Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experimental Analysis of the Impact of Starch and Xanthan Gum on the 3D Printing of Pumpkin Puree and Minced Pork

College of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Liaoning University of Technology, Jinzhou, 121001, China

* Corresponding Author: Yibo Wang. Email:

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(6), 1439-1457. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.062295

Received 15 December 2024; Accepted 15 April 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

Hydrocolloids are widely used in meat products and pureed foods as they offer thickening and viscosity-enhancing effects that facilitate shaping and improve stability. In this study, the static shear rheological and dynamic viscoelastic properties of pumpkin puree (S) and pork mince (P) with the addition of various hydrocolloids were considered. Dedicated material printing experiments were conducted by means of a three-dimensional printing platform by using a coaxial dual-nozzle for sandwich composite printing of four different materials. In particular, the impact of different process parameters (printing speed 10~30 mm/s, filling density 10%~50%) was assessed in terms of 3D printing adaptability and final shape of the pumpkin puree-pork mince products. The results have indicated that the addition of hydrocolloids significantly improves the rheological properties of these materials, enhancing their stability in the 3D printing process. Experiments have revealed that with an increase in the xanthan gum conte nt, the viscosity of pumpkin puree decreases. The relationship between the elastic modulus and viscous modulus for the minced pork follows the inequality P4 < P3 < P2 < P1 (1.17%, 1.75%, 2.13%, and 2.88% xanthan gum content, respectively). A “material formula” (detailed composition of the material) suitable for 3D food printing has been derived accordingly.Keywords

In the rapidly developing field of food science and technology today, 3D printing technology has brought revolutionary changes to the food industry with its unique innovation and customization capabilities. This technology can not only create foods with complex shapes and structures but also provide customized food solutions for specific groups of people, such as patients with dysphagia. This article focuses on a key aspect of 3D food printing technology—the study of the rheological properties of food materials [1–3].

Currently, many scholars have conducted research on the rheological properties of food materials. Lecanu et al. [4] predicted the gravity-driven flow of power-law fluids in a syringe and applied it to the rheological mapping for IDDSI (International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative) classification. Kadirvel and Narayana [5] extensively explored the extraction, processing, and application of edible gums in the food and healthcare sectors, as well as the functions of edible gums in changing rheology, gel formation, stability, encapsulation, and fat substitution. Chen et al. [6] studied the rheological properties, printability, and 3D printed geometries of mixtures of soy protein isolate (SPI) with sodium alginate and gelatin. The experimental results showed that SPI and its mixtures exhibited shear-thinning behavior, making them ideal materials for 3D printing. Li et al. [7] studied the effects of salt valency and ionic strength on the rheological properties and 3D printing performance of walnut protein emulsion gels. The results of rheological measurements and Lissajous curves indicated that the addition of salt enhanced the mechanical strength and deformation resistance of the gels. Mallesham et al. [8] used xanthan gum to improve the structural stability of 3D-printed cakes and conducted rheological and post-processing analyses. Jiang et al. [9] investigated the fermentation process of starch-gluten mixtures using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIR) and multivariate analysis. They predicted the storage modulus (G′), loss modulus (G″), complex viscosity (η), and loss factor (tan δ).

The addition of edible gums affects the stability of food structure, but their application in 3D food printing is relatively limited, and the impact of their addition on the effect of 3D food printing needs further exploration. Process parameters such as printing speed and material filling density also play a crucial role in improving the structural stability of the printed products.

The combination of pumpkin puree and minced pork not only complements each other nutritionally but also provides ideal rheological properties for 3D printing. Pumpkin puree is rich in dietary fiber and vitamins, while minced pork offers high-quality protein. This combination can meet the nutritional needs of specific populations, such as the elderly or patients with dysphagia. Moreover, the combination of the high water content of pumpkin puree and the adhesive properties of minced pork can improve the flowability and formability of the printing material, thereby enhancing the feasibility and quality of 3D printing. Pumpkin puree and pork mince materials cannot be directly used for 3D printing. It is necessary to add edible hydrocolloids to improve the viscosity, elasticity, and other rheological properties of the materials, thus obtaining a suitable material ratio for 3D printing to enhance the printability of the materials. Xanthan gum, as an efficient thickening and stabilizing agent, can significantly enhance the rheological properties of the printing material. By incorporating xanthan gum, the viscosity and elasticity of minced pork are increased, thereby improving the stability and precision of the printing process. Additionally, xanthan gum helps prevent excessive flow or collapse of the material during printing, ensuring the integrity of the printed structure. Unmodified corn starch has good solubility and stability, which can combine with the characteristics of pumpkin puree to further improve the rheological properties of the printing material. During the processing, corn starch exhibits good plasticity, which helps enhance the formability and printing quality of the printing material.

This paper provides an in-depth analysis of the static shear rheological properties and dynamic viscoelastic properties of two commonly used food materials, pumpkin puree and minced pork, after the addition of xanthan gum and starch. By adjusting the concentrations of these ingredients, the rheological properties and printability of the 3D printing materials were optimized. Different combinations of concentrations helped us identify the optimal formulation to achieve ideal printing results, including good extrusion performance, shaping accuracy, and structural stability. Through rheological measurements of different formulations of food materials, we successfully developed material formulations suitable for 3D food printing and consumption by patients with dysphagia, which were verified through printing experiments on the experimental platform. Additionally, based on the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI), we conducted texture measurements on the modified food materials. This sandwich structure ensures the safety and applicability of the food while maintaining the stability and aesthetic appeal of the structure. Moreover, this experimental design can also provide a reference for the future development of more food materials suitable for 3D printing.

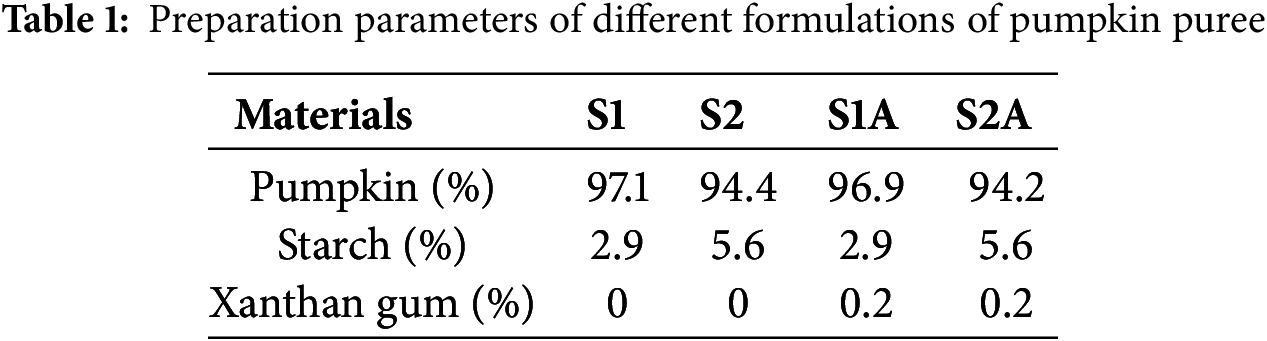

In this study, pumpkins with a moisture content of 75%–80% were selected and stored in a refrigerator at 4°C, to be used within three days. The cleaned pumpkin was peeled, seeded, and cut into small pieces, then placed in a steamer. The water level for steaming was kept below the height of the pumpkin pieces. The pumpkin was steamed for about 15–20 min until it became soft and tender, easily pierced with a chopstick. The steamed pumpkin pieces were then transferred to a blender, along with a small amount of the water produced during the steaming process. The pumpkin was blended into a smooth puree and sieved to remove fibers and particles. The pumpkin puree was then stored in a sealed container in the refrigerator at 4°C for up to three days before use. Based on preliminary experimental planning, four paste formulations were prepared, as shown in Table 1.

The addition of xanthan gum and starch influenced the size of particles in the pumpkin puree composite gel, forming a weak gel-like structure. Each colloidal mixture was supplemented with 6% water, manually shaken for 2 min to mix, and then stored in a covered tube in a refrigerator at 0–4°C for 2 h to allow for adequate hydration. Although a lower water content and shorter hydration time may limit the completeness of hydration, by optimizing the proportions of other ingredients (such as xanthan gum and starch), we were able to ensure that the material has good rheological properties during the printing process.

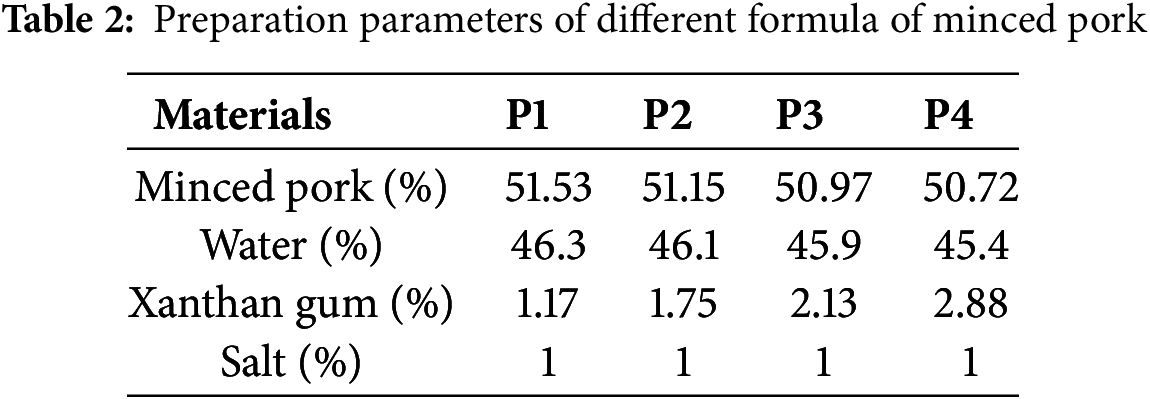

In this study, fresh pork loin was selected, from which connective tissue and fat were removed and divided into three batches. Each batch of pork was vacuum packaged and stored at −5°C until use. Based on the research requirements, four material formulations were initially prepared, and the resulting material samples were labeled P1, P2, P3, and P4, as shown in Table 2.

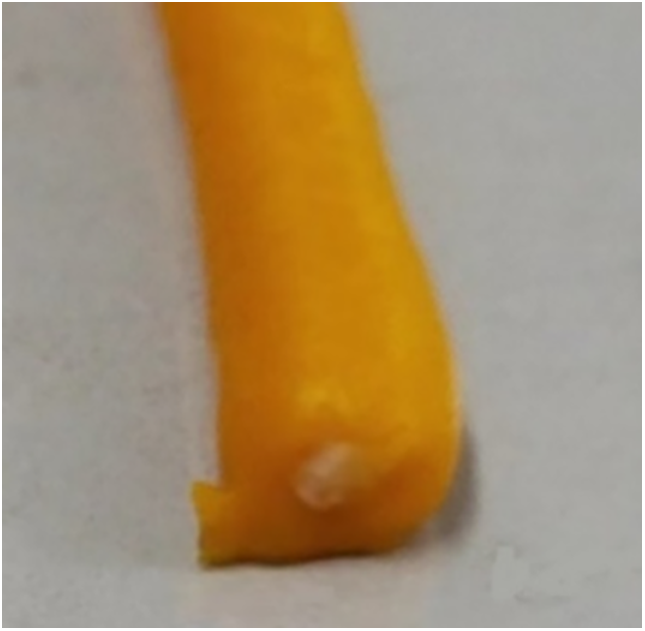

Each water-colloid mixture was manually shaken for 2 min to ensure mixing, and then stored in a covered tube in a refrigerator at 0–4°C for 2 h to allow for hydration. The pork was thawed at 0–4°C before cooking. The meat blocks were placed in a pot and boiled for 20 min. The cooked pork was cooled under running water and then refrigerated for 1.5 h. It was then ground using a multi-functional meat grinder. The ground pork was put into an oven set at 90°C for 3 h of drying. After being sifted through a fine mesh, it was mixed with the xanthan gum mixture in the meat grinder and stirred at speed 1 for 40 s to create the minced pork samples. When processing the pork sample, we used a sieve with a mesh size of 0.5 mm for sieving. The choice of this mesh size was to ensure the uniformity of the particle size of the minced pork, thereby avoiding the non-uniform viscosity of the mixture caused by oversized particles. Through the sieving process, we were able to obtain finer minced pork, which in turn improved the overall flowability of the printing material and the printing quality.

The selection of these ratios took into account both the nutritional properties of the materials and the rheological requirements during the printing process. In the two formulations, the adjustment of the ratios of xanthan gum and starch was aimed at optimizing the viscoelasticity and extrusion performance of the materials, while the ratios of pumpkin puree and minced pork were adjusted to balance nutrition and taste.

2.2 Measurement of Material Rheology

In this study, a Discovery TA-HR-10 rheometer was used to analyze the rheological properties of the materials. Commonly used testing fixtures include the concentric cylinder, cone and plate, parallel plate, and plate and ring types, among others. This paper utilizes a parallel plate measurement system.

This study utilized a rheometer to conduct both static and dynamic rheological measurements and analysis of the materials. The specific steps for the static rheological tests are as follows: A parallel plate with a diameter of 50 mm and a gap distance of 2 mm was used, with the test plate gap set to 1000 µm, the test temperature was maintained at 25°C, and the shear rate range was from 0.1 to 90, observing the trend of shear viscosity change with shear rate. Dynamic rheological properties of the materials were measured using dynamic oscillation frequency scanning. Parameters for dynamic rheological testing: strain was set at 0.1%, the indoor testing environment temperature is 25°C, humidity is controlled between 40% and 60% relative humidity (RH), and the scanning frequency ranged from 0.1 to 10 Hz, analyzing the dependence of the storage modulus (G′), loss modulus (G″), and loss tangent (tan δ) on frequency [10].

2.3.1 Analysis of Static Shear Rheological Properties

Materials for extrusion-based 3D food printing must possess shear-thinning properties. Materials that exhibit shear-thinning behavior are easier to extrude at high shear rates during the 3D printing process and maintain their structure after deposition. This paper employs Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and multiple comparison tests to assess the influence of various factors in food hydrocolloids and the printing process on response variables (such as rheological properties, printing accuracy, and structural stability). These statistical methods will aid in interpreting the experimental results more scientifically and provide data support for further discussions.

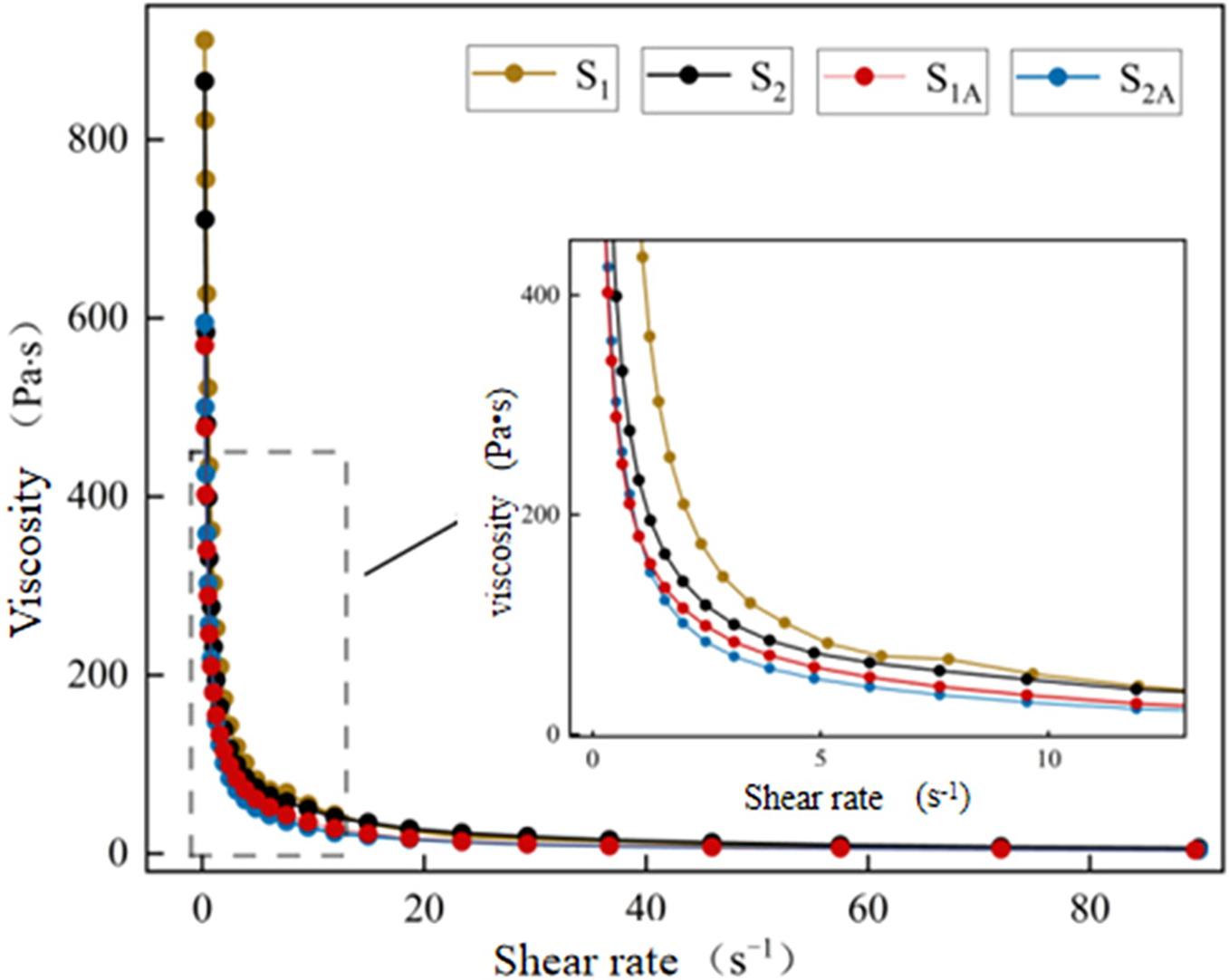

Fig. 1 illustrates the relationship between material viscosity and shear rate to evaluate the shear-thinning rheological properties. All samples exhibit significant non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior, with the viscosity of the pumpkin puree gradually decreasing as the shear rate increases. This indicates that the pumpkin puree material is a pseudoplastic fluid, having high viscosity at low shear rates [11].

Figure 1: The change of viscosity of pumpkin mud material with shear rate

Under the same shear rate, the addition of cornstarch reduced the viscosity of the pumpkin puree material. The viscosity of all samples from highest to lowest is S1 > S2 > S1A > S2A, indicating that cornstarch can increase the fluidity of the pumpkin puree, thereby reducing the mechanical negative pressure during the 3D printing process, which is conducive to extrusion.

Due to the mutual repulsion between the negatively charged starch and the negatively charged side chains of xanthan gum, it makes the starch difficult to gelatinize, thus the addition of xanthan gum reduces the viscosity of the material [12–15]. The viscosity of the material samples S1A and S2A, with xanthan gum added, is lower than that of the samples S1 and S2 without xanthan gum added.

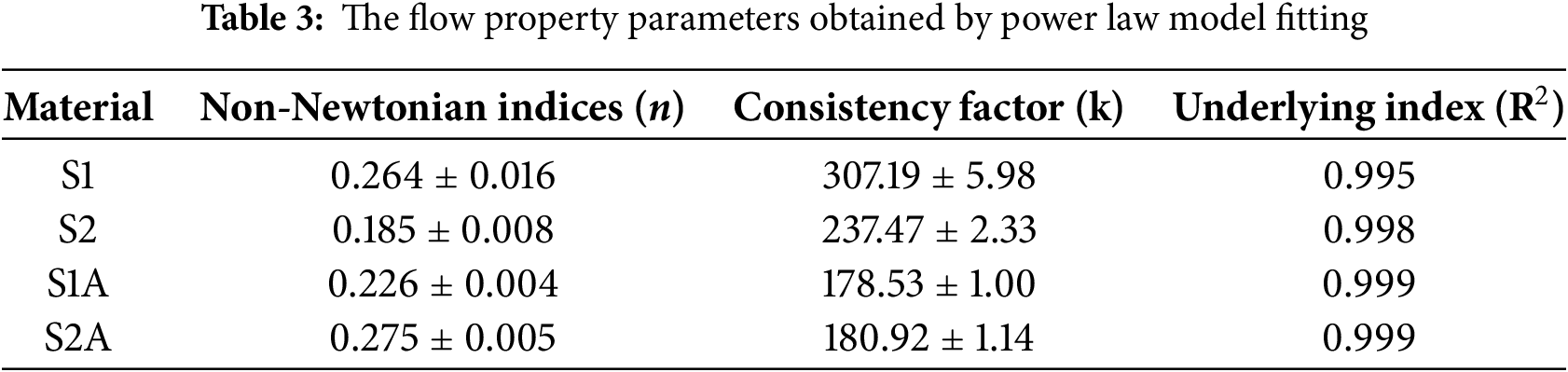

Based on the power-law fluid mechanics equation, the viscosity and shear rate data of the pumpkin puree material with different hydrocolloids added were fitted using the Origin software to obtain the non-Newtonian index n and the consistency coefficient k of the pumpkin puree material [16]. As can be seen from Table 3, the fitting coefficient R2 of the pumpkin puree material is above 0.995, indicating that the equation has a high degree of accuracy for the material’s static rheological data [17].

The non-Newtonian index n is less than 1, indicating that the pumpkin puree material with added xanthan gum and cornstarch is a non-Newtonian pseudoplastic fluid. The smaller the value of n, the stronger the pseudoplasticity [18]. The pumpkin puree materials S2 and S1A in the table have smaller n values, indicating that the material exhibits high viscosity at low shear rates and low viscosity with certain fluidity at high shear rates, which fits well with the force changes of the material during the 3D printing process, the smaller the n value, the easier it is for the material to be extruded.

The consistency coefficient k reflects the thickening ability of the material, with the order from largest to smallest being S1 > S2 > S2A > S1A. Among them, the properties of S1A (178.53 Pa · s) and S2A (180.92 Pa · s) are closer, indicating that the combination of xanthan gum and cornstarch reduces the thickening ability. Enhanced the printability of the material.

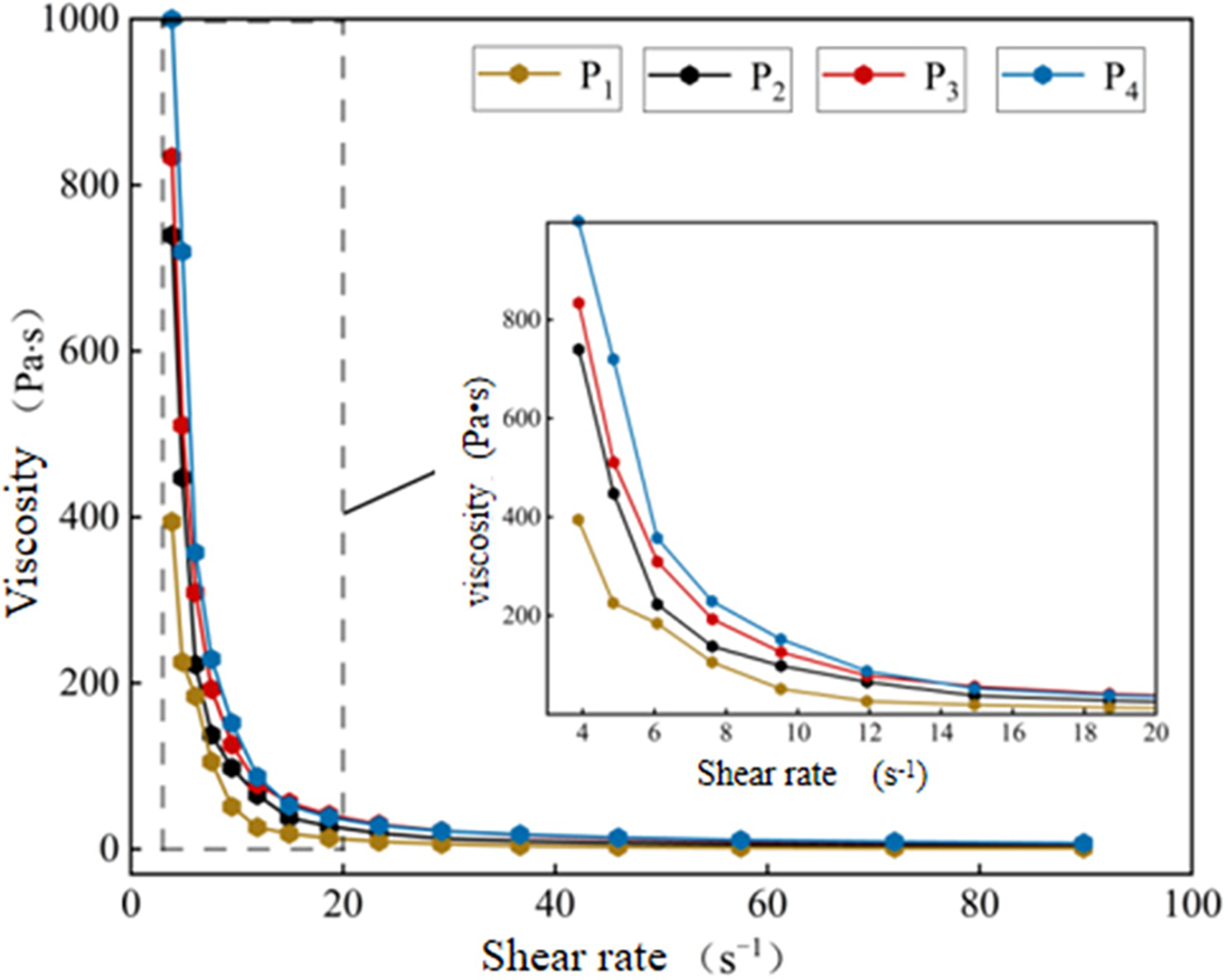

The variation of minced pork viscosity with shear rate is shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen from the figure, the apparent viscosity of the pork sample material significantly decreases with the increase of shear rate [19]. With the increase of xanthan gum addition, the apparent viscosity of the sample significantly increases, and there is a positive correlation between the amount of xanthan gum added and the apparent viscosity of the material, with the relationship between sample viscosities being P1 < P2 < P3 < P4. The addition of xanthan gum enhances the shear-thinning ability, self-supporting ability, and 3D printing capability of the pork paste. Material P4 has excessively high viscosity at low shear rates, which can easily lead to difficulties in extrusion through the nozzle.

Figure 2: The change of viscosity of minced pork material with shear rate

The shape stability of the printed product is related to the material’s yield stress. As can be seen from Table 4, with the addition of xanthan gum, the yield stress of the minced pork material continues to increase, indicating that its stability is improved, with sufficient mechanical strength and shape retention capability.

2.3.2 Analysis of Dynamic Viscoelastic Rheological Properties

By scanning the frequency, one can understand the material’s response to impact or gradually applied forces, thereby obtaining the material’s viscoelastic modulus.

Frequency scanning studies provide information on how materials respond to different frequencies. In the field of food research, the typical frequency range is between 0.1 and 10 Hz. The adaptability of materials for 3D printing includes extrudability and supportability. The storage modulus (G′) represents the magnitude of the material’s elasticity; while the loss modulus (G″) and apparent viscosity represent the size of the material’s viscosity.

G′ represents the elastic solid-like behavior and the mechanical strength of the material’s resistance to compression deformation. Research indicates that materials with a higher G′ are advantageous for extrusion and exhibit strong shape retention after extrusion.

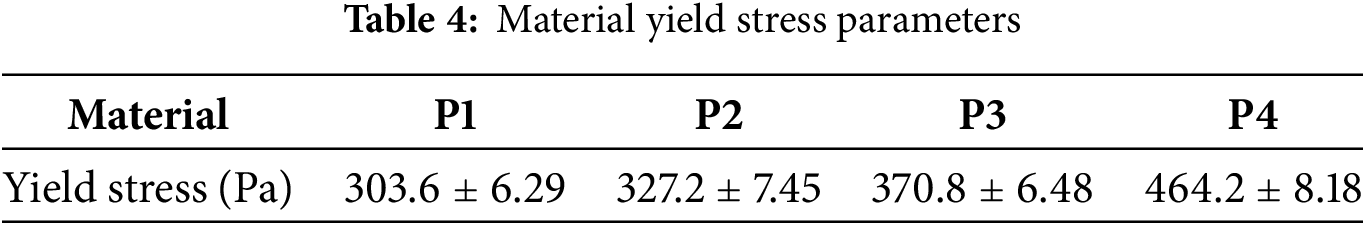

From Fig. 3, it can be seen that G″ is significantly lower than G′, and both G′ and G″ are related to frequency, indicating that the material samples are primarily elastic. Such highly elastic materials are prone to expansion during extrusion due to the lack of constraining forces from the printer nozzle walls. At the same frequency, as the content of starch or xanthan gum increases, G′ and G″ gradually decrease. This suggests that the amount of added cornstarch or xanthan gum is related to the material’s viscoelasticity.

Figure 3: Dynamic rheological curves of pumpkin mud materials under different hydrophilic colloid additions; (a) The storage modulus is affected by the change in frequency; (b) The loss modulus is affected by the change in frequency

Within the range of 0.1 to 10 Hz, the G′ and G″ values of all samples increase with the increase in frequency. All pumpkin sample materials exhibit a solid-like structure, with G′ values higher than G″. Sample S2A has the lowest G′ and G″ values, indicating that this material has the weakest self-supporting ability.

After adding different hydrocolloids, G′ and G″ decrease to varying degrees. The order of the storage modulus G′ and the loss modulus G″ is S1 > S2 > S1A > S2A. Sample S2 has a storage modulus G′ value close to S1A, which is consistent with the results of the previous static rheological analysis. Sample S2A has the lowest G′ and G″ values, indicating the weakest self-supporting ability of the sample; Sample S1 has the highest storage modulus G′ and loss modulus G″, indicating that the material has higher viscosity and elasticity, showing strong stability under external forces, but also prone to extrusion difficulties.

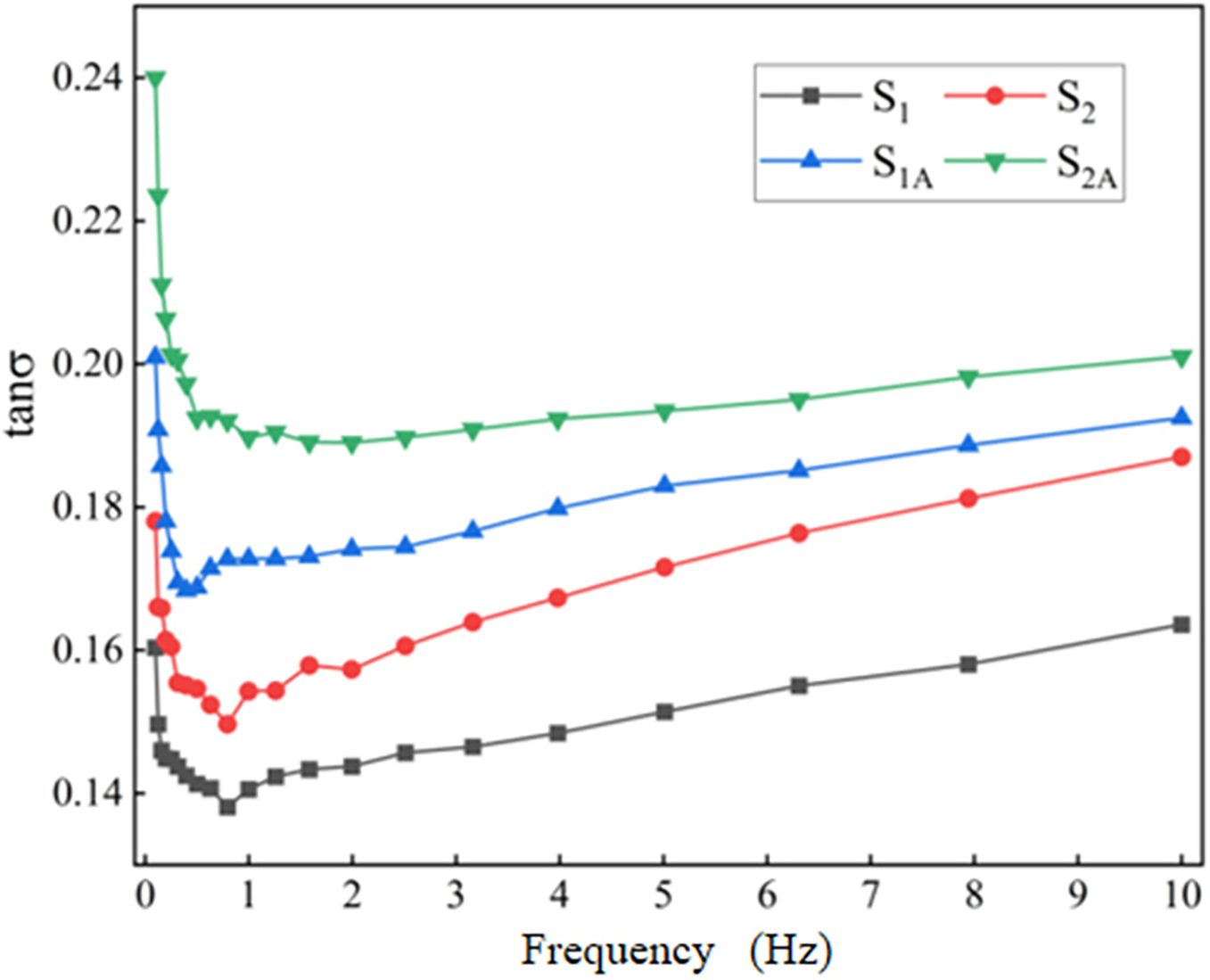

As shown in Fig. 4, within the linear viscoelastic range, the range of the loss tangent is between 0.13 and 0.25, indicating that the pumpkin puree mixture has the potential to form an elastic gel or gel-like structure. The larger the value, the greater the proportion of viscosity of the material, and the stronger the fluidity; the smaller the value indicates more solid-like behavior and poorer fluidity. The values of the four groups of samples from largest to smallest are S2A > S1A > S2 > S1, therefore, considering the material’s printing support ability and extrusion effect, samples S2 and S1A are more suitable for actual printing.

Figure 4: Loss tangent curve with frequency of S

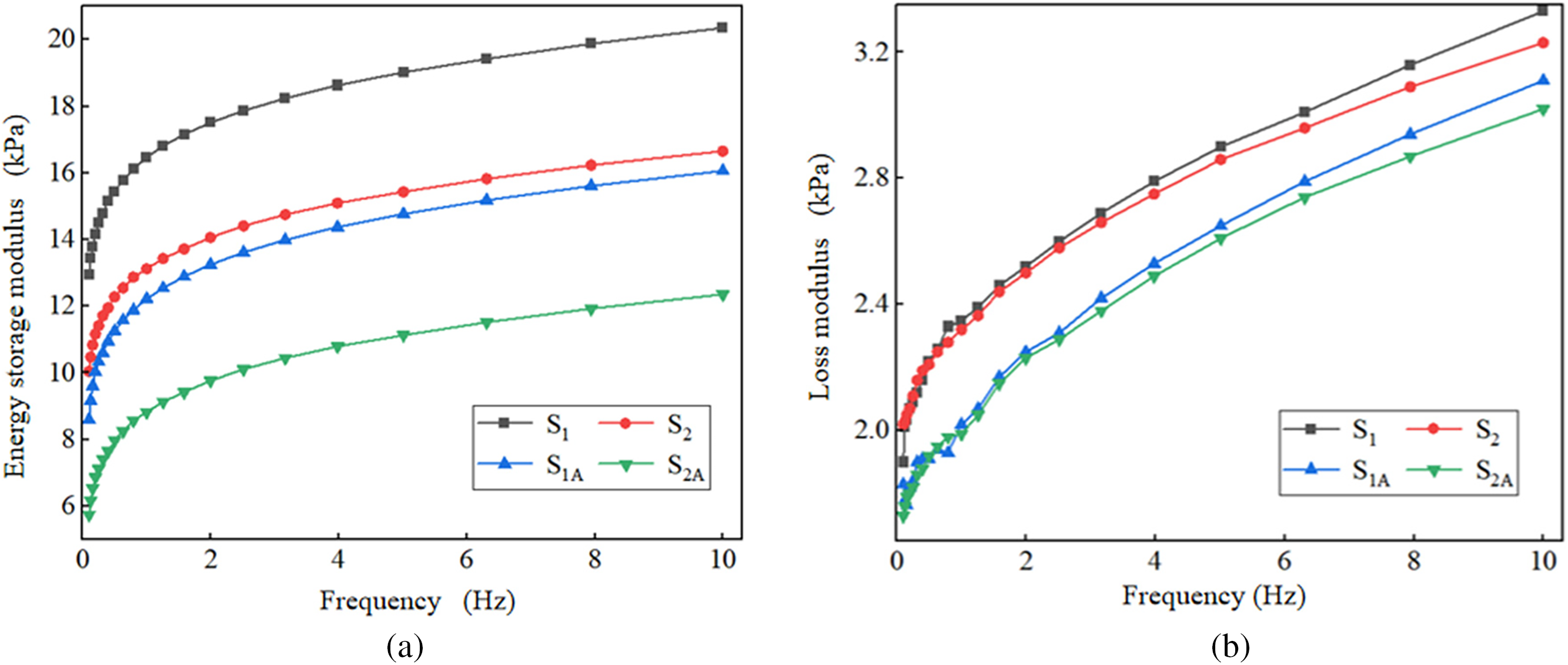

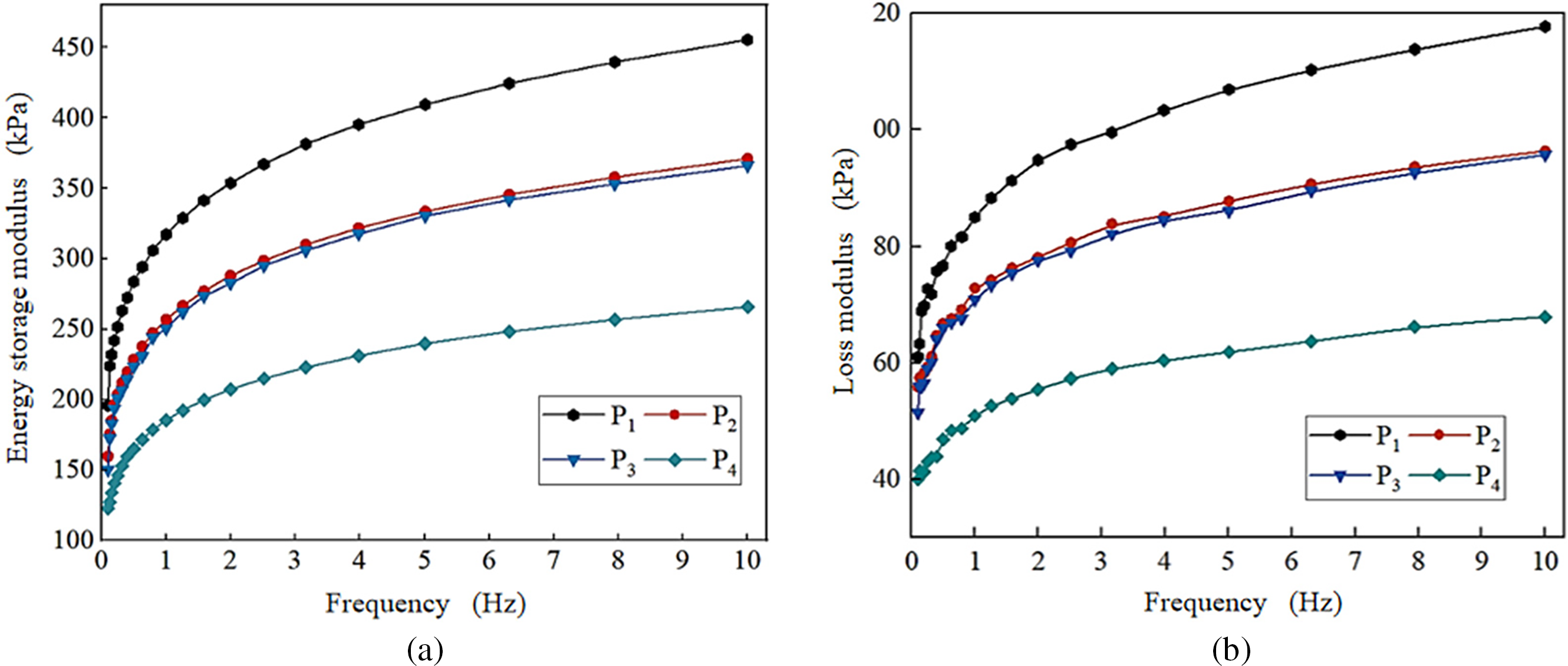

The self-supporting ability of the material deposited on the printing platform is related to the modulus from the storage modulus and loss modulus. Fig. 5 represents the dynamic rheological characteristics of the minced pork under the action of xanthan gum. It can be seen from the figure that within the range of 0.1 to 10 Hz, the G′ and G″ values of all samples increase with the increase of frequency. When the frequency continues to increase up to 4 Hz, the storage modulus and loss modulus of the minced pork material rise slowly and the growth rate tends to stabilize.

Figure 5: Dynamic rheological properties of pork paste materials added with xanthan gum; (a) The storage modulus is affected by the change in frequency; (b) The loss modulus is affected by the change in frequency

As shown in Fig. 5, among all the formulations, the relationship between the material’s elastic modulus and viscous modulus is P4 < P3 < P2 < P1. When the addition of xanthan gum is 1.75% (P2) and 2.13% (P3), the values of the storage modulus and loss modulus of the two materials are close.

From Fig. 5, it can be observed that within the range of 0.1 to 10 Hz, for all samples, G′ is greater than G″, which is beneficial for the support and shape retention between layers of the finished product after printing. When subjected to external forces, the material system can provide good support and is less likely to collapse.

The values of G′ and G″ for the material decrease with the increase in the addition of xanthan gum. Sample P4 has the lowest G′ and G″ values, indicating that this material has poor shape retention and molding effect during the 3D printing process. Sample P1 has a higher G′ than other experimental groups, thus the change in the elastic element is significant, which is not conducive to extrusion during printing.

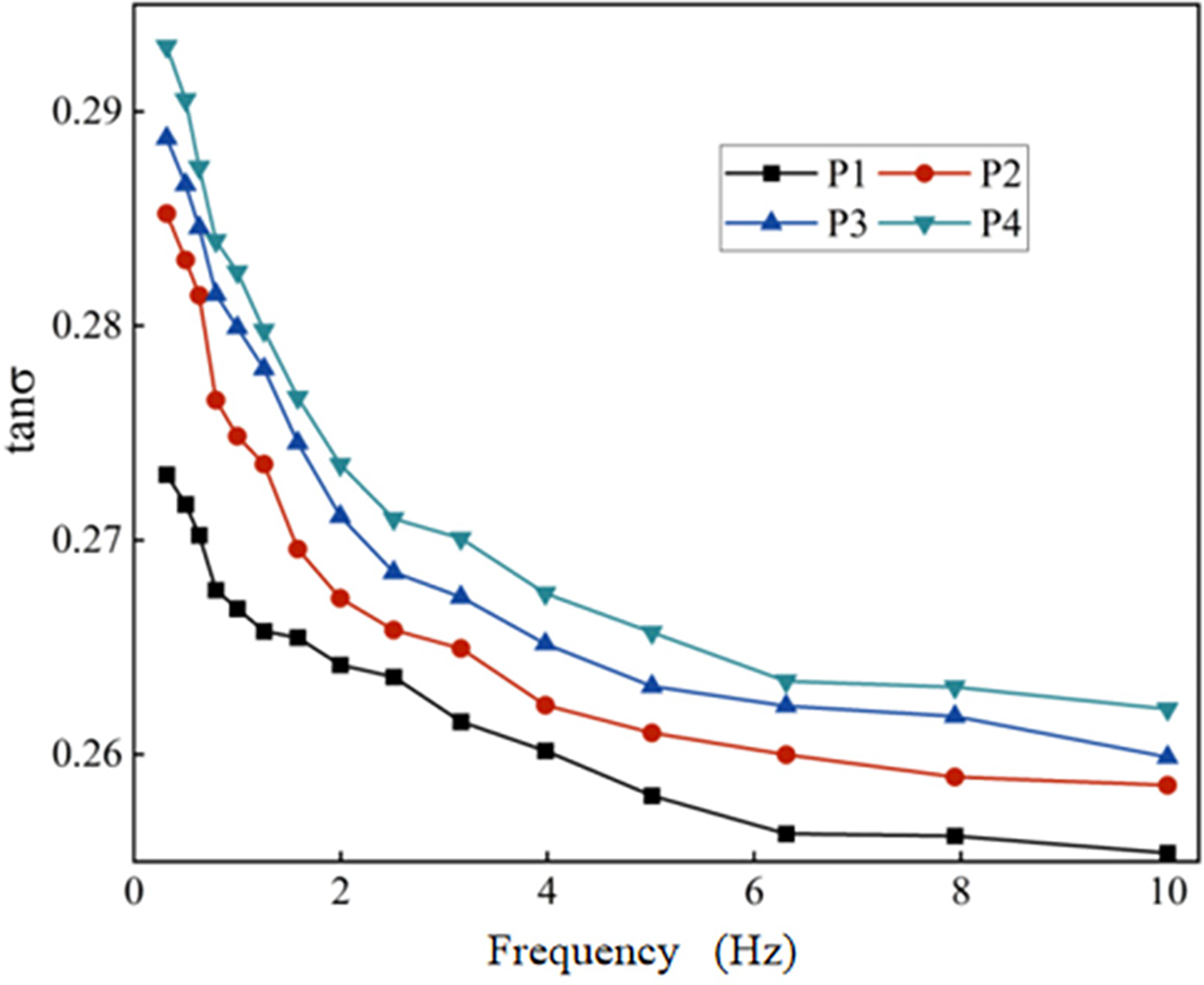

The loss tangent is used to characterize the viscoelastic behavior of the material. As can be seen from Fig. 6, for all formulations, the loss tangent is within the range of 0.25 to 0.3, which is less than 1, indicating that the minced pork material is an elastic fluid with strong intermolecular cross-linking and prominent solid characteristics. After the addition of xanthan gum, the loss tangent increases with the increase of the proportion of xanthan gum, and the mixed system exhibits superior viscoelasticity. This indicates that the addition of xanthan gum is beneficial for maintaining the shape stability of the material when printing with minced pork. The smaller the loss tangent, the greater the internal dissipation or internal friction force, and the stronger the system’s ability to dissipate energy. Therefore, considering the material’s printing support and extrusion effects comprehensively, it is more appropriate to choose samples P2 and P3 for actual printing.

Figure 6: Loss tangent curve with frequency of P

2.3.3 Texture Improvement Pumpkin Puree, Minced Pork 3D Printing

Patients with dysphagia typically consume pureed foods, which often have limited visual appeal and can easily lead to a decreased appetite and reduced nutritional intake. Food 3D printing technology can provide personalized shaping and nutritional customization for these pureed foods, helping to improve the nutritional intake of patients with dysphagia.

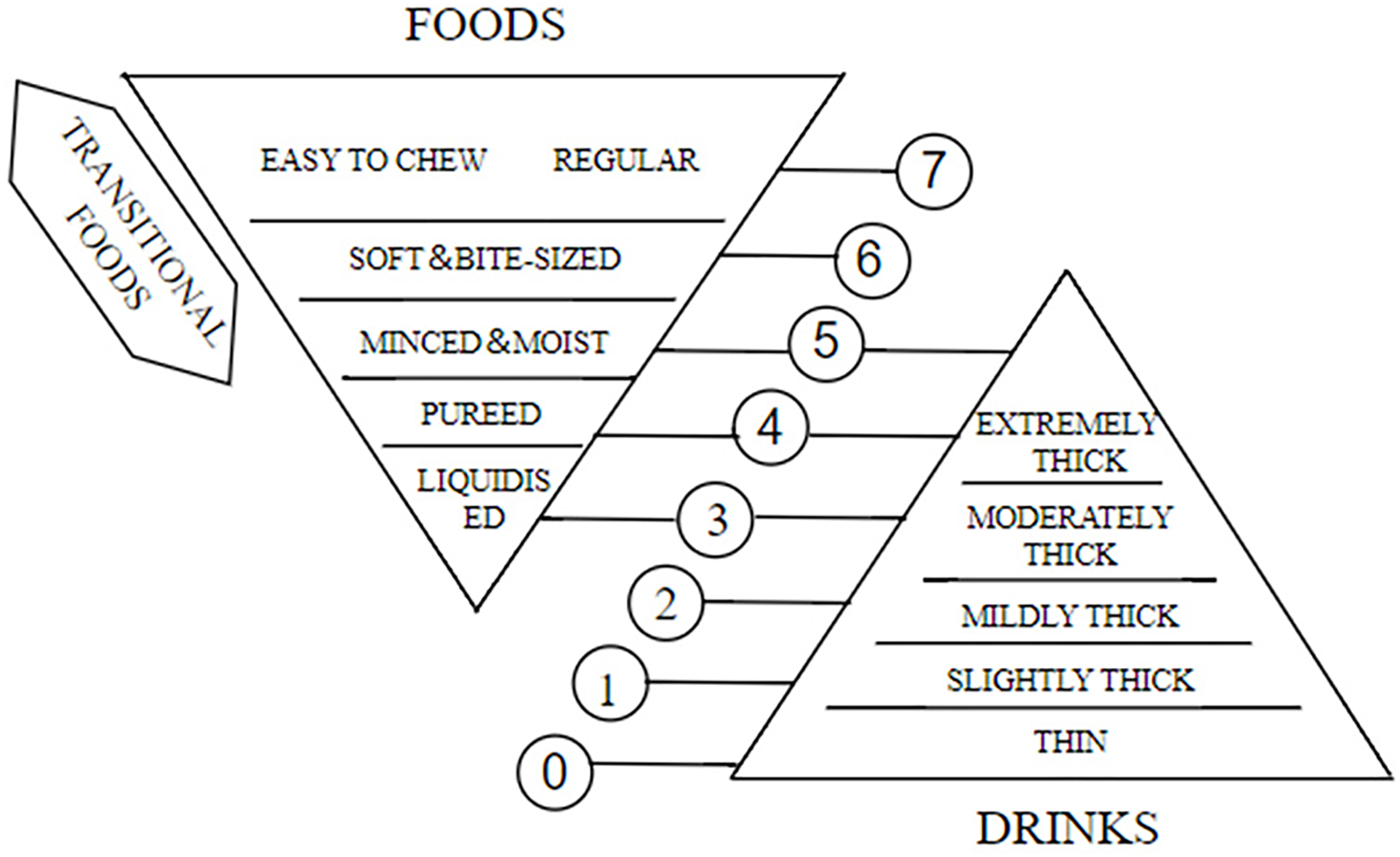

The measurement of the material’s texture is based on the methods described in the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI). The IDDSI framework classifies thickened liquids and food with modified texture into levels 0 to 7 based on viscosity and texture (as shown in Fig. 7). The IDDSI method uses basic tools such as a 10-mL syringe, a standard metal fork, chopsticks, or fingers.

Figure 7: International dysphagia standardization initiative (IDDSI)

Paste-like foods are one of the categories suitable for dysphagia diets, and IDDSI provides several methods for testing the hardness, cohesion, and adhesiveness of materials using household items.

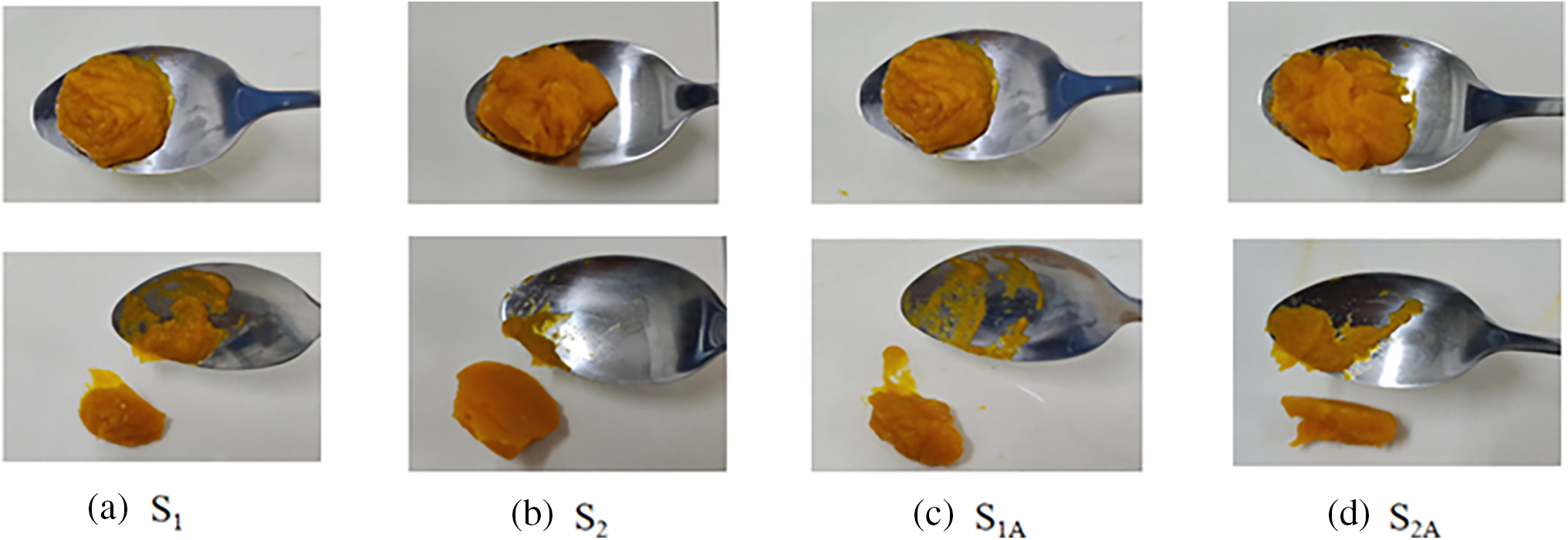

This study adopts the spoon tilt test and fork pressure test [20]. The spoon tilt test assesses the cohesion of the food by checking whether it slides off the spoon, characterized by the food maintaining its shape on the spoon and falling off as a whole. The test for food adhesiveness is conducted by tilting the spoon to 90 degrees, where the sample should slide out of the spoon without sticking or leaving minimal residue.

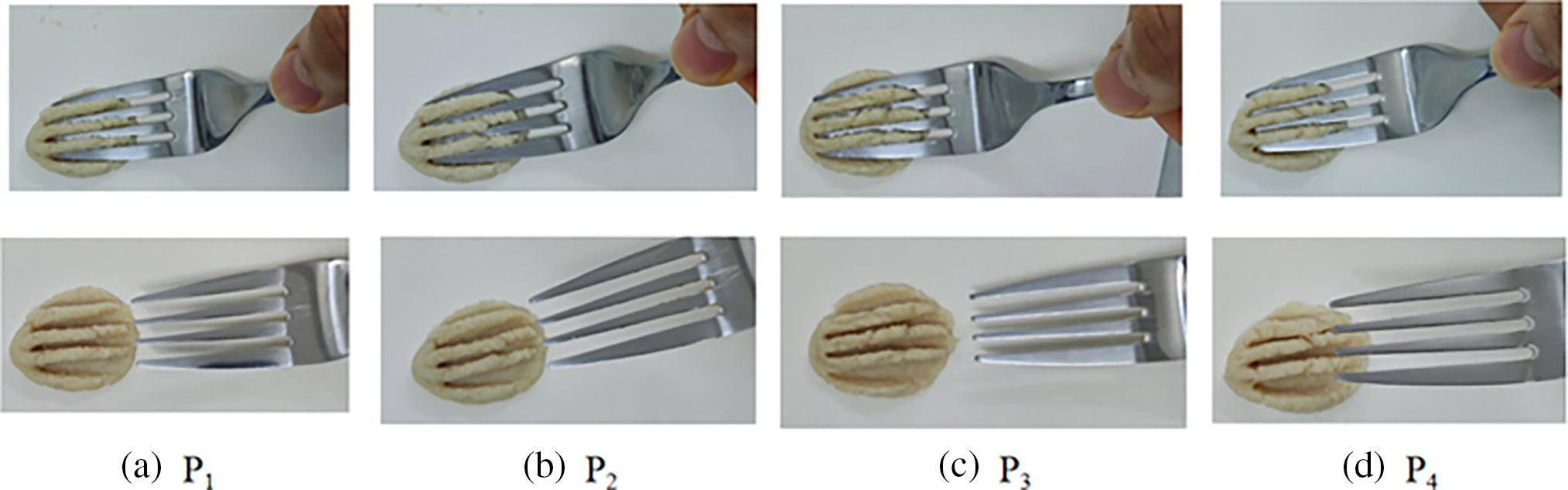

The fork pressure test is used to evaluate the hardness of the food and to show how easily it breaks down under the pressure of a fork. The amount of pressure required is measured by observing the blanching of the thumbnail, which is the same pressure as that applied by the tongue during swallowing. If the food breaks without the thumbnail turning white, then the food is at a lower IDDSI level.

Printing process parameters can affect the printing effect and precision of the pumpkin puree-pork mince material. The nozzle diameter determines the diameter of the extruded lines and the height when the lines are stacked. Therefore, the initial printing height and layer height should be consistent with the nozzle diameter to avoid the extruded lines being crushed or failing to make contact with the platform.

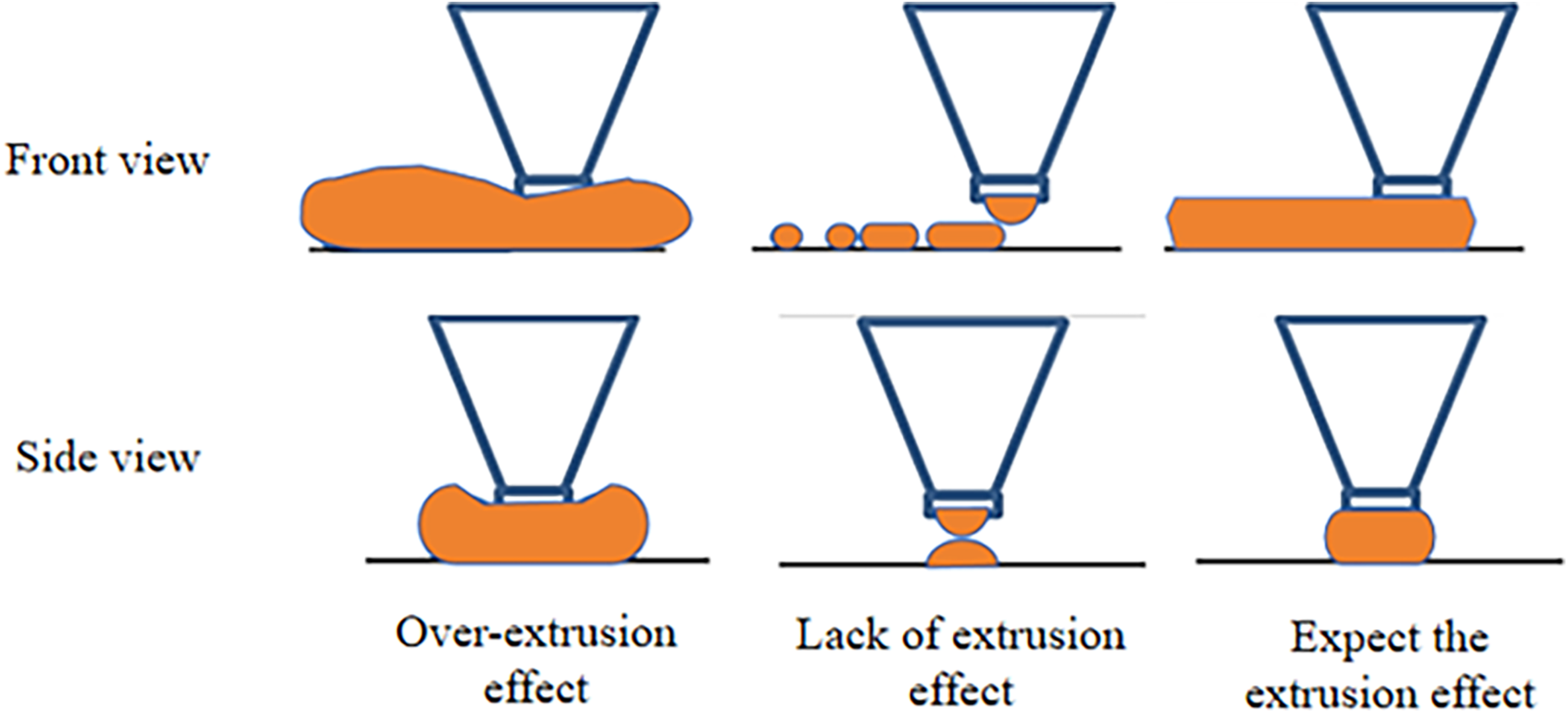

Printing speed refers to the movement speed of the print head relative to the printing platform during printing. Printing speed that is too fast or too slow can have a certain impact on the quality of the product. To assess the quality of the printed products, line printing experiments are conducted. Three different situations can be expected (as shown in Fig. 8). When the printing speed is too high, the printed product lines, due to insufficient extrusion of the printing material, cannot keep up with the printing speed in time, resulting in under-extrusion with printing breaks and uneven material output; when the printing speed is too low, the thickness of the printed product lines is much greater than the nozzle diameter, and the designed details are also lost. The nozzle will flatten the lines and drag across the previously printed area, resulting in an over-extrusion state; the printed product lines will achieve the desired effect only when the nozzle extrusion speed and the printhead movement speed are relatively appropriate and balanced with each other.

Figure 8: Nozzle extrusion effect diagram

In this experiment, the 3D printing model designed is an S-shaped line, studying the impact of print head printing speed on the adaptability of pumpkin puree-pork mince material to 3D printing. Five printing speeds (10, 15, 20, 25, 30 mm/s) are set for line printing tests. The printing accuracy is assessed based on the diameter of the printed line (i.e., roundness). The diameter of the printed line is predicted using the volume conservation and assuming the elliptical cross-sectional area of the printed product.

In the formula, Q represents the volumetric extrusion rate (mm3/s), A represents the cross-sectional area of the nozzle (mm2), V represents the printing speed (mm/s), a and b represent the width and height, respectively, of the elliptical cross-section of the finished product (mm).

The aspect ratio c is defined as the ratio of height to width. If the cross-section is a circle, then c = 1; however, if there is linear distortion, then c < 1.

Cylindrical Printing Experiments

Printing fill density refers to the compactness of the internal material filling in a 3D printed product, that is, the percentage of internal material filled [21]. The greater the printing fill density, the smaller the gaps between printed lines, the more compact the internal structure, and the better the support of the finished product, and vice versa. A cylindrical body with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 25 mm was generated using slicing software. Four different fill densities were used (0%, 20%, 40%, and 50%).

By printing cylindrical bodies with different filling levels and measuring the height of the cylinder after printing is completed, the 3D characteristic quality of the printed product can be obtained. This information provides a potential relationship between the shape retention of the printing material and the material’s rheological properties. The method of accuracy evaluation is as follows.

In the formula, η represents the printing accuracy; Hs is the height dimension of the 3D printed product (in millimeters); Hm is the dimension of the designed 3D printed model (in millimeters).

The IDDSI categorizes modified foods into eight levels (0–7) and has proposed a series of testing methods to confirm whether the texture of the material meets the dietary requirements for patients with dysphagia. In this paper, a spoon tilt test and a fork pressure test were conducted on 3D printed samples of bite-sized portions.

(1) Spoon tilt experiment

The pumpkin puree material complies with level 4 of the IDDSI International Dysphagia Food Standard Framework.

In this experiment, four pumpkin puree formulations were used as research materials, with the amount of food residue on a spoon serving as an indicator of material adhesiveness. As shown in Fig. 9, both S2 and S1A can slide off the spoon with minimal residue and no aggregation, meeting the requirements for Level 4 food characteristics. In contrast, the S1 and S2A formulations, even when the spoon is turned upside down by 90 degrees, are difficult to slide off the spoon and leave a significant amount of residue, obscuring the spoon’s surface beneath the material. This indicates that these two formulations have strong adhesiveness and poor flowability, making them unsuitable for swallowing. Therefore, these two material formulations are not suitable for patients with dysphagia.

Figure 9: Spoon overturning test

(2) Fork pressure test

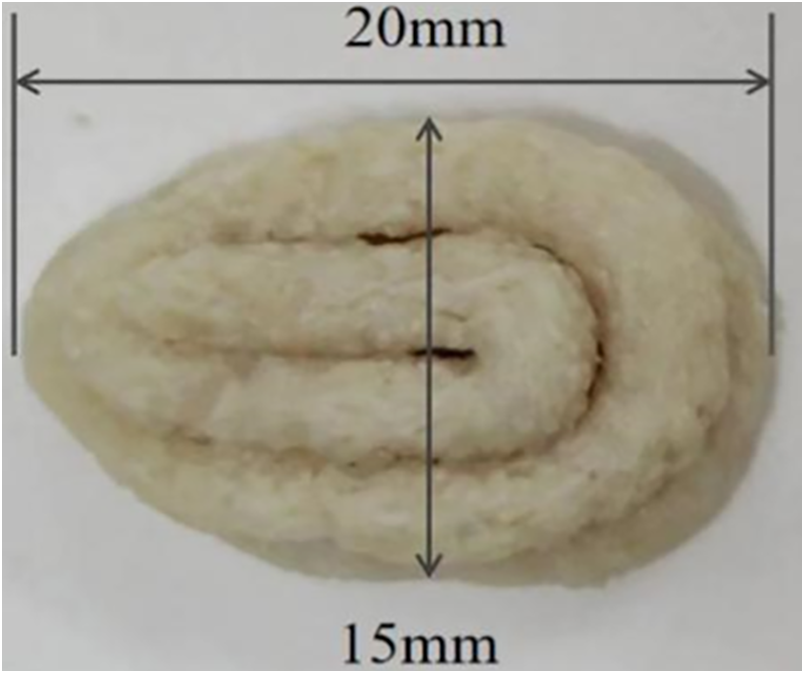

The minced pork material complies with level 6 of the IDDSI International Dysphagia Food Standard Framework. In this experiment, four minced pork formula samples were tested according to the level 6 IDDSI protocol. The printed minced pork material products, measuring 15 by 20 mm, are shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Pork paste material printing products

Fig. 11 displays the results of the fork pressure test conducted on the printed samples. As shown in the figure, samples P1, P2, and P3 meet the requirements of level 6 of the IDDSI framework. When the samples are pressed with the tines of a fork to the pressure that causes the thumbnail to turn white, they flatten, crumble, and deform, and do not return to their original shape upon removal of the fork. In contrast, sample P4, during the fork pressure test, causes more whitening of the thumb, requires greater pressure, and has lower softness, which corresponds to the conclusions drawn from the rheological analysis and is not suitable as material for subsequent printing research. The texture of samples P2 and P3 is more suitable for consumption by patients with dysphagia.

Figure 11: Fork pressure test

3.2 The Impact of Printing Speed on the Forming Effect of 3D Printing

The extrusion speed of the nozzle and its moving speed are collectively referred to as the printing speed of the printer. These parameters affect the forming effect and printing efficiency of 3D-printed products because they alter the length and extrusion volume of the sample within a unit of time [22].

For line printing, the printing process is captured along a straight line, and the printing accuracy is assessed based on the diameter of the printed line (i.e., its roundness). When the line shows significant spreading, it will not have a circular cross-section; therefore, the printing accuracy can be evaluated by the height and width of an elliptical cross-section. After optimization, the nozzle extrusion speed was set within the range of 10–30 mm/s, with a nozzle diameter of 8 mm. Since the printing material is in the form of a composite structure and the ideal cross-sectional shape is circular, the layer height was set to 8 mm, equivalent to the nozzle diameter.

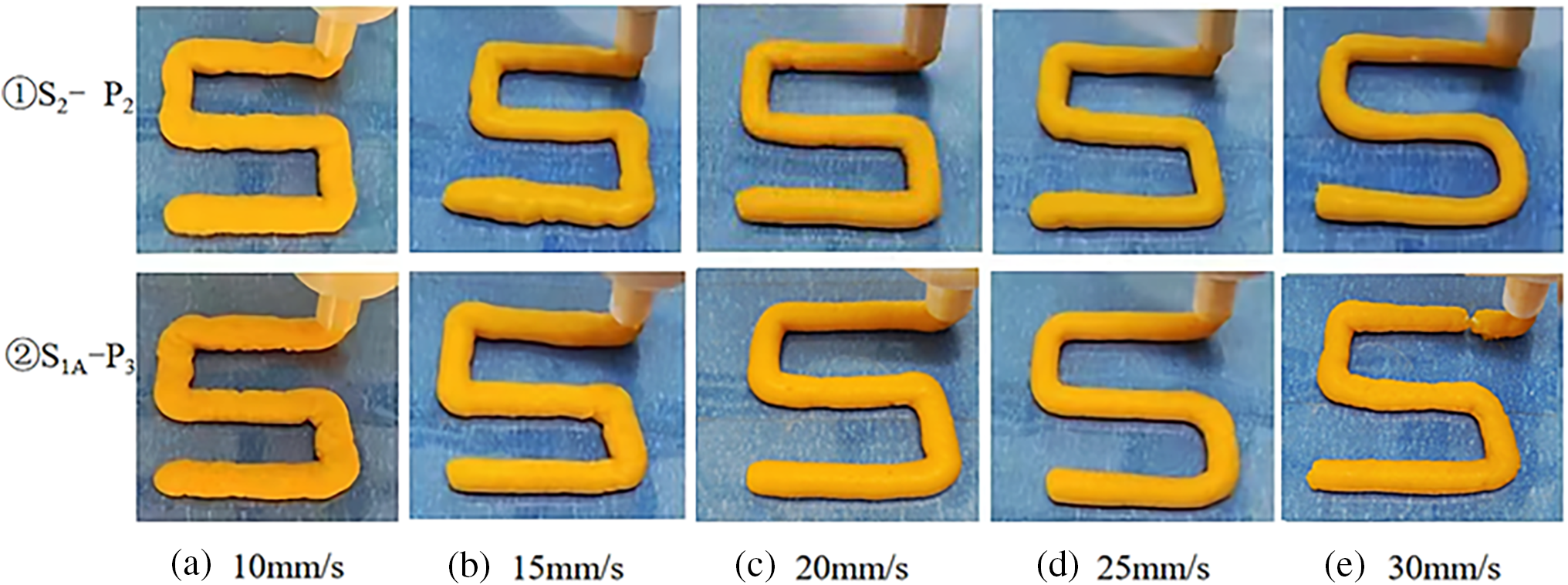

Fig. 12 presents the cross-sectional view of the dual-nozzle line printing product. Fig. 13 shows the printing effects of the S-line at different nozzle extrusion speeds. It can be seen that both excessively fast and slow nozzle extrusion speeds have negative impacts on the product quality.

Figure 12: Print the product profile

Figure 13: Line printing experimental image

When the nozzle movement speed is too fast, the printed lines of material groups ① and ② exhibit excessive stretching and breaking phenomena [23]. When the movement speed is set at 20 and 25 mm/s, the printing effect for material groups ① and ② significantly improves, with the printed product lines being smooth. However, at a printing speed of 25 mm/s, the lines of the finished product are thinner than those at a speed of 20 mm/s. At a printing speed of 20 mm/s, the printing effect for material groups ① and ② is optimal, with no uneven extrusion or printing breaks occurring, and the extrusion is sufficient to achieve uniformly smooth lines of consistent diameter. This is the best parameter for providing high-quality printed lines and obtaining exquisite products.

When the nozzle movement speed is set at 15 and 10 mm/s, the printing quality deteriorates, and the printed products of material groups ① and ② exhibit uneven extrusion and accumulation. The slower the printing speed, the more pronounced this phenomenon becomes.

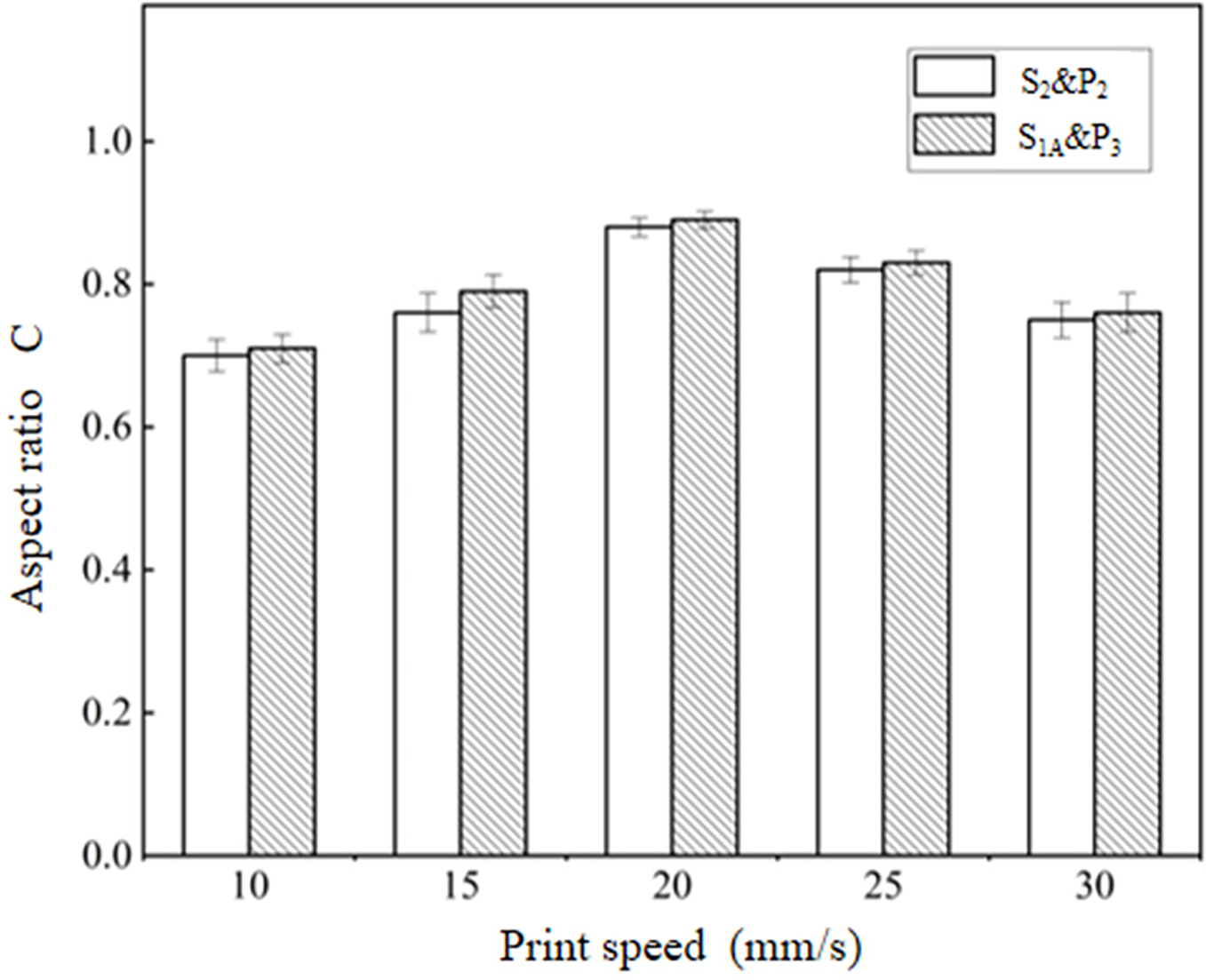

The closer the aspect ratio c is to 1, the better the printing accuracy, and it can be intuitively seen from Fig. 14 that with the increase of printing speed, the 3D printing accuracy of material groups ① and ② shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. When the printing speed is 20 mm/s, the accuracy of the 3D printed products of the two groups of materials is the best, and the aspect ratio c is about 0.9. When the printing speed is 10 and 30 mm/s, the aspect ratio c of the material groups ① and ② is smaller, and the printing accuracy is poor. Among the two groups of samples, ② groups of materials had the best printing stability, and the accuracy of the 3D printed products was the highest. This is basically consistent with the appearance analysis of the 3D printed product in Fig. 13.

Figure 14: The influence of different printing speeds on the accuracy of 3D printing products

3.3 The Effect of Filling Density on the Molding Effect of 3D Printing

The ability of a printed product to maintain its shape is related to the filling density at the time of printing, with the denser the filling, the better the product’s self-support ability [24]. In this paper, a 40 mm diameter and 30 mm height cylinder was generated using slicing software. The printhead print speed is set to 20 mm/s and the layer height is set to 7 mm.

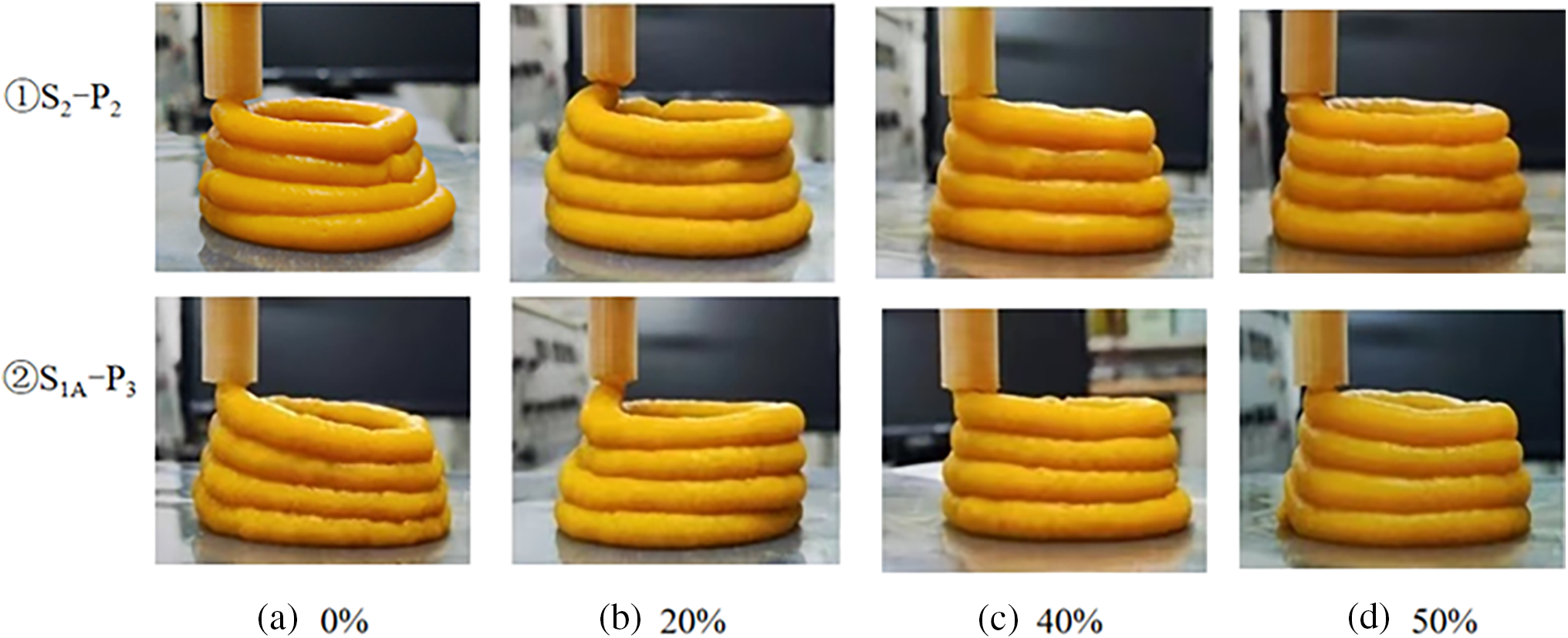

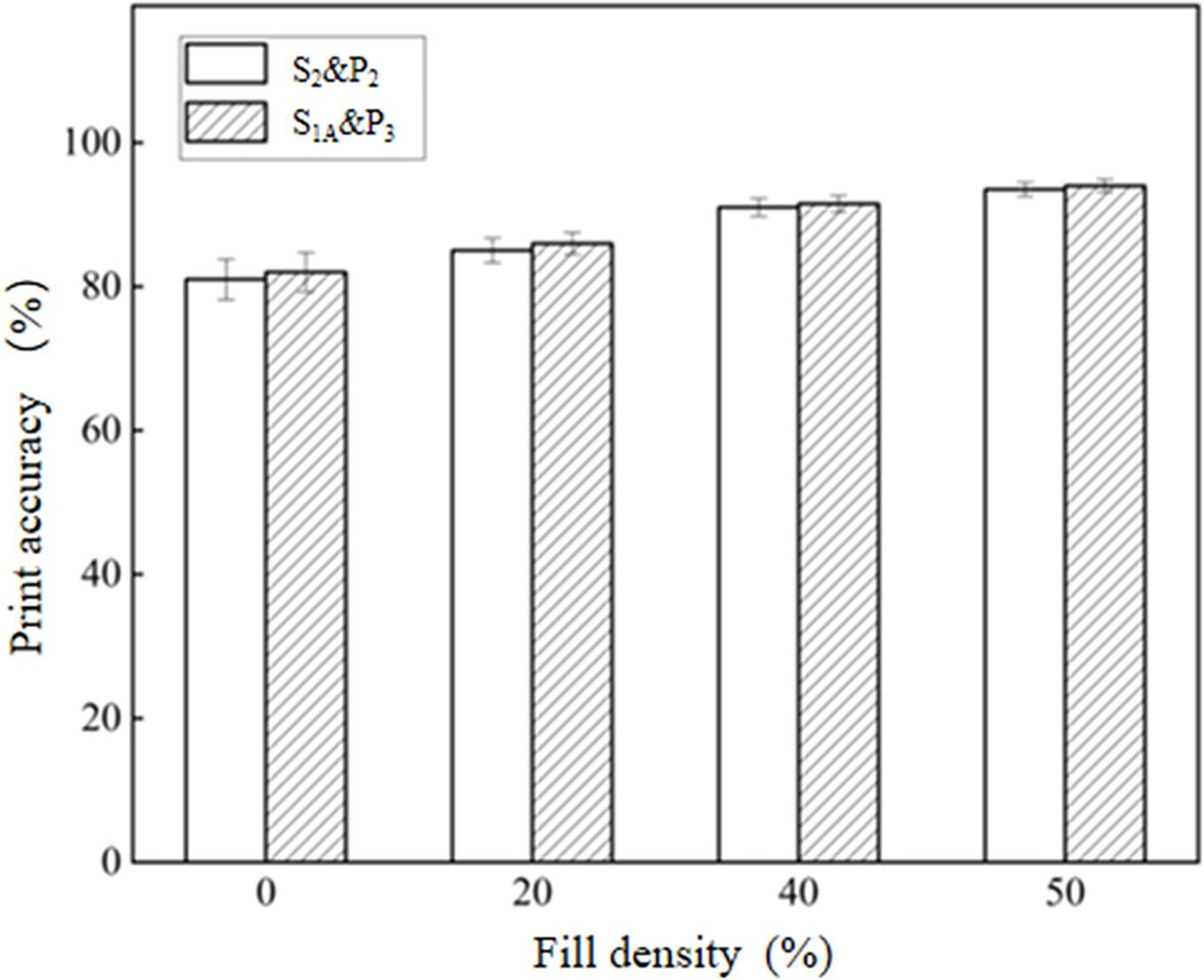

Figs. 15 and 16 show the cross-sectional view of the finished product printed with dual printheads and the 3D printed products with different filling densities, respectively. With the increase of printing filling density, the accuracy of 3D printing of materials (the degree of approximation to a circle) shows an upward trend. Printed products with a fill density of 0% have the lowest accuracy at all fill levels; When the filling density is 50%, the printing accuracy of the finished 3D printed product is the best. During the printing process, the printed product is subjected to the pressure of gravity, subsequent layers and moving print heads, and at a certain time or at a certain height, the existing cylinder will no longer support additional layers, and the cylinder may collapse.

Figure 15: Print the product profile

Figure 16: Cylinder printing experimental images at four filling levels

As shown in Fig. 17, the constructability of the material group ② is the best by analyzing and comparing the four groups of experimental materials. Therefore, when the printing filling density is 50%, the printing accuracy of the 3D printed product in the material group ② is optimal. When the infill density reaches above 50%, the gravitational force of the printing material can cause the layer height of the lower material to decrease, and may even lead to collapse.

Figure 17: The influence of different printing filling density on the accuracy of 3D printing products

The static shear and dynamic viscoelastic rheological properties of pumpkin puree and minced pork materials with different hydrocolloids were analyzed in this study. A material formula suitable for 3D food printing was developed, and a three-dimensional printing experimental platform was established for material printing experiments. Following the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI), the texture of the materials was tested, and the pumpkin puree (S2, S1A) and minced pork materials (P2, P3) suitable for patients with dysphagia were obtained through spoon overturning test and fork pressure test. The experimental results show that:

(1) The appropriate addition of xanthan gum and starch can significantly improve the static shear rheological properties and dynamic viscoelastic rheological properties of food materials, thereby improving their adaptability and stability during the 3D printing process.

(2) The n values of S2 and S1A of pumpkin puree samples are small, indicating good shear-thinning behavior and flowability, which facilitates extrusion from the nozzle; the storage modulus and loss modulus are high, and the material printing support capacity is strong. P2 and P3 of the minced pork samples exhibit good shear thinning properties, high yield stress, storage modulus, and loss modulus, resulting in strong mechanical strength, internal support capacity, and printability.

(3) Through the establishment of a 3D printing experimental platform, this study further explored the influence of process parameters such as printing speed and filling density on the printing effect, which provided important data support for optimizing the 3D food printing process. Finally, the experimental results show that the printing accuracy and printing stability of the material are the best when the printing platform is set with the diameter of the outer nozzle = 8 mm, the diameter of the inner nozzle = 3 mm, the initial height = 8 mm, the layer height = 8 mm, the nozzle extrusion speed and movement speed = 20 mm/s, and the material filling density = 50%.

In the future, hydrocolloids and food will be combined to develop more different material formulations and apply them to food 3D printing, so as to provide more diverse choices for the diet of patients with dysphagia.

Acknowledgement: The authors also gratefully acknowledge Liaoning University of Technology.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (Grant No. 62203198) and Key R&D project of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. 2022XGC010701).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Shourui Wang and Yibo Wang; methodology, Yibo Wang; software, Shourui Wang; validation, Shourui Wang, Yibo Wang and Kun Yang; formal analysis, Shourui Wang; investigation, Shourui Wang; resources, Yu Li; data curation, Xin Su; writing—original draft preparation, Shourui Wang; writing—review and editing, Shourui Wang; visualization, Yibo Wang; supervision, Yibo Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No external datasets were used in this study. All data were generated by the authors through experiments. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Fan M, Choi YJ, Wedamulla NE, Kim SH, Bae SM, Yang D, et al. Different particle sizes of Momordica charantia leaf powder modify the rheological and textural properties of corn starch-based 3D food printing ink. Heliyon. 2024;10(4):e24915. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24915. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zhong Y, Wang B, Lv WQ, Li GH, Lv Y, Cheng YQ. Egg yolk powder-starch gel as novel ink for food 3D printing: rheological properties, microstructure and application. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2024;91:103545. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2023.103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu T, Zheng J, Du J, He G. Food processing and nutrition strategies for improving the health of elderly people with dysphagia: a review of recent developments. Foods. 2024;13(2):215. doi:10.3390/foods13020215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Lecanu R, Della Valle G, Leverrier C, Ramaioli M. Predicting the gravity-driven flow of power law fluids in a syringe: a rheological map for the IDDSI classification. Rheol Acta. 2024;63(6):459–69. doi:10.1007/s00397-024-01449-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kadirvel V, Narayana PG. Edible gums—an extensive review on its diverse applications in various food sectors. Food Bioeng. 2023;2(4):384–405. doi:10.1002/fbe2.12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen J, Mu T, Goffin D, Blecker C, Richard G, Richel A, et al. Application of soy protein isolate and hydrocolloids based mixtures as promising food material in 3D food printing. J Food Eng. 2019;261:76–86. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.03.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li G, Wang B, Yang L, Lv W, Xiao H. Effect of salt valence ionic strength on the rheology 3D printing performance of walnut protein emulsion gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2025;164:111112. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2025.111112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mallesham P, Parveen S, Rajkumar P, Gurumeenakshi G, Naik R. Enhancing structural stability of 3D printed cake with xanthan gum: a rheological and post-process analysis. Food Biophys. 2025;20(1):46. doi:10.1007/s11483-025-09935-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang Q, Bao Y, Ma T, Tsuchikawa S, Inagaki T, Wang H, et al. Intelligent monitoring of post-processing characteristics in 3D-printed food products: a focus on fermentation process of starch-gluten mixture using NIR and multivariate analysis. J Food Eng. 2025;388:112357. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2024.112357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mishra A, Cleveland OR. Rheological properties of porcine organs: measurements and fractional viscoelastic model. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1386955. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1386955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao J, Li X, Ji D, Bae J. Extrusion-based 3D printing of soft active materials. Chem Commun. 2024;60(58):7414–26. doi:10.1039/D4CC01889C. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Maya S, Anders G, Michael L. Effect of various dynamic shear rheometer testing methods on the measured rheological properties of Bitumen. Materials. 2023;16(7):2745. doi:10.3390/ma16072745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dehtiar V, Sachko A, Radchenko A, Hrynchenko O, Gubsky S. Development of lentil aquafaba-based food emulsions with xanthan gum or pregelatinized corn starch as stabilizers. Biol Life Sci Forum. 2025;40(1):17. doi:10.3390/BLSF2024040017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Science—Food Science. Findings from Chiang Mai University provides new data on food science (Technological properties, invitro starch digestibility and invivo glycaemic index of bread containing crude malva nut gum). Food Wkly News. 2017;93–7. [Google Scholar]

15. Gago-Guillán M, García-Otero X, Anguiano-Igea S, Otero-Espinar FJ. Compression pressure-induced synergy in xanthan and locust bean gum hydrogels. Effect in drug delivery. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023;89:105025. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2023.105025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kang J, Yue H, Li X, He C, Li Q, Cheng L, et al. Structural, rheological and functional properties of ultrasonic treated xanthan gums. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;246:125650. doi:10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2023.125650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Gu H, Ma L, Zhao T, Pan T, Zhang P, Liu B, et al. Enhancing protein-based foam stability by xanthan gum and alkyl glycosides for the reduction of odor emissions from polluted soils. J Clean Prod. 2023;398:136615. doi:10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2023.136615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Krishna GC, Tomu K, Prasad K. Heat transfer of laminar non-Newtonian fluid flow through pipes boosted by inlet swirl. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2024;149(4):1777–91. doi:10.1007/S10973-023-12731-Y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hardacre AK, Yap SY, Lentle RG, Monro JA. The effect of fibre and gelatinised starch type on amylolysis and apparent viscosity during in vitro digestion at a physiological shear rate. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;123:80–8. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.01.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang T, Lu S, Hu X, Xu B, Bai C, Ma T, et al. Cellulose nanocrystals-gelatin composite hydrocolloids: application to controllable responsive deformation during 3D printing. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;151:109780. doi:10.1016/J.FOODHYD.2024.109780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Majooni Y, Fayazbakhsh K, Yousefi N. Toward mechanically robust and highly recyclable adsorbents using 3D printed scaffolds: a case study of encapsulated carrageenan hydrogel. Chem Eng J. 2024;494:152672. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.152672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jiang XY, Li L, Yan JN, Wang C, Lai B, Wu HT. Binary hydrogels constructed from lotus rhizome starch and different types of carrageenan for dysphagia management: nonlinear rheological behaviors and structural characteristics. Food Chem X. 2024;22:101466. doi:10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Molchanov VS, Glukhova SA, Philippova OE. Rheological behavior of polysaccharide hydrogels of alginate reinforced by a small amount of halloysite nanotubes for extrusion 3D printing. Mosc Univ Biol Sci Bull. 2024;78(Suppl 1):S72–7. doi:10.3103/S0096392523700268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Turaka S, Jagannati V, Pappula B, Makgato S. Impact of infill density on morphology and mechanical properties of 3D printed ABS/CF-ABS composites using design of experiments. Heliyon. 2024;10(9):e29920. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools