Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimization and Scheduling of Green Power System Consumption Based on Multi-Device Coordination and Multi-Objective Optimization

1 Division of New Energy Business, Shandong Electric Power Engineering Consulting Institute Co., Ltd., Jinan, 250013, China

2 School of Thermal Engineering, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, 250101, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jiying Liu. Email: ; Kaiyue Li. Email:

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(6), 2257-2289. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.063918

Received 28 January 2025; Accepted 14 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

The intermittency and volatility of wind and photovoltaic power generation exacerbate issues such as wind and solar curtailment, hindering the efficient utilization of renewable energy and the low-carbon development of energy systems. To enhance the consumption capacity of green power, the green power system consumption optimization scheduling model (GPS-COSM) is proposed, which comprehensively integrates green power system, electric boiler, combined heat and power unit, thermal energy storage, and electrical energy storage. The optimization objectives are to minimize operating cost, minimize carbon emission, and maximize the consumption of wind and solar curtailment. The multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm is employed to solve the model, and a fuzzy membership function is introduced to evaluate the satisfaction level of the Pareto optimal solution set, thereby selecting the optimal compromise solution to achieve a dynamic balance among economic efficiency, environmental friendliness, and energy utilization efficiency. Three typical operating modes are designed for comparative analysis. The results demonstrate that the mode involving the coordinated operation of electric boiler, thermal energy storage, and electrical energy storage performs the best in terms of economic efficiency, environmental friendliness, and renewable energy utilization efficiency, achieving the wind and solar curtailment consumption rate of 99.58%. The application of electric boiler significantly enhances the direct accommodation capacity of the green power system. Thermal energy storage optimizes intertemporal regulation, while electrical energy storage strengthens the system’s dynamic regulation capability. The coordinated optimization of multiple devices significantly reduces reliance on fossil fuels.Keywords

Addressing climate change becomes a core objective of the global energy transition, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions consequently emerges as a priority in national energy policies. Wind and solar energy, as primary renewable energy sources, gaining widespread adoption due to their low-carbon and environmentally friendly characteristics [1]. Unlike traditional fossil fuels, these renewable energy sources produce almost no harmful emissions during power generation and do not deplete finite natural resources, earning them the title of “green power energy” [2]. In addition, wind and solar energy show significant resource complementarity in both time and spatial scales. Solar energy reaches its peak generation during the day when radiation is strongest, while wind energy typically exhibits greater generation potential under high wind conditions [3]. Therefore, the combined use of wind and solar power becomes an important method for optimizing green power system. Effectively utilizing the temporal and spatial complementarity between wind and solar energy can significantly alleviate the random fluctuations of renewable energy production in the entire green electricity system [4]. In remote areas with abundant sunlight and wind, off-grid hybrid wind-solar-storage power generation systems hold considerable application value. By integrating green power system with fossil fuels and other energy forms, these systems fully exploit the advantages of different energy sources, overcoming the limitations of volatility and randomness associated with single energy sources, and providing solutions for stable energy supply across all weather conditions and seasons [5]. Despite the significant advantages of hybrid wind-solar-storage power generation systems in promoting low-carbon energy structures and improving renewable energy utilization efficiency, wind and solar power generation is still significantly affected by weather conditions, displaying intermittent, random, and uncertain characteristics [6,7]. Renewable energy technologies, including solar and wind energy, are pivotal in shaping a sustainable and resilient future power grid [8,9]. As the loads of electric vehicles continue to rise, grid-connected electric vehicle charging stations (EVCS) powered by solar and wind energy can further reduce energy costs and mitigate electricity surplus [10]. Meanwhile, due to the significant mismatch between the temporal and spatial distribution of load demands and the generation capabilities of wind and solar energy, coordinating the supply and demand of energy becomes difficult, leading to the issue of wind and solar curtailment [11,12]. In the actual scheduling of green electricity systems, how to reasonably schedule various devices under the dual constraints of complex load demands and fluctuations in wind and solar power generation, and efficiently absorb green electricity energy, remains a challenge in the field of energy optimization [13].

In recent years, both domestic and international scholars conducted research on the scheduling of green power system from multiple angles and directions, achieving results in areas such as equipment capacity configuration optimization and algorithm optimization [14–16]. Rational equipment capacity configuration optimization plays a crucial role in reducing wind and solar curtailment rates [17,18]. To smooth the fluctuations in green power generation from wind and solar energy and reduce wind and solar curtailment, a common solution is to utilize energy storage systems to store part of the generated energy [19]. Intermittent solar and wind power can be harnessed as energy sources for electric vehicle charging stations. Meanwhile, battery storage technology has enhanced the stability and reliability of power supply from renewable energy sources [20]. Designing microgrid power supply systems that include solar photovoltaics, wind turbines, and battery energy storage systems can provide the most stable power output and achieve optimal equipment configuration solutions in terms of economic benefits and environmental impact [21]. Reference proposes using numerical weather prediction models to generate photovoltaic power generation forecasts, which are then integrated into optimal control strategies that include battery storage to maximize the utilization efficiency of photovoltaic systems [22]. A techno-economic model is developed to determine and optimize the size and cost of lithium-ion battery storage systems, exploring the commercial feasibility of battery storage in the field of wind power accommodation [23]. Additionally, a four-step iterative method is developed to generate the optimal capacity and power configuration for battery energy storage systems, mitigating the output volatility of photovoltaic power generation, increasing solar power accommodation, and ensuring stable system operation [24]. However, load demand is complex, and battery energy storage system only provide short-term solutions. To address winter heating demands and explore more efficient and sustainable green power accommodation solutions, some researchers incorporate electric heating boilers into system configurations. A proposed integrated system based on combined heat and compressed air energy storage, electric boiler, and combined heat and power (CHP) technology can significantly enhance the operational flexibility of CHP unit, reducing wind curtailment and carbon emissions [25].

In the research focused on optimizing green electricity applications, a wide variety of algorithms have been employed [26,27], Table 1 showcases the published studies on algorithm applications and their corresponding research outcomes, spanning from the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm to the simulated annealing algorithm. These achievements illustrate the enhancements made during the algorithm iteration process, and this diversity serves as a foundation for the refinement and improvement of the algorithm in this research. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm is widely applied to solve nonlinear, multi-objective, and constrained optimization problems due to its simplicity, robustness, and strong global search capabilities [28]. The Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) algorithm, an extension of PSO, is specifically designed to address multi-objective optimization problems [29]. MOPSO updates the positions of the particle swarm globally and constructs a uniformly distributed non-dominated solution set based on Pareto dominance relationships. Compared to algorithms such as the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) and Genetic Algorithms (GA), MOPSO can effectively balance conflicts among objectives and converge more quickly to the Pareto front [30]. Leveraging the collaborative mechanism of the particle swarm, MOPSO performs parallel searches within the swarm, demonstrating superior global search capabilities compared to simulated annealing algorithms [31]. Additionally, MOPSO exhibits strong high-dimensional problem-solving capabilities, flexibility, and robustness when dealing with complex nonlinear coupling relationships of electro-thermal loads and multiple constraints, making it highly efficient in addressing such issues [32]. Therefore, MOPSO is an effective algorithmic tool for solving problems involving multi-device coordination and multi-objective optimization. MOPSO is used to explore the correlation between wind and solar power curtailment rates and the levelized cost of energy [33]. A dual-layer optimization algorithm based on multi-objective particle swarm optimization and ideal solution similarity ranking is employed to improve the dynamic behavior and performance of wind power hybrid systems with CHP units. The proposed optimization scheme, focusing on reducing wind power curtailment, significantly reduces wind power cutbacks and enhances the operational flexibility of CHP units [34].

{\leftskip0pt\rightskip0pt plus1fill}p{#1}}?> {\leftskip0pt plus1fill\rightskip0pt plus1fill}p{#1}}?>In summary, current research on the accommodation of green power systems is encompassed various aspects, including equipment capacity configuration optimization and algorithm optimization, achieving rational allocation of resources and energy while improving computational efficiency. These studies provide important references for optimizing green power system accommodation. However, most research tends to focus on single-objective optimization, such as economic or environmental optimization, lacking systematic exploration of coordinated dispatch for wind and solar curtailment. Additionally, the balance among economic benefits, environmental benefits, and energy utilization efficiency during system operation isn’t adequately considered [38–40]. When addressing multi-objective problems, some studies convert multi-objective optimization into single-objective optimization by assigning weights. However, this weighting approach relies on subjective judgment and lacks a scientific trade-off mechanism. The conflicts and complex trade-off relationships among multiple objectives are not fully incorporated, leading to biased optimization results [41]. Furthermore, in load optimization, many studies focus solely on meeting either electrical or heating loads, neglecting the coupling characteristics between electrical and heating loads, as well as the interactions and coordinated scheduling requirements among energy storage devices, thermal storage devices, and load demands. This oversight limits the overall dispatch efficiency of the system [42,43]. Furthermore, most static scheduling models find it challenging to address the temporal fluctuations of wind and solar power generation, as well as the dynamic variations in load demand.

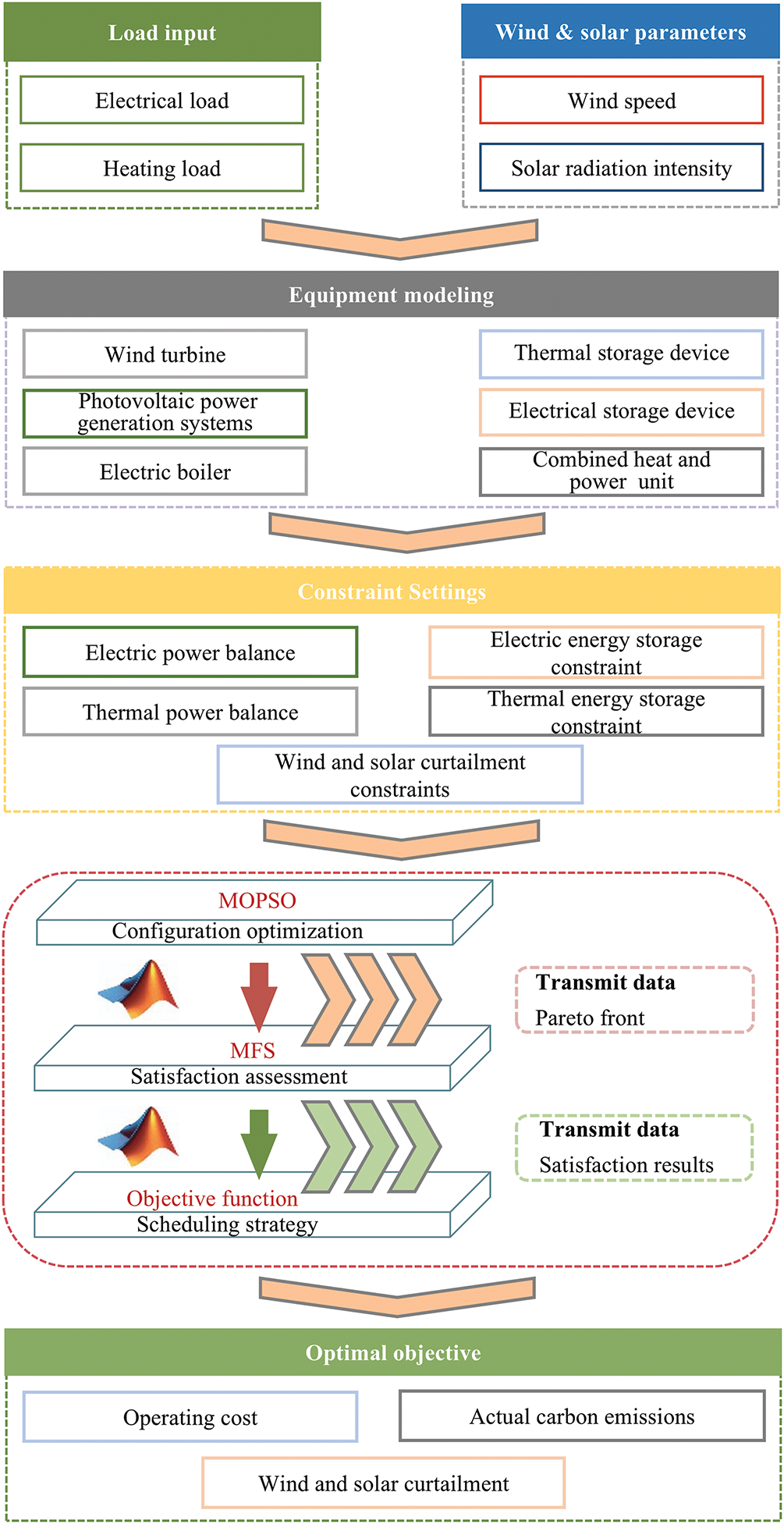

Based on the analysis above and the existing issues in current research, the green power system consumption optimization scheduling model (GPS-COSM) based on multi-device coordination and multi-objective optimization is proposed, as shown in Fig. 1. Electric boilers, thermal energy storage, electrical energy storage, and CHP units are systematically integrated, giving rise to a multi-equipment collaborative dispatching mechanism featuring cross-period dynamic adjustment. The crucial role of equipment collaboration in enhancing the consumption capacity of renewable energy is thoroughly demonstrated. This model is solved using the MOPSO algorithm, constructing a multi-objective optimization framework with the goals of minimizing operational costs, minimizing carbon emissions, and maximizing the consumption of wind and solar curtailment. This innovation overcomes the constraints of single-objective optimization commonly seen in traditional studies. MOPSO is employed. By integrating the calculation of crowding distance with the Pareto dominance relationship, it significantly boosts the efficiency of solving multi-objective high-dimensional constraint problems. The combination of the MOPSO algorithm and the fuzzy membership function enables scientific decision-making free from subjective weighting. The fuzzy membership function is utilized to assess the satisfaction of the Pareto optimal solution set, thereby resolving the issue of subjective weighting in the intricate trade-offs among multiple objectives. This not only strengthens the algorithm’s robustness under electro-thermal coupling constraints but also fills the theoretical void in the multi-objective trade-off mechanism for this type of system. As a result, GPS-COSM achieves a dynamic equilibrium among the economic viability, environmental sustainability, and energy efficiency of the green power system.

Figure 1: Architecture diagram of the GPS-COSM

2 Model Configuration and Operation Strategy

To address the inherent volatility and intermittency of wind and solar power generation and to effectively enhance the consumption capacity of renewable energy, the GPS-COSM is established based on multi-device coordination and multi-objective optimization. The model aims to dynamically balance the supply and demand of electrical and heating loads, integrating the collaborative operation of various energy storage devices. While maximizing the consumption of green power, the model optimizes system operating costs and carbon emissions, achieving comprehensive improvements in economic benefits, environmental benefits, and energy utilization efficiency.

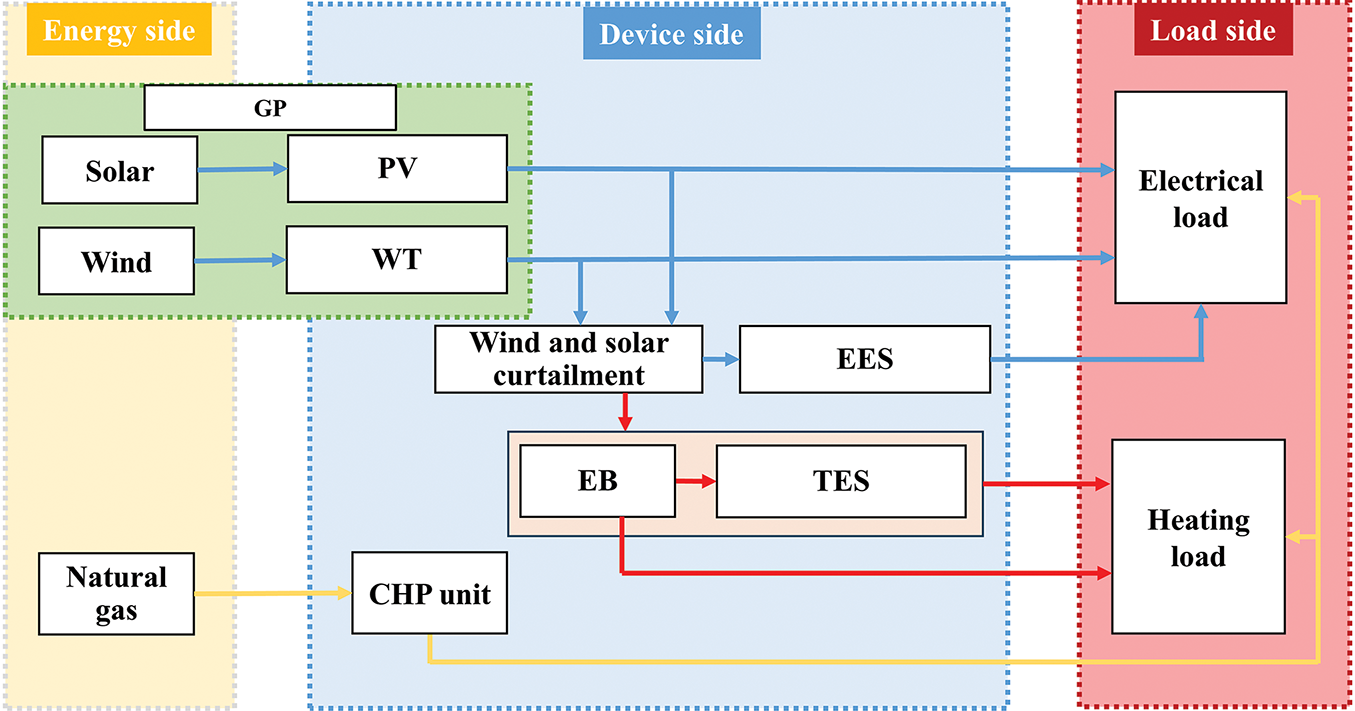

A schematic diagram of the model structure is shown in Fig. 2. The core components of the model include the green power system (GP), electric boiler (EB), thermal energy storage (TES), electrical energy storage (EES), and CHP unit. The GP consists of wind turbine (WT) and photovoltaic power generation system (PV), serving as the primary source of electricity supply to meet electrical load demands. However, its generation capacity is influenced by weather conditions, exhibiting randomness and intermittency, which can lead to wind and solar curtailment. To maximize the utilization efficiency of the GP, EB is used to convert excess electrical energy into thermal energy to meet heating load demands, working in coordination with TES for dynamic regulation of heating load. EES further balances electrical load fluctuations through peak shaving and valley filling functions. CHP unit, powered by natural gas as an external energy source, serve as auxiliary energy providers, meeting both electrical and heating load demands and ensuring the reliability of energy supply under special load conditions.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the model structure

To verify the proposed GPS-COSM, three typical operating modes were designed for comparative analysis, each representing the operational characteristics under different equipment configurations and dispatching logics.

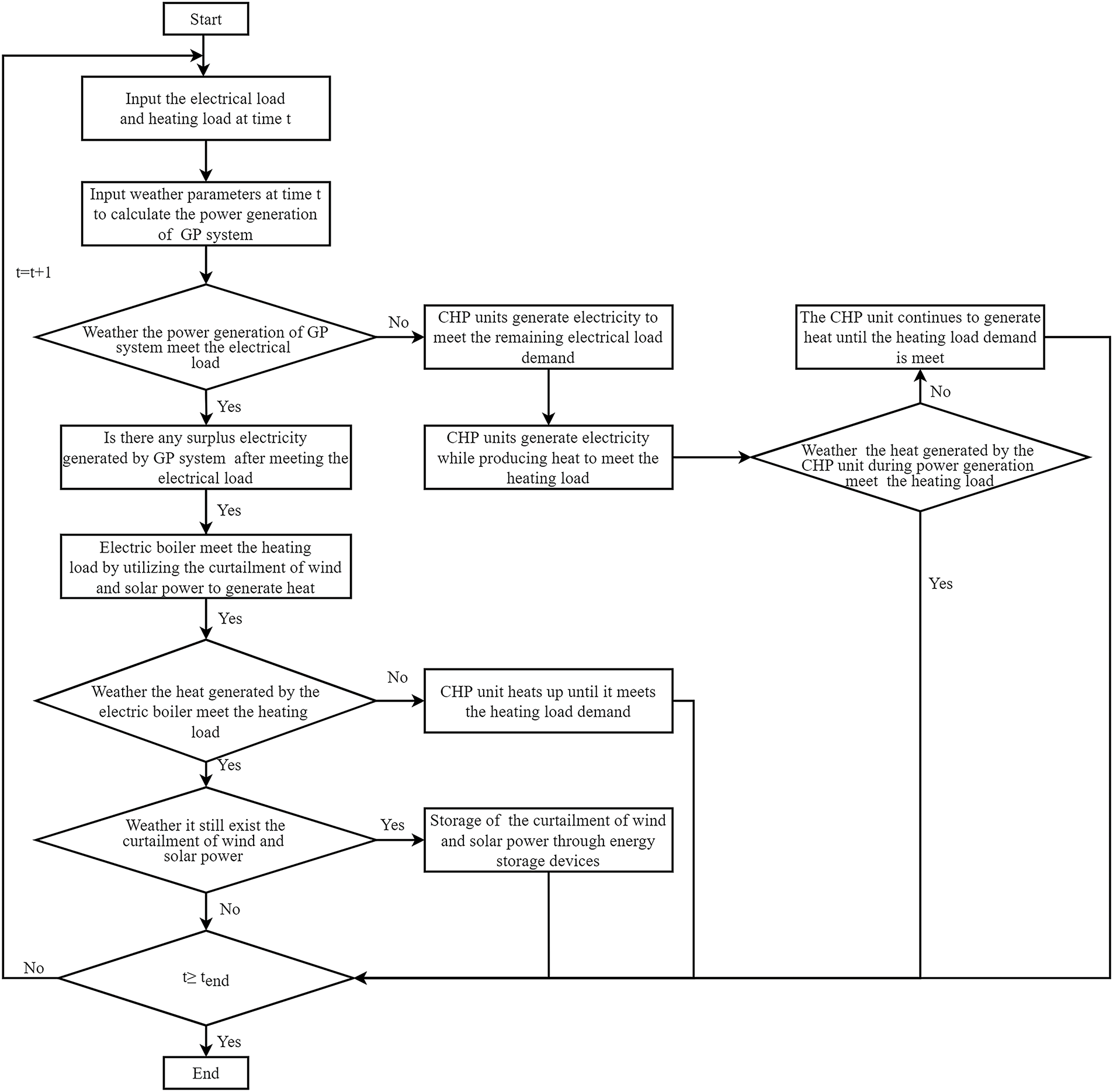

Operating Mode-1 (OM-1): Traditional Mode (Heat-Determined Electricity Generation)

In this mode, the GP, CHP unit, and EES are configured. The GP primarily meets the electrical load demand, and the remaining curtailment of wind and solar power is stored by the EES. The heating load is entirely supplied by the CHP unit, which also synchronize partial electrical load supply through the “heat-determined electricity generation” dispatching logic. The operational logic at time t is shown in the following Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Logical diagram of OM-1

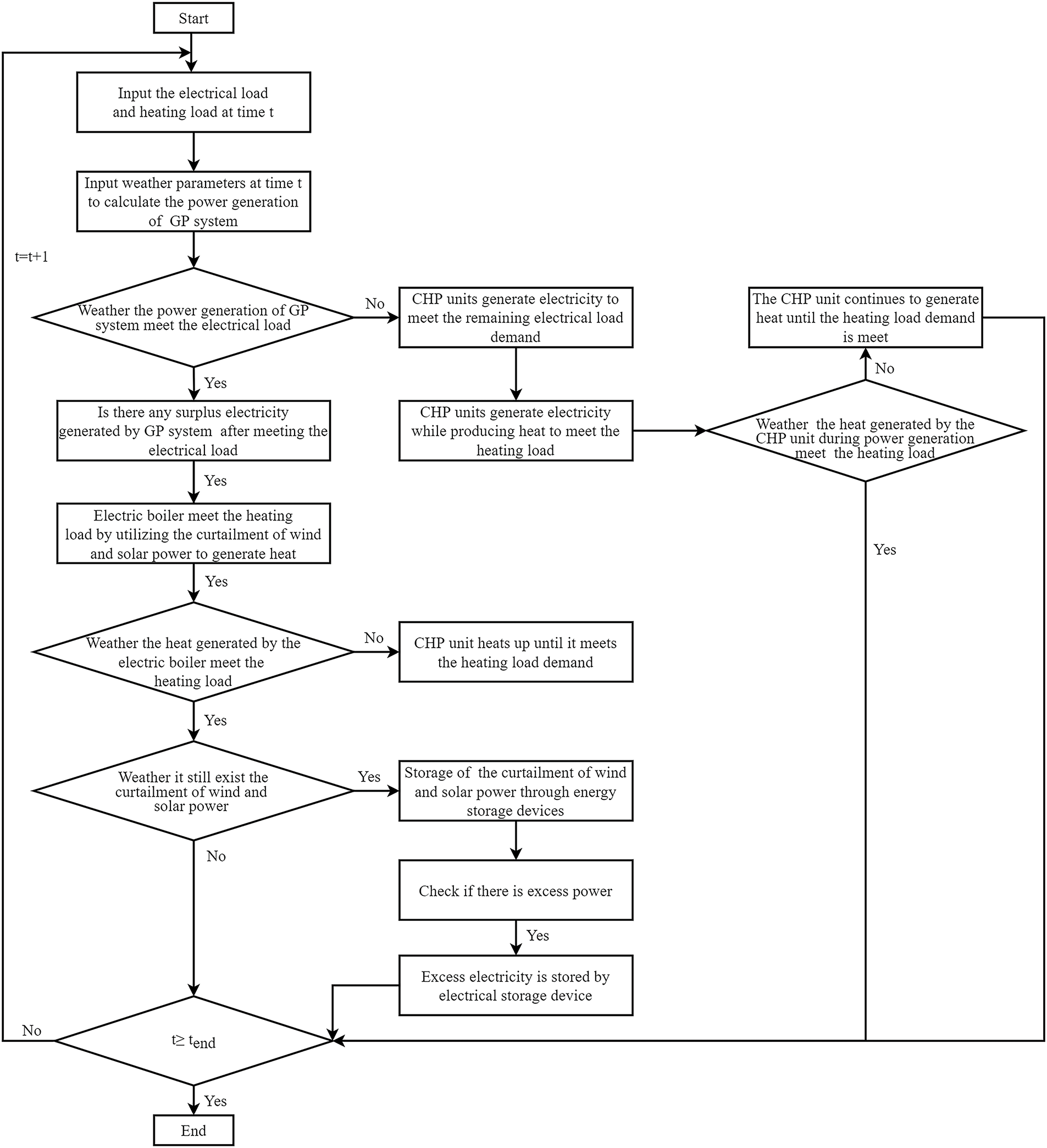

Operating Mode-2 (OM-2): Electric Boiler Mode (Adding EB)

Building on OM-1, EB is added to form a system configuration consisting of the GP, CHP unit, EB, and EES. GP prioritizes meeting the electrical load demand; the remaining curtailment of wind and solar power is converted into heat by the EB to meet the heating load. After satisfying the electrical and heating load, the excess curtailment of wind and solar power is stored in the EES. When the EB cannot fully meet the heating load, the CHP unit supplements the supply. The operational logic at time t is shown in Fig. 4 below.

Figure 4: Logical diagram of OM-2

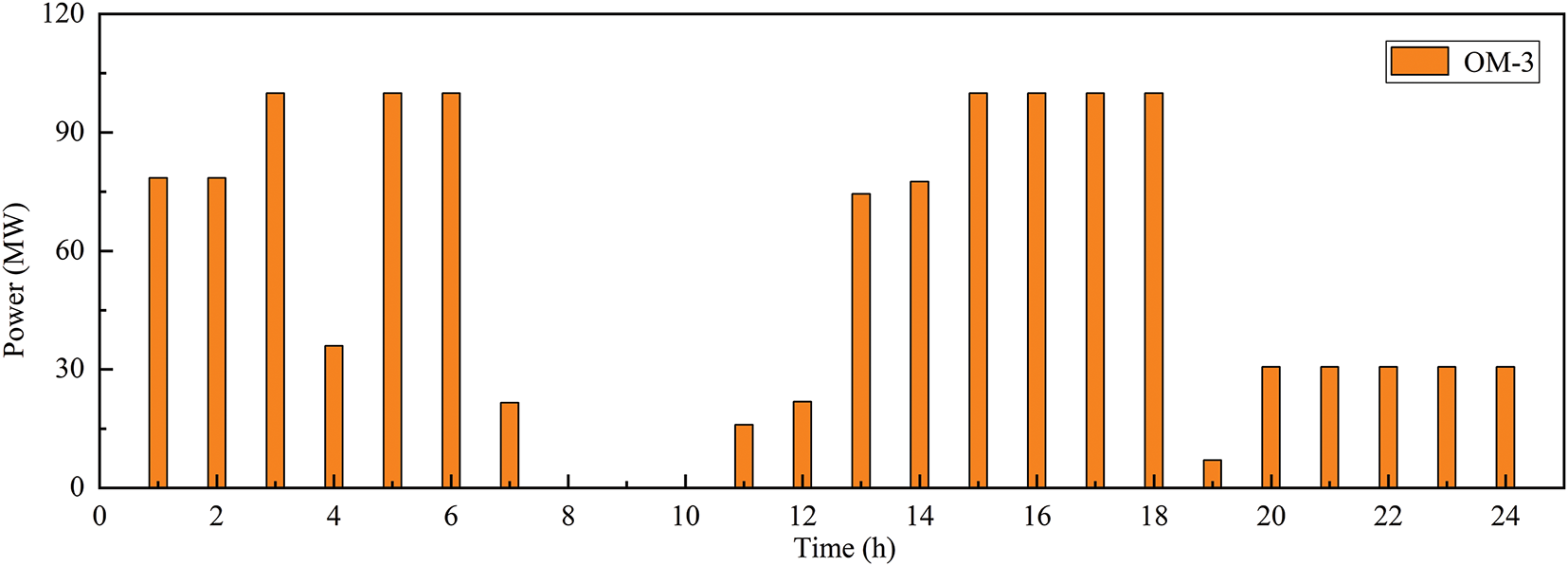

Operating Mode-3 (OM-3): Comprehensive Optimization Mode (GPS-COSM)

Building on OM-2, this mode further incorporates TES, forming the GPS-COSM that includes GP, CHP unit, EB, EES, and TES. GP prioritizes meeting the electrical load demand, while the remaining curtailment of wind and solar power is converted into thermal energy by the EB to meet the heating load demand. After the heating load demand is satisfied, the TES continue to consume the remaining curtailment of wind and solar power. When the TES reach full capacity, any remaining curtailment of wind and solar power is stored in EES. CHP unit acts as a supplementary source. The operational logic at time t is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Logical diagram of OM-3

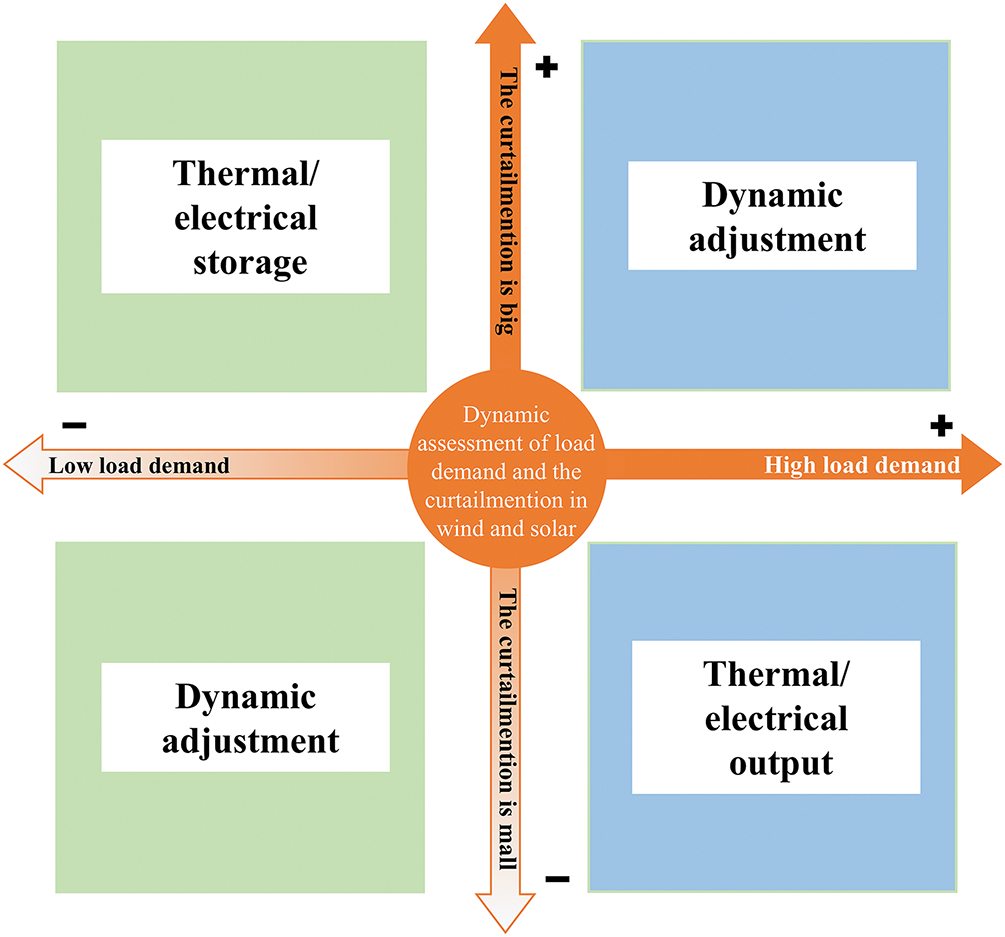

2.3 Curtailed Wind and Solar Power Scheduling Strategy

To maximize the model’s capacity for consuming green power and reduce energy waste caused by wind and solar curtailment, the scheduling strategy based on dynamic priority adjustment is designed, as shown in Fig. 6. By comprehensively analyzing electrical and heating load demands, the variability of wind and solar power generation, and the status of energy storage devices, the strategy achieves efficient utilization of the curtailment of wind and solar power. The scheduling priority is dynamically adjusted based on changes in the curtailment of wind and solar power and load demands, ensuring optimal energy allocation under different operating conditions [44,45].

Figure 6: Scheduling strategy diagram for the curtailment of wind and solar power

Specifically, when the curtailment of wind and solar power is high and the electrical load demand is low, the system prioritizes electrical storage. At this stage, EES efficiently store excess electricity, providing flexibility for subsequent electrical load demands. The core objective is to maximize the utilization efficiency of renewable energy and avoid energy waste caused by power surplus. Conversely, when the curtailment of wind and solar power is low and the electrical load demand is high, the system prioritizes discharging. EES quickly release stored electricity to meet load demands, ensuring power supply stability and system operational reliability.

In terms of thermal energy dispatch, when the curtailment of wind and solar power is high and the heating load demand is low, the system prioritizes thermal storage. At this stage, TES convert excess electricity into thermal energy for storage, improving the consumption efficiency of the curtailment of wind and solar power and providing flexibility for subsequent heating load adjustments. On the other hand, when the curtailment of wind and solar power is low and the heating load demand is high, the system prioritizes releasing stored thermal energy to meet heating load demands in a timely manner.

PV is one of the most important power sources in the GP. It converts solar energy directly into electricity through the photovoltaic effect [46].

where

where

WT is also one of the most important power sources in the GP, converting wind energy into electricity. Wind speed is the primary factor influencing the amount of wind energy that can be harnessed [47].

where

EB converts electrical energy into thermal energy to meet heating load demands [48].

where

TES is an important component of the GPS-COSM, serving two primary functions. It efficiently stores thermal energy and, through its integration with EB, plays a significant role in the consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power.

where

3.1.5 Combined Heat and Power Unit

CHP unit serve as a supplementary source for meeting both thermal and electrical load demands. Among them, gas turbines (GT) use natural gas as fuel to provide electricity and heat, achieving the cascaded utilization of energy [49].

where

where

3.1.6 Electrical Energy Storage

EES is an effective means for the system to consume the curtailment of wind and solar power [50].

where

Based on multi-device coordination and multi-objective optimization, GPS-COSM is established. The objective functions are to minimize system operating costs, maximize the consumption of wind and solar curtailment, and minimize the actual carbon emissions of the system. The aim is to balance economic benefits, renewable energy utilization efficiency, and the low-carbon operation of the system, seeking the optimal equilibrium among the three to achieve efficient system operation and green development goals.

The system operating costs primarily include fuel costs and the costs associated with wind and solar curtailment. Among these, fuel costs refer to the natural gas expenses required for the operation of CHP unit in the system. The costs of wind and solar curtailment represent the potential losses due to the underutilization of green power generation. Introducing the costs of wind and solar curtailment reflects the system’s capacity to consume green power during operation [44].

where

where

where

3.2.2 The Curtailment of Wind and Solar Power

The curtailed wind and solar power in the system is primarily consumed through EB, TES, and EES. Maximizing the system’s capacity to consume the curtailment of wind and solar power involves optimizing the coordinated operation of EB, TES, and EES. This ensures that the system achieves the maximum utilization of green power through rational dispatch [51].

where

3.2.3 The Actual Carbon Emissions of System

The actual carbon emissions of system originate from the carbon dioxide emissions produced by the combustion of natural gas during the operation of CHP unit. By rationally optimizing dispatch to reduce the system’s reliance on CHP unit, the goal of minimizing carbon emissions can be achieved [52].

where

3.3.1 System Energy Balance Constraints

The system operation must satisfy the electrical power balance constraint and the heating power balance constraint [53,54].

Electrical power balance:

where

Heating power balance:

where

3.3.2 Wind and Solar Curtailment Constraints

At any time t, ensure that the amount of the curtailment of wind power and the curtailment of solar power consumed by the system does not exceed the curtailment of wind power and the curtailment of solar power generated at that time.

3.3.3 Electrical Energy Storage Constraints

The operation of EES is subject to constraints on charging and discharging power [55].

The state of charge of EES must satisfy the upper and lower limit requirements:

where

The state of charge of EES must satisfy the following constraints.

where

3.3.4 Thermal Energy Storage Constraints

TES is subject to constraints on heat charging and discharging power as well as thermal storage capacity, ensuring efficient storage and release of thermal energy [56].

Capacity Constraints of TES:

where

Input and Output Power Constraints of TES:

where

At any given time, TES can only perform either heat storage or heat release activities.

4.1 Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization

The PSO algorithm was proposed by Kennedy and Eberhart in 1995, inspired by the foraging behavior of bird flocks and the movement patterns of fish schools. PSO uses position and velocity update mechanisms to leverage population collaboration in finding the optimal solution to a problem [57]. However, multi-objective optimization involves finding multiple solutions to describe the Pareto front rather than a single optimal solution. Since PSO was originally designed for single-objective optimization problems, it cannot be directly applied to multi-objective optimization [58]. In 2002, Coello and others introduced MOPSO, extending PSO to the field of multi-objective optimization [59]. Its core concepts are as follows: introducing the Pareto dominance concept to guide particles in searching the objective space; improving the velocity and position update rules of particles to meet the requirements of multi-objective optimization; and designing update strategies (e.g., crowding distance, grid-based distribution methods, clustering techniques) to maintain solution diversity, enhance diversity control, and avoid falling into local optima [60,61]. The main mathematical expressions are as follows:

(1) Particle velocity update formula

(2) Particle Position Update Formula

where

(3) Fitness Evaluation

where

(4) Pareto Dominance Determination

Given two solutions A and B, if A is not inferior to B in all objectives and is superior to B in at least one objective, then A is said to dominate B, denoted as A

(5) Crowding Distance Calculation

Ultimately, the aim of MOPSO is to produce a solution set that encompasses multiple Pareto optimal solutions. These solutions, taken together, vividly depict the trade-off relationships among diverse objectives. In the realm of multi-objective optimization, typically, there isn’t one solitary, all-encompassing global optimal solution [62]. Instead, what exists is a Pareto optimal solution set made up of numerous solutions, where each solution represents a compromise struck between different goals. During this procedure, to further refine the decision-making process, the research utilizes the Fuzzy Membership Function (MFS) to assess the satisfaction level of each solution within the Pareto solution set. By computing the satisfaction degree of each individual solution, the ultimate compromise solution can be pinpointed and selected [63].

(1) Design of the Fuzzy Membership Function

Minimization Objectives:

Maximization Objective:

where

(2) Calculation of Comprehensive Satisfaction Degree

where

(3) Selection of the Optimal Solution

where

The above formula calculates the satisfaction degree of each solution by mapping the objective function values to the range of [0, 1]. A higher satisfaction degree indicates that the solution performs better in the corresponding objective. By taking the weighted average of all objective functions, the overall satisfaction degree of each solution is obtained, to screen out the optimal compromise solution. In this way, we select the optimal solutions corresponding to the three objective functions. Table 2 shows the definitions of objective functions.

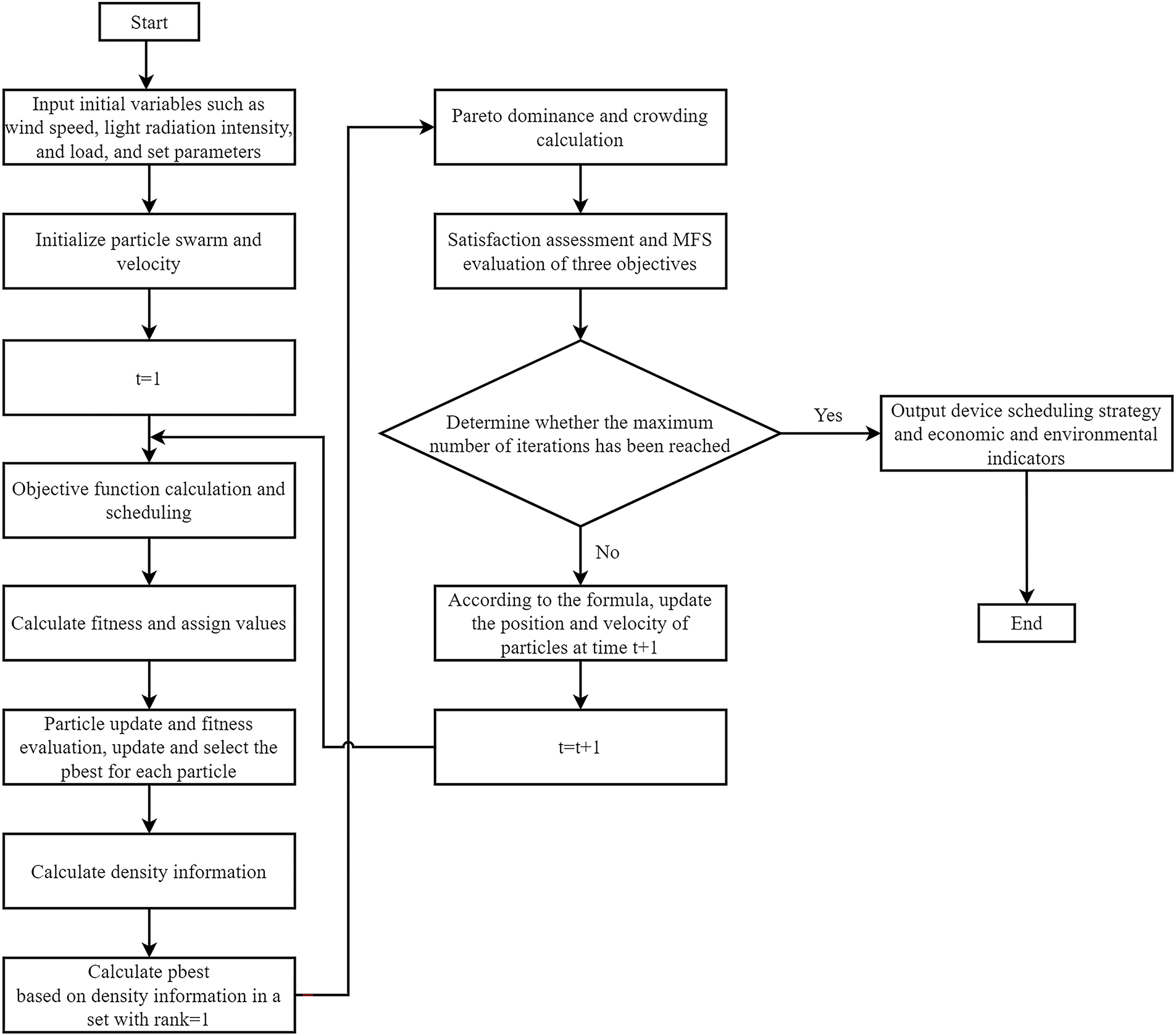

The solution process for applying the MOPSO algorithm to optimize the scheduling Model is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: MOPSO algorithm solution flowchart

The parameters used in the study for solving the application with the MOPSO algorithm are listed in Table 3, according to the results presented.

5.1 Basic Data for the Case Study

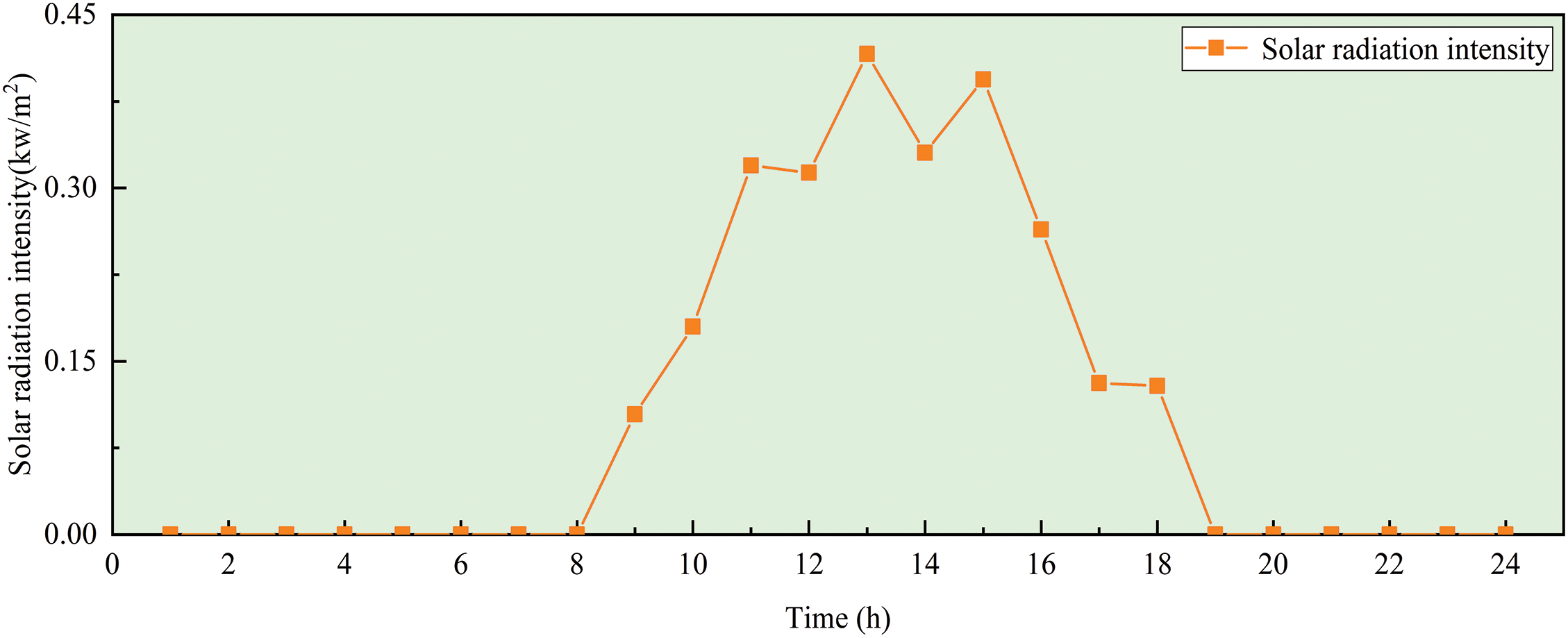

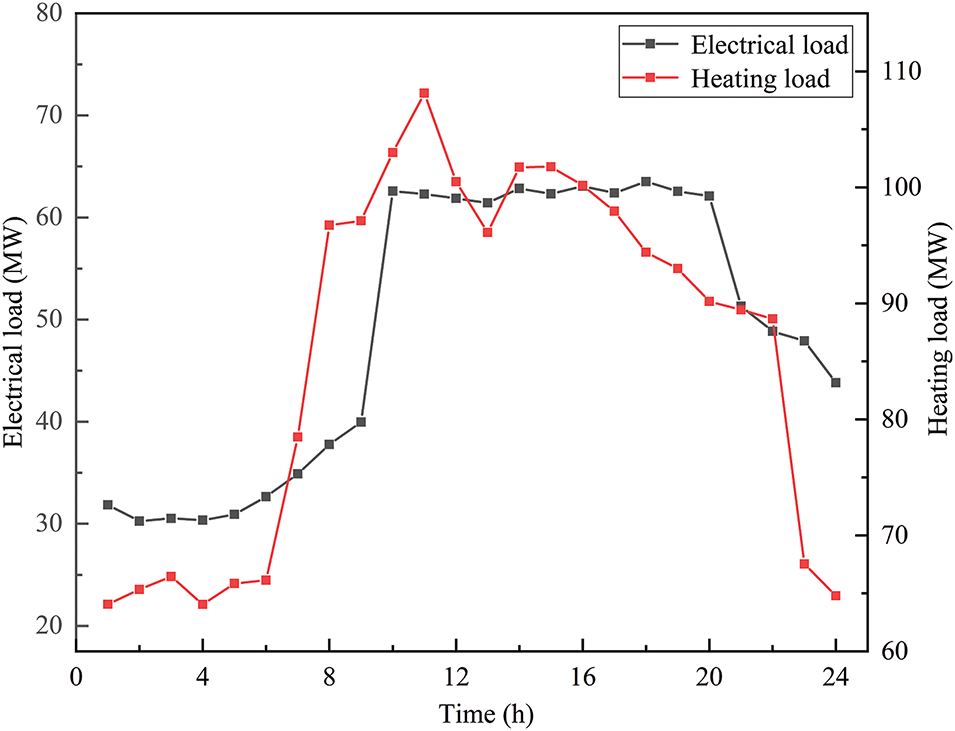

To verify the applicability and effectiveness of the GPS-COSM, actual project data from a certain area in Jinan City is used, and a 24-h operational scenario for a typical winter day is selected for analysis [64]. The dispatch cycle is set to one hour (Δt = 1), and the system’s operational characteristics under dynamic load demand and renewable energy supply variability are simulated on an hourly basis. The wind speed variation curve for the typical day in the green power system is shown in Fig. 8, illustrating the temporal distribution characteristics of wind resources. The solar radiation intensity variation is also depicted in Fig. 8, reflecting the supply variability of photovoltaic power generation. The heating and electrical load demand curves for the system are shown in Fig. 9, providing foundational data support for the operation of the scheduling model [65].

Figure 8: Parameter variation diagram of GP

Figure 9: Load demand variation diagram

The external energy purchased by the system is natural gas, which is primarily used for the operation of CHP unit. The natural gas purchase price is set at 3.3 CNY/Nm3. The main calculation parameters related to each device are listed in Table 4.

5.2 Comparative Analysis of Case Study Results

5.2.1 Economic and Environmental Benefits Comparison

Table 5 shows the comparison of operating costs and actual carbon emissions for different operating modes. Through a systematic comparative analysis for the economic and environmental benefits of the three operating modes, it reveals that OM-3 demonstrates significant advantages in overall performance. First, in terms of operating costs, OM-1, which adopts the traditional “heat-led electricity” approach, results in the highest operating costs due to the high-intensity operation of CHP unit, leading to substantial natural gas consumption. OM-2 introduces electric boilers to enhance the consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power, utilizing this excess energy to meet heating load demands, significantly reducing natural gas consumption and lowering operating costs to 9.55 million CNY, a 91.16% reduction compared to OM-1. OM-3 further incorporates thermal storage devices, optimizing the cross-temporal utilization of the curtailment of wind and solar power and improving energy efficiency, reducing operating costs further to 1.23 million CNY, an 87.12% reduction compared to OM-2.

Second, in terms of carbon emissions, OM-1 has the highest actual carbon emissions at 10,793.28 t, primarily due to the heavy reliance on natural gas for CHP unit operation, which significantly increases the system’s carbon intensity. In OM-2, the addition of EB to meet most of the heating load demand reduces the operational intensity of CHP unit, decreasing carbon emissions to 496.55 t, a 95.2% reduction. OM-3 further incorporates TES, optimizing the utilization efficiency of the curtailment of wind and solar power over time through coordinated regulation, further reducing the operational load of CHP unit and lowering carbon emissions to 280.88 t, a 43.3% reduction compared to OM-2. These results indicate that the rational configuration of EB and TES can significantly enhance the system’s ability to accommodate renewable energy, minimize the use of fossil fuels, and effectively achieve economical and low-carbon operation of the system.

5.2.2 Comparison of GP Generation and the Curtailment of Wind and Solar Power Consumption

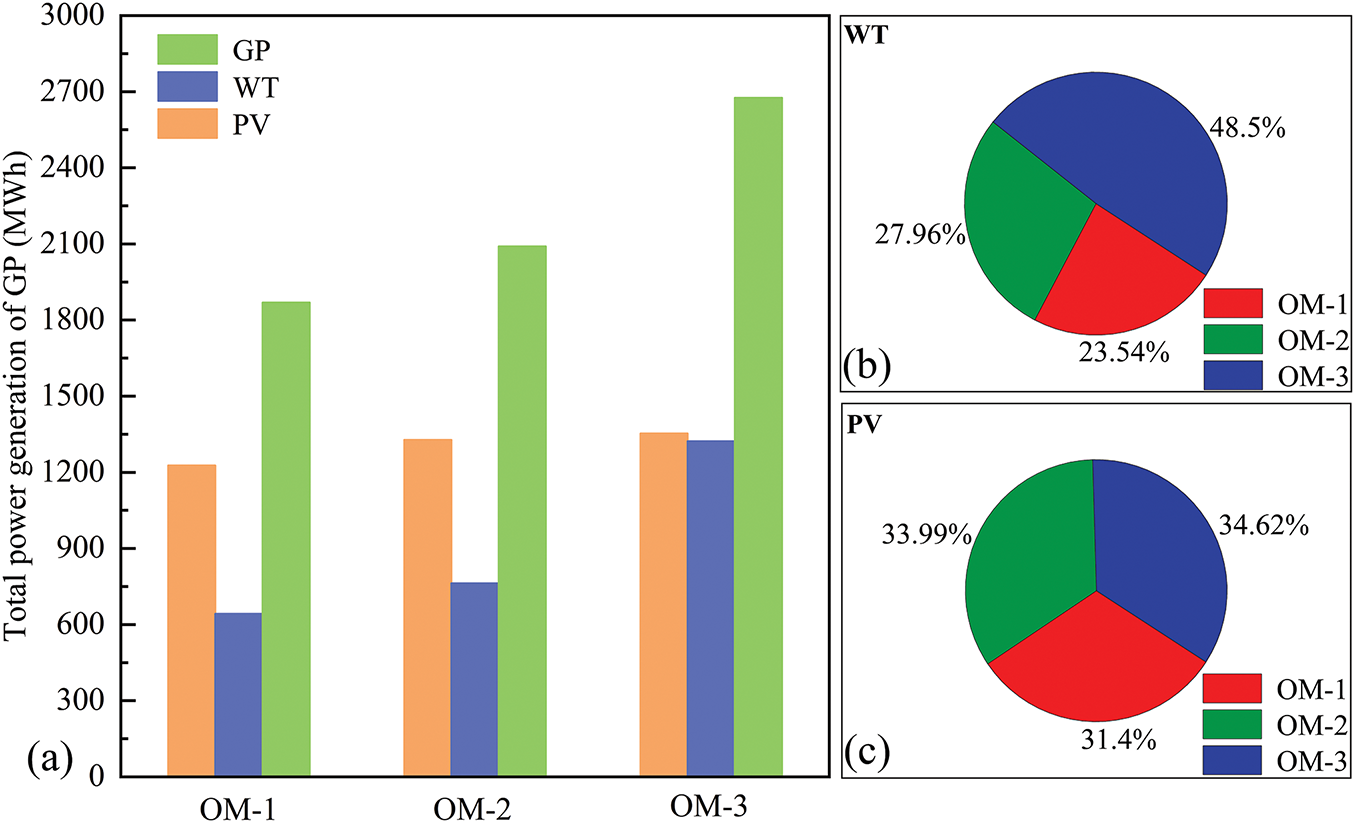

A comparative analysis of the total power generation of GP under the three operating modes is shown in Fig. 10. In OM-3, the photovoltaic power generation is 1352.82 MWh, and the wind power generation is 1322.83 MWh, resulting in a total green power system generation of 2675.65 MWh. In comparison, OM-2 achieves photovoltaic power generation of 1328.12 MWh and wind power generation of 762.55 MWh, with a total green power system generation of 2090.67 MWh. OM-1 has the lowest total green power system generation, indicating lower efficiency in renewable energy utilization.

Figure 10: Comparison of GP: (a) Comparison of green power generation; (b) Comparison of wind power generation; (c) Comparison of photovoltaic power generation

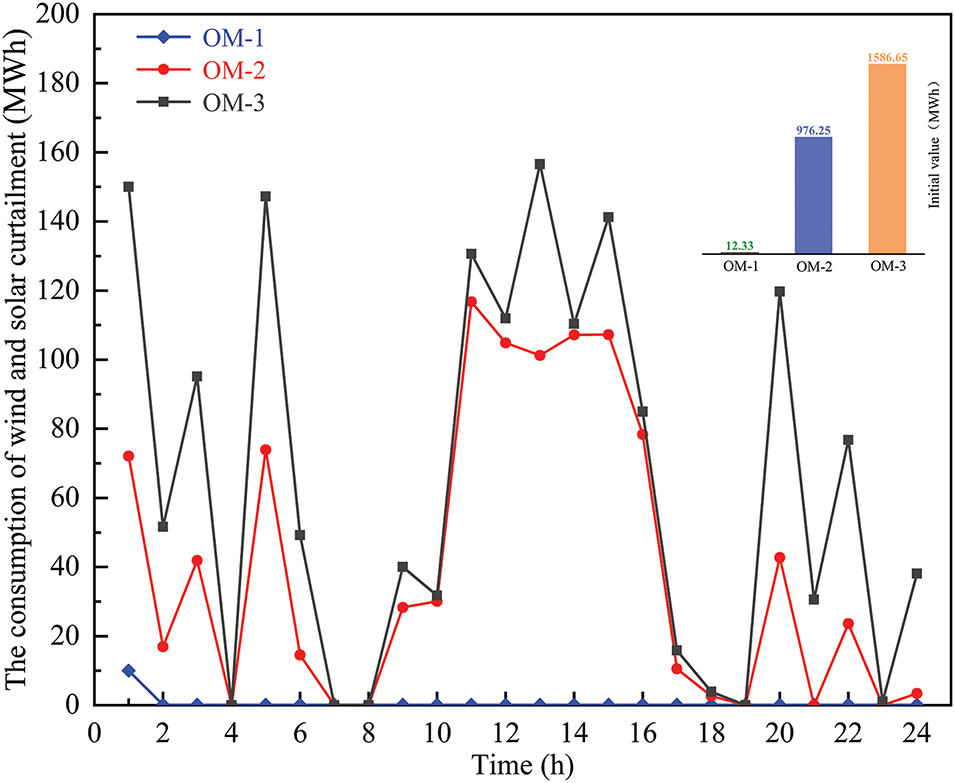

On this basis, a comparison of the consumption capacity for the curtailment of wind and solar power under the three operating modes in winter is shown in Fig. 11. While the differences in the total power generation of the GP among the three operating modes are not significant, there are notable differences in their ability to consume the curtailment of wind and solar power. OM-1, which only includes EES without the coordinated support of EB and TES, has a consumption capacity of only 12.33 MWh. OM-2, by adding EB and coordinating them with EES, significantly enhances the system’s ability to consume the curtailment of wind and solar power, achieving a consumption capacity of 976.25 MWh and a curtailment consumption rate of 91.95%. OM-3, building on OM-2, further introduces TES. Through the integrated scheduling of TES, EB and EES, the final consumption capacity reaches 1586.65 MWh, with a curtailment consumption rate of 99.58%, nearly achieving full consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power.

Figure 11: Comparison of consumption of the curtailment wind and solar power for the three operating modes in winter

To deeply explore the impact of different operation strategies on the consumption capacity of renewable energy, a comparison is carried out regarding the consumption capacity for the curtailment of wind and solar power of the three operation modes during the transitional season, and the results are shown in Fig. 12. It can be clearly seen from the data in the figure that OM-3 exhibits the most outstanding performance in the consumption capacity for the curtailment of wind and solar power, and significantly higher than that of OM-1 and OM-2. The consumption capacity for the curtailment of wind and solar power of OM-2 is also higher than that of OM-1. From the perspective of load characteristics, the heating load during the transitional season is significantly lower than that in winter, while the electrical load level shows an upward trend compared with that in winter. In the accommodation system for curtailment of wind and solar power, the EB, TES, and EES constitute the core accommodation carriers. Due to the high heating demand in winter, these devices can more fully participate in the accommodation process of the electrical energy from curtailed wind and solar power, thus significantly increasing the consumption for the curtailment of wind and solar power.

Figure 12: Comparison of consumption of the curtailment wind and solar power for the three operating modes in transitional season

From a holistic system perspective, OM-3 achieves comprehensive optimization in both green power system generation and the consumption capacity for the curtailment of wind and solar power, demonstrating the significant advantages of its multi-device coordinated scheduling strategy. EB efficiently consume the curtailment of wind and solar power to directly supply the heating load, while TES and EES further enhance the system’s flexibility and renewable energy utilization efficiency through cross-temporal regulation of the remaining green power. This approach achieves full consumption of green power resources.

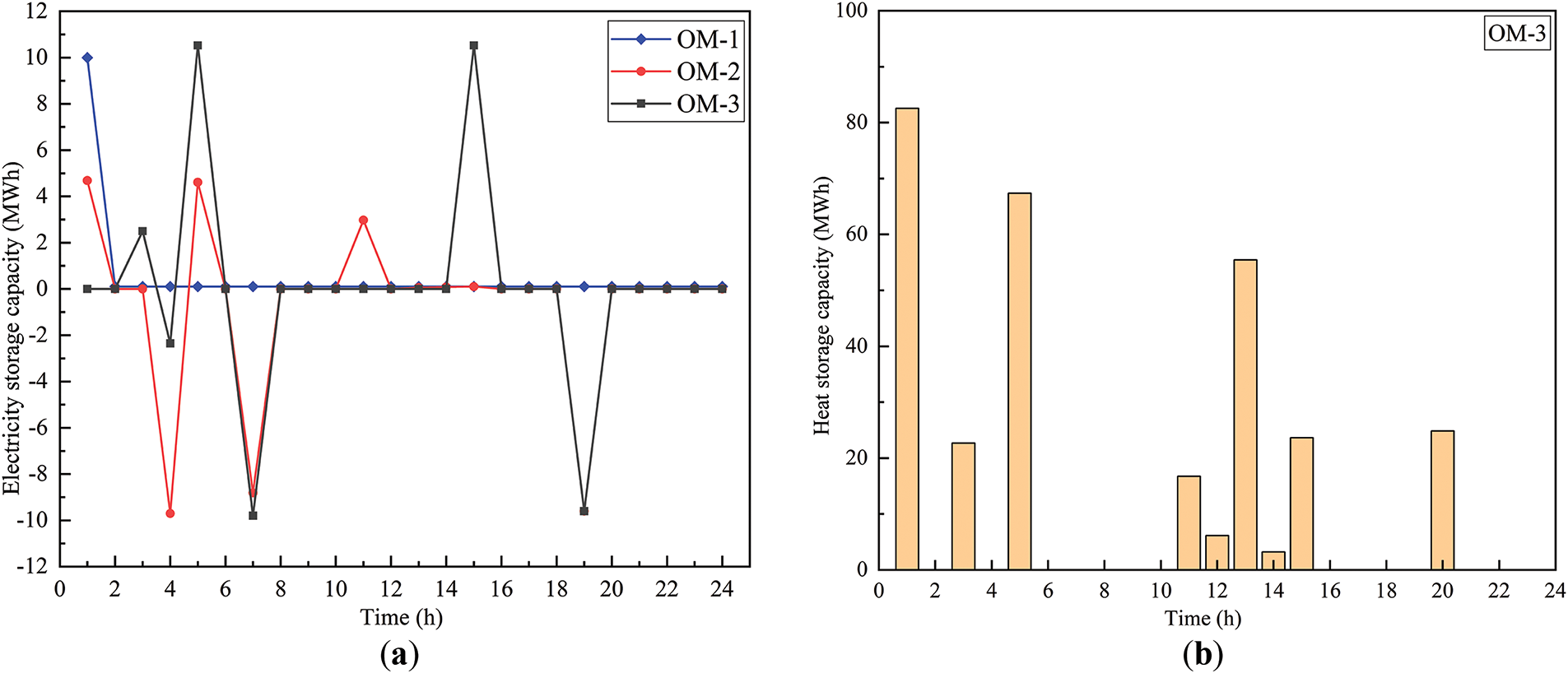

5.2.3 Comparison of Energy Storage Device Operating States

The advantage of OM-3 in consuming the curtailment of wind and solar power is not only reflected in the absolute value of consumption but also in the significant optimization of the uneven temporal distribution issue. A comparison of the operating states of EES and TES under the three operating modes is shown in Fig. 13. In OM-1, since the system primarily relies on CHP unit to meet the heating load demand while simultaneously generating electricity to satisfy the electrical load, the EES quickly reaches full capacity in the early stages of operation and does not discharge thereafter. This is because the CHP units’ supply of electricity demand prevents the electrical energy storage from fully participating in regulation during operation. OM-2 introduces EB to prioritize the consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power to meet the heating load demand, significantly reducing the operational intensity of CHP unit. With the participation of EB, the EES gradually engages in load regulation, enhancing the system’s flexibility by discharging to adjust load demand. OM-3 further integrates TES, establishing a multi-device coordinated dispatch mechanism alongside EB and EES. In this mode, TES smooths out the temporal distribution of heating load demand, while EES achieves precise temporal matching between dynamic load demand and the variability of wind and solar power generation. Through the coordinated operation of multiple devices, the uneven temporal distribution of the curtailment of wind and solar power is effectively mitigated, significantly improving the system’s energy utilization efficiency.

Figure 13: Comparison of operating states of EES and TES for the three operating modes: (a) Operating states of EES; (b) Operating states of HES

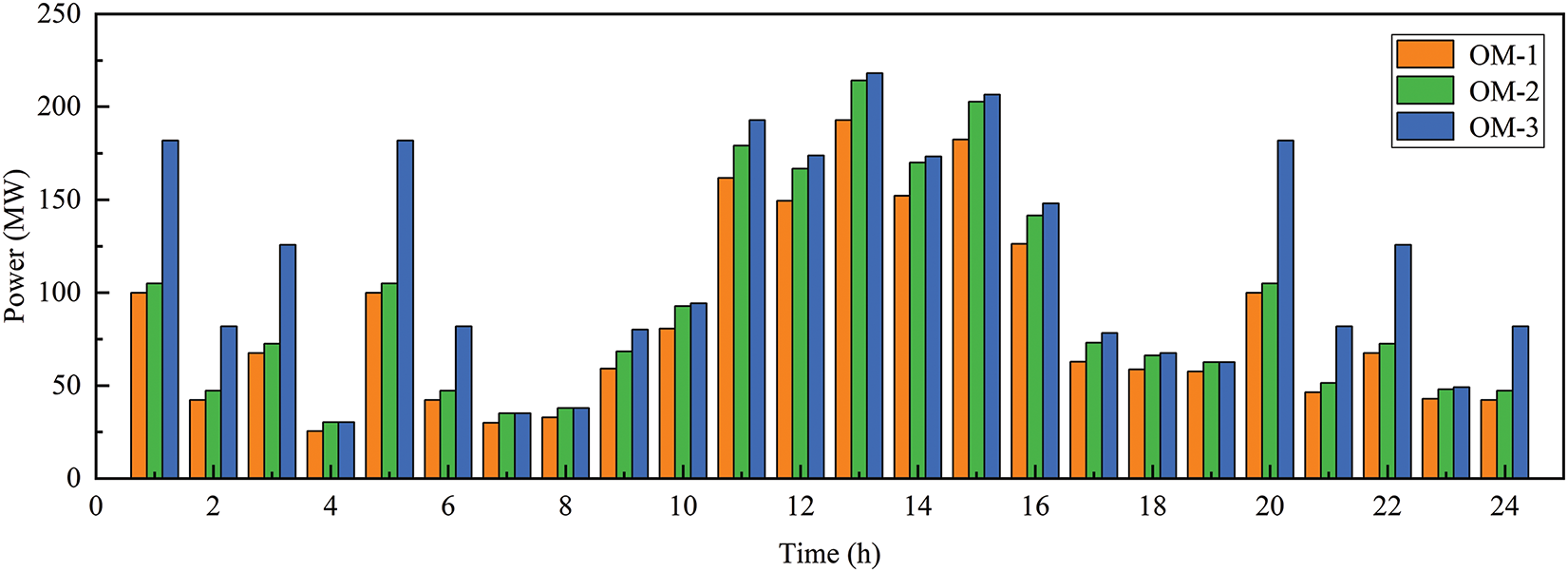

5.2.4 Comparison of Unit Output

A comparison of the unit output of GP under the three operating modes is shown in Fig. 14. OM-3 demonstrates the best optimization scheduling results, with the highest output from GP, fully utilizing renewable energy and achieving efficient consumption of green power resources.

Figure 14: Comparison of GP output for the three operating modes

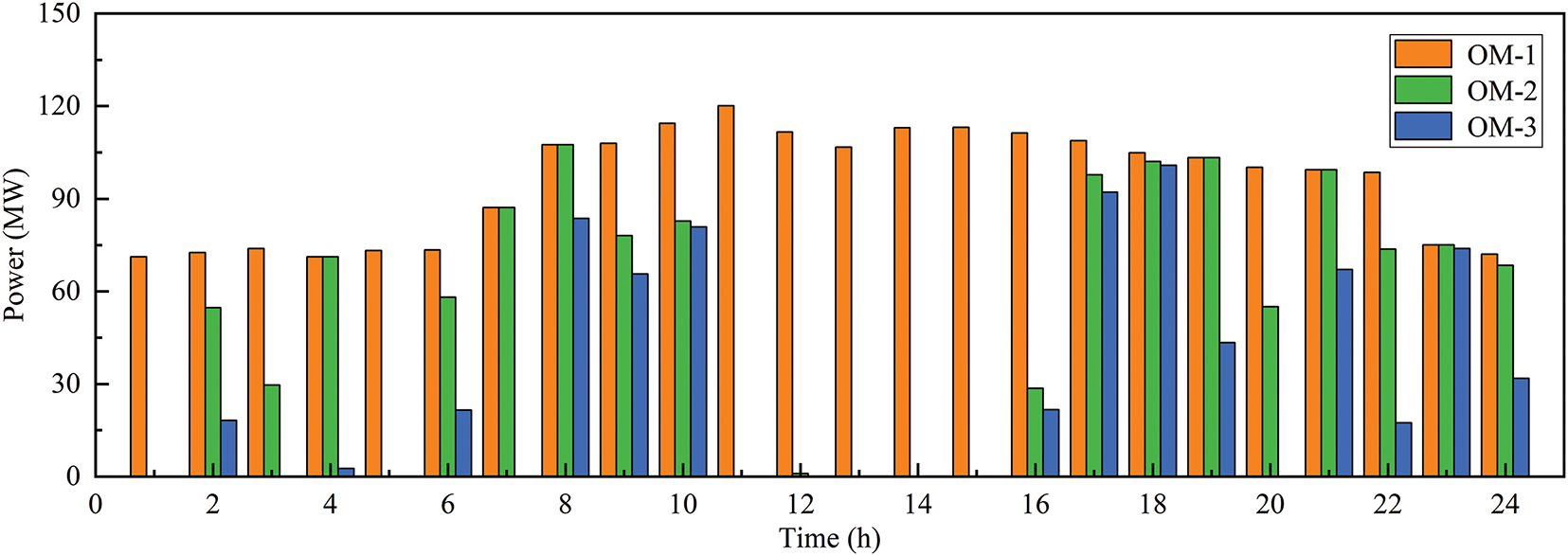

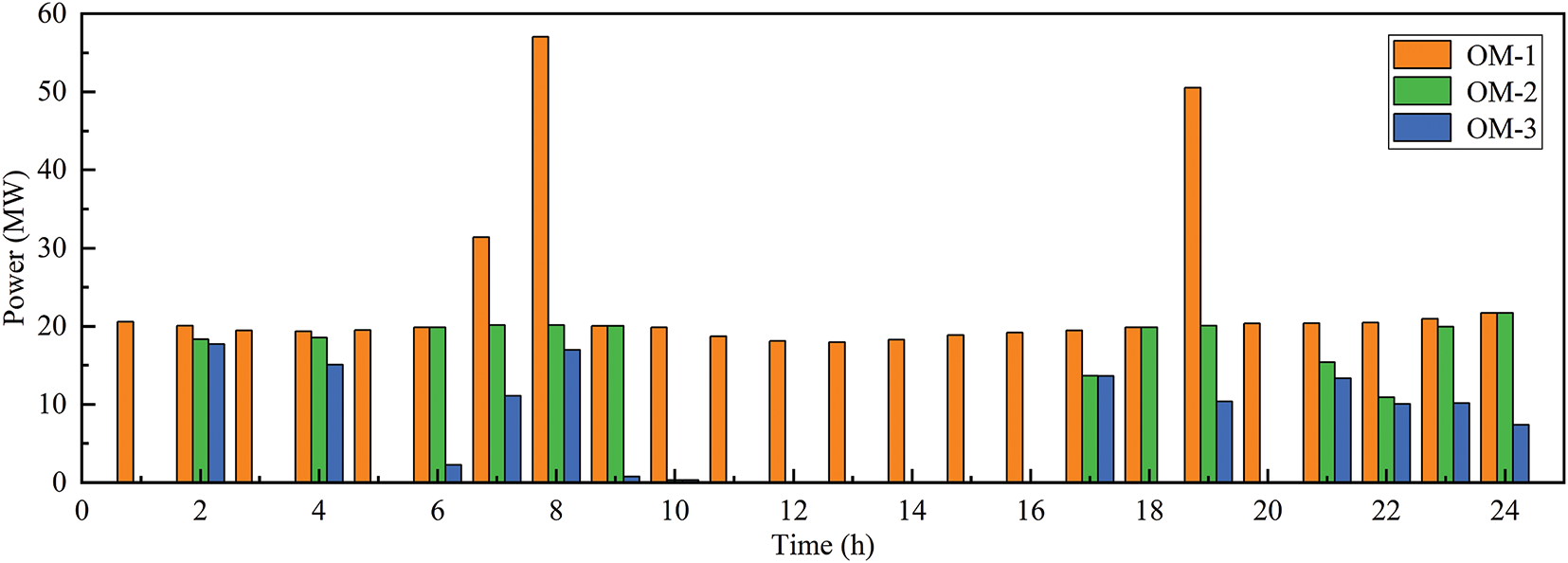

A comparison of the CHP unit output under the three operating modes during winter and the transitional season is shown in Figs. 15 and 16 below. In OM-3, the CHP unit output is the lowest, as EB and TES meet most of the heating load demand by consuming the curtailment of wind and solar power, reducing reliance on fossil fuels. In contrast, OM-1, with its single-device configuration, results in the lowest output from the green power system. Most of the electrical and heating load demands in the system rely on CHP unit, leading to the highest CHP unit output and significantly increasing fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions.

Figure 15: Comparison of CHP unit output for the three operating modes in winter

Figure 16: Comparison of CHP unit output for the three operating modes in transitional season

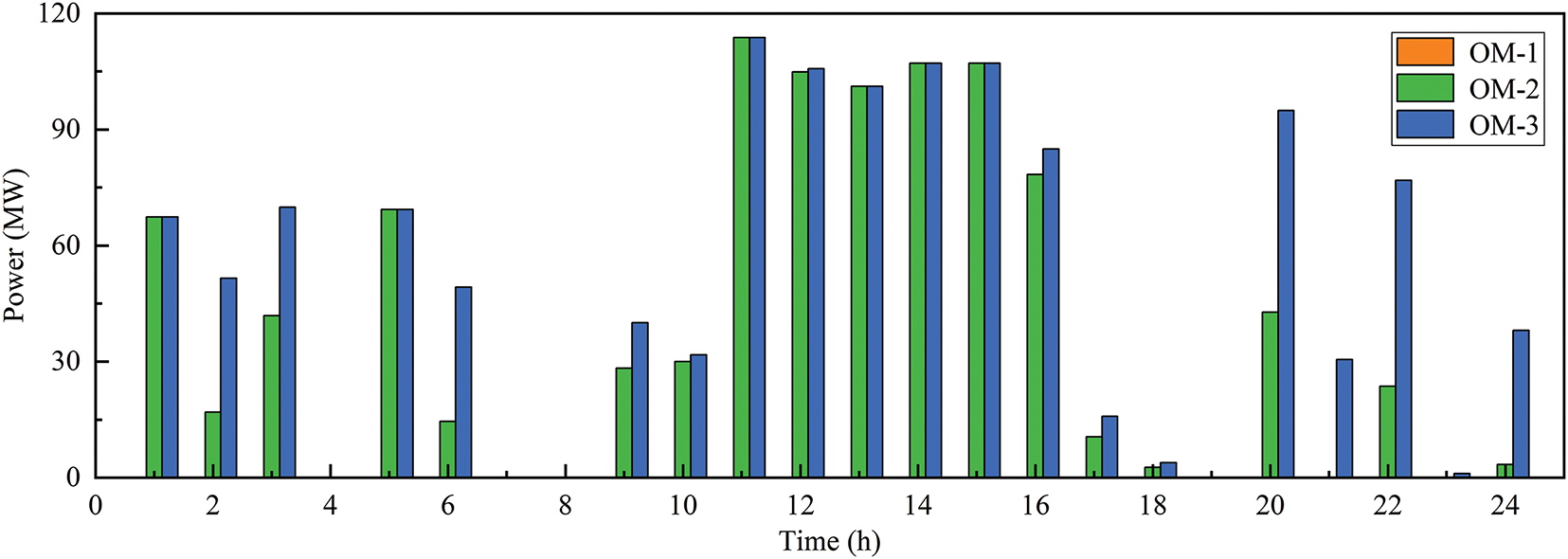

A comparison of the EB output under OM-2 and OM-3 is shown in Fig. 17. OM-2 significantly enhances the utilization efficiency of GP by incorporating EB, resulting in higher green power system output compared to OM-1. However, due to the lack of TES for cross-temporal regulation of the curtailment of wind and solar power, the output of EB in OM-2 is lower than in OM-3, and some of the heating load still needs to be supplemented by CHP unit. Compared to OM-3, while EB in OM-2 can consume some of the curtailment of wind and solar power, there are clear shortcomings in device coordination, limiting the overall scheduling flexibility of the system.

Figure 17: Comparison of EB output for the three operating modes

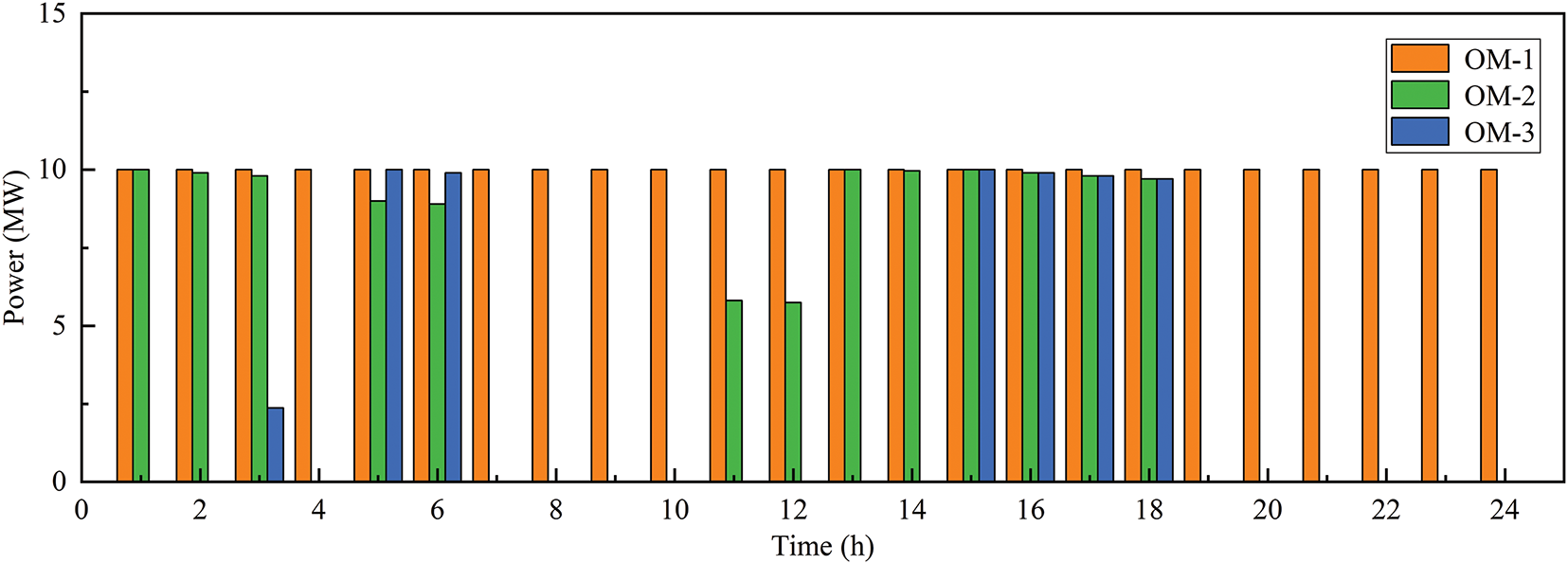

A comparison of the EES output under the three operating modes is shown in Fig. 18. Further analysis of the output characteristics of EES that OM-1 stores the most electricity but fails to utilize it subsequently, resulting in the lowest energy consumption efficiency. Although OM-2 stores more electricity than OM-3, its energy utilization efficiency is still inferior to OM-3 due to the lack of TES for consuming the curtailment of wind and solar power. In OM-3, while the amount of electricity stored in EES is slightly less than in OM-1 and 2, the coordinated operation with TES and EB achieves efficient consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power. Its primary role is reflected in peak shaving, valley filling, and dynamic regulation of grid load.

Figure 18: Comparison of EES output for the three operating modes

A comparison of the TES output under OM-3 is shown in Fig. 19. The consumption of TES significantly alleviates the uneven temporal distribution of the curtailment of wind and solar power and optimizes the operation strategy of EB, significantly enhancing the matching between renewable energy consumption capacity and load demand.

Figure 19: Comparison of TES output for OM-3

The proposed GPS-COSM, based on multi-device coordination and multi-objective optimization, achieves excellent operational performance through rational device configuration and dynamic optimization scheduling. In environments with significant variability in wind and solar power generation and dynamic changes in heating load and electrical load demands, this multi-objective optimization model effectively balances economic benefits, energy utilization efficiency, and environmental benefits. Through the coordinated optimization of TES, EES, and EB, the model not only achieves efficient consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power, significantly improving renewable energy utilization efficiency, but also reduces reliance on CHP unit, thereby decreasing fossil fuel consumption.

The study employs the MOPSO algorithm, combining the Pareto dominance principle with fuzzy membership functions, to address the complex trade-offs among operating costs, carbon emissions, and the consumption of wind and solar curtailment. Compared to traditional methods that convert multi-objective problems into single-objective optimization, MOPSO can simultaneously generate multiple Pareto optimal solution sets, covering trade-off relationships among different objectives and providing more options for optimization results. By evaluating the satisfaction level of solutions within the Pareto optimal solution set, the study can select the optimal compromise solution from the non-dominated set, making the result selection more scientific and rational. This demonstrates the applicability and superiority of the model in multi-objective optimization.

The proposed GPS-COSM dynamically adjusts scheduling priorities based on load demand, wind and solar power variability, and the status of energy storage devices. This dynamic scheduling strategy shows that, in scenarios with significant wind and solar power variability, a well-designed scheduling priority can maximize the consumption capacity of green power resources while effectively mitigating uneven temporal distribution issues, thereby improving system flexibility and renewable energy utilization efficiency. From the case study results, the optimization scheduling strategy of OM-3 performs best in terms of economic efficiency, environmental benefits, and energy utilization efficiency. Through the cross-temporal regulation of TES, the flexible response of EB, and the peak shaving and valley filling functions of EES, the model achieves substantial consumption of green power resources and significantly reduces system operating costs and carbon emissions.

This study centers on the collaborative optimization scheduling of the EB, TES, and EES. Under winter operating conditions, the heating load demand is substantial, and the coupling effect among the devices is intense. Therefore, core calculations are carried out focusing on the operation of the system under winter operating conditions. To validate the robustness of the algorithm, the transitional season is further incorporated into the scope of analysis to examine the consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power during this period, and to analyze the operational characteristics of the CHP.

The model proffered in this dissertation is applicable to regional energy systems replete with wind and solar resources, such as industrial parks and remote microgrids. It achieves the maximization of green power consumption through coordinated dispatching of multiple devices. The heat storage/electrical storage coordination mechanism can mitigate the volatility of wind and solar power, proffering a stable energy supply blueprint for remote regions bereft of grid access, like islands and plateaus. The dynamic priority adjustment strategy optimizes the load curve by leveraging electrical storage devices, diminishing the peak-valley disparity of the power grid, rendering it suitable for urban microgrids characterized by substantial fluctuations in electricity load.

Despite demonstrating effectiveness in boosting green power consumption and overall system performance, the optimization dispatch model has limitations. First, it doesn’t account for equipment initial investment costs. To address this, future practical applications should optimize the model in tandem with the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) over its full life cycle. Second, it does not fully account for potential issues in actual operations, such as heat loss in TES, the dynamic response speed of EB, and the potential impact of device aging on performance. Therefore, future research could focus on the following improvements: introducing uncertainty optimization methods and combining deep learning or time-series prediction techniques to enhance the accuracy of renewable energy output forecasting [66,67]; further investigating the economic aspects of TES and EES, comprehensively considering device investment and operating costs to improve the economic feasibility and practical applicability of the optimization model [68]; and considering the integration of hydrogen storage systems, establishing dynamic prediction models for the system, and combining them with optimal control theory to optimize the dynamic response of hydrogen systems using intelligent algorithms, thereby enhancing hydrogen storage capacity to quickly address uncertainties [69].

The study utilizes the MOPSO to address the optimization scheduling problem of GP in regional integrated energy systems with large-scale renewable energy integration, mainly focusing on the situation in winter. GPS-COSM is constructed with the objectives of minimizing operating costs, minimizing carbon emissions, and maximizing the consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power. The model employs fuzzy membership functions to evaluate the satisfaction level of the Pareto optimal solution set, from which the optimal compromise solution is selected. By integrating the coordinated configuration of GP, EB, TES, EES, and CHP unit, three typical operating modes are designed. Through case study analysis, the following main conclusions are drawn:

(1) OM-3 achieves low-carbon and low-cost system operation. Through multi-device coordinated scheduling, the reliance on CHP unit is significantly reduced, decreasing the demand for externally purchased natural gas and effectively lowering operating costs and carbon emissions. The operating cost of OM-3 is reduced to 1.23 million CNY, a decrease of 98.86% and 87.12% compared to OM-1 and 2, respectively. Carbon emissions are reduced to 280.88 t, a decrease of 97.4% and 43.44% compared to OM-1 and 2, respectively. The results indicate that rational device configuration and coordinated scheduling can achieve a good balance among economic efficiency, environmental benefits, and energy efficiency.

(2) EB plays a key role in the consumption of GP and heating load supply. By consuming the curtailment of wind and solar power and converting it into thermal energy, EB significantly improve the system’s energy utilization efficiency. In OM-2, EB increase the consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power from 12.33 MWh in OM-1 to 976.25 MWh, an increase of 7817.68%. OM-3 further integrates TES, achieving a consumption of 1586.65 MWh and a consumption rate of 99.58%. Compared to OM-1, which relies entirely on CHP unit for heating, EB directly meet most of the heating load demand by consuming green power, significantly reducing reliance on fossil fuels while enhancing the green power system’s consumption capacity.

(3) The synergy between TES and EES optimizes system performance. In OM-3, TES optimizes the temporal distribution of green power resources and their alignment with heating load demand through cross-temporal regulation, increasing the consumption of the curtailment of wind and solar power by 62.4% compared to OM-2. EES enhances the system’s ability to adapt to electrical load fluctuations through peak shaving and valley filling. The coordinated operation of TES and EES not only improves the system’s efficiency in consuming the curtailment of wind and solar power but also significantly enhances its adaptability to renewable energy variability. In contrast, OM-1 results in low utilization of EES and fails to effectively address the uneven temporal distribution of the curtailment of wind and solar power. OM-2, lacking TES support, exhibits significantly lower overall regulation capability compared to OM-3.

This research constructs the GPS-COSM, which is predicated on multi-device coordination and multi-objective optimization. It puts forward solutions to address the severe issues of wind and solar power curtailment in the context of high-proportion renewable energy integration, as well as the challenges in synchronizing the economic viability and low-carbon attributes of the system. By devising a multi-objective optimization framework that aims to minimize operating cost, minimize carbon emission, and maximize the consumption of wind and solar curtailment, an innovative coordinated dispatching mechanism for EB, TES, and EES is introduced. MOPSO, in conjunction with a fuzzy membership function, is employed to effectuate the dynamic balancing of Pareto optimal solutions. It is corroborated that the multi-device coordination exhibits remarkable capabilities in optimizing the spatial-temporal alignment between the fluctuating nature of wind and solar power and the load demands. The research findings fill the theoretical lacunae of subjective weighting methodologies in multi-objective optimization, surmount the technical impediments in decoupled dispatching of electric and heating loads and cross-period energy storage cooperation, furnishing a comprehensive solution that combines economic, environmental, and reliability aspects for the low-carbon transformation of regional integrated energy systems. This holds significant theoretical and practical engineering value for facilitating the large-scale assimilation of renewable energy.

Acknowledgement: This work acknowledges the support of Project for Research and Technical Services on Key Equipment and Systems of Electric Heating Boilers with Long-Term Energy Storage.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFE0106800) and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2021ME199).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Liang Tang, Xinyuan Zhu and Kaiyue Li; methodology, Liang Tang and Kaiyue Li; software, Hongwei Wang, Liang Tang and Kaiyue Li; validation, Liang Tang, Jiying Liu and Kaiyue Li; formal analysis, Hongwei Wang, Liang Tang; resources, Liang Tang, Xinyuan Zhu and Jiying Liu; writing original draft preparation, Liang Tang and Kaiyue Li; visualization, Hongwei Wang, Xinyuan Zhu and Kaiyue Li; supervision, Jiying Liu and Kaiyue Li; project administration, Liang Tang, Hongwei Wang and Jiying Liu; funding acquisition, Jiying Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| GPS-COSM | The green power system consumption optimization scheduling model |

| GP | Green power system |

| PV | Photovoltaic system |

| WT | Wind turbine |

| CHP | Combined heat and power unit |

| GT | Gas turbine |

| GB | Electric boiler |

| TES | Thermal energy storage |

| EES | Electrical energy storage |

| OM-1 | Operating Mode-1 |

| OM-2 | Operating Mode-2 |

| OM-3 | Operating Mode-3 |

References

1. Nwagu CN, Ujah CO, Kallon DVV, Aigbodion VS. Integrating solar and wind energy into the electricity grid for improved power accessibility. Unconv Resour. 2025;5:100129. doi:10.1016/j.uncres.2024.100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang Y, Gao Q, Li H, Shi X, Zhou D. Navigating the energy transition with the carbon-energy-green-electricity scheme: an industrial chain-based approach for China’s carbon neutrality. Energy Econ. 2024;140:107984. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Melo GdA, Cyrino Oliveira FL, Maçaira PM, Meira E. Exploring complementary effects of solar and wind power generation. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2025;209:115139. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.115139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lv M, Gou K, Chen H, Lei J, Zhang G, Liu T. Optimal design of Wind-Solar complementary power generation systems considering the maximum capacity of renewable energy. Energy. 2024;312:133650. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.133650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liang C, Ding C, Zuo X, Li J, Guo Q. Capacity configuration optimization of wind-solar combined power generation system based on improved grasshopper algorithm. Electr Power Syst Res. 2023;225:109770. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2023.109770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gou H, Ma C, Liu L. Optimal wind and solar sizing in a novel hybrid power system incorporating concentrating solar power and considering ultra-high voltage transmission. J Clean Prod. 2024;470:143361. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li F, Chen S, Ju C, Zhang X, Ma G, Huang W. Research on short-term joint optimization scheduling strategy for hydro-wind-solar hybrid systems considering uncertainty in renewable energy generation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023;50:101242. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2023.101242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yavari M, Bohreghi IM. Developing a green-resilient power network and supply chain: integrating renewable and traditional energy sources in the face of disruptions. Appl Energy. 2025;377:124654. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jayabal R. Towards a carbon-free society: innovations in green energy for a sustainable future. Results Eng. 2024;24:103121. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Das TK. Assessment of grid-integrated electric vehicle charging station based on solar-wind hybrid: a case study of coastal cities. Alex Eng J. 2024;103:288–312. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.05.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li W, Qian T, Zhang Y, Shen Y, Wu C, Tang W. Distributionally robust chance-constrained planning for regional integrated electricity-heat systems with data centers considering wind power uncertainty. Appl Energy. 2023;336:120787. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.120787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu X, Wu Y, Li H, Zhou H. Design and development of pilot plant applied to wind and light abandonment power conversion: electromagnetic heating of solid particles and steam generator. J Clean Prod. 2024;470:143313. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ren Y, Yao X, Liu D, Qiao R, Zhang L, Zhang K, et al. Optimal design of hydro-wind-PV multi-energy complementary systems considering smooth power output. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2022;50:101832. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2021.101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wei D, He M, Zhang J, Liu D, Mahmud MA. Enhancing the economic efficiency of wind-photovoltaic-hydrogen complementary power systems via optimizing capacity allocation. J Energy Storage. 2024;104:114531. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Koholé YW, Wankouo Ngouleu CA, Fohagui FCV, Tchuen G. A comprehensive comparison of battery, hydrogen, pumped-hydro and thermal energy storage technologies for hybrid renewable energy systems integration. J Energy Storage. 2024;93:112299. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.112299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. De Mel IA, Demis P, Dorneanu B, Klymenko OV, Mechleri ED, Arellano-Garcia H. Global sensitivity analysis for design and operation of distributed energy systems: a two-stage approach. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2023;56:103064. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2023.103064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mbungu NT, Bansal RC, Naidoo RM, Siti MW, Ismail AA, Elnady A, et al. Performance analysis of different control models for smart demand-supply energy management system. J Energy Storage. 2024;90:111809. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.111809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. de Siqueira LMS, Peng W. Control strategy to smooth wind power output using battery energy storage system: a review. J Energy Storage. 2021;35:102252. doi:10.1016/j.est.2021.102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chang F, Li Y, Peng Y, Cao Y, Yu H, Wang S, et al. A dual-layer cooperative control strategy of battery energy storage units for smoothing wind power fluctuations. J Energy Storage. 2023;70:107789. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.107789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lehtola T. Solar energy and wind power supply supported by battery storage and vehicle to grid operations. Electr Power Syst Res. 2024;228:110035. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2023.110035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ali MF, Sheikh MRI, Akter R, Islam KMN, Ferdous AHMI. Grid-connected hybrid microgrids with PV/wind/battery: sustainable energy solutions for rural education in Bangladesh. Results Eng. 2025;25:103774. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Poti KD, Naidoo RM, Mbungu NT, Bansal RC. Optimal hybrid power dispatch through smart solar power forecasting and battery storage integration. J Energy Storage. 2024;86:111246. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.111246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rayit NS, Chowdhury JI, Balta-Ozkan N. Techno-economic optimisation of battery storage for grid-level energy services using curtailed energy from wind. J Energy Storage. 2021;39:102641. doi:10.1016/j.est.2021.102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Vega-Garita V, Alpizar-Gutierrez V, Calderon-Obaldia F, Núñez-Mata O, Arguello A, Immonen E. Iterative sizing methodology for photovoltaic plants coupled with battery energy storage systems to ensure smooth power output and power availability. Energy Convers Manag X. 2024;24:100716. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2024.100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhao P, Gou F, Xu W, Shi H, Wang J. Energy, exergy, economic and environmental (4E) analyses of an integrated system based on CH-CAES and electrical boiler for wind power penetration and CHP unit heat-power decoupling in wind enrichment region. Energy. 2023;263:125917. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.125917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Verma M, Ghritlahre HK, Chaurasiya PK, Ahmed S, Bajpai S. Optimization of wind power plant sizing and placement by the application of multi-objective genetic algorithm (GA) in Madhya Pradesh. India Sustain Comput Inform Syst. 2021;32:100606. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2021.100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu A, Zhao P, Sun J, Xu W, Ma N, Wang J. Performance analysis of an electric-heat integrated energy system based on a CHP unit and a multi-level CCES system for better wind power penetration and load satisfaction. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;258:124644. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.124644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. He Y, Hong X, Xian N. Long-term scheduling strategy of hydro-wind-solar complementary system based on chaotic elite selection differential evolution algorithm with death penalty function. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;142:109878. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bade SO, Tomomewo OS. Optimizing a hybrid wind-solar-biomass system with battery and hydrogen storage using generic algorithm-particle swarm optimization for performance assessment. Clean Energy Syst. 2024;9:100157. doi:10.1016/j.cles.2024.100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alghamdi H, Khan TA, Hua LG, Hafeez G, Khan I, Ullah S, et al. A novel intelligent optimal control methodology for energy balancing of microgrids with renewable energy and storage batteries. J Energy Storage. 2024;90:111657. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.111657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Soheyli S, Shafiei MMH, Mehrjoo M. Modeling a novel CCHP system including solar and wind renewable energy resources and sizing by a CC-MOPSO algorithm. Appl Energy. 2016;184:375–95. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.09.110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li J, Hao J, Feng Q, Sun X, Liu M. Optimal selection of heterogeneous ensemble strategies of time series forecasting with multi-objective programming. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;166:114091. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xu X, Hu W, Cao D, Huang Q, Chen C, Chen Z. Optimized sizing of a standalone PV-wind-hydropower station with pumped-storage installation hybrid energy system. Renew Energy. 2020;147:1418–31. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.09.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao P, Gou F, Xu W, Shi H, Wang J. Multi-objective optimization of a hybrid system based on combined heat and compressed air energy storage and electrical boiler for wind power penetration and heat-power decoupling purposes. J Energy Storage. 2023;58:106353. doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Plathottam SJ, Salehfar H. Unbiased economic dispatch in control areas with conventional and renewable generation sources. Electr Power Syst Res. 2015;119:313–21. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2014.09.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chen M, Wei J, Yang X, Fu Q, Wang Q, Qiao S. Multi-objective optimization of multi-energy complementary systems integrated biomass-solar-wind energy utilization in rural areas. Energy Convers Manag. 2025;323:119241. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.119241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jadhav HT, Roy R. Gbest guided artificial bee colony algorithm for environmental/economic dispatch considering wind power. Expert Syst Appl. 2013;40(16):6385–99. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2013.05.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ghorbani N, Kasaeian A, Toopshekan A, Bahrami L, Maghami A. Optimizing a hybrid wind-PV-battery system using GA-PSO and MOPSO for reducing cost and increasing reliability. Energy. 2018;154:581–91. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.12.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhu X, Gui P, Zhang X, Han Z, Li Y. Multi-objective optimization of a hybrid energy system integrated with solar-wind-PEMFC and energy storage. J Energy Storage. 2023;72:108562. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.108562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lei Z, Wang G, Li T, Cheng S, Yang J, Cui J. Strategy analysis about the active curtailed wind accommodation of heat storage electric boiler heating. Energy Rep. 2021;7:65–71. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.02.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Iweh CD, Akupan ER. Control and optimization of a hybrid solar PV-hydro power system for off-grid applications using particle swarm optimization (PSO) and differential evolution (DE). Energy Rep. 2023;10:4253–70. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2023.10.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Fitzpatrick JJ, Dunphy R. Comparison of the carbon footprints of combined heat and power (CHP) systems and boiler/grid for supplying process plant steam and electricity. Chem Eng Sci. 2023;282:119303. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2023.119303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang X, Zhou J, Qin B, Guo L. Coordinated control of wind turbine and hybrid energy storage system based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for wind power smoothing. J Energy Storage. 2023;57:106297. doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.106297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li J, Fu Y, Li C, Li J, Xing Z, Ma T. Improving wind power integration by regenerative electric boiler and battery energy storage device. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2021;131:107039. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang L, Ma C, Wang L, Wang X. Theoretical analysis and economic evaluation of wind power consumption by electric boiler and heat storage tank for distributed heat supply system. Electr Power Syst Res. 2024;228:110060. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2023.110060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Gao Y, Ai Q, He X, Fan S. Coordination for regional integrated energy system through target cascade optimization. Energy. 2023;276:127606. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.127606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zong X, Yuan Y. Two-stage robust optimization of regional integrated energy systems considering uncertainties of distributed energy stations. Front Energy Res. 2023;11. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2023.1135056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Liu J, Li Y, Ma Y, Qin R, Meng X, Wu J. Two-layer multiple scenario optimization framework for integrated energy system based on optimal energy contribution ratio strategy. Energy. 2023;285:128673. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.128673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang J, Kong D, He Y, Fu X, Zhao X, Yao G, et al. Bi-layer energy optimal scheduling of regional integrated energy system considering variable correlations. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2023;148:108840. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2022.108840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Gao J, Yang Y, Gao F, Wu H. Two-stage robust economic dispatch of regional integrated energy system considering source-load uncertainty based on carbon neutral vision. Energies. 2022;15(4). doi:10.3390/en15041596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Newbery DM, Biggar DR. Marginal curtailment of wind and solar PV: transmission constraints, pricing and access regimes for efficient investment. Energy Policy. 2024;191:114206. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Yi T, Zhang C. Scheduling optimization of a wind power-containing power system considering the integrated and flexible carbon capture power plant and P2G equipment under demand response and reward and punishment ladder-type carbon trading. Int J Greenh Gas Control. 2023;128:103955. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2023.103955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wang J, Xing HJ, Wang HX, Xie BJ, Luo YF. Optimal operation of regional integrated energy system considering integrated demand response and exergy efficiency. J Electr Eng Technol. 2022;17(5):2591–603. doi:10.1007/s42835-022-01067-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Gao C, Lin J, Zeng J, Han F. Wind-photovoltaic co-generation prediction and energy scheduling of low-carbon complex regional integrated energy system with hydrogen industry chain based on copula-MILP. Appl Energy. 2022;328:120205. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Han F, Zeng J, Lin J, Gao C. Multi-stage distributionally robust optimization for hybrid energy storage in regional integrated energy system considering robustness and nonanticipativity. Energy. 2023;277:127729. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.127729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Jin B, Liu Z, Liao Y. Exploring the impact of regional integrated energy systems performance by energy storage devices based on a bi-level dynamic optimization model. Energies. 2023;16(6):2629. doi:10.3390/en16062629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Ding N, Jiang W, Xi Y, Li H, Su J, Prasad K. Strategic layout planning of carbon emission monitoring devices in the open industrial area based on an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm. Measurement. 2025;244:116436. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.116436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Yang Z, Luo X, Qiao J, Chen J, Liu P. Prediction of total heat exchange factor using an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm for the reheating furnace. Int J Therm Sci. 2025;210:109669. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2024.109669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Liang Z, Yan J, Zheng F, Wang J, Liu L, Zhu Z. Multi-objective multi-task particle swarm optimization based on objective space division and adaptive transfer. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;255:124618. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Wang P, Ma Y, Wang M. A dynamic multi-objective optimization evolutionary algorithm based on particle swarm prediction strategy and prediction adjustment strategy. Swarm Evol Comput. 2022;75:101164. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2022.101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Han H, Zhang L, Yinga A, Qiao J. Adaptive multiple selection strategy for multi-objective particle swarm optimization. Inf Sci. 2023;624:235–51. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.12.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Pandit M, Chaudhary V, Dubey HM, Panigrahi BK. Multi-period wind integrated optimal dispatch using series PSO-DE with time-varying Gaussian membership function based fuzzy selection. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2015;73:259–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2015.05.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Xie WB, Wu YQ, Zheng SQ, Wang YL. Asynchronous membership functions decoupling based event-triggered fuzzy networked control for nonlinear systems. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2025;512:109377. doi:10.1016/j.fss.2025.109377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Meteorological C. Meteorological Observation Dataset of Jinan City [Internet]. Beijing, China: China Meteorological Administration; 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 1]. Available from: http://data.cma.cn/data/detail/dataCode/A.0012.0001.html. [Google Scholar]

65. Li K, Ran J, Kim MK, Tian Z, Liu J. Optimizing long-term park-level integrated energy system through multi-stage planning: A study incorporating the ladder-type carbon trading mechanism. Results Eng. 2024;22:102107. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Zhang X, Jenne SP, Ding Y, Spencer J, He W, Wang J. A wind power curtailment mitigation strategy via co-location and co-operation of compressed air energy storage with wind power generation. Electr Power Syst Res. 2025;241:111318. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2024.111318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Li Y, Su Y, Zhang Y, Wu W, Xia L. Two-layered optimal scheduling under a semi-model architecture of hydro-wind-solar multi-energy systems with hydrogen storage. Energy. 2024;313:134115. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.134115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Desguers T, Friedrich D. Design of a high-temperature, power-constrained electrified district heating network with thermal storage and curtailed wind integration. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2024;67:103815. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2024.103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Abdelghany MB, Al-Durra A, Zeineldin H, Hu J. Integration of cascaded coordinated rolling horizon control for output power smoothing in islanded wind-solar microgrid with multiple hydrogen storage tanks. Energy. 2024;291:130442. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.130442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools