Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Analysis of the Use of Geothermal Energy for Heating in Azerbaijan

Department of Energy Technology, Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University, Baku, 1014, Azerbaijan

* Corresponding Author: Orkhan Jafarli. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrated Renewable Energy Systems for Heating, Cooling, Power Generation and Energy Management)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(9), 3595-3608. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.067982

Received 18 May 2025; Accepted 23 June 2025; Issue published 26 August 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the feasibility and efficiency of geothermal energy for heating applications in Azerbaijan, with a specific focus on the Khachmaz region. Despite the country’s growing interest in sustainable energy, limited research has addressed the potential of ground-source heat pump (GSHP) systems under local climatic and soil conditions. To address this gap, the study employs GeoT*SOL simulation to evaluate system performance, incorporating site-specific parameters such as soil thermal conductivity, heating demand profiles, and regional weather data. The results show that the GSHP system achieves a maximum seasonal performance factor (SPF) of 5.62 and an average SPF of 4.86, indicating high operational efficiency. Additionally, the system provides an estimated annual CO2 emissions reduction of 1956 kg per household, highlighting its environmental benefits. Comparative analysis with conventional heating systems demonstrates considerable energy savings and emissions mitigation. The study identifies technical (e.g., initial installation complexity) and economic (e.g., high upfront costs) challenges to widespread implementation. Based on these insights, practical recommendations are proposed: policymakers are encouraged to support financial incentives and policy frameworks; urban planners should consider GSHP integration in regional heating plans; and engineers may adopt the simulation-based approach presented here for feasibility studies. This research contributes to the strategic advancement of renewable heating technologies in Azerbaijan.Keywords

The construction sector substantially contributes to global energy demand, primarily driven by the swift advancement of urban development and technological progress in metropolitan areas. As of 2019, buildings were responsible for a considerable portion of global energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions—a situation exacerbated by the accelerating growth of the global population [1]. A recent assessment by the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicates that the building sector is responsible for 37% of worldwide energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Of this total, 27% results from the energy used during building operation, while the remaining 10% stems from the manufacturing of construction materials [2]. In 2021, space heating in buildings was responsible for nearly 80% of the sector’s direct CO2 output, amounting to around 2450 million metric tons. This figure corresponds to 6.8% of the total global CO2 emissions originating from fossil fuel combustion [3]. According to the latest data of the IEA, in 2017, the amount of CO2 emissions from burning fuels in Azerbaijan was 30.9 Mt (+6.6% since 2005; −42.1% since 1990). In 2022, this amount was 36.3 Mt, which is 0.1% of global CO2 emissions. Azerbaijan uses natural gas for approximately 99% of its heat supply [4]. In Azerbaijan, in 2022, the amount of heat obtained in boiler houses and fuel consumption were as follows:

• With natural gas fuel: 1,376,993 Gcal, corresponding to 193,236.9 m3 of gas consumption;

• With diesel fuel: 2584 Gcal, corresponding to 340.59 L of diesel;

• With electric boilers: 4300 Gcal, corresponding to 62,666.49 kWh of electricity consumption [5].

Addressing the decarbonisation of building heating is thus crucial in achieving sustainable urban development and meeting ambitious climate targets [3].

Utilizing geothermal heating solutions allows renewable energy to satisfy approximately 40%–70% of a building’s heating requirements, thereby substantially enhancing the total energy efficiency [6]. Properly designed ground heat exchangers adapted to site-specific conditions reduce both energy consumption and operational costs [7]. Findings from simulation models and on-site investigations across Europe and Asia suggest that integrating GSHP systems into buildings can lead to a 30%–60% reduction in yearly CO2 emissions when compared to traditional heating technologies [8].

Geothermal heating solutions have proven their effectiveness across both large-scale installations and individual homes. Multiple case studies validate that GSHP systems can successfully substitute conventional fossil fuel heating in single-family residences. For example, a residential property in Germany utilizing a vertical GSHP attained a Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) of 4.5, leading to a 60% decrease in yearly heating energy use compared to a natural gas boiler [9]. Likewise, in Sweden—where geothermal heating is commonly implemented in detached houses—energy savings reaching up to 65% have been documented, accompanied by lower maintenance expenses [10]. In cold regions, hybrid configurations that merge geothermal heating with solar thermal collectors enhance overall system efficiency. Research performed in Canada on a single-family residence revealed that combining ground source heat pumps with solar preheating lowered electricity consumption by 35% during the peak winter period [11].

As a result, geothermal energy systems provide considerable opportunities to lower greenhouse gas emissions and improve indoor air quality, while also enhancing environmental management in buildings—despite requiring higher upfront capital expenditures. In spite of these initial costs, geothermal technologies offer several benefits, including strong operational dependability, consistent availability throughout the year without relying on energy storage, and resistance to volatility in fossil fuel markets like oil and natural gas [12].

Despite the global momentum towards building decarbonization, limited research has been conducted on the application of geothermal heating technologies in Azerbaijan’s residential and regional contexts. Existing studies predominantly focus on countries with established geothermal markets, while the technical feasibility, performance, and environmental implications of Ground Source Heat Pump (GSHP) systems in Azerbaijan’s unique climatic and geological conditions remain largely unexplored. This study addresses this gap by evaluating the energy performance and CO2 mitigation potential of GSHP systems in the Khachmaz region—an area with untapped geothermal potential.

The novelty of the study lies in its site-specific simulation of geothermal heating performance using GeoT*SOL software, incorporating real climatic data, soil thermal conductivity, and local heating demand profiles. Furthermore, the study quantifies system efficiency through the Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) and assesses environmental benefits in terms of CO2 reduction, offering the first such empirical assessment for Azerbaijan.

The specific objectives of this research are:

1. To evaluate the thermal and environmental performance of GSHP systems in the Khachmaz region;

2. To compare geothermal heating outcomes with conventional fossil-fuel-based heating systems;

3. To provide policy-relevant insights for promoting renewable heating infrastructure in Azerbaijan.

By fulfilling these objectives, the study aims to contribute to national strategies for clean energy transition, particularly in the building sector.

2.1 Overview of Geothermal Heat Pump Technology

Geothermal energy, recognized for its accessibility and eco-friendly characteristics, has already been utilized extensively for heating purposes and as a means to reduce carbon emissions [13]. From a practical perspective, geothermal energy is mainly divided into two categories: power generation and direct utilization, each linked to varying depths and temperature levels underground. Power generation generally depends on deep, high-temperature geothermal reservoirs. On the other hand, direct use is among the earliest and most adaptable methods of geothermal application, typically harnessing shallow geothermal resources within several hundred meters of the Earth’s surface. This shallow geothermal energy is frequently applied for heating and cooling in buildings, greenhouses, and other facilities. Direct use systems typically function in one of two manners: (a) geothermal heat warms naturally present or artificially introduced groundwater, or (b) thermal energy is extracted via heat pumps to elevate the temperature of low-grade groundwater or soil heat. The latter approach is commonly referred to as a ground source heat pump (GSHP) system [14]. The adoption of geothermal heat pumps has risen in response to increasing demands for improved energy efficiency and sustainable energy solutions. These systems transfer thermal energy stored underground to provide heating or cooling for buildings. Geothermal heat pumps saw widespread use in North America and Europe starting in the 1970s, with their application expanding steadily since then. They are effective for delivering domestic hot water, space heating, and cooling across diverse climatic conditions [15].

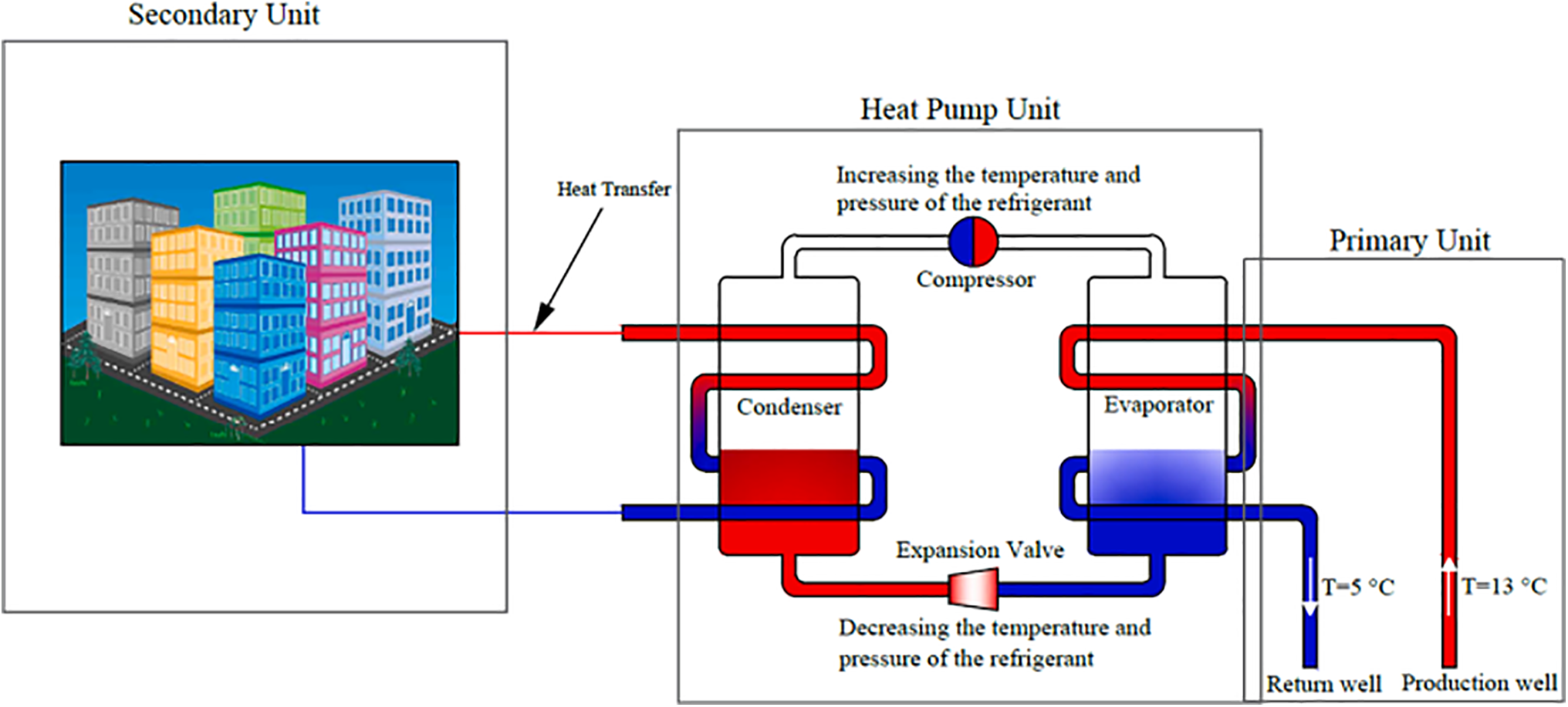

Generally, a GSHP system consists of three main components: the primary loop (ground loop), the heat pump unit, and the secondary loop responsible for heat distribution. Additionally, GSHP systems can be categorized based on their heat source—such as soil, surface water, groundwater, or hybrid sources—or by the configuration of the primary loop, which may be a vertical or horizontal closed loop, or an open loop system [16]. Fig. 1 illustrates the operational principle of the heat pump system, where groundwater from a chalk aquifer serves as the primary heat source. The groundwater is transported from the aquifer to the evaporator, transferring its thermal energy to the refrigerant. This causes the refrigerant to vaporize into a low-pressure gas. The vapor then moves to the compressor, where it is compressed into a high-pressure, high-temperature vapor. This high temperature vapor then enters the condenser, where it transfers its thermal energy to a secondary circulation fluid, ultimately providing heat to the building(s). The entire system operates in a closed loop, allowing the refrigerant to return to the evaporator and continue the vapor compression cycle [17].

Figure 1: Groundwater source heat pump working principle [17]

Ground Source Heat Pump (GSHP) systems are well-regarded for their high efficiency and dependable operation compared to traditional heating and cooling methods. Nonetheless, wider implementation is frequently limited by several obstacles, particularly the greater upfront installation expenses and a lack of awareness among designers. A major factor contributing to the increased initial cost is the drilling process needed for the ground heat exchanger (GHX), which can account for a significant share of the overall system investment [18].

2.2 Geothermal Sources in Azerbaijan

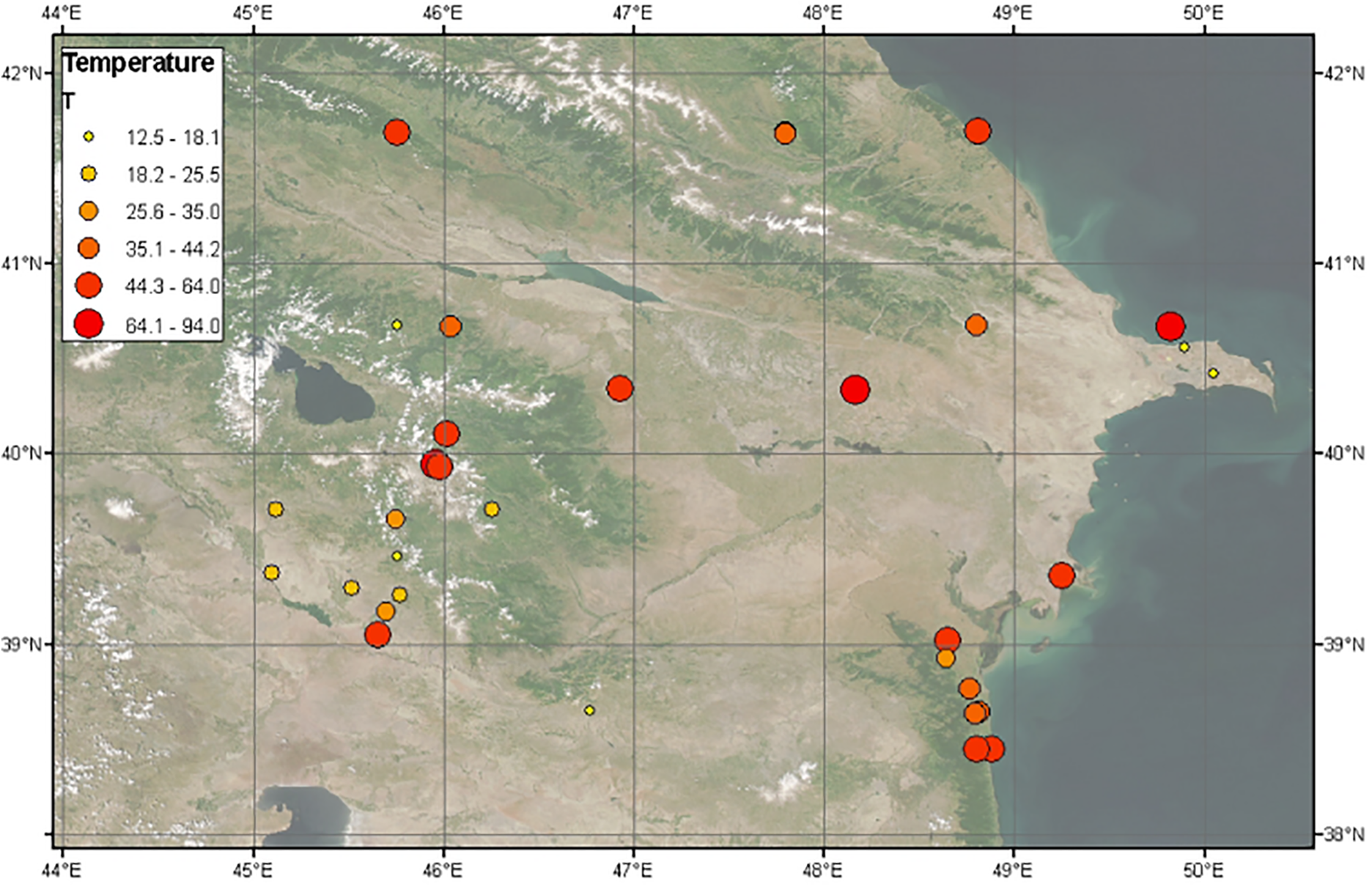

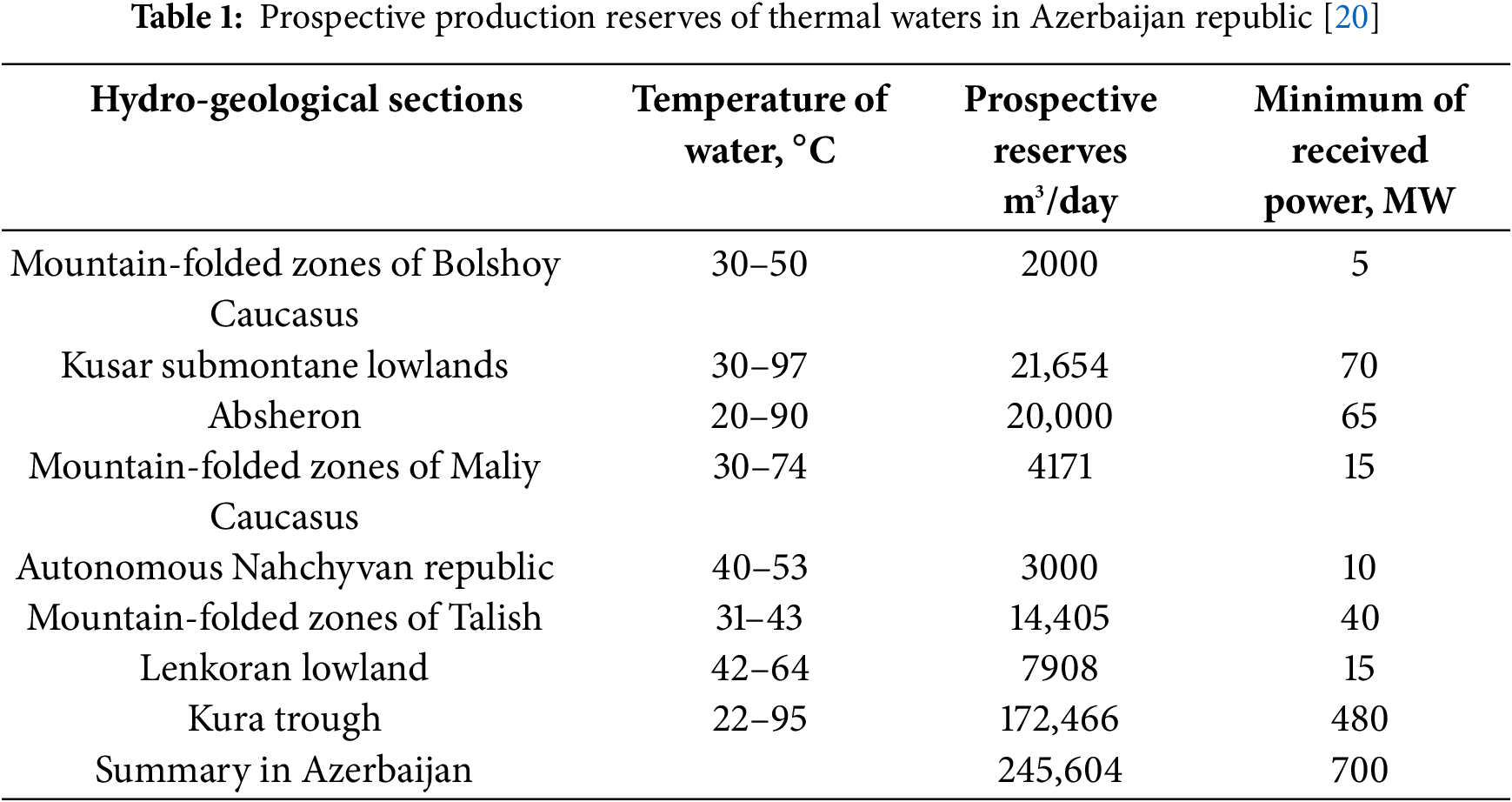

Azerbaijan possesses significant potential for geothermal energy development, with its main geothermal resources linked to thermal waters and natural hot springs. Numerous studies have highlighted promising geothermal opportunities in regions including Lankaran, Khudat, Ganja, and Jaarly. Notably, the Absheron and Talysh areas stand out due to their considerable geothermal energy capacity. Fig. 2 depicts a map showing the geographic locations and temperature ranges of Azerbaijan’s major thermal water sources [19]. The geothermal resources in Azerbaijan are generally characterized by low temperatures. Nevertheless, the development and utilization of these geothermal sources hold significant potential. Currently, by cooling thermal waters at temperatures between 20°C–40°C, it is estimated that a minimum total capacity of 700 MW can be harnessed from all sources combined. Table 1 provides details on the distribution of Azerbaijan’s thermal waters according to hydrogeological sections [20].

Figure 2: Range of temperatures (T, °C) for the mineral and thermal springs in Azerbaijan [19]

In Azerbaijan, thermal water reserves are mainly found in mountainous areas, with prominent springs such as Istisu and Bagyrsakh. At a depth of 100 m, Bagyrsakh registers temperatures near 80°C, while Istisu exhibits temperatures ranging from 62°C at 70 m to 75°C at depths of 300–350 m. The Upper Istisu spring has a high discharge rate of 800–900 m3/day, in contrast to the Lower Istisu spring, which produces about 25 m3/day. Other significant geothermal sites include the Lankaran, Astara, and Masalli districts, along with areas like Jarli, Sarysu, and various locations in the Kura lowland. For example, thermal waters in Donuzuten reach 64°C with flow rates exceeding 1.5 million liters per day. Additionally, the deep well Dzharly-3, drilled between Dzharly and Mollakend villages on the left bank of the Kura River, produces thermal water with an initial temperature of 96°C, currently recorded at 92°C at the outlet. Methane-rich geothermal waters are distinguished by high pressure, substantial flow rates, and temperatures generally between 64°C–95°C. It is estimated that around 200 methane-based geothermal sources exist in the country, including those in Masalli (Arkivan), Devechi (Lesh), and Salyan (Babazan-an) [21]. In the Precaspian-Guba area on the southeastern edge of the Greater Caucasus, eight wells have been drilled into thermal aquifers. These wells yield calcium-sodium bicarbonate-type waters with mineralization levels between 0.8 and 1.9 g/L and a total combined flow of about 20,470 m3/day, with temperatures ranging from 50°C to 84°C. Assuming only a 20°C temperature drop during energy extraction, the estimated thermal capacity of these wells is around 20 MW. Conversely, the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic is one of Azerbaijan’s less explored geothermal zones. Despite having known mineral water sources like Sirab, Badamli, and Vaykhir, the Daridagh thermal spring is particularly valuable due to its chemical content, including up to 20% arsenic and antimony. This spring produces sodium bicarbonate-type water with surface temperatures reaching 26.5°C. Wells drilled at depths of 137 to 665 m have recorded water temperatures between 41°C and 53°C and high mineralization levels of 14.3 to 21.3 g/L. Some of these wells exhibit flow rates between 25 and 34 L per second, indicating an estimated geothermal energy potential near 10 MW.

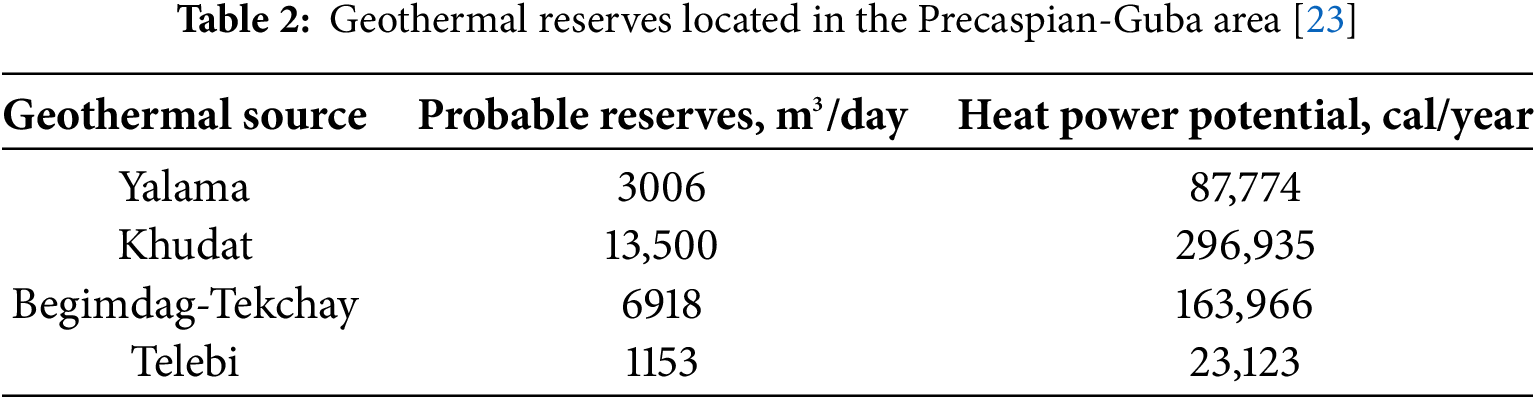

In Yalama one well exposed thermal water with the flow rate 500 m3/day and temperature 95°C. Minimum thermal capacity of these wells is respectively 1.2 and 0.5 MW [22]. In the Khachmaz region, a single thermal well produces around 1228 m3/day of water at a temperature of 58°C. Exploration boreholes in the Precaspian-Guba zone, targeting Mesocenozoic formations, have revealed thermal waters with temperatures between 50°C and 81°C and a total flow rate near 30,000 m3/day. Of particular note is well number 3 in this area, which reached thermal waters at 81°C and has a production capacity of 4500 m3/day. Table 2, based on the research by Babayev et al., provides an overview of the estimated geothermal water reserves in the Precaspian-Guba zone. Important geothermal sites in Khachmaz include Yalama, Begimdag-Tekchay, and Telebi [23].

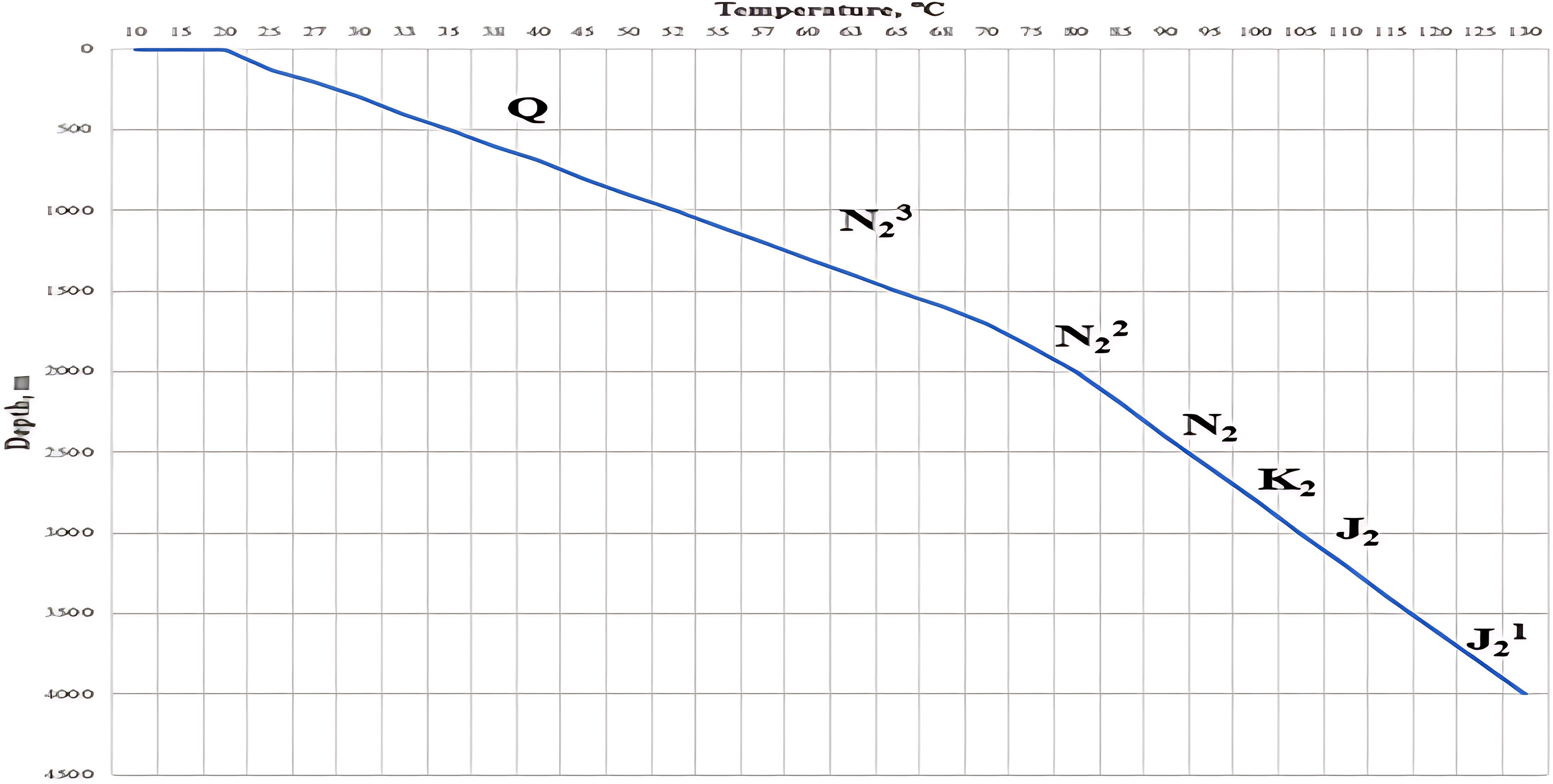

Temperature change as a function of depth in the Precaspian-Guba area is reflected in Fig. 3 [24].

Figure 3: Rock temperature variations as a function of depth [24]

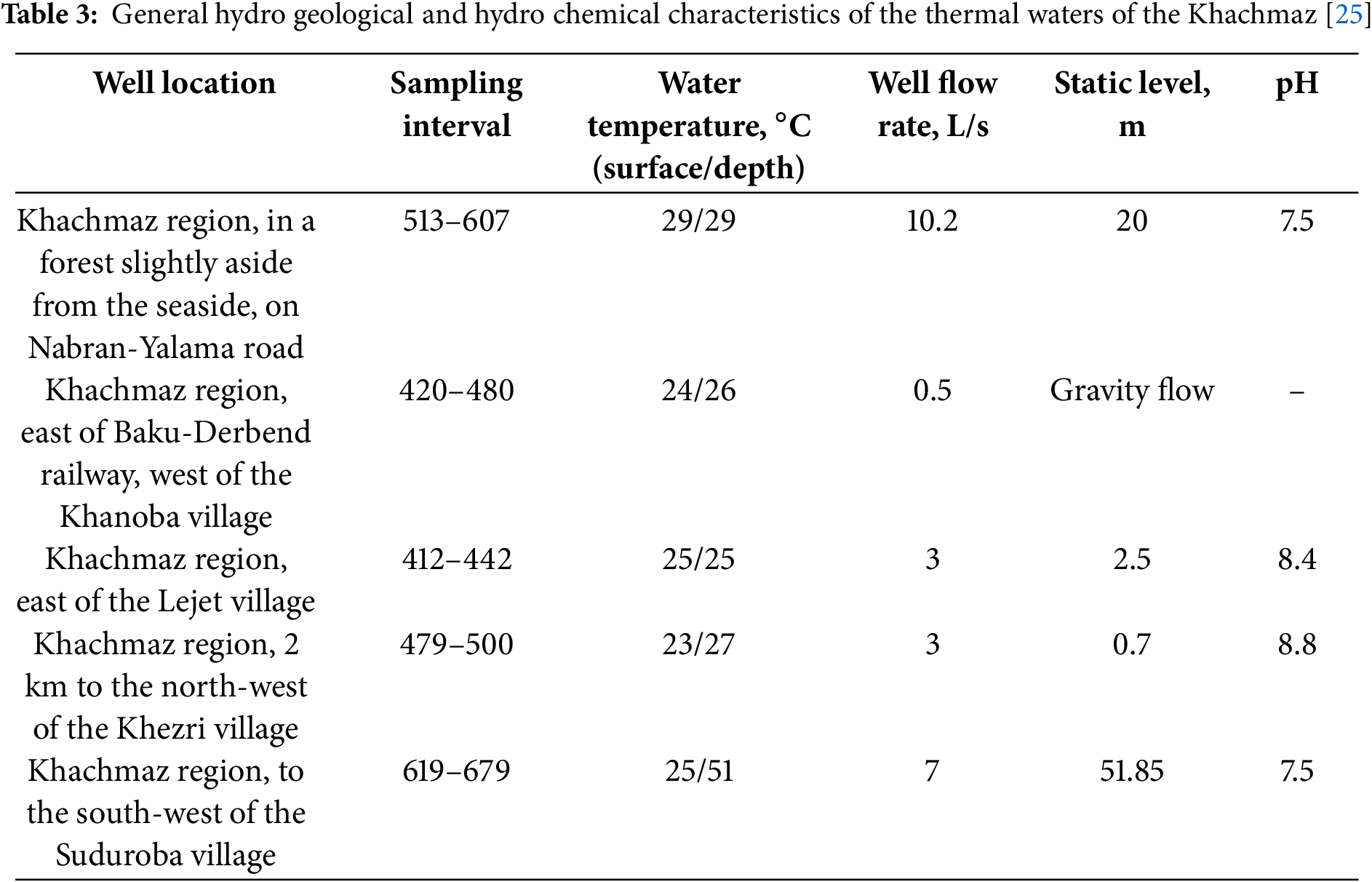

Table 3 shows the geothermal sources located in Khachmaz region [25]. These geothermal water sources are considered suitable for use in heat pumps in terms of both temperature and pH.

In this study, the GeoT*SOL 2025 simulation tool was used to evaluate the energy and environmental performance of a geothermal heating system under real climatic and operational conditions. GeoT*SOL is designed to model annual energy balances based on location-specific weather data, heat demand, and system parameters.

The simulation was based on the following key assumptions and methods:

1. Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) data was applied for the Khachmaz region to reflect actual climate conditions;

2. The heating source is a near-surface geothermal water resource with a natural temperature of approximately 20°C;

3. The chemical and physical quality of the geothermal water is suitable for direct circulation through the heat pump system, thus no intermediate heat exchanger was required;

4. The geothermal water is circulated directly into the heat pump loop, serving as the working fluid;

5. The building’s heating demand was modeled within GeoT*SOL based on floor area and regional winter temperatures.

Using these parameters, the system’s Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF), energy savings, and CO2 reduction potential were accurately estimated.

The inclusion of initial investment costs in the simulation tool was carried out based on a review of a number of scientific articles.

Winskel et al. reported that the equipment and installation costs of ground source heat pumps are approximately 1300–1350 Euros per kW [26]. Aditya et al. reported that the equipment and installation costs of ground source heat pumps are AUD 2000 per kW (about 1200 Euros) and drilling costs are 80 AUD/m (about 47 Euros/m). The equipment and installation costs of the gas boiler are 500 AUD/kW (about 295 Euros/kW) [27].

2.5 Seasonal Performance Ratio

In this research, the main focus is on the efficiency of the geothermal heat pump, which is related to the seasonal performance factor (SPF). The SPF and SPF4 of the system can be defined as follows:

here, SPF refers to the seasonal performance factor of the heat pump itself, while SPF4 denotes the seasonal performance factor of the entire system. Also, QCond,HP is the heat delivered to the HP condenser, and QSH and QDHW are the heat supplied for space heating and domestic hot water, respectively. Furthermore, EComp, EAux,SH, EAux,DHW and EPumps refer to the electrical energy consumed to run the compressor of the HP, auxiliary heaters for SH and DHW production, and the pumps, respectively [28].

3.1 Overview of the Simulated System

The simulation was carried out on underground geothermal water released by gravity flow in Khanoba village of Khachmaz region. Fig. 4 shows the satellite view of Khanoba.

Figure 4: Satellite view of Khanoba [29]

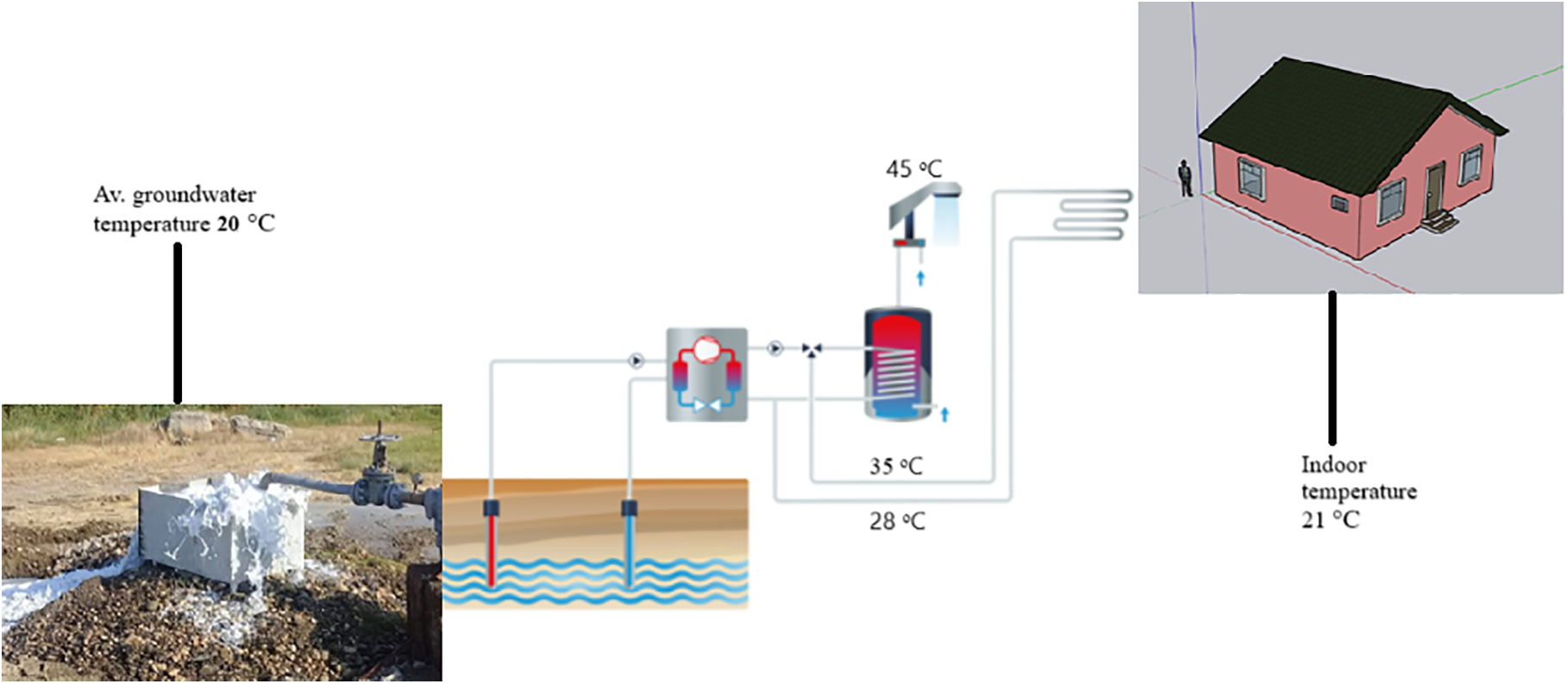

The water temperature can be up to 26°C above the air temperature. In the simulation, the average water temperature is 20°C.

The Khachmaz region was selected for this study due to several critical factors. Primarily, the area is known to have low-enthalpy geothermal water resources, making it naturally suitable for the deployment of ground source heat pump (GSHP) systems. The hydrogeological conditions in Khachmaz provide a favorable environment for extracting shallow geothermal energy. Additionally, the region experiences significant heating demand during winter months, with nearly exclusive reliance on natural gas-based heating, and limited application of renewable alternatives. Furthermore, the local climatic and soil properties offer a suitable basis for accurate simulation modeling. These characteristics make Khachmaz an ideal pilot area for assessing the technical and economic feasibility of geothermal heating systems in Azerbaijan. Fig. 5 below shows the simulated system.

Figure 5: Simulated system

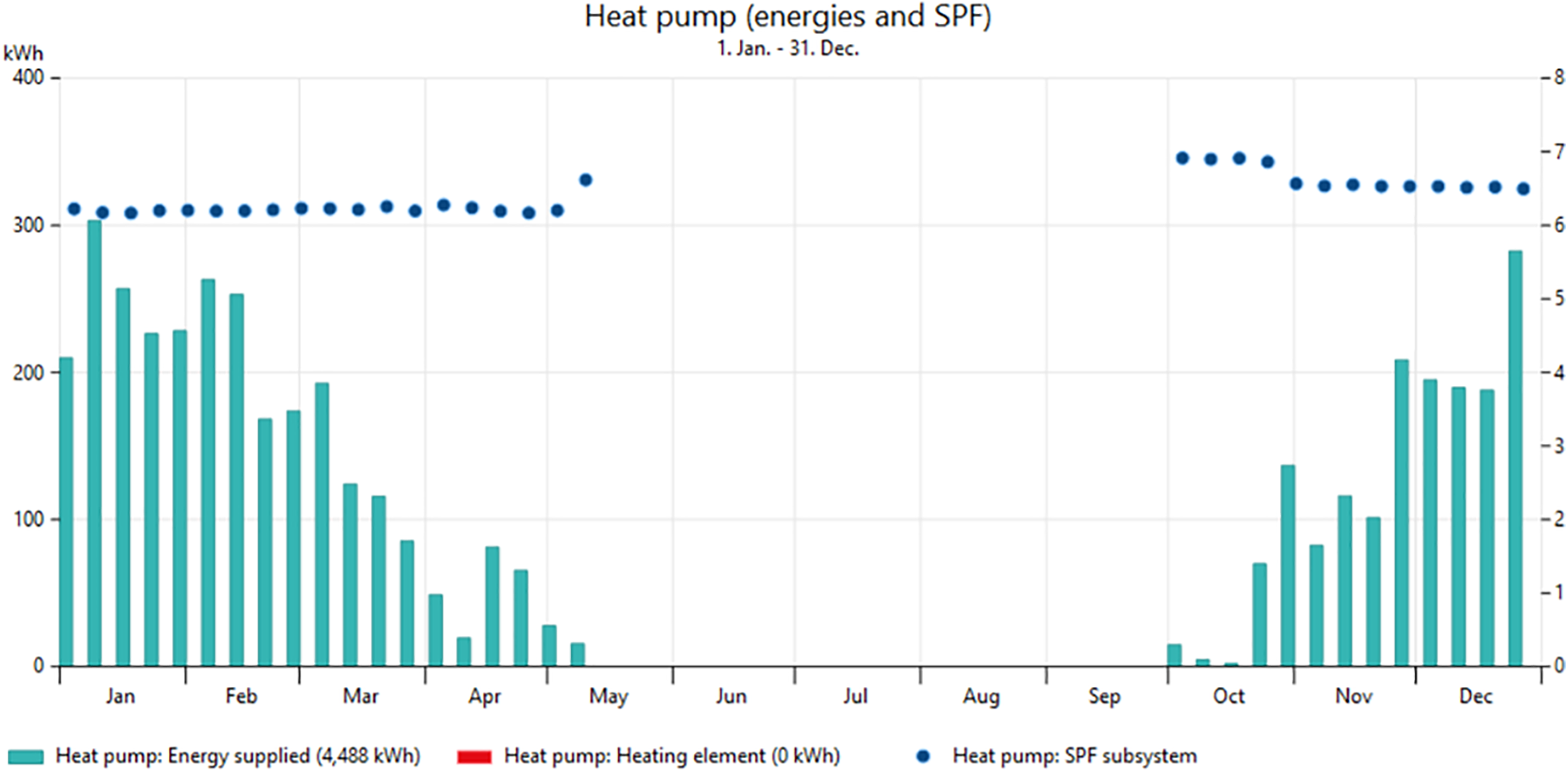

The supply and return temperatures of the heat carrier in the second circuit were taken as 35°C and 28°C, respectively. The seasonal performance factor (SPF) value and power consumption of the simulated system is given in Fig. 6. The average SPF value of the heat pump is equal to 5.49. The average SPF value of the heat pump system is equal to 4.86 and it generated 6804 kWh/year. The electricity consumed by the heat pump is 1239 kWh/year.

Figure 6: Heat pump energy supply and SPF

3.2 Comparison with Conventional Heating System

Based on the reviewed literature and heat pump capacity, the equipment and installation cost of the system was assumed to be $4915. For the conventional system, this price is equal to $1103. On the other hand, each kW of electricity needed for the heat pump was taken on average at 0.1 Azn ($0.059) according to the tariff of “Azerishiq” OJSC. The tariff given by “Azeristiliktechizat” for each GCal of heat supply is 30 Azn (about $17.64). According to the literature and official tariffs, the cost of heat production with the traditional system and the simulated system was 0.068 $/kWh and 0.157 $/kWh, respectively. The simulated system saved 1956 kg of CO2 emissions compared to the conventional system.

3.3 Regional Comparison of Geothermal Heating Performance and Costs

The simulation results obtained for the Khachmaz district in Azerbaijan demonstrate competitive performance metrics when compared to similar studies in neighboring regions such as Georgia, Türkiye, and Iran.

1. Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF):

While the heat pump SPF (SPFhp) in the study conducted in Bursa, Türkiye varied between 4.03 and 4.18 during the day [30], the system analyzed in the Khachmaz region of Azerbaijan exhibited a higher seasonal performance, with a maximum SPF of 5.62 and an average of 4.86, reflecting a more efficient long-term operation.

In comparison to the geothermal heat pump (GHP) system investigated in Tehran, Iran, which achieved a SPF of 5.6 [31], the system modeled for the Khachmaz region of Azerbaijan demonstrated comparable seasonal efficiency, with a maximum Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) of 5.62 and an average of 4.86. These findings suggest that despite climatic and geological differences between the two regions, the system performance in Khachmaz remains competitive, particularly when evaluated on a seasonal basis.

Compared to the ground source heat pump system applied to the Koksai Mosque in Almaty, Kazakhstan, where the experimentally obtained cycle SPF values ranged between 2.24 and 2.97 [32], the system developed for the Khachmaz region of Azerbaijan exhibited significantly higher seasonal efficiency, with a maximum Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) of 5.62 and an average of 4.86. This disparity highlights the potential impact of system design, operational strategy, and local hydrogeothermal conditions on the overall energy performance.

Among ten Russian cities examined in a comparative study, Saint Petersburg demonstrated the highest performance for ground source heat pump (GSHP) systems, with a maximum COP of 2.44 [33]. In comparison, the GSHP system modeled for the Khachmaz region of Azerbaijan exhibited substantially higher seasonal efficiency, achieving a maximum Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) of 5.62 and an average of 4.86. This suggests that the geothermal conditions and system design in Khachmaz may provide a more favorable operational environment for heat pump performance.

2. CO2 Emission Reduction:

In the study by Yousefi et al., ground source heat pump systems were evaluated in nine Iranian cities over a 25-year period, revealing annual CO2 savings of approximately 9.5 t in Khal Khal, 6 t in Mashhad, 5.7 t in Qaen, 5 t in Aq Qaleh, 4.2 t in Kerman, 3.8 t in Babolsar, 2.1 t in Jask, 1.3 t in Boushehr, and 1 t in Mirab [34]. In comparison, the geothermal system modeled for the Khachmaz region of Azerbaijan achieved an annual CO2 saving of 1.956 t. Although this value is lower than those recorded in some of the Iranian cities, it still indicates a substantial reduction in carbon emissions, highlighting the potential of such systems to contribute to climate change mitigation in moderately cold climatic zones like Khachmaz.

According to the Energy and Environment Report, the use of ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) in Russia results in an average annual CO2 saving of approximately 1.8 t compared to natural gas-based heating systems, and around 4.4 t when compared to diesel fuel systems [35]. This indicates that the performance in Khachmaz is slightly higher than the average saving observed against natural gas in Russia, though it remains below the level of emissions reduction achievable when replacing diesel systems, thus demonstrating a moderate yet meaningful contribution to decarbonization in the regional heating sector.

3. Cost of Heat Production:

Camdali and Tuncel reported that the unit cost of heat generation using natural gas-based systems in Türkiye ranges between 3 and 4 cents per kilowatt-hour, whereas ground source heat pump systems were found to cost approximately 9.12 cents per kilowatt-hour—indicating a 2.3 to 3-fold increase in heating cost [36]. Consistently, in the present study for the Khachmaz region of Azerbaijan, the levelized cost of heat production using geothermal technology was found to be around 2.3 times higher than that of conventional natural gas-based systems. This alignment underscores the broader economic challenge of geothermal adoption in regions where natural gas remains a low-cost heating source.

This study employed GeoT*SOL simulation to investigate the feasibility and efficiency of geothermal heating systems utilizing low-temperature geothermal water sources in the Khachmaz district of Azerbaijan. The region’s selection was motivated primarily by the presence of accessible surface geothermal waters with favorable temperature (around 20°C) and chemical properties, which eliminate the need for expensive deep drilling or intermediate heat exchangers, thereby reducing upfront investment and operational complexity.

The simulation results demonstrate that geothermal heat pump (GHP) systems can achieve high performance in the local climatic and geological context. Specifically, the system achieved a maximum Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) of 5.62 and an average SPF of 4.86, indicating excellent energy efficiency compared to conventional heating solutions. Environmentally, the system is capable of reducing CO2 emissions by approximately 1956 kg annually, signifying its potential role in mitigating Azerbaijan’s greenhouse gas footprint and aligning with national climate targets. These emission reductions are particularly significant given that heating in the building sector accounts for a large share of energy consumption and carbon emissions in the country.

Economically, while the levelized cost of heat production using geothermal technology was found to be approximately 2.3 times higher than traditional natural gas-based heating systems, the long-term benefits—including lower operational emissions, energy savings, and enhanced system reliability—offer compelling justification for its consideration. Moreover, this cost premium is expected to decrease with technological advancements, increased market adoption, and the incorporation of supportive policies.

By focusing on Khachmaz, this study fills an important research gap by providing localized data and simulation-based insights into geothermal energy’s potential in Azerbaijan, where research on shallow geothermal resources remains limited. The findings contribute to the body of knowledge by confirming the technical viability and environmental advantages of GHP systems in a real-world Azerbaijani context. This is crucial for supporting informed decision-making by policymakers, investors, and energy planners who are aiming to diversify the country’s heating energy mix and reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

Ultimately, the results emphasize the strategic importance of integrating geothermal energy into Azerbaijan’s energy transition framework. Policymakers are encouraged to consider tailored incentives and regulatory frameworks to promote geothermal system adoption, particularly in regions with favorable geothermal characteristics like Khachmaz. Such measures can accelerate the deployment of renewable heating technologies, contributing to national goals of energy efficiency, emission reduction, and sustainable urban development. The study underscores that geothermal heating, despite initial higher capital costs, represents a sustainable and resilient solution that aligns with Azerbaijan’s commitment to combating climate change while ensuring energy security.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li Y, Feng H. Pathways to urban net zero energy buildings in Canada: a comprehensive GIS-based framework using open data. Sustain Cities Soc. 2025;122(9):106263. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2025.106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Maierhofer D, Röck M, Ruschi Mendes Saade M, Hoxha E, Passer A. Critical life cycle assessment of the innovative passive nZEB building concept ‘be 2226’ in view of net-zero carbon targets. Build Environ. 2022;223(1):109476. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cornette JFP, Blondeau J. Operational greenhouse gas emissions of various energy carriers for building heating. Clean Energy Syst. 2024;9(57):100148. doi:10.1016/j.cles.2024.100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. IEA. Azerbaijan energy profile [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/azerbaijan-energy-profile. [Google Scholar]

5. Preliminary report on the production and financial-economic activity results of ‘Azeristiliktechizat’ JSC for the Year 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: https://azeristilik.gov.az/storage/media/1450/84A1323E-1CC6-43A9-9B6D-6D2F0657685D.pdf. [Google Scholar]

6. Florides G, Kalogirou S. Ground heat exchangers—a review of systems, models and applications. Renew Energy. 2007;32(15):2461–78. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2006.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lund JW, Freeston DH, Boyd TL. Direct utilization of geothermal energy 2010 worldwide review. Geothermics. 2011;40(3):159–80. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2011.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhao Y, Zhai XQ, Qu M. Simulation-based feasibility study of ground source heat pump systems for a public building in China. Appl Therm Eng. 2016;94(6):458–71. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2015.10.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sanner B, Karytsas C, Mendrinos D, Rybach L. Current status of ground source heat pumps and underground thermal energy storage in Europe. Geothermics. 2003;32(4–6):579–88. doi:10.1016/S0375-6505(03)00060-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lund JW, Boyd TL. Direct utilization of geothermal energy 2015 worldwide review. Geothermics. 2016;60(1):66–93. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2015.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mustafa Omer A. Ground-source heat pumps systems and applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2008;12(2):344–71. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2006.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Islam MM, Mun HS, Bostami ABMR, Ahmed ST, Park KJ, Yang CJ. Evaluation of a ground source geothermal heat pump to save energy and reduce CO2 and noxious gas emissions in a pig house. Energy Build. 2016;111:446–54. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.11.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang X, Zhan T, Liu G, Ni L. A field test of medium-depth geothermal heat pump system for heating in severely cold region. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;48(4):103125. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Adebayo P, Beragama Jathunge C, Darbandi A, Fry N, Shor R, Mohamad A, et al. Development, modeling, and optimization of ground source heat pump systems for cold climates: a comprehensive review. Energy Build. 2024;320(21):114646. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao S, Abed AM, Deifalla A, Al-Zahrani A, Aryanfar Y, García Alcaraz JL, et al. Competitive study of a geothermal heat pump equipped with an intermediate economizer for various ORC working fluids. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;45:102954. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.102954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang K, Liao PC. Ontology of ground source heat pump. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;49(2):51–9. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.04.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sezer T, Sani AK, Singh RM, Cui L, Boon DP, Woods M. Numerical investigation of a district scale groundwater heat pump system: a case study from Colchester, UK. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;236(3):121915. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.121915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pertzborn AJ, Nellis G, Klein S. Research on ground source heat pump design. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference; 2010 Jul 12–15; West Lafayette, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

19. Ibrahimova I. Application of GIS to available informatıon on thermal waters in the Azerbaijan Republic and its usefulness for environmental assessment [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: http://www.os.is/gogn/unu-gtp-report/UNU-GTP-2006-10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

20. Bayramova SM, Bayramov AA. Perspectives of geothermal power use in Azerbaijan [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: http://www.physics.gov.az/lab29/pdf_tpe_2006/res/z4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

21. Islamzade AV, Mukhtarov AS. Geological conditions for the development of geothermal energy in Azerbaijan. Geofiz Zhurnal. 2024;46(3):306353. doi:10.24028/gj.v46i3.306353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mukhtarov A, Nadirov R, Mammadova A. Geothermal energy development in Azerbaijan: conditions and business opportunities. 2015. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.5152.0725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Babayev N, Rustamov Y, Gadjiev T, Karimov V. Thermal waters of Azerbaijan—sources of renewable alternative energy. Bioenergy Bioresour. 2022;3(4):1–6. [Google Scholar]

24. Babaev N, Karimov V. Mineral and thermal water sources of Azerbaijan and prospects of their use. In: Proceedings of the Ukrainian Mining Forum-2021: Materials of the International Scientific and Technical Conference; 2021 Nov 4–5; Online. [Google Scholar]

25. Babayev N, Tagiyev I. New view on ways of use of Azerbaijan mineral and thermal water deposits. Slovak Int Sci J. 2017;10(10):21–31. [Google Scholar]

26. Winskel M, Heptonstall P, Gross R. Reducing heat pump installed costs: reviewing historic trends and assessing future prospects. Appl Energy. 2024;375:124014. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Aditya GR, Mikhaylova O, Narsilio GA, Johnston IW. Comparative costs of ground source heat pump systems against other forms of heating and cooling for different climatic conditions. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2020;42(4):100824. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2020.100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liravi M, Karkon E, Jamot J, Wemhoener C, Dai Y, Georges L. Energy efficiency and borehole sizing for photovoltaic-thermal collectors integrated to ground source heat pump system: a Nordic case study. Energy Convers Manag. 2024;313:118590. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Google Earth. Satellite image of Khanoba (41.6802° N, 46.8987° EAzerbaijan [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: http://www.Earth.google.com. [Google Scholar]

30. Pulat E, Coskun S, Unlu K, Yamankaradeniz N. Experimental study of horizontal ground source heat pump performance for mild climate in Turkey. Energy. 2009;34(9):1284–95. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2009.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Farzanehkhameneh P, Soltani M, Moradi Kashkooli F, Ziabasharhagh M. Optimization and energy-economic assessment of a geothermal heat pump system. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020;133:110282. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yerdesh Y, Amanzholov T, Aliuly A, Seitov A, Toleukhanov A, Murugesan M, et al. Experimental and theoretical investigations of a ground source heat pump system for water and space heating applications in Kazakhstan. Energies. 2022;15(22):8336. doi:10.3390/en15228336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Nikitin A, Deymi-Dashtebayaz M, Muraveinikov S, Nikitina V, Nazeri R, Farahnak M. Comparative study of air source and ground source heat pumps in 10 coldest Russian cities based on energy-exergy-economic-environmental analysis. J Clean Prod. 2021;321:128979. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yousefi H, Ármannsson H, Roumi S, Tabasi S, Mansoori H, Hosseinzadeh M. Feasibility study and economical evaluations of geothermal heat pumps in Iran. Geothermics. 2018;72:64–73. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2017.10.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. European Environment Agency. Energy and environment report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2008. 100 p. doi:10.2800/10548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Camdali U, Tuncel E. An economic analysis of horizontal ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) for use in heating and cooling in Bolu, Turkey. Energy Sources Part B Econ Plan Policy. 2013;8(3):290–303. doi:10.1080/15567240903452097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools