Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Second-Life Battery Energy Storage System Capacity Planning and Power Dispatch via Model-Free Adaptive Control-Embedded Heuristic Optimization

1 State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company, Chengdu, 610041, China

2 State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company Economic and Technological Research Institute, Chengdu, 610041, China

3 Sichuan New Power System Research Institute Co., Ltd., Chengdu, 610041, China

4 The College of Electric Engineering, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610065, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhengbo Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Construction and Control Technologies of Renewable Power Systems Based on Grid-Forming Energy Storage)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(9), 3573-3593. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.067785

Received 12 May 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 26 August 2025

Abstract

The increasing penetration of second-life battery energy storage systems (SLBESS) in power grids presents substantial challenges to system operation and control due to the heterogeneous characteristics and uncertain degradation patterns of repurposed batteries. This paper presents a novel model-free adaptive voltage control-embedded dung beetle-inspired heuristic optimization algorithm for optimal SLBESS capacity configuration and power dispatch. To simultaneously address the computational complexity and ensure system stability, this paper develops a comprehensive bilevel optimization framework. At the upper level, a dung beetle optimization algorithm determines the optimal SLBESS capacity configuration by minimizing total lifecycle costs while incorporating the charging/discharging power trajectories derived from the model-free adaptive voltage control strategy. At the lower level, a health-priority power dispatch optimization model intelligently allocates power demands among heterogeneous battery groups based on their real-time operational states, state-of-health variations, and degradation constraints. The proposed model-free approach circumvents the need for complex battery charging/discharging power control models and extensive historical data requirements while maintaining system stability through adaptive control mechanisms. A novel cycle life degradation model is developed to quantify the relationship between remaining useful life, depth of discharge, and operational patterns. The integrated framework enables simultaneous strategic planning and operational control, ensuring both economic efficiency and extended battery lifespan. The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through comprehensive case studies on hybrid energy storage systems, demonstrating superior computational efficiency, robust performance across different network configurations, and significant improvements in battery utilization compared to conventional approaches.Keywords

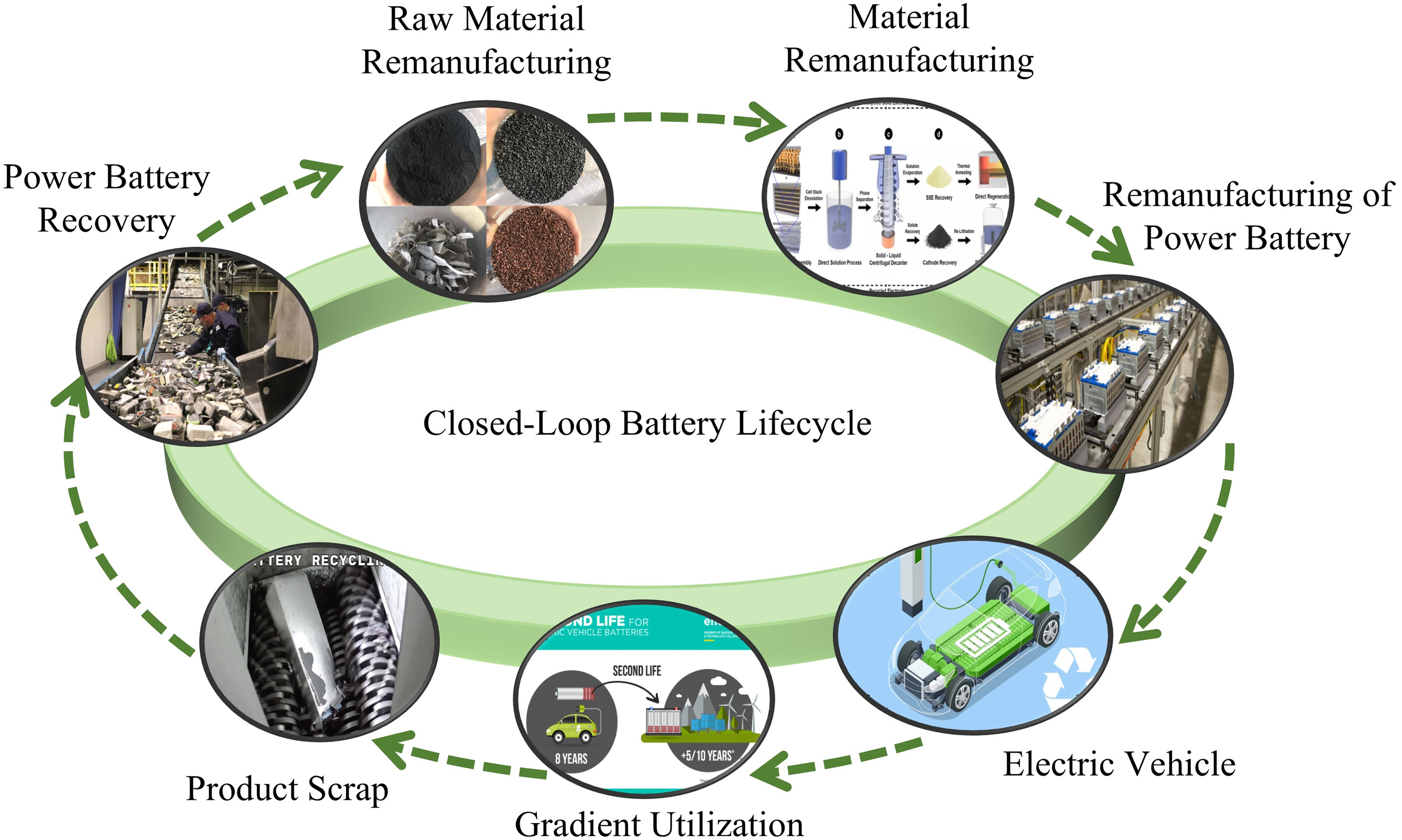

Power batteries undergo distinct life cycle stages, encompassing: electric vehicle (EV) application, cascaded utilization, retirement, recycling, raw material reprocessing, material remanufacturing, and battery reconstruction, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The implementation of SLBESS presents substantial technical challenges in both capacity configuration and power allocation, primarily due to the inherent heterogeneity of second-life batteries [1]. Inappropriate capacity configuration and power allocation strategy result in unbalanced degradation among battery packs that could cause severe system performance deterioration and reduce the overall service life. However, replacing degraded battery packs or adopting conventional uniform allocation strategies are uneconomical, as the performance variations among battery packs are not synchronous but time-varying [2,3]. Limited control measures are available for real-time adjustment when system performance deteriorates, posing significant challenges in maintaining optimal operational efficiency. Currently, the general practice is to configure capacity and allocate power based on the average state-of-health (SOH) of battery packs. Then the battery management system (BMS) performs uniform power distribution to maintain system stability. Nevertheless, the adoption of oversimplified control strategies induces heterogeneous battery degradation rates and compromises operational reliability. Besides, the varying SOH levels and dynamic operating conditions call for an adaptive management scheme [4,5]. Thus, an efficient and coordinated strategy for both capacity configuration and power allocation are urgently needed.

Figure 1: The closed-loop battery lifecycle

Recent research has extensively investigated SLBESS capacity configuration and power allocation strategies, yielding various methodological approaches. Ref. [6] proposes a multi-objective optimization model to determine the optimal capacity of SLBESS considering economic benefits and environmental impacts. However, this methodology exhibits substantial dependence on precise battery modeling and demonstrates limited adaptability to the dynamic changes in battery characteristics. The investigation in [7] presents a dynamic programming-based optimization approach to optimize the battery pack grouping strategy while accounting for the heterogeneous characteristics. Nevertheless, its computational burden becomes prohibitive when dealing with large-scale systems. Ref. [8] establishes a degradation-aware framework for capacity configuration that considers the varying aging rates of different battery packs. Yet this framework requires extensive historical data for model training. These capacity configuration methods generally suffer from model dependency and computational complexity issues. To address these fundamental challenges comprehensively, this study presents a model-free adaptive voltage control-embedded dung beetle optimization algorithm for SLBESS capacity configuration, which can effectively handle the system dynamics without requiring detailed battery models.

Power allocation strategies for heterogeneous battery systems have also been extensively investigated. The investigation presented in [9] introduces an advanced adaptive control methodology to distribute power demands among multiple battery groups based on their real-time states. Nevertheless, the scheme exhibits insufficient robustness against measurement uncertainties. Ref. [10] concerns the SOH variations in the power allocation process and proposes a SOH-aware dispatch strategy, but fails to consider the operational boundaries of the storage system. In [11], a hierarchical power distribution framework is developed for cascaded battery energy storage systems, although it fails to address the inconsistent internal resistance characteristics of repurposed batteries. Ref. [12] presents an adaptive power sharing algorithm considering the remaining useful life of second-life batteries, but, the thermal management constraints and safety boundaries are not adequately addressed in the optimization framework. These existing power allocation strategies typically lack comprehensive consideration of system operational boundaries and battery group characteristics. To avoid these issues, this paper develops an optimal power dispatch strategy for second-life batteries that operates within the charging and discharging power boundaries determined by the model-free adaptive voltage control strategy, ensuring both operational feasibility and efficient power distribution among battery groups.

Significant research attention has been directed toward the comprehensive characterization and systematic evaluation of second-life batteries, particularly focusing on performance assessment methodologies. Ref. [13] develops a comprehensive testing protocol for assessing the remaining capacity and performance of retired EV batteries, but the testing process is time-consuming and costly for large battery populations. Advanced statistical methodologies have been implemented in [14] to classify and group batteries based on their degradation patterns, though the accuracy heavily depends on the quality of historical data. Refs. [15,16] propose various modeling approaches to predict the remaining useful life of second-life batteries, yet these models often fail to capture the dynamic nature of battery characteristics. The main limitations of existing evaluation approaches lie in their dependency on complex models and extensive testing requirements. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a novel degradation assessment model for echelon battery energy storage systems that incorporates both cycle life characteristics and operational depth of discharge. Unlike the aforementioned approaches that rely heavily on extensive testing data or complex statistical models, our method establishes a quantitative relationship between remaining useful life, state of health, and operational patterns through empirical correlations. The proposed model enables efficient evaluation of battery degradation states while considering the practical operational constraints of second-life batteries, thereby providing a more feasible solution for large-scale echelon storage applications.

Moreover, multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approaches have been extensively applied in energy planning and battery energy storage system optimization. Ref. [17] employs the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate renewable energy alternatives by constructing hierarchical decision structures and conducting pairwise comparisons among evaluation criteria, focusing primarily on subjective weight assignment for alternative ranking. The Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment (WASPAS) method has been utilized in [18] for energy storage technology selection, combining weighted sum and weighted product models to rank different storage technologies based on predetermined criteria sets. Similarly, Ref. [19] presents a hybrid MCDM framework combining AHP-TOPSIS for battery energy storage system site selection, while ref. [20] integrates fuzzy AHP with VIKOR for energy storage capacity planning under uncertainty. These MCDM-based approaches typically focus on multi-criteria evaluation and ranking mechanisms through subjective criteria weighting and alternative scoring processes. However, they generally lack the capability to address the physical operational constraints and dynamic degradation characteristics inherent in second-life battery systems [21,22]. Unlike these conventional MCDM methods that primarily handle decision-making through criteria-based ranking and selection, our proposed Cycle Life Degradation Model operates within a bilevel optimization framework that explicitly considers the physical degradation dynamics of heterogeneous battery groups. Our approach integrates real-time adaptive power allocation with SOH-based operational constraints, fundamentally differing from MCDM methods by focusing on optimal power dispatch optimization rather than multi-criteria alternative ranking, thereby providing a more technically-oriented solution for practical SLBESS implementation.

Furthermore, existing methodologies predominantly rely on idealized assumptions and simplified system models, which may not adequately capture the complex dynamics inherent in practical SLBESS implementations. These theoretical approaches exhibit limited practical applicability due to their inherent inability to account for stochastic environmental variations, dynamic load profiles, and complex degradation mechanisms. To overcome these limitations, our study integrates a model-free adaptive voltage control strategy with dung beetle-inspired optimization for capacity configuration, followed by an optimal power dispatch strategy which is constrained by the system operational boundaries. This approach eliminates the need for complex battery models while ensuring efficient and practical operation of the SLBESS.

From the above literature review, further research is needed to address the following missing aspects:

(1) A computationally efficient optimization method for determining the optimal capacity configuration of heterogeneous battery packs under multiple operational constraints.

(2) A power allocation framework for coordinating multiple battery groups while considering their different degradation rates and dynamic operational states.

(3) A comprehensive evaluation model for characterizing the diversity of second-life batteries and their remaining useful life in grid-scale energy storage systems.

In order to fill the gap discussed above, an innovative model-free adaptive control-embedded dung beetle-inspired heuristic optimization algorithm is proposed for SLBESS capacity planning and power dispatch. The main novelty and contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) A coordinated bilevel optimization architecture is established where a dung beetle-inspired heuristic algorithm configures optimal SLBESS capacity at the upper level, while a heterogeneous battery group power dispatch model operates at the lower level, enabling simultaneous strategic planning and operational control.

(2) An innovative model-free adaptive voltage control strategy (MF-AVCS) is developed that eliminates dependency on complex battery charging/discharging models and historical data requirements, while maintaining system stability through real-time adaptive mechanisms—representing a paradigm shift from conventional model-based approaches.

(3) A novel power dispatch strategy is proposed that optimally allocates power demands among heterogeneous second-life battery groups while respecting operational boundaries derived from the MF-AVCS framework, explicitly addressing the unique degradation characteristics and performance variations inherent in second-life batteries.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the bilevel optimization framework is introduced. Section 3 presents the heuristic-adaptive optimization method for SLBESS, including system cost analysis, model-free adaptive control, and solving process. Section 4 details the health-priority power allocation strategy for echelon battery systems. Case studies and numerical results are provided in Section 5, and conclusions are drawn in Section 6.

2 Bilevel Optimization Framework

The repurposing of SLBESS for grid-scale energy storage applications presents promising economic benefits while simultaneously addressing environmental sustainability concerns. Nevertheless, the incorporation of second-life batteries into operational power systems presents considerable technical challenges, primarily attributed to their non-uniform degradation patterns and heterogeneous performance characteristics. This paper proposes a comprehensive hierarchical optimization framework that systematically addresses the coordinated operation of hybrid energy storage systems comprising both new and second-life batteries. The proposed methodology encompasses both techno-economic optimization and lifetime management strategies to enhance system reliability while maximizing the utilization of available storage resources.

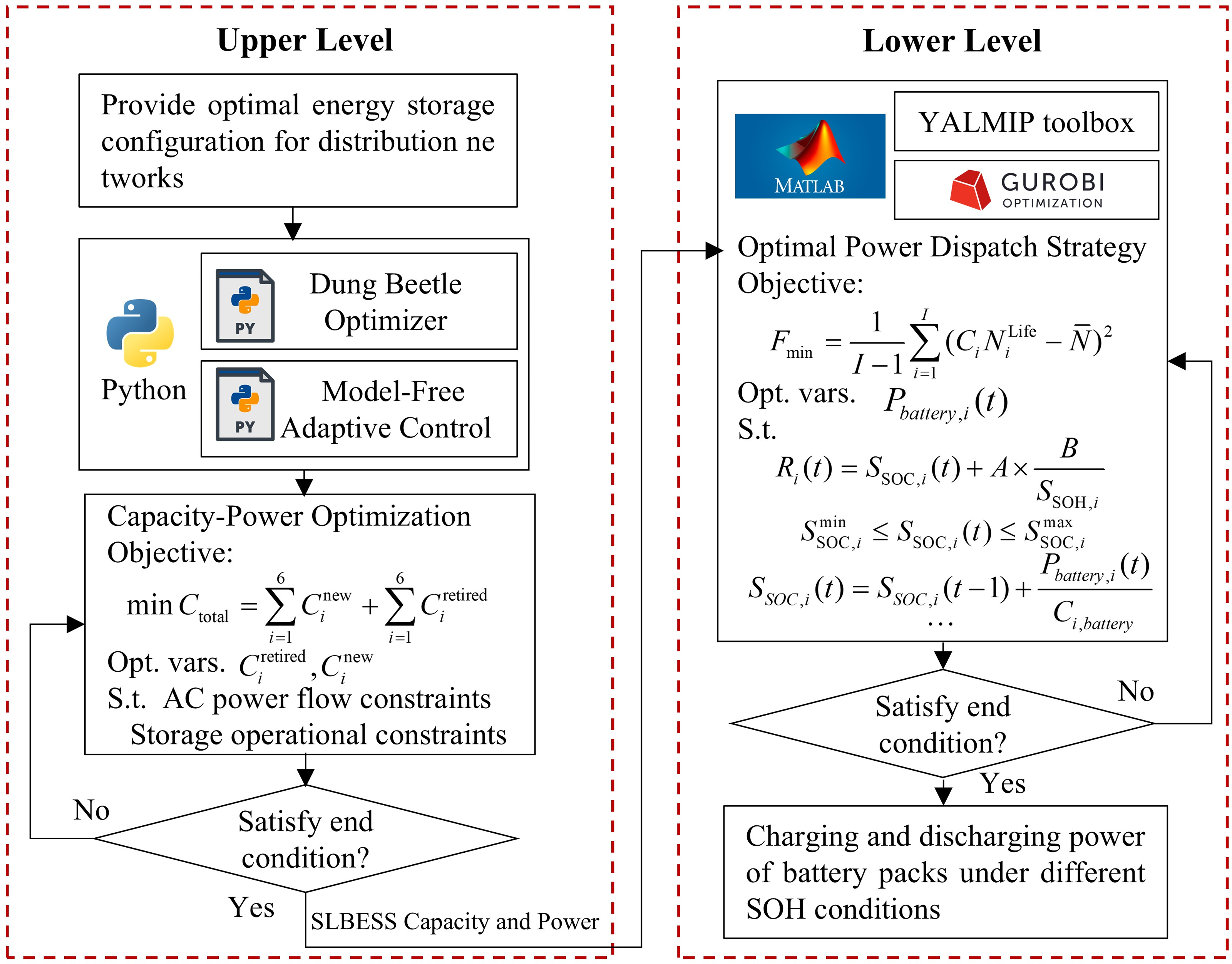

The proposed framework employs a bi-level optimization structure, where the upper and lower levels work in coordination to achieve comprehensive system optimization, as illustrated in Fig. 2. At the upper hierarchical level, the framework leverages an advanced meta-heuristic approach, specifically the Dung Beetle Optimizer Algorithm (DBOA), to determine the optimal capacity configuration of hybrid energy storage systems. This optimization process primarily focuses on minimizing the total investment costs while ensuring system reliability and performance. During this optimization process, a sophisticated Model-Free Adaptive Control (MFAC) strategy is implemented to manage the dynamic charging and discharging processes of the energy storage units. This adaptive control mechanism continuously adjusts its parameters based on real-time operational conditions, eliminating the need for complex mathematical models while maintaining robust performance.

Figure 2: The flowchart of bi-level optimization framework

The lower-level optimization introduces a detailed cycle life degradation model that considers critical factors affecting battery longevity, particularly the depth-of-discharge and charge-discharge cycles. This level primary objective is to maximize the remaining lifespan of the battery clusters through intelligent power distribution. By leveraging the capacity configuration and operational constraints established by the upper level, this stage determines the optimal power allocation ratios between new and retired energy storage units. This approach ensures that the power distribution strategy not only meets immediate operational requirements but also contributes to the long-term sustainability of the system.

Within this hierarchical optimization architecture, the upper-level optimization outcomes establish operational constraints and boundary conditions for the lower-level optimization process. The lower-level model determines the charging and discharging power allocation among battery clusters with different SOH values. This bi-level structure enables the framework to achieve dual objectives: the upper level ensures economic efficiency through optimal capacity configuration, while the lower level extends the lifespan of second-life battery clusters through intelligent power distribution strategies. The interaction between these two levels creates a comprehensive solution that not only addresses the economic viability of second-life battery storage systems but also maximizes their operational longevity through coordinated control.

3 Heuristic Optimization for Hybrid Energy Storage Systems Capacity-Power Dispatch

3.1 Hybrid Energy Storage Systems Cost

The comprehensive life-cycle cost architecture for pristine and SLBESS demonstrates structural consistency, comprising six fundamental cost components:

1. Battery Unit Cost: Includes procurement expenses for electrochemical cells and retired battery packs.

where Ce is the unit cost of battery capacity ($/Wh), E: Rated energy capacity of the energy storage system (Wh);

2. Power Conversion System Cost: Covers bidirectional inverters, DC/AC converters, and grid synchronization components to ensure voltage/frequency compliance.

where CP is Unit cost of PCS ($/W), P is Rated power capacity of the energy storage system (W);

3. Battery Management System Cost: Incorporates hardware (e.g., sensing modules, balancing circuits) and software (e.g., state-of-health estimation algorithms) for real-time monitoring and safety assurance.

where Cb is unit cost of BMS ($/Wh);

4. System Integration Cost: Involves structural engineering, thermal management (e.g., liquid cooling loops), and electrical interconnection (e.g., busbars, switchgear) to achieve modular scalability.

where Cj is unit cost of system integration ($/Wh);

5. Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Cost: Integrates fixed expenditures, variable maintenance activities, and lifecycle degradation considerations.

where Cw is annual O&M cost per unit energy capacity ($/(Wh·a));

6. Thermal and Safety System Cost: Includes fire suppression systems, gas venting mechanisms, and thermal runaway mitigation protocols.

where Cd is unit cost of the thermal-electrical safety system ($/Wh).

In order to derive the cost-optimal capacity configuration for hybrid second-life energy storage systems comprising new and retired battery units, the total cost minimization objective is defined as:

where Cinew represents the i-th cost category of new batteries (e.g., C1new = Cenew Enew), Ciretired represents the i-th cost category of retired batteries (e.g., C1retired = Ceretired Eretired).

The objective function is mathematically formulated to serve as the fitness evaluation criterion for the meta-heuristic DBO algorithm. Additionally, a model-free adaptive power control framework is integrated to dynamically adjust power dispatch without relying on electrochemical or grid-connection models.

3.2 Model-Free Adaptive Power Control

The voltage control system in distribution networks is conceptualized as a Multiple-Input Single-Output (MISO) discrete-time nonlinear system [23], which can be represented by the following mathematical formulation:

where Vi(k + 1) denotes the voltage of node i at time instant k + 1, u(k) denotes the system input at moment k (e.g., the active power of the energy storage system), f(·) denotes the nonlinear vector function characterizing the relationship between the output and input of the system, Ny and Nu represent the dimensions of the input and output of the system, respectively.

According to Theorem 3.1 in [24], when |Δu(k)| ≠ 0, the dynamic linearization of the distribution network voltage control system can be achieved through a Pseudo Partial Derivative (PPD) that is continuously adjusted based on historical sampling data. This allows the transformation of the original nonlinear system model in Eq. (3a) into a compact-form dynamic linearized data model, as shown in Eq. (3b):

where φ(k) denotes the PPD at moment k.

During this stage, the designed voltage control system should be able to manage system voltage at a desirable operating range, with the detailed optimization objective defined below:

where V∗ denotes the desired reference voltage, λ is introduced in the second item to restrict the changing rate of system input, thereby avoiding voltage disturbances on distribution grids.

Eq. (5) can be derived from Eq. (3b):

Bringing Eq. (5) into Eq. (4) and deriving it so that it is equal to 0 yields the following equation:

where

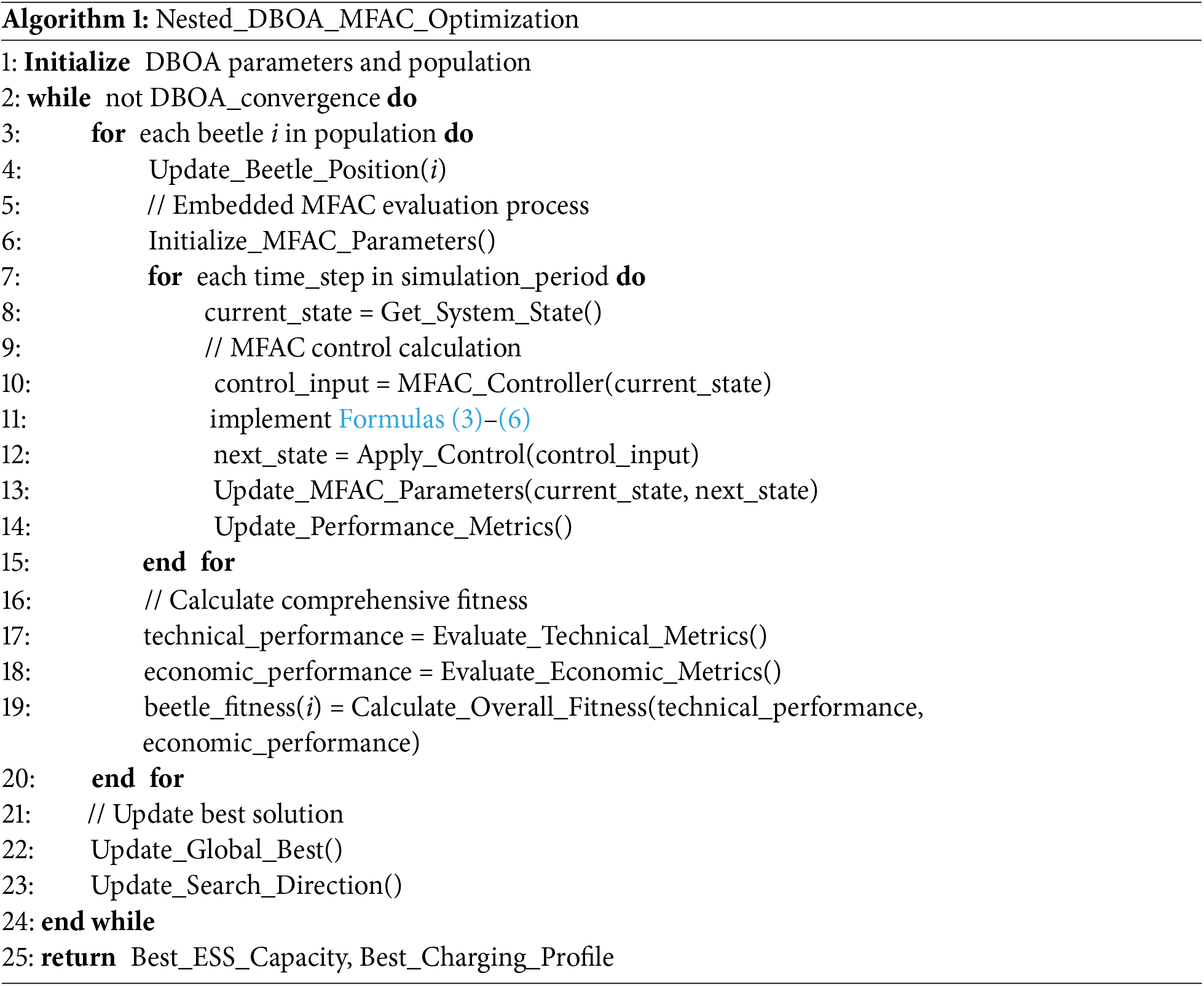

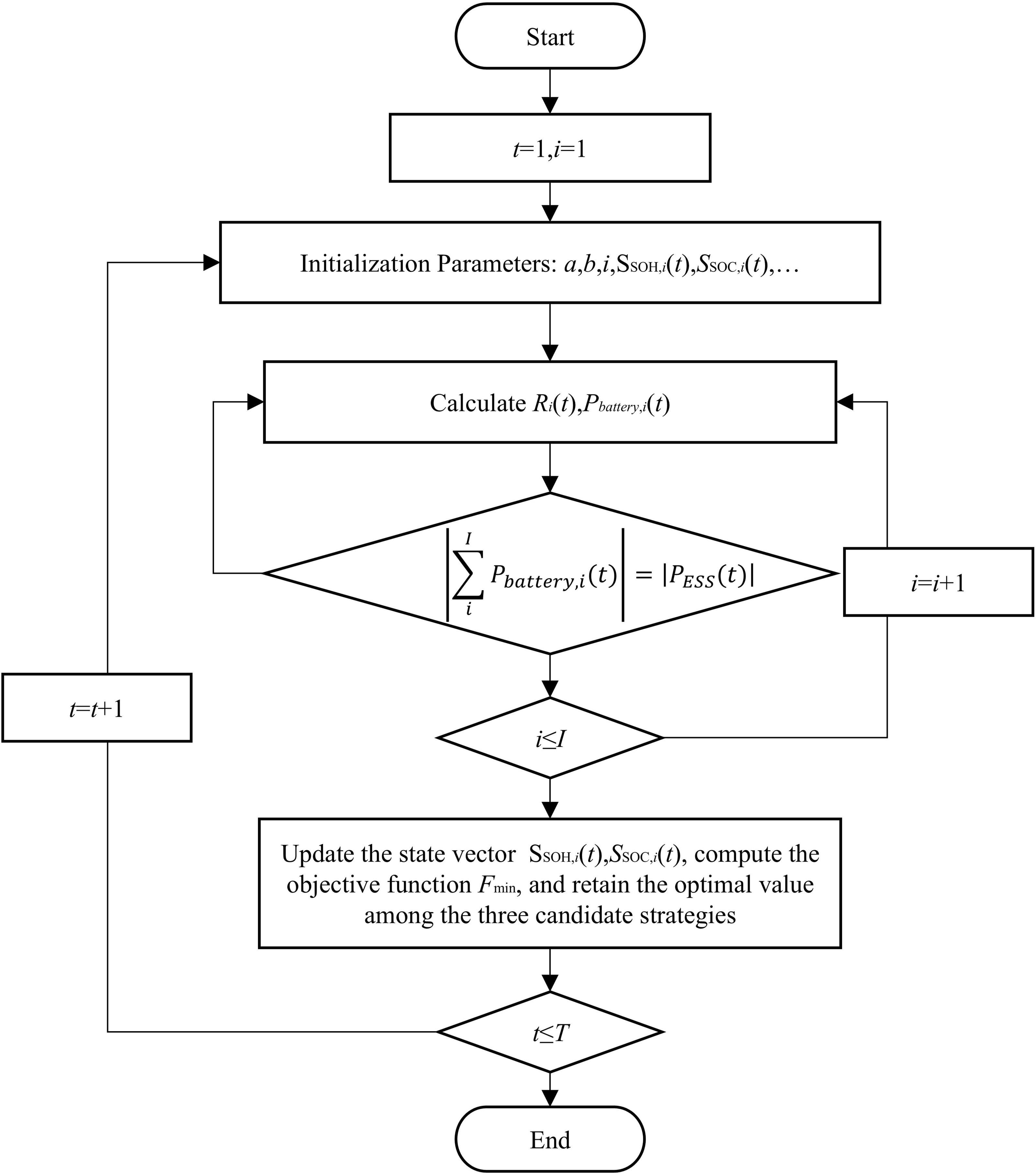

The proposed methodology integrates a model-free adaptive control strategy into the iterative process of the dung beetle optimization algorithm to simultaneously optimize the multi-level ESS capacity configuration and its charging/discharging profiles. During each iteration of dung beetle optimization algorithm, candidate solutions representing different ESS capacity configurations are evaluated through the embedded model-free adaptive control module, which determines the optimal charging/discharging power trajectories without relying on explicit system models. This hierarchical architecture facilitates the concurrent evaluation of capacity planning strategies and operational performance metrics within a unified optimization framework. The model-free adaptive control controller utilizes real-time measurement data to adaptively adjust the ESS power output, while the dung beetle optimization algorithm continuously updates the capacity configuration based on the system performance metrics derived from the control outcomes. The optimization process continues until the algorithm converges to an optimal solution that satisfies both the voltage constraints and economic objectives. This integrated approach ensures that the final ESS capacity configuration is optimized considering its actual operational capabilities and dynamic control characteristics, rather than treating the planning and operation aspects separately. The pseudo-code corresponding to the solution flow is shown in Algorithm 1.

4 Health-Priority Power Allocation in Echelon Battery System

4.1 Cycle Life Degradation Model for Echelon Energy Storage Systems

The remaining useful life of a battery pack refers to the number of remaining charge-discharge cycles under full charging/discharging conditions, which is typically characterized by the residual cycle count. The residual cycle count varies significantly with the depth of discharge during operation. To establish the quantitative relationship between remaining useful life, state of health, and operational depth of discharge, this study employs publicly available battery cycling datasets in [25] to derive empirical correlations through nonlinear regression analysis and the fitted relationships are expressed in Eq. (7).

where S1 denotes the state of health of the battery pack, l denotes the cycle count of the battery pack, a1, a2 and a3 represent the fitting coefficients (a1 = 0.978, a2 = 6.734, a3 = 1953), NumiESS denotes remaining cycle count of the i-th battery pack, SSOH,i denotes the state of health of the i-th battery pach.

This empirically-derived correlation model eliminates the need for subjective expert judgment in battery life assessment, as the coefficients are mathematically determined through comprehensive data analysis rather than expert consultation. The quantitative nature of this approach ensures reproducible and objective battery performance evaluation across different operational scenarios.

In echelon energy storage systems, the nonlinear degradation of battery packs under varying D-degree depth of discharge necessitates the application of the equivalent cycle Life method. This approach normalizes partial depth of discharge cycles to equivalent full depth of discharge cycles (100%) using a power-law model:

where LiD denotes equivalent cycle count of battery unit i at D-degree depth of discharge, quantifying the cumulative aging effect under specific discharge depth conditions, NiD denotes the remaining cycle life of battery unit i at D-degree depth of discharge.

where NiLife denotes total equivalent cycle count of battery unit i over the operational period, calculated as the weighted summation of cycles across all depth-of-discharge levels, m denotes the m-th charge-discharge cycle process in the historical cycling dataset Hm, M denotes the total number of recorded charge-discharge cycles.

4.2 Optimal Power Dispatch Strategy for Echelon Energy Storage Systems

The equivalent cycle life methodology provides a mathematically rigorous framework for handling complex degradation patterns without requiring subjective weighting of different operational conditions. This quantitative normalization process is based on established battery physics principles and validated through extensive cycling data analysis, distinguishing it from multi-criteria decision-making approaches that rely on expert opinion for criteria weighting. Given the disparities in charge/discharge capabilities and degradation rates among packs at different SOH levels [26], this investigation presents an advanced coordinated operational framework that optimizes system-level performance metrics while minimizing the accelerated degradation of storage units with diminished SOH values. The core methodology involves a dual-factor prioritization mechanism that simultaneously considers real-time state-of-charge and long-term SOH characteristics. To enable deeper charging/discharging cycles for high-SOH battery packs while implementing shallow cycles for low-SOH units, a prioritization mechanism is proposed to maximize the utilization of high-SOH battery packs while reducing the degradation rate of low-SOH units. The priority ranking criterion is determined by combining the battery pack State of Charge (SOC) with the reciprocal of its SOH. This approach ensures that when all battery packs have consistent SOC levels, high-SOH units are prioritized for charging operations, while the opposite applies for discharging scenarios. This strategy incorporates both SOC and SOH considerations while accounting for their respective weights in the ranking algorithm, as expressed in Eq. (9).

where Ri(t) denotes the charging/discharging priority value of battery pack i at time t, where a higher value corresponds to a higher priority in the charging/discharging sequence, A denotes the state identifier, where A = 1 indicates the battery pack is in charging mode and A = −1 signifies discharging mode, the scaling parameter B ensures dimensional consistency between SOC and reciprocal SOH values, determined by the physical characteristics of the battery system rather than subjective preferences.

From Eq. (8), the equivalent cycle number (i.e., life degradation) of different battery packs under given operating conditions can be obtained. When considering system life degradation as an optimization objective, it is crucial to address how to transform the life degradation of individual battery packs into an overall system-level degradation metric. This paper comprehensively considers both system-level and individual battery pack degradation, proposing a method for constructing the objective function of CESS life degradation. The corresponding minimization objective function Fmin is expressed as:

where I denote the number of battery packs in the echelon energy storage system. Ci denotes the weighting factor for battery pack i.

The proposed methodology formulates the objective function through the normalization of equivalent cycling metrics relative to the residual cycle capacity for battery packs with different health states. The objective function model is established to minimize the variance of life degradation percentages among battery packs, specifically:

The implementation of capacity allocation in the cascaded energy storage system through the three proposed methods requires iterative solutions subject to the corresponding charging/discharging power constraints, battery pack SOC constraints, and energy storage system power constraints. Specifically, the constraints encompass the following three aspects:

1. Charging/discharging power constraints

where Pbattery,i(t) denotes the power of battery pack i at time t. A positive value indicates charging mode, while a negative value represents discharging mode.

2. Battery pack SOC constraints

where

3. Energy storage system power constraints

The optimization algorithm iteratively determines the optimal power dispatch trajectories while maintaining compliance with multiple operational constraints and boundary conditions. Initially, the algorithm calculates priority values Ri(t) for each battery pack based on their SOC and SOH characteristics. Power allocation is then performed according to the priority sequence, subject to individual battery power limits, SOC thresholds, and system-level constraints defined in Eq. (11a,c). The equivalent cycle count is updated using Eq. (8), followed by objective function evaluation through the Formula (10). This process continues until the convergence criterion is satisfied, ensuring optimal power distribution and degradation management across the echelon storage system. The computational procedure is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The solution flow chart

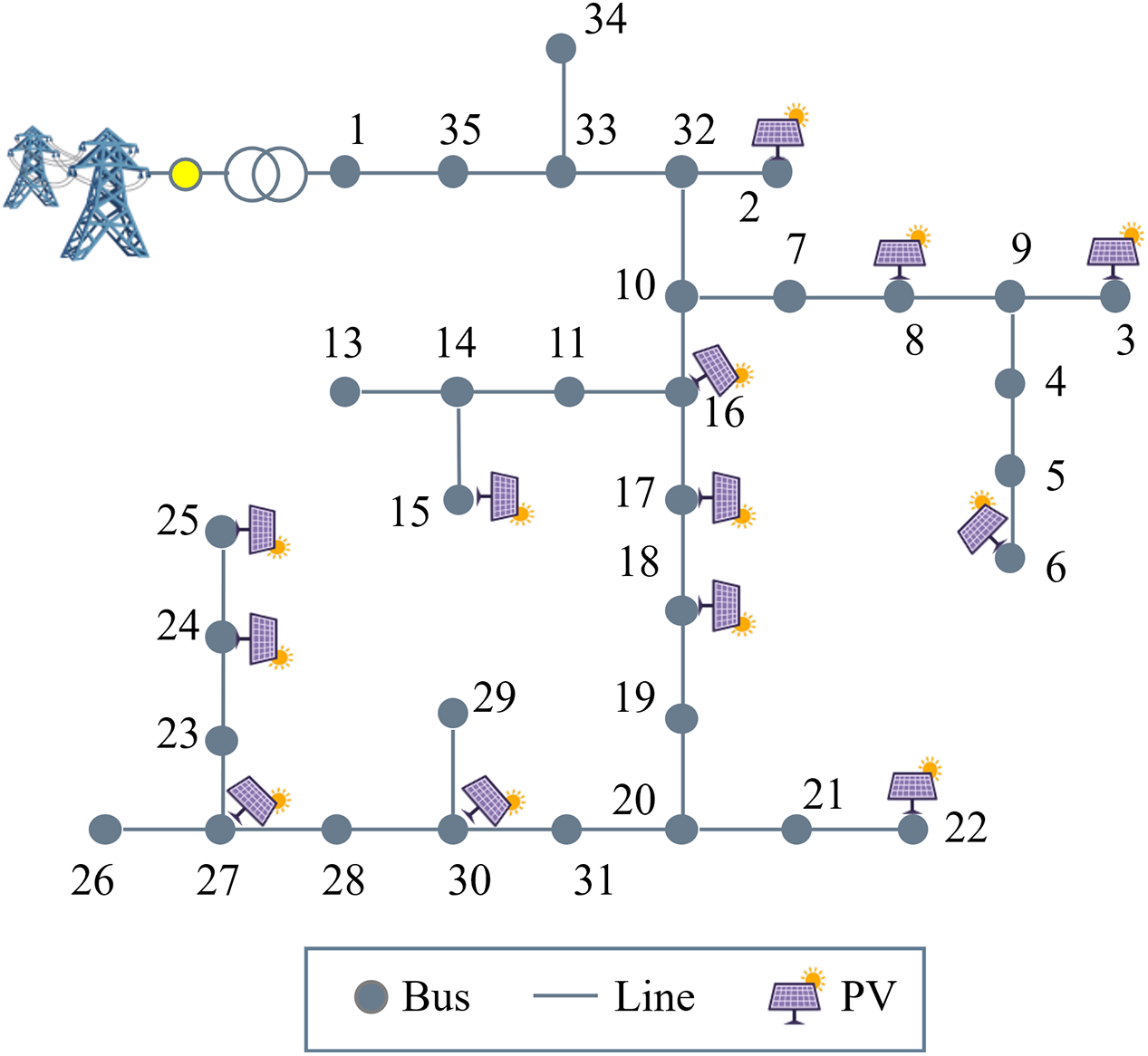

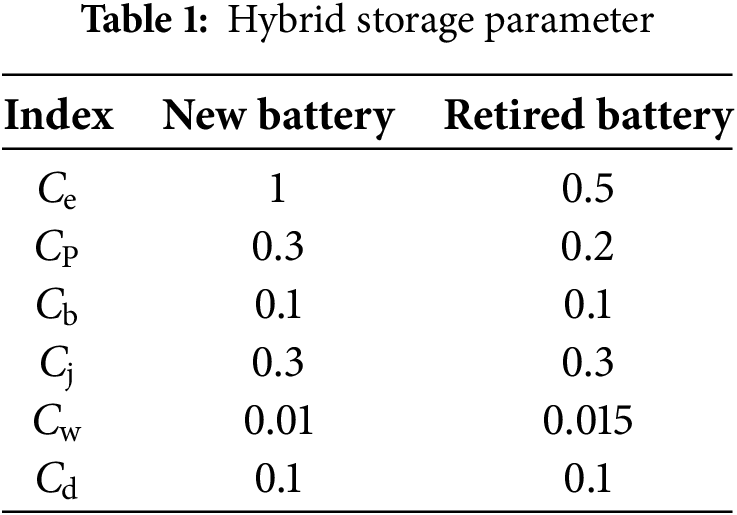

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, comprehensive case studies are conducted on two practical distribution feeders with 35 nodes and 66 nodes, respectively. The topology of the 35-node feeder is illustrated in Fig. 4, which comprises 35 load nodes, among which 13 nodes are equipped with distributed PV systems. It is assumed that second-life energy storage systems can be deployed at any node, with their technical parameters specified in Table 1. In Section 5.1, the effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through the optimal second-life energy storage systems capacity allocation, adaptive voltage control, and charge-discharge power dispatch on the 35-node feeder. Section 5.2 demonstrates the generalization capability of the proposed method through simulation studies on both 35-node, 66-node and 128-node feeders. Furthermore, comparative analyses are conducted to verify the superior performance of the proposed method in terms of economic benefits and the impact on second-life energy storage systems lifetime degradation.

Figure 4: 35-node system

5.1 Echelon Storage Configuration and Voltage Regulation Performance

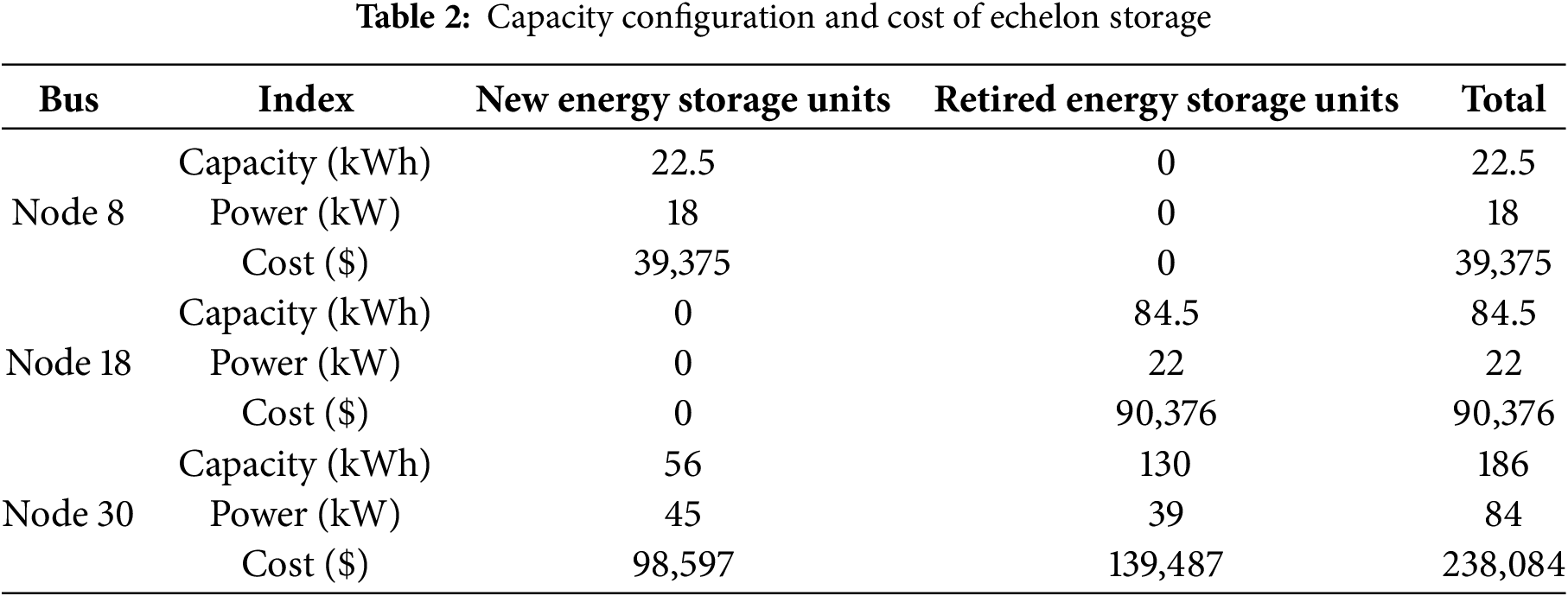

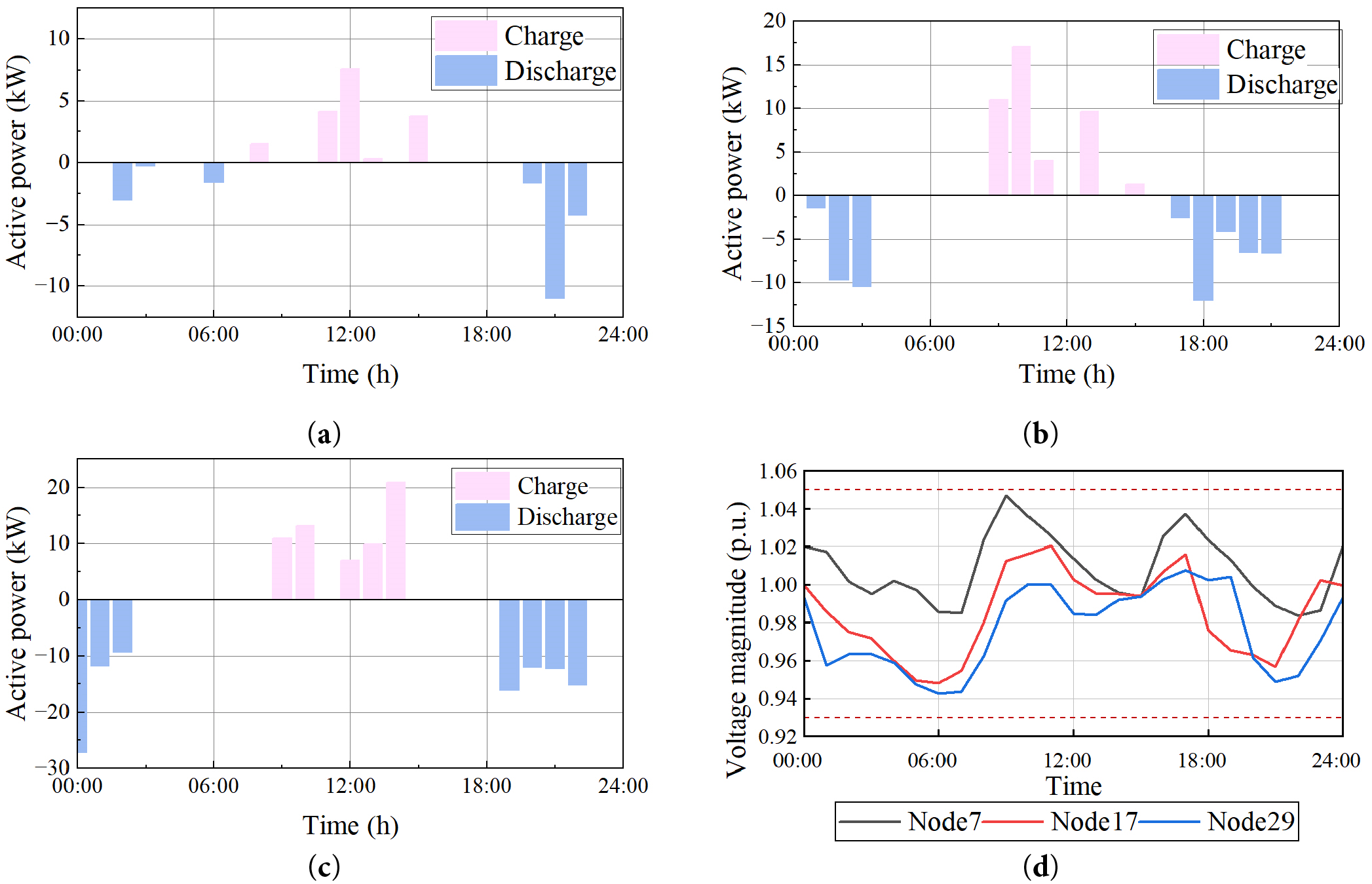

To thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conduct simulations on the 35-node systems. When the voltage deviation boundary is set to 0.93–1.05, the echelon energy storage configuration scheme results are shown in Table 2, and the charging/discharging power of the energy storage is illustrated in Fig. 5. Table 2 presents the capacity allocation and associated costs at nodes 8, 18, and 30. At node 30, which exhibits the highest load demand, a hybrid configuration of 56 kWh new ESS and 130 kWh SLESS is deployed, with total power rating of 84 kW. The total investment cost at this node amounts to $238,084, representing the most significant investment among all nodes. Node 18 is equipped solely with SLESS (84.5 kWh), while node 7 utilizes only new ESS (22.5 kWh), demonstrating the method’s ability to optimize storage type selection based on local requirements.

Figure 5: The power-voltage dynamics in second-life battery hybrid energy storage systems: (a) operation policies of echelon storage at node 8; (b) operation policies of echelon storage at node 18; (c) operation policies of echelon storage at node 30; (d) voltage profile on node 8, 18 and 30

The temporal evolution of power dispatch trajectories for the three critical nodes is visualized in Fig. 5. The results show effective coordination between charging and discharging periods, with peak discharge powers of 17.02, 10.98, and 20.86 kW observed at different time intervals for nodes 8, 18, and 30, respectively. This coordination helps maintain voltage profiles within acceptable ranges, as evidenced in Fig. 5d, where voltage magnitudes remain between 0.94 and 1.05 p.u. throughout the day.

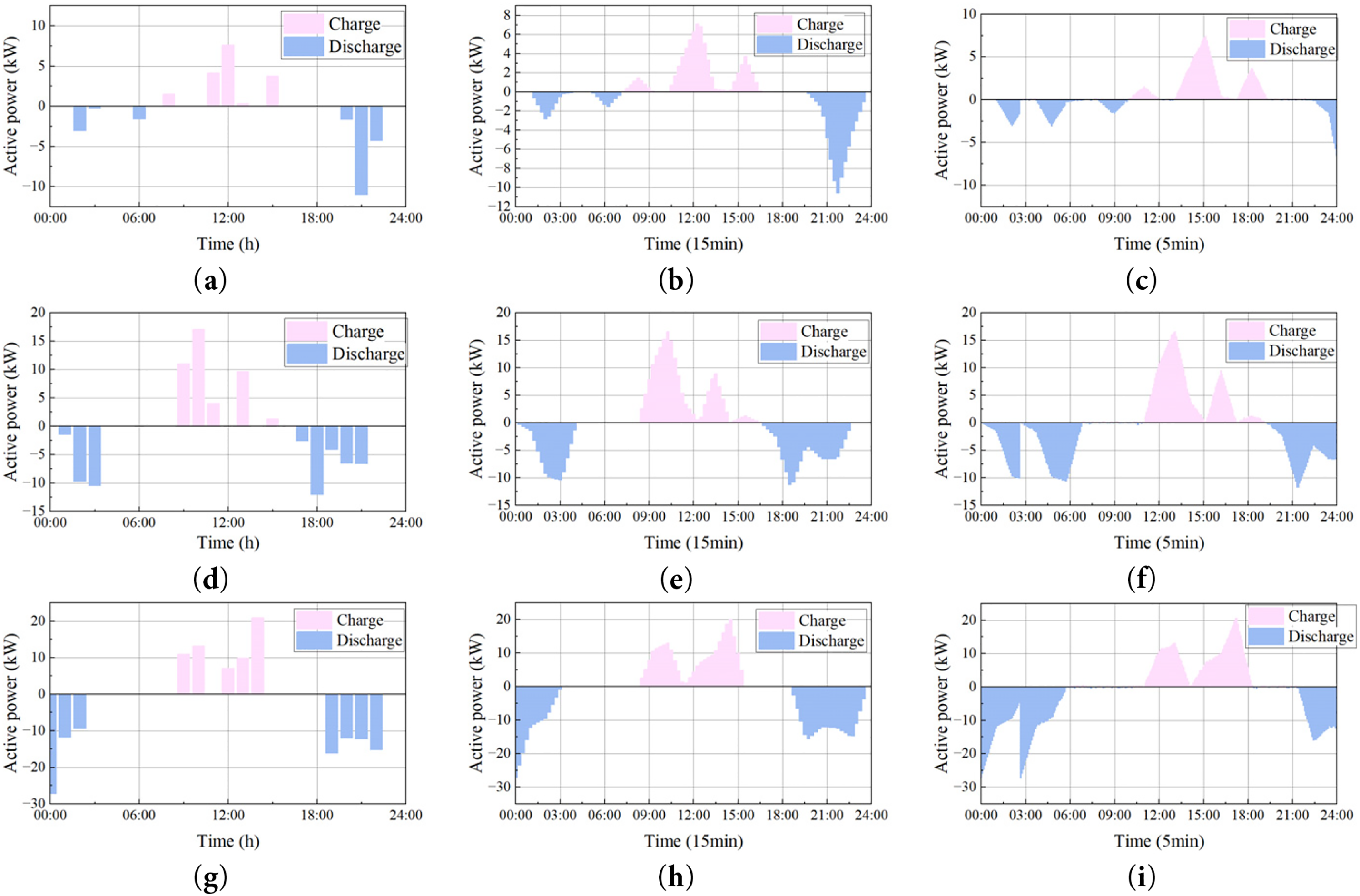

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed control strategy, comprehensive simulations were conducted on three energy storage systems under different temporal resolutions. The simulation results, as illustrated in Fig. 6, demonstrate the dynamic charging and discharging behaviors under 1-h, 15-min, and 5-min intervals. The power profiles reveal that higher temporal resolution enables more precise operational control and smoother power transitions. As shown in Fig. 6a,d,g the power dispatch exhibits stepped variations with distinct charging periods during midday (12:00–15:00) and discharging events in morning and evening peaks. When the temporal resolution increases to 15 min, intermediate power transitions become visible, providing a more accurate representation of the ESS operational characteristics. Further refinement to 5-min intervals captures detailed dynamic responses. The enhanced temporal granularity not only reveals the actual ramping behavior of the storage systems but also demonstrates the controller’s capability to maintain stable operation under frequent power transitions.

Figure 6: Power profiles of three energy storage systems under different temporal resolutions: (a) power profiles of echelon storage at node 8 under 1-h; (b) power profiles of echelon storage at node 8 under 15-min; (c) power profiles of echelon storage at node 8 under 5-min; (d) power profiles of echelon storage at node 18 under 1-h; (e) power profiles of echelon storage at node 18 under 15-min; (f) power profiles of echelon storage at node 18 under 5-min; (g) power profiles of echelon storage at node 30 under 1-h; (h) power profiles of echelon storage at node 30 Under 15-min; (i) power profiles of echelon storage at node 30 under 5-min

The comparative analysis across different temporal resolutions validates that the proposed control strategy effectively manages power dispatch at various time scales. Notably, the 5-min resolution profiles show superior performance in terms of power smoothing and operational flexibility, while maintaining the fundamental charging-discharging patterns observed in lower resolution scenarios. This multi-resolution analysis confirms the robustness and adaptability of the control algorithm in practical applications where high-frequency power adjustments are essential for grid stability and power quality management.

5.2 Effectiveness Analysis of Power Dispatch Strategy

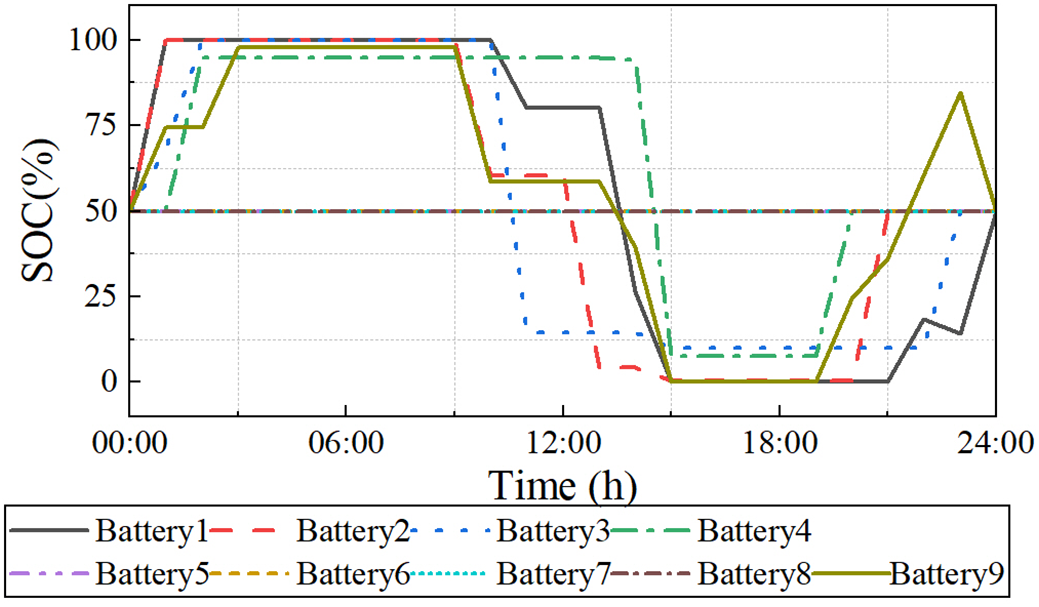

For detailed characterization of power allocation strategies at the critical node 30, the hybrid energy storage system is strategically divided into nine battery groups based on their initial characteristics and operational requirements. Specifically, the 56 kWh new ESS is partitioned into four groups (Groups 1–4) of equal capacity (14 kWh each), considering their uniform state of health and performance parameters. The 130 kWh second-life ESS is segregated into five groups (Groups 5–9), with Groups 5–8 each containing 28 kWh capacity, while Group 9 is designated as an 18 kWh balancing unit. This grouping strategy takes into account the heterogeneous degradation states of second-life batteries, with initial SOH values ranging from 0.75 to 0.85 for Groups 5–8, and 0.70 for Group 9. The differentiated grouping approach enables more precise control over charging/discharging operations while accounting for the distinct characteristics of new and second-life battery units.

To validate the effectiveness of the battery grouping strategy, Fig. 7 presents the SOC evolution for nine battery groups at node 30. The results reveal distinct charging/discharging patterns among groups, with SOC values ranging from 0.5 to 1.0. Groups 1–4 demonstrate more active utilization, frequently reaching their maximum SOC (1.0), while groups 5–8 maintain relatively stable SOC levels around 0.5. This differentiated usage pattern effectively extends battery lifetime by preventing simultaneous degradation of all battery units. The ninth group serves as a power balance unit, with SOC variations between 0.243 and 0.977, ensuring system stability while accommodating power fluctuations.

Figure 7: SOC variation curves under different batteries

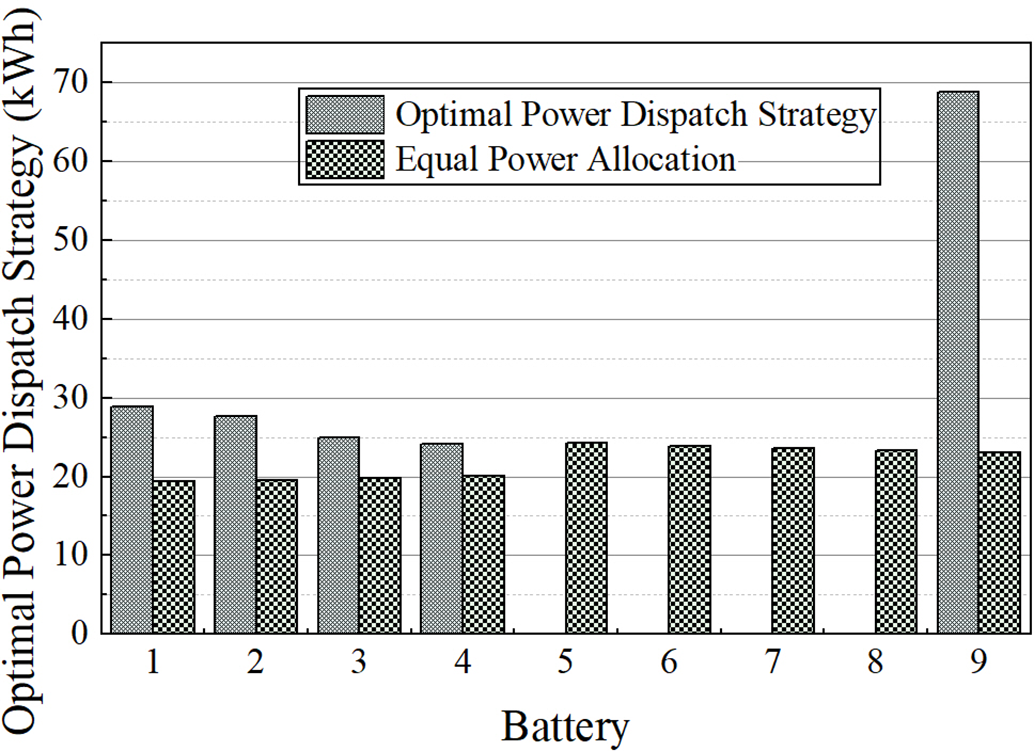

Additionally, to validate the effectiveness of the proposed power allocation strategy, a comparative simulation is conducted on node 30 with a SLBESS consisting of nine battery packs. Fig. 8 presents the power allocation results of both the proposed method and the traditional equal power distribution strategy.

Figure 8: Total charge-discharge capacity of different batteries

The simulation results reveal several significant findings. First, the proposed method demonstrates an adaptive power allocation strategy that considers the SOH differences among battery packs. Instead of distributing power equally, it intelligently allocates different power levels to each pack. Notably, packs 1–4 and pack 9 are actively utilized, while packs 5–8 are temporarily idle (0 kW). In contrast, the equal distribution strategy assigns similar power levels across all nine packs, ranging from 19.389 to 24.237 kW. While this approach appears more straightforward, it fails to account for the varying degradation states and operational capabilities of different battery packs. The uniform distribution of power might accelerate the degradation of weaker battery packs while underutilizing the potential of healthier ones.

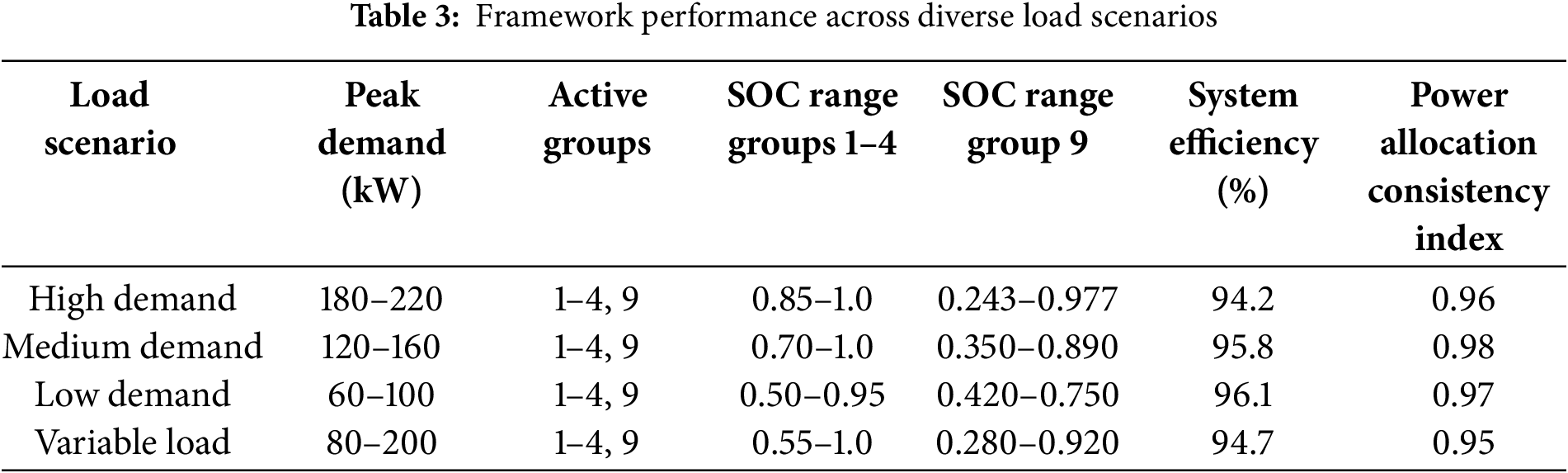

Additionally, the robustness of the proposed hybrid energy storage optimization framework is systematically evaluated under varying operational scenarios to demonstrate consistent algorithmic performance independent of external load conditions. Table 3 presents comprehensive performance metrics across four distinct load scenarios, ranging from low-demand periods (60–100 kW) to high-demand operations (180–220 kW).

The results demonstrate exceptional algorithmic consistency across all operational scenarios. Notably, the framework maintains the fundamental power allocation strategy with Groups 1–4 and Group 9 remaining active across all conditions, while Groups 5–8 are strategically preserved as reserve capacity. The Power Allocation Consistency Index, calculated as the correlation coefficient between power distribution patterns across different scenarios, remains above 0.95 in all cases, indicating robust algorithmic stability. System efficiency variations are minimal (94.2%–96.1%), confirming that the optimization framework adapts effectively to load variations without compromising performance quality.

5.3 Comparative Reliability Benchmarking

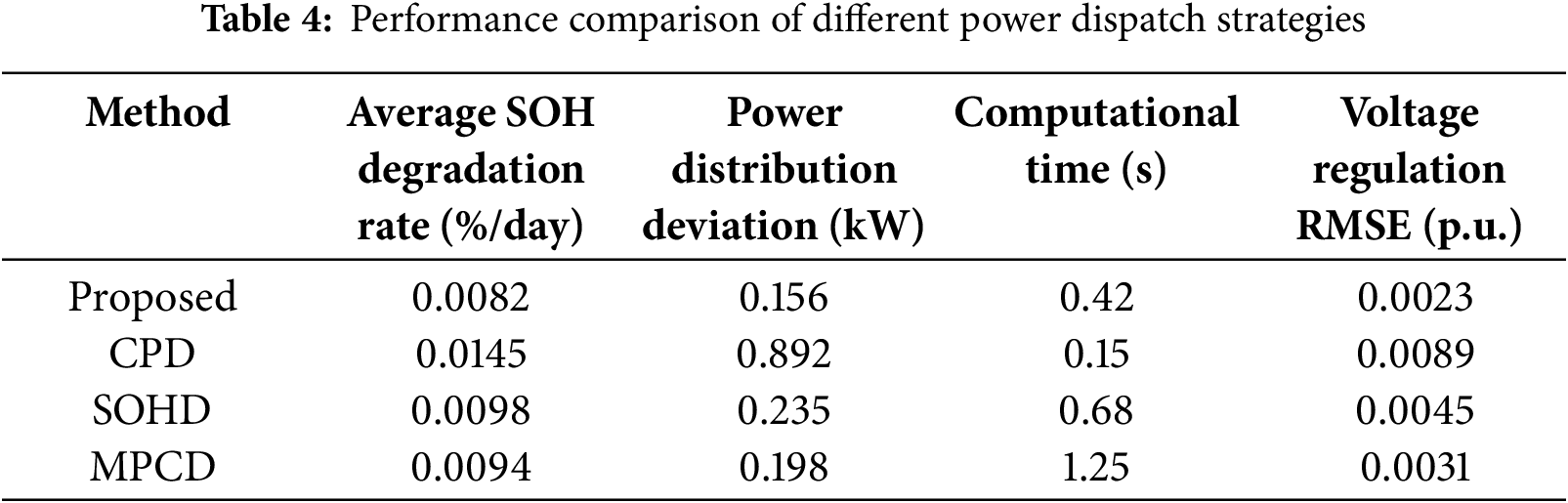

To further validate the superiority of the proposed power dispatch strategy, we conduct comprehensive comparisons with three mainstream methods: conventional proportional dispatch (CPD), state-of-health based dispatch (SOHD), and model predictive control-based dispatch (MPCD). The comparative results for node 30 over a 24-h operation period are summarized in Table 4.

The comparative analysis reveals several significant advantages of our proposed method. First, it achieves the lowest SOH degradation rate (0.0082%/day) among all methods, representing improvements of 43.4%, 16.3%, and 12.8% compared to CPD, SOHD, and MPCD, respectively [27]. This superior performance in battery lifetime preservation can be attributed to our health-priority allocation strategy that effectively considers both real-time operational states and long-term degradation patterns.

Furthermore, our method demonstrates excellent performance in power distribution accuracy, with a minimal deviation of 0.156 kW from the optimal dispatch targets. While the computational efficiency (0.42 s) is moderately higher than the simple CPD approach (0.15 s), it is significantly faster than both SOHD (0.68 s) and MPCD (1.25 s). The voltage regulation performance, measured by Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), also shows that our method maintains the most stable voltage profile (0.0023 p.u.) among all compared approaches, validating its effectiveness in coordinating multiple operational objectives.

These comprehensive comparison results substantiate that our proposed method achieves a better balance between computational efficiency, operational performance, and battery lifetime preservation compared to existing approaches. The superior performance in both technical and economic aspects demonstrates its practical value for real-world SLBESS applications.

5.4 Generalization Analysis among Different Network Structures

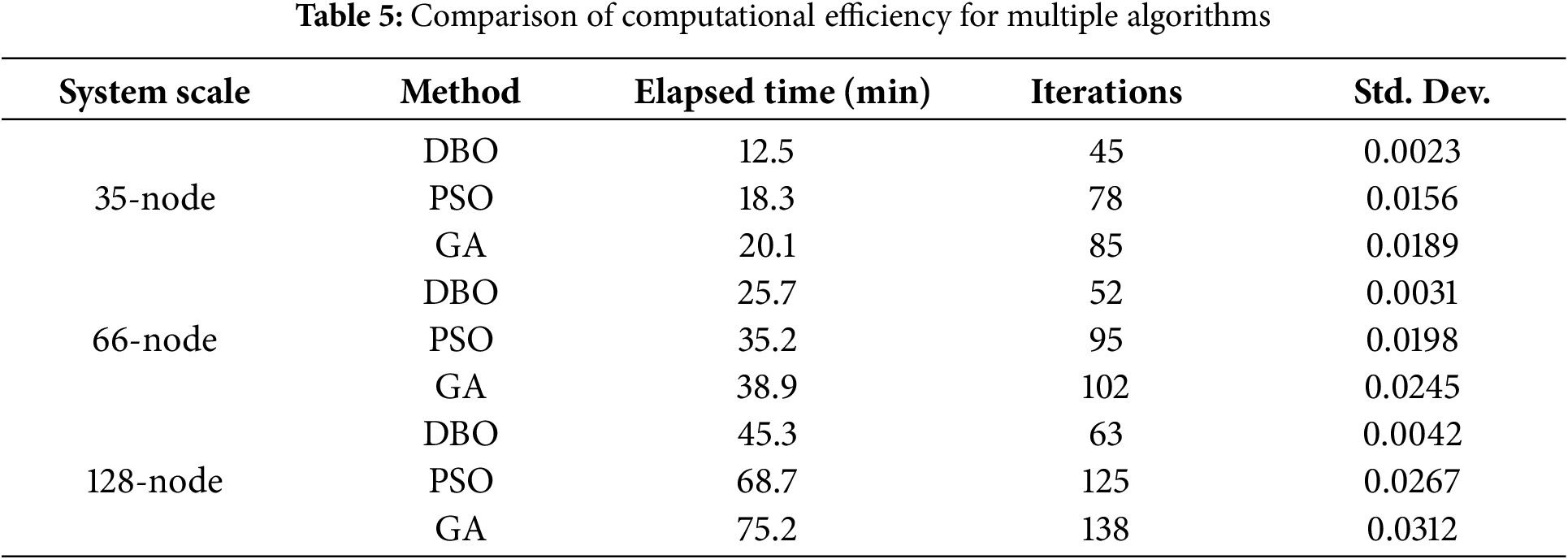

To thoroughly evaluate the scalability and effectiveness of the proposed EMVA-DBO algorithm, we conduct simulations on three IEEE test distribution systems of varying scales: the 35-node, 66-node, and 128-node systems. These systems represent different complexity levels of practical distribution networks, allowing us to assess the algorithm performance under diverse operating conditions.

The scalability analysis reveals the superior computational efficiency of the proposed EMVA-DBO algorithm, as illustrated in Table 5. When tested on the 35-node system, EMVA-DBO converges within 45 iterations (12.5 s), while PSO and GA require 78 and 85 iterations (18.3 and 20.1 s), respectively. This advantage becomes more pronounced in larger systems. For the 123-node system, EMVA-DBO maintains efficient performance with 63 iterations (45.3 s), whereas PSO and GA require 125 and 138 iterations (68.7 and 75.2 s), respectively. The standard deviation of solutions over 30 independent runs remains below 0.005 for EMVA-DBO across all test systems, indicating robust convergence stability.

This paper presents a novel bilevel optimization framework for optimal capacity configuration and power dispatch of second-life battery energy storage systems in distribution networks. The key findings of this research can be summarized as follows:

Effective Integration of Optimization Methods: The proposed framework successfully integrates a dung beetle-inspired heuristic optimization algorithm with a model-free adaptive voltage control strategy, effectively addressing the challenges of heterogeneous battery characteristics and uncertain degradation patterns through a bilevel optimization structure.

Superior Computational Performance: Case studies conducted on 35-node, 66-node, and 128-node distribution systems demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in terms of both computational efficiency and solution quality, validating the scalability and robustness of the approach across different network scales.

Enhanced Battery Lifetime Management: The health-priority power allocation strategy effectively extends battery lifetime by implementing differentiated charging/discharging patterns based on SOH levels, with new battery groups showing SOC variations between 0.5–1.0 while maintaining stable operation for others, demonstrating effective management of heterogeneous battery populations.

Practical Applicability: The upper-level optimization determines optimal SLBESS capacity configuration while considering charging/discharging power boundaries, while the lower-level optimization handles power allocation among heterogeneous battery groups based on their operational states and degradation constraints, providing a comprehensive solution for real-world implementation.

These results validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework in achieving both economic optimization and operational stability for second-life battery storage systems in modern distribution networks. The bilevel optimization approach provides a practical pathway for integrating retired EV batteries into distribution systems while maximizing their operational value and extending their useful lifetime. Future work will focus on long-term validation studies and integration with dynamic market mechanisms to further enhance the economic viability of second-life battery applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Financial support was provided by the State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company Science and Technology Project “Key Research on Development Path Planning and Key Operation Technologies of New Rural Electrification Construction” under Grant No. 52199623000G.

Author Contributions: Formal analysis, Youbo Liu; Investigation, Chuan Yuan and Chang Liu; Resources, Shijun Chen and Weiting Xu; Writing—original draft, Zhengbo Li; Writing—review & editing, Ke Xu and Jing Gou. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Zhengbo Li, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hu X, Deng X, Wang F, Deng Z, Lin X, Teodorescu R, et al. A review of second-life lithium-ion batteries for stationary energy storage applications. Proc IEEE. 2022;110(6):735–53. doi:10.1109/jproc.2022.3175614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Han W, Wik T, Kersten A, Dong G, Zou C. Next-generation battery management systems: dynamic reconfiguration. IEEE Ind Electron Mag. 2020;14:20–31. doi:10.36227/techrxiv.12676571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Omariba ZB, Zhang L, Sun D. Review of battery cell balancing methodologies for optimizing battery pack performance in electric vehicles. IEEE Access. 2019;7:129335–52. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2940090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bhatt A, Ongsakul W. Optimal techno-economic feasibility study of net-zero carbon emission microgrid integrating second-life battery energy storage system. Energy Convers Manag. 2022;266(1):115825. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Graber G, Calderaro V, Galdi V, Piccolo A. Battery second-life for dedicated and shared energy storage systems supporting EV charging stations. Electronics. 2020;9(6):939. doi:10.3390/electronics9060939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Deng Y, Zhang Y, Luo F, Mu Y. Hierarchical energy management for community microgrids with integration of second-life battery energy storage systems and photovoltaic solar energy. IET Energy Syst Integr. 2022;4(2):206–19. doi:10.1049/esi2.12055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Deng Y, Zhang Y, Luo F, Mu Y. Operational planning of centralized charging stations utilizing second-life battery energy storage systems. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2020;12(1):387–99. doi:10.1109/tste.2020.3001015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Steckel T, Kendall A, Ambrose H. Applying levelized cost of storage methodology to utility-scale second-life lithium-ion battery energy storage systems. Appl Energy. 2021;300:117309. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liu C, Cai X, Chen Q. Self-adaptation control of second-life battery energy storage system based on cascaded h-bridge converter. IEEE J Emerg Sel Top Power Electron. 2020;8(2):1428–41. doi:10.1109/jestpe.2018.2886965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Horesh N, Quinn C, Wang H, Zane R, Ferry M, Tong S, et al. Driving to the future of energy storage: techno-economic analysis of a novel method to recondition second life electric vehicle batteries. Appl Energy. 2021;295:117007. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Al-Jaljouli F, Mücke R, Roitzheim C, Sohn YJ, Yaqoob N, Finsterbusch M, et al. Chemo-thermal stress in all-solid-state batteries: impact of cathode active materials and microstructure. J Power Sources. 2025;644(26):237136. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2025.237136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Andrenacci N, Chiodo E, Lauria D, Mottola F. Life cycle estimation of battery energy storage systems for primary frequency regulation. Energies. 2018;11(12):3320. doi:10.3390/en11123320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Y, Li Y, Tao Y, Ye J, Pan A, Li X, et al. Performance assessment of retired EV battery modules for echelon use. Energy. 2020;193:116555. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.116555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mukherjee N, Strickland D. Control of second-life hybrid battery energy storage system based on modular boost-multilevel buck converter. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2014;62(2):1034–46. doi:10.1109/tie.2014.2341598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Fei Z, Zhang Z, Yang F, Tsui K-L, Li L. Early-stage lifetime prediction for lithium-ion batteries: a deep learning framework jointly considering machine-learned and handcrafted data features. J Energy Storage. 2022;52(5):104936. doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.104936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang J, Zhang S, Li C, Wu L, Wang Y. A data-driven method with mode decomposition mechanism for remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2022;37(11):13684–95. doi:10.1109/tpel.2022.3183886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li Y, Wang Y, Wang W, Fatehi P, Kozinski J, Kang K. Analytic hierarchy process-based life cycle assessment of the renewable energy production by orchard residual biomass-fueled direct-fired power generation system. J Clean Prod. 2023;419:138304. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Debnath B, Bari ABMM, Haq MM, de Jesus Pacheco DA, Khan MA. An integrated stepwise weight assessment ratio analysis and weighted aggregated sum product assessment framework for sustainable supplier selection in the healthcare supply chains. Supply Chain Anal. 2023;1(6):100001. doi:10.1016/j.sca.2022.100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Haktanır E, Kahraman C. Integrated AHP & TOPSIS methodology using intuitionistic Z-numbers: an application on hydrogen storage technology selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;239:122382. [Google Scholar]

20. Cheng X, Zhao H, Zhang Y, Hao X. A study on site selection of pumped storage power plants based on C-OWA-AHP and VIKOR-GRA: a case study in China. J Energy Storage. 2023;72(3):108623. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.108623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Roslan MF, Satpathy PR, Prasankumar T, Ramachandaramurthy VK, Mansor M, Walker SL. Second-life battery energy storage system for energy sustainability: recent advancements, key takeaways and future perspectives. J Energy Storage. 2025;123(4):116808. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.116808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Turan F, Boynuegri AR, Durmaz T. Comprehensive technical and economic evaluations of using second-life batteries as energy storage in off-grid applications: a customized cost analysis. J Energy Storage. 2025;120:116379. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.116379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Park B, Olama MM. A model-free voltage control approach to mitigate motor stalling and FIDVR for smart grids. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2020;12(1):67–78. doi:10.1109/tsg.2020.3012308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Guo Y, Wu Q, Gao H, Chen X, Østergaard J, Xin H. MPC-based coordinated voltage regulation for distribution networks with distributed generation and energy storage system. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2019;10(4):1731–9. doi:10.1109/tste.2018.2869932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Saxena S, Hendricks C, Pecht M. Cycle life testing and modeling of graphite/LiCoO2 cells under different state of charge ranges. J Power Sources. 2016;327(5):394–400. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.07.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang C, Wang J, Zhang L, Zhang W, Zhu T, Yang X-G, et al. Decoding battery aging in fast-charging electric vehicles: an advanced SOH estimation framework using real-world field data. Energy Storage Mater. 2025;78:104236. doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2025.104236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yu Y, Li J, Chen D. Optimal dispatching method for integrated energy system based on robust economic model predictive control considering source-load power interval prediction. Glob Energy Interconnect. 2022;5(5):564–78. doi:10.1016/j.gloei.2022.10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools