Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence of Variable Thermal Properties on Bioconvective Flow of a Reiner-Rivlin Nanofluid with Mass Suction: A Cattaneo-Christov Framework

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University of Madinah, Madinah, 42351, Saudi Arabia

2 Mechanical Engineering Program, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Jl. Ir. Sutami No. 36A, Surakarta, 57125, Central Java, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Iskander Tlili. Email:

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(6), 1339-1352. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.065295

Received 09 March 2025; Accepted 11 June 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study explores the bioconvective behavior of a Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid, accounting for spatially varying thermal properties. The flow is considered over a porous, stretching surface with mass suction effects incorporated into the transport analysis. The Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid model includes variable thermal conductivity, mass diffusivity, and motile microorganism density to accurately reflect realistic biological conditions. Radiative heat transfer and internal heat generation are considered in the thermal energy equation, while the Cattaneo-Christov theory is employed to model non-Fourier heat and mass fluxes. The governing equations are non-dimensionalized to reduce complexity, and a numerical solution is obtained using a shooting method. Parametric studies are conducted to examine the influence of key dimensionless parameters on velocity, temperature, concentration, and motile microorganism profiles. The results are presented through a series of graphs, offering insight into the dynamic interplay between physical mechanisms affecting heat and mass transfer in non-Newtonian bioconvective nanofluid systems.Keywords

The frontiers in thermal engineering have brought the idea of nanofluids, for which multidisciplinary applications are noticed in the engineering and heat transfer processes. The nanofluids are a familiar category of liquids that obey peak thermal properties. Special applications of nanomaterials are referred to in the energy sector. The nanofluids present a joint distribution of metallic particles with some base liquids. The exceptional roles of nanofluids are taken in solar energy, cooling processes, nuclear systems, automated operations, extrusion processes, etc. In recent years, wide applications of nanofluids have been suggested in the presence of distinct thermal sources and diverse geometries. For instance, Choi and Eastman [1] have explored the basic properties and idea of nanofluids, while Eshgarf et al. [2] presented a comprehensive literature review for nanofluids subject to multi-phase and single-phase models. Meanwhile, Alsabery et al. [3] observed the convection flow of nanofluid due to inner surfaces and Hafez et al. [4] discussed the Casson nanofluid flow in the presence of electroosmosis influence. The flow model was further updated with Newtonian heating outcomes. It was found by Nagaraja et al. [5] that the curved flow was caused by heat transfer based on Prandtl number nanofluid and entropy generation effects. Khan et al. [6] examined the stable performances of Williamson nanofluid damped with slip effects, while the lubricated flow of Walters B nanofluid was predicted by Smida et al. [7]. Gupta et al. [8] presented an understanding of heat fluctuation due to Wu’s slip interference against Carreau nanofluid. The flow was oriented by a linearly stretched cylinder. Aich et al. [9] tested the heat improvement with the utilization of metallic particles in a radiated moving surface. Seethamahalakshmi et al. [10] reported the Casson-Maxwell nanofluid flow in the presence of slip effects. Khan et al. [11] deduced a fractional model defining the collection of molybdenum disulfide and graphene oxide nanoparticles. Sultan et al. [12] addressed the thermal investigation in a copper tube with the interaction of nanofluid. Dinarvand et al. [13] presented a comprehensive review of the significance of nanofluids in flat tubes. Khadija et al. [14] focused on the future photovoltaic thermal impact of nanofluid with diverse features.

In the modern era, research in non-Newtonian fluids has become important due to the novel importance of such fluids in the engineering and industrial framework. The scientists have embarked on developing various relationships for non-Newtonian materials to identify the rhetorical properties in a more classic way [15–17]. In various classes of non-Newtonian fluids, the Reiner-Rivlin is a special kind of fluid model which occupies distinct rheology. The dilatancy features of non-Newtonian fluids can be justified by this model. The physical interpretation of the Reiner-Rivlin model is examined in the bio-fluid dynamics and industrial area. The Reiner-Rivlin model, a constitutive framework for non-Newtonian fluids, plays a significant role in both bio-fluid dynamics and industrial applications. Physically, it generalizes the Newtonian stress-strain relationship by allowing the stress tensor to be a function not only of the rate of strain but also of higher-order terms, thereby capturing complex rheological behavior such as shear thinning, viscoelasticity, and normal stress differences. In bio-fluid dynamics, the Reiner-Rivlin model is particularly relevant in describing the flow of blood, mucus, and synovial fluid—substances that often deviate from Newtonian assumptions due to cellular structures and protein content. These fluids exhibit time-dependent and nonlinear flow characteristics that are better captured by this model. Industrially, the model finds applications in polymer processing, food engineering, and lubrication, where materials like molten plastics, ketchup, and grease show pronounced non-Newtonian traits. The Reiner-Rivlin framework enables more accurate simulation and optimization of processes such as extrusion, mixing, and coating, thereby improving product quality and process efficiency. Its physical interpretation, rooted in continuum mechanics, offers insight into the internal structure of complex fluids and allows engineers and researchers to better design systems that handle such materials under varying stress and deformation conditions. The unique features of this model were identified by Reiner [18] and Rivlin [19]. The properties of the Reiner-Rivlin model are described by the spanning in biological liquids, polymers, chemicals, food products, the spectrum of materials, etc. Naqvi et al. [20] modeled a theoretical representation of the rotatory flow of Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid under the interference of slip. Khan et al. [21] depicted the entropy generation analysis for Reiner-Rivlin fluid subjected to metallic particle interaction. Arain et al. [22] addressed the squeezing flow of Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid in circular plates. The entropy production in Reiner-Rivlin fluid with the additional impact of thermo-diffusion applications was claimed by Khan et al. [23]. Selvi et al. [24] depicted the permeable layer effects in the spherical flow of Reiner-Rivlin material. Puspanathan et al. [25] observed the rotating disk analysis of Reiner-Rivlin fluid due to the shrinking surface. Alarabi et al. [26] examined the distinguished features of Reiner-Rivlin liquid with heat transfer effects. Yasin et al. [27] reported the properties of blood by following the Reiner-Rivlin liquid subject to Hall effects. Abdeljawad et al. [28] visualized the peristaltically driven Darcy flow of Reiner-Rivlin via theoretical assumptions, while Khan et al. [29] used the updated relations for assessing the heat transfer by using Reiner-Rivlin fluid.

Bioconvective transport is a physical phenomenon accounting for the pattern of microorganisms that float with minor densities. Owing to the concept of diverse instability, the microorganisms are able to swim in the upper layer of fluid, making it highly denser. The assessment of such denser effects is novel due to the stability impact. Utilizing the nanofluids with microorganisms results in more stable decomposition. The bioconvective phenomenon announcing applications in food products, biofuels, fertilizers, etc. Some recent research conducted on the bioconvective transport of nanofluid can be examined in Refs. [30–34].

The evaluation of the literature survey witnessed that diverse studies have been reported by researchers for the flow of non-Newtonian nanofluids, including those with bioconvective frameworks. However, the bioconvective transport of non-Newtonian nanomaterials has become more significant when the role of involved thermal features and temperature fluctuates. The aim of the current analysis is to highlight and disclose the outcomes of the bioconvective assessment of the Reiner-Rivlin (non-Newtonian) nanofluid by comprising the variable consequences of thermal conductivity, mass diffusivity, and motile density. The Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid model has been chosen to capture the complex non-Newtonian behavior of fluids that exhibit both viscous and elastic features, making it suitable for simulating enhanced heat and mass transfer in advanced engineering and biomedical systems. This model is particularly novel in modeling the flows through porous media, MHD effects, and bioconvective phenomenon. The porous moving surface with mass suction occurrence endorsed the flow while the heat source and radiative effects were utilized. The choice of a stretching surface for analyzing the heat and mass transfer phenomenon is especially valuable in processes such as polymer extrusion, fiber spinning, glass-fiber drawing, and metal sheet stretching, where the imposed surface strain directly governs boundary-layer development and thus controls the rates of thermal and solutal transport. The Cattaneo-Christov relations are used in heat and mass equations to modify the problem. Furthermore, convective boundary assumptions are used to analyze the flow. The numerical achievements are retained via a shooting scheme with fine accuracy, and the results are presented through physical visualization.

Current investigation pioneers a bioconvective investigation of a Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid with applications of variable thermal conductivity, mass diffusivity, and motile microorganism density within a porous, MHD-influenced moving surface featuring mass suction. Incorporating Cattaneo-Christov heat and mass flux models, convective boundary conditions, heat generation and thermal radiation and solving via a highly accurate shooting scheme, this analysis uniquely reveals how temperature-dependent transport properties and bioconvective interactions synergistically modulate flow, thermal, and concentration fields in advanced engineering and biomedical applications.

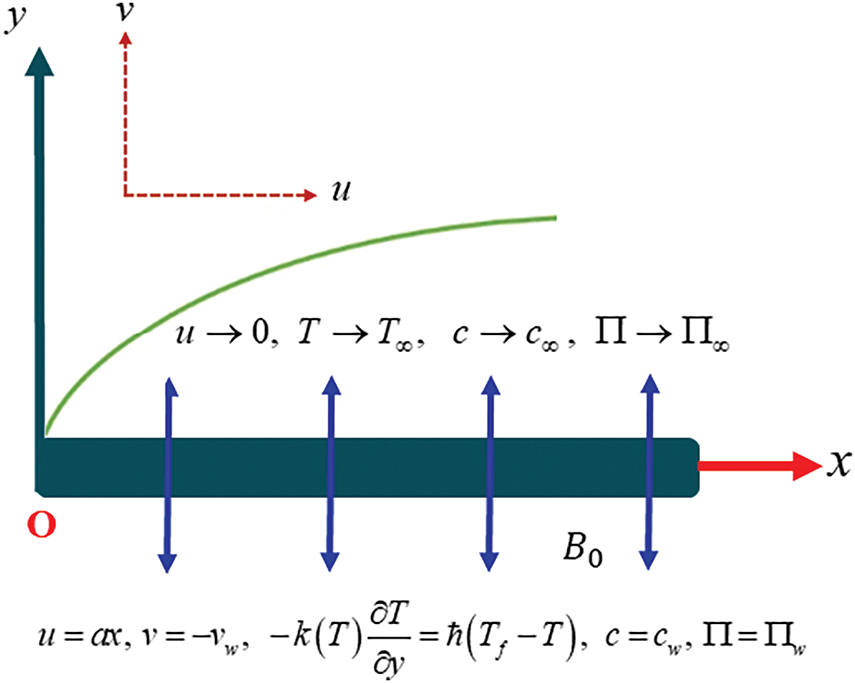

A uniform decomposition of Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid with microorganisms is considered. The flow is accounted for in two-dimensional space. The moving surface with velocity

Figure 1: Illustration of physical problem

The variable physical quantities

The novel physical quantities are

The problem is supported with following specific constraints:

where

Interpreting these defined variables leads to following set of dimensionless system:

where

The simplified boundary conditions are:

where

The dimensionless formulation of Nusselt coefficient, Sherwood coefficient and motile density number is defined as:

3 Numerical Solution of Problem

A higher order problem consisting of dimensionless equations has been solved numerically. The shooting numerical implication of problem is suggested to achieve the approximate solution. The motivated numerical scheme is associated to peak accuracy and excellent convergence. The simulations are started by conversion of problem into the first order system as follows:

The conversion of first order system is:

with:

The numerical computations are performed iteratively to achieve the desirable accuracy. In this technique, the bounded computational domain

with small real number

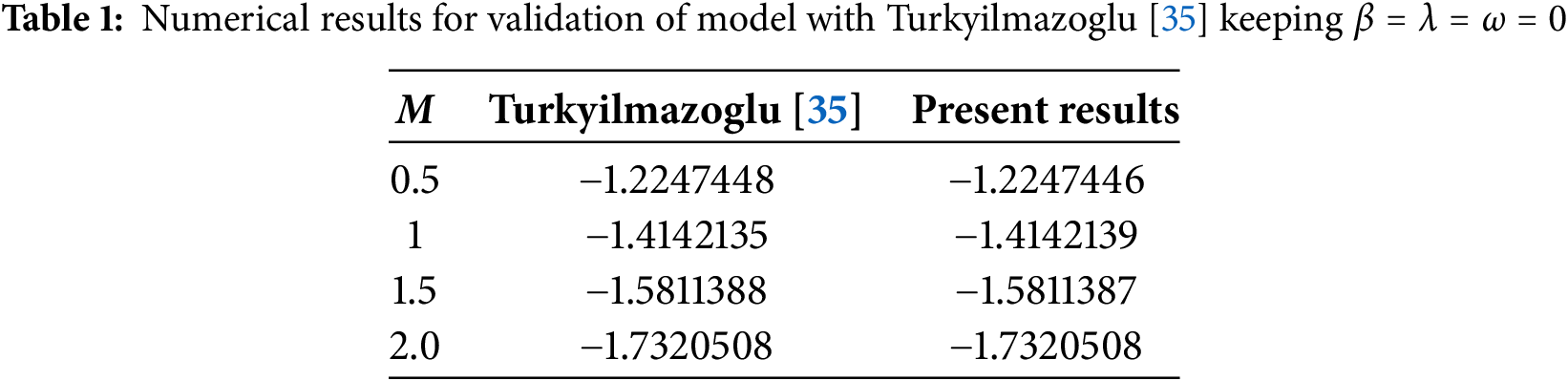

The validation of developed model is now ensured by comparing the work with Turkyilmazoglu [35] for some limiting constraints in Table 1. The numerical data evaluates the fine accuracy existed between both investigations.

5 Physical Analysis of Problem

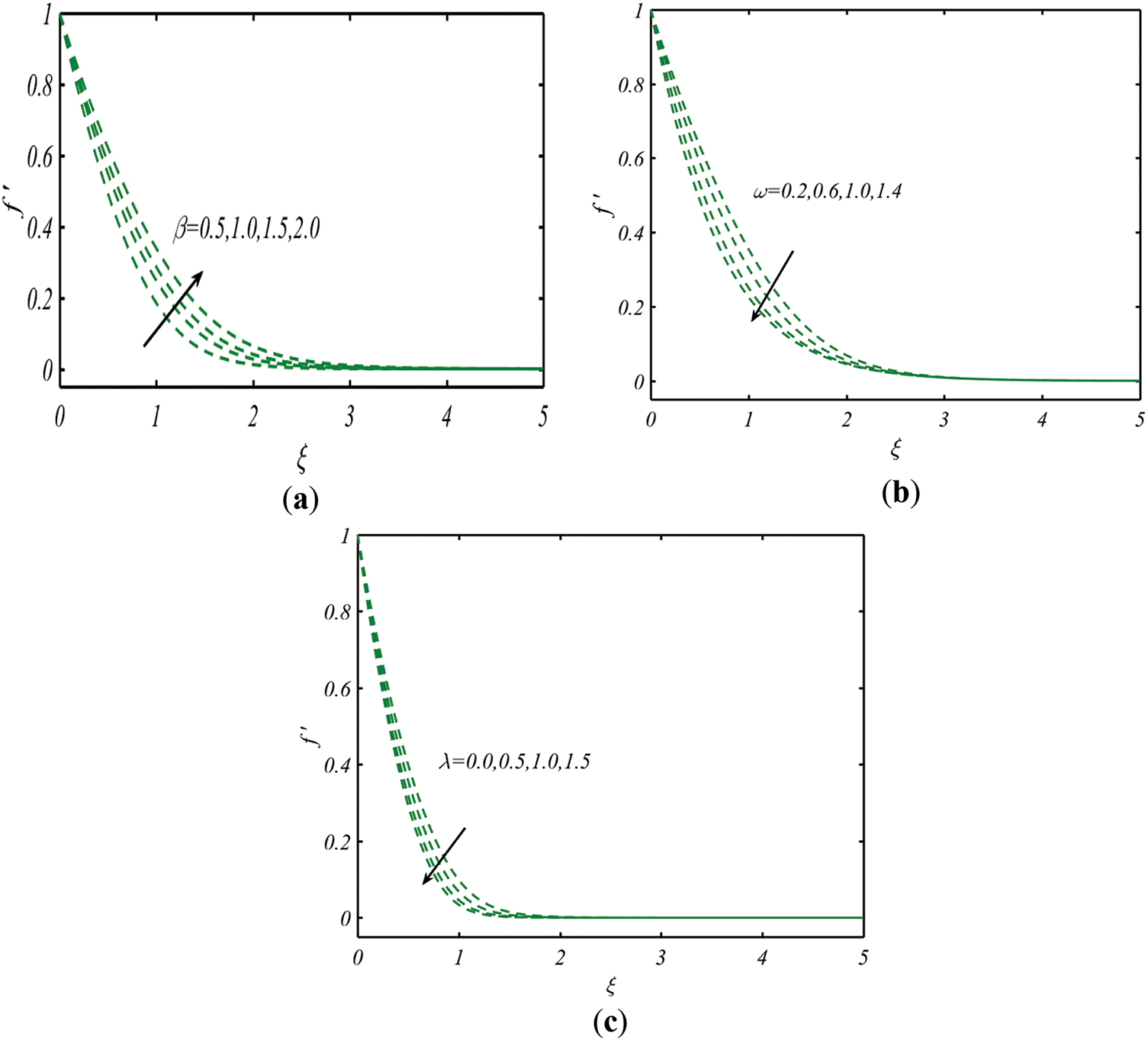

To address the physical dynamic of problem, the role of each parameter is important. In this section, the physical interpretation of results is focused. Fig. 2a addresses the effects of Reiner-Rivlin fluid parameter

Figure 2: Profile of

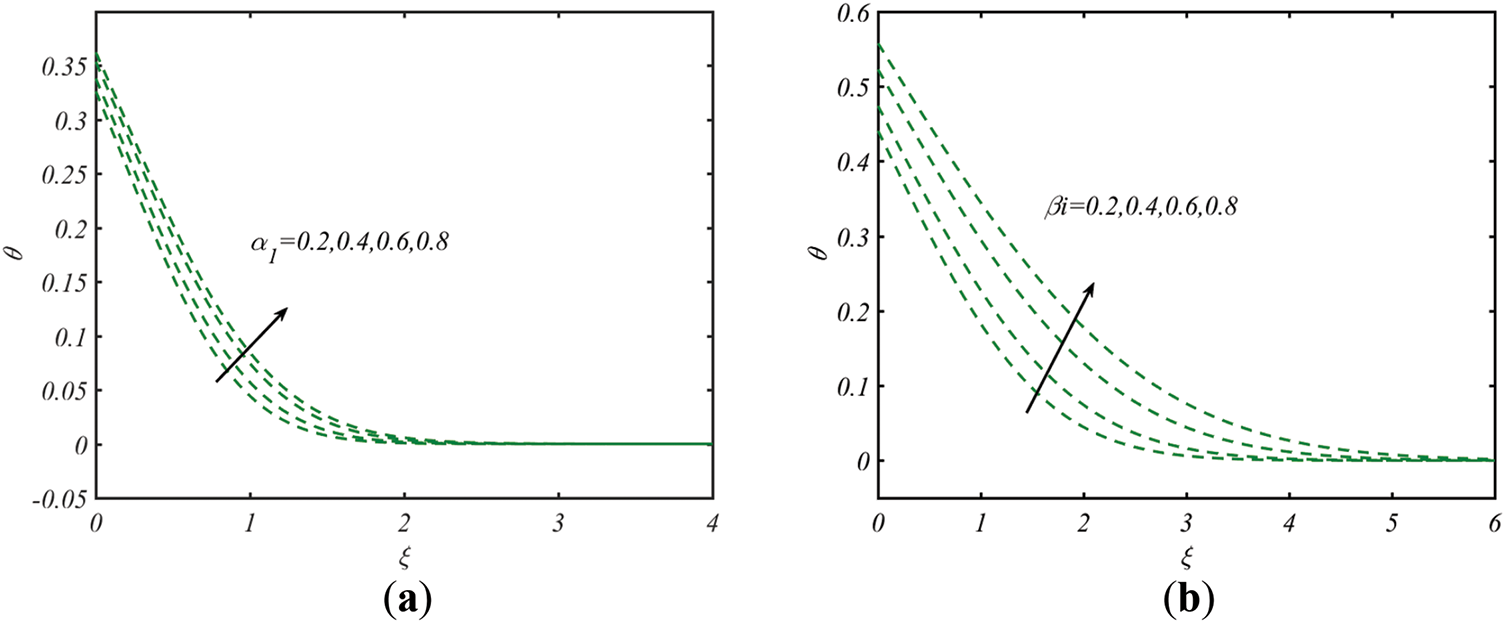

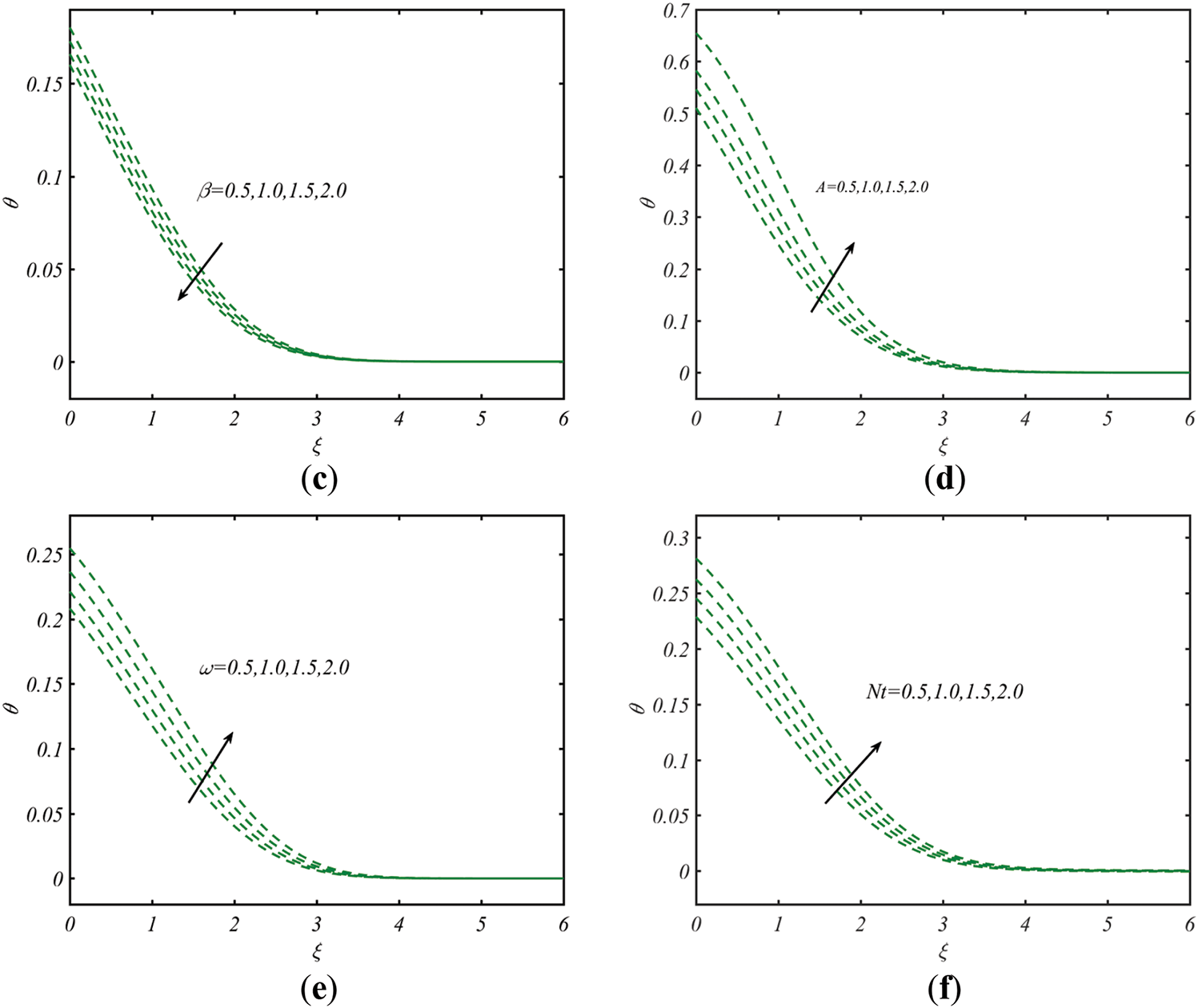

Fig. 3a incorporates the analysis for variable thermal conductivity parameter

Figure 3: Profile of

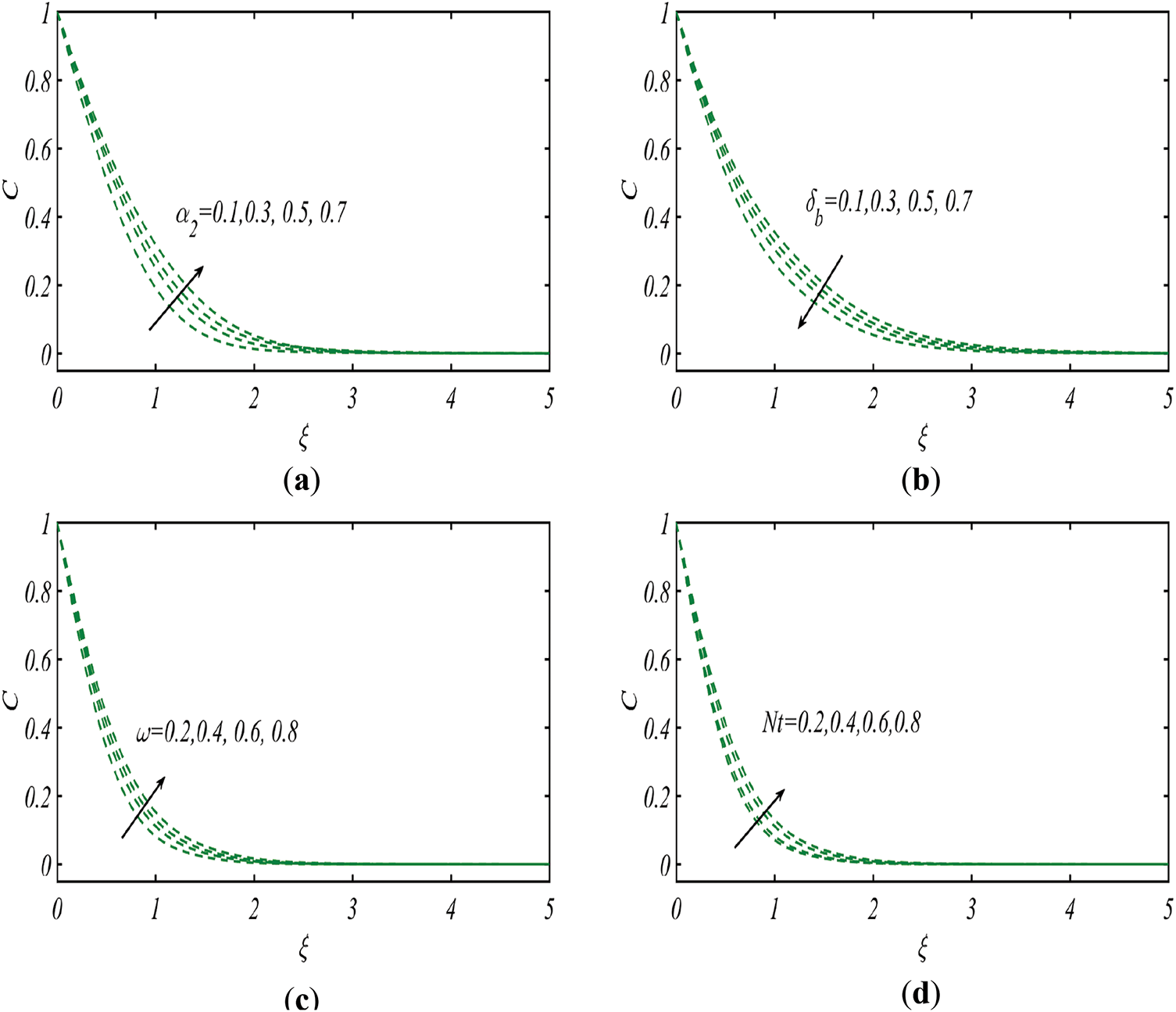

Fig. 4a justifies the influence of variable Brownian diffusivity coefficient

Figure 4: Profile of

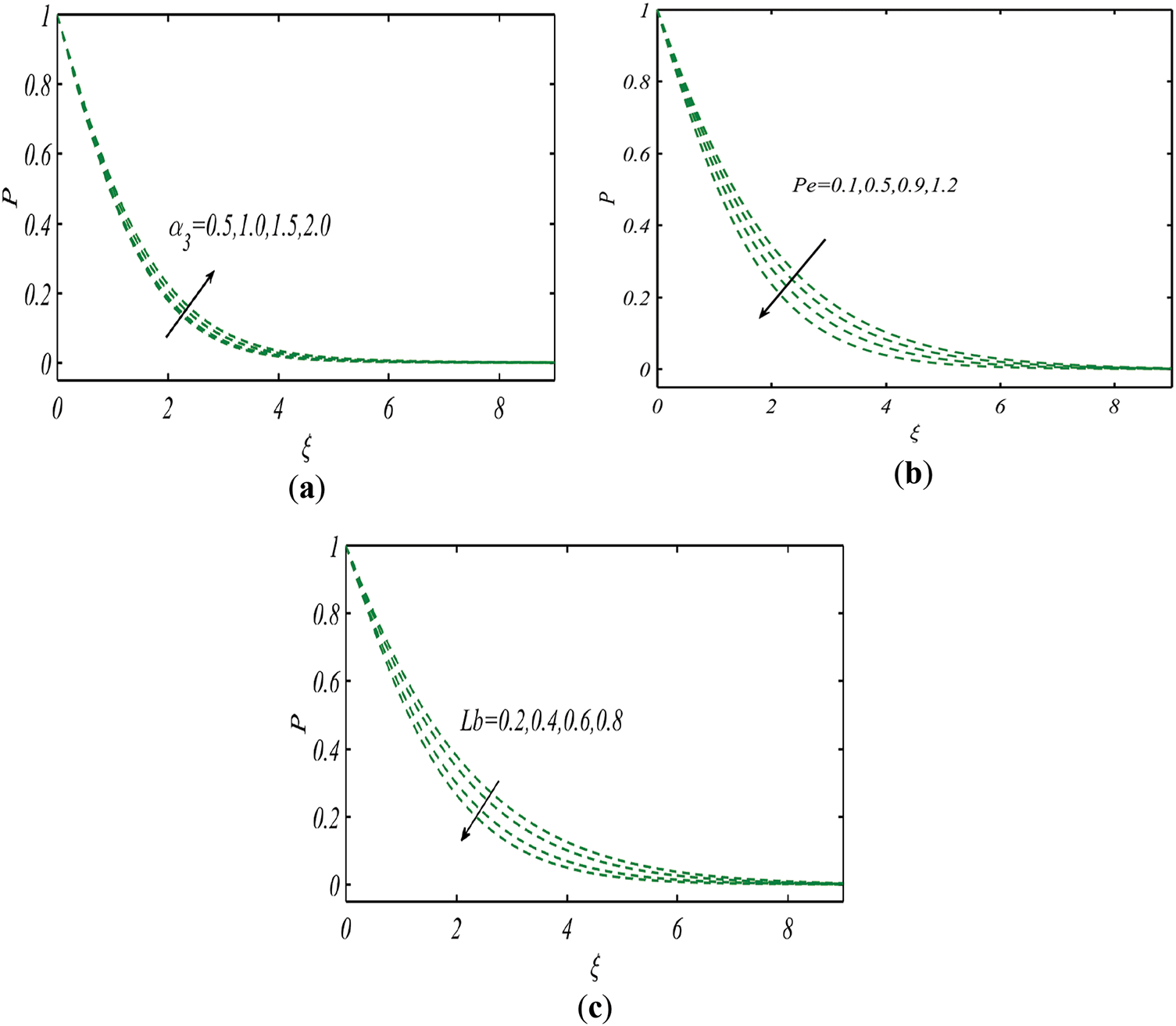

Fig. 5a–c presents results for microorganisms profile

Figure 5: Profile of

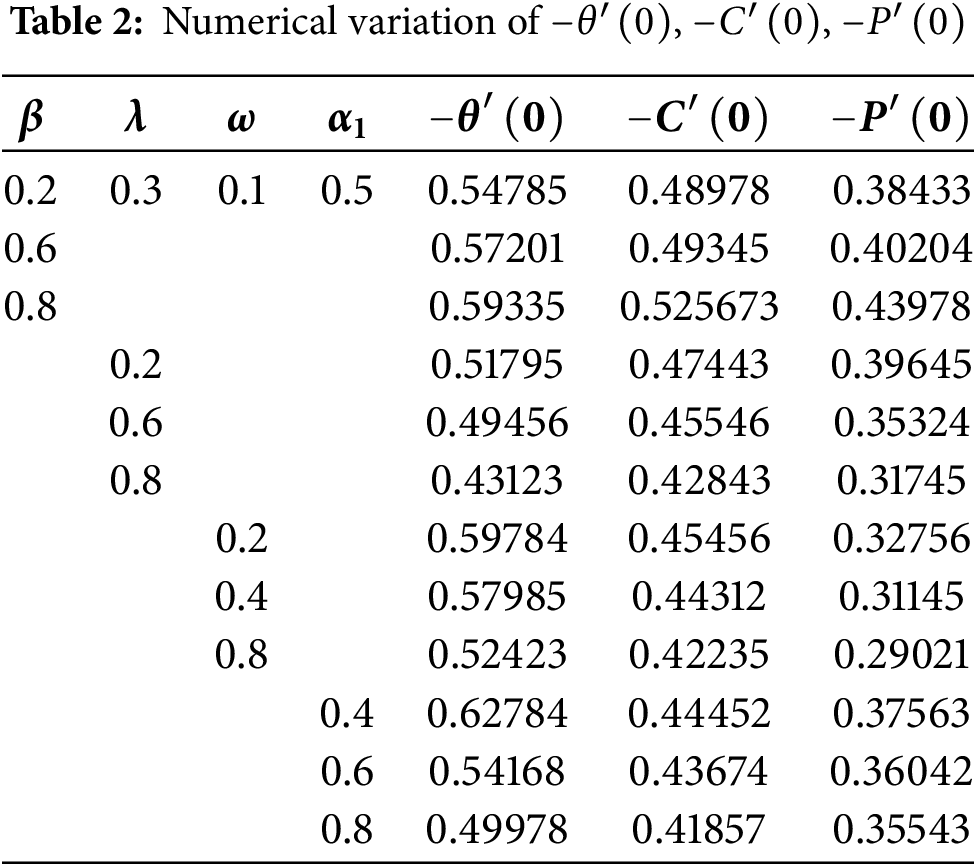

Table 2 represents the numerical variation of Nusselt number, Sherwood number and motile density number for

The bioconvective analysis for Reiner-Rivlin fluid parameters subject to variable thermal quantities and mass suction effects has been addressed. The problem is modeled with the Cattaneo-Christov approach. The shooting numerical scheme is used for the simulation process. The novel outcomes are listed as follows:

✠ The velocity profile reduces in the presence of mass suction.

✠ Upon raising the Reiner-Rivlin fluid parameter, the velocity profile increases.

✠ The presence of the variable thermal conductivity coefficient enhances the thermal phenomenon.

✠ The temperature profile declined for the Reiner-Rivlin fluid parameter.

✠ The presence of mass suction increases the temperature and concentration profile.

✠ A change in the Biot number leads to an improvement in heat transfer.

✠ The concentration profile reduces the concentration relaxation time parameter.

✠ The microorganism profile increases the variable motile density coefficient.

✠ The simulated observations have real potential applications in enhancing the heat transfer phenomenon, thermal recovery, cooling processes, energy systems, nuclear engineering etc.

Future recommendations in the current model can be explored by incorporating the Hall features, consideration of energy generation and higher order slip features, sensitivity analysis and hybrid nanofluids.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Mahmoud Bady—Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Fitrian Imaduddin—Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Iskander Tlili—Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Choi SUS, Eastman JA. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. In: Proceedings of the 1995 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exhibition; 1995 Nov 12–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

2. Eshgarf H, Nadooshan AA, Raisi A. A review of multi-phase and single-phase models in the numerical simulation of nanofluid flow in heat exchangers. Eng Anal Bound Elem. 2023;146(1):910–27. doi:10.1016/j.enganabound.2022.10.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alsabery AI, Abosinnee AS, Al-Hadraawy SK, Ismael MA, Fteiti MA, Hashim I, et al. Convection heat transfer in enclosures with inner bodies: a review on single and two-phase nanofluid models. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2023;183:113424. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hafez NM, Thabet EN, Khan Z, Abd-Alla AM, Elhag SH. Electroosmosis-modulated Darcy-Forchheimer flow of Casson nanofluid over stretching sheets in the presence of Newtonian heating. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;53:103806. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nagaraja B, Gireesha BJ, Almeida F, Kumar P, Ajaykumar AR. Entropy analysis of Darcy-Forchheimer model of Prandtl nanofluid over a curved stretching sheet and heat transfer optimization by ANOVA-Taguchi technique. J Appl Comput Mech. 2024;10(2):287–303. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2025.101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khan Z, Khan W, Arko YAS, Egami RH, Garalleh HAL. Numerical stability of magnetized Williamson nanofluid over a stretching/shrinking sheet with velocity and thermal slips effect. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2025;86(6):1763–83. doi:10.1080/10407790.2024.2321483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Smida K, Ahmad M, Khan SU, Taj M, Awan MW, Butt FM, et al. Lubricated stagnation point flow of Walters-B nanofluid with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model: hybrid Homotopy analysis simulations. Results Eng. 2024;21(1):101689. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gupta S, Jangid NK, Jain D, Singhal VK, Jain CP. Investigation of radiative MHD Carreau nanofluid over an inclined stretching cylinder with activating energy, Wu’s slip, and convective heating. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2024;85(1):1–19. doi:10.1080/10407790.2023.2223756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Aich W, Adnan, Abbas W, Bilal Riaz M, Ahmed MA, Ben Said L, et al. Impacts of nanoscaled metallic particles on the dynamics of ternary Newtonian nanofluid laminar flow through convectively heated and radiated surface. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;53(3):103969. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Seethamahalakshmi V, Rekapalli L, Rao TS, Santoshi PN, Reddy GVR, Oke AS. MHD slip flow of upper-convected casson and Maxwell nanofluid over a porous stretched sheet: impacts of heat and mass transfer. CFD Lett. 2023;16(3):96–111. doi:10.37934/cfdl.16.3.96111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Khan SU, Ali Q, Adnan. Thermal determination of hybrid nanofluid with molybdenum disulphide (MoS2) and graphene oxide (GO) nanoparticles: AB fractional simulations. Pramana. 2024;98(2):70. doi:10.1007/s12043-024-02764-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sultan AJ, Hussain ZN, Ali JM, Majdi HS, Al-Naseri H. Experimental study of forced convective heat transfer in a copper tube using three types of nanofluids. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2025;21(2):351–70. doi:10.32604/fdmp.2024.056292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abbasi A, Gharsi S, Dinarvand S. A review of the applications of nanofluids and related hybrid variants in flat tube car radiators. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2025;21(1):37–60. doi:10.32604/fdmp.2024.057545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mahmoud EM, Abdelowahed H, Khadija C. Modeling thermophysical properties of hybrid nanofluids: foundational research for future photovoltaic thermal applications. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2025;21(1):61–70. doi:10.32604/fdmp.2024.053458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang G, Luo J, Sun M, Yu Y, Chen J, Wang J, et al. A novel reliable parametric model for predicting the nonlinear hysteresis phenomenon of composite magnetorheological fluid. Smart Mater Struct. 2025;34(3):035060. doi:10.1088/1361-665x/adbf57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li N, Morozov IB, Fu LY, Deng W. Unified nonlinear elasto-visco-plastic rheology for bituminous rocks at variable pressure and temperature. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. 2025;130(3):e2024JB029295. doi:10.1029/2024JB029295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Muhammad K, Sarfraz M, Alrihieli HF, Elseesy IE. Significance of Brownian diffusion and thermophoresis in energy and mass optimization for Newtonian and Non-Newtonian fluid flow: a numerical study via Keller-Box method. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2025;72(4):106365. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2025.106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Reiner M. A mathematical theory of dilatancy. Am J Math. 1945;67(3):350. doi:10.2307/2371950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rivlin RS. The hydrodynamics of non-Newtonian fluids. I. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1948;193(1033):260–81. doi:10.1098/rspa.1948.0044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Naqvi SMRS, Kim HM, Muhammad T, Mallawi F, Ullah MZ. Numerical study for slip flow of Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid due to a rotating disk. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2020;116(6):104643. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Khan SA, Hayat T, Alsaedi A. Entropy generation in chemically reactive flow of Reiner-Rivlin liquid conveying tiny particles considering thermal radiation. Alex Eng J. 2023;66(6):257–68. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.11.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Arain MB, Bhatti MM, Zeeshan A, Alzahrani FS. Bioconvection Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid flow between rotating circular plates with induced magnetic effects, activation energy and squeezing phenomena. Mathematics. 2021;9(17):2139. doi:10.3390/math9172139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Khan SA, Hayat T, Alsaedi A. Simultaneous features of soret and dufour in entropy optimized flow of Reiner-Rivlin fluid considering thermal radiation. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;137(7):106297. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Selvi R, Maurya DK, Shukla P, Chamkha AJ. Analysis of a Reiner-Rivlin liquid sphere enveloped by a permeable layer. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(2):023303. doi:10.1063/5.0182706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Puspanathan S, Naganthran K, Hashmi MM, Hashim I, Momani S. Numerical investigation of Reiner-Rivlin fluid flow and heat transfer over a shrinking rotating disk. Chin J Phys. 2024;88(2):198–211. doi:10.1016/j.cjph.2024.01.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alarabi TH, Mahdy A, Abo-zaid OA. Distinctive approach for MHD natural bioconvection flow of Reiner-Rivlin nano-liquid due to an isothermal sphere. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;55:104179. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yasin M, Hina S, Naz R. Influence of Hall and Slip on MHD Reiner-Rivlin blood flow through a porous medium in a cylindrical tube. Soft Comput. 2024;28(4):2799–810. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-09538-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abdeljawad T, Sohail M, Mostapha DR. Impacts of Hall current and Joule heating of Cattaneo-Christov on peristaltic stenosed artery of Reiner-Rivlin liquid through Darcy-Forchheimer feature. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(5):102679. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2024.102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Khan SU, Adnan, Ramesh K, Riaz A, Awais M, Bhatti MM. Insights into the impact of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux on bioconvective flow in magnetized Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid. Sep Sci Technol. 2024;59(10–14):1172–82. doi:10.1080/01496395.2024.2366889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shamshuddin M, Saeed A, Mishra SR, Katta R, Eid MR. Homotopic simulation of MHD bioconvective flow of water-based hybrid nanofluid over a thermal convective exponential stretching surface. Int J Numer Meth Heat Fluid Flow. 2024;34(1):31–53. doi:10.1108/hff-03-2023-0128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bilal S, Pan K, Hussain Z, Kada B, Ali Pasha A, Khan WA. Darcy-Forchheimer chemically reactive bidirectional flow of nanofluid with magneto-bioconvection and Cattaneo-Christov properties. Tribol Int. 2024;193(9):109313. doi:10.1016/j.triboint.2024.109313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jayadevamurthy PGR, Rangaswamy NK, Prasannakumara BC, Nisar KS. Emphasis on unsteady dynamics of bioconvective hybrid nanofluid flow over an upward-downward moving rotating disk. Numerical Methods Partial. 2024;40(1):e22680. doi:10.1002/num.22680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ahmed SE, Arafa AAM, Hussein SA. Bioconvective flow of a variable properties hybrid nanofluid over a spinning disk with Arrhenius activation energy, Soret and Dufour impacts. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2024;85(6):900–22. doi:10.1080/10407782.2023.2193709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Puneeth V, Ali F, Khan MR, Anwar MS, Ahammad NA. Theoretical analysis of the thermal characteristics of Ree-Eyring nanofluid flowing past a stretching sheet due to bioconvection. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(7):8649–60. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02985-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Turkyilmazoglu M. The analytical solution of mixed convection heat transfer and fluid flow of a MHD viscoelastic fluid over a permeable stretching surface. Int J Mech Sci. 2013;77:263–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2013.10.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools