Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Heat Transfer Analysis of Temperature-Sensitive Ternary Nanofluid in MHD and Porous Media Flow: Influence of Volume Fraction and Shape

1 Centre for Sustainable Materials and Surface Metamorphosis, Chennai Institute of Technology, Chennai, 600069, India

2 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, 603203, India

3 Institute of Mathematics, Henan Academy of Sciences, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

4 Nuclear Engineering and Fluid Mechanics Department, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Nieves Cano 12, Vitoria-Gasteiz, 01006, Spain

* Corresponding Authors: Jagadeesan Sasikumar. Email: ; Samad Noeiaghdam. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Heat and Mass Transfer: Integrating Numerical Methods with Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Data-Driven Approaches)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(5), 1529-1554. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.067869

Received 14 May 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

The present study investigates the dynamic behavior of a ternary-hybrid nanofluid within a tapered asymmetric channel, focusing on the impact of unsteady oscillatory flow under the influence of a magnetic field. This study addresses temperature-sensitive water transport mechanisms relevant to industrial applications such as thermal management and energy-efficient fluid transport. By suspending nanoparticles of diverse shapes-platelets, blades, and spheres in a hybrid base fluid comprising cobalt ferrite, magnesium oxide, and graphene oxide, the study examines the influence of both small and large volume fraction values. The governing equations are converted into a dimensionless form. With suitable assumptions, the partial differential equations (PDEs) are simplified into ordinary differential equations (ODEs), which are then solved using an analytical method. The proposed solution is verified using a numerical approach with the BVP4C solver. The analysis yields detailed graphs that depict the behavior of key fluid flow parameters, such as velocity, temperature, concentration, skin friction, Nusselt number, and Sherwood number, within the tapered asymmetric channel.Keywords

Researchers and engineers have explored the interesting domain of nanofluids to improve energy-efficient heat transfer mechanisms and augment the efficacy of cooling systems. Nanofluids, consisting of colloidal suspensions of nanoparticles in a base fluid, represent a potential approach for enhancing heat transfer properties in many applications. Thermal management in intricate fluid dynamics settings is notably difficult; nevertheless, investigating temperature-sensitive ternary nanofluids presents a feasible remedy. Energy efficiency and sustainability have gained paramount significance in this age of rapid technological progress. The increased demand for heat transport media that can adapt to varying temperature and fluid conditions has driven research into novel heat transfer technologies. The flow of nanofluids in tapered asymmetric channels creates a distinctive setting for investigating their thermal behaviour due to the interplay of MHD and porous media. These topologies are found in many technical and environmental systems, such as geothermal reservoirs, oil recovery methods, and electronic cooling systems.

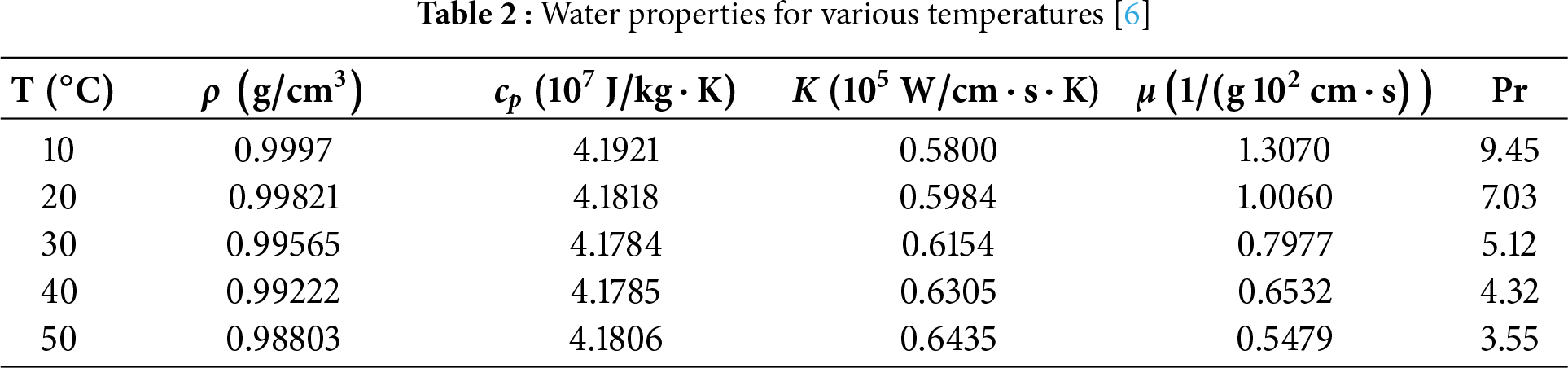

Xiu et al. [1] investigated influence of water-based nanofluids with the forced convective flow. The behaviour of dual-stretched ternary-hybrid nanofluids on wedge surfaces is analysed under various parameters, including the nanoparticles volume, shape, and density. It is noted that the friction between layers of ternary-hybrid nanofluid and the wall of the wedge decreases depending on the shape factor. Barman et al. [2] analysed coupled convective magnetized nanofluid flow properties and entropy generation. The authors examined the nanofluid flow, which primarily focused on the constant properties of water. Arif et al. [3] mentioned that using ternary hybrid nanofluids can enhance engine temperature and machinery longevity. Rajakumaret al. [4] investigated the axisymmetric mixed convection flow of water across a sphere with variable viscosity, Prandtl number, and magnetic field parameter. Eswara and Nath [5] studied how temperature variations affect incompressible, unsteady, laminar and boundary-layer flow over both 2-dimensional and axisymmetric structures. The results reveal that Skin friction and heat transfer rate respond strongly to unstable free stream velocity distributions. The action of unsteadiness and injection causes the zero-skin friction point to move upstream, whereas the influence of varied fluid characteristics causes it to move downstream. Barman et al. [6] investigated entropy formation in a bi-convective magnetized and radiative hybrid nanofluid flow with thermal sink/source effect. The result of the work has the potential to advance fluid flow and heat transfer rate in the various base fluids, including biological ones. The study also emphasizes the significance of developing nanoparticles and base fluid thermo-physical properties into account when constructing and analysing hybrid nanofluid flows. Shah et al. [7] examined the rate of thermal transmission and thermodynamic behaviour of second grad ternary nanofluid which flows past an oscillatory vertical plate using the Atangana-Baleanu time fractional integral. They presented the friction factor and heat transfer rate in tabular form and illustrated boundary layer profiles for velocity and temperature through graphical representations. Latha et al. [8] studied the MHD coupled non-Newtonian Hiemenz plane stagnation flow and heat transmission in a ternary nanofluid coating subjected to a transverse static magnetic field. The base fluid (polymeric) in engine oil is treated with various nanoparticles. It is noted that the tri-hybrid

Sasikumar et al. [9] investigated the complex dynamics of MHD oscillatory flow in a porous medium within a rotating wavy channel, considering the presence of a heat source. The importance of this study resides in the ability to comprehend asymmetric fluid flow behaviour which can be applied to engineering systems. Choi and Eastman’s [10] investigation helped to bring nanofluids to the forefront of thermal engineering research. Enhancing thermal conductivity through nanoparticle dispersion opened up new possibilities for improving heat transfer rate in various fields, with potentially transformative impacts on technology and industry. Tlili et al. [11] studied the effect of nanoparticles on the MHD Oldroyd-B ferrofluid’s unstable liquid film flow behaviour. The research advances the fundamental understanding of complex fluid behaviour and has potential applications in magnetic fields and ferrofluids systems. Sasikumar et al. [12] investigated the diffusion of chemically reactive species in the MHD oscillatory flow, considering the additional factors of thermal radiation, constant suction, and injection. The paper addresses the asymmetric wavy channel model as it raises the research gaps and opportunities for exploration. The behaviour of heterogeneous materials made up of two unique components with various thermal conductivities was discussed by Hamilton and Crosser [13]. Understanding the heat transfer properties of composite materials, which are frequently used in engineering applications, is essential. The publication paved the way for later studies on heat transmission and composite materials. It sparked additional research into the thermal behaviour of more intricate heterogeneous systems and inspired the creation of more precise predictive models. Sasikumar and Senthamarai [14] explored the dynamics of blood flow in a tapered asymmetric channel under several factors, including chemical reactions and viscous dissipation. Narayanan et al. [15] investigate the MHD oscillatory flow in an asymmetric wavy channel, incorporating mass and thermak transmission, chemical processes, and thermal sources.

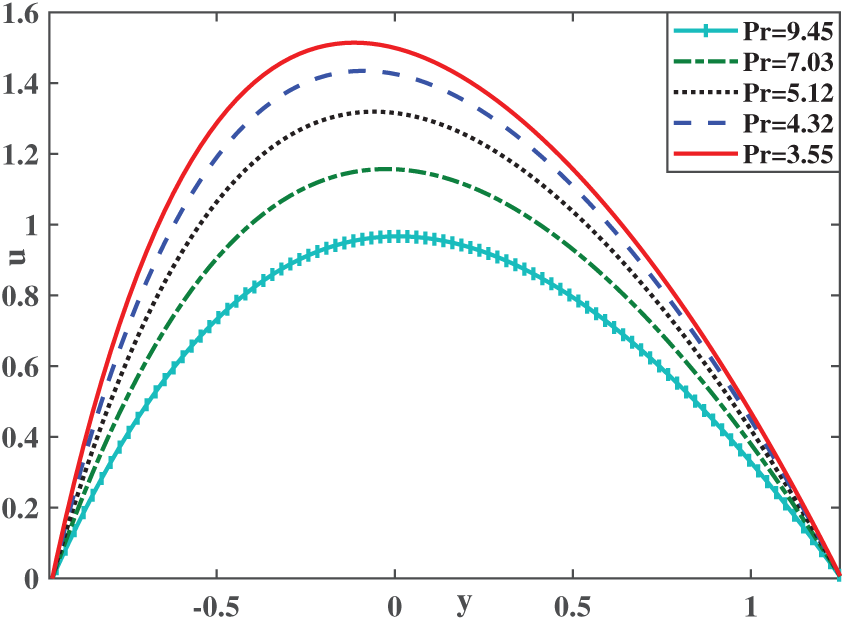

Aaizar et al. [16] analyzed the energy transfer dynamics in mixed convection unsteady MHD flow of an incompressible nanofluid within a channel filled with a saturated porous medium. To enhance the thermal properties of conventional base fluids, four distinct shapes of nanoparticles with equal volume fractions are introduced into ethylene glycol (EG) and water (

Vaidehi and Sasikumar [27] examined the development of velocity slip and the impact of heat transport in the MHD oscillatory flow of a Casson fluid. This flow transpires in a sinuous channel embedded inside a permeable material and is influenced by heat radiation. A comparative analysis characterises the behaviour of Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids, highlighting differences in velocity profiles for low and high plastic dynamic viscosity values by linear slope regression analysis. A hybrid nanofluid containing magnesium oxide and silver nanoparticles in water contained within a permeable and hollow ampoule was studied by Jamshed [28] under the influence of a magnetic field. An efficient thermos-physical model, as well as the Darcy-Forchheimer model, is employed in the study for the inertia of the penetrable layer. Based on the influence of radiation and Hall current, VeeraKrishna et al. [29] studied MHD unsteady free convective flow in a vertical channel filled with a porous medium. In this study, the authors examined the impact of various parameters on several critical aspects of the flow, including the velocity profiles, skin friction, temperature field, and heat transfer rate. Timofeeva et al. [30] examined the thermal conductivity and viscosity of alumina nanoparticles of various geometries suspended in a fluid mixture of equal proportions of ethylene glycol and water. Their investigation focused on the influence of nanoparticles and tiny agglomerates with elevated aspect ratios on the viscosity of the solution, resulting in a significant rise. The study by Alnahdi et al. [31] described the rheological aspects of blood circulation when metal and non-metal nanomaterials are dispersed in a squeezing channel. The research is motivated by its potential applications in areas like blood filtration systems, nano-pharmacology, hemodynamic in cases of obstruction, nano-hemodynamic, the management of hemodynamic diseases, and various other fields. The impact of nonlinear thermal radiation on the dynamics of these nanofluids in the context of MHD flow over a stretching sheet was investigated by Nasir et al. [32]. The nanoparticles chosen for this ternary hybrid nanofluid are

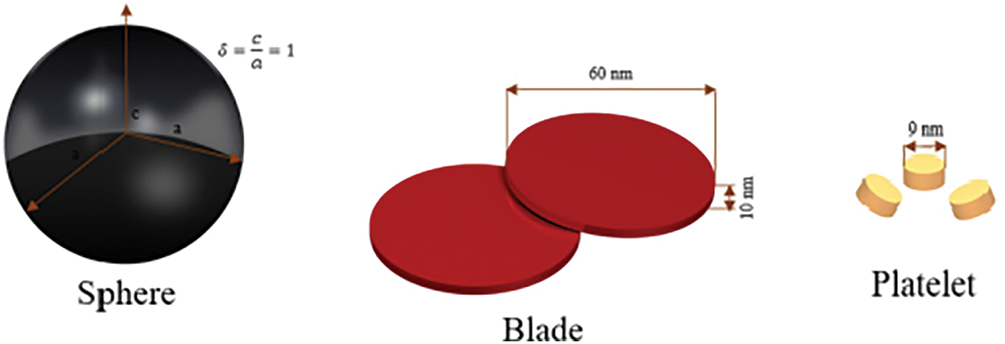

The choice of nanoparticle shapes-platelet, blade, and spherical-derives from their distinct geometric properties, which markedly affect thermal conductivity, heat transport, and fluid dynamics in nanofluids. Each form interacts uniquely with the base fluid and magnetic field, influencing factors such as surface area, drag force, and thermal transfer efficiency. Each form interacts with the base fluid and magnetic field uniquely, affecting parameters such as surface area, drag force, and heat transfer efficiency. The selection of cobalt ferrite, magnesium oxide, and graphene oxide for the nanoparticles is motivated by their distinct thermal, magnetic, and chemical properties, consistent with the objectives of the study. Cobalt ferrite was selected for its robust magnetic response, enabling a thorough investigation of the MHD effect. Magnesium oxide was chosen for its superior thermal conductivity and chemical stability, essential for enhancing heat transfer in temperature-sensitive applications. Graphene oxide, characterised by its layered architecture and significant surface area, was included for its capacity to improve heat conductivity and fluid stability. The amalgamation of these materials allows an exhaustive examination of many scenarios in nanofluid applications, providing significant insights into the interaction between material characteristics, geometric influence, and thermal dynamics.

The use of ternary nanofluids has gained considerable interest in recent years due to their ability to combine the unique properties of three distinct nanoparticles within a single base fluid. While single nanofluids such as graphene oxide (GO) offer excellent thermal conductivity, they may not meet all the multifunctional requirements of advanced thermal systems. Ternary combinations-such as those involving GO, magnesium oxide (MgO), and cobalt ferrite

The literature review underscores significant research gaps in the study of ternary nanofluids within tapered asymmetric channels, especially concerning the influence of nanoparticle shape on fluid dynamics and temperature sensitivity. It reveals a need for further exploration into how various nanoparticle shapes (spherical, platelet, blade) impact fluid flow, mass and heat trasmission. Additionally, the review highlights a lack of comprehensive studies on how temperature variations (ranging from

The principal investigation topics for focussing the exploration of transport phenomena are as follows:

1. How do different shapes of nanoparticles (spherical, platelet, blade) impact the fluid flow, heat transfer, and mass transfer characteristics within a tapered asymmetric channel?

2. How do the temperature-sensitive characteristics of nanoparticles concerning shape and volume behave in terms of fluid flow, velocity profile and temperature distribution?

3. In the context of dual cases A and B (small and large volumes of nanoparticles), how does the skin friction coefficient change with respect to different nanoparticle volume fractions in ternary nanofluids at

4. What are the underlying factors that contribute to the shape-induced variation in heat transfer rates of nanoparticle shapes (spherical, platelet, blade) in ternary nanofluids, and how do these findings contribute to understanding nanofluid dynamics?

5. What is the relationship between the temperature of a ternary nanofluid and its velocity, considering the reduction in fluid viscosity at elevated temperatures and its effect on fluid flow?

This study introduces several novel aspects to the field of nanofluid and MHD. It investigates the influence of various nanoparticle shapes-platelets, blades, and spheres-on fluid dynamics and heat transfer within tapered asymmetric channels, an area not extensively explored before. Furthermore, it combines temperature sensitivity with ternary nanofluids, revealing how temperature fluctuations affect flow characteristics and thermal performance. The research also explores the combined effect of magnetic fields and porous media on nanofluid behavior, providing a detailed analysis of these interactions in complex fluid systems. These contributions advance the understanding of nanofluid dynamics and support the development of improved heat transfer technologies.

This study examines nanofluid flow through a porous medium in a time-dependent model. To enhance the heat transfer rate cobalt ferrite, magnesium oxide, and graphene oxide are considered as ternary hybrid nanoparticles, with shapes like platelets, blades, and spheres in two cases (Case A: small volume fraction and Case B: large volume fraction) nanoparticle volume fractions (concentrations) are considered to assess their impact on fluid flow and heat transfer. Although the present study adopts a single-phase model, the use of a ternary nanofluid-comprising

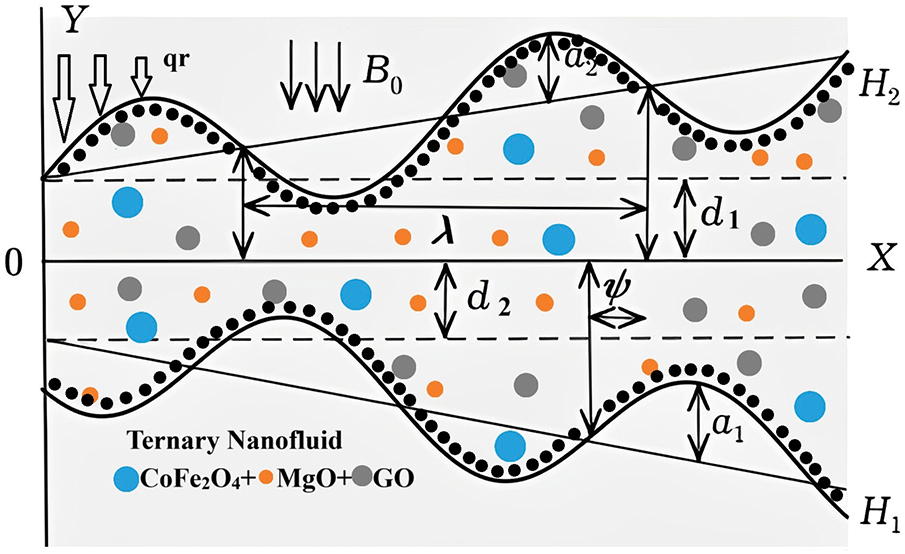

The study examines a viscous, incompressible, electrically conducting fluid that demonstrates chemical radiation in an optically thin medium situated within an asymmetric wavy channel as given in Fig. 1. The flow is affected by a thermal source and radiative heat transport. The fluid’s electrical conductivity and the resultant electromagnetic force are considered trivial relative to the externally imposed magnetic field, which is orthogonal to the channel walls. The physical arrangement is delineated using a coordinate system in which the

Figure 1: Physical configuration of the problem

Channel Wall Equations as follows [15]:

where the non-uniform parameter m represents the taperedness of the channel,

The governing equations are formulated to include temperature-dependent viscosity and thermal conductivity, reflecting realistic behavior under oscillatory thermal loads. The ternary nanofluid is modeled as a single-phase fluid with effective properties determined by the shape factor and concentration of each constituent nanoparticle. The influence of porosity, unsteady magnetic field, and asymmetric channel geometry is integrated into the momentum and energy equations, enhancing the originality of the formulation. The equations has been derived from the Navier-Stokes equations (Raisinghania [37] and Welty et al. [38]), with terms such as convective inertia neglected due to low Reynolds number (Sharpio et al. [39]), while key physical effects like magnetic field interaction, buoyancy forces, heat generation and molecular diffusion have been retained to accurately model the oscillatory nanofluid flow and its thermal and concentration gradients in the asymmetric channel.

The term

The study assumes a uniform baseline distribution of nanoparticles, consistent with the single-phase nanofluid model. However, due to the presence of external oscillatory forces, temperature gradients, and suction/injection at the channel boundaries, macroscopic concentration variations are introduced. The concentration equation captures this effective solutal transport under dynamic flow conditions and does not represent actual demixing or particle agglomeration. The imposed boundary conditions describe dimensionless concentration deviations about a mean concentration level, allowing for the simulation of mass transport phenomena within the single-phase approximation. C represents the concentration of a solute species involved in chemical reactions, and is distinct from the volume fraction of nanoparticles, which is assumed to be constant and uniformly distributed in the base fluid in accordance with the single-phase nanofluid model.

Cogley et al. [20] state that for an optically thin fluid with low density, the radiative heat flow is expressed as

where

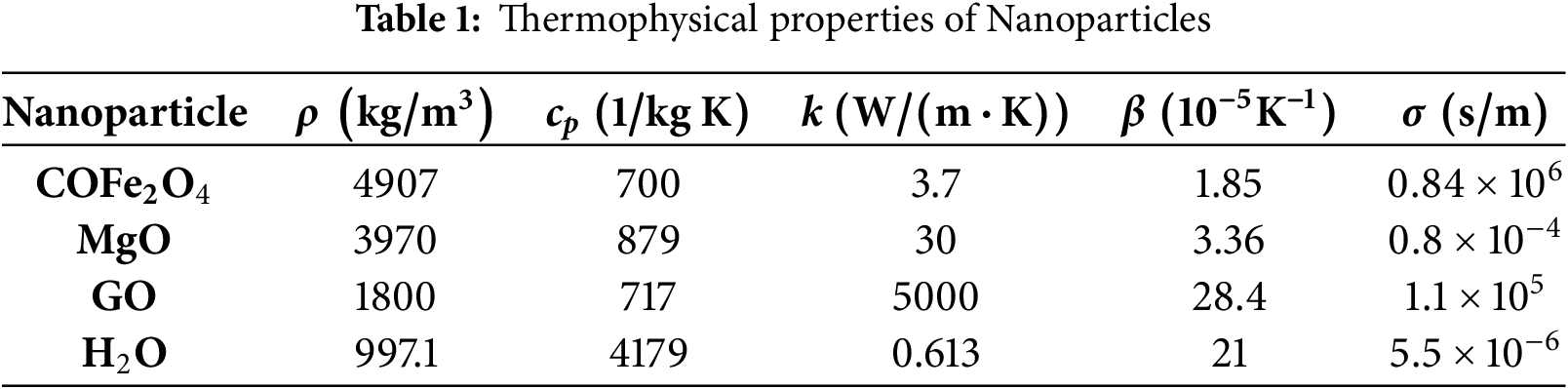

The Evaluation of Ternary Hybrid Nanofluid Properties

In this section, we present the mathematical expressions governing the thermophysical properties of ternary nanofluids Maxwell [40], Brinkman [41], Pak and Cho [42], Maiga et al. [43], Palm et al. [44], Eastman et al. [45] and Das et al. [46]). The effective density, thermal expansion coefficient and solutes expansion coefficient of a ternary nanofluid, denoted as

The electrical conductivity of the ternary nanofluid is calculated in stages, starting with the base nanofluid, where

The thermo-physical characteristics of thermal conductivity, and dynamical viscosity of the ternary hybrid nanofluid are affected not only by particle volumetric concentration but also by the shape of the nanoparticles. In this study, the temperature-sensitive base fluid with spherical, blade, and platelet-shaped nanoparticles are used as shown in Fig. 2. In this study, the impact of the volumetric concentration and shape of nanoparticles is theoretically investigated. The Hamilton and crosser model [13] can be used to calculate the thermal conductivity of the ternary nanofluid [16].

Figure 2: Particles shapes: sphere, blade and platelet

The subsequent dimensionless quantities are defined to non-dimensionalize the governing equations, and are given by [15]:

The non-dimensional governing equations of momentum, energy and concentration, along with the relevant boundary conditions (disregarding * symbols), can be expressed as follows:

The relevant boundary conditions in nondimensional form are as follows:

where

In Eq. (11),

The model includes both radiation and heat source terms, each addressing different aspects of thermal behavior. The heat source term

The current study, while providing a detailed analysis of ternary nanofluids in tapered asymmetric channels, does have several limitations and assumptions. Firstly, the study assumes a uniform distribution of nanoparticles throughout the base fluid, which may not fully represent real-world scenarios where particle agglomeration or sedimentation can occur. Additionally, the channel geometry used in the model is idealized, potentially oversimplifying the complexities of actual channel designs. The study also assumes constant thermophysical properties of the nanofluids, such as viscosity and heat conductivity, which can vary with temperature and concentration in practical situations. Furthermore, some complicated flow phenomena, like turbulence and non-Newtonian, are excluded, potentially impacting the accuracy of results under more sophisticated flow circumstances. Ultimately, the models for radiation and heat source effect rely on simplifying assumptions, necessitating a more comprehensive research to accurately assess their influence. These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the findings and suggest areas for future research to refine the model and address these assumptions. The inclusion of the chemical reaction term accounts for nanoparticle consumption over time, leading to spatial concentration gradients. Hence, the variation seen in the concentration profiles reflects the dynamic evolution of the system rather than a contradiction of the initial distribution assumption.

The governing partial differential equations representing momentum, energy, and mass transport Eqs.(2)–(4) are first nondimensionalized using suitable non-similarity transformations. Assuming a purely oscillatory flow, the variables pressure gradient, velocity, temperature, and concentration-are expressed using harmonic functions of the form

By considering a purely oscillatory flow and assuming the pressure gradient, velocity, temperature, and concentration, the system of PDEs (11)–(13) can be simplified into a system of ODEs in dimensionless form.

Substituting Eq. (15) in Eqs. (11)–(13).

Where the subjected boundary conditions given below are:

Eqs. (23)–(25) are obtained by applying the method of separation of variables to the simplified system of dimensionless ordinary differential equations Eqs. (16)–(18). Given that the equations contain constant coefficients and represent linear behavior, they are amenable to analytical solutions in exponential form. The temperature and concentration equations are first solved independently to obtain explicit expressions, which are subsequently substituted into the momentum equation to determine the velocity profile. The corresponding boundary conditions are then imposed to evaluate the integration constants and yield complete, closed-form solutions for the physical quantities of interest.

The solutions of the flow profile are obtained as:

The mathematical form of skin friction ‘

This section focuses on the discussion of the numerical and computational results obtained for the problem of an incompressible, electrically conducting, chemically reacting nanofluid flow with a magnetic field intensity through a tapered asymmetric wavy channel with heat source in a porous medium when

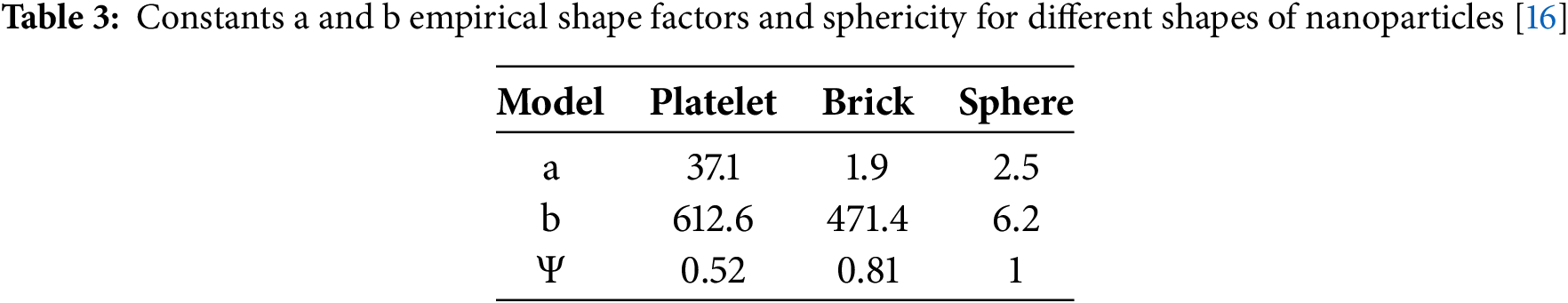

In Fig. 3, the velocity profile for various suction parameters has been analysed for platelet-shaped ternary hybrid nanofluid at

Figure 3: Velocity profile for various values of S over Platelet-shaped ternary hybrid nanofluid

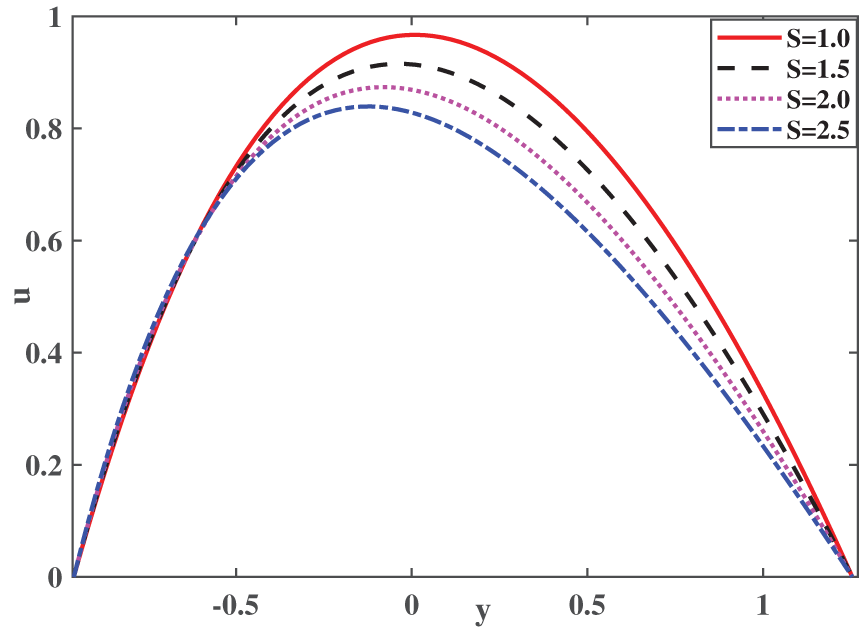

Figure 4: Velocity profile for various values of M over Blade-shaped ternary hybrid nanofluid

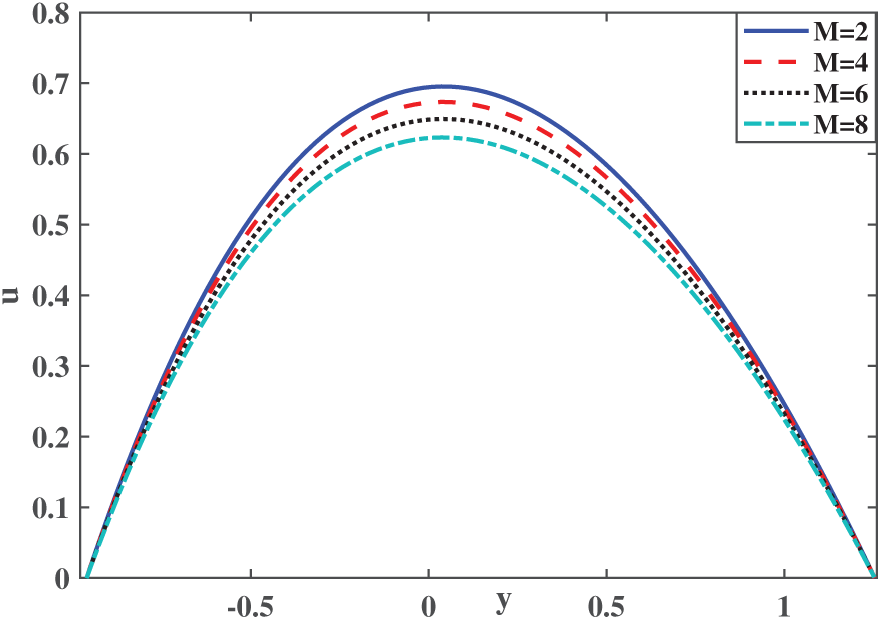

Figure 5: Velocity profile at different temperatures over sphere-shaped ternary hybrid nanofluid

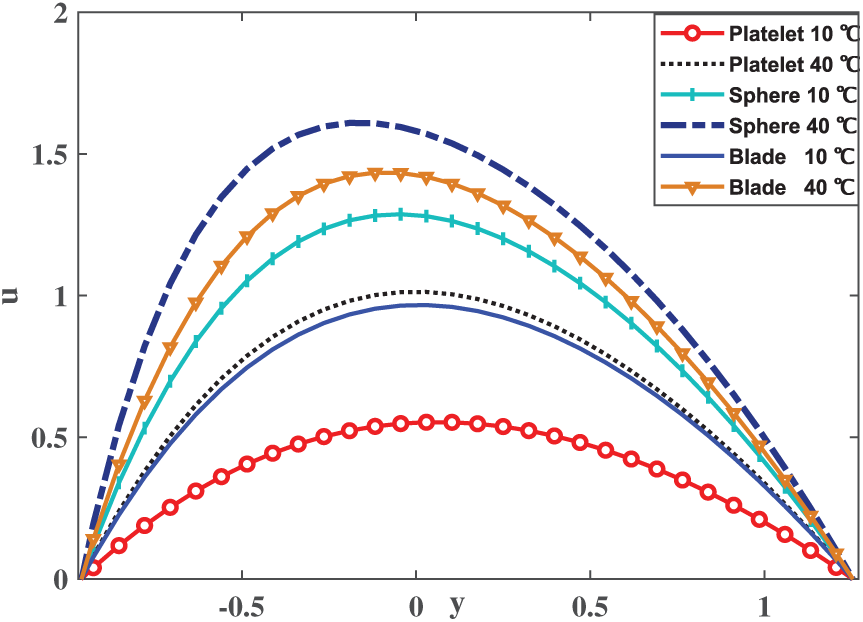

Figure 6: Velocity Profile for three different shapes at

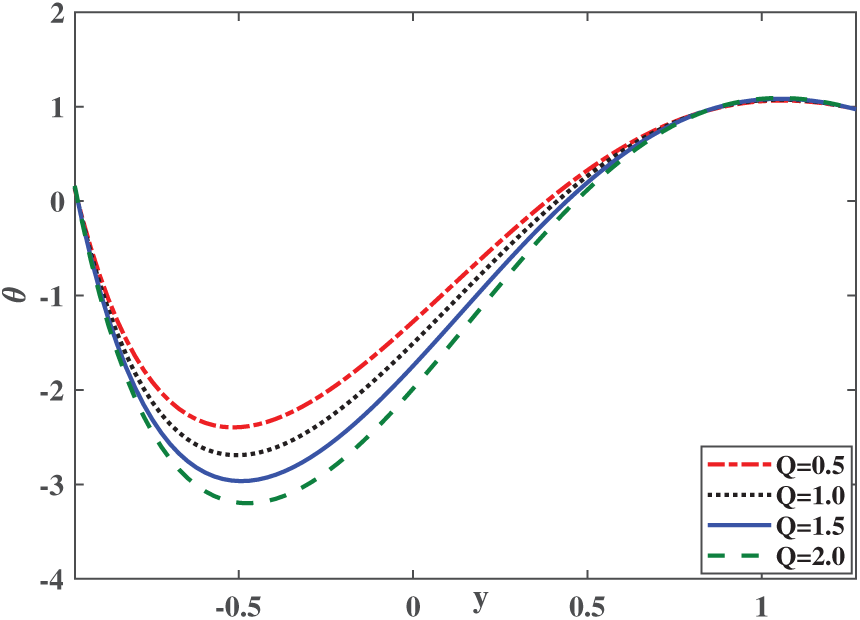

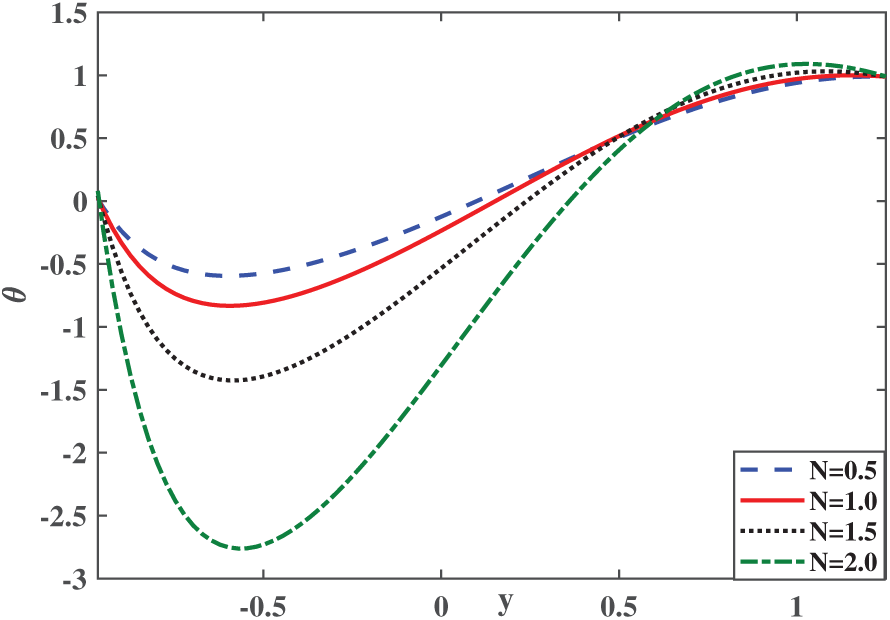

Figure 7: Temperature profile for various values of Q over platelet-shaped ternary hybrid nanofluid

Figure 8: Temperature profile for various values of N over sphere-shaped ternary hybrid nanofluid7

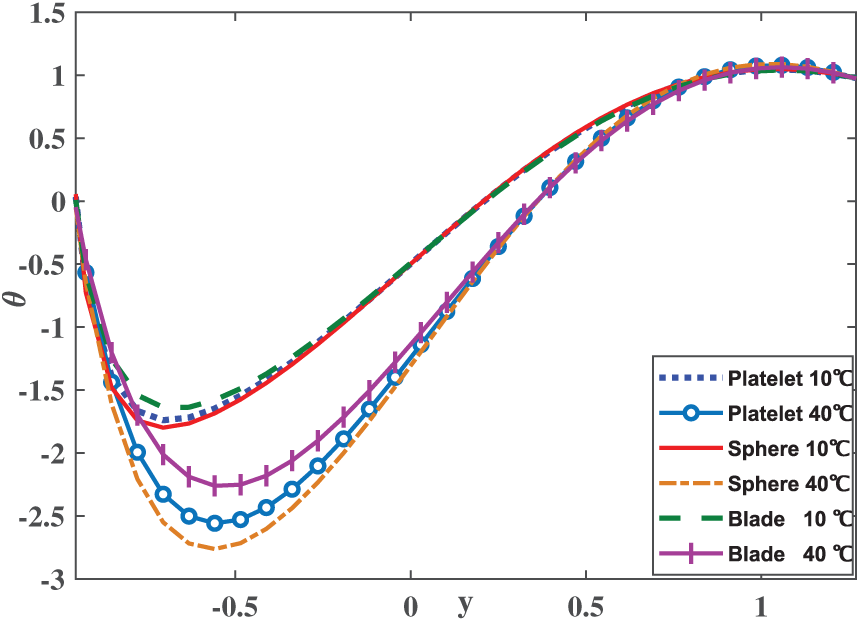

Temperature profile for blade, sphere and platelet shaped at

Figure 9: Temperature Profile for three different shapes at

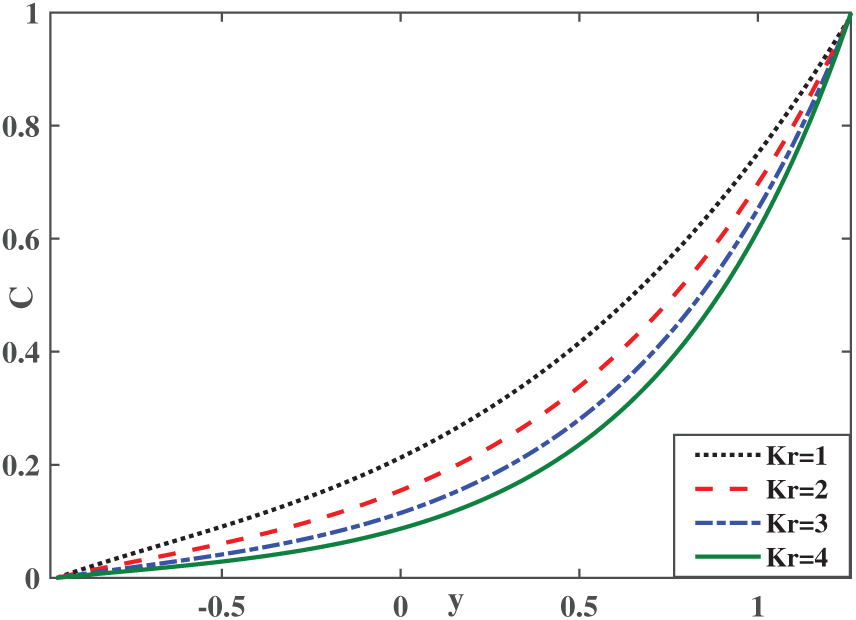

Figure 10: Concentration profile for various values of Kr over sphere-shaped ternary hybrid nanofluid

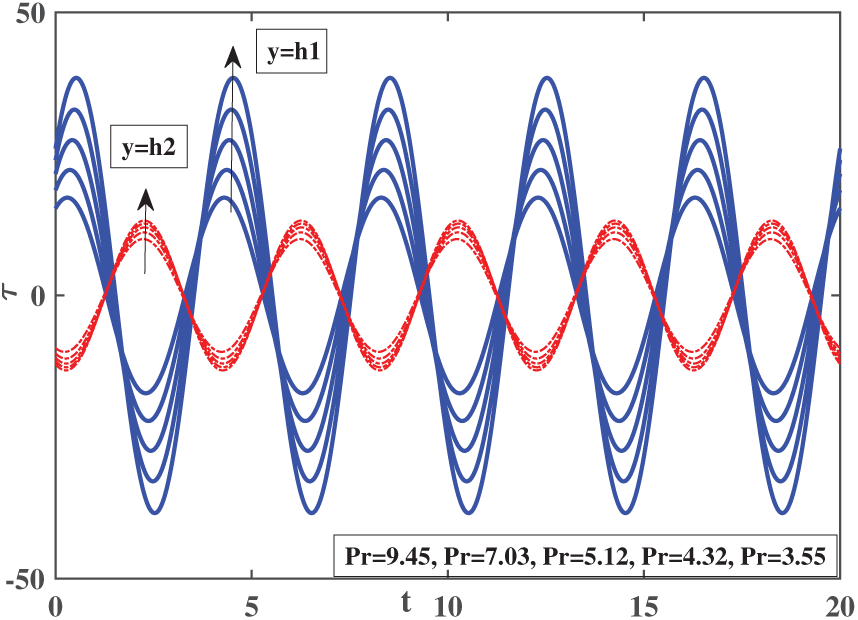

Figure 11: Impact of skin friction coefficient at different temperatures of the ternary hybrid nanofluid

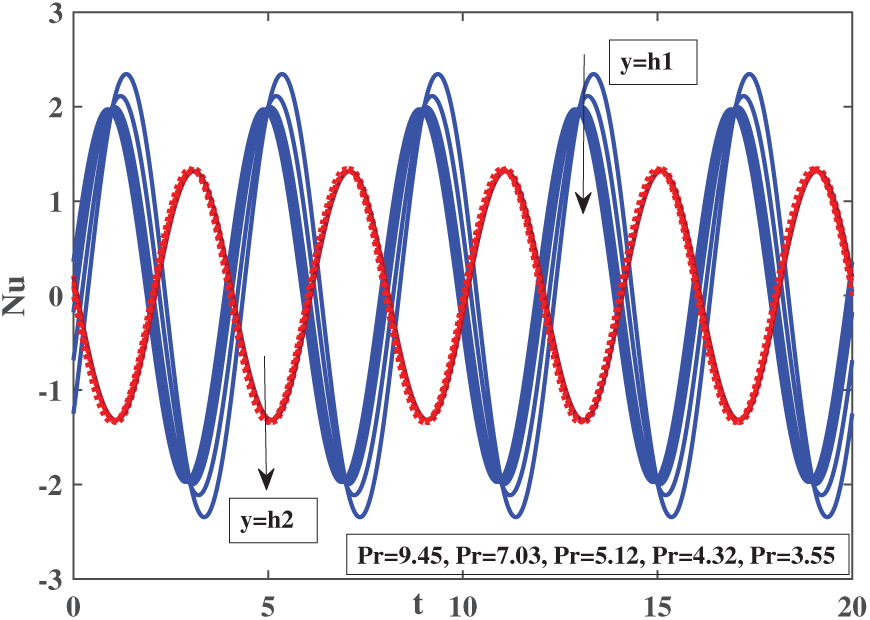

Figure 12: Impact of heat transfer rate at different temperatures of the ternary hybrid nanofluid

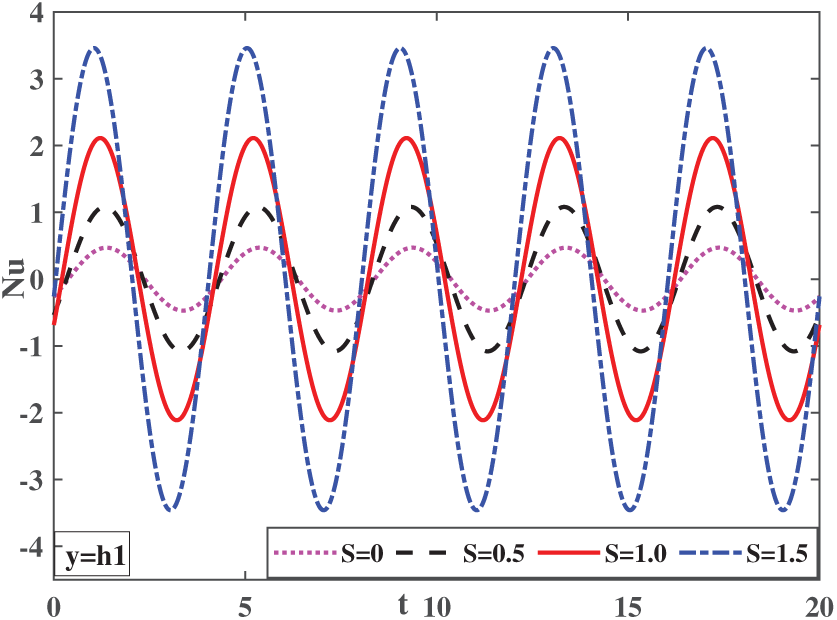

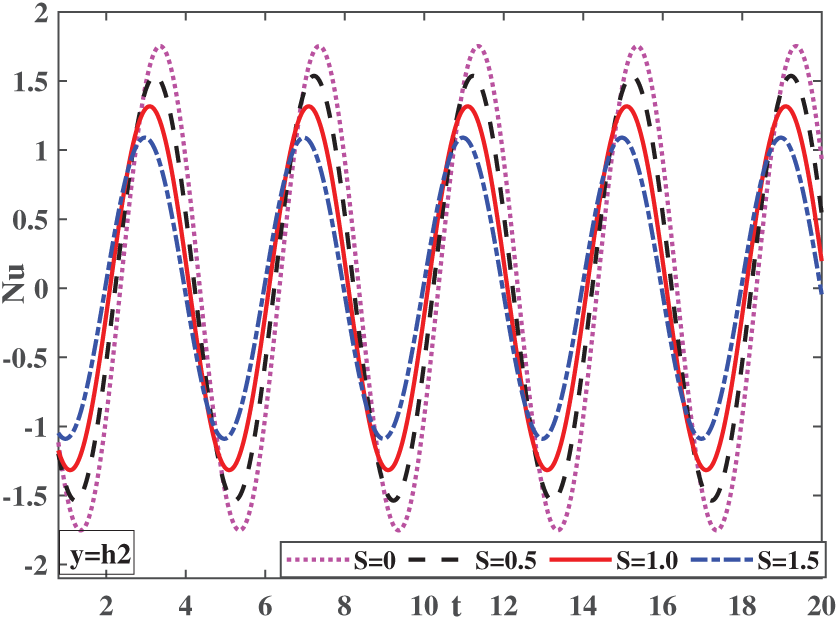

Figure 13: Impact of the heat transfer rate of the ternary hybrid nanofluid for various values of the suction parameter at

Figure 14: Impact of the heat transfer rate of the ternary hybrid nanofluid for various values of the suction parameter at

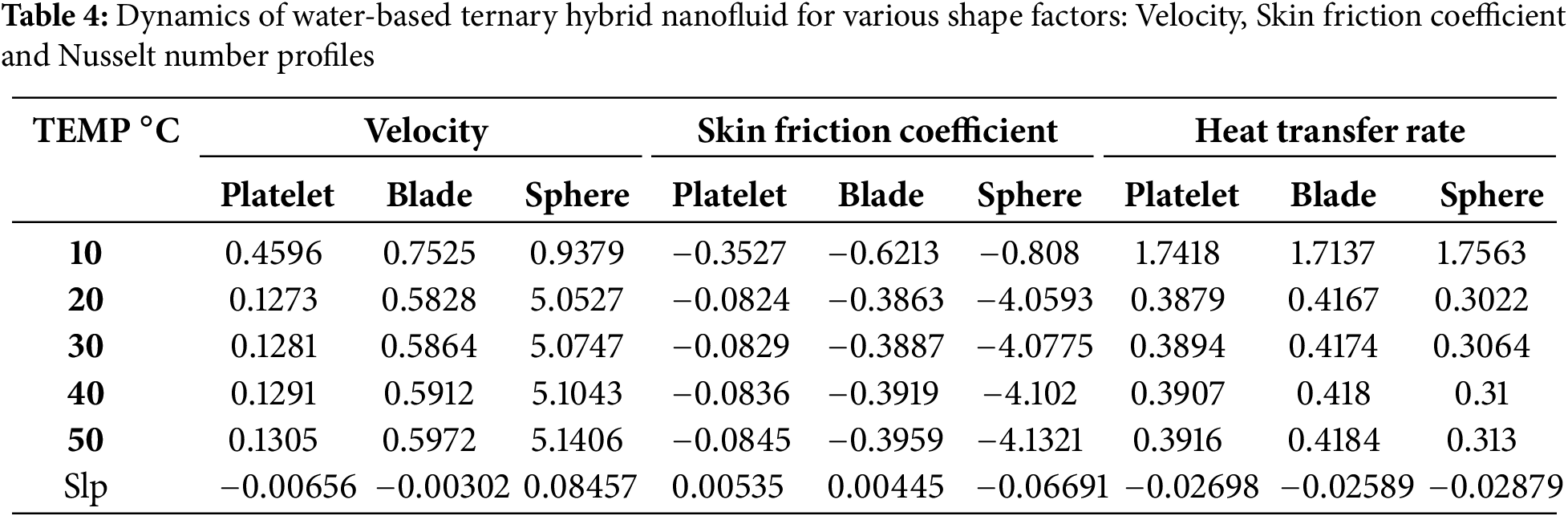

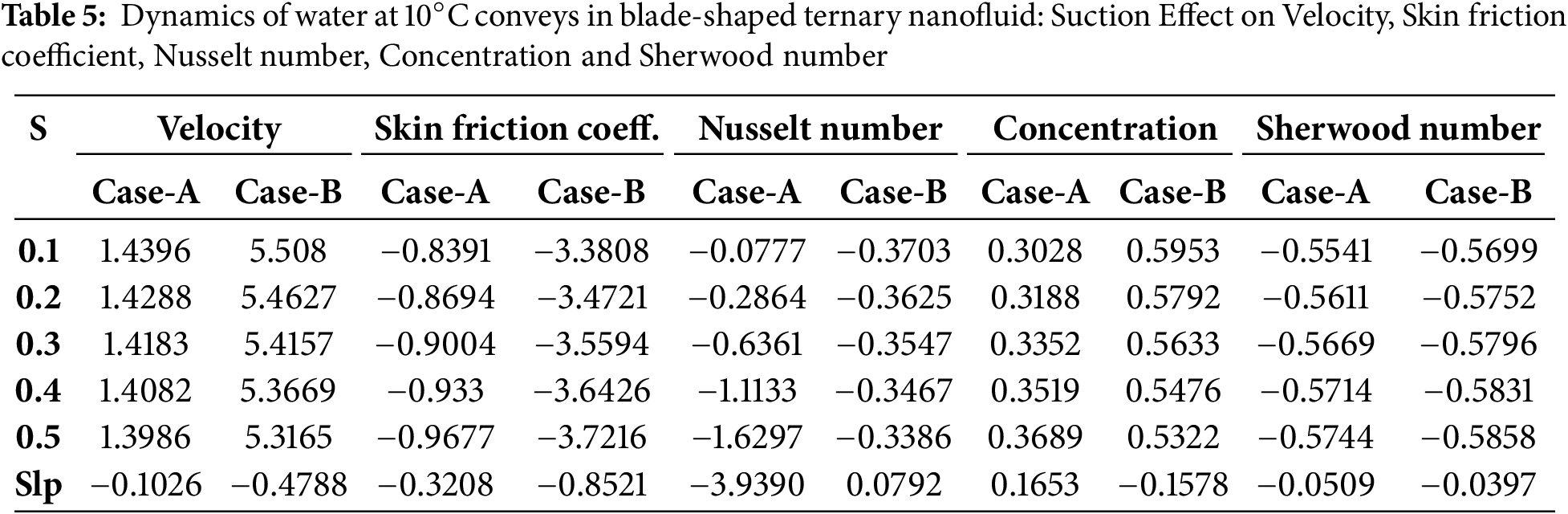

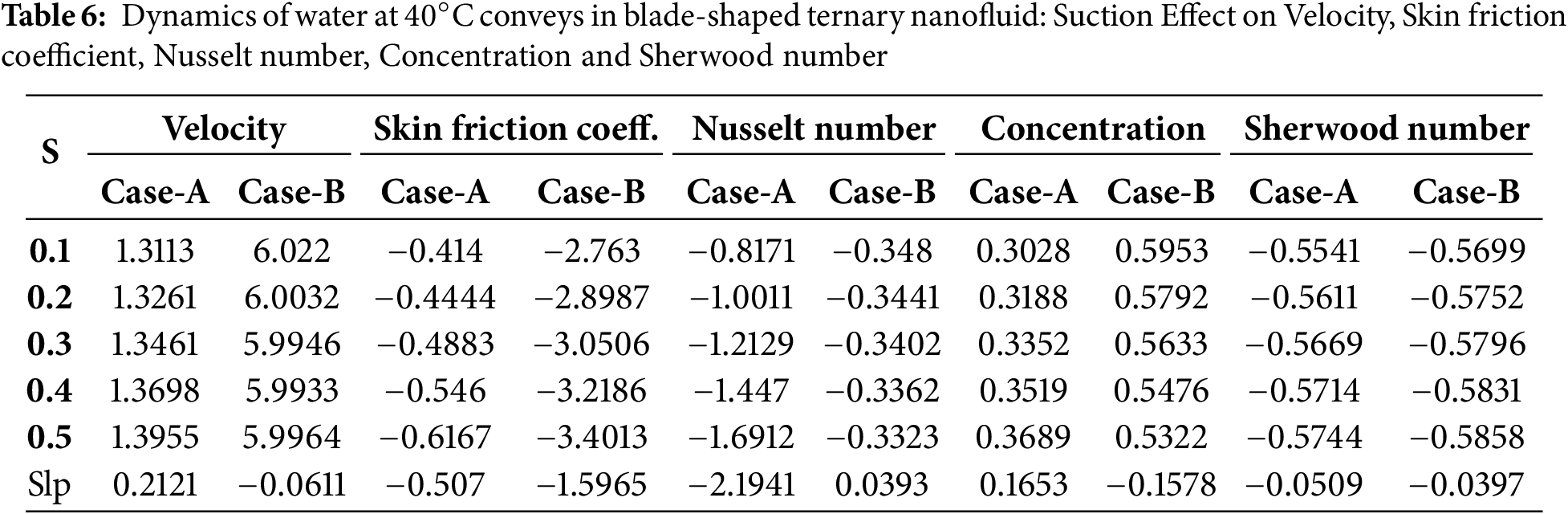

Table 4 illustrates the impact of temperature and nanoparticle shapes on fluid dynamics within a tapered asymmetric channel. The velocity increases with temperature, with the sphere-shaped nanoparticles showing the most significant enhancement, rising from 0.9379 at

The findings of this study have practical implications for temperature-sensitive water transport systems. For electronic cooling, the use of temperature-sensitive nanofluids can enhance heat dissipation, improving device performance and longevity. In geothermal energy systems, optimized thermal management can boost heat extraction efficiency. Additionally, the study contributes to advanced thermal storage solutions, enhancing the efficiency of energy storage and retrieval. These applications underscore the practical value of the research and its potential to enhance various technological and industrial processes.

4.1 Heat Transfer Characteristics of Nanofluid Composites

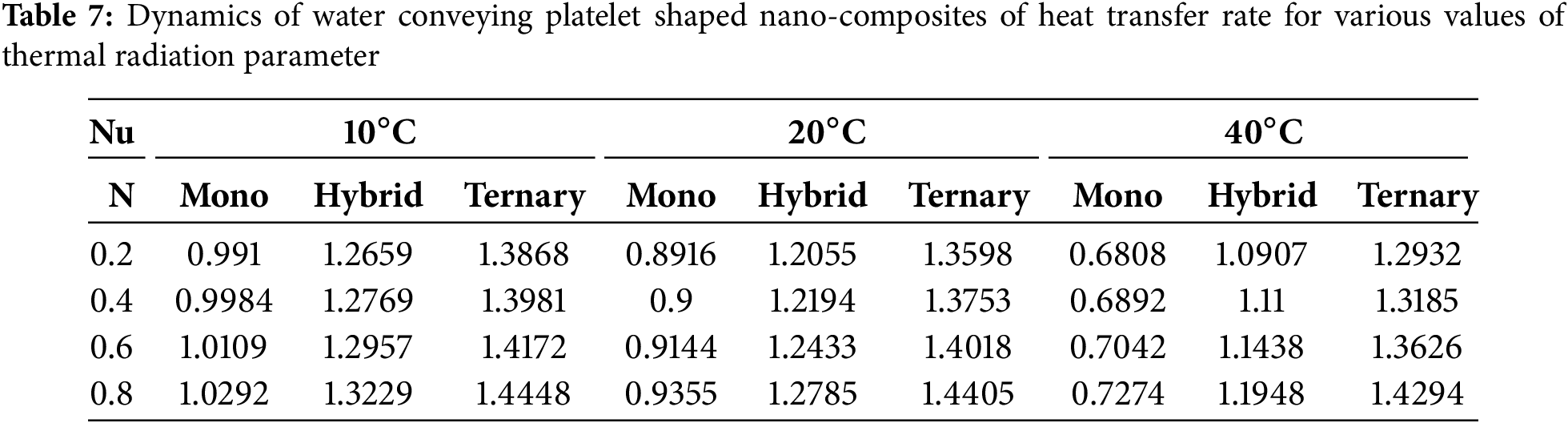

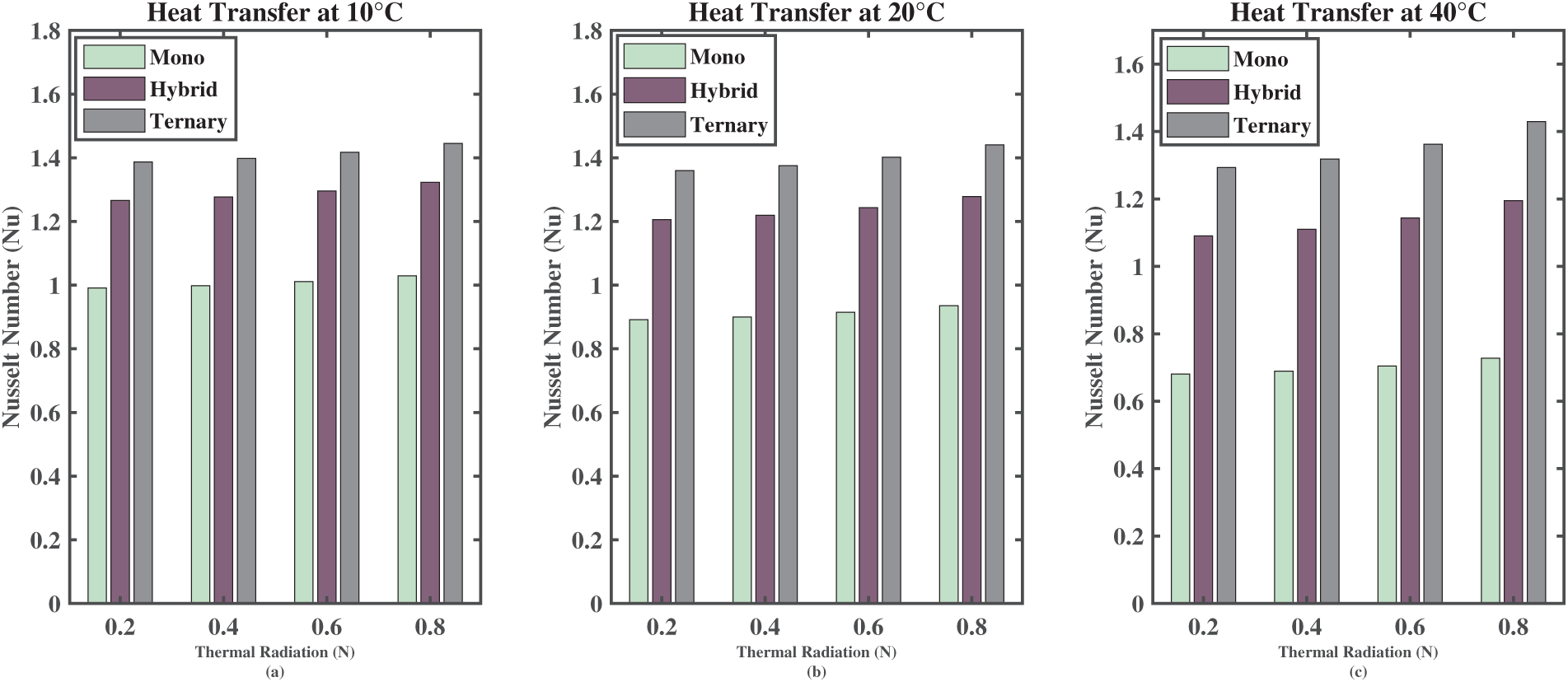

The selection of cobalt ferrite as the mono nanofluid was based on its strong magnetic properties, which are essential for evaluating MHD in oscillatory flow conditions. Unlike graphene oxide (GO), cobalt ferrite interacts directly with the magnetic field, allowing a better understanding of how magnetic nanoparticles influence heat transfer under oscillatory and porous conditions. The study follows a progressive comparison: starting with magnetic nanoparticles alone (mono), followed by the inclusion of a secondary nanoparticle to improve thermal conductivity (hybrid), and culminating in a ternary system where the addition of GO enhances thermal performance. This tiered evaluation highlights the synergetic effect of combining different nanoparticles rather than focusing on thermal conductivity alone. Table 7 and Fig. 15 summarizes the Nusselt number (Nu), which measures the heat transfer rate, for various shapes of nanofluid composites (mono, hybrid, and ternary) at different temperatures (

Figure 15: (a) Heat transfer at

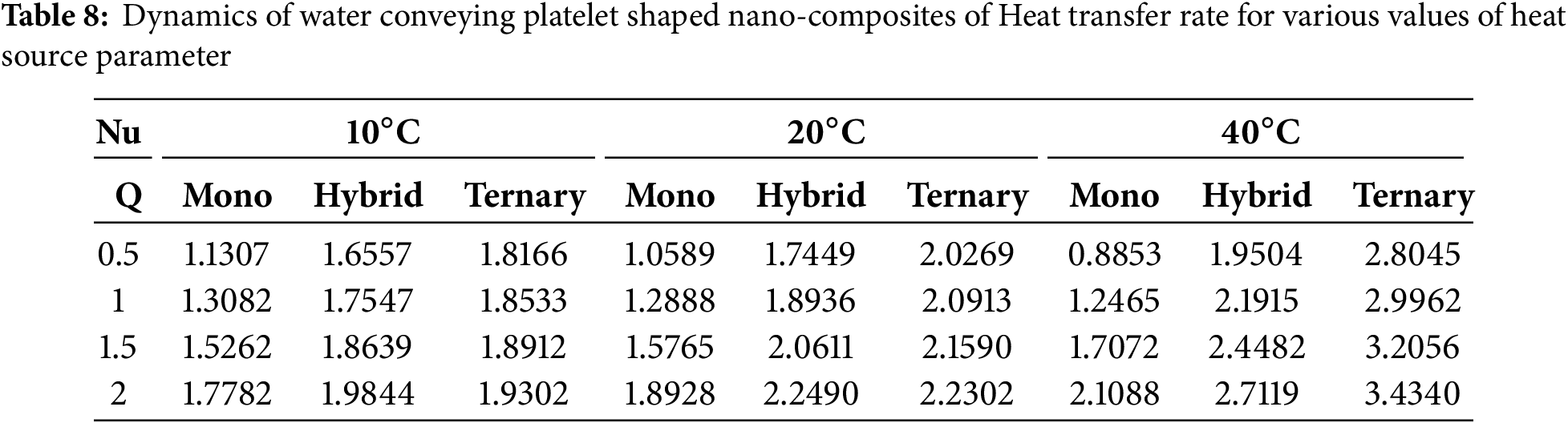

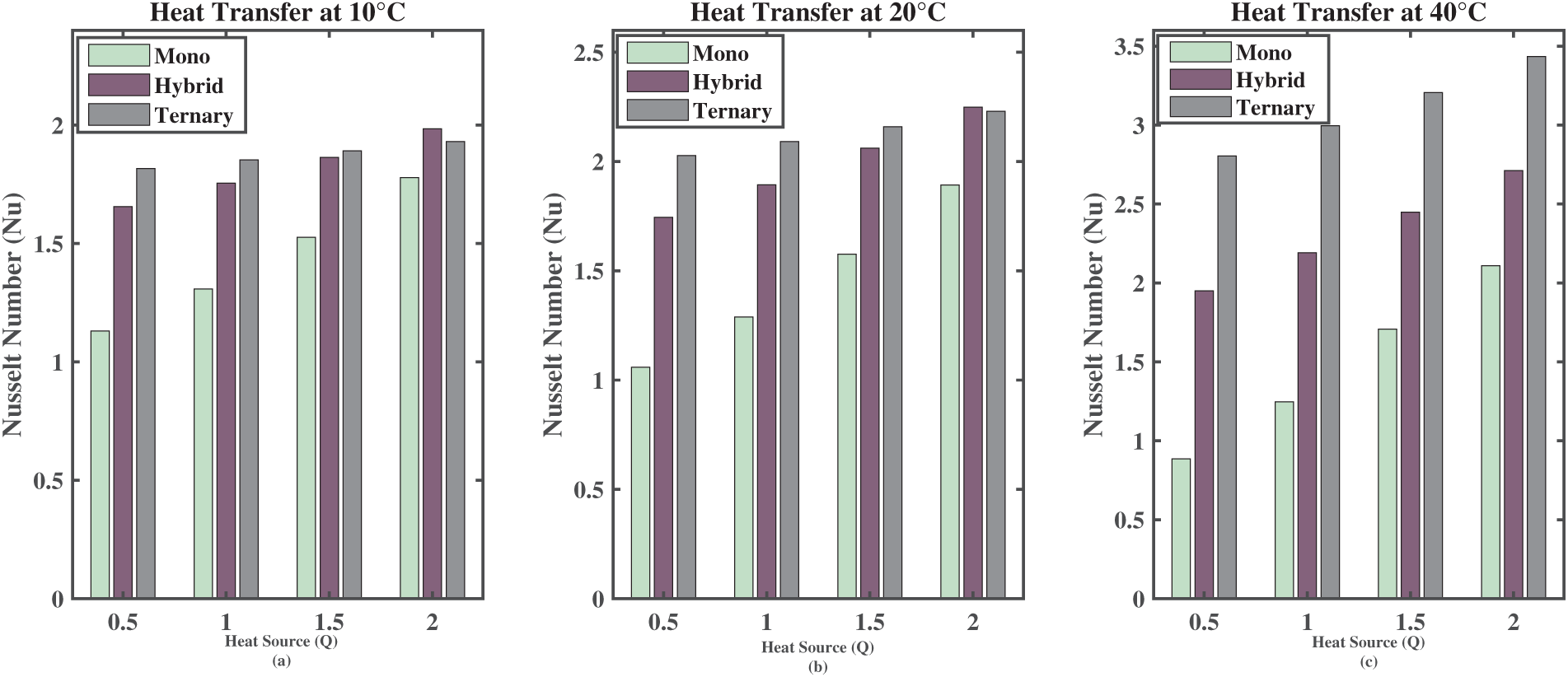

Table 8 and Fig. 16 summarize the Nusselt number (Nu), reflecting the heat transfer rates for mono, hybrid, and ternary nanofluids at different temperature levels (

Figure 16: (a) Heat transfer at

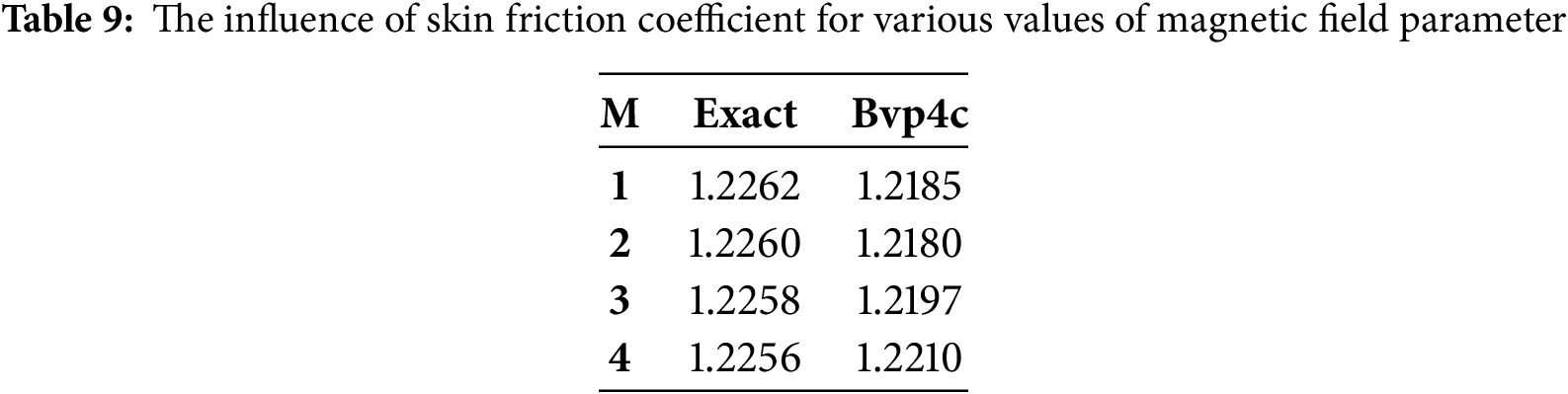

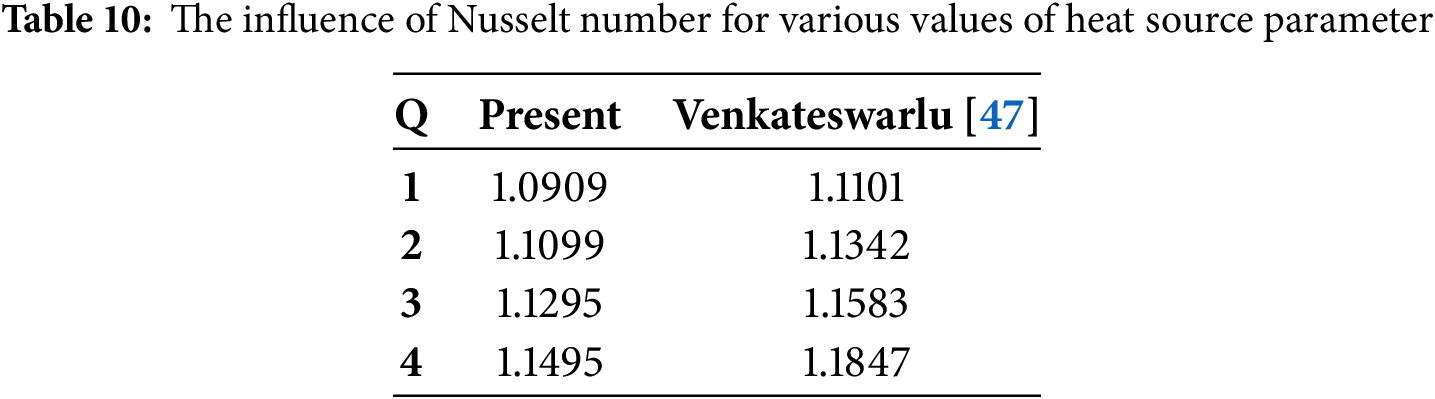

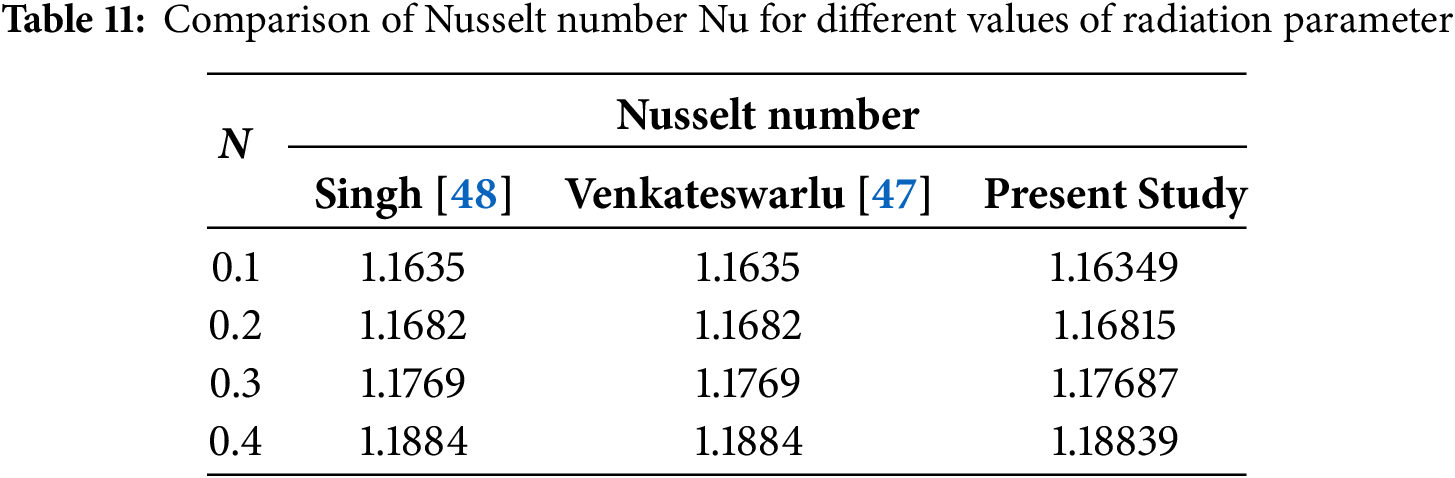

The exact values of the magnetic field parameters are contrasted with the numerical values acquired using the Bvp4c approach in Table 9. The Bvp4c numerical solver determines the magnetic field parameter for with excellent accuracy and good agreement between the two approaches. In Table 10, the heat transfer rate has been compared with the previous study [47] to validate the present study. We have observed that the heat transfer rate for various Heat Source values has been calculated by limiting the model. By reducing the novelty of the present study of ternary nanofluid, the results are also compared with the consequences of Venkateswarlu [47]. The results demonstrate good agreement to validate the study. The validation of the Nusselt number for various values of the radiation parameter (N) is presented in Table 11. This comparison includes results obtained by Singh [48], Venkateswarlu [47], and the present study. Table 11 demonstrates close agreement between the values obtained from the present study and those reported in the literature for radiation parameters ranging from 0.1 to 0.4. Specifically, the Nusselt numbers from the present study closely match the values reported by Singh and Venkateswarlu, indicating consistent results across different studies and validating the numerical methodology used in this investigation.

The study focuses on understanding the time-dependent electrically conducting flow of a ternary hybrid nanofluid through a permeable medium with heat source. A comparative study has been conducted utilizing the linear regression technique to analyse the skin friction coefficient, Nusselt number and Sherwood number for two cases at

1. The shape of nanoparticles significantly impacts fluid resistance. Platelet-shaped particles exhibit the least resistance, while spherical nanoparticles demonstrate superior heat transfer capabilities due to their efficient shape.

2. The study confirms that as the temperature of the ternary nanofluid increases, fluid viscosity decreases, resulting in higher flow velocity.

3. Spherical nanoparticles show the highest velocity increase, with an 8.46% rise per degree Celsius, making them highly effective in temperature-sensitive applications.

4. Spherical nanoparticles achieve the most significant skin friction reduction, decreasing by 6.69% per degree Celsius, optimizing energy efficiency in fluid systems.

5. Platelet-shaped nanoparticles show a slight decrease in heat transfer efficiency, with a 2.70% reduction per degree Celsius, suggesting careful shape selection for thermal management.

6. Velocity profiles indicate that spherical nanoparticles achieve the highest velocity, followed by blade and platelet shapes. These trends are consistent across both temperature conditions (

The study reveals that nanoparticle shape significantly affects fluid flow resistance in ternary nanofluid. Platelet-shaped particles offer minimal resistance, while spherical nanoparticles enhance heat transfer due to their geometry. Increasing the temperature of the ternary nanofluid increases velocity, primarily by reducing viscosity, which has practical implications for optimizing cooling and heating systems. These findings are relevant for applications in thermal management, microfluidics, and biomedical engineering. However, the study is limited to a specific temperature range and nanoparticle shapes. Future research could explore broader conditions, such as varying magnetic fields, different base fluids, and the impact of nanoparticle concentration and distribution. The linear regression analysis highlighted that larger nanoparticle volumes at lower temperatures notably reduce skin friction, consistent with the observed higher velocities of spherical nanoparticles.

6 Future Research Directions and Practical Applications

The findings of this study pave the way for several avenues of future research and practical applications. To build upon the current work, future investigations could explore the impact of additional nanoparticle shapes and materials on nanofluid performance within various geometries and flow conditions. This could involve studying nanoparticles with unique properties or shapes not covered in the present research. Furthermore, experimental validation of the theoretical models used in this study could provide more robust and reliable data, which would be invaluable for refining and enhancing predictive models. Additionally, the integration of more complex real-world scenarios, such as varying operating conditions and environmental factors, could offer a more comprehensive understanding of nanofluid behavior. From a practical standpoint, the development of advanced cooling technologies incorporating temperature-sensitive nanofluids could significantly improve energy efficiency and performance in applications ranging from electronic cooling systems to industrial heat exchangers. Exploring these technologies could lead to innovations in thermal management solutions and contribute to advancements in sustainable engineering practices. Overall, this study’s findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge on nanofluid dynamics and offer a foundation for further research aimed at optimizing heat transfer technologies and exploring new technological applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors appreciate the valuable feedback from the esteemed reviewers, which contributed to the improvements in this revised article.

Funding Statement: U. F. G. was supported by the Government of the Basque Country, programs: Elkartek Grant No. DBaskIN ELKARTEK 25/28 and Grant No.: KK-2024/00035 and ITSAS-REM Grant No.: IT1514-22. The work of Samad Noeiaghdam was funded by the High-Level Talent Research Start-up Project Funding of Henan Academy of Sciences (Project No. 241819246).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, original draft preparation, validation: Barkilean Jaismitha; conceptualization and validation: Jagadeesan Sasikumar; formal analysis, writing—review and editing: Samad Noeiaghdam; writing—review and editing: Unai Fernandez-Gamiz; formal analysis: Thirugnanasambandam Arunkumar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Requests for data can be made at any time.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Amplitudes of irregular channel [–] | |

| Empirical shape factor [–] | |

| Electromagnetic induction [–] | |

| Width of channel [–] | |

| Magnetic field intensity [–] | |

| Mean half width of channel [–] | |

| Grashof number [–] | |

| Modified Grashof number [–] | |

| Peclet number [–] | |

| Schmidt number [–] | |

| Axial velocity | |

| re | Reynolds Number [–] |

| Porous medium | |

| Chemical reaction [–] | |

| Dimensionless fluid pressure [–] | |

| Q | Heat Source [–] |

| Radiative heat flux | |

| Specific heat capacitance | |

| Specific heat capacitance | |

| Time | |

| wall condition [–] | |

| Channel walls [m] | |

| Dimensionless channel walls [–] | |

| Thermal radiation parameter [–] | |

| Nusselt Number [–]Sherwood Number [–] | |

| Greek symbols | |

| Mean radiation absorption coefficient | |

| Densities of base fluid | |

| Densities of solid nanoparticle | |

| Density of nanofluid | |

| Dynamic viscosity of | |

| Thermal expansion of | |

| Coefficient of mass expansion | |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion | |

| Heat capacitance of | |

| Thermal conductivity | |

| Volumetric coeff. of thermalexpansion of | |

| Volumetric coeff. of thermal | |

| Volume fraction [–] | |

| Fluid temperature [–] | |

| Pressure gradient Skin friction coefficient [–] | |

| Frequency of the oscillation [–] | |

References

1. Xiu W, Animasaun IL, Al-Mdallal QM, Alzahrani AK, Muhammad T. Dynamics of ternary-hybrid nanofluids due to dual stretching on wedge surfaces when volume of nanoparticles is small and large: forced convection of water at different temperatures. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;137(12):106241. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Barman T, Roy S, Chamkha AJ. Magnetized bi-convective nanofluid flow and entropy production using temperature-sensitive base fluid properties: a unique approach. J Appl Comput Mech. 2022;8(4):1163–75. doi:10.22055/jacm.2021.38204.3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Arif M, Kumam P, Kumam W, Mostafa Z. Heat transfer analysis of radiator using different shaped nanoparticles water-based ternary hybrid nanofluid with applications: a fractional model. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2022;31(3):101837. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2022.101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rajakumar J, Saikrishnan P, Chamkha A. Non-uniform mass transfer in MHD mixed convection flow of water over a sphere with variable viscosity and Prandtl number. Int J Numer Methods Heat Fluid Flow. 2016;26(7):2235–51. doi:10.1108/HFF-05-2015-0189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Eswara AT, Nath G. Unsteady nonsimilar two-dimensional and axisymmetric water boundary layers with variable viscosity and Prandtl number. Int J Eng Sci. 1994;32(2):267–79. doi:10.1016/0020-7225(94)90006-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Barman T, Roy S, Chamkha AJ. Analysis of entropy production in a bi-convective magnetized and radiative hybrid nanofluid flow using temperature-sensitive base fluid (water) properties. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):11831. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-16059-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Shah NA, Wakif A, El-Zahar ER, Thumma T, Yook SJ. Heat transfers thermodynamic activity of a second-grade ternary nanofluid flow over a vertical plate with Atangana-Baleanu time-fractional integral. Alex Eng J. 2022;61(12):10045–10053. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.03.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Latha K, Swetha B, Reddy MG, Tripathi D, Anwar Bég O, Kuharat S, et al. Computation of stagnation coating flow of electro–conductive ternary Williamson hybrid GO–AU–Co3O4/EO nanofluid with a Cattaneo–Christov heat flux model and magnetic induction. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):915–10972. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-37197-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sasikumar J, Harinisha N, Anitha S. MHD oscillatory flow through porous medium in rotating wavy channel with heat source. In: The 11th National Conference on Mathematical Techniques and Applications; 2019 Jan 11–12; Chennai, India. doi:10.1063/1.5112289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Choi S, Eastman JA. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. In: No. ANL/MSD/CP-84938; CONF-951135-29. Argonne, IL, USA: Argonne National Lab; 1995. [Google Scholar]

11. Tlili I, Samrat SP, Sandeep N, Nabwey HA. Effect of nanoparticle shape on unsteady liquid film flow of MHD Oldroyd-B ferrofluid. Ain Shams Eng J. 2021;12(1):935–41. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2020.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sasikumar J, Bhuvaneshwari S, Govindarajan A. Diffusion of chemically reactive species in MHD oscillatory flow with thermal radiation in the presence of constant suction and injection. J Phys Conf Ser. 2018;1000(1):012033. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1000/1/012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hamilton RL, Crosser OK. Thermal conductivity of heterogeneous two-component systems. Ind Eng Chem Fundam. 1962;1(3):187–91. doi:10.1021/i160003a005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sasikumar J, Senthamarai R. Chemical reaction and viscous dissipation effect on MHD oscillatory blood flow in tapered asymmetric channel. Math Model Comput. 2022;9(4):999–1010. doi:10.23939/mmc2022.04.999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Narayana PS, Venkateswarlu B, Devika B. Chemical reaction and heat source effects on MHD oscillatory flow in an irregular channel. Ain Shams Eng J. 2016;7(4):1079–88. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2015.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Aaiza G, Khan I, Shafie S. Energy transfer in mixed convection MHD flow of nanofluid containing different shapes of nanoparticles in a channel filled with saturated porous medium. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2015;10(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s11671-015-1144-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Ngiangia AT, Akaezue NN. Heat transfer of mixed convection electroconductivity flow of copper nanofluid with different shapes in a porous micro channel provoked by radiation and first order chemical reaction. Asian J Phys Chem Sci. 2019;7(1):1–14. doi:10.9734/AJOPACS/2019/46301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Selvi RK, Muthuraj R. MHD oscillatory flow of a Jeffrey fluid in a vertical porous channel with viscous dissipation. Ain Shams Eng J. 2018;9(4):2503–16. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2017.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jaismitha B, Sasikumar J. Heat transfer characteristics on MHD oscillatory radiative nanofluid with H2O/C2H6O2 (basefluida comparative study of different nanoparticles of various shapes. Int J Heat Tech. 2023;41(3):529–540. doi:10.18280/ijht.410305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Cogley AC, Vincent WG, Gilles SE. Differential approximation for radiative transfer in a nongrey gas near equilibrium. AIAA J. 1968;6(3):551–3. doi:10.2514/3.4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zeytounian RK. Joseph Boussinesq and his approximation: a contemporary view. Comptes Rendus Mecanique. 2003;331(8):575–86. doi:10.1016/S1631-0721(03)00120-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sasikumar J, Govindarjan A. Effect of heat and mass transfer on MHD oscillatory flow with chemical reaction and slip conditions in asymmetric wavy channel. J Eng Appl Sci. 2016;11(2):1164–70. doi:10.1063/5.0025530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ajibade AO, Kabir TM. Viscous dissipation effect on steady natural convection Couette flow with convective boundary condition. Int J Nonlinear Sci. 2022;24(4):1461–1476. doi:10.1515/ijnsns-2021-0055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Neeraja A, Devi RR, Devika B, Radhika VN, Murthy MK. Effects of viscous dissipation and convective boundary conditions on magnetohydrodynamics flow of Casson liquid over a deformable porous channel. Res Eng. 2019;4:100040. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2019.100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jaismitha B, Sasikumar J. Nonlinear dynamics of dissipative water conveying SWCNT/MWCNT/Ferro nanofluid subject to radiation: Thermal analysis by linear slope regression. Numer Heat Transf Part A App. 2024;1–27. doi:10.1080/10407782.2024.2350027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jaismitha B, Sasikumar J. Uncertainty analysis of MHD oscillatory flow of ternary nanofluids through a diverging channel: a comparative study of nanofluid composites. Int J Numer Methods Heat Fluid Flow. 2025;35(1):87–118. doi:10.1108/hff-04-2024-0281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Vaidehi P, Sasikumar J. Darcy flow of unsteady Casson fluid subject to thermal radiation and lorentz force on wavy walls: case of slip flow for small and large values of plastic dynamic viscosity. Thermal Sci Eng Prog. 2023;42(9):101885. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2023.101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jamshed W. Finite element method in thermal characterization and streamline flow analysis of electromagnetic silver-magnesium oxide nanofluid inside grooved enclosure. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;130(3):105795. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2021.105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. VeeraKrishna M, Subba Reddy G, Chamkha AJ. Hall effects on unsteady MHD oscillatory free convective flow of second grade fluid through porous medium between two vertical plates. Phys Fluids. 2018;30(2):931. doi:10.1063/1.5010863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Timofeeva EV, Routbort JL, Singh D. Particle shape effects on thermophysical properties of alumina nanofluids. J Appl Phys. 2009;106(1):KN. doi:10.1063/1.3155999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Alnahdi AS, Nasir S, Gul T. Couple stress ternary hybrid nanofluid flow in a contraction channel by means of drug delivery function. Math Comput Simul. 2023;210(9):103–19. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2023.02.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nasir S, Sirisubtawee S, Juntharee P, Berrouk AS, Mukhtar S, Gul T. Heat transport study of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow under magnetic dipole together with nonlinear thermal radiation. Appl Nanosci. 2022;12(9):2777–88. doi:10.1007/s13204-022-02583-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Vaidehi P, Sasikumar J. Thermo-diffusion and chemical reaction effect on MHD oscillatory flow of viscoelastic fluid in an asymmetric wavy channel under the influence of magnetic field. Math Eng Sci Aerosp. 2023;14(2). [Google Scholar]

34. Sohail M, El-Zahar ER, Mousa AAA, Nazir U, Althobaiti S, Althobaiti A, Shah NA, Chung JD. Finite element analysis for ternary hybrid nanoparticles on thermal enhancement in pseudo-plastic liquid through porous stretching sheet. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9219. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12857-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Mohammadfam Y, Heris SZ. An experimental study of the influence of Fe3O4, MWCNT-Fe3O4, and Fe3O4@ MWCNT nanoparticles on the thermophysical characteristics and laminar convective heat transfer of nanofluids: a comparative study. Surf Interfaces. 2023;43(1):103506. doi:10.1016/j.surfin.2023.103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zeinali Heris S, Zolfagharian N, Mousavi SB, Hosseini Nami S. Enhancing the synergistic properties of plate heat exchangers using nanohybrid MWCNTs-SiO2 EG-based nanofluids. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2025;150(8):1–20. doi:10.1007/s10973-025-14165-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Raisinghania MD. Fluid dynamics with complete Hydrodynamics and boundary Layer Theory. New Delhi, India: S. Chand Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

38. Welty J, Rorrer GL, Foster DG. Fundamentals of momentum, heat, and mass transfer. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

39. Shapiro AH, Jaffrin MY, Weinberg SL. Peristaltic pumping with long wavelengths at low Reynolds number. J Fluid Mech. 1969;37(4):799–825. doi:10.1017/s0022112069000899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Maxwell JC. A treatise on electricity and magnetism. Oxford, UK: Clarendon press; 1873. [Google Scholar]

41. Brinkman HC. The viscosity of concentrated suspensions and solutions. J Chem Phys. 1952;20(4):571–1. doi:10.1063/1.1700493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Pak BC, Cho YI. Hydrodynamic and heat transfer study of dispersed fluids with submicron metallic oxide particles. Experi Heat Trans Int J. 1998;11(2):151–70. doi:10.1080/08916159808946559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Maıga SEB, Nguyen CT, Galanis N, Roy G. Heat transfer behaviours of nanofluids in a uniformly heated tube. Superlatt Microstruct. 2004;35(3–6):543–57. doi:10.1016/j.spmi.2003.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Palm SJ, Roy G, Nguyen CT. Heat transfer enhancement with the use of nanofluids in radial flow cooling systems considering temperature-dependent properties. Appl Therm Eng. 2006;26(17–18):2209–18. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2006.03.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Eastman JA, Choi US, Li S, Soyez G, Thompson LJ, DiMelfi RJ. Novel thermal properties of nanostructured materials. In: Materials science forum. Vol 312. Wollerau, Switzerland: Trans Tech Publications Ltd.; 1999. p. 629. [Google Scholar]

46. Das SK, Choi SU, Yu W, Pradeep T. Nanofluids: science and technology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

47. Venkateswarlu B, Satya Narayana PV, Devika B. Effects of chemical reaction and heat source on MHD oscillatory flow of a viscoelastic fluid in a vertical porous channel. Int J Appl Comput Math. 2017;3(S1):937–52. doi:10.1007/s40819-017-0391-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Singh KD. Visco-elastic mixed convection MHD oscillatory flow through a porous medium filled in a vertical channel. Int J Phys Math Sci. 2012;3:194–205. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools