Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Magnetohydrodynamic Jeffrey Nanofluid Flow across an Inclined Stretching Sheet via Porous Media with Slip Effects

1 Department of Mathematics, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Green Fields, Vaddeswaram, 522302, India

2 Department of Mathematics, Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management (Deemed to be University), Visakhapatnam, 530045, India

3 Department of Industrial Systems and Technologies Engineering, University of Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze, 181/A, Parma, 43124, Italy

* Corresponding Authors: Shaik Mohammed Ibrahim. Email: ; Giulio Lorenzini. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(5), 1639-1660. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.069063

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

In this paper, the authors examine various slip effects on the magnetic field and thermal radiative impacts on the flow, mass and heat transfer of a Jeffrey nanofluid over a 2-dimensional inclined stretching sheet by a porous media. The offered work is modelled to be in the form of a combination of coupled highly nonlinear partial differential equations in dimensional contexts. Governing equations were obtained, dimensionless parameters were defined in terms of similarity parameters, and the solutions were obtained by the Homotopy Analysis Method (HAM). The analysis is significant as the effects of viscosity are identified and the important parameters are to be determined that could eventually control a type of flow behaviour, especially in promoting the flow and inhibiting flow of velocity, temperature, and concentrations. The findings show that such an increase in the magnetic parameter decreases the velocity profile by approximately 15% due to more Lorentz forces, and thermal radiation increases the temperature profile by up to 25%, therefore, enhancing the rate of heat transfer. The process of Brownian motion and thermophoresis increases the depth of the thermal boundary layer by 10–20 percent and reduces in concentration profiles by 12 percent when the Brownian motion parameter increases. A velocity slip parameter lowers the velocity field by about 18 percent, and a parameter of permeability lowers the momentum of flow by another 10 percent. The HAM solutions show very high accuracy levels, having an order of convergence at level 15 and error margins are well below 0.01 percent compared to the earlier studies. All these findings can provide profound knowledge in improving heat transmission in non-Newtonian fluid systems and can be used in biomedical engineering, thermal insulation, and industrial processes such as polymer extrusion and cooling technology. Principles of heat and mass transfer give us the crucial foundation on which to study the behavior of heat and material flows in other engineering and scientific disciplines. Such principles apply to various fields of study, including the following engineering fields: mechanical, chemical, aerospace, civil, and environmental.Keywords

Fluids play a crucial role today in all spheres of life, comprising mechanical and chemical engineering, manufacturing, healthcare, and other disciplines connected to several sectors. Based on time-varying, shear-thickening, and shear-thinning characteristics, fluids are classified as non-Newtonian and Newtonian in fluid dynamics. For Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids, many models, like the Buongiorno model, the Casson fluid model, the Jeffery and Williamson models, among others, can be explored to aid researchers in planning upcoming studies to discover more about the fluids’ occult properties.

The idea of Jeffery fluid flow traces back to the foundational studies by Jeffery in 1915, who derived exact solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations for fluid motion in two-dimensional, radially symmetric channels [1,2]. These solutions describe the flow of a viscous fluid between two non-parallel walls meeting at a point, a configuration now widely known as Jeffery flow. Due to its simplicity and practical relevance, especially in systems involving converging or diverging geometries, this model has become a cornerstone in fluid dynamics. Nallapu and Radhakrishnamacharya [3] proposed that the impact of MHD on Jeffrey fluids through a porous media, and as a result, they found that viscosity plays a vital role in thermal and momentum of the Jeffrey fluids flow. Ponalagusamy and Manchi [4] worked on the flow of bioconvection-type situations, including blood flow in a narrowed artery, particularly in the presence of an electromagnetic field. Over time, researchers have extended the classical problem to include more complex physical phenomena [5–7].

The colloidal suspension of nanoparticles ranging from (1–100 nm) in a base fluid, such as water or oil, is known as a nanofluid. These fluids are engineered to improve thermal conductivity and stability of the fluid. In medical science, the superior thermal properties of nanofluids significantly contribute to cancer treatments, drug delivery and cardiovascular treatments. Sus [8] initially proposed the idea of nanofluids; he reported that adding nanoparticles significantly improved thermal performance. As a follow-up, Buongiorno [9] laid the groundwork for the modulation of nanofluid dynamics in complex thermal systems by highlighting the crucial functions of Brownian motion and thermophoresis in improving convective heat and mass transmission. Heat exchangers, electronic cooling, and insulation systems are some of the many potential uses for nanofluids created by distributing nanoparticles of metals, oxides, or carbides into base fluids such as water or ethylene glycol.

The present study focuses on the combined influence of magnetic fields, thermal radiation, and multiple slip effects on Jeffrey nanofluid flow over an inclined stretching sheet embedded in porous media. Jeffrey fluid flow of unsteady oblique at the stagnation point through an oscillating stretching sheet theory was examined by Awan et al. [10]. Hayat et al. [11,12] investigated energy transfer and entropy generation in peristaltic flows and explored radiative effects using modified Darcy’s law with activation energy. The role of variable magnetic field of nanofluid flow in the presence of radiative and reactive components was reported by Mishra et al. [13], while Mohanty et al. [14] derived the same theory of work done by Mishra et al. [13] using the numerical method of finite difference technique. Thermal enhancement of MHD nanofluid flow past a stretchy surface with viscous dissipative and Joule heating was studied by Mishra and Kumar [15]. Further, studies have explored the interplay of thermal radiation with nanoparticle characteristics and geometrical configurations. Ahmed et al. [16] analyzed upward flow over a wavy cone with motile microorganisms, whereas Gangadhar et al. [17] examined exponential heat generation and nonlinear radiation in non-Newtonian nanofluids. Karthik et al. [18] and Pattnaik et al. [19] discussed the roles of thermophoresis and nanoparticle shape on thermal transport. Time-dependent flow over a porous rotating sphere was assessed by Madhukesh et al. [20], taking radiation and mass concentration effects into account. Mishra et al. [21] investigated the combined effects of radiation, Joule heating, and viscous dissipation across porous media containing copper-water and silver-water nanofluids. Many research scholars in their studies [22–26] have given the thermal and momentum characteristics by considering thermal radiation and magnetic effects under different geometries. The examination of fluid flow over an inclined enlarging surface grips momentous importance, given its extensive applications in thermal management structures, as well as heat exchangers, electronic device cooling, polymer extrusion, and nuclear reactor safety [27–29]. Over the last two decades, substantial explore has focused on non-Newtonian nanofluids under multi-slip and magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) circumstances, revealing complex heat and mass transfer features of the studies in Refs. [30–33]. Mabood and Shateyi [34] surveyed MHD Jeffrey nanofluid flow in porous constructions, importance of the behavior of external magnetic fields network with non-Newtonian stresses to yield nonlinear flow behavior. These possessions are pertinent not only in engineering but also in natural phenomena, such as stress-induced events in geophysical flows [35]. Sympathetic to these dynamics is vital for attractive system stability and thermal efficiency under high-stress or high-shear-rate situations. Tedjani [36] initiates that magnetic effects and slip conditions remarkably diminish heat transportation in magnetized non-Newtonian flows. Recent modeling approaches, such as those incorporating Buongiorno’s model and Arrhenius activation energy, have been applied to study convective heat transfer in rotating and porous geometries. Jiang et al. [37] explored heat radiation effects on nanofluid flow through porous media, while Khan et al. [38] examined radiation and chemical reaction effects on Casson fluid flows. The coupled Soret and Dufour effects in chemically reactive magnetized flows were analyzed by Mehta and Kataria [39]. Jeffrey fluid behavior in permeable sheet flow was discussed by Raghunath et al. [40].

Contempt widespread works on MHD nanofluid flows, here lies a distinguished gap in analyzing Jeffrey nanofluid flow over inclined elongating surfaces under multiple slip effects, predominantly in the occurrence of porous media, thermal radiation, chemical reactions, and heat sources. To address this, the contemporary study explores the convective MHD flow of Jeffrey nanofluids by means of the Buongiorno model for nanoparticle transportation, with non-similar transformations to handle the governing nonlinear PDEs. The problem is solved via the Homotopy Analysis Method (HAM), allowing high-accuracy semi-analytical resolutions. This investigation is inspired by the real-world standing of non-Newtonian fluids, such as Jeffrey fluids, in manufacturing and biomedical classifications. These fluids exhibit exceptional Jeffrey nanofluid behavior and are found in plentiful real-world constituents extending from shampoos, sauces, and syrups to pharmacological and food processing products. Applications of Jeffrey nanofluid flows embrace continuous casting, fiber spinning, and glass industry, where flow behavior near inclined, heated surfaces plays a critical role.

i) How do thermal radiation and heat source influence the boundary layer flow and features of thermal transmission of Casson nanofluids?

ii) What is the impact of Brownian motions and thermophoresis on the flow, thermal, and concentration profiles of Casson nanofluids in the presence of multiple slip effects?

iii) In what ways can magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) enhance or reduce the efficiency of heat transfer in Casson nanofluids?

iv) How can the HAM technique solver be utilized effectively to predict the implication of Casson fluid factors on thermal and flow distributions?

v) What is the role of Schmidt number and Prandtl number in optimizing heat transfer and flow dynamics in a Casson nanofluid system?

3 Physical and Mathematical Modelling

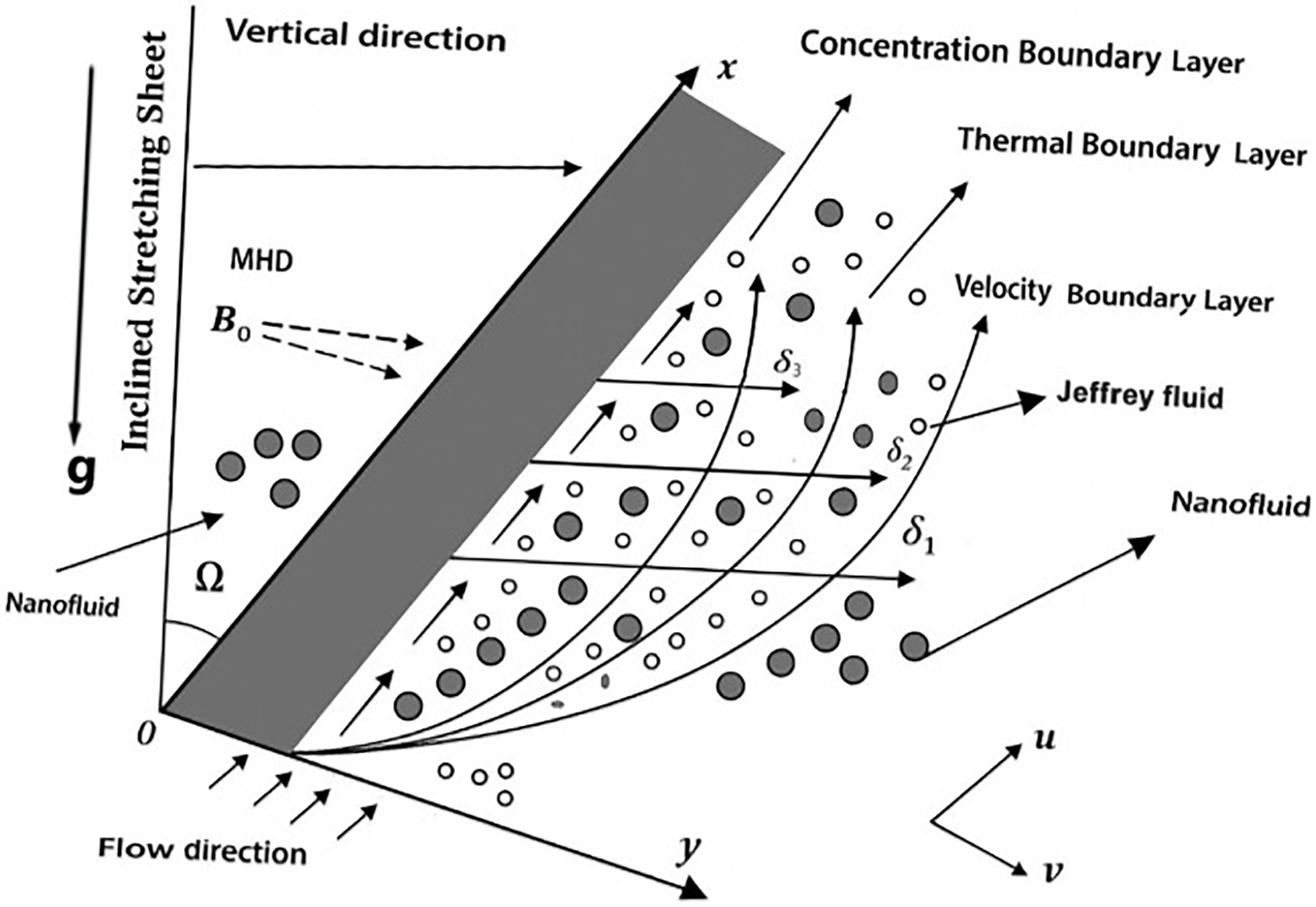

The fluid flow properties, heat and mass transport distribution, and non-Newtonian (Jeffrey) nanofluid behavior when the surface is stretched are studied in this paper. Its performance and its usefulness in practical engineering contexts are illuminated by the investigation. The velocity (stretching sheet) is represented as

Figure 1: Governing physical model

Under Jeffrey nanofluid flow, the following relation governs the Cauchy stress tensor:

Here the dynamic viscosity is represented as

i) To take into consideration the density fluctuations caused by gradients in concentration and temperature in the momentum equation, the Boussinesq approximation is used. We assume that all other thermophysical fluid parameters are constant except density, which adds a buoyancy factor to the momentum formulation.

ii) The study incorporates a linearized form of thermal radiation.

iii) It is Buongiorno’s two-phase method that is used to model the impacts of nanoparticle thermophoresis and Brownian motion.

Based on these assumptions, the following equations describe the flow: mass, momentum, energy, and species concentration in the coordinate system [41].

The (u, v) indicates the component of the velocities (x, y) and the g denotes the gravitational effect,

The suitable boundary constraints are:

where

3.1 Similarity Transformations

Transforming the governing Eqs. (1)–(4) into ordinary differential equations allows us to solve them while considering the boundary condition (5). This is accomplished by making use of the following appropriate similarity transformations.

where

Using Eq. (6) in Eqs. (1)–(4) yields the following system of ordinary differential equations.

Here are the boundary conditions that go along with it:

In this case, we take into account the following non-dimensional variables.

3.2 Physical Quantities of Interest

Many physical quantities matter in industrial and technical system design, comprehension, and optimization. They also improve machinery efficiency and safety.

The x-direction skin friction coefficient

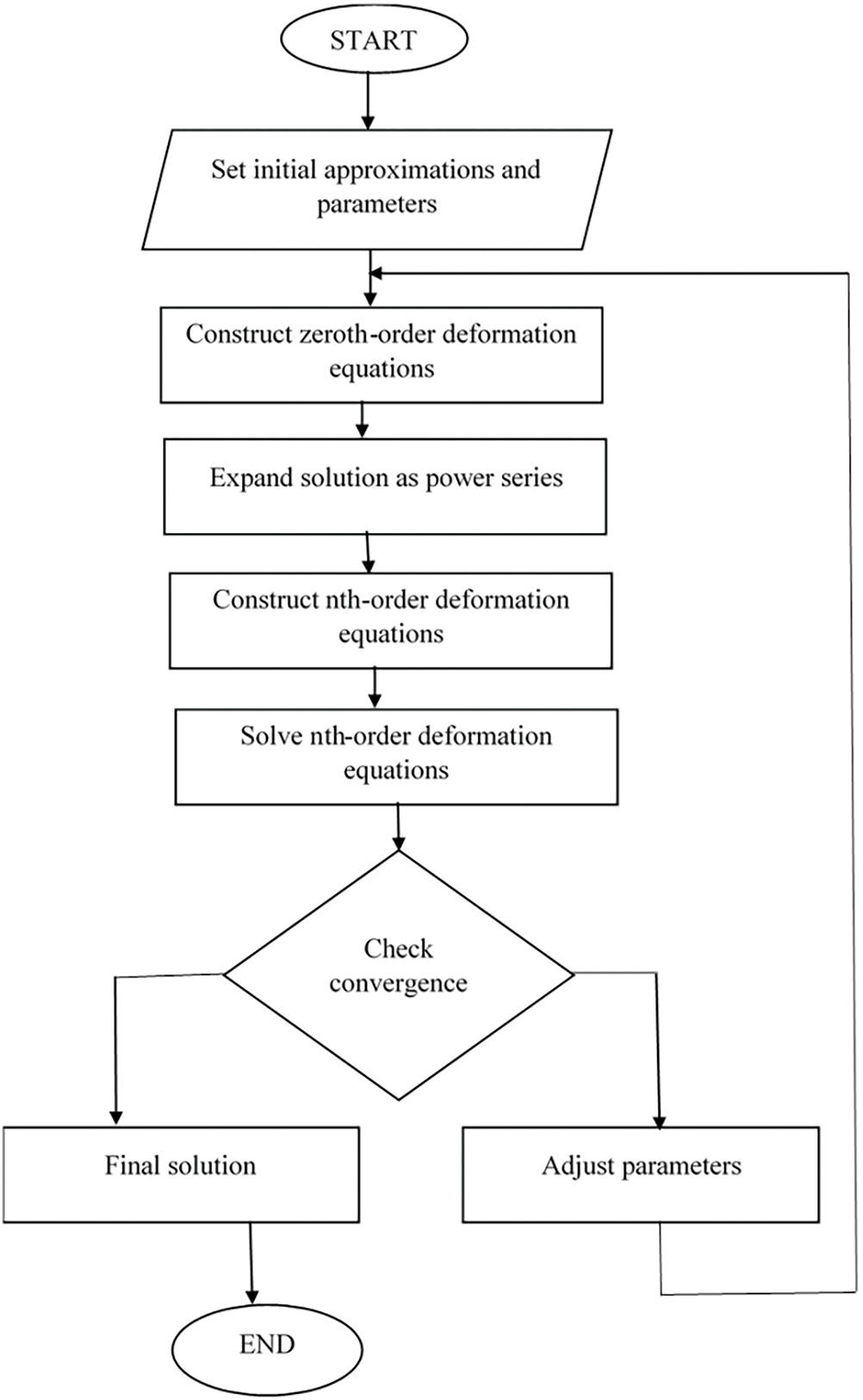

It is demonstrated that the HAM, also known as the Homotopy Analysis Method, is an effective semi-analytical method by the fact that it is utilized in a variety of research projects to handle boundary layer flow issues. As an illustration, it has been successfully utilized to acquire semi-analytical solutions for the thermal convection boundary layer flow of incompressible Casson fluids. These solutions incorporate features such as suction/injection and heat sink effects, both of which are essential in polymer coating applications. In addition, the ability of HAM to handle non-linear boundary value problems has been demonstrated by the fact that it has been utilized to produce mathematical expressions for velocity, heat and mass transfer in boundary layer flows that involve thermal radiation in the presence of multiple slip effects. The approach has also been utilized in the field of MHD, which has shed light on the impact that parameters like magnetic and Prandtl numbers have on flow characteristics. Additionally, the BVPh2.0 program has the capability to ease the implementation of HAM, which enables the efficient computing of solutions in complicated boundary layer situations that involve nanofluids and Jeffrey fluids.

The HAM is utilized to derive analytical solutions for Eqs. (7)–(9), taking into account the boundary conditions specified in Eq. (10). Initial approximations and linear operators are selected for the functions

with

where

Figure 2: Diagrammatic representation of HAM process

We construct the zero-th-order deformation equations:

subject to the boundary conditions.

where

where

The n-th-order deformation equations are follows:

with the following boundary conditions:

where

If we let

where the integral constants

The following linear homogeneous equations can be easily solved using MATHEMATICA in the given order

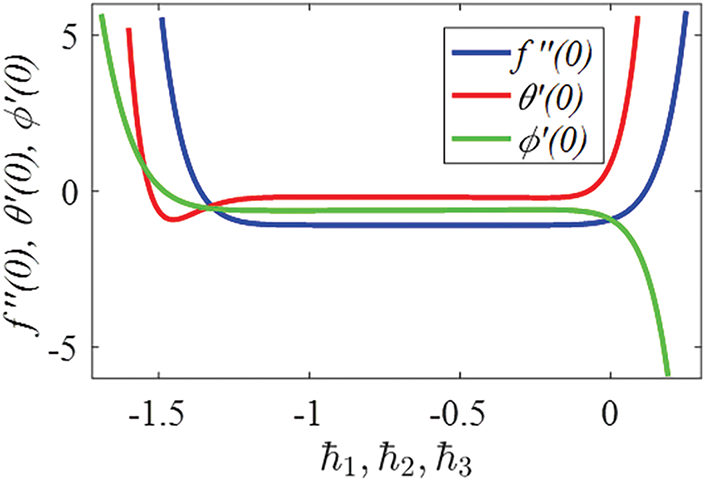

The convergence and interpolation rates of the specific results are notably affected by auxiliary parameters

Figure 3:

The governing system of Eqs. (7)–(9) under conditions (10) has been analyzed using HAM. The graphs are designed to analyze the affected physical characteristics of velocity, temperature, and concentration. This section focuses on the graphical representation of the physical characteristics involved in the flow phenomena.

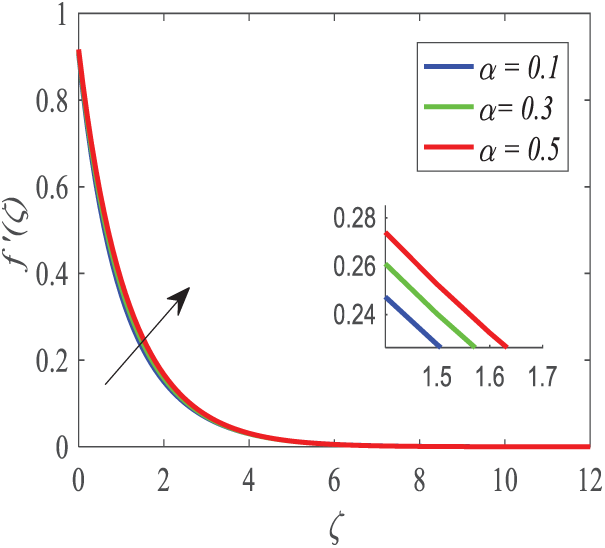

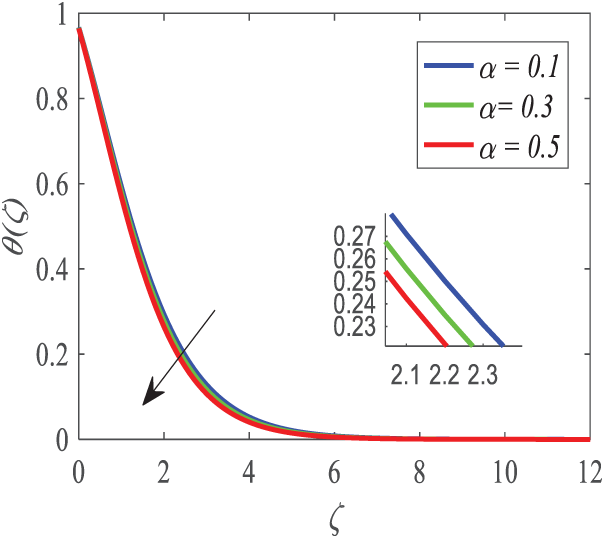

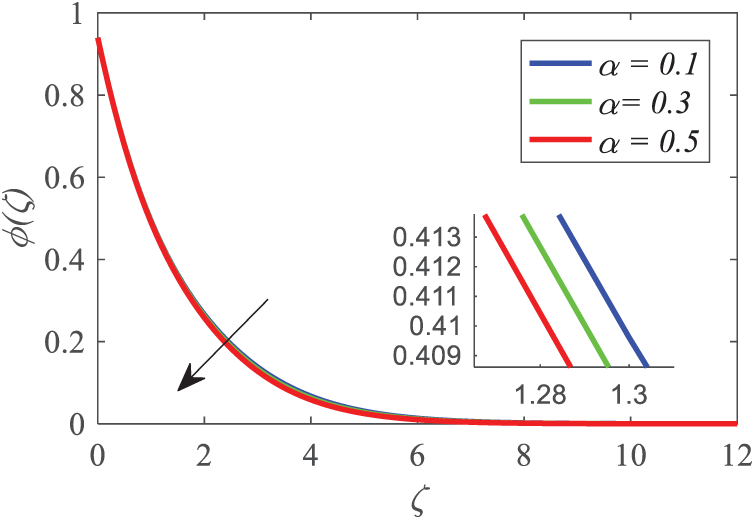

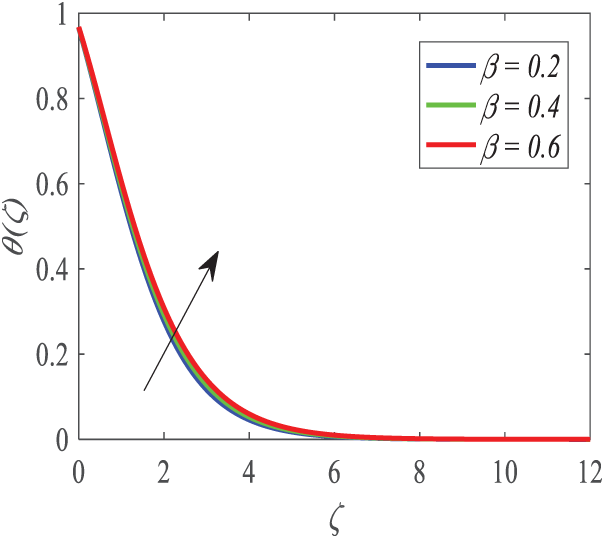

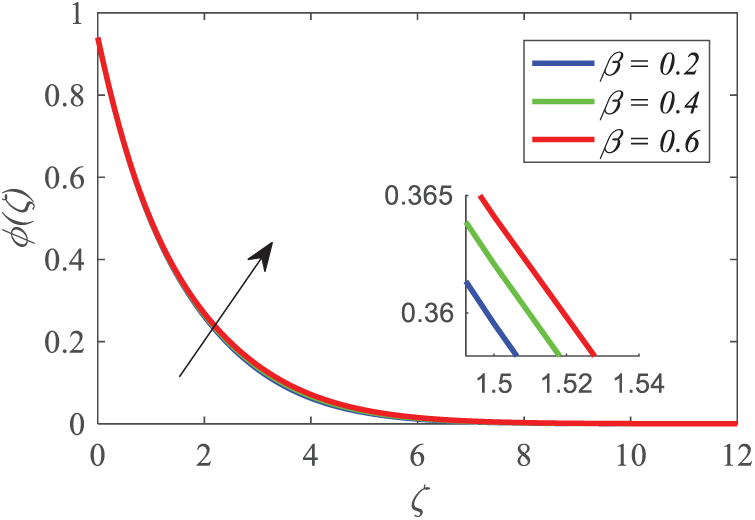

Figs. 4–6 illustrate the effect of the Deborah number parameter

Figure 4: Profiles of

Figure 5: Profiles of

Figure 6: Profiles of

Figs. 5 and 6 indicate that the profiles of temperature and concentration decline when

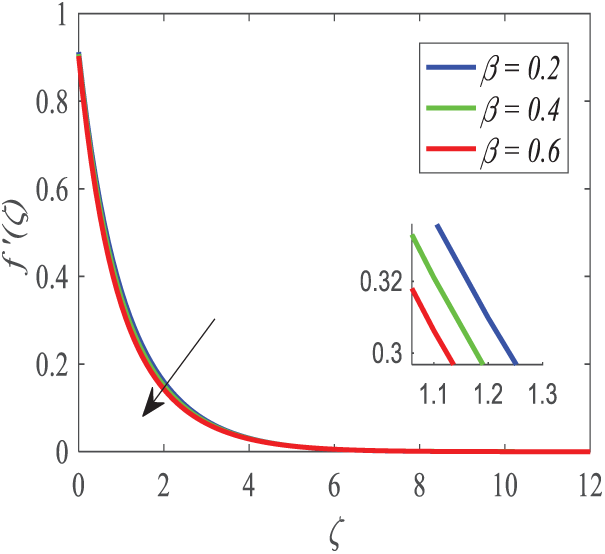

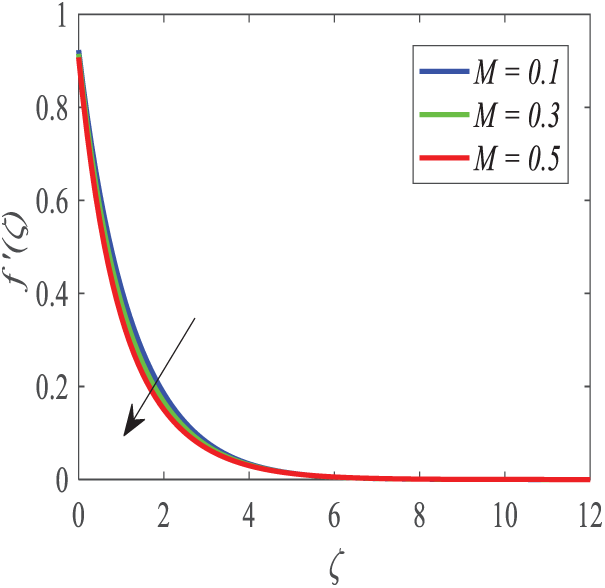

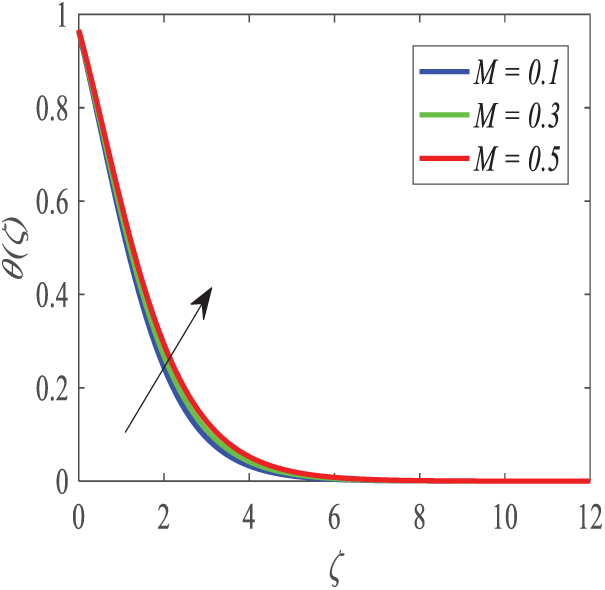

As shown in Fig. 7, the parameter

Figure 7: Profiles of

Figure 8: Profiles of

Figure 9: Profiles of

As shown in Fig. 10, fluid velocity

Figure 10: Profiles of

Figure 11: Profiles of

Figure 12: Profiles of

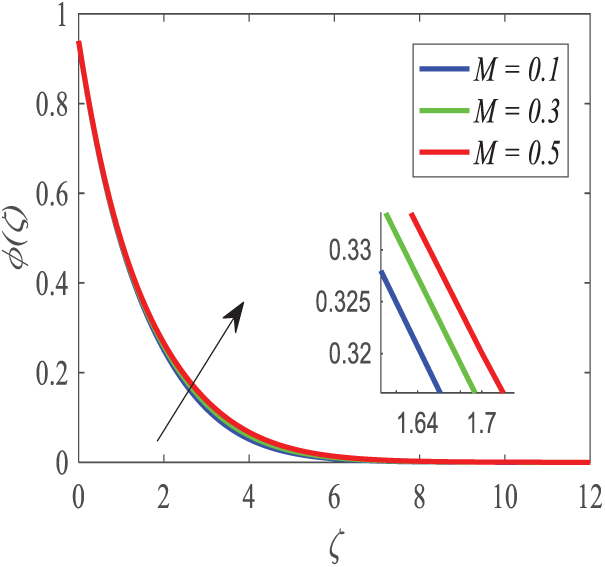

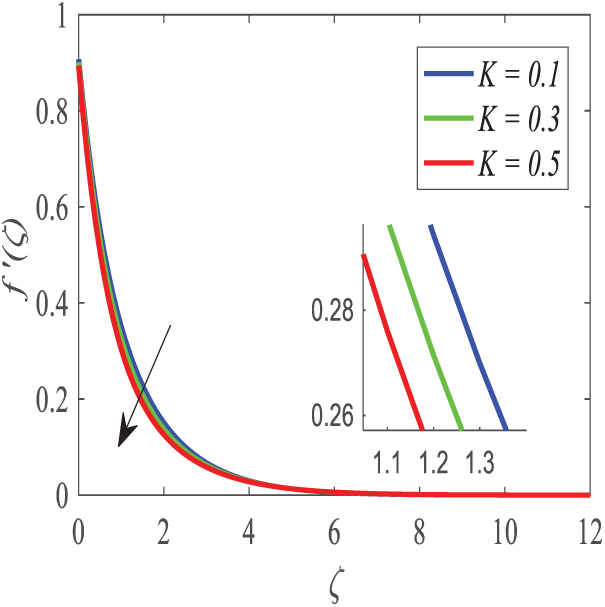

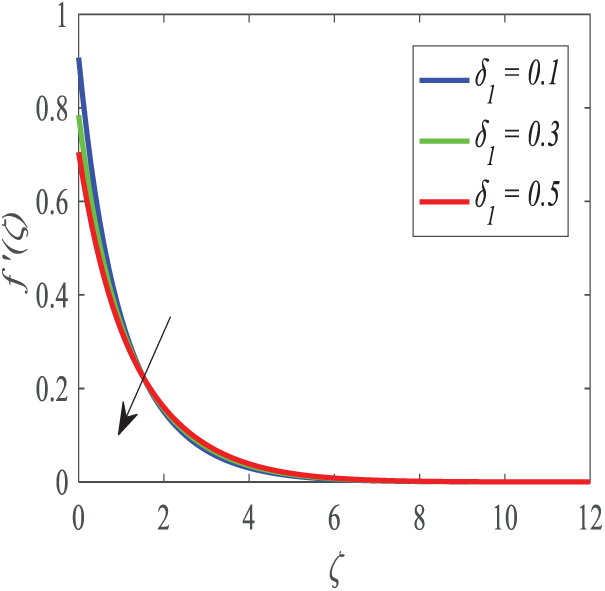

Moreover, as illustrated in Fig. 13, the porosity parameter K increases, resulting in an escalation of the drag force imposed by the porous structure, which counteracts the fluid’s motion and reduces its momentum, thus causing an additional decrease in the velocity distribution. Increased porosity diminishes flow velocity, although it might be beneficial in scenarios where prolonged fluid residence time is necessary for maximum performance. Illustrates the effect of the flow slip parameter

Figure 13: Profiles of

Figure 14: Profiles of

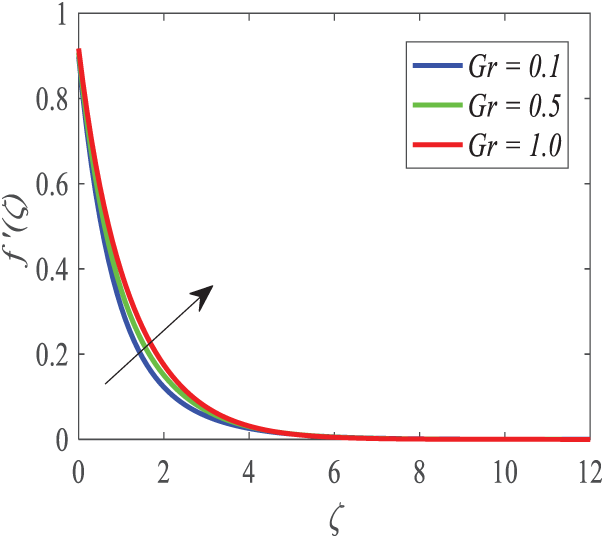

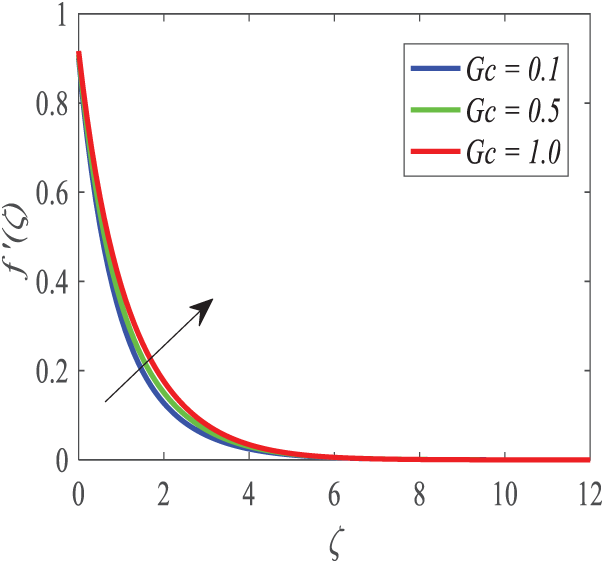

It is found in Fig. 15 that the effect of the local Grashof number

Figure 15: Profiles of

Figure 16: Profiles of

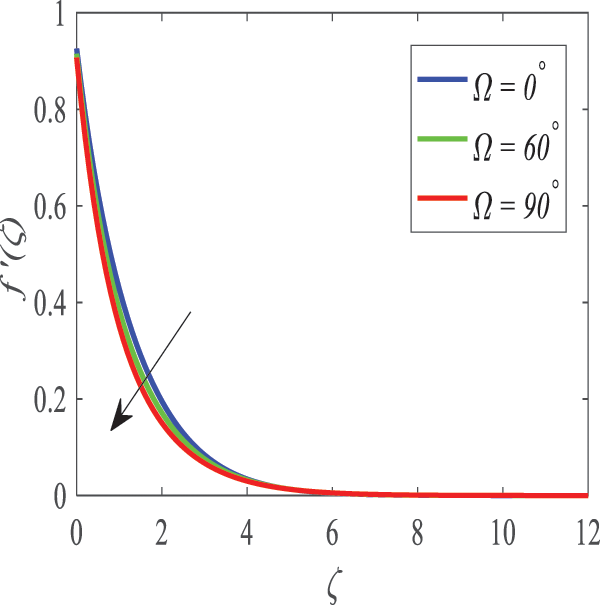

Fig. 17 shows that the velocity reduces with an increase in the inclination angle

Figure 17: Profiles of

Figure 18: Profiles of

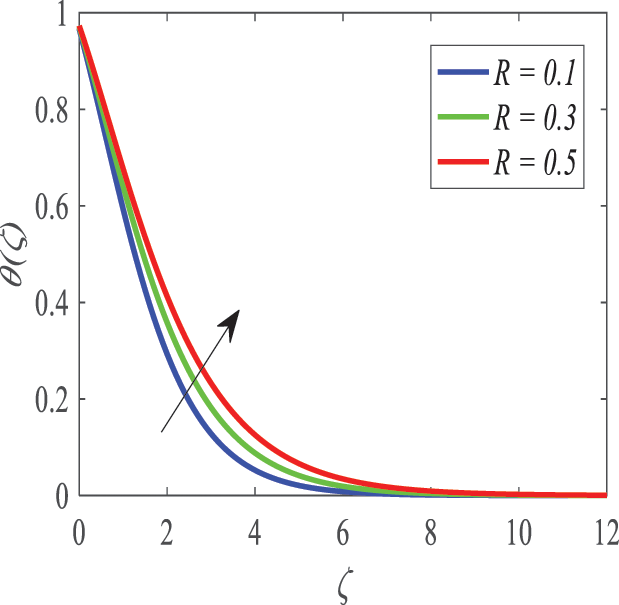

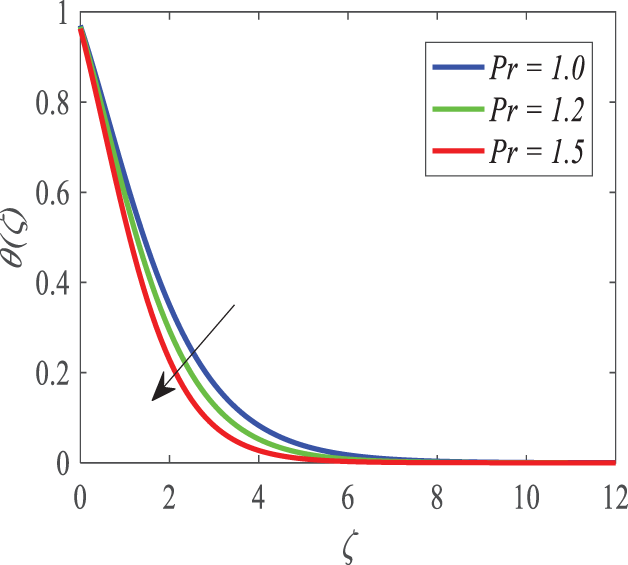

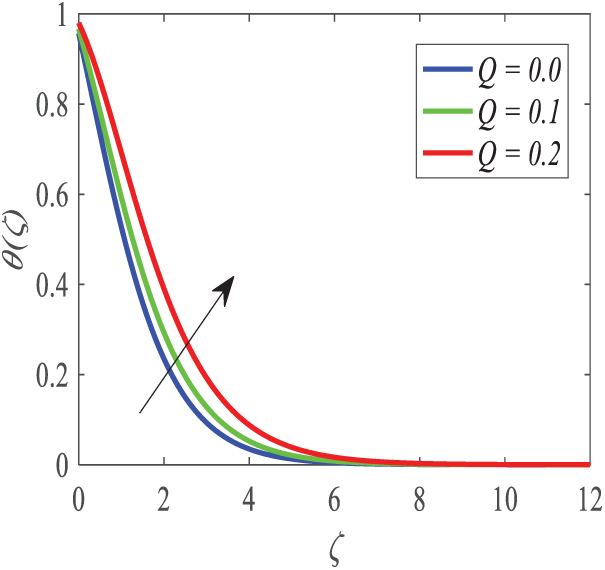

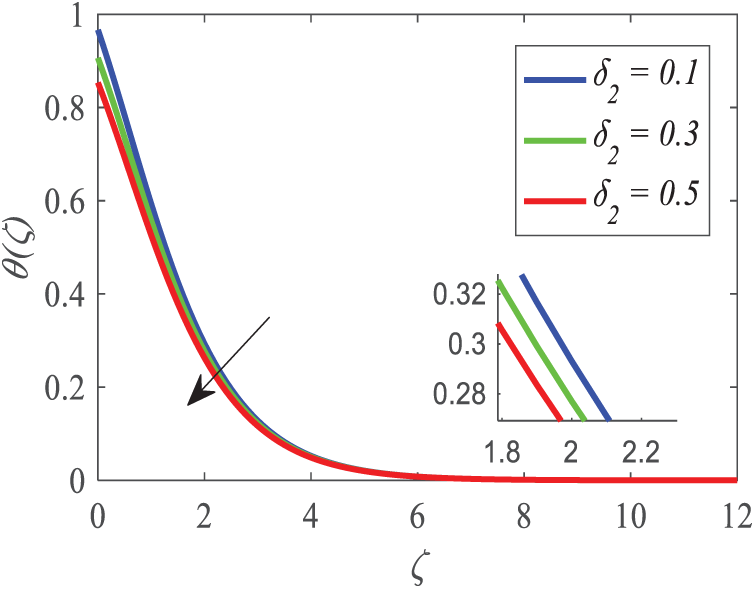

Fig. 19 demonstrates the manner in which Prandtl number Pr influences the distribution of temperature. As Pr increases, the thermal boundary layer decreases and reduces the temperature of the fluid. Since Pr and thermal diffusivity are inversely related, the larger is Prandtl number, the less is heat transfer. It can be seen, as demonstrated in Fig. 20, that the temperature profile is highly influenced by the parameter of heat generation/absorption (Q). Increased production of thermal boundary layer and elevated temperature of a fluid happen with internal heat production in both Q > 0. Conversely, there is a Q < 0, which implies the removal of heat, causing depreciation of fluid thermal energy. The thermal slip parameter (δ2) has an influence on the temperature field as illustrated in Fig. 21. When thermal slip also increases and the barrier becomes increasingly resistant to heat, surface temperature decreases. The decreased thermal insulation enhances energy dissipation, which implies that the thermal boundary layer is smaller and that heat transmission is increased.

Figure 19: Profiles of

Figure 20: Profiles of

Figure 21: Profiles of

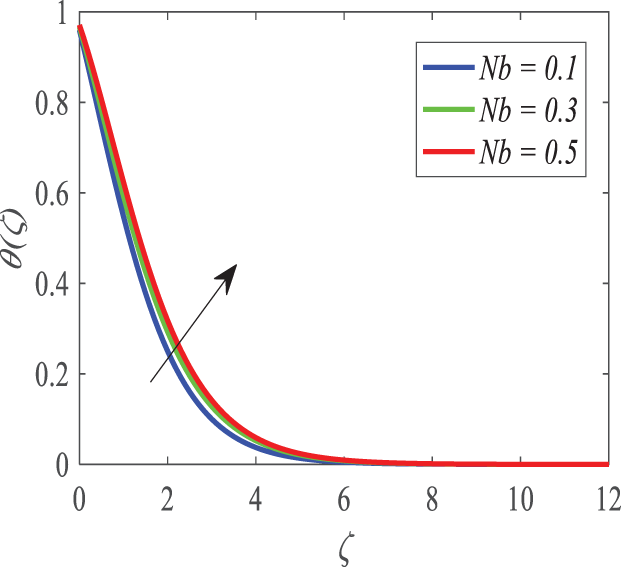

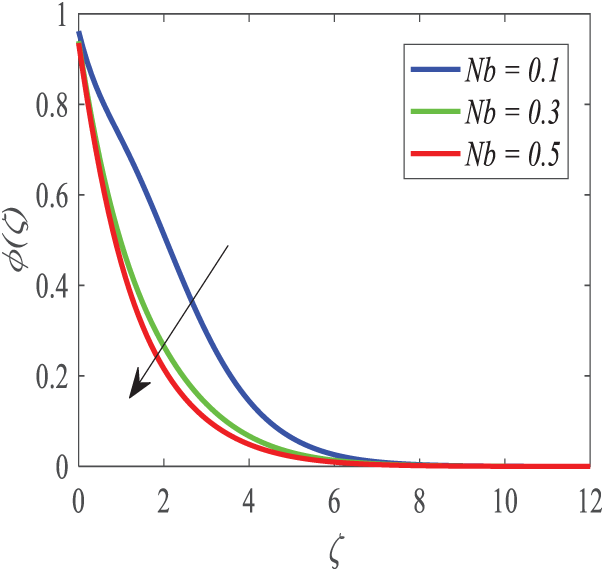

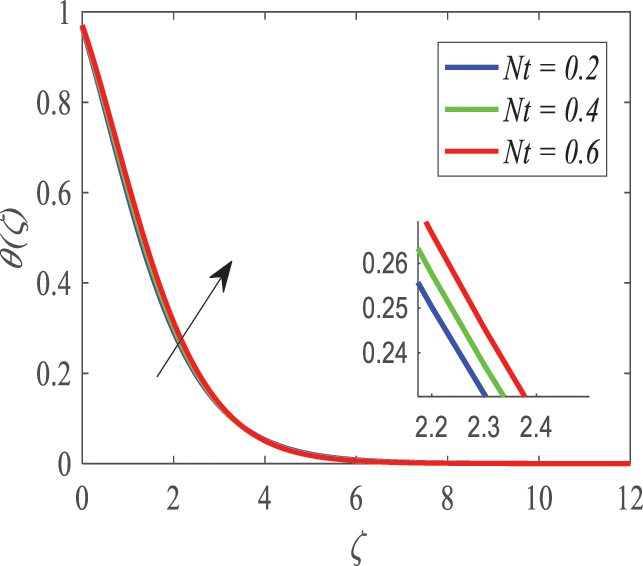

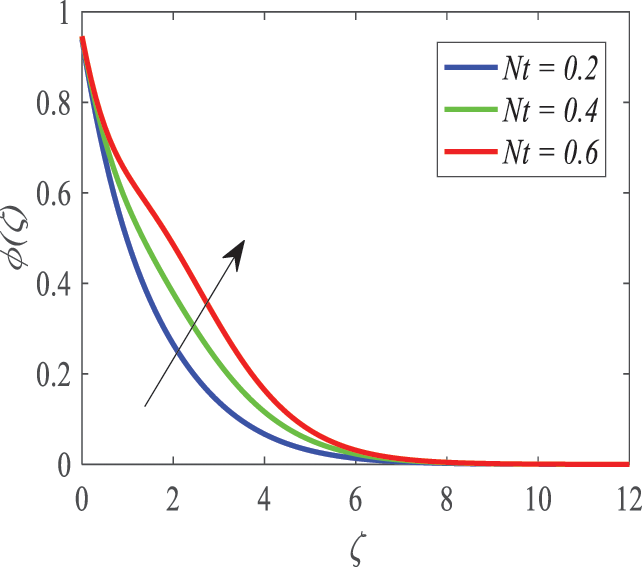

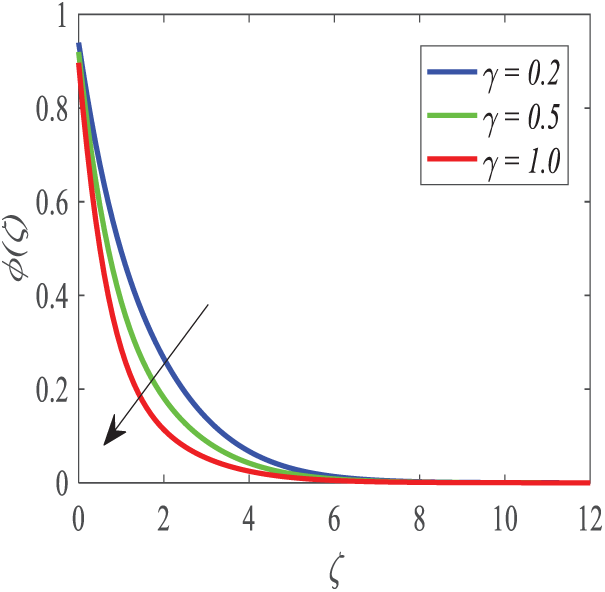

According to Fig. 22, the temperature profile is influenced by the Brownian motion parameter (Nb). The findings indicate that as Nb increases, the thermal boundary layer increases in size since the margins between the boundaries of the thermal boundary layer interspace. This is depicted in Fig. 23, which shows the relationship between the concentration profile and Nb. It has also been observed that the concentration boundary layer is thinner as Nb increases. By analyzing the plots, it can be seen that the thickness of the thermal boundary layer is practically independent of the factor defining the Brownian motion. It can be seen by studying Fig. 24, that the most highly underscored parameters remain limited, resulting in a rise in temperature of the fluid because of the thermophoresis (Nt). The use of large values led to the fact that the fluid temperature increased significantly. The positive force is known as the thermophoretic force, which is the physical force that carries the molecules of fluid in a hot place to a colder place. This force, on the other hand, causes thickening and densification of the thermal boundary layer, increasing the thermal energy of nanoparticle movement. Fig. 25 depicts the impact of the thermophoresis parameter on the concentration of nanoparticles. The concentration and the boundary layer thickness rise with the altitude. This is attributable to the increase in concentration by taking into consideration the high thermal conductivity, brought by an improved Nt.

Figure 22: Profiles of

Figure 23: Profiles of

Figure 24: Profiles of

Figure 25: Profiles of

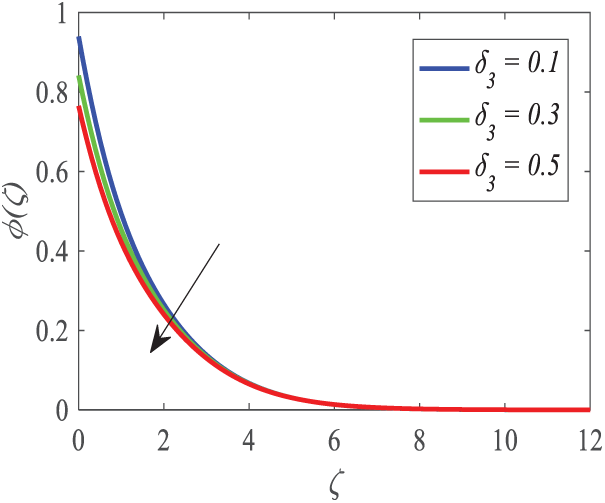

Fig. 26 displays the way the concentration profile changes with the concentration slip parameter

Figure 26: Profiles of

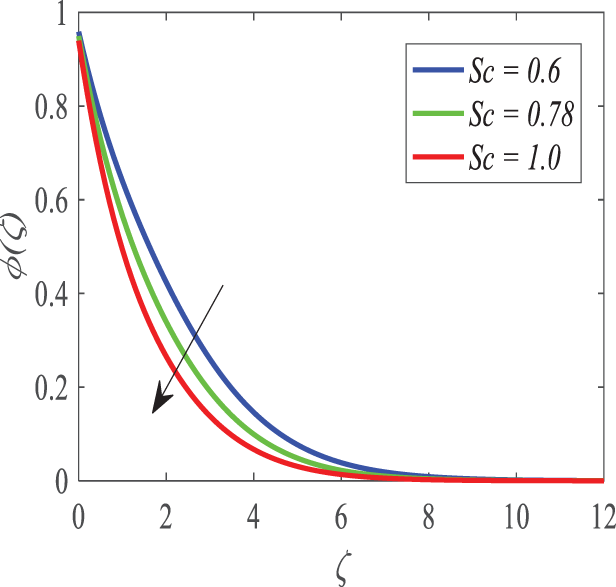

Schmidt number (Sc) affects nanoparticle concentration (Fig. 27). The concentration boundary layer decreases in concentration and thickness as Sc increases. Schmidt number is the ratio of momentum diffusivity to mass diffusivity, explaining this behavior. Higher Sc decreases mass diffusivity, limiting mass transfer and fluid concentration. Fig. 28 shows how the chemical reaction parameter affects dimensionless concentration. In mass transfer fluid flow systems, chemical reactions diminish responding species concentrations by consuming them during diffusion or convection.

Figure 27: Profiles of

Figure 28: Profiles of

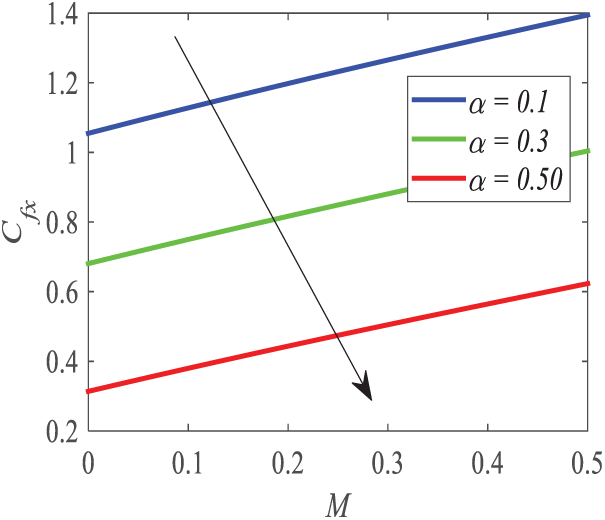

Fig. 29 shows how the skin friction coefficient is influenced by

Figure 29: Profiles of

Figure 30: Profiles of

Figure 31: Profiles of

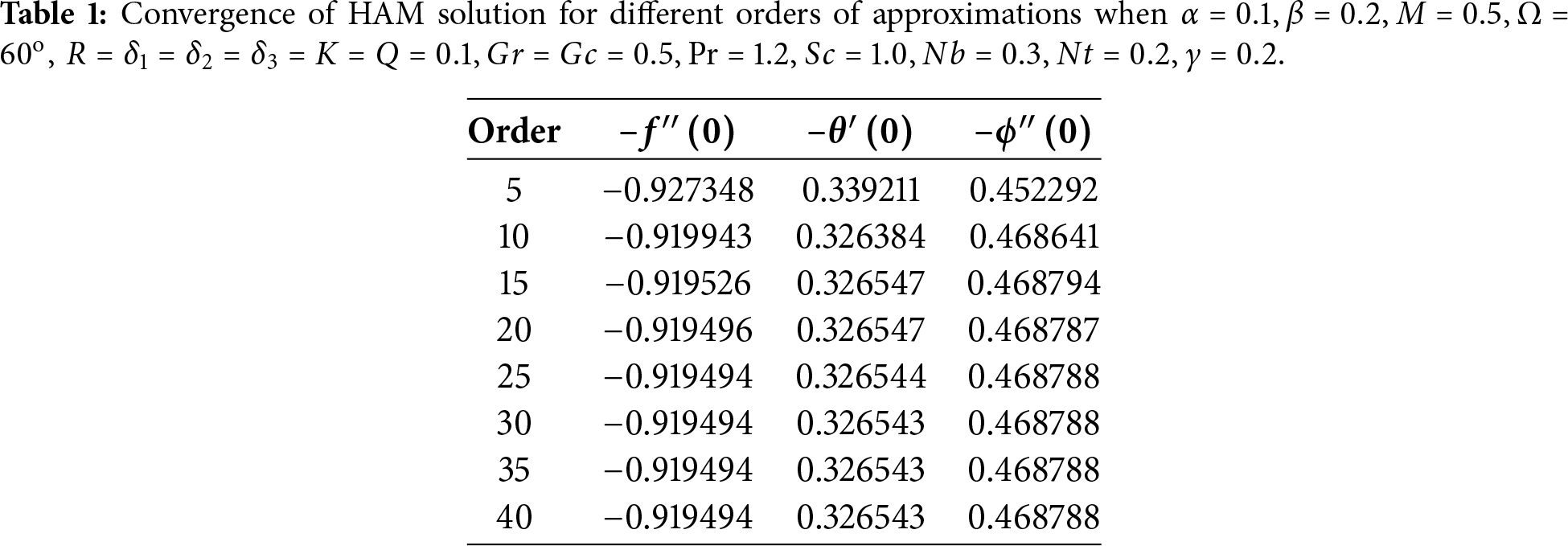

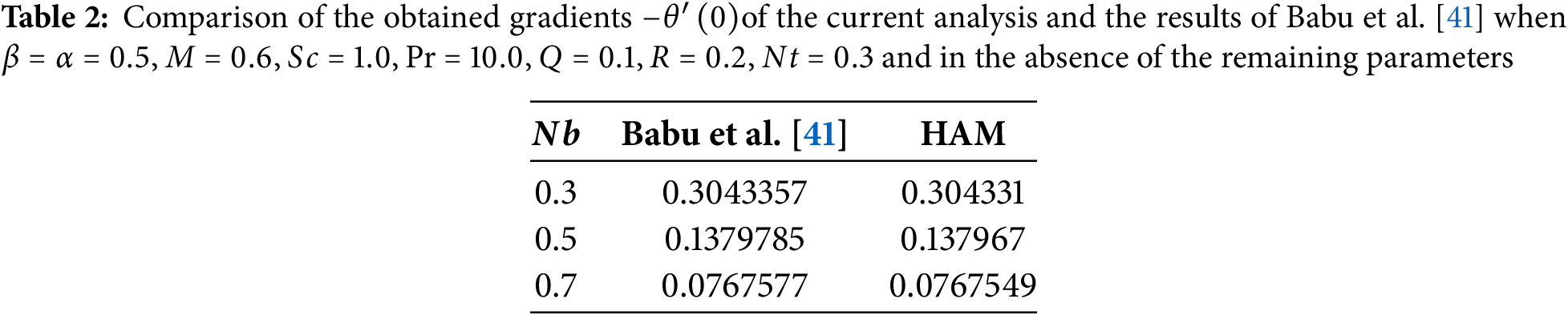

This section presents a comparison between the numerical results for Nusselt number and the findings obtained using the Homotopy Analysis Method (HAM) under limiting conditions, to validate the corresponding results represented by Babu et al. [41]. The close agreement observed between the two sets of results in Table 2 confirms the accuracy and reliability of the current study.

This paper is a numerical study of a Jeffrey nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet inclined in porous media. Besides, the thermal radiation and the heat generation, as well as the chemical reaction and various types of slip conditions, are also considered. The key findings from this analysis are summarized as follows.

• An increase in the magnetic parameter leads to a reduction in the velocity profiles of all nanofluids, attributed to the opposing Lorentz forces, which results in flattened velocity distributions. At the same time, it improves the temperature and concentration profiles by enhancing thermal mixing, especially in the context of the Jeffrey nanofluid.

• The result reveals that the greater values of the velocity slip factor degenerate the flow distribution. Similarly same behavior can be seen through the permeability parameter.

• The higher magnetic, thermophoresis, Brownian motion, and thermal radiation factors improved thermal boundary thickness.

• It is witnessed that the concentration plot retards as a Brownian motion factor, a chemical reaction and concentration slip factors.

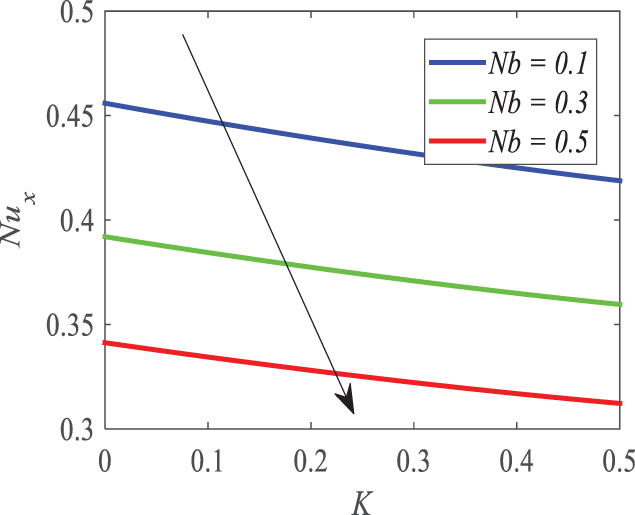

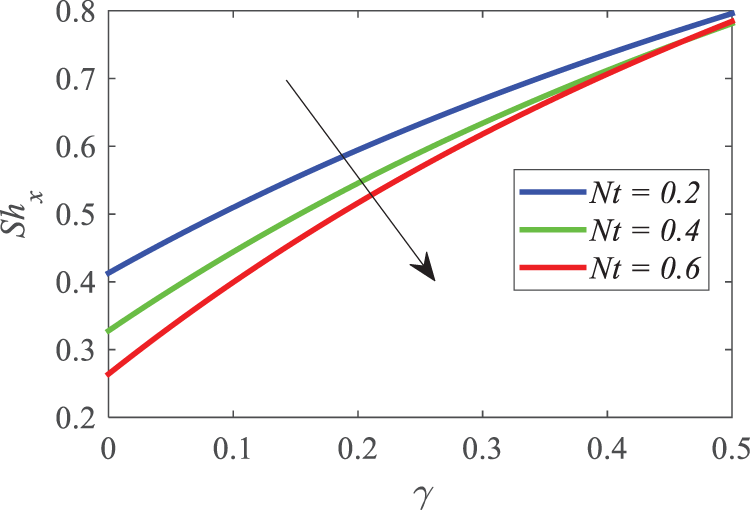

• The surface drag force increases with large estimates of a magnetic parameter. The heat transfer rate comes down when Nb and K. go up. The magnitude of the Sherwood number escalates for increasing estimates of the chemical reaction factor, however, an opposite behavior can be observed through thermophoresis.

• The study’s application of the HAM to predict the velocity and temperature profiles of nanofluids demonstrates its excellent accuracy. This accuracy is attributed to HAM’s capability to effectively handle non-linear differential equations, enabling the simulation of complex fluid behavior under various conditions.

• Various industrial applications can be addressed by expanding the current study to include other diffusive components in the working fluid and considering an unsteady condition.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Shaik Mohammed Ibrahim assigned the work contained in this paper to Pennelli Saila Kumari as part of her dissertation. Under his supervision, Pennelli Saila Kumari formulated the problem mathematically to develop an in-house source code framework. She conducted the simulation tests and validated the code with assistance from Prathi Vijaya Kumar. Subsequently, simulation runs were performed to generate the data presented in the paper. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by Pennelli Saila Kumari. After discussing the findings, Giulio Lorenzini co-supervised the research and collaborated on preparing the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Requests for data can be made at any time.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | SI Units |

| ms-1 | |

| T (Temperature) | K (kelvin) |

| radian (rad) | |

| T (Temperature) | Kelvin (K) |

| Kelvin (K) | |

| φ(ζ) (Concentration field) | |

| M (Magnetic parameter) | |

| k* (Mean absorption coefficient) | |

| Q (Heat generation coefficient) | |

| Pr (Prandtl number) | |

| Subscripts | |

References

1. Erdoğan ME. On a non-Newtonian fluid. Acta Mech. 1978;30(1):79–88. doi:10.1007/BF01177439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Barman PC, Kairi RR, Das A, Islam R. An overview of non-Newtonian fluid. Int J Appl Sci Eng. 2016;4(2):97. doi:10.5958/2322-0465.2016.00011.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Nallapu S, Radhakrishnamacharya G. Jeffrey fluid flow through porous medium in the presence of magnetic field in narrow tubes. Int J Eng Math. 2014;2014(1):713831. doi:10.1155/2014/713831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ponalagusamy R, Manchi R. Particle-fluid two phase modeling of electro-magneto hydrodynamic pulsatile flow of Jeffrey fluid in a constricted tube under periodic body acceleration. Eur J Mech B Fluids. 2020;81(3):76–92. doi:10.1016/j.euromechflu.2020.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Thoubaan MG, Al-Khafajy DGS, Wanas AK, Breaz D, Cotîrlă LI. Analysis of a bifurcation and stability of equilibrium points for Jeffrey fluid flow through a non-uniform channel. Symmetry. 2024;16(9):1144. doi:10.3390/sym16091144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Muthukumar DS, Kibanya NN, Metsebo J, Sekhar DC, Kuiate GF. Jeffrey fluid saturating a heated porous layer: dynamical and microcontroller execution probing. Phys Scr. 2024;99(7):075282. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/ad5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Didyala S, Ragoju R, Reddy GSK, Yadav D. Effect of throughflow on the study of linear and weakly nonlinear stability analysis of Jeffrey fluids in an anisotropic porous layer. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2024:1–16. doi:10.1080/10407782.2024.2361471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sus C. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluid with nanoparticles, developments, and applications of non-Newtonian flow. In: ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition; 1995 Nov 12–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 99–105. [Google Scholar]

9. Buongiorno J. Convective transmission in nanofluids. J Heat Transf. 2006;128(3):240–50. doi:10.1115/1.2150834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Awan AU, Abid S, Abbas N. Theoretical study of unsteady oblique stagnation point based Jeffrey nanofluid flow over an oscillatory stretching sheet. Adv Mech Eng. 2020;12(11):1687814020971881. doi:10.1177/1687814020971881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hayat T, Farooq S, Ahmad B, Alsaedi A. Effectiveness of entropy generation and energy transfer on peristaltic flow of Jeffrey material with Darcy resistance. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017;106:244–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.10.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hayat T, Bibi F, Farooq S, Khan AA. Nonlinear radiative peristaltic flow of Jeffrey nanofluid with activation energy and modified Darcy’s law. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng. 2019;41(7):296. doi:10.1007/s40430-019-1771-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mishra P, Acharya MR, Panda S. Mixed convection MHD nanofluid flow over a wedge with temperature-dependent heat source. Pramana. 2021;95(2):52. doi:10.1007/s12043-021-02087-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mohanty B, Jena S, Pattnaik PK. MHD nanofluid flow over stretching/shrinking surface in presence of heat radiation using numerical method. Int J Emerg Technol. 2019;10(2):119–25. [Google Scholar]

15. Mishra A, Kumar M. Thermal performance of MHD nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet due to viscous dissipation, joule heating and thermal radiation. Int J Appl Comput Math. 2020;6(4):123. doi:10.1007/s40819-020-00869-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ahmed SE, Arafa AAM, Hussein SA. A novel model of non-linear radiative Williamson nanofluid flow along a vertical wavy cone in the presence of gyrotactic microorganisms. Int J Model Simul. 2025;45(1):68–82. doi:10.1080/02286203.2023.2180023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gangadhar K, Prameela M, Chamkha AJ. Exponential space-dependent heat generation on Powell-Eyring hybrid nanoliquid under nonlinear thermal radiation. Indian J Phys. 2023;97(8):2461–73. doi:10.1007/s12648-022-02585-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Karthik K, Madhukesh JK, Kiran S, Nagaraja KV, Prasannakumara BC, Fehmi G. Impacts of thermophoretic deposition and thermal radiation on heat and mass transfer analysis of ternary nanofluid flow across a wedge. Int J Model Simul. 2024;2024(4):1–13. doi:10.1080/02286203.2023.2298234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pattnaik PK, Pattnaik JR, Mishra SR, Nisar KS. Variation of the shape of Fe3O4-nanoparticles on the heat transfer phenomenon with the inclusion of thermal radiation. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2022;147(3):2537–48. doi:10.1007/s10973-021-10605-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Madhukesh JK, Sahar F, Prasannakumara BC, Shehzad SA. Waste discharge concentration and quadratic thermal radiation influences on time-dependent nanofluid flow over a porous rotating sphere. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2025;86(7):2357–75. doi:10.1080/10407790.2024.2336205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mishra A, Kumar M. Viscous dissipation and joule heating influences past a stretching sheet in a porous medium with thermal radiation saturated by silver-water and copper-water nanofluids. Special Topics Rev Porous Media. 2019;10(2):171–86. doi:10.1615/specialtopicsrevporousmedia.2018026706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ahmed SE, Arafa AAM, Hussein SA. Dissipated-radiative compressible flow of nanofluids over unsmoothed inclined surfaces with variable properties. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2023;84(5):507–28. doi:10.1080/10407782.2022.2141389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gangadhar K, Kumari MA, Venkata Subba Rao M, Chamkha AJ. Oldroyd-B nanoliquid flow through a triple stratified medium submerged with gyrotactic bioconvection and nonlinear radiations. Arab J Sci Eng. 2022;47(7):8863–75. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-06412-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hussein SA. Numerical simulation for peristaltic transport of radiative and dissipative MHD Prandtl nanofluid through the vertical asymmetric channel in the presence of double diffusion convection. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2024;85(4):385–411. doi:10.1080/10407790.2023.2235886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gangadhar K, Sujana Sree T, Thumma T. Impact of Arrhenius energy and irregular heat absorption on generalized second grade fluid MHD flow over nonlinear elongating surface with thermal radiation and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux theory. Mod Phys Lett B. 2024;38(11):2450077. doi:10.1142/s0217984924500775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Prakash SB, Chandan K, Karthik K, Devanathan S, Varun Kumar RS, Nagaraja KV, et al. Investigation of the thermal analysis of a wavy fin with radiation impact: an application of extreme learning machine. Phys Scr. 2024;99(1):015225. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/ad131f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Veena N, Abraham A, Idicula JJ, Dinesh PA. A study on heat and flow of viscoelastic dielectric liquid over an inclined stretching sheet. J Mines Met Fuels. 2023:2278–88. doi:10.18311/jmmf/2023/36048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sobhana Babu PR, Murthy DVNSR, Srinivasulu C, Srinivasa Rao D, Ravindra N, Ramachandram VVS. Influence of joule heating on Burgers fluid subject to of chemical responses towards an inclined stretching sheet. J Nanofluids. 2024;13(1):28–40. doi:10.1166/jon.2024.2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Suriyakumar P, Suresh Kumar S, Muthtamilselvan M. A revised model on three-dimensional hydromagnetic convective flow of nanofluids over a nonlinearly inclined stretching sheet. Int J Mod Phys B. 2024;38(28):2450383. doi:10.1142/s0217979224503831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Oladapo OA, Akindele AO, Obalalu AM, Ajala OA. Important of slip effects in non-Newtonian nanofluid flow with heat generation for enhanced heat transfer devices. In: Defect and diffusion forum. Vol. 431. Wollerau, Switzerland: Trans Tech Publications, Ltd; 2024. p. 147–62. doi:10.4028/p-baacr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Das K, Sutradhar B, Kundu PK. Framing the effects of multiple slips on squeezing flow of chemical reacting hybrid nanofluid between two parallel discs. J Nanofluids. 2024;13(4):1009–20. doi:10.1166/jon.2024.2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Alhadri M, Riaz S, Khan SU, Nadeem MS, Ali Q, Kolsi L. Multiple slip flow of nanofluid with bioconvective transport phenomenon and porosity effects. Int J Model Simul. 2024;2024(1):1–10. doi:10.1080/02286203.2024.2338582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kanimozhi N, Vijayaragavan R, Rushi Kumar B. Impacts of multiple slip on magnetohydrodynamic Williamson and Maxwell nanofluid over a stretching sheet saturated in a porous medium. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2024;85(3):344–60. doi:10.1080/10407790.2023.2235079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mabood F, Shateyi S. Multiple slip effects on MHD unsteady flow heat and mass transfer impinging on permeable stretching sheet with radiation. Model Simul Eng. 2019;2019(1):3052790. doi:10.1155/2019/3052790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Jean S. Multiphysics aspects of seismic slip. Eur J Environ Civ Eng. 2009;13(7–8):889–910. doi:10.1080/19648189.2009.9693160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Tedjani AH. Numerical treatment via the spectral collocation method for Casson-Williamson nanofluid flow due to a stretching sheet with slip conditions. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;51(5):103588. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jiang Y, Sun H, Bai Y, Zhang Y. MHD flow, radiation heat and mass transfer of fractional Burgers’ fluid in porous medium with chemical reaction. Comput Math Appl. 2022;115:68–79. doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2022.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Khan Z, Rasheed HU, Khan I, Abu-Zinadah H, Aldahlan MA. Mathematical simulation of casson MHD flow through a permeable moving wedge with nonlinear chemical reaction and nonlinear thermal radiation. Materials. 2022;15(3). doi:10.3390/ma15030747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Mehta R, Kataria HR. Brownian motion and thermophoresis effects on MHD flow of viscoelastic fluid over stretching/shrinking sheet in the presence of thermal radiation and chemical reaction. Heat Transf. 2022;51(1):274–95. doi:10.1002/htj.22307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Raghunath K, Ganteda C, Lorenzini G. Effects of soret, rotation, Hall, and ion slip on unsteady MHD flow of a Jeffrey fluid through a porous medium in the presence of heat absorption and chemical reaction. J Mech Eng Res Dev. 2022;45(3):80–97. doi:10.52783/cana.v31.4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Babu DH, Ajmath KA, Venkateswarlu B, Satya Narayana PV. Thermal radiation and heat source effects on MHD non-Newtonian nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet. J Nanofluids. 2018;8(5):1085–92. doi:10.1166/jon.2019.1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools