Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Pigeon-Inspired Optimization Algorithm: Definition, Variants, and Its Applications in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

1 School of Communication and Electronic Engineering, Jishou University, Jishou, 416000, China

2 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Kai-Qing Zhou. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Bio-Inspired Optimization Algorithms: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 5 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.075099

Received 24 October 2025; Accepted 01 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The Pigeon-Inspired Optimization (PIO) algorithm constitutes a metaheuristic method derived from the homing behaviour of pigeons. Initially formulated for three-dimensional path planning in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), the algorithm has attracted considerable academic and industrial interest owing to its effective balance between exploration and exploitation, coupled with advantages in real-time performance and robustness. Nevertheless, as applications have diversified, limitations in convergence precision and a tendency toward premature convergence have become increasingly evident, highlighting a need for improvement. This review systematically outlines the developmental trajectory of the PIO algorithm, with a particular focus on its core applications in UAV navigation, multi-objective formulations, and a spectrum of variant models that have emerged in recent years. It offers a structured analysis of the foundational principles underlying the PIO. It conducts a comparative assessment of various performance-enhanced versions, including hybrid models that integrate mechanisms from other optimization paradigms. Additionally, the strengths and weaknesses of distinct PIO variants are critically examined from multiple perspectives, including intrinsic algorithmic characteristics, suitability for specific application scenarios, objective function design, and the rigor of the statistical evaluation methodologies employed in empirical studies. Finally, this paper identifies principal challenges within current PIO research and proposes several prospective research directions. Future work should focus on mitigating premature convergence by refining the two-phase search structure and adjusting the exponential decrease of individual numbers during the landmark operator. Enhancing parameter adaptation strategies, potentially using reinforcement learning for dynamic tuning, and advancing theoretical analyses on convergence and complexity are also critical. Further applications should be explored in constrained path planning, Neural Architecture Search (NAS), and other real-world multi-objective problems. For Multi-objective PIO (MPIO), key improvements include controlling the growth of the external archive and designing more effective selection mechanisms to maintain convergence efficiency. These efforts are expected to strengthen both the theoretical foundation and practical versatility of PIO and its variants.Keywords

Optimization, as a core method in the field of engineering, enhances efficiency, reduces costs, and improves performance under constraint conditions through systematic adjustment of parameters, resources, or strategies [1]. Since the proposal of Newton’s method in the 17th century, traditional optimization methods have evolved over centuries, evolving from the initial basic theory of calculus into a systematic mathematical tool encompassing linear programming, dynamic programming, etc., and have been widely applied with the advancement of computer technology in the 20th century.

Modern engineering scenarios (such as smart grid scheduling [2] and autonomous driving decision-making [3]) often involve high-dimensional, strongly nonlinear problems with dynamic constraints, posing fundamental challenges to the traditional optimization methods that relies on deterministic models [4–7]. This challenge is evident throughout the history of methodological evolution from Newton’s method [8] to gradient-based approaches [9], this kind of traditional algorithms are limited by strict differentiability assumptions. These methods struggle to address the triple complexity of real-world problems, which are the non-convexity in chemical multi-steady-state optimization, the non-differentiability in mechanical topology optimization, and the multi-objective conflicts in supply chain games. This inherent limitation motivates the exploration of gradient-free approaches. Breakthroughs in bionic intelligence offer a new alternative approach by simulating the behavior of biological groups (such as bird flock collaborative obstacle avoidance [10] and ant colony optimization [11]), swarm intelligence (SI) algorithms achieve a dynamic balance between global exploration and local exploitation in complex solution spaces.

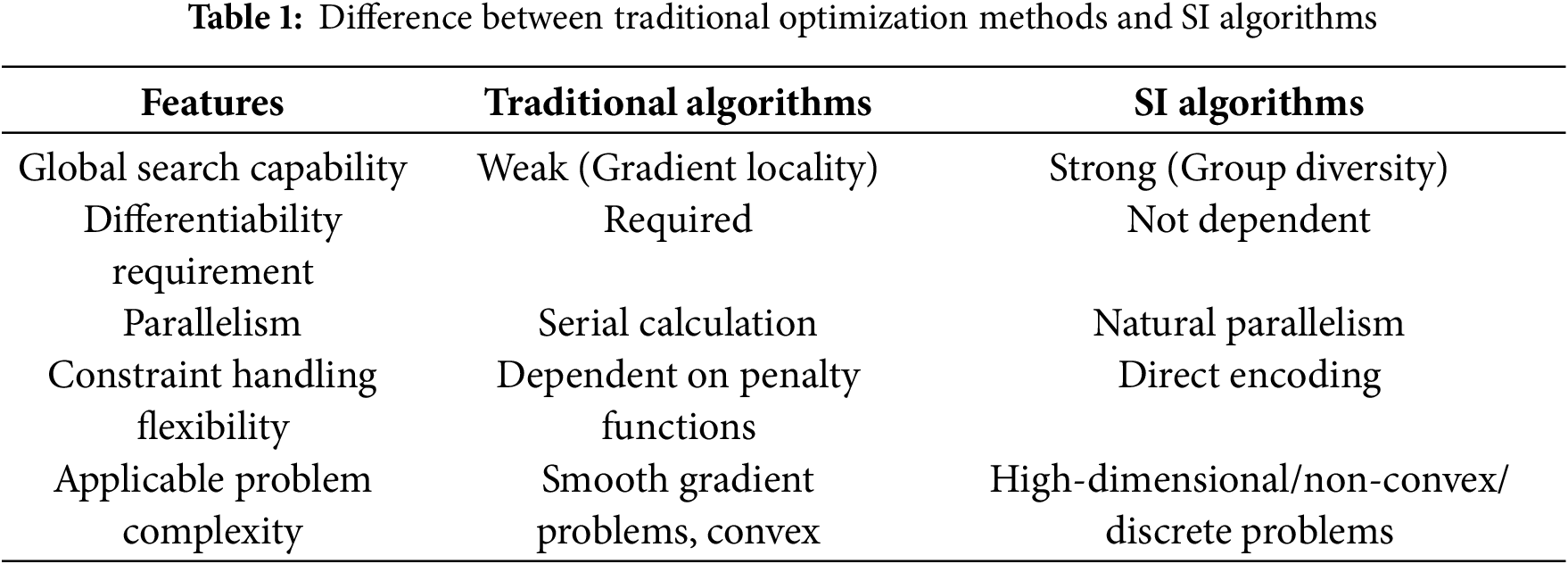

SI, originating from the imitation of various biological behaviors and phenomena [12–14], offers a new approach to optimization problems by simulating the interactions and collaborations within a group. Unlike traditional optimization algorithms, SI provides a new perspective for solving practical problems without needing gradient information, by evaluating objective function values [15,16]. Compared to traditional optimization algorithms, SI algorithms offer several advantages for modern, complex industrial optimization problems, including simplicity, a small number of tunable parameters, and ease of implementation [17–19]. Table 1 presents the comparative results across the following dimensions, which include global search capability, differentiability requirement, parallelism, flexibility in handling constraints, and applicable problem complexity.

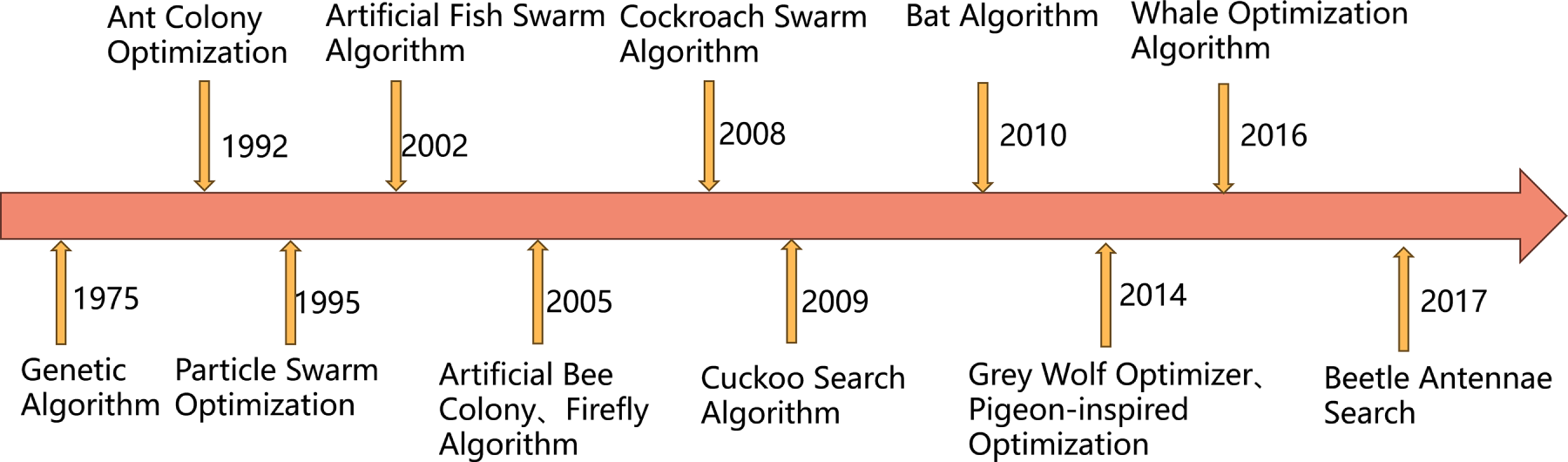

Table 1 illustrates that the traditional methods are suitable for small-scale, convex optimization scenarios with high real-time requirements, relying on precise models and gradient information. In contrast, the SI algorithms illustrate outstanding performance in black-box optimization, multi-objective problems, and joint optimization of structure and parameters in industrial optimization, such as UAV path planning [20–22], Neural Networks [23], Image Segmentation [24], and Workshop Scheduling Problem. Furthermore, Fig. 1 clearly outlines the key developmental trajectory.

Figure 1: Development history of SI algorithms

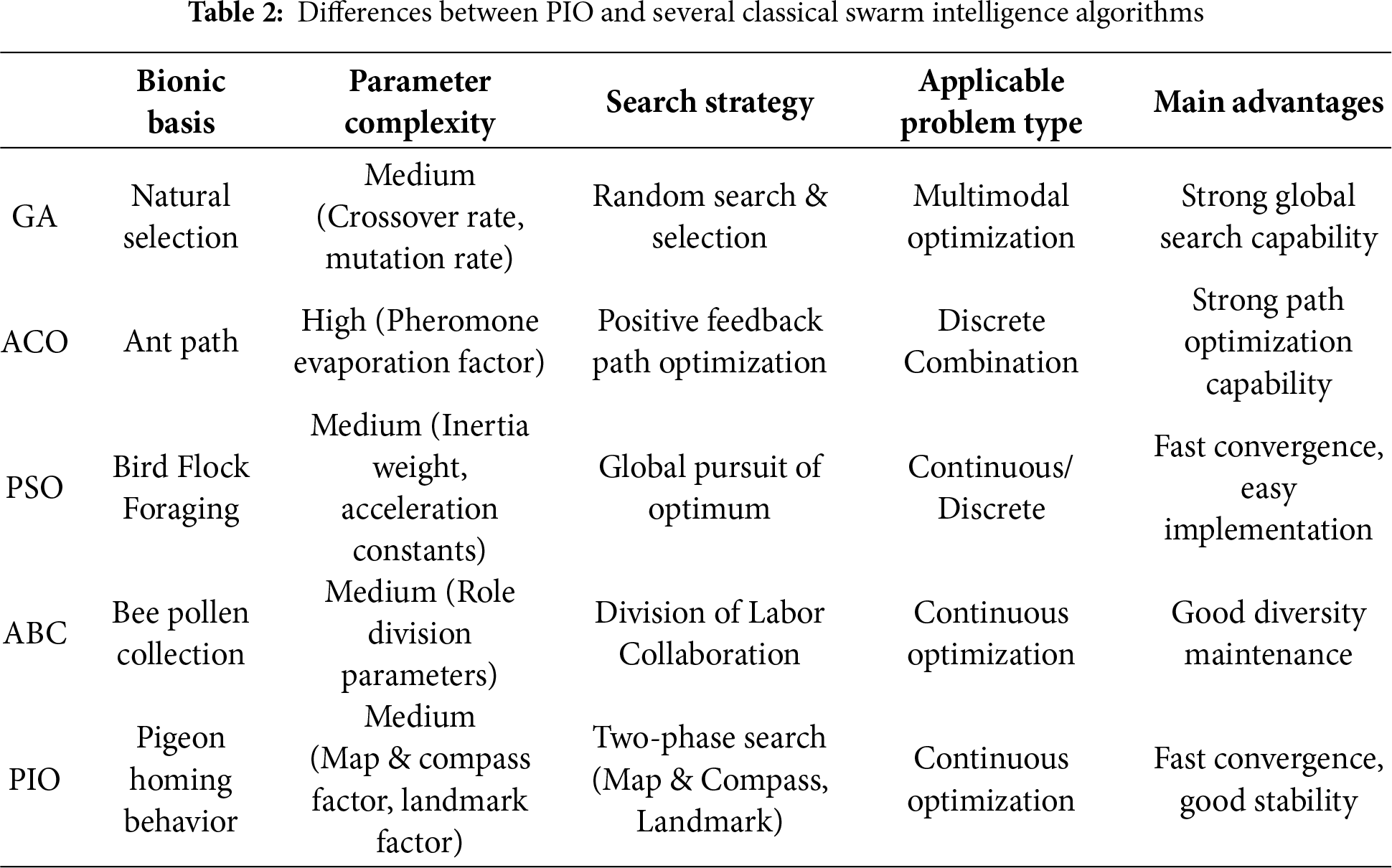

Fig. 1 indicates that some SI algorithms were primarily proposed between 1992 and 2017, which are Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [25], Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [26,27], Bacterial Foraging Algorithm [28], Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm [29], Firefly Algorithm [30], Cuckoo Search Algorithm [31–33], Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [34], Grey Wolf Algorithm [35], Pigeon-inspired optimization (PIO) [36], and Beetle Antennae Search Algorithm [37]. Notably, SI originated from the Genetic Algorithm (GA) proposed in 1975 [38]. An extensive comparison of some classical SI algorithms is presented in Table 2, covering five aspects: bionic basis, parameter complexity, search strategy, applicable problem types, and main advantages.

Based on Table 2 and the accompanying text, PSO has achieved widespread adoption due to its effective balance of conceptual simplicity, rapid convergence, and ease of implementation [39,40]. This combination enables efficient solutions across diverse continuous and discrete problems. Its foundation in bird flock foraging behavior translates into a straightforward global pursuit strategy with manageable parameter complexity (inertia weight, acceleration constants), facilitating both theoretical analysis and practical deployment [41,42]. This success establishes PSO as a foundational SI algorithm whose core principles continue to inspire new developments.

Given its success in establishing PSO as a foundational SI algorithm, Duan and Qiao [36] was inspired to propose the PIO in 2014 based on pigeon homing behavior [43]. PIO not only inherits the simplicity and efficiency of swarm intelligence algorithms but also demonstrates strong competitiveness in time-critical missions such as UAV control and air combat decision-making, owing to its two core advantages: rapid convergence and strong robustness [44]. Building on this foundation, researchers have continuously expanded and deepened the PIO. Qiu and Duan [45] proposed the Multi-Objective PIO (MPIO) algorithm in 2015. A series of improved PIO and MPIO s has been successfully applied to numerous emerging fields, including distributed obstacle clustering for UAVs [46], cooperative path planning for multi-UAV systems [47], and longitudinal parameter tuning for UAV automatic landing systems [48]. As applications deepen, research focus has gradually shifted from practical validation to rigorous analysis of theoretical properties such as algorithm convergence. Zhang et al. [49] rigorously proved the global convergence of PIO in continuous space optimization using the martingale method, while Qiu and Duan [45] conducted convergence analysis of MPIO operators upon its proposal, demonstrating convergence within feasible parameter ranges. Supported by extensive engineering applications and increasingly refined theoretical analyses, the PIO system has been studied more profoundly and broadly.

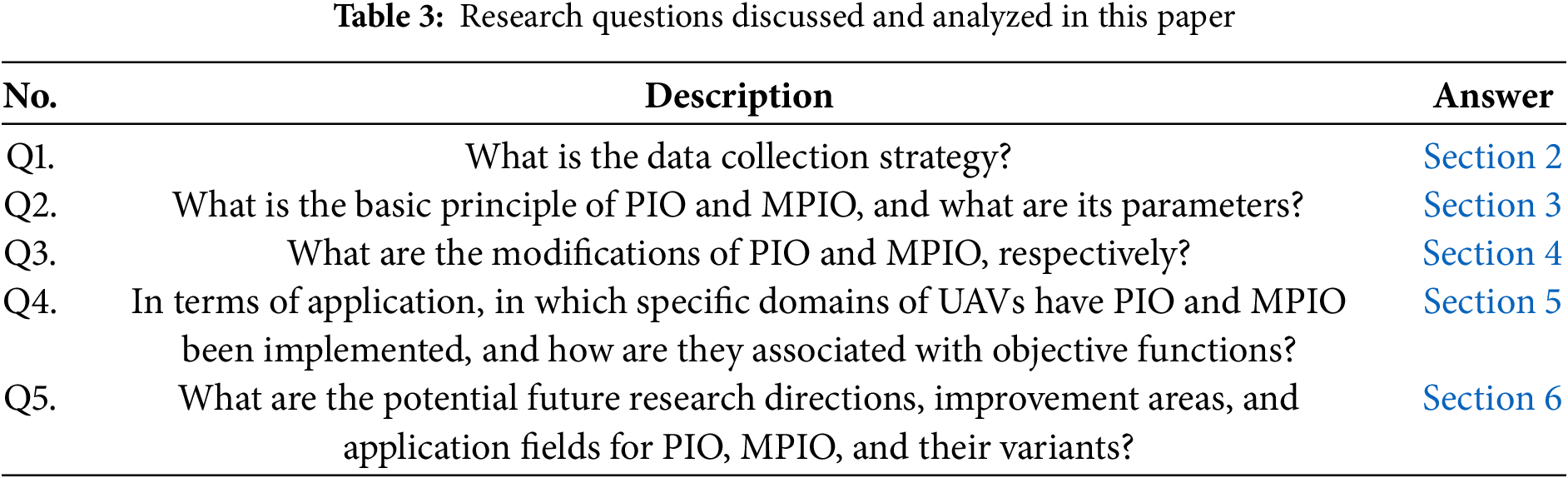

According to the “No Free Lunch” theorem [50], no single algorithm can outperform others across all possible problems. Given this fundamental constraint, researchers have developed various PIO variants to overcome its limitations and tailor it to different optimization scenarios. Some variants focus on optimizing algorithm parameters for enhanced adaptability and efficiency, while others explore hybrid approaches that combine PIO with other metaheuristic algorithms to complement their strengths. Given the rapid proliferation of these algorithmic innovations, a structured framework becomes imperative to comprehensively evaluate their theoretical contributions and practical impacts. To reveal the development trace of PIO, a comprehensive and systematic review is implemented, which is organized by five formulated research questions in this paper by exploring key aspects of PIO from multiple perspectives. These questions aim to define the scope and focus of the research, investigate variants of PIO and their challenges, and summarize the strengths and weaknesses of existing studies to guide future research. Table 3 lists these core questions, serving as the research framework for this literature review.

To address the research questions presented in Table 1, the remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed introduction to our research methodology and the strategies for literature collection. Section 3 delves into key concepts, offering readers a foundational understanding. Section 4 conducts an in-depth analysis of PIO and MPIO variants and thoroughly examines the literature. Section 5 analyzes the application of PIO and MPIO to drones. Section 6 synthesizes the findings of this review and emphasizes the future development directions of PIO and MPIO.

2 Methodology and Data Collection

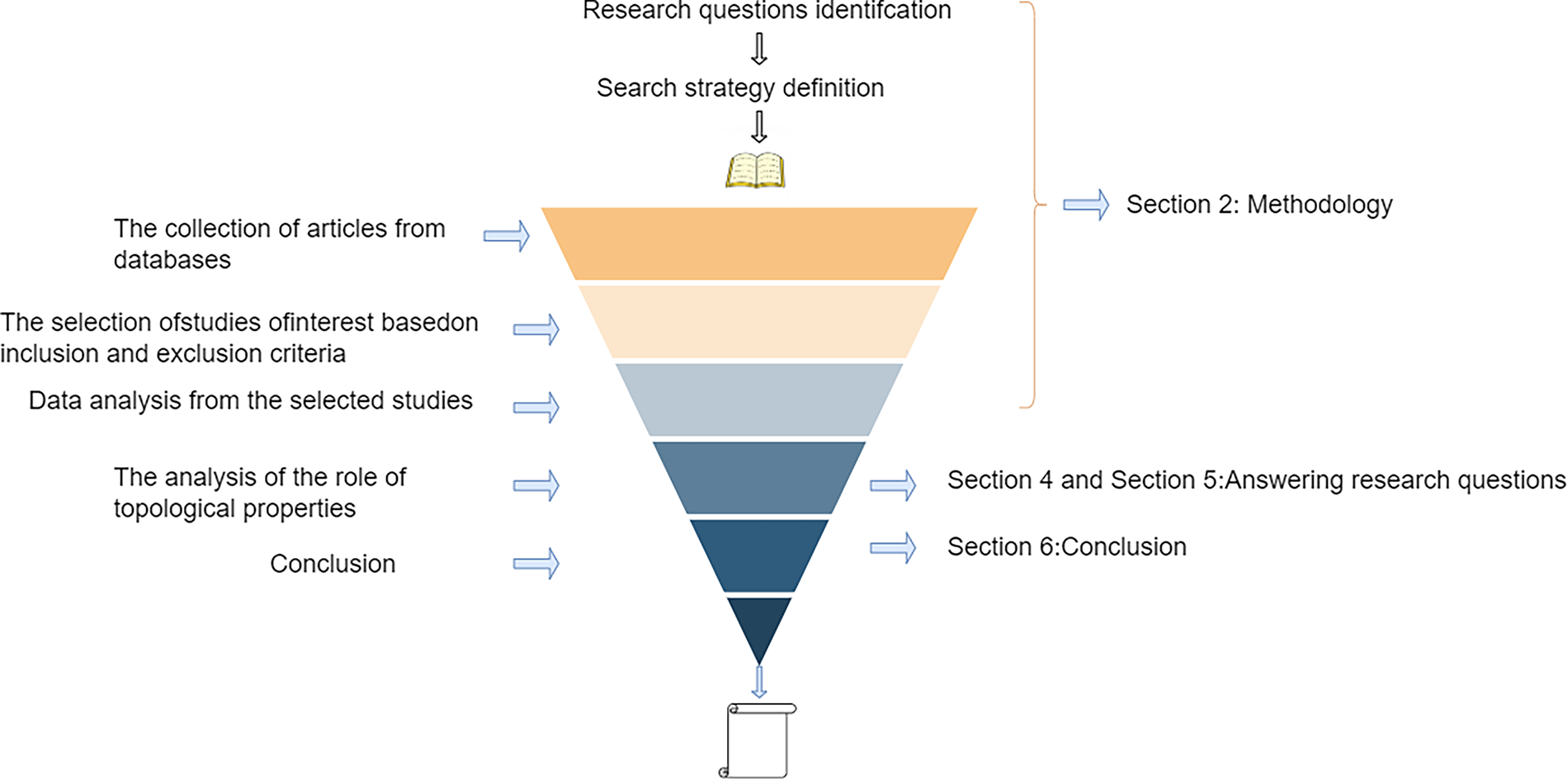

By analyzing the literature related to the PIO, we have clarified the key themes and scope of discussion and identified subtasks of research value to address Question 1. Subsequently, a coherent literature collection strategy was formulated to determine the core literature that needed to be analyzed, answering Question 3. The research method of this review is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Research framework of this manuscript

The framework is divided into three main phases: methodology design (Section 2), data analysis and research question resolution (Sections 4 and 5), and conclusion synthesis (Section 6). The research begins with defining the core questions and search strategy, then systematically retrieving target databases and screening relevant studies based on predefined criteria. Subsequently, quantitative/qualitative analysis and an in-depth exploration of topological properties (or domain-specific characteristics) are conducted. Finally, the results are synthesized to address the research questions and summarize theoretical contributions and practical implications. The process follows a linear progression with phased integration, ensuring methodological rigor and logical coherence throughout the study.

To enhance methodological rigour and mitigate potential research bias, this section details the literature review protocol, following the framework outlined in reference [51]. The protocol comprises the key components of search strategies, paper selection criteria, and associated methodologies.

A. Search strategy for the primary study.

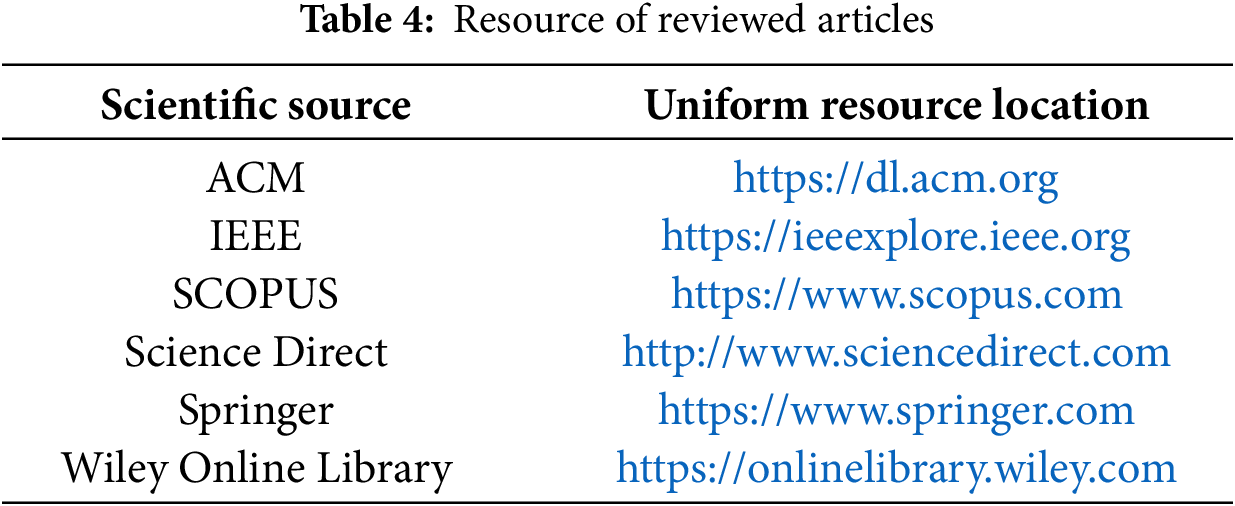

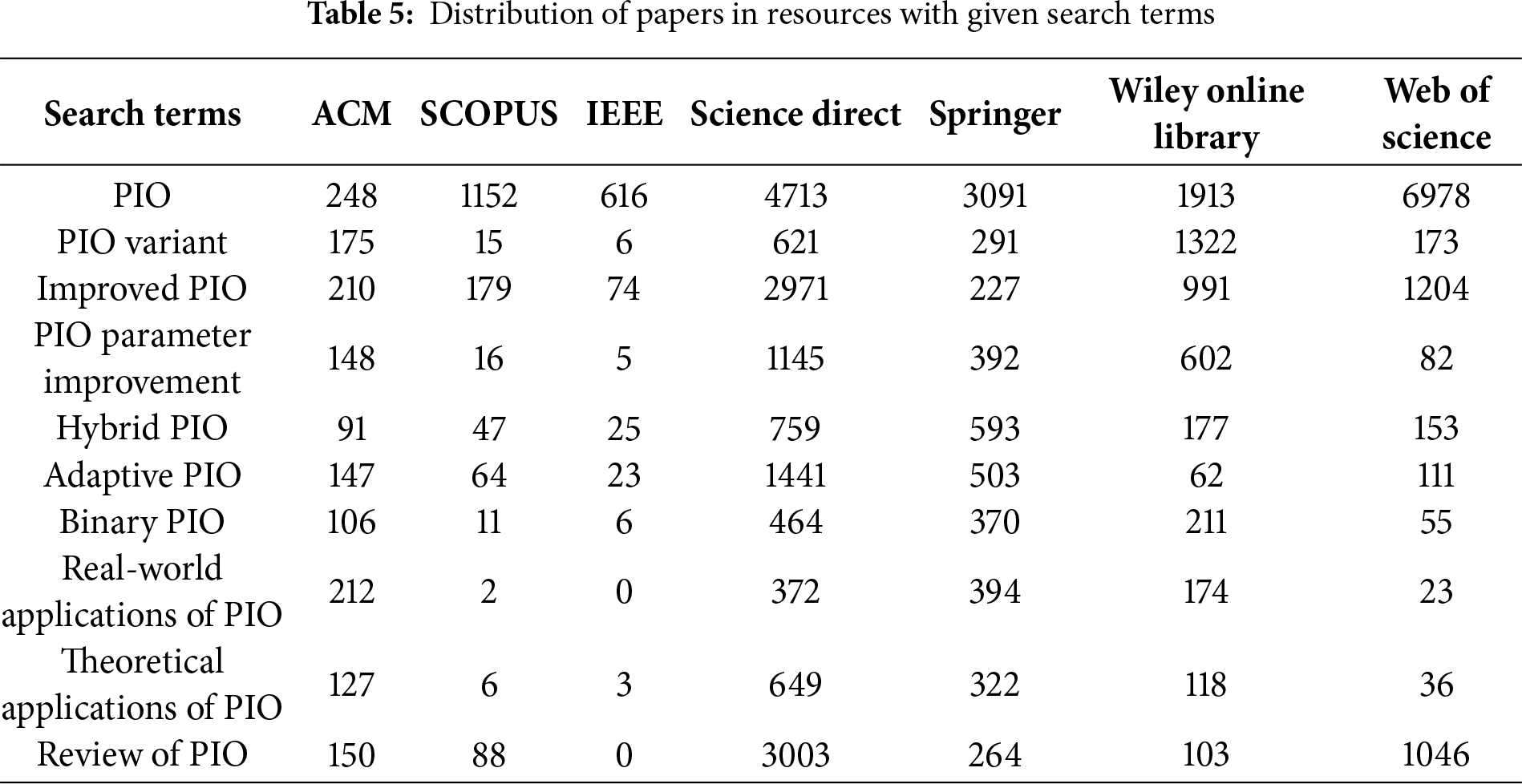

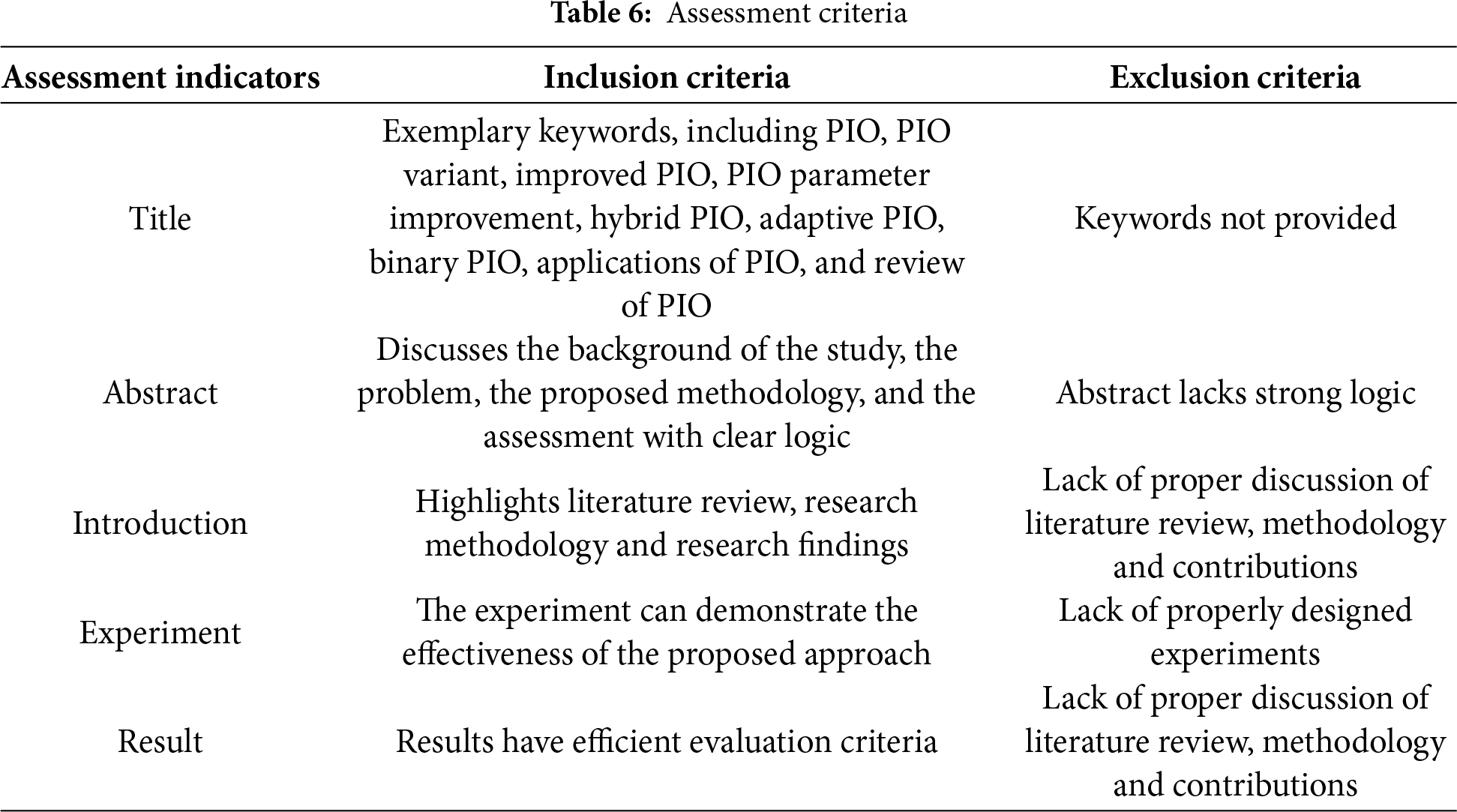

Six scientific databases were carefully selected as the main resources for comprehensive exploration, with detailed information shown in Table 4. The search terms are described as follows: (1) PIO, (2) PIO variants, (3) improved PIO, (4) PIO parameter improvement, (5) hybrid PIO, (6) adaptive PIO, (7) binary PIO, (8) practical applications of PIO, (9) theoretical applications of PIO, (10) PIO review.

B. Paper selection criteria.

In dealing with the extensive corpus of research on PIO, this paper adopted targeted selection criteria, adhering to the methodological guidelines described in references [52–54]. This literature review conducted searches across six databases or publishers: ACM, IEEE, SCOPUS, Science Direct, Springer, Wiley Online Library and Web of Science, focusing on comprehensive search keywords. The publication year range was set from 2019 to 2025, including both conference papers and journal articles. From the preliminary search, a large number of research papers were identified. The distribution of papers within the databases is summarized in Table 5.

Following the aforementioned search, it was found that there is a sufficient number of PIO articles to support the writing of a literature review, hence papers were selected from SCOPUS for the literature review based on the following criteria. The quality of the papers was assessed based on the title, abstract, introduction, experiments and results as delineated in Table 6.

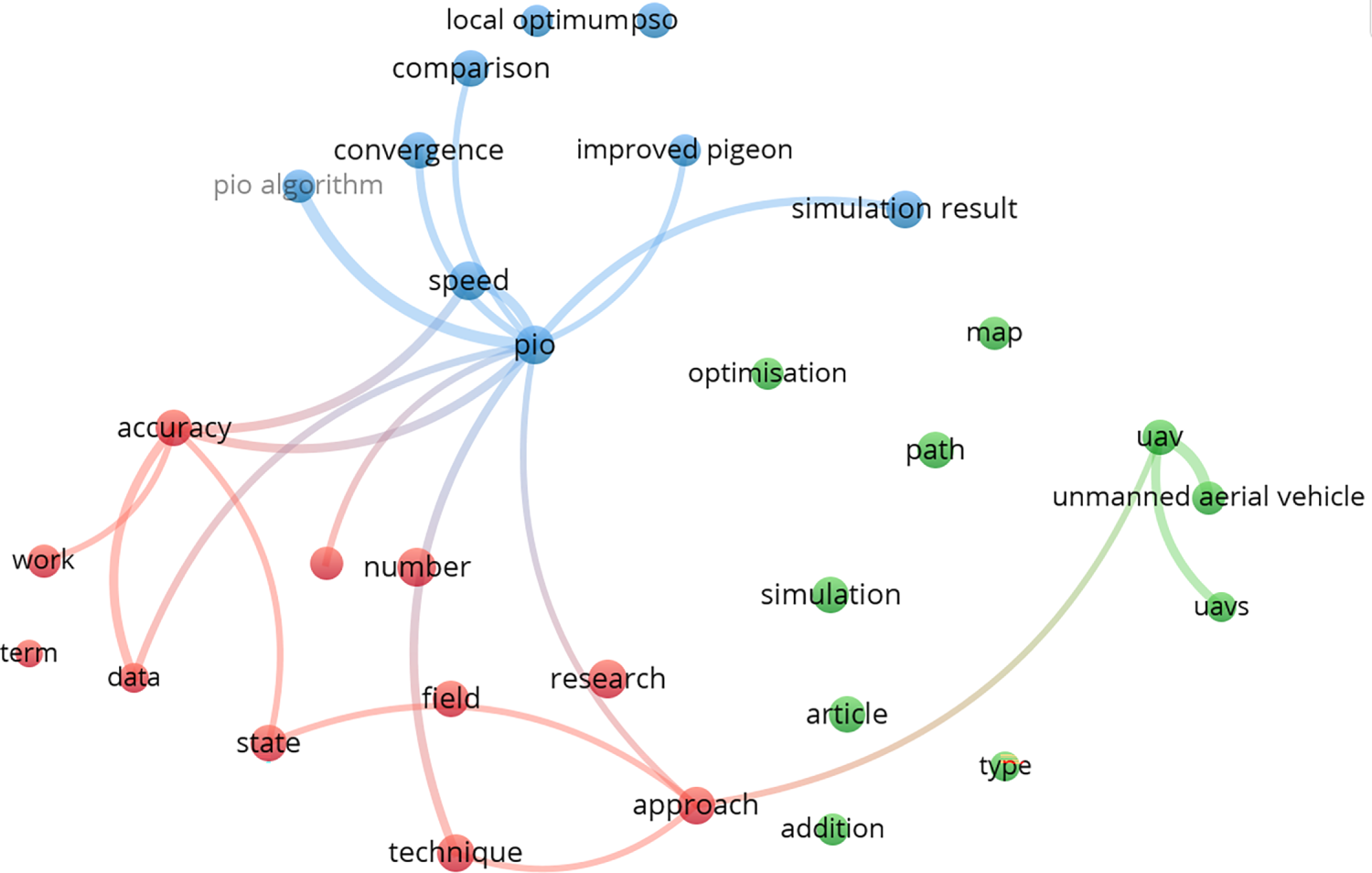

To explore the research domains related to PIO, this paper conducted further analysis using VOSviewer and obtained a keyword co-occurrence network of PIO, as shown in Fig. 3. The correlation shown in Fig. 3 indicates that the PIO is most closely related to Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) across numerous application domains. This intimacy suggests that PIO holds significant value and extensive potential for application in the field of UAVs. The complexity of UAV systems and their reliance on efficient algorithms provide a typical and challenging application scenario for PIO. Therefore, this paper will focus on UAV applications as the core and delve into the practical applications of the PIO in areas such as path planning, task allocation, and swarm cooperative control. It will analyze its advantages, characteristics, and directions for improvement in solving UAV-related optimization problems. Through this focused discussion, not only can the application potential of the PIO be revealed, but it can also provide references and lessons for research in related fields.

Figure 3: Relationship display of PIO keywords in VOSviewer

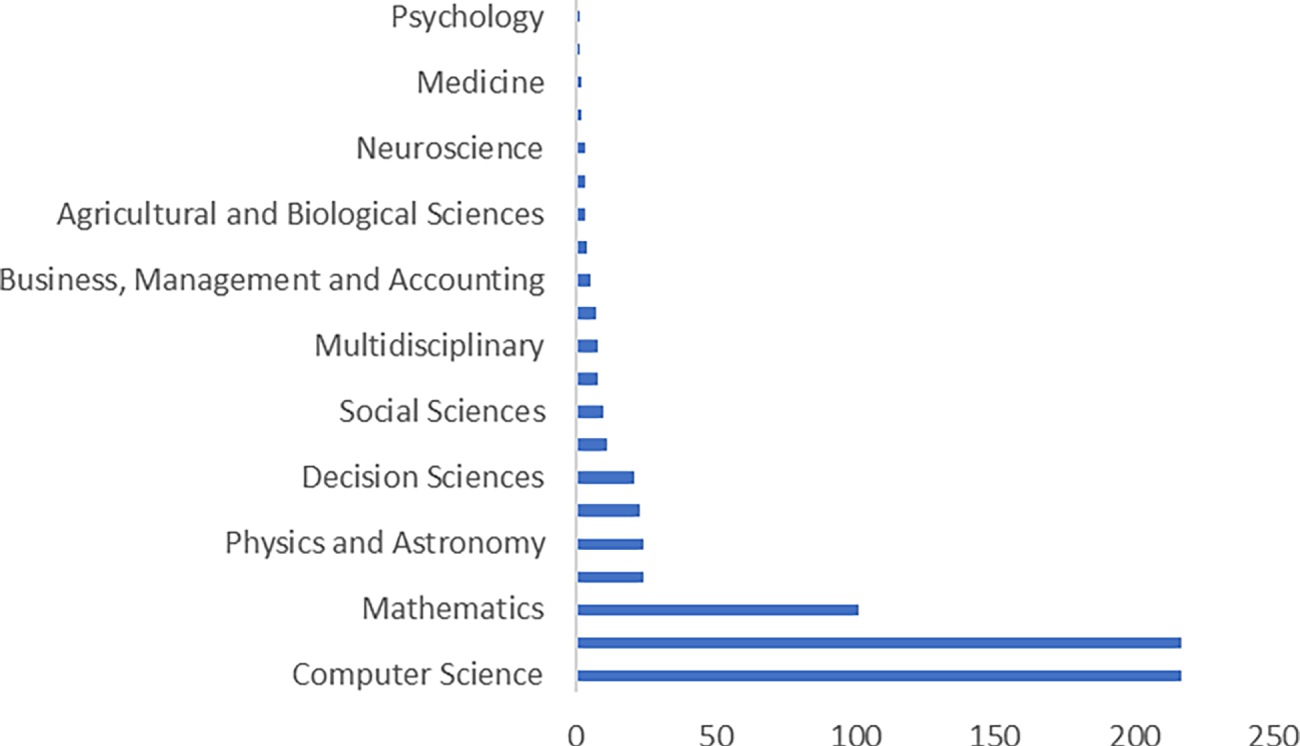

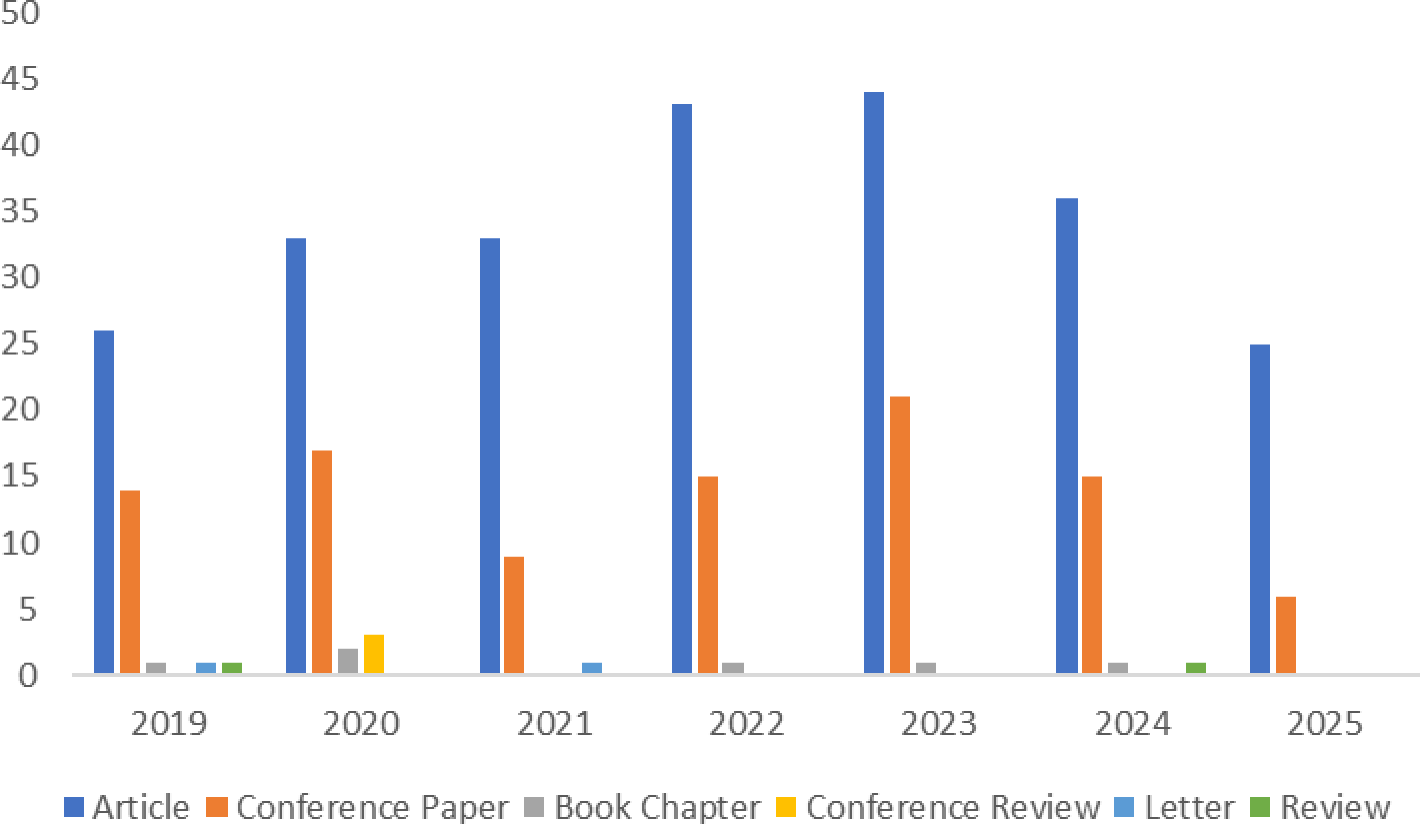

As a novel bio-inspired algorithm with sustained evolutionary potential, Figs. 4 and 5 reveal the dynamic characteristics of PIO research through publication growth trends and domain distribution mapping in the SCOPUS database. Statistical data indicate that although a foundational review in 2019 established the research framework, the subsequent years (2020–present) have witnessed an annual publication growth rate of 37.2% (as shown in Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Proportion of publication categories in recent years

Figure 5: Number of publications in recent years

Additionally, the application domains have expanded from traditional path planning to emerging interdisciplinary fields such as UAV swarm control and medical image processing (as depicted in Fig. 5). This sustained research momentum not only demonstrates the extensibility of the PIO methodology but also highlights under explored academic spaces within its theoretical framework. Building on this foundation, this study constructs an analytical framework targeting the latest literature from 2019 to 2025, systematically examining theoretical innovation trajectories and providing a detailed analysis and discussion of the innovations, developmental trajectories, and application cases in these studies.

The main contributions of this review paper are as follows:

A thorough and critical examination of PIO and its variants has been conducted. This review identifies the inherent limitations of current PIO variants and offers insightful suggestions for addressing these shortcomings. Moreover, the paper provides clear guidance, outlining the fundamental steps required to develop robust new PIO variants. Given the significant importance of PIO in the field of artificial intelligence, this paper attempts to provide an exhaustive review of its applications. This comprehensive approach ensures a sound and detailed understanding of the development, progress, and multifaceted applications of PIO across various disciplines.

Statistical analysis of PIO literature reveals only one relevant systematic review [55]. This review summarizes PIO-related work before 2019 from four aspects: components, operations, structures, and application extensions. However, he only described these studies based on the methods used to improve them. In contrast, this paper systematically reviews PIO-related work from 2019 to 2025, categorizing the research into single-objective and multi-objective sections. It connects the characteristics of PIO with unmanned aerial vehicles and distinguishes them based on improvement objectives, methods, and objective functions. Therefore, by reading this paper, readers can gain a more intuitive and in-depth understanding of the development of PIO.

3 Basic Concepts of PIO, MPIO and UAVs

This section introduces the core concepts of this paper, including the definition of the PIO, the definition of the MPIO, and the definitions related to drones. These discussions are directly related to Question 2.

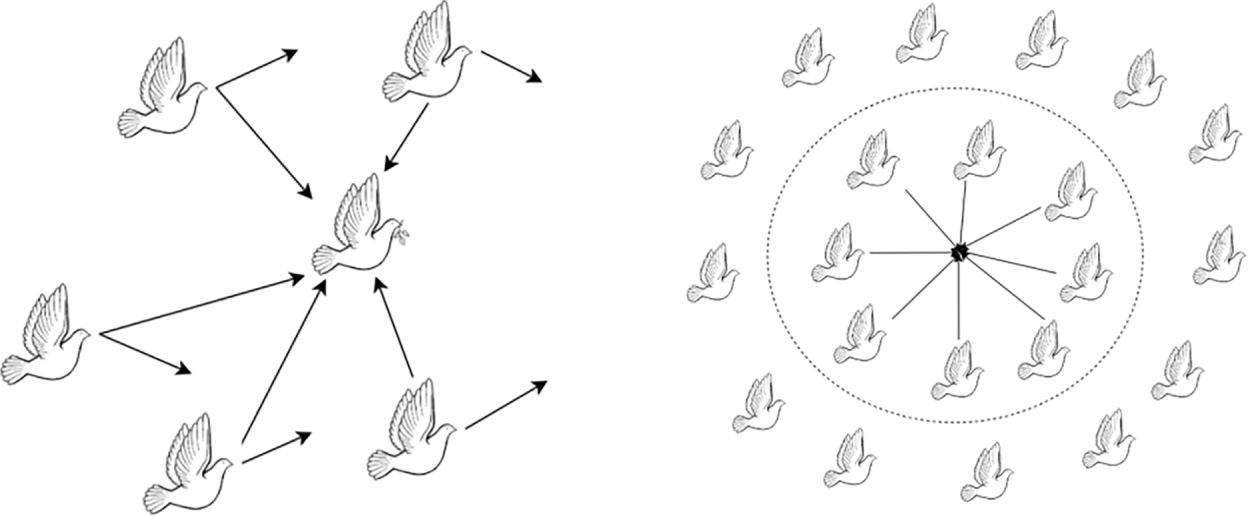

The PIO, by simulating the homing behavior of pigeons, abstracts two core operators: the Map and Compass Operator and the Landmark Operator. The former enables long-distance navigation based on the Earth’s magnetic field and the position of the sun, while the latter relies on visual landmarks for precise local positioning. Together, they efficiently balance global exploration and local exploitation in the search space. Its phased search mechanism and dynamic population adjustment strategy endow PIO with outstanding efficiency and robustness in continuous optimization problems.

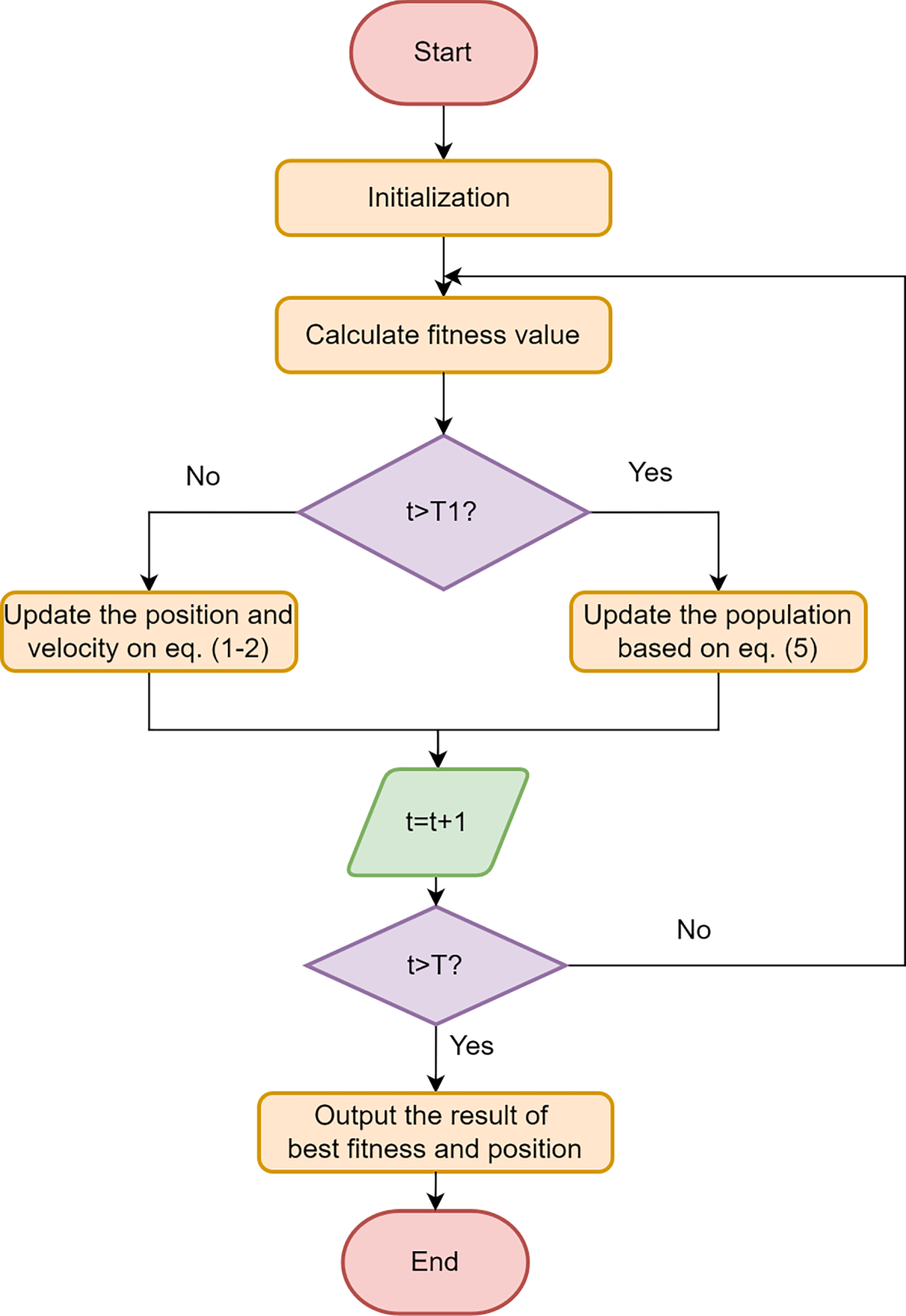

PIO’s basic principle is based on the simulation of the speed and position update equation from the homing behavior of pigeons. This behavior is divided into two parts: the map operator, the compass operator, and the landmark operator. Pigeons are assigned two vector velocities V and positions X. When initializing the flock, these two vectors are initialized as

Figure 6: Algorithm iteration process

In the calculation process of the map and compass operator, the pigeon flock will be updated strictly according to the following Eqs. (1) and (2):

Among them, t refers to the current number of iterations; R represents the map and compass operator ranging from 0 to 1; rand is a random number between 0 and 1; means the best individual in the pigeon flock during the current iteration; when t reaches the maximum number of iterations of the map and compass operator, the PIO will enter the landmark operator phase.

After the above iterations, the algorithm sorts the fitness values of the pigeons. Only half of the pigeons with the highest fitness values will be retained in the next iteration. This retention mechanism will be carried out in every generation. In this round of iteration, the PIO will be updated according to the following Eqs. (3)–(5):

where xc, is the center point that the pigeon flock is searching for; f is the fitness value of the pigeon; N represents the number of pigeons performing the landmark operator iteration each time. Depending on the requirements of the problem to be solved, it can be divided into maximization and minimization problems, as shown below:

As with the first phase, the landmark operator stops iterating when the maximum number of iterations is reached, and the algorithm ceases to work.

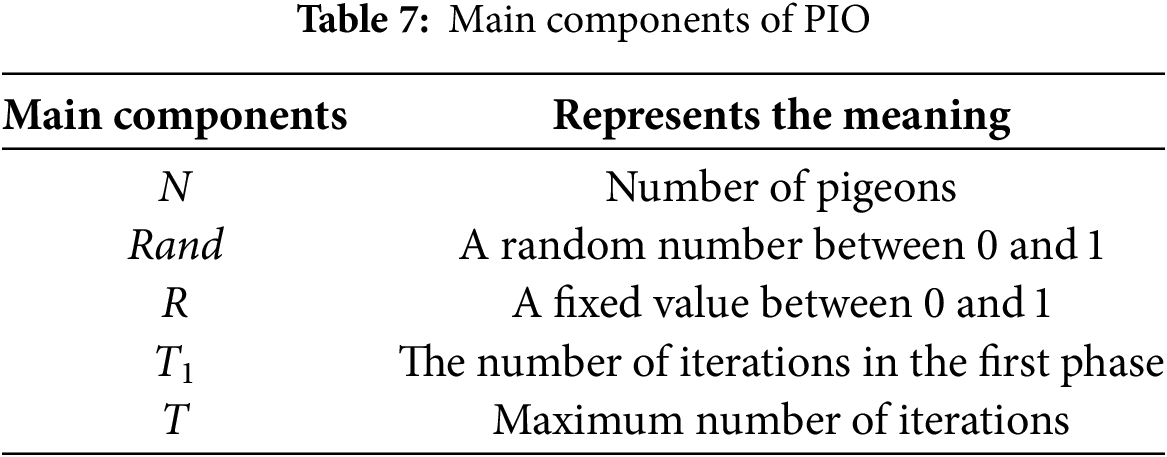

The inspiration of PIO is realized through the following main components. In the PIO, the map and compass factor is a key parameter that directly influences the convergence speed of the PIO. Typically, its value ranges between [0, 1]; the larger the R, the fewer iterations the algorithm will perform. Additionally, there is a parameter Rand that scales the step size for global optimal exploration to prevent the pigeons from bypassing the optimal point during the optimization process. T1 is the number of iterations for the PIO to enter the landmark operator exploration. When the number of explorations by the map and compass factor reaches T1, PIO will switch to the landmark operator for convergence and local exploration. At this stage, the pigeon flock rapidly converges towards the central individual. The termination condition is the total number of iterations of the pigeon flock, which is the sum of the exploration counts in both phases. Table 7 represents the components of PIO.

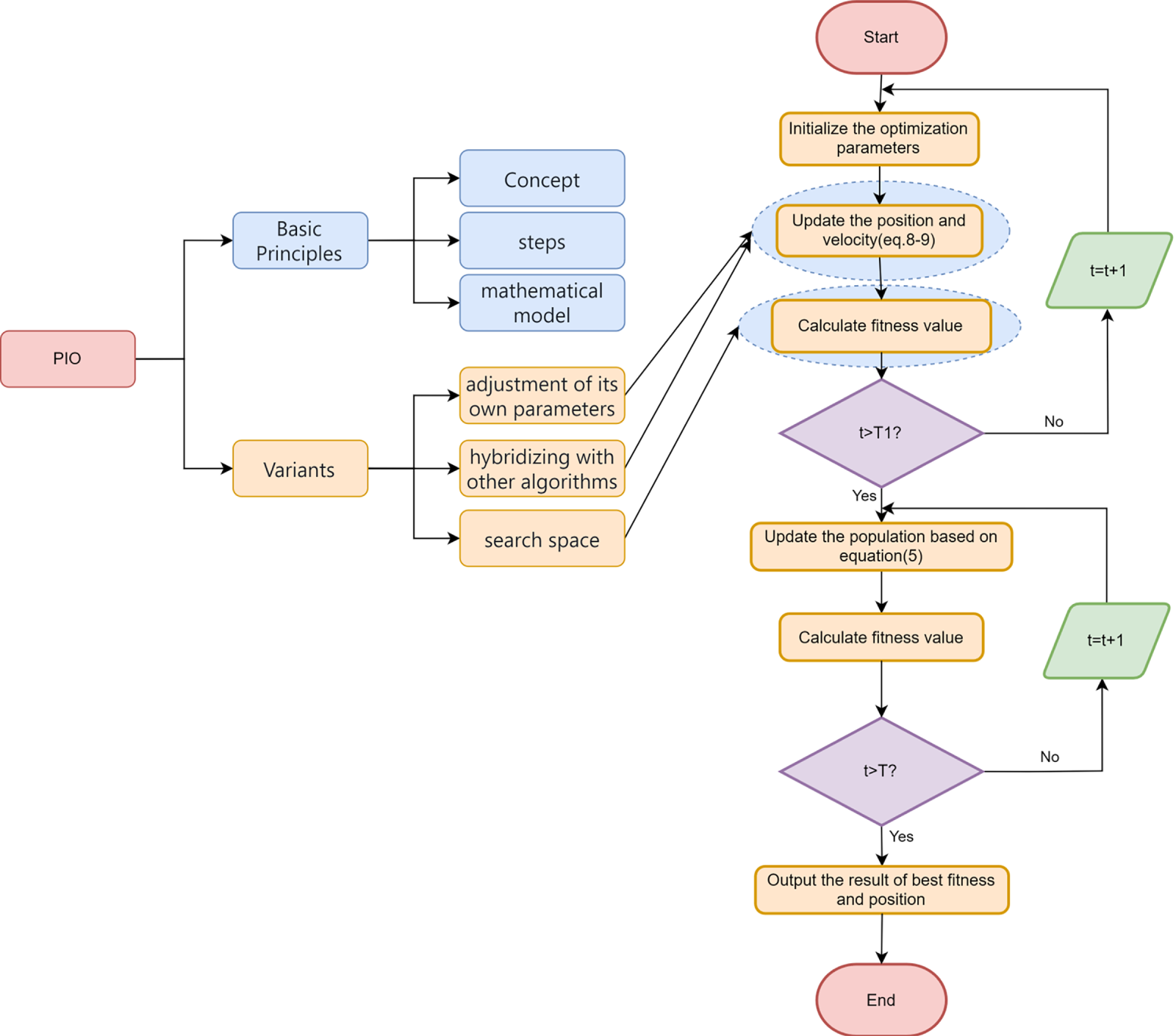

PIO starts with the initialization of key parameters, including population size, maximum number of iterations, and other related factors such as R, T1, T, and N. Subsequently, the position and velocity of each pigeon individual in the flock are randomly assigned, and the fitness value of each pigeon individual is evaluated. The pigeon individual with the best fitness value is selected as

Figure 7: PIO flowchart

i. Define the problem and initialize parameter values

The optimization of the problem mainly aims to find its maximum or minimum value. when the problem appears in the form of finding the minimum value, the objective function will take the following form:

where f(x) is the objective function, x is the solution vector composed of decision variables

In the initialization process of PIO, each parameter is initialized to its respective value. This includes the population size N, the maximum number of iterations T, the number of iterations for the Map and Compass operator T1, and the Map and Compass factor R.

ii. Initialize the population

Generate an initial population of N pigeons, each pigeon containing N dimensions corresponding to the dimensions of the target problem. Then, initialize the position and velocity for each pigeon,

iii. Update positions

All pigeons in the population update their positions and velocities according to Eq. (1), and when the number of iterations reaches T1, they switch to using Eq. (5) for position and velocity updates.

iv. Check the termination condition of the algorithm

During each iteration, a determination is made whether the maximum number of iterations T has been reached; if not, the algorithm will continue to proceed according to the above steps until the termination number is reached.

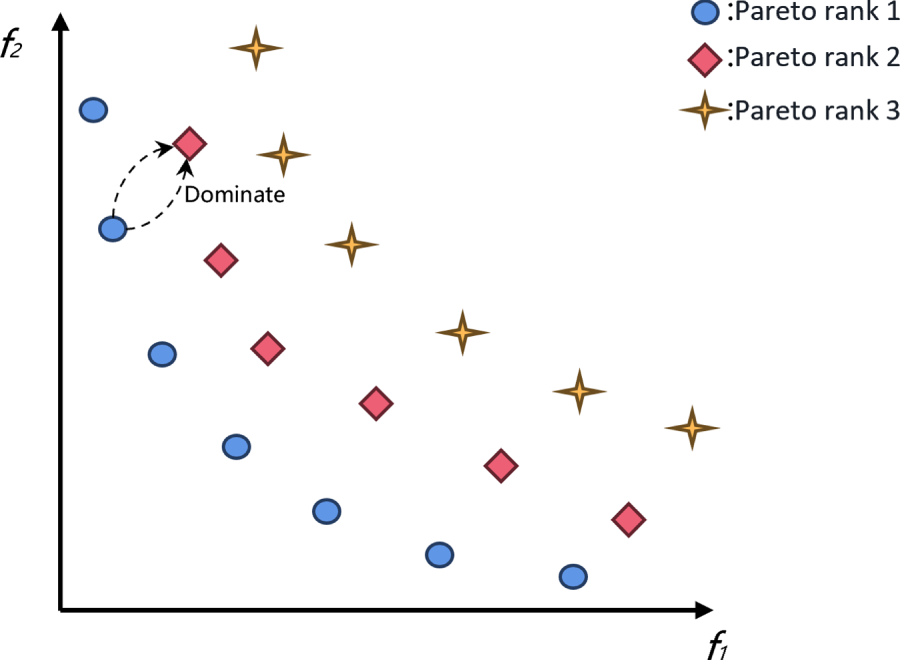

Before introducing MPIO, it is necessary to understand the concepts of multi-objective optimization and the Pareto principle. When solving multi-objective problems (MOP), general approaches include decomposition-based multi-objective algorithms, such as MOEA\D [56], or Pareto-based sorting multi-objective optimization algorithms, such as NSGA-Ⅱ [57]. The MPIO introduced in this paper is a Pareto-based sorting MOP, which incorporates the Pareto sorting mechanism to enable the basic PIO to solve MOP. The Pareto solutions obtained through MPIO are the strategies required for the problem.

3.2.1 Multi-Objective Optimization

In MOP, due to multiple conflicting objectives, it is usually impossible to find a solution optimal for all objectives [58,59]. Therefore, the goal is to find solutions that lie on the Pareto front, meaning they are as good as possible across all objectives, and no other solutions are better in at least one objective. Assuming the mathematical definition of the MOP minimization problem is as shown in Eq. (8):

where M represents the number of objective functions, and x is the solution vector or decision variable. The core task of MOP is to seek a set of non-dominated solutions with good diversity and convergence. Furthermore, if x dominates y or y is superior to x, then a decision variable x is called strictly dominated, and the other decision variable y can be expressed as x < y, as shown in Eq. (9):

In MOP, when a solution is not dominated by any other solution, it can achieve the Pareto optimal solution.

Pareto optimality is an important concept in MOP problems. It first evaluates each solution based on multiple criteria and then provides a subset of solutions that satisfy the Pareto optimality conditions. The resulting subset is the optimal solution that the algorithm seeks. The following is the definition of the Pareto optimal solution set.

If there is no decision vector in the feasible region that can dominate a certain specific decision vector, then that decision vector is called a Pareto optimal solution or non-dominated solution. The definition of a Pareto optimal solution or non-dominated solution is as follows:

Pareto optimality refers to a situation in MOP where it is impossible to improve any objective without making at least one other objective worse. For an optimization problem with m objective functions, all Pareto optimal solutions are mapped as points in an m-dimensional space, depending on the values of the objective functions. The region composed of these points is called the Pareto Optimal Frontier (POF), and its definition is as follows:

In the process of multi-objective problem solving, non-dominated solutions are classified as Pareto rank 1, which is the required Pareto front. Subsequently, the solutions that are dominated are classified as rank 2, 3, ..., n. As shown in the Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Pareto rank sorting diagram

In Fig. 8, the blue area represents Rank 1, which consists of the non-dominated solutions obtained through the solving process. The red area indicates the solutions dominated by Rank 1. Generally, the goal of solving such problems is to get the set of Rank 1 solutions.

Zhang et al. [59] proposed the MPIO. To simplify the problem, they combined the map-compass operator with the landmark operator by setting an integration parameter λ. The new implementation can be expressed as follows:

where T is the maximum number of iterations. As the number of iterations increases, the pigeons tend to favor

To integrate the map-compass operator and the landmark operator, a regulation parameter

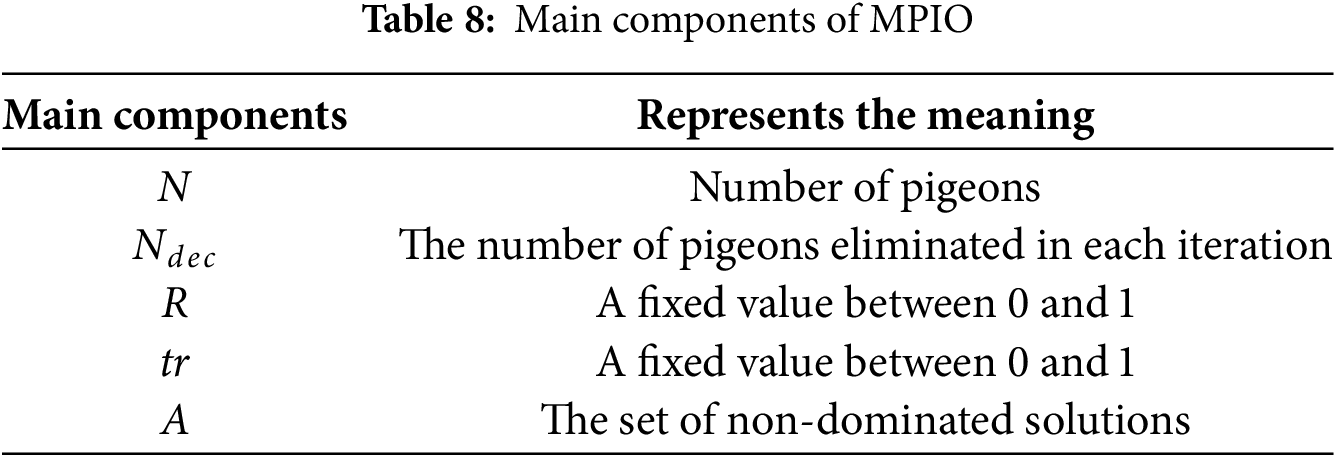

Table 8 presents the main parameters of MPIO, which directly affect the optimization process of MPIO.

The MPIO primarily consists of the following components, as shown in Table 8, The inspiration for MPIO is realized through the following main components. N is the number of individuals at the start of the iteration. Unlike PIO, a transition factor tr (0 < tr < 1) is introduced to merge the two phases into one. The parameter represents the number of pigeons eliminated in each iteration, and during the algorithm’s iteration process, are weeded out to reduce some unnecessary exploration in the later stages. The external set A is the collection that preserves the non-dominated solution set and also serves as the source for the selection of

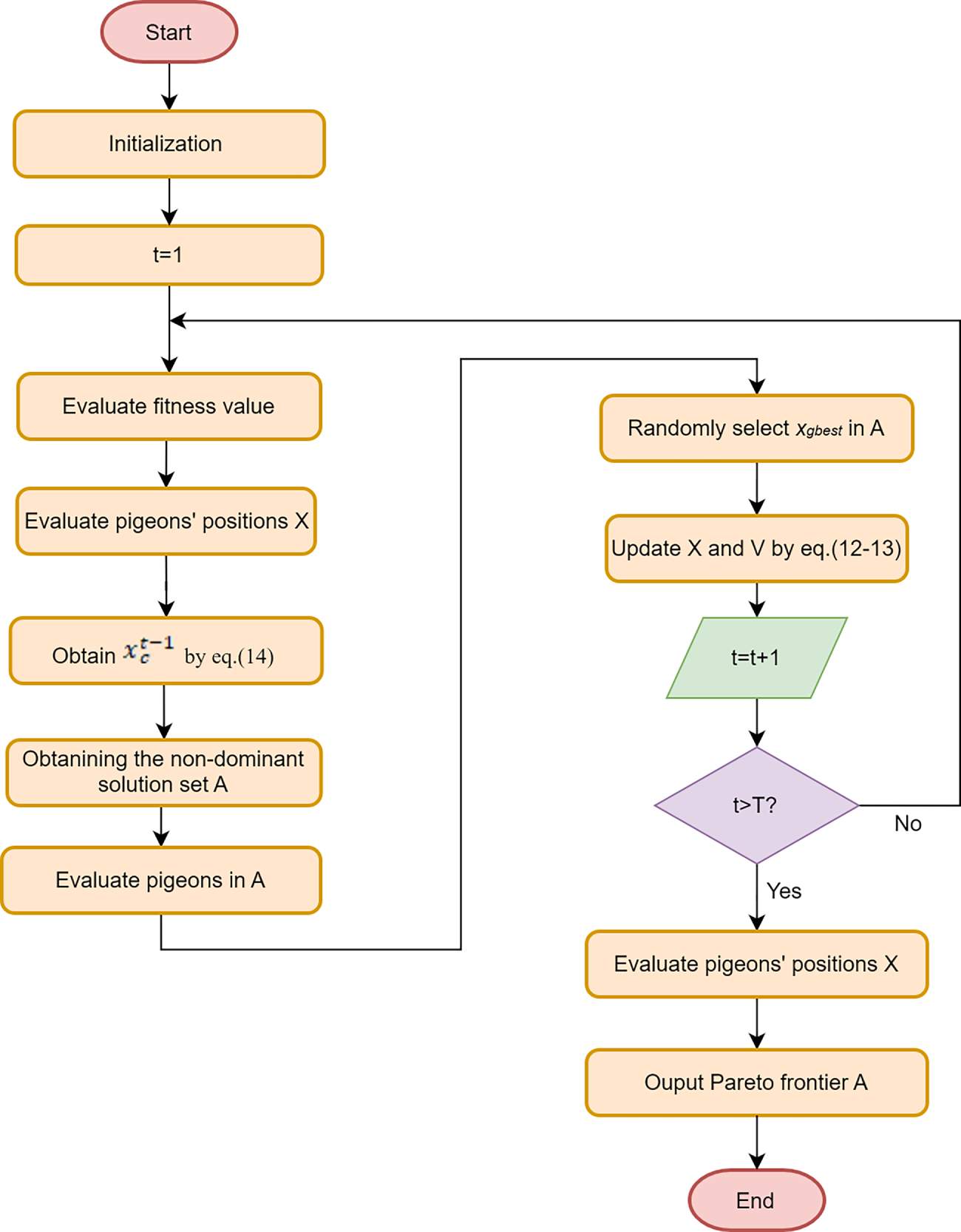

The MPIO begins by initializing parameters and setting the position and velocity of all pigeons. Then, it evaluates the positions of the pigeons using the Pareto ranking scheme and stores the non-dominated solutions into the external archive set A. Subsequently, the centroid position is determined from the external set

Figure 9: MPIO flowchart

i. Define the problem and initialize parameter values

In the solution of MOP, when solving for the minimum value, the objective function is set as follows:

In the initialization process of MPIO, each parameter is initialized to its respective value. This includes the population size N, the maximum number of iterations T, the map and compass factor R, the transition factor tr, and the number of pigeons

ii. Initialize population

Generate an initial population of N pigeons, where each pigeon contains N dimensions corresponding to the dimensions of the target problem. Then, initialize the position and velocity for each pigeon,

iii. Update positions and external archive set

All pigeons in the population update their positions and velocities according to the Eqs. (12) and (13), and during each iteration, they undergo Pareto sorting. The resulting non-dominated solutions are stored in the external archive A.

iv. Check the algorithm termination condition

During each iteration, a determination is made as to whether the maximum number of iterations T has been reached. If not, the algorithm will continue to proceed according to the aforementioned steps until the termination count is reached.

3.3 Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)

Assuming the terrain and threat area information of the environment are known, as well as the starting point and the target, the cost function for the flight path of an aerial robot can be defined as follows [60–62]:

Among them, the weight coefficients

For a given path, the length cost can be defined as:

Among them,

In the Eq. (19),

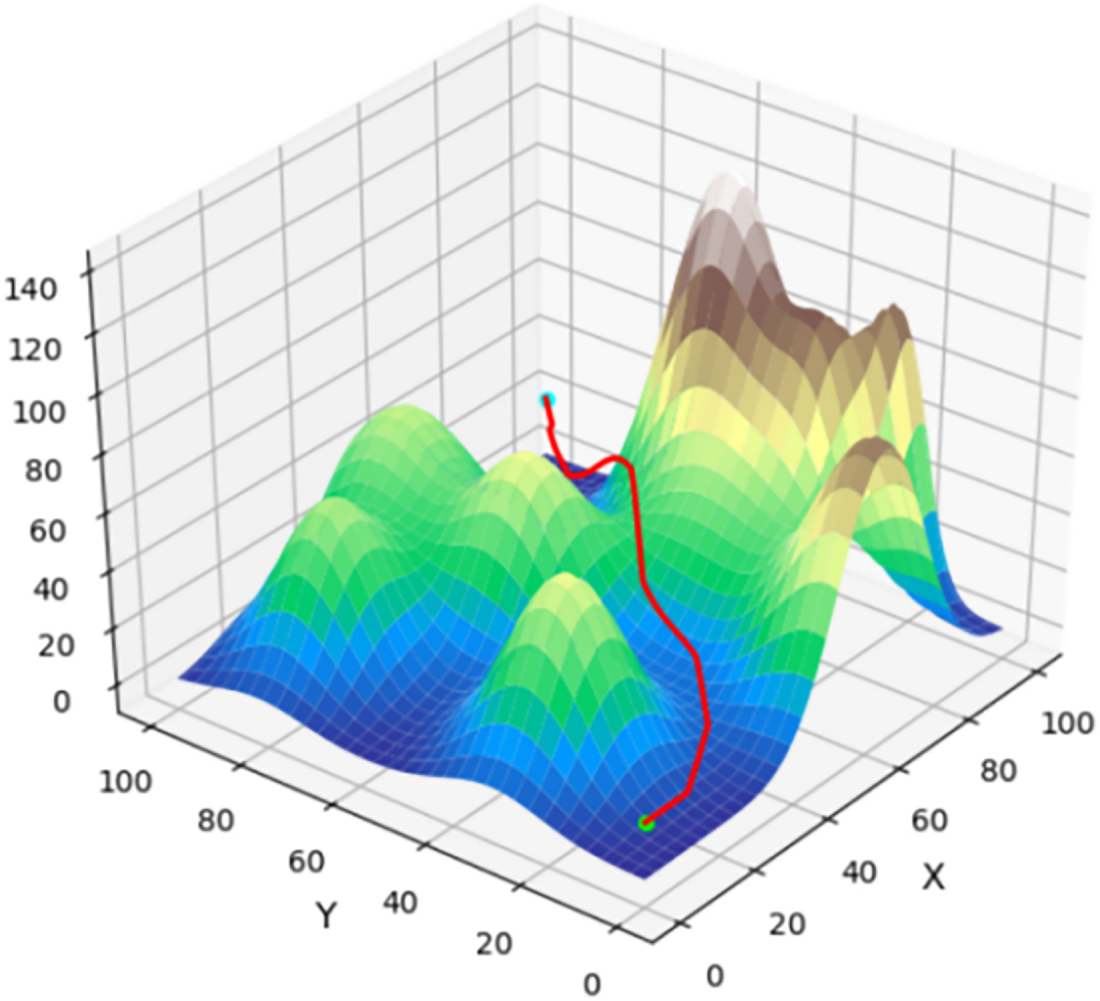

To simplify calculations and improve efficiency, a more effective approximation method is adopted. In this method, the threat cost between two discrete points is calculated through five points for each edge, as shown in Fig. 10. Assuming the unmanned aerial vehicle travels along the path

where

Figure 10: UAV three-dimensional path planning

In this section, the limitations of the basic PIO are introduced, the improvements of the basic PIO are discussed, and the steps to verify the effectiveness of PIO variants are introduced. An analysis of each parameter of PIO is conducted, which will answer questions Question 3.

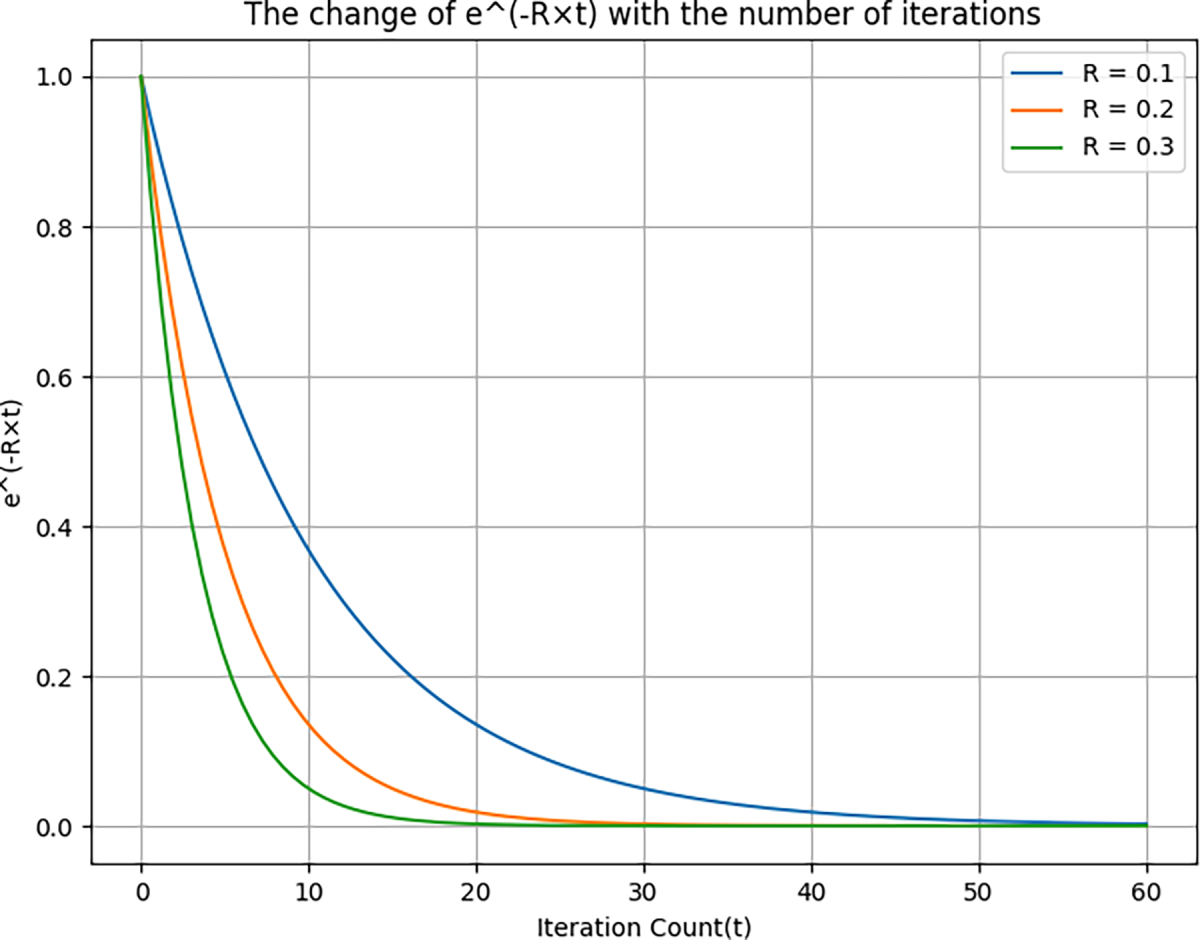

The update of the pigeon’s position is guided by the current velocity and the difference between the optimal position and the current position, as shown in the figure. As the number of iterations increases,

Figure 11: The change of

In summary, the main improvements of the PIO are as follows: (1) Adjustment of the parameter R to slow down the trend of premature convergence of the algorithm; (2) Integration of other search strategies to enhance global optimization search; (3) For the convergence issue in the second phase, the use of other methods to determine the number of pigeons to be reduced.

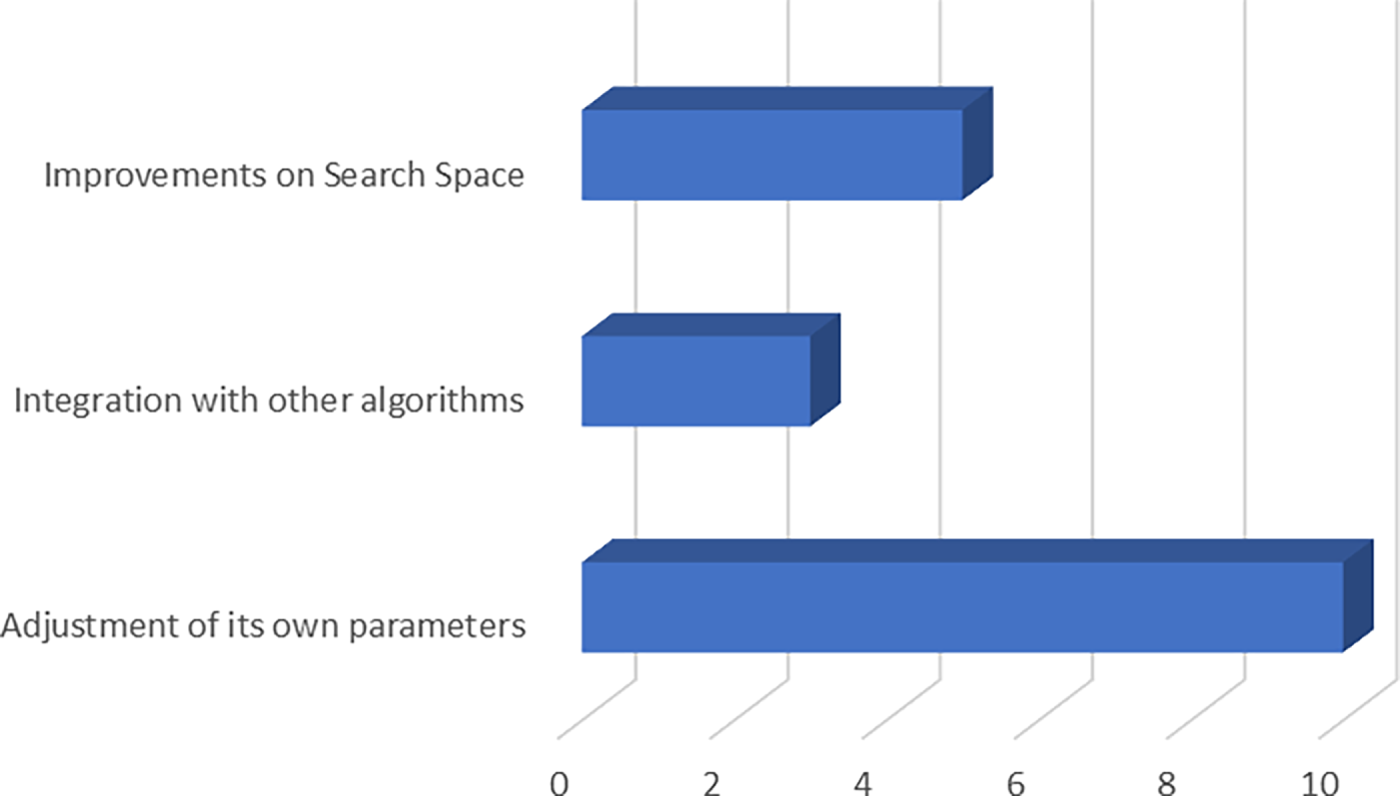

Therefore, the overview of the PIO improvement strategies can be mainly divided into the above three categories, as shown in the Fig. 12. They respectively improve the two components of the PIO.

Figure 12: Directions for PIO Improvement

4.1.1 Improvement Targeting Self-Parameters

Extensive metaheuristic algorithms have been developed and applied in various fields such as engineering, industry, and scientific applications [63,64]. However, no single optimization algorithm can stand out in the broad family of nature-inspired heuristics, as each algorithm has its unique strengths and limitations.

Due to the limitations of single heuristic algorithms in certain applications, researchers have begun to combine them based on their characteristics to achieve complementary advantages and improve algorithm performance, which is then applied to practical problems [65,66]. These hybrid algorithms have demonstrated greater efficiency and effectiveness in solving complex optimization problems [67–70]. A hybrid of GA and PSO has been applied to the design of Recurrent Neural Networks and Fuzzy Neural Networks. In the field of robotics, a hybrid algorithm combining the Attraction Potential Field and an improved ACO has been used for multi-robot formation control and global path optimization, demonstrating the effectiveness of combining different heuristic algorithms to achieve optimal solutions [71]. Additionally, in the study of vehicle routing problems, research explored the synergy between GA and ACO, showcasing the potential of combining different heuristic algorithms to solve complex problems.

This section focuses on the use of PIO in combination with other excellent metaheuristic algorithms. PIO also has its limitations; due to inherent reasons in its equation, a too rapid convergence speed may lead the algorithm to converge prematurely to a local optimal position. When dealing with the optimization of recurring problems, it is necessary to balance this point to improve the performance of PIO.

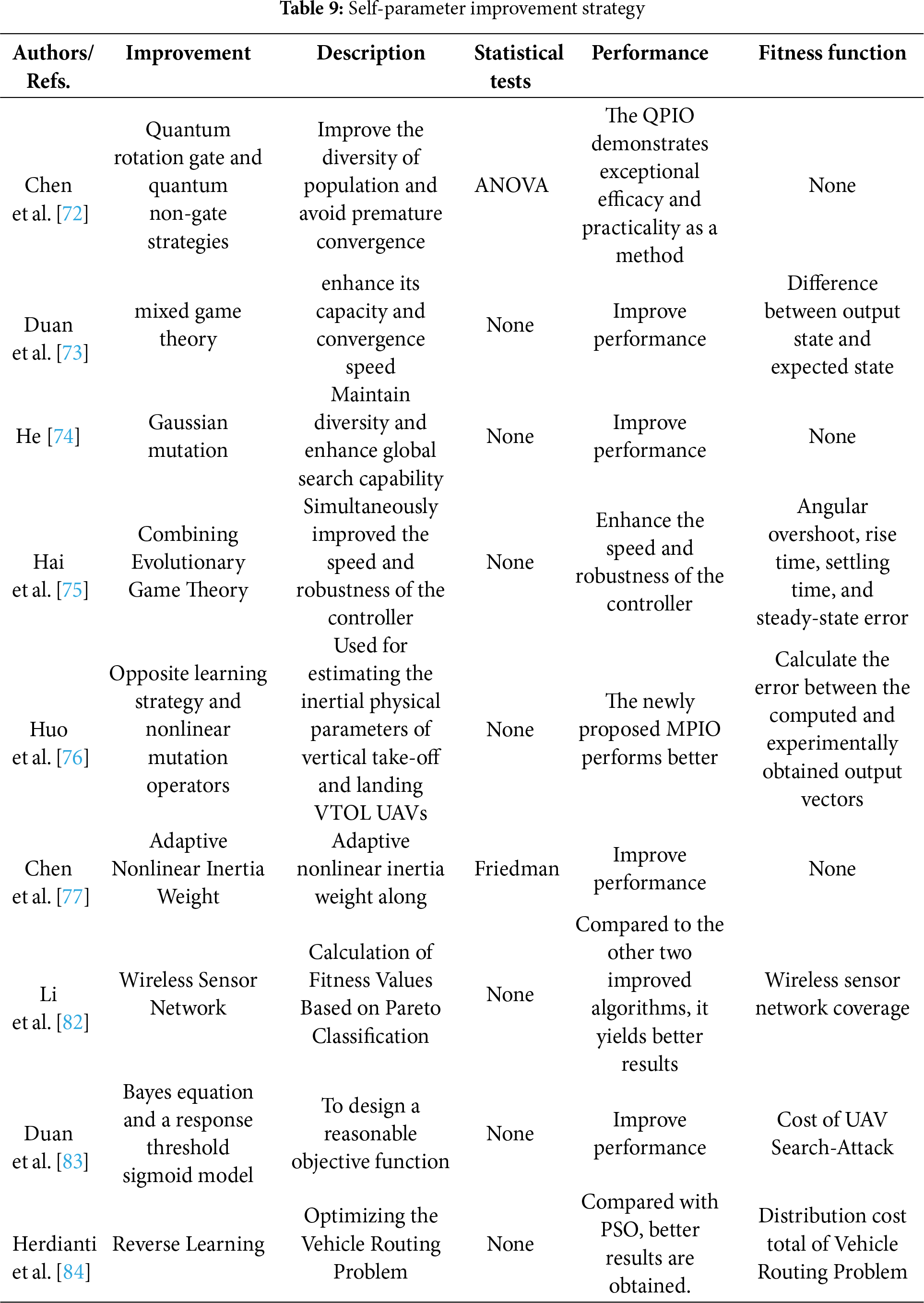

Chen et al. [72] proposed QPIO is a new optimization method suitable for dealing with small-scale high-dimensional multimodal and non-convex problems. This algorithm effectively maintains population diversity by adjusting the probability state of the optimal solution through quantum rotation gates, thus demonstrating excellent performance in global optimization. Experiments show that the algorithm performs well in maintaining stability and improving optimization accuracy, but it has not yet been studied for application in real optimization problems. Duan et al. [73] proposed an MGPIO for UAS swarm formation control, which combines the artificial potential field method with PIO, enhancing problem-solving capability and convergence speed while reducing computational effort. MGPIO improves optimization quality while maintaining diversity, and its application potential in drone formation control has been verified through comparison with PIO and PSO. He et al. [74] proposed an improved Gaussian PIO (GPIO), which maintains exploration diversity through Gaussian mutation and improves search accuracy using global optimal judgment. The algorithm excels in global optimization, especially in dealing with high-dimensional, multimodal, and non-convex problems. However, the GPIO has not been fully compared with other algorithms through extensive benchmark test functions, and its performance on high-dimensional problems needs further verification. Hai et al. [75] combined evolutionary game theory to propose an improved PIO (EGPIO) algorithm with an automatic parameter adjustment mechanism. In this algorithm, individuals of PIO can dynamically adjust their strategies according to the process of evolutionary games, thereby enhancing the adaptability of the original PIO. In the process of solving dynamic equations, it continuously generates better results to replace previous solutions, and the game eventually converges to an ESS that no mutant strategy can invade. Therefore, the optimal solution of the EGPIO is used to adjust the key parameters of ADRC to optimize the control of mobile robots. Simulation experiments have confirmed the effectiveness of the new controller. The results show that the ADRC optimized by EGPIO outperforms traditional ADRC in terms of control performance, efficiency, and robustness. Huo et al. [76] proposed the MPIO, which employs a dynamic opposite learning strategy and nonlinear mutation operators to enhance global search and convergence speed. By dynamically adjusting the position of the central pigeon to explore better regions, the algorithm, when applied to unmanned aerial vehicle systems, demonstrates excellent convergence and search performance, providing effective solutions for practical problems. Chen et al. [77] introduced the Adaptive Nonlinear Inertia Weight for improving the PIO (ODaPIO), which dynamically adjusts the inertia weight. The concept of inertia weight was introduced by Shi and Eberhart [78] to balance exploration and exploitation in PSO, and researchers have subsequently proposed various linear and nonlinear adjustment strategies to achieve this objective. The linear strategy [79] decreases the weight over iterations, shifting from global to local search; the nonlinear strategies [80,81] are more complex, adjusting the weight based on the number of iterations to adapt to different optimization problems. Experiments indicate that the solution quality of ODaPIO surpasses that of the basic PIO and other swarm intelligence methods, but it has not been verified on engineering problems. Li et al. [82] proposed an Improved PIO (IPIO) method to enhance node localization accuracy in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). The method optimizes fitness calculation through Pareto distance classification and improves the velocity equation with self-learning concepts, making the search more intelligent. In the later stages of the algorithm, a position correction factor is introduced to adjust the search direction based on pigeon positions and search history, reducing cumulative error and thus improving localization accuracy. Simulation results show that compared to improved PSO and CS algorithms, the IPIO more effectively enhances node localization precision. It not only reduces cumulative error from continuous localization but also improves the algorithm’s p0racticality. Therefore, the IPIO offers an effective solution for node localization in WSNs.

In addition, Duan et al. [83] proposed a dynamic discrete PIO that provides effective target allocation and search guidance for multiple drones using the Bayesian equation and the Sigmoid model. The algorithm shows good performance in various scenarios, including different threat and resource conditions. At the same time, they have developed a mission planning system integrated with a 3D visualization simulation module, enhancing the practicality and intuitiveness of the algorithm, making it easier for operators to monitor and optimize drone swarm behavior. Herdianti et al. [84] investigated how to optimize commodity distribution costs by modeling the problem as a Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP). Due to the exponential growth of the VRP solution space, manual optimization is impractical. The paper proposes a PIO method based on inverse learning mechanism to optimize VRP and compares it with the PSO method. Experimental results show that the PIO method outperforms PSO in optimizing distribution routes, finding shorter total distances and lower distribution costs. Table 9 presents the results of self-parameter tuning.

4.1.2 Integrate Other Algorithms

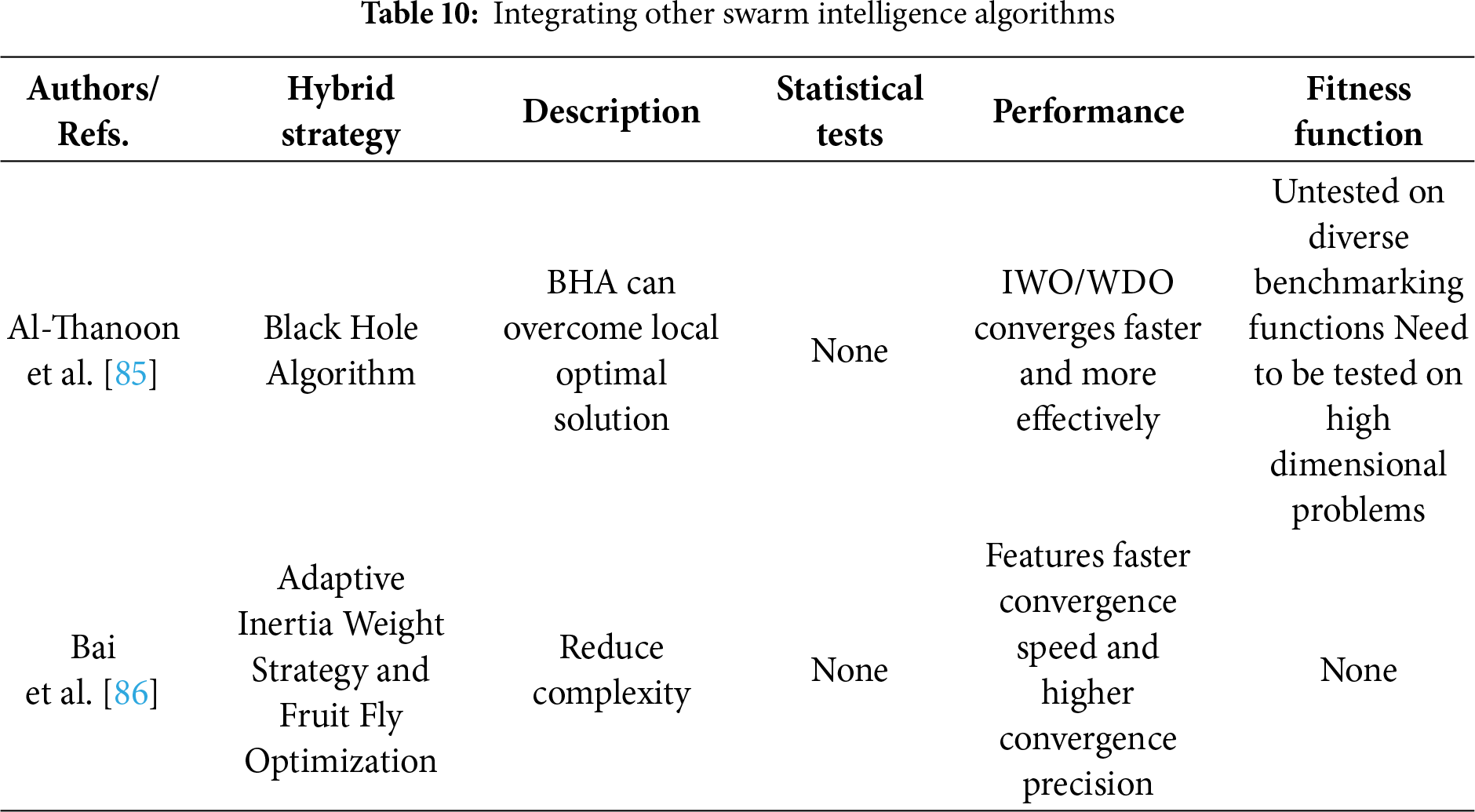

Al-Thanoon [85] proposed a novel hybrid PIO that effectively integrates the essence of PIO and Black Hole Algorithm. Experimental results show that this hybrid algorithm can fully utilize the advantages of PIO in solving the Multidimensional Knapsack Problem, and through extensive experimental evaluation on benchmark datasets, significantly outperforming other nature-inspired algorithms in handling MKP.

Bai et al. [86] proposed an improved PIO (RMSFOPIO) that integrates an adaptive inertia weight strategy with a fruit fly optimization strategy. The improvement is primarily implemented during the map and compass operator phase by introducing a new weighting coefficient. In this phase, if the original weight decays too rapidly, it would cause the pigeons to prematurely lose their inherited velocity, leading to random “blind search.” The esnhanced algorithm achieved through this method features faster convergence speed and higher convergence precision. Table 10 presents the comparison results of integrating with other swarm intelligence algorithms.

4.1.3 Improvements in the Search Space

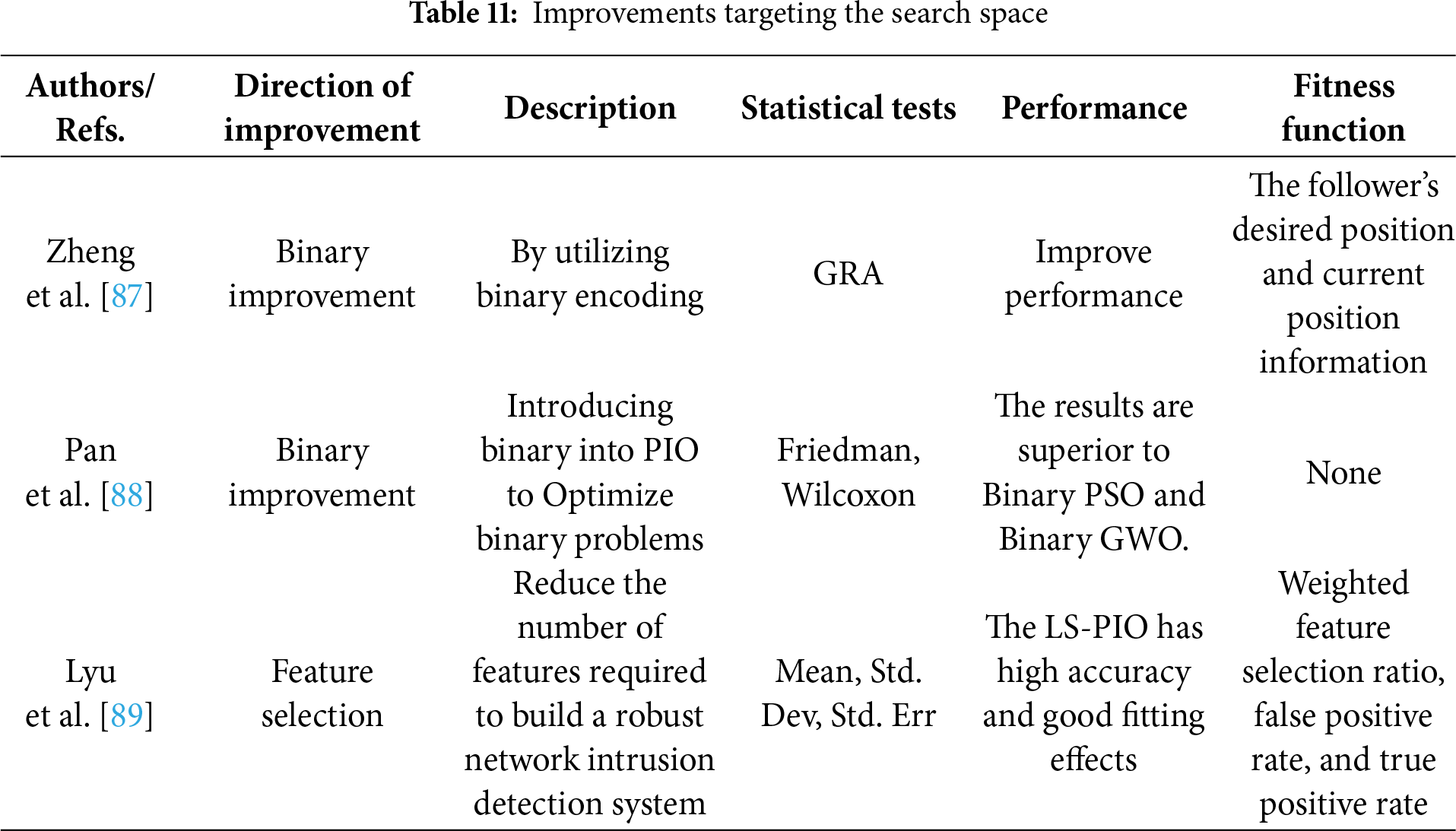

Zheng et al. [87] proposed the BPIO, which is an optimization strategy for quadrotor formation control based on PID control and suitable for binary solution space. The algorithm effectively avoids collisions and converges rapidly through binary encoding and a specially designed fitness function. Simulation experiments have proven its effectiveness and feasibility, but further research is needed to fully validate its performance. The velocity entry represents the state flipping probability, aiding in the exploration of the solution space, as defined in BPSO.

Pan et al. [88] proposed an improved BPIO, which enhances the solution quality for binary optimization problems through new transfer functions, velocity update schemes, and position update methods. Simulation experiments have shown that the improved BPIO outperforms BPSO and BGWO. This was verified using a variety of methods, including benchmark test functions, statistical analysis, Friedman test, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test. These multiple validation methods confirmed the effectiveness of the algorithm and the rationality of the dynamic velocity settings. Experiments on the UCI dataset indicate that BPIO excels in feature selection, but its practical application performance still needs to be verified. Lyu et al. [89] proposed an improved PIO to mitigate the effect of noise during information transmission in image fusion technology. Additionally, they integrated it with boundary processing based on convolutional sparse representation for the fusion of multi-focus noisy images. The algorithm determines the weight range through edge information and replaces the fitness function of the PIO with global information entropy. However, its performance on high-dimensional problems remains to be investigated. Table 11 presents the comparative content regarding improvements to the search space.

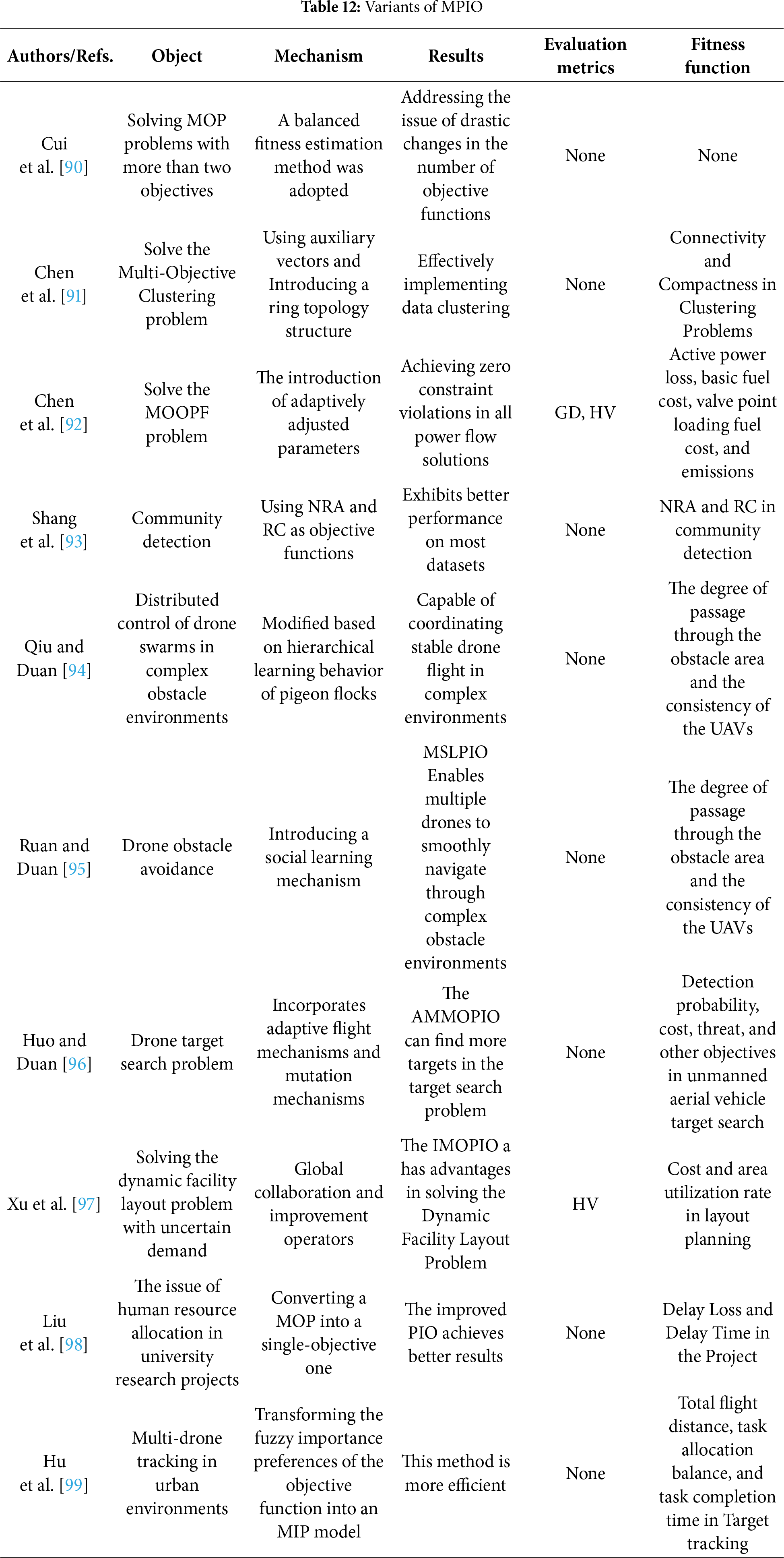

Cui et al. [90] proposed a Multi-Objective PIO (MaPIO) algorithm that uses a balanced fitness estimation method to balance the convergence and diversity of the population. By designing new rate and position update equations, the algorithm provides additional search directions from the central position to the global optimal position and solves the problem of drastic changes in the number of objective functions. Experimental results show that the MaPIO has great potential in solving MOP.

Chen et al. [91] proposed a combined multi-objective PIO (CMOPIO) based on a ring topology structure, aiming to solve multi-objective clustering problems. This method bridges continuous and discrete spaces using auxiliary vectors and introduces a ring topology structure to alleviate premature convergence and enhance the diversity of the pigeon flock. Experiments show that the CMOPIO can effectively achieve data clustering and performs well in handling large-scale datasets. Chen et al. [92] combined the MPIO with the COSR strategy to solve the MOOPF problem. The algorithm extends its application scope from single-objective optimization to multi-objective optimization by introducing adaptively adjusted parameters and an innovative landmark search model. Dual-objective and triple-objective tests on IEEE 30-bus, 57-bus, and 118-bus systems show that the MPIO-COSR algorithm can find a better Pareto front and achieve zero constraint violation for all power flow solutions. Shang et al. [93] started from the objective function, using Negative Ratio Association (NRA) and Ratio Cut (RC) as objective functions. The optimization of these two objective functions can balance the internal density and external sparsity of the detected community structure. By introducing genetic operations, they improved the representativeness and update method of the pigeon flock. Experimental results show that MOPIO excels in search precision and stability, especially on real data with standard community divisions. Compared to other methods, the MOPIO performs better on most datasets. Qiu and Duan [94] addressed the distributed control problem of drone swarms in complex obstacle environments by modifying the hierarchical learning behavior of pigeons. The improved MPIO can coordinate drones to fly stably in complex environments. Compared to the basic MPIO and the improved Non-dominated Sorting NSGA-II, the improved MPIO demonstrates advantages in handling MOP, especially with small population sizes and fewer iterations. Ruan and Duan [95] proposed a multi-drone obstacle avoidance control method based on the Multi-Objective Social Learning PIO (MSLPIO). By introducing a social learning mechanism, each pigeon learns from better pigeons, not necessarily the globally optimal pigeon, thus improving the algorithm’s convergence performance. Simulation results show that compared to the improved multi-objective PIO and the improved NSGA-II, MSLPIO has better convergence performance and can enable multiple drones to pass through complex obstacle environments smoothly. Huo and Duan [96] proposed an Adaptive Mutation-based Multi-Objective PIO (AMMOPIO) algorithm. The algorithm, which combines adaptive flight mechanisms and mutation mechanisms, effectively balances global exploration and local exploitation, improving search efficiency and diversity. Experimental results indicate that the AMMOPIO is feasible and effective in target search problems, finding more targets and reducing search time.

Xu et al. [97] proposed an Improved Multi-Objective PIO (IMOPIO) algorithm to solve the dynamic facility layout problem with uncertain demand, optimizing search through non-dominated sorting, global collaboration, improved map and compass factors, and crossover operators. Results show that the IMOPIO has better search capabilities and solution quality in solving DFLP problems. Liu et al. [98] transformed the MOP into a single-objective optimization problem through a weighted solution approach. The traditional PIO was discretized, and an adaptive parameter strategy was adopted to improve the shortcomings of the algorithm itself.

Hu et al. [99] proposed a fuzzy multi-objective PIO for task allocation in urban environments where multiple drones track multiple ground targets, converting the fuzzy importance preferences of the objective functions into a mixed integer programming model. Compared to traditional PSO, simulation experiments verified the effectiveness and efficiency of this method.

Table 12 presents the comparative content regarding variants of MPIO.

5 PIO and MPIO Applications in UAVs

UAV is an unmanned aircraft operated by radio remote control equipment or its programmed control devices for performing specific tasks [100]. Compared with manned aircraft, UAVs have advantages such as small size, high maneuverability, good concealment, low requirements for battlefield environment, strong survivability, and low cost. At the same time, UAVs are often used in civil aviation fields, such as disaster rescue, aerial photography, and pesticide spraying [101,102]. In recent decades, the development of UAVs and related technologies has been favored by countries around the world and has received increasing attention and application. However, with the complexity and diversity of mission requirements, the current development of UAV technology not only needs to improve the functionality and effectiveness of UAVs but also requires a comprehensive consideration of exploring and developing more fixed and effective UAV management and organization models. For optimizing UAV issues, a widely used method today is to abstract it as a mathematical model, convert it into an optimization problem, and solve it through heuristic algorithms. This method requires very little time in finding an acceptable solution, which is precisely the advantage of heuristic algorithms. This section resolves Question 4.

Duan and Qiao [36] first proposed the PIO in 2014 and applied it to the path planning problem of aerial robots. This marked the first time the PIO was introduced and successfully used to solve practical problems. Their experiments verified the effectiveness of PIO in optimization issues. Duan et al. [48] proposed a Predator-Prey PIO for the automatic landing system of fixed-wing UAVs in the longitudinal plane. The results of simulation experiments verified that the automatic landing system significantly improved the performance of UAVs during the landing phase. Yu et al. [64] proposed a new algorithm called Mixed Game PIO (MGPIO), which was designed for cluster formation control in Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). The MGPIO combines elements of mixed game theory and PIO strategy, not only enhancing the ability to handle complex problems but also improving convergence speed and reducing computational burden. Through comparative experiments with PIO and PSO, the application potential of MGPIO in the formation control of drone clusters has been confirmed.

In response to discrete problems, Duan et al. [73] proposes a Binary PIO to optimize the obstacle avoidance problem for quadrotor drones. Experimental results indicate that the proposed algorithm outperforms Binary PSO. Chen et al. [72] proposed a new method called Mutated PIO, which is based on the strategy of Dynamic Opposition-Based Learning. Experimental results show that the MPIO exhibits good performance in terms of convergence speed and overall search capability. Hai et al. [75] proposed an enhanced ADRC method for the attitude deformation system of autonomous mobile robots. By simulating the behavior of pigeons in the process of evolutionary games, this method dynamically adjusts its search strategy, thereby enhancing the adaptability and efficiency of the algorithm. Simulation experiment results confirm the method’s ability to suppress disturbances under normal operating conditions and its compensating effect on faults when they occur, demonstrating its superior performance. Huo et al. [103] applied the pigeon flock algorithm to real-flight obstacle avoidance experiments with UAVs. The experimental results show that the UAV flock was able to successfully navigate through multiple obstacle areas in a real flight environment and effectively avoid collisions with other UAVs. Li and Deng [104] proposed a Quantum Entangled PIO for optimizing UAV path planning. Compared with GA, PSO, and traditional PIO, the QEPIO has improved convergence speed and robustness to some extent, showing its potential in solving flight planning problems such as UAV path planning.

Wang et al. [105] presented a control strategy based on the Cauchy Mutated PIO. Simulation results showed that the proposed Cauchy mutated PIO method has better robustness and cooperative path planning strategies compared to traditional PIO, proving it to be effective and advanced. In terms of UAV formation, Xu and Zhang [106] proposed a Quantum Behavior PIO. The improved PIO, combined with UAV control variables, became part of the direct control loop in the control system. The control system’s effectiveness in tight formation control was demonstrated through comparative simulations.

Huo et al. [107] introduced a circular formation control method inspired by the homing behavior of pigeons. This method utilized the characteristics of nonlinear PID-like control methods, making the motion trajectory of the multi-agent system smoother. The effectiveness of this control strategy was confirmed through numerical simulations.

For formation control of quadrotor UAVs, Bai et al. [108] proposed using the PIO. By combining algebraic graph theory and matrix analysis, they established a nonlinear mathematical model to describe the dynamic behavior of quadrotor UAVs. Experimental results indicated that the PIO played a key role in the formation control of quadrotor UAVs. In the field of unmanned UAV combat, Yu et al. [109] proposed an improved PIO (CLPIO) algorithm based on a competitive learning mechanism to address the problem of attack target allocation in dynamic combat games involving UAV swarms. Through numerical simulation verification, the effectiveness and superiority of this method were confirmed. Experimental results indicate that the CLPIO can more effectively solve the attack target allocation problem. Ruan et al. [110] introduced an autonomous maneuvering decision-making method for unmanned combat aerial vehicles in air combat using Transfer Learning PIO (TLPIO). This method involves designing a target function that includes a mix of game strategies and utilizes the TLPIO for optimization to obtain the optimal mixed strategy. Simulation results have validated the effectiveness of the proposed autonomous maneuvering decision-making method. Bin et al. [111] proposed the Gaussian Adaptive Mutation PIO (GAMPIO) algorithm and developed a backstepping controller using a fully coupled dynamic model to control an UAV with a manipulator. Through a series of simulation experiments and comparisons with other optimization algorithms, the experimental results demonstrated the superiority of the GAMPIO in terms of performance.

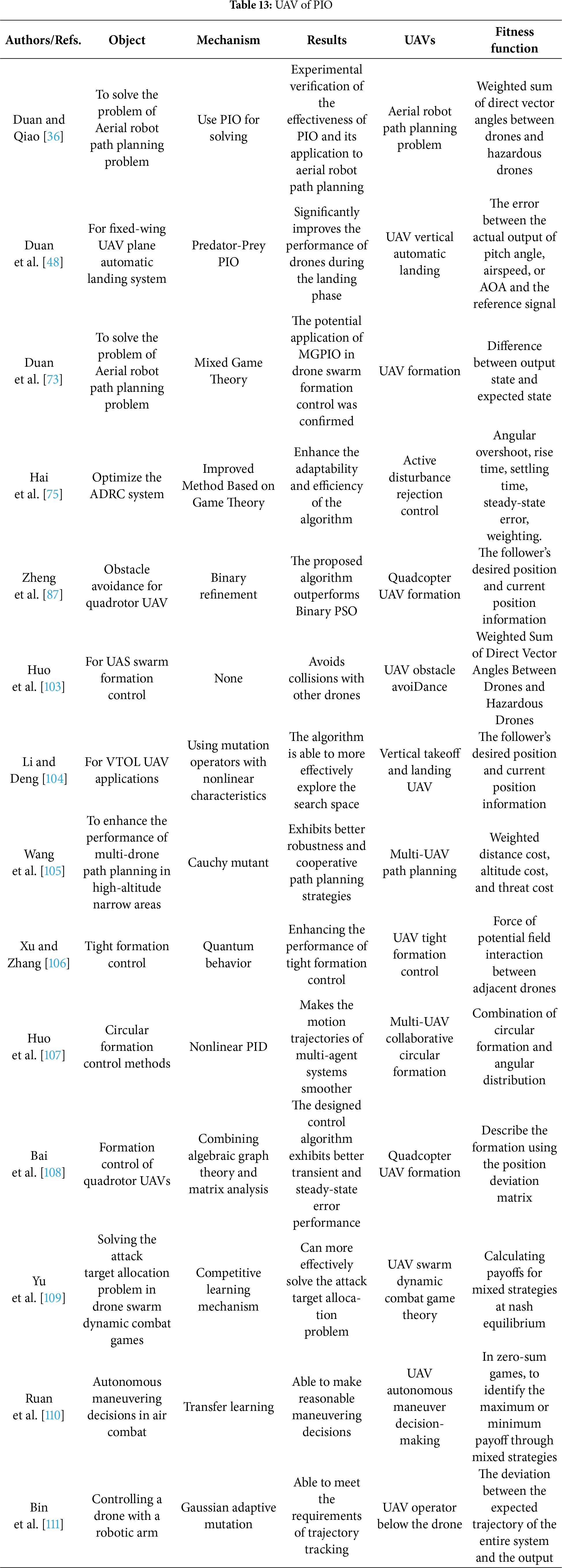

Zhou et al. [112] presented a method that combines the Hybrid GWO (HSGWO) with the Modified PIO, known as HSGWO-MPIO. The convergence, complexity, and accuracy of the algorithm were analyzed using linear difference equations to validate its performance. Simulation results indicated that the HSGWO-MPIO performs better in terms of robustness and optimization capabilities. Table 13 presents the application of PIO variant algorithms in UAV and the design of objective functions.

Qiu et al. [94] explores the distributed control of drone swarms in environments filled with complex obstacles. The paper adjusts the algorithm based on the hierarchical learning behavior of pigeons to form an improved MPIO that effectively coordinates the stable flight of drones in complex environments. By comparing it with the original MPIO and the improved NSGA-II, the study confirms the superiority of the improved MPIO in handling MOP, especially when the population size is small and the number of iterations is limited. Ruan and Duan [95] proposes a multi-drone obstacle avoidance control strategy named Multi-Objective Social Learning PIO (MSLPIO). By introducing a social learning mechanism, this strategy enables each drone to learn a better flight strategy, not just pursuing global optimality. This approach effectively improves the convergence of the algorithm. Simulation experiments have verified that MSLPIO outperforms the improved MPIO and the improved NSGA-II in terms of convergence performance, ensuring stable flight of multiple drones in complex obstacle environments.

Hu et al. [99] presents a fuzzy MOP algorithm inspired by pigeon behavior, aimed at solving the task allocation problem when multiple drones track multiple ground targets in urban environments. The algorithm incorporates the fuzzy importance preferences of the objective functions into a mixed integer programming model to optimize the task allocation plan. Compared with the traditional PSO, the simulation results prove the advantages of the proposed method in terms of effectiveness and efficiency.

Tong et al. [113] proposes a new method for drone path planning based on PIO and Differential Evolution. This method combines the pathfinding capabilities of PIO with the mutation strategy of differential evolution, effectively solving the problem of finding the optimal path for drones in complex environments. Comparison with PSO and Differential Evolution algorithms through simulation experiments shows that this method is superior in terms of path length, smoothness, and safety.

5.3 Discussion on PIO and Its Applications in UAVs

As a nature-inspired optimization algorithm, PIO has achieved significant development and has become a reliable tool for solving complex problems. It searches for near-optimal solutions for one-dimensional or multi-dimensional objective functions through a stochastic computational process, offering an easy-to-implement and efficient solution that is applicable across various fields. The comprehensive results presented in this paper fully demonstrate the outstanding performance of PIO, particularly in terms of its effectiveness and accuracy in achieving the best results. Compared to recently published articles, this paper conducts a rigorous examination and analysis of the results obtained by PIO, further confirming this point.

Each heuristic algorithm has its own limitations, and PIO is no exception. Complex optimization problems may lead to premature convergence. PIO has several parameters that users need to adjust according to specific issues. This section evaluates the enhancements of PIO through various methods, including adjustments to its own parameters, combination with other heuristic algorithms, and improvements on the search space, as shown in the table.

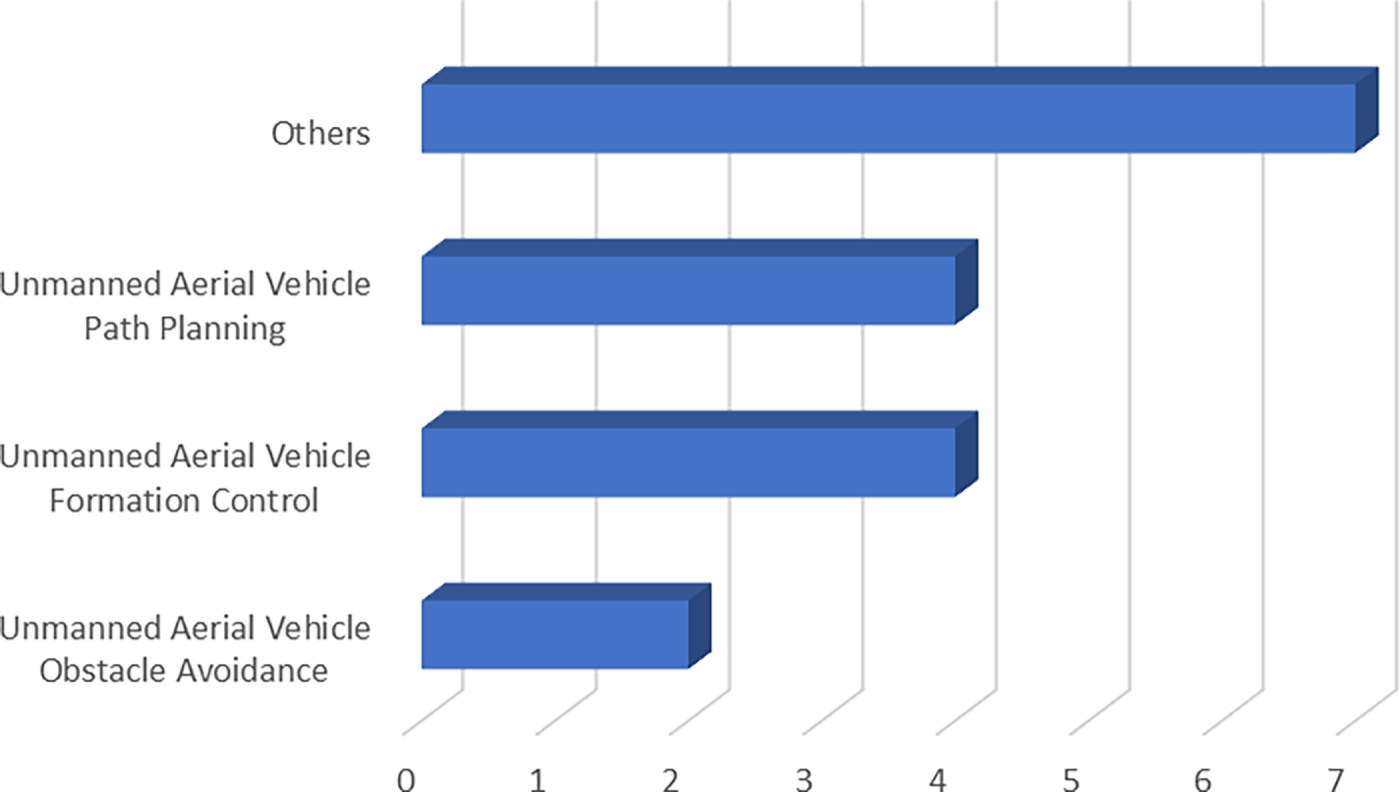

From Figs. 13 and 14, it can be seen that most improvements in PIO focus on parameter adjustment, as reported in references [72,73,75,77,82–84,87,88]. Expanding the algorithm to practical applications, there are fewer improvements in the search space, such as [88], which target binary problems for PIO improvement. References [80,85] improve PIO by integrating other swarm intelligence algorithms, and [86] also improves its own parameters, making it one of the few algorithms to have improved in two aspects.

Figure 13: PIO improvement methods classification statistics

Figure 14: Improved PIO application classification on UAVs

Clearly, by optimizing and improving parameters and combining novel metaheuristic algorithms with adaptive strategies, the shortcomings of the basic PIO can be specifically addressed. When configuring the PIO parameters, adjustments must be made based on the specific situation, so the parameter improvement method should be used to avoid affecting the optimization process’s stability. Secondly, for optimization problems sensitive to parameter changes, an adaptive parameter adjustment strategy should be employed. Thirdly, to address the PIO’s tendency to get stuck in local optima, a hybrid algorithm that combines specific metaheuristics can effectively avoid this problem. In summary, the key to the optimization process is to select appropriate optimization strategies for specific optimization problems, and a variety of optimization strategies can be flexibly combined during the optimization process.

As for the application of PIO in UAVs, most aspects are focused on the path planning, formation, and obstacle avoidance of drones, while others are aimed at optimizing the takeoff and landing, as well as combat gaming of UAVs. These issues have validated the effectiveness of PIO in problems with high real-time requirements, as well as its strong robustness characteristics.

5.4 Discussion on MPIO and Its Applications in UAVs

The solutions obtained from multi-objective algorithms are commonly evaluated using indicators such as HV, GD, and IGD to assess the obtained Pareto Front (PF). The HV index, as a widely used metric for classification, actually calculates the size of the space volume covered by the actual PF. A larger HV value indicates better diversity of the PF, and its equation is shown as follows:

where

To measure the distance between the obtained Pareto Front (PF) and the actual PF, the GD indicator, defined as Eq. (22), is used [114]:

In the Eq. (22),

IGD (Inverted Generational Distance) is a commonly used evaluation metric in MOP, which is used to assess both the convergence and diversity of algorithms simultaneously. IGD is based on the following concept: for a MOP, there exists a set of true Pareto optimal solutions, known as the True Pareto Front (TPF). The algorithm generates a set of approximate Pareto optimal solutions when solving the problem, called the Approximate Pareto Front (APF). IGD is defined as the average distance from each point in the TPF to the nearest point in the APF. Specifically, the calculation Eq. (23) for IGD is as follows:

where, |TPF| is the number of points in the TPF,

These indicators can be used to compare the advantages and disadvantages of multi-objective algorithms intuitively. Only references [92,97] in the aforementioned papers used the HV indicator, and GD was compared only in [97]. Unlike the single-objective PIO, multi-objective optimization must address multiple conflicting objective functions, so simply adjusting parameters is often ineffective for the issues at hand. Among various variants, more focus is on changing the search space, as in reference [91], or on transforming multi-objective problems into single-objective problems for solving, as in references [94,98].

The traditional PIO simplifies the two-phase algorithm into a single-phase algorithm by introducing a transition factor. It uses Pareto sorting to achieve multi-objective optimization. However, Pareto sorting requires re-ranking and filtering of solutions in the external set A at each iteration, increasing computational complexity. Reference [91] applied the improved MPIO to clustering problems, expanding the research on high-dimensional problems with MPIO, while reference [93] applied it to community detection. Multi-objective optimization is more suited to practical applications than single-objective optimization. Only one article [90] did not optimize for applications, whereas the other papers did.

References [91,93,99] improved the search space, with [91] adding a discrete space, [93] extending MPIO to community detection, [92] improving the objective function, and [99] introducing fuzzy preferences into the model. Additionally, reference [91] also enhanced diversity through topological structure, and references [90,96] balanced improvements in diversity and convergence.

For multi-objective algorithms, it is more necessary to make improvements based on practical problems. MPIO optimized the design of brushless DC motor parameters, and subsequent algorithms improved by leveraging PIO’s advantages on UAVs, continuously proposing new algorithms to expand UAV applications, such as multi-UAV formation, multi-UAV obstacle avoidance, and distributed control of UAV swarms.

6 Conclusion and Potential Research Domains

This section addresses Question 5. The review paper conducts an in-depth study of PIO, explores its applications across various research fields, and provides a detailed review of the latest advancements in the literature. The authors have invested considerable effort in writing this paper by extensively analyzing PIO-related research articles published between 2019 and 2025. The article aims to provide readers with a comprehensive understanding by discussing and summarizing the research findings on PIO in recent scientific literature. The paper reviews the applications and variants of the PIO, confirming its effectiveness as a swarm intelligence-based optimization method. PIO has demonstrated the ability to find practical solutions to multiple engineering problems, and its convergence in continuous search spaces has been proven [49]. Since its introduction in 2014, the algorithm has been extended to solve a variety of problems and scenarios. Research on variants of PIO highlights its flexibility and its ability to be customized to different needs, including hybrid and multi-objective versions. These variants aim to improve the efficiency of PIO operations while maintaining its core characteristics. Notably, most hybrid strategies have made significant progress in developing PIO. In many instances, combining different variants has enhanced the algorithm’s ability to solve complex problems. Looking to the future, the PIO is expected to continue developing and reducing sensitivity to parameter changes. Reinforcement learning technology may become an advanced means of developing parameter-free PIO, achieving dynamic parameter adjustment based on search environment feedback. Additionally, combining PIO with other metaheuristic algorithms to form hybrid models can maximize benefits, reduce limitations, and expand its application scope by leveraging the strengths of both.

As for MPIO, it inherits the advantages of basic PIO, with only a few key parameters and strong robustness, making it applicable to the optimization of other problems. At the time of its proposal, it was proven to be convergent [46]. However, some shortcomings have emerged from recent developments. Under the dual Pareto ranking, the continuously growing external set A can lead to slow convergence of the algorithm; secondly, the current velocity’s proportion decreases at an exponential rate, causing the group exploration to stagnate; finally, the selection of the optimal individual is too random, which may affect the convergence efficiency of the algorithm.

In summary, the following future development suggestions are proposed for PIO:

1. To address the sharp convergence issue of PIO, adjustments should be made to reduce performance loss due to premature convergence; during the second phase of landmark search, the number of pigeons seeking the landmark center decreases exponentially, and adjustments should be made to the reduced number of pigeons. The two-phase optimization search is fragmented, and integrating the two phases to balance exploitation and exploration is also a key research direction.

2. Expand the application of the PIO to practical problems, making suitable improvements for different issues; moreover, since the PIO has been widely verified on UAVs, whether the PIO has significant potential in constrained path planning problems is an issue that future researchers need to verify.

3. Only a few of the proposed variants of the PIO have been analyzed for convergence and complexity, so conducting theoretical analysis when proposing new variant algorithms is a key research direction.

4. Considering the advantages of PIO in search speed and robustness, it is worth considering its application prospects in Neural Architecture Search; additionally, the optimization of parameters by reinforcement learning is also a critical improvement direction, and given the number of parameters in PIO, it can become a parameter adjustment strategy in addition to adaptive adjustment.

For MPIO, the following future development suggestions are proposed:

1. Like the basic PIO, adjust the key parameters to reduce performance loss due to premature convergence; choosing a suitable scheme to limit the external set A is also a direction for algorithm improvement.

2. As mentioned above for PIO, the robustness advantage of MPIO also makes it suitable for application in NAS. For some practical problems with multiple objectives, such as accuracy and computation time, MPIO is more ideal for optimization than for solving a single-objective problem with weights.

3. The convergence speed of MPIO has been verified in real-time problems, such as drone formations; therefore, more consideration can be given to such issues in future improvements.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant number 62066016, the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China under grant number 2024JJ7395, International and Regional Science and Technology Cooperation and Exchange Program of the Hunan Association for Science and Technology under grant number 025SKX-KJ-04, Hunan Provincial Postgraduate Research Innovation Project under grant number CX20251611, Liye Qin Bamboo Slips Research Special Project of Jishou University 25LYY03.

Author Contributions: Yu-Xuan Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft. Kai-Qing Zhou: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition, Writing—Review & Editing. Wei-Lin Chen: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing. Zhou-Hua Liao: Validation, Resources, Supervision. Khairunnisa Hasikin: Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. Di-Wen Kang: Funding Acquisition, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lange K. Optimization. Vol. 95. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

2. Huang Y, Brocco A, Kuonen P, Courant M, Hirsbrunner B. SmartGRID: a fully decentralized grid scheduling framework supported by swarm intelligence. In: 2008 Seventh International Conference on Grid and Cooperative Computing; 2008 Oct 24–26; Shenzhen, China. p. 160–8. doi:10.1109/GCC.2008.24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang Y, Jiang J, Li S, Li R, Xu S, Wang J, et al. Decision-making driven by driver intelligence and environment reasoning for high-level autonomous vehicles: a survey. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(10):10362–81. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3275792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Liufu Y, Jin L, Li S. Adaptive noise-learning differential neural solution for time-dependent equality-constrained quadratic optimization. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(9):17253–64. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2025.3561415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Z, Zheng L, Li L, Deng X, Xiao L, Huang G. A new finite-time varying-parameter convergent-differential neural-network for solving nonlinear and nonconvex optimization problems. Neurocomputing. 2018;319(1):74–83. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2018.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jin L, Wei L, Li S. Gradient-based differential neural-solution to time-dependent nonlinear optimization. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 2023;68(1):620–7. doi:10.1109/TAC.2022.3144135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu M, Li Y, Chen Y, Qi Y, Jin L. A distributed competitive and collaborative coordination for multirobot systems. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(12):11436–48. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3397242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Polyak BT. Newton’s method and its use in optimization. Eur J Oper Res. 2007;181(3):1086–96. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2005.06.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hestenes MR. Multiplier and gradient methods. J Optim Theory Appl. 1969;4(5):303–20. doi:10.1007/BF00927673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kennedy J, Eberhart R. Particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks; 1995 Nov 27–Dec 1; Perth, WA, Australia; 1995. p. 1942–8. doi:10.1109/ICNN.1995.488968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Dorigo M, Birattari M, Stutzle T. Ant colony optimization. IEEE Comput Intell Mag. 2006;1(4):28–39. doi:10.1109/mci.2006.329691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kivi ME, Majidnezhad V. A novel swarm intelligence algorithm inspired by the grazing of sheep. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2022;13(2):1201–13. doi:10.1007/s12652-020-02809-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cao L, Chen H, Chen Y, Yue Y, Zhang X. Bio-inspired swarm intelligence optimization algorithm-aided hybrid TDOA/AOA-based localization. Biomimetics. 2023;8(2):186. doi:10.3390/biomimetics8020186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Fathy A, Bouaouda A, Hashim FA. A novel modified cheetah optimizer for designing fractional-order PID-LFC placed in multi-interconnected system with renewable generation units. Sustain Comput Inform Syst. 2024;43(2):101011. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2024.101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yue Y, Cao L, Zhang Y. Novel WSN coverage optimization strategy via monarch butterfly algorithm and particle swarm optimization. Wirel Pers Commun. 2024;135(4):2255–80. doi:10.1007/s11277-024-11143-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yue Y, Cao L, Chen H, Chen Y, Su Z. Towards an optimal KELM using the PSO-BOA optimization strategy with applications in data classification. Biomimetics. 2023;8(3):306. doi:10.3390/biomimetics8030306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Li PC, Zhang XY, Zain AM, Zhou KQ. An improved cuckoo search algorithm using elite opposition-based learning and golden sine operator. In: Artificial intelligence and security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 276–88. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-06794-5_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang CX, Zhou KQ, Ye SQ, Zain AM. An improved cuckoo search algorithm utilizing nonlinear inertia weight and differential evolution for function optimization problem. IEEE Access. 2021;9:161352–73. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3130640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang XS. Nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms. Bristol, UK: Luniver press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

20. Jorge N, Stephen JW , editors. Numerical optimization. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1999. doi:10.1007/b98874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Boyd S, Vandenberghe L. Convex optimization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

22. Hua C, Xu J, Huang Z, Liao B, Li S. Optimization-based finite-time multi-robot formation: a zeroing neurodynamics method. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2026;31(1):162–79. doi:10.26599/tst.2024.9010180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu M, Chen L, Du X, Jin L, Shang M. Activated gradients for deep neural networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;34(4):2156–68. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2021.3106044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Su H, Sun Y, Zeng Z, Duan H. Image segmentation model for vicinagearth security technology of unmanned aerial vehicle using improved pigeon-inspired optimization. Guid Navigat Control. 2024;4(3):2441002. doi:10.1142/s2737480724410024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Clerc M, Kennedy J. The particle swarm—explosion, stability, and convergence in a multidimensional complex space. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2002;6(1):58–73. doi:10.1109/4235.985692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Dorigo M, Colorni A, Maniezzo V. Distributed optimization by ant colonies. In: Proceedings of the First European Conference on Artificial Life; 1991 Dec 11–13; Paris, France. Vol. 142, p. 134–42. [Google Scholar]

27. Guntsch M, Middendorf M. A population based approach for ACO. In: Applications of evolutionary computing. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2002. p. 72–81. doi:10.1007/3-540-46004-7_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Das S, Biswas A, Dasgupta S, Abraham A. Bacterial foraging optimization algorithm: theoretical foundations, analysis, and applications. In: Foundations of computational intelligence. vol. 3. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. p. 23–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01085-9_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Luan X, Jin B, Liu T, Zhang Y. An improved artificial fish swarm algorithm and application. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing for Sustainable Energy and Environment; 2014 Sep 20–23; Shanghai, China. p. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

30. Yang XS. Firefly algorithms for multimodal optimization. In: International symposium on stochastic algorithms. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. p. 169–78 p. [Google Scholar]

31. Ye S, Zhou K, Zain AM, Wang F, Yusoff Y. A modified harmony search algorithm and its applications in weighted fuzzy production rule extraction. Front Inform Technol Electron Eng. 2023;24:1574–90. [Google Scholar]

32. Ye S-Q, Wang F-L, Ou Y, Zhang C-X, Zhou K-Q. An improved cuckoo search combing artificial bee colony operator with opposition-based learning. In: Proceedings of the 2021 China Automation Congress (CAC); 2021 Oct 22–24; Beijing, China. p. 1199–204. [Google Scholar]

33. Ye SQ, Zhou KQ, Zhang CX, Mohd Zain A, Ou Y. An improved multi-objective cuckoo search approach by exploring the balance between development and exploration. Electronics. 2022;11(5):704. doi:10.3390/electronics11050704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Karaboga D, Gorkemli B, Ozturk C, Karaboga N. A comprehensive survey: artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm and applications. Artif Intell Rev. 2014;42(1):21–57. doi:10.1007/s10462-012-9328-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ou Y, Qin F, Zhou KQ, Yin PF, Mo LP, Mohd Zain A. An improved grey wolf optimizer with multi-strategies coverage in wireless sensor networks. Symmetry. 2024;16(3):286. doi:10.3390/sym16030286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Duan H, Qiao P. Pigeon-inspired optimization: a new swarm intelligence optimizer for air robot path planning. Int J Intell Comput Cybern. 2014;7(1):24–37. doi:10.1108/ijicc-02-2014-0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang J, Chen H. BSAS: beetle swarm antennae search algorithm for optimization problems. arXiv:1807.10470. 2018. [Google Scholar]

38. Katoch S, Chauhan SS, Kumar V. A review on genetic algorithm: past, present, and future. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(5):8091–126. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-10139-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Deb K, Sindhya K, Hakanen J. Multi-objective optimization. In: Decision sciences. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2016. p. 145–84. doi:10.1201/9781315183176-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang Y, Wang S, Ji G. A comprehensive survey on particle swarm optimization algorithm and its applications. Math Probl Eng. 2015;2015(1):931256. doi:10.1155/2015/931256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang J, Lu Y, Wu Y, Wang C, Zang D, Abusorrah A, et al. PSO-based sparse source location in large-scale environments with a UAV swarm. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(5):5249–58. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3237570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. de Sá AO, Nedjah N, de Macedo Mourelle L. Distributed efficient localization in swarm robotic systems using swarm intelligence algorithms. Neurocomputing. 2016;172(1):322–36. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2015.03.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Guilford T, Roberts S, Biro D, Rezek I. Positional entropy during pigeon homing II: navigational interpretation of Bayesian latent state models. J Theor Biol. 2004;227(1):25–38. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zhang X, Duan H, Yang C. Pigeon-inspired optimization approach to multiple UAVs formation reconfiguration controller design. In: Proceedings of 2014 IEEE Chinese Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference; 2014 Aug 8–10; Yantai, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2014. p. 2707–12. doi:10.1109/CGNCC.2014.7007594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Qiu H, Duan H. Multi-objective pigeon-inspired optimization for brushless direct current motor parameter design. Sci China Technol Sci. 2015;58(11):1915–23. doi:10.1007/s11431-015-5860-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wu H, Duan H. Hierarchical pigeon inspired optimization based Multi-UAV obstacle avoidance control. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2025;159(6):109963. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2025.109963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang D, Duan H. Social-class pigeon-inspired optimization and time stamp segmentation for multi-UAV cooperative path planning. Neurocomputing. 2018;313(9):229–46. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2018.06.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Duan H, Huo M, Yang Z, Shi Y, Luo Q. Predator-prey pigeon-inspired optimization for UAV ALS longitudinal parameters tuning. IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst. 2019;55(5):2347–58. doi:10.1109/TAES.2018.2886612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]