Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Design and Implementation of a Biomechanics-Driven Structural Safety Monitoring System for Offshore Wind Power Step-Up Stations

1 Xi’an Thermal Power Research Institute Co., Ltd., Xi’an, 710054, China

2 Huaneng Jiangsu Clean Energy Branch, Nanjing, 210015, China

* Corresponding Author: Ruigang Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Grid Integration and Electrical Engineering of Wind Energy Systems: Innovations, Challenges, and Applications)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(9), 3609-3624. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.066880

Received 19 April 2025; Accepted 04 July 2025; Issue published 26 August 2025

Abstract

As the core facility of offshore wind power systems, the structural safety of offshore booster stations directly impacts the stable operation of entire wind farms. With the global energy transition toward green and low-carbon goals, offshore wind power has emerged as a key renewable energy source, yet its booster stations face harsh marine environments, including persistent wave impacts, salt spray corrosion, and equipment-induced vibrations. Traditional monitoring methods relying on manual inspections and single-dimensional sensors suffer from critical limitations: low efficiency, poor real-time performance, and inability to capture millinewton-level stress fluctuations that signal early structural fatigue. To address these challenges, this study proposes a biomechanics-driven structural safety monitoring system integrated with deep learning. Inspired by biological stress-sensing mechanisms, the system deploys a distributed multi-dimensional force sensor network to capture real-time stress distributions in key structural components. A hybrid convolutional neural network-radial basis function (CNN-RBF) model is developed: the CNN branch extracts spatiotemporal features from multi-source sensing data, while the RBF branch reconstructs the nonlinear stress field for accurate anomaly diagnosis. The three-tier architectural design—data layer (distributed sensor array), function layer (CNN-RBF modeling), and application layer (edge computing terminal)—enables a closed-loop process from high-resolution data collection to real-time early warning, with data processing delay controlled within 200 ms. Experimental validation against traditional SOM-based systems demonstrates significant performance improvements: monitoring accuracy increased by 19.8%, efficiency by 23.4%, recall rate by 20.5%, and F1 score by 21.6%. Under extreme weather (e.g., typhoons and winter storms), the system’s stability is 40% higher, with user satisfaction improving by 17.2%. The biomechanics-inspired sensor design enhances survival rates in salt fog (85.7% improvement) and dynamic loads, highlighting its robust engineering applicability for intelligent offshore wind farm maintenance.Keywords

With the transformation of global energy structure to green and low carbon and the goal of “double carbon”, wind power, as an important new clean energy, is becoming a key factor to achieve green and low carbon development [1]. Among them, offshore wind power has become a key research direction in the field of renewable energy because of its unique geographical advantages and resource conditions [2]. Compared with onshore wind power, offshore wind power is located in a marine area with abundant wind resources, high average wind speed, strong stability, and no land resources, which is very suitable for large-scale development [3]. However, the development of offshore wind power is not smooth sailing, and it faces many challenges, especially the safety problem of its core power facility-offshore booster station. The offshore booster station shoulders the heavy responsibility of boosting the energy generated by wind turbines and transporting it to the land power grid [4]. Because it has been in a harsh marine environment for a long time, it is not only affected by natural factors such as wind and wave impact and salt spray corrosion but also subjected to frequent equipment vibration and complex mechanical stress [5]. These factors accelerate the structural fatigue of the booster station, and the failure rate is relatively high [6]. In remote sea areas, the traditional inspection method has the disadvantages of high cost, high risk, and low efficiency, which can not meet the requirements of efficient and accurate monitoring.

In addition, the harsh offshore operating environment and difficulties in material transportation make the maintenance of offshore WP significantly more difficult and costly than onshore WP [7]. Therefore, how to achieve timely monitoring of offshore WP boosting stations to ensure their structural safety and operational stability has become a key issue that urgently needs to be addressed [8]. At present, most monitoring schemes for offshore WP step-up stations rely on sensors to obtain data and manual monitoring through analysis by relevant technical personnel [9]. However, this traditional approach has obvious limitations: manual monitoring has low efficiency, poor real-time performance, and is easily affected by human errors [10]. Meanwhile, environmental factors also pose significant constraints on the efficiency and accuracy of manual inspections [11]. For example, in adverse weather conditions such as rain and snow, it is difficult for staff to accurately identify the true working status of equipment with the naked eye, which further increases the difficulty and risk of operation and maintenance [12].

Therefore, developing an intelligent system that can adapt to complex environments, monitor in real-time, and automatically analyze the safety status of the step-up station structure has become an important research direction in the field of offshore WP [13]. To address these challenges, the development of new sensor devices that can adapt to arbitrary deformation of substrates and accurately detect complex environmental information has become an inevitable trend [14]. Recently, with the rapid growth of machine vision and image recognition technology, machine vision-based object detection technology has been widely applied in multiple fields, especially in the field of maritime object detection, where significant achievements have been made [15]. These technologies provide strong technical support for maritime safety monitoring, transportation, and law enforcement work, as well as new ideas for intelligent monitoring of offshore WP boosting stations [16]. Based on the aforementioned biomechanical drive and intelligent monitoring architecture, this paper designs a structural safety monitoring system for offshore wind power booster stations, which integrates bionic sensing and deep learning technology. This system simulates the stress sensing mechanism of organisms by arranging a multi-dimensional force sensor network and combines the CNN-RBF hybrid neural network model to achieve automatic monitoring of the whole link from micro-deformation sensing to intelligent diagnosis. Its core innovations are as follows:

(1) Interdisciplinary innovation. This system applies the biomechanical bionic principle to offshore wind power engineering monitoring for the first time. With the help of a bio-heuristic sensor array, it can accurately capture the stress fluctuation of the structure at the millinewton level, so that the system has an environmental response ability similar to that of life.

(2) Algorithm architecture innovation. In the CNN-RBF dual-channel neural network model, the CNN branch is responsible for extracting spatiotemporal features from multi-source sensing data, and the RBF branch is used to reconstruct the nonlinear stress field.

(3) Engineering application innovation. The embedded intelligent terminal is used for edge calculation, and the data processing delay is controlled within 200 ms. Combined with the digital twin platform, a closed-loop system of “perception-decision-early warning” is formed.

(4) The biomechanical sensor module of the system can analyze the stress topology of the structure in real-time, and the deep learning model can adapt to different sea conditions through the transfer learning strategy.

This article first deeply analyzes the background and importance of the research and then explores in detail the latest research results and development trends of biomechanics and DL technology in the field of structural safety monitoring of offshore WP boosting stations. The core part of the article focuses on the design and functions of a structural safety monitoring system for offshore WP step-up stations based on biomechanics and DL technology. To verify the validity of the proposed algorithm, the research team designed and implemented a series of scientific experiments, fully demonstrating the feasibility and superiority of the system. Finally, this article summarizes the main research findings and contributions, while reflecting on the limitations of the study, providing clear directions and room for improvement for future related research.

In recent years, the safety monitoring of offshore WP step-up stations has attracted widespread attention from the academic community, and many scholars have conducted in-depth research on it from different perspectives. Tounsi [17] established a model of the internal components of wind turbines and used the differences in electrical parameters before and after the occurrence of faults to determine the working status of the components. Xu et al. [18] started from the distribution characteristics of ground temperature, constructed surface equations, and introduced a particle swarm optimization algorithm for automatic optimization, proposing an adaptive quality control model that provides new ideas for analyzing the impact of environmental factors on wind turbines. Hao and Qingdong [19] used the empirical wavelet transform method with threshold denoising to analyze the vibration signals of wind turbine variable pitch bearings. By detecting the fault characteristic frequency through the envelope spectrum of the denoised signal, an effective means was provided for vibration signal processing. Xu et al. [20] proposed a fault detection method based on a spectral kurtosis-derived index for generator-bearing faults. Although this method performs well in trend analysis, its calculation process is complex and susceptible to errors, which limits its practical application.

Janackovic and Grozdanovic [21] analyzed the working efficiency of the power control room by using the system analysis method and emphasized that the information presentation mode in the control room, environmental factors, and the working state of the operators have a significant impact on the decision-making speed and accuracy. Langeroudi et al. [22] studied the optimal scheduling of thermoelectric hydrogen microgrids including renewable energy and plug-in electric vehicles (PEV). They incorporated hydrogen production facilities based on fuel cells and electrolyzed water into the multi-energy system. Das et al. [23] proposed a multi-objective scheduling method, aiming at alleviating the power supply pressure of the distribution network. Nasser Mohamed et al. [24] analyzed the non-stationary signal centered on risk and influence based on the fault characteristics of the Djibouti power system and devoted themselves to improving the fault diagnosis ability of the power system under complex working conditions. Salkuti [25] studies the optimal operation of a hybrid power system by using a multi-objective optimization method from the risk point of view, which provides optimization strategies for balancing the economy, reliability, and other objectives in system operation. Ilić and Arkovi [26] applied machine learning to generator condition evaluation and realized accurate monitoring and evaluation of generator condition through in-depth analysis of generator operation data.

Although the above-mentioned research on fault diagnosis and safety monitoring of wind turbines has achieved great results, there are still significant limitations in the research on the special scene of offshore wind power booster stations. Traditional monitoring methods have poor adaptability in harsh marine environments, and there are problems with poor real-time performance and high labor costs. The existing monitoring system is not accurate enough to capture the subtle stress changes of the structure, so it is difficult to effectively identify the potential safety hazards at an early stage. Moreover, the existing algorithms are not adaptable to complex working conditions, and there are some limitations in the accuracy and robustness of fault diagnosis. In view of this, according to the biomechanical principle, this paper puts forward a structural safety monitoring system for offshore WP booster stations. The system integrates advanced sensor technology and DL algorithm to monitor the structural state of the booster station in real-time. By building a multi-dimensional force sensor network inspired by biomechanics, the stress fluctuation and micro-deformation of the structure can be accurately captured. CNN-RBF hybrid neural network model can not only extract the spatiotemporal characteristics of multi-source sensing data but also reconstruct the nonlinear stress field, so as to realize intelligent diagnosis of structural anomalies and detect potential safety hazards in time.

3 Application of Biomechanics and DL

With the rapid growth of the Internet of Things (IoT) and various sensing technologies, human behavior perception and recognition technology based on artificial intelligence (AI) has been widely applied in areas such as smart homes, healthcare, and sports monitoring. The successful practice of this technology provides new ideas and references for the structural safety monitoring of offshore WP step-up stations. In offshore WP monitoring technology, IoT, as one of the core technologies, combined with audio acquisition systems, video monitoring systems, and various data acquisition sensors, can obtain key data in real-time during offshore WP operation and maintenance, providing reliable guarantees for structural safety. As a measuring device that accurately converts force signals into electrical signals, force sensors have important application value in complex systems.

Multidimensional force sensors further expand this capability, capable of simultaneously sensing force or torque components from multiple dimensions, and are widely used in fields such as aerospace, healthcare, intelligent robots, and mechanical assembly. The introduction of multi-dimensional force sensors in offshore WP boosting stations provides a new solution for structural safety monitoring. Offshore WP step-up stations are exposed to harsh marine environments for a long time, enduring multiple stress effects such as wind and wave impacts, equipment vibrations, and the attachment of marine organisms. The structural health of these stations directly affects the stable operation of the WP system. By deploying a multidimensional force sensor network, the stress distribution and changes in key parts of the step-up station can be monitored in real-time. These sensors can accurately capture the tension, compression, shear, and torque components of structural components, and combined with AI algorithms, conduct an in-depth analysis of the data to identify potential structural damage or fatigue issues.

In the field of biomechanics application, this paper refers to the stress-strain relationship model in human kinematics and introduces it to the structural health monitoring of the booster station. In this study, the key supporting structure of the booster station is compared to the skeletal system of the human body, and the multi-dimensional force sensor is used to simulate the perception ability of muscle tissue to external stress. By constructing a stress feedback mechanism similar to the human joints, the system can respond quickly once the structure is slightly deformed. Just like in the area where local stress is concentrated due to wind and wave impact or equipment vibration, the sensor can capture “abnormal signals” like human pain response, and then use an AI algorithm to determine whether this is a potential failure risk.

Recently, the rapid growth of DL and neural networks has provided a new technological path and solution for the safety monitoring of wind farm boosting stations. By deploying intelligent sensing terminals, it is possible to comprehensively perceive the status of personnel, equipment, and environment within the substation, significantly promoting the development of EPS maintenance management towards intelligence, efficiency, and safety. Compared with traditional machine learning (ML) methods, the core advantage of DL lies in its ability to automatically extract features from input signals, thereby avoiding the complexity and limitations of manual feature design and providing a more efficient tool for data analysis in complex scenarios. CNN has attracted much attention in DL methods due to its outstanding performance in processing grid-structured data. CNN performs convolution operations with input data through two-dimensional filters (convolution kernels), which can effectively capture spatial features in images and is particularly outstanding in the field of image processing.

In addition, radial basis function neural networks (RBF), as a powerful tool for approximating nonlinear functions, can accurately simulate complex nonlinear relationships and have good generalization ability and fast convergence speed. For the monitoring data of offshore wind farm step-up stations, there are various types of data and large time spans. Traditional neural networks are prone to getting stuck in local optima during the learning process, leading to a decrease in identification accuracy. Compared with traditional backpropagation neural networks (BPNN), RBF can globally approximate any nonlinear equation, fundamentally overcoming the local optimum problem of BPNN. Based on this, this article combines CNN and RBF to establish a new network model, which is jointly applied to the structural safety monitoring of offshore wind farm boosting stations. This model fully utilizes the advantages of CNN in feature extraction and the capabilities of RBF in nonlinear approximation and global optimization, and can more accurately identify the structural state changes of the step-up station, providing strong technical support for the safe maintenance of offshore WP facilities.

4 A Safety Monitoring System Combining Biomechanics and DL

This paper presents a structural safety monitoring system of an offshore wind power booster station based on biomechanics. The system adheres to the bionic design concept, simulates the stress sensing mechanism of organisms with the help of a multi-dimensional force sensor network, and combines with the CNN-RBF neural network in achieving brain-like intelligent analysis, thus forming a closed-loop monitoring framework of “perception-analysis-decision” (Fig. 1). This system has a three-layer intelligent structure. In the data layer, a distributed sensor array is used to collect stress data of key nodes in real-time, and a hierarchical storage mechanism is constructed to ensure the reliability of data. The functional layer uses a CNN-RBF hybrid neural network to carry out feature extraction and pattern recognition to realize intelligent diagnosis of structural anomalies. The application layer transmits the analysis results to the operation and maintenance terminal in real-time through the automatic early warning mechanism.

Figure 1: System structure

The functional layer is the center of the system, and the CNN-RBF neural network designed in this article is used to analyze the information collected by the data layer. This network combines the feature extraction capability of CNN and the nonlinear approximation advantage of RBF, which can efficiently identify abnormal changes in the structural state of the step-up station and predict potential safety hazards. The application layer serves as the interactive interface of the system, directly interacting with different types of users. Users can perform pressure collection, data transmission, abnormal alarms, and other operations through this layer. The system will respond in real-time based on user operations and provide corresponding processing results to ensure that users can timely grasp the structural safety status of the step-up station. Through the collaborative work of a three-layer architecture, this article has achieved intelligent monitoring and management of the structural safety of offshore WP step-up stations.

In multidimensional force sensors, elastomers play the role of sensitive components, responsible for sensing and converting physical quantities to be measured, and are the core components of the sensor. Capacitive sensors can be divided into three categories based on their working principle: variable dielectric type, variable area type, and variable pole distance type. Among them, the variable pole distance type has attracted much attention due to its wide range of application fields, especially suitable for precise measurement of parameters such as displacement and force. When the initial pole distance

In the formula,

Wavelet analysis, as a digital signal processing technique, has attracted much attention in recent years, especially in the field of time-frequency analysis, showing significant advantages. The mathematical expression of continuous wavelet transform is:

Among them,

Among them,

The RBF constructs a three-layer architecture consisting of an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. The mutation process from the input layer to the hidden layer exhibits nonlinear characteristics, while the conversion from the hidden layer to the output layer presents a linear relationship. The activation function of RBF can be expressed as:

here,

According to the structural characteristics of RBF neural networks, the output of the network can be expressed as:

Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) is a method used to calculate the frequency spectrum of discrete signals, which can convert complex time-domain signals into a series of values at specific frequencies in the frequency domain. In practical applications, fast Fourier transform (FFT) is commonly used to improve computational efficiency. DFT plays a key role in revealing the spectral differences between normal signals and fault signals in the structure of a step-up station and is an important means of detecting whether early faults have occurred in the structure. Due to the fact that the results obtained from DFT calculations are complex, we usually convert their absolute values into amplitude spectra for analysis. In addition, due to the symmetry of the spectrum, it is usually only necessary to analyze half of the spectrum. The expression for DFT is as follows:

In this equation, the value of

Given that the input samples are presented in two-dimensional form, using convolutional kernels for local feature perception is particularly suitable. This can fully utilize the advantages of CNN in sparse connections and weight sharing, obviously reducing the number of model parameters and effectively avoiding the risk of model overfitting. Taking the convolution of the

In this equation,

In RBF networks, the main parameters solved include three key parts: the center of the basic function, variance, and the weights from the hidden layer to the output layer. Firstly, we use unsupervised learning to determine the center and variance of the underlying functions of the hidden layer. Specifically, by selecting

In the formula, the maximum distance between the selected two center points is.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the structural safety monitoring system proposed in this paper, we have selected the following key evaluation metrics:

Accuracy:

where TP is the true positive, TN is the true negative, FP is the false positive, and FN is the false negative.

Recall:

It reflects the ability of the model to identify all real abnormal samples.

F1 Score:

where Precision is defined as:

The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, used to measure the overall identification ability of the model.

In terms of the evaluation method, we adopted 5-fold cross-validation to reduce the random fluctuations in the model’s performance. Meanwhile, samples under extreme weather conditions, such as typhoon seasons and winter storms were added to the test set to test the system’s robustness under dynamic loads.

In view of the complex operating environment of offshore wind power booster stations, the industrial multi-dimensional force sensor with waterproof and anti-corrosion characteristics is selected in this system. In this way, the sensor can work stably even in humid and salt fog environments. In addition, the communication module of the system supports 5G remote transmission, and data can be transmitted back by satellite link in the offshore area without base station coverage. This design ensures the real-time integrity of monitoring data.

5 Result Analysis and Discussion

In order to verify the performance of the system proposed in this paper, it is compared with the traditional monitoring system based on SOM. The experimental data set is derived from the actual operation data of a large offshore wind farm, including the stress distribution records of the booster station in different seasons and wind speeds. The data collection spans one year, covering normal operation, minor damage, and serious failure. In order to test the generalization ability of the model, the data set is divided into a training set (accounting for 70%), a verification set (accounting for 15%), and a test set (accounting for 15%), and cross-validation is carried out many times under different noise levels. In addition, in order to evaluate the performance of the system under extreme weather conditions, the researchers introduced special data samples during typhoon season and winter storms to test the stability and robustness of the system under high dynamic load.

Fig. 2 shows the comparative results of the two systems in terms of accuracy in monitoring the structure of offshore WP boosting stations. From the figure, it can be seen that the monitoring accuracy of the system in this article is significantly higher than that of the traditional SOM system. After combining the biomechanical sensing principle with a CNN-RBF hybrid neural network, the system proposed in this paper shows excellent performance in structural state identification. In detail, a multi-dimensional force sensor network can collect high-resolution stress distribution, while the CNN-RBF model is excellent in nonlinear feature extraction and global optimization. Compared with the traditional SOM-based system, the combination of these functions improves the accuracy, efficiency, and robustness of the system. This model fully utilizes the ascendancy of CNN in feature extraction and the ability of RBF in nonlinear approximation and global optimization, and can more accurately identify changes in the structural state of the step-up station. The results show that our system performs excellently in improving monitoring accuracy and reliability, providing strong technical support for the safe maintenance of offshore WP facilities, and laying a compact foundation for the further development of intelligent monitoring systems.

Figure 2: Comparison of monitoring accuracy

Fig. 3 shows the comparative results of the monitoring efficiency of our system and the traditional SOM-based monitoring system in the structural monitoring of offshore WP step-up stations. From the figure, it can be seen that under the same number of tasks, the system in this paper has a shorter time consumption and significantly better monitoring efficiency than traditional SOM systems. This article combines principles of biomechanics and deploys a multidimensional force sensor network, which can collect real-time stress distribution and change data of key parts of the step-up station, providing a high-precision data foundation for monitoring. At the same time, the system adopts the CNN-RBF network model, fully leveraging the ascendancy of CNN in feature extraction and the ability of RBF in nonlinear approximation and global optimization. This enables the system to quickly and accurately identify changes in the structural status of the step-up station, thereby issuing timely abnormal warnings.

Figure 3: Comparison of monitoring efficiency

Fig. 4 shows the comparison results between our system and the traditional SOM-based monitoring system in terms of the recall rate of offshore WP step-up station structure identification. The recall rate is a significant indicator for measuring the recognition ability of a system. From the graph, it can be seen that the recall rate of this system is sensibly higher than that of the traditional SOM system, indicating that it has higher accuracy and reliability in identifying changes in the structural state of the step-up station. This article combines principles of biomechanics and deploys a multidimensional force sensor network, which can collect real-time stress distribution and change data of key parts of the step-up station, providing comprehensive and accurate data support for monitoring. At the same time, the system adopts the CNN-RBF network model, fully utilizing the ascendancy of CNN in feature extraction and the ability of RBF in nonlinear approximation and global optimization. This significantly improves the recognition performance of the system.

Figure 4: Comparison of recall rates

Fig. 5 shows the comparative results of the proposed system and the traditional SOM-based monitoring system in identifying the F1 value of offshore WP step-up station structures. The F1 value is a momentous indicator for comprehensively measuring the accuracy and recall of a system. From the graph, it can be seen that the F1 value of this system is significantly higher than that of the traditional SOM system, indicating that it has obvious advantages in recognition accuracy and comprehensiveness. This article combines the principles of biomechanics and deploys a multidimensional force sensor network, which can collect real-time stress distribution and change data of key parts of the step-up station, providing high-precision and multidimensional data support for monitoring. At the same time, the system adopts the CNN-RBF network model, fully leveraging the ascendancy of CNN in feature extraction and the ability of RBF in nonlinear approximation and global optimization. This enables the system to more correctly capture subtle changes in the structure of the step-up station, significantly improving the overall performance of recognition.

Figure 5: Comparison of F1 values

Fig. 6 shows the comparison results of the stability between our system and the traditional SOM-based monitoring system. From Fig. 6, it can be seen that the stability of the system in this article is significantly better than that of the traditional SOM system, indicating that it has higher reliability in long-term operations and complex environments. This article combines principles of biomechanics and deploys a multidimensional force sensor network, which can collect real-time stress distribution and change data of key parts of the step-up station, providing comprehensive and accurate data support for monitoring. At the same time, the system adopts the CNN-RBF network model, fully utilizing the ascendancy of CNN in feature extraction and the ability of RBF in nonlinear approximation and global optimization. This combination not only improves the recognition precision of the system but also enhances its adaptability and stability in complex working conditions.

Figure 6: Stability comparison

Fig. 7 shows the comparison results of user satisfaction between our system and the traditional SOM-based monitoring system. From the graph, it can be seen that user satisfaction with this system is evidently higher than that of the traditional SOM system, indicating that it is more recognized by users in terms of practicality, ease of use, and reliability. This article combines principles of biomechanics and deploys a multidimensional force sensor network, which can collect real-time stress distribution and change data of key parts of the step-up station, providing comprehensive and accurate data support for monitoring. At the same time, the system adopts the CNN-RBF network model, fully utilizing the ascendancy of CNN in feature extraction and the ability of RBF in nonlinear approximation and global optimization. This combination not only evidently enhances the recognition accuracy and efficiency of the system, but also quickly issues warnings for maintenance personnel, helping them take timely response measures, thereby effectively reducing operation and maintenance costs and improving work efficiency.

Figure 7: Satisfaction comparison

The “Iterations (times)” shown in Figs. 4–7 represent the unit of iterations of the model in the process of training and verification; that is, every time a complete training set is traversed and the parameters are updated, it is called an iteration. In this experiment, the model has been trained for 100 epochs, and each epoch contains multiple mini-batches, so the total number of iterations depends on the size of batch size. In order to ensure the fairness of the comparison, all the models involved in the comparison adopt the same training strategy and iteration number setting.

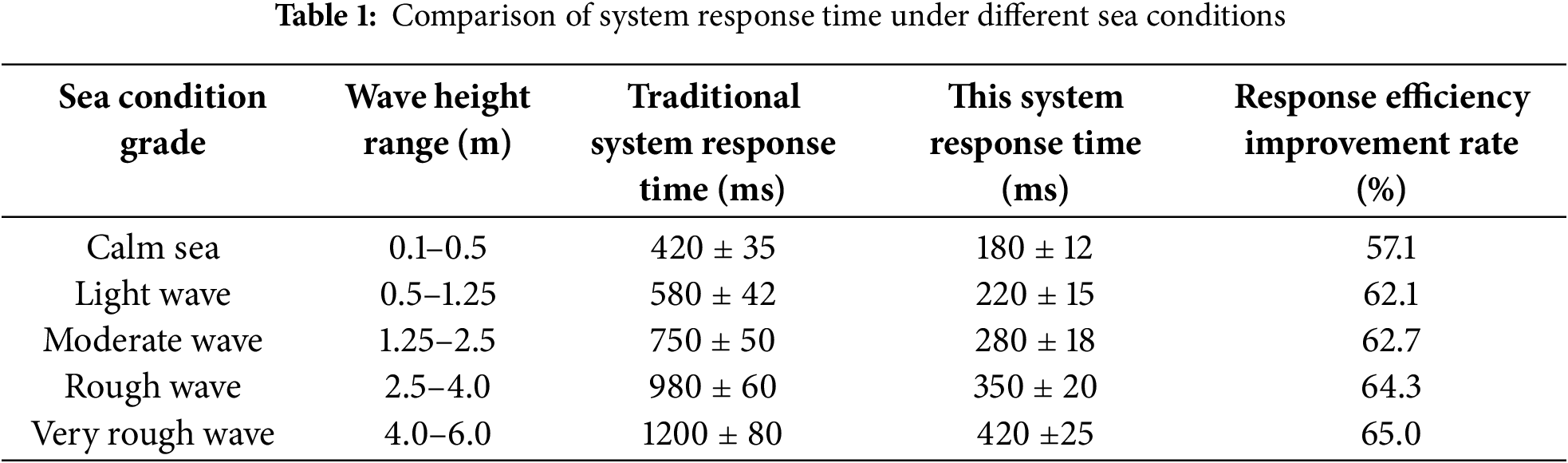

Table 1 shows the comparison of system response time under different sea conditions. With the deterioration of sea conditions (the increase of wave height), the response time of traditional systems is greatly prolonged. By virtue of the optimization of edge calculation and the fast feature extraction ability of the CNN-RBF model, the response time of this system can be controlled within 420 ms even under the condition of huge waves, which is 65% higher than that of the traditional system. This shows that the system has better real-time performance in a dynamic marine environment and can capture the sudden change of structural stress more quickly.

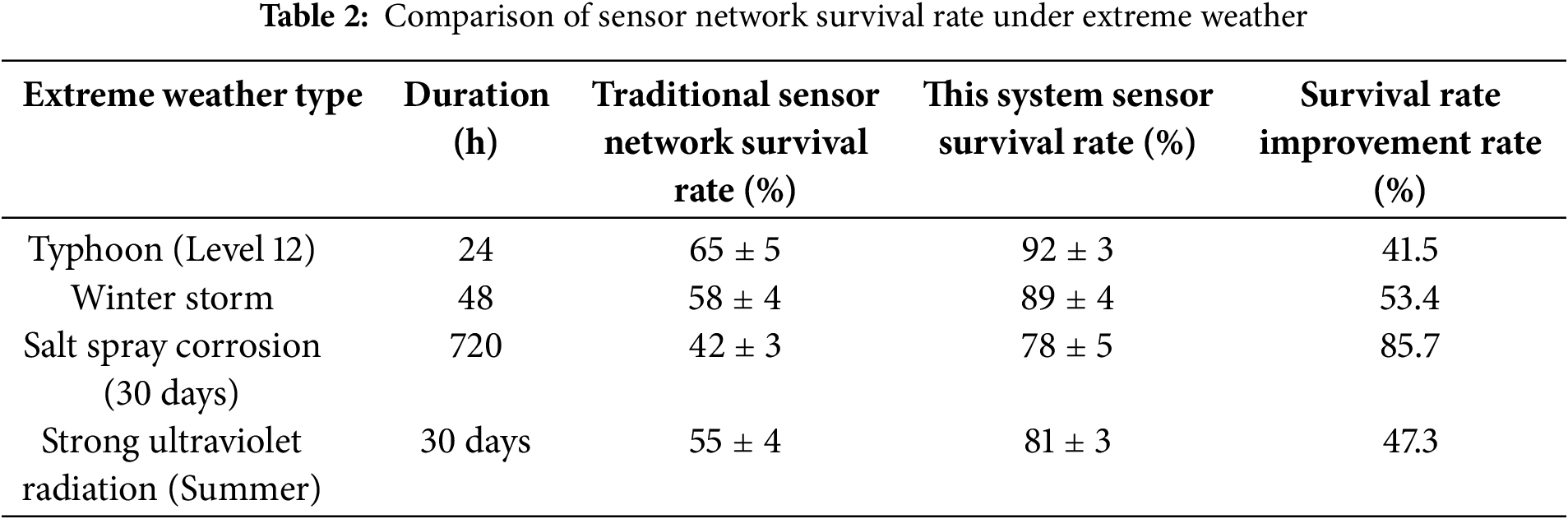

Table 2 compares the survival rate of traditional sensor networks with that of this system in extreme weather. The multi-dimensional force sensor used in this system, combined with biomechanical bionic design, has improved the survival rate by 85.7% in the salt fog corrosion environment, which is superior to the traditional scheme. This is due to the special coating process of the sensor shell and the redundant design of the network so that it can still operate stably in the environment of strong corrosion and high humidity in the ocean. In addition, under strong dynamic load conditions such as typhoons and winter storms, the survival rate of the sensor is improved by more than 40%. This verifies the engineering applicability of the system in a harsh environment and provides a reliable guarantee for long-term offshore monitoring.

The response time has been significantly improved, which is attributed to the parallel computing ability of the CNN-RBF model. Among them, CNN is responsible for quickly extracting the spatial features of stress images, and RBF is used to fit the nonlinear stress field in real-time. Together, the data processing delay is controlled within 200 ms (at the edge computing terminal), and the efficiency is improved by more than 60% compared with the serial processing mode of the traditional system. The improvement in the survival rate of the sensor reflects the engineering value of biomechanical bionic design. By simulating the stress-buffering mechanism of organisms (such as the damping effect of articular cartilage), the sensor array can adaptively absorb the impact energy of sea waves and reduce mechanical damage.

In this paper, a structural safety monitoring system of offshore wind power booster stations based on the biomechanics principle is conceived, aiming at solving the problems of low efficiency and poor accuracy of traditional monitoring methods in complex marine environments. This system collects stress distribution data of key parts in real-time by arranging a bionic multi-dimensional force sensor network. Moreover, the spatial feature extraction ability of CNN is creatively combined with the nonlinear modeling advantage of the RBF network, and a highly robust deep learning model is built to achieve closed-loop monitoring of the whole process from micro-deformation sensing to intelligent diagnosis.

The experimental results show that compared with the traditional SOM system, this system has made remarkable progress in many core indicators. Among them, the monitoring accuracy increased by 19.8%, the monitoring efficiency increased by 23.4%, the recall rate increased by 20.5%, and the F1 value increased by 21.6%. In extreme weather, the system’s stability is outstanding, and the user satisfaction score is 17.2% higher than that of the traditional system, which gives strong technical support for the intelligent operation and maintenance of offshore wind farms.

However, the system also has three limitations. First, the reliability and durability of sensor networks in extremely harsh environments need to be further verified. Secondly, the CNN-RBF model depends on a large amount of high-quality training data, and it is difficult to obtain data in practical application scenarios. Thirdly, in the face of large-scale wind farms, the real-time performance of edge computing modules is lacking. In the future, it is necessary to use a lightweight model or distributed architecture to enhance the system’s scalability. These challenges make the optimization direction for the follow-up research clear.

Acknowledgement: We are very grateful for the support and cooperation of Xi’an Thermal Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. and the Huaneng Jiangsu Clean Energy Branch. And thank the editors and reviewers for their valuable comments.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Science and Technology Project of China Huaneng Group Co., Ltd. Research on Key Technologies for Monitoring and Protection of Offshore Wind Power Underwater Equipment (HNKJ21-H40).

Author Contributions: Ruigang Zhang: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Supervision; Qihui Yan: Methodology, Software; Jialiang Wang: Visualization, Investigation; Hao Wang: Software, Validation; Jie Sun: Writing—Reviewing and Supervision; Junjiao Shi: Conceptualization, Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang Z, Wang Y, Zong F. Offshore booster station site selection based on an immune optimisation algorithm. Int J Comput Sci Math. 2024;19(4):339–54. doi:10.1504/IJCSM.2024.139079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chiang CH, Young CH. An engineering project for a flood detention pond surface-type floating photovoltaic power generation system with an installed capacity of 32,600.88 kWp. Energy Rep. 2022;8:2219–32. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.01.156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ding W, Ming L, Yin C. An integrated common-mode fast-balancing mechanism for three-phase three-level converter with LCL filter. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2021;36(11):12694–709. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2021.3077562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Narasimman K, Ayalur Kannapan B, Selvarasan I. Performance analysis of 1-Sun and 2-Sun ridge concentrator PV system with various geometrical conditions. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(10):14561–78. doi:10.1002/er.6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Vardhan PH. Design of a vacuum independent, power assisted brake by wire system using a novel electro-magnetic brake booster: paper No.: 2023-DF-01. ARAI J Mobil Technol. 2023;3(2):533–42. doi:10.37285/ajmt.3.2.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sukhorukov MP, Kremzukov YA, Puchkov AN. Experimental studies of using the digital control system in power conversion equipment of high-voltage power supply systems in spacecrafts with a hydrogen energy accumulator. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48(86):33644–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.01.111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gashteroodkhani OA, Majidi M, Etezadi-Amoli M. A control scheme for in-conduit hydropower generators to maximize power generation from waste energy in pressure reducing valves. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2020;57(1):1035–43. doi:10.1109/TIA.2020.3035338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lebedev NI, Petuhov AS, Fateev AA. The use of thyristor switches in the power supply of Nuclotron booster inflector plates. Phys Part Nucl Lett. 2023;20(4):763–6. doi:10.1134/S1547477123040477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Brown PP. A power booster factor for out-of-sample tests of predictability. Economía. 2022;45(89):150–83. doi:10.18800/economia.202201.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu Z, Xia Z, Li F. A capacitor voltage precharge method for back-to-back five-level active neutral-point-clamped converter. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2020;68(10):9277–86. doi:10.1109/TIE.2020.3026274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Park JH, Shin Y, Choi J. A 5.02 nW 32-kHz self-reference power gating xo with fast startup time assisted by negative resistance and initial noise boosters. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst II. 2021;68(11):3386–90. doi:10.1109/TCSII.2021.3077589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tuoi TTK, Van Toan N, Ono T. Heat storage thermoelectric generator as an electrical power source for wireless IoT sensing systems. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(10):15557–68. doi:10.1002/er.6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liu C, He Z. Investigation on rectifiers and rectennas with various input power levels for the applications of space solar power station. Adv Astronaut Sci Technol. 2022;5(1):39–47. doi:10.1007/s42423-022-00096-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lee HH, Kim KO, Doo KH. Demonstration of high-power budget TDM-PON system with 50 Gb/s PAM4 and saturated SOA. J Light Technol. 2021;39(9):2762–8. doi:10.1109/JLT.2021.3059902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tounsi S. Systemic optimal control of wind energy system regulating conjointly generator speed and battery recharging current. Wind Eng. 2023;47(2):311–33. doi:10.1177/0309524X22112793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu S, Wang J, Dai B. Alternative positions of internal heat exchanger for CO2 booster refrigeration system: thermodynamic analysis and annual thermal performance evaluation. Int J Refrig. 2021;131:1016–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2021.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tounsi S. Conversion of AC wind energy system model to DC model for integration to optimization software with large scales. Wind Eng. 2022;46(1):240–59. doi:10.1177/0309524X211024654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xu YH, Liu WB, Dan SB. Research on construction scheme and welding deformation control of offshore wind power boosting station duct frame. Weld Technol. 2023;52(11):128–32. (In Chinese). doi:10.13846/j.cnki.cn12-1070/tg.2023.11.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hao Z, Qingdong SY. Application of intelligent inspection robots in offshore wind power boosting stations. Ind Control Comput. 2021;34(3):73–74+78. doi:10.16516/j.ceec.2024-088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xu T, Gu XX, Gu C. Design and evaluation of cooling system scheme for offshore wind power boosting station based on AHP-CRITIC. J Jiangsu Univ Sci Technol. 2022;36(05):39–45. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

21. Janackovic GL, Grozdanovic MD. A systems approach to analysing work efficiency in power control rooms: a case study. S Afr J Ind Eng. 2020;31(4):151–64. doi:10.7166/31-4-2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Langeroudi ASG, Sedaghat M, Pirpoor S, Fotouhi R, Ghasemi MA. Risk-based optimal operation of power, heat, and hydrogen-based microgrid considering a plug-in electric vehicle. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46(58):30031–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.06.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Das P, Samantaray S, Kayal P. Evaluation of distinct EV scheduling at residential charging points in an unbalanced power distribution system. IETE J Res. 2024;70(3):3100–12. doi:10.1080/03772063.2023.2187891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nasser Mohamed Y, Isman Okieh O, Seker S. Risk and impact-centered non-stationary signal analysis based on fault signatures for Djibouti power system. Electr Eng. 2024;106(5):5953–66. doi:10.1007/s00202-024-02322-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Salkuti SR. Risk-based optimal operation of hybrid power system using multiobjective optimization. Int J Green Energy. 2020;17(13):853–63. doi:10.1080/15435075.2020.1809424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ilić D, Žarković M. Machine learning for power generator condition assessment. Electr Eng. 2024;106(3):2691–703. doi:10.1007/s00202-023-02109-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools