Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DPZTN: Data-Plane-Based Access Control Zero-Trust Network

The School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China

* Corresponding Author: Huachun Zhou. Email:

Computer Systems Science and Engineering 2025, 49, 499-531. https://doi.org/10.32604/csse.2025.068151

Received 22 May 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 10 October 2025

Abstract

The 6G network architecture introduces the paradigm of Trust + Security, representing a shift in network protection strategies from external defense mechanisms to endogenous security enforcement. While ZTNs (zero-trust networks) have demonstrated significant advancements in constructing trust-centric frameworks, most existing ZTN implementations lack comprehensive integration of security deployment and traffic monitoring capabilities. Furthermore, current ZTN designs generally do not facilitate dynamic assessment of user reputation. To address these limitations, this study proposes a DPZTN (Data-plane-based Zero Trust Network). DPZTN framework extends traditional ZTN models by incorporating security mechanisms directly into the data plane. Additionally, blockchain infrastructure is used to enable decentralized identity authentication and distributed access control. A pivotal element within the proposed framework is ZTNE (Zero-Trust Network Element), which executes access control policies and performs real-time user traffic inspection. To enable dynamic and fine-grained evaluation of user trustworthiness, this study introduces BBEA (Bayesian-based Behavior Evaluation Algorithm). BBEA provides a framework for continuous user behavior analysis, supporting adaptive privilege management and behavior-informed access control. Experimental results demonstrate that ZTNE combined with BBEA, can effectively respond to both individual and mixed attack types by promptly adjusting user behavior scores and dynamically modifying access privileges based on initial privilege levels. Under conditions supporting up to 10,000 concurrent users, the control system maintains approximately 65% CPU usage and less than 60% memory usage, with average user authentication latency around 1 s and access control latency close to 1 s.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The evolution of 6G networks brings urgent demands for the new generation of endogenous security architectures. This transformation reflects three fundamental shifts in network protection strategies: from external defense to internal security mechanisms, from passive response to proactive defense, and from static protection to adaptive security frameworks [1].

However, traditional authentication methods in centralized architectures are increasingly inadequate in large-scale and dynamic network environments [2]. Password-based authentication is vulnerable to brute-force and dictionary attacks. The certificate-based schemes are susceptible to compromise by malicious intermediaries. The use of unencrypted biometric identifiers such as fingerprints poses serious privacy risks. To address these limitations, blockchain technology has been progressively adopted in ZTN environments to support decentralized and tamper-resistant identity authentication [3].

Meanwhile, in highly dynamic and heterogeneous network scenarios, static access control methods can no longer meet the dual requirements of security and efficiency. Adaptive access strategies are urgently needed to reflect users’ real-time behavior changes and associated risk levels. Although traditional trust and reputation models provide a basis for access control, they often rely on static behavior profiles and lack adaptability to evolving threats. The integration of smart contracts within blockchain offers a promising alternative by enabling decentralized, automated reputation scoring, dynamic access policy updates, and global synchronization of behavior data.

Despite these advances, many existing ZTN frameworks remain incomplete. They do not integrate traffic monitoring with fine-grained security enforcement. This integration is collectively referred to as MaS (Monitoring and Security). As a result, PEPs (Policy Enforcement Points) are exposed to frequent and targeted attacks [4]. In this context, programmable switches have emerged as a viable solution, allowing direct in-network analysis of user behavior and traffic characteristics at the data plane [5]. In coordination with the control plane, programmable switches support dynamic adaptation of access control policies to meet the diverse security demands [6].

To address the above challenges, this paper proposes and implements ZTNE that embeds security functions directly within network infrastructure. As a core security component, ZTNE enhances trust enforcement by supporting in-network behavior analysis, making it capable of responding to challenges posed by user changes [7] and increasing traffic heterogeneity [8]. Building on ZTNE, a dynamic access control framework based on user behavior profiling is developed. This framework uses real-time monitoring, programmable data planes, and blockchain infrastructure to strengthen zero-trust enforcement in 6G networks. The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

• A zero-trust network architecture is proposed that implements data-plane-based access control. DPZTN uses blockchain-based registration, authentication, and policy enforcement to support continuous monitoring and adaptive access management through ZTNE components.

• A dynamic behavior evaluation algorithm, BBEA, is introduced and implemented via smart contracts. It monitors user behaviors in real time and applies Bayesian inference to calculate reputation scores, considering both historical behavior and potential risks.

• A programmable-switch-based ZTNE is developed to monitor authenticated traffic flows. ZTNE detects malicious behaviors and supplies behavior-related data to support reputation evaluation and policy refinement.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the DPZTN framework and related studies. Section 3 presents the system design and implementation details. Section 4 provides experimental results. Section 5 offers a security analysis. Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses directions for future research.

This section reviews recent research advancements in ZTNs and summarizes related studies on the integration of security functions within programmable switches.

2.1 ZTN Authentication and Access Control Methods

Most of the existing studies proposing ZTNs refer to the ZTN model proposed by NIST [9]. This section provides a comparative summary of authentication and access control used in representative ZTN implementations.

Bradatsch et al. proposed ZTSFC, a zero-trust architecture that integrates monitoring and security functions into the authentication decision-making process. This framework utilizes sensing components to collect contextual data and shares threat intelligence with the control plane through a dedicated database [7]. PEPs generate personalized PDP (Policy Decision Point) rules based on historical user behavior, enabling access to service functions aligned with individual policies.

Sengupta and Lakshminarayanan introduced DistriTrust, a distributed trust management mechanism employing threshold signature schemes across multiple PDPs [10]. This design enhances authentication robustness under adversarial conditions by preventing reliance on a single PDP, thereby mitigating centralization risks.

Federici et al. developed a two-step access control method to enforce zero-trust principles [11]. The framework supports fine-grained access policies through trusted automation, end-to-end policy enforcement, and protection of both network and edge domains.

Azad et al. designed a decentralized trust management system for social IoT environments [12]. The system uses homomorphic encryption to protect participant privacy and employs zero-knowledge proofs to ensure protocol compliance without relying on trusted intermediaries.

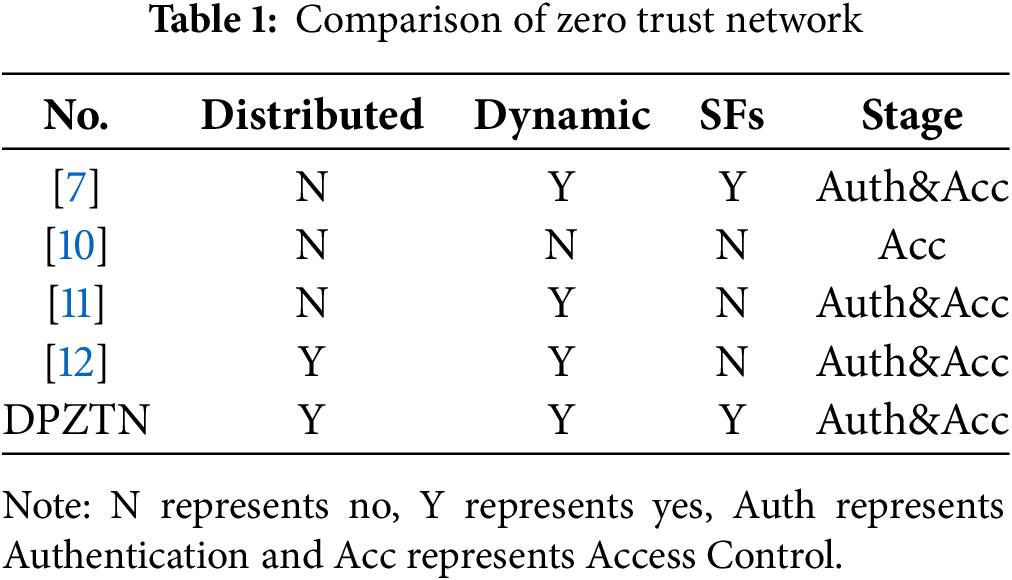

The DPZTN architecture proposed in this study utilizes blockchain technology to achieve decentralized access control and uses smart contracts to support dynamic policy adjustments. Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of representative ZTN frameworks, focusing on four key dimensions: distributed architecture, dynamic adaptability, support for SFs (Security Functions), and phase within the zero-trust process. The DPZTN model exhibits comprehensive capability across all evaluated aspects, highlighting its effectiveness as a fully integrated zero-trust solution.

2.2 ZTN Reputation Assessment Methods

This section analyzes representative reputation assessment techniques used in zero-trust environments, with a focus on algorithmic models and their deployment environments.

Tu and Kaur proposed BTRM, a multi-dimensional trust model designed to reduce assessment frequency without compromising IoT security [13]. The model evaluates behavior dimensions and integrates dynamic methods to establish trust relationships with connected users.

Taneja and Kanu introduced HA2CTMF, a trust management framework that enhances trust in cloud environments [14]. The framework evaluates cloud service provider reputation and availability using deep learning models to mitigate the effects of malicious behaviors.

Tian et al. presented MSLShard, a blockchain-enabled access control method for IoT [15]. The system comprises a Trust Management Model and a Smart Contract-based Network Segmentation Scheme. The segmentation strategy improves scalability, while intra-slice trust evaluation enhances security.

Baracaldo and Joshi designed a role-based access control model that dynamically adjusts privileges based on behavior patterns [16]. The model uses Colored Petri Nets to calculate risk levels and enforces least-privilege policies.

Dia et al. proposed the AALMOND framework, which implements distributed, risk-aware access control via smart contracts [17]. Risk values are computed based on security parameters and operational environment. If the risk exceeds a defined threshold, requests are sandboxed to contain potential threats.

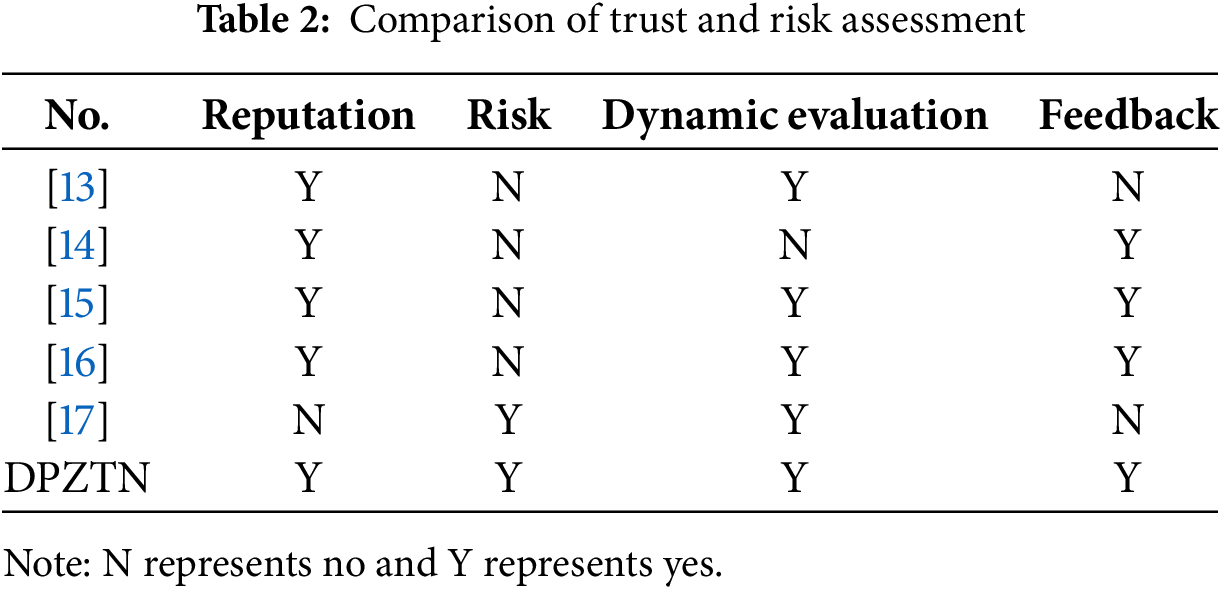

BBEA proposed in this paper integrates historical user behavior with predictive risk modeling to generate behavior scores that comprehensively reflect the credibility of user behaviors. Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of various trust and risk assessment methods, focusing on their treatment of reputation, risk factors, dynamic evaluation, and feedback mechanisms.

2.3 Programmable Switch Based Threat Detection

Traditional security functions based on AI models rely on batch training and processing, making it difficult to achieve real-time detection mechanisms [18]. Thus, this section reviews the application of programmable switches in implementing in-network threat detection mechanisms, validating their role in enhancing ZTN security functions.

Alevizos et al. introduced NetBeacon, an intelligent data plane framework that supports on-switch traffic analysis using embedded machine learning models [19]. The framework incorporates a multi-phase modeling structure, compact model representation, and indexed state management to handle concurrent data streams.

Saquetti et al. developed a neural-distributed defense architecture by deploying ANN (Artificial Neural Network) components across multiple switches [20]. This distributed ANN architecture enhances resilience against DDoS (Denial of Service Attack).

Mai et al. proposed an intelligent control architecture that allows network devices to autonomously adapt to dynamic conditions using learning-driven policies [21]. The architecture integrates centralized training with distributed inference and supports hybrid control strategies.

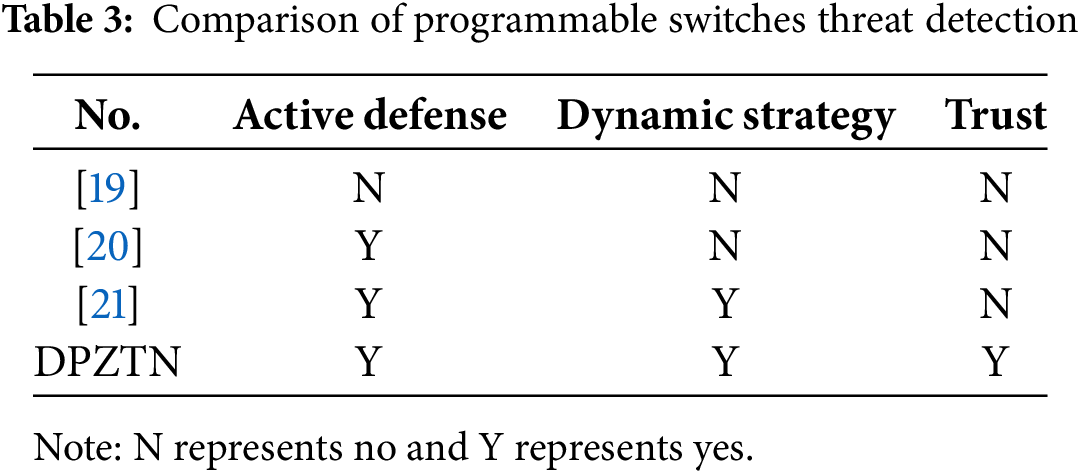

DPZTN uses blockchain for decentralized access control and smart contracts for dynamic policy adjustments. Table 3 illustrates that DPZTN excels across four key dimensions: active defense, dynamic strategy, and trust. Unlike traditional methods, DPZTN ensures real-time monitoring and adaptive security enforcement, making it a more scalable solution for dynamic network environments.

3 Design and Implementation of DPZTN

This section presents an overview of DPZTN, outlining the threat model it is designed to address. It concludes with a description of DPZTN’s overall workflow and a detailed implementation method for each functional component.

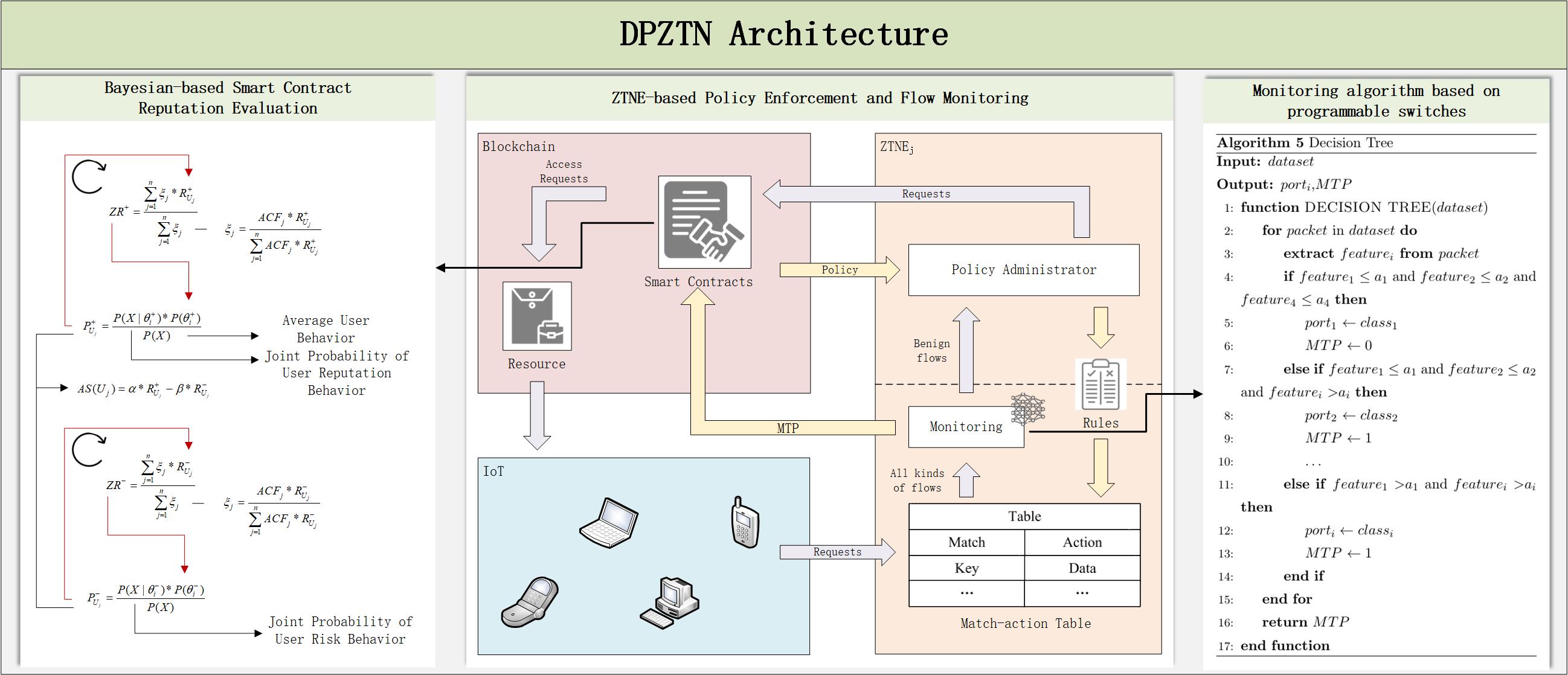

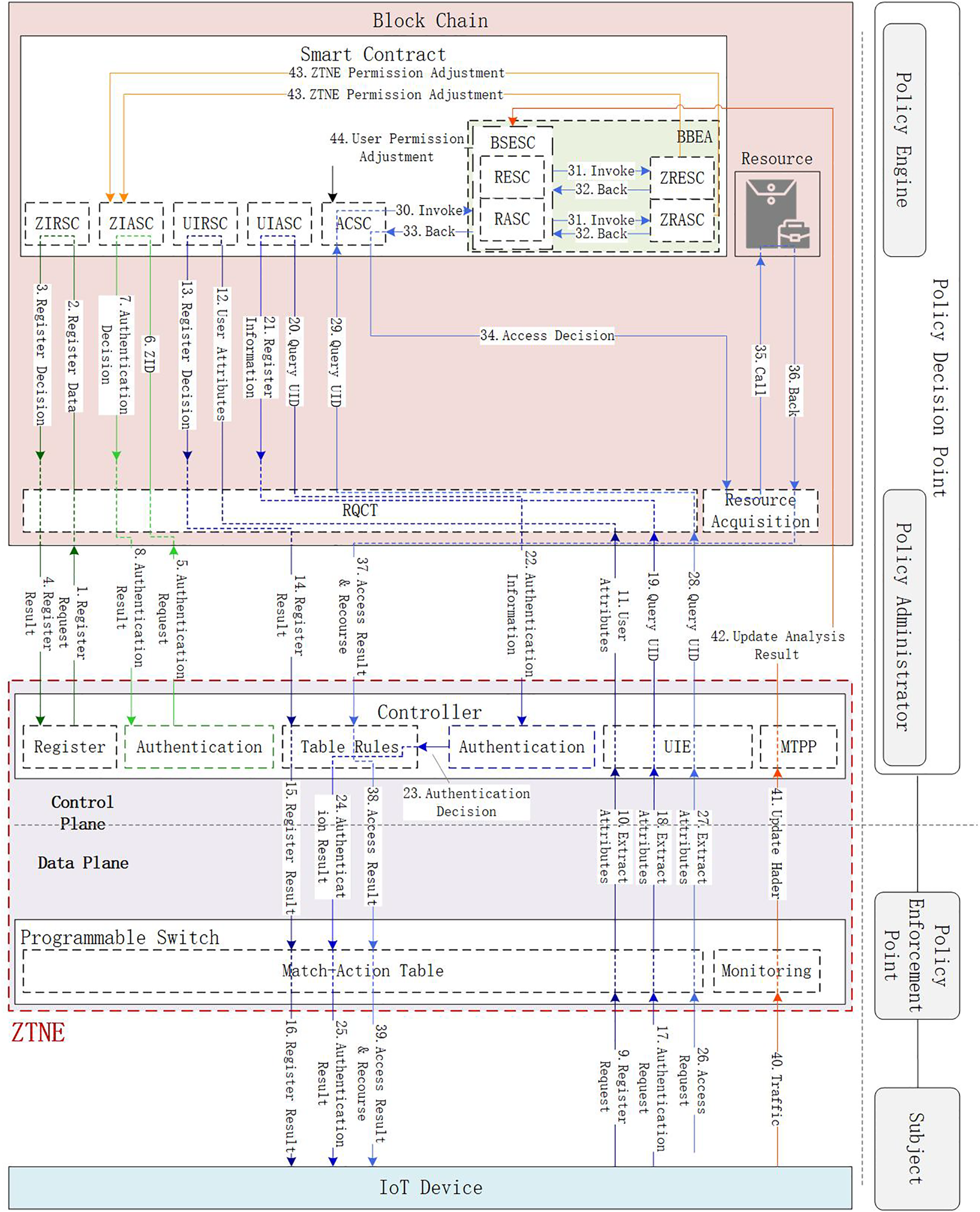

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the DPZTN architecture is divided into the data plane and the control plane. The programmable switch and its controller together form ZTNE. The data plane extracts essential packet features from user requests, performs real-time monitoring and traffic analysis for authorized users, and executes rules defined by the control plane. The control plane consists of the switch controller, blockchain, and the deployed smart contracts, which manage and issue access control policies while supporting data plane operations. The BBEA dynamically adjusts policies based on data plane feedback. The BBEA is implemented through a combination of several smart contracts. Additionally, a hybrid encryption algorithm ensures the integrity, authenticity, and confidentiality of communication. Blockchain technology stores user behavior records, providing the foundation for dynamic reputation evaluation. The logical components shown in Fig. 1 will be described in detail in Section 3.1.1.

Figure 1: DPZTN architecture and workflows

3.1.1 Logical Components of DPZTN

This section provides a detailed overview of the logical components involved in DPZTN, including their full names and specific functionalities.

• ZIRSC (ZTNE Identity Registration Smart Contract): Registers the identity information of gateways on the blockchain to ensure that each gateway is uniquely and reliably recognized by the access control system. Once registered, gateways can use their identity for subsequent authentication and access control requests.

• ZIASC (ZTNE Identity Authentication Smart Contract): Verifies the identity of gateways by matching authentication requests with registered identity data on the blockchain. Only successfully authenticated gateways are permitted to participate in data transmission and access control operations.

• UIRSC (User Identity Registration Smart Contract): Handles the registration of user identity information on the blockchain, ensuring that each user has a unique and verifiable identity within the system. Registered users can then utilize this identity for subsequent authentication and access control requests.

• UIASC (User Identity Authentication Smart Contract): Performs authentication of user identities by validating the provided credentials against registered identity data on the blockchain. Only authenticated users are authorized to access system resources.

• ACSC (Access Control Smart Contract): Enforces access control policies for both users and gateways. It verifies the access level and permissions of each requester, ensuring that all access requests comply with predefined system rules and preventing unauthorized behaviors.

• BSESC (Behavior Score Evaluation Smart Contract): Calculates a user’s behavior score based on both historical and current behavior data, providing a dynamic assessment of reliability. These scores serve as a reference for adjusting user permissions.

• RESC (Reputation Evaluation Smart Contract): Computes user reputation scores by analyzing their behavior across the system. Users with high scores may receive increased privileges, while those with low scores may face restrictions.

• RASC (Risk Assessment Smart Contract): Assesses user risk levels by evaluating behavior patterns, helping to estimate potential security threats. High-risk users may be subject to access limitations or stricter controls.

• ZRESC (ZTNE Reputation Evaluation Smart Contract): Evaluates the reputation of ZTNE gateways by analyzing their behavior and reliability in the system. Gateways with higher reputation scores are granted greater trust and access priority.

• ZRASC (ZTNE Risk Assessment Smart Contract): Monitors and evaluates the risk level of each gateway to assess its security status. Gateways with elevated risk levels may be subject to operational restrictions or alerts.

• RQCT (Request Classification): Receives and classifies incoming requests from users and gateways to determine the appropriate smart contract to invoke. This component streamlines system operations and optimizes resource utilization.

• UIE (User Information Extraction): Extracts relevant identity attributes of users to support authentication and authorization procedures. It ensures precise identity recognition and access environment determination.

• MTPP (Malicious Traffic Probability Prediction): Analyzes network traffic features to calculate the probability of malicious behavior. The resulting risk scores are used for dynamic permission adjustments and are stored on the blockchain.

• Traffic Monitoring: Continuously monitors real-time network traffic, extracts user packet features, and forwards them to MTPP for analysis and threat prediction.

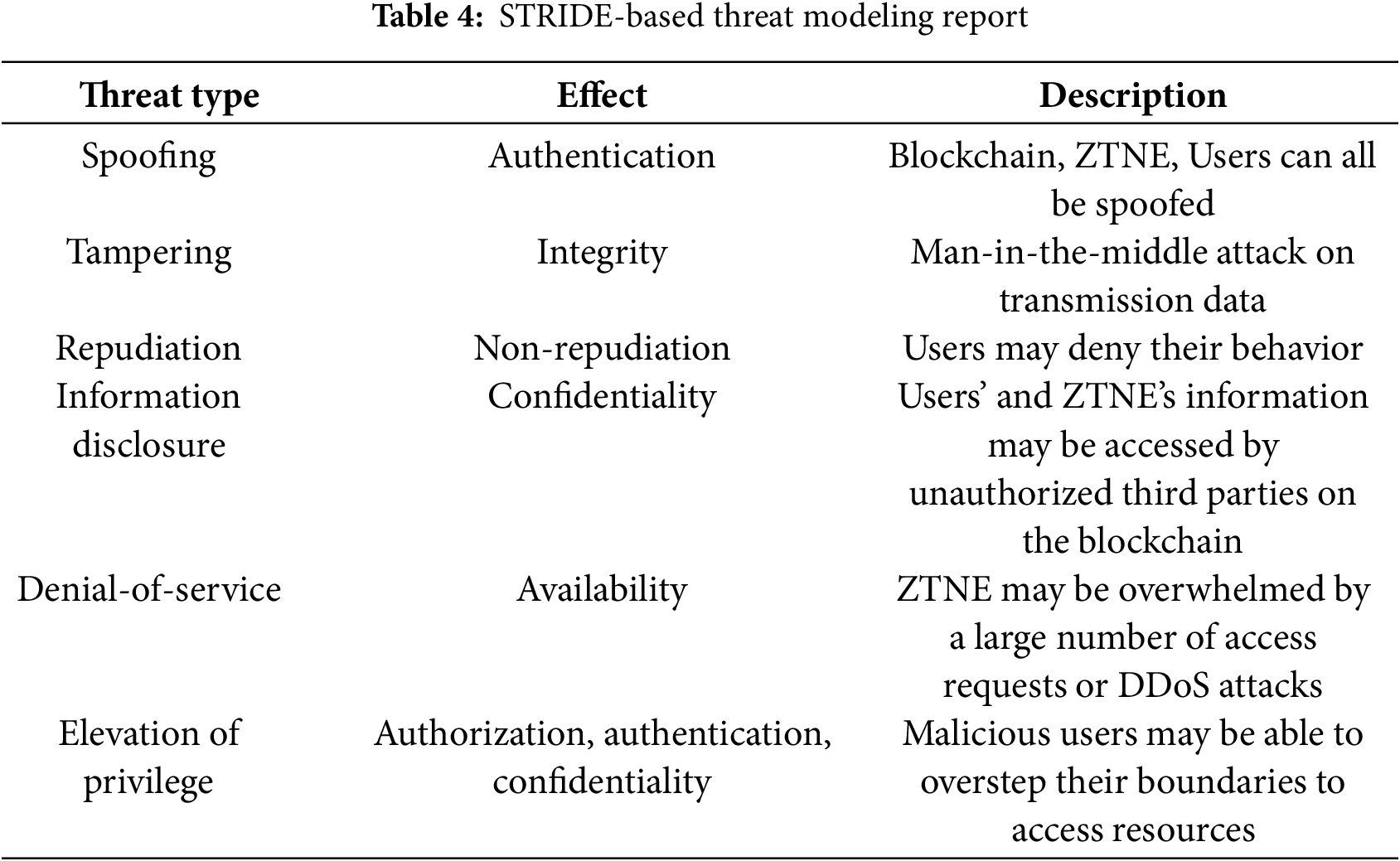

In this paper, the STRIDE (Spoofing-Tampering-Repudiation-Information disclosure-Denial of service-Elevation of privilege) model [22] is used to analyze the security threats in a zero-trust environment, as summarized in Table 4. To mitigate the risks associated with these threats, the following security requirements for the DPZTN are proposed.

• Requirement 1: Continuous verification. All devices and users within the DPZTN must undergo continuous identity verification. Any device or network that is not explicitly trusted should be distrusted, and all transmitted information must be protected against tampering. This requirement minimizes the risk of impersonation attacks and ensures the confidentiality and integrity of identities.

• Requirement 2: Behavior logging and query. The behaviors of all users and the status of ZTNEs must be logged to ensure the traceability and non-repudiation of each operation. Blockchain technology is utilized to guarantee the immutability of behavior data.

• Requirement 3: User behavior monitoring and malicious behavior detection. Network elements within the DPZTN must be capable of monitoring user behavior to prevent system DoS (denial-of-service) attacks, including those originating from DDoS.

• Requirement 4: Principle of least privilege and dynamic evaluation. DPZTN enforces stringent access control policies, adhering to the principle of least privilege, which restricts user and ZTNE access to only the necessary system resources.

The flow of the zero-trust architecture proposed in this paper is described according to the steps outlined in Fig. 1:

• Steps 1–4: When the ZTNE accesses the DPZTN for the first time, it submits an identity registration request to the blockchain. The request is verified through ZIRSC to ensure the uniqueness and legitimacy of the ZTNE. This process is detailed in Section 3.3.1.

• Steps 5–8: Following registration, the ZTNE undergoes authentication. The DPZTN verifies the ZTNE identity using ZIASC, enabling the ZTNE to perform subsequent access control operations. The authentication procedure is outlined in Section 3.3.1.

• Steps 9–16: When a user accesses the DPZTN for the first time, their identity information is stored on the blockchain through UIRSC. This ensures the user has an independent identity identifier and lays the groundwork for access control. The registration process is described in Section 3.3.2.

• Steps 17–25: The user then undergoes authentication. The legitimacy of the user’s identity is verified through UIASC, allowing the user to request access to DPZTN resources. This step is discussed in Section 3.3.2.

• Steps 26–39: When a user requests access, ACSC verifies the legitimacy and permissions of the request. It ensures the request complies with the user’s assigned access privileges and rejects unauthorized requests. The access control process is explained in Section 3.4.

• Steps 40–42: For authorized user traffic, MTP (the Malicious Traffic Probability) component calculates the malicious probability of the traffic in real time and records the result on the blockchain. This workflow is detailed in Section 3.5.

• Step 43: The system dynamically adjusts ZRV (the ZTNE Reputation Value) and ZRR (the ZTNE Risk Value) based on the outcomes from the ZRESC and ZRASC, ensuring the security of DPZTN resources. This is discussed in Sections 3.6.1 and 3.6.2.

• Step 44: Finally, based on evaluations from the BSESC and RESC, the DPZTN adjusts the user’s access privileges, restricting access for high-risk or low-reputation users. This process is described in Sections 3.6.3 and 3.6.4.

The DPZTN workflow ensures comprehensive coverage from user and ZTNE registration and authentication to dynamic access control. It enhances system security and flexibility through a dynamic adjustment mechanism based on user behavior assessment.

3.2 Encryption and Secure Communications

To ensure the integrity and confidentiality of the above access control workflow, secure communication must be established between users and network components. Therefore, we next elaborate on the encryption and secure communication strategies adopted in DPZTN.

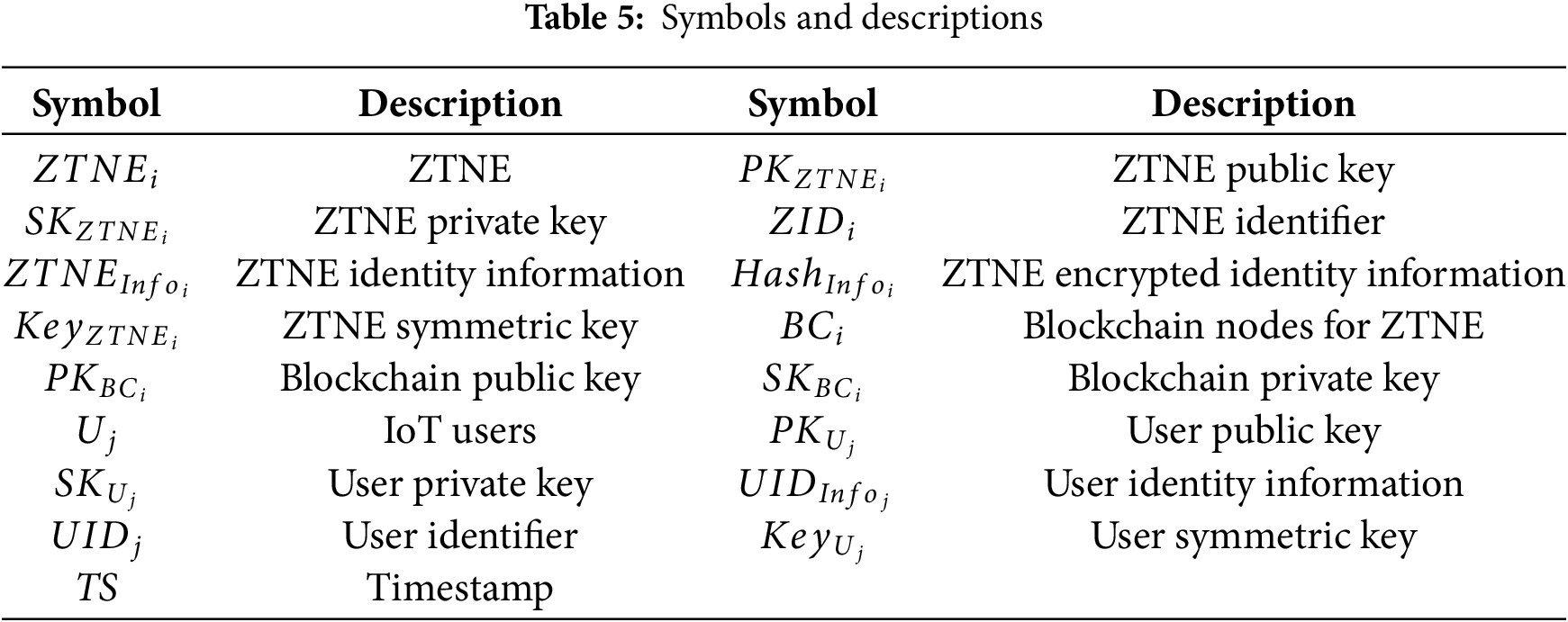

To enable secure communication between users and ZTNE in the DPZTN, a hybrid encryption algorithm combining ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) and AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) is used. These algorithms are used in different phases of the DPZTN: the ECC algorithm is applied during the identity information exchange in the registration phase, the AES algorithm is used for identity authentication during the authentication phase, and both algorithms contribute to the credibility assessment in the access control phase. To protect against unauthorized users accessing the identity information of other users and ZTNEs, all identity data stored in the blockchain is hashed and encrypted, further enhancing security. For users with granted access, the DPZTN continuously monitors, processes, and feeds back their traffic behavior via programmable ZTNEs. If malicious traffic is detected, the DPZTN immediately intercepts the traffic at the Network Layer and removes the user’s registration information from the blockchain.

3.3 Registration and Authentication

With secure channels in place, the next step is to establish trusted identities for users and network entities. This section outlines the registration and authentication mechanisms in DPZTN. Each ZTNE and user must register their identity information, and IoT users employ zero-knowledge proofs to enable anonymous authentication. The relevant symbols are listed in Table 5.

3.3.1 ZTNE Registration and Authentication

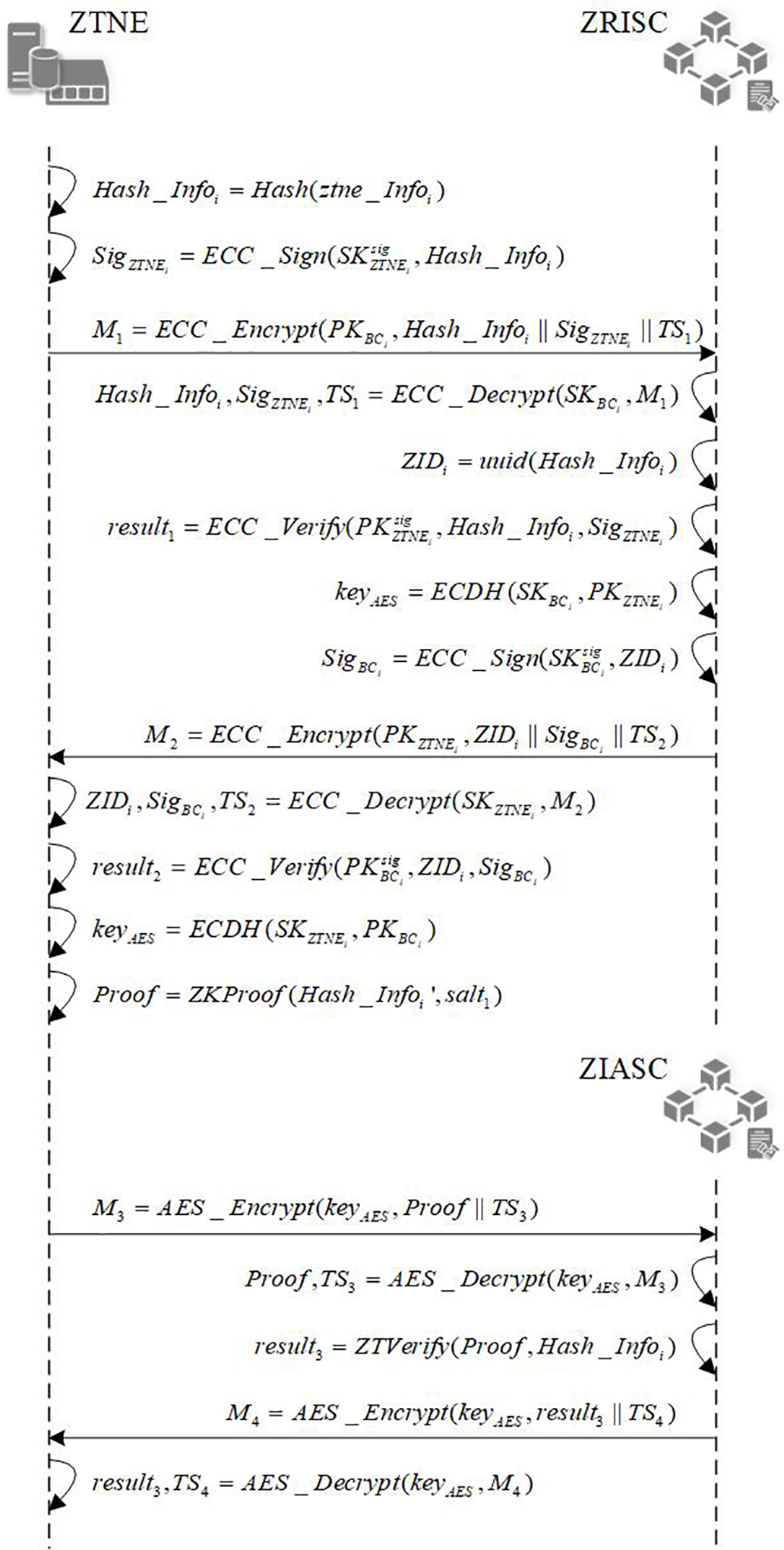

As 5G-AKA implements mutual authentication between the user and the service network, the ZTNE must also register its identity information and undergo bidirectional authentication with the blockchain. The registration and authentication process for the ZTNE is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: DPZTN architecture and workflows

ZTNE registration: Before the ZTNE registration,

ZTNE authentication: ZTNE recalculates its own identity information

3.3.2 User Registration and Authentication

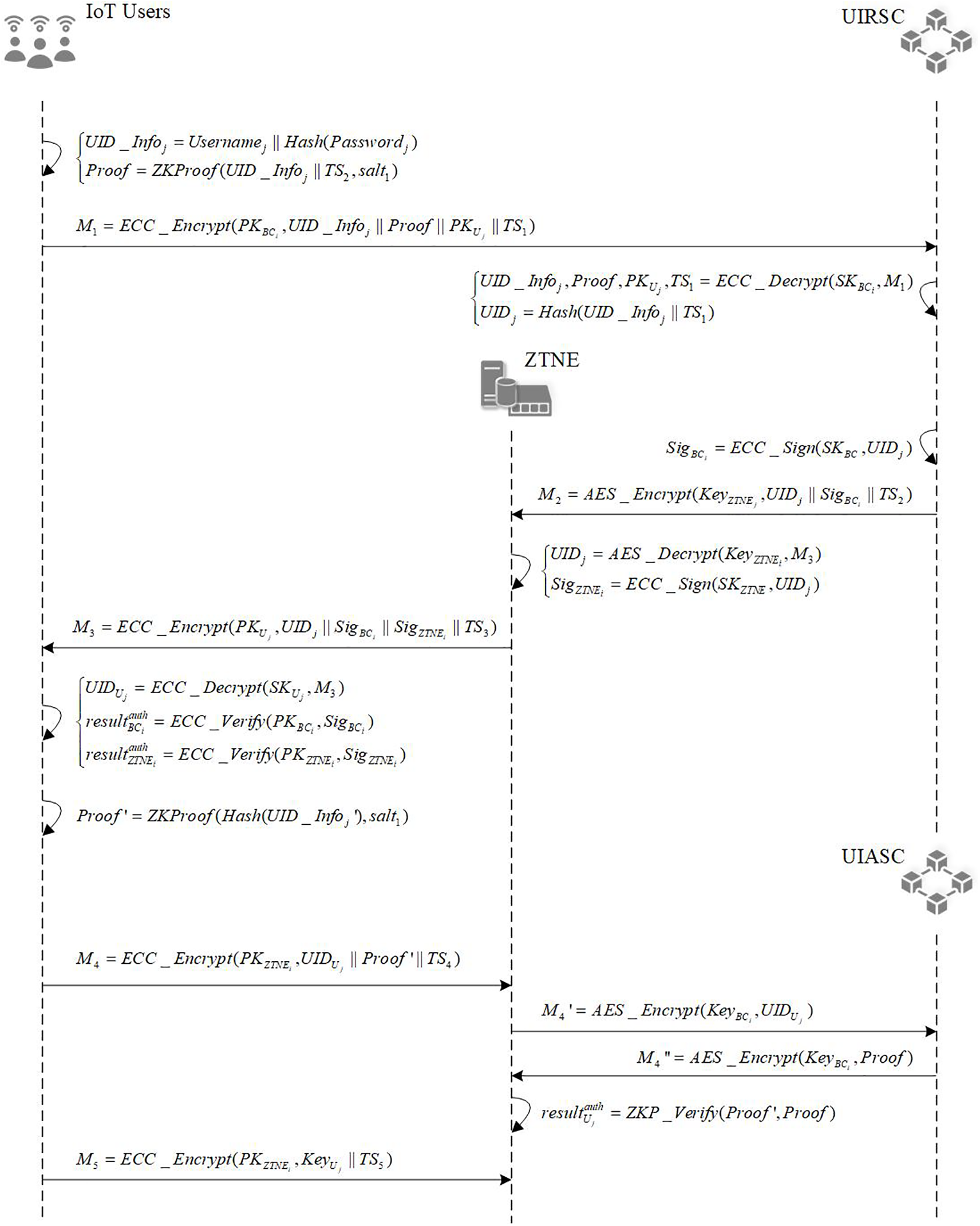

When a user connects to the DPZTN for the first time, the user must register the user identity information with the ZTNE. The ZTNE deposits the user information into the blockchain, the user identity registration and authentication process is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: User registration and authentication flows

User registration: Before registration, the public key exchange between

User authentication: The user is authenticated immediately after completing the registration process. The blockchain uses the

3.4 Access Control Based on User Behavior

Once the identities of users and ZTNEs have been securely verified, it becomes essential to determine whether access requests should be granted. The following section introduces a behavior-based access control scheme that adapts dynamically to user behavior.

3.4.1 User Behavior-Based Access Control

As shown in Fig. 3, users are assigned access privileges based on their roles after registration. The access privilege defines the maximum privilege boundaries for the user. Even if the user’s behavior is good, the user’s access privilege level cannot exceed the role’s permission boundary.

In the smart contract ACSC, this paper assign the user’s role as

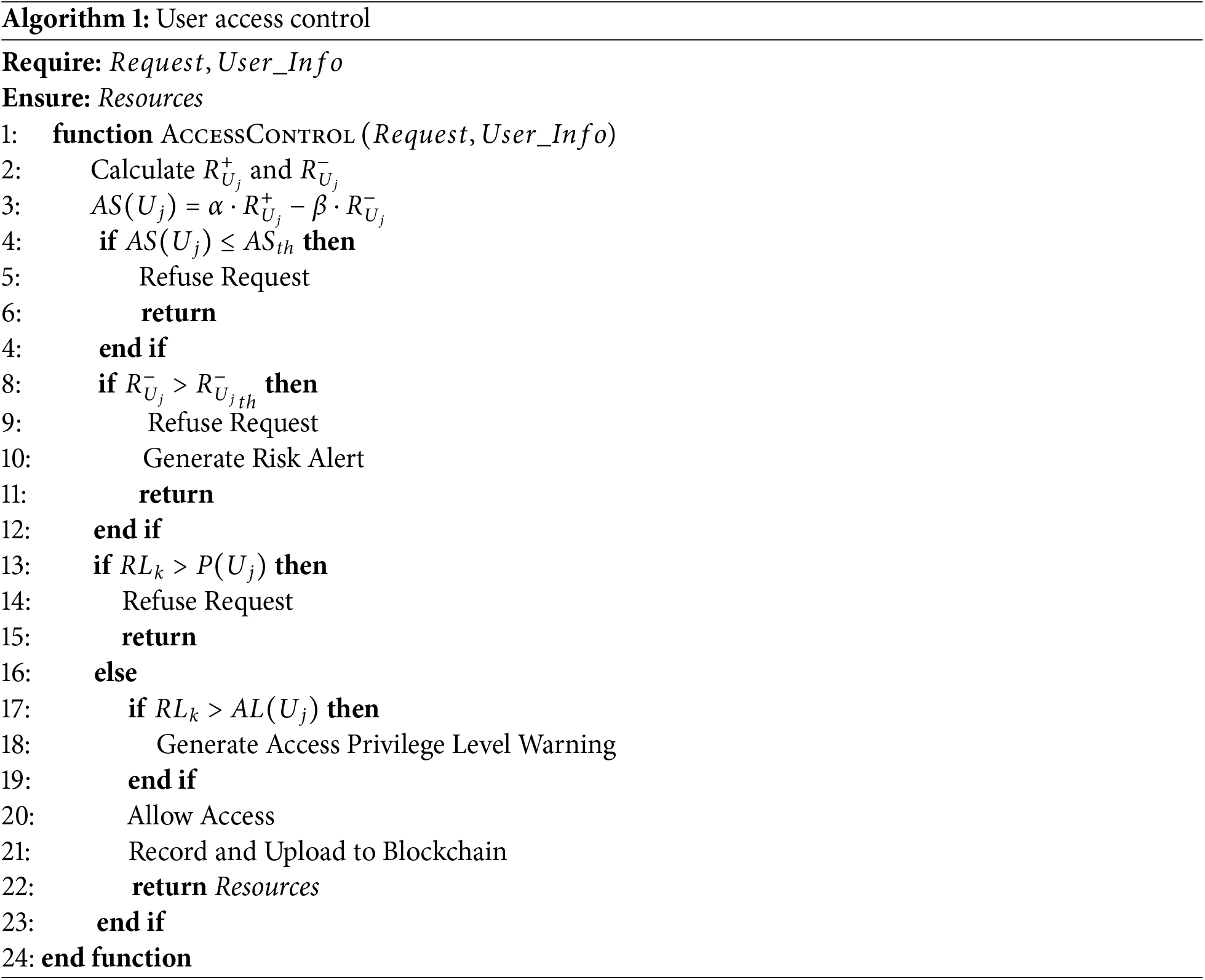

In this paper, a UABAC (user attribute-based access control) algorithm is implemented within the ACSC of the blockchain, as shown in Algorithm 1. Initially, the user’s behavior score is computed by evaluating the user’s reputation value

If the behavior score

Once the behavior score is validated, the ACSC further assesses whether the user’s risk value

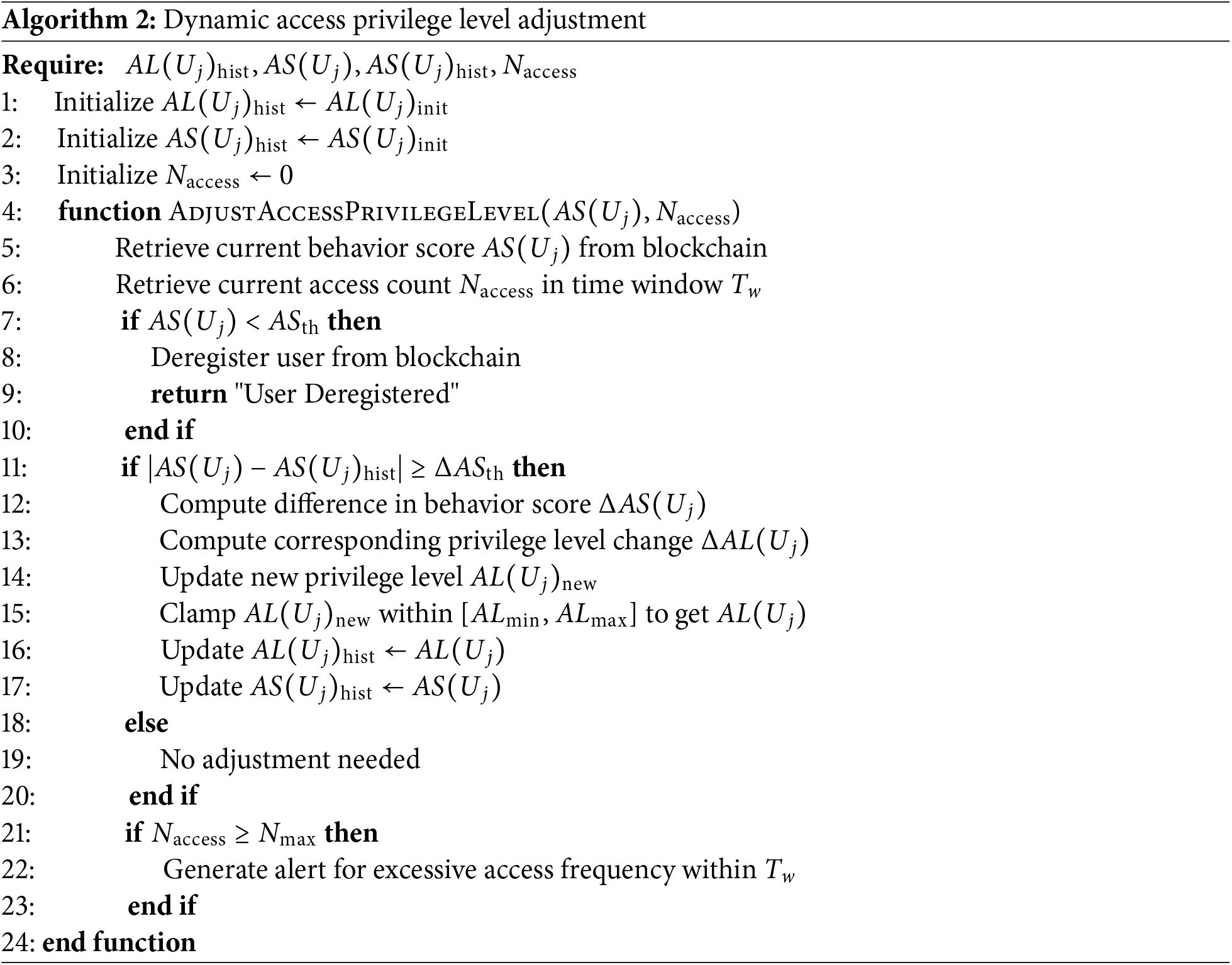

3.4.2 User Dynamic Access Privilege Level Adjustment

With the changing behavior of users, the access control system needs to dynamically adjust the access privilege level of users to ensure the safe access of resources. Dynamic adjustment is achieved through a comprehensive evaluation of the user’s current and historical behaviors. In this paper, the proposed dynamic adjustment of user’s access privilege level and behavior score is achieved by the following formula:

For the next time access privilege level assessment of the user,

On this basis, the system introduces a time window for access privilege level changes and a buffer for behavior scores. The system limits the frequency of access privilege level adjustments through a time window mechanism for access privilege level changes. Specifically, the system specifies that a user’s access privilege level is allowed to be adjusted only once within a fixed time window at

The system introduces a buffer interval

Algorithm 2 describes the dynamic access privilege level adjustment algorithm, which is realized in BSESC. The smart contract obtains the user’s current behavior score

The dynamic access privilege level algorithm adjusts the access privilege level based on user behavior scores, combining time windows and buffers. This approach not only ensures that the access privilege level is reasonably adjusted according to user behavior but also avoids frequent changes due to short-term behavior fluctuations or minor score variations.

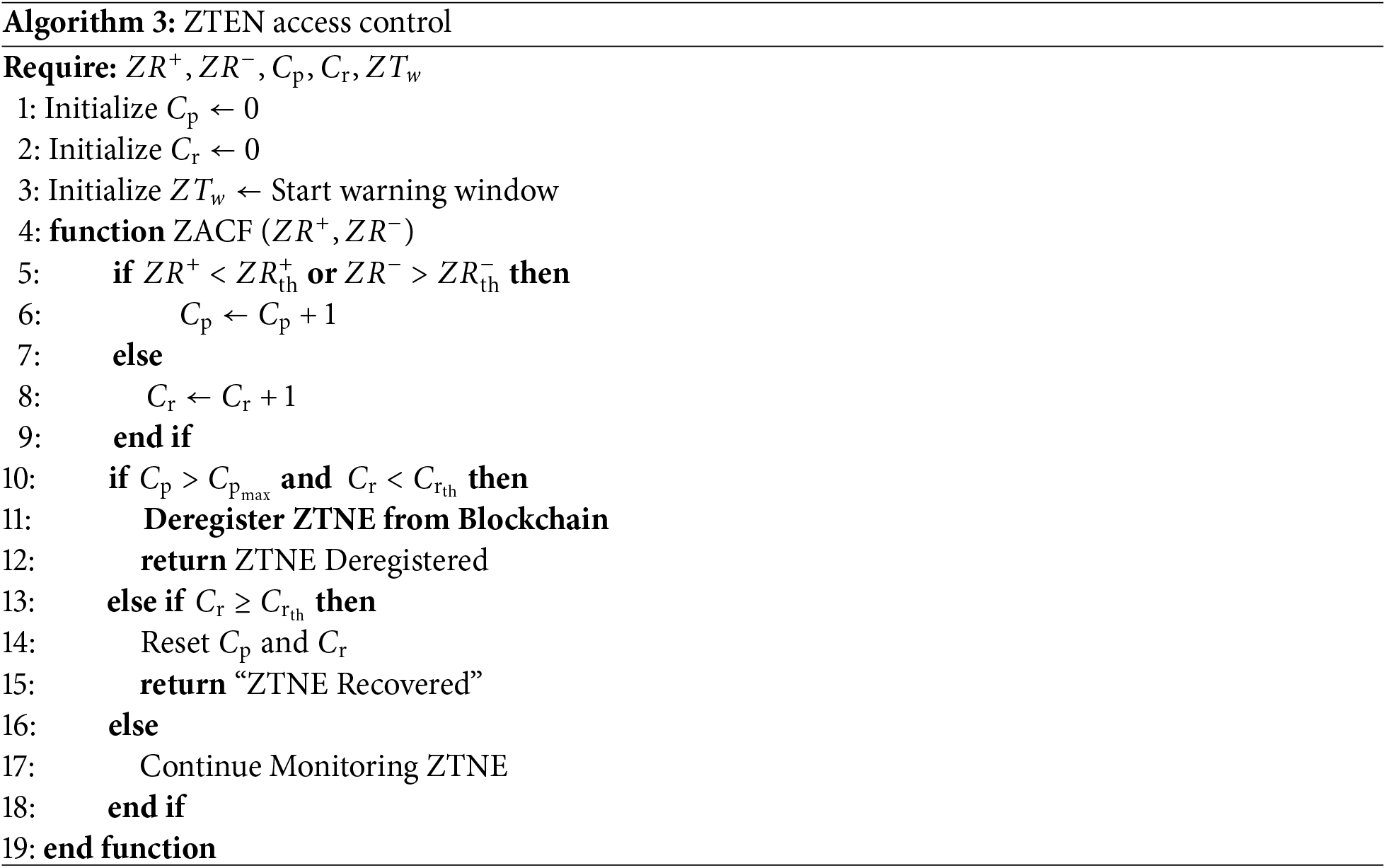

3.4.3 ZTNE Dynamic Privilege Adjustment

As shown in Algorithm 3, the dynamic privilege adjustment of ZTNE introduces the penalty-recovery mechanism, through which the dynamic management of ZTNE access control is realized.

First, the algorithm initializes the penalty counter

Subsequently, the algorithm checks the penalty and recovery conditions: if

By monitoring ZTNE’s reputation value

The successful enforcement of behavior-based access control policies depends on the real-time processing capabilities of the data plane. In this context, programmable switches play a pivotal role. This section outlines how ZTNEs utilize the data plane for policy enforcement and threat detection.

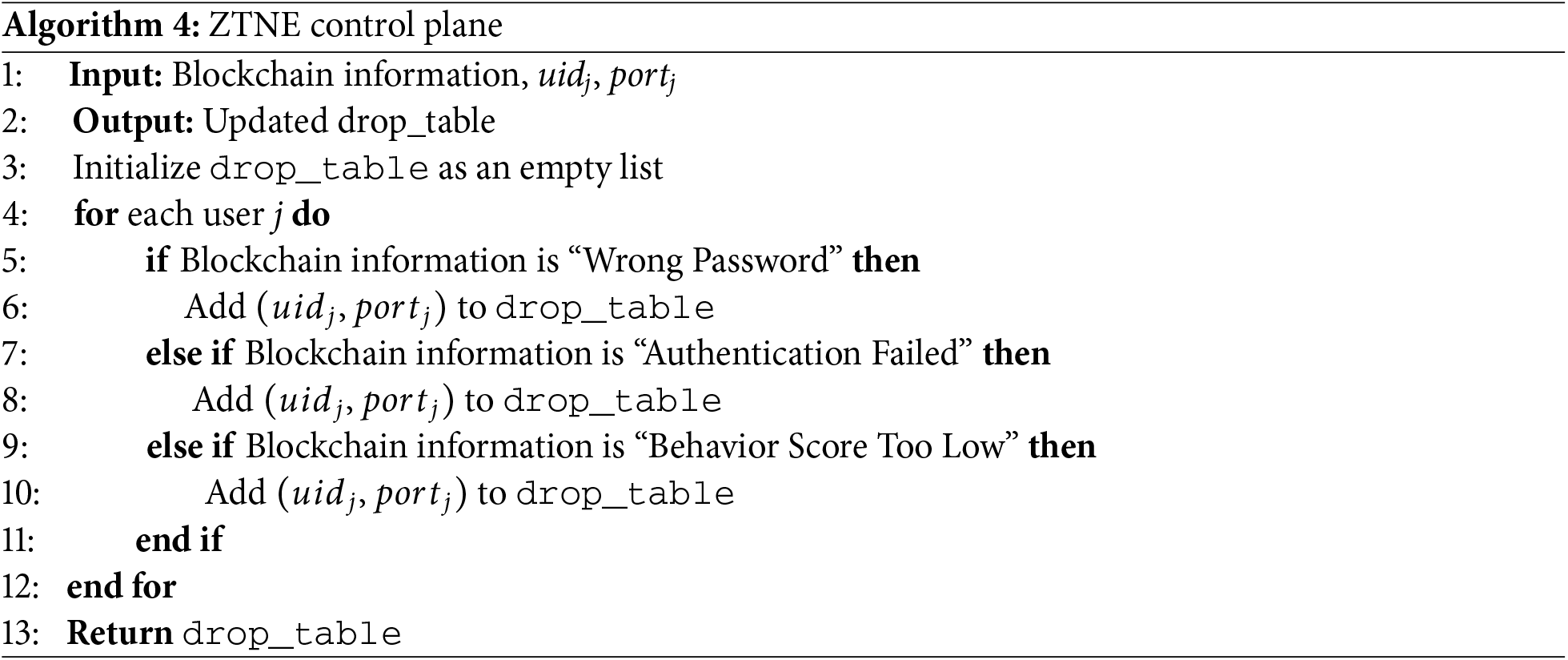

3.5.1 ZTNE Handles User Requests

When the user authentication or access control fails, the blockchain generates the corresponding message and sends it to the programmable switch controller. Algorithm 4 shows the pseudo-code for ZTNE user request processing.

The P4Runtime initializes an empty

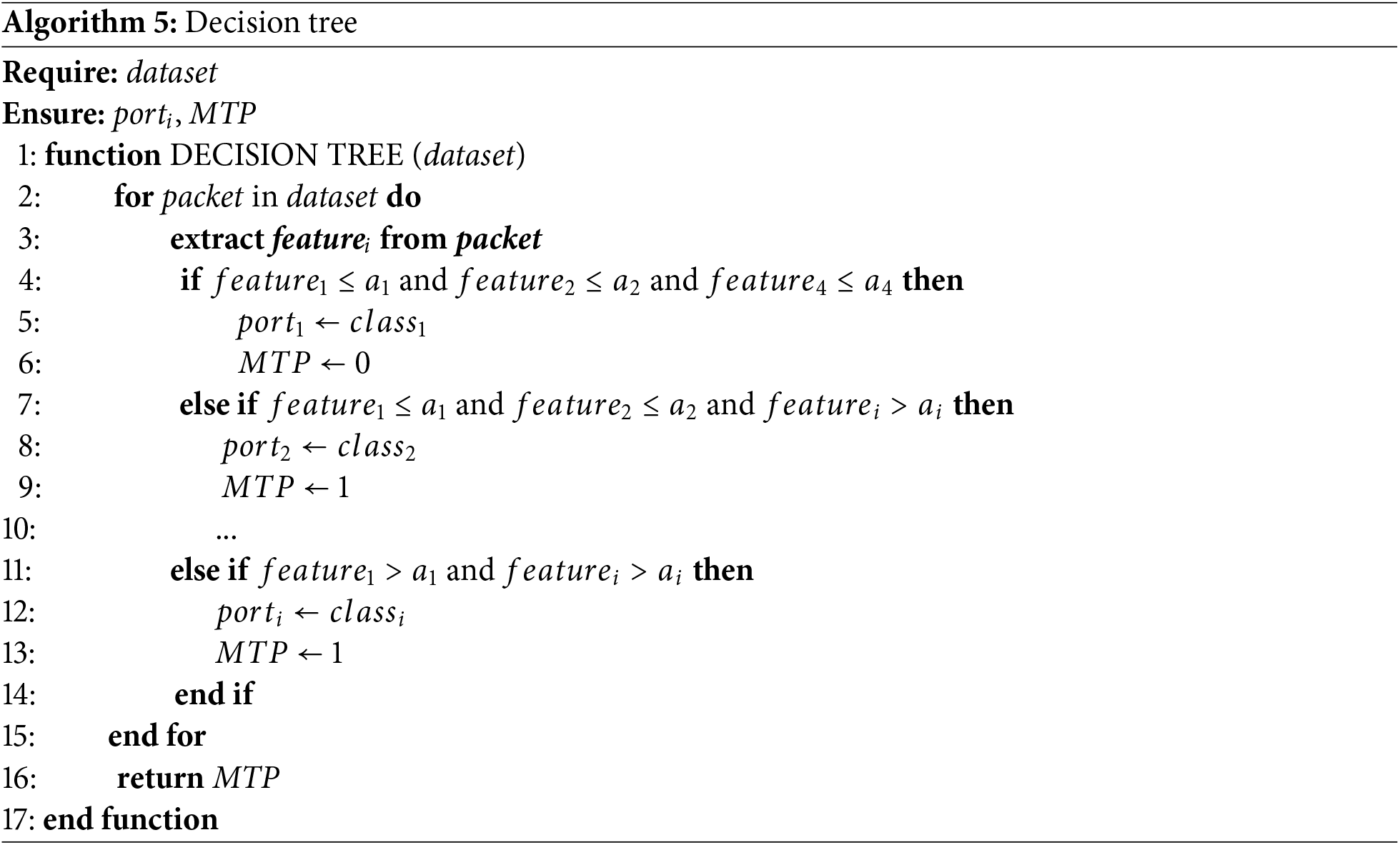

3.5.2 ZTNE Monitors User Traffic

The pseudo-code for the decision tree algorithm is presented in Algorithm 5. In the data plane, the ZTNE performs high-speed packet processing to extract

ZTNE utilizes the decision tree algorithm to predict attacks on each packet, enabling precise traffic classification through detailed feature extraction and hierarchical filtering. The decision tree rapidly generates hard labels, allowing malicious traffic to be redirected to alternative ports. Upon detecting malicious traffic, the system sets the MTP to 1 and reports this information to the blockchain for subsequent user behavior score adjustment. After completing the prediction process, the switch transmits the MTP of each packet to the blockchain via the control plane, providing essential data for future privilege adjustments and behavior analysis. This collaborative mechanism ensures that ZTNE can effectively mitigate network attacks, thereby enhancing the overall security of the network.

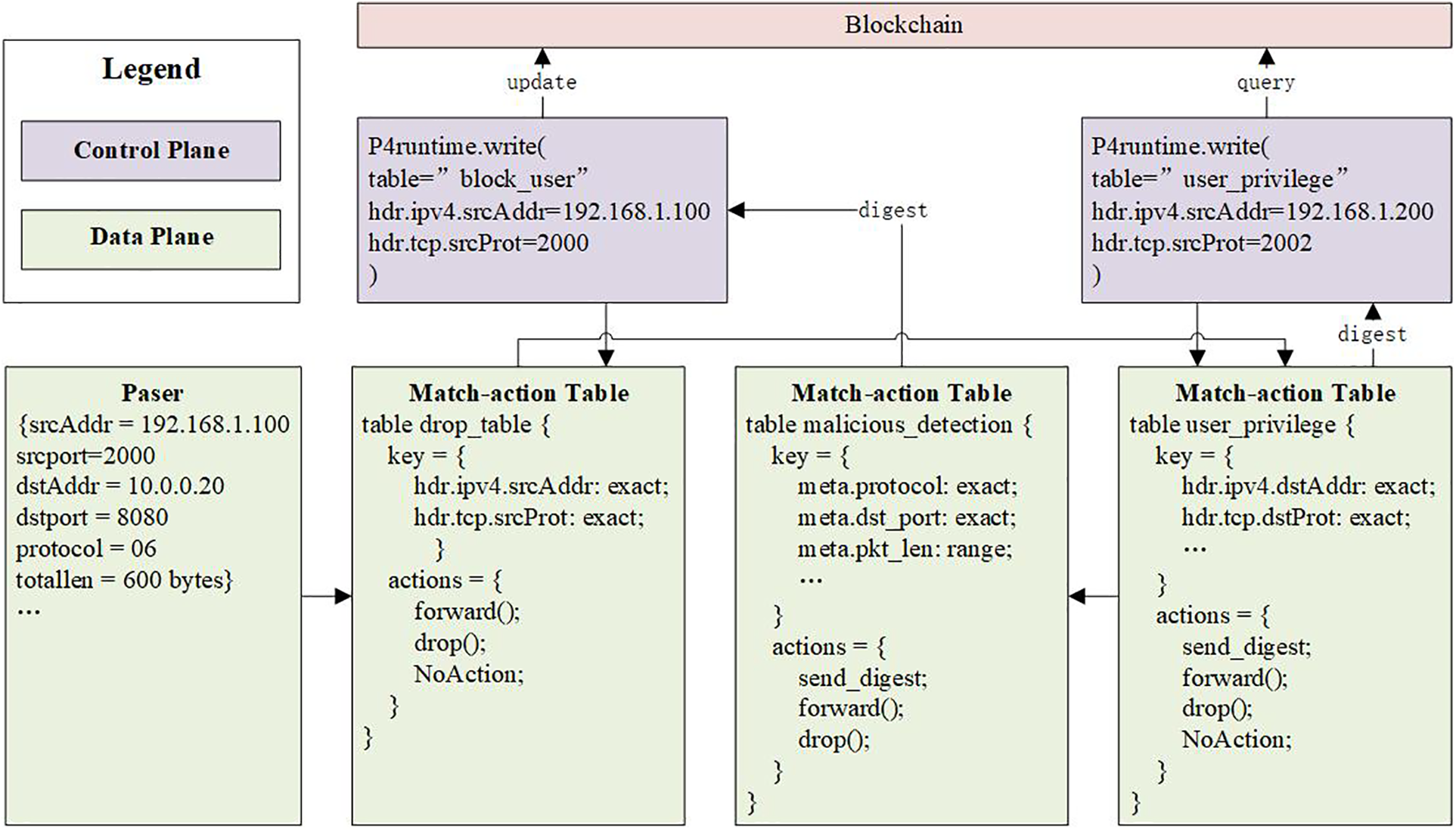

3.5.3 An Example of DPZTN Traffic Processing

In the proposed DPZTN (Data Plane Zero Trust Network) framework, the data plane processes incoming packets through a series of match-action tables, which are dynamically coordinated by a centralized control plane. The detailed mechanism is illustrated through the following packet processing example as Fig. 4 shown.

Figure 4: An example of DPZTN traffic processing

When a data packet arrives at the switch, its header fields are first extracted by the parser. Suppose the packet has the following characteristics: the source IPv4 address is 192.168.1.100, the source TCP port is 2000, the destination IP address is 10.0.0.20, the destination port is 8080, the protocol is TCP, and the total packet length is 600 bytes.

The packet first enters the drop_table, which checks whether the user is blacklisted by performing an exact match on the source IP address and source port. If a match is found, the drop action is executed and the packet is immediately discarded. Otherwise, the packet proceeds to the next phase.

Next, the packet is processed by the user_privilege table, which verifies whether the user has permission to access the specified destination IP and port. If the match indicates that the user’s access is authorized, the packet is forwarded normally. If not, the switch triggers a send_digest operation to report the access attempt to the control plane. The controller then evaluates whether the access request violates the user’s assigned privilege level and dynamically adjusts the user’s permission if necessary.

After that, the packet enters the malicious_detection table, which performs multi-field matching based on protocol type, destination port, packet length range, and other features. If the combination of these features matches a known malicious behavior pattern, the switch again triggers a send_digest operation, sending a digest message to the control plane that includes the source address and behavior-related metadata. Upon receiving the digest, the control plane queries the blockchain to assess the user’s trust status and may blacklist the user by updating the corresponding tables.

The control plane handles these digest messages by querying or updating the blockchain records and uses the P4Runtime interface to dynamically issue control commands to the data plane. For example, the controller can add the user and its port to the drop_table to enforce blocking, or update the user_privilege table to adjust the access level accordingly.

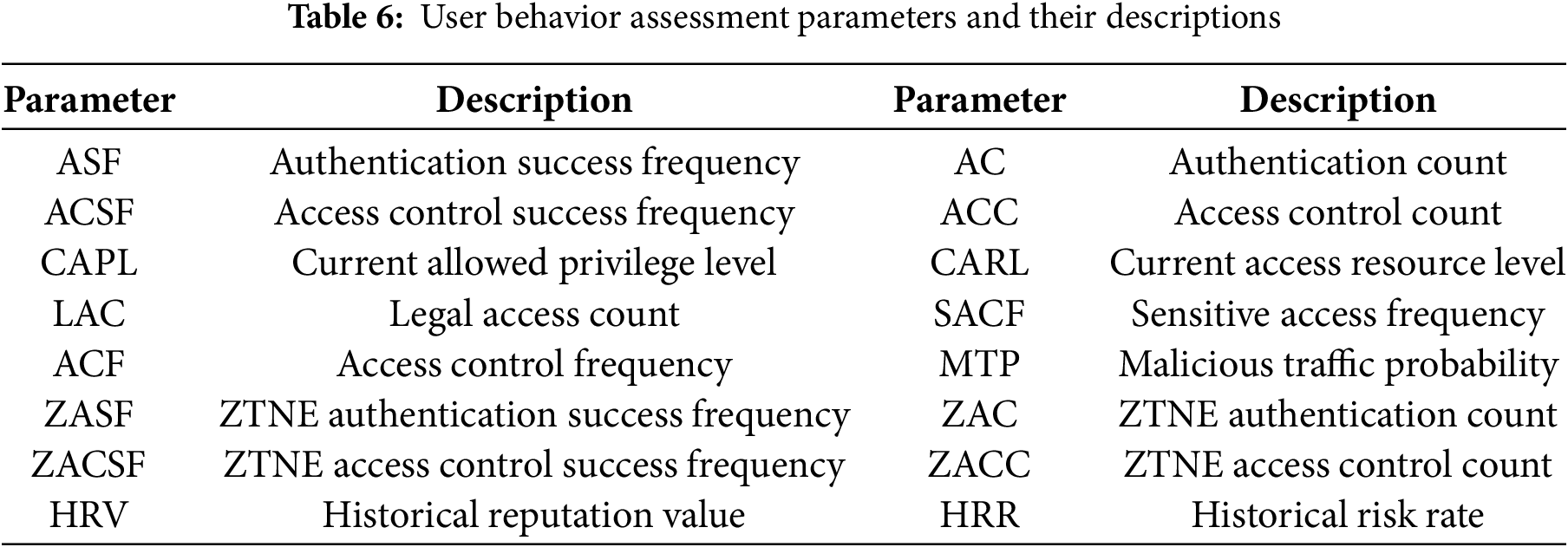

3.6 Bayesian-Based Behavior Evaluation Algorithm Assessment

To support fine-grained and adaptive access control, a robust behavior evaluation mechanism is essential. We thus propose a BBEA, which quantifies user credibility and risk based on real-time observations. BBEA for user behavior evaluation through the joint use of ZRESC, ZRASC, RESC, RASC, and BSESC. The parameters used in BBEA are listed in Table 6.

We implement the computation of the ZTNE reputation value using the ZRESC deployed on the blockchain. The reputation value

where

We have implemented the calculation of ZTNE risk value by applying ZRASC in the blockchain, and the ZTNE risk value

where

3.6.3 Users Reputation Value and Risk Value

In this paper, we adopt a Bayesian algorithm to dynamically update the user’s reputation and risk values. Specifically, the reputation value is derived from both prior and posterior probability distributions. The prior probabilities for reputation and risk are defined in Eqs. (7) and (8), respectively.

The

• User relative authentication success rate

• User relative access control success rate

• User legal access rate

• User’s resource level match privilege level: This is a segmented function with a match privilege level:

Combining Eqs. (9)–(11) to obtain combining evidence:

where

The formula for the user’s reputation value is:

The

• User authentication failure rate

• User access control success rate

• Access sensitive information frequency

Combining Eqs. (12), (16)–(18) and MTP, the combining evidence is obtained:

where

The formula for the user’s value-at-risk is:

The calculation of user behavior scores is implemented within the BSESC on the blockchain. These scores are computed by integrating both the user’s reputation value and risk value, providing a comprehensive assessment of the user’s overall behavior performance. The behavior score is formally defined by the following equation:

where:

•

•

When

To determine the optimal parameter configuration that results in the most rapid decline of behavior scores, we formulate an objective function and employ a global search strategy followed by local optimization.

where

To obtain a globally optimal solution within the parameter space, a grid search strategy is first applied to exhaustively scan discretized parameter combinations. The corresponding objective function values are evaluated to identify the configuration that leads to the most rapid decline in behavior scores.

To further enhance search accuracy and computational efficiency, simulated annealing is used for local refinement. The algorithm is initialized with the best result obtained from the grid search and iteratively adjusts the parameter set. During the annealing process, suboptimal solutions are accepted with a certain probability to avoid premature convergence to local optima.

This chapter first introduces the experimental environment, followed by an analysis of the security and dynamics of DPZTN, and concludes with a performance analysis of DPZTN.

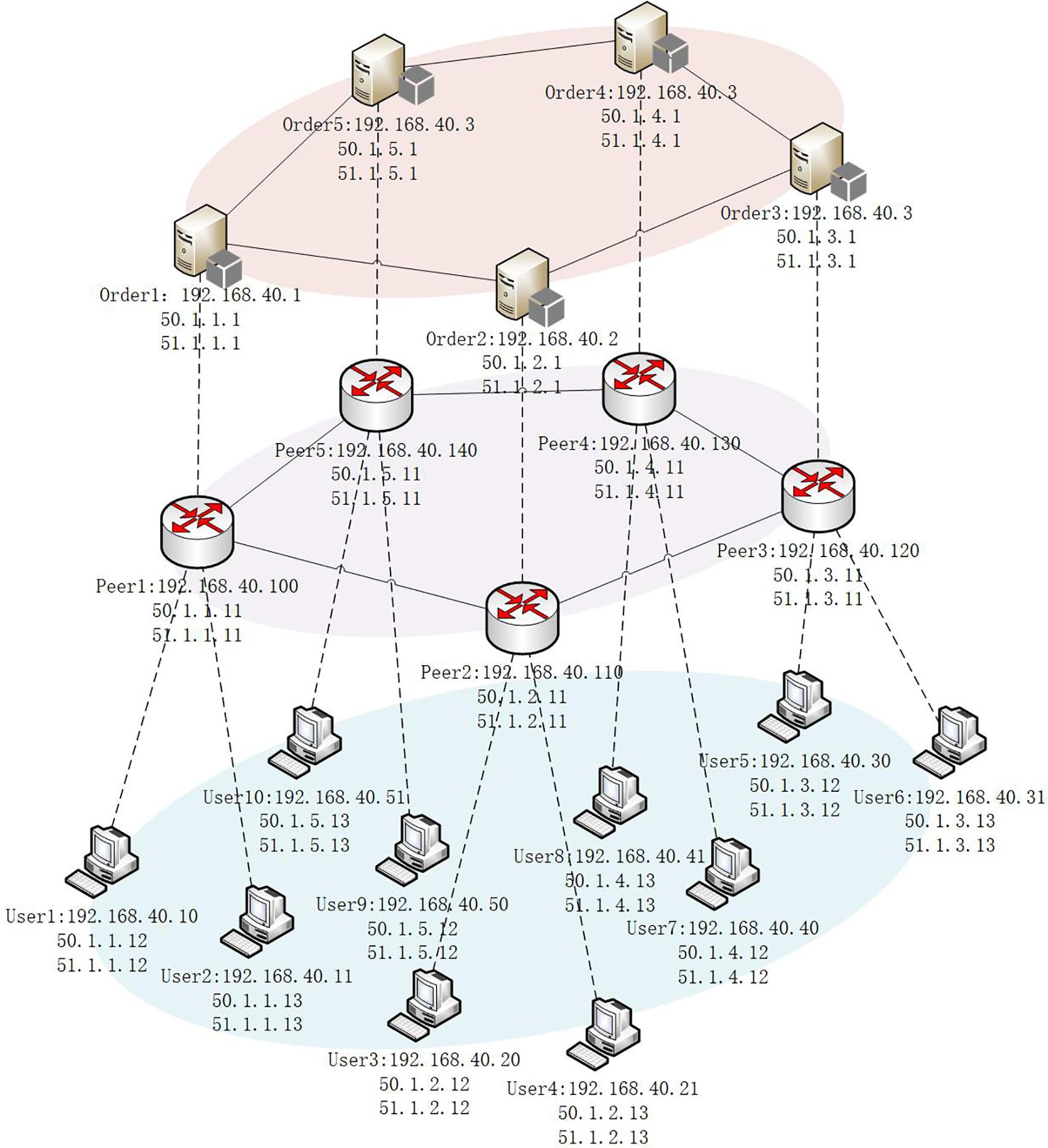

Environment configuration: In this study, the experimental environment is established using a Dell PowerEdge R720 server equipped with the VMware ESXi 6.0 virtualization platform. The platform is accessed and administrated from a personal computer via the VMware vSphere Client, enabling centralized management of the virtualized infrastructure. The virtual machine runs Ubuntu 18.04. Peer nodes play the role of ZTNEs and deploy a blockchain and programmable switch environment. Six virtual machines simulate users and attackers. The five Order nodes are used for sorting the nine blockchain peer nodes. The experimental topology is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Experimental topology

In the virtual machine, Python 3.11 is used to code the protocol part, while Go 1.10.3 is used to write and deploy smart contracts on Fabric 1.4. The ZTNE registration, ZTNE authentication, user registration, user authentication, and user access control processes are implemented by calling the Fabric smart contract interfaces from the Python code. Meanwhile, the smart contract records each user behavior. For users who obtain access privileges, their request behavior is continuously monitored using BMv2, and the probability of malicious behavior is returned in real time via its control plane interface. We have made the DPZTN code publicly available on GitHub: https://github.com/ILScience/DPZTN (accessed on 02 September 2025)

Dataset: The dataset used in this paper is the dataset liliMpro [24] generated and collected by our lab. This dataset was collected by the National Engineering Research Center for Mobile Private Networks of Beijing Jiaotong University, and this paper uses 14 DDoS attack types from it to simulate the attack behavior of malicious users after gaining access.

Malicious behavior: In this paper, three types of user malicious behaviors are used to test the proposed ZTN:

• Unauthorized access: A user elevates his or her privileges beyond their access privilege level. A user access request where they elevate their access privilege level (without being authorized) to achieve an access request that exceeds their privileges.

• Sensitive resource access: Users access sensitive data or resources that are within their normal privileges but should not be accessed frequently.

• DDoS attack: The attacker sends a large number of requests to the target system through multiple controlled computers at the same time, causing the target system to be unable to serve normally, thus interrupting the service.

Behavior patterns: Two malicious behavior patterns are defined to evaluate the system’s sensitivity and adaptability: continuous and intermittent malicious behavior.

• Continuous malicious behavior: This pattern is used to verify the effectiveness of the system in identifying malicious behaviors.

• Intermittent malicious behavior: This pattern is used to verify that the DPZTN maintains a certain degree of sensitivity to episodic malicious behaviors and that the DPZTN has coherent performance in terms of the reputation of cross-malicious behaviors.

With the experimental environment established, we next describe the configuration of key parameters used to evaluate system performance and behavior response.The parameters for user behavior scores are derived using the methods described in Sections 3.4.1 and 3.6.4.

The mapping relationship between the initial access privilege level and the role is as follows:

The value ranges of

Key variables—including initial user privilege levels, attack types, attack intensities, and behavior evaluation strategies—are carefully controlled to ensure that the observed outcomes can be attributed solely to the proposed methods, without interference from external confounding factors. The simulation framework adheres to deterministic rules, and the algorithmic processes are reproducible. Multiple independent trials are conducted to verify the stability and consistency of the results.

4.3 Security and Dynamics Analysis

After configuring the system, we conduct experiments to assess its dynamic security response capabilities under various malicious behavior patterns. In this section, the impact of different user behaviors on the reputation value and risk value of a ZTNE will be analyzed through the dynamic changes of user behavior scores and access privilege levels.

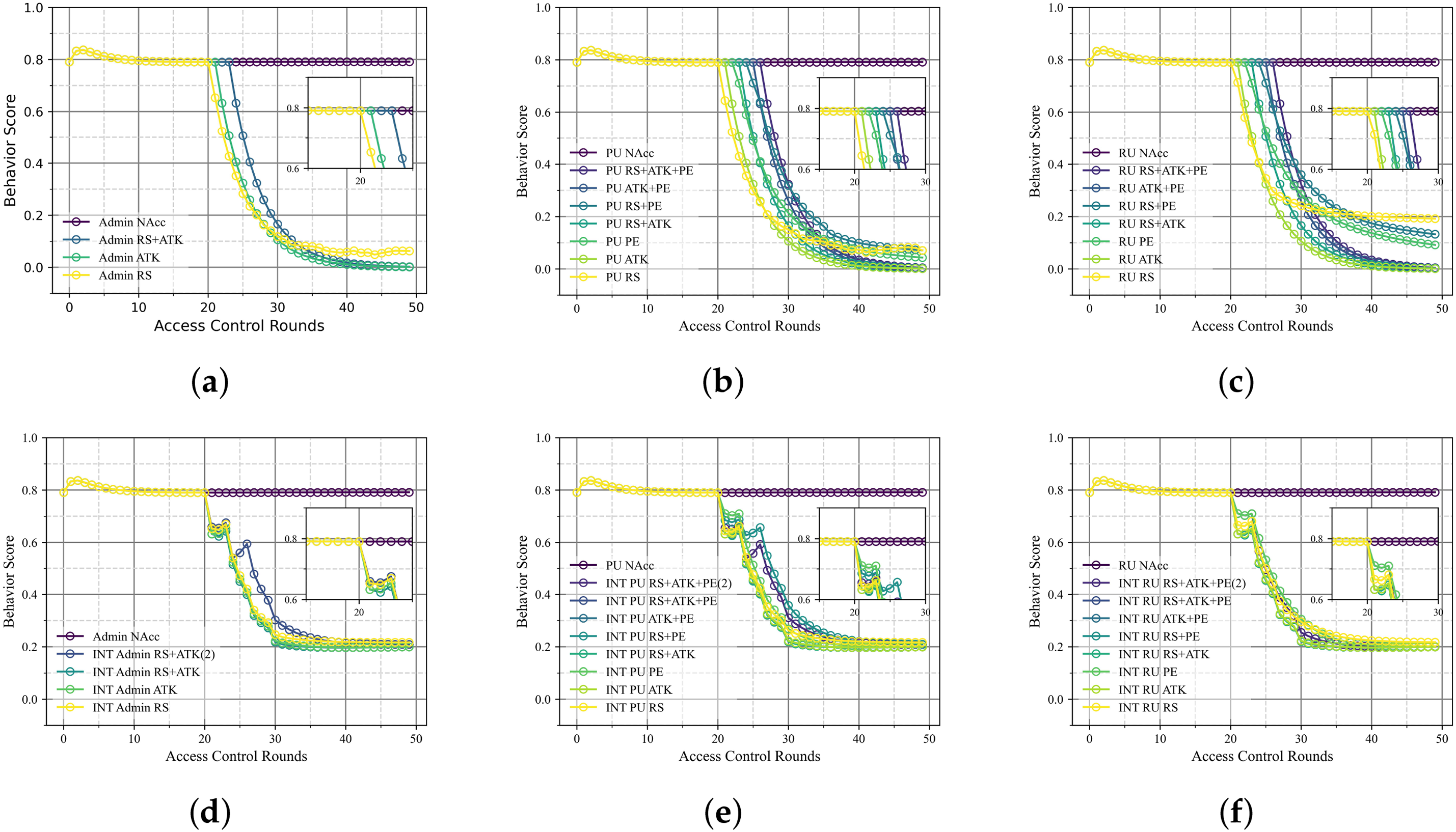

4.3.1 User Behavior Score Analysis

Fig. 6 offers an exposition of the trend of behavior scores of different levels of users (i.e., RU, PU and Admins) when they perform continuous or intermittent malicious behaviors. It is evident that by observing the dynamic changes in behavior scores, a rational foundation is established for the establishment of reasonable behavior score thresholds in the environment of user access control. These malicious behaviors include PE (Privilege Exceeded), RS (Resources Sensitive accessed), and ATK (DDoS Attacks). The figure also provides an analysis of various combinations of attacks (e.g., RS+ATK, RS+PE, ATK+PE, RS+ATK+PE), which serves to further validate the sensitivity of the behavior scores to different types of attacks.

Figure 6: Changes in user behavior score (a) Admin persistent malicious behavior; (b) PU persistent malicious behavior; (c) RU persistent malicious behavior; (d) Admin intermittent malicious behavior; (e) PU intermittent malicious behavior; (f) RU intermittent malicious behavior)

When calculating the behavior score, several constraints are imposed: if the number of illegal access control attempts exceeds 3, SACF is greater than 0.05, or a DDoS attack is detected, the user’s reputation value is penalized and the risk value is significantly increased. This design ensures that the behavior score remains highly sensitive to malicious behaviors.

In the change of behavior scores of Admin users as Fig. 6a shown, the behavior scores remain at a high level, close to 0.8, during normal access; the behavior scores drop rapidly after executing malicious behaviors. In particular, the combination of malicious behaviors leads to a sharp drop in behavior scores to 0.001, indicating that the combination of malicious behaviors has a more significant effect on Admins.

Fig. 6d shows the behavior score variation of the admin with intermittent malicious behavior. The Admin executes malicious behaviors in rounds 20, 23, 26, and 29, respectively, showing a stepwise decreasing trend. Each time the malicious behavior is triggered, the behavior score decreases rapidly, while it remains stable temporarily when it is stopped. As the number of rounds of malicious behavior accumulates, the score eventually converges to 0.197. Even intermittent malicious behavior continues to affect the score and eventually approaches the effect of continuous malicious behavior.

Behavior scores for PUs (Fig. 6b,e) and RUs (Fig. 6c,f) vary similarly to Admins. The behavior score stays around 0.8 for normal access. A single malicious act has a small effect on the behavior score, while a combination of malicious acts causes the behavior score to drop rapidly to near minimum values. Intermittent malicious behaviors also show a stepwise decrease, with the final score approaching 0.197.

Additionally, alternating different malicious behaviors—such as INT RS+ATK+PE (2) was also examined. The results indicate that such alternating behavior patterns do not prevent malicious users from experiencing a decline in behavior scores, thereby confirming the consistency and sensitivity of the scoring mechanism to diverse malicious activity patterns.

In s ummary, the DPZTN is highly sensitive to a wide range of malicious behaviors. Although the intermittent malicious behavior decreases in a stepwise manner, the final impact on the behavior score is comparable to that of the continuous malicious behavior. These results provide a basis for the setting of behavior score thresholds in dynamic access control, and in this paper, 0.7 is chosen as the threshold to effectively restrict the access of malicious users.

4.3.2 User Privilege Level Dynamics Analysis

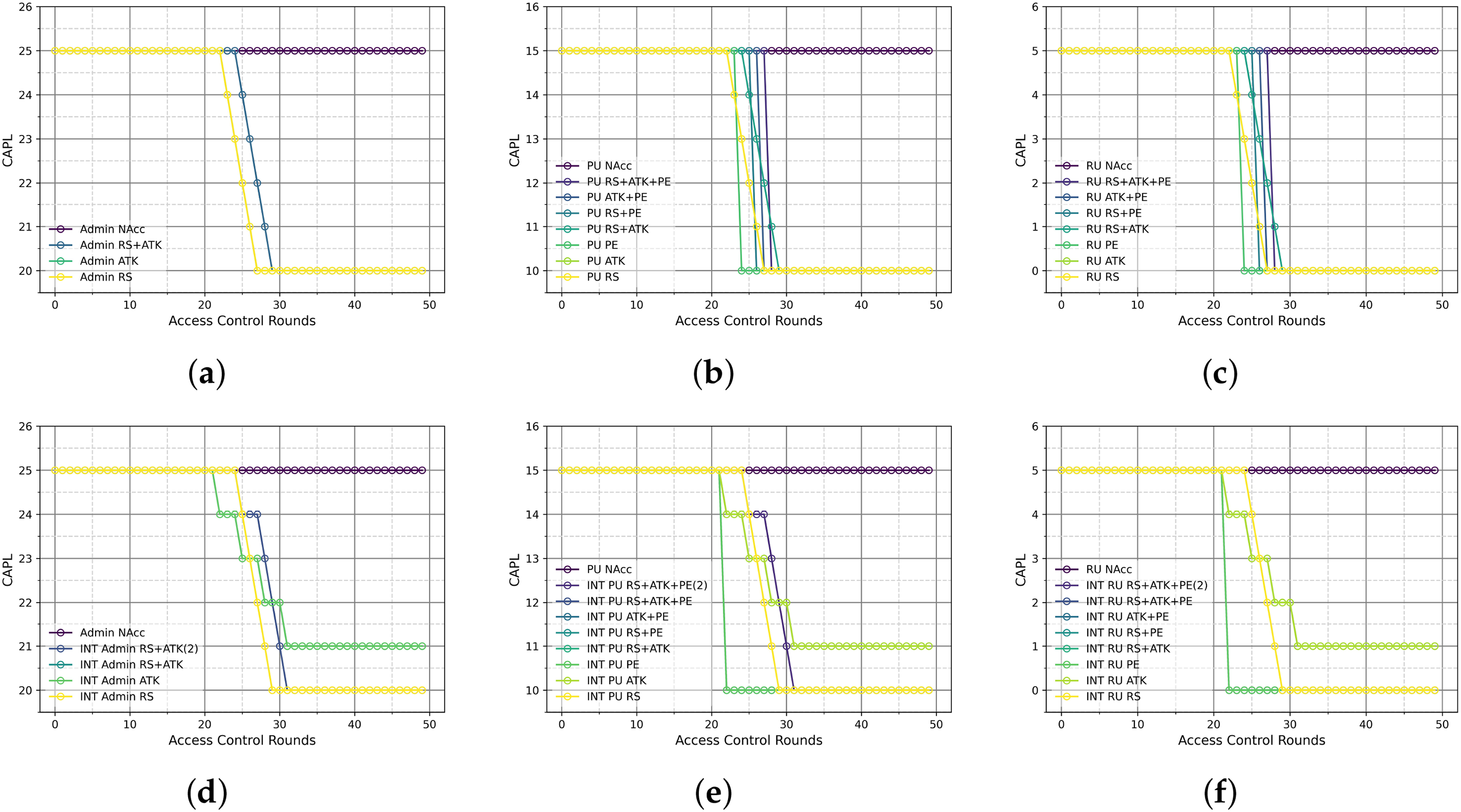

Fig. 7 illustrates the dynamic pattern change of CAPL for different levels of users when they perform continuous or intermittent malicious behavior. Different levels of users behave similarly when receiving malicious behaviors.

Figure 7: Dynamic change of user privilege levels (a) Admin persistent malicious behavior; (b) PU persistent malicious behavior; (c) RU persistent malicious behavior; (d) Admin intermittent malicious behavior; (e) PU intermittent malicious behavior; (f) RU intermittent malicious behavior

Taking the Admin as an example, in the scenario where the Admin sustains malicious behaviors (Fig. 7a), the CAPL stays at the initial value of 25 during normal access, and the CAPL decreases rapidly after the malicious behavior is triggered. The decline rate of combined malicious behavior is consistent with that of single malicious behavior, indicating that alternate malicious behavior fails to slow down the decline of CAPL.

Fig. 7d illustrates the change in CAPL for Admins under intermittent malicious behavior. Each time a malicious behavior is triggered, CAPL decreases significantly in a stepwise trend. When the malicious behavior stops, the CAPL briefly stabilizes but does not return to the previous privilege level, eventually converging to the lowest value of 20.

In summary, user CAPL is stable during normal access, while malicious behavior significantly reduces CAPL, suggesting that the privilege moderation mechanism effectively restricts access. The comparison of continuous and intermittent malicious behaviors shows that the cumulative effect of intermittent malicious behaviors is comparable to that of continuous malicious behaviors. Combined with the behavior score changes in, real-time adjustment of CAPL can effectively restrict malicious user access and improve system security. Moreover, the similarity in the variation trends of user behavior scores and user privilege level across different user levels under the same attack scenarios indicates the stability of the proposed algorithm.

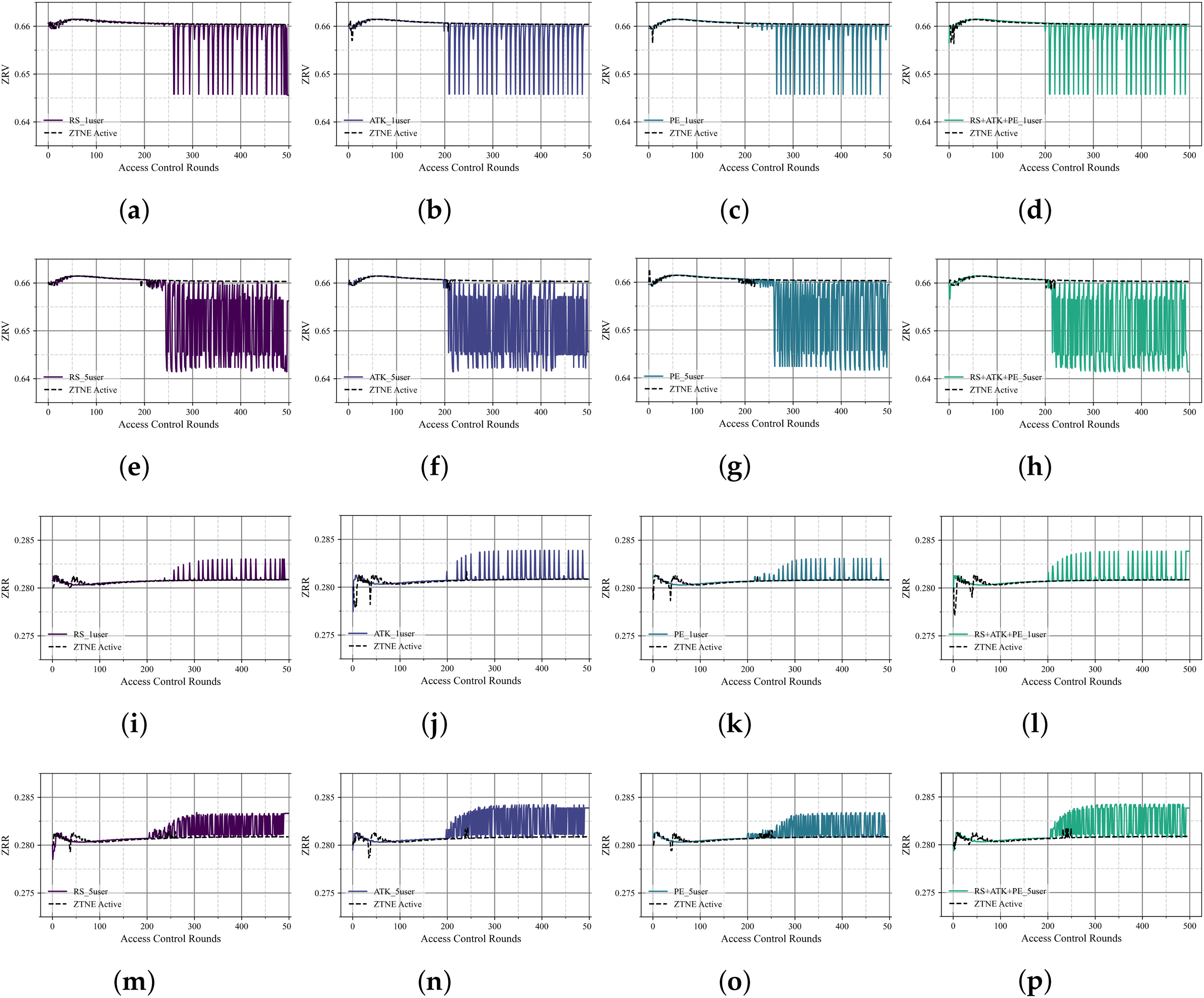

4.3.3 ZTNE Reputation Value and Risk Value Analysis

To assess the impact of malicious behavior on the reputation value of ZTNEs, changes in ZRV and ZRR were analyzed under both persistent and intermittent attack scenarios. The corresponding results are presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Dynamic change of ZRV and ZRR. (a) Changes in ZRV when a user experiences RS; (b) Changes in ZRV when a user experiences ATK; (c) Changes in ZRV when a user experiences PE; (d) Changes in ZRV when a user experiences RS+ATK+PE; (e) Changes in ZRV when 5 users experiences RS; (f) Changes in ZRV when 5 users experiences ATK; (g) Changes in ZRV when 5 users experiences PE; (h) Changes in ZRV when 5 users experiences RS+ATK+PE; (i) Changes in ZRR when a user experiences RS; (j) Changes in ZRR when a user experiences ATK; (k) Changes in ZRR when a user experiences PE; (l) Changes in ZRR when a user experiences RS+ATK+PE; (m) Changes in ZRR when 5 users experiences RS; (n) Changes in ZRR when 5 users experiences ATK; (o) Changes in ZRR when 5 users experiences PE; (p) Changes in ZRR when 5 users experiences RS+ATK+PE

Intermittent single malicious behavior: Intermittent malicious behavior significantly fluctuates the ZTNE reputation value in both single- and multi-user scenarios. ZRVs were affected despite normal behavior in between malicious behaviors. Due to the low frequency of malicious behaviors, the reputation value did not drop dramatically and remained stable overall, ensuring the continuity of normal user behaviors. The drop in the ZRV due to malicious behavior is difficult to recover quickly, and subsequent visits trigger fluctuations in ZRV due to the user’s lower behavior scores, increasing the risk of subsequent visits. DDoS attacks are detected significantly earlier than sensitive resource accesses and transgressing accesses, and the system has the lowest tolerance for DDoS, immediately reducing the user’s behavior scores in response to them once detected. In terms of the ZTNE ZRR, in the single-user scenario, the fluctuation of the ZRR is mainly centered on the periodic occurrence of DDoS attacks, and the ZRR rises and then gradually recovers. However, in multi-user scenarios, the synergistic effect of malicious behaviors leads to increased the ZRR fluctuations, which increases the difficulty of risk management in the system.

Intermittent alternating malicious behavior: The experiment analyzes the impact of alternating malicious behavior on the ZRV of ZTNE. The system first reacts to DDoS attacks, and as the malicious behaviors alternate, the ZRV fluctuation gradually increases, especially in the multi-user scenario, where multiple malicious users collaborate to attack, making the ZRV fluctuate more frequently. Although malicious behaviors occur intermittently, their cumulative effect makes it difficult for ZRV to recover quickly, further aggravating the interference with the system. The range of ZRR fluctuation is greater in alternating malicious behaviors. Multi-user combined malicious behaviors lead to faster ZRR growth and more significant fluctuations in ZRR, indicating that the existing protection mechanism is difficult to cope with complex combined malicious behaviors. It has a weaker inhibition effect on ZRR growth, and the combined malicious behaviors are more disruptive and challenging to the system.

It is worth noting that for the experiments presented in Section 4.3, each was repeated at least three times. However, due to limitations in result clarity, the repeated experimental results are not displayed in Section 4.3.

This section provides a statistical analysis of the CPU usage, memory usage, and the latency variations in the DPZTN workflow. Each system performance-related experiment was conducted at least three times to ensure the reliability and consistency of the results.

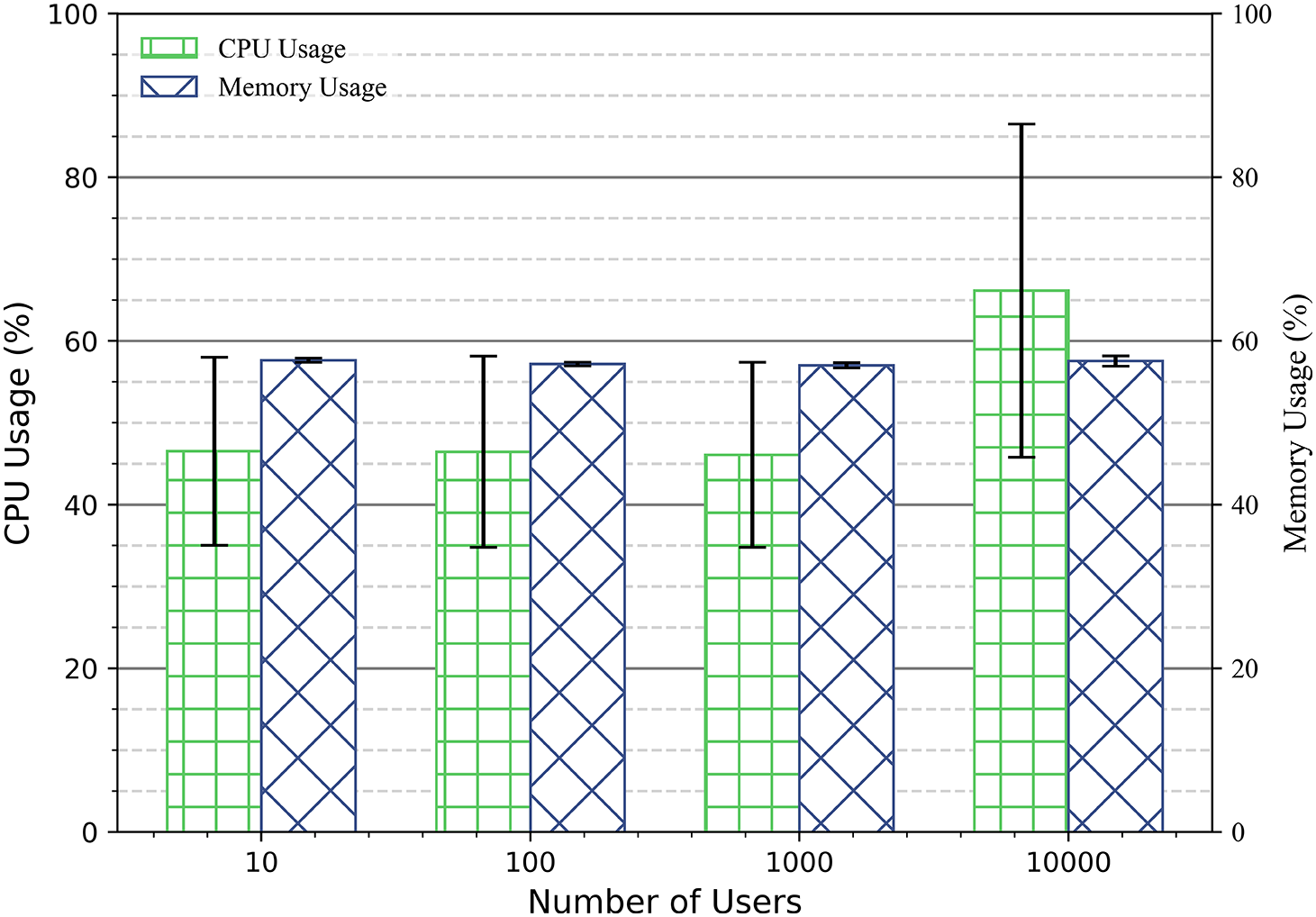

The experiment tested the CPU and memory resource utilization of the DPZTN for different number of users. From Fig. 9, it can be seen that the average CPU usage for 10, 100 and 1000 user scenarios is 50%, and the memory usage is about 60%. When the number of users is 10,000, the average CPU usage rises to about 70% and the memory usage remains the same.

Figure 9: Average CPU and memory usage of the DPZTN in scenarios with different numbers of users

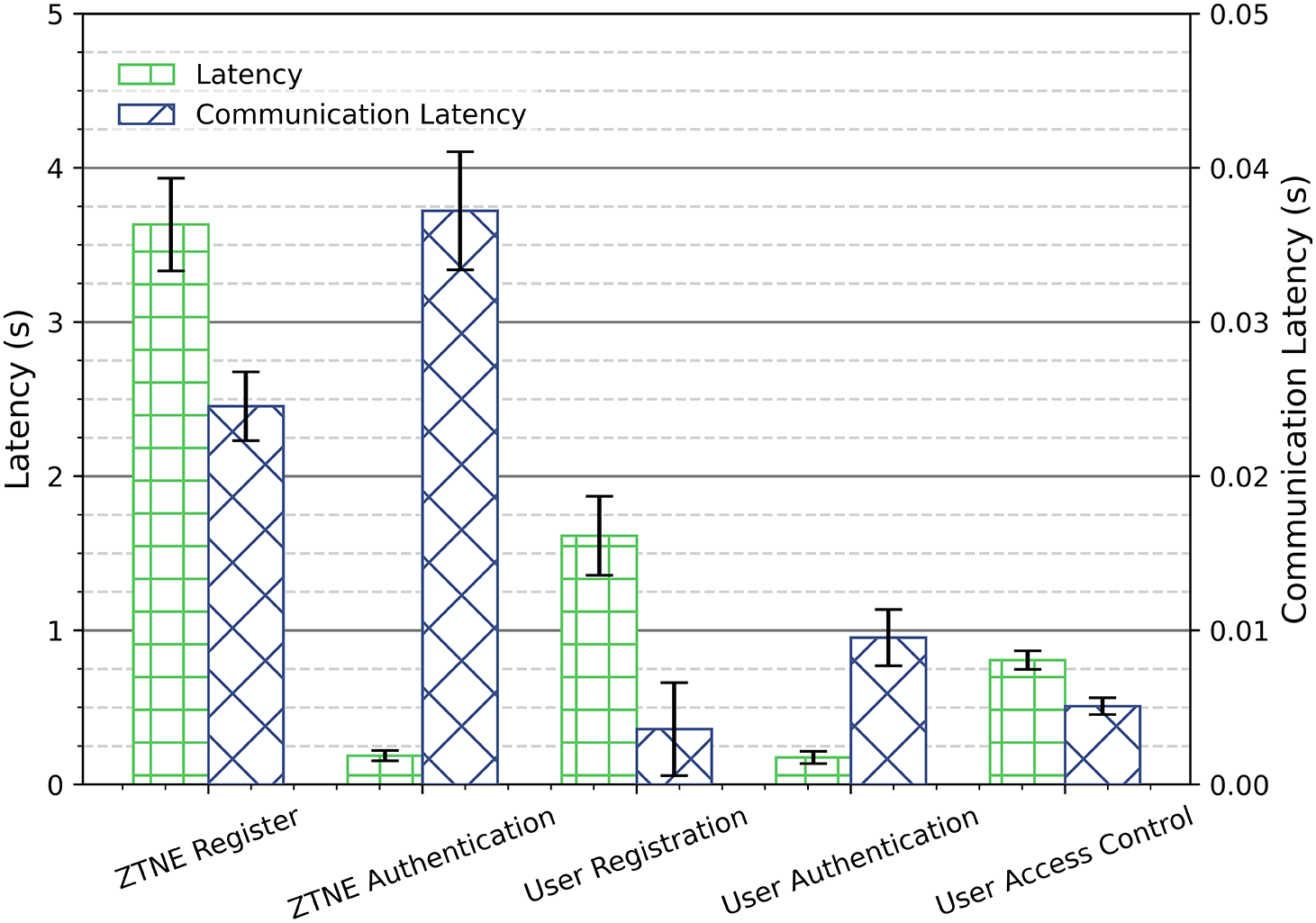

Fig. 10 shows the latency of each phase of the DPZTN. The registration phase has a long latency of about 3.8 s, which is mainly due to the blockchain writing initial information and multi-party verification. The user registration latency is about 2 s, which further validates the impact of blockchain writing on latency. The communication delay in the authentication phase is higher (about 0.06 s), but the total delay is only 0.5 s, indicating that the system optimizes the computational efficiency in the authentication phase. The total delay in the user authentication phase is 0.8 s, and the communication delay is about 0.02 s, with the main delay coming from the computation process. The access control phase has the lowest latency of 0.3 s, showing the efficiency of the session.

Figure 10: Average latency of each phase for the DPZTN

Although the study is based on simulations, the user behavior model, attack scenarios, and permission evolution mechanisms are designed to reflect common patterns observed in real network security incidents, thereby enhancing the realism and represent ativeness of the experiments. The algorithm was also tested under diverse initial conditions and various attack combinations to improve the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that simulation environments cannot fully capture the complexity and unpredictability of real systems. Future work will focus on extending the evaluation to real deployments or hybrid testbeds to further validate the applicability of the proposed model.

To demonstrate the security advantages of DPZTN in IoT environments, this paper presents the defense effectiveness of DPZTN against various threats faced by the network.

• Confidentiality: DPZTN protects against information leakage by encrypting the identity data of users and ZTNE using a hash algorithm before storing it on the blockchain. This prevents unauthorized access and ensures sensitive data remains confidential. Additionally, a mutual authentication mechanism minimizes the risk of impersonation among the blockchain, ZTNE, and users. The integration of ZTNE with blockchain further strengthens identity protection. Details are provided in Sections 3.2 and 3.3.

• Completeness: To defend against tampering, DPZTN stores all authentication and access control data on the immutable blockchain. Communication between IoT devices and ZTNE is encrypted, ensuring data integrity both at rest and in transit. This effectively prevents unauthorized modifications or forgery, as explained in Section 3.2.

• Undeniability: DPZTN immutably records all user identity registrations, access requests, and behavior logs on the blockchain. This ensures traceability and prevents users from denying their behaviors, enabling full auditability. The design prohibits any deletion or alteration of stored data, thereby guaranteeing accountability and transparency. Further details are provided in Sections 3.3 to 3.6.

• Usability: Through a dynamic reputation evaluation algorithm—BBEA, DPZTN limits access for high-risk users, mitigating the threat of DDoS-based resource abuse. ZTNE continuously monitors traffic and can promptly block abnormal behavior, maintaining system availability. See Section 3.5 for more information.

• Least privilege: To counter privilege escalation, DPZTN applies a Bayesian-based behavior scoring mechanism that evaluates user reputation and risk in real time. By continuously monitoring user behavior, the system adjusts privileges dynamically, ensuring access stays within authorized bounds. This ensures that only legitimate users access resources, enhancing overall system security. The mechanism is detailed in Sections 3.4 and 3.6.

This paper presents DPZTN and introduces a BBEA for user behavior-based access control. By integrating BBEA into smart contracts, DPZTN dynamically adjusts user access privileges. The deployed ZTNE accurately detects malicious user behavior using specialized algorithms and monitors changes in user behavior scores to identify and block abnormal behaviors in real time. Experimental results show that DPZTN’s ZTNE supports up to 10,000 users with multiple concurrent access requests. Significant delays only occur during network element and user registration, while access control and authentication introduce minimal latency, demonstrating strong performance and security. The ZTNE also enables zero-trust enforcement at the network element level, enhancing system security and providing dynamic access control.

To further enhance the effectiveness and applicability of the proposed DPZTN architecture, future research will focus on the following three key directions. Enhancing the capability of DPZTN to accurately assess and manage access requests from unknown or previously unseen users through online learning and behavior inference, thereby improving system resilience against zero-day threats. Designing and implementing optimized, resource-efficient smart contracts to enable real-time decision-making in large-scale or resource-constrained environments, such as edge and IoT networks. Extending the DPZTN framework to support secure identity federation and policy coordination across multiple administrative domains, enabling unified zero-trust enforcement in distributed network.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Basic Research Operating Expenses Postgraduate Innovation Programme (Grant No. W24YJS00010, received by J. Yan), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFA0701604, received by H. Zhou), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 62341102, received by H. Zhou).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Jingfu Yan; methodology, Jingfu Yan; validation, Jingfu Yan, Weilin Wang and Huachun Zhou; formal analysis, Jingfu Yan; resources, Jingfu Yan; data curation, Jingfu Yan; writing—original draft preparation, Jingfu Yan; writing—review and editing, Jingfu Yan, Weilin Wang and Huachun Zhou; visualization, Jingfu Yan; supervision, Weilin Wang and Huachun Zhou; funding acquisition, Jingfu Yan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are openly available in liliMpro at https://github.com/liliMpro/source_dataset (accessed on 02 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Group IGP. 6G Trusted Endogenous Security Architecture Study. IMT-2030(6G) Promotion Group; 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Nandy T, Idris MYIB, Md Noor R, Mat Kiah L, Lun LS, Annuar Juma’at NB, et al. Review on security of internet of things authentication mechanism. IEEE Access. 2019;7:151054–89. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2947723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhaofeng M, Jialin M, Jihui W, Zhiguang S. Blockchain-based decentralized authentication modeling scheme in edge and IoT environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(4):2116–23. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.3037733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bradatsch L, Miroshkin O, Kargl F. ZTSFC: a service function chaining-enabled zero trust architecture. IEEE Access. 2023;11(6):125307–27. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3330706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hauser F, Häberle M, Merling D, Lindner S, Gurevich V, Zeiger F, et al. A survey on data plane programming with P4: fundamentals, advances, and applied research. J Netw Comput Appl. 2023;212(3):103561. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2022.103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jose M, Lazri K, François J, Festor O. Stateful InREC: stateful in-network real number computation with recursive functions. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2023;20(1):830–45. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2022.3198008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Itodo C, Ozer M. Multivocal literature review on zero-trust security implementation. Comput Secur. 2024;141:103827. [Google Scholar]

8. Bala B, Behal S. AI techniques for IoT-based DDoS attack detection: taxonomies, comprehensive review and research challenges. Comput Sci Rev. 2024;52(10):100631. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2024.100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rose S, Borchert O, Mitchell S, Connelly S. Zero trust architecture. National institute of standards and technology [Internet]; 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800- 207.pdf. [Google Scholar]

10. Sengupta B, Lakshminarayanan A. DistriTrust: distributed and low-latency access validation in zero-trust architecture. J Inf Secur Appl. 2021;63(6):103023. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Federici F, Martintoni D, Senni V. A zero-trust architecture for remote access in industrial IoT infrastructures. Electronics. 2023;12(3):566. doi:10.3390/electronics12030566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Azad MA, Bag S, Hao F, Shalaginov A. Decentralized self-enforcing trust management system for social internet of things. IEEE I Things J. 2020;7(4):2690–703. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2962282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tu Z, Zhou H, Li K, Song H, Yang Y. A blockchain-based trust and reputation model with dynamic evaluation mechanism for IoT. Comput Netw. 2022;218(15):109404. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2022.109404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Taneja H, Kaur S. Reputation based novel trust management framework with enhanced availability for cloud. J Parallel Distr Comput. 2023;178(5):43–55. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2023.03.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tian J, Tian J, Du R. MSLShard: an efficient sharding-based trust management framework for blockchain-empowered IoT access control. J Parallel Distr Comput. 2024;185(12):104795. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2023.104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Baracaldo N, Joshi J. An adaptive risk management and access control framework to mitigate insider threats. Comput Secur. 2013;39:237–54. [Google Scholar]

17. Dia OA, Farkas C. Risk aware query replacement approach for secure databases performance management. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2015;12(2):217–29. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2014.2306675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Iftikhar N, Rehman MU, Shah MA, Alenazi MJF, Ali J. Intrusion detection in NSL-KDD dataset using hybrid self-organizing map model. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;143(1):639–71. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.062788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Alevizos L, Eiza MH, Ta VT, Shi Q, Read J. Blockchain-enabled intrusion detection and prevention system of APTs within zero trust architecture. IEEE Access. 2022;10(2):89270–88. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3200165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Saquetti M, Canofre R, Lorenzon AF, Rossi FD, Azambuja JR, Cordeiro W, et al. Toward in-network intelligence: running distributed artificial neural networks in the data plane. IEEE Commun Lett. 2021;25(11):3551–5. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2021.3108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mai T, Garg S, Yao H, Nie J, Kaddoum G, Xiong Z. In-network intelligence control: toward a self-driving networking architecture. IEEE Netw. 2021;35(2):53–9. doi:10.1109/mnet.011.2000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shostack A. Threat modeling: designing for security. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014. ISBN-13: 978-1-118-80999-0. [Google Scholar]

23. Yan J, Zhou H, Wang W. Intelligent network element: a programmable switch based on machine learning to defend against DDoS attacks. Inf Syst Front. 2025:1–20. doi:10.1007/s10796-024-10577-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Man L. LiliMpro/source_dataset [Internet]; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: https://github.com/liliMpro/source. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools