Open Access

Open Access

COMMUNICATIONS

Sustainable Circulating Energy System for Carbon Capture Usage and Storage (CCUS)

1 The Room of Emeritus Professor, Dokkyo Medical University, Mibu, Tochigi, 321-0293, Japan

2 Bioscience Laboratory, Environmental Engineering Co., Ltd., Takasaki, Gunma, 370-0041, Japan

3 The President Office, KSI, Takasaki, Gunma, 370-1201, Japan

4 Department of Energy and Nuclear Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science, Ontario Tech University, Oshawa, ON L1H 7K4, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Kenji Sorimachi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Approaches in Clean Energy Systems: Integration, Sustainability, and Policy Impact of Renewable Energy)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(6), 2177-2185. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.064975

Received 28 February 2025; Accepted 30 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

Recently, we developed an innovative CO2 capture and storage method based on simple chemical reactions using NaOH and CaCl2. In this technology, it was newly found that the addition of CO2 gas produced CaCO3 (limestone) in the solution of NaOH and CaCl2 at less than 0.2 N NaOH, while at more than 0.2 N NaOH, Ca(OH)2 formation occurred merely without CO2. The present study has been designed to develop an integrated system in which the electrolysis unit is combined with the CO2 fixation unit. As the electrolysis of NaCl produces simultaneously not only electricity but also H2 and Cl2, the produced H2 could be supplied to the hydrogen generator to produce further electricity, which could be used for the initial NaCl electrolysis for NaOH production. Contrarily, the combination of incinerators with electrolytic generators has already been established to supply electricity, as thermal power plants use coals or wastes. This electricity-providing unit could be replaced with a solar panel plant or with a storage buttery. The present integrated system, consisting of various electricity-providing methods and CO2 fixation units, is a sustainable circulating energy system and carbon capture, usage, and storage (CCUS) system without environmental concerns. In addition, an unexpected-tremendous amount of the burned wood, which was produced by the big mountain or forest fires, could be disposed of by our integrated CO2 fixing system with the incinerator without environmental concerns along with both H2 and CaCO3 productions. Thus, our simple technology must contribute immediately and economically to disaster recovery.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

In our fresh memory, huge hurricanes Helene and Carolina hit the southwest area of the USA, one after another, in 2024, and a tremendously wide area was damaged seriously. In addition, many wildfires broke out in Los Angeles in January 2025. Regarding the weather that induced these wildfires, the World Weather Attribution (WWA) reported that the weather conditions might cause a 35% increase in the probability of wildfire occurrence based on high temperature, dry air, and light rain, compared with that before the Industrial Revolution. In Japan, there were several mountain fires in Iwate, Okayama, and Ehime Prefectures, and their burned areas were 2900, 565, and 442 hectares, respectively, within February 2025. Fortunately, these fires were extinguished by the rain. Contrarily, a tremendous amount of burned wood, as well as a large amount of CO2 emission during the fire, was produced, although they had grown, followed by capturing a huge amount of CO2 before the fires.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded on 9 August 2021, that climate change has been caused by human activities that have produced carbon dioxide (CO2) since the Industrial Revolution [1]. To reduce atmospheric CO2 concentrations as a means of mitigating such effects, the so-called Paris Agreement was reached at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP20) in 2015. This agreement was based on the requirement to keep the increase in the mean global temperature below 2°C related to the temperature before the Industrial Revolution, preferably less than 1.5°C. China is the world’s largest emitter of CO2, while the President of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping, has declared that China will be carbon neutral by 2060. The former president of the USA, Joe Biden, rejoined the Paris Agreement on 20 January 2021, whereas the present US president, Donald Trump, quit the Paris Agreement on 21 January 2025. Incidentally, the USA is the world’s second-largest emitter of CO2. Scientists conclude that this fact will likely lead to dangerous irreversible levels of climate change [2]. People should notice that irreversible climate change cannot be repaired again with money and that we have induced the present climate change since the Industrial Revolution. Even if a carbon-neutral society could be immediately achieved, the accumulated atmospheric CO2 would not be reduced at present.

CO2 can be captured from the ambient air or gas via several technologies [3], including absorption [4], adsorption [5–9], and membrane gas separation [5,10]. Absorption with amines is currently the dominant technology. However, amines are organic solvents that chemical reactions must synthesize, and heat treatment is necessary to release CO2 from the CO2-amine complexes, resulting in heat decomposition of amines. Eventually, the amine technology is not used worldwide. Contrarily, Membrane and adsorption processes are still in the developmental stages, with the construction of primary pilot plants anticipated in the near future. However, to the best of our knowledge, these methods alone cannot achieve the necessary worldwide reductions in atmospheric CO2.

On the other hand, we recently developed an innovative method for CO2 fixation and storage [11]. This method is based on simple chemical reactions involving NaOH and CaCl2. Using low concentrations of these chemicals prevented the formation of Ca(OH)2 in the absence of CO2 but resulted in CaCO3 formation in the presence of CO2 bubbling. Additionally, a polyethylene tunnel-based improvement method for CO2 fixation with NaOH mists was proposed as an “artificial forest” model [12]. In this model, CO2 penetrates a large polyethylene tunnel and is then converted into CaCO3, which is stable and harmless. Namely, this CO2-fixing process is likened to photosynthesis, in which CO2 is converted to carbohydrates in the plant. The present study has been designed to develop a sustainable energy circulating system based on the integration of an energy circulating unit and CO2 capturing unit, consisting of low-cost based on simple chemical reactions and simple facilities to spread worldwide.

Reagent grade NaOH and CaCl2 were purchased from Wako Junyaku Kogyo (Tokyo, Japan).

The chimney model was prepared by combining two 1-L paper milk boxes, after which air (at approximately 100 cm3/s) and CO2 (approximately 10 cm3/s) were supplied into the lower box. A layer of gauze was placed between the two boxes, and approximately 4 mL of the solution, consisting of 0.05 N NaOH and 0.05 M CaCl2, was sprayed into the middle part of the lower box. The CO2 concentration (in %) was subsequently determined at the central point of the upper box using an XP-3140 instrument (COSMOS). All experiments were carried out at room temperature of around 25°C.

Our previous studies [11] showed that the NaOH mist can efficiently capture CO2 in the plastic pet bottle, representing the closed system. In experiments using a chimney model (Fig. 1a), when the chimney contained high CO2 concentrations, the amounts of NaOH and CaCl2 in the solution were insufficient to react with all the CO2 at a gas flow rate of approximately 110 cm3/s (Fig. 1b). Thus, the solution could only capture a relatively small amount of the CO2 in the chimney model.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of chimney model and its data. The data was published in Scientific Reports [12]. Two values are the means plus or minus one standard deviation based on either six or ten replicates

To continuously capture a large amount of CO2 from the ambient air or exhaust gases, a new CO2 capture model was developed, as shown in Fig. 2. Using a large chamber equipped with many spray nozzles, CO2 can be efficiently captured by droplets or mists of the NaOH solution. It is possible to expand the chamber in both directions, such as vertical and horizontal directions, increasing the chamber volume. It is easy to increase the number of nozzles that are equipped with pipelines, expanding three dimensions. Thus, it seems possible to use natural caves, mine galleries, used tunnels, and used buildings, which have a large space for the CO2 reaction with OH-, instead of new constructions, when the floor, wall, and ceiling are covered with polymer sheets. This unit could also be combined with the NaOH generating unit, which produces electricity.

Figure 2: The proposed CO2 fixation chamber. The original diagram was drawn by the author, and it was formally traced by the Matsushima Patent Office, using the software “Hanako” added in “Ichitaro”. The figure was already published in Scientific Reports [12]

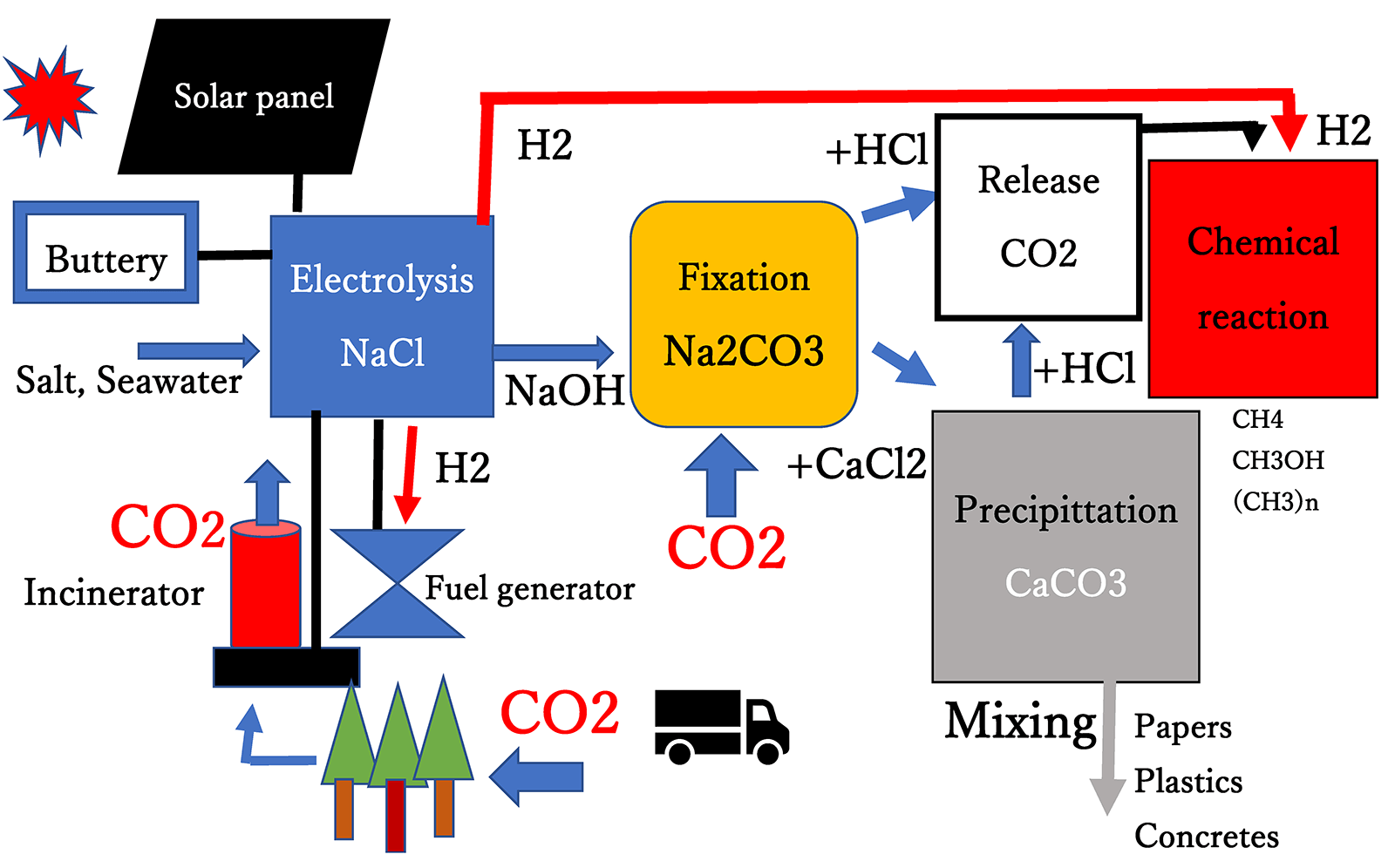

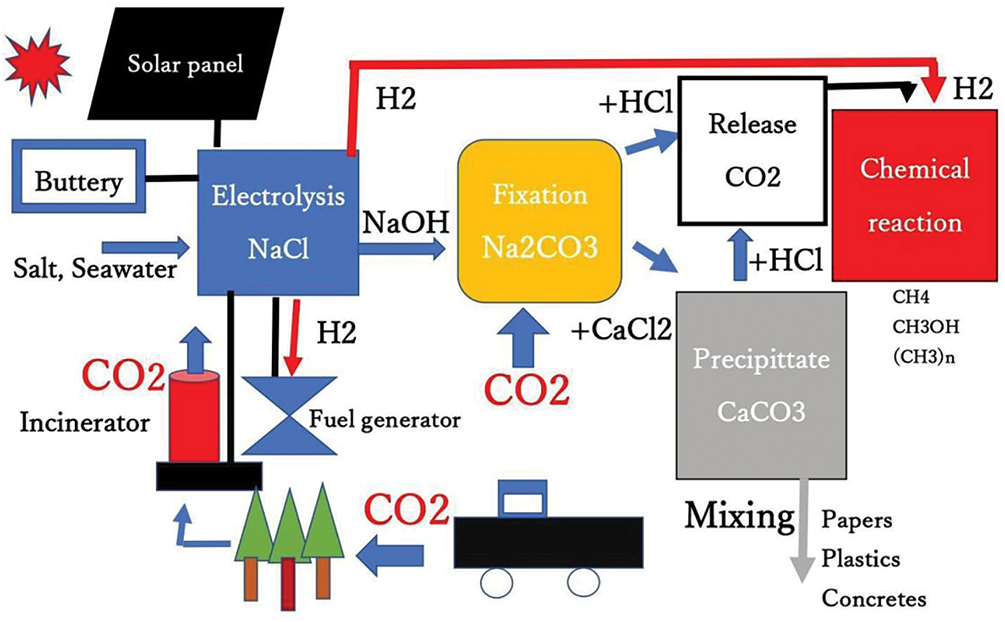

This system is applicable to thermal power plants, chemical plants, large ships, combustion operations, incinerators, and automobiles. For example, the incinerator could produce electricity, integrating with the generator, as shown in Fig. 3. The thermal power plant is already established, so it is easy to integrate the thermal power unit with the present CO2 capturing unit. In addition, as the electrolysis unit can produce HCl, the addition of HCl can convert Na2CO3, which is formed from CO2 and NaOH to pure concentrated CO2 and NaCl. Similarly, CaCO3 can be converted into CO2 and CaCl2 by the addition of HCl. The focused CO2 could be used for further chemical reaction materials. The synthesis of methanol from CO2 is practically important because methanol is a primary raw material for the production of numerous other chemicals [13]. Methane is produced from CO2 [14], and hydrocarbons are made from the ambient air by using a photo catalyzer in the presence of H2O [15–17]. These facts indicate that the presently proposed CO2-capturing technology is applicable to produce energy from CO2.

Figure 3: Flow sheet of CO2 capturing system

Electrolysis of NaCl solution produces H2 and Cl2 from the anode and cathode, respectively, as follows:

2Na+ + 2Cl- + 2H2O → H2↑+ Cl2↑ + 2OH- + 2Na+

CO2 easily reacts with OH- to produce CO32-.

CO2 + 2OH- → CO32- + H2O

CO32- reacts with Ca2+ to produce CaCO3.

CO32- + Ca2+ → CaCO3↓

The total reaction is:

H2O + CO2 + Ca2+ 2Cl- → H2↑ + Cl2↑ + CaCO3↓

Using the electrolysis of NaCl solution in a CO2 fixing unit, CO2 is converted to CaCO3 along with H2 and Cl2 productions followed by CaCl2 addition. Namely, the electrolysis of 2 mol NaCl produces 1 mol H2, 1 mol Cl2, and 1 mol CaCO3. When low-cost electricity could be provided for the electrolysis, the cost reduction of CO2 fixation could be obtained along with H2 production which has high potential as fuels and chemical materials.

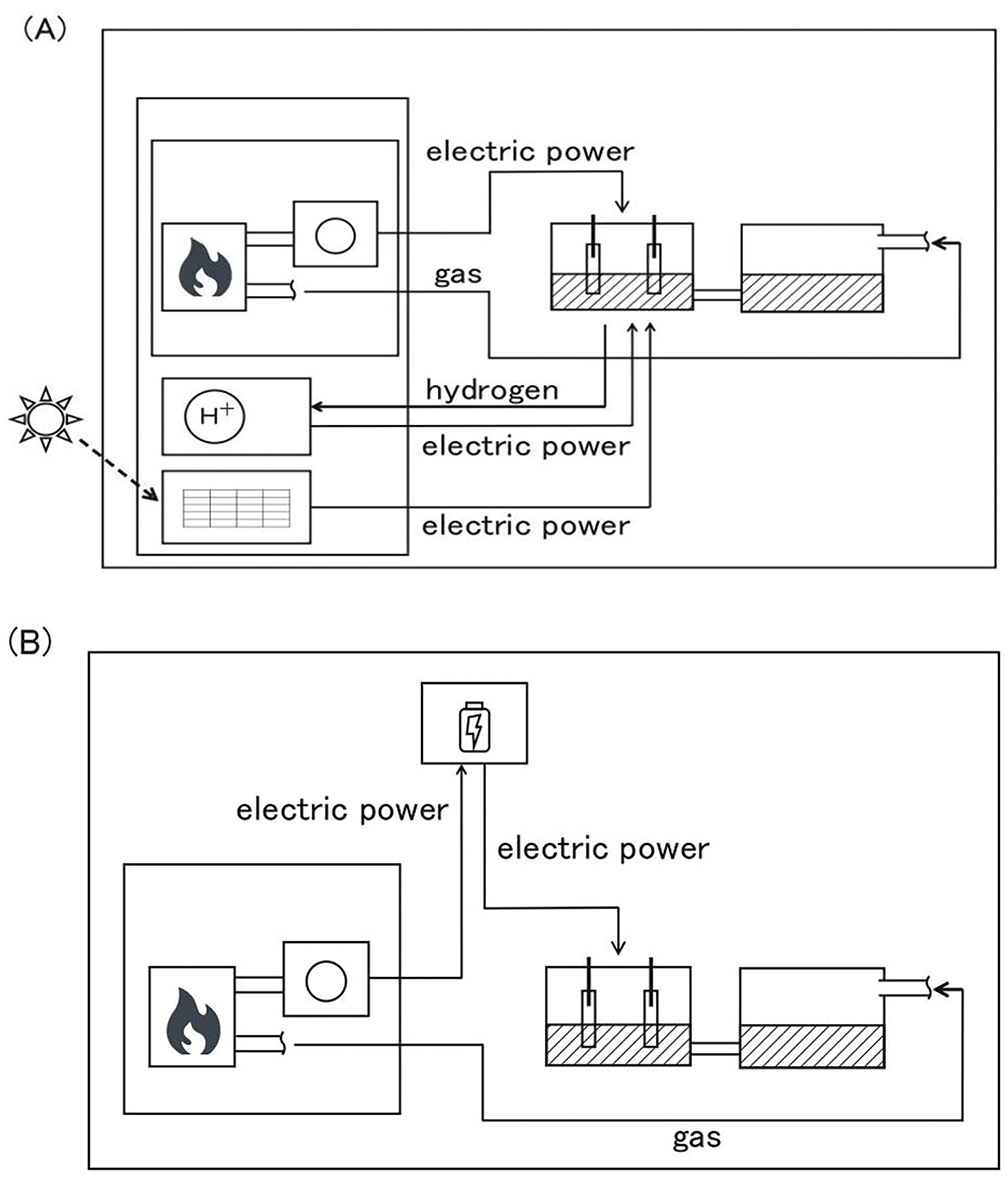

The H2 produced from the electrolysis based on the thermal power plant could be supplied not only to the hydrogen generator, which produces electricity but also to the chemical industry as fuel or starting materials of methane and ammonia [18,19]. Neglecting the energy loss due to the electrolysis and hydrogen generator, the integrated system is a complete energy circulation system. At the same time, the total energy might exceed the energy loss by the thermal power (Fig. 4A). Solar power panels are also capable of CO2 capturing unit, as shown in Fig. 4A. In this case, the integrated system consists of a CO2 capturing unit and solar power panel. The system is very simple without a thermal power unit (Fig. 4A). Similarly, not only renewable energy such as hydro power, wind power, geothermal power, and biomass plants but also even nuclear plants, could be applicable. The CO2 capturing from a thermal power unit is not necessary. In addition, by incorporating the storage battery into the integrated system, the system would be independent not only of weather conditions but also of time (Fig. 4B). This system must be very beneficial for the mass reduction of CO2 from the atmosphere. In addition, the system could be applied to the brown H2 production industry from brown coal and H2O, exhausting a large amount of CO2 which could be captured, and to the methane fermentation which produces simultaneously methane and CO2 to remove CO2.

Figure 4: Integrated flow sheets of energy and CO2 supplying systems. (A) The solar panel and hydrogen generator unit are incorporated into the integrated system. (B) The battery unit is incorporated into the integrated system

In our proposed CO2 fixation flow sheets (Figs. 3 and 4), the relationships between the energy-generating unit and the CO2 fixation unit are shown. Namely, only human beings found that burning fossil fuels, coal, oil, and natural gas, produces energy as well as wood, resulting in the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere. On the other hand, the accumulated CO2 could be removed by our technology without environmental concerns, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Flow sheet of energy and chemical components

Plants capture large quantities of CO2 based on photosynthesis and are distributed on the large parts of the earth, not only on the land surface but also in the shallow sea. However, the planet’s large forest, the Amazon, which greatly contributes to the removal of atmospheric CO2, is continuously shrinking because of commercial development and serious fires. The plant can spontaneously capture CO2 from the extremely low concentrations of CO2 in the ambient air and produce wood, leaves, fruits, and crops under sunlight. Eventually, as these natural products consist of organic compounds such as cellulose, lignin, and carbohydrates, they are basically flammable materials that potentially have high energy which was obtained from the concentrated thin sunlight energy.

Recently, we discovered that the high penetrability of CO2 in the gas phase caused “Pseudo-osmosis” against polymer elasticity not only cellulose membranes but also plastic membranes based on the CO2 concentration gradient [20]. In this phenomenon, CO2 can penetrate through the polymer membranes, such as latex and cellulose, while O2 and N2 whose penetrability is extremely lower compared with that of CO2, can’t penetrate the membrane. Therefore, when a latex glove partially filled with air is left in a glass bottle filled with high-concentration CO2 gas, the latex glove expands spontaneously. The CO2, air, and polymer membranes resemble water, impermeable compounds, and semipermeable membranes, respectively, in the osmosis. We named this discovery “pseudo-osmosis”. This characteristic of CO2 contributes to CO2 absorption from the air or water by plants as well as their pores.

The dead plants were converted to coals by geothermal heat and pressure deep underground in the Carboniferous period, while the remains of plants and animals were converted to oil in liquid condition and natural gas in the gas condition, respectively. Namely, these fossil fuels are high-energy materials, although they produce a large amount of CO2 at the time of combustion. Consequently, we have used valuable fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution because of their easy handiness, whether people living on the earth are wealthy or not. We make a certain amount of waste based on papers and foods in our daily lives, while our integrated CO2 capturing system is very beneficial for us to dispose of waste without environmental concerns.

Cyanobacteria have been thought that large quantities of CO2 were produced about 2.7 billion years ago by the photosynthesis of chlorophylls with CO2 and sunlight in the presence of H2O, in the shallow ocean, resulting in stromatolite, CaCO3, formation. Even at present, this organism still lives in Shark Bay, Australia. In the food chain, a large amount of phytoplankton breeds under sunlight, and CO2 exists in the ocean followed by the zooplankton prosperity which leads to animal foods. These processes contribute obviously to CO2 fixation in the ocean, although the organisms produce CO2 via their respiration [20]. Of course, organisms including humans release CO2 via the metabolism of carbohydrates, the TCA cycle, which are produced by plants. Interestingly, we found that not only sodium carbonates, NaHCO3, and Na2CO3 [21], but also amines [22] accelerated glucose consumption in cultured cells. These results indicate that the CO2 balance is reserved in nature but also organisms if it were not for CO2 production based on using the fossil fuel.

Recently, plastic waste has been shown to be a significant environmental pollutant, and microplastics have been found to affect marine organisms [23]. A small portion of the plastics used daily in human activities is recycled, while the remainder is simply treated as waste. Many of these materials could be incinerated but are typically sent to landfills. However, if the present CO2 fixing system becomes available, this waste could be readily disposed of by burning without environmental concerns and with the potential to generate energy.

CO2 also dissolves in the oceans to form H2CO3, HCO3- and CO32-, there is approximately 50 times as much carbon dissolved in the oceans in the atmosphere [24]. However, even though a certain amount of Ca2+ (0.4%) is dissolved in the ocean, CaCO3 formation does not take place in nature. This fact indicates that this reaction does not take place under natural inorganic conditions without organisms. Indeed, limestone, CaCO3, consists of the fossils of Fuslinids, belonging to protozoa in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras, several hundred million years ago, and at present, coral reefs and shells are formed by coral and shellfishes, respectively. In our experiments, the bubbling of the atmosphere into the seawater did not produce obvious CaCO3, whereas white precipitates of CaCO3 were formed by the addition of a small amount of NaOH (unpublished data). This experimental fact indicates that limestone and coral reef formations were carried out by living organisms based on biological reactions, not chemical reactions. These living organisms are indeed capturing spontaneously CO2 from the atmosphere or oceans on large parts of the earth. Therefore, environmental conditions where coal and plants can live continuously must be reserved to prevent climate change.

In our previous study [11], we found that CO2 is converted into CaCO3 as a result of NaOH and CaCl2. CaCO3 is a main component in limestone or coral and is almost insoluble in water and harmless to organisms. Contrarily, for CO2 storage, geo-sequestration by injecting CO2 into underground geological formations, such as oil fields, gas fields, and saline formations, has been suggested [25,26], although these systems are still projects for the future. Considering CO2 condensation, transportation, and storage technologies, the total CO2 storage cost might be extremely high, compared with our integrated CO2 technology.

It is impossible not to use fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, in our daily lives because the present acquired civilization is based on the consumption of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution. However, it seems possible to preserve the present daily lives using continuously fossil fuels if our proposed sustainable circulating energy system, which does not emit CO2 into the atmosphere, could be incorporated into our society immediately. Adopting the present system could improve climate change without social confusion.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Hiroyuki Okada, President of the Shinko-Sangyo Co. Ltd., Takasaki, Gunma, Japan, for a partial financial support, Hideaki Kato, President of the Takasaki Denka-Kogyo Co. Ltd., Takasaki, Gunma, Japan, for providing encouragement regarding the present work, Tsujimaru International Patent Office, Tokyo, Japan, and Matsushita Patent Office, Takasaki, Gunma, Japan for drawing schematic diagrams, Figs. 1, 3 and 4, and Fig. 2, respectively.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Kenji Sorimachi conceived, designed, and conducted the study and also wrote the manuscript. Toshinori Tsukad discussed the study and supported a partial financial support. Hossam A. Gabbar discussed the present study and revised the manuscript. All authors revied the results and approved the final revision of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

• Patents

[US 11,305,228 b2] Inventor Kenji Sorimachi; Assignee Kenji Sorimachi, Assignee Shinko Inc. Ind. Title of the patent; Method for fixing carbon dioxide, method for producing fixed carbon dioxide, and fixed carbon dioxide production apparatus. 2021, 8, 26/2022, 4, 19.

⟦JP 7408125⟧ Inventor Kenji Sorimachi; Assignee Kenji Sorimachi. Title of the patent; The carbon dioxide fixing device. 2022, 3, 28/2022, 4, 5.

The other related patents.

[JP 6739680], [JP 6830564], [JP 6878666], [JP 7433694], [JP 6817485], [JP 6788170], [JP 6788169], [JP 6788162], [JP 7048125], [JP 6864143], [JP 6783436], [JP 6906112], [JP 7221553], [JP 6906111].

References

1. Masson–Delmonte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors SL, Pean C, Berger S, et al. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. In: Intergovernmental pane on climate change (IPCC); 2021. [Google Scholar]

2. Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson A, Chapin FS, Lambin EF, et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 2009;461(7263):472–5. doi:10.1038/461472a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Espinal L, Poster DL, Wong-Ng W, Allen AJ, Green ML. Measurement, standards, and data needs for CO2 capture materials: a critical review. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(21):11960–75. doi:10.1021/es402622q. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Lv B, Guo B, Zhou Z, Jing G. Mechanisms of CO2 capture into monoethanolamine solution with different CO2 loading during the absorption/desorption processes. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(17):10728–35. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b02356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Jones CW. CO2 capture from dilute gases as a component of modern global carbon management. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2011;2(1):31–52. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Nandi M, Okada K, Dutta A, Bhaumik A, Maruyama J, Derks D, et al. Unprecedented CO2 uptake over highly porous N-doped activated carbon monoliths prepared by physical activation. Chem Commun. 2012;48(83):10283–5. doi:10.1039/c2cc35334b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Hajra S, Biswas A. Efficient chemical fixation and defixation cycle of carbon dioxide under ambient conditions. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15825. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71761-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Hiraide S, Sakanaka Y, Kajiro H, Kawaguchi S, Miyahara MT, Tanaka H. High-throughput gas separation by flexible metal-organic frameworks with fast gating and thermal management capabilities. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3867. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17625-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Modak A, Nandi M, Mondal J, Bhaumik A. Porphyrin based porous organic polymers: novel synthetic strategy and exceptionally high CO2 adsorption capacity. Chem Commun. 2012;48(2):248–50. doi:10.1039/c1cc14275e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Qiao Z, Zhao S, Wang J, Wang S, Wang Z, Guiver MD. A highly permeable aligned montmorillonite mixed-matrix membrane for CO2 separation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55(32):9321–5. doi:10.1002/anie.201603211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Sorimachi K. Innovative method for CO2 fixation and storage. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1694. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05151-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Sorimachi K. Novel method for CO2 fixation and storage preventing climate crisis: an artificial forest model. Petrol Chem Ind Int. 2022;5(1). doi:10.33140/pcii.05.01.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Guil-López R, Mota N, Llorente J, Millán E, Pawelec B, Fierro JG, et al. Methanol synthesis from CO2: a review of the latest developments in heterogeneous catalysis. Materials. 2019;12(23):3902. doi:10.3390/ma12233902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Aryal N, Odde M, Bøgeholdt Petersen C, Ditlev Mørck Ottosen L, Vedel Wegener Kofoed M. Methane production from syngas using a trickle-bed reactor setup. Bioresour Technol. 2021;333(2):125183. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Imanaka T, Takemoto T. Chemical synthesis of fuel hydrocarbon from CO2 and activated water, and purification of commercial light oil for dream oil. Edelweiss Chem Sci J. 2019;2019:23–6. doi:10.33805/2641-7383.111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Halfmann C, Gu L, Gibbons W, Zhou R. Genetically engineering cyanobacteria to convert CO2, water, and light into the long-chain hydrocarbon farnesene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(23):9869–77. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-6118-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Falter C, Batteiger V, Sizmann A. Climate impact and economic feasibility of solar thermochemical jet fuel production. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(1):470–7. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b03515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Moha V, Leitner W, Hölscher M. NH3 synthesis in the N2/H2 reaction system using cooperative molecular tungsten/rhodium catalysis in ionic hydrogenation: a DFT study. Chemistry. 2016;22(8):2624–8. doi:10.1002/chem.201504660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Xu G, Cai C, Wang T. Toward Sabatier optimal for ammonia synthesis with paramagnetic phase of ferromagnetic transition metal catalysts. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(50):23089–95. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c10603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sorimachi K. Epoch-making discovery for CO2 characteristics: pseudo osmosis in the gas phase. Sci J Health Sci Res. 2022;11(1):49–57. [Google Scholar]

21. Sorimachi K. Direct evidence for glucose consumption acceleration by carbonates in cultured cells. Int Natl J Pharm Phytopharm Res. 2019;9:1–8. [Google Scholar]

22. Sorimachi K. Amines mimic insulin in vitro and in vivo: acceleration of cellular glucose consumption. In: New advances in medicine and medical science. Vol. 2. BP International; 2023. p. 47–63. doi:10.9734/bpi/namms/v2/19254d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yang Y, Guo Y, O’Brien AM, Lins TF, Rochman CM, Sinton D. Biological responses to climate change and nanoplastics are altered in concert: full-factor screening reveals effects of multiple stressors on primary producers. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(4):2401–10. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b07040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Doney SC, Levine NM. How long can the ocean slow global warning? How much excess carbon dioxide can the ocean hold and how will it affect marine life? Oceanus magazine; 2006 Nov 29 [cited 2025 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/author/naomi-m-leveine/, http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/author/scott-c-doney/. [Google Scholar]

25. Eccles J, Pratson LF, Chandel MK. Effects of well spacing on geological storage site distribution costs and surface footprint. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(8):4649–56. doi:10.1021/es203553e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Carroll SA, Iyer J, Walsh SDC. Influence of chemical, mechanical, and transport processes on wellbore leakage from geologic CO2 storage reservoirs. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50(8):1829–37. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools