Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Thermodynamic Analysis of Marangoni Convection in Magnetized Nanofluid

1 Centre for Mathematical Needs, Department of Mathematics, Christ University, Bengaluru, 560029, India

2 Postgraduate and Research Center of Mathematics, Bharata Mata College (Autonomous), Thrikkakara, 682021, India

3 Department of Mathematics and Physics, Texas A&M International University, Laredo, TX 78041, USA

4 Department of Industrial Systems and Technologies Engineering, University of Parma, Parma, 43124, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Giulio Lorenzini. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Heat and Mass Transfer Applications in Engineering and Biomedical Systems: New Developments)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(2), 529-551. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.058702

Received 19 September 2024; Accepted 20 December 2024; Issue published 25 April 2025

Abstract

This article explores the optimization of heat transport in a magnetohydrodynamic nanofluid flow with mixed Marangoni convection by using the Response Surface Methodology. The convective flow is studied with external magnetism, radiative heat flux, and buoyancy. An internal heat absorption through the permeable surface is also taken into account. The governing system includes the continuity equation, Navier-Stokes momentum equation, and the conservation of energy equations, approximated by the Prandtl boundary layer theory. The entropy generation in the thermodynamic system is evaluated. Experimental data (Corcione models) is used to model the single-phase alumina-water nanofluid. The numerical solution for the highly nonlinear differential system is obtained via Ralston’s algorithm. It is observed that the applied magnetic field leads to a higher entropy generation which is engendered by the Lorentz force within the fluid system. The thermal radiation leads to a higher Bejan number, indicating the importance of the irreversibility of heat transport. Also, the heat absorption process via a permeable surface can be employed to regulate the thermal field. An optimized Nusselt number of 13.4 is obtained at the high levels of radiation, injection, and heat sink parameters. The modeled fluid flow scenario is often seen in drying, coating, and heat exchange processes, especially in microgravity environments.Keywords

Drying of silicon wafers, electron beam melting, growth of crystals, and convection cells involve surface tension gradient-induced flows. Such flows are called Marangoni convective flows in which the change in surface tension can be brought about by gradients in temperature (called thermal Marangoni convection) or solute (called solutal Marangoni convection) [1]. The Marangoni flow is undesirable in crystal growth and thermal Marangoni convection is dominant in semiconductor melts of Silicon [2]. At the interface, the surface tension (σ) is modeled such that it varies linearly with temperature as given below [3]:

where,

An applied magnetic field can be utilized to regulate the fluid flow and lead to higher thermal profiles. Therefore, magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flows prove to be useful for nanofluid flow applications. In silicon crystal growth and semiconductor processing, the Lorentz force formed due to the magnetism can decrease the unfavorable Marangoni velocity in the fluid layer. Since then, there have been various studies in this direction that analyze MHD flows, especially surface tension gradient-induced ones. The fully developed MHD flow over a revolving disk that involves a slip (second-order) and is optimized for entropy was analyzed by Abbas et al. [9]. The significant effect of applied magnetism was highlighted in the study. Recently, Jawad et al. [10] studied the flow of a nanomaterial past a vertical plate that involved surface tension gradients and cross-diffusion. The retardation of fluid velocity via the applied magnetic field was reported. The MHD Marangoni flow of a nanofluid across a porous medium was studied by Sneha et al. [11]. The significant influence of the fluid flow by the magnetic effect was reported. Some more studies that investigate the MHD flows in different convective scenarios can be found in the literature [12–14].

Conventional working fluids of machinery and thermal equipment have been replaced with nanofluids owing to their superior thermophysical properties. Suspensions of nano-sized particles like metals, metal oxides, carbides, or nanotubes are called nanofluids (as seen in the pioneering works of Choi et al. [15]). Driven by the practical applicability, researchers have adapted to nanofluids for convective flows past various geometries. Advances in nanofluid flows can be referred to from the extensive review by Mahian et al. [16]. The Marangoni convective flow of gasoline oil with aluminum alloy and Boehmite alumina nanoparticles was analyzed by Ullah [17]. The thermal performance and heat transfer of the nanofluid were scrutinized. Rehman et al. [18] explored the Marangoni convection on a nanofluid by dispersing carbon nanotubes over an elongated surface. The decrease in nanofluid velocity by increasing nanoparticle concentration was reported. Some more studies that analyze such nanofluid flows are found in the literature [19–21].

Statistical optimization using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is an efficient methodology to estimate the optimum levels of the factor variables. RSM is used to study the interactive effects and to optimize a response variable. It is based on a designed experiment that is chosen based on the cost efficiency and minimization of the error. Further, the estimated model for the response can be used to find the sensitivity. This methodology has recently been used in fluid flow problems to optimize the heat and mass transport in the flow. Shirvan et al. [22] evaluated the sensitivity of heat transport and heat exchanger effectiveness in the nanomaterial flow through a double-pipe heat exchanger. In this direction, Shafiq et al. [23] analyzed the bioconvective flow of a tangent hyperbolic nanomaterial. The sensitivity of the motile microorganism number and the Nusselt number against the variation in the thermophoresis parameter, Lewis number, and Brownian motion aspect was explored. Mahanthesh et al. [24] optimized the heat transport in the flow of a hybrid nanofluid over a wedge. The Brownian random motion aspect was found to have the highest sensitivity and the optimized heat transport was estimated using the quadratic model obtained from the RSM analysis. A detailed statistical analysis has been carried out to optimize the convective heat transfer in a square cavity by Huda et al. [25]. A correlation for the average heat transport with respect to the chosen input variables was modeled using RSM. Of late, such analysis methods have been widely used to analyze fluid flow phenomena [26–28].

The radiative heat transport in the mixed convective Marangoni boundary layer flow of a nanomaterial with heat sink, external magnetic field, and suction/injection has not yet been studied. Moreover, the optimization of the heat transfer and the sensitivity at various levels has not yet been reported in the literature. This information is useful for applications like semiconductor crystal heat transfer, growth of silicon wafers, and coating processes. Hence, the objectives of the present study are as follows:

• Model the physical phenomenon of the mixed Marangoni nanomaterial flow with thermal radiation, heat sink, magnetic field, and suction/injection.

• Explore the effect of the external parameters and discuss the physical significance.

• Analyze the entropy generation thermodynamics in the fluid system.

• Estimate the optimum heat transport in the system utilizing the optimization procedure-RSM.

• Calculate the heat transport sensitivity at different parameter levels.

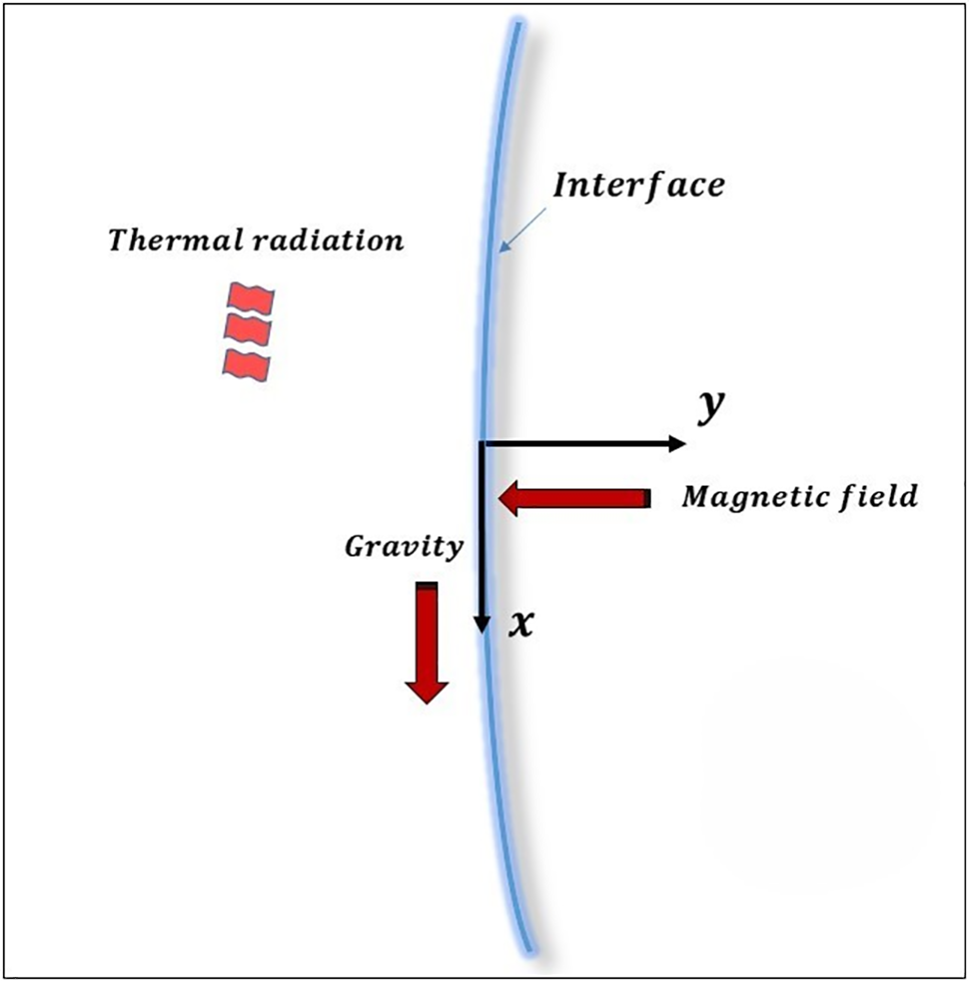

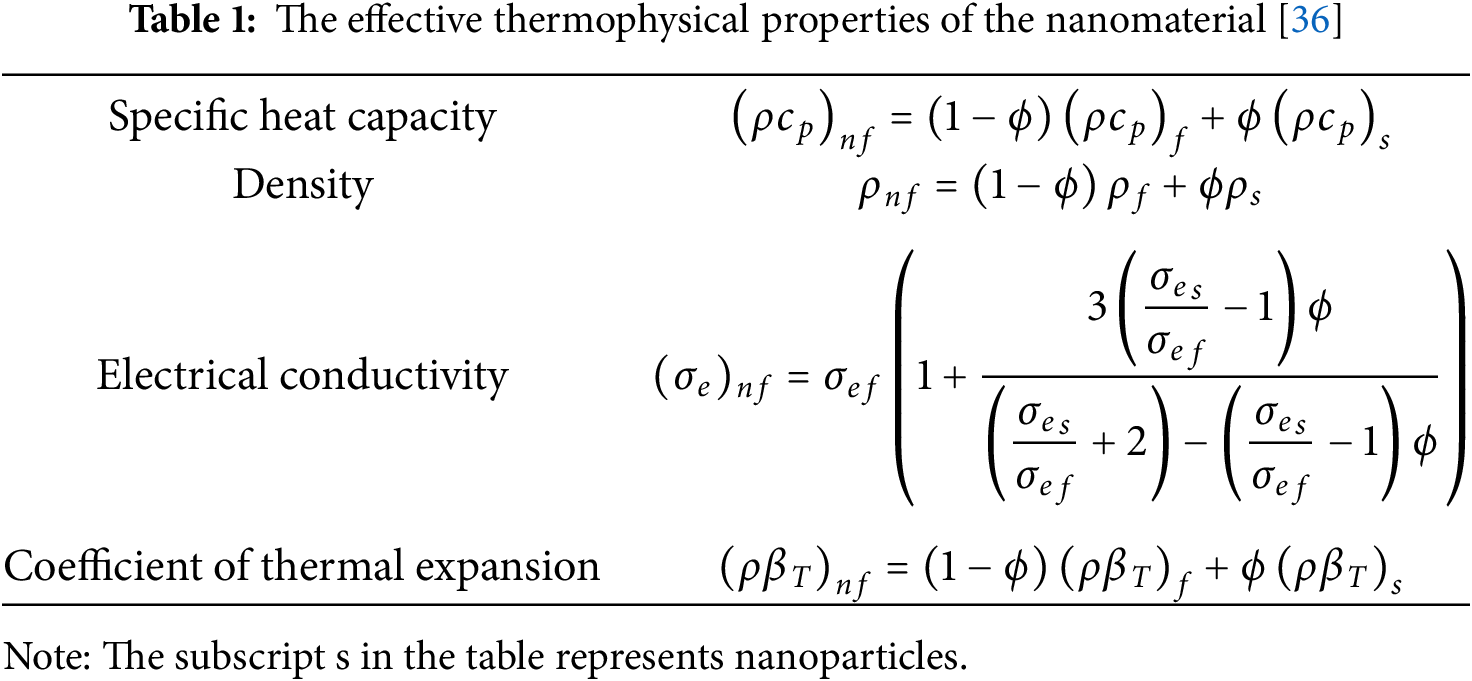

The surface-tension-induced boundary layer mixed convective flow of alumina-water nanomaterial is considered along with a significant buoyancy force. The buoyant force is significant because of the gravitational pull on the surface of the Earth. The working fluid considered in the study is alumina water as it possesses higher thermophysical properties, making it suitable for heat transfer applications. The alumina nanoparticles are suspended uniformly in thermal equilibrium and without slip. Fluid is incompressible and a laminar flow is considered. The nanomaterial is modeled using the homogeneous single-phase approach which includes the effective thermophysical properties of the nanomaterial. As seen in Fig. 1, the

Figure 1: Physical model and geometry

In the above equations, the velocity vector for the two-dimensional flow is

Neglecting the displacement currents, the Maxwell field equations (electromagnetic) are as follows (see Sutton et al. [31]):

where,

Under the Boussinesq and Prandtl’s boundary layer approximations, the governing equations for the two-dimensional steady flow are as follows:

The boundary conditions are given below:

where, ue denotes the external velocity, v0 is the suction/injection velocity and A is a constant. The third boundary condition at the interface (

In Eq. (8), the pressure gradient is reduced due to the presence of external flow, as shown below:

In various flow scenarios, the buoyant forces may assist or oppose the convective flow and hence, the dimensionless parameter

The optically dense nature of the water-based nanomaterial makes the Rosseland approximation suitable to model the radiative heat flux (see Rosseland [34]). Therefore, it is modeled as follows:

The expression in Eq. (13) is obtained by approximating the Taylor series expansion of

The single-phase nanofluid model is employed in conjunction with experimentally obtained relations to capture the properties of the 47 nm alumina-water nanomaterial. The nanomaterial viscosity is modeled using the Corcione model [35] which is an experimentally estimated relation as given below:

where,

The thermal conductivity is also modelled using the Corcione model [35] which is given as follows:

where,

The following variables are used to arrive at non-dimensionality in the equations.

In the above equations,

Using (17) in Eqs. (7)–(10), one can get:

where,

Self-similar solutions are computed by using the similarity transformations given below (see Golia et al. [29]):

where,

The set of ordinary differential equations is obtained as follows:

with

The non-dimensional scaled form of Eq. (11) is obtained as follows:

It is extremely important to make the heat transfer thermodynamically stable. Heat transfer produces thermodynamic irreversibility or entropy generation. Therefore, it is worth studying entropy generation. Lower entropy leads to lower energy loss. The viscous and Joule heating effects have been neglected in the energy equation to study heat transfer. But an order of magnitude analysis indicates that they are important in studying the entropy generation. Therefore, the entropy generation can be modelled as follows (see Bejan [37]):

Under the assumptions of the present problem:

The terms of

where,

The ratio of heat transfer irreversibility to the total irreversibility is called the Bejan number (

The value of

The system of equations Eqs. (25)–(27) is converted to a set of first-ordered differential equations using

This obtained system is then solved using Ralston’s fourth-order method [38]. This method is a self-starting numerical method with minimum truncation error which makes it advantageous to record accurate results. The method is a modified Runge-Kutta method which involves the following set of equations in the algorithm [38]:

where,

In the computations, infinity is rescaled to 5 as increasing this value does not have a significant change in the results. The domain is divided into 100 subintervals in the computational frame. The missing boundary conditions (

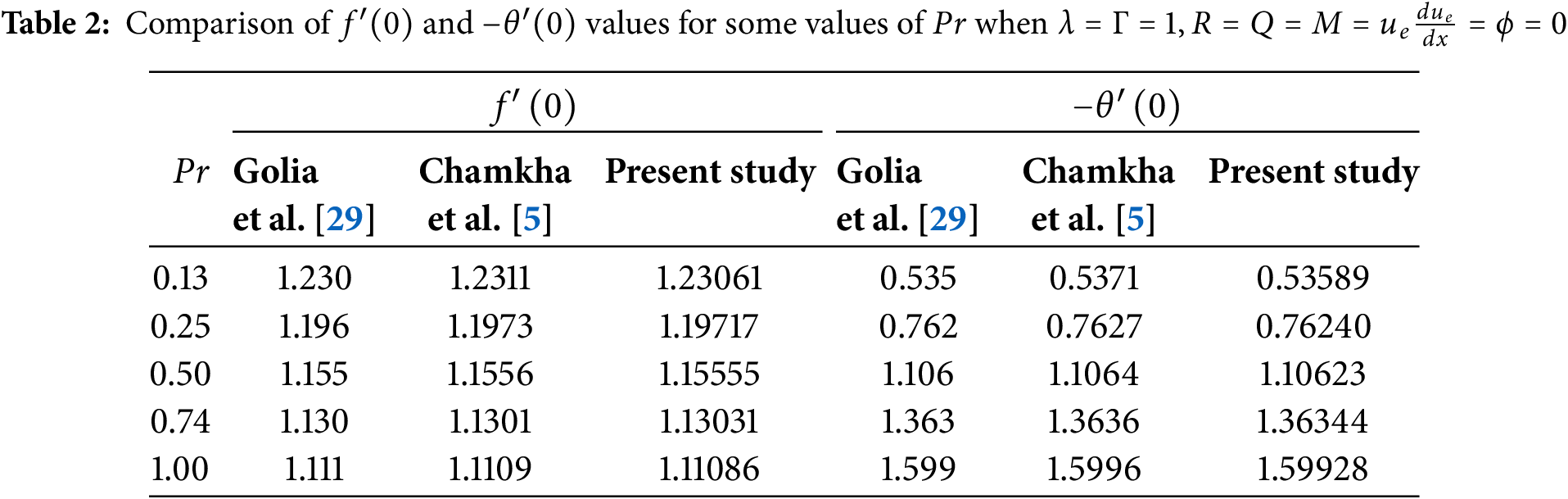

The numerical accuracy of the method is evaluated by a restrictive correspondence with the literature. The Marangoni-buoyant boundary layer case when the buoyancy is opposing is considered in the absence of radiative, magnetic, and heat sink effects. Golia et al. [29] employed the quasi-linearization method to arrive at numerical solutions whereas Chamkha et al. [5] used an implicit finite difference method. As seen in Table 2, the numerical values are accurate and hence uphold the accuracy of the numerical methodology employed in the present study.

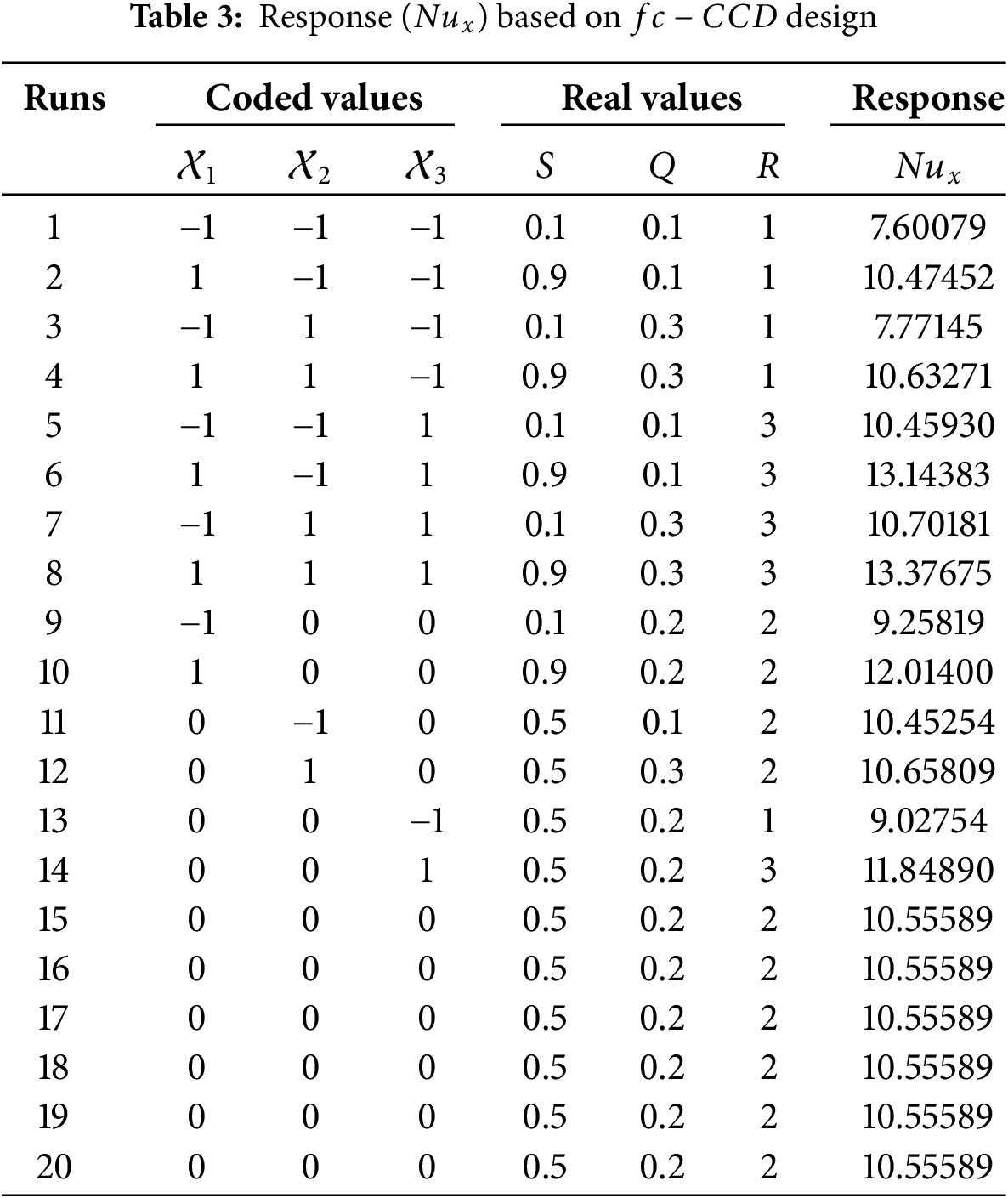

RSM is a robust tool based on Design of Experiments (DoE) which involves mathematical and statistical aspects. RSM is beneficial especially in situations to optimize a process and to study the interactive effects. Here, the heat transfer rate (quantified by

where, r0 is an intercept,

Optimization of the response variable is done based on the desirability value approach. The range of the desirability value is 0 to 1. For the maximization objective, the desirability value for each run is calculated as follows:

where,

The findings of the parametric and statistical computations are presented in this section and discussed with physical interpretations. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the heat transport is analyzed.

4.1 Discussion of Parametric Results

In this subsection, the impact of a single pertinent parameter on the flow and thermal profiles is analyzed by fixing the other parameters. The profiles for three types of boundaries (i.e., suction, impermeability, and injection) are compared. The Prandtl number which is a fluid property is fixed at 6.0674 (calculated for water at 300 K). Moreover, the domain is rescaled to 0 to 3 as there is no appreciable change in the numerical values by increasing the domain further.

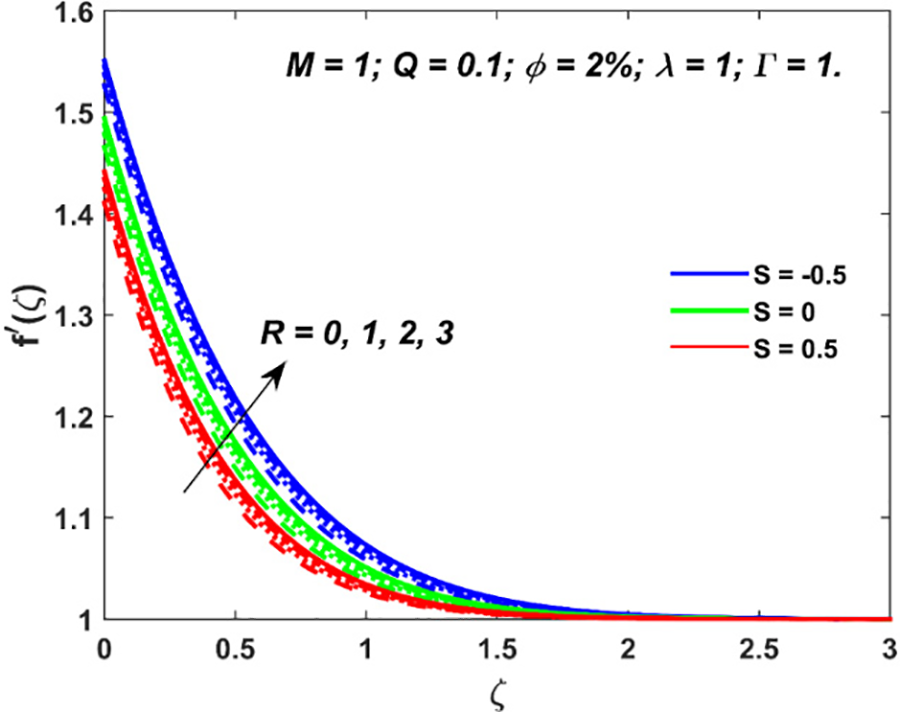

A larger radiative heat flux leads to a higher velocity of the nanomaterial as one can observe from Fig. 2. This is because of the higher energy supplemented to the system by the radiation. Also, the flow profile in the irradiative situation (

Figure 2: Variation in nanofluid velocity due to

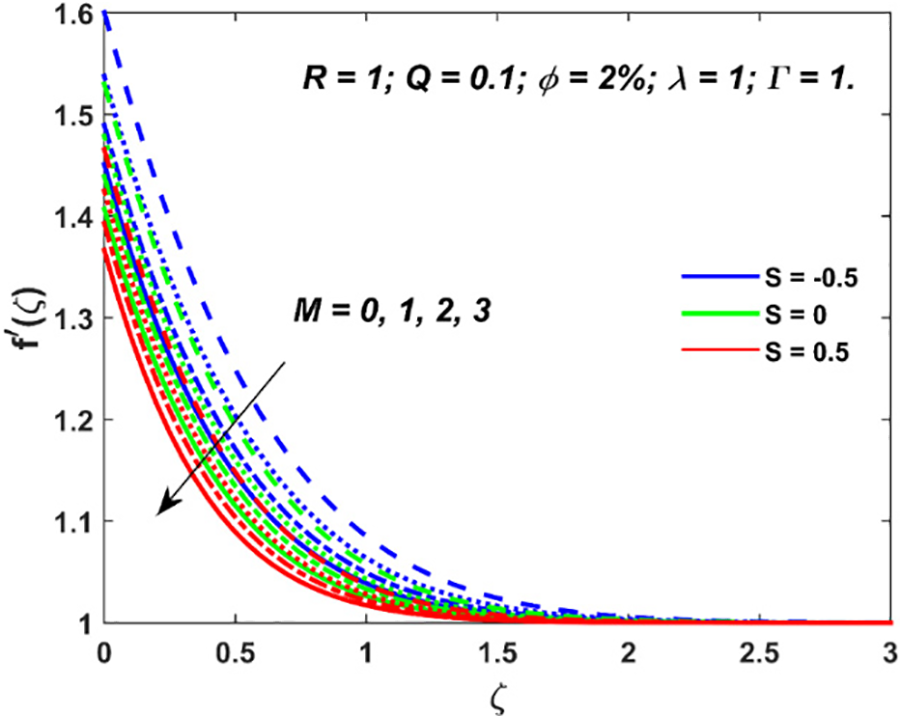

Figure 3: Variation in nanofluid velocity due to

The increment in

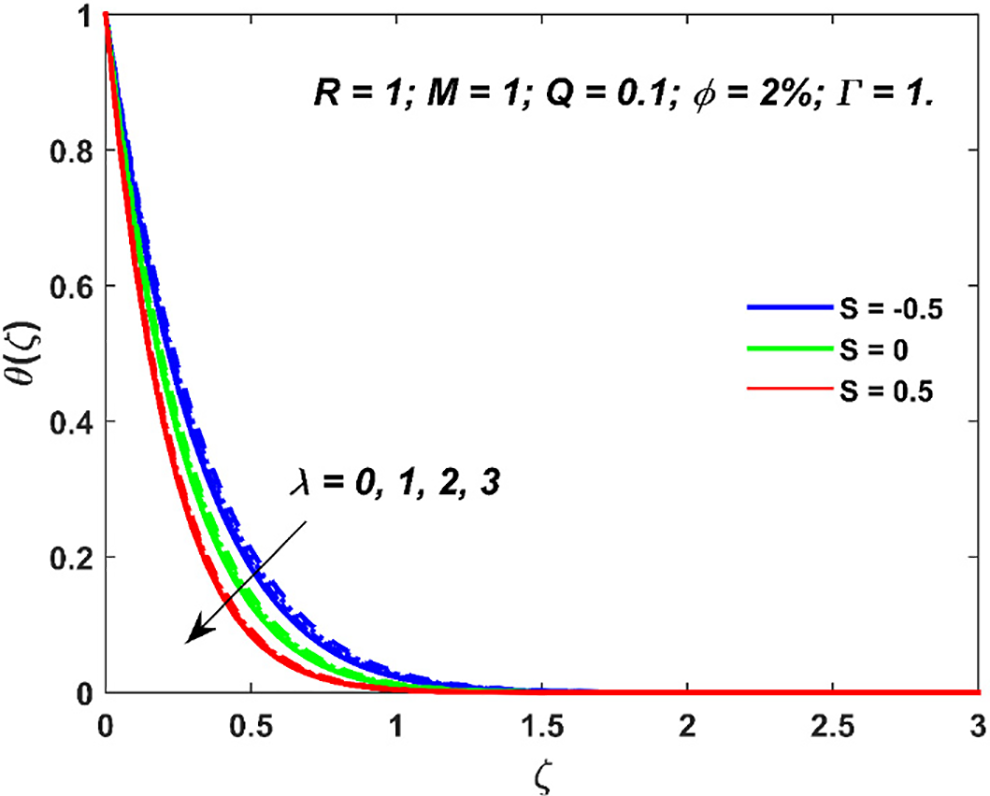

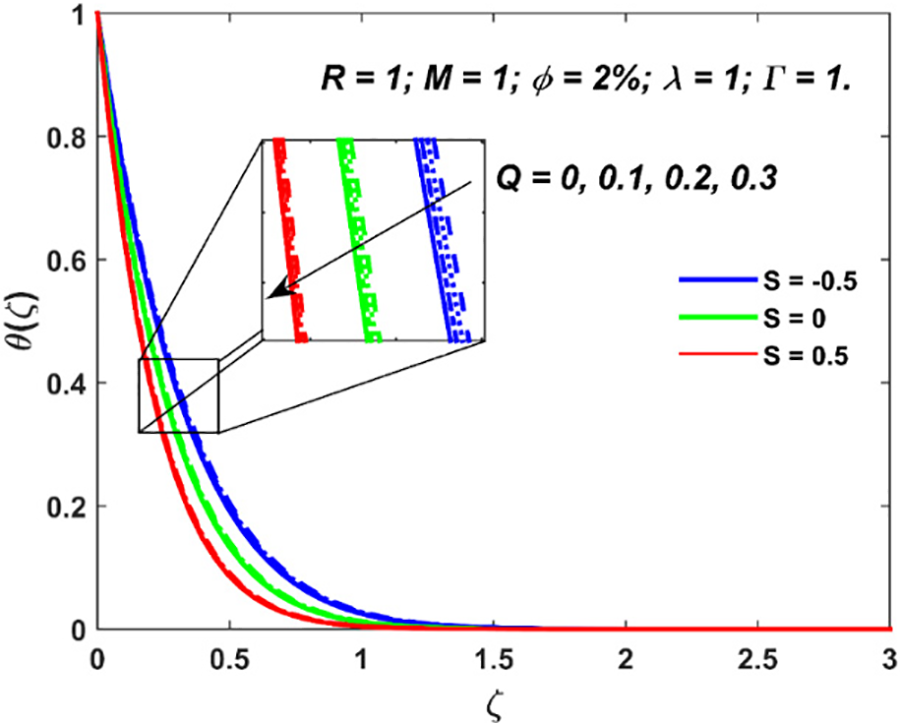

Figure 4: Variation in nanofluid temperature due to

Figure 5: Variation in nanofluid temperature due to

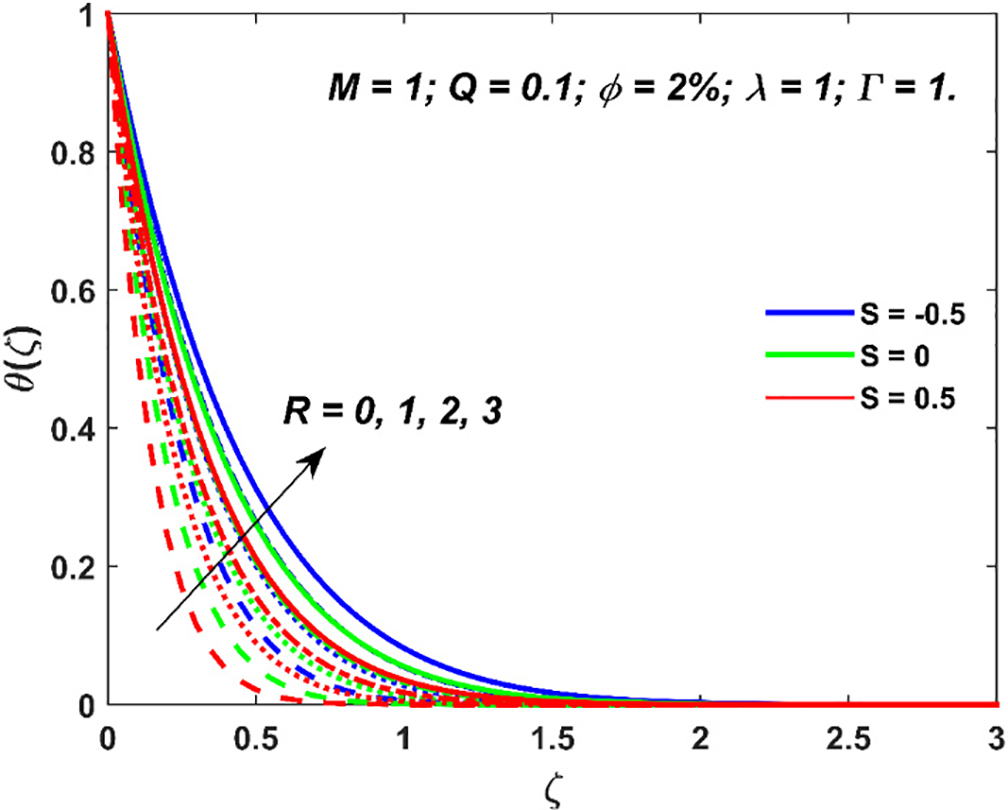

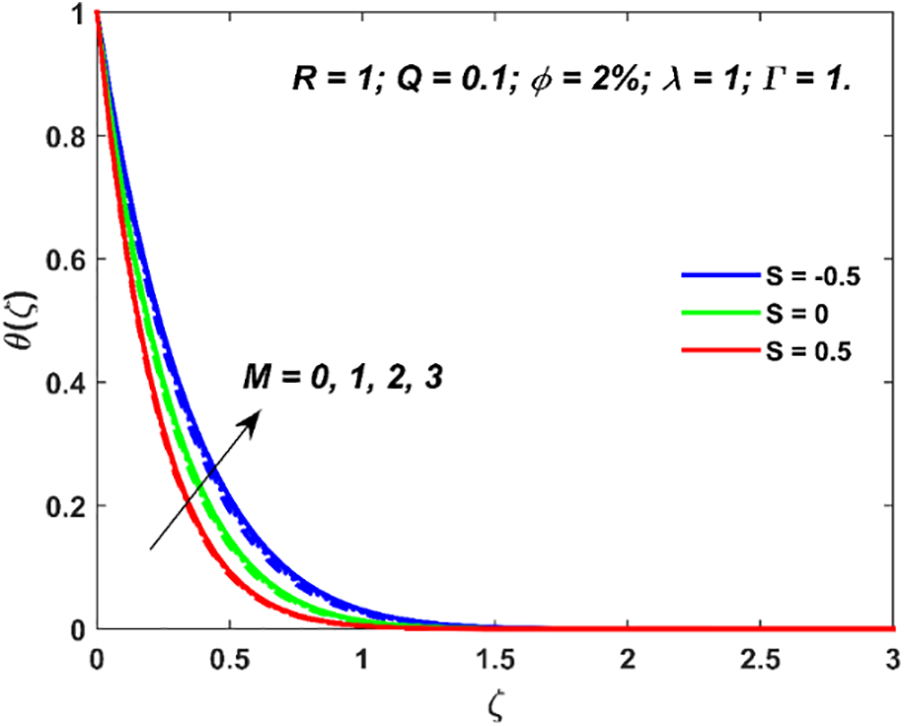

Figure 6: Variation in nanofluid temperature due to

Figure 7: Variation in nanofluid temperature due to

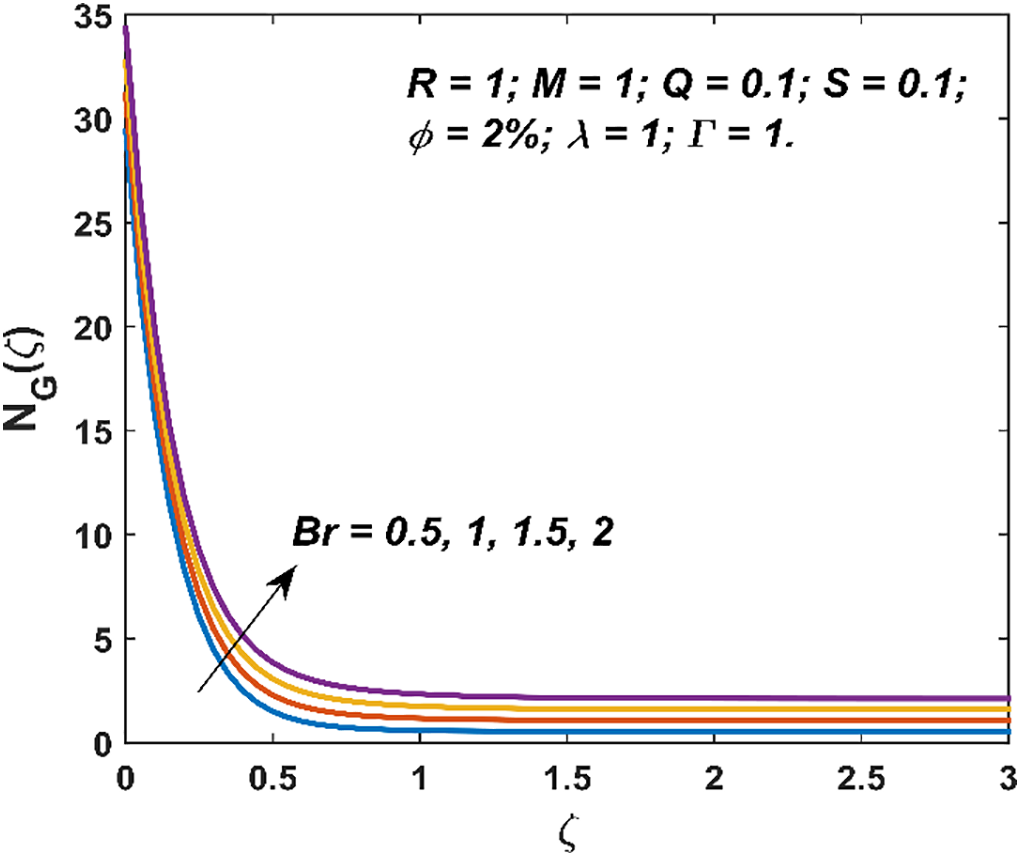

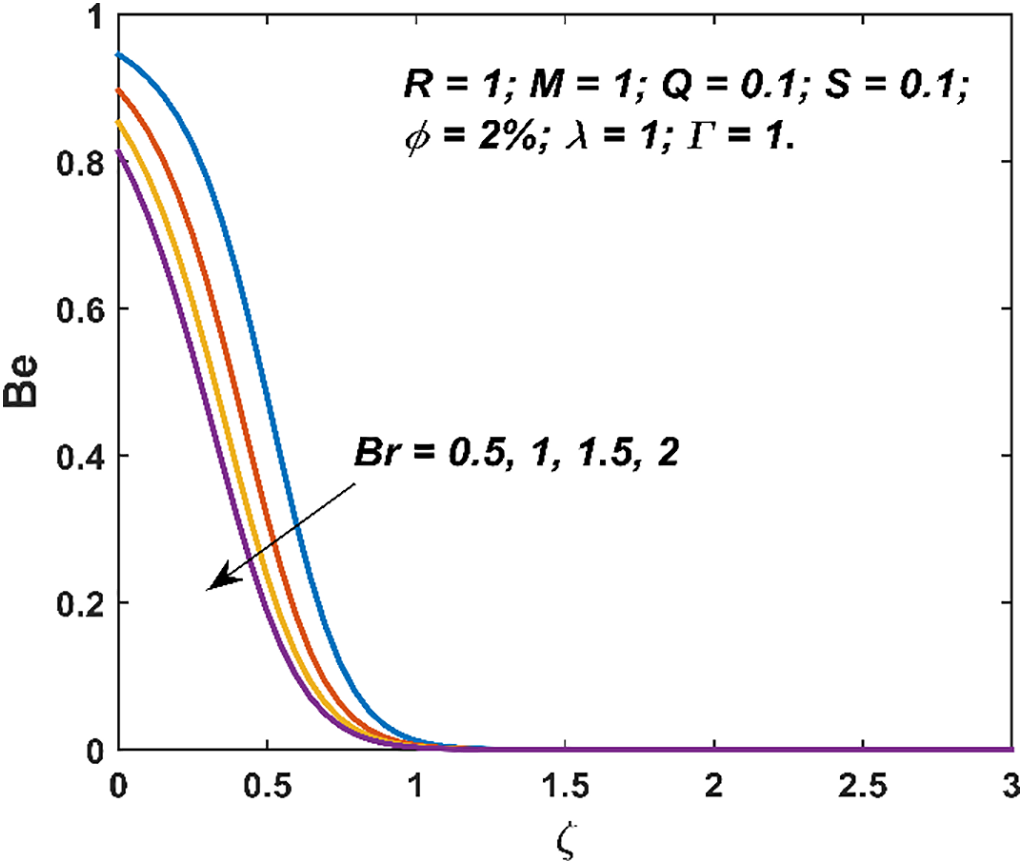

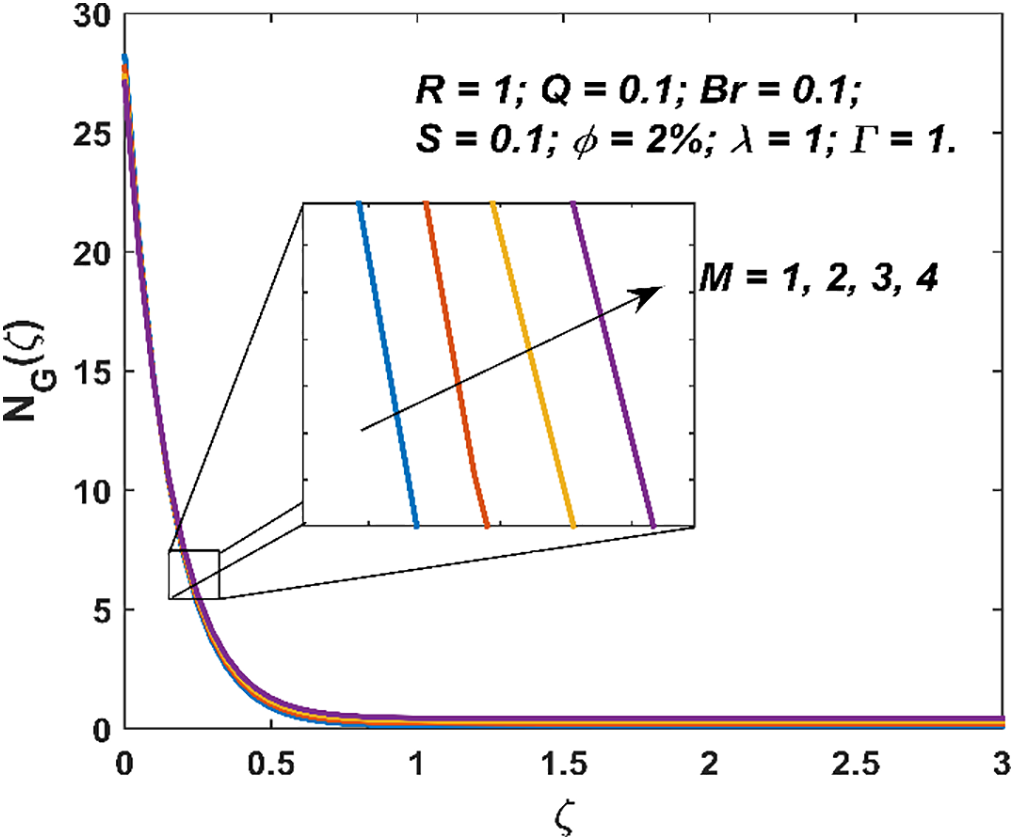

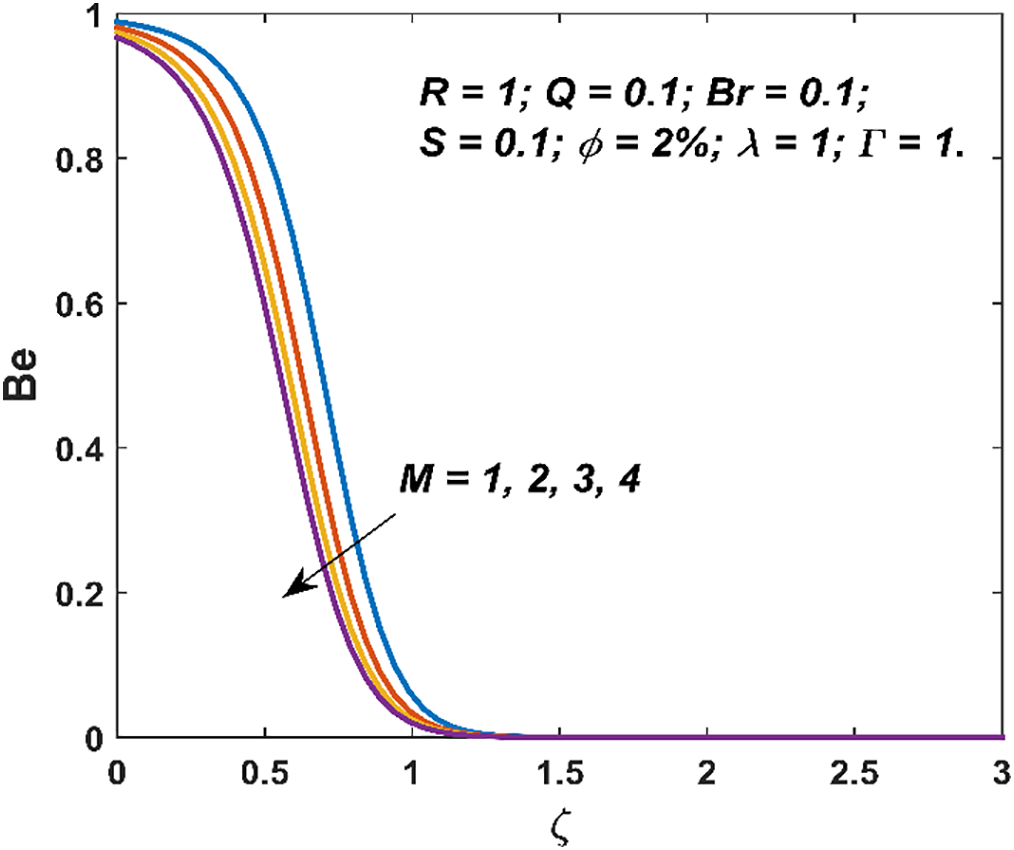

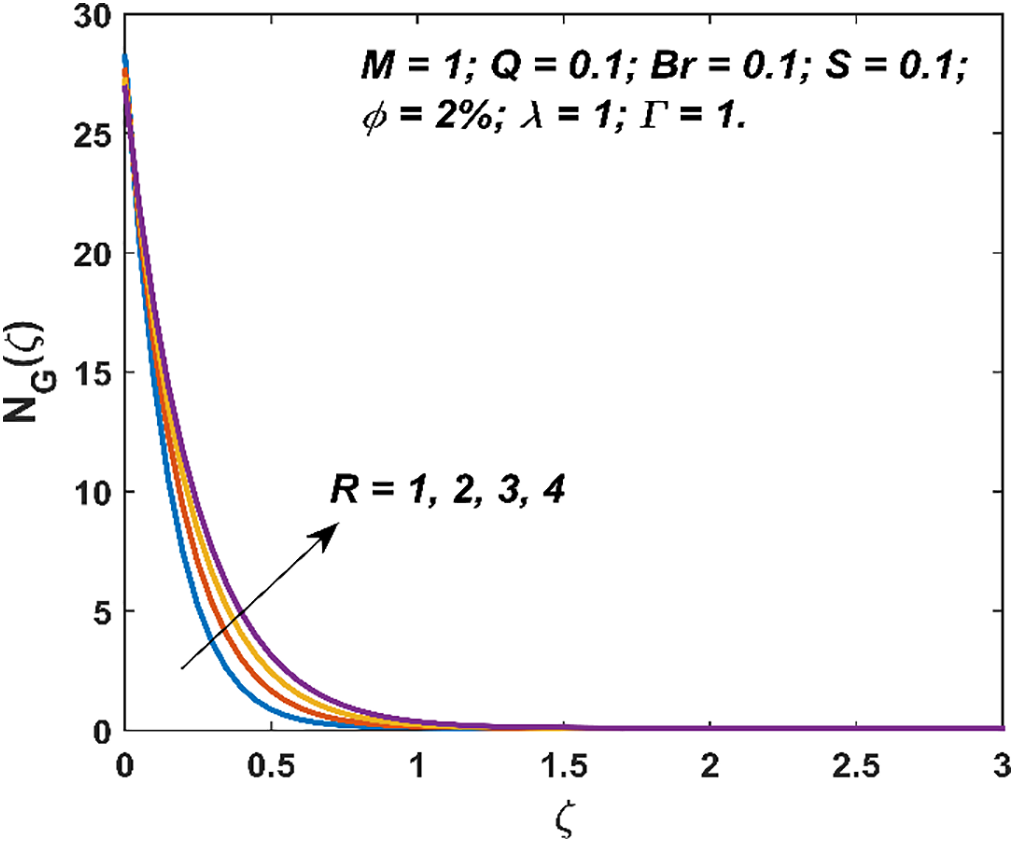

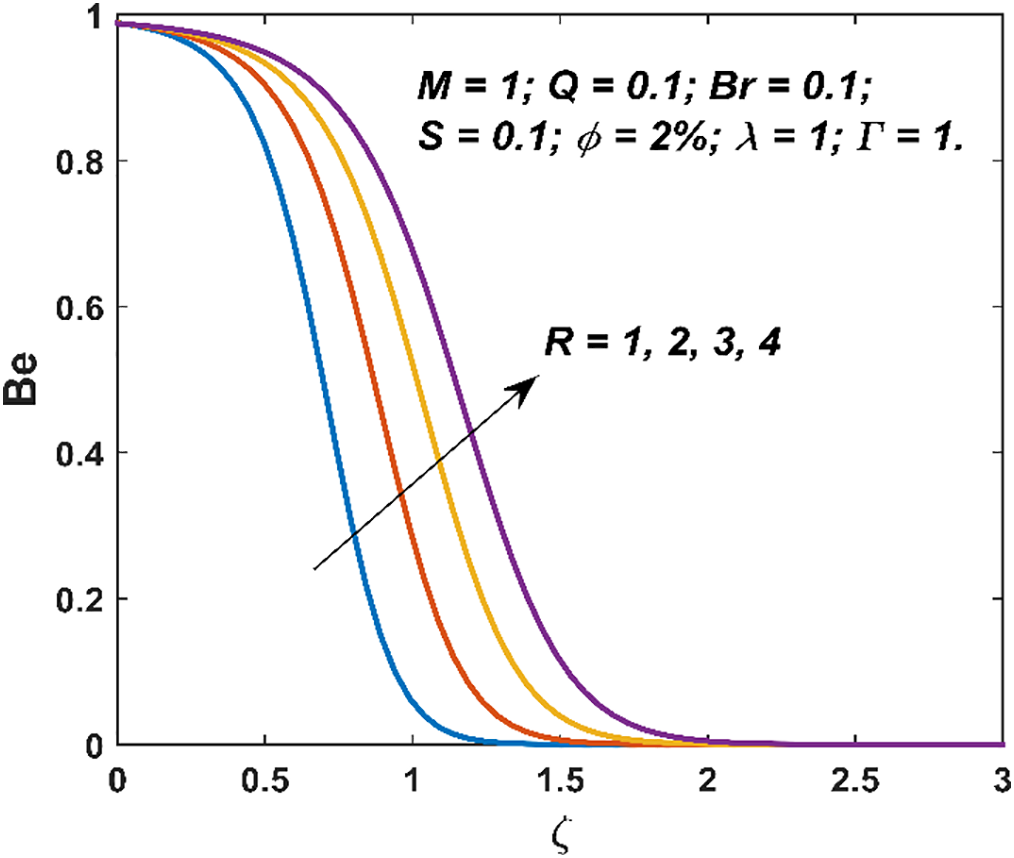

The characteristics of entropy generation and Bejan number are visualized in Figs. 8–13. The entropy generation decays with an increment in

Figure 8: Variation in entropy generation due to

Figure 9: Variation in Bejan number due to

Figure 10: Variation in entropy generation due to

Figure 11: Variation in Bejan number due to

Figure 12: Variation in entropy generation due to

Figure 13: Variation in Bejan number due to

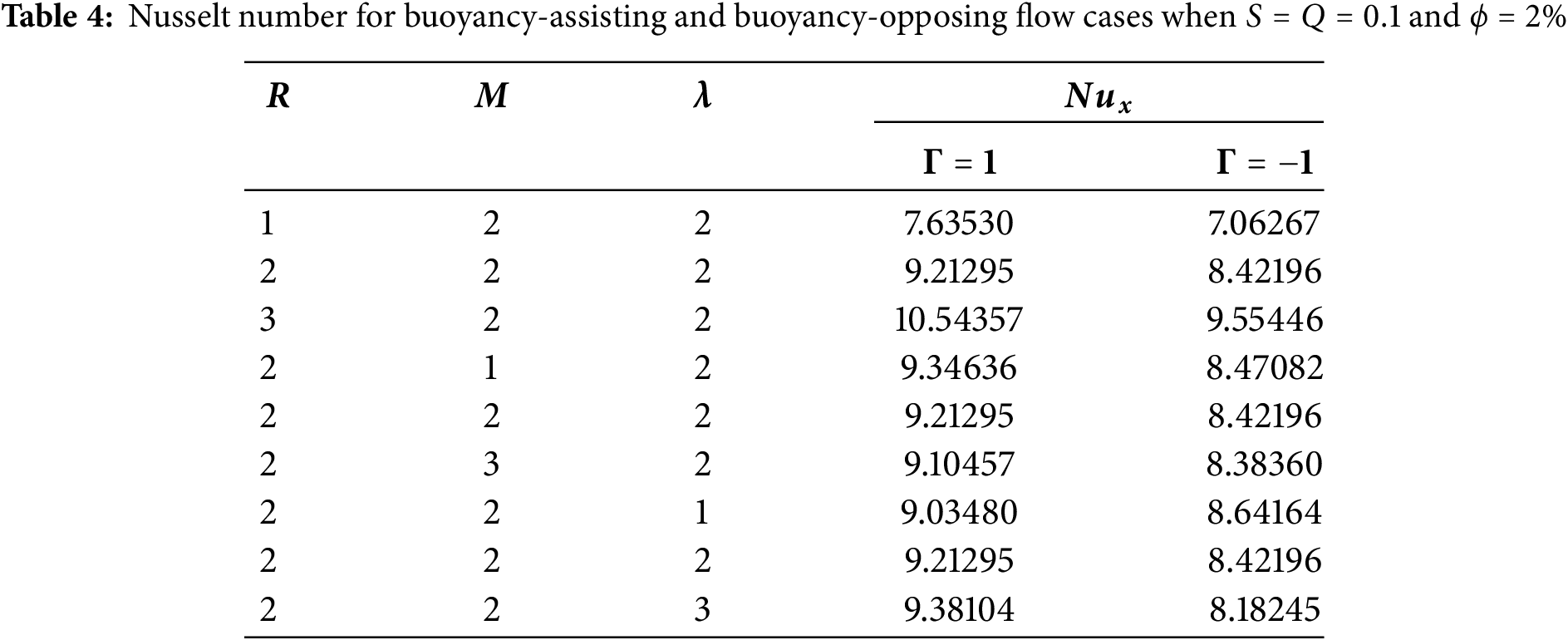

In Table 4, the heat transport at the interface for buoyancy assisting and buoyancy opposing flow scenarios are tabulated. The Nusselt number is higher when

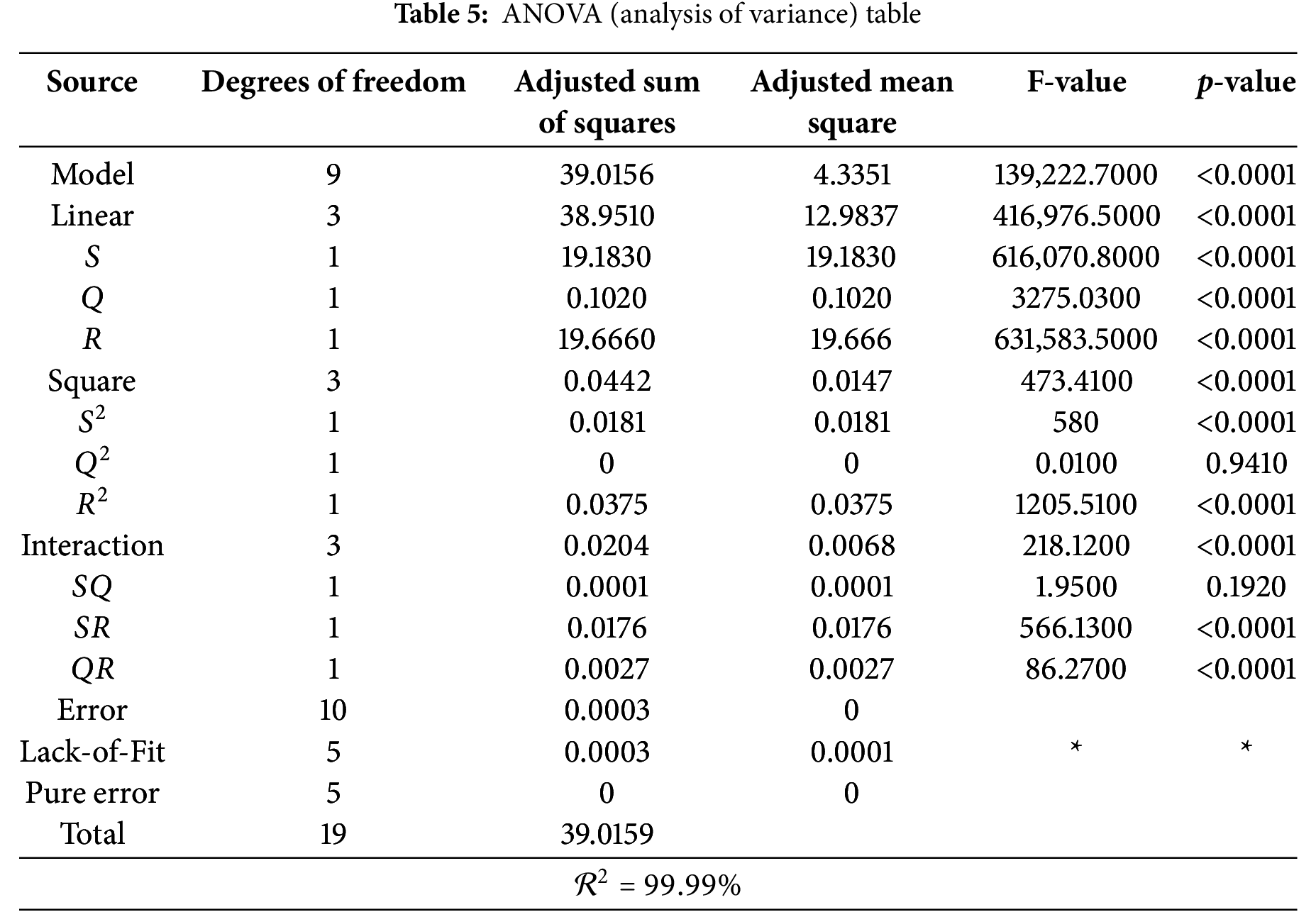

The output of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) table are given in Table 5. The significance of the RSM model terms is benchmarked via the p-value at 95% level of significance. The significance is assured if p-value < 0.05. The interaction term of

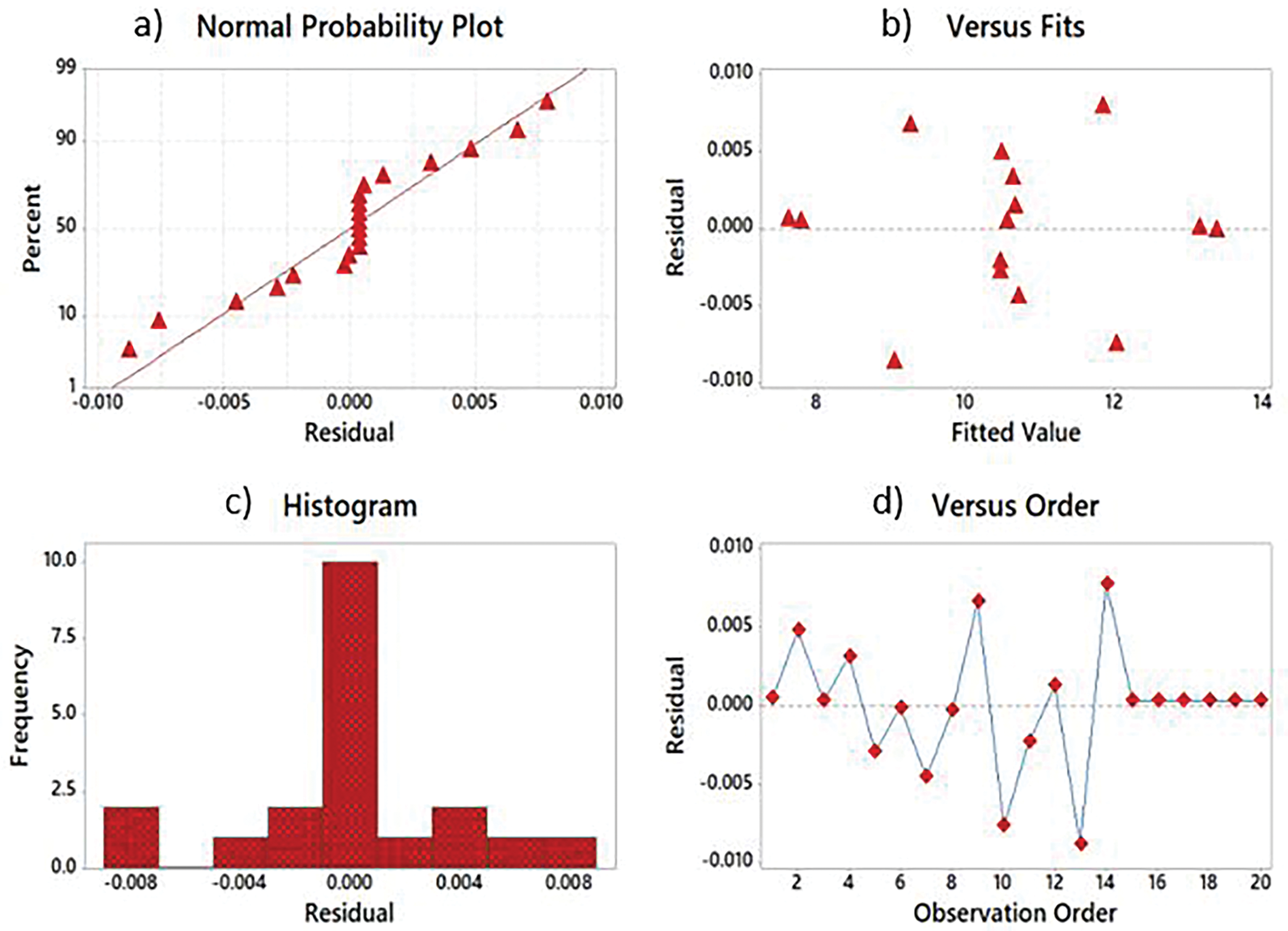

This fitted model can be used to accurately estimate the heat transport in the chosen ranges of the parameters due to high

Figure 14: Residual plots. (a) ‘Normal Probability plot’, (b) ‘Versus fits’, (c) ‘Histogram’, (d) ‘Versus Order’

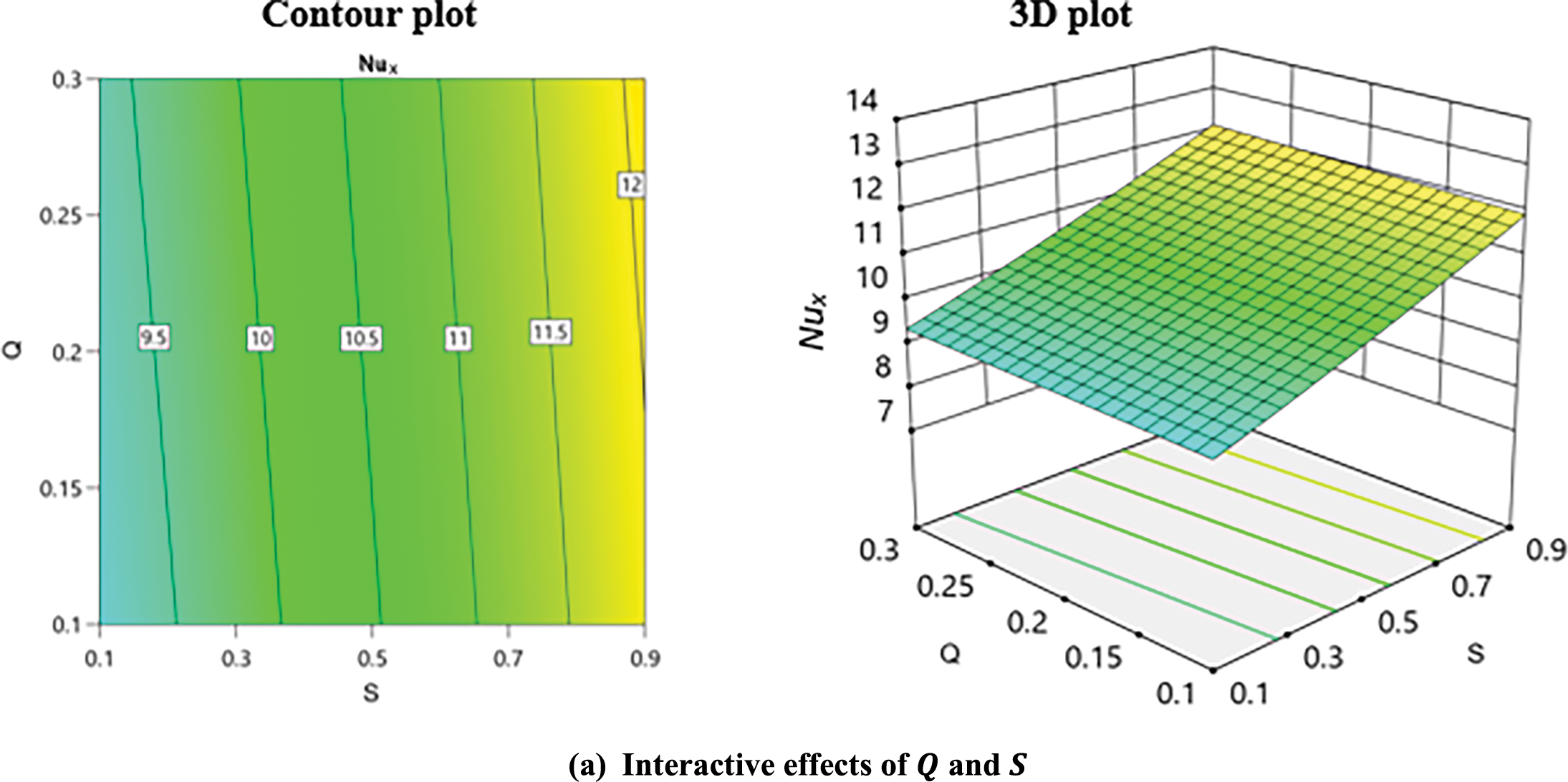

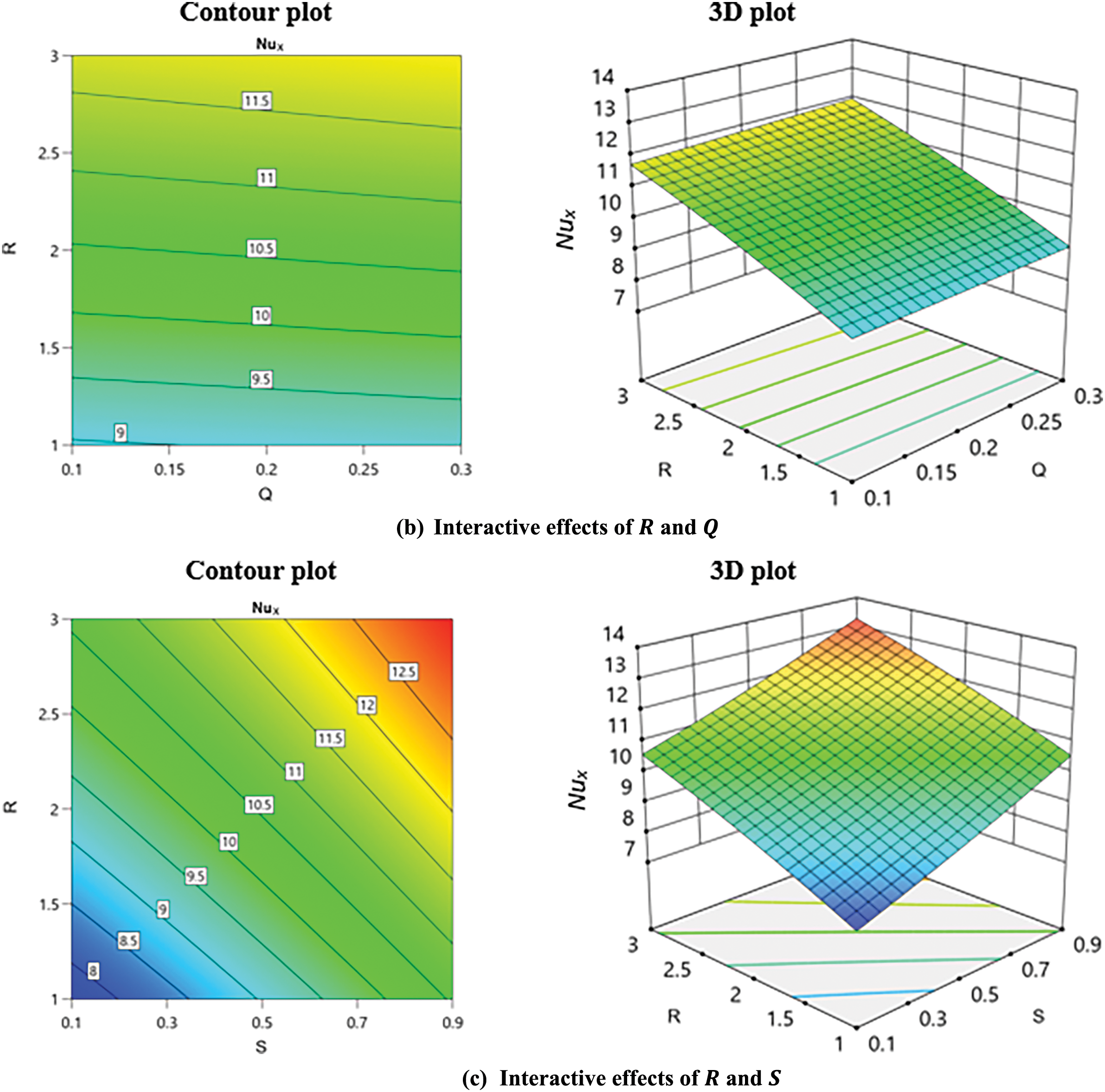

In Fig. 15, the interaction of two parameters is analyzed by fixing the third one at the medium level. Both

Figure 15: 3-D and contour plots for heat transport at the interface. (a) Interactive effects of Q and S. (b) Interactive effects of R and Q. (C) Interactive effects of R and S

Optimized

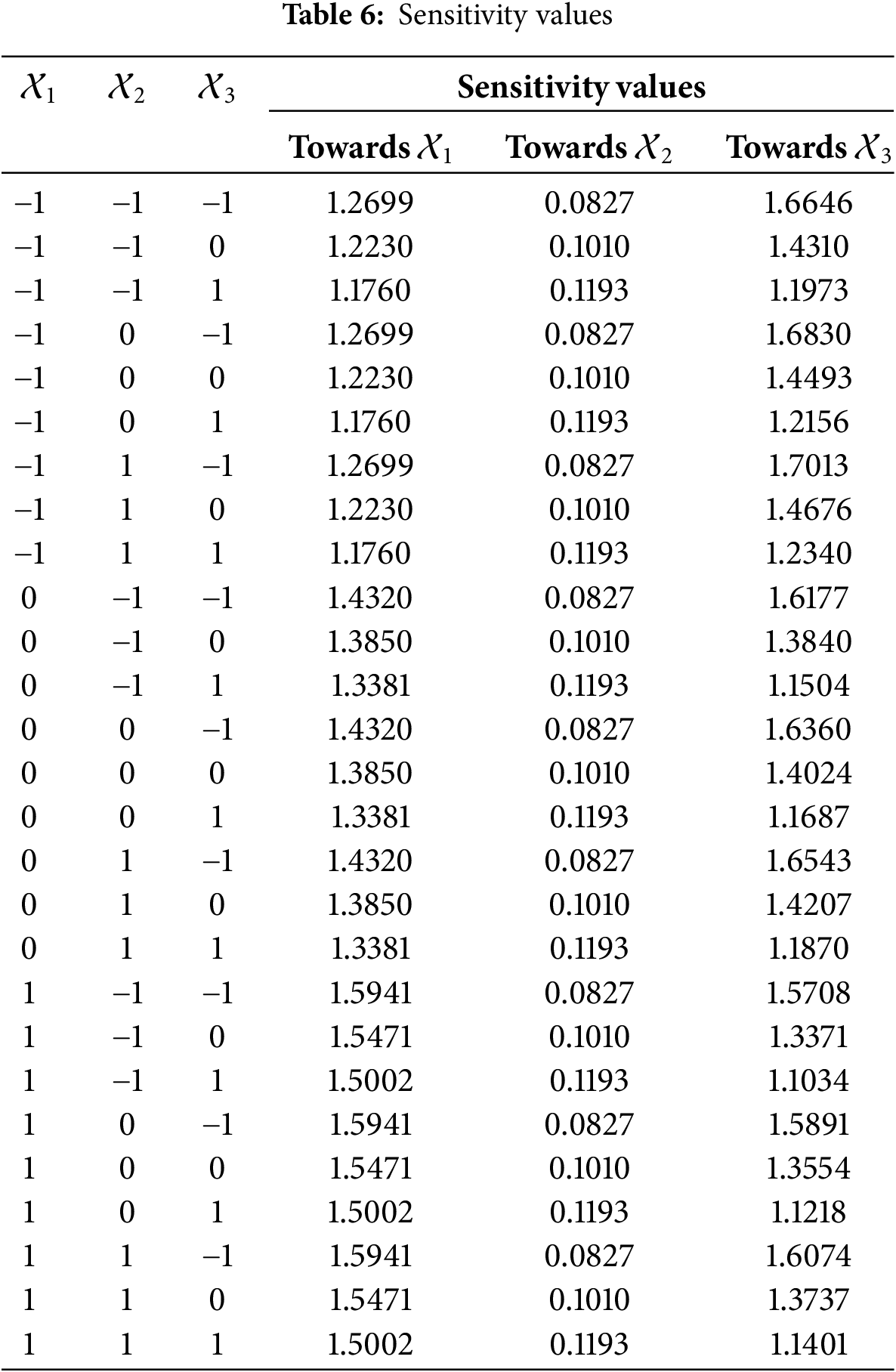

Analyzing the sensitivity of the heat transfer rate at the interface towards

Partial derivatives of Eq. (46) denote sensitivity functions for

Table 6 shows the sensitivity values of

The highest sensitivity is observed at the low levels of

The heat transfer rate in mixed thermal Marangoni convective flow of alumina-water nanoliquid in the presence of suction/injection and significant buoyant forces is optimized in this study. Additionally, radiative heat flux, magnetism, and an internal heat sink are considered in the model. The fourth order is Ralston’s method is used to find numerical solutions. This prototype developed to analyze the fluid flow and thermodynamic behavior with heat transfer optimization has led to the following major conclusions:

• The flow profiles and the thermal fields are superior in the presence of suction instead of impermeable and injection flow scenarios.

• The buoyant force has a prominent opposing effect on the temperature profile.

• The entropy generation increases with more thermal radiation. This also leads to a higher Bejan number, indicating that heat transfer irreversibility is predominant.

• The applied magnetism forms Lorentz forces in the fluid system which increment the disorderliness and hence generate more entropy.

• The highest sensitivity of 1.7013 for the Nusselt number is observed at the low levels of injection and thermal radiation when the heat sink is at the high level.

• The optimized heat transport (

• The 95% Confidence interval for the optimized heat transport is calculated to be [13.3659, 13.3881].

• The numerical results obtained via Ralston’s method were in good corroboration with the results of the limiting cases reported in the literature.

The model developed in this manuscript is a prototype for semiconductor crystal heat transfer, growth of silicon wafers, and coating processes [39].

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the learned reviewers and Editor for their constructive comments. The second author, Mahanthesh Basavarajappa, conducted this research during his tenure as a faculty member at Christ University. He sincerely thanks Christ University for the support.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Joby Mackolil, Mahanthesh Basavarajappa; analysis and interpretation of results: Joby Mackolil, Mahanthesh Basavarajappa, Giulio Lorenzini; draft manuscript preparation: Joby Mackolil, Mahanthesh Basavarajappa; editing and supervision of the manuscript: Giulio Lorenzini. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the finding are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bergman TL. Numerical simulation of double-diffusive Marangoni convection. Phys Fluids. 1986;29(7):2103–8. doi:10.1063/1.865597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Laknath R, Mendis A, Sekimoto A, Okano Y, Minakuchi H, Dost S. A numerical study on the exact onset of flow instabilities in thermo-solutal marangoni convection driven by opposing forces in a half-zone liquid bridge under zero gravity. J Chem Eng Japan. 2021;54(8):424–30. doi:10.1252/jcej.21we041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Rosenblat S, Davis SH, Homsy GM. Nonlinear Marangoni convection in bounded layers. Part 1. Circular cylindrical containers. J Fluid Mech. 1982;120:91–122. doi:10.1017/S0022112082002687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sen AK, Davis SH. Steady thermocapillary flows in two-dimensional slots. J Fluid Mech. 1982;121:163–86. doi:10.1017/S0022112082001840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chamkha AJ, Pop I, Takhar HS. Marangoni mixed convection boundary layer flow. Meccanica. 2006;41(2):219–32. doi:10.1007/s11012-005-3352-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khan MI, Qayyum S, Chu YM, Khan NB, Kadry S. Transportation of Marangoni convection and irregular heat source in entropy optimized dissipative flow. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2021;120:105031. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.105031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mackolil J, Mahanthesh B. Optimization of heat transfer in the thermal Marangoni convective flow of a hybrid nanomaterial with sensitivity analysis. Appl Mathem Mech-Eng Edit. 2021;42(11):1663–74. doi:10.1007/s10483-021-2784-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jiang Y, Dai C, Zhou X. Effect of interfacial heat transfer on hydrothermal wave propagation of nanofluid thermocapillary convection in rectangular cavity. Microgravity Sci Technol. 2024;36(43):1–17. doi:10.1007/s12217-024-10129-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Abbas SZ, Khan MI, Kadry S, Khan WA, Israr-Ur-Rehman M, Waqas M. Fully developed entropy optimized second order velocity slip MHD nanofluid flow with activation energy. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;190:105362. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Jawad M, Saeed A, Kumam P, Shah Z, Khan A. Analysis of boundary layer MHD Darcy-Forchheimer radiative nanofluid flow with Soret and Dufour effects by means of Marangoni convection. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2021;23(2):100792. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2020.100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sneha KN, Bognar G, Mahabaleshwar US, Singh DK, Singh OP. Magnetohydrodynamics effect of Marangoni nano boundary layer flow and heat transfer with CNT and radiation. J Magn Magn Mater. 2023;575:170721. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2023.170721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Khan D, Kumam P, Khan I, Sitthithakerngkiet K, Khan A, Ali G. Unsteady rotating MHD flow of a second-grade hybrid nanofluid in a porous medium: laplace and Sumudu transforms. Heat Transfer. 2022;51(8):8065–83. doi:10.1002/htj.22681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Khan D, Ali G, Kumam P, Sitthithakerngkiet K, Jarad F. Heat transfer analysis of unsteady MHD slip flow of ternary hybrid Casson fluid through nonlinear stretching disk embedded in a porous medium. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(2):102419. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2023.102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mohanty D, Mahanta G, Shaw S, Das M. Thermosolutal Marangoni stagnation point GO-MoS2/water hybrid nanofluid over a stretching sheet with the inclined magnetic field. Int J Mod Phys B. 2024;38:2450024. doi:10.1142/S0217979224500243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Choi SUS, Eastman JA. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. USA: Argonne National Lab Argonne IL; 1995. [Google Scholar]

16. Mahian O, Kolsi L, Amani M, Estellé P, Ahmadi G, Kleinstreuer C, et al. Recent advances in modeling and simulation of nanofluid flows—part I: fundamentals and theory. Phys Rep. 2019;790:1–48. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2018.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ullah I. Heat transfer enhancement in Marangoni convection and nonlinear radiative flow of gasoline oil conveying Boehmite alumina and aluminum alloy nanoparticles. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;132(9):105920. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rehman A, Khan D, Jan R, Aloqaily A, Mlaiki N. Scientific exploring of Marangoni convection in stagnation point flow of blood-based carbon nanotubes nanofluid over an unsteady stretching surface. Int J Thermofluids. 2023;20(5):100470. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2023.100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rehman A, Mahariq I, Ghazwani HA. Heat transfer analysis of mixed convection boundary layer blood base nanofluids with the influence of viscous dissipation. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;60(3):104784. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rehman A, Khun MC, Alsubaie AS, Inc M. Influence of Marangoni convection, viscous dissipation, and variable fluid viscosity of nanofluid flow on stretching surface analytical analysis. ZAMM-J Appl Mathem Mech/Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik. 2024;104:e202300413. doi:10.1002/zamm.202300413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Anusha T, Pérez LM, Mahabaleshwar US, Zeidan D. An MHD nanofluid flow with Marangoni laminar boundary layer over a porous medium with heat and mass transfer. Int J Model Simul. 2024. doi:10.1080/02286203.2024.2335112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shirvan KM, Mamourian M, Mirzakhanlari S, Ellahi R. Numerical investigation of heat exchanger effectiveness in a double pipe heat exchanger filled with nanofluid: a sensitivity analysis by response surface methodology. Powder Technol. 2017;313:99–111. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2017.02.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shafiq A, Sindhu TN, Khalique CM. Numerical investigation and sensitivity analysis on bioconvective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid flow towards stretching surface by response surface methodology. Alex Eng J. 2020;59:4533–48. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2020.08.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mahanthesh B, Shehzad SA, Mackolil J, Shashikumar NS. Heat transfer optimization of hybrid nanomaterial using modified Buongiorno model: a sensitivity analysis. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2021;171:121081. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.121081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Huda MN, Alam MS, Hossain SC. Optimization and sensitivity analysis of hydromagnetic convective heat transfer in a square cavity filled with a porous medium saturated by Ag-MgO/water hybrid nanofluid using response surface methodology. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;22:100626. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zeeshan A, Ellahi R, Rafique MA, Sait SM, Shehzad N. Parametric optimization of entropy generation in hybrid nanofluid in contracting/expanding channel by means of analysis of variance and response surface methodology. Inventions. 2024;9(5):92. doi:10.3390/inventions9050092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Khan SA, Liu H, Imran M, Farooq U, Yasmin S, Ma B, et al. Quadratic regression model for response surface methodology based on sensitivity analysis of heat transport in mono nanofluids with suction and dual stretching in a rectangular frame. Mech Time Depend Mater. 2024;28(3):1019–48. doi:10.1007/s11043-024-09715-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Alam MS, Huda MN, Rahman MM, Billah MM. Statistical and numerical analysis of magnetic field effects on laminar natural convection heat transfer of nanofluid in a hexagonal cavity. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;24(3):100856. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Golia C, Viviani A. Non isobaric boundary layers related to Marangoni flows. Meccanica. 1986;21(4):200–4. doi:10.1007/BF01556486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Napolitano LG, Viviani A, Savino R. Double-diffusive boundary layers along vertical free surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 1992;35(5):1003–25. doi:10.1016/0017-9310(92)90162-L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sutton GW, Sherman A. Engineering magnetohydrodynamics; USA: Courier Dover Publications; 2006. 576 p. [Google Scholar]

32. Zueco J, Bég OA. Network numerical simulation of hydromagnetic Marangoni mixed convection boundary layers. Chem Eng Commun. 2010;198(4):552–71. doi:10.1080/00986445.2010.512546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Cramer KR, Pai SI. Magnetofluid dynamics for engineers and applied physicists. USA: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1973. [Google Scholar]

34. Rosseland S. Physikalische grundlagen zum problem des sterninnern. In: Astrophysik. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 1931. p. 13–59. [Google Scholar]

35. Corcione M. Empirical correlating equations for predicting the effective thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of nanofluids. Energy Convers Manag. 2011;52(1):789–93. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2010.06.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rashad AM, Chamkha AJ, Ismael MA, Salah T. Magnetohydrodynamics natural convection in a triangular cavity filled with a Cu-Al2O3/water hybrid nanofluid with localized heating from below and internal heat generation. J Heat and Mass Trans. 2018;140(7):072502–13. doi:10.1115/1.4039213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bejan A. A study of entropy generation in fundamental convective heat transfer. J Heat Mass Trans. 1979;101(4):718–25. doi:10.1115/1.3451063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ralston A. Runge-Kutta methods with minimum error bounds. Math Comput. 1962;16(80):431–7. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1962-0150954-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yiantsios SG, Higgins BG. Marangoni flows during drying of colloidal films. Phys Fluids. 2006;18(8):1–12. doi:10.1063/1.2336262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools