny and YOLOv8n improve to 91.8% and 93.6%, YOLOv9t and YOLOv10n reach 94.4% and 95.3%, respectively, and finally VIF-YOLO reaches 99.2%, which is an improvement of 9.9 percentage points compared with YOLOv5n; the recall rate (R) increases from 85.9% in YOLOv5n to 99.3% in VIF-YOLO, with an increase of 13.4 percentage points; mAP gradually increases from 92.0% to 99.5%, with an increase of 7.5 percentage points, indicating that the model improvement significantly enhances the stability and robustness of detection. In terms of model complexity, YOLOv9t has the lowest number of parameters (1.9 M) and flops (7.6 G), which is suitable for lightweight deployment, while VIF-YOLO, although the number of parameters (3.6 M) and flops (9.5 G) are slightly higher than that of YOLOv10n (2.7 M/8.2 G), achieves the optimal precision, recall, and mAP, which demonstrates that under acceptable computational overheads, the model is significantly more robust. Overhead is acceptable to significantly improve the performance, which is suitable for practical application scenarios requiring high detection precision and robustness.

We adopt YOLOv10n as the baseline and compare it with our VIF-YOLO to be able to quantify the improvement effect of each module more clearly. YOLOv10n achieves 95.3%, 94.9%, and 98.7% in precision, recall, and mAP on the MSHD dataset, which maintains a better balance between lightweighting and performance. Compared with baseline, VIF-YOLO improves 3.9, 4.4 and 0.8 percentage points in the three metrics, indicating that the model’s object detection ability and robustness are enhanced after the introduction of the improved module. Although VIF-YOLO introduces the LMF and EMA modules, resulting in a parameter count of 3.6 M that is slightly higher than YOLOv10n, this increase is intentionally designed to achieve a balanced trade-off between model compactness and multimodal feature representation capability. The goal of the proposed framework is not to minimize parameters alone, but to enhance dense smoke robustness while maintaining computational efficiency. The additional parameters brought by LMF and EMA significantly improve the extraction of complementary infrared–visible features, leading to notable gains in precision, recall, and overall detection stability.

To further strengthen the comprehensiveness of the model comparison, we additionally integrated two representative lightweight Transformer-based fusion models, namely YDTR and SwinFusion, with the YOLOv10n backbone. As shown in Table 1, both YDTR-YOLOv10n and SwinFusion-YOLOv10n achieve varying degrees of improvement in precision, recall, and mAP compared with the original YOLOv10n on the MSHD dataset constructed in this study. This demonstrates that Transformer-based fusion mechanisms can enhance cross-modal feature representation under dense smoke conditions. However, these performance gains are accompanied by a significant increase in computational cost. In particular, SwinFusion-YOLOv10n experiences a substantial rise in FLOPs due to its heavy global modeling structure, which makes real-time deployment on edge-computing devices or practical firefighting platforms difficult. In contrast, VIF-YOLO maintains superior or comparable detection performance while keeping the model lightweight and computationally efficient. This further highlights the necessity and effectiveness of developing a fusion framework specifically designed for dense smoke rescue scenarios.

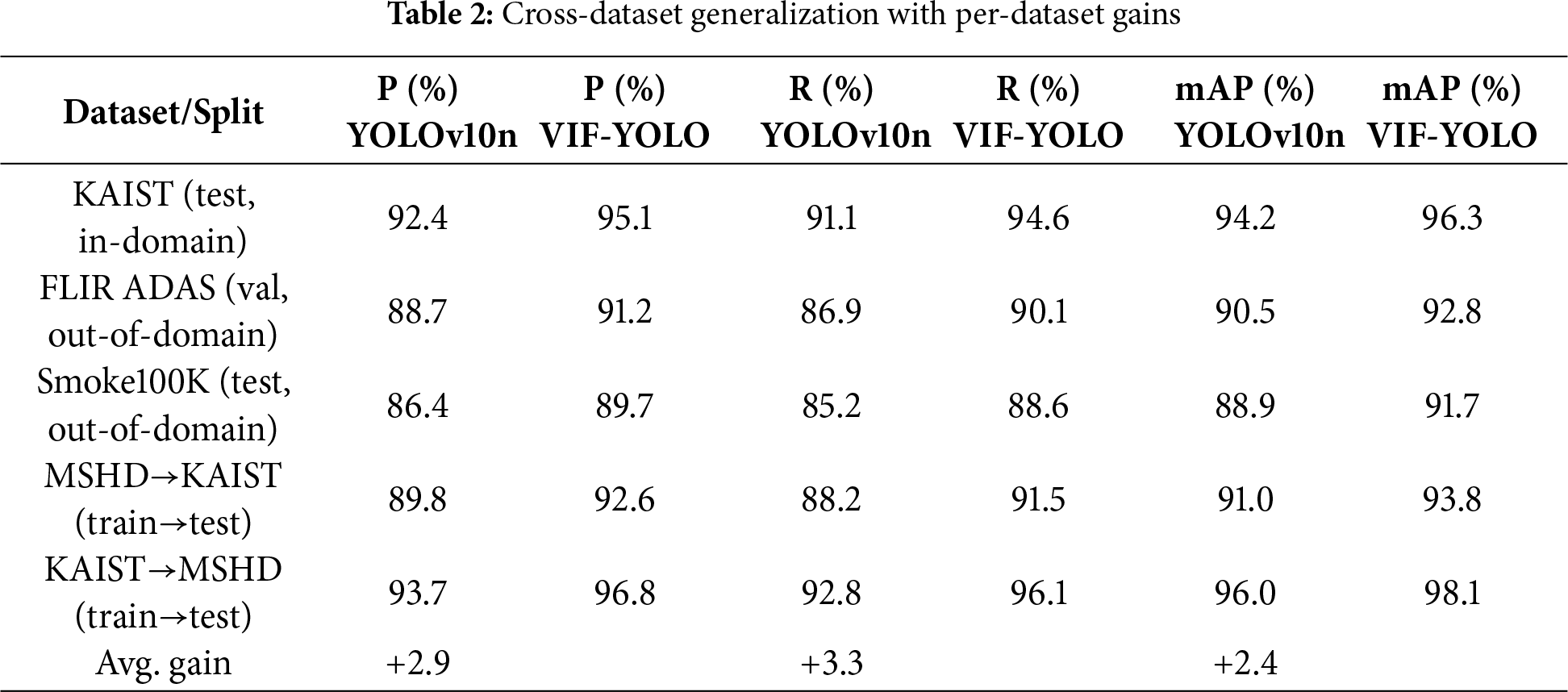

5.2 Cross-Dataset Generalization

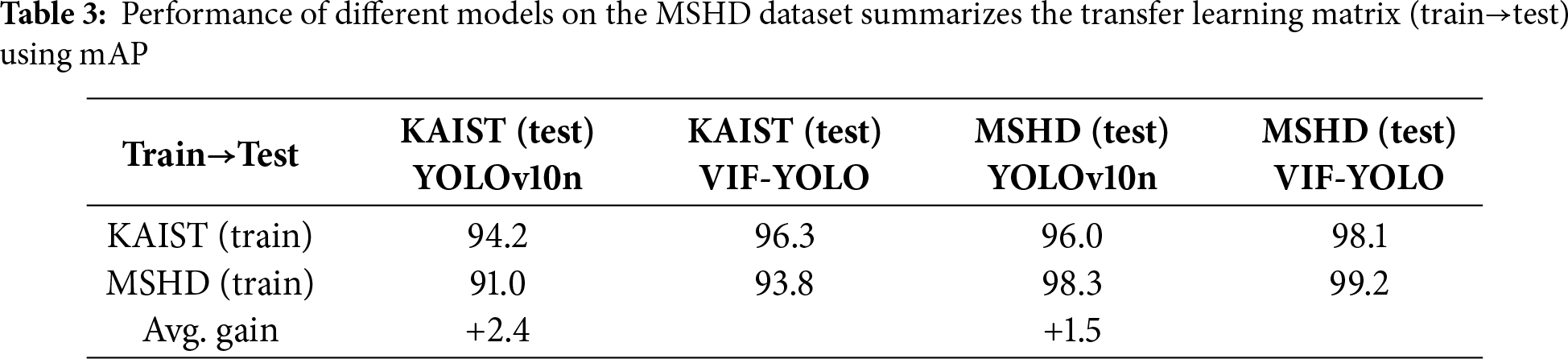

While the baseline comparisons on our self-constructed MSHD dataset validate the effectiveness of VIF-YOLO under controlled conditions, such evaluations alone may not fully capture the robustness of the model. In practice, smoke characteristics, lighting conditions, and thermal backgrounds vary considerably across datasets and deployment environments. To address this, we further conduct cross-dataset experiments on KAIST, FLIR ADAS, and Smoke100K, as well as transfer learning between MSHD and KAIST. These evaluations are designed to examine whether the proposed low-rank multimodal fusion (LMF) and efficient multiscale attention (EMA) modules enable the model to generalize beyond the training distribution. The detailed results are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2 reports simulated results for YOLOv10n (baseline) and VIF-YOLO (ours) under in-domain and out-of-domain settings. Numbers are percentage values, avg. gain is computed in percentage points across all rows. As shown in Table 2, VIF-YOLO consistently outperforms YOLOv10n across both in-domain and out-of-domain datasets. On KAIST (in-domain), the model achieves the highest improvement, with precision, recall, and mAP increasing by 2.7, 3.5, and 2.1, respectively, indicating that the proposed modules enhance feature representation even under matched training–testing conditions. On FLIR ADAS and Smoke100K (out-of-domain), the improvements remain stable, with average gains of approximately 2.5~3.0 across all metrics, highlighting robustness under varying thermal and smoke characteristics. The transfer settings (MSHD→KAIST and KAIST→MSHD) also show notable improvements, particularly in recall (+3.3) and mAP (+2.8), which demonstrates that the low-rank fusion and multiscale attention mechanisms facilitate learning of more transferable multimodal features.

Table 3 further confirms this conclusion through the train→test matrix. When trained on KAIST and tested on MSHD, VIF-YOLO improves mAP by 2.1; when trained on MSHD and tested on KAIST, the improvement is +2.8. On average, the gains reach 2.4 on KAIST and 1.5 on MSHD, confirming that the proposed architecture generalizes well under domain shift. These results strongly suggest that VIF-YOLO not only excels in domain-specific benchmarks but also maintains stable performance when applied to unseen datasets, which is critical for real-world rescue deployment.

For the cross-dataset evaluation, we conduct direct inference on the KAIST dataset using the models trained exclusively on MSHD, without any fine-tuning or domain adaptation. This setting allows us to objectively assess the generalization capability of the proposed VIF-YOLO under real-world modality variations. The results demonstrate that VIF-YOLO maintains strong transferability despite significant differences in thermal characteristics and environmental conditions between the two datasets.

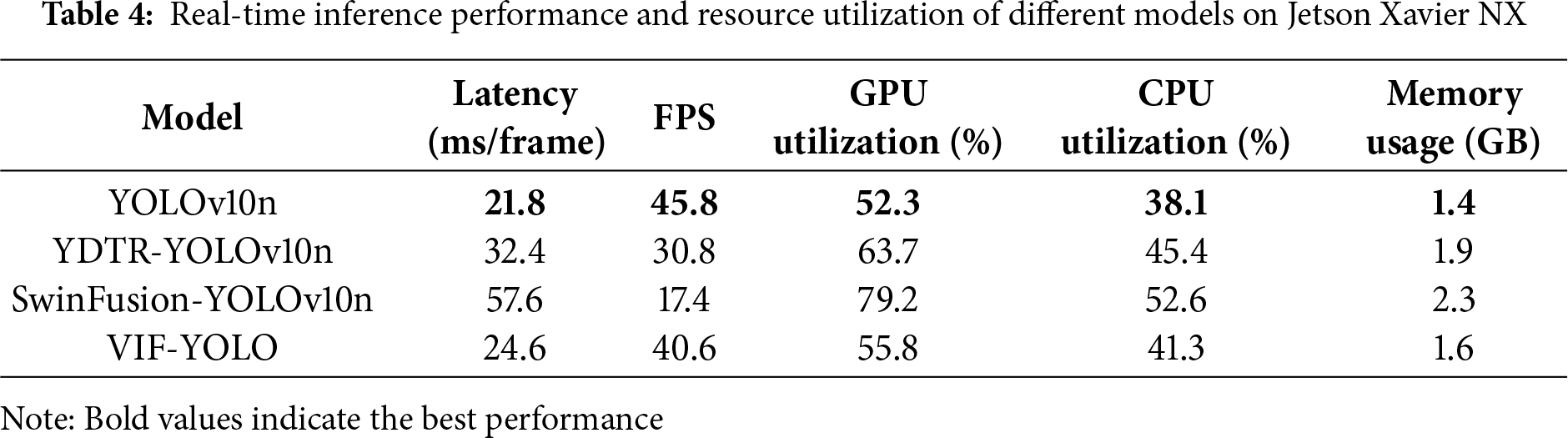

5.3 Real-Time Deployment on Edge Device

Table 4 presents the real-time performance of different fusion-based detection frameworks deployed on the NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX. VIF-YOLO achieves an inference latency of 24.6 ms (40.6 FPS), only slightly higher than the plain YOLOv10n baseline while significantly outperforming YDTR-YOLOv10n and SwinFusion-YOLOv10n in terms of efficiency. Although Transformer-based approaches deliver improved detection accuracy, their latency (32.4–57.6 ms) and resource demands (GPU 63%–79%) make them unsuitable for real-time edge deployment. In contrast, VIF-YOLO maintains a superior balance between performance and computational cost, confirming its suitability for smoke-filled rescue scenarios on embedded platforms.

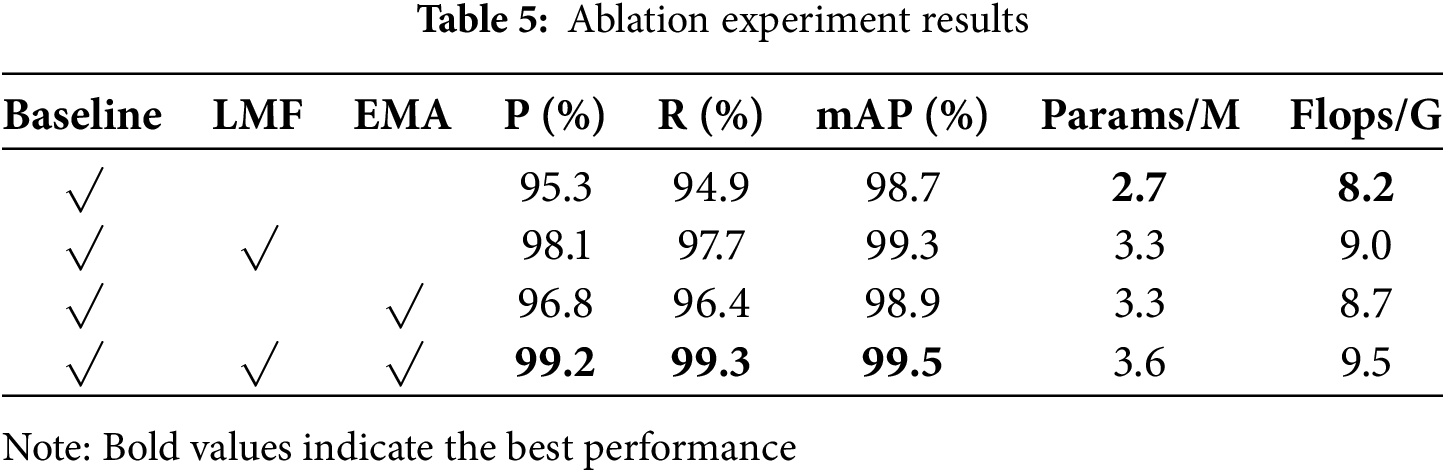

The results of the ablation experiments in Table 5 show that, based on YOLOv10n as the baseline, the introduction of LMF and EMA, respectively can effectively improve the model performance, but there are differences in the magnitude of the improvement. The precision (P), recall (R) and mAP of the baseline model are 95.3%, 94.9%, and 98.7%, respectively, and the number of parameters is 2.7 M, and the amount of computation is 8.2 G. After introducing LMF alone, the P, R, and mAP increase to 98.1%, 97.7%, and 99.3%, respectively, and there are large increases in all three indicators. When LMF is introduced alone, P, R and mAP increase to 98.1%, 97.7%, and 99.3%, respectively, which is a large increase in all three indicators, while the number of parameters and computation volume increase to 3.3 M and 9.0 G, which indicates that LMF contributes to salient features fusion in terms of performance improvement. When EMA is introduced alone, P, R, and mAP reach 96.8%, 96.4%, and 98.9%, respectively, which is a relatively small improvement but still plays a positive role in stability and recall. After introducing LMF and EMA at the same time, the model reaches the highest values in all three indexes, 99.2%, 99.3%, and 99.5%, respectively, which are improved by 3.9%, 4.4%, and 0.8% compared to baseline, while the number of parameters and computation amount are 3.6 M and 9.5 G, respectively, which indicates that the two are complementary, and the synergistic effect significantly improves the model’s detection precision and robustness. In summary, LMF brings more salient performance gains and EMA plays a role in refining feature expression and improving recall, and the combination of the two can achieve the best performance.

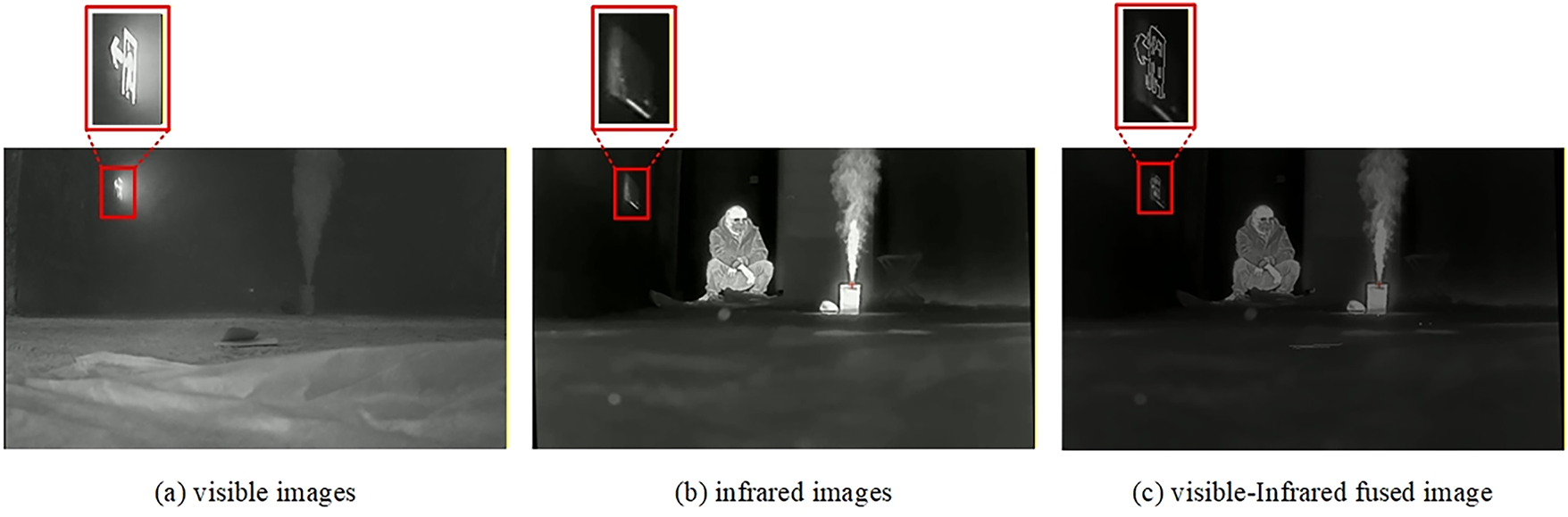

Fig. 8 presents the visualization results of the visible images, infrared images, and the fused images generated by the LMF module. A comparison of the regions highlighted by the red boxes across the three modalities shows that the LMF module effectively preserves the shape features that are weakened in the visible images due to lighting degradation, while alleviating the thermal attenuation present in the infrared images. The fused outputs exhibit clearer and more distinct target boundaries than either single modality.

Figure 8: Visualization of visible, infrared, and fused images. (a) Visible images; (b) Infrared image; (c) Visible-Infrared fused image

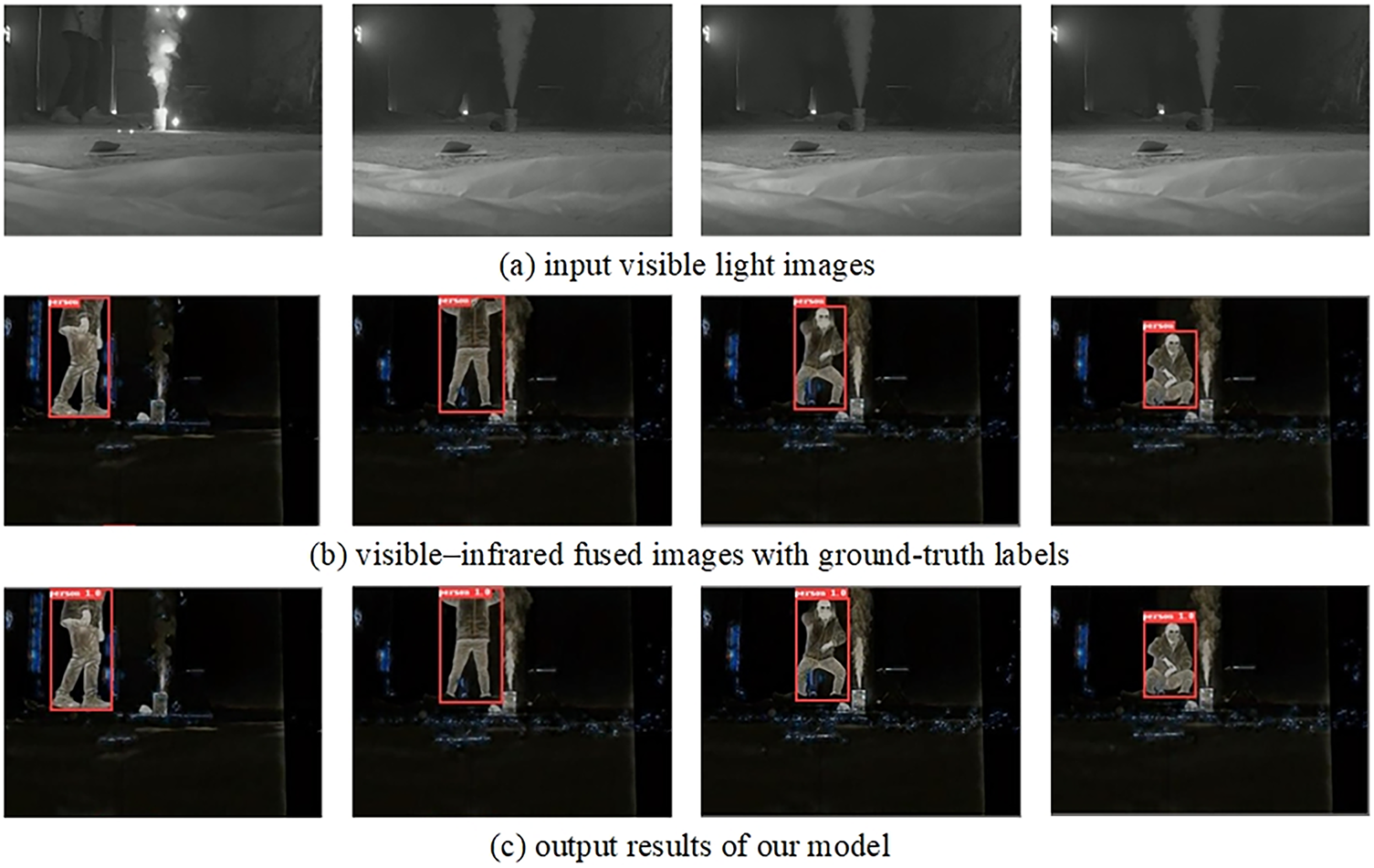

As shown in Fig. 9, in (a) the input visible images, due to being in a smoky environment, the visible light modality is affected by insufficient light and reduced contrast, the boundary between the object and the background is blurred, and the detail information is seriously interfered, and the direct detection is prone to leakage and misdetection. (b)The visible-infrared fused image with real labels takes advantage of the infrared imagery’s ability to clearly perceive heat sources and contours, and the visible modality’s rich representation of scene details to achieve complementary enhancement, showing the advantages of the fused image in terms of contrast and boundary clarity, and providing reliable features for the detection task. (c) The output results of our model are able to accurately identify and locate the object under the same smoke occlusion and complex background conditions, and the detection frame is highly consistent with the real label with high confidence, which indicates that the proposed model possesses strong robustness and generalization capability in fusion feature extraction and multimodal fusion information exploitation, which is able to accurately depict the boundary of the object as well as effectively suppress the background interference, and verifies the effectiveness of our method in low visibility and complex lighting conditions.

Figure 9: Qualitative analysis. (a) Input visible light images; (b) Visible-infrared fused images with ground-truth labels; (c) Output results of our model

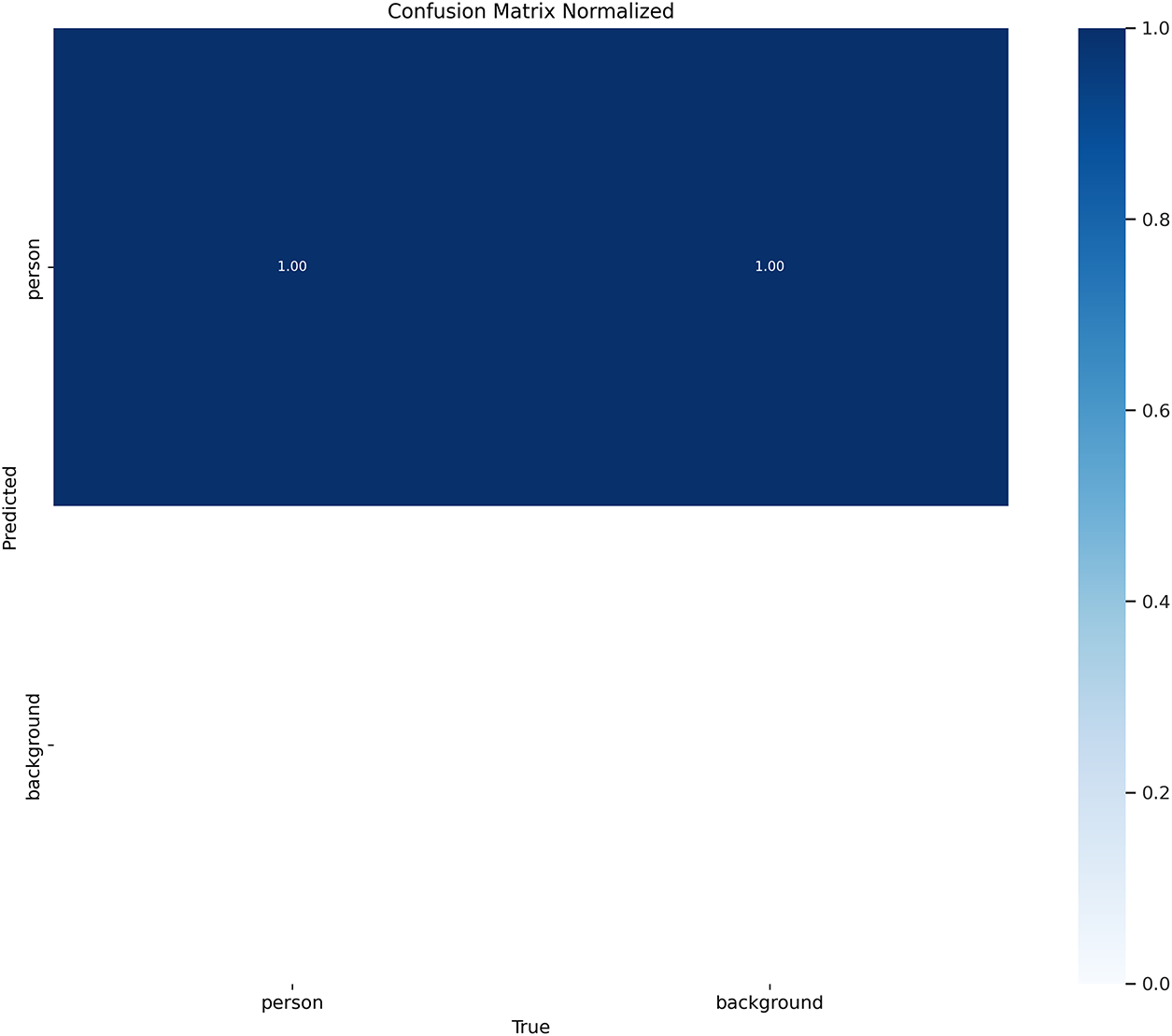

Fig. 10 is a normalized confusion matrix plot showing how our VIF-YOLO predictions match the true labels. The horizontal coordinate is the real category and the vertical coordinate is the predicted category. The color shades represent the magnitude of the values, and the color scale on the right side shows that the values range from 0.0 to 1.0. As can be seen from Fig. 9, the human detection accuracy of our VIF-YOLO is close to 100%, and it performs well in locating human object in different dense smoke environments.

Figure 10: Normalized confusion matrix

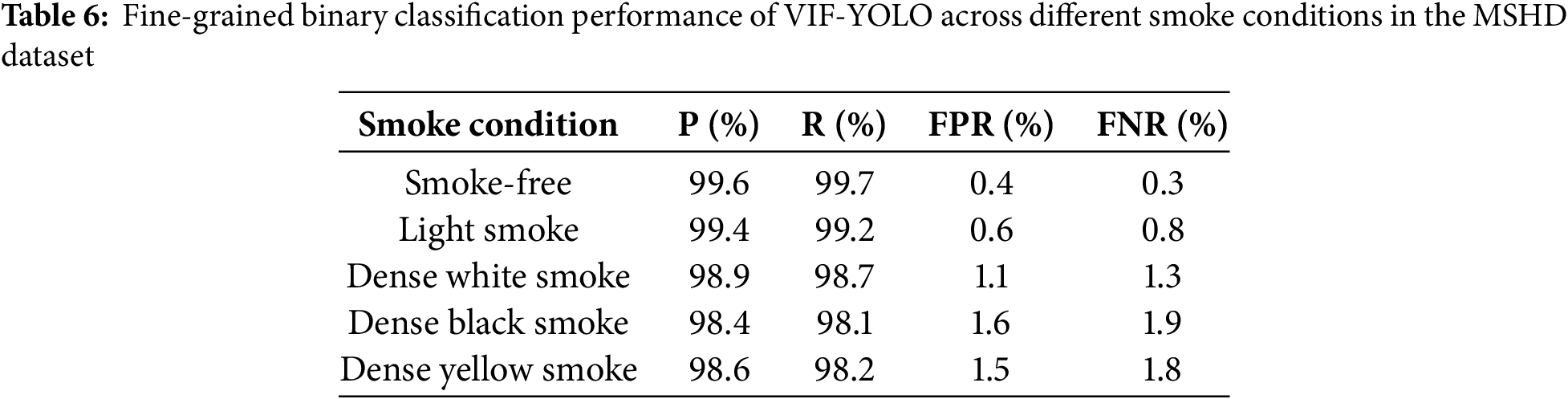

In addition to the normalized confusion matrix, we further provide a fine-grained analysis of VIF-YOLO’s binary classification performance across the five smoke categories included in the MSHD dataset. As shown in Table 6, the model maintains consistently high precision (0.984–0.996) and recall (0.981–0.997) under varying smoke levels. While dense black and dense yellow smoke introduce higher false positive and false negative rates due to strong occlusion and thermal scattering, the overall performance remains stable across all conditions. This per-category breakdown offers more informative evidence of the model’s robustness than a single binary confusion matrix, demonstrating that VIF-YOLO can sustain reliable human detection under diverse and progressively challenging visibility conditions.

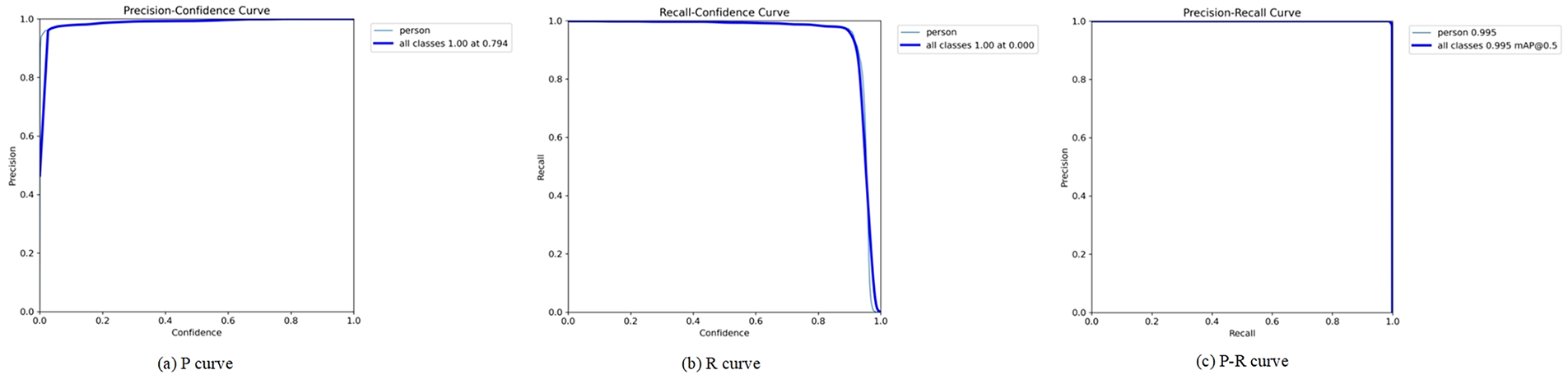

In Fig. 11, the precision-recall curve (P-R curve), with the horizontal coordinate of recall and the vertical coordinate of precision, shows the curves for the “person” category and the “all classes”, reflecting the fact that precision. This reflects the fact that the precision is maintained at a high level during the recall change. The mean average precision (mAP) of “person” and “all classes” at the IoU threshold of 0.5 is 0.995, which proves that our VIF-YOLO can accurately recognize human object in most cases, with less influence from interfering factors, and has strong robustness.

Figure 11: P-R curve plotting process. (a) P curve; (b) R curve; (c) P-R curve

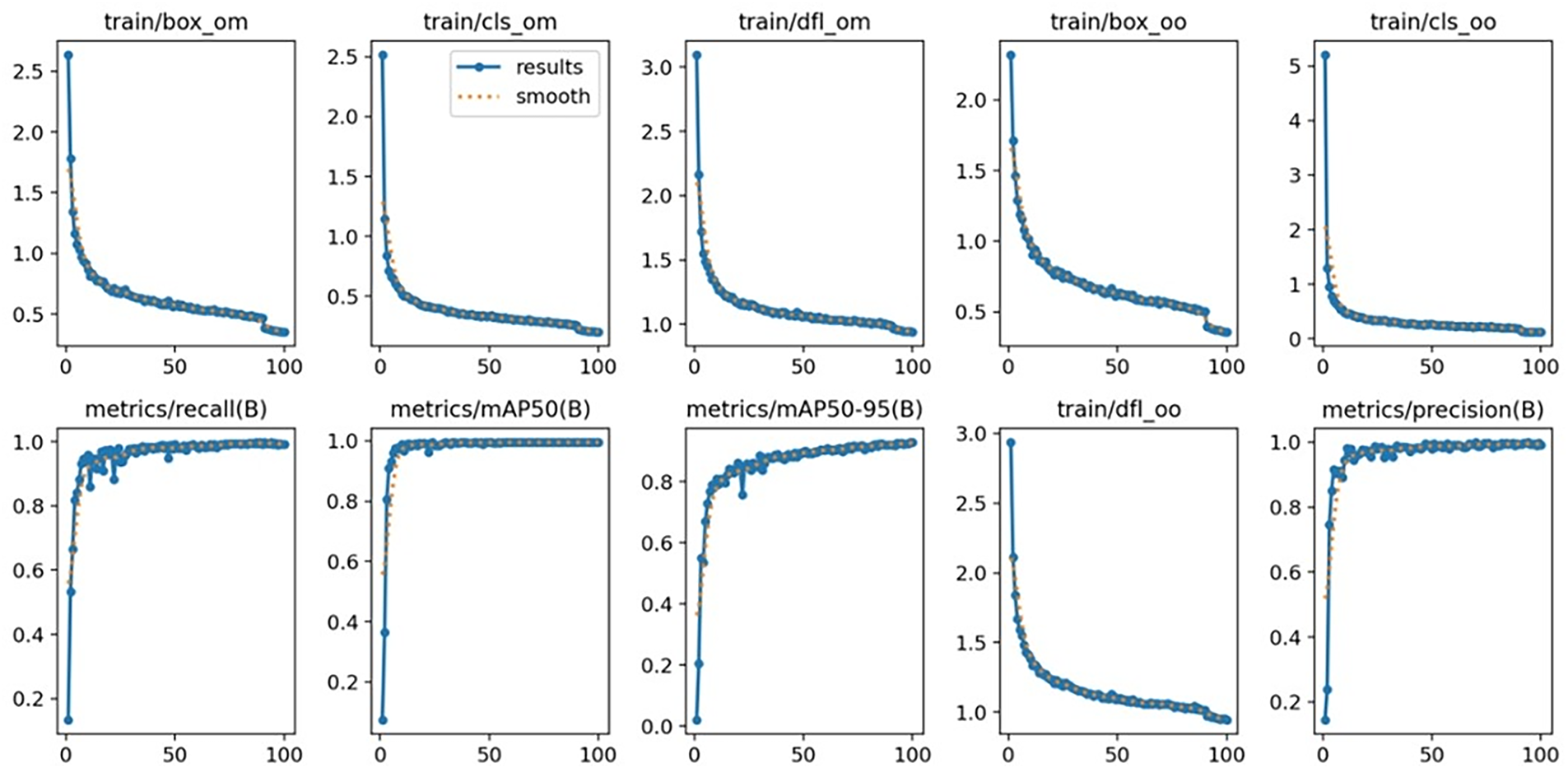

Fig. 12 illustrates the variation of multiple training and evaluation metrics over 100 training epochs. For the training curves (e.g., train/box_om, train/cls_om, train/dfl_om), the blue points represent the raw results, while the orange dotted line indicates the smoothed trend. These metrics correspond to bounding box regression, classification, and distribution focal loss, all of which decrease steadily as training progresses, indicating that the model is converging and the optimization process is stable. The evaluation curves (e.g., metrics/recall(B), metrics/mAP50(B), metrics/mAP50-95(B), metrics/precision(B)) depict recall, mean average precision (mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95), and precision. These metrics increase steadily and eventually plateau, suggesting continuous performance improvement and convergence.

Figure 12: Convergence curves of training and validation metrics

Overall, VIF-YOLO exhibits effective convergence during training, with progressive optimization of localization, classification, and distribution learning, ultimately achieving high detection accuracy and reliability across key performance indicators. Despite these promising results, several limitations remain. The current experiments are conducted primarily under controlled indoor smoke conditions, which cannot fully replicate the dynamic and highly unpredictable characteristics of real fire rescue scenarios. In practical environments, rapidly fluctuating thermal fields generated by open flames, turbulent smoke flow, and large-scale occlusion caused by multiple trapped individuals may introduce additional challenges beyond those captured in our dataset. These real-world complexities suggest that further efforts are needed in areas such as dynamic thermal scene simulation, multi-target occlusion modeling, and adaptive temporal perception to enhance the robustness and deployment reliability of the proposed framework in actual fire rescue missions.

In addition to the above limitations, it is important to note that high-temperature environments in real fire rescue scenes may further influence model performance. Extreme heat can distort infrared imaging, alter thermal distribution patterns, and introduce additional noise, potentially leading to degradation in key metrics such as detection accuracy and recall. Although such conditions are difficult to fully reproduce in controlled indoor experiments, acknowledging these challenges is crucial for practical deployment. Future work will therefore incorporate experiments involving dynamic high-temperature variations and real fire-scene thermal data to more comprehensively evaluate the robustness of VIF-YOLO under realistic firefighting conditions.

In this work, we propose VIF-YOLO, a lightweight visible–infrared fusion detector designed for real-time human detection in dense smoke environments. Experimental results on the MSHD dataset demonstrate that VIF-YOLO achieves a significant improvement over the YOLOv10n baseline, with increases of +3.9% in precision, +4.4% in recall, and +0.8% in mAP. Despite introducing only a modest number of additional parameters, the model maintains high computational efficiency. When deployed on the NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX, VIF-YOLO reaches 40.6 FPS with an average inference latency of 24.6 ms, validating its ability to operate under real-time constraints on edge-computing platforms. These quantitative findings confirm that VIF-YOLO provides a compelling balance between accuracy, robustness, and efficiency, offering strong potential for practical deployment in smoke-filled rescue scenarios.

Looking ahead, this study can be extended in several meaningful directions to bridge the existing gap between controlled experiments and real fire rescue conditions. First, future work will incorporate dynamic thermal field simulation and real fire-scene multimodal data collection to further improve the model’s ability to handle complex heat radiation patterns and flame-induced interference. Second, we plan to expand the dataset and introduce multi-target occlusion modeling, enhancing robustness in crowded rescue scenarios where multiple victims may partially obscure each other. Third, integrating online adaptive mechanisms and temporal modeling modules could strengthen real-time stability under rapidly evolving smoke and flame conditions. Fourth, we will further enhance the intensity and diversity of smoke simulation by incorporating extreme samples in which thermal radiation is severely attenuated in both visible and infrared modalities, causing human contours to become highly blurred or even unrecognizable. These enhancements will help narrow the discrepancy between laboratory settings and real-world deployment, making the proposed framework more suitable for practical fire rescue applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62306128, the Leading Innovation Project of Changzhou Science and Technology Bureau under Grant CQ20230072, the Basic Science Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Department of Education under Grant 23KJD520003, the Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Jilin Province under Grant 20240101382JC, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2023YFF1105102.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Wenhe Chen and Qi Pu; methodology, Wenhe Chen; data curation, Yue Wang and Caixia Zheng; writing—original draft preparation, Wenhe Chen and Xundiao Ma; writing—review and editing, Wenhe Chen and Qi Pu; visualization, Shuonan Shen and Leer Hua. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot MultiBox detector. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang L, Lin L, Liang X, He K. Is faster R-CNN doing well for pedestrian detection? In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 443–57. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46475-6_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hosang J, Benenson R, Schiele B. Learning non-maximum suppression. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 4507–15. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2017.685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bochkovskiy A, Wang CY, Liao HYM. LOv4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934. 2020. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang K, Luo W,Zhong Y,Ma L, Liu W, Li H. Adversarial spatio-temporal learning for video deblurring. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2018 Aug 29;28(1):291–301. [Google Scholar]

7. Tsai PF, Liao CH, Yuan SM. Using deep learning with thermal imaging for human detection in heavy smoke scenarios. Sensors. 2022;22(14):5351. doi:10.3390/s22145351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Qin X, Wang Z, Bai Y, Xie X, Jia H. FFA-net: feature fusion attention network for single image dehazing. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):11908–15. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dong H, Pan J, Xiang L, Hu Z, Zhang X, Wang F, et al. Multi-scale boosted dehazing network with dense feature fusion. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 2157–67. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu L, Ouyang W, Wang X, Fieguth P, Chen J, Liu X, et al. Deep learning for generic object detection: a survey. arXiv:1809.02165. 2019. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1809.02165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. arXiv:1506.02640. 2016. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1506.02640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. arXiv:1612.08242. 2016. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1612.08242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Redmon J, Farhadi AYO. LOv3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Khanam R, Hussain M. What is YOLOv5: a deep look into the internal features of the popular object detector. arXiv:2407.20892. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2407.20892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jegham N, Koh CY, Abdelatti M, Hendawi A. Evaluating the evolution of YOLO (you only look once) models: a comprehensive benchmark study of YOLO11 and its predecessors. arXiv:2411.00201. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2411.00201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sohan M, Sai Ram T, Rami Reddy CV. A review on YOLOv8 and its advancements. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics; 2024 Nov 18–20; Tirunelveli, India. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 529–45. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-7962-2_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang C-Y, Yeh I-H, Liao H-YMYO. LOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv:2402.13616. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2402.13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. LOv10: real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2405.14458. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2405.14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ma J, Yu W, Liang P, Li C, Jiang J. FusionGAN: a generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion. Inf Fusion. 2019;48(4):11–26. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2018.09.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang X, Demiris Y. Visible and infrared image fusion using deep learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(8):10535–54. doi:10.1109/tpami.2023.3261282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Xu H, Ma J, Jiang J, Guo X, Ling H. U2Fusion: a unified unsupervised image fusion network. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(1):502–18. doi:10.1109/tpami.2020.3012548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Dong L, He L, Mao M, Kong G, Wu X, Zhang Q, et al. CUNet: a compact unsupervised network for image classification. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2017;20(8):2012–21. doi:10.1109/tmm.2017.2788205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ma J, Tang L, Fan F, Huang J, Mei X, Ma Y. SwinFusion: cross-domain long-range learning for general image fusion via swin transformer. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2022;9(7):1200–17. doi:10.1109/jas.2022.105686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tang W, He F, Liu Y. YDTR: infrared and visible image fusion via Y-shape dynamic transformer. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2023;25(6):5413–28. doi:10.1109/tmm.2022.3192661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li H, Xu T, Wu XJ, Lu J, Kittler JLR. RNet: a novel representation learning guided fusion network for infrared and visible images. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(9):11040–52. doi:10.1109/tpami.2023.3268209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ouyang D, He S, Zhang G, Luo M, Guo H, Zhan J, et al. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/icassp49357.2023.10096516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cheng HY, Yin JL, Chen BH, Yu ZM. Smoke 100k: a database for smoke detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 8th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE); 2019 Oct 15–18; Osaka, Japan. p. 596–7. doi:10.1109/gcce46687.2019.9015309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools