Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effect of Surface Wettability on the Flow and Heat Transfer Performance of Pulsating Heat Pipe

School of Environment & Energy Engineering, Beijing University of Civil Engineering & Architecture, Beijing, 100044, China

* Corresponding Author: Wei Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances in Loop Heat Pipe)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(1), 361-381. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.059837

Received 17 October 2024; Accepted 03 December 2024; Issue published 26 February 2025

Abstract

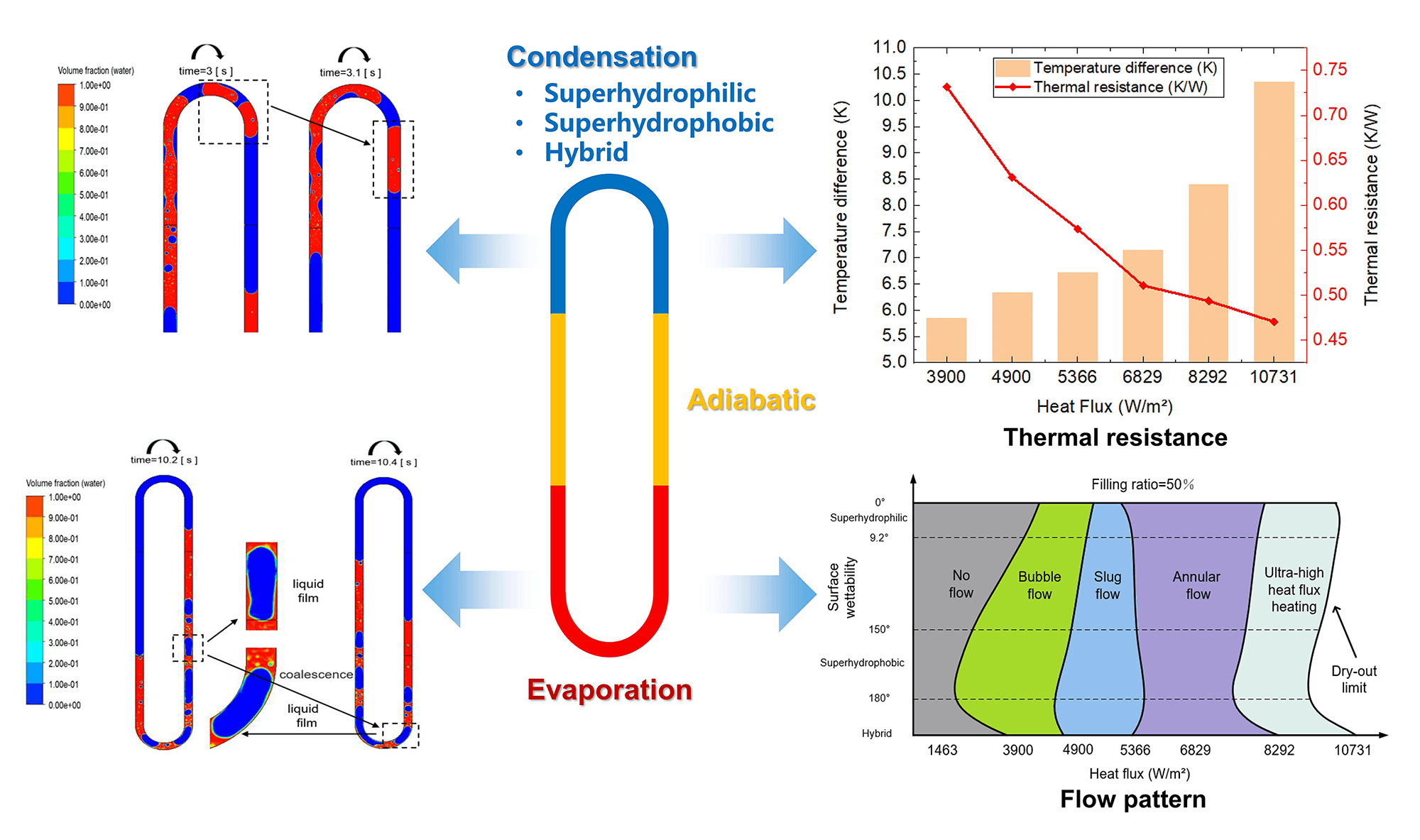

The present work deals with the numerical study of the two-phase flow pattern and heat transfer characteristics of single-loop pulsating heat pipes (PHPs) under three modified surfaces (superhydrophilic evaporation section paired with superhydrophilic, superhydrophobic, and hybrid condensation section). The Volume of Fluid (VOF) model was utilized to capture the phase-change process within the PHPs. The study also evaluated the influence of surface wettability on fluid patterns and thermo-dynamic heat transfer performance under various heat fluxes. The results indicated that the effective nucleation and detachment of droplets are critical factors influencing the thermal performance of the PHPs. The overall heat transfer performance of the superhydrophobic surface was significantly improved at low heat flux. Under medium to high heat flux, the superhydrophilic condensation section exhibits a strong oscillation effect and leads to the thickening of the liquid film. In addition, the hybrid surface possesses the heat transfer characteristics of both superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic walls. The hybrid condensation section exhibited the lowest thermal resistance by 0.45 K/W at the heat flux of 10731 W/m2. The thermal resistance is reduced by 13.1% and 5.4%, respectively, compared to the superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic conditions. The proposed surface-modification method for achieving highly efficient condensation heat transfer is helpful for the design and operation of device-cooling components.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Nomenclature

| List of Symbols | |

| C | Surface curvature, m−1 |

| d | Diameter of PHP, m |

| E | Mass-averaged energy, kJ/kg |

| F | Momentum source term in CSF model |

| G | Gravity acceleration, m/s2 |

| hLH | Latent heat of working fluid, J/kg |

| p | Pressure of working fluid, Pa |

| Q | Heat load, W |

| R | Thermal resistance, K/W |

| Sm, L | Mass source terms of liquid phase, W/(m3) |

| Sm, v | Mass source terms of vapor phase, W/(m3) |

| Sh | Source terms of energy, kg/(m3·s) |

| T | Temperature, K |

| ΔT | Temperature difference, K |

| Subscript | |

| sat | Saturation |

| e | Evaporation |

| c | Condensation |

| m | Mass |

| L | Liquid phase |

| V | Vapor phase |

| eff | Effective |

| Greek Symbols | |

| α | Volume fraction |

| ρ | Density of the mixture, kg/m3 |

| ν | Velocity of working fluid, m/s |

| Dynamic viscosity of mixture, Pa·s | |

| λ | Thermal conductivity, W/(m·K) |

| σ | Surface tension coefficient, N/m |

| Abbreviations | |

| PHP | Pulsating heat pipe |

| SHB | Superhydrophobic condensation section wall |

| SHL | Superhydrophilic condensation section wall |

| CSF | Surface tension model |

| CA | Contact angle |

Pulsating heat pipe (PHP) currently emerges as a highly effective electronic cooling component, which has the advantages of a simple structure without wicks, compactness, low cost, flexible layout, strong operability, and free power consumption [1]. Since first proposed in the 1990s, worldwide and domestic scholars have prompted extensive and in-depth research including theoretical analysis, visualization experiments, numerical simulations, and practical application [2]. The working fluid within the PHPs is heated in the evaporator and cooled in the condenser, respectively. If the heat transferred between the evaporation section and condensation section can reach the thermally-dynamic equilibrium through vapor-liquid two-phase transition, it contributes to ensuring the sustainable and stable operation of the PHPs. There exist many influencing factors and interactions on the heat transfer performance of PHPs. Surface wettability is one of the key parameters affecting the boiling and condensation heat transfer performance, which correspondingly impacts the operational conditions by altering the flow and heat transfer process of the working fluid.

The hydrophobic surfaces can lower the nucleation energy barrier and facilitate the bubble formation for the boiling process, while the hydrophilic surfaces can reduce the nucleation barrier and increase condensation sites for the condensation process [3,4]. Ji et al. [5] fabricated the inner surface of PHP coated with a microstructure layer of copper oxide (CuO), and the experimental comparison showed that the PHPs with CuO-coated micro-structure exhibited better heat transfer performance than the ordinary PHPs, and it was speculated that the superhydrophilic surface significantly enhancing evaporating heat transfer of the thin liquid film in the evaporation section. Dobson et al. [6] elucidated the effects of wettability on the length and thickness of the thin liquid film on the wall and derived the correlation of film thickness related to surface tension. Qu et al. [7] fabricated the inner surface coated with micro-particles of approximately 56 nm in diameter, which can improve the hydrophilic properties by altering the roughness of the inner surface. The results indicated that the bubbles can be more easily generated on coated structure than on smooth surfaces and also have a high frequency of bubble departure, thus the operational stability of the PHPs can be improved. Kim et al. [8] created a silicon-based pulsating heat pipe with a hydrophilic inner surface featured by the grooved structures using micro-fabrication technology, and the modified samples have a lower minimum the start-up power and thermal resistance at start-up process compared to conventional PHPs. Fumoto et al. [9] filled a PHPs with self-wetting water mixture, which can increase the surface tension with rising temperature. At higher temperatures, the increase of surface tension can pull the liquid towards the heated surface once dry spots appear, thereby the heat transfer characteristics of the evaporator section can be improved. Jose et al. [10] carried out the thermal performance prediction of a cylindrical heat pipe-based electronic thermal management system using steady-state experimental investigation.

Ji et al. [11] applied the inner surface of a PHP coated with a hydrophobic layer and the results indicated that the heat transfer performance of PHPs decreases with hydrophobic inner surface. It is attributed that when the hydrophobic surface is used, the thin liquid film cannot be maintain in the evaporation section, and thermal resistance is significantly increased. Betancur et al. [12] also reported that PHPs with superhydrophobic and hydrophobic surfaces can deteriorate heat transfer and lead to the drying out of working fluid. Wang et al. [13] found that the superhydrophobic PHPs generate more slugs than the superhydrophilic PHPs and result in greater flow resistance in the superhydrophobic channel compared to the corresponding superhydrophilic channel. Hao et al. [14] experimentally compared three types of PHPs with different surface modifications and found that compared with the conventional copper surface, the PHPs with superhydrophilic evaporation and superhydrophobic condensation can reduce thermal resistance by 5%–20%. Zhang et al. [15] concluded that the condensation enhancement is inapplicable for the condensation section of PHPs and the superhydrophilic PHPs exhibit the best heat transfer performance.

Extensive research has laid emphasis on the impact of surface wettability on the heat transfer performance of micro-channel PHPs. In the condensation process, the generation and continuous regeneration of condensation sites, droplet growth, and detachment are involved. For superhydrophilic surfaces, it is favorable for the formation of condensation sites, but the latent heat of vapor condensation is expected to pass through the condensation liquid film to reach the cooling surface, thus it leads to the increase of thermal resistance. For superhydrophobic surfaces, the introduction of hydrophobicity can significantly reduce flow resistance by sacrificing condensation sites at the end thus the working fluid can flow easily. Therefore, there exists a trade-off between condensation nucleation and the rapid departure of condensation droplets. It is crucial for promoting efficient condensation and enhancing the overall heat transfer performance of PHPs by the selection of appropriate condensation surfaces for different operating conditions.

This study adopted three kinds of surface-modified PHP coated with superhydrophilic, superhydrophobic, and hybrid surfaces (hydrophilic on the left and hydrophobic on the right) of condensation section corresponding to superhydrophilic surface of evaporation sections. The study numerically analyzed the influence of surface wettability on the flow pattern and heat transfer characteristics of PHPs under different heat fluxes. The work can be helpful for analyzing the heat transfer performance of PHPs with different surface wettability and providing theoretical guidance for enhancing heat transfer performance under stable operation conditions of PHPs. The objectives of this study are as follows:

• Investigate the vapor-liquid flow behavior and thermally-dynamic performance of single-loop and closed PHPs under varying operational conditions.

• Analyze the impact of heat flux and surface wettability on the flow and heat mass performance of the PHPs.

• Construct the flow pattern diagram for different surface wettability and identify the optimally modified surfaces to enhance flow fluctuation and heat transfer within the heat pipe.

2 Modelling and Parameter Setup

2.1 Geometric Model and Mesh-Independence Verification

The geometric structure of a two-dimensional single-loop PHP was constructed as shown in Fig. 1. The lengths of evaporation, adiabatic, and condensation sections are 54, 60, and 44 mm, respectively. The tube spacing is 20 mm and the total length is 158 mm. The liquid water is chosen as the working fluid due to its high thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity. In consideration of Bond number and critical diameter, the tube diameter was selected as 4 mm.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of single-loop PHPs

The ANSYS Meshing was used to perform quadrilateral meshing of PHPs as shown in Fig. 2. The local mesh refinement neighboring the wall was performed using expansion settings with 5 layers and a growth rate of 1.2 for improving the overall accuracy of the numerical simulation.

Figure 2: Meshing and local detailed enlargement

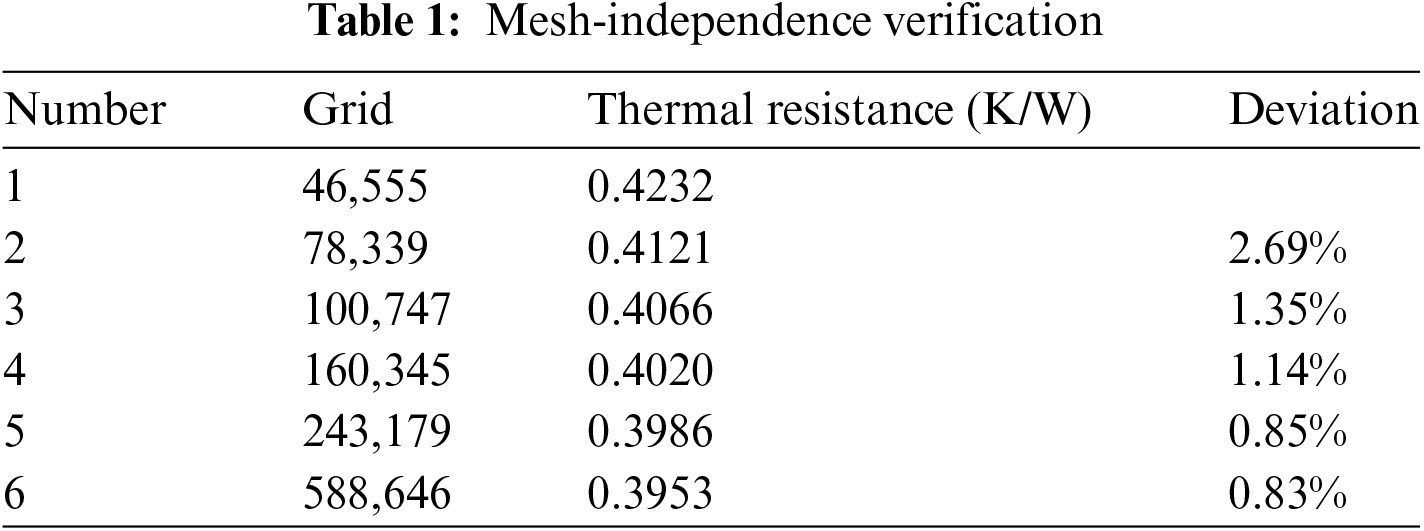

The number of grid cells significantly affects the accuracy of numerical results. To minimize grid-discretization errors, the mesh-independence verification is required with different grid numbers. The meshing numbers 46,555, 78,339, 100,747, 160,345, 243,179, and 588,646 were employed. Table 1 shows the relationship between thermal resistance and grid number. It indicates that the deviation of thermal resistance is decreased gradually with the increase of grid number, and the deviation of thermal resistance is 1.14% when the grid number is up to 160,345. Therefore, the grid number with 160,345 grids was selected considering the computational cost and the reliability of numerical results.

For the simplicity of numerical simulation, the following assumptions are made:

(1) Water vapor is considered as the compressible ideal gas and liquid water is incompressible;

(2) Thermophysical properties of working fluid, i.e., thermal conductivity, specific heat, viscosity, and density, are assumed to be constant;

(3) The friction between the vapor slug and the tube wall is neglected;

(4) The thermal resistance of tube thickness is ignored.

The equations of mass, momentum, and energy of the flow and heat transfer of PHPs can be expressed [16,17]:

The governing equations:

where

The momentum conservation equation:

where

The energy conservation equation:

where

For evaporation and condensation process, the mass transfer can be expressed as:

The surface tension model (CSF) was adopted as body force to the source term of the momentum conservation equation:

where

The thermal resistance is an important indicator to evaluate the heat transfer performance of PHPs [18]:

where

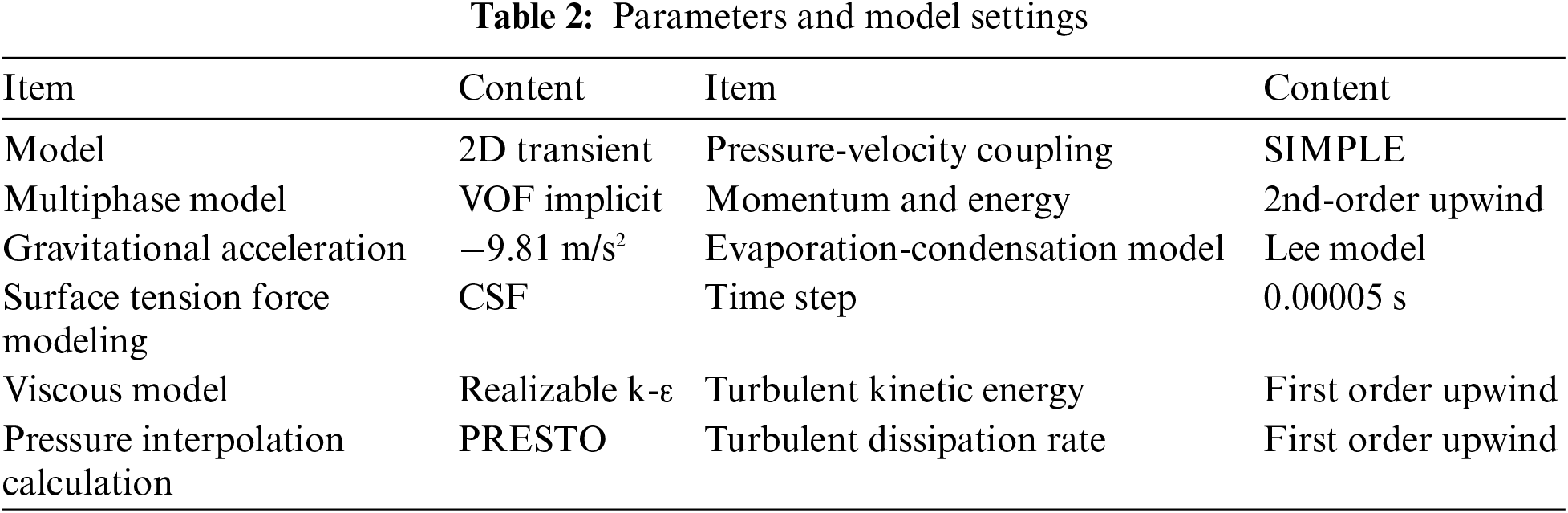

The filling rate of working fluid is set as 50%. The surface tension between the gas and liquid phases is set to 0.072 N/m. The convergence criteria for the continuity, momentum and energy equation are set to 10−6. The computational time step is set as 5 × 10−5 s and total computational time of each simulation case is set to 20 s. The parameters and model settings in numerical process are shown in Table 2.

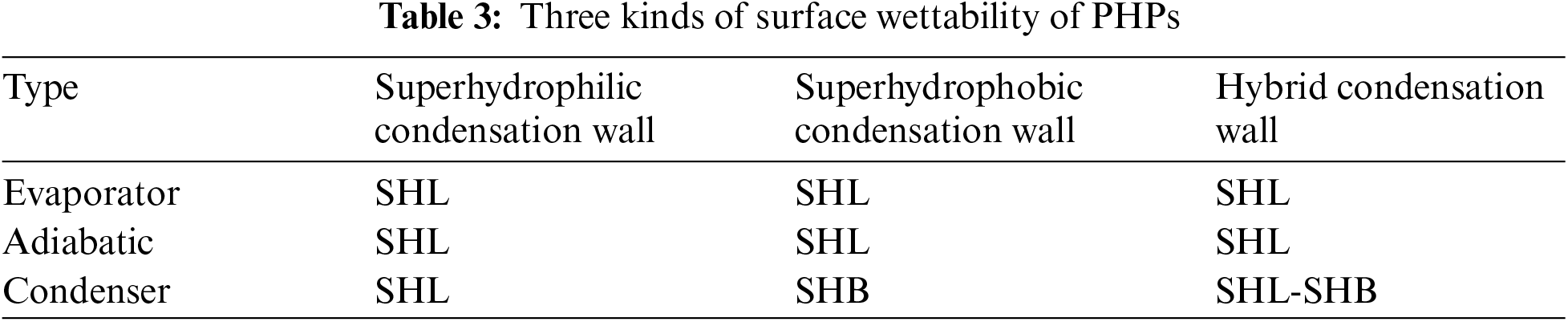

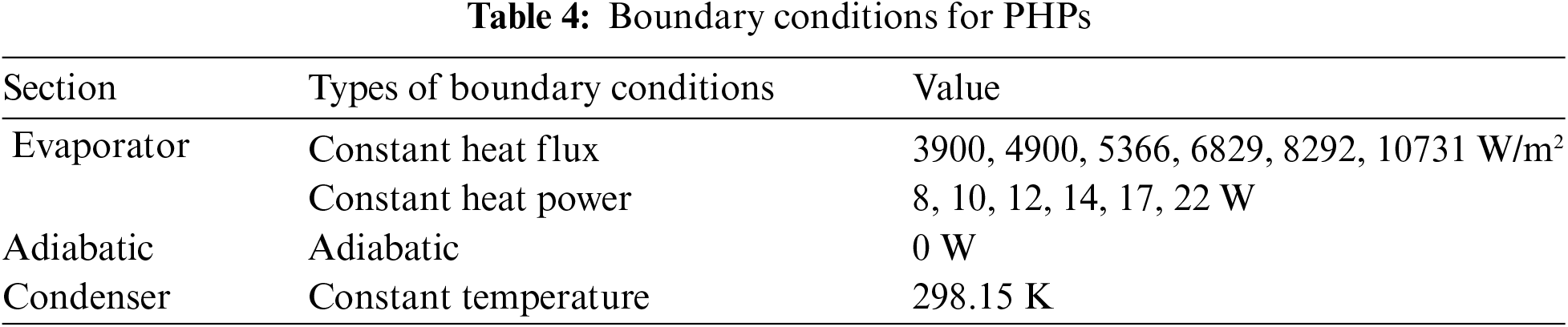

The surface wettability of the tube wall is a critical factor affecting the boiling in the evaporation section and condensation in the condensation section, which is characterized by the contact angle between the liquid phase working fluid and the wall surface [19]. According to Reference [20], the surface is considered superhydrophilic when the contact angle is less than 10°, and superhydrophobic when it is greater than 150°. In this study, the contact angle for the superhydrophilic surface is set to 9.2°, and for the superhydrophobic surface to 150°. The ANSYS FLUENT wall adhesion function is utilized to implement different contact angles in the condensation section, allowing for comparative analysis under three surface modifications: superhydrophilic condensation section wall (SHL) at contact angle of 9.2°, superhydrophobic condensation section wall (SHB) at contact angle of 150°, and hybrid condensation section wall (Hybrid) at contact angle of 9.2° on the left side and 150° on the right side, as shown in Table 3. The heat flux boundary conditions are shown in Table 4.

Numerical validation is necessary to ensure the correctness of the numerical method. The simulation model and setup are coincident with the Reference [21]. The heat power of 18, 35.77, 55.8, 86.62, and 97.11 W were applied to the evaporation section. The thermal resistances were quantitatively compared with experimental results from the literature. As shown in Fig. 3, the results exhibit similar trends to the experimental results. At a heat power of 55.80 W, the maximum deviation is 0.07 K/W, with a computational deviation of 8.9%. The smallest deviation is 0.34% at a heat power of 86.62 W. This indicates that the numerical simulation method is reliable. Additionally, the consistency of the flow patterns between the numerical and experimental results further confirms the reliability of the numerical simulation results. A comparison of thermal resistances and flow patterns shows that both results fall within the acceptable error range, validating the numerical methods for simulating two-phase flow and heat transfer.

Figure 3: Validation of the numerical method with the Reference [18]: (a) deviation of thermal resistance between the numerical and experimental results; (b) comparison of flow patterns

Heat flux plays a crucial role in generating different flow patterns and enhancing the heat transfer performance of PHPs. The heat fluxes of 1463, 3900, 4900, 5366, 6829, 8292, 10,731, and 11,220 W/m2 were selected for the comparative analysis. If the heat flux is below the start-up power, it is difficult to trigger the fluctuation of working fluid with PHPs. When the heat flux is increased to 3900 W/m2, a few nucleation sites appear on the inner surface, and tiny bubbles are generated at t = 7.4 s. The buoyant force continuously increases as the bubbles gradually expand. When the buoyant force exceeds the adhesion force between the bubble and the wall, the entire bubble smoothly detaches from the heating surface due to the center-seeking effect [22]. In addition, the superhydrophilic surface generates smaller bubbles with higher detachment frequency and enhances the liquid disturbance neighboring the surface. Therefore, the localized minor oscillations occurred with a distance difference between liquid columns, as shown in Fig. 4a. As the evaporation section temperature rises, the nucleate boiling intensifies and larger bubbles disperse in the working fluid. The oscillatory flow under the drive of buoyancy and pressure appears on the two sides of PHPs, and the height difference of the liquid obviously improves, as shown in Fig. 4b. In the PHP with constant volume, the internal vapor-liquid phases are transferred by both saturation pressure and saturation temperature of working fluid. The saturation temperature is increased with the rise of saturation pressure of working fluid. As the pressure variation of the working fluid intensifies due to the bubble growth, mergence and detachment, the average temperature of working fluid the fluctuated correspondingly. When the pressure difference between the evaporation and condensation sections is beyond a certain value, the working fluid starts moving toward the condensation section and the average temperature in the evaporation section fluctuates frequently. Therefore, it is indicated that the start-up of the PHPs at t = 8.4 s, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 4: Vapor-liquid slug distribution in the superhydrophilic PHPs during the start-up process: (a) localized minor oscillations; (b) obvious oscillation on both sides

Figure 5: Average temperature of evaporation section

The bubble formation, growth, emergence, and detachment from the heating surface continuously and periodically occurred. As shown in Fig. 6a, the nucleate boiling regions were observed from t = 9 to 11 s. As shown in Fig. 6b, the large bubbles have evolved into vapor slugs that developed gradually from t = 11 to 13.6 s. The accumulated pressure difference between the hot and cold sections can offset the gravity, frictional flow resistance, and capillary resistance. Under the steady state, the major oscillatory flow is dominated by bubble flow, resulting in the vapor-liquid slugs distributed within the PHPs channel randomly and intermittently and enhancing the heat mass transfer throughout the entire PHPs.

Figure 6: Vapor-liquid slug distribution for superhydrophilic PHPs during the stable process: (a) bubble evolution; (b) vapor-liquid slug distribution

As shown in Fig. 7, the vapor plugs begin merging into longer vapor plugs after t = 14.8 s. The liquid film near the wall in the evaporation section gradually thins and ruptures, causing direct vapor contact without liquid cooling, and the wall temperature increases and ultimately reaches the dry out limit of the PHPs.

Figure 7: Vapor-liquid slug distribution in superhydrophilic PHPs

When the heat flux is increased to 4900 W/m2, the average temperature of the evaporation section of superhydrophilic PHPs were shown in Fig. 8. It indicates the start-up time is nearly 6.2 s and earlier by 2.2 s compared to the condition at 3900 W/m2. The stable slug flow consists of a series of vapor slugs and the dimension is close to the diameter of PHPs. The vapor slugs are surrounded by the thin liquid film and length-varied liquid columns are interspersed within the PHPs. For the superhydrophilic surface, the deposition of the liquid film causes a narrow liquid film at the tail of the liquid slug adjacent to the wall, as shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 8: Average temperature of the evaporation section in superhydrophilic PHPs

Figure 9: Thin liquid film inside superhydrophilic PHPs

The annular flow is also predominantly observed at the heat flux of 8292 W/m2. The flow patterns in a superhydrophilic PHPs are shown in Fig. 10, the bubble flow, slug flow, slug/annular flow, and annular flow were sequentially observed throughout the oscillation process of PHPs, which is consistent with the previous research results [23].

Figure 10: Flow patterns in superhydrophilic PHPs

At the heat flux 11,220 W/m2, it is observed that the bubble flow formed rapidly in the PHPs as shown in Fig. 11. The dispersed bubbles grow and merge to form slugs, but then evolve into long vapor slugs and it results in a rapid heat transfer deterioration. In conclusion, when the heat flux is less than 1463 W/m2, the superhydrophilic PHPs cannot achieve the pressure difference over a long start-up period, ultimately leading to the gentle dry out of the working fluid. When the heat flux exceeds the heat flux of 11,220 W/m2, the liquid in the superhydrophilic PHPs tends to dry out quickly.

Figure 11: Vapor-liquid slug distribution of superhydrophilic PHPs under heat flux 11,220 W/m2

As shown Fig. 12 shows the temperature curve of superhydrophilic PHPs under different heat fluxes. As shown in the figure, it is noted that when the input power exceeds the minimum start-up power, the start-up time of the PHPs gradually decreases with the increase of heat flux. All the start-up processes of the PHPs present a smooth start-up type and undergoes a stable oscillation transition period before reaching the steady operation state without boiling lag [24]. During stable operation of working fluid, under medium to high heat flux heating conditions, the pulsation frequency and amplitude of working fluid are larger, due to the larger temperature gradient from the evaporation section to the condensation section generated by higher heat input. When the heating power is 4900 and 8292 W/m2, the average temperatures at the evaporation section of the PHPs are 31.15°C and 33.98°C, respectively, and the flow pattern is transferred from slug flow to annular flow. This indicates that under the medium to high heat flux, the superhydrophilic PHPs present better heat transfer performance.

Figure 12: Temperature curve of superhydrophilic PHPs under different heat flux. (a) 3900 W/m2; (b) 4900 W/m2; (c) 5366 W/m2; (d) 6829 W/m2; (e) 8292 W/m2; (f) 10,731 W/m2

Fig. 13 illustrates the temperature difference and thermal resistance in the superhydrophilic PHPs. As shown in the figure, the temperature difference between the evaporation and condensation sections of the PHPs increases and the thermal resistance decreases continuously with the rise of heat flux. The thermal resistance presents a rapid decrease and then becomes a gradual stabilization. When the heat flux is 3900 W/m2, the thermal resistance value is 0.7317 K/W, and when the heat flux further increases to 10,731 W/m2, the thermal resistance is decreased to 0.4735 K/W.

Figure 13: Temperature difference and overall average thermal resistance in superhydrophilic PHPs

3.2 Effect of Surface Wettability

The effect of surface wettability on the heat transfer performance of the PHPs was analyzed at the heat flux of 8292 W/m2. At condensation section, the vapor continues to condense on the droplet surface and the tiny droplets appear to grow continuously, once the droplets reach a certain size, the adjacent droplets begin merging and eventually detach from the wall surface [25].The high-free-energy hydrophilic surface can promote the spreading of the droplets on the inner walls [26]. Subsequently, the superhydrophilic PHPs quickly forms water film with the concave-shape interface in the condensation section, as shown in Fig. 14.

Figure 14: Flow pattern of superhydrophilic condensation section

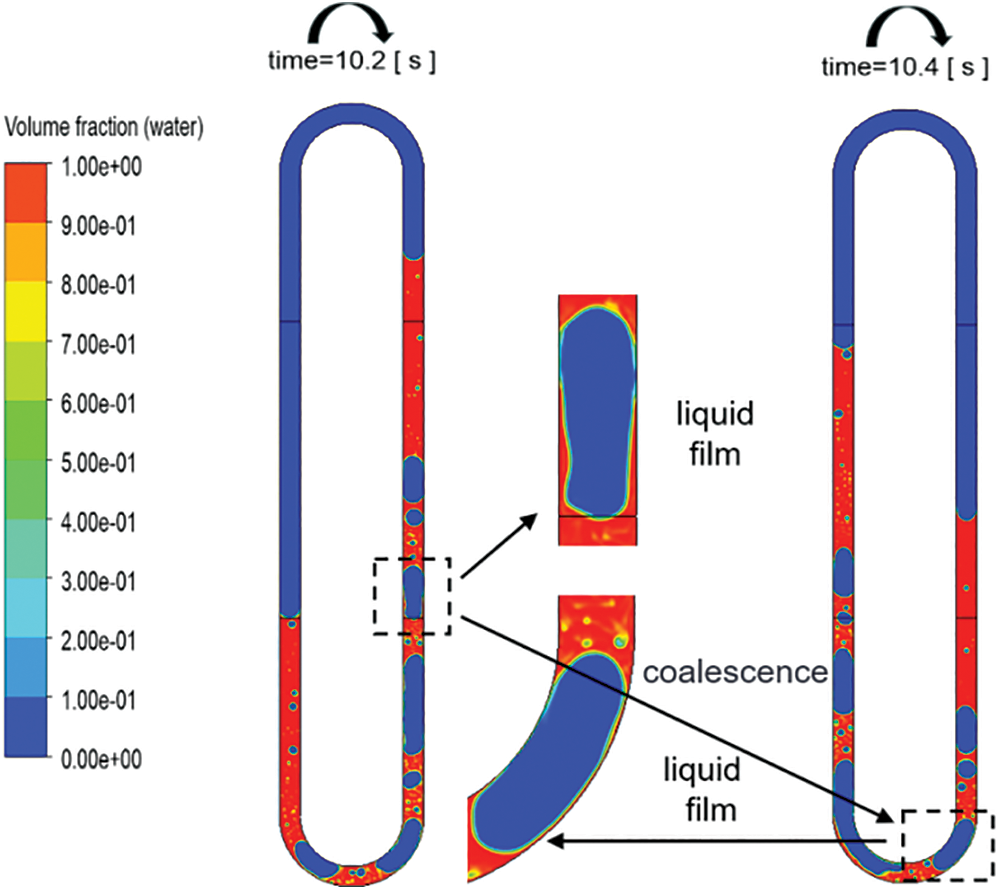

As shown in Fig. 15, the small vapor bubbles within liquid slugs tend to coalesce on the superhydrophobic wall. The coalesced bubbles eventually form a vapor slug and the liquid slug easily slips along the steam surface to the merging of adjacent liquid slugs. The hydrophilic surfaces can effectively reduce the required interfacial energy to facilitate nucleation during droplet formation [27]. Therefore, condensation nucleation is preferentially formed on the superhydrophilic surfaces than that on hydrophilic surfaces [28].

Figure 15: Flow pattern of superhydrophobic condensation section: (a) coalescence of small vapor bubbles; (b) coalescence of liquid slugs

The flow pattern of PHPs with a hybrid condensation section at the heat flux of 8292 W/m2 is shown in Fig. 16. In the hybrid PHPs, the thin liquid film forms on the left superhydrophilic wall, while the vapor slug directly contacts the tube wall on the right superhydrophobic wall. Under these conditions, the working fluid in the PHPs with hybrid condensation section reaches the higher temperature at the condensation section, indicating that the heat absorbed in the evaporation section is rapidly transferred to the condensation section. The heat transfer coefficient in the evaporation section for the hybrid conditions are significantly higher than that of the superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic conditions, as shown in Fig. 17.

Figure 16: Flow pattern of PHPs with the hybrid condensation section

Figure 17: Comparison of fluid temperature in condensation section and heat transfer coefficient in evaporation section of three types of PHPs

3.3 Start-Up Time and Thermal Resistance

As mentioned above, when the input heat flux is low, the flow patterns inside the PHPs are primarily bubble flow and slug flow with limited pulsation amplitude. The pulsation amplitude of the working fluid increased with the increase of heat flux, and the flow pattern within the tube gradually transferred from slug flow to annular flow. The start-up time of PHPs was shortened with the increasing heat flux, and under high heat flux conditions, the working fluid can tend to stabilize quickly. However, under the same heat flux conditions, the start-up times were nearly similar.

The overall average thermal resistance for three types of PHPs are shown in Fig. 18. At a heat flux of 8292 W/m2, the thermal resistances of PHPs with hybrid, superhydrophilic, and superhydrophobic condensation sections are 0.462, 0.4936, and 0.5206 K/W, respectively. The thermal resistance of hybrid PHPs reduces by 12.7% compared to the superhydrophobic condensation section, and by 6.8% compared to the superhydrophilic condensation section. At heat flux of 10731 W/m2, the hybrid PHPs have the lowest thermal resistance 0.4464 K/W, while the thermal resistances of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic PHPs are 0.4705 and 0.5048 K/W, respectively.

Figure 18: Start-up time and overall average thermal resistance for three types of PHPs: (a) start-up time; (b) overall average thermal resistance

The effects of heat flux and surface wettability on single-loop PHPs have been studied, and then the flow pattern diagram can be constructed from the prior discussion, as shown in Fig. 19. When the input heat flux is low, the flow patterns inside the PHPs are primarily bubble flow and slug flow, while the annular flow commonly appears at the higher heat flux. Besides, the pulsation amplitude of working fluid can be enhanced and the flow pattern gradually transfers from slug flow to annular flow with the increase of heat flux.

Figure 19: Flow pattern diagram for three modified surfaces at filling ratio = 50%

In conclusion, the low heat flux can weaken the pumping effect and decrease the heat transfer rate, thus it is difficult in the oscillatory flow and heat exchange of working fluid. The hydrophobic surface facilitates the droplets detaching from the condensation wall and merging, and further, it accelerates the return of the liquid slug and promotes dropwise condensation heat transfer [29]. Conversely, for the superhydrophilic condensation wall, due to insufficient pumping-driven capability, the limited heat transfer area of the liquid slug in the condensation section severely weakens the heat transfer of the liquid slug. On the superhydrophilic condensation wall, the oscillated liquid slugs give rise to progressive accumulation and thickening of liquid film on the channel walls along the direction of flow in the condensation section. The accumulated continuous film layer can hinder the condensation heat transfer [30].

As the heat flux increases, the annular flow becomes the dominant flow pattern. The PHPs with superhydrophilic surfaces gradually present more prominent heat transfer performance compared with superhydrophobic surfaces. The increase in heat flux significantly accelerates the evaporation rate of working fluid and the thin liquid film was elongated in the evaporation section, thereby the heat transfer coefficient in the evaporator was enhanced [31]. The smaller flow resistance in the superhydrophilic condensation section wall enhances the driving force for the pulsation amplitude and frequency of liquid slugs [32]. The good spreading of liquid slug on the condensation wall facilitates heat dissipation by increasing the heat exchange area between the thin liquid film and the cooling wall. The presence of thin liquid film shortens the length of the liquid slug and enhances the oscillatory heat transfer effect [33]. It is evident that the increase in amplitude and frequency plays a crucial role in the sensible heat exchange of the PHPs [34]. Conversely, the PHPs with a superhydrophobic condensation section have a low pulsation amplitude and frequency and weaken the heat transfer performance of liquid slug oscillation. The medium to high heat fluxes accelerates the evaporation rate, with high-speed steam continuously scouring over the tube wall and thinning the condensation liquid film. The faster evaporation rate also induces high pressure difference and mass transfer.

For the higher heat flux, the thickness of the liquid film on the superhydrophilic condensation wall will increase with the rise in oscillation frequency [35], leading to a decrease in the heat transfer coefficient [36]. The hybrid condensation wall weakens the deposition of liquid film, significantly enhancing the heat transfer performance as the condensation liquid film reduces. Moreover, the working fluid in the condensation section exhibits the reciprocating oscillation from the superhydrophobic side back to the superhydrophilic side and enables the condensation of the working fluid. Under high heat flux, the PHPs with the hybrid condensation section exhibit the most satisfactory heat transfer performance, followed by superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic condensation sections. Therefore, the PHPs with hybrid condensation sections are feasible for the design and operation of highly-effective device cooling components.

The vapor-liquid flow behavior and thermally dynamic performance of single-loop and closed pulsating heat pipes under three modified surfaces were numerically investigated. The effects of surface wettability on the flow pattern, thermal resistance, and start-up characteristics of PHPs under various heat fluxes were analyzed. The following conclusions were drawn:

(1) Heat flux plays a crucial role in generating different flow patterns and enhancing the heat transfer performance of PHPs. When the heat flux is less than 1463 W/m2, the PHPs tend to have the gently dry out over a long period, and when the heat flux exceeds the heat flux of 11,220 W/m2, the liquid in the PHPs dries out quickly. The feasible range of heat fluxes can be selected to balance the evaporation-condensation process of working fluid and heat transfer enhancement of the PHPs.

(2) The exhibits the most satisfactory heat transfer performance compared with superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic surfaces. The hybrid surface contributes to enhance the oscillation and heat transfer of working fluid. At the heat flux of 10,731 W/m2, the thermal resistance of hybrid PHPs is decreased to 0.4464 K/W. The working fluid forms the concave and convex interface in superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic surfaces, respectively.

(3) The start-up characteristic of the PHPs is primarily influenced by the surface wettability of the evaporator sections. The thermal resistance of three types of PHPs decreases with increasing heat flux. The pulsation amplitude of working fluid is enhanced and the flow pattern gradually transfers from bubble flow and slug flow to annular flow with the increase of heat flux.

Acknowledgement: We thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on the paper.

Funding Statement: The authors would like to acknowledge the support by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (3194046) and BUCEA Post Graduate Innovation Project.

Author Contributions: Wei Zhang: Conceptualization, Supervision and Methodology; Haojie Chen: Investigation, Formal Analysis and Writing—Original Draft; Kunyu Cheng: Conceptualization, Software and Investigation; Yulong Zhang: Investigation, Formal Analysis and Writing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shang F, Fan S, Yang Q, Liu C, Liu J. Study on heat transfer characteristics of single-layer double-row pulsating heat pipe. Therm Sci. 2022;26(4):3325–34. doi:10.2298/TSCI210226253S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mushan SG, Deshmukh VN. A review of pulsating heat pipes encompassing their dominant factors, flexible structure, and potential applications. Int J Green Energy. 2024;21(11):2559–96. doi:10.1080/15435075.2024.2319229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cho HJ, Preston DJ, Zhu Y, Wang EN. Nanoengineered materials for liquid-vapour phase-change heat transfer. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;2(2):16092. doi:10.1038/natrevmats.2016.92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Fletcher NH. Size effect in heterogeneous nucleation. J Chem Phys. 1958;29(3):572–6. doi:10.1063/1.1744540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ji Y, Xu C, Ma H, Pan X. An experimental investigation of the heat transfer performance of an oscillating heat pipe with Copper Oxide (CuO) microstructure layer on the inner surface. J Heat Transf. 2013;135(7):074504. doi:10.1115/1.4023749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dobson R, Swanepoel G. An experimental investigation of the thickness of the liquid-film deposited at the trailing end of a liquid plug moving in the capillary tube of a pulsating heat pipe. Front Heat Pipes. 2010;1(1):013004. doi:10.5098/fhp.v1.1.3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Qu J, Ying WH, Cheng P. Thermal performance of an oscillating heat pipe with Al2O3–water nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2010;37(2):111–5. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2009.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kim W, Kim SJ. Effect of reentrant cavities on the thermal performance of a pulsating heat pipe. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;133:61–9. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.01.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Fumoto K, Kawaji M, Kawanami T. Study on a pulsating heat pipe with self-rewetting fluid. J Electron Packag. 2010;132(3):031005. doi:10.1115/1.4001855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jose J, Kumar Hotta T. Thermal performance analysis and optimization of a heat pipe-based electronic thermal management system using experimental data-driven neuro-genetic technique. Ther Sci Eng Progress. 2024;54:102860. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2024.102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ji Y, Chen H-H, Kim YJ, Yu Q, Ma X, Ma HB. Hydrophobic surface effect on heat transfer performance in an oscillating heat pipe. J Heat Transf. 2012;134(7):074502. doi:10.1115/1.4006111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Betancur L, Mangini D, Mantelli M, Marengo M. Experimental study of thermal performance in a closed loop pulsating heat pipe with alternating superhydrophobic channels. Ther Sci Eng Progress. 2020;17(17–18):100360. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2019.100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang J, Xie J, Liu X. Investigation of wettability on performance of pulsating heat pipe. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;150(2):119354. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.119354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hao T, Ma X, Lan Z, Li N, Zhao Y. Effects of superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic surfaces on heat transfer and oscillating motion of an oscillating heat pipe. J Heat Transf. 2014;136(8):082001. doi:10.1115/1.4027390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang QZ, Ji YL, Li HT, Sun D, Sun YQ. Effect of surface wettability on heat transfer performance of oscillating heat pipe. In: Papers of the Chinese society of engineering thermophysics; 2016 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

16. Tao WQ. Numerical heat transfer. 2nd ed. Xi’an, China: Xi’an Jiaotong University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

17. Zhang D, Jiang E, Shen C, Zhou J, He Z. Numerical simulation on pulsating heat pipe with connected-path structure. J Enhanc Heat Transf. 2021;28(2):1–17. doi:10.1615/JEnhHeatTransf.2020035771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Winkler M, Rapp D, Mahlke A, Zunftmeister Felix, Vergez Marc, Wischerhoff Erik, et al. Small-sized pulsating heat pipes/oscillating heat pipes with low thermal resistance and high heat transport capability. Energies. 2020;13(7):1736. doi:10.3390/en13071736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cousins JRL, Duffy BR, Wilson SK, Mottram NJ. Young and Young-Laplace equations for a static ridge of nematic liquid crystal, and transitions between equilibrium states. Proc Royal Soc A: Mathemat Phys Eng Sci. 2022;478(2259):20210849. doi:10.1098/rspa.2021.0849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zheng W, Huang J, Li S, Ge M, Teng L, Chen Z, et al. Advanced materials with special wettability toward intelligent oily wastewater remediation. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2021;13(1):67–87. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c18794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Saha N, Das PK, Sharma PK. Influence of process variables on the hydrodynamics and performance of a single loop pulsating heat pipe. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2014;2014(74):238–50. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.02.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pradhan S, Counts S, Enget C, Bikkina PK. Effect of wettability on vacuum-driven bubble nucleation. Processes. 2022;10(6):1073. doi:10.3390/pr10061073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu X, Sun Q, Zhang C, Wu L. High-speed visual analysis of fluid flow and heat transfer in oscillating heat pipes with different diameters. Appl Sci. 2016;6(11):321. doi:10.3390/app6110321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Scheiff V, Yada S, Fdhila RB. Experimental investigation and quasi-steady modeling of nucleate boiling in mini-channel thermosyphons. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;256(1):124033. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.124033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wu S, Dai H, Wang H, Shen C, Liu X. Role of condensation on boiling heat transfer in a confined chamber. Appl Therm Eng. 2021;185(11):116309. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.116309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Atkins P, Paula JD, Keeler J. Physical chemistry. 12th ed. UK: Oxford University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

27. Song T, Lan Z, Ma X, Bai T. Molecular clustering physical model of steam condensation and the experimental study on the initial droplet size distribution. Int J Therm Sci. 2009;48(12):2228–36. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2009.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bai H, Wang L, Ju J, Sun R, Zheng Y, Jiang L. Efficient water collection on integrative bioinspired surfaces with star-shaped wettability patterns. Adv Mater Deerfield. 2014;26(29):5025–30. doi:10.1002/adma.201400262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Aljallis E, Sarshar MA, Datla R, Sikka V, Jones A, Choi C-H. Experimental study of skin friction drag reduction on superhydrophobic flat plates in high Reynolds number boundary layer flow. Phys Fluids. 2013;25(2):025103. doi:10.1063/1.4791602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Parker AR, Lawrence CR. Water capture by a desert beetle. Nature. 2001;2001(414):33–4. doi:10.1038/35102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Che Z, Wang T, Sun F, Jiang Y. Research on heat transfer capability of liquid film in three-phase contact line area. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;195(23–24):123158. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jung C, Kim SJ. Effects of oscillation amplitudes on heat transfer mechanisms of pulsating heat pipes. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2021;165:120642. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.120642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Srinivasan V, Khandekar S. Thermo-hydrodynamic transport phenomena in partially wetting liquid plugs moving inside micro-channels. Sādhanā. 2017;42(4):607–24. doi:10.1007/s12046-017-0618-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yasuda Y, Matsumoto Y, Shinohara T, Nabeshima F, Horiuchi K, Nagai H. Visualization of the working fluid in a flat-plate pulsating heat pipe by neutron radiography. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2023;213:124291. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2023.124291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang X, Nikolayev VS. Physics and modeling of liquid films in pulsating heat pipes. Phys Rev Fluids. 2023;8(8):084002. doi:10.1103/PhysRevFluids.8.084002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rouaze G, Marcinichen JB, Cataldo F, Aubin P, Thome JR. Simulation and experimental validation of pulsating heat pipes. Appl Therm Eng. 2021;196:117271. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.117271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools