Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Artificial Neural Networks for Optimizing Alumina Al2O3 Particle and Droplet Behavior in 12kK Ar-H2 Atmospheric Plasma Spraying

1 UR22ES12: Modeling, Optimization and Augmented Engineering, ISLAIB, University of Jendouba, Beja, 9000, Tunisia

2 IRCER, UMR CNRS 7315, University of Limoges, 12 rue Atlantis, Limoges, 87068, France

3 ICAM School of Engineering, Nantes Campus, 35 Av. Champ de Manoeuvres, Carquefou, 44470, France

4 Research Lab, Technology Energy and Innovative Materials, Faculty of Sciences, University of Gafsa, Gafsa, 2112, Tunisia

5 Department of Physics, College of Science, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, 15551, United Arab Emirates

6 Lab. Mechanical Modeling, Energy and Materials (M2EM), ENIG, University of Gabes, Gabes, 6029, Tunisia

7 Laboratory of Electro-Mechanic Systems, ENIS, University of Sfax, Sfax, 3038, Tunisia

* Corresponding Author: Ridha Djebali. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(2), 441-461. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.063375

Received 13 January 2025; Accepted 18 March 2025; Issue published 25 April 2025

Abstract

This paper investigates the application of Direct Current Atmospheric Plasma Spraying (DC-APS) as a versatile thermal spray technique for the application of coatings with tailored properties to various substrates. The process uses a high-speed, high-temperature plasma jet to melt and propel the feedstock powder particles, making it particularly useful for improving the performance and durability of components in renewable energy systems such as solar cells, wind turbines, and fuel cells. The integration of nanostructured alumina (Al2O3) thin films into multilayer coatings is considered a promising advancement that improves mechanical strength, thermal stability, and environmental resistance. The study highlights the importance of understanding injection parameters and their impact on coating properties and uses simulation tools such as the Jets & Poudres (JP) code for in-depth analysis. Furthermore, the paper discusses the implementation of Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to optimize the coating process by predicting flight characteristics and improving operating conditions. The results show that ANN models are effective in achieving highly accurate prediction values, highlighting the potential of AI in improving thermal spray technology.Keywords

A DC Atmospheric Plasma Spraying (DC-APS) is a versatile thermal spraying technique used to deposit a wide range of coatings on various substrates [1]. The process uses a high-velocity, high-temperature plasma beam generated by a direct current arc to melt raw material powder particles and project them onto the substrate, creating a dense coating. This technique finds extensive applications in energy technologies because of the ability to create coatings with tailor-made properties, such as high wear resistance, corrosion resistance and thermal barrier opportunities [2] resulting in reduced friction coefficient and wear rate of carbon coated sample and that hardness of carbon coated NiCu alloy was larger than that of graphene.

With renewable energy, DC APs plays a crucial role in improving the performance and sustainability of components in solar energy systems, wind turbines and fuel cells. For example, it can be used to create protective coatings on solar cells to improve their efficiency and lifespan [3]. Similarly, it can improve the corrosion resistance of wind turbine sheets and the durability of fuel cell components. The sustainable energy sector benefits from DC apps by creating efficient and sustainable energy storage systems, which improves the total lifespan and performance of infrastructure for renewable energy [3]. A particularly promising advancement in this area is the use of nanostructured aluminum oxide (Al2O3) thin films in multilayer coatings. These thin films offer unique properties such as increased surface area, enhanced mechanical strength, and superior thermal stability, making them ideal candidates for energy applications. The incorporation of nanostructured Al2O3 into multilayer coatings can significantly improve barrier properties against environmental degradation, so extending the lifetime of critical components in energy systems [4]. However, straining of Al2O3 coating caused defects that altered barrier properties.

In solar energy applications, Al2O3 thin films can serve as protective barriers and also as photovoltaic efficiency enhancers when integrated into multilayer coatings on solar cells. Their tunable optical properties allow for improved light absorption and reduced reflectance, which can lead to higher energy conversion efficiencies [5,6]. Moreover, in wind energy, multilayer coatings incorporating nanostructured alumina can provide enhanced resistance to abrasion and erosion, crucial for maintaining turbine blades integrity under harsh operational conditions [7]. In fuel cells, Al2O3 coatings contribute to improved ionic conductivity and thermal management, as essential for optimal performance and longevity. In fact, Al2O3’s thermal stability ensures better heat dissipation, preventing overheating and extending lifespan of fuel cell components. Besides, the ability to deposit various materials, including ceramics, metals, and composites, makes DC-APS a highly adaptable technique for addressing specific challenges in energy applications.

Ongoing research continues to expand the applications of DC-APS in developing innovative solutions for sustainable energy technologies. The precise control over coating properties and the introduction of advanced materials like nanostructured alumina make it a valuable tool in optimizing energy conversion and storage processes, ultimately contributing to the advancement of green energy solutions.

