Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mathematical Modeling and Thermal Analysis of Salt Gradient Solar Pond

1 School of Mechanical Engineering, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, 100081, China

2 Faculty of Mechanical and Automotive Engineering Technology, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah, Pekan, 26600, Pahang, Malaysia

3 Centre for Research in Advanced Fluid & Processes, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah, Gambang, 26300, Pahang, Malaysia

4 Centre for Automotive Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah, Pekan, 26600, Pahang, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Rahool Rai. Email: ; Sudhakar Kumarasamy. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(5), 1477-1493. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.067933

Received 16 May 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

The increasing demand due to development and advancement in every field of life has caused the depletion of fossil fuels. This depleting fossil fuel reserve throughout the world has enforced to get energy from alternative/renewable sources. One of the economical ways to get energy is through the utilization of solar ponds. In this study, a mathematical model of a salt gradient solar pond under the Islamabad climatic conditions has been analyzed for the first time. The model uses a one-dimensional finite difference explicit method for optimization of different zone thicknesses. The model depicts that NCZ (Non-Convective Zone) thickness has a significant effect on LCZ (Lower Convective Zone) temperature and should be kept less than 1.7 m for the optimal temperature. It is also observed that for long-term operation of a solar pond, heat should be extracted by keeping the mass flow rate of 17.3 kg/m2/day. The model also suggests that when the bottom reflectivity is about 0.3, then only 24% of the radiation is absorbed in the pond.Keywords

The world will face severe energy crises due to the dearth of fossil fuels in the coming days. For this reason, countries across the world are trying to fulfill their energy needs from alternative energy sources. In Pakistan, 81% of electricity demand is being fulfilled by oil and natural gas [1]. In this study, alternative energy solutions are suggested to reduce the dependency on fossil fuels. One of the competitive, sustainable, and alternative energy sources is solar energy [2]. Due to the dilute nature and intermittent energy sources, there are greater challenges in the utilization of solar energy [3]. A large area is required to collect solar energy with separate storage to meet the load demand at night and on cloudy days [4]. The cost of collecting and storing solar energy for a long time is high, due to which solar energy utilization is limited. Therefore, it is becoming essential to build up a solar collecting system that can collect and store solar energy economically and efficiently for long periods of time. One of the examples of such systems is a solar pond. The solar pond collects solar energy in the form of heat, which can be used for various applications [5]. Solar pond is being widely used in many countries of the world for various applications such as water desalination [6,7], power generation by Rankine cycle [8,9], crop drying, industrial process heat [10] and space heating [11]. In a natural pond, when solar radiation falls on the pond surface, water in the bottom becomes hot and lighter and rises to the surface and loses the stored heat to the ambient through convection. In a solar pond, this phenomenon is prevented by dissolving more salt into the bottom layer, which increases the density of the water and prevents water from rising to the surface [12].

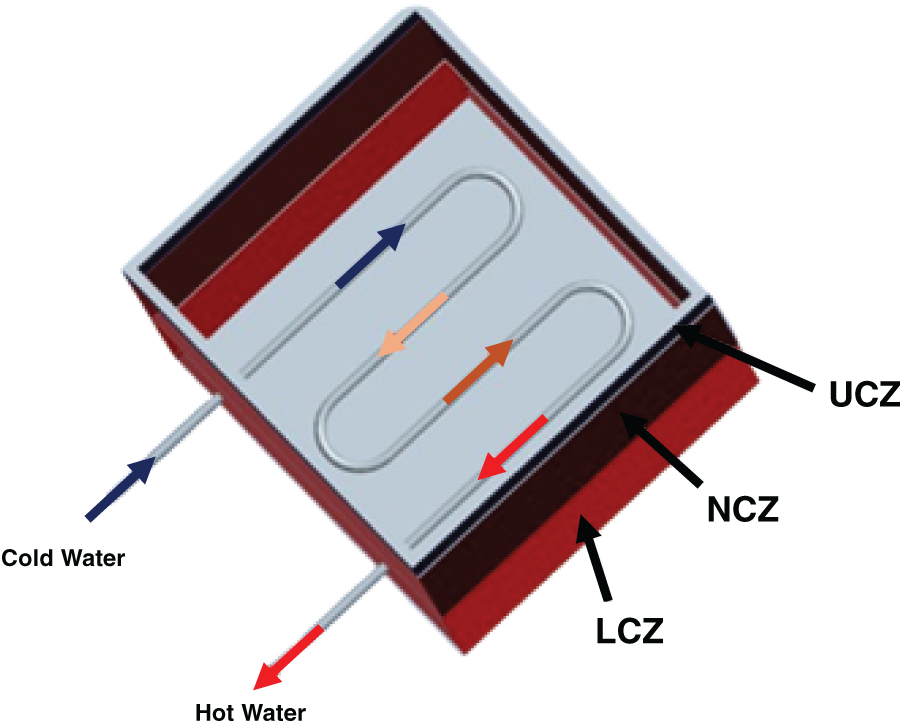

The salt gradient solar pond consists of three zones. The outer layer/zone is known as an Upper Convective Zone (UCZ) containing fresh water or water with a low concentration of salt (1% to 2%) and is directly subjected to solar radiation. The bottom layer is known as the Lower Convective Zone (LCZ), which contains saturated saline water with a homogenous concentration of salt throughout the layer and has the highest percentage of salinity. This layer is also known as the Heat Storage Zone (HSZ) because solar energy is stored in this zone. In between UCZ and LCZ, there is a Non-Convective Zone (NCZ), also known as the Gradient Zone (GZ), in which salt concentration increases with depth and it prevents the water from losing stored heat by convection [5]. Various studies have been carried out on the salinity gradient solar pond. Poyyamozhi has discussed the effect of salt diffusion on pond performance [13]. The effect of different salt concentrations on the LCZ temperature has been observed by using Simulink and COMSOL [14,15], in which increasing salt concentration increased the temperature of the pond, but it choked the heat exchanger pipes also. Abdulsalam et al. have suggested the pond as a two-zone model in their study [16]. He has investigated the effect of radiation penetrating the pond without considering reflection. It has been modified by Husain et al. to reduce calculation time and the effect of reflection from each zone has also been suggested [17,18]. One one-dimensional model for calculating pond performance by changing the zone thickness on pond performance has been carried out by Jaferzadeh [19,20]. The effect of the water table on LCZ temperature is studied by Saxena et al. [21]. The objective of the current study is to develop mathematical models for a salt gradient solar pond under Islamabad climatic conditions by selecting appropriate zone thickness and investigating the effect of heat extraction on solar pond performance.

Mathematical models of salt gradient solar ponds (SGSPs) have been developed recently, each improving accuracy, computational efficiency, and applicability across regions. High-accuracy models show strong agreement with experiments, achieving low root mean square errors (RMSE) of 1.21°C and 1.54°C for upper and lower convective zones, and R2 values up to 0.9359, confirming predictive reliability [22,23]. Integrating reflectors into SGSP models enhances performance, with temperature increases of 15.49% and energy efficiency improvements of 42.73% compared to conventional setups [24,25]. Two-and three-dimensional models capture double-diffusive convection and heat transfer more accurately, though requiring higher computational resources [26]. Simplified one-dimensional transient models have been developed for large-scale ponds (e.g., 50,000 m2), balancing accuracy with efficiency. These models demonstrate versatility across Iran, Kuwait, Egypt, and Morocco, where climate-specific adjustments ensure reliable predictions under diverse conditions [27–29]. These advances show that SGSP models offer valuable insights into thermal behavior and performance optimization, while identifying opportunities for refinement in balancing accuracy, efficiency, and applicability.

However, literature has unequivocally demonstrated the remarkable thermal performance and optimization potential of salt gradient solar ponds (SGSPs) through advanced numerical modeling techniques. By employing sophisticated two-dimensional models, researchers have delved into the intricate physical phenomena of double-diffusive convection, solar radiation absorption, and the critical Soret and Dufour effects, offering profound insights into non-convective zone (NCZ) erosion and unparalleled heat storage capabilities [30,31]. Models grounded in Navier-Stokes equations and salt transport have further underscored the extraordinary ability of SGSPs to attain elevated temperatures within the heat storage zone (HSZ) [29]. Simultaneously, one-dimensional models have meticulously assessed the impact of variables such as water turbidity, bottom reflectivity, and the type of working fluid (e.g., seawater and bittern) on thermal performance [32]. Pioneering studies have also concentrated on optimizing entropy generation and heat transfer using innovative spiral corrugated heat exchangers [33]. To propel performance to new heights, recent research has explored the integration of reflectors and coal cinder, with numerical results aligning closely with experimental data, boasting a mere 5% deviation [24,25]. Moreover, cutting-edge optimization techniques, including multivariable analysis of heat exchanger areas and the evaluation of diverse heat extraction methods, have conclusively shown that vertical tube configurations deliver superior energy and exergy efficiencies [28,34]. Collectively, these rigorously validated models irrefutably affirm the immense potential of SGSPs for efficient thermal energy storage and offer invaluable strategies for system enhancement.

Furthermore, recent studies have explored the integration of solar ponds with trans critical CO2 heat pump systems, demonstrating substantial improvements in heat extraction performance and system efficiency under optimized operating conditions [35]. While such hybrid systems highlight the potential of solar ponds in advanced thermal applications, there remains a need to optimize standalone SGSPs under specific regional climates to ensure reliable and efficient energy capture. Although extensive research has been conducted on the thermal modeling of salt gradient solar ponds (SGSPs), most of these studies have concentrated on generalized climate conditions or analyses of individual variables. There is still a notable lack of location-specific optimization, especially concerning the distinct climate of Islamabad. Additionally, few studies have explored the combined effects of non-convective zone (NCZ) thickness, mass flow rate, and bottom reflectivity on the thermal efficiency of SGSPs using a one-dimensional finite difference method. This research seeks to address this gap by creating a customized numerical model that evaluates these parameters simultaneously to enhance the pond’s thermal performance. The findings offer fresh insights into the interactions between these parameters and provide practical recommendations for designing efficient SGSPs in similar semi-arid environments.

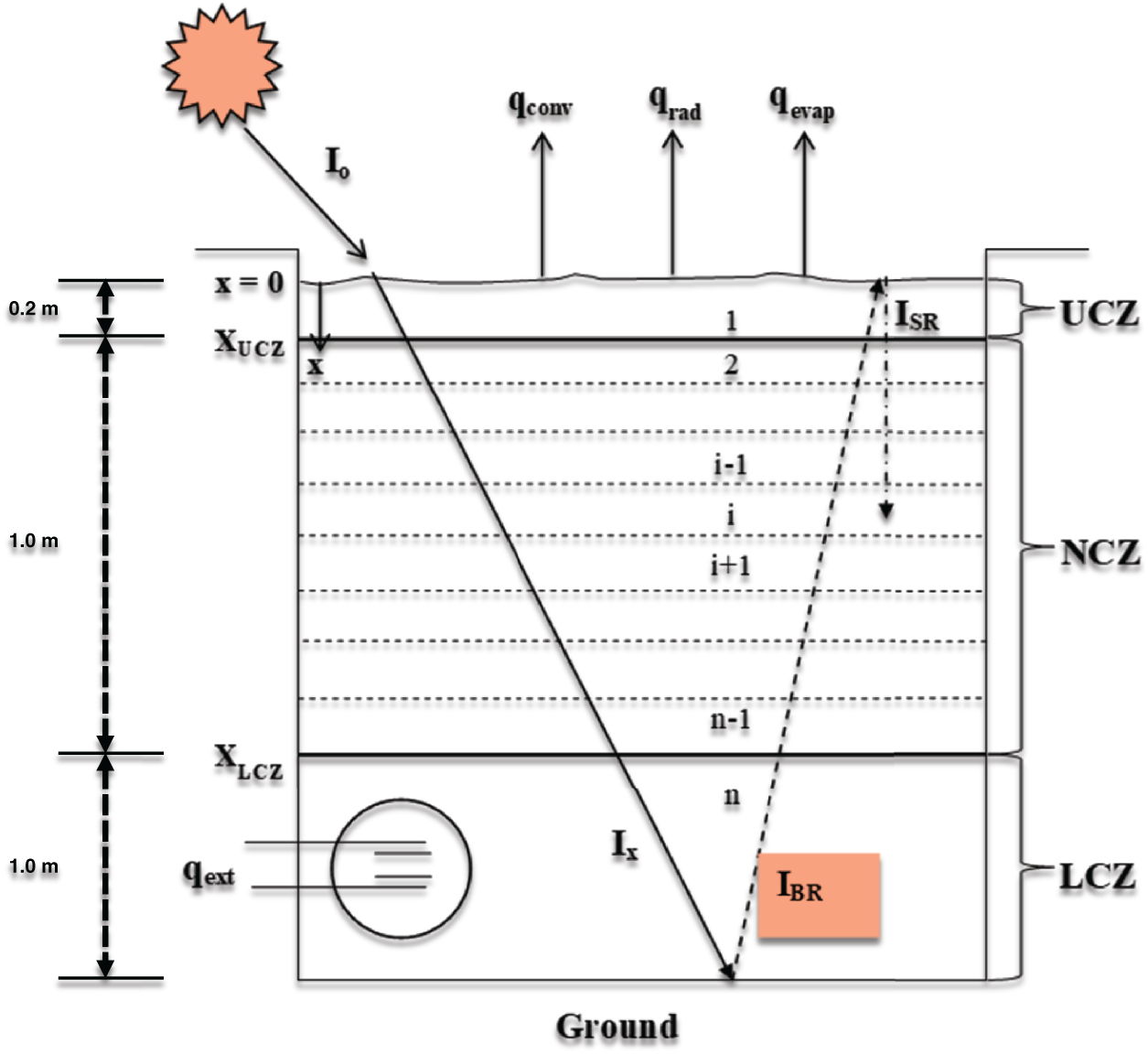

A mathematical model of a salt gradient solar pond has been developed using one one-dimensional transient method. The thickness of UCZ, NCZ and HSZ is considered to size 0.2, 1.0 and 1.0 m, respectively, for the base case, so that optimum zone thickness can be selected. The value of “x” is taken as zero at the surface, which increases downward by using a vertical Cartesian coordinate system. It is further considered that at the start of the simulation, ponds have uniform temperature throughout all the layers and are artificially stabilized, i.e., salt concentration rises linearly with depth in NCZ, while UCZ and HSZ have homogeneous concentration, same as the concentration of fresh water and saturated saline water, respectively. In NCZ, convection is suppressed due to varying concentration of salt; therefore, heat is lost from NCZ by conduction only. The generalized form of the temperature variation in different layers of a solar pond is given by

where ρ, Cp and k are density, specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity of brine [15].

Solar radiation absorbed and reflected at the Pond Surface. The Portion of the solar radiation incident on the pond surface is reflected. The reflection of solar light depends on the incident angle of the radiation as well as the condition of the pond surface, like turbulence. Reflection of light from the pond surface, having negligible turbulence, is assumed for the current study, which is calculated by Fresnel’s Equation [36,37].

where Fr,

where

Figure 1: Salt gradient solar pond model

The amount of solar radiation absorbed at a certain depth of the pond (IR) is given by

The value of θ′ depends on certain parameters like concentration of salt, turbidity of water, radiation propagating in water layers and bottom reflection. Its value is considered 0.85 for the current study [39]. The thermo-physical properties of pond saline water in terms of the temperature and salt concentration are calculated using the following relations.

where ‘s’ is the concentration of salt in kg/m3.

Two boundary conditions have been considered, at the upper boundary, x = XUCZ and the lower boundary x = XUCZ + XNCZ. The energy conservation equation was used to calculate the temperature at the upper boundary as well as at the lower boundary.

2.1 Energy Balance for Different Zones of the Solar Pond

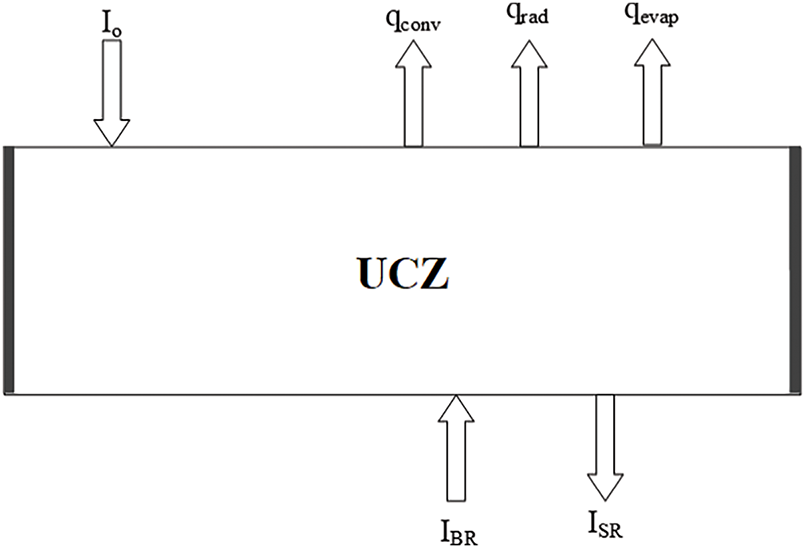

Due to convention, UCZ acts like a single layer; therefore, temperature variations in this zone are assumed to be constant. Three main losses take place from this zone are conduction losses (qcond), convection losses (qconv) and radiation losses (qrad) as depicted in Fig. 2. The energy balance to calculate the temperature variation in this zone is given as:

Figure 2: Energy balance diagram for UCZ

Solving the above-mentioned equation gives the following results:

where qUCZ is the quantity of heat loss per unit area, which is due to convection, radiation and evaporation losses, and is given by:

The convection heat losses from UCZ depend on the wind speed and the temperature difference between UCZ and the ambient, which are determined using the following relation:

where hconv is the convection heat transfer coefficient and is given by

where “V” is the wind speed. Weather data for Islamabad is provided in Table 1, which was obtained from the Meteonorm database [40,41]. Furthermore, the radiation heat loss is calculated by

where σ and εw are Stefan Boltzmann’s constant and emissivity of water; their values are 5.67 × 10−8 W/m2 K4 and 0.83, respectively. T1 and Tsky are UCZ temperature and sky temperature in Kelvin, respectively. The sky temperature is determined by

The heat loss due to evaporation is given by

where Pv is the vapor pressure of water in mmHg and Pa is the partial pressure of water vapor in mmHg [27] given by

Rh is the relative humidity, which is the ratio of partial pressure of water vapor in the atmosphere (Pa) to the saturation vapor pressure (Pv) of water corresponding to the ambient temperature (Tamb).

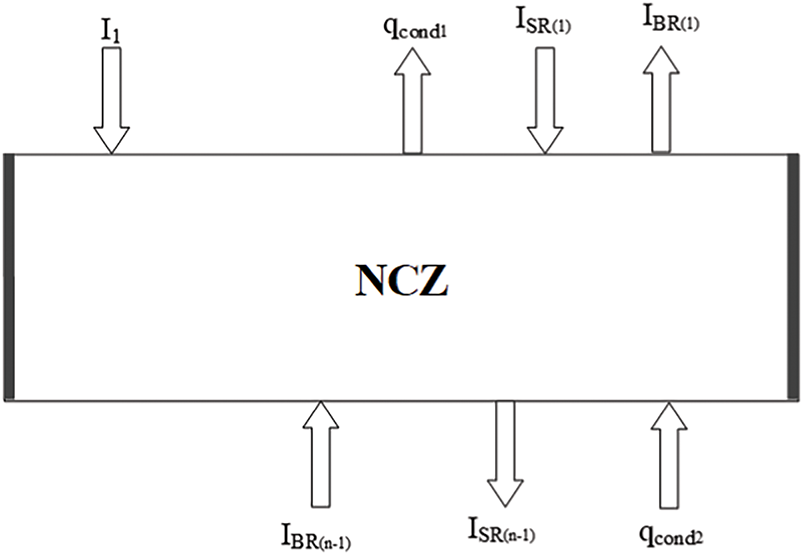

The energy equation is formulated by dividing NCZ into different layers. In this zone, losses take place by conduction only. The temperature of the first layer of this zone is represented by 2 and the last layer by n − 1, as shown in Fig. 1. The energy balance for NCZ is shown in Fig. 3. The generalized form of the energy balance equation for NCZ is given by

Figure 3: Energy balance diagram for NCZ

In the above equation, qcond2, qcond1, IRn−1 and IRn are the heat added from the bottom layer, heat removed to the upper layer, radiation absorbed in (n − 1)-th layer and nth layer, respectively. The Eq. (18) is solved using the finite difference method (explicit) to find the following relation in terms of temperature:

where

The temperature of the nodes i + 1, i, i − 1 is known at time ‘t = 0’, from the initial and the boundary conditions. The Eq. (19) can be used to find the temperature at a new time t + ∆t. The Value of ‘i’ for NCZ ranges from 2 to n − 1. τ represents the stability criteria of the explicit method [42].

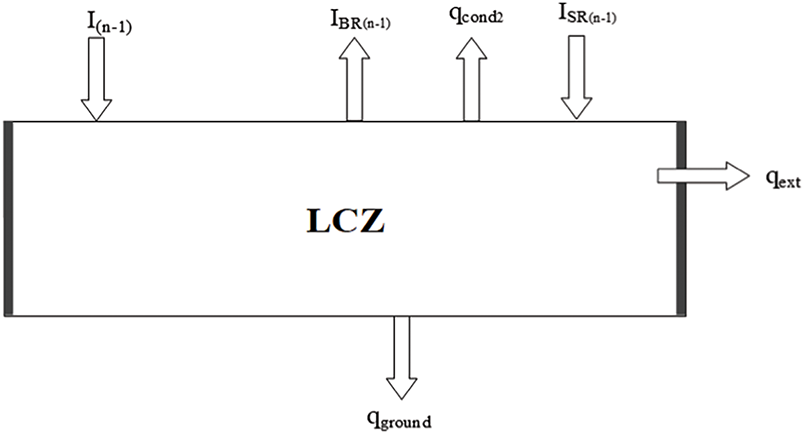

LCZ is the main zone in which heat is trapped and stored. Two main losses take place from this zone, that is, ground losses and the transfer of heat from LCZ to the NCZ through conduction. The energy balance for LCZ is shown in Fig. 4. The generalized form of the energy balance equation for the LCZ is given by

where qg is the ground losses and qext is the amount of energy extracted from LCZ. If heat is not extracted from LCZ, the value of qext is considered as zero. The ground losses take place owing to pond water contact with soil; these losses depend on the thermal conductivity of soil, pond geometry and ground temperature. The Eq. (20) can be rewritten as

Figure 4: Energy balance diagram for LCZ

In Eq. (21) “dw” is the depth of the groundwater table.

The input data, such as hourly solar radiation, ambient temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity data, are obtained from “Meteonorm” at different geographical locations. The simulations were started by considering the temperature of all layers of the pond equal to the ambient temperature, which was 25°C at t = 0. The simulations first evaluated the fraction of radiation available, properties of saline solution for different layers and heat losses from the pond, which were used to find the temperature of different layers at selected time spans.

2.2 Heat Extraction from the LCZ of the Solar Pond

An internal heat exchanger made from polyethylene is designed for the heat extraction from the LCZ of the solar pond. The advantage of polyethylene is that it is lightweight and can be easily bent into the desired shape [43,44]. It is considered that there is no fouling, heat is extracted at a temperature nearly equal to pond temperature and water input to the heat exchanger is maintained at 25°C. The schematic view of the heat exchanger is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Salt gradient pond with heat exchanger

The rate of heat extraction can be given by [28]

where “U” represents the overall heat transfer coefficient, “A” represents the external area of the pipe, and subscripts Tout, Tin and Tp represent outlet, inlet and pond temperature.

where kpi is the thermal conductivity of the pipe, and hin and hout represent the coefficient of heat transfer inside and outside of the pipe.

3.1 Optimization of UCZ Thickness

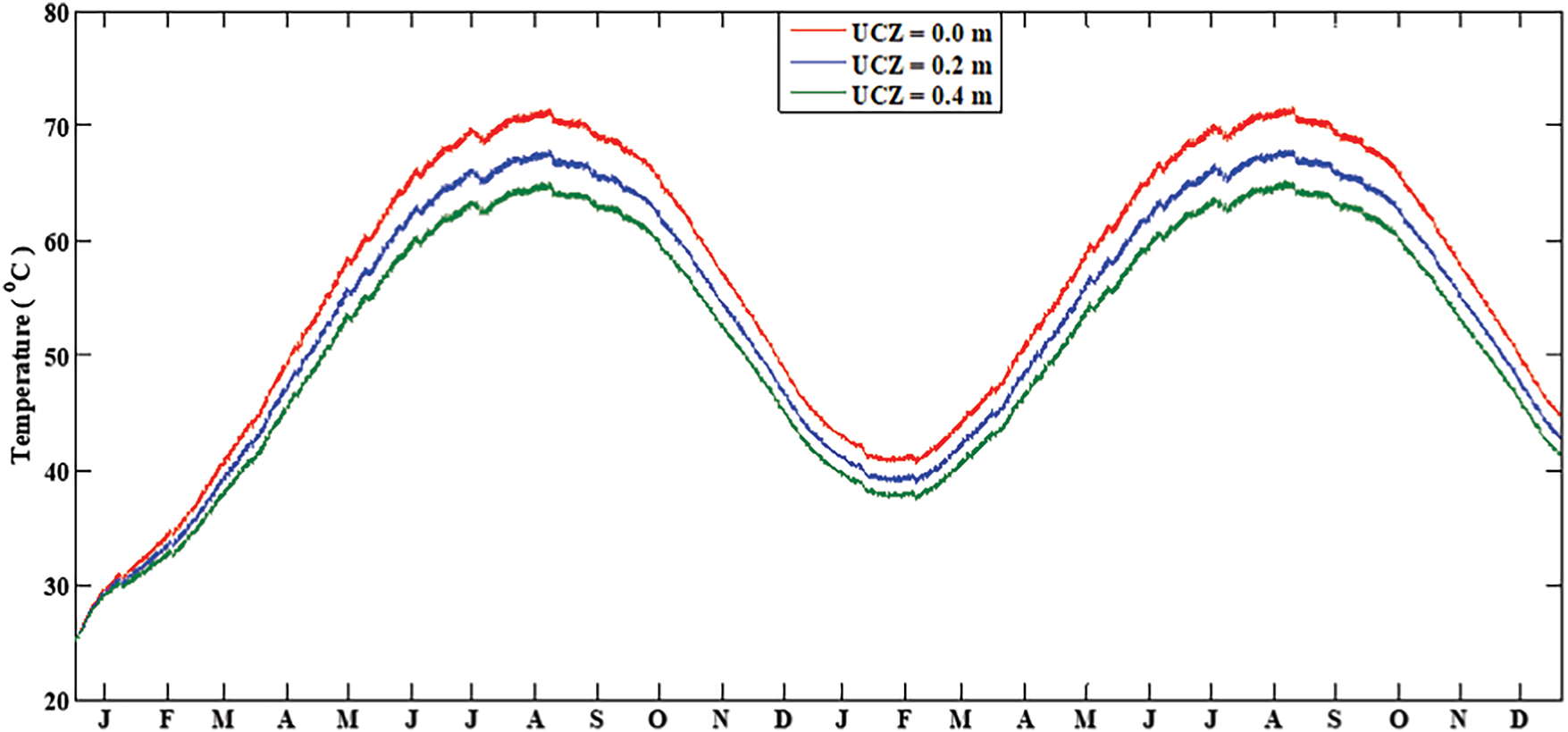

Simulations were initiated and it was considered that the pond is at 25°C at the start of operation. Simulation results for the consecutive two years are shown in Fig. 6. Fig. 6 depicts that till March, Pond charged up and became stabilized. The maximum temperature achieved by the pond is observed from June to September because solar radiation is higher in these months and the ambient temperature is also high, as shown in Table 1. Weather data of Islamabad. The results also revealed that pond temperature from September to January is decreasing because both ambient temperature and solar radiation are decreasing in these months. The effect of the change in UCZ thickness on pond temperature for 2 years is shown in Fig. 6. Effect of UCZ thickness. It is observed that when there is no UCZ, then the temperature achieved by the solar pond is 72°C. However, raising the thickness of UCZ is not in favor of pond temperature, so to attain maximum temperature, the thickness of UCZ should be as small as possible. However, from a practical point of view thickness of UCZ 0.2 m is unavoidable [45].

Figure 6: Effect of UCZ thickness

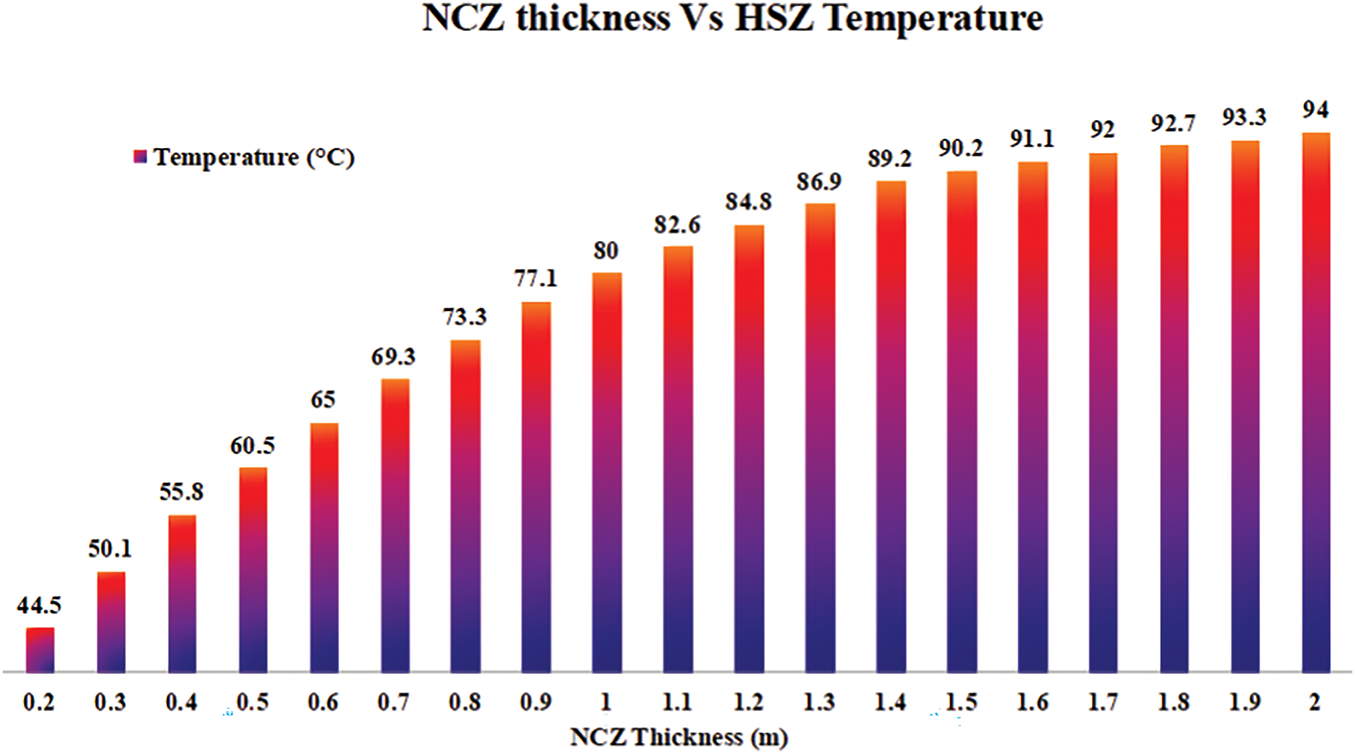

3.2 Optimization of NCZ Thickness

The variation of maximum temperature achieved by HSZ is shown in Fig. 7: Selection of NCZ thickness. It is observed that a rise in the thickness of NCZ also raises the temperature of the HSZ/LCZ. This is because NCZ provides insulation and prevents the heat losses taking place from HSZ to UCZ. The heat losses only take place by conduction in this zone. As water’s specific heat capacity is high, which means water can absorb more heat and takes more time to lose heat to the outer surface by conduction only. The results also reveal that the maximum temperature achieved by HSZ is not linearly proportional to the thickness growth of the NCZ, as the intensity of solar radiation decreases with depth. That’s why when the thickness of NCZ is increased from 0.2 to 1.7 m, a 47.5°C rise in temperature is observed. The further rise in thickness does not raise the temperature of HSZ/LCZ significantly because the intensity of solar radiation is reducing with depth, and the quantity of water is increasing, which may also disturb the stability of the pond.

Figure 7: Selection of NCZ thickness

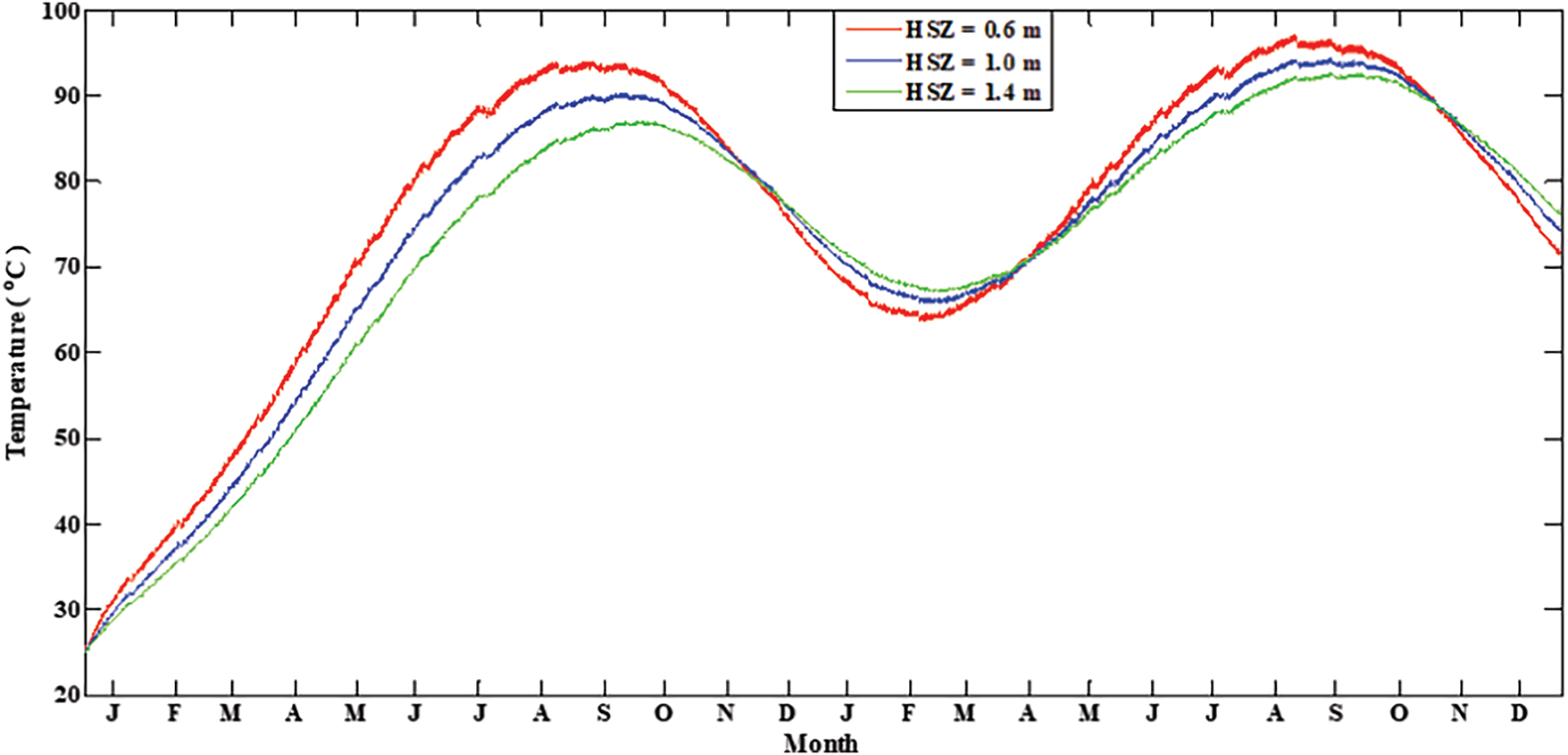

3.3 Optimization of HSZ Thickness

The variation in HSZ temperature for 2 years is shown in Fig. 8. Effect of LCZ thickness on HSZ temperature, Fig. 8, whereas the thickness of UCZ and NCZ are kept 0.2 and 1.4 m, respectively. It is observed that when the thickness of LCZ is 0.7 m, the pond can store more heat from March to September. And when winter starts, the losses to the environment are increased due to a higher temperature gradient between ambient and HSZ temperature. Therefore, the temperature of LCZ having less thickness reduces more in the winter months. It is also noted that when the thickness of LCZ is increasing, then the fluctuation in the temperature of the LCZ is reduced throughout the year. The selection of LCZ thickness depends on the operating temperature requirement and on the application purpose. For higher temperature applications, the thickness of LCZ should be lower, but the fluctuation in temperature from winter months to summer will be greater.

Figure 8: Effect of the LCZ thickness on HSZ temperature

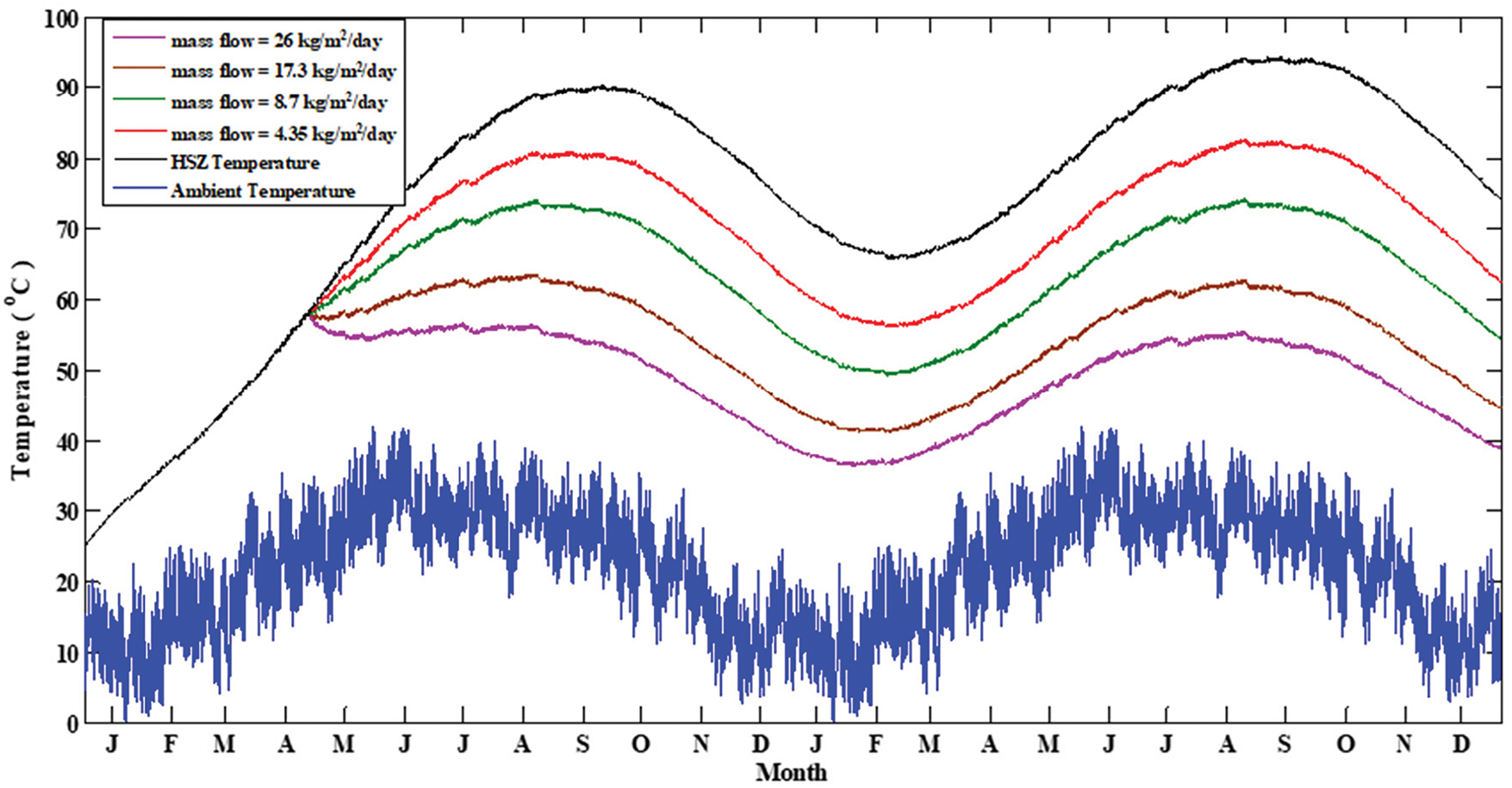

3.4 Heat Extraction from Solar Pond

The temperature development in HSZ using the heat extraction system is shown in Fig. 9 for a period of 2 years. In this study effect of boiling is ignored so that a simplified temperature development model can be obtained. However, in practice, the solar pond temperature does not go above the local boiling point of saline solution, otherwise the salinity gradient will be disturbed. To extract heat from a salt gradient solar pond, at least 5°C temperature difference is required between the heat transfer fluid and the LCZ fluid. For end-use application, at least a further 5°C temperature difference is required [46]. So, for an end-use application, it is considered that water at 45°C must be present. Fig. 9 shows the effect of heat extraction on pond LCZ temperature for various mass flow rates. The results reveal that heat extraction started after 4 months of operation when the temperature of the pond was suitable. It is pragmatic that heat extraction has a significant effect on pond temperature. As the mass flow rate increases, pond temperature decreases, which means the quality of energy available for end-use applications is also reducing. The results also depict that when the mass flow rate is 26 kg/m2/day, then pond temperature drops below 45°C during winter months, which may not be suitable. Therefore, it is suggested that if a constant flow rate is required, then 17.3 kg/m2/day may be considered as the optimum mass flow rate.

Figure 9: LCZ temperature when heat is being extracted

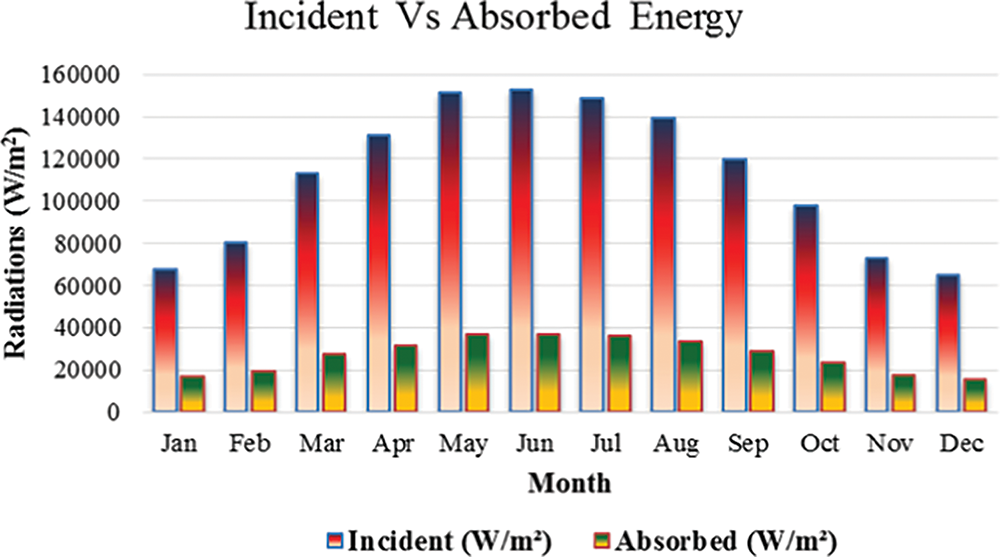

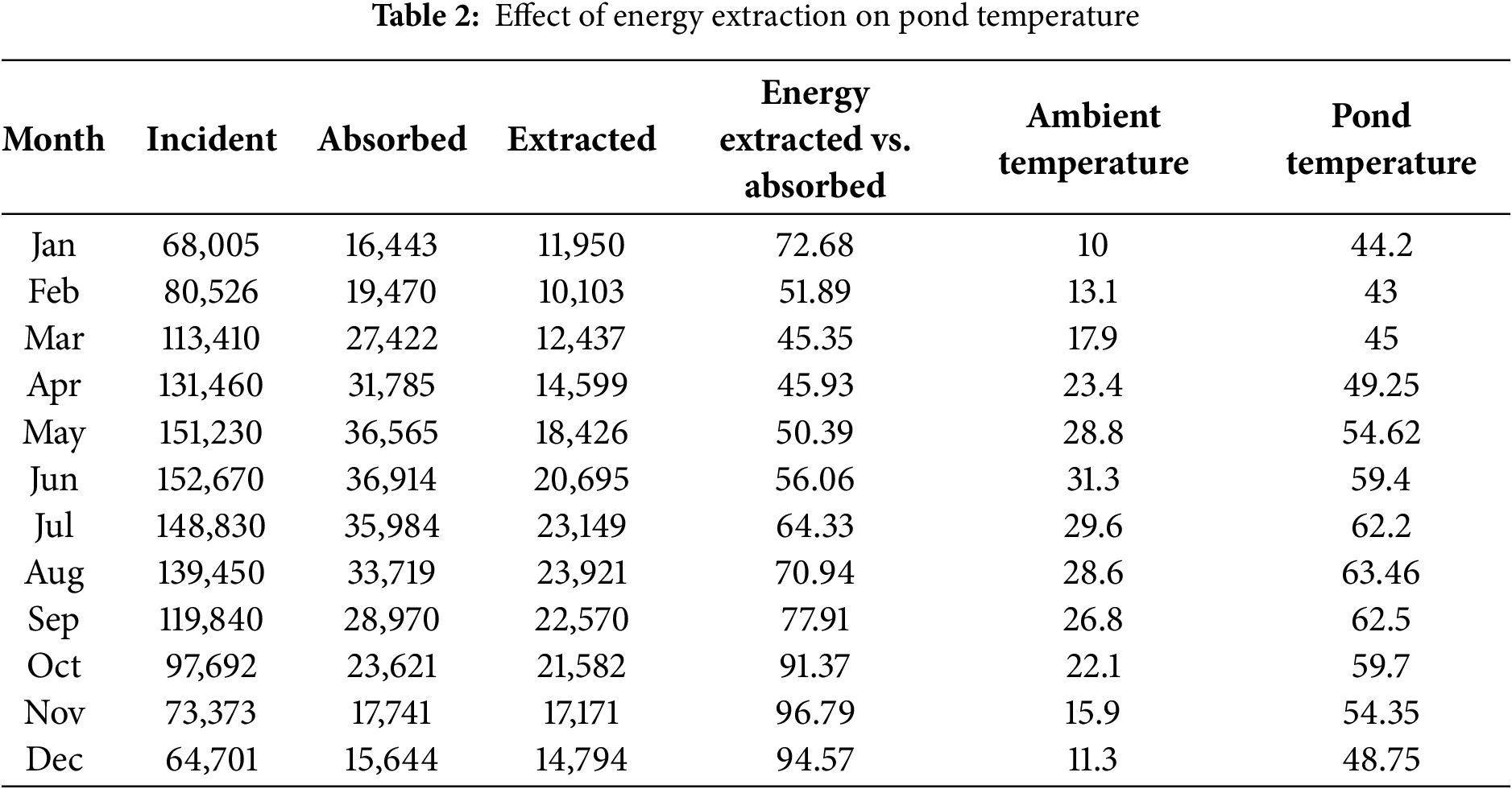

Fig. 10 shows incident and absorbed solar radiation in the pond. The results reveal that when the bottom reflectivity of 0.3 is considered, then small portions of radiation are absorbed in the pond, approximately 24%. These results agree with the study by Soğukpınar and Bozkurt [47]. The effect of energy extraction on the pond temperature during the second year of operation is shown in Table 2. The results reveal that during summer, less energy is extracted in comparison to absorbed energy as the remaining portion of energy is rising pond temperature during the summer season. In the winter season, more energy is extracted in comparison to absorbed energy, as more energy was trapped in the summer season. Due to less energy available and reduced ambient temperature, the pond temperature reduces during the winter season.

Figure 10: Incident vs. absorbed energy

The validity of the developed one-dimensional finite difference model was ensured by benchmarking its predictions against recent numerical and experimental studies on salt gradient solar ponds (SGSPs). Previous works have shown that one-dimensional models can reliably capture the thermal performance and layer thicknesses of SGSPs, with good agreement to experimental data [48]. In line with these findings, our model reproduced consistent trends in heat storage zone (HSZ) temperature rise, non-convective zone (NCZ) stability, and overall energy storage efficiency when compared to reported values [30]. Additionally, the simulated daily temperature rise in the HSZ and the predicted range of energy storage efficiency were in close agreement with published data (25.6%–36.5%) [29], confirming the physical accuracy of the model. These validations, combined with grid independence and energy balance checks, demonstrate the reliability and robustness of the reported results.

Furthermore, Recent studies have proposed strategies to optimize the thermal performance of SGSPs. Integration of reflectors improves energy efficiency by 35%–40% compared to conventional ponds [25]. External heat sources like ETSCs can raise temperatures, though heat addition and removal must be balanced [49]. Proper optimization of layer thickness improves temperature distribution, while mixed media in the LCZ enhances storage capacity [50]. Improvements include composite salt mixtures [51], high-melting-point PCMs for cold seasons [52], and ZnO nanofluids, which increase thermal efficiency by up to 35% [53]. Additionally, spiral coil heat exchangers offer higher heat transfer performance. These optimizations, validated through numerical and experimental approaches, demonstrate pathways for improving SGSP efficiency [54].

In this study, a mathematical model has been discretized by using the finite difference explicit method to study the thermal behavior of a salt gradient pond for the climatic conditions of Islamabad, Pakistan. The temperature distribution within the pond has been calculated for various zone thicknesses. The results obtained showed good approximation with the literature. The following conclusions were made:

• Solar pond is a reliable solar energy collector that can provide more energy in the summer months.

• The thickness of UCZ should be kept small so that losses from the pond surface can be reduced.

• The NCZ acts as an insulating layer and the thickness of the NCZ should be between 1.0 and 1.7 m. The decreasing thickness below 1.0 m increases the conduction losses, and increasing the thickness above 1.5 m does not raise the temperature significantly.

• The thickness of LCZ depends on the end-use application.

• Heat can be extracted at higher temperatures significantly during the summer months.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express a deep sense of gratitude and profound thanks to Dr. Adeel Waqas from NUST Islamabad for help and support this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Mahesh Kumar; methodology, Mahesh Kumar and Rahool Rai; software, Mahesh Kumar; validation, Rahool Rai and Sudhakar Kumarasamy; formal analysis, Mahesh Kumar; investigation, Maesh Kumar and Rahool Rai; data curation, Mahesh Kumar and Sudhakar Kumarasamy; writing—original draft preparation, Mahesh Kumar and Rahool Rai; writing—review and editing, Mahesh Kumar and Sudhakar Kumarasamy; visualization, Mahesh Kumar; supervision, Mahesh Kumar; project administration, Maesh Kumar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Io | Hourly solar radiations |

| Ix | Radiations at depth x |

| IXR | Radiations reflected from pond bottom |

| Tamb | Ambient temperature |

| Tsky | Sky temperature |

| T1 | Upper convective zone temperature |

| Tg | Ground temperature |

| t | Time |

| k | Thermal conductivity |

| kpi | Thermal conductivity of pipe |

| Cp | Specific heat capacity |

| Pv | Partial Pressure |

| Pa | Vapor Pressure |

| Tp | LCZ temperature |

| Tin | Water inlet temperature to heat exchanger |

| Tout | Water outlet temperature to heat exchanger |

References

1. Ahmad SS, Al Rashid A, Raza SA, Zaidi AA, Khan SZ, Koç M. Feasibility analysis of wind energy potential along the coastline of Pakistan. Ain Shams Eng J. 2022;13(1):101542. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2021.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Durrani AA, Khan IA, Ahmad MI. Analysis of electric power generation growth in Pakistan: falling into the vicious cycle of coal. Eng. 2021;2(3):296–311. doi:10.3390/eng2030019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Platikanov S, Tauler R, Cortina JL, Valderrama C. Multivariate analysis of the operational parameters and environmental factors of an industrial solar pond. Sol Energy. 2021;223(12):113–24. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2021.05.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Preet S, Mathur S, Mathur J, Smith ST, Saini H. Multivariate optimization of mechanically ventilated photovoltaic double-skin façade system for the cold conditions of composite climate zone. Build Eng. 2025;3(2):1946. doi:10.59400/be1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Panchal H, Sadasivuni KK, Essa FA, Shanmugan S, Sathyamurthy R. Enhancement of the yield of solar still with the use of solar pond: a review. Heat Trans. 2021;50(2):1392–409. doi:10.1002/htj.21935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. El Mansouri A, Hasnaoui M, Amahmid A, Hasnaoui S. Feasibility analysis of reverse osmosis desalination driven by a solar pond in Mediterranean and semi-arid climates. Energy Convers Manag. 2020;221(1):113190. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen C, Jiang Y, Ye Z, Yang Y, Hou L. Sustainably integrating desalination with solar power to overcome future freshwater scarcity in China. Glob Energy Interconnect. 2019;2(2):98–113. doi:10.1016/j.gloei.2019.07.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tchanche BF, Lambrinos G, Frangoudakis A, Papadakis G. Low-grade heat conversion into power using organic Rankine cycles—a review of various applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2011;15(8):3963–79. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Singh R, Tundee S, Akbarzadeh A. Electric power generation from solar pond using combined thermosyphon and thermoelectric modules. Sol Energy. 2011;85(2):371–8. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2010.11.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Schoeneberger CA, McMillan CA, Kurup P, Akar S, Margolis R, Masanet E. Solar for industrial process heat: a review of technologies, analysis approaches, and potential applications in the United States. Energy. 2020;206(C5):118083. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.118083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rabl A, Nielsen CE. Solar ponds for space heating. Sol Energy. 1975;17(1):1–12. doi:10.1016/0038-092X(75)90011-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sakthivadivel D, Balaji K, Dsilva Winfred Rufuss D, Iniyan S, Suganthi L. Solar energy technologies: principles and applications. In: Renewable-energy-driven future. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2021. p. 3–42. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-820539-6.00001-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Poyyamozhi N, Logesh K, Karthikeyan L, Vengadesan E, Arulprakasajothi M. Comparative analysis of salt gradient solar pond energy storage and PCM-coupled TiO2 nanoparticles for enhanced solar energy utilization. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2025;150(5):3549–57. doi:10.1007/s10973-024-13964-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Elmurodov NS, Kodirov IN, Toshboev AR, Makhamov Kht, Ruzieva ZK, Kurbonov BE. Modeling thermal-technical parameters of a solar pond using COMSOL multiphysics. E3S Web Conf. 2024;583(1):04004. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202458304004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ali MI, Madhu S, Yuvaraj R. Thermal modeling of solar pond in Matlab. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:110481885. [Google Scholar]

16. Abdulsalam A, Idris A, Mohamed TA, Ahsan A. The development and applications of solar pond: a review. Desalin Water Treat. 2015;53(9):2437–49. doi:10.1080/19443994.2013.870710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Uzakov G, Elmurodov N, Toshboev A, Sultonov S. Mathematical modeling the heat balance of a solar pond device. BIO Web Conf. 2023;71(1):02023. doi:10.1051/bioconf/20237102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Husain M, Patil SR, Patil PS, Samdarshi SK. Simple methods for estimation of radiation flux in solar ponds. Energy Convers Manag. 2004;45(2):303–14. doi:10.1016/S0196-8904(03)00122-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jaefarzadeh MR. Thermal behavior of a large salinity-gradient solar pond in the city of Mashhad. Iran J Sci Technol Trans B-Eng. 2005;29(2):219–28. [Google Scholar]

20. Kanan S, Dewsbury J, Lane-Serff G. A simple heat and mass transfer model for salt gradient solar ponds. Int J Mech Ind Sci Eng. 2014;8(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

21. Saxena AK, Sugandhi S, Husain M. Significant depth of ground water table for thermal performance of salt gradient solar pond. Renew Energy. 2009;34(3):790–3. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2008.04.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Amigo J, Meza F, Suárez F. A transient model for temperature prediction in a salt-gradient solar pond and the ground beneath it. Energy. 2017;132(490):257–68. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.05.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Baghizade A, Farahbod F, Alizadeh O. Laboratory and mathematical investigation of salt deposition in a closed solar desalination pond. Env Dev Sustain. 2024;26(8):20583–95. doi:10.1007/s10668-023-03493-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Vinoth Kumar J. Enhancing thermal performance of trapezoidal porous medium solar ponds experimental and numerical analysis. [cited 2025 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.sae.org/content/2025-28-0207. [Google Scholar]

25. Vinoth Kumar J. Exploring trapezoidal salt gradient solar pond performance a combined numerical and experimental analysis with and without reflective covered surface. [cited 2025 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.sae.org/content/2025-28-0201. [Google Scholar]

26. Rghif Y, Colarossi D, Principi P. Effects of double-diffusive convection on calculation time and accuracy results of a salt gradient solar pond: numerical investigation and experimental validation. Sustainability. 2023;15(2):1479. doi:10.3390/su15021479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Anagnostopoulos A, Sebastia-Saez D, Campbell AN, Arellano-Garcia H. Finite element modelling of the thermal performance of salinity gradient solar ponds. Energy. 2020;203(4):117861. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.117861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. El Mansouri A, Hasnaoui M, Amahmid A, Dahani Y. Transient theoretical model for the assessment of three heat exchanger designs in a large-scale salt gradient solar pond: energy and exergy analysis. Energy Convers Manag. 2018;167:45–62. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.04.087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. El Mansouri A, Hasnaoui M, Bennacer R, Amahmid A. Transient thermal performances of a salt gradient solar pond under semi-arid Moroccan climate using a 2D double-diffusive convection model. Energy Convers Manag. 2017;151:199–208. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2017.08.093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. El Mansouri A, Hasnaoui M, Amahmid A, Bennacer R. Transient modeling of a salt gradient solar pond using a hybrid finite-volume and cascaded lattice-boltzmann method: thermal characteristics and stability analysis. Energy Convers Manag. 2018;158:416–29. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2017.12.085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Rghif Y, Zeghmati B, Bahraoui F. Soret and dufour effects on thermal storage and storage efficiency of a salt gradient solar pond. In: 2020 5th International Conference on Renewable Energies for Developing Countries (REDEC); 2020 Jun 29–30; Marrakech, Morocco. doi:10.1109/REDEC49234.2020.9163880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang H, Xie M, Sun W, Ge S. Simulation and experiment of thermal performance of a salt-gradient solar pond. J Eng Thermophys. 2006;27:65–8. [Google Scholar]

33. Li W, Zehforoosh A, Singh Chauhan B, Uday Kumar Nutakki T, Fayaz Ahmad S, Muhammad T, et al. Entropy generation analysis on heat transfer characteristics of twisted corrugated spiral heat exchanger utilized in solar pond. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;52(418–419):103650. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ravandeh A, Feilizadeh M, Bagherpour M. Mathematical modeling and multivariable optimization of the multi-effect distillation coupled to a salt gradient solar pond. Sol Energy. 2025;294:113484. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2025.113484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Khoshvaght-Aliabadi M, Hojjati F, Tae Kang Y. Theoretical analysis to optimize heat extraction from a solar pond integrated with a carbon dioxide heat pump. Energy Convers Manag. 2024;316:118850. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xiao T, Yao XX, Zheng Y. See more from reflection with Fresnel’s equations. Phys Teach. 2025;63(1):56–9. doi:10.1119/5.0169559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Poyyamozhi N, Kumar SS, Kumar RA, Soundararajan G. An investigation into enhancing energy storage capacity of solar ponds integrated with nanoparticles through PCM coupling and RSM optimization. Renew Energy. 2024;221(8):119733. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.119733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chen XL, Zeng L, Duan YF, Zhang HW, Ji P. Observation and modeling of irradiance near water surface of a photovoltaic pond. Sol Energy. 2024;271(8):112442. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2024.112442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Rghif Y, Bahraoui F, Zeghmati B. Experimental and numerical investigations of heat and mass transfer in a salt gradient solar pond under a solar simulator. Sol Energy. 2022;236:841–59. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2022.03.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Escandón R, Calama-González CM, Alonso A, Suárez R, León-Rodríguez ÁL. How do different methods for generating future weather data affect building performance simulations? A comparative analysis of southern europe. Buildings. 2023;13(9):2385. doi:10.3390/buildings13092385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Rodríguez-Urdaneta A. Geographical mapping of the building envelope surface optimal optical properties minimizing the energy used to maintain indoor conditions [master’s thesis]. Le Bourget du Lac, France: European Solar Engineering School; 2020. [Google Scholar]

42. Becker M. Heat transfer: a modern approach. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

43. Sayer AH, Al-Hussaini H, Campbell AN. New comprehensive investigation on the feasibility of the gel solar pond, and a comparison with the salinity gradient solar pond. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;130(5):672–83. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.11.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kasaeian A, Sharifi S, Yan WM. Novel achievements in the development of solar ponds: a review. Sol Energy. 2018;174:189–206. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2018.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sayer AH, Monjezi AA, Campbell AN. Behaviour of a salinity gradient solar pond during two years and the impact of zonal thickness variation on its performance. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;130(1):1191–8. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.11.116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Verma S, Das R. Transient study of a solar pond under heat extraction from non-convective and lower convective zones considering finite effectiveness of exchangers. Sol Energy. 2021;223(2):437–48. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2021.05.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Soğukpinar H, Bozkurt İ. The determination of the heat extraction ratio in the solar pond. Isı Bilim Ve Tek Derg. 2022;42(1):17–24. doi:10.47480/isibted.1106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Derakhshan S, Mirazimzadeh SE, Pazireh S. Study of buoyancy-driven flow effect on salt gradient solar ponds performance. J Energy Resour Technol. 2018;140(10):101203. doi:10.1115/1.4040189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ganguly S, Date A, Akbarzadeh A. Investigation of thermal performance of a solar pond with external heat addition. J Sol Energy Eng. 2018;140(2):024501. doi:10.1115/1.4038788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Assari MR, Tabrizi HB, Parvar M, Nejad AK, Beik AJG. Experiment and optimization of mixed medium effect on small-scale salt gradient solar pond. Sol Energy. 2017;151:102–9. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2017.04.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Sathish D, Jegadheeswaran S. Experimental investigation on a novel composite salt gradient solar pond with an east-west side reflector. J Therm Sci Eng Appl. 2022;14(3):031004. doi:10.1115/1.4051243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Dhaidan NS, Rashid FL, Alkhekany ZAK, Kadhim SA, Hammoodi KA, Al-Obaidi MA, et al. Review of solar pond performance with PCM and NePCM. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2025;166(1):109135. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2025.109135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Beiki H, Soukhtanlou E. Improvement of salt gradient solar ponds’ performance using nanoparticles inside the storage layer. Appl Nanosci. 2019;9(2):243–54. doi:10.1007/s13204-018-0906-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Yakubu M, Shuja SZ, Yilbas BS, Al-Qahtani M. Influence of working fluid on a novel solar pond coil. J Energy Resour Technol. 2021;143(4):042105. doi:10.1115/1.4048260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools