Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Adaptive Virtual Impedance Control for Voltage and Frequency Regulation of Islanded Distribution Networks Based on Multi-Agent Consensus

1 State Grid Hunan Electric Power Research Institute, Changsha, 410200, China

2 Electrical and Information Engineering College, Changsha University of Science and Technology, Changsha, 410114, China

* Corresponding Author: Chun Chen. Email:

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(6), 2465-2483. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.065453

Received 13 March 2025; Accepted 27 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

In the islanded operation of distribution networks, due to the mismatch of line impedance at the inverter output, conventional droop control leads to inaccurate power sharing according to capacity, resulting in voltage and frequency fluctuations under minor external disturbances. To address this issue, this paper introduces an enhanced scheme for power sharing and voltage-frequency control. First, to solve the power distribution problem, we propose an adaptive virtual impedance control based on multi-agent consensus, which allows for precise active and reactive power allocation without requiring feeder impedance knowledge. Moreover, a novel consensus-based voltage and frequency control is proposed to correct the voltage deviation inherent in droop control and virtual impedance methods. This strategy maintains voltage and frequency stability even during communication disruptions and enhances system robustness. Additionally, a small-signal model is established for system stability analysis, and the control parameters are optimized. Simulation results validate the effectiveness of the proposed control scheme.Keywords

The penetration of renewable energy sources (RES) into distribution networks has been steadily increasing. Microgrids (MGs) represent an effective solution for integrating RES [1–3]. MGs enhance power supply reliability and quality, and increase grid resilience to load variations and external disturbances [4,5]. MGs can operate in grid-connected mode or island mode. In island mode, MGs maintain power supply independently from the main grid, which is particularly important for remote areas or under adverse weather conditions to ensure the reliability of critical loads [6,7].

Under islanded conditions, distributed generation (DG) units are expected to share power proportionally to their rated capacities. Droop control is widely adopted to enable autonomous power sharing among DG units [8]. However, the performance of conventional droop control is limited by mismatched output line impedances between parallel inverters, resulting in inaccurate active and reactive power sharing [9]. Ref. [10] proposed an advanced control that regulates the voltage at suitable values and ensures proper reactive power sharing among the energy sources. Ref. [11] proposed that reactive power is controlled to be proportional to the derivative of the DG output voltage to compensate for the line impedance mismatch. While this approach reduces the reactive power sharing error, it does not eliminate the impact of line impedance mismatch. Ref. [12] proposed a novel method to achieve accurate power sharing without conventional droop control. By employing a modified double-loop voltage control strategy, the proposed approach eliminates the inherent power-sharing errors and stability issues of droop control. However, the use of proportional-resonant (PR) control may affect system stability, requiring additional compensation loops. Ref. [13] proposed power decoupling techniques to improve sharing accuracy. Nevertheless, these approaches require precise knowledge of line impedance parameters, which limits their applicability in practice. Overall, the existing literature has primarily focused on either power decoupling or line impedance mismatch but rarely considers both issues simultaneously. As a result, these control methods may be less suitable for low-voltage distribution networks.

To address these issues, virtual impedance control is a promising way. Virtual impedance control is mainly categorized into two approaches: one combined with the virtual synchronous generator (VSG) concept, and the other integrated with droop control. Ref. [14] proposes a transient power angle stability control strategy for VSGs, incorporating frequency difference feedback and virtual impedance, enhancing frequency regulation performance. However, the VSG-based control method may cause power oscillations in multi-level parallel systems [15,16]. Several studies have proposed the use of virtual impedance as a supplementary component to droop control [17]. Virtual impedance can directly compensate for line impedance mismatch and convert the inverter’s output impedance into an inductive form, achieving decoupling of active and reactive power control [18,19]. Ref. [20] established an equivalent model of the DG feeder impedance based on feeder current and impedance measurements and addressed the mismatch by adaptively adjusting the output virtual impedance. However, these methods require precise knowledge of feeder impedance, which is difficult to measure accurately in practical applications. Additionally, when the microgrid structure changes, the power sharing method becomes ineffective. To reduce dependence on line impedance, Refs. [21,22] introduced an adaptive virtual impedance approach. Ref. [23] improved precise power sharing by virtually adjusting the inverter’s output impedance. However, droop control combined with the additional virtual impedance can result in significant voltage deviation at the DG output, preventing the output voltage of each DG from being regulated at the rated voltage of the microgrid. An adaptive virtual impedance method based on a consensus algorithm was proposed in [24,25], which eliminates the voltage deviation caused by virtual impedance. However, this method does not consider the impact of communication interruptions, and the control may fail under such conditions.

Therefore, based on the above analysis, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) To address the inaccurate power distribution caused by power coupling and impedance mismatch at the inverter output during active islanding operation of distribution networks, an adaptive virtual impedance control based on multi-agent consensus is proposed. This method can eliminate the influence of line impedance mismatch between DGs without the need for line impedance measurement, achieving precise power distribution.

(2) To mitigate the voltage deviation from the rated voltage due to the inherent characteristics of droop control and virtual impedance, a novel consensus-based voltage and frequency control is proposed. It reduces the voltage amplitude deviation of the system bus by approximately 9.6% compared to traditional adaptive virtual impedance control. The bus voltage amplitude can always be maintained at the rated voltage of 311 V, and the frequency deviation is no more than 0.01 Hz. Compared with the traditional consensus method, the voltage fluctuation is reduced by 300% and the frequency fluctuation is controlled within 0.1 Hz under communication interruption.

(3) A small-signal stability analysis of the inverter employing this control method is conducted to determine the optimal control parameters and validate the stability of the control system.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 presents the power distribution characteristics of parallel inverters and multi-intelligent communication. Section 3 introduces the adaptive virtual impedance control based on dynamic synchronous stability. In Section 4, the virtual impedance small signal model of dynamic synchronization stability is established. Section 5 designs the controller parameters and analyzes the example. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2 Power Distribution and Multi-Agent Communication

where

When two distributed power supplies with equal capacity operate in parallel, the output voltage of the inverter connected to a line with a higher inductive reactance value is observed to be elevated. Voltage as a local variable can experience variations in line lengths when different DG units are connected to the Point of Common Coupling (PCC), resulting in differences in the line impedance between inverters. This impedance imbalance hampers the equitable distribution of reactive power, leading to the overloading of certain DG units.

According to the basic power characteristics of drop control, the condition for the reactive power output of distributed power sources to be proportional to their rated capacity is that the reactive power droop coefficient is inversely proportional to their rated capacity. In other words, it satisfies the following conditions:

Eqs. (1) and (2) can be derived as follows:

If the reactive power output of the distributed power supply is inversely proportional to its reactive droop coefficient, it implies that the equivalent output impedance needs to satisfy the following conditions:

However, due to the different line reactance in reality, therefore, the virtual reactance is utilized to match the different line reactances of DG units. When the line reactance

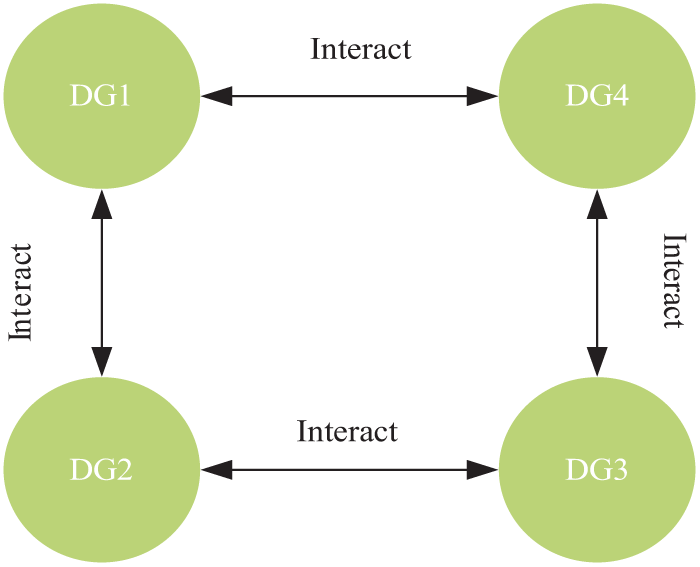

Fig. 1 presents a concise model that illustrates the communication dynamics among the four agents. Employing graph theory as a descriptive framework, the inter-agent communication is bidirectional, and their relationship can be represented by

Figure 1: A communication topology with four agents

When consense control is adopted, adjacency matrix

The change of each agent is influenced by its own current state as well as the current states of its neighboring agents. The first-order dynamic characteristics can be described by the equation

The matrix form should be rewritten as follows:

where

3 Adaptive Virtual Impedance Control Based on Multi-Agent Consensus

3.1 Virtual Impedance Control Method

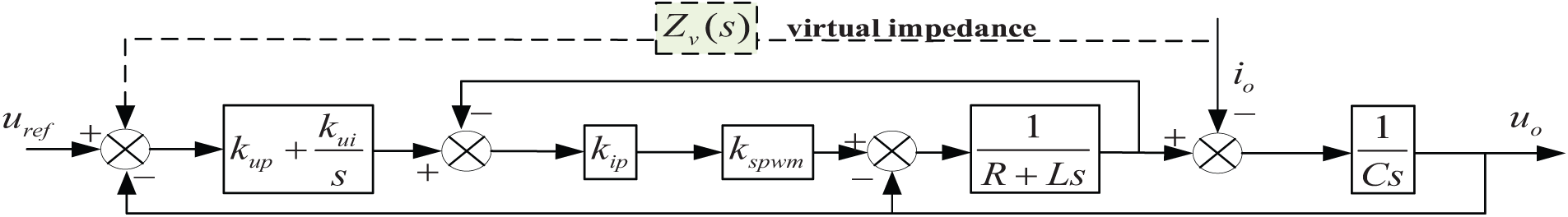

The virtual impedance

Figure 2: Presents the block diagram of the virtual impedance voltage-current double-loop control equivalent transfer function

After incorporating the virtual impedance, the system’s transfer function and equivalent output impedance are obtained:

where

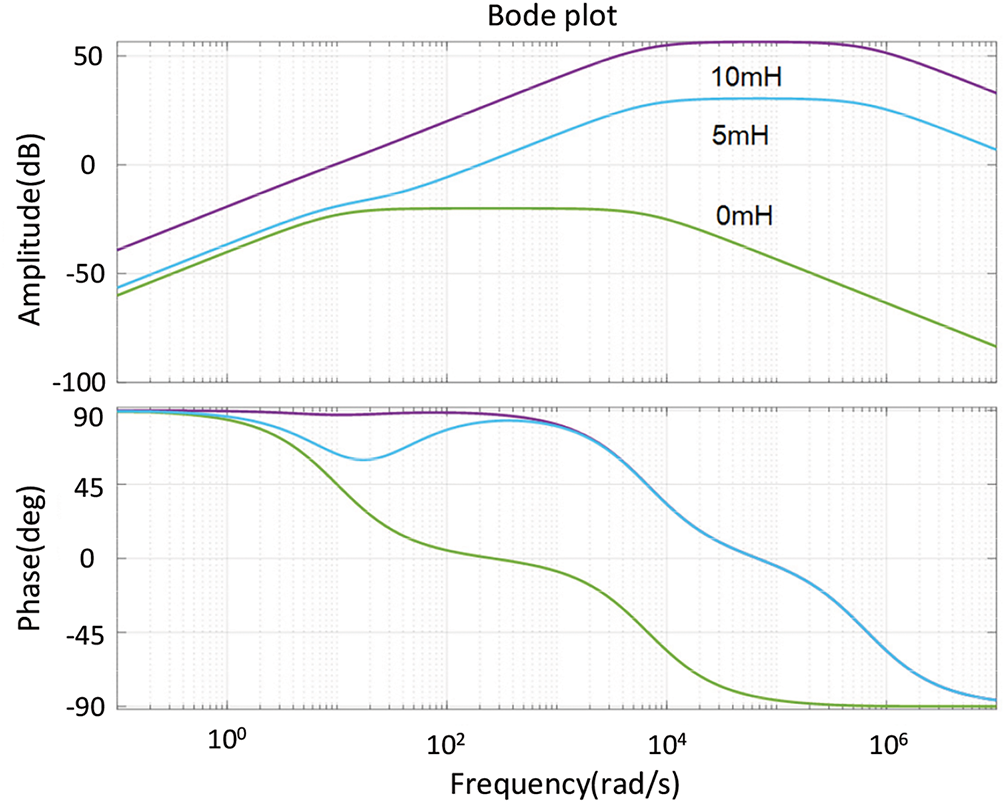

The pure inductive virtual impedance

Figure 3: The equivalent Bode diagram of the system output impedance after adding virtual impedances with different impedance values

3.2 Adaptive Virtual Impedance Control Method Based on Multi-Agent Consensus

The introduction of virtual reactance should satisfy the following Eq. (8) in order to achieve accurate reactive power distribution when meeting

where

The adaptive control of virtual impedance is achieved through the implementation of a multi-agent consensus algorithm in order to ensure proportional power distribution. It is necessary to select a target value

The variable

The overall system can be formulated as follows:

By employing Lyapunov analysis to construct candidate functions for demonstrating system stability, in conjunction with the system description, we establish the following model as a potential function:

where

The derivation of Eq. (12), simultaneous Eqs. (10) and (11) can be obtained as follows:

The stability of the system can be assessed based on the Lyapunov function, given that

Configure the control parameters of the proportional integral controller to facilitate adjustment for reactive power correction, thereby determining the required compensation of reactive power by the distributed power supply line. Subsequently, calculate the corrective factor for virtual reactance:

where

Similarly, in order to enhance the precision of active power distribution under minor external disturbances experienced by the distributed power supply, an adaptive virtual resistance is introduced into the system for adjustment purposes. Its control model bears a resemblance to Eq. (16) and can be summarized as follows:

where

The active and reactive power sharing among DG units is regulated by adjusting the equivalent impedance. A correction term based on reactive power mismatch is introduced as the input to the PI controller, which adaptively modifies the size of the virtual impedance, as shown in Eqs. (16) and (17). When the reactive power of the microgrid is proportionally shared among the DG units, the multi-agent consensus control will automatically eliminate the reactive power mismatch to zero. This technique does not require knowledge of line impedance and adjusts the virtual impedance to eliminate the reactive power sharing error caused by feeder mismatch.

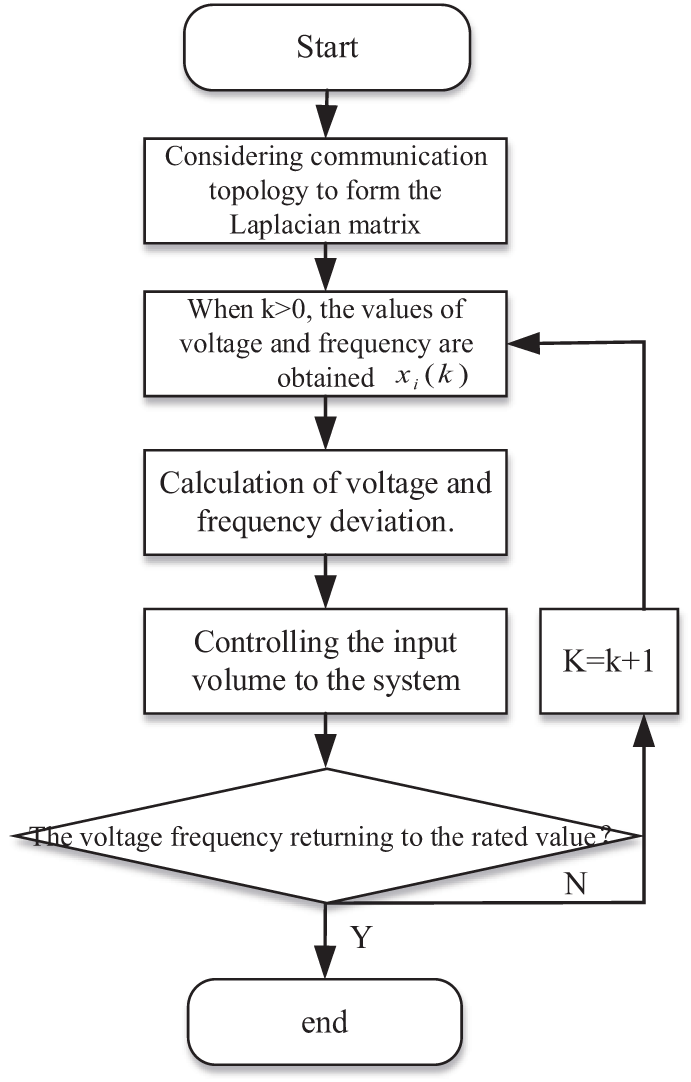

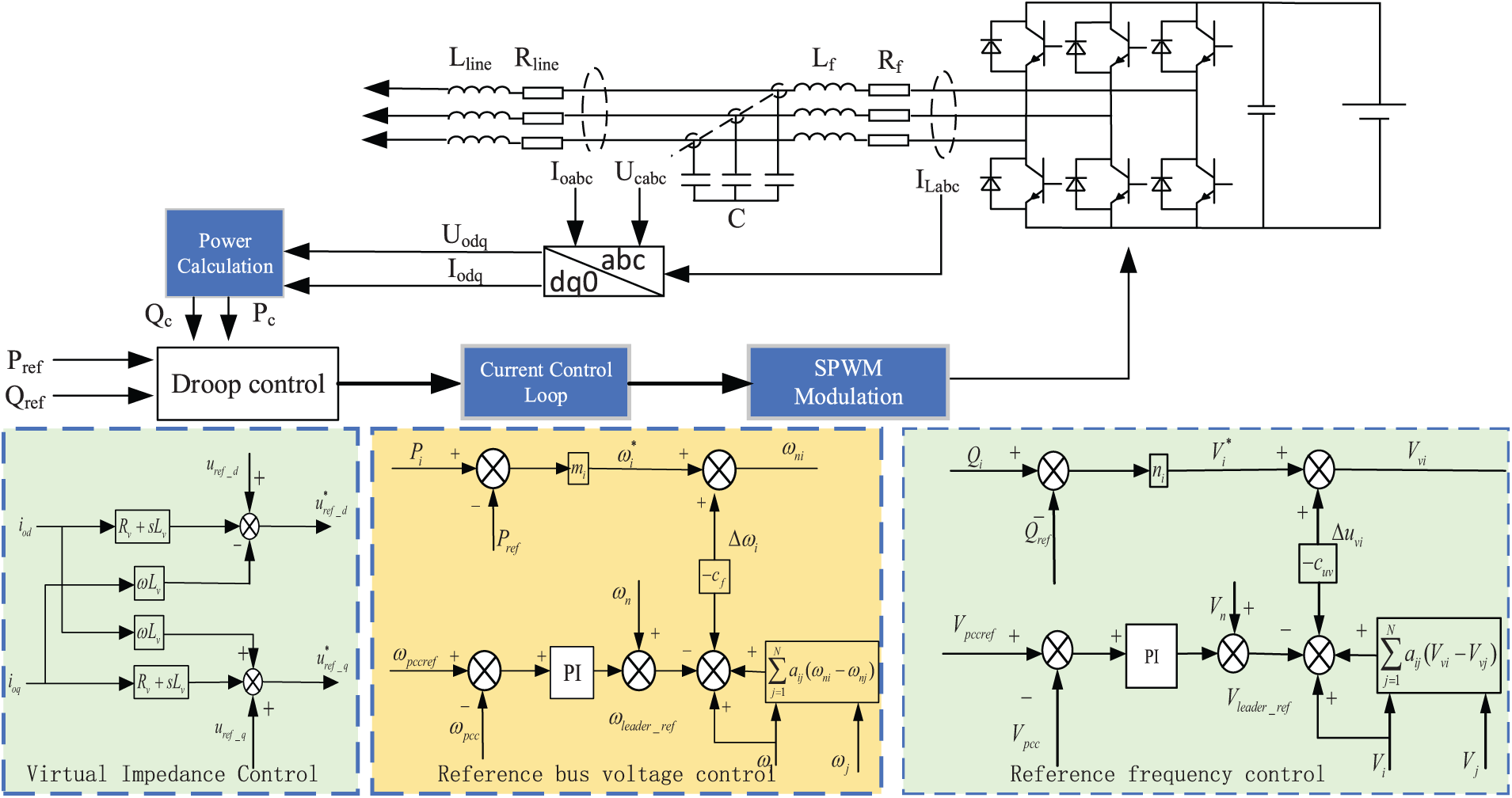

3.3 Consensus-Based Voltage and Frequency Control

The introduction of a virtual impedance within the feedback loop results in a voltage drop caused by the feedback current. This induced voltage is then negatively fed back to the reference voltage of the voltage control loop, effectively establishing a new and unique voltage reference value

The virtual inductance value

Figure 4: Flow chart of dynamic synchronous stability control

The reference voltage amplitude of the distributed power supply obtained by the local layer is as follows:

where

The secondary voltage control is incorporated based on this premise, thereby enabling the representation of the most recent voltage amplitude reference value for the distributed power supply as follows:

The variable represents the final reference voltage amplitude of the inveter

Taking into account the communication delay of size

The control parameter of the voltage controller,

Figure 5: Adaptive virtual impedance control block diagram based on dynamic synchronous stability

The reference value of system frequency compensation can be derived in a similar manner:

where

When a communication failure occurs, other agents are unable to receive the control reference information from the agent’s output. Consequently, if the consistency algorithm continues to enforce the consistency of each output control target, it may cause system instability or even loss of control. Therefore, ensuring stability becomes the primary objective when dealing with communication failures. In this context, the agent itself acts as the main controller. By employing a distributed hierarchical control strategy, we shift our focus from maintaining consistency to monitoring and regulating the rated voltage and frequency of the system.

4 System Small Signal Model Based on Dynamic Synchronization Stability

The traditional small signal model of an inverter comprises several components, including the power control small signal model, the voltage and current control small signal model, and the output circuit small signal model. Building upon this foundation, a small signal model for the active island system of a distribution network is established based on dynamic synchronous stability and adaptive virtual impedance to analyze the system’s stability.

where,

For the convenience of calculation and formula derivation, the auxiliary term for voltage elimination control is named

Then, by linearizing Eqs. (10)–(12) and the control model equation with the introduced virtual impedance equations Eqs. (16) and (17), we can obtain:

Due to the introduction of secondary voltage and frequency control in the system, the feedback loop has modified the synthesis reference voltage model, leading to changes in the small signal model of the dual-loop control of voltage and current in the system. Therefore, based on dynamic synchronous stability, the small signal model of the adaptive virtual impedance-controlled inverter is as follows:

using an improved voltage control model, as shown below:

where

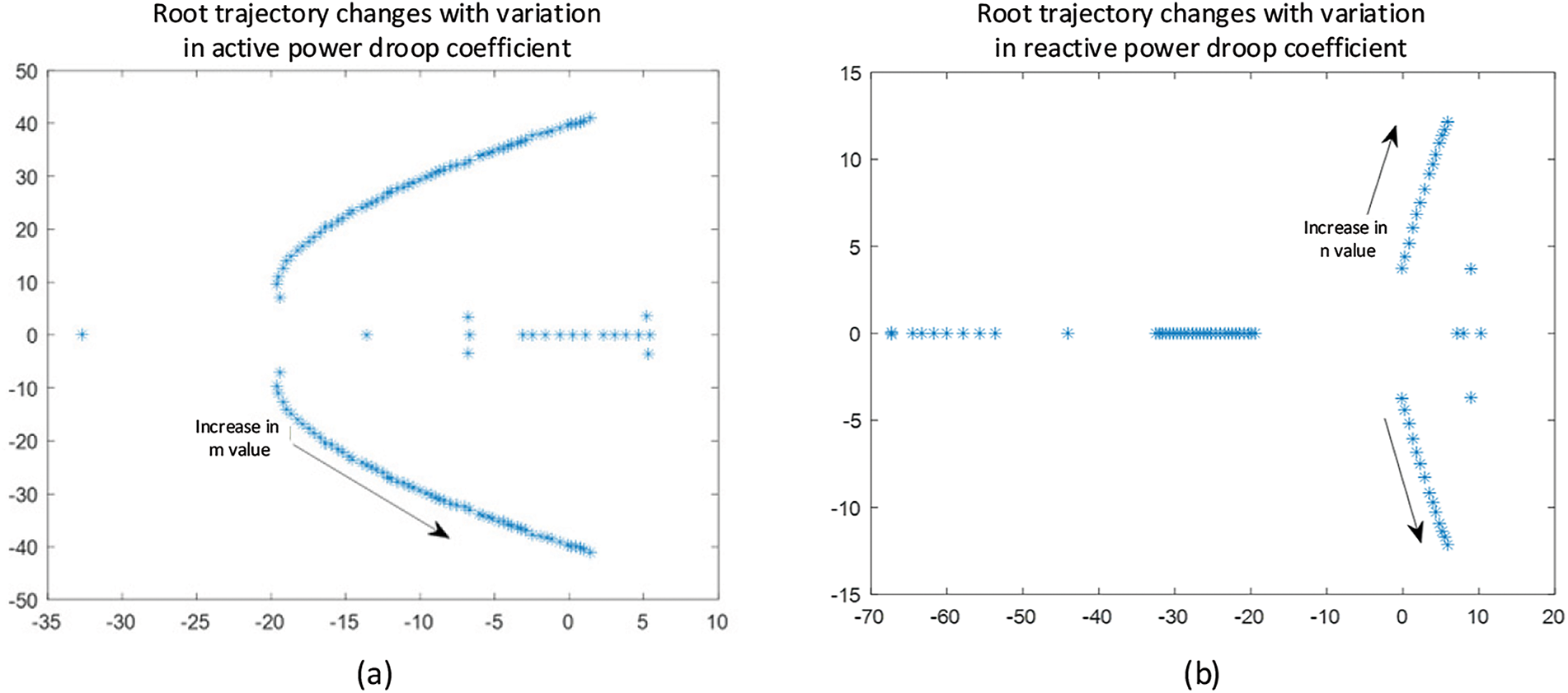

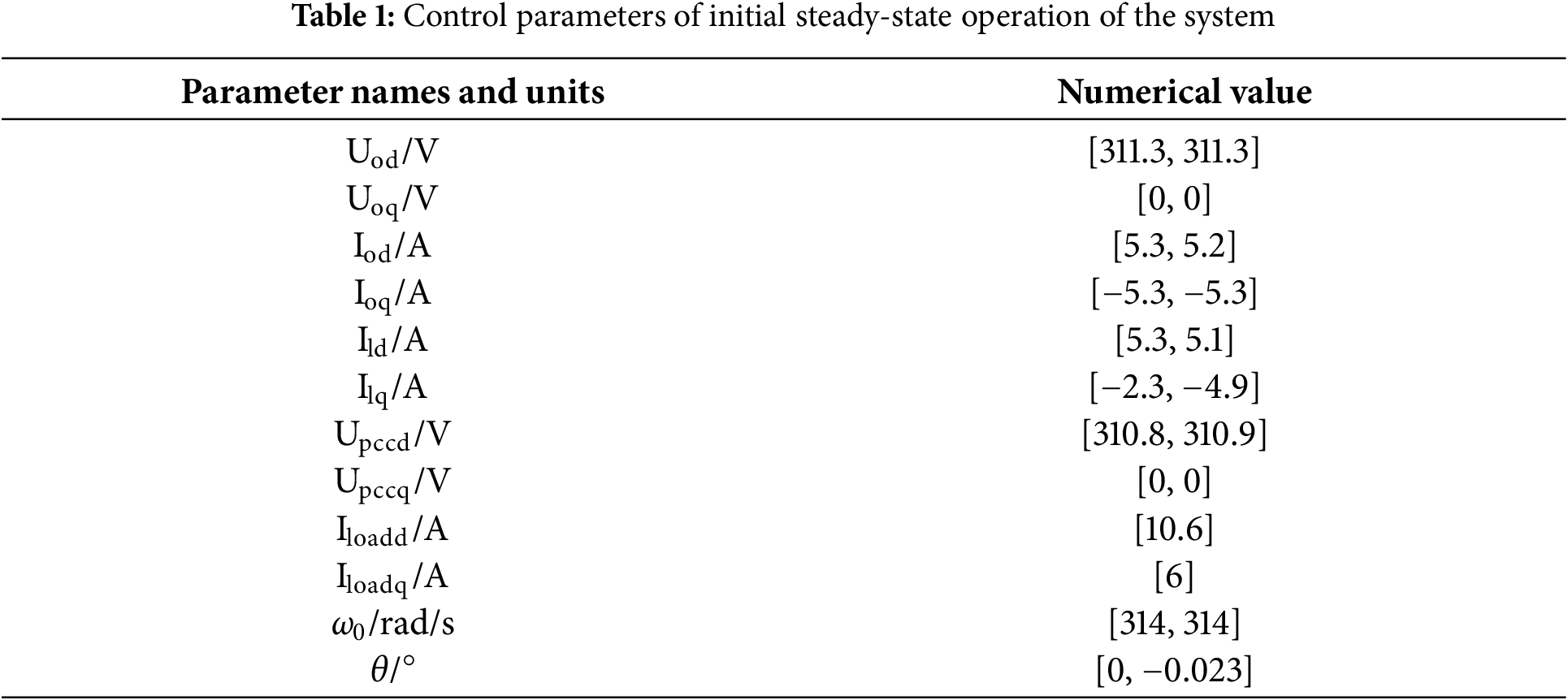

According to the obtained small signal model, the stability of systems with different control parameters was analyzed. In Fig. 6a, as the active power droop coefficient m increases, the system poles gradually move from the left half-plane toward the right. When m increases to the point where the poles approach 40, the system becomes critically stable. Therefore, the active power droop coefficient should be in the range of 0.001 to 0.05. In Fig. 6b, as the reactive power droop coefficient n increases, the poles quickly move to the right, and when n reaches the point where the poles approach a real part of −10, the system approaches critical stability. The reactive power droop coefficient is in the range of 0.01 to 0.3 p.u. In Fig. 6c, when the line impedance is sufficiently small, all the poles are located in the left half-plane, and the system remains stable. The virtual impedance should be less than 0.1 p.u. In Fig. 6d, as the communication delay increases, the poles move toward the right half-plane, potentially leading to instability. A communication delay

Figure 6: Stability analysis with parameter variations. (a) the System Stability when active power droop changes; (b) the System Stability when reactive power droop changes; (c) the System Stability when the line reactance changes; (d) the System Stability when communication delay changes

5 Control Parameter Design and Simulation

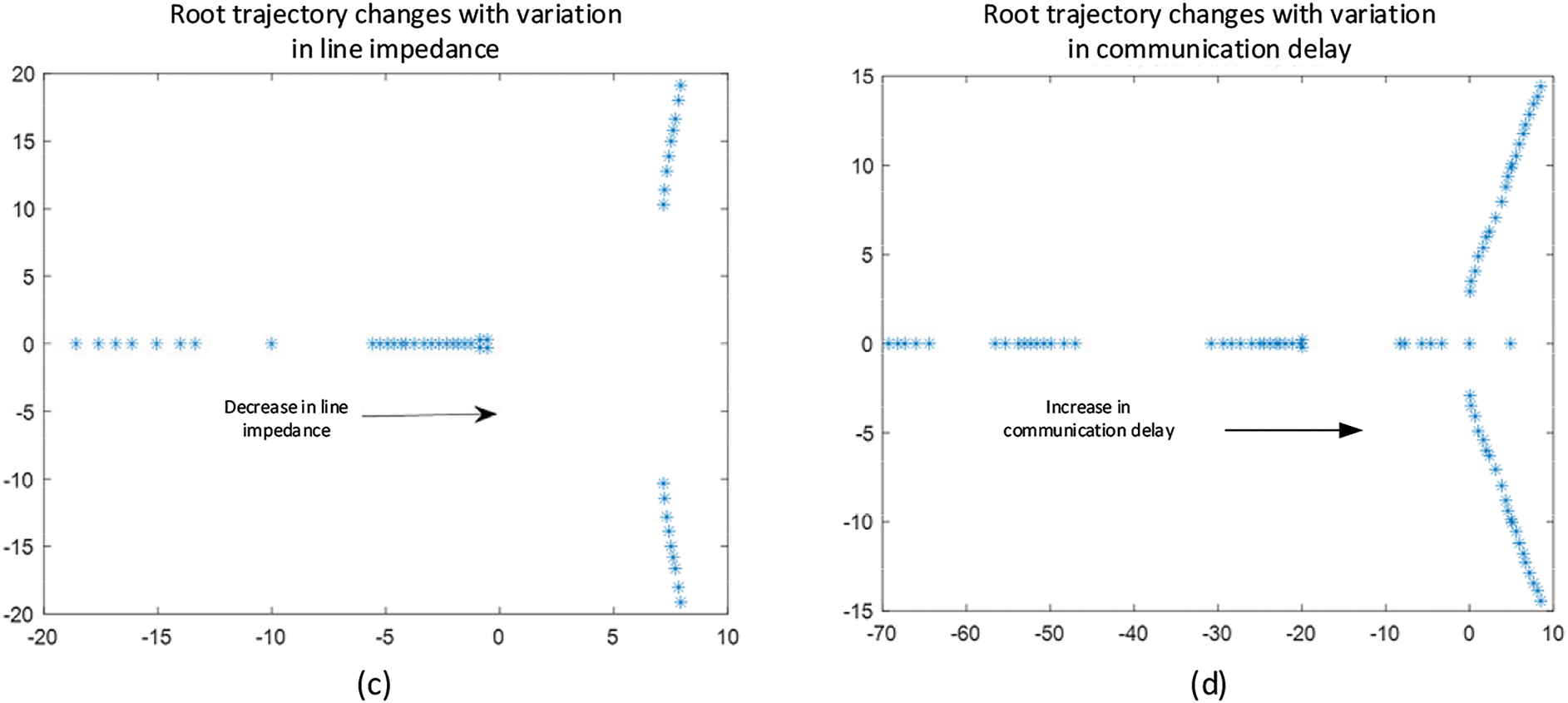

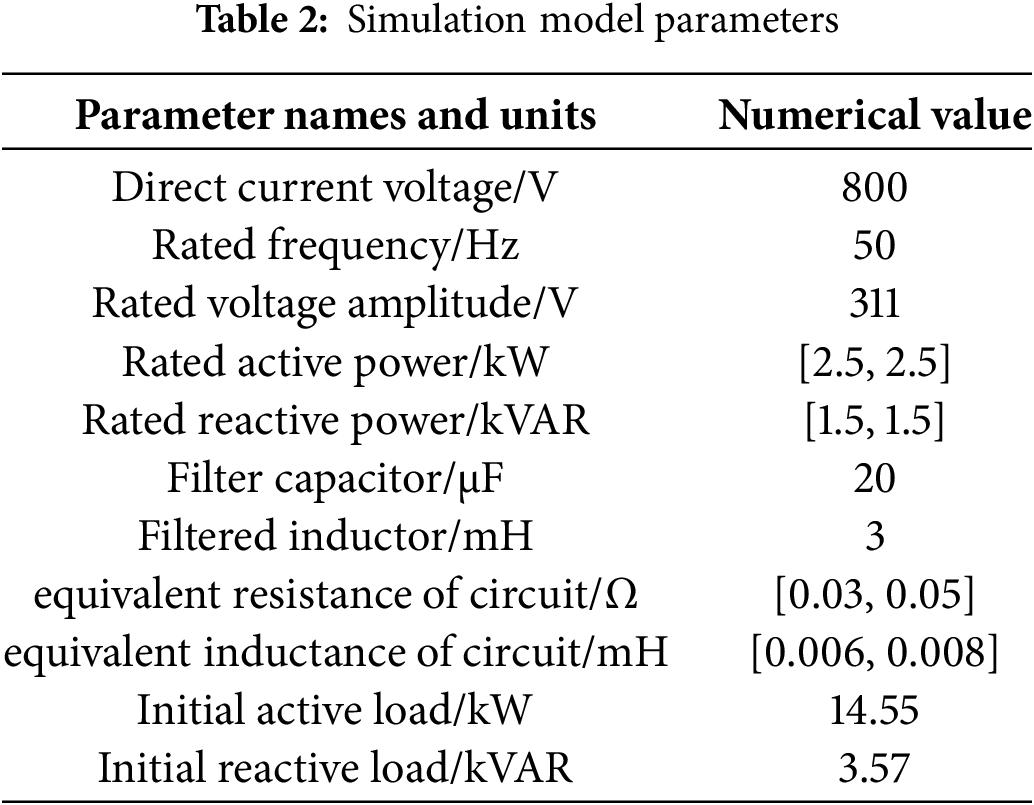

The small-signal model of the system, derived through mathematical derivation, explores the significant role that control parameters play in ensuring system stability. The specific parameters associated with the control circuit are presented in Table 1 as follows.

Two simulation models for distributed powersupply are developed using the Matlab/Simulink platform. The comparison of system voltage, frequency, and output distribution is conducted under two control strategies: traditional adaptive virtual impedance control and adaptive virtual impedance control based on dynamic synchronization stability. Simulations are conducted over a total duration of 3 s, with a load disturbance applied at 1 s and removed at 2 s. The simulation step size is set to 5 × 10−6. Table 2 presents the specific parameters of the main circuit in the simulation model.

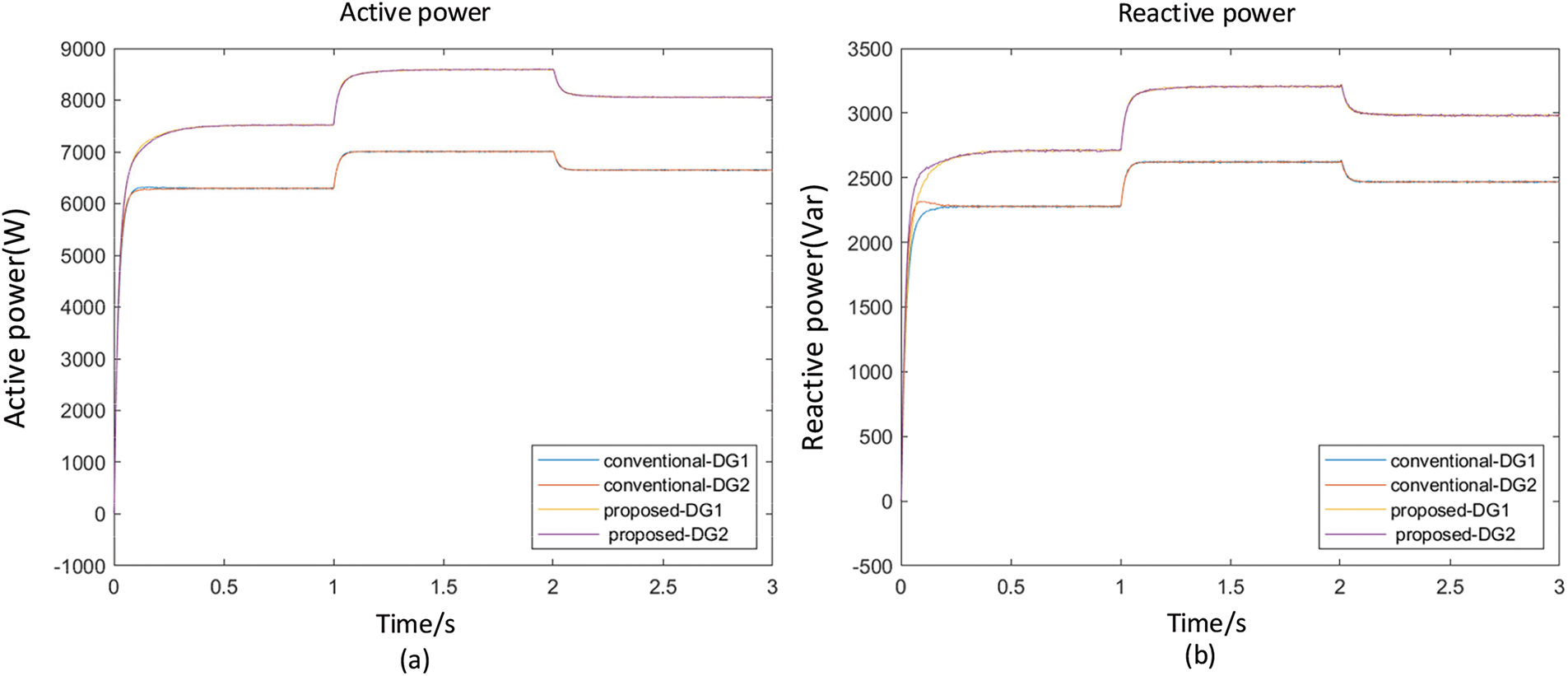

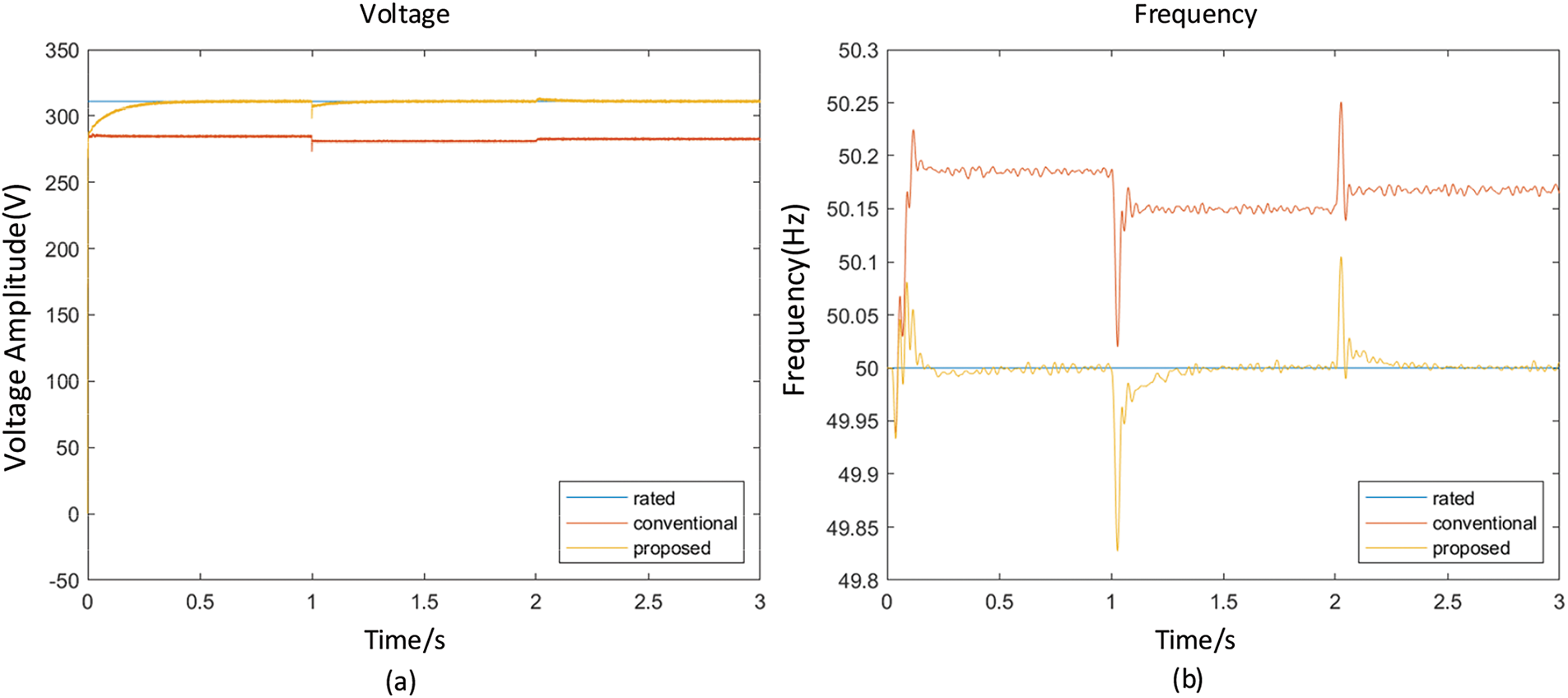

At T = 1 s, a load disturbance of 2 kW + 0.5 kVAR is introduced. Subsequently, at T = 2 s, the system load is reduced by 1 kW + 0.25 kVAR to observe the equal distribution of active power and reactive power. Figs. 7 and 8 below illustrate the comparison between improved adaptive virtual impedance control and the traditional method in terms of their ability to achieve this equal division.

Figure 7: Comparison of power distribution. (a) active power distribution; (b) reactive power distribution

Figure 8: Voltage and frequency amplitude fluctuation. (a) voltage magnitude fluctuation; (b) frequency magnitude fluctuation

By observing Fig. 7, it can be seen that traditional adaptive virtual impedance control achieves reactive power balance but with a longer response time. In contrast, the improved control strategy results in a more accurate active power distribution.

As shown in Fig. 8a,b, the integration of improved adaptive virtual impedance enables uniform power distribution without requiring secondary voltage compensation. However, this led to a voltage drop, causing the bus voltage amplitude to deviate from the rated value of 311 V. Load mutation also triggers a drop in voltage, which prevents the bus frequency from being held at the rated value of 50 Hz. A sudden load disturbance induces a frequency deviation exceeding 0.2 Hz, which cannot be restored to the rated frequency.

In contrast, with secondary voltage compensation applied, the bus voltage amplitude can consistently remain at its rated value of 311 V. Furthermore, once load mutation occurs and adjustments are made, the bus voltage is restored to its rated voltage level while maintaining a stable frequency of 50 Hz. Observations indicate that under load mutation, the resulting frequency deviation does not exceed 0.01 Hz. After applying secondary frequency compensation, the bus retains a stable operating frequency at its nominal 50 Hz rating.

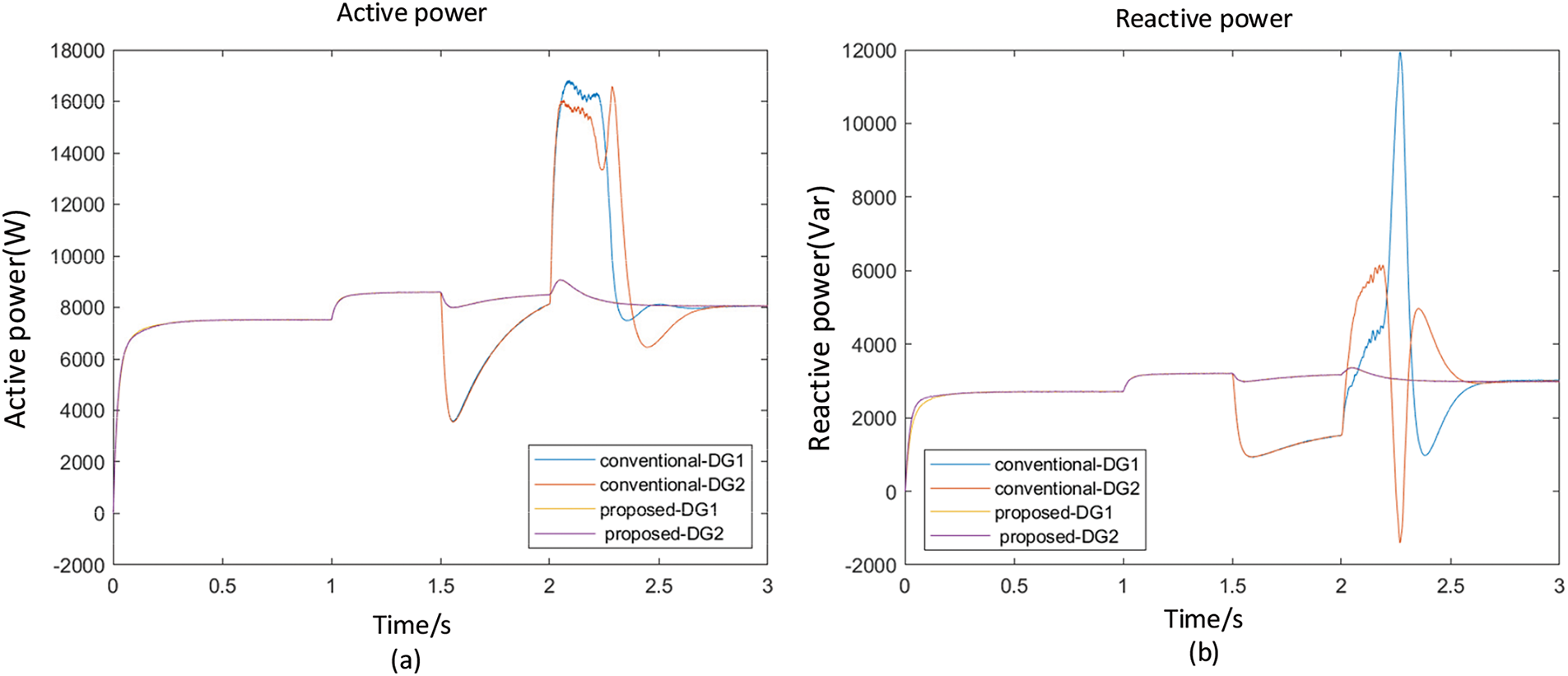

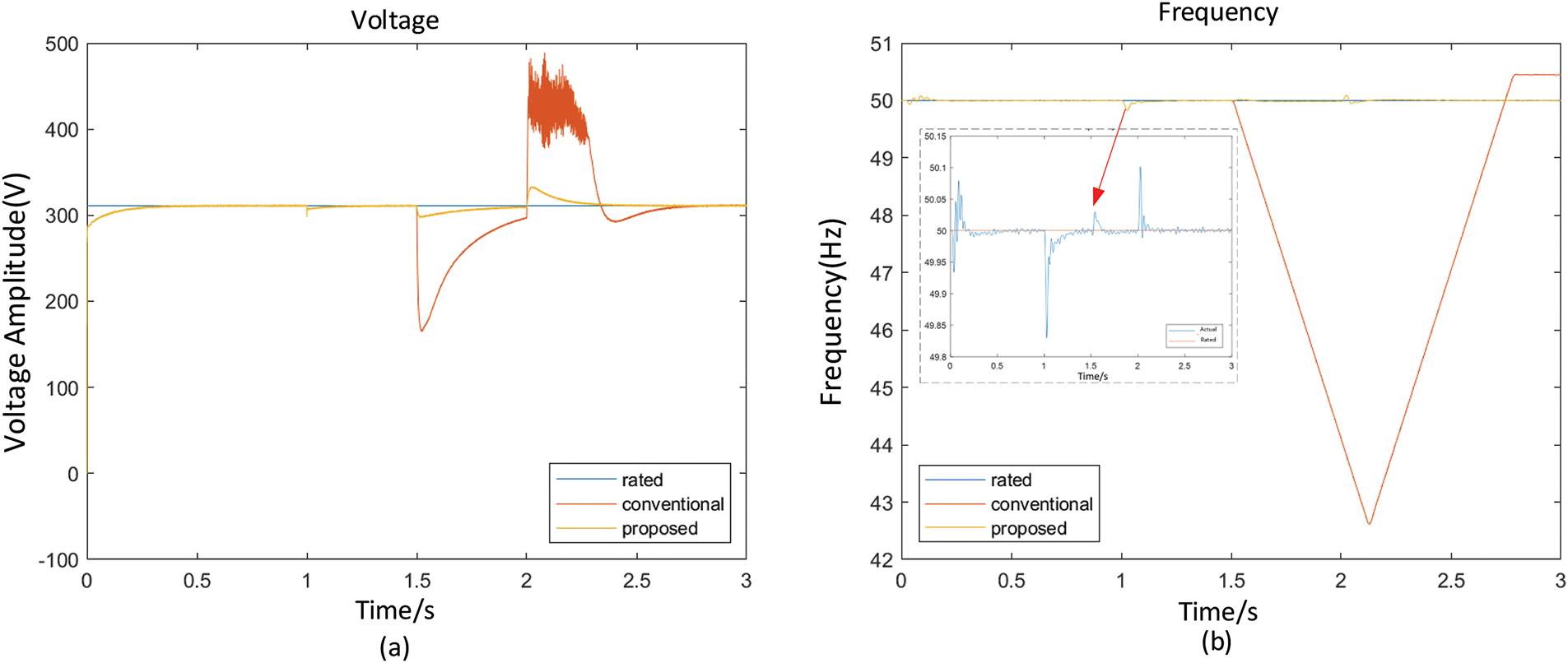

The other parameters of the simulation remain unchanged. Considering the possibility of communication faults in the control system, communication interruptions are simulated during the experiment, where there is no communication between agents. Specifically, we assume that the communication between systems is interrupted at a simulation duration of 1.5 s, with signal transmission between distributed power supplies set to zero. Communication is then restored at a simulation time of 2 s. The effects of this experiment are observed and analyzed.

The paper focuses on addressing the communication problem by introducing a rating judgment module in addition to the traditional consistency control. In the case of a communication fault, the agent will disconnect from the faulty line and automatically adjust itself as the main leadership module, ensuring a stable output. By observing Fig. 9, it can be seen that in conventional adaptive virtual impedance control, power sharing of both active and reactive power becomes unstable under communication failures. In contrast, the control strategy proposed in this paper maintains stable power distribution even during such failures. Experimental simulations depicted in Fig. 10a,b demonstrate that when relying solely on traditional consistency control, significant fluctuations occur in both system frequency and voltage when the communication line fails at 1.5 s. The voltage drops approximately 150 V below its rated value of 311 V, while the system frequency decreases by about 7 Hz from the rated 50 Hz, resulting in severe instability. However, with distributed hierarchical control implemented, it is observed that even during such faults, both output voltage and frequency remain within acceptable limits, with minimal fluctuation—less than a 10 V voltage drop and less than a 0.1 Hz frequency deviation—thus ensuring system stability.

Figure 9: Comparison of power distribution during communication interruption. (a) active power distribution; (b) reactive power distribution

Figure 10: Voltage and frequency magnitude fluctuation during communication interruption. (a) voltage magnitude fluctuation; (b) frequency magnitude fluctuation

In this paper, we propose an adaptive virtual impedance control strategy based on multi-agent consensus to address the voltage and frequency fluctuation caused by traditional droop control during islanded operation of distribution networks due to impedance mismatch in the inverter outlet line. The following conclusions are drawn:

(1) By utilizing adaptive virtual impedance control based on multi-agent consensus, our system can rapidly adapt to line impedance variations and effectively mitigate interference fluctuations caused by load imbalance and external disturbances.

(2) Our proposed algorithm significantly reduces the voltage amplitude deviation of the system bus by approximately 9.6% compared to traditional adaptive virtual impedance control. Additionally, it limits the load mutation-induced frequency deviation to below 0.01 Hz, thereby eliminating deviations caused by virtual impedance and droop characteristics of the system.

(3) In scenarios where communication links fail, adopting traditional consistency control methods leads to severe instability within the system. However, the consensus-based voltage and frequency control proposed in this paper considers communication failure and significantly enhances system stability, with voltage drops limited within 10 V and frequency fluctuations kept within 0.1 Hz, while also improving response time.

In future work, we plan to implement the proposed control scheme on a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing platform and subsequently validate it through a laboratory-scale microgrid prototype to further assess real-time performance and robustness under realistic operating conditions. Building upon this study, we will further investigate methods for suppressing voltage and frequency fluctuations during active island operations of multi-source distribution networks using different control strategies.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52007009), Natural Science Foundation of Excellent Youth Project of Hunan Province of China (2023JJ20039), and Science and Technology Projects of State Grid Hunan Provincial Electric Power Co., Ltd. (5216A522001K, SGHNDK00PWJS2310173).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jiran Zhu and Chun Chen; methodology, Silin He; validation, Jiran Zhu, Chun Chen, and Li Zhou; formal analysis, Li Zhou; investigation, Silin He; resources, Silin He; data curation, Hongqing Li; writing—original draft preparation, Di Zhang; writing—review and editing, Fenglin Hua; visualization, Tianhao Zhu; supervision, Silin He; project administration, Chun Chen; funding acquisition, Jiran Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors with reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang Z, Li H, He H, Sun Y. Robust distributed finite-time secondary frequency control of islanded AC microgrids with event-triggered mechanism. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT); 2023 Jan 16–19; Washington, DC, USA. doi:10.1109/ISGT51731.2023.10066379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xu J, Zhang T, Du Y, Zhang W, Yang T, Qiu J. Islanding and dynamic reconfiguration for resilience enhancement of active distribution systems. Electr Power Syst Res. 2020;189:106749. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2020.106749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mohammadi F, Mohammadi-Ivatloo B, Gharehpetian GB, Ali MH, Wei W, Erdinç O, et al. Robust control strategies for microgrids: a review. IEEE Syst J. 2022;16(2):2401–12. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2021.3077213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Vijay AS, Parth N, Doolla S, Chandorkar MC. An adaptive virtual impedance control for improving power sharing among inverters in islanded AC microgrids. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2021;12(4):2991–3003. doi:10.1109/TSG.2021.3062391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Alzayed M, Lemaire M, Chaoui H, Massicotte D. A novel bi-directional grid inverter control based on virtual impedance using neural network for dynamics improvement in microgrids. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2025;40(1):612–22. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2024.3400039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dawn S, Ramakrishna A, Ramesh M, Das SS, Rao KD, Islam MM, et al. Integration of renewable energy in microgrids and smart grids in deregulated power systems: a comparative exploration. Adv Energy Sustain Res. 2024;5(10):2400088. doi:10.1002/aesr.202400088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xu L, Feng K, Lin N, Perera ATD, Poor HV, Xie L, et al. Resilience of renewable power systems under climate risks. Nat Rev Electr Eng. 2024;1(1):53–66. doi:10.1038/s44287-023-00003-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Reza M, Sudarmadi D, Viawan FA, Kling WL, van der Sluis L. Dynamic stability of power systems with power electronic interfaced DG. In: Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE PES Power Systems Conference and Exposition; 2006 Oct 29–Nov 1; Atlanta, GA, USA. doi:10.1109/PSCE.2006.296510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Planas E, Gil-de-Muro A, Andreu J, Kortabarria I, Martínez de Alegría I. General aspects, hierarchical controls and droop methods in microgrids: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2013;17(1):147–59. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.09.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Minetti M, Rosini A, Denegri GB, Bonfiglio A, Procopio R. An advanced droop control strategy for reactive power assessment in islanded microgrids. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2022;37(4):3014–25. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2021.3124062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lee CT, Chu CC, Cheng PT. A new droop control method for the autonomous operation of distributed energy resource interface converters. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2013;28(4):1980–93. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2012.2205944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. He J, Pan Y, Liang B, Wang C. A simple decentralized islanding microgrid power sharing method without using droop control. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2018;9(6):6128–39. doi:10.1109/TSG.2017.2703978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Peng Z, Wang J, Bi D, Wen Y, Dai Y, Yin X, et al. Droop control strategy incorporating coupling compensation and virtual impedance for microgrid application. IEEE Trans Energy Convers. 2019;34(1):277–91. doi:10.1109/TEC.2019.2892621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang D, Yin Q, Wang H, Chen J, Miao H, Chen Y. Improve strategy for transient power angle stability control of VSG combining frequency difference feedback and virtual impedance. Energy. 2025;122(2):651–66. doi:10.32604/ee.2025.057670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao C, Chai W, Rui B, Chen L. Analysis of sub-synchronous oscillation of virtual synchronous generator and research on suppression strategy in weak grid. Energy. 2023;120(11):2683–705. doi:10.32604/ee.2023.029620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang Q, Yan L, Chen X, Chen Y, Wen J. A distributed dynamic inertia-droop control strategy based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for multiple paralleled VSGs. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2023;38(6):5598–612. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2022.3221439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. He J, Li YW, Guerrero JM, Blaabjerg F, Vasquez JC. An islanding microgrid power sharing approach using enhanced virtual impedance control scheme. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2013;28(11):5272–82. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2013.2243757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Guerrero JM, de Vicuna LG, Matas J, Castilla M, Miret J. Output impedance design of parallel-connected UPS inverters with wireless load-sharing control. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2005;52(4):1126–35. doi:10.1109/TIE.2005.851634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yao W, Chen M, Matas J, Guerrero JM, Qian ZM. Design and analysis of the droop control method for parallel inverters considering the impact of the complex impedance on the power sharing. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2011;58(2):576–88. doi:10.1109/TIE.2010.2046001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhu Y, Zhuo F, Wang F, Liu B, Zhao Y. A wireless load sharing strategy for islanded microgrid based on feeder current sensing. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2015;30(12):6706–19. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2014.2386851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang J, Shu J, Ning J, Huang L, Wang H. Enhanced proportional power sharing strategy based on adaptive virtual impedance in low-voltage networked microgrid. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 2018;12(11):2566–76. doi:10.1049/iet-gtd.2018.0051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zandi F, Fani B, Sadeghkhani I, Orakzadeh A. Adaptive complex virtual impedance control scheme for accurate reactive power sharing of inverter interfaced autonomous microgrids. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 2018;12(22):6021–32. doi:10.1049/iet-gtd.2018.5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sellamna H, Pavan AM, Mellit A, Guerrero JM. An iterative adaptive virtual impedance loop for reactive power sharing in islanded meshed microgrids. Sustain Energy Grids Netw. 2020;24(7):100395. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2020.100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang H, Kim S, Sun Q, Zhou J. Distributed adaptive virtual impedance control for accurate reactive power sharing based on consensus control in microgrids. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2017;8(4):1749–61. doi:10.1109/TSG.2015.2506760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Fan B, Li Q, Wang W, Yao G, Ma H, Zeng X, et al. A novel droop control strategy of reactive power sharing based on adaptive virtual impedance in microgrids. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2022;69(11):11335–47. doi:10.1109/TIE.2021.3123660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools