Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Conveyor Belt Crop Dryer Modelling: A Comprehensive Review

Department of Mechanical Engineering, The American University in Cairo (AUC), New Cairo, 11835, Egypt

* Corresponding Author: Omar Abdelaziz. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(1), 1-54. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.059710

Received 15 October 2024; Accepted 19 December 2024; Issue published 26 February 2025

Abstract

This review paper presents an in-depth investigation of the modeling techniques used to study conveyor belt dryers. These techniques are classified into four categories: theoretical modeling, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), empirical, and performance under different control strategies. Within the theoretical and CFD categories, the models are further classified as transient and steady state, as well as one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional. The empirical approach involves conducting experimental studies to collect moisture ratio data during the drying process and comparing it with empirical models. The methods of control are divided into classical and advanced controllers, with classical controllers including proportional-integral (PI), proportional-integral-derivative (PID), and quantitative feedback theory (QFT) controllers. Advanced controllers consist of artificial intelligence-based controllers, such as artificial neural networks (ANN), adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS), nonlinear autoregressive exogenous (NARX) models, model predictive control (MPC), and soft sensors. This review elucidated the methodologies and software employed for each modeling technique, as well as their prospective utility in industrial contexts. The utilization of theoretical and CFD methodologies is advantageous in forecasting the dynamics of complex systems. Conversely, empirical techniques serve the purpose of validating theoretical models and procuring data to facilitate model refinement. Controllers play a crucial role in the optimization of the drying process and the attainment of desired outputs.Keywords

Nomenclature

| Water activity of air stream leaving the product | |

| Specific surface area of product m2 | |

| Width of the product bed m | |

| Specific heat capacity J/kg.K | |

| Diffusion coefficient of the moisture vapor in the air m2/s | |

| Capillary diffusivity of water in air m2/s | |

| Drying constant | |

| Water diffusion coefficient in the gas phasem2/s | |

| Drying potentialkJ/kgvapor | |

| Thermodynamically drying potentialkJ/kgvapor | |

| Evaporation mass flux density in one pelletkg/m2.s | |

| Mass velocity of drying airkg/m2.s | |

| Heat Transfer coefficientW/m2.K | |

| Height of the product bedm | |

| Relative Humidity of air% | |

| Mass Transfer coefficientm/s | |

| Thermal conductivityW/m2.K | |

| Length of the beltm | |

| Air mass flow ratekg/s | |

| Moisture ratio | |

| Partial pressure of water vapor on–surface of moist materialPa | |

| Prandtl number | |

| Thermal EnergykJ | |

| Outside surface moisture index | |

| Reynolds Number | |

| Gas constant of water vapourJ/kg.K | |

| Times | |

| Absolute zero°C | |

| T | Residence times |

| Product temperature°C | |

| Air velocitym/s | |

| Velocity of the beltm/s | |

| Kinematic viscositym2/s | |

| Moisture content of the productkgwater/kgdry solid | |

| Equilibrium moisture content of the productkgwater/kgdry solid | |

| Absolute humidity of air streamkgwater/kgdry solid | |

| Logarithmic mean temperature difference | |

| Density of the productkg/m3 | |

| Material porosity | |

| Viscosity of drying airPa.s |

Crop preservation through drying is a well-established method [1], reducing moisture content to inhibit microbial activity and enzymatic reactions that cause spoilage [2]. By maintaining low moisture levels, dried products can be stored at room temperature without compromising quality, leading to significant cost savings [3]. Food drying involves convection or conduction heat and mass transfer [4]. Drying techniques primarily include convective and conductive methods. Over 400 designs have been reported in the literature [4]. Convective drying, where the heating medium directly contacts the product, is the most common, accounting for over 85% of industrial drying applications. Conversely, conductive drying transfers heat indirectly, often utilizing specialized equipment to preserve heat-sensitive materials [5].

Within the broad scope of drying technologies, conveyor belt dryers have emerged as a versatile and efficient choice, especially for continuous drying processes [6]. Continuous conveyor belt dryers are particularly valued in the food industry for their ability to handle a range of products, providing high throughput and uniform drying. By continuously moving the product through the drying chamber, conveyor belt dryers help prevent damp zones and ensure consistent quality [6].

This review specifically focuses on conveyor belt dryers used in agricultural crop drying, with a comprehensive analysis of the various modeling techniques applied to study these systems. Unlike previous review articles, which often focus on type of dryer, this work consolidates multiple modeling techniques—including theoretical models, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and empirical approaches—to provide a holistic perspective on conveyor belt drying. The novelty of this review lies in its comparative approach, evaluating each technique’s benefits, limitations, and practical applications in crop drying.

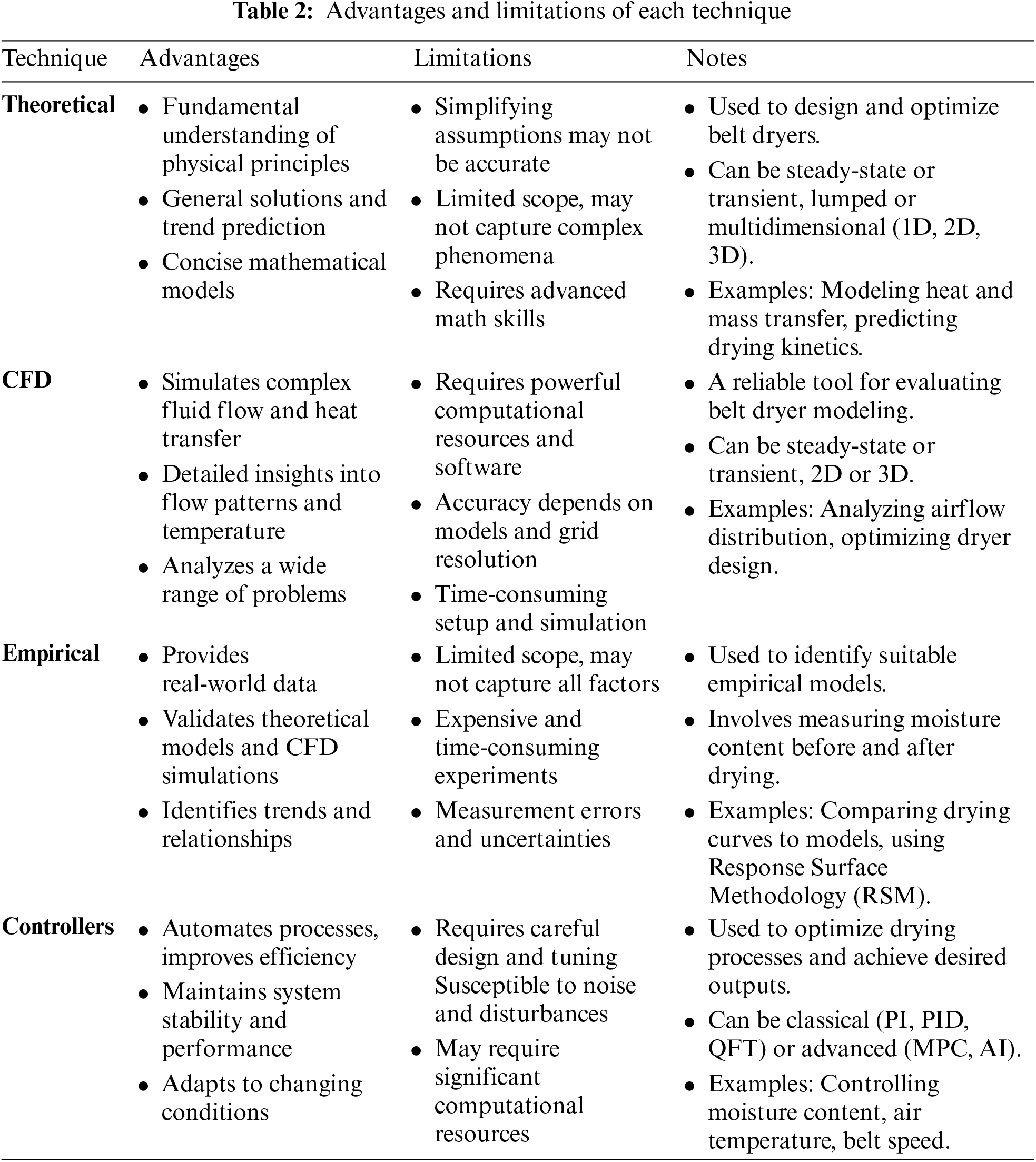

Furthermore, this paper explores control strategies that enhance the performance of conveyor belt dryers, detailing how different controllers are implemented and optimized to maintain precise drying conditions. To aid in understanding, a comparative table highlights the strengths and limitations of each modeling approach, guiding researchers in selecting the techniques that are best suited for their application requirements.

The goal of this review is to provide a valuable resource for researchers and practitioners interested in the modeling and optimization of conveyor belt dryers, contributing to advancements in agricultural drying processes that preserve product quality while enhancing energy efficiency.

2 Heat and Mass Transfer in Conveyor Belt Dryers

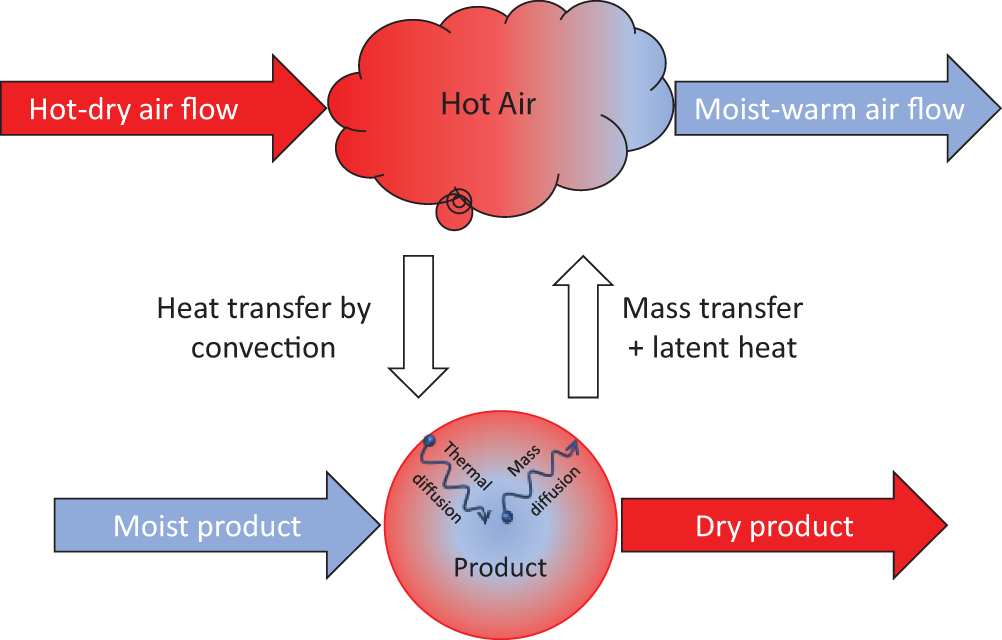

The drying process in conveyor belt dryers involves complex interactions between heat and mass transfer mechanisms, which govern the moisture removal from wet products. This section explores these mechanisms, highlighting the principles behind heat and mass transfer and their application in different conveyor belt drying systems. The discussion begins with the role of double diffusion. Double diffusion allows mass transfer or moisture release. Initially, moisture diffuses from the product core to the outer layer. The moisture then transfers from the product’s surface to the drying agent, which is drier. The heat and mass transfer processes, In Fig. 1, the Fourier law, and Fick’s second law of diffusion [7] control heat and mass transfer Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

Figure 1: Heat and mass transfer process in convective drying process

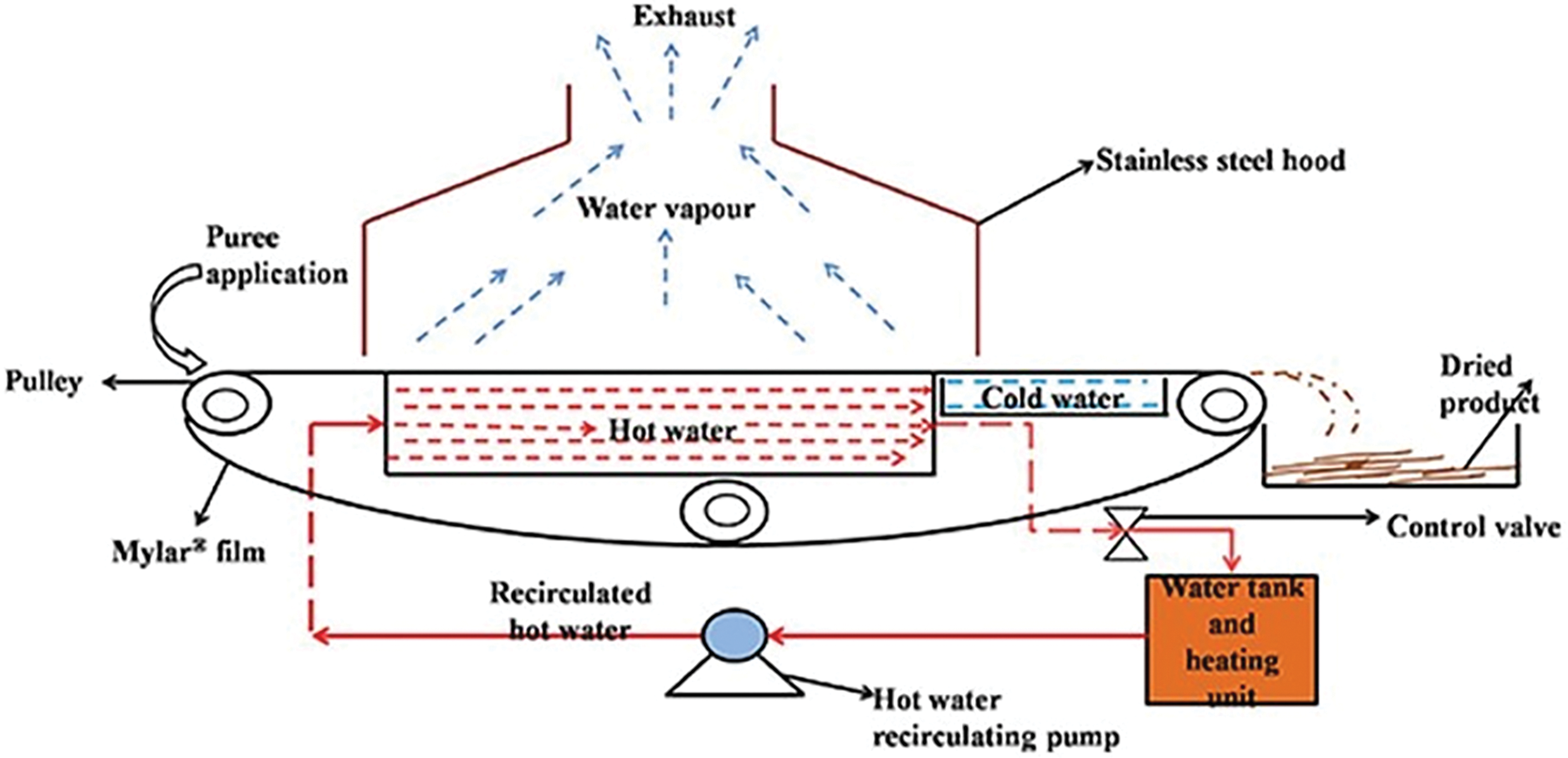

In normal drying, heat transfer increases the moist/wet product’s temperature, enhancing evaporation. Water vapor from the product is transported away by heated air. This continues until the product is dry enough. Product quality degrades as temperature rises. Thus, the best drying procedure should preserve the product’s aroma and flavour [6]. Belt drying, suitable for convection or conduction heating, is the most prevalent. Continuous conveyor belt dryers are the most versatile dryers for varied products [6]. Convection heating uses a heat exchanger to heat air or nitrogen, which is then sent to the tunnel or drying chamber where the belt moves the product. This dryer has high throughput and fast drying. Belt motion prevents damp zones and improves product quality [6]. In a conductive refractance window dryer (RWD), shown in Fig. 2, the desired product is made as a thin-film material on a polyethylene conveyor belt. The product is heated by the belt on a circulating hot water bath. After some length, the belt moves on a circulating cooling water bath to cool the product to avoid sticking. This drying method works for heat-sensitive materials but has a specific operational capacity [8]. Tayel et al. [9] reported in their research that the total capacity of RWD was about 0.326 kg/h.

Figure 2: Refractance window dryer [10]

Conveyor belt dryers are integral to many industrial drying processes due to their versatility and efficiency. These dryers consist of a moving belt that transports the product through a drying chamber, where heated air or other drying agents facilitate moisture removal. Conveyor belt dryers, like the one shown in Fig. 3 redesigned to efficiently dry products as they move along a continuous belt through a controlled environment. The image illustrates a typical conveyor belt dryer, featuring a mesh belt, a drying chamber, and temperature controls. Such systems are versatile and widely used for drying various products, especially those requiring uniform drying and consistent quality.

Figure 3: Actual image of conveyor belt dryer [11]

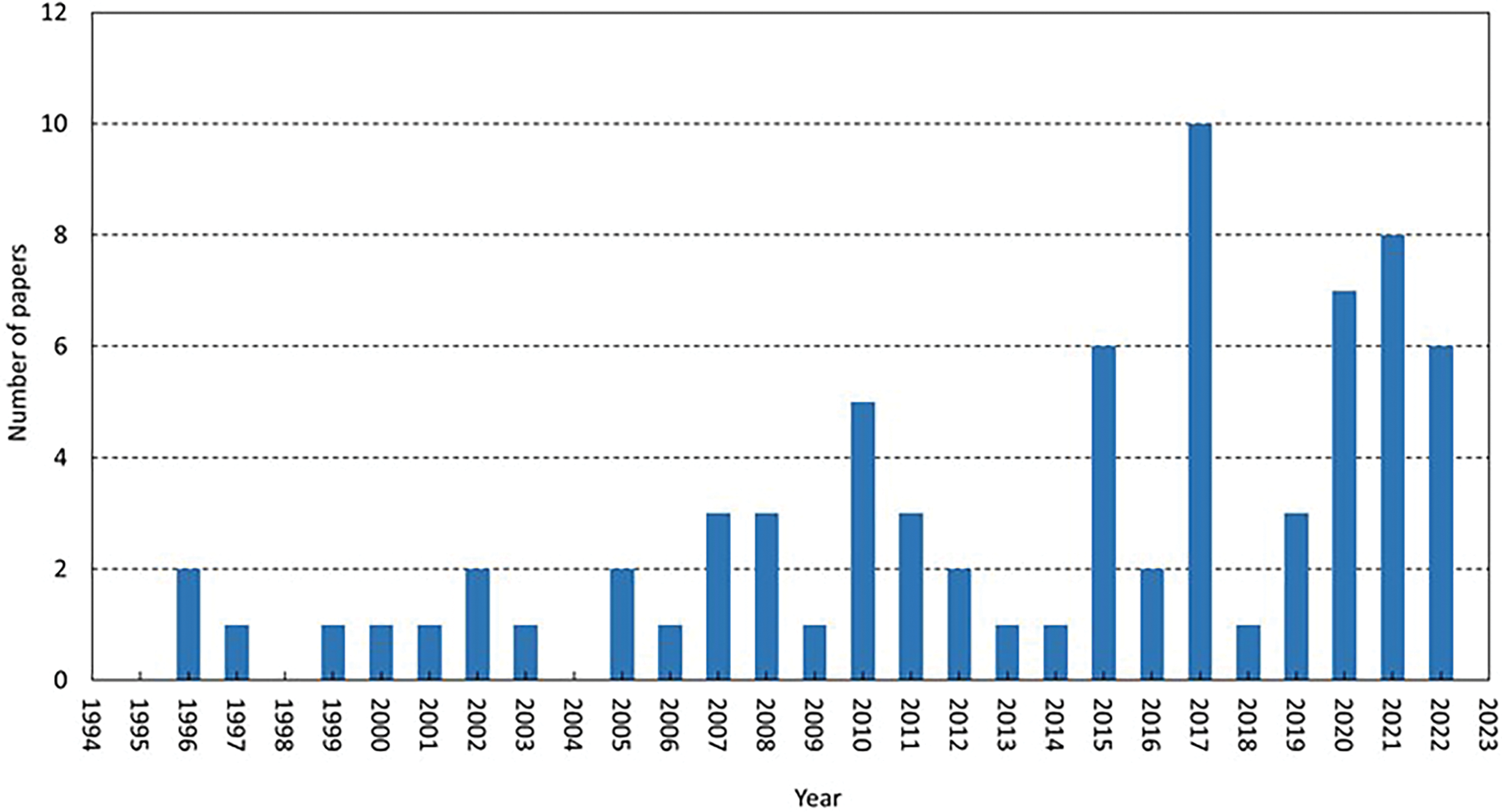

A comprehensive review of the existing body of literature reveals a consistent stream of research publications focused on developing and improving modelling techniques for conveyor belt dryers. These efforts aim to improve and control the performance of such dryers. Fig. 4 illustrates the number of annual publications on modelling studies generated over the past three decades. The figure is generated by searching for the phrases “Modelling + Conveyor-belt dryer” on various research platforms, including Lens [12], Science Direct [13], and Web of Science [14].

Figure 4: Number of relevant publications each year

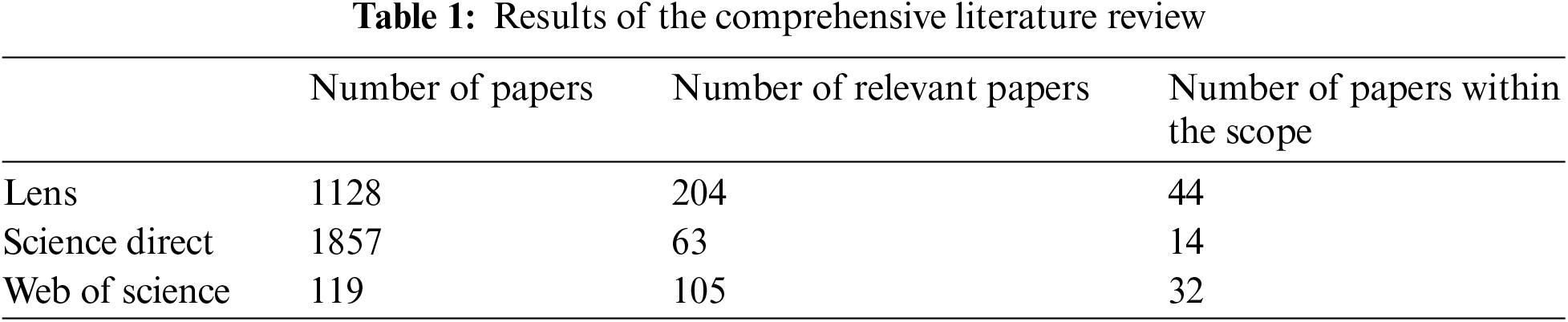

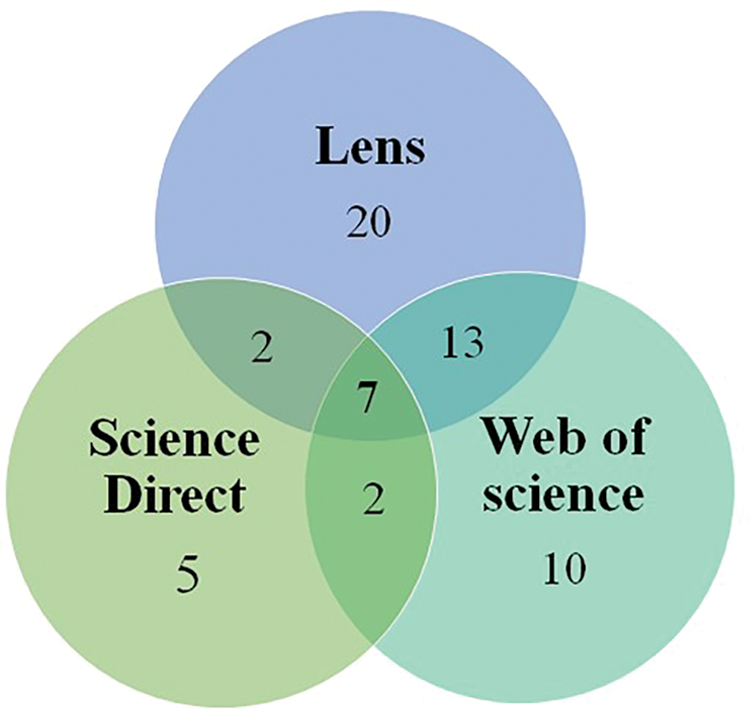

These findings demonstrate the extensive number of studies in this field. The total number of publications is then reduced to a set of “relevant articles” through a process of reviewing the titles and the abstracts of the papers in detail. The final set of papers is evaluated through a comprehensive review of each manuscript. The results of the exhaustive examination of relevant scholarly sources are presented in Table 1. Some of the reviewed papers appeared in more than one search engine, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Vin diagram for papers found in the different scientific search engines

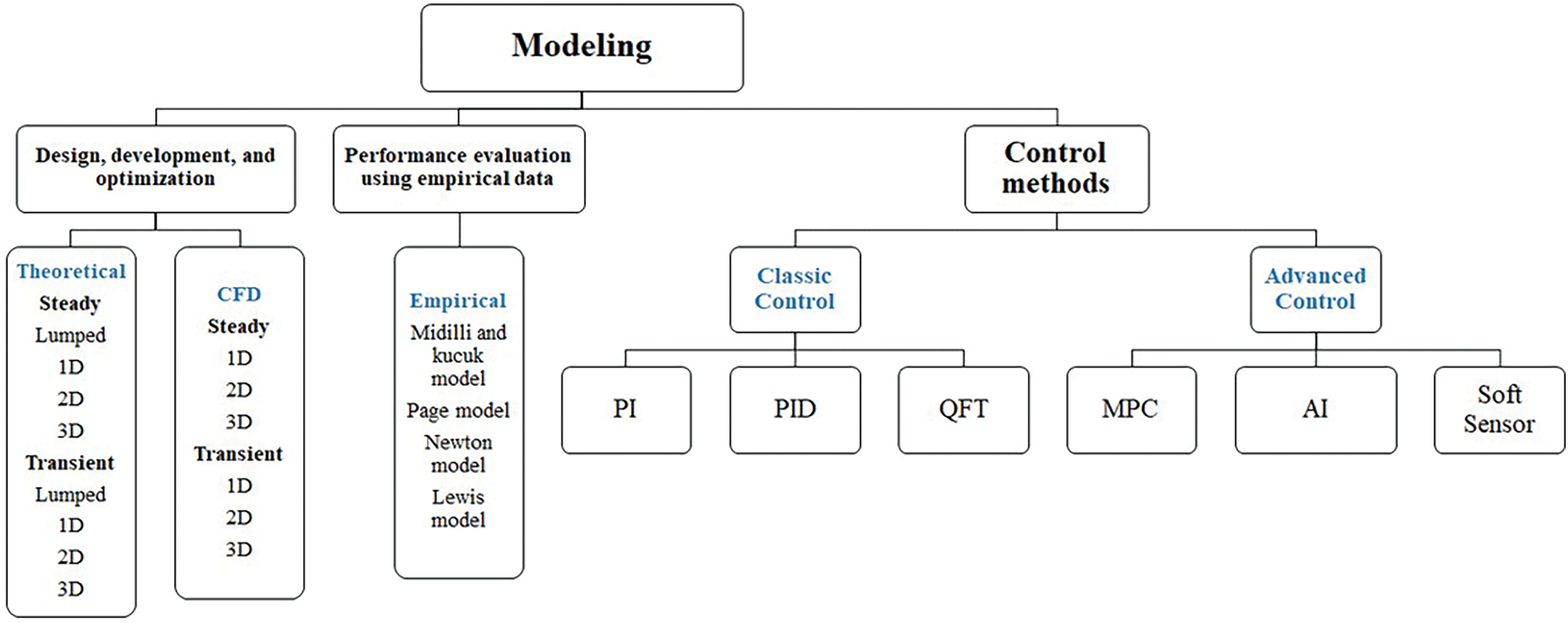

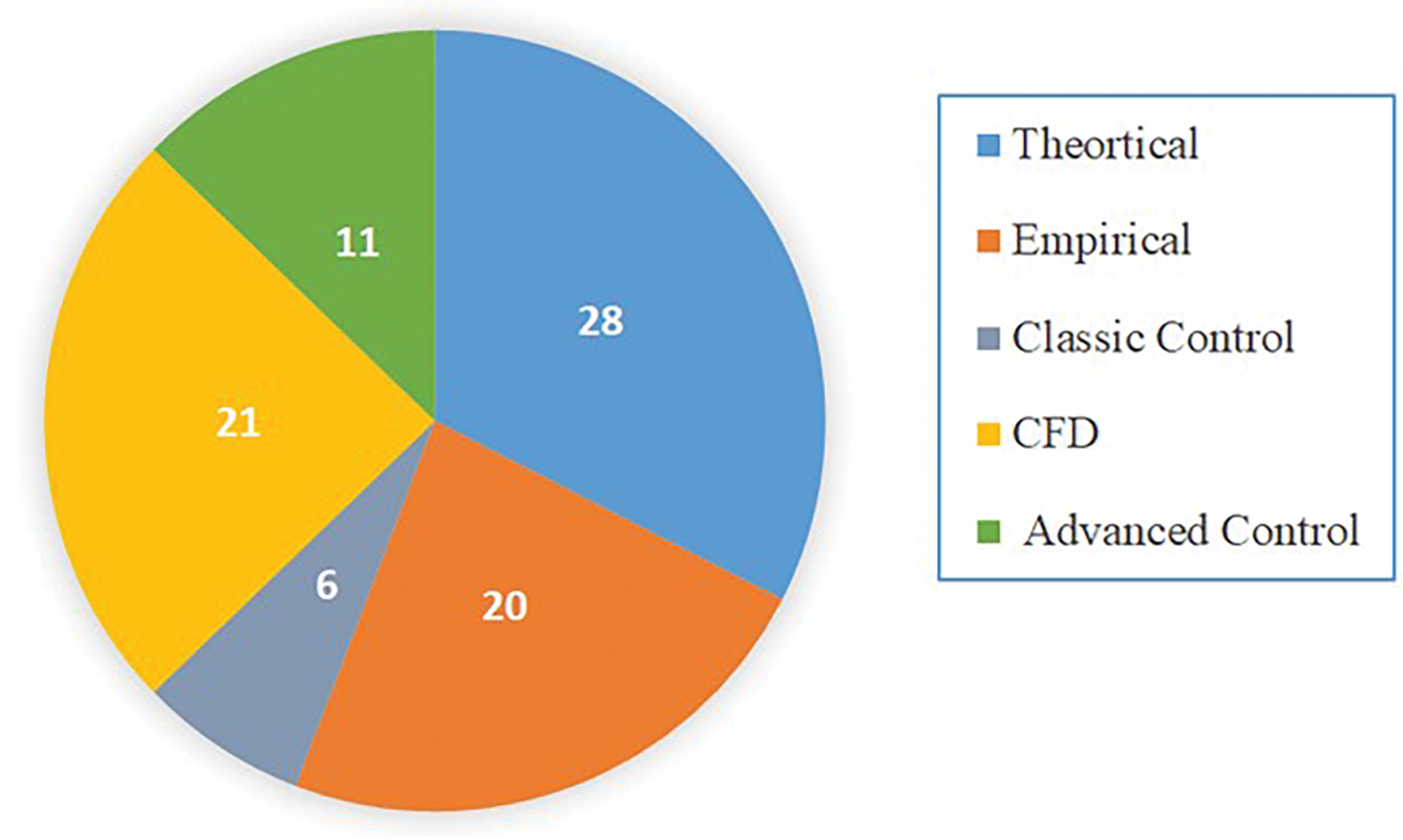

An examination of the published research in the field of modelling the drying process in conveyor belt dryers reveals that the predominant methodologies utilized in these studies include theoretical, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), empirical, and performance evaluation of control strategies, as depicted in Fig. 6. The number of publications for each modelling technique is also displayed in Fig. 7. A detailed comparison of the advantages and limitations of each methodology—namely theoretical, CFD, empirical, and control strategies—is presented in Table 2. The methods discussed in this text focus on several aspects of conveyor belt dryer systems, including:

Figure 6: Belt-dryers modelling techniques and the corresponding number of publications for each technique

Figure 7: Number of publications of each modelling technique

• Design, development, and optimization.

• Performance evaluation using empirical data.

• Control methods.

Both theoretical and CFD modelling are used to design, develop, and optimize the operational parameters. The design of belt dryers and the optimization of the control parameters are topics covered by theoretical modelling methods. Most research on CFD modelling focused on improving the dryer efficiency by homogenizing the airflow distribution. Theoretical modelling and CFD simulations can be either steady or transient. These models can further be categorized as lumped or multidimensional (1-D, 2-D, and 3-D).

In performance evaluation using empirical data, empirical techniques are utilized to identify the most suitable empirical model, with coefficients, which can accurately represent the performance of the drying process. First, the moisture content of the product is measured pre- and post-drying to compute the overall moisture ratio for the drying process, as described in Eq. (3). Subsequently, several empirical models, such as those based on Midilli et al. [15], Hendreson et al. [16], Newton [17], and Lewis [18], are used to match the overall moisture ratio. Ultimately, the optimal empirical model and its corresponding coefficients are chosen to depict the performance of the drying process accurately. The selection criteria are based on the correlation coefficient (

where

Various techniques can be found in the literature that address the control of conveyor belt dryers. Conveyor belt dryers are challenging to regulate because changes in the dryer’s intake, such as the inlet solid moisture content, are not immediately apparent at its output. This information delay can considerably affect the performance of the dryer [6]. The controllers used can be classified to

• Classic Control

• Advanced Control

Classical controllers include proportional-integral (PI), proportional-integral-derivative (PID), and quantitative feedback theory (QFT) controllers. QFT is a robust controller technique that can handle plant uncertainty and is developed using robust specifications. Advanced controllers include model predictive controllers (MPC) and artificial intelligence (AI) controllers.

4 Theoretical Modelling Techniques

The review of literature reveals that various researchers have studied drying processes using conveyor belts, fluidized beds, rotary dryers, and belt dryers. Steady lumped models are detailed below in Section 4.1, 1D models are reported in Section 4.2, and a 2-D model is presented in Section 4.3 for belt dryers. Transient modelling of conveyor belts is presented in Section 4.4 for lumped model, in Section 4.5 for 1-D models, and in Section 4.6 for multidimensional models. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 3.

4.1 Steady Lumped Modelling Studies

In 1993, Kiranoudis et al. [19] established a mathematical model for constructing a conveyor belt dryer. The model was used to determine the best flow-sheet structure, building characteristics, and operating conditions with respect to total annual cost. The analysis of the belt structure assumed that the belt dryer was composed of a series of drying chambers and that the drying chamber was an elementary module. The mathematical model was then applied to one elementary module and repeated for the entire dryer. The heat transfer coefficient was assumed to be sufficiently high so that the product and air streams would be in thermal equilibrium at the end of the dryer. The authors used the mass-transfer coefficient reported in Bruin et al. [20]. The proposed methodology implemented to design a drying plant for drying 2400 tons of raw potato per year. To achieve this, the raw material is first cut into 10-mm cubes and then introduced into the processing dryer at a rate of 200 kg of dry solid per hour. The initial moisture content of the raw material is 5 kg of water per kg of dry material (on a dry basis), and the desired moisture content at the dryer’s exit is 0.05 kg of water per kg of dry material (also on a dry basis). It is crucial to ensure that the product does not exceed a temperature threshold of 75°C during the drying process to prevent degradation. The maximum available area for constructing the plant’s chambers is 5 square meters, and the belt load at the entrance of each drying section is maintained at 50 kg per square meter (on a wet basis).

In 1996, Kiranoudis et al. [21] extended their previous work on conveyor belt dryers to include convective industrial dyers: conveyor belts, fluidized beds, and rotary. Mathematical modelling was used to determine the most effective way to build and run each type of dryer for a given production capacity. The results indicated that the design cost of rotary dryers was higher compared to fluidized bed dryers. However, in terms of operational efficiency, the situation is reversed due to the superior heat transfer achieved in rotary dryers. On the other hand, conveyor-belt dryers fall somewhere in between, delivering satisfactory results in both design and operation.

4.2 Steady One-Dimensional Modelling Studies

Hosseinizand et al. [22] conducted an economic analysis for a conveyor belt dryer used to of dry microalgae chlorella. Their work focused on the potential for heat regeneration from an adjacent power plant. To identify the crucial design variables, they analytically modelled the belt dryer. An empirical equation for the mass-transfer coefficient was obtained from the experimental data. With the assumption of lumped coordinates for the width and thickness, a 1-D steady-state problem. They used a finite difference approach to solve the system with a convergence criterion of

Sebastian et al. [23] performed a 1-D numerical simulation to analyse a conveyor belt dryer. Their study involved differential relations of the balance equations and transfer functions. Heat and mass transfer networks (HMEN) were developed using the NTU approach, resulting in the formulation of a nonlinear algebraic system of equations. The solution of the nonlinear drying system was obtained by MLTCONV software, employing iterative techniques such as the Newton-Raphson approach. They reported that simulation results using MLTCONV improved computational efficiency compared to traditional methods.

de Souza Barrozo et al. [24] studied the simultaneous heat and mass transfer phenomena in moving bed dryer between air and soybean seeds. A 1-D boundary value problem was developed and solved numerically using a computational algorithm that employed the axial integration differential/algebraic system solver (DASSL) code [25]. Backward differential formula techniques were implemented in the FORTRAN code to solve a broad collection of implicit initial value differential-algebraic equations with a differential index of no more than one. The simulation results were slightly higher when compared to their experimental data, with average variances for air humidity and seed temperature of 3.6% and 2.2%, respectively.

4.3 Steady Two-Dimensional Modelling Study

Holowaty et al. [26] modelled a double pass belt conveyer dryer to dry yerba mate. An experimental setup was constructed to determine the water diffusion coefficient as a function of temperature and moisture content. Then, the analytical equations obtained from the energy and mass balances at each node of the product were reported. Finally, they solved the system of equations using the forward finite difference method. Validation was performed by comparing the experimental results for the same conditions with the mathematical showing RMSE of 0.02, demonstrating that the fit is superior to that of comparable modelling results acquired in the case of a single belt dryer. Simulation results under different drying conditions showed that the dryer’s energy efficiency could be improved by recirculating 15% of the exhaust air.

4.4 Transient Lumped Modelling Studies

Vaxelaire et al. [27] developed a numerical model based on experimental laboratory data for drying residual sludge using a belt dryer. They used their experimental data and optimization software to develop a single empirical equation, Eq. (4), which represents the drying kinetics of the sludge. In addition, they used their experimental data to develop an expression for drying potential, Eq. (5), to reduce the set of operating conditions, namely the dry-bulb temperature and relative humidity. The authors then developed a mathematical model that described the mass and energy balances of the process using the developed empirical equations.

where

Xue et al. [28] proposed a prediction model to develop the operating parameters of a vacuum belt dryer in which the moisture content of the product during the drying process was predicted using a numerical simulation employing boiling and evaporation models. The numerical simulation was improved by connecting the boiling and evaporation processes with the transient model. Lab-scale and industrial production tests validated the numerical model. The results showed that conveyor belt speed played the most critical role in the vacuum belt dryer process.

Friso [29] proposed mathematical modelling and design guidelines for a conveyor belt dryer. Starting from a simple energy and mass balance on an elementary area of the product, he assumed a temperature distribution inside the dryer and the inlet and exit air temperatures to obtain the heat transfer coefficient. In addition, he assumed that the product temperature was constant during the drying period and was equivalent to the wet-bulb temperature of the incoming air. Moreover, an experimental setup for a pilot-belt dryer was built to validate the proposed mathematical model.

In 2021, Friso [30] optimized his mathematical model in the form of specific two ordinary differential equations (ODEs). The solution of the ODEs performed a relation between the initial and final moisture content and the input and exit air temperatures. Moreover, the experimental model was used to verify the optimized model.

Eng et al. [31] improved the theoretical model developed by Nindo et al. [32] to investigate the temperature gradient of mango puree during the drying process in RWD. For this, a system of partial differential equations with a single product layer and a small-time increment was developed. An experimental model for the RWD was constructed to validate the mathematical model. The model fitted well with the experimental results, showing a p value of less than 0.05, and thus, it can be used to predict the temperatures and heat profiles for the RWD.

Shirinbakhsh et al. [33] designed and simulated a large-scale solar-assisted conveyer-belt dryer for biomass drying using a numerical model implemented in MATLAB [34]. The design parameters from their numerical model were used to perform economic optimization. Their model was verified by comparing the drying time obtained to that of drying gelatine and carrot in the conveyor belt dryer obtained using correlations from [35] and [36]. In their numerical model, the authors used empirical equations for the equilibrium moisture content, the drying time constant, and the drying time, as shown in Eqs. (6)–(8), respectively.

where

A genetic algorithm was used to carry out the economic optimization, under different economic scenarios to minimize the total annual cost (TAC) for the solar-assisted conveyer-belt dryer. The significant variables that affect the economic analysis were identified using the degrees-of-freedom analysis. Based on which, the system’s capital and operating costs were calculated. It was shown that low solar fraction scenarios resulted in an infeasible alternative compared with the fossil fuel dryers.

4.5 Transient One-Dimensional Modelling Studies

Canabarro et al. [37] studied the effects of drying conditions on the olive leaf supercritical extracts’ composition. They developed a mathematical model, based on energy and mass balances, to predict both temperature and moisture content of the leaf. The mass transfer coefficient and the convection heat transfer coefficient were estimated by fitting the experimental data with a mathematical model using the least squared method. The results suggested that drying on a conveyor belt dryer is an appealing alternative to dry leaves aimed at supercritical extraction.

Mirzahoseinkashani et al. [38] proposed a mathematical model to study the crossflow conveyor belt dryer. The developed model was a function in moisture content, as presented in Eqs. (9) to (11), The model was based on the finite-volume method. Finally, they used MATLAB, version 7 [34] to implement a computational code and obtained numerical results. The results of the moisture content were compared to experimental data of the fixed bed to validate the methodology. Consideration of the porosity variation by the grain moisture content resulted in more accurate results from the mathematical modelling proposed.

where

De Holanda et al. [39] performed a mathematical model that describes the drying process of the silkworm cocoon in a conveyor belt dryer. The authors used the changing parameters, as specific heat, density, and relative humidity, developed by Jumah et al. [40], and Rossi [39]. The heat transfer coefficient was obtained from Incropera 2002 [41]. They used the finite-volume method to discretize the equation system by integrating them over the control volume and time. The system was solved by generating a computational code using Mathematica [42]. The validation was done by comparing the numerical results of moisture content with the experimental results of fixed bed reports which obtained no errors.

Salemović et al. [43] posed a mathematical model for drying of thin layer of potatoes in a conveyor belt dryer. They studied the process with the assumption that the layers of the moist potatoes were separated into segments. Each segment had its own drying agent, heater, fan, and belt velocity. The model was made in the form of four non-linear partial differential equations. The equations were transferred to two ODEs with constant coefficients, Eqs. (12) and (13). This is in addition to an extra equation of a transcendent character, Eq. (14). These equations were solved numerically by the Euler method of simple finite differences. The obtained results using the developed mathematical model provided a clear image for the variation of moisture and temperature in the thin layer of the material.

where

Faggion et al. [44] investigated mechanisms for heat and mass transfer coefficients of ilex paraguariensis during drying in cross flow conveyor dryer. The value of biot (Bi) numbers and the corresponding rates of heat and mass transfer impacted the entire analysis. The mechanism was obtained analytically by solving Fick’s second law as well as heat transfer from the chart of Heisler or in a long cylinder with finite surface resistances. Experimental setup was used to validate the model. Their modelling results were able to agree well with the experimental data.

Schmalko et al. [45] proposed a mathematical model to evaluate the temperature and moisture content of yerba mate leaves and twigs during the drying process. The model was solved using the finite difference method. The model was validated using experimental data obtained at the factory. The predicted values of moisture and chlorophyll content were in good agreement with the experimental data with RMSE value equals to 0.0033.

Burmester et al. [46] focused on heat and mass transfer of coffee during drying in a vacuum belt dryer. They built an experimental model to investigate the thermal conductivity and influence of the porosity of coffee. Based on these experimental results a numerical model was developed to clarify the coupled heat and mass transfer.

Pang et al. [47] developed a mathematical model to simulate the drying process of wood chips in a moving bed dryer. A system of equations was solved numerically to calculate the changes in moisture and temperature with respect to the location along the dryer length and through the bed thickness. Moreover, it was validated by the experimental data they obtained from their experimental model.

Neto [48] developed a detailed continuous, conveyor belt dryer simulator. Then to reduce the production cost and meet production specifications, they optimized the operating parameters, including drying air velocity and drying air temperature. The system of equations is composed of two parts, the equations describing the distributed mass and energy balance around the food particle and the mass and energy balance describing the drying air. The first subsystem was solved using the Method of Lines (MOL). The MOL modifies an Initial Value Partial Differential Equation (IV-PDE) into a system of coupled First-Order ODE. The second one was solved by the Fourth Order Runge-Kutta method, since this is a set of non-stiff Ordinary Differential Equations.

4.6 Transient Multi-Dimensional

Ostrikov et al. [49], used a hybrid approach for modelling the drying process of tube-shaped pasta. They started with an empirical equation for the drying time and mass transfer by Dzhamasheva [49]. The authors then simplified the detailed energy and mass transfer equations which resulted in a set of ODEs, as shown in Eqs. (15)–(19). Then they were solved numerically by the fourth order Runge-Kutta method.

While

Koop et al. [50] presented a transient two-dimensional model used to investigate the drying of mate leaves in a deep bed dryer. They modified their earlier transient model [51] that focused on thin layer drying in the conveyor belt. The mathematical modelling combined the dependable thin-layer continuous differential equation subsystem with a partial subset of partial differential equations (PDEs). Moreover, empirical equations of the heat and mass transfer coefficient for different products were developed, in terms of bed porosity, density of the product, moisture content of the product, and air properties (density and humidity). The two-dimensional model was modelled as a set of ODEs solved numerically using the Euler method using MATLAB version 6.1 [34]. Their model was verified experimentally. Sorokovaya et al. [52] proposed a mathematical model and optimization for the drying of thermolabile materials. The model investigated phase changes in colloidal capillary-porous materials as well as heat and mass transfer. The system of differential equations was solved numerically using an explicit three-layer difference mesh of Nikitenko [53]. To assess the accuracy and effectiveness of the mathematical model and numerical method that were developed, they conducted a comparison between the results obtained from a numerical simulation using these tools and the results obtained from a physical experiment. The calculated results closely align with the corresponding experimental data, with a maximum error of only 2.2%.

5 Computational Fluid Dynamics

CFD is considered as a reliable tool for evaluating the modelling of belt dryer in food applications. Steady 2-D CFD models are reported in Section 5.1 and 3-D CFD models are presented in Section 5.2. Transient 1-D CFD model is presented in Section 5.3, while 2-D CFD models are reported in Section 5.4, and 3-D CFD modelling technique was reported in Section 5.5. A summary of these studies is presented hereinafter and a summary of the findings from these studies can be found in Table 4.

Khankari et al. [54] used the finite-volume method to develop steady 2-D numerical CFD model for a double-deck conveyor dryer. They used their model to evaluate the performance of a moving bed dryer. The governing equations illustrate the conservation of momentum, heat, and moisture in the computational domain. The momentum source term represented the air side pressure drop, while that in the energy equation for air side represented the thermal energy exchange with the product. The source term in the air moisture equation represented the moisture exchange with the product. Their numerical model was solved using the finite volume method which was implemented through the adaptation routine of a general-purpose CFD code designed by Innovative Research Inc, Plymouth, MN.

Böhner et al. [55] used FLUENT [56] using the (k-ε) standard turbulence model, to study the addition of guide vanes, with different flap angle as an improvement to the distribution of the air flow inside a belt dryer. An experimental model was also built to support the CFD model by measurements. By adjusting the flap setting to 45°, the moisture content became more similar on both sides at different belts. Furthermore, after installing inclined roof-style air guiding plates below the first belt, the hot air from the sides reached the middle of the belt, leading to improved and more uniform drying across the belt. With the air guiding plates, the moisture content ranged from 65.4% to 74.1% wet basis (w.b.) at the end of the first belt and between 3.7% and 4.2% w.b. at the end of the fifth belt.

Zhang et al. [57] used ANSYS Fluent [56], version 16.0, using the (k-ε) standard turbulence model, to study the air distribution in a belt dryer. The CFD model evaluated five different product thicknesses. A finite volume method with porous media formulation was used in the simulation. Their numerical model was validated experimentally using extruded fresh catfish feed. There was negligible difference observed between the simulated values and the experimental values.

Mondal et al. [58] used ANSYS Fluent [56], version 16.0. with the (k-ω) model and shear stress transport (SST) to study the air profile inside a convective dryer. The model was utilized to modify the air distribution sieve to improve the air uniformity over the dryer width. The study was focused on the influence of the uniformity of air flow on moisture variability in the dryer. The model predictions were verified with on-field measured air velocity data from the plant dryer. The air distribution sieve, with an opening of 17%, significantly enhanced the downward velocity component and improved air flow uniformity by 64% compared to the base case.

Chang et al. [59] proposed a numerical simulation and optimization for a multilayer belt dryer. They built a mathematical model depending on CFD techniques to study the simultaneous heat and mass transfer. The system of equations was solved using the finite difference method and programmed in C language. The model validation was compared with experimental data. The appropriate parameters for the structure and operating conditions of the dryer have been determined. When the belt velocity is 0.004 m/s, the conveyor flip time falls between 25 to 30 min. The belt length ranges from 6 to 7 m, and the multilayer belt dryer consists of 6 layers. The height of the air duct is between 0.2 to 0.3 m, and the material bed thickness is 10 cm. The air velocity ranges from 2.0 to 3.0 m/s. In summary, the drying kinetic data obtained from simulations were used to discuss and determine the optimal parameters for the dryer structure and operating conditions. The parameters included the length of the belt for each layer, the height of the air channel between layers, and the number of belt layers. Additionally, the operating conditions discussed were the height of the material bed, belt velocity, and air velocity.

Alamia et al. [60] modelled the drying process of a belt dryer using two methods. The first one was a macroscopic heat and mass balances which describe the whole system. They were solved using the commercial process modelling software Aspen Plus V8.2 [61]. In the second method the authors created a 2-D transient CFD model using ANSYS Fluent 13.0 [56]. The necessary inputs of the macroscopic model, such as the temperature history of the biomass particles and the steam, as well as the change in particle moisture content over time, were obtained from the CFD simulations. Macroscopic modelling combined with CFD simulation, to propose a simple tool to estimate the dryer design. The macroscopic model was also verified experimentally to further improve its precision and reliability. The proposed CFD simulation setup can be utilized for optimizing the dryer design by considering three key aspects: bed height, steam injection temperatures, and fuel type.

Selimefendigil et al. [62] developed a numerical analysis for heat and mass transfer of a moving porous moist object in a two-dimensional channel, as a representation for a conveyor belt dryer. The process was simulated in 2-D laminar channel flow for different flow conditions by using the Finite Element method (FEM) with Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE), using COMSOL Multiphysics [63]. The findings revealed that the heat transfer coefficient of the porous moist object in motion is not constant over time and varies locally. The study also highlighted the significant effects of increasing air temperature and velocity on the heat and mass transfer characteristics.

5.5 Transient Three-Dimensional

In 2017, Zhang et al. [64] used ANSYS Fluent [56] to study the impact of material thickness on a belt dryer’s material moisture content and homogeneity as well as air velocity, temperature, and relative humidity. The results of their model were validated experimentally. In their model, they used Newton’s second law, Eq. (20), to describe the change rate in the momentum. Also, they used porous medium and evaporation models and applied the mass and energy balance equations on an infinitesimal volume. Viscous dissipation was added to the energy equation using a User Define Function (UDF). In this function they used an empirical equation, Eq. (21), developed by Thorpe [65] for the source term in the energy equation together with a relationship developed by Hunter [66] for the adsorption heat on the surface of areca nuts and the latent heat of vaporization in free water, Eq. (22).

where

In 2021, Zhang et al. [67] installed an auxiliary device in the drying chamber to modify how the air passages are organized. They used ANSYS Fluent [56] to figure out the best shape and angle of stacked feedstock. The modelling results were validated experimentally. The source terms were described and compiled as UDF by using the programming language C. The main findings indicated that a specific stacking method, known as vertical serration stacking with a 30° angle and a 43.0 mm interval, can enhance drying performance.

Çoban et al. [68] investigated the heat and mass transfer process of a conveyor belt dryer numerically using COMSOL 5.5 [63]. The authors used the study of Akpinar and Dincer [69] for convective drying of potato, to validate their study. A moving mesh path was used for providing the movement of the belt through the Arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian (ALE) framework. The governing equations which describe the system were solved using the finite element discretization technique for the 3D transient problem. The results of the study highlighted the significant influence of varying parameters on the drying behaviour. Specifically, the impact of air velocity on evaporation was observed, with higher air velocities leading to increased evaporation rates. The most substantial reduction in moisture content, amounting to 63.12% loss, was achieved at an air velocity of 0.8 m/s.

Shen et al. [70] used COMSOL Multiphysics [63] to investigate the heat and mass transfer in microwave belt dryer, for germinated brown rice, numerically. They validated their model experimentally. The model describes the heat and mass transfer and the multi-physics fields including the transmission of microwave field. A discrete-combined approach was used as the strategy of the simulation to achieve the continuous movement of the samples in COMSOL using MATLAB [34] to create their three-dimensional model. The simulation improved understanding of heat and mass transfer processes. It showed that arranging magnetrons and adjusting microwave power could create a uniform electric field, aiding high energy absorption. Grain layer movement reduced energy absorption, leading to uniform temperature and moisture content distribution. Controlling microwave energy improved drying efficiency. Overall, the simulation offers insights for optimizing drying processes and controlling quality in materials like GBR.

Zhou et al. [71] used COMSOL Multiphysics [63] to simulate the heating process of a potato in a microwave conveyor belt dryer. They proposed a novel algorithm method using the implicit function and level set methods. The governing equations include the heat transfer process as well as electromagnetic field calculations. The moisture transfer was not considered in their simulation. The feasibility and accuracy of the methods were validated experimentally using temperature variations along the process. The proposed method demonstrated superior performance in calculating electric fields, scattering parameters, and power absorption curves. Validation results indicated that the method was more accurate and effective, with a five-fold increase in calculation efficiency compared to conventional methods.

Zhang et al. [72] investigated the berry slices’ puffing properties under continuous microwave conditions in belt dryer using COMSOL Multiphysics software [63]. They used models of coupled multi-physics fields to study heat and mass transfer, as well as deformation of the slices. The model was validated experimentally. Results revealed insights into heat and mass transfer, deformation processes, and uniformity within the slices. The distribution of electric field profiles influenced microwave energy absorption and heat transfer, leading to volume expansion. Temperature, moisture content, and pressure exhibited local “hot spots” in the central region, stabilizing as the slice moved. Overall, the study provides valuable guidance for optimizing technology parameters and controlling the puffing quality of berry slices.

Zhang et al. [73], in 2017, investigated the correlation between airflow velocity and feed thickness in a single-conveyor belt dryer using the (k-ε) standard turbulence model in ANSYS Fluent [56]. They used the 3D porous media formulation to model the process. They used experimental measurements to validate their model. In 2022, Zhang et al. [74] extended their research for four different fan frequencies using CFD simulation and experimental verification. Results showed that as feed thickness increased, airflow velocity became more uneven. At a feed thickness of 140 mm, airflow velocity was most even, ranging from 3.0 to 4.2 m/s. However, at higher thicknesses, such as 300 mm, the airflow velocity varied significantly, ranging from 2.4 to 6 m/s. The region of highest airflow velocity shifted from the outlet to the middle zone as feed thickness increased. The optimal feed thickness was found to be 140 mm due to the high airflow velocity near the outlet.

Ortiz-Jerez et al. [75] investigated a heat and mass transfer model to simulate the pumpkin slices drying process in RWD using COMSOL Multiphysics 4.3a [63]. They considered the impact of a typical plastic sheet’s optical characteristics (Mylar®) on the radiative component of heat transfer. Equations for the conservation of mass and energy are developed that take into account the diffusion, capillary, and convective modes of movement. They performed the RWD drying experiment on thick slabs of pumpkin. The heat and mass transfer model were validated using two separate sets of experimental data for temperature and moisture. The results showed that there was only a 5% increase in the transmission of infrared (IR) radiation when a dry material was replaced by a wet material, challenging the notion of a “window” effect in RW drying as reported in the literature. For thin samples, the study found that moisture loss was sensitive to the temperature of water bath. The comparatively low temperatures detected in the samples were attributed to a substantial drop in the effective heat conductivity of food susbtance, which prevented the product temperature from approaching the water bath temperature. Conduction was identified as the primary mode of heat transfer to the material, with thermal radiation contributing only 1% of the total heat transfer.

Zhang et al. [76] used the finite volume method in ANSYS Fluent [56] to study the impact of conveyor positions on the distribution of airflow in three dryers. The CFD model used was the turbulent model for porous media with standard (k-ε). The three types of dryers (A, B and C), differ in their structure number of conveyors and feed thickness. The airflow through the dryer chambers was examined and illustrated using heatmaps based on the simulation findings. The following conclusions were drawn from the simulated results: Type C and type B dryers exhibited more uniform airflow distribution compared to type A dryer when the total feed thickness was the same. However, the use of four conveyors in types B and C led to higher production costs. Airflow velocity decreased when penetrating the feeds. The direction of airflow was from the left (inlet) to the right (outlet), with different airflow velocities observed on different conveyors due to their positions.

This section presents an overview of the empirical modelling techniques presented in the literature. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 5.

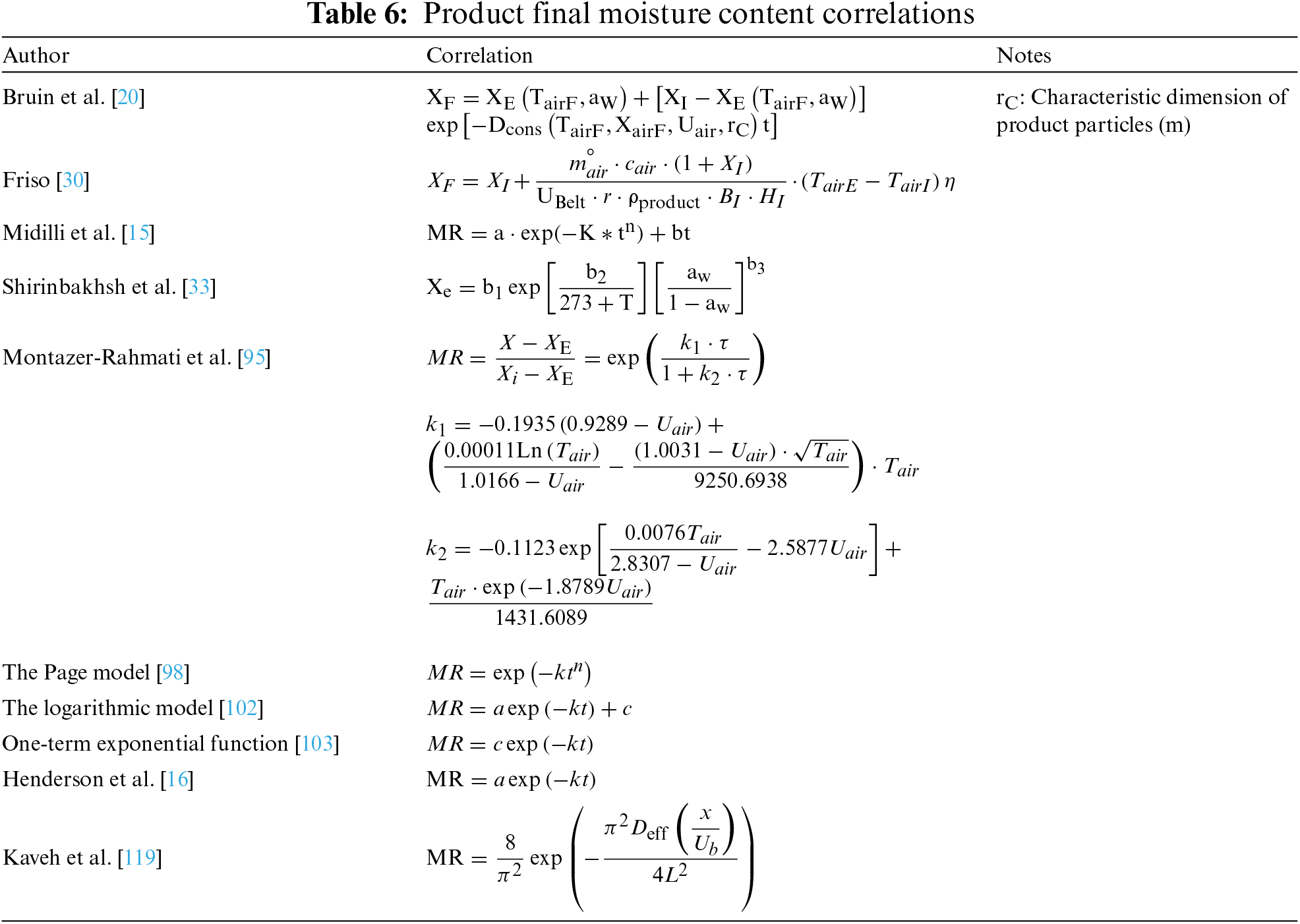

Soodmand-Moghaddam et al. [77] performed drying experiments, at three levels of air velocity and three levels of drying temperature, to dry lemon verbena. They used a continuous flow dryer with solar-powered pre-heating system. The authors compared ten different mathematical models, to both older [16,78–80] and newer [17,81–84] models published after 2000 as well as the most established correlation: to their experimental results [15]. Different regression models were performed using MATLAB [34] and SPSS 11.5.1 software package [85]. The highest matching model was the Midilli and Kucuk’s model [15]. A summary of most relevant final moisture content correlation is found in Table 6.

Soodmand-Moghaddam et al. [86] investigated the fuel consumption and the drying characteristics of lemon verbena leaves in a continuous dryer. They prepared an experimental model using 4 conveyor belts. Experiments were conducted at three drying air temperature levels and three air velocity levels. The drying system worked by two working conditions, solar gas drying (SGD) and gas drying (GD). The central composite design-Face Cantered technique with response surface methodology was used for the optimization of the drying process. The optimized drying conditions for lemon verbena leaves were achieved at a drying temperature of 39.54°C and an air velocity of 2 m/s. Under these conditions, no fuel was consumed, the drying time was 131.48 min, and the essential oil (EO) content was 0.52%.

Chayjan et al. [87] prepared an experimental setup for the conveyor belt dryer, used for drying fresh samples of the terebinth fruit. The experiments were performed to study the effect of different drying conditions, specifically air temperature and velocity, on the thermal and physical properties of the terebinth fruit, namely effective moisture diffusivity, activation energy, changes in shrinkage, colour, and mechanical properties. The experiment was done with five replicates. The authors compared six different mathematical models, older models [18], and newer models [15,83,88,89] published after 2000, that can describe the moisture content at various stages of drying, to their experimental results. Using the curve expert software [90], they found that the highest matching model was the Midilli empirical model [15].

Jafarifar et al. [91] prepared an experimental setup for drying walnut kernel. The experiments were performed to study the effect of various drying techniques on the thermal and physical properties of the walnut kernel, namely shrinkage, colour changes, activation energy and effective diffusivity. The experimental results were collected under various drying conditions, namely air temperature and velocity, and fitted with 10 different thin layer drying models’ moisture ratios, older models [16,18,78,80], and newer models [82,89,92–94] published after 2000 as well as the most established correlation: [15]. The selection of the best model was done through three criteria:

Montazer-Rahmati et al. [95] designed and constructed a bench-scale semi-continuous convective dryer for picrate drying. The moisture contents both final and equilibrium, at various air temperatures and air velocities, were experimentally evaluated using the Karl-Fischer test [96]. The experimental crude data were processed to calculate the moisture ratio, the drying flux, the moisture diffusivity, and the internal and external mass transfer coefficients. The curves were then plotted and fitted using the Table Curve software in Microsoft Excel [97]. To relate the model parameters to the drying conditions, a stepwise multi-linear and nonlinear regression analysis based on the Levenberg-Marquardt (L-M) algorithm. The exponential-hyperbolic decay model was the best describing model to predict the moisture ratio of picrate. Internal mass transfer coefficient empirical correlation was modelled as function of moisture content and presented in Table 7.

Yang et al. [98] developed a small-scale infrared belt dryer for rapeseed. To investigate the drying performance, they fitted the experimental data obtained to five commonly thin-layer drying models [16,78,83,84,99]. The two-term model [84], followed by Page model [78], provided the best fit to the experimental results. The effective moisture diffusivity was calculated by graphing experimental drying data vs. the drying time and the natural logarithm of MR.

Ostrikov et al. [100] proposed an empirical-mathematical modelling approach to explore the drying kinetics of cereals with a fluctuating heat supply using the stitched method. The proposed technique is based on assembling drying curves together. Control variables such as the specific load of grain, the air temperature, velocity, and humidity at the entrance into the drying layer, and other control variables were assumed to be piecewise constant functions. As such, the drying process was separated into discrete time regions. All calculations were investigated in a specially designed software program to perform the calculation of the drying process with respect to changes in air humidity. The modelling method was validated experimentally. A software-based algorithm for controlling the drying process under variable heat supply was developed, leading to the design of a grain dryer that can adjust the grain layer height from compartment to compartment. This design facilitates uniform drying and minimal energy consumption.

Ogunnaike et al. [101] used a continuous flow belt dryer to investigate the influence of the drying variables on the fish feed drying kinetics. The experimental data were obtained under various drying conditions, particularly air temperature and velocity and belt velocity. To select the most accurate model describing the drying process, the experimental data results were collected and fitted, using the non-linear regression approach on Microsoft Excel, to seven empirical models, older models [78–80] and newer models [15,81,84,99] published after 2000. The most accurate model was given by Midilli et al. [15].

Liu et al. [102] performed a mathematical model for panax notoginseng drying in a vacuum belt dryer. An experimental set up was developed to investigate the impact of the drying parameters as temperature, feeding speed and belt speed on the drying rate. Experiments were conducted under different conditions then five mathematical models [16,18,78,80,83] were fitted to the drying curves to evaluate the most accurate model. The logarithmic model [83] was the best-fit one to predict the drying process.

Fumagalli et al. [103] developed a pilot-scale belt dryer to analyse the drying of brachiaria brizantha seeds in different dryer modes at different temperatures and velocities. The equipment developed could operate in different modes such as fixed-or fluidizied-bed mode, or conveyor belt mode, providing homogeneous drying. The experimental data of moisture content variations along the dryer was plotted vs. the drying time. The resulted curves were fitted to a one-term exponential model [104] to obtain the correlation coefficients. Results showed that inlet air velocity variations had no significant effect on drying kinetics. Drying kinetics were similar in fixed, conveyor belt, and fluidized bed modes at the same temperature. Drying in a fluidized bed mode yielded better germination potential. A drying temperature of 50°C and storage moisture content below 10% were recommended for maintaining physiological quality. The proposed approach was advantageous over traditional conveyor belt drying, requiring a shorter belt length for the same moisture reduction.

Xu et al. [105] used a continuous vacuum dryer to investigate the kinetics of removing moisture from tortilla chips. The experiments were conducted at three conduction plate temperatures and three product thicknesses. Four empirical models [2,16,78,105] were applied to fit the experimental data, to study the influence of drying thickness and temperature on the drying rate. The authors observed that the variable drying coefficient model [105] and the Page model [82] perfectly match the experimental data.

Jafari et al. [106] fabricated a semi-industrial continuous microwave dryer to investigate the energetic and exergetic performance of the dryer and observe the qualitative changes of the crop during drying. The experiments were carried out at different thickness of the product, different product feed velocity and microwave power. The experimental results were fitted with five empirical and semi-empirical models [16,18,78,80,84] to choose the appropriate model. The Wang et al. model [80] and the Page model [78] were found to be the best models for a thickness of 6 mm at powers of 90 and 450 W, and a thickness of 6 mm at power of 270 W, respectively. On the other hand, the Lewis model [18] and the two-term model [84] were found to be the best models for a thickness of 12 mm at powers of 270 and 450 W, and a thickness of 12 mm at power of 90 W, respectively.

Zareiforoush et al. [107] tested and refined the performance of a solar-assisted multi-belt dryer. To study the effect of thermal energy sources on stevia leaf drying, an experimental setup was constructed using solar-gas water heaters and solar-powered infrared (IR) lamps. The experiment examined how drying air velocity, temperature, and IR lamp power affected the drying process. To improve the drying system, a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) analysis was performed, concentrating on performance factors. Two operational modes were identified: a hybrid mode and a solar-assisted mode. The study analysed Overall Specific Energy (OSE), Non-Solar Specific Energy (NSE), Overall Energy Efficiency (OEE), and Solar-Assisted Energy Efficiency (SEE) of a drying system. The lowest OSE (17.30 MJ/kg water evaporated) was achieved at 7 m/s air speed and 40°C without IR power. The lowest NSE (2.71 MJ/kg) was at 7 m/s, 40°C and 300 W. Maximum OEE (13.92%) and SEE (88.71%) were at 7 m/s and 40°C with 300 W IR power for SEE and none for OEE. RSM identified the optimum conditions as 7 m/s, 39.96°C and 300 W, with drying time of 180.95 min, NSE of 1.062 MJ/kg, and SEE of 84.63%.

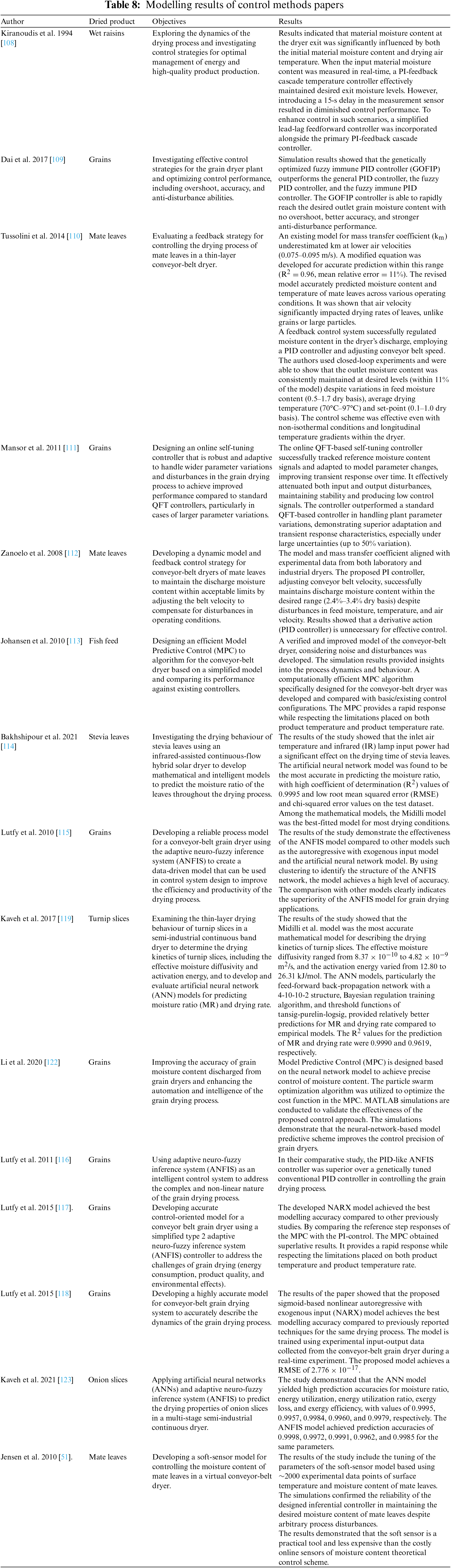

The literature review shows that several researchers have conducted studies on the performance behavior of belt dryers using various control systems. Classic control systems were employed in several studies [108–112] to evaluate the performance of belt dryers for processes like drying mate leaves, grains, and raisins. These systems typically utilized PI and PID controllers in feedback loops to regulate parameters such as moisture content, air temperature, and belt speed, relying on real-time measurements and predefined setpoints. In some cases, cascade configurations were employed for enhanced disturbance rejection. While effective, these controllers faced challenges with complex nonlinear drying dynamics, such as sensor delays and parameter uncertainties, which were addressed through strategies like feedforward compensation, adaptive tuning, and numerical optimization. Johansen Van Delft [113] used the model predictive control, A detailed dynamic model of the conveyor belt dryer, incorporating relevant physical and chemical phenomena, was developed and verified. This model provides the foundation for MPC, which anticipates future conditions by predicting drying behavior. By optimizing control actions over a set prediction horizon, MPC ensures efficient operation and maintains product quality, especially in complex multivariable control scenarios with constraints. While in recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS), have gained attention as advanced control systems [114–117]. These controllers can handle the nonlinearities and uncertainties of the drying process more effectively than traditional methods.

• ANNs are implemented by training the network with old data to predict drying outcomes. Once trained, ANNs can adjust operational parameters like temperature and belt speed dynamically to achieve optimal drying conditions. The optimization of ANN-based controllers involves tuning the network structure and learning parameters to balance accuracy and computational efficiency.

• ANFIS combines the adaptability of neural networks with the interpretability of fuzzy logic, utilizing fuzzy if-then rules to guide control actions. ANFIS models are optimized through hybrid learning, which adjusts the fuzzy membership functions and rules for accurate and adaptive control. This hybrid approach allows ANFIS to maintain effective control in response to varying drying conditions.

Finally, Jensen et al. [51] presented an empirical software-sensor model, which uses data-driven methods to estimate drying parameters indirectly. This approach allows for real-time monitoring and control without requiring physical sensors for every variable, which can be beneficial in reducing costs and complexity. The results of these investigations are presented in Table 8.

Kiranoudis et al. [108] investigated the dynamic behaviour of the drying process by belt dryer. For this aim, they made a mathematical model composed of algebraic equations as well as ODEs. The algebraic equations were solved through a Newton-like method employing a Broyden-type approximation for the calculation of the system’s Jacobian matrix. While the ODEs were calculated for each step using Simpson’s method of numerical integration. The proposed procedure yielded a transfer function of the second order as shown in Eq. (23). To achieve excellent control of material moisture content at the exit of each chamber in the dryer, a PI-feedback cascade temperature controller was employed, assuming instant measurement of the input material moisture content.

While

Dai et al. [109] constructed a genetically optimized fuzzy immune PID controller (GOFIP) for the drying process of a conveyor belt dryer. This controller operates by both intelligent fuzzy immune feedback control and traditional control. Then they simulated two other controllers, the general PID controller and the fuzzy PID controller. The three controllers were compared with an experimental model. The GOFIP controller was found to be superior compared to the other two simulated controllers.

Tussolini et al. [110] experimentally evaluated a feedback strategy for the control of drying mate leaves in a conveyor belt dryer. A dynamic drying model, consisting of two partial differential equations representing energy and mass balances within the solid phase of the dryer, was employed. PID controller parameters and manipulated conveyor velocities were calculated using this model under conditions identical to the experimental setup. The dynamic 1-D drying model was solved using the numerical method of lines by applying a backward differentiation formula to the first-order time and space derivatives.

Mansor et al. [111] developed Quantitative Feedback Theory (QFT) based self-tuning controller for drying grain plants in the conveyor belt dryer. On the basis of real-time input/output data, system identification was used to develop a mathematical model of the grain dryer. An experimental setup has been built, collecting its input and output data to be used in the mathematical model. Moreover, the MATLAB System Identification Toolbox (MSIT) [34] was used to simplify the calculations into a linear process to be used in the QFT technique. Prediction Error Minimization (PEM) was used to estimate the model parameters. QFT-based self-tuning controller demonstrated superior performance in tracking reference signals, attenuating disturbances, and adapting to parameter variations compared to the standard QFT-based controller.

Zanoelo et al. [112] proposed a semi empirical model to reproduce the kinetics of drying mate leaves under transient conditions in a continuous shallow packed bed drier. They investigated a model for transient drying and the mathematical procedure to solve it, the numerical method of lines approximates the first order spatial and time derivative using a backward differentiation formula (BDF). The subsequent step was designing the control system. Using this reliable model, a control strategy was proposed to maintain an acceptable discharge moisture content by manipulating the velocity of conveyor belt to account for variations in operating conditions. The performance of a PID and PI controller was evaluated by comparing the open- and closed-loop responses of discharge moisture content to random variations in the discharge moisture content, drying temperature, and air velocity. The PI controller was found suitable for controlling moisture content in conveyor-belt dryers of mate leaves, with the derivative action of the PID controller deemed insignificant. Time variations in feed moisture content, drying temperature, and air velocity were considered key factors affecting the process.

Johansen Van Delft [113] developed a predictive control model for a conveyor belt dryer. His mathematical model was composed of a system of PDEs that were simplified using a finite difference approximation. These equations were further simplified and linearized to form a set of ODEs to be used in model-based control solution. Heat and mass transfer were described in Eqs. (24), (25). The ODEs system was solved by MATLAB ode23tb function [34]. Further, by balanced residuals, the model was reduced to fit Model Predictive Control (MPC).

where

Bakhshipour et al. [114] proposed two methods for modelling of drying stevia leaves in an infrared-assisted continuous hybrid solar dryer. In the first method, they used mathematical modelling. MATLAB’s curve fitting toolbox [34] was used to determine the constants of the evaluated models. They found that the Midilli et al. [15] model provided the best results in 24 conditions. In the second method, they used intelligent modelling methods such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Adaptive Network-based Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS). Both models were developed with different structures to predict the MR data. Both models were compared to the experimental data using 3 criteria:

Lutfy et al. [115] developed a reliable conveyor belt dryer model using system identification techniques based on ANFIS modelling capabilities. They built a laboratory-scale conveyor belt grain dryer to compare the experimental MR results with the ANFIS model. Moreover, a comparative study was made by other models to determine the effectiveness of the proposed model. The other models used were the Auto Regressive with Xogenous input (ARX) and ANN. The modelling performance was evaluated using the RMSE criterion. The comparative study with the three models showed the superiority of the ANFIS model over the other two models.

Lutfy et al. [116] later modified their previous ANFIS model [115] to deal with the dehydration process’ inherent complexity and nonlinearity. Specifically, a laboratory-scale conveyor belt grain dryer for rough rice was designed and built. The system identification technique was applied to the experimental data, collected from the dryer, for the development of the ANFIS model. MATLAB “anfis” function [34] was used to employ this hybrid training technique for the initial ANFIS structure. A simplified PID-like ANFIS controller is used as a main controller to control the drying process. RMSE was utilized to evaluate the performance of the ANFIS modelling system. A comparative study has demonstrated that the PID-like ANFIS controller is superior to a genetically tuned conventional PID controller for controlling the grain drying process.

Lutfy et al. [117] then introduced type 2 fuzzy sets to cope with the uncertainties that can exist in the fuzzy system’s rule basis. They employed a Nonlinear AutoRegressive with eXogenous input (NARX) network to model the conveyor belt grain dryer using input–output data obtained during an experiment to dry paddy grains. The type 2 simplified ANFIS controller was proposed to control the NARX-based dryer model. The equations were obtained by the MATLAB “nlarx” function [34]. Results showed that the developed NARX model obtained the highest modelling precision compared to other previous studies.

Finally, Lutfy et al. [118] represented the belt dryer model by a sigmoid-based NARX network as it achieves the best modelling performance comparing to other neural networks. An experimental laboratory scale setup was built to compare the results obtained from the NARX model with the experimental data. Using the RMSE criterion, the modelling precision of the optimized sigmoid-based NARX model was evaluated. The proposed sigmoid-based NARX model obtained a 99.74% optimal performance index. Kaveh et al. [119] investigated the thin-layer drying characteristics of turnip slices in a multistage semi-industrial continuous band dryer. An experimental model was set up by varying the drying factors as air temperature, velocity, and belt velocity. They proposed two methods for modelling. In the first method, they used six mathematical models to fit the experimental data. The Midilli et al. [15] model was selected as the best mathematical model. The other models [78,80,84,120,121] showed inferior performance. In the second method, they used an ANN model for the drying process. After proper training of ANN models, it was determined that they were superior to empirical models.

Li et al. [122] designed a control scheme for grain dryers using NARX based PSO-MPC neural network as a prediction tool. They used a mathematical model developed by Li and Cao [122] due to the unavailability of actual dryers, so they can generate data for neural network training to improve the fitting precision. A NARX neural network was proposed to represent the dynamic characteristics of the dryer, and an MPC controller with a PSO optimization algorithm was designed for accurate closed-loop control. Simulations based on a rough mathematical model were conducted due to the unavailability of actual dryers, providing abundant data to train the NARX neural network and test the control scheme’s performance. The PSO-MPC scheme demonstrated an error of less than 1% in grain humidity and a control precision of under 0.52% in outlet grain moisture content in simulations under different conditions.

Kaveh et al. [123] used two intelligent methods, ANNs and ANFIS to predict the MR, Energy Utilization (EU), Energy Utilization Ratio (EUR), exergy loss and exergy efficiency of drying process for onion slices in a multi-stage semi-industrial continuous belt. An experimental setup was built and worked for various air temperature, air velocity and belt velocity levels. The results demonstrated that the values of effective moisture diffusivity, colour change, EU, EUR, and exergy loss increase when high levels of air temperature and velocity are combined with a low belt linear motion. While drying time, Specific Energy Consumption (SEC) and exergy efficiency decrease.

Jensen et al. [51] presented a soft-sensor empirical model for controlling the moisture content of mate leaves in a virtual conveyor belt drier. The model was trained on a set of 2000 experimental data points, which were collected from batch drying experiments at various temperature ranges. It was correlated using two PDEs derived from the energy and mass balance for water in the dryer’s solid phase. The controller adjusted the tray velocity to compensate for random disturbances in feed moisture content and drying temperature, as verified by successful comparisons between open- and closed-loop responses of discharge moisture content.

In summary, this review paper has presented an in-depth review of the various modeling techniques employed for studying the drying process in a belt drier. The methodologies have been categorized into four distinct groups, including theoretical, CFD, empirical, and controllers. Theoretical and CFD methods have been further sub-grouped into transient and steady-state models, as well as 1-D, 2-D, and 3-D models. The empirical methodology involved the collection of moisture ratio data throughout the drying process, which is subsequently compared to empirical models produced by other researchers. The control method studies have been categorized into two groups: classical control and advanced control studies. The advanced control studies incorporate artificial intelligence-based methodologies, including ANN, ANFIS, and NARX models.

In general, the review has elucidated the methodologies and software employed for each modeling technique, as well as their prospective utility in industrial contexts. The utilization of theoretical and CFD methodologies is advantageous in forecasting the dynamics of complex systems. Conversely, empirical techniques serve the purpose of validating theoretical models and procuring data to facilitate model refinement. Controllers play a crucial role in the optimization of the drying process and the attainment of desired outputs.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the American University in Cairo, Egypt.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the American University in Cairo, Egypt. The authors have no financial or personal relationships to disclose that could be perceived as biasing their work. Agreement Number: CCI-SSE-MENG-10.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mohamed El-Morsi, Omar Abdelaziz; data collection: Gehad Azmy; analysis and interpretation of results: Gehad Azmy, Mohamed El-Morsi, Omar Abdelaziz; draft manuscript preparation: Gehad Azmy, Mohamed El-Morsi, Omar Abdelaziz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Esper A, Mühlbauer W. Solar drying—an effective means of food preservation. Renew Energy. 1998;15(1):95–100. doi:10.1016/S0960-1481(98)00143-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fellows PJ. Food processing technology. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2007. [Google Scholar]

3. Omolola AO, Jideani AIO, Kapila PF. Quality properties of fruits as affected by drying operation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017 Jan;57(1):95–108. doi:10.1080/10408398.2013.859563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Qiu J. Mild conductive drying of foods. Wageningen; 2019. doi:10.18174/469413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. EL-Mesery HS. Improving the thermal efficiency and energy consumption of convective dryer using various energy sources for tomato drying. Alex Eng J. 2022 Dec;61(12):10245–61. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.03.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ziegler T, Jubaer H, Teodorov T. Bottlenecks in continuous hops drying with conveyor-belt dryer. Dry Technol. 2022;40(13):2598–616. doi:10.1080/07373937.2021.1950168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pasban A, Sadrnia H, Mohebbi M, Shahidi SA. Spectral method for simulating 3D heat and mass transfer during drying of apple slices. J Food Eng. 2017;212(3):201–12. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.05.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Qiu J, Acharya P, Jacobs DM, Boom RM, Schutyser MAI. A systematic analysis on tomato powder quality prepared by four conductive drying technologies. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2019;54:103–12. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2019.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tayel SA, Alkatary HS, Nagy KS, Younes OS. Dehydration of onion slices in IR-refractance window drying system. MISR J Agricul Eng. 2012;29(1):409–28. [Google Scholar]

10. Mahanti NK, Chakraborty SK, Sudhakar A, Verma DK, Shankar S, Thakur M, et al. Refractance WindowTM-drying vs. other drying methods and effect of different process parameters on quality of foods: a comprehensive review of trends and technological developments. Future Foods. 2021 Jun 01;3(1):100024. doi:10.1016/j.fufo.2021.100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Genesis. Genesis screen printing conveyor dryer–6ft. Available from: https://screenprintingsupply.com/products/genesis-screen-printing-conveyor-dryer-6ft. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

12. The Lens. Available from: https://www.lens.org/. [Accessed 2023]. [Google Scholar]

13. ScienceDirect. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/. [Accessed 2023]. [Google Scholar]

14. Web of Science. Available from: https://www.webofscience.com/. [Accessed 2023]. [Google Scholar]

15. Midilli A, Kucuk H, Yapar Z. A new model for single-layer drying. Dry Technol. 2002;20(7):1503–13. doi:10.1081/DRT-120005864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Henderson SM, Pabis S. Grain drying theory (I) temperature effect on drying coefficient. J Agric Eng Res. 1961;6:169–74. [Google Scholar]

17. Kaya A, Aydin O, Demirtaş C. Drying kinetics of red delicious apple. Biosyst Eng. 2007 Apr;96(4):517–24. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2006.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lewis WK. The rate of drying of solid materials. J Ind Eng Chem. 1921 May;13(5):427–32. doi:10.1021/ie50137a021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kiranoudis CT, Maroulis ZB, Marinos-Kouris D. Modelling and design of conveyor belt dryers. J Food Eng. 1994;23(3):375–96. [Google Scholar]

20. Bruin S, Luyben KCAM. Drying of food materials: a review of recent developments. Adv Dry. 1980;1. [Google Scholar]

21. Kiranoudis CT, Maroutis ZB, Marinos-Kouris D. Design and operation of convective industrial dryers. AIChE J. 1996;42(11):3030–40. [Google Scholar]

22. Hosseinizand H, Lim CJ, Webb E, Sokhansanj S. Economic analysis of drying microalgae Chlorella in a conveyor belt dryer with recycled heat from a power plant. Appl Therm Eng. 2017;124:525–32. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.06.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sebastian P, Nadeau JP, Puiggali JR. Designing dryers using heat and mass exchange networks: an application to conveyor belt dryers. Chem Eng Res Des. 1996;74(8):934–43. doi:10.1205/026387696523102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. de Souza Barrozo MA, Murata VV, Assis AJ, Freire JT. Modeling of drying in moving bed. Dry Technol. 2006;24(3):269–79. doi:10.1080/07373930600564530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Petzold LR. DASSL. A differential/algebraic system solver. In: Technical report. Washington, DC, USA: USDOE; 1982 Sep 1. [Google Scholar]

26. Holowaty SA, Schmalko ME, Schvezov CE. Modeling of a double pass belt conveyer dryer of yerba mate. Dry Technol. 2022;40(5):938–47. doi:10.1080/07373937.2020.1839488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Vaxelaire J, Puiggali JR. Analysis of the drying of residual sludge: from the experiment to the simulation of a belt dryer. Dry Technol. 2002;20(4–5):989–1008. doi:10.1081/DRT-120003773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xue Q, Miao K, Yu Y, Li Z. A novel method for vacuum belt drying process optimization of licorice. J Food Eng. 2022 Sep;328(20):111075. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2022.111075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Friso D. Conveyor-belt dryers with tangential flow for food drying: mathematical modeling and design guidelines for final moisture content higher than the critical value. Inventions. 2020;5(2):1–15. doi:10.3390/inventions5020022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Friso D. Conveyor-belt dryers with tangential flow for food drying: development of drying odes useful to design and process adjustment. Inventions. 2021;6(1):1–12. doi:10.3390/inventions6010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Eng MJA, Amer BMA. Process Engineering Mathematical Modeling of temperature and heat profiles in pilot Refractance Window drying system; 2011. Available from: 10.21608/mjae.2011.102614. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nindo CI, Tang J, Powers JR, Bolland K. Energy consumption during Refractance Window® evaporation of selected berry juices. Int J Energy Res. 2004 Oct;28(12):1089–100. doi:10.1002/er.1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shirinbakhsh M, Amidpour M. Design and optimization of solar-assisted conveyer-belt dryer for biomass. Energy Equipment Syst. 2017;5(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

34. The MathWorks Inc. Statistics and machine learning toolbox. Natick, MA, USA: The Math Works Inc.; 2022. [Google Scholar]

35. Perry RH, Green DW. Perry’s chemical engineer’s. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

36. Maroulis ZB, Saravacos GD. Food process design. New York, USA: Marcel Dekker; 2003. [Google Scholar]

37. Canabarro NI, Mazutti MA, do Carmo Ferreira M. Drying of olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves on a conveyor belt for supercritical extraction of bioactive compounds: mathematical modeling of drying/extraction operations and analysis of extracts. Ind Crops Prod. 2019 Sep;136(2):140–51. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mirzahoseinkashani E, Kasiri N. Mathematical modeling of a cross flow conveyor belt dryer. Sci Iran. 2008;15(4):494–501. [Google Scholar]

39. Rossi SJ. ìPsychrometryî. Jo, o Pessoa: FUNAPE; 1987 (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

40. Jumah RY, Mujumdar AS, Raghavan GSV. A mathematical model for constant and intermittent batch drying of grains in a novel rotating jet spouted bed. Dry Technol. 1996;14(3–4):765–802. [Google Scholar]

41. Incropera FP, DeWitt DP. Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

42. Inc. Wolfram Research. Mathematica. 14. Available from: https://www.wolfram.com/mathematica/. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

43. Salemović DR, Dedić AD, Ćuprić NL. A mathematical model and simulation of the drying process of thin layers of potatoes in a conveyor-belt dryer. Therm Sci. 2015;19(3):1107–18. doi:10.2298/TSCI130920020S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Faggion H, Tussolini L, Freire FB, Freire JT, Zanoelo EF. Mechanisms of heat and mass transfer during drying of mate (Ilex paraguariensis) twigs. Dry Technol. 2016;34(4):474–82. doi:10.1080/07373937.2015.1060498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]