The following presents a detailed investigation into the influence of varied alumina powder injection parameters on critical output factors within the DC-APS process. This includes a systematic analysis of how changes in input factors: injection velocity, angle, particle size (diameter dp) distribution, and injection position affect key characteristics of the Al2O3 particles (outputs) upon impact with the substrate. Specifically, we examine the resulting particle velocity, temperature, molten ratio, surface flux, and impact position to improve the predictability and efficiency of the deposition process. The goal is to optimize these parameters to enhance the performance and quality of the resulting Al2O3 coatings, ultimately leading to improved material properties and application outcomes in various energy technologies.

The plasma jet and plasma coating process is outlined in Fig. 1 with the essential subsystems, namely: plasma generation subsystem (power supply often using direct current, electrode configuration including anode and cathode configurations that generate the plasma arc), feedstock delivery system (feedstock including powders, wires or other materials that will be vaporized and deposited; feed mechanism that can be pneumatic, mechanical or gravity-fed systems that transport the feedstock into the plasma), plasma jet control subsystem (gas flow control regulating the flow of gas: inert gases such as argon, nitrogen or reactive gases used to stabilize and shape the plasma; nozzle design shaping the plasma jet and controlling its speed and temperature); the substrate handling system (workpiece clamping, motion mechanism allowing the substrate to move relative to the plasma jet); the coating chamber subsystem (vacuum or atmospheric pressure chamber, substrate and plasma process temperature control); the cooling subsystem (cooling mechanisms that include water or air cooling systems to manage the plasma torch and substrate temperature). The accumulation phenomenon around the solid particle/droplet is also illustrated.

Figure 1: Sketch of the plasma spraying process and a zoomed view of a μ-sized particle momentum, heat and mass transfer phenomena occurring in its surrounding boundary layers

3 Computer Aided Process Design

Modeling and simulation are performed by solving the governing flow and heat and mass transfer equations for the turbulent plasma jet (Ar-H2Ar 75/25% in this case) using the finite difference method of the JP code. This approach allows for a detailed analysis of the jet dynamics and thermal characteristics. Additionally, a particle tracking model, which considers both dynamic and thermal history, is integrated into the JP code. This functionality allows for a comprehensive understanding of the behavior of the particles when they interact with the plasma jet. More details may be found in [8].

3.2 Validation of the Particle Tracking Model

The JP code has been extensively validated and is widely recognized for its computational efficiency and reliability across a range of models, establishing it as a trusted tool in the field of thermal spray coatings [9–11]. Its effectiveness has been demonstrated in numerous applications, earning accolades for its performance. For further details, please refer to [10–13]. In this study, the JP code is validated against experimental data [14] for a 58 μm dense ZrO2 particle injected into a 35 kW Ar-H2 plasma (40-7 slm). Fig. 2 illustrates the accuracy of the JP code in tracking both particle dynamics and thermal behavior. Specifically, the thin and thick thermal models, which account for differences between the particle surface temperature (Ts) and core temperature, show excellent agreement with the experimental data reported by Smith et al. [14]. This validation underscores the robustness and precision of the JP code in simulating particle behavior under realistic conditions.

Figure 2: Validation of the JP dynamic and thermal models with experimental findings [8,14] * thin model. ** thick model, where conduction mechanism counts within the molten particle

4.1 Effects of Injection Parameter Variability

In literature, the variability of input factors (injection conditions such as injection velocity, injection angles, particle shape, powder size distribution, injection position, and injection temperature) has been modeled and quantified in various ways [12,15–19]. This issue remains a topic of ongoing interest. In this section, the plasma gun and power properties given in Table 1 are used allowing Tmax = 12,000 K and Vmax = 980 m/s. It is aimed to explore the effect of the dispersion of factors related to the injection of Alumina (Al2O3) powder, as illustrated in Table 2, on the properties of output factors, namely all properties and behavior of the powder upon arrival at the impact screen (piece to coat) such as velocities, accelerations, molten ratio, temperature, surface flux, and impact position, etc. Will be used 4 samples of 500 particles of size according to a normal distribution dp~N(50,8) in the range 25–75 μm, an injector placed at (xinj, yinj) = (5.2, −8) mm past the nozzle exit and a carrier gas flow 1.53 NL/min leading to injection velocity Vinj = 10 m/s. At the injector outlet, the powder is injected in different directions with a dispersion −10 ≤ αinj, βinj ≤ 10 in the (x, y) plane and −10 ≤ βinj ≤ 10 in the plane (z, y), see Figs. 3 and 4.

Figure 3: Variation in the injection angle α (°) with the particle size dispersion

Figure 4: Variation in the injection angle β (°) with the particle size dispersion

Understanding how these input factor variations influence the coating process is crucial for optimizing the performance and quality of thermal spray coatings. By systematically analyzing these factors, we can improve the predictability and efficiency of the deposition process, ultimately leading to enhanced material properties and application outcomes. This investigation will provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of particle behavior in plasma spraying and inform future research and development efforts in the field. Results are depicted in Figs. 5–14. The JP results indicate a prior way to coat.

Figure 5: Sketch of the droplet stream crossing the plasma jet isotherms

Figure 6: Cloud of the droplet arrival positions at the substrate screen

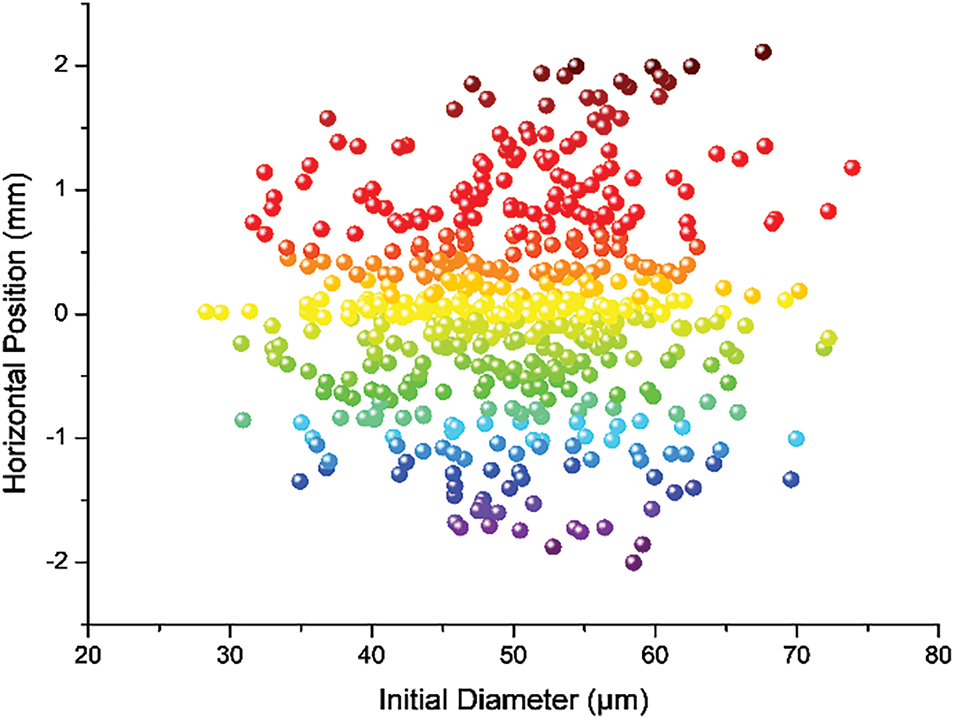

Figure 7: Cloud of the arrival horizontal position with the particle size dispersion

Figure 8: Variation in the arrival radial position with the particle size dispersion

Figure 9: Variation in the splash deposited mass (%) with the particle size dispersion

Figure 10: Variation in the arrival powder axial velocity with the particle size dispersion

Figure 11: Variation in the powder flight time with the particle size dispersion

Figure 12: Variation in the arrival surface temperature with the particle size dispersion

Figure 13: Variation in the arrival molten rato with the particle size dispersion

Figure 14: Spatial distribution of the splash deposited mass (%) with in the (z, y) plane

Fig. 5 shows the flow of droplets through the plasma jet isotherms. The dynamic history of the droplet (trajectory and velocity) defines the heat transfer between the droplet and the hot gas, which in turn determines the “deposition” behavior (it may bounce or splash) and subsequently defines the microstructure of the coating that will be formed. However, within such a particle beam there will be significant variability in the thickness of the deposit, which will be discussed in detail later with reference to Fig. 15. This variability can arise from several factors, including fluctuations in particle injection parameters, variations in plasma jet conditions, and interaction dynamics between the particles and the substrate. Understanding these influences is essential to optimize coating processes and achieve uniform depositions in thermal spray applications.

Figure 15: ANN principle. Above: typical ANN feed forward architecture, below: draw of a neuron mathematical model

Figs. 6 and 7 depict the particle cloud arrival positions at the substrate sieve, as well as the horizontal cloud arrival position under particle size dispersion. Although particles may have the same diameter at injection, they can exhibit varying injection directions (alpha and beta angles), which significantly influence their dynamic and thermal histories. Furthermore, if the particles do not share the same initial diameter at injection—such as in the Gaussian distribution adopted in this study—the complexity of the process increases significantly. This is particularly evident as particles traverse different regions of the plasma jet (hot gas) with varying dynamic and thermal properties. These observations underscore the complexity of the process and highlight the necessity for a comprehensive study to control particle state and impact behavior.

Figs. 8 and 9 illustrate the variation in radial arrival positions and the deposited spray mass as a function of particle size dispersion. Due to their inertia, larger particles tend to pass through the hot gas jet, deviating from the center and impacting the substrate at greater radial distances. Once melted, these particles splash upon impact, contributing to coating formation. However, if they remain unmelted, they bounce off, leading to inefficiencies in the deposition process. Fig. 8 demonstrates that the radial arrival position is nearly a linear function of the initial particle diameter. Small particles (dp ≈ or < 30 μm) arrive close to the plasma jet axis, while larger particles (dp ≈ or > 70 μm) arrive near the outer edge of the plasma jet (radial position ≈ 5 mm). As a result, these larger particles do not receive sufficient heating. This is further evidenced in Fig. 9, where some large particles exhibit a splash factor of zero, indicating that they arrive in a solid state. Conversely, other particles of similar size (dp > 70 μm) have a splash factor strictly greater than zero, indicating that they arrive in a molten state and contribute effectively to deposit formation.

These findings emphasize the critical role of particle size and heating conditions in determining coating quality and uniformity. They also highlight the importance of advanced modeling and optimization tools, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), to predict and control these parameters effectively, ensuring optimal coating performance. Figs. 10 and 11 show the variation of the axial powder arrival velocity and powder flight time as a function of the particle size distribution. Small particles have high axial velocities because their trajectories are close to the jet axis, where the plasma jet velocity is highest. This allows them to be efficiently transported and accelerated, resulting in shorter flight times. In contrast, larger particles cross the plasma jet at high radial impact positions and hit areas of the jet with lower velocities. Therefore, they experience lower acceleration, resulting in longer flight times, even tmax/tmin ≈ 1.35. The flight time is precisely calculated using the JP code, but it can also be estimated using the following formula. The variability in axial velocity or residence time Δtres for particles of the same diameter is attributed to their injection in different directions, depending on angles α and β.

In this formula, L represents the standoff distance and V is the velocity of the particles at that distance. This calculation assumes that when a particle enters the spray stream, it begins with no axial velocity and accelerates to its final measured velocity V over the distance L.

Figs. 12 and 13 represent the variation in the arrival powder axial velocity and the powder flight (residence) time with the particle size dispersion. Although these particles move around (or next to) the jet axis and reach high velocities, their short residence time does not prevent them from becoming excessively superheated, causing them to reach temperatures above the melting point Tm = 2327 K. Both figures illustrate that particles smaller than about 43 μm reach the substrate at temperatures above Tm and a melting rate of 100%. Thereafter, the melting rate decreases sharply to 0% with increasing particle size, although the surface temperature remains largely the same Tm. In general, these molten particles do not contribute significantly to the formation of the precipitate, and if they arrive at high speed, their nuclei can bounce off the substrate. This observation leads to the following figure (Fig. 14), in which the precipitations are clearly horizontally symmetric but exhibit radial asymmetry. Like the residence time, the melting ratio M% is accurately calculated in the JP results, but it can be estimated using the proposed formula of Vaidya et al. [20] which describes the particle state as follows:

However, Zhang et al. [21] analytically proposed a new concept of improved description which is non-material specific for the melt index (or ratio). The proposed model uses the fundamental thermal parameters: density ρ, conductivity k, heat of fusion hf and melting temperature Tm of the material.

where TS is the particle surface temperature measured at the arrival, Bi = h dp/2 K is the Biot number and h (W/m2K) is the heat transfer coefficient.

4.2 ANN Control of Coating Characteristics

This section addresses the limitations of current simulation diagnostic tools in effectively tuning operating conditions. It presents the application of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to control coating characteristics through a feedback system.

(a) ANN Model Development and Implementation

The previous section highlighted the insufficiency of current simulation diagnostic tools for optimizing coating performance. To address this, a feedback system leveraging artificial intelligence (AI), particularly artificial neural networks (ANNs), is proposed. ANNs have proven effective in predicting particle in-flight characteristics and coating properties based on processing parameters, making them versatile across various fields [22–26]. ANNs excel at identifying complex relationships between inputs (I) and outputs (O) through simple mathematical operations performed by neurons, enabling data-driven optimization of coating processes. Fig. 15 depicts the typical ANN feed forward architecture as well as a draw of a neuron mathematical model.

Two in-house ANN models were developed: a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) implemented and tuned using scikit-learn (MLPRegressor) and a second model created using the keras provided building blocks for using its high-level API. Additionally, XGBoost was used for comparison. The MLP, a fundamental deep learning architecture, consists of multiple fully connected layers, allowing it to model complex data relationships through nonlinear transformations. A digital database of 2000 data points was used for training, divided into training (70%), testing (20%), and validation (10%) subsets. The trained ANN achieved less than 2% error in predicting particle flight and impact characteristics, demonstrating its potential for optimizing coating processes.

MLPs are computationally efficient compared to advanced deep learning models, making them suitable for resource-constrained applications. They iteratively adjust weights during training, enabling them to generalize from structured data and learn complex patterns. This makes MLPs ideal for tasks like classification, regression, and time series forecasting. Their scalability and simplicity have led to widespread adoption in industries like finance, healthcare, and technology.

Hyperparameter optimization using RandomizedSearchCV further enhanced ANN performance. Both ANN models achieved over 98% accuracy, while XGBoost reached nearly 97% accuracy. Results, including accuracy and loss variations over epochs, are shown in Fig. 16, highlighting the models’ robustness. These findings underscore the potential of AI-driven systems for real-time optimization in coating applications.

Figure 16: ANN models reliability. Left: Keras model and right: MLPRegressor model

(b) Control of Coating Characteristics

The application of ANNs in controlling coating characteristics represents a significant advancement in the field. By integrating ANNs into the feedback system, it becomes possible to dynamically adjust operating conditions to achieve desired coating properties. This approach not only improves the precision of the coating process but also reduces material waste and enhances overall efficiency since optimization.

The ANN models were specifically designed to predict and control key coating characteristics such as thickness, uniformity, and adhesion strength. These predictions are based on real-time data analysis, enabling the system to adapt to variations in processing conditions. For instance, if the system detects deviations in particle velocity or temperature, it can automatically adjust parameters such as spray distance or nozzle pressure to maintain optimal coating quality. The feedback system leverages the predictive capabilities of ANNs to continuously monitor and refine the coating process. This real-time optimization ensures that the final product meets stringent quality standards, even in the presence of external disturbances or variability in raw materials. The integration of ANNs also facilitates the identification of optimal processing windows, which can be used to guide future experiments and process improvements.

Furthermore, the use of ANNs enables the system to learn from historical data, improving its predictive accuracy over time. This self-learning capability is particularly valuable in industrial settings, where process conditions may evolve due to equipment wear or changes in environmental factors. By continuously updating its models, the ANN-based system ensures consistent performance and reliability.

The results of this study demonstrate the potential of ANNs to revolutionize the control of coating characteristics. With their ability to handle complex, nonlinear relationships and adapt to changing conditions, ANNs offer a powerful tool for optimizing coating processes and achieving superior product quality. Future work will focus on expanding the application of ANNs to other aspects of the coating process, as well as exploring the integration of additional AI techniques to further enhance system performance. See models architecture in Appendix A.

A simulation (prediction) of 500 particles behavior was performed using the MLPRegressor ANN model, based on the conditions specified in Table 2. In the simulation, the axial injection position and velocity of Al203 particles in the sample are varied. These parameters are not accessible with the JP code. In Fig. 17, one can see that 1000 particles (two samples of 500 in vertical lines) are injected by the JP under Vinj = 10 m/s and 1000 others under Vinj = 15 m/s. However, the ANN trained model allows injecting particles under Vinj varied between 10 and 15 m/s. Fig. 17 shifts focus on the impact of injection axial velocity on flight time and particle Reynolds number. The data presented illustrate how variations in axial velocity influence both particle flight duration and their corresponding Reynolds numbers. Higher injection velocities lead to shorter flight times, suggesting more efficient particle transport through the plasma jet. Additionally, the Reynolds number, which characterizes the particles flow regime, increases with axial velocity, indicating a transition in flow conditions at elevated velocities. This figure emphasizes the critical role of injection parameters in determining the behavior of particles during the coating process, highlighting the need for precise control to optimize thermal spray applications effectively. The figure further demonstrates that the ANN model can predict quantities related to droplet behavior based on input factors, such as injection velocity, which are not accessible through the JP software. This limitation applies to any other factors that may be experimentally challenging to measure or prohibitive in terms of cost.

Figure 17: Effect of injection axial-velocity on flight time and particle Reynolds number

In Fig. 18, the JP simulations compare well the ANN predictions for the arrival surface temperature and arrival particle axial velocity vs. initial particle size. The numericals are detailed in Table 3, which present the input and output fields of the ANN model, together with the maximum, average, minimum values and standard deviation of the impact characteristics. In particular, the average values for temperature, axial velocity, melting ratio and impact angle are promising. However, it is essential to physically interpret the values from the ANN forecasts. For example, a melting ratio greater than 100% indicates complete melting, while a melting ratio below 0% suggests that the particle arrives in a solid state. This nuanced concept is crucial for the accurate application of simulation results in practical contexts. Fig. 19 illustrates the distribution of particle temperature, axial velocity, and molten ratio, represented by floods and iso-contours, as functions of the selected input factors. The significant non-linearity observed in the profiles highlights and reinforces the complexity of the process, underscoring the necessity for optimization.

Figure 18: Comparison of results between the J&P simulation and ANN prediction for (left) the arrival surface temperature and (right) arrival particle axial velocity vs. initial particle size (uniform distribution)

Figure 19: Distribution (floods and iso-contours) of particle temperature, axial velocity and molten ratio as functions selected input factors

(c) Optimization and Desirability Approach

In the field of arc plasma thermal spray studies, the temperature and axial impact velocity of particles (droplets) on the substrate are two of the most frequently evaluated properties. These two properties serve as the foundation for investigating other critical characteristics, such as the melting ratio and the splashing ratio, which are also key parameters targeted for optimization. In this study, quadratic correlations with interactions among the input factors Xi (where i = 1–5, as listed in Table 2) are established using polynomial feature handling techniques implemented via the sklearn and NumPy libraries. The correlations derived are presented in Table 4.

Evidently these correlations are complex and, consequently, not practical for direct application. To address this, an autocorrelation matrix is employed. Analysis of this matrix reveals that the melting ratio and splashing ratio exhibit marginal dependence on the input factors X3 and X4, which correspond to the initial injection position and the injection angle α, respectively. This suggests that these two terms may be excluded. Nevertheless, we conserve them for possible interaction terms. Consequently, new quadratic correlations with interactions are proposed, focusing on the weighted effects of the factors using p-values. The Generalized Least Squares Autoregressive (GLSAR) model, which is slightly superior to the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model, is utilized for this purpose. The study demonstrates that all p-values for the interaction terms exceed 0.191, suggesting that these terms can be excluded. The results are summarized in Fig. 20. Note that no interactions were considered for responses Y1 (Molten ratio) and Y2 (Splashing ratio) and that the fit for response Y2 is quite poor.

Figure 20: GLSAR regression results for Y1 (Molten ratio) and Y2 (Splashing ratio)

Subsequently, an optimization analysis is conducted to maximize the melting ratio (Y1) and minimize the splashing ratio (Y2) using the desirability function approach. This approach is widely adopted in industrial settings for optimizing processes with multiple responses. It is based on the principle that the overall quality of a product is deemed unacceptable if any quality characteristic falls outside predefined limits. The objective is to identify operating conditions that yield the most favorable responses. For each response Yk(x), a desirability function dk(Yk) assigns a value between 0 and 1, where 0 represents an undesirable outcome and 1 signifies an ideal response. These individual desirability values are aggregated using the geometric mean to compute the overall desirability D. This method enables the simultaneous optimization of multiple responses, providing a comprehensive measure of overall desirability (see Derringer et al. (1980) [27]).

According to Derringer et al. (1980) [27], the individual desirability function depends on whether a particular response Yk is to be minimized, maximized, or assigned a target value.

Using the scipy.optimize tool an objective function is optimized and yields the optimal combination of imput factors: dp = 26.2764 μm, Vinj = 15 m/s, Xinj = 5.2 mm, Injection angle α = 100° and Injection angle β = 0.37°. This yields a molten ratio = 100% and a splashing ratio = 5.104 and an overall desirability 0.92398.

A verification test was performed with the help of JP code and the aforementioned optimized conditions indicates that the particle impact the substrate after 0.64 s with a axial velocity 281.3 m/s, a temperature 3133 K, splashing ratio of 6.6 and a full molten state (100%) since t = 0.21 s.

This study investigates the optimization of alumina (Al2O3) particle and droplet behavior in a 12kK Ar-H2 atmospheric plasma spraying (DC-APS) process using advanced modeling techniques and artificial neural networks (ANNs). The research focuses on understanding the influence of various injection parameters, such as particle size, injection velocity, position, and angles, on key output factors like particle velocity, temperature, molten ratio, and splashing ratio. The findings provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of particle behavior during plasma spraying and offer practical solutions for optimizing coating processes. The study addresses the following key kindings:

a. Injection Parameters and Particle Behavior:

–Particle size significantly affects the radial arrival position and molten ratio. Smaller particles (dp ≈ or < 30 μm) tend to arrive close to the plasma jet axis, while larger particles (dp ≈ or > 70 μm) deviate radially and may not receive sufficient heating, leading to incomplete melting.

– Injection velocity and angles influence particle flight time and axial velocity. Higher injection velocities result in shorter flight times and higher Reynolds numbers, indicating more efficient particle transport through the plasma jet.

b.Molten and Splashing Ratios:

– The molten ratio (Y1) and splashing ratio (Y2) are critical for coating quality. The study found that particles smaller than 43 μm reach the substrate fully molten (100% melting ratio), while larger particles exhibit a sharp decrease in melting ratio.

– The splashing ratio, which affects coating uniformity, is influenced by particle size and injection conditions. Larger particles that remain unmelted tend to bounce off the substrate, reducing deposition efficiency.

c.ANN-Based Optimization:

– Artificial neural networks (ANNs) were successfully implemented to predict and optimize particle in-flight characteristics and coating properties. The ANN models achieved over 98% accuracy in predicting particle behavior, demonstrating their effectiveness in real-time process control.

– The ANN models allowed for the simulation of particle behavior under varying injection conditions, including axial velocity and position, which are not accessible through traditional simulation tools like the Jets & Poudres (JP) code.

d.Desirability Function Approach:

– The desirability function approach was used to simultaneously optimize the melting ratio (maximized) and splashing ratio (minimized). The optimal conditions were found to be:

∘Particle diameter (Dp) = 26.2764 μm

∘ Injection velocity (Vinj) = 15 m/s

∘ Injection position (Xinj) = 5.2 mm

∘ Injection angles (α = 100°, β = 0.37°)

–These conditions yielded a 100% molten ratio and a splashing ratio of 5.104, with an overall desirability of 0.92398.

e.Validation and Practical Implications:

– The optimized conditions were validated using the JP code, confirming that particles impact the substrate with an axial velocity of 281.3 m/s, a temperature of 3133 K, and a 100% molten ratio after 0.21 s.

– The study highlights the importance of precise control over injection parameters to achieve uniform and high-quality coatings, which is crucial for applications in renewable energy systems such as solar cells, wind turbines, and fuel cells.

Pertinent Values:

– Particle Size: Optimal particle diameter for complete melting = 26.2764 μm.

– Injection Velocity: Optimal injection velocity = 15 m/s.

– Molten Ratio: Achieved 100% melting ratio under optimized conditions.

– Splashing Ratio: Reduced to 5.104 under optimized conditions.

– Overall Desirability: 0.92398, indicating a highly favorable balance between melting and splashing ratios.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the members of Editorial staff and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism and valuable feedback, which contributed to enhancing the quality of this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Ridha Djebali, Bernard Pateyron. Methodology: Ridha Djebali, Moktar Ferhi, Karim Khemiri, Ridha Ennetta. Software: Ridha Djebali, Bernard Pateyron. Validation: Ridha Djebali, Bernard Pateyron, Karim Khemiri, Ridha Ennetta. Formal Analysis: Ridha Djebali, Bernard Pateyron, Moktar Ferhi, Mohamed Ouerhani, Karim Khemiri, Montassar Najari, M. Ammar Abbassi, Chohdi Amri, Ridha Ennetta, Zied Driss. Investigation: Ridha Djebali. Resources: Ridha Djebali, Bernard Pateyron. Data Curation: All authors. Writing—Original Draft: Ridha Djebali. Writing—Review & Editing: All authors. Visualization: Ridha Djebali, Moktar Ferhi, Karim Khemiri. Supervision: Ridha Djebali, Bernard Pateyron. Project Administration: Ridha Djebali, Ridha Ennetta. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Ridha Djebali, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Sub-Code of the Used MLP Model (Architecture and Parameters Tuning)

Architecture of the Scikit-Learn ANN Model (MLPRegressor)

# OPTIMIZATION of MLP model using RandomizedSearchCV Parameters

Tuning

from sklearn.neural_network import MLPRegressor

from sklearn.model_selection import RandomizedSearchCV,

GridSearchCV

mlp = MLPRegressor (random_state =41)

param_grid_random = {‘ hidden_layer_sizes ’ : [(20,), (20 ,20 ,),

(20,20,20,)],

‘ activation ’: [‘ tanh ’,‘relu’,‘logistic’],

‘solver’: [‘sgd’, ‘adam’,‘lbfgs’],

‘learning_rate’: [‘constant’,‘adaptive’,‘invscaling’],

‘alpha’: [0.0001,.005, 0.05],

‘max_iter’: [1000000],

‘early_stopping’: [False],

‘warm_start’: [False]}

GS_random = RandomizedSearchCV (mlp, param_distributions =

param_grid_random,n_jobs =1,cv=5,

scoring=‘r2’,n_iter=100,random_state=41)

GS_random.fit(X_train,y_train)

print(GS_random.best_params_)

print(GS_random.best_estimator_)

print(GS_random.best_score_)

Architecture of the Keras Built ANN Model

model =tf.keras.models.Sequential()

model.add (tf.keras.layers.Dense (256, activation=‘relu’,

input_shape=(5,))) # ou ‘input_dim=5’ # hidden layer 1 with input

model.add(tf.keras.layers.Dense(256, activation=‘relu’))

model.add(tf.keras.layers.Dense(256, activation=‘relu’))

model.add(tf.keras.layers.Dense(13, activation=‘relu’))

References

1. Fauchais P, Vardelle A, Dussoubs B. Quo vadis thermal spraying? J Therm Spray Tech. 2001;10(1):44–66. doi:10.1361/105996301770349510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zou J, Guan J, Wang X, Du X. Corrosion and wear resistance improvements in NiCu alloys through flame-grown honeycomb carbon and CVD of graphene coatings. Surf Coat Technol. 2023;473:130040. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.130040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alamri HR, Rezk H, Abd-Elbary H, Ziedan HA, Elnozahy A. Experimental investigation to improve the energy efficiency of solar PV panels using hydrophobic SiO2 nanomaterial. Coatings. 2020;10(5):503. doi:10.3390/coatings10050503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Vähä-Nissi M, Sundberg P, Kauppi E, Hirvikorpi T, Sievänen J, Sood A, et al. Barrier properties of Al2O3 and alucone coatings and nanolaminates on flexible biopolymer films. Thin Solid Films. 2012;520(22):6780–5. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2012.07.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zi W, Mu F, Lu X, Liu Z, Pang X, Yu Z, et al. Sputtering Al2O3 as an effective interface layer to improve open-circuit voltage and device performance of Sb2Se3 thin-film solar cells. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2023;153(6):107185. doi:10.1016/j.mssp.2022.107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abdelfatah A, Mohamed LZ, Elmahallawi I, Abd El-Fattah H. Comparison of structure and solar-selective absorbance properties of Al2O3 thin films with Al and Ni reflector interlayers. Chem Pap. 2023;77(9):5047–57. doi:10.1007/s11696-023-02842-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kjærside Storm B. Surface protection and coatings for wind turbine rotor blades. In: Brøndsted P, Nijssen RPL, editors. Advances in wind turbine blade design and materials. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2013. p. 387–412. doi:10.1533/9780857097286.3.387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Pateyron B. Jets & Poudres. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 17]. Available from: http://jets.poudres.free.fr/en/home.html. [Google Scholar]

9. Ben Ettouil F, Pateyron B, Ageorges H, El Ganaoui M, Fauchais P, Mazhorova O. Fast modeling of phase changes in a particle injected within a d.c plasma jet. J Therm Spray Tech. 2007;16(5–6):744–50. doi:10.1007/s11666-007-9075-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Djebali R, Pateyron B, ElGanaoui M. Scrutiny of plasma spraying complexities with case study on the optimized conditions toward coating process control. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2015;6(3):171–81. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2015.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Djebali R, Pateyron B, El Ganaoui M. A lattice boltzmann based investigation of powder in-flight characteristics during APS process, part II: effects of parameter dispersions at powder injection. Surf Coat Technol. 2013;220(3):157–63. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2013.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Djebali R, El Ganaoui M, Jaouabi A, Pateyron B. Scrutiny of spray jet and impact characteristics under dispersion effects of powder injection parameters in APS process. Int J Therm Sci. 2016;100(5):229–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2015.09.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ridha D, Mohamed El G, Bernard P. A lattice Boltzmann-based investigation of powder in-flight characteristics during APS process, part I: modelling and validation. Prog Comput Fluid Dyn. 2012;12(4):270–8. doi:10.1504/PCFD.2012.048250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Smith W, Jewett TJ, Sampath S, Swank WD, Fincke JR. Plasma processing of functionally graded materials part I: process diagnostics. In: Thermal Spray 1997: Proceedings of the International Thermal Spray Conference (ITSC); 1997 Sep 15–18; Indianapolis, IN, USA. p. 599–605. [Google Scholar]

15. Jia Z, Wang W, Qi W, Zhang J, Song K. Effect of process parameters on yttria-stabilized zirconia particles in-flight behavior and melting state in atmospheric plasma spraying. Adv Eng Mater. 2024;26(21):2400550. doi:10.1002/adem.202400550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wan YP, Gupta V, Deng Q, Sampath S, Prasad V, Williamson R, et al. Modeling and visualization of plasma spraying of functionally graded materials and its application to the optimization of spray conditions. J Therm Spray Tech. 2001;10(2):382–9. doi:10.1361/105996301770349475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bobzin K, Öte M, Knoch MA, Alkhasli I. Macroscopic modeling of an agglomerated and sintered particle in air plasma spraying. J Therm Spray Tech. 2020;29(1-2):13–24. doi:10.1007/s11666-019-00964-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhu T, Baeva M, Testrich H, Kewitz T, Foest R. Effect of a spatially fluctuating heating of particles in a plasma spray process. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2023;43(1):1–24. doi:10.1007/s11090-022-10290-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rat V, Chazelas C, Goutier S, Keromnes A, Mariaux G, Vardelle A. In-flight mechanisms in suspension plasma spraying: issues and perspectives. J Therm Spray Tech. 2022;31(4):699–715. doi:10.1007/s11666-022-01376-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Vaidya A, Bancke G, Sampath S, Herman H. Influence of process variables on the plasma sprayed coatings:an integrated study, thermal spray 2001. In: Proceedings from the International Thermal Spray ConferenceITSC2001; May 28–30, 2001; Singapore. p. 1345–9. Paper No.: itsc2001p1345. doi:10.31399/asm.cp.itsc2001p1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang H, Xiong HB, Zheng LL, Vaidya A, Li L, Sampath S. Melting behavior of in-flight particles and its effects on splat morphology in plasma spraying. In: ASME 2002 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; 2002 Nov 17–22; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 309–16. [Google Scholar]

22. Fauchais P, Vardelle M, Vardelle A. Reliability of plasma-sprayed coatings: monitoring the plasma spray process and improving the quality of coatings. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2013;46(22):224016. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/46/22/224016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu T, Planche M-P, Deng S, Montavon G, Kanta A-F. Spray operating parameters optimization based on artificial intelligence during plasma process. In: Lima RS, editor. Proceedings of the International Thermal Spray Conference (ITSC 2012) 2012 May 21–24; Houston, TX, USA. p. 562–7. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhu J, Wang X, Kou L, Zheng L, Zhang H. Application of combined transfer learning and convolutional neural networks to optimize plasma spraying. Appl Surf Sci. 2021;563:150098. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.150098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Paturi UMR, Cheruku S, Geereddy SR. Process modeling and parameter optimization of surface coatings using artificial neural networks (ANNsstate-of-the-art review. Mater Today Proc. 2021;38(5):2764–74. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.08.695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kanta A-F, Planche M-P, Montavon G, Coddet C. In-flight and upon impact particle characteristics modelling in plasma spray process. Surf Coat Technol. 2010;204(9–10):1542–8. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2009.09.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Derringer G, Suich R. Simultaneous optimization of several response variables. J Qual Technol. 1980;12(4):214–9. doi:10.1080/00224065.1980.11980968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools