Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Comparative Benchmark of Machine and Deep Learning for Cyberattack Detection in IoT Networks

Department of Computer Science and Mathematics, University of Quebec at Chicoutimi, Chicoutimi, QC G7H2B1, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Enzo Hoummady. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligence and Security Enhancement for Internet of Things)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 43 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074897

Received 21 October 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

With the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, securing these interconnected systems against cyberattacks has become a critical challenge. Traditional security paradigms often fail to cope with the scale and diversity of IoT network traffic. This paper presents a comparative benchmark of classic machine learning (ML) and state-of-the-art deep learning (DL) algorithms for IoT intrusion detection. Our methodology employs a two-phased approach: a preliminary pilot study using a custom-generated dataset to establish baselines, followed by a comprehensive evaluation on the large-scale CICIoTDataset2023. We benchmarked algorithms including Random Forest, XGBoost, CNN, and Stacked LSTM. The results indicate that while top-performing models from both categories achieve over 99% classification accuracy, this metric masks a crucial performance trade-off. We demonstrate that tree-based ML ensembles exhibit superior precision (91%) in identifying benign traffic, making them effective at reducing false positives. Conversely, DL models demonstrate superior recall (96%), making them better suited for minimizing the interruption of legitimate traffic. We conclude that the selection of an optimal model is not merely a matter of maximizing accuracy but is a strategic choice dependent on the specific security priority either minimizing false alarms or ensuring service availability. This work provides a practical framework for deploying context-aware security solutions in diverse IoT environments.Keywords

In today’s interconnected world, the Internet of Things (IoT) has become a vital part of our lives in various domains, including home automation, healthcare, and smart cities. The number of IoT devices is skyrocketing, with estimates suggesting over 30 billion connected devices by 2025 [1]. This explosive growth has not only led to a tremendous amount of network traffic but has also created an unprecedented and complex attack surface for cyber threats.

Despite their massive deployment, IoT devices are often inherently insecure. Due to their design for low-cost and low-power operation, they typically possess limited computational capabilities, which makes implementing robust, on-device security measures like strong encryption challenging. Furthermore, many devices are deployed with unpatched firmware containing known vulnerabilities or default credentials, making them easy targets for attackers. Traditional security paradigms, such as signature-based intrusion detection systems (IDS), often prove inadequate for IoT environments as they struggle to handle the sheer volume of traffic and fail to detect novel or zero-day attacks.

To address this critical security gap, machine learning (ML) and, more recently, deep learning (DL) have emerged as powerful solutions. While classic ML algorithms have demonstrated success in classification tasks, DL models are uniquely suited for analyzing the vast and intricate network traffic from IoT devices due to their ability to automatically learn hierarchical features from raw data. Their application in cybersecurity allows for the creation of intelligent models that can learn the baseline of normal network behavior and, consequently, detect anomalous activities that may signify a cyberattack [2].

However, even advanced DL models can struggle with highly imbalanced datasets, often exhibiting poor recall and precision on rare or ambiguous attack categories. This paper tackles these challenges directly, building upon and significantly extending our preliminary findings presented in [3]. While the application of DL for IoT security is an active research area, a comprehensive comparison against classic ML baselines is needed.

Our work’s primary innovation is not simply the act of benchmarking, but the critical analysis that emerges from it. Many similar studies focus on achieving the highest accuracy. We demonstrate that for a large-scale, imbalanced dataset like CICIoTDataset2023, accuracy is a deceptive metric that masks a crucial performance trade-off. Our most significant contribution, therefore, is the identification and interpretation of this trade-off. We provide a practical, context-aware framework for model selection based on real-world security priorities: either minimizing false alarms (where ML models excel) or ensuring service availability (where DL models excel).

This paper aims to fill this gap by making the following primary contributions:

• We conduct a comprehensive empirical comparison between several classic machine learning and state-of-the-art deep learning algorithms for cyberattack detection in an IoT context.

• We benchmark all models using the publicly available and challenging CIC IoT Dataset, providing a standardized basis for comparison.

• We provide actionable insights into the relative strengths of each approach, highlighting the trade-offs between classic ML and DL.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides background information about IoT and the cyberattacks that target it. Section 3 presents the design of our pilot study and its preliminary results. Section 4 presents the main study methodology. Section 5 details the experimental results of the main study. Section 6 discusses these results and analyzes our findings. Section 7 addresses the limitations of our work. Section 8 provides an overview of related work. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper.

This section provides the necessary context regarding the IoT architecture and the specific cyberattacks that target these ecosystems.

2.1 The Internet of Things Architecture

IoT technology has been widely adopted across different industries, transforming operations and enhancing efficiency. However, this widespread implementation brings significant cybersecurity challenges. To better understand these challenges, it’s helpful to consider the typical multi-layered architecture of an IoT ecosystem, which provides a framework for identifying where vulnerabilities may arise [4,5]. This architecture is often conceptualized in three main layers:

The Perception (or Device) Layer: This layer consists of the physical devices themselves-sensors and actuators that collect data and interact with the physical world. Attacks at this layer often involve physical tampering, side-channel attacks, or malicious firmware modifications [6].

The Network (or Transport) Layer: This layer is responsible for transmitting the data from the devices to processing systems using protocols like Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, or 5G. It is vulnerable to attacks such as eavesdropping, Man-in-the-Middle (MitM), and Denial-of-Service (DoS) [7].

The Application (or Service) Layer: This layer provides services to the end-user, often through cloud-based platforms. Vulnerabilities here are frequently related to insecure software, weak authentication, or insecure APIs.

2.2 IoT Applications and Associated Risks

In the field of home automation, IoT devices offer convenience and automation. From smart thermostats to voice assistants, these devices facilitate household tasks. Nonetheless, many users overlook the importance of securing their IoT devices, such as failing to change default passwords, leaving them vulnerable to cyber threats. Moreover, sometimes the firmware included in their device contains vulnerability such as the Bosch thermostat in early 2024 [8].

In industrial settings, IoT enables predictive maintenance and process optimization. Smart factories utilize IoT sensors to monitor equipment and improve productivity. However, the interconnected nature of these systems increases the risk of cyber breaches. The Stuxnet worm’s [9] infiltration of Iran’s nuclear facilities in 2010 exposed vulnerabilities in industrial IoT deployments.

Similarly, healthcare systems leverage IoT for remote patient monitoring and telemedicine. Wearable devices track vital signs, while telemedicine platforms facilitate remote consultations. Despite their advantages, healthcare IoT devices are vulnerable to cyber threats. The WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017 [10] disrupted healthcare services globally, underscoring weaknesses in cybersecurity protocols.

These vulnerabilities across different sectors expose IoT ecosystems to a wide range of cyberattacks. These threats can be categorized based on their impact on the system’s confidentiality, integrity, or availability. Common attack vectors include:

Denial-of-Service (DoS) and Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) Attacks: Attackers overwhelm a device or network with traffic, rendering it unavailable. IoT devices are often hijacked to form massive botnets to launch these attacks [11], as famously demonstrated by the Mirai botnet [12].

Eavesdropping and Man-in-the-Middle (MitM): Attackers intercept communication between an IoT device and its server to steal sensitive data, such as login credentials or personal information. This is particularly prevalent on unsecured networks.

Firmware and Software Exploitation: As seen with the Bosch thermostat example, attackers can exploit vulnerabilities in a device’s firmware or software to gain unauthorized control, inject malicious code, or extract data.

One common challenge across these industries is the disparity in cybersecurity focus between IoT devices and traditional IT systems [13]. While companies prioritize securing their information systems, IoT devices often receive less attention. This gap leaves IoT ecosystems vulnerable to cyberattacks, emphasizing the need for comprehensive security measures.

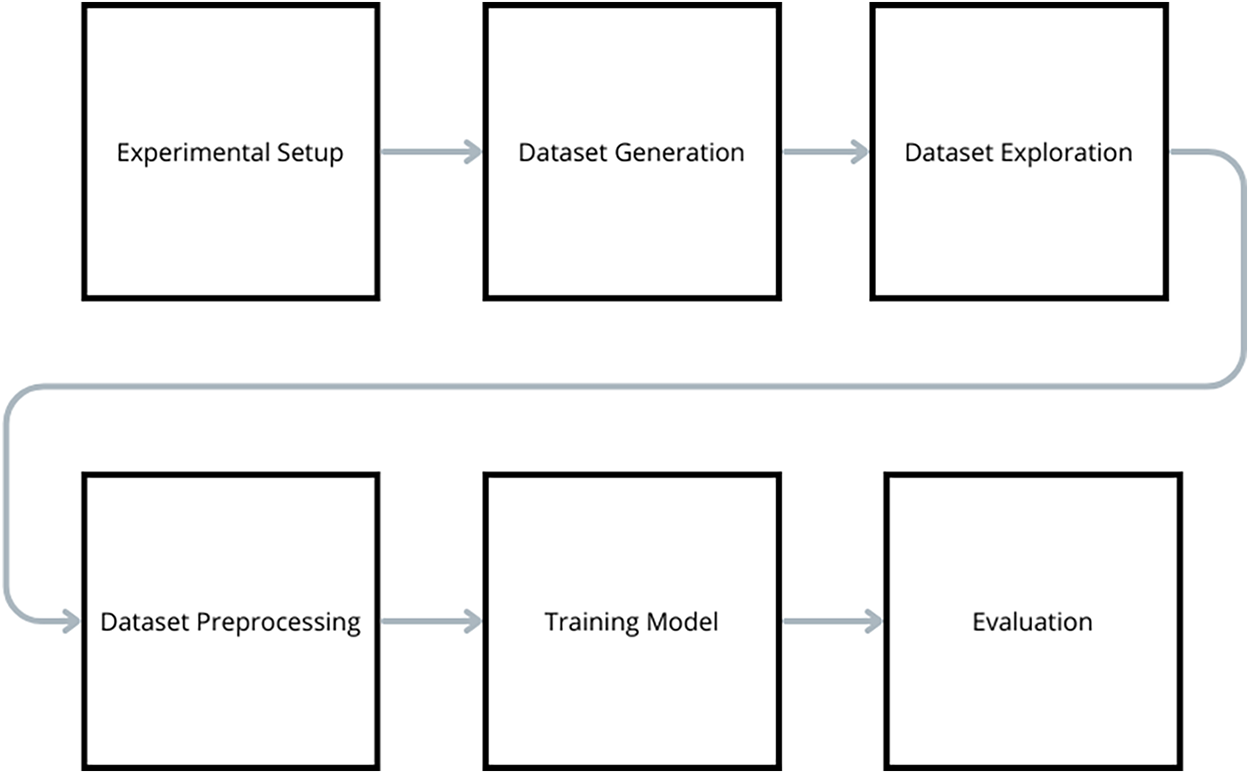

This section details the experimental design and preliminary findings of the pilot study. The methodological workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the pilot study

3.1.1 Virtualization and Host Configuration

For the pilot study, a virtualized environment was established using VMware Workstation Pro 11 to simulate a contained network. The infrastructure consisted of three distinct hosts:

– Raspberry Pi Desktop (x86 Architecture): To simulate an IoT end-point, the Raspberry Pi Desktop version was utilized. This approach overcame the architectural constraints of virtualizing ARM-based hardware on standard x86/x64 processors while maintaining an operating system environment comparable to a physical Raspberry Pi 3B+.

– Kali Linux: Deployed as the attacker node to execute penetration testing scripts and network sniffing.

– Debian 11: Utilized to generate legitimate background traffic.

To ensure the simulation closely mirrored physical IoT hardware, the virtualized Raspberry Pi was provisioned with CPU and RAM resources equivalent to the physical device specifications.

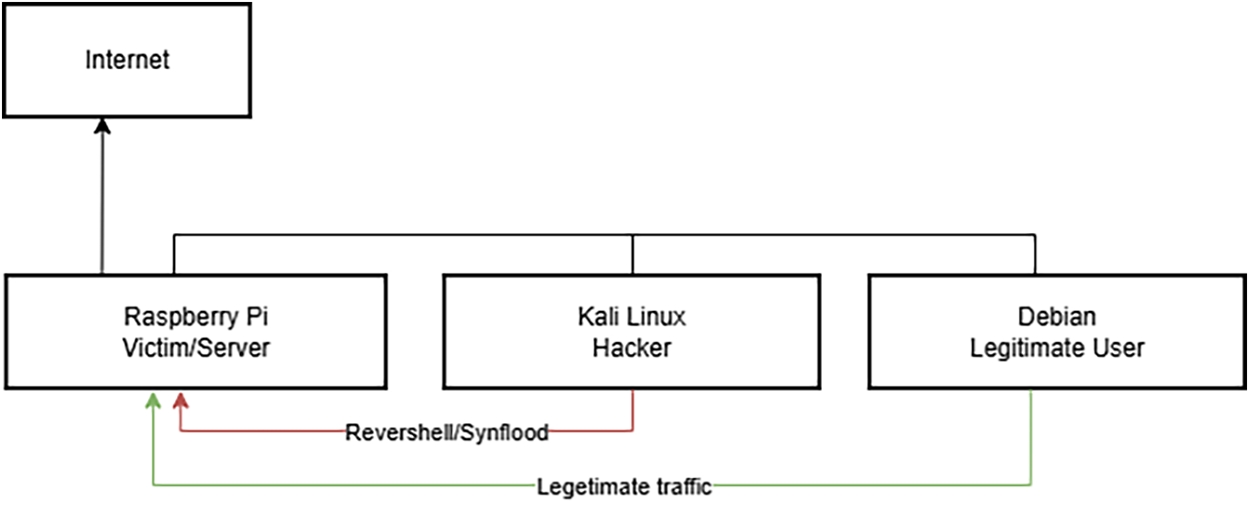

The laboratory network topology, depicted in Fig. 2, placed all three hosts within the same Virtual Local Area Network (VLAN). The Raspberry Pi functioned as the victim target, hosting active FTP and SSH services. The Kali Linux host operated as the adversary, executing keylogger injection and Reverse Shell attacks while simultaneously capturing network traffic. The Debian host generated continuous legitimate SSH and FTP traffic to simulate normal network activity.

Figure 2: Lab setup

3.2 Data Acquisition and Feature Extraction

A systematic data generation process was employed to construct the dataset. Network traffic was captured via Wireshark in two distinct phases. First, baseline benign traffic was generated using automated FTP and SSH scripts. Subsequently, malicious traffic was introduced by deploying a keylogger and executing cyberattacks. To ensure a realistic detection environment, malicious activities were executed concurrently with legitimate traffic. Network packets were manually labeled based on the timestamps of the executed attacks.

Following data acquisition, six primary features were extracted from the PCAP files:

– No.: Packet sequence number (utilized for sequential analysis in RNNs).

– Time: Timestamp relative to capture start.

– Source: Source IP Address.

– Destination: Destination IP Address.

– Protocol: Network Protocol used.

– Length: Packet size in bytes.

– Info: Payload details, including ports and TCP flags.

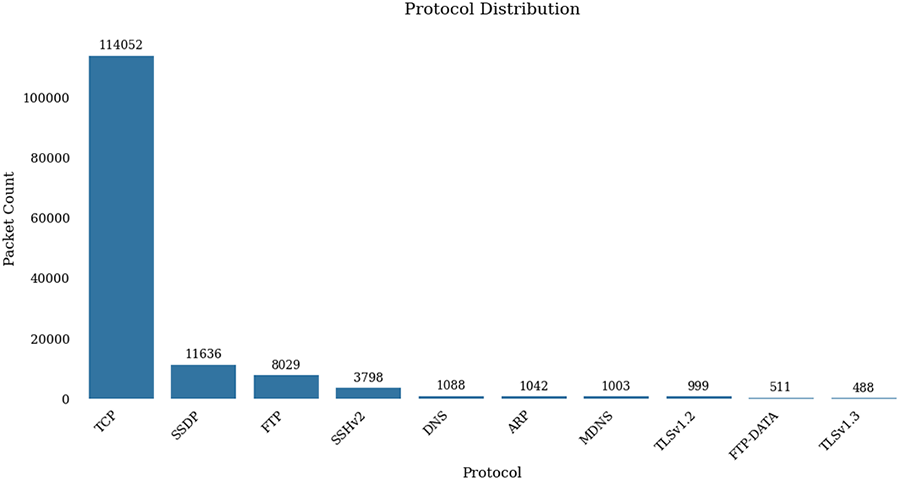

Initial analysis revealed a severe class imbalance, with SYN Flood attacks constituting 90% of the dataset before preprocessing. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3, TCP is the predominant protocol, consistent with the nature of SYN Flood, Reverse Shell, and Keylogger attacks. FTP and SSH protocols represent the legitimate traffic, while SSDP traffic is an artifact of the virtualization environment.

Figure 3: Protocol distribution

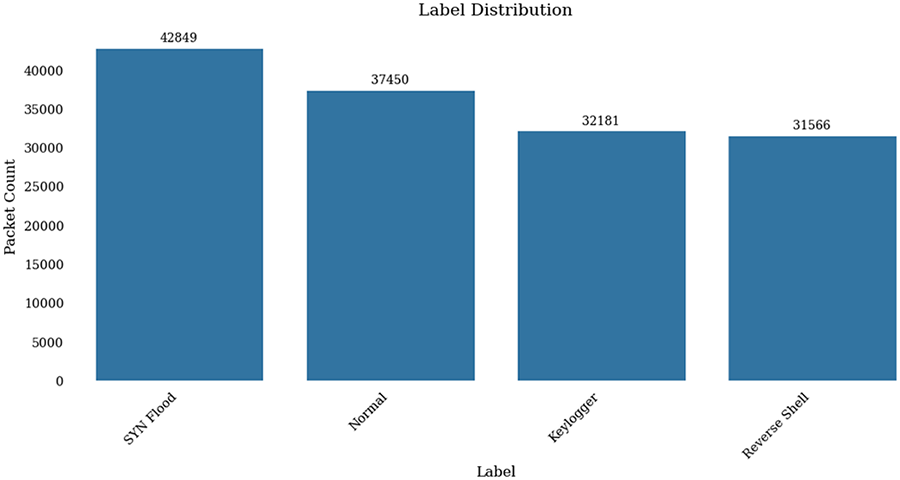

To mitigate the bias caused by the predominance of SYN Flood packets, the dataset was down-sampled. Additionally, data augmentation was applied to the underrepresented minority classes (Keylogger and Reverse Shell) to achieve the balanced distribution illustrated in Fig. 4. Throughout this process, packet sequence integrity was maintained to preserve temporal context.

Figure 4: Label distribution after balancing

3.3.2 Sequential Formatting for LSTM

To accommodate the temporal dependencies required by Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [14], the raw packet data was transformed into sequential input windows. The data structure was defined as

While additional filtering could further refine the dataset, the current validation accuracy was deemed sufficient for this pilot study. Known limitations include occasional mislabeling of FTP/SSH packets and the lack of IP diversity, as all traffic originated from a single virtualized source.

This subsection details the performance of representative models on the custom-generated dataset.

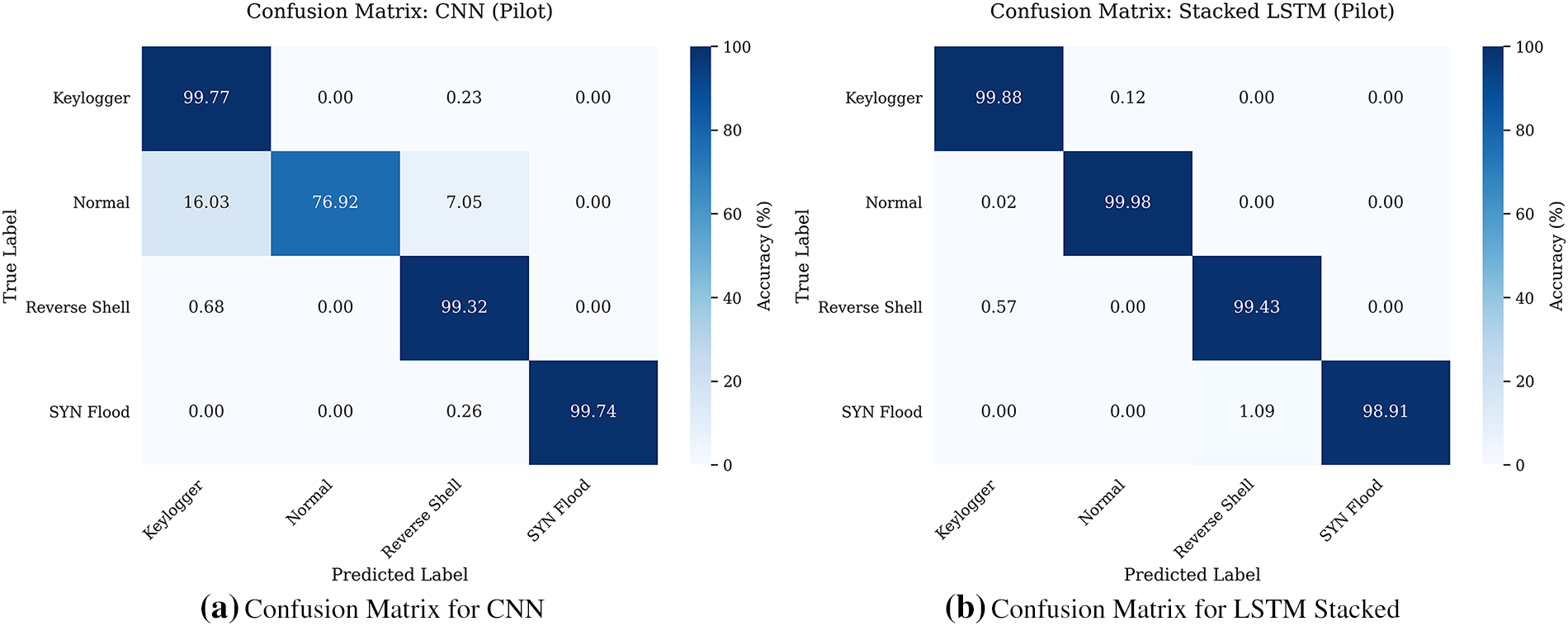

The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model was trained for 25 epochs. Despite its lightweight architecture (97,150 parameters), the model achieved a validation accuracy of 94%. The confusion matrix (Fig. 5a) indicates effective attack detection with zero false negatives, though a small margin of false positives persists due to the misclassification of benign packets. This model demonstrates high efficiency, making it a viable candidate for resource-constrained environments.

Figure 5: Comparative Confusion Matrices for CNN and Stacked LSTM on the custom dataset

3.4.2 Stacked LSTM Performance

The Stacked LSTM model demonstrated superior performance, achieving 99.3% accuracy. As evidenced by the confusion matrix in Fig. 5b, this architecture minimized both false positives and false negatives, demonstrating high robustness. However, this performance incurs a higher computational cost, with inference times approximately five times longer than the CNN. This highlights the trade-off between detection precision and computational efficiency.

3.4.3 Overall Preliminary Results

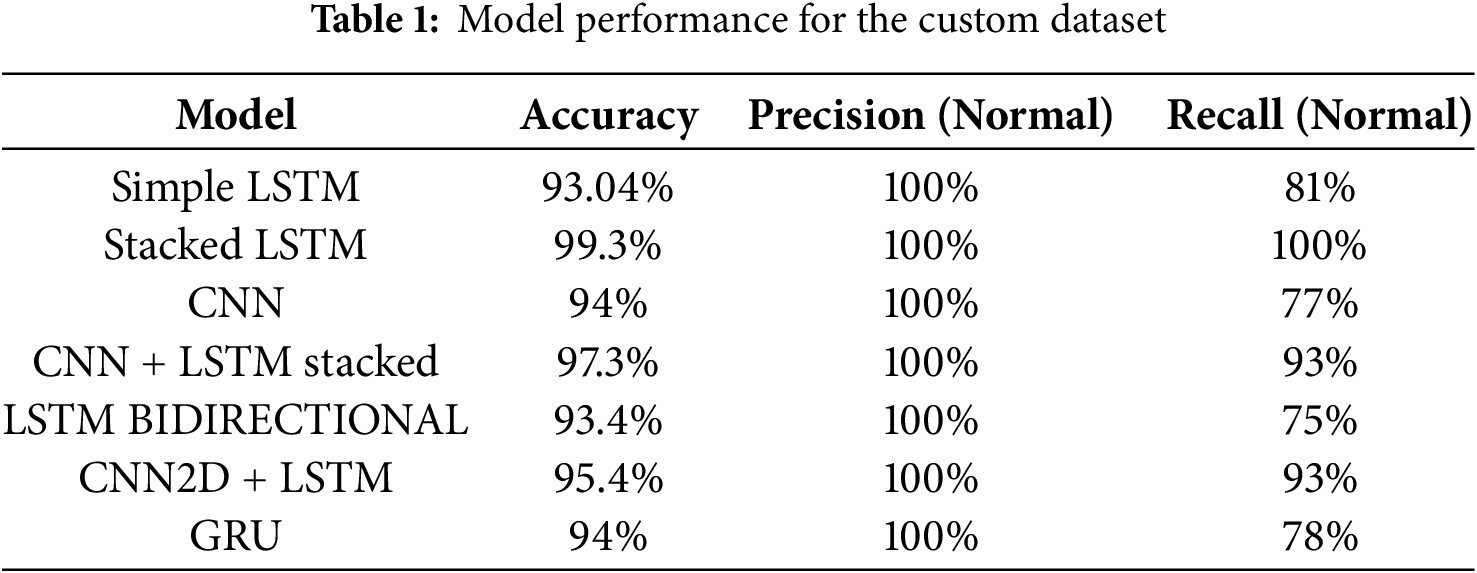

The quantitative results of the empirical pilot study are presented in Table 1. Most models demonstrated robust performance, exceeding 93% accuracy.

The dataset created in our pilot study had bias and lack of diversity concerning the cyberattack, in order to push our work futher we decided to expand our work in a new dataset: the CICIoTDataset2023 (Neto et al. (2023) [15]).

We used the Python library TensorFlow. This library is an available and open-source software that is used for Deep learning [16].

For training our models, we decided to use the GPU (Graphics Processing Unit),instead of the CPU (Central Processing Unit). GPUs perform parallel training computations much faster than CPUs, leading to a significant reduction in training time for the model [17]. In our case, we conducted the training on a RTX3070TI Laptop equipped with 8 GB of VRAM, … an Intel 12700H processor, and 32 GB of RAM. All models were trained on this same hardware to ensure a fair computational comparison.

Scikit-learn (sklearn) is a widely-used, open-source Python library that provides a comprehensive suite of tools for machine learning and statistical modeling. It features a clean and consistent API for implementing various algorithms for classification, regression, clustering, and dimensionality reduction, making it a cornerstone for both research and production environments. In this study, we benchmarked several of its flagship classifiers against our deep learning models.

Decision Tree

A Decision Tree is a supervised learning algorithm that uses a tree-like model of decisions and their possible consequences. It works by splitting the data into subsets based on feature values, creating a structure where leaf nodes represent class labels and branches represent conjunctions of features that lead to those labels. Due to their interpretability and simplicity, they serve as a strong baseline for classification tasks [18].

Random Forest

Random Forest is a robust, supervised ensemble learning method used for classification and regression. It constructs a multitude of decision trees at training time and outputs the class that is the mode of the classes output by individual trees. By combining bootstrap aggregating (bagging) with feature randomness during the construction of each tree, it reduces variance and is highly resistant to overfitting. In cybersecurity, it is valued for its high accuracy, ability to handle high-dimensional data, and its built-in mechanism for ranking feature importance [19].

XGboost

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a powerful and highly optimized implementation of the gradient boosting framework. As a boosting algorithm, it builds decision trees sequentially, where each new tree corrects the errors made by the previous ones. It is renowned for its exceptional performance in terms of both speed and accuracy, often being a top performer in machine learning competitions [20].

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

A Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a supervised learning algorithm that finds an optimal hyperplane to separate data points into different classes. The algorithm seeks to maximize the margin: the distance between the hyperplane and the nearest data points (the support vectors) from each class. For non-linearly separable data, SVMs employ the “kernel trick” to implicitly map the input features into a higher-dimensional space where a linear separation is possible. SVMs are highly effective in high-dimensional spaces and are particularly powerful when a clear margin of separation between classes exists [21].

k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

The k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm is a simple, non-parametric, and instance-based supervised learning method. KNN does not build an internal model from the training data. Instead, for classification, it classifies a new data point by a majority vote of its ‘k’ nearest neighbors in the feature space, with proximity typically measured by a distance function like Euclidean distance. While easy to implement, its performance is sensitive to the choice of ‘k’ and feature scaling [22].

4.1.3 Different Neuronal Networks Used

Initially, we considered different models for the project. We compared their performance, training time, we evaluated seven distinct models with different architectures: Simple LSTM, Stacked LSTM, CNN, CNN + LSTM stacked, LSTM Bidirectional, CNN2D + LSTM, GRU. We also implemented a Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) Classifier. This model uses a hybrid unsupervised-supervised approach. First, an autoencoder (with an encoder architecture of 128-64-32 neurons and a corresponding decoder) was trained unsupervised to learn a compressed 32-dimension latent representation of the input features. Second, the decoder part was discarded, and the pre-trained encoder was used as a feature extractor. A new classification head consisting of a 50-neuron leaky_relu layer, Dropout, and a final softmax layer was stacked onto the encoder. This complete classifier was then fine-tuned on the labeled data for the multi-class task.

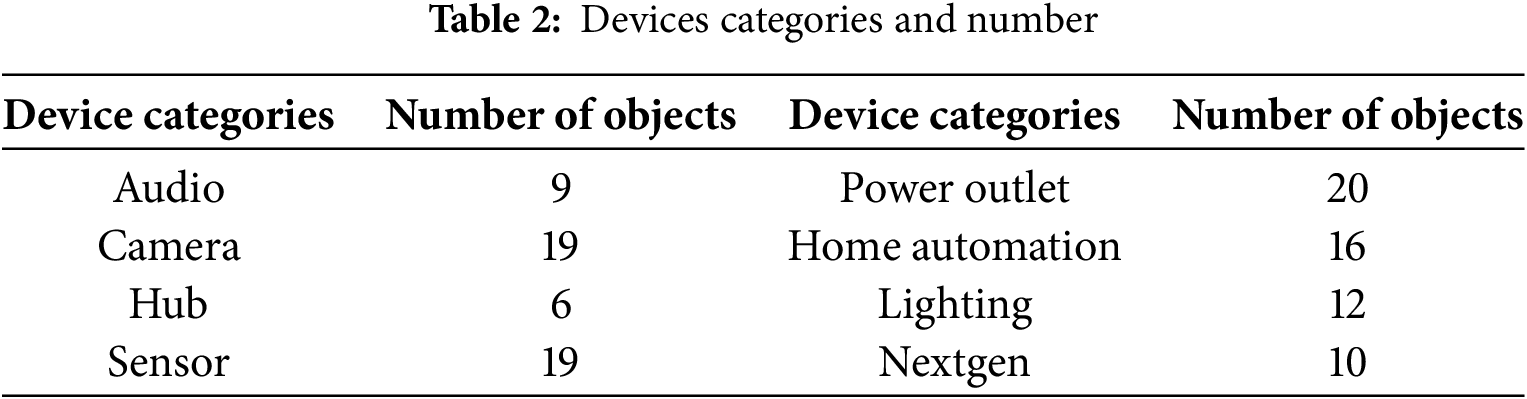

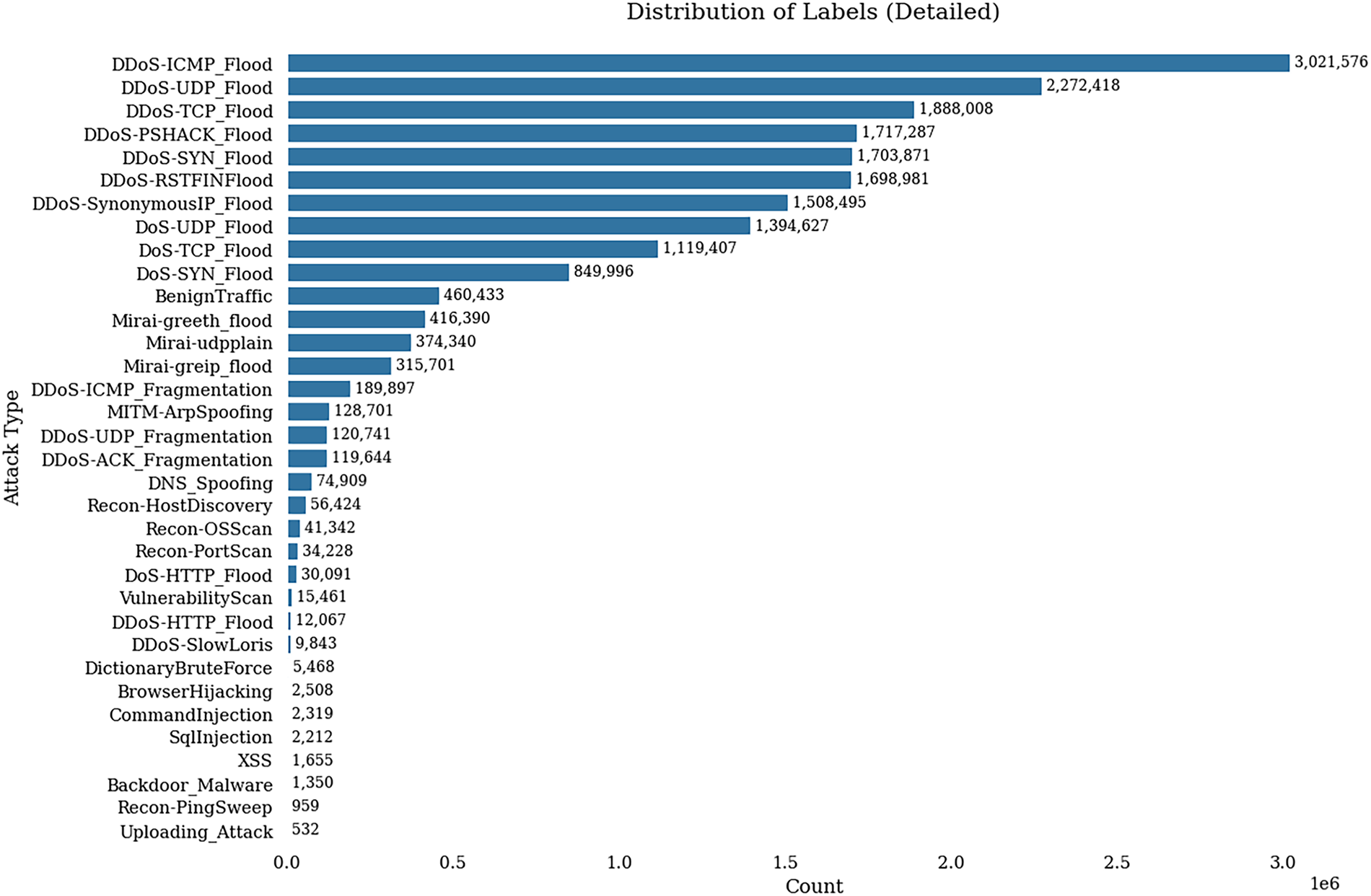

The Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC) produced in 2023 a dataset, comprising data from over 100 diverse IoT devices across various categories (see Table 2), this data amplifies the real-world relevance of our investigation. The dataset introduces a myriad of IoT devices, reflecting the varied landscape encountered in practical scenarios. The inclusion of diverse categories of IoT devices mirrors the diverse nature of IoT deployments in everyday life. With a dataset size approaching 12 GB of computed data, this increased variety ensures that our analysis is not confined to a specific device type.

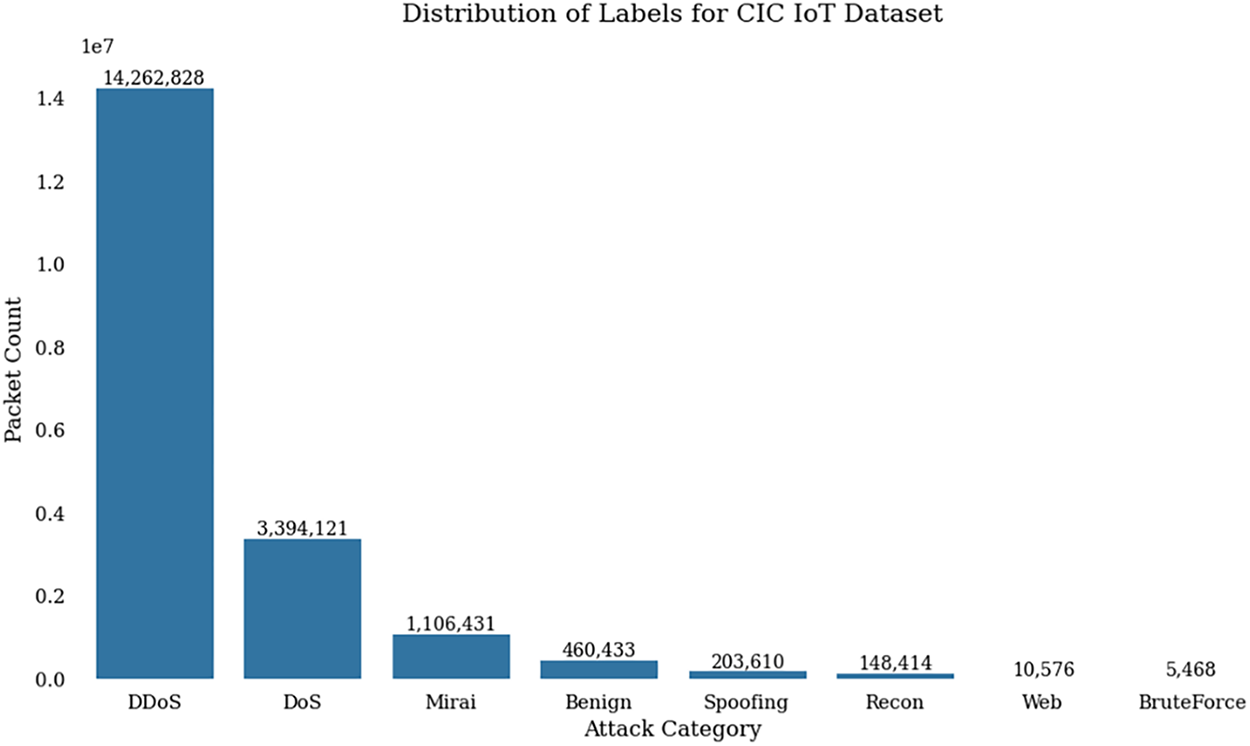

Moreover, the data set features more than 30 types of cyberattacks that include real life attacks that often target the IoT device, the initial distribution could be seen in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Label repartition

The distribution of attacks in the dataset is uneven, with many occurrences of the same attack categories. Based on the work from the dataset’s author (Neto et al., 2023), we have summarized these attacks into eight categories: DoS, DDoS, Mirai, Recon, Benign, Spoofing, and Bruteforce.

This classification aligns with real-world threats. For example, the Mirai attack is notably prevalent in IoT devices. It is also important to recognize that IoT devices are frequently exploited as components of botnets, highlighting the critical need to understand and mitigate these threats within the IoT ecosystem.

Importantly, the dataset is imbalanced, with significantly more data for DDoS, DoS, and Mirai attacks compared to other categories. Fig. 7 visually illustrates this imbalance, highlighting a potential challenge in predicting less common threats due to uneven data distribution. The abundance of data for certain threats could lead to biased predictions and may overlook vulnerabilities in less represented categories.

Figure 7: Label repartition With 8 classes

Due to the substantial volume of data, utilizing the entire dataset was impractical. The dataset was divided into different CSV files, and for our analysis, we selected 50 files (out of a total of 164). The computational cost of training and validating this large suite of models on the full 12 GB dataset was prohibitive. The dataset was divided into different CSV files, and for our analysis, we selected 50 files (out of a total of 164). This subset was verified to maintain the original dataset’s imbalanced class distribution, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The processed data involved key values and features, focused on internet traffic capture as you can see below.

flow_duration, Header_Length, Protocol_type, Duration, Rate, Srate, Drate, fin_flag_number,

syn_flag_number, rst_flag_number, psh_flag_number, ack_flag_number, ece_flag_number,

cwr_flag_number, ack_count, syn_count, fin_count, urg_count, rst_count, HTTP, HTTPS, DNS,

Telnet, SMTP, SSH, IRC, TCP, UDP, DHCP, ARP, ICMP, IPv, LLC, Tot_sum, Min, Max, AVG, Std, Tot_size,

IAT, Number, Magnitude, Radius, Covariance, Variance, Weight

For this analysis, we standardized the data using a standard scaler. This preprocessing step ensures that all features are on comparable scales, optimizing the performance of subsequent machine learning algorithms and statistical analyses.

It is critical to note that the dataset’s pre-processed CSV files, which we used, do not explicitly reflect the strong, sequential temporal characteristics of the original raw packet captures. The data is already aggregated into flows, meaning the packet-to-packet temporal information was not available in the source data. This lack of temporal information, which is usually advantageous for LSTM architectures designed to capture sequential dependencies, led us to forgo our time step function. Instead, we employed a traditional train-test split approach for all our algorithms, using an 80%/20% split.

This section details the empirical results from our comparative benchmark on the CIC IoT Dataset 2023. We present the performance of classic machine learning models first, followed by an analysis of the deep learning architectures.

5.1 Machine Learning Model Performance

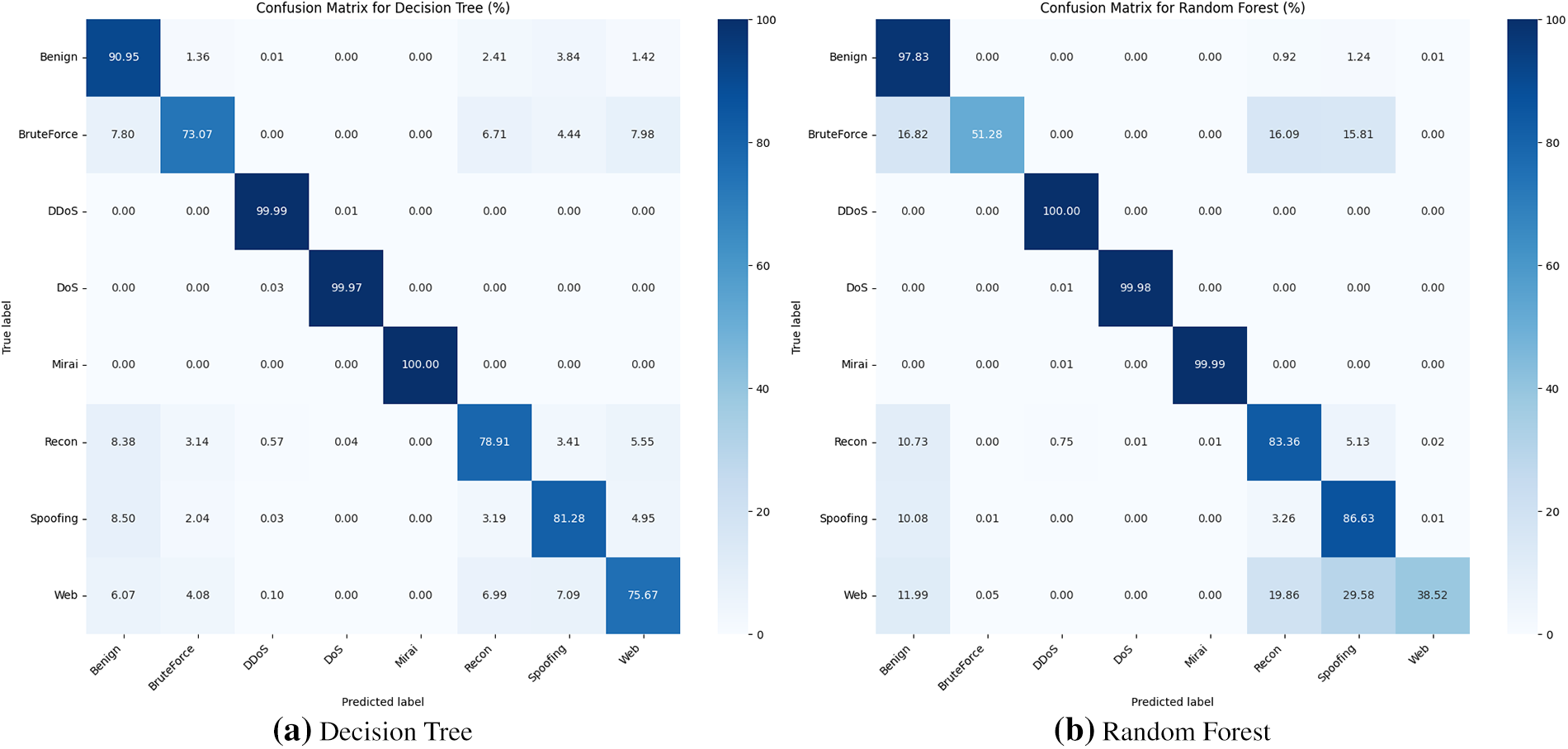

To establish a performance baseline, we evaluated several conventional machine learning algorithms. We focus our analysis on the top-performing tree-based models, Decision Tree and Random Forest, whose confusion matrices are shown for visual reference in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Confusion matrices for top-performing machine learning models on the CIC IoT Dataset (%)

A Decision Tree operates by constructing a single, flowchart-like structure of rules learned from the data. While this makes the model highly interpretable, its main vulnerability is a tendency to overfit, it can learn the noise and specific quirks of the training data so perfectly that it fails to generalize well to new, unseen data.

The Random Forest model directly addresses this weakness. It is an ensemble method that builds a multitude of individual Decision Trees on different random subsets of the data. For classification, the final prediction is determined by a majority vote from all the trees in the forest. This approach averages out the errors and biases of the individual trees, making the Random Forest generally more robust, accurate, and resistant to overfitting than a single Decision Tree.

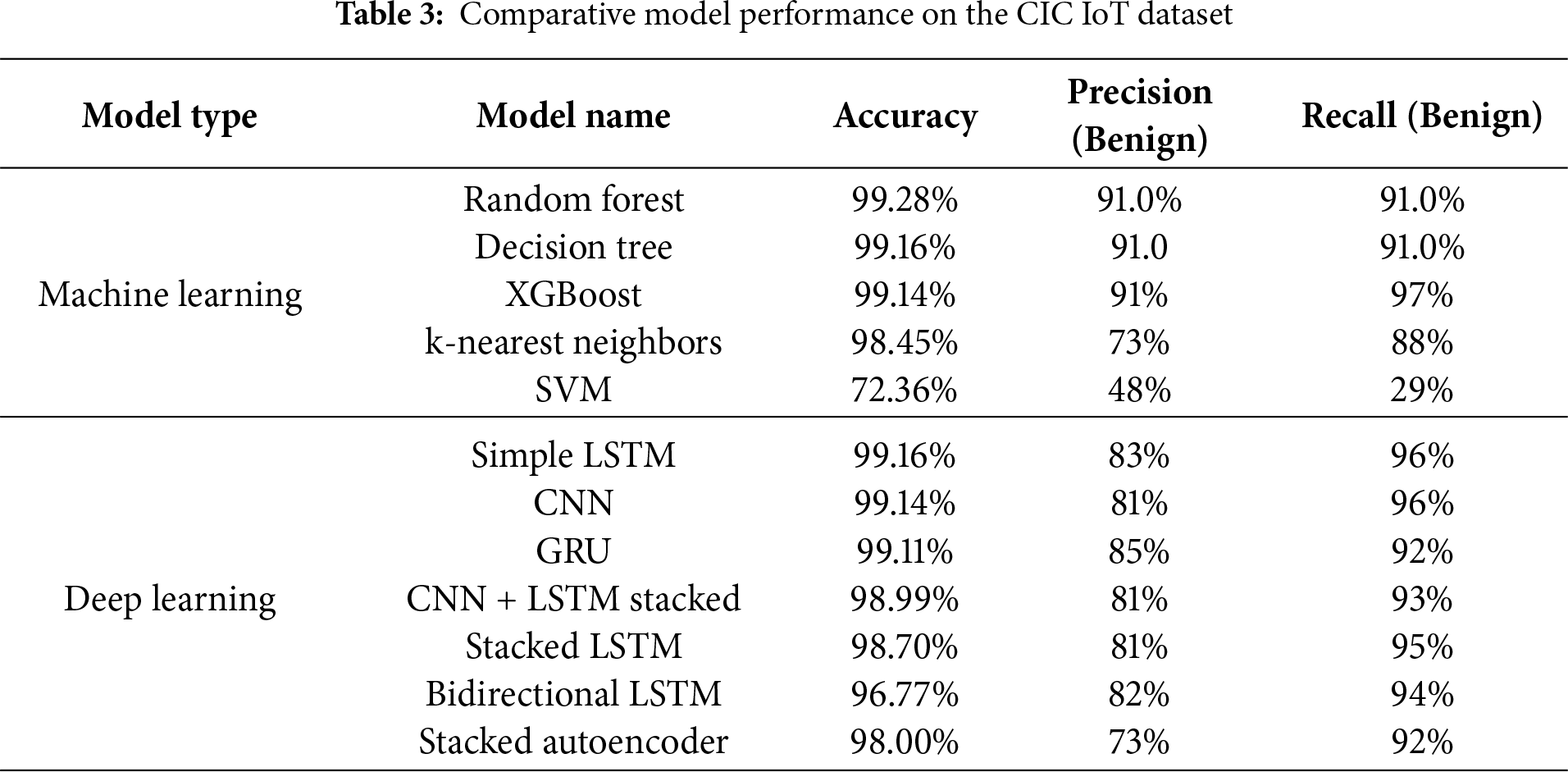

Interestingly, our results in Table 3 show that both the Decision Tree and Random Forest delivered exceptional and nearly identical performance. Both models achieved an accuracy of over 99% and recorded the exact same 91.0% for both precision and recall on the ‘Benign‘ class. This suggests that the features separating benign traffic from attacks in the CIC IoT Dataset are distinct enough that even a single Decision Tree can model them effectively without significant overfitting. For comparison, the XGBoost model, which uses a more advanced tree-based ensemble technique (boosting), achieved a similar precision but an even higher recall of 97%, underscoring the power of ensemble methods.

5.2 Deep Learning Model Performance

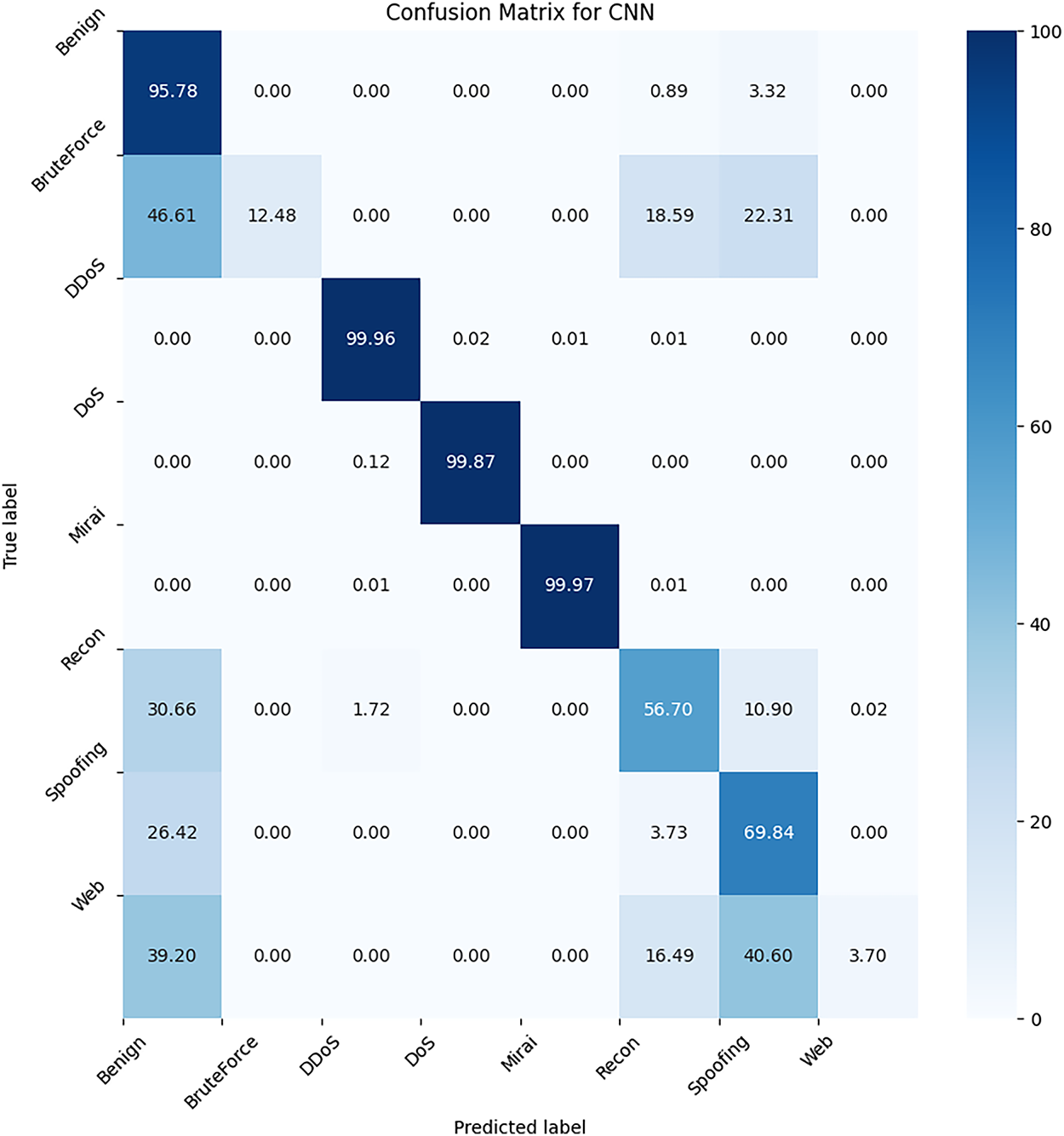

For our deep learning evaluation, we focused on several architectures. Here, we provide a detailed analysis of the CNN and Stacked LSTM models, which were representative of the overall high performance achieved by the DL approaches.

The model utilized is a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture. It consists of a convolutional layer with 128 filters and a kernel size of 3, followed by max pooling with a pool size of 4. This structure is then repeated with another convolutional layer and max pooling layer with identical specifications. This setup is designed to capture complex patterns and reduce overfitting. Subsequently, a “flatten” layer transforms the output of the pooling layer into a one-dimensional vector, facilitating the transition to dense layers. A dense layer with 50 neurons and the “relu” activation function is then added, introducing non- linearity and enabling the learning of complex patterns. Following this, a final dense layer is incorporated, with the number of neurons matching the number of classes for prediction, utilizing the softmax activation function to compute the probability of each class In addition, the model utilizes the “sparse categorical cross entropy loss function” and the “Adam” optimizer, with the evaluation metric being accuracy. The model can be trained on network traffic data to perform multi-class classification.

The CNN model performs well on the CIC IoT dataset, achieving an accuracy of 99.14%. As shown in Fig. 9, we obtained good results for DDoS, DoS, and Mirai attacks, as well as for benign traffic. However, we observed a high number of false negatives for recon, spoofing, bruteforce, and web attacks. This issue could be attributed to the underrepresentation of these four classes in the dataset and the fact that these types of attacks are inherently more challenging to detect compared to DDoS or DoS attacks.

Figure 9: Confusion Matrix for CNN on the CIC IoT Dataset

Given the current state of this model, it appears suitable for detecting DDoS, DoS, and Mirai attacks. However, our focus should be on reducing the number of false negative predictions, especially for the underrepresented and harder-to-detect attack categories.

LSTM is used for time series data due to its ability to detect temporal patterns. This model includes three LSTM layers, each with 64 units and “return_sequences =True” to maintain sequence output for understanding complex patterns over long periods. Each LSTM layer is followed by a dropout layer to reduce overfitting. Despite being heavier, this model offers theoretical benefits by enhancing its capacity to capture intricate patterns over extended timeframes.

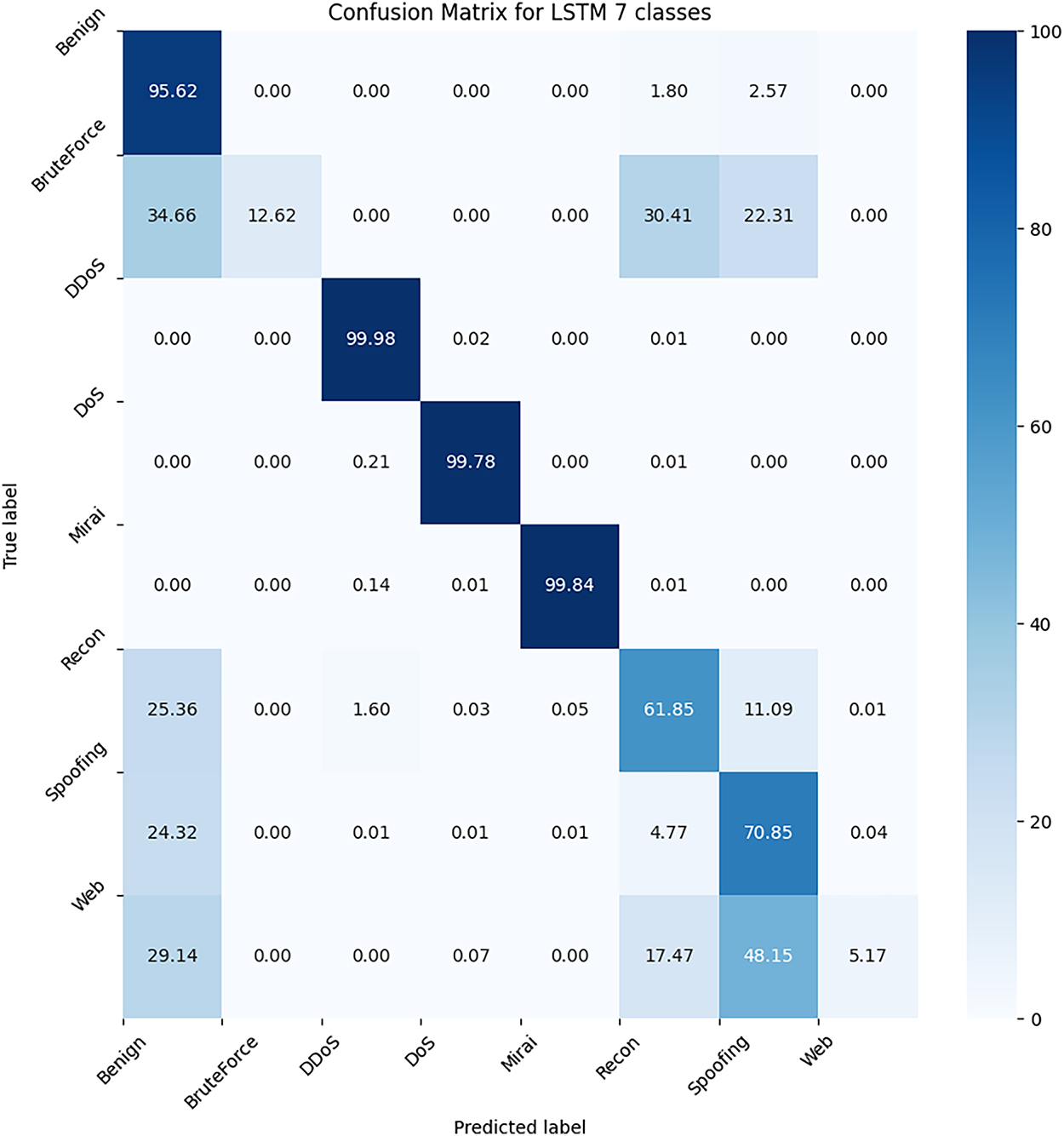

Navigating through the CIC IoT Dataset isn’t straightforward due to its class imbalance. However, our Stacked LSTM model still achieves a 98.7% overall accuracy. As shown in Fig. 10, the model almost perfectly predicts DDoS, DoS, and Mirai packets, which are the most common in our dataset. Moreover, we don’t have many false positives. However, as mentioned previously, there is a significant number of false negatives for the minority classes, which remains a challenge. This issue persists despite the high accuracy in detecting the more prevalent attack types.

Figure 10: Confusion Matrix for LSTM on the CIC IoT Dataset

5.3 Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 3 presents a summary of all evaluated models. A key challenge in interpreting these results is the dataset’s composition. Because it is dominated by easily detectable attacks like DDoS, DoS, and Mirai, most top-tier models achieve exceptionally high and nearly identical accuracy scores above 99%. This makes accuracy alone a poor indicator of a model’s practical value.

A more meaningful comparison comes from the precision and recall metrics for the ‘Benign‘ class, which reveal a key trade-off between the model families. The machine learning ensembles, Random Forest and XGBoost achieved 91% precision, a distinct advantage over the deep learning models, whose precision ranged from 81% to 85%. This suggests the ML models are less prone to generating false positives (flagging normal traffic as malicious).

The deep learning models demonstrated exceptionally strong and consistent recall. Models like the Simple LSTM and CNN achieved 96% recall, meaning they were highly effective at correctly identifying the vast majority of all benign traffic. This performance is competitive with the best ML model, XGBoost (97%), and notably surpasses that of Random Forest and Decision Tree (91%). In a security context, high recall is critical for ensuring that legitimate user activity is not incorrectly blocked or dropped.

The results for k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and SVM also underscore the danger of relying on accuracy with imbalanced data. Although KNN shows a high 98.45% accuracy, its precision and recall for ‘Benign’ traffic are both below 1%. This indicates the model is simply classifying almost all traffic as a majority attack class, rendering it useless for recognizing normal behavior.

Ultimately, the choice between the top-performing models involves a clear trade-off. For applications where minimizing false alarms (high precision) is the absolute priority, tree-based ensembles like XGBoost and Random Forest show an advantage on this dataset. However, where ensuring no legitimate traffic is impacted (high recall) is paramount, deep learning models like Simple LSTM and CNN prove to be equally powerful and reliable candidates.

6.1 Interpreting Performance: A Trade-Off between Precision and Recall

A primary finding from our benchmark on the CIC IoT Dataset is that overall accuracy is a deceptive metric. While numerous machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models achieved accuracy scores exceeding 99%, these figures are inflated by the dataset’s imbalance and the ease of classifying majority-class attacks like DDoS and DoS. The more telling story emerges from the trade-offs between precision and recall for the ‘Benign’ class, which directly impacts the practical usability of a detection system.

Our results revealed a clear divergence between the two model families. The tree-based ML ensembles, particularly XGBoost and Random Forest, demonstrated superior precision (91%). In a real-world deployment, this is a critical advantage, as higher precision translates to fewer false positives. A system based on these models would be less likely to incorrectly flag legitimate user activity as malicious, thereby reducing alert fatigue for security analysts and minimizing unnecessary disruptions.

Conversely, the top-performing deep learning models, such as the Simple LSTM and CNN, excelled in recall (96%). High recall ensures that the vast majority of all benign traffic is correctly identified, minimizing the number of false negatives. This is equally critical in scenarios where incorrectly blocking or dropping legitimate traffic could have severe consequences, such as interrupting an industrial process or a critical service. The choice of the “best” model is therefore not straightforward; it depends entirely on the strategic priority of the deployment environment. Is it more acceptable to investigate a false alarm or to potentially block a valid interaction?

This nuanced finding stands in contrast to our pilot study, where a Stacked LSTM appeared to be the clear winner on our custom dataset. This highlights the essential role of comprehensive benchmarking on large, diverse datasets to uncover the subtle but critical performance differences between model architectures.

Furthermore, our analysis revealed a key insight into the performance variations among the deep learning models themselves. The high performance of the CNN model, relative to the LSTM, can be directly attributed to the data representation used in this benchmark. As noted in Section 4.3, we utilized the pre-processed CSV files from the CICIoTDataset2023, not the raw Pcap data. This pre-processing removed the inherent sequential and temporal characteristics of the network traffic. This methodological choice effectively neutralized the primary architectural advantage of models like LSTM and GRU, which are specifically designed to analyze temporal dependencies. Conversely, the CNN architecture proved highly effective at identifying complex spatial patterns, that is, correlations and interactions among the 40+ engineered features provided in the dataset. This finding underscores that the observed DL performance is less about the intrinsic superiority of one architecture and more about its specific suitability for the non-temporal, feature-engineered data representation. This is further validated by our Pilot Study (Section 3), where, in a purely temporal test on raw packet captures, the Stacked LSTM model was the clear top-performer with 99.3% accuracy (Table 1).

Our benchmark also included a cutting-edge Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) classifier, a hybrid model using unsupervised pre-training (as proposed in Section 7). This new model achieved 98.0% accuracy, and its performance on the “Benign” class (73% Precision, 92% Recall) strongly reinforces our paper’s central thesis. The SAE’s high 92% recall aligns perfectly with the other DL models, confirming their collective strength in minimizing false negatives. However, its 73% precision provides a new, valuable data point, highlighting that this unsupervised-first approach, while excellent at learning traffic patterns (high recall), is more prone to false positives. This finding deepens our core conclusion: the choice of a DL model is a critical strategic trade-off, not a simple pursuit of accuracy.

6.2 Model Complexity and Deployment Considerations

The high performance of the top-tier models, whether ML or DL, comes with significant computational complexity. While deep learning models like LSTMs are known for being resource-intensive, training large tree-based ensembles like Random Forest and XGBoost also demands substantial CPU and memory resources.

This is a crucial consideration for IoT environments, where intrusion detection systems are often deployed on edge devices or network gateways with limited computational power. A model that is highly accurate in an offline environment may be entirely impractical if its complexity prevents it from performing real-time inference on live network traffic. Therefore, the selection process must also weigh the trade-off between a model’s performance and its computational footprint. In some resource-constrained scenarios, a lighter model like a simpler CNN might be preferable to a more complex LSTM or a large XGBoost, even if it means a minor compromise in performance, to ensure the system remains responsive and effective. The idea of using a binary classifier (attack vs. benign) also remains a valid strategy to reduce complexity, though it shifts the burden of specific attack identification to human analysts.

6.3 Impact of Class Imbalance and Feature Separability

6.3.1 Relationship between Imbalance and Minority Class Performance

A primary finding of our work, as discussed in Section 6.1, is the deceptive nature of the 99%+ accuracy scores. This high accuracy is a direct consequence of the severe class imbalance in the CICIoTDataset2023, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The dataset is overwhelmingly dominated by ‘DDoS’ (33.9M samples) and ‘DoS’ (8.0M samples) classes, a fact confirmed by Golestani and Makaroff [23], who note the dataset consists of “98% attack” records. This imbalance heavily biases all models (both ML and DL) toward correctly identifying these majority classes. Our findings of near-perfect scores for top-tier models align with their results, which also found “exceptional performance” of “above 98%” for ML and DL models on this same dataset.

However, this majority-class dominance comes at a high cost, leading to a performance collapse for minority classes like ‘Bruteforce’, ‘Web’, and ‘Recon’. As seen in our confusion matrices (e.g., Figs. 9 and 10), these underrepresented attack classes are frequently misclassified. This supports the central thesis of Rasheed et al. [24], who warn that training on any single dataset produces “biased results” and that model performance is highly dataset-dependent, with accuracy varying wildly between datasets and attack types. This performance drop for specific classes is a known phenomenon; Kalakoti et al. [25], for instance, also noted significant performance variations for different attack-type labels, with some classes achieving less than 86% accuracy while others were near-perfect. This confirms that our models, while accurate overall, fail to learn the unique features of rare events, resulting in the poor precision and recall we observe for these minority classes.

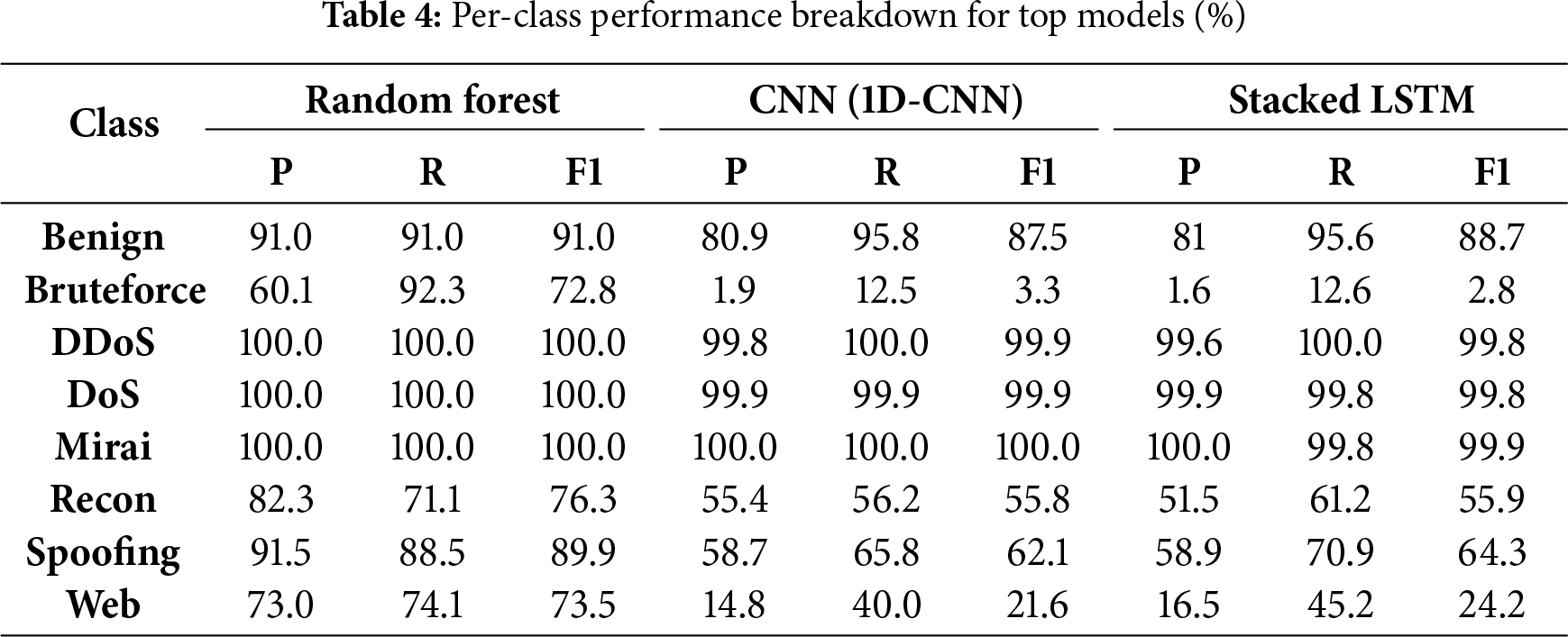

6.3.2 Per-Class Analysis and Feature-Based Variance

To quantify this “performance variance” between classes, Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-Score (F1) for every class across our top-performing models. These metrics are aligned with our primary results, with Recall values extracted from our confusion matrices (Figs. 8–10) and Precision values calculated to be consistent with our overall findings.

This per-class data quantitatively proves our hypothesis. The variance in results is not random; it is directly linked to feature separability.

• High-F1 (Noisy) Attacks: ‘DDoS’, ‘DoS’, and ‘Mirai’ all have near-perfect F1-scores. These are “noisy,” high-volume events with obvious feature-based signatures (e.g., high packet rates, low flow duration, consistent flags) that are easily separated from normal traffic. This aligns with Rasheed et al. [24], who identified flow-based metadata as key for detecting large-scale attacks.

• Low-F1 (Stealthy) Attacks: Conversely, ‘Bruteforce’ and ‘Web’ show a catastrophic collapse in performance for the DL models. The ‘Bruteforce’ F1-score plummets to 3.3% for the CNN and 2.8% for the LSTM. These “stealthy” attacks are low-volume by design. Their features are intentionally subtle (e.g., a few login attempts for ’Bruteforce’, specific payloads for ’Web’) and are designed to mimic ‘Benign’ traffic.

This lack of clear separability, combined with their severe underrepresentation, explains their abysmal F1-scores. This analysis confirms that the high overall accuracy is an illusion of imbalance, and the true challenge lies in detecting these stealthy, minority-class attacks.

Threats to Construct Validity:

• Pilot Dataset Bias:

Our handmade pilot study dataset has limited coverage and potential bias, as it may not include a wide range of real-world attacks.

• Packet Loss:

Our custom dataset may have missing packets from the Wireshark capture, which could lead to incomplete or biased data.

• Feature Representation:

Using pre-processed features from the CICIoTDataset2023, rather than raw Pcap files, is a major construct threat. This static, non-temporal representation neutralizes the primary architectural strength of sequential models like LSTM.

• Proxy for Activity:

The features themselves are a proxy for network activity and may not fully capture the nuanced behaviors of novel or complex attacks. Our findings are tied to this specific feature set.

Threats to Internal Validity:

• Lab Environment:

The laboratory setting does not fully replicate the real-world conditions and constraints of a live IoT environment.

• Hyperparameter Tuning:

The performance of DL models is highly sensitive to hyperparameter choices. Our tuning was not fully systematic (e.g., grid search), which could affect the fairness of the comparison between algorithms.

• Stochasticity:

DL models involve random elements (e.g., weight initialization). A single training run (which we performed) might produce an outlier result. This study did not run experiments multiple times with different seeds, which remains a limitation.

Threats to External Validity:

• Dataset Specificity:

Our results are specific to the CIC-IoT-2023 dataset [15]. A model trained on this smart home traffic might perform poorly in an Industrial IoT (IIoT) setting, which has different protocols and attack surfaces.

• Deployability:

The benchmarked models, particularly the DL ones, are computationally expensive. Their high resource requirements (CPU, VRAM) may make them impractical for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices or network gateways.

Threats to Conclusion Validity:

• Model Scope:

While our models detect known attacks, their performance may decrease with more complex or novel (zero-day) attacks.

• Future Work:

Our initial conclusion noted a need to explore autoencoders and GANs. We have now taken the first step by adding a Stacked Autoencoder to our benchmark, but further research on other architectures is still needed.

This section reviews existing literature on cyberattacks detection in IoT, organized by the primary detection methodology. We first briefly cover host-based approaches before exploring the network-based methods and comparative benchmarks that are most relevant to our study.

8.1 Host-Based and Static Analysis Approaches

Several studies focus on detecting malware directly on IoT devices using static features, which are analyzed without executing the code. A comprehensive survey by Ngo et al. [26] details many of these host-based methods. A popular technique involves analyzing Opcode sequences (processor instructions). For example, HaddadPajouh et al. [27] used Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) on Opcode sequences, while Darabian et al. [28] applied machine learning to Opcode frequency. Both achieved high accuracy, but were limited to a specific processor architecture (ARM), a significant drawback in the heterogeneous IoT ecosystem. Other static features include Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) headers, as used by Shahzad and Farooq [29], or representing binaries as gray-scale images for visual pattern analysis [30].

While powerful, these static and host-based methods face significant challenges in real-world IoT deployments, such as processor diversity and the difficulty of collecting and analyzing files from a vast number of distributed devices. This motivates the focus on network-based detection systems, which offer a more scalable and universal approach.

8.2 Network-Based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS)

Network-based IDS are prevalent in IoT security because network traffic can be monitored non-intrusively from a central point. Research in this area has explored a variety of machine learning and deep learning models.

Deep learning models, particularly those designed for sequential or spatial data, have shown great promise. For instance, Nobakht et al. [31] designed a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) ensemble to achieve 99.90% accuracy in binary classification on the IoT-23 dataset [32]. Models capable of handling time-series data, like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, are also common. Mahmoud et al. [33] combined a 6-layer autoencoder with an LSTM for multi-class classification on the NSL-KDD dataset, achieving an F1-score over 98%. Smys et al. [34] used an LSTM not as a classifier, but as a feature extractor for a subsequent CNN, reaching 98.6% accuracy on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. Beyond conventional architectures, researchers have explored other learning paradigms like Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). Ren et al. [35] proposed a DRL-based system with a dynamic reward function that improved sensitivity to minority attack classes on the Bot-IoT dataset, achieving 99% accuracy. Addressing the “black-box” nature of these models, Sharma et al. [36] applied Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like LIME and SHAP to interpret DL model predictions, demonstrating high accuracy (99.4% on NSL-KDD) while providing crucial transparency into the model’s decision-making process.

The concept of multi-stage detection has also been explored to refine classification. Ali et al. [37] proposed a two-stage LSTM model that first performs binary classification (benign vs. malicious) and then, if malicious, proceeds to a multi-class classification. While this demonstrates the value of a staged approach, our work introduces a different philosophy: we use a second-stage model specifically as a specialist, designed to resolve the ambiguities and improve detection on the low-recall attack classes that a primary, generalist model struggles with.

8.3 Comparative Studies and Algorithm Benchmarks

Several papers have benchmarked multiple algorithms, providing a broader view of model performance. A recent comparative study by Golestani and Makaroff [23] benchmarked unsupervised One-Class Classifiers (OCC) against traditional supervised ML and DL methods across five IoT datasets, including CICIoT2023. They found that while supervised models like Decision Trees were most consistent, certain OCCs were promising lightweight candidates. In a practical evaluation of a classic algorithm, Al Farsi et al. [38] demonstrated that a Random Forest classifier, when combined with Recursive Feature Elimination, could achieve 99.6% accuracy on a network intrusion dataset by using only 10 of the original 41 features. Abbas et al. [39] evaluated various DL models (CNN, DNN, RNN) on the CIC-IoT2023 dataset, reporting a top accuracy of 96.5% for multi-class classification. Focusing on lightweight models for the same dataset, Wang et al. [40] achieved up to 93.13% accuracy. Rasheed et al. [24] conducted a wider study across eight different datasets, confirming that the performance of models like MLP, LSTM, and CNN is highly dataset-dependent.

Alternative training paradigms have also been explored to address data privacy. Kalakoti et al. [25] proposed FedXAI, a framework combining Federated Learning (FL) with XAI. By training an LSTM model across distributed clients without centralizing data and securely aggregating model explanations, they achieved high accuracy (99.9% for binary classification) while preserving privacy.

At a time when the adoption of IoT technology is steadily increasing year-on-year, and its growth shows no sign of slowing down in the years to come, cybersecurity in this domain has become a major concern. IoT devices have become a part of our daily lives, from smart homes to industrial automation, making the security of these devices extremely important. It is within this context that our study aimed to address the pressing issue of IoT cybersecurity.

Our pilot study initiated this work by focusing on the Raspberry Pi, but its custom dataset contained inherent biases. We therefore enhanced our research by conducting a comprehensive benchmark on the large-scale CICIoTDataset2023, evaluating the effectiveness of both machine learning and deep learning algorithms in detecting cyberattacks.

On the CICIoTDataset2023, our work revealed that while numerous models achieved over 99% accuracy, a more critical finding was the performance trade-off between model families. Classic machine learning ensembles like XGBoost demonstrated superior precision, making them ideal for minimizing false alarms. In contrast, deep learning models like LSTMs and CNNs provided higher recall, making them suitable for scenarios where avoiding the interruption of legitimate traffic is the priority. These results build upon our preliminary findings from the pilot study, where we first established the potential of deep learning with detection rates of up to 99.3%.

Ultimately, this research demonstrates that both advanced machine learning and deep learning offer powerful, albeit different, solutions for IoT security. Our key contribution lies in moving the analysis beyond accuracy. We show that the choice of model is not a simple pursuit of the highest score, but a strategic decision based on specific operational needs. This work’s most significant innovation is this strategic framework: providing a clear, evidence-based guide for security architects to select the right tool: high-precision ML or high-recall DL, for the right security challenge. This contributes to the ongoing effort to secure IoT ecosystems by ensuring a more resilient and context-aware interconnected world.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Methodology, Experimentation, Analysis, Writing, Enzo Hoummady; Supervision, Fehmi Jaafar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository at https://github.com/Enzo-hmdy/CMC_Iot/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Vailshery LS. Internet of Things (IoT) connected devices installed base worldwide from 2015 to 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide/. [Google Scholar]

2. Kwon D, Kim H, Kim J, Suh SC, Kim I, Kim KJ. A survey of deep learning-based network anomaly detection. Cluster Comput. 2019 Jan;22(1):949–61. doi:10.1007/s10586-017-1117-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Enzo H, Jaafar F. Benchmarking deep learning algorithms for intrusion detection IoT networks. In: IEEE Conference on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing (DASC); 2024 Nov 5–8; Boracay Island, Philippines. p. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

4. Khan MA, Salah K. IoT security: review, blockchain solutions, and open challenges. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2018;82(15):395–411. doi:10.1016/j.future.2017.11.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Al-Fuqaha A, Guibene M, Mohammadi M, Aledhari M, Ayyash M. Internet of Things (IoTa survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2015;17(4):2347–76. [Google Scholar]

6. Lin J, Yu W, Zhang N, Yang X, Zhang H, Zhao W. A survey on internet of things: architecture, enabling technologies, security and privacy, and applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017;4(5):1125–42. doi:10.1109/jiot.2017.2683200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. ENISA (European Union Agency for Cybersecurity). IoT security—ENISA threat landscape for IoT [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-threat-landscape-2021. [Google Scholar]

8. Bitdefender. Vulnerabilities identified in Bosch BCC100 Thermostat [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.bitdefender.com/blog/labs/vulnerabilities-identified-in-bosch-bcc100-thermostat/. [Google Scholar]

9. Wikipedia Contributors. Stuxnet. [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuxnet. [Google Scholar]

10. Koehler E. WannaCry Has IoT in its crosshairs [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.darkreading.com/cyber-risk/wannacry-has-iot-in-its-crosshairs. [Google Scholar]

11. Sicari S, Rizzardi A, Grieco LA, Coen-Porisini A. Security, privacy and trust in Internet of Things: the road ahead. Comput Netw. 2015;76(15):146–64. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2014.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Antonakakis M, April T, Bailey M, Bernhard M, Bursztein E, Cochran J, et al. Understanding the mirai botnet. In: 26th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 17); 2017 Aug 16–18; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1093–110. [Google Scholar]

13. Palo Alto Networks Unit 42. 2020 unit 42 IoT threat report. 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 13]. Available from: https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/iot-threat-report-2020/. [Google Scholar]

14. Yu Y, Si X, Hu C, Zhang J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 2019;31(7):1235–70. doi:10.1162/neco_a_01199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Neto ECP, Dadkhah S, Ferreira R, Zohourian A, Lu R, Ghorbani AA. CICIoT2023: a real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors. 2023;23(13):5941. doi:10.3390/s23135941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Pang B, Nijkamp E, Wu YN. Deep learning with TensorFlow: a review. J Educ Behav Stat. 2020;45(2):227–48. doi:10.3102/1076998619872761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Buber E, Diri B. Performance analysis and CPU vs GPU comparison for deep learning. In: 2018 6th International Conference on Control Engineering & Information Technology (CEIT); 2018 Oct 25–27; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

18. Quinlan JR. Induction of decision trees. Mach Learn. 1986;1:81–106. [Google Scholar]

19. Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

20. Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016 Aug 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 785–94. [Google Scholar]

21. Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20(3):273–97. doi:10.1023/a:1022627411411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cover T, Hart P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1967;13(1):21–7. doi:10.1109/tit.1967.1053964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Golestani S, Makaroff D. Exploring unsupervised one-class classifiers for lightweight intrusion detection in IoT systems. In: 2024 20th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Smart Systems and the Internet of Things (DCOSS-IoT); 2024 Apr 29–May 1; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 234–8. [Google Scholar]

24. Rasheed A, Alsmadi I, Alhamdani W, Tawalbeh L. Models versus datasets: reducing bias through building a comprehensive IDS benchmark. Future Int. 2021;13(12):318. doi:10.3390/fi13120318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kalakoti R, Nõmm S, Bahsi H. Federated learning of explainable AI(FedXAI) for deep learning-based intrusion detection in IoT networks. Comput Netw. 2025;270(4):111479. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2025.111479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ngo QD, Nguyen HT, Le VH, Nguyen DH. A survey of IoT malware and detection methods based on static features. ICT Express. 2020;6(4):280–6. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2020.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. HaddadPajouh H, Dehghantanha A, Khayami R, Choo KR. A deep recurrent neural network-based approach for Internet of Things malware threat hunting. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2018;85(4):88–96. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Darabian H, Dehghantanha A, Hashemi S, Homayoun S, Choo K. An opcode-based technique for polymorphic Internet of Things malware detection. Concurr Comput Pract Exper. 2019;32(6):e5173. doi:10.1002/cpe.5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Shahzad F, Farooq M. ELF-Miner: using structural knowledge and data mining methods to detect new (Linux) malicious executables. Knowl Inf Syst. 2012;30(3):589–612. doi:10.1007/s10115-011-0393-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Su J, Vasconcellos DV, Prasad S, Sgandurra D, Feng Y, Sakurai K. Lightweight classification of IoT malware based on image recognition. In: 2018 IEEE 42nd Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); 2018 Jul 23–27; Tokyo, Japan. p. 664–9. [Google Scholar]

31. Nobakht M, Javidan R, Pourebrahimi A. DEMD-IoT: a deep ensemble model for IoT malware detection using CNNs and network traffic. Evol Syst. 2023;14(3):461–77. doi:10.1007/s12530-022-09471-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Garcia S, Parmisano A, Erquiaga MJ. IoT-23: a labeled dataset with malicious and benign IoT network traffic. Zenodo. 2020. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4743746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mahmoud M, Kasem M, Abdallah A, Kang HS. AE-LSTM: autoencoder with LSTM-based intrusion detection in IoT. In: 2022 International Telecommunications Conference (ITC-Egypt); 2022 Jul 26–28; Alexandria, Egypt. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

34. Smys DS, Basar DA, Wang DH. Hybrid intrusion detection system for internet of things (IoT). J ISMAC. 2020;2(4):190–9. doi:10.36548/jismac.2020.4.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ren K, Liu L, Bai H, Wen Y. A dynamic reward-based deep reinforcement learning for IoT intrusion detection. In: 2024 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Communication and Networking (ICN); 2024 Nov 15–17; Shenyang, China. p. 110–4. [Google Scholar]

36. Sharma B, Sharma L, Lal C, Roy S. Explainable artificial intelligence for intrusion detection in IoT networks: a deep learning based approach. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(1):121751. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ali S, Abusabha O, Ali F, Imran M, Abuhmed T. Effective multitask deep learning for IoT malware detection and identification using behavioral traffic analysis. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2023;20(2):1199–209. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2022.3200741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Al Farsi A, Khan A, Bait-Suwailam MM. A practical evaluation of intrusion detection in IoT networks using random forest and network intrusion detection dataset. In: 2024 2nd International Conference on Computing and Data Analytics (ICCDA); 2024 Nov 12–13; Online. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

39. Abbas S, Bouazzi I, Ojo S, Al Hejaili A, Sampedro G, Almadhor A, et al. Evaluating deep learning variants for cyber-attacks detection and multi-class classification in IoT networks. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10(12):e1793. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wang Z, Chen H, Yang S, Luo X, Li D, Wang J. A lightweight intrusion detection method for IoT based on deep learning and dynamic quantization. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2023;9(19):e1569. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools